Prolongatie van antimicrobiële profylaxe

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is het effect van postoperatieve profylactische toediening van antibiotica bij patiënten die een operatie ondergaan op de preventie van postoperatieve wondinfecties?

Aanbeveling

Ter preventie van postoperatieve wondinfecties is het niet noodzakelijk of wenselijk de perioperatieve intraveneuze antibiotische profylaxe te continueren na de operatie.

De toediening van perioperatieve intraveneuze antibiotische profylaxe (ter voorkoming van postoperatieve wondinfecties) dient te voldoen aan de volgende voorwaarden:

- Eerste dosering <60 min voor incisie of aanleggen bloedleegte gegeven

- Direct postoperatief staken

Voor herdosering verwijst de werkgroep naar de SWAB-richtlijn Peri-operatieve profylaxe (2019). (paragraaf Organisatie, timing en duur van de profylaxe)

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Als matig beoordeeld bewijs uit een meta-analyse van 58 gerandomiseerde gecontroleerde onderzoeken (RCT's) met 20.918 deelnemers toonde geen doorslaggevend bewijs voor het voordeel van het voortzetten van antibiotische profylaxe na de operatie voor het verminderen van de incidentie van postoperatieve wondinfecties (POWI’s) in vergelijking met onmiddellijke stopzetting. Vergelijkingen van postoperatieve regimes van verschillende duur toonde eveneens geen doorslaggevend bewijs in het voordeel van langdurige regimes.

Subgroep analyse toonde aan dat de effectiviteit van het stopzetten van antibiotische profylaxe na de operatie afhankelijk is of de chirurgische antibiotische profylaxe in de praktijk juist is toegepast. Wanneer de profylaxe juist is toegepast (d.w.z. tijdige toediening van de eerste dosis en herhaalde toediening indien aangewezen volgens de duur van de ingreep), toonde de studies met matige bewijskracht aan dat er geen voordeel is in het voortzetten van antibiotische profylaxe na de operatie voor het verminderen van POWI in vergelijking met het stopzetten ervan. Studies met matige bewijskracht toonden aan dat het voortzetten van antibiotische profylaxe na de operatie alleen effectief was wanneer de chirurgische antibiotische profylaxe niet juist was toegepast.

Enig bewijs uit verkennende analyse geeft aan dat het voortzetten van antibiotische profylaxe na de operatie het risico op POWI geassocieerd met maxillofaciale en cardiale chirurgie zou kunnen verminderen; echter, er waren heel weinig studies beschikbaar voor de subgroep maxillofaciale chirurgie en hartchirurgie.

Wanneer kosten en bijwerkingen werden gerapporteerd, leek het voortzetten na de operatie de kosten te verhogen en leidde het tot meer bijwerkingen. Antibioticagebruik is geassocieerd met belangrijke bijwerkingen op een tijdsafhankelijke manier (Branch-Elliman 2019, Hartbarth 2000, Stevens 2011). Op hun beurt zijn deze bijwerkingen geassocieerd met een aanzienlijke economische last die bijdraagt aan aanvullende verwervings- en administratiekosten in verband met het voortzetten van antibiotische profylaxe na de operatie (Cunha 2018, Dubbekerke 2012, OECD 2018).

Internationale richtlijnen

Deze bevindingen zijn in lijn met de aanbevelingen van de CDC (Berrios-Torres 2017) en de WHO (WHO 2018) over dit onderwerp. Beide richtlijnen raden niet aan om extra antimicrobiële profylaxe na de operatie toe te dienen ter voorkoming van POWI. De NICE-richtlijn heeft geen aanbeveling gedaan.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

Voor de individuele patiënt kan een kortere duur van antibiotica leiden tot een korter ziekenhuisverblijf en minder gebruik van antibiotica, met de bijbehorende bijwerkingen. Bijwerkingen van de gebruikte antibiotica zijn vaak gastro-intestinale klachten zoals misselijkheid, braken, diarree en buikpijn. Minder antibiotica zullen waarschijnlijk leiden tot minder bijwerkingen. Bovendien is er meer onderzoek gedaan naar de negatieve impact van antibiotica op de darmmicrobiota met zowel korte- als langetermijngevolgen voor de gezondheid (Patangia, 2022; Ramirez 2020). Bovendien kan minder antibiotica leiden tot minder antimicrobiële resistentie tegen bepaalde antibiotica.

Het is belangrijk om patiënten te informeren over het nut en de noodzaak van de behandeling. Voor de rol van de patiënt bij het herkennen van een infectie verwijst de werkgroep naar de module Patiëntbetrokkenheid van deze richtlijn.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

Kosten werden matig gerapporteerd, zo niet volledig, en er konden geen zinvolle meta-analyses worden uitgevoerd om deze resultaten te beoordelen. Wanneer kosten werden gerapporteerd, leek het voortzetten van profylaxe na de operatie de kosten te verhogen.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

Er zijn geen problemen te verwachten met betrekking tot de haalbaarheid van de verlenging van antimicrobiële profylaxe voor implementatie in de klinische praktijk.

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

We hebben geen bewijs gevonden voor het voordeel van het voortzetten van antibiotische profylaxe na de operatie in vergelijking met het stopzetten op het verminderen van de incidentie van POWI. Opmerkelijk genoeg bood het voortzetten na de operatie geen extra voordeel bij het voorkomen van POWI, vooral wanneer chirurgische antibiotische profylaxe juist werd toegepast. Onze bevindingen ondersteunen de aanbevelingen van de WHO tegen het voortzetten van chirurgische antibiotische profylaxe na de operatie. Gezien de bijbehorende nadelige effecten, met name antimicrobiële resistentie, heeft deze veelvoorkomende toepassing in de praktijk geen basis. Toegenomen bewustzijn en educatie zijn vereist onder zowel zorgprofessionals als patiënten, vooral door inspanningen voor stewardship te prioriteren onder chirurgen en anesthesisten en te blijven aandringen op andere preventiemaatregelen naast chirurgische antibiotische profylaxe. Toekomstig onderzoek om het voordeel van het voortzetten van antibiotische profylaxe na de operatie te verduidelijken, indien aanwezig, zou vooraf de monitoring van bijwerkingen moeten specificeren, gedetailleerde gegevens verstrekken over kosten en het tijdstip van toediening voorafgaand aan de operatie en herhaalde toediening van antibiotica tijdens de operatie moeten standaardiseren.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Het gebruik van antibiotica staat momenteel onder toezicht vanwege zorgen over de opkomst van antimicrobiële resistentie en andere schadelijke bijwerkingen. Wereldwijd is ongeveer één op de zes voorschriften voor antibiotica in het ziekenhuis bedoeld voor chirurgische antibiotische profylaxe, die vaak gedurende meerdere dagen na de operatie wordt voortgezet. Hoewel de effectiviteit van een juiste antibiotische profylaxe bij het voorkomen van postoperatieve wondinfecties (POWIs) bij aangewezen procedures algemeen erkend is, suggereren toenemende bewijzen dat een enkele preoperatieve dosis antibiotica, met extra intra-operatieve toediening indien nodig, mogelijk even effectief is als een langdurig postoperatief regime bij verschillende procedures.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

|

Moderate GRADE |

Postoperative continuation of surgical prophylactic intravenous antibiotics is unlikely to reduce the number of postoperative surgical site infections, if the prophylactic intravenous antibiotics have been correctly administered (first dose less than 60 minutes before incision, perioperative re-dosing four hours after the previous dose and in case of excessive peroperative bleeding).

Bronnen: De Jonge + update (Aberg, 1993; Abro, 2014; Abubakar, 2001; Adaji, 2020; Ahmed, 2019; Balbo, 1991; Baquin, 2004; Bates, 1992; Becker, 2008; Becker, 1991; Bentley, 1999; Berry, 2019; Bidkar, 2014; ; Bozorgzadeh, 1999; Buckley, 1990; Campos, 2015; Cartana, 1994; Carroll, 2003; Chang, 2005; Chauhan, 2018; Cioca, 2002; Crist, 2018; Danda, 2010; Davis, 2016; Eshghpour, 2014; Fujita, 2015; Fujita, 2007; Fridrich, 1994; Garcia, 2020; Gargotta, 1991; Gupta, 2010; Haga, 2012; Hall, 1998; Hanif, 2015; Hellbusch, 2008; Hussain, 2012; Imamura, 2012; Irato, 1997; Ishibashi, 2014; Ishibashi, 2009; Jansisyanont, 2008; Jiang, 2004; Kang, 2009; Karren, 1993; Kim, 2017; Kow, 1995; Lau, 1990; Liberman, 1995; Lin, 2011; Lindeboom, 2003; Liu, 2008; Loozen, 2017; Lyimo, 2013; Madadi, 2019; Maier, 1992; Mann, 1990; McArdle, 1995; Meijer, 1993; Mohri, 2007; Mui, 2005; Niederhauser, 1997; Nooyen, 1994; Nusrath, 2020; Olak, 1991; Orjuela, 2020; Orlando, 2015; Otani, 2004; Rajabi, 2012; Rajan, 2005; Regimbeau, 2014; Righi, 1996; Sadraei-Moosavi, 2017; Salih, 2018; Santibañes, 2018; Sawyer, 1990; Scher, 1997; Sgroi, 1990; Shaheen, 2014; Su, 2005; Sugawara, 2016; Suzuki, 2011; Takayama, 2019; Takemoto, 2015; Tamayo, 2008; Tan, 2020; Togo, 2007; Tsang, 1992; Turano, 1992; Unemura, 2000; Urquhart, 2019; Wahab, 2013; Westen, 2015; Yamamoto, 2018; Yang, 2001). |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

Ninety-eight studies were included in the analysis of the literature, in which 10,227 patients were involved.

Fifty-eight RCTs compared postoperative continuation of antibiotic prophylaxis of any duration with direct postoperative discontinuation (Aberg, 1993; Abro, 2014; Balbo, 1991; Bates, 1992; Becker, 2008; Berry, 2019; Buckley, 1990; Campos, 2015; Cartana, 1994; Chauhan, 2018; Cioca, 2002; Crist, 2018; Danda, 2010; Fujita, 2007; Gargotta, 1991; Haga, 2012; Hall, 1998; Hellbusch, 2008; Hussain, 2012; Imamura, 2012; Irato, 1997; Jiang, 2004; Kang, 2009; Kim, 2017; Kow, 1995; Liberman, 1995; Lindeboom, 2003; Loozen, 2017; Lyimo, 2013; Madadi, 2019; Maier, 1992; Mann, 1990; Meijer, 1993; Mohri, 2007; Mui, 2005; Nooyen, 1994; Nusrath, 2020; Olak, 1991; Orjuela, 2020; Orlando, 2015; Rajabi, 2012; Rajan, 2005; Regimbeau, 2014; Sadraei-Moosavi, 2017; Salih, 2018; Santibañes, 2018; Scher, 1997; Sgroi, 1990; Shaheen, 2014; Su, 2005; Suzuki, 2011; Tamayo, 2008; Tan, 2020; Tsang, 1992; Turano, 1992; Unemura, 2000; Wahab, 2013; Westen, 2015).

One RCT compared postoperative continuation of antibiotic prophylaxis (multiple doses) for less than 24 hours with a single postoperative dose (Karren, 1993).

