Lichaamsbeweging in de zwangerschap ter preventie van vroeggeboorte

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is de waarde van lichaamsbeweging bij zwangere vrouwen ter voorkoming van vroeggeboorte?

Aanbeveling

Bespreek met vrouwen met en zonder verhoogd risico op vroeggeboorte de algemene adviezen over lichamelijke activiteit in de zwangerschap, vanwege het gunstige effect zonder dat er een verhoogd risico is op vroeggeboorte.

Fysieke inspanning voor 2-4 uur per week verdeeld over tenminste 3 momenten is een praktische handreiking voor een advies ten aanzien van bewegen.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Ten aanzien van het beantwoorden van de vraag naar de waarde van lichaamsbeweging bij zwangere vrouwen ter voorkoming van vroeggeboorte, werd één systematische review uit 2018 geïncludeerd (met 27 RCTs) en aanvullend drie RCTs met recentere verschijningsdatum. Deze studies onderzochten het effect van prenatale bewegingsprogramma’s op de uitkomstmaat vroeggeboorte. RCTs gericht op interventie-vragen, starten op een hoog niveau van bewijskracht. De bewijskracht voor de uitkomstmaat vroeggeboorte <37 weken was laag (afwaardering met twee niveaus vanwege imprecisie en risico op bias). Voor de uitkomstmaat vroeggeboorte <34 weken was de bewijskracht zeer laag (deze uitkomstmaat werd alleen gerapporteerd door de RCT van Wang 2017). Er was geen data beschikbaar betreffende de cruciale uitkomstmaat vroeggeboorte <28 weken. De overall bewijskracht voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten was zeer laag. Er was geen data beschikbaar betreffende de belangrijke uitkomstmaten.

De meerwaarde van interventieprogramma’s om het bewegen te stimuleren en daarmee risico op vroeggeboorte te reduceren is tot heden dus niet in RCTs aangetoond. Echter, er zijn wel aanwijzingen dat beweging een gunstig effect heeft op de zwangerschap en mogelijk ook op de reductie van vroeggeboorte (Aune, 2017). Voor de algemene populatie zwangeren kan lichamelijke activiteit aanbevolen worden. Er is geen bewezen effectieve (en dus kosteneffectieve) strategie die de zwangere helpt om tot meer bewegen te komen ter reductie van vroeggeboorte.

Er zijn enkele studies gepubliceerd die het effect van lichaamsbeweging op vroeggeboorte hebben onderzocht binnen een populatie met een verhoogd risico op deze uitkomstmaat. Omdat dit secundaire analyses van RCTs waren, waarin dus de beweging zelf niet de interventie betrof, zijn deze studies niet naar voren gekomen in onze initiële search. Deze studies concludeerden dat er geen verhoogd risico op vroeggeboorte is door lichamelijke inspanning, en mogelijk juist een beschermend effect.

Grobman (2013) verrichte een RCT naar het effect van 17-α-hydroxyprogesteron caproate bij nullipara eenling zwangerschappen met een cervix korter dan 30 mm. Wekelijks werd gevraagd of de vrouwen een vorm van activiteiten restrictie was opgelegd. Vroeggeboorte onder de 37 weken kwam significant vaker voor in de groep vrouwen die enige vorm van activiteiten restrictie was opgelegd ook na correctie voor confounding (adjusted odds ratio 2.37, 95% confidence interval 1.60–3.53). De onderzoeksgroep concludeerde dat adviezen ter restrictie van activiteiten bij nullipara met een eenlingzwangerschap en een korte cervix niet leidde tot de reductie van vroeggeboorte.

Saccone (2017) verrichten een RCT naar het effect van pessarium therapie voor vrouwen met een eenlingzwangerschap en zonder een vroeggeboorte in de anamnese maar met een asymptomatische korte cervixlengte (25mm of korter tussen 18+0 en 23+6 weken). Door middel van een vragenlijst werd navraag gedaan naar de lichamelijke activiteit van de zwangere in de studie. Zij concludeerde dat bij vrouwen met een eenlingzwangerschap en een korte cervix, lichamelijke activiteit van meer dan 20 minuten, meer dan 2 dagen per week niet geassocieerd was met een verhoogd risico op vroeggeboorte, maar geassocieerd met een niet significant verlaagd risico.

Zemet (2018) verrichte een prospectief cohortonderzoek naar lichamelijke activiteit bij vrouwen met een verhoogd risico op vroeggeboorte. Het gemiddelde aantal stappen per dag was omgekeerd gecorreleerd met het risico op vroeggeboorte, ook na correctie voor maternale leeftijd, BMI, zwangerschapsduur op tijdstip inclusie, cervixlengte, ontsluiting, meerlingzwangerschap. Samenvattend laten deze drie studies dus een gunstig effect van lichaamsbeweging op vroeggeboorte risico zien. De bewijskracht van deze studies was echter laag. Daarnaast is er geen goede onderbouwing voor het actief ontmoedigen van lichamelijke activiteit.

De ontwikkelaars van de Canadese richtlijn over fysieke activiteit in de zwangerschap (Mottola ,2018)) hebben een review geschreven over de absolute en relatieve contra-indicaties die veelal expert opinion based zijn. Hierbij zijn zij tot nieuwe aanbevelingen gekomen. Een eerdere contra-indicatie waarvoor er minimaal empirisch bewijs is, dat lichamelijke activiteit kan leiden tot zwangerschapscomplicaties, komt hierbij te vervallen. Door deze groep vrouwen te beperken in lichamelijk activiteit, wordt hen namelijk de kans op gunstige gezondheidseffecten en zwangerschapsuitkomsten ontzegd (reductie in zwangerschapsdiabetes, pre eclampsie, prenatale depressie, en macrosomie).

Als handreiking naar uniforme informatievoorziening aan vrouwen met een risico op vroeggeboorte, biedt deze richtlijn een mooi handvat in het advies aan zwangeren.

Tabel 1. Adviezen over beweging per patiëntengroep (Mottola, 2018)

|

Patiëntengroep |

Bewegingsadviezen |

|

Actieve vroeggeboorte Pijnlijke uterus contracties in rust |

Lichamelijke activiteiten vermijden en medische hulp zoeken |

|

Cervixinsufficiëntie Premature pijnloze ontsluiting (evt. in combinatie met vroeggeboorte in de voorgeschiedenis) zonder dat er tekenen zijn van preterme weeenactiviteit, chorio amnionitis of foetale chromosomale afwijkingen. |

Dagelijkse activiteiten voortzetten. Eventueel aangevuld met lichte weerstandsoefeningen van het bovenlichaam. Matige tot intensieve lichamelijke activiteit vermijden. |

|

PPROM Gebroken vliezen <37 weken |

Dagelijkse activiteiten voort te zetten, aangevuld met lichte lichamelijke inspanning (bijvoorbeeld wandelen). |

|

Dreigende vroeggeboorte Vrouwen met een korte cervix (<25mm) zonder andere bijkomende factoren |

Standaard aanbevelingen voor lichamelijke activiteit (minimaal 150 minuten per week, verspreid over tenminste 3 dagen)*. High impact of grote krachtsinspanningen vermijden. |

*Bij gebrek aan bewijs van nadelige effecten van deze lichamelijke activiteit op het risico op vroeggeboorte en gezien de aanwijzingen voor een gunstig effect van lichamelijke activiteit voor het beloop van de zwangerschap.

In februari 2022 is er nog een systematic review gepubliceerd in de Jama door Teede (2022) wat noemenswaardig is in het kader van leefstijlinterventies. Dit artikel beschrijft de relatie tussen het effect van antenatale dieet- en beweeg interventies en maternale en neonatale ongunstige uitkomsten. De studies die beweging interventies onderzochten lieten geen effect hiervan op het risico op vroeggeboorte zien (niet voordelig, niet nadelig). Dieet interventies blijken wel een reducerend effect op vroeggeboorte te hebben met een verschil in vroeggeboorte van 6.3% in de controle groep en 3.9% in de interventie groep (2.4 absolute % difference; OR (95%CI) 0.43 (0.22-0.84); I2 47.2%).

