Omega-3 suppletie ter preventie van vroeggeboorte

Uitgangsvraag

Wat zijn de (on)gunstige effecten van omega-3 vetzuren suppletie tijdens de zwangerschap ter voorkoming van spontane vroeggeboorte bij eenling zwangerschap?

Aanbeveling

Bespreek met zwangere vrouwen die niet voldoende vis eten om omega-3 supplementen te gebruiken in de gehele zwangerschap vanwege een mogelijk lagere kans op vroeggeboorte.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Op basis van de literatuur kan met een redelijke mate van vertrouwen worden geconcludeerd dat het gebruik van omega-3 supplementen gedurende de zwangerschap in een verschil resulteert op de cruciale uitkomstmaat vroeggeboorte <37 weken. Daarnaast kan worden gesteld dat het gebruik van omega-3 supplementen mogelijk resulteert in een lichte afname van de cruciale uitkomstmaat vroeggeboorte <34 weken (GRADE laag). Voor de derde cruciale uitkomstmaat, vroeggeboorte <28 weken, was geen data beschikbaar. De geïncludeerde studies rapporteerden deze uitkomstmaat niet.

De bewijskracht voor de belangrijke uitkomstmaten loopt uiteen van redelijk tot zeer laag. Voor 5 van de 7 belangrijke uitkomstmaten was de bewijskracht laag (respiratoir distress syndroom; intraventriculaire bloeding; necrotiserende enterocolitis; neonatale sterfte; samengestelde uitkomstmaat). Betreffende neonatale sepsis kan gezien de zeer lage bewijskracht geen conclusie worden getrokken. Het gebruik van omega-3 supplementen resulteert waarschijnlijk in weinig tot geen verschil betreffende perinatale sterfte (moderate GRADE).

Secundaire analyses omega-3 en vroeggeboorte: dosis-respons relatie

Verschillende secundaire analyses van RCTs naar omega-3 suppletie bij zwangere vrouwen zijn uitgevoerd om de relatie tussen omega-3 en vroeggeboorte verder te duiden. Door Carlson (2013; 2018) werd een dosis-respons relatie gevonden tussen DHA en vroeggeboorte (<34 weken). Nadat capsule-inname van omega-3 was omgezet naar DHA dosis per dag, was de dosis-respons van DHA in de reductie van extreme vroeggeboorte zichtbaar tot aan een inname van bijna 600 mg/dag.

Subgroepen

Er zijn verschillende factoren die mogelijk van invloed lijken te zijn op de relatie tussen omega-3 en vroeggeboorte, bijvoorbeeld of het een eenling- dan wel meerlingzwangerschap betreft (aanname hierbij is dat de drijvers van vroeggeboorte bij meerlingzwangerschappen kunnen verschillen van eenlingzwangerschappen) en de BMI van de vrouw (metabolische verschillen tussen slanke vrouwen versus vrouwen met overgewicht/obesitas) (Simmonds 2019; Smid 2019). De omega-3 baselinestatus van de vrouw in de vroege zwangerschap (totale omega-3 bloedwaarde) is mogelijk van invloed op welke vrouwen profijt zouden kunnen hebben van omega-3 suppletie. De studie van Simmonds (2019) geeft aanwijzingen dat zwangere vrouwen met omega-3 suppleren met reeds een hoge omega-3 baselinestatus, het risico op vroeggeboorte wellicht juist doet verhogen.

Omega-3 suppletie in de late zwangerschap en risico op serotiniteit

Vijf trials opgenomen in de Cochrane review van Middleton (2018) vergeleken het gebruik van omega-3 supplementen met geen omega-3 ten aanzien van de uitkomstmaat zwangerschapsduur >42 weken. Makrides (2019) rapporteerde tevens over een zwangerschapsduur >42 weken, Olsen (2019) rapporteerde post-terme zwangerschap (niet verder gedefinieerd). Een post-terme zwangerschap werd gevonden in 150 van de 8691 (1.7%) vrouwen die omega-3 supplementen gebruikten, vergeleken met 82 of 6887 (1.2%) vrouwen die geen omega-3 gebruikten in de zwangerschap (RR 1.35 (95% CI 1.03 to 1.76)) (Middleton, 2018; Makrides, 2019; Olsen, 2019).

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

Het belangrijkste doel van inname van omega-3 supplementen is de reductie van het aantal vroeggeboortes. De inname van omega-3 supplementen reduceert mogelijk het aantal vroeggeboortes voor 34 weken in lichte mate. Zowel de zwangere als de neonaat heeft hier direct voordeel van door bijvoorbeeld kortere opname in het ziekenhuis. Een ander voordeel van de interventie is de weinig invasieve aard. Echter kunnen sommige patiënten het dagelijks innemen van tabletten wel zien als nadeel. Voor patiënten met een vroeggeboorte in de voorgeschiedenis zal dit mogelijk minder als nadeel wegen, omdat zij ervaren hebben wat een vroeggeboorte met zich meebrengt.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

De inname van omega-3 supplementen is een relatief goedkope interventie. Gezien de hoge kosten van vroeggeboorte (met name < 34 weken) zal reductie van het aantal vroeggeboortes hoogstwaarschijnlijk kosteneffectief zijn. Omega-3 supplementen zijn zelfzorgmiddelen, omdat patiënten de supplementen zelf aanschaffen legt het geen extra druk op de zorgkosten. De kosten voor de patiënt kunnen echter mogelijk wel voor weerstand zorgen. Voor patiënten met een lage sociaal economische status, die ook een verhoogd risico hebben op vroeggeboorte, kan dit wel een drempel zijn. Echter zijn de kosten per maand relatief laag (vanaf ongeveer €5 per maand), daarom wordt verwacht dat na uitleg van de voordelen het grootste deel van de patiënten geen bezwaar zullen hebben.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

Er is voor zover bekend geen onderzoek gedaan naar de aanvaardbaarheid en haalbaarheid van de interventie. In de beschreven literatuur werd de interventie goed geaccepteerd en verdragen door de patiënten. Er zijn weinig bezwaren te bedenken voor het gebruik van omega-3 supplementen. Ook patiënten met een laag inkomen hebben toegang tot de interventie. Het is een simpele en goedkope interventie, waardoor er weinig belemmerende factoren aanwezig zijn.

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

Op basis van de literatuur kan met een redelijke mate van vertrouwen worden geconcludeerd dat het gebruik van omega-3 supplementen gedurende de zwangerschap in een verschil resulteert in vroeggeboorte <37 weken. Daarnaast kan worden gesteld dat het gebruik van omega-3 supplementen mogelijk resulteert in een lichte afname van vroeggeboorte <34 weken. Voor vroeggeboorte < 28 weken was geen data beschikbaar. Verder verlagen omega-3 supplementen mogelijk de kans op respiratoire distress syndroom en samengestelde neonatale uitkomst. Gezien het gunstige bijwerkingsprofiel en de lage kosten lijken de voordelen op te wegen tegen de nadelen.

De Gezondheidsraad heeft in juni 2021 verschillende voedingsadviezen uitgebracht voor zwangere vrouwen, waaronder ten aanzien van het eten van vis en omega-3. Dit advies van de Gezondheidsraad houdt in: ‘Eet tweemaal per week vis, waarvan eenmaal vette vis en eenmaal magere vis en kies vissoorten zonder te veel schadelijke stoffen. Voor vrouwen die deze hoeveelheid vis niet kunnen of willen eten: neem een supplement met Omega-3vetzuren (op basis van vis of plantaardige stoffen) dat 250 tot 450 milligram DHA per dag bevat.’

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Omega-3 vetzuren kunnen bijdragen aan het verminderen van de inflammatoire respons en oxidatieve stress. Dit heeft mogelijk een gunstig effect op het voorkomen van spontane vroeggeboorte. Omega-3 vetzuren zitten met name in vette vissoorten, die door zwangere vrouwen weinig worden geconsumeerd. Omdat er geen eenduidige landelijke informatie bestaat is er een grote praktijkvariatie in Nederland ten aanzien van het advies over suppletie van omega-3 vetzuren.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

|

Moderate GRADE |

The use of omega-3 supplements in pregnant women likely results in a reduction in the outcome preterm birth <37 weeks compared to no use of omega-3 supplements.

Sources: Middleton, 2018; Makrides 2019; Olsen, 2019 |

|

Low GRADE |

The use of omega-3 supplements in pregnant women may result in a reduction in the outcome preterm birth <34 weeks compared to no use of omega-3 supplements.

Sources: Middleton, 2018; Makrides 2019; Olsen, 2019 |

|

Low GRADE |

The use of omega-3 supplements in pregnant women may result in little to no difference in the outcome intraventricular hemorrhage compared to no use of omega-3 supplements.

Sources: Middleton, 2018 (Makrides, 2010; Olsen, 2000) |

|

Low GRADE |

The use of omega-3 supplements in pregnant women may result in little to no difference in the outcome necrotizing enterocolitis compared to no use of omega-3 supplements.

Sources: Middleton, 2018 (Makrides, 2010); Makrides 2019 |

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of using omega-3 supplements during pregnancy on the outcome neonatal sepsis.

Sources: Middleton, 2018 (Helland, 2001; Makrides, 2010); Markides 2019 |

|

Low GRADE |

The use of omega-3 supplements in pregnant women may result in little to no difference in the outcome neonatal death compared to no use of omega-3 supplements.

Sources: Middleton, 2018; Makrides 2019; Olsen, 2019 |

|

Moderate GRADE |

The use of omega-3 supplements in pregnant women likely results in little to no difference in the outcome perinatal death compared to no use of omega-3 supplements.

Sources: Middleton, 2018; Makrides 2019 |

|

Low GRADE |

The use of omega-3 supplements in pregnant women may decrease a composite outcome of neonatal morbidity and mortality slightly compared to no use of omega-3 supplements.

