Negatieve druktherapie

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is het effect van profylactisch gesloten incisionele negatieve druktherapie bij patiënten die chirurgische ingrepen ondergaan op het risico van een postoperatieve wondinfectie (POWI)?

Aanbeveling

Gebruik postoperatief negatieve druktherapie op de gesloten incisie ter preventie van postoperatieve wondinfecties.

Houd bij het prioriteren van chirurgische wonden voor negatieve druktherapie rekening met de a priori kans op POWI.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

De analyses uitgevoerd door Groenen (eClinicalMedicine, 2023) laten het effect zien van iNDT op het percentage POWI’s vergeleken met standaard wondverzorging met reguliere wondverbanden bij chirurgische patiënten. De resultaten toonden een significante, klinisch relevante vermindering van POWI’s bij gebruik van iNDT in vergelijking met standaard wondverzorging, met een hoog niveau van bewijs (7,9% vs. 11,6% (RR 0.67; 95% CI: 0.59–0.76).

Het effect van iNDT verschilde niet van standaard wondverzorging voor secundaire uitkomstmaten zoals wonddehiscentie, seroma, hematoom, mortaliteit, necrose, aantal heropnames of aantal heroperaties. Voor huidblaarvorming werd een vijfvoudige toename gevonden bij patiënten met iNDT vergeleken met standaard wondverbanden. De heterogeniteit was hoog (I2 = 74%, en de incidentie van huidblaarvorming varieerde sterk, tussen 3% en 28%. Huidblaarvorming werd gemeld als een minimaal behandelbare bijwerking, maar moet in overweging worden genomen en worden besproken met patiënten voordat iNDT wordt gestart. De zekerheid van de effecten voor de secundaire uitkomstmaten varieerde van GRADE matig tot laag.

Er is geen biologische reden waarom men een verschil in effect tussen verschillende soorten chirurgie zou verwachten. Willekeurige opsplitsing van de beschikbare gegevens over chirurgische subspecialismen zonder bewijs voor effectmodificatie ondermijnt de statistische kracht en brengt het risico van schijnresultaten met zich mee. Desondanks willen zorgverleners resultaten opgesplitst per subspecialisme, en daarom worden subgroep analyses op basis van het type operatie gevraagd.

Het type operatie verschilde tussen de onderzoeken. Uit een subgroep analyse bleek dat iNDT het risico op POWI vermindert bij patiënten die een buikoperatie, orthopedische of traumachirurgie, vaatchirurgie of hartchirurgie ondergaan, terwijl er geen effect van iNDT was op POWI bij gynaecologische of verloskundige chirurgie, plastische chirurgie, algemene chirurgie en borstchirurgie.

De opgenomen studies gebruikten verschillende niveaus van subatmosferische druk. De subgroep analyse toonde aan dat zowel een subatmosferische druk van 75-80 mmHg als een subatmosferische druk van 120-125 mmHg beide effectief waren bij het verminderen van het percentage POWI. Slechts één studie gebruikte een zelfregulerende subatmosferische druk variërend van 50-200 mmHg, wat niet effectief was bij het verminderen van het POWI-percentage.

Aanvullende sensitiviteitsanalyses werden uitgevoerd om te evalueren of de betrokkenheid van de industrie of de studiekwaliteit onze bevindingen beïnvloedde. De aanvullende analyses toonden aan dat iNDT effectief was bij het verminderen van het POWI-percentage, ongeacht het niveau van betrokkenheid van de industrie (zie Subgroup analysis on the effect of iNPWT versus standard wound care on SSI across different levels of industry involvement. I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval). Soortgelijke resultaten werden gevonden voor de studiekwaliteit. Studies werden gecategoriseerd op basis van het algehele risico op bias met behulp van de ROB-2 tool. De analyses toonden aan dat iNDT effectief was bij het verminderen van het POWI-percentage, ongeacht de studiekwaliteit (zie Subgroup analysis on the effect of iNPWT versus standard wound care on SSI across different levels of risk of bias (low versus some concerns versus high risk of bias). ROB: risk of bias; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval.).

Over het algemeen vermindert iNDT het POWI-percentage in vergelijking met standaard wondverzorging bij patiënten die chirurgische ingrepen ondergaan, vooral bij degenen die abdominale, orthopedische of traumachirurgie, vaatchirurgie of hartchirurgie ondergaan, met subatmosferische drukniveaus van zowel 75-80 mmHg als 120-125 mmHg.

Internationale richtlijnen

De CDC-richtlijn geeft geen aanbeveling voor iNDT, terwijl de WHO-richtlijn het gebruik van iNDT aanbeveelt bij volwassen patiënten met primair gesloten chirurgische incisies in hoog risico wonden, met als doel het voorkomen van POWI. De bevindingen van Groenen (2023) ondersteunen de aanbeveling van de WHO om iNDT te gebruiken bij patiënten die chirurgische ingrepen ondergaan.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

De analyse van de effectiviteit houdt geen rekening met het ongemak van iNDT noch met de praktische overwegingen. iNDT kan de noodzaak voor dagelijkse verbandwisselingen wegnemen en lijkt daarom gunstig voor de patiënt. Echter, het apparaat kan niet losgekoppeld worden voor het douchen en in sommige gevallen beperkt de plaatsing van het apparaat de mobiliteit van de patiënt. Mobiliteitsbeperkingen zijn sterk afhankelijk van de locatie van de wond. Bovendien werd een significante toename van huidblaarvorming gevonden bij patiënten met iNDT. Huidblaarvorming werd gemeld als een minimaal en behandelbare bijwerking. Desalniettemin moet hiermee rekening worden gehouden en worden besproken met patiënten voordat iNDT wordt gestart.

Over het algemeen moeten de nadelige effecten en de voordelen zorgvuldig tegen elkaar worden afgewogen in samenspraak met de patiënt, idealiter met behulp van de principes van gedeelde besluitvorming.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

De directe kosten van POWI kunnen onder andere een langer ziekenhuisverblijf, heropname, poliklinische en spoedbezoeken, verdere chirurgie en langdurige antibioticabehandeling omvatten. Indirecte kosten zijn moeilijker te kwantificeren, maar kunnen verloren productiviteit van de patiënt en het gezin omvatten, evenals een tijdelijke of permanente afname van functionele of mentale capaciteit. De geschatte kosten voor het beheersen van POWI verschillen sterk, van minder dan 400 dollar per geval voor oppervlakkige POWI tot meer dan 30.000 dollar per geval voor ernstige infecties van organen of ruimtes.

De studie van Eckmann (2022) onderzocht de prevalentie en de klinische en economische impact van chirurgische site-infecties (SSI) in Duitse ziekenhuizen. Patiënten met SSI hadden significant hogere mortaliteit (9,3% versus 4,5%) en een langere opnameduur (28 versus 12 dagen). De kosten per geval waren ook significant hoger voor de SSI-groep (19.008 versus 9.040 euro). Daarom moet de preventie van POWI na de operatie een hoge prioriteit krijgen.

De kosten voor iNDT-apparaten variëren van €120 tot €185 (130 dollar tot 200 dollar) per apparaat en daarom lijkt het gebruik van iNDT zeer kostenefficiënt te zijn.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

iNDT-apparaten zijn wijdverspreid verkrijgbaar en makkelijk in gebruik. Het is een simpel aan te brengen apparaat na geringe training van personeel. Een gespecialiseerde wondverpleegkundige is niet vereist. Er lijken geen majeure barrières te zijn voor de implementatie van iNDT.

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

Aangezien iNDT effectief is gebleken in het verminderen van POWI, wijdverspreid verkrijgbaar en makkelijk in gebruik, beveelt de werkgroep het gebruik van iNDT aan bij patiënten die chirurgische ingrepen ondergaan met als doel POWI te verminderen. Hoewel de literatuuranalyse enkele studies m.b.t. volwassen patiënten heeft geïncludeerd is het niet aannemelijk dat het werkingsmechanisme bij kinderen anders is.

De kans op POWI kan a priori variëren afhankelijk van factoren zoals de mate van contaminatie, risicoprofiel van de patiënt en het specifieke type chirurgische ingreep. Echter wordt er een algemene aanbeveling gedaan omdat er geen biologische rationale is voor een relatief verschil in effect van iNPWT op POWI tussen de verschillende specialismen.

Subgroep analyse per type chirurgie resulteert in ondermijning van de statistische kracht door o.a. een kleinere sample size per subgroep waardoor resultaten onnauwkeuriger worden met een breed betrouwbaarheidsinterval. Dit geldt ook voor opsplitsing van data in hoog risico versus laagrisicogroepen. Het relatieve effect is vergelijkbaar over diverse subgroepen; Het absolute effect is naar verwachting groter bij patiëntpopulatie met een hoog risico op POWI.

De geplande duur van de behandeling lijkt geen belangrijke voorspeller van het effect op SSI (p = 0,69) – zie bijlage. Studies waarin een langere geplande behandelduur met NPWT werd gebruikt, hadden geen verschil in SSI. Tussen 5-7 dagen lijkt een optimale behandelduur.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Postoperatieve wondcomplicaties (PWC’s) vormen een last voor patiënten, chirurgen en beleidsmakers, omdat PWC’s het risico op morbiditeit, mortaliteit en kosten verhogen. Met het toepassen van incisionele negatieve drukwondtherapie (iNDT) wordt verondersteld dat bacteriële contaminatie van chirurgische wonden voor her-epitheliasatie wordt voorkomen, de bloedstroom wordt verbetert en lymfedrainage wordt bevorderd, terwijl oedeem, hematoom of seroma-ophoping beperkt wordt. Deze werkmechanismen suggereren dat iNDT niet alleen kan helpen bij het voorkomen van POWI’s, maar ook wonddehiscentie, huidnecrose, seroma en mogelijk hematoom voorkomt.

Zwanenburg et al. (2019) voerde een systematische review (SR) uit en vond dat iNDT het risico op een POWI vermindert met een hoog niveau van bewijs, en mogelijk ook het risico op wonddehiscentie, huidnecrose en seroma, zij het met een laag tot zeer laag niveau van bewijs. Vanwege het beperkte aantal studies dat destijds beschikbaar was, includeerde Zwanenburg et al. (2019) niet-gerandomiseerde studies. Sindsdien zijn er tal van RCT’s gepubliceerd, en is een systematische update van de literatuur nodig. In deze module is een SR, meta-analyse en een GRADE-beoordeling uitgevoerd van gerandomiseerde studies om het effect van iNDT als interventie te evalueren, met het gebruik van standaard wondverbanden als controle op de preventie van PWC’s.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

iNPWT versus standard wound care

|

High GRADE |

iNPWT reduces surgical site infections compared to standard wound care in patients undergoing surgical procedures.

Source: Groenen, 2023 |

|

Moderate GRADE |

iNPWT may reduce wound dehiscence compared to standard wound care in patients undergoing surgical procedures.

Source: Groenen, 2023 |

|

Low GRADE |

iNPWT may have little or no effect on the number of reoperations compared to standard wound care in patients undergoing surgical procedures.

Source: Groenen, 2023 |

|

Moderate GRADE |

iNPWT may reduce seroma compared to standard wound care in patients undergoing surgical procedures.

Source: Groenen, 2023 |

|

Low GRADE |

iNPWT may reduce hematoma compared to standard wound care in patients undergoing surgical procedures.

Source: Groenen, 2023 |

|

Low GRADE |

iNPWT may have little or no effect on the mortality compared to standard wound care in patients undergoing surgical procedures.

Source: Groenen, 2023 |

|

Low GRADE |

iNPWT may have little or no effect on the number of readmissions compared to standard wound care in patients undergoing surgical procedures.

Source: Groenen, 2023 |

|

Moderate GRADE |

iNPWT may increase skin blistering compared to standard wound care in patients undergoing surgical procedures.

Source: Groenen, 2023 |

|

Low GRADE |

iNPWT may reduce necrosis compared to standard wound care in patients undergoing surgical procedures.

