Triclosan gecoate hechtingen

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is het effect van het gebruik van met triclosan gecoate hechtingen versus niet-gecoate hechtingen bij volwassen patiënten die chirurgische ingrepen ondergaan op de preventie van postoperatieve wondinfecties (POWI’s)?

Aanbeveling

Overweeg het gebruik van triclosan gecoate hechtingen bij chirurgische patiënten ter preventie van postoperatieve wondinfecties.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

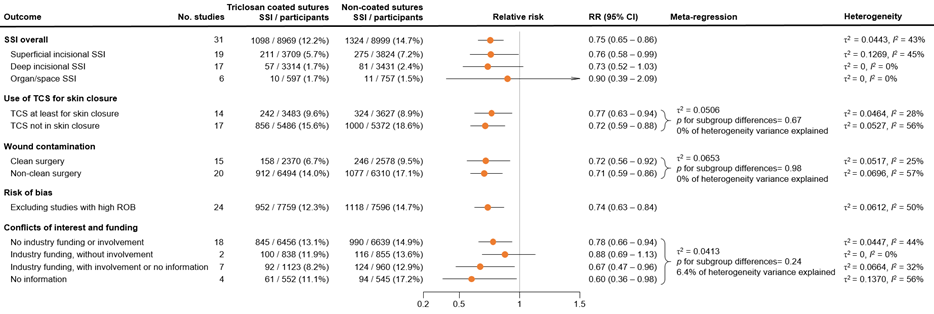

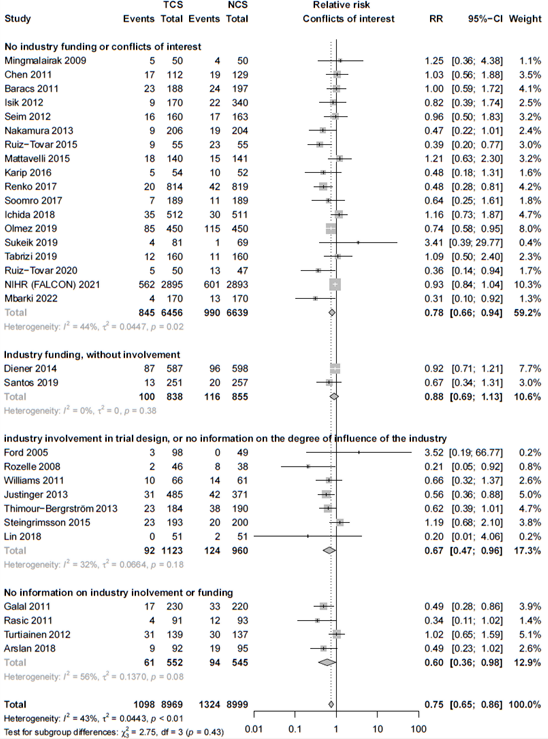

De systematische literatuur analyse en meta-analyse van Jalalzadeh (2023, ongepubliceerd) onderzocht het effect van triclosan gecoate hechtingen (TCS) op het ontstaan van postoperatieve wondinfecties (POWI’s) in patiënten die chirurgie ondergaan. Er werd bewijs met redelijke GRADE gevonden dat het risico op POWI vermindert met het gebruik van TCS, in vergelijking met vergelijkbare niet-gecoate hechtingen (NCS) (RR 0.75; 95%CI 0.65 - 0.86).

Het gunstige effect werd vooral gezien voor oppervlakkige POWI (RR 0,76; 95% CI 0,58 - 0,99) en diepe POWI (RR 0,73; 95% CI 0,58 - 1,03). Orgaan/anatomische ruimte POWI had een zeer lage incidentie in zowel de TCS-groep (1,7%) als de NCS-groep (1,5%) en vertoonde geen SSI-reductie (RR 0,90; 95% CI 0,39 - 2,09). Meta-regressie analyse liet zien dat het gunstige effect van TCS generaliseerbaar was tussen schone en niet-schone chirurgische wonden, evenals het gebruik van TCS in ten minste de huidlaag (huid, subcutis en fascie) versus alleen in diepere lagen. In de sensitiviteitsanalyse van studies met een laag risico op bias bleek het effect robuust (RR 0,74; 95% CI 0,63 - 0,84). Bovendien liet de trial sequential analysis zien dat er voldoende bewijs bestaat voor een relatieve risicovermindering van 15% en dat het onwaarschijnlijk is dat meer bewijs de richting van de effectschatter zal veranderen.

Bijwerkingen door TCS zijn ook onderzocht, hoewel dit slechts in zeven van de 31 studies werd vermeld. In geen van de onderzoeken werd vermoed dat de bijwerkingen verband hielden met het gebruik van TCS. Triclosan resistentie werd in geen van de studies onderzocht.

Overige effecten van de interventie

Resistentie

Triclosan is een antisepticum (desinfectans) dat niet alleen in de gezondheidszorg wordt toegepast, maar in veel hogere concentraties wordt toegevoegd aan consumentenproducten zoals zeep, tandpasta. Intrinsieke bacteriële resistentie voor triclosan is beschreven (Poole, 2002; Webber, 2008). Het gebruik van triclosan kan – net als andere antiseptica – volgens in vitro onderzoek bijdragen aan het ontstaan van (verworven) bacteriële resistentie tegen triclosan, en kan volgens recent (in vitro) onderzoek ook resulteren in kruisresistentie tegen belangrijke antibiotica (Chuanchuen, 2001; Yazdankhah, 2006; Zhang, 2023).

De klinische relevantie van de zeer lage concentratie triclosan in hechtingen en potentiële impact - van een veel lagere concentratie vergeleken met die in consumentenproducten - op intrinsieke en verworven triclosan resistentie is nog onduidelijk door gebrek aan klinische data. Datzelfde geldt voor de mate waarin triclosan gebruik bijdraagt aan de ontwikkeling en selectie van antibiotica resistentie.

Het mogelijk ontstaan van antibiotica resistentie als ongewenst effect van het gebruik van desinfectantia heeft recent geleid tot aanbevelingen om het gebruik van desinfectantia, waaronder triclosan en chloorhexidine, te beperken tot die situaties waarin effectiviteit is aangetoond (Gezondheidsraad, 2016). Voor het gebruik van triclosan gecoate hechtingen is de vereiste doeltreffendheid bewezen. Daarom is het belangrijk om het effect van triclosan gecoate hechtingen op minder antibiotische druk door het verlagen van de incidentie van POWI’s af te wegen tegen de potentiële bijdrage van het gebruik van triclosan gecoate hechtingen aan het ontstaan van antibioticaresistentie (kruisresistentie). Daarnaast ontbreekt inzicht in de relatieve bijdrage van het gebruik van triclosan in chirurgische hechtingen aan antimicrobiële resistentie in vergelijking tot het gebruik van triclosan in consumentenproducten en andere toepassingen.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

Er zijn geen voorkeuren van patiënten met betrekking tot het gebruik van TCS omdat deze hechtingen niet leiden tot meer schadelijke effecten op patiënt gerelateerde uitkomsten.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

POWI is een dure complicatie en daarom draagt het voorkomen van SSI meer bij aan kostenreductie dan het verschil in kosten tussen individuele hechtingen.

Er zijn twee studies gevonden die de kosteneffectiviteit van TCS in alle typen chirurgie hebben onderzocht.

In Leaper (2017) werd een meta-analyse uitgevoerd in 34 gerandomiseerde en niet-gerandomiseerde studies.

- Alle wondklassen (schoon, schoon-besmet, en besmette wonden), werd een gemiddeld besparing per operatie gevonden van €65,23 (90% betrouwbaarheidsinterval van €19,83 tot €120,87) door het gebruik van TCS.

- Schone chirurgische wonden werd een kostenbesparing van gemiddeld €285,93 (90% BI €72,24 tot €541,91) gevonden. In besmette en vieze wonden werd een besparing van €105,09 (€57,15 tot 164,41) per operatie gevonden.

In Singh (2014) werd bij het gebruik van TCS gemiddeld $4,109–$13,975 bespaard door het ziekenhuis (kosten TCS en extra ligdagen bij POWI), $4,133–$14,297 door de betalende partij (kosten TCS en ziekenhuisopname/behandelingskosten), en $40,127–$53,244 besparing door de maatschappij (ziekenhuisopname/behandelingskosten, productiviteitsverlies en mortaliteit) per voorkomen POWI SSI als een operatie minstens een 15% POWI risico heeft.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

TCS zijn wijd verkrijgbaar en gemakkelijk te gebruiken. Er lijken geen belemmeringen te zijn wat betreft de haalbaarheid van implementatie in de klinische praktijk.

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

Er lijkt een gunstig effect van het gebruik van triclosan gecoate hechtingen (TCS) ten opzichte van niet-antimicrobiële hechtingen bij de preventie van POWI bij chirurgische patiënten. Dit effect wordt gezien in alle wondklassen samen (de vier contaminatiegraden schoon, schoon-gecontamineerd, gecontamineerd, infectieus/vies), evenals voor elke afzonderlijke wondklassen (schoon en niet-schoon). Bovendien blijken uit de literatuur geen nadelige gevolgen voor de patiënt bij het gebruik van TCS. Triclosan resistentie en kruisresistentie tegen belangrijke antibiotica zijn in vitro beschreven naar aanleiding van gebruik in consumentenproducten zoals tandpasta, maar de klinische relevantie en impact van de lage concentraties van triclosan in hechtingen hierop zijn nog onduidelijk, en reductie van POWI’s door triclosan gecoate hechtingen vermindert antibiotische druk. Uit twee kosteneffectiviteitsanalysen blijkt dat het gebruik van TCS kosteneffectief is.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

POWI’s zijn een veelvoorkomende complicatie bij alle chirurgische specialismen, resulterend in verhoogde morbiditeit en mortaliteit. Er wordt gesuggereerd dat hechtingen een potentieel broeiplaats voor infecties zouden kunnen zijn, aangezien bacteriën zich aan hechtingen kunnen hechten en biofilms kunnen vormen met een verhoogde kans op infectie (Henry-Stanley 2010; Kathju 2013). Triclosan (TCS), een bacteriedodend middel, is toegepast op hechtingen om kolonisatie op het oppervlak van de hechting te remmen en de kans op POWI te minimaliseren (Barbolt 2002). In het afgelopen decennium hebben gerandomiseerde studies naar de doeltreffendheid van met TCS gecoate hechtingen enige inconsistentie in de resultaten laten zien, evenals verschillende meta-analyses die op inconsistente wijze diverse studies al dan niet hebben opgenomen of uitgesloten. Daarom is voor deze module gekozen om een update uit te voeren op de beoordeling van de bewijskracht op het gebruik van TCS voor de preventie van SSI. Het effect van andere antimicrobieel gecoate hechtingen wordt in deze module buiten beschouwing gelaten.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

Surgical site infections

|

Moderate GRADE |

Using antimicrobial triclosan-coated sutures likely reduces the number of surgical site infections when compared with no antimicrobial triclosan-coated sutures in patients undergoing surgical procedures.

