Screenen op bacteriële vaginose ter preventie van recidief vroeggeboorte

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is de waarde van screening op en behandeling van bacteriële vaginose (gediagnosticeerd met de Nugent score 4-10) ter reductie van het aantal vroeggeboorten, bij zwangere vrouwen met een laag en hoog risico op vroeggeboorte?

De uitgangsvraag bevat de volgende onderliggende subvragen:

- Wat is de waarde van screenen op bacteriële vaginose (gediagnosticeerd met de Nugent score 4-10) gevolgd door behandeling ter reductie van het aantal vroeggeboorten, bij zwangere vrouwen met een laag en hoog risico op vroeggeboorte?

- Wat is de waarde van het behandelen van bacteriële vaginose (gediagnosticeerd met de Nugent score 4-10) ter reductie van het aantal vroeggeboorten, bij zwangere vrouwen met een laag en hoog risico op vroeggeboorte?

Aanbeveling

Verricht geen routinematige screening naar bacteriële vaginose ter preventie van spontane vroeggeboorte. Dit geldt zowel voor vrouwen met en zonder vroeggeboorte in de voorgeschiedenis.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Sub question 1. Screening for bacterial vaginosis during pregnancy

Van de artikelen over screening die niet geïncludeerd zijn, zijn er twee die wel enige bruikbare informatie opleveren, de RCTs van Kiss (2004) en Lee (2019).

De RCT van Kiss (2004) werd uitgevoerd in Wenen, Oostenrijk. Er werden 4155 vrouwen geïncludeerd met een eenlingzwangerschap tussen 15+0 en 19+6 weken zwangerschapsduur. Drie procent had een vroeggeboorte in de anamnese. In beide groepen werden vaginale swabs afgenomen, maar alleen in de interventiegroep werd de uitslag bekend gemaakt aan de obstetricus en werden de vrouwen behandeld. Bacteriële vaginose kwam voor bij 7% van de vrouwen, daarnaast had 13% candidiasis en bijna 0,1% Trichomonas vaginalis. De frequentie van spontane vroeggeboorte <37 weken was 5,3% in de controlegroep en 3,0% in de interventiegroep. Het Number Needed to Treat was 43 (95% betrouwbaarheidsinterval 28 tot 83). Deze studie is niet in de literatuursamenvatting meegenomen omdat er breder werd gescreend op vaginale infecties, en niet alleen op bacteriële vaginose.

De studie van Lee (2019) was een cluster randomised trial van screening en behandeling, uitgevoerd in Bangladesh. Ook hier werd niet alleen gescreend op bacteriële vaginose maar ook op urineweginfecties. In totaal werden er 9712 vrouwen geïncludeerd tussen 13 en 19 weken zwangerschapsduur. In de interventiegroep was de prevalentie van abnormale vaginale flora 16,3%, en van urineweginfecties 8,6%. Er werd geen statistisch significant verschil gevonden in het optreden van vroeggeboortes voor 37 weken zwangerschapsduur, 21,8% vs 20,6%. Het relatieve risico was 1,07 (95% betrouwbaarheidsinterval 0,91 tot 1,24). Deze studie is niet in de literatuursamenvatting meegenomen omdat ook hier niet alleen op bacteriële vaginose werd gescreend en behandeld, maar ook op urineweginfecties. Bovendien wekte het hoge percentage vroeggeboortes (rond 20%) twijfel omtrent de vergelijkbaarheid van de onderzochte populatie met Nederlandse zwangere vrouwen.

Bijwerkingen en complicaties waren geen uitkomstmaat in de analyse. Het risico hierop (en klinische relevantie) wordt als laag ingeschat.

De studie van Kiss (2004) beschrijft geen verschil in risico op vroeggeboorte door de interventie in de verschillende groepen van amenorroeduur. Wel beschrijven zij het effect bij lagere geboortegewichten, wat als een proxy voor vroegere amenorroeduur kan worden beschouwd. Hierbij is er nog steeds een effect zichtbaar.

Naar aanleiding van deze RCT publiceerde dezelfde groep in 2010 een retrospectieve cohort studie (Kiss 2010), de prevalentie van vroeggeboorte in deze groep is vergelijkbaar met de Nederlandse situatie. De effect size in deze groep is groter, en in deze studie wordt apart een amenorroeduur <33 wk beschreven, waarbij er een voordeel voor interventie is.

Sub question 2. Treatment of bacterial vaginosis during pregnancy

De literatuuranalyse werd gebaseerd op een Cochrane meta-analyse van Brocklehurst e.a. uit 2013 met toevoeging van de PREMEVA-trial door Subtil e.a. uit 2018. Alleen de studies die het effect van antibiotica op de uitkomst vroeggeboorte hebben onderzocht bij zwangere vrouwen met bacteriële vaginose, zijn geselecteerd (totaal 14 studies).

Samenvatting conclusie literatuur

De Cochrane systematische review van Brocklehurst uit 2013 liet zien, op basis van 13 studies, dat een behandeling met antibiotica tijdens de zwangerschap de kans op een vroeggeboorte niet lijkt te reduceren, ook niet als de behandeling voor 20 weken zwangerschap wordt gestart of wanneer er specifiek wordt gekeken naar de subgroep van vrouwen die eerder een vroeggeboorte hebben gehad.

De grote PREMEVA trial van Subtil (2018) wijst in dezelfde richting als de resultaten van Brocklehurst (2013). Ook een behandeling met antibiotica die al voor 20 weken zwangerschap gestart wordt, lijkt geen effect te hebben op het voorkomen van een vroeggeboorte voor 34 weken, en ook niet op een vroeggeboorte voor 37 weken. Hoewel in sommige van de conclusies staat dat er mogelijk een ongunstig effect zou kunnen zijn van antibiotica op het risico van vroeggeboorte, is het bewijs hiervoor zeer onzeker. Daarom wordt dit niet verder uitgewerkt.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

Voor een zwangere vrouw en haar partner is het belangrijk om de kans op een vroeggeboorte zo klein mogelijk te maken.

Het afnemen van een smear voor het verrichten van een Nugent score kan als belastend worden ervaren. Het beoordelen van een smear door het verrichten van een Nugent score vindt niet in elk laboratorium plaats, dit geldt voor zowel de eerste lijn als de tweede lijn. Het is geen gebruikelijke zorg om een Nugent score bij de eerstelijns verloskundige af te nemen, in sommige huisartspraktijken gebeurt dit wel.

Toenemend gebruik van antibiotica kan leiden tot resistentie. Een kritische blik ten aanzien van het gebruik van antbiotica is noodzakelijk.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

Afname van een Nugent score, lab bepaling en gebruik antibiotica leiden tot kostenverhoging. Er is geen kosteneffectiviteitsstudie gedaan naar de winst ten aanzien van minder kosten ten gevolge van potentiële afname (dreigende) vroeggeboorte. Echter, aangezien er geen duidelijke winst is in de aantallen vroeggeboorte, is het dus niet kosteneffectief.

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

Er is geen gerandomiseerde studie verricht naar een screeningsstrategie. Derhalve is er geen bewijs voor een grootschalige screening bij zwangere vrouwen met laag en/of hoog risico op vroeggeboorte op basis van een eerdere vroeggeboorte in de voorgeschiedenis.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Vroeggeboorte heeft een breed scala aan oorzaken. Een van de belangrijkste oorzaken is een vaginale infectie. Bacteriële vaginose zorgt mogelijk voor een hoger risico op een spontane vroeggeboorte. Of screening op en behandeling van de bacteriële vaginose met orale antibiotica (metronidazol of clindamycine) de kans op een vroeggeboorte verlaagt is echter onduidelijk. De huidige zorg is in veel klinieken het screenen van vrouwen met een vroeggeboorte (< 34 weken) in de voorgeschiedenis; en indien er sprake is van een Nugent score van >4 of een positieve kweek of PCR te behandelen met orale of vaginale antibiotica. Er bestaat echter veel praktijkvariatie en daarmee variatie in kosten.

Een hoog risico op vroeggeboorte is hier gedefinieerd als een vroeggeboorte in de voorgeschiedenis (AD < 37 weken).

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

Sub question 1. Screening for bacterial vaginosis during pregnancy

No studies were found that complied with the inclusion criteria for this sub question.

Sub question 2. Treatment of bacterial vaginosis during pregnancy

Analysis 1: any antibiotic versus no antibiotic or placebo

1.1 Preterm birth <37 weeks:

|

Low GRADE |

The evidence suggests that antibiotics do not reduce or increase the risk of preterm birth <37 weeks in pregnant women with bacterial vaginosis compared to placebo or no treatment.

Brocklehurst (2013), Subtil (2018) |

1.2 Preterm birth <34 weeks

|

Low GRADE |

Antibiotics may increase the risk of preterm birth <34 weeks in pregnant women with bacterial vaginosis compared to placebo or no treatment.

Brocklehurst (2013), Subtil (2018) |

1.3 Preterm birth <32 weeks:

|

Low GRADE |

Antibiotics may increase the risk of preterm birth <32 weeks in pregnant women with bacterial vaginosis compared to placebo or no treatment.

Brocklehurst (2013) |

Analysis 2: subgroup analysis: previous preterm birth versus no previous preterm birth

2.1 Preterm birth <37 weeks:

Subgroup 2.1.1: previous preterm birth

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of antibiotics compared to placebo or no treatment on the risk of preterm birth <37 weeks in pregnant women with bacterial vaginosis who have had a previous preterm birth.

Brocklehurst (2013) |

Subgroup 2.1.2: no previous preterm birth

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of antibiotics compared to placebo or no treatment on the risk of preterm birth <37 weeks in pregnant women with bacterial vaginosis who have not had a previous preterm birth.

Brocklehurst (2013), Subtil (2018) |

2.2 Preterm birth <34 weeks:

Subgroup 2.2.1: previous preterm birth

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of antibiotics compared to placebo or no treatment on the risk of preterm birth <34 weeks in pregnant women who have had a previous preterm birth.

Brocklehurst (2013) |

Subgroup 2.2.2: no previous preterm birth

|

Low GRADE |

Antibiotics may increase the risk of preterm birth <34 weeks in pregnant women with bacterial vaginosis who have not had a previous preterm birth compared to placebo or no treatment.

Brocklehurst (2013), Subtil (2018) |

2.3 Preterm birth <32 weeks:

No analysis was done for this outcome.

