Hyperoxygenatie

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is de waarde van het peroperatief/intra-operatief toedienen van hoge FiO2-concentraties op het aantal postoperatieve wondinfecties bij patiënten die chirurgische procedures ondergaan?

Aanbeveling

Overweeg bij patiënten die een operatie ondergaan (korter dan 12 uur) met endotracheale intubatie, toediening van hogere FiO2-concentraties dan een FiO2 van 0.30-0.35 tijdens de operatie ter preventie van postoperatieve wondinfecties.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

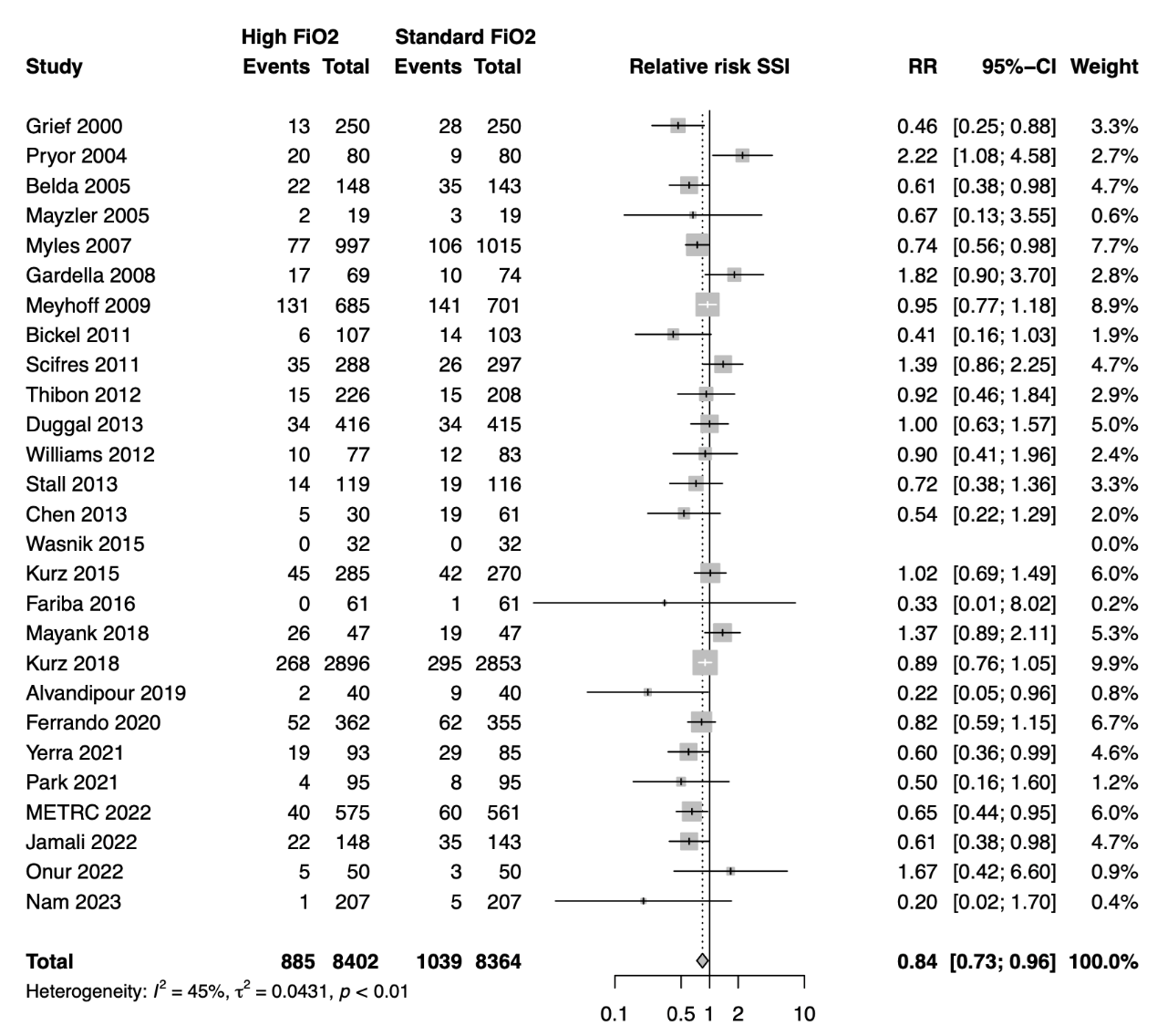

Er is literatuuronderzoek uitgevoerd naar het effect van het preventief toedienen van hoge FiO2-concentraties op het aantal postoperatieve wondinfecties bij patiënten die chirurgische procedures ondergaan. Er werd bewijs met lage GRADE gevonden dat het risico op postoperatieve wondinfecties waarschijnlijk niet verschilt indien peroperatief een hoge FiO2-concentratie wordt toegediend in vergelijking met een standaard FiO2-concentratie (RR 0.84; 95% CI 0.73 tot 0.96).

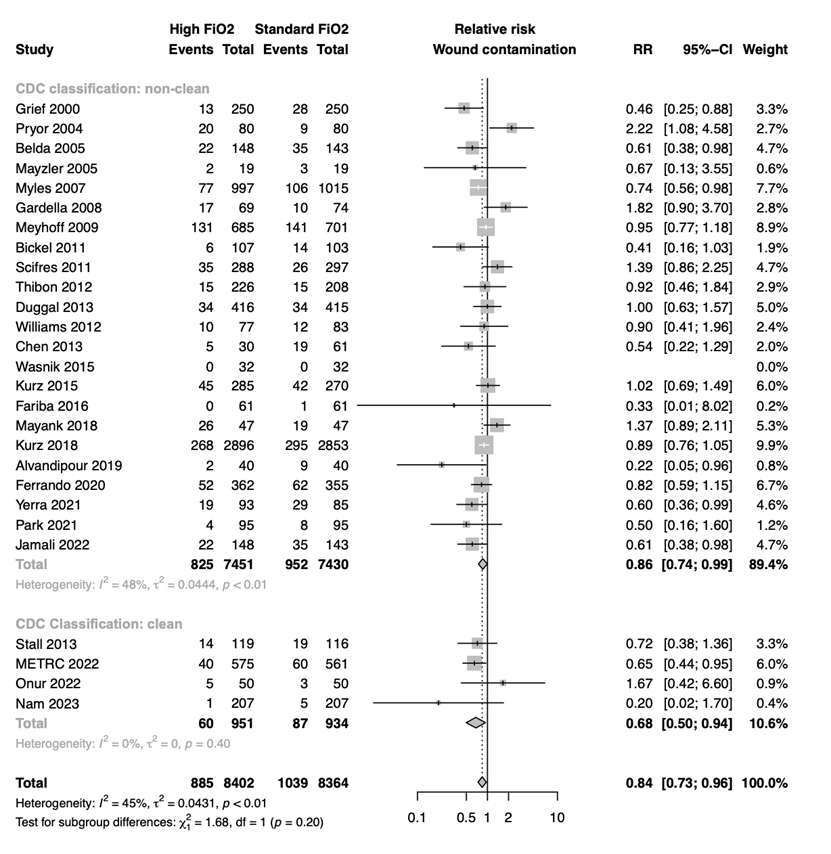

Wel lieten verscheidene sensitiviteitsanalyses (subgroep analyses) zien dat in bepaalde patiëntengroepen een peroperatieve hoge FiO2-concentratie een voordelig effect kan hebben op het aantal postoperatieve wondinfecties. Er werd met een redelijke GRADE in 22 studies aangetoond dat een hoge FiO2 toediening via endotracheale intubatie waarschijnlijk resulteert in minder postoperatieve infecties (RR 0.79; 95% BI 0.68 tot 0.91). Daarnaast leek er ook een positief effect te zijn voor peroperatieve hoge FiO2-concentraties bij patiënten met ‘schone’ wonden volgens de classificering van de CDC (RR 0.68; 95% BI 0.50 tot 0.94). Hogere FiO2-concentraties bij wakkere patiënten met beademing werd met vijf studies onderzocht en liet geen significant verschil zien. Ook andere subgroep analyses lieten geen meerwaarde zien voor een hoge peroperatieve FiO2 toediening.

Er zijn ook zorgen over mogelijke nadelige effecten bij het gebruik van hoge FiO2 -concentratie, zoals atelectase, respiratoire insufficiëntie, cardiovasculaire complicaties en mortaliteit (Chu, 2018). In de systematische review van Chu et al. werden 25 studies geïncludeerd met voornamelijk patiënten met kritieke ziekte, CVA, myocardinfarct of asystolie of acute chirurgie gerandomiseerd in hoge en lage FiO2 -concentratie. De uitkomsten waren onder andere mortaliteit (ziekenhuissterfte, alsmede 30 dagen mortaliteit). Er werd een RR gevonden van 1.21 (95% BI 1.03 - 1.43) in het nadeel van een hoge FiO2 -concentratie voor ziekenhuissterfte, en een RR van 1.14 (95% BI 1.01 – 1.29) voor 30 dagen mortaliteit.

Er bestaat verdeeldheid over de heersende opvattingen omtrent het toepassen hyperoxygenatie (Sperna Weiland, 2020; Weenink, 2020). Overall laat de literatuur op dit moment zien dat er geen nadelen zijn van hoge FiO2 als het voor beperkte tijd op de OK wordt ingezet (minder 12 uur) (Mattishent, 2019). Atelectasen worden door de PEEP die op OK wordt gebruikt volledig opgeheven; pneumonie of ischaemie wordt in geen van de grote trials perioperatief gezien. Studies die schade laten zien van hyperoxygenatie zijn in een totaal ander setting op de ICU met langdurig gebruik van hoge zuurstoffracties en zijn niet te vergelijken met de studies geïncludeerd in de systematische review in de operatieve setting. De werkgroep is daarom van mening dat de voordelen opwegen tegen de potentiële nadelen.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

Er zijn geen voorkeuren van patiënten met betrekking tot het gebruik van de concentratie FiO2 op patiënt gerelateerde uitkomsten. Het is belangrijk om patiënten te informeren over het nut en de noodzaak van de behandeling. Door hen op de hoogte te stellen van wat ze kunnen verwachten en waarvoor een specifieke behandeling dient, bevordert men niet alleen begrip maar ook betrokkenheid van de patiënt bij zijn of haar eigen zorgproces. Dit draagt bij aan een positieve behandelervaring.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

Er is 1 studie gevonden die de kosteneffectiviteit van hoge FiO2 hebben onderzocht op POWI in laag- en middeninkomen landen (NIHR 2023). Er werd een mogelijke kostenreductie gevonden bij het gebruik van hoge FiO2. POWI is een dure complicatie en het voorkomen van POWI draagt bij aan de kostenreductie.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

Een hoge FiO2 concentratie is een interventie die zeer wisselend wordt toegepast. De zuurstofconcentratie die wordt toegediend kan worden ingesteld en aangepast.

