Kleine sessiele poliepen 6-9 mm bij poliepectomie

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is de meest optimale endoscopische techniek om een colorectale poliep van 6 tot 9 mm te verwijderen?

Aanbeveling

Gebruik voor het verwijderen van een colorectale poliep tussen 6 en 9 mm een koude snaar techniek. Hiervoor wordt het gebruik van een dedicated cold snare geadviseerd.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Er is literatuuronderzoek verricht naar de effecten van koude snaar poliepectomie vergeleken met andere resectie technieken voor poliepen tussen 6 en 9 mm. De uitkomstmaat effectiviteit, waaronder R0 resectie en recidief binnen 6 maanden en 5 jaar, was gedefinieerd als cruciale uitkomstmaat. Op basis van het wetenschappelijk bewijs kan geconcludeerd worden dat er geen verschil is in R0 resectie tussen koude en warme snaar poliepectomie voor kleine poliepen tussen de 6 en 9 mm. De uitkomstmaten recidief binnen 6 maanden en 5 jaar zijn niet gerapporteerd in de studies. De overall bewijskracht van deze cruciale uitkomstmaat is hierdoor beoordeeld als zeer laag.

De uitkomstmaat veiligheid, waaronder postpoliepectomie syndroom, perforatie, intraprocedurele bloeding en postprocedurele bloeding, is gedefinieerd als belangrijke uitkomstmaat. Intraprocedurele bloeding lijkt vaker op te treden bij koude snaar poliepectomie vergeleken met warme snaar poliepectomie. Echter, postprocedurele bloeding lijkt minder vaak op te treden bij koude snaar poliepectomie vergeleken met warme snaar poliepectomie. De bewijskracht is echter beoordeeld als zeer laag, mede vanwege het risico op bias en imprecisie.

In de studie van Aizawa (2019), werd in beide groepen 35% van alle wondbedden dicht geclipt. Hierdoor is het effect op nabloedingen niet goed te schatten. De meta-analyse door Qu (2018) includeerde verschillende studies die koude snaar poliepectomie met warme snaar poliepectomie vergeleek. Hierbij waren er verschillende studies die submucosale injectie gebruikten. Hierdoor is de warme snaar poliepectomie een enigszins heterogene groep waar met en zonder submucosale injectie door elkaar lopen. Er zijn echter geen subgroup analyses uitgevoerd.

Hier is de studie van Kim (2020) interessant; die randomiseerde tussen HSP (met submucosale injectie) en HSP (zonder submucosale injectie). In deze studie werden 362 poliepen geïncludeerd bij 272 patiënten. Er was een significant verschil in effectiviteit (R0 resecties; gedefinieerd als pathologisch vrij snijvlak) 49.7% in de HSP groep zonder submucosale injectie en 74.8% in de HSP groep met submucosale injectie. Er was geen verschil in het aantal complete resecties (gedefinieerd als geen adenomateus weefsel in de biopten van het litteken). Er was geen verschil in het optreden van intra- en postprocedurele bloeding en perforatie.

Het ligt voor de hand te concluderen dat beide technieken vergelijkbaar zijn in het verkrijgen van een complete resectie. De beoordeelbaarheid van een R0 resectie is in het voordeel van de HSP met submucosale injectie, ook wel endoscopische mucosale resectie (EMR) genoemd.

De voordelen van koude snaar poliepectomie is dat het een techniek is waarbij geen coagulatiestroom wordt gebruikt. Theoretisch voordeel is dat er minder kans zou zijn op perforatie en postpoliepectomie syndroom. Een nadeel is dat er perprocedureel iets meer bloedverlies optreedt. Het voordeel van warme snaar poliepectomie is dat het nauwelijks leidt tot bloedverlies. Het nadeel is dat er coagulatie stroom wordt gebruikt, wat geassocieerd is met meer pijn direct na de colonoscopie. Daarnaast is meer kans is op diepe coagulatie schade in de darmwand wat kan leiden tot (late) perforatie en postpoliepectomie syndroom.

Er is weinig literatuur beschikbaar naar de rol van de verschillende snaren voor poliepectomie. Voor koude snaar poliepectomie wordt een kleine dunne snaar geadviseerd die goed door de mucosa snijdt. Een gerandomiseerde studie laat zien dat gebruik van een toegewijde (kleine dunne) snaar vaker tot een radicale poliepectomie leidt in vergelijking tot een traditionele (grotere dikkere) snaar (91% (89/98) versus 79% (88/112), P = 0.015). De vorm van de snaar (circulair, ovaal, hexagonaal, et cetera) heeft geen duidelijk voordeel boven de ander (Dwyer, 2017).

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en eventueel hun verzorgers)

De belangrijkste doelen van de interventie zijn een effectieve en veilige poliepectomie verrichten met zo min mogelijk nadelige effecten (zoals postpoliepectomie pijn). Pijn na de poliepectomie is het nadeel van de warme snaar techniek en is waarschijnlijk ook belangrijk in de patiënt beleving. Derhalve zou de voorkeur waarschijnlijk uitgaan naar een koude snaar poliepectomie.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

Studies over de kosteneffectiviteit van koude snaar en warme snaar ontbreken. Koude snaar poliepectomie is sneller dan warme snaar poliepectomie. Daarnaast wordt bij een warme snaar poliepectomie vaak ook submucosale injectie toegepast, waarbij er een extra naald wordt gebruikt en een electrode plaat.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

Bij een koude snaar poliepectomie kunnen vaker bloedingen ontstaan, deze intraprocedurele bloedingen stoppen spontaan. Om de bloedingen te stoppen en om het poliepectomie wondvlak te beoordelen kan het handig zijn om de waterjet op het wondbed te zetten. Hierdoor komt er water in de submucosa terecht wat zorgt voor tamponade van de bloedvaatjes. Een ander argument kan zijn dat doordat er iets meer weefsel in de lis komt het soms lastig kan zijn het weefsel door te snijden met de snaar. Daarom adviseert de werkgroep een dedicated koude snaar te gebruiken die doorgaans wat makkelijker snijdt. Soms kan het nodig zijn om de shaft van de snare tegelijk met het snijden, richting de scoop te trekken waardoor het weefsel kan worden doorgenomen.

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

De veiligheidsaspecten, met name de kans op nabloeding en postpoliepectomiesyndroom, zijn doorslaggevend in het advies om poliepen van 6 tot 9 mm te verwijderen met een koude snaar techniek. Uit de meta-analyse komt geen significant verschil in het risico op nabloeding, echter het absolute aantal nabloedingen in warme snaargroep ligt hoger dan in de koude snaar groep. Tevens is er in patiënten die coagulantia gebruiken een significant hoger risico op nabloedingen dan bij patiënten die geen coagulantie gebruiken (Horiuchi, 2014).

De meta-analyse van Qu (2019) toont dat de procedure tijd van een koude snaar poliepectomie sneller is dan die van de warme snaar poliepectomie. Het gebruik maken van de koude snaar techniek lijkt daarmee tijds efficiënter (Kawamura, 2018).

Pijnklachten na warme snaar poliepectomie zijn vaker aanwezig dan na toepassing van de koude snaar techniek. Vanuit patiënt perspectief lijkt hiermee ook een voorkeur te zijn voor de koude snaar poliepectomie (De Benito Sanz, 2020).

