Esketamine

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is de (in)effectiviteit van het toevoegen van esketamine aan standaard zorg bij kinderen die een chirurgische ingreep ondergaan?

Aanbeveling

Overweeg het perioperatief toedienen van esketamine wanneer matige tot ernstige postoperatieve pijn wordt verwacht.

Wees bij neonaten terughoudend om esketamine als langdurige postoperatieve pijnstilling toe te dienen.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Er is literatuuronderzoek verricht naar de gunstige en ongunstige effecten van ketamine bij kinderen die een chirurgische ingreep ondergaan. Er werden dertien RCT’s geïncludeerd, die perioperatief ketamine IV vergeleken met standaardzorg. Het aantal patiënten per arm varieerde van 15 tot 42. De leeftijd van de patiënten was van 0,5 jaar tot 18 jaar.

Postoperatieve pijn was gedefinieerd als cruciale uitkomstmaat en postoperatief opioïdengebruik, angst, adverse events en opnameduur als belangrijke uitkomstmaten.

Voor postoperatieve pijn was de bewijskracht laag voor alle tijdspunten (verkoever, 4 tot 8 uur en 24 uur). Daarmee komt de totale bewijskracht uit op laag. Deze literatuur laat zien dat ketamine niet tot nauwelijks effect heeft op postoperatieve pijn.

Voor postoperatief opioïdengebruik kon er geen conclusie getrokken worden voor gebruik op de PACU vanwege onvoldoende bewijs. In 24 uur en de totale postoperatieve periode werd niet tot nauwelijks verschil gezien door de toevoeging van ketamine (lage bewijskracht).

Voor de adverse events ademhalingsdepressie, misselijkheid en braken, sufheid en hallucinaties konden er geen conclusie getrokken worden (zeer lage bewijskracht). Dit geldt ook voor opnameduur. Angst en duizeligheid werden niet gerapporteerd.

De literatuur kan onvoldoende richting geven aan de besluitvorming. De aanbeveling is daarom gebaseerd op aanvullende argumenten waaronder expert opinie, waar mogelijk aangevuld met (indirecte) literatuur.

Postoperatief continueren van ketamine

De nieuwe module ketamine bij postoperatieve pijn bij volwassenen laat zien dat het continueren van ketamine postoperatief mogelijk een reductie van postoperatief opioïdengebruik geeft, in vergelijking tot alleen peroperatief ketamine gebruik (bolus). Hier moet aan toegevoegd worden dat de bewijskracht wel laag is vanwege de kleine studiepopulaties.

In deze huidige richtlijn werd bij 5 van de 13 studies de ketamine postoperatief gecontinueerd (Bazin, 2010; Dix, 2003; Perello, 2017; Pestieau, 2014; Ricciardelli, 2020). Alleen Ricciardelli liet bij scoliose chirurgie in de ketamine groep postoperatief significant minder opioïdgebruik zien. Bij de andere studies was er geen klinisch relevant verschil tussen beide groepen, mogelijk had een optimaal pijnbeleid in de controlegroep met paracetamol, een NSAID en opioïden effect op de uitkomst.

Een meta-analyse uit 2011 over ketamine en postoperatieve pijn bij kinderen, liet alleen bij een subgroep, waar intra- en postoperatief geen opiaten was gegeven, een klinisch relevant effect van ketamine op de postoperatieve pijn zien (Dahmani, 2011).

Farmacologie

Verschillende kleine studies lieten bij kinderen (1,5 – 12 jaar) een grotere variatie en een kortere context-sensitieve halfwaardetijd zien. Daarnaast was er een hoger continu infuus nodig vergeleken met volwassenen voor het handhaven van steady-state concentratie in het bloed (Dallimore, 2008; Flint 2017; Grant, 1983; Idvall, 1979; Weber 2004). Mogelijk zou dit bij kunnen dragen aan bovenstaande conclusies over het gebrek aan effect van ketamine als adjuvans naast opioïden, echter aanvullend onderzoek met grotere studiepopulaties is nodig om te beoordelen of deze resultaten robuust zijn.

In de geïncludeerde studies werd niet altijd toegelicht of de interventies bestonden uit esketamine of racemisch ketamine. Racemisch ketamine is internationaal de meest gebruikte variant, de werkgroep acht de kans groot dat deze werd toegediend. Esketamine heeft een twee keer grotere potentie dan racemisch ketamine.

Neurotoxiciteit

Verschillende dierexperimentele studies, bij knaagdieren en primaten, hebben laten zien dat het toedienen van ketamine een schadelijk effect heeft op de ontwikkeling van de hersenen door o.a. neuro-apoptose. De schade werd waargenomen na langdurige blootstelling (24 uur) met hoge doseringen en hoe jonger het brein, hoe groter het effect (Ikonomidou, 1999; Scallet 2004; Slikker, 2007). Dierexperimentele data vertalen naar de mens blijft ingewikkeld vanwege vele factoren. De studies die bij kinderen onderzochten of deze neurotoxiciteit later ook een klinisch relevant effect veroorzaken, publiceren wisselende uitkomsten (Guerra, 2011; Bhutta, 2012; Ing, 2017; Simpao, 2023). De laatste (retrospectieve) studie uit 2023 keek naar een groep neonaten die congenitale cardiale chirurgie ondergingen en daardoor meerdere keren algehele anesthesie moesten ondergaan, wat cumulatief werd bijgehouden waarna de kinderen neurologisch vervolgd werden. Dampvormige anesthetica, opioïden, benzodiazepine en dexmedetomidine hadden geen effect op de cognitieve functies. Alleen ketamine had een negatief effect op de motoriek (Simpao, 2023). Meer onderzoek is nodig om hier harde uitspraken over te kunnen doen.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

In de praktijk wordt esketamine vaak gestart bij grote operaties met de intentie om de postoperatieve pijn te reduceren en opioïdengebruik te verminderen. Minder opioïden zorgen vaak onder andere voor minder obstipatie, misselijkheid en sufheid. Daar staat tegenover dat we in de praktijk bij esketamine vaker visuele hallucinaties en levendige dromen/nachtmerries zien, hoewel hier in de literatuuranalyse geen duidelijke evidence voor is. Dit moet vooraf besproken worden met ouders en patiënt. Indien dit ontstaat kan de esketamine in dosering worden aangepast of worden gestaakt, waarna de bijwerkingen naar verwachting binnen een aantal uur zullen verdwijnen.

Het starten en eventueel continueren van esketamine is afhankelijk van de operatie, de te verwachten postoperatieve pijn en de patiëntkarakteristieken. Deze medische beslissing is voorbehouden aan de anesthesioloog. Voor de patiënt die een grote operatie heeft ondergaan, is het starten van esketamine geen extra belasting omdat de patiënt postoperatief sowieso meerdere dagen ligt opgenomen met infuus.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

Ten aanzien van het gebruik van geneesmiddelen zal het gebruik van esketamine niet leiden tot een kostenstijging. Esketamine moet worden voorgeschreven, echter mogelijk zorgt dit weer voor minder opioïdengebruik. Met het oog op het postoperatieve traject zal het postoperatief continueren van esketamine niet leiden tot een kostenstijging, omdat het Acute Pijn Service (APS) team de patiënt toch al zal vervolgen voor postoperatief intraveneus opioïdengebruik, dan wel een epiduraal. Het is onduidelijk of postoperatief toedienen van esketamine effect invloed heeft op de ziekenhuisopnameduur en de daarbij horende kosten.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

Indien esketamine postoperatief wordt gecontinueerd, zal het APS-team betrokken moeten zijn. Gezien het feit dat esketamine bij kinderen meestal alleen bij grote operaties postoperatief gecontinueerd wordt, zal het APS-team sowieso al betrokken zijn en zal dit geen extra tijd kosten. Esketamine is in elk ziekenhuis op voorraad vanwege intra-operatief gebruik. Een standaard infuuspomp is ook reeds overal aanwezig. Mogelijk zijn niet alle verpleegkundige bekend met esketamine en dan is training van het personeel noodzakelijk.

Rationale van aanbeveling 1: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

In de praktijk wordt ketamine vaak gestart bij grote operaties met de intentie om de postoperatieve pijn te reduceren en opioïdengebruik te verminderen. De literatuur kan echter onvoldoende richting geven aan de besluitvorming gezien de zeer lage bewijskracht door onder andere de kleine studiepopulaties. In deze huidige richtlijn werd bij 5 van de 13 RCT’s ketamine postoperatief gecontinueerd (Bazin, 2010; Dix, 2003; Perello, 2017; Pestieau, 2014; Ricciardelli, 2020). Alleen Ricciardelli liet bij scoliosechirurgie in de ketamine groep postoperatief significant minder opioïdgebruik zien. Bij de andere studies was er geen klinisch relevant verschil tussen beide groepen, mogelijk had een optimaal pijnbeleid in de controlegroep met paracetamol, een NSAID en opioïden effect op de uitkomst.

De aangeraden dosering van esketamine voor postoperatieve pijnstilling als aanvulling op andere analgetica staat beschreven in het Kinderformularium (Esketamine, Kinderformularium).