Source: Groenen, 2023 |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

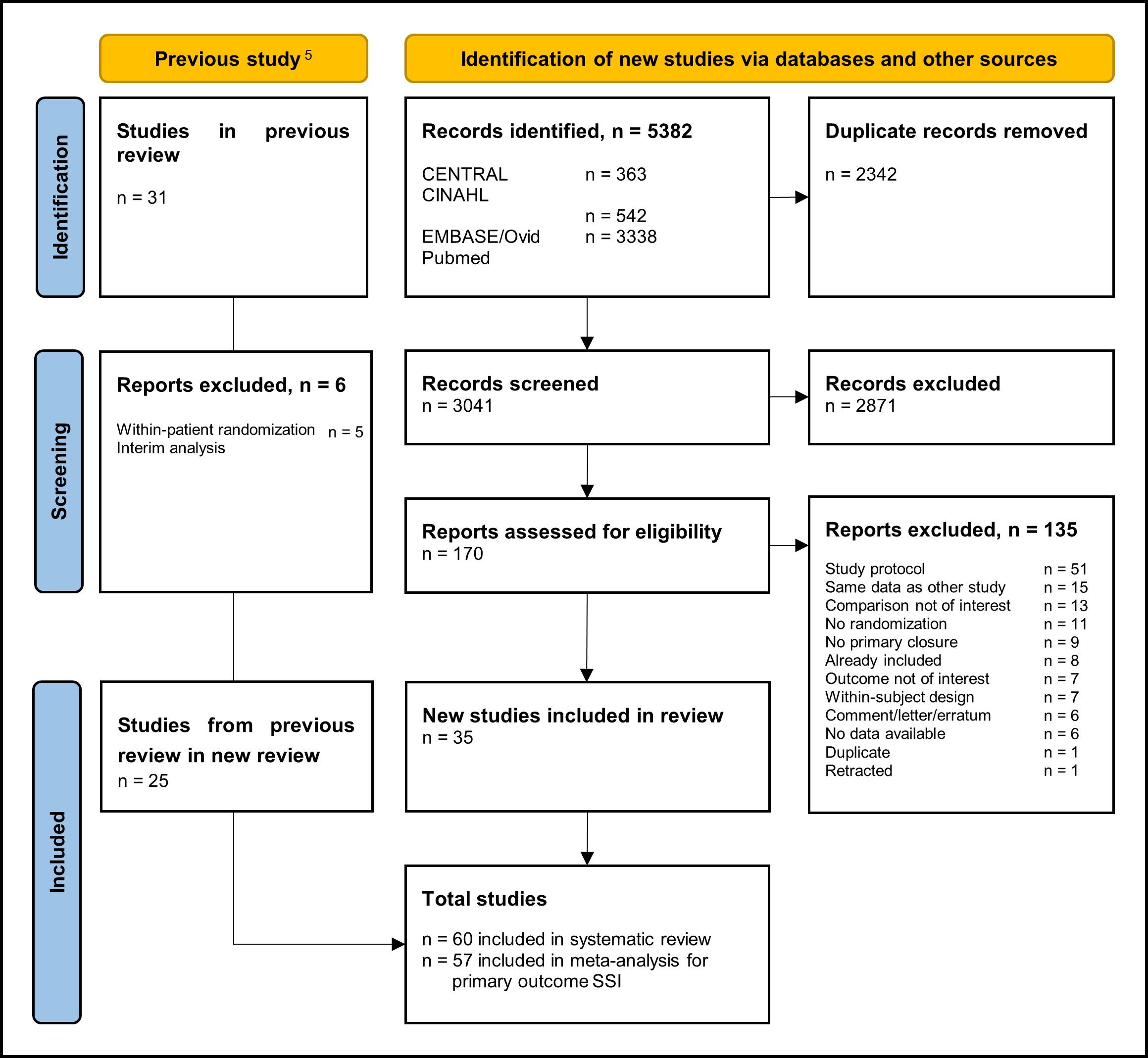

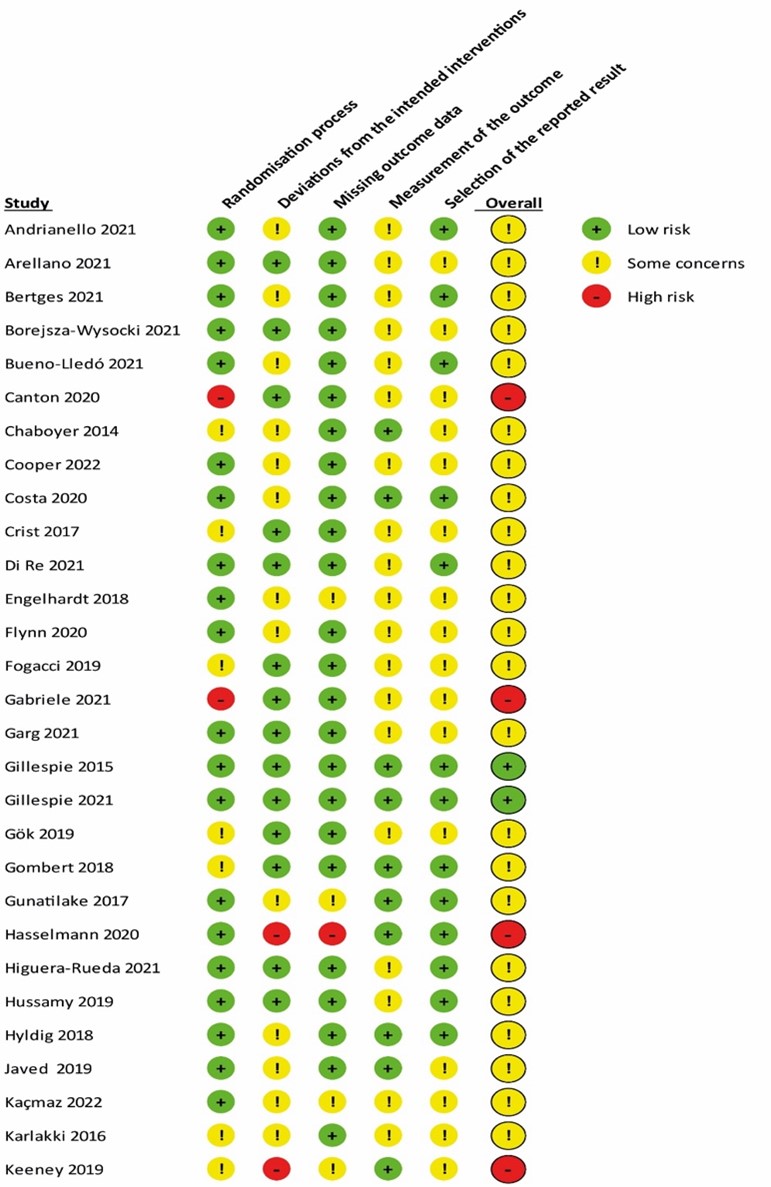

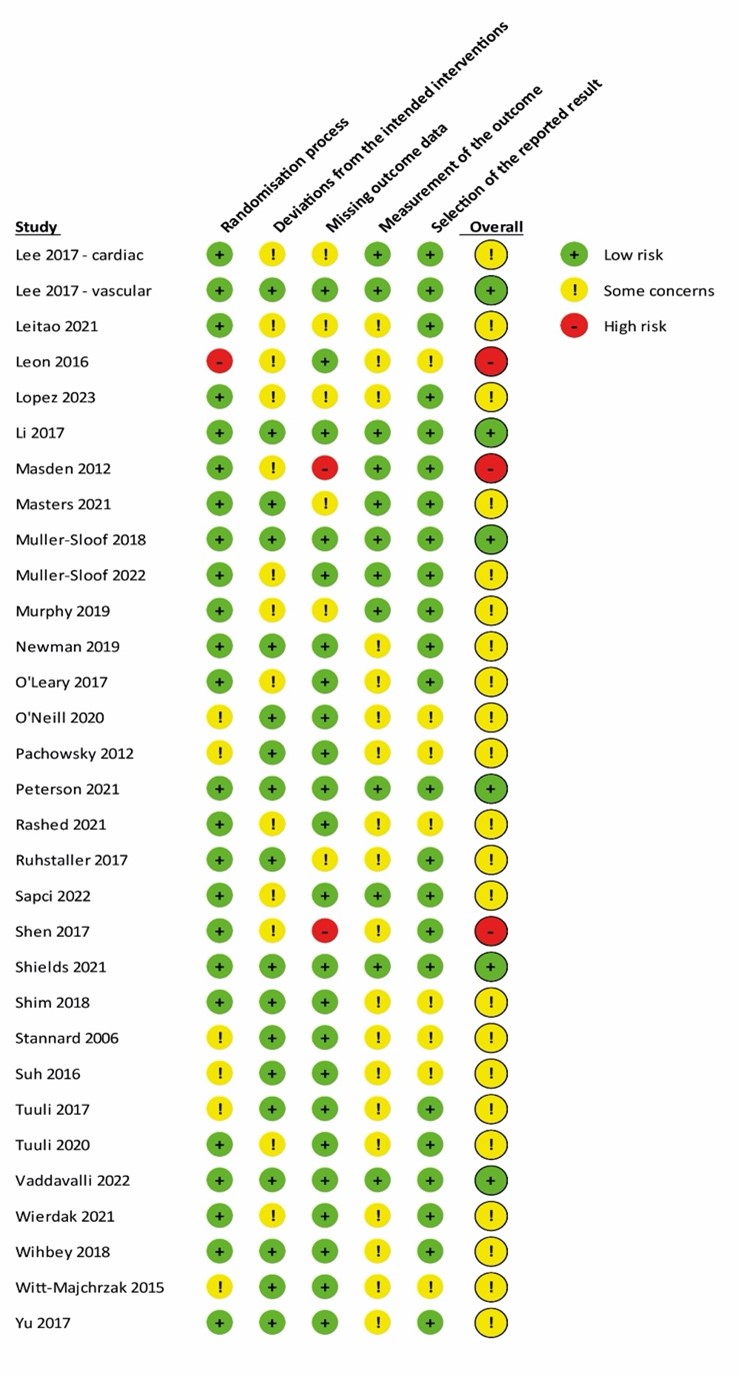

Sixty studies were included in the systematic review. A detailed PRISMA flow diagram for updating systematic reviews is presented in Figure 1. Zwanenburg et. al included 31 RCTs from which five were excluded due to methodological issues (within patient randomization), and the other study is an interim analysis of another included trial. Together with the 35 studies included from this update, we finally included 60 studies in the systematic review. Study characteristics of the included RCTs are summarized in table 1 in Study characteristics of included randomized controlled trials. The risk of bias assessment is summarized in the risk of bias tables in Risk of Bias Assessment ROB2.

Figure 1. PRISMA 2020 flow diagram for updated systematic reviews which included searches of databases and registers only.

Type of surgery

Type of surgery differed across the included studies included in the systematic review. Eighteen studies (n= 2,327) evaluated prophylactic closed incisional negative pressure therapy in patients after abdominal surgery, thirteen studies (n= 3,593) in patients with trauma or orthopedic surgery, eleven studies (n= 6,260) in patients after obstetrics or gynecology surgery, seven studies (n= 987) in patients after vascular surgery, four studies (n=316) in patients after cardiothoracic surgery, 3 studies (n= 182) in patients after plastic surgery, three studies (n= 138) in patients with general surgery, and one study (n= 100) in patients with breast surgery.

Industry involvement

An overview of all statements on industry involvement of studies is presented in Statements Industry involvement. Studies were categorized into four main categories to determine the influence of industry involvement: category 1= no industry funding or involvement, category 2= industry funding, without involvement in trial design, category 3= industry involvement in trial design, and category 4 = no information. Sixteen studies (n= 3,412) report no industry involvement, in 19 studies (n= 7,237) the industry (partially) funded the trial without involvement in the design, in 13 studies (n= 2,285) there was industry involvement in the trial design, and in twelve studies (n = 969) no information was provided on industry involvement.

Negative pressure

Different negative pressure values were used for iNPWT. In thirty studies (n= 6,318) the negative pressure in the iNPWT group was set to 120-125 mmHg, twenty-five studies (n= 7,293) used a negative pressure of 75-80 mmHg, one study (n= 44) used an adjustable device with a negative pressure between 50 and 200 mmHg, and one study (n= 100) used a system with oscillating cyclic negative pressure between 50 and 125 mmHg.

iNPWT devices

Different iNPWT devices were used. Twenty-three studies (n= 5,538) used the Prevena with a negative pressure of 125 mmHg, 23 studies (n= 7,129) used the PICO with a negative pressure set to 80 mmHg, five studies (n= 258) used the VAC, of which two with a negative pressure of 125 mmHg, one with an negative pressure between 50-200 mmHg, one set to 75 mmHg and one did not mention the pressure. Two studies (n= 151) used the CuraVac with a negative pressure of 75 mmHg or a cyclic negative pressure regulation ranging from 50 to 125, one study (n= 104) used the VivanoTec with a negative pressure of 125 mmHg, one study (n=71) used the VSD with a negative pressure of 125 mmHg, one study (n=72) used a custom made device with a negative pressure of 120 mmHg, one study (n= 75) used the NANOVA with a negative pressure of 125 mmHg, and another study (n= 311) did not report the type of de device but reported a negative pressure of 125 mmHg.

Study quality

Risk of bias was assessed using the ROB2-tool. In total ten studies (n= 2,746) had low risk of bias, 43 studies (n= 10,015) had some concerns and 7 studies (n= 1,142) had high risk of bias.

