Farmacotherapie

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is de plaats van farmacotherapie bij PTSS?

De uitgangsvraag omvat de volgende deelvragen:

- What are the benefits and risks of anti-depressants (SNRIs, SSRIs, NaSSaS, RIMAs, TCAs, MAIOs), compared with placebo for patients with PTSS?

- What are the benefits and risks of hypnotics (benzodiazepines and benzodiazepine-agonists) compared with placebo for patients with PTSS?

- What are the benefits and risks of anticonvulsants compared with placebo for patients with PTSS?

- What are the benefits and risks of alfa blockers compared with a placebo for patients with PTSS?

- What are the benefits and risks of antipsychotics compared with placebo for patients with PTSS?

- What are the benefits and risks of dopamine beta-hydroxylase inhibitors compared with placebo for patients with PTSS?

- What are the benefits and risks of ganaxalone compared with placebo for patients with PTSS?

Aanbeveling

Start een behandeling voor PTSS niet met farmacotherapie.

Overweeg farmacotherapie alleen voor een symptoomgerichte aanpak

- bij ernstige PTSS klachten,

- bij onvoldoende respons op psychologische behandeling als er geen directe toegang tot psychologische behandeling is.

Wees te allen tijde zeer terughoudend met het voorschrijven van benzodiazepines.

Hanteer altijd het principe van gezamenlijke besluitvorming (‘shared decision making’) bij het indiceren, voorschrijven en het al dan niet continueren van farmacotherapie.

Voorzie de patiënt van adequate informatie over de medicatie, zoals dosering, instructies, voorlichting, waarschuwingen, effecten, bijwerkingen en afbouwschema.

Monitor de respons en overweeg een andere vorm van (symptoomgerichte) farmacotherapie bij onvoldoende respons

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

De wetenschappelijke onderbouwing voor de effectiviteit van de meeste farmacotherapeutische middelen bij de behandeling van PTSS is overwegend zwak. De huidige onderzoeken slagen er niet in overtuigend aan te tonen dat deze middelen daadwerkelijk effectief zijn in het verlichten van PTSS-symptomen (Williams et al., 2022).

Hoewel er soms enig bewijs voor effectiviteit bestaat, is dit vaak onvoldoende om tot duidelijke conclusies te komen, grotendeels vanwege de beperkingen in de studieopzet, zoals korte behandelperioden, gebrekkige randomisatie, kleine steekproeven en inconsistente resultaten. Zo zijn de behandelperioden vaak te kort om een volledig beeld te krijgen van de effectiviteit van de middelen op lange termijn. Daarnaast is er sprake van onduidelijkheid en problemen met betrekking tot de randomisatie en de toewijzing van behandelingen, wat kan leiden tot vertekeningen in de resultaten. Ook zijn de onderzoeksgroepen vaak te klein, wat de statistische kracht van de bevindingen vermindert en de betrouwbaarheid van de resultaten in twijfel trekt. De brede betrouwbaarheidsintervallen wijzen op een aanzienlijke mate van onzekerheid, en de onderzoeksresultaten zijn vaak heterogeen, wat betekent dat er veel variatie is tussen de bevindingen van verschillende studies. Bovendien lijkt het percentage uitvallers tijdens de behandeling vergelijkbaar te zijn tussen de verschillende onderzochte middelen en placebo, wat de bewijskracht voor effectiviteit verder ondermijnt.

Er werden geen resultaten gerapporteerd voor de uitkomstmaat ‘loss of diagnosis’. De gevolgen voor de kwaliteit van leven werden slechts beperkt gerapporteerd en alleen voor de alfablokker prazosine, waarbij geen effect op de vermindering van PTSS symptomen werd gevonden in vergelijking met placebo. Uit onze analyse blijkt dat er geen overtuigend bewijs is dat farmacotherapie een klinisch effectieve behandelmethode is voor PTSS-patiënten.

Deze bevindingen suggereren dat de positie van farmacotherapie ten opzichte van de eerdere richtlijn heroverwogen moet worden. Benzodiazepinen nemen hierin een opmerkelijke positie in, aangezien ze nog steeds veelvuldig worden voorgeschreven. Er zijn echter aanwijzingen uit studies dat het gebruik van benzodiazepinen het risico op het ontwikkelen van PTSS kan verhogen (Campos, 2022). Bovendien bieden benzodiazepinen geen langdurige of effectieve oplossing voor de behandeling van PTSS (Guina, 2015).

Vanwege de risico's op afhankelijkheid en het gebrek aan substantiële ondersteuning voor de effectiviteit ervan, wordt geadviseerd uiterst terughoudend te zijn bij het gebruik van benzodiazepines als onderdeel van de behandeling van PTSS. Het terugdringen van het voorschrijven van benzodiazepinen kan effectief worden gerealiseerd door het bevorderen van alternatieve behandelingsopties die bewezen effectief zijn. Bovendien kan ondersteuning worden geboden voor het stoppen met benzodiazepinen door verschillende afbouwstrategieën aan te bieden.

Kwaliteit van het bewijs

I Vergelijking van Farmacotherapie en Placebo

Placebo-gecontroleerde gerandomiseerde gecontroleerde onderzoeken (RCT's) spelen een belangrijke rol in het klinisch onderzoek naar de behandeling van PTSS. Dit komt vooral door de noodzaak om objectief bewijs te verzamelen over de effectiviteit van nieuwe therapieën. RCTs zijn essentieel voor het verkrijgen van regelgevende goedkeuring voor nieuwe medicijnen. Bovendien bieden ze een consistente vergelijkingsbasis om de werkzaamheid van verschillende behandelingen te beoordelen.

Echter, uit de studies blijkt dat RCT’s in het onderzoek naar farmacotherapie voor PTSS ook nadelen hebben. Een van deze nadelen is de vaak korte duur van de behandeling in vergelijking met placebo in de meeste studies. Daarnaast richt farmacotherapie zich mogelijk niet altijd op de achterliggende biologische mechanismen die een rol spelen bij PTSS. PTSS is een complexe aandoening met biologische, psychologische en sociale componenten, waardoor een enkele farmacologische interventie niet alle onderliggende mechanismen en de diversiteit aan symptomen effectief kan aanpakken.

II Voortschrijdend inzicht vergelijking tussen Farmacotherapie en Psychotherapie

In recente jaren heeft er een opmerkelijke verschuiving plaatsgevonden in de opzet van verschillende nieuwe studies naar de behandeling van PTSS. De traditionele RCT's met placebo worden aangevuld of vervangen door directe vergelijkingen tussen farmacotherapie en psychotherapie. Deze benadering erkent de noodzaak om de effectiviteit van medicatie in relatie tot niet-farmacologische behandelingen te beoordelen.

Recent gepubliceerde onderzoeken, waaronder een meta-analyse door Sonis en Cook (2019), hebben geprobeerd deze twee behandelmodaliteiten te vergelijken, maar vonden onvoldoende bewijs om een duidelijk verschil in effectiviteit tussen SSRI's en traumagerichte psychotherapieën voor het verminderen van PTSS-symptomen aan te tonen. Ondanks enige kritiek op de gebruikte studies vanwege potentiële bias en bovengenoemde beperkingen, bieden ze waardevolle inzichten en richtingen voor toekomstig onderzoek.

Bijvoorbeeld, het werk van Rauch (2019), dat juist geen significante verschillen vond tussen behandeling met sertraline en 'prolonged exposure' therapie na 24 weken, en Zoellner (2019), die de invloed van patiëntvoorkeur op behandeluitkomsten belichtte, tonen aan dat zowel medicatie als psychotherapie effectief kunnen zijn voor PTSS. Deze bevindingen benadrukken het belang van het betrekken van patiënten bij de keuze van hun behandeling om therapietrouw en uiteindelijk de effectiviteit van de behandeling te bevorderen.

Onderzoek naar toevoeging van farmacotherapie bij psychotherapie is schaars. De huidige resultaten van farmacologische augmentatie zijn over het algemeen gemengd en heterogeen voor de farmacologische middelen die in meer dan één studie zijn getest. Aanvullende studies en replicaties zijn nodig om te identificeren welke farmacologische middelen effectief zijn, in welke combinaties, en om patiëntgroepen te identificeren die het meeste baat hebben bij een op maat gemaakte behandeling van PTSS (Meister, 2023). Recent onderzoek naar de toevoeging van MDMA bij de psychotherapeutische behandeling van PTSS is veelbelovend maar nog niet voldoende implementeerbaar in de klinische praktijk (Hoskins, 2021).

III Benadering voor inzet farmacotherapie

Het is van belang te erkennen dat, hoewel volgens onze vastgestelde criteria de medicijnen die we hebben onderzocht geen klinisch significante voordelen vertoonden ten opzichte van placebo, het toch belangrijk is om de waarde van farmacotherapie voor PTSS vanuit een andere invalshoek te beschouwen (Friedman en Bernardi, 2017). De behandeling van PTSS vormt namelijk een uitdaging voor clinici vanwege de complexe en heterogene aard van de stoornis (Brady, 2000; Galatzer-Levy & Bryant, 2013). PTSS omvat uit een breed scala aan symptomen, gegroepeerd in vier hoofdclusters, die zich zeer divers kunnen manifesteren. Deze diversiteit van de symptomen van PTSS heeft een aanzienlijke nadelige impact op de ontwikkeling van effectieve farmacotherapieën. Deze stoornis omvat een breed scala aan symptomen, waaronder angst, depressie, slaapproblemen, hyperarousal, nachtmerries, dissociatie, en stemmingswisselingen. Deze variatie in symptomen maakt het lastig om één enkele farmacologische behandeling te ontwikkelen die effectief is voor alle patiënten. Deze diversiteit benadrukt daarentegen juist wel de mogelijkheid van een symptoomgerichte benadering, die zich niet richt op de stoornis als geheel maar op de individuele symptoomclusters, zoals de symptomen waar de patient het meeste last heeft (Birkeland, 2020).