Sources: Jalalzadeh (2023, submitted) |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

Systematic reviews

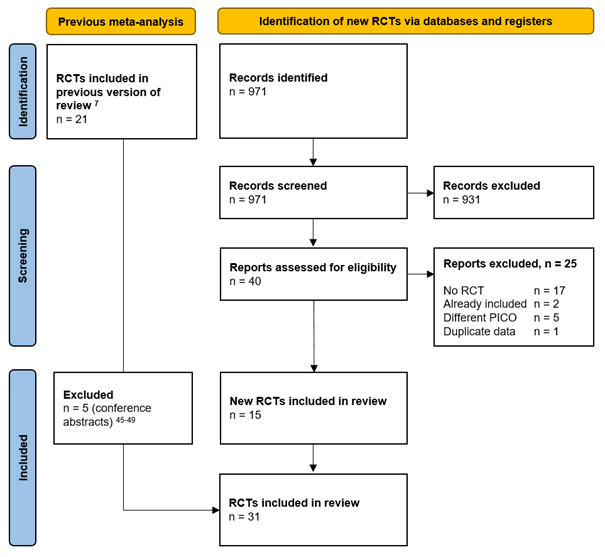

The systematic review of Jalalzadeh (2023, submitted) investigated the effect of triclosan-coated sutures in the prevention of surgical site infections, which was an update of a previously published systematic review (De Jonge, 2016).

All published randomized controlled trials comparing the effect of triclosan-coated sutures on the incidence of surgical site infections with the same, but uncoated, sutures were included. In vitro studies, animal studies, non-randomized studies, and studies with incomparable suture types in the control group were excluded. In total, Jalalzadeh (2023, submitted) included 31 trials, comprehending a total of 8969 patients randomized to triclosan-coated sutures and 8999 to standard sutures without triclosan coating (Arslan, 2014; Baracs, 2011; Chen, 2011; Diener, 2014; Diener, 2014; Ford, 2005; Galal, 2011; Ichida 2018; Isik, 2011; Justinger, 2013; Karip 2016; Lin, 2018; Mattavelli, 2015; Mbarki, 2022; Mingmalairak, 2009; Nakamura, 2013; NIHR, 2021; Olmez, 2019; Rasic, 2011; Renko, 2017; Rozelle, 2008; Ruiz-Tovar, 2015; Ruiz-Tovar, 2020; Santos, 2019; Seim, 2012; Soomro, 2017; Steingrimsson, 2015; Sukeik, 2019; Thimour-Bergstrom, 2013; Turtianen, 2012; Williams, 2011) and in thirteen additional trials (Arslan, 2018; Ichida, 2018; Lin, 2018; NIHR, 2021; Olmez, 2019; Renko, 2016; Ruiz-Tovar, 2019; Ruiz-Tover, 2015; Santos, 2019; Soonro, 2017; Steingrimsson, 2015; Sukeik, 2019; Tabrizi, 2019). The risk of bias was assessed with the Cochrane Collaboration’s tool and publication bias was assessed using a funnel plot. The reported outcome in Jalalzadeh (2023, submitted) was the incidence of surgical site infections.

Randomized controlled trials

The randomized controlled trial of Mbarki (2022) investigated the effect of triclosan-coated sutures with sutures without triclosan coating in patients undergoing obstetric surgery. In total, 340 patients were included and randomly assigned to either the intervention (n=170) group who received triclosan-coated sutures or the control group (n=170) who received sutures without triclosan coating. Ten participants in the intervention group were lost to follow-up compared to twelve participants in the control group. The length of follow-up was 30 days after surgery. The reported outcome in the trial was the incidence of surgical site infections.

The NIHR Global Research Health Unit on Global Surgery (2021) investigated the effect of triclosan-coated sutures with sutures without triclosan coating in patients undergoing abdominal surgery. In total, 5788 patients were included and randomly assigned to either the intervention (n=2895) group who received triclosan-coated sutures or the control group (n=2893) who received sutures without triclosan coating. Eighteen participants in the intervention group were lost to follow-up compared to twelve participants in the control group. The length of follow-up was 30 days after surgery. The reported outcome in the trial was the incidence of surgical site infections.

The randomized controlled trial of Olmez (2019) investigated closure of fascia with triclosan-coated sutures with standard sutures in patients who underwent abdominal surgery. In total, 900 patients were included and randomly assigned to either the intervention group (n=450) who received triclosan-coated sutures or the control group (n=450) who received standard sutures without triclosan coating. Two patients in the intervention group were lost to follow-up compared to four patients in the control group. The length of follow-up was fourteen days after surgery. The reported outcome in the trial was the incidence of surgical site infections.

The randomized controlled trial of Ruiz-Tovar (2019) compared the effect of triclosan-coated barbed sutures with non-barbed triclosan-free sutures in the closure of abdominal fascia in patients undergoing emergent surgery. In total, 100 patients were included and randomly assigned to either the intervention group (n=50) who received triclosan-coated barbed sutures or the control group (n=50) who received non-barbed triclosan-free sutures. None of the patients were lost to follow-up. The length of follow-up was 30 days after surgery. The reported outcome in the trial was the incidence of surgical site infections.

The randomized controlled trial of Santos (2019) investigated the efficacy of triclosan-coated sutures compared to non-antibiotic sutures in saphenectomy wounds of patients undergoing coronary artery bypass graft surgery. In total, 508 patients were included and randomly assigned to either the intervention group (n=251) who received triclosan-coated sutures or the control group (n=257) who received non-antibiotic sutures. None of the patients were lost to follow-up. The length of follow-up was 30 days after surgery. The reported outcome in the trial was the incidence of surgical site infections.

The randomized controlled trial of Sukeik (2019) investigated the effect of triclosan-coated sutures compared with non-coated sutures on wound healing in patients undergoing primary hip- and knee arthroplasties. In total, 150 patients were included and randomly assigned to either the intervention group (n=81) who received triclosan-coated sutures or the control group (n=69) who received non-coated sutures. None of the patients were lost to follow-up. The length of follow-up was six weeks after surgery. The reported outcome in the trial was the incidence of surgical site infections.

The randomized controlled trial of Tabrizi (2019) investigated the effect of triclosan-coated sutures compared with sutures without triclosan coating in patients undergoing dental implant surgery. In total, 320 patients were included and randomly assigned to either the intervention group (n=160) who received triclosan-coated sutures or the control group (n=160) who received sutures without triclosan coating. None of the patients were lost to follow-up. The length of follow-up was 28 days after surgery. The reported outcome in the trial was the incidence of surgical site infections.

The randomized controlled trial of Arslan (2018) investigated the effect of triclosan-coated sutures compared with monofilament polypropylene retention sutures in patients undergoing surgery for pilonidal disease. In total, 187 patients were included and randomly assigned to either the intervention group (n=92) who received triclosan-coated sutures or the control group (n=95) who received polypropylene retention sutures. None of the patients were lost to follow-up. The length of follow-up was 30 days after surgery. The reported outcome in the trial was the incidence of surgical site infections.

The randomized controlled trial of Ichida (2018) investigated the effect of triclosan-coated sutures compared with sutures without triclosan-coating in patients undergoing gastroenterological surgery with abdominal wound closure. In total, 1023 patients were included and randomly assigned to either the intervention group (n=512) who received triclosan-coated sutures or the control group (n=511) who received sutures without a triclosan coating. None of the patients were lost to follow-up. The length of follow-up was 30 days after surgery. The reported outcome in the trial was the incidence of surgical site infections.

The randomized controlled trial of Lin (2018) investigated the effect of triclosan-coated sutures compared with standard sutures in patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty. In total, 102 patients were included and randomly assigned to either the intervention group (n=51) who received triclosan-coated sutures or the control group (n=51) who received standard sutures. None of the patients were lost to follow-up. The length of follow-up was three months after surgery. The reported outcome in the trial was the incidence of surgical site infections.

The randomized controlled trial of Soomro (2017) investigated the effect of triclosan-coated polyglactin sutures compared with plain polyglactin sutures in patients undergoing breast surgery. In total, 378 patients were included and randomly assigned to either the intervention group (n=189) who received triclosan-coated sutures or the control group (n=189) who received standard sutures. None of the patients were lost to follow-up. The length of follow-up was 30 days after surgery. The reported outcome in the trial was the incidence of surgical site infections.

The randomized controlled trial of Karip (2016) investigated the effect of triclosan-coated sutures compared with standard sutures in patients undergoing Karydaki flap repair for pilonidal disease. In total, 36 patients were included and randomly assigned to either the intervention group (n=16) who received triclosan-coated sutures or the control group (n=20) who received standard sutures. None of the patients were lost to follow-up. The length of follow-up was six months after surgery. The reported outcome in the trial was the incidence of surgical site infections.

The randomized controlled trial of Renko (2016) investigated the effect of sutures coated or impregnated with triclosan compared with ordinary absorbing sutures in children younger than eighteen years undergoing elective or emergency surgery. In total, 1633 children were included and randomly assigned to either the intervention group (n=814) who received ordinary absorbing sutures or the control group (n=819) who received ordinary absorbing sutures. None of the patients were lost to follow-up. The length of follow-up was 30 days after surgery. The reported outcome in the trial was the incidence of surgical site infections.

The randomized controlled trial of Ruiz-Tovar (2015) compared the effect of triclosan-coated sutures with ordinary sutures in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting. In total, 110 patients were included and randomly assigned to either the intervention group (n=55) who received triclosan-coated barbed sutures or the control group (n=55) who received ordinary sutures. None of the patients were lost to follow-up. The length of follow-up was 60 days after surgery. The reported outcome in the trial was the incidence of surgical site infections.

The randomized controlled trial of Steingrimsson (2015) compared the effect of triclosan-coated sutures with sutures without triclosan coating in the closure of the abdominal wall in patients with fecal peritonitis. In total, 393 patients were included and randomly assigned to either the intervention group (n=193) who received triclosan-coated sutures or the control group (n=200) who received sutures without triclosan coating. Seventeen patients in the intervention group and twelve patients in the control group were lost to follow-up. The length of follow-up was 60 days after surgery. The reported outcome in the trial was the incidence of surgical site infections.

Results

Surgical site infections (critical)

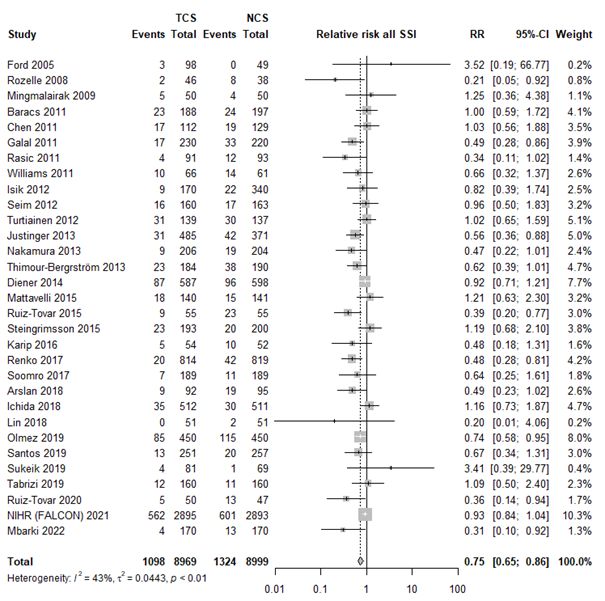

Surgical site infections were reported in 31 trials, retrieved from the systematic review Jalalzadeh (2023, submitted) (Arslan, 2014; Baracs, 2011; Chen, 2011; Diener, 2014; Diener, 2014; Ford, 2005; Galal, 2011; Ichida 2018; Isik, 2011; Justinger, 2013; Karip 2016; Lin, 2018; Mattavelli, 2015; Mbarki, 2022; Mingmalairak, 2009; Nakamura, 2013; NIHR, 2021; Olmez, 2019; Rasic, 2011; Renko, 2017; Rozelle, 2008; Ruiz-Tovar, 2015; Ruiz-Tovar, 2020; Santos, 2019; Seim, 2012; Soomro, 2017; Steingrimsson, 2015; Sukeik, 2019; Thimour-Bergstrom, 2013; Turtianen, 2012; Williams, 2011) and in thirteen additional trials (Arslan, 2018; Ichida, 2018; Lin, 2018; NIHR, 2021; Olmez, 2019; Renko, 2016; Ruiz-Tovar, 2019; Ruiz-Tover, 2015; Santos, 2019; Soonro, 2017; Steingrimsson, 2015; Sukeik, 2019; Tabrizi, 2019).