Sources: Middleton, 2018 (Makrides, 2010) |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

Middleton (2018) performed a Cochrane review (update of the published review in 2006) on omega-3 fatty acid addition during pregnancy on maternal, perinatal, and neonatal outcomes and longer-term outcomes for mother and child. For this update, a literature search was conducted up to 16 August 2018. Primary outcomes were preterm birth <37 weeks, early preterm birth <34 weeks, and prolonged gestation >42 weeks. Inclusion criteria were a randomised controlled trial (RCT)-study design and the study population should encompass pregnant women (regardless of their risk for pre-eclampsia, preterm birth or intrauterine growth restriction). Seventy RCTs were included in the qualitative synthesis, with 61 studies included in the meta-analysis (no outcomes could be reported for 9 studies).

A total of 19,927 women were involved in the included trials. The omega-3 fatty acids supplements in the intervention groups were mostly oral docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) and/or eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) or mainly DHA/EPA. Four main types of intervention were identified by Middleton (2018): (1) omega-3 supplements only versus placebo or no omega-3 fatty acids (50 trials); (2) omega-3 supplements/enrichment plus food/dietary advice versus placebo or no omega-3 fatty acids (7 trials); (3) omega-3 food/dietary advice only versus placebo or no omega-3 fatty acids (3 trials); and (4) omega-3 supplements plus other agents versus placebo or no omega-3 fatty acids (12 trials).

The doses DHA+EPA were low (<500 mg/day) in 24 trials, mid (500 mg/day to 1 g/day) in 21 trials and high (>1 g/day) in 23 trials (five trials: other dose). Forty of the 70 trials reported eligibility criteria relating to omega-3 intake, such as excluding women with an allergy to fish or fish products and/or excluding women taking omega-3, fish oil or DHA supplements or regular/any intake of fish. Gestational age when commenced with omega-3 supplements was >20 weeks gestation in 33 trials and ≤20 weeks gestation in 33 trials. An increased or high baseline risk of adverse maternal and birth outcomes was found in 34 trials, any or mixed risk in 8 trials, and a low risk in 29 trials.

Makrides (2019) conducted a multicenter RCT in Australia (ORIP trial: Omega-3 to Reduce the Incidence of Preterm Birth) and included 5544 pregnancies in 5517 women. Pregnant women with a single fetus or multiple fetuses were eligible for inclusion, excluded were women taking daily supplements containing more than 150 mg of n−3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids. Women could participate in the trial for successive pregnancies and underwent a separate randomization for each pregnancy (n=27). The intervention (2770 pregnancies in 2766 women) consisted of three 500-mg fish-oil capsules per day, which provided a total of approximately 900 mg of n−3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acid per day (approximately 800 mg of DHA and approximately 100 mg of EPA). The assigned capsules were to be taken orally from the time of trial entry (<20 weeks of gestation) until 34 weeks of gestation or until delivery, whichever occurred sooner. Women in the control group (2774 pregnancies in 2765 women) received three 500-mg capsules per day containing an isocaloric vegetable-oil blend that provided a total of approximately 15 mg of DHA and approximately 4 mg of EPA per day (i.e., control capsules were formulated to be consistent with the fatty acid composition of a typical Australian diet). In both groups, 6.7% of the mothers had a previous preterm delivery (37 weeks of gestation).

Olsen (2019) performed a multicenter 3-group parallel RCT (n=5118) in 6 areas of the Peoples’ Republic of China: in 3 areas the populations had very low intake of LC n-3 PUFAs. Women were eligible if pregnant in gestation weeks 16–24. Women with known multiple gestation were excluded as well as users of fish oil (>1 week) or prostaglandin inhibitors (e.g., aspirin). Women randomised in the high fish oil (HFO) group (n=1706) received 2.0 g/d of LC n-3 PUFAs. In the low fish oil (LFO) group (n=1695) women received a 1:3 mixture of fish oil to olive oil, containing 0.5 g/d of LC n-3 PUFAs. Pregnant women were asked to take four 0.72-g gelatin capsules per day until the last day of 37 completed gestational weeks. In the control group (n=1717) the capsules contained only olive oil (0 g/d of LC n-3 PUFAs). In the HFO group 4.3% of the women hand a previous spontaneous abortion, 4.9% in the LFO group, and 5.2% in the control group. The trial would randomly assign 10,803 women but this was in reality only half of this intended number. Olsen experienced slower recruitment rates than expected combined with short shelf-life of capsules in the first phases of the study, and in the end, recruitment was discontinued because of lack of funding.

Results

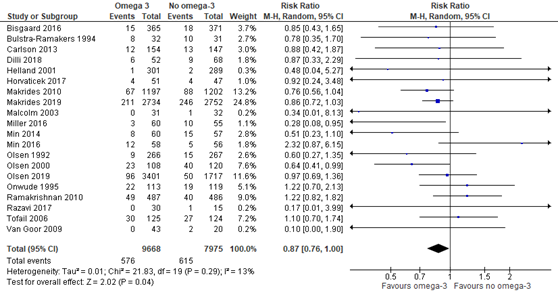

Outcome measure 1: preterm birth <37 weeks

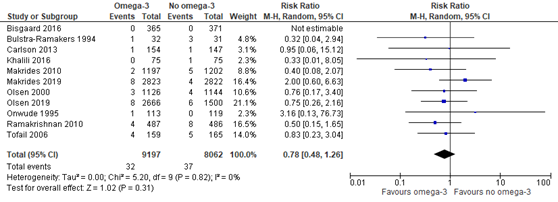

Eighteen trials that were included in the Cochrane review of Middleton (2018) compared omega-3 supplements versus no omega-3 regarding the outcome measure preterm birth <37 weeks. In addition, the recent RCTs of Makrides (2019) and Olsen (2019) reported on the outcome preterm birth <37 weeks as well. Preterm birth <37 weeks was reported for 576 of 9668 (6.0%) infants of mothers receiving omega-3 supplements compared to 615 of 7975 (7.7%) infants of mothers receiving no omega-3 supplements (RR 0.87 (95% CI 0.76 to 1.00)) (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1. Preterm birth <37 weeks, comparison omega-3 supplements versus no omega-3

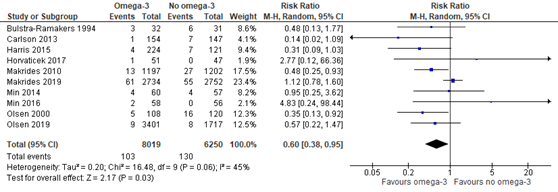

Outcome measure 2: early preterm birth <34 weeks

In the Cochrane review of Middleton (2018) eight trials were included comparing omega-3 supplements versus no omega-3 on the outcome measure early preterm birth <34 weeks. Moreover, the recent RCTs of Makrides (2019) and Olsen (2019) reported on early preterm birth <34 weeks as well. Preterm birth <34 weeks was reported for 103 of 8019 (1.3%) infants of mothers receiving omega-3 supplements compared to 130 of 6250 (2.1%) infants of mothers receiving no omega-3 supplements (RR 0.60 (95% CI 0.38 to 0.95)) (Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2. Preterm birth <34 weeks, comparison omega-3 supplements versus no omega-3

Outcome measure 3: extremely preterm birth <28 weeks

None of the studies reported on preterm birth <28 weeks. Middleton (2018) reported on miscarriage <24 weeks, Makrides used the cut-off below 20 weeks gestation for the outcome measure miscarriage.

Outcome measure 4: respiratory distress syndrome

The Cochrane review of Middleton (2018) has included one trial (Carlson, 2013) reporting on respiratory distress syndrome, comparing the group of mothers receiving omega-3 supplements versus mothers that received no omega-3 supplements. Respiratory distress syndrome was not reported by Makrides (2019) or Olsen (2019). Respiratory distress syndrome was found in 9 of 154 (5.8%) infants of mothers receiving omega-3 supplements compared to 12 of 147 (8.2%) infants of mothers receiving no omega-3 (RR 0.72 (95% CI 0.31 to 1.65)).

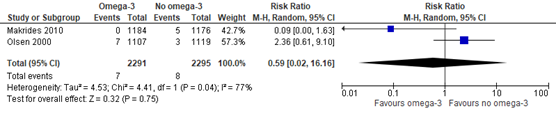

Outcome measure 5: intraventricular hemorrhage

Two trials (Makrides 2010; Olsen 2000) that were included in the Cochrane review of Middleton (2018) compared omega-3 supplements versus no omega-3 regarding the outcome measure intraventricular hemorrhage. In addition, Makrides (2019) reported on any brain injury (including intraventricular hemorrhage), Olsen (2019) on intracranial hemorrhage in the infant. Because of the different and broader definitions that were applied, the studies of Makrides (2019) and Olsen (2019) were not pooled with the two trials of the Cochrane review.

Intraventricular hemorrhage was found in 7 of 2291 (0.3%) infants of mothers receiving omega-3 supplements compared to 8 of 2295 (0.3%) infants of mothers receiving no omega-3 (RR 0.59 (95% CI 0.02 to 16.16)) (Figure 1.3).

Figure 1.3. Intraventricular hemorrhage, comparison omega-3 supplements versus no omega-3

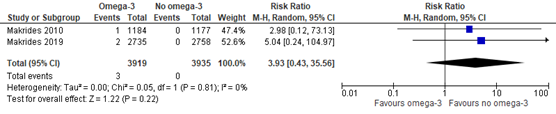

Outcome measure 6: necrotizing enterocolitis

In the Cochrane review of Middleton (2018) one trial (Makrides 2010) was included comparing omega-3 supplements versus no omega-3 on the outcome measure necrotizing enterocolitis. In addition, the recent RCT of Makrides (2019) reported on necrotizing enterocolitis as well. Necrotizing enterocolitis was found in 3 of 3919 (0.08%) infants of mothers receiving omega-3 supplements compared to 0 of 3935 (0%) infants of mothers receiving no omega-3 (RR 3.93 (95% CI 0.43 to 35.56)) (Figure 1.4).

