Clonidine als additivum aan lokaal anestheticum

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is de plaats van alfa-2-agonist clonidine als additivum aan lokaal anestheticum aan het locoregionaal of neuraxiaal blok bij kinderen die een chirurgische ingreep ondergaan?

Voor clonidine intraveneus/oraal, zie module Clonidine.

Aanbeveling

Overweeg clonidine toe te voegen als adjuvans aan een lokaal anestheticum voor een perifere of neuraxiale zenuwblokkade, wanneer een verlengend analgetisch effect gewenst is.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Er is literatuuronderzoek verricht naar de gunstige en ongunstige effecten van de toevoeging van de alfa-2-agonist clonidine aan het locoregionaal blok bij kinderen die een chirurgische ingreep ondergaan. Er zijn 28 RCT’s geïncludeerd in de literatuursamenvatting. De operaties die de kinderen ondergingen waren divers. In de meeste studies werd clonidine als additivum aan een lokaal anestheticum bij een caudaal blok onderzocht, in enkele studies betrof het een perifere zenuwblokkade, zoals dorsaal penis blok of buikwandblok.

De studies waren doorgaans klein en hadden methodologische beperkingen. Hierdoor was er risico op vertekening van resultaten (risk of bias) en werd de optimale populatiegrootte (OIS) niet behaald door kleine aantallen. Daarom is de bewijskracht voor alle uitkomstmaten in meer of mindere mate afgewaardeerd. Bovendien werden in de geïncludeerde studies verschillende meet- en rapportage methoden gebruikt (bijvoorbeeld verschillende pijn meetinstrumenten zoals Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario Pain Scale (CHEOPS) en de

Children and Infants Postoperative Pain Scale (CHIPPS); en verschillen in rapportages zoals mediaan of gemiddelden) of waren de resultaten gelimiteerd beschreven in de studies, waardoor het bij de meeste uitkomstmaten niet mogelijk was om de resultaten te poolen. Derhalve zijn de resultaten vaak per studie beschreven.

Postoperatieve pijn op 0, 6 en 24 uur was gedefinieerd als cruciale uitkomstmaat. Voor postoperatieve pijn was de bewijskracht laag. De totale bewijskracht komt daarmee uit op laag. Alleen op 6 uur na de operatie werd een mogelijk pijn verlagend effect gevonden in het voordeel van de toevoeging van clonidine; op 0 uur en 24 uur na was een geen verschil in effect.

Angst, postoperatief gebruik van opioïden, en adverse events (apneu, ademhalingsdepressie, hypotensie, sedatie, en delirium) waren gedefinieerd als belangrijke uitkomstmaten.

Voor adverse events apneu en delier werd geen bewijs gevonden. Voor de uitkomstmaten hypotensie en sedatie is de bewijskracht literatuur laag en toont het bewijs dat er mogelijk geen verschil is in effect tussen de onderzochte groepen.

Samenvattend kan de literatuur onvoldoende richting geven aan de besluitvorming. De aanbeveling is daarom gebaseerd op aanvullende argumenten waaronder expert opinie, waar mogelijk aangevuld met (indirecte) literatuur.

Clonidine heeft mogelijk een positief effect op postoperatieve pijn na 6 uur wanneer dit wordt toegevoegd aan lokaal anesthetica. Er is zijn beperkte resultaten op latere tijdspunten, dus over de duur van het mogelijke positieve effect is geen uitspraak te doen. Er zijn geen nadelige effecten van het toedienen van clonidine als adjuvans naar voren gekomen in deze literatuurstudie. Het toevoegen van clonidine kan dan ook veilig gebruikt worden als adjuvans en is te overwegen.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

Voor de ouders en de patiënt is goede pijnbestrijding met zo min mogelijke bijwerkingen belangrijk. Van de patiënt of ouders van de patiënt kan men niet verwachten dat deze zoveel kennis van medicatie heeft om de keuze voor toevoeging van clonidine aan het locoregionaal blok kan maken te bespreken. Deze keuze dient te worden gemaakt door de behandelend zorgverlener, op basis van zijn/haar kennis en ervaring. De patiënt en ouders mogen verwachten van de behandelend arts dat deze de kennis heeft van de medicatie om een keuze van medicament te maken.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

Clonidine is een goedkoop middel en zal bij implementatie niet tot substantieel hogere kosten leiden. Ten opzichte van andere alfa-2-agonisten, zoals dexmedetomidine, is het een goedkoper medicament.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

De werkgroep is van mening dat implementatie er geen bezwaren zijn op het gebied van aanvaardbaarheid of haalbaarheid. Clonidine behoort tot de standaard anesthesiemiddelen en is daardoor breed beschikbaar. Bij de keuze voor dit middel dienen uiteraard de contra-indicaties van clonidine in acht genomen te worden.

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

Er zijn aanwijzingen dat toevoegen van clonidine mogelijk een positief additief effect heeft op de analgetisch effect van lokaal anesthetica bij perifere en neuraxiale zenuwblokkades. Het toevoegen van clonidine aan een lokaal anestheticum lijkt niet te leiden tot een toename van adverse events. De medicatie brengt minimale kosten met zich mee en minimale bezwaren ten aanzien van implementatie. Dit alles in acht nemend is het toevoegen van clonidine aan lokaal anesthetica te overwegen.

Het Kinderformularium heeft een doseringsadvies beschreven voor clonidine als adjuvans bij andere analgetica (Clonidine, Kinderformularium).

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Regelmatig worden er zowel neuraxiale blokken (caudaal of epiduraal) geplaatst bij kinderen als perifere zenuwblokkades. Bij beide groepen kan het gaan om een singleshot techniek of met een katheter voor continue pijnstilling. Er wordt dan gebruik gemaakt van een lokaal anestheticum waarbij soms een additivum gebruikt wordt. Clonidine, een alfa-2-agonist kan toegevoegd worden als additivum. Het doel van een additivum is de duur van het blok verlengen en het gebruik van opioïden te verlagen en mogelijk angst te verminderen.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

Postoperative pain

|

Low GRADE |

Clonidine as adjuvant to a local anesthetic may result in little to no difference in postoperative pain at PACU arrival/ 0 hours when compared with a local anesthetic alone in children undergoing a surgical procedure.

Source: Anouar 2016; Bhati 2022; El-Hennway 2009; Joshi 2004; Koul 2009; Mostafa 2021; Potti 2017; Tripi 2005; Visoiu 2021 |

|

Low GRADE |

Clonidine as adjuvant to a local anesthetic may result in reduced postoperative pain at 6 hours when compared with a local anesthetic alone in children undergoing a surgical procedure.

Source: Anouar 2016; Bhati 2022; Jindal 2011; Narasimhamurthy 2016; Parameswari 2010; Potti 2017; Visoiu 2021 |

|

Low GRADE |

Clonidine as adjuvant to a local anesthetic may result in little to no difference in postoperative pain at 24 hours when compared with a local anesthetic alone in children undergoing a surgical procedure.

Source: Anouar 2016; Bhati 2022; El-Hennway 2009; Joshi 2004; Mostafa 2021; Narasimhamurthy 2016; Potti 2017; Visoiu 2021 |

Anxiety

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of clonidine as adjuvant to a local anesthetic on anxiety when compared with local anesthetic alone in children undergoing a surgical procedure.

Source: Visoiu, 2021 |

Postoperative opioid consumption

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of clonidine as adjuvant to a local anesthetic on postoperative opioid consumption in PACU when compared with local anesthetic alone in children undergoing a surgical procedure.

Source: Anouar 2016; Joshi 2004; Tripi 2005 |

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of clonidine as adjuvant to a local anesthetic on postoperative opioid consumption in 24 hours when compared with local anesthetic alone in children undergoing a surgical procedure.

Source: Joshi 2004; Tripi 2005 |

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of clonidine as adjuvant to a local anesthetic on total postoperative opioid consumption when compared with local anesthetic alone in children undergoing a surgical procedure.

Source: Akin 2010; De Negri 2001; Ivani 2000; Kalachi 2007; Tripi 2005 |

Adverse events

|

No GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding the effect of clonidine as adjuvant to a local anesthetic compared with local anesthetic alone on adverse events apnea and postoperative emergence delirium in children undergoing abdominal surgery.

Source: - |

|

Low GRADE |

Clonidine as adjuvant to a local anesthetic may result in little to no difference in adverse events respiratory depression and hypotension when compared with a local anesthetic alone in children undergoing a surgical procedure.

Sources respiratory depression: Akbas 2005; Akin 2010; Bajwa 2010; Bhati 2022; El-Hennway 2009; Koul 2009; Narasimhamurthy 2016; Parameswari 2010; Potti 2017; Sanwatsarka 2017; Shaikh 2015; Singh 2012; Tripi 2005

Sources hypotension: Akbas 2005; Akin 2010; El-Hennway 2009; Parameswari 2010; Potti 2017; Sanwatsarka 2017; Shaikh 2015; Singh 2012; Tripi 2005 |

|

Low GRADE |

Clonidine as adjuvant to a local anesthetic may result in little to no difference in sedation when compared with a local anesthetic alone in children undergoing a surgical procedure.

Source: Bawja 2010; Ivani 2000; Jindal 2011; Koul 2009; Potti 2017; Mostafa 2021; Narasimhamurthy 2016; Sanwatsarka 2017; Tripi 2005; Visoiu 2021 |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

A description with study characteristics of each RCT is presented in Table 1. As shown in the table, studies were conducted in patients undergoing various surgeries. Number of patients per arm varied from 15 to 50. The mean age of children in the studies varies from 3 years to almost 14 years. The percentage of males was often not specified, but for the studies that did report the sex of the patients, the male percentage was high.