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

Zwangere vrouwen met een verhoogd risico op, of angst voor een vroeggeboorte zijn gebaat bij eenduidige informatievoorziening vanuit de zorgverleners. Tevens moet ervoor gewaakt worden dat er niet onnodig té voorzichtig wordt geadviseerd, omdat zij dan ook geen kans hebben op de gunstige effecten van lichamelijke inspanning.

Tot heden ontbreekt uniforme informatievoorziening ten aanzien van lichamelijke activiteit voor zwangere vrouwen met een risico op vroeggeboorte. Tevens zijn er geen landelijke initiatieven die voorzien in informatie over het belang van fysieke inspanning in de zwangerschap in het algemeen. Dit is een hiaat wat binnen de preventieve zorg en met leefstijlinterventies aangepakt dient te worden ten einde de zwangerschapsuitkomsten voor moeder en kind te verbeteren.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

De kosten van het ontwikkelen van eenduidige informatie zijn eenmalig en overzichtelijk. Zij kunnen onderdeel zijn van de patiëntinformatie die bij deze richtlijn worden ontwikkeld.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

Naast de ontwikkeling van eenduidige informatie, moeten ook de zorgverleners die de patiënten spreken goed geïnstrueerd worden over wat de algemeen geldende adviezen zijn. De ene zorgverlener is geneigd om voorzichtiger advies te geven dan de ander. Discussies binnen obstetrische teams, aan de hand van de handreikingen in deze module, kunnen ervaren barrières naar boven brengen en bijdragen aan een meer uniforme werkwijze. Het gebrek aan hoge kwaliteit onderzoek en adviezen kan een drempel zijn. Sommige zorgverleners kunnen er daardoor toe geneigd zijn om restrictief te handelen: het is niet bewezen dat een normale inspanning veilig is. Echter is er wel enig bewijs dat het niet leidt tot meer vroeggeboorte en zelfs potentieel een gunstig effect kan zijn. Daarnaast moeten de gunstige effecten van inspanning in acht worden genomen. Verder onderzoek naar het effect van informatievoorziening aan zwangere vrouwen ten aanzien van lichamelijke inspanning, de daadwerkelijk verrichte activiteiten en zwangerschapsuitkomsten zoals vroeggeboorte, maakt dat er meer informatie komt om voorgesteld beleid te continueren danwel onderbouwd aan te passen.

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

Er is geen reden om in de algemene populatie terughoudend te zijn met het advies ten aanzien van lichaamsbeweging aan zwangeren. Het heeft bewezen gezondheidsvoordelen zoals de reductie van pre-eclampsie en zwangerschapsdiabetes, zonder dat er aanwijzingen zijn op een nadelig effect zoals vroeggeboorte.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

De NVOG richtlijn Preventie recidief spontane vroeggeboorte (2007) beschrijft dat wordt verondersteld dat (extreme) lichamelijke activiteit invloed heeft op (voortijdige) uteruscontractiliteit. Dit werkt een terughoudend advies van lichaamsbeweging in de hand bij een zwangerschap met een verhoogd risico op vroeggeboorte. Daar tegenover staat dat het effect van bedrust ter preventie van vroeggeboorte onbekend is en mogelijk zelfs risico’s heeft zoals trombose en verslechtering van de algemene lichamelijke conditie door immobiliteit en spiermassaverlies. Zwangere vrouwen in het algemeen, en diegene met een gecompliceerde zwangerschap in de anamnese (bijvoorbeeld door vroeggeboorte) zijn zoekende naar de beste adviezen om een volgende zwangerschap door te komen. Uit patiëntinterviews van de Care4Neo, komt naar voren dat zij weinig concrete ofwel tegenstrijdige adviezen krijgen op het gebied van bijvoorbeeld lichaamsbeweging en zwangerschap. De behoefte hieraan is groot, wat de aanleiding was om deze module in de richtlijn op te nemen.

Een levensstijl waar regelmatig lichaamsbeweging een vast onderdeel is, leidt in het algemeen tot gunstige fysieke en geestelijke gezondheidseffecten, zo ook in de zwangerschap voor moeder en foetus. Het positieve effect van fysieke inspanning in de zwangerschap is uitgebreid beschreven in de Canadese richtlijn voor lichamelijke activiteit in de zwangerschap (Mottola, 2018). Tenminste 150 minuten bewegen in de week, bij voorkeur gespreid over 3 of meer dagen, leidt tot een reductie in zwangerschapsdiabetes (38%; 39 minder per 1000 (range 25minder -50minder)), pre-eclampsie (41%; 12 minder per 1000 (range 2 minder - 19 minder)), prenatale depressie (67%; 134 minder per 1000 (range 90 minder - 163 minder)), en macrosomie (39%; 30 minder per 1000 (range 6 minder -47 minder). Deze activiteit was niet geassocieerd met een verhoogd risico op vroeggeboorte, laag geboortegewicht, miskraam, perinatale sterfte.

Voor deze Nederlandse richtlijn hebben we de relatie tussen fysieke lichamelijke inspanning en het risico op vroeggeboorte verder uitgewerkt.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

|

Low GRADE |

A prenatal exercise program may result in little to no difference in preterm birth <37 weeks.

Sources: Barakat, 2018; Da Silva, 2017; Davenport, 2018; Wang, 2017 |

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of following a prenatal exercise program on preterm birth <34 weeks.

Sources: Wang, 2017 |

|

- GRADE |

No data was available on the outcome measures preterm birth <28 weeks; respiratory distress syndrome; intraventricular hemorrhage; necrotizing enterocolitis; neonatal sepsis; neonatal death; perinatal death; composite outcome of neonatal morbidity and mortality. |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

Davenport (2018) performed a systematic review and meta-analysis to evaluate the effect of prenatal exercise on neonatal and childhood health outcomes. A literature search was conducted up to 6 January 2017. Exercise (subtype of physical activity but used interchangeably by Davenport) was defined as any bodily movement generated by the skeletal muscles that resulted in energy expenditure above the resting levels. The population of interest was pregnant women without absolute or relative contraindication to exercise (according to the SOGC/CSEP and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists guidelines). Outcomes assigned as critical by Davenport were: preterm birth, low birth weight (<2500g), high birth weight (>4000g), small for gestational age (SGA), large for gestational age (LGA), intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR), neonatal hypoglycaemia and childhood obesity. Preterm birth was not further defined by Davenport. If fewer than 2000 women were included in the meta-analysis of RCTs for a given outcome, the impact of prenatal exercise on the specific outcome was explored further using evidence from observational studies. Studies were only included in the meta-analyses if the study did include a non-exercising control group.

A total of 135 studies were included in the review. Two main types of intervention were identified by Davenport: 1) exercise only studies (61 RCTs and 3 non-randomised interventions); 2) exercise plus co-intervention (diet, insulin, education about healthy pregnancy and behaviour change, and relaxation techniques). Based on our clinical question, we were only interested in the exercise only studies. Davenport included 28 RCTs with exercise-only interventions regarding the outcome measure preterm birth (n=5,354 women) (one study reported narratively): 21 studies involved supervised exercise, others involved unsupervised exercise. Twelve studies consisted of aerobic exercise interventions, 11 interventions with various types of exercise, 1 pelvic floor muscle training (PFMT) intervention and 3 including resistance training. The frequency of the interventions ranged from 1-7 days per week, the intensity from low to vigorous (up to 85% HR max) and the duration ranged from 15-60 minutes per session. Fifteen of the 28 studies included women who were previously sedentary, others included women with unspecified activity levels. In addition, six studies only included women who were overweight or obese prior to pregnancy, three studies only included women with gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM).