Als er toch wordt gekozen voor het toepassen van een warme snaar techniek om een poliep van 6 tot 9 mm te verwijderen dan is er een voorkeur voor submucosale injectie voorafgaand aan de warme snaar techniek. In de grootste gerandomiseerde studie (Kawamura, 2018) worden de poliepen allemaal onderspoten. Submucosale injectie vergroot de veiligheid van de poliepectomie doordat dit het risico op diepe coagulatie schade (van de spierlaag) verkleint en de kans op een mechanische perforatie verkleint. De meest gebruikte submucosale vloeistof die hiervoor gebruikt wordt is NaCl. Een systematisch review en meta-analyse van 54 studies, waarvan 11 gerandomiseerde studies concludeert dat hyaluronzuur en NaCl injectie even effectief zijn in het voorkomen van postpoliepectomie complicaties (Ferreira, 2016).

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Het verrichten van een poliepectomie van poliepen van 6 tot 9 mm kent een grote praktijkvariatie. De technieken variëren van koude snaar poliepectomie tot het onderspuiten van de poliep met aansluitend een warme snaar poliepectomie (EMR). Momenteel ontbreekt er een wetenschappelijk onderbouwd advies over wat de meest aangewezen techniek is voor de verwijdering van deze subset van poliepen. Hier willen we onderzoeken wat de meest effectieve en veilige endoscopische resectie techniek is voor het verwijderen van poliepen van 6 tot 9 mm.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

R0 resection

|

Moderate GRADE |

Cold snare polypectomy is probably equally effective as hot snare polypectomy with regard to complete resection rate for small colorectal polyps (6 to 9 mm).

Sources: Qu, 2018; De Benito Sanz, 2020 |

Perforation

|

Low GRADE |

Cold snare polypectomy compared to hot snare polypectomy may result in little to no difference in perforation for small colorectal polyps (6 to 9 mm).

Sources: Qu, 2018 |

Intraprocedural bleeding

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of cold snare polypectomy compared to hot snare polypectomy for intraprocedural bleeding for small colorectal polyps (6 to 9 mm).

Sources: Qu, 2018; Aizawa, 2019; De Benito Sanz, 2020 |

Postprocedural bleeding

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of cold snare polypectomy compared to hot snare polypectomy for postprocedural bleeding for small colorectal polyps (6 to 9 mm).

Sources: Qu, 2018; Aizawa, 2019; De Benito Sanz, 2020 |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

Cold snare versus hot snare polypectomy

Qu (2018) conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to compare cold snare polypectomy (CSP) and hot snare polypectomy (HSP) for diminutive (≤ 5 mm) or small colorectal polyps (6 to 10 mm). The study was performed according to PRISMA guidelines. The databases Medline, EMBASE, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), and Web of Science were searched from the inception to April, 2018. Studies that included patients from randomized controlled trials that compared CSP and HSP for either or both the effectiveness and safety in the treatment of colorectal polyps sized ≤ 10 mm were included. A total of twelve trials involving 2481 patients and 4535 polyps were included, of which eight full-text studies and four meeting abstracts. We only included the eight full-text studies in our literature review. The number of patients ranged from 70 to 578 per study. The studies were conducted in Japan (n=4), Greece, (n=2), China (n=1), and the United States (n=1). Outcomes included complete resection rate between CSP and HSP (defined as a negative pathological margin (R0 resection) from the edge of the resected polyps or a negative biopsy from the polypectomy site), immediate bleeding, and postpolypectomy bleeding (defined as hemorrhage after colonoscopy requiring endoscopic hemostasis, oral antithrombotic administration, emergency department presentation, or hospitalization within 30 days of the procedure).

Aizawa (2019) performed a multicenter RCT in six Japanese centers to compare cold snare polypectomy (CSP) and hot snare polypectomy (HSP) in patients undergoing endoscopic resection of colorectal polyps ≤ 10 mm. A total of 273 patients and 727 polyps were included; 139 patients (367 polyps) were randomized to CSP and 134 patients (360 polyps) to HSP. The mean age ± SD was 62.2 ± 8.8 years, with 68.9% male. Outcomes include immediate bleeding during the procedure, and delayed bleeding (24 hours or later after resection).

De Benito Sanz (2020) performed a multicenter RCT in seven Spanish centers to compare cold snare polypectomy (CSP) and hot snare polypectomy (HSP) in colorectal polyps of 5 to 9 mm. A total of 496 patients were randomized: 237 (394 polyps) to CSP and 259 (397 polyps) to HSP. Eight of these patients (five in CSP group and three in HSP) were excluded owing to retrieval failure of at least one of their polypectomy specimens. Among the remaining 488 patients, 211 (43.2%) presented one 5 to 9 mm polyp, 91 (18.6 %) presented 2 polyps, 37 (7.6 %) presented 3, and the remaining 149 patients (30.5%) presented more than 4 lesions. The median age was 64.7 (IQR 56.7 to 70.5) years in the CSP group and 64.7% were male, compared to a median age of 64.5 (IQR 57 to 70.7) years in the HSP group, and 66.0% male. Outcomes include complete resection, defined as the presence of normal mucosa or burn artifacts in the biopsies from the margins of the mucosal defect, intraprocedural and delayed bleeding (bleeding between discharge and the telephone follow-up contact 21 to 28 days after the colonoscopy).

Results

R0 resection

The systematic review by Qu (2018) described the pooled effect of CSP compared to HSP on complete resection rate. Complete resection rate was defined as a negative pathological margins (R0 resection) from the edge of the resected polyps or a negative biopsy from the polypectomy site). De Benito Sanz (2020) also described the effects of CSP compared to HSP on this outcome measure.

Qu (2018) reported a pooled RR from seven studies for the effect of CSP compared to HSP on complete resection rate of 0.86 (95%CI 0.60 to 1.24). The complete resection rates in the individual studies ranged from 77.3% to 98.2% in the CSP group and from 85.0% to 98.5% in the HSP group.

De Benito Sanz (2020) reported a complete resection rate of 92.5% (358/387 polyps) in the CSP group, compared to 94.0% (362/385) in the HSP group.

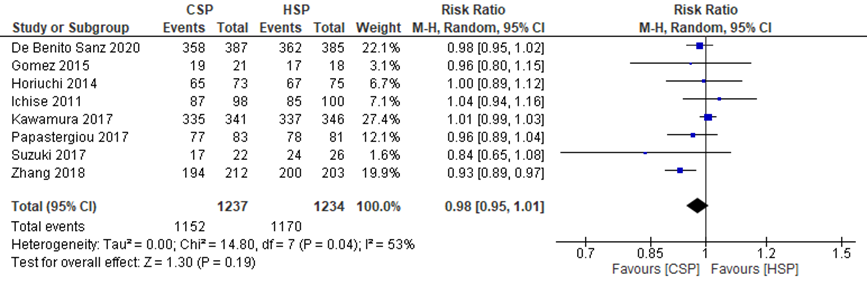

The pooled effects from these eight studies showed a RR of 0.98 (95%CI 0.95 to 1.01) (Figure 1). This difference is not clinically relevant.

Figure 1 Forest plot for the effect of CSP compared to HSP on complete resection rate

Recurrence (within 6 months and 5 years)

None of the included studies compared cold snare with another endoscopic technique on recurrence rate.

Postpolypectomy syndrome

None of the included studies compared cold snare with another endoscopic technique on the occurrence of the postpolypectomy syndrome.

Perforation

The systematic review by Qu (2018) described the effect of CSP compared to HSP on perforation. They reported that no perforation occurred in any of the included studies.