Rationale van aanbeveling 2: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

Verschillende dierexperimentele studies, bij knaagdieren en primaten, hebben laten zien dat het toedienen van ketamine een schadelijk effect heeft op de ontwikkeling van de hersenen door o.a. neuro-apoptose. De schade werd waargenomen na langdurige blootstelling (24 uur) met hoge doseringen en hoe jonger het brein, hoe groter het effect (Ikonomidou, 1999; Scallet 2004; Slikker, 2007). Studies die bij kinderen onderzochten of deze neurotoxiciteit later ook een klinisch relevant effect veroorzaken publiceren wisselende uitkomsten (Guerra, 2011; Bhutta, 2012; Ing, 2017; Simpao, 2023). Kortdurend en eenmalige toediening van o.a. ketamine lijkt veilig, echter het cumulatief effect van ketamine op kinderen die op jonge leeftijd al meerdere malen langdurig anesthesie en/of analgesie nodig hebben blijft onduidelijk.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

(S)(+)-ketamine is de linksdraaiende isomeer van het racemische mengsel ketamine. Het blokkeert de N-methyl-D-aspartaat (NMDA) receptoren en heeft een analgetisch en anesthetisch effect. Daarnaast potentieert het de werking van mu-opioïdagonisten en wordt daarom vaak gegeven als adjuvans bij opioïden. Ook bij kinderen wordt esketamine regelmatig gegeven, met name bij grote operaties in het perioperatieve traject. Echter, de dosering en tijdstip van toediening wisselen; zo wordt het als eenmalige bolus intra-operatief of als bolus plus intra-operatieve continue infusie of als bolus plus intra-operatieve en postoperatieve continue infusie gegeven. De vraag rijst wat de toegevoegde waarde is van esketamine voor postoperatieve pijn bij kinderen.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

Postoperative pain (critical)

|

Low GRADE |

Ketamine may result in little to no difference in postoperative pain in PACU when compared with standard care in children undergoing surgery.

Sources: Abu-Shawan, 2008; Bazin, 2010; Dal, 2007; Darabi, 2008; Honarmand, 2013; Inanoglu, 2009; Umuroglu, 2004. |

|

Ketamine may result in little to no difference in postoperative pain at 4 to 8 hours when compared with standard care in children undergoing surgery.

Sources: Bazin, 2010; Da Conceicao, 2006; Darabi, 2008; Inanoglu, 2009; Umuroglu, 2004. |

|

|

Ketamine may result in little to no difference in postoperative pain at 24 hours when compared with standard care in children undergoing surgery.

Sources: Bazin, 2010; Da Conceicao, 2006; Darabi, 2008; Dix, 2003; Inanoglu, 2009; Pestieau, 2014. |

Postoperative opioid consumption (important)

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of ketamine on postoperative opioid consumption in PACU when compared with standard care in children undergoing surgery.

Sources: Abdelhalim, 2013; Abu-Shawan, 2008. |

|

Low GRADE |

Ketamine may result in little to no difference in postoperative opioid consumption in 24 hours when compared with standard care in children undergoing surgery.

Sources: Dix, 2003; Perello, 2016; Pestieau, 2014. |

|

Ketamine may result in little to no difference in postoperative opioid consumption in the total postoperative period when compared with standard care in children undergoing surgery.

Sources: Abu-Shawan, 2008; Perello, 2016; Ricciardelli; 2020. |

Anxiety (important)

|

No GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding the effect of ketamine on anxiety when compared with standard care in children undergoing surgery.

Source: - |

Adverse events (important)

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of ketamine on respiratory depression when compared with standard care in children undergoing surgery.

Source: Perello, 2016; Pestieau, 2014. |

|

No GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding the effect of ketamine on dizziness when compared with standard care in children undergoing surgery.

Source: - |

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of ketamine on postoperative nausea and vomiting when compared with standard care in children undergoing surgery.

Sources: Abdelhalim, 2013; Abu-Shawan, 2008; Bazin, 2010; Da Conceicao, 2006; Dal, 2007; Darabi, 2008; Honarmand, 2013; Inanoglu, 2009; Perelló, 2017; Pestieau, 2014; Ricciardelli, 2020; Umuroglu, 2004. |

|

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of ketamine on drowsiness when compared with standard care in children undergoing surgery.

Source: Darabi, 2008; Dix, 2003. |

|

|

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of ketamine on visual hallucinations when compared with standard care in children undergoing surgery.

Source: Bazin, 2010; Da Conceicao, 2006; Dal, 2007; Darabi, 2008; Dix, 2003; Honarmand, 2013; Perelló, 2017; Pestieau, 2014; Ricciardelli, 2020; Umuroglu, 2004. |

Length of stay (important)

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of ketamine on length of stay when compared with standard care in children undergoing surgery.

Source: Perello, 2016; Ricciardelli, 2020. |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

As shown in table 1, studies were conducted in patients undergoing various surgeries. Varying doses of ketamine were used and administered intraoperatively, postoperatively or both. Patients per arm varied from 15 to 42. The age of studies varied from 0.5 years to 18 years.

Table 1. Characteristics of included studies.

|

Author, year

|

Population (I/C), mean age; %M |

Surgical procedure |

Intervention |

Ketamine timing |

Control |

|

Abdelhalim, 2013 |

N: 40/40, age 3-7 y; 60%M |

Tonsillectomy |

Ketamine IV (0.5 mg/kg) Peroperative: fentanyl, acetaminophen, dexamethasone Postoperative fentanyl (0.5 μg/kg, rescue) |

End of surgery |

Peroperative: saline + fentanyl, acetaminophen, dexamethasone Postoperative fentanyl (0.5 μg/kg, rescue) |

|

Abu-Shawan, 2008 |

N: 42/40, age 2–12 y; 61.9%M |

Adenotonsillectomy |

Ketamine (0.25 mg/kg) Peroperative acetaminophen + morphine (0.1 mg/kg) Postoperative morphine + acetaminophen + codeine |

After induction |

Peroperative acetaminophen + morphine (0.1 mg/kg) Postoperative morphine + acetaminophen + codeine |

|

Bazin, 2010 |

N: 18/19, age 0.5–6 y; 72.2%M |

Ambulatory surgeries |

Ketamine (0.15 mg/kg + 1.4 mg/kg/h) Peroperative caudal analgesia, acetaminophen + diclofenac Postoperative nalbuphine + acetaminophen + diclofenac |

After induction, 24h postoperative |

Peroperative caudal analgesia, acetaminophen + diclofenac Postoperative nalbuphine + acetaminophen + diclofenac |

|

Da Conceicao, 2006 |

N: 30/30/30, age 5–7 y; %M not reported |

Adenotonsillectomy |

Ketamine IV (0.5 mg/kg) Peroperative diclofenac Postoperative acetaminophen + morphine |

I) After induction II) End of surgery |

Peroperative saline + diclofenac Postoperative acetaminophen + morphine |

|

Dal, 2007 |

N: 30/30, age 2–12 y; 35.5%M |

Adenotonsillectomy |

Ketamine IV (0.5 mg/kg) Peroperative: fentanyl Postoperative: metamizole + acetaminophen |

After induction |

Peroperative: saline + fentanyl Postoperative: metamizole + acetaminophen |

|

Darabi, 2008 |

N: 25/25, age 1–6 y; 100%M |

Inguinal hernia repair |

Ketamine IV (0.25 mg/kg) Peroperative remifentanil + diclofenac Postoperative diclofenac + proparacetamol |

After induction |

Peroperative saline + remifentanil + diclofenac Postoperative diclofenac + proparacetamol |

|

Dix, 2003 |

N: 25/25/25, age 6-15 y; 56.7%M |

Appendicectomy |

I) Ketamine IV (0.5 mg/kg) II) Ketamine IV (0.5 mg/kg + 4 µg/kg/min) Peroperative fentanyl + diclofenac + bupivacaine infiltration Postoperative PCA + acetaminophen |

I) After induction II) After induction, postoperative |

Peroperative saline + fentanyl + diclofenac + bupivacaine infiltration Postoperative PCA + acetaminophen |

|

Honarmand, 2013 |

N: 30/30, age 2-15 y; 56.7%M |

Tonsillectomy |

Ketamine IV (0.5 mg/kg) + peritonsillar tramadol (2 mg/kg) Postoperative rectal acetaminophen (20 mg/kg, rescue) |

After induction |

Peritonsillar tramadol (2 mg/kg) Postoperative rectal acetaminophen (20 mg/kg, rescue) |

|

Inanoglu, 2009 |

N: 30/30, age 2-12 y; 46.7%M |

Adenotonsillectomy |

Ketamine (0.5 mg/kg) + peritonsillar bupivacaine Peroperative: fentanyl and acetaminophen Postoperative: fentanyl and acetaminophen |

After induction |

Peroperative: saline + peritonsillar bupivacaine fentanyl and acetaminophen Postoperative: fentanyl and acetaminophen |

|

Perelló, 2017 |

N: 21/23, age 12-18 y; 23.8%M |

Scoliosis |

Ketamine (0.5 mg/kg) Peroperative: morphine (150 μg/kg) Postoperative: PCA morphine + IV acetaminophen 15 mg/kg |

