Timing van antimicrobiële profylaxe

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is het optimale tijdstip voor toediening van antibioticaprofylaxe en hoe beïnvloedt het tijdstip van toediening van de chirurgische antibioticaprofylaxe het risico op wondinfectie?

Aanbeveling

Indien intraveneuze antibiotische profylaxe is geïndiceerd ter preventie van postoperatieve wondinfecties, lijkt toediening binnen 60 minuten voor incisie of aanleggen bloedleegte de voorkeur te hebben.

Houd hierbij rekening met farmacokinetiek van het antibioticum, en ook de individuele karakteristieken van de patiënt.

Voor herdosering verwijst de werkgroep naar de SWAB-richtlijn Peri-operatieve profylaxe (2019). (Paragraaf Organisatie, timing en duur van de profylaxe.)

Voor prolongatie van antibiotische profylaxe verwijst de werkgroep naar de module Prolongatie van antimicrobiële profylaxe.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Samenvatting vanuit de literatuur

De toediening van chirurgische antibioticaprofylaxe (afgekort profylaxe) meer dan 120 minuten vóór de incisie is geassocieerd met een hoger risico op een postoperatieve wondinfectie (POWI), vergeleken met toediening binnen 120 minuten vóór de incisie. De toediening van profylaxe tussen 120 en 60 minuten was ook geassocieerd met een hoger risico op een POWI vergeleken met toediening binnen 60 minuten vóór de incisie. Bovendien was de toediening van profylaxe meer dan 30 minuten vóór de incisie geassocieerd met een hoger risico op een POWI vergeleken met toediening binnen 30 minuten vóór de incisie. De bewijskracht werd als zeer laag beoordeeld.

Voor ‘all-cause’ mortaliteit werd geen verschil gevonden tussen toediening van profylaxe tussen 60 en 30 minuten, vergeleken met 30 minuten vóór de incisie. Geen van de geïncludeerde studies rapporteerde de uitkomst ‘all-cause’ chirurgische re-interventies voor verschillende tijdstippen waarop profylaxe werd toegediend.

Internationale richtlijnen

De Amerikaanse Center for Disease Control and Prevention (Berrios-Torres 2017) stelt ‘Er kunnen geen verdere verfijningen worden aangebracht in het tijdstip van antimicrobiële middelen voorafgaand aan de operatie op basis van klinische uitkomsten.’ Het Britse National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE 2019) adviseert om ‘Houd bij het geven van antibiotica profylaxe rekening met de timing en farmacokinetiek (bijvoorbeeld de serumhalfwaardetijd) en de benodigde infusietijd van het antibioticum.’ Het WHO-panel “beveelt de toediening van chirurgische antibioticaprofylaxe aan binnen 120 minuten vóór de incisie, waarbij rekening wordt gehouden met de halfwaardetijd van het antibioticum.’

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

Een factor voor de voorkeur van de patiënt zou kunnen zijn dat hoe eerder een patiënt profylaxe toegediend krijgt, hoe langer de totale perioperatieve periode kan zijn. Het is belangrijk om patiënten te informeren over het nut en de noodzaak van de behandeling. Door hen op de hoogte te stellen van wat ze kunnen verwachten en waarvoor een specifieke injectie dient, bevordert men niet alleen begrip maar ook betrokkenheid van de patiënt bij zijn of haar eigen zorgproces. Dit draagt bij aan een positieve behandelervaring.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

Er zijn geen kosteneffectiviteitsstudies beschikbaar. Echter, een POWI is een kostbare complicatie. De kosten van profylaxe wegen niet op tegen de kosten die gepaard gaan met een POWI.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

De toediening van profylaxe vóór een chirurgische ingreep is standaardpraktijk. We verwachten geen problemen met betrekking tot de haalbaarheid bij het toedienen van profylaxe op verschillende tijdstippen van toediening voor implementatie in de klinische praktijk.

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

Er werd een literatuuronderzoek uitgevoerd naar het optimale tijdstip van de toediening van chirurgische antimicrobiële profylaxe bij volwassenen. Slechts één RCT werd in de analyse opgenomen, de overige studies betroffen observationele studies. De bevindingen geven aan dat er voldoende weefselconcentraties van het antibioticum aanwezig moeten zijn op het moment van de incisie en gedurende de procedure voor een effectieve profylaxe. Dit vereist profylaxe toediening voorafgaand aan de incisie. Hoewel op basis van het beschikbare bewijs niet mogelijk is om het optimale tijdstip binnen het interval van 120 minuten nauwkeuriger vast te stellen, kunnen antibiotica met een korte halfwaardetijd minder effectief zijn als ze vroeg in dit tijdsinterval worden gegeven dan wanneer ze dichter bij het moment van incisie worden toegediend. Het wordt daarom aanbevolen rekening te houden met de halfwaardetijd van de toegediende antibiotica om de exacte toedieningstijd binnen 120 minuten voor incisie vast te stellen (bijvoorbeeld toediening dichter bij het tijdstip van incisie (<60 minuten) voor antibiotica met een korte halfwaardetijd, zoals cefazoline, cefoxitine en penicillines in het algemeen). Bovendien moeten patiëntkenmerken, zoals leeftijd, nierfunctie, ondervoeding en gewicht (BMI), in overweging worden genomen.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Er is onduidelijkheid over het tijdstip van chirurgische antibioticaprofylaxe (afgekort profylaxe). Er bestaan verschillende aanbevelingen over het optimale tijdstip voor de toediening van de profylaxe om het risico op een postoperatieve wondinfectie (POWI) te verminderen.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

1. Surgical site infections

|

Very low GRADE |

If intravenous antibiotic prophylaxis is indicated for prevention of postoperative wound infections, administration within 60 minutes before incision seems preferable. Keep in mind pharmacokinetics of the antibiotic, as well as the individual characteristics of the patient.

Bron: De Jonge et al 2017 |

2. Mortality

|

Moderate GRADE |

Administration of intravenous antibiotic prophylaxis between 60 and 30 minutes before incision, probably results in little or no reduction in mortality compared with administration of intravenous antibiotic prophylaxis between 30 and 0 minutes before incision.

Sources: Weber (2017). |

3. All-cause surgical reinterventions

|

No GRADE |

Due to lack of data in the included studies in this guideline, it is not possible to draw conclusions regarding the outcome all-cause surgical reinterventions in patients undergoing surgical procedures with an indication of surgical antimicrobial prophylaxis.

Sources: - |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

The systematic review of de Jonge (2016) investigated the effectiveness of different timing for administration of SAP to reduce SSI in indicated surgical procedures. De Jonge (2016) conducted a systematic search in Medline (PubMed), Excerpta Medica Database (EMBASE), Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), and the World Health Organization regional medical databases. The final search was performed on the 12th of August 2016. All clinical studies comparing the outcome of SSI with different timing intervals of preoperative antibiotic prophylaxis in indicated procedures were considered for eligibility. This comprised all clean contaminated, contaminated, and implant surgery in all surgical fields. Duplicates, congress abstracts, experimental studies, studies with insufficient data for comparison and studies without clear description of the compared timing intervals were excluded from the analysis. In total, De Jonge (2016) included fourteen studies for the qualitative analysis (zie PRISMA Flow chart of study selection). Of these, nine studies were included for the quantitative analysis. For the purpose of this guideline, we only included the eight studies, involving 20,347 participants, from the quantitative analysis (Classen, 1992; Garey, 2006; Kasatbipal, 2006; Lizan Garcia, 1997; Munoz, 1995; Steinberg, 2009; Van Kasteren, 2007; Weber, 2008). One study (Ho, 2011) had no raw data in the manuscript and could not be included in the analysis. The mean age of participants ranged between 26 and 69 years. The included studies compared different timing intervals of preoperative antibiotic prophylaxis, such as >120 minutes versus <120 minutes prior to incision, between 120-60 minutes versus between 60-0 minutes prior to incision, > 60 minutes versus <60 minutes prior to incision, between 60-30 minutes versus between 30-0 minutes prior to incision, and >30 minutes versus < 30 minutes prior to incision. The other studies included in de Jonge (2016) were excluded because they did not report raw data for the outcomes under study in this guideline. The risk of bias was assessed with the Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale for cohort studies and publication bias was assessed using a funnel plot. The reported outcome in De Jonge (2016) was the incidence of surgical site infections.

The observational cohort study of De Jonge (2019) investigated if administration of SAP between 60 minutes to 30 minutes prior to incision differs from the risk of surgical site infections when SAP was administered between 30 and zero minutes prior to incision. De Jonge (2019) included adult patients undergoing primary surgical procedures that indicated SAP and did not receive direct pre- or postoperative antibiotics. In total, 3,001 patients were analyzed. Four patients received SAP more than 120 minutes prior to incision, 273 patients received SAP between 120 and 60 minutes prior to incision, 1062 patients received SAP 60 to 30 minutes prior to incision, 1550 patients received SAP 30 to zero minutes prior to incision, and 112 patients received SAP after incision. For the purpose of this guideline, we did not include patients that received SAP after incision. Patients were followed for the occurrence of SSI for 30 days. The reported outcome in the study of de Jonge (2019) was SSI.

