Cognitieve gedragstherapie bij volwassenen met overgewicht of obesitas

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is de toegevoegde waarde van cognitieve gedragstherapie (CGT) toegevoegd aan een gecombineerde leefstijlinterventie (GLI) bij volwassenen met overgewicht (in combinatie met een vergrote buikomvang en/of comorbiditeit) of obesitas?

Aanbeveling

- Overweeg bij patiënten met een BMI ≥ 40 kg/m2 of ≥ 35 BMI < 40 kg/m2 in combinatie met een vergrote buikomvang en/of comorbiditeit, op geleide van bevindingen tijdens de diagnostische fase, doorverwijzing naar een gespecialiseerde GLI waarbij cognitieve gedragstherapie onderdeel uitmaakt van deze GLI (zie module ‘Gespecialiseerde GLI’).

- Adviseer een GLI met cognitieve gedragstherapie (gespecialiseerde GLI) indien er sprake is van milde psychische problematiek die de behandeling van obesitas belemmert.

- Adviseer cognitieve gedragstherapie indien er sprake is van matig tot ernstig verstoord eetgedrag en/of bijkomende psychopathologie.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Cognitieve gedragstherapie (CGT) toegevoegd aan een gecombineerde leefstijl interventie levert mogelijk een gewichtsdaling op. De meeste studies rapporteren gewichtsdaling maar zijn beperkt in de follow-up duur waardoor deze studies alleen korte termijn data presenteren <12 maanden. Slechts twee studies (Forman, 2016; Lillis 2016) hebben het effect van CGT toegevoegd gerapporteerd met een follow-up >2 jaar waarbij sprake lijkt van een trend ten gunste van de toevoeging van CGT aan een GLI. Over het effect op de belangrijke uitkomstmaten de eet psychopathologie en de kwaliteit van leven is geen lange termijn data beschikbaar.

Gewichtsverlies

De gevonden bewijskracht voor de cruciale uitkomstmaat gewicht is laag. De bewijskracht wordt met name beperkt door ernstige imprecisie en het risico van bias in de studie opzet.

Alle geïncludeerde studies hebben cognitieve gedragstherapie (CGT) toegevoegd aan een GLI vergeleken met standaard gedragstherapie (SGT) binnen een GLI. De interventies betroffen acceptatie en commitment therapie, cognitieve technieken, Mindfulness Based Cognitieve Therapie, compassie training, dialectische gedragstherapie, gedragstherapeutische technieken, gedragstechnieken met betrekking tot omgevingsverandering, motiverende gespreksvoering, emotie-regulatietraining en impulsregulatietraining, stimulus controle, zelfmonitoring, doelen stellen, probleemoplossende vaardigheden vergroten en sociale steun zoeken of geen/minimale therapie (vaak omdat deelnemers op een wachtlijst stonden). Deze studies lieten een positief effect zien met betrekking tot het toevoegen van CGT aan een GLI, waardoor het zinvol lijkt om aandacht te hebben voor bovenstaande technieken.

Binnen de psychologie wordt gewichtsverlies ook zelden als enige doel genomen en is inzicht in en verandering van gedrag de focus van behandeling. De module ‘Uitkomstmaten’ geeft inzicht in de andere uitkomstmaten die voor de patiënt en behandeling relevant zijn. CGT betreft verder ook één van de beschikbare behandelmodaliteiten als onderdeel van de behandeling van obesitas. Gepersonaliseerde behandeling van obesitas is essentieel (zie module ‘Gepersonaliseerde zorg’). Hierbij is het eveneens van belang dat zorgverleners eerst inzicht krijgen in eventuele onderliggende aandoeningen, bijdragende en in standhoudende factoren voor obesitas (zie module ‘Diagnostiek’), voordat men start met een gepersonaliseerde behandeling van obesitas.

Met betrekking tot de belangrijke uitkomstmaten gewichtsbehoud, leefstijlveranderingen, eetpsychopathologie en kwaliteit van leven is de bewijskracht beoordeeld als zeer laag, waardoor deze geen richting kan geven aan de besluitvorming. Het is onduidelijk of CGT een effect heeft op gewichtsbehoud en leefstijlverandering. De hypothese is dat CGT geïndiceerd is voor patiënten die gemotiveerd zijn en de mogelijkheid hebben om gedrag en gedachten die samenhangen met gewichtsbehoud en leefstijlverandering onder de loep te nemen en aan te passen.

Eetpathologie:

Lijngericht eetpatroon

Psychologische behandeling lijkt effectief te zijn bij een lijngericht eetpatroon. Uit de systematische review van Jacob (2018) blijkt dat CGT een significant effect heeft op lijngericht eetpatroon. Lijngericht eetpatroon wordt gezien als niet effectief bij obesitas, omdat het gepaard gaat met een afwisselend te lage calorie inname en te hoge restrictie waarna er periodiek ontremming is en verhoogde calorie inname. CGT geeft inzicht in dit patroon door onder meer registratie en heeft als effect dat het eetpatroon (regelmatig en gezond) wordt genormaliseerd en excessen worden voorkomen (Keijsers, 2017).

In de review van Lawlor (2020) wordt CGT vergeleken met SGT waarbij geen verschil wordt gevonden in effectiviteit tussen beide groepen.

Emotie eten

Uit de review van Jacob (2018) blijkt dat CGT ten opzichte van SGT een significant maar geen klinisch relevant effect heeft op emotie eten. Lawlor (2020) concludeert dat er geen verschil is in effectiviteit tussen personen behandeld met CGT t.o.v. personen behandeld met SGT. Emotie eten wordt in psychologische behandeling veranderd door vergroten van inzicht in emotionele triggers die leiden tot over-eten (meer eten dan gepland, vaak hoog calorisch), en omgezet in effectieve coping bij emoties (hulp zoeken, zelf geruststellende of helpende gedachten formuleren, probleem oplossende vaardigheden vergroten).

Eetbuien

Uit de studie van Raman (2019) blijkt dat CGT effectief is in afname van aantal eetbuien ten opzichte van de controlegroep: in deze studie werd cognitieve remediatie therapie toegepast: deze behandeling gaat uit van de veronderstelling dat mensen met een eetstoornis minder goed in staat zijn om van oplossingsstrategie te wisselen. Met oefeningen en gedragsexperimenten wordt de mentale flexibiliteit vergroot met als doel de eetbuien (als enige strategie) te verminderen.

Ontremming

Uit de review van Lawlor (2020) blijkt dat CGT in vergelijking met SGT een significant effect heeft op vermindering van de ontremming. Naast dat ontremming een aangeleerd gedragspatroon kan zijn bij patiënten met obesitas groeit inzicht in de belangrijke rol van hormonen op ontremming.

Mindful eten

Uit twee studies die Lawlor (2020) beschrijft, blijkt dat CGT in vergelijking met SGT een klinische relevant effect heeft op het aanleren van mindful eten. Deze derde generatie CGT zal mogelijk in de komende jaren een grotere rol krijgen in het onderzoek naar effectieve verandering van eetgedrag. Mindfulness richt training op aandacht voor het hier-en-nu. Met betrekking tot eetgedrag leidt het onder meer tot verbetering van moment van verzadiging.

Honger

Vier studies in de review van Lawlor (2020) konden geen klinisch relevant effect aantonen van de behandeling met CGT in vergelijking met SGT op de mate van honger. Honger zal voor een groot deel samenhangen met verstoord/verminderd verzadigingsgevoel bij obesitas.

Lichaamsontevredenheid/ negatief zelfbeeld

Uit twee studies die Lawlor (2020) beschrijft, blijkt er geen verschil te zijn in behandeling met CGT in vergelijking met SGT met betrekking tot de verbetering van lichaamsbeeld. Succesvolle behandeling wordt echter niet enkel bepaald door verbetering van het lichaamsbeeld maar hangt mede af van de gestelde behandeldoelen (zie module ‘Uitkomstmaten’). Voor de aanpak van een negatief zelfbeeld zou een patiënt baat kunnen hebben bij een psychologische behandeling gericht op aanpak van het negatieve zelfbeeld. Meest toegepast is de COMET (COmpetitive MEmory Training) (Korrelboom, 2011).

Kwaliteit van leven:

Depressie

De reviews van Lawlor (2020) en Jacob (2018) laten geen vermindering zien van depressieve symptomatologie na CGT, terwijl Raman (2019) wel een afname van aantoont in de RCT van de patiënten die de Cognitieve Remediatie Therapie ondergingen in vergelijking met patiënten die SGT ondergingen.

Vergroting van mentale flexibiliteit kan depressieve symptomatologie verminderen (Keijsers, 2017).

Stress

In de review van Lawlor (2020) werd er op basis van vier studies geen effect gevonden van behandeling middels derde generatie CGT op stress. Stress werd hier niet als primaire behandelfocus gekozen maar als bij-effect van de CGT gericht op obesitas.

Angst

Binnen de review van Lawlor (2020) werd er op basis van vier studies geen verschil gevonden in de effectiviteit van derde generatie CGT in vergelijking met SGT op angst. Angst werd niet als primaire behandelfocus gekozen maar als bij-effect van de CGT op obesitas.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

CGT behandeling wordt op maat (i.e. de inzet van bepaalde technieken) aangeboden, wat de samenwerking zal optimaliseren en de inzet zal vergroten. Patiënten vinden het prettig als de zorg dichtbij huis kan plaatsvinden, flexibel is in tijd en ruimte, aansluit bij hun behoefte, voorkeur en cultuur. Patiënten vinden het prettig als er contact is met lotgenoten bij wie ze herkenning ervaren.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

CGT heeft een vastomlijnd aantal sessies, waarbinnen doelen regelmatig geëvalueerd worden, gaat uit van de doelen die voor de patiënt belangrijk zijn en helpt probleemoplossende vaardigheden te vergroten. Hiermee verkrijgt de patiënt vaardigheden die ook een gunstig effect hebben op de andere levensgebieden, terwijl de kosten van deze therapie beperkt zijn.