After induction, peroperative and until 72 hours postoperative |

Peroperative: saline + morphine (150 μg/kg) Postoperative: PCA morphine + IV acetaminophen 15 mg/kg |

|

Pestieau, 2014 |

N: 29/21, age 10-18 y; 17%M |

Scoliosis |

Ketamine (0.5 mg/kg + 0.25 mg/kg/h peroperative, 0.1 mg/kg postoperative) Peroperative: fentanyl, remifentanil Postoperative: PCA morphine + acetaminophen + diazepam |

After induction, peroperative and until 72 hours postoperative |

Peroperative: saline + fentanyl, remifentanil Postoperative: PCA morphine + acetaminophen + diazepam |

|

Ricciardelli, 2020 |

N: 24/25, age 12-16 y; 9.1%M |

Scoliosis |

Ketamine (0.5 mg/kg + 0.2 mg/kg/h) Postoperative PCA morphine + IV acetaminophen 15 mg/kg After 24h: ketorolac IV 0.5 mg/kg After 48h: ibuprofen po 10 mg/kg |

After induction until 48 hours postoperative |

Saline Postoperative PCA morphine + IV acetaminophen 15 mg/kg After 24h: ketorolac IV 0.5 mg/kg After 48h: ibuprofen po 10 mg/kg |

|

Umuroglu, 2004 |

N: 15/15, age 5-12 y; 66.7%M |

Adenotonsillectomy |

Ketamine (0.5 mg/kg + 10 µg/kg/min) Postoperative pethidine + acetaminophen |

After induction and peroperative |

Peroperative: saline Postoperative pethidine + acetaminophen |

Results

1. Postoperative pain

1.1 Postoperative pain in PACU

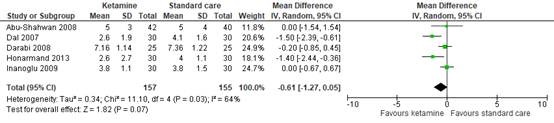

Five studies reported postoperative pain in PACU. Figure 1 shows a mean difference (MD) of -0.61 (95% CI -1.27 to 0.05). This difference is not clinically relevant in favor of ketamine.

Figure 1. Postoperative pain in PACU / 0 hours.

95% CI: 95% confidence interval

In addition to the pooled analysis, two studies reported data on postoperative pain, but could not be added to the pooled analysis.

Bazin (2010) presented postoperative Children's Hospital of Eastern Ontario Pain Scale (CHEOPS) scores graphically. At 0 hours, the pain scores in both groups were similar between both groups.

Umuroglu (2004) presented postoperative numeric rating scale (NRS) and CHEOPS scores graphically. At 0 hours, the both the NRS and CHEOPS scores were lower in the ketamine group compared to the standard care group. These differences were clinically relevant in favor of ketamine.

These results are to some extend in line with the pooled analysis.

1.2 Postoperative pain at 4 to 6 hours

Bazin (2010) presented postoperative CHEOPS scores graphically. At 6 hours, the pain scores in both groups were similar between both groups.

Da Conceicao (2006) reported pain scores on the Oucher scale (0-100) graphically. At 4 hours post-surgery, the pain scores in the ketamine and standard care group were similar.

Darabi (2008) reported postoperative pain scores at the CHEOPS (scale 4-13). At 6 hours, pain in the ketamine group was 6.52 (SD 1.08) and in the standard care group 6.76 (SD 1.2) (MD -0.24; 95% CI -0.87 to 0.39).

Inanoglu (2009) reported pain scores assessed by the Objective Pain Scale (OPS 0-10). At 4 hours, pain in the ketamine group was 1.1 (SD 0.8) and in the standard care group 2.2 (SD 0.4) (MD -1.10; 95% CI -1.42 to -0.78).

Umuroglu (2004) presented postoperative NRS and CHEOPS scores graphically. At 6 hours, the NRS and CHEOPS scores were similar in the ketamine and standard care group.

The studies show similar results. Inanoglu (2009) is the only study reporting a clinically relevant effect in favor of ketamine.

1.3 Postoperative pain at 24 hours

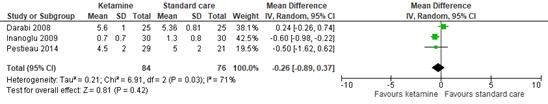

Three studies reported postoperative pain at 24 hours. Figure 2 shows a mean difference of -0.26 (95% CI -0.89 to 0.37). This difference is not clinically relevant in favor of ketamine.

Figure 2. Postoperative pain at 24 hours.

95% CI: 95% confidence interval

In addition to the pooled analysis, three studies reported data on postoperative pain, but could not be added to the pooled analysis.

Bazin (2010) presented postoperative CHEOPS scores graphically. At 24 hours, the pain scores in both groups were similar between both groups.

Da Conceicao (2006) reported pain scores on the Oucher scale graphically. At 24 hours post-surgery, the pain scores in the ketamine and standard care group were both 0.

Dix (2003) reported pain scores on a visual analog scale (VAS) (0-10) in 24 hours as median (range). In the bolus ketamine group, median pain score was 4 (range 1–9). In the ketamine infusion group, the pain score was 4 (range 0–7). In the control group, the pain score was 2 (range 0–8).

The studies show relatively similar results to the pooled analysis, except for Dix (2003). This is the only study reporting a clinically relevant difference in favor of standard care.

2. Postoperative opioid consumption

2.1 Postoperative opioid consumption in PACU

Abdelhalim (2013) reported the fentanyl dose in PACU. In the ketamine group, fentanyl consumption was 0.19 mcg/kg (SD 0.34) and in the standard care group 0.32 mcg/kg (SD 0.43). The MD was -0.13 (95% CI -0.30 to 0.04).

Abu-Shahwan (2008) reported no quantified data on opioid consumption. Morphine consumption was less in the ketamine group during the immediate postoperative period.

Both studies reported results in favor of ketamine.

2.2 Postoperative opioid consumption in 24 hours

Three studies reported postoperative opioid consumption in 24 hours. No pooled analysis could be performed, as only one study reported absolute data for morphine equivalents.

Dix (2003) reported median morphine consumption in 24 hours. In the bolus ketamine group, median consumption was 0.44 mg/kg (range 0.043–0.112). In the ketamine infusion group, median consumption was 0.348 mg/kg (range 0.02–0.1514). In the control group, the morphine consumption was 0.313 mg/kg (range 0–0.945).

Perello (2016) reported postoperative morphine consumption in 24 hours. In the ketamine group, mean morphine consumption was 0.76 mg/kg (SD 0.3) and in the standard care group 0.68 mg/kg (SD 0.33) (MD 0.08; 95% CI -0.11 to 0.27).

Pestieau (2014) reported morphine equivalent consumption graphically. The postoperative opioid consumption in 24 hours was similar between both groups (MD -0.04 mg/kg; 95% CI not reported).

2.3 Postoperative opioid consumption in total postoperative period

Three studies reported postoperative opioid consumption in total postoperative period. No pooled analysis could be performed, as only two studies reported morphine equivalents.

Abu-Shahwan (2008) reported no quantified data on opioid consumption. Total morphine consumption over the course of the study was not statistically different between the two groups (P = 0.48).

Perello (2016) reported postoperative morphine consumption. In the ketamine group, mean opioid consumption was 3.13 mg/kg (SD 1.13) and in the standard care group 2.72 mg/kg (SD 1.13) (MD 0.41; 95% CI -0.26 to 1.08).

Ricciardelli (2020) reported opioid consumption in morphine equivalents. In the ketamine group, mean opioid consumption was 0.577 mg/kg (SD 0.374) and in the standard care group 0.83 mg/kg (SD 0.466) (MD -0.25; 95% CI -0.49 to -0.02).

The studies show conflicting results.

3. Anxiety

None of the included studies reported the outcome measure ‘anxiety’.

4. Adverse events

4.1 Respiratory depression

Two studies reported respiratory depression.

Perello (2016) reported no cases of respiratory depression in both groups (RD 0.00; 95% CI -0.08 to 0.08).

Pestieau (2014) also reported no cases of respiratory depression in both groups (RD 0.00; 95% CI -0.06 to 0.06).

4.2 Dizziness

None of the included studies reported the outcome measure ‘dizziness’.

4.3 Postoperative nausea and vomiting

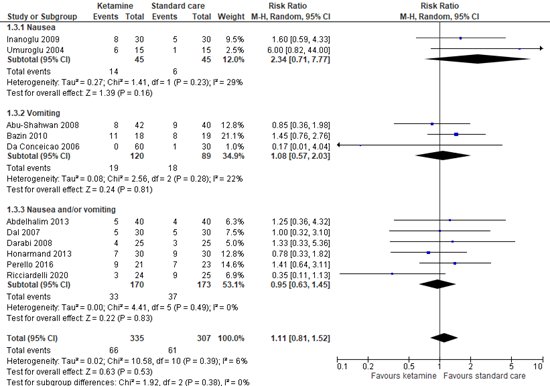

Eleven studies reported the incidence of visual hallucinations. Figure 3 shows a risk ratio of 1.11 (95% CI 0.81 to 1.52). This difference is not clinically relevant in favor of standard care.

Figure 3. Incidence of postoperative nausea and vomiting.

95% CI: 95% confidence interval

In addition to the pooled analysis, Pestieau (2014) reported similar incidences of nausea and vomiting in both groups. No absolute data was presented.