Thirty-one RCTs compared postoperative continuation of antibiotic prophylaxis for more than 24 hours with postoperative continuation equal or less than 24 hours (Abubakar, 2001; Ahmed, 2019; Baquin, 2004; Becker, 1991; Bentley, 1999; Bidkar, 2014; Bozorgzadeh, 1999; Carroll, 2003; Chang, 2005; Eshghpour, 2014; Fujita, 2015; Fridrich, 1994; Garcia, 2020; Hanif, 2015; Ishibashi, 2014; Ishibashi, 2009; Jansisyanont, 2008; Lau, 1990; Lin, 2011; Liu, 2008; Madadi, 2019; McArdle, 1995; Mui, 2005; Niederhauser, 1997; Rajabi, 2012; Righi, 1996; Takayama, 2019; Takemoto, 2015; Urquhart, 2019; Yamamoto, 2018; Yang, 2001).

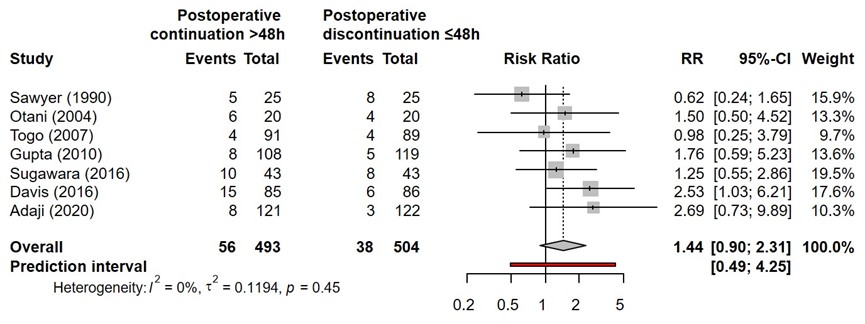

Seven RCTs compared postoperative continuation of antibiotic prophylaxis for more than 48 hours with postoperative continuation equal or less than 48 hours (Adaji, 2020; Davis, 2016; Gupta, 2010; Otani, 2004; Sawyer, 1990; Sugawara, 2016; Togo, 2007).

One RCT compared postoperative continuation of antibiotic prophylaxis for more than 72 hours with postoperative continuation equal or less than 72 hours (Park, 2010).

Results

1. Surgical site infections

A. Postoperative continuation versus immediate discontinuation

SSI for postoperative continuation versus immediate discontinuation were reported in 58 studies (Aberg, 1993; Abro, 2014; Balbo, 1991; Bates, 1992; Becker, 2008; Berry, 2019; Buckley, 1990; Campos, 2015; Cartana, 1994; Chauhan, 2018; Cioca, 2002; Crist, 2018; Danda, 2010; Fujita, 2007; Gargotta, 1991; Haga, 2012; Hall, 1998; Hellbusch, 2008; Hussain, 2012; Imamura, 2012; Irato, 1997; Jiang, 2004; Kang, 2009; Kim, 2017; Kow, 1995; Liberman, 1995; Lindeboom, 2003; Loozen, 2017; Lyimo, 2013; Madadi, 2019; Maier, 1992; Mann, 1990; Meijer, 1993; Mohri, 2007; Mui, 2005; Nooyen, 1994; Nusrath, 2020; Olak, 1991; Orjuela, 2020; Orlando, 2015; Rajabi, 2012; Rajan, 2005; Regimbeau, 2014; Sadraei-Moosavi, 2017; Salih, 2018; Santibañes, 2018; Scher, 1997; Sgroi, 1990; Shaheen, 2014; Su, 2005; Suzuki, 2011; Tamayo, 2008; Tan, 2020; Tsang, 1992; Turano, 1992; Unemura, 2000; Wahab, 2013; Westen, 2015).

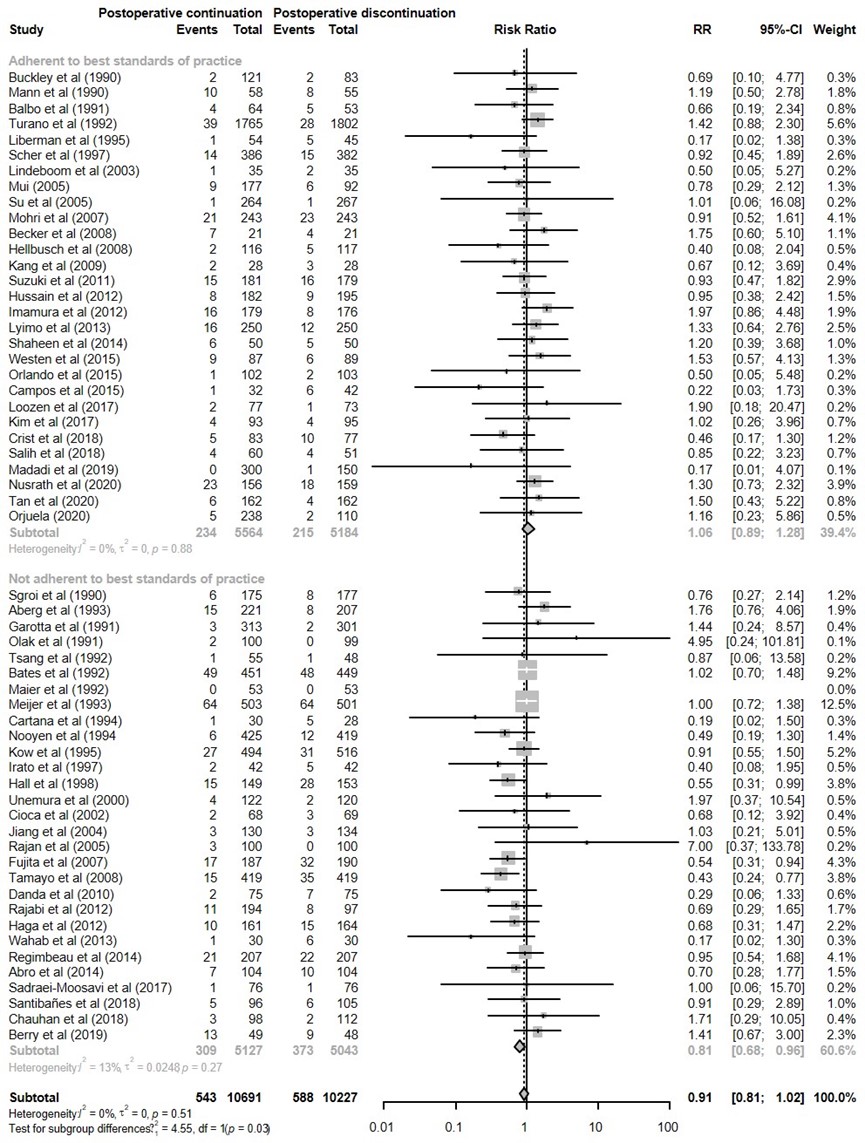

The results were pooled in a meta-analysis. The pooled number of SSI in the postoperative continuation group was 543/10691 (5.1%), compared to 588/10227 (5.7%) in the immediate discontinuation group. This resulted in a pooled relative risk ratio (RR) of 0.91 (95% CI 0.81 to 1.02), in favour of the postoperative continuation group (figure 1). This was not considered as a clinically relevant difference.

The studies were divided in three different categories:

(I) studies that adhered to the best standard of practice versus studies that did not adhere to the best standard of practice;

(II) studies that timed the first dose within 60 minutes before surgery versus studies that did not time the first dose within 60 minutes before surgery; and

(III) studies that specified intraoperative repeated administration when indicated versus studies that did not specify intraoperative repeated administration when indicated.

|

Analysis |

N |

SSI in longer regimen |

SSI shorter regimen |

Relative risk (95%CI) |

|

Overall analysis |

58 |

543 of 10.691 |

588 of 10.227 |

0.91 (0.81 - 1.02) |

|

Adherence to current best practice standards of SAP (repeat dose + timing correct) |

||||

|

Yes |

29 |

234 of 5.564 |

215 of 5.184 |

1.06 (0.88 - 1.28) |

|

No |

29 |

543 of 10.691 |

588 of 10.227 |

0.81 (0.68 - 0.96) |

|

Timing of first dose specified and within 60 min before surgery |

||||

|

Yes |

39 |

354 of 7.214 |

352 of 6.831 |

0.99 (0.86 - 1.15) |

|

No |

19 |

189 of 3.477 |

236 of 3.396 |

0.77 (0.61 - 0.96) |

|

Intraoperative repeat administration specified when indicated |

||||

|

Yes |

39 |

303 of 7.042 |

317 of 6.576 |

0.92 (0.79 - 1.08) |

|

No |

19 |

240 of 3.649 |

271 of 3.651 |

0.88 (0.72 - 1.08) |

Table 1. Meta-analysis and subgroup analyses of incidence of SSI associated with postoperative continuation versus postoperative discontinuation of antibiotic prophylaxis.

I. Adherent to best standards of practice versus not adherent to best standards of practice

Current best practice standards for surgical antibiotic prophylaxis are described in the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists clinical practice guidelines on antimicrobial prophylaxis in surgery (Bratzler 2013):

1) timing of the first preoperative dose within 60 min before incision;

2) repeat administration when the procedure duration exceeded two times the half-life of the antibiotic used.

The subgroup analyses indicates that compliance with best practice standards for surgical antibiotic prophylaxis significantly modified the association between postoperative continuation of antibiotic prophylaxis and the incidence of SSI (Figure 1).

In the subgroup analysis of 29 trials that were not compliant with abovementioned best practice standards of surgical antibiotic prophylaxis, continuation of antibiotic prophylaxis after surgery resulted in significant less SSI, compared with its immediate discontinuation (RR 0.81 [0.68-0.96]; corresponding heterogeneity was moderate (I² = 13%).

When the analysis was restricted to 29 trials that were compliant with abovementioned best practice standards of surgical antibiotic prophylaxis, there was no benefit of postoperative continuation of antibiotic prophylaxis (1.06 [0.89-1.28]). The corresponding heterogeneity in effect size was low (I² < 0.1%).

Figure 1. Forest plot showing the comparison between postoperative continuation of antibiotic prophylaxis to immediate discontinuation of antibiotic prophylaxis for surgical site infections (SSI) - Adherent to best standards of practice versus not adherent to best standards of practice. Pooled relative risk ratio (RR), random effects model. Z: p-value of overall effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2; SD: standard deviation; statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval.

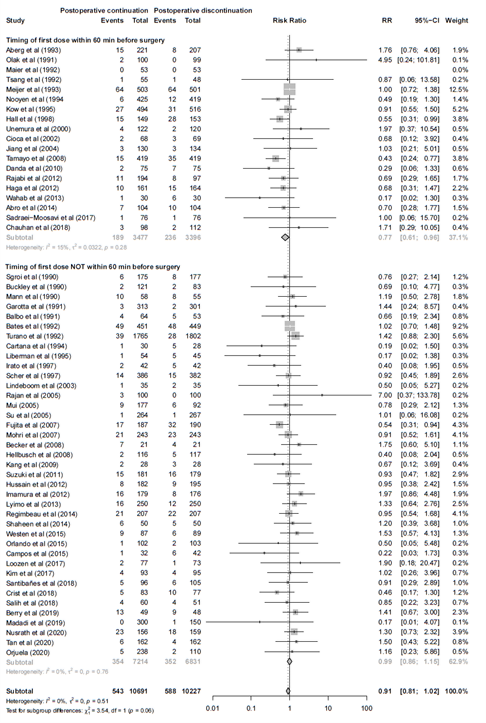

II. Timing of first dose within 60 minutes before surgery versus timing of first dose not within 60 minutes before surgery

Adequate timing alone did affect the effect estimate (Figure 2). In 19 trials where the first preoperative dose given >60 min before incision, continuation of antibiotic prophylaxis after surgery prevented SSI compared with its immediate discontinuation, RR 0.77 (95% CI 0.61 – 0.96). In the 39 studies with adequate timing of the first dose of antibiotic prophylaxis (<60 min prior to incision) there was no benefit found for continuation of antibiotic prophylaxis after surgery, RR 0.99 (0.86 - 1.15).