Alhoewel er een CGT protocol is voor de behandeling van obesitas binnen de GGZ, is er geen DBC GGZ Obesitas. Dit maakt dat op dit moment patiënten niet verwezen kunnen worden met de diagnose obesitas voor psychologische behandeling binnen de GGZ. Voor de andere diagnoses, zoals een eetstoornis in engere zin, en andere GGZ problematiek wel.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

Bij gedragsverandering is het belangrijk om obesitas te beschouwen als ziekte en de patiënt te laten beseffen dat het overgewicht niet zijn eigen schuld is. De zorgverlener dient helder te maken dat eigen inzet is gevraagd om ziekte-last en verergering te verkleinen. Doelen dienen in samenspraak met de patiënt/cliënt te worden gesteld en dienen realistisch en persoonsgericht te zijn. Hierbij dient men ook rekening te houden bij wat past bij de patiënt en wat er beschikbaar is in de omgeving. Het is belangrijk om niet enkel te focussen op gewichtsverlies en buikomvang, maar ook op verbetering van kwaliteit van leven en comorbiditeiten. Motiveer in ieder geval tot gewichtsbehoud (zie module ‘Uitkomstmaten’ voor relevante uitkomstmaten met betrekking tot de behandeling van patiënten met obesitas). Bekrachtig alle kleine stappen die worden gezet en betrek partner en naasten bij doelstellingen. Wees tenslotte alert op psychische problematiek als belemmerende factor bij inzetten GLI gericht op gedragsverandering.

Een ander belangrijk aspect in verbetering van de (praktische) toegankelijkheid voor psychosociale zorg en psychologische behandeling bij obesitas is gebruikmaking van nieuwe technieken in telefonische, online behandeling en VR toepassingen. Momenteel wordt dit onderzoek vooral toegepast in bariatrische trajecten (Cassin 2016, Manzoni 2016).

Een voorwaarde die drempelverhogend is voor CGT is een bepaalde mate van gezondheidsvaardigheden en beheersing van de Nederlandse taal: er wordt uitgegaan van de mogelijkheid te kunnen schrijven (registreren), informatie kunnen lezen en psychologisch reflecteren op gedrag en gedachten. Alhoewel er steeds meer hulpmiddelen worden ontwikkeld voor anderstaligen en laaggeletterden, dient hier nog een belangrijke afstand in te worden overbrugd. 1 op de 3 Nederlanders heeft beperkte gezondheidsvaardigheden. Zij hebben moeite om informatie over gezondheid te vinden, te begrijpen en toe te passen. Voor deze groepen is het belangrijk dat informatie op maat gegeven wordt (bijv. gesprekskaarten van Pharos).

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

In hoeverre een behandeling succesvol genoemd kan worden, hangt mede af van de gestelde behandeldoelen en welke doelen voor de patiënt van waarde zijn (zie module ‘Uitkomstmaten’). Houd bij de behandeling van obesitas rekening met bijdragende psychosociale factoren die een rol spelen bij het ontstaan en in stand houden van obesitas: maatwerk is essentieel. Kijk per situatie of de behandeling van deze psychosociale factoren nodig is. Besteed aandacht aan psychosociale factoren, maar deze hoeven de behandeling van obesitas, middels een GLI, niet in de weg te staan. Indien door de zorgverlener wordt ingeschat dat CGT noodzakelijk is voor duurzame gedragsverandering wordt doorverwijzing naar een multidisciplinair team aanbevolen. De psychische stoornissen die veel voorkomen zijn belemmerend voor het kunnen profiteren van een behandeling gericht op obesitas en dienen eerst behandeld te worden (zie module ‘Diagnostiek’). Licht verstoord eetgedrag zoals lijngericht en emotie eten past binnen een basis GLI. CGT naast een GLI is raadzaam wanneer de obesitas gepaard gaat met psychische problematiek die een succesvolle behandeling belemmert. Indien er sprake is van een matige tot ernstige vorm van verstoord eetgedrag en/of bijkomende psychopathologie dan hoort dit thuis binnen de psychologische behandeling van de basis GGZ (B-GGZ) en gespecialiseerde GGZ (S-GGZ). Eetstoornissen worden behandeld binnen de B-GGZ en S-GGZ (zie Zorgstandaard eetstoornissen). Het is van belang dat het effect van de psychologische behandeling geëvalueerd wordt en gekeken wordt welke volgende stap nodig is (zie module ‘Uitkomstmaten’). De aanbeveling is tot stand gekomen door de gegevens uit de studies te combineren met de ervaringen vanuit de huidige praktijk van ondersteuning en zorg voor volwassenen met overgewicht of obesitas.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Binnen de behandeling van obesitas is regelmatig psychologische ondersteuning nodig, zowel bij verandering van gedrag (op eetpatroon en leefstijl) als bij andere veelvoorkomende psychische klachten. Het Zorginstituut Nederland (2020) heeft recent onderzocht wat de werkzame onderdelen zijn bij een gespecialiseerde Gecombineerde Leefstijl Interventie (GLI) en constateerde dat Cognitieve Gedragstherapie (CGT) een werkzaam element is bij GLI om langdurige gedragsverandering te bewerkstelligen. Ook werd gesteld dat het bij de toepassing van deze technieken belangrijk is dat er gekeken wordt naar psychische comorbiditeiten die vaak voorkomen bij de populatie.

De werkwijze van CGT is gericht op gedrag en cognities. De technieken die we onder CGT scharen zijn: registratie, stimulus controle, cue exposure, en onderdelen uit de stromingen mindfulness, Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT), Dialectische Gedragstherapie (DGT), EMDR en schema therapie. Hiermee worden zelfregulering, eigen effectiviteit, probleemoplossend vermogen verbeterd. Een aantal van deze technieken worden ook gebruikt bij reguliere psychologische interventies gericht op gedragsverandering. CGT wordt uitgeoefend door Klinisch Psychologen, Psychotherapeuten en GZ psychologen, basispsychologen, POH GGZ en cognitief gedragstherapeutisch medewerkers. Onderdelen van deze behandeling (i.e. verschillende technieken zoals stimuluscontrole, zelfmonitoring en eigen effectiviteit) worden uitgevoerd door gekwalificeerde professionals betrokken bij een GLI of gespecialiseerde GLI (leefstijlcoaches, diëtisten, bewegingsagogen).

Om de toegevoegde waarde van CGT bij (ernstige) obesitas te bepalen wordt gekeken naar de onderzoeken van de afgelopen jaren om tot een advies te komen in welke mate CGT kan bijdragen aan de behandeling. In de internationale literatuur is GLI geen standaard behandeling bij obesitas en wordt derhalve meer algemeen gekeken naar werkzame onderdelen van CGT bij obesitas.

Introduction

Treatment of obesity often requires regular support from psychological treatment, both for support with behaviour change (regarding diet and lifestyle) and other psychological complaints that often occur.The National Health Care Institute recently (2020) investigated the active components of a specialized Combined Lifestyle Intervention (CLI) and found that Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) is an effective element in a CLI to achieve long-term behavioural change. It was also stated that when applying these techniques it is important to look for psychological comorbidities that often occur within this population.

CBT focuses on behaviour and cognitions. Techniques used in CGT therapy are:registration, stimulus control, cue exposure, and components from the fields of mindfulness, Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT), Dialectical Behavior Therapy, EMDR and schema therapy. This improves self-regulation, self-effect, problem-solving ability. Some of these techniques are also used in regular psychological interventions aimed at behavioural change. CBT is practiced by Clinical Psychologists, Psychotherapists and GZ psychologists, master psychologists and cognitive behavioral workers. Parts of this treatment (i.e. different techniques such as stimulus control, self-monitoring and self-efficacy) are performed by qualified professionals involved in a CLI or specialized CLI (lifestyle coaches, dieticians).

Studies of recent years are examined In order to determine the added value of CBT in (severe) obesity, to give an advice on the extent to which CBT can contribute to treatment. In the international literature, CLI is not a standard treatment for obesity and therefore active components of CBT in obesity are more generally looked at.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

|

low GRADE |

Weight loss

It is likely that cognitive behavioural therapy may result in little to no difference in reduction of weight at 3 to 9 months follow up compared to standard behavioural therapy, in adults with obesity or overweight.

Sources: Jacob, 2018; Lawlor, 2020 |

|

Low GRADE |

It is likely that cognitive behavioural therapy may result in little to no difference in reduction of weight at 3 to 9 months follow up compared to no/minimal intervention, in adults with obesity or overweight.

Sources: Jacob, 2018; Lawlor, 2020 |

|

low GRADE |

It is likely that cognitive behavioural therapy may result in little to no difference in reduction of weight at 12 to 36 months follow up compared to standard behavioural therapy, in adults with obesity or overweight.

Sources: Jacob, 2018; Lawlor, 2020 |

|

Very low GRADE |

Weight maintenance

It is not clear from the literature if cognitive behavioural therapy may increase weight maintenance compared to standard behavioural therapy, in adults with obesity or overweight.

Sources: 1e Madjd, 2020 |

|

Very ow GRADE |

Lifestyle changes

It is not clear from the literature if cognitive behavioural therapy may increase physical activity compared to standard behavioural therapy, in adults with obesity or overweight.

Sources: 1e Madjd, 2020; Godfrey, 2019 |

|

Very low GRADE |

Eating psychopathology

It is not clear from the literature if cognitive behavioural therapy may improve eating psychopathology compared to standard behavioural therapy, in adults with obesity or overweight.

Sources: Jacob, 2018; Lawlor, 2020 |

|

Very low GRADE |

Quality of life

It is not clear from the literature if cognitive behavioural therapy may improve quality of life compared to standard behavioural therapy, in adults with obesity or overweight.