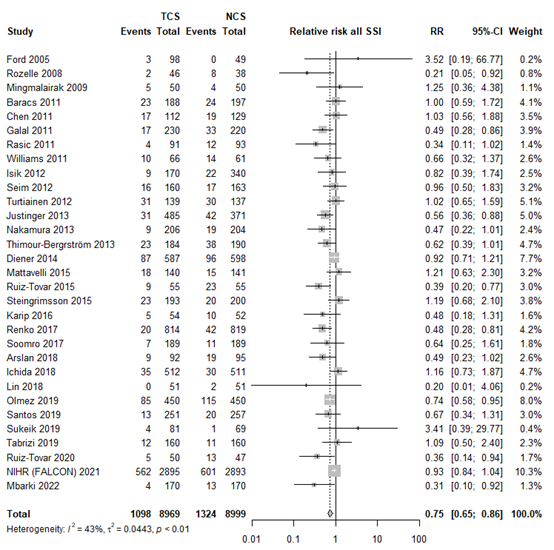

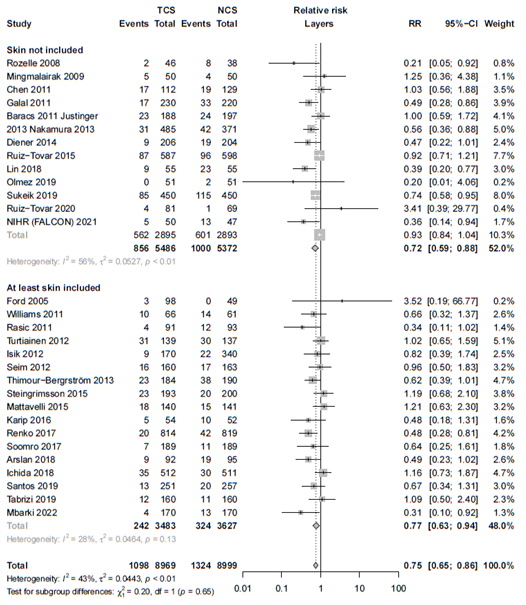

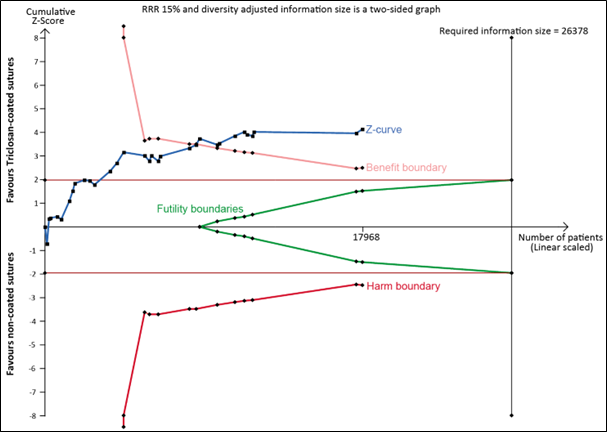

The results were pooled in a meta-analysis. The pooled number of surgical site infections in the triclosan-coated sutures group was 1098/8969 (12.2%), compared to 1324/8999 (14.7%) in the non-triclosan coated sutures group. This resulted in a pooled relative risk ratio (RR) of 0.75 (95% CI 0.65 to 0.86), in favor of the triclosan-coated sutures group (figure 1). This was considered as a clinically relevant difference.

Figure 1. Forest plot showing the comparison between triclosan-coated sutures and non-triclosan coated sutures for surgical site infections. Pooled relative risk ratio, random effects model. Z: p-value of overall effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2; statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval.

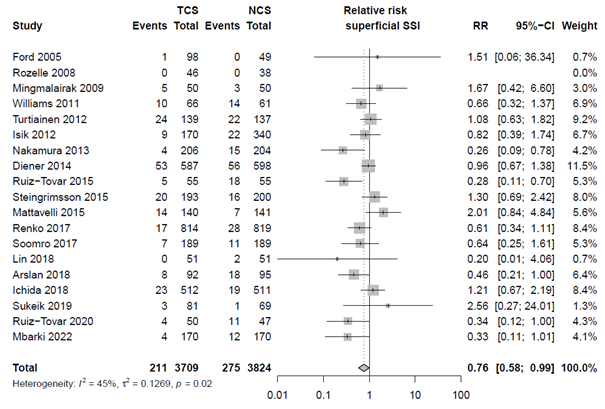

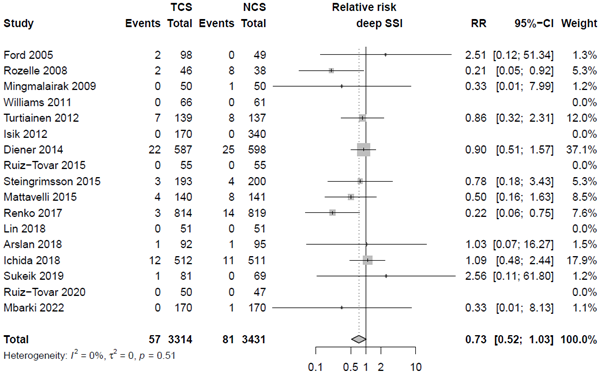

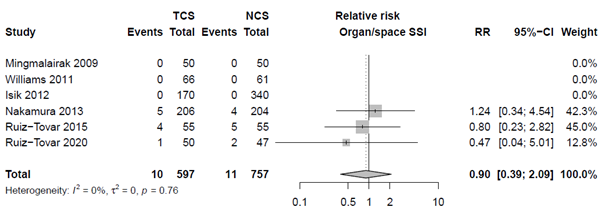

Type of SSI

Nineteen studies categorized SSI into subtypes of SSI. For studies specifically investigating superficial infection, we found an RR of 0.76 (95% CI 0.58 - 0.99), for deep SSI an RR of 0.73 (95% CI 0.52 - 1.03) and for organ/space infections we found an RR of 0.90 (95% CI 0.39 - 2.09). The results are shown in Forest plots of secondary outcomes.

Subgroup and sensitivity analyses

In fourteen RCTs, TCS were investigated being applied in at least at the skin layer (RR 0.77; 95% CI 0.63 - 0.84). In remaining studies, TCS were investigated being applied only in the deeper layers (RR 0.72; 95% CI 0.59 - 0.88). Subgroup and meta-regression analysis indicated comparable results in both groups (τ2 = 0.0506, p-value for subgroup differences= 0.67, 0% of heterogeneity variance explained).

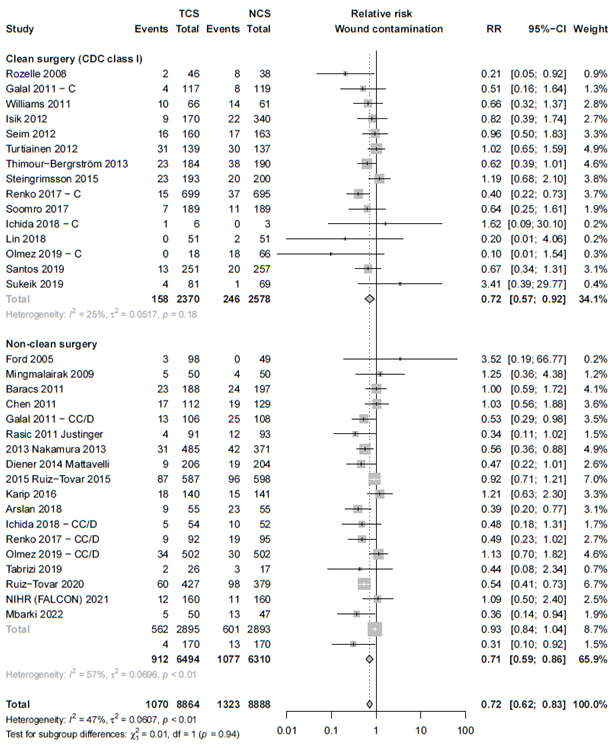

We found comparable efficacy for patients with clean surgical wounds (RR 0.72; 95% CI 0.56 – 0.92) and non-clean surgical wounds (RR 0.71; 95% CI 0.59 – 0.86) compared to the overall analysis (τ2 = 0.0506, p-value = 0.67).

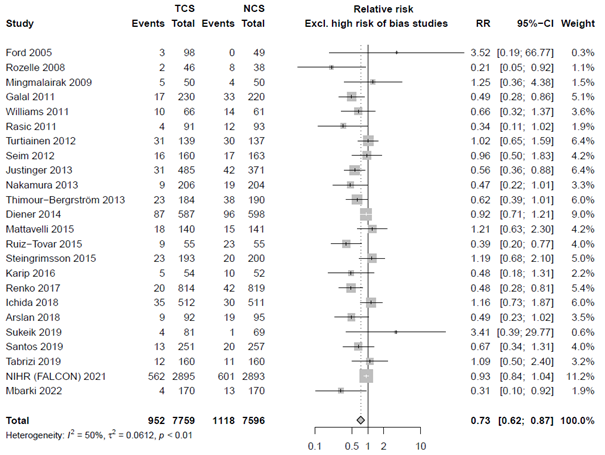

In the sensitivity analysis, excluding studies with high risk of bias we found an RR of 0.74 (95% CI 0.63 – 0.84). Sensitivity analysis of 18 studies without conflicts of interest and industry funding resulted in a similar summary effect estimate as the overall analysis (RR 0.78, 95% CI 0.65 - 0.94).

We were unable to perform an analysis comparing TCS in open abdominal versus laparoscopic abdominal procedures, since 10 studies included only open procedures, and three studies included both open and laparoscopic procedures.

The results of the subgroup and sensitivity analyses can be found in Forest plots of secondary outcomes, figure 3 and Forest plots for subgroup and sensitivity analyses - see tab "evidence tabellen".

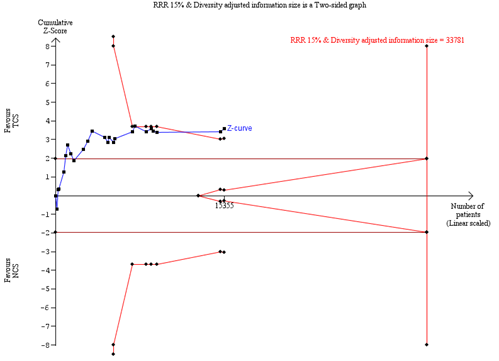

Trial sequential analysis

In the TSA of all trials in the meta-analysis, the cumulative Z-curve crossed the trial sequential monitoring boundary for benefit, indicating that sufficient evidence exists for a 15% relative risk reduction in SSI (Trial sequential analysis). This result was substantiated in a sensitivity TSA excluding studies with high risk of bias (Trial sequential analysis). This means that further evidence is unlikely to modify the direction of the effect estimate.