Intraprocedural bleeding

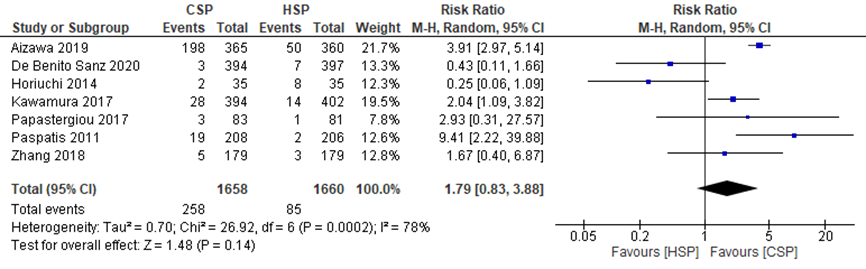

The systematic review by Qu (2018) described the pooled effect of CSP compared to HSP on intraprocedural bleeding. Aizawa (2019) and De Benito Sanz (2020) also described the effects of CSP compared to HSP on this outcome measure. Intraprocedural bleeding was defined as bleeding during the procedure.

Qu (2018) reported a pooled RR from four studies for the effect of CSP compared to HSP on intraprocedural bleeding of 2.86 (95%CI 1.34 to 6.10).

Aizawa (2019) reported that intraprocedural bleeding occurred in 198/365 polyps (54.4%) in the CSP group and in 50/360 polyps (13.9%) in the HSP group.

De Benito Sanz (2020) reported that intraprocedural bleeding was observed in 3/394 (0.8%) CSP procedures and 7/397 (1.8%) HSP procedures.

The pooled effects from these six studies showed a RR of 1.79 (95%CI 0.83 to 3.88), in favor of the CSP group (Figure 2), meaning that intraprocedural bleeding occurred more often in the CSP group. This difference is clinically relevant.

Figure 2 Forest plot for the effect of CSP compared to HSP on early bleeding

Postprocedural bleeding

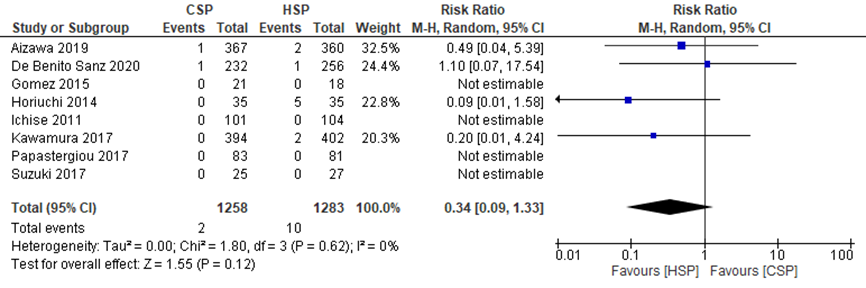

The systematic review by Qu (2018) described the pooled effect of CSP compared to HSP on postprocedural bleeding. Aizawa (2019) and De Benito Sanz (2020) also described the effects of CSP compared to HSP on this outcome measure. Postprocedural bleeding was defined as bleeding that occurred 24 hours or more after the procedure.

Qu (2018) reported a pooled RR from eight studies for the effect of CSP compared to HSP on postprocedural bleeding of 0.74 (95%CI 0.21 to 2.64).

Aizawa (2019) reported that postprocedural bleeding occurred in 1/367 polyps (0.3%) in CSP group and 2/360 polyps (0.6%) in HSP group (after 24 hours).

De Benito Sanz (2020) reported that 1/232 in the CSP group and 1/256 in the HSP group presented postprocedural bleeding at 24 and 48 hours after the procedure.

The pooled effects from these ten studies showed a RR of 0.34 (95%CI 0.09 to 1.33), in favor of the HSP group (Figure 3), meaning that postprocedural bleeding occurred more often in the HSP group. This difference is clinically relevant.

Figure 3 Forest plot for the effect of CSP compared to HSP on delayed bleeding

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence regarding R0 resection came from a meta-analysis of RCTs and therefore starts at high. The level of evidence was downgraded by one level to moderate because of risk of bias (concealment of allocation unclear, blinding unclear; -1).

The level of evidence regarding perforation came from RCTs and therefore starts at high. The level of evidence was downgraded by two levels to low because of risk of bias (concealment of allocation unclear, blinding unclear; -1) and imprecision (no events; -1).

The level of evidence regarding early bleeding came from RCTs and therefore starts at high. The level of evidence was downgraded by three levels to very low because of risk of bias (concealment of allocation unclear, blinding unclear; -1) and inconsistency (conflicting results, crossing border of clinical relevance; -2).

The level of evidence regarding delayed bleeding came from RCTs and therefore starts at high. The level of evidence was downgraded by three levels to very low because of risk of bias (concealment of allocation unclear, blinding unclear; -1), imprecision (low number of events, crossing borders of clinical relevance; -2).

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question:

What is the efficacy and safety of cold snare versus other endoscopic techniques for the removal of colorectal polyps (6 to 9 mm)?

P (patients): patients with small colorectal polyps (6 to 9 mm);

I (intervention): cold snare polypectomy;

C (control): hot snare polypectomy, jumbo biopsy, hot biopsy, endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) with submucosal solution injection;

O (outcomes): efficacy: R0 resection, recurrence within 6 months, recurrence within 5 years; safety: postpolypectomy syndrome, perforation, intraprocedural and postprocedural bleeding

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered efficacy (including R0 resection, recurrence within 6 months, recurrence within 5 years) as a critical outcome measure for decision making; and safety (including postpolypectomy syndrome, perforation, intraprocedural and postprocedural bleeding) as an important outcome measure for decision making.

A priori, the working group did not define the outcome measures listed above but used the definitions used in the studies.

The working group defined the GRADE standard limit of 25% difference for dichotomous outcomes (RR < 0.8 or > 1.25) and 10% for continuous outcomes as a minimal clinically (patient) important difference.

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms until 9 April, 2021. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 141 hits, including 24 systematic reviews (SRs) and 117 randomized controlled trials (RCTs). Studies examining the effects of cold snare polypectomy versus other endoscopic techniques for polyps from 6 to 9 mm were selected. A total of 15 studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, three studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and eleven studies met the inclusion criteria, of which five SRs and 6 RCTs. All five SRs described the same comparison and included similar studies; therefore, we included the SR with the highest quality and excluded the other four SRs. In addition, four of the six RCTs were also described in the included SR. Therefore, the final selection included three studies; of which one SR and two additional RCTs.

Results

A total of three studies were included in the analysis of the literature. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- Aizawa, M., Utano, K., Tsunoda, T., Ichii, O., Kato, T., Miyakura, Y.,... & Togashi, K. (2019). Delayed hemorrhage after cold and hot snare resection of colorectal polyps: a multicenter randomized trial (interim analysis). Endoscopy international open, 7(9), E1123.

- de Benito Sanz M, Hernández L, Garcia Martinez MI, Diez-Redondo P, Joao Matias D, Gonzalez-Santiago JM, Ibáñez M, Núñez Rodríguez MH, Cimavilla M, Tafur C, Mata L, Guardiola-Arévalo A, Feito J, García-Alonso FJ; POLIPEC HOT-COLD Study Group. Efficacy and safety of cold versus hot snare polypectomy for small (5 to 9 mm) colorectal polyps: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. Endoscopy. 2020 Dec 2. doi: 10.1055/a-1327-8357.