The cohort study of Sommerstein (2019) investigated the optimal time to administer SAP within the 120 minutes window prior to the incision for patients about to have cardiac surgery. Sommerstein (2019) included all patients who underwent cardiac surgery procedures, including coronary artery bypass graft, valve repair/replacement, and placement of implantable cardiovascular devices. In total, 15,576 patients were analyzed. Of these, 5536 patients received SAP between 120 and 60 minutes prior to incision, 5724 patients received SAP between 59 and 45 minutes prior to incision, 6780 patients received SAP between 44 and 30 minutes prior to incision, and 2967 patients received SAP between 29 and zero minutes prior to incision. Length of follow-up for surgical site infections was one month. The reported outcome in the study of Sommerstein (2019) was SSI.

The phase III randomized controlled trial of Weber (2017) investigated the effect of early administration with late administration in patients who underwent general surgery procedures (specifically gastrointestinal, hernia, endocrine, and breast surgery) as well as orthopaedic, trauma and vascular procedures with SAP indicated according to international guidelines. In total, 5175 patients were randomized to either early administration of SAP (n=2589) or late administration of SAP (n=2586). Early administration was considered as administration of SAP approximately between 75 and 30 minutes prior to incision, while late administration was considered as administration of SAP between 30 and zero minutes prior to incision. The length of follow-up was 30 days. The reported outcomes in the study of Weber (2017) were SSI and (all-cause) 30-day mortality.

Results

1. Surgical site infections

Surgical site infections were reported in twelve studies, nine studies were retrieved from the systematic review of de Jonge (2016) (Classen, 1992; Garey, 2006; Ho, 2011; Kasatbipal, 2006; Lizan Garcia, 1997; Munoz, 1995; Steinberg, 2009; Van Kasteren, 2007; Weber, 2008) and three additional studies were identified in the search (de Jonge, 2019; Sommerstein, 2019; Weber, 2017).

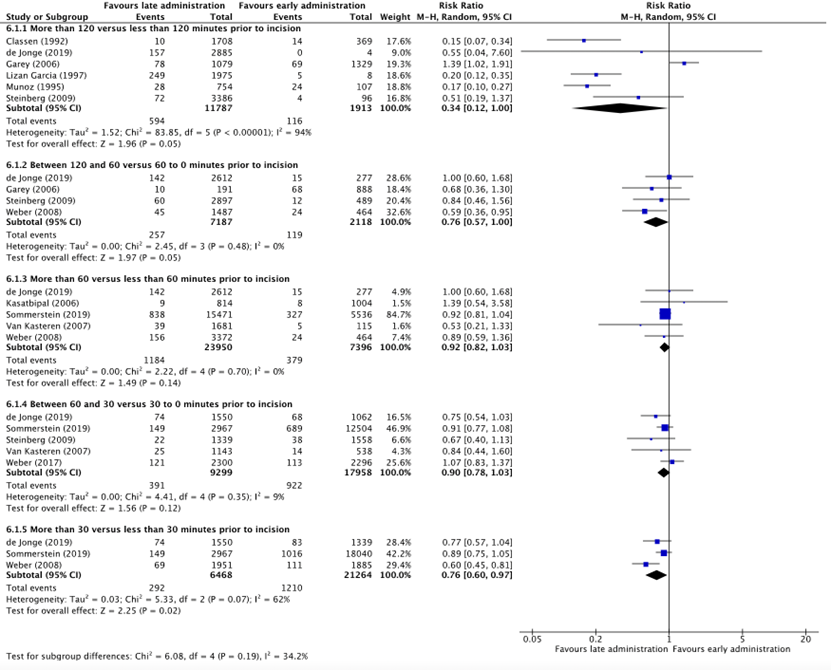

1.1. More than 120 minutes versus less than 120 minutes prior to incision

Six studies reported surgical site infections in patients who received SAP more than 120 minutes prior to incision (early administration) versus patients who received SAP less than 120 minutes prior to incision (late administration) (Classen, 1992; de Jonge, 2019; Garey, 2006; Lizan-Garcia, 1997; Munoz, 1995; Steinberg, 2009). The results were pooled in a meta-analysis. The number of surgical site infections in the early administration group was 116/1913 (6.1%), compared to 594/11787 (5.0%) in the late administration group. This resulted in a pooled relative risk ratio (RR) of 0.34 (95% CI 0.12 to 1.00), in favor of the late administration group (figure 1). This was considered as a clinically relevant difference.

1.2. Between 120 and 60 minutes versus between 60 and zero minutes prior to incision

Four studies reported surgical site infections in patients who received SAP between 120 and 60 minutes (early administration) and 60 to zero minutes prior to incision (late administration) (de Jonge, 2019; Garey, 2006; Steinberg, 2009; Weber, 2008). The results were pooled in a meta-analysis. The number of surgical site infections in the early administration group was 119/2118 (5.6%), compared to 257/7187 (3.6%) in the late administration group. This resulted in a pooled relative risk of 0.76 (95% CI 0.57 to 1.00), in favor of the late administration group (figure 1). This was considered as a clinically relevant difference.

1.3. More than 60 minutes versus less than 60 minutes prior to incision

Five studies reported surgical site infections in patients who received SAP more than 60 minutes prior to incision (early administration) versus patients who received SAP less than 60 minutes prior to incision (late administration) (de Jonge, 2019; Kasatbipal, 2006; Sommerstein, 2019; Van Kasteren, 2007; Weber, 2008). The results were pooled in a meta-analysis. The number of surgical site infections in the early administration group was 379/7396 (5.1%), compared to 1184/23950 (4.9%) in the late administration group. This resulted in a pooled relative risk ratio (RR) of 0.92 (95% CI 0.82 to 1.03), in favor of the late administration group (figure 1). This was not considered as a clinically relevant difference.

1.4. Between 60 and 30 minutes versus between 30 and zero minutes prior to incision

Five studies reported surgical site infections in patients who received SAP between 60 and 30 minutes (early administration) and 30 to zero minutes prior to incision (late administration) (de Jonge, 2019; Sommerstein, 2019; Steinberg, 2009; Van Kasteren, 2007; Weber, 2017). The results were pooled in a meta-analysis. The number of surgical site infections in the early administration group was 922/17958 (5.1%), compared to 391/9299 (4.2%) in the late administration group. This resulted in a pooled relative risk of 0.90 (95% CI 0.78 to 1.03), in favor of the late administration group (figure 1). This was not considered as a clinically relevant difference.

1.5. More than 30 minutes versus less than 30 minutes prior to incision

Three studies reported surgical site infections in patients who received SAP more than 30 minutes prior to incision (early administration) versus patients who received SAP less than 30 minutes prior to incision (late administration) (de Jonge, 2019; Sommerstein, 2019; Weber, 2008). The results were pooled in a meta-analysis. The pooled number of surgical site infections in the early administration group was 1210/21264 (5.7%), compared to 292/6468 (4.5%) in the late administration group. This resulted in a relative risk ratio (RR) of 0.76 (95% CI 0.60 to 0.97), in favor of the late administration group (figure 1). This was considered as a clinically relevant difference.

Figure 1: Forest plot showing the comparison between early administration of SAP to late administration of SAP prior to incision for surgical site infections. Pooled risk ratio, random effects model. Z: p-value of overall effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2; statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval.

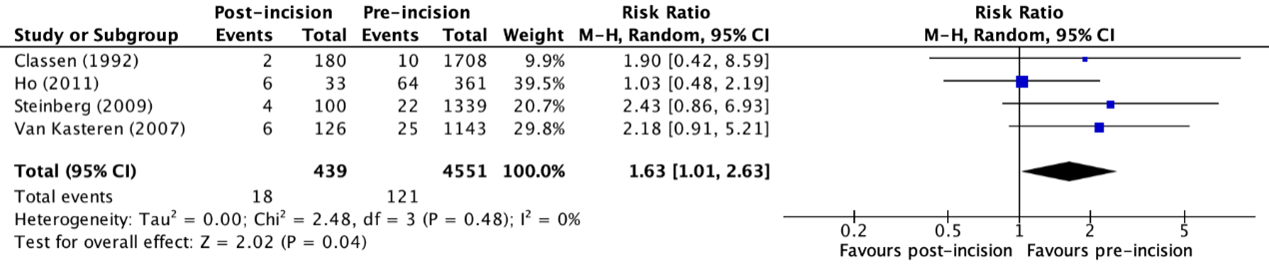

1.6 Administration post-incision versus administration pre-incision

Four studies reported surgical site infections in patients who received SAP pre-incision (early administration) and post-incision (late administration) (Classen, 1992; Steinberg, 2009; Van Kasteren, 2007; Ho, 2011). The results were pooled in a meta-analysis. The number of surgical site infections in the early administration group was 121/4551 (2.7%), compared to 18/439 (4.1%) in the late administration group. This resulted in a pooled relative risk of 1.63 (95% CI 1.01 to 2.63), in favor of the pre-incision administration group (figure 2). This was considered as a clinically relevant difference.

Figure 2: Forest plot showing the comparison between administration of SAP post-incision to pre-incision for surgical site infections. Pooled risk ratio, random effects model. Z: p-value of overall effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2; statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval.

2. Mortality

(All-cause) 30-day mortality was reported in one study (Weber, 2017). The early administration group received SAP between 60 and 30 minutes prior to incision, while the late administration group received SAP between 30 and zero minutes prior to incision. The incidence of 30-day mortality in the early administration group was 29/2301 (1.3%), compared to 24/2306 (1.0%) in the late administration group. This resulted in a relative risk ratio (RR) of 0.83 (95% CI 0.48 to 1.41), in favor of the late administration group. This was not considered as a clinically relevant difference.

