Darmvoorbereiding

Uitgangsvraag

What is the effect of different methods of bowel preparation on the incidence of surgical site infections (SSI), anastomotic leakage (AL) and mortality in patients undergoing elective colorectal surgery?

Aanbeveling

Overweeg om patiënten voorafgaand aan colorectale chirurgie, ter preventie van postoperatieve wondinfecties (en naadlekkages), met de volgende darmvoorbereiding:

- Alleen orale antibiotica, of

- Orale antibiotica in combinatie met mechanische darmvoorbereiding

Bespreek met patiënten de voor- en nadelen van mechanische darmvoorbereiding.

Behandel patiënten voorafgaand aan colorectale chirurgie niet met alleen mechanische darmvoorbereiding met als doel preventie van postoperatieve wondinfecties en naadlekkages.

Voor advies t.a.v. keuze van het middel, dosering en duur van de behandeling verwijzen wij naar de lokale SWAB-richtlijnen. Deze aanbeveling is in aanvulling op de intraveneuze chirurgische antibiotische profylaxe (indien geïndiceerd).

Overwegingen

Summary of the evidence

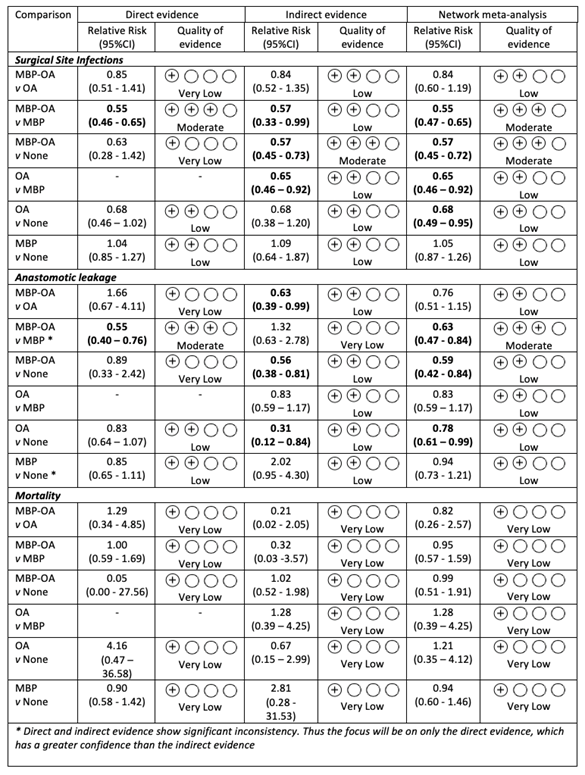

The network meta-analysis by Jalalzadeh et al. (2022) showed the effect of different types of bowel preparation on the rates of surgical site infections, anastomotic leakage, and mortality for patients undergoing elective colorectal surgery. The results showed a significant reduction of SSI when using MBP-OA compared with only MBP or no preparation and for OA alone compared with MBP. MBP-OA and OA showed comparable effectiveness (for SSI reduction NNT 13 and 18, respectively). There was no difference in effect between MBP and no preparation.

Overall, the certainty of evidence was graded as moderate to low because of imprecision of the results and risk of bias. Furthermore, MBP-OA and OA may both be effective for the prevention of anastomotic leakage, whereas MBP was not.

There was no clear association between the method of bowel preparation and all-cause mortality rate. Only in a sensitivity analysis of studies that focused on laparoscopic surgery or a mixed laparoscopic/open population, MBP-OA seemed more effective than other methods.

International guidelines

The findings are of added value to existing guideline recommendations. The results are partly in line with current international guidelines but give an important new perspective. WHO (2018) and NICE (2019) guidelines both advise against the use of only MBP as routine preparation. The WHO advises MBP-OA in colorectal surgery. However, both guidelines did not include studies investigating the effect of OA alone. The NICE guidelines acknowledge this limitation and state that their current guideline should be updated with newly published evidence, including studies investigating the effect of OA alone. The current guideline of the CDC (O’Hara 2018) does not mention bowel preparation. Previous, non-network meta-analyses have shown results in favor of MBP-OA compared to MBP (Rollins 2019) and no clear difference between MBP and no preparation (Güenaga 2011). These results are still in line with present study but lack the relative effect of OA alone. One of the trials investigating the effect of OA alone (Mulder 2020), ended prematurely due to results of a new non-randomized study favoring OA (Mulder 2019). The authors no longer considered clinical equipoise.

A recent NMA (Woodfield 2022) concludes that OA without MBP shows the greatest reduction in SSI. This is not in line with our findings. Current evidence from present NMA shows that effectiveness of OA alone does not significantly differ from that of MBP-OA (RR 0.81, 95% CI 0.54 – 1.19). Our results support the use of OA alone, and we do not find MBP-OA to be superior to OA. The most recent NMA has not included some of these new RCTs, which explains the difference in results. Some studies were published after the search date, others were excluded for unknown reasons. An earlier NMA (Toh 2018) has identified a knowledge gap with respect to effectiveness of OA as few studies compared OA alone to MBP-OA or no preparation. We included four additional RCTs investigating OA as sole intervention without MBP; all published since 2020. One RCT compared OA alone to MBP-OA (Suzuki 2020) and three studies compared OA alone to no preparation (Arezzo 2021, Espin-Basany 2020, Mulder 2020).

Subgroup: minimal invasive procedures

In recent years, minimally invasive procedures are widely performed and a distinction between effects of the various bowel preparations in open and laparoscopic procedures could be very helpful in clinical practice. Therefore, an additional sensitivity analysis was performed, excluding RCTs with only open surgical procedures. In the remaining cohort for analysis, still 40% of the procedures were open procedures. It was not possible to attribute SSI to either laparoscopic or open surgery among these mixed studies as such details were not supplied in the original publications. Therefore, it is not possible to draw firm recommendations on the various bowel preparation methods between open and laparoscopic procedures. More studies including only laparoscopic procedures are needed to draw definite conclusions.

Patient preferences

Analysis of effectivity does not take the discomfort and possible harms (e.g., electrolytes imbalance and dehydration) of MBP into consideration nor its practical concerns such as early hospital admission and discomfort for the patient. The harms and benefits should be carefully weighed with patients, ideally using the principles of shared decision making justifying the additional value of MBP to OA.

Pros and cons of mechanical bowel preparation

Pros may include:

- Improvement of operative handling of the bowels

Cons may include:

- Bad taste and large amount of solution

- Increase of bowel movements over period of hours

- Nausea and vomiting

- Electrolyte imbalance

- Temporary decrease of absorption of other medication

Resource use

There are no cost-effective studies available.

Sustainability, feasibility, and implementation

There seems to be no issues regarding the feasibility for implementation in clinical practice. Mechanical bowel preparation is often done since no feces can enter the abdominal cavity. Mechanical preparation prior to surgery also gives a better view that may be beneficial during surgery. This may be a barrier for applying OA alone.

Rationale of the recommendation

Present findings revealed that MBP-OA and OA alone reduce SSI and likely reduce AL rates compared to no bowel preparation and that MBP-OA results in little to no difference in SSI and AL rates compared to OA alone. For the consideration of adding MBP to OA, one should consider patient preferences, using principles of shared decision making, explaining possible discomfort or harms (e.g., electrolytes imbalance and dehydration), and practical issues.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Surgical site infections (SSI) and anastomotic leakage (AL) are serious complications after colorectal surgery and associated with high morbidity, mortality, and costs. Incidence of 5-25% for SSI and 3-12% for AL have been reported. Bowel preparation may prevent a large proportion of SSI and can be performed using mechanical bowel preparation (MBP), oral antibiotics alone (OA) and a combination of both (MBP-OA). Here, we provide an up-to-date evaluation on the effect of different methods of bowel preparation on surgical site infections, anastomotic leakage, and mortality after elective colorectal surgery.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

Surgical site infections (SSI)

MBP-OA versus OA

|

Low GRADE |

The evidence suggests that mechanical bowel preparation combined with oral antibiotics results in little to no difference in surgical site infections compared to only oral antibiotics in patients undergoing elective colorectal surgery. |

MBP-OA versus MBP

|

Moderate GRADE |

Mechanical bowel preparation combined with oral antibiotics likely reduces surgical site infections compared to only mechanical bowel preparation in patients undergoing elective colorectal surgery. |

MBP-OA versus None

|

Moderate GRADE |

Mechanical bowel preparation combined with oral antibiotics likely reduces surgical site infections compared with no preparation in patients undergoing elective colorectal surgery. |

OA versus MBP

|

Low GRADE |

The evidence suggests only oral antibiotics reduces surgical site infections compared to only mechanical bowel preparation in patients undergoing elective colorectal surgery. |

OA versus None

|

Low GRADE |

The evidence suggests only oral antibiotics reduces surgical site infections compared to no preparation in patients undergoing elective colorectal surgery.

|

MBP versus None

|

Low GRADE |

The evidence suggests that only mechanical bowel preparation results in little to no difference in surgical site infections compared to no preparation in patients undergoing elective colorectal surgery. |

Anastomotic leakage

MBP-OA versus OA

|

Low GRADE |

The evidence suggests that mechanical bowel preparation combined with oral antibiotics results in little to no difference of anastomotic leakage compared to only oral antibiotics in patients undergoing elective colorectal surgery. |

MBP-OA versus MBP

|

Moderate GRADE |

Mechanical bowel preparation combined with oral antibiotics likely reduces anastomotic leakage compared to only mechanical bowel preparation in patients undergoing elective colorectal surgery. |

MBP-OA versus None

|

Low GRADE |

The evidence suggests mechanical bowel preparation combined with oral antibiotics reduces anastomotic leakage compared to no preparation in patients undergoing elective colorectal surgery. |

OA versus MBP

|

Low GRADE |

The evidence suggests that only oral antibiotics results in little to no difference of anastomotic leakage compared to only mechanical bowel preparation in patients undergoing elective colorectal surgery. |

OA versus None

|

Low GRADE |

The evidence suggests that only oral antibiotics may result in a slight reduction of anastomotic leakage compared with no preparation in patients undergoing elective colorectal surgery. |

MBP versus None

|

Low GRADE |

The evidence suggests that mechanical bowel preparation results in little to no difference in anastomotic leakage compared to no preparation in patients undergoing elective colorectal surgery. |

Mortality

MBP-OA versus OA

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of mechanical bowel preparation combined with oral antibiotics on mortality compared with only oral antibiotics in patients undergoing elective colorectal surgery. |

