Voeding

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is het advies ten aanzien van voeding bij patiënten met PDS?

Aanbeveling

1. Adviseer patienten met PDS de Richtlijnen goede voeding 2015 te volgen.

2. Bij gebruik van 1 of enkele duidelijke voedingsgerelateerde triggers zoals gasvormers, lactose, frisdrank, overmatig vet, pittige kruiden, cafeïne, alcohol, sorbitol, kunstmatige zoetstoffen en tarwezemelen kan de voeding hierop aangepast worden. Uitgangspunt is het behoud van een evenwichtig voedingspatroon.

3. Overweeg het gebruik van psylliumvezels (zonder hulpstoffen zoals sorbitol, inuline of aspartaam) als mogelijke aanvulling op de adviezen over goede voeding, wanneer deze adviezen onvoldoende verbetering geven, of wanneer de voeding te weinig vezels bevat:

- Dosering 1-3 sachets per dag.

- Bespreek de voordelen (klachtenverlichting, weinig bijwerkingen) en nadelen (smaak, kosten, enige gasvorming, met name in de eerste week toename van buikklachten).

- Adviseer de vochtinname aan te passen op grond van de consistentie van de ontlasting (dat wil zeggen met veel vocht bij obstipatie, en met weinig bij diarreeklachten).

4. Verwijs patiënten met PDS laagdrempelig naar de diëtist voor voedingsadvies:

- wanneer er meerdere voedingsgerelateerde triggers bestaan

- wanneer er sprake is van een onevenwichtig voedingspatroon

- als de patiënt (als mogelijke volgende stap in de dieetbehandeling) in aanmerking zou kunnen komen voor het laag-FODMAP-dieet.

Zie het factsheet Voedingsadvies bij PDS is maatwerk voor wat de diëtist kan betekenen voor een patiënt met PDS.

Voor de praktische uitwerking voor de diëtist, zie bijlage.

We bevelen een glutenvrij dieet bij PDS niet aan.

Gebruik bij verwijzing naar een diëtist bij voorkeur de verwijsreden ‘Dieetbehandeling bij PDS’ omdat de diëtist dan aan de hand van het diëtistisch onderzoek maatwerkgericht een dieetbehandelplan kan opstellen.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

In deze uitgangsvragen onderzochten we de effectiviteit van het glutenvrije dieet, het laag-FODMAP-dieet, het NICE-IBS-dieet en psylliumvezels bij patiënten met PDS. Er zijn diverse RCT’s uitgevoerd naar glutenvrij dieet, laag-FODMAP-dieet en psylliumvezels bij patiënten met PDS. De diëten werden afzonderlijk van elkaar vergeleken met een controledieet. Het NICE-IBS-dieet werd alleen beschreven als controledieet, maar is in feite al een dieetinterventie.

Over het NICE-IBS-dieet in vergelijking met het gebruikelijke voedingspatroon is geen relevante literatuur gevonden, dus kan over de effectiviteit van dit dieet geen conclusie worden getrokken. De plaats van de diëten ten opzichte van elkaar is dus niet bestudeerd.

Hieronder beschrijven we kort de resultaten, en de voor- en nadelen van de 4 diëten afzonderlijk.

Glutenvrij dieet

De geïdentificeerde onderzoeken beschreven de uitkomstmaten buikpijn, algemene verbetering en verlichting van klachten. Kwaliteit van leven werd niet beschreven. De bewijskracht was zeer laag en daarmee kunnen ook geen uitspraken worden gedaan over de effectiviteit van een glutenvrij dieet bij patiënten met PDS. Het volgen van een glutenvrij dieet is intensief en heeft een grote sociale en financiële impact. Bovendien bevatten glutenvrije producten vaak meer vet, suiker en zout en minder vezels, vitamines en mineralen dan de reguliere producten, wat ongunstig is voor de algehele gezondheid. Gezien de aanzienlijke publieke interesse in dit type dieetbehandeling dient middels gerandomiseerde gecontroleerde onderzoeken meer bewijs te worden verzameld. Temeer omdat de mogelijke verbetering na een glutenvrij dieet niet door het elimineren van gluten per se wordt veroorzaakt, maar mogelijk door reductie van inname van fructanen (een FODMAP) of zogenaamde Amylase Trypsin Inhibitors (ATI’s). ATI’s zijn specifieke eiwitten die je in alle glutenbevattende granen vindt en ook een immunologische reactie kunnen uitlokken (Shewry, 2021).

Over het algemeen is een glutenvrije voeding minder gezond (meer vet, suiker en zout en minder vezels, vitamines en mineralen dan de reguliere producten) en zijn de gezondheidsrisico’s op de langere termijn onbekend.

Laag FODMAP-dieet

De geïncludeerde onderzoeken beschreven de uitkomstmaten buikpijn, global improvement, kwaliteit van leven en verlichting van klachten. De bewijskracht was laag tot zeer laag. Het laag-FODMAP-dieet lijkt een klinisch relevant effect te hebben op de uitkomstmaat algemene verbetering. Over de uitkomstmaten buikpijn, kwaliteit van leven en verlichting van klachten kunnen geen uitspraken worden gedaan omdat het bewijs op deze uitkomstmaten zeer laag is. Meta-analyses van de uitkomstmaat algemene verbetering laten zien dat het effect van het laag-FODMAP-dieet groter is wanneer het wordt vergeleken met het normale dieet van de patiënt of met een hoog-FODMAP-dieet, dan wanneer het wordt vergeleken met een alternatief dieet – vaak een (aangepast) NICE-IBS-dieet dat relatief weinig FODMAP’s bevat.

Een belangrijke aantekening hierbij is dat de metingen in de onderzoeken plaatsvonden op het moment dat alle hoog-FODMAP-producten al enkele weken vermeden waren, maar niet na de herintroductieperiode. Hoe het laag-FODMAP-dieet scoort op de gedefinieerde uitkomstmaten na herintroductie van FODMAP’s is dus niet bekend.

Ook de langetermijneffecten van het laag-FODMAP-dieet zijn nog niet bekend. FODMAP’s vormen het substraat voor het darmmicrobioom en depletie van deze koolhydraten kan nadelige effecten hebben op de samenstelling en de activiteit van het microbioom. Bovendien zijn FODMAP’s ook een bron van korteketenvetzuren, die een positief effect hebben op het darmepitheel (bron van energie en antioxidante werking) (Hamer, 2008).

Belangrijk is dat het laag-FODMAP-dieet, in tegenstelling tot veel andere diëten, niet bedoeld is om langere tijd te volgen. Het laag-FODMAP-dieet is alleen bedoeld om uit te zoeken op welke FODMAP’s de patiënt reageert en op welke niet. Binnen een paar maanden is het dieet klaar en gaat de patiënt weer ‘normaal’ eten zonder de FODMAP’s die veel klachten geven.

FODMAP’s hebben een osmotisch effect en zijn substraten voor bacteriële fermentatie, en zullen dus vooral diarree, krampen en overmatige gasvorming veroorzaken. Dat geldt in het bijzonder voor mensen met de viscerale overgevoeligheid die kenmerkend is voor PDS.

Het laag-FODMAP-dieet vergt veel inspanning van de patiënt en mag alleen gevolgd worden onder begeleiding van een diëtist vanwege het risico op deficiënties bij verkeerde toepassing. In samenspraak met de diëtist vermijdt de patiënt 2-6 weken lang alle producten uit het normale dieet die veel FODMAP’s bevatten en vervangt die door producten die weinig FODMAP’s bevatten. De keuze aan voedingsmiddelen is dus beperkt. Wanneer de PDS-klachten tijdens de eliminatieperiode verminderen, worden de geëlimineerde voedingsmiddelen onder begeleiding van de diëtist stuk voor stuk opnieuw geïntroduceerd en wordt gemonitord hoe de patiënt erop reageert. Vooralsnog zijn er geen onderzoeken verricht naar deze herintroductiefase en naar de klachten die PDS-patiënten daarna ervaren.

Gezien de intensieve aard van het dieet kan, in overleg met de diëtist, eerst worden gepoogd een aantal FODMAP-rijke producten te beperken alvorens over te gaan tot een volledig laag-FODMAP-dieet. Voor deze specifieke benadering is echter geen wetenschappelijk bewijs voorhanden.

NICE dieet

Er is geen relevante literatuur gevonden waarin het NICE-IBS-dieet wordt vergeleken met het gebruikelijke voedingspatroon bij patiënten met PDS. Er kan daarom geen conclusie worden getrokken over de uitkomstmaten bij dit dieet. Patiënten met PDS hebben vaak een ongezond eetpatroon: vezelarm en vetrijk, zeer eenzijdig of zeer onregelmatig. Uit de praktijk blijkt dat patiënten doorgaans al een stuk minder klachten ervaren door normalisering van hun voeding. Het NICE-IBS-dieet sluit in grote lijnen aan bij de Richtlijnen goede voeding 2015 van de Gezondheidsraad, met een extra beperking van voedingsmiddelen die PDS-klachten kunnen uitlokken, zoals gasvormers, cafeïne, alcohol en frisdranken. Het NICE-IBS-dieet bevat relatief weinig FODMAP’s en is minder restrictief dan bijvoorbeeld het FODMAP-dieet, maar toch kan ook dit dieet voor de patiënt lastig op te volgen zijn, niet alleen omdat veranderen van (voedings)gedrag moeilijk is, maar ook omdat het individueel bepaald is welke voedingsmiddelen de PDS-klachten triggeren, in welke hoeveelheden en op welk moment.