3. All-cause surgical reinterventions

None of the included studies reported the outcome measure (surgical) interventions for different moments of administration of SAP in patients undergoing surgical procedures with an indication of surgical antibiotic prophylaxis.

Level of evidence of the literature

1. Surgical site infections

1.1 More than 120 minutes vs less than 120 minutes prior to incision

The level of evidence regarding the outcome surgical site infections for administration of SAP more than 120 minutes versus less than 120 minutes prior to incision was derived from observational studies and therefore started low. The level of evidence was downgraded by one level because of the wide confidence interval crossing the upper border of clinical relevance (imprecision, -1). The level of evidence was considered as very low.

1.2 Between 120 and 60 minutes vs between 60 and zero minutes prior to incision

The level of evidence regarding the outcome surgical site infections for administration of SAP between 120 minutes and 60 minutes versus 60 and zero minutes prior to incision was derived from observational studies and therefore started low. The level of evidence was downgraded by one level because of the wide confidence interval crossing the upper border of clinical relevance (imprecision, -1). The level of evidence was considered as very low.

1.3 More than 60 minutes vs less than 60 minutes prior to incision

The level of evidence regarding the outcome surgical site infections for administration of SAP more than 60 minutes versus less than 60 minutes prior to incision was derived from observational studies and therefore started low. The level of evidence was downgraded by one level because of a lack of information regarding the adjustments for confounding in several studies (risk of bias, -1). The level of evidence was considered as very low.

1.4 Between 60 and 30 minutes vs between 30 and zero minutes prior to incision

The level of evidence regarding the outcome surgical site infections for administration of SAP between 60 minutes and 30 minutes versus 30 and zero minutes prior to incision was derived from observational studies and therefore started low. The level of evidence was downgraded by one level because of a lack of information regarding adjustments for confounding in several studies (risk of bias, -1) and the wide confidence interval crossing the upper border of clinical relevance (imprecision, -1). The level of evidence was considered as very low.

1.5 More than 30 minutes versus less than 30 minutes prior to incision

The level of evidence regarding the outcome surgical site infections for administration of SAP more than 30 minutes versus less than 30 minutes prior to incision was derived from observational studies and therefore started low. The level of evidence was downgraded by one level because of the wide confidence interval crossing the upper border of clinical relevance (imprecision, -1). The level of evidence was considered as very low.

1.6 Administration post-incision versus administration pre-incision

The level of evidence regarding the outcome surgical site infections for administration of SAP post-incision versus pre-incision was derived from observational studies and therefore started low. The level of evidence was downgraded by one level because of the wide confidence interval crossing the upper border of clinical relevance (imprecision, -1). The level of evidence was considered as very low.

2. Mortality

The level of evidence regarding the outcome surgical site infections for administration of SAP more than 30 minutes versus less than 30 minutes prior to incision was derived from a randomized controlled trial and therefore started high. The level of evidence was downgraded by one level because of the wide confidence interval crossing the upper border of clinical relevance (imprecision, -1). The level of evidence was considered as moderate.

3. All-cause surgical reinterventions

Because of a lack of data, it was not possible to grade the literature for the outcome all-cause surgical reinterventions in patients undergoing surgical procedures with an indication of surgical antibiotic prophylaxis (SAP).

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question: What is the optimal timing for administration of SAP in adult patients undergoing surgical procedures?

P: Adult patients undergoing surgical procedures with an indication of surgical antimicrobial prophylaxis (SAP)

I: Different periods of administration of SAP (120-60 minutes, 60-0, 60-30, 30-0 minutes prior to incision)

C: Different periods of administration compared with each other.

O: Surgical site infections (SSI), (SSI-attributed) mortality, all-cause surgical reinterventions.

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered surgical site infections as a critical outcome measure for decision making; and mortality and all-cause surgical reinterventions as important outcome measures for decision making.

The working group defined a threshold of 10% for continuous outcomes and a relative risk (RR) for dichotomous outcomes of <0.80 and >1.25 as a minimal clinically (patient) important difference.

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms until the 1st of December 2020. The detailed search strategy is available on request via https://richtlijnendatabase.nl/. The systematic literature search resulted in 638 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria: systematic reviews (SRs), randomized controlled trials (RCTs), and observational studies on the timing of preoperative antibiotic administration. Six studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, two studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion in the table of excluded studies under the tab 'Evidence tabellen'), and four studies were included.

Results

Four studies, one systematic review, one phase three RCT, and two observational studies were included in the analysis of the literature under the tab 'Samenvatting literatuur'. Important study characteristics and results and quality assessments are summarized in the evidence tables and risk of bias tables under the 'evidence tabellen' tab.

Referenties

- Berríos-Torres SI, Umscheid CA, Bratzler DW, et al. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Guideline for the Prevention of Surgical Site Infection, 2017. JAMA Surg. 2017;152(8):784–791. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2017.0904

- Classen DC, Evans RS, Pestotnik SL, Horn SD, Menlove RL, Burke JP. The timing of prophylactic administration of antibiotics and the risk of surgical-wound infection. N Engl J Med. 1992 Jan 30;326(5):281-6. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199201303260501. PMID: 1728731.

- de Jonge SW, Gans SL, Atema JJ, Solomkin JS, Dellinger PE, Boermeester MA. Timing of preoperative antibiotic prophylaxis in 54,552 patients and the risk of surgical site infection: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017 Jul;96(29):e6903. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000006903. PMID: 28723736; PMCID: PMC5521876.

- de Jonge SW, Boldingh QJJ, Koch AH, Daniels L, de Vries EN, Spijkerman IJB, Ankum WM, Kerkhoffs GMMJ, Dijkgraaf MG, Hollmann MW, Boermeester MA. Timing of Preoperative Antibiotic Prophylaxis and Surgical Site Infection: TAPAS, An Observational Cohort Study. Ann Surg. 2021 Oct 1;274(4):e308-e314. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000003634. PMID: 31663971.

- Garey KW, Dao T, Chen H, Amrutkar P, Kumar N, Reiter M, Gentry LO. Timing of vancomycin prophylaxis for cardiac surgery patients and the risk of surgical site infections. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2006 Sep;58(3):645-50. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkl279. Epub 2006 Jun 27. PMID: 16807254.

- Global guidelines for the prevention of surgical site infection, second edition. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- Kasatpibal N, Nørgaard M, Sørensen HT, Schønheyder HC, Jamulitrat S, Chongsuvivatwong V. Risk of surgical site infection and efficacy of antibiotic prophylaxis: a cohort study of appendectomy patients in Thailand. BMC Infect Dis. 2006 Jul 12;6:111. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-6-111. PMID: 16836755; PMCID: PMC1553447.

- Sommerstein R, Atkinson A, Kuster SP, Thurneysen M, Genoni M, Troillet N, Marschall J, Widmer AF; Swissnoso. Antimicrobial prophylaxis and the prevention of surgical site infection in cardiac surgery: an analysis of 21 007 patients in Switzerland†. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2019 Oct 1;56(4):800-806. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezz039. PMID: 30796448.

- Steinberg JP, Braun BI, Hellinger WC, Kusek L, Bozikis MR, Bush AJ, Dellinger EP, Burke JP, Simmons B, Kritchevsky SB; Trial to Reduce Antimicrobial Prophylaxis Errors (TRAPE) Study Group. Timing of antimicrobial prophylaxis and the risk of surgical site infections: results from the Trial to Reduce Antimicrobial Prophylaxis Errors. Ann Surg. 2009 Jul;250(1):10-6. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181ad5fca. PMID: 19561486.

- SWAB-richtlijn peri-operatieve profylaxe. 2019. Peri-operatieve profylaxe - Algemene informatie | SWAB

- Weber WP, Mujagic E, Zwahlen M, Bundi M, Hoffmann H, Soysal SD, Kraljević M, Delko T, von Strauss M, Iselin L, Da Silva RXS, Zeindler J, Rosenthal R, Misteli H, Kindler C, Müller P, Saccilotto R, Lugli AK, Kaufmann M, Gürke L, von Holzen U, Oertli D, Bucheli-Laffer E, Landin J, Widmer AF, Fux CA, Marti WR. Timing of surgical antimicrobial prophylaxis: a phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2017 Jun;17(6):605-614. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30176-7. Epub 2017 Apr 3. Erratum in: Lancet Infect Dis. 2017 Dec;17 (12 ):1232. PMID: 28385346.

Evidence tabellen

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C)

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

|

De Jonge (2016) |

SR and meta-analysis of prospective and retrospective cohort studies

Literature search up to 12th of August 2016.

