Preventieve interventies rOMA

Uitgangsvraag

Welke verschillende vormen van preventieve behandelingen zijn er, en wanneer zijn deze geïndiceerd?

Aanbeveling

Volg het advies conform het Rijks Vaccinatie Programma (RVP) bij kinderen in de preventie van episodes van otitis media acuta (OMA). Informeer ouders en kind (afhankelijke van leeftijd en ontwikkelingsniveau) over de voor- en nadelen en het potentiële effect. Hanteer hierbij de principes van Samen Beslissen.

Geef niet standaard probiotica ter voorkoming van otitis media acuta.

Geef niet standaard (systemische) antibioticaprofylaxe voor het voorkomen van episodes van otitis media acuta. Overweeg het toedienen van antibioticaprofylaxe voor het voorkomen van episodes van otitis media acuta alleen op indicatie (bijvoorbeeld in het geval van invaliderende, heftige, frequente episodes zonder onderliggende pathologie) en neem daarbij de kans op resistentievorming mee.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Er is literatuuronderzoek uitgevoerd naar het effect van preventieve behandeling ter voorkoming van otitis media bij kinderen tussen de nul en achttien jaar oud. Preventieve behandelingen die relevant voor de PICO van deze module werden geacht waren pneumokokken vaccinaties, influenzavaccins en/of omgevingsfactoren en het gebruik van profylactische antibiotica. Er werd gezocht naar studies die een vergelijking maakten tussen een preventieve behandeling en placebo, geen behandeling of verschillende behandelingen onderling met elkaar vergeleken, waarbij er werd geprioriteerd om alleen de, volgens de werkgroep, meest relevante preventieve behandelingen voor de Nederlandse situatie met elkaar te vergelijken. Daarom zijn er twee vragen uitgewerkt in deze module, namelijk het preventieve effect van vaccinaties (PICO 1) en omgevingsfactoren (PICO 2). Omgevingsfactoren werden breed geformuleerd in de literatuursearch om zodoende zo veel mogelijk factoren te vangen in de resultaten van de literatuursearch. Uiteindelijk werden er alleen studies gevonden naar het preventieve effect van probiotica en borstvoeding en geen andere omgevingsfactoren. Het preventieve effect op otitis media werd als enige uitkomstmaat gedefinieerd. Dit werd geïnterpreteerd als het aantal episodes van otitis media per persoon per jaar.

Daarnaast werd er een derde vraag uitgewerkt, waarin werd gekeken naar het effect van antibiotica profylaxe op acute otitis media (OMA) in vergelijking met placebo of geen behandeling (PICO 3).

Vaccinaties

Er werden twee systematische reviews geïncludeerd in de literatuuranalyse. In totaal bevatten beide systematische reviews samengenomen zeven gerandomiseerde studies die in aanmerking kwamen voor inclusie in deze richtlijnmodule. Drie trials vergeleken een pneumokokken vaccinatie met een meningokokken vaccinatie, één trial vergeleek een pneumokokken vaccinatie met een hepatitis B vaccinatie en drie trials vergeleken een influenzavaccinatie met een placebo. Bij de studies waarbij het pneumokokken- en influenzavaccin werd vergeleken met een ander, voor de prevalentie van OMA indifferent vaccin, is de opzet om de deelnemende kinderen in de alternatieve behandeling arm niet te benadelen. Twee van deze trials rapporteerden informatie over het effect van een pneumokokken vaccinatie in vergelijking met een meningokokken vaccinatie op het aantal episoden van otitis media per persoon per jaar en de effectiviteit van een pneumokokken vaccinatie met een meningokokken vaccinatie. Voor beide uitkomstmaten werd er geen klinisch relevant verschil gevonden tussen beide preventieve behandelingen. De bewijskracht voor beide uitkomstmaten werd gegradeerd als laag.

Ook wanneer een pneumokokken vaccinatie werd vergeleken met een hepatitis B vaccinatie, werd er eveneens geen klinisch relevant verschil gevonden tussen beide groepen, met een lage bewijskracht en gebaseerd op één enkele trial. Geen van de studies rapporteerde het aantal episoden per persoon per jaar voor een pneumokokken vaccinatie versus een hepatitis B vaccinatie.