Barakat (2018) conducted a RCT between March 2014 and January 2017 in two primary care medical centres in Madrid (Spain), to examine the influence of a supervised moderate exercise program throughout pregnancy in healthy pregnant women. Inclusion criteria were a singleton uncomplicated pregnancy (no type 1, 2 or gestational diabetes at baseline) and no history or risk of preterm delivery. Exclusion criteria were having any serious medical conditions (contraindications) that prevented women from exercising safely (ACOG recommendations). Women in the intervention group (n=255) followed an exercise program three days per week (55–60 min per session) from the 9–11th week to the end of the third trimester (weeks 38–39). A total of 83–85 group training sessions was originally planned for each participant in the event of no preterm delivery. The program included the following seven sections: 1) gradual warm-up; 2) aerobic resistance; 3) light muscle strengthening; 4) coordination and balance exercises; 5) stretching exercises; 6) pelvic floor strengthening; 7) relaxation and final talk. Women in the control group (n=253) received standard prenatal care were not discouraged from exercising during pregnancy on their own. They received general nutrition and physical activity counselling from the health-care provider. Women in the control group who exercised since the beginning of their pregnancy three times per week or more, with a total duration of 20 minutes or more each day, were excluded from the study. Eleven percent of the women in the intervention group and 20.2% in the control group were lost to follow-up. The primary outcome studied was the length of the stages of labour. Secondary outcomes included preterm delivery (<37 weeks).

Da Silva (2017) performed an RCT, nested into the 2015 Pelotas (Brazil) Birth Cohort Study, to evaluate the efficacy of a supervised prenatal exercise-based intervention to prevent maternal and newborn negative health outcomes. Included were pregnant women (<20 weeks of gestation) of 18 years or older whose pregnancy exercise levels did not include self-reported participation in an exercise program. Exclusion criteria were self-reported hypertension, cardiovascular disease, or diabetes diagnosed before pregnancy; history of miscarriage or preterm birth; in vitro fertilization in the current pregnancy; twin pregnancy confirmed by ultrasound; persistent bleeding in the current pregnancy; body mass index (BMI) > 35 kg/m2; or heavy smoking (> 20 cigarettes a day). Women in the intervention group (n=213) received a supervised moderate intensity exercise program for 1 hour, 3 days per week for 16 weeks from 16-20 to 32-36 weeks’ gestation. A training session consisted of a warm-up period, aerobic exercise, strength training/floor exercise, and stretching. Women in the control group (n=426) received standard antenatal care and encouragement to continue normal daily activities. The mean attendance to the intervention program was 27 sessions (± 17.2) (out of a potential 48). The main outcomes of this study were preterm birth <27 weeks and pre-eclampsia.

Wang (2017) performed a RCT to test the efficacy of a program of regular moderate-intensity exercise in early pregnancy in Chinese overweight/obese pregnant women (Peking University First Hospital from December 2014 through July 2016). Included were nonsmoking women with a singleton pregnancy (<12+6 weeks’ gestation ) and a pre-pregnancy BMI of ≥24 kg/m2. Exclusion criteria were <18 years of age; cervical insufficiency; the use of medication for preexisting hypertension, diabetes, cardiac disease, renal disease, systemic lupus erythematosus, thyroid disease, or psychosis; treated with metformin or corticosteroid; or a cervical length <25 mm at any time during the study. Women in the intervention group (n=150) followed a supervised cycling program with at least 3 sessions per week initiated within 3 days of randomization and continued to the end of the third trimester (weeks 36-37). Women in the control group (n=150) continued with their usual daily activities and were not discouraged from participating in exercise sessions on their own. All women received standard prenatal care and all women received general advice about the positive effects of physical activity during pregnancy, no special dietary recommendations were given. A total of 38 (25.3%) and 36 (24%) participants did not complete the follow-up in the exercise group and the control group, respectively, and the main reason was their unwillingness to participate further. The primary outcome of the study was the incidence of GDM, a secondary outcome was preterm birth (<37 and <34 weeks).

Results

Outcome measure 1: preterm birth <37 weeks

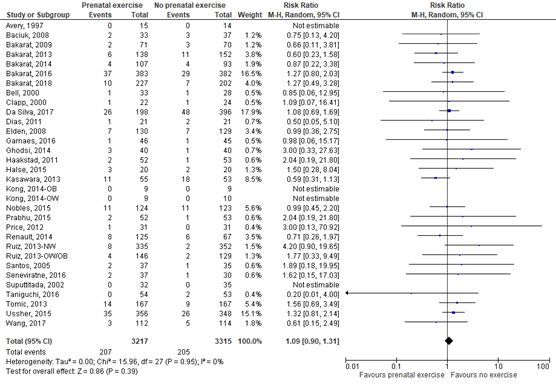

Twenty-seven RCTs included in the meta-analysis of Davenport (2018) compared a prenatal exercise intervention with no prenatal exercise intervention on the outcome measure preterm birth. Preterm birth was not further defined by Davenport, however, it was assumed by the guideline working group that it could be defined as preterm birth <37 weeks. In addition, the recent RCTs of Barakat (2018), Da Silva (2017), and Wang (2017) reported on the outcome measure preterm birth <37 weeks as well. Preterm birth <37 weeks was reported for 207 of 3217 (6.4%) infants of mothers receiving a prenatal exercise intervention compared to 205 of 3315 (6.2%) infants of mothers receiving no prenatal exercise intervention (RR 1.09 (95% CI 0.90 to 1.31)) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Preterm birth, comparison prenatal exercise intervention versus no prenatal exercise intervention

Outcome measure 2: preterm birth <34 weeks

One RCT (Wang, 2017) reported on the outcome measure preterm birth <34 weeks. Preterm birth <34 weeks was reported for 0 of 112 (0%) infants of mothers receiving a prenatal exercise intervention compared to 1 of 114 (0.9%) infants of mothers receiving no prenatal exercise intervention (RR 0.34 (95% CI 0.01 to 8.24).

Outcome measure 3: preterm birth <28 weeks

None of the included studies reported on the outcome measure preterm birth <28 weeks.

Outcome measure 4: respiratory distress syndrome

None of the included studies reported on the outcome measure respiratory distress syndrome.

Outcome measure 5: intraventricular hemorrhage

None of the included studies reported on the outcome measure intraventricular hemorrhage.

Outcome measure 6: necrotizing enterocolitis

None of the included studies reported on the outcome measure necrotizing enterocolitis.

Outcome measure 7: neonatal sepsis

None of the included studies reported on the outcome measure neonatal sepsis.

Outcome measure 8: neonatal death

None of the included studies reported on the outcome measure neonatal death.

Outcome measure 9: perinatal death

None of the included studies reported on the outcome measure perinatal death.

Outcome measure 10: composite outcome of neonatal morbidity and mortality

None of the included studies reported on the composite outcome neonatal morbidity and mortality.

Level of evidence of the literature

Studies for intervention questions with a randomized controlled design start at a high GRADE. The following eight outcome measures were not reported: preterm birth <28 weeks; respiratory distress syndrome; intraventricular hemorrhage; necrotizing enterocolitis; neonatal sepsis; neonatal death; perinatal death, and a composite outcome of neonatal morbidity and mortality.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure preterm birth <37 weeks was downgraded by two levels to a low GRADE because of risk of bias (performance bias, no intention to treat) (-1), and imprecision (-1) (the 95% confidence interval of the pooled effect includes no effect as well as a clinically relevant effect in favour for the control group).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure preterm birth <34 weeks was downgraded by three levels to a very low GRADE because of imprecision (-2) (only one RCT and number of events was low: 0/112 in the intervention group and 1/114 in the control group. The 95% confidence interval of the effect included both the upper and lower limits of clinical relevance) and risk of bias (-1) (a quarter of the participants withdrew from the study and were excluded from the analysis).

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question:

What are the (un)favourable effects of physical exercise interventions during pregnancy in the prevention of spontaneous preterm birth in singleton pregnancies?

| P: patients | women with a singleton pregnancy |

| I: intervention | life style intervention during pregnancy existing of physical exercise of moderate intensity |

| C: control | no physical exercise intervention during pregnancy |

| O: outcome measure | preterm birth <37 weeks, preterm birth <34 weeks, preterm birth <28 weeks, respiratory distress syndrome, intraventricular hemorrhage, necrotizing enterocolitis, neonatal sepsis, neonatal death, perinatal death, composite outcome of neonatal morbidity and mortality |

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered preterm birth <37 weeks, preterm birth <34

weeks, and preterm birth <28 weeks as critical outcome measures for decision making;

and respiratory distress syndrome, intraventricular hemorrhage, necrotizing enterocolitis,

neonatal sepsis, neonatal death, perinatal death, a composite outcome of neonatal

morbidity and mortality as important outcome measures for decision making.