Table 1: Descriptives of included studies.

|

Author, year

|

Population (I/C), mean age; sex (M/F) |

Surgical procedure |

Intervention |

Control |

|

Akbas, 2005

Turkey |

N: 25/ 25 Age (years) ± SD: 6.08 ± 2.87/ 5.64 ± 3.13 M:F: not reported |

Inguinal hernia repair and circumcision |

ropivacaine 0.2% 0.75 ml/kg) plus clonidine 1 µg/kg) (group RC)* caudal block |

received ropivacaine 0.2%, 0.75 ml/kg) (group R)*

*Drugs were diluted in 0.9% saline (0.75 ml/kg ) |

|

Akin, 2010

Turkey |

N (I1/I2/C): 20/ 20/ 20 Age (years) ± SD: 4.1 ± 2/ 4.1 ± 2/ 4.1 ± 2 M:F: not reported |

Inguinal hernia repair or orchidopexy surgery |

I1: Levobupivacaine 0.25% 0.75 ml/kg) and 2 µg/kg) clonidine caudally and 5 ml normal saline i.v. (Group L-Ccau)

I2: Levobupivacaine 0.25%, 0.75 ml/kg) and 2 µg/kg) clonidine in 5 ml normal saline i.v. (Group L-Civ) |

Levobupivacaine 0.25% 0.75 ml/kg) and 5 ml normal saline i.v (group L) |

|

Anouar, 2016

Tunisia |

N: 20/ 20 Age (months) ± SD: 30 ±3.12/ 25.2 ± 5 M:F: 20:0/20:0 |

Day-case male circumcision |

ml/Kg of bupivacaine 0.5% with 1 µg/kg of clonidine in each side dorsal penile nerve block |

0.1 ml/kg of bupivacaine 0.5% with placebo in each side |

|

Bajwa, 2010

India |

N: 22/ 22 Age (years) ± SD: 3.4 ± 1.42 / 3.1 ± 1.68 M:F: not reported |

Elective lower abdominal surgery (hernia surgery)

|

0.25% ropivacaine, 0.5 ml/kg, with an addition of 2 µg/kg clonidine via the caudal route* |

0.25% ropivacaine, 0.5 ml/kg*

*with a total volume being constant at 0.5 ml/kg in both the study groups |

|

Bhati 2022

India |

N: 20/ 20 Age (years) ± SD: 3.85 ± 1.39/ 3.40 ± 1.31 M:F: 20:0/20:0 |

Infraumbilical elective surgery |

caudal injection of 0.25% levobupivacaine at a dose of 1 mL/kg body weight with clonidine 0.5 µg/kg |

caudal injection of 0.25% levobupivacaine at a dose of 1 mL/kg body weight |

|

De Mey, 2000

Belgium |

N: 30/ 30 Age (months) ± SD: 39.1 ± 29.4/ 38.3 ± 32.2 M:F: 30:0/30:0 |

Hypospadias repair |

0.5 mL kg−1 bupivacaine 0.25% caudally + 1 μg kg−1 clonidine (group II) |

0.5 mL kg−1 bupivacaine 0.25% caudally (group I) |

|

De Negri, 2001

Italy |

N (I1/I2/I3/C): 15/ 15/ 15/ 15 Age (months) ± SD: 31 ±10/ 28±14/ 32 ±9/ 28 ± 12 M:F: 15:0/ 15:0/ 15:0/ 15:0 |

Hypospadias repair

|

I1: ropivacaine 0.08% 0.16 mg/kg/h plus clonidine 0.04 mg/kg/h (Group RC1)

I2: ropivacaine 0.08% 0.16 mg/kg/h plus clonidine 0.08 mg/kg/h (Group RC2)

I3: ropivacaine 0.08% 0.16 mg/kg/h plus clonidine 0.12 mg/kg/h (Group RC3) Epidural |

plain ropivacaine 0.1% 0.2 mg/kg/h (Group R) |

|

El-Hennway, 2009

Egypt |

N: 30/ 30 Age (months) (range): 45 (6–69)/ 43 (7–66) M:F: not reported |

Lower abdominal surgeries |

bupivacaine 0.25% (1 ml/ kg) with clonidine 2 mg/kg in normal saline 1 ml caudal block |

bupivacaine 0.25% (1 ml/kg) with normal saline 1 ml |

|

Ivani, 2000

Italy |

N: 20/ 20 Median age (years) (range): 3 (1–7)/ 3 (1–7) M:F: 16:4/ 18:2 |

Elective sub-umbilical surgery |

caudal block with 1 ml/kg of ropivacaine 0.1% with the addition of clonidine 2 mg/kg

|

caudal block with 1 ml/kg of ropivacaine 0.2%

|

|

Jindal, 2011

India |

N: 25/ 25 Age (months) ± SD: 8.48 ± 7.11/ 7.92 ± 6.48 M:F: 17:8/19:6 |

Elective cleft lip repair |

clonidine from a 150 μg/ml ampoule was diluted and 1 μg/kg was drawn with a tuberculin syringe and added to 0.5 ml of 0.5% bupivacaine; the resulting mixture was reconstituted with saline to a volume of 1 ml to maintain a bupivacaine concentration of 0.25% |

solution of 1 ml 0.25% bupivacaine solution was prepared by adding 0.5 ml saline to 0.5 ml of 0.5% bupivacaine |

|

Joshi, 2004

USA |

N: 18/ 17 Age (months) ± SD: 28 ± 22 / 44 ± 31 M:F: 3:15/ 2:15 |

Unilateral hernia, hydrocelectomy, or orchidopexy |

2 µg/kg) of clonidine (100 µg/ml) in addition to the bupivacaine. Caudal block |

equal volume of preservative-free normal saline |

|

Koul, 2009

India |

N: 20/ 20 Age (years) ± SD: 3.45 ± 2.06/ 3.28 ± 1.65 M:F: not reported |

Inguinalherniotomy |

Caudal epidural injection of 0.75ml/kg of 0.25% bupivacaine with 2 μg/kg of clonidine

|

Caudal epidural injection of 0.75 ml/kg of 0.25% bupivacaine |

|

Laha, 2012

India |

N: 15/ 15 Age (years) ± SD: 4.8 (±2.6)/ 4.7 (±2.6) M:F: 11:4/11:4 |

Lower abdominal, perineal, and lower limb surgeries

|

caudal injection of mixture of ropivacaine 0.2% (1 ml/kg) with clonidine 2 μg/kg |

caudal injection of plain ropivacaine 0.2% (1 ml/kg) |

|

Mostafa, 2021

Egypt |

N: 30/ 30 Age (years) ± SD: 5.68 ± 1.7/ 5.37 ± 1.6 M:F: not reported |

Laparoscopic orchiopexy |

levobupivacaine plus clonidine transversus abdominis plane block |

levobupivacaine plus normal saline

|

|

Narasimhamurthy, 2016

India |

N: 30/ 30 Age (years) ± SD: 4.8 + 1.7/ 4.7 + 1.7 M:F: 25:5/ 26:4 |

Infraumbilical surgeries (circumcision, herniotomy and orchidopexy) |

mixture of 0.2% Ropivacaine and preservative free Clonidine 1 μg/kg. caudal block |

mixture of 0.2% Ropivacaine and normal saline |

|

Parameswari, 2010

India |

N: 50/ 50 Age (months): 19/ 21 M:F: 47:3/ 47:3

|

Subumbilical surgeries under general anesthesia (circumcision; orchidopexy; herniotomy) |

Bupivacaine with 1 μg/kg clonidine caudal block |

Plain bupivacaine |

|

Potti, 2017

India |

N (I1/I2/C): 25/ 25/ 25 Age (years) ± SD: 4.7 ± 2/ 4.6 ± 1/ 4.32 ± 2 M:F: not reported |

Elective infraumbilicial surgeries |

I1: Group B (n = 25) received levobupivacaine 0.25% 1 mL/kg with 1 µg/kg clonidine caudally and 5 mL of normal saline i.v

I2: Group C (n = 25) received levobupivacaine 0.25% 1 mL/kg caudally and 1 µg/kg clonidine in 5 mL normal saline i.v |

Group A (n = 25) received levobupivacaine 0.25% 1 mL/kg caudally and 5 mL of normal saline i.v

|

|

Priolkar, 2016

India |

N: 30/ 30 Age (years) ± SD: 4.43+1.52/ 4.63+1.73 M:F: not reported

|

Infraumbilical operations |

Group: BC: Mixture of 1 ml/kg of 0.125% bupivacaine with preservative free clonidine 1 μg/kg. Caudal block |

Group: B: 1 ml/kg of 0.125% bupivacaine solution |

|

Rawat, 2019

India |

N: 32/ 32 Age (years) ± SD: 4.14 ± 1.05/ 4.16 ± 1.87 M:F: 15:7/14:8 |

Elective perineal surgeries |

Group III – 0.25% levobupivacaine (1 mL/kg) with clonidine 1 µg/kg Caudal block |

Group I - 0.25% levobupivacaine (1 mL/kg) |

|

Sanwatsarkar, 2017

India

|

N: 25/ 25 Age (years) ± SD: 6.28 ± 1.21/ 6.64 ± 1.29 M:F: 23:2/22:3 |

Umbilical surgeries under general anesthesia |

Group BC received 1 ml/kg 0.25% bupivacaine + 1 μg/kg clonidine in normal saline Caudal block |