Figure 1.4. Necrotizing enterocolitis, comparison omega-3 supplements versus no omega-3

Outcome measure 7: neonatal sepsis

Two trials (Helland, 2001; Makrides, 2010) that were included in the Cochrane review of Middleton (2018), and the recent RCT of Makrides (2019), compared omega-3 supplements versus no omega-3 regarding the outcome measure neonatal sepsis. Neonatal sepsis was found in 18 of 4220 (0.4%) infants of mothers receiving omega-3 supplements compared to 15 of 4224 (0.4%) infants of mothers receiving no omega-3 (RR 1.17 (95% CI 0.53 to 2.57)) (Figure 1.5).

Figure 1.5. Neonatal sepsis, comparison omega-3 supplements versus no omega-3

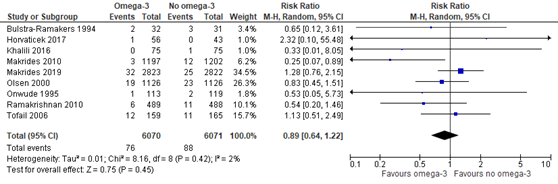

Outcome measure 8: neonatal death

Nine trials that were included in the Cochrane review of Middleton (2018) compared omega-3 supplements versus no omega-3 regarding the outcome measure neonatal death (not further defined by Middleton). Moreover, Makrides (2019) reported on neonatal death as well (not further defined) and Olsen (2019) on infant death <42 days. Neonatal death was found in 32 of 9197 (0.3%) infants of mothers receiving omega-3 supplements compared to 37 of 8062 (0.5%) infants of mothers receiving no omega-3 (RR 0.78 (95% CI 0.48 to 1.26)) (Figure 1.6).

Figure 1.6. Neonatal death, comparison omega-3 supplements versus no omega-3

Outcome measure 9: perinatal death

In the Cochrane review of Middleton (2018) eight trials were included comparing omega-3 supplements versus no omega-3 on the outcome measure perinatal death (not further defined by Middleton). In addition, Makrides (2019) reported on perinatal death as well, defined as stillbirth and death within the first 28 days of birth. Perinatal death was found in 76 of 6070 (1.3%) fetuses/infants of women receiving omega-3 supplements compared to 88 of 6071 (1.4%) fetuses/infants of women receiving no omega-3 (RR 0.89 (95% CI 0.64 to 1.22)) (Figure 1.7).

Figure 1.7. Perinatal death, comparison omega-3 supplements versus no omega-3

Outcome measure 10: composite outcome of neonatal morbidity and mortality

In the Cochrane review of Middleton (2018) one trial (Makrides, 2010) was included comparing omega-3 supplements versus no omega-3 on the outcome measure serious adverse events for neonate/infant. Serious adverse events for neonate/infant were found in 36 of 1197 (3.0%) infants of mothers receiving omega-3 supplements compared to 54 of 1202 (4.5%) infants of mothers receiving no omega-3 (RR 0.67 (95% CI 0.44 to 1.01)).

Level of evidence of the literature

Studies with a randomized, placebo-controlled design start at a high GRADE. The following outcome measure was not reported: preterm birth <28 weeks.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure preterm birth <37 weeks was downgraded by one level to a moderate GRADE because of imprecision (-1) (the 95% confidence interval of the pooled effect includes no effect as well as a clinically relevant effect in favour for the intervention group).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure preterm birth <34 weeks was downgraded by two levels to a low GRADE because of imprecision (-2) (number of events was low: 103/8019 in the intervention group and 130/6250 in the control group. The 95% confidence interval of the pooled effect includes no effect as well as a clinically relevant effect in favour for the intervention group).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure respiratory distress syndrome was downgraded by two levels to a low GRADE because of imprecision (-2) (one RCT and number of events was low: 9/154 in the intervention group and 12/147 in the control group.

The 95% confidence interval of the effect includes both the upper and lower limits of clinical relevance).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure intraventricular hemorrhage was downgraded by two levels to a low GRADE because of inconsistency (-1) (substantial heterogeneity) and imprecision (-1) (number of events was low: 7/2291 in the intervention group and 8/2295 in the control group).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure necrotizing enterocolitis was downgraded by two levels to a low GRADE because of imprecision (-2) (number of events was low: 3/3919 in the intervention group and 0/3935 in the control group. The 95% confidence interval of the pooled effect includes both the upper and lower limits of clinical relevance).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure neonatal sepsis was downgraded by three levels to a very low GRADE because of high risk of bias (-1) (incomplete outcome data by substantial withdrawal from trial) and imprecision (-2) (number of events was low: 18/4220 in the intervention group and 15/4224 in the control group. The 95% confidence interval of the pooled effect includes both the upper and lower limits of clinical relevance).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure neonatal death was downgraded by two levels to a low GRADE because of imprecision (-2) (number of events was low: 32/9197 in the intervention group and 37/8062 in the control group. The 95% confidence interval of the pooled effect includes both the upper and lower limits of clinical relevance).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure perinatal death was downgraded by one level to a moderate GRADE because of imprecision (-1) (the 95% confidence interval of the pooled effect includes no effect as well as a clinically relevant effect in favour for the intervention group).

The level of evidence regarding the composite outcome measure of neonatal morbidity and mortality was downgraded by two levels to low GRADE because of imprecision (-2) (one RCT and number of events was low: 36/1197 in the intervention group and 54/1202 in the control group. The 95% confidence interval of the effect includes no effect as well as a clinically relevant effect in favour for the intervention group).

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question:

What are the (un)favourable effects of omega-3 supplementation during pregnancy in the prevention of spontaneous preterm birth in singleton pregnancies?

|

P: patients |

pregnant women with singleton pregnancies |

|

I: intervention |

omega-3 fatty acids supplementation |

|

C: control |

no omega-3 fatty acids supplementation or placebo |

|

O: outcome measure |

preterm birth <37 weeks, preterm birth <34 weeks, preterm birth <28 weeks, respiratory distress syndrome, intraventricular hemorrhage, necrotizing enterocolitis, neonatal sepsis, neonatal death, perinatal death, composite outcome of neonatal morbidity and mortality |

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered preterm birth <37 weeks, preterm birth <34

weeks, and preterm birth <28 weeks as critical outcome measures for decision making;

and respiratory distress syndrome, intraventricular hemorrhage, necrotizing enterocolitis,

neonatal sepsis, neonatal death, perinatal death, a composite outcome of neonatal

morbidity and mortality as important outcome measures for decision making.

A priori, the working group did define the crucial outcome measures preterm birth: i.e., preterm <37 weeks, early preterm birth <34 weeks, and extremely preterm birth <28 weeks. The important outcome measures were not defined a priori, but the definitions applied in the studies were used.

The working group defined a relative risk ≤0.9 or ≥1.1 as a minimal clinically important difference for preterm birth and ≤0.8 or ≥1.25 as a minimal clinically important difference for all other outcome measures.

Search and select (Methods)

Based on an orientation search on (preconceptional) life style changes and premature labour performed in an earlier stage, the working group decided to use the Cochrane review of Middleton (2018) on omega-3 fatty acid supplementation during pregnancy as the starting point for the additional systematic literature search. This search was performed in the databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) to find the most recent literature published between January 2018 and April 2020. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 118 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria: 1) the study compared omega-3 fatty acids supplementation during pregnancy versus no omega-3 fatty acids supplementation or placebo; 2) at least one of the predefined outcome measures was reported. Fifteen studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, 12 studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and three studies were included. One of the studies that was found with this search was the Cochrane review of Middleton (2018) that we defined as key article a priori.

Results

Three studies were included in the analysis of the literature (Middelton, 2018; Makrides, 2019; Olsen, 2019). Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- Carlson SE, Colombo J, Gajewski BJ, et al. DHA supplementation and pregnancy outcomes. Am J Clin Nutr. 2013;97(4):808-815. doi:10.3945/ajcn.112.050021

- Carlson SE, Gajewski BJ, Alhayek S, Colombo J, Kerling EH, Gustafson KM. Dose-response relationship between docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) intake and lower rates of early preterm birth, low birth weight and very low birth weight. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2018;138:1-5. doi:10.1016/j.plefa.2018.09.002

- Gezondheidsraad. Voedingsaanbevelingen voor zwangere vrouwen. Nr. 2021/26, Den Haag, 22 juni 2021. https://www.gezondheidsraad.nl/documenten/adviezen/2021/06/22/voedingsaanbevelingen-voor-zwangere-vrouwen

- Makrides M, Best K, Yelland L, McPhee A, Zhou S, Quinlivan J, Dodd J, Atkinson E, Safa H, van Dam J, Khot N, Dekker G, Skubisz M, Anderson A, Kean B, Bowman A, McCallum C, Cashman K, Gibson R. A Randomized Trial of Prenatal n-3 Fatty Acid Supplementation and Preterm Delivery. N Engl J Med. 2019 Sep 12;381(11):1035-1045. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1816832. PubMed PMID: 31509674.

- Middleton P, Gomersall JC, Gould JF, Shepherd E, Olsen SF, Makrides M. Omega-3 fatty acid addition during pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018 Nov 15;11:CD003402. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003402.pub3. PubMed PMID: 30480773; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC6516961.

