(Vroeg)mobilisatie

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is het effect van vroegmobilisatie voor patiënten opgenomen op de intensive care?

Aanbeveling

Start met mobiliseren van intensive care patiënten zodra het mogelijk en veilig is.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Er is literatuuronderzoek verricht naar het effect van vroegmobilisatie op beademingsduur, IC-opnameduur, functionele uitkomst, slaap kwaliteit en optreden van delier bij patiënten opgenomen op de IC.

Er is sprake van een klinisch relevant effect in het voordeel van de interventiegroep die vroegmobilisatie heeft gehad vergeleken met de controlegroep die geen vroegmobilisatie, of standaardzorg heeft gehad voor de cruciale uitkomstmaat beademingsduur. Voor de cruciale uitkomstmaat IC-opnameduur werd geen klinisch relevant verschil gevonden en voor de cruciale uitkomstmaat functionele uitkomst waren de gevonden effecten heterogeen.

De bewijskracht voor deze gevonden effecten is laag vanwege methodologische beperkingen in de studieopzet (risk-of-bias) en brede betrouwbaarheidsintervallen (imprecisie). De overall bewijskracht is hiermee ook laag. De beperkingen in studieopzet hebben in de meeste gevallen te maken met het gebrek aan blindering van de patiënten, de behandelaar, de onderzoeker; maar ook het gebrek aan duidelijkheid rondom de randomisatieprocedure. Brede betrouwbaarheidsintervallen worden waarschijnlijk veroorzaakt door de verschillen in de definitie van vroegmobilisatie tussen de studies (methodologische heterogeniteit).

Voor de belangrijke uitkomstmaat slaapkwaliteit was geen data beschikbaar. Hier ligt een kennislacune. Voor de belangrijke uitkomstmaat delier werd geen klinisch relevant verschil gevonden in incidentie tussen de interventie- en de controlegroep. De bewijskracht voor dit gevonden effect was ook laag. Hiermee kunnen de belangrijke uitkomstmaten ook weinig richting geven aan de besluitvorming. Echter, een recente systematic review met meta-analyse aangaande het effect van vroegmobilisatie op delier, die pas werd gepubliceerd nadat onze search was afgerond, laat zien dat vroegmobilisatie wellicht toch het optreden van delier kan reduceren. Verder concludeert men in deze studie dat vroegmobilisatie de ernst van delier zou kunnen verminderen, maar waarschuwt men ook dat langdurig mobiliseren (bijvoorbeeld iemand langdurig in een stoel laten zitten), delier kan verergeren (Nydahl, 2023).

Opvallend is dat in vrijwel alle geïncludeerde studies, de controlegroep ook gemobiliseerd wordt. Hieruit blijkt dat het mobiliseren van patiënten op de IC vrijwel overal standaardzorg is. Het is dan ook niet zozeer de vraag of men patiënten op de intensive care zou moeten mobiliseren, maar wat de juiste timing en dosering is. Dit is in lijn met de reacties op de grote trial van Hodgson (2022), die in eerste instantie lijkt te suggereren dat vroegmobilisatie niet effectief is, maar eigenlijk geïnterpreteerd zou moeten worden als een studie naar verschillende intensiteiten van vroegmobilisatie (Hodgson, 2023; Moss, 2022; Schweickert, 2022).

Veiligheid

Uit praktijkervaringen is gebleken dat (vroeg)mobilisatie risico’s met zich mee kan brengen, zoals bloeddrukdaling, vasovagale syncope, vallen of dislocatie van lijnen. Uit de literatuur blijkt dit risico echter verwaarloosbaar klein is. In een meta-analyse van Nydahl (2017) vond men dat er slechts in 2,6% van de mobilisatie sessies in de ICU sprake was van een complicatie, zoals afname van zuurstofsaturatie, hemodynamische veranderingen, vallen, dislocatie van intravasculaire katheter, dislocatie van endotracheale tube, hartritmeproblematiek of cardiac arrest. In maar 0,6 % van de sessies was sprake van een complicatie met medische consequenties. Zeker wanneer men voorafgaand aan vroegmobilisatie screent op contra-indicaties, zoals beschreven in het KNGF behandelprotocol, dan is het aannemelijk dat vroegmobilisatie veilig is. In tabel 3 is een overzicht te vinden van de belangrijkste contra-indicaties.

Tabel 3. Belangrijkst contra-indicaties, zoals beschreven in het KNGF behandelprotocol

|

Hemodynamische, respiratoire of neurologische instabiliteit, zie uitgebreide lijst van contra-indicaties voor concrete afkapwaarden |

|

Instabiele fracturen, open thorax |

|

Aanwezigheid van lijnen die mobilisatie onveilig maken |

Voor zorgverleners kan het begeleiden van vroegmobilisatie risico’s met zich meebrengen, met het optreden van rugklachten als grootste punt van zorg (Silverwood and Haddock, 2006). Goede scholing op gebied van transfers maken en aanwezigheid van hulpmiddelen (tilliften, draaischijven etc.) zijn belangrijk om problemen op dit vlak te voorkomen.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

Uit de achterbanraadpleging van IC-Connect (zie bijlage) is gebleken dat patiënten veel waarde hechten aan vroegmobilisatie. Meer dan 65% is op de IC afdeling al uit bed geweest en heeft fysiotherapie gehad tijdens de opname. De helft van de respondenten heeft fysiotherapie op de IC als zeer waardevol ervaren, ondanks het gegeven dat 62% van de respondenten aangaf niet betrokken te zijn geweest in het opstellen van een fysiotherapeutisch plan. Ook is er volgens minder dan de helft van de respondenten gecommuniceerd over de fysiotherapeutische behandeling en doelen. Ondanks dit ervaren gebrek aan communicatie geeft meer dan de helft van de respondenten aan het effect van de behandeling te hebben gemerkt en geeft 75% van deze respondenten de behandeling als cijfer een 7 of hoger.

Uit kwalitatieve studies blijkt dat patiënten zich zo zwak kunnen voelen, dat ze overrompeld kunnen worden door het idee van mobiliseren. Ze kunnen zich onbegrepen en gefrustreerd voelen. Ze voelen zich vaak uitgeput en hebben angst voor toename van pijn en kortademigheid bij inspanning. Ze kunnen zich zorgen maken of het wel voordelig voor ze is en of ze daarmee de lijnen infusen en andere technologische toepassingen niet kunnen schaden. Daarbij hebben ze vaak geen controle, en moeten ze vertrouwen op het handelen van de zorgprofessionals. Echter, wanneer ze uitleg krijgen over het belang van mobiliseren, wanneer patiënten inspraak krijgen over de timing en duur van mobiliseren, en wanneer afspraken worden nagekomen, dan erkennen patiënten wel het belang van vroegmobilisatie en zijn ze ook te overtuigen om het te gaan doen (Laerkner, 2019; Sottile, 2015). Wanneer patiënten op de IC mobiliseren kunnen ze zich meer levendig, meer alert en weer meer ‘normaal’ gaan voelen. Het veranderen van positie kan leiden tot afname van pijn en kortademigheid. Wanneer patiënten in een stoel mobiliseren voelen ze zich minder hulpeloos en gebonden. Dit wordt als een grote stap en als een bevrijding ervaren. Vroegmobilisatie kan ook leiden tot een gevoel van controle over het lichaam. Het geeft hoop op herstel, bevordert het gevoel van strijdbaarheid, en het streven naar onafhankelijkheid. De positieve ervaringen met vroegmobilisatie worden bevorderd wanneer de zorgverleners informatie geven, ondersteuning geven, aanmoediging geven, bevestiging geven, en uitdaging bieden (Söderberg, 2022). Het is belangrijk is om patiënten te coachen tijdens mobiliseren en te luisteren naar hun wensen. Er moet een gezonde balans zijn tussen het opzoeken van grenzen en het behouden van een veilig gevoel.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

Eerdere studies hebben aangetoond dat vroegmobilisatieprogramma’s kosteneffectief zijn, ervan uitgaande dat vroegmobilisatie leidde tot verkorte IC opnameduur (Lord, 2013).

In onze literatuurstudie vonden we dat de bij patiënten waarbij vroegmobilisatie was toegepast gemiddeld 1.24 dag korter afhankelijk waren van mechanische beademing.

Echter we vonden geen evidentie voor verkorte IC-opnameduur.