Sources: Jacob, 2018; Lawlor, 2020; Raman, 2019 |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

The systemic review and meta-analysis by Jacob (2018) compares the effects of cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) weight loss interventions on weight loss and psychological outcomes in adults with overweight or obesity, by comparing CBT to a comparison group that either included only behavioural techniques (e.g. stimulus control, self-monitoring, goal setting), or targeting a lifestyle factor (e.g. physical activity or diet and/or education). The article did not described whether interventions were delivered as group sessions or individual sessions. Jacob (2018) covers the literature until May 2016 and includes 12 RCTs conducted between 2005 and 2015. Sample sizes ranged from 18 to 5,145 participants. The median age of study participants was 46 years (range of average age, 11–59 years). Follow-up periods ranged from 4 to 162 months. Six studies were conducted in the United States and six in Europe. The duration of the interventions ranged from 4 weeks to 48 months (median=26 weeks) and the mean number of sessions was 27. The Downs and Black reporting quality score was used to assess the quality of reporting of the studies. Ranges were defined as follows: excellent (26–28); good (20 –25); fair (15–19); and poor (≤14 and these ranges were then dichotomized into two categories: (a) good reporting quality studies with a score ≥20; and (b) lower quality reporting studies with a score of ≤19. Using this score seven out of 12 studies (58%) were deemed to be of good quality, with a median score of 23 (ranging from 20 to 25) and five out of 12 (42%) were deemed low quality, with a median score of 17 (ranging from 16 to 19).

The systemic review and network meta-analysis by Lawlor (2020) searched for the effectiveness of third-wave CBTs (3wCBT): Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, Dialectal Behaviour Therapy, Mindfulness Based Cognitive Behavioural Therapy and Compassion-focused Therapy. On body weight and psychological outcomes in adults with overweight or obesity, 3wCBT was compared to no/minimal intervention or standard behavioural treatment (SBT) including diet, physical activity advice and standard behaviour change techniques (e.g. Goal setting, Self-monitoring, problem solving, social support). Lawlor (2020) covers the literature until September 2019 and included 37 studies, of which 17 studies used a two-group RCT, four used a three-group RCT, and one used a two-group cluster RCT design. Fourteen studies used a pre-intervention to post-intervention one-group design, and one study was a non-randomized three-group study. In 25 studies, the intervention was delivered as group sessions, 4 studies examined individual sessions and in seven studies group sessions and individual sessions were combined. Included studies were conducted in the United States (n=28), New Zealand (n=1), Italy (n=1), United Kingdom (n=3), the Netherlands (n=2), Finland (n=1), and Portugal (n=1). Studies sample sizes ranged from 10 to 283 participants. In total, studies included 2726 participants with 75% being female (n=2035/2726). Mean age was 46 years (ranged from 21 to 58 years), and mean BMI was 35.6 kg/m2. Risk of bias was assessed using the Risk of Bias 2 tool (RoB 2) or the Risk Of Bias In Non-randomized Studies of Interventions tool (ROBINS-I), dependent upon study design. Of the RCTs, the risk of bias was rated as 'high' in four 'some concern' in eleven and 'low' in seven studies. Of the 15 non-RCTs, the risk of bias was rated as 'serious' in nine and 'moderate' in six studies (see Table S4b; Lawlor, 2020).

Raman (2018) conducted an RCT comparing cognitive remediation therapy (CRT) following a behavioural weight loss program for obesity versus no treatment following a behavioural weight loss program within a randomised controlled trial, in terms of improving cognitive flexibility, reducing binge eating behaviour, improving quality of life and helping with weight loss. The behavioural weight loss program targets diet and exercise through behavioural modification techniques and wass delivered individually. Raman (2018) included adults with overweight or obesity BMI ≥30 kg/m2, age 18-55 years and a current weight under 180 kg (n=80). All participants received behaviour weight loss therapy for 3 weeks before being randomized to either the CRT group (n=42) or the no treatment group (n=38). Outcomes included weight change, binge eating, BMI, depression and quality of life. Data were collected at baseline, end-of-treatment and the 3-month follow-up. Participants were mostly female (86 %). At baseline participants in the control group had a mean BMI of 39.2 (SD=7) kg/m2, weight of 108.1 (SD=18.7) kg, mean age of 42.2 (SD=8.8) years, and scored 13.3 (SD=12.2) on depression and 45.7 (SD=9.4) on health related quality of life. Participants in the treatment group had a mean BMI of 40.3 (SD=7.8) kg/m2, weight of 111.7 (SD=21.5) kg, mean age of 40.6 (SD=7.0) years, and scored 19.1 (SD=11.2) on depression and 46.9 (SD=8.4) on health related quality of life. Baseline measures did not show any significant difference between groups except for depression scores, which were higher in the treatment group

Godfrey (2019) conducted an RCT comparing the effect of acceptance based therapy (ABT) versus SBT on intentions for physical activity. Godfrey (2019) included adults with overweight or obesity BMI of 27–50 kg/m2 and aged 18–70 years (n=189). Participants were assigned to SBT (n=90) or ABT (n=99) groups using randomization stratified by gender and ethnicity. The intervention was delivered as group sessions. The baseline assessment was conducted during the first 3 weeks of weight loss treatment. Mid-treatment and end-of-treatment assessments were conducted at 6 and 12 months, respectively. Outcomes included physical activity intention, physical activity behaviour and weight. Participants had a mean baseline BMI of 36.9 kg/m2 (SD=5.8), mean baseline weight of 100.7 kg (SD=18.9) and mean age of 51.1 years (SD=9.8). Participants were mostly female (82.0%), Caucasian (69.3%). These demographic characteristics did not differ between group.

Madjd (2020) conducted an RCT comparing the effect of CBT versus no treatment on weight maintenance. The RCT by Madjd (2020) was sponsored by a non-commercial organisation. Madjd (2020) included adults who lost at least 10% of their body weight with a post weight loss BMI of 23–30 kg/m2 and aged 18–45 years (n=113). Participants randomly assigned to the CBT group (n=56) or control group (n=57). The intervention was delivered as group sessions. The primary outcome addressed in this study was the difference in maintenance of body weight loss after the 24-week CBT program. Anthropometric measurements including weight, BMI, and WC were taken at the start of the weight-maintenance program as baseline, at 12 weeks and after 24 weeks. At baseline participants in the control group had a mean BMI of 27.58 kg/m2 (SD=1.78), weight of 72.14 (SD=4.39) kg, mean age of 32 (SD=6.3) years, and waist circumference of 88 (SD=6.07) cm. Participants in the treatment group had a mean BMI of 17.56 kg/m2 (SD=1.83), weight of 71.32 (SD=5.52) kg, mean age of 31 (SD=6), and waist circumference of 87 (SD=7.35) cm. Baseline measures did not show any significant difference between groups.

Results

Weight loss

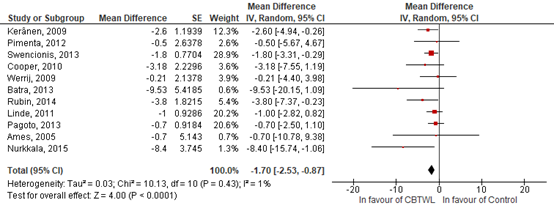

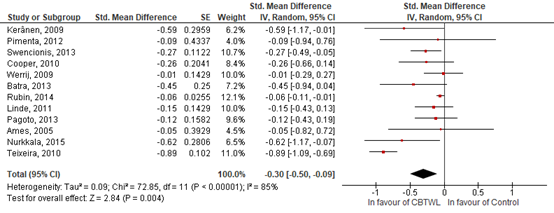

Jacob (2018) converted weight to kilograms and pre/post intervention values were used to conduct the analysis. Compared to control conditions CBT resulted in a significant, but not a clinical relevant mean difference of -1.70 kg; (95%CI -2.53 to -0.87), meaning that on average participants receiving CBT lost 1.70 kg more compared to participants in the control group including behavioural techniques, education or waiting list (Figure 5.1). The pooled effect estimate (standardized mean difference, SMD) on weight demonstrated a significant, but not a clinical relevant difference (SMD=-0.30; 95%CI -0.51 to -0.09) with a low level of heterogeneity (I2=1%), favouring CBT (Figure 5.2).

Figure 5.1. Forrest plot showing the effect of cognitive behavioural treatment on weight compared to standard behavioural treatment. Mean differences, random effects model (Jacob, 2018).

Figure 5.2 Forrest plot showing the effect of cognitive behavioural treatment on weight compared to standard behavioural treatment. Standardized mean differences, random effects model (Jacob, 2018).

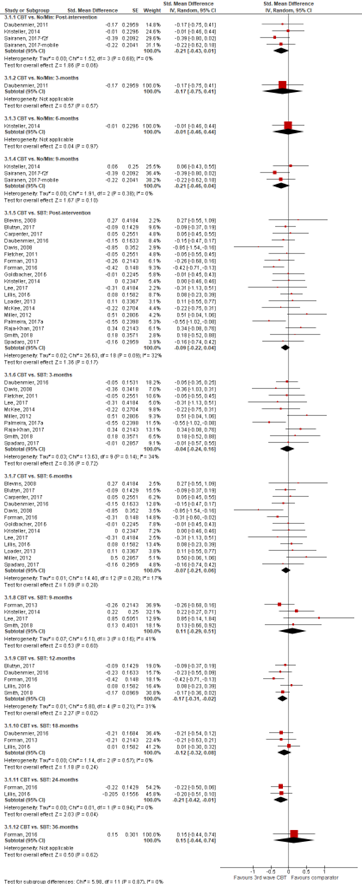

Lawlor (2020) included 25 studies that reported an absolute weight change (kg or lb), four studies reported percent change from baseline weight, and six studies reported BMI change. Standardized mean difference in weight or BMI for 3wCBT was SMD=−0.84; (95%CI −1.06 to −0.62; I2=93%) from baseline to post-intervention, equating an absolute weight change of 5.5 kg in favour of the 3wCBT group compared to the control group. This is a significant, but not a clinical relevant difference.

Pairwise random-effects meta-analysis by Lawlor (2020) showed that 3wCBT does not result in significant or clinical relevant greater weight loss compared to no/minimal intervention at post intervention (SMD=−0.21; 95% CI −0.43 to 0.01; I2 = 0%), 3 months (SMD=−0.17; 95% CI −0.75 to 0.41), 6 month (SMD=−0.01; 95%CI −0.46 to 0.44), and 9 months follow-up from baseline (SMD=−0.21; 95% CI −0.46 to 0.04; I2 = 0%) (Figure 3).