- Olsen SF, Halldorsson TI, Li M, et al. Examining the Effect of Fish Oil Supplementation in Chinese Pregnant Women on Gestation Duration and Risk of Preterm Delivery [published correction appears in J Nutr. 2019 Nov 1;149(11):2073]. J Nutr. 2019;149(11):1942?1951. doi:10.1093/jn/nxz153

- Simmonds LA, Sullivan TR, Skubisz M, et al. Omega-3 fatty acid supplementation in pregnancy-baseline omega-3 status and early preterm birth: exploratory analysis of a randomised controlled trial. BJOG. 2020;127(8):975-981. doi:10.1111/1471-0528.16168

- Smid MC, Stuebe AM, Manuck TA, Sen S. Maternal obesity, fish intake, and recurrent spontaneous preterm birth. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2019;32(15):2486-2492. doi:10.1080/14767058.2018.1439008

Evidence tabellen

Evidence table for systematic review of RCTs and observational studies (intervention studies)

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C)

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size

|

Comments |

|

Middleton, 2018

[study characteristics and results are extracted from the SR (unless stated otherwise)] |

SR and meta-analysis 70 RCTs were included in the qualitative synthesis, with 61 studies included in the meta-analysis (no outcomes could be reported for 9 studies).

Literature search up to August 2018

Omega-3 supplements/enrichment plus food/dietary advice versus placebo or no omega-3 fatty acids (7 trials)

Ali 2017; Bergmann 2007; Bisgaard 2016; Boris 2004; Bosaeus 2015; Bulstra-Ramakers 1994;Carlson 2013; Chase 2015; D’Almedia 1992; de Groot 2004; Dilli 2018; Dunstan 2008; England 1989; Freeman 2008; Furuhjelm 2009; Giorlandino 2013; Gustafson 2013; Haghiac 2015; Harper 2010; Harris 2015; Hauner 2012; Helland 2001; Horvaticek 2017; Hurtado 2015; Ismail 2016; Jamilian 2016; Jamilian 2017; Judge 2007; Judge 2014; Kaviani 2014; Keenan 2014; Khalili 2016; Knudsen 2006;Krauss-Etschmann 2007;Krummel 2016; Laivuori 1993; Makrides 2010; Malcolm 2003; Mardones 2008; Martin-Alvarez 2012; Miller 2016; Min 2014; Min 2016; Mozurkewich 2013;Mulder 2014;Noakes 2012;Ogundipe 2016; Oken 2013; Olsen 1992; Olsen 2000; Onwude 1995; Otto 2000; Pietrantoni 2014; Ramakrishnan 2010; Ranjkesh 2011;Razavi 2017; Rees 2008; Ribeiro 2012; Rivas-Echeverria 2000; Samimi 2015; Sanjurjo 2004; Smuts 2003a; Smuts 2003b; Su 2008; Taghizadeh 2016; Tofail 2006; Valenzuela 2015; Van Goor 2009; Van Winden 2017; Vaz 2017

The included trials have been published over nearly three decades: from 1989 to 2018.

Study design: RCT, all trials were individually randomised. Ten were multi-arm trials.

Setting and Country: most (but not all) in upper-middle or high-income countries

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: Funding sources were reported by 56 of the 70 included trials. Funding bodies listed by the trials were mostly non-commercial organisations. However, commercial organisations, mainly pharmaceutical companies, were reported as the only or main funding sources in 11 trials. Thirteen trials did not report any funding. |

Inclusion criteria SR: -RCTs (incl quasi-randomised trials and trials published in abstract form) -pregnant women, regardless of their risk for pre-eclampsia, preterm birth or intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR)

Exclusion criteria SR: -cross-over trials

Important patient characteristics at baseline:

supplements commenced: >20 weeks gestation: 33 trials; ≤20 weeks gestation: 33 trials

Groups comparable at baseline? Imbalance in baseline characteristics is considered by the Cochrane review in the category Other potential sources of bias (as one of the components). 34 trials were considered low risk, 34 trials unclear risk, and 2 trials high risk of other bias. |

Omega-3 fatty acids (mostly oral DHA and/or EPA or mainly DHA/EPA) supplements)

Doses DHA+EPA: -Low (<500 mg/day): 24 trials -Mid (500 mg/day to 1 g/day): 21 trials -High (>1 g/day): 23 trials -Other: 5 trials

40 of the 70 trials reported eligibility criteria relating to omega-3 intake, such as excluding women with an allergy to fish or fish products and/or excluding women taking omega-3, fish oil or DHA supplements or regular/any intake of fish.

|

Placebo or no omega-3 treatment

|

End-point of follow-up: not summarized for the whole body of evidence, but probably until birth or close after birth. In some trials there were several periods of childhood follow-up.

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? (intervention/ control) 13 trials were judged to be at low risk of attrition bias, with minimal losses to follow-up, and similar numbers/reasons for losses to follow-up in each group. 27 trials were judged to be at a high risk of attrition bias. The remaining 30 trials were judged to be at an unclear risk of attrition bias.

|

Omega-3 versus no omega-3

Outcome measure-1: preterm birth < 37 weeks RR 0.89, 95% CI 0.81 to 0.97; 26 trials, 10,304 participants; high-quality evidence; Analysis 1.1 Favouring omega-3.

Outcome measure-2: early preterm birth < 34 weeks RR 0.58, 95% CI 0.44 to 0.77; 9 trials, 5204 participants; high-quality evidence; Analysis 1.2. Favouring omega-3.

Outcome measure-3: miscarriage <24 weeks RR 1.07, 95% CI 0.80 to 1.43; 9 trials, 4190 participants; Analysis 1.11)

Outcome measure-4: perinatal deaths RR 0.75, 95% CI 0.54 to 1.03; 10 trials, 7416 participants; moderate-quality evidence; Analysis 1.32.

Outcome measure-5: neonatal deaths RR 0.61, 95% CI 0.34 to 1.11; 9 trials, 7448 participants; Analysis 1.34.

Outcome measure-6: Intraventricular haemorrhage RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.29 to 3.49; random effects; Tau² = 0.63; P = 0.12, I² = 53%; 3 trials; 5423 participants

Outcome measure-7: respiratory distress syndrome average RR 1.17, 95% CI 0.54 to 2.52; Tau² = 0.21; P = 0.09; I² = 66%; 2 trials; 1129 participants; Analysis 1.51

Outcome measure-8: necrotising enterocolitis RR 0.97, 95% CI 0.26 to 3.55; 2 trials; 3198 participants; Analysis 1.52

Outcome measure-9: neonatal sepsis (proven) RR 0.97, 95% CI 0.44 to 2.14; 3 trials; 3788 participants; Analysis 1.53

|

Authors conclusion: For our primary review outcomes, there was an 11% reduced risk (95% confidence interval (CI) 3% to 19%) of preterm birth < 37 weeks (high-quality evidence) and a 42% reduced risk (95% CI 23% to 56%) of early preterm birth < 34 weeks (high-quality evidence) for women receiving omega-3 LCPUFA compared with no omega-3. The number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome (NNTB) to prevent one preterm birth < 37 weeks is 68 (95% CI 39 to 238), and the NNTB to prevent a preterm birth < 34 weeks is 52 (95% CI 39 to 95).

Omega-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids (LCPUFA), particularly docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), supplementation during pregnancy is a simple and effective way to reduce preterm, early preterm birth and low birthweight, with low cost and little indication of harm. The effect of omega-3 LCPUFA on most child development and growth outcomes is minimal or remains uncertain.

|

Evidence table for intervention studies (randomized controlled trials and non-randomized observational studies [cohort studies, case-control studies, case series])1

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics 2 |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C) 3

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size 4

|

Comments |

|

Makrides, 2019 |

Type of study: RCT: Omega-3 to Reduce the Incidence of Preterm Birth (ORIP) trial; ACTRN1261300 1142729

Setting and country: multicenter (six centers in four states) from November 1, 2013, to April 26, 2017, Australia

Funding and conflicts of interest: Funded by the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council and the Thyne Reid Foundation. The trial capsules were donated by Croda UK and Efamol/Wassen UK; neither company had any other role in the trial. The funders were not involved in the design of the trial, the collection or analysis of the data, or the writing of the manuscript. |

Inclusion criteria: -pregnant with a single fetus or multiple fetuses -women could participate in the trial for successive pregnancies and underwent a separate randomization for each pregnancy

Exclusion criteria: -taking daily supplements containing more than 150 mg of n−3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids -unwilling to discontinue daily supplements containing 150 mg or less of n−3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids. -having coagulopathy -known history of substance abuse - fetus with a known congenital abnormality.

N total at baseline: 5544 pregnancies in 5517 women

Intervention: 2770 pregnancies in 2766 women Control: 2774 pregnancies in 2765 women

27 women participated in the trial twice and underwent a separate randomization for each pregnancy

Important prognostic factors2: Median maternal age, years (IQR) I: 30.0 (26.0–34.0) C: 30.0 (27.0–33.0)

Median gestation, weeks (IQR) I: 14.1 (12.7–16.4) C: 14.1 (12.7–16.6)

Mother consumed dietary n-3 supplements in the previous 3 months, n (%) I: 374 (13.5) C: 368 (13.3)

Mother was primiparous, n (%) I: 1223/2754 (44.4) C: 1209/2765 (43.7)

Pregnancy with multiple fetuses, n (%) I: 52/2698 (1.9) C: 48/2721 (1.8)

Mother had previous preterm delivery <37 weeks of gestation), n (%) I: 185/2754 (6.7) C: 184/2766 (6.7)

Groups comparable at baseline? There were no significant differences between the groups in any baseline characteristics except for the number of mothers who completed a high school education (P=0.047) |

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

n-3 group: three 500-mg fish-oil capsules per day, which provided a total of approximately 900 mg of n−3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acid per day (approximately 800 mg of DHA and approximately 100 mg of eicosapentaenoic acid [Incromega DHA 500TG capsules]

The assigned capsules were to be taken orally from the time of trial entry (<20 weeks of gestation) until 34 weeks of gestation or until delivery, whichever occurred sooner. |

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

control: three 500-mg capsules per day containing an isocaloric vegetable-oil blend that provided a total of approximately 15 mg of DHA and approximately 4 mg of eicosapentaenoic acid per day.