Drie trials rapporteerden het aantal episoden per persoon per jaar voor een influenzavaccinatie in vergelijking met placebo. Ook hier werd geen klinisch relevant verschil gevonden tussen beide behandelingen. De bewijskracht hiervoor was laag. Er kon geen GRADE-conclusie worden opgesteld voor het aantal episoden per persoon per jaar voor de vergelijking van een pneumokokken vaccinatie met een hepatitis B vaccinatie en voor de effectiviteit van het vaccin voor de vergelijking van een influenzavaccinatie met placebo, omdat geen van de geïncludeerde studies hier statistische informatie over verschafte.

Omgevingsfactoren

Naast vaccinaties, zoals onderzocht in PICO 1, is er ook literatuuronderzoek verricht naar het effect van omgevingsfactoren (zoals probiotica of borstvoeding in vergelijking met geen aanwezigheid van omgevingsfactoren, standaardzorg of placebo) op het voorkomen van OMA bij kinderen. Eén van de omgevingsfactoren die uit het literatuuronderzoek naar voren kwam ter preventie van otitis media is het gebruik van probiotica. De Cochrane review van Scott (2019) includeerde maar liefst zestien RCTs en werd geïncludeerd in de literatuuranalyse van PICO 2. In de analyse heeft deze module zich alleen gericht op het algehele effect van probiotica op het voorkomen van OMA. Naast deze overkoepelende analyse naar het effect van antibiotica, werden in Scott (2019) een aantal sensitiviteitsanalyses gedaan, waaronder een analyse bij uitsluitend kinderen zonder specifieke gevoeligheid voor otitis media. . In deze analyse werd een lager aantal gevallen van OMA gevonden bij kinderen die probiotica ontvingen ten opzichte van kinderen die geen probiotica ontvingen (Relatief Risico [RR] 0.64; 95% Betrouwbaarheidsinterval [BI] 0.49 tot 0.84; gebaseerd op elf RCTs en een totaal aantal van 2227 kinderen; moderate GRADE). Tevens werd er een sensitiviteitsanalyse gedaan in kinderen die wel vatbaar waren voor otitis media. Er werd in deze groep kinderen geen verschil gevonden tussen kinderen die probiotica ontvangen vergeleken met kinderen die geen probiotica ontvingen. (RR 0.97; 95% BI 0.85 tot 1.11; gebaseerd op vijf RCTs en een totaal aantal van 734 kinderen; high GRADE). Hierbij moet wel de kanttekening worden geplaatst dat er veel variatie bestond in de dosis, frequentie en toedieningsduur tussen de RCTs. Echter, een sensitiviteitsanalyse liet geen publicatiebias zien (zie bijlage bij deze module), waardoor met enige voorzichtigheid geconcludeerd kan worden dat probiotica een positieve rol zou kunnen spelen in het voorkomen van OMA bij kinderen die hier niet gevoelig voor zijn. De optimale duur, frequentie en timing van probiotica wordt uit de literatuur niet duidelijk, waardoor hierover geen uitspraak kan worden gedaan. Dit is een kennislacune. Het verschil in effect van probiotica tussen kinderen die OMA gevoelig zijn en kinderen die niet OMA gevoelig zijn kan worden verklaard door verschillen in patiëntkarakterstieken tussen deze twee groepen. Dit verschil in patiëntkarakterstieken verklaart mogelijk ook de discrepanties in de effecten die gevonden zijn in de sensitiviteitsanalyses en het effect dat gevonden werd in de overkoepelende populatie (OMA-gevoelig en niet OMA-gevoelig samen).

Naast probiotica werden verschillende studies gevonden waarin het effect van borstvoeding op het voorkomen van otitis media bij kinderen werd onderzocht. De systematische review van Bowatte (2015) includeerde 24 studies (achttien cohortstudies en zes cross-sectionele studies). Vanwege het observationele studiedesign van de geïncludeerde studies in de systematische review van Bowatte (2015) zijn deze studies niet meegenomen in de literatuuranalyse en niet gegradeerd middels de GRADE-methodiek, maar worden deze studies hier in de overwegingen wel kort beschreven. De meerderheid van deze studies lieten een beschermende associatie zien van borstvoeding voor otitis media in de eerste twee levensjaren ten opzichte van kinderen die geen borstvoeding ontvingen (Odds Ratio [OR] 0.85; 95% BI 0.70 tot 1.02). In een sub-analyse van de review leek borstvoeding in de eerste zes maanden geassocieerd te zijn met de beste protectie op otitis media (OR 0.57; 95% BI 0.44 tot 0.75).