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

Bewijs met lage GRADE laat zien dat het risico op postoperatieve wondinfecties in alle operaties waarschijnlijk niet verschilt met peroperatief hoge FiO2-concentraties in vergelijking met een standaard FiO2-concentratie. Bij endotracheale intubatie wordt er met redelijke bewijskracht gevonden dat het aantal postoperatieve wondinfecties mogelijk vermindert bij een hogere FiO2-concentratie.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Er is bewijs dat een optimale bloedstroom naar de chirurgische incisie het aantal postoperatieve wondinfecties (POWI) vermindert door middel van het vermijden van hypothermie en hypoxie (Kurz, 1996; Dalfino, 2011; Greif, 2000). Sinds 2000 zijn er verschillende onderzoeken gepubliceerd over het gebruik van hoge FiO2 -concentraties tijdens de perioperatieve periode en de mogelijke associatie met lager percentage POWI. De SSI/POWI-preventierichtlijnen van SHEA/IDSA bevelen aan de weefseloxygenatie te optimaliseren door het toedienen van extra zuurstof tijdens en onmiddellijk na chirurgische ingrepen waarbij mechanische beademing plaatsvindt. In deze module is getracht om het beschikbare bewijs over het effect van hoge FiO2-concentraties op het aantal postoperatieve wondinfecties bij patiënten die chirurgische procedures ondergaan samen te vatten.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

Overall analysis

|

Low GRADE |

High FiO2 may result in little to no difference in surgical site infections when compared with standard FiO2 in patients undergoing surgical procedures.

Sources: de Jonge (2019) (Belda, 2005; Bickel, 2011; Chen, 2013; Duggal, 2013; Fariba, 2016; Gardella, 2008; Greif, 2000; Kurz, 2015; Mayzler, 2005; Meyhoff, 2009; Myles, 2007; Pryor, 2004; Scifres, 2011; Stall, 2013; Thibon, 2012; Wasnik, 2015; Williams, 2012).

Update: Alvandipour (2019); Ferrando (2020); Jamali (2022); Kurz (2018); Mayank (2018); METRC (2022); Nam (2023); Onur (2022); Park (2021); Yerra (2021). |

Sensitivity analysis

1. Oxygen administration via tracheal intubation

|

Moderate GRADE |

High FiO2 likely results in less surgical site infections when compared with standard FiO2 in patients undergoing surgical procedures and receiving oxygen via tracheal intubation.

Sources: de Jonge (2019) (Belda, 2005; Bickel, 2011; Chen, 2013; Greif, 2000; Kurz, 2015; Mayzler, 2005; Meyhoff, 2009; Myles, 2007; Pryor, 2004; Stall, 2013; Thibon, 2012; Wasnik, 2015).

Update: Alvandipour (2019); Ferrando (2020); Jamali (2022); Kurz (2018); Mayank (2018); METRC (2022); Nam (2023); Onur (2022); Park (2021); Yerra (2021). |

2. Oxygen administration via a face mask without tracheal intubation

|

Moderate GRADE |

High FiO2 likely results in little to no difference in surgical site infections when compared with standard FiO2 in patients undergoing surgical procedures and receiving oxygen via a face mask without tracheal intubation.

Sources: de Jonge (2019) (Duggal, 2013; Fariba, 2016; Gardella, 2008; Scifres, 2011; Williams, 2012). |

3. CDC classification: non-clean

|

Moderate GRADE |

High FiO2 likely results in little to no difference in surgical site infections when compared with standard FiO2 in patients undergoing surgical procedures and non-clean wounds according to the CDC wound classification.

Sources: de Jonge (2019) (Belda, 2005; Bickel, 2011; Chen, 2013; Duggal, 2013; Fariba, 2016Gardella, 2008; Greif, 2000; Kurz, 2015; Mayzler, 2005; Meyhoff, 2009; Myles, 2007; Pryor, 2004; Scifres, 2011; Thibon, 2012; Wasnik, 2015; Williams, 2012).

Update: Alvandipour (2019); Ferrando (2020); Jamali (2022); Kurz (2018); Mayank (2018); Park (2021); Yerra (2021). |

4. CDC classification: clean

|

Low GRADE |

High FiO2 may result in less surgical site infections when compared with standard FiO2 in patients undergoing surgical procedures and clean wounds according to the CDC wound classification.

Sources: de Jonge (2019) (Stall, 2013).

Update: METRC (2022); Nam (2023); Onur (2022). |

5. Colorectal surgery

|

Very low GRADE |

The level of evidence is very uncertain about the effect of high FiO2 on surgical site infections when compared with standard FiO2 in patients undergoing colorectal surgical procedures.

Sources: de Jonge (2019) (Belda, 2005; Chen, 2013; Greif, 2000; Kurz, 2015; Mayzler, 2005).

Update: Alvandipour (2019); Jamali (2022); Kurz (2018); Mayank (2018); Yerra (2021). |

6. Non-colorectal surgery

|

Moderate GRADE |

High FiO2 likely results in little to no difference in surgical site infections when compared with standard FiO2 in patients undergoing non-colorectal surgical procedures.

Sources: de Jonge (2019) (Bickel, 2011; Duggal, 2013; Fariba, 2016; Gardella, 2008; Meyhoff, 2009; Myles, 2007; Pryor, 2004; Scifres, 2011; Stall, 2013; Thibon, 2012; Wasnik, 2015; Williams, 2012).

Update: Ferrando (2020); METRC (2022); Nam (2023); Onur (2022); Park (2021). |

7. Gas mixture with N2O

|

Very low GRADE |

The level of evidence is very uncertain about the effect of high FiO2 on surgical site infections when compared with standard FiO2 in patients who received gas mixture with N2O.

Sources: de Jonge (2019) (Chen, 2013; Greif, 2000; Mayzler, 2005; Myles, 2007; Pryor, 2004).

Update: Alvandipour (2019); Mayank (2018) |

8. Gas mixture without N2O

|

Low GRADE |

High FiO2 may result in little to no difference in surgical site infections when compared with standard FiO2 in patients who received gas mixture without N2O.

Sources: de Jonge (2019) (Belda, 2005; Bickel, 2011; Duggal, 2013; Fariba, 2016; Gardella, 2008; Kurz, 2015; Meyhoff, 2009; Scifres, 2011; Stall, 2013; Thibon, 2012; Wasnik, 2015; Williams, 2012).

Update: Ferrando (2020); Jamali (2022); Kurz (2018); METRC (2022); Nam (2023); Onur (2022); Park (2021); Yerra (2021). |

Samenvatting literatuur

Study characteristics

The study characteristics of the included studies are summarized in table 1.