Pairwise random-effects meta-analysis by Lawlor (2020) showed that 3wCBT does not result in significant or clinical relevant greater weight loss compared to SBT at post-intervention (SMD=-0.09; 95% CI -0.22 to 0.04; I2=32%), 3 months (SMD=−0.04; 95% CI −0.24 to 0.16; I2=34%), 6 months (SMD=−0.07; 95%CI −0.21 to 0.06; I2=17%), and 9 months (SMD=−0.11; 95% CI −0.29 to 0.51; I2=41%) (Figure 5.3).

Figure 5.3 Forrest plot showing the effect of cognitive behavioural treatment on weight compared to no/minimum treatment and compared to standard behavioural treatment. Standardized mean differences, random effects model (Lawlor, 2020).

Raman (2018) defined weight change as the difference (percentage reduction) in weight between weight at baseline period and 3 month follow up. The CRT group reported significantly higher weight change percentage compared to control after 3 months follow-up (P <0.001). After 3 months follow-up, participants who completed CRT had lost on average 6.6%; (95% CI 5.6; 9.1), of weight which crosses the threshold of clinical relevance (5%). In contrast, controls gained 1.2% (95% CI -4.6 to 2.5) of weight. The effect size for this difference between groups was large, with a Cohen's d of 1.3 (95% CI -2.007 to -0.589). In addition, more participants in the CRT group (68%) achieved weight loss of 5% or more compared to the control group (15%). The RR for achieving weight loss was 4.98 (95% CI 2.35 to 10.55) in favour of the CRT group. This is a significant and clinical relevant difference.

Weight loss – long term results

Lawlor (2020) included five studies that reported long term follow-up weight loss results. five studies reported results after 12 months follow-up, three after 18 months follow-up, two after 24 months follow-up and one after 36 months follow-up. Pairwise random-effects meta-analysis by Lawlor (2020) showed that 3wCBT does not result in significant or clinical relevant greater weight loss compared to SBT at 12 months (SMD=−0.17; 95%CI −0.31 to 0.02; I2=31%), 18 months (SMD=−0.12; 95% CI −0.32 to 0.08; I2=0%), 24 months (SMD=−0.21; 95% CI −0.42 to 0.00) and 36 months (SMD=−0.15; 95% CI −0.44 to 0.74) (Figure 3).

Weight maintenance

Madjd (2020) reported on weight maintenance in women receiving CBT who lost at least 10% of their body weight and found significant difference in weight change between groups. Compared with control group, CBT improved weight loss maintenance with a mean difference (MD)=−2.2 kg; (95% CI −3.50 to −0.94) at the end of the 24-week intervention, which is considered clinical relevant. In line with improved weight loss, CBT also significantly improved BMI (MD=−0.77 kg/m²; 95% CI −1.25 to −0.28), and waist circumference (MD=−2.08 cm; 95% CI −3.31 to −0.844) at the end of the 24-week intervention, compared with the control group.

Lifestyle changes

Madjd (2020) compared physical activity based on daily steps between groups and found them to be similar at baseline with daily steps of 5897 (SD=537) in the control and 5757 (SD=551) in the CBT group. Compared with baseline, daily steps of participants in the control group decreased over time but in the CBT group daily steps increased significantly (P < 0.001, absolute numbers were not reported).

Godfrey (2019) compares physical activity intentions between groups and shows that participants in the ABT group show higher intentions to undertake physical activity compared to the SBT group. ABT had a significantly higher increase than SBT in physical activity intention minutes at mid-treatment and end of treatment (p < 0.001, absolute numbers were not reported), and both groups had nonlinear increases in moderate-to-vigorous physical activity that were not significantly different. Mixed effects models of minutes of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity per week did not find an significant effect for between treatment groups (P=0.74, absolute numbers were not reported)

Eating psychopathology

Cognitive restraint

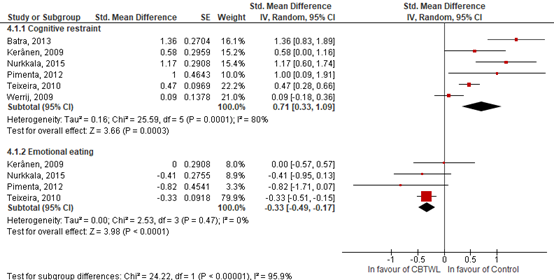

Six studies included in Jacob (2018) reported on cognitive restraint/restraint eating. The pooled effect estimate on cognitive restraint was SMD=0.71; (95% CI 0.33 to 1.09), with a high level of heterogeneity (I2=81%), showing that CBT was associated with a significant and clinical relevant increase in cognitive restraint (Figure 5.4).

Figure 5.4 Forrest plot showing the effect of cognitive behavioural treatment on cognitive restraint and emotional eating compared to standard behavioural treatment. Standardized mean differences, random effects model (Jacob, 2018).

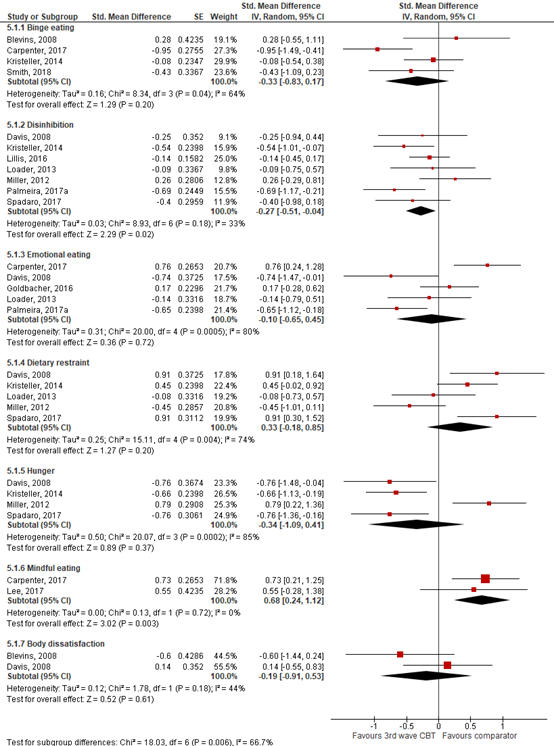

Five studies included in Lawlor (2020) reported on the effect of 3wCBT on dietary restraint. Pooled arm-specific showed no evidence of a significant and clinical relevant difference in dietary restraint (SMD=0.33; 95%CI -0.18 to 0.85; I2= 74%) (Figure 5.5).

Figure 5.5 Forrest plot showing the effect of cognitive behavioural treatment on eating psychopathology compared to standard behavioural treatment. Standardized mean differences, random effects model

(Lawlor, 2020).

Emotional eating

Four studies included in Jacob (2018) reported on emotional eating. The pooled effect on emotional eating was SMD=-0.33; (95% CI -0.49 to -0.17); I2=0%), showing that CBT was associated with a significant but not a clinical relevant decrease in emotional eating

(Figure 5.6).

Five studies included in Lawlor (2020) reported on the effect of 3wCBT on emotional eating. Pooled arm-specific estimates showed no evidence of a difference compared to SBT in emotional eating (SMD=-0.10; 95% CI -0.65 to 0.44; I2=80%) (Figure 5).

Binge eating

Jacob (2018) could not conduct a meta-analysis for binge eating because of heterogeneity in the nature of the outcomes and the limited number of studies that included each type of outcome.

Four studies included in Lawlor (2020) reported on the effect of 3wCBT on dietary binge eating. Pooled arm-specific showed no evidence of a significant or clinical relevant difference between the groups in binge eating (SMD=-0.33; 95% CI -0.83 to 0.17; I2=64%), compared to SBT (Figure 5).

Disinhibition

Seven studies included in Lawlor (2020) reported on the effect of 3wCBT on disinhibition. Pooled arm-specific showed a significant but not a clinical relevant decrease in disinhibition when compared to SBT (SMD=-0.27; 95% CI -0.51 to -0.04; I2=33%) (Figure 5).

Mindful eating

Two studies included in Lawlor (2020) reported on the effect of 3wCBT on mindful eating. Pooled arm-specific estimates showed no significant increase in mindful eating for 3wCBT when compared to SBT (SMD=0.68; 95% CI 0.24 to 1.12; I2=0%) (Figure 5). This difference was however clinical relevant.

Hunger

Four studies included in Lawlor (2020) reported on the effect of 3wCBT on hunger. Pooled arm-specific estimates showed no significant or clinical relevant decrease in hunger for 3wCBT when compared to SBT (SMD=-0.34; 95% CI -1.09 to 0.41; I2=85%) (Figure 5).

Body dissatisfaction

Two studies included in Lawlor (2020) reported on the effect of 3wCBT on body dissatisfaction. Pooled estimates by showed no evidence of a significant or clinical relevant change in body dissatisfaction (SMD=-0.19; 95% CI -0.91 to 0.53; I2=44%) compared to SBT (Figure 5).

Quality of life

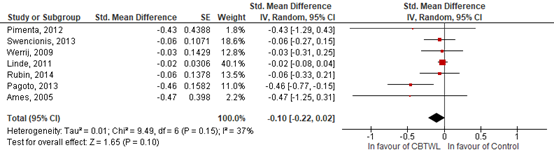

Depressive symptoms

Six studies included in Jacob (2018) reported on depressive symptoms. The pooled effect estimate for depressive symptoms was SMD=-0.10 (95% CI: -0.22 to 0.02) with a moderate level of heterogeneity (I2=37%), showing that CBT was not associated with a significant or clinical relevant effect in depressive symptoms (Figure 5.6).

Figure 5.6 Standardized mean differences showing the effect of cognitive behavioural treatment on depressive symptoms compared to standard behavioural treatment (Jacob, 2018).