Het mobiliseren van patiënten op de intensive care is een arbeidsintensieve bezigheid. Interdisciplinaire afstemming en voorbereidingstijd inbegrepen duurt een mobilisatiemoment zeker 30 minuten. De tijd die zowel verpleegkundigen als fysiotherapeuten besteden aan vroegmobilisatie kunnen ze niet aan andere activiteiten besteden. Naast de personele inzet zijn er ook kosten verbonden aan materiele inzet bij vroegmobilisatie zoals bijvoorbeeld tilliften, bedfietsen, sta-tafels, draaischijven en loophulpmidddelen.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

Het vroegtijdig mobiliseren van patiënten op een IC is een gezamenlijke verantwoordelijkheid van artsen, verpleegkundigen en fysiotherapeuten, en is over het algemeen wel geïmplementeerd op Nederlandse IC’s. Belemmerende factoren voor implementatie van vroegmobilisatie zijn o.a. sedatie, hemodynamische instabiliteit, onvoldoende kennis van veiligheidscriteria, en onvoldoende ‘dedicated’ personeel (Schweickert, 2022). In Nederland is de fysiotherapeutische zorg gestandaardiseerd middels het KNGF behandelprotocol ‘fysiotherapie op de intensive care’. Verdere implementatie vindt plaats door middel van post-HBO scholing voor fysiotherapeuten werkzaam op de IC. De optimale dosis en timing van vroegmobilisatie zijn nog niet bekend (Moss, 2022).

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

Vroegmobilisatie heeft een gunstig effect op beademingsduur en mogelijk op functionele uitkomst. In potentie heeft het ook gunstige effecten op delier. Verder kan vroegmobilisatie ertoe leiden dat mensen zich minder afhankelijk en minder beperkt voelen. Het bevordert het gevoel van controle en hoop op herstel. Nadelige bijwerkingen of veiligheidsrisico’s van vroegmobilisatie zijn te verwaarlozen, zeker wanneer men screent op contra-indicaties voorafgaand aan mobiliseren en wanneer men de individuele patiënt voor ogen houdt in de balans tussen het opzoeken van grenzen en het voorkomen van overbelasting.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Volgens de “kwaliteitsstandaard organisatie van Intensive Care” is het aannemelijk dat fysiotherapie van IC-patiënten veilig is en een versneld en vollediger herstelproces geeft. Fysiotherapie op de intensive care heeft het doel om fysieke achteruitgang te voorkomen en fysiek functioneren (inclusief respiratoir functioneren) te optimaliseren (zie KNGF Behandelprotocol fysiotherapie op de intensive care). In de literatuur is een diversiteit aan negatieve gevolgen van bedrust en inactiviteit beschreven die we kunnen scharen onder de term ‘deconditionering’. Voorbeelden van deconditionering zijn: afname van (adem)spierkracht, afname van uithoudingsvermogen, afname van longfunctie, afname van botmineralisatie, afname van huiddoorbloeding en decubitus, afname van darmfunctie, maar ook afname van cognitief functioneren. Een vroegtijdige start van activeren en mobiliseren zou deze deconditionering kunnen beperken en resulteren in kortere beademingsduur, kortere IC opnameduur en betere functionele uitkomsten zoals minder verlies van zelfstandigheid bij activiteiten als zitten, staan, lopen en traplopen. Ook zijn er aanwijzingen dat vroegmobilisatie een rol kan spelen in het voorkomen of behandelen van delier en slaapstoornissen, echter dit doel wordt momenteel niet genoemd in de diverse richtlijnen.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

1. Duration of mechanical ventilation (critical)

|

Low GRADE |

Early mobilisation may shorten the duration of mechanical ventilation when compared with no mobilisation, no intervention or usual care in adult ICU patients.

Sources: Dong, 2014; Dong, 2016; Eggmann, 2018; Hodgson, 2016; Kho, 2019; Maffei, 2017; Moss, 2016; Schweickert, 2009. |

2. Duration of ICU stay (critical)

|

Low GRADE |

Early mobilisation may result in little to no difference in the duration of ICU stay when compared with no mobilisation, no intervention or usual care in adult ICU patients.

Sources: Afxonidis, 2021; Eggmann, 2018; Hodgson, 2016; Kho, 2019; Morris, 2015; Schaller, 2016; Schweickert, 2009; Wright, 2017. |

3. Functional outcome (critical)

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of early mobilisation on functional outcome when compared with no mobilisation, no intervention or usual care in adult ICU patients.

Sources: Hodgson, 2022; Nickels, 2020; Schujmann, 2020; Schweickert, 2009. |

4. Sleep quality (important)

|

No GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding the effect of early mobilisation on sleep quality when compared with no mobilisation, no intervention or usual care in adult ICU patients.

Sources: - |

5. Delirium incidence (important)

|

Low GRADE |

Early mobilisation may result in little to no difference in delirium incidence when compared with usual care in adult ICU patients.

Sources: Fossat, 2018; Nickels, 2020; Nydahl, 2022. |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

The five systematic reviews and meta-analyses included 14 studies that described early mobilisation in ICU-patients. The systematic reviews assessed the risk-of-bias for each study (results are shown in evidence tables). In general, blinding of patients and therapists was lacking, but was impossible due to the nature of the intervention. However, some studies also lacked blinding of outcome assessors, which could have been prevented.

Furthermore, trials were underpowered because recruitment stopped early or a sample size calculation was not executed. The systematic reviews were slightly different in their inclusion and exclusion criteria, which could have caused heterogeneity in the studies that were selected by the reviews (mainly caused by differences in the criteria for the intervention group).

Additionally, five RCTs that were published from 2020 and could not have been included in the systematic reviews, were added to the analysis of the literature. Table 1 provides an overview of the study descriptives for all RCTs.

Table 1: Study descriptives for individual RCTs

|

Study |

Reviews |

Population |

Intervention |

Control |

Outcome |

|

Schweickert, 2009 |

Castro-Avila, 2015; Klem, 2021; Monsees, 2022; Zhang, 2019 |

ICU patients (n=104) |

Physical therapy, occupational therapy and interruption of sedation (n=49) |

Usual care and nurse care (n=55) |

Duration of ICU stay (days) Duration of mechanical ventilation (days) Functional outcome (walking without assistance) |

|

Denehy, 2013 |

Castro-Avila, 2015 |

ICU patients, five or more days in ICU, intensive care specialist agreed with their participation (n=150) |

Exercise sessions based in baseline PFIT, including sitting out of bed, sit to stand, marching on the spot and shoulder elevation (n=74) |

Usual care (n=76) |

Duration of ICU stay (days)

|

|

Brummel, 2014 |

Castro-Avila, 2015 |

Shock, haemorrhagic shock, and/or septic shock patients. Clinically stable (n=78) |

Early PT + Cognitive therapy (CT): it also included exercises to improve orientation, attention and memory (n=65) |

ordered by treating clinician (n=22) |

Duration of ICU stay (days)

|

|

Dong, 2016 |

Klem, 2021 |

Coronary artery bypass surgery patients (n=106) |

Pre-surgical information and early mobilization twice daily |

Rehabilitation with assistance from family following discharge from intensive care |

Duration of mechanical ventilation (days) Duration of ICU stay (days) |

|

Eggmann, 2018 |

Klem, 2021 |

Mixed ICU patients (n=115) |

Early progressive mobilisation with in-bed cycle ergometry up to three times daily on weekdays + standard treatment |

Standard treatment (early mobilisation, respiratory physiotherapy and passive/ active exercises) |

Duration of ICU stay (days) Duration of mechanical ventilation (days) |

|

Hodgson, 2016 |

Klem, 2021; Monsees, 2022; Zhang, 2019 |

Mixed ICU patients (n=50) |

Early mobilization according to standard protocol for one hour a day |

Unit's standard interventions: passive movement |

Duration of ICU stay (days) Duration of mechanical ventilation (days) |

|

Kho, 2019 |

Klem, 2021; Zhang, 2019 |

Surgical and medical ICU patients (n=66) |

In-bed cycle ergometry + standard treatment |

Standard treatment (passive/active exercises and early mobilisation) |

Duration of ICU stay (days) Duration of mechanical ventilation (days) |

|

Morris, 2016 |

Klem, 2021; Monsees, 2022; Zhang, 2019 |

Medical ICU patients (n=300) |

Intensive early mobilization according to standard protocol three times a day |

Standard treatment on weekdays when prescribed |

Duration of ICU stay (days)

|

|

Moss, 2016 |

Klem, 2021; Zang, 2019 |

Mixed ICU patients (n=120) |

Level-appropriate early mobilization once a day |

Standard treatment three times a week (passive exercises, positioning and functional rehabilitation) |

Duration of ICU stay (days) Duration of mechanical ventilation (days) |

|

Schaller, 2016 |

Klem, 2021; Monsees, 2022; Zhang, 2019 |

Surgical ICU patients (n=25) |

Early mobilization across five levels |

Mobilisation in accordance with departmental guidelines. |

Duration of ICU stay (days) Duration of mechanical ventilation (days) |

|

Wright, 2017 |

Klem, 2021 |

Mixed ICU patients (n=308) |

Intensive early mobilisation for 90 minutes on Weekdays |

Standard treatment for 30 minutes on weekdays |

Duration of ICU stay (days) |

|

Maffei, 2017 |

Monsees, 2022 |

Liver transplant patients (n=40) |

protocol of early and intensive rehabilitation (based on a written protocol validated by physicians and an evaluation by physiotherapist, with 2 sessions a day) |

usual treatment applied in the ICU (based on physician prescription for the physiotherapist, with one session a day) |

