Muziek tijdens het postoperatieve proces

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is de toegevoegde waarde van muziek tijdens het postoperatieve proces voor patiënten die een invasieve operatie onder anesthesiologische begeleiding ondergaan?

Aanbeveling

De werkgroep kan geen aanbeveling doen voor het luisteren naar postoperatieve muziek.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Er is voor de literatuursamenvatting gebruik gemaakt van drie systematische reviews waarin de effecten van perioperatieve muziek op angst en/of pijn (Kühlmann, 2018), op de fysiologische stressrespons (Fu, 2019), en op het gebruik van medicatie en opnameduur (Fu, 2020) zijn beschreven. Een aanvullende zoektocht naar recente studies leverde vijf relevante RCT’s op het gebied van postoperatieve muziek op, dit betrof in alle gevallen opgenomen muziek.

De meta-analyse van Kühlmann (2018) op basis van 19 RCT’s liet een klinisch relevant verschil zien voor pijn (SMD>0.2) en een aantal van de recente RCT’s lieten ook een klinisch relevant verschil zien voor pijn (verschil tussen de groepen meer dan 1,2 punten op de NRS of VAS 0-10), alle ten gunste van muziek. De bewijskracht was laag.

Voor angst lieten de meta-analyse van Kühlmann (2018) op basis van 10 RCT’s (SMD>0,2) en één van de twee recente RCT’s een klinisch relevant verschil ten gunste van muziek zien (het verschil tussen de groepen was ruim 27 punten op de STAI (vergelijkbaar met >12 mm op een VAS). De bewijskracht was laag.

Wat betreft medicatie liet de meta-analyse van Fu (2020) zien dat muziek voor, tijdens en/of na de operatie tot een klinisch relevant verschil in gebruik van opioïden, propofol en midazolam leidde, ten gunste van muziek (SMD>0,2). Het effect van alleen postoperatieve muziek is niet duidelijk doordat hier geen subgroepanalyse naar werd gedaan. Eén recente RCT liet een klein verschil zien in het gebruik van opioïden, waarbij niet bepaald kon worden of dit verschil klinisch relevant was. Eén recente RCT rapporteerde dat op de eerste postoperatieve dag het gebruik van zowel opioïden als non-opioïden hoger was in de interventiegroep, waarbij dit verschil een dag later niet langer aanwezig was. Ook hier kon niet bepaald worden of het verschil klinisch relevant was. De bewijskracht was zeer laag.

Voor twee van de belangrijke uitkomsten – stress en opnameduur – werden resultaten gerapporteerd. De meta-analyse van Fu (2019) liet zien dat er aan het eind van de operatie geen klinisch relevant verschil was in cortisolniveau (SMD<0,2), terwijl er postoperatief wel een klein klinisch relevant verschil werd gevonden ten gunste van muziek (SMD>0,2). Er was echter wel sprake van variatie in het effect tussen de studies. Het effect van alleen postoperatieve muziek is niet duidelijk doordat hier geen subgroepanalyse naar werd gedaan. Eén recente RCT liet ook verschillen zien in door de patiënt gerapporteerde stress ten gunste van muziek, maar het was niet duidelijk of deze verschillen klinisch relevant waren. Voor opnameduur liet de meta-analyse van Fu (2020) geen klinisch relevant verschil zien (SMD<0,2). De bewijskracht van deze belangrijke uitkomsten was zeer laag. Voor delier, slaapkwaliteit en patiënttevredenheid werden geen resultaten gerapporteerd.

Bewijskracht

De bewijskracht voor de cruciale uitkomsten was laag (pijn en angst) tot zeer laag (medicatie). De bewijskracht voor de belangrijke uitkomsten stress en opnameduur was zeer laag. Er werd onder andere afgewaardeerd vanwege het risico op bias (onder andere het onvolledig rapporteren van de methodologie en onvolledige blindering), indirectheid (omdat de populatie niet geheel overeenkwam met onze criteria, of omdat de uitkomstmaat cortisol werd gebruikt), heterogeniteit, het kleine aantal geïncludeerde patiënten en/of publicatiebias.

Het grootste punt van kritiek op deze studies is de heterogeniteit van de studies, de kleine populaties die onderzocht zijn en de matige kwaliteit van enkele studies, wat het lastig maakt om algehele, sterke aanbevelingen te doen. De hoge mate van heterogeniteit die in vrijwel alle onderzoeken wordt gevonden kan worden verklaard door de verschillende populaties, ingrepen en muziekinterventies die zijn onderzocht. Hoewel heterogeniteit in klinisch onderzoek over het algemeen niet gewenst is, kan het in dit geval ook worden vertaald naar een brede toepassing voor deze eenvoudige interventie.

Op basis van de gerapporteerde resultaten kan in algemene zin geconcludeerd worden dat muziek mogelijk een positieve uitwerking heeft op de patiënt tijdens het postoperatieve proces aangaande pijn en angst. Daarnaast zijn er geen aanwijzingen dat het aanbieden van muziek nadelige effecten heeft op patiënten, wat strookt met het geneeskundige grondbeginsel ‘primair niet schaden’.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en eventueel. hun verzorgers)

Het belangrijkste doel van luisteren naar muziek rondom de operatie is de verbetering van het zorgproces voor de patiënt die wordt geopereerd, zodat de ervaring met de zorg verbetert en het herstel bespoedigd wordt. Manieren om dit te meten zijn bijvoorbeeld het reduceren van angst en/of pijn, de hoeveelheid medicatie die wordt gebruikt (analgetica of sedativa) of parameters van de stressreactie van het lichaam (zoals fysiologische parameters (hartslag, bloeddruk) of cortisol) rond een operatie. Het optimaliseren van slaapkwaliteit is een voorbeeld van een uitkomst die helpt in een voorspoedig herstel.

Op de preoperatieve polikliniek, of in de preoperatieve informatiefolder, kan de patiënt worden gewezen op de mogelijkheden van het luisteren naar muziek en kan de patiënt geïnformeerd worden hoe het luisteren naar muziek praktisch gezien in zijn werk gaat. De toepassing van muziek in het ziekenhuis vereist beperkte kennis en vaardigheden. Een klein deel van de patiënten, voornamelijk de oudere patiënt, zal hulp nodig hebben bij het gebruik van de muziekapparatuur. Ten aanzien van de soort muziek wordt de voorkeursmuziek van de patiënt aangehouden. Dit kunnen voor de patiënt specifieke muziekstukken zijn, maar er kan ook op basis van genre worden gekozen. Het meest praktische is dat patiënten zelf het volume van de muziek instellen, eventueel kan een volumebegrenzer helpen. Belangrijk is om het volume niet te luid in te stellen, mede vanwege de tijdelijke paralyse van de musculus stapedius bij het in werking treden van algehele anesthesie.

Overigens is er ook een groep van patiënten die niet van muziek houdt en hier perioperatief dan ook geen behoefte aan zal hebben. Vanzelfsprekend blijft dit dan achterwege.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

Er zijn tot op heden geen kosteneffectiviteitsstudies uitgevoerd naar het toepassen van muziek tijdens het perioperatieve proces. Gezien het werkingsmechanisme van muziek zou de kosteneffectiviteit kunnen voortkomen uit de vermindering van angst en pijn rondom de operatie. Hierdoor zou het gebruik van anxiolytica en analgetica kunnen afnemen. Een afname van angst en pijn kan ook leiden tot verkorte opnameduur, en daarmee een daling in complicaties en het risico op delier (voornamelijk maar niet uitsluitend bij de oudere patiëntenpopulatie). De grootte van dit effect, en de eventuele kostenbesparing die hiermee gepaard gaat, zal berekend moeten worden in kosteneffectiviteitsstudies.

Qua mogelijke uitgaven kan er worden gedacht aan eenmalige kosten van aanschaf van apparatuur om muziek af te spelen of op te beluisteren, eventuele abonnementskosten voor online streamingdiensten om muziek af te spelen (met name voor patiënten die dit zelf niet mee hebben), en indien nodig werktijd van zorgprofessionals om te ondersteunen in het afspelen van de muziek. De ervaring uit diverse RCT’s en implementatietrajecten is dat de meeste patiënten hun eigen muziekdrager met hoofdtelefoon of oortelefoon (‘oortjes’) meenemen met eigen muziek. Veel ziekenhuizen hebben al tablets met een hoofd- of oortelefoon in huis.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

In het kader van de procesevaluatie zijn er een aantal verschillende implementatiestudies uitgevoerd naar (perioperatieve) muziekinterventies, waaronder ook een Nederlandse pilot implementatiestudie. De resultaten van deze studie zijn nog niet gepubliceerd, wel is het studieprotocol beschikbaar (Kakar, 2021). Het gaat om een studie uitgevoerd in een Nederlands ziekenhuis waarbij gestreefd werd tenminste 100 patiënten te includeren die een operatie ondergingen wegens een chronische darmontsteking (IBD) of colorectaal carcinoom. De eerste resultaten van deze studie laten zien dat 75% van de patiënten met een op-maat-gemaakte strategie de muziek aangeboden kreeg door zorgprofessionals op verschillende levels (polikliniek, verpleegafdeling). 72% van de patiënten die muziek aangeboden kreeg heeft hier gebruik van gemaakt. Er werden weinig potentiële bezwaren geregistreerd ten aanzien van de muziekinterventie, wel werd benadrukt dat het belangrijk is de voorkeursmuziek van de patiënt te gebruiken.

In de praktijk zal de voornaamste belasting die de postoperatieve interventie met zich meebrengt liggen bij de recoveryverpleegkundige en afdelingsverpleegkundige. Het is daarom met name van belang om de recoveryverpleegkundigen en afdelingsverpleegkundigen te informeren over de aanbeveling betreffende perioperatieve muziek en vaardigheden in het ondersteunen bij het luisteren naar muziek te trainen. Deze training kan gekoppeld worden aan bestaande bij- en nascholingsprogramma’s.