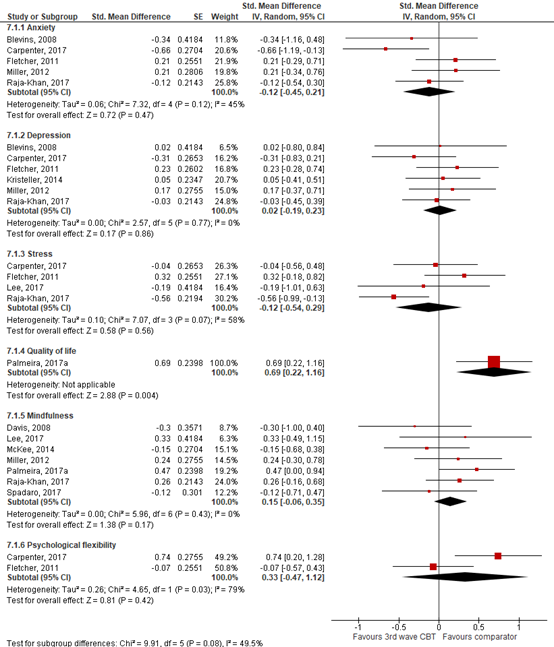

Six studies included in Lawlor (2020) reported on the effect of 3wCBT on depression. Pooled estimates showed no evidence of significant or clinical relevant differences in depression (SMD=0.02; 95% CI -0.19 to 0.23; I2=0%) (Figure 5.7).

Raman (2019) showed that participants in the CRT group reported a significant decrease in depression scores over time compared to the control group. On average, participants in the CRT-group had a depression score (on the DASS) of 19.1 (SD=11.2) at baseline, but at 3 month follow-up this had reduced to an average score of 5.8 (SD= 8.6; Cohen's d=-1.332; 95% CI -2.044; -0.62). This is a significant and clinical relevant difference. In contrast, the control condition had a depression score (on the DASS) of 13.3 (SD=12.2) on average at baseline decreasing to 11.9 (SD: 12.1) at 3-month follow-up (Cohen's d=-0.12; 95% CI -0.635 to 0.654). This is not a significant or clinical relevant difference

Stress

Four studies included in Lawlor (2020) reported on the effect of 3wCBT on stress. Pooled estimates showed no evidence of significant or clinical relevant differences in stress (SMD=-0.13; 95% CI -0.54 to -0.29; I2=58%) (Figure 5.7).

Anxiety

Jacob (2018) did not conduct meta-analyses for anxiety since there were only 2 studies. Both studies however did not found a significant or clinical relevant effect of CBT on reducing anxiety symptoms.

Five studies included in Lawlor (2020) reported on the effect of 3wCBT on anxiety. Pairwise estimates showed no evidence of significant or clinical relevant differences in anxiety (SMD=-0.12; 95% CI -0.45 to 0.21; I2=45%) compared to SBT (Figure 5.7)

Mental health related quality of life

Seven studies included in Lawlor (2020) reported on mindfulness. Pairwise estimates did not show significant or clinical relevant greater increase in mindfulness in (SMD=0.15; 95% CI -0.06 to 0.35; I2=0%), compared to SBT (Figure 7).This was measured by MAAS (Mindful Attention Awereness Scale), FFMQ (Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire) and TMS (Toronto Mindfulness Scale)

Lawlor (2020) included one study which reported 3wCBT resulted in a significant and clinical relevant greater increase in quality of life compared to SBT (SMD=0.69; 95% CI 0.22 to 1.16)

( Figure 5.7).

Raman (2019) showed that on average participants in the CRT-group had a mental Health quality of life score of 46.9 (part of HRQol = Health related Quality of Life) (SD=8.35) at baseline, but at 3 month follow-up this had increased to an average of 50.5 (SD= 10.7) (Cohen's d=-0.375; 95% CI -0.275 to 1.025). This is not a significant or clinical relevant difference. In contrast, the control condition had a mental health quality of life score of 45.7 (SD=9.4) on average at baseline increasing to 48.3 (SD=12.1) at 3-month follow-up (Cohen's d=0.24; 95% CI -0.635 to 0.654). This is not a significant or clinical relevant difference.

Figure 5.7 Forrest plot showing the effect of cognitive behavioural treatment on psychological outcomes and quality of live compared to no/minimum treatment and compared to standard behavioural treatment. Standardized mean differences, random effects model (Lawlor, 2020).

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence of RCTs starts high. The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure weight loss was downgraded to low because of risk of bias and serious imprecision. There was high risk of bias since blinding of the trials was unclear or not possible, and the results cross the line of clinical relevance

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure weight maintenance and lifestyle changes were downgraded to very low because of risk of bias and serious imprecision. There was high risk of bias since blinding of the trials was unclear or not possible. Moreover, only one study reported results on weight maintenance and two studies reporting on intentions to physical activity reported different outcome measures (imprecision)

Eating psychopathology included cognitive restraint, emotional eating, binge eating, disinhibition, mindful eating, hunger and body dissatisfaction. Quality of life included depressive symptoms, stress, anxiety and mental health related QoL. The level of evidence regarding the outcome measures eating psychopathology and quality of life were downgraded to very low because of risk of bias, inconsistency and imprecision. There was high risk of bias since blinding of the trials was unclear or not possible. Secondly, the results cross the line of clinical relevance (inconsistency). Finally, due to wide confidence intervals of effect size (imprecision).

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question:

What is the effectiveness of cognitive behavioural therapy added to a combined lifestyle intervention compared to a diet and/or exercise intervention alone in the treatment of adults with overweight and comorbidities or adults with obesity?

P: Adults with obesity (BMI >30 kg/m2) or overweight (BMI ≥25 kg/m2) with comorbidities.

I: Cognitive behavioural therapy: cue-exposure therapy, cognitive therapy, Eye Movement Desensitization Reprocessing (EMDR), schema focussed therapy, Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, mindfulness, stimulus-control therapy, self-control therapy.

C: Combined lifestyle intervention, diet, exercise.

O: Weight (loss), weight maintenance, quality of life (psychological domain if reported), lifestyle changes (nutrition or physical activity), eating psychopathology (binge eating or grazing).

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered weight loss as a critical outcome measure for decision making; and weight maintenance, lifestyle changes, eating psychopathology and quality of life as an important outcome measure for decision making.

The working group defined the following outcomes as a minimal clinically (patient) important difference.

- Weight loss: 5% weight loss

- Weight maintenance: ≥10% weight loss

- Life style changes, eating psychopathology and quality of life: SMD>0.5

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms from the 1st of January 2000 until the 30th of June 2020. An additional systematic search was performed covering literature from 1st of January 2016 until the 6th of October 2020 to select randomized controlled trials (RCTs) published after the search date for SRs. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 311 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria: systematic reviews (with meta-analyses), investigating the effect of cognitive behavioural therapy for obesity on weight loss in obese and overweight adults compared to obese and overweight adults receiving placebo. The systematic literature was search was updated to include randomized controlled trials (RCT) published between from the 1st of January 2016 until the 6th of October 2020 resulting in a further 553 hits bringing the total to 864 hits. Of these, Thirty-two studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, 25 studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and 7 studies were included.

Results

Two systemic reviews were included in the analysis of literature and reported on the impact of cognitive behavioral interventions on weight loss and psychological outcomes in overweight adults or obesity (Jacob, 2018; Lawlor, 2020). Jacob (2018) included 12 randomized controlled trials identified by a systematic search. Lawlor (2020) included 22 randomized controlled trials and 15 studies that used a pre-intervention to post-intervention group design. Three RCTs were included in the analysis of literature of which one reported on the effects of cognitive behavioural interventions on weight loss, quality of life, and psychologic outcomes (Raman, 2018), one RCT reported on the effects of cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) on weight maintenance after successful weight loss (Madjd, 2020), and one RCT reported on the effect of CBT on intentions for physical activity (Godfrey, 2019).

Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- Cassin, S. E., Sockalingam, S., Du, C., Wnuk, S., Hawa, R., & Parikh, S. V. (2016). A pilot randomized controlled trial of telephone-based cognitive behavioural therapy for preoperative bariatric surgery patients. Behaviour research and therapy, 80, 1722.

- de Graaf, R., Ten Have, M., van Gool, C., & van Dorsselaer, S. (2012). Prevalence of mental disorders and trends from 1996 to 2009. Results from the Netherlands Mental Health Survey and Incidence Study-2. Social psychiatry and psychiatric epidemiology, 47(2), 203-213.

- Godfrey, K. M., Schumacher, L. M., Butryn, M. L., & Forman, E. M. (2019). Physical activity intentions and behavior mediate treatment response in an acceptance-based weight loss intervention. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 53(12), 1009-1019.

- Jacob, A., Moullec, G., Lavoie, K. L., Laurin, C., Cowan, T., Tisshaw, C., ... & Bacon, S. L. (2018). Impact of cognitive-behavioral interventions on weight loss and psychological outcomes: A meta-analysis. Health Psychology, 37(5), 417.

- Keijsers, G. V., Van Minnen, A., Verbraak, M., Hoogduin, K., & Emmelkamp, P. (2017). Protocollaire behandelingen voor volwassenen met psychische klachten.

- Korrelboom, K. (2011). COMET voor negatief Zelfbeeld: Competitive memory training bij lage zelfwaardering en negatief zelfbeeld Bohn Stafleu van Loghum

- Kwaliteitsstandaard Psychosociale zorg bij somatische ziekte. (2019).

- Lawlor, E. R., Islam, N., Bates, S., Griffin, S. J., Hill, A. J., Hughes, C. A., ... & Ahern, A. L. (2020). Third?wave cognitive behaviour therapies for weight management: A systematic review and network meta?analysis. Obesity Reviews.

- Madjd, A., Taylor, M. A., Delavari, A., Malekzadeh, R., Macdonald, I. A., & Farshchi, H. R. (2019). Effects of cognitive behavioral therapy on weight maintenance after successful weight loss in women; a randomized clinical trial. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 1-9.

- Manzoni, G. M., Cesa, G. L., Bacchetta, M., Castelnuovo, G., Conti, S., Gaggioli, A., Mantovani, F., Molinari, E., Cárdenas-López, G., & Riva, G. (2016). Virtual Reality-Enhanced Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Morbid Obesity: A Randomized Controlled Study with 1 Year Follow-Up. Cyberpsychology, behavior and social networking, 19(2), 134140.

- Raman, J., Hay, P., Tchanturia, K., & Smith, E. (2018). A randomised controlled trial of manualized cognitive remediation therapy in adult obesity. Appetite, 123, 269-279.