A: Classen (1992) B: Garey (2006) C: Ho (2011) D: Kasatpibal (2006) E: Lizan Garcia (1997) F: Munoz (1995) G: Steinberg (2009) H: Van Kasteren (2007) I: Weber (2008)

Study design: RCT [parallel / cross-over], cohort [prospective / retrospective], case-control

Setting and Country:

Source of funding

Conflicts of interest: [commercial / non-commercial / industrial co-authorship]

|

Inclusion criteria SR:

Exclusion criteria SR:

10 studies included

Important patient characteristics at baseline:

N A: N = 2847 B: N = 2048 C: N = 605 D: N = 1972 E: N = 1983 F: N = 2083 G: N = 3656 H: N = 1922 I: N = 3836

mean age A: 53 (11 to 97) B: 64 (12) C: 59.7 (17.8) D: 26 (16 to 39) E: 48 (23) F: 55.8 (20.6) G: NA H: 68.8 (10.8) I: NA

Sex: A: 62% females B: 32% females C: 52% females D: 53.1% females E: 47% females F: 52% females G: NA H: 69% females I: 49% females

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes. |

Describe intervention:

A:

B: Vancomycin infusion 0-15, 16-60, and 61-120 before incision

C: 0-30 minutes prior to incision >30 minutes prior to incision

D: <60 minutes preoperatively

E: <120 minutes prior to incision

F: <120 minutes prior to incision

G: 61-120, 31-60, 0-30, 1-30 minutes prior to incision.

H: 31-60, 1-30 minutes prior to incision.

I: 45-59, 30-44, 15-29, 0-14 minutes prior to incision

|

Describe control:

A: -1440 to -60 minutes

B: Vancomycin infusion 121-180 and >180 minutes before incision

C: >30 minutes prior to incision

D: >60 minutes preoperatively

E: >120 minutes prior to incision

F: >120 minutes prior to incision

G: >120 minutes prior to incision

H: >60 minutes prior to incision

I: 75-120, 60-74 minutes prior to incision |

End-point of follow-up:

A: Until discharge B: 30 days C: 30 days D: 30 days E: Until discharge F: Until discharge G: 30 days to 1 year H: 30 days to 1 year I: 30 days to 1 year

|

Outcome measure: Surgical site infections, n/N (%) more than 120 minutes prior to incision vs >120 less

A (Classen, 1992) I: 14/369 (3.8%) C: 10/1708 (0.6%)

B (Garey, 2006) I: 69/1329 (5.2%) C: 78/1079 (7.2%)

E (Lizan-Garcia (1997) I: 5/8 (62.5%) C: 249/1975 (12.6%)

F (Munoz, 1995) I: 24/107 (22.4%) C: 28/754 (3.7%)

G (Steinberg, 2009) I: 4/96 (4.1%) C: 72/3386 (2.1%)

Pooled effect (random effects model / fixed effects model): …. [95% CI …to…] favoring …. Heterogeneity (I2):

Outcome measure: Surgical site infections, n/N (%) – 120-60 vs 60-0

B (Garey, 2006) I1: 68/888 (7.7%) I2: 10/191 (5.2%)

G (Steinberg, 2009) I1: 12/489 (2.5%) I2: 60/2897 (2.1%)

I: (Weber, 2008) I1: 24/464 (5.2%) I2: 45/1487 (3.0%)

Pooled effect (random effects model / fixed effects model): …. [95% CI …to…] favoring …. Heterogeneity (I2):

Outcome measure: Surgical site infections, n/N (%) – <60 vs >60

D (Kasatbipal, 2006) I1: 9/184 (1.2%) I2: 8/1004 (0.7%)

H (Van Kasteren, 2007) I1: 39/1681 (2.3%) I2: 5/115 (4.3%)

I: (Weber, 2008) I1: 24/464 (5.2%) I2: 156/3372 (4.6%)

Outcome measure: Surgical site infections, n/N (%) – 60-30 vs 30-0

G (Steinberg, 2009) I1: 38/1558 (2.4%) I2: 22/1339 (1.6%)

H (Van Kasteren, 2007) I1: 14/538 (2.6%) I2: 25/1143 (2.2%)

Pooled effect (random effects model / fixed effects model): …. [95% CI …to…] favoring …. Heterogeneity (I2):

Outcome measure: Surgical site infections, n/N (%) <30 vs >30

C (Ho, 2011) I1: no raw data I2: no raw data Adj. OR 1.725 (95% CI 1.15 to 2.6)

I: (Weber, 2008) I1: 111/1885 (5.9%) I2: 69/1951 (3.5%)

|

Evidence tables randomized controlled trials and observational studies

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics 2 |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C) 3

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size 4 |

Comments |

|

Sommerstein (2019) |

Type of study: Cohort study.

Setting and country: Fourteen cardiac surgery centres in Switzerland, including the five Swiss university hospitals, from January 2009 through December 2017.

Funding and conflicts of interest: None declared. |

Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

N total at baseline: I1 (-120 to -60): N = 5536 I2 (-59 to 45): N = 5724 I3 (-44 to -30): N = 6780 I4 (-29 to 0): N = 2967 Total: N = 15.576

Important prognostic factors2: Age I1: 68.9 (60.0 to 75.8) years I2: 68 (59.4 to 75.0) years I3: 69 (60.2 to 75.4) years I4: 69 (60.0 to 76.0) years P=0.031

Sex: I1: 26% females (N=1441) I2: 25% females (N=1429) I3: 26% females (N=1760) I4: 26.3% females (N=780)

Groups comparable at baseline? No. Age, ASA-scores, BMI were different on baseline.

|

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

I1: SAP -120 to -60 minutes before incision.

I2: SAP -59 to -45 minutes before incision.

I3: SAP -44 to -30 minutes before incision.

I4: SAP -29 to 0 minutes before incision.

|

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

- |

Length of follow-up: One year.

Loss-to-follow-up: Not reported.

Incomplete outcome data: Not reported.

|

Outcome measure: Surgical site infections, n/N (%) -120 to -60

I1: 327/5536 (5.9%) I2: 318/5724 (5.6%) I3: 371/6780 (5.5%) I4: 149/2967 (5.0%) P=0.048

|

Author’s conclusion: In conclusion, this large prospective study provides substantial arguments that administration of SAP close to the time of the incision is more effective than the earlier provision of prophylaxis in cardiac surgery, making compliance with SAP administration easier. The choice of SAP appears to play a significant role in the prevention of all SSIs, even after adjusting for confounding variables.

|

|

Weber (2017) |

Type of study: Phase 3 randomized controlled trial.

Setting and country: Two Swiss hospitals in Basel and Aarau.

Funding and conflicts of interest: WPW reports grants from the Swiss National Science Foundation, Hospital of Aarau, University of Basel, Gottfried und Julia Bangerter- Rhyner Foundation, Hippocrate Foundation, and Nora van Meeuwen- Häfliger Foundation, during the conduct of the study; WPW received a research grant from Takeda Pharmaceuticals International for another randomised controlled trial not related to this work and has consulted for Genomic Health in the past. EM, MB, HH, SDS, MKa, TD, MvS, LI, RXSDS, JZ, HM, CK, PM, RS, AKL, MKr, LG, DO, EB-L, JL, CAF, and WRM report grants from the Swiss National Science Foundation, Hospital of Aarau, University of Basel, Gottfried und Julia Bangerter- Rhyner Foundation, Hippocrate Foundation, and Nora van Meeuwen- Häfliger Foundation, during the conduct of the study. MZ reports grants from Swiss National Science Foundation, during the conduct of the study; and grants from Swiss National Science Foundation, AstraZeneca, Aptalis Pharma, Dr Falk Pharma, Germany, GlaxoSmithKline, Nestlé, Switzerland, Receptos, Regeneron; and personal fees from Board member of Bern Cancer League and World Cancer Research Fund International, outside the submitted work. RR reports grants from the Swiss National Science Foundation, Hospital of Aarau, University of Basel, Gottfried und Julia Bangerter-Rhyner Foundation, Hippocrate Foundation, and Nora van Meeuwen-Häfliger Foundation, during the conduct of the study, outside the submitted work; and is an employee of F Hoffmann-La Roche since May 1, 2014. The present study has no connection to RR’s employment by the company, and RR continues to be affiliated with the University of Basel. AFW reports grants from the Swiss National Science Foundation, Commission for Technology and Innovation, and University of Basel, during the conduct of the study.

|

Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

N total at baseline: I1 (30-75 minutes): N = 2589 I2 (0-30 minutes): N = 2586

Important prognostic factors2: Age I1: 58.4 (43.5 to 71.9) I2: 59.0 (42.4 to 71.5)

Sex: I1: 1412/2589 (55%) M I2: 1390/2586 (54%) M

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes. |

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

I1: SAP between 30-75 minutes before incision.

|

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

I2: SAP between 0-30 minutes before incision.

|

Length of follow-up: 30 days.

Loss-to-follow-up: N = 293 (11%)

Incomplete outcome data: N = 286 (11%)

|

Outcome measure: Surgical site infections, n/N (%) - -75 to -30 versus 0-30 I1: 113/2296 (5%) I2: 121/2300 (5%)

Outcome measure: (all-cause) 30-day mortality, n/N (%) - -75 to -30 versus 0-30 I1: 29/2296 (1%) I2: 24/2300 (1%)

|

Author’s conclusion: In conclusion, early administration of cefuroxime (plus metronidazole in colorectal surgery) did not significantly lower the risk of SSI compared with late administration before incision. Even though the present results do not rule out a beneficial effect of early administration of SAP on the risk of SSI, they do not support changing current recommendations to administer SAP during the 60 min before incision.

|

|

De Jonge (2019) |

Type of study: Observational cohort study.

Setting and country: Six operating rooms dedicated to these specialities in the AMC.