Uit de studie bleek verder dat 28% van de patiënten geen behoefte had aan de interventie. Hierbij is niet verder gevraagd naar de reden, mogelijk zouden ze beter geïnformeerd kunnen worden ten aanzien van de voordelen van het luisteren naar muziek, hoewel het luisteren naar muziek in de perioperatieve setting anders is dan op de polikliniek. Morele en ethische bezwaren zijn niet van toepassing bij deze interventie.

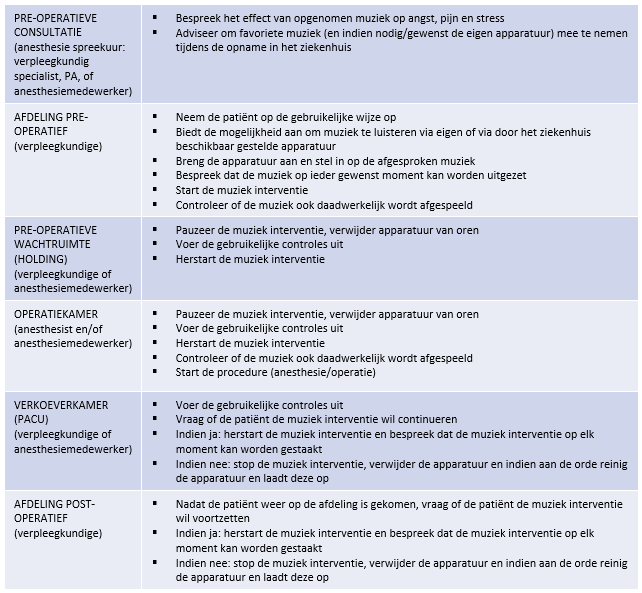

In de pilot implementatie studie werd een inschatting gemaakt van de mate van belasting voor zorgverleners. De voornaamste belasting werd ingeschat op tijd en impact op werkzaamheden van verpleegkundigen die de patiënt in de apparatuur voorzien, en de totale belasting werd laag ingeschat. Zie voor de toepassing Figuur 1 (Kühlmann, 2019).

Figuur 1: Werkwijze voor het aanbieden van het luisteren naar muziek tijdens het perioperatieve proces

Deze richtlijnmodule heeft alleen betrekking op patiënten die klinisch worden geopereerd. Het luisteren naar muziek kan worden gestart op de verpleegafdeling, de patiënt kan met de muziekapparatuur en gekozen muziek naar de holding worden vervoerd en vervolgens gedurende de operatie naar muziek luisteren. Ook postoperatief kan de patiënt naar muziek (blijven) luisteren. In de studies die geïncludeerd zijn in de literatuursamenvatting voor postoperatieve muziek varieert de frequentie en de duur van het luisteren naar muziek aanzienlijk. Hierbij kan gesteld worden dat de frequentie en duur van de muziek en ook het genre en volume afgestemd dienen te worden op de voorkeuren van de patiënt. Op bepaalde momenten zal de muziek onderbroken moeten worden, om goede communicatie met patiënt en zorgverleners toe te staan, bijvoorbeeld tijdens overdrachten en veiligheidsprocedures (time-out procedure etc.).

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van de argumenten voor en tegen postoperatieve muziek

Gezien de overwegend (zeer) lage bewijskracht kan de werkgroep op basis van het beschikbare bewijs geen aanbeveling doen voor het aanbieden van postoperatieve muziek. Ook op basis van de overige overwegingen slaat de balans niet duidelijk uit in het voordeel van het aanbieden van muziek, aangezien hieraan ook kosten zijn verbonden in de vorm van mogelijke aanschaf en onderhoud van apparatuur, en tijd van het zorgpersoneel om het luisteren naar muziek met de patiënt te bespreken en de patiënt zonodig te ondersteunen bij het luisteren naar muziek. Mocht een patiënt aangeven naar muziek te willen luisteren dan kan besproken worden of en hoe dit gefaciliteerd kan worden.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Veel patiënten die een operatie moeten ondergaan in het ziekenhuis krijgen te maken met angst, stress en pijn. Niet alleen leidt dit tot vervelende ervaringen voor de patiënt, ook kunnen deze factoren het herstel van patiënten na een operatie nadelig beïnvloeden. Het ervaren van angst en stress vóór een operatie kan leiden tot een toename van pijn na de operatie. Luisteren naar muziek rondom het gehele perioperatieve proces (zowel pre-, intra- of post-, alsook een combinatie) kan mogelijk leiden tot een significante vermindering van angst en pijn bij de patiënt. Het luisteren naar muziek activeert het limbische systeem in de hersenen, waardoor er verschillende hormonen zoals serotonine en endogene opioïden vrijkomen, wat leidt tot een vermindering van angst en pijn. Neurofysiologisch onderzoek en fMRI scans laten een verbeterde voortgeleiding van impulsen zien in de hersenen onder invloed van muziek. Ook neemt de activiteit van de sympathicus af waardoor fysiologische symptomen van stress verminderen (denk aan een rustigere hartslag, lagere bloeddruk). Muziek is breed toegankelijk en goedkoop, is duurzaam, mogelijk kostenbesparend en komt daarmee mogelijk het welzijn van de patiënt ten goede.

Deze richtlijn bestaat uit vier verschillende modules. In elke aparte module wordt besproken of preoperatieve, dan wel intraoperatieve, dan wel postoperatieve, dan wel perioperatieve muziek bij volwassen patiënten die geopereerd worden in het ziekenhuis, leidt tot positieve uitkomsten voor de patiënt. Goed is te weten dat deze richtlijn gaat over het luisteren naar opgenomen muziek en niet over muziektherapie. Bij muziektherapie wordt muziek aangeboden door een muziektherapeut, waarbij de werkwijze afgestemd wordt op de individuele patiënt. Het is hierbij niet mogelijk om het effect van de muziek alleen te evalueren, omdat er mogelijk ook een effect is van de interactie tussen de muziektherapeut en de patiënt. Tot slot, de richtlijn gaat ook niet over live muziek aangezien over deze vorm van het aanbieden van muziek vrijwel geen literatuur beschikbaar is.

Deze module betreft postoperatieve muziek.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

None of the included studies reported on the effect of live music that only involved listening to music. One study in the review by Kühlmann (2018) used live music but since patients were actively engaged, this study was outside the scope of this guideline. Therefore no conclusions can be drawn about the effect of live music on the selected outcomes.

Pain (crucial outcome)

|

Low GRADE |

Recorded music in the postoperative setting may reduce pain when compared with no music in patients undergoing invasive surgery.

Sources: (Kühlmann, 2018; Aris, 2019; Laframboise-Otto, 2020; Sfaniakis, 2017) |

Anxiety (crucial outcome)

|

Low GRADE |

Recorded music in the postoperative setting may reduce anxiety when compared with no music in patients undergoing invasive surgery.

Sources: (Kühlmann, 2018; Ashok, 2019; Lee, 2017) |

Medication use (analgesics and hypnotics) (crucial outcome)

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of recorded music in the postoperative setting on postoperative opioid requirement when compared with no music in patients undergoing invasive surgery.

Sources: (Fu, 2020; Aris, 2019; Laframboise-Otto, 2020) |

Stress (important outcome)

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of recorded music in the postoperative setting on cortisol levels when compared with no music in patients undergoing invasive surgery.

Sources: (Fu, 2019; Laframboise-Otto, 2020) |

Length of stay (important outcome)

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of recorded music in the postoperative setting on length of stay in the PACU, ICU and hospital when compared with no music in patients undergoing invasive surgery.

Sources: (Fu, 2020) |

Delirium, sleep disturbance/sleep quality, patient satisfaction

|

- GRADE |

No evidence (systematic reviews or RCTs) was found regarding the effect of postoperative music on delirium, sleep disturbance/sleep quality, and patient satisfaction when compared with no music in patients undergoing invasive surgery. |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

The three systematic reviews and meta-analyses included studies evaluating the effectiveness of postoperative music on anxiety and/or pain (Kühlmann, 2018), the physiological stress response (Fu, 2019), medication requirement and hospital length of stay (Fu, 2020). The five recent RCTs (Aris, 2019; Ashok, 2019; Laframboise-Otto, 2020; Lee, 2017; Sfaniakis, 2017) assessed the effects of postoperative music on pain, anxiety, medication use, and stress.

Kühlmann (2018) included RCTs investigating the effect of music interventions on anxiety and pain during invasive surgery. Studies were included in the meta-analysis only if they included measures of dispersion of a particular outcome. For anxiety, 13 RCTs reported on music interventions in the postoperative setting and 10 of these RCTs were included in the meta-analysis. For pain, 27 RCTs reported on music interventions in the postoperative setting and 19 of these RCTs were included in the meta-analysis (see Table 4.1).

In total, this review included 29 RCTs evaluating the effectiveness of music on anxiety and/or pain in the postoperative setting. Studies reporting on music in the postoperative setting were conducted in North America (n=15), Asia (n=9), and Europe (n=5). Patients in these studies underwent a wide variety of invasive types of surgery. Twenty-eight studies used recorded music, not necessarily through headphones. One study used live music. This intervention is outside the scope of this guideline, as patients were actively engaged in music making, for example through singing, playing an instrument, or moving to music. In twelve studies patients listened to recorded music during one session, for a duration of 20 to 117 minutes. Fifteen studies offered multiple (range three to six) sessions of music listening, with a duration of 15 to 156 minutes. Difference music genres were used, the research team often selected classical, relaxing, sedative, easy listening music, while in some studies music genre was patient-selected. Patients in the control group received nothing, routine care, quiet rest period, or (noise-cancelling) headphones.

