Wondirrigatie

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is het effect van verschillende oplossingen voor profylactische, intra-operatieve, incisionele wondirrigatie op het risico van postoperatieve wondinfecties bij chirurgische patiënten?

Aanbeveling

Onderstaande aanbevelingen hebben betrekking op de wondholte en niet op de preoperatieve huiddesinfectie:

- Gebruik een (steriel) antisepticum opgelost in water (niet in alcohol) voor profylactische, intra-operatieve, incisionele wondirrigatie ter preventie van postoperatieve wondinfecties.*#

* Tenzij er bij specifieke operaties, kans is op weefselschade of als de patiënt bekend is met allergie.

# Voor schone chirurgische interventies kan geen specifieke aanbeveling worden gedaan.

- Gebruik geen antibioticum/antibiotica opgelost in water wegens lagere bewijskracht, risico op resistentie ontwikkeling, en gelijk effect aan antiseptica.

- Gebruik niet enkel een zoutoplossing wegens beperkte effectiviteit.

Houd bij het prioriteren van chirurgische wonden voor wondirrigatie rekening met de a priori kans op POWI.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Bij de nieuwste inzichten voor de GRADE methodologie wordt rekening gehouden met klinische relevantie van een effect, waarbij voor- en nadelen tegen elkaar af worden gewogen. Deze methode verschilt hierin met de GRADE zoals toegepast op de andere modules binnen de richtlijn. Toelichting op de gehanteerde methode is te vinden in GRADE assessment onder het tabblad 'Evidence tabellen'. Uit deze door Groenen et al. gehanteerde methode volgt een hoge bewijskracht voor een klinisch significant effect van wondirrigatie met antiseptica opgelost in water op het verminderen van postoperatieve wondinfecties (POWI) ten opzichte van spoelen met zoutoplossing of niet spoelen.

Voor wondirrigatie met antibiotica opgelost in water is redelijke bewijskracht ten opzichte van spoelen met zoutoplossing en lage bewijskracht ten opzichte van niet spoelen dan de wond voor reductie van POWI. Daarnaast is er redelijk bewijs dat er weinig tot geen verschil is in effect tussen wondirrigatie met zoutoplossing en niet irrigeren. Er is weinig tot geen verschil in effect op POWI tussen wondirrigatie met antiseptica en antibiotica opgelost in water, maar de bewijskracht hiervoor is zeer laag.

Alleen in de subgroep voor niet gecontamineerde chirurgie werden afwijkende resultaten gevonden. Binnen deze subgroep werd alleen voor wondirrigatie met antiseptica opgelost in water ten opzichte van wondirrigatie met zoutoplossing een significant effect gevonden. De bewijskracht van de effecten binnen deze subgroep is echter niet vastgesteld door gebrek aan data.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

Het spoelen van de wond is geen voorkeursgevoelige beslissing. Echter, indien er bekende specifieke (huid)reacties van de patiënt op een bepaald antisepticum zijn, dient hier rekening mee te worden gehouden. Controleer daarom altijd of er bekende huidreacties zijn op een antisepticum.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

Er is geen kosteneffectiviteitsanalyse beschikbaar. Echter is POWI een kostbare complicatie en draagt de reductie hiervan meer bij aan kostenbesparing dan de minimale individuele extra kosten voor een antisepticum opgelost in water.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

De interventie wordt reeds in wisselende mate ingezet, afhankelijk van soort ingreep, centrum en voorkeur operateur. Er zijn geen zorgen over de aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie. De antiseptica die voor wondirrigatie gebruikt kunnen worden moeten in water opgelost zijn. Deze producten zijn als oplossing in water beschikbaar en verkrijgbaar. In de statements on method of wound irrigation is te zien welke verschillende oplossingen er gebruikt zijn in de studies voor bijvoorbeeld povidone-iodine worden concentraties tussen de 0,35 en 10% gehanteerd.

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

Deze netwerk meta-analyse laat een significant voordeel zien van intra-operatieve, incisionele wondirrigatie met zowel een antisepticum als een antibioticum ter preventie van postoperatieve wondinfecties, vergeleken met wondirrigatie met zoutoplossing en geen wondirrigatie.

Wondirrigatie met een antisepticum opgelost in water geniet de voorkeur boven antibioticum opgelost in water om de volgende redenen:

- Het effect van antiseptica kent een hogere bewijskracht;

- Er is weinig tot geen verschil in effect op POWI tussen irrigatie met antibiotica en antiseptica;

- er zijn serieuze zorgen over de bacteriële resistentie tegen antibiotica. Daarentegen zijn er geen tekenen dat bacteriële gevoeligheid voor jodium of chloorhexidine over de tijd afneemt.

In de subgroep voor schone chirurgie werd alleen voor wondirrigatie met antiseptica opgelost in water ten opzichte van wondirrigatie met zoutoplossing een significant effect gevonden. De andere vergelijkingen laten zeer brede betrouwbaarheidsintervallen zien, hoogstwaarschijnlijk als gevolg van het uitdunnen van data (slechts 11/41 geïncludeerde RCTs analyseren schone chirurgie) en daarmee het verlies aan statistische kracht, wat het moeilijk maakt om conclusies op subgroep niveau te trekken. Bovendien is een meta-regressie analyse niet mogelijk met de gebruikte methode (frequentist methode).

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Postoperatieve wondinfecties (POWI’s) zijn verantwoordelijk voor het merendeel van de complicaties na een operatie. Ze zijn geassocieerd met extra morbiditeit, mortaliteit, kosten en een verlengde opnameduur.1,2 Het risico op een POWI kan worden verminderd door gebruik van profylactische intra-operatieve irrigatie van de incisiewond (pIOWI), waarbij vuil, stofwisselingsafval en exsudaat, mogelijk besmet met micro-organismen, voorafgaand aan het sluiten van de wond worden weggespoeld.3 Er is een variëteit aan spoelvloeistoffen en toepassingsmethoden.

Internationale richtlijnen m.b.t. de preventie van POWI’s en eerder gepubliceerde (netwerk) meta-analyses geven tegenstrijdige aanbevelingen met betrekking tot het gebruik van pIOWI. Sinds de publicatie van de internationale richtlijnen zijn er veel RCTs over dit onderwerp gepubliceerd.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

Surgical site infections (SSI)

Antibiotic vs antiseptic

|

Very low GRADE |

Antibiotic solutions may have little to no effect on SSI when compared with antiseptic solutions in surgical patients, but the evidence is very uncertain. |

Antibiotic vs saline

|

Moderate GRADE |

Antibiotic solutions likely reduce SSI when compared with saline in surgical patients. |

Antibiotic vs no irrigation

|

Low GRADE |

Antibiotic solutions may result in a reduction of SSI when compared with no irrigation in surgical patients. |

Antiseptic vs saline

|

High GRADE |

Antiseptic solutions result in a reduction of SSI when compared with saline in surgical patients. |

Antiseptic vs no irrigation

|

High |

Antiseptic solutions result in a reduction of SSI when compared with no irrigation in surgical patients. |

Saline vs no irrigation

|

Moderate GRADE |

Saline solutions likely result in little to no difference in SSI when compared with no irrigation in surgical patients. |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

We included 41 RCTs in our systematic review and 37 RCTs in the network meta-analysis, due to lack of events in all arms in four studies. The study characteristics of the RCTs included in the systematic review are listed in study characteristics. Irrigation solutions were grouped into antiseptic, antibiotic, or saline solutions.

The antibiotics applied in a solution in the different studies were cefazolin, gentamicin, rifampicin, imipenem, clindamycin, ceftriaxone, metronidazole and bacitracin. All but two studies described the antibiotic solutions to be aqueous. All antiseptic solutions studied were aqueous. Most antiseptic solutions were iodine based, with 18 RCTs nvestigating iodine solutions ranging from 0.1% to 10% in concentration. Other antiseptics in the included RCTs were polyhexanide, chlorhexidine, hydrogen peroxide and ESAAS (Electrolyzed Strongly Acidic Aqueous Solution). In the saline irrigation group, all studies described irrigation with saline 0.9%, except for one RCT in which Ringers’ lactate was used. Volume of irrigation and application method varied among all studies and irrigation groups (Statements on method of wound irrigation).