Group B received 1 ml/ kg 0.25% bupivacaine in normal saline |

|

Shaikh, 2015

India |

N: 30/ 30 Age (months) ± SD: 58.30 ± 27.92/ 74.40 ± 37.34 M:F: 27:3/ 28:2

|

Elective sub-umbilical, perineal and lower limb surgeries |

Group B received caudal 0.25% bupivacaine 1 ml/Kg with clonidine 1 μg/Kg as an adjuvant made to 0.5 ml with normal saline |

Group A received caudal 0.25% bupivacaine plain with 0.5 ml Normal saline |

|

Singh, 2012

Nepal |

N: 20/ 20 Age (years) ± SD: 5.45±2.5 / 6.10 ± 2.19 M:F: not reported |

Below umbilical surgeries |

Group BC received 0.75 ml/kg of 0.25% bupivacaine with 1 μg/ kg of clonidine in normal saline Caudal block |

Group B received 0.75 ml/kg of 0.25% bupivacaine in normal saline |

|

Tripi, 2005

India |

N: 18/ 17 Age (months) ± SD: 59.0 ± 30.4 / 67.6 ± 30.5 M:F: 2:16/ 5:12 |

Ureteroneocystostomy |

1 ml/kg 0.125% bupivacaine with 1 µg/kg clonidine Caudal block |

preincision caudal block consisting of either 1 ml/kg 0.125% bupivacaine |

|

Visoiu, 2021

USA |

N: 26/ 24 Median age (years) (Q1,Q3): 13.0 (11.0, 15.0)/ 13.0 (11.5, 15.5) %F: 46/ 54

|

Laparoscopic appendectomy |

The R+C group received two 20 ml syringes with 10 ml of ropivacaine 0.5 % and 1 µg/kg of clonidine (100 µg =1 ml) for a total volume of 11 ml. Each patient in the R+C group received a total of 2 µg/kg clonidine. Rectus sheath nerve block |

The RO group received two 20 ml syringes, each with 10 ml of ropivacaine 0.5% and a 1 ml of normal saline |

Results

- Postoperative pain

In the included studies different pain scales were used to assess postoperative pain. Table 2 includes the descriptions of these different scales.

Table 2. Different pain scales used to assess postoperative pain.

|

Name |

Abbreviation |

Scoring |

Score range |

Meaning |

|

Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario Pain Scale (CHEOPS) |

CHEOPS |

6 categories of pain behavior: Cry, facial, verbal, torso, touch, and legs |

0 to 2 or 1 to 3 is assigned to each activity, total score range 4-13 |

higher scores indicating greater level of pain |

|

Children and Infants Postoperative Pain Scale (CHIPPS) |

CHIPPS |

4 items: crying, facial expression, trunk's posture, legs' posture and motor restlessness |

0 to 2 points per item, total score range 0-8 |

higher scores indicating greater level of pain |

|

FACES scale |

- |

five categories: crying, facial expression, position of torso, position of legs and motor restlessness |

Complication score 1, none; 2, moderate; 3, severe |

higher scores indicating greater level of pain |

|

FACES Pain Rating Scale (Wong-Baker) |

- |

6 faces; the first face represents a pain score of 0, and indicates "no hurt". The second face represents a pain score of 2, and indicates "hurts a little bit". The third face represents a pain score of 4, and indicates "hurts a little more". The fourth face represents a pain score of 6, and indicates "hurts even more" |

0-6 |

higher scores indicating greater level of pain |

|

Face, Legs, Activity, Cry, Consolability (FLACC) Behavioral Pain Scale |

FLACC |

5 categories: face, legs, activity, cry, and consolability |

0 to 2 points per category, total score range 0-10 |

higher scores indicating greater level of pain |

|

Numeric pain rating scale |

NRS |

0 being no pain and 10 the worst imaginable pain |

0-10 |

higher scores indicating greater level of pain |

|

Objective Pain Scale |

OPS |

4 pain behaviors: crying, movement, agitation, and verbalization |

0 to 2 points per category, total score range 0-10

|

higher scores indicating greater level of pain |

|

Visual analog scale |

VAS |

A continuous scale ranging from no pain to worst pain |

0 to 10 |

higher scores indicating greater level of pain |

1.1. Postoperative pain at PACU arrival/ 0 hours

Nine studies reported on postoperative pain at PACU arrival or pain assessed at 0 hours. All studies used different measurement and reporting methods. Therefore, the results are described per study.

Anoar (2016) assessed pain using the CHEOPS and reported mean pain scores (± standard deviation, SD). The mean pain scores were 5.8 (± 0.9) and 6.4 (± 0.8) in the clonidine (n=20) and control group (n=20), respectively (MD -0.60, 95% CI -1.13 to -0.07). This difference is not clinically relevant.

Bhati (2022) used the OPS and reported only mean pain scores. The mean pain score was 0 for both the intervention (n=20) and control group (n=20), respectively (MD 0).

El-Hennway (2009) assessed pain with the FLACC and reported participant’s pain intensity in percentages per score. For the intervention group the distribution of the scores was as follows, score 0= 45%, score 1= 40%, score 2= 15%, and for the control group scores were 0 = 25%, score 1= 45%, score 2= 30%.

Joshi (2004) assessed with the FACES scale reported by a nurse and reported mean pain scores (±SD). A pain score of 6.7 (±1.5) in the intervention group (n=18) and a pain score of 6.8 (±1.7) the control group (n=17) was found (mean difference (MD) -0.10; 95 % CI -1.16 to 0.96). This difference is not clinically relevant.

Koul (2009) assessed pain with the OPS at 30 minutes, 1 hour and 2 hours and reported mean OPS scores (±SD) over these time-intervals. The mean pain scores were 4.65 (± 0.25) and 4.55 (± 0.25) in the intervention (n=20) and control group (n=20), respectively (MD - 0.10 95% CI -0.05 to 0.25). This difference is not clinically relevant.

Mostafa (2021) assessed pain using the CHEOPS and reported mean pain scores (±SD). The mean pain scores were 4.00 (± 0.1) and 4.10 (± 0.3) in the intervention (n=30) and control group (n=30), respectively (MD - 0.10 95% CI -0.47 to 0.27). This difference is not clinically relevant.

Potti (2017) assessed pain using the CHIPPS and authors reported the number of patients experiencing each score (Table 3).

Table 3. CHIPPS pain scores at 1 hour (Potti 2017).

|

CHIPPS score |

0 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

≥4 |

|

I1: (n = 25) levobupivacaine 0.25% 1 mL/kg with 1 mug/kg clonidine caudally and 5 mL of normal saline i.v |

25 (100%) |

|

|

|

|

|

I2: (n = 25) levobupivacaine 0.25% 1 mL/kg caudally and 1 mug/kg clonidine in 5 mL normal saline i.v |

25 (100%) |

|

|

|

|

|

C: (n = 25) levobupivacaine 0.25% 1 mL/kg caudally and 5 mL of normal saline i.v |

20 (80%) |

3 (12%) |

2 (8%) |

|

|

Tripi (2005) assessed pain using the FACES Pain Rating Scale for children 1 to 3 years old, and

the FLACCS for children 4 years or older. Only mean values were reported; the mean pain scores were 0.90 and 1.18 in the intervention (n=18) and control group (n=17), respectively (MD -0.28). This difference is not clinically relevant.

Visoiu (2021) assessed pain using a NRS and reported mean pain scores (±SD). The mean pain scores were 1.20 (± 2.55) and 1.79 (± 2.78) in the intervention (n=25) and control group (n=19), respectively (MD -0.59, 95% CI -2.19 to 1.01). This difference is not clinically relevant.

1.2. Postoperative pain at 6 hours

Seven studies reported on postoperative pain at 6 hours. All studies used different measurement and reporting methods. Therefore, the results are described per study.

Anoar (2016) used the CHEOPS and reported mean pain scores (±SD). The mean pain scores were 4.5 (±0.5) and 6.2 (±1.1) in the intervention (n=20) and control group (n=20), respectively (MD -1.70, 95% CI -2.23 to -1.17). This difference is clinically relevant, in favor of clonidine.

Bhati (2022) used the OPS and reported only mean pain scores. The mean pain score was 0.75 versus 5 for the intervention (n=20) and control group (n=20), respectively (MD -4.25). This difference is clinically relevant, in favor of clonidine.

Jindal (2011) assessed pain with the FLACC and reported participant’s pain intensity in percentages per predefined score-ranges. For the intervention group (n=25) the distribution of the scores was as follows, 0-3 (no pain to mild pain) 24 (96%) 4-6 (moderate pain) 1 (4%); and for the control group (n=25) the scores were 0-3 (no pain to mild pain) 21 (84%) 4-6 (moderate pain) 3 (12%).

Narasimhamurthy (2016) assessed pain with the FLACC and reported number of patients with a score ≥ 4. Zero of 30 patients (0%) in the clonidine group; and 18 of 30 patients (60%) in the control group had a pain score ≥ 4. This difference in percentages is in favor of clonidine.

Parameswari (2010) assessed pain with the FLACC scale and reported results into categorized scores of four groups of pain severity (0 = No pain; 1 - 3 = Mild pain; 4 - 7 = Moderate pain; 8 - 10 = Severe pain). In the clonidine group, 33 of 50 patients (66%) had no to mild pain compared to 12 of 50 patients (24%) in the control group; and 17 patients (34%) in the clonidine group experienced moderate to severe pain compared to 38 patients (76%) in the control group. This difference in percentages in in favor of clonidine.