Fu (2019) included RCTs investigating the effect of preoperative, intraoperative and/or postoperative music on the stress response to surgery. Eighteen RCTs were included, of which four RCTs compared the effect of a music intervention in the postoperative setting on the physiological stress response, as compared with no music (see Table 4.2).

These four RCTs were performed in North America (n=1) and Europe (n=3). Patients underwent a variety of invasive types of surgery. Patients in the intervention group listened to different genres of recorded music, including classical, pop, jazz, and new age music, for 15, 30, or 60 minutes. Patients in the control group received standard care or headphones without music.

Fu (2020) included RCTs that evaluated the effect of preoperative, intraoperative and/or postoperative music on medication requirement or length of stay. Out of 55 included RCTs, 23 RCTs reported the effect of music in the postoperative setting on medication. Four of these RCTs and three additional RCTs reported hospital, PACU, or ICU length of stay (see Table 4.3).

Studies were performed in North America (n=10), Asia (n=8), and Europe (n=8) and included patients undergoing a diverse range of surgical procedures. Patients in the intervention group listened to different genres of recorded music, including jazz, classical and new age music. Sixteen RCTs reported that patients selected music to listen to (by choosing a CD, track, music genre, or their ‘own favorite music’). In 13 RCTs, patients listened to music during one single session and in 12 RCTs, patients listened to music during multiple sessions, sometimes spread over multiple days. Patients in the control group received standard care, rest, no music, or headphones without music.

The five recent RCTs evaluating the effect of postoperative music (Aris, 2019; Ashok, 2019; Laframboise-Otto, 2020; Lee, 2017; Sfaniakis, 2017) were performed in North America (n=1), Asia (n=3), and Europe (n=1) (see Table 4.4). Surgery included total knee arthroplasty (TKA), coronary artery bypass graft (CABG), elective knee or hip arthroplasty orthopedic surgery, major abdominal surgery, and multiple surgery types. Patients listened to various genres of recorded music, including classical music, soothing music, sedative music without lyrics, or music of patients’ choice via internet radio. In two studies music was selected by the research team, while in the other three studies music was selected by patients (from a list). In three studies, patients in the intervention group listened to music during 1 to 2 sessions of 30 to 60 minutes, in the recovery unit, PACU and/or the surgical ward. In the other two studies, patients listened to music during multiple sessions over several days (up to seven days) postoperatively. Patients in the control groups received usual care, which could include cardiac rehabilitation after CABG, analgesic medication, or routine nursing observation.

Results

Pain

The review by Kühlmann (2018) included 26 RCTs that evaluated the effect of postoperative music on pain. A meta-analysis of 19 of these RCTs showed that the pooled standardized mean difference was -0.53 (95% CI -0.79 to -0.28); p<0.001, I2=82.

Three out of six recent RCTs assessed pain (Aris, 2019; Laframboise-Otto, 2020; Sfaniakis, 2017). Because of differences in reporting of results (median or mean pain scores) no meta-analysis was performed and results are described per study.

Aris (2019) used an NRS (0-10) to assess pain at 0, 10, 20, 30 and 60 minutes in the recovery unit. At all-time points, lower median pain scores were reported in the intervention group (0) compared with the control group (1.5 to 2). At 60 minutes, this difference was statistically significant (U = 277, z =−2004, p = 0.045) with a small effect size of 0.27.

Laframboise-Otto (2020) used an NRS (0-10) to assess pain intensity on the evening after surgery and then three times a day for postoperative day 1 and 2. At all-time points, pain scores were lower in the music group as compared with the control group. These differences were statistically significant in the evening on the day of surgery (mean 3.94 versus 4.67; p=0.02), and for all three measurements on postoperative day 1 (3.39 versus 4.29; p=0.04, 3.25 versus 4.36; p=0.01, and 5.05 versus 5.67; p=0.21).

Sfaniakis (2017) used a VAS (0-10) to assess pain scores before and after the postoperative intervention (timing not further specified). Before the intervention, mean pain scores were 4.42 (SD 2.24) in the music group and 3.98 (SD 1.66) in the control group. After the intervention, mean pain scores were 2.64 (SD 1.90) in the music group and 3.76 (1.39) in the control group. A significant interaction was found between ‘type of intervention’ and ‘VAS’ (F (1, 26.552) = 69.606, p<0.001)).

Anxiety

The review by Kühlmann (2018) included 13 studies that evaluated the effect of postoperative music on anxiety. A meta-analysis of 10 of these RCTs showed that the pooled standardized mean difference was -0.66 (95% CI -1.07 to -0.25); p=0.002, I2=87.

Two recent RCTs assessed anxiety (Ashok, 2019; Lee, 2017). Because of differences in reporting of results (median or mean anxiety scores) no meta-analysis was performed and results are described per study.

Ashok (2019) used the HADS (0-21) to assess anxiety. On the preoperative day, median scores were 7.56 (IQR 5 to 12.75) in the intervention group and 7.50 (IQR 7 to 9) in the control group, p=0.49. On postoperative day 2, median scores were 6 (IQR 4 to 9) in both the intervention and control group. On postoperative day 7, median scores were 1 (IQR 0 to 3) in the intervention group and 1.50 (IQR 0 to 5) in the control group, p=0.31.

Lee (2017) used the STAI (20-80) to assess anxiety before and after the intervention. Before the intervention, STAI scores were similar between the groups (59 versus 58.94). After the intervention, mean anxiety scores were 31.20 (SD 4.84) in the intervention group and 58.78 (SD 5.49) in the control group (p<0.001).

Medication use (analgesics and hypnotics)

The review by Fu (2020) included 22 RCTs that evaluated the effect of postoperative music on analgesics. Out of these, 20 RCTs assessed the effect of music on postoperative opioid requirement, one RCT assessed the effect on postoperative patient-controlled analgesia requirement, and one RCT assessed the effect on postoperative analgesic medication requirement. A meta-analysis was performed for the effect of preoperative, intraoperative, and/or postoperative music on postoperative opioid requirement, propofol, and midazolam. Results should be interpreted with caution because no subgroup analysis was performed for music in the postoperative setting solely.

For postoperative opioid requirement, a meta-analysis of 20 RCTs (including eight RCTs using music in the postoperative setting) showed a pooled standardized mean difference of -0.31 (95% CI -0.45 to -0.16); p<0.001, I2=44.3. The forest plot provided in the review demonstrated inconsistency, with several studies showing a lower postoperative opioid requirement in the music group, but also a number of studies showing no difference between the groups, and a few studies showing a lower postoperative opioid requirement in the control group.

For propofol, a meta-analysis of nine RCTs (not including any RCTs using music in the postoperative setting) showed a pooled standardized mean difference of -0.72 (95% CI -1.01 to -0.43); p=0.00001, I2=61.1.

For midazolam, a meta-analysis of three RCTs (not including any RCTs using music in the postoperative setting) showed a pooled standardized mean difference of -1.07 (95% CI -1.70 to -0.44); p<0.001, I2=73.1.

Two RCTs evaluated the effect of postoperative music on analgesics (Aris, 2019; Laframboise-Otto, 2020). Aris (2019) reported that the average total amount of opioids used was 2.36 mg (SD 4.34; range 0-14) in the intervention group and 2.77 mg (SD 3.27; range 0 to 12) in the control group (p=0.141). Laframboise-Otto (2020) reported analgesic usage in terms of Opioid Morphine Equivalency (OME; mg) and nonopioid acetaminophen equivalency (NOAE; mg). On postoperative day 1, mean use of opioids was 51.52 mg (SD 37.49) in the music group and 35.00 (SD 27.43) in the control group (p=0.10). On postoperative day 2, mean use of opioids was 42.81 (SD 35.54) in the music group and 40.56 (SD 32.93) in the control group (p=0.88).

For non-opioids, mean usage on postoperative day 1 was 1,814.58 mg (SD 1,027.39) in the music group and 1,554.35 mg (SD 969.85) in the control group (p=0.38). On postoperative day 2, mean nonopioid usage was 1,746.88 mg (SD 1,310.12) in the music group and 1,661.11 (SD 1,715.47) in the control group (p=0.89).

Stress

The review by Fu (2019) included four RCTs that evaluated the effect of postoperative music on the physiological stress response. A meta-analysis was performed for the effect of preoperative, intraoperative, and/or postoperative music on cortisol levels. Results should be interpreted with caution because no subgroup analysis was performed for music in the postoperative setting solely.

A meta-analysis of five RCTs reporting cortisol levels at the end of surgery (including one RCT using music in the postoperative setting) showed a pooled standardized mean difference of –0.14 (95% CI -0.57 to 0.28); p=0.50, I2=60.15.

A meta-analysis of six RCTs reporting cortisol levels postoperatively (including one RCT using music in the postoperative setting) showed a pooled standardized mean difference of –0.30 (95% CI -0.53 to -0.07); p=0.01, I2=0.

One recent RCT evaluated the effect of postoperative music on stress. Laframboise-Otto (2020) used an NRS (0-10) to assess pain distress on the evening after surgery and then three times a day for postoperative day 1 and 2. At all-time points, pain distress scores were lower in the music group as compared with the control group. These differences were statistically significant in the morning (mean 1.42 versus 2.67; p=0.02) and afternoon (1.86 versus 2.79; p=0.01) on postoperative day 1, and in the morning on postoperative day 2 (mean 1.88 versus 3.11; p=0.003).

Length of stay

The review by Fu (2020) included seven RCTs that evaluated the effect of postoperative music on hospital, PACU or ICU length of stay. A meta-analysis was performed for the effect of preoperative, intraoperative, and/or postoperative music on length of stay. Results should be interpreted with caution because no subgroup analysis was performed for music in the postoperative setting.

