Behandeling claudicatio intermittens bij PAV

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is de beste behandelstrategie bij patiënten met claudicatio intermittens?

Aanbeveling

Start bij patiënten met claudicatio intermittens altijd eerst gesuperviseerde looptraining onder begeleiding van een fysiotherapeut of oefentherapeut. Bij het uitblijven van voldoende verbetering van kwaliteit van leven of persisterend ziekteverzuim zal een endovasculaire of zelfs chirurgische revascularisatie overwogen moeten worden.

Overweeg om direct te starten met een endovasculaire behandeling met aanvullende gesuperviseerde looptraining bij patiënten waarbij een langdurig ziekteverzuim niet aanvaardbaar is of bij patiënten met een verwacht inspanningsniveau dat niet met gesuperviseerde looptraining alleen behaald kan worden.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Er is literatuuronderzoek verricht naar de effectiviteit van 1) een endovasculaire behandeling versus gesuperviseerde looptraining, en 2) endovasculaire behandeling met gesuperviseerde looptraining versus alleen gesuperviseerde looptraining, bij patiënten met claudicatio intermittens. Er zijn één systematische review, één RCT en twee follow-up studies van RCT’s die uitgewerkt zijn in het systematische review geïncludeerd in deze module. Daarnaast zijn zes kosten-effectiviteitsstudies uitgewerkt.

Een veel gebruikt onderzoek om de “walking ability”, ofwel het loopvermogen van een patiënt, te kwantificeren is de loopbandtest. Loopafstanden gemeten op een loopband zijn echter veelal geen goede afspiegeling van de ervaren beperking. Daarnaast is de mate van beperking bij een bepaalde loopafstand voor elke patiënt verschillend. Ook de waarde van de toename van de loopafstand na een behandeling middels gesuperviseerde looptraining of endovasculaire interventie is voor elke patiënt verschillend. Relatief jonge patiënten vinden het bijvoorbeeld extra belangrijk om te kunnen blijven sporten en lopen. Ook willen zij goed geïnformeerd zijn over de werking van medicijnen en welke invloed dit heeft op het dagelijks leven. Zij willen vooral niet ziek zijn en/of de stempel van het ziek zijn hebben.

Onderzoek van Dörenkamp (2016) laat zien dat patiëntkarakteristieken en aanwezigheid van co-morbiditeit invloed hebben op de gemeten maximale pijnvrije loopafstand. Factoren zoals vrouwelijk geslacht, een verhoogde leeftijd, hoog lichaamsgewicht en cardiale co-morbiditeit zijn geassocieerd met een kleinere verbetering van de pijnvrije loopafstand. Voor deze factoren is niet gecorrigeerd in de geïncludeerde studies. De gedachte bestaat dat tegenvallende resultaten na gesuperviseerde looptraining kunnen zorgen voor een grotere behoefte aan re-vascularisatie. Klaphake (2020) heeft echter geen associatie kunnen vinden tussen deze variabelen. Daarom lijkt het waardevoller om de impact van de beperking op het dagelijks leven van deze patiënten te meten, zoals kwaliteit van leven, deelname aan sociale activiteiten, sport, vrijwilligerswerk, en ziekteverzuim. Indien deze uitkomstmaten niet verschillen tussen de verschillende behandelingen, zou kosteneffectiviteit een argument kunnen zijn. De keuze die gemaakt wordt dient samen met de patiënt afgewogen te gaan worden, waarbij niet alleen de loopafstand als beoordeling/uitkomst moet gelden, maar vooral ook de zelfstandigheid van de patiënt, wel of niet kunnen werken en sociaal functioneren.

Voor de eerste vergelijking, endovasculaire behandeling versus gesuperviseerde looptraining, werd gevonden dat een endovasculaire behandeling niet leidt tot een langer maximale of pijnvrije loopafstand, maar mogelijk wel de ziekte-specifieke kwaliteit van leven (cruciale uitkomstmaat) op de korte termijn (6 tot 18 maanden) zou kunnen verbeteren. De bewijskracht hiervoor was laag. De bewijskracht voor ziekte-specifieke kwaliteit van leven op de lange termijn (~5 jaar) was te laag om een conclusie te kunnen trekken. Voor kosteneffectiviteit (cruciale uitkomstmaat) na 12 maanden tot 5 jaar werd gevonden dat gesuperviseerde looptraining een grotere kans zou kunnen hebben om kosteneffectief te zijn, vergeleken met een endovasculaire behandeling (lage bewijskracht). Voor de cruciale uitkomstmaat ziekteverzuim zijn geen studies gevonden die deze vergelijking hebben onderzocht. Daarnaast kan er geen conclusie worden getrokken op basis van de belangrijke uitkomstmaten pijnvrije en maximale loopafstand, omdat de bewijskracht voor beide uitkomsten zeer laag was.

Voor de tweede vergelijking, endovasculaire behandeling met gesuperviseerde looptraining versus alleen gesuperviseerde looptraining, werd geen verschil gevonden in de kwaliteit van leven op zowel de korte termijn (6 tot 12 maanden) als op de lange termijn (5 jaar)(lage bewijskracht). Voor de uitkomstmaat ziekteverzuim werden wederom geen studies gevonden die deze vergelijking hebben onderzocht. De bewijskracht voor de andere uitkomstmaten (kosteneffectiviteit, ziekte-specifieke kwaliteit van leven, pijnvrije loopafstand en maximale loopafstand) was zeer laag en er kon daarom geen conclusie worden getrokken.

Een andere uitkomstmaat die niet is meegenomen in de literatuursamenvatting, maar die wel werd beschreven in enkele studies, is de enkel-arm index (EAI) (Mazari, 2016; Klaphake, 2020). Een EAI tussen de 0,9 en 1,3 representeert een normale EAI waarde. Een waarde <0.9 is afwijkend en impliceert een verminderde arteriële perfusie van het aangedane been. Deze uitkomstmaat werd op de lange termijn gerapporteerd (~5 jaar). Mazari (2016) suggereert dat de EAI in rust en na inspanning het laagste is voor de gesuperviseerde looptraining groep en het hoogste voor de endovasculaire behandeling groep. Klaphake (2020) laat daarentegen zien dat de gemiddelde EAI na inspanning hoger was dan de gemiddelde EAI in rust, voor zowel de combinatiegroep als ook de gesuperviseerde looptraining groep. Ook in deze studie waren de EAI in rust en na inspanning het laagste in de gesuperviseerde looptraining groep. De EAI lijkt echter weinig relevant voor de patiënt, omdat dit weinig tot niets zegt over de kwaliteit van leven en het functioneren van de patiënt.

Een belangrijke beperking voor alle uitkomstmaten is het feit dat er in nagenoeg alle studies geen blindering is toegepast. Dit kan mogelijk invloed hebben gehad op de (subjectieve) uitkomstmaten en geeft daarmee een risico op vertekening. Er is om deze reden voor alle uitkomstmaten afgewaardeerd vanwege beperkingen in de studieopzet. Ook werd de studie van Koelemay (2022) vroegtijdig beëindigd en was er een hoge drop-out rate in deze studie. Er is daarnaast voor alle uitkomstmaten met één of twee levels afgewaardeerd voor imprecisie, ofwel vanwege imprecisie rondom de puntschatter door het overschrijden van de klinisch relevante grenzen, ofwel vanwege een te kleine patiëntengroep. Tot slot was er bij sommige uitkomstmaten sprake van tegenstrijdige resultaten. Door de (zeer) lage bewijskracht zal de keuze voor de ene dan wel de andere behandeling bij patiënten met etalagebenen voor beide vergelijkingen dus (ook) afhangen van andere factoren, waaronder de behoeften en voorkeuren van de patiënt.

Er bestaan een aantal netwerk meta-analyses die uitkomsten van RCT’s op dit gebied met elkaar hebben vergeleken. Deze zijn echter niet geïncludeerd in de literatuursamenvatting, omdat netwerk meta-analyses niet ge-updatet kunnen worden met recentere literatuur, en deze daarnaast meer vergelijkingen omvatten dan dat er gedefinieerd zijn voor deze uitgangsvraag. De meest recente netwerk meta-analyse over dit onderwerp (Thanigaimani, 2021) heeft onder andere gekeken naar de twee gedefinieerde vergelijkingen in deze module (endovasculaire behandeling versus gesuperviseerde looptraining, en endovasculaire behandeling plus gesuperviseerde looptraining versus alleen gesuperviseerde looptraining). De belangrijkste conclusie van deze netwerk meta-analyse is dat zowel een endovasculaire behandeling met gesuperviseerde looptraining als ook alleen gesuperviseerde looptraining effectief zijn in het verbeteren van de maximale loopafstand binnen twee jaar. Na deze twee jaar zijn beide behandelingen niet meer effectief in het verbeteren van de maximale loopafstand.

Interpretatie

Uit de resultaten blijkt dat beide behandelingen effectief zijn. Dit betekent dat een afweging gemaakt moet worden tussen een invasieve behandeling met het risico op complicaties versus een niet-invasieve behandeling met aandacht voor gedragsverandering op de langere termijn. Een structurele aanpassing in leefstijl, zoals meer lopen, is gunstig voor het verminderen van de cardiovasculaire risico’s (Kesaniemi, 2001). Uit de geïncludeerde studies blijkt dat beide behandelingen zorgen voor verbetering van de maximale loopafstand. Gedrag en motivatie van de patiënt zijn daarbij mogelijk belangrijke componenten voor de lange termijneffecten en moeten daarom niet onderschat worden (Jansen, 2020).

In een studie van Bouwens (2019) bleek endovasculaire interventie na gesuperviseerde looptraining bij 82% van de patiënten na twee jaar niet nodig. In dit onderzoek is ook bekeken of er verschil zit in locatie van de obstructie. De hypothese was dat bij een hogere obstructie eerder een endovasculaire effectiever zou zijn dan bij een distale obstructie. Dat bleek geen verschil te maken in de effecten. De conclusie was dat de locatie van de obstructie niet bepalend is of een endovasculaire behandeling eerder uitgevoerd dient te worden. Deze resultaten zijn een belangrijk argument om bij de meeste patiënten te starten met gesuperviseerde looptraining, waarbij endovasculaire behandeling wordt ingezet bij inadequate respons op de gesuperviseerde looptraining. Hoe de inadequate respons te beoordelen is, wordt niet benoemd.