Potti (2017) assessed pain using the CHIPPS and reported the number of patients experiencing each score (Table 4). The difference between both clonidine groups and the control group is in favor of the clonidine groups.

Table 4. CHIPPS pain scores at 6 hours (Potti 2017).

|

CHIPPS score |

0 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

≥4 |

|

I1: (n = 25) levobupivacaine 0.25% 1 mL/kg with 1 mug/kg clonidine caudally and 5 mL of normal saline i.v |

6 (24%) |

18 (72%) |

1 (4%) |

|

|

|

I2: (n = 25) levobupivacaine 0.25% 1 mL/kg caudally and 1 mug/kg clonidine in 5 mL normal saline i.v |

1 (4%) |

5 (20%) |

12 (48%) |

4 (16%) |

3 (12%) |

|

C: (n = 25) levobupivacaine 0.25% 1 mL/kg caudally and 5 mL of normal saline i.v |

|

|

1 (4%) |

|

24 (96%) |

Visoiu (2021) assessed pain using a NRS and reported mean pain scores (±SD). The mean pain scores were 2.28 (± 2.49) and 2.43 (± 2.95) in the intervention (n=18) and control group (n=14), respectively (MD -0.15, 95% CI -2.08 to 1.78). This difference is not clinically relevant.

1.3. Postoperative pain at 24 hours

Seven studies reported on postoperative pain at 24 hours. All studies used different measurement and reporting methods. Therefore, the results are described per study.

Anoar (2016) used the CHEOPS and reported mean pain scores (±SD). The mean pain scores were 5.8 (± 0.9) and 7.7 (± 0.4) in the intervention (n=20) and control group (n=20), respectively (MD -1.90, 95% CI -2.33 to -1.47). This difference is clinically relevant.

Bajwa (2010) used the OPS and reported mean pain scores (±SD). The mean pain scores were 3.58 (± 0.40) and 3.72 (± 0.42) in the intervention (n=22) and control group (n=22), respectively (MD -0.14; 95% CI -0.38 to 0.10). This difference is not clinically relevant.

El-Hennway (2009) assessed pain with the FLACC and reported participant’s pain intensity in percentages per score. At 24 hours postoperatively, for the intervention group (n=30) the distribution of the scores was as follows, score 1 (30%), score 2 (40%), score 3 (30%), and for the control group (n=30) score 1 (40%), score 2 (40%), score 2 (20%).

Joshi (2004) assessed pain at 24 hours postoperatively based on parent reported visual analog scale (VAS) scores (0 representing no pain, and 10 representing worst imaginable pain) at rest and during movement. At rest, a pain score of 1.9 (±2.7) in the intervention group (n=18) and a pain score of 1.8 (±1.9) in the control group (n=17) was found (MD 0.10; 95 % CI -1.44 to 1.64).

This difference is not clinically relevant. During movement, a pain score of 3.6 (±3.3) in the intervention group (n=18) and a pain score of 3.2 (±2.3) the control group (n=17) was found (MD 0.40; 95 % CI -1.48 to 2.28). This difference is not clinically relevant.

Mostafa (2021) assessed pain using CHEOPS and reported mean pain scores (±SD). The mean pain scores were 4.13 (± 0.3) and 4.13 (± 0.3) in the intervention (n=30) and control group (n=30), respectively (MD 0.00, 95% CI -0.45 to 0.15). This difference is not clinically relevant.

Narasimhamurthy (2016) assessed pain with the FLACC scale and reported number of patients with a score ≥ 4. Three of 30 patients in the clonidine group (10%); and 2 of 30 patients in the control group (6.6%) had a pain score ≥ 4.

Potti (2017) assessed pain using the CHIPPS and reported the number of patients experiencing each score (Table 5).

Table 5. CHIPPS pain scores at 24 hours (Potti 2017)

|

CHIPPS score |

0 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

≥4 |

|

I1: (n = 25) levobupivacaine 0.25% 1 mL/kg with 1 mug/kg clonidine caudally and 5 mL of normal saline i.v |

|

1 (4%) |

3 (12%) |

1 (4%) |

20 (80%) |

|

I2: (n = 25) levobupivacaine 0.25% 1 mL/kg caudally and 1 mug/kg clonidine in 5 mL normal saline i.v |

|

|

1 (4%) |

|

24 (96%) |

|

C: (n = 25) levobupivacaine 0.25% 1 mL/kg caudally and 5 mL of normal saline i.v |

|

|

|

|

25 (100%) |

1.4. Reporting of postoperative pain with incomplete information

Ten other included studies did measure postoperative pain but only reported limited or unreadable data in the results section:

Akbas (2005) used the observational Oucher Pain Scale and only reported that there were no statistically significant differences among the groups with respect to the pain scoring.

Akin (2010) used the CHIPPS and presented results in a graph from which the data are not readable. The graph shows that the control group had higher pain scores during the first postoperative hour but were similar with the intervention group at 6h and 24h postoperatively.

De Mey (2000) used a VAS in children older than 5 years and CHEOPS in children less than 5 years of age, but no absolute pain scores are reported in the results section. The authors only report that the pain scores at 2, 6 and 12h postoperatively were not significantly different among the groups.

De Negri (2001) used the CHEOPS once in the recovery room and every 4h if the patient was awake, but only reported that pain scores were lower in the group receiving ropivacaine plus clonidine 0.12 mg compared to ropivacaine plus lower doses of clonidine (0.04 and 0.08 mg) and plain ropivacaine.

Ivani (2000) used the OPS and registered the mean of the maximum scores for each individual patient who did not require supplemental analgesia during the 24h study period. They report that OPS scores were similar between the control (mean: 1, range: 0–4; n=20) and the intervention (mean: 1, range: 0–4; n=20) groups (MD: 0).

Laha (2012) used the CHEOPS at PACU, 4h, 8h and 24h, and presented results in a graph from which the data are not readable. The graph shows that pain scores were (slightly) higher for the clonidine group compared to the control group - with pain scores increasing over time.

Rawat (2019) used the CHIPSS and presented results in a graph from which the data are not readable. The graph shows that pain scores are lower in the clonidine compared to the control group at 0, 6, and 12h after surgery.

Sanwatsarka (2017) used the FLACC scale and presented results in a graph from which the data are not readable. The authors report that: FLACC pain score never reached ≥4 during the first 3h after surgery in both groups; the number of patients with FLACC pain score ≥4 were significantly more in the control group at the end of 4th (46%), 8th (56%) and 12th (72%) hour postoperatively compared to the clonidine group; more children in the control group had moderate to severe pain at 4h, 8h and 12h postoperatively, compared to children in the clonidine group.

Shaikh (2015) used the FLACC scale and presented data in a graph from which the data are not readable. The graph shows at that the FLACC score begins at a score of 0 at 0h postoperatively for both groups; that the clonidine group has a much lower score compared to the control group at 4-8hr; and that at 24h postoperatively the clonidine group still has lower pain scores, but there is less difference with the control group.

Singh (2012) used the FLACC scale and presented results in a graph from which the data are not readable. In this study, efficacy of ketamine, fentanyl and clonidine were compared with a control group and the authors report that the FLACC pain score in the clonidine group was statistically significant lower compared to the other groups.

- Anxiety

Only one study (Visoiu, 2021) reported on the outcome anxiety. In children undergoing bilateral rectus sheath blocks for laparoscopic appendectomy surgery, they used the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for Children (scores can range from 20 to 80, with higher scores correlating with greater anxiety) six hours after rectus sheath injections to score postoperative anxiety. The mean STAIC anxiety scores were 29.0 (26.0, 32.0) and 30.0 (27.0, 30.0) in the clonidine (n=23) and control group (n=18), respectively (MD -1 in favor of the clonidine group).

3. Postoperative opioid consumption

3.1. Postoperative opioid consumption in PACU

Three studies reported on postoperative opioid consumption in PACU. All three studies used different reporting methods, which meant that the results could not be pooled, and the results are described per study. In the study by Anouar (2016) supplemental analgesia of intravenous nalbuphine increments of 0.2 µg/kg was provided if the CHEOPS pain score was >7. The authors reported that no patient in the intervention group (n=20) nor in the control group (n=20) needed nalbuphine [RD: 0; 95% CI -0.09 to 0.09]. This difference is not clinically relevant.

In the study by Joshi (2004) fentanyl was given if the child had observable moderate or severe pain based on the faces scale (compilation score ≥2; see postoperative pain section, Table 2). The dose of fentanyl was 0.6 (±0.4) µg/kg in the intervention group compared to 0.8 (± 0.5) µg/kg in the control group (MD -0.20, 95% CI -0.50 to 0.10). This difference is not clinically relevant.

In the study by Tripi (2005) only mean intravenous morphine requirements for rescue therapy were reported (no SD). The consumption of morphine in PACU was 0.02 mg/kg in the intervention group compared to 0.05 mg/kg in the control group (MD 0.03). This difference is clinically relevant in favor of the control group.

3.2. Postoperative opioid consumption in 24 hours

Two studies reported on postoperative opioid consumption in 24h. In the study by Joshi (2004) doses of tylenol/codeine were given by the parents if their child appeared to be in pain. The mean number of doses of tylenol/codeine at 24h was 2.6 (±1.4) in the intervention group compared to 2.8 (± 2.5) in the control group (MD 0.20, 95% CI -1.13 to 1.53). This difference is not clinically relevant.