MBP-OA versus MBP

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of mechanical bowel preparation combined with oral antibiotics on mortality compared to only mechanical bowel preparation in patients undergoing elective colorectal surgery. |

MBP-OA versus None

|

Very Low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of mechanical bowel preparation combined with oral antibiotics on mortality compared to no bowel preparation in patients undergoing elective colorectal surgery. |

OA versus MBP

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of only oral antibiotics on mortality compared to mechanical bowel preparation in patients undergoing elective colorectal surgery. |

OA versus None

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of only oral antibiotics on mortality compared to no preparation in patients undergoing elective colorectal surgery. |

MBP versus None

|

Very Low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of mechanical bowel preparation on mortality compared to no preparation among patients undergoing elective colorectal surgery. |

Samenvatting literatuur

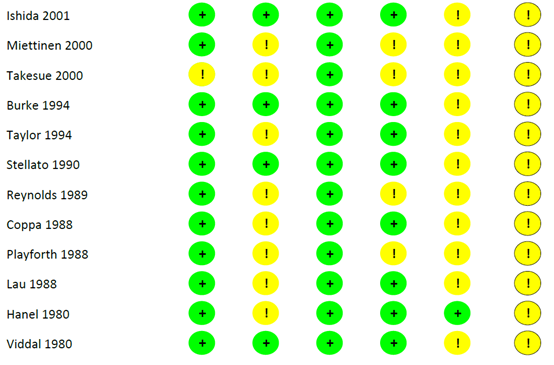

Description of studies

Forty-eight RCTs were included in the analysis of the literature, involving 13,611 patients. In total, 23 RCTs compared MBP-OA and MBP (Abis, 2019; Anjum, 2017; Espin-Basany, 2005; Coppa, 1988; Hata, 2016; Horie, 2007; Ikeda, 2016; Ishida, 2001; Kobayashi, 2007; Lau, 1988; Lewis, 2002; Oshima, 2013; Papp, 2021; Playforth, 1988; Reynolds, 1989; Roos, 2011; Rybakov, 2021; Sadahiro, 2013; Schardey, 2020; Stellato, 1990; Takesue, 2000; Taylor, 1994; Uchino, 2019), sixteen RCTs compared MBP and no preparation (Bertani, 2011; Bhat, 2016; Bhattacharjee, 2015; Bretagnol, 2010; Bucher, 2005; Burke, 1994; Contant, 2007; Fa-Si-Oen, 2005; Jung, 2007; Mai-Phan, 2019; Miettinen, 2000; Pena-Soria, 2008; Platell, 2006; Ram, 2005; Sasaki, 2012; Watanabe, 2010), five RCTs compared OA with no preparation (Arezzo, 2021; Espin-Basany, 2020; Hanel, 1980; Mulder, 2020; Viddal, 1980), three RCTs compared OA and MBP-OA (Suzuki, 2020; Zmora, 2003; Zmora, 2006) and one RCT compared MBP-OA and no preparation (Koskenvuo, 2019).

The following solutions were used for MBP, alone or in combination with others: polyethylene glycol solution (n=24), sodium picosulfate (n=10), sodium phosphate (n=8), magnesium citrate (n=5), bisacodyl (n=2), mannitol (n=1), and senna (n=1). Risk of bias was assessed with the Cochrane Risk of Bias-2 (RoB2) tool. The reported outcomes were surgical site infections.

The protocols regarding OA in the 32 studies varied greatly. Aminoglycosides (e.g., kanamycin, tobramycin and neomycin) or erythromycin were used in 27 out of 32 studies, of which in fourteen studies in combination with metronidazole. OA were usually started the day before surgery. Alternative protocols span from three days preoperative until postoperative day seven, ranging from two till four times a day.

For intravenous surgical antimicrobial prophylaxis, cephalosporins (1 to 2 grams) alone or in combination with metronidazole (0.5 to 1 grams), or flomoxef (a cephamycin, 1 gram) were often used. Redosing of SAP during surgery was performed in fifteen out of 48 studies, if surgery lasted longer than two to four hours depending on the half-life of antibiotics used.

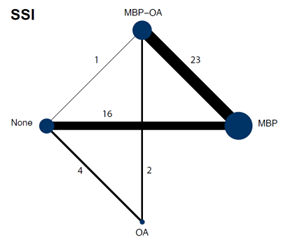

1. Surgical site infections (SSI)

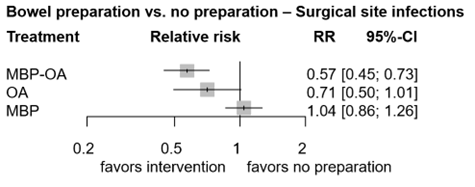

A network meta-analysis was carried out to investigate the effect of the different treatment modalities on SSI. In total, 47 RCTs contributed to the overall NMA. A network graph, including all studies is presented in figure 1. The forest plot of the results of the different preparation methods compared to no preparation is shown in figure 2.

Figure 1. Network graph of all studies for outcome surgical site infections in network meta-analysis (Jalalzadeh, 2022)

Figure 2. Forest plot shows the pooled estimates from the included studies, comparing different bowel preparation methods with no preparation for outcome total SSI. (Jalalzadeh, 2022)

1.1 MBP-OA versus OA

In total, two studies (n= 631) contributed with a direct comparison to the NMA investigating the effect of MBP-OA versus OA on SSI (Suzuki, 2020; Zmora, 2003). The overall network RR was 0.81 (95% CI 0.54, 1.19), a non-significant nor clinically relevant difference between groups.

1.2 MBP-OA versus MBP

In total, twenty-three studies (n=6197) contributed with a direct comparison to the NMA investigating the effect of MBP-OA versus MBP on SSI (Abis, 2019; Anjum, 2017; Coppa, 1988; Espin-Basany, 2005; Hata, 2016; Horie, 2007; Ikeda, 2016; Ishida, 2001; Kobayashi, 2007; Lau, 1988; Lewis, 2002; Oshima, 2013; Papp, 2021; Playforth, 1988; Reynolds, 1989; Roos, 2011; Rybakov, 2021; Sadahiro, 2013; Schardey, 2020; Stellato, 1990; Takesue, 2000; Taylor, 1994; Uchino, 2019). The overall network RR was 0.55 (95% CI 0.46, 0.65), a significant and clinically relevant difference favoring MBP-OA.

1.3 MBP-OA versus no preparation

In total, one study (n=396) contributed with a direct comparison to the NMA investigating the effect of MBP-OA versus no preparation on SSI (Koskenvuo, 2019). The overall network RR was 0.57 (95% CI 0.45, 0.73), with a corresponding number needed to treat of 13, which is a significant and clinically relevant difference favoring MBP-OA.

Clarification of the number needed to treat calculation

CER* = 561 / 3229 = 0.174

TER** = CER x RR = 0.174 x 0.57 = 0.099

ARR*** = CER – TER = 0.174 – 0.099 = 0.075

NNT = 1 / ARR = 1 / 0.075 = 13

*CER (event rate in control group) = 561 / 3229 = 0.174

**TER (event rate in treatment group)

***ARR (absolute risk reduction)

1.4 OA versus MBP

There were no studies that contributed with a direct comparison to the NMA investigating the effect of OA versus MBP on SSI. Therefore, indirect estimates of the comparison of OA versus MBP in the NMA were reported. The overall network RR was 0.68 (95% CI 0.46, 0.99), a significant and clinically relevant difference favoring OA.

1.5 OA versus no preparation

In total, five studies (n=927) contributed with a direct comparison to the NMA investigating the effect of OA versus no preparation on SSI (Mulder, 2020; Arezzo, 2021; Espin-Basany, 2020; Hanel, 1980; Viddal, 1980). The overall network RR was 0.71 (95% CI 0.50, 1.01), with a corresponding number needed to treat of 18, which is a non-significant but clinically relevant difference favoring OA.

Clarification of the number needed to treat calculation

CER* = 561 / 3229 = 0.174

TER** = CER x RR = 0.174 x 0.68 = 0.118

ARR*** = CER – TER = 0.174 – 0.118 = 0.056

NNT = 1 / ARR = 1 / 0.056 = 18

*CER (event rate in control group) = 561 / 3229 = 0.174

**TER (event rate in treatment group)

***ARR (absolute risk reduction)

1.6 MPB versus no preparation

In total, sixteen studies (n=5211) contributed with a direct comparison to the NMA investigating the effect of MPB versus no preparation on SSI (Bertani, 2011; Bhat, 2016; Bhattacharjee, 2015; Bretagnol, 2010; Bucher, 2005; Burke, 1994; Contant, 2007; Fa-Si-Oen, 2005; Jung, 2007; Mai-Phan, 2019; Miettinen, 2000; Pena-Soria, 2008; Platell, 2006; Ram, 2005; Sasaki, 2012; Watanabe, 2010). The overall network RR was 1.04 (95% CI 0.86, 1.26), which is a non-significant nor clinically relevant difference between groups; corresponding number needed to treat is negative and number needed to harm is 111.

Clarification of the number needed to treat calculation

CER* = 561 / 3229 = 0.174

TER** = CER x RR = 0.174 x 1.05 = 0.183

ARR*** = CER – TER = 0.174 – 0.183 = -0.009

NNT = 1 / ARR = 1 / -0.009 = negative

ARI**** = TER – CER = 0.183 – 0.174 = 0.009

NNH = 1 / ARI = 1 / 0.009 = 111

*CER (event rate in control group) = 561 / 3229 = 0.174

**TER (event rate in treatment group)

***ARR (absolute risk reduction)

****ARI (absolute risk difference)

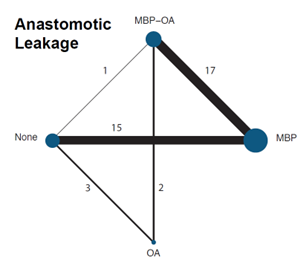

2. Anastomotic leakage

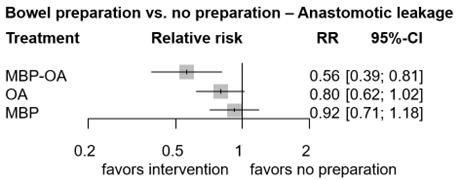

A network meta-analysis was carried out to investigate the effect of the different treatment modalities on anastomotic leakage. In total, 38 RCTs contributed to the overall NMA. A network graph, including all studies is presented in figure 3. The forest plot of the results of the different preparation methods compared to no preparation is shown in figure 4.