4.4 Drowsiness

Two studies reported drowsiness.

Darabi (2008) reported no cases of drowsiness in the ketamine group (0 out of 25) and in the standard care group (0 out of 25) (RD 0.00; 95% CI -0.07 to 0.07).

Dix (2003) reported drowsiness in 0 out of 25 patients in the ketamine group and 1 out of 23 (4.3%) in the standard care group (RD -0.04; 95% CI -0.15 to 0.07).

These studies show similar results.

4.5 Visual hallucinations

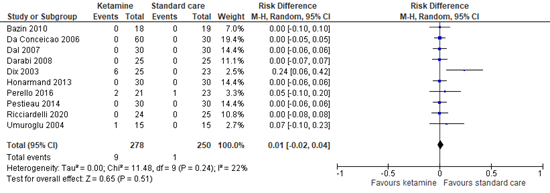

Ten studies reported the incidence of visual hallucinations. Figure 4 shows a risk difference of 0.01 (95% CI -0.02 to 0.04). This difference is not clinically relevant in favor of standard care.

Figure 4. Incidence of visual hallucinations.

95% CI: 95% confidence interval

5. Length of stay

Two studies reported the length of stay.

Perello (2016) reported a mean stay of 8.6 days (SD 1.1) in the ketamine group and 8.7 days (SD 1.6) in the standard care group (MD -0.10; 95% CI -0.91 to 0.71).

Ricciardelli (2020) reported a mean stay of 5.46 days (SD 0.7341) in the ketamine group and 5.52 days (SD 0.6541) in the standard care group (MD -0.06; 95% CI -0.45 to 0.33).

These studies show similar result and are not clinically relevant in favor of ketamine.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence regarding all outcome measures started at high, since the included studies were RCTs.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure postoperative pain in PACU was downgraded by two levels because of study limitations (risk of bias due to lack of blinding, -1); the pooled effect crossing one threshold for clinical relevance (imprecision, -1). The level of evidence is low.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure postoperative pain at 4 to 6 hours was downgraded by two levels because of study limitations (risk of bias due to lack of blinding, -1); and the relatively small sample size (imprecision, -1). The level of evidence is low.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure postoperative pain at 24 hours was downgraded by two levels because of study limitations (risk of bias due to lack of blinding, -1); number of included patients (imprecision, -1). The level of evidence is low.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure postoperative opioid consumption in PACU was downgraded by three levels because of study limitations (risk of bias due to lack of blinding, -1); number of included studies and small sample size (imprecision, -2). The level of evidence is very low.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure postoperative opioid consumption in 24 hours was downgraded by two levels because of the number of included studies and small sample size (imprecision, -2). The level of evidence is low.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure postoperative opioid consumption in the total postoperative period was downgraded by three levels because of conflicting results (inconsistency, -1); number of included studies and small sample size (imprecision, -2). The level of evidence is low.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure respiratory depression was downgraded by three levels because there were no events in a small sample size (imprecision, -3). The level of evidence is very low.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure postoperative nausea and vomiting was downgraded by three levels because of study limitations (risk of bias due to lack of blinding, -1); the pooled effect crossing two thresholds for clinical relevance (imprecision, -2). The level of evidence is very low.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure drowsiness was downgraded by three levels because of the very low number of events in a small sample size (imprecision, -3). The level of evidence is very low.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure visual hallucinations was downgraded by three levels because of the very low number of events (imprecision, -3). The level of evidence is very low.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure length of stay was downgraded by three levels because of the very small sample size (imprecision, -3). The level of evidence is very low.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measures anxiety and dizziness could not be graded as none of the included studies reported these.

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question:

What is the (in)effectiveness of s-ketamine IV intra- and/or postoperative compared to standard care in children undergoing a surgical procedure?

|

P: |

Children undergoing a surgical procedure |

|

I: |

S-ketamine IV intra- and/or postoperative |

|

C: |

Standard care (opioids + paracetamol, NSAID optional) |

|

O: |

Postoperative pain, postoperative opioid consumption, anxiety, adverse events, length of stay |

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered postoperative pain as a critical outcome measure for decision making; and postoperative opioid consumption, anxiety, adverse events, and length of stay as important outcome measures for decision making.

The working group defined the outcome measures as follows:

- Postoperative pain à PACU / 0 hours, 6 and 24 hours (at rest; if nothing was reported about the condition in which pain was assessed (at rest or during mobilization) it was assumed pain was measured at rest)

- Postoperative opioid consumption à PACU, 24h and total

- Adverse events à respiratory depression, dizziness, postoperative nausea and vomiting, drowsiness, visual hallucinations

- Length of stay à length of stay in hospital in days

A priori, the working group did not define the outcome measure ‘anxiety’ but used the definitions used in the studies.

The working group defined one point as a minimal clinically (patient) important difference on a 10-point pain scale and 10 mm on a 100 mm pain scale. Regarding postoperative opioid consumption, a difference of 20% was considered clinically relevant. Regarding length of stay, a difference of one day was considered clinically relevant. For dichotomous variables, a difference of 10% was considered clinically relevant (RR ≤0.91 or ≥1.10; RD 0.10). For standardized mean differences (SMD), 0.5 was considered clinically relevant.

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms until 6 November 2022. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 390 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria:

- Randomized controlled trials

- Comparing ketamine with standard care

- In children undergoing a surgical procedure

- Reporting at least one of the predefined outcomes

- Published ≥ 2000

Thirty studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, seventeen studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and thirteen studies were included.

Results

Thirteen studies were included in the analysis of the literature. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- Abdelhalim AA, Alarfaj AM. The effect of ketamine versus fentanyl on the incidence of emergence agitation after sevoflurane anesthesia in pediatric patients undergoing tonsillectomy with or without adenoidectomy. Saudi J Anaesth. 2013 Oct;7(4):392-8. doi: 10.4103/1658-354X.121047. PMID: 24348289; PMCID: PMC3858688.

- Abu-Shahwan I. Ketamine does not reduce postoperative morphine consumption after tonsillectomy in children. Clin J Pain. 2008 Jun;24(5):395-8. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e3181668aad. PMID: 18496303.

- Bazin V, Bollot J, Asehnoune K, Roquilly A, Guillaud C, De Windt A, Nguyen JM, Lejus C. Effects of perioperative intravenous low dose of ketamine on postoperative analgesia in children. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2010 Jan;27(1):47-52. doi: 10.1097/EJA.0b013e32832dbd2f. PMID: 19535988.

- Bhutta AT, Schmitz ML, Swearingen C, et al. Ketamine as a neuroprotective and anti-inflammatory agent in children undergoing surgery on cardiopulmonary bypass: a pilot randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2012;13:328337.

- Da Conceição MJ, Bruggemann Da Conceição D, Carneiro Leão C. Effect of an intravenous single dose of ketamine on postoperative pain in tonsillectomy patients. Paediatr Anaesth. 2006 Sep;16(9):962-7. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9592.2006.01893.x. PMID: 16918659.

- Dahmani, S., Michelet, S., Abback, P., Wood, C., Brasher, C., Nivoche, Y., & Mantz, J. (2011b). Ketamine for perioperative pain management in children: a meta-analysis of published studies. Pead Anaesth, 21, 636-652

- Dal D, Celebi N, Elvan EG, Celiker V, Aypar U. The efficacy of intravenous or peritonsillar infiltration of ketamine for postoperative pain relief in children following adenotonsillectomy. Paediatr Anaesth. 2007 Mar;17(3):263-9. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9592.2006.02095.x. PMID: 17263742.

- Dallimore D, Anderson BJ, Short TG, Herd DW: Ketamine anesthesia in children-- exploring infusion regimens. Paediatr Anaesth 2008; 18: 708-14

- Darabi ME, Mireskandari SM, Sadeghi M, Salamati P, Rahimi E. Ketamine has no pre-emptive analgesic effect in children undergoing inguinal hernia repair.

- Dix P, Martindale S, Stoddart PA. Double-blind randomized placebo-controlled trial of the effect of ketamine on postoperative morphine consumption in children following appendicectomy. Paediatr Anaesth. 2003 Jun;13(5):422-6. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9592.2003.01090.x. PMID: 12791116.

- Flint, R. B., et al , Pharmacokinetics of S-ketamine during prolonged sedation at the pediatric intensive care unit, Paediatr Anaesth, 2017, 27(11), 1098-1107

- Grant IS, Nimmo WS, McNicol LR, Clements JA: Ketamine disposition in children and adults. Br J Anaesth 1983; 55: 1107-11

- Guerra GG, Robertson CM, Alton GY, et al. Neurodevelopmental outcome following exposure to sedative and analgesic drugs for complex cardiac surgery in infancy. Paediatr Anaesth. 2011;21:932941.

- Idvall J, Ahlgren I, Aronsen KR, Stenberg P: Ketamine infusions: pharmacokinetics and clinical effects. Br J Anaesth 1979; 51: 1167-73

- Ikonomidou C, Bosch F, Miksa M, Bittigau P, Vöckler J, Dikranian K, Tenkova TI, Stefovska V, Turski L, Olney JW. Blockade of NMDA receptors and apoptotic neurodegeneration in the developing brain. Science. 1999 Jan 1;283(5398):70-4. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5398.70. PMID: 9872743.