A meta-analysis of nine RCTs (including four RCTs using music in the postoperative setting, reporting hospital and ICU length of stay) showed a pooled standardized mean difference of –0.18 (95% CI -0.43 to 0.067); p=0.15, I2=56.0.

None of the six recent RCTs reported on the effect of postoperative music on length of stay.

Patient satisfaction, delirium, sleep disturbance/sleep quality

None of the three systematic reviews or six recent RCTs reported on these outcomes of music in the postoperative setting.

Level of evidence of the literature

All evidence was derived from randomized controlled trials, therefore, the level of evidence for all outcomes started at ‘high quality’.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure pain was downgraded by two levels because of study limitations (-2; risk of bias because randomization procedure was inadequate, lack of blinding, loss to follow-up, and incomplete reporting of study methodology).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure anxiety was downgraded by two levels because of study limitations (-1; risk of bias for lack of blinding, loss to follow-up, and incomplete reporting of study methodology); and publication bias (-1; as the funnel plot in the review by Kühlmann 2018 raised the possibility of publication bias).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure medication use (analgesics/hypnotics) was downgraded by four levels because of study limitations (-1; risk of bias for lack of blinding, loss to follow-up, and incomplete reporting of study methodology); inconsistency (-1; for heterogeneity); applicability (-1; bias due to indirectness because of different timing of the music intervention); and publication bias (-1; the funnel plot in the review by Fu 2020 raised the possibility of publication bias).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure stress was downgraded by four levels because of study limitations (-1; risk of bias for lack of blinding, loss to follow-up, and incomplete reporting of study methodology); conflicting results (-1; for inconsistency); applicability (-1; bias due to indirectness of the outcome cortisol); and imprecision (-1; low number of patients included).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure length of stay was downgraded by three levels because of study limitations (-1; risk of bias because of lack of blinding and incomplete reporting of study methodology); conflicting results (-1; for inconsistency); and imprecision (-1; low number of included patients).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measures delirium, sleep disturbance/sleep quality, and patient satisfaction could not be assessed because none of the included studies reported these outcomes.

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question: ‘What are the effects of music (recorded or live) in the postoperative setting on patients undergoing invasive surgery with anaesthesia care when compared to no music?’

P: patients undergoing invasive surgery with anaesthesia care (general anaesthesia, regional anaesthesia, or both);

I: postoperative music (recorded or live), in case of recorded music patients listened to the music through headphones;

C: no music (no active intervention);

O: pain, anxiety, medication use (analgesics and hypnotics), stress, delirium, sleep disturbance/sleep quality, patient satisfaction, length of stay.

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group, although aware that there are many different goals which are aspired in music interventions, considered pain, anxiety and medication use (analgesics and hypnotics) as critical outcome measures for decision making; and stress, delirium, sleep disturbance/sleep quality, patient satisfaction and length of stay as important outcome measures for decision making.

A priori, the working group did not define the outcome measures listed above but used the definitions used in the studies. Outcomes had to be assessed using validated instruments. The outcome stress could be assessed using patient reported outcomes or cortisol levels.

- Pain: The working group defined 12 mm on a Visual Analogue Scale as a minimal clinically (patient) important difference.

- Anxiety: The working group defined 12 mm on a Visual Analogue Scale as a minimal clinically (patient) important difference.

- Stress: the working group defined a difference equal to 0.5 standard deviation between the groups as a minimal clinically (patient) important difference.

- Delirium: The working group defined 1 point on the DOS (Delirium Observatie Screening) as a minimal clinically (patient) important difference.

- Patient satisfaction: the working group defined a difference of 10% as a minimal clinically (patient) important difference.

- Length of stay: The working group defined 0.5 days as a minimal clinically (patient) important difference.

If studies reported a standardized mean difference, a difference >0.2 between the groups was considered as a minimal clinically (patient) important difference (Cohen, 1988).

Search and select (Methods)

Three systematic reviews were suggested by members of the guideline working group. This included a systematic review and meta-analysis by Kühlmann (2018) about the effect of perioperative music interventions on anxiety and pain in surgery, a systematic review and meta-analysis by Fu (2019) about the effect of perioperative music on the physiological stress response to surgery, and a systematic review and meta-analysis by Fu (2020) about the effect of perioperative music on medication requirement and hospital length of stay. The working group decided to use these reviews as a starting point and perform an update of the search to identify recent publications. Although the searches by Fu were conducted more recently (2019), the search conducted by Kühlmann (2018) on 20 October 2016 was more sensitive as it was not limited to studies reporting on specific outcomes (stress response, medication, length of stay).

The databases Embase (through Embase.com), Medline (through OVID), and PsycInfo (through OVID) were searched with relevant search terms from 1 January 2016 until 23 November 2020 for the question regarding the effects of perioperative music on patients undergoing invasive surgery with anaesthesia care. The search was limited to systematic reviews and randomized controlled trials. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 472 hits.

Studies were selected based on the following criteria:

(1) systematic review or randomized controlled trial;

(2) full-text English language publication;

(3) adult patients;

(4) invasive surgery with general anaesthesia, regional anaesthesia or both;

(5) music intervention having melody, harmony and rhythm;

(6) either live music (where the musician gives a live performance at the patient’s bedside) or recorded music (where patients listen to music through headphones);

(7) the intervention should only involve listening to music and no active participation such as patients making music or singing along;

(8) outcomes were assessed using a validated method.

180 studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, 175 studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods) and 5 randomized controlled trials were included.

Results

The three systematic reviews by Kühlmann (2018), Fu (2019) and Fu (2020) (including 92, 18, and 55 RCTs) are summarized in the evidence tables. This guideline consists of four parts, based on the timing of the music intervention (preoperative/ intraoperative/ postoperative/ multiple times). Studies included in the three reviews are presented in the relevant part of the guideline, for example. 29/92 RCTs included in the review by Kühlmann (2018) evaluated a postoperative music intervention. These 29 studies are summarized in Table 4.1. The quality assessment of the systematic reviews is summarized in Table 4.6.

The update of the search identified five RCTs that were published from 2016 and were not included in the reviews by Kühlmann (2018), Fu (2019) or Fu (2020). Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. and the assessment of the risk of bias for the RCTs is summarized in the risk of bias tables (Table 4.5).

Referenties

- Fu VX, Oomens P, Sneiders D, van den Berg SAA, Feelders RA, Wijnhoven BPL, Jeekel J. The Effect of Perioperative Music on the Stress Response to Surgery: A Meta-analysis. J Surg Res. 2019 Dec;244:444-455. Doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2019.06.052. Epub 2019 Jul 18. PMID: 31326711.

- Fu VX, Oomens P, Klimek M, Verhofstad MHJ, Jeekel J. The Effect of Perioperative Music on Medication Requirement and Hospital Length of Stay: A Meta-analysis. Ann Surg. 2020 Dec;272(6):961-972. Doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000003506. PMID: 31356272; PMCID: PMC7668322.

- Kühlmann AYR, de Rooij A, Kroese LF, van Dijk M, Hunink MGM, Jeekel J. Meta-analysis evaluating music interventions for anxiety and pain in surgery. Br J Surg. 2018 Jun;105(7):773-783. Doi: 10.1002/bjs.10853. Epub 2018 Apr 17. PMID: 29665028; PMCID: PMC6175460.

- Aris A, Sulaiman S, Che Hasan MK. The influence of music therapy on mental well-being among postoperative patients of total knee arthroplasty (TKA). Enferm Clin. 2019 Sep;29 Suppl 2:16-23. English, Spanish. Doi: 10.1016/j.enfcli.2019.04.004. Epub 2019 Jun 14. PMID: 31208927.

- Ashok A, Shanmugam S, Soman A. Effect of music therapy on hospital induced anxiety and health related quality of life in coronary artery bypass graft patients: a randomised controlled trial. J Clin Diagn Res. 2019 Nov;13(11): YC05-YC09. Doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2019/42725.13274.

- Laframboise-Otto JM, Horodyski M, Parvataneni HK, Horgas AL. A Randomized Controlled Trial of Music for Pain Relief after Arthroplasty Surgery. Pain Manag Nurs. 2021 Feb;22(1):86-93. Doi: 10.1016/j.pmn.2020.09.003. Epub 2020 Oct 28. PMID: 33129705.

- Lee WP, Wu PY, Lee MY, Ho LH, Shih WM. Music listening alleviates anxiety and physiological responses in patients receiving spinal anesthesia. Complement Ther Med. 2017 Apr;31:8-13. Doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2016.12.006. Epub 2017 Jan 7. PMID: 28434475.

- Sfaniakis MZ, Karteraki M, Kataki P, Christaki O, Sorrou E, Chatzikou V, Melidoniotis E. Effect of music therapy intervention in acute postoperative pain among obese patients. International Journal of Caring Sciences. 2017. May-August;10(2): 937-945.

- Cohen, J. 1988. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd Edition.

Routledge. - Kakar E, Ista E, Klimek M, Jeekel J. Implementation of music in the perioperative standard care of colorectal surgery: study protocol of the IMPROVE Study. BMJ Open. 2021 Oct 28;11(10):e051878. Doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-051878. PMID: 34711596; PMCID: PMC8557300.

- Kühlmann AYR (2019). The Sound of Medicine – Evidence-based music interventions in healthcare practice (ISBN 978-94-6375-451-4 Dissertatie, Erasmus Universiteit Rotterdam). https://www.publicatie-online.nl/publicaties/rosalie-kuhlmann/

Evidence tabellen

Table 4.1 Evidence table for systematic review of RCTs on the effects of music in the postoperative setting on anxiety and/or pain

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Type of surgery |

Type of anaesthesia |

Intervention

|

Comparison / control |

Anxiety scale and results |

Pain scale and results |

Comments |

|

Kühlmann (2018)

|

Systematic review and meta-analysis of RCTs

Literature search up to 20 October 2016. 92 RCTs were included in the review and 81 in the meta-analysis.