Bij de endovasculaire behandeling van patiënten met claudicatio intermittens wordt in principe de meest proximale afwijking behandeld om de inflow in het been te verbeteren. Gesuperviseerde looptraining heeft een breder effect op de algehele gezondheidstoestand. Beweging en training heeft een positieve invloed op hypercholesterolemie, hypertensie en diabetes mellitus (Patterson, 1997). Dit heeft ook weer invloed op afname van cardiovasculaire mortaliteit en morbiditeit (Pinto, 1997). Hierin blijkt dat gesuperviseerde looptraining niet alleen invloed heeft op de oorzaak, maar ook op het ontstaan en beloop van de aandoening.

Wat niet in de studies is meegenomen, is de tijdspanne van de behandeling. Het effect op kwaliteit van leven en loopafstand op drie en zes maanden is gelijk. In relatie tot de uitkomstmaat werkverzuim kan de tijdspanne wel van invloed zijn om te kiezen voor een snelle interventie middels endovasculaire behandeling waarbij al snel de loopafstand en ervaren pijn verbetert, in tegensteling tot de gesuperviseerde looptraining waar veelal pas na drie maanden intensieve training en inzet resultaat wordt ervaren. Het is aannemelijk dat de jongere doelgroep die hun werk vanwege de klachten niet (volledig) kan uitvoeren vanwege het snelle resultaat een voorkeur voor de endovasculaire behandeling heeft, waarna wel de gesuperviseerde looptraining en begeleiding gestart dient te worden om de gedragsverandering en leefstijlfactoren voor de lange termijn te borgen.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

Voor patiënten is goede uitleg over de behandelopties en de daarbij te maken afwegingen van belang. Relevante te bespreken onderwerpen zijn onder meer de voor- en nadelen of risico’s van de verschillende behandelopties, waaronder de impact van een endovasculaire ingreep, risico’s, herstelperiode, gevolgen voor functioneren en andere voor de patiënt van belang zijnde aspecten. Patiënten hebben ook behoefte aan informatie over de medicatie, de bijwerkingen en de invloed op het dagelijks leven. De behandelaar stelt samen met de patiënt vast aan welke informatie hij/zij behoefte heeft, welke afwegingen voor de patiënt van belang zijn en de mate waarin de patiënt deze afweging wil en kan maken.

De belangrijkste doelen voor de patiënt en naasten zijn het opbouwen van conditie en zo lang mogelijk pijnvrij kunnen lopen. De beoogde pijnvrije loopafstand is voor elke patiënt verschillend. Jonge patiënten willen veelal snel weer aan het werk, sporten en volledig klachtenvrij zijn. Bij oudere patiënten is de beoogde pijnvrije loopafstand soms minder ambitieus, maar is zelfstandig activiteiten (blijven) ondernemen vaak een belangrijk einddoel.

De meerwaarde van gesuperviseerde looptraining is met name de deskundige begeleiding door de fysiotherapeut of oefentherapeut. Het helpt patiënten naar hun lichaam te luisteren en te herkennen wat wel en niet goed is in ieders individuele situatie. Een goed programma met stimulerende coaching helpt om door te pijn heen te lopen. Patiënten vinden het belangrijk om tijdens het programma te leren wat ze medisch gezien mogen en kunnen. Dit helpt bij het consequent blijven bewegen op de lange termijn. Gezien het feit dat de verandering van gewoontes een belangrijk aspect is, geven patiënten ook aan dat een (leefstijl-)therapeut zou kunnen helpen. Bijvoorbeeld bij het stoppen met roken, aanpassingen in voeding en/of blijvend bewegen.

Na gesuperviseerde looptraining vinden sommige patiënten het lastig om dit zonder begeleiding vol te houden. Een nieuwe verwijzing naar een fysiotherapeut of oefentherapeut kan hierbij helpen, ondanks dat er geen vergoeding uit de basisverzekering is. Bij afname van de pijnvrije loopafstand of veranderingen van de gezondheidssituatie kan het wenselijk zijn om nogmaals gesuperviseerde looptraining te volgen om wederom lichamelijke conditie op te bouwen en inzicht te krijgen in wat medisch gezien mag en kan. Tot slot kunnen groepssessies of lotgenotencontact helpen om het bewegen na de gesuperviseerde looptraining blijvend vol te houden.

Een patiënt moet goed geïnformeerd worden over de voordelen van het verbeteren van beweeggedrag op lange termijn. Daarbij hoort ook informatie geven over de voor- en nadelen van een endovasculaire behandeling versus gesuperviseerde looptraining. Uitgebreide voorlichting is cruciaal om tot een geïnformeerde voorkeur vanuit de patiënt te komen. De ervaring van patiënt is wisselend: een categorie wil eerst de voorwaarde creëren (endovasculaire behandeling), de ander wil graag zelf werken aan blijvende verandering (gesuperviseerde looptraining). Uitgebreide voorlichting en uitleg is cruciaal in het samen beslissen met de patiënt. Daarnaast kan de Keuzehulp etalagebenen het proces van samen beslissen ondersteunen.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

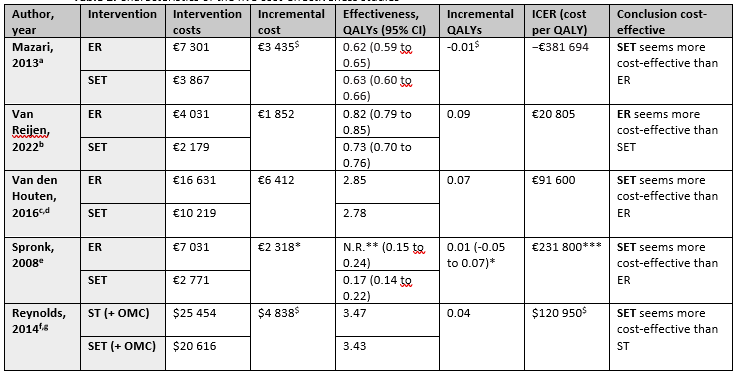

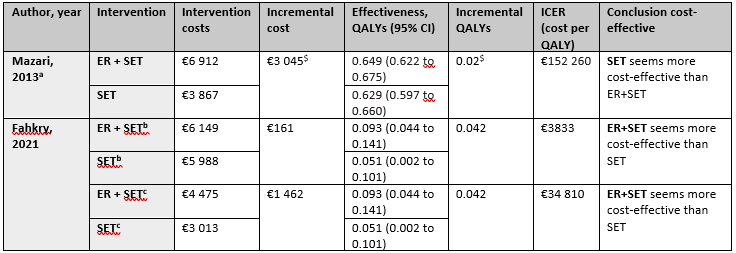

Er zijn in totaal zes kosteneffectiviteitsstudies uitgewerkt in de literatuursamenvatting. Op basis van de geïncludeerde kosteneffectiviteitsstudies lijkt gesuperviseerde looptraining een hogere kans te hebben om kosteneffectief te zijn dan een endovasculaire behandeling. Daarnaast wijzen de twee studies die de tweede vergelijking, endovasculaire behandeling plus gesuperviseerde looptraining versus alleen gesuperviseerde looptraining, hebben onderzocht allebei een andere kant op. De geïncludeerde studies zijn echter wel uitgevoerd in verschillende landen en met verschillende kostenperspectieven.

Op basis van het bovenstaande is het te verdedigen om alle patiënten met claudicatio intermittens klachten allereerst een behandeling middels gesuperviseerde looptraining aan te bieden. Het nadeel van de gesuperviseerde looptraining is dat het een langdurig traject en dat het einddoel per patiënt sterk kan verschillen. Patiënten die dermate beperkt zijn dat zij hun werk niet meer uit kunnen oefenen, zijn vermoedelijk beter geholpen met een combinatie van gesuperviseerde looptraining en een endovasculaire behandeling om het ziekteverzuim te beperken. Ook patiënten met een ambitieuze doelstelling, die vermoedelijk met alleen gesuperviseerde looptraining niet behaald kan worden, lijken gebaat bij een combinatie van gesuperviseerde looptraining een endovasculaire behandeling. Dit zijn bijvoorbeeld patiënten die veel moeten lopen vanwege hun beroep of als mantelzorger, maar ook fervente wandelaars en andere sportbeoefenaars.

Voor de meeste zorgverzekeraars geldt dat er eenmaal en maximaal 37 behandelingen voor de totale verzekeringsduur (binnen 12 maanden verbruiken) vergoed worden vanuit het basispakket. Via een aanvullende verzekering kunnen er nog extra behandelingen worden vergoed. Voor een tweede episode van gesuperviseerde looptraining geldt veelal dat de betrokken fysiotherapeut of oefentherapeut een aanvraag in moet dienen, waarna de tweede episode mogelijk alsnog vergoed wordt. De insteek van het behandeltraject is dat de patiënt na een jaar zelfredzaam en actief aan slag kan gaan. Echter blijkt uit de praktijk dat een paar jaar later de patiënt lang niet altijd het verband ziet tussen klachten in linkerbeen versus klachten in rechterbeen. Herhaling (van een verkort) traject waarin uitleg over de noodzaak van het volhouden van het beweeg- en loopgedrag wordt herhaald, kan worden overwogen. Dit wordt niet uit de basisverzekering vergoed, maar wordt door aanvullende verzekering of eigen middelen van patiënt betaald. Hierdoor zou een endovasculaire behandeling wellicht niet noodzakelijk zou hoeven zijn. Nadruk van de behandeling moet dan liggen op het achterhalen van de oorzaak van het niet vol kunnen houden van het gewenste loop- en beweeggedrag.