A priori, the working group did define the crucial outcome measures preterm birth: i.e., preterm <37 weeks, preterm birth <34 weeks, and preterm birth <28 weeks. The important outcome measures were not defined a priori, but the definitions applied in the studies were used.

The working group defined a relative risk ≤0.9 or ≥1.1 as a minimal clinically important difference for preterm birth and ≤0.8 or ≥1.25 as a minimal clinically important difference for all other outcome measures.

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms from 2010 to June 2020. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 460 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria: 1) the study compared a physical exercise intervention in pregnant women versus no physical exercise intervention; 2) the study design comprised a RCT or a meta-analysis of RCTs; and 3) at least the outcome measure preterm birth was reported. Nineteen studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, 15 studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and four studies were included.

Results

Four studies (Davenport, 2018; Da Silva, 2017; Wang, 2017; Bakarat, 2018) were included in the analysis of the literature. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- Aune D, Schlesinger S, Henriksen T, Saugstad OD, Tonstad S. Physical activity and the risk of preterm birth: a systematic review and meta-analysis of epidemiological studies. BJOG. 2017 Nov;124(12):1816-1826. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.14672. Epub 2017 May 30. PMID: 28374930.

- Barakat R, Franco E, Perales M, López C, Mottola MF. Exercise during pregnancy is associated with a shorter duration of labor. A randomized clinical trial. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2018 May;224:33-40. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2018.03.009. Epub 2018 Mar 6. PMID: 29529475.

- da Silva SG, Hallal PC, Domingues MR, Bertoldi AD, Silveira MFD, Bassani D, da Silva ICM, da Silva BGC, Coll CVN, Evenson K. A randomized controlled trial of exercise during pregnancy on maternal and neonatal outcomes: results from the PAMELA study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2017 Dec 22;14(1):175. doi: 10.1186/s12966-017-0632-6. PMID: 29273044; PMCID: PMC5741924.

- Davenport MH, Meah VL, Ruchat SM, Davies GA, Skow RJ, Barrowman N, Adamo KB, Poitras VJ, Gray CE, Jaramillo Garcia A, Sobierajski F, Riske L, James M, Kathol AJ, Nuspl M, Marchand AA, Nagpal TS, Slater LG, Weeks A, Barakat R, Mottola MF. Impact of prenatal exercise on neonatal and childhood outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2018 Nov;52(21):1386-1396. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2018-099836. PMID: 30337465.

- Grobman WA, Gilbert SA, Iams JD, Spong CY, Saade G, Mercer BM, Tita ATN, Rouse DJ, Sorokin Y, Leveno KJ, Tolosa JE, Thorp JM, Caritis SN, Peter Van Dorsten J; Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units (MFMU) Network*. Activity restriction among women with a short cervix. Obstet Gynecol. 2013 Jun;121(6):1181-1186. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182917529. PMID: 23812450; PMCID: PMC4019312.

- Mottola MF, Davenport MH, Ruchat SM, Davies GA, Poitras VJ, Gray CE, Jaramillo Garcia A, Barrowman N, Adamo KB, Duggan M, Barakat R, Chilibeck P, Fleming K, Forte M, Korolnek J, Nagpal T, Slater LG, Stirling D, Zehr L. 2019 Canadian guideline for physical activity throughout pregnancy. Br J Sports Med. 2018 Nov;52(21):1339-1346. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2018-100056. PMID: 30337460.

- Saccone G, Maruotti GM, Giudicepietro A, Martinelli P; Italian Preterm Birth Prevention (IPP) Working Group. Effect of Cervical Pessary on Spontaneous Preterm Birth in Women With Singleton Pregnancies and Short Cervical Length: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2017 Dec 19;318(23):2317-2324. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.18956. Erratum in: JAMA. 2018 May 1;319(17 ):1824. PMID: 29260226; PMCID: PMC5820698.

- Teede HJ, Bailey C, Moran LJ, Bahri Khomami M, Enticott J, Ranasinha S, Rogozinska E, Skouteris H, Boyle JA, Thangaratinam S, Harrison CL. Association of Antenatal Diet and Physical Activity-Based Interventions With Gestational Weight Gain and Pregnancy Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2022 Feb 1;182(2):106-114. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2021.6373. Erratum in: JAMA Intern Med. 2022 Oct 1;182(10):1108. PMID: 34928300; PMCID: PMC8689430.

- Wang C, Wei Y, Zhang X, Zhang Y, Xu Q, Sun Y, Su S, Zhang L, Liu C, Feng Y, Shou C, Guelfi KJ, Newnham JP, Yang H. A randomized clinical trial of exercise during pregnancy to prevent gestational diabetes mellitus and improve pregnancy outcome in overweight and obese pregnant women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Apr;216(4):340-351. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2017.01.037. Epub 2017 Feb 1. PMID: 28161306.

- Zemet R, Schiff E, Manovitch Z, Cahan T, Yoeli-Ullman R, Brandt B, Hendler I, Dorfman-Margolis L, Yinon Y, Sivan E, Mazaki-Tovi S. Quantitative assessment of physical activity in pregnant women with sonographic short cervix and the risk for preterm delivery: A prospective pilot study. PLoS One. 2018 Jun 11;13(6):e0198949. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0198949. PMID: 29889906; PMCID: PMC5995449.

Evidence tabellen

Evidence table meta-analysis

Evidence tables RCTs

Risk of bias tables

Table of quality assessment for systematic reviews of RCTs and observational studiesd

|

Study

First author, year |

Appropriate and clearly focused question?1

Yes/no/unclear |

Comprehensive and systematic literature search?2

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of included and excluded studies?3

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of relevant characteristics of included studies?4

Yes/no/unclear |

Appropriate adjustment for potential confounders in observational studies?5

Yes/no/unclear/notapplicable |

Assessment of scientific quality of included studies?6

Yes/no/unclear |

Enough similarities between studies to make combining them reasonable?7

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential risk of publication bias taken into account?8

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential conflicts of interest reported?9

Yes/no/unclear |

|

Davenport, 2018 |

Yes |

Yes

Search strategies in Medline and Embase (amongst other databases) are depicted in the online supplementary material (page 177). |

Yes

References excluded with reasons are found in the online supplementary material (page 204). |

No

Characteristics of individual studies were described, however, potential confounders were not mentioned. |

Not applicable

For the outcome measure preterm birth, only RCTs were included. |

Unclear

The Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) framework was used to assess the quality of evidence across studies (online supplementary tables 2–17).

However, the quality of evidence was only presented per outcome measure. The quality of individual studies (risk of bias) was not presented. |

Yes

To answer our clinical question, we were only interested in the exercise-only studies. This was a more homogenous subgroup compared to the main analysis of Davenport in which exercise-only studies were pooled together with exercise+co-intervention studies.

I2 was reported. |

Unclear

In the methods section it was stated: publication bias was assessed if possible (ie, at least 10 studies were included in the forest plot) via funnel plots (see online supplementary materials). If there were fewer than 10 studies, publication bias was deemed non-estimable and not rated down.

However, for the outcome measure preterm birth no funnel plot was found in the online supplementary material. |

No

Source of funding was only reported for the systematic review itself but not for each of the included studies. |

Derived from the supplementary material from Davenport 2018:

Davenport MH, Meah VL, Ruchat SM, Davies GA, Skow RJ, Barrowman N, Adamo KB, Poitras VJ, Gray CE, Jaramillo Garcia A, Sobierajski F, Riske L, James M, Kathol AJ, Nuspl M, Marchand AA, Nagpal TS, Slater LG, Weeks A, Barakat R, Mottola MF. Impact of prenatal exercise on neonatal and childhood outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2018 Nov;52(21):1386-1396. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2018-099836. PMID: 30337465.