Duration of ICU stay (days) |

|

Dong, 2014 |

Klem, 2021 |

General ICU patients (n=60) |

Early mobilization twice daily |

Not described |

Duration of ICU stay (days) Duration of mechanical ventilation (days) |

|

Fossat, 2018 |

Zhang, 2019 |

Critically ill adult patients at 1 ICU (n=314) |

Early in-bed leg cycling plus electrical stimulation of the quadriceps muscles added to standardized early rehabilitation (n = 159) |

Standardized early rehabilitation alone (usual care) (n = 155) |

Delirium |

|

Additional RCTs |

|||||

|

Afxonidis, 2021 |

Patients undergoing cardiac surgery under extracorporeal circulation (n=78) |

Early mobilisation and physiotherapy strategy during post-operative day zero and an extra-supplementary physiotherapy session taking place in the afternoon of the first three post-operative days or until ICU discharge (n=39) |

Usual physiotherapy care (respiratory physiotherapy and physical activity (n=39) |

Duration of ICU stay (days) |

|

|

Hodgson, 2022 |

Adults (≥18 years of age) who were expected to undergo mechanical ventilation in the ICU beyond the calendar day after randomization and whose condition was sufficiently stable to make mobilisation potentially possible (n=750) |

Daily physiotherapy, which could be provided in one or more sessions. The sessions were individually tailored to achieve the highest possible level of mobilisation that was deemed to be safe for the patient at the initiation of daily therapy (n=372) |

Usual care: A level of mobilisation that was normally provided at each side (n=378) |

Functional outcome (IMS 7 or higher) |

|

|

Nickels, 2020 |

Critically ill patients expected to be mechanically ventilated for more than 48 h, recruited within 96 h of their ICU admission, and expected to remain in the ICU for more than 48 h from study enrolment (n=74) |

Routine physiotherapy in addition to in-bed leg cycling using a cycle ergometer (in the ICU or in an acute hospital ward) (n=37) |

Routine physiotherapy interventions that included a daily assessment of physical and respiratory status and treatment (n=37) |

Functional status (score for the ICU) Delirium |

|

|

Nydahl, 2022 |

Critically ill patients ≥18 years old, Richmond Agitation Sedation Score (RASS) ≥ -3 and were responsive, could be assessed for delirium, and were able to being mobilized out of bed according to local policies, and were expected to spend at least one night in the ICU (n=46) |

Early mobilisation according to a protocol for mobilisation with similar criteria for conducting or withholding mobilisation (n=26) |

Patients in the control group received usual care and were mobilized during the day by physiotherapists and nurses. If necessary, they received the same pharmacological treatment as patients in the intervention group, as per local policies. Patients in the control group could be mobilized during the evening, too, on the basis of nurses' clinical judgement (n=20) |

Delirium |

|

|

Schujmann, 2020 |

ICU patients 18 years old or older scoring 100 points on the Barthel index (BI) in the 2 weeks prior to ICU admission (n=135) |

A combined therapy consisting of a combination of conventional physiotherapy and a program of early and progressive mobilization at the appropriate level of activity for each patient (n=68) |

Conventional treatment offered by the unit physiotherapists, with active assists and active mobilisation as well as bed positioning, bedside and armchair transfers, orthostatism, and ambulation. The physiotherapist defined the type of therapy and did not use a preestablished routine. No equipment was used for the CG (n=67) |

Functional status (BI) |

|

|

Abbreviations: ICU, Intensive Care Unit; BI, Barthel Index; IMS, ICU mobility scale. |

|||||

Results

1. Duration of mechanical ventilation (critical)

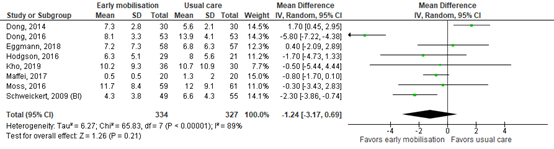

Duration of mechanical ventilation was assessed by eight studies, comprising 661 patients. Pooled data resulted in a mean difference (MD) of -1.24 days (standard deviation (SD) -3.17 to 0.69), indicating a clinically relevant difference in favor of the intervention group receiving early mobilisation. Results are shown in figure 1.

Figure 1. Forest plot showing the effect of early mobilisation compared usual care on the duration of mechanical ventilation in ICU patients.

2. Duration of ICU stay (critical)

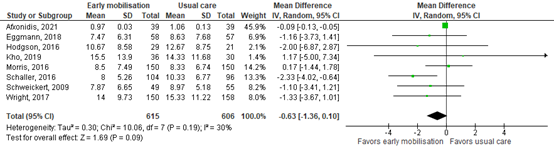

Duration of ICU stay was assessed by eight studies comprising 1221 patients. Pooled data resulted in an MD of -0.63 days (CI -1.36 – 0.10), indicating no clinically relevant difference. Results are shown in figure 2.

Figure 2. Forest plot showing the effect of early mobilisation compared usual care on the duration of ICU stay in ICU patients.

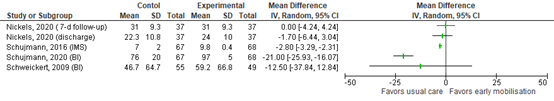

3. Functional outcome (critical)

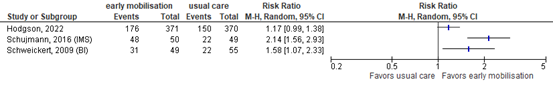

Functional outcome was assessed by four studies comprising 1052 patients. Results are shown in Table 2.

Table 2: Functional outcomes

Study |

Population size, n |

Scale/definition |

Range |

Timing |

Early mobilisation * |

Usual care * |

Effect measure |

Clinically relevant (yes/no) |

|

Hodgson (2022) |

741 |

IMS ≥ 7, n/N (%) |

0% - 100% |

Mobilisation in ICU |

176/371 (47.4%) |

150/370 (40.5%) |

RR: 1.17 |

No |

|

Schujmann (2020) |

135 |

ICU mobility Scale (IMS) |

0 – 32 |

Hospital discharge |

9.8 ± 0.4 |

7 ± 2 |

MD: -2.8 |

No |

|

Independent patients, n/N (%) |

0% - 100% |

Hospital discharge |

48/50 (95%) |

22/49 (44%) |

RR: 2.14 |

Yes |

||

|

Barthel index score |

0 – 100 |

Hospital discharge |

97 ± 5 |

76 ± 20 |

MD: -21.0 [-25.9 – 16.1] |

Yes |

||

|

Schweickert (2009) |

104 |

Barthel index score |

0 – 100 |

Hospital discharge |

75 (7.5 – 95) |

55 (0 – 85) |

MD: -12.5 [37.8 – 12.8] |

Yes |

|

Patients (n) walking without assistance |

0% - 100% |

Hospital discharge |

29/49 (59%) |

19/55 (35%) |

RR: 1.58 |

Yes |

||

|

Nickels (2020) |

72 |

Functional status score |

0 – 36 |

ICU discharge |

23 (18 – 31) |

23 (15 – 29) |

MD: -1.7 [-6.4 – 3.0] |

No |

|

Functional status score |

0 – 36 |

7 days following ICU discharge |

35 (23 – 35) |

35 (23 – 35) |

MD: 0.0 [-4.2 – 4.2] |

No |

Abbreviations: IMS: ICU mobility scale, ADL: activities of daily living, EQ-5D-5L: EuroQol Group 5-Dimension Self-Report Questionnaire, EQ VAS: EuroQol Visual Analogue Scale, IADL: Lawton Instrumental Activities of Daily Living, WHODAS: World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule , ICU: intensive care unit, RR: risk ratio, MD: mean difference.

* Data were presented by n/N (%), mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median (interquartile ranges). If data were presented by medians (interquartile ranges), data were converted for calculating the mean difference by the conversion tool described by Weir (2018).

4. Sleep quality (important)

Sleep quality was assessed by none of the included studies.

5. Delirium incidence (important)

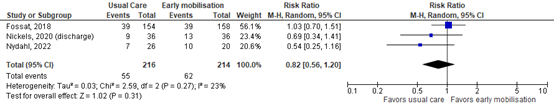

Delirium was assessed by three study comprising 430 patients. Pooled data resulted in a risk ratio (RR) of 0.82 (95% CI 0.56 to 1.20), indicating no clinically relevant difference. Results are shown in figure 3.