Figure 2. Forest plot showing the comparison between postoperative continuation of antibiotic prophylaxis to immediate discontinuation of antibiotic prophylaxis for surgical site infections (SSI) - Timing of first dose within 60 minutes before surgery versus timing of first dose not within 60 minutes before surgery. Pooled relative risk ratio (RR), random effects model. Z: p-value of overall effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2; SD: standard deviation; statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval.

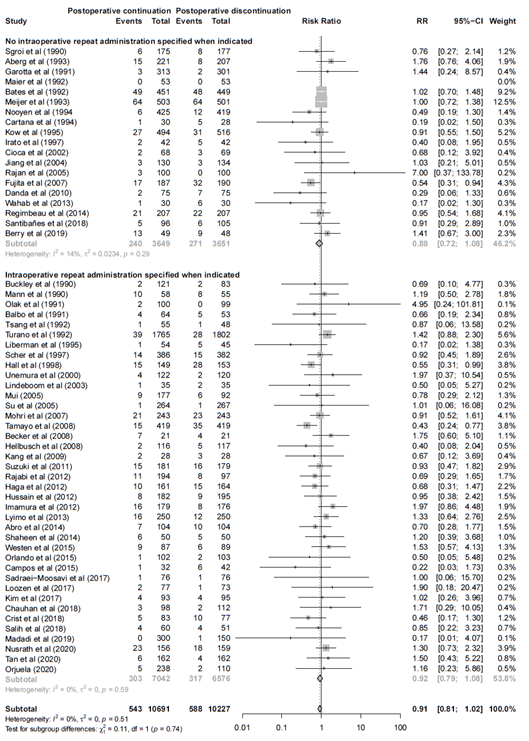

III. Intraoperative repeat administration specified when indicated versus intraoperative repeat administration not specified when indicated

Adequate repeat administration alone did not affect the effect estimate (Figure 3). In the 39 studies with adequate repeat administration antibiotic prophylaxis the pooled relative risk was 0.92 (95% CI 0.79 – 1.08), versus no adequate timing RR 0.88 (95% CI 0.72 – 1.08) in 19 studies.

Figure 3. Forest plot showing the comparison between postoperative continuation of antibiotic prophylaxis to immediate discontinuation of antibiotic prophylaxis for surgical site infections (SSI) - Intraoperative repeat administration specified when indicated versus intraoperative repeat administration not specified when indicated. Pooled relative risk ratio (RR), random effects model. Z: p-value of overall effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2; SD: standard deviation; statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval.

B. Postoperative postoperative continuations of antibiotic prophylaxis (multiple doses) for <24h versus a single postoperative dose

One study (Karran, 1993) compared postoperative continuation (multiple doses) for <24h versus a single dose after surgery. The number of SSI was 44/113 (38.9%) in the group with longer antibiotic prophylaxis, versus 39/114 (34.2%) in the group with a single postoperative dose. This resulted in a RR of 0.82 (0·57–1·40). This was not considered as a clinically relevant difference.

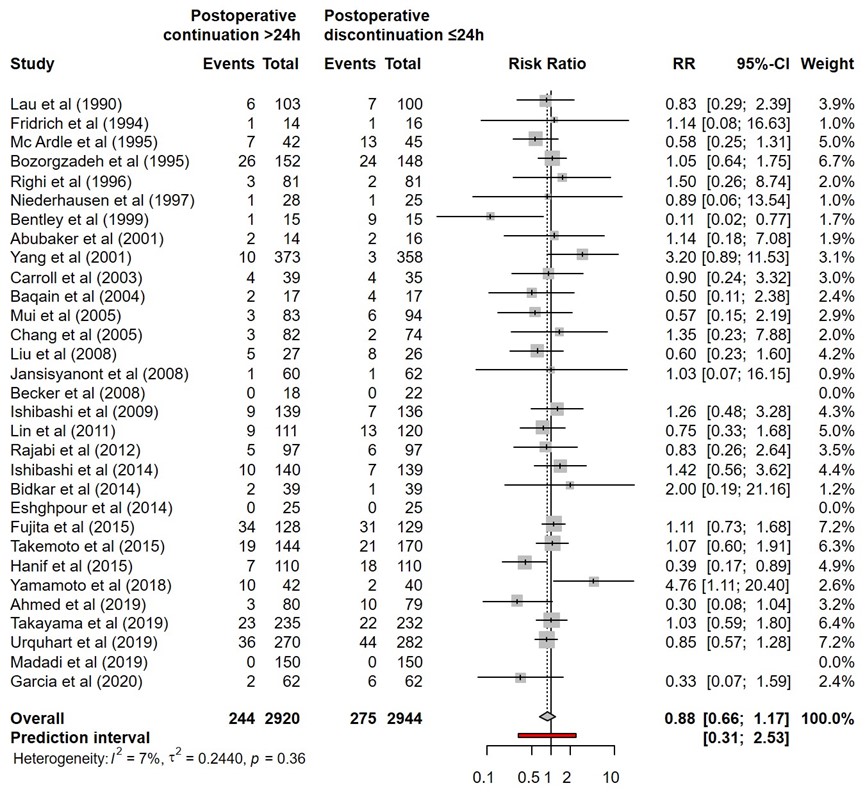

C. Postoperative continuation of surgical antibiotic prophylaxis for more than 24 hours versus postoperative continuation of surgical antibiotic prophylaxis equal or less than 24 hours

SSI for postoperative continuation for more than 24 hours versus postoperative continuation of surgical antibiotic prophylaxis equal or less than 24 hours were reported in 31 studies (Abubakar, 2001; Ahmed, 2019; Baquin, 2004; Becker, 1991; Bentley, 1999; Bidkar, 2014; Bozorgzadeh, 1999; Carroll, 2003; Chang, 2005; Eshghpour, 2014; Fujita, 2015; Fridrich, 1994; Garcia, 2020; Hanif, 2015; Ishibashi, 2014; Ishibashi, 2009; Jansisyanont, 2008; Lau, 1990; Lin, 2011; Liu, 2008; Madadi, 2019; McArdle, 1995; Mui, 2005; Niederhauser, 1997; Rajabi, 2012; Righi, 1996; Takayama, 2019; Takemoto, 2015; Urquhart, 2019; Yamamoto, 2018; Yang, 2001). The results were pooled in a meta-analysis. The pooled number of SSI in the postoperative continuation for more than 24 hours group was 244/2920 (8.4%), compared to 275/2944 (9.3%) in the postoperative continuation equal or less than 24 hours group. This resulted in a pooled relative risk ratio (RR) of 0.88 (95% CI 0.66 to 1.17), in favour of the postoperative continuation for more than 24 hours group (figure 4). This was not considered as a clinically relevant difference.

Figure 4. Forest plot showing the comparison between postoperative continuation of antibiotic prophylaxis for more than 24 hours to postoperative continuation of antibiotic prophylaxis equal or less than 24 hours for surgical site infections (SSI). Pooled relative risk ratio (RR), random effects model. Z: p-value of overall effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2; SD: standard deviation; statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval.

D. Postoperative continuation of surgical antibiotic prophylaxis for more than 48 hours versus postoperative continuation of surgical antibiotic prophylaxis equal or less than 48 hours

SSI for postoperative continuation for more than 48 hours versus postoperative continuation of surgical antibiotic prophylaxis equal or less than 48 hours were reported in seven studies (Adaji, 2020; Davis, 2016; Gupta, 2010; Otani, 2004; Sawyer, 1990; Sugawara, 2016; Togo, 2007). The results were pooled in a meta-analysis. The pooled number of SSI in the postoperative continuation for more than 48 hours group was 56/493 (11.4%), compared to 38/504 (7.5%) in the postoperative continuation equal or less than 48 hours group. This resulted in a pooled relative risk (RR) of 1.44 (95% CI 0.90 to 2.31), in favor of the postoperative continuation equal or less than 48 hours group (Figure 5). This was considered as a clinically relevant difference.

Figure 5. Forest plot showing the comparison between postoperative continuation of antibiotic prophylaxis for more than 48 hours to postoperative continuation of antibiotic prophylaxis equal or less than 48 hours for surgical site infections (SSI). Pooled relative risk ratio (RR), random effects model. Z: p-value of overall effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2; SD: standard deviation; statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval.

E. Postoperative continuation of surgical antibiotic prophylaxis for more than 72 hours versus postoperative continuation of surgical antibiotic prophylaxis equal or less than 72 hours

SSI for postoperative continuation for more than 72 hours versus postoperative continuation of surgical antibiotic prophylaxis equal or less than 72 hours was reported in one study (Park, 2020).

The number of SSI for more than 72 hours antibiotics prophylaxis was 3/125 (2.4%), versus 4/130 (3.1%) in the postoperative continuation equal or less than 72 hours. This resulted in a RR of 0.61 (0.14 – 2.63). This was not considered as a clinically relevant difference.

2. Exploratory subgroup analysis

To investigate potential procedure-specific effects, we also did post-hoc exploratory subgroup analyses by procedure type.