Online Supplement Table 8: The association between prenatal exercise and preterm birth.

|

Quality assessment |

№ of participants |

Effect |

Quality |

Importance |

||||||||||||

|

№ of studies |

Study design |

Risk of bias |

Inconsistency |

Indirectness |

Imprecision |

Other considerations |

prenatal exercise |

no exercise |

Relative |

Absolute |

||||||

|

Association between prenatal exercise (exercise-only interventions and exercise + co-interventions) and preterm birth. |

||||||||||||||||

|

41 (pooled estimate of effect; n=40a,b, 1 study reported narratively) |

randomized trials |

serious c |

not serious |

serious e |

serious f |

none |

324/5231 (6.2%) |

319/5001 (6.4%) |

OR 1.00 |

0 fewer per 1,000 |

⨁◯◯◯ |

CRITICAL |

||||

|

Narrative summary: One study was included (Intervention, n= 34; Control, n=37) and found no association between prenatal exercise and preterm birth (Cavalcante et al. 2009). Additional data from one study included in the pooled analysis. Miquuelutti et al. (2013) found no association between prenatal exercise and preterm birth. d |

||||||||||||||||

|

Sensitivity analysis: Association between exercise-only interventions and preterm birth. |

||||||||||||||||

|

28 (pooled estimate of effect; n=27g,h, 1 study reported narratively) |

randomized trials |

serious c |

not serious |

not serious |

serious f |

none |

168/2680 (6.3%) |

145/2603 (5.6%) |

OR 1.12 |

6 more per 1,000 |

⨁⨁◯◯ |

CRITICAL |

||||

|

Narrative summary: One study was included (Intervention, n= 34; Control, n=37) and found no association between prenatal exercise and preterm birth (Cavalcante et al. 2009). |

||||||||||||||||

|

Sensitivity analysis: Association between exercise+co-interventions and preterm birth. |

||||||||||||||||

|

14 h,j |

randomized trials |

serious i |

not serious |

serious e |

serious f |

none |

156/2551 (6.1%) |

174/2398 (7.3%) |

OR 0.88 |

8 fewer per 1,000 |

⨁◯◯◯ |

CRITICAL |

||||

|

Additional data from one study included in the pooled analysis. Miquuelutti et al. (2013) found no association between prenatal exercise and preterm birth. d |

||||||||||||||||

Explanations

a. Four studies reported no cases of preterm birth (not estimable result) and are not included in the pooled analysis.

b. Six studies reported data on different sub-groups of women. These studies were counted only once.

c. Serious risk of bias. High risk of performance bias (women who did not complete the majority of the intervention [>75%] were excluded). Reporting bias was an issue in one study; results were reported narratively. One study included "other risk" of bias (included women who smoked during pregnancy that may have affected preterm birth).

d. One study reported data that was included in the meta-analysis and additional data reported narratively. This study was counted only once.

e. Serious indirectness. Exercise-only interventions and exercise+co-interventions were combined for analysis.

f. Serious imprecision. The 95% CI crosses the line of no effect, and is wide, such that interpretation of the data would be different if the true effect were at one end of the CI or the other.

g. Four studies reported no cases of preterm birth (not estimable result) and are not included in the pooled analysis.

h. Two studies reported data on different sub-groups of women. These studies were counted only once.

i. Serious risk of bias. High performance risk of bias.

j. One study reported no cases of preterm birth (not estimable result) and is not included in the pooled analysis.

Risk of bias tables RCTs

|

Study reference

(first author, publication year) |

Describe method of randomisation1 |

Bias due to inadequate concealment of allocation?2

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate blinding of participants to treatment allocation?3

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate blinding of care providers to treatment allocation?3

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate blinding of outcome assessors to treatment allocation?3

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to selective outcome reporting on basis of the results?4

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to loss to follow-up?5

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to violation of intention to treat analysis?6

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

|

Barakat, 2018 |

A computer-generated list of random numbers was used to allocate the participants into the study groups. The randomization blinded process (sequence generation, allocation concealment and implementation) was performed by three different authors. The treatment allocation system was set up so that the researcher who was in charge of randomly assigning participants to each group did not know in advance which treatment the next person would receive, a process termed “allocation concealment”. |

Unlikely

A computer-generated list of random numbers was used to allocate the participants into the study groups. The randomization blinded process (sequence generation, allocation concealment and implementation) was performed by three different authors. |

Unlikely

Participants were aware of the allocations.

However, it is not likely that this results in risk of bias for the outcome measure of interest (i.e., preterm birth).

|

Unclear |

Unclear

The assessors were not mentioned. |

Unlikely

Outcome measures listed in the Methods section are reported in the Results section.

|

Likely

11% in the intervention group and 20.2% in the control group were lost to follow-up.

|

Unlikely

Outcomes of interest analyzed in the study are presented in Table 3 (per protocol) and Table 4 (intention to treat). |

|

Da Silva, 2017 |

Participants were then assigned to either an exercise or control group using a computerized random-number generator. The randomization process occurred in blocks of nine pregnant women. Each block resulted in the allocation of three women for the intervention and six women for the control group, ensuring a recruitment balance of 1:2 throughout the study. We used 2 controls to 1 case in order to increase precision and statistical power of detecting a statistically significant difference if such a difference exists |

Unlikely

A computerized random-number generator was used. |

Unlikely

The nature of this trial meant that participants and staff were not masked to the type of intervention.

However, it is not likely that this results in risk of bias for the outcome measure of interest (i.e., preterm birth).

|

Unclear

The principal researcher was not involved in the exercise training and analyses were performed blinded for group allocation. Also, the staff involved with exercise intervention or outcome assessments had no influence on the randomization procedure.

|

Unlikely

The assessors of the primary study outcomes were blinded. |

Unlikely

Outcome measures listed in the Methods section are reported in the Results section.

Primary outcomes in the study protocol and published report are the same. |

Unlikely

Loss to follow-up was in both groups 7% with the reasons not captured in the perinatal study or invalid last menstrual period. |

Unlikely

Statistical analyses were conducted primarily on intention-to-treat (ITT) basis and per protocol analyses were also performed including only those adhering to the protocol (at least 34/48 (70%) sessions attended). |

|

Wang, 2017 |

Eligible women were randomly allocated (ratio 1:1) into either an exercise intervention group or a control group following an allocation concealment process using an automatic computer-generated random number table. The 3 parts of the randomization process, that is, sequence generation, allocation concealment, and implementation, were conducted by 3 different individuals. Due to the nature of the intervention, all participants and research staff were aware of the allocations. |

Unlikely

An allocation concealment process using an automatic computer-generated random number table was followed.

Sequence generation, allocation concealment, and implementation, were conducted by 3 different individuals |

Unlikely

Due to the nature of the intervention, all participants and research staff were aware of the allocations.

However, it is not likely that this results in risk of bias for the outcome measure of interest (i.e., preterm birth).

|

Unclear |

Unclear

The assessors were not mentioned but research staff was aware of the allocations. |

Unlikely

Outcome measures listed in the Methods section are reported in the Results section. |

Unclear

A quarter of the participants withdrew from the study which is a substantial amount.

and 36 (24%) participants did not complete the follow-up in the exercise group and the control group, respectively, and the main reason was their unwillingness to participate further.

|

Unlikely

Analysis was by intention to treat. |

- Randomisation: generation of allocation sequences have to be unpredictable, for example computer generated random-numbers or drawing lots or envelopes. Examples of inadequate procedures are generation of allocation sequences by alternation, according to case record number, date of birth or date of admission.

- Allocation concealment: refers to the protection (blinding) of the randomisation process. Concealment of allocation sequences is adequate if patients and enrolling investigators cannot foresee assignment, for example central randomisation (performed at a site remote from trial location) or sequentially numbered, sealed, opaque envelopes. Inadequate procedures are all procedures based on inadequate randomisation procedures or open allocation schedules.

- Blinding: neither the patient nor the care provider (attending physician) knows which patient is getting the special treatment. Blinding is sometimes impossible, for example when comparing surgical with non-surgical treatments. The outcome assessor records the study results. Blinding of those assessing outcomes prevents that the knowledge of patient assignement influences the proces of outcome assessment (detection or information bias). If a study has hard (objective) outcome measures, like death, blinding of outcome assessment is not necessary. If a study has “soft” (subjective) outcome measures, like the assessment of an X-ray, blinding of outcome assessment is necessary.