Analysis 3: subgroup analysis: treatment at <20 weeks’ gestation versus >20 weeks’ gestation

3.1 Preterm birth <37 weeks:

Subgroup 3.1.1 Treatment <20 weeks’ gestation

|

Low GRADE |

Antibiotics treatment may result in little to no difference in risk of preterm birth <37 weeks in pregnant women with bacterial vaginosis who start treatment before 20 weeks’ gestation compared to placebo or no treatment.

Brocklehurst (2013), Subtil (2018) |

Subgroup 3.1.2 Treatment >20 weeks’ gestation

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of antibiotics compared to placebo or no treatment on the risk of preterm birth <37 weeks in pregnant women with bacterial vaginosis who start treatment after 20 weeks’ gestation.

Brocklehurst (2013) |

3.2 Preterm birth <34 weeks

Subgroup 3.2.1 Treatment <20 weeks’ gestation

|

Low GRADE |

The evidence suggests that antibiotics do not reduce or increase the risk of preterm birth <34 weeks in pregnant women with bacterial vaginosis who start treatment before 20 weeks’ gestation compared to placebo or no treatment.

Subtil (2018) |

Subgroup 3.2.2 Treatment >20 weeks’ gestation

|

Low GRADE |

Antibiotics may increase the risk of preterm birth <34 weeks in pregnant women with bacterial vaginosis who start treatment after 20 weeks’ gestation compared to placebo or no treatment.

Brocklehurst (2013) |

3.3 Preterm birth <32 weeks

No analysis was done for this outcome.

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

Sub question 1. Screening for bacterial vaginosis during pregnancy

No studies were found that complied with the inclusion criteria for this sub question.

Sub question 2. Treatment of bacterial vaginosis during pregnancy

The Cochrane systematic review by Brocklehurst (2013) assesses whether the use of antibiotics for bacterial vaginosis in pregnancy can: (a) improve maternal symptoms; (b) decrease incidence of adverse perinatal outcomes. The Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth’s Trial Register (including detailed strategies for CENTRAL, MEDLINE and Embase) was searched for relevant studies until May, 31st 2012. Brocklehurst (2013) included only RCTs that compared either one antibiotic with a placebo or no treatment, or two antibiotics with each other in pregnant women with bacterial vaginosis or intermediate vaginal flora whether symptomatic or asymptomatic and detected through screening. Of the 21 included studies by Brocklehurst (2013), 14 were included in meta-analyses reporting one of the following outcomes: birth less than 37 weeks' gestation, birth less than 34 weeks' gestation and birth less than 32 weeks' gestation. Those trials were performed in the UK (3 trials), Indonesia, Finland, Italy, Sweden, Austria, Australia, Iran, The Netherlands and multinationally (2 trials). Predefined sub analyses were done for the following subgroups: 1) previous preterm birth (high risk) versus no previous preterm birth (low risk) pregnancies, 2) both intermediate flora and bacterial vaginosis (Nugent 4-10) versus no intermediate flora but bacterial vaginosis only (Nugent 7-10) and 3) treatment initiation <20 weeks’ gestation versus treatment initiation >20 weeks’ gestation. The Risk of Bias for this SR and the included RCTs was considered low.

The PREMEVA trial by Subtil e.a. (2018) is a double blinded RCT performed in 40 centers in France. A total of 84 530 women in North France were screened before 14 weeks’ gestation, of which 5630 were diagnosed with bacterial vaginosis (Nugent score >7). The study divided the trial into a low risk trial (women with no history of either late miscarriage from 16 to 21+6 weeks or preterm delivery from 22 to 36+6 weeks) and a high risk trial. In the low risk trial, women were assigned to one of three groups: two intervention groups (a single-course clindamycin group or a triple course clindamycin group) or the placebo group. The high risk trial did not include a placebo group, and was therefore not included here. The primary outcome was a composite of late miscarriage (16-21 weeks) or spontaneous very preterm birth (22-32+6 weeks), regardless of whether or not the baby was alive. A secondary outcome was spontaneous preterm delivery before 36+6 weeks. The Risk of Bias of this RCT was considered low.

Results

Sub question 1. Screening for bacterial vaginosis during pregnancy

No studies were found that complied with the inclusion criteria for this sub question.

Sub question 2. Treatment of bacterial vaginosis during pregnancy

The results of the analysis are presented according to the reported outcome measure (preterm birth <37 weeks, preterm birth <34 weeks, preterm birth <32 weeks). None of the included studies reported on the outcome preterm birth <28 weeks. The first analysis combines data from all included patients, in the subsequent analyses subgroups are analysed separately, i.e. previous preterm birth versus no previous preterm birth and treatment at <20 weeks’ gestation versus >20 weeks’ gestation. The third subgroup analysis is not presented here, since the subgroups intermediate flora or bacterial vaginosis (Nugent 4-10) and no intermediate flora but bacterial vaginosis (Nugent 7-10) are not distinct, but overlapping groups..

Analysis 1: any antibiotic versus no antibiotic or placebo

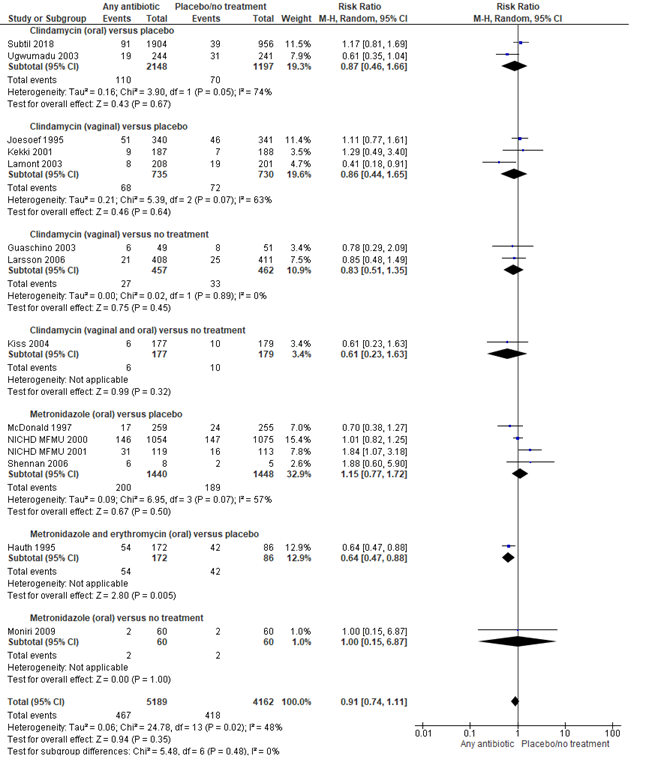

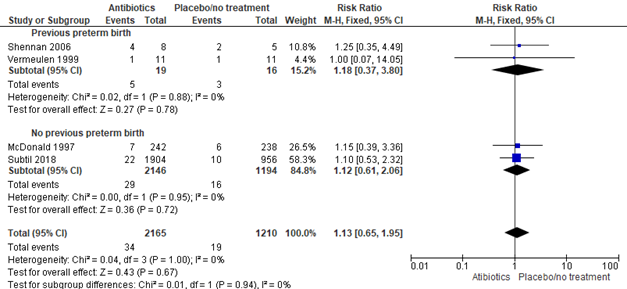

1.1 Preterm birth <37 weeks

Brocklehurst (2013) included 13 trials with 6491 participants to assess the effect of any antibiotic versus no antibiotic or placebo on the outcome preterm birth before 37 weeks in pregnant women with bacterial vaginosis. The PREMEVA trial by Subtil (2018) was added to the analysis, resulting in a total of 14 trials with 9351 participants. Subgroups were made on the basis of antibiotics type (clindamycin, metrodinazole or metrodinazole + erythromycin), way of administration (oral or vaginal) and the control group (placebo or no treatment). Overall, no significant effect of antibiotics compared to placebo/no treatment was found on preterm birth before 37 weeks in pregnant women with bacterial vaginosis (14 trials, 9351 women, RR 0.91, 95%CI 0.74 to 1.11). Heterogeneity between studies was moderate (I2=48%). The trial by Hauth et al. 1995 including 258 women, the only trial comparing metrodinazole + erythromycin against placebo, with low Risk of Bias according to Brocklehurst (2013), found a statistically significant and clinically relevant effect (RR [95% CI] 0.64 [0.47; 0.88]; NNT [95% CI] 6 [3; 20] of antibiotics on preventing preterm birth before 37 weeks in pregnant women with bacterial vaginosis.

Figure 1. Any antibiotic versus placebo/no treatment on preterm birth <37 weeks, stratified by antibiotics type and way of administration

Source: Brocklehurst, 2013 and Subtil, 2018, Z: p-value of the pooled effect, df: degrees of freedom, I2: statistical heterogeneity, CI: confidence interval

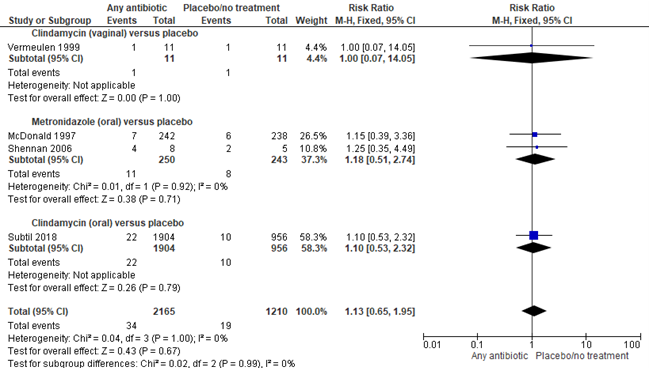

1.2 Preterm birth <34 weeks

Brocklehurst (2013) included 3 trials with 515 participants in the analysis of the effect of any antibiotic versus placebo on preterm birth before 34 weeks in pregnant women with bacterial vaginosis. The PREMEVA trial by Subtil (2018), containing 2860 participants, was added to the analysis, resulting in a total of 4 trials and 3375 women. Subgroups were made on the basis of the antibiotics type (clindamycin or metrodinazole) and the way of administration (oral or vaginal). Overall, no statistically significant effect was found of

antibiotics on the prevention of preterm birth before 34 weeks in pregnant women with bacterial vaginosis (4 trials, 2860 women, RR 1.13, 95%CI 0.65 to 1.95).