Table 1. Characteristics of the included studies

|

Study |

Design, scope, participants |

Type of surgery, procedure duration |

Outcome definition (CDC), follow-up |

Intervention vs control |

Postoperative oxygenation |

Tracheal intubation |

Base gas |

Preoperative antibiotics |

Temperature regimen |

Fluids |

|

Greif (2000) |

RCT, MC 500 |

Colorectal surgery, 3.1 h |

No, 15 days |

80% vs 30% |

2 h |

Yes |

N2 |

Yes |

≥36 °C |

15 ml kg−1 h−1 |

|

Pryor (2004) |

RCT, SC 160 |

Major abdominal surgery, 3.7 h |

No, 14 days |

80% vs 30% |

2 h |

Yes |

NA, N2O included |

Yes |

NA |

NA |

|

Belda (2005) |

RCT, MC 291 |

Colorectal surgery, >1 h |

Yes, 14 days |

80% vs 30% |

6 h |

Yes |

Air |

Yes |

Active |

15 ml kg−1 h−1 |

|

Mayzler (2005) |

RCT, SC 38 |

Colorectal surgery, 2.3 h |

Yes, 30 days |

80% vs 30% |

2 h |

Yes |

N2, N2O |

Yes |

≥35.5 °C |

15 ml kg−1 h−1 |

|

Myles (2007) |

RCT, MC 2012 |

Surgery >2 h, 3.3 h |

Yes, 30 days |

80% vs 30% |

No |

Yes |

N2, N2O |

Institutional practice |

>35.5 °C |

Anaesthesiologist's discretion |

|

Gardella (2008) |

RCT, SC 143 |

Caesarean section, 0.8 h |

No, 14 days |

80% vs 30% |

2 h |

No |

Air |

No |

NA |

NA |

|

Meyhoff (2009) |

RCT, MC 1386 |

Laparotomies, 2.2 h |

Yes, 14 days |

80% vs 30% |

2 h |

Yes |

NA, N2O free |

Yes |

NA |

Only to replace deficits |

|

Bickel (2011) |

RCT, SC 210 |

Open appendectomy, 0.5 h |

No, 14 days |

80% vs 30% |

2 h |

Yes |

Air and N2 |

Yes |

Active |

NA |

|

Scifres (2011) |

RCT, SC 585 |

Caesarean section, 1 h |

Yes, 4 weeks |

80% vs 30% |

2 h |

No |

Air |

Yes |

NA |

NA |

|

Thibon (2012) |

RCT, MC 434 |

Abdominal, gynaecological, and breast surgery, 1.5 h |

Yes, 30 days |

80% vs 30% |

No |

Yes |

NA |

NA |

NA |

NA |

|

Duggal (2013) |

RCT, SC 831 |

Caesarean section, NA |

Yes plus endometritis, 2 weeks |

80% vs 30% (after cord clamping) |

1 h |

No |

Air |

No |

NA |

NA |

|

Williams (2013) |

RCT, SC 160 |

Caesarean section, 0.9 h |

Yes plus endometritis, 30 days |

80% vs 30% |

2 h |

No |

Air |

No |

NA |

NA |

|

Stall (2013) |

RCT, SC 235 |

Open reduction and internal fixation, 3.8 h |

Yes, 12 weeks |

80% vs 30% |

2 h |

Yes |

NA |

Yes |

NA |

NA |

|

Chen (2013) |

RCT, SC 91 |

Colorectal surgery, |

Yes, 30 days |

80% vs 30% |

24 h |

Yes |

N2, N2O |

Yes |

>35.5 °C |

Anaesthesiologist's discretion |

|

Kurz (2015) |

RCT, MC 586 |

Colorectal surgery, 3.5 h |

Yes, 30 days |

80% vs 30% |

1 h |

Yes |

N2 |

Yes |

36 °C |

10–11 ml kg−1 h−1 |

|

Wasnik (2015) |

RCT, SC 64 |

Appendectomy 1 h |

No, NA |

80% vs 30% |

2 h |

Yes |

NA |

Yes |

NA |

NA |

|

Fariba (2016) |

RCT, SC 122 |

Caesarean section, 1 h |

No, 14 days |

80% vs 30% |

6 h |

No |

Air |

NA |

NA |

NA |

|

Mayank (2018) |

RCT, SC 94 |

Colorectal surgery, 3.7 h |

Yes, 30 days |

80% vs 33% |

6 h |

Yes |

N2O |

Yes |

At 36 °C |

15 ml kg−1 h−1 |

|

Kurz (2018) |

RCT, SC 5749 |

Major intestinal surgery, 4 h |

Yes, 30 days |

80% vs 30% |

No |

Yes |

NA |

Yes |

Active |

10 ml kg−1 h−1 |

|

Alvandipour (2019) |

RCT, SC 80 |

Colorectal surgery, 1.6 h |

Yes, 30 days |

80% vs 30% |

1 h |

Yes |

N2O |

Yes |

At 36 °C |

6-10 ml kg−1 h−1 |

|

Ferrando (2020) |

RCT, MC 717 |

Major abdominal surgery, 3.5 h |

Yes, 30 days |

80% vs 30% |

3 h |

Yes |

NA |

Yes |

NA |

NA |

|

Yerra (2021) |

RCT, MC 178 |

Major abdominal surgery, 2.6 h |

Yes, 14 days |

80% vs 30% |

2 h |

Yes |

Air |

Yes |

NA |

NA |

|

Park (2021) |

RCT, SC 190 |

Abdominal surgery, NA |

No, 30 days |

60% vs 35% |

0.25 h |

Yes |

Air |

Yes |

NA |

NA |

|

METRC (2022) |

RCT, MC 1136 |

Orthopedic trauma surgery, NA |

Yes, 182 days |

80% vs 30% |

2 h |

Yes |

NA |

NA |

No regimen |

NA |

|

Jamali (2022) |

RCT, SC 291 |

Colorectal surgery, 1 h |

Yes, 15 days |

80% vs 30% |

No |

Yes |

Air |

Yes |

NA |

NA |

|

Onur (2022) |

RCT, SC 100 |

Coronary artery bypass graft surgery, 3.4 h |

Yes, 90 days |

100% vs 40% |

No |

Yes |

NA |

NA |

At 31-32 °C |

NA |

|

Nam |

RCT, MC 417 |

Off-pump coronary artery bypass grafting, 4.3 h |

Yes, 30 days |

80% vs 30% |

No |

Yes |

N2O |

Yes |

NA |

NA |

Results

1. Surgical site infections

Overall analysis

Surgical site infections were reported in all 17 trials from the systematic review of de Jonge (2019) (Belda, 2005; Bickel, 2011; Chen, 2013; Duggal, 2013; Fariba, 2016; Gardella, 2008; Greif, 2000; Kurz, 2015; Mayzler, 2005; Meyhoff, 2009; Myles, 2007; Pryor, 2004; Scifres, 2011; Stall, 2013; Thibon, 2012; Wasnik, 2015; Williams, 2012) and in ten additional trials as a result of the updated literature search (Alvandipour, 2019; Ferrando, 2020; Jamali, 2022; Kurz, 2018; Mayank, 2018; METRC, 2022; Nam, 2023; Onur, 2022; Park, 2021; Yerra, 2021). The results were pooled in a meta-analysis. The pooled number of SSIs in the high FiO2 treatment group was 885/8402 (10.5%), compared to 1039/8364 (12.4%) in the standard FiO2 treatment group. This resulted in a pooled relative risk ratio of 0.84 (95% CI 0.73 to 0.96), in favor of high FiO2 treatment (see figure 1). This was not considered as a clinically relevant difference.

Figure 1: Forest plot showing the comparison between high FiO2 to standard FiO2 for surgical site infections (overall analysis). Pooled risk-ratio, random effects model. Z: p-value of overall effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2; statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval.

Subgroup analyses

Four subgroup analysis were performed:

- The incidence of SSI in patients in which high FiO2 or standard FiO2 was administered via tracheal intubation versus a face mask without tracheal intubation.

- The incidence of SSI in patients with clean versus non-clean wounds according to the CDC wound classification in which high FiO2 or standard FiO2 was administered.

- The incidence of SSI in patients who underwent colorectal surgery versus non-colorectal surgery and in which high FiO2 or standard FiO2 was administered.

- The incidence of SSI in patients who received gas mixture with versus without N2O and in which high FiO2 or standard FiO2 was administered.

1. Oxygen administration via tracheal intubation versus face-mask without tracheal intubation

Surgical site infections in patients who received high or standard FiO2 administered via tracheal intubation were reported in twelve trials from the systematic review of de Jonge (2019) (Belda, 2005; Bickel, 2011; Chen, 2013; Greif, 2000; Kurz, 2015; Mayzler, 2005; Meyhoff, 2009; Myles, 2007; Pryor, 2004; Stall, 2013; Thibon, 2012; Wasnik, 2015) and in ten additional trials as a result of the updated literature search (Alvandipour, 2019; Ferrando, 2020; Jamali, 2022; Kurz, 2018; Mayank, 2018; METRC, 2022; Nam, 2023; Onur, 2022; Park, 2021; Yerra, 2021). The results were pooled in a meta-analysis. The pooled number of SSIs in the high FiO2 treatment group, administered via tracheal intubation, was 789/7491 (10.5%), compared to 956/7434 (12.9%) in the standard FiO2 treatment group, administered via tracheal intubation. This resulted in a pooled relative risk ratio of 0.79 (95% CI 0.68 to 0.91), in favor of high FiO2 treatment (see figure 2). This was considered as a clinically relevant difference.

Surgical site infections in patients who received high or standard FiO2 administered via a face mask without tracheal intubation were reported in five trials from the systematic review of de Jonge (2019) (Duggal, 2013; Gardella, 2008; Fariba, 2016; Scifres, 2011; Williams, 2012). The results were pooled in a meta-analysis. The pooled number of SSIs in the high FiO2 treatment group, administered via a face mask without tracheal intubation, was 96/911 (10.5%), compared to 83/930 (8.9%) in the standard FiO2 treatment group, administered via a face mask without tracheal intubation. This resulted in a pooled relative risk ratio of 1.20 (95% CI 0.91 to 1.58), in favor of standard FiO2 treatment (see figure 2). This was not considered as a clinically relevant difference.

Figure 2: Forest plot showing the comparison between high FiO2 to standard FiO2 for surgical site infections in patients who received oxygen administration via tracheal intubation and a face mask without tracheal intubation. Pooled risk-ratio, random effects model. Z: p-value of overall effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2; statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval.

2. CDC classification: clean versus non-clean

Surgical site infections in patients with non-clean wounds according to the CDC wound classification who received high or standard FiO2 were reported in sixteen trials from the systematic review of de Jonge (2019) (Belda, 2005; Bickel, 2011; Chen, 2013; Duggal, 2013; Fariba, 2016Gardella, 2008; Greif, 2000; Kurz, 2015; Mayzler, 2005; Meyhoff, 2009; Myles, 2007; Pryor, 2004; Scifres, 2011; Thibon, 2012; Wasnik, 2015; Williams, 2012) and in seven additional trials as a result of the updated literature search (Alvandipour, 2019; Ferrando, 2020; Jamali, 2022; Kurz, 2018; Mayank, 2018; Park, 2021; Yerra, 2021). The results were pooled in a meta-analysis. The pooled number of SSIs in the high FiO2 treatment group with non-clean wounds, was 825/7451 (11.1%), compared to 952/7430 (12.8%) in the standard FiO2 treatment group with non-clean wounds. This resulted in a pooled relative risk ratio of 0.86 (95% CI 0.74 to 0.99), in favor of high FiO2 treatment (see figure 3). This was not considered as a clinically relevant difference.

Surgical site infections in patients with clean wounds according to the CDC wound classification who received high or standard FiO2 were reported in one trial from the systematic review of de Jonge (2019) (Stall, 2013) and in three additional trials as a result of the updated literature search (METRC, 2022; Nam, 2023; Onur, 2022). The results were pooled in a meta-analysis. The pooled number of SSI’s in the high FiO2 treatment group with clean wounds, was 60/951 (6.3%), compared to 87/934 (8.9%) in the standard FiO2 treatment group with clean wounds. This resulted in a pooled relative risk ratio of 0.68 (95% CI 0.50 to 0.94), in favor of high FiO2 treatment (see figure 3). This was not considered as a clinically relevant difference.

Figure 3: Forest plot showing the comparison between high FiO2 to standard FiO2 for surgical site infections in patients with clean and non-clean wounds according to the CDC wound classification. Pooled risk-ratio, random effects model. Z: p-value of overall effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2; statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval.

3. Colorectal surgery versus non-colorectal surgery

Surgical site infections in patients who underwent colorectal surgery and received high or standard FiO2 were reported in five trials from the systematic review of de Jonge (2019) (Belda, 2005; Chen, 2013; Greif, 2000; Kurz, 2015; Mayzler, 2005) and in five additional trials as a result of the updated literature search (Alvandipour, 2019; Jamali, 2022; Kurz, 2018; Mayank, 2018; Yerra, 2021). The results were pooled in a meta-analysis. The pooled number of SSIs in the high FiO2 treatment group who underwent colorectal surgery was 424/3956 (10.7%), compared to 514/3911 (13.1%) in the standard FiO2 treatment group who underwent colorectal surgery. This resulted in a pooled relative risk ratio of 0.75 (95% CI 0.59 to 0.94), in favor of high FiO2 treatment (see figure 4). This was considered as a clinically relevant difference.