Anxiety 13 RCTs used music in the postoperative setting and 10 of these RCTs were included in the meta-analysis.

B: Liu, 2015, China* C: Zhou, 2015, China* G: Cutshall, 2011, USA* J: Allred, 2010, USA N: Nilsson, 2009, Sweden O: Ebneshahidi, 2008, Iran Q: Sendelbach, 2006, USA S: Voss, 2004, USA U: Nilsson, 2003b, Sweden V: Good, 1999, USA Z: Barnason, 1995, USA* AA: Good, 1995, USA* AC: Mullooly, 1988, USA

Pain 27 RCTs used music in the postoperative setting and 19 of these RCTs were included in the meta-analysis

A: Finlay, 2016, UK B: Liu, 2015, China* D: Mirbagher Ajorpaz, 2014, Iran* E: Jafari, 2012, Iran* F: Vaajoki, 2012, Finland* G: Cutshall, 2011, USA* H: Ghetti, 2011, USA* I: Li, 2011, China* J: Allred, 2010, USA* K: Easter, 2010, USA L: Good, 2010, USA* M: Şen, 2010, Turkey* N: Nilsson, 2009, Sweden* O: Ebneshahidi, 2008, Iran* P: McCaffrey, 2006, USA* Q: Sendelbach, 2006, USA* R: Masuda, 2005, Japan* S: Voss, 2004, USA* T: Nilsson, 2003a, Sweden* U: Nilsson, 2003b, Sweden* V: Good, 1999, USA* W: Good, 1998, Taiwan* X: Taylor, 1998, USA* Y: Zimmerman, 1996, USA* AA: Good, 1995, USA AB: Heitz, 1992, USA AC: Mullooly, 1988, USA*

Source of funding: This work was funded by Stichting Coolsingel (Rotterdam, The Netherlands) and Stichting Swart-van Essen (Rotterdam, The Netherlands). The funders of the study had no role in the study design, data collection, data analysis, manuscript preparation and publication decision.

Conflicts of interest: M.G.M.H. was supported by ZonMw, the European Institute for Biomedical Imaging Research, European Society of Radiology and Cambridge University Press outside of the submitted work. The authors declare no other conflict of interest.

|

Inclusion criteria SR: -full-text article of an RCT; -investigating effects of music interventions on anxiety and/or pain; -mean age of participants at least 18 years; -written in English; -invasive surgical procedures, either open or laparoscopic, such as abdominal surgery or total knee surgery; -use of general anaesthesia, regional anaesthesia or both; - use of any recorded or live music intervention having melody, harmony and rhythm; - intervention offered by a researcher or a music therapist; - intervention performed in a hospital or outpatient clinic.

Exclusion criteria SR: -studies involving non-invasive procedures such as endoscopy; -studies using quasi- or pseudo-randomization; -nature sounds were considered only when they were used in addition to music;

Important patient characteristics

N, total and per group (music versus no music) A: 98, 72/17 B: 98, 47/51 C: 170, 85/85 D: 60, 30/30 E: 60, 30/30 F: 167, 83/84 G: 100, 49/51 H: 18, 9/9 I: 120, 60/60 J: 56, 28/28 K: 213, 111/102 L: 198, 95/103 M: 70, 35/35 N: 58, 28/30 O: 77, 38/39 P: 124, 62/62 Q: 86, 50/36 R: 44, 22/22 S: 40, 19/21 T: 100, 51/49 U: 125, 62/63 V: 227, 118/109 W: 38, 16/22 X: 40, 20/20 Y: 64, 32/32 Z: 67, 33/34 AA: 42, 21/21 AB: 40, 20/20 AC: 28, 14/14

Mean age ± SD or range A: 68.1 ± 8.0 B: 53.2 ± 15.8 C: 47.0 ± 9.5 D: - E: 57.8 ± 10.7 F: 63.0 ± 12.0 G: 62.8 ± 12.9 H: 50.1 ± 10.3 I: 45.0 ± 9.4 J: 63.9 ± 9.5 K: 53.5 ± 14.1 L: 48.7 ± 12.1 M: 30.2 ± 3.9 N: 66.6 ± 10.0 O: 25.2 ± 4.37 P: 75.7 ± 6.1 Q: 63.0 ± 13.5 R: 69.0 ± 6.0 S: 63.0 ± 13.0 T: 54.0 ± 13.4 U: 52.5 ± 13.7 V: 45.4 ± 11.0 W: 40.6 ± 6.8 X: 39.0 ± 7.9 Y: 67.0 ± 9.9 Z: 67.0 ± 9.9 AA: 46.0 ± 12.5 AB: 49.0 ± 4.2 AC: 47.0 ± 5.0

Sex (% men) A: 41% B: 66% C: 50% D: 48% E: 43.4% F: 50% G: 77% H: 59% I: 0% J: 45% K: 32.5% L: 32% M: 0% N: - O: 0% P: 35% Q: 70% R: 41% S: 64% T: 69% U: 50% V: 17% W: 8% X: 4% Y: 68% Z: 68% AA: 25% AB: 7% AC: 0%

|

A: TKA B: thoracic C: radical mastectomy D: open heart E: CABG/ valve repair F: major abdominal G: CABG/ valve-repair H: organ Tx I: breast cancer J: TKA K: eye, oral, neurologic, general gastro-enterologic, gynecologic orthopedic, urologic L: major abdominal M: CS N: CABG/ valve O: CS P: hip/knee Q: cardiac R: orthopedic S: open heart T: varicose vein and inguinal hernia U: varicose vein and inguinal hernia V: gynecologic gastro-intestinal, exploratory, urinary W: major gynecologic or surgical abdominal X: abdominal hysterectomy Y: CABG Z: CABG AA: abdominal AB: mastectomy, thyroidectomy, parathyroidectomy AC: elective abdominal hysterectomy

|

A: regional B: general C: general D: general E: general F: general G: general H: - I: - J: both K: both L: - M: general N: general O: general P: - Q: general R: both S: general T: general U: general V: - W: general X: general Y: general Z: - AA: - AB: general AC: - |

Music genre (sessions; minutes)

Recorded music A: standard non lyrical classical, jazz, popular, folk, ethnic (daily (3 days); 15) B: standard soft, 60-80 BPM (3; 30) C: Chinese relaxation, classical folk, religious songs recommended by AAMT (2; 30) D: sedative non-lyrical, 60-80BPM music, no strong rhythm/ percussion (1; 30) E: cultural relaxation music pieces (1; 30) F: self-chosen pop/ classical Finland music (3; 30) G: summer, autumn, bird, night song (6; 20) I: light music, classical Chinese folk, popular world, Chinese relaxation or recommended by AAMT (twice daily, 30) J: easy listening (1; 20) K: country, easy listening, gospel, rock (1; -) L: background music (synthesizer, harp, piano, orchestra, slow jazz, inspiration) (multiple; 30) M: self-chosen, not specified (1; 60) N: standard new age (1; 30) O: self-brought favorite tape (1; 30) P: CD musical preference, lullabies when awakening (4 days; 60) Q: relaxing music (jazz, easy listening, pop) (twice daily; 20) R: western classical, gagak, noh, enka (1; 20) S: sedative non-lyrical music, synthesizer, harp, piano, orchestra, slow jazz, flute (1; 30) T: soft, slow, flowing rhythmic instrumental new-age synthesizer (1; 60) U: soft, relaxing, calm classical (1; 117) V: soothing music: synthesizer, harp, piano, orchestral, slow jazz (2; 15) W: western music: harp, synthesizer, orchestral piano, jazz (2; 15) S: self-brought (-; -) Y: soothing, relaxing country western instrument, fresh (2; 30) Z: soothing instrument (country) (multiple; 30) AA: sedative music: synthesizer, harp, piano, orchestral, slow jazz (multiple; 156) AB: calm classical, stimulative classical, or popular calm quality (1; 93) AC: easy listening instrument music (2; 10)

Live music H: active engagement selection preferred genre (spiritual/religious, 1930-1940, musical, country, popular, rock, R&B) (1; 30-40) |

A: noise-cancelling headphones B: nothing C: routine care D: no disturbance E: - F: no intervention G: 20 rest H: standard care I: nothing J: quiet rest period K: no CD / headset L: standard care, quietly lying M: no music N: nothing O: headphone no music P: standard care Q: quiet rest period R: nothing S: - T: blank CD U: blank tape V: quietly lying in bed W: resting in bed X: headphone only Y: undisturbed bed rest Z: undisturbed scheduled rest 30 AA: routine care AB: no headphone AC: no intervention |

Scale B: STAI C: STAI G: VAS J: VAS N: NRS O: VAS Q: STAI S: VAS U: STAI V: VAS Z: STAI, NRS AA: STAI, Distress of Pain Scale AC: VAS 0-5

Results meta-analysis pooled standardized mean difference: -0.66 (95% CI -1.07 to -0.25); p=0.002, I2=87 |

Scale A: VAS B: VAS D: VAS E: NRS F: VAS G: VAS H: NRS I: VAS J: VAS K: DOS 0-10 L: VAS M: VAS N: NRS O: VAS P: VAS Q: NRS R: VAS S: VAS T: NRS U: VAS V: VAS W : VAS X : VRS Y : VRS AA: Line 0-10 with 3 anchors AB: VAS AC: VAS

Results meta-analysis pooled standardized mean difference: -0.53 (95% CI -0.79 to -0.28); p<0.001, I2=82

|

Authors’ conclusion This meta-analysis found a statistically significant decrease in both anxiety and pain in adults receiving music interventions pre-, intra-, and/or postoperatively

Selection criteria This review excluded seven studies that generated randomization sequences inadequately

Risk of bias Overall, risk of bias in the included studies was moderate to high. Many studies did not adequately address methodological considerations (randomization techniques and power) and risk of bias, and were therefore scored as having an unclear risk.