Results

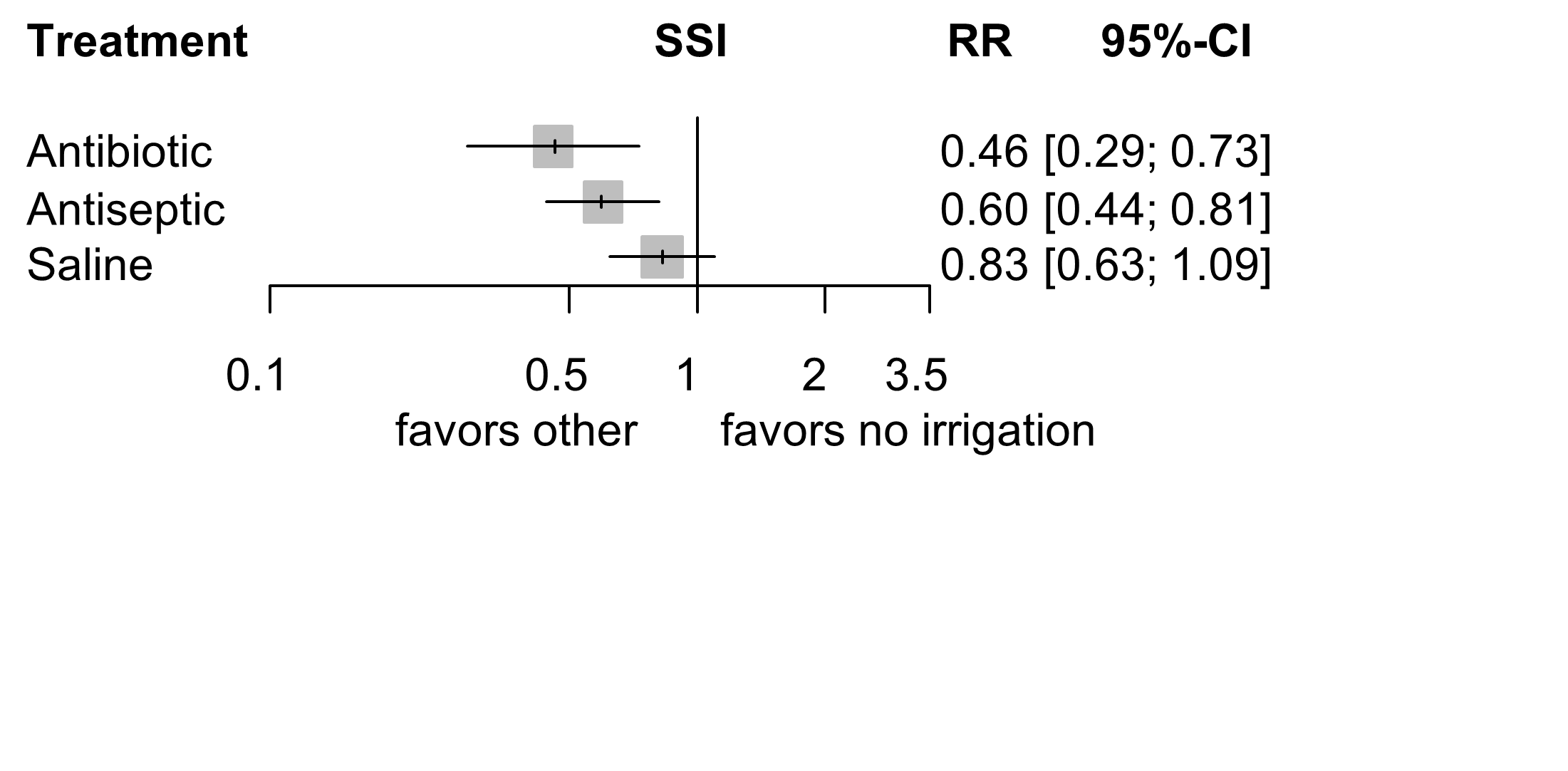

In total, 17,188 patients were included in the systematic review, reporting 1,328 SSI corresponding to an overall incidence of 7.7%. Figure 1 shows the forest plot for the efficacy of the different types of irrigation solutions compared to no irrigation; the league table for this data is presented in Table 1. Antibiotic (RR 0.46 [95% CI 0.29 - 0.73]) and antiseptic (RR 0.60 [0.95% CI 0.44 - 0.81]) solutions both showed a significant effect in reducing SSI when compared to no irrigation. Saline irrigation showed no significant effect (RR 0.83 [95% CI 0.63 - 1.09]) compared to no irrigation. The effects on SSI reduction of antibiotic solutions and antiseptic solutions were not significantly different (RR 0.77; 95% CI 0.50 - 1.19).

Results from the subgroup- and sensitivity analyses can be found in subgroup and sensitivity analyses .

Level of evidence of the literature

Full evaluation of the certainty of evidence and considerations for grading are detailed in Table 2 and GRADE assessment . GRADE assessment, incorporating minimally important difference, resulted in a high certainty of evidence for two comparisons (antiseptic versus saline irrigation and antiseptic versus no irrigation) and moderate certainty for two comparisons (antibiotic versus saline irrigation and saline versus no irrigation). Low certainty of evidence was found for the comparison of antibiotic versus no irrigation, and very low certainty for antibiotic versus antiseptic irrigation.