Funding and conflicts of interest: None declared.

|

Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

N total at baseline: I1 (>120 minutes): N = 4 I2 (120-60 minutes): N = 273 I3 (60-30 minutes): N = 1062 I4 (30 to 0 minutes): N = 1550

Important prognostic factors2:

Sex: I1: 2/4 (50%) males I2: 163/273 (59.7%) males I3: 478/1062 (45.0%) males I4: 575/1550 (37.1%) males

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes.

|

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

I1: SAP > 120 minutes before incision.

I2: SAP 120-60 minutes before incision.

I3: SAP 60-30 minutes before incision.

I4: SAP 30-0 minutes before incision.

|

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

- |

Length of follow-up: 30 days (for the occurrence of SSI).

Loss-to-follow-up: None reported.

|

Outcome measure: All (superficial and deep) surgical site infections, n/N (%)

I1: 0/4 (0%) I2: 15/273 (5.5%) I3: 68/1062 (6.4%) I4: 74/1550 (4.8%)

|

Author’s conclusion: We found no evidence of a superior timing interval for administration of SAP with short infusion time within the 60-minute interval before incision. These findings are in line with recent recommendations by the World Health Organization and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to administer antibiotic prophy- laxis before incision while considering the half-life of the agent.

|

Quality assessment systematic review and meta-analysis

|

Study

First author, year |

Appropriate and clearly focused question?1

Yes/no/unclear |

Comprehensive and systematic literature search?2

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of included and excluded studies?3

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of relevant characteristics of included studies?4

Yes/no/unclear |

Appropriate adjustment for potential confounders in observational studies?5

Yes/no/unclear/not applicable |

Assessment of scientific quality of included studies?6

Yes/no/unclear |

Enough similarities between studies to make combining them reasonable?7

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential risk of publication bias taken into account?8

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential conflicts of interest reported?9

Yes/no/unclear |

|

De Jonge (2016) |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Quality assessment randomized controlled trials

|

Study reference

(first author, publication year) |

Was the allocation sequence adequately generated?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was the allocation adequately concealed?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Blinding: Was knowledge of the allocated interventions adequately prevented? Were patients blinded? Were healthcare providers blinded? Were data collectors blinded? Were outcome assessors blinded? Were data analysts blinded?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no

|

Was loss to follow-up (missing outcome data) infrequent?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Are reports of the study free of selective outcome reporting?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was the study apparently free of other problems that could put it at a risk of bias?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Overall risk of bias If applicable/necessary, per outcome measure

Low Some concerns High

|

|

Weber (2017) |

Definitely yes

Reason: patients were randomly assigned to receive SAP early (2798 patients) or late (2782 patients).

|

Definitely yes.

Reason: For the purpose of communication of treatment allocation to the anaesthesia team, the randomisation list was linked with the clinical data system (developed by ProtecData, Boswil, Switzerland). To see the result of randomisation, the members of the anaesthesia team had to log into the clinical data system and press a button with a time stamp. This button was a mandatory item to print their routine preoperative assessment sheet with the treatment plan on the day of surgery. It only appeared if a patient was included in the study. The result was then presented for that specific patient and procedure on-screen and was included in the printed sheet. At no time did the anaesthesiologists or anaesthesia nurses have access to the randomisation list.

|

Definitely yes

Reason: Patients and the outcome assessment team were blinded to group assignment.

|

Probably no

Reason: lost to follow up almost equal between both groups. |

Probably yes

Reason: all predefined outcomes were reported. |

Probably yes |

Low. |

Quality assessment observational studies

|

Author, year |

Selection of participants

Was selection of exposed and non-exposed cohorts drawn from the same population?

Definitely yes, probably yes, probably no, definitely no |

Exposure

Can we be confident in the assessment of exposure?

Definitely yes, probably yes, probably no, definitely no |

Outcome of interest

Can we be confident that the outcome of interest was not present at start of study?

Definitely yes, probably yes, probably no, definitely no |

Confounding-assessment

Can we be confident in the assessment of confounding factors?

Definitely yes, probably yes, probably no, definitely no |

Confounding-analysis

Did the study match exposed and unexposed for all variables that are associated with the outcome of interest or did the statistical analysis adjust for these confounding variables?

Definitely yes, probably yes, probably no, definitely no |

Assessment of outcome

Can we be confident in the assessment of outcome?

Definitely yes, probably yes, probably no, definitely no |

Follow up

Was the follow up of cohorts adequate? In particular, was outcome data complete or imputed?

Definitely yes, probably yes, probably no, definitely no |

Co-interventions

Were co-interventions similar between groups?

Definitely yes, probably yes, probably no, definitely no |

Overall Risk of bias

Low, Some concerns, High |

|

De Jonge (2019) |

Definitely yes

Reason: From March 2010 until March 2012 the timing of surgical antibiotic prophylaxis and surgical site infections cohort study recruited consecutive patients undergoing general, orthopedic, or gynaecologic surgical procedures in 6 operating rooms dedicated to these specialties in the AMC, a tertiary care center in Amsterdam, the Netherlands.

|

Probably yes

|

No information.

|

Definitely yes

Reason: adjusted for confounding through multivariable logistic regression.

|

Definitely yes

Reason: The risk of SSI was compared between patients, categorized by the time interval between SAP administration and incision, and adjusted for confounding through multivariable logistic regression.

|

Probably yes

|

Probably yes

Reason: We assumed that missing data occurred at random and used multiple imputation by chained equation to suitably impute missing values, generating 10 copies of the data. Multivariable logistic regres- sion analysis was then used to analyze each copy of the data independently as described by Van Buuren.18 Group Lasso with 10-fold cross validation was used independently in each copy of the data for model selection among candidate confounders.

When patients were dismissed from outpatient follow up, and did not return to the emergency room or outpatient clinic with wound healing problems as instructed, it was assumed there was no SSI.

|

Probably yes

Reason: Patients were followed as part of routine clinical care and outpatient follow up, including SSI surveillance according to the CDC definition.

|

Low

|

|

Sommerstein (2019) |

Probably yes

Reason: All patients in the surveillance programme who underwent car- diac surgery procedures, including coronary artery bypass graft, valve repair/replacement and placement of implantable cardio- vascular devices (e.g. ventricular assist devices, excluding pacemakers) between 2009 and 2017

|

Probably yes |

No information. |

Probably yes, except for one confounder

Reason: we only considered the timing of the first agent applied earliest before the incision, a potential confounder we were un- able to control for.

|

Probably yes

Reason: after adjusting for confounding variables.

|

Probably yes |

Probably yes

Reason: Missing data (including loss to follow-up) were investigated using multiple imputation, assuming missingness was random

|

No information |

Some concerns. |

|

Classen (1992) |

Probably yes.

Reason: all patients who underwent elective operations at the study institution.

|

No information. |

Probably yes. |

No information. |

No information |

Probably yes |

No information |

No information |

Some concerns. Lack of information for multiple topics. |

|

Garey, 2006 |

Probably yes |

No information. |

Probably yes

Reason: Patients were excluded if surgery was due to an infection-related diagnosis such as endo- carditis, if they had undergone previous cardiac surgery within the past year or if they did not receive vancomycin prophylaxis.

|

Probably yes.

Reason: Risk factors were checked for confounding, collinearity and interaction.

|

Probably yes

Reason: Because the process of assigning patients to different study groups was not random, potential selection bias among study groups due to unknown or unobserved confounders could not be completely excluded. To ensure that the study results were not significantly affected by the potential selection bias, the effect of vancomycin prophylaxis timing on the incidence of SSI was re-estimated using a two-stage Heckman model

|

Probably yes. |

No information. |

Probably yes. |

Some concerns. |

|

Kasatbipal, 2006) |

Probably yes

|

No information |

Probably yes

Reason: We excluded appendectomies inci- dental to other operative procedures and the patients who were on antibiotic therapy.

|

No information. |

No information. |

Probably yes

Reason: We used criteria of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) NNIS System to diagnose SSI. Infec- tions were classified as superficial incisional, deep inci- sional, or organ/space SSI

|

No information. |

No information. |

Some concerns. Lack of information for several topics. |

|

Lizan Garcia (1997) |

Probably yes |

No information |

No information. |

No information |

Probably yes |

Probably yes |

Probably yes |

No information. |

Some concerns. |

|

Munoz (1995) |

Probably yes |

Probably yes. |

Probably yes. |

No information |

Probably yes |

Probably yes |

Probably yes |

No information. |

Some concerns. |

|

Steinberg (2009) |

Definitely yes |

Probably yes |

Probably yes. |

Definitely yes

Reason: Conditional lo- gistic regression was also used to examine the effect of potential confounding factors such as period of measurement, group status, procedure type, procedure duration, and ASA score of the patient undergoing the procedure.

|

Probably yes.