Results

Primary outcome

Surgical Site infections

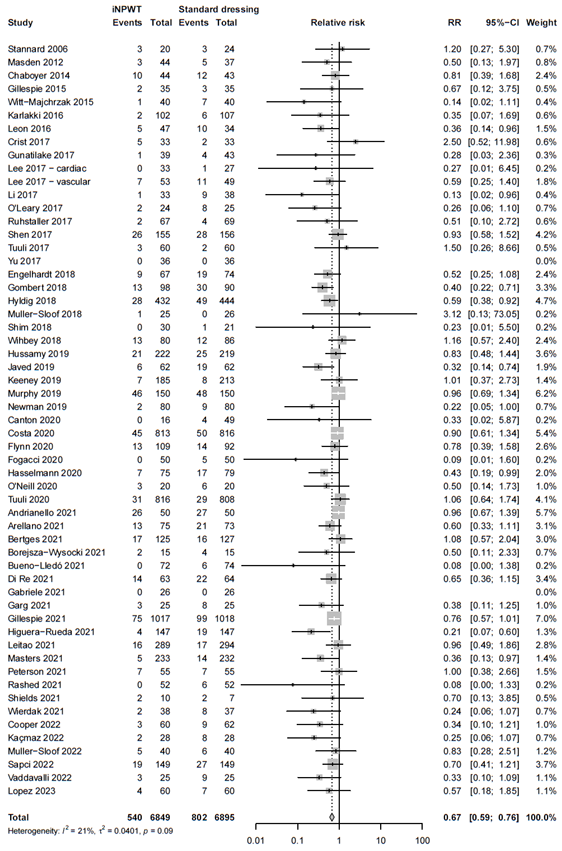

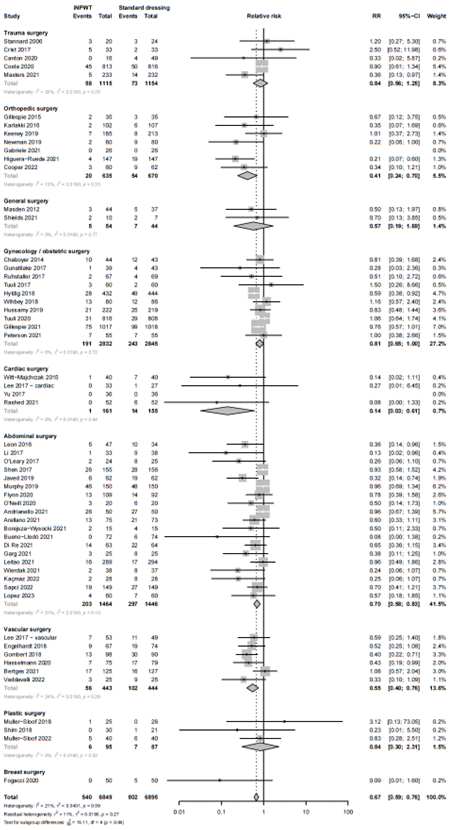

In total 13,744 patients were randomly assigned to receive iNPWT (n= 6,849) or standard wound care (n= 6,895). In total 1,342 SSI were reported, corresponding with an overall SSI rate of 9.8%. The meta-analysis showed that 540 of 6,849 patients had SSI in de iNPWT group (7.9%), and 802 of 6,895 patients had SSI in the control group (11.6%), resulting in an overall relative risk (RR) of 0.67 (95%CI 0.59 - 0.76), a statistically significant difference favoring the iNPWT group. Heterogeneity between studies was moderate (I2= 21%, τ2 = 0.0401, p = 0.09). The forest plot for SSI is presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Risk Ratio for the effect of iNPWT versus standard wound care on SSI, I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval.

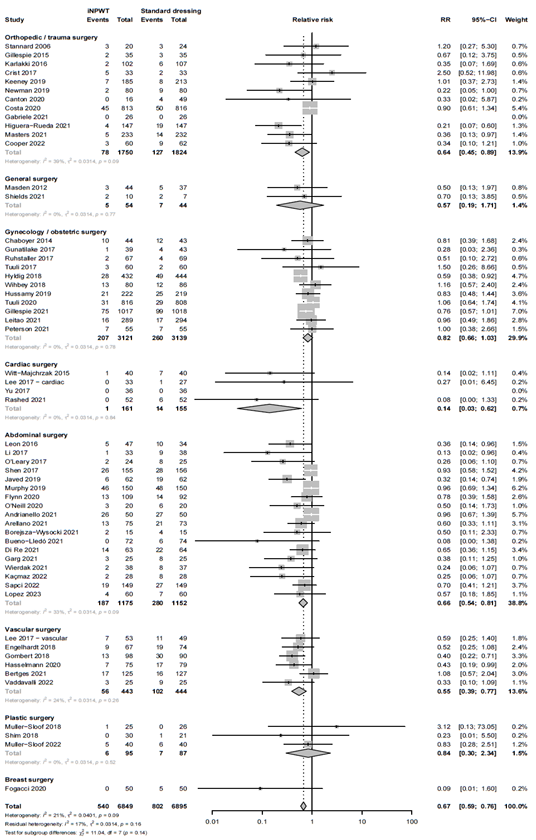

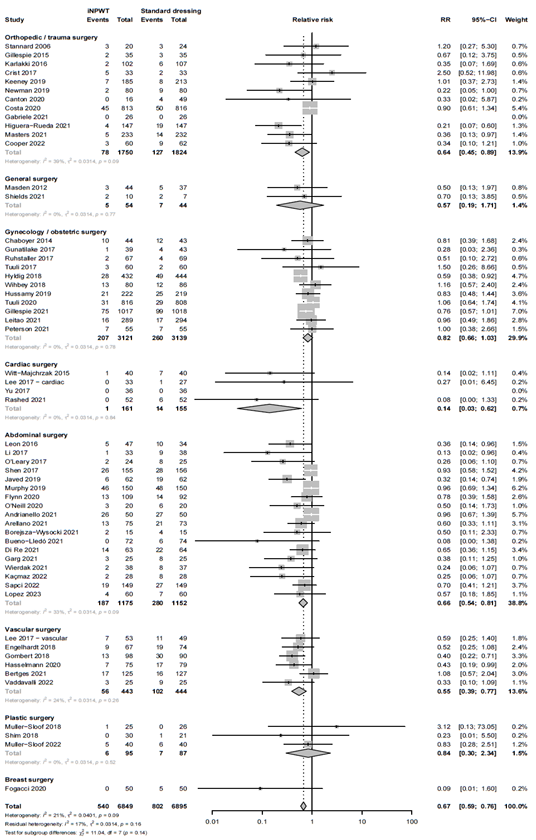

Subgroup analysis: type of surgery

We performed a subgroup analysis to evaluate the efficacy of iNPWT on SSI across different types of surgery. The subgroup analysis with forest plot is presented in Figure 3. A statistically significant difference favoring iNPWT on SSI was found in abdominal surgery (RR 0.66; 95%CI 0.54 - 0.81), orthopedic or trauma surgery (RR 0.64; 95%CI 0.46 - 0.89), vascular surgery (RR 0.55; 95%CI 0.39 to 0.77) and cardiac surgery (RR 0.14; 95%CI 0.03 to 0.62). No statistically significant difference between groups for SSI was found in obstetric surgery (RR 0.82; 95%CI 0.66 - 1.03), plastic surgery (RR 0.84; 95%CI 0.30 – 2.33), general surgery (RR 0.57; 95%CI 0.19 - 1.72) and breast surgery (RR 0.09; 95%CI 0.01 - 1.60).

Figure 3A. Subgroup analysis on the effect of iNPWT versus standard wound care on SSI across different types of surgery (clustering orthopedic and trauma surgery), I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval.

Figure 3B. Subgroup analysis on the effect of iNPWT versus standard wound care on SSI across different types of surgery (splitting orthopedic and trauma surgery), I: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval.

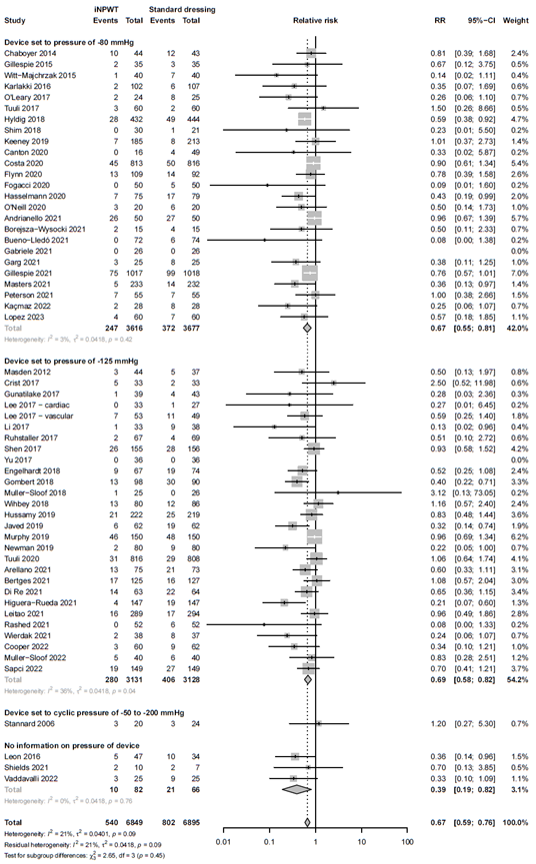

Subgroup analysis: negative pressure

The negative pressure differed across the studies. To evaluate whether the height of the negative pressure influences the efficacy of iNPWT on SSI we performed a subgroup analysis. The forest plot of the subgroup analysis is presented in Figure 4. Both, a negative pressure of 75-80 mmHg and a negative pressure of 120-125 mmHg were effective for the prevention of SSI, RR 0.67 (95%CI 0.55 - 0.81) and RR 0.69 (95%CI 0.58 - 0.82), respectively. There was no significant difference in SSI seen in a device with negative pressure ranging from 50-200 mmHg versus standard wound care (RR 1.20; 95%CI 0.27 - 5.30).

Figure 4. Subgroup analysis on the effect of iNPWT versus standard wound care on SSI across different subatmospheric pressures, I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval.

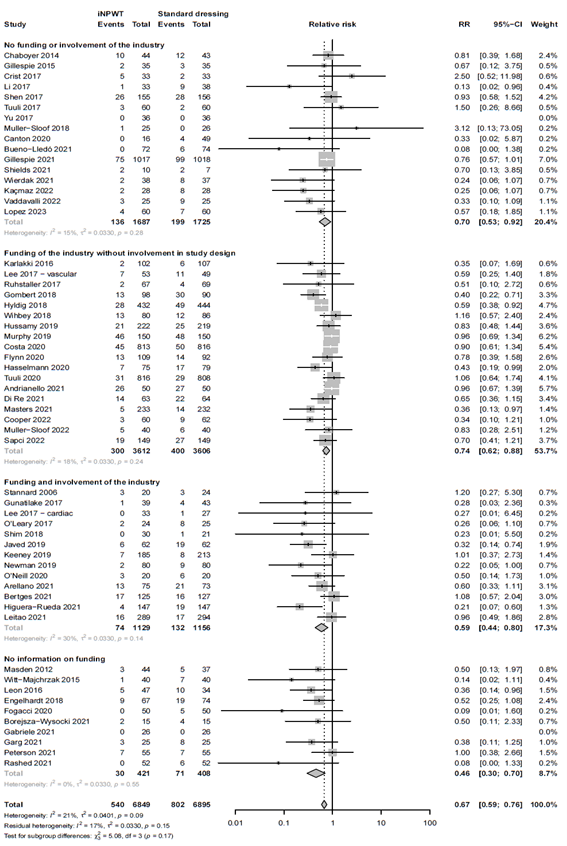

Subgroup analysis: industry involvement

To evaluate whether industry involvement influences the efficacy of iNPWT on SSI we performed a subgroup analysis. Subgroup analysis revealed that the efficacy of iNPWT on SSI was significantly across the different categories; category 1; no industry funding or involvement (RR 0.70; 95%CI 0.53 - 0.92), category 2; industry funding, without involvement in trial design (RR 0.74; 95%CI 0.62 - 0.88), category 3; industry involvement in trial design (RR 0.59; 95%CI 0.44 - 0.80), and category 4; no information (RR 0.46; 95%CI 0.30 - 0.70). The forest plot is presented in Figure 5.

Figure 5. Subgroup analysis on the effect of iNPWT versus standard wound care on SSI across different levels of industry involvement. I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval.