- Dwyer et al. A prospective comparison of cold snare polypectomy using traditional or dedicated cold snares for the resection of small sessile colorectal polyps. Endosc Int Open. 2017 Nov;5(11):E1062-E1068. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-113564. Epub 2017 Oct 27.

- Ferreira, A. O., Moleiro, J., Torres, J., & Dinis-Ribeiro, M. (2016). Solutions for submucosal injection in endoscopic resection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Endoscopy international open, 4(01), E1-E16.

- Horiuchi, A., Nakayama, Y., Kajiyama, M., Tanaka, N., Sano, K., & Graham, D. Y. (2014). Removal of small colorectal polyps in anticoagulated patients: a prospective randomized comparison of cold snare and conventional polypectomy. Gastrointestinal endoscopy, 79(3), 417-423.

- Kawamura, T., Takeuchi, Y., Asai, S., Yokota, I., Akamine, E., Kato, M.,... & Tanaka, K. (2018). A comparison of the resection rate for cold and hot snare polypectomy for 4 to 9 mm colorectal polyps: a multicentre randomised controlled trial (CRESCENT study). Gut, 67(11), 1950-1957.

- Kim, S. J., Lee, B. I., Jung, E. S., Kim, J. S., Jun, S. Y., Kim, W.,... & Choi, M. G. (2020). Hot snare polypectomy versus endoscopic mucosal resection for small colorectal polyps: a randomized controlled trial. Surgical Endoscopy, 1-8.

- Qu, J., Jian, H., Li, L., Zhang, Y., Feng, B., Li, Z., & Zuo, X. (2019). Effectiveness and safety of cold versus hot snare polypectomy: A meta‐analysis. Journal of gastroenterology and hepatology, 34(1), 49-58.

Evidence tabellen

Evidence table for intervention studies (randomized controlled trials and non-randomized observational studies (cohort studies, case-control studies, case series))1

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics 2 |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C) 3 |

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size 4 |

|

Aizawa (2019) |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: Six centers (Aizu Medical Center, Takeda General Hospital, Fukushima Rosai Hospital, Hokkaido Gastroenterology Hospital, Saitama Medical Center, and Fujita General Hospital) in Japan

Funding and conflicts of interest: funding not reported; no competing interests. |

Inclusion criteria: Patients undergoing polypectomy for diminutive colon polyps (≤ 9 mm)

Exclusion criteria: (1) patients with polyps measuring ≥ 10mm in a previous colonoscopy; (2) patients unable to discontinue anticoagulants or antiplatelet therapy, according to the Japanese guidelines or who had an existing hemorrhagic diathesis; (3) history of inflammatory bowel disease; (4) history of familial adenomatous polyposis; (5) an apparently invasive colorectal cancer

N total at baseline: Intervention: 139 (367 polyps) Control: 134 (360 polyps)

Important prognostic factors2:

Mean age ± SD: I: 65.7 ± 8.8 C: 66.7 ± 8.8

Sex: I: 66.9% male C: 70.9% male

Groups were comparable at baseline. |

Cold snare polypectomy (CSP)

|

Hot snare polypectomy (HSP)

|

Length of follow-up: 1 month

Loss-to-follow-up: None

|

Intraprocedural bleeding I: 198/365 polyps (54.4%) C: 50/360 polyps (13.9%)

Postprocedural bleeding (≥ 24 hours after resection) I: 1/367 polyps (0.3%) C: 2/360 polyps (0.6%)

|

|

De Benito Sanz (2020) |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: Seven Spanish centers, including primary, secondary, and tertiary hospitals

Funding and conflicts of interest: Gerencia Regional de Salud, Junta de Castilla y Leon 1715/A/18; the authors declare that they have no conflict of interest. |

Inclusion criteria: Patients over the age of 18 years referred for colonoscopy for any indication (positive fecal occult blood test, postpolypectomy follow-up, CRC family history/other screening, previous CRC, or symptoms)

Exclusion criteria: - pregnancy - polypectomy contraindication owing to continuation of anticoagulant/antithrombotic agents (except aspirin) - uncorrected severe coagulopathy/thrombocytopenia

N total at baseline: Intervention: 237 patients Control: 259 patients

Important prognostic factors2:

Median age (IQR): I: 64.7 (56.7 to 70.5) C: 64.5 (57 to 70.7)

Sex: I: 64.7% male C: 66.0% male

Groups were comparable at baseline. |

Cold snare polypectomy (CSP)

|

Hot snare polypectomy (HSP)

|

Length of follow-up: 21–28 days after the colonoscopy

Loss-to-follow-up: 5 in intervention group and 3 in control group were excluded due to loss of polypectomy specimen |

Complete resection I: 358/387 polyps (92.5%%) C: 362/385 polyps (94.0%)

Intraprocedural bleeding I: 3/394 (0.8%) C: 7/397 (1.8%)

Postprocedural bleeding (≥ 24 hours after resection) I: 1/232 (0.43%) C: 1/256 (0.39%)

|

- Prognostic balance between treatment groups is usually guaranteed in randomized studies, but non-randomized (observational) studies require matching of patients between treatment groups (case-control studies) or multivariate adjustment for prognostic factors (confounders) (cohort studies); the evidence table should contain sufficient details on these procedures.

- Provide data per treatment group on the most important prognostic factors ((potential) confounders).

- For case-control studies, provide sufficient detail on the procedure used to match cases and controls.

- For cohort studies, provide sufficient detail on the (multivariate) analyses used to adjust for (potential) confounders.

Evidence table for systematic review of RCTs and observational studies (intervention studies)

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C) |

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

|

Qu, 2018

(Individual study characteristics deduced from Qu, 2018

PS., study characteristics and results are extracted from the SR (unless stated otherwise) |

SR and meta-analysis of RCTs

Literature search up to April 2018

A: Kawamura, 2017 B: Papastergiou, 2017 C: Suzuki, 2017 D: Gomez, 2015 E: Horiuchi, 2014 F: Ichise, 2011 G: Paspatis, 2011 H: Zhang, 2018

Study design: RCT

Setting and Country: A: Japan B: Greece C: Japan D: USA E: Japan F: Japan G: Greece H: China

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: - |

Inclusion criteria SR: RCTs that compared CSP and HSP for either or both the effectiveness or safety in the treatment of colorectal polyps sized ≤ 10 mm

Exclusion criteria SR: - only one arm - no CSP in one of the arms

Twelve studies were included, of which 8 full-text studies and 4 meeting abstracts

Important patient characteristics at baseline:

Sample size A: 578 patients B: 155 patients C: 52 patients D: Not reported E: 70 patients F: 80 patients G: 414 patients H: 358 patients

Sex: A: not reported B: 58.7% male C: 75% male D: not reported E: 70% male F: 66.3% male G: 56% male H: 55% male

Age: A: not reported B: I: 63.1 ± 10.3 C: 64.1 ± 10.9 C: I: 66.9 ± 7.7 C: 66.5 ± 9.8 D: not reported E: I: 67.0 ± 13 C: 67.3 ± 12 F: I: 65.1 ± 11 C: 65.5 ± 12 G: I: 59.4 ± 13.6 C: 61.3 ± 11 H: I: 65.1 ± 11 C: 65.5 ± 12 |

Describe intervention:

A: CSP B: CSP-EMR C: CSP D: CSP E: CSP F: CSP G: CSP H: CSP

|

Describe control:

A: HSP B: HSP-EMR C: HSP D: HSP E: HSP F: HSP G: HSP H: HSP

|

Within 30 days of the procedure

|

Complete resection rate Defined as a negative pathological margins (R0 resection) from the edge of the resected polyps or a negative biopsy from the polypectomy site.