|

Probably yes |

Probably yes |

No information |

Low |

|

Van Kasteren (2007) |

Probably yes |

Probably yes. |

Probably yes. |

No information |

Probably yes |

Probably yes |

Probably yes |

No information. |

Some concerns. |

|

Weber (2008) |

Probably yes |

Probably yes. |

Probably yes. |

Probably yes |

Probably yes |

Probably yes |

Probably yes |

No information. |

Low. |

Table of excluded studies

|

|

Reference: |

Reason for exclusion: |

|

De Jonge 2017 |

Akinyoola 2011 |

Article did not asses an association between timing of pre-operative antibiotic prophylaxis and SSI |

|

Butts 1997 |

Irrelevant study type (i.e. conference abstract/narrative review/ survey) |

|

|

Goede 2013 |

Article did not asses an association between timing of pre-operative antibiotic prophylaxis and SSI |

|

|

Hawn 2008 |

No different timing groups compared / timing groups unclear* |

|

|

Hawn 2013 |

No different timing groups compared / timing groups unclear* |

|

|

Hollenbeak 2000 |

No different timing groups compared / timing groups unclear* |

|

|

Junker 2012 |

Irrelevant study type (i.e. conference abstract/narrative review/ survey) |

|

|

Keller 1996 |

Article did not asses an association between timing of pre-operative antibiotic prophylaxis and SSI |

|

|

Lallemand 2002 |

No different timing groups compared / timing groups unclear* |

|

|

Lee 2013 |

No different timing groups compared / timing groups unclear* |

|

|

Matuschka 1996 |

Irrelevant study type (i.e. conference abstract/narrative review/ survey) |

|

|

Miliani 2009 |

No different timing groups compared / timing groups unclear* |

|

|

Misteli 2012 |

Article did not asses an association between timing of pre-operative antibiotic prophylaxis and SSI |

|

|

Montes 2014 |

No different timing groups compared / timing groups unclear* |

|

|

Nishant 2013 |

Study provided insufficient data for comparison |

|

|

Norman 2013 |

Irrelevant study type (i.e. conference abstract/narrative review/ survey) |

|

|

Oh 2014 |

Article did not asses an association between timing of pre-operative antibiotic prophylaxis and SSI |

|

|

Peterson 1990 |

Article did not asses an association between timing of pre-operative antibiotic prophylaxis and SSI |

|

|

Silver 1996 |

Article did not asses an association between timing of pre-operative antibiotic prophylaxis and SSI |

|

|

Sorenson 1992 |

Irrelevant study type (i.e. conference abstract/narrative review/ survey) |

|

|

Soriano 2008 |

Article did not asses an association between timing of pre-operative antibiotic prophylaxis and SSI |

|

|

Turner Vosseler 2016 |

Irrelevant study type (i.e. conference abstract/narrative review/ survey) |

|

|

Walz 2006 |

No different timing groups compared / timing groups unclear* |

|

|

Wang 2012 |

Article did not asses an association between timing of pre-operative antibiotic prophylaxis and SSI |

|

|

Willemsen 2007 |

Article did not asses an association between timing of pre-operative antibiotic prophylaxis and SSI |

|

|

Wu 2014 |

No different timing groups compared / timing groups unclear* |

|

|

Update |

El-Mahallawy 2013 |

No data available |

|

De Jonge 2017 |

Systematic review |

|

|

Koch 2012 |

No data available |

|

|

Koch 2013 |

No data available |

|

|

Tantigate 2017 |

Outcome not of interest |

|

|

Turner Vosseler 2016 |

Irrelevant study type (i.e. conference abstract/narrative review/ survey) |

|

|

Wu 2014 |

No data available |

|

|

Akinyoola AL, Adegbehingbe OO, Odunsi A. Timing of antibiotic prophylaxis in tourniquet surgery. JFoot Ankle Surg. 2011;50(4):374-376. Butts JD, Wolford ET. Timing of perioperative antibiotic administration. AORN J. 1997;65(1):109-115. de Jonge SW, Gans SL, Atema JJ, Solomkin JS, Dellinger PE, Boermeester MA. Timing of preoperative antibiotic prophylaxis in 54,552 patients and the risk of surgical site infection: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96(29):e6903. El-Mahallawy HA, Hassan SS, Khalifa HI, et al. Comparing a combination of penicillin G and gentamicin to a combination of clindamycin and amikacin as prophylactic antibiotic regimens prevention of clean contaminated wound infections in cancer surgery. J Egypt Natl Canc Inst 2013;25:31–5. Goede WJ, Lovely JK, Thompson RL, Cima RR. Assessment of prophylactic antibiotic use in patients with surgical site infections. HospPharm. 2013;48(7):560-567. Hawn MT, Itani KM, Gray SH, Vick CC, Henderson W, Houston TK. Association of timely administration of prophylactic antibiotics for major surgical procedures and surgical site infection. JAmCollSurg. 2008;206(5):814-819. Hawn MT, Richman JS, Vick CC, et al. Timing of surgical antibiotic prophylaxis and the risk of surgical site infection. JAMA Surg. 2013;148(7):649-657. Hollenbeak CS, Murphy DM, Koenig S, Woodward RS, Dunagan WC, Fraser VJ. The clinical and economic impact of deep chest surgical site infections following coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Chest. 2000;118(2):397-402. Junker T, Mujagic E, Hoffmann H, et al. Prevention and control of surgical site infections: review of the Basel Cohort Study. SwissMedWkly. 2012;142:w13616. Keller CE, Cobb AB, Moseley B. Timing of prophylactic antibiotics in selected surgical procedures. JMissState MedAssoc. 1995;36(6):166-167. Koch CG, Nowicki ER, Rajeswaran J, et al. When the timing is right: antibiotic timing and infection after cardiac surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2012;144:931–7. Koch CG, Li L, Hixson E, et al. Is it time to refine? An exploration and simulation of optimal antibiotic timing in general surgery. JAm Coll Surg 2013;217:628–35. Lallemand S, Thouverez M, Bailly P, Bertrand X, Talon D. Non-observance of guidelines for surgical antimicrobial prophylaxis and surgical-site infections. PharmWorld Sci. 2002;24(3):95-99. Lee FM, Trevino S, Kent-Street E, Sreeramoju P. Antimicrobial prophylaxis may not be the answer: Surgical site infections among patients receiving care per recommended guidelines. AmJInfectControl. 2013;41(9):799-802. Matuschka PR. Improving the timing of antimicrobial prophylaxis. AmJHealth SystPharm. 1996;53(15):1846, 1849. Miliani K, L'Heriteau F, Astagneau P. Non-compliance with recommendations for the practice of antibiotic prophylaxis and risk of surgical site infection: results of a multilevel analysis from the INCISO Surveillance Network. JAntimicrobChemother. 2009;64(6):1307-1315. Misteli H, Widmer AF, Weber WP, et al. Successful implementation of a window for routine antimicrobial prophylaxis shorter than that of the World Health Organization standard. InfectControl HospEpidemiol. 2012;33(9):912-916. Montes CV, Vilar-Compte D, Velazquez C, Golzarri MF, Cornejo-Juarez P, Larson EL. Risk Factors for Extended Spectrum beta-Lactamase-Producing Escherichia coli versus Susceptible E. coli in Surgical Site Infections among Cancer Patients in Mexico. Surg Infect(Larchmt). 2014. Nishant, Kailash KK, Vijayraghavan PV. Prospective randomized study for antibiotic prophylaxis in spine surgery: choice of drug, dosage, and timing. Asian Spine J. 2013;7(3):196-203. Norman BA, Bartsch SM, Duggan AP, et al. The economics and timing of preoperative antibiotics for orthopaedic procedures. JHospInfect. 2013;85(4):297-302. Oh AL, Goh LM, Nik Azim NA, Tee CS, Shehab Phung CW. Antibiotic usage in surgical prophylaxis: a prospective surveillance of surgical wards at a tertiary hospital in Malaysia. JInfectDevCtries. 2014;8(2):193-201. Peterson CD, Schultz NJ, Goldberg DE. Pharmacist monitoring of the timing of preoperative antibiotic administration. AmJHospPharm. 1990;47(2):384-386. Silver A, Eichorn A, Kral J, et al. Timeliness and use of antibiotic prophylaxis in selected inpatient surgical procedures. The Antibiotic Prophylaxis Study Group. AmJSurg. 1996;171(6):548-552. Sorensen R. Preoperative antibiotics and time of administration. P and T.18(3):1993. Soriano A, Bori G, Garcia-Ramiro S, et al. Timing of antibiotic prophylaxis for primary total knee arthroplasty performed during ischemia. ClinInfectDis. 2008;46(7):1009-1014. Tantigate D, Jang E, Seetharaman M, et al. Timing of Antibiotic Prophylaxis for Preventing Surgical Site Infections in Foot and Ankle Surgery. Foot Ankle Int. 2017;38(3):283-288 Turner Vosseller J, Tantigate D, Jang E, et al. Timing of antibiotic prophylaxis for preventing surgical site infections in foot and ankle surgery. Foot and Ankle Surgery. 2016;1):57-58. Walz JM, Paterson CA, Seligowski JM, Heard SO. Surgical site infection following bowel surgery: a retrospective analysis of 1446 patients. Arch Surg. 2002;141(10):1014-1018. Wang F, Chen XZ, Liu J, et al. Short-term versus long-term administration of single prophylactic antibiotic in elective gastric tumor surgery. Hepatogastroenterology. 2012;59(118):1784-1788. Willemsen I, van den Broek R, Bijsterveldt T, et al. A standardized protocol for perioperative antibiotic prophylaxis is associated with improvement of timing and reduction of costs. Journal of Hospital Infection.67(2):October. Wu W-T, Tai F-C, Wang P-C, Tsai M-L. Surgical site infection and timing of prophylactic antibiotics for appendectomy. Surgical Infections. 2014;15(6):781-785. |

||

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Laatst beoordeeld : 01-12-2024

Algemene gegevens

De ontwikkeling/herziening van deze richtlijnmodule werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten (www.demedischspecialist.nl/kennisinstituut) en werd gefinancierd uit de Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS). De financier heeft geen enkele invloed gehad op de inhoud van de richtlijnmodule.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijnmodules 2 tot 16 is in 2020 op initiatief van de NVvH een multidisciplinaire werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen (zie hiervoor de Samenstelling van de werkgroep) die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor preventie van postoperatieve wondinfecties. Daarnaast is in 2022 op initiatief van het Samenwerkingsverband Richtlijnen Infectiepreventie (SRI) een separate multidisciplinaire werkgroep samengesteld voor de herziening van de WIP-richtlijn over postoperatieve wondinfecties: module 17-22. De ontwikkelde modules van beide werkgroepen zijn in deze richtlijn samengevoegd.