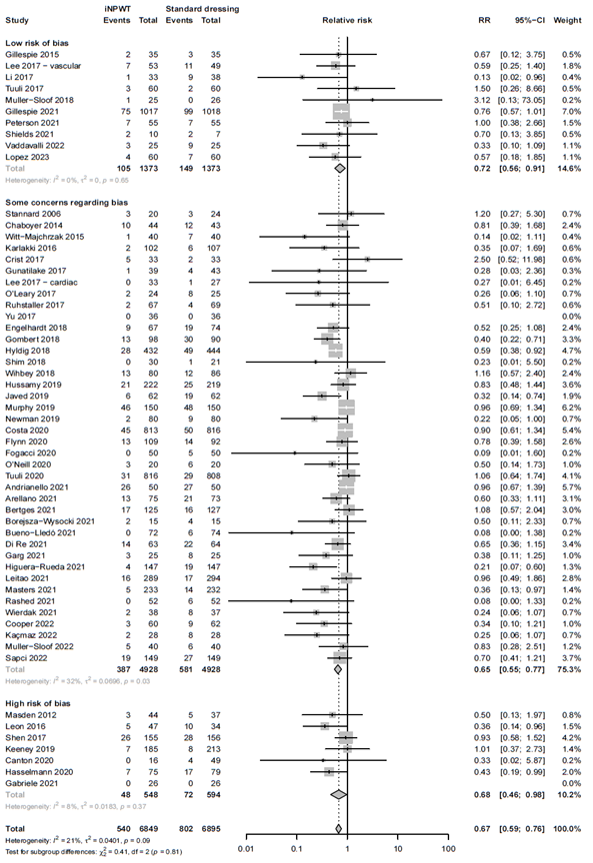

Subgroup analysis: study quality

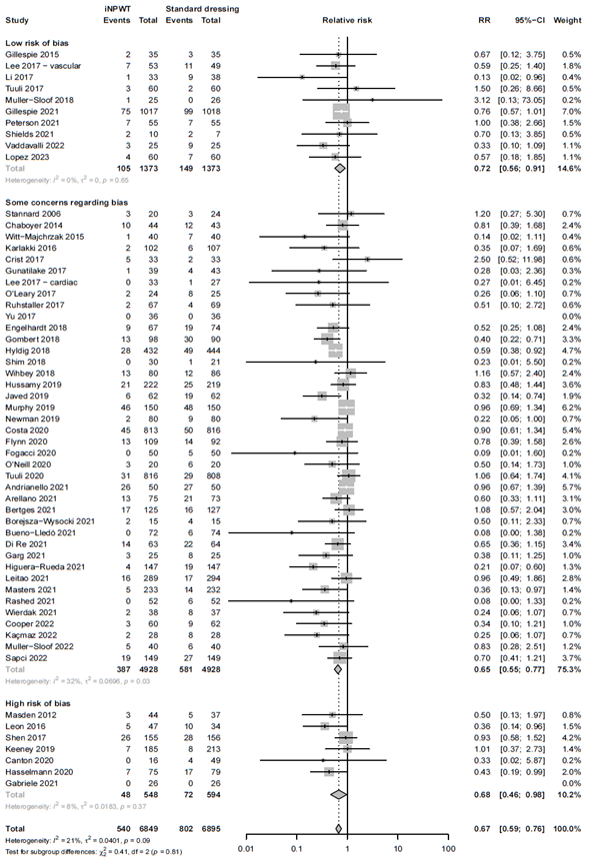

We evaluated if the quality of the included studies influences the efficacy of iNPWT by performing a sensitivity analysis. The results of the sensitivity analysis excluding studies at high risk of bias showed comparable results to the overall analysis. The efficacy of iNPWT on SSI in studies with low risk of bias or those with some concerns was RR 0.72 (95%CI 0.56 - 0.90), and RR 0.65 (95%CI 0.55 - 0.77). This was similar in studies with high risk of bias RR 0.68 (95%CI 0.46 - 0.98). The sensitivity analysis, separating studies with high risk of bias from those with low or risk of bias is presented in Figure 6.

Figure 6A. Subgroup analysis on the effect of iNPWT versus standard wound care on SSI across different levels of risk of bias (low versus some concerns versus high risk of bias). ROB: risk of bias; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval.

Figure 6B. Subgroup analysis on the effect of iNPWT versus standard wound care on SSI across different levels of risk of bias (low/some concerns versus high risk of bias). ROB: risk of bias; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval.

Secondary outcomes

There was no significant difference between the effect of iNPWT versus standard wound care on wound dehiscence (RR 0.85; 95%CI 0.71 - 1.02), reoperation (RR 0.91; 95%CI 0.69 - 1.20), seroma (RR 0.83; 95% 0.65 - 1.06), hematoma (RR 0.77; 95%CI 0.48 - 1.23), mortality (RR 0.94; 95%CI 0.58 - 1.52), readmission (RR 0.96; 95%CI 0.69 - 1.35) and necrosis (RR 0.46; 95%CI 0.14 - 1.46). Skin blistering increased significantly with the use of iNPWT (RR 5.10; 95%CI 1·99 - 13·05) with high between study heterogeneity (I2 = 72%, τ2 = 1·6404, p < 0·01). All results are presented in the evidence table in Evidence table, all RR with corresponding 95% CI.

Wound dehiscence

The effect of iNPWT on wound dehiscence was evaluated in 8,867 patients. In total 719 patients had wound dehiscence, corresponding with an overall wound dehiscence rate of 8.1%. There was no significant difference in wound dehiscence in patients treated with iNPWT compared to standard wound dressings (RR 0.85; 95%CI 0.71 -1.02). The forest plot of the meta-analysis is presented in Figure 7.

Figure 7. Risk Ratio for the effect of iNPWT versus standard wound care on wound dehiscence, I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval.

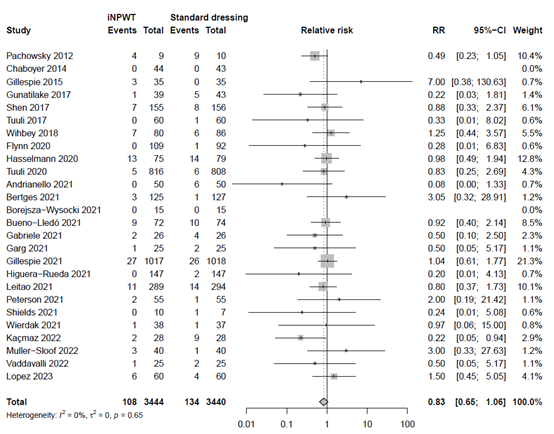

Seroma

The effect of iNPWT on seroma was evaluated in 6,884 patients. In total 242 patients had seroma after surgery, corresponding with an overall seroma rate of 3.5%. There was no significant difference in seroma between patients treated with iNPWT compared to standard wound care (RR 0.83; 95%CI; 0.65 to 1.06). The forest plot of the meta-analysis is presented in Figure 8.

Figure 8. Risk Ratio for the effect of iNPWT versus standard wound care on seroma, I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval.

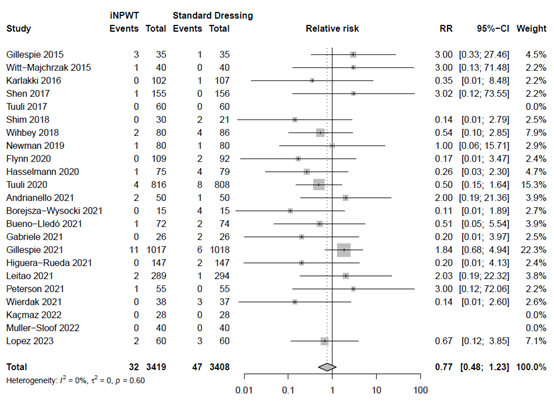

Hematoma

The effect of iNPWT on necrosis was evaluated in 6,827 patients. In total 79 patients had had hematoma after surgery, corresponding with an overall hematoma rate of 1.2%. There was no significant difference in hematoma between patients treated with iNPWT compared to standard wound care (RR 0.77; 95%CI 0.48 to 1.23). The forest plot with meta-analysis is presented in Figure 9.

Figure 9. Risk Ratio for the effect of iNPWT versus standard wound care on hematoma, I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval.

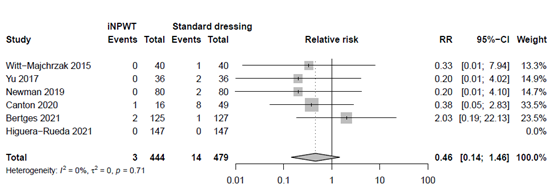

Necrosis

The effect of iNPWT on hematoma was evaluated in 923 patients. In total 17 patients had had hematoma after surgery, corresponding with an overall necrosis rate of 1.8%. There was no significant difference in necrosis between patients treated with iNPWT compared to standard wound care (RR 0.46; 95%CI 0.14 to 1.46). The forest plot with meta-analysis is presented in Figure 10.

Figure 10. Risk Ratio for the effect of iNPWT versus standard wound care on necrosis, I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval.

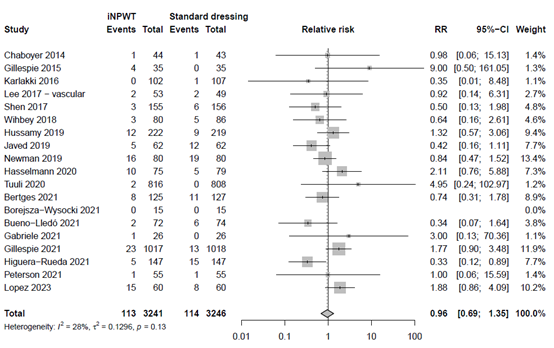

Readmission

The effect of iNPWT on readmission was evaluated in 6,487 patients. In total 227 readmissions were reported, corresponding with an overall readmission rate of 3.5%. There was no significant difference in number of readmissions between patients treated with iNPWT compared to standard wound care (RR 0.96; 95%CI 0.69 to 1.35). The forest plot with meta-analysis is presented in Figure 11.

Figure 11. Risk Ratio for the effect of iNPWT versus standard wound care on readmission, I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval.

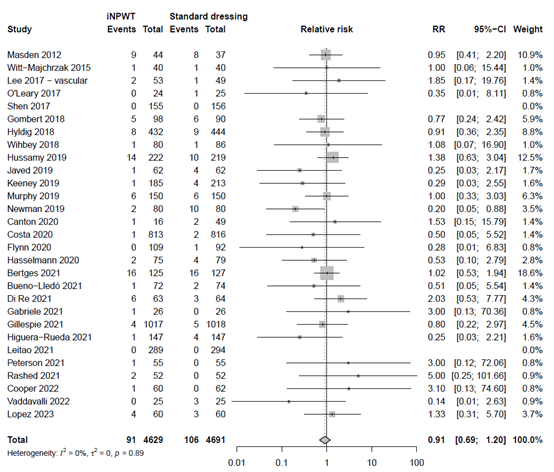

Reoperation

The effect of iNPWT on reoperation was evaluated in 9,320 patients. In total 197 reoperations were reported, corresponding with an overall reoperation rate of 2.1%. There was no significant difference in number of reoperations between patients treated with iNPWT compared to standard wound care (RR 0.91; 95%CI 0.69 to 1.20). The forest plot with meta-analysis is presented in Figure 12.

Figure 12. Risk Ratio for the effect of iNPWT versus standard wound care on reoperation, I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval.

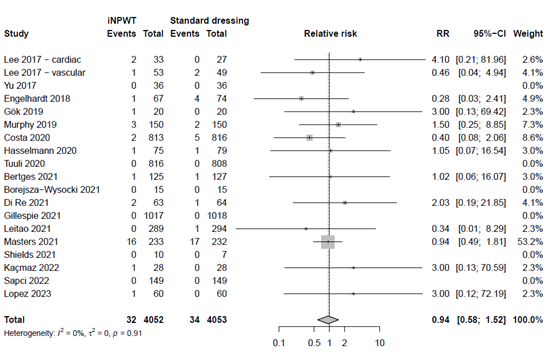

Mortality

The effect of iNPWT on mortality was evaluated in 8,105 patients. In total 66 mortalities were reported, corresponding with an overall reoperation rate of 0.8%. There was no significant difference in number of deaths between patients treated with iNPWT compared to standard wound care (RR 0.94; 95%CI 0.58 to 1.52). The forest plot with meta-analysis is presented in Figure 13.

Risk Ratio for the effect of iNPWT versus standard wound care on mortality, I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval.

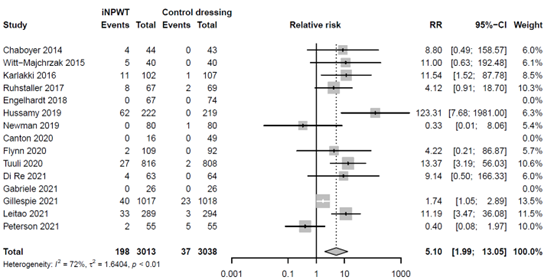

Skin blistering

The effect of iNPWT on skin blistering was evaluated in 6,051 patients. In total 235 patients experience skin blistering, corresponding with an overall reoperation rate of 3.9%. There was a large significant difference in number of skin blistering between patients treated with iNPWT compared to standard wound care (RR 5.10; 95%CI 1.99 to 13.05). The forest plot with meta-analysis is presented in Figure 14.

Figure 14. Risk Ratio for the effect of iNPWT versus standard wound care on skin blistering, I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval.