Systemische antibiotica profylaxe

Er werd één systematische review geïncludeerd waarin het effect van antibioticaprofylaxe op OMA werd vergeleken met placebo (Leach, 2006). In deze systematische review werden zeventien gerandomiseerde studies geïncludeerd. De studie rapporteerde de proportie kinderen met een episode van OMA en/of chronische etterende otitis media en het aantal bijwerkingen gedurende de behandelperiode. Leach (2006) maakte geen onderscheid in de resultaten tussen het aantal episoden OMA en het aantal episoden chronische etterende otitis media, waardoor deze uitkomstmaat niet aan de PICO voldeed en zodoende niet werd uitgewerkt in de literatuuranalyse. Desondanks lieten de resultaten zien dat behandeling met antibioticaprofylaxe resulteert in een klinisch relevant verschil in het aantal episoden OMA en/of chronische etterende otitis media (RR 0.65; 95% BI 0.53 tot 0.79, gebaseerd op veertien studies). Leach (2006) rapporteerde een klinisch relevant verschil voor het aantal bijwerkingen in het voordeel van placebo of geen behandeling met antibioticaprofylaxe (RR 1.99; 95% BI 0.25 tot 15.89). Echter, de bewijskracht voor bijwerkingen werd gegradeerd op zeer laag vanwege het zeer kleine aantal events en het brede betrouwbaarheidsinterval, welke beide grenzen van klinische relevantie onderschreed. Dit houdt in dat de literatuur erg onzeker is over het daadwerkelijke effect van antibioticaprofylaxe op het aantal bijwerkingen, waardoor de resultaten voorzichtig geïnterpreteerd dienen te worden.

De meta-analyse van Rosenfeld (2003) laat bij profylactisch continu gebruik van antibiotica een afname van rOMA zien van 0,09 episode (95% BI 0.05 tot 0.12; number needed to treat [NNT]: 11) per patiënt per maand ofwel 1,1 episode per jaar (95% BI 0.6 tot 1.4). Dit betekent dat een enkele episode van rOMA kan worden voorkomen door één kind elf maanden of elf kinderen gedurende één maand te behandelen. Bij profylactisch antibioticagebruik neemt de kans op nieuwe OMA episodes af met 21% (95% BI 13% tot 30%; NNT 5) bij een mediane studieduur van zes maanden. Bovendien nam ook de kans op het doormaken van drie of meer episodes af met 8% (95% BI 4% tot 12%; NNT 12). De meeste studies excludeerden kinderen met OME, kinderen met immuundeficiëntie, schisis, craniofaciale afwijkingen of het syndroom van Down. Dit maakt dat men voorzichtig dient om te gaan met extrapolatie van de resultaten naar deze groepen. In een Cochrane review (Leach 2006) wordt beschreven dat 4,2% (9/211) van de kinderen die continu profylactisch antibiotica kregen rOMA doormaakte gedurende de interventie-periode in vergelijking met 10,2% (12/118) in de controlegroep (vijf studies, risicoverschil van 6,0% 95% BI 5.4% tot 6.6%; NNT 17). In twee studies wordt resistentie gerapporteerd bij profylactisch antibiotica gebruik. Na drie maanden wordt in de antibioticagroep in 31 van de 101 (31%) kinderen een beta-lactam resistente H. Influenza en/of M. cattarhalis gevonden, in vergelijking met 18 van de 80 kinderen (23%) in de controle groep (RR 1.37; 95% BI 0.83 tot 2.26).

Otitis media is een veel voorkomende ziekte op de kinderleeftijd, met gevolgen voor de patiënt en zijn of haar ouders. Het betreft een bij uitstek multifactoriële ziekte, hetgeen ruimte biedt voor verschillende preventieve maatregelen. Het voorkomen van frequente episodes met otitis media biedt potentiele voordelen. Daarentegen is de belasting van verschillende maatregelen en behandelingen relatief groot met een vooraf niet in te schatten effect op het voorkomen van ziekte Vaccinaties (pneumokokken en influenza vaccinaties)voor veel voorkomende verwekkers hebben een bredere uitwerking dan alleen op het voorkomen van otitis media. Bij kinderen met zeer frequente periodes van otitis media is een profylactische behandeling met laag gedoseerde antibiotica dikwijls een last-resort maatregel , waarbij rekening moet worden gehouden met het voorkomen van reeds resistente micro-organismen.