Omdat de klachten zo uiteenlopen blijft voedingsadvies maatwerk. Wanneer de patiënt hiervoor openstaat, kan de diëtist ondersteunend en motiverend zijn bij de verandering van voedingsgedrag en helpen om voedingstriggers te elimineren en te onderzoeken. Daarnaast zal de diëtist een adequate voedingsinname waarborgen.

Psylliumvezels

De geïdentificeerde systematische review beschreef enkel de uitkomstmaat ‘algemene verbetering’. De bewijskracht voor deze uitkomstmaat was redelijk: het gebruik van psylliumvezels heeft een positief effect op de algemene verbetering, maar informatie over de dosis ontbreekt. De follow-upduur van de geïncludeerde onderzoeken is kort en dus is het lastig om uitspraken te doen over de voordelen van psylliumvezels op de lange termijn. Psylliumvezels zijn beperkt fermenteerbaar door colonbacteriën en geven daardoor weinig gasvormingsklachten. Bij obstipatie is voldoende vochtinname essentieel om coprostase te voorkomen. Bij diarree daarentegen moeten psylliumvezels met zo min mogelijk vocht ingenomen worden. Op basis van klinische ervaring lijken de bijwerkingen gering.

Algemene aandachtspunten bij diëten

Patiënten mijden vaak bepaalde voedingsmiddelen op eigen initiatief door een geconditioneerde, maar vaak maladaptieve respons als gevolg van door voeding uitgelokte darmklachten. Als de voeding te eenzijdig wordt, kan dit ook negatieve gevolgen hebben op de gezondheid en het microbioom [Leerning 2019]. Er kan dan een neerwaartse spiraal ontstaan. Het is belangrijk om de patiënt hierop te wijzen omdat dit op termijn kan leiden tot een eetstoornis zoals Avoidant Restrictive Food Intake Disorder (ARFID).

Het gevaar van eliminatiediëten zoals het glutenvrij of het laag-FODMAP-dieet is de kans op voedingsdeficiënties, zowel in kwantitatieve als kwalitatieve zin, en op een te restrictief eetpatroon. Derhalve is het noodzakelijk om een dergelijke dieetinterventie onder begeleiding van een ter zake kundige diëtist uit te voeren.

Terughoudendheid met betrekking tot eliminatiediëten is belangrijk bij patiënten met kenmerken die wijzen op een eetstoornis (onder andere ARFID) of wanneer er aanwijzingen voor een onderliggende angst- of paniekstoornis zijn. Verwijs de patiënt in dat geval naar een psycholoog.

Kwaliteit van bewijs

- Glutenvrij dieet: kwaliteit van bewijs zeer laag.

- Laag-FODMAP-dieet: bewijskracht voor de korte termijn laag tot zeer laag, mede door kleine aantallen, gebrek aan blindering en heterogeniteit in de onderzoeken. Voor de lange termijn zijn er nog niet voldoende onderzoeken.

- NICE-dieet: geen onderzoeken geïncludeerd.

- Psylliumvezels: bewijskracht laag.

De gekozen uitkomstmaten zijn subjectief en kunnen op veel verschillende manieren gemeten worden. Bij de uitkomstmaat ‘verlichting van klachten’ worden verschillende klachten gemeten die per onderzoek kunnen verschillen.

Het blinderen van patiënten was in veel onderzoeken niet mogelijk. Ook al gaven de onderzoekers aan dat de patiënten geblindeerd werden, dan nog konden de deelnemers eenvoudig achterhalen of zij in de interventiegroep of controlegroep waren geplaatst.

Bovenstaande punten maken het poolen van resultaten complex of niet mogelijk.

Waarden en voorkeuren van de patiënt

Van de PDS-patiënten rapporteert 80% dat de klachten een relatie hebben met hun voedingsinname (Böh, 2013). Afhankelijk van motivatie, voorkeuren en bereidheid om het voedingsgedrag aan te passen, kan een gepaste dieetinterventie worden aangeboden. Het volgen van een dieet kan voor een deel van de PDS-patiënten tijdelijk zwaar zijn, maar veel patiënten hebben dat er wel voor over. Immers, het merendeel ervaart dat de voeding invloed heeft op de klachten. De meeste patiënten begrijpen ook het principe van eliminatie en provocatie om persoonlijke triggers op te sporen. De dieetbehandeling vergt wel enige inspanning van de patiënt zelf; de zorgverlener heeft hierbij een adviserende en ondersteunende rol. Het is belangrijk om ook de verwachtingen te bespreken; aanpassingen van het dieet zullen over het algemeen niet leiden tot klachtenvrij kunnen eten, aangezien PDS-klachten multifactorieel bepaald worden.

Kosten

- Glutenvrije producten zijn over het algemeen duurder dan reguliere producten.

- De kosten van een laag-FODMAP-dieet verschillen niet erg van een eetpatroon volgens de Richtlijnen goede voeding.

- De kosten van het NICE-IBS-dieet verschillen weinig van een eetpatroon volgens de Richtlijnen goede voeding.

- De kosten van psylliumvezels variëren per merk en worden niet vergoed.

- Het tarief van een diëtist is ongeveer € 60-70 per uur. In 2022 vergoedt de basisverzekering de eerste 3 behandeluren bij een diëtist; dit gaat af van het eigen risico. De behandeling kan worden verdeeld over meerdere zorgjaren. Een aanvullende verzekering vergoedt vaak meer uren. De beperkte vergoeding van diëtetiek vanuit het basispakket kan een belemmerende factor zijn voor patiënten, zeker als het eigen risico nog niet aangesproken is.

Aanvaardbaarheid

Glutenvrij dieet

Het is maatschappelijk aanvaardbaar om zelf minder gluten te gebruiken als er een verband met buikklachten wordt ervaren, maar gezien het beperkte bewijs en de gezondheidsrisico’s op de lange termijn is er medisch gezien geen reden om dit dieet te adviseren. Patiënten die de onzekerheid over de effectiviteit geen probleem vinden en die voldoende gemotiveerd zijn, staat het vrij dit dieet toch te volgen. Daarbij moet wel gewezen worden op de financiële en sociale impact. Restaurants, horeca, winkels, bakkers en feestjes bij familie en bekenden zijn vaak niet ingericht op een glutenvrij dieet.

Laag FODMAP dieet

Het wordt algemeen aanvaard dat mensen hun dieet aanpassen om minder klachten te hebben. De sociale en financiële impact van het laag-FODMAP-dieet is minder groot dan van het glutenvrije dieet, maar toch aanzienlijk. Herintroductie van FODMAPs is essentieel in verband met het voorkomen van deficiënte voeding/ gezondheidsrisico’s op de lange termijn.

NICE-dieet

Het wordt algemeen aanvaard dat mensen hun dieet aanpassen om minder klachten te hebben. Het NICE-IBS-dieet overlapt met de Richtlijnen goede voeding 2015 en zal waarschijnlijk geaccepteerd worden door de patiënt.

Psylliumvezels

Het wordt over het algemeen aanvaard dat mensen iets innemen (anders dan medicatie) om minder klachten te hebben.

Haalbaarheid en implementatie

Glutenvrij dieet

Een glutenvrij dieet vergt gezien de restrictieve aard substantiële inspanningen van de patiënt. Het is belangrijk zich bewust te zijn van het risico op deficiënties bij het weglaten van gluten uit het dieet. Glutenvrije producten bevatten vaak meer vetten en suikers, en weinig vezels, ijzer, zink, magnesium en vitamine B. Bij de overgang naar een glutenvrij dieet is voedingseducatie en begeleiding van een diëtist met kennis van glutenvrije voeding raadzaam.

Laag FODMAP-dieet

Een laag-FODMAP-dieet vergt gezien de restrictieve aard substantiële inspanningen van de patiënt. Het is een tijdelijk dieet dat bedoeld is om uit te zoeken welke groepen voedingsmiddelen klachten geven, en is niet geschikt voor de lange termijn. Het volgen van een laag-FODMAP-dieet mag alleen gebeuren onder begeleiding van een diëtist met kennis van dit dieet. De beschikbaarheid van diëtisten met specifieke kennis over het laag-FODMAP-dieet kan een belemmering zijn.

NICE dieet

Het NICE-IBS-dieet is deels vergelijkbaar met de Richtlijnen goede voeding 2015. Het maakt deel uit van een breder concept van gezonde leefstijl en hangt samen met algemene gezondheidsvaardigheden. Mensen met lage gezondheidsvaardigheden zullen doorgaans meer moeite hebben met de therapietrouw.

Psylliumvezels

Psylliumvezels zijn afkomstig van de zaden en zaadhuiden van de plant Plantago ovata. Het feit dat dit geen farmacologisch (chemisch) supplement is, kan mensen aanspreken. Psylliumvezels zijn vrij verkrijgbaar bij drogist, supermarkt en online. Bepaalde psylliumvezelpreparaten bevatten echter toevoegingen (bijvoorbeeld sorbitol, een FODMAP) die juist bij PDS-patiënten voor een toename van klachten zorgen.

Dieetbehandeling

De meeste huisartsenpraktijken hebben al een korte lijn met een diëtistenpraktijk. De diëtist werkzaam in het gezondheidscentrum, de huisartsenpraktijk of de afdeling diëtetiek van het regionale ziekenhuis beschikt over een regionale sociale kaart van diëtisten en hun specialismen, zoals de subspecialisatie ‘PDS/laag-FODMAP’.

Terughoudendheid met betrekking tot een eliminatiedieet is belangrijk bij patiënten met kenmerken die wijzen op een eetstoornis (zoals ARFID) of wanneer er aanwijzingen zijn voor een onderliggende angst- of paniekstoornis. Verwijs de patiënt in dat geval naar een psycholoog of andere ter zake kundige zorgprofessional.