Tripi (2005) only reported mean intravenous morphine requirements for rescue therapy at 24h were reported (no SD). The consumption of morphine at 24h was 0.1 mg/kg in the intervention group compared to 0.2 mg/kg in the control group (MD 0.1). This difference is clinically relevant in favor of the intervention group.

3.3. Postoperative opioid consumption in total postoperative period

Five studies reported on postoperative opioid consumption in total postoperative period. All studies used different reporting methods, which meant that the results could not be pooled, and the results are described per study.

In the study by Akin (2010) patients with a CHIPPS score ≥4 were given tramadol oral drops (2 mg/kg). The authors reported on the number of patients requiring tramadol in the first 24h postoperatively: 19 of 20 (95%) patients who received clonidine caudally (I1); 13 of 20 (65%) patients who received clonidine in normal saline (I2) and 17 of 20 (85%) patients who only received levobupivacaine (C) required the rescue analgesic (RR I1 vs C: 1.12; 95% CI 0.91 to 1.38; RR I2 vs C: 0.76; 95% CI 0.53 to 1.11).

In the study by De Negri (2001) each child was prescribed acetaminophen/codeine suppositories to be given by the nurse if patients had CHEOPS scores >9 on two consecutive assessments 5min apart during the 48h study period. No absolute values were presented in the results section, but the authors report that the median number of postoperative analgesic doses was 4.0 in the control group, 4.0 in the group receiving clonidine 0.04 mg, 1.0 in in the group receiving clonidine 0.08 mg, and 1.0 in the group receiving clonidine 0.04 mg.

In the study by Ivani (2000) a fixed combination paracetamol (350 mg)-codeine (15 mg) suppository was administered if the patient’s OPS score was >5. Fewer patients needed supplemental paracetamol-codeine suppositories during the 24-h study period in the intervention group (2 of 20; 10%) compared to the control group (9 of 20; 45%) (RR: 0.22; 95% CI 0.05 to 0.90).

In the study by Kalachi (2007) tramadol 1–2 mg/kg IV was used for rescue analgesia if the pain score was ≥30 mm on a 0-100 mm VAS. Need for rescue analgesic during the first 24h after surgery was reported as yes/no. In the clonidine group, 29 of 42 (69%) needed tramadol compared to 26 of 63 patients in the control group (RR 1.67, 95% CI 1.17 to 2.39).

In the study by Tripi (2005) total number of patients requiring mean intravenous morphine requirements for rescue therapy during the 24h study period was reported. Five of 18 patients (27.7%) in the clonidine group received no postoperative morphine, compared to 1 of 15 (6.7%) in the control group (RR 4.17, 95% CI 0.54 to 31.88).

4. Adverse events

4.1. Apnea

Not reported.

4.2. Respiratory depression

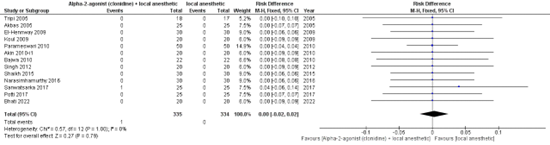

Thirteen studies reported on the incidence of respiratory depression (a decrease in oxygen saturation <93%, requiring oxygen by face mask). Figure 1 shows that there is no difference in risk between the pooled clonidine group (n=335) and pooled control group (n=334) (RD 0.00, 95% CI -0.02 TO 0.02).

Figure 1: respiratory depression.

4.3. Hypotension

Ten studies reported incidence of hypotension (systolic blood pressure (SBP) <70 mm Hg). Figure 2 shows that there is no difference in risk between the pooled clonidine group (n=304) and pooled control group (n=324) (RD 0.03, 95% CI -0.00 to 0.07).

Figure 2: Hypotension.

4.4. Sedation

In total 20 studies reported on sedation levels. Eleven studies reported data that could be interpreted for (clinical) relevance (Table 6). The other studies (n=9) only reported limited information or unreadable data in the results section and are described below the table. All studies used different measurement and reporting methods. Therefore, the results are described per study.

Table 6. Sedation scores per study.

|

Study |

Sedation scale |

Time |

Reporting |

Clonidine group |

N |

Control group |

N |

Outcome (MD, RD) |

Clinically relevant? |

|

Bawja (2010) |

three-point scale (opening of eyes: 3 = spontaneously, 2 = to verbal command, 1 = to physical shaking, 0 =not arousable) |

24 h time interval (10-min interval after extubation and thereafter at intervals of 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 12, 18 and 24 h) |

Mean (±SD) |

2.86 (± 0.52) |

22 |

2.68 (± 0.56) |

22 |

MD 0.18, 95% CI -0.14 to 0.50 |

No |

|

Ivani (2000) |

a four-point scale [0 (alert)–3 (not arousable)] |

Until the patients were once again alert as indicated by spontaneous eye opening |

Mean (range) |

mean: 1, range: 0–2 |

20 |

mean: 1, range: 0–1 |

20 |

MD 0 |

No |

|

Jindal (2011) |

University of Michigan sedation scale (UMSS) (0-3 score range) |

At extubation (PACU) |

% per sedation score [0:1:2:3] |

24%, 48%, 24%, 4% |

25 |

16%, 40%, 32%, 16% |

25 |

Similar distribution |

No |

|

Koul (2009) |

four-point sedation score (1: asleep, not arousable by verbal contact; 2: asleep, arousable by verbal contact; 3: drowsy not sleeping; 4: alert/aware) |

30minutes, 1 hour and 4 hours after the operation |

mean sedation scores over these time-intervals |

2.8 (± 0.45) |

20 |

2.83 (± 0.47) |

20 |

MD -0.03 95% CI -0.32 to 0.26 |

No |

|

Potti (2017) |

Ramsay Sedation Score |

1h, 6h, 12h |

Mean (±SD) |

PACU (1h) I_B: 2.52 ± 0.51 I_C: 2.40 ± 0.50

6 hours I_B: 2.00 ± 0.00 I_C: 2.00 ± 0.00

12 hours I I_B: 2.00 ± 0.00 I_C: 2.00 ± 0.00

|

25 |

PACU (1h) 2.40 ± 0.50

6 hours 2.00 ± 0.00

24 hours not reported

|

25 |

PACU (1h) 2.40 ± 0.50

6 hours 2.00 ± 0.00

|

|

|

Mostafa (2021) |

five-point sedation score (1. awake and alert, 2. sleeping but easily arouses to voice or light touch, 3. Arouses to loud voice or shaking, 4. arouses with painful stimuli and 5. cannot be aroused) |

After the block |

Mean (±SD) |

1.33 (± 0.1) |

30 |

1.17 (± 0.1) |

30 |

MD 0.16, 95% CI 0.11 to 0.21 |

No |

|

Narasimhamurthy (2016) |

three-point sedation score (0- awake, 1- arousable by voice, 2- arousable to pain, 3- unarousable) |

First 2 hours |

Number of patients per score |

Score = 0 22 of 30

Score = 1 8 of 30 |

30 |

Score = 0 22 of 30

Score =1 8 of 30 |

30 |

Score = 0 RD 0.00 95% CI -0.22 to 0.22

Score =1 RD 0.00 95% CI -0.22 to 0.22 |

No |

|

Sanwatsarka (2017) |

a four-point sedation score (1 Asleep, not arousable by verbal contact; 2 Asleep, arousable by verbal contact; 3 Drowsy not sleeping; 4 Alert/awake) |

0,1,2,4,8,12h |

Mean (±SD) |

0h 1.88±0.2112

4h 3.08±0.2208

12h 3.72±0.4032 |

25 |

0h 2.84±0.2688

4h 3.8±0.32

12h 4±0.0 |

25 |

0h MD -0.96 95% CI -1.09 to -0.83

4h MD -0.72 95% CI -0.87 to -0.57

12h MD -0.28 |

No |

|

Tripi (2005) |

5-point sedation score ranging from 1 (asleep, no response to painful stimulus) to 5 (crying, agitated or restless). |

15-minute intervals in the PACU |

Mean |

Initial score 3.2

All scores 3.4 |

18 |

Initial score 3.0

All scores 3.4 |

17 |

Initial score MD 0.2

All scores MD 0 |

No |

|

Visoiu (2021) |

Sedation Level (0, 1, 2)

|

PACU |

% of patients per score [0, 1, 2] |

18%, 77%, 5% |

26 |

19%, 76%, 5% |

24 |

Similar distribution |

No |

MD= mean difference; PACU=post anesthesia care unit; RD=risk difference; SD=standard deviation

Akbas (2005) used a three-point score (1, awake; 2, asleep but arousable by verbal contact; 3, asleep and not arousable by verbal contact) and only reported that sedation scores were higher in the clonidine group for the first 1-h period after the operation compared to the control group.

Akin (2010) used the Ramsay Sedation Score (1, awake: agitated or restless or both; 2, awake: cooperative, oriented, and tranquil; 3, awake but responds to commands only; 4, asleep: brisk response to light glabellar tap or loud auditory stimulus), but the data were presented in a graph from which the data was not readable. The authors reported that the mean postoperative sedation score was higher in the group that received levobupivacaine + clonidine caudally at 30-, 60- and 240-min post procedure compared to the group that received only levobupivacaine (control) and the group that received levobupivacaine + clonidine i.v. but not at extubation, 15 and 120 min and 6, 12 and 24 h postoperatively.