Aangezien er in de studies weinig complicaties optraden, kon er voor deze belangrijke uitkomstmaat geen conclusie getrokken worden wat betreft het optreden van het aantal bijwerkingen/complicaties in de interventie- en controlegroepen. Bij het geven van probiotica worden klachten van de tractus digestivus genoemd als bijwerking. Daarnaast is er bij langdurig, profylactisch antibiotica gebruik, naast eveneens klachten van de tractus digestivus, ook risico op resistentievorming.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

De belangrijkste doelen van de preventieve maatregelen en behandelingen voor de patiënt en zijn of haar ouders zijn het verminderen van het aantal en de ernst van de ziekte episodes, daar deze vaker gepaard gaan met (hevige) oorpijn, algehele malaise al dan niet met koorts, het optreden van slapeloze nachten en het optreden van eventueel ziekteverzuim van zowel ouder als kind als gevolg daarvan.

Bij preventie is het oordeel en de voorkeur van ouders vaak doorslaggevend in de beslissing hier wel of geen gebruik van te maken. Het is de taak van de behandelaar ouders en kind (afhankelijke van leeftijd en ontwikkelingsniveau) begrijpelijk en volledig te informeren over de voor- en nadelen en het potentiële effect en hier middels het toepassen van Samen Beslissen samen met ouders en kind een beslissingen over te nemen. Het is een taak van de publieke gezondheid in Nederland om gezinnen nog beter te informeren over mogelijke preventieve maatregelen die zij zelf kunnen kiezen (borstvoeding en Rijks Vaccinatie Programma).

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

Er is geen wetenschappelijk bewijs gevonden voor de kosteneffectiviteit van de beschreven preventieve maatregelen en behandelingen, dus het is niet met zekerheid te zeggen of de gunstige effecten opwegen tegen de extra kosten voor de patiënt en maatschappij (en de impact daarvan op het ziekenhuis/afdelingsbudget). Vaccinaties opgenomen in het Rijks Vaccinatie Programma zijn over het algemeen kosten-effectief.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

Vaccinaties zoals opgenomen in het Rijksvaccinatieschema zijn aanvaardbaar en haalbaar. De implementatie hiervan is geborgd en beschikbaar voor alle in Nederland woonachtige kinderen. Het wel of niet geven van borstvoeding en/of probiotica gebeurt in het algemeen buiten het zicht van de zorgverlener in de tweede lijn. Kinderen met frequente periodes van otitis media hebben toegang tot zorg bij de huisarts en KNO-arts en zullen op indicatie, in overleg met ouders, behandeld kunnend worden met profylactische antibiotica, waarbij de mogelijkheid van resistentie vorming moet worden meegenomen in de afweging.

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

Recidiverende episoden van acute otitis media is een veel voorkomende aandoening. De betreffende kinderen en ouders ervaren een grote ziektelast door frequente perioden van oorpijn, algemene malaise, slapeloze nachten en verloren tijd op de crèche of schoolverzuim. Het betreft een bij uitstek multifactoriële ziekte, hetgeen ruimte biedt voor verschillende preventieve maatregelen. Vaccinaties tegen bekende verwekkers binnen het Rijks Vaccinatie Programma, hebben ook een plek in voorkomen van otitiden. ziekte. Er is onvoldoende bewijs/reden om influenza vaccinatie, buiten het RVP, aan te bevelen in de preventie van otitis media acuta. "

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Otitis media acuta (OMA) is een multifactoriële ziekte waarbij verschillende patiëntgebonden en omgevingsfactoren van invloed zijn. Dit geeft ook aanknopingspunten voor preventief handelen. Er bestaan een aantal preventieve maatregelen, medicamenteuze interventies en vaccinaties. De werkgroep heeft gekeken naar voor- en nadelen van vaccinatie voor OMA gerelateerde verwekkers. Hierbij is, vanuit ethische overwegingen, de controlegroep vaak geen placebo maar een niet OMA gerelateerde verwekker. Daarnaast zijn de beschermende effecten van borstvoeding, probiotica en systemische antibioticaprofylaxe op het voorkomen van OMA episodes beoordeeld.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

PICO 1: Vaccinations versus standard of care, placebo, no vaccination, or non-OME related vaccinations.