Figure 2. Any antibiotic versus placebo/no treatment on preterm birth <34 weeks, stratified by antibiotics type and way of administration

Source: Brocklehurst, 2013 and Subtil, 2018, Z: p-value of the pooled effect, df: degrees of freedom, I2: statistical heterogeneity, CI: confidence interval

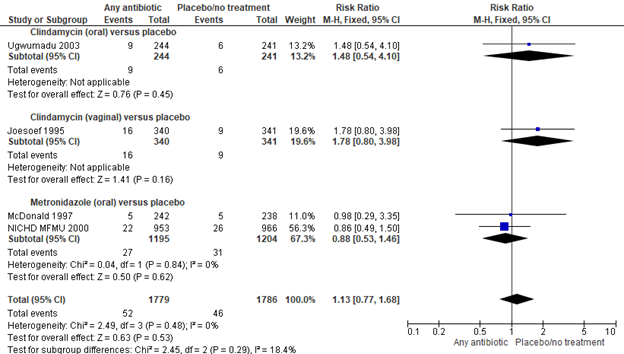

1.3 Preterm birth <32 weeks

Brocklehurst (2013) included 4 trials with 3565 participants to investigate the effect of any antibiotic versus placebo on preterm birth before 32 weeks in pregnant women with bacterial vaginosis. Subgroups were made on the basis of the antibiotics type (clindamycin or metrodinazole) and the way of administration (oral or vaginal). Overall, no significant effect was found of any antibiotic on the prevention of preterm birth before 32 weeks in pregnant women with bacterial vaginosis (4 trials, 3565 women, RR 1.13, 95%CI 0.77 to 1.68).

Figure 3. Any antibiotic versus placebo/no treatment on preterm birth <32 weeks, stratified by antibiotics type and way of administration

Source: Brocklehurst, 2013, Z: p-value of the pooled effect, df: degrees of freedom, I2: statistical heterogeneity, CI: confidence interval

Analysis 2: subgroup analysis 1: previous preterm birth versus no previous preterm birth

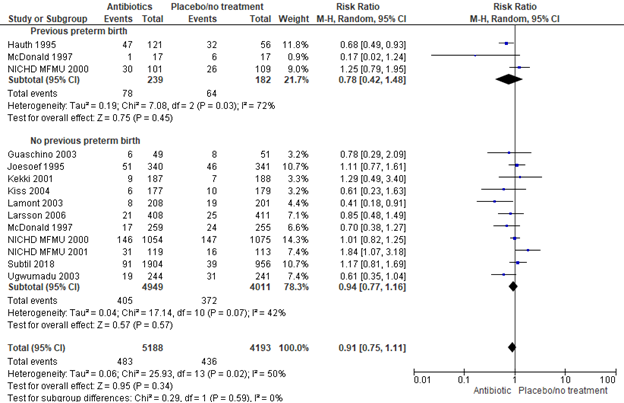

2.1 Preterm birth <37 weeks:

Subgroup 2.1.1: previous preterm birth

Brocklehurst (2013) included 3 trials, 421 women, to investigate the effect of antibiotics versus placebo or no treatment on preterm birth before 37 weeks in pregnant women with bacterial vaginosis and a previous preterm birth. No statistically significant effect was found of antibiotics versus placebo on the prevention of preterm birth before 37 weeks in pregnant wome with a previous preterm birth (RR [95% CI] 0.78 [0.42; 1.48]). Heterogeneity in between studies was substantial (I2=72%).

Subgroup 2.1.2: no previous preterm birth

Brocklehurst (2013) included 10 trials to investigate the effect of antibiotics versus placebo or no treatment on preterm birth before 37 weeks in pregnant women with bacterial vaginosis without previous preterm birth, to which the PREMEVA trial of Subtil (2018) was added, resulting in a total of 11 trials with 9379 women. No statistically significant effect was found for antibiotics on the prevention of preterm birth in pregnant women with bacterial vaginosis and no previous preterm birth (11 trials, 9319 women, RR 0.94, 95%CI 0.77 to 1.16). Heterogeneity between studies was moderate (I2=42%).

Figure 4. Any antibiotic versus placebo/no treatment on preterm birth <37 weeks, stratified by previous preterm birth

Source: Brocklehurst, 2013 and Subtil, 2018 Z: p-value of the pooled effect, df: degrees of freedom, I2: statistical heterogeneity, CI: confidence interval

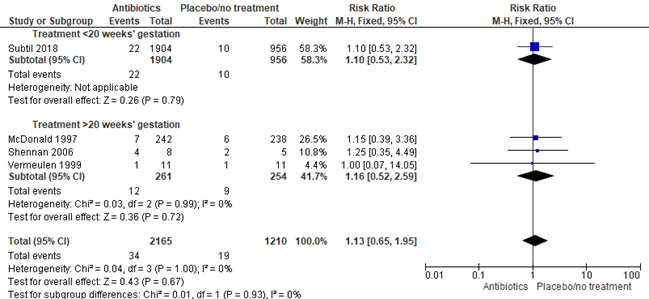

2.2 Preterm birth <34 weeks:

Subgroup 2.2.1: previous preterm birth

Brocklehurst (2013) included 2 trials, 35 women, to investigate the effect of antibiotics versus placebo or no treatment on preterm birth before 34 weeks in pregnant women with bacterial vaginosis and a previous preterm birth. No statistically significant effect was found of antibiotics on the reduction of preterm birth before 34 weeks in pregnant women with bacterial vaginosis and a previous preterm birth (2 trials, 35 women, RR 1.18, 95%CI 0.37 to 3.80).

Subgroup 2.2.2: no previous preterm birth

Brocklehurst (2013) included one trial (n= 480) to investigate the effect of antibiotics versus placebo or no treatment on preterm birth before 34 weeks in pregnant women with bacterial vaginosis and no previous preterm birth. The results of the PREMEVA trial by Subtil (2018) were added to the analysis resulting in a total of two trials and 3340 women. No significant effect was found of antibiotics on the reduction of preterm birth before 34 weeks in pregnant women with bacterial vaginosis and no previous preterm birth (2 trials, 3340 women, RR 1.12, 95%CI 0.61 to 2.06).

Figure 5. Any antibiotic versus placebo/no treatment on preterm birth <34 weeks, stratified by previous preterm birth

Source: Brocklehurst, 2013 and Subtil, 2018 Z: p-value of the pooled effect, df: degrees of freedom, I2: statistical heterogeneity, CI: confidence interval

2.3 Preterm birth <32 weeks:

No subgroup analysis could be done on the effect of antibiotics versus placebo or no treatment on preterm birth <32 weeks in pregnant women with or without a previous preterm birth.

Analysis 3: subgroup analysis 2: treatment at <20 weeks’ gestation versus >20 weeks’ gestation

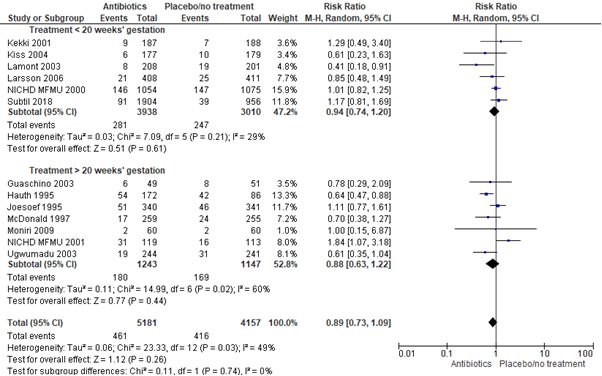

3.1 Preterm birth <37 weeks:

Subgroup 3.1.1 Treatment <20 weeks’ gestation

Brocklehurst included 5 trials to investigate the effect of earlier treatment initiation (<20 weeks’ gestation) with antibiotics versus placebo or no treatment in pregnant women with bacterial vaginosis. The PREMEVA trial by Subtil was added to the analysis, resulting in a total of 6 trials with 6948 women. No statistically significant effect was found of antibiotic treatment initiation before 20 weeks’ gestation on preterm birth before 37 weeks in pregnant women with bacterial vaginosis (6 trials, 6948 women, RR 0.94, 95% CI 0.74 to 1.20).

Subgroup 3.1.2 Treatment >20 weeks’ gestation

Brocklehurst included 7 trials, 2390 women, to investigate the effect of later treatment initiation (>20 weeks’ gestation) with antibiotics versus placebo or no treatment in pregnant women with bacterial vaginosis. No significant effect was found of antibiotic treatment after 20 weeks’ gestation on preterm birth before 37 weeks in pregnant women with bacterial vaginosis (7 trials, 2390 women, RR 0.88, 95% CI 0.63 to 1.22).

Figure 6. Any antibiotic versus placebo/no treatment on preterm birth <37 weeks, stratified by treatment <20 weeks’ gestation and treatment >20 weeks’ gestation

Source: Brocklehurst, 2013 and Subtil, 2018. Z: p-value of the pooled effect, df: degrees of freedom, I2: statistical heterogeneity, CI: confidence interval

3.2 Preterm birth <34 weeks

Subgroup 3.2.1 Treatment <20 weeks’ gestation

Brocklehurst (2013) did not report this subgroup analysis, because none of the included studies reported the effect of earlier treatment initiation (<20 weeks’ gestation) on preterm birth before 34 weeks in pregnant women with bacterial vaginosis. The PREMEVA trial (Subtil 2018) did not find a statistically significant effect of antibiotic treatment initiated before 20 weeks’ gestation on preterm birth before 34 weeks in pregnant women with bacterial vaginosis (1 trial, 2860 women, RR 1.10, 95% CI 0.53 to 2.32).

Subgroup 3.2.2 Treatment >20 weeks’ gestation

Brocklehurst et al. included 3 trials, 515 women, in the subgroup with later treatment initiation (>20 weeks’ gestation). No statistically significant effect was found of antibiotic treatment after 20 weeks’ gestation on preterm birth before 34 weeks (3 trials, 515 women, RR 1.16, 95%CI 0.52 to 2.59).

Figure 7. Any antibiotic versus placebo/no treatment on preterm birth <34 weeks, stratified by treatment <20 weeks’ gestation and treatment >20 weeks’ gestation

Source: Brocklehurst, 2013 and Subtil, 2018. Z: p-value of the pooled effect, df: degrees of freedom, I2: statistical heterogeneity, CI: confidence interval

3.3 Preterm birth <32 weeks

No studies were included that started antibiotic treatment specifically before 20 weeks’ gestation (or reported subgroups) and reported the outcome preterm birth before 32 weeks in pregnant women with bacterial vaginosis.

Level of evidence of the literature

Sub question 1. Screening for bacterial vaginosis during pregnancy

No studies were found that complied with the inclusion criteria for this sub question.