Control capsules were formulated to be consistent with the fatty acid composition of a typical Australian diet. |

Length of follow-up: not reported, probably until birth or close after birth

Incomplete outcome data/loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: 63 pregnancies in 63 women did not have outcome data available 63/2770 (2.3%) Reasons: 12 withdrew consent, 36 miscarried or terminated pregnancy <20 weeks, 8 terminated pregnancy ≥20 weeks, 7 women were lost to follow-up

Control: 50 pregnancies in 50 women did not have outcome data available 50/2774 (1.8%) Reasons: 14 withdrew consent, 22 miscarried or terminated pregnancy <20 weeks, 8 terminated pregnancy ≥20 weeks, 6 women were lost to follow-up

Primary outcome data were available for 5431 pregnancies (98%). After multiple imputation for missing data, 5486 pregnancies were included in the primary analysis (2734 in the n−3 group and 2752 in the control group).

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Early preterm delivery <34 weeks, n(%) I: 61/2734 (2.2) C: 55/2752 (2.0) unadjusted RR 1.13; 95% CI, 0.79 to 1.63; P=0.50) adjusted RR* 1.13 (0.79 to 1.63; p=0.50)

Preterm delivery <37 weeks, n(%) I: 211/2734 (7.7) C: 246/2752 (8.9) unadjusted RR 0.86 (0.72 to 1.03) adjusted RR 0.86 (0.72 to 1.03)

Prolonged gestation >42 weeks, n(%) I: 12/2734 (0.4) C: 12/2752 (0.4) unadjusted RR: 1.01 (0.43 to 2.36) adjusted RR: NA

Necrotizing enterocolitis I: 2/2735 (0.1) C: 0/2758 (0.0) unadjusted RR: NA adjusted RR: NA

Sepsis I: 11/2735 (0.4) C: 6/2758 (0.2) unadjusted RR 1.85 (0.68 to 4.99) adjusted RR: NA

Any brain injury (including intraventricular haemorrhage) I: 9/2735 (0.3) C: 9/2758 (0.3) unadjusted RR 1.01 (0.38 to 2.66) adjusted RR: NA

Perinatal death, n(%) (stillbirth and death within first 28 days of birth) I: 32/2823 (1.1) C: 25/2822 (0.9) unadjusted RR 1.28 (0.76–2.17), p=0.36

Stillbirth, n(%) I: 16/2823 (0.6) C: 13/2822 (0.5) unadjusted RR 1.23 (0.59–2.55), p=0.58

Neonatal death, n(%) I: 8/2823 (0.3) C: 4/2822 (0.1) unadjusted RR 2.00 (0.60–6.63), p=0.26

Miscarriage <20 weeks of gestation, n(%) I: 32/2823 (1.1) C: 18/2822 (0.6) unadjusted RR 1.78 (1.00–3.16), p=0.05

Any serious adverse event in an infant or related to the pregnancy, n(%) Defined as maternal, neonatal or fetal deaths (stillbirth); fetal loss (miscarriage); maternal admissions to intensive care; admissions to intensive care for infants born after 34 weeks’ gestation and major congenital anomalies. I: 142/2823 (5.0) C: 112/2822 (4.0) unadjusted RR 1.27 (0.99–1.62), p=0.06

*The adjusted values were adjusted for randomization strata: recruitment hospital and consumption of dietary n-3 supplements in the previous 3 months (yes or no). Except in the case of the primary outcome, the 95% confidence intervals were not adjusted for multiplicity and therefore should not be used to infer treatment effects |

Authors conclusions: We found that women who received supplementation with n−3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids from approximately 14 weeks of gestation until 34 weeks of gestation did not have a lower risk of early preterm delivery (<34 weeks) or preterm delivery (<37 weeks) than women in the control group.

The baseline level of n−3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids in the women in this trial may have been higher than that in previous studies, and this may have contributed to the absence of appreciable effects of supplementation on outcomes. Approximately 80% of Australian women now consume perinatal supplements, many of which contain small doses of DHA. Although we excluded women who were taking more than 150 mg of DHA per day, we enrolled more than 700 women who were known to have been regularly consuming a low dose of DHA (≤150 mg per day). This may have influenced the baseline level of DHA among the women included in the ORIP trial. |

|

Olsen, 2019 |

Type of study: 3-group parallel RCT; NCT02770456

Setting and country: multicenter trial, from 18 March 2008 to 5 July 2015, China

Funding and conflicts of interest: The authors declare no conflict of interests.

Financial support was received from March of Dimes (grant no. 6-FY01- 317), Danish National Research Foundation (Danish Epidemiology Science Centre), Innovation Fund Denmark (grant no. 09-067124, Centre for Fetal Programming), Shanghai Municipal Health and Family Planning Commission (grant no. 201640249), and Nutricia Research Foundation (grant no. 2014-E8). The funding agencies did not have any role in design or conduct of the study; collection, management, or interpretation of the data; or preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript |

Inclusion criteria: -pregnant in gestation weeks 16–24 -expected to deliver at 1 of the participating hospitals in 6 areas of the Peoples’ Republic of China. In in 3 areas the populations had very low intake of LC n-3 PUFAs

Exclusion criteria: -women aged <20 y -uncertain last menstrual period (LMP) and no ultrasound <20 wk -known multiple gestation -placental abruption -vaginal bleeding in previous pregnancy (minor bleeding in present pregnancy was allowed). -allergies to fish or fish oil -users of fish oil (>1 wk) or prostaglandin inhibitors (e.g., aspirin) -disorders with increased bleeding tendency -severe chronic diseases (hypertension, diseases of liver, kidney, and metabolism)

N total at baseline: N=5118 HFO: N=1706 LFO: N=1695 Controls: N=1717

Important prognostic factors2: Maternal age, mean±SD HFO:26.5 ± 4.1 LFO: 26.6 ± 4.2 Controls: 26.5 ± 4.2

Mother was primiparous, % HFO: 82.1% LFO: 81.5% Controls: 81.0%

Previous spontaneous abortions, % HFO: 4.3% LFO: 4.9% Controls: 5.2%

Combined maternal fish intake, % Low, ≤2 g/d HFO: 41.9% LFO: 43.6% Controls: 42.9% High, >2 g/d HFO: 58.1% LFO: 56.4% Controls: 57.1%

Intake of ALA in g/d HFO: 1.99 ± 1.70 LFO: 2.03 ± 1.82 Controls: 1.97 ± 1.70

Groups comparable at baseline? Baseline characteristics were all evenly distributed across the 3 randomly assigned study arms. |

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

High fish oil (HFO) group 2.0 g/d of LC n-3 PUFAs

Low fish oil (LFO) group a 1:3 mixture of fish oil to olive oil: 0.5 g/d of LC n-3 PUFAs

Pregnant women were asked to take four 0.72-g gelatin capsules per day until the last day of 37 completed gestational weeks (day 258), at which time they were asked to stop.

In this study all women were asked to stop taking oil capsules at 259 days of gestation, because in 2 earlier trials the authors had seen increased occurrences of post-term delivery after supplementation with fish oil. |

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

Control group olive oil: 0 g/d of LC n-3 PUFAs

|

Length of follow-up: not reported, probably until birth or close after birth

Loss-to-follow-up: Women lost to follow-up 298/5531 (5%) or who withdrew from treatment 618/5531 (11%). Reasons for withdrawal: -diseases during pregnancy: 9/618 (1.4%) -capsule related reasons (safety concerns, off-taste, inconvenient to take): 247/618 (40.0%) -Unknown reason: 362/618 (58.6%)

Incomplete outcome data: -Among 5531 women initially randomly assigned, 413 (7.5%) could not be included in the analyses with gestational age as outcome -The number of pregnancies of which information was available varied widely between outcome measures: for the outcome measure Apgar <7 at 5 min, n=3792; for spontaneous abortion, n=5232.

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Preterm birth <37 weeks (<259 days of gestation) -Controls: 50/1717 (2.9%) -HFO: 45/1706 (2.6%); HRR 0.90 (0.60, 1.35); p-value 0.61 -LFO: 51/1695 (3.0%); HRR 1.04 (0.70, 1.53); p-value 0.86

Early preterm birth <34 weeks (<238 days of gestation) -Controls: 8/1717 (0.5%) -HFO: 4/1706 (0.2%); HRR 0.50 (0.15, 1.67); p-value 0.26 -LFO: 5/1695 (0.3%); HRR 0.63 (0.21, 1.94); p-value 0.42

Early term birth <39 weeks (<273 days of gestation) -Controls: 304/1717 (17.7%) -HFO: 278/1706 (16.3%); HRR 0.91 (0.77, 1.07); p-value 0.77 -LFO: 300/1695 (17.7%); HRR 1.01 (0.86, 1.18); p-value 0.86

Post-term delivery ≥42 weeks* -Controls: 29/1706 (1.7) -HFO: 33/1737 (1.9) -LFO: 39/1696 (2.3) p-value 0.45

Spontaneous abortion (not further defined)* -Controls: 10/1667 (0.6%) -HFO: 6/1500 (0.4%) -LFO: 16/1778 (0.9%) p-value 0.09

Stillbirth (not further defined)* -Controls: 5/1667 (0.3%) -HFO: 6/1500 (0.4%) -LFO: 16/1778 (0.9%) p-value 0.03

Stillbirth in the post-term period (not further defined)* -Controls: 0/? (0.0%) -HFO: 0/? (0.0%) -LFO: 0/? (0.0%) p-value 1.00

Infant death <42 days* -Controls: 6/1500 (0.4%) -HFO: 4/1333 (0.3%) -LFO: 4/1333 (0.3%) p-value 0.78

Intracranial hemorrhage in infant* -Controls: 2/2000 (0.1%) -HFO: 3/1500 (0.2%) -LFO: 1/1000 (0.1%) p-value 0.60

*An estimation was made of the total number of women in the HFO, LFO, and Control-group per outcome measure, because in the published article of Olsen (Table 5) only the number of cases with percentages were given for the outcome measures.

|

Authors conclusions: We did not detect statistically significant associations between taking fish oil supplements during the preterm period of pregnancy and risk of preterm birth and risk of delivering before 273 days of gestation. Our trial may not have had sufficient power to detect an effect on preterm birth.