Figure 3. Forest plot showing the effect of early mobilization compared usual care on delirium incidence in ICU patients

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence regarding all outcome measures started at high because it was based on randomized controlled trials.

1. Duration of mechanical ventilation

The level of evidence was downgraded by two levels due to lack of appropriate concealment of randomization and blinding (risk-of-bias, -1); and results crossing the borders of clinical relevance (imprecision, -1). The final level is low.

2. Duration of ICU stay

The level of evidence was downgraded by two levels due to lack of appropriate concealment of randomization and blinding (risk-of-bias, -1); and results crossing the borders of clinical relevance (imprecision, -1). The final level is low.

3. Functional outcome

The level of evidence was downgraded by three levels due to lack of appropriate concealment of randomization and blinding (risk-of-bias, -1); and indirect evidence for the outcome that was differently defined than reported in the results section (indirectness, -1) and wide confidence intervals (imprecision, -1). The final level is very low.

4. Sleep quality

The level of evidence was not graded because of lack of data.

5. Delirium incidence

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure delirium was downgraded by three levels due to performance and detection bias (risk-of-bias, -1); and results crossing the borders of clinical relevance (imprecision, -1). The final level is low.

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question: What is the effect of early mobilisation on duration of mechanical ventilation, duration of ICU stay, functional outcome, sleep quality and delirium incidence?

P: adult ICU patients

I: mobilizing interventions with associated FITT-criteria (frequency, intensity, therapy, time)

C: no mobilisation, no intervention, usual care

O: Duration of mechanical ventilation, duration of ICU stay, functional outcome, sleep quality, delirium incidence.

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered duration of mechanical ventilation, duration of ICU stay, and functional outcome as critical outcome measures for decision making; sleep quality and delirium were considered as important outcome measures for decision making.

The working group defined the outcome measures as follows:

- Duration of mechanical ventilation: The number of days with mechanical ventilation.

- Duration of ICU stay: The number of days spent in the ICU.

- Functional outcome: Measured with the ICU mobility scale (IMS; range: 0-10; higher score is better mobility), the functional status score (FSS; range 6-30; higher score is more severe dysfunction), the Cardiopulmonary Exercise Test (CPET; expressed as cc/kg/min; higher score means better peak oxygen consumption), the Morton Mobility Index (DEMMI; range 0-100; higher score means better outcome) or the 6 minute walk-test (6MWT; expressed in meters; higher score means better outcome), Barthel Index (range: 0-100; higher score means more independence in activities in daily life.)

- Sleep quality: Measured with the Richards-Campbell Sleep Questionnaire (RCSQ), NRS sleep scale or the Richmond agitation and sedation scale (RASS).

- Delirium incidence: The number of participants who were diagnosed with delirium during IC/hospital stay.

The working group defined the following minimal clinically (patient) important difference per outcome measure:

- Duration of mechanical ventilation: A difference of one day.

- Duration of ICU stay: A difference of one day.

- Functional outcome: For continuous outcomes, a difference of 10% on each test scale or a standardized mean difference (SMD) below -0.5 or above 0.5 for pooled results from different test scales. For dichotomous outcomes, a risk ratio ≤ 0.8 or ≥ 1.25 was considered clinically relevant.

- Sleep quality: A difference of 10mm points on the RCSQ; a difference of 1 point on the NRS; a difference of 2 points on the RASS.

- Delirium: A difference of 5% in delirium incidence (RR ≤ 0.95 RR ≥ 1.05).

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms until June 21st, 2021. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 337 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria:

- Describing adult patients in the intensive care unit;

- Describing mobilizing interventions with associated FITT-criteria, defined as a type of intervention that facilitates the movement of patients and expends energy with a goal of improving patient outcomes Amidei (2012);

- Study design: systematic reviews (SRs) of RCTs with a detailed description of included studies, a risk-of-bias judgement; a detailed description of the literature search strategy and included a meta-analysis;

- Articles published in English or Dutch;

- Describing at least one of the following outcome measures: Duration of mechanical ventilation, duration of ICU stay, functional outcome, sleep quality, delirium

- At least 20 patients included in the study.

19 systematic reviews were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, 14 systematic reviews were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and five systematic reviews were included. Additionally, eight RCTs published after 2000 were selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full-text, two RCTs were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods) and six RCTs were included. Early mobilisation is a broad term which has known several different definitions. In line with the definition of Amidei (2012), we think that it is crucial that early mobilisation increases patients’ energy expenditure, and therefore we define early mobilisation as a range of activities varying from active exercises in bed (active range of motion, active cycling, sitting up in bed, chair position in bed, or similar), to out-of-bed activities (sitting on the edge of bed, standing, transfer into a chair, walking, or similar) (Amidei, 2012). We chose to exclude studies, if the study intervention only concerned cycling, NMES or passive exercise. The term “early” suggests that a certain timing or time frame should be included in the definition. However, we know that these time frames strongly differ among studies, therefore we did not exclude studies based on the timing of the intervention (Clarissa, 2019).

Results

Five systematic reviews describing a total of 13 studies were included in the analysis of the literature. Additionally, six RCTs were included in the analysis of the literature. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- Amidei C. (2012). Mobilisation in critical care: a concept analysis. Intensive & critical care nursing, 28(2), 73-81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iccn.2011.12.006

- Castro-Avila, A. C., Serón, P., Fan, E., Gaete, M., & Mickan, S. (2015). Effect of Early Rehabilitation during Intensive Care Unit Stay on Functional Status: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PloS one, 10(7), e0130722. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0130722

- Clarissa C, Salisbury L, Rodgers S, Kean S. Early mobilisation in mechanically ventilated patients: a systematic integrative review of definitions and activities. J Intensive Care. 2019 Jan 17;7:3. doi: 10.1186/s40560-018-0355-z. PMID: 30680218; PMCID: PMC6337811.

- Hodgson, C.L., Kho, M.E. & da Silva, V.M. To mobilise or not to mobilise: is that the right question?. Intensive Care Med (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-023-07088-7

- Laerkner, E., Egerod, I., Olesen, F., Toft, P., & Hansen, H. P. (2019). Negotiated mobilisation: An ethnographic exploration of nurse-patient interactions in an intensive care unit. Journal of clinical nursing, 28(11-12), 2329-2339. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.14828

- Klem, H. E., Tveiten, T. S., Beitland, S., Malerød, S., Kristoffersen, D. T., Dalsnes, T., Nupen-Stieng, M. B., & Larun, L. (2021). Early activity in mechanically ventilated patients - a meta-analysis. Tidlig aktivitet hos respiratorpasienter - en metaanalyse. Tidsskrift for den Norske laegeforening : tidsskrift for praktisk medicin, ny raekke, 141(8), 10.4045/tidsskr.20.0351. https://doi.org/10.4045/tidsskr.20.0351

- Lord, R. K., Mayhew, C. R., Korupolu, R., Mantheiy, E. C., Friedman, M. A., Palmer, J. B., & Needham, D. M. (2013). ICU early physical rehabilitation programs: financial modeling of cost savings. Critical care medicine, 41(3), 717-724. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182711de2

- Monsees, J., Moore, Z., Patton, D., Watson, C., Nugent, L., Avsar, P., & O'Connor, T. (2022). A systematic review of the effect of early mobilisation on length of stay for adults in the intensive care unit. Nursing in critical care, 10.1111/nicc.12785. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1111/nicc.12785

- Moss M. (2022). Early Mobilisation of Critical Care Patients - Still More to Learn. The New England journal of medicine, 387(19), 1807-1808. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMe2212360

- Nydahl, P., Jeitziner, M., Vater, V., Sivarajah, S., Howroyd, F., McWilliams, D., Osterbrink, J. (2023). Early mobilisation for prevention and treatment of delirium in critically ill patients: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Intensive and Critical Care Nursing, 74; 103334. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iccn.2022.103334

- Nydahl, P., Sricharoenchai, T., Chandra, S., Kundt, F. S., Huang, M., Fischill, M., & Needham, D. M. (2017). Safety of Patient Mobilisation and Rehabilitation in the Intensive Care Unit. Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Annals of the American Thoracic Society, 14(5), 766-777. https://doi.org/10.1513/AnnalsATS.201611-843SR

- Schweickert, W. D., Patel, B. K., & Kress, J. P. (2022). Timing of early mobilisation to optimize outcomes in mechanically ventilated ICU patients. Intensive care medicine, 48(10), 1305-1307. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-022-06819-6

- Söderberg, A., Karlsson, V., Ahlberg, B. M., Johansson, A., & Thelandersson, A. (2022). From fear to fight: Patients experiences of early mobilisation in intensive care. A qualitative interview study. Physiotherapy theory and practice, 38(6), 750-758. https://doi.org/10.1080/09593985.2020.1799460