Sub question 2. Treatment of bacterial vaginosis during pregnancy

Analysis 1: any antibiotic versus no antibiotic or placebo

1.1 Preterm birth <37 weeks:

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure preterm birth <37 weeks was downgraded by 2 levels to a ‘low GRADE’, one level because of inconsistency (heterogeneity was moderate) and one level because of imprecision (confidence interval of pooled effect exceeds the lower limit of clinical relevance (≤0.9)).

1.2 Preterm birth <34 weeks:

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure preterm birth <34 weeks was downgraded by 2 levels to a ‘low GRADE’ because of imprecision (confidence interval of pooled effect exceeds both the lower limit of clinical relevance (≤0.9) and the upper limit of clinical relevance (≥1.1)).

1.3 Preterm birth <32 weeks:

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure preterm birth <32 weeks was downgraded by 2 levels to a ‘low GRADE’ because of imprecision (confidence interval of pooled effect exceeds both the lower limit of clinical relevance (≤0.9) and the upper limit of clinical relevance (≥1.1)).

Analysis 2: subgroup analysis 1: previous preterm birth versus no previous preterm birth

2.1 Preterm birth <37 weeks:

Subgroup 2.1.1: previous preterm birth

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure preterm birth <37 weeks, subgroup previous preterm birth, was downgraded by 3 levels to a ‘very low GRADE’, one level because of inconsistency (substantial heterogeneity) and two levels because of imprecision (confidence interval of pooled effect exceeds both the lower limit of clinical relevance (≤0.9) and the upper limit of clinical relevance (≥1.1)).

Subgroup 2.1.2: no previous preterm birth

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure preterm birth <37 weeks, subgroup no previous preterm birth, was downgraded by 3 levels to a ‘low GRADE’, one level because of inconsistency (moderate heterogeneity) and two levels because of imprecision (confidence interval of pooled effect exceeds both the lower limit of clinical relevance (≤0.9) and the upper limit of clinical relevance (≥1.1)).

2.2 Preterm birth <34 weeks:

Subgroup 2.2.1: previous preterm birth

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure preterm birth <34 weeks, subgroup previous preterm birth, was downgraded by 3 levels to a ‘very low GRADE’ because of imprecision (n=35; confidence interval of pooled effect exceeds both the lower limit of clinical relevance (≤0.9) and the upper limit of clinical relevance (≥1.1)).

Subgroup 2.2.2: no previous preterm birth

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure preterm birth <34 weeks, subgroup no previous preterm birth, was downgraded by 2 levels to a ‘low GRADE’ because of imprecision (confidence interval of pooled effect exceeds both the lower limit of clinical relevance (≤0.9) and the upper limit of clinical relevance (≥1.1)).

2.3 Preterm birth <32 weeks:

No analysis was done for this outcome.

Analysis 3: subgroup analysis: treatment at <20 weeks’ gestation versus >20 weeks’ gestation

3.1 Preterm birth <37 weeks:

Subgroup 3.1.1 Treatment <20 weeks’ gestation

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure preterm birth <37 weeks, subgroup treatment <20 weeks’ gestation is downgraded by 2 levels to a ‘low GRADE’ because of imprecision (confidence interval of pooled effect exceeds both the lower limit of clinical relevance (≤0.9) and the upper limit of clinical relevance (≥1.1)).

Subgroup 3.1.2 Treatment >20 weeks’ gestation

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure preterm birth <37 weeks, subgroup treatment >20 weeks’ gestation, was downgraded by 3 levels to a ‘very low GRADE’, one level because of inconsistency (moderate heterogeneity) and one level because of imprecision (confidence interval of pooled effect exceeds both the lower limit of clinical relevance (≤0.9) and the upper limit of clinical relevance (≥1.1)).

3.2 Preterm birth <34 weeks

Subgroup 3.2.1 Treatment <20 weeks’ gestation

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure preterm birth <34 weeks, subgroup treatment <20 weeks’ gestation, was downgraded by 2 levels to a ‘low GRADE’ because of imprecision (two levels downgrade because confidence interval of pooled effect exceeds both the lower limit of clinical relevance (≤0.9) and the upper limit of clinical relevance (≥1.1)).

Subgroup 3.2.2 Treatment >20 weeks’ gestation

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure preterm birth <34 weeks, subgroup treatment <20 weeks’ gestation, was downgraded by 2 levels to a ‘low GRADE’ because of imprecision (confidence interval of pooled effect exceeds both the lower limit of clinical relevance (≤0.9) and the upper limit of clinical relevance (≥1.1)) an only 21 events).

3.3 Preterm birth <32 weeks

No analysis was done for this outcome.

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following sub questions:

Sub question 1. What is the effect of screening followed by treatment for bacterial vaginosis during pregnancy on the occurrence of preterm birth?

| P: | Pregnant women (at low and high risk for preterm birth) |

| I: | Screening followed by treatment for bacterial vaginosis |

| C: | No screening |

| O: | Preterm birth (<37 weeks, <34 weeks and <28 weeks) |

Sub question 2. What is the effect of treatment bacterial vaginosis with metronidazole or clindamycin during pregnancy on the occurrence of preterm birth?

| P: | Pregnant women (at low and high risk for preterm birth) with bacterial vaginosis |

| I: | Treatment of bacterial vaginosis using metronidazole or clindamycin |

| C: | No treatment or placebo |

| O: | Preterm birth (<37 weeks, <34 weeks and <28 weeks) |

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered preterm birth <37 weeks as a crucial outcome measure for decision making and preterm birth <34 weeks and <28 weeks as important outcome measures.

The working group defined a relative risk (RR) of ≤0.9 or ≥1.1 for the outcomes preterm birth and serious side effects as a minimal clinically important difference.

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms until October 16th, 2019. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 671 hits. The PICO consisted of two sub questions (see Search and select).

Sub question 1. Screening for bacterial vaginosis followed by treatment during pregnancy

The inclusion criteria for sub question 1 were:

- A comparison of screening versus no screening for bacterial vaginosis during pregnancy;

- A report of at least the crucial outcome ‘preterm birth <37 weeks’

Based on title and abstract screening, 33 studies were initially selected. After reading full text, all 33 studies were excluded and none was included. The reasons for exclusion can be found in the Table of excluded studies.

Sub question 2. Treatment of bacterial vaginosis during pregnancy

The inclusion criteria for sub question 2 were:

- A comparison of antibiotic treatment (with metronidazole or clindamycin) versus no treatment or placebo for bacterial vaginosis during pregnancy;

- A report of at least the crucial outcome ‘preterm birth’ (either <37 weeks, <34 weeks or <28 weeks)

- It involves the original study data (when more publications were found about one study, the most comprehensive paper was used)

Thirty studies were selected based on title and abstract screening. Of these, 28 were excluded and 1 systematic review (Cochrane review) and 1 RCT were included in the literature analysis. The reasons for exclusion can be found in the table of excluded studies.

Results

For sub question 1 about the effect of screening for and treatment of bacterial vaginosis during pregnancy on preterm birth no relevant articles were found. In the analysis of the literature of sub question 2 about the effect of treatment of bacterial vaginosis during pregnancy on preterm birth one SR and one RCT were included. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- Brocklehurst P, Gordon A, Heatley E, Milan SJ. Antibiotics for treating bacterial vaginosis in pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;

- Subtil D, Brabant G, Tilloy E, Devos P, Canis F, Fruchart A, Bissinger MC, Dugimont JC, Nolf C, Hacot C, Gautier S, Chantrel J, Jousse M, Desseauve D, Plennevaux JL, Delaeter C, Deghilage S, Personne A, Joyez E, Guinard E, Kipnis E, Faure K, Grandbastien B, Ancel PY, Goffinet F, Dessein R. Early clindamycin for bacterial vaginosis in pregnancy (PREMEVA): a multicentre, double-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2018 Nov 17;392(10160):2171-2179.

Evidence tabellen

Evidence tables: systematic review by Brocklehurst e.a. 2013 and RCT by Subtil e.a. 2018

Research question: sub question 2: What is the effect of treatment of bacterial vaginosis with metronidazole or clindamycin to reduce preterm birth?

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C)

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

Brocklehurst, 2013

|

SR and meta-analysis of RCTs

Literature search up to May, 31st 2012.

A: Ugwumadu, 2003 B: Joesoef, 1995 C: Kekki, 2001 D: Lamont, 2003 E: Guaschino, 2003 F: Larsson, 2006 G: Kiss, 2004 H: McDonald, 1997 I: NICHD MFMU, 2000 (Carey, 2000) J: NICHD MFMU, 2001 (Klebanoff, 2001) K: Shennan, 2006 L: Hauth, 1995 M: Moniri 2009 N: Vermeulen 1999

Study design: RCT

Setting and Country: A: St George’s Hospital, London, UK, and St Helier Hospital, Surrey, UK B: 3 Maternity clinics in Jakarta and in 4 maternity clinics in Surabaya, Indonesia. The clinics were public clinics serving mostly low-income families. C: The study centres were the Departments of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Helsinki and University of Oulu (17 antenatal clinics), Health Centers of the City Health Department of Helsinki (7 antenatal clinics), and the County of Vihti (4 antenatal clinics), Finland. D: Northwick Park Hospital, Jessop Hospital, Sheffield and Bolton General Hospital. E: Outpatient obstetric services of participating centres (Clinica Ostetrica e Ginecologica di Trieste, Torino e Milano). F: South East Health Care region of Sweden G: Vienna H: 4 South Australian perinatal centres serving a large metropolitan area. I: Multi-centre J: Multi-centre (15 participating sites). K: 14 UK Hospitals L: abstract only M: Shabih Khani maternity hospital, Kashan, Iran N: 12 city hospitals in The Netherlands

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: A: “PH has received payment for lectures and consultancy from Osmetech, 3M, amd Pharmacia and Upjohn, and has received funding for trials and to attend conferences from these companies.” B: No access full text C: “This study was supported by a research grant from the Helsinki University Central Hospital Research Funds and a grant from Pharmacia-Upjohn and Paulo Foundation, Finland.” D: “Provision of active drug and placebo and funding for research midwives, and monitoring of case report forms provided by Pharmacia/Upjohn, Kalamazoo, MI. E: No access full text F: “P.-G.L. has received payment for lectures and funding for trials from Pharmacia Ltd.” G: “: Fund “Healthy Austria” (“Fonds Gesundes Österreich”) grant PNr. 205/V/12 and Federal Ministry of Education, Science, and Culture grant” H: “This study was supported by grants from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia; Government Employees Medical Research Fund; Queen Victoria Hospital Foundation; Queen Victoria Hospital Special Purposes Pathology Fund; and the Queen Victoria Hospital Special Purposes Research, Education and Training Fund.” I: “Supported by grants from the National Institute of Child Health and Human and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases” J: “Supported by grants from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.” “Dr. Hillier has been a member of the Searle speakers’ bureau, has served as a consultant to Pharmacia Upjohn, and has received honorariums and research funding from 3M Pharmaceuticals.” K: “This study was funded by Tommy’s the baby Charity. Thischarity had no involvement in the study.” L: abstract only M: This work was financially supported by a research grant from Deputy for Researches, Kashan University of Med - ical Sciences and Health Services, Kashan, Iran. N: |

Inclusion criteria SR: “Women of any age, at any stage of pregnancy with a diagnosis of bacterial vaginosis regardless of method of diagnosis (detected because of symptoms or asymptomatic as part of a screening programme). Co-infection with other sexually transmitted infections is not a reason to exclude a study from the review. Women classified as Nugent score four to six (intermediate flora) are included.”