- Results of all predefined outcome measures should be reported; if the protocol is available, then outcomes in the protocol and published report can be compared; if not, then outcomes listed in the methods section of an article can be compared with those whose results are reported.

- If the percentage of patients lost to follow-up is large, or differs between treatment groups, or the reasons for loss to follow-up differ between treatment groups, bias is likely. If the number of patients lost to follow-up, or the reasons why, are not reported, the risk of bias is unclear

- Participants included in the analysis are exactly those who were randomized into the trial. If the numbers randomized into each intervention group are not clearly reported, the risk of bias is unclear; an ITT analysis implies that (a) participants are kept in the intervention groups to which they were randomized, regardless of the intervention they actually received, (b) outcome data are measured on all participants, and (c) all randomized participants are included in the analysis.

Table of excluded studies

|

Author and year |

Reason for exclusion |

|

Aune 2017 |

Older meta-analysis than Davenport 2018, inclusion of mostly observational studies |

|

Di Mascio 2016 |

Older meta-analysis than Davenport 2018 and wrong population (only women with a normal body mass index) |

|

Kahn 2016 |

Older systematic review than Davenport 2018 |

|

Magro-Malosso 2017a |

Wrong outcome measure (meta-analysis on gestational hypertensive disorders) |

|

Magro-Malosso 2017b |

Wrong intervention and population (aerobic exercise and dietary counseling combined; overweight and obese women specifically) |

|

Matei 2019 |

Wrong study design (review of systematic reviews on primary and secondary prevention of preterm birth) |

|

Meah 2020 |

Wrong subject (systematic review to evaluate the evidence related to medical disorders which may warrant contraindication to prenatal exercise) |

|

Muktabhant 2015 |

Older meta-analysis than Davenport 2018 |

|

Rogozińska 2017 |

Wrong intervention (meta-analysis on antenatal diet and physical activity combined) |

|

Rong 2020 |

Wrong intervention (meta-analysis on a specific type of prenatal exercise: prenatal yoga) |

|

Satterfield 2016 |

Wrong study design (no systematic review) |

|

Shepherd 2017 |

Wrong intervention (cochrane review on combined diet and exercise intervention for preventing gestational diabetes mellitus) |

|

Sosa 2015 |

Wrong intervention (cochrane review on bed rest) |

|

Thangaratinam 2012 |

Older meta-analysis than Davenport 2018 |

|

Wen 2017 |

Older meta-analysis than Davenport 2018, inclusion of mostly observational studies |

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Publicatiedatum : 10-02-2025

Beoordeeld op geldigheid : 20-11-2024

Algemene gegevens

De ontwikkeling van deze richtlijnmodule werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten (www.demedischspecialist.nl/kennisinstituut) en werd gefinancierd uit de Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS). De financier heeft geen enkele invloed gehad op de inhoud van de richtlijnmodule.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijnmodule is in 2019 een multidisciplinaire werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen (zie hiervoor de Samenstelling van de werkgroep) die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor zwangere vrouwen zonder klinische verschijnselen van een vroeggeboorte, die al dan niet in een eerdere zwangerschap een spontane vroeggeboorte hebben doorgemaakt.

Werkgroep

- Prof. dr. M.A. Oudijk, gynaecoloog, NVOG (voorzitter)

- Dr. N. Horree, gynaecoloog, NVOG

- Dr. J.B. Derks, gynaecoloog, NVOG

- Dr. T.A.J. Nijman, gynaecoloog, NVOG

- Dr. F. Vlemmix, gynaecoloog, NVOG

- Dr. D.A.A. van der Woude, gynaecoloog, NVOG

- L.T. Brammerloo-Read, MSc, verloskundige, KNOV

- Dr. M.A.C. Hemels, kinderarts-neonatoloog, NVK

- F.A.B.A. Schuerman, MSc, kinderarts-neonatoloog, NVK

- J.D.M. Wagemaker, patiëntenvereniging, Care4Neo

Met ondersteuning van:

- Dr. L. Viester, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van Medisch Specialisten (tot augustus 2022)

- T. Geltink, MSc, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van Medisch Specialisten (vanaf augustus 2022)

Belangenverklaringen

De Code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling is gevolgd. Alle werkgroepleden hebben schriftelijk verklaard of zij in de laatste drie jaar directe financiële belangen (betrekking bij een commercieel bedrijf, persoonlijke financiële belangen, onderzoeksfinanciering) of indirecte belangen (persoonlijke relaties, reputatiemanagement) hebben gehad. Gedurende de ontwikkeling of herziening van een module worden wijzigingen in belangen aan de voorzitter doorgegeven. De belangenverklaring wordt opnieuw bevestigd tijdens de commentaarfase.

Een overzicht van de belangen van werkgroepleden en het oordeel over het omgaan met eventuele belangen vindt u in onderstaande tabel. De ondertekende belangenverklaringen zijn op te vragen bij het secretariaat van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

|

Werkgroeplid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

Prof. dr. M.A. Oudijk |

Gynaecoloog |

Voorzitter Pijler FMG van de NVOG, onbetaald, alleen vacatiegelden. Voorzitter wetenschapscommissie pijler FMG, onbetaald. Member of the board of the foundation 'Stoptevroegbevallen'; a non-profit foundation with the purpose to raise funds for research projects on preterm labour/birth, onbetaald. Member of the scientific committee of the 'Fonds Gezond Geboren', a non-profit foundation with the purpose to raise funds for reserarch projects on preterm birth and placental insufficiency, onbetaald. Member of the advisory board of the N3, the Dutch Neonatology research network, onbetaald. President of the European Spontaneous Preterm Birth Congress to be held in Haarlem, The Netherlands, www. espbc.eu, onbetaald |

2015 ZonMW836041012 The effect of tocolysis with nifedipine or atosiban on infant development: the APOSTEL III follow-up study. € 43,772. 2015 ZonMW 836041006 Low dose aspirin in the prevention of recurrent spontaneous preterm labour: the APRIL study € 351.898. 2016 Zon|MW 80-84800-98-41027 Atosiban versus placebo in the treatment of late threatened preterm labour: the APOSTEL VIII study € 1.393.639. Hoofdaanvrager/projectleider van deze vroeggeboorte studies. Subsidie wordt alleen aangewend ten behoeve van het onderzoek, promoventi etc. Geen persoonlijke salariëring vanuit deze ZonMw studie |

geen restricties |

|

Dr. N. Horree |

Gynaecoloog |

geen |

Participatie binnen ziekenhuis aan consortium studies vanuit de NVOG. Hieronder vallen ook onderzoek naar vroeggeboorte (o.a. Apnel studies) en preventie vroeggeboorte (April). QP PC - studies |

geen restricties |

|

Dr. J.B. Derks |

Gynaecoloog |

Lid bestuur werkgroep perinatologie en maternale ziektes (onbetaald); Lid otterlo groep (Cie. Ontwikkeling richtlijnen obstetrie) (onbetaald) |

Deelname consortiumstudies waaronder de April studie |

geen restricties |

|

T.A.J. Nijman |

Gynaecoloog |

Lid Commissie Gynaecongres, VAGO-vertegenwoordiger, onbetaald; Lid Koepel Wetenschap. VAGO-vertegenwoordiger, onbetaald |