Zo ondersteunt de betrokkenheid van diverse neurobiologische systemen in de pathofysiologie van PTSS, zoals het serotonerge, GABA, glutamaat, dopamine, en noradrenaline systemen (Singewald, 2023), rationale voor een dergelijke gerichte farmacotherapeutische interventie. Een hierop gebaseerde meer symptoom/systeemgerichte aanpak kan richting geven aan interventies gericht op specifieke pathofysiologische mechanismen, en biedt daarmee mogelijke behandelopties die nauw aansluiten bij de individuele symptomatologie van PTSS-patiënten.

Een symptoomgerichte farmacotherapeutische benadering kan helpen om de intensiteit en frequentie van symptomen te verminderen. SSRI's kunnen effectief zijn in het verminderen van angst- en depressieve symptomen, terwijl andere medicijnen, zoals prazosine, nuttig zijn bij de behandeling van slaapstoornissen en nachtmerries (Boschloo, 2023; Reist, 2021; Zhang, 2020). Hoewel bijvoorbeeld een symptoomgerichte aanpak voor slaapproblemen bij PTSS de slaapkwaliteit aanzienlijk kan verbeteren, leidt dit niet altijd tot een volledige verlichting van het gehele klachtenbeeld of een vermindering van PTSS als geheel. Andere symptomen, zoals angst en hyperarousal, kunnen blijven bestaan en vereisen aanvullende behandelingen om het algehele herstel te bevorderen. Ofschoon onderzoek naar deze symptoomgerichte behandelaanpak ontbreekt, en terughoudenheid in het voorschrijven van deze medicatie op zijn plaats is, kan er in individuele gevallen voor gekozen worden op deze wijze de meest invaliderende en meest verstorende symptomen gericht aan te pakken.

Op deze manier kan het ook een mogelijkheid geven om patiënten in staat te stellen om deel te nemen aan andere vormen van behandeling, zoals psychotherapie. Voor sommige patiënten kunnen de symptomen van PTSS immers zo overweldigend zijn dat ze niet in staat zijn om te profiteren van therapieën zoals cognitieve gedragstherapie (CGT) of eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR). Door gericht deze symptomen te verminderen, kan medicatie patiënten ook helpen om meer betrokken en ontvankelijk te zijn voor deze behandelingen.

Het is belangrijk te benadrukken dat terwijl farmacotherapie niet de benadeling van voorkeur is, de klinische indruk bestaat dat er verschillende symptoomclusters zijn waarvoor medicamenteuze interventies ingezet kunnen worden:

- Angst en paniek: SSRI's zoals sertraline en paroxetine zijn effectief in het verminderen van algemene angstsymptomen;

- Depressieve symptomen: SSRI's en SNRI's, inclusief venlafaxine, bieden ondersteuning bij depressieve symptomen;

- Slaapproblemen en nachtmerries: alfa1-adrenerge antagonisten zijn effectief voor PTSS-gerelateerde nachtmerries, zoals bijvoorbeeld prazosine of doxazosine, of lage dosis quetiapine;

- Hyperarousal en hypervigilantie, en psychotische symptomen: antipsychotica zoals quetiapine en olanzapine, risperidon of kort gebruik van propanolol kunnen deze symptomen verminderen;

- Stemmingswisselingen: stemmingsstabilisatoren zoals lamotrigine, valproaat of topiramaat kunnen ingezet worden;

- Dissociatieve symptomen: lamotrigine of antipsychotica, of naltrexon kunnen in sommige gevallen overwogen worden.

Sommige van de genoemde symptomen reagren vrij snel, en kunnen kortdurend zijn, zolas angst en paniek en interventie voor slaap, interventie gerricht op andere klachten vereisen en wat lager durende behnadeling (zolas stemming of depressieve symptomen). Het is belangrijk te benoemen dat er nog slechts weinig bekend is over de risico's op terugval, recidive van PTSS en de duurzaamheid van interventies. In het kader van gezamenlijke besluitvorming kunnen patiënten samen met hun zorgverlener beslissen om interventies af te bouwen, ondanks de onzekerheden die hieromtrent bestaan.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (geschreven door MIND)

Communicatie en bejegening bij farmacotherapie

Patiënten met PTSS ervaren vaak klachten zoals angst, nachtmerries, slaapproblemen, prikkelbaarheid, dissociatie en vermijdingsgedrag, die voortkomen uit onverwerkte trauma's. Psychotherapie speelt een centrale rol in de verwerking van trauma's, soms ondersteund door medicatie. Deze klachten, die zowel bio-psycho-sociale oorzaken en gevolgen hebben als variëren in ernst, vereisen een empathische en patiëntgerichte benadering in de behandeling.

Hoewel er geen medicatie tegen PTSS bestaat kan symptoomgerichte medicatie als verlichtend ervaren worden in het geval wanneer klachten als te heftig en/of te intrusief zijn. Hierbij is het belangrijk dat de zorgverlener(s) en de patiënt gezamenlijk tot een integraal behandelplan komen.

Bij het overwegen van farmacotherapie gericht op symptoomreductie bij (te) heftige PTSS-klachten:

- Overweeg de inzet van psychofarmaca voor symptoomclusters als de ernst van de symptomen de traumabehandeling en de traumaverwerking in de weg zitten indien er geen alternatieven zijn voor ondersteuning.

- Patiënten zijn gebaat bij een grondige voorlichting over effectiviteit (klinische relevantie) en over de specifieke werkzaamheid van medicatie, inclusief bijwerkingen en (klachten bij) afbouw van de medicatie.

- Het is belangrijk om de langetermijneffecten van medicatie te erkennen en te communiceren, aangezien deze vaak niet uitgebreid in studies worden onderzocht.

- Medicatie zo kort mogelijk, met een zo laag mogelijke dosering voorschrijven, inclusief een duidelijk afbouwplan. Tussendoor monitoren via regelmatige evaluaties en gezondheidschecks om het welzijn van de cliënt te waarborgen vanwege mogelijke bijwerkingen.

- Alternatieve ondersteuningsopties, zoals WRAP-cursussen en lotgenotencontact, bieden aanvullende hulpbronnen.

- Gebruik de beschikbare begeleidingsmogelijkheden binnen de GGZ en huisartspraktijken, zoals ondersteuning door POH-GGZ en herstelcoaches.

- Versterk het netwerk van de patiënt, inclusief netwerkpsychiatrie, om een ondersteunende omgeving te creëren.

In crisissituaties:

Beperk medicatie tot noodzakelijke gevallen. Patiëntervaringen tonen aan dat menselijk contact en ondersteuning essentieel zijn bij het overwinnen van een crisis.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

Veel van de farmacotherapeutische opties voor PTSS worden off-label voorgeschreven, wat betekent dat ze worden gebruikt voor doeleinden buiten de indicaties waarvoor ze oorspronkelijk zijn goedgekeurd door regelgevende instanties. Bovendien zijn veel van deze medicijnen generiek, wat betekent dat ze geen patentbescherming meer hebben en over het algemeen tegen lagere kosten beschikbaar zijn. Deze factoren kunnen leiden tot aanzienlijke kostenbesparingen in de gezondheidszorg, vooral in situaties waar de budgetten beperkt zijn. Daarnaast vergroten lagere kosten de toegankelijkheid van behandelingen, waardoor een breder scala aan patiënten betaalbare toegang heeft tot noodzakelijke medicatie.

Desalniettemin vereist het off-label gebruik van medicatie zorgvuldige overweging en monitoring. Hoewel deze praktijk het potentieel heeft om de behandelingsmogelijkheden voor PTSS te verbreden, is de effectiviteit en veiligheid van het medicijn voor de specifieke off-label toepassing niet altijd even grondig onderzocht als tijdens het initiële registratieproces. Dit betekent dat zorgverleners zich goed bewust moeten zijn van het bestaande bewijs voor de effectiviteit van een medicijn voor een bepaalde off-label indicatie, evenals van mogelijke risico's en bijwerkingen.

Daarnaast moeten voorschrijvers zich bewust zijn van de juridische implicaties en aansprakelijkheidskwesties die gepaard gaan met het off-label voorschrijven van medicijnen. Het is van belang dat artsen hun beslissingen om medicijnen off-label voor te schrijven baseren op solide wetenschappelijk bewijs en “best practices” en dat zij deze beslissingen zorgvuldig documenteren, rekening houdend met zowel de potentiële voordelen voor de patiënt als de mogelijke risico's.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

Over het algemeen wordt farmacotherapie gezien als een acceptabele behandeloptie (Watts, 2015; Simiola, 2015; Swift, 2017; Zoellner, 2019), mits de medicatie wordt voorgeschreven door een deskundige arts met ervaring op het gebied van PTSS-behandeling. Eén van de belangrijkste overwegingen bij het voorschrijven van deze medicatie betreft de potentiële bijwerkingen, die kunnen variëren afhankelijk van het specifieke medicament en de individuele reactie van de patiënt.

Voor een gedetailleerd inzicht in de mogelijke bijwerkingen van verschillende psychofarmaca verwijzen we naar het Farmacotherapeutisch Kompas. Deze bijwerkingen moeten zorgvuldig worden gemonitord door de behandelend arts om de veiligheid van de patiënt te waarborgen en het behandelproces zo effectief mogelijk te maken. Dit vereist een actieve en continue opvolging van de patiënt, waarbij eventuele bijwerkingen nauwgezet worden geobserveerd en behandeld. Het is van groot belang dat zorgverleners alert zijn op mogelijke bijwerkingen en deze bespreken met de patiënt, zodat zij goed geïnformeerd zijn en de juiste ondersteuning ontvangen tijdens hun behandeling.

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

Het ontbreekt aan wetenschappelijk bewijs voor de superioriteit van farmacotherapie ten opzichte van placebo in de behandeling van PTSS. Daarom wordt geadviseerd om de initiële behandeling van PTSS niet met farmacotherapie te beginnen. Deze aanpak erkent de waarde van psychologische interventies als eerstelijnsbehandeling voor PTSS, wat in lijn is met een brede consensus over hun effectiviteit. Daarnaast wordt sterk afgeraden om benzodiazepines voor te schrijven, gezien de potentiële risico's en beperkte effectiviteit in de behandeling van PTSS.