Een endovasculaire behandeling mag te allen tijde gedeclareerd worden, ook als de patiënt vooraf niet behandeld is middels gesuperviseerde looptraining.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

Het belang van leefstijladviezen en secundaire preventie bij patiënten met perifeer arterieel vaatlijden is onomstreden. Een wezenlijk onderdeel van een gezonder leven is meer bewegen. Derhalve is gesuperviseerde looptraining op voorhand een goede optie voor alle patiënten met claudicatio intermittens klachten. De fysiotherapeut of oefentherapeut begeleidt en stimuleert de patiënt bij de gesuperviseerde looptraining, maar ook bij de andere aspecten van een gezonderde manier van leven. Dit uit zich in het ontwikkelen van een bepaalde discipline, maar ook in het begrijpen en doorgronden van de klachten en de achterliggende fysiologie. Harteraad werkt met Harteraad beweegpartners verspreid over het hele land. Bij de beweegpartners zijn Harteraad beweegcoaches werkzaam, die speciaal opgeleid zijn voor het begeleiden van mensen met een hart- of vaataandoening.

Bij patiënten met chronisch aandoeningen wordt het verbeteren van de fysieke activiteit vaak als prioriteit gezien. Aangezien bij deze patiënten vaak sprake is van multimorbiditeit, is een beter begrip van het verband tussen fysieke activiteit en multimorbiditeit noodzakelijk om deze patiëntengroep doelgerichter te kunnen behandelen (Dörenkamp, 2015). Het is bekend dat personen met cardiovasculaire aandoeningen, COPD en diabetes mellitus de laagste score hebben op de gemeten fysieke activiteit. Multimorbiditeit kan pleiten voor gesuperviseerde looptraining wanneer de andere aandoening positief beïnvloed worden door beweeg of gesuperviseerde looptraining (denk daarbij aan de COPD, artrose aan onderste extremiteit en bij overgewicht). Richtlijnen (KNGF) schrijven bij deze aandoeningen beweegbegeleiding en gedragsverandering ten aanzien van beweging als eerste voorkeur voor. Daardoor beïnvloedt de stimulering en bevordering van een actiever beweegpatroon meerdere aandoeningen en symptomen positief. Echter wanneer door de ervaren beperking van pijn in het been als gevolg van PAV dermate beperkend is dat het actieve beweegpatroon niet uitgevoerd kan worden, kan de endovasculaire behandeling een snelle verbetering geven, waarna de gesuperviseerde looptraining als minder belastend wordt ervaren door de patiënt. Hierin is een uitgebreide analyse door arts en fysiotherapeut of oefentherapeut in nauwe samenspraak noodzakelijk om tot de juiste conclusie en plan te komen. Daarvoor pleit de start van de gesuperviseerde looptraining, waarna de fysiotherapeut of oefentherapeut advies kan geven aan de vaatchirurg als verwacht wordt dat de endovasculaire behandeling een extra dan wel noodzakelijk vermindering aan ervaren klacht geeft.

Invloed van andere factoren op loopafstand bij patiënten met PAV

Naast dat gesuperviseerde looptraining bewezen gunstige effecten heeft, laat de studie van Dörenkamp (2015) zien dat onvoldoende fysieke activiteit (gedefinieerd als het niet nakomen van beweegrichtlijnen zoals de Nederlandse Norm voor Gezond Bewegen (NNGB)) een negatieve impact heeft op de biomarkers voor perifeer arterieel vaatlijden. Daarnaast laat deze studie zien dat een tekort aan fysieke activiteit geassocieerd is met een verhoogde aanwezigheid van ontstekingsmarkers, coagulatie, lipide profielen, glucose, endogene fibrinolyse en insuline resistentie (Dörenkamp, 2015). Een tekort aan fysieke activiteit lijkt er ook voor te zorgen dat de myokine respons in de skeletspier verandert door minder spiercontracties. Gevolg hiervan is een verhoogde pro-inflammatoire status.

Het verband tussen het niet naleven van beweegrichtlijnen en cardiovasculaire biomarkers kan mogelijk verklaard worden doordat onvoldoende spiercontracties de lipoproteïnelipase activiteit onderdrukken, de opname van triglyceriden en HDL-niveaus verminderen en de insulineresistentie verhogen. Ook lijkt onvoldoende fysieke activiteit te zorgen voor aantasting van de endotheelfunctie als gevolg van arteriële wandverstijving en een vernauwing van de slagaderdiameter. Samengevat leiden deze factoren tot een slechtere gezondheidsprognose bij patiënten met PAV.

Om deze (spier)activiteiten positief te beïnvloeden, heeft gesuperviseerde looptraining de voorkeur. Het verbeteren en onderhouden van meer activiteiten kan vooral bewerkstelligt worden door leefstijlverandering en zelfmanagement. Wanneer samen met de patiënt wordt besloten dat leefstijlverandering en zelfmanagement aandacht behoeven, kan men overwegen om gesuperviseerde looptraining boven een endovasculaire behandeling te verkiezen. Gesuperviseerde looptraining richt zich namelijk niet enkel op de lokale vascularisatie, maar heeft ook invloed op de cardiopulmonale en mentale conditie van de patiënt (Jansen, 2022).

Het nadeel van endovasculaire behandeling is dat niet altijd voldoende wordt stilgestaan bij de invloed van eigen gedrag (rookstop, bewegen en voeding) om recidief te voorkomen. Tijdens gesuperviseerde looptraining wordt meer appel gedaan op eigen invloed en verantwoordelijk op eigen gedrag van patiënt. Alleen al de factor tijd speelt mee: de fysiotherapeut of oefentherapeut heeft 37 maal in het jaar moment om deze zaken te bespreken versus een paar bezoeken aan de vaatchirurg/ vasculair verpleegkundige.

Gesuperviseerde looptraining is niet altijd populair bij de patiënt. Belemmeringen zijn de kosten, tijd en vervoer naar de therapie (Spannbauer, 2017). Dit kan verklaren waarom de gesuperviseerde looptraining minder effectief kan zijn. Dit zijn internationale onderzoeken. De genoemde factoren zijn in Nederland al goed georganiseerd: vergoeding voor de behandeling komt uit basisverzekering. De afstand naar de fysiotherapeut of oefentherapeut is beperkt door een ruim aanbod van gespecialiseerde fysiotherapeuten en oefentherapeuten. De tijdsinvestering is er nog steeds. De vierde reden die gegeven wordt door patiënten is dat de patiënt liever kiest voor een ‘quick fix’ oplossing in plaats van een jaar therapie en begeleiding.

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

Omdat op basis van de literatuur de conservatieve behandeling op de verschillende eindpunten niet beter is dan een invasieve behandeling, moeten de voor- en nadelen van de beide strategieën met de patiënt besproken worden. Er lijkt echter een belangrijk systemisch voordeel van gesuperviseerde looptraining ten opzichte van een endovasculaire interventie. Ook zijn de kosten van gesuperviseerde looptraining over het algemeen lager dan die van een endovasculaire interventie.

Er kleven echter ook belangrijke nadelen aan gesuperviseerde looptraining. Het duurt vaak enkele maanden alvorens er verbetering van de klachten wordt ervaren. Er zijn patiënten die bijvoorbeeld vanwege hun werk of zorg voor een familielid gebaat zijn bij een snelle verbetering van de klachten. Daarnaast zijn de verwachtingen van sommige patiënten niet altijd haalbaar met alleen een behandeling middels gesuperviseerde looptraining. Denk daarbij aan fanatiek sporten of lange wandelingen in de bergen.

Een endovasculaire behandeling kent ook nadelen. Het betreft een invasieve ingreep, hetgeen kan leiden tot complicaties (nabloeding, dissectie, distale embolieën). Daarnaast is de kans op een recidief in sommige arteriële trajecten groot.

Om tot een goed behandelplan te komen is het van belang het bovenstaande met de patiënt te bespreken en gezamenlijk een besluit te nemen (samen beslissen).

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Patiënten met claudicatio intermittens (ook wel etalagebenen genoemd) worden geadviseerd te stoppen met roken en medicijnen te nemen om de kans op een hartinfarct of beroerte te verkleinen (secundaire preventie). De loopafstand kan worden verbeterd door looptraining onder begeleiding van een fysiotherapeut of oefentherapeut (in het kort: gesuperviseerde looptraining), middels een endovasculaire behandeling of door middel van een combinatie van een endovasculaire behandeling en gesuperviseerde looptraining. Het is niet duidelijk wat de beste behandeling of behandelcombinatie is om de klachten te verminderen op de korte- en lange termijn.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

Comparison 1: endovascular treatment versus supervised exercise training

Pain-free walking distance

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of supervised exercise training on short-term pain-free walking distance (6 to 12 months) when compared with endovascular treatment in patients with intermittent claudication. Source: Fahkry, 2018; Koelemay, 2022

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of supervised exercise training on long-term pain-free walking distance (18 months to 7 years) when compared with endovascular treatment in patients with intermittent claudication. Source: Fahkry, 2018; Mazari, 2016 |

Quality of life

|

Low GRADE |

Endovascular treatment may slightly increase short-term quality of life (6 to 18 months) when compared with supervised exercise training in patients with intermittent claudication. Source: Fahkry, 2018; Koelemay, 2022 |

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of supervised exercise training on long-term quality of life (5 years) when compared with endovascular treatment in patients with intermittent claudication. Source: Mazari, 2016 |

Cost-effectiveness

|

Low GRADE |

The evidence suggests that supervised exercise training may have a higher probability on being cost-effective in comparison to endovascular treatment, in patients with intermittent claudication. Source: Mazari, 2013; Van Reijen, 2022; Van den Houten, 2016; Spronk, 2008; Reynolds, 2014 |

Maximum walking distance

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of supervised exercise training on short-term maximum walking distance (6 to 12 months) when compared with endovascular treatment in patients with intermittent claudication. Source: Fahkry, 2018; Koelemay, 2022

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of supervised exercise training on long-term maximum walking distance (18 months to 7 years) when compared with endovascular treatment in patients with intermittent claudication. Source: Fahkry, 2018; Mazari, 2016 |