Study characteristics

|

Study |

SSI / N total |

Treatment 1 |

Treatment 2 |

Type of surgery |

Wound class § |

SAP |

ROB |

Follow-up |

SSI definition |

|

Antibiotic vs Antiseptic (RR 0.77; 95% CI 0.50 – 1.19) |

|||||||||

|

Inojie 2023 |

8 / 80 |

Gentamicin in saline |

3.5% PI |

Open spine surgery |

1 |

Yes |

Some concerns |

30 days |

CDC |

|

Karuserci 2022*

|

2 / 200 |

Rifampicin in saline |

10% PI |

Caeserean section |

2 |

Yes |

Some concerns |

30 days |

CDC |

|

Nguyen 2021 |

11 / 88 |

Cefazolin, gentamicin, and bacitracin in saline |

0.05% chlorhexidine gluconate |

Bilateral mastectomy with tissue expander reconstruction |

1 |

Yes |

Some concerns |

28 days |

CDC |

|

Karuserci 2020*

|

28 / 200 |

Rifampicin in saline |

10% PI |

Gynecologic oncology surgery |

2 |

Yes |

High |

30 days |

CDC |

|

Karusersi 2019*

|

7 / 200 |

Rifampicin in saline |

10% PI |

Benign gynecologic surgery |

2 |

Yes |

Some concerns |

30 days |

¶a |

|

Antibiotic vs Saline (RR 0.56; 95% CI 0.37 – 0.83) |

|||||||||

|

Zeb 2023 |

12 / 106 |

Imipenem in saline |

Saline |

Open appendectomy |

2 – 4 |

Yes |

Some concerns |

3 weeks |

NR |

|

Karuserci 2022*

|

6 / 200 |

Rifampicin in saline |

Saline |

Caeserean section |

2 |

Yes |

Some concerns |

30 days |

CDC |

|

Shah 2021

|

14 / 80 |

Imipenem in saline |

Saline |

Appendectomy |

3 – 4 |

NR |

Some concerns |

NR |

NR |

|

Okunlola 2021

|

3 / 132 |

Ceftriaxone in saline |

Saline |

Neurosurgery |

1 |

Yes |

Some concerns |

30 days |

¶b |

|

Karuserci 2020*

|

28 / 200 |

Rifampicin in saline |

Saline |

Gynecologic oncology surgery |

2 |

Yes |

High |

30 days |

CDC |

|

Emile 2020*

|

17 / 150 |

Gentamicin in saline |

Saline |

Open appendectomy |

1 – 3 |

Yes |

Some concerns |

6 weeks |

CDC |

|

Karusersi 2019*

|

13 / 200 |

Rifampicin in saline |

Saline |

Benign gynecologic surgery |

2 |

Yes |

Some concerns |

30 days |

¶a |

|

Oller 2015 |

0 / 51 |

I. Gentamicin in saline |

Saline |

Axillary lymph node dissection in breast cancer |

1 |

Yes |

Some concerns |

2 weeks |

NR |

|

Ruiz-Tovar 2013¤ |

0 / 40 |

Gentamicin in saline |

Saline |

Elective axillary lymph node dissection due to axillary metastasis |

1 |

Yes |

Some concerns |

NR |

NR |

|

Etaati 2012*

|

5 / 100 |

Cefazolin in saline |

Saline |

Caeserean section |

2 |

Yes |

High |

1 week |

¶c |

|

Mirsharifi 2008

|

12 / 102 |

Cefazolin |

Saline |

Open cholecystectomy |

2 – 3 |

NR |

Some concerns |

6 weeks |

¶d |

|

Bhargava 2006

|

28 / 60 |

Metronidazole in saline |

Saline |

Exploratory laparotomy |

4 |

Yes |

High |

30 days |

¶e |

|

Antibiotic vs No irrigation (RR 0.46; 95% CI 0.29 – 0.73) |

|||||||||

|

Emile 2020*

|

17 / 150 |

Gentamicin in saline |

No irrigation |

Open appendectomy |

1 – 3 |

Yes |

Some concerns |

6 weeks |

CDC |

|

Etaati 2012*

|

5 / 150 |

Cefazolin in saline |

No irrigation |

Caeserean section |

2 |

Yes |

High |

1 week |

¶c |

|

Köşüş 2010

|

12 / 1272 |

Rifamycin |

No irrigation |

Caeserean section |

2 |

Yes |

Some concerns |

30 days |

CDC |

|

Antiseptic vs No irrigation (RR 0.60; 95% CI 0.44 – 0.81) |

|||||||||

|

Mueller 2023* |

44 / 394 |

0.04% polyhexanide |

No irrigation |

Emergency and elective abdominal laparotomy |

2 – 4 |

Yes |

Low |

30 days |

CDC |

|

Al-Abdulla 2021* |

16 / 80 |

1% PI |

No irrigation |

Open appendectomy |

3 – 4 |

Yes |

Some concerns |

10 days |

¶f |

|

Haider 2018

|

43 / 600 |

1% PI |

No irrigation |

Clean elective surgery |

1 |

Yes |

Some concerns |

4 weeks |

¶f |

|

Mahomed 2016 |

291 / 3270 |

10% PI |

No irrigation |

Caeserean section |

2 |

Yes |

Some concerns |

4 weeks |

CDC |

|

Iqbal 2015 |

25 / 166 |

1% PI

|

No irrigation |

Open appendectomy |

3 |

Yes |

Some concerns |

30 days |

¶f |

|

Kokavec 2008 |

2 / 162 |

3.5% PI |

No irrigation |

Orthopedic surgery of proximal femur, hip and pelvis in pediatric patients |

1 |

Yes |

Some concerns |

2 months |

¶g |

|

Antiseptic vs Saline (RR 0.72; 95% CI 0.57 – 0.93) |

|||||||||

|

Mueller 2023* |

68 / 587 |

0.04% polyhexanide |

Saline

|

Emergency and elective abdominal laparotomy |

2 – 4 |

Yes |

Low |

30 days |

CDC |

|

Maemoto 2023

|

60 / 950 |

10% PI |

Saline |

Elective gastroenterological surgery |

2 |

Yes |

Some concerns |

30 days |

CDC |

|

Zhao 2023

|

20 / 340 |

1% PI |

Saline |

Radical gastrectomy |

2 |

Yes |

Some concerns |

30 days |

CDC |

|

Karuserci 2022*

|

6 / 200 |

10% PI |

Saline |

Caeserean section |

2 |

Yes |

Some concerns |

30 days |

CDC |

|

Maghsoudipour 2022 |

0 / 50 |

3% hydrogen peroxide |

Saline |

Rhinoplasty |

1 |

NR |

Some concerns |

8 weeks |

¶h |

|

Al-Abdulla 2021* |

14 / 80 |

1% PI

|

Saline |

Open appendectomy |

3 – 4 |

Yes |

Some concerns |

10 days |

¶f |

|

Cohen 2020¤

|

3 / 173 |

0.35% PI |

Saline |

Pediatric posterior spinal fusion |

1 |

Yes |

Some concerns |

90 days |

CDC |

|

Akhavan - Sigari 2020 |

26 / 936 |

3.5% PI |

Saline |

Spinal fusion surgery |

1 |

Yes |

Some concerns |

12 months |

CDC |

|

Karuserci 2020*

|

28 / 200 |

10% PI |

Saline |

Gynecologic oncology surgery |

2 |

Yes |

High |

30 days |

CDC |

|

Strobel 2020 |

111 / 456 |

0.04% polyhexanide

|

Saline |

Elective abdominal laparotomy |

2 – 3 |

Yes |

Some concerns |

30 days |

CDC |

|

Karusersi 2019*

|

18 / 200 |

10% PI |

Saline |

Benign gynecologic surgery |

2 |

Yes |

Some concerns |

30 days |

¶a |

|

Vinay 2019 |

16 / 180 |

5% PI

|

Saline |

Elective laparotomy |

2 |

Yes |

Some concerns |

4 weeks |

CDC |

|

De Luna 2017 |

3 / 50 |

3% PI |

Saline |

Spine surgery |

1 |

Yes |

Some concerns |

30 days |

CDC |

|

Fei 2017 |

12 / 80 |

0.1% PI |

Saline |

Posterior lumbar interbody fusion surgery |

1 |

NR |

Some concerns |

NR |

NR |

|

Neeff 2016 |

41 / 197 |

0.04% polyhexanide |

Ringer’s solution |

Colorectal surgery |

2 – 4 |

NR |

Some concerns |

NR |

NR |

|

Takesue 2011 |

48 / 400 |

Electrolyzed Strongly Acidic Aqueous Solution |

Saline |

Elective colorectal surgery |

2 – 3 |

Yes |

Some concerns |

30 days |

¶a |

|

Chang 2006 |

6 / 244 |

0.35% PI |

Saline |

Lumbosacral posterolateral fusion surgery |

1 |

Yes |

Some concerns |

14 months |

NR |

|

Cheng 2005

|

7 / 414 |

0.35% PI |

Saline |

Spine surgery |

1 |

Yes |

Some concerns |

6 months |

¶i |

|

Saline vs No Irrigation (RR 0.83; 95% CI 0.63- 1.09) |

|||||||||

|

Mueller 2023* |

50 / 397 |

Saline |

No irrigation |

Emergency and elective abdominal laparotomy |

2 – 4 |

Yes |

Low |

30 days |

CDC |

|

Gomaa 2022

|

221 / 2890 |

Saline |

No irrigation |

Caeserean section |

2 |

NR |

Some concerns |

30 days |

¶j |

|

Al-Abdulla 2021*

|

18 / 80 |

Saline |

No irrigation |

Open appendectomy |

3 – 4 |

Yes |

Some concerns |

10 days |

¶f |

|

Gül 2021

|

18 / 230 |

Saline |

No irrigation |

Caeserean section |

2 |

Yes |

Some concerns |

7 days |

¶k |

|

Emile 2020*

|

17 / 150 |

Saline |

No irrigation |

Open appendectomy |

1 – 3 |

Yes |

Some concerns |

6 weeks |

CDC |

|

Aslan 2018

|

25 / 204 |

Saline |

No irrigation |

Caeserean section |

2 |

Yes |

Some concerns |

30 days |

NR |

|

Etaati 2012*

|

5 / 150 |

Saline |

No irrigation |

Caeserean section |

2 |

Yes |

High |

1 week |

¶c |

|

Güngördük 2010

|

36 / 520 |

Saline |

No irrigation |

Caeserean section |

2 |

Yes |

Some concerns |

6 weeks |

¶l |

|

Al-Ramahi 2006

|

21 / 206 |

Saline |

No irrigation |

Abdominal gynecologic surgery |

2 |

Yes |

High |

1 month |

¶m |

|

Platt 2003

|

0 / 30 |

Saline |

No irrigation |

Bilateral breast reduction |

1 |

NR |

Some concerns |

8 weeks |

NR |

|

Cervantes-Sánchez 2000 |

12 / 255 |

Saline |

No irrigation |

Appendectomy |

1 – 3 |

Yes |

Some concerns |

4 weeks |

¶n |

|

* Studies compare three wound irrigation solutions ¤ SSI secondary outcome, thus not adequately powered to detect SSI § 1: Clean, 2: Clean-contaminated, 3: Contaminated, 4: Dirty

SSI definitions, other than CDC: ¶a: National Nosocomial Infections Surveillance System (NNIS).1 ¶b: a modified scoring system: grade 0, normal healing; grade I, normal healing with mild erythema or epidermolysis; grade II, superficial wound infection with galeal/fascia intact; grade III, deep wound infection below the galeal/fascia but with intact dural; grade IIIa, no osteomyelitis; grade IIIb, with osteomyelitis; grade IIIc, with pachy meningitis; grade IV, meningitis without tissue breakdown excluding chemical meningitis; grade V, meningitis with breakdown of dural and fascia; grade VI, intracranial or intraspinal intradural abscess; grade Via, subdural empyema; grade Vib, intraparenchymal abscess; grade Vic, intraventricular abscess; grade Vid, combination. ¶c: at the time of discharge, the patients of all groups were trained to go to the hospital if they had fever or if they saw any erythema, swelling or discharge at the surgical site. Then, the patients were daily followed by telephone to see if they had signs of symptoms of SSIs. ¶d: infection was defined according to clinical symptoms: purulent discharge, pain, heat, swelling or erythema at site of the wound. Final diagnosis was made by the surgeon. ¶e: postoperatively, the wound was inspected after 48 h for any discharge, soakage, erythema, tenderness and pain. ¶f: Southampton grading: grade 0, healing is normal; grade I, normal healing + mild bruising; grade II, erythema / tenderness / heat; grade III, serous discharge; grade IV, purulent discharge. ¶g: infection was assumed when there was unexpected or increased pain, redness, swelling, increased temperature or discharge from the wound. ¶h: presence of infection was examined and reported as positive or negative. ¶i: infection was suspected when unusual pain, tenderness, erythema, induration, fever, or wound drainage was noted. Such findings were investigated with measurement of erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, and bacteriological cultures from the operative site or blood. ¶j: tenderness, redness, hotness, swelling, purulent discharge. ¶k: purulent discharge or erythema, fever, induration, and tenderness in the surgical site, which required separation of the incision, indicated an infection. ¶l: wound infection was diagnosed when a wound drained purulent material or serosanguineous fluid in association with induration, warmth and tenderness. Suspected wound infections were opened for confirmation and wound cultures were taken. Haematoma, seroma, or wound breakdown in the absence of the previously discussed signs was not considered a wound infection. ¶m: defined as wound discontinuation associated with purulent discharge from the wound and local tenderness, hotness, and/or redness within 1 month of surgery. ¶n: a wound was considered to be infected accordingly to Krukowski et al.2 when there was a collection of pus or a positive bacteriologic culture from a wound discharge (as described by Ljunqvist3).

CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; N, number of patients; NR, not reported; PI, povidone iodine; ROB, risk of bias; RR, relative risk; SAP, systemic antibiotic prophylaxis; SSI, surgical site infection; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval

1 Emori, T. G. et al. National nosocomial infections surveillance system (NNIS): description of surveillance methods. Am J Infect Control 19, 19-35, doi:10.1016/0196-6553(91)90157-8 (1991). 2 Krukowski, Z. H., Irwin, S. T., Denholm, S. & Matheson, N. A. Preventing wound infection after appendicectomy: a review. Br J Surg 75, 1023-1033, doi:10.1002/bjs.1800751023 (1988). 3 Ljungqvist, U. Wound Sepsis after Clean Operations. Lancet 1, 1095-1097, doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(64)91291-7 (1964).

|

|||||||||

Statements on method of wound irrigation

|

Study |

Statements on method of wound irrigation

|

|

Mueller 2023 |

After randomization, patients received IOWI with 1000 ml of a 0·04% PHX solution, IOWI with 1000 ml NaCl 0·9%, or no irrigation. The wound was rinsed carefully with the respective solution and the excess was removed by suction. Debris and blood clots were removed from the wound using irrigation and suction. The wound was left moistened with the irrigation solution to ensure sufficient contact time (> 10 min). |

|

Maemoto 2023 |

IOWI is performed for one minute with 40 mL of aqueous 10% PVP-I (POVIDONE-IODINE solution 10% “MEIJI”; Meiji Seika Pharma Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) in the study group, and the same procedure is performed with 100 mL of saline (Isotonic Sodium Chloride Solution “Hikari”; Hikari Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) in the control group. |

|

Zhao 2023 |

After closing the peritoneal sutures with size 0 VICRYL Plus (Johnson & Johnson - Ethicon Endo-Surgery, Inc., Cincinnati, OH, USA), the wound was irrigated with either 500 mL of 1% PVI solution or 500 ml of 0.9% NS. Size 4-0 VICRYL Plus intradermic sutures were used in all patients. |

|

Inoje 2023 |

Patients randomized into Group A had their spine wound irrigated with saline containing gentamicin solution (a liter of normal saline mixed with 80 mg of gentamicin injection) in a quantity sufficient to fill the wound to the level of the skin without overflow. The saline containing gentamicin solution was maintained in the incision for 3 minutes, after which the wound was flushed with the remaining saline containing gentamicin solution. Group B patients’ wounds were irrigated with a liter of 3.5% diluted PI solution. The surgical wound was filled with PI in a volume sufficient to fill the wound to the level of the skin without overflow. The PI solution was maintained in the incision for 3 minutes, after which the wound was flushed with the remaining dilute PI solution. |

|

Zeb 2023 |

Before the wound was stitched up, the tissues in group I were irrigated with one litre of saline containing one gramme of imipenem (1 mg/ml), while group II received one litre of regular saline. |

|

Karuserci 2022 |

All subcutaneous tissues were irrigated with 250 ml of saline. Then 3–5ml 10% povidone-iodine in group 2 and 250 mg/3 ml rifampicin in group 3 was applied directly on the subcutaneous tissue without diluting. The excess liquid was cleaned off and the subcutaneous tissue scrubbed with gauze. |

|

Gomaa 2022 |

Subcutaneous irrigation by 200cc saline before closure of the skin.