- Ing C, Sun M, Olfson M, DiMaggio CJ, Sun LS, Wall MM, Li G: Age at exposure to surgery and anesthesia in children and association with mental disorder diagnosis. Anesth Analg 2017; 125:1988-98

- Honarmand A, Safavi M, Kashefi P, Hosseini B, Badiei S. Comparison of effect of intravenous ketamine, peritonsillar infiltration of tramadol and their combination on pediatric posttonsillectomy pain: A double-blinded randomized placebo-controlled clinical trial. Res Pharm Sci. 2013 Jul;8(3):177-83. PMID: 24019827; PMCID: PMC3764669.

- Ikonomidou, C., Bosch, F., Miksa, M., Bittigau, P., Vockler, J., Dikranian, K., Tenkova, T. I., Stefovska, V., Turski, L., and Olney, J. W. Blockade of NMDA receptors and apoptotic neurodegeneration in the developing brain. Science 1999; 283, 7074.

- Inanoglu K, Ozbakis Akkurt BC, Turhanoglu S, Okuyucu S, Akoglu E. Intravenous ketamine and local bupivacaine infiltration are effective as part of a multimodal regime for reducing post-tonsillectomy pain. Med Sci Monit. 2009 Oct;15(10):CR539-543. PMID: 19789514.

- Perelló M, Artés D, Pascuets C, Esteban E, Ey Batlle AM. Prolonged Perioperative Low-Dose Ketamine Does Not Improve Short and Long-term Outcomes After Pediatric Idiopathic Scoliosis Surgery. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2017 Mar;42(5):E304-E312. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000001772. PMID: 27398889.

- Pestieau SR, Finkel JC, Junqueira MM, Cheng Y, Lovejoy JF, Wang J, Quezado Z. Prolonged perioperative infusion of low-dose ketamine does not alter opioid use after pediatric scoliosis surgery. Paediatr Anaesth. 2014 Jun;24(6):582-90. doi: 10.1111/pan.12417. PMID: 24809838.

- Ricciardelli RM, Walters NM, Pomerantz M, Metcalfe B, Afroze F, Ehlers M, Leduc L, Feustel P, Silverman E, Carl A. The efficacy of ketamine for postoperative pain control in adolescent patients undergoing spinal fusion surgery for idiopathic scoliosis. Spine Deform. 2020 Jun;8(3):433-440. doi: 10.1007/s43390-020-00073-w. Epub 2020 Feb 27. PMID: 32109313.

- Scallet, A., Schmued, L. C., Slikker, W., Grunberg, N., Faustino, P. J., Davis, H., Lester, D., Pine, P. S., Sistare, F., and Hanig, J. P. Developmental neurotoxicity of ketamine: Morphometric confirmation, exposure parameters, and multiple fluorescent labeling of apoptotic neurons. Toxicol. Sci. 2004; 81, 364-370.

- Simpao AF, Randazzo IR, Chittams JL, Burnham N, Gerdes M, Bernbaum JC, Walker T. Anesthesia and sedation exposure and neurodevelopmental outcomes in infants undergoing congenital cardiac surgery: a retrospective cohort study. Anesthesiology 2023;139:393-404.

- Slikker W, Zou X, Hotchkiss CE, Divine RL, Sadovova N, Twaddle NC, Doerge DR, Scallet AC. Ketamine-induced neuronal cell death in the perinatal rhesus monkey. Toxicological sciences 2007; 98(1), 145-158.

- Umuroğlu T, Eti Z, Ciftçi H, Yilmaz Gö?ü? F. Analgesia for adenotonsillectomy in children: a comparison of morphine, ketamine and tramadol. Paediatr Anaesth. 2004 Jul;14(7):568-73. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9592.2004.01223.x. PMID: 15200654.

- Weber, F., et al, S-ketamine and s-norketamine plasma concentrations after nasal and i.v. administration in anesthetized children, Paediatr Anaesth , 2004, 14(12), 983-988

Evidence tabellen

Risk of bias table for intervention studies (randomized controlled trials; based on Cochrane risk of bias tool and suggestions by the CLARITY Group at McMaster University)

|

Study reference

(first author, publication year) |

Was the allocation sequence adequately generated?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was the allocation adequately concealed?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Blinding: Was knowledge of the allocated interventions adequately prevented?

Were patients blinded?

Were healthcare providers blinded?

Were data collectors blinded?

Were outcome assessors blinded?

Were data analysts blinded? Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was loss to follow-up (missing outcome data) infrequent?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Are reports of the study free of selective outcome reporting?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was the study apparently free of other problems that could put it at a risk of bias?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Overall risk of bias If applicable/necessary, per outcome measure

LOW Some concerns HIGH

|

|

Abdelhalim, 2013 |

Definitely yes;

Reason: computer-generated random numbers were used |

No information |

Probably no;

Reason: health care providers and outcome assessors are blinded. Patients are assumably blinded, but this is not reported. |

Definitely yes;

Reason: no loss to follow-up |

Definitely yes;

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported |

Definitely yes;

Reason: No other problems noted |

Some concerns

Reason: lack of blinding |

|

Abu-Shahwan, 2008 |

Definitely yes;

Reason: randomized into groups using a computer-generated random number table |

No information |

Probably no;

Reason: study is double-blinded, but it is not mentioned who are blinded |

Probably yes;

Reason: Loss to follow-up was infrequent in intervention and control group. |

Definitely yes;

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported |

Definitely yes;

Reason: No other problems noted |

Some concerns

Reason: lack of blinding |

|

Bazin, 2010 |

Probably no;

Reason: randomization method is not described |

Probably no;

Reason: sealed envelopes were used, but randomization method might not be adequate |

Probably no;

Reason: Outcome assessors are blinded. Blinding of patients and healthcare providers is not mentioned, but assumed |

Probably yes;

Reason: Loss to follow-up was infrequent in intervention and control group. |

Definitely yes;

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported |

Definitely yes;

Reason: No other problems noted |

Some concerns

Reason: lack of information on randomization, lack of blinding |

|

Da Conceicao, 2006 |

Probably no;

Reason: randomization method is not described |

No information |

Probably no;

Reason: Outcome assessors are blinded. Blinding of patients and healthcare providers is not mentioned, but assumed |

Probably yes;

Reason: loss to follow-up was not reported and not assumed |

Definitely yes;

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported |

Definitely yes;

Reason: No other problems noted |

Some concerns

Reason: lack of information on randomization, lack of blinding |

|

Dal, 2007 |

Probably yes;

Reason: An anesthesiologist randomized participants to one of three study groups using a computer-generated random number table |

No information |

Probably no;

Reason: Outcome assessors are blinded. Blinding of patients and healthcare providers is not mentioned, but assumed |

Definitely yes;

Reason: no loss to follow-up |

Definitely yes;

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported |

Definitely yes;

Reason: No other problems noted |

Some concerns

Reason: lack of blinding |

|

Darabi, 2007 |

Probably no;

Reason: randomization method is not described |

No information |

Probably no;

Reason: Outcome assessors are blinded. Blinding of patients and healthcare providers is not mentioned, but assumed |

Definitely yes;

Reason: no loss to follow-up |

Definitely yes;

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported |

Definitely yes;

Reason: No other problems noted |

Some concerns

Reason: lack of information on randomization, lack of blinding |

|

Dix, 2003 |

Probably yes;

Reason: randomization by drawing envelopes |

Probably yes;

Reason: sealed envelopes were used |

Probably no;

Reason: study is double-blind, but other than the ward staff, it is not mentioned who is blinded. |

Probably yes;

Reason: Loss to follow-up was infrequent in intervention and control group. |

Definitely yes;

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported |

Definitely yes;

Reason: No other problems noted |

Some concerns

Reason: lack of blinding |

|

Honarmand, 2013 |

Probably no;

Reason: randomization method is not described |

No information |

Probably no;

Reason: health care providers and outcome assessors are blinded. Patients are assumably blinded, but this is not reported. |

Definitely yes;

Reason: no loss to follow-up |

Definitely yes;

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported |

Definitely yes;

Reason: No other problems noted |

Some concerns

Reason: lack of information on randomization, lack of blinding |

|

Inanoglu, 2009 |

Probably yes;

Reason: A nurse who was not part of the investigation was responsible for randomization and preparation of the study drugs |

No information |

Probably yes;

Reason: Patients, and health care providers and outcome assessors are blinded. Data analysts not mentioned |

Definitely yes;

Reason: no loss to follow-up |

Definitely yes;

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported |

Definitely yes;

Reason: No other problems noted |

LOW |

|

Perello, 2017 |

Probably yes;

Reason: randomization and allocation performed by the pharmacy. |

Definitely yes;

Reason: concealment of allocation by opaque envelopes. |

Probably yes;

Reason: Patients, health care providers and outcome assessors are blinded. Data analysts not mentioned |

Probably yes;

Reason: Loss to follow-up was infrequent in intervention and control group. |

Definitely yes;

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported |

Definitely yes;

Reason: No other problems noted |

LOW |

|

Pestieau, 2014 |

Definitely yes;

Reason: computerized randomization schedule created via a uniform random number generator was used. |