- Sottile, P. D., Nordon-Craft, A., Malone, D., Schenkman, M., & Moss, M. (2015). Patient and family perceptions of physical therapy in the medical intensive care unit. Journal of critical care, 30(5), 891-895. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrc.2015.04.119

- Tipping, C. J., Harrold, M., Holland, A., Romero, L., Nisbet, T., & Hodgson, C. L. (2017). The effects of active mobilisation and rehabilitation in ICU on mortality and function: a systematic review. Intensive care medicine, 43(2), 171-183. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-016-4612-0

- Weir, C. J., Butcher, I., Assi, V., Lewis, S. C., Murray, G. D., Langhorne, P., & Brady, M. C. (2018). Dealing with missing standard deviation and mean values in meta-analysis of continuous outcomes: a systematic review. BMC medical research methodology, 18(1), 25. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-018-0483-0

- Zhang, J., Zhao, X., & Wang, A. (2019). Earlyrehabilitation to prevent post-intensive care syndrome in critical illness patients: a Meta-analysis. Zhonghua Wei Zhong Bing Ji Jiu Yi Xue, 31(8), 1008-1012. https://doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.issn.2095-4352.2019.08.019

Evidence tabellen

Forest plots functional outcome

Figure A. Forest plot showing the effect of early mobilization compared usual care on functional outcome (dichotomous outcomes) in ICU patients.

Figure B. Forest plot showing the effect of early mobilization compared usual care on functional outcome (continuous outcomes) in ICU patients.

Evidence table for systematic review of RCTs and observational studies (intervention studies)

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C) |

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

SR and meta-analysis of RCTs

Literature search up to April, 2014

A: Schweickert, 2009 B: Routsi, 2010 C: Hanekom, 2012 D: Denehy, 2013 E: Brummel, 2014

Study design: RCT

Setting and Country: University of Queensland, Autralia

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: The authors have no support or funding to report.

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist |

Inclusion criteria SR: Eligible studies were randomised or controlled clinical trials comparing rehabilitation to usual care in ICU/HDU patients. Adult patients had to be admitted to ICU/HDU for at least 48 hours and be followed for outcomes until ICU discharge.

Exclusion criteria SR: compared passive therapies (i.e., not involving conscious muscle activation) to usual care; started rehabilitation after ICU/HDU discharge; evaluated interventions in the same patient (e.g., electrical stimulation is applied in one limb and the other serves as control); enrolled more than 20% of patients under 18 years; or had patients admitted to an ICU/HDU due to neurological conditions (e.g., stroke, acquired or traumatic brain injury, multiple sclerosis, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, brain tumour, spinal cord injury, neuromuscular diseases), or trauma that could limit rehabilitation (e.g., major trauma, fractures, joint replacement).

5 studies included

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

A: PT + OT + interruption of sedation. Sessions started with passive range of motion and when patient was able to interact, it progressed to active assisted and active range of motion exercises in supine and sitting in the bed. B: Usual care+ electrical muscle stimulation in vastus lateralis, vastus medialis and peroneous longus of both lower limbs. They used biphasic, symmetric impulses of 45 Hz, 400 μsec pulse duration, 12 seconds on (0.8 second rise time and 0.8 second fall time) and 6 seconds off. C: Protocol-based intervention, including one algorithm for each of the following conditions: Upper abdominal surgery, rehabilitation for chronic ventilated patients, thoracic injuries, acute lung injury, pulmonary dysfunction. D: Exercise sessions based in baseline PFIT, including sitting out of bed, sit to stand, marching on the spot and shoulder elevation. Rehabilitation continued in the general ward, but the intensity was adjusted according to 6MWT results E: Early PT + Cognitive therapy (CT): it also included exercises to improve orientation, attention and memory |

A: Standard medical and nurse care. Physical and occupational therapy as ordered by primary care team B: Standard medical and nurse care. Physiotherapy care included passive range of motion, sitting out of bed, transferring from bed to chair and sitting on a chair. C: Decisions related to activities and intervention frequency were based on clinical decision of the therapist responsible for patient care. D: Usual care. E: ordered by treating clinician. |

End-point of follow-up:

A: hospital discharge B: n.r. C: n.r. D: hospital discharge E: 3 months after hospital discharge

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? (intervention/control) n.r.

|

Functional outcome Defined as walking without assistance at hospital discharge

Effect measure: risk ratio [95% CI]: A: 1.58 [1.07 – 2.33] C: n.r. D: n.r. E: n.r.

|

Author’s conclusion: Early rehabilitation during ICU stay was not associated with improvements in functional status, muscle strength, quality of life or healthcare utilisation outcomes, although it seems to improve walking ability compared to usual care. Results from ongoing studies may provide more data on the potential benefits of early rehabilitation in critically ill patients.

Risk of bias (total score PEDro) A: 8/10 B: 4/10 C: 7/10 D: 6/10 E: 7/10 |

|

|

Klem, 2021 |

SR and meta-analysis of RCTs

Literature search up to April, 2020

A: Schweickert, 2009 B: Dong, 2016 C: Santos, 2018 D: Eggman, 2018 E: Hodgson, 2016 F: Kho, 2019 G: Morris, 2016 H: Schaller, 2016 I: Wright, 2018

Study design: RCT

Setting and Country: Section or Orthopaedic Rehabilitation, Department of Orthopaedics, Oslo University Hospital.

Source of funding and conflicts of interest:

The author has completed the ICMJE form and declares no conflicts of interest. |

Inclusion criteria SR: Design Randomised controlled trials Participants Patients aged over 18 years Patients who received mechanical ventilation in an ICU, with oral intubation or tracheostomy Interventions Respiratory muscle training Active or active-assisted exercises for the extremities Mobilisation to the edge of the bed, to sitting in a chair, or to a standing or ambulatory position In-bed cycle ergometry Comparison Control group receiving a different treatment or no treatment Primary outcome measures Duration of mechanical ventilation Weaning time from ventilator Mortality in the hospital, at 1–3 months, 1–6 months and after 1 year Secondary outcome measures ICU length of stay Hospital length of stay Patient safety, adverse events Publication date and language Publication date 1.1.2006–27.4.2020 English or Scandinavian language Only published studies were included

Exclusion criteria SR: Patients with injury- or disease-specific muscle wasting; Intervention was passive or almost exclusively passive Studies with other outcome measures or publication years, or in other languages; Studies with high risk of bias

9 studies included

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

A: Early mobilization once a day B: Pre-surgical information and early mobilisation twice daily C: Active exercises with resistance bands D: Early progressive mobilisation with in-bed cycle ergometry up to three times daily on weekdays + standard treatment E: Early mobilization according to standard protocol for one hour a day F: In-bed cycle ergometry + standard treatment G: Intensive early Mobilisation according to standard protocol three times a day H: Early mobilization across five levels I: Intensive early mobilisation for 90 minutes on weekdays |

A: Standard treatment when prescribed B: Rehabilitation with assistance from family following discharge from intensive care C: Passive exercises and positioning D: Standard treatment (early mobilisation, respiratory physiotherapy and passive/active exercises) E: Unit’s standard interventions: passive movement F: Standard treatment (passive/active exercises and early mobilisation) G: Standard treatment on weekdays when prescribed H: Mobilisation in accordance with departmental guidelines I: Standard treatment for 30 minutes on weekdays |

End-point of follow-up: n.r.

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? (intervention/ control) n.r.

|

Duration of mechanical ventilation Effect measure: mean difference [95% CI] A: 2.24 [0.69 – 3.79] EX+NMES 9.10 [5.31 – 12.89]

Pooled effect (random effects model): 2.23 [95% CI -0.27 to 4.73] favoring early mobilisation Heterogeneity (I2): 84%

Duration of ICU stay Effect measure: mean difference [95% CI] A: 1.10 [-1.21 – 3.41]

Pooled effect (random effects model): 1.08 [95% CI 0.21 to 1.95] favoring early mobilisation Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

|

Author’s conclusion This systematic review and meta-analysis show that early mobilisation of mechanically ventilated adult ICU patients probably shortens the duration of mechanical ventilation and the ICU length of stay. Early mobilisation and inspiratory muscle training probably have no effect on mortality. Inspiratory muscle training may have little or no effect on the duration of mechanical ventilation or weaning time. Relatively few studies have examined inspiratory muscle training to date, however, and further studies are required. Additional studies should be conducted on long-term patient-reported outcome measures, and studies will hopefully provide more information about the effects of in-bed cycle ergometry.

Risk of bias A: Lack of blinding |

|

Monsees, 2022 |

SR and meta-analysis of RCTs

Literature search up to November 2020.

A: Schweickert, 2009 B: Hodgson, 2016 C: Morris, 2016 D: Schaller, 2016 E: Maffei, 2017

Study design: RCT

Setting and Country: British Association of Critical Care Nurses.