Surgical site infections in patients who did not undergo colorectal surgery and received high or standard FiO2 were reported in twelve trials from the systematic review of de Jonge (2019) (Bickel, 2011; Duggal, 2013; Fariba, 2016; Gardella, 2008; Meyhoff, 2009; Myles, 2007; Pryor, 2004; Scifres, 2011; Stall, 2013; Thibon, 2012; Wasnik, 2015; Williams, 2012) and in five additional trials as a result of the updated literature search (Ferrando, 2020; METRC, 2022; Nam, 2023; Onur, 2022; Park, 2021). The results were pooled in a meta-analysis. The pooled number of SSIs in the high FiO2 treatment group who did not undergo colorectal surgery was 461/4446 (10.4%), compared to 525/4453 (11.8%) in the standard FiO2 treatment group who did not undergo colorectal surgery. This resulted in a pooled relative risk ratio of 0.91 (95% CI 0.76 to 1.09), in favor of high FiO2 treatment (see figure 4). This was not considered as a clinically relevant difference.

Figure 4: Forest plot showing the comparison between high FiO2 to standard FiO2 for surgical site infections in patients who did underwent colorectal surgery and patients who did not undergo colorectal surgery. Pooled risk-ratio, random effects model. Z: p-value of overall effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2; statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval.

4. Gas mixture with N2O versus mixture without N2O

Surgical site infections in patients who received gas mixture with N2O and received high or standard FiO2 were reported in five trials from the systematic review of de Jonge (2019) (Chen, 2013; Greif, 2000; Mayzler, 2005; Myles, 2007; Pryor, 2004) and in two additional trials as a result of the updated literature search (Alvandipour, 2019; Mayank, 2018). The results were pooled in a meta-analysis. The pooled number of SSIs in the high FiO2 treatment group who received gas mixture with N2O was 145/1463 (9.9%), compared to 193/1512 (12.8%) in the standard FiO2 treatment group who received gas mixture with N2O. This resulted in a pooled relative risk ratio of 0.80 (95% CI 0.50 to 1.28), in favor of high FiO2 treatment. This was considered as a clinically relevant difference.

Surgical site infections in patients who did not receive gas mixture with N2O and received high or standard FiO2 were reported in twelve trials from the systematic review of de Jonge (2019) (Belda, 2005; Bickel, 2011; Duggal, 2013; Fariba, 2016; Gardella, 2008; Kurz, 2015; Meyhoff, 2009; Scifres, 2011; Stall, 2013; Thibon, 2012; Wasnik, 2015; Williams, 2012) and in eight additional trials as a result of the updated literature search (Ferrando, 2020; Jamali, 2022; Kurz, 2018; METRC, 2022; Nam, 2023; Onur, 2022; Park, 2021; Yerra, 2021). The results were pooled in a meta-analysis. The pooled number of SSIs in the high FiO2 treatment group who did not receive gas mixture with N2O was 740/6939 (10.7%), compared to 864/6852 (12.8%) in the standard FiO2 treatment group who did not receive gas mixture with N2O. This resulted in a pooled relative risk ratio of 0.85 (95% CI 0.74 to 0.96), in favor of high FiO2 treatment. This was not considered as a clinically relevant difference.

Figure 5: Forest plot showing the comparison between high FiO2 to standard FiO2 for surgical site infections in patients who received gas mixture with N2O and patients who received gas mixture without N2O. Pooled risk-ratio, random effects model. Z: p-value of overall effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2; statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval.

Level of evidence of the literature

Overall analysis

The level of evidence regarding the outcome surgical site infection was derived from randomized controlled trials and therefore started high. The level of evidence was downgraded by two levels because of possible limitations in the randomization process (risk of bias, -1) and the wide confidence interval crossing the lower threshold of clinical relevance (imprecision, -1). The level of evidence was considered as low.

Subgroup analysis

1. Oxygen administration via tracheal intubation

The level of evidence regarding the outcome surgical site infection in patients in which oxygen was administered via tracheal intubation was derived from randomized controlled trials and therefore started high. The level of evidence was downgraded by one level because of the wide confidence interval crossing the lower threshold of clinical relevance (imprecision, -1). The level of evidence was considered as moderate.

2. Oxygen administration via a face mask without tracheal intubation

The level of evidence regarding the outcome surgical site infection in patients in which oxygen was administered via a face mask without tracheal intubation was derived from randomized controlled trials and therefore started high. The level of evidence was downgraded by one level because of the wide confidence interval crossing the lower threshold of clinical relevance (imprecision, -1). The level of evidence was considered as moderate.

3. CDC classification: non-clean

The level of evidence regarding the outcome surgical site infection in patients in with non-clean wounds according to the CDC classification was derived from randomized controlled trials and therefore started high. The level of evidence was downgraded by one level because of the wide confidence interval crossing the lower threshold of clinical relevance (imprecision, -1). The level of evidence was considered as moderate.

4. CDC classification: clean

The level of evidence regarding the outcome surgical site infection in patients in with clean wounds according to the CDC classification was derived from randomized controlled trials and therefore started high. The level of evidence was downgraded by two levels because of possible limitations in the randomization process (risk of bias, -1) and the wide confidence interval crossing the lower threshold of clinical relevance (imprecision, -1). The level of evidence was considered as low.

5. Colorectal surgery

The level of evidence regarding the outcome surgical site infection in patients who underwent colorectal surgery was derived from randomized controlled trials and therefore started high. The level of evidence was downgraded by three levels because of possible limitations in the randomization process (risk of bias, -1), heterogeneity in the study results (inconsistency, -1), and the wide confidence interval crossing the lower threshold of clinical relevance (imprecision, -1). The level of evidence was considered as very low.

6. Non-colorectal surgery

The level of evidence regarding the outcome surgical site infection in patients who did not undergo colorectal surgery was derived from randomized controlled trials and therefore started high. The level of evidence was downgraded by one level because of the wide confidence interval crossing the lower threshold of clinical relevance (imprecision, -1). The level of evidence was considered as moderate.

7. Gas mixture with N2O

The level of evidence regarding the outcome surgical site infection in patients who received gas mixture with N2O was derived from randomized controlled trials and therefore started high. The level of evidence was downgraded by two levels because of heterogeneity in the study results (inconsistency, -1) and the wide confidence interval crossing both thresholds of clinical relevance (imprecision, -2). The level of evidence was considered as very low.

8. Gas mixture without N2O

The level of evidence regarding the outcome surgical site infection in patients who did not receive gas mixture with N2O was derived from randomized controlled trials and therefore started high. The level of evidence was downgraded by two levels because of possible limitations in the randomization process (risk of bias, -1) and the wide confidence interval crossing the lower threshold of clinical relevance (imprecision, -1). The level of evidence was considered as low.

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question: What are the (un)beneficial effects of perioperative high FiO2 oxygen administration compared with standard FiO2 oxygen administration in patients undergoing any surgical procedure?

P: Adult patients undergoing surgical procedures.

I: High (80%) FiO2.

C: Standard (30-35%) FiO2.

O: Surgical site infections (SSI), SSI-attributable mortality.

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered SSI as a critical outcome for decision making; and SSI-attributable mortality as an important outcome for decision making.

The working group defined a threshold of 10% for continuous outcomes and a relative risk (RR) for dichotomous outcomes of <0.80 and >1.25 as a minimal clinically (patient) important difference.

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms, based on the literature search of de Jonge (2019) from the 20th of April 2018 up to the 18th of August 2023. The detailed search strategy is available on request via https://richtlijnendatabase.nl/. The systematic literature search resulted in 1935 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria: systematic reviews and randomized controlled trials on high FiO2 to prevent postoperative wound infections. 19 studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, 9 studies were excluded, and 10 studies were included (+ 17 studies included in the previous version of the review (de Jonge 2019) (see the 'Samenvatting literatuur' tab).

Results

Twenty-seven studies were included in the analysis of the literature under the tab 'Samenvatting literatuur'. Important study characteristics and results and quality assessments are summarized in the evidence tables and risk of bias tables under the 'evidence tabellen' tab.

Referenties

- Alvandipour M, Mokhtari-Esbuie F, Baradari AG, Firouzian A, Rezaie M. Effect of Hyperoxygenation During Surgery on Surgical Site Infection in Colorectal Surgery. Ann Coloproctol. 2019 Feb;35(1):9-14. doi: 10.3393/ac.2018.01.16. Epub 2019 Feb 28. PMID: 30879279; PMCID: PMC6425249.

- Belda FJ, Aguilera L, García de la Asunción J, Alberti J, Vicente R, Ferrándiz L, Rodríguez R, Company R, Sessler DI, Aguilar G, Botello SG, Ortí R; Spanish Reduccion de la Tasa de Infeccion Quirurgica Group. Supplemental perioperative oxygen and the risk of surgical wound infection: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2005 Oct 26;294(16):2035-42. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.16.2035. Erratum in: JAMA. 2005 Dec 21;294(23):2973. PMID: 16249417.

- Bickel A, Gurevits M, Vamos R, Ivry S, Eitan A. Perioperative hyperoxygenation and wound site infection following surgery for acute appendicitis: a randomized, prospective, controlled trial. Arch Surg. 2011 Apr;146(4):464-70. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2011.65. Erratum in: Arch Surg. 2011 Aug;146(8):993. Dosage error in article text. PMID: 21502457.Gardella C, Goltra LB, Laschansky E, Drolette L, Magaret A, Chadwick HS, Eschenbach D. High-concentration supplemental perioperative oxygen to reduce the incidence of postcesarean surgical site infection: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2008 Sep;112(3):545-52. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318182340c. Erratum in: Obstet Gynecol. 2008 Dec;112(6):1392. PMID: 18757651.

- Chen Y, Liu X, Cheng CH, Gin T, Leslie K, Myles P, Chan MT. Leukocyte DNA damage and wound infection after nitrous oxide administration: a randomized controlled trial. Anesthesiology. 2013 Jun;118(6):1322-31. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31829107b8. PMID: 23549382.

- Chu DK, Kim LH, Young PJ, Zamiri N, Almenawer SA, Jaeschke R, Szczeklik W, Schünemann HJ, Neary JD, Alhazzani W. Mortality and morbidity in acutely ill adults treated with liberal versus conservative oxygen therapy (IOTA): a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2018 Apr 28;391(10131):1693-1705. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30479-3. Epub 2018 Apr 26. PMID: 29726345.