No information

|

Probably yes;

Reason: Patients, health care providers and outcome assessors are blinded. Data analysts not mentioned |

Probably yes

Reason: Loss to follow-up was infrequent in intervention and control group. |

Definitely yes

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported; |

Definitely yes;

Reason: No other problems noted |

LOW

|

|

Ricciardelli, 2020 |

Probably yes;

Reason: Randomization performed by the pharmacy. Method not described. |

Probably yes;

Reason: Study mentions concealment of the allocation, method not described. |

Probably yes;

Reason: Patients, health care providers and outcome assessors are blinded. Data analysts not mentioned |

Probably yes

Reason: Loss to follow-up was infrequent in intervention and control group. |

Definitely yes

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported; |

Definitely yes;

Reason: No other problems noted |

LOW

|

|

Umuroglu, |

Probably yes;

Reason: randomization by drawing envelopes |

Probably yes;

Reason: sealed envelopes were used |

Probably no;

Reason: study is double-blinded, but it is not mentioned who is blinded |

Probably yes

Reason: Loss to follow-up was infrequent in intervention and control group. |

Definitely yes

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported; |

Definitely yes;

Reason: No other problems noted |

Some concerns

Reason: lack of blinding |

Evidence table for intervention studies (randomized controlled trials and non-randomized observational studies [cohort studies, case-control studies, case series])1

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics 2 |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C) 3

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size 4 |

Comments |

|

Abdelhalim, 2013 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: Saudi Arabia

Funding and conflicts of interest: None declared |

Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria: a history of sleep apnea, cognitive or developmental disorders or those using sedative medication, children who were agitated or combative during the induction of anesthesia and any neurological condition that may limit a patient’s ability to communicate with or understand nursing personnel

N total at baseline: Intervention: 40 Control: 40

Important prognostic factors2: age 3-7 y; 60%M

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

Ketamine IV (0.5 mg/kg) Peroperative: fentanyl, acetaminophen, dexamethasone Postoperative fentanyl (0.5 μg/kg, rescue)

|

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

Peroperative: saline + fentanyl, acetaminophen, dexamethasone Postoperative fentanyl (0.5 μg/kg, rescue) |

Length of follow-up: PACU discharge

Loss-to-follow-up: None

Incomplete outcome data: None

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

We refer to the literature analysis for the outcomes of interest |

Authors conclusion:

The intravenous administration of either ketamine 0.5 mg/kg or fentanyl 1 μg/kg before the end of surgery in sevoflurane‑anesthetized children undergoing tonsillectomy with or without adenoidectomy reduces the incidence of post-operative agitation without delaying emergence |

|

Abu-Shawan, 2008 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: Canada

Funding and conflicts of interest: NR |

Inclusion criteria: children, 2 to 12-year-olds, undergoing elective outpatient tonsillectomy

Exclusion criteria: contraindications to the use of any of the study drugs, psychiatric illness, documented sleep apnea, or chronic use of pain medications

N total at baseline: Intervention: 42 Control:40

Important prognostic factors2: age 2–12 y; 61.9%M

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

Ketamine (0.25 mg/kg) Peroperative acetaminophen + morphine (0.1 mg/kg) Postoperative morphine + acetaminophen + codeine

|

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

Peroperative acetaminophen + morphine (0.1 mg/kg) Postoperative morphine + acetaminophen + codeine

|

Length of follow-up: 24 h

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: N (%) = 0 Reasons (describe)

Control: N = 2 (4.8%) Reasons (describe): incomplete follow-up information

Incomplete outcome data: See above

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

We refer to the literature analysis for the outcomes of interest |

Authors conclusion: The addition of ketamine 0.25 mg/kg at induction of anesthesia did not decrease postoperative morphine consumption in children undergoing tonsillectomy. |

|

Bazin, 2010 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: France

Funding and conflicts of interest: NR |

Inclusion criteria: children with ASA 1 or 2 from 6 to 60 months of age, undergoing scheduled surgery

Exclusion criteria: contraindications to caudal puncture (coagulation defects, infection at the puncture site or evolutive neurological disease), failure of caudal analgesia and use of opioids the week before surgery

N total at baseline: Intervention: 18 Control:19

Important prognostic factors2: age 0.5–6 y; 72.2%M

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

Ketamine (0.15 mg/kg + 1.4 mg/kg/h) Peroperative caudal analgesia, acetaminophen + diclofenac Postoperative nalbuphine + acetaminophen + diclofenac

|

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

Peroperative caudal analgesia, acetaminophen + diclofenac Postoperative nalbuphine + acetaminophen + diclofenac |

Length of follow-up: 24 h

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: N (%) = 1 Reasons (describe) protocol violation

Control: N (%) = 0

Incomplete outcome data: See above

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

We refer to the literature analysis for the outcomes of interest |

Authors conclusion: he study failed to show any evidence of benefit of ketamine to improve analgesia in children when given in addition to a multimodal analgesic therapy with paracetamol, a NSAID and an opiate. |

|

Da Conceicao, 2006 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: Brazil

Funding and conflicts of interest: NR |

Inclusion criteria: pediatric patients, 5–7 years old, scheduled for elective tonsillectomy, ASA I or II

Exclusion criteria: None

N total at baseline: Intervention: 30 Control:30

Important prognostic factors2: age 5–7 y; %M not reported

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

Ketamine IV (0.5 mg/kg) Peroperative diclofenac Postoperative acetaminophen + morphine

|

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

Peroperative saline + diclofenac Postoperative acetaminophen + morphine |

Length of follow-up: 24 h

Loss-to-follow-up: None

Incomplete outcome data: None

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

We refer to the literature analysis for the outcomes of interest |

Authors conclusion: The use of a single small dose of ketamine in a pediatric population undergoing tonsillectomy could reduce the frequency or even avoid the use of rescue analgesia in the postoperative period independent of whether used before or after the surgical procedure |

|

Dal, 2007 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: Turkey

Funding and conflicts of interest: departmental funding |

Inclusion criteria: children between 2 and 12 years of age, ASA physical status I or II scheduled to undergo elective adenotonsillectomy

Exclusion criteria: psychiatric illness, pulmonary and/or cardiac disease and a history of allergy to any of the study drugs, peritonsillar abscess and analgesic usage within 24 h prior to surgery.

N total at baseline: Intervention: 30 Control:30

Important prognostic factors2: age 2–12 y;

35.5 %M

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

Ketamine IV (0.5 mg/kg) Peroperative: fentanyl Postoperative: metamizol + acetaminophen

|

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

Peroperative: saline + fentanyl Postoperative: metamizol + acetaminophen

|

Length of follow-up: PACU discharge

Loss-to-follow-up: None

Incomplete outcome data: None

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

We refer to the literature analysis for the outcomes of interest |

Authors conclusion:

Low dose ketamine given i.v. or by peritonsillar infiltration perioperatively provides efficient pain relief without side-effects in children undergoing adenotonsillectomy |

|

Darabi, 2008 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: Bahrami Children Hospital in Tehran

Funding and conflicts of interest: No competing interests |

Inclusion criteria: male children, ASA class I or II, aged between 1 and 6 years, scheduled for inguinal hernia repair

Exclusion criteria: None

N total at baseline: Intervention: 30 Control:30

Important prognostic factors2: age 1–6 y; 100%M

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

Ketamine IV (0.25 mg/kg) Peroperative remifentanil + diclofenac Postoperative diclofenac + proparacetamol

|

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

Peroperative saline + remifentanil + diclofenac Postoperative diclofenac + proparacetamol |

Length of follow-up: 24 h

Loss-to-follow-up: None

Incomplete outcome data: None

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

We refer to the literature analysis for the outcomes of interest |

Authors conclusion: We found that low dose racemic ketamine administered prior to surgical incision has no pre-emptive effect on post-operative pain and supplementary analgesic requirement during the first 24 h after herniorrhaphy in pediatric patients |

|

Dix, 2003 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: Bristol Royal Hospital for Children, Bristol, UK

Funding and conflicts of interest: not reported |

Inclusion criteria: ASA 1 or 2 children aged 7–16 years undergoing appendicectomy

Exclusion criteria: None

N total at baseline: Intervention: 25 Control: 25

Important prognostic factors2: age 6-15 y; 56.7%M

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

I) Ketamine IV (0.5 mg/kg) II) Ketamine IV (0.5 mg/kg + 4 µg/kg/min) Peroperative fentanyl + diclofenac + bupivacaine infiltration Postoperative PCA + acetaminophen |

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

Peroperative saline + fentanyl + diclofenac + bupivacaine infiltration Postoperative PCA + acetaminophen |

Length of follow-up: 2 weeks

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: N =1 Reasons (describe) unable to be traced

Control: N = 1 Reasons (describe): unable to be traced

Incomplete outcome data: See above

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

We refer to the literature analysis for the outcomes of interest |

Authors conclusion: In this paediatric population intravenous ketamine did not have a morphine sparing effect. The increased incidence of side-effects, especially hallucinations, reported by patients given a ketamine infusion may limit the further use of postoperative ketamine in children |

|

Honarmand, 2013 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: Iran

Funding and conflicts of interest: NR |

Inclusion criteria: children ages 2-15 years with ASA of physical status I or II, scheduled for elective tonsillectomy

Exclusion criteria: NR

N total at baseline: Intervention: 30 Control:30

Important prognostic factors2: age 2-15 y; 56.7%M

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

Ketamine IV (0.5 mg/kg) + peritonsillar tramadol (2 mg/kg) Postoperative rectal acetaminophen (20 mg/kg, rescue) |

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

Peritonsillar tramadol (2 mg/kg) Postoperative rectal acetaminophen (20 mg/kg, rescue) |

Length of follow-up: 24 h

Loss-to-follow-up: None

Incomplete outcome data: See above

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

We refer to the literature analysis for the outcomes of interest |

Authors conclusion:

Combined use of IV ketamine 0.5 mg/kg with peritonsillar infiltration of tramadol 2 mg/kg provided better and more prolong analgesic effects compared with using each drug alone in patients undergoing tonsillectomy. |

|

Inanoglu, 2009 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: Turkey

Funding and conflicts of interest: NR |

Inclusion criteria: children ages 2–12, with ASA physical status I or II, who were scheduled for elective tonsillectomy

Exclusion criteria: signs of acute pharyngeal infection, bleeding disorders, and known hypersensitivity to bupivacaine.