Adverse events

Adverse events of the skin related to the study intervention, including skin blistering and pain, were mentioned in 32 RCTs and are listed in Adverse events. Five studies reported no adverse events in both study arms.

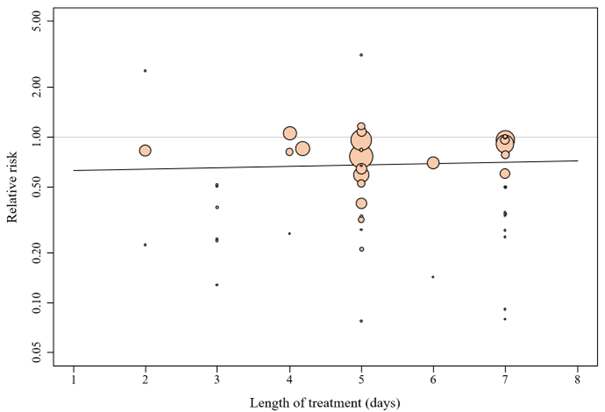

Duration of treatment

Meta-regression analysis showed that intended duration of treatment is not a significant effect size predictor (p = 0.69). Studies with longer intended iNPWT treatment duration were not associated with a difference in SSI, with a regression coefficient of 0.020. The bubble plot is presented in Figure 15.

Figure 15. Bubble plot of intended duration of treatment

Meta-regression showed that intended duration of treatment is not a significant effect size predictor (p = 0.69). Studies with longer intended duration of iNPWT treatment were not associated with a larger reduction in SSI, with a regression coefficient of 0.020. This means that for every additional intended day, the effect size (relative risk) is expected to rise by 0.020.

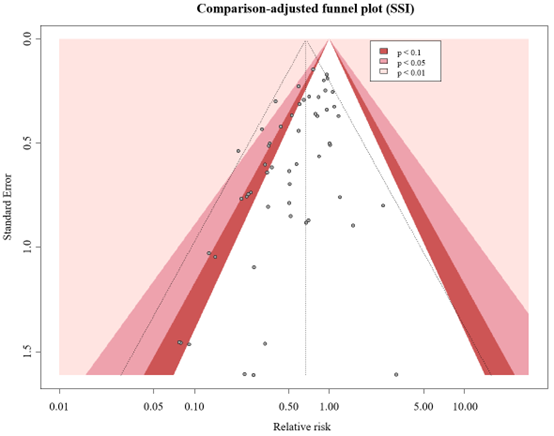

Level of evidence of the literature

The GRADE approach for rating the certainty of estimates of treatment effects was used. Since all included studies are randomized controlled trials, the rating for the GRADE starts high for all outcomes. Each outcome can be downgraded due to one of the following reasons: risk of bias: the quality assessment of the individual studies is presented in the risk of bias tables in Risk of Bias Assessment ROB2; inconsistency: similarity of point estimates, extent of overlap of confidence intervals, and statistical criteria including tests of heterogeneity and I2; imprecision: For point estimates with 95%CIs that crosses the null-effect threshold and boundaries for clinical decision making we downgraded with one or two dimensions. If the boundaries are not crossed, we did not downgrade. Publication bias: The comparison-adjusted funnel plot showed no sign of small-study effects (see funnel plot diagrams). The certainty of the evidence, and absolute effects per outcome are presented in the GRADE-table in GRADE-table. A visual presentation of the absolute differences between iNPWT and standard wound care with GRADE certainty levels is presented in Figure 16.

Figure 16. Visual presentation showing the absolute differences between iNPWT and standard wound care with GRADE certainty levels per outcome measure.

|

|

Certainty assessment |

№ of patients |

Effect |

Certainty |

||||||||

|

|

№ of studies |

Study design |

Risk of bias |

Inconsistency |

Indirectness |

Imprecision |

Other considerations |

iNPWT |

Control dressings |

Relative |

Absolute |

|

|

Primary outcome |

||||||||||||

|

SSI |

57 |

RCTs |

Not serious |

Not serious (I2 = 21%) |

Not serious |

Not serious |

None |

540 / 6849 (7·9%) |

802 / 6895 (11·6%) |

RR 0·67 (0·59 - 0·76) |

38 fewer per 1.000 |

⨁⨁⨁⨁ High |

|

Secondary outcomes |

||||||||||||

|

Wound dehiscence |

35 |

RCTs |

Not serious |

Not serious (I2 = 13%) |

Not serious |

Serious† (-1) |

None |

332 / 4417 (7·5%) |

387 / 4450 (8·7%) |

RR 0·85 (0·71 - 1·02) |

13 fewer per 1.000 |

⨁⨁⨁◯ Moderate |

|

Reoperation |

29 |

RCTs |

Not serious |

Not serious (I2 = 0%) |

Not serious |

Serious‡ (-2) |

None |

91 / 4629 (2·0%) |

106 / 4691 (2·3%) |

RR 0·91 (0·69 - 1·20) |

2 fewer per 1.000 |

⨁⨁◯◯ |

|

Seroma |

26 |

RCTs |

Not serious |

Not serious (I2 = 0%) |

Not serious |

Serious† (-1) |

None |

108 / 3444 (3·1%) |

134 / 3440 (3·9%) |

RR 0·83 (0·65 - 1·06) |

7 fewer per 1.000 |

⨁⨁⨁◯ Moderate |

|

Hematoma |

23 |

RCTs |

Not serious |

Not serious (I2 = 0%) |

Not serious |

Serious‡ (-2) |

None |

32 / 3419 (0·9%) |

47 / 3408 (1·4%) |

RR 0·77 (0·48 - 1·23) |

3 fewer per 1.000 |

⨁⨁◯◯ |

|

Mortality |

19 |

RCTs |

Not serious |

Not serious (I2 = 0%) |

Not serious |

Serious‡ (-2)

|

None |

32 / 4052 (0·8%) |

34 / 4053 (0·8%) |

RR 0·94 (0·58 - 1·52) |

1 fewer per 1.000 |

⨁⨁◯◯ Low |

|

Readmission |

19 |

RCTs |

Not serious |

Not serious (I2 = 28%) |

Not serious |

Serious‡ (-2) |

None |

113 / 3241 (3·5%) |

114 / 3246 (3·5%) |

RR 0·96 (0·69 - 1·23) |

1 fewer per 1.000 |

⨁⨁◯◯ |

|

Skin blistering |

11 |

RCTs |

Not serious |

Serious (-1) (I2 = 72%) |

Not serious |

Not serious

|

None |

198 / 3013 (6·6%) |

37 / 3808 (1·2%) |

RR 5·10 (1·99 - 13·05) |

50 more per 1.000 |

⨁⨁⨁◯ Moderate |

|

Necrosis |

6 |

RCTs |

Not serious |

Not serious (I2 = 0%) |

Not serious |

Serious‡ (-2) |

None |

3 / 444 (0·7%) |

14 / 479 (2·9%) |

RR 0·46 (0·14 - 1·46) |

16 fewer per 1.000 |

⨁⨁◯◯ Low |

|

NS = not serious; *Risk of bias (Appendix 10); † 95% CI overlaps no effect; ‡ 95% CI overlaps no effect but fails to exclude considerable benefit or harm (default relative risk reduction >0·20); § 95%CI excludes no effect but fails to exclude considerable benefit or harm (default relative risk reduction >0·20). |

||||||||||||

Figure 17. Comparison-adjust funnel plot

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question:

‘What is the effect of closed incisional negative pressure wound therapy (iNPWT) vs. conventional dressings on SSI in adult patients undergoing surgical procedures?’

P: Adult patients undergoing surgical procedures

I: Closed incisional negative pressure therapy (iNPWT)

C: No prophylactic iNPWT (conventional dressing)

O: Surgical site infections, wound dehiscence, reoperation, seroma, hematoma, mortality, readmission, skin blistering, skin necrosis

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered SSI as a critical outcome measure for decision making and wound dehiscence, seroma, hematoma, skin necrosis, readmission, and reoperations as important outcomes for clinical decision making.

The working group defined a threshold of 10% for continuous outcomes and a relative risk (RR) for dichotomous outcomes of <0.80 and >1.25 as a minimal clinically (patient) important difference.

Search and select (Methods)

This systematic review is reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for updating Systematic Reviews (PRISMA) statement). We update the review by Zwanenburg et al. who searched the literature up to December 18, 2018. In this update we searched the databases Pubmed, Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) up to 24-10-2022. Search terms included: surgical site infection, post-operative wound infection, post-operative care, prophylactic closed incisional NPWT, vacuum assisted closure, wound care, dressing. The detailed search strategy is available on request via https://richtlijnendatabase.nl/.

We included RCTs that compared closed incisional NPWT (iNPWT) with standard wound care compromising the use of conventional dressings (no iNPWT). Non-randomized studies, cross-over studies, opinion papers, proceedings, editorials, studies in paediatric patients, animal studies and studies not focusing on primary wound closure were excluded. Two reviewers (HJ and HG) independently executed title and abstract screening and full text review of potential eligible studies. Discrepancies between the two reviewers were resolved through discussion and, if necessary, the senior author (MAB) was consulted. Additional articles were identified by backward and forward citation tracking of previously published studies.

The update of the search resulted in 5383 hits. Five studies were additionally included based on citation tracking. One hundred sixty-nine records were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full-text, 135 studies were excluded, and 34 additional studies were included (see the 'Samenvatting literatuur' tab). Reasons for exclusion after full text review are reported in the exclusion table in the table of excluded studies under the 'Evidence tabellen' tab.

Referenties

- Anderson V, Chaboyer W, Gillespie BM, Fenwick J. The use of negative pressure wound therapy dressing in obese women undergoing caesarean section:: a pilot study. Evidence Based Midwifery. 2014;12(1):23.

- Andrianello S, Landoni L, Bortolato C, et al. Negative pressure wound therapy for prevention of surgical site infection in patients at high risk after clean-contaminated major pancreatic resections: A single-center, phase 3, randomized clinical trial. Surgery. May 2021;169(5):1069-1075. doi:10.1016/j.surg.2020.10.029

- Arellano M, Barragan Serrano C, Guedea M, et al. Surgical Wound Complications after Colorectal Surgery with Single-Use Negative-Pressure Wound Therapy Versus Surgical Dressing over Closed Incisions: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Adv Skin Wound Care. Dec 1 2021;34(12):657-661. doi:10.1097/01.ASW.0000756512.87211.13

- Astagneau P, Rioux C, Golliot F, Brucker G, Group INS. Morbidity and mortality associated with surgical site infections: results from the 1997-1999 INCISO surveillance. J Hosp Infect. Aug 2001;48(4):267-74. doi:10.1053/jhin.2001.1003

- Atkins BZ, Tetterton JK, Petersen RP, Hurley K, Wolfe WG. Laser Doppler flowmetry assessment of peristernal perfusion after cardiac surgery: beneficial effect of negative pressure therapy. Int Wound J. Feb 2011;8(1):56-62. doi:10.1111/j.1742-481X.2010.00743.x

- Beecher SM, O'Leary DP, McLaughlin R, Kerin MJ. The Impact of Surgical Complications on Cancer Recurrence Rates: A Literature Review. Oncol Res Treat. 2018;41(7-8):478-482. doi:10.1159/000487510

- Bertges DJ, Smith L, Scully RE, et al. A multicenter, prospective randomized trial of negative pressure wound therapy for infrainguinal revascularization with a groin incision. J Vasc Surg. Jul 2021;74(1):257-267 e1. doi:10.1016/j.jvs.2020.12.100

- Borejsza-Wysocki M, Bobkiewicz A, Francuzik W, et al. Effect of closed incision negative pressure wound therapy on incidence rate of surgical site infection after stoma reversal: a pilot study. Wideochir Inne Tech Maloinwazyjne. Dec 2021;16(4):686-696. doi:10.5114/wiitm.2021.106426

- Bueno-Lledo J, Franco-Bernal A, Garcia-Voz-Mediano MT, Torregrosa-Gallud A, Bonafe S. Prophylactic Single-use Negative Pressure Dressing in Closed Surgical Wounds After Incisional Hernia Repair: A Randomized, Controlled Trial. Ann Surg. Jun 1 2021;273(6):1081-1086. doi:10.1097/SLA.0000000000004310

- Canton G, Fattori R, Pinzani E, Monticelli L, Ratti C, Murena L. Prevention of postoperative surgical wound complications in ankle and distal tibia fractures: results of Incisional Negative Pressure Wound Therapy. Acta Biomed. Dec 30 2020;91(14-S):e2020006. doi:10.23750/abm.v91i14-S.10784

- Chaboyer W, Anderson V, Webster J, Sneddon A, Thalib L, Gillespie BM. Negative Pressure Wound Therapy on Surgical Site Infections in Women Undergoing Elective Caesarean Sections: A Pilot RCT. Healthcare (Basel). Sep 30 2014;2(4):417-28. doi:10.3390/healthcare2040417