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: Jonas Monsees received a research grant from Tallaght University. Hospital. No further funding was awarded for this work. Open access funding provided by IReL. |

Inclusion criteria SR: RCTs, early and active mobilisation on critically ill adult patients, published in English, report ICU length of stay.

Exclusion criteria SR: Non-RCT studies, passive exercise only regimes, focus on post-ICU-discharge interventions, not reporting ICU length of stay, cycle ergometry only studies.

5 studies included

Groups comparable at baseline? No |

A: progressive mobilisation regime B: progressive mobilisation regime sessions/day

|

A: daily interruption of sedation with therapy as ordered by the primary care team |

End-point of follow-up: n.r.

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? (intervention/control) n.r.

|

Duration of ICU stay Effect measure: mean difference [95% CI] A: 1.10 [-1.21 – 3.41] Pooled effect (random effects model): 1.13 [95% CI -0.21 to 2.46] favoring early mobilisation Heterogeneity (I2): 34%

Duration of mechanical ventilation Effect measure: mean difference [95% CI] A: 2.24 [0.69 – 3.79]

Pooled effect (random effects model): 1.32 [95% CI 0.35 to 2.29] favoring early mobilisation Heterogeneity (I2): 22%

|

Author’s conclusion This review has applied stricter time limits than previous SRs for the commencement of EM protocols, as patients had to be enrolled within four days of ICU admission or intubation. The emerging results give a strong indication that the commencement of EM has a positive effect on ICU LOS. In addition, there is a trend towards improved outcomes for Hospital LOS, duration of MV, and increased functional independence, than was the case with previous SRs. EM remains a safe intervention and does not influence mortality rates. However, findings are limited by small sample sizes and sources of bias. Further research and large-scale trials are required to solidify findings. However, based on the evidence of this SR, the application of EM should be widely considered in ICU settings, as ongoing RCTs will likely require years to complete.

Risk of bias A: Peformance bias |

|

Zhang, 2019 |

SR and meta-analysis of RCTs

Literature search up to March, 2019

A: Schweickert, 2009 B: Hodgson, 2016 C: Kho, 2019 D: Morris, 2016 E: Moss, 2016 F: Schaller, 2016 G: Fossat, 2018

Study design: RCT

Setting and Country: University of Notre Dame Australia, AUSTRALIA

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: This work was supported by the Science and Technology Planning Project of Yuzhong District of Chongqing (grant number 20180136 to JM). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. The authors have declared that no competing interests exist. |

Inclusion criteria SR: Adult patients, RCT, intervention was early mobilisation (applied when patients were stable and was applied earlier than in control group), mobilisation was defined as range of motion, motion involving axial loading exercises, movements against gravity, active activities, activities that require energy expenditure, control group received standard or usual care, outcomes included muscle strength, functional mobility capacity, duration of mechanical ventilation, ventilator-free days, mortality, discharged-to-home rate and adverse events.

Exclusion criteria SR: Patients with neurological conditions, inclusion of ineligible interventions, exercises performed after ICU discharge, reviews, abstracts, case reports and pediatric, animal or cell-based studies.

7 studies included

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes

|

A: Physical therapy, occupational therapy and interruption of sedation |

A: Usual care and nurse care |

End-point of follow-up: n.r.

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? (intervention/ control) n.r.

|

Delirium Effect measure: risk ratio [95% CI] A: n.r. |

Author’s conclusion Regardless of the different techniques and periods of mobilisation applied, early mobilisation may be initiated safely in the ICU setting and appears to decrease the incidence of ICU-AW, improve the functional capacity, and increase the number of patients who are able to stand, number of ventilator-free days and discharged-to-home rate without increasing the rate of adverse events. However, due to the substantial heterogeneity among the included studies, the evidence has a low quality and the results of this study should be interpreted with caution. Further large-scale and well-designed research studies are needed to provide more robust evidence to support the effectiveness and safety of the early mobilisation of critically ill patients in the ICU setting.

Risk of bias A: Low risk |

Evidence table for RCTs (intervention studies)

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics 2 |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C) |

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size 4 |

Comments |

|

Afxonidis, 2021 |

Type of study: A double-blinded randomized clinical trial

Setting and country: Single-centre, Greece.

Funding and conflicts of interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest. This research received no external funding. |

Inclusion criteria: (1) a written informed consent to participate in the study, (2) a Glasgow Coma Scale score = 15, and (3) musculoskeletal and cardiopulmonary conditions suitable for the accomplishment of the proposed activities.

Exclusion criteria: (1) emergency, non-elective cardiac surgery, (2) hemodynamic instability preventing protocol performance, (3) breathing discomfort or invasive ventilator support or oxygen saturation below 90%, (4) severe neurological sequelae or neurodegenerative disorders, and (5) any mobile disability that did not allow them to perform exercise according to our protocol.

N total at baseline: Intervention: 39 Control: 39

Important prognostic factors2: age (SD): I: 63.5 (8.9) C: 65.1 (8.9)

Sex: I: 87.2% M C: 79.5% M

BMI (SD) I: 26.8 (4.2)

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

Patients were provided with an extra physiotherapy session during first three post-operative days or until ICU discharge (three sessions per day). Except for the aforementioned enhanced physiotherapy strategy, patients of the EEPC group also received an early physiotherapy session performed during zero post-operative day in the ICU.

|

Usual physiotherapy care was applied to participants of the CPC group twice a day commencing on the first post-operative day until their discharge. |

Length of follow-up: Post-intervention

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: 0 (0%) Control: 0 (0%)

Incomplete outcome data: n.r.

|

Duration of ICU stay (days) Effect measure: mean difference [95% CI] 0.09 [0.05 – 0.13] days favoring early mobilisation. |

Author’s conclusion In patients undergoing open heart surgery, early mobilisation and physical activity, along with enhanced respiratory physiotherapy, significantly decreased the length of both ICU and hospitalization stay. However, these outcomes were not reflected in significant differences in post-intervention hemodynamic and laboratory parameters, except for increased PO2 and decreased lactate levels. Larger randomized, controlled trials are warranted to establish certain physiotherapy strategies and a structured physiotherapy program, which might lead to better clinical outcomes and faster postoperative recovery, decreasing the length of hospitalization and the subsequent financial burden. |

|

Hodgson, 2022 |

Type of study: multicenter, randomized, controlled trial

Setting and country: Multicenter, Australia

Funding and conflicts of interest: The trial was funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia and the Health Research Council of New Zealand. The management committee designed the trial, which was endorsed by the Australian and New Zealand Intensive Care Society and the Irish Critical Care Trials Group. The institutions that managed the trial and monitored data quality are listed in the Supplementary Appendix (available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org). |

Inclusion criteria: Eligible patients were adults (≥18 years of age) who were expected to undergo mechanical ventilation in the ICU beyond the calendar day after randomization and whose condition was sufficiently stable to make mobilisation potentially possible.

Exclusion criteria: Dependency in any activity of daily living in the month before hospitalization, rest-in-bed orders, and proven or suspected acute primary brain or spinal injury.

N total at baseline: Intervention: 372 Control: 378

Important prognostic factors2:

age (SD): I: 60.5 (14.8) C: 59.5 (15.2)

Sex: I: 34.5% M C: 39.5% M

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

Our intervention, which included minimization of sedation as required, was hierarchical and began after randomization with daily physiotherapy, which could be provided in one or more sessions. The sessions were individually tailored to achieve the highest possible level of mobilisation that was deemed to be safe for the patient at the initiation of daily therapy. The highest level of mobilisation was provided for as long as possible before a step-down to lower levels of activity if the patient became fatigued, as measured on the ICU Mobility Scale. This validated scale rates the level of mobilisation from 0 to 10, with 0 indicating no mobilisation and 10 indicating independent walking. |

Patients who were assigned to the usual-care group received a level of mobilisation that was normally provided at each site. |

Length of follow-up: 28 days after randomisation and 180 days of follow-up.

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: 3 (0.8%) Control: 14 (3.7%)

Reasons: Withdrawal of consent (all data or 180 days of follow-up).

Incomplete outcome data (primary outcome): Intervention: 3 (0.4%) Control: 5 (1.5%)

Reasons: n.r.

|

Functional outcome Defined as the number of patients with an IMS score ≥ 7.

Effect measure: risk ratio [95% CI] 1.17 [0.99 to 1.38] favoring early mobilisation. |

Author’s conclusion Thus, for adults undergoing mechanical ventilation in the ICU, increased early active mobilisation did not affect the number of days that they were alive and out of the hospital as compared with the usual level of mobilisation received in the ICU. |

|

Nickels, 2020 |

Type of study: parallel two-arm, RCT

Setting and country: 26-bed tertiary mixed medical, surgical and trauma ICU in Brisbane, Australia.