1. Pneumococcal conjugate vaccine versus Meningococcus type C conjugate vaccine

1.1 Episodes of otitis media

|

Low GRADE |

Treatment with a pneumococcal conjugate vaccine may result in little to no difference in the number of episodes of otitis media when compared with a meningococcus type C conjugate vaccine in children aged between zero and eighteen years of age.

Sources: Dagan (2001); O’Brien (2008). |

1.2 (Serious) adverse events

|

No GRADE |

Due to a lack of statistical information, it was not possible to draw a conclusion with regards to the outcome (serious) adverse events for treatment with a pneumococcal conjugate vaccine versus a meningococcus type C conjugate vaccine in children aged between zero and eighteen years of age.

Sources: - |

2. Pneumococcal conjugate vaccine versus Hepatitis B vaccine

2.1 Episodes of otitis media

|

Low GRADE |

Treatment with a pneumococcal conjugate vaccine may result in little to no difference in vaccine efficacy for otitis media when compared with a hepatitis B vaccine in children aged between zero and eighteen years of age.

Sources: Eskola (2001). |

2.2 (Serious) adverse events

|

No GRADE |

Due to a lack of statistical information, it was not possible to draw a conclusion with regards to the outcome (serious) adverse events for treatment with a pneumococcal conjugate vaccine versus a hepatitis B vaccine in children aged between zero and eighteen years of age.

Sources: Eskola - |

3. Trivalent, live, cold-adapted influenza vaccine versus placebo

3.1 Episodes of otitis media

|

Low GRADE |

Treatment with a trivalent, live, cold-adapted influenza vaccine may result in little to no difference in the number of episodes of otitis media when compared with placebo in children aged between zero and eighteen years of age.

Sources: Hoberman (2003), Lum (2010); Vesikari (2006). |

3.2 (Serious) adverse events

|

No GRADE |

Due to a lack of statistical information, it was not possible to draw a conclusion with regards to the outcome (serious) adverse events for treatment with a trivalent, live, cold-adapted influenza vaccine versus placebo in children aged between zero and eighteen years of age.

Sources: - |

PICO 2: Probiotics or breastfeeding versus no probiotics, no breastfeeding, standard of care, or placebo Conclusions

1. Episodes of acute otitis media

|

Low GRADE |

Treatment with probiotics may result in a reduction of episodes of acute otitis media during the treatment when compared with standard of care, placebo, or no probiotics in children aged between zero and eighteen years of age.

Sources: Scott (2019) - (Cohen, 2013; Corsello, 2017; Di Nardo, 2014; Di Pierro, 2016; Hatakka, 2001; Hatakka, 2007; Hojsak, 2010; Hojsak, 2016; Karpova, 2015; Marchisio, 2015; Nocerino, 2017; Rautava, 2009; Roos, 2001; Taipale, 2011; Taipale, 2016; Tano, 2002) |

2. (Serious) adverse events

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of probiotics on (serious) adverse events during the treatment when compared with standard of care, placebo, or no probiotics in children aged between zero and eighteen years of age.

Sources: Scott (2019) – (Marchisio, 2015; Rautava, 2009; Roos, 2001; Taipale, 2011) |

PICO 3: Antibiotic prophylaxis versus placebo Conclusions

1. Episodes of acute otitis media

|

No GRADE |

It was not possible to draw a conclusion with regards to the outcome episodes of acute otitis media for treatment with antibiotic prophylaxis versus no antibiotic prophylaxis or placebo in children aged between zero and eighteen years of age.

Sources: - |

2. (Serious) adverse events

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of antibiotic prophylaxis on (serious) adverse events during the treatment (any clinical side effect, such as diarrhea and vomiting or allergic reactions that are sufficient to recommend cessation of intervention) when compared with no antibiotic prophylaxis or placebo in children aged between zero and eighteen years of age.

Sources: Scott (2019) – (Marchisio, 2015; Rautava, 2009; Roos, 2001; Taipale, 2011) |

Samenvatting literatuur

PICO 1: Vaccinations versus standard of care, placebo, no vaccination, or non-OME related vaccinations.