- Zorginstituut (2020). Literatuuronderzoek naar werkzame elementen van een gecombineerde leefstijlinterventie voor personen met een extreem verhoogd gewichtsgerelateerde gezondheidsrisico. Geraadpleegd 1 september 2021, van https://www.zorginstituutnederland.nl/Verzekerde+zorg/gecombineerde-leefstijlinterventie-gli-zvw/documenten/publicatie/2020/03/31/literatuuronderzoek-naar-werkzame-elementen-van-gli-plus

Evidence tabellen

Evidence table for systematic review of RCTs and observational studies (intervention studies)

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C)

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

Jacob, 2018

|

SR and meta-analysis of RCTs

Literature search up to May 2016

A: Ames, 2005 B: Werrij, 2009 C: Keranen, 2009 D: Cooper, 2010 E: Teixeira, 2010 F: Linde, 2011 G: Pimenta 2012 H: Batra, 2013 I: Pagota,2013 J: Rubin 2014 K: Swencionis, 2013 L: Nurkkala, 2015

Study design: RCT parallel group design (A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H, I, J, K L)

Setting and Country: A: United States B: Netherlands C: Finland D: United Kingdom E: Portugal F: United States G: Portugal H: United States I: United States J: United States K: United States L: Finland

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: Not reported for the individual studies

|

Inclusion criteria SR: RCTs comparing at least one active treatment including a CBT component to either another non-CBT active treatment and/or a waiting list/usual care comparison group in overweight adults without amajor comorbid chronic disease.

Exclusion criteria SR: Observational studies , reviews, editorials, in-progress studies, gray/ unpublished literature, or studies published in a language other than English or French

12 studies included

Important patient characteristics at baseline: N=6.805; median age 46 years (range of average age, 11–59 years); follow-up periods ranged from 4 to 162 months; duration of the interventions ranged from 4 weeks to 48 months (median=26 weeks); the mean number of sessions was 27

N, mean age A: 26 patients, 22 yrs B: 200 patients, 44 yrs C: 49 patients, 50 yrs D: 150 patients, 41 yrs E: 225 patients, 38 yrs F: 203 patients, 52 yrs G: 18 patients, 51 yrs H: 95 patients, 49 yrs I: 161 patients, 46 yrs J: 5.145 patients, 57 yrs K: 474 patients, 52 yrs L: 76 patients, 46 yrs

Sex: A: 100% female B: 84% female C: 74% female D: 100% female E: 100% female F: 100% female G: 100% female H: 73% female I: 100% female J: 59% female K: 82% female L: 71% female

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

Describe intervention A: CBT B: CBT C: CBT D: CBT E: CBT F: CBT G: CBT H: CBT I: CBT J: CBT K: CBT L: CBT

|

Describe control A: No CBT B: No CBT C: No CBT D: No CBT E: No CBT F: No CBT G: No CBT H: No CBT I: No CBT J: No CBT K: No CBT L: No CBT

|

End-point of follow-up A: 26 weeks B: 10 weeks C: 20 weeks D: 44 weeks E: 52 weeks F: 26 weeks G: 8 weeks H: 26 weeks I: 26 weeks J: 192 weeks K: 52 weeks L: 36 weeks

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? (intervention/control) A: 41/67 (61%) B: 4/204 (2%) C: 33/82 (40%) D: 0/150 (0%) E: 0/225 (0%) F: 0/203 (0%) G: 3/21 (14%) H: 38/133 (29%) I: 0/161 (0%) J: 0/5145 (0%) K: 114/588 (19%) L: 44/120 (37%)

|

Outcome weight loss Effect CBT on weight loss; standard mean difference [95% CI: A: SMD=-0.05; (95% CI -0.82, 0.72) B: SMD=-0.01; (95% CI -0.29, 0.26) C: SMD=-0.59; (95% CI -1.17, -0.01) D: SMD=-0.26; (95% CI -0.66, 0.13) E: SMD=-0.89; (95% CI -1.09, -0.70) F: SMD=-0.15; (95% CI -0.43, 0.12) G: SMD=-0.09; (95% CI -0.94, 0.77) H: SMD=-0.45; (95% CI -0.94, 0.04) I: SMD=-0.12; (95% CI -0.43, -0.19) J: SMD=-0.06; (95% CI -0.11, -0.00) K: SMD=-0.27; (95% CI -0.49, -0.04) L: SMD=-0.62; (95% CI -1.17, -0.07)

Pooled effect (random effects model): SMD=-0.30; (95% CI -0.51, -0.09) favouring CBT

Heterogeneity (I2): 86%

Effect CBT on weight loss; raw mean difference kg [95% CI: A: MD=-0.70; (95% CI -10.78, 9.38) B: MD=-0.21; (95% CI -4.40, 3.98) C: MD=-2.60; (95% CI -4.94, -0.26) D: MD=-3.18; (95% CI -7.55, 1.19) E: NA F: MD=-1.00; (95% CI -2.82, 0.82) G: MD=-0.50; (95% CI -5.67, 4.67) H: MD=-9.53; (95% CI -20.15, 1.09) I: MD=-0.70; (95% CI -2.50, 1.10) J: MD=-3.80; (95% CI -7.37, -0.23) K: MD=-1.80; (95% CI -3.31, -0.28) L: MD=-8.40; (95% CI -15.74, -1.06)

Pooled effect (random effects model): SMD=-1.69; (95% CI -2.52, -0.86) favouring CBT

Heterogeneity (I2): 86%

Outcome cognitive restraint Effect CBT on cognitive restraint; standard mean difference [95% CI: A: NA B: SMD=0.09; (95% CI -0.18, 0.37) C: SMD=0.58; (95% CI 0.00, 1.16) D: NA E: SMD=0.47; (95% CI 0.28, -0.66) F: NA G: SMD=1.00; (95% CI 0.09, 1.91) H: SMD=1.36; (95% CI 0.83, 1.88) I: NA J: NA K: NA L: SMD=1.17; (95% CI 0.60, 1.74)

Pooled effect (Random effects model): SMD=0.71; (95% CI 0.33, 1.09) favouring CBT

Heterogeneity (I2): 81%

Outcome emotional eating Effect CBT on emotional eating; standard mean difference [95% CI: A: NA B: NA C: SMD=0.00; (95% CI -0.57, -0.57) D: NA E: SMD=-0.33; (95% CI -0.51, -0.14) F: NA G: SMD=-0.82; (95% CI -1.71, 0.07) H: NA I: NA J: NA K: NA L: SMD=-0.41; (95% CI -0.95, 0.14)

Pooled effect (Random effects model): SMD=-0.32; (95% CI -0.49, 1.09) favouring CBT

Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

Outcome weight depressive symptoms Effect CBT on depressive symptoms; standard mean difference [95% CI: A: SMD=-0.47; (95% CI -1.25, 0.31) B: SMD=-0.03; (95% CI -0.31, 0.25) C: NA D: NA E: NA F: SMD=-0.06; (95% CI -0.33, 0.22) G: SMD=-0.43; (95% CI -1.29, 0.44) H: NA I: SMD=-0.46; (95% CI -0.77, -0.15) J: SMD=-0.02; (95% CI -0.08, -0.03) K: SMD=-0.06; (95% CI -0.27, 0.16) L: NA

Pooled effect (Random effects model): SMD=-0.10; (95% CI -0.21, 0.03) favouring CBT

Heterogeneity (I2): 36%

|

Facultative: The authors conclude that CBTWL may be an efficient intervention for not only weight reduction, but also for psychologically related eating behaviors (i.e., cognitive restraint and emotional eating)

|

|

Lawlor, 2020 |

SR and meta-analysis of RCTs

Literature search up to September 2019

Study design: RCT design (all included studies)

Setting and country: See Table 1; Lawlor (2020) for setting and country of the individual RCTs

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: Not reported for the individual studies

|

Inclusion criteria SR: Adults (≥18 years) with overweight or obesity (BMI ≥25 kg/m2). Studies had to include a 3wCBT intervention for the purpose of weight management. Multi-component interventions were acceptable. Interventions could be of any duration.

Exclusion criteria SR: Not meeting the above inclusion criteria

36 studies included

Important patient characteristics at baseline:

See Table 1; Lawlor (2020) for baseline characteristics of the individual RCTs

|

Describe intervention: - MBCT - ACT - DBT

|

Describe control - SBT - No/minimal

|

End-point of follow-up 2,5 to 24 months. See Table 1; Lawlor (2020) for follow-up duration of the individual RCTs

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? See Table 1; Lawlor (2020) for the number of participants included in individual RCTs |

Outcome weight loss See Figure 2, Lawlor (2020) for the outcome for each individual RCT

Pooled effect 3wCBT vs no/minimal post-intervention (random effects model): SMD=-0.21; (95% CI -0.44, -0.01).

Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

Pooled effect 3wCBT vs no/minimal 3-months (random effects model): SMD=-0.17; (95% CI -0.75, 0.40).

Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

Pooled effect 3wCBT vs no/minimal 6-months (random effects model): SMD=-0.01; (95% CI -0.46, 0.44).

Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

Pooled effect 3wCBT vs no/minimal 9-months (random effects model): SMD=-0.21; (95% CI -0.46, -0.03).

Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

Pooled effect 3wCBT vs SBT post-intervention (random effects model): SMD=-0.09; (95% CI -0.22, 0.04).

Heterogeneity (I2): 32.4%

Pooled effect 3wCBT vs SBT 3-months (random effects model): SMD=-0.04; (95% CI -0.24, 0.17).

Heterogeneity (I2): 34.1%

Pooled effect 3wCBT vs SBT 6-months (random effects model): SMD=-0.06; (95% CI -0.20, 0.08).

Heterogeneity (I2): 19.1%

Pooled effect 3wCBT vs SBT 9-months (random effects model): SMD=0.11; (95% CI -0.29, 0.51).

Heterogeneity (I2): 40.4%

Pooled effect 3wCBT vs SBT 12-months (random effects model): SMD=-0.17; (95% CI -0.36, 0.02).

Heterogeneity (I2): 33.3%

Pooled effect 3wCBT vs SBT 18-months (random effects model): SMD=-0.12; (95% CI -0.32, 0.08).

Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

Pooled effect 3wCBT vs SBT 24-months (random effects model): SMD=-0.21; (95% CI -0.42, 0.00).

Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

Pooled effect 3wCBT vs SBT 36-months (random effects model): SMD=-0.15; (95% CI -0.44, 0.13).

Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

|

Facultative: The authors conclude that 3wCBT (especially ACT) is an efficient intervention for weight reduction.

|

Evidence table for intervention studies (randomized controlled trials and non-randomized observational studies [cohort studies, case-control studies, case series])1

This table is also suitable for diagnostic studies (screening studies) that compare the effectiveness of two or more tests. This only applies if the test is included as part of a test-and-treat strategy – otherwise the evidence table for studies of diagnostic test accuracy should be used.

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics 2 |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C) 3

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size 4 |

Comments |

|

Raman, 2018 |

Type of study: Randomized control trial

Setting and country: Australia

Funding and conflicts of interest: Non-commercial; Diabetes Australia Research Trust; NSW Institute of Psychiatry Fellowship.

One author received royalties from publishers |

Inclusion criteria: Inclusion BMI ≥30 kg/m2, age 18-55 years, current weight <180 kg, ability to provide informed consent and having completed 10 years of education in English.

Participants were recruited from 15th January 2013 to 25th March 2014

Exclusion criteria: history of psychosis, head injury, neurological disorder, diagnosed attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, epilepsy, developmental or intellectual disability; unable to complete the ; were on regular sedative or stimulant medication; and/or report regular substance use or abuse

N total at baseline: Treatment: n=38 Control: n=42

Important prognostic factors2:

Treatment/control age ± SD: 40.6±7.0/42.2±8.8

BMI ± SD 40.3±7.8/39.2±7.4

Weight ± SD 111.7±21.5/108.1±18.)

Depression ± SD 19.1±11.2/13.3±12.2

Mental health related QoL ± SD 46.9±8.4/45.7±9.4

Binge Eating Frequency ± SD 9.3±8.7/9.3±10.6

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes, except for the depression scores, which were higher in the treatment group (p=0.03). |

Describe intervention:

Participants received three weekly sessions of group Behavioural Weight Loss and then were randomised to 8 sessions of individual cognitive remediation therapy n=38)

|

Describe control:

Participants received three weekly sessions of group Behavioural Weight Loss and then were randomised to a no-treatment control group and were instructed to continue their weight loss efforts, but were not instructed how to do this (n=42)

|

Length of follow-up: 3 months

Loss-to-follow-up; n (%): Post therapy Treatment group n=7 (18)

Control: n=1 (2)

3-month follow-up Treatment group n=12 (32)

Control: n=5 (12)

No reason for loss of follow-up described described

Incomplete outcome data: No incomplete data

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Post treatment (Treatment/control)

Weight ± SD 108.1± 21.3/111.3± 20.7

Weight change percentage ± SD 0.04± 0.03)/-0.02± 0.04

BMI ± SD 38.9± 7.6/39.7± 8.4)

Depression ± SD 4.5± 5.1/15.4± 12.2

Mental health related QoL ± SD 53.1± 7.6)/ 45.2± 13.4

Binge eating frequency ± SD 3.2± 5.7/11.6±11.9

3 month follow-up (Treatment/control)

Weight ± SD 105.5± 20.7/109.3± 18.9

Weight change percentage ± SD 6.6± 4.0/-1.2± 7.5

BMI ± SD 38.3± 7.6/38.8±8.4

Depression ± SD 5.8± 8.6/11.9± 12.1

Mental health related QoL ± SD 50.5± 10.7/48.3± 12.0

Binge eating frequency ± SD 3.4 ± 6.0/9.2± 10.6 |

The authors conclude that CRT is an efficacious treatment to enhance weight loss, improve cognitive flexibility and reduce binge eating behaviour in individuals with obesity.

Power calculation: Determined based on power estimates using Cohen's tables for an estimated medium effect size of 0.6, power of 0.8, one-tailed test, P < .05 and attrition of 20%. The effect size of 0.6 was considered by the pilot data. One tailed was chosen because expected difference to be only in one direction.

RoB Randomisation and allocation concealment were conducted using an online randomizer. |

|

Forman, 2019 |

Type of study: Randomized control trial

Setting and country: USA

Funding and conflicts of interest: Non-commercial funding, but authors reported receiving royalties from Oxford Press for books on ABT |

Inclusion criteria: Inclusion BMI 27-50 kg/m2; age 18-70 years,

Exclusion criteria: Severe medical or psychiatric conditions; conditions that precluded adherence to the exercise prescription of the program; recent change in dosage of weight-influencing medications; pregnancy; recent weight loss of greater than 5% body weight; binge eating disorder diagnosis

N total at baseline: ABT: n=100 SBT: n=90

Important prognostic factors2: Sex (%) 82.1% female;

Ethnicity (%) Caucasian70.5% ; African American 24.7% ; Hispanic 3.7%; Asian 1.1%;

Age ± SD 51.64±0.73

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes

|

Describe intervention:

Participants were randomly assigned (stratified by gender and ethnicity) to two yearlong ABT (n = 100).

|

Describe control:

Participants were randomly assigned (stratified by gender and ethnicity) to two yearlong SBT (n = 90)

|

Length of follow-up:

Assessments were completed at months 0 (baseline), 6 (midpoint), 12 (posttreatment), 24 (1-year follow-up), and 36 (2-year follow-up).

Loss-to-follow-up; n (%): 12 months (posttreatment) ABT=20 (22) SBT=21 (21)

24 months (1-year follow-up) ABT=5(6) SBT=1 (1)

36 months (2-year follow-up) ABT=4 (4) SBT=4 (4)

Incomplete outcome data: No incomplete data

|

Outcome measures and effect size:

24-months (1 year follow-up) Weight loss (%±SD) ACT=7.5% ± 9.0% SBT=5.6% ± 8.2% (P = 0.15)

Proportion 10% weight loss (%) ACT=34.0 SBT=31.1 (P=0.67; OR = 1.14)

Quality of life (mean ± SD) ACT = 3.70 ± 2.89 SBT = 2.82 ± 3.06 (P<0.01)

Depression (mean ± SD) ABT = 6.85 ± 6.66 SBT = 8.19 ± 7.62 (P=0.32)

36-months (1 year follow-up) Weight loss (%±SD) ABT=7.5% ± 9.0% SBT=4.7% ± 10.1% (P = 0.31)

Proportion 10% weight loss (%) ACT=25.0 SBT=14.4 (P=0.07; OR = 1.97)

Quality of life (mean ± SD) ABT = 3.61 ± 3.05 SBT = 2.76 ± 2.95 (P=0.02)

Depression (mean ± SD) ABT = 6.85 ± 7.18 ± 6.25 SBT = 8.78 ± 7.60 (P=0.15)

|

The authors conclude that SBT for weight loss with acceptance-based strategies enhances weight loss initially, but effects fade in the years following the withdrawal of treatment. Participants receiving ABT were about twice as likely to maintain 10% weight loss at 36 months, and reported higher quality of life.

|

|

Godfrey, 2019 |

Type of study: Randomized control trial

Setting and country: USA

Funding and conflicts of interest: National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases

Authors receive royalties from editing and authoring books on acceptance-based treatment |

Inclusion criteria: Inclusion BMI 27-50 kg/m2; age 18-70 years,

Exclusion criteria: medical/psychiatric conditions that could interfere with intervention engagement or the safety of weight loss, current or planned pregnancy, changes to medications related to weight or appetite in the past 3 months, a weight loss of more than 5% in the 6 months prior to recruitment, prior bariatric surgery, or meeting diagnostic criteria for binge eating disorder

N total at baseline: ABT: n=99 SBT: n=90

Important prognostic factors2:

Female n (%) ABT = 81 (81.8) SBT = 74 (82.2) (P=0.94)

African American n (%) ABT = 22 (22.2) SBT = 23 (25.6) (P=0.29)

White n (%) ABT = 67 (67.7) SBT = 64 (71.1)

Hispanic n (%) ABT = 5 (5.1) SBT = 2 (2.2)

Age M (SD) ABT = 52.0 (9.42) SBT = 51.7 (10.2) (P=0.84)

Baseline BMI Mean (SD) ABT = 36.5 (5.4) SBT = 37.4 (6.2) (P=0.30)

Baseline weight Mean (SD) ABT = 100.0 (18.6) SBT = 101.5 (19.3) (P=0.60)

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes

|

Describe intervention:

Participants (n=90) were assigned to ABT using randomization stratified by gender and ethnicity. Twenty-five 75 min manualized treatment groups were held during the 12 month intervention period with weekly meetings for the first 16 weeks, then tapering to biweekly for five sessions, two monthly sessions, and the remaining two sessions bimonthly.

|

Describe control:

Participants (n=99) were assigned to SBT using randomization stratified by gender and ethnicity.

|

Length of follow-up: 12 months

Loss-to-follow-up; n (%): Physical activity data; n(%) Baseline = 3 (2%)/ Mid treatment = 32(19) End of treatment = 49(26)

Incomplete outcome data: No incomplete data

|

Outcome measures and effect size:

PA = Physical activity MVPA = moderate-to-vigorous physical activity

Mid-treatment PA intention min/week; Mean (SD) ABT = 306.10 (56.03) SBT = 283.26 (62.45)

MVPA min/week; Mean (SD) ABT = 135.34 (107.19) SBT = 124.05 (129.05)

MVPA days/week; Mean (SD) ABT = 3.23 (2.00) SBT = 3.06 (2.12)

MVPA bouts; Mean (SD) ABT = 0.75 (0.60) SBT = 0.81 (0.84)

MVPA min/bout; Mean (SD) ABT = 24.22 (12.04) SBT = 28.68 (12.62)

End of treatment PA intention min/week; Mean (SD) ABT = 274.13 (86.70) SBT = 226.79 (83.36)

MVPA min/week; Mean (SD) ABT = 103.08 (109.08) SBT = 106.88 (135.94))

MVPA days/week; Mean (SD) ABT = 2.69 (2.07) SBT = 2.63 (2.38))

MVPA bouts; Mean (SD) ABT = 0.64 (0.65) SBT = 0.69 (0.80)

MVPA min/bout; Mean (SD) ABT = 24.61 (15.33)) SBT = 24.93 (12.31)

|

The authors conclude that the effect of ABT on weight loss throughout treatment resulted, in part, from participants increasing intentions for PA |

|

Madjd, 2020 |

Type of study: Randomized control trial

Setting and country: Iran

Funding and conflicts of interest: Non-commercial; The School of Life Sciences, The University of Nottingham, UK and The Digestive Disease Research Institute |

Inclusion criteria: BMI 23-30 kg/m2; age 18-45 years; weight loss of at least 10% of body weight within the 6 months before enrollment; premenopausal status.