Rationale van de aanbeveling: Waarom deze aanbeveling?

Patiënten met PDS hebben vaak een ongezond eetpatroon en een ongezonde leefstijl. Deze patiënten hebben allereerst baat bij normalisering van hun voeding. De Richtlijnen goede voeding 2015 van de Gezondheidsraad zijn gericht op de algemene bevolking. Bepaalde voedingsmiddelen uit deze richtlijnen kunnen (tijdelijk) PDS-klachten triggeren, daarom is het raadzaam deze triggers te onderzoeken en zo nodig (tijdelijk) te verminderen of te elimineren. Uit onderzoek blijkt dat mensen die ernstige PDS-symptomen ervaren, vaker en heviger reageren op voedingstriggers (Rijnaarts, 2021). Angst-gerelateerd aan gastro-intestinale klachten kan de reactie op voedingstriggers versterken.

Het NICE-IBS-dieet geeft richting aan het opsporen van voedingstriggers die PDS-klachten kunnen verergeren. Omdat voedingstriggers individueel bepaald worden, is het meestal niet nodig alle voedingstriggers te elimineren en is verminderen of elimineren van alleen de persoonlijke triggers veelal genoeg.

Het onderzoeken van voedingstriggers (moet) bij voorkeur plaatsvinden onder professionele begeleiding van een diëtist en moet gericht zijn op zo min mogelijk (tijdelijke) eliminaties. Indien de PDS-klachten het toelaten, is het advies om de Richtlijnen goede voeding 2015 te volgen en alleen de nodige triggers te beperken of te elimineren.

Bij het bestaan van meerdere voedingsgerelateerde triggers en/of een onevenwichtig voedingspatroon kan een diëtist voedingsadvies geven (zie factsheet Voedingsadvies bij PDS is maatwerk). Geef als verwijsreden bij voorkeur ‘Dieetbehandeling bij PDS’, dan kan de diëtist aan de hand van het diëtistisch onderzoek maatwerkgericht een dieetbehandelplan opstellen.

Het gebruik van psylliumvezels zou PDS-klachten kunnen verlichten en heeft maar beperkte bijwerkingen. Dit maakt dat psylliumvezels als dieetbehandeling kunnen worden ingezet naast de Richtlijnen goede voeding 2015, vooral als de patiënt te weinig voedingsvezels (groente, fruit, volkoren granen) eet. Verschillende psylliumproducten bevatten hulpstoffen zoals sorbitol of aspartaam, en smaakstoffen voor een verbeterde smaakervaring. Deze hulpstoffen kunnen PDS-klachten juist doen verergeren; adviseer daarom psylliumproducten zonder deze hulpstoffen.

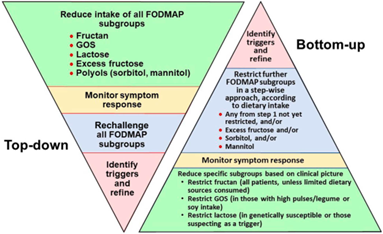

Een gepersonaliseerd laag-FODMAP-dieet wordt aanbevolen als mogelijke volgende stap in een dieetbehandeling omdat dit dieet effect kan hebben op de algemene verbetering. Het is bedoeld om uit te zoeken welke groepen voedingsmiddelen klachten geven en niet geschikt voor de lange termijn. Geadviseerd wordt bij dit dieet maatwerk toe te passen en het alleen te volgen onder begeleiding van een diëtist met kennis van dit dieet. Aangezien het klassieke laag-FODMAP-dieet veel vraagt van de patiënt en bij gebrek aan kwalitatief hoogstaand wetenschappelijk onderzoek grotendeels gebaseerd is op klinische ervaring en expertise, valt te overwegen om dit dieet in overleg met de patiënt bottom-up aan te pakken in plaats van top-down (zie figuur 1). Bij de stapsgewijze bottom-up-aanpak wordt op basis van het diëtistisch onderzoek eerst een selectie van FODMAP’s geëlimineerd en de symptoomrespons hierop afgewacht, alvorens het dieet in samenspraak met de patiënt verder te intensiveren (Singh, 2022). Bij de ‘klassieke’ top-down-aanpak worden gedurende 2-6 weken (bij voorkeur zo kort mogelijk) zoveel mogelijk FODMAP’s geëlimineerd, waarna de verschillende FODMAP’s weer langzaam stuk voor stuk worden geïntroduceerd en gemonitord.

Figuur 1: Top-down” of “bottom-up” aanpak van het laag FODMAP dieet (bron: Singh, 2022).

Er is onvoldoende wetenschappelijk bewijs voor de effectiviteit van een glutenvrij dieet bij PDS. Derhalve dient dit niet te worden geadviseerd aan patiënten. Als er een sterk vermoeden is dat de patiënt toch op gluten reageert, is het verstandig coeliakie uit te sluiten (zie Anamnese).

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Dieetaanpassing is een belangrijke initiële behandelstap bij patiënten met PDS. Er zijn verschillende soorten dieetinterventies en er is veel publieke en wetenschappelijke interesse voor de verschillende diëten. Deze toegenomen aandacht heeft ervoor gezorgd dat meer mensen zich zijn gaan verdiepen in voeding en darmklachten. Het gevaar daarbij is dat er vaak (digitale) bronnen geraadpleegd worden die niet noodzakelijkerwijs de meest accurate informatie weergeven. Veel patiënten volgen een bepaald dieet, vaak op eigen initiatief, zonder adequate (medische of diëtistische) begeleiding. Dit kan leiden tot nadelige gezondheidsuitkomsten, zoals deficiënties of ongewenste gewichtsverandering.

In deze module worden 4 dieetinterventies vergeleken met de Richtlijnen goede voeding 2015 van de Gezondheidsraad. Deze 4 dieetinterventies zijn uitgekozen omdat ze op dit moment populair zijn bij PDS-patiënten en er vragen zijn over de effectiviteit.

Glutenvrij dieet

Gluten is een mengsel van eiwitten dat van nature voorkomt in bepaalde granen, zoals tarwe (waaronder spelt), rogge en gerst. Bij een glutenvrij dieet worden producten die gluten bevatten vermeden. Een gedeelte van de PDS-patiënten geeft aan te denken dat ze overgevoelig of intolerant zijn voor gluten, zonder dat ze coeliakie hebben.

Laag FODMAP-dieet

FODMAP is de verzamelnaam voor een aantal koolhydraten die slecht of niet opgenomen worden in de dunne darm: fermenteerbare oligosacchariden, disacchariden, monosacchariden en polyolen. FODMAP’s trekken door hun osmotische werking vocht aan in het darmlumen en dit kan zorgen voor dunne ontlasting. De fermentatie van deze koolhydraten in het colon leidt bovendien tot overmatige gasvorming.

Het laag-FODMAP-dieet is een eliminatiedieet dat berust op het tijdelijk (bij voorkeur zo kort mogelijk) vermijden van de FODMAP-koolhydraten. Na 2-6 weken worden de verschillende groepen koolhydraten weer langzaam een voor een getest. Na meerdere keren testen weet de patiënt welke groepen FODMAP’s klachten geven. Daarna kan de patiënt weer ‘normaal’ eten, zij het met minder of geen van de koolhydraten die tot de FODMAP’s behoren die klachten geven.

NICE-PDS

Het NICE-IBS-dieet maakt deel uit van het voedings- en leefstijladvies in de Britse NICE-Guideline Irritable bowel syndrome. Het dieet beschrijft onder andere regelmatig en rustig eten, met aandacht voor voldoende inname van (oplosbare) voedingsvezels en vocht bij beperkte inname van voedingsmiddelen die klachten geven zoals gasvormers, cafeïne, alcohol en frisdranken.

Psyllium

Psylliumvezels zijn oplosbare viskeuze vezels die maar beperkt fermenteerbaar zijn en die veel water kunnen opnemen. Psylliumvezels kunnen zowel bij obstipatie als bij diarreeklachten worden gebruikt om de ontlasting te verbeteren.

Bij obstipatie is het van belang om de psylliumvezels met ruim voldoende vocht in te nemen. De ontlasting wordt dan zachter en zwelt wat op, wat de stoelgang stimuleert. Bij te weinig vochtinname kan hinderlijke coprostase ontstaan.

Bij diarree moeten de psylliumvezels met zo min mogelijk vocht ingenomen worden. Dan kunnen ze in de darm het teveel aan vocht binden en zo de ontlasting juist vaster maken.

Doordat psylliumvezels beperkt fermenteerbaar zijn in het colon geven ze minder gasvormingsklachten dan andere typen vezels (So 2021).

Samenvatting literatuur

Since four different dietary interventions were included in the clinical question, we divided this summary into four parts, each part describing one of the dietary interventions.

1. Gluten free diet

Description of studies

Dionne (2018) conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials examining the efficacy of exclusion diets (low FODMAP and gluten-free

diets) in IBS. A search of the literature was conducted in MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials and Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews until November 2017. RCTs that evaluated an FODMAP exclusion diet versus an alternative or usual diet and assessed improvement in either global IBS symptoms or abdominal pain were included. Data were synthesized as relative risk of symptoms remaining using a random effects model. A total of nine studies were eligible for inclusion. There were two RCTs describing a gluten free diet (111 participants) and seven RCTs comparing a low FODMAP diet with various control interventions (397 participants). Below the two RCT included in this review on a gluten free diet (Biesiekierski and Shahbazkhani) are described in detail.