Farmacotherapie kan worden overwogen als een symptoomgerichte benadering, vooral in situaties van ernstige klachten, het ontbreken van een effectieve respons op psychologische interventies, of wanneer de inzet van psychotherapeutische behandelingen niet op korte termijn beschikbaar is. Hoewel het off-label gebruik van medicatie nieuwe behandelopties kan openen, blijft het gebrek aan specifiek onderzoek naar de effectiviteit en veiligheid bij PTSS een punt van zorg. Dit vraagt om een kritische wetenschappelijke attitude, een algemeen beleid van terughoudendheid en extra deskundigheid van de voorschrijver.

Het belang van gezamenlijke besluitvorming ('shared decision making') staat centraal bij het indiceren, voorschrijven en al dan niet continueren van farmacotherapeutische interventies, waarbij de patiënt een actieve rol speelt in het behandelproces. Dit respecteert de autonomie en voorkeur van de patiënt, wat bijdraagt aan een meer persoonlijke en effectieve behandelervaring. Hoewel dit principe ideaal is, kan de praktische uitvoering complex zijn, vooral wanneer patiënten aangeven moeite te hebben met het begrijpen van de nuances van hun behandelopties.

Patiënten dienen gedetailleerde en begrijpelijke informatie te ontvangen over de voorgeschreven medicatie, inclusief dosering, gebruiksinstructies, mogelijke bijwerkingen en een duidelijk afbouwschema. Deze informatieverstrekking dient als basis voor geïnformeerde toestemming en stelt patiënten in staat om weloverwogen keuzes te maken over hun behandeling.

De respons op farmacotherapie dient goed te worden gemonitord en, indien nodig, de behandelstrategie dient aangepast door eventueel over te stappen op een alternatieve vorm van (symptoomgerichte) farmacotherapie bij een onvoldoende respons. Deze aanpak waarborgt een adaptieve en responsieve behandeling die is afgestemd op de individuele behoeften en vooruitgang van de patiënt. De noodzaak voor continue monitoring en potentieel aanpassen van de behandeling kan echter ook als belastend worden ervaren door zowel patiënten als zorgverleners, en vereist aanzienlijke middelen.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

De behandeling van PTSS blijft een uitdaging binnen de GGZ. Een belangrijk knelpunt in de huidige behandelingsstrategieën is de gangbare neiging om medicatie voor te schrijven. Hoewel medicijnen breed worden ingezet, ontbreekt het vaak aan een wetenschappelijke onderbouwing wat betreft de behandeling van PTSS. Recente wetenschappelijke inzichten tonen aan dat therapeutische behandelingen doorgaans effectiever zijn dan farmacotherapie. Dit heeft ertoe geleid dat de rol van medicatie in de behandeling van PTSS steeds vaker ter discussie wordt gesteld.

Het doel van deze richtlijn voor farmacotherapie bij PTSS is het beschrijven van de huidige situatie, het identificeren van specifieke knelpunten en het bepalen van de mate waarin en de manier waarop farmacotherapie een gerichte aanvulling kan zijn op de psychologische behandeling van PTSS. Het is daarbij van belang om de effectiviteit van farmacotherapie zo goed mogelijk te begrijpen en te beschrijven, zodat rekening gehouden kan worden met de diverse behandelopties en met de individuele behoeften en voorkeuren van de patiënt.

Sinds 2001 zijn sertraline en paroxetine de enige voor PTSS geregistreerde medicijnen. In de praktijk worden echter verschillende andere farmaceutische middelen off-label toegepast. Er blijkt sprake van een afname in het aantal patiënten dat medicatie voor PTSS ontvangt. Dit kan wijzen op twijfel over de effectiviteit en bijwerkingen van deze medicijnen, of mogelijk op een verbeterde toegang tot evidence-based psychotherapie voor PTSS, waardoor medicatie minder vaak geïndiceerd en noodzakelijk wordt (Holder, 2021). Ondanks deze trends en ontwikkelingen blijven selectieve serotonineheropnameremmers (Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors, SSRI) en serotonine-noradrenalineheropnameremmer (Serotonin-Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitor, SNRIs), als Fluoxetine, Sertraline, Citalopram, Paroxetine, Venlafaxine en Duloxetine de meest voorgeschreven medicijnen voor PTSS. Tegelijkertijd is er een toename in het gebruik van tweede generatie antipsychotica en een sterkte afname in gebruik van benzodiazepinen (Reinhard, 2021). Deze trend van frequent en grootschalig off-label voorschrijven van psychofarmaca voor PTSS benadrukt de noodzaak aan duidelijke behandelrichtlijnen.

Deze module richt zich op de vraagstukken betreffende farmacotherapeutische opties voor PTSS-behandeling, gebaseerd op strikt gedefinieerde zoekcriteria.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

1.1.1 TCAs versus placebo

|

Very low GRADE |

It is unclear whether amitriptyline and imipramine result in a decrease in PTSS symptoms compared to placebo.

Source: Davidson 1990, Kosten 1991 |

1.1.1 TCAs versus placebo

|

Very low GRADE |

Amitriptyline and imipramine may result in more study drop-out compared to placebo, but the evidence is very uncertain.

Source: Davidson 1990, Kosten 1991 |

1.1.2 MAOIs beta-hydroxylase inhibitors versus placebo

|

Very low GRADE |

It is unclear whether MAOIs beta-hydroxylase inhibitors result in a decrease in PTSS symptoms compared to placebo.

Source: Kosten 1991 |

1.1.2 MAOIs beta-hydroxylase inhibitors versus placebo

|

Very low GRADE |

It is unclear whether phenelzine results in more study drop-out compared to placebo.

Source: Kosten, 1991 |

1.1.3 NaSSas versus placebo

|

Low GRADE |

Mirtazapine may result in little to no difference in decrease in PTSS symptoms compared to placebo.

Source: Davis 2020 |

|

Low GRADE |

Mirtazapine may result in little to no difference in study drop-out compared to placebo.

Source: (Davidson 2003; Davis 2020; Chung 2004) |

1.1.4 RIMAs versus placebo

|

Very low GRADE |

Brofaromine may result in little to no difference in decrease in PTSS symptoms compared to placebo, but the evidence is very uncertain.

Source: Baker, 1995; Katz 1994 |

|

Very low GRADE |

Brofaromine may result in little to no difference in study drop-out compared to placebo, but the evidence is very uncertain.

Source: (Katz, 1994) |

1.1.4 SNRIs versus placebo

|

Low GRADE |

Venlafaxine may decrease in PTSS symptoms compared to placebo, but this is not clinically relevant.

Source: Davidson 2006a; Davidson 2006b |

|

Low GRADE |

Venlafaxine may result in little to no difference in study drop-out compared to placebo.

Source: Davidson 2006a |

1.1.5 SSRIs versus placebo

|

Very low GRADE |

It is unclear whether SSRIs result in a decrease in PTSS symptoms as compared to placebo.

Source: Brady 2000, Davidson 2001a, Davidson 2006b, GSK 29060 627, Marshall 2001, Marshall 2007, NCT01681849, Pfizer 588, Pfizer 589, SKB627, SKB650, Tucker 1001, Tucker 2003, Van Der Kolk 2007, Zohar 2002 |

|

Very Low GRADE |

SSRIs may result in little to no difference in study drop-out compared to placebo.

Source: Brady 2000, Connor 1999a, Davidson 2005, GSK 29060 627, Hertzberg 2000, Li 2017, Marshall 2001, Marshall 2007, Martenyi 2002a, Martenyi 2002b, NCT01681849, Panahi 2011, Pfizer 588, Pfizer 589, SKB627, Tucker 1001, Tucker 2003, Van Der Kolk 1994, Van Der Kolk 2007, Zohar 2002 |

1.2.1 Benzodiazepines versus placebo

|

Low GRADE |

Benzodiazepines may result in no difference in study drop-out compared to placebo.

Source: Braun, 1990 |

1.2.2 benzodiazepine-agonists versus placebo

|

Low GRADE |

Eszopiclone use may result in no difference in decrease in PTSS symptoms compared to placebo.

Source: Dowd 2020 |

|

Low GRADE |

Eszopiclone use may result in a difference in drop-out due to any reason compared to placebo.

Source: Dowd 2020 |

1.3 Anticonvulsants versus placebo

|

Very Low GRADE |

It is unclear whether topiramate, lamotrigine, tiagabine and topiramate may decrease PTSD symptoms compared to placebo.

Source: (Davidson 2007; Davis 2008, Hamner 2008; Tucker 2007; Yeh 2011) |

|

Very low GRADE |

It is unclear whether divalproex, lamotrigine, tiagabine and topiramate results in a difference in study drop-out compared to placebo.

Source: Connor 2006; Davidson 2007; Davis 2008; Hamner 2008; Hertzberg 1999; Tucker 2007; Yeh 2011 |

1.4 Alpha-blockers versus placebo

|

Low GRADE |

Prazosine may result in a decrease in PTSD symptoms compared to placebo.

Source: Raskind, 2018 |

|

Low GRADE |

Prazosine may result in difference in study drop-out compared to placebo.

Source: Raskind, 2018 |

|

Low GRADE |

Prazosine may result in little to no difference in quality of life compared to placebo.

Source: Raskind, 2018 |

1.5 Antipsychotics versus placebo

|

Very low GRADE |

It is unclear whether antipsychotics may result in more reduction of PTSD symptoms as measured by CAPS compared to placebo.

Source: (Carey 2012; Reich 2004; Villarreal 2016) |

|

Low GRADE |

Antipsychotics may result in more study drop-out due to any reason compared to placebo.

Source: (Butterfield 2001; Padala 2006; Reich 2004; Villarreal 2016) |

1.6 Dopamine beta-hydroxylase inhibitors versus placebo

|

Low GRADE |

Nepiscastat may result in little to no difference in decrease in PTSS symptoms as compared to placebo.

Source: NCT00659230 |

|

Low GRADE |

Nepiscastat may result in little to no difference in study drop-out compared to placebo. .

Source: NCT00659230 |

1.7 Ganaxalone versus placebo

|

Low GRADE |

Ganaxalone may result in in a decrease in PTSS symptoms as compared to placebo.