Inclusion period: March 2015 and October 2015

Exclusion criteria: using medications for blood glucose or lipid control; pregnancy; cancer or chemotherapy/radiotherapy; participation in a competitive sport; abnormal thyroid hormone concentration; intake of medications that could affect body weight and/or energy expenditure; depression; immune-compromised conditions; smoking; cardiovascular disease.

N total at baseline: CBT: n=56 Control: n=57

Important prognostic factors2: W= waist circumference, TC=total cholesterol, TG=triglyceride, FPG=fasting plasma glucose, 2hppG=2 h postprandial glucose, Hb A1C=glycated hemoglobin, HOMA-IR=homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance

Age; y (SD) CBT = 72.14 (4.39) Control = 71.32 (5.52)

Body weight; kg (SD) CBT = 71.32 (5.52) Control = 72.14 (4.39))

BMI; kg/m² (SD) CBT = 27.56 (1.83) Control =27.68 (1.78)

WC; cm (SD) CBT = 87 (7.35) Control = 88 (6.07)

TC; mmol/l (SD) CBT = 4.26 (0.61) Control = 4.24 (0.63)

HDL-C; mmol/l (SD) CBT = 1.36 (0.21) Control = 1.34 (0.23)

LDL-C; mmol/l (SD) CBT = 2.37 (0.68) Control = 2.34 (0.72)

TG; mmol/l (SD) CBT = 1.48 (0.20) Control = 1.48 (0.16)

FPG; mmol/l (SD) CBT = 4.56 (0.41) Control = 4.70 (0.47)

2hpp; mmol/l (SD) CBT = 6.56 (0.60) Control = 6.55 (0.56)

HA1C; % (SD) CBT = 4.76 (0.40) Control = 4.88 (0.38)

Insulin, m U/l (SD) CBT = 13.64 (2.84) Control = 13.18 (3.31)

HOMA (SD) CBT = 2.85 (0.78) Control = 2.77 (0.83

|

Describe intervention: Participants were randomly assigned after baseline to a CBT group. Participants received CBT classes plus instructions to follow the weight-maintenance diet |

Describe control: Participants were randomly assigned after baseline to a control group. Participants were asked to continue the weight maintenance diet only |

Length of follow-up: 6 months

Loss-to-follow-up; n (%): CBT = 5 (9) 1 participant = relocated 2 participants = time constraint 1 participant = no reason 1 participant = pregnancy

Control = 8(14) 3 participant = dissatisfied with program 2 participants = relocation 1 participant = dissatisfied with diet 1 participant = time constraint

Incomplete outcome data: No incomplete data

|

Outcome measures and effect size:

24 week follow-up Body weight; kg (SD) CBT = 70.05 (4.63) Control = 72.76 (4.30)

BMI; kg/m² (SD) CBT = 27.07 (1.49) Control = 27.91 (1.75)

WC; cm (SD) CBT = 85.13 (5.87) Control = 88.26 (5.83)

Difference between groups; Mean, (95%CI)

Body weight; kg −2.22 (−3.50; −0.94)

BMI; kg/m² −0.77 (−1.25; −0.28)

WC; cm −2.08 (−3.31; −0.84)

|

The authors conclude that cognitive behavioral therapy is an effective tool for weight maintenance over a 24-week period in successful weight losers, with corresponding maintenance of a reduced energy intake and doing more physical activity

Power calculation: The power calculation was based on prior data [α = 0.05, power (1 − β) = 0.85], and was performed on the basis of expected differences in weight loss maintenance between the intervention groups of 1.9 and an SD of 3.2 kg to determine the targeted final sample size (n = 102). When considering a dropout rate of 10%, the sample size required was 113.

RoB: randomized, single-blind, controlled trial. Participants were randomly assigned after baseline measures by using a computer-generated random numbers method by the project coordinator with allocation concealed from the participants and dietitians until the randomization was revealed to the study participants at the initial intervention clinic appointment |

Notes:

- Prognostic balance between treatment groups is usually guaranteed in randomized studies, but non-randomized (observational) studies require matching of patients between treatment groups (case-control studies) or multivariate adjustment for prognostic factors (confounders) (cohort studies); the evidence table should contain sufficient details on these procedures

- Provide data per treatment group on the most important prognostic factors [(potential) confounders]

- For case-control studies, provide sufficient detail on the procedure used to match cases and controls

- For cohort studies, provide sufficient detail on the (multivariate) analyses used to adjust for (potential) confounders

Risk of bias table for systematic reviews of RCTs and observational studies.

|

Study

First author, year |

Appropriate and clearly focused question?1

Yes/no/unclear |

Comprehensive and systematic literature search?2

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of included and excluded studies?3

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of relevant characteristics of included studies?4

Yes/no/unclear |

Appropriate adjustment for potential confounders in observational studies?5

Yes/no/unclear/notapplicable |

Assessment of scientific quality of included studies?6

Yes/no/unclear |

Enough similarities between studies to make combining them reasonable?7

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential risk of publication bias taken into account?8

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential conflicts of interest reported?9

Yes/no/unclear |

|

Jacob, 2018 |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Not applicable |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Lawlor, 2020 |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Not applicable |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

- Research question (PICO) and inclusion criteria should be appropriate and predefined

- Search period and strategy should be described; at least Medline searched; for pharmacological questions at least Medline + EMBASE searched

- Potentially relevant studies that are excluded at final selection (after reading the full text) should be referenced with reasons

- Characteristics of individual studies relevant to research question (PICO), including potential confounders, should be reported

- Results should be adequately controlled for potential confounders by multivariate analysis (not applicable for RCTs)

- Quality of individual studies should be assessed using a quality scoring tool or checklist (Jadad score, Newcastle-Ottawa scale, risk of bias table etc.)

- Clinical and statistical heterogeneity should be assessed; clinical: enough similarities in patient characteristics, intervention and definition of outcome measure to allow pooling? For pooled data: assessment of statistical heterogeneity using appropriate statistical tests (e.g. Chi-square, I2)?

- An assessment of publication bias should include a combination of graphical aids (e.g., funnel plot, other available tests) and/or statistical tests (e.g., Egger regression test, Hedges-Olken). Note: If no test values or funnel plot included, score “no”. Score “yes” if mentions that publication bias could not be assessed because there were fewer than 10 included studies.

- Sources of support (including commercial co-authorship) should be reported in both the systematic review and the included studies. Note: To get a “yes,” source of funding or support must be indicated for the systematic review AND for each of the included studies.

Risk of bias table for intervention studies (randomized controlled trials)

|

Study reference

(first author, publication year) |

Describe method of randomisation1 |

Bias due to inadequate concealment of allocation?2

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate blinding of participants to treatment allocation?3

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate blinding of care providers to treatment allocation?3

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate blinding of outcome assessors to treatment allocation?3

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to selective outcome reporting on basis of the results?4

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to loss to follow-up?5

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to violation of intention to treat analysis?6

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

|

Raman, 2018 |

Randomisation using a random number generator to assign patients to treatment or placebo arms. |

Unlikely Randomisation and allocation concealment were conducted using an online randomizer. |

Likely Lack of blinding of participants and assessor |

Likely Lack of blinding of care providers |

Likely Lack of blinding of participants and assessor |

Unlikely Protocol has been published (Raman, Hay, & Smith, 2014) |

Unlikely Limited loss to follow-up is mentioned

|

Unclear Not mentioned |

|

Godfrey, 2019 |

Randomisation using computer-based random allocation to assign patients to treatment or placebo arms. |

Unclear Not reported |

Unclear Not reported |

Unclear Not reported |

Unclear Not reported |

Unclear Not reported |

Unlikely Limited loss to follow-up is mentioned |

Unclear Not mentioned |

|

Madjd, 2020 |

Randomly assigned after baseline measures by using a computer-generated random numbers method |

Unlikely randomly assigned after baseline measures by using a computer-generated random numbers method by the project coordinator with allocation concealed from the participants and |

Likely Randomization was revealed to the study participants at the initial intervention clinic appointment. |

Likely Randomization was revealed to the study participants at the initial intervention clinic appointment. |

Likely Randomization was revealed after the randomization process |

Unikely Trial conducted as registered on clinicaltrials.gov (NCT02398253) |

Unlikely Limited loss to follow-up is mentioned |

Unlikely All participants who were randomly assigned and completed an initial assessment were included in the final results by using an intention-to-treat analysis.

|

- Randomisation: generation of allocation sequences have to be unpredictable, for example computer generated random-numbers or drawing lots or envelopes. Examples of inadequate procedures are generation of allocation sequences by alternation, according to case record number, date of birth or date of admission.

- Allocation concealment: refers to the protection (blinding) of the randomisation process. Concealment of allocation sequences is adequate if patients and enrolling investigators cannot foresee assignment, for example central randomisation (performed at a site remote from trial location) or sequentially numbered, sealed, opaque envelopes. Inadequate procedures are all procedures based on inadequate randomisation procedures or open allocation schedules.

- Blinding: neither the patient nor the care provider (attending physician) knows which patient is getting the special treatment. Blinding is sometimes impossible, for example when comparing surgical with non-surgical treatments. The outcome assessor records the study results. Blinding of those assessing outcomes prevents that the knowledge of patient assignment influences the process of outcome assessment (detection or information bias). If a study has hard (objective) outcome measures, like death, blinding of outcome assessment is not necessary. If a study has “soft” (subjective) outcome measures, like the assessment of an X-ray, blinding of outcome assessment is necessary.