- Biesiekierski (2011) performed a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial undertaken in patients with IBS who were symptomatically controlled on a gluten-free diet. After a two-week run-in period, participants continued the gluten free diet. After the two-week run-in period, all participants continued the gluten free diet and received in addition two bread slices and one muffin per day for six weeks. In the gluten group the bread and muffin contained gluten (total intake of 16 g / day). In the for the placebo group the bread and muffin were gluten free. with a gluten-free diet for up to six weeks. A total of 34 patients (aged 29 – 59 years, 12% men) completed the study. Nineteen patients were included in the gluten group and fifteen in the gluten free group. The primary outcome was the proportion of patients answering “ no ” on more than half of the symptom assessments to the question. “ Over the last week were your symptoms adequately controlled? ” was asked at the end of each study week or at withdrawal if premature. Secondary outcomes were change in overall and individual gastrointestinal symptoms as assessed by the visual analog scale.

- Shahbazkhani (2015) studied the effect of a gluten-free diet on gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with IBS. In a double-blind RCT, 148 IBS patients fulfilling the Rome III criteria were enrolled. The gluten free diet was started in 102 IBS patients; 22 patients found it hard and difficult to continue with the gluten-free diet and subsequently were withdrawn from study. Eighty patients responded to the diet and achieved significant improvement. From this group 8/80 did not follow a strict gluten free diet and were unwilling to continue the diet any further, and the remaining 72 patients commenced on a gluten-free diet for up to six weeks and completed the study. From this group, 35 out of 72 were randomized in the gluten group and 37 out of 72 were in the placebo group for six weeks. The mean age in the gluten group was 44.5 ± 10 years and 43.2 ± 17 years in the placebo group. Six patients (17.1%) in the gluten group and 13 in the placebo group (35.1%) were male. In the second stage after six weeks, patients whose symptoms improved to an acceptable level were randomly divided into two groups; patients either received packages containing powdered gluten (35 cases) or patients received placebo (gluten free powder) (37 cases). Both groups still continued their gluten free diet. Outcomes were assessed using a symptom questionnaire containing the question for the primary outcomes including bloating, abdominal pain, defecation satisfaction, nausea, fatigue and overall symptoms, and scored with visual analogue scale (VAS), with 0 representing no symptoms and 10 indicating severe clinical signs and symptoms.

Zanwar (2016) aimed to evaluate the effects of gluten on IBS symptoms. A double-blind randomized placebo-controlled rechallenge trial was performed in a tertiary care hospital with IBS patients who fulfilled the Rome III criteria. The participants were administered a gluten-free diet for 4 weeks and were asked to complete a symptom-based questionnaire to assess their overall symptoms, abdominal pain, bloating, wind, and tiredness on the visual analog scale (0−100) at the baseline and every week thereafter. The participants who showed improvement were randomly assigned to one of two groups to receive either a placebo (gluten-free breads) or gluten (whole cereal breads) as a rechallenge for the next 4 weeks. Sixty-five patients underwent randomization; 34 received gluten and 31 received placebo. Sixty patient completed the study.

Table 2: Description of study characteristics

|

Included in SR |

RCT |

Participants |

Study duration |

Total intervention / controls |

Intervention vs control |

Outcome measures |

|

Dionne (2018) |

Biesiekierski (2011) |

Rome III IBS patients intolerant of gluten but celiac excluded |

4 weeks |

19/20 |

Diet spiked with 16g gluten vs placebo |

Patients answering “no” to the question “Over the last week were your symptoms adequately controlled?” |

|

Dionne (2018) |

Shahbazkhani (2015) |

Rome III IBS patients intolerant of gluten but celiac excluded. |

6 weeks |

37/35 |

Packages containing powdered gluten vs gluten-free powder in addition to a gluten free diet |

“Symptom control” unclear what these symptoms were but it is implied that this includes stool satisfaction, pain, and bloating. |

|

|

Zanwar (2016) |

ROME III IBS criteria, tertiary care |

4 weeks |

34/31 |

Gluten containing bread vs gluten free bread in addition to a gluten free diet |

Abdominal pain, relief of symptoms |

Results

Summary of Findings Table 3.

|

Outcome

|

Study results and measurements |

Absolute effect estimates |

Certainty of the Evidence (Quality of evidence) |

Plain text summary |

|

|

Advice healthy nutrition |

Gluten free diet |

||||

|

Abdominal pain

|

Based on data from 166 patients in 3 studies Follow up 4-6 weeks |

Two studies reported that the severity score for pain was significantly higher for those consuming the gluten diet compared to the gluten free diet. One study reported no statistically significant difference. |

Very Low Severe risk of bias, severe indirectness, severe imprecision1 |

We are uncertain about the effect of a gluten free diet on abdominal pain in IBS patients. |

|

|

Global improvement

|

Hazard Ratio: 0.42 (CI 95% 0.11 - 1.55) Based on data from 111 patients in 2 studies Follow up 6 weeks |

727 per 1000 |

286 per 1000 |

Very Low Severe risk of bias, severe imprecision, severe indirectness2 |

We are uncertain about the effect of a gluten free diet on global improvement in IBS patient |

|

|

|||||

|

Quality of life |

x |

x |

No Grade |

x |

|

|

Relief of symptoms

|

Based on data from 166 patients in 3 studies Follow up 4-6 weeks |

1: Over the entire study period, the severity scores of pain, satisfaction with stool consistency, and tiredness were significantly higher for those consuming the gluten diet. No adequate control of symptoms gluten n = 13/19 (68%), gluten free: n = 6/15 (40 %) 2. Patients in the gluten-containing group exhibited worsening of symptoms, with significantly higher weekly median overall symptom VAS, compared to those in the gluten free group (P <0.05). 3. Gluten: symptoms were controlled in nine patients (25.7%), gluten free: symptoms were controlled in 31 patients (83.8%) |

Very Low Severe risk of bias, severe imprecision, severe indirectness3 |

We are uncertain about the effect of a gluten free diet on reducing gastrointestinal symptoms in IBS patients. |

|

1. Risk of bias: Serious. Incomplete data and / or a lot of drop-out of participants (loss to follow up); Indirectness: Serious. Only patients who showed improvement on a gluten-free diet were enrolled in some of the studies; Imprecision: Serious. Low number of patients (<100) / Average number of patients (100-300);

2. Risk of bias: Serious. Incomplete data and / or a lot of drop-out of participants (loss to follow up); Indirectness: Serious. Only patients who showed improvement on a gluten-free diet were enrolled in the studies; Imprecision: Serious. Low number of patients (<100) / Average number of patients (100-300);

3. Risk of bias: Serious. Incomplete data and / or a lot of drop-out of participants (loss to follow up); Indirectness: Serious. Only patients who showed improvement on a gluten-free diet were enrolled in the studies; Imprecision: Serious. Low number of patients (<100) / Average number of patients (100-300);

Abdominal pain

Biesiekierski (2011) found that, over the entire study period, the severity score for pain was statistically significantly higher for those consuming the gluten diet compared to the gluten free diet. Absolute numbers were not reported in the paper but estimated from the included graph. After 6 weeks, the score for pain was 38 in the gluten group and 18 in the gluten free group (approximation).

Shahbazkhani (2015) found that in the gluten-containing group, abdominal pain increased (from mean 3.1 ± 2.3 to 5.1 ± 2.2 measured on a VAS) one week after starting the gluten diet. No absolute number were reported for any of the other weeks. A graph was included in the result section of the paper but it was not possible to read the absolute values from it. However, after six weeks, no statistically significant difference between the two groups was observed.

Zanwar (2016) found that after four weeks of gluten free diet, the median value for abdominal pain (measured on a VAS scale) was 15. After four weeks rechallenge, patients in the gluten group reported a median VAS of 30, while patients in the gluten free group reported a mean VAS of 10. Patients in the gluten group showed statistically significantly higher changes in the abdominal pain VAS scores from the fourth week of GFD to each of the 4 rechallenge weeks, compared to the patients in the placebo group (P<0.05).

Global improvement

Dionne (2018) performed a meta-analysis with primary outcome global improvement in IBS symptoms. If global improvement was not reported, abdominal pain was used as the outcome of interest. If different definitions of symptom improvement were provided in the same study, the most stringent outcome reported was used that minimized placebo response rate (e.g., an improvement in IBS symptoms of >50% would be chosen ahead of an improvement in symptoms of >25%).

A greater proportion of participants had an exacerbation of their IBS symptoms among

those allocated to have their diet spiked with gluten, compared with those remaining on a gluten free diet. The pooled RR was 0.42; 95% CI 0.11 to 1.55; I2 = 88%.

Quality of life

None of the included studies reported the outcome measure quality of life.

Relief of symptoms (likertscale; number of days without symptoms)

Biesiekierski (2011) found that significantly more patients in the gluten group (68 %; n = 13 / 19) reported no adequate control of symptoms on more than half of the symptom assessments compared to those using no gluten (40 % ; n = 6 / 15) ( P = 0.001; generalized estimating equation). Changes in symptoms from baseline to end of week 1 as scored on the visual analog scale after 1 week ’s therapy were significantly greater in those patients who consumed the gluten diet for overall symptoms, pain, bloating, satisfaction with stool consistency, and tiredness, but not for wind or nausea. Over the entire study period, the severity scores of pain, satisfaction with stool consistency, and tiredness were significantly higher for those consuming the gluten diet. Absolute numbers were not reported in the paper but were read from the graph included in the study. After 6 weeks, the VAS score for overall symptoms was 38 in the gluten group compared to 24 in the gluten free group.

