Screening en diagnostiek PDNP

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is de optimale methode voor het screenen op, en vaststellen van neuropathische pijn bij volwassen personen met diabetes mellitus?

- Wat is de plaats van gestructureerde vragenlijsten bij het screenen op, en vaststellen van neuropathische pijn bij volwassen personen met diabetes mellitus?

- Wat is de plaats van anamnese en lichamelijk onderzoek (inclusief bedside testen) bij het stellen van de diagnose polyneuropathie bij volwassen personen met diabetes mellitus die positief screenen voor neuropathische pijn?

Aanbeveling

Bij personen met diabetes in het kader van de jaarlijkse controle, of tussentijds:

- Vraag de persoon of er sprake is van pijn aan de voeten en/of handen.

- Als er sprake is van pijn, verricht de DN4; een score van 4 of hoger betekent waarschijnlijk neuropathische pijn.

- Controleer op de aanwezigheid van alarmsymptomen die niet passen bij een geleidelijk progressieve sensibele of sensomotorische distale, symmetrische polyneuropathie of dunne vezel neuropathie: acuut begin, asymmetrie, een voornamelijk proximale aandoening, overwegend motorische klachten, of snelle progressie of veel pijn.

- Bespreek bij aanwezigheid van neuropathische pijn het mogelijke belang van goede diabetes regulatie en de mogelijkheid van symptomatische therapie.

Start bij stap 2 als een persoon met diabetes mellitus bij de jaarlijkse controle of tussentijds zelf aangeeft pijn te hebben aan de voeten en/of handen.

Nederlandse versie van DN4: www.neuropathie.nu/download/Vragenlijsten/DN4.pdf

Verwijs een persoon met diabetes mellitus met alarmsymptomen door naar een neuroloog voor nader onderzoek.

Overweeg bij pijnklachten en een DN4 score van minder dan 4 een andere oorzaak voor de pijn, bijvoorbeeld vasculair, arthrogeen, medicamenteus.

Overwegingen

De werkgroep heeft de toegevoegde waarde van het gebruik van gestructureerde vragenlijsten als hulpmiddel geëvalueerd bij het screenen op pijnlijke diabetische neuropathie bij volwassen personen met diabetes.

Geconstateerd kan worden dat de meeste gestructureerde vragenlijsten (waarbij soms ook gericht lichamelijk onderzoek onderdeel van het screeningsinstrument is) slecht onderzocht en gevalideerd zijn, zeker in de Nederlandse situatie. De enige goed onderzochte vragenlijst die ook in de Nederlandse vertaling geëvalueerd is met voldoende sensitiviteit (74%) en specificiteit (79%) voor de aan- of afwezigheid van neuropathische pijn is de DN4. De Nederlandse versie is niet specifiek onderzocht bij mensen met diabetes. De Italiaanse versie toont bij diabetespatiënten een sensitiviteit van 80 en een specificiteit van 92%. Nadeel is dat de reproduceerbaarheid in de diabetes populatie niet is onderzocht. De DN4 is in de originele taal (Frans) echter wel goed onderzocht bij patiënten met neuropathische pijn op reproduceerbaarheid, en betrouwbaar gebleken (Bouhassira, 2005). De DN4 bestaat uit een aantal gestandaardiseerde vragen, aangevuld met enkele delen van het lichamelijk onderzoek.

Vanuit het perspectief van de patiënt en van de professional lijkt de DN4 ook een aantrekkelijke keuze: het betreft een beperkt aantal redelijk eenduidige vragen die snel beantwoord kunnen worden. Er is een eenvoudig score-systeem waardoor snel een eindoordeel volgt. De test kan bij de jaarlijkse screening worden uitgevoerd, en worden vergeleken met de uitkomst van eerdere testen. De DN4 kan worden uitgevoerd door diabetesverpleegkundigen, praktijkondersteuners en medisch pedicures. Hiermee lijkt de DN4 ondanks de eerder aangegeven beperkingen de test van keuze bij de jaarlijkse algemene screening als bij patiënten die tussentijds onder de aandacht komen. Het uiteindelijke advies om de DN4 te gebruiken komt daarmee overeen met de NHG-Standaard Diabetes mellitus type 2 (derde herziening; NHG, 2013) en de NHG-Standaard Pijn (NHG, 2015). In de richtlijn polyneuropathie van 2005 van de NVN (NVN, 2005) wordt het gebruik van de DN4 niet genoemd, maar de meeste literatuur hierover is van recentere datum. De werkgroep is van mening dat bij pijn en een negatieve DN4 aan een andere oorzaak moet worden gedacht voor de pijn, bijvoorbeeld vasculair, arthrogeen of medicamenteus.

DN4-vragenlijst (Douleur Neuropathique)

De DN4-vragenlijst (Douleur Neuropathique) bestaat uit vier vragen en tien items die met Ja of Nee beantwoord worden. Bij vier of meer positieve antwoorden is (een bijdrage van) neuropathische pijn waarschijnlijk.

Tabel 1 DN4-screeningsvragenlijst

|

DN4 |

|

|

Heeft de pijn één of meerdere van de volgende kenmerken: |

|

|

Branderig |

꙱ Ja ꙱ Nee |

|

Pijnlijk koude gevoel |

꙱ Ja ꙱ Nee |

|

Elektrische schokken |

꙱ Ja ꙱ Nee |

|

Gaat de pijn gepaard met één of meerdere van de volgende symptomen in hetzelfde gebied? |

|

|

Tintelingen |

꙱ Ja ꙱ Nee |

|

Prikkelingen |

꙱ Ja ꙱ Nee |

|

Doofheid |

꙱ Ja ꙱ Nee |

|

Jeuk |

꙱ Ja ꙱ Nee |

|

Is er in het pijngebied t.o.v. een normaal aanvoelend gebied een verminderd gevoel bij: |

|

|

Aanraking |

꙱ Ja ꙱ Nee |

|

Prikken (cocktailprikker) |

꙱ Ja ꙱ Nee |

|

Wordt de pijn verergerd door: |

|

|

Wrijven |

꙱ Ja ꙱ Nee |

Indien een vraag met ‘ja’ wordt beantwoord, wordt 1 punt toegekend. Bij score ≥ 4 punten is neuropathische pijn waarschijnlijk.

Er zijn geen diagnostische accuratessestudies beschikbaar van screeningsinstrumenten voor diabetische polyneuropathie (aanvullende anamnese, lichamelijk onderzoek, eenvoudige bedside testen) waarin een betrouwbare referentietest werd gebruikt bij mensen met diabetes mellitus die positief screenen voor neuropathische pijn. Wel zijn er verschillende gestandaardiseerde anamnese-vragen, al dan niet in combinatie met lichamelijk onderzoek, en bedside testen die de diagnose polyneuropathie of dunne vezel neuropathie kunnen ondersteunen. Helaas is van deze onderzoeken de bewijskracht zeer laag, wanneer wordt getracht bovenstaande specifieke vraag te beantwoorden, tot maximaal laag, wanneer alleen het vaststellen van een polyneuropathie als vraag wordt genomen. Een aantal testen lijken dan een redelijk goede sensitiviteit te hebben, maar de specificiteit is vaak veel minder goed. Voor een screeningsinstrument kunnen dit op zich goede testkarakteristieken zijn, maar gezien de relatief hoge sensitiviteit en specificiteit die al wordt behaald met de DN4 voor het vaststellen van neuropathische pijn, is het zeer de vraag of extra testen wat zullen toevoegen, maar dit is niet formeel onderzocht.

Wanneer alleen het vaststellen van een polyneuropathie of een dunne vezel neuropathie het doel is bij mensen met diabetes mellitus, dan lijken een aantal testen in aanmerking te kunnen komen. Voor het vaststellen van een polyneuropathie kan voor de dikke vezel component de vibratieperceptie worden bepaald. Verschillende methodes zijn hiervoor beschikbaar. Het gebruik van een stemvork lijkt de meest eenvoudige methode. Een groot onderzoek bij mensen met diabetes mellitus toont dat een gegradeerde stemvork van 128 Hz een redelijke sensitiviteit en specificiteit heeft (Kästenbauer, 2004). In Nederland wordt echter bij andere polyneuropathieën steeds meer gebruik gemaakt van de 64 Hz gegradeerde Rydel-Seiffer stemvork (Martina, 1998). Hiervan zijn goede leeftijdsafhankelijke normaalwaardes beschikbaar, maar deze stemvork is alleen onderzocht in een gemengde polyneuropathie populatie, waarbij een deel met diabetes mellitus type 2. Hoewel niet formeel onderzocht, lijkt dit ook een relatief goedkope methode. Indien bij een patiënt met een PDNP een stoornis van dikke zenuwvezels aangetoond kan worden is separaat onderzoek naar dunne zenuwvezels niet meer nodig.

Indien een stoornis van dikke zenuwvezels niet aangetoond kan worden, lijkt de Neuropad (een teststrip die verkleurt als reactie op zweet, niet verkleuren duidt op sudomotore disfunctie en daarmee op neuropathie) als eenvoudige test een voldoende sensitiviteit te hebben voor het beoordelen van de dunne vezel component, echter de specificiteit lijkt lager. Daarnaast is er sprake van grote en onverklaarbare heterogeniteit in testkarakteristieken tussen individuele diagnostische accuratessestudies. Verder onderzoek is nodig voordat de neuropad kan worden aanbevolen. Er is geen kosteneffectiviteitsanalyse beschikbaar.

Hoewel het dus op grond van het beschikbare onderzoek lastig is de diagnose polyneuropathie geformaliseerd definitief te stellen, is het van belang dat het beeld past bij de meest voorkomende distale vooral sensibele polyneuropathie, met aan benen meer klachten dan aan armen. Bij een acuut begin, asymmetrie, een voornamelijk proximale aandoening, overwegend motorische klachten, of snelle progressie of veel pijn (alarmsymptomen) past het beeld hier dus niet bij, en is verwijzing naar een neuroloog voor aanvullend onderzoek noodzakelijk. Ook kan dit zinvol zijn als er behoefte is aan aanvullende therapieadviezen.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

In Nederland zijn er in 2015 naar schatting 930.000 mensen met gediagnosticeerde diabetes mellitus (VTV, 2014). De medische zorg voor mensen met diabetes mellitus wordt voor het grootste deel verzorgd door de eerste lijn (huisarts, praktijkondersteuner (POH), specialist ouderengeneeskunde) en tweede lijn (internist, diabetesverpleegkundige(DVK)). In de eerste lijn wordt de meerderheid van de type 2 diabetespatiënten gezien, in de tweede lijn de mensen met diabetes mellitus type 1, zeldzame vormen van diabetes, en patiënten met gecompliceerde type 2 diabetes. Tijdens de jaarlijkse controle door de huisarts, internist, POH en/of DVK worden cardiovasculaire risicofactoren in kaart gebracht en wordt nagegaan of er complicaties zijn opgetreden. Diabetische polyneuropathie is een van de meest voorkomende complicaties van diabetes en komt in populatiestudies bij 30 tot 90% van alle volwassen mensen met diabetes voor. De kans op een pijnlijke diabetische polyneuropathie neemt toe met het aantal jaren dat de patiënt diabetes mellitus heeft, met een slechte glykemische controle (hoog HbA1c) en met de aanwezigheid van andere systemische afwijkingen (nefro- en retinopathie). 16 tot 34% van de mensen met diabetes mellitus heeft een pijnlijke diabetische neuropathie (Javed, 2015).