Figure 3. Network graph of all studies for outcome anastomotic leakage in network meta-analysis (Jalalzadeh, 2022)

Figure 4. Forest plot shows the pooled estimates from the included studies, comparing different bowel preparation methods with no preparation for outcome anastomotic leakage. (Jalalzadeh, 2022)

2.1 MBP-OA versus OA

In total, two studies (n= 631) contributed with a direct comparison to the NMA investigating the effect of MBP-OA versus OA on AL (Suzuki, 2020; Zmora, 2003). The overall network RR was 0.70 (95% CI 0.46, 1.08), a non-significant but clinically relevant difference favoring MBP-OA.

2.2 MBP-OA versus MBP

In total, eighteen studies (n=4585) contributed with a direct comparison to the NMA investigating the effect of MBP-OA versus MBP on AL (Abis, 2019; Anjum, 2017; Coppa, 1988; Espin-Basany, 2005; Hata, 2016; Horie, 2007; Ikeda, 2016; Ishida, 2001; Lau, 1988; Papp, 2021; Playforth, 1988; Roos, 2011; Rybakov, 2020; Sadahiro, 2014; Schardey, 2020; Stellato, 1990; Takesue, 2000; Taylor, 1994;). Espin-Basany (2005) reported zero AL in both arms and was thus excluded from the NMA, leaving 17 studies in the final NMA (figure 2).

Node splitting the results showed this comparison had significant inconsistencies between direct and indirect evidence. The direct evidence has higher quality of evidence, thus we valued the direct comparison over the indirect comparison (and use this for our conclusion).

The overall direct RR was 0.55 (95% CI 0.40, 0.76), a significant and clinically relevant difference favoring MBP-OA.

2.3 MBP-OA versus no preparation

In total, one study (n=396) contributed with a direct comparison to the NMA investigating the effect of MBP-OA versus no preparation on AL (Koskenvuo, 2019). The overall network RR was 0.56 (95% CI 0.39, 0.81), a significant and clinically relevant difference favoring MBP-OA.

2.4 OA versus MBP

There were no studies that contributed with a direct comparison to the NMA investigating the effect of OA versus MBP on AL. Therefore, only the indirect estimates of the comparison between OA and MBP was reported. The overall network RR was 0.87 (95% CI 0.61, 1.23), a non-significant nor clinically relevant difference between groups.

2.5 OA versus no preparation

In total, four studies (n=860) contributed with a direct comparison to the NMA investigating the effect of OA versus no preparation on AL (Arezzo, 2021; Espin-Basany, 2020; Mulder, 2020; Vidal, 1980). Vidal (1980) reported zero AL in both arms and was thus excluded from the NMA, leaving three studies in the final NMA (figure 2). The overall network RR was 0.80 (95% CI 0.62, 1.02), a non-significant but clinically relevant difference favoring OA.

2.6 MPB versus no preparation

In total, sixteen studies (n=5211) contributed with a direct comparison to the NMA investigating the effect of MBP versus no preparation on AL (Bertani, 2011; Bhat, 2016; Bhattacharjee, 2015; Bretagnol, 2010; Bucher, 2005; Burke, 1994; Contant, 2007; Fa-Si-Oen, 2005; Jung, 2007; Mai-Phan, 2019; Miettinen, 2000; Pena-Soria, 2008; Platell, 2006; Ram, 2005; Sasaki, 2012; Watanabe, 2010). Watanabe (2010) reported zero AL in both arms and was thus excluded from the NMA, leaving 15 studies in the final NMA (figure 2).

Node splitting the results showed this comparison had significant inconsistencies between direct and indirect evidence. The direct evidence has higher quality of evidence, thus we valued the direct comparison over the indirect comparison (and use this for our conclusion).

The overall direct RR was 0.85 (95% CI 0.71, 1.18), a non-significant nor clinically relevant difference.

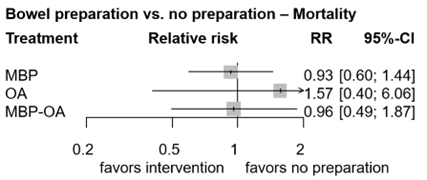

3. Mortality

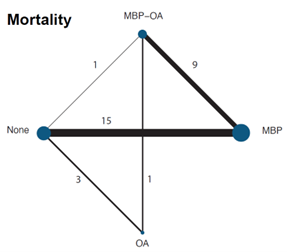

A network meta-analysis was carried out to investigate the effect of the different treatment modalities on mortality. In total, 20 RCTs contributed to the overall NMA. A network graph, including all studies is presented in figure 3.

Figure 5. Network graph of all studies for outcome mortality in network meta-analysis (Jalalzadeh, 2022)

Figure 6. Forest plot shows the pooled estimates from the included studies, comparing different bowel preparation methods with no preparation for outcome mortality. (Jalalzadeh, 2022)

3.1 MBP-OA versus OA

In total, two studies (n= 631) contributed with a direct comparison to the NMA investigating the effect of MBP-OA versus OA on mortality (Suzuki, 2020; Zmora, 2003). Suzuki (2020) reported zero deaths in both arms and was thus excluded from the NMA, leaving one study in the final NMA (figure 3). The overall network RR was 0.61 (95% CI 0.17, 2.26), a non-significant nor clinically relevant difference between groups.

3.2 MBP-OA versus MBP

In total, eleven studies (n=3062) contributed with a direct comparison to the NMA investigating the effect of MBP-OA versus MBP on mortality (Abis, 2019; Coppa, 1988; Horie, 2007; Ikeda, 2016; Lewis, 2002; Papp, 2021; Playforth, 1988; Roos, 2011; Schardey, 2020; Stellato, 1990; Taylor, 1994). Ikeda (2016) and Horie (2007) reported zero deaths in both arms and were excluded from the NMA, leaving 9 studies in the final NMA (figure 3). The overall network RR was 0.97 (95% CI 0.58, 1.62), a non-significant nor clinically relevant difference between groups.

3.3 MBP-OA versus no preparation

In total, one study (n=396) contributed with a direct comparison to the NMA investigating the effect of MBP-OA versus no preparation on mortality (Koskenvuo, 2019). The overall network RR was 0.96 (95% CI 0.49, 1.87), a non-significant nor clinically relevant difference between groups.

3.4 OA versus MBP

There were no studies that contributed with a direct comparison to the NMA investigating the effect of OA versus MBP on mortality. Therefore, indirect estimates of the comparison of OA versus MBP in the NMA were reported. The overall network RR was 1.69 (95% CI 0.44, 6.25), a non-significant nor clinically relevant difference between groups.

3.5 OA versus no preparation

In total, two studies (n=282) contributed with a direct comparison to the NMA investigating the effect of OA versus no preparation on mortality (Arezzo, 2021; Mulder, 2020). Mulder (2020) reported zero deaths in both arms and was thus excluded from the NMA, leaving one study in the final NMA (figure 3). The overall network RR was 1.57 (95% CI 0.40, 6.06), a non-significant nor clinically relevant difference between groups.

3.6 MPB versus no preparation

In total, fourteen studies (n=5090) contributed with a direct comparison to the NMA investigating the effect of MBP versus no preparation on mortality (Bhat, 2016; Bertani, 2011; Bhattacharjee, 2015; Bretagnol, 2010; Bucher, 2005; Burke, 1994; Contant, 2007; Fa-Si-Oen, 2005; Jung, 2007; Mai-Phan, 2019; Miettinen, 2000; Pena-Soria, 2008; Platell, 2006; Ram, 2005). Mai-Phan (2019), Bhat (2016), Bertani (2011), Bucher (2005), Fa-Si-Oen (2005) and Miettienen (2000) reported zero events in both arms, leaving eight studies in the final NMA. The overall RR was 0.93 (95% CI 0.60, 1.44), a non-significant nor clinically relevant difference between groups.

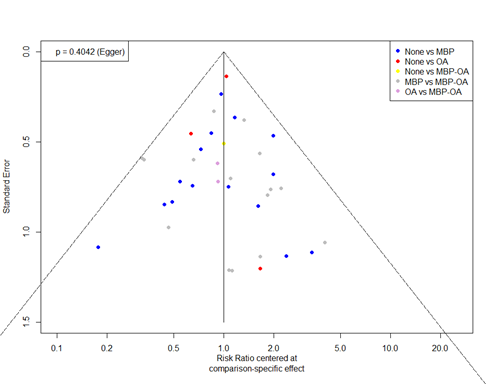

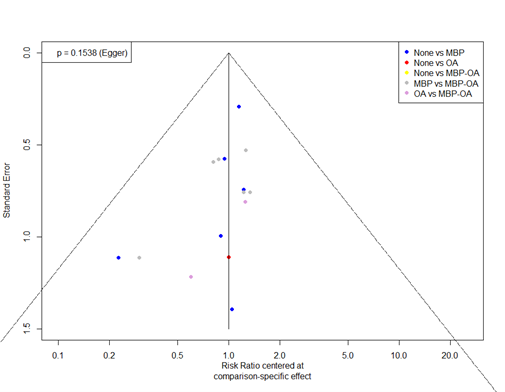

Level of evidence of the literature

The GRADE approach for rating the certainty of estimates of treatment effects was used. Since all included studies are randomized controlled trials, the rating for the GRADE starts high for all comparisons. Each comparison can be downgraded due to one of the following reasons: risk of bias: the quality assessment of the individual studies is presented in the risk of bias tables; inconsistency: similarity of point estimates, extent of overlap of confidence intervals, and statistical criteria including tests of heterogeneity and I; imprecision: For point estimates with 95%CIs that crosses the null-effect threshold and boundaries for clinical decision making we downgraded with one or two dimensions. If the boundaries are not crossed, we did not downgrade. Publication bias: The comparison-adjusted funnel plot showed no sign of small-study effects (see funnel plot diagrams).

If only direct or indirect evidence is available for a given comparison, the network quality rating will be based on that estimate. When, for a particular comparison, both direct and indirect evidence are available, we used the highest of the two quality ratings as the quality rating for the NMA estimate. The quality of the network estimate can be upgraded if precision is greater than direct or indirect estimates.