Two other explanations exist, for which data from the trial provide some supportive evidence. Mean intake in the trial population of α-linolenic acid (ALA) was estimated at 2 g/d. This is about twice as high as that found for some US and European populations. The other possible explanation rests on the fact that we had asked all women to stop taking oil capsules at 259 days of gestation, that is at a point in time when >95% of the trial population was still pregnant.

Remarks: The trial would randomly assign 10,803 women but this was in reality a smaller number (5531) for the following reasons: slower recruitment rates than expected combined with short shelf-life of capsules in the first phases of the study; and, in the end, because of lack of funding to continue recruitment.

Using α = 0.05, and using two-thirds of the cases and 1710 persons per group to calculate power for 2-group comparisons, for preterm birth we would have power of 61%, 72%, and 85% to detect RRs of 0.70, 0.65, and 0.60, respectively, or less. |

Notes:

- Prognostic balance between treatment groups is usually guaranteed in randomized studies, but non-randomized (observational) studies require matching of patients between treatment groups (case-control studies) or multivariate adjustment for prognostic factors (confounders) (cohort studies); the evidence table should contain sufficient details on these procedures

- Provide data per treatment group on the most important prognostic factors [(potential) confounders]

- For case-control studies, provide sufficient detail on the procedure used to match cases and controls

- For cohort studies, provide sufficient detail on the (multivariate) analyses used to adjust for (potential) confounders

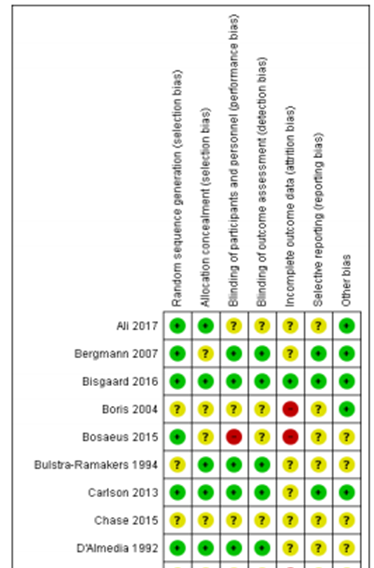

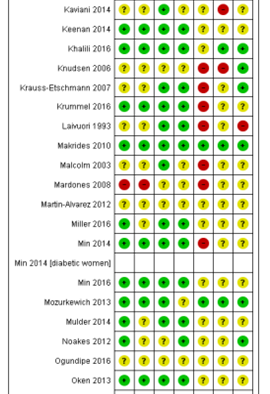

Risk of bias assessment

Table of quality assessment for systematic reviews of RCTs and observational studies

Based on AMSTAR checklist (Shea et al.; 2007, BMC Methodol 7: 10; doi:10.1186/1471-2288-7-10) and PRISMA checklist (Moher et al 2009, PLoS Med 6: e1000097; doi:10.1371/journal.pmed1000097)

|

Study

First author, year |

Appropriate and clearly focused question?1

Yes/no/unclear |

Comprehensive and systematic literature search?2

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of included and excluded studies?3

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of relevant characteristics of included studies?4

Yes/no/unclear |

Appropriate adjustment for potential confounders in observational studies?5

Yes/no/unclear/notapplicable |

Assessment of scientific quality of included studies?6

Yes/no/unclear |

Enough similarities between studies to make combining them reasonable?7

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential risk of publication bias taken into account?8

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential conflicts of interest reported?9

Yes/no/unclear |

|

Middleton, 2018 |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

No, relevant confounders not reported |

Not applicable |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

1. Research question (PICO) and inclusion criteria should be appropriate and predefined

2. Search period and strategy should be described; at least Medline searched; for pharmacological questions at least Medline + EMBASE searched

3. Potentially relevant studies that are excluded at final selection (after reading the full text) should be referenced with reasons

4. Characteristics of individual studies relevant to research question (PICO), including potential confounders, should be reported

5. Results should be adequately controlled for potential confounders by multivariate analysis (not applicable for RCTs)

6. Quality of individual studies should be assessed using a quality scoring tool or checklist (Jadad score, Newcastle-Ottawa scale, risk of bias table etc.)

7. Clinical and statistical heterogeneity should be assessed; clinical: enough similarities in patient characteristics, intervention and definition of outcome measure to allow pooling? For pooled data: assessment of statistical heterogeneity using appropriate statistical tests (e.g. Chi-square, I2)?

8. An assessment of publication bias should include a combination of graphical aids (e.g., funnel plot, other available tests) and/or statistical tests (e.g., Egger regression test, Hedges-Olken). Note: If no test values or funnel plot included, score “no”. Score “yes” if mentions that publication bias could not be assessed because there were fewer than 10 included studies.

9. Sources of support (including commercial co-authorship) should be reported in both the systematic review and the included studies. Note: To get a “yes,” source of funding or support must be indicated for the systematic review AND for each of the included studies.

Derived from the Cochrane review of Middleton (2018)

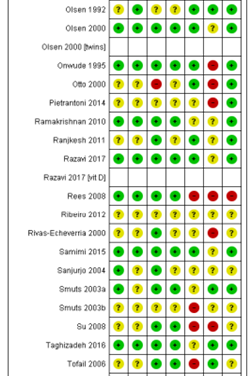

Figure X. Risk of bias summary Cochrane review

Risk of bias table for intervention studies (randomized controlled trials)

|

Study reference

(first author, publication year) |

Describe method of randomisation1 |

Bias due to inadequate concealment of allocation?2

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate blinding of participants to treatment allocation?3

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate blinding of care providers to treatment allocation?3

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate blinding of outcome assessors to treatment allocation?3

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to selective outcome reporting on basis of the results?4

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to loss to follow-up?5

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to violation of intention to treat analysis?6

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

|

Makrides, 2019 |

Women were randomly assigned, with the use of a Web-based randomization service, to receive either n−3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acid capsules (n−3 group) or vegetable-oil capsules (control group); the randomization schedule was prepared by an independent statistician, with balanced variable blocks and stratification according to trial center and previous use of n−3 longchain polyunsaturated fatty acid supplements (yes or no). |

Unlikely

|

Unlikely

At randomization, women were provided with five bottles, each containing 90 capsules. Additional capsules were reissued as necessary.

The bottles and capsules of n−3 fatty acid and control were identical in appearance, and the control capsules contained 5% tuna oil to aid in the masking of the group assignment

|

Unlikely

Participants, clinicians, and researchers remained unaware of the group assignments until the data analysis was complete.

|

Unlikely

Data were extracted from maternal and infant medical records 6 weeks after delivery by trained trial staff who were not members of the clinical care team. |

Unlikely

Outcomes in the study protocol (Zhou, 2017) are similar to the reported outcomes in Makrides, 2019.

|

Unlikely

Primary outcome data were available for 5431 of 5544 pregnancies (98%). 2.3% of the outcome data was not available in the intervention group, for the control group 1.8%. Reasons for loss to follow-up were similar.

|

Unlikely

The primary analysis was performed on an intention-to-treat basis. |

|

Olsen, 2019 |

Women were randomly assigned in a ratio of 1:1:1 and in blocks of 18 within strata defined by hospitals/ centers, conducted by an independent statistician. |

Unlikely

|

Unlikely

Capsules were nontransparent, identical in appearance, and provided in blister packages. Participating women and trial personnel were all blinded to the type of oil content in the capsules, which were nontransparent and identical in appearance

|

Unlikely

Capsules were nontransparent, identical in appearance, and provided in blister packages. Un-blinding was done 1 y after random assignment of the last woman after having a formal Statistical Analysis Plan completed and filed with an independent third party (Scientific-Ethical Committee of Copenhagen). |

Unlikely

Trial personnel was blinded. Moreover, objective outcome measures were reported (preterm birth; death, intracranial hemmorrhage) |

Unlikely

Study protocol not available. Outcomes listed in the methods section are similar with those in the results section (preterm birth <34 weeks reported in Supplement Table 2). |

Likely

Loss to follow-up Women lost to follow-up 298/5531 (5%) or who withdrew from treatment 618/5531 (11%). Reasons for withdrawal: -diseases during pregnancy: 9/618 (1.4%) -capsule related reasons (safety concerns, off-taste, inconvenient to take): 247/618 (40.0%) -Unknown reason: 362/618 (58.6%)

Incomplete outcome data: -Among 5531 women initially randomly assigned, 413 (7.5%) could not be included in the analyses with gestational age as outcome -The number of pregnancies of which information was available varied widely between outcome measures: for the outcome measure Apgar <7 at 5 min, n=3792; for spontaneous abortion, n=5232. |

Unclear

To the extent possible, all analyses presented followed intention-to-treat principles. |

- Randomisation: generation of allocation sequences have to be unpredictable, for example computer generated random-numbers or drawing lots or envelopes. Examples of inadequate procedures are generation of allocation sequences by alternation, according to case record number, date of birth or date of admission.