Return to work

|

No GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding the effect of supervised exercise training on return to work (short- and long-term) when compared with endovascular treatment in patients with intermittent claudication. |

Comparison 2: endovascular treatment with supervised exercise training versus supervised exercise training

Pain-free walking distance

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of supervised exercise training on short-term pain-free walking distance (6 to 12 months) when compared with endovascular treatment plus supervised exercise training in patients with intermittent claudication. Source: Fahkry, 2018

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of supervised exercise training on long-term pain-free walking distance (2 to 5 years) when compared with endovascular treatment plus supervised exercise training in patients with intermittent claudication. Source: Fahkry, 2018; Klaphake, 2020; Mazari, 2016 |

Quality of life

|

Low GRADE |

Supervised exercise training may result in little to no difference in short-term quality of life (6 to 12 months) when compared with endovascular treatment plus supervised exercise training in patients with intermittent claudication. Source: Fahkry, 2018

Supervised exercise training may result in little to no difference in long-term quality of life (5 years) when compared with endovascular treatment plus supervised exercise training in patients with intermittent claudication. Source: Klaphake, 2020; Mazari, 2016 |

Cost-effectiveness

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of endovascular treatment + supervised exercise training on the cost-effectiveness (12 months) when compared to supervised exercise training alone, in patients with intermittent claudication. Source: Mazari, 2013; Fahkry, 2021 |

Maximum walking distance

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of supervised exercise training on short-term maximum walking distance (6 to 12 months) when compared with endovascular treatment plus supervised exercise training in patients with intermittent claudication. Source: Fahkry, 2018

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of supervised exercise training on long-term maximum walking distance (2 to 5 years) when compared with endovascular treatment plus supervised exercise training in patients with intermittent claudication. Source: Fahkry, 2018; Mazari, 2016 |

Return to work

|

No GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding the effect of supervised exercise training on return to work (short- and long-term) when compared with endovascular treatment plus supervised exercise training in patients with intermittent claudication.

|

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

Fahkry (2018) conducted a systematic review to describe the (added) effects of endovascular revascularisation on quality of life and performance in patients with intermittent claudication (IC). Only RCTs were included that compared endovascular revascularization (ER) (± conservative therapy) versus conservative therapies (=supervised exercise therapy, SET) or no specific therapy for intermittent claudication. Studies with any kind of surgical revascularization in the comparison group and studies that compared different types of endovascular revascularization procedures were excluded. The review systematically searched multiple databases (Cochrane Vascular Specialized Register, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, ClinicalTrials.gov, World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform, and the International Standard Randomized Controlled Trial Number (ISRCTN) Register) from inception to February 2017. Moreover, the reference lists of all eligible studies were hand searched for additional relevant studies. A total of 10 RCTs described in 25 publications were included, comprising of 1087 participants in total. For the comparisons relevant to our analysis (ER versus SET, and ER + SET versus SET) a total of seven studies were included. Outcome measures included in this review were maximum walking distance, pain-free walking distance, secondary invasive interventions, quality of life, procedure related complications, cardiovascular events, non-treadmill functional performance measures, and mortality. The risk of bias for each included study was assessed by two independent reviewers using the Cochrane ‘Risk of bias’ tool.

Koelemay (2022) performed a multicenter RCT to compare endovascular revascularization (ER) with supervised exercise therapy (SET) in patients with IC caused by iliac artery stenosis or occlusion. The study was performed between November 2010 and May 2015. Patients were randomly allocated to SET (n=114) or ER (n=126). The trial was terminated prematurely after inclusion of 240 patients. Patients were included if they had disabling IC resulting from >50% stenosis or occlusion of the common or external iliac artery as seen on color duplex scanning (CDS), magnetic resonance angiography (MRA), or computed tomography angiography (CTA), graded as TASC A, B, and C. Patients with a concomitant > 50% stenosis or occlusion of the SFA were also included. Patients were also included if they could walk at least two minutes at 3.2 km/h on the treadmill with a 10% incline, if they had a maximum walking distance (MWD) between 100 and 300 meters, and if they had given written informed consent. Patients were excluded if they 1) had a life expectancy <3 months, 2) were unable to complete self-reported questionnaires, 3) had an allergy to contrast agents, 4) were pregnant, 5) had contraindications to anticoagulant therapy, 6) had symptoms for less than three months, 7) had ipsilateral common femoral artery (CFA) stenosis > 50% or occlusion, 8) had heart failure or angina pectoris NYHA III or IV, 9) participated in another study, 10) already had SET, and 11) had renal insufficiency (serum creatinine > 150 mmol/L). Outcome measures included change in MWD and disease-specific QoL (primary outcomes), and pain-free walking distance (PFWD), generic QoL (SF-36), health status (EQ-5D), complications, treatment failure and additional interventions (secondary outcomes). The follow-up time was one year.

Additionally, two articles (Klaphake, 2020; Mazari, 2016) describing the long-term outcomes of two RCTs included in Fahkry (2016) were added to the analysis. The study design and descriptions of the original studies (Fakhry, 2015; Mazari, 2012) can be found in the evidence table for systematic reviews.

Characteristics of the six cost-effectiveness studies are described in Table 1.

Table 1. Characteristics of the included cost-effectiveness studies (n=6)

Results

Comparison 1: endovascular treatment versus supervised exercise training

1. Pain-free walking distance (PFWD)

Short-term PFWD

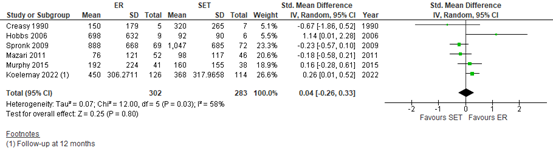

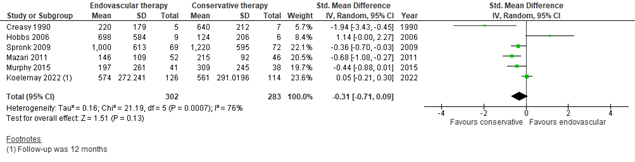

Fahkry (2018) and Koelemay (2022) reported the outcome measure pain-free walking distance (PFWD) at 6 to 12 months follow-up. Pooled data from these 6 studies (n=302 in the endovascular revascularization (ER) group, versus n=283 in the supervised exercise training (SET) group) showed a standardized mean difference (SMD) of 0.04 (95% CI -0.26 to 0.33)(Figure 1), in favor of ER. This was considered to be a trivial difference.

Figure 1: Pain-free walking distance at 6 to 12 months; ER vs SET.

Z: p-value of overall effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval; ER: endovascular revascularization; SET: supervised exercise therapy.

Long-term PFWD

Murphy (2015)(Fahkry, 2018) reported PFWD at 18 months. The mean PFWD in the ER group (n=32) was 160 meters (SD 240), versus 181 meters (SD 208) in the SET group (n=32). The mean difference (MD) was 21 meters (95% CI -131.04 to 89.04) in favor of SET. This was not considered to be a clinically relevant difference.

Spronk (2009)(Fahkry, 2018) reported the PFWD at ~7 years. The mean PFWD in the ER group (n=47) was 1022 meters (SD 784), versus 804 meters (SD 709) in the SET group (n=36). The mean difference was 218 meters (95% CI -104.30 to 540.30) in favor of ER. This was not considered to be a clinically relevant difference.

Mazari (2016), who reported long-term follow-up results of Mazari (2012)(Fahkry, 2018), reported the patient-reported walking distance (PRWD) at ~5 years. The median PRWD was 800 meters (95% CI 124.91 to 1000) in the ER (n=39), versus 200 meters (95% CI 96.94 to 800) in SET group (n=35). The difference in medians was 600 meters, in favor of ER.

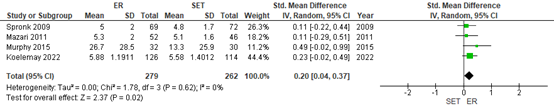

2. Quality of life

Fahkry (2018) and Koelemay (2022) reported disease-specific quality of life (QoL). Spronk (2009) and Mazari (2011)(Fahkry, 2018) and Koelemay (2022) reported the VascuQoL sumscore, whereas Murphy (2015)(Fahkry, 2018) used the Peripheral Artery Questionnaire (PAQ). Pooled data from these studies (n=279 in the ER group, versus n=262 in the SET group) reveiled a standardized mean difference (SMD) of 0.20 (95% CI 0.04 to 0.37), in favor of ER (Figure 2). This was considered to be a small difference.

Figure 2: Disease-specific quality of life; ER vs SET

Z: p-value of overall effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval; ER: endovascular revascularization; SET: supervised exercise therapy.

Additionally, Mazari (2016) reported the long-term results at ~5 years of disease-specific QoL. They reported a median VasquQoL sumscore of 5.92 (95% CI 4.85 to 6.43) in the ER group (n=39), versus a median sumscore of 4.64 (95% CI 3.90 to 5.26) in the SET group (n=35). The median difference was 1.28 points, in favour of ER.

3. Cost-effectiveness

Five studies reported the cost-effectiveness of ER versus SET (Mazari, 2013; Van Reijen, 2022; Van den Houten, 2016; Spronk, 2008; Reynolds, 2014). Results are displayed in Table 2. Although the studies are performed in different countries (i.e. the Netherlands, UK, USA) using different costing perspectives, four out of five studies indicate that SET is more cost-effective than ER. Thus, SET seems to have a higher probability on being cost-effective than ER.

Table 2. Characteristics of the five cost-effectiveness studies

Foot notes: a Healthcare provider perspective, b Restricted societal perspective, c Dutch healthcare payer perspective, d Markov model-study, e Societal perspective, f US societal perspective, g Results of the Markov model at 5 years, $ Self-calculated based on study data, * adjusted mean difference and a 99% CI, ** Mean QALY not reported, *** ICER adjusted for baseline variables. Abbreviations: ER, Endovascular Revascularization; SET, Supervised Exercise Therapy; OMC, Optimal Medical Care; ST, stenting; WTP, Willingness-To-Pay threshold.