Source: Rasmusson, 2017 |

|

Low GRADE |

Ganaxalone may result in little to no difference in study drop-out compared to placebo.

Source: Rasmusson, 2017 |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

Williams (2022) is a Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis of double-blind randomised controlled trials that compared pharmacotherapies with placebo in adults with PTSD. In this review a systematic search was performed in Cochrane, Medline, Embase and Psychinfo till November 13 2022. The review included a total of 66 RCTs (ranging from 13 days to 28 weeks, totaling 7442 participants, ages of participants ranging from 18 to 85 years), of which 54 RCTs were included in a meta-analysis.

Outcomes that were used in the guideline were reduction of PTSD symptoms as determined from the total score on the CAPS, treatment tolerability by dropout due to any cause, and quality of life. The results are summarized below.

Results

1.1 Anti-depressants

1.1.1 TCAs versus placebo

Loss of diagnosis PTSS

This was not reported.

Decrease in PTSS symptoms (continuous)

There was no evidence of a benefit for amitriptyline and imipramine compared to placebo for reducing total IES symptom severity (SMD −0.54 points, 95% CI −1.18 to 0.10; 2 trials, 74 participants; (Davidson 1990; Kosten 1991), There was moderate heterogeneity for the total IES symptom severity outcome (Chi 2 = 1.83, df = 1 (P = 0.18); I2 = 45%).

Drop-out

More participants dropped out of the amitriptyline and imipramine groups (34%) due to any cause when compared to placebo RR 0.79 (95%CI 0.62 to 0.99) (Davidson 1990; Kosten 1991).

Quality of life

Data on quality of life were not reported.

Level of evidence of the literature

Decrease in PTSS symptoms

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure decrease in PTSS symptoms was very low; it was downgraded by two levels because of study limitations (-1) (many details about randomization and treatment allocation were unclear) and imprecision (-2) as minimal information size was not reached.

Drop-out

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure drop-out was very low downgraded because of study limitations (-1) (many details about randomization and treatment allocation were unclear) and imprecision (-2) as minimal information size was not reached.

1.1.2 MAIOs versus placebo

Loss of diagnosis PTSS

This was not reported.

Decrease in PTSS symptoms (continuous),

There was evidence of a benefit of the MAOI phenelzine compared to placebo for reducing total PTSD symptoms on the IES (SMD −1.06 points, 95% CI −1.75 to −0.36) for 1 trial with 37 participants (Kosten 1991).

Drop-out

Drop-out due to any cause was comparable between the phenelzine group (21%) and placebo group (11%), RR 0.89 (95% CI 0.67 to 1.1.8) (Kosten 1991).

Quality of life

Data on quality of life were not reported.

Level of evidence of the literature

Decrease in PTSS symptoms

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure decrease in PTSS symptoms was very low; it was downgraded by because of study limitations (-1) (many details about randomization and treatment allocation were unclear) and imprecision (-2) as minimal information size was not reached.

Drop-out

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure drop-out was very low; downgraded by because of study limitations (-1) (many details about randomization and treatment allocation were unclear) and imprecision (-2) as minimal information size was not reached.

1.1.3 NaSSa versus placebo

Loss of diagnosis PTSS

This was not reported.

Decrease in PTSS symptoms (continuous),

There was no evidence of beneficial effect of mirtazapine for reducing PTSD symptoms on the CAPS total symptom scale (MD −3.20 points, (95% CI −14.74 to 8.34); 1 trial, 61 participants; (Davis 2020. Similarly, we found no evidence of a benefit of an effect for reducing PTSD symptoms on the self-rated DTS (SMD −0.31 points, 95% CI −1.02 to 0.41; 2 trials, 87 participants; Davidson 2003; Davis 2020).

Drop-out

There was no evidence of a difference in the number of participants who withdrew due to any cause for the mirtazapine (17%) and placebo (19%) groups, RR 0.86 (95% CI 0.48 to 1.52) (Davidson 2003; Davis 2020; Chung 2004).

Quality of life

Data on quality of life were not reported.

Level of evidence of the literature

Decrease in PTSS symptoms.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure decrease in PTSS symptoms was low; downgraded by because of study limitations (-1) (many details about randomization and treatment allocation were unclear) and imprecision (-1) as confidence intervals were very broad.

Drop-out

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure drop-out due to any cause was low downgraded because of study limitations (-1) (many details about randomization and treatment allocation were unclear) and imprecision (-1) as confidence interval crossed the borders of no effect.

1.1.4 RIMAs versus placebo

Loss of diagnosis PTSS

This was not reported.

Decrease in PTSS symptoms (continuous),

There was no evidence of a benefit of a reduction in PTSD symptoms following treatment with brofaromine compared to placebo for CAPS total (MD −5.06 points, 95% CI −15.93 to 5.81, 2 trials, 178 participants; Baker 1995; Katz 1994).

Drop-out

There was also no evidence of a difference for the number of participants who withdrew due to any cause from the brofaromine (30%) and placebo groups (29%), RR 1.04 (95% CI 0.49 tot 2.22) (Katz 1994).

Quality of life

Data on quality of life were not reported.

Level of evidence of the literature

Decrease in PTSS symptoms

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure decrease in PTSS symptoms was downgraded to very low because of study limitations (-1) (many details about randomization and treatment allocation were unclear) and imprecision (-2) as confidence intervals were very broad and overlapped with the borders of clinical relevance.

Drop-out

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure drop-out due to any cause was downgraded to very low because of study limitations (-1) (many details about randomization and treatment allocation were unclear) and imprecision (-2) as confidence interval crossed the borders of no effect and clinical relevance.

1.1.4 SNRIs versus placebo

Loss of diagnosis PTSS

This was not reported.

Decrease in PTSS symptoms (continuous),

There was evidence of a benefit of the SNRI venlafaxine compared to placebo for reducing total PTSD symptoms on the CAPS total (MD −8.11 points, 95% CI −12.29 to −3.92; 2 trials, 687 participants; Davidson 2006a; Davidson 2006b).

We also found evidence of a benefit of venlafaxine compared to placebo for reducing PTSD symptoms on the CGI-S (SMD −0.31 points, 95% CI −0.46 to −0.16; 2 trials, 687 participants; Davidson 2006a; Davidson 2006b). Moreover, we found evidence of a benefit of venlafaxine on total DTS symptom severity (SMD −0.26 points, 95% CI −0.47 to −0.05; 1 trial, 358 participants; Davidson 2006b.

Drop-out

There was also no evidence of a difference for the number of participants who withdrew due to any cause from the venlafaxine (30%) and placebo groups (33%), RR 1.04 (95% CI 0.90 to 1.21) (Davidson 2006a).

Quality of life

Data on quality of life were not reported.

Level of evidence of the literature

Decrease in PTSS symptoms

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure decrease in PTSS symptoms was low; downgraded by two levels because of study limitations (-1) (many details about randomization and treatment allocation were unclear) and imprecision (-1) as confidence intervals overlapped with the borders of clinical relevance.

Drop-out

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure drop-out due to any cause was low; downgraded because of study limitations (-1) (many details about randomization and treatment allocation were unclear) and imprecision (-1).

1.1.5 SSRIs versus placebo

Loss of diagnosis PTSS

This was not reported.

Decrease in PTSS symptoms (continuous),

There was evidence of a benefit of the SSRIs compared to placebo for reducing total PTSD symptoms on the CAPS (MD −4.91 points, 95% CI −7.48 to −2.34), 15 trials, 2615 participants.

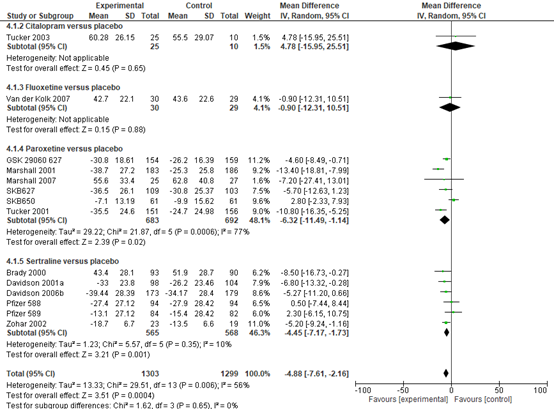

The pattern of symptom severity on the CAPS for the separate SSRI medications was similar to all SSRIs, see Figure 1, with both paroxetine MD −6.32 points, 95% CI −11.49 to −1.14; 6 trials, 1375 participants; and sertraline (MD −4.45 points, 95% CI −7.17 to −1.73; 6 trials, 1133 participants, demonstrating evidence of a benefit of a reduction in PTSD symptoms. There was insufficient evidence to determine whether fluoxetine was effective in reducing total PTSD (MD −0.90 points, 95% CI −12.31 to 10.51; 1 trial, 59 participants, as well as citalopram (MD 4.78 points, 95% CI −15.95 to 25.51; 1 trial, 35 participants), compared to placebo.

There was evidence of a benefit of the SSRIs fluoxetine, paroxetine and sertraline compared to placebo for the reduction of PTSD symptoms on the CGI-S (SMD −0.32 points, 95% CI −0.55 to −0.09; 6 trials, 862 participants; Connor 1999a; Davidson 2006b; GSK 29060 627; Hertzberg 2000; Li 2017; Panahi 2011). There was considerable heterogeneity in effect size estimates for this outcome (Chi2 = 10.24, df = 5 (P = 0.07); I2 = 51%). There was no evidence of a benefit of the SSRIs compared to placebo for a reduction in total PTSD symptoms on the DTS (SMD 0.11, 95% CI −0.50 to 0.72; 10 trials, 1698 participants; Brady 2000; Connor 1999a; Davidson 2005; Davidson 2006b; GSK 29060 627; Hertzberg 2000; Li 2017; Panahi 2011; SKB650; Tucker 2003), and this is confirmed by the substantial heterogeneity found between trials (Chi2 = 295.12, df = 9 (P < 0.001); I2 = 97%).