Shahbazkhani (2015) found after six weeks of the diet, that symptoms were controlled in nine patients (25.7%) in the gluten-containing group, compared to 31 patients (83.8%) in the gluten free group, indicating that 26 out of 35 patients in the gluten group became symptomatic on a gluten containing diet (p < 0.001). In the gluten-containing group, all symptoms significantly increased one week after starting the gluten. Mean bloating VAS before starting the gluten-free diet in the gluten group was 8.4 ± 1.5, and after the six-week diet was decreased to 3.1 ± 2.3. Overall time trend analysis revealed statistically significant satisfaction with stool consistency (p = 0.01) and bloating (p = 0.05) (but no statistically significant difference between the two groups). After a one-week gluten challenge, the mean score was increased to 4 ± 2.1, which was not statistically significant compared with the gluten free group. But this symptom continued to increase to 5.1 ± 2.2 in the fifth week.

Zanwar (2016) found that out of the initial group of 180 patients on a gluten free diet, overall symptom VAS improved for 65 patients after a gluten free diet. These 65 were subsequently randomized to a gluten free diet or gluten containing diet. After four weeks of food rechallenge, patients in the gluten-containing group exhibited worsening of symptoms, with significantly higher weekly median overall symptom VAS, compared to those in the gluten free group (P <0.05). The mean VAS in the gluten group was 25 and in the gluten free group 10 for overall symptoms. During the entire rechallenge period, the median VAS scores for abdominal pain, bloating, and tiredness were significantly higher in the gluten group compared to the placebo. Patients in the gluten group showed significantly higher changes in the abdominal pain, bloating, and tiredness VAS scores from the fourth week of GFD to each of the four rechallenge weeks, compared to the patients in the placebo group (P <0.05). However, VAS score for wind was not significantly different in both groups following the rechallenge (P >0.05). Within the gluten group, the VAS scores for abdominal pain, bloating, wind, tiredness, and overall symptoms, differed significantly over the entire study period. The placebo group also showed similar changes in the VAS symptom scores over the study period; however, only the changes in abdominal pain and wind VAS scores after rechallenge remained significantly different following post hoc analysis (P <0.05).

Conclusions gluten free diet

- We are uncertain about the effect of a gluten free diet on abdominal pain in IBS patients.

- We are uncertain about the effect of a gluten free diet on global improvement in IBS patient

- The outcome measure ‘Quality of live’ was not reported in the included studies

- We are uncertain about the effect of a gluten free diet on reducing gastrointestinal symptoms in IBS patients.

2. Low FODMAP diet

Description of studies

One systematic review and five RCTs were identified. To enhance readability the studies are described briefly and the information per study is displayed in table 3.

The systematic review of Dionne (2018) is described on page 41. Table 2.1.4 describes the individual study characteristics. Seven RCTs were included that compared a low FODMAP diet with various control interventions in 397 participants (Staudacher, 2012, Eswaran, 2016; McIntosh, 2017; Böhn, 2015; Halmos, 2014; Hustoft, 2017; Staudacher, 2017).

Zahedie (2017) compared a low FODMAP diet with a standard diet according to the British Dietetic Association’s guidelines in patients with IBS-D. Participants were randomly assigned to the low FODMAP diet (n=55) or general dietary advice group N=55). All participants met with the specialized dietitians to educate and receive dietary plan in a 45-min one-to one appointment. The low FODMAP diet was supplied less than 0.5 gr per meal fermentable oligosaccharides, monosaccharides, disaccharides, and polyols. The general dietary advice group received recommendations such as limitation of caffeine, alcohol, spicy food, fatty food, and carbonated drinks; to eat small frequency meals; to eat slowly and in peace; and avoidance of chewing gums and sweeteners containing polyols. Participants had to follow the diet for six weeks. One-hundred-and-one participants completed the study.

Eswaran (2016/2017) compared a low FODMAP diet with a modified diet recommended by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (mNICE) in patients with IBS-D. Eswaran conducted two studies using the same patient population. One study (Eswaran 2016, included in the review of Dionne) included the outcome measures adequate relief. The other study (Eswaran 2017) included the outcome measure quality of life. Participants were randomly assigned to the low FODMAP diet (n=50) or the mNICE diet (n=42). Specially trained research dieticians gave standardized instructions about the diet interventions. The mNICE group was instructed to eat small frequent meals, avoid trigger foods, and avoid excess alcohol and caffeine. Foods containing FODMAPs were not specifically excluded as part of the mNICE instructions provided to study participants. Participants had to follow the diet for four weeks. Eighty-four participants completed the study

Harvie (2017) compared a low FODMAP diet with no dietary advices in patients with IBS. Patients were randomly assigned to the low FODMAP diet (n=23) or to the control group (n=27). At three months, the comparator group crossed over to a low FODMAP diet and the initial low FODMAP group started re-challenging foods. Dietary advice was provided to individual participants in a standardized manner by an experienced registered dietitian. At the initial consultation all participants were advised to significantly reduce their intake of excess fructose, lactose, sorbitol, mannitol, Fructooligosaccharide (FOS) and Galactooligosaccharide (GOS). At follow-up (after 3 months) participants were taught to systematically try to reintroduce FODMAP molecules individually, one follow-up appointment was scheduled and then additional appointments were provided on demand. Fifty patients completed the study.

Patcharatrakul (2019) compared a structural individual low FODMAP diet with a commonly recommended diet in patients with IBS. Patients with moderate-to-severe IBS were randomized to a low FODMAP diet (n=33) or a brief advice on a commonly recommended diet (n=33). Patients randomized to the low FODMAP diet received a maximum of 30 minutes of advice. High-FODMAP items that might aggravate the patient’s symptoms were identified from an individual 7-day food diary. Then, the investigator discussed with the patients to avoid high-FODMAP items and modify recipe/menu with the commonly available low-FODMAP items. The control group received brief advice on a commonly recommended diet, which included reducing certain foods that have been traditionally recognized as triggers for gas, bloating, or abdominal pain, including fruits, vegetables, nuts, beans, and garlic, and avoidance of large meals. Patients followed the diet for four weeks. Sixty-four patients completed the study.

Pedersen (2014) compared a low FODMAP diet to a normal Danish/Western Diet in patients with IBS. Patients were randomized to a low FODMAP diet (n=42) or a normal Danish/Western diet (n=40). Each patient allocated to the low FODMAP diet was instructed

during a one hour session by nutritionists or dietitians. Patients allocated to the normal diet were requested to follow an unchanged normal (Danish/Western) diet during the 6-wk study. Seventy-one patients completed the study.

Table 4: Description of study characteristics – low FODMAP

Results

Table 5 shows the summary of findings for the various outcome measures. Below the table, more detailed information on the outcomes can be found. Forest plots can be found in the attachment 5.

Table 5 Summary of Findings table low FODMAP diet

|

Outcome

|

Study results and measurements |

Absolute effect estimates |

Certainty of the Evidence (Quality of evidence) |

Plain text summary |

|

|

Control |

Low FODMAP diet |

||||

|

Abdominal pain

|

Based on data from 308 patients in 4 studies Follow up 4 weeks - 3 months |

All studies show that a low FODMAP diet results in less abdominal pain. Since abdominal pain is measured in different ways using different instruments the results of individual studies are described in table 2.1.1 |

Very low Because of severe risk of bias, severe indirectness and severe imprecision1

|

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of a low FODMAP diet on abdominal pain |

|

|

Global improvement (measured as symptoms remaining after diet)

|

Relative risk: 0.69 (CI 95% 0.54 - 0.88) Based on data from 397 patients in 7 studies

|

616 per 1000 |

432 per 1000 |

Low Because of severe risk of bias andsevere indirectness2 |

A low FODMAP diet may increase global improvement. |

|

Difference: 184 fewer per 1000

|

|||||

|

Global Improvement (IBS-SSS)

|

Measured by: IBS-SSS Scale: 0-500 High better Based on data from 217 patients in 3 studies Follow up 4 week - 3 months |

|

|

Low Because of severe risk of bias and severe indirectness2 |

A low FODMAP diet may increase global improvement. |

|

Difference: MD 83.64 lower (CI 95% 48.96 lower - 118.33 lower) |

|||||

|

Global improvement (0-100 VAS) 4 weeks |

Based on data from 66 patients in 1 studies Follow up 4 weeks |

The group on the low FODMAP diet started at 61.2±21 at baseline and improved to 38.5 ± 20 at 4 weeks. The control group started at 56.3± 17.8 at baseline and improved to 53.5 ±19.2 at 4 weeks. |

Low Because of severe risk of bias and severe indirectness2 |

A low FODMAP diet may increase global improvement. |

|

|

Quality of life

|

Measured by: IBS-QoL Scale: 0-100 High better Based on data from 310 patients in 4 studies Follow up 4 weeks - 3 months |

|

|

Very low Because of severe risk of bias, severe indirectness and severe imprecision3

|

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of a low FODMAP diet on quality of life. |

|

Difference: MD 7.29 higher (CI 95% -1.12 higher - 15.71 higher) |

|||||

|

Relief of symptoms

|

Based on data from 176 patients in 2 studies Follow up 4-6 weeks |

The results are very wide spread, sometimes in favour of low FODMAP diet, sometimes in favour of the control diet. Since relief of symptoms is measured in different ways using different instruments the results of indivual studies are described in table X. |

Very Low Because of severe risk of bias, severe inconsistency, severe indirexctness and severe imprecision4

|

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of a low FODMAP diet on relief of symptoms |

|

1. Risk of bias: Serious. Insufficient blinding / lack of blinding of the participants and researchers, which may cause bias; Indirectness: Serious. Wrong control group, follow-up duration insufficient; Imprecision: Serious. Low number of patients (<100) / Average number of patients (100-300);

2. Risk of bias: Serious. Insufficient blinding / lack of blinding of the participants and researchers, which may cause bias; ; Indirectness: Serious. Wrong control group, follow-up duration insufficient

3. Risk of bias: Serious. Insufficient blinding / lack of outcome assessors, possibly causing detection bias; ; Indirectness: Serious. Wrong control group, follow-up duration insufficient; Imprecision: Serious. Low number of patients (<100) / Average number of patients (100-300);

4. Risk of bias: Serious. Insufficient blinding / lack of outcome assessors, possibly causing detection bias; Inconsistency: Serious. Unexplained variability of the data; Indirectness: Serious. Wrong control group, follow-up duration insufficient; Imprecision: Serious. Low number of patients (<100) / Average number of patients (100-300)

Abdominal pain

Zahedi (2017), Harvie (2017), Pederson (2014) and Patcharatrakul (2019) reported the outcome measure abdominal pain. A meta-analysis was not possible because different measurement instruments were used to measure abdominal pain and not all studies reported the absolute values. A summary of the results is presented in table 2.1.6. All studies showed a reduction in abdominal pain for the low FODMAP group compared to the control group. This difference is in some cases a clinically relevant difference.