4. Maximum walking distance

Short-term MWD

Fahkry (2018) and Koelemay (2022) reported the maximum walking distance (MWD) at 6 to 12 months follow-up. Pooled data from these 6 studies (n=302 in the ER group, versus n=283 in the SET group) showed a SMD of -0.31 (95% CI -0.71 to 0.09)(Figure 3), in favor of SET. This was considered to be a small difference.

Figure 3: Maximum walking distance at 6 to 12 months; ER vs SET.

Z: p-value of overall effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval; ER: endovascular revascularization; SET: supervised exercise therapy.

Long-term MWD

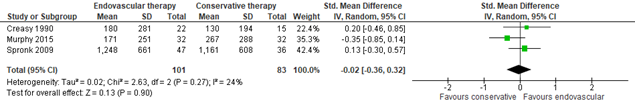

Three studies in Fahkry (2018) reported long-term MWD, with follow-up time varying from 18 months to 7 years. Pooled data from these three studies (n=101 in the ER group, versus n=83 in the SET group) showed a SMD of -0.02 (95% CI -0.36 to 0.32)(Figure 4), in favor of SET. This was considered to be a trivial difference.

Figure 4: Long-term maximum walking distance; ER vs SET.

Z: p-value of overall effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval; ER: endovascular revascularization; SET: supervised exercise therapy.

Mazari (2016) reported the median MWD at ~5 years. The median MWD was 118.25 meters (95% CI 68.07 to 215.00) in the ER group (n=39), versus 78.12 meters (95% CI 56.03 to 102.80) in the SET group (n=35). The difference in medians was 40.13 meters, in favor of ER.

5. Return to work

Return to work was not reported in any of the included studies.

Comparison 2: endovascular treatment with supervised exercise training versus supervised exercise training

1. Pain-free walking distance (PFWD)

Short-term PFWD

Two studies in Fahkry (2018) reported the outcome measure pain-free walking distance (PFWD) at 6 to 12 months follow-up. Mazari (2011)(Fahkry, 2018) reported a mean PFWD of 99 meters (SD 119, n=47) in the ER + SET group, versus a mean PFWD of 98 meters (SD 117, n=46) in the SET alone group (mean difference (MD) 1 meter, 95% CI -46.96 to 48.96). This was not considered to be a clinically relevant difference.

Fahkry (2015)(Fahkry, 2018) reported a mean PFWD of 1120 meters (SD 675, n=106) in the ER + SET group, versus a mean PFWD of 712 meters (SD 640, n=106) in the SET alone group (MD 408 meters, 95% CI 230.92 to 585.08). This was considered to be a clinically relevant difference, in favor of the ER + SET group.

Long-term PFWD

Greenhalgh (2008)(Fahkry, 2018) reported long-term PFWD (after 2 year follow-up) in two separate trials – the aortoiliac trial (n=34) and the femoropopliteal trial (n=93). In the femoropopliteal trial, 63% of patients in the ER + SET group versus 22% of patients in the SET alone group attained 200 meters without claudication pain (adjusted hazard ratio 3.11, 95% CI 1.42 to 6.81). In the aortoiliac trial, 61% of patients in the ER + SET group versus 25% of patients in the SET alone group attained 200 meters without claudication pain (adjusted hazard ratio 3.6, 95% CI 1.0 to 12.8). Both were in favor of the ER + SET group.

Klaphake (2020) and Mazari (2016) reported the PFWD and PRWD, respectively, at ~5 years follow-up time. Klaphake (2020) reported a mean PFWD of 976 meters (95% CI 824 to 1128) in the ER + SET group (n=68), versus 865 meters (99% CI 709 to 1021) in the SET alone group (n=60). The MD was 111 meters (95% CI -102.91 to 324.91), in favor of the ER + SET group.

Mazari (2016) reported a median PRWD of 300 meters (95% CI 100 to 800) in the ER + SET group (n=37), versus 200 meters (95% CI 96.94 to 800) in the SET alone group (n=35). The median difference was 100 meters in favor of the ER + SET group.

2. Quality of life

Two studies in Fahkry (2018) reported disease-specific QoL. Both used the VascuQoL questionnaire. Mazari (2011)(Fahkry, 2018) reported a mean VascuQoL score of 5.2 (SD 1.0) in the ER + SET group (n=58), versus a mean score of 5.1 (SD 1.6) in the SET group (n=60). The MD was 0.10 (95% CI -0.38 to 0.58. Fahkry (2015)(Fahkry, 2018) reported a mean VascuQoL score of 5.8 (SD 1.5) in the ER + SET group (n=106), versus a mean score of 5.2 (SD 1.6) in the SET group (n=106). The MD was 0.60 (95% CI 0.18 to 1.02). Both differences were in favor of the ER + SET group. This difference is not considered to be clinically relevant.

Additionally, Klaphake (2020) and Mazari (2016) reported the long-term results health-related QoL at ~5 years, using the VascuQoL questionnaire. Klaphake (2020) reported a mean VasquQoL score of 1.60 (99% CI 1.31 to 1.89) in the ER + SET group (n=106), versus a mean VasquQoL score of 1.36 (99% CI 1.06 to 1.66) in the SET alone group (n=106). The MD was 0.24 (95% CI -0.17 to 0.65), in favor of the ER + SET group. This difference is not considered to be clinically relevant.

Mazari (2016) reported a median VasquQoL sumscore of 5.08 (95% CI 4.25 to 6.03) in the ER + SET group (n=37), versus a median sumscore of 4.64 (95% CI 3.90 to 5.26) in the SET alone group (n=35). The median difference was 0.44, in favor of the ER + SET group. This difference is not considered to be clinically relevant.

3. Cost-effectiveness

Two studies (Mazari, 2013; Fahkry, 2021) studied the cost-effectiveness of ER + SET versus SET. The results are displayed in Table 3. Fahkry (2021) depict that ER + SET seems to be more cost-effective than SET alone, whereas Mazari (2013) depict that ER + SET seems not to be more cost-effective than SET alone.

Table 3. Characteristics of the two cost-effectiveness studies

Foot notes: a Healthcare provider perspective, b Societal perspective, c Health care perspective, $ Self-calculated based on study data. Abbreviations: ER, Endovascular Revascularization; SET, Supervised Exercise Therapy; ST, stenting; WTP, Willingness-To-Pay threshold.

4. Maximum walking distance

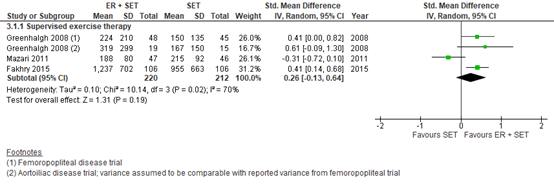

Fahkry (2018) reported the maximum walking distance (MWD) at 6 to 12 months follow-up. Pooled data from these four studies (n=220 in the ER + SET group, versus n=212 in the SET group) showed a SMD of 0.26 (95% CI -0.13 to 0.64)(Figure 5). This was considered to be a small difference, in favor of ER + SET.

Figure 5: Maximum walking distance at 6 to 12 months; ER + set vs SET.

Z: p-value of overall effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval; ER: endovascular revascularization; SET: supervised exercise therapy.

Long-term MWD

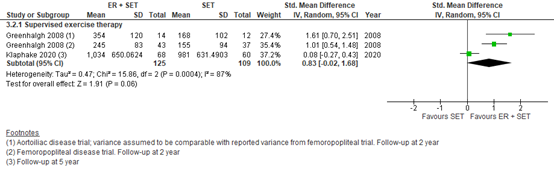

Greenhalgh(2009)(Fahkry, 2018) and Klaphake (2020) reported long-term MWD with a follow-up time of 2 years and 5 years, respectively. Pooled data from these three studies (n=125 in the ER + SET group, versus n=109 in the SET group) showed a SMD of 0.83 (95% CI -0.02 to 1.68)(Figure 6). This was considered to be a large difference in favor of ER + SET.

Figure 6: Long-term maximum walking distance; ER + set vs SET.

Z: p-value of overall effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval; ER: endovascular revascularization; SET: supervised exercise therapy.

Mazari (2016) reported the median MWD at ~5 years. The median MWD was 111.08 meters (95% CI 79.11 to 215.00) in the ER + SET group (n=37), versus 78.12 meters (95% CI 56.03 to 102.80) in the SET group (n=35).

5. Return to work

Return to work was not reported in any of the studies.

Level of evidence of the literature

Comparison 1: endovascular treatment versus supervised exercise training

Pain-free walking distance

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure short-term pain-free walking distance was downgraded from high to very low because of study limitations (due to premature termination and a high drop-out rate in Koelemay (2022) and no blinding, risk of bias -1) and the confidence interval around the SMD crossing both the upper and lower threshold for a small effect (imprecision, -2).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure long-term pain-free walking distance was downgraded from high to very low because of study limitations (no blinding, risk of bias -1); conflicting results between studies (inconsistency, -1), and the wide confidence intervals and small number of included patients (imprecision, -1).

Quality of life

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure quality of life (short-term) was downgraded from high to low because of study limitations (due to premature termination and a high drop-out rate in Koelemay (2022) and no blinding, risk of bias -1) and the confidence interval around the SMD crossing one threshold for a small effect (imprecision, -1).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure quality of life (5 years) was downgraded from high to very low because of study limitations (no blinding, risk of bias -1) and the very small number of included patients (imprecision, -2).

Cost-effectiveness

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure cost-effectiveness (12 months to 5 year) was downgraded from high to low because of conflicting results (inconsistency, -1) and number of included patients (imprecision, -1).

Maximum walking distance

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure short-term maximum walking distance was downgraded from high to very low because of study limitations (due to premature termination and a high drop-out rate in Koelemay (2022) and no blinding, risk of bias -1) and the confidence interval around the SMD crossing two thresholds for no effect to a moderate effect (imprecision, -2).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure long-term maximum walking distance was downgraded from high to very low because of study limitations (no blinding, risk of bias -1); conflicting results between studies (inconsistency, -1) and the small number of included patients (imprecision, -1).