Adverse events

Adverse events were mentioned in seven studies. In none of the studies the adverse events were suspected to be related to the use of TCS, see Table 1.

|

Arslan 2018 |

not reported |

|

Baracs 2011 |

not reported |

|

Chen 2011 |

not reported |

|

Diener 2014 |

“The reported rate of serious adverse events did not differ between the groups.” |

|

Ford 2005 |

“None of the adverse events were device-related, and there was no difference between treatment groups.” |

|

Galal 2011 |

not reported |

|

Ichida 2018 |

not reported |

|

Isik 2012 |

not reported |

|

Justinger 2013 |

not reported |

|

Karip 2016 |

not reported |

|

Lin 2018 |

“Triclosan-coated sutures did not cause adverse local or systemic reactions: similar changes in serial inflammatory response occurred in both groups.” |

|

Mattavelli 2015 |

not reported |

|

Mbarki 2022 |

not reported |

|

Mingmalairak 2009 |

“No complication related suture was identified after follow-up of 1 year.” |

|

Nakamura 2013 |

not reported |

|

NIHR 2021 |

“Serious adverse events were predefined as mortality, allergy, or combustion. There were no reports of combustions or allergic events.” |

|

Olmez 2019 |

not reported |

|

Rasic 2011 |

not reported |

|

Renko 2017 |

“The absorbable sutures did not resorb as expected in 45 (6%) of 778 in the triclosan group and in 46 (6%) of 779 in the control group (table 3). No other adverse events were reported in either of the groups.” |

|

Rozelle 2008 |

“No suture-related adverse events were reported in either group.” |

|

Ruiz-Tovar 2015 |

not reported |

|

Ruiz-Tovar 2020 |

not reported |

|

Santos 2020 |

not reported |

|

Seim 2012 |

not reported |

|

Soomro 2017 |

not reported |

|

Steingrimsson 2015 |

not reported |

|

Sukeik 2019 |

not reported |

|

Tabrizi 2019 |

not reported |

|

Thimour Bergrstrom 2013 |

not reported |

|

Turtianen 2012 |

not reported |

|

Williams 2011 |

not reported |

Table 1 Adverse events as reported in the included randomized controlled trials

Level of evidence of the literature

Surgical site infections (critical)

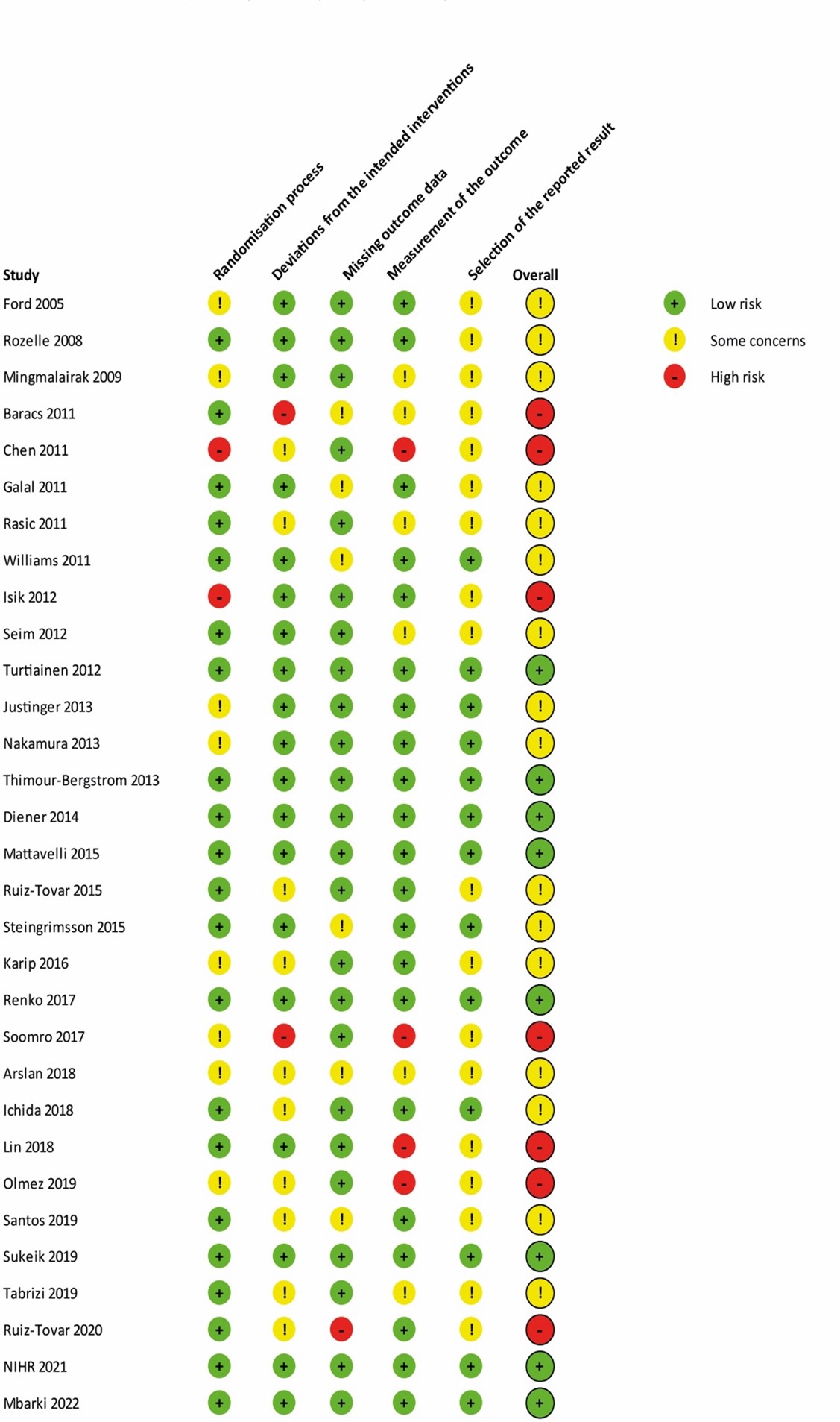

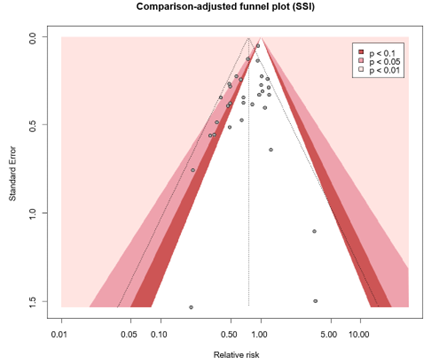

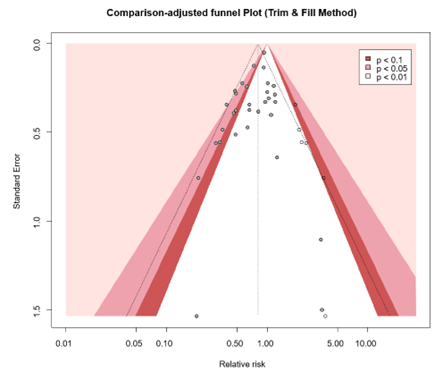

The level of evidence regarding the outcome surgical site infections was derived from randomized controlled trials and therefore started high. The risk of bias was assessed as not serious because the results of sensitivity analysis excluding studies with high risk of bias were comparable to the overall analysis. Inconsistency was deemed serious because signs of statistical heterogeneity were present (τ2 = 0.0443, I2 = 43%, χ2 p <0.01), resulting in a downgrade for this domain. All included studies reported in the same population (surgical patients), intervention (TCS), control (non-coated sutures) and outcome (SSI), indicating no indirectness. Regarding imprecision, it was assessed as not serious as the overall 95% CI of the treatment effect did not cross the thresholds of minimally clinically important benefit or harm. A comparison-adjusted funnel plot was generated and showed some asymmetry, revealing signs of small-study effects (Comparison-adjusted funnel plot for primary outcome SSI). Subsequently, we performed the Egger’s test which indicated the presence of publication bias (intercept: -0.8294, CI -0.0448 to 0.0669, p = 0.015). We performed the trim and fill method, resulting in the imputation of six missing studies (Comparison-adjusted funnel plot after trim and fill analysis) corresponding to an adjusted RR of 0.81 (95% CI 0.70 - 0.94). Hence, no downgrade was done for publication bias.

Adverse events

Adverse events were poorly reported, and no GRADE could be performed.

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question: What is the effect of using triclosan-coated sutures (c) versus non-coated sutures (i) in adult patients undergoing surgical procedures (p) in the prevention of SSI?

P: Patients undergoing any surgical procedure

I: Antimicrobial triclosan coated sutures

C: Sutures without antimicrobial triclosan coating

O: Surgical site infections, adverse events

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered surgical site infections (SSI) and adverse events as a critical outcome measure for decision making.

The working group defined a threshold of 10% for continuous outcomes and a relative risk (RR) for dichotomous outcomes of <0.80 and >1.25 as a minimal clinically (patient) important difference.

Search and select (Methods)

We performed an update of a previously published systematic review (de Jonge, 2017) and searched in Embase and Ovid/Medline for publications from January 2015 up to March 14th 2023, for RCTs comparing wound closure with TCS to the exact same but uncoated sutures with outcome SSI in surgical patients. Search terms included: sutures, triclosan, polyglactin, monocryl, polydiaxanone, vicryl, polyglactin 910, antiseptic, antimicrobial, surgical site infection. There were no restrictions on language of publication. Studies published prior to the year 1990, in vitro studies, animal studies, and studies with non-comparable suture types in the control group were all excluded. Additionally, we excluded conference abstracts, including those included in the previous meta-analysis, since they provide little information, and are frequently variable in terms of reliability, accuracy, and level of detail. (Cochrane handbook chapter 5) The detailed search strategy is available on request via https://richtlijnendatabase.nl/.

Forty studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, 25 studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion in Reasons for exclusion after full text review and fifteen additional studies were included, totaling to 31 included studies comprising 17,968 patients (Summary of literature).

Results

Thirty-one studies and 17,968 patients were included in the analysis of the literature. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- Arslan NC, Atasoy G, Altintas T, Terzi C. Effect of triclosan-coated sutures on surgical site infections in pilonidal disease: prospective randomized study. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2018 Oct;33(10):1445-1452. doi: 10.1007/s00384-018-3138-z. Epub 2018 Jul 30. PMID: 30062657.

- Barbolt TA. Chemistry and safety of triclosan, and its use as an antimicrobial coating on Coated VICRYL* Plus Antibacterial Suture (coated polyglactin 910 suture with triclosan). Surg Infect (Larchmt). 2002;3 Suppl 1:S45-53. doi: 10.1089/sur.2002.3.s1-45. PMID: 12573039.

- <span data-teams="true">Chuanchuen R, Beinlich K, Hoang TT, Becher A, Karkhoff-Schweizer RR, Schweizer HP. Cross-resistance between triclosan and antibiotics in Pseudomonas aeruginosa is mediated by multidrug efflux pumps: exposure of a susceptible mutant strain to triclosan selects nfxB mutants overexpressing MexCD-OprJ. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2001 Feb;45(2):428-32. doi: 10.1128/AAC.45.2.428-432.2001. PMID: 11158736; PMCID: PMC90308

- Henry-Stanley MJ, Hess DJ, Barnes AM, Dunny GM, Wells CL. Bacterial contamination of surgical suture resembles a biofilm. Surg Infect (Larchmt). 2010 Oct;11(5):433-9. doi: 10.1089/sur.2010.006. PMID: 20673144; PMCID: PMC2967823.

- Ichida K, Noda H, Kikugawa R, Hasegawa F, Obitsu T, Ishioka D, Fukuda R, Yoshizawa A, Tsujinaka S, Rikiyama T. Effect of triclosan-coated sutures on the incidence of surgical site infection after abdominal wall closure in gastroenterological surgery: a double-blind, randomized controlled trial in a single center. Surgery. 2018 Mar 10:S0039-6060(17)30893-0. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2017.12.020. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 29402448.