Figure 1 Separate SSRI medications SSRIs: citalopram, fluoxetine, paroxetine and setraline versus placebo, reduction of PTSD symptoms as measured by CAPS

Drop-out

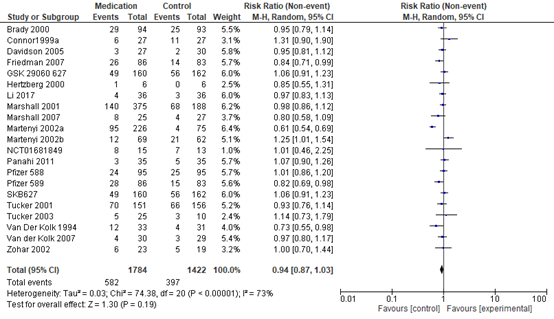

We observed similar dropout rates in the medication (33%) and placebo arms (28%); see Figure 2 RR 0.94 (95% CI 0.87 to 1.03).

Figure 2 SSRIs versus placebo, dropout due to any cause

Quality of life

Data on quality of life were not reported.

1.1.5 SSRIs versus placebo

Level of evidence of the literature

Decrease in PTSS symptoms

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure decrease in PTSS symptoms was downgraded to very low; by two levels because of study limitations (-1) (many details about randomization and treatment allocation were unclear) and as results were heterogeneous (inconsistency) (-1) and imprecision (as confidence intervals overlapped with clinically relevant effect).

Drop-out

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure drop-out symptoms was downgraded to very low; because of study limitations (-1) (many details about randomization and treatment allocation were unclear) by one level as results were very heterogeneous (inconsistency) (-1) and imprecision (-1) as minimal information size was not reached (<300 patients).

1.2 Hypnotics versus placebo

1.2.1 Benzodiazepines versus placebo (Braun, 1990)

Loss of diagnosis PTSS

This was not reported.

Decrease in PTSS symptoms (continuous),

This was not reported.

Drop-out

The overall dropout rate was similar for the alprazolam (43%) and placebo groups (33%); 16 participants in 1 trial, RR 0.86 (95%CI 0.39 to 1.89) (Braun 1990).

Quality of life

Data on quality of life were not reported.

1.2.1 Benzodiazepines versus placebo

Level of evidence of the literature

Drop-out

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure drop-out was very low; it was downgraded by two levels because of study limitations (-1) (many details about randomization and treatment allocation were unclear) and imprecision (-1) as minimal information size was not reached.

1.2.2 benzodiazepine-agonists: eszopiclone

1.2.2 benzodiazepine-agonists versus placebo

Loss of diagnosis PTSS

This was not reported.

Decrease in PTSS symptoms (continuous),

There was no evidence of a benefit of eszopiclone in reducing PTSD symptoms on the CAPS total (MD −1.00 points, 95% CI −19.57 to 17.57; 1 trial, 16 participants; or on the CGI-S (SMD −0.09 points, 95% CI −1.08 to 0.90; 1 trial, 16 participants. (Dowd 2020).

Drop-out

We found no evidence of a difference for dropouts due to any cause for the eszopiclone (46%) and placebo (25%) group, even though dropouts were higher in the medication arm RR -2.67 (95%CI -12.68 to 7.34) (Dowd 2020).

Quality of life

Data on quality of life were not reported.

1.2.2 benzodiazepine-agonists versus placebo

Level of evidence of the literature

Decrease in PTSS symptoms

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure decrease in PTSS symptoms was low; it was downgraded by two levels because of study limitations (-1) (many details about randomization and treatment allocation were unclear) and imprecision (-1) as minimal information size was not reached.

Drop-out

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure drop-out was low; it was downgraded by two levels because of study limitations (-1) (many details about randomization and treatment allocation were unclear) and imprecision (-1) as confidence intervals were very broad.

1.3 Anticonvulsants versus placebo

Loss of diagnosis PTSS

This was not reported.

Decrease in PTSS symptoms (continuous)

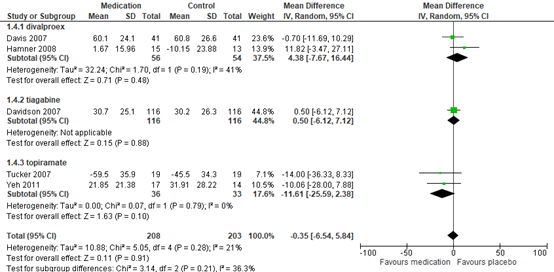

Data on the reduction of PTSD symptoms, measured by the CAPS (total score), in five studies (411 participants) was measured comparing divalproex, tiagabine and topiramate to placebo (MD−0.35 points, 95% CI −6.54 to 5.84); see figure 3. There was no evidence of a beneficial effect. When looking into subgroups (figure 3) divalproex (MD 4.38, 95% CI -7.67; 16.44), tiagabine (MD 0.50, 95% CI -6.12 to 7.12) and topiramate (MD-11.61, 95% CI -25.59 to 2.38) were compared to placebo (total MD−0.35 points, 95% CI −6.54 to 5.84) these differences were also not clinically relevant.

Figure 3 Anticonvulsants presented in subgroups of divalproex, tiagabine and topiramate versus placebo, reduction of PTSD symptoms as measured by Clinically Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS)

Drop-out

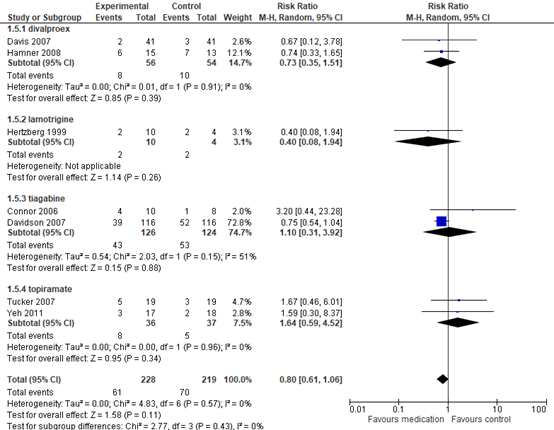

Drop-out rates due to adverse events were low in RCTs of divalproex (MD 0.73 95%CI 0.35 to 1.51), lamotrigine (MD 0.40, 95% CI 0.08 to 1.94), tiagabine (MD 1.10 95% CI 0.31 to 3.92) and topiramate (MD 1.64, 95% CI 0.59 to 4.52), and were comparable to those observed in the placebo arms (11% versus 9%, respectively) (RR 0.98, 95% CI 0.92 to 1.06). For all anticonvulsants these were comparable to those observed in the placebo arms (11% versus 9%, respectively) (RR 0.98, 95% CI 0.92 to 1.06); see Figure 4. These differences were not clinically relevant.

Figure 4 Anticonvulsants presented in subgroups of divalproex, tiagabine and topiramate versus placebo versus placebo, dropout due to any cause

Quality of life

Data on quality of life were not reported.

Level of evidence of the literature

1.3 Anticonvulsants versus placebo

Decrease in PTSS symptoms

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure decrease in PTSS symptoms was downgraded by three levels to very low because of study limitations (-1) (details about randomization and treatment allocation were unclear) and imprecision (-2) (broad confidence intervals that overlap with no effect and borders of clinical relevance).

Drop-out

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure drop-out was very low; downgraded by three levels to very low because of study limitations (-1) (details about randomization and treatment allocation were unclear) and downgraded for imprecision (-2) as results crossed border of clinical relevance and no effect.

1.4 Alpha-blockers versus placebo (RCT Raskind 2018)

Loss of diagnosis

This was not reported.

Decrease in PTSS symptoms (continuous)

One RCT in the review made this comparison on a multi-site study in 271 veterans using the CAPS (Raskind 2018). In this RCT, there was no evidence of a benefit of prazosin compared to placebo for the reduction of PTSD symptoms on the CAPS total (Prazosine 68.9 (SD 19.9) N=135, placebo 68.8 (SD 23.9, N=136) mean difference (MD) 0.10 points, (95% CI −5.13 to 5.33).

Drop-out

A similar proportion of participants withdrew from the prazosin group (20%) compared to the placebo group (19%), RR 1.03 (95% CI 0.65 to 1.62) (Raskind 2018).

Quality of life

Alpha-blockers versus placebo

Quality of life was measured using the Quality of life inventory (QOLI). It was 0.1 ± 1.6 for prazosine at week 10 and 0.1 ±1.8 at week 10 for placebo. A change from baseline between groups of 0.1 (-0.3 to 0.4), p= 0.68 (Raskind 2018). This difference was not clinically relevant.

Level of evidence of the literature

1.4 Alpha-blockers versus placebo

Loss of diagnosis

This was not reported.

Decrease in PTSD symptoms

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure decrease in PTSS symptoms was downgraded by two levels to low because of study limitations (risk of bias (-1) due to unclear randomization and treatment allocation) and broad confidence intervals (imprecision (-1), due to not meeting border of clinical relevance).

Drop-out

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure drop-out was downgraded by two levels to low because of study limitations (risk of bias (-1) due to unclear randomization and treatment allocation) and low number of included patients (imprecision (-1), due to not meeting border of clinical relevance).

Quality of life

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure quality of life was downgraded by two levels to low because of study limitations (risk of bias (-1) due to unclear randomization and treatment allocation) and low number of included patients imprecision (-1), due to not meeting border of clinical relevance).

1.5 Antipsychotics versus placebo

Loss of diagnosis PTSD

This was not reported.

Decrease in PTSD symptoms (continuous)

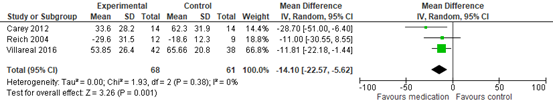

There was evidence of a benefit for the reduction of PTSD symptoms following treatment with olanzapine, risperidone or quetiapine compared to placebo for the CAPS total (MD −14.10 points, 95% CI −22.57 to −5.62); see Figure 5. The substantial heterogeneity for this outcome is partially reflected in the large medication effect observed in Carey 2012 (MD −15.10 points, 95% CI −24.47 to −5.73). Removing this trial resulted in a substantially reduced and statistically non-significant treatment effect (MD −2.50 points, 95% CI −6.93 to 1.93), with no heterogeneity observed across the effects for the remaining trials (Chi2 = 0.05, df = 1 (P = 0.82); I2 = 0%).