Table 2. Level of evidence per comparison for surgical site infection, anastomotic leakage, and mortality.

|

|

Reasons for downgrading |

||

|

Direct evidence |

Indirect evidence |

Network meta-analysis |

|

|

Surgical site infections |

|

|

|

|

MBP-OA vs. OA |

-2 imprecision -1 risk of bias |

-2 imprecision -1 risk of bias |

-2 imprecision -1 risk of bias |

|

MBP-OA vs. MBP |

-1 risk of bias |

-1 imprecision -1 risk of bias |

-1 risk of bias |

|

MBP-OA vs. None

|

-2 imprecision -1 risk of bias |

-1 risk of bias |

-1 risk of bias |

|

OA vs. MBP |

N.a.

|

-1 imprecision -1 risk of bias |

-1 imprecision -1 risk of bias |

|

OA vs. None

|

-1 imprecision -1 risk of bias |

-1 imprecision -1 risk of bias |

-1 imprecision -1 risk of bias |

|

MBP vs. None

|

-1 imprecision -1 risk of bias |

-2 imprecision -1 risk of bias |

-1 imprecision -1 risk of bias |

|

Anastomotic leakage |

|

|

|

|

MBP-OA vs. OA |

-2 imprecision -1 risk of bias |

-1 imprecision -1 risk of bias |

-1 imprecision -1 risk of bias |

|

MBP-OA vs. MBP

|

-1 risk of bias |

-2 imprecision -1 risk of bias |

-1 risk of bias |

|

MBP-OA vs. None

|

-2 imprecision -1 risk of bias |

-1 imprecision -1 risk of bias |

-1 imprecision -1 risk of bias |

|

OA vs. MBP |

N.a

|

-1 imprecision -1 risk of bias |

-1 imprecision -1 risk of bias |

|

OA vs. None

|

-1 imprecision -1 risk of bias |

-1 imprecision -1 risk of bias |

-1 imprecision -1 risk of bias |

|

MBP vs. None

|

-1 imprecision -1 risk of bias |

-1 imprecision -1 risk of bias |

-1 imprecision -1 risk of bias |

|

Mortality |

|

|

|

|

MBP-OA vs. OA

|

-2 imprecision -1 risk of bias |

-2 imprecision -1 risk of bias |

-2 imprecision -1 risk of bias |

|

MBP-OA vs. MBP

|

-2 imprecision -1 risk of bias |

-2 imprecision -1 risk of bias |

-2 imprecision -1 risk of bias |

|

MBP-OA vs. None

|

N.a. |

-2 imprecision -1 risk of bias |

-2 imprecision -1 risk of bias |

|

OA vs. MBP

|

-2 imprecision -1 risk of bias |

-2 imprecision -1 risk of bias |

-2 imprecision -1 risk of bias |

|

OA vs. None

|

-2 imprecision -1 risk of bias |

-2 imprecision -1 risk of bias |

-2 imprecision -1 risk of bias |

|

MBP vs. None

|

-2 imprecision -1 risk of bias |

-2 imprecision -1 risk of bias |

-2 imprecision -1 risk of bias |

Table 2. Relative risk plus the level of evidence per comparison for surgical site infection, anastomotic leakage, and mortality.

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question:

P: Adults undergoing elective colorectal surgery.

I: Mechanical bowel preparation (MBP), oral antibiotics alone (OA), a combination of

oral antibiotics and mechanical bowel preparation (MBP-OA).

C: No bowel preparation, MBP, OA, or MBP-OA.

O: Surgical site infections (SSI), anastomotic leakage, mortality.

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered the occurrence of surgical site infections as a critical outcome measure for decision making; and anastomotic leakage and mortality as important outcome measures for clinical decision making.

The working group defined a threshold of 10% for continuous outcomes and a relative risk (RR) for dichotomous outcomes of <0.80 and >1.25 as a minimal clinically (patient) important difference.

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Pubmed, Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms until 10-08-2021. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 3040 hits, eight additional studies were found through forward and backward citation tracking. Studies were selected based on the following criteria: systematic reviews and RCTs on the question of the effect of MBP with oral antibiotics, MBP alone, and oral antibiotics alone. One hundred twenty-three studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, 75 studies were excluded (see the exclusion table with reasons for exclusion), and 48 studies were included.

Results

Forty-eight studies were included in the final analysis. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- Abis GSA, Stockmann HBAC, Bonjer HJ, et al. Randomized clinical trial of selective decontamination of the digestive tract in elective colorectal cancer surgery (SELECT trial). Br J Surg. 03 2019;106(4):355-363. doi:10.1002/bjs.11117

- Anjum N, Ren J, Wang G, et al. A Randomized Control Trial of Preoperative Oral Antibiotics as Adjunct Therapy to Systemic Antibiotics for Preventing Surgical Site Infection in Clean Contaminated, Contaminated, and Dirty Type of Colorectal Surgeries. Dis Colon Rectum. Dec 2017;60(12):1291-1298. doi:10.1097/DCR.0000000000000927

- Arezzo A, Mistrangelo M, Bonino MA, et al. Oral neomycin and bacitracin are effective in preventing surgical site infections in elective colorectal surgery: a multicentre, randomized, parallel, single-blinded trial (COLORAL-1). Updates Surg. Jun 20 2021;doi:10.1007/s13304-021-01112-5

- Bertani E, Chiappa A, Biffi R, et al. Comparison of oral polyethylene glycol plus a large volume glycerine enema with a large volume glycerine enema alone in patients undergoing colorectal surgery for malignancy: a randomized clinical trial. Colorectal Dis. Oct 2011;13(10):e327-34. doi:10.1111/j.1463-1318.2011.02689.x

- Bhat AH, Parray FQ, Chowdri NA, et al. Mechanical bowel preparation versus no preparation in elective colorectal surgery: a prospective randomized study. International Journal of Surgery Open. 2016;2:26-30.

- Bhattacharjee PK, Chakraborty S. An Open-Label Prospective Randomized Controlled Trial of Mechanical Bowel Preparation vs Nonmechanical Bowel Preparation in Elective Colorectal Surgery: Personal Experience. Indian J Surg. Dec 2015;77(Suppl 3):1233-6. doi:10.1007/s12262-015-1262-3

- Bretagnol F, Panis Y, Rullier E, et al. Rectal cancer surgery with or without bowel preparation: The French GRECCAR III multicenter single-blinded randomized trial. Ann Surg. Nov 2010;252(5):863-8. doi:10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181fd8ea9

- Bucher P, Gervaz P, Soravia C, Mermillod B, Erne M, Morel P. Randomized clinical trial of mechanical bowel preparation versus no preparation before elective left-sided colorectal surgery. Br J Surg. Apr 2005;92(4):409-14. doi:10.1002/bjs.4900

- Burke P, Mealy K, Gillen P, Joyce W, Traynor O, Hyland J. Requirement for bowel preparation in colorectal surgery. Br J Surg. Jun 1994;81(6):907-10. doi:10.1002/bjs.1800810639

- Coppa GF, Eng K. Factors involved in antibiotic selection in elective colon and rectal surgery. Surgery. Nov 1988;104(5):853-8.

- Contant CM, Hop WC, van't Sant HP, et al. Mechanical bowel preparation for elective colorectal surgery: a multicentre randomised trial. Lancet. Dec 2007;370(9605):2112-7. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61905-9

- Espin Basany E, Solís-Peña A, Pellino G, et al. Preoperative oral antibiotics and surgical-site infections in colon surgery (ORALEV): a multicentre, single-blind, pragmatic, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 08 2020;5(8):729-738. doi:10.1016/S2468-1253(20)30075-3

- Fa-Si-Oen P, Roumen R, Buitenweg J, et al. Mechanical bowel preparation or not? Outcome of a multicenter, randomized trial in elective open colon surgery. Dis Colon Rectum. Aug 2005;48(8):1509-16. doi:10.1007/s10350-005-0068-y

- Güenaga KF, Matos D, Wille‐Jørgensen P. Mechanical bowel preparation for elective colorectal surgery. Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2011(9).

- Hanel KC, King DW, McAllister ET, Reiss-Levy E. Single-dose parenteral antibiotics as prophylaxis against wound infections in colonic operations. Dis Colon Rectum. Mar 1980;23(2):98-101. doi:10.1007/BF02587603

- Hata H, Yamaguchi T, Hasegawa S, et al. Oral and Parenteral Versus Parenteral Antibiotic Prophylaxis in Elective Laparoscopic Colorectal Surgery (JMTO PREV 07-01): A Phase 3, Multicenter, Open-label, Randomized Trial. Ann Surg. Jun 2016;263(6):1085-91. doi:10.1097/SLA.0000000000001581

- Horie T. Randomized controlled trial on the necessity of chemical cleaning as preoperative preparation for Colorectal Cancer Surgery. 2007;

- Ikeda A, Konishi T, Ueno M, et al. Randomized clinical trial of oral and intravenous versus intravenous antibiotic prophylaxis for laparoscopic colorectal resection. Br J Surg. Nov 2016;103(12):1608-1615. doi:10.1002/bjs.10281

- Ishida H, Yokoyama M, Nakada H, Inokuma S, Hashimoto D. Impact of oral antimicrobial prophylaxis on surgical site infection and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection after elective colorectal surgery. Results of a prospective randomized trial. Surgery today. 2001;31(11):979-983.

- Jalalzadeh H, Wolfhagen N, Harmsen WJ, Griekspoor M, Boermeester MA. A Network Meta-Analysis and GRADE Assessment of the Effect of Preoperative Oral Antibiotics with and Without Mechanical Bowel Preparation on Surgical Site Infection Rate in Colorectal Surgery. Annals of Surgery Open. 2022 Sep 1;3(3):e175.

- Kobayashi M, Mohri Y, Tonouchi H, et al. Randomized clinical trial comparing intravenous antimicrobial prophylaxis alone with oral and intravenous antimicrobial prophylaxis for the prevention of a surgical site infection in colorectal cancer surgery. Surg Today. 2007;37(5):383-8. doi:10.1007/s00595-006-3410-7

- Koskenvuo L, Lehtonen T, Koskensalo S, et al. Mechanical and oral antibiotic bowel preparation versus no bowel preparation for elective colectomy (MOBILE): a multicentre, randomised, parallel, single-blinded trial. Lancet. 09 2019;394(10201):840-848. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31269-3

- Lewis RT. Oral versus systemic antibiotic prophylaxis in elective colon surgery: a randomized study and meta-analysis send a message from the 1990s. Can J Surg. Jun 2002;45(3):173-80.