A: I: 335/341 C: 337/346 B: I: 77/83 C: 78/81 C: I 17/22 C:24/26 D: I: 19/21 C: 17/18 E: I: 65/73 C: 67/75 F: I: 87/98 C: 85/100 G: - H: I: 194/212 C: 200/203

|

Risk of bias table for intervention studies (randomized controlled trials; based on Cochrane risk of bias tool and suggestions by the CLARITY Group at McMaster University)

|

Study reference

(first author, publication year) |

Was the allocation sequence adequately generated? a

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was the allocation adequately concealed?b

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Blinding: Was knowledge of the allocated interventions adequately prevented?c

Were patients blinded?

Were healthcare providers blinded?

Were data collectors blinded?

Were outcome assessors blinded?

Were data analysts blinded?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was loss to follow-up (missing outcome data) infrequent?d

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Are reports of the study free of selective outcome reporting?e

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was the study apparently free of other problems that could put it at a risk of bias?f

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Overall risk of bias If applicable/necessary, per outcome measureg

LOW Some concerns HIGH |

|

Aizawa (2019) |

Definitely yes;

Reason: Random allocation was performed using a computer-generated randomization sequence. |

Definitely yes;

Reason: Random allocation was performed using a computer-generated randomization sequence. |

Definitely no;

Reason: Just before colonoscopy, the allocation was made known to the operator and the patients. So, patients and health care providers were not blinded. |

Probably yes;

Reason: There was no loss-to-follow up; alle patients who were randomized were analysed. |

Definitely yes;

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported |

Definitely yes;

Reason: No other problems noted |

Some concerns |

|

De Benito Sanz (2020) |

Definitely yes;

Reason: Randomization using a computer-generated random sequence, stratified by institution. Each center received a unique set of completely opaque, sequentially numbered envelopes containing the assignments. |

Definitely yes;

Reason: Randomization using a computer-generated random sequence, stratified by institution. Each center received a unique set of completely opaque, sequentially numbered envelopes containing the assignments. |

Probably no;

Reason: Health care provider was not blinded. Outcome assessors (pathologist and interviewer) were blinded. It was not reported whether patients were blinded. |

Probably yes

Reason: Eight patients (5 in CSP group and 3 in HSP) were excluded owing to retrieval failure of at least one of their polypectomy specimens. In addition, 16 polypectomy samples showing normal colonic mucosa (5 CSP and 11 HSP) and 3 lesions whose marginal biopsy containers were lost (2 CSP and 1 HSP) were excluded from the resection rate analysis. |

Definitely yes

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported |

Definitely yes;

Reason: No other problems noted |

Some concerns |

- Randomization: generation of allocation sequences have to be unpredictable, for example computer generated random-numbers or drawing lots or envelopes. Examples of inadequate procedures are generation of allocation sequences by alternation, according to case record number, date of birth or date of admission.

- Allocation concealment: refers to the protection (blinding) of the randomization process. Concealment of allocation sequences is adequate if patients and enrolling investigators cannot foresee assignment, for example central randomization (performed at a site remote from trial location). Inadequate procedures are all procedures based on inadequate randomization procedures or open allocation schedules.

- Blinding: neither the patient nor the care provider (attending physician) knows which patient is getting the special treatment. Blinding is sometimes impossible, for example when comparing surgical with non-surgical treatments, but this should not affect the risk of bias judgement. Blinding of those assessing and collecting outcomes prevents that the knowledge of patient assignment influences the process of outcome assessment or data collection (detection or information bias). If a study has hard (objective) outcome measures, like death, blinding of outcome assessment is usually not necessary. If a study has “soft” (subjective) outcome measures, like the assessment of an X-ray, blinding of outcome assessment is necessary. Finally, data analysts should be blinded to patient assignment to prevents that knowledge of patient assignment influences data analysis.

- If the percentage of patients lost to follow-up or the percentage of missing outcome data is large, or differs between treatment groups, or the reasons for loss to follow-up or missing outcome data differ between treatment groups, bias is likely unless the proportion of missing outcomes compared with observed event risk is not enough to have an important impact on the intervention effect estimate or appropriate imputation methods have been used.

- Results of all predefined outcome measures should be reported; if the protocol is available (in publication or trial registry), then outcomes in the protocol and published report can be compared; if not, outcomes listed in the methods section of an article can be compared with those whose results are reported.

- Problems may include: a potential source of bias related to the specific study design used (e.g. lead-time bias or survivor bias); trial stopped early due to some data-dependent process (including formal stopping rules); relevant baseline imbalance between intervention groups; claims of fraudulent behavior; deviations from intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis; (the role of the) funding body. Note: The principles of an ITT analysis implies that (a) participants are kept in the intervention groups to which they were randomized, regardless of the intervention they actually received, (b) outcome data are measured on all participants, and (c) all randomized participants are included in the analysis.

- Overall judgement of risk of bias per study and per outcome measure, including predicted direction of bias (e.g. favors experimental, or favors comparator). Note: the decision to downgrade the certainty of the evidence for a particular outcome measure is taken based on the body of evidence, i.e. considering potential bias and its impact on the certainty of the evidence in all included studies reporting on the outcome.

Table of quality assessment for systematic reviews of RCTs and observational studies

Based on AMSTAR checklist (Shea, 2007; BMC Methodol 7: 10; doi:10.1186/1471-2288-7-10) and PRISMA checklist (Moher, 2009; PLoS Med 6: e1000097; doi:10.1371/journal.pmed1000097)

|

Study

First author, year |

Appropriate and clearly focused question?1

Yes/no/unclear |

Comprehensive and systematic literature search?2

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of included and excluded studies?3

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of relevant characteristics of included studies?4

Yes/no/unclear |

Appropriate adjustment for potential confounders in observational studies?5

Yes/no/unclear/notapplicable |

Assessment of scientific quality of included studies?6

Yes/no/unclear |

Enough similarities between studies to make combining them reasonable?7

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential risk of publication bias taken into account?8

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential conflicts of interest reported?9

Yes/no/unclear |

|

Qu 2019 |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

Not applicable |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Unclear |

- Research question (PICO) and inclusion criteria should be appropriate and predefined.

- Search period and strategy should be described; at least Medline searched; for pharmacological questions at least Medline + EMBASE searched.

- Potentially relevant studies that are excluded at final selection (after reading the full text) should be referenced with reasons.

- Characteristics of individual studies relevant to research question (PICO), including potential confounders, should be reported.

- Results should be adequately controlled for potential confounders by multivariate analysis (not applicable for RCTs).

- Quality of individual studies should be assessed using a quality scoring tool or checklist (Jadad score, Newcastle-Ottawa scale, risk of bias table et cetera).

- Clinical and statistical heterogeneity should be assessed; clinical: enough similarities in patient characteristics, intervention and definition of outcome measure to allow pooling? For pooled data: assessment of statistical heterogeneity using appropriate statistical tests (for example Chi-square, I2)?