Project groep April studie, ZonMW gesponsorde Consortium studie naar aspirine vs placebo bij preventie herhaalde vroeggeboorte. |

geen restricties |

|

Dr. F. Vlemmix |

Gynaecoloog |

Lid werkgroep patiëntcommunicatie NVOG |

geen |

geen restricties |

|

Dr. D.A.A. van der Woude |

Gynaecoloog & postdoc |

geen |

geen |

geen restricties |

|

L.T. Brammerloo-Read |

Verloskundige |

geen |

De praktijk + kliniek waarin werkzaam heeft deelname in cervix-meting van patiënten om vroeggeboorte op te kunnen sporen, hierbij geen financieel belang. |

geen restricties |

|

Dr. M.A.C. Hemels |

Kinderarts-neonatoloog |

Faculty cursus antibiotica bij kinderen, betaald |

Deelname APRIL studie, meelezen protocol betreffende de neonatale uitkomst maten |

geen restricties |

|

F.A.B.A. Schuerman |

Kinderarts-neonatoloog |

Bestuurslid stichting kindersedatie Nederland (betaald) |

geen |

geen restricties |

|

J.D.M. Wagemaker |

Patiëntvertegenwoordiger care |

geen |

geen |

geen restricties |

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Er werd aandacht besteed aan het patiëntenperspectief door uitnodigen van Patiëntenfederatie Nederland, Stichting Kind en Ziekenhuis en Vereniging Ouders Couveusekinderen voor de schriftelijke knelpunteninventarisatie en een afgevaardigde patiëntenvereniging in de werkgroep. De verkregen input is meegenomen bij het opstellen van de uitgangsvragen, de keuze voor de uitkomstmaten en bij het opstellen van de overwegingen. De conceptrichtlijn is tevens voor commentaar voorgelegd aan Patiëntenfederatie Nederland, Stichting Kind en Ziekenhuis en Vereniging Ouders Couveusekinderen en de eventueel aangeleverde commentaren zijn bekeken en verwerkt.

Kwalitatieve raming van mogelijke financiële gevolgen in het kader van de Wkkgz

Bij de richtlijn is conform de Wet kwaliteit, klachten en geschillen zorg (Wkkgz) een kwalitatieve raming uitgevoerd of de aanbevelingen mogelijk leiden tot substantiële financiële gevolgen. Bij het uitvoeren van deze beoordeling zijn richtlijnmodules op verschillende domeinen getoetst (zie het stroomschema op de Richtlijnendatabase).

Uit de kwalitatieve raming blijkt dat er waarschijnlijk geen substantiële financiële gevolgen zijn.

Werkwijze

AGREE

Deze richtlijnmodule is opgesteld conform de eisen vermeld in het rapport Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 van de adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwaliteit. Dit rapport is gebaseerd op het AGREE II instrument (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II; Brouwers, 2010).

Knelpuntenanalyse en uitgangsvragen

Tijdens de voorbereidende fase inventariseerde de werkgroep de knelpunten in de zorg voor zwangere vrouwen zonder klinische verschijnselen van een vroeggeboorte, die al dan niet in een eerdere zwangerschap een spontane vroeggeboorte hebben doorgemaakt. Tevens zijn er knelpunten aangedragen door Patiëntenfederatie Nederland, Verpleegkundigen & Verzorgenden Nederland, Nederlandse Vereniging voor Kindergeneeskunde, Nederlandse Vereniging voor Medische Microbiologie, LAREB, Nederlandse Vereniging voor Klinische Fysica, Kind en Ziekenhuis via een schriftelijke knelpunteninventarisatie .

Op basis van de uitkomsten van de knelpuntenanalyse zijn door de werkgroep concept-uitgangsvragen opgesteld en definitief vastgesteld.

Uitkomstmaten

Na het opstellen van de zoekvraag behorende bij de uitgangsvraag inventariseerde de werkgroep welke uitkomstmaten voor de patiënt relevant zijn, waarbij zowel naar gewenste als ongewenste effecten werd gekeken. Hierbij werd een maximum van acht uitkomstmaten gehanteerd. De werkgroep waardeerde deze uitkomstmaten volgens hun relatieve belang bij de besluitvorming rondom aanbevelingen, als cruciaal (kritiek voor de besluitvorming), belangrijk (maar niet cruciaal) en onbelangrijk. Tevens definieerde de werkgroep tenminste voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten welke verschillen zij klinisch (patiënt) relevant vonden.

Methode literatuursamenvatting

Een uitgebreide beschrijving van de strategie voor zoeken en selecteren van literatuur is te vinden onder ‘Zoeken en selecteren’ onder Onderbouwing. Indien mogelijk werd de data uit verschillende studies gepoold in een random-effects model. Review Manager 5.4 werd gebruikt voor de statistische analyses. De beoordeling van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs wordt hieronder toegelicht.

Beoordelen van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs

De kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs werd bepaald volgens de GRADE-methode. GRADE staat voor ‘Grading Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation’ (zie http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/). De basisprincipes van de GRADE-methodiek zijn: het benoemen en prioriteren van de klinisch (patiënt) relevante uitkomstmaten, een systematische review per uitkomstmaat, en een beoordeling van de bewijskracht per uitkomstmaat op basis van de acht GRADE-domeinen (domeinen voor downgraden: risk of bias, inconsistentie, indirectheid, imprecisie, en publicatiebias; domeinen voor upgraden: dosis-effect relatie, groot effect, en residuele plausibele confounding).

GRADE onderscheidt vier gradaties voor de kwaliteit van het wetenschappelijk bewijs: hoog, redelijk, laag en zeer laag. Deze gradaties verwijzen naar de mate van zekerheid die er bestaat over de literatuurconclusie, in het bijzonder de mate van zekerheid dat de literatuurconclusie de aanbeveling adequaat ondersteunt (Schünemann, 2013; Hultcrantz, 2017).

|

GRADE |

Definitie |

|

Hoog |

|

|

Redelijk |

|

|

Laag |

|

|

Zeer laag |

|

Bij het beoordelen (graderen) van de kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs in richtlijnen volgens de GRADE-methodiek spelen grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming een belangrijke rol (Hultcrantz, 2017). Dit zijn de grenzen die bij overschrijding aanleiding zouden geven tot een aanpassing van de aanbeveling. Om de grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming te bepalen moeten alle relevante uitkomstmaten en overwegingen worden meegewogen. De grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming zijn daarmee niet één op één vergelijkbaar met het minimaal klinisch relevant verschil (Minimal Clinically Important Difference, MCID). Met name in situaties waarin een interventie geen belangrijke nadelen heeft en de kosten relatief laag zijn, kan de grens voor klinische besluitvorming met betrekking tot de effectiviteit van de interventie bij een lagere waarde (dichter bij het nuleffect) liggen dan de MCID (Hultcrantz, 2017).

Overwegingen (van bewijs naar aanbeveling)

Om te komen tot een aanbeveling zijn naast (de kwaliteit van) het wetenschappelijke bewijs ook andere aspecten belangrijk en worden meegewogen, zoals aanvullende argumenten uit bijvoorbeeld de biomechanica of fysiologie, waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten, kosten (middelenbeslag), aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie. Deze aspecten zijn systematisch vermeld en beoordeeld (gewogen) onder het kopje ‘Overwegingen’ en kunnen (mede) gebaseerd zijn op expert opinion. Hierbij is gebruik gemaakt van een gestructureerd format gebaseerd op het evidence-to-decision framework van de internationale GRADE Working Group (Alonso-Coello, 2016a; Alonso-Coello 2016b). Dit evidence-to-decision framework is een integraal onderdeel van de GRADE methodiek.

Formuleren van aanbevelingen

De aanbevelingen geven antwoord op de uitgangsvraag en zijn gebaseerd op het beschikbare wetenschappelijke bewijs en de belangrijkste overwegingen, en een weging van de gunstige en ongunstige effecten van de relevante interventies. De kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs en het gewicht dat door de werkgroep wordt toegekend aan de overwegingen, bepalen samen de sterkte van de aanbeveling. Conform de GRADE-methodiek sluit een lage bewijskracht van conclusies in de systematische literatuuranalyse een sterke aanbeveling niet a priori uit, en zijn bij een hoge bewijskracht ook zwakke aanbevelingen mogelijk (Agoritsas, 2017; Neumann, 2016). De sterkte van de aanbeveling wordt altijd bepaald door weging van alle relevante argumenten tezamen. De werkgroep heeft bij elke aanbeveling opgenomen hoe zij tot de richting en sterkte van de aanbeveling zijn gekomen.