Het is wenselijk tijdig met meer zekerheid de diagnose PDNP vast te kunnen stellen, zowel om lichamelijke klachten van de patiënt te kunnen verklaren, als om een behandeling te kunnen starten. Optimalisatie van de diabetesregulatie lijkt een eerste logische stap. Bij DM1 is aangetoond dat verbetering van glucoseregulatie en daling van het HbA1c door intensieve insulinebehandeling neuropathie voorkomt; bij DM2 is hiervoor onvoldoende bewijs (Fullerton, 2014; Hemmingsen, 2013 en 2015; UKPDS, 1998; DCCT, 1995). Optimale glucoseregulatie verlaagt de kans op neuropathie en bij patiënten met PDNP kan optimale glucoseregulatie de klachten mogelijk verminderen. In deze langdurige follow-up studies is echter niet apart gekeken naar de vermindering van neuropathische pijn. Een kleinere studie met zowel DM1 als DM2 patiënten geeft hiervoor wel ondersteuning (Archer, 1983). De patiënten hadden allemaal een snelle en ernstige gewichtsreductie met daarbij een gestoorde diabetesregulatie, waarbij na herstel hiervan de neuropathische klachten verbeterden. Naast optimalisatie van de diabetesregulatie kan medicamenteuze of niet-medicamenteuze symptomatische therapie worden overwogen.

Om de optimale methode vast te stellen om neuropathische pijn bij volwassen personen met diabetes mellitus vast te stellen, is besloten twee deelvragen te formuleren.

De eerste deelvraag is om te onderzoeken of er betrouwbare, gevalideerde en voor de dagelijkse praktijk bruikbare gestructureerde vragenlijsten bestaan voor het vaststellen van neuropathische pijn bij volwassen personen met diabetes mellitus die door de zorgverleners kunnen worden gehanteerd bij de jaarcontrole of tussentijds, wanneer patiënten zich melden met klachten die bij neuropathische pijn kunnen passen.

De tweede (vervolg) deelvraag is of bij volwassen personen met diabetes mellitus die bij een vragenlijst positief screenen voor neuropathische pijn bij (aanvullende) anamnese, lichamelijk onderzoek en eenvoudige bedside testen de diagnose distale symmetrische pijnlijke polyneuropathie kan worden gesteld. De voorkeur gaat dan uit naar gestandaardiseerde vragen in de anamnese en gestandaardiseerde testen bij het lichamelijk onderzoek, eenvoudige bedside testen, of combinaties hiervan. Een groot aantal vragenlijsten, testen bij het lichamelijk onderzoek en eenvoudige bedside testen is beschikbaar, maar het is noodzakelijk hierin op grond van sensitiviteit en specificiteit de beste keuze te maken. Van belang is dat het gaat om het vaststellen van de meest voorkomende vormen van diabetische polyneuropathie, gekarakteriseerd door een langzaam progressieve, symmetrische, distale, sensibele of sensomotorische zenuwuitval.

Doel van de uitgangsvraag is om te onderzoeken of er betrouwbare, gevalideerde en voor de dagelijkse praktijk bruikbare vragenlijsten, gestandaardiseerde anamnesevragen, kenmerken bij het lichamelijk onderzoek en bedside testen zijn, voor het vaststellen van de diagnose pijnlijke diabetische polyneuropathie. Alle testen moeten geschikt zijn om te worden afgenomen in zowel de eerste als de tweede lijn, zowel af te nemen bij de jaarlijkse algemene screening als bij patiënten die tussentijds onder de aandacht komen.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

1. Wat is de plaats van vragenlijsten bij het screenen op, en vaststellen van neuropathische pijn bij volwassen personen met diabetes mellitus?

|

Zeer laag GRADE |

De originele versies van de DN4 (Franse taal), S-LANSS (Engels), PainDETECT (Duits) en NPQ (Engels) lijken een voldoende sensitiviteit (≥70%) te hebben bij het vaststellen van neuropathische pijn.

De originele versies van de DN4 (Frans), LANSS (Engels), S-LANSS (Engels), PainDETECT (Duits), NPQ (Engels), en NPQ-SF (Engels) lijken een voldoende specificiteit (≥70%) te hebben bij het vaststellen van neuropathische pijn.

De originele versies van DN4 (Franse taal), S-LANSS (Engels), PainDETECT (Duits), en NPQ (Engels) lijken zowel een voldoende sensitiviteit als specificiteit (≥70%) te hebben bij het vaststellen van neuropathische pijn.

Van de originele versies van de screeningsinstrumenten, lijken de DN4 (Frans) en ID Pain (Engels) een voldoende betrouwbaarheid (reproduceerbaarheid) te hebben.

Bij patiënten met chronische pijn (tenminste drie maanden): algemene en specifieke pijncondities (neuropathische pijn, nociceptieve pijn, gemengde pijn).

Van de patiënten met de klinische diagnose neuropathische pijn wordt 10-20 procent niet gedetecteerd (fout-negatief).

Het bepalen van de optimale screeningsvragenlijst wordt bemoeilijkt door een relatief gebrek aan direct vergelijkend onderzoek, onderzoek waarin de verschillende screeningsinstrumenten worden vergeleken in dezelfde studiepopulatie.

Bronnen (Mathieson, 2015) |

|

Zeer laag GRADE |

DN4 en PainDETECT zijn beschikbaar in de Nederlandse taal.

De Nederlandse versie van de DN4 is gevalideerd bij patiënten met chronische pijn en lijkt een voldoende sensitiviteit (74%) en specificiteit (79%) te hebben, maar een onvoldoende betrouwbaarheid (reproduceerbaarheid).

De Testaccuratesse en betrouwbaarheid van de Nederlandse versie van PainDETECT zijn onbekend.

Er zijn geen screeningsinstrumenten in de Nederlandse taal die zijn gevalideerd bij mensen met diabetes.

Bronnen (Mathieson, 2015) |

|

Zeer laag GRADE |

De DN4 is het enige screeningsinstrument dat is gevalideerd bij mensen met diabetes (studiepopulatie bestaande uit patiënten met en zonder pijn): de Italiaanse versie van de DN4 lijkt een voldoende sensitiviteit (80%) en specificiteit (92%) te hebben. De betrouwbaarheid (reproduceerbaarheid) is niet onderzocht.

Er zijn geen studies die de testaccuratesse of betrouwbaarheid van verschillende screeningsvragenlijsten vergelijken bij mensen met diabetes.

Bronnen (Mathieson, 2015) |

|

- |

Er zijn geen licentiekosten verbonden aan het gebruik van de screeningsvragenlijsten.

De vragenlijsten bevatten vergelijkbare, en een vergelijkbaar aantal, items (Tabel 1). Het bepalen en interpreteren van de totaalscores door de behandelaar is vergelijkbaar tussen de screeningsinstrumenten en relatief eenvoudig, alleen bij de NPQ en NPQ-SF is een (simpele) berekening nodig.

DN4 en LANSS combineren een patiëntenvragenlijst met klinische onderzoeksvragen (DN4-interview betreft alleen de patiëntenvragenlijst).

De S-LANSS combineert een patiëntenvragenlijst met zelfonderzoek.

ID Pain, PainDETECT, modified PainDETECT, NPQ en NPQ-SF en DN4-interview bevatten geen klinische onderzoeksvragen.

Bronnen (Mathieson, 2015; originele publicaties) |

2. Wat is de plaats van anamnese en lichamelijk onderzoek (inclusief bedside testen) bij het stellen van de diagnose polyneuropathie bij volwassen personen met diabetes mellitus die positief screenen voor neuropathische pijn?

|

--- |

Er zijn geen diagnostische accuratessestudies van screeningsinstrumenten voor diabetische polyneuropathie (anamnese, lichamelijk onderzoek, bedside testen) waarin een betrouwbare referentietest werd gebruikt in onderzoek bij mensen met diabetes mellitus die positief screenen voor neuropathische pijn. |

|

Zeer laag GRADE |

Er zijn aanwijzingen dat de Neuropad voldoende sensitiviteit (79 tot 91%) biedt als test voor diabetische polyneuropathie, de specificiteit lijkt laag (51 tot 76%).

Er zijn enige aanwijzingen dat de Neuropad met name gevoelig is voor dunnevezel neuropathie.

Er is sprake van grote en onverklaarbare heterogeniteit in testkarakteristieken tussen individuele diagnostische accuratessestudies.

Bronnen (Tsapas, 2014 (SR); Ponirakis, 2014) |

|

Zeer laag GRADE |

Er zijn enige aanwijzingen dat de Sudoscan en NIS-LL een vergelijkbare sensitiviteit en specificiteit bieden als test voor diabetische polyneuropathie.

Bronnen (Casellini, 2013) |

|

Zeer laag GRADE |

Er zijn enige aanwijzingen dat een Biothesiometer (handheld) en stemvork (128 Hz) voldoende sensitiviteit en specificiteit bieden als test voor dikkevezel polyneuropathie bij diabetes mellitus.

Sensitiviteit en specificiteit lijken aanzienlijk lager als test voor dunnevezel polyneuropathie bij diabetes mellitus.

Bronnen (Pourhamidi, 2014) |

|

Zeer laag GRADE |

Er zijn aanwijzingen dat bij patiënten met type 1 diabetes, de Vibratron II een hoge sensitiviteit maar lage specificiteit heeft, het monofilament (SWMF) een hoge specificiteit maar lage sensitiviteit heeft, en MNSI een hoge sensitiviteit en redelijke specificiteit heeft.

Betreft patiënten van middelbare leeftijd met een vroege diagnose van type 1 diabetes (voor het zeventiende levensjaar).

Bronnen (Pambianco, 2011) |

|

Zeer laag GRADE |

Er zijn aanwijzingen dat met name monofilament (SWMF) en stemvork (128 Hz), al dan niet in combinatie met onderzoek naar uiterlijk van de voet en enkelreflexen (MNSI), de diagnose diabetische polyneuropathie kunnen ondersteunen.