Return to work

The level of evidence for return to work could not be established as no studies reported this outcome measure.

Comparison 2: endovascular treatment with supervised exercise training versus supervised exercise training

Pain-free walking distance

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure short-term pain-free walking distance was downgraded from high to very low because of study limitations (no blinding, risk of bias -1); heterogeneity between studies (inconsistency, -1) and the small number of included patients (imprecision, -1).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure long-term pain-free walking distance was downgraded from high to very low because of study limitations (no blinding, risk of bias -1) and the small number of included patients (imprecision, -2).

Quality of life

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure short-term quality of life was downgraded from high to low because of study limitations (no blinding, risk of bias -1) and the small number of included patients (imprecision, -1).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure long-term quality of life was downgraded from high to low because of study limitations (no blinding, risk of bias -1) and the small number of included patients (imprecision, -1).

Cost-effectiveness

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure cost-effectiveness was downgraded from high to very low, because of conflicting results between studies (inconsistency, -2) and number of included patients (imprecision, -1).

Maximum walking distance

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure short-term maximum walking distance was downgraded from high to very low because of study limitations (no blinding, risk of bias -1) and the confidence interval around the SMD crossing two thresholds for no effect to a moderate effect (imprecision, -2).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure long-term maximum walking distance was downgraded from high to very low because of study limitations (no blinding, risk of bias -1) and the confidence interval around the SMD crossing three thresholds for no effect to a big effect (imprecision, -2).

Return to work

The level of evidence for return to work could not be established as no studies reported this outcome measure.

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question:

What is the effectiveness of endovascular treatment (with or without supervised exercise training) compared to supervised exercise training alone in patients with intermittent claudication?

P = patients with intermittent claudication.

I = endovascular treatment (with or without SET).

C = supervised exercise training (SET).

O = pain-free walking distance, quality of life, cost-effectiveness, improved vascularization (ankle-brachial index), maximum walking distance, return to work.

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered quality of life, return to work, and cost-effectiveness as critical outcome measures for decision making; and maximum walking distance and pain-free walking distance as important outcome measures for decision making.

A priori, the working group did not define the outcome measures listed above but used the definitions used in the studies.

The working group defined the following thresholds as a minimal clinically (patient) important differences per outcome:

- Pain-free walking distance and maximum walking distance: a trivial effect (standardized mean difference (SMD) = 0 to 0.2), a small effect (SMD = 0.2 to 0.5), a moderate effect (SMD = 0.5 to 0.8), and a large effect (SMD >0.8). For mean differences, a standard deviation of 0.5 was defined to be clinically relevant.

- Quality of life: 0.87 points difference on the VascuQoL questionnaire or a related disease-specific questionnaire (Conijn, 2014). If different questionnaires were pooled, then differences were defined as: a trivial effect (standardized mean difference (SMD) = 0 to 0.2), a small effect (SMD = 0.2 to 0.5), a moderate effect (SMD = 0.5 to 0.8), and a large effect (SMD >0.8).

- Return to work: 25% (RR < 0.8 or RR > 1.25).

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms until February 16th 2022. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 411 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria: systematic reviews of RCT’s or comparative studies comparing the effectiveness of (supervised) exercise training (SET) with endovascular treatment with or without SET in patients with intermittent claudication. 35 studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, 25 studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and ten studies were included.

Results

Ten studies (one systematic review, one RCT, two long-term follow-up studies and six cost-effectiveness studies) were included in the analysis of the literature. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- Baer-Bositis HE, Hicks TD, Haidar GM, Sideman MJ, Pounds LL, Davies MG. Outcomes of reintervention for recurrent symptomatic disease after tibial endovascular intervention. J Vasc Surg. 2018 Sep;68(3):811-821.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2017.11.096. Epub 2018 Mar 8. PMID: 29525414.

- Bath J, Lawrence PF, Neal D, Zhao Y, Smith JB, Beck AW, Conte M, Schermerhorn M, Woo K. Endovascular interventions for claudication do not meet minimum standards for the Society for Vascular Surgery efficacy guidelines. J Vasc Surg. 2021 May;73(5):1693-1700.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2020.10.067. Epub 2020 Nov 27. Erratum in: J Vasc Surg. 2021 Oct;74(4):1436. PMID: 33253869; PMCID: PMC8189641.

- Bouwens E, Klaphake S, Weststrate KJ, Teijink JA, Verhagen HJ, Hoeks SE, Rouwet EV. Supervised exercise therapy and revascularization: Single-center experience of intermittent claudication management. Vasc Med. 2019 Jun;24(3):208-215. doi: 10.1177/1358863X18821175. Epub 2019 Feb 22. PMID: 30795714; PMCID: PMC6535809.

- Dörenkamp S, Mesters I, Teijink J, de Bie R. Difficulties of using single-diseased guidelines to treat patients with multiple diseases. Front Public Health. 2015 Apr 29;3:67. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2015.00067. PMID: 25973414; PMCID: PMC4413518.

- Dörenkamp S, Mesters I, de Bie R, Teijink J, van Breukelen G. Patient Characteristics and Comorbidities Influence Walking Distances in Symptomatic Peripheral Arterial Disease: A Large One-Year Physiotherapy Cohort Study. PLoS One. 2016 Jan 11;11(1):e0146828. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0146828. PMID: 26751074; PMCID: PMC4708998.

- Fakhry F, Fokkenrood HJ, Spronk S, Teijink JA, Rouwet EV, Hunink MGM. Endovascular revascularisation versus conservative management for intermittent claudication. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018 Mar 8;3(3):CD010512. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010512.pub2. PMID: 29518253; PMCID: PMC6494207.

- Fakhry F, Rouwet EV, Spillenaar Bilgen R, van der Laan L, Wever JJ, Teijink JAW, Hoffmann WH, van Petersen A, van Brussel JP, Stultiens GNM, Derom A, den Hoed PT, Ho GH, van Dijk LC, Verhofstad N, Orsini M, Hulst I, van Sambeek MRHM, Rizopoulos D, Moelker A, Hunink MGM. Endovascular Revascularization Plus Supervised Exercise Versus Supervised Exercise Only for Intermittent Claudication: A Cost-Effectiveness Analysis. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2021 Jul;14(7):e010703. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.121.010703. Epub 2021 Jul 13. PMID: 34253049.

- Jansen SCP, Hoeks SE, Nyklí?ek I, Scheltinga MRM, Teijink JAW, Rouwet EV. Supervised Exercise Therapy is Effective for Patients With Intermittent Claudication Regardless of Psychological Constructs. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2022 Mar;63(3):438-445. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2021.10.027. Epub 2021 Dec 6. PMID: 34887208.

- Kesaniemi YK, Danforth E Jr, Jensen MD, Kopelman PG, Lefèbvre P, Reeder BA. Dose- response issues concerning physical activity and health: an evidence-based symposium. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2001 Jun;33(6 Suppl):S351-8. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200106001-00003. PMID: 11427759.

- Klaphake S, Fakhry F, Rouwet EV, van der Laan L, Wever JJ, Teijink JA, Hoffmann WH, van Petersen A, van Brussel JP, Stultiens GN, Derom A, den Hoed PT, Ho GH, van Dijk LC, Verhofstad N, Orsini M, Hulst I, van Sambeek MR, Rizopoulos D, van Rijn MJE, Verhagen HJM, Hunink MGM. Long-Term Follow-up of a Randomized Clinical Trial Comparing Endovascular Revascularization Plus Supervised Exercise with Supervised Exercise only for Intermittent Claudication. Ann Surg. 2020 Dec 23;Publish Ahead of Print. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000004712. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 33378308.

- Koelemay MJW, van Reijen NS, van Dieren S, Frans FA, Vermeulen EJG, Buscher HCJL, Reekers JA; SUPER Study Collaborators; SUPER Study Data Safety Monitoring Committee. Editor's Choice - Randomised Clinical Trial of Supervised Exercise Therapy vs. Endovascular Revascularisation for Intermittent Claudication Caused by Iliac Artery Obstruction: The SUPER study. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2022 Mar;63(3):421-429. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2021.09.042. Epub 2022 Feb 10. PMID: 35151572.

- Mazari FA, Khan JA, Samuel N, Smith G, Carradice D, McCollum PC, Chetter IC. Long-term outcomes of a randomized clinical trial of supervised exercise, percutaneous transluminal angioplasty or combined treatment for patients with intermittent claudication due to femoropopliteal disease. Br J Surg. 2017 Jan;104(1):76-83. doi: 10.1002/bjs.10324. Epub 2016 Oct 20. PMID: 27763685.

- Mazari FA, Khan JA, Carradice D, Samuel N, Gohil R, McCollum PT, Chetter IC. Economic analysis of a randomized trial of percutaneous angioplasty, supervised exercise or combined treatment for intermittent claudication due to femoropopliteal arterial disease. Br J Surg. 2013 Aug;100(9):1172-9. doi: 10.1002/bjs.9200. PMID: 23842831.

- Patterson RB, Pinto B, Marcus B, Colucci A, Braun T, Roberts M. Value of a supervised exercise program for the therapy of arterial claudication. J Vasc Surg. 1997 Feb;25(2):312-8; discussion 318-9. doi: 10.1016/s0741-5214(97)70352-5. PMID: 9052565.

- Pinto BM, Marcus BH, Patterson RB, Roberts M, Colucci A, Braun C. On-Site Versus Home Exercise Programs: Psychological Benefits for Individuals With Arterial Claudication. Journal of Aging & Physical Activity 1997;5(4):311.

- Reynolds MR, Apruzzese P, Galper BZ, Murphy TP, Hirsch AT, Cutlip DE, Mohler ER 3rd, Regensteiner JG, Cohen DJ. Cost-effectiveness of supervised exercise, stenting, and optimal medical care for claudication: results from the Claudication: Exercise Versus Endoluminal Revascularization (CLEVER) trial. J Am Heart Assoc. 2014 Nov 11;3(6):e001233. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.114.001233. PMID: 25389284; PMCID: PMC4338709.