Summary of literature

Description of studies

Systematic review(s)

The systematic Cochrane review of De Sévaux (2020) investigated the effect of pneumococcal conjugate vaccines in preventing acute otitis media in children up to twelve years of age. De Sévaux (2020) searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), which contains the Cochrane Acute Respiratory Infections Specialised Register, MEDLINE (1995 up to the 11th of June 2020); Embase (1995 up to the 11th of June 2020), CINAHL (2007 up to the 11th of June 2020), Latin American and Caribbean Health Science Information database (LILACS) (2007 up to the 11th of June 2020), and Science Citation Index-Science (2007 up to the 11th of June 2020), and Current Chemicals Reactions (2007 up to the 11th of June 2020). Randomized controlled trials (RCTs), irrespective of type, assessing the effect of pneumococcal conjugate vaccines versus placebo or control vaccine in preventing acute otitis media with a minimum follow-up duration of six months were eligible for inclusion. Studies that did not report outcome data relevant to this review were excluded. In total, four trials from the systematic review of De Sévaux (2020), involving 40,738 participants, were included (Black, 2000; Dagan, 2001; Eskola, 2001; O’Brien, 2008). The risk of bias was assessed with the Cochrane risk assessment tool. The included outcomes in De Sévaux (2020) were incidence numbers and episodes of otitis media and vaccine efficacy. The individual study characteristics of the included studies are described in the evidence table of this guideline.

The systematic Cochrane review of Norhayati (2017) investigated the effectiveness of influenza vaccine in reducing the occurrence of acute otitis media in infants and children. Norhayati (2017) searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), which contains the Cochrane Acute Respiratory Infections Specialised Register (up to the 15th of February 2017), MEDLINE (1946 up to the 15th of February 2017); Embase (1947 up to the 15th of February 2017), CINAHL (1981 up to the 15th of February 2017), Latin American and Caribbean Health Science Information database (LILACS) (1982 up to the 15th of February 2017) and Web of Science (1955 up to the 15th of February 2017). Randomized controlled trials (RCTs), blinded and open-label designs, comparing influenza vaccine with placebo or no treatment and studies that included infants and children aged younger than six years of age of either sex and of any ethnicity, with or without a history of recurrent acute otitis media were eligible for inclusion. In total, three trials from the systematic review of Norhayati (2017), involving 2,948 participants, were included (Hoberman, 2003; Lum, 2010; Vesikari, 2006). The risk of bias was assessed with the Cochrane risk assessment tool. The included outcomes in Norhayati (2017) were episodes of acute otitis media, fever, rhinorrhoea, and pharyngitis. The individual study characteristics of the included studies are described in the evidence table of this guideline.

Results

1. Pneumococcal conjugate vaccine versus meningococcus type C conjugate vaccine

1.1 Episodes of otitis media

Two studies reported information regarding all-cause episodes of otitis media per person-year (Dagan, 2001; O’Brien, 2008) and three studies reported the relative risk reduction in all-cause acute otitis media (Black, 2000; Dagan, 2001; O’Brien, 2008).

Dagan (2001) performed a per-protocol analysis and reported the episodes of otitis media per person-year for preventive treatment with a pneumococcal conjugate vaccine compared with a meningococcus type C vaccine. The number of episodes of otitis media per person-year in the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine group was 0.66, compared to 0.79 episodes in the meningococcus type C conjugate vaccine group. This resulted in a difference in incidence of episodes per person-year between both groups of -0.14 (95% CI –0.29 to 0.02), in favor of a pneumococcal conjugate vaccine. This was not considered as a clinically relevant difference.

O’Brien (2008) performed an intention-to-treat analysis and reported the episodes of otitis media per person-year for preventive treatment with a pneumococcal conjugate vaccine compared with a meningococcus type C vaccine. The number of episodes of otitis media per person-year in the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine group was 1.43, compared to 1.36 episodes in the meningococcus type C conjugate vaccine group. This resulted in a difference in incidence of episodes of otitis media per person-year between both groups of 0.07 (95% CI -0.05 to 0.18), in favor of the meningococcus type C conjugate vaccine group. This was not considered as a clinically relevant difference.

Black (2000) performed an intention-to-treat analysis and reported the efficacy of preventive treatment with a pneumococcal conjugate vaccine compared with a meningococcus type C vaccine expressed as a relative reduction in risk. The relative reduction in risk of otitis media between both groups was 6% (95% CI 4% to 9%), in favor the pneumococcal conjugated vaccine group. This was not considered as a clinically relevant difference.