Gebaseerd op een analyse van de positieve en negatieve likelihood ratio’s.

Bronnen (Kanji, 2010 (SR)) |

|

Zeer laag GRADE |

Er zijn aanwijzingen dat de aanwezigheid van diabetische polyneuropathie kan worden voorspeld op basis van leeftijd, HbA1c, HDL-C en diabetische retinopathie.

Gebaseerd op een enkel onderzoek waarin de voorspellingsregel (prediction rule) is ontwikkeld en getest in dezelfde patiëntenpopulatie.

Bronnen (Jurado, 2009) |

|

Zeer laag GRADE |

Er zijn aanwijzingen dat de UENS een enigszins hogere sensitiviteit heeft dan MDNS en NIS-LL.

Gebaseerd op een enkel onderzoek met een gemengde eerste- en tweedelijns patiëntenpopulatie. Specificiteit van de testen wordt niet gerapporteerd.

Bronnen (Singleton, 2008) |

|

Zeer laag GRADE |

Er zijn aanwijzingen dat vibratieperceptie (kwantitative stemvork en neurothesiometer) en monofilament een hoge specificiteit maar lage sensitiviteit hebben voor detectie van diabetische polyneuropathie in een eerstelijns populatie van type 2 diabetes patiënten.

In een onderzoek waarin beide indextesten deel uit maakten van de referentietest.

Bronnen (Jurado, 2007) |

|

Zeer laag GRADE |

Er zijn aanwijzingen dat een gegradeerde stemvork (128 Hz) een hoge sensitiviteit maar lage specificiteit heeft in de detectie van symptomatische en asymptomatische diabetische polyneuropathie bij jaarlijkse diabetes controle in de tweede lijn.

In een onderzoek waarin de referentietest was gebaseerd op Achilles reflex en SWMF, en waarin de prevalentie zeer laag was.

Bronnen (Kästenbauer, 2004) |

Samenvatting literatuur

1. Wat is de plaats van vragenlijsten bij het screenen op, en vaststellen van neuropathische pijn bij volwassen personen met diabetes mellitus?

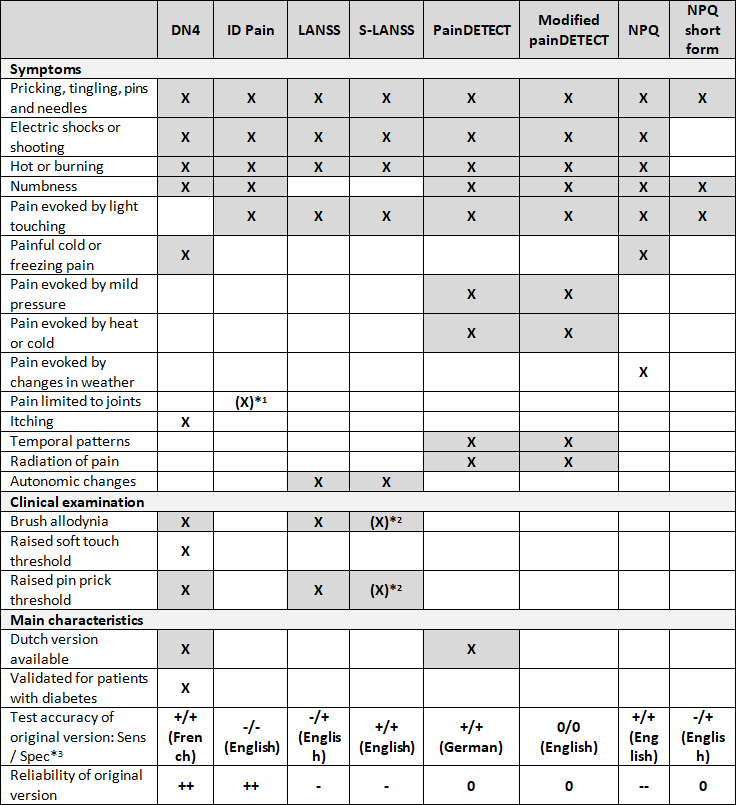

Mathieson (2015) is een systematische review van zeer goede kwaliteit (zie Table of quality assessment). Mathieson (2015) analyseert de door de IASP (International Association for the Study of Pain) aanbevolen vragenlijsten (Haanpää, 2011) voor screening van neuropathische pijn (DN4, ID Pain, LANSS, PainDETECT, NPQ), inclusief modificaties en/of adaptaties (S-LANSS, modified painDETECT, NPQ-SF; zie tabel 1 voor een verklaring van de afkortingen). Mathieson (2015) beperkt zich tot publicaties in het Engels, maar kent geen restricties met betrekking tot de studiepopulatie waarin de vragenlijsten worden getest.

Mathieson (2015) includeert 37 studies en beoordeelt de psychometrische eigenschappen van genoemde screeningsvragenlijsten aan de hand van de COSMIN criteria (Terwee, 2007; Mokkink, 2010): inhoudsvaliditeit (content validity), criterionvaliditeit (testaccuratesse in relatie tot de gouden standaard), constructvaliditeit, betrouwbaarheid (reproduceerbaarheid: test-retest, intrabeoordelaar en interbeoordelaar), interne consistentie (internal consistency), en responsiviteit. De methodologische kwaliteit van onderzoek met betrekking tot criterionvaliditeit (testaccuratesse, sensitiviteit en specificiteit) wordt bepaald met het QUADAS-2 instrument, en de COSMIN checklijst wordt gebruikt bij de beoordeling van de methodologische kwaliteit in relatie tot de overige psychometrische eigenschappen (Terwee, 2012). Tenslotte wordt de bewijskracht bepaald met behulp van de GRADE methodiek, met enkele aanpassingen die een beoordeling van psychometrische eigenschappen van meetinstrumenten mogelijk maakt (zie evidence-tabel).

Meta-analyses zijn niet verantwoord door een te grote klinische heterogeniteit, met name veroorzaakt door verschillen tussen studiepopulaties (pijnconditie), verschillen in de wijze waarop de diagnose neuropathische pijn werd gesteld (referentietest), verschillen in de wijze waarop de vragenlijsten werden afgenomen (indextest), en verschillen in uitvoering (taal) van de meetinstrumenten (zie evidence-tabel). Pijncondities variëren van postherpetische neuralgie, trigeminus neuralgie, en radiculopathie, tot specifieke pijncondities zoals chronische rugpijn, lepra, kanker en fibromyalgie. Elf studies (30%) gebruiken inadequate methodes voor het vaststellen van neuropathische pijn (indextest) bijvoorbeeld uitsluitend op basis van een beoordeling van het medisch dossier, of op basis van zelfrapportage.

Onderstaande literatuuranalyse richt zich op de door de werkgroep benoemde meest relevante uitkomstmaten: testaccuratesse en betrouwbaarheid (kritieke uitkomstmaten), bruikbaarheid en geschiktheid, en kosten (belangrijke uitkomstmaten). De overige psychometrische eigenschappen komen, voor zover relevant voor de besluitvorming, terug in de Overwegingen. Tabel 1 geeft een overzicht van de test-items en de belangrijkste karakteristieken van de meetinstrumenten (gebaseerd op respectievelijk Bennett (2007) en Mathieson (2015); zie voor meer details de evidence-tabel).

In de literatuuranalyse wordt geen onderscheid gemaakt tussen de twee zoekvragen omdat er nauwelijks onderzoek gedaan is naar testaccuratesse en betrouwbaarheid van screeningsinstrumenten voor neuropathische pijn bij mensen met diabetes, en er geen onderzoek is dat zich specifiek richt op gebruik bij de jaarlijkse diabetescontrole, of bij mensen met diabetes die zich melden met pijn of pijn-gerelateerde klachten in eerste en tweede lijn.

Diagnostische testaccuratesse en betrouwbaarheid – kritieke uitkomstmaten

In slechts 7 van de 37 geïncludeerde studies wordt de testaccuratesse van twee of meer screeningsinstrumenten rechtstreeks met elkaar vergeleken bij dezelfde patiëntenpopulatie, de overige studies analyseren een enkel screeningsinstrument. Studies die de testaccuratesse van screeningsvragenlijsten vergelijken bij mensen met diabetes ontbreken geheel.

Waarschijnlijk mede veroorzaakt door de grote klinische heterogeniteit, bestaat er een aanzienlijke variatie in diagnostische testaccuratesse zowel binnen dezelfde taalversies van een screeningsinstrument, als tussen verschillende taalversies van een screeningsinstrument. De bandbreedtes van sensitiviteit en specificiteit bij de verschillende screeningsinstrumenten laten een grote overlap zien (zie de evidence-tabel voor meer details). De sensitiviteit van de screeningsinstrumenten varieert tussen 47 tot 100% (DN4), 50 tot 83% (ID Pain), 22 tot 90% (LANSS), 52 tot 74% (S-LANSS), 64 tot 85% (PainDETECT), 50 tot 75% (NPQ) en 51 tot 65% (NPQ-SF). De specificiteit varieert tussen 45 tot 100% (DN4), 65 tot 86% (ID Pain), 42 tot 100% (LANSS), 76 tot 80% (S-LANSS), 53 tot 84% (PainDETECT), 65 tot 100 (NPQ) en 61 tot 79% (NPQ-SF). Sensitiviteit en specificiteit van de modified PainDETECT zijn niet gerapporteerd.

Uitgaande van de screeningsinstrumenten in hun originele taal (zie tabel 1), en een voldoende beoordeling van sensitiviteit en specificiteit bij een waarde van tenminste 70%, hebben DN4, S-LANSS, PainDETECT en NPQ voldoende sensitiviteit, en DN4, LANSS, S-LANSS, PainDETECT, NPQ, en NPQ-SF voldoende specificiteit. De originele versies van DN4 (Franse taal), S-LANSS (Engels), PainDETECT (Duits) en NPQ (Engels) hebben zowel voldoende sensitiviteit als specificiteit. Bij een beoordeling van de betrouwbaarheid (reproduceerbaarheid) van de screeningsinstrumenten in hun originele taal, scoren alleen DN4 (Frans) en ID Pain (Engels) een voldoende.