Heterogeneity The overall level of heterogeneity was high (I2=87% for anxiety and I2=82% for pain). There was a wide variety of surgical procedures, a variety in control conditions, and diverse methods of anesthesia.

Publication bias The funnel plot for anxiety raises the possibility of publication bias. Previous publications of mainly favourable results might affect the conclusion of this review. |

Abbreviations: TKA: total knee arthroplasty; CABG: Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting; CS: Caesarean Section; BPM: Beats Per Minute; AAMT: American Association of Music Therapy; VAS: Visual Analog Scale; STAI: State-Trait Anxiety Inventory; NRS: Numerical Rating Scale; DOS: Descriptive Ordinal Scale; VRS: Verbal Rating Scale; Tx: transplantation.

* included in meta-analysis

Table 4.2 Evidence table for systematic review of RCTs on the effects of music in the postoperative setting on stress

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Type of surgery |

Type of anaesthesia |

Intervention

|

Comparison / control |

Cortisol outcome measures and results |

Comments |

|

Fu (2019)

|

Systematic review and meta-analysis of RCTs

Literature search up to 5 February 2019. 18 RCTs were included in the review and 8 in the meta-analysis.

Cortisol 4 RCTs used music in the postoperative setting

A: Conrad, 2007, USA B: Finlay, 2016, UK C: Nilsson, 2005, Sweden* D: Nilsson, 2009b, Sweden

Source of funding: No external funding was received for this study.

Conflicts of interest: The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

|

Inclusion criteria SR: -randomized controlled trials (RCTs) investigating the effect of recorded music pre-, intra-, and/or postoperatively; -adult surgical patients aged ≥18 y; -stress response to surgery assessed by measuring stress response biomarker levels; - full text, peer-reviewed published papers in the English language.

Exclusion criteria SR: -music intervention did not contain the elements melody, harmony and rhythm; -use of multiple, concomitant interventions; -live music with a musical therapist; -intervention consisted solely of nature sounds.

Important patient characteristics

N, total and per group (music versus control) A: 10, 5/5 B: 89, 72/17 C: 50, 25/25 D: 58, 28/30

Mean age ± SD or range (music versus control) A: - B: 68.07 ± 8.03 C: 56 ± 16.8 / 57 ± 11.6 D: 64 ± 11.5 / 69 ± 7.5

Sex (% men) (music versus control) A: - B: 41% C: 96% / 96% D: -

|

A: major pulmonary, abdominal, aortic, and polytrauma surgery requiring ICU stay B: total knee arthroplasty C: open hernia repair (Lichtenstein) D: coronary artery bypass graft or aortic valve replacement

|

A: general B: spinal C: general D: general

|

Live/recorded All 4 studies used recorded music

Music genre (duration in minutes) A: classical music (Mozart piano sonatas) (60) B: 32 tracks of pop, classical, jazz, folk and ethnic music (15) C: soft, relaxing, new age synthesizer melodies (60) D: soft, relaxing, new age style music using music pillow (30)

Research team selected

|

A: headphones without music B: headphones without music C: standard care D: standard care

|

Outcome measures A : cortisol B : salivary cortisol C : serum cortisol D: serum cortisol

Results A meta-analysis of five RCTs reporting cortisol levels at the end of surgery (including one RCT using music in the postoperative setting) showed a pooled standardized mean difference of –0.14 (95% CI -0.57 to 0.28); p=0.50, I2=60.15.

A meta-analysis of six RCTs reporting cortisol levels postoperatively (including one RCT using music in the postoperative setting) showed a pooled standardized mean difference of –0.30 (95% CI -0.53 to -0.07); p=0.01, I2=0.

|

Authors’ conclusion Perioperative music can attenuate the physiological and neuroendocrine stress response to surgery. As none of the included studies assessed postoperative complications or patient outcome, the clinical implications are not yet totally clear.

Intervention Music delivery was achieved in a majority of the studies through headphones (11 studies, 61%) or a music pillow (three studies, 17%)

Outcomes Only data on cortisol were extracted from this review, because this outcome has the strongest association with patient experienced stress

Risk of bias Several studies provided insufficient details to assess all quality domains. Risk of performance bias was high, as it is difficult to achieve adequate blinding to the music intervention. Most included studies in the meta-analysis had a relatively small number of patients

Heterogeneity The patients, surgical procedures, and anesthesia method used and perioperative care offered differed substantially

Publication bias Publication bias was not assessed, as less than 10 studies were included in the meta-analysis |

* included in meta-analysis

Table 4.3 Evidence table for systematic review of RCTs on the effects of music in the postoperative setting on medication and length of stay

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Type of surgery |

Type of anaesthesia |

Intervention

|

Comparison / control

|

Outcome measure(s) and results medication |

Outcome measure(s) and results length of stay |

Comments |

|

Fu (2020)

|

Systematic review and meta-analysis of RCTs

Literature search up to 7 January 2019. 55 RCTs were included in the review and 33 in the meta-analysis.

Medication 23 RCTs used music solely in the postoperative setting

A: Allred, 2010, USA B: Ames, 2017, USA C: Cutshall, 2011, USA* D: Easter, 2010, USA E: Ebneshahidi, 2008, Iran* F: Finlay, 2016, UK G: Good, 1995, USA* H: Heitz, 1992, USA* I: Iblher, 2011, Germany J: Ignacio, 2012, Singapore K: Liu, 2015, China L: Macdonald, 2003, UK M: McCaffrey, 2006, USA N: Miladinia, 2017, Iran* O: Nilsson, 2003a, Sweden* P: Nilsson, 2005, Sweden* Q: Nilsson, 2009a, Sweden R: Nilsson, 2009b, Sweden* S: Santhna, 2015, Malaysia U: Şen, 2010, Turkey* V: Tse, 2005, USA W: Vaajoki, 2012, Finland Y: Zimmerman, 1996, USA

Length of stay 7 RCTs used music solely in the postoperative setting

C: Cutshall, 2011, USA* D: Easter, 2010, USA L: Masuda, 2005, Japan* T: Schwartz, 2009, USA* W: Vaajoki, 2012, Finland X: Zhou, 2011, China* Y: Zimmerman, 1996, USA

Source of funding: No external funding was received for this study.

Conflicts of interest: The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

|

Inclusion criteria SR: -available, peer-reviewed, full-text articles of randomized controlled trials in the English language; -adult patients 18 years old; -undergoing an inhospital or outpatient invasive, surgical procedure; -investigating the use of recorded music pre-, intra-, and/or postoperatively with either medication requirement, hospital length of stay or direct medical costs as outcome measures.

Exclusion criteria SR: -studies investigating solely nature sounds; -studies investigating live music with a music therapist; -studies investigating music with an additional, concomitant intervention were excluded, except if this additional intervention was used in both the intervention and control group.

Important patient characteristics

N, total and per group (music versus control) A: 56, 28/28 B: 41, 20/21 C: 100, 49/51 D: 213, 111/102 E: 77, 38/39 F: 89, 72/17 G: 42, 21/21 H: 60, 20/20/20 I: 50, 25/25 J: 21, 12/9 K: 98, 47, 51 L: 58, 30/28 M: 44, 22/22 N: 124, 62/62 O: 60, 30/30 P: 125, 62/63 Q: 50, 25/25 R: 40, 20/20 S: 58, 28/30 T: 40, 20/20 U: 67, 35/32 V: 70, 35/35 W: 57, 27/30 X: 168, 83/85 Y: 120, 60/60 Z: 64, 32/32

Mean age ± SD or range (music versus control) A: 64.3 ± 9.6 / 63.5 ± 9.6 B: 52.45 ± 13.48 / 52.95 ± 15.09 C: 62.8 ± 12.9 D: 53.5 ± 14.1 E: 25.2 ± 4.37 F: 68.1 ± 8.0 G: 46.0 ± 12.5 H: 49.0 ± 4.2 I: 65.8 ± 9.7 / 65.5 ± 6.2 / 68.6 ± 8 J: - K: 54.45 ± 15.90 / 52.02 ± 15.62 L: 39.2 ± 10.1 / 40.5 ± 9.2 M: 69.0 ± 6.0 N: 75.7 ± 6.1 O: 34.83 ± 10.52 / 31.70 ± 9.98 P: 53 ± 14.1 / 52 ± 13.2 Q: 56 ± 16.8 / 57 ± 11.6 R: 64 ± 10.0 / 67 ± 7.5 S: 64 ± 11.5 / 69 ± 7.5 T: 63.80 ± 5.64 / 64.90 ± 6.94 U: - V: 30.23 ± 3.94 / 29.00 ± 5.40 W: 39.2 ± 14.4 / 40.6 ± 14.5 X: 63.0 ± 12.0 Y: 44.88 ± 9.37 / 45.13 ± 9.48 Z: 67.0 ± 9.9