- Duggal N, Poddatorri V, Noroozkhani S, Siddik-Ahmad RI, Caughey AB. Perioperative oxygen supplementation and surgical site infection after cesarean delivery: a randomized trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2013 Jul;122(1):79-84. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318297ec6c. Erratum in: Obstet Gynecol. 2013 Sep;122(3):698. Ppddatorri, Vineela [corrected to Poddatoori, Vineela]. PMID: 23743467.

- Fariba, F. & Loghman, G. & Roshani, Daem & Dina, Sumaiya & Jamal, S.. (2016). Effect of supplemental oxygen on the incidence and severity of Wound Infection after cesarean surgery. 9. 3320-3325.

- Ferrando C, Aldecoa C, Unzueta C, Belda FJ, Librero J, Tusman G, Suárez-Sipmann F, Peiró S, Pozo N, Brunelli A, Garutti I, Gallego C, Rodríguez A, García JI, Díaz-Cambronero O, Balust J, Redondo FJ, de la Matta M, Gallego-Ligorit L, Hernández J, Martínez P, Pérez A, Leal S, Alday E, Monedero P, González R, Mazzirani G, Aguilar G, López-Baamonde M, Felipe M, Mugarra A, Torrente J, Valencia L, Varón V, Sánchez S, Rodríguez B, Martín A, India I, Azparren G, Molina R, Villar J, Soro M; iPROVE-O2 Network. Effects of oxygen on post-surgical infections during an individualised perioperative open-lung ventilatory strategy: a randomised controlled trial. Br J Anaesth. 2020 Jan;124(1):110-120. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2019.10.009. Epub 2019 Nov 22. PMID: 31767144.

- Greif R, Akça O, Horn EP, Kurz A, Sessler DI; Outcomes Research Group. Supplemental perioperative oxygen to reduce the incidence of surgical-wound infection. N Engl J Med. 2000 Jan 20;342(3):161-7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200001203420303. PMID: 10639541.

- Kurz A, Kopyeva T, Suliman I, Podolyak A, You J, Lewis B, Vlah C, Khatib R, Keebler A, Reigert R, Seuffert M, Muzie L, Drahuschak S, Gorgun E, Stocchi L, Turan A, Sessler DI. Supplemental oxygen and surgical-site infections: an alternating intervention-controlled trial. Br J Anaesth. 2018 Jan;120(1):117-126. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2017.11.003. Epub 2017 Nov 23. PMID: 29397118.

- Kurz A, Fleischmann E, Sessler DI, Buggy DJ, Apfel C, Akça O; Factorial Trial Investigators. Effects of supplemental oxygen and dexamethasone on surgical site infection: a factorial randomized trial‡. Br J Anaesth. 2015 Sep;115(3):434-43. doi: 10.1093/bja/aev062. Epub 2015 Apr 20. PMID: 25900659.

- Mattishent, K, Thavarajah, M., Sinha, A., Peel, A., Egger, M., Solomkin, J., de Jonge, S., Latif, A., Berenholtz, S., Allegranzi, B., & Loke, Y. K. (2019). Safety of 80% vs 30-35% fraction of inspired oxygen in patients undergoing surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. British journal of anaesthesia, 122(3), 311–324. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bja.2018.11.026

- Mayank M, Mohsina S, Sureshkumar S, Kundra P, Kate V. Effect of Perioperative High Oxygen Concentration on Postoperative SSI in Elective Colorectal Surgery-A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Gastrointest Surg. 2019 Jan;23(1):145-152. doi: 10.1007/s11605-018-3996-2. Epub 2018 Oct 8. PMID: 30298417.

- Mayzler O, Weksler N, Domchik S, Klein M, Mizrahi S, Gurman GM. Does supplemental perioperative oxygen administration reduce the incidence of wound infection in elective colorectal surgery? Minerva Anestesiol. 2005 Jan-Feb;71(1-2):21-5. PMID: 15711503.

- Meyhoff CS, Wetterslev J, Jorgensen LN, Henneberg SW, Høgdall C, Lundvall L, Svendsen PE, Mollerup H, Lunn TH, Simonsen I, Martinsen KR, Pulawska T, Bundgaard L, Bugge L, Hansen EG, Riber C, Gocht-Jensen P, Walker LR, Bendtsen A, Johansson G, Skovgaard N, Heltø K, Poukinski A, Korshin A, Walli A, Bulut M, Carlsson PS, Rodt SA, Lundbech LB, Rask H, Buch N, Perdawid SK, Reza J, Jensen KV, Carlsen CG, Jensen FS, Rasmussen LS; PROXI Trial Group. Effect of high perioperative oxygen fraction on surgical site infection and pulmonary complications after abdominal surgery: the PROXI randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2009 Oct 14;302(14):1543-50. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1452. PMID: 19826023.

- Myles PS, Leslie K, Chan MT, Forbes A, Paech MJ, Peyton P, Silbert BS, Pascoe E; ENIGMA Trial Group. Avoidance of nitrous oxide for patients undergoing major surgery: a randomized controlled trial. Anesthesiology. 2007 Aug;107(2):221-31. doi: 10.1097/01.anes.0000270723.30772.da. PMID: 17667565.

- NIHR Global Health Research Unit on Global Surgery; GlobalSurg Collaborative; NIHR Global Health Research Unit on Global Surgery Writing committee; GlobalSurg Collaborative writing group; GlobalSurg Collaborative patient representatives; Protocol development; GlobalSurg Collaborative national leads; GlobalSurg Collaborative protocol translators. Exploring the cost-effectiveness of high versus low perioperative fraction of inspired oxygen in the prevention of surgical site infections among abdominal surgery patients in three low- and middle-income countries. BJA Open. 2023 Jul 15;7:100207. doi: 10.1016/j.bjao.2023.100207. PMID: 37655933; PMCID: PMC10457493.

- Park M, Jung K, Sim WS, Kim DK, Chung IS, Choi JW, Lee EJ, Lee NY, Kim JA. Perioperative high inspired oxygen fraction induces atelectasis in patients undergoing abdominal surgery: A randomized controlled trial. J Clin Anesth. 2021 Sep;72:110285. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2021.110285. Epub 2021 Apr 7. PMID: 33838534.

- Pryor KO, Fahey TJ 3rd, Lien CA, Goldstein PA. Surgical site infection and the routine use of perioperative hyperoxia in a general surgical population: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004 Jan 7;291(1):79-87. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.1.79. PMID: 14709579.

- Scifres CM, Leighton BL, Fogertey PJ, Macones GA, Stamilio DM. Supplemental oxygen for the prevention of postcesarean infectious morbidity: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011 Sep;205(3):267.e1-9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.06.038. Epub 2011 Jun 17. PMID: 22071059.

- Sperna Weiland, N. H., Berger, M. M., & Helmerhorst, H. J. F. (2020). CON: Routine hyperoxygenation in adult surgical patients whose tracheas are intubated. Anaesthesia, 75(10), 1297–1300. https://doi.org/10.1111/anae.15026

- Stall A, Paryavi E, Gupta R, Zadnik M, Hui E, O'Toole RV. Perioperative supplemental oxygen to reduce surgical site infection after open fixation of high-risk fractures: a randomized controlled pilot trial. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013 Oct;75(4):657-63. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3182a1fe83. PMID: 24064879.

- Thibon P, Borgey F, Boutreux S, Hanouz JL, Le Coutour X, Parienti JJ. Effect of perioperative oxygen supplementation on 30-day surgical site infection rate in abdominal, gynecologic, and breast surgery: the ISO2 randomized controlled trial. Anesthesiology. 2012 Sep;117(3):504-11. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3182632341. PMID: 22790961.

- Wasnik, Nitin & Agrawal, Vijay & Yede, Jitendra & Gupta, Arpit & Soitkar, Sagar. (2015). Role of supplemental oxygen in reducing surgical site infection in acute appendicities: Our experience of sixty four cases. International Journal of Biomedical and Advance Research. 6. 124. 10.7439/ijbar.v6i2.1654.

- Weenink, R. P., de Jonge, S. W., Preckel, B., & Hollmann, M. W. (2020). PRO: Routine hyperoxygenation in adult surgical patients whose tracheas are intubated. Anaesthesia, 75(10), 1293–1296. https://doi.org/10.1111/anae.15027

- Williams NL, Glover MM, Crisp C, Acton AL, Mckenna DS. Randomized controlled trial of the effect of 30% versus 80% fraction of inspired oxygen on cesarean delivery surgical site infection. Am J Perinatol. 2013 Oct;30(9):781-6. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1333405. Epub 2013 Jan 28. PMID: 23359237.

- Yerra P, Sistla SC, Krishnaraj B, Shankar G, Sistla S, Kundra P, Sundaramurthi S. Effect of Peri-Operative Hyperoxygenation on Surgical Site Infection in Patients Undergoing Emergency Abdominal Surgery: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Surg Infect (Larchmt). 2021 Dec;22(10):1052-1058. doi: 10.1089/sur.2021.005. Epub 2021 Jul 27. PMID: 34314615.