- Mai-Phan AT, Nguyen H, Nguyen TT, Nguyen DA, Thai TT. Randomized controlled trial of mechanical bowel preparation for laparoscopy-assisted colectomy. Asian J Endosc Surg. Oct 2019;12(4):408-411. doi:10.1111/ases.12671

- Miettinen RP, Laitinen ST, Mäkelä JT, Pääkkönen ME. Bowel preparation with oral polyethylene glycol electrolyte solution vs. no preparation in elective open colorectal surgery: prospective, randomized study. Dis Colon Rectum. May 2000;43(5):669-75; discussion 675-7. doi:10.1007/BF02235585

- Mulder T, Crolla RMPH, Kluytmans-van den Bergh MFQ, et al. Preoperative Oral Antibiotic Prophylaxis Reduces Surgical Site Infections After Elective Colorectal Surgery: Results From a Before-After Study. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;69(1):93-99. doi:10.1093/cid/ciy839

- Mulder T, Kluytmans-van den Bergh M, Vlaminckx B, et al. Prevention of severe infectious complications after colorectal surgery using oral non-absorbable antimicrobial prophylaxis: results of a multicenter randomized placebo-controlled clinical trial. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. Jun 15 2020;9(1):84. doi:10.1186/s13756-020-00745-2

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). 2019 exceptional surveillance of surgical site infections: prevention and treatment (NICE guideline NG125)

- Lau WY, Chu KW, Poon GP, Ho KK. Prophylactic antibiotics in elective colorectal surgery. Br J Surg. Aug 1988;75(8):782-5. doi:10.1002/bjs.1800750819

- O'Hara LM, Thom KA, Preas MA. Update to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee Guideline for the Prevention of Surgical Site Infection (2017): A summary, review, and strategies for implementation. Am J Infect Control. 2018;46(6):602-609. doi:10.1016/j.ajic.2018.01.018

- Oshima T, Takesue Y, Ikeuchi H, et al. Preoperative oral antibiotics and intravenous antimicrobial prophylaxis reduce the incidence of surgical site infections in patients with ulcerative colitis undergoing IPAA. Dis Colon Rectum. Oct 2013;56(10):1149-55. doi:10.1097/DCR.0b013e31829f71a0

- Papp G, Saftics G, Szabó BE, et al. Systemic versus Oral and Systemic Antibiotic Prophylaxis (SOAP) study in colorectal surgery: prospective randomized multicentre trial. Br J Surg. Apr 2021;108(3):271-276. doi:10.1093/bjs/znaa131

- Pena-Soria MJ, Mayol JM, Anula R, Arbeo-Escolar A, Fernandez-Represa JA. Single-blinded randomized trial of mechanical bowel preparation for colon surgery with primary intraperitoneal anastomosis. J Gastrointest Surg. Dec 2008;12(12):2103-8; discussion 2108-9. doi:10.1007/s11605-008-0706-5

- Platell C, Barwood N, Makin G. Randomized clinical trial of bowel preparation with a single phosphate enema or polyethylene glycol before elective colorectal surgery. Br J Surg. Apr 2006;93(4):427-33. doi:10.1002/bjs.5274

- Playforth MJ, Smith GM, Evans M, Pollock AV. Antimicrobial bowel preparation. Oral, parenteral, or both? Dis Colon Rectum. Feb 1988;31(2):90-3. doi:10.1007/BF02562635

- Ram E, Sherman Y, Weil R, Vishne T, Kravarusic D, Dreznik Z. Is mechanical bowel preparation mandatory for elective colon surgery? A prospective randomized study. Arch Surg. Mar 2005;140(3):285-8. doi:10.1001/archsurg.140.3.285

- Reynolds J, Jones J, Evans D, Hardcastle J. Do preoperative oral antibiotics influence sepsis rates following elective colorectal surgery in patients receiving perioperative intravenous prophylaxis. Surg Res Commun. 1989;7:71-77.

- Rollins KE, Javanmard-Emamghissi H, Acheson AG, Lobo DN. The Role of Oral Antibiotic Preparation in Elective Colorectal Surgery: A Meta-analysis. Ann Surg. 2019;270(1):43-58. doi:10.1097/SLA.0000000000003145

- Roos D, Dijksman LM, Oudemans-van Straaten HM, de Wit LT, Gouma DJ, Gerhards MF. Randomized clinical trial of perioperative selective decontamination of the digestive tract versus placebo in elective gastrointestinal surgery. Br J Surg. Oct 2011;98(10):1365-72. doi:10.1002/bjs.7631

- Rybakov E, Nagudov M, Sukhina M, Shelygin Y. Impact of oral antibiotic prophylaxis on surgical site infection after rectal surgery: results of randomized trial. Int J Colorectal Dis. Feb 2021;36(2):323-330. doi:10.1007/s00384-020-03746-0

- Sadahiro S, Suzuki T, Tanaka A, et al. Comparison between oral antibiotics and probiotics as bowel preparation for elective colon cancer surgery to prevent infection: prospective randomized trial. Surgery. Mar 2014;155(3):493-503. doi:10.1016/j.surg.2013.06.002

- Sasaki J, Matsumoto S, Kan H, et al. Objective assessment of postoperative gastrointestinal motility in elective colonic resection using a radiopaque marker provides an evidence for the abandonment of preoperative mechanical bowel preparation. J Nippon Med Sch. 2012;79(4):259-66. doi:10.1272/jnms.79.259Schardey HM,

- Stellato TA, Danziger LH, Gordon N, et al. Antibiotics in elective colon surgery. A randomized trial of oral, systemic, and oral/systemic antibiotics for prophylaxis. Am Surg. Apr 1990;56(4):251-4.

- Suzuki T, Sadahiro S, Tanaka A, et al. Usefulness of Preoperative Mechanical Bowel Preparation in Patients with Colon Cancer who Undergo Elective Surgery: A Prospective Randomized Trial Using Oral Antibiotics. Dig Surg. 2020;37(3):192-198. doi:10.1159/000500020

- Takesue Y, Yokoyama T, Akagi S, et al. A brief course of colon preparation with oral antibiotics. Surg Today. 2000;30(2):112-6. doi:10.1007/PL00010059

- Taylor EW, Lindsay G. Selective decontamination of the colon before elective colorectal surgery. West of Scotland Surgical Infection Study Group. World J Surg. 1994 Nov-Dec 1994;18(6):926-31; discussion 931-2. doi:10.1007/BF00299111

- Toh JWT, Phan K, Hitos K, et al. Association of Mechanical Bowel Preparation and Oral Antibiotics Before Elective Colorectal Surgery With Surgical Site Infection: A Network Meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1(6):e183226. Published 2018 Oct 5. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.3226

- Uchino M, Ikeuchi H, Bando T, et al. Efficacy of Preoperative Oral Antibiotic Prophylaxis for the Prevention of Surgical Site Infections in Patients With Crohn Disease: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Ann Surg. 03 2019;269(3):420-426. doi:10.1097/SLA.0000000000002567

- Viddal KO, Semb LS. Tinidazole and doxycycline compared to doxycycline alone as prophylactic antimicrobial agents in elective colorectal surgery. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1980;59:21-4.

- Watanabe M, Murakami M, Nakao K, Asahara T, Nomoto K, Tsunoda A. Randomized clinical trial of the influence of mechanical bowel preparation on faecal microflora in patients undergoing colonic cancer resection. Br J Surg. Dec 2010;97(12):1791-7. doi:10.1002/bjs.7253

- Woodfield JC, Clifford K, Schmidt B, Turner GA, Amer MA, McCall JL. Strategies for Antibiotic Administration for Bowel Preparation Among Patients Undergoing Elective Colorectal Surgery: A Network Meta-analysis. JAMA Surg. 2022;157(1):34-41. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2021.5251

- World Health Organization (WHO). Global guidelines for the prevention of surgical site infection, second edition. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- Zmora O, Mahajna A, Bar-Zakai B, et al. Colon and rectal surgery without mechanical bowel preparation: a randomized prospective trial. Ann Surg. Mar 2003;237(3):363-7. doi:10.1097/01.SLA.0000055222.90581.59

Evidence tabellen

Evidence tables

|

MBP vs MBP-OA: 23 RCTs |

|||||||||

|

Study |

SSI*/ N total |

N – T1 |

N - T2 |

Type of surgery |

Open / laparoscopic |

MBP regimen |

OA regimen |

Preoperative IV SAP and intraoperateive redosing |

|

|

Papp 2021 1 |

52 / 529 |

276 |

253 |

Colorectal surgery with anastomosis (excl loop CC) |

Mixed |

40ml castor oil + 20ml paraffin day before surgery + enema day before and morning of surgery |

Metronidazole 500mg + neomycin sulphate 1g day before surgery (13h, 15h, 19h) |

Ceftriaxone 2g + metronidazole 500mg, Redose > 4hrs and/or blood loss > 1500ml |

|

|

Rybakov 2020 2 |

17 / 116 |

57 |

59 |

(L)AR, APR, intersphincteric resection |

Mixed |

PEG day before surgery (16h) |

Erythromycin 500mg + metronidazole 500mg day before surgery (17h, 20h, 23h) |

Ceftriaxone 1000mg |

|

|

Schardey 2020 3 |

15 / 80 |

40 |

40 |

(L)AR |

Mixed |

PEG + electrolytes 3-6L day before surgery |

Polymyxin B 100 mg + tobramycin 80 mg + vancomycin 125 mg, day before surgery till day 7, 4 times daily |

Decided by surgeon |

|

|

Abis 2019 4 |

65 / 455 |

227 |

228 |

LAR, LH, RH, TH, SR, other |

Mixed |

Unknown kind * Only patients undergoing left-sided colonic, sigmoid and LAR |

Amphotericin B 500 mg + 5 colistin sulphate 100 mg + tobramycin 80 mg, 3 days before till minimum of 3 days after surgery, 4 times daily |

Cefazolin 1g + metronidazole 500 mg, Redose > 4hrs |

|

|

Uchino 2019 5 |

63 / 325 |

162 |

163 |

Intestinal resection (Small bowel resections included |

Open |

Sodium picosulphate hydrate 20ml 0.75% |

Kanamycin 500mg + metronidazole 500mg day before surgery (14h, 15, 21h) |

Flomoxef Redose every 3 hrs |

|

|

Anjum 2017 6 |

34 / 184 |

93 |

91 |

LAR, LH, RH |

Mixed |

Sodium phosphate 133ml twice day before surgery |

Metronidazole 400 mg + levofloxacin 200 mg day before surgery (15h, 19h, 23h) |

Cephalosporin (2nd gen) + metronidazole, Redose every 3 hrs |

|

|

Hata 2016 7 |

58 / 579 |

290 |

289 |

AR, APR, colectomy |

laparoscopic |

Sodium picosulphate 75mg + magnesium citrate 34 g + water 180ml, day before surgery |