Funding and conflicts of interest: No funding body had a role in study design, collection, management, analysis and interpretation of data; writing of the report; and the decision to submit the report for publication. There were no declarations of competing interest declared. |

Inclusion criteria: Eligible patients were adults (≥18 years of age) who were expected to undergo mechanical ventilation in the ICU beyond the calendar day after randomization and whose condition was sufficiently stable to make mobilisation potentially possible.

Exclusion criteria: Dependency in any activity of daily living in the month before hospitalization, rest-in-bed orders, and proven or suspected acute primary brain or spinal injury.

N total at baseline: Intervention: 372 Control: 378

Important prognostic factors2:

age (SD): I: 60.5 (14.8) C: 59.5 (15.2)

Sex: I: 34.5% M C: 39.5% M

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

The cycling group received the same usual-care interventions; they also received once daily (up to six-days per week) in-bed leg cycling using aMOTOmed Letto2 (RECK-Technik GmbH & Co. KG, Betzenweiler, Germany) cycle ergometer either in the ICU or in an acute hospital ward. The intervention co-ordinator (MRN) set-up and delivered the cycling sessions. Safety guidelines adapted from previous exercise intervention studies and recommendations were used to guide these sessions. Cycling sessions were chosen as they could be delivered to participants passively and progressed to active or resisted exercise depending on participants' ability and level of consciousness. Alert participants were encouraged to exercise at a moderate to hard level of perceived exertion, with the cycle ergometer resistance added and adjusted during the cycling session to achieve an appropriate level of exertion. Cycling sessions were delivered for a maximum of 30 min. However, sessions could be ceased early on participant request or if safety concerns arose. |

The usual-care group received routine physiotherapy interventions that included a daily assessment of physical and respiratory status and treatment. Physical treatments were directed to functional task achievement including; sitting, standing and mobilising. In-bed cycling was not a routine intervention at the site prior to the study. Consequently, usual care group participants were not scheduled to participate in the cycling intervention. |

Length of follow-up: 10 days after study enrolment, 3 months post-hospital admission and 6 months post-hospital admission.

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: 6 (16.2%) Control: 6 (16.2%)

Reasons: Withdrawal, ischaemic spinal cord injury, death prior to assessment, discharge prior to completing primary outcome assessment, death before follow-up, lost to follow-up, unable, decline further participation.

Incomplete outcome data (primary outcome): n.r.

|

Functional status Defined by the functional status score for the intensive care unit.

Effect measure: median [IQR] Intervention: 23 [18-31] Control: 23 [15-29]

Delirium Effect measure: risk ratio [95% CI] 0.69 [0.23 – 1.41] favoring usual care. |

Author’s conclusion In-bed cycling did not reduce acute muscle wasting in critically ill adults, but this study provides useful effect estimates and learnings for large-scale clinical trials. |

|

Nydahl, 2022 |

Type of study: pilot, multi-centre, randomized, controlled trial

Setting and country: mixed ICUs within two university hospitals in Germany.

Funding and conflicts of interest: This work is funded by the Delirium Research Prize of the German Interdisciplinary Association for Intensive Care and Emergency Medicine (DIVI) and the Philips company. Both entities did not have any influence in designing, conducting, analysing, interpreting, or writing the study. No conflict of interests were reported. |

Inclusion criteria: Patients were included, irrespective of their status of being on MV or not, who fulfilled all following conditions: (a) ≥18 years old, (b) Richmond Agitation Sedation Score (RASS) ≥ 3 and were responsive, (c) could be assessed for delirium, and (d) were able to being mobilized out of bed according to local policies, and (e) were expected to spend at least one night in the ICU.

Exclusion criteria: (a) expectation of death within the next 72 hours, (b) no informed consent for the study, (c) pre-existing immobility, (d) contraindication against mobilisation, (e) delirium already present before recruitment, (f) positive pregnancy test (routinely carried out in all patients of childbearing age upon admission to ICU), (g) delirium assessment not possible (coma, foreign language, aphasia, etc.), and (h) participation in a competitive study with the outcome of delirium.

N total at baseline: Intervention: 26 Control: 20

Important prognostic factors: age (SD): I: 64.4 (11.9) C: 60 (17.3)

Sex: I: 73.1% M C: 70% M

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

The early mobilisation intervention was provided by an additional mobilisation team. Mobilisation teams have been successfully used in other studies.16,24 The teams were made up of two people recruited from the study centres and consisted of trained intensive care nurses and/or physiotherapists and could be complemented by medical professionals.

|

Patients in the control group received usual care and were mobilized during the day by physiotherapists and nurses. |

Length of follow-up: 28 days after ICU admission.

Loss-to-follow-up: Total: 7 (13.2%)

Reasons: Rejection of intervention and lost to follow-up.

Incomplete outcome data (primary outcome): n.r.

|

Delirium Effect measure: risk ratio [95% CI] 0.54 [0.25 – 1.16] favoring usual care. |

Author’s conclusion In mixed ICU patients, a study of mobilisation in the evening to prevent and treat delirium is feasible. The intervention can be delivered to three of four occasions, while exceptions happen in a few cases because of examinations, patients' refusal, or other reasons. The intervention appears to be safe. Mobilisation shows signs of beneficial effects on preventing and treating delirium, but more research is needed to prove further hypotheses, such as a dose–response relationship between mobilisation and delirium. We estimate that a trial reaching statistical significance would require three times the number of patients, study duration, and costs, compared with this pilot study. |

|

Schujmann, 2020 |

Type of study: randomized and controlled trial

Setting and country: Central Institute of Hospital das Clínicas, University of São Paulo, Brazil.

Funding and conflicts of interest: Supported, in part, by Fundação de Amparo a Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP), Brazil. Ms. Schujmann, Ms. Teixeira Gomes, Mr. Zoccoler Lamano, Ms. Lunardi, Ms. Pimentel, Ms. Peso, Ms. Araujo, and Dr. Fu’s institutions received funding from Fundação de Amparo a Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo. The remaining authors have disclosed that they do not have any potential conflicts of interest. |

Inclusion criteria: Patients were excluded if 1) they had been previously hospitalized at other hospitals; 2) they had neurologic alterations; 3) they stayed less than 4 days in the ICU; 4) they were amputees upon admission; 5) they had contraindications for mobilisation; or 6) they had cognitive impairment with an inability to understand commands and perform tests.

Exclusion criteria: N total at baseline: Intervention: 68 Control: 68

Important prognostic factors: age (SD): I: 48 (15) C: 55 (12)

Sex: I: 54% F C: 46% F

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

The intervention group (IG) underwent a combined therapy consisting of a combination of conventional physiotherapy and a program of early and progressive mobilisation at the appropriate level of activity for each patient. |

The control group (CG) underwent the conventional treatment offered by the unit physiotherapists, with active assists and active mobilisation as well as bed positioning, bedside and armchair transfers, orthostatism, and ambulation. The physiotherapist defined the type of therapy and did not use a preestablished routine. No equipment was used for the CG. |

Length of follow-up: 3 months after discharge.

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: 7 (10.3%) Control: 11 (16.4%)

Reasons: discharge before evaluation, discharge IC before 3 days, death.

Incomplete outcome data (primary outcome): n.r.

|

Functional status Defined by the number of independent patients (defined by a barthel index score ≥ 85).

Effect measure: risk ratio [95% CI] 2.14 [1.56 – 2.93] favoring early mobilisation. |

Author’s conclusion An early and progressive mobilisation program for ICU patients may improve functional outcomes upon discharge and 3 months following hospitalization. Participation in a rehabilitation program in the ICU, as well as an increase in the level of physical activity during this period, proved to protect against the loss of functional status and to reduce the duration of ICU stay. |

Table of quality assessment for systematic reviews of RCTs and observational studies

Based on AMSTAR checklist (Shea et al.; 2007, BMC Methodol 7: 10; doi:10.1186/1471-2288-7-10) and PRISMA checklist (Moher et al 2009, PLoS Med 6: e1000097; doi:10.1371/journal.pmed1000097)

|

Study

First author, year |

Appropriate and clearly focused question?1

Yes/no/unclear |

Comprehensive and systematic literature search?2

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of included and excluded studies?3

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of relevant characteristics of included studies?4

Yes/no/unclear |

Appropriate adjustment for potential confounders in observational studies?5

Yes/no/unclear/notapplicable |

Assessment of scientific quality of included studies?6

Yes/no/unclear |

Enough similarities between studies to make combining them reasonable?7

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential risk of publication bias taken into account?8

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential conflicts of interest reported?9

Yes/no/unclear |

|

Castro-Avila, 2015 |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Not applicable |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Klem, 2021 |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Not applicable |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Monsees, 2022 |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Not applicable |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Zhang, 2019 |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Not applicable |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Table of quality assessment for RCTs

|

Study reference

(first author, publication year) |

Was the allocation sequence adequately generated? a

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was the allocation adequately concealed?b

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Blinding: Was knowledge of the allocated interventions adequately prevented?c

Were patients blinded?