|

|

Maghsoudipour 2022 |

Irrigation with hydrogen peroxide or placebo was performed right before closure of the surgical site with sutures, using irrigation syringes prepared by a pharmacist at the time they were needed. In the intervention group, hydrogen peroxide 3% solution was used, while 0.9% sodium chloride solution was used in the placebo group. |

|

Al-Abdulla 2021 |

In this study group A, before skin closure, subcutaneous tissue was irrigated by 1% povidone iodine using 10cc syringe, kept there for 2 to 3 minute and then aspirated. Group B the subcutaneous tissue was washed by normal saline using 10cc syringe. Group C no irrigation was done. |

|

Shah 2021 |

NR

|

|

Nguyen 2021 |

TAS contained 1 g of cefazolin, 50,000 U of bacitracin, and 80 mg of gentamicin in 500 mL of normal saline. Both the Tissue Expander and mastectomy pocket were bathed in the respective solutions, and a 1-minute dwell time was employed based on data presented on the IrriSept website reporting similar efficacy with 1- or 5-minute exposure times for most organisms. |

|

Okunlola 2021 |

The patients in the subject group received 2 g of intravenous ceftriaxone (Roche-Rocephin) at induction of anaesthesia followed by 1 g 12 hourly for 24 h post-operatively and intra-operative wound irrigation with 250 mg/ml of ceftriaxone in normal saline. The patients in the control group received 2 g of intravenous (Roche-Rocephin) at induction of anaesthesia followed by 1 g 12 hourly for 24 h post-operatively and intraoperative wound irrigation with plain normal saline. The irrigation was done by jet and or droplets from 50 ml syringe. |

|

Gül 2021 |

The subcutaneous tissue was irrigated with 200 ml of saline solution (0.9% NaCl) in patients in the experimental group (Group 1, n=115), and not irrigated in those in the control group (n=115) before the skin was closed. |

|

Cohen 2020 |

After the initial culture collection, nonviable tissues were debrided and the wound was soaked for 3 minutes with enough 0.35% PVP-I or sterile saline to be in contact with the entire wound. No antibiotics were added to sterile saline. The wound was then irrigated with 2 L of saline regardless of randomization to limit confounding, since PVP-I must be irrigated with saline. |

|

Akhavan - Sigari 2020 |

Before bone grafting, the surgical wounds in the normal ssaline group were filled and soaked with 0.9% normal saline, suction was performed; the irrigation being repeated three times. In the PVI group, surgical wounds were irrigated with PVI 3% to fill and soak the wound for two minutes followed by normal saline irrigation. |

|

Karuserci 2020 |

All subcutaneous tissues were irrigated with 250 mL of saline. Then 10 mL of 10 % povidone-iodine in Group 2 and 500 mg/6 mL of rifampicin in Group 3 was applied directly on the subcutaneous tissue without being diluted. The excess liquid was cleaned off and the subcutaneous tissue scrubbed with a gauze. |

|

Strobel 2020 |

At the end of the operation, the peritoneal cavity was rinsed routinely with 0.9% sodium chloride solution at body temperature (Braun, Melsungen, Germany). Before closure of fascia, instruments and gloves were changed. After the closure of fascia, subcutaneous irrigation with 250mL 0.9% saline (Braun, Melsungen, Germany) or 250mL antiseptic 0.04% polyhexanide solution (Serasept2, Serag-Wiessner) was done according to the randomization list. The application time for polyhexanide was 10 minutes and for saline as biologically inactive agent 1 minute. |

|

Emile 2020 |

In group I, upon closure of the peritoneum gentamicin-saline solution (160 mg of gentamicin in 400 ml of normal saline 0.9%) was used by a 20-cm syringe for irrigation of every layer of the wound before its closure. The first layer was between the peritoneal membrane and the internal oblique muscles, the second layer was between the approximated internal oblique muscles and the external oblique aponeurosis, and finally the third layer (the subcutaneous space) after closure of the external oblique aponeurosis (Fig. 1). In group II, layer by layer irrigation of the wound with normal saline solution was performed in a similar manner. In group III, layer-by-layer closure of the surgical wound with polyglactin 2/0 sutures took place without irrigation. |

|

Karuserci 2019 |

All subcutaneous tissues were irrigated with 250 ml of saline. Then 500 mg/6 ml of rifampicin in group 2 and 10 ml of povidone iodine in group 3 was applied directly on the subcutaneous tissue without dilution. The excess liquid was cleaned off and the subcutaneous tissue scrubbed with gauze. |

|

Vinay 2019 |

In Group A, the incision site was treated with 400 ml, 0.9% normal saline and 100 ml 5% povidone-iodine solution. In Group B, the incision site was treated with 500 ml 0.9% normal saline solution. |

|

Haider 2018 |

In group A, before skin closure subcutaneous tissues were irrigated with 5 ml 1 % PVI solution in normal saline. The solution was kept in wound for five minutes then aspirated. In group B, no irrigation was done. |

|

Aslan 2018 |

Before the subcutaneous tissue closure in the saline group the subcutaneous saline irrigation was performed with a 200cc of saline (0.9%NaCl). No subcutaneous irrigation was applied in the control group before the skin closure. |

|

De Luna 2017 |

In group A, before applying the bone graft, low-pressure irrigation (Bio Pulse, Leader Medica) with PVP-I diluted to a 3% concentration (30 g/l) in 2 litres of saline for between 5 and 10 minutes was performed and then washed out by 1 litre of sodium chloride solution through a pulse irrigation device. In group B, low-pressure irrigation with 2 litres of saline solution for between 5 and 10 minutes was performed before applying bone graft. |

|

Fei 2017 |

The incision was flushed with 0.1% iodine solution (volume: 200 ml) and soaked for 2 min, then the incisions were flushed with normal saline under adequate hemostasis conditions. The incisions were flushed with saline solution in the usual way. |

|

Mahomed 2016 |

The intervention was wound irrigation with about 50 mls of 10% aqueous PVI solution (Betadine group). The solution in a bowl was poured in and around the incision site. |

|

Neeff 2016 |

NR

|

|

Oller 2015 |

All patients underwent a first lavage of the axillary surgical bed with physiologic saline. Group 1 underwent a second lavage with saline. Group 2 had a second lavage with a 240-mg gentamicin solution (Group 2), and Group 3 had a second lavage with a 600-mg clindamycin solution. |

|

Iqbal 2015 |

In the study group A, before skin closure, the subcutaneous tissue was irrigated with 4-5 cc of 1% diluted povidone-iodine solution. The solution was sprayed into the subcutaneous wound with the help of a 5cc syringe, kept there for 2-3 minutes and was then aspirated. However, in the control group B, no irrigation was done. |

|

Ruiz-Tovar 2013 |

In both groups, prior to the lavage, a microbiological sample from the surgical bed was obtained with a swab (sample 1), followed by a lavage with 500 ml normal saline. After aspiration of the saline, a new microbiological sample was obtained (sample 2). In Group 1 a second lavage with 500 ml normal saline was performed, while in Group 2 the second lavage was performed with an antibiotic solution, including gentamicin (240 mg) dissolved in 500 ml normal saline. |

|

Etaati 2012 |

In one group, after the surgery and before closing up the patients, 2 grams of cefazolin in 5 cc of distilled water were used to irrigate the patients. In the second group, 150 cc of normal saline was used to irrigate the patients and in the last group, no irrigation was used. |

|

Takesue 2011 |

In the ESAAS group the surgical wound was irrigated with at least 500 mL of ESAAS after the completion of fascial suture. In the saline solution group, the same amount of saline solution was used for wound irrigation. |

|

Güngördük 2010 |

In the study group, before skin closure, the subcuticular tissue was irrigated with 100 ml of sterile saline with a 30–60 ml syringe. The skin was then closed using a 3-0 Vicryl suture. In the control group, the subcuticular tissue was not irrigated with sterile saline and the skin was closed using a 3-0 Vicryl suture. |

|

Köşüş 2010 |

In the second group subcutaneous tissue was irrigated with rifamycin SV/ 250 mg, before closure of subcutaneous tissue. |

|

Kokavec 2008 |

Approximately 1 ml of betadine was diluted by adding approx. 30 ml of sterile saline solution to a concentration of about 0.35% povidone iodine for perioperative use (2-3 minutes) |

|

Mirsharifi 2008 |

One gram of injectable cefazolin was used to wash the wound after the surgery and just before closing the incision site, and the control group was without topical antibiotic. |

|

Bhargava 2006 |

In group A the wound was irrigated with normal saline and in group B 50–100mL of metronidazole (from a single manufacturer). The concentration used was 500 mg/100 mL, which was infiltrated in the subcutaneous tissues making sure that the area of infiltration exceeds that of the incision. |

|

Chang 2006 |

In group 1 composed of patients with odd serial numbers (study group), wounds were irrigated with 0.35% povidone-iodine solution to soak for 3 min, followed by an irrigation with 2000 c.c. of normal saline to remove povidone-iodine solution. No more wound irrigation was given after. In contrast, group 2 with patients even numbered (control group) was wound irrigated only with 2000 c.c. of normal saline. |

|

Al-Ramahi 2006 |

The 104 patients in the odd number group (group 1), underwent wound irrigation with 50 mL of normal saline solution (NaCl 0.9%) following surgery and before skin closure. The 102 patients in the even-number group (group 2) received no wound irrigation. |

|

Cheng 2005 |

The commercially available betadine solution used had a concentration of 10% povidoneiodine (100 mg of povidoneiodine per 1 mL of solution). Approximately 5 mL of povidoneiodine was diluted with normal saline to achieve a 0.35% povidoneiodine (3.5% betadine) solution for use during operation. The wound was irrigated with copious amounts of normal saline (2000 mL) after betadine solution irrigation. In group 2, irrigation with copious normal saline (2000 mL) was performed alone. |

|

Platt 2003 |

Each breast was preinfiltrated with 300 mL saline containing adrenaline diluted to 1:500,000, lignocaine, and hyaluronidase (Hyalase; CP Pharmaceuticals Ltd, Wrexham, UK). Infiltration was performed uniformly throughout the breast using a spinal needle and syringe, sparing the pedicle. |

|

Cervantes-Sánchez 2000 |

Group I (control) was treated with surgery and prophylactic systemic antibiotics and group II (experimental) was treated with surgery, antibiotics, and wound syringe pressure irrigation as follows: after closure of the fascial planes, we irrigated the subcutaneous fat tissue with 300 ml of normal saline solution, delivered with a 20-ml syringe with a 19-gauge intravenous (IV) catheter, applying to the embolus the force of one hand, at a distance of 2 cm from the wound tissues, aspirating the fluid collected in the wound with a bulb syringe. |

|

ESAAS, Electrolyzed Strongly Acidic Aqueous Solution; IOWI, intraoperative wound irrigation; NaCl, sodiumchloride; NR, not reported PHX, polyhexanide; PI, povidone-iodine; PVI, povidone-iodine; PVP-I, povidone-iodine; TAS, Triple Antibiotic Solution; NR, not reported |

|

Subgroup and sensitivity analyses

The forest plots show the network relative risks (RR) with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI) compared with no irrigation.