- Spannbauer A, Berwecki A, Ridan T, Mika P, Chwa?a M. Atherosclerotic ischaemia of the lower limbs what the physiotherapist and the nurse should know. Piel?gniarstwo Chirurgiczne i Angiologiczne/Surgical and Vascular Nursing. 2017;11(4):117-127.

- Spronk S, Bosch JL, den Hoed PT, Veen HF, Pattynama PM, Hunink MG. Cost-effectiveness of endovascular revascularization compared to supervised hospital-based exercise training in patients with intermittent claudication: a randomized controlled trial. J Vasc Surg. 2008 Dec;48(6):1472-80. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2008.06.016. Epub 2008 Sep 4. PMID: 18771879.

- van den Houten MM, Lauret GJ, Fakhry F, Fokkenrood HJ, van Asselt AD, Hunink MG, Teijink JA. Cost-effectiveness of supervised exercise therapy compared with endovascular revascularization for intermittent claudication. Br J Surg. 2016 Nov;103(12):1616-1625. doi: 10.1002/bjs.10247. Epub 2016 Aug 11. PMID: 27513296.

- van Reijen NS, van Dieren S, Frans FA, Reekers JA, Metz R, Buscher HCJL, Koelemay MJW; SUPER-study collaborators. Cost Effectiveness of Endovascular Revascularisation vs. Exercise Therapy for Intermittent Claudication Due to Iliac Artery Obstruction. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2022 Mar;63(3):430-437. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2021.10.048. Epub 2022 Feb 9. PMID: 35148946.Symptomatisch perifeer arterieel vaatlijden [richtlijn] [Internet]. Symptomatisch Perifeer-arterieel-vaatlijden. [cited 2023Mar8]. Available from: https://www.kngf.nl/kennisplatform/richtlijnen/symptomatisch-perifeer-arterieel-vaatlijden

Evidence tabellen

Evidence table for systematic review of RCTs and observational studies (intervention studies)

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C)

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

Fahkry, 2018 |

SR and meta-analysis of RCTs

Literature search up to February, 2017.

A: Creasy, 1990 B: Hobbs, 2006 C: Mazari, 2012 D: Murphy, 2015 E: Spronk, 2009 F: Fahkry, 2015 G: Greenhalgh, 2008

Study design: SR of RCTs Setting and Country: A: United Kingdom, Oxford Regional Vascular Service B: United Kingdom, Department of Vascular Surgery at University of Birmingham C: United Kingdom, Vascular Surgical Unit of a university hospital D: United States, university and non-university hospitals E: Netherlands, outpatient clinic at a non-university hospital F: Netherlands, university and non-university hospitals G: United Kingdom, university and non-university hospitals

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: A: Oxford District Research Committee B: Health Technology Assessment Grant C: BJS research bursary, European Society of Vascular Surgery research grant, and support from the Academic Vascular Surgical Unit, University of Hull D: grants from National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Financial support from Cordis/Johnson & Johnson (Warren, NJ), eV3 (Plymouth,MN), and Boston Scientific (Natick, MA). Cilostazol was donated to all study participants by Otsuka America, Inc (San Francisco, CA). Pedometers were donated by Omron Healthcare, Inc (Lake Forest, IL). Krames Staywell (San Bruno, CA) donated print materials on exercise and diet. E: not applicable F: grant from Netherlands organization for health research and development G: Camelia Botnar Arterial Research Foundation with independent educational grants from Bard Ltd., Boston Scientific Ltd., and Cook

|

Inclusion criteria SR: - Studies comparing endovascular revascularisation (± conservative therapy) versus conservative therapies or no specific therapy for intermittent claudication.

Exclusion criteria SR: - Studies providing any kind of surgical revascularisation in the comparison group. - Studies comparing different types of endovascular revascularisation procedures (e.g. angioplasty vs angioplasty plus stenting).

7 studies were included four our two comparisons

Important patient characteristics at baseline:

N randomised, mean age A: 36 patients, 63.6 yrs (group 1) and 62.2 yrs (group 2) B: 23 patients, median 67 yrs (group 1), median 67 yrs (group 2), and median 67 years (group 3) C: 178 patients, median 69.5 yrs (group 1), median 70 yrs (group 2), and median 69 years (group 3) D: 119 patients, median 65 yrs (group 1), median 64 yrs (group 2), and median 62 years (group 3) E: 151 patients, 65 yrs (group 1) and 66 yrs (group 2) F: 212 patients, 64 yrs (group 1) and 66 yrs (group 2) G: - Aortoiliac trial: 34 randomized, 63.9 yrs (group 1) and 62.5 yrs (group 2)

Sex male, n (%) A: 15 (75%) in group 1, and 12 (75%) in group 2 B: 6 (67%) in group 1, 6 (86%) in group 2, and 4 (57%) in group 3 C: 33 (57%) in group 1, 37 (62%) in group 2, and 37 (62%) in group 3 D: 32 (70%) in group 1, 21 (49%) in group 2, and 16 (73%) in group 3 E: 44 (59%) in group 1, and 39 (52%) in group 2 F: 60 (57%) in group 1, and 72 (68%) in group 2 G: - Femoropopliteal trial: 33 (69%) in group 1, and 26 (58%) in group 2 - Aortoiliac trial: 12 (62%) in group 1, and 10 (67%) in group 2

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

Describe intervention:

A: endovascular revascularisation without stenting, n = 20 (n = 30 at 6 years' follow-up) B: endovascular revascularisation without stenting plus best medical therapy, n = 9 C: - Group 1: endovascular revascularisation without stenting plus supervised exercise therapy, n = 58 - Group 2: endovascular revascularisation without stenting, n = 60 D: endovascular revascularisation with primary stenting plus claudication pharmacotherapy (cilostazol), n = 46 E: endovascular revascularisation with selective stenting, n = 76 F: endovascular revascularisation with selective stenting plus supervised exercise therapy, n = 106 G: endovascular revascularisation with selective stenting plus supervised exercise therapy, n = 48 (femoropopliteal disease trial), and n = 19 (aortoiliac disease trial)

|

Describe control:

A: supervised exercise therapy for 6 months (2 sessions/week, 30 minutes/session), n = 16 (n = 26 at 6 years' follow-up) B: supervised exercise therapy plus best medical therapy for 12 weeks (2 sessions/week, 60 minutes/session), n = 7 C: supervised exercise therapy for 12 weeks (3 sessions/week), n = 60 D: supervised exercise therapy for 26 weeks (3 sessions/week, 1 hour/session) supplemented by 12-month telephone-based (1 to 2 calls/mo) programme to adhere and maintain adherence plus claudication pharmacotherapy (cilostazol), n = 43 E: supervised exercise therapy for 24 weeks (2 sessions/week, 30 minutes/session), n = 75 F: supervised exercise therapy for 12 months (2 to 3 sessions/week 0 to 3 months, 1 session/week 3 to 6 months, 1 session/mo 6 to 12 months, 60 minutes/session), n = 106 G: supervised exercise therapy for 6 months (≥ 1 session/week, 30 minutes/session), n = 45 (femoropopliteal disease trial), and n = 15 (aortoiliac disease trial)

|

End-point of follow-up:

A: 3, 6, 9, 12, 15 months and 6 years B: 3 and 6 months C: 1, 3, 6, and 12 months D: 6 and 18 months E: 1, 6, 12 months and 7 years F: 1, 6, and 12 months G: : 6, 12, and 24 months

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? (intervention / control)

Loss to follow-up: A: 4 / 5 (at 6 years of follow-up) B: 0 / 1 C: 10 / 8 / 14 (group 1, 2, 3, respectively) D: 5 / 8 E: 2 / 0 (after 7 years: 14 / 22) F: 5 / 8 G: - Femoropopliteal trial: 3 / 6 - Aortoiliac trial: 4 / 1

|

Comparison 1: endovascular revascularisation versus conservative therapy (supervised exercise therapy)

Maximum walking distance (MWD) MWD (6 to 12 months) Effect measure: standardized mean difference [95% CI]: A: -1.94[-3.43,-0.45] B: 1.14[-0,2.27] C: -0.68[-1.08,-0.27] D: -0.44[-0.88,0.01] E: -0.36[-0.7,-0.03]

Pooled effect (random effects model): -0.42 [95% CI -0.87 to 0.04] favoring SET. Heterogeneity (I2): 68.72%

Long-term MWD A: 0.2[-0.46,0.85] D: -0.35[-0.85,0.14] E: 0.13[-0.3,0.57]

Pooled effect (random effects model): -0.02 [95% CI 0.36 to 0.32] favoring SET. Heterogeneity (I2): 23.85%

Pain-free walking distance Pain-free walking distance (6 to 12 months) Effect measure: standardized mean difference [95% CI]: A: -0.67[-1.86,0.52] B: 1.14[0.01,2.28] C: -0.18[-0.58,0.21] D: 0.16[-0.28,0.61] E: -0.23[-0.57,0.1]

Pooled effect (random effects model): -0.05 [95% CI -0.38 to 0.29] favoring SET. Heterogeneity (I2): 47.47%

Long-term pain-free walking distance Effect measure: standardized mean difference [95% CI]: D: -0.09[-0.58,0.4] E: 0.29[-0.15,0.72]

Pooled effect (random effects model / fixed effects model): 0.11 [95% CI -0.26 to 0.48] favoring endovascular treatment. Heterogeneity (I2): 22.08%

Quality of life Defined as disease-specific quality of life.

Effect measure: standardized mean difference [95% CI]: C: 0.11[-0.29,0.51] D: 0.49[-0.02,0.99] E: 0.11[-0.22,0.44]

Pooled effect (random effects model): 0.18 [95% CI -0.04 to 0.41] favoring endovascular treatment. Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

Ankle brachial index (ABI) Not reported.

Return to work Not reported.

Comparison 2: endovascular revascularisation plus conservative therapy versus conservative therapy (supervised exercise therapy)

Maximum walking distance Defined as short- and long-term MWD.