Dagan (2001) performed a per-protocol analysis and reported the efficacy of preventive treatment with a pneumococcal conjugate vaccine compared with a meningococcus type C conjugate vaccine expressed as a relative reduction in risk. The relative reduction in risk of otitis media between both groups was 17% (95% CI -2% to 33%), in favor the pneumococcal conjugated vaccine group. This was not considered as a clinically relevant difference.

O’Brien (2008) performed an intention-to-treat analysis and reported the efficacy of preventive treatment with a pneumococcal conjugate vaccine compared with a meningococcus type C vaccine expressed as a relative reduction in risk. The relative reduction in risk of otitis media between both groups was -5% (95% CI -25% to 12%), in favor of the meningococcus type C conjugate vaccine group. This was not considered as a clinically relevant difference.

1.2 (Serious) adverse events

None of the included studies in this guideline reported information regarding (serious) adverse events for treatment with a pneumococcal conjugate vaccine compared with a meningococcus type C conjugate vaccine.

2. Pneumococcal conjugate vaccine versus Hepatitis B vaccine

2.1 Episodes of otitis media

One study reported information regarding all-cause episodes of otitis media (Eskola, 2001).

Eskola (2001) performed a per-protocol analysis and reported the episodes of otitis media per person-year for preventive treatment with a pneumococcal conjugate vaccine compared with a hepatitis B vaccine. The number of episodes of otitis media per person-year in the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine group was 1.16, compared to 1.24 episodes in the hepatitis B vaccine group. This resulted in a difference in incidence of episodes per person-year between both groups of -0.08, in favor of the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine group. A 95% CI could not be calculated, as person-time across treatment groups was not reported.

Eskola (2001) performed a per-protocol analysis and reported the efficacy of preventive treatment with a pneumococcal conjugate vaccine compared with a hepatitis B vaccine expressed as a relative reduction in risk. The relative reduction in risk of otitis media between both groups was -6% (95% CI -4% to 16%), in favor of the hepatitis B vaccine group. This was not considered as a clinically relevant difference.

2.2 (Serious) adverse events

None of the included studies in this guideline reported information regarding (serious) adverse events for treatment with a pneumococcal conjugate vaccine compared with a hepatitis B vaccine.

3. Trivalent, live, cold-adapted influenza vaccine versus placebo

3.1 Episodes of otitis media

Three studies reported information regarding the number of patients with at least one episode of acute otitis media for treatment with trivalent, live, cold-adapted influenza vaccine compared with placebo (Hoberman, 2003; Lum, 2010; Vesikari, 2006).

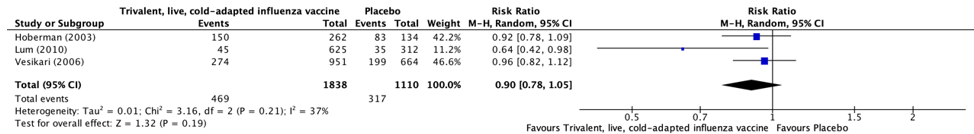

The results were pooled in a meta-analysis. The pooled number of patients with at least one episode of otitis media in the trivalent, live, cold-adapted influenza vaccine treatment group was 469/1838 (25.5%), compared to 317/1110 (28.6%) in the placebo group. This resulted in a pooled relative risk ratio (RR) of 0.90 (95% CI 0.78 to 1.05), in favor of treatment with trivalent, live, cold-adapted influenza vaccine (Figure 1). This was not considered as a clinically relevant difference.

Figure 1. Forest plot showing the comparison between live, cold-adapted influenza vaccine to placebo for patients with at least one episode of otitis media. Pooled risk ratio, random effects model. Z: p-value of overall effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2; statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval.

3.2 (Serious) adverse events

None of the included studies in this guideline reported information regarding (serious) adverse events for treatment with trivalent, live, cold-adapted influenza vaccine compared with placebo.

Level of evidence of the literature

1. Pneumococcal conjugate vaccine versus meningococcus type C conjugate vaccine

The level of evidence regarding the outcome episodes of otitis media was derived from randomized controlled trials and therefore started high. The level of evidence was downgraded by two levels because of several study limitations, such as a lack of blinding of patients in the study and more lost to follow-up in one treatment group compared to the other (risk of bias, -1) and the small number of events (imprecision, -1). The level of evidence was considered as low.