In the lower triangle of the league tables the network RR with corresponding 95% CI are shown. The upper triangle shows the RR of only the direct comparisons (comparable with a regular pairwise meta-analysis).

For instance, in Bijlage 6.a, the first column (in the lower triangle) shows the network RR with corresponding 95% CI of antibiotic compared with the other irrigation solutions. The last column (upper triangle) shows the direct RR with corresponding 95% CI of no irrigation compared with the other irrigation solutions.

A. Only clean surgery (CDC wound classification I)

Forest plot

League table

|

Antibiotic |

1.29 [0.34; 4.84] |

2.00 [0.15; 27.20] |

- |

|

1.95 [0.59; 6.42] |

Antiseptic |

0.17 [0.07; 0.43] |

0.65 [0.21; 2.04] |

|

0.40 [0.10; 1.60] |

0.21 [0.08; 0.51] |

Saline |

- |

|

1.26 [0.24; 6.59] |

0.65 [0.21; 2.04] |

3.12 [0.73; 13.35] |

No irrigation |

B. Excluding studies with only clean surgery

Forest plot

League table

|

Antibiotic |

1.04 [0.41; 2.60] |

0.55 [0.36; 0.84] |

0.19 [0.06; 0.58] |

|

0.61 [0.39; 0.95] |

Antiseptic |

0.79 [0.62; 1.02] |

0.81 [0.56; 1.17] |

|

0.52 [0.35; 0.77] |

0.85 [0.67; 1.07] |

Saline |

0.77 [0.57; 1.03] |

|

0.42 [0.27; 0.66] |

0.68 [0.52; 0.90] |

0.80 [0.63; 1.03] |

No irrigation |

C. Only upper-middle and high income countries

Forest plot

League table

|

Antibiotic |

0.82 [0.37; 1.84] |

0.45 [0.19; 1.10] |

0.04 [0.00; 0.74] |

|

0.63 [0.31; 1.27] |

Antiseptic |

0.68 [0.50; 0.92] |

0.81 [0.48; 1.35] |

|

0.46 [0.23; 0.92] |

0.73 [0.54; 0.97] |

Saline |

0.76 [0.48; 1.18] |

|

0.39 [0.18; 0.83] |

0.61 [0.41; 0.92] |

0.85 [0.58; 1.24] |

No irrigation |

D. Only low and lower-middle income countries

Forest plot

League table

|

Antibiotic |

7.00 [0.80; 61.57] |

0.63 [0.37; 1.08] |

0.25 [0.07; 0.91] |

|

0.97 [0.46; 2.03] |

Antiseptic |

0.56 [0.24; 1.31] |

0.68 [0.34; 1.37] |

|

0.62 [0.37; 1.03] |

0.64 [0.35; 1.15] |

Saline |

0.71 [0.40; 1.25] |

|

0.50 [0.26; 0.95] |

0.51 [0.29; 0.90] |

0.80 [0.50; 1.30] |

No irrigation |

E. Excluding studies with high risk of bias

Forest plot

League table

|

Antibiotic |

0.79 [0.30; 2.09] |

0.59 [0.32; 1.09] |

0.18 [0.05; 0.63] |

|

0.72 [0.42; 1.24] |

Antiseptic |

0.68 [0.51; 0.91] |

0.76 [0.51; 1.14] |

|

0.54 [0.32; 0.90] |

0.74 [0.57; 0.97] |

Saline |

0.72 [0.50; 1.03] |

|

0.43 [0.24; 0.76] |

0.60 [0.43; 0.82] |

0.80 [0.59; 1.09] |

No irrigation |

F. Only studies with adequate description of systemic antibiotic prophylaxis

Forest plot

League table

|

Antibiotic |

1.06 [0.49; 2.30] |

0.52 [0.30; 0.91] |

0.18 [0.06; 0.61] |

|

0.73 [0.44; 1.21] |

Antiseptic |

0.67 [0.49; 0.92] |

0.75 [0.46; 1.21] |

|

0.52 [0.32; 0.83] |

0.71 [0.53; 0.95] |

Saline |

0.71 [0.47; 1.06] |

|

0.41 [0.24; 0.70] |

0.56 [0.39; 0.80] |

0.79 [0.56; 1.11] |

No irrigation |

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question:

What is the effect of prophylactic intra-operative incisional wound irrigation using antiseptic, antibiotic or saline solutions (i) versus other solutions in adult patients undergoing surgical procedures (p) in the prevention of SSI?

P: Adults undergoing any surgical procedure

I: Prophylactic intra-operative incisional wound irrigation using antiseptic, antibiotic or saline solutions

C: Prophylactic intra-operative incisional wound irrigation using other antiseptic, antibiotic or saline solutions or no irrigation

O: SSI

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered occurrence of SSI as a crucial outcome measure for decision making. The working group defined thresholds for clinically relevant outcomes in accordance with current GRADE guidance and methodology.

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (PubMed), Excerpta Medica Database (EMBASE) and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trial (CENTRAL) were searched with relevant search terms until June 12, 2023. The detailed search strategy is available on request via https://richtlijnendatabase.nl/. The systematic literature search resulted in 1583 hits. Studies were selected based on the following inclusion criteria: unpublished and published RCTs that investigated the effect of prophylactic incisional intra-operative wound irrigation on SSI rates in any type of surgery, using antiseptic, antibiotic, or saline solutions, compared to each other or to no irrigation. Other solutions investigated in the literature (e.g., castile soap by Bhandari et al)4 were not included because they did not fit into either an antiseptic or an antibiotic profile. Furthermore, studies investigating intra-cavity lavage (i.e. abdominal, peritoneal or mediastinal) or surgical lavage of any other kind were excluded. 146 studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, 105 studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion in Reasons for exclusion after full text review ) and 41 studies were included.

Results

Forty-one studies were included in the systematic review and 37 RCTs in the network meta-analysis of the literature. Important study characteristics and results and quality assessments are summarized in the evidence tables and risk of bias tables under the 'evidence tabellen' tab and 'Study characteristics' under the 'Samenvatting literatuur' tab.

Referenties

- Aftab R, Dodhia VH, Jeanes C, Wade RG. Bacterial sensitivity to chlorhexidine and povidone-iodine antiseptics over time: a systematic review and meta-analysis of human-derived data. Sci Rep. Jan 7 2023;13(1):347. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-26658-1

- Akhavan-Sigari R, Abdolhoseinpour H. Operative site irrigation with povidone-iodine solution in spinal surgery for surgical site infection prevention: Can it be used safety? Anaesth Pain Intensi. Jul-Sep 2020;24(3):314-319. doi:10.35975/apic.v24i3.1282

- Al-Abdulla MOKK, A.M.; Al-Katrani, H.A.S. Topical Application of Povidone Iodine to Minimize Post Appendectomy Wound Infection. Indian Journal of Forensic Medicine & Toxicology. 2021;15(4):1743-1747.

- Al-Ramahi M, Bata M, Sumreen I, Amr M. Saline irrigation and wound infection in abdominal gynecologic surgery. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. Jul 2006;94(1):33-6.

- Aslan Çetin B, Aydogan Mathyk B, Barut S, Koroglu N, Zindar Y, Konal M, Atis Aydin A. The impact of subcutaneous irrigation on wound complications after cesarean sections: A prospective randomised study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. Aug 2018;227:67-70. doi:10.1016/j.ejogrb.2018.06.006

- Badia JM, Casey AL, Petrosillo N, Hudson PM, Mitchell SA, Crosby C. Impact of surgical site infection on healthcare costs and patient outcomes: a systematic review in six European countries. J Hosp Infect. May 2017;96(1):1-15. doi:10.1016/j.jhin.2017.03.004

- Barakat NA, Rasmy SA, Hosny AE-DMS, Kashef MT. Effect of povidone-iodine and propanol-based mecetronium ethyl sulphate on antimicrobial resistance and virulence in Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrobial Resistance & Infection Control. 2022/11/11 2022;11(1):139. doi:10.1186/s13756-022-01178-9

- Barreto R, Barrois B, Lambert J, Malhotra-Kumar S, Santos-Fernandes V, Monstrey S. Addressing the challenges in antisepsis: focus on povidone iodine. Int J Antimicrob Agents. Sep 2020;56(3):106064. doi:10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.106064

- Bhargava PK, N.M.A. Wound infection after metronidazole infiltration. Tropical Doctor. 2006;36:37-38.