- Cooper HJ, Santos WM, Neuwirth AL, et al. Randomized Controlled Trial of Incisional Negative Pressure Following High-Risk Direct Anterior Total Hip Arthroplasty. Journal of Arthroplasty. Aug 2022;37(8):S931-S936. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2022.03.039

- Costa ML, Achten J, Knight R, et al. Effect of Incisional Negative Pressure Wound Therapy vs Standard Wound Dressing on Deep Surgical Site Infection After Surgery for Lower Limb Fractures Associated With Major Trauma: The WHIST Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. Feb 11 2020;323(6):519-526. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.0059

- Crist BD, Oladeji LO, Khazzam M, Della Rocca GJ, Murtha YM, Stannard JP. Role of acute negative pressure wound therapy over primarily closed surgical incisions in acetabular fracture ORIF: A prospective randomized trial. Injury. Jul 2017;48(7):1518-1521. doi:10.1016/j.injury.2017.04.055

- Di Re AM, Wright D, Toh JWT, et al. Surgical wound infection prevention using topical negative pressure therapy on closed abdominal incisions - the 'SWIPE IT' randomized clinical trial. J Hosp Infect. Apr 2021;110:76-83. doi:10.1016/j.jhin.2021.01.013

- Eckmann C, Kramer A, Assadian O, et al. Clinical and economic burden of surgical site infections in inpatient care in Germany: A retrospective, cross-sectional analysis from 79 hospitals. PLoS One. 2022;17(12):e0275970. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0275970

- Eckmann, C., Kramer, A., Assadian, O., Flessa, S., Huebner, C., Michnacs, K., Muehlendyck, C., Podolski, K. M., Wilke, M., Heinlein, W., & Leaper, D. J. (2022). Clinical and economic burden of surgical site infections in inpatient care in Germany: A retrospective, cross-sectional analysis from 79 hospitals. PloS one, 17(12), e0275970. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0275970

- Engelhardt M, Rashad NA, Willy C, et al. Closed-incision negative pressure therapy to reduce groin wound infections in vascular surgery: a randomised controlled trial. Int Wound J. Jun 2018;15(3):327-332. doi:10.1111/iwj.12848

- Flynn J, Choy A, Leavy K, et al. Negative Pressure Dressings (PICO(TM)) on Laparotomy Wounds Do Not Reduce Risk of Surgical Site Infection. Surg Infect (Larchmt). Apr 2020;21(3):231-238. doi:10.1089/sur.2019.078

- Fogacci T, Cattin F, Semprini G, Frisoni G, Fabiocchi L, Samorani D. The negative pressure therapy with PICO as a prevention of surgical site infection in high-risk patients undergoing breast surgery. Breast J. May 2020;26(5):1071-1073. doi:10.1111/tbj.13659

- Gabriele L, Gariffo G, Grossi S, Ipponi E, Capanna R, Andrean L. Closed Incisional Negative Pressure Wound Therapy (ciNPWT) in Oncological Orthopedic Surgery: Preliminary Report. Surg Technol Int. May 20 2021;38:451-454. doi:10.52198/21.STI.38.OS1429

- Galiano RD, Hudson D, Shin J, et al. Incisional Negative Pressure Wound Therapy for Prevention of Wound Healing Complications Following Reduction Mammaplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. Jan 2018;6(1):e1560. doi:10.1097/GOX.0000000000001560

- Garg A, Jayant S, Gupta AK, Bansal LK, Wani A, Chaudhary P. Comparison of closed incision negative pressure wound therapy with conventional dressing in reducing wound complications in emergency laparotomy. Pol J Surg. 2021;93(5)doi:10.5604/01.3001.0014.9759

- Gillespie BM, Rickard CM, Thalib L, et al. Use of Negative-Pressure Wound Dressings to Prevent Surgical Site Complications After Primary Hip Arthroplasty: A Pilot RCT. Surg Innov. Oct 2015;22(5):488-95. doi:10.1177/1553350615573583

- Gillespie BM, Webster J, Ellwood D, et al. Closed incision negative pressure wound therapy versus standard dressings in obese women undergoing caesarean section: multicentre parallel group randomised controlled trial. BMJ. May 5 2021;373:n893. doi:10.1136/bmj.n893

- Gok MA, Kafadar MT, Yegen SF. Comparison of negative-pressure incision management system in wound dehiscence: A prospective, randomized, observational study. J Med Life. Jul-Sep 2019;12(3):276-283. doi:10.25122/jml-2019-0033

- Gombert A, Babilon M, Barbati ME, et al. Closed Incision Negative Pressure Therapy Reduces Surgical Site Infections in Vascular Surgery: A Prospective Randomised Trial (AIMS Trial). Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. Sep 2018;56(3):442-448. doi:10.1016/j.ejvs.2018.05.018

- Groenen H, Jalalzadeh H, Buis DR, Dreissen YEM, Goosen JHM, Griekspoor M, Harmsen WJ, IJpma FFA, van der Laan MJ, Schaad RR, Segers P, van der Zwet WC, de Jonge SW, Orsini RG, Eskes AM, Wolfhagen N, Boermeester MA. Incisional negative pressure wound therapy for the prevention of surgical site infection: an up-to-date meta-analysis and trial sequential analysis. EClinicalMedicine. 2023 Jul 24;62:102105. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2023.102105. PMID: 37538540; PMCID: PMC10393772.

- Gunatilake RP, Swamy GK, Brancazio LR, et al. Closed-Incision Negative-Pressure Therapy in Obese Patients Undergoing Cesarean Delivery: A Randomized Controlled Trial. AJP Rep. Jul 2017;7(3):e151-e157. doi:10.1055/s-0037-1603956

- Hasselmann J, Bjork J, Svensson-Bjork R, Acosta S. Inguinal Vascular Surgical Wound Protection by Incisional Negative Pressure Wound Therapy: A Randomized Controlled Trial-INVIPS Trial. Ann Surg. Jan 2020;271(1):48-53. doi:10.1097/SLA.0000000000003364

- Higuera-Rueda CA, Emara AK, Nieves-Malloure Y, et al. The Effectiveness of Closed-Incision Negative-Pressure Therapy Versus Silver-Impregnated Dressings in Mitigating Surgical Site Complications in High-Risk Patients After Revision Knee Arthroplasty: The PROMISES Randomized Controlled Trial. J Arthroplasty. Jul 2021;36(7S):S295-S302 e14. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2021.02.076

- Hinrichs WL, Lommen EJ, Wildevuur CR, Feijen J. Fabrication and characterization of an asymmetric polyurethane membrane for use as a wound dressing. J Appl Biomater. Winter 1992;3(4):287-303. doi:10.1002/jab.770030408

- Horasan ES, Dag A, Ersoz G, Kaya A. Surgical site infections and mortality in elderly patients. Med Mal Infect. Oct 2013;43(10):417-22. doi:10.1016/j.medmal.2013.07.009

- Howell RD, Hadley S, Strauss E, Pelham FR. Blister formation with negative pressure dressings after total knee arthroplasty. Current Orthopaedic Practice. 2011;22(2):176-179.

- Hussamy DJ, Wortman AC, McIntire DD, Leveno KJ, Casey BM, Roberts SW. Closed Incision Negative Pressure Therapy in Morbidly Obese Women Undergoing Cesarean Delivery: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Obstet Gynecol. Oct 2019;134(4):781-789. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000003465

- Hutton B, Salanti G, Caldwell DM, et al. The PRISMA extension statement for reporting of systematic reviews incorporating network meta-analyses of health care interventions: checklist and explanations. Ann Intern Med. Jun 2 2015;162(11):777-84. doi:10.7326/M14-2385

- Hyldig N, Vinter CA, Kruse M, et al. Prophylactic incisional negative pressure wound therapy reduces the risk of surgical site infection after caesarean section in obese women: a pragmatic randomised clinical trial. BJOG. Apr 2019;126(5):628-635. doi:10.1111/1471-0528.15413

- Javed AA, Teinor J, Wright M, et al. Negative Pressure Wound Therapy for Surgical-site Infections: A Randomized Trial. Ann Surg. Jun 2019;269(6):1034-1040. doi:10.1097/SLA.0000000000003056

- Kacmaz HY, Baser M, Sozuer EM. Effect of Prophylactic Negative-Pressure Wound Therapy for High-Risk Wounds in Colorectal Cancer Surgery: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Advances in Skin & Wound Care. Nov 2022;35(11):597-603. doi:10.1097/01.Asw.0000874168.60793.10

- Karlakki SL, Hamad AK, Whittall C, Graham NM, Banerjee RD, Kuiper JH. Incisional negative pressure wound therapy dressings (iNPWTd) in routine primary hip and knee arthroplasties: A randomised controlled trial. Bone Joint Res. Aug 2016;5(8):328-37. doi:10.1302/2046-3758.58.BJR-2016-0022.R1

- Keeney JA, Cook JL, Clawson SW, Aggarwal A, Stannard JP. Incisional Negative Pressure Wound Therapy Devices Improve Short-Term Wound Complications, but Not Long-Term Infection Rate Following Hip and Knee Arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. Apr 2019;34(4):723-728. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2018.12.008

- Kilpadi DV, Cunningham MR. Evaluation of closed incision management with negative pressure wound therapy (CIM): hematoma/seroma and involvement of the lymphatic system. Wound Repair Regen. Sep-Oct 2011;19(5):588-96. doi:10.1111/j.1524-475X.2011.00714.x

- Koek MBG, van der Kooi TII, Stigter FCA, et al. Burden of surgical site infections in the Netherlands: cost analyses and disability-adjusted life years. J Hosp Infect. Nov 2019;103(3):293-302. doi:10.1016/j.jhin.2019.07.010

- Kwon J, Staley C, McCullough M, et al. A randomized clinical trial evaluating negative pressure therapy to decrease vascular groin incision complications. J Vasc Surg. Dec 2018;68(6):1744-1752. doi:10.1016/j.jvs.2018.05.224

- Lee AJ, Sheppard CE, Kent WD, Mewhort H, Sikdar KC, Fedak PW. Safety and efficacy of prophylactic negative pressure wound therapy following open saphenous vein harvest in cardiac surgery: a feasibility study. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. Mar 1 2017;24(3):324-328. doi:10.1093/icvts/ivw400

- Lee K, Murphy PB, Ingves MV, et al. Randomized clinical trial of negative pressure wound therapy for high-risk groin wounds in lower extremity revascularization. J Vasc Surg. Dec 2017;66(6):1814-1819. doi:10.1016/j.jvs.2017.06.084

- Leitao MM, Jr., Zhou QC, Schiavone MB, et al. Prophylactic Negative Pressure Wound Therapy After Laparotomy for Gynecologic Surgery: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Obstet Gynecol. Feb 1 2021;137(2):334-341. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000004243

- Leon MB, C.; Garcia Perez, J.C.; Guedea, M.; Sanz, G.; Gonzalez, C.; Arrayo, A.; Rubio, I.; Gonzalez, C,; Gazo, J.; Cantero-Cid, R. Negative pressure therapy to reduce SSI in open colorectal surgery: prospective, randomised and multicenter study. Colorectal Disease. 2016;18:6-12. doi:10.1111/codi.13441

- Li PY, Yang D, Liu D, Sun SJ, Zhang LY. Reducing Surgical Site Infection with Negative-Pressure Wound Therapy After Open Abdominal Surgery: A Prospective Randomized Controlled Study. Scand J Surg. Sep 2017;106(3):189-195. doi:10.1177/1457496916668681

- Lopez-Lopez V, Hiciano-Guillermo A, Martinez-Alarcon L, et al. Postoperative negative-pressure incision therapy after liver transplant (PONILITRANS study): A randomized controlled trial. Surgery. Apr 2023;173(4):1072-1078. doi:10.1016/j.surg.2022.11.011

- Mahmoud NN, Turpin RS, Yang G, Saunders WB. Impact of surgical site infections on length of stay and costs in selected colorectal procedures. Surg Infect (Larchmt). Dec 2009;10(6):539-44. doi:10.1089/sur.2009.006

- Masden D, Goldstein J, Endara M, Xu K, Steinberg J, Attinger C. Negative pressure wound therapy for at-risk surgical closures in patients with multiple comorbidities: a prospective randomized controlled study. Ann Surg. Jun 2012;255(6):1043-7. doi:10.1097/SLA.0b013e3182501bae

- Masters J, Cook J, Achten J, Costa ML, Group WS. A feasibility study of standard dressings versus negative-pressure wound therapy in the treatment of adult patients having surgical incisions for hip fractures: the WHISH randomized controlled trial. Bone Joint J. Apr 2021;103-B(4):755-761. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.103B4.BJJ-2020-1603.R1

- Meeker J, Weinhold P, Dahners L. Negative pressure therapy on primarily closed wounds improves wound healing parameters at 3 days in a porcine model. J Orthop Trauma. Dec 2011;25(12):756-61. doi:10.1097/BOT.0b013e318211363a