Belangenverklaringen

De Code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling is gevolgd. Alle werkgroepleden hebben schriftelijk verklaard of zij in de laatste drie jaar directe financiële belangen (betrekking bij een commercieel bedrijf, persoonlijke financiële belangen, onderzoek financiering) of indirecte belangen (persoonlijke relaties, reputatiemanagement) hebben gehad. Gedurende de ontwikkeling of herziening van een module worden wijzigingen in belangen aan de voorzitter doorgegeven. De belangenverklaring wordt opnieuw bevestigd tijdens de commentaarfase.

Een overzicht van de belangen van werkgroepleden en het oordeel over het omgaan met eventuele belangen vindt u in onderstaande tabel. De ondertekende belangenverklaringen zijn op te vragen bij het secretariaat van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

|

Werkgroeplid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

Mevr. prof. dr. M.A. Boermeester |

Chirurg |

* Medisch Ethische Commissie, Amsterdam UMC, locatie AMC * Antibiotica Commissie, Amsterdam UMC |

Persoonlijke financiële belangen Hieronder staan de beroepsmatige relaties met bedrijfsleven vermeld waarbij eventuele financiële belangen via de AMC Research B.V. lopen, dus institutionele en geen persoonlijke gelden zijn: Skillslab instructeur en/of spreker (consultant) voor KCI/3M, Smith&Nephew, Johnson&Johnson, Gore, BD/Bard, TELABio, GDM, Medtronic, Molnlycke.

Persoonlijke relaties Geen.

Extern gefinancierd onderzoek Institutionele grants van KCI/3M, Johnson&Johnson en New Compliance.

Intellectuele belangen en reputatie Ik maak me sterk voor een 100% evidence-based benadering van maken van aanbevelingen, volledig transparant en reproduceerbaar. Dat is mijn enige belang in deze, geen persoonlijk gewin.

Overige belangen Geen.

|

Extra kritische commentaarronde. |

|

Dhr. dr. M.J. van der Laan |

Vaatchirurg |

Vice voorzitter Consortium Kwaliteit van Zorg NFU, onbetaald

|

Persoonlijke financiële belangen Geen.

Persoonlijke relaties Geen.

Extern gefinancierd onderzoek Geen.

Intellectuele belangen en reputatie Geen.

Overige belangen Geen.

|

Geen.

|

|

Dhr. dr. W.C. van der Zwet |

Arts-microbioloog |

Lid Regionaal Coördinatie Team, Limburgs infectiepreventie & ABR Zorgnetwerk (onbetaald) |

||

|

Dhr. dr. D.R. Buis |

Neurochirurg |

Lid Hoofdredactieraad Tijdschrift voor Neurologie & Neurochirurgie - onbetaald |

||

|

Dhr. dr. J.H.M. Goosen |

Orthopaedisch Chirurg |

Inhoudelijke presentaties voor Smith&Nephew en Zimmer Biomet. Deze worden vergoed per uur. |

||

|

Mw. drs. H. Jalalzadeh |

Arts-onderzoeker |

Geen. |

Persoonlijke financiële belangen Geen.

Persoonlijke relaties Geen.

Extern gefinancierd onderzoek Geen.

Intellectuele belangen en reputatie Geen.

Overige belangen Geen. |

Geen.

|

|

Dhr. dr. N. Wolfhagen |

AIOS chirurgie |

|||

|

Mw. drs. H. Groenen |

Arts-onderzoeker |

|||

|

Dhr. dr. F.F.A. Ijpma |

Traumachirurg |

|||

|

Dhr. dr. P. Segers |

Cardiothoracaal chirurg |

|||

|

Mw. Y.E.M. Dreissen |

AIOS neurochirurgie |

|||

|

Dhr. R.R. Schaad |

Anesthesioloog |

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Er werd aandacht besteed aan het patiëntenperspectief door uitnodigen van de Patiëntenfederatie Nederland voor de invitational conference. De verkregen input is meegenomen bij het opstellen van de uitgangsvragen, de keuze voor de uitkomstmaten en bij het opstellen van de overwegingen. De conceptmodules zijn tevens voor commentaar voorgelegd aan de Patiëntenfederatie Nederland en de eventueel aangeleverde commentaren zijn bekeken en verwerkt. Voor de modules 17-22 was de patiëntfederatie vertegenwoordigd in de werkgroep.

Wkkgz & Kwalitatieve raming van mogelijke substantiële financiële gevolgen

Bij de richtlijn is conform de Wet kwaliteit, klachten en geschillen zorg (Wkkgz) een kwalitatieve raming uitgevoerd of de aanbevelingen mogelijk leiden tot substantiële financiële gevolgen. Bij het uitvoeren van deze beoordeling zijn richtlijnmodules op verschillende domeinen getoetst (zie het stroomschema op de Richtlijnendatabase).

Uit de kwalitatieve raming blijkt dat er waarschijnlijk geen substantiële financiële gevolgen zijn.

Voor module 8 (Negatieve druktherapie) geldt dat uit de toetsing volgt dat de aanbeveling(en) breed toepasbaar zijn (5.000 - 40.000 patiënten). Tevens volgt uit de toetsing dat het geen nieuwe manier van zorgverlening of andere organisatie van zorgverlening betreft. Er worden daarom geen substantiële financiële gevolgen verwacht.

Voor de overige modules en aanbevelingen geldt dat uit de toetsing volgt dat de aanbeveling(en) breed toepasbaar zijn (>40.000 patiënten). Tevens volgt uit de toetsing dat het overgrote deel (±90%) van de zorgaanbieders en zorgverleners al aan de norm voldoet en het geen nieuwe manier van zorgverlening of andere organisatie van zorgverlening betreft. Ook wordt geen toename in het aantal in te zetten voltijdsequivalenten aan zorgverleners verwacht of een wijziging in het opleidingsniveau van zorgpersoneel. Er worden daarom geen substantiële financiële gevolgen verwacht.

Methode ontwikkeling

Evidence based

Implementatie

Zie voor de implementatie het implementatieplan in het tabblad 'Bijlagen'.

Werkwijze

AGREE

Deze richtlijnmodule is opgesteld conform de eisen vermeld in het rapport Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 van de adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwaliteit. Dit rapport is gebaseerd op het AGREE II instrument (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II; Brouwers, 2010).

Knelpuntenanalyse en uitgangsvragen

Tijdens de voorbereidende fase inventariseerde de werkgroepen de knelpunten in de zorg voor patiënten die chirurgie ondergaan. Tevens zijn er knelpunten aangedragen door middel van een invitational conference. De verslagen hiervan zijn opgenomen onder aanverwante producten.

Op basis van de uitkomsten van de knelpuntenanalyse zijn door de werkgroep concept-uitgangsvragen opgesteld en definitief vastgesteld.

Uitkomstmaten

Na het opstellen van de zoekvraag behorende bij de uitgangsvraag inventariseerde de werkgroep welke uitkomstmaten voor de patiënt relevant zijn, waarbij zowel naar gewenste als ongewenste effecten werd gekeken. Hierbij werd een maximum van acht uitkomstmaten gehanteerd. De werkgroep waardeerde deze uitkomstmaten volgens hun relatieve belang bij de besluitvorming rondom aanbevelingen, als cruciaal (kritiek voor de besluitvorming), belangrijk (maar niet cruciaal) en onbelangrijk. Tevens definieerde de werkgroep tenminste voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten welke verschillen zij klinisch (patiënt) relevant vonden.

Methode literatuursamenvatting

Een uitgebreide beschrijving van de strategie voor zoeken en selecteren van literatuur is te vinden onder ‘Zoeken en selecteren’ onder Onderbouwing. Indien mogelijk werd de data uit verschillende studies gepoold in een random-effects model. De beoordeling van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs wordt hieronder toegelicht.

Beoordelen van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs

De kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs werd bepaald volgens de GRADE-methode. GRADE staat voor ‘Grading Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation’ (zie http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/). De basisprincipes van de GRADE-methodiek zijn: het benoemen en prioriteren van de klinisch (patiënt) relevante uitkomstmaten, een systematische review per uitkomstmaat, en een beoordeling van de bewijskracht per uitkomstmaat op basis van de acht GRADE-domeinen (domeinen voor downgraden: risk of bias, inconsistentie, indirectheid, imprecisie, en publicatiebias; domeinen voor upgraden: dosis-effect relatie, groot effect, en residuele plausibele confounding).