Bhati (2022) used the Ramsay Sedation Score at PACU at arrival and then every hour, but only reported in the results section that the score was 3 at 60 minutes post-block and that all children were awake and alert 120 minutes post-block.

De Negri (2001) assessed the degree of sedation with a three-point sedation scale based on eye opening (0 5 eyes open spontaneously; 1 5 eyes open to speech; 2 5 eyes open in response to physical stimulation) in the recovery room and every 4 h if the patient was awake for 48 h study period and presented data in a figure that was not readable. It was only reported that no statistical difference was found among the different study groups.

Joshi (2004) sedation level was scored with 0 corresponding to ‘asleep’ and 10 corresponding to ‘awake’. In the results section no absolute values are reported, but author report “there was no difference between the groups with respect to sedation the night of surgery or the following morning.”

Kaaibachi (2005) using a three-point scale (0, alert; 1, asleep but easy arousable; 2, asleep but not easily arousable) to measure sedation. In the results section they only report that there was no significant difference in the sedation scores between both groups either in recovery room (sedation score 2, 5% in the clonidine group versus 48% in the control group) or during the first 6 h.

Rawat (2019) used the Ramsay Sedation Score and presented data in a (bar) graph from which the values are not readable. The graph shows that sedation scores are higher in the clonidine group compared to the control group over all time points (0, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12 h post-surgery).

Shaikh (2015) used a sedation score 0-3 according to child’s alertness and arousability. Data were presented in a figure and not readable. Sedation scores up to 8 hours postoperatively were lower in the control group as compared to the clonidine group. At 8 hours, both groups had a sedation score of 0.

Singh (2012) assessed sedation by using a four-point sedation score (Patient sedation score was defined as 1: Asleep, not arousable by verbal contact 2: Asleep, arousable by verbal contact, 3: Drowsy, not sleeping, 4: Alert/ awake) at every hour for the first eight hours. Data presented in figure not readable and further not reported by the authors. From the figure it can be observed that the intervention group had higher sedation scores throughout all timepoints as compared to the control group.

4.5. Postoperative emergence delirium

Not reported.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence for all outcome measures started as high, since the included studies were RCTs.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure postoperative pain at PACU arrival/ 0 hours was downgraded by two levels to low because of study limitations (risk of bias, -1); and number of included patients (imprecision, -1).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure postoperative pain at 6 hours was downgraded by two levels to low because of study limitations (risk of bias, -1); and number of included patients (imprecision, -1).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure postoperative pain at 24 hours was downgraded by two levels to low because of study limitations (risk of bias); and number of included patients (imprecision, -1).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure anxiety was downgraded by three levels to very low because only one study with a limited number of included patients was included (imprecision, -3).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure postoperative opioid consumption in PACU was downgraded by three levels to very low because of study limitations (risk of bias, -1); and number of included patients (imprecision, -2).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure postoperative opioid consumption in 24 hours was downgraded by three levels to very low because of study limitations (risk of bias, -1); and number of included patients (imprecision, -2).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure postoperative opioid consumption in the total postoperative period was downgraded by three levels to very low because of study limitations (risk of bias, -1); and number of included patients (imprecision, -2).

The level of evidence regarding the adverse events apnea and postoperative emergence delirium could not be assessed as no evidence was available.

The level of evidence regarding the adverse event respiratory depression was downgraded by one level to moderate because of study limitations (risk of bias, -1).

The level of evidence regarding the adverse event hypotension was downgraded by two levels to low because of study limitations (risk of bias, -1); and conflicting results (inconsistency, -1).

The level of evidence regarding the adverse event sedation was downgraded by two levels to low because of study limitations (risk of bias, -1); and number of included patients (imprecision, -1).

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question: What is the effect of adding an alpha-2-agonist (clonidine) to the locoregional block compared with not adding alpha-2-agonist to the locoregional block in children undergoing a surgical procedure?

| P: | Children undergoing a surgical procedure |

| I: | Alpha-2-agonist (clonidine) + local anesthetic (ropivacaine or L-bupivacaine) |

| C: | Local anesthetic (ropivacaine or L-bupivacaine) |

| O: |

Postoperative pain Anxiety Postoperative opioid consumption Adverse events |

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered postoperative pain as a critical outcome measure for decision making; and anxiety, postoperative opioid consumption, complications and postoperative emergence delirium as important outcome measures for decision making.

The working group defined the outcome measures as follows:

- Postoperative pain à PACU / 0 hours, 6 and 24 hours (at rest; if nothing was reported about the condition in which pain was assessed (at rest or during mobilization) it was assumed pain was measured at rest)

- A priori, the working group did not define the outcome measure 'anxiety' but used the definitions used in the studies.

- Postoperative opioid consumption à morphine equivalent in PACU, at 24 hours and in total

- Adverse events à apnea, respiratory depression, hypotension, sedation, postoperative emergence delirium

The working group defined one point as a minimal clinically (patient) important difference on a 10-point pain scale and 10 mm on a 100 mm pain scale. Regarding postoperative opioid consumption, a difference of 20% was considered clinically relevant. For dichotomous variables, a difference of 10% was considered clinically relevant (RR ≤0.91 or ≥1.10; RD 0.10).

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms until 12-2-2023 + 18-2-2023. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 419 unique hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria;

Inclusion criteria:

- Systematic review (SR) of randomized controlled trails (RCTs) or RCT

- Published ≥ 2000

- Children

- Conform PICO

Exclusion criteria:

- No original research

- N≤10 per arm

A total of 86 studies (16 SRs, 70 RCTs) were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, 61 studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and 24 studies (all RCTs) were included.

Results

A total of 24 RCTs were included in the analysis of the literature. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- Akbas M, Akbas H, Yegin A, Sahin N, Titiz TA. Comparison of the effects of clonidine and ketamine added to ropivacaine on stress hormone levels and the duration of caudal analgesia. Paediatr Anaesth. 2005 Jul;15(7):580-5. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9592.2005.01506.x. PMID: 15960642.

- Akin A, Ocalan S, Esmaoglu A, Boyaci A. The effects of caudal or intravenous clonidine on postoperative analgesia produced by caudal levobupivacaine in children. Paediatr Anaesth. 2010 Apr;20(4):350-5. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9592.2010.03259.x. Epub 2010 Feb 11. PMID: 20158620.

- Anouar J, Mohamed S, Sofiene A, Jawhar Z, Sahar E, Kamel K. The analgesic effect of clonidine as an adjuvant in dorsal penile nerve block. Pan Afr Med J. 2016 Apr 21;23:213. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2016.23.213.5767. PMID: 27347302; PMCID: PMC4907766.

- Bajwa SJ, Kaur J, Bajwa SK, Bakshi G, Singh K, Panda A. Caudal ropivacaine-clonidine: A better post-operative analgesic approach. Indian J Anaesth. 2010 May;54(3):226-30. doi: 10.4103/0019-5049.65368. PMID: 20885869; PMCID: PMC2933481.

- Bhati K, Saini N, Aeron N, Dhawan S. A Comparative Study to Evaluate the Efficacy of Dexmedetomidine and Clonidine to Accentuate the Perioperative Analgesia of Caudal 0.25% Isobaric Levobupivacaine in Pediatric Infraumbilical Surgeries. Cureus. 2022 Aug 9;14(8):e27825. doi: 10.7759/cureus.27825. PMID: 36106237; PMCID: PMC9455914.

- de Mey JC, Strobbet J, Poelaert J, Hoebeke P, Mortier E. The influence of sufentanil and/or clonidine on the duration of analgesia after a caudal block for hypospadias repair surgery in children. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2000 Jun;17(6):379-82. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2346.2000.00690.x. PMID: 10928438.

- De Negri P, Ivani G, Visconti C, De Vivo P, Lonnqvist PA. The dose-response relationship for clonidine added to a postoperative continuous epidural infusion of ropivacaine in children. Anesth Analg. 2001 Jul;93(1):71-6. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200107000-00016. PMID: 11429342.

- El-Hennawy AM, Abd-Elwahab AM, Abd-Elmaksoud AM, El-Ozairy HS, Boulis SR. Addition of clonidine or dexmedetomidine to bupivacaine prolongs caudal analgesia in children. Br J Anaesth. 2009 Aug;103(2):268-74. doi: 10.1093/bja/aep159. Epub 2009 Jun 18. PMID: 19541679.

- Ivani G, De Negri P, Conio A, Amati M, Roero S, Giannone S, Lönnqvist PA. Ropivacaine-clonidine combination for caudal blockade in children. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2000 Apr;44(4):446-9. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-6576.2000.440415.x. PMID: 10757579.

- Jindal P, Khurana G, Dvivedi S, Sharma JP. Intra and postoperative outcome of adding clonidine to bupivacaine in infraorbital nerve block for young children undergoing cleft lip surgery. Saudi J Anaesth. 2011 Jul;5(3):289-94. doi: 10.4103/1658-354X.84104. PMID: 21957409; PMCID: PMC3168347.

- Joshi W, Connelly NR, Freeman K, Reuben SS. Analgesic effect of clonidine added to bupivacaine 0.125% in paediatric caudal blockade. Paediatr Anaesth. 2004 Jun;14(6):483-6. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9592.2004.01229.x. PMID: 15153211.

- Koul A, Pant D, Sood J. Caudal clonidine in day-care paediatric surgery. Indian J Anaesth. 2009 Aug;53(4):450-4. PMID: 20640207; PMCID: PMC2894500.