Sex (% men) (music versus control) A: 50% / 39.3% B: 50% / 57% C: 77% D: 32.5% E: 0% F: 41% G: 25% H: 7% I: 80% / 83.3% / 76% J: - K: 65% / 68% L: 0% / 0% M: 41% N: 35% O: 70% / 60% P: 71% / 76% Q: 96% / 96% R: 85% / 75% S: - T: 30% / 10% U: - V: 0% / 0% W: 41% / 43% X: 50% Y: 0% / 0% Z: 68%

|

A: total knee arthroplasty B: surgical procedures requiring ICU stay C: coronary artery bypass graft and/ or cardiac valve surgery D: elective outpatient surgery procedures E: elective cesarean section surgery F: total knee arthroplasty G: elective, open abdominal surgery H: (para)thyroidectomy or unilateral modified radical mastectomy I: open heart surgery (coronary bypass, valvular transplant, or both combined) J: elective spine, hip or knee surgery K: thoracic surgery L: total abdominal hysterectomy M: orthopedic surgery N: elective hip or knee surgery O: abdominal surgery P: daycare surgery: varicose veins, open inguinal hernia repair Q: open hernia repair (Lichtenstein) R: coronary artery bypass graft and/ or aortic valve replacement S: coronary artery bypass graft or aortic valve replacement T: total knee replacement surgery U: coronary artery bypass graft surgery V: elective caesarian section W: endoscopic sinus surgery or tubinectomy X: elective major abdominal midline incision surgery Y: radical mastectomy Z: coronary artery bypass graft surgery

|

A: general or spinal with femoral block B: general C: general D: not specified E: general F: spinal with nerve block G: general H: general I: general J: general K: general L: not specified M: general and spinal N: not specified O: general P: general Q: general R: general S: general T: not specified U: general V: general W: not specified X: general Y: general Z: general

|

Live/recorded all 23 studies used recorded music

Music genre (duration) A: choice of easy listening, nonlyrical music (POD 1, 20 min before and after first ambulation) B: MusiCure (POD 1-2, 50 min, 1-8 times) C: choice of 4 CD’s (2 x 20 min on POD 2-4, 120 min in total) D: choice of easy-listening, country, gospel, rock (during length of stay in PACU) E: own favorite music (30 min in the recovery room) F: 32 tracks with range of genres (15 min) G: choice of sedative nonlyrical piano, harp, synthesizer orchestral or slow jazz music (60 min during the first 2 d after surgery) H: choice of 3 instrumental classical tapes (15 min after PACU arrival until discharge) I: baroque organ, flute, string orchestra music with 60-80 bpm (60 min after ICU admission / 60 min after sedation stop) J: not specified (2 x 30 min) K: soft, melodious music 60-80 bpm (30 min daily on POD 1-3) L: own favorite music (2-6 h on day of surgery) M: choice of Noh, Gagaku, classical or Enka music (20 min) N: choice of CD’s (60 min 4 times a day) O: relaxing nonlyrical music with a bpm of 60–80 (3 x 10 min sessions on day of surgery) P: soft, relaxing and calming classical music (PACU arrival until patient chose to stop) Q: soft, new-age synthesizer (1 h after PACU arrival) R: MusiCure using music pillow (30 min on POD1) S: soft, relaxing, new age style music using music pillow (30 min on POD1) T: choice of soothing and relaxing nonlyrical piano or violin music (60 min, 4 times a day) U: light piano music (patient’s choice in ICU) V: own favorite music (60 min) W: choice of Chinese, Western or own favorite music (2 x 30 min after surgery and on POD1) X: choice of 2000 popular music songs (total of 7 x 30 min) Y: choice of 202 songs (2 x 30 min daily) Z: choice of 5 soothing music tapes (30 min daily during POD1-3) |

A: quiet rest period B: 50 min quiet rest C: standard care with bed rest for 20 min D: no music E: headphones without music F: headphones without music G: standard care H: headphones without music (control group 1) or standard care (control group 2) I: standard care J: no music K: standard care L: standard care M: standard care N: standard care O: standard care P: headphones without music Q: headphones without music R: standard care S: standard care T: standard care U: standard care V: no music W: standard care X: standard care Y: standard care Z: scheduled rest of 30 min

|

Outcome measures A: postoperative opioid requirement B: postoperative opioid requirement C: postoperative opioid requirement D: postoperative opioid requirement E: postoperative opioid requirement F: postoperative opioid requirement G: postoperative opioid requirement H: postoperative opioid requirement I: postoperative opioid requirement J: postoperative opioid requirement K: postoperative patient-controlled analgesia requirement L: postoperative patient-controlled analgesia requirement N: postoperative opioid requirement O: postoperative opioid requirement P: postoperative opioid requirement Q: postoperative opioid requirement R: postoperative opioid requirement S: postoperative opioid requirement T: postoperative opioid requirement V: postoperative opioid requirement W: postoperative analgesic medication requirement X: postoperative opioid requirement Z: postoperative opioid requirement

Results meta-analysis For postoperative opioid requirement, a meta-analysis of 20 RCTs (including eight RCTs using music in the postoperative setting) showed a pooled standardized mean difference of -0.31 (95% CI -0.45 to -0.16); p<0.001, I2=44.3

For propofol, a meta-analysis of nine RCTs (not including any RCTs using music in the postoperative setting) showed a pooled standardized mean difference of -0.72 (95% CI -1.01 to -0.43); p=0.00001, I2=61.1

For midazolam, a meta-analysis of three RCTs (not including any RCTs using music in the postoperative setting) showed a pooled standardized mean difference of -1.07 (95% CI -1.70 to -0.44); p<0.001, I2=73.1

|

Outcome measures C: hospital length of stay D: PACU length of stay H: PACU length of stay M: hospital length of stay U: ICU length of stay X: hospital length of stay Y: hospital length of stay Z: hospital length of stay

Results meta-analysis A meta-analysis of nine RCTs (including four RCTs using music in the postoperative setting, reporting hospital and ICU length of stay) showed a pooled standardized mean difference of –0.18 (95% CI -0.43 to 0.067); p=0.15, I2=56.0

|

Authors’ conclusion Perioperative music can reduce postoperative opioid and intraoperative sedative medication requirement. Therefore, perioperative music may potentially improve patient outcome and reduce medical costs, as a higher opioid dosage is associated with an increased risk of adverse events and chronic opioid use. No effect of perioperative music on length of stay was demonstrated.

Intervention In a majority of studies, music delivery was achieved using a music player and headphones (41 studies, 75%). Other reported music delivery methods were a music pillow (3 studies, 5.5%), CD-player (3 studies, 5.5%), personal stereo (1 study, 1.8%), an integrated music system in the patient room (1 study, 1.8%), or not specified (6 studies, 11%).

Outcomes Only postoperative opioids were assessed, as other analgesic medications were often not reported. Some included studies did report that perioperative music also reduced nonopioid analgesic requirement postoperatively.

Risk of bias A potentially high risk of selection bias was present in several studies, and several studies provided insufficient details to assess selection bias. A moderate to high risk of performance bias was present, as blinding of patients for the music intervention is only possible when the intervention is performed solely intraoperatively during general anesthesia.

Heterogeneity The included studies contained different surgical patients, surgical procedures, and follow-up duration of the outcome assessment. This was reflected in the moderate to high level of heterogeneity observed.

Publication bias A funnel plot to investigate publication bias of studies assessing the effect of perioperative music on postoperative opioid requirement showed a near funnel-shaped plot, lacking a small number of studies in the lower-left corner which could be indicative of studies with relatively small samples sizes and small effect sizes being potentially absent

|

Abbreviations: POD: postoperative day

* included in meta-analysis

Table 4.4 Evidence table of recent RCTs on the effects of music in the postoperative setting

|

Study population |

Type of surgery |

Type of anaesthesia

General perioperative pain protocol |

Intervention (I)

|

Comparison / control (C)

|

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

|

Aris (2019)

Malaysia

|

Inclusion criteria: -aged 18 and above -undergoing TKA under central neural block (spinal, epidural or combined) -good hearing and sight -good interaction to understand Malay language instructions -oriented to person, place and time -prescribed with patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) as postoperative pain management -classified as ASA 1, 2 or 3

Exclusion criteria -using antipsychotic drugs -allergy to opioids -unstable hemodynamic -admitted to the intensive care unit after surgery

N at baseline and analysis I: 28 C: 28

Important prognostic factors

Mean age ± SD I: 63.71 ± 11.005 C: 64.50 ± 8.851

Sex: I: 32.1% M C: 32.1% M

Groups comparable at baseline

|

Total knee arthroplasty (TKA) |

Central neural block anesthesia (spinal, epidural or combined).

Post-operative pain management was patient-controlled analgesia, as specified in the inclusion criteria. No type of medication within PCA was specified |

Various types of music (Celtic Flutes, World Flutes, Beethoven’s Moonlight, Native American Flute and Guitar, Peaceful Harp, Chopin’s Nocturne, Zikir) through headphones

Recorded music

Selected by patient from list

Postoperatively for 30-60 minutes

|

Usual care provided by the hospital based on current practice

(management of pain, oxygenation, ventilation, medication (analgesic and anti-emetic), fluids, observation of general condition, monitoring of the level of consciousness, vital signs, side effects of anesthesia and wound care). |

Timing of measurements: at 0, 10, 20, 30 and 60 minutes in the recovery unit

Pain (NRS (0-10)) median, mean rank

0 minutes I: 0, 25.68 C: 2, 31.32 p=0.171

10 minutes I: 0, 25.5 C: 2, 31.5 p=0.146

20 minutes I: 0, 25.7 C: 1.5, 31.3 p=0.174

30 minutes I: 0, 24.82 C: 2, 32.18 p=0.075

60 minutes I: 0, 24.39 C: 1.5, 32.61 p=0.045

Post-operative opioids (mg of morphine) mean ± SD I: 2.36 ± 4.34 C: 2.77 ± 3.27 p=0.141 |

This study also assessed anxiety. However, it was only reported that there were no statistically significant differences at any time point. No anxiety scores were reported, making it impossible to judge whether the differences could be clinically relevant.

|

|

Ashok (2019)