Were healthcare providers blinded?

Were data collectors blinded?

Were outcome assessors blinded?

Were data analysts blinded?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was loss to follow-up (missing outcome data) infrequent?d

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Are reports of the study free of selective outcome reporting?e

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was the study apparently free of other problems that could put it at a risk of bias?f

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Overall risk of bias If applicable/ necessary, per outcome measureg

LOW Some concerns HIGH |

|

Afxonidis, 2021 |

Definitely yes;

Reason: Participants were allocated in each group through computer-generated random numbers. |

No information;

Reason: No information was provided about allocation concealment. |

Definitely yes;

Reason: The study was a double-blinded trial so that the participants were unaware of the existence of the other group. The blinded researcher was also not aware whether the patients were in the CPC group or in the EEPC group. After collecting the data, the blinded researcher measured the defined outcomes of interest. |

Definitely yes;

Reason: No patients were lost to follow-up |

Definitely yes;

Reason: Results of predefined outcome measures were presented. |

Definitely no;

Reason: The trial was single-centered, the protocol was not registered in a protocol database, pre-operative physiotherapy was not incorporated in the analysis, the results could have been attributed to enhanced physiotherapy sessions. |

LOW |

|

Hodgson, 2022 |

Definitely yes;

Reason: We randomly assigned patients in a 1:1 ratio to receive early mobilisation or usual care using a centralized Web-based interface. The trial statistician generated the assignment sequence using computer-generated random numbers stratified according to the trial center with variable block sizes. |

No information;

Reason: No information was provided about allocation concealment. |

Definitely no;

Reason: Blinding of mobilisation in the ICU was not possible; however, trained staff who were unaware of trial-group assignments ascertained patient-reported outcomes, and the statistical analysis was performed in a blinded manner. |

Definitely yes;

Reason: Losses to follow-up were infrequent (2,3%). |

Definitely yes;

Reason: Results of predefined outcome measures were presented. |

Definitely no;

Reason: Some data related to patient-reported outcomes at day 180 were missing; patients in the usual care group received a higher level of mobilisation than those in other cohort studies and previous trials; changes in practice could have affected treatment in the usual care group; not all patients were actively mobilized in the ICU. |

Moderate |

|

Nickels, 2020 |

Definitely yes;

Reason: A computer-generated randomisation sequence was created by an investigator (SMM) not involved in the screening, consenting, allocation or assessment processes. |

Definitely yes;

Reason: The randomised sequence was uploaded onto a secure web-based computer application, the Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) [24]. Group allocation was revealed to the intervention coordinating investigator (MRN) after informed consent (from the patient or surrogate decision-maker) was granted. |

Probably no;

Reason: Blinded assessment of the primary outcome was completed with over 85% of participants enrolled. No information was provided about blinding of patients, healthcare providers and data analysts. |

Probably yes: |

Definitely yes;

Reason: Results of predefined outcome measures were presented. |

Definitely no;

Reason: The study was single-centre; for the secondary outcomes the study was underpowered; variability in primary measure was greater than expected; only one sonographer completed the ultrasound assessment, |

Moderate |

|

Nydahl, 2022 |

Definitely yes;

Reason: this study randomized patients in a 1:1 ratio to the intervention or usual care group. Randomization was completed without blocks using a pseudo-random number generator based on a query at www. randomizer.org. |

No information;

Reason: No information was provided about allocation concealment. |

Definitely no;

Reason: Because of the obvious character of the intervention, blinding was not feasible (for everyone). |

Probably yes;

Reason: Lost to follow-up was infrequent (7,5% in the intervention group) |

Definitely no;

Reason: The primary outcome measure was changes after registration. |

Probably no;

Reason: Results may not be generizable among other centres; patients were only mobilized on three consecutive evenings (too short). |

Some concerns |

|

Schujmann, 2020 |

Definitely yes;

Reason: An independent statistician performed the randomization with a computerized random numbers table and numbered brown envelopes in sequence with the group assignment inside.

|

No information;

Reason: No information was provided about allocation concealment |

Definitely no;

Reason: The evaluator was blind to group assignment and recorded the results in a specific worksheet. Unfortunately, the patients and physiotherapists who performed the interventions could not be blinded due to the characteristics of the intervention and physical space of the ICU. |

Definitely no;

Reason: Losses to follow-up were frequent (26,7%). |

Definitely yes;

Reason: Results of predefined outcome measures were presented. |

Definitely yes;

Reason: No other problems reported. |

Moderate |

Table of excluded systematic reviews

|

Reference |

Reason for exclusion |

|

Albuquerque, I., Machado, A.D.S., Tatsch Ximenes Carvalho, M., Soares, J.C. (2015). Impact of early mobilisation in intensive care patients. Salu(i)Ciencia, 21(4), 1667-8982. |

Article was not full-tekst available. |

|

Hu, Y., Hu, X., Xiao, J., & Li, D. (2019). Zhonghua wei zhong bing ji jiu yi xue, 31(4), 458–463. https://doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.issn.2095-4352.2019.04.017 |

Article was not full-tekst available. |

|

Jacob, Prasobh; Surendran, Praveen Jayaprabha; E M, Muhamed Aleef; Papasavvas, Theodoros; Praveen, Reshma; Swaminathan, Narasimman; Milligan, Fiona. Early Mobilisation of Patients Receiving Vasoactive Drugs in Critical Care Units: A Systematic Review. Journal of Acute Care Physical Therapy: January 2021 - Volume 12 - Issue 1 - p 37-48 doi: 10.1097/JAT.0000000000000140 |

Review of non-RCTs. |

|

Menges, D., Seiler, B., Tomonaga, Y., Schwenkglenks, M., Puhan, M. A., & Yebyo, H. G. (2021). Systematic early versus late mobilisation or standard early mobilisation in mechanically ventilated adult ICU patients: systematic review and meta-analysis. Critical care (London, England), 25(1), 16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-020-03446-9 |

Review did not describe predescribed outcome measures. |

|

Nieto-García, L., Carpio-Pérez, A., Moreiro-Barroso, M. T., & Alonso-Sardón, M. (2021). Can an early mobilisation programme prevent hospital-acquired pressure injures in an intensive care unit?: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International wound journal, 18(2), 209–220. https://doi.org/10.1111/iwj.13516 |

Review of non-RCTs. |

|

Nydahl, P., Sricharoenchai, T., Chandra, S., Kundt, F. S., Huang, M., Fischill, M., & Needham, D. M. (2017). Safety of Patient Mobilisation and Rehabilitation in the Intensive Care Unit. Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Annals of the American Thoracic Society, 14(5), 766–777. https://doi.org/10.1513/AnnalsATS.201611-843SR |

No systematic methodology. |

|

Ramos Dos Santos, P. M., Aquaroni Ricci, N., Aparecida Bordignon Suster, É., de Moraes Paisani, D., & Dias Chiavegato, L. (2017). Effects of early mobilisation in patients after cardiac surgery: a systematic review. Physiotherapy, 103(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physio.2016.08.003 |

Wrong comparison (also including other interventions). |

|

Snelson, C., Jones, C., Atkins, G., Hodson, J., Whitehouse, T., Veenith, T., Thickett, D., Reeves, E., McLaughlin, A., Cooper, L., & McWilliams, D. (2017). A comparison of earlier and enhanced rehabilitation of mechanically ventilated patients in critical care compared to standard care (REHAB): study protocol for a single-site randomised controlled feasibility trial. Pilot and feasibility studies, 3, 19. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40814-017-0131-1 |

Wrong study design (protocol) |

|

Tipping, C. J., Harrold, M., Holland, A., Romero, L., Nisbet, T., & Hodgson, C. L. (2017). The effects of active mobilisation and rehabilitation in ICU on mortality and function: a systematic review. Intensive care medicine, 43(2), 171–183. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-016-4612-0

|

Review did not describe predescribed outcome measures. |

|

Vollenweider, R., Manettas, A. I., Häni, N., de Bruin, E. D., & Knols, R. H. (2022). Passive motion of the lower extremities in sedated and ventilated patients in the ICU - a systematic review of early effects and replicability of Interventions. PloS one, 17(5), e0267255. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0267255 |

Review did not describe predescribed outcome measures. |

|

Wang, J., Ren, D., Liu, Y., Wang, Y., Zhang, B., & Xiao, Q. (2020). Effects of early mobilisation on the prognosis of critically ill patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International journal of nursing studies, 110, 103708. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2020.103708 |

Lack of presentation of individual study results (no meta-analysis). |

|