- Allocation concealment: refers to the protection (blinding) of the randomisation process. Concealment of allocation sequences is adequate if patients and enrolling investigators cannot foresee assignment, for example central randomisation (performed at a site remote from trial location) or sequentially numbered, sealed, opaque envelopes. Inadequate procedures are all procedures based on inadequate randomisation procedures or open allocation schedules..

- Blinding: neither the patient nor the care provider (attending physician) knows which patient is getting the special treatment. Blinding is sometimes impossible, for example when comparing surgical with non-surgical treatments. The outcome assessor records the study results. Blinding of those assessing outcomes prevents that the knowledge of patient assignement influences the proces of outcome assessment (detection or information bias). If a study has hard (objective) outcome measures, like death, blinding of outcome assessment is not necessary. If a study has “soft” (subjective) outcome measures, like the assessment of an X-ray, blinding of outcome assessment is necessary.

- Results of all predefined outcome measures should be reported; if the protocol is available, then outcomes in the protocol and published report can be compared; if not, then outcomes listed in the methods section of an article can be compared with those whose results are reported.

- If the percentage of patients lost to follow-up is large, or differs between treatment groups, or the reasons for loss to follow-up differ between treatment groups, bias is likely. If the number of patients lost to follow-up, or the reasons why, are not reported, the risk of bias is unclear

- Participants included in the analysis are exactly those who were randomized into the trial. If the numbers randomized into each intervention group are not clearly reported, the risk of bias is unclear; an ITT analysis implies that (a) participants are kept in the intervention groups to which they were randomized, regardless of the intervention they actually received, (b) outcome data are measured on all participants, and (c) all randomized participants are included in the analysis.

Table of excluded studies

|

Author and year |

Reason for exclusion |

|

Abu-Saad 2020 |

Cohort study on preconceptual dietary intake |

|

Carlson 2018 |

Secondary analysis of RCT on dose-response relationship |

|

Ciesielski 2019 |

No intervention study |

|

Colombo 2019 |

Wrong outcome measure (long-term behavioral and cognitive outcome) |

|

Hoge, 2020 |

No intervention study |

|

Nykjaer 2019 |

No intervention study |

|

Olsen 2018 |

No intervention study |

|

Samuel 2019 |

Narrative review |

|

Sebastiani 2019 |

Narrative review |

|

Simmonds 2020 |

Exploratory analysis of the included RCT of Makrides 2019 |

|

Smid 2019 |

Secondary analysis of RCT (association study fish intake and preterm birth in lean, overweight, and obese women) |

|

Wieland 2019 |

Summary article of the included Cochrane review of Middleton 2018 |

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Publicatiedatum : 10-02-2025

Beoordeeld op geldigheid : 20-11-2024

Algemene gegevens

De ontwikkeling van deze richtlijnmodule werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten (www.demedischspecialist.nl/kennisinstituut) en werd gefinancierd uit de Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS). De financier heeft geen enkele invloed gehad op de inhoud van de richtlijnmodule.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijnmodule is in 2019 een multidisciplinaire werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen (zie hiervoor de Samenstelling van de werkgroep) die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor zwangere vrouwen zonder klinische verschijnselen van een vroeggeboorte, die al dan niet in een eerdere zwangerschap een spontane vroeggeboorte hebben doorgemaakt.

Werkgroep

- Prof. dr. M.A. Oudijk, gynaecoloog, NVOG (voorzitter)

- Dr. N. Horree, gynaecoloog, NVOG

- Dr. J.B. Derks, gynaecoloog, NVOG

- Dr. T.A.J. Nijman, gynaecoloog, NVOG

- Dr. F. Vlemmix, gynaecoloog, NVOG

- Dr. D.A.A. van der Woude, gynaecoloog, NVOG

- L.T. Brammerloo-Read, MSc, verloskundige, KNOV

- Dr. M.A.C. Hemels, kinderarts-neonatoloog, NVK

- F.A.B.A. Schuerman, MSc, kinderarts-neonatoloog, NVK

- J.D.M. Wagemaker, patiëntenvereniging, Care4Neo

Met ondersteuning van:

- Dr. L. Viester, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van Medisch Specialisten (tot augustus 2022)

- T. Geltink, MSc, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van Medisch Specialisten (vanaf augustus 2022)

Belangenverklaringen

De Code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling is gevolgd. Alle werkgroepleden hebben schriftelijk verklaard of zij in de laatste drie jaar directe financiële belangen (betrekking bij een commercieel bedrijf, persoonlijke financiële belangen, onderzoeksfinanciering) of indirecte belangen (persoonlijke relaties, reputatiemanagement) hebben gehad. Gedurende de ontwikkeling of herziening van een module worden wijzigingen in belangen aan de voorzitter doorgegeven. De belangenverklaring wordt opnieuw bevestigd tijdens de commentaarfase.

Een overzicht van de belangen van werkgroepleden en het oordeel over het omgaan met eventuele belangen vindt u in onderstaande tabel. De ondertekende belangenverklaringen zijn op te vragen bij het secretariaat van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

|

Werkgroeplid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

Prof. dr. M.A. Oudijk |

Gynaecoloog |

Voorzitter Pijler FMG van de NVOG, onbetaald, alleen vacatiegelden. Voorzitter wetenschapscommissie pijler FMG, onbetaald. Member of the board of the foundation 'Stoptevroegbevallen'; a non-profit foundation with the purpose to raise funds for research projects on preterm labour/birth, onbetaald. Member of the scientific committee of the 'Fonds Gezond Geboren', a non-profit foundation with the purpose to raise funds for reserarch projects on preterm birth and placental insufficiency, onbetaald. Member of the advisory board of the N3, the Dutch Neonatology research network, onbetaald. President of the European Spontaneous Preterm Birth Congress to be held in Haarlem, The Netherlands, www. espbc.eu, onbetaald |

2015 ZonMW836041012 The effect of tocolysis with nifedipine or atosiban on infant development: the APOSTEL III follow-up study. € 43,772. 2015 ZonMW 836041006 Low dose aspirin in the prevention of recurrent spontaneous preterm labour: the APRIL study € 351.898. 2016 Zon|MW 80-84800-98-41027 Atosiban versus placebo in the treatment of late threatened preterm labour: the APOSTEL VIII study € 1.393.639. Hoofdaanvrager/projectleider van deze vroeggeboorte studies. Subsidie wordt alleen aangewend ten behoeve van het onderzoek, promoventi etc. Geen persoonlijke salariëring vanuit deze ZonMw studie |

geen restricties |

|

Dr. N. Horree |

Gynaecoloog |

geen |

Participatie binnen ziekenhuis aan consortium studies vanuit de NVOG. Hieronder vallen ook onderzoek naar vroeggeboorte (o.a. Apnel studies) en preventie vroeggeboorte (April). QP PC - studies |

geen restricties |

|

Dr. J.B. Derks |

Gynaecoloog |

Lid bestuur werkgroep perinatologie en maternale ziektes (onbetaald); Lid otterlo groep (Cie. Ontwikkeling richtlijnen obstetrie) (onbetaald) |

Deelname consortiumstudies waaronder de April studie |

geen restricties |

|

T.A.J. Nijman |

Gynaecoloog |

Lid Commissie Gynaecongres, VAGO-vertegenwoordiger, onbetaald; Lid Koepel Wetenschap. VAGO-vertegenwoordiger, onbetaald |

Project groep April studie, ZonMW gesponsorde Consortium studie naar aspirine vs placebo bij preventie herhaalde vroeggeboorte. |

geen restricties |

|

Dr. F. Vlemmix |

Gynaecoloog |

Lid werkgroep patiëntcommunicatie NVOG |

geen |

geen restricties |

|

Dr. D.A.A. van der Woude |

Gynaecoloog & postdoc |

geen |

geen |

geen restricties |

|

L.T. Brammerloo-Read |

Verloskundige |

geen |

De praktijk + kliniek waarin werkzaam heeft deelname in cervix-meting van patiënten om vroeggeboorte op te kunnen sporen, hierbij geen financieel belang. |

geen restricties |

|

Dr. M.A.C. Hemels |

Kinderarts-neonatoloog |

Faculty cursus antibiotica bij kinderen, betaald |

Deelname APRIL studie, meelezen protocol betreffende de neonatale uitkomst maten |

geen restricties |

|

F.A.B.A. Schuerman |

Kinderarts-neonatoloog |

Bestuurslid stichting kindersedatie Nederland (betaald) |

geen |

geen restricties |

|

J.D.M. Wagemaker |

Patiëntvertegenwoordiger care |

geen |

geen |

geen restricties |

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Er werd aandacht besteed aan het patiëntenperspectief door uitnodigen van Patiëntenfederatie Nederland, Stichting Kind en Ziekenhuis en Vereniging Ouders Couveusekinderen voor de schriftelijke knelpunteninventarisatie en een afgevaardigde patiëntenvereniging in de werkgroep. De verkregen input is meegenomen bij het opstellen van de uitgangsvragen, de keuze voor de uitkomstmaten en bij het opstellen van de overwegingen. De conceptrichtlijn is tevens voor commentaar voorgelegd aan Patiëntenfederatie Nederland, Stichting Kind en Ziekenhuis en Vereniging Ouders Couveusekinderen en de eventueel aangeleverde commentaren zijn bekeken en verwerkt.

Kwalitatieve raming van mogelijke financiële gevolgen in het kader van de Wkkgz

Bij de richtlijn is conform de Wet kwaliteit, klachten en geschillen zorg (Wkkgz) een kwalitatieve raming uitgevoerd of de aanbevelingen mogelijk leiden tot substantiële financiële gevolgen. Bij het uitvoeren van deze beoordeling zijn richtlijnmodules op verschillende domeinen getoetst (zie het stroomschema op de Richtlijnendatabase).