India |

Inclusion criteria: -subjects 30-80 years of age -both male and female -CABG both on pump and off pump -patients with LVEF <60% -patients with 2 grafts

Exclusion criteria -hearing impairments -patients after postoperative day 7, enter into phase 2 rehabilitation -multiple procedures -patients who do not have interest in music -contraindicated to 6 minute walk test

N at baseline and analysis I: 20 C: 20

Important prognostic factors

Mean age ± SD I: 60.8 ± 7.75 C: 59.85 ± 7.92

Sex I: 30% M C: 30% M

No significant difference at baseline between groups. No significant difference in baseline measurements of HADS anxiety. |

CABG

|

Anesthesia was not described, but because of the type of surgery, general anesthesia can be assumed.

|

Sedative music, without lyrics (60-80 beats per minute) via headphones

Recorded music

Selected by research team

Post-operative, for 20 minutes once daily from postoperative day 1 to postoperative day 7

Music was delivered along with the Phase I cardiac rehabilitation programme |

Phase I cardiac rehabilitation from postoperative day 1 to 7. Patients received 20 minutes of cardiac rehabilitation in a day and the protocol was purely individualised.

|

Timing of measurements: preoperative day and postoperative day 2 and 7

Anxiety (HADS (0-21)) median (IQR)

Preoperative

I: 7.56, (IQR 5 to 12.75) C: 7.50 (IQR 7 to 9) p=0.49

Postoperative day 2 I: 6 (IQR 4 to 9) C: 6 (IQR 4 to 9) p=0.92

Postoperative day 7 I: 1 (IQR 0 to 3) C: 1.5 (IQR 0 to 5) p=0.31

|

|

|

USA

|

Inclusion criteria: -age 18 to 90 -undergoing knee or hip arthroplasty surgery -medical plan to stay at least 1 night in the hospital -planned discharge and recovery at home -internet connected device that they could bring into the hospital for listening to music

Exclusion criteria: -Self-reported presence of verbal, visual, auditory, psychomotor, cognitive or affective impairments -inability to speak and understand the English language.

N at baseline / analysis I: 24 / 24 C: 26 / 23

Important prognostic factors

Mean age ± SD I: 64.58 ± 8.81 C: 68.69 ± 8.62

Sex I: 46% M C: 38% M

Groups comparable at baseline |

Elective knee or hip arthroplasty orthopedic surgery |

Type of anesthesia not described in article.

All patients had an anesthetic nerve block for pain management. Duration after surgery varies. |

Music of patients’ choice via internet radio

Recorded music

Patient selected internet radio channel

Post-operatively, at hospital (30 minutes once during the evening postsurgery and three times a day on postoperative days 1 and 2)

In addition to music, analgesic medication was given

|

Analgesic medication only

|

Timing of measurements: Three times a day, either before and after music (I) or before and after mealtimes (C)

Pain intensity (PI)/pain distress (PD) (NRS (0-10)) mean (adjusted for pretest score)

Day of surgery: evening PI I: 3.94 / C: 4.67 p=0.02 PD I: 2.28 / C: 2.69 p=0.26

Postoperative day 1: morning PI I: 3.39 / C: 4.29 p=0.04 PD I: 1.42 / C: 2.67 p=0.02

Postoperative day 1: noon PI I: 3.25 / C: 4.36 p=0.01 PD I: 1.86 / C: 2.79 p=0.01

Postoperative day 1: evening PI I: 5.05 / C: 5.67 p=0.21 PD I: 3.33 / C: 4.24 p=0.09

Postoperative day 2: morning PI I: 4.49 / C: 5.06 P=0.08 PD I: 1.88 / C: 3.11 p=0.003

Postoperative day 2: noon PI I: 5.08 / C: 5.55 P=0.31 PD I: 2.81 / C: 4.30 p=0.09

Postoperative day 2: evening PI I: 5.36 / C: 6.18 P=0.18 PD I: 3.26 / C: 3.65 p=0.62

Analgesic usage (opioids) Opioid Morphine Equivalency (mg) mean ± SD and nonopioid acetaminophen equivalency (mg) mean ± SD

Postoperative day 1 OME I: 51.52 ± 37.49 OME C: 35.00 ± 27.43 p=0.10 NOAE I: 1,814.58 ± 1,072.39 NOAE C: 1,554.35 ± 969.85 p=0.38

Postoperative day 2 OME I: 42.81 ± 35.54 OME C: 40.56 ± 32.93 p=0.88 NOAE I: 1,746.88 ± 1,310.12 NOAE C: 1,661.11 ± 1,715.47 p=0.89 |

Headphones were not explicitly mentioned, but patients had to bring an internet-connected device to listen to music.

Large amount of incomplete data

Part of the intervention took place at home. Only the measurements at the hospital are shown in this Table.

|

|

Lee (2017)

Taiwan

|

Inclusion criteria: -receiving spinal anesthesia for the first time -over 20 years of age with no vision or hearing impairment -conscious, literate and able to communicate in Mandarin and Taiwanese -completed and signed consent form

Exclusion criteria: -receiving local or general anesthesia -experienced changes in condition when they underwent spinal anesthesia or surgery

N at baseline and analysis I: 50 C: 50

Important prognostic factors

Mean age ± SD I: 47.8 ± 14.55 C: 51.36 ± 14.04

Sex I: 48% M C: 54% M

Groups comparable at baseline |

Multiple surgery types included (rectal/urological/orthopedic/trauma/ gynaecologic) |

First time spinal anesthesia.

No other perioperative pain protocol was described. |

Soothing music (nature, piano, harp, orchestral, jazz or synthetic) through over ear headphones

Recorded music

Patient selected after listening to 30 seconds of music from six categories

Post-operatively, for 30 minutes in the PACU

|

Normal nursing care |

Timing of measurements: Operating room waiting area, after completion of music listening in PACU

Anxiety (STAI (20-80)) mean ± SD I: 31.20 ± 4.84 C: 58.78 ± 5.49 P<0.001

|

|

|

Sfaniakis (2017)

Greece

|

Inclusion criteria: -aged between 18-70 years old (adults but not very elderly) -classified as overweight (Body Mass Index –BMI≥25%), or obese (BMI≥30%) according to the international classification adult obesity, published by WHO -have been operated in the abdomen at the same day of music therapy intervention

Exclusion criteria: -

N total at baseline and analysis: I: 45 C:42

Important prognostic factors:

Mean age ± SD: Men I: 43.13 ± 12.54 C: 44.81 ± 9.97

Women I: 41.30 ± 11.59 C: 43.35 ± 12.47

Sex: I: 33% M C: 38% M

Groups not comparable at baseline Men in the intervention group had a lower BMI than men in the music group (40.8 versus 44.2) There are differences in the type of operation; more patients in the intervention group than control group underwent sleeve gastrectomy (57.8% versus 42.9%). VAS score before the intervention (if any) was higher in the intervention group (4.42±2.24) than the control group (3.98±1.66) |

Major abdominal surgery (including sleeve gastrectomy, open cholecystectomy, open inguinal hernia repair, and large bowel resection) |

No details reported about anaesthesia but since patients underwent major abdominal surgery, it was assumed that general anaesthesia was used.

The analgesic medication was the same at usual routine dosages for both study groups. |

Orchestral classical track through earphones

Recorded music

Selected by research team

Post operatively,

30 minutes in the Post Anesthesia Care Unit (PACU)

and

30 minutes in the surgical nursing ward, upon return from PACU

|

Routine nursing observation |

Timing of measurements: Before and after intervention (both postoperatively)

Before intervention

Pain (VAS; 0-10) mean ± SD I: 4.42 ± 2.24 C: 3.98 ± 1.66

After intervention

Pain (VAS; 0-10) mean ± SD I: 2.64 ± 1.90 C: 3.76 ± 1.39

Significant interaction between intervention and VAS (F (1, 26.552) = 69.606; p<0.001)

|

This study was performed in a population of obese patients,

It is not clear when measurements were performed exactly (e.g., before the first music session in the PACU, and then after the second session on the ward?) |

Abbreviations: CABG: Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting; ET = emotional thermometer; HADS: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; NOAE: nonopioid acetaminophen equivalency; NRS: Numerical Rating Scale; OME: Opioid Morphine Equivalency; PI: pain intensity; PD: pain distress; VAS: Visual Analog Scale.

Table 4.5 Risk of bias table for recent RCTs on the effects of music in the postoperative setting

Research question: ‘What are the effects of music (recorded or live) in the postoperative setting on patients undergoing invasive surgery with anaesthesia care when compared to no music?’

|

Study reference

(first author, publication year) |

Was the allocation sequence adequately generated? a

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was the allocation adequately concealed?b

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Blinding: Was knowledge of the allocated interventions adequately prevented?c

Were patients blinded?

Were healthcare providers blinded?

Were data collectors blinded?

Were outcome assessors blinded?

Were data analysts blinded? Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was loss to follow-up (missing outcome data) infrequent?d

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Are reports of the study free of selective outcome reporting?e

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was the study apparently free of other problems that could put it at a risk of bias?f

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Overall risk of bias If applicable/necessary, per outcome measureg

LOW Some concerns HIGH

|

|

Aris (2019)

|

Probably yes;

Reason: patients consented to participate were randomized by immediately being given a selection of envelopes containing letter ‘A’ (indicative of intervention group) and ‘B’ (indicative of a control group) to choose from |

Probably yes;

Reason: not specified whether envelopes were opaque or sealed |

Definitely no;

Reason: patients were not blinded

|

Probably yes;

Reason: no missing outcome data

|

Probably yes;

Reason: all outcomes described in the Methods section are reported but no trial registration or protocol was available |

Probably yes;

|

Some concerns (pain, opioids)

|