Twee screeningsinstrumenten zijn beschikbaar in de Nederlandse taal, DN4 (Van Seventer, 2012) en PainDETECT (Timmerman, 2013). Er zijn geen gegevens gepubliceerd met betrekking tot testaccuratesse en betrouwbaarheid van de Nederlandse versie van PainDETECT. Van alle screeningsinstrumenten is alleen de DN4 gevalideerd in de Nederlandse taal (Van Seventer, 2012). Van Seventer (2012) onderzocht testaccuratesse en betrouwbaarheid van de DN4 bij patiënten met chronische pijn (langer dan drie maanden): overwegend posttraumatische pijn (36%), (pseudo)radiculaire pijn (14%), of mechanische rugpijn (12%). De klinische diagnose Van deze patiënten kreeg 43% de klinische diagnose neuropathische pijn, 29% nociceptieve pijn, en bij 28% was sprake van een gemengde pijn. De Nederlandse versie van de DN4 heeft voldoende sensitiviteit en specificiteit, respectievelijk 74% en 79%. De betrouwbaarheid scoort onvoldoende (Mathieson, 2015).

De DN4 is het enige screeningsinstrument dat is gevalideerd bij volwassen personen met diabetes, zij het in de Italiaanse taal (Spallone, 2012). Spallone (2012) includeert zowel patiënten met pijn en verdenking PDNP als patiënten zonder pijn (routinematige controle), en rapporteert een sensitiviteit van 80% en specificiteit van 92%. De positief en negatief voorspellende waarde bedraagt respectievelijk 82% en 91%, en de positieve en negatieve Likelihood ratio 9,6 (LR+) en 0,22 (LR-). De betrouwbaarheid werd niet onderzocht. Als afname van de DN4 wordt beperkt tot de patiëntenvragenlijst (DN4-interview) bedragen sensitiviteit en specificiteit 84%.

Tabel 1 Vergelijking van test-items bij screeningsinstrumenten voor neuropathische pijn

*1 item relating to whether pain is located in the joints, used to identify nociceptive pain

*1 item relating to whether pain is located in the joints, used to identify nociceptive pain

*2 patients are asked to examine themselves

*3 ++ = satisfactory measurement property, low level of evidence; + = satisfactory measurement property, very low level of evidence; -- = unsatisfactory measurement property, low level of evidence; - = unsatisfactory measurement property, very low level of evidence; 0 = no evidence (not reported). Assessment of measurement properties and the level of evidence are based on the COSMIN criteria and GRADE criteria, respectively (taken from Mathieson 2015). Note that the level of evidence (GRADE) is low or very low.

Afkortingen: DN4: Douleur Neuropathique; ID Pain: acronym voor ID Pain Neuropathic Pain Screening Questionnaire; LANSS: Leeds Assessment of Neuropathic Symptoms and Signs; PainDETECT: acronym voor PainDETECT Questionnaire; NPQ: Neuropathic Pain Questionnaire; S-LANSS: Self-reported LANSS; modified painDETECT: gemodificeerde Paindetect; NPQ-SF: NPQ Short-Form

De grijze vakken in de tabel geven aan dat een test-item in tenminste twee screeningsinstrumenten voorkomt (gebaseerd op Bennett, 2007). De voor de uitgangsvraag belangrijkste karakteristieken van de meetinstrumenten zijn aangegeven (gebaseerd op Mathieson, 2015); zie voor meer details de evidence-tabel.

Bruikbaarheid en geschiktheid, en kosten - belangrijke uitkomstmaten

Mathieson (2015) heeft de bruikbaarheid en geschiktheid, en kosten van de screeningsinstrumenten niet onderzocht. Enig inzicht in hanteerbaarheid, tijdsbeslag, begrijpelijkheid voor patiënt en belasting voor de patiënt kan wel worden verkregen uit de geïncludeerde primaire studies. Twee screeningsinstrumenten (DN4, LANSS) combineren een patiëntenvragenlijst met klinisch onderzoek, in de S-LANSS (Self-reported LANSS) zijn de klinische onderzoeksvragen vervangen door vergelijkbare vragen geschikt voor zelfonderzoek. De overige vragenlijsten bevatten geen klinische onderzoeksvragen. Bij geen van de screeningsinstrumenten is er sprake van licentiekosten. De vragenlijsten bevatten veel overeenkomstige items (zie Tabel 1), en de vragen zijn relatief eenvoudig en snel te beantwoorden. Met uitzondering van de NPQ-SF dat uit slecht drie vragen bestaat, is het aantal vragen bij de overige screeningsinstrumenten vergelijkbaar. Ook het bepalen en interpreteren van de totaalscores door de behandelaar is in grote lijnen vergelijkbaar tussen de screeningsinstrumenten en relatief eenvoudig. Alleen bij de NPQ en NPQ-SF moeten item-scores worden vermenigvuldigd met coëfficiënten en een constante worden afgetrokken van de totaalscore, dit maakt deze screeningsinstrumenten wat bewerkelijker. Twee screeningsinstrumenten zijn beschikbaar in de Nederlandse taal, DN4 (Van Seventer, 2012) en PainDETECT (Timmerman, 2013). De DN4 is gevalideerd in de Nederlandse taal, maar niet specifiek bij mensen met diabetes.

Bewijskracht van de literatuur

De bewijskracht is gebaseerd op de analyse van Mathieson (2015) die de methodologische kwaliteit van onderzoek (risk of bias) bepaald met het QUADAS-2 instrument en de COSMIN checklijst, en de bewijskracht met behulp van de GRADE methodiek, met enkele aanpassingen die een beoordeling van psychometrische eigenschappen van meetinstrumenten mogelijk maakt (zie evidence-tabel). De bewijskracht bepaald door Mathieson (2015) moet voor de huidige uitgangsvraag, die specifiek betrekking heeft op Nederlandse personen met diabetes, nog met tenminste een niveau worden verlaagd vanwege indirectheid. De bewijskracht met betrekking tot testaccuratesse (sensitiviteit, specificiteit) en betrouwbaarheid (reproduceerbaarheid) is daarom zeer laag. Bij de uitkomstmaten bruikbaarheid en geschiktheid, en kosten kan door een gebrek aan data geen bewijskracht worden bepaald.

2. Wat is de plaats van anamnese en lichamelijk onderzoek (inclusief bedside testen) bij het stellen van de diagnose polyneuropathie bij volwassen personen met diabetes mellitus die positief screenen voor neuropathische pijn?

Er bestaan grote verschillen tussen de geïncludeerde onderzoeken met betrekking tot indextest(en) en referentietest(en), de onderzochte patiëntenpopulatie, en de methodologische kwaliteit (zie risk of bias tabellen). Vanwege te grote klinische heterogeniteit is een meta-analyse niet verantwoord. In de SR van Tsapas (2014) wordt wel een meta-analyse uitgevoerd voor de sensitiviteit en specificiteit van Neuropad, maar is de validiteit van deze meta-analyse twijfelachtig vanwege zeer grote en onverklaarde statistische heterogeniteit. Vanwege het grote aantal indextesten dat is onderzocht, en de grote klinische heterogeniteit die een meta-analyse in de weg staat, kunnen de studies alleen individueel worden beoordeeld. In plaats van een beschrijving van elke studie in de tekst, is gekozen voor een tabel met een overzicht van de belangrijkste karakteristieken en uitkomsten (tabel 2).

Diagnostische testaccuratesse en betrouwbaarheid – kritieke uitkomstmaten

Tabel 2 geeft een overzicht van de voor de uitgangsvraag belangrijkste karakteristieken van de meetinstrumenten, met betrekking tot de diagnostische accuratesse zijn alleen de sensitiviteit en specificiteit vermeld. Voor een uitgebreidere beschrijving met meer details, zoals likelihood ratio’s, wordt verwezen naar de evidence-tabel.

Bruikbaarheid en geschiktheid, en kosten - belangrijke uitkomstmaten

Incidenteel wordt in de geïncludeerde studies aandacht besteed aan de bruikbaarheid en geschiktheid, kosten worden nauwelijks belicht (zie tabel 2).

Tabel 2 Belangrijkste karakteristieken en resultaten van de geïncludeerde diagnostische accuratessestudies naar de waarde van anamnese en lichamelijk onderzoek (inclusief bedside testen) bij het stellen van de diagnose polyneuropathie bij volwassen personen met diabetes mellitus (zie de evidence-tabel voor een meer gedetailleerd overzicht)

|

Reference |

Design |

Patients |

Index tests |

Reference test |

Sensitivity |

Specificity |

Conclusions, comments |

|

Tsapas 2014

|

SR 18 studies, N=3470 |

Adult outpatients, excl high-risk populations, 15% T1, 85% T2, dur diab 11-18 yrs, HbA1c 6.3-8.3% |

Neuropad (cut-off = complete color change)

|

Reference varies per study: NDS, MDNS, DNI, signs and score, combination of signs, symptoms and NCS Prevalence 12-75% (range) |

0.43-1.00 Pooled: 0.86 [0.79−0.91] I2 = 90% |

0.22-1.00 Pooled: 0.65 [0.51−0.76] I2 = 95% |

Simple triage test with reasonable Sens to rule out foot at risk; Spec is low: patients testing pos should be referred; high heterogeneity; low inter- and intra-observer variability; can be used by patients |

|

Ponirakis 2014

|

DTA N=127 |

Patients from UK Diabetes Centre, 54% T1, 46% T2

|

Neuropad (cut-off % colour change)

|

Multiple refence tests: Large fibre assessments NDS (>2) Small fibre assessments Warm percept thresh Corneal nerve fibre dens Corn nerve fibre length Prevalence 30% (based on Toronto criteria) |

Depending on reference test 0.70

0.68 0.74 0.83 |

0.50

0.49 0.60 0.80 |

Practical diagnostic test for small fibre neuropathy; uses % colour change; uses multiple reference tests (multiple testing) |

|

Casellini 2013

|

DTA 83 patients 210 healthy controls |

USA Diabetes center, 24% T1, 76% T2

|

Sudoscan (ESC) NIS-LL

|

Toronto criteria (TNS>2) Prevalence 60/83 (72%) 46/83 (55% painful)

|

Hands ESC: 0.78 Feet ESC: 0.78 NIS-LL: 0.77 |

Hands ESC: 0.86 Feet ESC: 0.92 NIS-LL: 0.86 |

Sudoscan is Sensitive tool; conducted in 3 min, no special training; not clear how patients with diabetes were selected; in DTA analysis, patients possibly combined with unmatched HCs. |

|

Pourhamidi 2014

|

DTA N=119

|

Population based prevention program, prim care, Sweden; consec participants with NGT or IGT, or T2 diab |

Vibration VPT (biothesiom) Vibration (tuning fork) Pressure (SWMF) Skin biopsies (microscopy)

|

Two reference tests: Large fiber weighted def = abnormal NCS + NDS ≥2 Small fiber weighted def = normal NCS + abnormal thermal thresholds + NDS ≥2 Prevalence 20% ‘large fiber’ 24% ‘small fiber’ |

‘Large fiber’ 0.82 0.77 not reported 0.73 ‘Small fiber’ 0.67 0.44 not reported 0.74 |