GRADE onderscheidt vier gradaties voor de kwaliteit van het wetenschappelijk bewijs: hoog, redelijk, laag en zeer laag. Deze gradaties verwijzen naar de mate van zekerheid die er bestaat over de literatuurconclusie, in het bijzonder de mate van zekerheid dat de literatuurconclusie de aanbeveling adequaat ondersteunt (Schünemann, 2013; Hultcrantz, 2017).

|

GRADE |

Definitie |

|

Hoog |

|

|

Redelijk |

|

|

Laag |

|

|

Zeer laag |

|

Bij het beoordelen (graderen) van de kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs in richtlijnen volgens de GRADE-methodiek spelen grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming een belangrijke rol (Hultcrantz, 2017). Dit zijn de grenzen die bij overschrijding aanleiding zouden geven tot een aanpassing van de aanbeveling. Om de grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming te bepalen moeten alle relevante uitkomstmaten en overwegingen worden meegewogen. De grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming zijn daarmee niet één op één vergelijkbaar met het minimaal klinisch relevant verschil (Minimal Clinically Important Difference, MCID). Met name in situaties waarin een interventie geen belangrijke nadelen heeft en de kosten relatief laag zijn, kan de grens voor klinische besluitvorming met betrekking tot de effectiviteit van de interventie bij een lagere waarde (dichter bij het nuleffect) liggen dan de MCID (Hultcrantz, 2017).

Overwegingen (van bewijs naar aanbeveling)

Om te komen tot een aanbeveling zijn naast (de kwaliteit van) het wetenschappelijke bewijs ook andere aspecten belangrijk en worden meegewogen, zoals aanvullende argumenten uit bijvoorbeeld de biomechanica of fysiologie, waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten, kosten (middelenbeslag), aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie. Deze aspecten zijn systematisch vermeld en beoordeeld (gewogen) onder het kopje ‘Overwegingen’ en kunnen (mede) gebaseerd zijn op expert opinion. Hierbij is gebruik gemaakt van een gestructureerd format gebaseerd op het evidence-to-decision framework van de internationale GRADE Working Group (Alonso-Coello, 2016a; Alonso-Coello 2016b). Dit evidence-to-decision framework is een integraal onderdeel van de GRADE methodiek.

Formuleren van aanbevelingen

De aanbevelingen geven antwoord op de uitgangsvraag en zijn gebaseerd op het beschikbare wetenschappelijke bewijs en de belangrijkste overwegingen, en een weging van de gunstige en ongunstige effecten van de relevante interventies. De kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs en het gewicht dat door de werkgroep wordt toegekend aan de overwegingen, bepalen samen de sterkte van de aanbeveling. Conform de GRADE-methodiek sluit een lage bewijskracht van conclusies in de systematische literatuuranalyse een sterke aanbeveling niet a priori uit, en zijn bij een hoge bewijskracht ook zwakke aanbevelingen mogelijk (Agoritsas, 2017; Neumann, 2016). De sterkte van de aanbeveling wordt altijd bepaald door weging van alle relevante argumenten tezamen. De werkgroep heeft bij elke aanbeveling opgenomen hoe zij tot de richting en sterkte van de aanbeveling zijn gekomen.

In de GRADE-methodiek wordt onderscheid gemaakt tussen sterke en zwakke (of conditionele) aanbevelingen. De sterkte van een aanbeveling verwijst naar de mate van zekerheid dat de voordelen van de interventie opwegen tegen de nadelen (of vice versa), gezien over het hele spectrum van patiënten waarvoor de aanbeveling is bedoeld. De sterkte van een aanbeveling heeft duidelijke implicaties voor patiënten, behandelaars en beleidsmakers (zie onderstaande tabel). Een aanbeveling is geen dictaat, zelfs een sterke aanbeveling gebaseerd op bewijs van hoge kwaliteit (GRADE gradering HOOG) zal niet altijd van toepassing zijn, onder alle mogelijke omstandigheden en voor elke individuele patiënt.

|

Implicaties van sterke en zwakke aanbevelingen voor verschillende richtlijngebruikers |

||

|

|

Sterke aanbeveling |

Zwakke (conditionele) aanbeveling |

|

Voor patiënten |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen en slechts een klein aantal niet. |

Een aanzienlijk deel van de patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen, maar veel patiënten ook niet. |

|

Voor behandelaars |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak moeten ontvangen. |

Er zijn meerdere geschikte interventies of aanpakken. De patiënt moet worden ondersteund bij de keuze voor de interventie of aanpak die het beste aansluit bij zijn of haar waarden en voorkeuren. |

|

Voor beleidsmakers |

De aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kan worden gezien als standaardbeleid. |

Beleidsbepaling vereist uitvoerige discussie met betrokkenheid van veel stakeholders. Er is een grotere kans op lokale beleidsverschillen. |

Organisatie van zorg

In de knelpuntenanalyse en bij de ontwikkeling van de richtlijnmodule is expliciet aandacht geweest voor de organisatie van zorg: alle aspecten die randvoorwaardelijk zijn voor het verlenen van zorg (zoals coördinatie, communicatie, (financiële) middelen, mankracht en infrastructuur). Randvoorwaarden die relevant zijn voor het beantwoorden van deze specifieke uitgangsvraag zijn genoemd bij de overwegingen. Meer algemene, overkoepelende, of bijkomende aspecten van de organisatie van zorg worden behandeld in de module Organisatie van zorg.

Commentaar- en autorisatiefase

De conceptrichtlijnmodule werd aan de betrokken (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd ter commentaar. De commentaren werden verzameld en besproken met de werkgroep. Naar aanleiding van de commentaren werd de conceptrichtlijnmodule aangepast en definitief vastgesteld door de werkgroep. De definitieve richtlijnmodule werd aan de deelnemende (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd voor autorisatie en door hen geautoriseerd dan wel geaccordeerd.

Adaptatie

Een aantal modules van deze richtlijn betreft een adaptatie van modules van de World Health Organization (WHO)-richtlijn ‘Global guidelines for the prevention of surgical site infection’ (WHO, 2018), te weten:

- Module Normothermie

- Module Immunosuppressive middelen

- Module Glykemische controle

- Module Antimicrobiële afdichtingsmiddelen

- Module Wondbeschermers bij laparotomie

- Module Preoperatief douchen

- Module Preoperatief verwijderen van haar

- Module Chirurgische handschoenen: Vervangen en type handschoenen

- Module Afdekmaterialen en operatiejassen

Methode

- Uitgangsvragen zijn opgesteld in overeenstemming met de standaardprocedures van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

- De inleiding van iedere module betreft een korte uiteenzetting van het knelpunt, waarbij eventuele onduidelijkheid en praktijkvariatie voor de Nederlandse setting wordt beschreven.

- Het literatuuronderzoek is overgenomen uit de WHO-richtlijn. Afhankelijk van de beoordeling van de actualiteit van de richtlijn is een update van het literatuuronderzoek uitgevoerd.

- De samenvatting van de literatuur is overgenomen van de WHO-richtlijn, waarbij door de werkgroep onderscheid is gemaakt tussen ‘cruciale’ en ‘belangrijke’ uitkomsten. Daarnaast zijn door de werkgroep grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming gedefinieerd in overeenstemming met de standaardprocedures van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten, en is de interpretatie van de bevindingen primair gebaseerd op klinische relevantie van het gevonden effect, niet op statistische significantie. In de meta-analyses zijn naast odds-ratio’s ook relatief risico’s en risicoverschillen gerapporteerd.

- De beoordeling van de mate van bewijskracht is overgnomen van de WHO-richtlijn, waarbij de beoordeling is gecontroleerd op consistentie met de standaardprocedures van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten (GRADE-methode; http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/). Eventueel door de WHO gerapporteerde bewijskracht voor observationele studies is niet overgenomen indien ook gerandomiseerde gecontroleerde studies beschikbaar waren.

- De conclusies van de literatuuranalyse zijn geformuleerd in overeenstemming met de standaardprocedures van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

- In de overwegingen heeft de werkgroep voor iedere aanbeveling het bewijs waarop de aanbeveling is gebaseerd en de aanvaardbaarheid en toepasbaarheid van de aanbeveling voor de Nederlandse klinische praktijk beoordeeld. Op basis van deze beoordeling is door de werkgroep besloten welke aanbevelingen ongewijzigd zijn overgenomen, welke aanbevelingen niet zijn overgenomen, en welke aanbevelingen (mits in overeenstemming met het bewijs) zijn aangepast naar de Nederlandse context. ‘De novo’ aanbevelingen zijn gedaan in situaties waarin de werkgroep van mening was dat een aanbeveling nodig was, maar deze niet als zodanig in de WHO-richtlijn was opgenomen. Voor elke aanbeveling is vermeld hoe deze tot stand is gekomen, te weten: ‘WHO’, ‘aangepast van WHO’ of ‘de novo’.

Voor een verdere toelichting op de procedure van adapteren wordt verwezen naar de Bijlage Adapteren.

Literatuur

Agoritsas T, Merglen A, Heen AF, Kristiansen A, Neumann I, Brito JP, Brignardello-Petersen R, Alexander PE, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Guyatt GH. UpToDate adherence to GRADE criteria for strong recommendations: an analytical survey. BMJ Open. 2017 Nov 16;7(11):e018593. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018593. PubMed PMID: 29150475; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5701989.

Alonso-Coello P, Schünemann HJ, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Rada G, Rosenbaum S, Morelli A, Guyatt GH, Oxman AD; GRADE Working Group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 1: Introduction. BMJ. 2016 Jun 28;353:i2016. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2016. PubMed PMID: 27353417.