- Karde PA, Sethi KS, Mahale SA, Mamajiwala AS, Kale AM, Joshi CP. Comparative evaluation of two antibacterial-coated resorbable sutures versus noncoated resorbable sutures in periodontal flap surgery: A clinico-microbiological study. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2019 May-Jun;23(3):220-225. doi: 10.4103/jisp.jisp_524_18. PMID: 31143002; PMCID: PMC6519104.

- Kathju S, Nistico L, Tower I, Lasko LA, Stoodley P. Bacterial biofilms on implanted suture material are a cause of surgical site infection. Surg Infect (Larchmt). 2014 Oct;15(5):592-600. doi: 10.1089/sur.2013.016. Epub 2014 May 15. PMID: 24833403; PMCID: PMC4195429.

- Leaper DJ, Edmiston CE Jr, Holy CE. Meta-analysis of the potential economic impact following introduction of absorbable antimicrobial sutures. Br J Surg. 2017 Jan;104(2):e134-e144. doi: 10.1002/bjs.10443. Epub 2017 Jan 17. PMID: 28093728.

- Lin SJ, Chang FC, Huang TW, Peng KT, Shih HN, Lee MS. Temporal Change of Interleukin-6, C-Reactive Protein, and Skin Temperature after Total Knee Arthroplasty Using Triclosan-Coated Sutures. Biomed Res Int. 2018 Jan 15;2018:9136208. doi: 10.1155/2018/9136208. PMID: 29568771; PMCID: PMC5820568.

- NIHR Global Research Health Unit on Global Surgery. Reducing surgical site infections in low-income and middle-income countries (FALCON): a pragmatic, multicentre, stratified, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2021 Nov 6;398(10312):1687-1699. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01548-8. Epub 2021 Oct 25. PMID: 34710362; PMCID: PMC8586736.

- Olmez T, Berkesoglu M, Turkmenoglu O, Colak T. Effect of Triclosan-Coated Suture on Surgical Site Infection of Abdominal Fascial Closures. Surg Infect (Larchmt). 2019 Dec;20(8):658-664. doi: 10.1089/sur.2019.052. Epub 2019 May 7. PMID: 31009327.

- <span data-teams="true">Poole K. Mechanisms of bacterial biocide and antibiotic resistance. Symp Ser Soc Appl Microbiol. 2002;(31):55S-64S. PMID: 12481829.

- Rahman, Syed & Soomro, Rufina. (2017). Does antibiotic coated polyglactin helps in reducing surgical site infection in clean surgery?. Medical Forum Monthly. 28. 23-26.

- Renko M, Paalanne N, Tapiainen T, Hinkkainen M, Pokka T, Kinnula S, Sinikumpu JJ, Uhari M, Serlo W. Triclosan-containing sutures versus ordinary sutures for reducing surgical site infections in children: a double-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2017 Jan;17(1):50-57. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(16)30373-5. Epub 2016 Sep 19. PMID: 27658562.

- Ruiz-Tovar J, Alonso N, Morales V, Llavero C. Association between Triclosan-Coated Sutures for Abdominal Wall Closure and Incisional Surgical Site Infection after Open Surgery in Patients Presenting with Fecal Peritonitis: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Surg Infect (Larchmt). 2015 Oct;16(5):588-94. doi: 10.1089/sur.2014.072. Epub 2015 Jul 14. PMID: 26171624.

- Ruiz-Tovar J, Llavero C, Jimenez-Fuertes M, Duran M, Perez-Lopez M, Garcia-Marin A. Incisional Surgical Site Infection after Abdominal Fascial Closure with Triclosan-Coated Barbed Suture vs Triclosan-Coated Polydioxanone Loop Suture vs Polydioxanone Loop Suture in Emergent Abdominal Surgery: A Randomized Clinical Trial. J Am Coll Surg. 2020 May;230(5):766-774. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2020.02.031. Epub 2020 Feb 27. PMID:

32113031. - Santos PS Filho, Santos M, Colafranceschi AS, Pragana ANS, Correia MG, Simões HH, Rocha FA, Soggia MEV, Santos APMS, Coutinho AA, Figueira MS, Tura BR. Effect of Using Triclosan-

Impregnated Polyglactin Suture to Prevent Infection of Saphenectomy Wounds in CABG: A Prospective, Double-Blind, Randomized Clinical Trial. Braz J Cardiovasc Surg. 2019 Dec

1;34(5):588-595. doi: 10.21470/1678-9741-2019-0048. PMID: 31719010; PMCID: PMC6852449. - Singh A, Bartsch SM, Muder RR, Lee BY. An economic model: value of antimicrobial-coated sutures to society, hospitals, and third-party payers in preventing abdominal surgical site infections. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2014 Aug;35(8):1013-20. doi: 10.1086/677163. Epub 2014 Jun 20. PMID: 25026618.

- Steingrimsson S, Thimour-Bergström L, Roman-Emanuel C, Scherstén H, Friberg Ö, Gudbjartsson T, Jeppsson A. Triclosan-coated sutures and sternal wound infections: a prospective randomized clinical trial. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2015 Dec;34(12):2331-8. doi: 10.1007/s10096-015-2485-8. Epub 2015 Oct 2. PMID: 26432552.

- Sukeik M, George D, Gabr A, Kallala R, Wilson P, Haddad FS. Randomised controlled trial of triclosan coated vs uncoated sutures in primary hip and knee arthroplasty. World J Orthop. 2019 Jul 18;10(7):268-277. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v10.i7.268. PMID: 31363457; PMCID: PMC6650636.

- Tabrizi R, Mohajerani H, Bozorgmehr F. Polyglactin 910 suture compared with polyglactin 910 coated with triclosan in dental implant surgery: randomized clinical trial. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2019 Oct;48(10):1367-1371. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2019.01.011. Epub 2019 Feb 6. PMID: 30738711.

- <span data-teams="true">Webber MA, Randall LP, Cooles S, Woodward MJ, Piddock LJ. Triclosan resistance in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2008 Jul;62(1):83-91. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkn137. Epub 2008 Apr 3. PMID: 18388112.

- <span data-teams="true">Yazdankhah SP, Scheie AA, Høiby EA, Lunestad BT, Heir E, Fotland TØ, Naterstad K, Kruse H. Triclosan and antimicrobial resistance in bacteria: an overview. Microb Drug Resist. 2006 Summer;12(2):83-90. doi: 10.1089/mdr.2006.12.83. PMID: 16922622.

- <span data-teams="true">Zhang D, Lu S. A holistic review on triclosan and triclocarban exposure: Epidemiological outcomes, antibiotic resistance, and health risk assessment. Sci Total Environ. 2023 May 10;872:162114. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.162114. Epub 2023 Feb 9. PMID: 36764530.

Evidence tabellen

Evidence tables

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C)

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

|

De Jonge (2016) |

SR and meta-analysis of RCTs

Literature search up to November 2015.

A: Arslan (2014) B: Baracs (2011) C: Chen (2011) D: Defazio (2005) E: Diener (2014) F: Ford (2005) G: Galal (2011) H: Isik (2012) I: Justinger (2013) J: Khachatryan (2011) K: Mattavelli (2015) L: Mingmalairak (2009) M: Nakamura (2013) N: Rasic (2011) O: Rozelle (2008) P: Seim (2012) Q: Singh (2010) R: Thimour Bergstrom (2013) S: Turtianen (2012) T: Williams (2011) U: Yam (2013)

Study design: RCT [parallel / cross-over], cohort [prospective / retrospective], case-control

Setting and Country:

Source of funding

Conflicts of interest: [commercial / non-commercial / industrial co-authorship]

|

Inclusion criteria SR:

Exclusion criteria SR:

20 studies included

Important patient characteristics at baseline:

N total (analyzed) A: N = 177 (N = 177) B: N = 485 (N = 385) C: N = 241 (N = 241) D: N = 93 (N = 93) E: N = 1224 (N = 1185) F: N = 151 (N = 147) G: N = 450 (N = 450) H: N = 510 (N = 510) I: N = 967 (N = 856) J: N = 133 (N = 133) K: N = 300 (N = 281) L: N = 100 (N = 100) M: N = 410 (N = 410) N: N = 184 (N = 184) O: N = 84 (N = 84) P: N = 328 (N = 323) Q: N = 100 (N = 100) R: N = 392 (N = 374) S: N = 276 (N = 276) T: N = 150 (N = 127) U: N = 26 (N = 26)

mean age Not reported.

Sex: Not reported.

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes. |

Describe intervention:

A: TCS B: TCS C: TCS D: TCS E: TCS F: TCS G: TCS H: TCS I: TCS J: TCS K: TCS L: TCS M: TCS N: TCS O: TCS P: TCS Q: TCS R: TCS S: TCS T: TCS U: TCS

|

Describe control:

A: NCS B: NCS C: NCS D: NCS E: NCS F: NCS G: NCS H: NCS I: NCS J: NCS K: NCS L: NCS M: NCS N: NCS O: NCS P: NCS Q: NCS R: NCS S: NCS T: NCS U: NCS

|

End-point of follow-up:

A: 30 days. B: 30 days after discharge, by telephone. C: not reported. D: 6 weeks. E: 30 days. F: 80 days. G: 30 days or 1 year. H: 30 days I: 2 weeks after discharge. J: not reported. K: 30 days L: 30 days, 6 months, 1 year. M: 30 days. N: to discharge. O: 6 months. P: 4 weeks. Q: 30 days. R: 60 days. S: 30 days. T: 6 weeks. U: not reported.

|

Outcome measure: SSI

High-quality peer-reviewed full-text publications

E (Diener, 2014) I: 87/587 ( C: 96/598

R (Thimour Bergstrom, 2013) I: 23/184 C: 38/190

S (Turtianen, 2012) I: 31/139 C: 164/925

Other peer-reviewed full-text publications

B (Baracs, 2011) I: 23/188 C: 24/197

C (Chen, 2011) I: 17/112 C: 19/129

F (Ford, 2005) I: 3/98 C: 0/49

G (Galal, 2011) I: 17/230 C: 33/220

H (Isik, 2012) I: 9/170 C: 22/340

I: Justinger, 2013) I: 31/485 C: 42/371

K (Mattavelli, 2015) I: 18/140 C: 15/141

L (mingmalairak, 2009) I: 5/50 C: 4/50

M (Nakamura, 2013) I: 9/206 C: 19/204

N (Rasic, 2011) I: 4/91 C: 12/93

O (Rozzelle, 2008) I: 2/46 C: 8/38

P (Seim, 2012) I: 16/160 C: 17/183

T (Williams, 2011) I: 10/66 C: 14/61

Congress abstracts

A (Arslan, 2014) I: 8/86 C: 18/91

D (Defazio, 2005) I: 4/43 C: 4/50

J (Khachatryan, 2011) I: 6/65 C: 14/68

Q (Singh, 2010) I: 6/50 C: 16/50

U (Yam, 2013) I: 1/12 C: 5/14

|

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics 2 |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C) 3

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size 4 |

Comments |

|

Ruiz-Tovar (2015) |

Type of study: Multi-center RCT

Setting and country: Spain.

Funding and conflicts of interest: No competing financial interests exist.

|

Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

N total at baseline: Intervention: N = 55 Control: N = 55

Important prognostic factors2: age ± SD: I: 65.6 (14.9) C: 63.8 (15.5)

Sex: I: 31/51 M C: 31/50 M

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes.

|

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

Sutures coated with triclosan

|

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

No triclosan-coated sutures. |

Length of follow-up: 5, 30, and 60 days after surgery.