- Brignardello-Petersen R, Bonner A, Alexander PE, et al. Advances in the GRADE approach to rate the certainty in estimates from a network meta-analysis. J Clin Epidemiol. Jan 2018;93:36-44. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.10.005

- Brignardello-Petersen R, Guyatt GH, Mustafa RA, Chu DK, Hultcrantz M, Schunemann HJ, Tomlinson G. GRADE guidelines 33: Addressing imprecision in a network meta-analysis. J Clin Epidemiol. Nov 2021;139:49-56. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2021.07.011

- Brignardello-Petersen R, Mustafa RA, Siemieniuk RAC, et al. GRADE approach to rate the certainty from a network meta-analysis: addressing incoherence. J Clin Epidemiol. Apr 2019;108:77-85. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2018.11.025

- Brignardello-Petersen R, Tomlinson G, Florez I, et al. Grading of recommendations assessment, development, and evaluation concept article 5: addressing intransitivity in a network meta-analysis. J Clin Epidemiol. Aug 2023;160:151-159. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2023.06.010

- Cervantes-Sanchez CR, Gutierrez-Vega R, Vazquez-Carpizo JA, Clark P, Athie-Gutierrez C. Syringe pressure irrigation of subdermic tissue after appendectomy to decrease the incidence of postoperative wound infection. World J Surg. Jan 2000;24(1):38-41; discussion 41-2. doi:10.1007/s002689910008

- Chang FY, Chang MC, Wang ST, Yu WK, Liu CL, Chen TH. Can povidone-iodine solution be used safely in a spinal surgery? Eur Spine J. Jun 2006;15(6):1005-14. doi:10.1007/s00586-005-0975-6

- Cheng MTC, M.C.; Wang, S.T.; Yu, W.K.; Liu, C.L.; Chen, T.H. Efficacy of Dilute Betadine Solution Irrigation in the Prevention of Postoperative Infection of Spinal Surgery. SPINE. 2005;30(15):1689-1693.

- Cohen LL, Schwend RM, Flynn JM, et al. Why Irrigate for the Same Contamination Rate: Wound Contamination in Pediatric Spinal Surgery Using Betadine Versus Saline. J Pediatr Orthop. Nov/Dec 2020;40(10):e994-e998. doi:10.1097/BPO.0000000000001620

- De Luna V, Mancini F, De Maio F, Bernardi G, Ippolito E, Caterini R. Intraoperative Disinfection by Pulse Irrigation with Povidone-Iodine Solution in Spine Surgery. Adv Orthop. 2017;2017:7218918. doi:10.1155/2017/7218918

- Efthimiou O, Rücker G, Schwarzer G, Higgins JPT, Egger M, Salanti G. Network meta-analysis of rare events using the Mantel-Haenszel method. Statistics in Medicine. 2019;38(16):2992-3012. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.8158

- Emile SH, Elfallal AH, Abdel-Razik MA, El-Said M, Elshobaky A. A randomized controlled trial on irrigation of open appendectomy wound with gentamicin- saline solution versus saline solution for prevention of surgical site infection. Int J Surg. Sep 2020;81:140-146. doi:10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.07.057

- Etaati ZR, M.; Rajaee, M.; Askari, A.; Hosseini, S. Cefazoline or Normal Saline Irrigation Doesn’t Reduce Surgical Site Infections After Cesarean. International Electronic Journal of Medicine (IEJM). 2012;1(2):6-11.

- Fei J, Gu J. Comparison of Lavage Techniques for Preventing Incision Infection Following Posterior Lumbar Interbody Fusion. Med Sci Monit. Jun 20 2017;23:3010-3018. doi:10.12659/msm.901868

- Garner JS. CDC guideline for prevention of surgical wound infections, 1985. Supersedes guideline for prevention of surgical wound infections published in 1982. (Originally published in November 1985). Revised. Infect Control. Mar 1986;7(3):193-200. doi:10.1017/s0195941700064080

- Gillespie BM, Harbeck E, Rattray M, et al. Worldwide incidence of surgical site infections in general surgical patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis of 488,594 patients. Int J Surg. Nov 2021;95doi:ARTN 106136

- Gomaa EA, Abou-Gamrah AA, Eltalbanty EMM, Kamel OI. The effect of subcutaneous saline irrigation on wound complication after cesarean section: a randomized controlled trial. Voprosy ginekologii, akušerstva i perinatologii. 2022;21(2):25-32. doi:10.20953/1726-1678-2022-2-25-32

- Gül DK. The role of saline irrigation of subcutaneous tissue in preventing surgical site complications during cesarean section: A prospective randomized controlled trial. Journal of Surgery and Medicine. 2021;5(1):8-11. doi:10.28982/josam.842145

- Güngördük K, Asicioglu O, Celikkol O, Ark C, Tekirdag AI. Does saline irrigation reduce the wound infection in caesarean delivery? J Obstet Gynaecol. 2010;30(7):662-6. doi:10.3109/01443615.2010.494206

- Haider S, Basit A, Abbasi SH, Shah FH, Kiani YM. Efficacy of irrigation with povidone iodine solution before skin closure to reduce surgical site infections in clean elective surgeries. Rawal Medical Journal. Jul-Sep 2018;43(3):467-470.

- Inojie MO, Okwunodulu O, Ndubuisi CA, Campbell FC, Ohaegbulam SC. Prevention of Surgical Site Infection Following Open Spine Surgery: The Efficacy of Intraoperative Wound Irrigation with Normal Saline Containing Gentamicin Versus Dilute Povidone-Iodine. World Neurosurgery. May 2023;173:E1-E10. doi:10.1016/j.wneu.2022.12.134

- Investigators F, Bhandari M, Jeray KJ, et al. A Trial of Wound Irrigation in the Initial Management of Open Fracture Wounds. N Engl J Med. Dec 31 2015;373(27):2629-41.

- Iqbal MJ, M.; Qureshi, A.; Iqbal, S. Effect of povidone-iodine irrigation on post appendectomy wound Infection: randomized control trial. J Postgrad Med Inst. 2015;29(3):160-4.

- Karuserci OK, Sucu S, Ozcan HC, Tepe NB, Ugur MG, Guneyligil T, Balat O. Topical Rifampicin versus Povidone-Iodine for the Prevention of Incisional Surgical Site Infections Following Benign Gynecologic Surgery: A Prospective, Randomized, Controlled Trial. New Microbiologica. Oct 2019;42(4):205-209.

- Karuserci OK, Sucu S. Subcutaneous irrigation with rifampicin vs. povidone-iodine for the prevention of incisional surgical site infections following caesarean section: a prospective, randomised, controlled trial. J Obstet Gynaecol. Jul 4 2022;42(5):951-956. doi:10.1080/01443615.2021.1964453

- Karuserci OKB, O. Subcutaneous rifampicin versus povidone-iodine for the prevention of incisional surgical site infections following gynecologic oncology surgery - a prospective, randomized, controlled trial. Ginekol Pol. 2020;91(9):513-518. doi:10.5603/GP.a2020.0134

- Kokavec MF, M. Efficacy of Antiseptics in the Prevention of Post-Operative lnfections of the Proximal Femur, Hip and Pelvis Regions in Orthopedic Pediatric Patients. Analysis of the First Results. Acta Chirurgiae Orthopaedicae et Traumatologiae Cechoslovaca. 2008;75:105-109.

- Köşüş AK, N.; Güler, A.; Çapar, M. Rifamycin SV Application to Subcutanous Tissue for Prevention of Post-Cesarean Surgical Site Infection. European Journal of General Medicine. 2010;7(3):269-276.

- Laxminarayan R, Matsoso P, Pant S, Brower C, Rottingen JA, Klugman K, Davies S. Access to effective antimicrobials: a worldwide challenge. Lancet. Jan 9 2016;387(10014):168-75. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00474-2

- Maemoto R, Noda H, Ichida K, et al. Aqueous Povidone-Iodine Versus Normal Saline For Intraoperative Wound Irrigation on The Incidence of Surgical Site Infection in Clean-Contaminated Wounds After Gastroenterological Surgery: A Single-Institute, Prospective, Blinded-Endpoint, Randomized Controlled Trial. Annals of Surgery. May 2023;277(5):727-733. doi:10.1097/Sla.0000000000005786

- Maghsoudipour N, Mohammadi A, Nazari H, Nazari H, Ziaei N, Amiri SM. The effect of 3 % hydrogen peroxide irrigation on postoperative complications of rhinoplasty: A double-blinded, placebo-controlled Randomized Clinical Trial. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. Sep 2022;50(9):681-685. doi:10.1016/j.jcms.2022.06.012

- Mahomed K, Ibiebele I, Buchanan J, Betadine Study G. The Betadine trial - antiseptic wound irrigation prior to skin closure at caesarean section to prevent surgical site infection: A randomised controlled trial. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. Jun 2016;56(3):301-6. doi:10.1111/ajo.12437

- Mirsharifi SRERSHJ, S.; Bateni, H. The effect of antibiotic irrigation of surgical Incisions in prevention of Surgical Site Infection. Tehran University Medical Journal 2008;65(11):71-75.

- Mueller TCK, V.; Dimpel, R.; Blankenstein, C.; Egert-Schwender, S.; Strudthoff, J.; Lock, J.F.; Wiegering, A.; Hadian, A.; Lang, H.; Albertsmeier, M.; Neuberger, M.; Von Ehrlich-Treuenstätt, V.; Mihaljevic, A.L.; Knebel, P.; Pianka, F.; Braumann, C.; Uhl, W.; Bouchard, R.; Petrova, E.; Bork, U.; Distler, M.; Tachezy, M.; Izbicki, J.R.; Reissfelder, C.; Herrle, F.; Vay, C.; Knoefel, W.T.; Buia, A.; Hanisch, E.; Friess, H.; Reim, D. on behalf of the IOWISI Study Group. Intraoperative wound irrigation for the prevention of surgical site infection after laparotomy: the multicenter, double-blind, randomized controlled IOWISI trial (DRKS00012251) of the Study Centre of the German Surgical Society (SDGC CHIR-Net). only preprint2023.