|

Analysis |

SG |

N |

SSI in longer regimen |

SSI shorter regimen |

Relative risk (95%CI) |

|

Overall analysis |

|

58 |

543 of 10.691 |

588 of 10.227 |

0.91 (0.81 - 1.02) |

|

Subgroup analyses |

|||||

|

Maxillofacial surgery |

A |

6 |

9 of 268 |

27 of 279 |

0.38 (0.18 - 0.80) |

|

B |

3 |

4 of 95 |

11 of 105 |

0.44 (0.14 - 1.39) |

|

|

Cardiac surgery |

A |

3 |

21 of 1.144 |

48 of 988 |

0.43 (0.26 - 0.71) |

|

B |

1 |

0 of 300 |

1 of 150 |

0.17 (0.01- 4.08) |

|

|

Vascular Surgery |

A |

1 |

15 of 149 |

28 of 153 |

0.55 (0.31 - 0.99) |

|

B |

0 |

NA |

NA |

NA |

|

|

Appendectomy |

A |

7 |

35 of 798 |

34 of 604 |

0.75 (0.47 - 1.20) |

|

B |

4 |

22 of 473 |

24 of 383 |

0.76 (0.43 - 1.37) |

|

|

Colorectal surgery |

A |

2 |

32 of 368 |

48 of 269 |

0.68 (0.40 - 1.15) |

|

B |

1 |

15 of 181 |

16 of 179 |

0.93 (0.47 - 1.82) |

|

|

Upper GI surgery |

A |

4 |

51 of 647 |

51 of 636 |

0.98 (0.62 - 1.54) |

|

B |

3 |

41 of 486 |

36 of 472 |

1.11 (0.63 - 1.97) |

|

|

Cholecystectomy |

A |

6 |

39 of 693 |

37 of 712 |

1.06 (0.69 – 1.64) |

|

B |

2 |

6 of 170 |

5 of 168 |

1.19 (0.37 - 3.86) |

|

|

Hepatobiliary Surgery |

A |

1 |

64 of 503 |

64 of 501 |

1.00 (0.72 - 1.38) |

|

B |

0 |

NA |

NA |

NA |

|

|

Mixed general surgery |

A |

9 |

187 of 3.773 |

170 of 3.817 |

1.11 (0.91 - 1.35) |

|

B |

4 |

83 of 2.328 |

65 of 2.364 |

1.30 (0.95 - 1.78) |

|

|

Caesarean section |

A |

4 |

37 of 549 |

27 of 551 |

1.38 (0.85 - 2.22) |

|

B |

4 |

37 of 549 |

27 of 551 |

1.38 (0.85 - 2.22) |

|

|

Gynaecological surgery |

A |

3 |

4 of 336 |

11 of 337 |

0.37 (0.12 - 1.17) |

|

B |

1 |

1 of 264 |

1 of 267 |

1.01 (0.06 -16.08) |

|

|

Ortho/Trauma surgery |

A |

4 |

12 of 633 |

19 of 578 |

0.57 (0.28 - 1.18) |

|

B |

3 |

9 of 320 |

17 of 277 |

0.48 (0.22 - 1.06) |

|

|

Thoracic surgery |

A |

2 |

5 of 230 |

3 of 233 |

1.44 (0.36 - 5.87) |

|

B |

0 |

NA |

NA |

NA |

|

|

Head and neck surgery |

A |

2* |

13 of 159 |

8 of 156 |

1.60 (0.43 - 5.95) |

|

B |

1 |

10 of 58 |

8 of 55 |

1.19 (0.50 - 2.78) |

|

|

Transplantation surgery |

A |

2 |

14 of 151 |

11 of 151 |

1.29 (0.63 - 2.64) |

|

B |

1 |

1 of 102 |

2 of 203 |

0.50 (0.05 - 5.48) |

|

|

SG: Subgroup, A: Overall analysis, B: Adherence to current standards of practice subgroup, N: Number of studies, SSI: Surgical site infection, 95%CI: 95% confidence interval, NA: Not available, tau2: Tau-squared, MR: Meta-regression, MA: Meta-analysis, % of heterogeneity variance explained: * One study excluded from analysis because of no events in both arms |

|||||

Table 2. Results of the subgroup analysis by surgical subspecialty

3. Adverse events

24 studies (17 included in the primary analysis) described possible harmful effects or adverse events related to surgical antibiotic prophylaxis (Table 2). Of these, 18 studies could not attribute adverse events to antibiotic use in both the intervention and control groups (Becker 2008, Carrol 2003, Cartana 1994, Danda 2010, Eshghpour 2014, Fujita 2015, Imamura 2012, Kang 2009, Lindeboom 2003, Liu 2008, Loozen 2017, Maier 1992, Mohri 2007, Rajabi 2012, Regimbeau 2007, Righi 1996, Sawyer 1990, Suzuki 2011). The remaining six studies reported increased adverse events in the groups with prolonged regimens (Bidkar 2014, Karran 1993, Mui 2005, Rajan 2005, de Santibañes 2018, Turano 1992). Of these, one study reported increased cases of C difficile infection in the prolonged postoperative continuation group (Mui 2005). The other studies reported an increased frequency of rash and pruritus, erythema, phlebitis, hypotension, gastrointestinal disturbance (including nausea and diarrhoea), and unspecified local and systemic side-effects with postoperative continuation of antibiotic prophylaxis. No study reported on antimicrobial resistance. Owing to heterogeneity between studies in the comparisons made and the outcomes measured, no meta-analysis could be done of adverse effects.

|

Study |

Adverse event definition |

Longer postoperative regimens |

Shorter postoperative regimens |

|

Mui 2005¶ |

Clostridium difficile confirmed by fecal clostridium toxin |

5 of 177 |

0 of 92 |

|

Karran 1993 † |

Hypotension, phlebitis, rash, erythema |

5 of 114 |

1 of 113 |

|

Turano 1992 * |

Thrombophlebitis, allergic reaction and gastrointestinal disturbances |

40 of 1517 |

10 of 1700 |

|

Bidkar 2014 ‡ |

Gastrointestinal disturbances |

19 of 39 |

1 of 39 |

|

Rajan 2005 * |

Nausea, diarrhea, skin rash, pruritus |

29 of 100 |

2 of 100 |

|

de Santibañes 2018 * |

Unspecified |

4 of 96 |

3 of 105 |

|

Liu 2008 ‡ |

No adverse events attributable to antibiotic use in both the intervention and control group. |

||

|

Carrol 2003 ‡ |

No adverse events attributable to antibiotic use in both the intervention and control group. |

||

|

Righi 1996 ‡ |

No adverse events attributable to antibiotic use in both the intervention and control group. |

||

|

Maier 1992 * |

No adverse events attributable to antibiotic use in both the intervention and control group. |

||

|

Sawyer 1990 § |

No adverse events attributable to antibiotic use in both the intervention and control group. |

||

|

Kang 2009 * |

No adverse events attributable to antibiotic use in both the intervention and control group. |

||

|

Lindeboom 2003 * |

No adverse events attributable to antibiotic use in both the intervention and control group. |

||

|

Suzuki 2011 * |

No adverse events attributable to antibiotic use in both the intervention and control group. |

||

|

Fujita 2015 * |

No adverse events attributable to antibiotic use in both the intervention and control group. |

||

|

Imamura 2012 * |

No adverse events attributable to antibiotic use in both the intervention and control group. |

||

|

Mohri 2007 * |

No adverse events attributable to antibiotic use in both the intervention and control group. |

||

|

Regimbeau 2007 * |

No adverse events attributable to antibiotic use in both the intervention and control group. |

||

|

Becker 2008 * |

No adverse events attributable to antibiotic use in both the intervention and control group. |

||

|

Cartana 1994 * |

No adverse events attributable to antibiotic use in both the intervention and control group. |

||

|

Eshghpour 2014 ‡ |

No adverse events attributable to antibiotic use in both the intervention and control group. |

||

|

Loozen 2017 * |

No adverse events attributable to antibiotic use in both the intervention and control group. |

||

|

Rajabi 2012 ¶ |

No adverse events attributable to antibiotic use in both the intervention and control group. |

||

|

Danda 2010 * |

No adverse events attributable to antibiotic use in both the intervention and control group. |

||

|

* Postoperative continuation vs immediate discontinuation of SAP; † Postoperative continuation for 24h vs a single dose after surgery; ‡ Postoperative continuation for >24h vs ≤ 24h; § Postoperative continuation for >48h vs ≤ 48h; ¶ Postoperative continuation vs immediate discontinuation of SAP and Postoperative continuation for >24h vs ≤ 24h |

|||

Table 3. Studies reporting adverse events related to SAP

4. Studies reporting costs of SAP continuation

Five studies (Chang 2005, Liberman 1995, Orlando 2015, Rajan 2005, Su 2005) addressed cost-effectiveness and reported a cost increase associated with longer antibiotic prophylaxis regimens, in some cases as a result of treatment for side-effects and hospitalisation time in addition to prophylaxis treatment, which varied from US$36.90 to $78.95 (Table 4). None of these studies calculated costs associated with the emergence of antimicrobial resistance. All five studies were done in high-income countries (Australia, Italy, Taiwan, and the USA).

|

Study |

Cost included |

Cost postoperative continuation |

Cost postoperative discontinuation |

Absolute difference |

Relative difference |

|

Liberman 1995* |

Antibiotics |

$ 54.80 |

$ 17.90 |

+ $ 36.90 |

3.06 |

|

Chang 2005† |

Total costs |

$ 1,768.00 |

$ 1,728.00 |

+ $ 40.00 |

1.02 |

|

Rajan 2005* |

Total costs |

$ 93.45 |

$ 14.50 |

+ $ 78.95 |

6.44 |

|

Su 2005* |

Antibiotics |

$ 48.00 |

$ 3.50 |

+ $ 44.50 |

13.71 |

|

Orlando 2015 |

Antibiotics |

$ 38.80 |

$ 3.88 |

+ $ 34.92 |

10.00 |

|

* Postoperative continuation vs immediate discontinuation of SAP; † Postoperative continuation for>24 h vs ≤ 24 h |

|||||

Table 4: Studies reporting costs of SAP continuation

Level of evidence of the literature

Surgical site infections

The level of evidence regarding the outcome SSI was derived from randomized controlled trials and therefore started high. The level of evidence was downgraded by one level because of risk of bias. The level of evidence was considered as moderate.

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question: What is the effect of postoperative continuation of antibiotic prophylaxis on the incidence of SSI compared with its postoperative discontinuation in adult patients undergoing surgical procedures?

P: Adult patients undergoing any surgical procedure.

I: Postoperative continuation of antibiotic prophylaxis.

C: Postoperative discontinuation of antibiotic prophylaxis.

O: Surgical site infections (SSI).

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered surgical site infections as a critical outcome for decision making.

The working group defined a threshold of 10% for continuous outcomes and a relative risk (RR) for dichotomous outcomes of <0.80 and >1.25 as a minimal clinically (patient) important difference.

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms, based on the literature search of de Jonge (2020) from the 24th of July 2018 up to the 28th of January 2021. The detailed search strategy is available on request via https://richtlijnendatabase.nl/. The systematic literature search resulted in 992 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria: systematic reviews and randomized controlled trials on the postoperative administration of antibiotics to prevent postoperative wound infections. One hundred eighty-eight studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, 90 studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion in the table of excluded studies under the tab 'Evidence tabellen'), and 98 studies were included.

Results

Ninety-eight studies were included in the analysis of the literature under the tab 'Samenvatting literatuur'. Important study characteristics and results and quality assessments are summarized in the evidence tables and risk of bias tables under the 'evidence tabellen' tab.

Referenties

- Aberg, C., and M. Thore. "Single Versus Triple Dose Antimicrobial Prophylaxis in Elective Abdominal Surgery and the Impact on Bacterial Ecology." Journal of hospital infection 18.2 (1991): 149-54.

- Abro, A. H., et al. "Single Dose Versus 24 - Hours Antibiotic Prophylaxis against Surgical Site Infections." Journal of the Liaquat University of Medical and Health Sciences 13.1 (2014): 27-31.

- Abubaker, A. O., and M. K. Rollert. "Postoperative Antibiotic Prophylaxis in Mandibular Fractures: A Preliminary Randomized, Double-Blind, and Placebo-Controlled Clinical Study." Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery 59.12 (2001): 1415-19.

- Adaji, J. A., et al. "Short Versus Long-Term Antibiotic Prophylaxis in Cesarean Section: A Randomized Clinical Trial." Niger Med J 61.4 (2020): 173-79.

- Ahmed, M., et al. "Perioperative Antibiotic Use for Surgical Site Infection in Penetrating Hollow Viscus Injury - a Placebo-Controlled Study." Pakistan Journal of Medical & Health Sciences 13.4 (2019): 851-54.

- Balbo, G., et al. "Antibiotic Prophylaxis with Mezlocillin in Gastric Surgery. Comparison between Two Regimen. [Italian]." Chirurgia 4.7-8 (1991): 412-16.

- Baqain, Z. H., et al. "Antibiotic Prophylaxis for Orthognathic Surgery: A Prospective, Randomised Clinical Trial." Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 42.6 (2004): 506-10.

- Bates, T., et al. "A Randomized Trial of One Versus Three Doses of Augmentin as Wound Prophylaxis in at-Risk Abdominal Surgery." Postgraduate Medical Journal 68.804 (1992): 811-16.

- Becker, A., L. Koltun, and J. Sayfan. "Impact of Antimicrobial Prophylaxis Duration on Wound Infection in Mesh Repair of Incisional Hernia - Preliminary Results of a Prospective Randomized Trial." European Surgery - Acta Chirurgica Austriaca 40.1 (2008): 37-40.