Metronidazole 750mg + kanamycin 1g 13hrs and 9hrs before surgery |

Cefmetazole 1g, Redose every 3 hrs |

|

|

Ikeda 2016 8 |

51 / 511 |

256 |

255 |

AR, APR, colonic surgery |

laparoscopic |

Magnesium citrate + sodium picosulphate day before surgery (8h + 11h) |

Metronidazole 750mg + kanamycin 1g day before surgery (15h, 21h) |

Cefmetazole, Redose >3hrs |

|

|

Sadahiro 2014 9 |

38 / 194 |

99 |

95 |

Resection of colorectal tumor |

Mixed |

Sodium picosulphate 10ml 2 days before surgery + PEG 2.000ml day before surgery (morning) |

Kanamycin 500mg + metronidazole 500mg day before surgery (13h, 14h, 23h) |

Flomoxef 1g, Redsose >3hrs |

|

|

Oshima 2013 10 |

28 / 195 |

98 |

97 |

Proctocolectomy |

Open |

Magnesium citrate solution 1.8L day before surgery (11h) |

Kanamycin 500mg + metronidazole 500mg day before surgery (14h, 15h, 21h) |

Flomoxef 1g, Redose >3hrs |

|

|

Roos 2011 11 |

60 / 289 |

146 |

143 |

LH, RH, TH, (L)AR, ICR, SR, PC, CC, hepatopan-creatobiliary surgery, esophageal /gastric resection, other |

Mixed |

PEG + electrolytes or sodium picosulphate |

Polymixin B sulphate 100mg + tobramycin 80mg + amphotericin B 500mg |

Cefuroxime 1.5g + metronidazole 500mg |

|

|

Horie 2007 12 |

26 / 91 |

45 |

46 |

Resection of colorectal tumor |

Open |

PEG 2L 16hrs before surgery |

Kanamycin 1500mg daily start 3 days before surgery |

Cefotiam hydrochloride |

|

|

Kobayashi 2007 13 |

43 / 484 |

242 |

242 |

AR, APR, anoabdomino -rectal resection, Hartmann’s procedure |

N/A |

PEG 2L day before surgery (10h) |

Kanamycin 1g + erythromycin 400mg day before surgery (14h, 15h, 23 h) |

Cefmetazole 1g after, Redose >3hrs |

|

|

Espin Basany 2005 14 |

32 / 300 |

100 |

200 |

AR, APR, SR, segmental colon resection, TME-coloanal |

Open |

Sodium phosphate oral solution 45ml diluted in 90 ml of water day before surgery (11h, 17h) |

Neomycin 1g + metronidazole 1g day before surgery (15h, 19h, 23h) OR Neomycin 1g + metronidazole 1g day before surgery (15h) |

Cefoxitin 1g |

|

|

Lewis 2002 15 |

27 / 208 |

104 |

106 |

AR, APR, LH, RH, TH |

N/A |

Sodium phosphate until clear rectal effluent. If required, additional saline enemas day before surgery (18h) |

Neomycin 2g + metronidazole 2g day before surgery (19h, 23h) |

Amikacin 1g + metronidazole 1g |

|

|

Ishida 2001 16 |

45 / 143 |

71 |

72 |

AR, APR, PC, colectomy, total pelvic exenteration, other |

N/A |

PEG 2L day before surgery (15h-19h) |

Kanamycin 500mg + erythromycin 400mg, start 2 days before surgery, 4 times daily |

Cefotiam 1g |

|

|

Takesue 2000 17 |

16 / 83 |

45 |

38 |

LAR, APR, LH, RH, TH, SR, ICR |

N/A |

PEG day before surgery (10h-14h) |

Kanamycin 500mg + metronidazole 500mg day before surgery (14h, 15h, 23h) |

Cefmetazole 1g |

|

|

Taylor 1994 18 |

83 / 368 |

189 |

179 |

APR, colo(rectal) resection, Hartmann’s resection, other |

N/A |

Sodium picosulphate 1 sachets, day before surgery twice daily |

Ciprofloxacin 500mg, 2 doses day before surgery |

Piperacillin 4g |

|

|

Stellato 1990 19 |

10 / 102 |

51 |

51 |

(Colo)rectal resection |

N/A |

Magnesium citrate 1.745 g in 296ml (morning) + (bi)phosphate enema 118ml (evening) day before and day of surgery |

Neomycin 1g + erythromycin 1g day before surgery (11h, 14h, 23h) |

Cefoxitin 2g |

|

|

Reynolds 1989 20 |

35 / 400 |

104 |

107 |

(Colo)rectal resection |

N/A |

Magnesium sulphate 4g (up to 8 times) start 3 days before surgery + sodium picosulphate twice on day before surgery |

Metronidazole 500mg (3 times daily) + neomycin 1g start day before surgery, 4 times daily |

Piperacillin 2g |

|

|

Coppa 1988 21 |

35 / 310 |

141 |

169 |

(Colo)rectal resection |

N/A |

Sodium phosphate day 2 and 3 before surgery + saline enemas two days before surgery |

Neomycin 8g/day, including loading dose + erythromycin 4g/day in doses for 24hrs before surgery |

Cefoxitin 1-2g (weight adjusted) |

|

|

Lau 1988 22 |

16 / 132 |

67 |

65 |

(L)AR, APR, LH, RH, TH, SR, subtotal colectomy, pelvic exenteration, palliative bypass |

Open |

Bisacodyl and magnesium sulphate + saline enemas |

Neomycin 1g + erythromycin 1g day before surgery (13h, 14h, 23h) |

Metronidazole 500mg + gentamicin 2mg/kg |

|

|

Playforth 1988 23 |

36 / 119 |

58 |

61 |

(Colo)rectal resection |

N/A |

Mannitol 100g in 1L water day before operation |

Neomycin 1g every six hrs + metronidazole 200mg every four hrs start 24hrs before surgery

|

Metronidazole 0.5g |

|

|

MBP vs no preparation: 16 RCTs |

|||||||||

|

Mai-Phan 2019 24 |

21 / 122 |

62 |

60 |

Colectomy |

Laparoscopic |

Sodium phosphate 2 bottles or PEG 2L |

|

Yes, unknown kind |

|

|

Bhat 2016 25 |

28 / 202 |

98 |

104 |

(L)AR, APR, LH, RH, TH, SR |

N/A |

PEG 2 packs in 4L water 12–16hrs before surgery |

|

Ceftriaxone 1g + metronidazole 500mg |

|

|

Bhattacharjee 2015 26 |

27 / 71 |

38 |

33 |

LAR, APR, LH, RH, SR, PC |

Open |

PEG 1 pack in 2L water afternoon before surgery |

|

Cefuroxime 1.5g + metronidazole 500 mg, |

|

|

Sasaki 2012 27 |

6 / 79 |

38 |

41 |

LH, RH |

Mixed |

Sodium picosulphate hydrate 10mL start evening 2 days before surgery + 2L PEG morning before surgery |

|

Flomoxef 1g, Redose >3hrs |

|

|

Bertani |

42 / 229 |

114 |

115 |

LAR, LH, RH, TH, |

Mixed |

PEG 70mg in 1L, day before surgery four times (16h-20h) + glycerin enema 5% 2L day of surgery |

|

Cefoxitin 2g (allergy: gentamicin 80mg + clindamycin 600mg or metronidazole 500mg) |

|

|

Bretagnol 2010 29 |

34 / 178 |

89 |

89 |

Rectal cancer sphincter saving resection |

Mixed |

Senna solution 1-2 packs in water 24h before surgery + povidone-iodine enema 1L evening before and >2h before surgery |

|

Ceftriaxone 1g + metronidazole 500mg, Redose >2hrs |

|

|

Watanabe 2010 30 |

3 / 42 |

21 |

21 |

Colonic resection |

Mixed |

Magnesium citrate 1.8L, 16–19h before surgery + glycerin enema 120mL, day of surgery |

|

Cefmetazole, Redose every 3hrs |

|

|

Pena-Soria 2008 31 |

37 / 129 |

65 |

64 |

Colon or proximal rectal resection |

Open |

PEG 3L + conventional enemas |

|

Gentamicin 80mg + metronidazole 500mg |

|

|

Contant 2007 32 |

283 / 1354 |

670 |

684 |

Colorectal surgery with anastomosis |

Open |

PEG 2-4L + bisacodyl or sodium phosphate solution |

|

Local guideline |

|

|

Jung 2007 33 |

142 / 1343 |

686 |

657 |

Surgery of the colon with anastomosis |

Open |

PEG, sodium phosphate Some patients only received enema |

|

Local guideline |

|

|

Platell 2006 34 |

52 / 294 |

147 |

147 |

AR, RH, TH, PC, (sub)total colectomy |

Open |

PEG 3L day before surgery |

Sodium phosphate enema, 2-4hrs before surgery |

Ticarcillin disodium / clavulanate potassium 3.1 g or gentamicin 2mg/kg + metronidazole 500mg |

|

|

Bucher 2005 35 |

23 / 153 |

78 |

75 |

AR, LH, TH, closure of Hartmann’s |

Mixed |

PEG 3L, 12-16hrs before surgery + saline enema 250ml before AR |

Saline enema 250 mL when AR |

Metronidazole + ceftriaxone |

|

|

Fa-Si-Oen 2005 36 |

29 / 250 |

125 |

125 |

LH, RH, TH, SR, other |

Open |

PEG 4L |

|

Cefazolin 2g + metronidazole 1.5g or gentamicin 240mg + metronidazole 1.5g |

|

|

Ram 2005 37 |

38 / 329 |

164 |

165 |

(L)AR, APR, , LH, RH, TH, SR, subtotal colectomy |

Open |

Sodium phosphate day before surgery |

|

Metronidazole 500mg + ceftriaxone 1g |

|

|

Miettinen 2000 38 |

23 / 267 |

138 |

129 |

(L)AR, APR, LH, RH, CC, ileal pouch |

Open |

PEG until clear fluid day before surgery |

|

Ceftriaxone 2g + metronidazole 1g |

|

|

Burke 1994 39 |

14 / 169 |

82 |

87 |

AR, LH |

N/A |

Sodium picosulphate 10mg, day before surgery (morning, afternoon) |

|

Ceftriaxone 1g + metronidazole 500mg |

|

|

OA vs None: 5 RCTs |

|||||||||

|

Arezzo 2021 40 |

34/204 |

100 |

104 |

RH, ICR, TH, LH, AR, subtotal colectomy, Hartmann procedure, other |

Mixed |

* Some patients undergoing left sided colonic and anterior resections received MBP according to local guidelines |

Neomycin 25.000 UI (≈ 33mg) + bacitracin 2500 UI (≈ ,33mg) (24h, 16h + 8h before surgery) |