- Neeff HP, Anna MS, Holzner PA, Wolff-Vorbeck G, Hopt UT, Makowiec F. Effect of Polyhexanide on the Incidence of Surgical Site Infections After Colorectal Surgery. Gastroenterology. Apr 2016;150(4):S1244-S1244. doi:Doi 10.1016/S0016-5085(16)34202-0

- Nguyen L, Afshari A, Green J, Joseph J, Yao J, Perdikis G, Higdon KK. Post-Mastectomy Surgical Pocket Irrigation With Triple Antibiotic Solution vs Chlorhexidine Gluconate: A Randomized Controlled Trial Assessing Surgical Site Infections in Immediate Tissue Expander Breast Reconstruction. Aesthet Surg J. Oct 15 2021;41(11):NP1521-NP1528. doi:10.1093/asj/sjab290

- Okunlola AI, Adeolu AA, Malomo AO, Okunlola CK, Shokunbi MT. Intra-operative wound irrigation with ceftriaxone does not reduce surgical site infection in clean neurosurgical procedures. Br J Neurosurg. Dec 2021;35(6):766-769. doi:10.1080/02688697.2020.1812518

- Oller I, Ruiz-Tovar J, Cansado P, Zubiaga L, Calpena R. Effect of Lavage with Gentamicin vs. Clindamycin vs. Physiologic Saline on Drainage Discharge of the Axillary Surgical Bed after Lymph Node Dissection. Surg Infect (Larchmt). Dec 2015;16(6):781-4. doi:10.1089/sur.2015.020

- Papadakis M. Wound irrigation for preventing surgical site infections. World J Methodol. Jul 20 2021;11(4):222-227. doi:10.5662/wjm.v11.i4.222

- Platt AJ, Mohan D, Baguley P. The effect of body mass index and wound irrigation on outcome after bilateral breast reduction. Ann Plast Surg. Dec 2003;51(6):552-5. doi:10.1097/01.sap.0000095656.18023.6b

- Puhan MA, Schunemann HJ, Murad MH, et al. A GRADE Working Group approach for rating the quality of treatment effect estimates from network meta-analysis. BMJ. Sep 24 2014;349:g5630. doi:10.1136/bmj.g5630

- Ruiz-Tovar J, Cansado P, Perez-Soler M, et al. Effect of gentamicin lavage of the axillary surgical bed after lymph node dissection on drainage discharge volume. Breast. Oct 2013;22(5):874-8. doi:10.1016/j.breast.2013.03.008

- Shah A, Sasoli NA, Sami F. Compare the Incidence of Surgical Site Infection after Appendectomy Wound Irrigation with Normal Saline and Imipenem Solutions. Pakistan Journal of Medical and Health Sciences. 2021;15(8):2184-2186. doi:10.53350/pjmhs211582184

- Song F, Glenny AM. Antimicrobial prophylaxis in colorectal surgery: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Br J Surg. Sep 1998;85(9):1232-41. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2168.1998.00883.x

- Strobel RM, Leonhardt M, Krochmann A, et al. Reduction of Postoperative Wound Infections by Antiseptica (RECIPE)?: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Ann Surg. Jul 2020;272(1):55-64. doi:10.1097/SLA.0000000000003645

- Takesue Y, Takahashi Y, Ichiki K, Nakajima K, Tsuchida T, Uchino M, Ikeuchi H. Application of an electrolyzed strongly acidic aqueous solution before wound closure in colorectal surgery. Dis Colon Rectum. Jul 2011;54(7):826-32. doi:10.1007/DCR.0b013e318211b83a

- Teillant A, Gandra S, Barter D, Morgan DJ, Laxminarayan R. Potential burden of antibiotic resistance on surgery and cancer chemotherapy antibiotic prophylaxis in the USA: a literature review and modelling study. Lancet Infect Dis. Dec 2015;15(12):1429-37. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00270-4

- Turner RM, Davey J, Clarke MJ, Thompson SG, Higgins JP. Predicting the extent of heterogeneity in meta-analysis, using empirical data from the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. Int J Epidemiol. Jun 2012;41(3):818-27. doi:10.1093/ije/dys041

- Ventola CL. The antibiotic resistance crisis: part 1: causes and threats. P t. Apr 2015;40(4):277-83.

- Vinay HGKR, G.; Arudhra, P.; Udayeeteja, B. Comparison of the Efficacy of Povidone-Iodine and Normal Saline Wash in Preventing Surgical Site Infections in Laparotomy Wounds-Randomized Controlled Trial. Surgery: Current Research. 2019;08(02)doi:10.4172/2161-1076.1000319

- Zeb AK, M.S.; Iqbal, A.; Khan, A.; Ali, I.; Ahmad, M. Compare the Frequency of Surgical Site Infections Following Irrigation of Appendectomy Wounds with Sterile Saline Solution Vs Imipenem Solution. 2023;17(2):617-619. doi:10.53350/pjmhs2023172617

- Zeng L, Brignardello-Petersen R, Hultcrantz M, et al. GRADE Guidance 34: update on rating imprecision using a minimally contextualized approach. J Clin Epidemiol. Oct 2022;150:216-224. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2022.07.014

- Zeng L, Brignardello-Petersen R, Hultcrantz M, et al. GRADE guidelines 32: GRADE offers guidance on choosing targets of GRADE certainty of evidence ratings. J Clin Epidemiol. Sep 2021;137:163-175. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2021.03.026

- Zhao LY, Zhang WH, Liu K, Chen XL, Yang K, Chen XZ, Hu JK. Comparing the efficacy of povidone-iodine and normal saline in incisional wound irrigation to prevent superficial surgical site infection: a randomized clinical trial in gastric surgery. J Hosp Infect. Jan 2023;131:99-106. doi:10.1016/j.jhin.2022.10.005

Evidence tabellen

GRADE assessment

The Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) methodology was used to evaluate the the certainty of the evidence using a minimally contextualized approach for direct, indirect and the complete network meta-analysis evidence sequentially.

Minimally important benefit, -harm, or trivial to no effect was chosen as the target estimate based on the point estimate in relation to the minimally important difference. Considering the inherently different trade-offs between saline, antiseptic and antibiotic irrigation with respect to concerns on resistance and other adverse effects we defined different minimally important differences (MID) for these interventions. In line, the precedent set by the long standing practice to reserve surgical antibiotic prophylaxis for clean-contaminated procedures (unless special considerations such as the use of implant material apply), we defined the MID as 3.5% for the routine use of antibiotic irrigation based on the upper limit of the incidence of SSI in clean procedures at the time (5%) and the RR of SSI after the use of surgical antibiotic prophylaxis in common clean-contaminated procedures (0.35). The MID for other interventions was defined as 2% based on the default for appreciable benefit and harm of 25% and the SSI incidence of 8% without irrigation in the presented data.

Since all included studies are randomised controlled trials, the rating for the GRADE starts high for all direct comparisons. Starting GRADE for the indirect evidence was based on the lowest of the two most dominant first order direct comparisons contributing to the indirect evidence. Starting GRADE for the network meta-analysis evidence was based on the highest certainty of evidence of the contributing direct and indirect evidence or whichever of the two was available.

Each comparison can be downgraded due to one of the following reasons:

- Risk of bias

Of the 41 studies included in the network meta-analysis, four had an overall “High risk of bias”. Due to the network meta-analysis, this may have an effect on all the network estimates of all comparisons. We performed a (network) sensitivity meta-analysis excluding studies with high risk of bias. The results were comparable with the overall analysis, and downgrading for risk of bias was not needed. - Inconsistency

Low, moderate, and high inconsistency were characterized using the first and third quantiles of the empirical distribution of non-pharmacological interventions on subjective outcomes. For the direct evidence, -1 downgrade for inconsistency was necessary for the comparison antibiotic versus antiseptic (I2 = 50.6%, τ2 = 1.12). Coherence was only applied to the network meta-analysis evidence. For the assessment of coherence both the point estimates, confidence intervals and outcomes from the Separate Indirect from Direct Design Evidence node splitting (Appendix 5) analysis were interpreted in context.

Indirectness

Transitivity was only applied to indirect evidence. Due to the broad inclusion criteria and consequential clinical heterogeneity some intransitivity was anticipated. We evaluated transitivity by comparing the SSI incidence in the common control group between the two contributing direct comparisons and considered relative differences larger than 25% sufficient concern for downgrading. - Imprecision

Imprecision was only applied to the final evaluation of the evidence. Imprecision was evaluated taking the minimally important differences into account and assessing the optimal information size in case of large effects by calculating the ratio between the lowest and highest boundary of the confidence interval with a threshold for downgrading of 2.5. - Publication bias

The comparison-adjusted funnel plot showed in Appendix 8 shows no sign of small-study effects.

Network evidence

For all comparisons, both direct and indirect evidence are available. Therefore, we used the highest of the two certainty ratings as the certainty rating for the NMA estimate. The certainty of the network estimate can be upgraded if precision is greater than direct or indirect estimates.

|

Comparison |

Direct evidence |

Indirect evidence |

Network meta-analysis |

||||

|

Relative Risk (95%CI) |

Certainty of evidence |

Relative Risk (95%CI) |

Certainty of evidence |

Relative Risk (95%CI) |

Certainty of evidence |

Target |

|

|

Antibiotic vs antiseptic |

1.07 (0.51 – 2.24) |

ÅOOO very low |

0.64 (0.37 – 1.10) |

ÅÅOO low |

0.77 (0.50 – 1.19) |

ÅOOO very low |

Trivial to no effect |

|

Antibiotic vs saline |

0.57 (0.37 – 0.90) |

ÅÅÅO moderate |

0.59 (0.20 - 1.75) |

ÅOOO very low |

0.56 (0.37 – 0.83) |

ÅÅÅO moderate |

Minimally important benefit |

|

Antibiotic vs no irrigation |

0.19 (0.06 – 0.59) |

ÅÅOO low |

0.55 (0.34 - 0.90) |

ÅOOO very low |

0.46 (0.29 - 0.73) |

ÅÅOO |

Minimally important benefit |

|

Antiseptic vs saline |

0.67 (0.51 – 0.88) |

ÅÅÅÅ high |

1.00 (0.61 – 1.65) |

ÅOOO very low |

0.72 (0.57 – 0.93) |

ÅÅÅÅ high |

Minimally important benefit |

|

Antiseptic vs no irrigation |

0.77 (0.52 – 1.13) |

ÅÅÅO moderate |

0.40 (0.24 – 0.66) |

ÅÅOO low |

0.60 (0.44 – 0.81) |

ÅÅÅÅ high |

Minimally important benefit |

|

Saline vs no irrigation |

0.75 (0.54 – 1.04) |

ÅÅÅO moderate |

1.10 (0.59 – 2.08) |

ÅOOO very low |

0.83 (0.63 – 1.09) |

ÅÅÅO moderate |

Trivial to no effect |

|

Comparison |

Reasons for downgrading |

||

|

Direct evidence |

Indirect evidence |

Network meta-analysis |

|

|

Antibiotic vs antiseptic |

-1 inconsistency -3 imprecision |

-1 imprecision |

-2 imprecision |

|

Antibiotic vs saline |

-1 imprecision |

-3 imprecision -1 intransivity |

-1 imprecision |

|

Antibiotic vs no irrigation |

-2 imprecision |

-1 intransivity |

-1 incoherence |

|

Antiseptic vs saline |

no downgrade |

-3 imprecision

|

no downgrade |

|

Antiseptic vs no irrigation |

-1 imprecision |

-1 intransivity

|

no downgrade |

|

Saline vs no irrigation |

-1 imprecision |

-1 intransitivity -3 imprecision |

-1 imprecision |

GRADE conclusions surgical site infections (SSI)