Table 6: Results of a low FODMAP diet on abdominal pain measures

|

Study |

Pain |

Measurement method |

Low FODMAP (Mean ± SD)

|

Control (Mean ± SD) |

Difference* between low FODMAP and control group |

|

Zehedi (2017) |

Pain intensity |

IBS-SSS subscale |

48.38 ± 29.57 at baseline to 16.13 ± 13.13

Mean difference*: -32.26 (95% CI -41.3 - -23.17) SE 4.576 |

Mean ± SD 47.38 ± 33.03 to 25.88 ± 21.11

Mean difference*: -21.5 (95%CI -32.4 - -10.7) SE 5.489 |

-10.76 (95% CI -24.8 – 3.2) P=0.1361

Favors low FODMAP diet |

|

|

Pain frequency |

IBS-SSS subscale |

37.38 ± 31.63 to 13.25 ± 14.21 P<0.001 Mean difference*: -24.13 (95% CI -33.9 - -14.4) SE 4.904 |

32 ± 28.75 to 16.75 ± 17.74 P<0.001 Mean difference*: -15.25 (95%CI -24.6 - -5.9) SE 4.731 |

-8.88 (95% CI -22.23 – 4.48) P=0.19

Favors low FODMAP diet |

|

Harvie (2017) |

Pain intensity |

IBS-SSS subscale

Absolute numbers were not reported |

No effect of the low FODMAP diet was seen on severity of pain. |

|

X |

|

|

Pain frequency |

IBS-SSS subscale (days of pain in ten days) |

Reduction in how often participants experienced pain: 3.4 ± 2.9 d in ten days

|

Reduction in how often participants experienced pain: 0.2 ± 1.9 d in ten days

|

Difference in reduction in how often participants experienced pain 3.2 days (95% CI 1.81 – 4.59) P=0.00

Favors low FODMAP diet

|

|

Patcharatrakul (2019) |

Pain |

0-10 VAS |

4.8 (range 0 - 6.9) at baseline to 1.7 (range 0 –4.1) Mean difference*: -0.7 |

from mean 4.4 (range 0.5–6.4) to mean 3.9 (range 0–5.2) Mean difference*: -0.5 |

-0.2

Favors low FODMAP diet |

|

|

Percentage responders |

the proportion of subjects who had at least a 30% decrease in the average daily worst abdominal pain or abdominal discomfort |

18 out of 30 patients responded to the diet (60%) |

9 out of 32 responded to the diet (28%) |

35% |

|

Pederson (2014) |

Pain intensity |

IBS-SSS subscale (0-100) VAS

Absolute numbers were not reported but read from a graph. This is an approximation |

From 64 to 30 Difference*: -34 |

From 68 to 56 Difference*: -12 |

-22

Favors low FODMAP diet

|

|

|

Pain severity |

IBS-SSS subscale (0-100) VAS

Absolute numbers were not reported but read from a graph. This is an approximation. |

From 58 to 36 Difference*: -22 |

From 48 to 46 Difference*: -2 |

-20

Favors low FODMAP diet

|

*: Not reported in the study but calculated by Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

Global improvement

Global improvement was measured in different ways across the studies, which made it not possible to pool the results of all studies. We used the meta-analysis of Dionne as a measure for global improvement and performed a meta-analysis on the results of the RCTs that reported the IBS-SSS. We describe the results of Patcharatrakul separately since they could not be combined with any of the meta-analysis.

Dionne (2018) included 7 RCTs in the meta-analysis (figure 1 –Attachment 5). The primary outcome was global improvement in IBS symptoms. If global improvement was not reported, abdominal pain was used as the outcome of interest. If different definitions of symptom improvement were provided in the same study an improvement in IBS symptoms of >50% would be chosen ahead of an improvement in symptoms of >25%. This approach may lead to an underestimation of the effect of a low FODMAP diet. The relative risk of symptoms not improving in IBS compared with control was 0.69 (95%CI 0.54 – 0.88).

Three studies used the IBS-SSS as an outcome measure (Zehedi, Harvie, Pedersen). We performed a meta-analysis by extracting the mean difference in IBS-SSS score between the endpoint and baseline for the low FODMAP group and the control group for all studies. If this information was not available, we calculated it ourselves by using the data from the papers. Pooled mean difference was -83.6 (-118.3, -49.0) meaning that patients in the low FODMAP group scored 83.6 points lower on the IBS-SSS compared to the control group (Figure 2 – Attachment 5).

Patcharatrakul (2019) measured global IBS symptom severity using a VAS scale (0-100). The group on the low FODMAP diet started at 61.2±21 at baseline and improved to 38.5 ± 20 at 4 weeks. The control group started at 56.3± 17.8 at baseline and improved to 53.5 ±19.2 at 4 weeks.

Quality of life

Five studies assessed quality of life (QoL) by the OBS-QoL (0= worst quality of life, 100=best quality of life). (Eswaran, Harvie, Zahedi, Pederson, Staudacher 2017). The results of four of these studies could be pooled in a meta-analysis (figure 3 – Attachment 5). From each study, we extracted the mean difference in QoL score between the endpoint and baseline for the low FODMAP group and the control group. If this information was not available in the studies we calculated it ourselves by using the data from the papers. We calculated a pooled mean difference of 7.29 (-1.1, 15.7) meaning that patients in the low FODMAP group scored 7.3 points higher on the IBS-QoL compared to the control group.

Relief of symptoms

The systematic review of Dionne (2018) did not report on relief of symptoms. Patcharatrakul (2019) assessed abdominal discomfort, bloating, belching and stool urgency.

In the low FODMAP group, abdominal discomfort and bloating improved statistically significant after four weeks. In the control group, none of the symptoms improved statistically significant. When comparing the improvement in the low FODMAP group with the improvement in the control group there was no clinically relevant differences between both group and no statistically significant difference.

Table 7 Results of a low FODMAP diet on abdominal pain measures

|

Study |

Symptom |

Measurement method |

Low FODMAP baseline and after follow-up |

Control group at baseline and after follow-up |

Difference* |

|

Patcharatrakul (2019) |

Stool urgency |

0–10 cm VAS |

0 (0–8.1) to 0 (0–5.4) Difference*: 0 |

2.3 (0–6.6) to 0 (0–4.2) Difference*: -2.3 |

2.3

Favors control group |

|

Zahedi (2017) |

Stool consistency |

Bristol stool form scale |

5.92 ± 0.45 to 4.3 ± 0.5 Difference: -1.62 ± 0.51 |

5.67 ± 0.61 to 4.61 ± 0.69 Difference: -1.05 ± 0.79 |

-0.57 (95% CI -0.83 - -0.31)

Favors low FODMAP diet |

|

Zahedi (2017) |

Stool frequency |

number of stools per day |

3.29 ± 0.87 to -1.91 ± 0.56 Difference: - 1.37 ± 0.62 |

3.3 ± 0.77 to 2.6 ± 0.96 Difference: -0.7 ± 0.88 |

-0.67 (95% CI -0.97 - -0.37)

Favors low FODMAP diet |

|

Zahedi (2017) |

Abdominal distension |

IBS-SSS subscale |

60.50 ± 26.98 to 26.25 ± 18.35 Difference*: -34.25 (95% CI -43.4 - -25.1) SE 4.614 |

58.75 ± 27.09 to 36.88 ± 15.83 Difference*: -21.87 (95% CI -30.59 - -13.15) SE 4.394

|

-12.38 (95% CI -24,87 - - 0.11)

Favors low FODMAP diet |

|

Patcharatrakul (2019) |

Abdominal discomfort |

0–10 cm VAS |

5.5 (range 4.5–7.1) To 3.2 (range 1.7–5.5) Difference*: -2.3 |

5.6 (range 4.1–7.1) to 4.5 (range 2.6–6.6) Difference*: -1.1 |

-1.2

Favors low FODMAP diet |

|

Patcharatrakul (2019) |

Bloating |

0–10 cm VAS |

5.1 (2.5–7.5) to 3.1 (1.8–5.7) Difference*: -2 |

6.2 (2.1–7.8) to 4.0 (0–6.2) Difference*: -2.2 |

0.2

Favors control group |

|

Patcharatrakul (2019) |

Belching |

0–10 cm VAS |

1.4 (0–5.5) to 0.7 (0–4.7) Difference*: -0.7 |

2.7 (0–5.6) to 1.0 (0–5.4) Difference*: -1.7 |

1

Favors control group |

Conclusions

- The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of a low FODMAP diet on abdominal pain.