Exclusion criteria SR: -

14 studies included

Important patient characteristics at baseline:

N, gestational age at study entry, Nugent score A: 494 patients, 12-22 weeks, Nugent 7-10 or Gram stain score B: 681 patients, 14-26 weeks, Gram stain score > 6 and pH of vaginal fluid > 4.5 C: 375 patients, 10-17 weeks, Spiegels criteria for BV D: 409 patients, 13-20 weeks, Nugent 4-10 (intermediate flora or BV) E: 100 patients, 14-25 weeks, diagnosis method not reported F: 819 patients, 10-14 weeks, Nugent 6-10 G: 356 patients (only BV positives), 15-19 weeks, Nugent 7-10 H: 879 patients, 16-26 weeks, Gram stain (~107 organisms/mL) I: 1953 women, 16-23+6 weeks, Gram’s-staining score of 7 or higher in conjunction with a vaginal pH higher than 4.4 J: 617 patients, 16-23+6 weeks, pH and Gram’s Staining positive for bacterial vaginosis and a positive culture for T. vaginalis K: 13 (only BV positives), 23-24+6 weeks, Nugent 7-10 L: 623 patients, 22-24 weeks, BV diagnosed by diagnosed by Amsels criteria M: 120 patients, 20-34 weeks, diagnosed BV based on clinical and laboratory findings N: 168 patients, 26 weeks and 32 weeks, all high risk women for preterm birth with and without bacterial vaginosis

|

Describe intervention:

A: Oral clindamycin 300 mg, n = 244 B: Clindamycin cream 2% - 5 g intravaginally at bedtime for 7 days, n =340 C: 2% vaginal clindamycin cream (single course) for 7 days, n = 187 D: g of 2% clindamycin intravaginal cream (+ 100 mg) for 3 nights, n = 199 E: Intravaginal clindamycin 2% cream once daily for 7 days, n = 49 F: 7 days of clindamycin vaginal cream, n = 408 G: 2% vaginal clindamycin cream for 6 days, given 7-10 days after diagnosis. (12-19 weeks). Retreated if still present @ follow-up, n = 2058 H: MET 400 mg x 2/day for 2 days at 24 weeks' gestation, n = 439 I: 8 x 250 mg dose oral MET or plus repeat dose in 48 hrs (@ 16-23 + 6 weeks' gestation). Second treatment at 24-30 weeks' gestation, n = 966 J: 8 x 250 mg dose oral MET plus repeat dose in 48 hrs n = 320 Second treatment at 24-30 weeks' gestation K: MET 400 mg tds for 7 days L: MET 250 mg x 3/day for 7 days plus erythromycin base 333 mg x 3/day for 14 days M: MET 500 mg BID for 7 days, n = 60 N: 2% clindamycin vaginal cream for 7 days at 26 weeks and again at 32 weeks or n = 83 |

Describe control:

A: Placebo twice daily for 5 days, n = 241. B: Matching placebo. 43% enrolled @ less than 20 weeks, n = 341. C: Matching placebo for 7 days, n = 188. D: Matched placebo, n = 205 E: No treatment n = 51 (no placebo, just no treatment) F: No treatment, n = 411 G: No treatment for control group, n = 2097 H: Matching placebo, n = 440 I: Matching lactose placebo, n = 987 J: Placebo with same regimen n = 297 K: Identical placebo L: Matching placebo M: No treatment, n = 60. N: Matching placebo cream daily for 7 days at 26 weeks and again at 32 weeks n = 85. |

End-point of follow-up:

A: Until birth or miscarriage B: Until birth or miscarriage C: Until birth or miscarriage D: Until birth or miscarriage E: Until birth or miscarriage F: Until birth or miscarriage G: Until birth or miscarriage H: Until birth or miscarriage I: Until birth or miscarriage J: Until birth or miscarriage K: Until birth or miscarriage M: Until birth or miscarriage N: Until birth or miscarriage

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? (intervention/control) A: 9 loss to follow up (5 intervention, 4 placebo), reasons for loss to follow up reported and intention to treat performed B: 64 loss to follow up (unclear how many which group), reasons for loss not reported, unclear whether the analysis was intention to treat C: No drop outs/loss to follow up, intention to treat analysis performed D: 5 Loss to follow up reported, intention to treat performed E: 12 Loss to follow up (6 in each group), analysis was not intention to treat F: 55 Loss to follow up because declined treatment, intention to treat performed. 34 patients excluded post-randomization because of multiple pregnancies (n=19), iatrogenic or induced preterm deliveries (n=12) and treatment outside the study with MET or clindamycin (n=3). In total 13 from the intervention group and 21 from the control group. G: Not intention-to-treat. 274 excluded from analysis post randomisation leaving 177 AB vs 179 placebo. Lost to follow-up 8 in BV group and 13 in controls H: The women included in this review were the subset of women with BV, (56% of total trial cohort). Women with a heavy growth of Gardnerella but no BV have not been included. Loss to follow-up - 10/439 (2%) MET group, 12/440 (3%) placebo group. Leaving BV positive randomised to 242 AV vs 238 placebo. Additional information supplied by investigator I: Low recruitment response - only 29% BV+ women were enrolled. Outcome data were available for 1919 of the 1953 women (98.3%) J: Parallel study to NICHD MFMU 2000 assessing Met vs placebo for those with positive trichomonas. Subgroup that had BV plus trichomonas analysed. 119 AB vs 113 placebo. Outcome data were available for 604 out of 617 women who underwent randomisation (97.9 %) K: No loss to follow-up of the women who screened positive for BV L: 8 Women were lost to follow-up. 7 were lost from the treatment group (from 433 to 426) and 1 was lost from the control group (191 to 190), the analysis was not intention to treat M: Appears to be no loss to follow-up according to the results presented but not documented N: Only 11 BV positive women in AB group vs 11 placebo. Intention-to-treat analysis. No loss to follow up. Patients with incomplete outcome data or not taking the medication a “complete trial of medication” was performed. |

Analysis 1: any antibiotic versus no antibiotic or placebo

1.1 Preterm birth <37 weeks:

Subgroup 1.1.1 Clindamycin (oral) versus placebo

Effect measure: RR, RD, mean difference [95% CI]: A: 0.61 [0.35 to 1.04]

Subgroup 1.1.2 Clindamycin (vaginal) versus placebo B: 1.11 [0.77 to 1.61] C: 1.29 [0.49 to 3.4] D: 0.41 [0.18 to 0.91]

Subtotal (95% CI): 0.86 [0.44 to 1.65]

Subgroup 1.1.3 Clindamycin (vaginal) versus no treatment

E: 0.78 [0.29 to 2.09] F: 0.85 [0.48 to 1.49]

Subtotal (95% CI): 0.83 [0.51 to 1.35]

Subgroup 1.1.4 Clindamycin (vaginal and oral) versus no treatment

G: 0.61 [0.23 to 1.63]

Subgroup 1.1.5 Metronidazole (oral) versus placebo H: 0.7 [0.38 to 1.27] I: 1.01 [0.82 to 1.25] J: 1.84 [1.07 to 3.18] K: 1.88 [0.6 to 5.9] Subtotal (95% CI): 1.15 [0.77 to 1.72]

Subgroup 1.1.6 Metronidazole and erythromycin (oral) versus placebo L: 0.64 [0.47 to 0.88]

Subgroup 1.1.7 Metronidazole (oral) versus no treatment M: 1 [0.15 to 6.87]

Pooled effect (random effects model): 0.88 [0.71 to 1.09] favouring antibiotics Heterogeneity (I2): 47.8%

1.2 Preterm birth <34 weeks: Subgroup 1.2.1 Clindamycin (vaginal) versus placebo N: 1 [0.07 to 14.05]

Subgroup 1.2.2 Metronidazole (oral) versus placebo H: 1.15 [0.39 to 3.36] K: 1.25 [0.35 to 4.49] Subtotal (95% CI): 1.18 [0.51 to 2.74]

Pooled effect (fixed effects model): 1.16 [0.52 to 2.59] favouring placebo Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

1.3 Preterm birth <32 weeks: Subgroup 1.3.1 Clindamycin (oral) versus placebo A: 1.48 [0.54 to 4.1]

Subgroup 1.3.2 Clindamycin (vaginal) versus placebo B: 1.78 [0.8 to 3.98]

Subgroup 1.3.3 Metronidazole (oral) versus placebo H: 0.98 [0.29 to 3.35] I: 0.86[0.49 to 1.5] Subtotal (95% CI): 0.88 [0.53 to 1.46]

Pooled effect (fixed effects model): 1.13[0.77 to 1.68] favouring placebo Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

Analysis 2: subgroup analysis: previous preterm birth versus no previous preterm birth

2.1 Preterm birth <37 weeks:

Subgroup 2.1.1 Previous preterm birth L: 0.68 [0.49 to 0.93] H: 0.17 [0.02 to 1.24] I: 1.25 [0.79 to 1.95] Subtotal (95% CI): 0.78 [0.42 to 1.48]

Subgroup 2.1.2 No previous preterm birth E: 0.78 [0.29 to 2.09] B: 1.11 [0.77 to 1.61] C: 1.29 [0.49 to 3.4] G: 0.61 [0.23 to 1.63] D: 0.41 [0.18 to 0.91] F: 0.85 [0.48 to 1.49] H: 0.7 [0.38 to 1.27] I: 1.01 [0.82 to 1.25] J: 1.84 [1.07 to 3.18] A: 0.61 [0.35 to 1.04] Subtotal (95% CI): 0.9 [0.71 to 1.14]