Loss-to-follow-up: None.

|

Outcome measure: SSI I: 5/55 C: 18/55

|

Author’s conclusion: The use of triclosan-coated sutures in fecal peritonitis surgery reduces the incidence of incisional SSI.

|

|

Steingrimsson (2015) |

Type of study: Randomized controlled trial, single-center.

Setting and country: Sweden.

Funding and conflicts of interest: A.J. has received speaker’s honorarium from Ethicon, Inc. The authors declare that there are no other conflicts of interest.

|

Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

N total at baseline: Intervention: N = 193 Control: N = 200

Important prognostic factors2: age ± SD: I: 67.6 (8.1) C: 66.7 (8.2)

Sex: I: 22.9% F C: 15.7% F

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes.

|

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

Closure of wounds with triclosan-coated sutures.

|

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

Closure of wounds without triclosan-coated sutures. |

Length of follow-up: 4, 30, and 60 days postoperative.

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: N = 17

Control: N = 12

|

Outcome measure: SSI I: 23/193 C: 20/200

|

Author’s conclusion: |

|

Renko (2017) |

Type of study: Randomised controlled trial, single center.

Setting and country: Finland.

Funding and conflicts of interest: MR received grants from The Alma and K A Snellman Foundation (Oulu, Finland) during the conduct of the study, and grants from The Finnish Medical Foundation and the Foundation for Pediatric Research, outside the submitted work. J-JS received grants from Emil Aaltonen Foundation, Finska Läkaresällskapet Foundation, The Alma and K A Snellman Foundation, Vaasa Foundation of Physicians and personal fees from Bioretec Ltd and MSD Finland Ltd, outside the submitted work. WS received grants from Foundation for Pediatric Research, outside the submitted work. None of the other authors declare any competing interests.

|

Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

N total at baseline: Intervention: N = 814 Control: N = 819

Important prognostic factors2: age ± SD: I: 7.2 (5.4) years C: 7.1 (5.5) years

Sex: I: 483 M C: 502 M

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes.

|

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

Sutures with triclosan during surgery.

|

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

Ordinary absorbable sutures during surgery. |

Length of follow-up: 30 days after the surgical procedure.

Loss-to-follow-up: None.

|

Outcome measure: SSI I: 20/814 C: 42/819

|

Author’s conclusion: SSIs cause much morbidity and mortality after surgical procedures, and economic evaluations recommend the use of triclosan-containing material.41,42 This randomised, controlled study shows that even in low-risk settings, where other prophylactic measures are available to use, triclosan-containing sutures effectively prevented the occurrence of SSIs in children.

|

|

Soomro (2017) |

Type of study: Randomized controlled trial, single center.

Setting and country: Pakistan.

Funding and conflicts of interest: The study has no conflict of interest to declare by any author.

|

Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

N total at baseline: Intervention: N = 189 Control: N = 189

Important prognostic factors2: age ± SD: I: 25.86 (3.51) years C: 25.70 (3.10) years

Sex: No information.

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes.

|

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

Triclosan coated-sutures.

|

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

Sutures without triclosan. |

Length of follow-up: 3, 7, and 30 days postoperative.

Loss-to-follow-up: None.

|

Outcome measure: SSI I: 7/189 C: 11/189

|

Author’s conclusion: The study did not demonstrate a statistically significant reduction of superficial surgical site infection when triclosan coated polyglactin suture was used in clean wounds. More studies need to be conducted with larger sample size to look at its effects on other wound categories.

|

|

Arslan (2018) |

Type of study: Randomized controlled trial.

Setting and country: Turkey.

Funding and conflicts of interest: No information. |

Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

N total at baseline: Intervention: N = 92 Control: N = 95

Important prognostic factors2: age ± SD: I: 25.8 (6.5) years C: 25.5 (5.5) years

Sex: I: 79 M C: 76 M

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes.

|

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

Triclosan-coated sutures.

|

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

No triclosan-coated sutures. |

Length of follow-up: 30 days postoperative.

Loss-to-follow-up: None.

|

Outcome measure: SSI I: 9/92 C: 19/95 |

Author’s conclusion: Triclosan-coated sutures decreased surgical site infection rate but had no effect on time to healing in pilonidal disease. Seroma and wound dehiscence were more common in triclosan groups. Randomized trials are needed to clear the effect of triclosan-coated sutures on postoperative wound complications.

|

|

Ichida (2018) |

Type of study: Randomized controlled trial.

Setting and country: Japan.

Funding and conflicts of interest: No information reported. |

Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

N total at baseline: Intervention: N = 512 Control: N = 511

Important prognostic factors2: age ± SD: I: 67.0 (11.5) years C: 67.5 (11.6) years

Sex: I: 304 M C: 322 M

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes.

|

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

Abdominal wound closure with triclosan-coated sutures.

|

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

Abdominal wound closure without triclosan-coated sutures.

|

Length of follow-up: 30 days.

Loss-to-follow-up: None.

|

Outcome measure: SSI I: 35/512 C: 30/511

|

Author’s conclusion: |

|

Lin (2018) |

Type of study: Randomized controlled trial.

Setting and country: No information.

Funding and conflicts of interest: All authors state that they have no conflicts of interest.

|

Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

N total at baseline: Intervention: N = 51 Control: N = 51

Important prognostic factors2: age ± SD: I: 71.3 (7.7) C: 70.0 (7.1)

Sex: I: 36 F C: 40 F

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes.

|

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

Triclosan-coated polyglactin sutures.

|

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

Plain polyglactin sutures. |

Length of follow-up: 2, weeks, 4 weeks, and 3 months after surgery.

Loss-to-follow-up: None.

|

Outcome measure: SSI I: 0/51 C: 2/51 |

Author’s conclusion: Triclosan-coated sutures did not cause adverse local or systemic reactions: similar changes in serial inflammatory response occurred in both groups. Furthermore, falling levels of IL-6 imply that triclosan-coated sutures had a positive effect on postoperative knee inflammation. A more sensitive analytical measurement tool is needed to investigate local and systemic complications, especially in the early subclinical stage.

|

|

Karde (2019) |

Type of study: Randomized controlled trial.

Setting and country: Department of periodontology.

Funding and conflicts of interest: There are no conflicts of interest or external funding. |

Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

N total at baseline: Intervention: N = 10 Control: N = 10

Important prognostic factors2: age ± SD: 39.2 (10.76) years

Sex: 13 males and 17 females.

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes.

|

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

TCS

|

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

NCS |

Length of follow-up: 30 days.

Loss-to-follow-up: None.

|

Outcome measure: SSI I: 0/10 C: 0/10 |

Author’s conclusion: TCS or CCS sutures can be used in periodontal surgeries to reduce the bacterial load at the surgical sites. |

|

Olmez (2019) |

Type of study: Randomized controlled trial.

Setting and country: No information.

Funding and conflicts of interest: The authors have no financial conflicts of interest related to this manuscript.

|

Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

N total at baseline: Intervention: N = 450 Control: N = 450

Important prognostic factors2: age ± SD: I: 55.1 (16.3) years C: 54.6 (16.9) years

Sex: I: 192 M C: 223 M

Groups comparable at baseline? Not for BMI, smoking, previous abdominal midline incision, co-morbidities, ASA class, and target organ for operation.

|

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

Triclosan-coated sutures.

|

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

Standard sutures without triclosan-coating. |

Length of follow-up: 14 days after surgery.

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: N = 2

Control: N = 4

|

Outcome measure: SSI I: 85/450 C: 115/450

|

Author’s conclusion: Surgical site infections are an important and expensive healthcare problem around the world. This study found that using triclosan-coated sutures to close the fascia after lap- arotomy reduced the SSI rate by as much as 24%. Although the SSIs had multiple causes, and some of them might have been preventable. In this situation, surgical innovations and clinical research should be prioritized. The use of triclosan- coated suture for closing laparotomy incisions may reduce the rate of SSIs in all subgroups of incision classifications in a single-center experience. We demonstrated that using triclosan-coated suture reduced SSIs in patients with clean, clean-contaminated, and contaminated wounds, especially in colorectal operations, which have a high infection rate.

|

|

Santos (2019) |

Type of study: Randomized controlled trial.

Setting and country: Brazil.

Funding and conflicts of interest: This study was funded by Ethicon Inc., represented in Brazil by Johnson & Johnson do Brasil Indústria e Comércio de Produtos para Saúde Ltda. Grant # 10-107.

This study was funded by Ethicon Inc., represented in Brazil by Johnson & Johnson do Brasil Indústria e Comércio de Produtos para Saúde Ltda. Grant # 10-107.

|

Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

N total at baseline: Intervention: N = 251 Control: N = 257

Important prognostic factors2: age ± SD: I: 62.01 (8.62) C: 60.39 (9.03)

Sex: I: 175 (69.7%) M C: 180 (70%) M

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes, except for wound pain and wound hyperthermia.

|

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

Triclosan-coated 910 sutures.

|

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

Conventional 910 polyglactin suture. |

Length of follow-up: 30 days.

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: N (%) Reasons (describe)

Control: N (%) Reasons (describe)

Incomplete outcome data: Intervention: N (%) Reasons (describe)

Control: N (%) Reasons (describe)

|

Outcome measure: SSI I: 13/251 C: 20/257

|

Author’s conclusion: In patients undergoing saphenectomy during CABG, the most frequent variables, such as demographic, clinical, and those related to saphenectomy wounds, were male gender, diabetes, erythema, and necrosis. Pain and hyperthermia in the wound were less frequent in patients sutured with triclosan. The patients with triclosan-coated sutures presented smaller infection rate in saphenectomy than those with non-coated sutures undergoing CABG, although the differences were not statistically significant.

|

|

Sukeik (2019) |

Type of study: Randomized controlled trial.

Setting and country: UK

Funding and conflicts of interest: No potential conflicts of interest to declare. No external financial support.

|

Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

N total at baseline: Intervention: N = 81 Control: N = 61

Important prognostic factors2: age ± SD: I: 68.85 (10.90) years C: 67.85 (9.85) years

Sex: I: 24 M C: 25 M

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes.

|

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

Coated polyglactin 910 sutures with triclosan

|

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

Coated polyglactin 910 sutures. |

Length of follow-up: 6 weeks postoperative.

Loss-to-follow-up: None.

|

Outcome measure: SSI I: 4/81 C: 1/69

|

Author’s conclusion: The current literature supports the use of triclosan-coated sutures in some disciplines of general surgery but the evidence in orthopaedic surgery especially in arthroplasty procedures remains inconclusive. This trial supports the findings from other studies that triclosan-coated sutures do not provide any benefits over non-coated sutures in protecting against wound complications and infections after hip and knee arthroplasty surgery. Therefore, we recommend against the routine use of those sutures and advise that efforts should continue to emphasise the benefits of preventative measures against infections and explore new modalities of reducing surgical site infections. The utilisation of a well-designed randomised controlled trial will help in answering whether any of those new modalities will stand the challenge of time and optimal outcomes.

|

|

Tabrizi (2019) |

Type of study: Randomized controlled trial.

Setting and country: Iran.

Funding and conflicts of interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest. The manuscript did not meet any conflict of interest.

Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences funded the research.

|

Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

N total at baseline: Intervention: M = 160 Control: N = 160

Important prognostic factors2: age ± SD: I: 44.73 (12.82) years C: 44.64 (12.24) years

Sex: I: 83 M C: 77 M

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes.

|

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

Triclosan-coated sutures

|

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

Conventional sutures. |

Length of follow-up: 28 days postoperative.