- An assessment of publication bias should include a combination of graphical aids (for example funnel plot, other available tests) and/or statistical tests (for example Egger regression test, Hedges-Olken). Note: If no test values or funnel plot included score “no”. Score “yes” if mentions that publication bias could not be assessed because there were fewer than 10 included studies.

- Sources of support (including commercial co-authorship) should be reported in both the systematic review and the included studies. Note: To get a “yes,” source of funding or support must be indicated for the systematic review AND for each of the included studies.

Table of excluded studies

|

Author, year |

Reason for exclusion |

|

De Benito Sanz, 2020 |

Duplicate study |

|

Fujiya, 2016 |

Systematic review - search performed in only 1 database |

|

Horiuchi, 2014 |

Study already included in the systematic review |

|

Jegadeesan, 2019 |

Systematic review - similar to Qu (2018) |

|

Kawamura, 2018 |

Study already included in the systematic review |

|

Kawamura, 2020 |

Systematic review - similar to Qu (2018) |

|

Kim, 2015 |

No control group of interest (cold forceps polypectomy) |

|

Papastergiou, 2018 |

Study already included in the systematic review |

|

Shinozaki, 2018 |

Systematic review - similar to Qu (2018) |

|

Srinivasan, 2021 |

Polyps ≤5 mm |

|

Tranquillini, 2018 |

Systematic review - similar to Qu (2018) |

|

Zhang, 2018 |

Study already included in the systematic review |

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Laatst beoordeeld : 02-02-2022

Uiterlijk in 2026 bepaalt het bestuur van de NVMDL of de modules van deze richtlijn nog actueel zijn. Op modulair niveau is een onderhoudsplan beschreven. Bij het opstellen van de richtlijn heeft de werkgroep per module een inschatting gemaakt over de maximale termijn waarop herbeoordeling moet plaatsvinden en eventuele aandachtspunten geformuleerd die van belang zijn bij een toekomstige herziening (update). De geldigheid van de richtlijn komt eerder te vervallen indien nieuwe ontwikkelingen aanleiding zijn een herzieningstraject te starten.

De NVMDL is regiehouder van deze richtlijn en eerstverantwoordelijke op het gebied van de actualiteitsbeoordeling van de richtlijn. De andere aan deze richtlijn deelnemende wetenschappelijke verenigingen of gebruikers van de richtlijn delen de verantwoordelijkheid en informeren de regiehouder over relevante ontwikkelingen binnen hun vakgebied.

De voorliggende richtlijn betreft een herziening van de NVMDL richtlijn Endoscopische poliepectomie van het colon uit 2019. Alle modules zijn beoordeeld op actualiteit. Vervolgens is een prioritering aangebracht welke modules een daadwerkelijke update zouden moeten krijgen. Hieronder staan de modules genoemd met de wijzigingen. Tevens is per module een inschatting gemaakt voor de beoordeling voor herziening.

|

Uitgangsvraag/onderwerpen |

Wijzigingen richtlijn 2021 |

Uiterlijk jaar voor herziening |

|

Randvoorwaarden voor poliepectomie |

Minimale (tekstuele) aanpassingen |

2026 |

|

Minuscule poliepen ≤ 5 mm en poliepen tussen 10 en 20 mm |

Minimale (tekstuele) aanpassingen |

2026 |

|

Poliepen 6 – 9 mm |

Gereviseerd |

2026 |

|

Sessiele en vlakke poliepen > 20 mm |

Gereviseerd |

2026 |

|

Herkenning van een potentieel maligne poliep |

Gereviseerd |

2026 |

|

Verwijdering van een potentieel maligne poliep |

Wordt behandeld in de CRC richtlijn |

- |

|

Behandeling en preventie van complicaties |

Minimale (tekstuele) aanpassingen |

2026 |

|

Preventief dichtclippen van wondvlak |

Nieuw ontwikkeld |

2026 |

|

Lokaal recidief na poliepectomie |

Gereviseerd |

2026 |

|

Behandeling van lokaal recidief |

Nieuw ontwikkeld |

2026 |

|

Pathologie: biopteren |

Nieuw ontwikkeld |

2026 |

|

Pathologie: weefselverwerking |

Minimale (tekstuele) aanpassingen |

2026 |

|

Prestatie indicatoren |

Minimale (tekstuele) aanpassingen |

2026 |

Belangrijkste wijzigingen ten opzichte van vorige versie

In de gereviseerde modules is de literatuur opnieuw systematisch gezocht en/of is de literatuursamenvatting aangepast. De strekking van de aanbevelingen is nagenoeg hetzelfde gebleven. Tevens zijn er drie nieuwe modules aan de richtlijn toegevoegd. De overige modules zijn opnieuw beoordeeld waarbij er minimale (tekstuele) aanpassingen gedaan. De module 'Verwijderen van een potentieel maligne poliep' is teruggetrokken. Dit onderwerp komt terug in de richtlijn Colorectaal carcinoom.

Algemene gegevens

De ontwikkeling en herziening van deze richtlijnmodules werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten en werd gefinancierd uit de Stichting Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS). De financier heeft geen enkele invloed gehad op de inhoud van de richtlijn.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijnmodule is in het voorjaar van 2021 een multidisciplinaire werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen die direct betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor patiënten met poliepen in het rectum en colon.

Werkgroep

- Dr. L.M.G. (Leon) Moons (voorzitter), MDL-arts UMC Utrecht, Nederlandse Vereniging van Maag-Darm-Leverartsen

- Dr. T. (Tom) Seerden (vice-voorzitter), MDL-arts Amphia Breda, Nederlandse Vereniging van Maag-Darm-Leverartsen

- B.A.J. (Barbara) Bastiaansen, MDL-arts Amsterdam UMC, Nederlandse Vereniging van Maag-Darm-Leverartsen

- Dr. J.J. (Jurjen) Boonstra, MDL-arts, LUMC Leiden, Nederlandse Vereniging van Maag-Darm-Leverartsen

- Dr. A.D. (Arjun) Koch, MDL-arts, Erasmus MC Rotterdam, Nederlandse Vereniging van Maag-Darm-Leverartsen

- Dr. B.W.M. (Marcel) Spanier, MDL-arts, Rijnstate ziekenhuis, Nederlandse Vereniging van Maag-Darm-Leverartsen

- Dr. Y. (Yara) Backes, MDL-arts i.o., Meander Medisch Centrum Amersfoort, Nederlandse Vereniging van Maag-Darm-Leverartsen

- Dr. L. (Lindsey) Oudijk, patholoog Erasmus MC Rotterdam, Nederlandse Vereniging voor Pathologie

- Dr. M.M. (Miangela) Laclé, patholoog UMC Utrecht, Nederlandse Vereniging voor Pathologie

- C. (Christiaan) Hoff, chirurg Medisch Centrum Leeuwarden, Nederlandse Vereniging voor Heelkunde

- R. (Ruud) Blankenburgh, Internist-Oncoloog Saxenburgh Hardenberg, Nederlandse Internisten Vereniging

Klankbordgroep

- J.J. (Jan) Meeuse, NIV

- S. (Silvie) Dronkers, Stichting Darmkanker

- J. (Jannie) Verheij - van der Wiel, Stomavereniging

- J.H.M.A. (Ans) Dietvorst, Stichting Lynch Polyposis

Met ondersteuning van

- Dr. A.N. (Anh Nhi) Nguyen, adviseur Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- Dr. E.V. (Ekaterina) van Dorp-Baranova, adviseur Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

Belangenverklaringen

De Code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling is gevolgd. Alle werkgroepleden hebben schriftelijk verklaard of zij in de laatste drie jaar directe financiële belangen (betrekking bij een commercieel bedrijf, persoonlijke financiële belangen, onderzoeksfinanciering) of indirecte belangen (persoonlijke relaties, reputatiemanagement) hebben gehad. Gedurende de ontwikkeling of herziening van een module worden wijzigingen in belangen aan de voorzitter doorgegeven. De belangenverklaring wordt opnieuw bevestigd tijdens de commentaarfase.