Furthermore, there was evidence of a beneficial effect of olanzapine and quetiapine compared to placebo in the reduction of PTSD symptoms on the symptom severity CGI-S scale (SMD −0.55 points, 95% CI −0.94 to −0.17; 2 trials, 108 participants; Carey 2012; Villarreal 2016), with no evidence of a benefit on the self-rated DTS (SMD −0.47 points, 95% CI −1.06 to 0.11; 3 trials, 119 participants; Butterfield 2001; Carey 2012; Villarreal 2016). There was moderate heterogeneity for the total score on the self-rated measures (Chi2 = 3.75, df = 2 (P = 0.15); I2 = 47%).

Figure 5 Antipsychotics versus placebo, reduction of PTSD symptoms as measured by CAPS

Drop-out

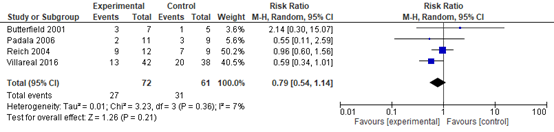

Although differences in dropout rates due to any cause in the medication (38%) and placebo (51%) arms were evident, no evidence of a difference was found across the four trials with 133 participants, RR 0.79 (95% CI 0.54 to 1.14) see Figure 6.

Figure 6 Antipsychotics versus placebo, dropout due to any cause

Quality of life

Data on quality of life were not reported.

1.5 Antipsychotics versus placebo

Level of evidence of the literature

Decrease in PTSS symptoms

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure decrease in PTSS symptoms was downgraded by three levels to very low because of study limitations (-2) (many details about randomization and treatment allocation were unclear and one trial had a large impact on results) and imprecision (-2) due to crossing borders of clinical relevance and no effect.

Drop-out

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure drop-out was low; it was downgraded by two levels because of study limitations (-1) (many details about randomization and treatment allocation were unclear). It was also downgraded for imprecision (-1) as the estimate overlapped the border of clinical relevance.

1.6 Dopamine beta-hydroxylase inhibitors versus placebo (NCT00659230)

Loss of diagnosis PTSS

This was not reported.

Decrease in PTSS symptoms (continuous),

We found no evidence of a benefit of nepicastat on CAPS total symptom severity (MD −5.27 points, 95% CI −16.72 to 6.18), in one trial with 86 participants (NCT00659230).

Drop-out

Overall there were 12 (24%) dropouts in the nepicastat group and nine (18%) dropouts in the placebo group, (RR 1.39, 95% CI 0.64 to 3.00); 1 trial, 100 participants (NCT00659230).

Quality of life

Data on quality of life were not reported.

1.6 Dopamine beta-hydroxylase inhibitors versus placebo

Level of evidence of the literature

Decrease in PTSS symptoms

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure decrease in PTSS symptoms was downgraded by two levels to low because of study limitations (-1) (many details about randomization and treatment allocation were unclear) and imprecision (-1) due to crossing borders of clinical relevance.

Drop-out

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure drop-out was downgraded by two levels to low because of study limitations (-1) (many details about randomization and treatment allocation were unclear) and imprecision (-1) due to crossing borders of clinical relevance.

1.7 Ganaxalone versus placebo (NCT00659230)

Loss of diagnosis PTSS

This was not reported.

Decrease in PTSS symptoms (continuous),

No evidence of a benefit was observed for ganaxolone medication on CAPS total symptom severity MD −2.50 points, (95% CI −10.92 to 5.92; 1 trial, 99 participants); (Rasmusson 2017); Similarly, no evidence of a benefit of ganaxolone versus placebo was observed for the reduction in PTSD symptoms on the PCL scale (self-rated measure) (SMD −0.17 points, 95% CI −0.59 to 0.25; 1 trial, 86 participants; see Rasmusson 2017).

Drop-out

There was no difference in dropouts due to any cause for the ganaxolone intervention arm (33%) compared to the placebo arm (17%), RR 1.93 (95% CI 0.94 to 3.92), even though more dropouts were observed in the medication arm (Rasmusson 2017).

Quality of life

Data on quality of life were not reported.

1.7 Ganaxalone versus placebo

Level of evidence of the literature

Decrease in PTSS symptoms

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure decrease in PTSS symptoms was downgraded by two levels to low because of study limitations (-1) (many details about randomization and treatment allocation were unclear) and imprecision (-1) as confidence intervals were very broad.

Drop-out

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure drop-out was downgraded by two levels to low because of study limitations (-1) (many details about randomization and treatment allocation were unclear) and imprecision (-1) as confidence intervals were very broad.

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question: What are the benefits and risks of pharmacotherapy compared with placebo for patients with PTSS?

| P: | Patients with PTSS confirmed diagnosis of PTSS by a professional (using CAPS) |

| I: |

SSRI (citalopram, dapoxetine, escitalopram, fluoxetine, fluvoxamine paroxetine, sertraline); anticonvulsants (carbamazepine, divalproex, lamotrigine, tiagabine, topiramate); benzodiazepines (alprazolam, bromazepam, brotizolam, clobazam, clorazepinezuur, diazepam, flunitrazepam, flurazepam, loprazolam, lorazepam, lormetazepam, midazolam, nitrazepam, oxazepam, prazepam, remimazolam, temazepam, zolpidem, zopiclon); antipsychotica (amisulpride, aripiprazole, brexpiprazol, cariprazine, clozapine, lurasidone, olanzapine, paliperidone, quetiapine, risperidone, sertindol, sulpiride, broomperidol, chloorprotixeen, flupentixol, fluspirileen, haloperidol, penfluridol, pimozide, pipamperone, zuclopentixol); antidepressiva (bupropion, esketamine, vortioxetine, amitriptyline, clomipramine, dosulepine, doxepine, imipramine, maprotiline, nortriptyline, mianserine, mirtazapine); alfablokkers (alfuzosine, doxazosine, fentolamine, silodosine, tamsulosine, terazosine, urapidil) overig (promethazine) |

| C: | Placebo |

| O: |

Outcome measure: Critical: Loss of diagnosis PTSS, Decrease in PTSS symptoms (continuous), Drop-out, Quality of life |

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered loss of diagnosis PTSD and PTSD symptom decrease and as a critical outcome measure for decision making; and drop-out and quality of life as an important outcome measure for decision making.

The working group defined the outcome measures as follows:

Loss of diagnosis: using CAPS interview; no longer fulfilling diagnostic criteria (or using another clinical interview)

PTSD symptom decrease: decrease in CAPS score compared to baseline or another validated self-report instrument.

Drop-out: drop-out due to any reason

For quality of life, the working group did not define the outcome measure a priori but used the definition used in the studies.

The working group defined loss of diagnosis of 10% as clinically relevant.

- PTSD symptom decrease: the working group defined >12 points on CAPS4 or 6 points on CAPS5 decrease as clinically relevant, which was similar or an SMD of 0.5 (Stefanovics, 2018).

- Drop-out: The working group defined >20% drop-out as clinically relevant.

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms until 05-09-2022. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 463 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria: systematic reviews, pharmacotherapy, about adults, PTSS (not anxiety disorders) and fulfilling the PICO. Studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text one study was used for the summary of literature.

Results

One systematic review was included in the analysis of the literature as it was most recent, complete and fulfilled the PICO (Williams, (2022). Study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- Bajor, L. A., Balsara, C., & Osser, D. N. (2022). An evidence-based approach to psychopharmacology for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD)-2022 update. Psychiatry Research, 114840.

- Bedard-Gilligan, M., Lehinger, E., Cornell-Maier, S., Holloway, A., & Zoellner, L. (2022). Effects of cannabis on PTSD recovery: review of the literature and clinical insights. Current addiction reports, 9(3), 203-216.

- Blake D,Weathers F, Nagy L, Kaloupek D, Klauminzer G, Charney D,Keane T, Buckley TC: Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS) Instructional Manual. West Haven, Conn, National Center for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder, Behavioral Science DivisionBoston Neurosciences Division, 2000

- Bredemeier, K., Larsen, S., Shivakumar, G., Grubbs, K., McLean, C., Tress, C., & Thase, M. (2022). A comparison of prolonged exposure therapy, pharmacotherapy, and their combination for PTSD: What works best and for whom; study protocol for a randomized trial. Contemporary Clinical Trials, 119, 106850.

- Birkeland, M. S., Greene, T., & Spiller, T. R. (2020). The network approach to posttraumatic stress disorder: A systematic review. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 11(1), 1700614. doi:10.1080/20008198.2019.1700614

- Britnell, S. R., Jackson, A. D., Brown, J. N., & Capehart, B. P. (2017). Aripiprazole for post-traumatic stress disorder: a systematic review. Clinical Neuropharmacology, 40(6), 273-278.

- Boschloo L, Hieronymus F, Lisinski A, Cuijpers P, Eriksson E. The complex clinical response to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in depression: a network perspective. Transl Psychiatry. 2023 Jan 21;13(1):19. Doi: 10.1038/s41398-022-02285-2. PMID: 36681669; PMCID: PMC9867733.

- Burback, L., Brémault-Phillips, S., Nijdam, M. J., McFarlane, A., & Vermetten, E. (2023). Treatment of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: A State-of-the-art Review. Curr. Neuropharmacol.

- Campos, B., Vinder, V., Passos, R. B. F., Coutinho, E. S. F., Vieira, N. C. P., Leal, K. B., & Berger, W. (2022). To BDZ or not to BDZ? That is the question! Is there reliable scientific evidence for or against using benzodiazepines in the aftermath of potentially traumatic events for the prevention of PTSD? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 36(4), 449-459.

- Davis, A. K., Xin, Y., Sepeda, N., & Averill, L. A. (2023). Open-label study of consecutive ibogaine and 5-MeO-DMT assisted-therapy for trauma-exposed male Special Operations Forces Veterans: prospective data from a clinical program in Mexico. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 49(5), 587-596.