Loss-to-follow-up: None.

|

Outcome measure: SSI I: 12/160 C: 11/160

|

Author’s conclusion: In conclusion, triclosan-coated Vicryl sutures did not decrease the incidence of surgical site infection following dental implant surgery. The incidence of dehis- cence was slightly higher in the Vicryl Plus group, which calls for further caution when using Vicryl Plus sutures.

|

|

Ruiz-Tovar (2019) |

Type of study: Randomized controlled trial.

Setting and country: Not reported.

Funding and conflicts of interest: No information reported. |

Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

N total at baseline: Intervention: N = 50 Control: N = 50

Important prognostic factors2: age ± SD: I: C:

Sex: I: % M C: % M

Groups comparable at baseline?

|

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

Polydioxanone plus loop

|

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

Standard polydioxanone loop suture. |

Length of follow-up: 30 days postoperatively.

Loss-to-follow-up: None.

|

Outcome measure: SSI I: 5/50 C: 13/50

|

Author’s conclusion: The use of triclosan-coated sutures in emergent surgery reduced the incidence of incisional SSI, postoperative pain, and analytical acute phase reactants. The use of barbed sutures reduced the incidence of evisceration. Triclosan-coated barbed sutures can be considered as rec- ommended sutures for aponeurotic closure in emergent mid-line approaches.

|

|

NIHR Global Research Health Unit on Global Surgery (FALCON) 2021 |

Type of study: Randomized controlled trial.

Setting and country: Benin, Ghana, India, Mexico, Nigeria, Rwanda, and South Africa.

Funding and conflicts of interest: National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Global Health Research Unit Grant, BD.

We declare no competing interests.

|

Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

N total at baseline: Intervention: N = 2895 Control: N = 2893

Important prognostic factors2: age >18 years I: N = 2895 C: N = 2893

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes.

|

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

Triclosan coated sutures

|

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

Non-coated sutures. |

Length of follow-up: 30 days after surgery.

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: N = 18

Control: N = 12

|

Outcome measure: SSI I: 562/2895 C: 601/2893

|

Author’s conclusion: Both overall and per stratum reported SSI rates were high, confirming that specific assessment of patients for SSIs will lead to their highest detection.26 This finding highlights the quality of the FALCON trial processes, including proactive training of masked outcome assessors and high completion of follow-up. These very high SSI rates represent a preventable complication that is causing unnecessary suffering and burden to patients and systems. Small randomised trials should now be avoided and should be replaced with larger trials that can more robustly identify or refute pragmatic solutions. |

Up-to-date meta-analysis and trial sequential analysis versus previous meta-analyses of triclosan coated sutures for the prevention of surgical-site infection

Hasti Jalalzadeh MD, LLM, Allard S Timmer MD, Dennis R Buis MD, PhD, Yasmine EM Dreissen MD, PhD, Jon HM Goosen MD, PhD, Haitske Graveland PhD, Mitchel Griekspoor MSc, Frank FA IJpma MD, PhD, Maarten J van der Laan MD, PhD,7 Roald R Schaad MD, Patrique Segers MD, PhD, Wil C van der Zwet MD, PhD, Stijn W de Jonge, MD, PhD, Niels Wolfhagen MD, PhD, Prof Marja A Boermeester MD, PhD

Reasons for exclusion after full text review

|

de Jonge 2017 |

Cruz 2013 |

Different PICO (pomade: iodoform plus calendula coating) |

|

Delieart 2009 |

Different PICO (SSI not assessed) |

|

|

Fleck 2007 |

No RCT (retrospective study) |

|

|

Fujita 2014 |

No RCT (commentary) |

|

|

Heger 2011 |

No RCT (study protocol) |

|

|

Hoshino 2013 |

No RCT (retrospective study) |

|

|

Huszár 2012 |

Duplicate data of Baracs 2011 |

|

|

Jeppsson 2012 |

Duplicate data of Thimour-Bergrström 2013 |

|

|

Justinger 2011 |

No RCT (non-randomized study) |

|

|

Mattavelli 2011 |

Duplicate data of Mattavelli 2015 |

|

|

Mattavelli 2013 |

Duplicate data of Mattavelli 2015 |

|

|

Okada 2014 |

No RCT (non-randomized trial) |

|

|

Picó 2008 |

Different PICO (triclosan versus gentamicin coating) |

|

|

Rogers 2012 |

No RCT (commentary) |

|

|

Sakaguchi 2009 |

Duplicate data of Singh 2010 |

|

|

Sprowson 2014 |

No RCT (study protocol) |

|

|

Stone 2010 |

No RCT (follow-up of Rozzelle 2008) |

|

|

Zhang 2011 |

Control group not comparable |

|

|

Zhuang 2009 |

Control group not comparable |

|

|

Update |

Carella 2019 |

Different PICO (triclosan versus chlorhexidine coating) |

|

|

ChiCTR2000031795 |

No RCT (study protocol) |

|

Diener 2014 |

Already included |

|

|

Dixit 2018 |

Different PICO (triclosan versus triclosan coating) |

|

|

DRKS00010047 |

No RCT (study protocol of Matz 2019) |

|

|

Karde 2019 |

Different PICO (SSI not assessed) |

|

|

Lozano 2020 |

No RCT (non-randomized study) |

|

|

Mattavelli 2015 |

Already included |

|

|

Matz 2019 |

No RCT (study protocol) |

|

|

McCallum 2016 |

No RCT (study protocol, withdrawn) |

|

|

Miyoshi 2022 |

No RCT (non-randomized study) |

|

|

NCT02533492 |

No RCT (study protocol of Lin 2018) |

|

|

NCT02847936 |

No RCT (study protocol of Mbarki 2022) |

|

|

NCT02863874 |

No RCT (study protocol) |

|

|

NCT03386240 |

No RCT (study protocol) |

|

|

NCT03659344 |

No RCT (study protocol of Tabrizi 2019) |

|

|

NCT03763279 |

No RCT (study protocol of Ruiz-Tovar 2020) |

|

|

NCT04255927 |

No RCT (study protocol) |

|

|

NCT04256824 |

No RCT (study protocol) |

|

|

NCT04622267 |

No RCT (study protocol) |

|

|

Roy 2019 |

Different PICO (chlorhexidine versus chlorhexidine coating) |

|

|

Serlo 2016 |

Duplicate data of Renko 2017 |

|

|

Sprowson 2018 |

Quasi-randomisation (per month) |

|

|

Tae 2018 |

Different PICO (chlorhexidine versus chlorhexidine coating) |

|

|

UMIN000021892 |

No RCT (study protocol) |

|

|

Carella S, Fioramonti P, Onesti MG, Scuderi N. Comparison between antimicrobial-coated sutures and uncoated sutures for the prevention of surgical site infections in plastic surgery: a double blind control trial. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2019;23(3):958-964. ChiCTR2000031795. http://www.who.int/trialsearch/Trial2.aspx?TrialID=ChiCTR2000031795 Cruz F, Leite F, Cruz G, Cruz S, Reis J, Pierce M et al. Sutures coated with antiseptic pomade to prevent bacterial colonization: a randomized clinical trial. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol 2013; 116: e103–e109. Deliaert AE, Van den Kerckhove E, Tuinder S, Fieuws S, Sawor JH, Meesters-Caberg MA et al. The effect of triclosan-coated sutures in wound healing. A double blind randomised prospective pilot study. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 2009; 62: 771–773. Dixit A, Nadkarni P, Thakkar A. Safety and efficacy of triclosan-coated polyglactin 910 suture in prevention of surgical site infection in postpartum women : A randomized controlled trial. J Ind Med Ass 2018; 116. DRKS00010047, https://www.cochranelibrary.com/central/doi/10.1002/central/CN-01852897/full Fleck T, Moidl R, Blacky A, Fleck M, Wolner E, Grabenwoger M et al. Triclosan-coated sutures for the reduction of sternal wound infections: economic considerations. Ann Thorac Surg 2007; 84: 232–236. Fujita T. Antibiotic sutures against surgical site infections. Lancet 2014; 384:1424–1425. Heger U, Voss S, Knebel P, Doerr-Harim C, Neudecker J, Schuhmacher C et al. Prevention of abdominal wound infection (PROUD trial, DRKS00000390): study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 2011; 12: 245. Hoshino S, Yoshida Y, Tanimura S, Yamauchi Y, Noritomi T, Yamashita Y. A study of the efficacy of antibacterial sutures for surgical site infection: a retrospective controlled trial. Int Surg 2013; 98: 129–132. Huszár O, Baracs J, Tóth M, Damjanovich L, Kotán R, Lázár G et al. [Comparison of wound infection rates after colon and rectal surgeries using triclosan-coated or bare sutures – a multi-center, randomized clinical study.]. Magy Seb 2012; 65: 83–91. Jeppsson A, Thimour-Bergström L, Gudbjartsson T, Aneman C, Friberg O. Triclosan-coated sutures reduce surgical site infections after open vein harvesting in coronary artery bypass graft patients: a prospective randomized controlled trial. Interactive Cardiovascular and Thoracic Surgery Conference: 26th Annual Meeting of the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery, EACTS 2012, Barcelona, 27–31 October 2012; 15: S134. Justinger C, Schuld J, Sperling J, Kollmar O, Richter S, Schilling MK. Triclosan-coated sutures reduce wound infections after hepatobiliary surgery-a prospective non-randomized clinical pathway driven study. Langenbecks Arch Surg 2011; 396: 845–850. Karde PA, Sethi KS, Mahale SA, Mamajiwala AS, Kale AM, Joshi CP. Comparative evaluation of two antibacterial-coated resorbable sutures versus noncoated resorbable sutures in periodontal flap surgery: A clinico-microbiological study. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2019;23(3):220-225. Lozano CC, Garcia-Botello S, Martí-Arévalo, Bauzá Collado J, Pla Martí V et al. P1668 Use of triclosan-coated barbed monifilmaent suture (TCBMS) to reduce surgical site infection in elective colorectal surgery. American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons 2020 Anuual Scientifici Meeting abstracts. 2020: 60:3 e441. Mattavelli I, Nespoli L, Alfieri S, Cantore F, Sebastian-Douglas S, Cobianchi L et al. Triclosan-coated suture to reduce surgical site infection after colorectal surgery. Surg Infect (Larchmnt) 2011; 12: A14–A15. Mattavelli I, Nespoli L, Alfieri S, Cantore F, Cobianchi L, Luperto M et al. Effect of triclosan-coated suture on surgical site infection after colorectal surgery: final results of a multicenter, prospective, randomized trial. Surg Infect (Larchmnt) 2013; 14: A9. Matz D, Teuteberg S, Wiencierz A, Soysal SD, Heizmann O. Do antibacterial skin sutures reduce surgical site infections after elective open abdominal surgery? - Study protocol of a prospective, randomized controlled single center trial. Trials. 2019;20(1):390. NCT02533492, https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02533492 NCT02847936, https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02847936 NCT02863874, https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02863874 NCT03386240, https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03386240 NCT03659344, https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03659344 NCT03763279, https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03659344 NCT04255927, https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04255927 NCT04256824, https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04256824 NCT04622267, https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04622267 Okada N, Nakamura T, Ambo Y, Takada M, Nakamura F, Kishida A et al. Triclosan-coated abdominal closure sutures reduce the incidence of surgical site infections after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Surg Infect (Larchmnt) 2014; 15: 305–309. Picó RB, Jiménez LA, Sánchez MC, Castelló CH, Bilbao AM, Arias MP et al. [Prospective study comparing the incidence of wound infection following appendectomy for acute appendicitis in children: conventional treatment versus using reabsorbable antibacterial suture or gentamicin-impregnated collagen fleeces.] Cir Pediatr 2008; 21:199–202. Rogers P. Effect of triclosan-coated sutures on incidence of surgical wound infection after lower limb revascularization surgery: a randomized controlled trial. By Turtiainen et al. DOI:10.1007/s00268-012-1655-4. World J Surg 2012; 36: 2535–2536. Roy PK, Kalita P, Lalhlenmawia H, Dutta RS, Thanzami K, Zothanmawia C. Comparison of surgical site infection rate between antibacterial coated surgical suture and conventional suture: a randomized controlled single centre study for preventive measure of postoperative infection. 2019 International Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences and Research, 10, 2385-91. Sakaguchi H, Singh H, Klima U, Lee C, Kofidis T. Antibacterial suture reduces surgical site infections in coronary artery bypass grafting. 17th Annual Meeting of the Asian Society For Cardiovascular and Thoracic Surgery (ASCVTS), Taipei, Taiwan, 5–8 March 2009; 111–114. Serlo W, Renko M, Paalanne N, Tapaiainen T, Hinkanen M et al. 44th Annual Meeting of International Society for Pediatric Neurosurgery, Kobe, Japan, Oct 23–27, 2016. Child’s Nerv Syst, 32, 1957-2040. Sprowson AP, Jensen CD, Parsons N, Partington P, Emmerson K, Carluke I et al. The effect of triclosan coated sutures on rate of surgical site infection after hip and knee replacement: a protocol for a double-blind randomised controlled trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2014; 15: 237. Stone J, Gruber TJ, Rozzelle CJ. Healthcare savings associated with reduced infection rates using antimicrobial suture wound closure for cerebrospinal fluid shunt procedures. Pediatr Neurosurg 2010; 46: 19–24. Tae BS, Park JH, Kim JK, et al. Comparison of intraoperative handling and wound healing between (NEOSORB® plus) and coated polyglactin 910 suture (NEOSORB®): a prospective, single-blind, randomized controlled trial. BMC Surg. 2018;18(1):45. UMIN000021892, https://center6.umin.ac.jp/cgi-open-bin/ctr_e/ctr_view.cgi?recptno=R000025218 Zhang ZT, Zhang HW, Fang XD, Wang LM, Li XX, Li YF et al. Cosmetic outcome and surgical site infection rates of antibacterial absorbable (polyglactin 910) suture compared to Chinese silk suture in breast cancer surgery: a randomized pilot research. Chin Med J (Engl) 2011; 124: 719–724. Zhuang C, Cai G, Wang Y. Comparison of two absorbable sutures in abdominal wall incision. Journal of Clinical Rehabilitative Tissue Engineering Research 2009; 13: 4045–4048. |