Amoxicillin 2g + clavulanic acid 200mg (allergy: clindamycin 600mg + gentamycin 2mg/kg) Redosing if prolonged surgery |

|

|

Espin Basany 2020 41 |

193 / 536 |

267 |

269 |

LH, RH, colectomy, segment resection, other |

Mixed |

|

Ciprofloxacin 750mg day before surgery (12h, midnight) + metronidazole 250mg day before surgery (12h, 18h, midnight) |

Cefuroxime 5g + metronidazole 1g |

|

|

Mulder 2020 42 |

11 / 78 |

39 |

39 |

LAR, LH, RH, SR, (sub) total colectomy, other |

Mixed |

|

Tobramycin 80mg + colistin sulphate 100mg start 3 days before surgery 4 times daily |

According to national guideline |

|

|

Hanel 1980 43 |

0 / 67 |

34 |

33 |

(Colo)rectal resection |

N/A |

Daily enemas, start 4 days before surgery |

Metronidazole 200mg start four days before surgery 4 times daily + neomycin 1g start two day before surgery twice daily + daily enemas, start 4 days before surgery |

Clindamycin 7mg/kg + cefazolin sodium 1g |

|

|

Viddal 1980 44 |

2 / 42 |

21 |

21 |

LAR, LH, RH, APR, PC, CC, jejunoileostomy, ileotransversostomy |

Open |

Enemas for 3 days before surgery |

Tinidazole 2g start day before surgery and day 3-5 postoperatively + enemas for 3 days before surgery |

Doxycycline 200mg |

|

|

OA vs MBP-OA: 3 RCTs |

|||||||||

|

Suzuki 2020 45 |

15 / 251 |

126 |

125 |

Colectomy |

Mixed |

Sodium picosulphate 10mL, 2 days before surgery + PEG 2L, morning before surgery |

Kanamycin sulfate 500mg + metronidazole 500mg day before surgery (13h, 14h, 23h) |

Flomoxef 1g, Redose >3hrs |

|

|

Zmora 2006 46 |

32 / 249 |

129 |

120 |

(L)AR, LH, SR, closure of Hartmann’s |

N/A |

PEG 1 gallon day before surgery + sodium (bi)phosphate enema day of rectal surgery |

Neomycin 1g + erythromycin 1g day before surgery, 3 doses + sodium (bi)phosphate enema day of rectal surgery |

Metronidazole 500mg + gentamicin 240 mg + ampicillin 1g |

|

|

Zmora 2003 47 |

36 / 380 |

193 |

187 |

AR, LH, RH, SR, APR closure of Hartmann’s |

N/A |

PEG 1 gallon 12hrs-16hrs before surgery + sodium (bi)phosphate enema day of rectal surgery |

Neomycin + erythromycin, 3 doses (unknown dose and timing) + sodium (bi)phosphate enema day of rectal surgery |

Broad spectrum |

|

|

MBP-OA vs None: 1 RCT |

|||||||||

|

Koskenvuo 2019 48 |

34 / 397 |

196 |

200 |

LH, RH, TH, AR, ICR, SR, subtotal colectomy, other |

Mixed |

PEG 2L + 1L clear fluid day before surgery |

Neomycin 2g (19h) + metronidazole 2g (23h) day before surgery |

Cefuroxime 1500 mg + metronidazole 500 mg, Redose >3hrs and/or blood loss >1,5L |

|

|

APR: abdominoperineal resection, CC: colostoma closure, ICR: ileocecal resection, (L)AR: (low) anterior resection, LH: left hemicolectomy, N/A: not available PC: proctocolectomy, PEG: polyethylene glycol, RH: right hemicolectomy, SG: sigmoid resection, TH: transverse hemicolectomy, TME: total mesorectal excision. * Anastomotic leakage included in SSI |

|||||||||

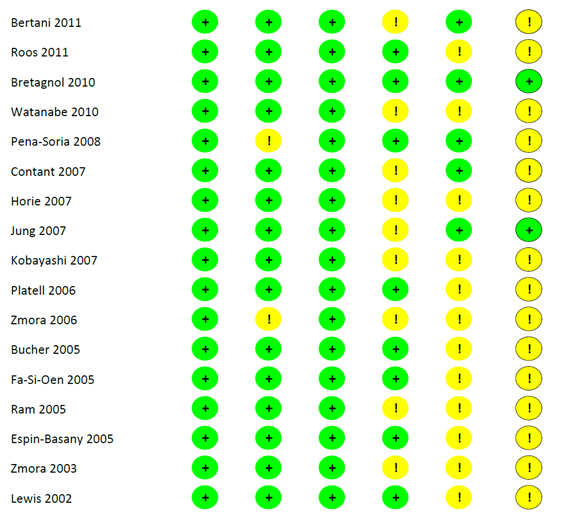

Risk of bias assessment

Funnel plots

6.a. Total SSI

6.b. Anastomotic leakage

6.c. Mortality

Table of excluded studies

|

|

Author, Year |

Reason for exclusion |

|

1. |

Apte 2020 |

Study protocol |

|

2. |

Vadwana 2020 |

No RCT |

|

3. |

Mulder 2018 |

Study protocol |

|

4. |

Vignaud 2018 |

Study protocol |

|

5. |

Hu 2018 |

Language outside scope |

|

6. |

Kobayashi 2015 |

Language outside scope |

|

7. |

Beerdawood 2014 |

Emergency surgeries included |

|

8. |

Collin 2014 |

Irrelevant outcome or comparison |

|

9. |

Saha 2014 |

Emergency surgeries included |

|

10. |

Dijksman 2012 |

Irrelevant outcome or comparison |

|

11. |

Kolovrat 2012 |

No RCT |

|

12. |

Scabini 2012 |

Retracted |

|

13. |

Van’t Sant 2012 |

Subanalysis of Contant 2007 |

|

14. |

Khan 2011 |

Not retrievable |

|

15. |

Roig 2011 |

No RCT |

|

16. |

Van’t Sant 2011 |

Subanalysis of Contant 2007 |

|

17 |

Scabini 2010 |

Retracted |

|

18. |

Van’t Sant 2010 |

Subanalysis of Contant 2007 |

|

19. |

Gravante 2009 |

Comment or letter |

|

20. |

Roos 2009 |

No RCT |

|

21. |

Alcantara Moral 2009 |

Language outside scope |

|

22. |

Takesue 2009 |

Poster presentation |

|

23. |

Leiro 2008 |

Language outside scope |

|

24. |

Itani 2007 |

Irrelevant outcome or comparison |

|

25. |

Pena-Soria 2007 |

Interim analysis Pena-Soria 2008 |

|

26. |

Platell 2007 |

Comment or letter |

|

27. |

Reddy 2007 |

No preoperative iv SAP |

|

28. |

Verma 2007 |

Not retrievable |

|

29. |

Bucher 2006 |

Irrelevant outcome or comparison |

|

30. |

Bucher 2006 |

Erratum |

|

31. |

Fa-Si-Oen 2005 |

Irrelevant outcome or comparison |

|

32. |

Gray 2005 |

No RCT |

|

33. |

Van Geldere 2002 |

No RCT |

|

34. |

Young Tabusso 2002 |

Language outside scope |

|

35. |

Fillmann 2001 |

Not retrievable |

|

36. |

Kale 1998 |

Irrelevant outcome or comparison |

|

37. |

Torres Panuncia 1998 |

Not retrievable |

|

38. |

Yabata 1997 |

No preoperative iv SAP |

|

39. |

Fillman 1995 |

Language outside scope |

|

40. |

Santos Jr 1994 |

Children included |

|

41. |

Tan 1993 |

Not retrievable |

|

42. |

Brownson 1992 |

Abstract only |

|

43. |

Tsimoyiannis 1991 |

Irrelevant outcome or comparison |

|

44. |

Gardini 1990 |

Language outside of scope |

|

45. |

Nohr 1990 |

Not retrievable |

|

46. |

Vacher 1990 |

Language outside of scope |

|

47. |

Cann 1988 |

Irrelevant outcome or comparison |

|

48. |

Gruttadauria 1987 |

Not retrievable |

|

49. |

Peruzzo 1987 |

Not retrievable |

|

50. |

Gottrup 1985 |

No preoperative iv SAP |

|

51. |

Sgarlato 1984 |

Irrelevant outcome or comparison |

|

52. |

Hinchey 1983 |

Irrelevant outcome or comparison |

|

53. |

May 1983 |

No RCT |

|

54. |

Gerritsen 1982 |

No preoperative iv SAP |

|

55. |

Keighley 1982 |

Irrelevant outcome or comparison |

|

56. |

Lazorthes 1982 |

No preoperative iv SAP |

|

57. |

Burdon 1981 |

Not retrievable |

|

58. |

Goldring 1981 |

Not retrievable |

|

59. |

Lewis 1981 |

No preoperative iv SAP |

|

60. |

Barber 1979 |

Not retrievable |

|

61. |

Condon 1979 |

No preoperative iv SAP |

|

62. |

Molin 1979 |

Not retrievable |

|

63. |

Montariol 1979 |

Language outside scope |

|

64. |

Wapnick 1979 |

No preoperative iv SAP |

|

65. |

Brogden 1978 |

No RCT |

|

66. |

Gillespie 1978 |

No preoperative iv SAP |

|

67. |

Hojer 1978 |

No preoperative iv SAP |

|

68. |

Matheson 1978 |

No preoperative iv SAP |

|

69. |

Vargish 1978 |

No preoperative iv SAP |

|

70. |

Clarke 1977 |

No preoperative iv SAP |

|

71. |

Mendes da Costa 1977 |

Not retrievable |

|

72. |

Nichols 1977 |

Irrelevant outcome or comparison |

|

73. |

Semb 1977 |

Abstract only |

|

74. |

Schneiders 1977 |

No preoperative iv SAP |

|

75. |

Wetterfors 1976 |

No preoperative iv SAP |

|

76. |

Goldring 1975 |

No preoperative iv SAP |

|

77. |

Nichols 1973 |

No preoperative iv SAP |

|

78. |

Barker 1971 |

No preoperative iv SAP |

|

79. |

Hulbert 1967 |

No preoperative iv SAP |

|

*SAP = surgical antimicrobial prophylaxis |

||

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Publicatiedatum : 17-12-2024

Beoordeeld op geldigheid : 01-12-2024

Algemene gegevens

De ontwikkeling/herziening van deze richtlijnmodule werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten (www.demedischspecialist.nl/kennisinstituut) en werd gefinancierd uit de Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS). De financier heeft geen enkele invloed gehad op de inhoud van de richtlijnmodule.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijnmodules 2 tot 16 is in 2020 op initiatief van de NVvH een multidisciplinaire werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen (zie hiervoor de Samenstelling van de werkgroep) die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor preventie van postoperatieve wondinfecties. Daarnaast is in 2022 op initiatief van het Samenwerkingsverband Richtlijnen Infectiepreventie (SRI) een separate multidisciplinaire werkgroep samengesteld voor de herziening van de WIP-richtlijn over postoperatieve wondinfecties: module 17-22. De ontwikkelde modules van beide werkgroepen zijn in deze richtlijn samengevoegd.