- Du, R., Han, R., Niu, K., Xu, J., Zhao, Z., Lu, G., & Shang, Y. (2022). The multivariate effect of ketamine on PTSD: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in psychiatry, 13, 813103.

- Feder, A., Rutter, S. B., Schiller, D., & Charney, D. S. (2020). The emergence of ketamine as a novel treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder. Advances in Pharmacology, 89, 261-286.

- Feder, A., Costi, S., Rutter, S. B., Collins, A. B., Govindarajulu, U., Jha, M. K., & Charney, D. S. (2021). A randomized controlled trial of repeated ketamine administration for chronic posttraumatic stress disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry, 178(2), 193-202.

- Friedman, M. J., & Bernardy, N. C. (2017). Considering future pharmacotherapy for PTSD. Neuroscience letters, 649, 181-185.

- Friedman, M. J., & Sonis, J. H. (2020). Pharmacotherapy for PTSD: What psychologists need to know.

- Galatzer-Levy, I.R., & Bryant, R.A. (2013). 636,120 ways to have posttraumatic stress disorder. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 8(6), 651-662. doi.org/10.1177/1745691613504115

- Giovanna, G., Damiani, S., Fusar-Poli, L., Rocchetti, M., Brondino, N., de Cagna, F., & Politi, P. (2020). Intranasal oxytocin as a potential therapeutic strategy in post-traumatic stress disorder: a systematic review. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 115, 104605.

- Guina, J., Rossetter, S. R., DeRhodes, B. J., Nahhas, R. W., & Welton, R. S. (2015). Benzodiazepines for PTSD: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Psychiatric Practice®, 21(4), 281-303.

- Hadlandsmyth, K., Bernardy, N. C., & Lund, B. C. (2022). Gender differences in medication prescribing patterns for veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder: A 10?year follow?up study. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 35(6), 1586-1597.

- Holder, N., Woods, A., Neylan, T. C., Maguen, S., Seal, K. H., Bernardy, N., & Cohen, B. E. (2021). Trends in medication prescribing in patients with PTSD from 2009 to 2018: a National Veterans Administration Study. The Journal of clinical psychiatry, 82(3), 32806.

- Hoskins, M. D., Sinnerton, R., Nakamura, A., Underwood, J. F., Slater, A., Lewis, C., & Clarke, L. (2021). Pharmacological-assisted Psychotherapy for Post Traumatic Stress Disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 12(1), 1853379.

- Inslicht, S. S., Niles, A. N., Metzler, T. J., Lipshitz, S. A. L., Otte, C., Milad, M. R., & Neylan, T. C. (2022). Randomized controlled experimental study of hydrocortisone and D-cycloserine effects on fear extinction in PTSD. Neuropsychopharmacology, 47(11), 1945-1952.

- Khan, A. J., Bradley, E., O’Donovan, A., & Woolley, J. (2022). Psilocybin for trauma-related disorders. Disruptive Psychopharmacology, 319-332.

- Kindt, M., & Soeter, M. (2023). A brief treatment for veterans with PTSD: an open-label case-series study. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 14.

- Kitchiner, N. J., Lewis, C., Roberts, N. P., & Bisson, J. I. (2019). Active duty and ex-serving military personnel with post-traumatic stress disorder treated with psychological therapies: systematic review and meta-analysis. European journal of psychotraumatology, 10(1), 1684226.

- Krediet, E., Janssen, D. G., Heerdink, E. R., Egberts, T. C., & Vermetten, E. (2020). Experiences with medical cannabis in the treatment of veterans with PTSD: Results from a focus group discussion. European Neuropsychopharmacology, 36, 244-254.

- Krediet, E., Bostoen, T., Breeksema, J., van Schagen, A., Passie, T., & Vermetten, E. (2020). Reviewing the potential of psychedelics for the treatment of PTSD. International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology, 23(6), 385-400.

- Kothgassner, O. D., Pellegrini, M., Goreis, A., Giordano, V., Edobor, J., Fischer, S., & Huscsava, M. M. (2021). Hydrocortisone administration for reducing post-traumatic stress symptoms: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 126, 105168.

- Lehrner, A., Hildebrandt, T., Bierer, L. M., Flory, J. D., Bader, H. N., Makotkine, I., & Yehuda, R. (2021). A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of hydrocortisone augmentation of Prolonged Exposure for PTSD in US combat veterans. Behaviour research and therapy, 144, 103924.

- Martin, A., Naunton, M., Kosari, S., Peterson, G., Thomas, J., & Christenson, J. K. (2021). Treatment guidelines for PTSD: a systematic review. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 10(18), 4175.

- Marx, B. P., Lee, D. J., Norman, S. B., Bovin, M. J., Sloan, D. M., Weathers, F. W., & Schnurr, P. P. (2022). Reliable and clinically significant change in the clinician-administered PTSD Scale for DSM-5 and PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 among male veterans. Psychological assessment, 34(2), 197.

- Meister, L., Dietrich, A. C., Stefanovic, M., Bavato, F., Rosi-Andersen, A., Rohde, J., & Kleim, B. (2023). Pharmacological memory modulation to augment trauma-focused psychotherapy for PTSD: a systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Translational psychiatry, 13(1), 207.

- de Moraes Costa, G., Zanatta, F. B., Ziegelmann, P. K., Barros, A. J. S., & Mello, C. F. (2020). Pharmacological treatments for adults with post-traumatic stress disorder: A network meta-analysis of comparative efficacy and acceptability. Journal of psychiatric research, 130, 412-420.

- Mitchell, J. M., Otalora G, M., van der Kolk, B., Shannon, S., Bogenschutz, M., Gelfand, Y., & MAPP2 Study Collaborator Group. (2023). MDMA-assisted therapy for moderate to severe PTSD: a randomized, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Nature Medicine, 29(10), 2473-2480.

- Nijdam, M. J., Vermetten, E., & McFarlane, A. C. (2023). Toward staging differentiation for posttraumatic stress disorder treatment. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 147(1), 65-80.

- Oehen, P., & Gasser, P. (2022). Using a MDMA-and LSD-group therapy model in clinical practice in Switzerland and highlighting the treatment of trauma-related disorders. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 13, 863552.

- Raskind, M. A., Peskind, E. R., Chow, B., Harris, C., Davis-Karim, A., Holmes, H. A., Hart, K. L., McFall, M., Mellman, T. A., Reist, C., Romesser, J., Rosenheck, R., Shih, M. C., Stein, M. B., Swift, R., Gleason, T., Lu, Y., & Huang, G. D. (2018). Trial of Prazosin for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder in Military Veterans. The New England journal of medicine, 378(6), 507-517.

- Petersen, M., Koller, K., Straley, C., & Reed, E. (2021). Effect of cannabis use on PTSD treatment outcomes in veterans. Mental Health Clinician, 11(4), 238-242.

- Rauch, S. A., Kim, H. M., Powell, C., Tuerk, P. W., Simon, N. M., Acierno, R., & Hoge, C. W. (2019). Efficacy of prolonged exposure therapy, sertraline hydrochloride, and their combination among combat veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA psychiatry, 76(2), 117-126.

- Raut, S. B., Canales, J. J., Ravindran, M., Eri, R., Benedek, D. M., Ursano, R. J., & Johnson, L. R. (2022). Effects of propranolol on the modification of trauma memory reconsolidation in PTSD patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 150, 246-256.

- Reist, C., Streja, E., Tang, C. C., Shapiro, B., Mintz, J., & Hollifield, M. (2021). Prazosin for treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. CNS spectrums, 26(4), 338-344. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1092852920001121

- Reinhard, M. A., Seifert, J., Greiner, T., Toto, S., Bleich, S., & Grohmann, R. (2021). Pharmacotherapy of 1,044 inpatients with posttraumatic stress disorder: current status and trends in German-speaking countries. European archives of psychiatry and clinical neuroscience, 271(6), 1065-1076.

- Watts, B.V., Schnurr, P.P., Zayed, M., Young-Xu, Y., Stender, P., Llewellyn-Thomas, H. (2015). A randomized controlled clinical trial of a patient decision aid for posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychiatric Services, 66(2, 149-54.

- Williams, T., Phillips, N. J., Stein, D. J., & Ipser, J. C. (2022). Pharmacotherapy for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). The Cochrane database of systematic reviews, 3(3), CD002795.

- Schmidt, U. (2015). A plea for symptom-based research in psychiatry. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 6(1), 27660. doi:10.3402/ejpt.v6.27660

- Singewald, N., Sartori, S. B., Reif, A., & Holmes, A. (2023). Alleviating anxiety and taming trauma: Novel pharmacotherapeutics for anxiety disorders and posttraumatic stress disorder. Neuropharmacology, 109418.

- Starke, J. A., & Stein, D. J. (2017). Management of treatment-resistant posttraumatic stress disorder. Current Treatment Options in Psychiatry, 4, 387-403.

- Schottenbauer, M. A., Glass, C. R., Arnkoff, D. B., Tendick, V., & Gray, S. H. (2008). Nonresponse and dropout rates in outcome studies on PTSD: Review and methodological considerations. Psychiatry: Interpersonal and biological processes, 71(2), 134-168.

- Simiola, V., Neilson, E.C., Thompson, R., Cook, J.M. (2015). Preferences for trauma treatment: A systematic review of the empirical literature. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 7, 516-24.

- Stefanovics, E. A., Rosenheck, R. A., Jones, K. M., Huang, G., & Krystal, J. H. (2018). Minimal Clinically Important Differences (MCID) in Assessing Outcomes of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. The Psychiatric quarterly, 89(1), 141-155. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11126-017-9522-y

- Sippel, L. M., Holtzheimer, P. E., Friedman, M. J., & Schnurr, P. P. (2018). Defining treatment-resistant posttraumatic stress disorder: a framework for future research. Biological psychiatry, 84(5), e37-e41.

- Sonis, J., & Cook, J. M. (2019). Medication versus trauma-focused psychotherapy for adults with posttraumatic stress disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Research, 282, 112637.

- Sutar, R., & Sahu, S. (2019). Pharmacotherapy for dissociative disorders: A systematic review. Psychiatry research, 281, 112529.