- Bentley, K.C., T.W. Head, and G.A. Aiello. "Antibiotic Prophylaxis in Orthognathic Surgery: A 1-Day Versus 5-Day Regimen." J.Oral Maxillofac.Surg 57.3 (1999): 226-30.

- Berrios-Torres, S. I., et al. "Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Guideline for the Prevention of Surgical Site Infection, 2017." JAMA Surg 152.8 (2017): 784-91.

- Berry, P. S., et al. "Intraoperative Versus Extended Antibiotic Prophylaxis in Liver Transplant Surgery: A Randomized Controlled Pilot Trial." Liver Transplantation 25.7 (2019): 1043-53.

- Bidkar, V.G., et al. "Perioperative Only Versus Extended Antimicrobial Usage in Tympanomastoid Surgery: A Randomized Trial." Laryngoscope 124.6 (2014): 1459-63.

- Bozorgzadeh, A., et al. "The Duration of Antibiotic Administration in Penetrating Abdominal Trauma." Am.J.Surg 177.2 (1999): 125-31.

- Branch-Elliman, W., et al. "Association of Duration and Type of Surgical Prophylaxis with Antimicrobial-Associated Adverse Events." JAMA Surg 154.7 (2019): 590-98.

- Bratzler, D. W., et al. "Clinical Practice Guidelines for Antimicrobial Prophylaxis in Surgery." Am J Health Syst Pharm 70.3 (2013): 195-283.

- Buckley, R., et al. "Perioperative Cefazolin Prophylaxis in Hip Fracture Surgery." Canadian Journal of Surgery 33.2 (1990): 122-25.

- Campos, G. B. P., et al. "Efficacy Assessment of Two Antibiotic Prophylaxis Regimens in Oral and Maxillofacial Trauma Surgery: Preliminary Results." International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Medicine 8.2 (2015): 2846-52.

- Carroll, W. R., et al. "Three-Dose Vs Extended-Course Clindamycin Prophylaxis for Free-Flap Reconstruction of the Head and Neck." Archives of otolaryngology--head & neck surgery 129.7 (2003): 771-4.

- Cartana, J., et al. "Antibiotic Prophylaxis in Wertheim-Meigs Surgery. A Single Dose Vs Three Doses." European Journal of Gynaecological Oncology 15.1 (1994): 14-18.

- Chang, W. C., et al. "Short Course of Prophylactic Antibiotics in Laparoscopically Assisted Vaginal Hysterectomy." Journal of Reproductive Medicine for the Obstetrician and Gynecologist 50.7 (2005): 524-28.

- Chauhan, V. S., et al. "Can Post-Operative Antibiotic Prophylaxis Following Elective Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy Be Completely Done Away with in the Indian Setting? A Prospective Randomised Study." Journal of Minimal Access Surgery 14.3 (2018): 192-96.

- Cioaca, R. E., et al. "Comparative Study of Clinical Effectiveness of Antibiotic Prophylaxis in Aseptic Mouth-Jaw- and Facial Surgery. [German]." Mund-, Kiefer- und Gesichtschirurgie : MKG 6.5 (2002): 356-59.

- Crist, B. D., et al. "Evaluating the Duration of Prophylactic Post-Operative Antibiotic Agents after Open Reduction Internal Fixation for Closed Fractures." Surg Infect (Larchmt) 19.5 (2018): 535-40.

- Cunha, C. B. "The Pharmacoeconomic Aspects of Antibiotic Stewardship Programs." Med Clin North Am 102.5 (2018): 937-46.

- Danda, A. K., et al. "Single-Dose Versus Single-Day Antibiotic Prophylaxis for Orthognathic Surgery: A Prospective, Randomized, Double-Blind Clinical Study." Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery 68.2 (2010): 344-46.

- Davis, Cm, et al. "Prevalence of Surgical Site Infections Following Orthognathic Surgery: A Double-Blind, Randomized Controlled Trial on a 3-Day Versus 1-Day Postoperative Antibiotic Regimen." Journal of oral and maxillofacial surgery 75.4 (2017): 796-804.

- de Santibañes, M., et al. "Extended Antibiotic Therapy Versus Placebo after Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy for Mild and Moderate Acute Calculous Cholecystitis: A Randomized Double-Blind Clinical Trial." Surgery (2018).

- Dubberke, E. R., and M. A. Olsen. "Burden of Clostridium Difficile on the Healthcare System." Clin Infect Dis 55 Suppl 2.Suppl 2 (2012): S88-92.

- Eshghpour, M., et al. "Value of Prophylactic Postoperative Antibiotic Therapy after Bimaxillary Orthognathic Surgery: A Clinical Trial." Iranian Journal of Otorhinolaryngology 26.77 (2014): 207-10.

- Fridrich, K. L., B. E. Partnoy, and D. L. Zeitler. "Prospective Analysis of Antibiotic Prophylaxis for Orthognathic Surgery." Int J Adult Orthodon Orthognath Surg 9.2 (1994): 129-31.

- Fujita, S., et al. "Randomized, Multicenter Trial of Antibiotic Prophylaxis in Elective Colorectal Surgery: Single Dose Vs 3 Doses of a Second-Generation Cephalosporin without Metronidazole and Oral Antibiotics." Archives of Surgery 142.7 (2007): 657-61.

- Fujita, T., and H. Daiko. "Optimal Duration of Prophylactic Antimicrobial Administration and Risk of Postoperative Infectious Events in Thoracic Esophagectomy with Three-Field Lymph Node Dissection: Short-Course Versus Prolonged Antimicrobial Administration." Esophagus 12.1 (2015): 38-43.

- Garcia, E. S., et al. "Postoperative Antibiotic Prophylaxis in Reduction Mammaplasty: A Randomized Controlled Trial." Plastic and reconstructive surgery 145.6 (2020): 1022e‐28e.

- Garotta, F., and F. Pamparana. "Antimicrobial Prophylaxis with Ceftizoxime Versus Cefuroxime in Orthopedic Surgery. Ceftizoxime Orthopedic Surgery Italian Study Group." J Chemother 3 Suppl 2 (1991): 34-5.

- Gupta, A., et al. "Comparison of 48 H and 72 H of Prophylactic Antibiotic Therapy in Adult Cardiac Surgery: A Randomized Double Blind Controlled Trial." J.Antimicrob.Chemother. 65.5 (2010): 1036-41.

- Haga, N., et al. "A Prospective Randomized Study to Assess the Optimal Duration of Intravenous Antimicrobial Prophylaxis in Elective Gastric Cancer Surgery." International Surgery 97.2 (2012): 169-76.

- Hall, J. C., et al. "Duration of Antimicrobial Prophylaxis in Vascular Surgery." American Journal of Surgery 175.2 (1998): 87-90.

- Hanif, A; Gillani, M; Alia, I; Farooq Dar, U; Mirza, A. "Comparison of Surgical Site Infection Rate in Case of Penetrating Hollow Viscus Injury after Perioperative Antibiotics Use for 24 Hours Versus 5 Days." P J M H S 9.4 (2015): 1396-98.

- Harbarth, S., et al. "Prolonged Antibiotic Prophylaxis after Cardiovascular Surgery and Its Effect on Surgical Site Infections and Antimicrobial Resistance." Circulation 101.25 (2000): 2916-21.

- Hellbusch, L. C., et al. "Single-Dose Vs Multiple-Dose Antibiotic Prophylaxis in Instrumented Lumbar Fusion--a Prospective Study." Surgical neurology 70.6 (2008): 622-7; discussion 27.

- Hussain, M.I., et al. "Role of Postoperative Antibiotics after Appendectomy in Non-Perforated Appendicitis." J.Coll.Physicians Surg Pak. 22.12 (2012): 756-59.

- Imamura, H., et al. "Intraoperative Versus Extended Antimicrobial Prophylaxis after Gastric Cancer Surgery: A Phase 3, Open-Label, Randomised Controlled, Non-Inferiority Trial." Lancet Infect Dis 12.5 (2012): 381-7.

- Irato, S., et al. "Prophylaxis with Single Administration of Cefotetan in Patients Undergoing Abdominal Hysterectomy. [Italian]." Giornale Italiano di Ostetricia e Ginecologia 19.4 (1997): 235-36.

- Ishibashi, K., et al. "Short-Term Intravenous Antimicrobial Prophylaxis for Elective Rectal Cancer Surgery: Results of a Prospective Randomized Non-Inferiority Trial." Surgery Today 44.4 (2014): 716-22.

- Ishibashi, K., et al. "Short-Term Intravenous Antimicrobial Prophylaxis in Combination with Preoperative Oral Antibiotics on Surgical Site Infection and Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus Infection in Elective Colon Cancer Surgery: Results of a Prospective Randomized Trial." Surgery Today 39.12 (2009): 1032-39.

- Jansisyanont, P., et al. "Antibiotic Prophylaxis for Orthognathic Surgery: A Prospective, Comparative, Randomized Study between Amoxicillin-Clavulanic Acid and Penicillin." J Med Assoc Thai 91.11 (2008): 1726-31.

- Jiang, L., et al. "Prophylactic Cefuroxime in General Thoracic Surgery. [Chinese]." Chinese Journal of Antibiotics 29.7 (2004): 412-14.

- Kang, S. H., J. H. Yoo, and C. K. Yi. "The Efficacy of Postoperative Prophylactic Antibiotics in Orthognathic Surgery: A Prospective Study in Le Fort I Osteotomy and Bilateral Intraoral Vertical Ramus Osteotomy." Yonsei Medical Journal 50.1 (2009): 55-59.

- Kim, E. Y., et al. "Is There a Real Role of Postoperative Antibiotic Administration for Mildmoderate Acute Cholecystitis? A Prospective Randomized Controlled Trial." Journal of Hepato-Biliary-Pancreatic Sciences 24.10 (2017): 550-58.

- Kow, L., et al. "Comparison of Cefotaxime Plus Metronidazole Versus Cefoxitin for Prevention of Wound Infection after Abdominal Surgery." World Journal of Surgery 19.5 (1995): 680-86.

- Lau, W. Y., et al. "Systemic Antibiotic Regimens for Acute Cholecystitis Treated by Early Cholecystectomy." Aust N Z J Surg 60.7 (1990): 539-43.

- Liberman, M.A., et al. "Single-Dose Cefotetan or Cefoxitin Versus Multiple-Dose Cefoxitin as Prophylaxis in Patients Undergoing Appendectomy for Acute Nonperforated Appendicitis." J Am Coll Surg 180 (1995): 77-80.

- Lin, M. H., et al. "Prospective Randomized Study of Efficacy of 1-Day Versus 3-Day Antibiotic Prophylaxis for Preventing Surgical Site Infection after Coronary Artery Bypass Graft." Journal of the Formosan Medical Association 110.10 (2011): 619-26.

- Lindeboom, J. A., E. M. Baas, and F. H. Kroon. "Prophylactic Single-Dose Administration of 600 Mg Clindamycin Versus 4-Time Administration of 600 Mg Clindamycin in Orthognathic Surgery: A Prospective Randomized Study in Bilateral Mandibular Sagittal Ramus Osteotomies." Oral surgery, oral medicine, oral pathology, oral radiology, and endodontics 95.2 (2003): 145-9.

- Liu, S. A., et al. "Preliminary Report of Associated Factors in Wound Infection after Major Head and Neck Neoplasm Operations--Does the Duration of Prophylactic Antibiotic Matter?" Journal of laryngology and otology 122.4 (2008): 403-8.