- Muller-Sloof E, de Laat E, Kenc O, et al. Closed-Incision Negative-Pressure Therapy Reduces Donor-Site Surgical Wound Dehiscence in DIEP Flap Breast Reconstructions: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. Oct 2022;150:38s-47s. doi:10.1097/Prs.0000000000009541

- Muller-Sloof E, de Laat HEW, Hummelink SLM, Peters JWB, Ulrich DJO. The effect of postoperative closed incision negative pressure therapy on the incidence of donor site wound dehiscence in breast reconstruction patients: DEhiscence PREvention Study (DEPRES), pilot randomized controlled trial. J Tissue Viability. Nov 2018;27(4):262-266. doi:10.1016/j.jtv.2018.08.005

- Murphy PB, Knowles S, Chadi SA, et al. Negative Pressure Wound Therapy Use to Decrease Surgical Nosocomial Events in Colorectal Resections (NEPTUNE): A Randomized Controlled Trial. Ann Surg. Jul 2019;270(1):38-42. doi:10.1097/SLA.0000000000003111

- Newman JM, Siqueira MBP, Klika AK, Molloy RM, Barsoum WK, Higuera CA. Use of Closed Incisional Negative Pressure Wound Therapy After Revision Total Hip and Knee Arthroplasty in Patients at High Risk for Infection: A Prospective, Randomized Clinical Trial. J Arthroplasty. Mar 2019;34(3):554-559 e1. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2018.11.017

- Nordmeyer M, Pauser J, Biber R, et al. Negative pressure wound therapy for seroma prevention and surgical incision treatment in spinal fracture care. Int Wound J. Dec 2016;13(6):1176-1179. doi:10.1111/iwj.12436

- O'Leary DP, Peirce C, Anglim B, et al. Prophylactic Negative Pressure Dressing Use in Closed Laparotomy Wounds Following Abdominal Operations: A Randomized, Controlled, Open-label Trial: The P.I.C.O. Trial. Ann Surg. Jun 2017;265(6):1082-1086. doi:10.1097/SLA.0000000000002098

- O'Neill CH, Martin RCG, 2nd. Negative-pressure wound therapy does not reduce superficial SSI in pancreatectomy and hepatectomy procedures. J Surg Oncol. Sep 2020;122(3):480-486. doi:10.1002/jso.25980

- Pachowsky M, Gusinde J, Klein A, et al. Negative pressure wound therapy to prevent seromas and treat surgical incisions after total hip arthroplasty. Int Orthop. Apr 2012;36(4):719-22. doi:10.1007/s00264-011-1321-8

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. Mar 29 2021;372:n71. doi:10.1136/bmj.n71

- Pauser J, Nordmeyer M, Biber R, et al. Incisional negative pressure wound therapy after hemiarthroplasty for femoral neck fractures - reduction of wound complications. Int Wound J. Oct 2016;13(5):663-7. doi:10.1111/iwj.12344

- Perry KL, Rutherford L, Sajik DM, Bruce M. A preliminary study of the effect of closed incision management with negative pressure wound therapy over high-risk incisions. BMC Vet Res. Nov 9 2015;11:279. doi:10.1186/s12917-015-0593-4

- Peterson AT, Bakaysa SL, Driscoll JM, Kalyanaraman R, House MD. Randomized controlled trial of single-use negative-pressure wound therapy dressings in morbidly obese patients undergoing cesarean delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM. Sep 2021;3(5):100410. doi:10.1016/j.ajogmf.2021.100410

- Pleger SP, Nink N, Elzien M, Kunold A, Koshty A, Boning A. Reduction of groin wound complications in vascular surgery patients using closed incision negative pressure therapy (ciNPT): a prospective, randomised, single-institution study. Int Wound J. Feb 2018;15(1):75-83. doi:10.1111/iwj.12836

- PREVENA F. Incision Management System 510(k) Premarket Notification. Available at: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/cdrh_docs/pdf10/. Accessed August 14, 2018.

- Rashed A, Csiszar M, Beledi A, Gombocz K. The impact of incisional negative pressure wound therapy on the wound healing process after midline sternotomy. Int Wound J. Feb 2021;18(1):95-102. doi:10.1111/iwj.13497

- Ruhstaller K, Downes KL, Chandrasekaran S, Srinivas S, Durnwald C. Prophylactic Wound Vacuum Therapy after Cesarean Section to Prevent Wound Complications in the Obese Population: A Randomized Controlled Trial (the ProVac Study). Am J Perinatol. Sep 2017;34(11):1125-1130. doi:10.1055/s-0037-1604161

- Sapci I, Hull T, Ashburn JH, et al. Effect of Incisional Negative Pressure Wound Therapy on Surgical Site Infections in High Risk Re-Operative Colorectal Surgery: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Dis Colon Rectum. May 2021;64(5)

- Schweizer ML, Cullen JJ, Perencevich EN, Vaughan Sarrazin MS. Costs Associated With Surgical Site Infections in Veterans Affairs Hospitals. JAMA Surg. Jun 2014;149(6):575-81. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2013.4663

- Sears ED, Wu L, Waljee JF, Momoh AO, Zhong L, Chung KC. The Impact of Deep Sternal Wound Infection on Mortality and Resource Utilization: A Population-based Study. World J Surg. Nov 2016;40(11):2673-2680. doi:10.1007/s00268-016-3598-7

- Shen P, Blackham AU, Lewis S, et al. Phase II Randomized Trial of Negative-Pressure Wound Therapy to Decrease Surgical Site Infection in Patients Undergoing Laparotomy for Gastrointestinal, Pancreatic, and Peritoneal Surface Malignancies. J Am Coll Surg. Apr 2017;224(4):726-737. doi:10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2016.12.028

- Shields DW, Razii N, Doonan J, Mahendra A, Gupta S. Closed incision negative pressure wound therapy versus conventional dressings following soft-tissue sarcoma excision: a prospective, randomized controlled trial. Bone Joint Open. Dec 2021;2(12):1049-1056. doi:10.1302/2633-1462.212.Bjo-2021-0103.R1

- Shim HS, Choi JS, Kim SW. A Role for Postoperative Negative Pressure Wound Therapy in Multitissue Hand Injuries. Biomed Res Int. 2018;2018:3629643. doi:10.1155/2018/3629643

- Stannard JP, Robinson JT, Anderson ER, McGwin G, Jr., Volgas DA, Alonso JE. Negative pressure wound therapy to treat hematomas and surgical incisions following high-energy trauma. J Trauma. Jun 2006;60(6):1301-6. doi:10.1097/01.ta.0000195996.73186.2e

- Stannard JP, Volgas DA, McGwin G, 3rd, et al. Incisional negative pressure wound therapy after high-risk lower extremity fractures. J Orthop Trauma. Jan 2012;26(1):37-42. doi:10.1097/BOT.0b013e318216b1e5

- Sterne JAC, Savovic J, Page MJ, et al. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. Aug 28 2019;366:l4898. doi:10.1136/bmj.l4898

- Suh H, Lee AY, Park EJ, Hong JP. Negative Pressure Wound Therapy on Closed Surgical Wounds With Dead Space: Animal Study Using a Swine Model. Ann Plast Surg. Jun 2016;76(6):717-22. doi:10.1097/SAP.0000000000000231

- Suh HS, Hong JP. Effects of Incisional Negative-Pressure Wound Therapy on Primary Closed Defects after Superficial Circumflex Iliac Artery Perforator Flap Harvest: Randomized Controlled Study. Plast Reconstr Surg. Dec 2016;138(6):1333-1340. doi:10.1097/PRS.0000000000002765

- Tuuli MG, Liu J, Tita ATN, et al. Effect of Prophylactic Negative Pressure Wound Therapy vs Standard Wound Dressing on Surgical-Site Infection in Obese Women After Cesarean Delivery: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. Sep 22 2020;324(12):1180-1189. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.13361

- Tuuli MG, Martin S, Stout MJ, et al. 412: Pilot randomized trial of prophylactic negative pressure wound therapy in obese women after cesarean delivery. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2017;216(1)doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2016.11.670

- Urban J. A. (2006). Cost analysis of surgical site infections. Surgical infections, 7 Suppl 1, S19–S22. https://doi.org/10.1089/sur.2006.7.s1-19

- Vaddavalli VV, Savlania A, Behera A, Kaman L, Rastogi A, Abuji K. Prophylactic Incisional Negative Pressure Wound Therapy Versus Standard Dressing After Major Lower Extremity Amputation: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Journal of Vascular Surgery. Apr 2022;75(4):14s-14s.

- Wierdak M, Pisarska-Adamczyk M, Wysocki M, et al. Prophylactic negative-pressure wound therapy after ileostomy reversal for the prevention of wound healing complications in colorectal cancer patients: a randomized controlled trial. Tech Coloproctol. Feb 2021;25(2):185-193. doi:10.1007/s10151-020-02372-w

- Wihbey KA, Joyce EM, Spalding ZT, et al. Prophylactic Negative Pressure Wound Therapy and Wound Complication After Cesarean Delivery in Women With Class II or III Obesity: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Obstet Gynecol. Aug 2018;132(2):377-384. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000002744

- Witt-Majchrzak A, Zelazny P, Snarska J. Preliminary outcome of treatment of postoperative primarily closed sternotomy wounds treated using negative pressure wound therapy. Pol Przegl Chir. Feb 3 2015;86(10):456-65. doi:10.2478/pjs-2014-0082

- Yu Y, Song Z, Xu Z, et al. Bilayered negative-pressure wound therapy preventing leg incision morbidity in coronary artery bypass graft patients: A randomized controlled trial. Medicine (Baltimore). Jan 2017;96(3):e5925. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000005925

- Zwanenburg PR, Tol BT, de Vries FEE, Boermeester MA. Incisional Negative Pressure Wound Therapy for Surgical Site Infection Prophylaxis in the Post-Antibiotic Era. Surg Infect (Larchmt). Nov/Dec 2018;19(8):821-830. doi:10.1089/sur.2018.212

- Zwanenburg PR, Tol BT, Obdeijn MC, Lapid O, Gans SL, Boermeester MA. Meta-analysis, Meta-regression, and GRADE Assessment of Randomized and Nonrandomized Studies of Incisional Negative Pressure Wound Therapy Versus Control Dressings for the Prevention of Postoperative Wound Complications. Ann Surg. Jul 2020;272(1):81-91. doi:10.1097/SLA.0000000000003644