N total at baseline: Intervention: 30 Control: 30

Important prognostic factors2: age 2-12 y; 46.7%M

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

Ketamine (0.5 mg/kg) + peritonsillar bupivacaine Peroperative: fentanyl and acetaminophen Postoperative: fentanyl and acetaminophen |

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

Peroperative: saline + peritonsillar bupivacaine fentanyl and acetaminophen Postoperative: fentanyl and acetaminophen |

Length of follow-up: 24 h

Loss-to-follow-up: None

Incomplete outcome data: None

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

We refer to the literature analysis for the outcomes of interest |

Authors conclusion: Intravenous ketamine and peritonsillar infiltration with bupivacaine are safe and effective as part of a multimodal regime in reducing post-tonsillectomy pain. |

|

Perelló, 2017 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: Spain

Funding and conflicts of interest: Public Research Entity funding, no other financial support |

Inclusion criteria: male and female patients between 10 and 18 years with idiopathic scoliosis (ASA I or II) undergoing surgical posterior vertebral fusion

Exclusion criteria: chronic preoperative pain, opioid addiction, mental health disorders, pregnancy, repeat scoliosis surgery, inability to self-administer morphine using a PCA pump, elective postoperative ventilation, or an allergy or intolerance to the drugs

N total at baseline: Intervention: 21 Control:23

Important prognostic factors2: age 12-18 y; 23.8%M

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

Ketamine (0.5 mg/kg) Peroperative: morphine (150 μg/kg) Postoperative: PCA morphine + IV acetaminophen 15 mg/kg |

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

Peroperative: saline + morphine (150 μg/kg) Postoperative: PCA morphine + IV acetaminophen 15 mg/kg |

Length of follow-up: 6 months

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: N =3 (12.5%) Reasons (describe) informed consent withdrawal (N=1), failure eligibility criteria (N=1), unplanned surgery (N=1)

Control: N =3 (12.5%) Reasons (describe) lost to follow-up at 6 months (N=2), respiratory failure (N=1)

Incomplete outcome data: Intervention: N = 3 (%) Reasons (describe) see above

Control: N =2 Reasons (describe) see above

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

We refer to the literature analysis for the outcomes of interest |

Authors conclusion: We may conclude from this study, therefore, that the use of subanesthetic ketamine doses during prolonged perioperative periods in pediatric patients with idiopathic scoliosis undergoing posterior spinal fusion does not reduce postoperative morphine consumption. In our study, no differences between groups were observed in short- or long-term results, pain, adverse effects, postoperative recovery, or the incidence of chronic pain |

|

Pestieau, 2014 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: USA

Funding and conflicts of interest: No conflicts of interest declared. Funding from the department. |

Inclusion criteria: Male and female patients (ages 10 to 18 years, ASA I, II, or III) scheduled for posterior spinal fusion for scoliosis

Exclusion criteria: personal or family history of malignant hyperthermia, significant renal or hepatic disorders, history of dysrhythmias or congenital heart disease, a scheduled surgical subprocedure (i.e. anterior spinal fusion), planned postoperative mechanical ventilation, allergy to morphine, remifentanil, or ketamine, inability to self-administer morphine using a PCA pump, and recent opioid exposure (within 1 month of surgery)

N total at baseline: Intervention: 29 Control:21

Important prognostic factors2: age 10-18 y; 17%M

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

Ketamine (0.5 mg/kg + 0.25 mg/kg/h peroperative, 0.1 mg/kg postoperative) Peroperative: fentanyl, remifentanil Postoperative: PCA morphine + acetaminophen + diazepam

|

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

Peroperative: saline + fentanyl, remifentanil Postoperative: PCA morphine + acetaminophen + diazepam |

Length of follow-up: 96 hours

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: N =1 (3.3%) Reasons (describe) Discontinued intervention (n = 1, morphine allergy)

Control: N = 3 (12.5%) Reasons (describe) Discontinued intervention (n = 3, loss of neuromonitoring signals x2, protocol breech x1)

Incomplete outcome data: See above

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

We refer to the literature analysis for the outcomes of interest |

Authors conclusion: These findings do not support the use of perioperative low-dose ketamine to decrease opioid use in children with scoliosis undergoing posterior spinal fusion. |

|

Ricciardelli, 2020 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: USA

Funding and conflicts of interest: No funding |

Inclusion criteria: ASA I, II, and III patients aged 18 and under who were having posterior spinal fusion performed by a single surgeon

Exclusion criteria: None

N total at baseline: Intervention: 24 Control:25

Important prognostic factors2: age 12-16 y; 9.1%M

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

Ketamine (0.5 mg/kg + 0.2 mg/kg/h) Postoperative PCA morphine + IV acetaminophen 15 mg/kg After 24h: ketorolac IV 0.5 mg/kg After 48h: ibuprofen po 10 mg/kg |

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

Saline Postoperative PCA morphine + IV acetaminophen 15 mg/kg After 24h: ketorolac IV 0.5 mg/kg After 48h: ibuprofen po 10 mg/kg |

Length of follow-up: 48 h

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: N = 0 Reasons (describe)

Control: N = 1 (%) Reasons (describe) failure to receive study drug

Incomplete outcome data: Intervention: For pain score N =1 (4%) Reasons (describe): failure to record any pain score

Control: N =0

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

We refer to the literature analysis for the outcomes of interest |

Authors conclusion: The application of ketamine as an analgesic in conjunction with the current standard of morphine equivalent therapy may serve as a superior pain control regimen for spinal surgeries in young population. This regimen enhancement may be generalizable to other surgery subtypes within similar populations. |

|

Umuroglu, 200 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: Turkey

Funding and conflicts of interest: Not reported |

Inclusion criteria: children (age 5–12 years, ASA 1–2 status) scheduled for adeno-tonsillectomy

Exclusion criteria: history of allergy, pulmonary or cardiac diseases

N total at baseline: Intervention: 15 Control: 15

Important prognostic factors2: age 5-12 y

Sex: 66.7%M

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

Ketamine (0.5 mg/kg + 10 µg/kg/min) Postoperative pethidine + acetaminophen |

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

Peroperative: saline Postoperative pethidine + acetaminophen |

Length of follow-up: 360 min

Loss-to-follow-up: Not reported, not assumed

Incomplete outcome data: See above

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

We refer to the literature analysis for the outcomes of interest |

Authors conclusion:

Morphine hydrochloride 0.1 mg/kg) i.v. administered during induction of anaesthesia provides efficient pain relief in children undergoing adenotonsillectomy. |

Table of excluded studies

|

Reference |

Reason for exclusion |

|

Aldamluji N, Burgess A, Pogatzki-Zahn E, Raeder J, Beloeil H; PROSPECT Working Group collaborators*. PROSPECT guideline for tonsillectomy: systematic review and procedure-specific postoperative pain management recommendations. Anaesthesia. 2021 Jul;76(7):947-961. doi: 10.1111/anae.15299. Epub 2020 Nov 17. PMID: 33201518; PMCID: PMC8247026. |

wrong study design

|

|

Archer V, Robinson T, Kattail D, Fitzgerald P, Walton JM. Postoperative pain control following minimally invasive correction of pectus excavatum in pediatric patients: A systematic review. J Pediatr Surg. 2020 May;55(5):805-810. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2020.01.023. Epub 2020 Jan 30. PMID: 32081359. |

Multiple interventions |

|

Assouline B, Tramèr MR, Kreienbühl L, Elia N. Benefit and harm of adding ketamine to an opioid in a patient-controlled analgesia device for the control of postoperative pain: systematic review and meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials with trial sequential analyses. Pain. 2016 Dec;157(12):2854-2864. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000705. PMID: 27780181. |

wrong population, mostly adults |

|

Aydin ON, Ugur B, Ozgun S, Eyigör H, Copcu O. Pain prevention with intraoperative ketamine in outpatient children undergoing tonsillectomy or tonsillectomy and adenotomy. J Clin Anesth. 2007 Mar;19(2):115-9. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2006.06.003. PMID: 17379123. |