- Loozen, C. S., et al. "Randomized Clinical Trial of Extended Versus Single-Dose Perioperative Antibiotic Prophylaxis for Acute Calculous Cholecystitis." Br J Surg 104.2 (2017): e151-e57.

- Lyimo, F. M., et al. "Single Dose of Gentamicin in Combination with Metronidazole Versus Multiple Doses for Prevention of Post-Caesarean Infection at Bugando Medical Centre in Mwanza, Tanzania: A Randomized, Equivalence, Controlled Trial." BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth 13.123 (2013).

- Madadi, S., et al. "Postoperative Antibiotic Prophylaxis in the Prevention of Cardiac Implantable Electronic Device Infection." Pacing and clinical electrophysiology : PACE 42.2 (2019): 161‐65.

- Maier, W., and J. Strutz. "Perioperative Single-Dose Prophylaxis with Cephalosporins in Ent Surgery. A Prospective Randomized Study. [German]." Laryngo- Rhino- Otologie 71.7 (1992): 365-69.

- Mann, W., and J. Maurer. "[Perioperative Short-Term Preventive Antibiotics in Head-Neck Surgery]." Laryngo- rhino- otologie 69.3 (1990): 158-60.

- McArdle, C. S., et al. "Value of Oral Antibiotic Prophylaxis in Colorectal Surgery." British journal of surgery 82.8 (1995): 1046-8.

- Meijer, W. S., and P. I. Schmitz. "Prophylactic Use of Cefuroxime in Biliary Tract Surgery: Randomized Controlled Trial of Single Versus Multiple Dose in High-Risk Patients. Galant Trial Study Group." British journal of surgery 80.7 (1993): 917-21.

- Mohri, Y., et al. "Randomized Clinical Trial of Single- Versus Multiple-Dose Antimicrobial Prophylaxis in Gastric Cancer Surgery." British Journal of Surgery 94.6 (2007): 683-88.

- Mui, L. M., et al. "Optimum Duration of Prophylactic Antibiotics in Acute Non-Perforated Appendicitis." ANZ Journal of Surgery 75.6 (2005): 425-28.

- Niederhauser, U., et al. "Cardiac Surgery in a High-Risk Group of Patients: Is Prolonged Postoperative Antibiotic Prophylaxis Effective?" J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 114.2 (1997): 162-8.

- Nooyen, S. M., et al. "Prospective Randomised Comparison of Single-Dose Versus Multiple-Dose Cefuroxime for Prophylaxis in Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting." European journal of clinical microbiology & infectious diseases 13.12 (1994): 1033-7.

- Nusrath, S., et al. "Single-Dose Prophylactic Antibiotic Versus Extended Usage for Four Days in Clean-Contaminated Oncological Surgeries: A Randomized Clinical Trial." Indian Journal of Surgical Oncology 11.3 (2020): 378-86.

- OECD. Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development. Stemming the Superbug Tide: Just a Few Dollars More. Nov 7, 2018. Https://Www.Oecd.Org/Health/Stemming-the-Superbug-Tide- 9789264307599-En.Htm (Accessed April 28, 2020).

- Olak, J., et al. "Randomized Trial of One-Dose Versus Six-Dose Cefazolin Prophylaxis in Elective General Thoracic Surgery." Annals of Thoracic Surgery 51.6 (1991): 956-58.

- Orjuela, A., and L. P. Cardozo. "Comparison of Two Prophylactic Antibiotic Protocols in Implantable Cardiac Stimulation Devices: “Comprofilaxia”." Revista colombiana de cardiologia 27.4 (2020): 330‐36.

- Orlando, G., et al. "One-Shot Versus Multidose Perioperative Antibiotic Prophylaxis after Kidney Transplantation: A Randomized, Controlled Clinical Trial." Surgery (United States) 157.1 (2015): 104-10.

- Otani, S., et al. "Feasibility of Short-Term Antibiotic Prophylaxis after Pulmonary Resection. [Japanese]." Kyobu geka The Japanese journal of thoracic surgery. 57.13 (2004): 1171-74; discussion 75-76.

- Patangia, D., et al. “Impact of antibiotics on the human microbiome and consequences for host health.” Microbiology Open. 11.1 (2022): e1260.

- Rajabi-Mashhadi, M. T., et al. "Optimum Duration of Perioperative Antibiotic Therapy in Patients with Acute Non-Perforated Appendicitis: A Prospective Randomized Trial." Asian Biomedicine 6.6 (2012): 891-94.

- Rajan, G. P., et al. "Antibiotic Prophylaxis in Septorhinoplasty? A Prospective, Randomized Study." Plastic and reconstructive surgery 116.7 (2005): 1995-98.

- Ramirez, J. et al. “Antibiotics as Major Disruptors of Gut Microbiota.” Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology 10 (2020): 572912.

- Regimbeau, J. M., et al. "Effect of Postoperative Antibiotic Administration on Postoperative Infection Following Cholecystectomy for Acute Calculous Cholecystitis: A Randomized Clinical Trial." JAMA - Journal of the American Medical Association 312.2 (2014): 145-54.

- Righi, M., et al. "Short-Term Versus Long-Term Antimicrobial Prophylaxis in Oncologic Head and Neck Surgery." Head Neck 18.5 (1996): 399-404.

- Sadraei-Moosavi, S-M, N Nikhbakhsh, and A-A Darzi. "Postoperative Antibiotic Therapy after Appendectomy in Patients with Non-Perforated Appendicitis." Caspian journal of internal medicine 8.2 (2017): 104-07.

- Salih, E. K., et al. "Comparative Study of Single Dose Per-Operative Metronidazole Versus Multiple Doses Postoperative Metronidazole in Acute Non-Complicated Appendicitis: A View on Postoperative Complications." Journal of Krishna Institute of Medical Sciences University 7.4 (2018): 78-84.

- Sawyer, R., et al. "Metronidazole in Head and Neck Surgery--the Effect of Lengthened Prophylaxis." Otolaryngol.Head Neck Surg 103.6 (1990): 1009-11.

- Scher, K. S. "Studies on the Duration of Antibiotic Administration for Surgical Prophylaxis." American surgeon 63.1 (1997): 59-62.

- Sgroi, G., et al. "Prophylactic Antibiotics in Abdominal Surgery: A Single Peroperative Dose Versus Ultra Short-Term Prophylaxis." Chirurgia 3.12 (1990): 652-6.

- Shaheen, S., and S. Akhtar. "Comparison of Single Dose Versus Multiple Doses of Anitibiotic Prophylaxis in Elective Caesarian Section." Journal of Postgraduate Medical Institute 28.1 (2014): 83-86.

- Stevens, V., et al. "Cumulative Antibiotic Exposures over Time and the Risk of Clostridium Difficile Infection." Clin Infect Dis 53.1 (2011): 42-8.

- Su, H. Y., et al. "Prospective Randomized Comparison of Single-Dose Versus 1-Day Cefazolin for Prophylaxis in Gynecologic Surgery." Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica 84.4 (2005): 384-89.

- Sugawara, G., et al. "Duration of Antimicrobial Prophylaxis in Patients Undergoing Major Hepatectomy with Extrahepatic Bile Duct Resection: A Randomized Controlled Trial." Ann Surg 267.1 (2018): 142-48.

- Suzuki, T., et al. "Optimal Duration of Prophylactic Antibiotic Administration for Elective Colon Cancer Surgery: A Randomized, Clinical Trial." Surgery 149.2 (2011): 171-78.

- Takayama, T., et al. "Antimicrobial Prophylaxis for 1 Day Versus 3 Days in Liver Cancer Surgery: A Randomized Controlled Non-Inferiority Trial." Surgery Today 49.10 (2019): 859-69.

- Takemoto, R. C., et al. "Appropriateness of Twenty-Four-Hour Antibiotic Prophylaxis after Spinal Surgery in Which a Drain Is Utilized: A Prospective Randomized Study." The Journal of bone and joint surgery American volume. 97.12 (2015): 979-86.

- Tamayo, E., et al. "Comparative Study of Single-Dose and 24-Hour Multiple-Dose Antibiotic Prophylaxis for Cardiac Surgery." Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery 136.6 (2008): 1522-27.

- Tan, X., et al. "Effects of Antibiotics on Prevention of Infection, White Blood Cell Counts, and C-Reactive Protein Levels at Different Times in the Perioperative Period of Cesarean Section " International journal of clinical pharmacology and therapeutics 58.6 (2020): 310‐15.

- Togo, S., et al. "Duration of Antimicrobial Prophylaxis in Patients Undergoing Hepatectomy: A Prospective Randomized Controlled Trial Using Flomoxef." Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 59.5 (2007): 964-70.

- Tsang, T. M., P. K. Tam, and H. Saing. "Antibiotic Prophylaxis in Acute Non-Perforated Appendicitis in Children: Single Dose of Metronidazole and Gentamicin." Journal of the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh 37.2 (1992): 110-2.

- Turano, A. "New Clinical Data on the Prophylaxis of Infections in Abdominal, Gynecologic, and Urologic Surgery. Multicenter Study Group." American journal of surgery 164.4 A Suppl (1992): 16S-20S.

- Unemura, Y., et al. "Prevention of Postoperative Infection Following Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy - Comparison between Single Dose and 2-Day Dose Administration of Antibiotic Prophylaxis. [Japanese]." Japanese Journal of Gastroenterological Surgery 33.12 (2000): 1880-84.

- Urquhart, J. C., et al. "The Effect of Prolonged Postoperative Antibiotic Administration on the Rate of Infection in Patients Undergoing Posterior Spinal Surgery Requiring a Closed-Suction Drain: A Randomized Controlled Trial." Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery - American Volume 101.19 (2019): 1732-40.

- Wahab, P. U. A., et al. "Antibiotic Prophylaxis for Bilateral Sagittal Split Osteotomies: A Randomized, Double-Blind Clinical Study." International Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery 42.3 (2013): 352-55.

- Westen, E. H. M. N., et al. "Single-Dose Compared with Multiple Day Antibiotic Prophylaxis for Cesarean Section in Low-Resource Settings, a Randomized Controlled, Noninferiority Trial." Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica 94.1 (2015): 43-49.

- World Health Organization (WHO). Global Guidelines for the Prevention of Surgical Site Infection, Second Edition. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018. Licence: Cc by-Nc-Sa 3.0 Igo.

- Yamamoto, T., et al. "Dual-Center Randomized Clinical Trial Exploring the Optimal Duration of Antimicrobial Prophylaxis in Patients Undergoing Pancreaticoduodenectomy Following Biliary Drainage." Annals of Gastroenterological Surgery 2.6 (2018): 442-50.

- Yang, Z. "[Short-Term Versus Long-Term Antimicrobial Prophylaxis in Abdominal Surgery: A Multicenter Open Randomized Comparative Trial]." Zhonghua Wai Ke Za Zhi 39.10 (2001): 770-2.