Uit de kwalitatieve raming blijkt dat er waarschijnlijk geen substantiële financiële gevolgen zijn.

Werkwijze

AGREE

Deze richtlijnmodule is opgesteld conform de eisen vermeld in het rapport Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 van de adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwaliteit. Dit rapport is gebaseerd op het AGREE II instrument (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II; Brouwers, 2010).

Knelpuntenanalyse en uitgangsvragen

Tijdens de voorbereidende fase inventariseerde de werkgroep de knelpunten in de zorg voor zwangere vrouwen zonder klinische verschijnselen van een vroeggeboorte, die al dan niet in een eerdere zwangerschap een spontane vroeggeboorte hebben doorgemaakt. Tevens zijn er knelpunten aangedragen door Patiëntenfederatie Nederland, Verpleegkundigen & Verzorgenden Nederland, Nederlandse Vereniging voor Kindergeneeskunde, Nederlandse Vereniging voor Medische Microbiologie, LAREB, Nederlandse Vereniging voor Klinische Fysica, Kind en Ziekenhuis via een schriftelijke knelpunteninventarisatie .

Op basis van de uitkomsten van de knelpuntenanalyse zijn door de werkgroep concept-uitgangsvragen opgesteld en definitief vastgesteld.

Uitkomstmaten

Na het opstellen van de zoekvraag behorende bij de uitgangsvraag inventariseerde de werkgroep welke uitkomstmaten voor de patiënt relevant zijn, waarbij zowel naar gewenste als ongewenste effecten werd gekeken. Hierbij werd een maximum van acht uitkomstmaten gehanteerd. De werkgroep waardeerde deze uitkomstmaten volgens hun relatieve belang bij de besluitvorming rondom aanbevelingen, als cruciaal (kritiek voor de besluitvorming), belangrijk (maar niet cruciaal) en onbelangrijk. Tevens definieerde de werkgroep tenminste voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten welke verschillen zij klinisch (patiënt) relevant vonden.

Methode literatuursamenvatting

Een uitgebreide beschrijving van de strategie voor zoeken en selecteren van literatuur is te vinden onder ‘Zoeken en selecteren’ onder Onderbouwing. Indien mogelijk werd de data uit verschillende studies gepoold in een random-effects model. Review Manager 5.4 werd gebruikt voor de statistische analyses. De beoordeling van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs wordt hieronder toegelicht.

Beoordelen van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs

De kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs werd bepaald volgens de GRADE-methode. GRADE staat voor ‘Grading Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation’ (zie http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/). De basisprincipes van de GRADE-methodiek zijn: het benoemen en prioriteren van de klinisch (patiënt) relevante uitkomstmaten, een systematische review per uitkomstmaat, en een beoordeling van de bewijskracht per uitkomstmaat op basis van de acht GRADE-domeinen (domeinen voor downgraden: risk of bias, inconsistentie, indirectheid, imprecisie, en publicatiebias; domeinen voor upgraden: dosis-effect relatie, groot effect, en residuele plausibele confounding).

GRADE onderscheidt vier gradaties voor de kwaliteit van het wetenschappelijk bewijs: hoog, redelijk, laag en zeer laag. Deze gradaties verwijzen naar de mate van zekerheid die er bestaat over de literatuurconclusie, in het bijzonder de mate van zekerheid dat de literatuurconclusie de aanbeveling adequaat ondersteunt (Schünemann, 2013; Hultcrantz, 2017).

|

GRADE |

Definitie |

|

Hoog |

|

|

Redelijk |

|

|

Laag |

|

|

Zeer laag |

|

Bij het beoordelen (graderen) van de kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs in richtlijnen volgens de GRADE-methodiek spelen grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming een belangrijke rol (Hultcrantz, 2017). Dit zijn de grenzen die bij overschrijding aanleiding zouden geven tot een aanpassing van de aanbeveling. Om de grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming te bepalen moeten alle relevante uitkomstmaten en overwegingen worden meegewogen. De grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming zijn daarmee niet één op één vergelijkbaar met het minimaal klinisch relevant verschil (Minimal Clinically Important Difference, MCID). Met name in situaties waarin een interventie geen belangrijke nadelen heeft en de kosten relatief laag zijn, kan de grens voor klinische besluitvorming met betrekking tot de effectiviteit van de interventie bij een lagere waarde (dichter bij het nuleffect) liggen dan de MCID (Hultcrantz, 2017).

Overwegingen (van bewijs naar aanbeveling)

Om te komen tot een aanbeveling zijn naast (de kwaliteit van) het wetenschappelijke bewijs ook andere aspecten belangrijk en worden meegewogen, zoals aanvullende argumenten uit bijvoorbeeld de biomechanica of fysiologie, waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten, kosten (middelenbeslag), aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie. Deze aspecten zijn systematisch vermeld en beoordeeld (gewogen) onder het kopje ‘Overwegingen’ en kunnen (mede) gebaseerd zijn op expert opinion. Hierbij is gebruik gemaakt van een gestructureerd format gebaseerd op het evidence-to-decision framework van de internationale GRADE Working Group (Alonso-Coello, 2016a; Alonso-Coello 2016b). Dit evidence-to-decision framework is een integraal onderdeel van de GRADE methodiek.

Formuleren van aanbevelingen

De aanbevelingen geven antwoord op de uitgangsvraag en zijn gebaseerd op het beschikbare wetenschappelijke bewijs en de belangrijkste overwegingen, en een weging van de gunstige en ongunstige effecten van de relevante interventies. De kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs en het gewicht dat door de werkgroep wordt toegekend aan de overwegingen, bepalen samen de sterkte van de aanbeveling. Conform de GRADE-methodiek sluit een lage bewijskracht van conclusies in de systematische literatuuranalyse een sterke aanbeveling niet a priori uit, en zijn bij een hoge bewijskracht ook zwakke aanbevelingen mogelijk (Agoritsas, 2017; Neumann, 2016). De sterkte van de aanbeveling wordt altijd bepaald door weging van alle relevante argumenten tezamen. De werkgroep heeft bij elke aanbeveling opgenomen hoe zij tot de richting en sterkte van de aanbeveling zijn gekomen.

In de GRADE-methodiek wordt onderscheid gemaakt tussen sterke en zwakke (of conditionele) aanbevelingen. De sterkte van een aanbeveling verwijst naar de mate van zekerheid dat de voordelen van de interventie opwegen tegen de nadelen (of vice versa), gezien over het hele spectrum van patiënten waarvoor de aanbeveling is bedoeld. De sterkte van een aanbeveling heeft duidelijke implicaties voor patiënten, behandelaars en beleidsmakers (zie onderstaande tabel). Een aanbeveling is geen dictaat, zelfs een sterke aanbeveling gebaseerd op bewijs van hoge kwaliteit (GRADE gradering HOOG) zal niet altijd van toepassing zijn, onder alle mogelijke omstandigheden en voor elke individuele patiënt.

|

Implicaties van sterke en zwakke aanbevelingen voor verschillende richtlijngebruikers |

||

|

|

||

|

|

Sterke aanbeveling |

Zwakke (conditionele) aanbeveling |

|

Voor patiënten |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen en slechts een klein aantal niet. |

Een aanzienlijk deel van de patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen, maar veel patiënten ook niet. |

|

Voor behandelaars |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak moeten ontvangen. |

Er zijn meerdere geschikte interventies of aanpakken. De patiënt moet worden ondersteund bij de keuze voor de interventie of aanpak die het beste aansluit bij zijn of haar waarden en voorkeuren. |

|

Voor beleidsmakers |

De aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kan worden gezien als standaardbeleid. |

Beleidsbepaling vereist uitvoerige discussie met betrokkenheid van veel stakeholders. Er is een grotere kans op lokale beleidsverschillen. |

Organisatie van zorg

In de knelpuntenanalyse en bij de ontwikkeling van de richtlijnmodule is expliciet aandacht geweest voor de organisatie van zorg: alle aspecten die randvoorwaardelijk zijn voor het verlenen van zorg (zoals coördinatie, communicatie, (financiële) middelen, mankracht en infrastructuur). Randvoorwaarden die relevant zijn voor het beantwoorden van deze specifieke uitgangsvraag zijn genoemd bij de overwegingen. Meer algemene, overkoepelende, of bijkomende aspecten van de organisatie van zorg worden behandeld in de module Organisatie van zorg.

Commentaar- en autorisatiefase

De conceptrichtlijnmodule werd aan de betrokken (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd ter commentaar. De commentaren werden verzameld en besproken met de werkgroep. Naar aanleiding van de commentaren werd de conceptrichtlijnmodule aangepast en definitief vastgesteld door de werkgroep. De definitieve richtlijnmodule werd aan de deelnemende (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd voor autorisatie en door hen geautoriseerd dan wel geaccordeerd.

Literatuur

Agoritsas T, Merglen A, Heen AF, Kristiansen A, Neumann I, Brito JP, Brignardello-Petersen R, Alexander PE, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Guyatt GH. UpToDate adherence to GRADE criteria for strong recommendations: an analytical survey. BMJ Open. 2017 Nov 16;7(11):e018593. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018593. PubMed PMID: 29150475; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5701989.

Alonso-Coello P, Schünemann HJ, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Rada G, Rosenbaum S, Morelli A, Guyatt GH, Oxman AD; GRADE Working Group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 1: Introduction. BMJ. 2016 Jun 28;353:i2016. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2016. PubMed PMID: 27353417.

Alonso-Coello P, Oxman AD, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Vandvik PO, Meerpohl J, Guyatt GH, Schünemann HJ; GRADE Working Group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 2: Clinical practice guidelines. BMJ. 2016 Jun 30;353:i2089. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2089. PubMed PMID: 27365494.