- Mostafa MF, Hamed E, Amin AH, Herdan R. Dexmedetomidine versus clonidine adjuvants to levobupivacaine for ultrasound-guided transversus abdominis plane block in paediatric laparoscopic orchiopexy: Randomized, double-blind study. Eur J Pain. 2021 Feb;25(2):497-507. doi: 10.1002/ejp.1689. Epub 2020 Nov 17. PMID: 33128801.

- Narasimhamurthy GC, Patel MD, Menezes Y, Gurushanth KN. Optimum Concentration of Caudal Ropivacaine & Clonidine - A Satisfactory Analgesic Solution for Paediatric Infraumbilical Surgery Pain. J Clin Diagn Res. 2016 Apr;10(4):UC14-7. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2016/18946.7665. Epub 2016 Apr 1. PMID: 27190923; PMCID: PMC4866221.

- Parameswari A, Dhev AM, Vakamudi M. Efficacy of clonidine as an adjuvant to bupivacaine for caudal analgesia in children undergoing sub-umbilical surgery. Indian J Anaesth. 2010 Sep;54(5):458-63. doi: 10.4103/0019-5049.71047. PMID: 21189886; PMCID: PMC2991658.

- Potti LR, Bevinaguddaiah Y, Archana S, Pujari VS, Abloodu CM. Caudal Levobupivacaine Supplemented with Caudal or Intravenous Clonidine in Children Undergoing Infraumbilical Surgery: A Randomized, Prospective Double-blind Study. Anesth Essays Res. 2017 Jan-Mar;11(1):211-215. doi: 10.4103/0259-1162.200233. PMID: 28298787; PMCID: PMC5341679.

- Priolkar S, D'Souza SA. Efficacy and Safety of Clonidine as an Adjuvant to Bupivacaine for Caudal Analgesia in Paediatric Infra-Umbilical Surgeries. J Clin Diagn Res. 2016 Sep;10(9):UC13-UC16. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2016/19404.8491. Epub 2016 Sep 1. PMID: 27790555; PMCID: PMC5072055.

- Rawat J, Shyam R, Kaushal D. A Comparative Study of Tramadol and Clonidine as an Additive to Levobupivacaine in Caudal Block in Pediatric Patients Undergoing Perineal Surgeries. Anesth Essays Res. 2019 Oct-Dec;13(4):620-624. doi: 10.4103/aer.AER_127_19. Epub 2019 Dec 16. PMID: 32009705; PMCID: PMC6937898.

- Sanwatsarkar S, Kapur S, Saxena D, Yadav G, Khan NN. Comparative study of caudal clonidine and midazolam added to bupivacaine during infra-umbilical surgeries in children. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol. 2017 Apr-Jun;33(2):241-247. doi: 10.4103/0970-9185.209739. PMID: 28781453; PMCID: PMC5520600.

- Shaikh SI, Atlapure BB. Clonidine as an adjuvant for bupivacaine in caudal analgesia for sub-umbilical surgery: A prospective randomized double blind study. Anaesthesia, Pain & Intensive Care. 2019 Jan 27:240-6.

- Singh J, Shah RS, Vaidya N, Mahato PK, Shrestha S, Shrestha BL. Comparison of ketamine, fentanyl and clonidine as an adjuvant during bupivacaine caudal anaesthesia in paediatric patients. Kathmandu Univ Med J (KUMJ). 2012 Jul-Sep;10(39):25-9. doi: 10.3126/kumj.v10i3.8013. PMID: 23434957.

- Tripi PA, Palmer JS, Thomas S, Elder JS. Clonidine increases duration of bupivacaine caudal analgesia for ureteroneocystostomy: a double-blind prospective trial. J Urol. 2005 Sep;174(3):1081-3. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000169138.90628.b9. PMID: 16094063.

- Visoiu M, Scholz S, Malek MM, Carullo PC. The addition of clonidine to ropivacaine in rectus sheath nerve blocks for pediatric patients undergoing laparoscopic appendectomy: A double blinded randomized prospective study. J Clin Anesth. 2021 Aug;71:110254. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2021.110254. Epub 2021 Mar 19. PMID: 33752119.

Evidence tabellen

Evidence table for intervention studies (randomized controlled trials and non-randomized observational studies [cohort studies, case-control studies, case series])

|

Study reference (first author, publication year) |

Was the allocation sequence adequately generated?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was the allocation adequately concealed?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Blinding: Was knowledge of the allocated interventions adequately prevented? Were patients blinded? Were healthcare providers blinded? Were data collectors blinded? Were outcome assessors blinded? Were data analysts blinded? |

Was loss to follow-up (missing outcome data) infrequent?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Are reports of the study free of selective outcome reporting?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was the study apparently free of other problems that could put it at a risk of bias?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Overall risk of bias If applicable/necessary, per outcome measure

LOW Some concerns HIGH |

|

Akbas 2005 |

Probably no

Reason: not reported |

Probably no

Reason: not reported |

Probably yes

Reason: Drugs were diluted in 0.9% saline (0.75 mlÆkg) and prepared by a staff anesthesiologist not otherwise involved in the study. |

Probably yes

Reason: not reported, complete outcome data for 25 included patients per arm. |

Probably yes

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported, but no absolute data were reported for all outcomes. |

Probably yes

Reason: funding and conflicts not reported. |

High

Reason: allocation, randomization and blinding |

|

Akin 2010 |

Probably no

Reason: not reported |

Probably yes

Reason: Children were randomized, using a sealed envelope technique, to one of the three treatment groups before caudal block was performed |

Probably yes

Reason: The study drug was prepared by an investigator unaware of the group assignment. |

Probably yes

Reason: not reported, complete outcome data for 25 included patients per arm. |

Probably yes

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported, but no absolute data were reported for all outcomes. |

Probably yes

Reason: funding and conflicts not reported. |

High

Reason: allocation, blinding |

|

Anouar 2016 |

Probably no

Reason: not reported |

Probably yes

Reason: Each patient was randomly assigned to one of the two groups by drawing from a sealed envelope |

Probably yes

Reason: double-blind study. After surgery, patients were observed in PACU (Post Anesthesia Care Unit) for 6 hours by a nurse blinded to the study. |

Probably yes

Reason: not reported, complete outcome data for 25 included patients per arm. |

Probably yes

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported, but no absolute data were reported for all outcomes. |

Probably yes

Reason: funding and conflicts not reported. |

Some concerns

Reason: allocation |

|

Bajwa 2010 |

Definitely yes

Reason: patients were randomly allocated according to a computer generated randomization |

Probably no

Reason: not reported |

Probably yes

Reason: double-blind study. The syringes for the study solutions were prepared by a senior resident of the anesthesiology department who was given written protocols for drug preparation and was unaware of the patients and operation theatre team. |

Probably yes

Reason: not reported, complete outcome data for 25 included patients per arm. |

Probably yes

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported, but no absolute data were reported for all outcomes. |

Definitely yes

Reason: No other problems noted |

Some concerns

Reason: allocation |

|

Bhati 2022 |

Definitely yes

Reason: Children enlisted for the study were randomly allocated into three groups using a computer-generated randomization chart |

Probably no

Reason: not reported |

Definitely yes

Reason: double-blind study. The volume of each local anesthetic solution was prepared by one anesthetist in a coded transparent 10 mL syringe and labeled with the patient’s study number. All healthcare personnel, parents and guardians, and the anesthetist who performed the block were blinded to the caudal medications administered. |

Definitely no

Reason: consort diagram (figure 1) shows there were no dropouts, all patients were followed up till 24 hours. |

Probably yes

Reason: all relevant outcomes were reported, but mainly descriptive |

Definitely yes

Reason: No other problems noted |

Some concerns

Reason: Allocation, reporting of results |

|

De Negri 2001 |

Probably no

Reason: it is only stated that patients were randomly allocated into 2 equal groups |

Probably no

Reason: not reported |

Definitely no

Reason: Randomized, observer-blinded study. Assessments of the variables studied were recorded by nurse observers unaware of the mixture used for epidural infusions. |

Probably no

Reason: not reported |

Probably yes

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported, but no absolute data were reported for all outcomes. |

Definitely yes

Reason: No other problems noted |

High

Reason: blinding, allocation and reporting of results |

|

El-Hennway 2009 |

Definitely yes

Reason: Using a computer-generated list, the subjects were randomly and evenly assigned into three groups: A, B, and C.

|

Probably no

Reason: not reported |

Definitely yes

Reason: All health-care personnel providing direct patient care, the subjects, and their parents or guardians were blinded to the caudal medications administered. All medications were prepared by pharmacy staff not participating in the study except for preparing the drugs. They received and kept the computer-generated table of random numbers according to which random group assignment was performed. After obtaining subjects weight, and according to the randomizing table, the volume to be injected in the caudal block was prepared in syringes with labels indicating only the serial number of the patient. |

Definitely no

Reason: 60 patients were enrolled into the study and none of the 60 attempted caudal blocks was perceived as being a failed attempt |

Probably yes

Reason: all relevant outcomes were reported, but absolute data not readable |

Definitely yes

Reason: No other problems noted |

Some concerns

Reason: allocation |

|

Ivani 2001 |

Definitely yes

Reason: Computer generated randomization was used to divide the patients |

Probably no

Reason: not reported |

Definitely no

Reason: observer-blinded study. Observers unaware of which drug had been administered evaluated the onset of the block and duration of postoperative analgesia. |