No standard care |

|

Butkovic D, Kralik S, Matolic M, Jakobovic J, Zganjer M, Radesic L. Comparison of a preincisional and postincisional small dose of ketamine for postoperative analgesia in children. Bratisl Lek Listy. 2007;108(4-5):184-8. PMID: 17694802. |

No standard care |

|

Engelhardt T, Zaarour C, Naser B, Pehora C, de Ruiter J, Howard A, Crawford MW. Intraoperative low-dose ketamine does not prevent a remifentanil-induced increase in morphine requirement after pediatric scoliosis surgery. Anesth Analg. 2008 Oct;107(4):1170-5. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e318183919e. PMID: 18806023. |

No standard care |

|

Gupta A, Mo K, Movsik J, Al Farii H. Statistical Fragility of Ketamine Infusion During Scoliosis Surgery to Reduce Opioid Tolerance and Postoperative Pain. World Neurosurg. 2022 Aug;164:135-142. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2022.04.121. Epub 2022 May 5. PMID: 35525439. |

wrong outcome, wrong population (mostly adults) |

|

O'Flaherty JE, Lin CX. Does ketamine or magnesium affect posttonsillectomy pain in children? Paediatr Anaesth. 2003 Jun;13(5):413-21. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9592.2003.01049.x. PMID: 12791115. |

No standard care |

|

Javid MJ, Hajijafari M, Hajipour A, Makarem J, Khazaeipour Z. Evaluation of a low dose ketamine in post tonsillectomy pain relief: a randomized trial comparing intravenous and subcutaneous ketamine in pediatrics. Anesth Pain Med. 2012 Fall;2(2):85-9. doi: 10.5812/aapm.4399. Epub 2012 Sep 13. PMID: 24223344; PMCID: PMC3821120. |

No standard care |

|

Elshammaa N, Chidambaran V, Housny W, Thomas J, Zhang X, Michael R. Ketamine as an adjunct to fentanyl improves postoperative analgesia and hastens discharge in children following tonsillectomy - a prospective, double-blinded, randomized study. Paediatr Anaesth. 2011 Oct;21(10):1009-14. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9592.2011.03604.x. Epub 2011 May 17. PMID: 21575100. |

No standard care

|

|

Chen JY, Jia JE, Liu TJ, Qin MJ, Li WX. Comparison of the effects of dexmedetomidine, ketamine, and placebo on emergence agitation after strabismus surgery in children. Can J Anaesth. 2013 Apr;60(4):385-92. doi: 10.1007/s12630-013-9886-x. Epub 2013 Jan 24. PMID: 23344921. |

placebo; post-op analgesic not described |

|

Aspinall RL, Mayor A. A prospective randomized controlled study of the efficacy of ketamine for postoperative pain relief in children after adenotonsillectomy. Paediatr Anaesth. 2001 May;11(3):333-6. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9592.2001.00676.x. PMID: 11359593. |

no pain scores |

|

Becke K, Albrecht S, Schmitz B, Rech D, Koppert W, Schüttler J, Hering W. Intraoperative low-dose S-ketamine has no preventive effects on postoperative pain and morphine consumption after major urological surgery in children. Paediatr Anaesth. 2005 Jun;15(6):484-90. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9592.2005.01476.x. PMID: 15910349. |

No standard care |

|

Eghbal MH, Taregh S, Amin A, Sahmeddini MA. Ketamine improves postoperative pain and emergence agitation following adenotonsillectomy in children. A randomized clinical trial. Middle East J Anaesthesiol. 2013 Jun;22(2):155-60. PMID: 24180163. |

No standard care |

|

Hasnain F, Janbaz KH, Qureshi MA. Analgesic effect of ketamine and morphine after tonsillectomy in children. Pak J Pharm Sci. 2012 Jul;25(3):599-606. PMID: 22713948. |

wrong comparator |

|

Mariscal G, Morales J, Pérez S, Rubio-Belmar PA, Bovea-Marco M, Bas JL, Bas P, Bas T. Meta-analysis of the efficacy of ketamine in postoperative pain control in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis patients undergoing spinal fusion. Eur Spine J. 2022 Dec;31(12):3492-3499. doi: 10.1007/s00586-022-07422-5. Epub 2022 Oct 17. PMID: 36253657. |

relevant RCTs were included from the SR |

|

Khademi S, Ghaffarpasand F, Heiran HR, Yavari MJ, Motazedian S, Dehghankhalili M. Intravenous and peritonsillar infiltration of ketamine for postoperative pain after adenotonsillectomy: a randomized placebo-controlled clinical trial. Med Princ Pract. 2011;20(5):433-7. doi: 10.1159/000327657. Epub 2011 Jul 11. PMID: 21757932. |

No standard care |

|

Ghobrial HZ, Shaker EH. Effectiveness of multimodal preemptive analgesia in major pediatric abdominal cancer surgery. Anaesthesia, Pain & Intensive Care. 2019 Oct 12:256-62. |

Wrong intervention |

|

Dahmani S, Michelet D, Abback PS, Wood C, Brasher C, Nivoche Y, Mantz J. Ketamine for perioperative pain management in children: a meta-analysis of published studies. Paediatr Anaesth. 2011 Jun;21(6):636-52. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9592.2011.03566.x. Epub 2011 Mar 29. PMID: 21447047. |

relevant RCTs were included from the SR |

|

Michelet D, Hilly J, Skhiri A, Abdat R, Diallo T, Brasher C, Dahmani S. Opioid-Sparing Effect of Ketamine in Children: A Meta-Analysis and Trial Sequential Analysis of Published Studies. Paediatr Drugs. 2016 Dec;18(6):421-433. doi: 10.1007/s40272-016-0196-y. PMID: 27688125. |

relevant RCTs were included from the SR |

|

Ng KT, Sarode D, Lai YS, Teoh WY, Wang CY. The effect of ketamine on emergence agitation in children: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Paediatr Anaesth. 2019 Dec;29(12):1163-1172. doi: 10.1111/pan.13752. Epub 2019 Oct 20. PMID: 31587414. |

wrong outcome |

|

Tarkkila P, Viitanen H, Mennander S, Annila P. Comparison of remifentanil versus ketamine for paediatric day case adenoidectomy. Acta Anaesthesiol Belg. 2003;54(3):217-22. PMID: 14598618. |

No standard care |

|

Yenigun A, Et T, Aytac S, Olcay B. Comparison of different administration of ketamine and intravenous tramadol hydrochloride for postoperative pain relief and sedation after pediatric tonsillectomy. J Craniofac Surg. 2015 Jan;26(1):e21-4. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000001250. PMID: 25569408. |

wrong comparator |

|

Zhou L, Yang H, Hai Y, Cheng Y. Perioperative Low-Dose Ketamine for Postoperative Pain Management in Spine Surgery: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Pain Res Manag. 2022 Mar 31;2022:1507097. doi: 10.1155/2022/1507097. PMID: 35401887; PMCID: PMC8989618. |

relevant RCTs were included from the SR |

|

Zhu A, Benzon HA, Anderson TA. Evidence for the Efficacy of Systemic Opioid-Sparing Analgesics in Pediatric Surgical Populations: A Systematic Review. Anesth Analg. 2017 Nov;125(5):1569-1587. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000002434. PMID: 29049110. |

background article |

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Laatst beoordeeld : 17-12-2024

Algemene gegevens

De ontwikkeling/herziening van deze richtlijn werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten (www.demedischspecialist.nl/kennisinstituut) en werd gefinancierd uit de Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS). De financier heeft geen enkele invloed gehad op de inhoud van de richtlijnmodule.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijn is in 2022 een multidisciplinaire werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen (zie hiervoor de Samenstelling van de werkgroep) die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor kinderen met postoperatieve pijn.

Werkgroep

Dr. L.M.E. (Lonneke) Staals, anesthesioloog, voorzitter, NVA

Dr. C.M.A. (Caroline) van den Bosch, anesthesioloog-pijnspecialist, NVA

Drs. A.W. (Alinde) Hindriks-Keegstra, anesthesioloog, NVA

Drs. G.A.J. (Geranne) Hopman, anesthesioloog, NVA

Drs. L.J.H. (Lea) van Wersch, anesthesioloog, NVA

Dr. C.M.G. (Claudia) Keyzer-Dekker, kinderchirurg, NVvH

Drs. F.L. (Femke) van Erp Taalman Kip, orthopedisch kinderchirurg, NOV

Dr. L.M.A. (Laurent) Favié, ziekenhuisapotheker, NVZA

J. (Jantine) Boerrigter-van Ginkel, verpleegkundig specialist kinderpijn, V&VN

S. (Sharine) van Rees-Florentina, recovery verpleegkundige, BRV

E.C. (Esen) Doganer en M. (Marjolein) Jager, beleidsmedewerker, Kind & Ziekenhuis

Klankbordgroep

Dr. L.M. (Léon) Putman, cardiothoracaal chirurg, NVT

R. (Remko) ter Riet, MSc, anesthesiemedewerker/physician assistant, NVAM

Drs. L.I.M. (Laura) Meltzer, KNO-arts, NVKNO

Met ondersteuning van

Dr. L.M.P. Wesselman, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

I. van Dijk, junior adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

Belangenverklaringen