‘Large fiber’ 0.70 0.67 0.97 0.70 ‘Small fiber’ 0.46 0.67 0.97 0.61 |

Biothesiometer is Sensitive and Specific method for large nerve fibre dysfunction. Combining skin biopsies with routine clinical tools (e.g.tuning fork) is of greater use considering less advanced (small fiber) than more advanced (large fiber) neuropathy; mixed group of individuals with and w/o diabetes (Spec data may be less relevant); multiple testing |

|

Pambianco 2011 |

DTA N=195

|

Sec care USA, T1 diabetes; <17 years of age at diagnosis; attending the 18 year examination, dur diab ~35 yrs, HbA1c ~7.5% |

Vibratron II [age-adjusted] NC-stat SNAP NC-stat Sensory NC-stat Motor Neurometer 2000 Hz Neurometer 250 Hz Neurometer 5 Hz MNSI Monofilament |

clinical history, symptoms, neurological examination (reflex, pain, tuning fork, sensation) Prevalence not reported

|

0.91 0.79 0.53 0.46 0.71 0.79 0.51 0.87 0.20 |

0.26 0.48 0.77 0.76 0.42 0.32 0.61 0.49 0.98 |

Vibratron II and MNSI highest Sens (>87%), monofilament highest Spec (98%) but lowest Sens (20%); MNSI also had highest NPV (83%) and presents single best combination of Sens and Spec in longstanding type 1 diabetes (: middle-aged patients with early-onset type 1 diabetes) |

|

Mythili 2010 |

DTA N=100

|

Sec care India, consecutive T2 diab patients, dur diab 6.9 yrs, HbA1c 8%, Hist foot ulcers 13% |

DNS DNE Monofilament (SWMF) Vibration VPT (biothesiometer) |

NCS Prevalence 71% |

not reported 0.83 0.96 0.86 |

not reported 0.79 0.55 0.76 |

DNE similar to VPT in evaluation of neuropathy in diabetic clinic; monofilament highly Sensitive but less Specific; selective outcome reporting; setting may be less relevant to situation in NL; very high prevalence |

|

Kanji 2010

|

SR 9 DTA N=37-426 per study

Note: no meta-analysis; most index tests only reported in a single study

|

Diabetes patients (mostly); (almost) only T2 patients |

Large number of index tests: Symptoms Italian screening question Neurological Symptom Score Any single symptom Physical ‘Signs’ -Individual components Vibration 128Hz tuning fork SW monofilament (3 studies) 1 2 3 Inability to walk on heels Deep tendon reflexes Combinations of findings Neurologic examination NDS 5-Test Score MNSI Clinical examination |

NCS (‘large fiber’) Prevalence 23-78% (range)

|

Symptoms 0.85 [0.72-0.94] 0.73 [0.54-0.87] 0.75 [0.55-0.89] Physical ‘Signs’

not reported

0.93 [0.77-0.99] 0.57 [0.44-0.69] Not reported 0.25 [0.16-0.37] 0.71 [0.51-0.86]

0.94 [0.83-0.99] 0.85 [0.76-0.91] 0.22 [0.12-0.33] 0.65 [0.53-0.76] 0.75 [0.55-0.89] |

Symptoms 0.79 [0.72-0.85] 0.30 [0.21-0.42] 0.25 [0.09-0.49] Physical ‘Signs’

not reported

1.00 [0.63-1.00] 0.95 [0.86-0.99] Not reported 0.98 [0.86-1.00] 0.80 [0.56-0.93]

0.92 [0.87-0.96] 0.82 [0.64-0.92] 0.94 [0.68-0.99] 0.83 [0.74-0.89] 0.70 [0.46-0.88] |

Based on a comparison of LR+ (see evidence table) authors conclude that physical examination is most useful: abnormal results on SWMF and vibratory perception (alone or in combination with appearance of feet, ulceration, and ankle reflexes = MNSI) are most helpful signs; meta-analyses not performed; for most diagnostic tools only one study was included (3 studies for SWMF but using different protocols i.e. with high clinical heterogeneity)

|

|

Jurado 2009 |

DTA N=307 |

Prim care, random sample, T2 diabetes, Spain; dur diab 8.6 yrs; HbA1c 7.0% |

‘DPN selection method’ set of 4 clinical parameters identified by logistic regression analysis: age, HbA1c, HDL-C, Retinopathy |

Clinical Neurol Examination (CNE) bilateral signs and symptoms Prevalence 23% |

0.74 |

0.75 |

Useful tool in primary care settings; note that index test = prediction rule, which was developed and tested in the same study population (high risk of bias) |

|

Singleton 2008 |

DTA N=215 |

Mixed prim and sec care; USA; diabetes or prediabetes |

UENS MDNS NIS-LL |

NCS, QST, QSART, skin biopsies (symptoms of neuropathy confirmed by 2 confirmatory electrodiagn, electrophysiol, or histol tests) Prevalence 40% |

0.92 0.67 0.81 |

Not reported (but ‘similar between index tests’) |

UENS Sens (92%) higher than MDNS or NIS-LL without sacrificing Spec. UENS more closely correlated with change in small-fiber neuropathy over 1 year follow-up than MDNS or NIS-LL; note that cut-off values were not reported; Spec not reported; differences between tests not stat sign |

|

Jurado 2007 |

DTA N=305 |

Prim care, random sample, T2 diabetes, Spain |

VPT-neurothesiometer NTS VPT-quant tuning fork QTF SW-MF Olmos technique SW-MF MDNS criteria |

CNE based on symptoms, phys exam, sensory tests (VPT; SWMF) Prevalence 23% |

0.44 0.52 0.28 0.42 |

0.95 0.95 0.96 0.98 |

VPTs and SWMF have high Spec but low Sens in primary care settings; patient characteristics not described; cut-off values UENS and NIS-LL not reported |

|

Kästenbauer 2004 |

DTA N=2022 |

Sec care; Austria; annual diabetes check; 35% T1, 65% T2; HbA1c 8.1% |

VPT (RS tuning fork) |

2 reference tests: DPN = ‘abnormal bedside tests’ (abnormal Achilles tendon reflexes + abnormal SWMF) Symptomatic DPN = DPN + >=3 neuropathic symptoms Prevalence 6.3% (DPN); 5.1% (symptom DPN) |

0.96

0.97 |

0.45

0.42 |

Tuning fork is a useful screening test for diabetic neuropathy (graduated tuning fork is superior to standard tuning forks); note very low prevalence of DPN |

|

Viswanathan 2002 |

DTA N=910 |

Sec care; India; routine screening for neuropathy; dur diab 9.7 yrs [T1/T2 not reported] |

Temp perception (Tip-therm)

|

2 reference tests VPT (biothesiometry) SWMF Prevalence 32.7% (VPT), 26.5% (SWMF) |

0.97 0.98 |

1.00 0.92 |

Tip-therm appears to be highly Sensitive, and Specific device for detection DPN; note that ‘gold standard’ is questionable; relatively old study, setting may be less relevant to situation in NL |

|

Perkins 2001

|

DTA N=478 |

Sec care; Canada; 'mixed' cohort 4 sources including unselected diabetes patients, patients referred for suspected DPN, and ‘reference subjects’; <20% T1; diab duration 9-15 yrs; HbA1c 8.0-8.7% |

SWMF Vibrat on-off (tuning fork) Vibrat timed (tuning fork) Superficial pain (Neurotip) [Note: different cut-off values used for abnormal versus normal test result] |

NCS Prevalence 78%

|

‘abnormal test’ 0.41 0.27 0.37 0.28 ‘normal test’ 0.68 0.92 0.61 0.82 |

‘abnormal test’ 0.96 0.99 0.98 0.97 ‘normal test’ 0.77 0.53 0.80 0.59 |

Tests show comparable Sens and Spec; vibration ‘timed’ takes longer and interpretation is more complicated; note that study population is not representative of any primary of secundary care patient population; prevalence of DPN is very high (78%); different cut-offs were used for ‘abnormal’ and ‘normal’ test |

Afkortingen: NDS: Neurop Disab Score; DNI: Diab Neurop Index; MDNS: Michigan Diab Neurop Score; NCS: Neuro Conduction Studies; MNSI: michigan neuropathy screening instrument; Toronto criteria: abnormal NCS, and symptoms/signs NDS>2; NIS-LL: Neuropathy Impairment Score—Lower Legs; DNS: Diabetic Neuropathy Symptom score; DNE: Diabetic Neuropathy Examination score; UENS: Utah Early Neuropathy Scale; NGT: normal glucose tolerance; IGT: impaired glucose tolerance; SWMF: Semmes-Weinstein monofilament; VPT: Vibration Perception Threshold

Bewijskracht van de literatuur

De bewijskracht met betrekking tot testaccuratesse (sensitiviteit, specificiteit) moet met een niveau worden verlaagd vanwege beperkingen in onderzoeksopzet (zie risk of bias tabellen), met een tot twee niveaus vanwege indirectheid (met name vanwege van de praktijk afwijkende patiëntenpopulatie), en met een niveau vanwege imprecisie (slechts een enkele studie beschikbaar, of een breed betrouwbaarheidsinterval dat overlapt met de grens voor klinische besluitvorming). De redenen voor downgraden verschillen enigszins per indextest, maar in alle gevallen is de uiteindelijke bewijskracht zeer laag. Bij de uitkomstmaten bruikbaarheid en geschiktheid, en kosten kan door een gebrek aan data geen bewijskracht worden bepaald.

Zoeken en selecteren

1. Wat is de plaats van vragenlijsten bij het screenen op, en vaststellen van neuropathische pijn bij volwassen personen met diabetes mellitus?

Om de uitgangsvraag te kunnen beantwoorden is er een systematische literatuuranalyse verricht naar de volgende zoekvragen:

Zoekvraag 1: Wat zijn de voor- en nadelen (testaccuratesse, betrouwbaarheid, bruikbaarheid en geschiktheid, kosten) van diverse vragenlijsten voor screening op neuropathische pijn van volwassen personen met diabetes mellitus bij de jaarlijkse diabetescontrole in eerste en tweede lijn?

Zoekvraag 2: Wat zijn de voor- en nadelen (testaccuratesse, betrouwbaarheid, bruikbaarheid en geschiktheid, kosten) van diverse vragenlijsten voor screening op neuropathische pijn van volwassen personen met diabetes mellitus die zich melden met pijn en pijn-gerelateerde klachten die kunnen wijzen op PDNP in eerste en tweede lijn?

In een gecombineerde zoekactie is gezocht naar diagnostische karakteristieken van vragenlijsten voor screening van neuropathische pijn bij volwassen personen met diabetes mellitus type 1 of 2, met het klinisch oordeel van de behandelaar als referentietest, en met testkarakteristieken, betrouwbaarheid, bruikbaarheid en geschiktheid, en kosten als uitkomstmaten.