Short-term MWD Effect measure: standardized mean difference [95% CI]: C: -0.31[-0.72,0.1] F: 0.41[0.14,0.68]

Pooled effect (random effects model): 0.26 [95% CI -0.13 to 0.64] favoring combined therapy. Heterogeneity (I2): 70.43%

Long-term MWD Effect measure: standardized mean difference [95% CI]: 1.01[0.54,1.48]

Pooled effect (random effects model): 1.18 [95% CI 0.65 to 1.7] favoring combined therapy. Heterogeneity (I2): 24.09%

Pain-free walking distance Short-term pain-free walking distance Effect measure: standardized mean difference [99% CI]: C: 0.01[-0.4,0.41] F: 0.62[0.34,0.89]

Pooled effect (random effects model): 0.33 [95% CI -0.26 to 0.93] favoring combined therapy. Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

Quality of life Defined as disease-specific quality of life.

Effect measure: standardized mean difference [95% CI]: C: 0.07[-0.29,0.44] F: 0.39[0.11,0.66]

Pooled effect (random effects model): 0.25 [95% CI -0.05 to 0.56] favoring combined therapy. Heterogeneity (I2): 45.16%

Ankle brachial index (ABI) Not reported.

Return to work Not reported.

|

|

Evidence table for intervention studies (randomized controlled trials and non-randomized observational studies [cohort studies, case-control studies, case series])1

This table is also suitable for diagnostic studies (screening studies) that compare the effectiveness of two or more tests. This only applies if the test is included as part of a test-and-treat strategy – otherwise the evidence table for studies of diagnostic test accuracy should be used.

Research question:

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics 2 |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C) 3

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size 4 |

Comments |

|

Koelemay, 2022 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: multicentre trial conducted in 18 hospitals in The Netherlands and allied physiotherapy practices

Funding and conflicts of interest: This work was supported by the Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development (ZonMw Grant 171102025). ZonMw did not play any role in the conduct and writing of this research. |

Inclusion criteria: - patients with disabling IC resulting from > 50% stenosis or occlusion of the common or external iliac artery as seen on colour duplex scanning (CDS), magnetic resonance angiography (MRA), or computed tomography angiography (CTA), graded as TASC A, B, and C. - Patients with a concomitant > 50% stenosis or occlusion of the SFA - Patients could walk at least two minutes on a treadmill at 3.2 km/h and 10% incline, had a maximum walking distance (MWD) on the treadmill between 100 and 300 m, and gave written informed consent.

Exclusion criteria: Life expectancy of less than three months, inability to complete self reported questionnaires, contrast agent allergy, pregnancy, contraindication to anticoagulant therapy, symptoms of less than three months, ipsilateral common femoral artery (CFA) stenosis > 50% or occlusion, heart failure or angina pectoris NYHA III or IV, participation in another study, already had SET, and renal insufficiency (serum creatinine > 150 mmol/L).

N total at baseline: Intervention (SET): 114 Control (ER): 126

Important prognostic factors2:

Age, mean (SD) I: 63 (8) C: 61 (9)

Sex male, n (%) I: 63 (55%) C: 83 (66%)

Smoking status, Current I: 60 (53%) C: 68 (54%) Former I: 48 (42%) C: 53 (42%) Never I: 6 (5%) C: 5 (4%)

Comorbidity Hypertension I: 54 (47%) C: 60 (48%) Hypercholesterolaemia I: 64 (56%) C: 82 (65%) Diabetes I: 19 (17%) C: 26 (21%) Ischaemic heart disease I: 23 (20%) TIA I: 6 (5%) C: 8 (6%) Stroke I: 4 (4%) C: 5 (4%) COPD Mild I: 19 (17%) C: 1 (1%) Concomitant musculoskeletal disorders Previous I: 13 (11%) I: 6 (5%) C: 5 (4%)

Previous endovascular revascularisation I: 10 (9%) C: 13 (10%)

Groups comparable at baseline? Slight imbalance between groups: more men and patients with history of ischaemic heart disease in the control group. |

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

Supervised exercise therapy (SET) (n=114). This consisted information by a physical therapist (PT) about the training programme. At the first meeting the patient walked on a treadmill to the ACSM claudication pain rating scale 3, and there was room for walking pattern improvement and enhancement of endurance and strength, tailored to the individual physiotherapy practice and the individual needs of the patient. All patients were given homework and set individual goals to stimulate walking. Each for weeks the patients did a treadmill test and received advise from the PT.

SET lasted for 6 months, with the first 12 weeks comprising of 2 sessions per week, then one session per week for 8 weeks, and finally one session per two weeks for the last four weeks.

|

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

Endovascular revascularization (ER) (n=126), performed according to local practice by an experienced interventional radiologist certified by the Dutch Society of Interventional Radiology according to local protocol.

Additional insertion of a stent was done for recanalisation of an occlusion, for a residual mean pressure gradient > 10 mmHg over the treated stenosis, or for a > 30% residual stenosis. |

Length of follow-up: 1, 6, and 12 months.

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: Follow-up was complete for 90/114 (79%) patients. Reasons: - No show (n=8) - Concomitant illness (n=3) - Died (n=2)

Control: Follow-up was complete for 104/126 (83%) patients. Reasons: - No show (n=15) - Concomitant illness (n=3) - Died (n=3)

Incomplete outcome data: Not reported. The article only reported that missing data for the VascuQoL was imputed.

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Maximum walking distance (MWD) in meters, mean (95%CI) Baseline I: 187 (175-200) C: 196 (184-208)

1 month I: 411 (360-462) C: 493 (445-542) p-value: 0.016

6 months I: 528 (475-581) C: 531 (483-579) p-value: 0.93

12 months I: 561 (507-615) C: 574 (526-624) p-value: 0.69

Pain-free walking distance in meters, mean (95%CI) Baseline I: 83 (75-92) C: 88 (79-95)

1 month I: 186 (131-242) C: 347 (294-400) p-value: <0.001

6 months I: 268 (211-325) C: 384 (332-436) p-value: 0.002

12 months I: 368 (309-427) C: 450 (396-503) p-value: 0.036

Quality of life VascuQoL sumscore,mean (95% CI) Baseline I: 4.24 (4.02-4.46) C: 4.28 (4.11-4.45)

1 month I: 4.95 (4.72-5.18) C: 5.88 (5.67-6.10)

6 months I: 5.22 (4.98-5.47) C: 5.98 (5.77-6.19)

12 months I: 5.58 (5.32-5.82) C: 5.88 (5.67-6.09)

Ankle brachial index (ABI) Not reported.

Return to work Not reported.

|

Note 1:

Note 2: Within one year of follow up 33/114 (29%) patients allocated to SET underwent additional ER of the iliac arteries, and 2/114 (2%) had a surgical revascularisation. Some 10/126 (8%) of the patients allocated to ER underwent additional ER within one year, and another 10 (8%) had an additional surgical revascularisation. These operations comprised aortobifemoral bypass (n ¼ 1), tromboendarterectomy of the iliac (n ¼ 1), common femoral (n ¼ 4), and popliteal arteries (n ¼ 1), and femoropopliteal bypass (n ¼ 6).

|

|

Klaphake, 2020

(Long-term follow-up of the ERASE study) |

Described in evidence table for systematic reviews (Fahkry, 2015) |

Described in evidence table for systematic reviews (Fahkry, 2015) |

Described in evidence table for systematic reviews (Fahkry, 2015)

Endovascular revascularisation with selective stenting plus supervised exercise therapy, n = 106

|

Described in evidence table for systematic reviews (Fahkry, 2015)

Supervised exercise therapy for 12 months (2 to 3 sessions/week 0 to 3 months, 1 session/week 3 to 6 months, 1 session/mo 6 to 12 months, 60 minutes/session), n = 106

|

Length of follow-up: Median follow-up: 5.4 years (IQR 4.9–5.7).

Loss-to-follow-up: 24 (11%) out of 212 patients were lost-to-follow-up, and 34 patients (16%) died. Of the 154 patients who were available for follow-up, the treadmill test was not performed in 26 patients; 10 patients were unable to perform the test, and the reason was unknown in 16 patients.

|

Maximum walking distance (5 years), mean (99% CI) I: 1034 (825 to 1244), n=68 C: 981 (764 to 1199), n=60

Pain-free walking distance (5 years), mean (99% CI) I: 976 (773 to 1178), n=68 C: 865 (657 to 1074), n=60

Quality of life (5 years) VascuQol, mean (99% CI) I: 1.60 (1.31 to 1.89), filled in by 79/106 C: 1.36 (1.06 to 1.66), filled in by 67/106

Ankle brachial index (ABI) (5 years), mean (99% CI) At rest I: 0.13 (0.07 to 0.19) C: 0.08 (-0.15 to 0.06)

After exercise I: 0.28 (0.20 to 0.37) C: 0.22 (0.13 to 0.31)

Return to work Not reported.

|

|

|

Mazari, 2016 |

Described in evidence table for systematic reviews (Mazari, 2012) |

Described in evidence table for systematic reviews (Mazari, 2012) |

Described in evidence table for systematic reviews (Mazari, 2012) |

Described in evidence table for systematic reviews (Mazari, 2012) |

Length of follow-up: Median follow-up: 5.2 years (05% CI 4.6 to 5.7)

Loss-to-follow-up: 39 (24.4%) out of 178 patients died before the follow-up visit. Follow-up was complete for 111 patients. In total, follow-up was completed for 39 patients (65%) in the PTA group, for 35 patients (58%) in the SEP group, and for 37 patients (64%) in the PTA+SEP group. |

Comparison 1: percutaneous transluminal angioplasty versus supervised exercise programme

Maximum walking distance Median MWD (95% CI) I: 118.25 (68.07 to 215.00) C: 78.12 (56.03 to 102.80)

Pain-free walking distance Patient-reported walking distance, median (95% CI) I: 800.00 (124.91 to 1000.00) C: 200.00 (96.94 to 800.00)

Quality of life VascuQol, median (95% CI) I: 5.92 (4.85 to 6.43) C: 4.64 (3.90 to 5.26)