Evidence tabellen

Risk of Bias Assessment ROB2

Evidence table, all RR with corresponding 95% CI

|

|

No. studies |

SSIs / participants iNPWT |

SSIs / participants standard wound care |

RR (95% CI)* |

GRADE |

|

Primary outcome |

|||||

|

SSI overall |

57 |

540 / 6849 (7·9%) |

802 / 6895 (11·6%) |

0·67 (0·59 - 0·76) |

High |

|

Type of Surgery |

p value for subgroup differences = 0·14 |

||||

|

Abdominal |

18 |

187 / 1175 (15·9%) |

280 / 1152 (24·3%) |

0·66 (0·54 - 0·81) |

|

|

Breast |

1 |

0 / 50 (0%) |

5 / 50 (10·0%) |

0·09 (0·01 - 1·60) |

|

|

Cardiac |

4 |

1 / 161 (0·6%) |

14 / 155 (9·0%) |

0·14 (0·03 - 0·62) |

|

|

General |

2 |

5 / 54 (9·3%) |

7 / 44 (15·9%) |

0·57 (0·19 - 1·72) |

|

|

Obstetric |

11 |

207 / 3121 (6·6%) |

260 / 3139 (8·3%) |

0·82 (0·66 - 1·03) |

|

|

Orthopedic / trauma |

12 |

78 / 1750 (4·5%) |

127 / 1824 (7·0%) |

0·64 (0·46 - 0·89) |

|

|

Plastic |

3 |

6 / 95 (6·3%) |

7 / 87 (8·0%) |

0·84 (0·30 - 2·34) |

|

|

Vascular |

6 |

56 /443 (12·6%) |

102 / 444 (23·0%) |

0·55 (0·39 - 0·77) |

|

|

Industry involvement |

p value for subgroup differences = 0·17 |

||||

|

No funding or involvement |

16 |

136 / 1687 (7·1%) |

199 / 1752 (11·4%) |

0·70 (0·53 - 0·92) |

|

|

Funding, no involvement |

18 |

300 / 3612 (8·3%) |

400 / 3606 (11·1%) |

0·74 (0·62 - 0·88) |

|

|

Funding + involvement |

13 |

74 / 1129 (6·6%) |

132 / 1156 (11·4%) |

0·59 (0·44 - 0·80) |

|

|

No information |

10 |

30 / 421 (7·1%) |

71 / 408 (17·4%) |

0·46 (0·30 - 0·70) |

|

|

Risk of Bias |

p value for subgroup differences = 0·81 |

||||

|

Low risk of bias |

10 |

105 / 1373 (7·6%) |

149 / 1373 (10·9%) |

0·72 (0·56 - 0·91) |

|

|

Some concerns |

40 |

387 / 4928 (7·9%) |

581 / 4928 (11·8%) |

0·65 (0·55 - 0·77) |

|

|

Low + Some concerns |

50 |

492 / 6301 (7·8%) |

730 / 6301 (11·6%) |

0·67 (0·58 - 0·77) |

|

|

High risk of bias |

7 |

48 / 548 (8·8%) |

72 / 594 (12·1%) |

0·68 (0·46 - 0·98) |

|

|

Pressure of the device |

p value for subgroup differences = 0·45 |

||||

|

-125 mmHg |

28 |

280 / 3131 (8·9%) |

406 / 3128 (13·0%) |

0·69 (0·58 - 0·82) |

|

|

-80 mmHg |

25 |

247 / 3616 (6·8%) |

372 / 3677 (10·1%) |

0·67 (0·55 - 0·81) |

|

|

Cyclic pressure |

1 |

3 / 20 (15·0%) |

3 / 24 (12·5%) |

1·20 (0·27 - 5·30) |

|

|

No information |

3 |

10 / 82 (12·2%) |

21 / 66 (31·8%) |

0·39 (0·19 - 0·82) |

|

|

Secondary outcomes |

|||||

|

Wound dehiscence |

35 |

332 / 4417 (7·5%) |

387 / 4450 (8·7%) |

0·85 (0·71 - 1·02) |

Moderate |

|

Reoperation |

29 |

91 / 4629 (2·0%) |

106 / 4691 (2·3%) |

0·91 (0·69 - 1·20) |

Low |

|

Seroma |

26 |

108 / 3444 (3·1%) |

134 / 3440 (3·9%) |

0·83 (0·65- 1·06) |

Moderate |

|

Hematoma |

23 |

32 / 3419 (0·9%) |

47 / 3408 (1·4%) |

0·77 (0·48 - 1·23) |

Low |

|

Mortality |

19 |

32 / 4052 (0·8%) |

34 / 4053 (0·8%) |

0·94 (0·58 - 1·52) |

Low |

|

Readmission |

19 |

113 / 3241 (3·5%) |

114 / 3246 (3·5%) |

0·96 (0·69 - 1·35) |

Low |

|

Skin blistering |

15 |

198 / 3013 (6·6%) |

37 / 3038 (1.2%) |

5·10 (1·99 - 13·05) |

Moderate |

|

Necrosis |

6 |

3 / 444 (0·7%) |

14 / 479 (2·9%) |

0·46 (0·14 - 1·46) |

Low |

|

* Studies with no events in both arms were excluded from quantitative analysis |

|||||

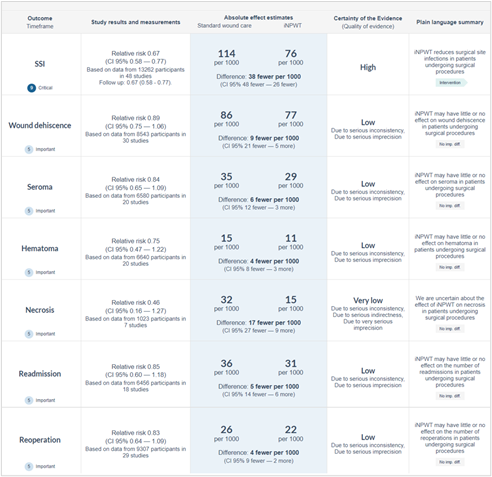

GRADE-table

Main outcome presenting the overall RR (95%CI), absolute effect estimates, GRADE certainty levels of the evidence and a plain language summary.

Table of excluded studies

|

|

Study |

Reason for exclusion |

|

1 |

Abesamis 20191 |

No randomization |

|

2 |

Achten 20182 |

Protocol |

|

3 |

ACTRN12619000785101, 20193 |

Protocol |

|

4 |

Anderson4 |

Interim analysis of included study (Chaboyer 20145) |

|

5 |

Biao 20196 |

Comparison not of interest |

|

6 |

Brennfleck 20207 |

Protocol |

|

7 |

Brown 20208 |

Protocol |

|

8 |

Campolier 20199 |

Conference abstract of included study (Costa 202010) |

|

9 |

Carrano 202111 |

No primary closure |

|

10 |

Chaboyer 202112 |

Secondary analysis of included study (Gillespie 202113) |

|

11 |

Chang 201814 |

Comment |

|

12 |

Chen 201915 |

Comparison not of interest |

|

13 |

Chetter 202116 |

Protocol |

|

14 |

ChiCTR1900022165, 201917 |

Protocol |

|

15 |

ChiCTR2000034266, 2020 18 |

Protocol |

|

16 |

Chu 201819 |

Comparison not of interest |

|

17 |

Clark 201920 |

Outcome not of interest |

|

18 |

Cocjin 201921 |

Comparison not of interest |

|

19 |

Cook 201922 |

No primary closure |

|

20 |

Costa 201823 (Health Technol Assess.) |

No primary closure |

|

21 |

Costa 201824 (JAMA) |

No primary closure |

|

22 |

Costa 202025 (Health Technol Assess.) |

Same data as included study (Costa 202010,JAMA) |

|

23 |

CTRI/2019/05/019225, 201926 |

Protocol |

|

24 |

CTRI/2019/08/020895, 201927 |

Protocol |

|

25 |

CTRI/2019/09/021388, 201928 |

Protocol |

|

26 |

Dadras 202229 |

Comparison not of interest |

|

27 |

Darwisch 202030 |

Conference abstract: no data available |

|

28 |

Davis 202031 |

Comparison not of interest |

|

29 |

Di Re 202032 |

Protocol |

|

30 |

Dondossola 202033 |

Letter to the editor |

|

31 |

Donlon 201934 |

Protocol |

|

32 |

DRKS00015136, 201935 |

Protocol |

|

33 |

DRKS00021494, 202036 |

Protocol |

|

34 |

Engelhardt 201837 |

Already included |

|

35 |

Fang 202038 |

No randomization |

|

36 |

Fernandes 202139 |

Conference abstract: no randomisation |

|

37 |

Ferrando 202140 |

Conference abstract: trial protocol |

|

38 |

Fogacci 201941 |

Conference abstract of included study (Fogacci 201942) |

|

39 |

Galiano 201843 |

Within-subject experimental design |

|

40 |

Gombert 201844 |

Already included |

|

41 |

Gombert 201945 |

No randomization |

|

42 |

Gombert 202046 |

Erratum |

|

43 |

Gonzalez 202047 |

Conference abstract: no data available |

|

44 |

Haddad 202148 |

Conference abstract of ongoing trial (NCT03773575) |

|

45 |

Halama 201949 |

Outcome not of interest |

|

46 |

Hasselmann 201950 |

Conference abstract of Hasselmann 202052 (Ann Surg.) |

|

47 |

Hasselmann 202051 (Surg Infect. [Larchmt]) |

Same data as Hasselmann 202052 (Ann Surg.) |

|

48 |

Howell 201153 |

Within-subject experimental design |

|

49 |

Hyldig 201954 |

Already included |

|

50 |

Hyldig 201955 |

Outcome not of interest |

|

51 |

Jaimes 202056 |

Conference abstract: outcome not of interest |

|

52 |

Javed 201957 |

Already included |

|

53 |

Jenkins 202258 |

Outcome not of interest |

|

54 |

Jørgensen 201859 |

Protocol |

|

55 |

BJOG. 2019 Apr;126(5):636 (No author listed) 60 |

Comment |

|

56 |

KCT0004063, 201961 |

Protocol |

|

57 |

Kim 202062 |

Protocol |

|

58 |

Knight 201963 |

Protocol |

|

59 |

Kojima 202164 |

No primary closure |

|

60 |

Kuncewitch 201965 |

Same data as Shen 201766 |

|

61 |

Kwon 201867 |

Within-subject experimental design |

|

62 |

Lee 201768 |

Already included |

|

63 |

Leitao 202069 |

Conference abstract of included study (Leitao 202170) |

|

64 |

Lopez 202271 |

Conference abstract of included study (Lopez-Lopez 202372) |

|

65 |

Low 202273 |

Protocol |

|

66 |

Lozano-Balderas 201774 |

No primary closure |

|

67 |

Lychagin 202075 |

Comparison not of interest |

|

68 |

Martin 201976 |

Conference abstract of included study (O’neill 202077) |

|

69 |

Masters 201878 |

Same data as Masters 202179 |

|

70 |

Molina 202180 |

Conference abstract: no data available |

|

71 |

Mondal 202281 |

Comparison not of interest |

|

72 |

Mujahid 202082 |

Outcome not of interest |

|

73 |

Muller-Sloof 201883 |

Already included |

|

74 |

Murphy 201984 |

Already included |

|

75 |

Myllykangas 202185 |

No randomization |

|

76 |

NCT03815370, 201986 |

Protocol |

|

77 |

NCT03816293, 201987 |

Protocol |

|

78 |

NCT03820219, 201988 |

Protocol |

|

79 |

NCT03871023, 201989 |

Protocol |

|

80 |

NCT03886818, 201990 |

Protocol |

|

81 |

NCT03900078, 201991 |

Protocol |

|

82 |

NCT03905213, 201992 |

Protocol |

|

83 |

NCT03935659, 201993 |

Protocol |

|

84 |

NCT03948412, 201994 |

Protocol |

|

85 |

NCT04003038, 201995 |

Protocol |

|

86 |

NCT04039659, 201996 |

Protocol |

|

87 |

NCT04063111, 201997 |

Protocol |

|

88 |

NCT04088162, 201998 |

Protocol |

|

89 |

NCT04110353, 201999 |

Protocol |

|

90 |

NCT04174183, 2019100 |

Protocol |

|

91 |

NCT04265612, 2020101 |

Protocol |

|

92 |

NCT04434820, 2020102 |

Protocol |

|

93 |

NCT04453319, 2020103 |

Protocol |

|

94 |

NCT04455724, 2020104 |

Protocol |

|

95 |

NCT04496180, 2020105 |

Protocol |

|

96 |

NCT04520841, 2020106 |

Protocol |

|

97 |

NCT04539015, 2020107 |

Protocol |

|

98 |

NCT04584957, 2020108 |

Protocol |

|

99 |

Newman 2019, 2020109 |

Already included |

|

100 |

Ni 2020110 |

No primary closure |

|

101 |

Nip 2020111 |

Conference abstract: no randomisation |

|

102 |

Nordmeyer112 |

No data available |

|

103 |

Ozkan 2020113 |

No randomisation |

|

104 |

Paim / RBR-5c8y6v, 2019114 |

Protocol |

|

105 |

Pape 2021115 |

Conference abstract: secondary analysis of included study (Tuuli 2020116) |

|

106 |

Park 2019117 |

No randomization |

|

107 |

Pauser 2016118 |

Comparison not of interest (drain in wound) |

|

108 |

Png 2020119 |

Same as Costa 202010 |

|

109 |

Pleger 2018120 |

Within-subject experimental design |

|

110 |

Rajabaleyan 2019121 |

Conference abstract: no primary closure |

|

111 |

Rezk 2019122 |

Protocol |

|

112 |

Sandy-Hodgetts 2017123 |

Protocol |

|

113 |

Sandy-Hodgetts 2020124 |

Protocol |

|

114 |

Sapci 2021125 |

Conference abstract of included study (Sapci 2022126) |

|

115 |

Schmid 2020127 |

Within-subject experimental design |

|

116 |

Schwartzmann 2021128 |

No randomization |

|

117 |

Seidel 2020129 |

Comparison not of interest |

|

118 |

Seidel 2020130 |

No primary closure |

|

119 |

Serra 2019131 |

No randomization |

|

120 |

Shim 2018132 |

Duplicate |

|

121 |

Stannard 2012133 |

Within-subject experimental design |

|

122 |

Sun 2019134 |

Comparison not of interest |

|

123 |

Svensson-Björk 2021135 |

Outcome not of interest |

|

124 |

Szmeja 2020136 |

Conference abstract: no data available |

|

125 |

Tanaydin 2018137 |

Within-subject experimental design |

|

126 |

Tanaydin 2018138 |

Erratum |

|

127 |

Venkatadass 2013139 |

Retracted |

|

128 |

Wang 2019140 |

Comparison not of interest |

|

129 |

Wilkin 2021141 |

Protocol |

|

130 |

Wilkin 2021141 |

Protocol, duplicate |

|

131 |

Wilkin 2022142 |

Conference abstract: protocol |

|

132 |

Yang 2020143 |

Comparison not of interest |

|

133 |

Yilmaz 2022144 |

Protocol |

|

134 |

Zhao 2020145 |

No randomization |

|

135 |

Zwanenburg 2020146 |

Comment |

|