Relevante uitkomstmaten

De werkgroep achtte diagnostische testaccuratesse (sensitiviteit, specificiteit, positieve en negatieve Likelihoods ratio’s) en betrouwbaarheid (reproduceerbaarheid) voor de besluitvorming kritieke uitkomstmaten; en bruikbaarheid en geschiktheid, en kosten voor de besluitvorming belangrijke uitkomstmaten.

De werkgroep definieerde niet a priori de genoemde uitkomstmaten, maar hanteerde de in de studies gebruikte definities. De uitkomstmaat: bruikbaarheid en geschiktheid, staat voor bruikbaarheid in de dagelijkse praktijk: hanteerbaarheid, tijdsbeslag, begrijpelijkheid voor patiënt en belasting voor de patiënt.

Zoeken en selecteren (Methode)

Een oriënterende zoekactie leverde een recente systematische review van zeer goede kwaliteit op (Mathieson, 2015) die de literatuur dekt tot mei 2013. In de database Medline (OVID) is aanvullend gezocht met relevante zoektermen naar diagnostisch onderzoek aan screeningsinstrumenten voor neuropathische pijn bij mensen met diabetes. De zoekverantwoording is weergegeven onder het tabblad Verantwoording. De literatuurzoekactie leverde 136 treffers op. Studies werden geselecteerd op grond van de volgende selectiecriteria: diagnostische studie, screeningsinstrument (vragenlijst) voor neuropathische pijn, volwassen personen met diabetes, en diagnostische testaccuratesse als uitkomstmaat. Op basis van titel en abstract werden in eerste instantie 22 studies voorgeselecteerd. Na raadpleging van de volledige tekst, werden vervolgens alle studies geëxcludeerd (zie exclusietabel onder het tabblad Verantwoording).

De literatuuranalyse is gebaseerd op een onderzoek, de SR van Mathieson (2015). Voor een volledig overzicht van studiekarakteristieken en resultaten van de systematische review van Mathieson (2015) en beoordeling van de individuele studieopzet (risk of bias) van de geïncludeerde studies wordt verwezen naar de bewuste publicatie. De belangrijkste studiekarakteristieken, resultaten, en beoordeling van de geïncludeerde studies in Mathieson (2015) zijn opgenomen in de evidence-tabellen.

2. Wat is de plaats van anamnese en lichamelijk onderzoek (inclusief bedside testen) bij het stellen van de diagnose polyneuropathie bij volwassen personen met diabetes mellitus die positief screenen voor neuropathische pijn?

Om de uitgangsvraag te kunnen beantwoorden is er een systematische literatuuranalyse verricht naar de volgende zoekvraag:

Wat zijn de voor- en nadelen (testaccuratesse, betrouwbaarheid, bruikbaarheid en geschiktheid, kosten) van (onderdelen van de) anamnese en lichamelijk onderzoek (of combinaties) bij het stellen van de diagnose polyneuropathie bij volwassen personen met diabetes mellitus die positief screenen voor neuropathische pijn?

Er is gezocht naar diagnostische karakteristieken van anamnese (vragenlijsten), bevindingen bij lichamelijk/neurologisch onderzoek, bedside tests, en combinaties hiervan, bij het stellen van de diagnose polyneuropathie bij volwassen personen met diabetes mellitus (type 1 of 2) en neuropathische pijn, met EMG en klinisch oordeel van de behandelaar als referentietest, en met testkarakteristieken, betrouwbaarheid, bruikbaarheid en geschiktheid, en kosten als uitkomstmaten.

Relevante uitkomstmaten

De werkgroep achtte diagnostische testaccuratesse (sensitiviteit, specificiteit, positieve en negatieve Likelihoods ratio’s) en betrouwbaarheid (reproduceerbaarheid) voor de besluitvorming kritieke uitkomstmaten. Met betrekking tot de testaccuratesse is met name een hoge sensitiviteit van belang (een laag percentage fout-negatieven), specificiteit (een laag percentage fout-positieven) is weliswaar ook een kritieke uitkomstmaat maar hoeft slechts acceptabel te zijn (zie de Overwegingen). Bruikbaarheid en geschiktheid, en kosten zijn voor de besluitvorming belangrijke uitkomstmaten.

De werkgroep definieerde niet a priori de genoemde uitkomstmaten, maar hanteerde de in de studies gebruikte definities. De uitkomstmaat ‘bruikbaarheid en geschiktheid’ staat voor bruikbaarheid in de dagelijkse praktijk: hanteerbaarheid, tijdsbeslag, begrijpelijkheid voor patiënt en belasting voor de patiënt.

Zoeken en selecteren (Methode)

In de database Medline (OVID) is met relevante zoektermen gezocht naar diagnostisch onderzoek aan screeningsinstrumenten voor polyneuropathie bij mensen met diabetes. De zoekverantwoording is weergegeven onder het tabblad Verantwoording. De literatuurzoekactie leverde 278 treffers op. Studies werden geselecteerd op grond van de volgende selectiecriteria: diagnostische studie, screening (anamnese, lichamelijk onderzoek, bedside testen) voor diabetische polyneuropathie, volwassen personen met diabetes, en diagnostische testaccuratesse als uitkomstmaat. Elektrofysiologie/EMG en andere specialistische diagnostische testen vallen niet onder de mogelijke indextesten. Gouden standaard is bij voorkeur EMG en als dit normaal is, het klinische oordeel van de behandelaar, maar de aard van de referentietest (gouden standaard) werd niet als een a priori in- of exclusiecriterium gebruikt. Studies gepubliceerd voor 2001 werden door de werkgroep als minder relevant beoordeeld en alsnog geëxcludeerd. Op basis van titel en abstract werden in eerste instantie 41 studies voorgeselecteerd. Na raadpleging van de volledige tekst, werden vervolgens 28 studies geëxcludeerd (zie exclusietabel onder het tabblad Verantwoording) en 13 studies definitief geselecteerd.

Dertien onderzoeken, twee systematische reviews (SR’s) en elf primaire diagnostische studies, zijn opgenomen in de literatuuranalyse. De belangrijkste studiekarakteristieken en resultaten zijn opgenomen in de evidence-tabellen. De beoordeling van de studieopzet (risk of bias) is opgenomen in de risk of bias tabellen. De beoordeling van de risk of bias van de studies die deel uitmaken van de twee SR’s is niet opnieuw beoordeeld maar overgenomen uit de bewuste publicaties en opgenomen in de evidence-tabel.

Referenties

- Archer AG, Watkins PJ, Thomas PK, et al. The natural history of acute painful neuropathy in diabetes mellitus. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1983;46(6):491-9. PubMed PMID: 6875582; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC1027437.

- Bennett MI, Attal N, Backonja MM, et al. Using screening tools to identify neuropathic pain. Pain. 2007;127(3):199-203. Epub 2006 Dec 19. Review. PubMed PMID: 17182186.

- Bouhassira D, Attal N, Alchaar H, et al. Comparison of pain syndromes associated with nervous or somatic lesions and development of a new neuropathic pain diagnostic questionnaire (DN4). Pain. 2005;114(1-2):29-36. PubMed PMID: 15733628.

- Casellini CM, Parson HK, Richardson MS, et al. Sudoscan, a noninvasive tool for detecting diabetic small fiber neuropathy and autonomic dysfunction. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2013;15(11):948-53. doi: 10.1089/dia.2013.0129. Epub 2013 Jul 27. PubMed PMID: 23889506; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3817891.

- DCCT. The effect of intensive diabetes therapy on the development and progression of neuropathy. The Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Research Group. Ann Intern Med. 1995;122(8):561-8. PubMed PMID: 7887548.

- Fullerton B, Jeitler K, Seitz M, et al. Intensive glucose control versus conventional glucose control for type 1 diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;2:CD009122. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009122.pub2. Review. PubMed PMID: 24526393.

- Haanpää M, Attal N, Backonja M, et al. NeuPSIG guidelines on neuropathic pain assessment. Pain. 2011;152(1):14-27. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.07.031. Epub 2010 Sep 19. Review. PubMed PMID: 20851519.

- Hemmingsen B, Lund SS, Gluud C, et al. Targeting intensive glycaemic control versus targeting conventional glycaemic control for type 2 diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;11:CD008143. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008143.pub3. Review. Update in: Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;7:CD008143. PubMed PMID: 24214280.

- Hemmingsen B, Lund SS, Gluud C, et al. WITHDRAWN: Targeting intensive glycaemic control versus targeting conventional glycaemic control for type 2 diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;7:CD008143. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008143.pub4. Review. PubMed PMID: 26222248.

- Javed S, Petropoulos IN, Alam U, et al. Treatment of painful diabetic neuropathy. Ther Adv Chronic Dis. 2015;6(1):15-28. doi: 10.1177/2040622314552071. Review. PMID: 25553239 /pubmed/25553239.

- Jurado J, Ybarra J, Pou JM. Isolated use of vibration perception thresholds and semmes-weinstein monofilament in diagnosing diabetic polyneuropathy: "the North Catalonia diabetes study". Nurs Clin North Am. 2007;42(1):59-66. PubMed PMID: 17270590.

- Jurado J, Ybarra J, Romeo JH, et al. Clinical screening and diagnosis of diabetic polyneuropathy: the North Catalonia Diabetes Study. Eur J Clin Invest. 2009;39(3):183-9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2008.02074.x. PubMed PMID: 19260947.

- Kanji JN, Anglin RE, Hunt DL, et al. Does this patient with diabetes have large-fiber peripheral neuropathy? JAMA. 2010;303(15):1526-32. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.428. Review. PubMed PMID: 20407062.

- Kästenbauer T, Sauseng S, Brath H, et al. The value of the Rydel-Seiffer tuning fork as a predictor of diabetic polyneuropathy compared with a neurothesiometer. Diabet Med. 2004;21(6):563-7. PubMed PMID: 15154940.

- Martina IS, van Koningsveld R, Schmitz PI, et al. Measuring vibration threshold with a graduated tuning fork in normal aging and in patients with polyneuropathy. European Inflammatory Neuropathy Cause and Treatment (INCAT) group. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1998;65(5):743-7. PubMed PMID: 9810949; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC2170371.

- Mathieson S, Maher CG, Terwee CB, et al. Neuropathic pain screening questionnaires have limited measurement properties. A systematic review. J Clin Epidemiol. 2015;68(8):957-66. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.03.010. Review. PubMed PMID: 25895961.