Evidence tabellen

|

Study |

Design, scope, participants |

Type of surgery, procedure duration |

Outcome definition (CDC), follow-up |

Intervention vs control |

Postoperative oxygenation |

Tracheal intubation |

Base gas |

Preoperative antibiotics |

Temperature regimen |

Fluids |

|

Greif (2000) |

RCT, MC 500 |

Colorectal surgery, 3.1 h |

No, 15 days |

80% vs 30% |

2 h |

Yes |

N2 |

Yes |

≥36 °C |

15 ml kg−1 h−1 |

|

Pryor (2004) |

RCT, SC 160 |

Major abdominal surgery, 3.7 h |

No, 14 days |

80% vs 30% |

2 h |

Yes |

NA, N2O included |

Yes |

NA |

NA |

|

Belda (2005) |

RCT, MC 291 |

Colorectal surgery, >1 h |

Yes, 14 days |

80% vs 30% |

6 h |

Yes |

Air |

Yes |

Active |

15 ml kg−1 h−1 |

|

Mayzler (2005) |

RCT, SC 38 |

Colorectal surgery, 2.3 h |

Yes, 30 days |

80% vs 30% |

2 h |

Yes |

N2, N2O |

Yes |

≥35.5 °C |

15 ml kg−1 h−1 |

|

Myles (2007) |

RCT, MC 2012 |

Surgery >2 h, 3.3 h |

Yes, 30 days |

80% vs 30% |

No |

Yes |

N2, N2O |

Institutional practice |

>35.5 °C |

Anaesthesiologist's discretion |

|

Gardella (2008) |

RCT, SC 143 |

Caesarean section, 0.8 h |

No, 14 days |

80% vs 30% |

2 h |

No |

Air |

No |

NA |

NA |

|

Meyhoff (2009) |

RCT, MC 1386 |

Laparotomies, 2.2 h |

Yes, 14 days |

80% vs 30% |

2 h |

Yes |

NA, N2O free |

Yes |

NA |

Only to replace deficits |

|

Bickel (2011) |

RCT, SC 210 |

Open appendectomy, 0.5 h |

No, 14 days |

80% vs 30% |

2 h |

Yes |

Air and N2 |

Yes |

Active |

NA |

|

Scifres (2011) |

RCT, SC 585 |

Caesarean section, 1 h |

Yes, 4 weeks |

80% vs 30% |

2 h |

No |

Air |

Yes |

NA |

NA |

|

Thibon (2012) |

RCT, MC 434 |

Abdominal, gynaecological, and breast surgery, 1.5 h |

Yes, 30 days |

80% vs 30% |

No |

Yes |

NA |

NA |

NA |

NA |

|

Duggal (2013) |

RCT, SC 831 |

Caesarean section, NA |

Yes plus endometritis, 2 weeks |

80% vs 30% (after cord clamping) |

1 h |

No |

Air |

No |

NA |

NA |

|

Williams (2013) |

RCT, SC 160 |

Caesarean section, 0.9 h |

Yes plus endometritis, 30 days |

80% vs 30% |

2 h |

No |

Air |

No |

NA |

NA |

|

Stall (2013) |

RCT, SC 235 |

Open reduction and internal fixation, 3.8 h |

Yes, 12 weeks |

80% vs 30% |

2 h |

Yes |

NA |

Yes |

NA |

NA |

|

Chen (2013) |

RCT, SC 91 |

Colorectal surgery, |

Yes, 30 days |

80% vs 30% |

24 h |

Yes |

N2, N2O |

Yes |

>35.5 °C |

Anaesthesiologist's discretion |

|

Kurz (2015) |

RCT, MC 586 |

Colorectal surgery, 3.5 h |

Yes, 30 days |

80% vs 30% |

1 h |

Yes |

N2 |

Yes |

36 °C |

10–11 ml kg−1 h−1 |

|

Wasnik (2015) |

RCT, SC 64 |

Appendectomy 1 h |

No, NA |

80% vs 30% |

2 h |

Yes |

NA |

Yes |

NA |

NA |

|

Fariba (2016) |

RCT, SC 122 |

Caesarean section, 1 h |

No, 14 days |

80% vs 30% |

6 h |

No |

Air |

NA |

NA |

NA |

|

Mayank (2018) |

RCT, SC 94 |

Colorectal surgery, 3.7 h |

Yes, 30 days |

80% vs 33% |

6 h |

Yes |

N2O |

Yes |

At 36 °C |

15 ml kg−1 h−1 |

|

Kurz (2018) |

RCT, SC 5749 |

Major intestinal surgery, 4 h |

Yes, 30 days |

80% vs 30% |

No |

Yes |

NA |

Yes |

Active |

10 ml kg−1 h−1 |

|

Alvandipour (2019) |

RCT, SC 80 |

Colorectal surgery, 1.6 h |

Yes, 30 days |

80% vs 30% |

1 h |

Yes |

N2O |

Yes |

At 36 °C |

6-10 ml kg−1 h−1 |

|

Ferrando (2020) |

RCT, MC 717 |

Major abdominal surgery, 3.5 h |

Yes, 30 days |

80% vs 30% |

3 h |

Yes |

NA |

Yes |

NA |

NA |

|

Yerra (2021) |

RCT, MC 178 |

Major abdominal surgery, 2.6 h |

Yes, 14 days |

80% vs 30% |

2 h |

Yes |

Air |

Yes |

NA |

NA |

|

Park (2021) |

RCT, SC 190 |

Abdominal surgery, NA |

No, 30 days |

60% vs 35% |

0.25 h |

Yes |

Air |

Yes |

NA |

NA |

|

METRC (2022) |

RCT, MC 1136 |

Orthopedic trauma surgery, NA |

Yes, 182 days |

80% vs 30% |

2 h |

Yes |

NA |

NA |

No regimen |

NA |

|

Jamali (2022) |

RCT, SC 291 |

Colorectal surgery, 1 h |

Yes, 15 days |

80% vs 30% |

No |

Yes |

Air |

Yes |

NA |

NA |

|

Onur (2022) |

RCT, SC 100 |

Coronary artery bypass graft surgery, 3.4 h |

Yes, 90 days |

100% vs 40% |

No |

Yes |

NA |

NA |

At 31-32 °C |

NA |

|

Nam |

RCT, MC 417 |

Off-pump coronary artery bypass grafting, 4.3 h |

Yes, 30 days |

80% vs 30% |

No |

Yes |

N2O |

Yes |

NA |

NA |

Figure S1. Risk of bias graphic representation

Figure S2. Overall funnel plot.

Table S2 Sensitivity analysis including the four excluded papers.

|

|

No. of studies |

No. of SSI in the intervention groups |

No. of SSI in the control groups |

Relative risk (95% CI) |

Test of interaction from meta-regression (P-value) |

Between study variance (τ2) |

Percent variance explained |

|

Overall |

|||||||

|

All |

21 |

495 of 4176 |

611 of 4217 |

0.80 (0.67 - 0.97) |

NA |

0.075 |

NA |

|

By delivery of oxygen: intubation Yes/No |

|||||||

|

Yes |

16 |

399 of 3265 |

528 of 3287 |

0.72 (0.59 - 0.88) |

0.015 |

0.052 |

31% |

|

No |

5 |

96 of 911 |

83 of 930 |

1.20 (0.91 - 1.58) |

|||

|

By type of procedure: colorectal Yes/No |

|||||||

|

Yes |

7 |

100 of 814 |

152 of 827 |

0.67 (0.52 - 0.87) |

0.108 |

0.075 |

0% |

|

No |

14 |

395 of 3362 |

459 of 3390 |

0.89 (0.70 - 1.12) |

|||

|

By gas mixture: N2O Yes/No |

|||||||

|

Yes |

4 |

104 of 1126 |

137 of 1175 |

0.92 (0.48 - 1.73) |

0.565 |

0.092 |

0% |

|

No |

17 |

391 of 3050 |

474 of 3042 |

0.78 (0.64 - 0.96) |

|||

SSI: surgical site infection

Table S3 GRADE assessment

The overall quality of studies including patients undergoing general anaesthesia with endotracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation.

|

Certainty assessment |

№ of patients |

Effect |

Certainty |

||||||||

|

№ of studies |

Study design |

Risk of bias |

Inconsistency |

Indirectness |

Imprecision |

Other considerations |

80% FiO2 |

30-35% FiO2 |

Relative |

Absolute |

|

|

Outcome: surgical site infection |

|||||||||||

|

12 |

Randomised trials |

Not serious |

Serious a |

Not serious |

Not serious |

None |

350/2978 (11.8%) |

431/2998 (14.4%) |

RR 0.80 |

29 fewer per 1000 |

⨁⨁⨁◯ |

CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio

a. High heterogeneity, tau2 = 0.051, Chi2 P = 0.043, I2 = 46.7%.

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Publicatiedatum : 17-12-2024

Beoordeeld op geldigheid : 01-12-2024

Algemene gegevens

De ontwikkeling/herziening van deze richtlijnmodule werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten (www.demedischspecialist.nl/kennisinstituut) en werd gefinancierd uit de Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS). De financier heeft geen enkele invloed gehad op de inhoud van de richtlijnmodule.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijnmodules 2 tot 16 is in 2020 op initiatief van de NVvH een multidisciplinaire werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen (zie hiervoor de Samenstelling van de werkgroep) die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor preventie van postoperatieve wondinfecties. Daarnaast is in 2022 op initiatief van het Samenwerkingsverband Richtlijnen Infectiepreventie (SRI) een separate multidisciplinaire werkgroep samengesteld voor de herziening van de WIP-richtlijn over postoperatieve wondinfecties: module 17-22. De ontwikkelde modules van beide werkgroepen zijn in deze richtlijn samengevoegd.

Belangenverklaringen

De Code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling is gevolgd. Alle werkgroepleden hebben schriftelijk verklaard of zij in de laatste drie jaar directe financiële belangen (betrekking bij een commercieel bedrijf, persoonlijke financiële belangen, onderzoek financiering) of indirecte belangen (persoonlijke relaties, reputatiemanagement) hebben gehad. Gedurende de ontwikkeling of herziening van een module worden wijzigingen in belangen aan de voorzitter doorgegeven. De belangenverklaring wordt opnieuw bevestigd tijdens de commentaarfase.

Een overzicht van de belangen van werkgroepleden en het oordeel over het omgaan met eventuele belangen vindt u in onderstaande tabel. De ondertekende belangenverklaringen zijn op te vragen bij het secretariaat van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

|

Werkgroeplid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

Mevr. prof. dr. M.A. Boermeester |

Chirurg |

* Medisch Ethische Commissie, Amsterdam UMC, locatie AMC * Antibiotica Commissie, Amsterdam UMC |

Persoonlijke financiële belangen Hieronder staan de beroepsmatige relaties met bedrijfsleven vermeld waarbij eventuele financiële belangen via de AMC Research B.V. lopen, dus institutionele en geen persoonlijke gelden zijn: Skillslab instructeur en/of spreker (consultant) voor KCI/3M, Smith&Nephew, Johnson&Johnson, Gore, BD/Bard, TELABio, GDM, Medtronic, Molnlycke.

Persoonlijke relaties Geen.

Extern gefinancierd onderzoek Institutionele grants van KCI/3M, Johnson&Johnson en New Compliance.

Intellectuele belangen en reputatie Ik maak me sterk voor een 100% evidence-based benadering van maken van aanbevelingen, volledig transparant en reproduceerbaar. Dat is mijn enige belang in deze, geen persoonlijk gewin.

Overige belangen Geen.

|

Extra kritische commentaarronde. |

|

Dhr. dr. M.J. van der Laan |

Vaatchirurg |

Vice voorzitter Consortium Kwaliteit van Zorg NFU, onbetaald

|

Persoonlijke financiële belangen Geen.