Evidence tabellen

|

|

Author, Year |

Scope, participants |

Type of surgery |

Wound class. |

CDC SSI definition, Follow-up |

Intervention |

Control |

|

|

|

Postoperative continuation of surgical antibiotic prophylaxis vs. postoperative discontinuation of surgical antibiotic prophylaxis |

|||||||||

|

1 |

Sadraei-Moosavi 2018 |

Single centre 152* |

Appendectomy (open, uncomplicated) |

II-III |

No |

1g Ceftriaxone & 0.5g Metronidazole IV preoperatively + 24h postoperatively |

1g Ceftriaxone & 0.5g Metronidazole IV preoperatively |

No |

Yes |

|

2 |

Hussain 2012 |

Single centre 377 |

Appendectomy (open, uncomplicated) |

II-III |

Noa, 30 days |

Cefuroxime & Metronidazole IV preoperatively + 1x postoperatively |

Cefuroxime & Metronidazole IV preoperatively |

Yes |

Yes |

|

3 |

Liberman 1995 |

Single centre 99* |

Appendectomy (open uncomplicated) |

II-III |

Noa, 3 weeks |

2g Cefoxitin IV preoperatively + 3x q 6h postoperatively |

2g Cefoxitin IV preoperatively |

Yes |

Yes |

|

4 |

Tsang 1992 |

Single centre 103** |

Appendectomy (open, uncomplicated) |

II-III |

Noa, 4 weeks |

1.5 mg/kg Gentamicin IV & 7.5 mg/kg Metronidazole IV preoperatively +2x q 8h postoperatively |

1.5 mg/kg Gentamicin IV & 7.5 mg/kg Metronidazole IV preoperatively |

No |

Yes |

|

5 |

Salih 2018 |

Single centre 111* |

Appendectomy (open, uncomplicated) |

II-III |

CDC, 10 days |

0.5 mg metronidazole IV preoperatively + 9x q 8h postoperatively |

0.5 mg metronidazole IV preoperatively |

Yes |

Yes |

|

6 |

Suzuki 2011 |

Single centre 370 |

Colorectal surgery |

II-III |

Nof, 30 days |

1g Flomoxef IV preoperatively + 4x q 12h |

1g Flomoxef IV preoperatively |

Yes |

Yes |

|

7 |

Fujita 2007 |

Multi centre 377 |

Colorectal surgery |

II-III |

Nod, NR |

1g Cefmetazole IV preoperatively + 2x q 8h |

1g Cefmetazole IV preoperatively |

Yes |

No |

|

8 |

Imamura 2012 |

Multi centre 355 |

Upper GI surgery |

II |

CDC, 30 days |

1g of Cefazolin IV preoperatively +1 x direct postoperative & 4x q 12h postoperative |

1g of Cefazolin IV preoperatively |

No |

Yes |

|

9 |

Haga 2012 |

Single centre 325 |

Upper GI surgery |

II |

CDC, 30 days |

1g of Cefazolin IV preoperatively + 5x q 12h postoperatively |

1g of Cefazolin IV preoperatively |

No |

Yes |

|

10 |

Balbo 1991 |

Multi centre 117 |

Upper GI surgery |

II-III |

Nov, 30 days |

2g Mezlocillin IV preoperatively + 2x q 6h postoperatively |

2g Mezlocillin iv preoperatively |

Yes |

Yes |

|

11 |

Mohri 2007 |

Multi centre 486 |

Upper GI surgery |

II |

CDC, 6 weeks |

1g Cefazolin IV or 1.5 g Ampicillin sulbactam IV preoperatively + 7x q 12h postoperatively |

1g Cefazolin IV or 1.5 g Ampicillin sulbactam IV preoperatively |

Yes |

Yes |

|

12 |

Chauhan 2018 |

Single centre 210* |

Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy |

II-III |

Nod, 30 days |

1g Ceftriaxone IV preoperatively + 4x q 12h postoperatively |

1g Ceftriaxone IV preoperatively |

No |

No |

|

13 |

Santibañes 2018 |

Single centre 201 |

Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy |

II-III |

Nod, 30 days |

Ampicillin sulbactam IV q 6h preoperatively (admission – surgery, < 5 days) + 1g Amoxicillin/Clavulanic acid PO 15x q 8h |

Ampicillin sulbactam IV q 6h preoperatively (admission until surgery, < 5 days) + 1g Placebo PO 15x q 8h |

No |

No |

|

14 |

Kim 2017 |

Multi centre 188 |

Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy |

II-III |

Yes, 30 days |

1g Cefoxitin IV preoperatively + q 8h IV or PO if tolerated until POD 3 |

1g Cefoxitin IV preoperatively + placebo q 8h IV or PO if tolerated until POD 3 |

Yes |

Yes |

|

15 |

Loozen 2017 |

Single centre 150 |

Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy |

II-III |

Nou |

2g Cefazolin IV preoperatively + 0.75g Cefazoline IV & 0.5g Metronidazole IV 9x q 8h |

2g Cefazolin IV preoperatively |

Yes |

Yes |

|

16 |

Regimbeau 2014 |

Multi centre 414 |

Open or laparoscopic Cholecystectomy |

II-III |

CDC, 30 days |

2g Amoxiclav IV 3dd before surgery & preoperatively + 15x q 8h IV or PO if tolerated |

2g Amoxiclav IV 3dd before surgery & preoperatively |

Yes |

No |

|

17 |

Unemura 2000 |

Multi centre 242 |

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy |

II-III |

Noa, NR |

2g Cephalosporin IV preoperatively + 4x q 12h postoperatively |

2g Cephalosporin IV preoperatively |

No |

Yes |

|

18 |

Meijer 1993 |

Multi centre 1004 |

Hepatobiliary surgery |

II |

Noi, 4-6 weeks |

1.5g Cefuroxime IV preoperatively + 0.75g Cefuroxime IV 2x q 8h postoperatively |

1.5g Cefuroxime IV preoperatively |

No |

No |

|

19 |

Abro 2014 |

Single centre 208 |

Mixed general surgery |

I-III |

Noj, 35 days |

2g Ceftriaxone IV preoperatively + 1g Ceftriaxone IV 2x q 8h postoperatively (& 0.25g Gentamicin & 0.5g Metronidazole when indicated) |

2g Ceftriaxone IV preoperatively (& 0.25g Gentamicin & 0.5g Metronidazole when indicated) |

No |

Yes |

|

20 |

Becker 2008 |

Single centre 44 |

Mixed general surgery |

I |

CDC, 30 days |

1g Cefazoline IV preoperatively + 3dd postoperatively until drains were removed |

1g Cefazoline IV preoperatively |

Yes |

Yes |

|

21 |

Scher 1997 |

Single centre 768 |

Mixed general surgery |

II |

Nod, NR |

1g of Cefazolin IV preoperatively + 1g Cefazolin IV 3x q 8h postoperatively |

1g of Cefazolin IV preoperatively |

Yes |

Yes |

|

22 |

Kow 1995 |

Single centre 1010* |

Mixed general surgery |

II-III |

Nob, 4-6 weeks |

2g Cefoxitin IV & 0.5 Metronidazole IV preoperatively + 2x q 6h postoperatively |

2g Cefoxitin IV & 0.5g Metronidazole IV preoperatively |

No |

No |

|

1g Cefotaxime IV & 0.5g metronidazole IV preoperatively + 2x q 6h postoperatively |

1g Cefotaxime IV & 0.5g metronidazole IV preoperatively |

||||||||

|

23 |

Nusrath 2020 |

Single centre 312 |

Mixed oncological surgery |

II |

CDC, 30 days |

1.5g Cefuroxime IV preoperatively + 12x q 8h 1.5g Cefuroxime IV postoperatively |

1.5g Cefuroxime IV preoperatively |

Yes |

No |

|

24 |

Turano 1992 |

Single centre 3567* |

Abdominal, Gynaecological and Urological surgery |

II-III |

Noa, 7 days |

1g Cefotaxime IV preoperatively + 2x q 6h after the first dose |

1g Cefotaxime IV preoperatively |

Yes |

Yes |

|

25 |

Bates 1992 |

Multi centre 900* |

Mixed general surgery |

II-IV |

Nob, 30 days |

0.25g/0.125g Amoxicillin/clavulanic acid IV preoperatively + 2x q 8h postoperatively |

0.25g/0.125g Amoxicillin/clavulanic acid IV preoperatively |

Yes |

No |

|

26 |

Aberg 1991 |

Single centre 428* |

Mixed general surgery |

II-III |

Noa, 30 days |

1.5g Cefuroxime IV preoperatively + 2x q 8h (& 0.5g metronidazole when indicated) |

1.5g Cefuroxime IV preoperatively (& 0.5g metronidazole when indicated) |

No |

No |

|

27 |

Sgroi 1990 |

Single centre 352 |

Mixed general |

II-III |

Noa, NR |

1 x Cephalosporin preoperatively + 2x q 8h postoperatively |

1 x Cephalosporin preoperatively |

Yes |

No |

|

28 |

Westen 2015 |

Multi centre 176 |

C-section |

II |

Nok, 30 days |

1g Ampicillin IV & 0.5g Metronidazole IV preoperatively + 0.5 Amoxicillin & 0.5g Metronidazole IV 2x q 8h postoperatively followed by 0.5g Amoxicillin PO and 0.4g metronidazole PO 9x q 8h |

1g Ampicillin IV & 0.5g Metronidazole IV preoperatively |

Yes |

Yes |

|

29 |

Shaheen 2014 |

Single centre 100 |

C-section |

II |

Nol, 6 weeks |

1g Cefotaxime IV preoperatively + 2 x q 12h postoperatively followed by 0.4g Cefuroxime PO for 5 days |

1g Cefotaxime IV preoperatively |

Yes |

Yes |

|

30 |

Lyimo 2013 |

Single centre 500 |

C-section |

II |

CDC, 30 days |

3 mg/kg Gentamicin IV & 0.5g Metronidazole I + preoperatively Metronidazole 0.5g 3x q 8h postoperatively |

3 mg/kg Gentamicin IV & 0.5g Metronidazole IV preoperatively |

Yes |

Yes |

|

31 |

Tan 2020 |

Single centre 486 |

C-section |

II |

Noae, NI |

2 g Cefuroxime IV preoperatively + 3 days postoperatively |

2 g Cefuroxime IV preoperatively |

Yes |

Yes |

|

32 |

Su 2005 |

Single centre 532 |

Gynaecological surgery |

II |

Nom, 90 days |

1g Cefazolin preoperatively + 3x q 6h postoperatively |

1g Cefazolin IV preoperatively |

Yes |

Yes |

|

33 |

Irato 1997 |

Single centre 84 |

Gynaecological surgery |

II-III |

Now, NR |

2g cefotetan IV preoperatively + 10x q 12h |

2g cefotetan IV preoperatively |

Yes |

No |

|

34 |

Cartaña 1994 |

Single centre 58 |

Gynaecological surgery |

II |

Nod, 4 days |

4g Piperacillin preoperatively + 2x q 6h postoperatively |

4g Piperacillin IV preoperatively |

Yes |

No |

|

35 |

Buckley 1990 |

Single centre 204 |

Orthopaedic / trauma surgery |

I |

Noa, 6 weeks |

2g Cefazolin IV preoperatively + 1g Cefazolin 3x q 6h postoperatively |

2g Cefazolin IV preoperatively |

Yes |

Yes |

|

36 |

Garotta 1991 |

Multi centre 614 |

Orthopaedic / trauma surgery |

I |

Noc, 1 year |

2g Ceftizoxime IV preoperatively + 1x q 12h postoperatively |

2g Ceftizoxime IV preoperatively |

Yes |

No |

|

37 |

Hellbusch 2008 |

Multi centre 233 |

Orthopaedic / trauma surgery |

I |

Noo, >21 days |

1g<100kg<2g Cefazolin IV preoperatively + 9x q 8h postoperatively followed by 0.5g Cephalexin PO 28x q 6h |