- Mokkink LB, Terwee CB, Patrick DL, et al. The COSMIN study reached international consensus on taxonomy, terminology, and definitions of measurement properties for health-related patient-reported outcomes. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63(7):737-45. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.02.006. PubMed PMID: 20494804.

- Mythili A, Kumar KD, Subrahmanyam KA, et al. A Comparative study of examination scores and quantitative sensory testing in diagnosis of diabetic polyneuropathy. Int J Diabetes Dev Ctries. 2010;30(1):43-8. doi: 10.4103/0973-3930.60007. PubMed PMID: 20431806.

- NDF. Zorgstandaard Diabetes. 2015. Link: http://www.zorgstandaarddiabetes.nl/ [geraadpleegd op 20 januari 2017].

- Rutten GEHM, De Grauw WJC, Nijpels G, et al. NHG-Standaard Diabetes mellitus type 2 (derde herziening). Huisarts Wet 2013;56(10):512-525. https://www.nhg.org/standaarden/volledig/nhg-standaard-diabetes-mellitus-type-2.

- De Jong L, Janssen PGH, Keizer D, et al. NHG-Standaard Pijn. NHG-Werkgroep Pijn. 2015. https://www.nhg.org/standaarden/volledig/nhg-standaard-pijn.

- NVN. Richtlijn Polyneuropathie Nederlandse Vereniging voor Neurologie. 2005. https://www.neurologie.nl/uploads/136/87/richtlijnen_-_polyneuropathie.pdf.

- Pambianco G, Costacou T, Strotmeyer E, et al. The assessment of clinical distal symmetric polyneuropathy in type 1 diabetes: a comparison of methodologies from the Pittsburgh Epidemiology of Diabetes Complications Cohort. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2011;92(2):280-7. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2011.02.005. PubMed PMID: 21411172.

- Perkins BA, Olaleye D, Zinman B, et al. Simple screening tests for peripheral neuropathy in the diabetes clinic. Diabetes Care. 2001;24(2):250-6. PubMed PMID: 11213874.

- Ponirakis G, Petropoulos IN, Fadavi H, et al. The diagnostic accuracy of Neuropad for assessing large and small fibre diabetic neuropathy. Diabet Med. 2014;31(12):1673-80. doi: 10.1111/dme.12536. Epub 2014 Jul 14. PubMed PMID: 24975286; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC4236278.

- Pourhamidi K, Dahlin LB, Englund E, et al. Evaluation of clinical tools and their diagnostic use in distal symmetric polyneuropathy. Prim Care Diabetes. 2014;8(1):77-84. doi: 10.1016/j.pcd.2013.04.004. Epub 2013 May 9. PubMed PMID: 23664849.

- Singleton JR, Bixby B, Russell JW, et al. The Utah Early Neuropathy Scale: a sensitive clinical scale for early sensory predominant neuropathy. J Peripher Nerv Syst. 2008;13(3):218-27. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8027.2008.00180.x. PubMed PMID: 18844788.

- Spallone V, Morganti R, D'Amato C, et al. Validation of DN4 as a screening tool for neuropathic pain in painful diabetic polyneuropathy. Diabet Med. 2012;29(5):578-85. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2011.03500.x. PubMed PMID: 22023377.

- Terwee CB, Bot SD, de Boer MR, et al. Quality criteria were proposed for measurement properties of health status questionnaires. J Clin Epidemiol. 2007;60(1):34-42. Epub 2006 Aug 24. PubMed PMID: 17161752.

- Terwee CB, Mokkink LB, Knol DL, et al. Rating the methodological quality in systematic reviews of studies on measurement properties: a scoring system for the COSMIN checklist. Qual Life Res. 2012;21(4):651-7. doi: 10.1007/s11136-011-9960-1. Epub 2011 Jul 6. PubMed PMID: 21732199

- Timmerman H, Wolff AP, Schreyer T, et al. Cross-cultural adaptation to the Dutch language of the PainDETECT-Questionnaire. Pain Pract. 2013;13(3):206-14. doi: 10.1111/j.1533-2500.2012.00577.x. PubMed PMID: 22776283.

- Tsapas A, Liakos A, Paschos P, et al. A simple plaster for screening for diabetic neuropathy: a diagnostic test accuracy systematic review and meta-analysis. Metabolism. 2014;63(4):584-92. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2013.11.019. Epub 2013 Dec 7. Review. PubMed PMID: 24405753.

- UKPDS. Intensive blood-glucose control with sulphonylureas or insulin compared with conventional treatment and risk of complications in patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 33). UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group. Lancet. 1998;352(9131):837-53.

- Van Seventer R, Vos C, Giezeman M, et al. Validation of the Dutch version of the DN4 diagnostic questionnaire for neuropathic pain. Pain Pract. 2013;13(5):390-8. doi: 10.1111/papr.12006. Epub 2012 Oct 31. PubMed PMID: 23113981.

- Viswanathan V, Snehalatha C, Seena R, et al. Early recognition of diabetic neuropathy: evaluation of a simple outpatient procedure using thermal perception. Postgrad Med J. 2002;78(923):541-2. PubMed PMID: 12357015.

- VTV. Volksgezondheid Toekomst Verkenning 2014. 2014. RIVM, in opdracht van het ministerie van VWS. http://www.eengezondernederland.nl/Een_gezonder_Nederland.

Evidence tabellen

1. Wat is de plaats van gestructureerde vragenlijsten bij het screenen op, en vaststellen van neuropathische pijn bij volwassen personen met diabetes mellitus?

Table of quality assessment for systematic reviews of diagnostic studies

Based on AMSTAR checklist (Shea et al.; 2007, BMC Methodol 7: 10; doi:10.1186/1471-2288-7-10) and PRISMA checklist (Moher et al 2009, PLoS Med 6: e1000097; doi:10.1371/journal.pmed1000097)

Research question: What is the value of measuring instruments (questionnaires) for screening and diagnosis of neuropathic pain, in patients with diabetes without known pain complaints (during annual diabetes checks), and in patients with pain complaints suspected of having painful diabetic polyneuropathy (PDNP)?

|

Study

First author, year |

Appropriate and clearly focused question?1

Yes/no/unclear |

Comprehensive and systematic literature search?2

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of included and excluded studies?3

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of relevant characteristics of included studies?4

Yes/no/unclear |

Assessment of scientific quality of included studies?5

Yes/no/unclear |

Enough similarities between studies to make combining them reasonable?6

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential risk of publication bias taken into account?7

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential conflicts of interest reported?8

Yes/no/unclear |

|

Mathieson 2015 |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

No*1 |

No*1 |

*1 but risk of bias is low

- Research question (PICO) and inclusion criteria should be appropriate and predefined

- Search period and strategy should be described; at least Medline searched

- Potentially relevant studies that are excluded at final selection (after reading the full text) should be referenced with reasons

- Characteristics of individual studies relevant to research question (PICO) should be reported

- Quality of individual studies should be assessed using a quality scoring tool or checklist (preferably QUADAS-2; COSMIN checklist for measuring instruments)

- Clinical and statistical heterogeneity should be assessed; clinical: enough similarities in patient characteristics, diagnostic tests (strategy) to allow pooling? For pooled data: assessment of statistical heterogeneity using appropriate statistical tests?

- An assessment of publication bias should include a combination of graphical aids and/or statistical tests. Note: If no test values or plots included, score “no”. Score “yes” if mentions that publication bias could not be assessed because there were fewer than 10 included studies.

- Sources of support (including commercial co-authorship) should be reported in both the systematic review and the included studies. Note: To get a “yes,” source of funding or support must be indicated for the systematic review AND for each of the included studies.

Evidence table for measuring instruments (questionnaires)

Research question: What is the value of measuring instruments (questionnaires) for screening and diagnosis of neuropathic pain, in patients with diabetes without known pain complaints (during annual diabetes checks), and in patients with pain complaints suspected of having painful diabetic polyneuropathy (PDNP)?

|

Study reference |

Per type of instrument |

Method of diagnosis (‘golden standard’) |

Patient characteristics

|

Language of measuring instrument |

Test accuracy Sensitivity Specificity (validity and level of evidence) |

Reliability (validity and level of evidence) |

Usability

|

Other comments |

|

Mathieson 2015

[Studies included in Mathieson 2015] |

a Questionnaire cut-off values used to determine sensitivity and specificity: DN4 value was 4 (except Harifi 2011 in which a value of 3 was Used, and van Seventer using a value of 5). ID Pain was 2 (except Chan 2011 which a value of 3 was used). LANSS and S-LANSS were 12. PainDETECT value was19 (except Gauffin 2013 which a value of 17 was used). NPQ and short form were 0. b Scale development. c Evaluation study. d Phone administration. e Mail administration. f Test-retest study |

|

|

|

Sens / Spec (%) NA, not reported

Validity (Cosmin criteria) and Level of evidence (modified GRADE approach): Overall, per measuring instrument and language version ++++ = satisfactory measurement property, high level of evidence; +++ = satisfactory measurement property, moderate level of evidence; ++ = satisfactory measurement property, low level of evidence + = satisfactory measurement property, very low level of evidence 0 = no evidence (not reported); ---- = unsatisfactory measurement property, high level of evidence; --- = unsatisfactory measurement property, moderate level of Evidence -- = unsatisfactory measurement property, low level of evidence; - = unsatisfactory measurement property, very low level of evidence |

Validity (Cosmin criteria) and Level of evidence (modified GRADE approach): idem |

For primary and secondary care; for screening and diagnosis; items to consider: length (number of questions), time required, costs (licence required?)

Note: usability was not analysed in Mathieson 2015; based on original publications on the measuring instrument and on NeuPSIG guidelines (Haanpää 2011), EFSN guidelines (Cruccu 2010), and Bennett (2007)

Haanpää (2011): PubMed PMID: 20851519

Cruccu (2010): PubMed PMID: 20298428

Bennett (2007): PubMed PMID 17182186 |

Authors use a modified GRADE approach to determine the level of evidence per measurement property (overall, i.e. based on all studies included reporting the measurement property): scores started at high level of evidence and were downgraded for inconsistency, risk of bias and imprecision.

Inconsistency: no downgrade if >75% results the same in a single measurement property; downgrade-1 if ≤75% results consistent

Risk of Bias: no downgrade if Excellent or good COSMIN score OR low QUADAS-2 score; downgrade-1 if Majority fair COSMIN scores OR unclear QUADAS-2 score; downgrade-2 if Majority poor or mixture of COSMIN scores OR high QUADAS-2 score

Imprecision: no downgrade if >400 participants; downgrade-1 if <400 participants; downgrade-2 if Very wide confidence interval (CI) or wide CI plus <400 participants |

|

DN4 DN4, Douleur Neuropathique 4 |

||||||||

|

Bouhassira 2005 |

Clinical history and sensory testing by Pain specialist, neurologist |

160 chronic pain patients in France |

French [original] |

82.9 / 89.9 + / + (overall) |

++ (overall) |

The DN4 was developed in 160 patients with either neuropathic or nociceptive pain.