In de GRADE-methodiek wordt onderscheid gemaakt tussen sterke en zwakke (of conditionele) aanbevelingen. De sterkte van een aanbeveling verwijst naar de mate van zekerheid dat de voordelen van de interventie opwegen tegen de nadelen (of vice versa), gezien over het hele spectrum van patiënten waarvoor de aanbeveling is bedoeld. De sterkte van een aanbeveling heeft duidelijke implicaties voor patiënten, behandelaars en beleidsmakers (zie onderstaande tabel). Een aanbeveling is geen dictaat, zelfs een sterke aanbeveling gebaseerd op bewijs van hoge kwaliteit (GRADE gradering HOOG) zal niet altijd van toepassing zijn, onder alle mogelijke omstandigheden en voor elke individuele patiënt.

|

Implicaties van sterke en zwakke aanbevelingen voor verschillende richtlijngebruikers |

||

|

|

||

|

|

Sterke aanbeveling |

Zwakke (conditionele) aanbeveling |

|

Voor patiënten |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen en slechts een klein aantal niet. |

Een aanzienlijk deel van de patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen, maar veel patiënten ook niet. |

|

Voor behandelaars |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak moeten ontvangen. |

Er zijn meerdere geschikte interventies of aanpakken. De patiënt moet worden ondersteund bij de keuze voor de interventie of aanpak die het beste aansluit bij zijn of haar waarden en voorkeuren. |

|

Voor beleidsmakers |

De aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kan worden gezien als standaardbeleid. |

Beleidsbepaling vereist uitvoerige discussie met betrokkenheid van veel stakeholders. Er is een grotere kans op lokale beleidsverschillen. |

Organisatie van zorg

In de knelpuntenanalyse en bij de ontwikkeling van de richtlijnmodule is expliciet aandacht geweest voor de organisatie van zorg: alle aspecten die randvoorwaardelijk zijn voor het verlenen van zorg (zoals coördinatie, communicatie, (financiële) middelen, mankracht en infrastructuur). Randvoorwaarden die relevant zijn voor het beantwoorden van deze specifieke uitgangsvraag zijn genoemd bij de overwegingen. Meer algemene, overkoepelende, of bijkomende aspecten van de organisatie van zorg worden behandeld in de module Organisatie van zorg.

Commentaar- en autorisatiefase

De conceptrichtlijnmodule werd aan de betrokken (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd ter commentaar. De commentaren werden verzameld en besproken met de werkgroep. Naar aanleiding van de commentaren werd de conceptrichtlijnmodule aangepast en definitief vastgesteld door de werkgroep. De definitieve richtlijnmodule werd aan de deelnemende (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd voor autorisatie en door hen geautoriseerd dan wel geaccordeerd.

Literatuur

Agoritsas T, Merglen A, Heen AF, Kristiansen A, Neumann I, Brito JP, Brignardello-Petersen R, Alexander PE, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Guyatt GH. UpToDate adherence to GRADE criteria for strong recommendations: an analytical survey. BMJ Open. 2017 Nov 16;7(11):e018593. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018593. PubMed PMID: 29150475; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5701989.

Alonso-Coello P, Schünemann HJ, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Rada G, Rosenbaum S, Morelli A, Guyatt GH, Oxman AD; GRADE Working Group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 1: Introduction. BMJ. 2016 Jun 28;353:i2016. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2016. PubMed PMID: 27353417.

Alonso-Coello P, Oxman AD, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Vandvik PO, Meerpohl J, Guyatt GH, Schünemann HJ; GRADE Working Group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 2: Clinical practice guidelines. BMJ. 2016 Jun 30;353:i2089. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2089. PubMed PMID: 27365494.

Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, Burgers JS, Cluzeau F, Feder G, Fervers B, Graham ID, Grimshaw J, Hanna SE, Littlejohns P, Makarski J, Zitzelsberger L; AGREE Next Steps Consortium. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. CMAJ. 2010 Dec 14;182(18):E839-42. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090449. Epub 2010 Jul 5. Review. PubMed PMID: 20603348; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3001530.

Hultcrantz M, Rind D, Akl EA, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Iorio A, Alper BS, Meerpohl JJ, Murad MH, Ansari MT, Katikireddi SV, Östlund P, Tranæus S, Christensen R, Gartlehner G, Brozek J, Izcovich A, Schünemann H, Guyatt G. The GRADE Working Group clarifies the construct of certainty of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017 Jul;87:4-13. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.05.006. Epub 2017 May 18. PubMed PMID: 28529184; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC6542664.

Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 (2012). Adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwalitieit. http://richtlijnendatabase.nl/over_deze_site/over_richtlijnontwikkeling.html

Neumann I, Santesso N, Akl EA, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Alonso-Coello P, Agoritsas T, Mustafa RA, Alexander PE, Schünemann H, Guyatt GH. A guide for health professionals to interpret and use recommendations in guidelines developed with the GRADE approach. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016 Apr;72:45-55. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.11.017. Epub 2016 Jan 6. Review. PubMed PMID: 26772609.

Schünemann H, Brożek J, Guyatt G, et al. GRADE handbook for grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. Updated October 2013. The GRADE Working Group, 2013. Available from http://gdt.guidelinedevelopment.org/central_prod/_design/client/handbook/handbook.html.

Zoekverantwoording

Literature search strategy

|

What are the (un)favourable effects of physical exercise interventions during pregnancy in the prevention of spontaneous preterm birth in singleton pregnancies? |

|

|

Database(s): Medline, Embase |

Date: 22-6-2020 |

|

Publication date range: 2010-June 2020 |

Languages: English |

|

Database |

Zoektermen |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Embase

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Medline (OVID)

|

1 exp Obstetric Labor, Premature/ or ((labo*r or delivery or parturition or birth or childbirth) adj3 (premature or preterm or 'pre term' or early or prior)).ti,ab,kw. (60853) 2 exp Pregnancy/ or exp Pregnant Women/ or pregnan*.ti,ab,kf. (1009684) 3 exp Exercise/ or exp Sports/ or 'physical* activ*'.ti,ab,kf. or exceris*.ti,ab,kf. or sport*.ti,ab,kf. or training*.ti,ab,kf. or aerobic*.ti,ab,kf. or 'moderate intensity'.ti,ab,kf. or fitness.ti,ab,kf. (857945) 4 1 and 2 and 3 (746) 5 limit 4 to (english language and yr="2010 -Current") (417) 6 (meta-analysis/ or meta-analysis as topic/ or (meta adj analy$).tw. or ((systematic* or literature) adj2 review$1).tw. or (systematic adj overview$1).tw. or exp "Review Literature as Topic"/ or cochrane.ab. or cochrane.jw. or embase.ab. or medline.ab. or (psychlit or psyclit).ab. or (cinahl or cinhal).ab. or cancerlit.ab. or ((selection criteria or data extraction).ab. and "review"/)) not (Comment/ or Editorial/ or Letter/ or (animals/ not humans/)) (451378) 7 (exp clinical trial/ or randomized controlled trial/ or exp clinical trials as topic/ or randomized controlled trials as topic/ or Random Allocation/ or Double-Blind Method/ or Single-Blind Method/ or (clinical trial, phase i or clinical trial, phase ii or clinical trial, phase iii or clinical trial, phase iv or controlled clinical trial or randomized controlled trial or multicenter study or clinical trial).pt. or random*.ti,ab. or (clinic* adj trial*).tw. or ((singl* or doubl* or treb* or tripl*) adj (blind$3 or mask$3)).tw. or Placebos/ or placebo*.tw.) not (animals/ not humans/) (1994808) 8 Epidemiologic studies/ or case control studies/ or exp cohort studies/ or Controlled Before-After Studies/ or Case control.tw. or (cohort adj (study or studies)).tw. or Cohort analy$.tw. or (Follow up adj (study or studies)).tw. or (observational adj (study or studies)).tw. or Longitudinal.tw. or Retrospective*.tw. or prospective*.tw. or consecutive*.tw. or Cross sectional.tw. or Cross-sectional studies/ or historically controlled study/ or interrupted time series analysis/ [Onder exp cohort studies vallen ook longitudinale, prospectieve en retrospectieve studies] (3457253) 9 5 and 6 (43) 10 (5 and 7) not 9 (80) 11 (5 and 8) not (9 or 10) (165) 12 9 or 10 or 11 (288) |