Een overzicht van de belangen van werkgroepleden en het oordeel over het omgaan met eventuele belangen vindt u in onderstaande tabel. De ondertekende belangenverklaringen zijn op te vragen bij het secretariaat van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

|

Werkgroeplid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Restrictie (zie ook tekst onder de tabel) |

|

Moons (voorzitter) |

MDL-arts, interventie endoscopist, UMC Utrecht, Utrecht, Nederland |

Geen |

Consultant Boston Scientific |

Geen |

|

Seerden (vice-voorzitter) |

MDL arts, Medisch specialistisch bedrijf Amphia te Breda |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Bastiaansen |

MDL-arts Amsterdam UMC |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Boonstra |

MDL-arts, LUMC, Leiden |

Geen |

Consultant Boston Scientific |

Geen |

|

Koch |

MDL-arts, Erasmus MC, Universitair Medisch Centrum Rotterdam |

Geen |

Consultant Boston Scientific. Pentax Medical, ERBE Elektromedizin, DrFalk Pharma |

Geen |

|

Spanier |

Als vrijgevestigd MDL-arts in dienst bij Cooperatie Medisch Specialisten Rijnstate u.a. (CMSR) |

Bestuurslid CMSR, 4 dagdelen, betaald, vergoeding naar vakgroep MDL Rijnstate |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Backes |

aios MDL, Meander Medisch Centrum Amersfoort |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Oudijk |

Patholoog, Erasmus MC Rotterdam |

PPM patholoog Palga: Motiveren gebruik PALGA protocollen, contactpersoon voor PALGA rapportage gebruik protocollen, mede-pathologen en MDO-leden, clinici. Onbetaald. Lid wetenschappelijke commissie Dutch Thyroid Cancer Group: onbetaald. Lid wetenschappelijke adviescommissie Stichting Bijniernetwerk Nederland: onbetaald |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Laclé |

Patholoog UMC Utrecht |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Hoff |

Chirurg Medisch Centrum Leeuwarden (via Heelkunde Friesland Groep) (0,6) medisch cobestuurder MCL 0,4) |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Blankenburgh |

Internist-Oncoloog, Saxenburgh te Hardenberg |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

Het Kennisinstituut in zijn rol als methodologisch ondersteuner, de NVMDL als initiërende vereniging en de richtlijnwerkgroep zijn zich bewust van de belangen die spelen binnen de richtlijnwerkgroep, maar het werd toch noodzakelijk geacht om de betreffende inhoudelijk experts op dit gebied bij de richtlijn te betrekken. Tijdens de commentaarfase werd de NVMDL verzocht om bij het aanleveren van commentaar kritisch te zijn op de gemelde belangen en geformuleerde aanbevelingen en onderbouwing en om experts, vrij van belangen, expliciet te verzoeken om de richtlijn te beoordelen.

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Er werd aandacht besteed aan het patiëntenperspectief door afgevaardigden vanuit patiëntenverenigingen in de klankbordgroep met de conceptrichtlijn mee te laten lezen. De commentaren zijn besproken in de werkgroep en verwerkt. De conceptrichtlijn is tevens voor commentaar voorgelegd aan de Patiëntenfederatie Nederland, Stichting Darmkanker, Stomavereniging en Stichting Lynch Polyposis.

Methode ontwikkeling

Evidence based

Implementatie

In de verschillende fasen van de richtlijnontwikkeling is rekening gehouden met de implementatie van de richtlijnmodules en de praktische uitvoerbaarheid van de aanbevelingen. Daarbij is uitdrukkelijk gelet op factoren die de invoering van de richtlijn in de praktijk kunnen bevorderen of belemmeren. Het implementatieplan is te vinden in de bijlagen. De werkgroep heeft ook interne kwaliteitsindicatoren ontwikkeld.

Werkwijze

AGREE

Deze richtlijnmodule is opgesteld conform de eisen vermeld in het rapport Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 van de adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwaliteit. Dit rapport is gebaseerd op het AGREE II instrument (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II; Brouwers, 2010).

Knelpuntenanalyse en uitgangsvragen

Tijdens de voorbereidende fase inventariseerde de werkgroep de knelpunten. De werkgroep beoordeelde de aanbeveling(en) uit de eerdere richtlijn (Nederlandse Vereniging van Maag-Darm-Leverartsen, 2019) op noodzaak tot revisie. Op basis van de geprioriteerde knelpunten zijn door de werkgroep concept-uitgangsvragen opgesteld en definitief vastgesteld.

Uitkomstmaten

Na het opstellen van de zoekvraag behorende bij de uitgangsvraag inventariseerde de werkgroep welke uitkomstmaten voor de patiënt relevant zijn, waarbij zowel naar gewenste als ongewenste effecten werd gekeken. Hierbij werd een maximum van acht uitkomstmaten gehanteerd. De werkgroep waardeerde deze uitkomstmaten volgens hun relatieve belang bij de besluitvorming rondom aanbevelingen, als cruciaal (kritiek voor de besluitvorming), belangrijk (maar niet cruciaal) en onbelangrijk. Tevens definieerde de werkgroep tenminste voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten welke verschillen zij klinisch (patiënt) relevant vonden.

Methode literatuursamenvatting

Een uitgebreide beschrijving van de strategie voor zoeken en selecteren van literatuur en de beoordeling van de risk-of-bias van de individuele studies is te vinden onder ‘Zoeken en selecteren’ onder Onderbouwing. De beoordeling van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs wordt hieronder toegelicht.

Beoordelen van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs

De kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs werd bepaald volgens de GRADE-methode. GRADE staat voor ‘Grading Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation’ (zie http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/). De basisprincipes van de GRADE-methodiek zijn: het benoemen en prioriteren van de klinisch (patiënt) relevante uitkomstmaten, een systematische review per uitkomstmaat, en een beoordeling van de bewijskracht per uitkomstmaat op basis van de acht GRADE-domeinen (domeinen voor downgraden: risk of bias, inconsistentie, indirectheid, imprecisie, en publicatiebias; domeinen voor upgraden: dosis-effect relatie, groot effect, en residuele plausibele confounding).

GRADE onderscheidt vier gradaties voor de kwaliteit van het wetenschappelijk bewijs: hoog, redelijk, laag en zeer laag. Deze gradaties verwijzen naar de mate van zekerheid die er bestaat over de literatuurconclusie, in het bijzonder de mate van zekerheid dat de literatuurconclusie de aanbeveling adequaat ondersteunt (Schünemann, 2013; Hultcrantz, 2017).

|

GRADE |

Definitie |

|

Hoog |

|

|

Redelijk |

|

|

Laag |

|

|

Zeer laag |

|

Bij het beoordelen (graderen) van de kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs in richtlijnen volgens de GRADE-methodiek spelen grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming een belangrijke rol (Hultcrantz, 2017). Dit zijn de grenzen die bij overschrijding aanleiding zouden geven tot een aanpassing van de aanbeveling. Om de grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming te bepalen moeten alle relevante uitkomstmaten en overwegingen worden meegewogen. De grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming zijn daarmee niet één op één vergelijkbaar met het minimaal klinisch relevant verschil (Minimal Clinically Important Difference, MCID). Met name in situaties waarin een interventie geen belangrijke nadelen heeft en de kosten relatief laag zijn, kan de grens voor klinische besluitvorming met betrekking tot de effectiviteit van de interventie bij een lagere waarde (dichter bij het nuleffect) liggen dan de MCID (Hultcrantz, 2017).