DN4 consists of 7 items related to symptoms and 3 related to clinical examination (Bouhassira 2005).

The DN4 is easy to score and a total score of 4 out of 10 or more suggests neuropathic pain. [but note that e.g. van Seventer uses a cut-off value of 5]

The 7 sensory descriptors can be used as a self-report questionnaire with similar results (Bouhassira 2005).

|

|

|

|

Attal 2011 |

Clinical history, sensory testing, additional tests by Neurologist, rheumatologist |

132 low back pain patients in France |

French [original] |

80 / 92

|

|

|

||

|

Harourn 2012 |

Clinical history and sensory testing by Investigator |

80 leprosy patients in Ethiopia |

Amharic |

100 / 45 + / - |

0 |

Compares DN4 with LANSS: Sens/Spec 100/45 vs 85/42 |

||

|

Harifi 2011

|

Clinical history, sensory testing, additional tests by Clinician |

170 chronic pain patients in Morocco |

Arabic |

89.4 / 72.4 + / + |

++ |

|

||

|

van Seventer 2012 |

Inadequate methods; Anaesthetists and neurologist |

269 chronic pain patients in The Netherlands |

Dutch |

75 / 79 (cut-off=5) + / + |

- |

Note: Dutch version; patients mostly with posttraumatic (36%), (pseudo) radicular (14%), and mechanical back pain (12%); diagnosis for nociceptive, neuropathic or mixed pain by 2 physicians (independently; blinded) using ‘whichever diagnostic tools they felt were appropriate’: identical diagnosis of pain in 196 / 248 patients, 85 with neuropathic pain, 57 with nociceptive pain, and 54 with mixed pain; sens and spec of DN4-interview was 74 / 79% (cut-off=3) |

||

|

Walsh 2012 |

Inadequate methods; Physiotherapist |

45 low back-leg pain patients in Ireland |

English |

NA / NA 0 / 0 |

0 |

Compares DN4 with S-LANSS: Sens/Spec NA/NA vs NA/NA |

||

|

Lasry-Levy 2011 |

Clinical history and sensory testing;Clinician |

101 leprosy patients in India |

Hindi and Marathi |

78.6 / 100 ++ / ++ |

0 |

|

||

|

Spallone 2012 |

Clinical history and sensory testing by Investigator |

158 patients with diabetes in Italy |

Italian |

80 / 92 (cut-off=4) + / + (overall) |

0 (overall) |

Note: only validation study in patients with diabetes (with and w/o pain complaints) 158 patients with diabetes: 50 PDNP, 47 DNP, 61 w/o DNP; PPV = 82%; NPV = 91%; LR+ = 9.6; LR- = 0.22. PS. At the cut-off of 3, DN4-interview (i.e. w/o clinical questions) showed sens and spec of 84%, PPV of 71%, NPV of 92%, and LR+ of 5.3 |

||

|

Pauda 2013

|

Clinical history, sensory testing, additional tests; Clinician |

392 peripheral nerve disease patients in Italy |

Italian |

82 / 81

|

|

Compares DN4 with ID Pain: Sens/Spec 82/81 vs 78/74 |

||

|

Santos 2010

|

Clinical history, sensory testing, additional tests; Pain specialist, neurologist, orthopedist |

101 chronic pain patients in Brazil |

Portuguese |

100 / 93.2 + / + |

+ - |

|

||

|

Perez 2007

|

Clinical history, sensory testing, additional tests; Pain specialist |

158 chronic pain patients in Spain |

Spanish |

79.8 / 78 + / + |

+ |

|

||

|

Hallstrom and Norrbrink 2011 |

Clinical history and sensory testing; Neurologist and pain physician |

40 spinal cord injury patients in Sweden |

Swedish |

92.9 / 75.0 ++ / ++ |

++ |

Compares DN4, LANSS, PainDETECT, NPQ: Sens/Spec 93/75 vs 36/100 vs 68/83 vs 50/100 |

||

|

Unal Cevik 2010 |

Clinical history, sensory testing, additional tests; Neurologist, pain specialist, and physiatrists |

180 pain patients in Turkey |

Turkish |

95 / 96.6 + / + |

++ |

|

||

|

ID Pain |

||||||||

|

Portenoy 2006 b,c |

Clinical history and sensory testing; Pain specialist |

308 chronic pain patients in America |

English [original] |

NA / NA - / - (overall) |

++ (overall) |

The tool was developed in 586 patients with chronic pain of nociceptive, mixed or neuropathic etiology, and validated in 308 patients with similar pain classification.

ID-Pain consists of 5 sensory descriptor items and 1 item relating to whether pain is located in the joints (used to identify nociceptive pain); it does not require a clinical examination (Portenoy 2006).

|

|

|

|

Reyes-Gibby 2010 d |

Inadequate methods; Self-reported |

240 breast cancer survivors patients in America |

English [original] |

50 / 86

|

|

|

||

|

Chan 2011

|

Clinical history, sensory testing, additional tests; Pain specialist |

92 pain patients in Hong Kong |

Chinese |

81 / 65 + / - (overall) |

- (overall) |

|

||

|

Li 2012 |

Inadequate methods; Pain specialist |

140 chronic pain patients in China |

Chinese |

78 / 74

|

|

Compares ID Pain, LANSS, NPQ: Sens/Spec 78/74 vs 80/53 vs 53/91 |

||

|

Pauda 2013

|

Clinical history, sensory testing, additional tests; Not described |

392 peripheral nerve disease patients in Italy |

Italian |

78 / 74 + / + |

0 |

Compares DN4 with ID Pain: see DN4 |

||

|

Kitisomprayoonkul 2011 |

Inadequate methods; Physiatrists off site |

100 pain patients in Thailand |

Thai |

83 / 80 + / + |

0 |

|

||

|

LANSS LANSS, Leeds Assessment of Neuropathic Symptoms and Signs |

||||||||

|

Bennett 2001 b,c

|

Clinical history, sensory testing, additional tests; Pain clinician |

60 chronic pain patients in UK |

English [original] |

83 / 87 - / + (overall) |

- (overall) |

The original LANSS was developed in a sample of 60 patients with chronic nociceptive or neuropathic pain and validated in a further sample of 40 patients.

The LANSS contains 5 symptom and 2 clinical examination items.

LANSS is easy to score within clinical settings (Bennett, 2001).

|

|

|

|

Potter 2003 |

Clinical history and sensory testing; Pain specialist |

25 head and neck cancer patients in UK |

English [original] |

79 / 100

|

|

|

||

|

Tampin 2013

|

Clinical history, sensory testing, additional tests; Physiotherapist |

152 neck and upper limb pain patients in Australia |

English [original] |

22 / 88

|

|

Compares LANSS with PainDETECT: Sens/Spec 22/88 vs 64/62 |

||

|

Harourn 2012 |

Clinical history and sensory testing; Investigator |

80 leprosy patients in Ethiopia |

Amharic |

85 / 42 + / - |

0 |

Compares DN4 with LANSS: see DN4 |

||

|

Li 2012 |

Inadequate methods; Pain specialist |

140 chronic pain patients in China |

Chinese |

80 / 52.9 + / + |

0 |

Compares ID Pain, LANSS, NPQ: see ID Pain |

||

|

Mercandante 2009

|

Clinical history, sensory testing, additional tests; Physician |

167 chronic cancer patients in Italy |

Italian |

29.5 / 91.4 -- / ++ |

0 |

Compares LANSS, NPQ, NPQ-SF: Sens/Spec 30/91 vs 51/65 vs 51/61 |

||

|

Barbosa 2013

|

Clinical history, sensory testing, additional tests; Pain clinician |

167 chronic pain patients in Portugal |

Portuguese |

89 / 74 + / + (overall) |

++ (overall) |

|

||

|

Schestatsky 2011

|

Clinical history, sensory testing, additional tests; Neurologist |

90 chronic pain patients in Brazil |

Portuguese |

NA / NA

|

|

|

||

|

Hallstrom and Norrbrink 2011 |

Clinical history and sensory testing; Neurologist, pain physician |

40 spinal cord injury patients in Sweden |

Swedish |

35.7 / 100 -- / ++ |

++ |

Compares DN4, LANSS, PainDETECT, NPQ: see DN4 |

||

|

Yucel 2004 |

Clinical history, sensory testing, additional tests; Pain specialist |

101 pain patients in Turkey |

Turkish |

89.9 / 94.2 + / + |

0 |

|

||

|

S-LANSS Self-reported LANSS |

||||||||

|

Bennett 2005

|

Clinical history, sensory testing, additional tests; Pain specialist |

200 chronic pain patients in UK |

English [original] |

74 / 76 + / + (overall) |

- (overall) |

See LANSS: validated as a self-report tool = the S-LANSS (Bennett 2005); the 2 clinical examination items of LANSS were reworded asking the patients to examine themselves |

|

|

|

Walsh 2012 |

Inadequate methods; Physiotherapist |

45 low back-leg pain patients in Ireland |

English [original] |

NA / NA

|

|

Compares DN4 with S-LANSS: see DN4 |

||

|

Weingarten 2007 d,e |

Clinical history and sensory testing; Pain specialist |

205 chronic pain patients in America |

English [original] |

52 / 78

|

|

|

||

|

Elzahaf 2013 c,e,f |

Inadequate methods; Self-reported |

13 and 25 chronic pain patients in Libya |

Arabic |

NA / NA 0 / 0 |

+ |

|

||

|

Koc and Erdemoglu 2010

|

Clinical history, sensory testing, additional tests; Pain specialist |

244 chronic pain patients in Turkey |

Turkish |

72.3 / 80.4 +++ / +++ |

-- |

|

||

|

PainDETECT |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Freynhagen 2006

|

Clinical history, sensory testing, additional tests; Pain specialist |

392 pain patients in Germany |

German [original] |

85 / 80 + / + |

0 |

This questionnaire was validated in a multicentre study of 392 patients with either neuropathic or nociceptive pain (Freynhagen 2006).

There are 7 weighted sensory descriptor items (never to very strongly) and 2 items relating to the spatial (radiating) and temporal characteristics of the individual pain pattern.

incorporates an easy to use patient-based (self-report) questionnaire with 9 items that do not require a clinical examination.

|

|

|

|

Timmerman 2013 |

Inadequate methods; Physician |

60 pain patients in The Netherlands & Belgium |

Dutch |

NA / NA 0 / 0 |

0 |

Note: Dutch version |

||

|

Tampin 2013

|