Pooled effect (random effects model): 0.88 [0.71 to 1.09] favouring antibiotics Heterogeneity (I2): 50.86%

2.2 Preterm birth <34 weeks: Subgroup 2.2.1 Previous preterm birth K: 1.25 [0.35 to 4.49] N: 1 [0.07 to 14.05] Subtotal (95% CI): 1.18 [0.37 to 3.8]

Subgroup 2.2.2 No previous preterm birth H: 1.15 [0.39 to 3.36]

Pooled effect (fixed effects model): 1.16 [0.52 to 2.59] favouring antibiotics Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

Analysis 3: subgroup analysis: intermediate flora/bacterial vaginosis (Nugent 4-10) versus no intermediate flora/bacterial vaginosis

3.1 Preterm birth <37 weeks:

Subgroup 3.1.1 Intermediate flora/bacterial vaginosis D: 0.41 [0.18 to 0.91] A: 0.61 [0.35 to 1.04] Subtotal (95% CI): 0.53 [0.34 to 0.84]

Subgroup 3.1.2 No intermediate flora/bacterial vaginosis E: 0.78 [0.29 to 2.09] L: 0.64 [0.47 to 0.88] B: 1.11 [0.77 to 1.61] C: 1.29 [0.49 to 3.4] G: 0.61 [0.23 to 1.63] F: 0.85 [0.48 to 1.49] H: 0.7 [0.38 to 1.27] M: 1 [0.15 to 6.87] I: 1.01 [0.82 to 1.25] J: 1.84 [1.07 to 3.18] Subtotal (95% CI): 0.93 [0.75 to 1.16]

Pooled effect (random effects model): 0.86 [0.69 to 1.07] favouring antibiotics Heterogeneity (I2): 79.2%

3.2 Preterm birth <34 weeks Not included in SR by Brocklehurst 2013

3.3 Preterm birth <32 weeks

Subgroup 3.3.1 Intermediate flora/bacterial vaginosis A: 1.48 [0.54 to 4.1]

Subgroup 3.3.2 No intermediate flora/bacterial vaginosis B: 1.78 [0.8 to 3.98] H: 0.98 [0.29 to 3.35] I: 0.86 [0.49 to 1.5] Subtotal (95% CI): 1.08 [0.71 to 1.66]

Pooled effect (fixed effects model): 1.13 [0.77 to 1.68] favouring placebo Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

Analysis 4: subgroup analysis: treatment at <20 weeks’ gestation versus >20 weeks’ gestation

4.1 Preterm birth <37 weeks Subgroup 4.1.1 Treatment <20 weeks’ gestation C: 1.29 [0.49 to 3.4] G: 0.61 [0.23 to 1.63] D: 0.41 [0.18 to 0.91] F: 0.85 [0.48 to 1.49] I: 1.01 [0.82 to 1.25] Subtotal (95% CI): 0.85 [0.62 to 1.17]

Subgroup 4.1.2 Treatment >20 weeks’ gestation E: 0.78 [0.29 to 2.09] L: 0.64 [0.47 to 0.88] B: 1.11 [0.77 to 1.61] H: 0.7 [0.38 to 1.27] M: 1 [0.15 to 6.87] J: 1.84 [1.07 to 3.18] A: 0.61 [0.35 to 1.04] Subtotal (95% CI): 0.88 [0.63 to 1.22]

Pooled effect (random effects model): 0.86 [0.69 to 1.07] favouring antibiotics Heterogeneity (I2): 48.62%

4.2 Preterm birth <34 weeks Subgroup 4.2.1 Treatment <20 weeks’ gestation *This analysis is added on the basis of Subtil 2018

|

Facultative:

Authors conclusion: “The evidence to date does not suggest any benefit in screening and treating all pregnant women for asymptomatic bacterial vaginosis to prevent preterm birth.”

“Most trials have tested treatment in the second trimester; some as late as 28 weeks' gestation. This may be too late to prevent the consequences of any ascending infection and may be one of the main reasons for the observed lack of a statistically significant effect on the preterm birth rates.”

Level of evidence: no GRADE. Overall, the studies performed well in the risk of bias analysis. Reporting bias was assessed for analysis 1: any antibiotic versus no antibiotic or placebo on preterm birth <37 weeks. On visual inspection of the funnel plot, there appeared to be no reporting bias.

Heterogeneity: heterogeneity appeared to be substantial in the primary analysis (comparing any antibiotics versus placebo or no treatment on preterm birth <37 weeks), with an I2=48%. However, the test for subgroup differences to investigate heterogeneity was not significant (P = 0.39, I2 = 5.1%).

|

|

Subtil, 2018 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: 40 centres in Nord-Pas de Calais region of France

Funding and conflicts of interest: “The funder of the study had no role in the study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report. The corresponding author had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.” |

Inclusion criteria: “all pregnant women in the Nord-Pas de Calais region of France were offered free screening for bacterial vaginosis during their first trimester of pregnancy, with self-collected vaginal samples. Bacterial vaginosis was defined by a Nugent score of 7 or higher with these samples. Women with bacterial vaginosis and at low risk of preterm delivery (with no history of either late miscarriage from 16 to 21 weeks and 6 days or preterm delivery from 22 to 36 weeks and 6 days) were asked to participate. Participants were eligible if they were aged 18 years or older, had a gestational age less than 15 weeks, and were able to speak French and provide written informed consent.”* Exclusion criteria: “Participants were excluded if they had a known allergy to clindamycin, vaginal bleeding within the week before proposed screening of bacterial vaginosis, or planned to give birth in a different region.”

N total at baseline: Intervention one clindamycin course: 943 Intervention three clindamycin courses: 968 Control (placebo): 958

Important prognostic factors2:

N, gestational age at study entry, Nugent score: 2869 patients, …-15 weeks (mean 12.4 weeks), Nugent score ≥7 |

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test): Either one course clindamycin: 300 mg oral clindamycin twice-daily, followed by two 4-day courses of placebo twice-daily, spaced 1 month apart (single-course clindamycin); Or three courses clindamycin: three 4-day courses of 300 mg clindamycin twice-daily, spaced 1 month apart (triple-course clindamycin).

|

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

Three four day placebo courses |

Length of follow-up: until miscarriage or birth

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention, N (%): 7 (0.37%) Reasons (describe): not reported

Control, N (%): 2 (0.20%) Reasons (describe): not reported

Incomplete outcome data: Intervention, N (%): 450 (23.5%) Reasons (describe): - 374 stopped or incomplete treatment - 92 >15 weeks’ gestation at randomization - 10 missing data for inclusion criteria - 7 Nugent score <7 at randomization - 1 previous preterm delivery

Control, N (%): 189 (19.7%) Reasons (describe): - 156 stopped or incomplete treatment - 39 >15 weeks’ gestation at randomization - 4 missing data for inclusion criteria - 1 previous preterm delivery

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Analysis 1: any antibiotic versus no antibiotic or placebo

1. Preterm birth <37 weeks: Subgroup 1.1.1 Clindamycin (oral) versus placebo RR, 95%CI: 1.17 [0.81 to 1.69]

2. Preterm birth <34 weeks: Subgroup 1.2.3 Clindamycin (oral) versus placebo RR, 95%CI: 1.10 (0.53 to 2.32)

Analysis 2: subgroup analysis: previous preterm birth versus no previous preterm birth

1. Preterm birth <37 weeks:

Subgroup 2.1.2 No previous preterm birth RR, 95%CI: 1.17 [0.81 to 1.69]

2. Preterm birth <34 weeks:

Subgroup 2.2.2 No previous preterm birth RR, 95%CI: 1.10 (0.53 to 2.32)

Analysis 3: subgroup analysis: intermediate flora/bacterial vaginosis (Nugent 4-10) versus no intermediate flora/bacterial vaginosis

1. Preterm birth <37 weeks:

Subgroup 3.1.2 No intermediate flora/bacterial vaginosis RR, 95%CI: 1.17 [0.81 to 1.69]

Analysis 4: subgroup analysis: treatment at <20 weeks’ gestation versus >20 weeks’ gestation

1. Preterm birth <37 weeks Subgroup 4.1.1 Treatment <20 weeks’ gestation RR, 95%CI: 1.17 [0.81 to 1.69]

|

Authors conclusion: “The PREMEVA trial showed no evidence of a reduction in risk of late miscarriage or spontaneous very preterm delivery after early treatment by oral clindamycin in women at low risk of preterm birth with bacterial vaginosis during the first trimester of pregnancy.”

*Women with previous preterm delivery were not excluded but included in a subtrial. The results of this subtrial are not reported here because a placebo group or no treatment group was missing.

|

Quality assessment tables

1. Quality assessment systematic review Brocklehurst, 2013

|

Study

|

Appropriate and clearly focused question?1

Yes/no/unclear |

Comprehensive and systematic literature search?2

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of included and excluded studies?3

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of relevant characteristics of included studies?4

Yes/no/unclear |

Appropriate adjustment for potential confounders in observational studies?5

Yes/no/unclear/not applicable |

Assessment of scientific quality of included studies?6

Yes/no/unclear |

Enough similarities between studies to make combining them reasonable?7

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential risk of publication bias taken into account?8

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential conflicts of interest reported?9

Yes/no/unclear |

|

Brocklehurst, 2013 |

Yes |

Yes, CENTRAL, MEDLINE, EMBASE and more |

Yes |

Yes |

Not applicable |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Unclear: only reported for the review itself but not for the included studies. |