- Swift, J.K., Greenberg, R.P., Tompkins, K.A., Parkin, S.R. (2017). Treatment refusal and premature termination in psychotherapy, pharmacotherapy, and their combination: A meta-analysis of head-to-head comparisons. Psychotherapy (Chic)., 54(1), 47-57.

- Thomaes, K., Dorrepaal, E., Draijer, N., Jansma, E. P., Veltman, D. J., & van Balkom, A. J. (2014). Can pharmacological and psychological treatment change brain structure and function in PTSD? A systematic review. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 50, 1-15.

- Vermetten, E., & Yehuda, R. (2020). MDMA-assisted psychotherapy for posttraumatic stress disorder: A promising novel approach to treatment. Neuropsychopharmacology, 45(1), 231-232.

- Vermetten, E., Vythilingam, M., Southwick, S. M., Charney, D. S., & Bremner, J. D. (2003). Long-term treatment with paroxetine increases verbal declarative memory and hippocampal volume in posttraumatic stress disorder. Biological psychiatry, 54(7), 693-702.

- Van der Kolk, B. A., Spinazzola, J., Blaustein, M. E., Hopper, J. W., Hopper, E. K., Korn, D. L., & Simpson, W. B. (2007). A randomized clinical trial of eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR), fluoxetine, and pill placebo in the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder: treatment effects and long-term maintenance. Journal of clinical psychiatry, 68(1), 37.

- Van Zuiden, M., Frijling, J. L., Nawijn, L., Koch, S. B., Goslings, J. C., Luitse, J. S., & Olff, M. (2017). Intranasal oxytocin to prevent posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms: a randomized controlled trial in emergency department patients. Biological psychiatry, 81(12), 1030-1040.

- Weiss, B., Dinh-Williams, L. A. L., Beller, N., Raugh, I. M., Strauss, G. P., & Campbell, W. K. (2023). Ayahuasca in the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder: Mixed-methods case series evaluation in military combat veterans. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy.

- Williams, T., Phillips, N. J., Stein, D. J., & Ipser, J. C. (2022). Pharmacotherapy for post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). The Cochrane database of systematic reviews, 3(3), CD002795. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD002795.pub3

- Zhang Y, Ren R, Sanford LD, Yang L, Ni Y, Zhou J, Zhang J, Wing YK, Shi J, Lu L, Tang X. The effects of prazosin on sleep disturbances in post-traumatic stress disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med. 2020 Mar;67:225-231. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2019.06.010. Epub 2019 Jun 22. PMID: 31972510; PMCID: PMC6986268.

- Zhang, Z. X., Liu, R. B., Zhang, J., Xian-Yu, C. Y., Liu, J. L., Li, X. Z., & Zhang, C. (2023). Clinical outcomes of recommended active pharmacotherapy agents from NICE guideline for post-traumatic stress disorder: Network meta-analysis. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry, 125, 110754.

- Zoellner, L. A., Roy-Byrne, P. P., Mavissakalian, M., & Feeny, N. C. (2019). Doubly randomized preference trial of prolonged exposure versus sertraline for treatment of PTSD. American Journal of Psychiatry, 176(4), 287-296.

Evidence tabellen

Table of excluded studies

|

Reference |

Reason for exclusion |

|

Germain, 2012 |

Also used cognitive behavioral therapy |

|

Hoskins, 2021 |

Broader inclusion criteria than conform PICO |

|

Petrakis, 2016 |

Comorbid alcohol abuse |

|

Raskind 2003 |

Trial classified as an augmentation trial for treatment-resistant PTSD. |

|

Raskind, 2007 |

concurrent psychotherapy |

|

Raskind, 2013 |

Secondary publication |

|

Reist, 2021 |

Broader inclusion criteria than conform PICO |

|

Simpson, 2015 |

Comorbid alcohol |

|

Taylor, 2008 |

N=13 |

|

|

|

|

Zhang, 2020 |

Broader inclusion criteria than conform PICO |

|

Zhao, 2020 |

Broader inclusion criteria than conform PICO |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Publicatiedatum : 10-03-2025

Beoordeeld op geldigheid : 06-03-2025

V&VN autoriseert de richtlijn, maar niet Module – Farmacotherapie, omdat de rol en bevoegdheden van de Verpleegkundig Specialist hierin niet correct worden weergegeven.

Algemene gegevens

De herziening van deze richtlijnmodules werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten (www.demedischspecialist.nl/kennisinstituut) en werd gefinancierd uit de Stichting Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS).

De financier heeft geen enkele invloed gehad op de inhoud van de richtlijnmodule.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijnmodule is in 2021 een multidisciplinaire werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen (zie hiervoor de Samenstelling van de werkgroep) die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor patiënten met PTSS.

Werkgroep

- prof. dr. E. (Eric) Vermetten, psychiater en voorzitter van de werkgroep, staflid Afdeling Psychiatrie, Leids Universitair Medisch Centrum, namens de Nederlandse Vereniging voor Psychiatrie (NVvP)

- prof. dr. M. (Maartje) Schoorl, klinisch psycholoog en vice-voorzitter van de werkgroep, werkzaam bij Universiteit Leiden en Leids Universitair Behandel en Expertise Centrum (LUBEC), namens de Nederlandse Vereniging voor Psychotherapie (NVP)

- dr. R.A. (Rianne) de Kleine, GZ psycholoog en vice-voorzitter, werkzaam bij Universiteit Leiden en Leids Universitair Behandel en Expertise Centrum (LUBEC), namens Nederlands Insitutuut van Psychologen (NIP)

- dr. R.A. (Ruud) Jongedijk, psychiater, werkzaam bij ARQ, namens de NVvP

- dr. A. (Anja) Lok, psychiater, werkzaam bij Amsterdam Universitair Medisch Centrum, namens de NVvP

- J.P. (Joop) de Jong, psychiater, werkzaam bij Psyq, namens de NVvP

- prof. dr. G.T.M. (Trudy) Mooren, klinisch psycholoog, werkzaam bij ARQ Centrum’45 en verbonden aan de Universiteit Utrecht, namens de Nederlandse Vereniging voor Psychotrauma (NTVP)

- dr. S. (Samrad) Ghane, klinisch psycholoog, werkzaam bij Parnassiagroep, namens de NTVP

- H. (Henriëtte) Markink, MSc, verpleegkundig specialist, werkzaam bij Argo GGZ, namens V&VN Vakcommissie GGZ en Verpleegkundig Specialisten

- Prof. dr. A. (Ad) de Jongh, gz-psycholoog, werkzaam bij PSYTREC, namens P3NL

- dr. N. (Nathan) Bachrach, klinisch psycholoog/associate professor, werkzaam bij GGZ Oost-Brabant en RINO Zuid/Universiteit van Tilburg, namens NIP

- dr. W.J. (Mia) Scheffers, psychomotorisch therapeut werkzaam bij Hogeschool Windesheim Zwolle, namens de Federatie voor vaktherapeutische beroepen (FVB)

- dr. J.T. (Jooske) van Busschbach, pedagoog therapeut, werkzaam bij Hogeschool Windesheim Zwolle, tevens Universitair Centrum Psychiatrie/UMCG Groningen, namens de FVB

- drs. S.U.M. (Stefanie) Terpstra, ervaringsdeskundige, namens MIND, tot 21 februari 2024

- drs. K.Q.M. (Katharina) Ka, ervaringsdeskundige, namens MIND, tot 16-10-2024

- P.G. (Paul) Ulrich, ervaringsdeskundige, namens MIND, tot 16-10-2024

- M.H. (Marijke) Delsing, ervaringsdeskundige, namens MIND, tot 21 februari 2024

Adviesgroep

- prof. dr. mr. C.H. (Christiaan) Vinkers, psychiater, werkzaam bij Amsterdam UMC, namens de NVvP

- prof. dr. B.P.F. (Bart) Rutten, psychiater, werkzaam bij Maastricht Universitair Medisch Centrum, namens de NVvP

- dr. K. (Kathleen) Thomaes, psychiater, werkzaam bij Sinai, namens de NVvP

- drs. S. (Sjef) Berendsen, klinisch psycholoog, werkzaam bij Psytrec, namens P3NL

Met ondersteuning van

- Dr. M.L. (Marja) Molag, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- Drs. B. (Beatrix) Vogelaar, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

Belangenverklaringen

De Code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling is gevolgd. Alle werkgroepleden hebben schriftelijk verklaard of zij in de laatste drie jaar directe financiële belangen (betrekking bij een commercieel bedrijf, persoonlijke financiële belangen, onderzoeksfinanciering) of indirecte belangen (persoonlijke relaties, reputatiemanagement) hebben gehad. Gedurende de ontwikkeling van een module worden wijzigingen in belangen aan de voorzitter doorgegeven. De belangenverklaring wordt opnieuw bevestigd tijdens de commentaarfase.

Een overzicht van de belangen van werkgroepleden en het oordeel over het omgaan met eventuele belangen vindt u in onderstaande tabel. De ondertekende belangenverklaringen zijn op te vragen bij het secretariaat van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

|

Werkgroeplid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

Prof. Dr. E. Vermetten |

Psychiater en voorzitter |

hoogleraar en staflid afdeling psychiatrie bij LUMC Leiden, Kolonel b.d, adjunct professor New York Universirty, School of medicine, consultant bij internationaal strafhof, VN, Adviesgroep PTSS Politie, Nederlands Veteraneninstituut, |

geen |

geen restricties |

|

Prof. Dr.M. Schoorl |

Bijzonder hoogleraar klinische psychologie, LUBEC, vice-voorzitter |

Consulent hoogleraar TOPGGZ eetstoornissen, vz landelijke opleidingsraad psychologische BIG-beroepen |

geen |

geen restricties |

|

Dr. R.A. De Kleine |

Universitair docent klinisch psychologie en vice-vice voorzitter |

GZ-Psycholoog in opleiding tot specialist LUBEC |

geen |

geen restricties |

|

Dr. R.A. Jongedijk |

Psychiater |

Senior strategisch adviseur bij ARQ |

geen |

geen restricties |

|

Dr. A. Lok |

Psychiater |

|