||

Study characteristics

|

Publication |

Participants/analyzed |

Surgery type |

Suture types |

CDC wound class |

Definition for SSI |

Duration of follow up |

Perioperative IV antibiotics |

Risk of bias |

|

Arslan 2018 Turkey |

177 / 177 |

Pilonidal cyst surgery |

Retention: Polypropylene vs. Polydiaxanone + Subcutis: Polyglactin 910 vs. Polyglactin 910+ Skin: Polypropylene vs. Polydiaxanone + |

II – III |

CDC |

30 days |

Yes |

Some concerns |

|

Baracs 2011 Hungary |

485 / 385 |

Colorectal surgery - open (100%) |

Abdominal fascia: Polydiaxanone vs. Polydiaxanone + Skin: Poliglecaprone 25+ |

II |

CDC |

30 days after discharge, by telephone |

Yes |

High |

|

Chen 2011 Taiwan |

241 / 241 |

Head and neck surgery |

Intra-oral flaps: Silk sutures Subcutis: Polyglactin 910 vs. Polyglactin 910+ Skin: Nylon sutures |

II |

No § |

Not described |

n.r. |

High |

|

Diener 2014 Germany |

1224 / 1185 |

Laparotomy |

Abdominal fascia: Polydiaxanone vs. Polydiaxanone + Skin: Staples |

I (282) |

CDC |

30 days |

Yes |

Low |

|

Ford 2005 USA |

151 / 147 |

Pediatric general surgery |

Polyglactin 910 vs. Polyglactin 910+ |

I-II |

No ¶ |

80 days |

n.r. |

Some concerns |

|

Galal 2011 Egypt |

450 / 450 |

Various |

Surgical steps: Polyglactin 910 vs. Polyglactin 910+ Skin: Poliglecaprone 25 OR Polypropylene |

I (236) |

CDC |

30 day, 1 year |

n.r. |

Some concerns |

|

Ichida 2018 Japan |

1023 / 1013 |

Gastroenterologic surgery - open (42%) - laparoscopy (58%)

|

Abdominal fascia and peritoneum: Polyglactin 910 vs. Polyglactin 910+ Skin: Polydiaxanone vs. Polydiaxanone + |

I (9) II (990) III (14) |

CDC |

30d |

Yes |

Some concerns |

|

Isik 2012 Turkey |

510 / 510 |

Cardiac surgery |

Polyglactin 910 vs. Polyglactin 910+ |

I |

CDC |

30 days |

n.r. |

High |

|

Justinger 2013 Germany |

967 / 856 |

Laparotomy

|

Abdominal fascia: Polydiaxanone vs. Polydiaxanone + Subcutis: No sutures Skin: Staples |

I (531) |

CDC |

2 weeks after discharge |

Yes |

Some concerns |

|

Karip 2016 Turkey |

142 / 106 |

Pilonidal cyst surgery with flap reconstruction |

Poliglecaprone 25 vs. Poliglecaprone 25+ |

II – III |

No ¶ |

1, 2 weeks, 1,3, and 6 months |

Yes |

Some concerns |

|

Lin 2018 Taiwan |

102 / 102 |

Total knee arthroplasty |

Arthrotomy, fascial layer, and subcutis: Polyglactin 910 vs. Polyglactin 910+ Skin: Staples |

I |

n.r. |

3 months |

Yes |

High |

|

Mattavelli 2015 Italy |

300 / 281 |

Colorectal surgery - open (19%) - laparoscopy (81%) |

Peritoneum: Polyglactin 910 vs. Polyglactin 910+ Abdominal fascia: Polydiaxanone vs. Polydiaxanone+ Subcutis and skin: Polyglactin 910 vs. Polyglactin 910+ |

II |

CDC |

30 days |

Yes |

Low |

|

Mbarki 2022 Tunisia |

340 / 318 |

Obstetric surgery |

Uterus, aponeurosis, subcutis and skin: Polyglactin 910 vs. Polyglactin 910+ |

II |

CDC |

30 days |

Yes |

Low |

|

Mingmalairak 2009 Thailand |

100 / 100 |

Appendectomy - open (100%) |

Abdominal fascia: Polyglactin 910 vs. Polyglactin 910+ |

III (24) |

CDC |

30 days, 6 months, 1 year |

Yes |

Some concerns |

|

Nakamura 2013 Japan |

410 / 410 |

Colorectal surgery - open (45%) - laparoscopy (55%) |

Polyglactin 910 vs. Polyglactin 910+ Skin: Staples OR interrupted sutures |

II (408) |

CDC |

30 days |

Yes |

Some concerns |

|

NIHR 2021 UK |

5788 / 5713 |

Abdominal surgery - open (>99%) - laparoscopy (<1%) |

Abdominal fascia: Unknown vs. Polydiaxanone + (OR Polyglactin 910+ for children) |

II (3091) III – IV (2697) |

CDC |

30 days |

Yes |

Low |

|

Olmez 2019 Turkey |

900 / 890 |

Laparotomy |

Abdominal fascia: Polydiaxanone vs. Polydiaxanone + Subcutis: No suture Skin: Polypropylene |

I (84) II (651) IV (3) |

No ¶ |

7, 14 and 30 days |

Yes |

High |

|

Rasic 2011 Croatia |

184 / 184 |

Colorectal surgery - open (100%) |

Single mass layer (peritoneum, muscle, fascia): Polyglactin 910 vs. Polyglactin 910+ |

II |

n.r. |

To discharge |

Yes |

Some concerns |

|

Renko 2017 Finland |

1633 / 1557 |

Peadiatric surgery |

Polyglactin 910 OR Polydiaxanone OR Poliglecaprone 25 vs. Polyglactin 910+ OR Polydiaxanone + OR Poliglecaprone25+

|

I (1394) II (53) III (1) M (109) |

CDC |

30 days |

Yes (in 31%) |

Low |

|

Rozelle 2008 USA |

84 / 84 |

CSF shunt implantation |

Galea and fascia: Polyglactin 910 vs. Polyglactin 910+ Skin: Poliglecaprone 25 |

I |

No ‡ |

6 months |

Yes |

Some concerns |

|

Ruiz-Tovar 2015 Spain |

110 / 101 |

Laparotomy with abdominal wall closure and fecal peritonitis

|

Abdominal fascia: Polyglactin 910 vs. Polyglactin 910+ Subcutis: No suture Skin: Staples |

IV |

CDC |

5, 30 and 60 days |

Yes |

Some concerns |

|

Ruiz-Tovar 2020 Spain |

100 / 92 |

Laparotomy with abdominal wall closure |

Abdominal fascia: Polydiaxanone vs. Polydiaxanone + Subcutis: No suture Skin: Staples |

IV |

CDC |

30 days |

Yes |

High |

|

Santos 2020 Brazil |

583 / 508 |

Saphenectomy for coronary bypass graft |

Skin: Polyglactin 910 vs. Polyglactin 910+ |

I |

No § |

30 days |

Yes |

Some concerns |

|

Seim 2012 Norway |

328/323 |

Saphenectomy for coronary bypass graft |

Skin: Polyglactin 910 vs. Polyglactin 910+ |

I |

No ‡ |

4wk |

Yes |

Some concerns |

|

Soomro 2017 Pakistan |

378 / 378 |

Benign breast surgery |

Subcutis: Polyglactin 910 vs. Polyglactin 910+ Skin: Polyglactin 910 vs. Polyglactin 910+ |

I |

n.r. |

3, 7 and 30 days |

Yes |

High |

|

Steingrimsson 2015 Sweden |

392 / 357 |

Coronary bypass graft |

Sternum: Steel wires Fascia and subcutis: Polyglactin 910 vs. Polyglactin 910+ Skin: Poliglecaprone 25 vs. Poliglecaprone 25+ |

I |

CDC, ASEPSIS score |

3 and 30 days |

Yes |

Some concerns |

|

Sukeik 2019 UK |

150 / 150 |

Hip and knee arthroplasty |

Surgical steps: Polyglactin 910 vs. Polyglactin 910+ Skin: Staples |

I |

ASEPSIS score |

2 and 6 weeks |

Yes |

Low |

|

Tabrizi 2019 Iran |

320 / 320 |

Dental implant surgery |

Polyglactin 910 vs. Polyglactin 910+

|

II |

No § |

7, 14, 21 and 28 days |

Yes |

Some concerns |

|

Thimour-Bergrström 2013 Sweden |

392 / 374 |

Coronary bypass graft |

Subcutis: Polyglactin 910 vs. Polyglactin 910+ Skin: Poliglecaprone 25 vs. Poliglecaprone 25+ |

I |

CDC |

60 days |

Yes |

Low |

|

Turtianen 2012 Finland |

276 / 276 |

Lower limb arterial reconstruction |

Subcutis: Polyglactin 910 vs. Polyglactin 910+ Skin: Poliglecaprone 25 vs. Poliglecaprone 25+ |

I |

CDC |

30 days |

Yes |

Low |

|