- A low FODMAP diet may increase global improvement.

- The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of a low FODMAP diet on quality of life.

- The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of a low FODMAP diet on relief of symptoms

3. NICE diet

There were no studies identified that met the PICO.

4. Psyllium fibre

Description of studies

One systematic review was identified on psyllium fibre.

Ford (2018) aimed to assess the efficacy of psyllium fibre compared to placebo on global improvement in IBS symptoms and quality of life in a systematic review. MEDLINE, EMBASE, EMBASE classic, PsychINFO and the Cochrane central register of controlled trials were searched until July 2017. Fifteen RCTs were identified on fibre, of which seven described ispaghula husk (psyllium) in 499 patients. A meta-analysis was performed on global improvement, defined as symptoms or abdominal pain persisting with intervention compared with control. This was expressed as a relative risk (RR) with 95 % confidence intervals (CIs).

Table 8: Description of study characteristics

|

Included in SR |

RCT |

Participants |

Study duration |

Total intervention / controls |

Intervention vs control |

Outcome measures |

|

Ford (2018) |

Ritchie (1979) |

Author-defined IBS, tertiary care |

3 months |

12/12 |

Ispaghula husk vs placebo |

Dichotomous assessment of IBS symptoms: “ improved ” or “ not improved ” |

|

Ford (2018) |

Longstreth (1981) |

Author-defined IBS, secondary care. |

8 weeks |

37/40 |

Ispaghula vs placebo |

Global assessment of IBS symptoms on Likert scale. Much or a little better from baseline symptoms |

|

Ford (2018) |

Arthurs (1983) |

Author-defined IBS, secondary care. |

4 weeks |

40/38 |

Ispaghula husk vs placebo |

Global assessment of IBS symptoms on Likert scale. Resolved or improved from baseline symptoms |

|

Ford (2018) |

Nigam (1984) |

Author-defined IBS, secondary care. |

3 months |

21/21 |

Ispaghula husk vs placebo |

Dichotomous assessment of IBS: “ improved ” or “ not improved ” |

|

Ford (2018) |

Prior (1987) |

Author-defined IBS, tertiary care |

12 weeks |

40/40 |

Ispaghula husk vs placebo |

Overall improvement in well-being discussed with patient, and rated as “ satisfactory ” or “ unsatisfactory ” |

|

Ford (2018) |

Jalihal (1990) |

Author-defined IBS, secondary care |

4 weeks |

11/9 |

Ispaghula husk vs placebo |

Dichotomous assessment of IBS: “ improved ” or “ no change ” |

|

Ford (2018) |

Bijkerk (2009) |

Author-defined or Rome II IBS., primary care |

12 weeks |

85/93 |

20g Ispaghula husk vs placebo |

Adequate relief of IBS related abdominal pain or discomfort in the last week, with responders defined as those with adequate relief for 2 out of the last 4 weeks |

Results

Table X shows the summary of findings for the various outcome measures. Below the table, more detailed information on the outcomes can be found. Forest plots can be found in the attachment 5.

Table 9. Summary of Findings table Psyllium fibre

|

Outcome Timeframe |

Study results and measurements |

Absolute effect estimates |

Certainty of the Evidence (Quality of evidence) |

Plain text summary |

|

|

Comparator |

Psyllium |

||||

|

Global improvement1

|

Relative risk: 0.83 (CI 95% 0.73 - 0.94) Based on data from 499 patients in 7 studies2 NNT 7 (4 – 25) Follow up 4 weeks - 3 months |

703 per 1000 |

583 per 1000 |

Low Because of severe risk of bias and severe imprecision3 |

The evidence suggests the use of psyllium fibre may result in an increase in global improvement |

|

Difference: 120 fewer per 1000 (CI 95% 190 fewer - 42 fewer) |

|||||

|

Abdominal pain

|

x |

x |

x |

The outcome abdominal pain was not reported in the included studies. |

The outcome abdominal pain was not reported in the included studies. |

|

|

|||||

|

Quality of life

|

x |

x |

x |

The outcome quality of life was not reported in the included studies. |

The outcome quality of life was not reported in the included studies. |

|

|

|||||

|

Relief of symptoms

|

x |

x |

x |

The outcome relief of symptoms was not reported in the included studies. |

The outcome relief of symptoms was not reported in the included studies. |

|

|

|||||

1.symptoms not improving

2.Risk of bias: Serious. Inadequate or unclear randomization; Imprecision: Serious. Wide confidence interval, not a minimal clinically important difference;

Abdominal pain

Not reported.

Global improvement

Ford (2018) conducted a meta-analysis for the outcome measure global improvement, including 7 RCTs and 499 patients. If this was not available then improvement in abdominal pain was taken as the primary outcome. When more than one definition was provided for improvement in the primary outcome, the most stringent definition with the lowest placebo response rate was taken. The pooled risk ratio of global symptoms not improving of Ispaghula (psyllium) versus placebo was 0.83 95%CI: 0.73, 0.94, meaning that Ispaghula (psyllium) is beneficial in treating IBS symptoms. The number needed to treat (NNT) was 7 (95% 4-25).

Quality of live

Not reported.

Relief of symptoms

Not reported.

Conclusions

- Use of psyllium fibre may result in an increase in global improvement

- The outcome abdominal pain was not reported in the included studies.

- The outcome quality of life was not reported in the included studies.

- The outcome relief of symptoms was not reported in the included studies.

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the PICO:

|

Patients |

Patients with IBS (primary and secondary care; all subgroups of IBS) |

|

Intervention A Intervention B Intervention C Intervention D |

gluten free diet low FODMAP diet NICE-IBS diet psyllium fiber |

|

Control |

Dietary advice on healthy balanced diet/ Dutch guideline of a healthy diet |

|

Outcomes |

Abdominal pain (crucial) Global improvement)/ IBS-SSS (crucial) Quality of life (crucial) Relief of symptoms (crucial) |

|

Selection criteria |

Study design: systematic reviews and RCTs |

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered abdominal pain, global improvement / IBS-symptom severity score, quality of life, relief of symptoms (Likert scale; number of days without symptoms) as critical outcome measures for decision making.

The working group defined 20% as a minimal clinically (patient) important difference for all outcome measures, except the IBS-SSS. That means a Standardized Mean Difference (SMD) > 0.50, OR or RR < 0.75 or > 1.25 and a change of (10-)20% of the total score on a questionnaire. A 10% (50 points) improvement on the IBS-SSS is considered a minimal clinically (patient) important difference (based on literature).

The working group defined the outcome measures as follows:

- Abdominal pain: abdominal pain can be measured on different scales, for example VAS-scale or the IBS-SSS subscale

- Global improvement / IBS symptom severity scale (IBS-SSS): global improvement or global relief is usually measured by asking patients if their symptoms were adequately controlled in the past 7 days. The IBS-SSS is in this literature summary used as a measure for global improvement.

- Quality of life: measured with a general questionnaire, such as the SF 36, or disease-specific (IBS-QOL)

- Relief of symptoms: there are many different symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome, for example bloating, nausea, stool consistency. All symptoms described in the included papers are used.

Search and select (Methods)

The databases [Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com)] were searched with relevant search terms from 2000 until November 2020. The detailed search strategy is depicted in the Annex (Totstandkoming)/ under the tab Methods. Studies were selected based on the following criteria as described in the PICO. Attachment 1 contains the PRISMA flowchart showing the number of hits, and Attachment 2 contains the reasons of exclusion.

Results

Two systematic reviews (SR) and eight RCTs were included in the analysis of the literature, see Table 2.1.1 Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables (Attachment 3). The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables (Attachment 4).

Table 1. Results of systematic literature search

|

Intervention |

Studies included |

|

Gluten free diet |

SR: Dionne (2018) RCTs: Biesiekierski (2011), Shahbazkhani (2015), Zanwar (2016) |

|

Low FODMAP diet |

SR: Dionne (2018), RCTs: Zahedie (2017), Eswaran (2017), Harvie (2017), Patcharatrakul (2019), Pedersen (2014) |

|

NICE-IBS diet |

X |

|

Psyllium fiber |

SR: Ford (2018) |

Referenties

- Biesiekierski JR, Newnham ED, Irving PM, Barrett JS, Haines M, Doecke JD, Shepherd SJ, Muir JG, Gibson PR. Gluten causes gastrointestinal symptoms in subjects without celiac disease: a double-blind randomized placebo-controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011 Mar;106(3):508-14; quiz 515. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.487. Epub 2011 Jan 11. PMID: 21224837.

- Dionne J, Ford AC, Yuan Y, Chey WD, Lacy BE, Saito YA, Quigley EMM, Moayyedi P. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Evaluating the Efficacy of a Gluten-Free Diet and a Low FODMAPs Diet in Treating Symptoms of Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018 Sep;113(9):1290-1300. doi: 10.1038/s41395-018-0195-4. Epub 2018 Jul 26. PMID: 30046155.

- Shahbazkhani B, Sadeghi A, Malekzadeh R, Khatavi F, Etemadi M, Kalantri E, Rostami-Nejad M, Rostami K. Non-Celiac Gluten Sensitivity Has Narrowed the Spectrum of Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A Double-Blind Randomized Placebo-Controlled Trial. Nutrients. 2015 Jun 5;7(6):4542-54. doi: 10.3390/nu7064542. PMID: 26056920; PMCID: PMC4488801.