Persoonlijke relaties Geen.

Extern gefinancierd onderzoek Geen.

Intellectuele belangen en reputatie Geen.

Overige belangen Geen.

|

Geen.

|

|

Dhr. dr. W.C. van der Zwet |

Arts-microbioloog |

Lid Regionaal Coördinatie Team, Limburgs infectiepreventie & ABR Zorgnetwerk (onbetaald) |

||

|

Dhr. dr. D.R. Buis |

Neurochirurg |

Lid Hoofdredactieraad Tijdschrift voor Neurologie & Neurochirurgie - onbetaald |

||

|

Dhr. dr. J.H.M. Goosen |

Orthopaedisch Chirurg |

Inhoudelijke presentaties voor Smith&Nephew en Zimmer Biomet. Deze worden vergoed per uur. |

||

|

Mw. drs. H. Jalalzadeh |

Arts-onderzoeker |

Geen. |

Persoonlijke financiële belangen Geen.

Persoonlijke relaties Geen.

Extern gefinancierd onderzoek Geen.

Intellectuele belangen en reputatie Geen.

Overige belangen Geen. |

Geen.

|

|

Dhr. dr. N. Wolfhagen |

AIOS chirurgie |

|||

|

Mw. drs. H. Groenen |

Arts-onderzoeker |

|||

|

Dhr. dr. F.F.A. Ijpma |

Traumachirurg |

|||

|

Dhr. dr. P. Segers |

Cardiothoracaal chirurg |

|||

|

Mw. Y.E.M. Dreissen |

AIOS neurochirurgie |

|||

|

Dhr. R.R. Schaad |

Anesthesioloog |

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Er werd aandacht besteed aan het patiëntenperspectief door uitnodigen van de Patiëntenfederatie Nederland voor de invitational conference. De verkregen input is meegenomen bij het opstellen van de uitgangsvragen, de keuze voor de uitkomstmaten en bij het opstellen van de overwegingen. De conceptmodules zijn tevens voor commentaar voorgelegd aan de Patiëntenfederatie Nederland en de eventueel aangeleverde commentaren zijn bekeken en verwerkt. Voor de modules 17-22 was de patiëntfederatie vertegenwoordigd in de werkgroep.

Wkkgz & Kwalitatieve raming van mogelijke substantiële financiële gevolgen

Bij de richtlijn is conform de Wet kwaliteit, klachten en geschillen zorg (Wkkgz) een kwalitatieve raming uitgevoerd of de aanbevelingen mogelijk leiden tot substantiële financiële gevolgen. Bij het uitvoeren van deze beoordeling zijn richtlijnmodules op verschillende domeinen getoetst (zie het stroomschema op de Richtlijnendatabase).

Uit de kwalitatieve raming blijkt dat er waarschijnlijk geen substantiële financiële gevolgen zijn.

Voor module 8 (Negatieve druktherapie) geldt dat uit de toetsing volgt dat de aanbeveling(en) breed toepasbaar zijn (5.000 - 40.000 patiënten). Tevens volgt uit de toetsing dat het geen nieuwe manier van zorgverlening of andere organisatie van zorgverlening betreft. Er worden daarom geen substantiële financiële gevolgen verwacht.

Voor de overige modules en aanbevelingen geldt dat uit de toetsing volgt dat de aanbeveling(en) breed toepasbaar zijn (>40.000 patiënten). Tevens volgt uit de toetsing dat het overgrote deel (±90%) van de zorgaanbieders en zorgverleners al aan de norm voldoet en het geen nieuwe manier van zorgverlening of andere organisatie van zorgverlening betreft. Ook wordt geen toename in het aantal in te zetten voltijdsequivalenten aan zorgverleners verwacht of een wijziging in het opleidingsniveau van zorgpersoneel. Er worden daarom geen substantiële financiële gevolgen verwacht.

Methode ontwikkeling

Evidence based

Implementatie

Zie voor de implementatie het implementatieplan in het tabblad 'Bijlagen'.

Werkwijze

AGREE

Deze richtlijnmodule is opgesteld conform de eisen vermeld in het rapport Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 van de adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwaliteit. Dit rapport is gebaseerd op het AGREE II instrument (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II; Brouwers, 2010).

Knelpuntenanalyse en uitgangsvragen

Tijdens de voorbereidende fase inventariseerde de werkgroepen de knelpunten in de zorg voor patiënten die chirurgie ondergaan. Tevens zijn er knelpunten aangedragen door middel van een invitational conference. De verslagen hiervan zijn opgenomen onder aanverwante producten.

Op basis van de uitkomsten van de knelpuntenanalyse zijn door de werkgroep concept-uitgangsvragen opgesteld en definitief vastgesteld.

Uitkomstmaten

Na het opstellen van de zoekvraag behorende bij de uitgangsvraag inventariseerde de werkgroep welke uitkomstmaten voor de patiënt relevant zijn, waarbij zowel naar gewenste als ongewenste effecten werd gekeken. Hierbij werd een maximum van acht uitkomstmaten gehanteerd. De werkgroep waardeerde deze uitkomstmaten volgens hun relatieve belang bij de besluitvorming rondom aanbevelingen, als cruciaal (kritiek voor de besluitvorming), belangrijk (maar niet cruciaal) en onbelangrijk. Tevens definieerde de werkgroep tenminste voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten welke verschillen zij klinisch (patiënt) relevant vonden.

Methode literatuursamenvatting

Een uitgebreide beschrijving van de strategie voor zoeken en selecteren van literatuur is te vinden onder ‘Zoeken en selecteren’ onder Onderbouwing. Indien mogelijk werd de data uit verschillende studies gepoold in een random-effects model. De beoordeling van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs wordt hieronder toegelicht.

Beoordelen van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs

De kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs werd bepaald volgens de GRADE-methode. GRADE staat voor ‘Grading Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation’ (zie http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/). De basisprincipes van de GRADE-methodiek zijn: het benoemen en prioriteren van de klinisch (patiënt) relevante uitkomstmaten, een systematische review per uitkomstmaat, en een beoordeling van de bewijskracht per uitkomstmaat op basis van de acht GRADE-domeinen (domeinen voor downgraden: risk of bias, inconsistentie, indirectheid, imprecisie, en publicatiebias; domeinen voor upgraden: dosis-effect relatie, groot effect, en residuele plausibele confounding).

GRADE onderscheidt vier gradaties voor de kwaliteit van het wetenschappelijk bewijs: hoog, redelijk, laag en zeer laag. Deze gradaties verwijzen naar de mate van zekerheid die er bestaat over de literatuurconclusie, in het bijzonder de mate van zekerheid dat de literatuurconclusie de aanbeveling adequaat ondersteunt (Schünemann, 2013; Hultcrantz, 2017).

|

GRADE |

Definitie |

|

Hoog |

|

|

Redelijk |

|

|

Laag |

|

|

Zeer laag |

|

Bij het beoordelen (graderen) van de kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs in richtlijnen volgens de GRADE-methodiek spelen grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming een belangrijke rol (Hultcrantz, 2017). Dit zijn de grenzen die bij overschrijding aanleiding zouden geven tot een aanpassing van de aanbeveling. Om de grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming te bepalen moeten alle relevante uitkomstmaten en overwegingen worden meegewogen. De grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming zijn daarmee niet één op één vergelijkbaar met het minimaal klinisch relevant verschil (Minimal Clinically Important Difference, MCID). Met name in situaties waarin een interventie geen belangrijke nadelen heeft en de kosten relatief laag zijn, kan de grens voor klinische besluitvorming met betrekking tot de effectiviteit van de interventie bij een lagere waarde (dichter bij het nuleffect) liggen dan de MCID (Hultcrantz, 2017).

Overwegingen (van bewijs naar aanbeveling)

Om te komen tot een aanbeveling zijn naast (de kwaliteit van) het wetenschappelijke bewijs ook andere aspecten belangrijk en worden meegewogen, zoals aanvullende argumenten uit bijvoorbeeld de biomechanica of fysiologie, waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten, kosten (middelenbeslag), aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie. Deze aspecten zijn systematisch vermeld en beoordeeld (gewogen) onder het kopje ‘Overwegingen’ en kunnen (mede) gebaseerd zijn op expert opinion. Hierbij is gebruik gemaakt van een gestructureerd format gebaseerd op het evidence-to-decision framework van de internationale GRADE Working Group (Alonso-Coello, 2016a; Alonso-Coello 2016b). Dit evidence-to-decision framework is een integraal onderdeel van de GRADE methodiek.

Formuleren van aanbevelingen

De aanbevelingen geven antwoord op de uitgangsvraag en zijn gebaseerd op het beschikbare wetenschappelijke bewijs en de belangrijkste overwegingen, en een weging van de gunstige en ongunstige effecten van de relevante interventies. De kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs en het gewicht dat door de werkgroep wordt toegekend aan de overwegingen, bepalen samen de sterkte van de aanbeveling. Conform de GRADE-methodiek sluit een lage bewijskracht van conclusies in de systematische literatuuranalyse een sterke aanbeveling niet a priori uit, en zijn bij een hoge bewijskracht ook zwakke aanbevelingen mogelijk (Agoritsas, 2017; Neumann, 2016). De sterkte van de aanbeveling wordt altijd bepaald door weging van alle relevante argumenten tezamen. De werkgroep heeft bij elke aanbeveling opgenomen hoe zij tot de richting en sterkte van de aanbeveling zijn gekomen.