1g<100kg<2g Cefazolin IV preoperatively |

Yes |

Yes |

|

38 |

Crist 2018 |

Single centre 227 |

Orthopaedic / trauma surgery |

I |

Nox |

1g<100kg<2g Cefazolin IV preoperatively + 2x q 8h postoperatively |

1g<100kg<2g Cefazolin IV preoperatively + 2x q 8h Saline |

Yes |

Yes |

|

39 |

Nooyen 1994 |

Single centre 844 |

Cardiothoracic surgery |

I |

Noc, NR |

20mg/kg Cefuroxime IV preoperatively + 0.75g Cefuroxime IV 9x q 8h postoperatively |

20mg/kg Cefuroxime IV preoperatively |

Yes |

No |

|

40 |

Tamayo 2008 |

Single centre 838 |

Cardiothoracic surgery |

I |

CDC, 12 months |

2g Cefazolin IV preoperativel + 1g Cefazolin IV 2x q 8h postoperatively |

2g Cefazolin IV preoperatively |

No |

Yes |

|

41 |

Olak 1991 |

Single centre 199 |

Cardiothoracic surgery |

II |

Noa, 6 weeks |

2g Cefazolin IV preoperatively + 1g Cefazolin IV 5x q 8h postoperatively |

2g Cefazolin IV preoperatively |

No |

Yes |

|

42 |

Orjuela 2020 |

Single centre 360 |

Cardiac surgery |

I |

Noaf, 2 years |

1g Cefazolin IV preoperatively + 1g Cefazolin IV 3x q 8h postoperatively |

1g Cefazolin IV preoperatively |

Yes |

Yes |

|

43 |

Madadi 2019 |

Single centre 300 |

Cardiothoracic surgery |

I |

Noaa, 30 days |

1-2 g Cephazolin IV preoperatively + Cephazolin IV 3x q 8h |

1-2 g Cephazolin IV preoperatively |

Yes |

Yes |

|

1-2 g Cephazolin IV preoperatively + Cephazolin IV 3x q 8h & Ciprofloxacin PO 14x q 12h |

1-2 g Cephazolin IV preoperatively |

Yes |

Yes |

||||||

|

44 |

Jiang 2004 |

Multi centre 264 |

Thoracic surgery |

II-III |

CDC, 30 days |

1.5g cefuroxime IV preoperatively + 15x 0.75g q 8h postoperatively |

1.5g cefuroxime IV preoperatively |

No |

No |

|

45 |

Hall 1998 |

Single centre 302 |

Vascular surgery |

I |

Noc, 42 days |

3.0g/0.1g Ticarcillin Clavulanic acid IV preoperatively + q 6h postoperatively until lines were removed |

3.0g/0.1g Ticarcillin Clavulanic acid IV preoperatively |

No |

Yes |

|

46 |

Orlando 2015 |

Multi centre 205 |

Transplant surgery |

I |

CDC, 30 days |

2g Cefazolin IV or 1g Cefotaxime IV preoperatively + q 12h postoperatively until removal of Foley catheter |

2g Cefazolin IV or 1g Cefotaxime IV preoperatively |

Yes |

Yes |

|

47 |

Berry 2019 |

Single centre 97

|

Liver transplant surgery |

II |

CDC, 30 days |

3.375 g Piperacillin/Tazobactam IV OR 2g Cefepime IV & 0.5 mg Metronidazole IV OR 1g Vancomycin IV & 0.4 mg Ciprofloxacin IV preoperatively + 8x q 8h 3.375 g Piperacillin/Tazobactam IV OR 2g Cefepime IV & 0.5 mg Metronidazole IV OR 1g Vancomycin IV & 0.4 mg Ciprofloxacin IV postoperatively |

3.375 g Piperacillin/Tazobactam IV OR 2g Cefepime IV & 0.5 mg Metronidazole IV OR 1g Vancomycin IV & 0.4 mg Ciprofloxacin IV preoperatively

|

Yes |

No |

|

48 |

Maier 1992 |

Single centre 106 |

Head and neck surgery |

I-II |

Nod, NR |

1.5 g Cefuroxime IV preoperatively + 2x q 8h postoperatively |

1.5 g Cefuroxime IV preoperatively |

Yes |

No |

|

49 |

Mann 1990 |

Single centre 113 |

Head and neck surgery |

II |

Noa, NR |

2g Cefotiam IV & 0.5g Metronidazole IV preoperatively + 2x q 8h postoperatively |

2g Cefotiam IV & 0.5g Metronidazole IV preoperatively |

Yes |

Yes |

|

50 |

Rajan 2005 |

Single centre 200 |

Head and neck surgery |

II |

Nod, 30 days |

2.2g Amoxicillin / clavulanic acid IV preoperatively + 1g Amoxicillin/ clavulanic acid PO 14x q 12h postoperatively |

2.2g Amoxicillin / clavulanic acid IV preoperatively |

Yes |

No |

|

51 |

Campos 2015 |

Single centre 74 |

Maxillofacial surgery |

I-II |

Noe, 6 weeks |

2g Cefazolin IV preoperatively + 1g Cefazolin IV 4x q 6h postoperatively |

2g Cefazolin IV preoperatively |

Yes |

Yes |

|

52 |

Lindeboom 2003 |

Single centre 70 |

Maxillofacial surgery |

II |

Nos, 3 months |

0.4g Clindamycin IV preoperatively + Clindamycin IV 4x q 6h postoperatively |

0.4g Clindamycin IV preoperatively |

Yes |

Yes |

|

53 |

Cioaca 2002 |

Single centre 140* |

Maxillofacial surgery |

II |

Noa, 14 days |

2.4 mg Amoxicillin/ Clavulanic acid IV preoperatively + 15x q 8h postoperatively |

2.4 mg Amoxicillin/ Clavulanic acid IV preoperatively |

No |

No |

|

2g Cefazolin IV preoperatively + 15x q 8h postoperatively |

2g Cefazolin IV preoperatively |

||||||||

|

54 |

Wahab 2013 |

Single centre 60* |

Maxillofacial surgery |

II |

CDC, 2 months |

1g Amoxicillin IV preoperatively + 0.5g Amoxicillin IV 2x q 4h postoperatively |

1g Amoxicillin IV preoperatively |

No |

No |

|

55 |

Danda 2010 |

Single centre 150* |

Maxillofacial surgery |

II |

Nob, 4 weeks |

1g Ampicillin IV preoperatively + Ampicillin 0.5g IV 4x q 6h postoperatively |

1g Ampicillin IV preoperatively |

No |

No |

|

56 |

Kang 2009 |

Single centre 56 |

Maxillofacial surgery |

II |

CDC, 2 weeks |

1g Cefpiramide IV preoperatively + 6x q 12h postoperatively |

1g Cefpiramide IV preoperatively |

Yes |

Yes |

|

57 |

Rajabi 2012 |

Single centre 291* |

Appendectomy (open, uncomplicated) |

II-III |

Noa, 10 days after discharge |

1g Ceftriaxone IV & 0.5g Metronidazole IV preoperatively + 1g Ceftriaxone IV q 12h & 0.5g Metronidazole IV q 8h For 1 OR 3 days postoperatively |

1g Ceftriaxone IV & 0.5g Metronidazole IV preoperatively |

No |

Yes |

|

58 |

Mui 2005 |

Single centre 269* |

Appendectomy (open, uncomplicated) |

II-III |

Noa, 30 days |

1.5g Cefuroxime IV & 0.5 g Metronidazole IV preoperatively + 2x postoperatively OR a 5-day course IV until PO was tolerated (Cefuroxime 0.25g 2dd + metronidazole 0.4g 3dd) |

1.5g Cefuroxime IV & 0.5 g Metronidazole IV preoperatively |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Postoperative continuation of surgical antibiotic prophylaxis for multiple postoperative doses <24h vs. postoperative continuation of surgical antibiotic prophylaxis for one postoperative dose |

|||||||||

|

59 |

Karran 1993 |

Single centre 227 |

Colorectal surgery |

II-III |

Nog, 6-8 weeks |

1g Imipenem IV preoperatively + 1x 3h postoperatively followed by 0.5 Imipenem IV 2x q 8 h |

1g Imipenem IV preoperatively + 1x 3h postoperatively |

No |

No |

|

Postoperative continuation of surgical antibiotic prophylaxis > 24h vs postoperative continuation of surgical antibiotic prophylaxis <= 24h |

|||||||||

|

60 |

Rajabi 2012 |

Single centre 194* |

Appendectomy (open, uncomplicated) |

II-III |

Noa, 10 days after discharge |

1.5g Cefuroxime IV & 0.5 g Metronidazole IV preoperatively + 1g Ceftriaxone 6x q 12h & 0.5g Metronidazole IV q 9x q 8h postoperatively |

1.5g Cefuroxime IV & 0.5 g Metronidazole IV preoperatively + 1g Ceftriaxone 2x q 12h & 0.5g Metronidazole IV 3x q 8h postoperatively |

No |

Yes |

|

61 |

Mui 2005 |

Single centre177* |

Appendectomy (open, uncomplicated) |

II-III |

Noa, 30 days |

1.5g Cefuroxime IV & 0.5 g Metronidazole IV preoperatively + 5-day course IV until PO was tolerated (Cefuroxime 250mg 2dd + metronidazole 400mg 3dd) |

1.5g Cefuroxime IV & 0.5 g Metronidazole IV preoperatively + 2x for 1 day postoperatively |

Yes |

Yes |

|

62 |

Ishibashi 2014 |

Single centre 297 |

Colorectal surgery |

II-III |

CDC, 30 days |

1g Flomoxef IV + 1x 1h postoperatively followed by 4x q 12h |

1g Flomoxef IV + 1x 1h postoperatively |

No |

Yes |

|

63 |

Ishibashi 2009 |

Single centre 275 |

Colorectal surgery |

II-III |

CDC, 30 days |

1g Cefotiam IV or Cefmetazole IV + 1x 1h postoperatively followed by 4 x q 12h |

1g Cefotiam IV or 1g Cefmetazole IV + 1x 1h postoperatively |

No |

Yes |

|

64 |

McArdle 1995 |

Single centre 169 |

Colorectal surgery |

II-III |

Noa, 4 weeks after discharge |

0.5g Metronidazole IV & 0.12g Gentamicin IV + 0.5g Metronidazole IV & 0.08g Gentamicin 9x q 8h |

0.5g Metronidazole IV & 0.12g Gentamicin IV+ 0.5g Metronidazole IV & 0.08g gentamicin IV 2x q 8h |

Yes |

Yes |

|

65 |

Becker 1991 |

Single centre 40 |

Colorectal surgery |

II-III |

Nob, 56 days |

2g Cefoxitin IV preoperatively + 2x q 6h after the initial dose followed by 1g Cefoxitin IV 20x q 6h postoperatively |

2g Cefoxitin IV preoperatively + 2x q 6h after the initial dose |

Yes |

No |

|

66 |

Fujita 2015 |

Single centre 257 |

Upper GI surgery |

II |

CDC, 30d |

1g Cefmetazole IV 4x q 3h starting preoperatively + 4x q 12h postoperatively |

1g Cefmetazole IV 4x q 3h starting preoperatively |

Yes |

Yes |

|

67 |

Lau 1990 |

Single centre 203 |

Open cholecystectomy |

II-III |

Noh, 1 year |

2g Cefamandole IV preoperatively + 0.5g Cefamandole IV 30x q 6h after the initial dose |

2g Cefamandole IV preoperatively + 0.5g Cefamandole IV 2x q 6h after the initial dose |

Yes |

No |

|

68 |

Yang 2001 |

Multi centre 731 |

Mixed general |

II-III |

Nod, NR |