2. Risk of bias assessment for individual RCTs derived from Brocklehurst, 2013

|

Study reference

(first author, publication year) |

Random sequence generation (selection bias) |

Allocation concealment (selection bias) |

Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) |

Selective reporting (reporting bias) |

Other bias |

Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) |

Blinding of outcome assessors (performance bias) |

|

Guaschino, 2003 |

Low risk |

Low risk |

Low risk |

Low risk |

Low risk |

High risk |

High risk |

|

Hauth, 1995

|

Low risk |

Low risk |

Low risk |

Low risk |

Low risk |

Low risk |

Unclear |

|

Joesoef, 1995

|

Low risk |

Low risk |

Unclear |

Low risk |

Low risk |

Low risk |

Low risk |

|

Kekki, 2001

|

Low risk |

Low risk |

Low risk |

Low risk |

Low risk |

Low risk |

Low risk |

|

Kiss, 2004

|

Low risk |

Low risk |

Low risk |

Low risk |

Low risk |

High risk |

High risk |

|

Lamont, 2003

|

Low risk |

Unclear |

Low risk |

Low risk |

Low risk |

Low risk |

Unclear |

|

Larsson, 2006

|

Low risk |

Low risk |

Unclear |

Low risk |

Low risk |

Unclear |

Unclear |

|

McDonald, 1997 |

Unclear |

Unclear |

Low risk |

Low risk |

Low risk |

Low risk |

Low risk |

|

Moniri, 2009

|

Unclear |

Unclear |

Unclear |

High risk |

Low risk |

High risk |

Low risk |

|

NICHD MFMU, 2000 |

Low risk |

Low risk |

Low risk |

Low risk |

Low risk |

Low risk |

Low risk |

|

NICHD MFMU, 2001 |

Low risk |

Low risk |

Low risk |

Low risk |

Low risk |

Low risk |

Low risk |

|

Shennan, 2006

|

Low risk |

Low risk |

Low risk |

Low risk |

Low risk |

Low risk |

Unclear |

|

Ugwumadu, 2003 |

Low risk |

Low risk |

Low risk |

Low risk |

Low risk |

Low risk |

Low risk |

|

Vermeulen, 1999 |

Low risk |

Low risk |

Low risk |

Low risk |

Low risk |

Low risk |

Low risk |

*All assessments from Brocklehurst, 2013

3. Risk of bias table for RCT Subtil, 2018

|

Study reference

|

Describe method of randomisation1 |

Bias due to inadequate concealment of allocation?2

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate blinding of participants to treatment allocation?3

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate blinding of care providers to treatment allocation?3

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate blinding of outcome assessors to treatment allocation?3

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to selective outcome reporting on basis of the results?4

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to loss to follow-up?5

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to violation of intention to treat analysis?6

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

|

Subtil, 2018 |

“A computer-generated random allocation sequence with a block size of six to three parallel groups.” |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

Unlikely: loss to follow up was small and similar among groups |

Unlikely: intention to treat analysis |

Table of excluded studies

Sub question 1: What is the effect of screening for bacterial vaginosis to reduce preterm birth?

|

Author and year |

Reason for exclusion |

|

Batra, 2017 |

Wrong participants |

|

Calonge, 2008 |

No study data |

|

Carey, 2003 |

Non systematic review |

|

Chapman, 2016 |

Non systematic review |

|

Colli, 1996 |

Narrative review |

|

Dennemark, 1997 |

Wrong study design: no RCT |

|

Flynn, 1999 |

Wrong participants |

|

Glantz, 1997 |

Narrative review |

|

Guise, 2001 |

No full text available |

|

Haahr, 2016 |

Wrong intervention |

|

Kiss, 2004 |

Wrong intervention: screening for vaginal infection |

|

Kiss, 2005 |

No full text available |

|

Kiss, 2010 |

Wrong study design: no RCT |

|

Larsson, 2006 |

Wrong intervention |

|

Larsson, 2007 |

Wrong intervention |

|

Lee, 2019 |

Wrong intervention: screening for bacterial vaginosis and urinary tract infections; participants differ from Dutch population (over 20% preterm birth) |

|

Leitich, 2003 |

Wrong intervention |

|

McGregor, 1995 |

Wrong study design: no RCT |

|

Morales, 1994 |

Wrong intervention |

|

Nygren, 2008 |

More recent systematic review available by Sangkomkamhang 2015 |

|

Potter, 2004 |

Narrative review |

|

Sangkomkamhang, 2008 |

Earlier version of Sangkomkamhang 2015 |

|

Sangkomkamhang, 2015 |

Wrong intervention: screening for vaginal infection |

|

Simcox, 2007 |

Wrong intervention |

|

Tebes, 2003 |

Wrong intervention |

|

Varma, 2006 |

Wrong intervention |

|

Villar, 1998 |

Wrong intervention |

Sub question 2: What is the effect of treatment of bacterial vaginosis with metronidazole or clindamycin to reduce preterm birth?

|

Author and year |

Reason for exclusion |

|

Carey 2000 |

Included in Brocklehurst 2013 |

|

Guaschino 2003 |

Included in Brocklehurst 2013 |

|

Gupta 2013 |

Wrong participants: abnormal vaginal flora including bacterial vaginosis (ca 75%), candidiasis (ca 20%) or both |

|

Haahr 2016 |

SR, Less transparant than Brocklehurst 2013 |

|

Hantoushzadeh 2012 |

Wrong comparison: probiotics versus antibiotics |

|

Hauth 1995 |

Included in Brocklehurst 2013 |

|

Joesoef 1995 |

Included in Brocklehurst 2013 |

|

Kekki 2001 |

Included in Brocklehurst 2013 |

|

Kiss 2004 |

Included in Brocklehurst 2013 |

|

Kurkinen-Räty 2000 |

Same data as Kekki 2001 |

|

Lamont 2003 |

Included in Brocklehurst 2013 |

|

Lamont 2011 |

SR, older than Brocklehurst 2013 |

|

Larsson 2006 |

Included in Brocklehurst 2013 |

|

Leitich 2003 |

Not about treatment |

|

Matei 2019 |

Systematic Review of Systematic Reviews |

|

Mc Gregor 1990 |

Intervention too late in pregnancy |

|

McDonald 1997 |

Included in Brocklehurst 2013 |

|

Morales 1994 |

Included in Brocklehurst 2013 |

|

Nygren 2008 |

SR, older than Brocklehurst 2013 |

|

Okun 2005 |

SR, older than Brocklehurst 2013 |

|

Rebouças 2019 |

SR, less transparent than Brocklehurst 2013 |

|

Riggs 2004 |

SR, older than Brocklehurst 2013 |

|

Sangkomkamhang 2015 |

Different intervention |

|

Sheehy 2015 |

Less transparent than Brocklehurst 2013 |

|

Simcox 2007 |

SR, older than Brocklehurst 2013 |

|

Tebes 2003 |

SR, older than Brocklehurst 2013 |

|

Ugwumadu 2003 |

SR, older than Brocklehurst 2013 |

|

Varma 2006 |

SR, older than Brocklehurst 2013 |

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Laatst beoordeeld : 20-11-2024

Algemene gegevens

De ontwikkeling van deze richtlijnmodule werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten (www.demedischspecialist.nl/kennisinstituut) en werd gefinancierd uit de Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS). De financier heeft geen enkele invloed gehad op de inhoud van de richtlijnmodule.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijnmodule is in 2019 een multidisciplinaire werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen (zie hiervoor de Samenstelling van de werkgroep) die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor zwangere vrouwen zonder klinische verschijnselen van een vroeggeboorte, die al dan niet in een eerdere zwangerschap een spontane vroeggeboorte hebben doorgemaakt.

Werkgroep

- Prof. dr. M.A. Oudijk, gynaecoloog, NVOG (voorzitter)

- Dr. N. Horree, gynaecoloog, NVOG

- Dr. J.B. Derks, gynaecoloog, NVOG

- Dr. T.A.J. Nijman, gynaecoloog, NVOG

- Dr. F. Vlemmix, gynaecoloog, NVOG

- Dr. D.A.A. van der Woude, gynaecoloog, NVOG

- L.T. Brammerloo-Read, MSc, verloskundige, KNOV

- Dr. M.A.C. Hemels, kinderarts-neonatoloog, NVK

- F.A.B.A. Schuerman, MSc, kinderarts-neonatoloog, NVK

- J.D.M. Wagemaker, patiëntenvereniging, Care4Neo

Met ondersteuning van:

- Dr. L. Viester, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van Medisch Specialisten (tot augustus 2022)

- T. Geltink, MSc, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van Medisch Specialisten (vanaf augustus 2022)

Belangenverklaringen

De Code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling is gevolgd. Alle werkgroepleden hebben schriftelijk verklaard of zij in de laatste drie jaar directe financiële belangen (betrekking bij een commercieel bedrijf, persoonlijke financiële belangen, onderzoeksfinanciering) of indirecte belangen (persoonlijke relaties, reputatiemanagement) hebben gehad. Gedurende de ontwikkeling of herziening van een module worden wijzigingen in belangen aan de voorzitter doorgegeven. De belangenverklaring wordt opnieuw bevestigd tijdens de commentaarfase.

Een overzicht van de belangen van werkgroepleden en het oordeel over het omgaan met eventuele belangen vindt u in onderstaande tabel. De ondertekende belangenverklaringen zijn op te vragen bij het secretariaat van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

|

Werkgroeplid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

Prof. dr. M.A. Oudijk |

Gynaecoloog |

Voorzitter Pijler FMG van de NVOG, onbetaald, alleen vacatiegelden. Voorzitter wetenschapscommissie pijler FMG, onbetaald. Member of the board of the foundation 'Stoptevroegbevallen'; a non-profit foundation with the purpose to raise funds for research projects on preterm labour/birth, onbetaald. Member of the scientific committee of the 'Fonds Gezond Geboren', a non-profit foundation with the purpose to raise funds for reserarch projects on preterm birth and placental insufficiency, onbetaald. Member of the advisory board of the N3, the Dutch Neonatology research network, onbetaald. President of the European Spontaneous Preterm Birth Congress to be held in Haarlem, The Netherlands, www. espbc.eu, onbetaald |

2015 ZonMW836041012 The effect of tocolysis with nifedipine or atosiban on infant development: the APOSTEL III follow-up study. € 43,772. 2015 ZonMW 836041006 Low dose aspirin in the prevention of recurrent spontaneous preterm labour: the APRIL study € 351.898. 2016 Zon|MW 80-84800-98-41027 Atosiban versus placebo in the treatment of late threatened preterm labour: the APOSTEL VIII study € 1.393.639. Hoofdaanvrager/projectleider van deze vroeggeboorte studies. Subsidie wordt alleen aangewend ten behoeve van het onderzoek, promoventi etc. Geen persoonlijke salariëring vanuit deze ZonMw studie |

geen restricties |

|

Dr. N. Horree |

Gynaecoloog |

geen |

Participatie binnen ziekenhuis aan consortium studies vanuit de NVOG. Hieronder vallen ook onderzoek naar vroeggeboorte (o.a. Apnel studies) en preventie vroeggeboorte (April). QP PC - studies |

geen restricties |

|

Dr. J.B. Derks |

Gynaecoloog |

Lid bestuur werkgroep perinatologie en maternale ziektes (onbetaald); Lid otterlo groep (Cie. Ontwikkeling richtlijnen obstetrie) (onbetaald) |