In de GRADE-methodiek wordt onderscheid gemaakt tussen sterke en zwakke (of conditionele) aanbevelingen. De sterkte van een aanbeveling verwijst naar de mate van zekerheid dat de voordelen van de interventie opwegen tegen de nadelen (of vice versa), gezien over het hele spectrum van patiënten waarvoor de aanbeveling is bedoeld. De sterkte van een aanbeveling heeft duidelijke implicaties voor patiënten, behandelaars en beleidsmakers (zie onderstaande tabel). Een aanbeveling is geen dictaat, zelfs een sterke aanbeveling gebaseerd op bewijs van hoge kwaliteit (GRADE gradering HOOG) zal niet altijd van toepassing zijn, onder alle mogelijke omstandigheden en voor elke individuele patiënt.

|

Implicaties van sterke en zwakke aanbevelingen voor verschillende richtlijngebruikers |

||

|

|

Sterke aanbeveling |

Zwakke (conditionele) aanbeveling |

|

Voor patiënten |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen en slechts een klein aantal niet. |

Een aanzienlijk deel van de patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen, maar veel patiënten ook niet. |

|

Voor behandelaars |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak moeten ontvangen. |

Er zijn meerdere geschikte interventies of aanpakken. De patiënt moet worden ondersteund bij de keuze voor de interventie of aanpak die het beste aansluit bij zijn of haar waarden en voorkeuren. |

|

Voor beleidsmakers |

De aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kan worden gezien als standaardbeleid. |

Beleidsbepaling vereist uitvoerige discussie met betrokkenheid van veel stakeholders. Er is een grotere kans op lokale beleidsverschillen. |

Organisatie van zorg

In de knelpuntenanalyse en bij de ontwikkeling van de richtlijnmodule is expliciet aandacht geweest voor de organisatie van zorg: alle aspecten die randvoorwaardelijk zijn voor het verlenen van zorg (zoals coördinatie, communicatie, (financiële) middelen, mankracht en infrastructuur). Randvoorwaarden die relevant zijn voor het beantwoorden van deze specifieke uitgangsvraag zijn genoemd bij de overwegingen. Meer algemene, overkoepelende, of bijkomende aspecten van de organisatie van zorg worden behandeld in de module Organisatie van zorg.

Commentaar- en autorisatiefase

De conceptrichtlijnmodule werd aan de betrokken (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd ter commentaar. De commentaren werden verzameld en besproken met de werkgroep. Naar aanleiding van de commentaren werd de conceptrichtlijnmodule aangepast en definitief vastgesteld door de werkgroep. De definitieve richtlijnmodule werd aan de deelnemende (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd voor autorisatie en door hen geautoriseerd dan wel geaccordeerd.

Adaptatie

Een aantal modules van deze richtlijn betreft een adaptatie van modules van de World Health Organization (WHO)-richtlijn ‘Global guidelines for the prevention of surgical site infection’ (WHO, 2018), te weten:

- Module Normothermie

- Module Immunosuppressive middelen

- Module Glykemische controle

- Module Antimicrobiële afdichtingsmiddelen

- Module Wondbeschermers bij laparotomie

- Module Preoperatief douchen

- Module Preoperatief verwijderen van haar

- Module Chirurgische handschoenen: Vervangen en type handschoenen

- Module Afdekmaterialen en operatiejassen

Methode

- Uitgangsvragen zijn opgesteld in overeenstemming met de standaardprocedures van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

- De inleiding van iedere module betreft een korte uiteenzetting van het knelpunt, waarbij eventuele onduidelijkheid en praktijkvariatie voor de Nederlandse setting wordt beschreven.

- Het literatuuronderzoek is overgenomen uit de WHO-richtlijn. Afhankelijk van de beoordeling van de actualiteit van de richtlijn is een update van het literatuuronderzoek uitgevoerd.

- De samenvatting van de literatuur is overgenomen van de WHO-richtlijn, waarbij door de werkgroep onderscheid is gemaakt tussen ‘cruciale’ en ‘belangrijke’ uitkomsten. Daarnaast zijn door de werkgroep grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming gedefinieerd in overeenstemming met de standaardprocedures van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten, en is de interpretatie van de bevindingen primair gebaseerd op klinische relevantie van het gevonden effect, niet op statistische significantie. In de meta-analyses zijn naast odds-ratio’s ook relatief risico’s en risicoverschillen gerapporteerd.

- De beoordeling van de mate van bewijskracht is overgnomen van de WHO-richtlijn, waarbij de beoordeling is gecontroleerd op consistentie met de standaardprocedures van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten (GRADE-methode; http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/). Eventueel door de WHO gerapporteerde bewijskracht voor observationele studies is niet overgenomen indien ook gerandomiseerde gecontroleerde studies beschikbaar waren.

- De conclusies van de literatuuranalyse zijn geformuleerd in overeenstemming met de standaardprocedures van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

- In de overwegingen heeft de werkgroep voor iedere aanbeveling het bewijs waarop de aanbeveling is gebaseerd en de aanvaardbaarheid en toepasbaarheid van de aanbeveling voor de Nederlandse klinische praktijk beoordeeld. Op basis van deze beoordeling is door de werkgroep besloten welke aanbevelingen ongewijzigd zijn overgenomen, welke aanbevelingen niet zijn overgenomen, en welke aanbevelingen (mits in overeenstemming met het bewijs) zijn aangepast naar de Nederlandse context. ‘De novo’ aanbevelingen zijn gedaan in situaties waarin de werkgroep van mening was dat een aanbeveling nodig was, maar deze niet als zodanig in de WHO-richtlijn was opgenomen. Voor elke aanbeveling is vermeld hoe deze tot stand is gekomen, te weten: ‘WHO’, ‘aangepast van WHO’ of ‘de novo’.

Voor een verdere toelichting op de procedure van adapteren wordt verwezen naar de Bijlage Adapteren.

Literatuur

Agoritsas T, Merglen A, Heen AF, Kristiansen A, Neumann I, Brito JP, Brignardello-Petersen R, Alexander PE, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Guyatt GH. UpToDate adherence to GRADE criteria for strong recommendations: an analytical survey. BMJ Open. 2017 Nov 16;7(11):e018593. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018593. PubMed PMID: 29150475; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5701989.

Alonso-Coello P, Schünemann HJ, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Rada G, Rosenbaum S, Morelli A, Guyatt GH, Oxman AD; GRADE Working Group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 1: Introduction. BMJ. 2016 Jun 28;353:i2016. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2016. PubMed PMID: 27353417.

Alonso-Coello P, Oxman AD, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Vandvik PO, Meerpohl J, Guyatt GH, Schünemann HJ; GRADE Working Group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 2: Clinical practice guidelines. BMJ. 2016 Jun 30;353:i2089. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2089. PubMed PMID: 27365494.

Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, Burgers JS, Cluzeau F, Feder G, Fervers B, Graham ID, Grimshaw J, Hanna SE, Littlejohns P, Makarski J, Zitzelsberger L; AGREE Next Steps Consortium. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. CMAJ. 2010 Dec 14;182(18):E839-42. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090449. Epub 2010 Jul 5. Review. PubMed PMID: 20603348; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3001530.

Hultcrantz M, Rind D, Akl EA, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Iorio A, Alper BS, Meerpohl JJ, Murad MH, Ansari MT, Katikireddi SV, Östlund P, Tranæus S, Christensen R, Gartlehner G, Brozek J, Izcovich A, Schünemann H, Guyatt G. The GRADE Working Group clarifies the construct of certainty of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017 Jul;87:4-13. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.05.006. Epub 2017 May 18. PubMed PMID: 28529184; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC6542664.

Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 (2012). Adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwalitieit. http://richtlijnendatabase.nl/over_deze_site/over_richtlijnontwikkeling.html

Neumann I, Santesso N, Akl EA, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Alonso-Coello P, Agoritsas T, Mustafa RA, Alexander PE, Schünemann H, Guyatt GH. A guide for health professionals to interpret and use recommendations in guidelines developed with the GRADE approach. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016 Apr;72:45-55. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.11.017. Epub 2016 Jan 6. Review. PubMed PMID: 26772609.

Schünemann H, Brożek J, Guyatt G, et al. GRADE handbook for grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. Updated October 2013. The GRADE Working Group, 2013. Available from http://gdt.guidelinedevelopment.org/central_prod/_design/client/handbook/handbook.html.

World Health Organization. Global guidelines for the prevention of surgical site infection,

second edition. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018. (https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241550475, accessed 12 June 2023).

Zoekverantwoording

Agoritsas T, Merglen A, Heen AF, Kristiansen A, Neumann I, Brito JP, Brignardello-Petersen R, Alexander PE, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Guyatt GH. UpToDate adherence to GRADE criteria for strong recommendations: an analytical survey. BMJ Open. 2017 Nov 16;7(11):e018593. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018593. PubMed PMID: 29150475; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5701989.

Alonso-Coello P, Schünemann HJ, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Rada G, Rosenbaum S, Morelli A, Guyatt GH, Oxman AD; GRADE Working Group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 1: Introduction. BMJ. 2016 Jun 28;353:i2016. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2016. PubMed PMID: 27353417.

Alonso-Coello P, Oxman AD, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Vandvik PO, Meerpohl J, Guyatt GH, Schünemann HJ; GRADE Working Group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 2: Clinical practice guidelines. BMJ. 2016 Jun 30;353:i2089. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2089. PubMed PMID: 27365494.

Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, Burgers JS, Cluzeau F, Feder G, Fervers B, Graham ID, Grimshaw J, Hanna SE, Littlejohns P, Makarski J, Zitzelsberger L; AGREE Next Steps Consortium. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. CMAJ. 2010 Dec 14;182(18):E839-42. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090449. Epub 2010 Jul 5. Review. PubMed PMID: 20603348; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3001530.

Hultcrantz M, Rind D, Akl EA, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Iorio A, Alper BS, Meerpohl JJ, Murad MH, Ansari MT, Katikireddi SV, Östlund P, Tranæus S, Christensen R, Gartlehner G, Brozek J, Izcovich A, Schünemann H,

Guyatt G. The GRADE Working Group clarifies the construct of certainty of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017 Jul;87:4-13. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.05.006. Epub 2017 May 18. PubMed PMID: 28529184; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC6542664.

Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 (2012). Adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwalitieit. http://richtlijnendatabase.nl/over_deze_site/over_richtlijnontwikkeling.html

Neumann I, Santesso N, Akl EA, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Alonso-Coello P, Agoritsas T, Mustafa RA, Alexander PE, Schünemann H, Guyatt GH. A guide for health professionals to interpret and use recommendations in guidelines developed with the GRADE approach. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016 Apr;72:45-55. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.11.017. Epub 2016 Jan 6. Review. PubMed PMID: 26772609.

Schünemann H, Brożek J, Guyatt G, et al. GRADE handbook for grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. Updated October 2013. The GRADE Working Group, 2013. Available from http://gdt.guidelinedevelopment.org/central_prod/_design/client/handbook/handbook.html.

World Health Organization. Global guidelines for the prevention of surgical site infection,

second edition. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018. (https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241550475, accessed 12 June 2023).