Overwegingen (van bewijs naar aanbeveling)

Om te komen tot een aanbeveling zijn naast (de kwaliteit van) het wetenschappelijke bewijs ook andere aspecten belangrijk en worden meegewogen, zoals aanvullende argumenten uit bijvoorbeeld de biomechanica of fysiologie, waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten, kosten (middelenbeslag), aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie. Deze aspecten zijn systematisch vermeld en beoordeeld (gewogen) onder het kopje ‘Overwegingen’ en kunnen (mede) gebaseerd zijn op expert opinion. Hierbij is gebruik gemaakt van een gestructureerd format gebaseerd op het evidence-to-decision framework van de internationale GRADE Working Group (Alonso-Coello, 2016a; Alonso-Coello, 2016b). Dit evidence-to-decision framework is een integraal onderdeel van de GRADE-methodiek.

Formuleren van aanbevelingen

De aanbevelingen geven antwoord op de uitgangsvraag en zijn gebaseerd op het beschikbare wetenschappelijke bewijs en de belangrijkste overwegingen, en een weging van de gunstige en ongunstige effecten van de relevante interventies. De kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs en het gewicht dat door de werkgroep wordt toegekend aan de overwegingen, bepalen samen de sterkte van de aanbeveling. Conform de GRADE-methodiek sluit een lage bewijskracht van conclusies in de systematische literatuuranalyse een sterke aanbeveling niet a priori uit, en zijn bij een hoge bewijskracht ook zwakke aanbevelingen mogelijk (Agoritsas, 2017; Neumann, 2016). De sterkte van de aanbeveling wordt altijd bepaald door weging van alle relevante argumenten tezamen. De werkgroep heeft bij elke aanbeveling opgenomen hoe zij tot de richting en sterkte van de aanbeveling zijn gekomen.

In de GRADE-methodiek wordt onderscheid gemaakt tussen sterke en zwakke (of conditionele) aanbevelingen. De sterkte van een aanbeveling verwijst naar de mate van zekerheid dat de voordelen van de interventie opwegen tegen de nadelen (of vice versa), gezien over het hele spectrum van patiënten waarvoor de aanbeveling is bedoeld. De sterkte van een aanbeveling heeft duidelijke implicaties voor patiënten, behandelaars en beleidsmakers (zie onderstaande tabel). Een aanbeveling is geen dictaat, zelfs een sterke aanbeveling gebaseerd op bewijs van hoge kwaliteit (GRADE gradering HOOG) zal niet altijd van toepassing zijn, onder alle mogelijke omstandigheden en voor elke individuele patiënt.

|

Implicaties van sterke en zwakke aanbevelingen voor verschillende richtlijngebruikers |

||

|

|

Sterke aanbeveling |

Zwakke (conditionele) aanbeveling |

|

Voor patiënten |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen en slechts een klein aantal niet. |

Een aanzienlijk deel van de patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen, maar veel patiënten ook niet. |

|

Voor behandelaars |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak moeten ontvangen. |

Er zijn meerdere geschikte interventies of aanpakken. De patiënt moet worden ondersteund bij de keuze voor de interventie of aanpak die het beste aansluit bij zijn of haar waarden en voorkeuren. |

|

Voor beleidsmakers |

De aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kan worden gezien als standaardbeleid. |

Beleidsbepaling vereist uitvoerige discussie met betrokkenheid van veel stakeholders. Er is een grotere kans op lokale beleidsverschillen. |

Organisatie van zorg

Randvoorwaarden die relevant zijn voor het beantwoorden van deze specifieke uitgangsvraag zijn genoemd bij de overwegingen. Meer algemene, overkoepelende, en bijkomende aspecten van de organisatie van zorg worden behandeld in de module Randvoorwaarden.

Commentaar- en autorisatiefase

De conceptrichtlijnmodule werd aan de betrokken (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd ter commentaar. De commentaren werden verzameld en besproken met de werkgroep. Naar aanleiding van de commentaren werd de conceptrichtlijn aangepast en definitief vastgesteld door de werkgroep. De definitieve richtlijn werd aan de deelnemende (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd voor autorisatie en door hen geautoriseerd dan wel geaccordeerd.

Literatuur

Agoritsas T, Merglen A, Heen AF, Kristiansen A, Neumann I, Brito JP, Brignardello-Petersen R, Alexander PE, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Guyatt GH. UpToDate adherence to GRADE criteria for strong recommendations: an analytical survey. BMJ Open. 2017 Nov 16;7(11):e018593. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018593. PubMed PMID: 29150475; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5701989.

Alonso-Coello P, Schünemann HJ, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Rada G, Rosenbaum S, Morelli A, Guyatt GH, Oxman AD; GRADE Working Group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 1: Introduction. BMJ. 2016 Jun 28;353:i2016. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2016. PubMed PMID: 27353417.

Alonso-Coello P, Oxman AD, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Vandvik PO, Meerpohl J, Guyatt GH, Schünemann HJ; GRADE Working Group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 2: Clinical practice guidelines. BMJ. 2016 Jun 30;353:i2089. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2089. PubMed PMID: 27365494.

Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, Burgers JS, Cluzeau F, Feder G, Fervers B, Graham ID, Grimshaw J, Hanna SE, Littlejohns P, Makarski J, Zitzelsberger L; AGREE Next Steps Consortium. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. CMAJ. 2010 Dec 14;182(18):E839-42. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090449. Epub 2010 Jul 5. Review. PubMed PMID: 20603348; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3001530.

Hultcrantz M, Rind D, Akl EA, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Iorio A, Alper BS, Meerpohl JJ, Murad MH, Ansari MT, Katikireddi SV, Östlund P, Tranæus S, Christensen R, Gartlehner G, Brozek J, Izcovich A, Schünemann H, Guyatt G. The GRADE Working Group clarifies the construct of certainty of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017 Jul;87:4-13. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.05.006. Epub 2017 May 18. PubMed PMID: 28529184; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC6542664.

Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 (2012). Adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwalitieit. https://richtlijnendatabase.nl/over_deze_site/richtlijnontwikkeling.html.

Neumann I, Santesso N, Akl EA, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Alonso-Coello P, Agoritsas T, Mustafa RA, Alexander PE, Schünemann H, Guyatt GH. A guide for health professionals to interpret and use recommendations in guidelines developed with the GRADE approach. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016 Apr;72:45-55. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.11.017. Epub 2016 Jan 6. Review. PubMed PMID: 26772609.

Schünemann H, Brożek J, Guyatt G, et al. GRADE handbook for grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. Updated October 2013. The GRADE Working Group, 2013. Available from http://gdt.guidelinedevelopment.org/central_prod/_design/client/handbook/handbook.html

Zoekverantwoording

Zoekacties zijn opvraagbaar. Neem hiervoor contact op met de Richtlijnendatabase.