Deelname consortiumstudies waaronder de April studie |

geen restricties |

|

T.A.J. Nijman |

Gynaecoloog |

Lid Commissie Gynaecongres, VAGO-vertegenwoordiger, onbetaald; Lid Koepel Wetenschap. VAGO-vertegenwoordiger, onbetaald |

Project groep April studie, ZonMW gesponsorde Consortium studie naar aspirine vs placebo bij preventie herhaalde vroeggeboorte. |

geen restricties |

|

Dr. F. Vlemmix |

Gynaecoloog |

Lid werkgroep patiëntcommunicatie NVOG |

geen |

geen restricties |

|

Dr. D.A.A. van der Woude |

Gynaecoloog & postdoc |

geen |

geen |

geen restricties |

|

L.T. Brammerloo-Read |

Verloskundige |

geen |

De praktijk + kliniek waarin werkzaam heeft deelname in cervix-meting van patiënten om vroeggeboorte op te kunnen sporen, hierbij geen financieel belang. |

geen restricties |

|

Dr. M.A.C. Hemels |

Kinderarts-neonatoloog |

Faculty cursus antibiotica bij kinderen, betaald |

Deelname APRIL studie, meelezen protocol betreffende de neonatale uitkomst maten |

geen restricties |

|

F.A.B.A. Schuerman |

Kinderarts-neonatoloog |

Bestuurslid stichting kindersedatie Nederland (betaald) |

geen |

geen restricties |

|

J.D.M. Wagemaker |

Patiëntvertegenwoordiger care |

geen |

geen |

geen restricties |

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Er werd aandacht besteed aan het patiëntenperspectief door uitnodigen van Patiëntenfederatie Nederland, Stichting Kind en Ziekenhuis en Vereniging Ouders Couveusekinderen voor de schriftelijke knelpunteninventarisatie en een afgevaardigde patiëntenvereniging in de werkgroep. De verkregen input is meegenomen bij het opstellen van de uitgangsvragen, de keuze voor de uitkomstmaten en bij het opstellen van de overwegingen. De conceptrichtlijn is tevens voor commentaar voorgelegd aan Patiëntenfederatie Nederland, Stichting Kind en Ziekenhuis en Vereniging Ouders Couveusekinderen en de eventueel aangeleverde commentaren zijn bekeken en verwerkt.

Kwalitatieve raming van mogelijke financiële gevolgen in het kader van de Wkkgz

Bij de richtlijn is conform de Wet kwaliteit, klachten en geschillen zorg (Wkkgz) een kwalitatieve raming uitgevoerd of de aanbevelingen mogelijk leiden tot substantiële financiële gevolgen. Bij het uitvoeren van deze beoordeling zijn richtlijnmodules op verschillende domeinen getoetst (zie het stroomschema op de Richtlijnendatabase).

Uit de kwalitatieve raming blijkt dat er waarschijnlijk geen substantiële financiële gevolgen zijn.

Werkwijze

AGREE

Deze richtlijnmodule is opgesteld conform de eisen vermeld in het rapport Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 van de adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwaliteit. Dit rapport is gebaseerd op het AGREE II instrument (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II; Brouwers, 2010).

Knelpuntenanalyse en uitgangsvragen

Tijdens de voorbereidende fase inventariseerde de werkgroep de knelpunten in de zorg voor zwangere vrouwen zonder klinische verschijnselen van een vroeggeboorte, die al dan niet in een eerdere zwangerschap een spontane vroeggeboorte hebben doorgemaakt. Tevens zijn er knelpunten aangedragen door Patiëntenfederatie Nederland, Verpleegkundigen & Verzorgenden Nederland, Nederlandse Vereniging voor Kindergeneeskunde, Nederlandse Vereniging voor Medische Microbiologie, LAREB, Nederlandse Vereniging voor Klinische Fysica, Kind en Ziekenhuis via een schriftelijke knelpunteninventarisatie .

Op basis van de uitkomsten van de knelpuntenanalyse zijn door de werkgroep concept-uitgangsvragen opgesteld en definitief vastgesteld.

Uitkomstmaten

Na het opstellen van de zoekvraag behorende bij de uitgangsvraag inventariseerde de werkgroep welke uitkomstmaten voor de patiënt relevant zijn, waarbij zowel naar gewenste als ongewenste effecten werd gekeken. Hierbij werd een maximum van acht uitkomstmaten gehanteerd. De werkgroep waardeerde deze uitkomstmaten volgens hun relatieve belang bij de besluitvorming rondom aanbevelingen, als cruciaal (kritiek voor de besluitvorming), belangrijk (maar niet cruciaal) en onbelangrijk. Tevens definieerde de werkgroep tenminste voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten welke verschillen zij klinisch (patiënt) relevant vonden.

Methode literatuursamenvatting

Een uitgebreide beschrijving van de strategie voor zoeken en selecteren van literatuur is te vinden onder ‘Zoeken en selecteren’ onder Onderbouwing. Indien mogelijk werd de data uit verschillende studies gepoold in een random-effects model. Review Manager 5.4 werd gebruikt voor de statistische analyses. De beoordeling van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs wordt hieronder toegelicht.

Beoordelen van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs

De kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs werd bepaald volgens de GRADE-methode. GRADE staat voor ‘Grading Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation’ (zie http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/). De basisprincipes van de GRADE-methodiek zijn: het benoemen en prioriteren van de klinisch (patiënt) relevante uitkomstmaten, een systematische review per uitkomstmaat, en een beoordeling van de bewijskracht per uitkomstmaat op basis van de acht GRADE-domeinen (domeinen voor downgraden: risk of bias, inconsistentie, indirectheid, imprecisie, en publicatiebias; domeinen voor upgraden: dosis-effect relatie, groot effect, en residuele plausibele confounding).

GRADE onderscheidt vier gradaties voor de kwaliteit van het wetenschappelijk bewijs: hoog, redelijk, laag en zeer laag. Deze gradaties verwijzen naar de mate van zekerheid die er bestaat over de literatuurconclusie, in het bijzonder de mate van zekerheid dat de literatuurconclusie de aanbeveling adequaat ondersteunt (Schünemann, 2013; Hultcrantz, 2017).

|

GRADE |

Definitie |

|

Hoog |

|

|

Redelijk |

|

|

Laag |

|

|

Zeer laag |

|

Bij het beoordelen (graderen) van de kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs in richtlijnen volgens de GRADE-methodiek spelen grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming een belangrijke rol (Hultcrantz, 2017). Dit zijn de grenzen die bij overschrijding aanleiding zouden geven tot een aanpassing van de aanbeveling. Om de grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming te bepalen moeten alle relevante uitkomstmaten en overwegingen worden meegewogen. De grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming zijn daarmee niet één op één vergelijkbaar met het minimaal klinisch relevant verschil (Minimal Clinically Important Difference, MCID). Met name in situaties waarin een interventie geen belangrijke nadelen heeft en de kosten relatief laag zijn, kan de grens voor klinische besluitvorming met betrekking tot de effectiviteit van de interventie bij een lagere waarde (dichter bij het nuleffect) liggen dan de MCID (Hultcrantz, 2017).

Overwegingen (van bewijs naar aanbeveling)

Om te komen tot een aanbeveling zijn naast (de kwaliteit van) het wetenschappelijke bewijs ook andere aspecten belangrijk en worden meegewogen, zoals aanvullende argumenten uit bijvoorbeeld de biomechanica of fysiologie, waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten, kosten (middelenbeslag), aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie. Deze aspecten zijn systematisch vermeld en beoordeeld (gewogen) onder het kopje ‘Overwegingen’ en kunnen (mede) gebaseerd zijn op expert opinion. Hierbij is gebruik gemaakt van een gestructureerd format gebaseerd op het evidence-to-decision framework van de internationale GRADE Working Group (Alonso-Coello, 2016a; Alonso-Coello 2016b). Dit evidence-to-decision framework is een integraal onderdeel van de GRADE methodiek.

Formuleren van aanbevelingen

De aanbevelingen geven antwoord op de uitgangsvraag en zijn gebaseerd op het beschikbare wetenschappelijke bewijs en de belangrijkste overwegingen, en een weging van de gunstige en ongunstige effecten van de relevante interventies. De kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs en het gewicht dat door de werkgroep wordt toegekend aan de overwegingen, bepalen samen de sterkte van de aanbeveling. Conform de GRADE-methodiek sluit een lage bewijskracht van conclusies in de systematische literatuuranalyse een sterke aanbeveling niet a priori uit, en zijn bij een hoge bewijskracht ook zwakke aanbevelingen mogelijk (Agoritsas, 2017; Neumann, 2016). De sterkte van de aanbeveling wordt altijd bepaald door weging van alle relevante argumenten tezamen. De werkgroep heeft bij elke aanbeveling opgenomen hoe zij tot de richting en sterkte van de aanbeveling zijn gekomen.

In de GRADE-methodiek wordt onderscheid gemaakt tussen sterke en zwakke (of conditionele) aanbevelingen. De sterkte van een aanbeveling verwijst naar de mate van zekerheid dat de voordelen van de interventie opwegen tegen de nadelen (of vice versa), gezien over het hele spectrum van patiënten waarvoor de aanbeveling is bedoeld. De sterkte van een aanbeveling heeft duidelijke implicaties voor patiënten, behandelaars en beleidsmakers (zie onderstaande tabel). Een aanbeveling is geen dictaat, zelfs een sterke aanbeveling gebaseerd op bewijs van hoge kwaliteit (GRADE gradering HOOG) zal niet altijd van toepassing zijn, onder alle mogelijke omstandigheden en voor elke individuele patiënt.

|

Implicaties van sterke en zwakke aanbevelingen voor verschillende richtlijngebruikers |

||

|

|

||

|

|

Sterke aanbeveling |

Zwakke (conditionele) aanbeveling |

|

Voor patiënten |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen en slechts een klein aantal niet. |

Een aanzienlijk deel van de patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen, maar veel patiënten ook niet. |

|

Voor behandelaars |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak moeten ontvangen. |

Er zijn meerdere geschikte interventies of aanpakken. De patiënt moet worden ondersteund bij de keuze voor de interventie of aanpak die het beste aansluit bij zijn of haar waarden en voorkeuren. |

|