- Zanwar VG, Pawar SV, Gambhire PA, Jain SS, Surude RG, Shah VB, Contractor QQ, Rathi PM. Symptomatic improvement with gluten restriction in irritable bowel syndrome: a prospective, randomized, double blinded placebo controlled trial. Intest Res. 2016 Oct;14(4):343-350. doi: 10.5217/ir.2016.14.4.343. Epub 2016 Oct 17. PMID: 27799885; PMCID: PMC5083263.

- Dionne J, Ford AC, Yuan Y, Chey WD, Lacy BE, Saito YA, Quigley EMM, Moayyedi P. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Evaluating the Efficacy of a Gluten-Free Diet and a Low FODMAPs Diet in Treating Symptoms of Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018 Sep;113(9):1290-1300. doi: 10.1038/s41395-018-0195-4. Epub 2018 Jul 26. PMID: 30046155.

- Eswaran S, Chey WD, Jackson K, Pillai S, Chey SW, Han-Markey T. A Diet Low in Fermentable Oligo-, Di-, and Monosaccharides and Polyols Improves Quality of Life and Reduces Activity Impairment in Patients With Irritable Bowel Syndrome and Diarrhea. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017 Dec;15(12):1890-1899.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2017.06.044. Epub 2017 Jun 28. PMID: 28668539.

- Harvie RM, Chisholm AW, Bisanz JE, Burton JP, Herbison P, Schultz K, Schultz M. Long-term irritable bowel syndrome symptom control with reintroduction of selected FODMAPs. World J Gastroenterol. 2017 Jul 7;23(25):4632-4643. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i25.4632. PMID: 28740352; PMCID: PMC5504379.

- Patcharatrakul T, Juntrapirat A, Lakananurak N, Gonlachanvit S. Effect of Structural Individual Low-FODMAP Dietary Advice vs. Brief Advice on a Commonly Recommended Diet on IBS Symptoms and Intestinal Gas Production. Nutrients. 2019 Nov 21;11(12):2856. doi: 10.3390/nu11122856. PMID: 31766497; PMCID: PMC6950148.

- Pedersen N, Andersen NN, Végh Z, Jensen L, Ankersen DV, Felding M, Simonsen MH, Burisch J, Munkholm P. Ehealth: low FODMAP diet vs Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG in irritable bowel syndrome. World J Gastroenterol. 2014 Nov 21;20(43):16215-26. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i43.16215. PMID: 25473176; PMCID: PMC4239510.

- Zahedi MJ, Behrouz V, Azimi M. Low fermentable oligo-di-mono-saccharides and polyols diet versus general dietary advice in patients with diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome: A randomized controlled trial. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018 Jun;33(6):1192-1199. doi: 10.1111/jgh.14051. Epub 2018 Feb 21. PMID: 29159993.

- Ford AC, Moayyedi P, Chey WD, Harris LA, Lacy BE, Saito YA, Quigley EMM; ACG Task Force on Management of Irritable Bowel Syndrome. American College of Gastroenterology Monograph on Management of Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018 Jun;113(Suppl 2):1-18. doi: 10.1038/s41395-018-0084-x. PMID: 29950604.

- Böhn L, Störsrud S, Törnblom H, Bengtsson U, Simrén M. Self-reported food-related gastrointestinal symptoms in IBS are common and associated with more severe symptoms and reduced quality of life. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013 May;108(5):634-41. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.105. PMID: 23644955.

- Geisslitz S, Shewry P, Brouns F, America AHP, Caio GPI, Daly M, D'Amico S, De Giorgio R, Gilissen L, Grausgruber H, Huang X, Jonkers D, Keszthelyi D, Larré C, Masci S, Mills C, Møller MS, Sorrells ME, Svensson B, Zevallos VF, Weegels PL. Wheat ATIs: Characteristics and Role in Human Disease. Front Nutr. 2021 May 28;8:667370. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2021.667370. PMID: 34124122; PMCID: PMC8192694.

- Hamer HM, Jonkers D, Venema K, Vanhoutvin S, Troost FJ, Brummer RJ. Review article: the role of butyrate on colonic function. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008 Jan 15;27(2):104-19. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03562.x. Epub 2007 Oct 25. PMID: 17973645.

- Leeming ER, Johnson AJ, Spector TD, Le Roy CI. Effect of Diet on the Gut Microbiota: Rethinking Intervention Duration. Nutrients. 2019;11(12):2862. Published 2019 Nov 22. doi:10.3390/nu11122862

- Singh P, Tuck C, Gibson PR, Chey WD. The Role of Food in the Treatment of Bowel Disorders: Focus on Irritable Bowel Syndrome and Functional Constipation. Am J Gastroenterol. 2022 Jun 1;117(6):947-957. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000001767. Epub 2022 Apr 8. PMID: 35435179; PMCID: PMC9169760.

- So D, Gibson PR, Muir JG, Yao CK. Dietary fibres and IBS: translating functional characteristics to clinical value in the era of personalised medicine. Gut. 2021 Dec;70(12):2383-2394. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2021-324891. Epub 2021 Aug 20. PMID: 34417199.

- Tigchelaar EF, Mujagic Z, Zhernakova A, Hesselink MAM, Meijboom S, Perenboom CWM, Masclee AAM, Wijmenga C, Feskens EJM, Jonkers DMAE. Habitual diet and diet quality in Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A case-control study. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2017 Dec;29(12). doi: 10.1111/nmo.13151. Epub 2017 Jul 17. PMID: 28714091

Evidence tabellen

Diet – Evidence table for intervention studies (baseline characteristics) – Gluten free diet

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison/control (C) |

Follow-up |

|

Biesiekierski, 2011 |

Type of study: double blind randomized placebo controlled trial

Setting and country: patients recruited through advertisements and by referral in private dietetic practice, Australia

Funding: the Helen Macpherson Smith Trust, the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) of Australia, and the Vera and Les Erdi Foundation

Conflicts of interest: Susan J. Shepherd has published cookbooks directed toward issues of dietary fructan restrictions, fructose malabsorption, and celiac disease. She has also published shopping guides for low FODMAPs and low fructose and fructan foods. |

Inclusion criteria: age > 16 years, symptoms of IBS fulfilling Rome III criteria that have improved on a gluten-free diet, and adherence to the diet for at least 6 weeks immediately before screening

Exclusion criteria: Celiac disease, significant gastrointestinal disease (such as cirrhosis or inflammatory bowel disease), excessive alcohol intake, intake of non- steroidal anti-inflammatory agents, and unable to give written informed consent

N total at baseline: Intervention (gluten): 19 Control (gluten free): 15

Important prognostic factors2: Median age (range): Gluten: 40 (29-55) Gluten free:49 (33-51)

Sex: Gluten: 16% Gluten free: 7%

Number with predominant bowel habit Gluten: constipation (16%), diarrhea (58%), alternation (26%) Glutenfree: Constipation (20%), diarrhea (33%), alternating (47%)

Groups comparable at baseline? No statistical analysis were performed to compare groups at baseline |

Before participating in the study patients had to adhere to a gluten free diet for at least 6 weeks immediately before screening. Patients were randomized to either the gluten or the placebo treatment group. Participants continued on a gluten-free diet throughout the study, but were asked to consume one study muffin and two study slices of bread containing gluten (total intake of 16 g / day) every day for 6 weeks. |

Before participating in the study patients had to adhere to a gluten free diet for at least 6 weeks immediately before screening. Patients continued their gluten free diet and received one study muffin and two study slices of bread containing no gluten every day for 6 weeks. . |

Length of follow-up: 9 weeks (three weeks after completion of the intervention)

Loss-to-follow-up: Gluten: N: 6, withdrew after a median of 7 (range 2 – 18) days Reasons (describe)

Gluten free: N: 3, withdrew after a median of 16 (range 11 – 21) days

There were no statistical differences between the groups in frequency and timing of withdrawal.

Incomplete outcome data: NA |

|

Zanwar, 2016 |

Type of study: a prospective, randomized, double blinded placebo controlled trial

Setting and country: tertiary health care center in the gastroenterology outpatient clinic affiliated to a University Medical College in Mumbai, India

Funding: None

Conflicts of interest: None |

Inclusion criteria: patients aged >16 years, symptoms of IBS as per the Rome III criteria, willing to adhere to the prescribed diet

Exclusion criteria: Patients already on a gluten free diet, presence of cirrhosis or inflammatory bowel disease, excessive alcohol intake, patients currently prescribed and using systemic immunosuppressants, nonsteroidal anti- inflammatory agents, or medications affecting gastrointestinal motility, abnormal thyroid function tests, presence of a psychiatric disease, pregnancy, inability to give written informed consent

N total at baseline: 180 patients started a gluten free diet. 65 Patients responded to the gluten free diet. Those 65 patients were randomized. 5 patients were lost to follow up. N total = 60 Gluten: N = 30 Gluten free: N=30

Important prognostic factors2: Age mean (+- SD) Gluten: 37 (18-60) Gluten free 35 (18-56)

Male Sex: Gluten: 17 (56%) Gluten free: 18 (60%)

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes (based on age, gender, bmi, duration of illness, IgA tTG antibody level, ESR) |

At the beginning of the study, a dietician provided advice to all patients on following a gluten free diet for 4 weeks. Patients who responded adequately to the gluten free diet and had improvement in their symptoms, defined as a 30% decrease in symptom VAS from the baseline for at least 50% of the time, were included in the study. Patients who did not respond to the GFD were allowed to withdraw from the study. After 4 weeks of the washout (elimination diet) period, the responding patients were randomly assigned into two groups for a double-blind, placebo-controlled rechallenge.

Rechallenge: The patients in the gluten group consumed two slices of bread containing gluten each morning for the course of the rechallenge. Rechallenge lasted 4 weeks and the patients were advised to maintain a gluten free diet throughout this period. |