Probably no

Reason: 40 patients were enrolled and loss-to follow up is not reported, but results show no missing data |

Probably yes

Reason: all relevant outcomes were reported, but absolute data not readable |

Definitely yes

Reason: No other problems noted |

Some concerns

Reason: Allocation and lack of blinding |

|

Jindal 2011 |

Definitely yes

Reason: For randomization, computer generated numbers equal to the number of patients who were scheduled for the study was put into serially labelled opaque sealed envelopes. Before surgery, an envelope containing the random number was drawn for each patient. |

Definitely yes

Reason: See text in left column |

Probably no

Reason: It is only reported that the patient, anesthesiologist who performed the block, and surgeon were blinded to which anesthetic agent would be used. |

Probably no

Reason: 50 patients were enrolled and loss-to follow up is not reported, but results show no missing data |

Probably yes

Reason: all relevant outcomes were reported, but absolute data not reported or not readable |

Definitely yes

Reason: No other problems noted |

Some concerns

Reason: lack of blinding |

|

Joshi 2004 |

Probably no

Reason: not reported |

Probably no

Reason: not reported |

Probably no

Reason: It is only reported that a nurse blinded to group assignment treated postoperative pain. |

Probably no

Reason: 36 patients were enrolled and loss-to follow up is not reported, but results show no missing data |

Probably yes

Reason: all relevant outcomes were reported, but absolute data not reported or not readable |

Reason: No other problems noted |

High

Reason: allocation, blinding, outcome reporting |

|

Koul 2009 |

Probably no

Reason: not reported |

Probably no

Reason: not reported |

Probably no

Reason: it is reported this was a double-blind study, but no further information is provided on allocation and blinding. |

Probably no

Reason: it is not reported how many patients were enrolled and whether there was loss to follow-up. |

Probably yes

Reason: all relevant outcomes were reported, but absolute data not reported or not readable |

Reason: No other problems noted |

High

Reason: allocation, blinding, follow-up |

|

Laha, 2012 |

Probably no

Reason: not reported |

Probably no

Reason: not reported |

Probably no

Reason: it is reported this was a double-blind study, but no further information is provided on allocation and blinding. |

Probably no

Reason: it is not reported how many patients were enrolled and whether there was loss to follow-up. |

Probably yes

Reason: all relevant outcomes were reported, but absolute data not reported or not readable |

Reason: No other problems noted |

High

Reason: allocation, blinding, follow-up |

|

Mostafa, 2021 |

Probably yes

Reason: randomization computer- generated table using Microsoft Excel by a statistician who did not participate in the patients’ management |

Probably yes

Reason: not reported |

Probably yes

Reason: double blind study; the trial was planned that neither the investigators (surgeons and anesthesiologists) nor the patients’ guardians were aware of the group allocation and the drug combination received. An independent investigator who was not involved in performing the TAP block, or engaged with patient monitoring and data collection was entrusted with preparing and administering the study drugs. |

Definitely no

Reason: CONSORT flow diagram |

Definitely yes

Reason: all (mean) data of relevant outcome measures provided |

Reason: No other problems noted |

Low |

|

Narasimhamurthy 2016 |

Probably yes

Reason: randomization method is not reported

|

Probably yes

Reason: the patients were randomly allocated into two groups. |

Probably yes

Reason: The attending anesthesiologist administered the appropriate drug according to the code in the envelope. Name, age, hospital number, diagnosis and procedure were written in the same envelope, sealed and handed over to the investigator at the end of the procedure. A second observer did the patient assessment and data collection. The anesthesiologist who was collecting the data was blinded to the contents of the study drug. After all the cases had been completed at the end of the study, the code was broken, study drug contents revealed, and data compiled. |

Probably no

Reason: not reported |

Probably yes

Reason: all (mean) data of relevant outcome measures provided |

Reason: No other problems noted |

Some concerns

Reason: randomization method |

|

Parameswari 2010 |

Probably no

Reason: Randomization was done by picking random lots from a sealed bag |

Probably no

Reason: not reported |

Probably no

Reason: The drug was loaded by an anesthesiologist who did not participate in the study. Post-operative assessment was done by another anesthesiologist in the PACU who was not aware of the drug administered and by a nurse in the ward who was also blinded. |

Probably no

Reason: not reported |

Probably yes

Reason: all relevant outcomes were reported, but absolute data not reported or not readable |

Reason: No other problems noted |

Some concerns

Reason: allocation and blinding |

|

Potti 2017 |

Probably yes

Reason: patients were randomly allocated to one of the three groups by a computer-generated list and delivered in opaque, sealed numbered envelopes. |

Probably yes

Reason: see text in left column |

Probably no

Reason: double blind study, anesthesiologist who performed blocks was blinded to study drug, no further information stated

|

Probably no

Reason: not reported |

Probably yes

Reason: all relevant outcomes were reported, but absolute data not reported or not readable |

Reason: No other problems noted |

Some concerns

Reason: blinding, patients |

|

Priolkar 2016 |

Probably no

Reason: not reported |

Probably no

Reason: not reported |

Probably no

Reason: no information reported other than it was a double-blind study |

Probably no

Reason: not reported |

Probably yes

Reason: all relevant outcomes were reported, but absolute data not reported or not readable |

Reason: No other problems noted |

High

Reason: allocation, blinding, follow-up |

|

Rawat, 2019 |

Probably yes

Reason: use of a computer-generated list |

Probably no

Reason: not reported |

Probably no

Reason: no information reported other than it was a double-blind study |

Probably no

Reason: not reported |

Probably yes

Reason: all relevant outcomes were reported, but absolute data not reported or not readable |

Reason: No other problems noted |

Some concerns

Reason: allocation, blinding |

|

Sanwatsarkar, 2017 |

Probably yes

Reason: Randomization was done by picking random lots from a sealed bag |

Probably no

Reason: not reported |

Probably no

Reason: only stated that the drug was loaded by an anesthesiologist who did not participate in the study. |

Probably yes

Reason: not reported |

Probably yes

Reason: all relevant outcomes were reported, but absolute data not reported or not readable |

Reason: No other problems noted |

Some concerns

Reason: allocation, blinding |

|

Shaikh, 2015

|

Probably no

Reason: simple lottery method |

Probably no

Reason: not reported |

Probably no

Reason: all healthcare personnel, the patients and parents/guardians were blinded |

Probably no

Reason: not reported |

Probably yes

Reason: all relevant outcomes were reported, but absolute data not reported or not readable |

Reason: No other problems noted |

Some concerns

Reason: allocation |

|

Singh, 2012

|

Probably no

Reason: not reported |

Probably no

Reason: not reported |

Probably no

Reason: it is only reported that the caudal anesthesia was given by anesthesia technicians, who were blinded about the drugs being used |

Probably no

Reason: not reported |

Probably yes

Reason: all relevant outcomes were reported, but absolute data not reported or not readable |

Reason: No other problems noted |

High

Reason: allocation, blinding, follow-up |

|

Tripi, 2005 |

Probably no

Reason: randomization by random number assignment |

Probably no

Reason: not reported |

Probably yes

Reason: The anesthesiologist, surgeon and nurses caring for each patient were blinded to the contents of the administered solution, which was prepared by an anesthesia provider not caring for the patient. |

Probably no

Reason: not reported |

Probably no

Reason: results only in text, without absolute values |

Reason: No other problems noted |

High

Reason: allocation, reporting of results |

|

Visoiu 2021 |

Definitely yes

Reason: computer-generated random number table. |

Probably yes

Reason: The study medications were prepared and labeled as study drug by the pharmacy and released in identical syringes with a volume of 11 ml each. |

Probably yes

Reason: Patients as well as all members of the care team, except the pharmacist, were blinded to group allocation. |

Definitely no

Reason: loss to follow-up described in consort flow diagram |

Probably yes

Reason: all (mean) data of relevant outcome measures provided

|

Reason: No other problems noted |

Low |

Table of excluded studies

|

Reference |

Reason for exclusion |

|

Ansermino, M. and Basu, R. and Vandebeek, C. and Montgomery, C. |

more recent SR available |

|

Engelman, E. and Marsala, C. |

no quality assessment |

|

Lundblad, M. and Trifa, M. and Kaabachi, O. and Ben Khalifa, S. and Fekih Hassen, A. and Engelhardt, T. and Eksborg, S. and Lönnqvist, P. A. |

more recent SR available |

|

Schnabel, A. and Poepping, D. M. and Pogatzki-Zahn, E. M. and Zahn, P. K. |

no quality assessment |

|

Shah, Ushma J. and Karuppiah, Niveditha and Karapetyan, Hovhannes and Martin, Janet and Sehmbi, Herman |

more recent SR available |

|

Wang, Y. and Guo, Q. and An, Q. and Zhao, L. and Wu, M. and Guo, Z. and Zhang, C. |

no quality assessment |

|

Xiong, C. and Han, C. and Lv, H. and Xu, D. and Peng, W. and Zhao, D. and Lan, Z. |

more recent SR available |

|

Ahuja, S. and Aggarwal, M. and Joshi, N. and Chaudhry, S. and Madhu, S. V. |

Not conform PICO (I/C): wrong comparison (fentanyl vs. clonidine) |

|

Bhowmick, D. K. and Akhtaruzzaman, K. M. and Ahmed, N. and Islam, M. S. and Hossain, M. M. and Islam, M. M. |

Article not retrectable |

|