Antibiotic vs antiseptic

|

Very low GRADE |

Antibiotics solutions may have little to no effect on SSI when compared with antiseptic solutions in surgical patients but the evidence is very uncertain. |

Antibiotic vs saline

|

Moderate GRADE |

Antibiotic solutions likely reduce SSI when compared with saline in surgical patients. |

Antibiotic vs no irrigation

|

Low GRADE |

Antibiotic solutions may result in a reduction of SSI when compared with no irrigation in surgical patients. |

Antiseptic vs saline

|

High GRADE |

Antiseptic solutions result in a reduction of SSI when compared with saline in surgical patients. |

Antiseptic vs no irrigation

|

High |

Antiseptic solutions result in a reduction of SSI when compared with no irrigation in surgical patients. |

Saline vs no irrigation

|

Moderate GRADE |

Saline solutions likely result in little to no difference in SSI when compared with saline in surgical patients. |

Figures and Tables

Figure 1: Forest plot

The forest plot shows the efficacy of different wound irrigation solutions in the prevention of surgical site infections (SSI) compared to no irrigation. Data are relative risk (RR) with corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI).

Table 1: League table

|

Antibiotic |

1.07 [0.51; 2.24] |

0.57 [0.37; 0.90] |

0.19 [0.06; 0.59] |

|

0.77 [0.50; 1.19] |

Antiseptic |

0.67 [0.51; 0.88] |

0.77 [0.52; 1.13] |

|

0.56 [0.37; 0.83] |

0.72 [0.57; 0.93] |

Saline |

0.75 [0.54; 1.04] |

|

0.46 [0.29; 0.73] |

0.60 [0.44; 0.81] |

0.83 [0.63; 1.09] |

No irrigation |

The league table is a square matrix showing all pairwise comparisons in the network meta-analysis. In the lower triangle of the league table the network relative risks (RR) with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI) are shown. The upper triangle shows the relative risks of only the direct comparisons (comparable with a regular pairwise meta-analysis).

For instance, the first column (in the lower triangle) shows the network RR with corresponding 95% CI of antibiotic compared with the other irrigation solutions. The last column (upper triangle) shows the direct RR with corresponding 95% CI of no irrigation compared with the other irrigation solutions.

Table 2: GRADE assessment

|

Comparison |

Direct evidence |

Indirect evidence |

Network meta-analysis |

||||

|

Relative Risk (95%CI) |

Certainty of evidence |

Relative Risk (95%CI) |

Certainty of evidence |

Relative Risk (95%CI) |

Certainty of evidence |

Target |

|

|

Antibiotic vs antiseptic |

1.07 (0.51 – 2.24) |

ÅOOO very low |

0.64 (0.37 – 1.10) |

ÅÅOO low |

0.77 (0.50 – 1.19) |

ÅOOO very low |

Trivial to no effect |

|

Antibiotic vs saline |

0.57 (0.37 – 0.90) |

ÅÅÅO moderate |

0.59 (0.20 - 1.75) |

ÅOOO very low |

0.56 (0.37 – 0.83) |

ÅÅÅO moderate |

Minimally important benefit |

|

Antibiotic vs no irrigation |

0.19 (0.06 – 0.59) |

ÅÅOO low |

0.55 (0.34 - 0.90) |

ÅOOO very low |

0.46 (0.29 - 0.73) |

ÅÅOO |

Minimally important benefit |

|

Antiseptic vs saline |

0.67 (0.51 – 0.88) |

ÅÅÅÅ high |

1.00 (0.61 – 1.65) |

ÅOOO very low |

0.72 (0.57 – 0.93) |

ÅÅÅÅ high |

Minimally important benefit |

|

Antiseptic vs no irrigation |

0.77 (0.52 – 1.13) |

ÅÅÅO moderate |

0.40 (0.24 – 0.66) |

ÅÅOO low |

0.60 (0.44 – 0.81) |

ÅÅÅÅ high |

Minimally important benefit |

|

Saline vs no irrigation |

0.75 (0.54 – 1.04) |

ÅÅÅO moderate |

1.10 (0.59 – 2.08) |

ÅOOO very low |

0.83 (0.63 – 1.09) |

ÅÅÅO moderate |

Trivial to no effect |

Network evidence

For all comparisons, both direct and indirect evidence are available. Therefore, we used the highest of the two certainty ratings as the certainty rating for the NMA estimate. The certainty of the network estimate can be upgraded if precision is greater than direct or indirect estimates.

GRADE = Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation

Elaborate risk of bias assessment

Reasons for exclusion after full text review

|

|

Study |

Reason for exclusion |

|

1 |

Abdelrahman 20201 |

No data available |

|

2 |

Actrn 20202 |

Intra-cavity lavage |

|

3 |

Actrn 20123 |

Outcome, comparison or setting not of interest |

|

4 |

Akhavan-Sigari 20194 |

Conference abstract of included study (Akhavan-Sigari 2020)5 |

|

5 |

Aneja 20226 |

Study protocol |

|

6 |

Arslan 20207 |

No randomisation |

|

7 |

Baker 19948 |

Before the year 2000 |

|

8 |

Bhandari 20159 |

Outcome, comparison or setting not of interest |

|

9 |

Bourgeois 198510 |

Before the year 2000 |

|

10 |

Calkins 201911 |

Same data as Calkins 202012 |

|

11 |

Calkins 202012 |

Outcome, comparison or setting not of interest |

|

12 |

Conover 198413 |

Before the year 2000 |

|

13 |

Ctri 202314 |

Study protocol |

|

14 |

Ctri 202215 |

Study registration: no data available |

|

15 |

Ctri 202116 |

Study registration: no data available |

|

16 |

Ctri 202117 |

Study registration: intra-cavity lavage |

|

17 |

Ctri 201218 |

Study registration: no data available |

|

18 |

De Jong 198219 |

Before the year 2000 |

|

19 |

Dineen 201520 |

No randomisation |

|

20 |

Donnenfeld 198621 |

Before the year 2000 |

|

21 |

Drks 202222 |

Intra-cavity lavage |

|

22 |

Drks 201423 |

No randomisation |

|

23 |

Drks 201324 |

Study registration: no data available |

|

24 |

Elliott 198625 |

Before the year 2000 |

|

25 |

Englund 201926 |

No randomisation |

|

26 |

Euctr 201727 |

Study protocol of included study (Mueller 2023)28 |

|

27 |

Freischlag 198429 |

Before the year 2000 |

|

28 |

Greig 198730 |

Before the year 2000 |

|

29 |

Hargrove 200631 |

Outcome, comparison or setting not of interest |

|

30 |

Harrigill 200332 |

Intra-cavity lavage |

|

31 |

Irct20140503017537N, 201933 |

Study protocol |

|

32 |

Irct20200126046261N, 202034 |

Study protocol |

|

33 |

Isrctn 200535 |

Intra-cavity lavage |

|

34 |

Karuserci 202136 |

Same data as included study (Karuserci 2022)37 |

|

35 |

Kellum 198538 |

Before the year 2000 |

|

36 |

Ko 199239 |

Before the year 2000 |

|

37 |

Lavery 198640 |

Before the year 2000 |

|

38 |

Levin 198341 |

Before the year 2000 |

|

39 |

Lindsey 198242 |

Before the year 2000 |

|

40 |

Liu 201743 |

Intra-cavity lavage |

|

41 |

Lord 198344 |

Before the year 2000 |

|

42 |

Lord 197745 |

Before the year 2000 |

|

43 |

Maatman 201946 |

Intra-cavity lavage |

|

44 |

Maemoto 202147 |

Study protocol of included study (Maemoto 2023)48 |

|

45 |

Magann 199349 |

Before the year 2000 |

|

46 |

Mahomed 201650 |

Conference abstract of included study (Mahomed 2016)51 |

|

47 |

Marti 197952 |

Before the year 2000 |

|

48 |

Mashbari 201853 |

Intra-cavity lavage |

|

49 |

Mathelier 199254 |

Before the year 2000 |

|

50 |

Mohd 201055 |

Outcome, comparison or setting not of interest |

|

51 |

Moradi 201956 |

Intra-cavity lavage |

|

52 |

Mueller 201757 |

Study protocol of included study (Mueller 2023)28 |

|

53 |

Nct 202258 |

Study protocol |

|

54 |

Nct 202259 |

Study protocol |

|

55 |

Nct 202260 |

Study protocol |

|

56 |

Nct 202061 |

Study protocol |

|

57 |

Nct 202062 |

Study protocol of included study (Emile 2020)63 |

|

58 |

Nct 201964 |

Study protocol of included study (Strobel 2020)65 |

|

59 |

Nct 201866 |

Study protocol |

|

60 |

Nct 201867 |

Study protocol of included study (Emile 2020)63 |

|

61 |

Nct 201768 |

Intra-cavity lavage |

|

62 |

Nct 201669 |

Intra-cavity lavage |

|

63 |

Nct 201570 |

Same data as included study (Nguyen 2021)71 |

|

64 |

Nct 201572 |

Study protocol of included study (Cohen 2020)73 |

|

65 |

Nct 201474 |

Outcome, comparison or setting not of interest |

|

66 |

Nct 201275 |

No data available |

|

67 |

Nct 201276 |

Study protocol of included study (Etaati 2012)77 |

|