Belangenverklaringen

De Code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling is gevolgd. Alle werkgroepleden hebben schriftelijk verklaard of zij in de laatste drie jaar directe financiële belangen (betrekking bij een commercieel bedrijf, persoonlijke financiële belangen, onderzoek financiering) of indirecte belangen (persoonlijke relaties, reputatiemanagement) hebben gehad. Gedurende de ontwikkeling of herziening van een module worden wijzigingen in belangen aan de voorzitter doorgegeven. De belangenverklaring wordt opnieuw bevestigd tijdens de commentaarfase.

Een overzicht van de belangen van werkgroepleden en het oordeel over het omgaan met eventuele belangen vindt u in onderstaande tabel. De ondertekende belangenverklaringen zijn op te vragen bij het secretariaat van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

|

Werkgroeplid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

Mevr. prof. dr. M.A. Boermeester |

Chirurg |

* Medisch Ethische Commissie, Amsterdam UMC, locatie AMC * Antibiotica Commissie, Amsterdam UMC |

Persoonlijke financiële belangen Hieronder staan de beroepsmatige relaties met bedrijfsleven vermeld waarbij eventuele financiële belangen via de AMC Research B.V. lopen, dus institutionele en geen persoonlijke gelden zijn: Skillslab instructeur en/of spreker (consultant) voor KCI/3M, Smith&Nephew, Johnson&Johnson, Gore, BD/Bard, TELABio, GDM, Medtronic, Molnlycke.

Persoonlijke relaties Geen.

Extern gefinancierd onderzoek Institutionele grants van KCI/3M, Johnson&Johnson en New Compliance.

Intellectuele belangen en reputatie Ik maak me sterk voor een 100% evidence-based benadering van maken van aanbevelingen, volledig transparant en reproduceerbaar. Dat is mijn enige belang in deze, geen persoonlijk gewin.

Overige belangen Geen.

|

Extra kritische commentaarronde. |

|

Dhr. dr. M.J. van der Laan |

Vaatchirurg |

Vice voorzitter Consortium Kwaliteit van Zorg NFU, onbetaald

|

Persoonlijke financiële belangen Geen.

Persoonlijke relaties Geen.

Extern gefinancierd onderzoek Geen.

Intellectuele belangen en reputatie Geen.

Overige belangen Geen.

|

Geen.

|

|

Dhr. dr. W.C. van der Zwet |

Arts-microbioloog |

Lid Regionaal Coördinatie Team, Limburgs infectiepreventie & ABR Zorgnetwerk (onbetaald) |

||

|

Dhr. dr. D.R. Buis |

Neurochirurg |

Lid Hoofdredactieraad Tijdschrift voor Neurologie & Neurochirurgie - onbetaald |

||

|

Dhr. dr. J.H.M. Goosen |

Orthopaedisch Chirurg |

Inhoudelijke presentaties voor Smith&Nephew en Zimmer Biomet. Deze worden vergoed per uur. |

||

|

Mw. drs. H. Jalalzadeh |

Arts-onderzoeker |

Geen. |

Persoonlijke financiële belangen Geen.

Persoonlijke relaties Geen.

Extern gefinancierd onderzoek Geen.

Intellectuele belangen en reputatie Geen.

Overige belangen Geen. |

Geen.

|

|

Dhr. dr. N. Wolfhagen |

AIOS chirurgie |

|||

|

Mw. drs. H. Groenen |

Arts-onderzoeker |

|||

|

Dhr. dr. F.F.A. Ijpma |

Traumachirurg |

|||

|

Dhr. dr. P. Segers |

Cardiothoracaal chirurg |

|||

|

Mw. Y.E.M. Dreissen |

AIOS neurochirurgie |

|||

|

Dhr. R.R. Schaad |

Anesthesioloog |

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Er werd aandacht besteed aan het patiëntenperspectief door uitnodigen van de Patiëntenfederatie Nederland voor de invitational conference. De verkregen input is meegenomen bij het opstellen van de uitgangsvragen, de keuze voor de uitkomstmaten en bij het opstellen van de overwegingen. De conceptmodules zijn tevens voor commentaar voorgelegd aan de Patiëntenfederatie Nederland en de eventueel aangeleverde commentaren zijn bekeken en verwerkt. Voor de modules 17-22 was de patiëntfederatie vertegenwoordigd in de werkgroep.

Wkkgz & Kwalitatieve raming van mogelijke substantiële financiële gevolgen

Bij de richtlijn is conform de Wet kwaliteit, klachten en geschillen zorg (Wkkgz) een kwalitatieve raming uitgevoerd of de aanbevelingen mogelijk leiden tot substantiële financiële gevolgen. Bij het uitvoeren van deze beoordeling zijn richtlijnmodules op verschillende domeinen getoetst (zie het stroomschema op de Richtlijnendatabase).

Uit de kwalitatieve raming blijkt dat er waarschijnlijk geen substantiële financiële gevolgen zijn.

Voor module 8 (Negatieve druktherapie) geldt dat uit de toetsing volgt dat de aanbeveling(en) breed toepasbaar zijn (5.000 - 40.000 patiënten). Tevens volgt uit de toetsing dat het geen nieuwe manier van zorgverlening of andere organisatie van zorgverlening betreft. Er worden daarom geen substantiële financiële gevolgen verwacht.

Voor de overige modules en aanbevelingen geldt dat uit de toetsing volgt dat de aanbeveling(en) breed toepasbaar zijn (>40.000 patiënten). Tevens volgt uit de toetsing dat het overgrote deel (±90%) van de zorgaanbieders en zorgverleners al aan de norm voldoet en het geen nieuwe manier van zorgverlening of andere organisatie van zorgverlening betreft. Ook wordt geen toename in het aantal in te zetten voltijdsequivalenten aan zorgverleners verwacht of een wijziging in het opleidingsniveau van zorgpersoneel. Er worden daarom geen substantiële financiële gevolgen verwacht.

Methode ontwikkeling

Evidence based

Implementatie

Zie voor de implementatie het implementatieplan in het tabblad 'Bijlagen'.

Werkwijze

AGREE

Deze richtlijnmodule is opgesteld conform de eisen vermeld in het rapport Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 van de adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwaliteit. Dit rapport is gebaseerd op het AGREE II instrument (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II; Brouwers, 2010).

Knelpuntenanalyse en uitgangsvragen

Tijdens de voorbereidende fase inventariseerde de werkgroepen de knelpunten in de zorg voor patiënten die chirurgie ondergaan. Tevens zijn er knelpunten aangedragen door middel van een invitational conference. De verslagen hiervan zijn opgenomen onder aanverwante producten.

Op basis van de uitkomsten van de knelpuntenanalyse zijn door de werkgroep concept-uitgangsvragen opgesteld en definitief vastgesteld.

Uitkomstmaten

Na het opstellen van de zoekvraag behorende bij de uitgangsvraag inventariseerde de werkgroep welke uitkomstmaten voor de patiënt relevant zijn, waarbij zowel naar gewenste als ongewenste effecten werd gekeken. Hierbij werd een maximum van acht uitkomstmaten gehanteerd. De werkgroep waardeerde deze uitkomstmaten volgens hun relatieve belang bij de besluitvorming rondom aanbevelingen, als cruciaal (kritiek voor de besluitvorming), belangrijk (maar niet cruciaal) en onbelangrijk. Tevens definieerde de werkgroep tenminste voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten welke verschillen zij klinisch (patiënt) relevant vonden.

Methode literatuursamenvatting

Een uitgebreide beschrijving van de strategie voor zoeken en selecteren van literatuur is te vinden onder ‘Zoeken en selecteren’ onder Onderbouwing. Indien mogelijk werd de data uit verschillende studies gepoold in een random-effects model. De beoordeling van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs wordt hieronder toegelicht.

Beoordelen van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs

De kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs werd bepaald volgens de GRADE-methode. GRADE staat voor ‘Grading Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation’ (zie http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/). De basisprincipes van de GRADE-methodiek zijn: het benoemen en prioriteren van de klinisch (patiënt) relevante uitkomstmaten, een systematische review per uitkomstmaat, en een beoordeling van de bewijskracht per uitkomstmaat op basis van de acht GRADE-domeinen (domeinen voor downgraden: risk of bias, inconsistentie, indirectheid, imprecisie, en publicatiebias; domeinen voor upgraden: dosis-effect relatie, groot effect, en residuele plausibele confounding).

GRADE onderscheidt vier gradaties voor de kwaliteit van het wetenschappelijk bewijs: hoog, redelijk, laag en zeer laag. Deze gradaties verwijzen naar de mate van zekerheid die er bestaat over de literatuurconclusie, in het bijzonder de mate van zekerheid dat de literatuurconclusie de aanbeveling adequaat ondersteunt (Schünemann, 2013; Hultcrantz, 2017).

|

GRADE |

Definitie |

|

Hoog |

|

|

Redelijk |

|

|

Laag |

|

|

Zeer laag |

|

Bij het beoordelen (graderen) van de kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs in richtlijnen volgens de GRADE-methodiek spelen grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming een belangrijke rol (Hultcrantz, 2017). Dit zijn de grenzen die bij overschrijding aanleiding zouden geven tot een aanpassing van de aanbeveling. Om de grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming te bepalen moeten alle relevante uitkomstmaten en overwegingen worden meegewogen. De grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming zijn daarmee niet één op één vergelijkbaar met het minimaal klinisch relevant verschil (Minimal Clinically Important Difference, MCID). Met name in situaties waarin een interventie geen belangrijke nadelen heeft en de kosten relatief laag zijn, kan de grens voor klinische besluitvorming met betrekking tot de effectiviteit van de interventie bij een lagere waarde (dichter bij het nuleffect) liggen dan de MCID (Hultcrantz, 2017).

Overwegingen (van bewijs naar aanbeveling)