Due to a lack of statistical information, it was not possible to GRADE the literature for (serious) adverse events for the comparison of a pneumococcal conjugate vaccine versus a meningococcus type C conjugate vaccine in children aged between zero and eighteen years of age.

2. Pneumococcal conjugate vaccine versus Hepatitis B vaccine

The level of evidence regarding the outcome episodes of otitis media was derived from a randomized controlled trial and therefore started high. The level of evidence was downgraded by two levels because of several study limitations, such as a lack of blinding of patients in the study and the wide confidence interval crossing the thresholds of clinical relevance (imprecision, -1). The level of evidence was considered as low.

Due to a lack of statistical information, it was not possible to GRADE the literature for (serious) adverse events for the comparison of a pneumococcal conjugate vaccine versus a hepatitis B vaccine in children aged between zero and eighteen years of age.

3. Trivalent, live, cold-adapted influenza vaccine versus placebo

The level of evidence regarding the outcome episodes of otitis media was derived from randomized controlled trials and therefore started high. The level of evidence was downgraded by two levels because of more lost to follow-up in one treatment group compared to the other (risk of bias, -1) and the wide confidence interval crossing the lower threshold of clinical relevance (imprecision, -1). The level of evidence was considered as low.

Due to a lack of statistical information, it was not possible to GRADE the literature for (serious) adverse events for otitis media for the comparison of a trivalent, live, cold-adapted influenza vaccine versus placebo in children aged between zero and eighteen years of age.

PICO 2: Probiotics or breastfeeding versus no probiotics, no breastfeeding, standard of care, or placebo

Summary of literature

Description of studies

Systematic review(s)

The systematic (Cochrane) review of Scott (2019) investigated the effect of probiotics to prevent the occurrence of acute otitis media in children. Scott (2019) searched the electronic databases of Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (up to the 4th of October 2018), PubMed (from 1946 to the 4th of October 2018), Embase Elsevier (from 1947 up to the 4th of October 2018), CINAHL (from 1982 up to the 4th of October 2018), LILACS (from 1982 up to the 4th of October), and Web of Science (from 1900 up to the 4th of October 2018). Randomized controlled trials who included children aged up to eighteen years and trials comparing probiotics with placebo or usual care or no probiotics were eligible for inclusion. Children with chromosomal and genetic disorders, craniofacial abnormalities (including cleft palate), children taking systemic corticosteroids or with immune deficiency status, or children with cystic fibrosis or primary ciliary dyskinesia were excluded. In total, nineteen references, that reported on seventeen trials were included (Cohen, 2013; Corsello, 2017; Di Nardo, 2014; Di Pierro, 2016; Hatakka, 2001; Hatakka, 2007; Hojsak, 2010; Karpova, 2015; Maldonado, 2012; Maldonado, 2015; Marchisio, 2015; Nocerino, 2017; Rautava, 2009; Roos, 2001; Stecksen-Blicks, 2009; Taipale, 2011; Taipale, 2016; Tano, 2002). Two trials also reported two- or three-year follow-up data (Maldonado, 2015; Taipale, 2016). Five trials reported on children prone to otitis (Cohen 2013; Hatakka 2007; Marchisio 2015; Roos 2001; Tano 2002), whilst the remaining trials reported on children not prone to otitis. The definition of 'otitis-prone' was not clear and may have involved a subjective element. Two trials included synbiotics, that is a combination of prebiotic and probiotic (Cohen 2013; Maldonado 2012/Maldonado 2015); the remaining trials tested probiotics consisting of single or multiple bacterial strains. Eleven trials evaluated Lactobacillus-containing probiotics (Corsello 2017; Di Nardo 2014; Hatakka 2001; Hatakka 2007; Hojsak 2010; Hojsak 2016; Maldonado 2012/Maldonado 2015; Nocerino 2017; Rautava 2009; Stecksen-Blicks 2009; Taipale 2011/Taipale 2016); six trials evaluated Streptococcus-containing probiotics (Cohen 2013; Di Pierro 2016; Karpova 2015; Marchisio 2015; Roos 2001; Tano 2002). Duration of administration of the probiotic ranged from twenty days, in Roos (2001), to two years, in Taipale (2016). The risk of bias was assessed with the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. The reported outcomes in Scott (2019) were the proportion of children with acute otitis media and adverse events.

Results

1. Episodes of otitis media

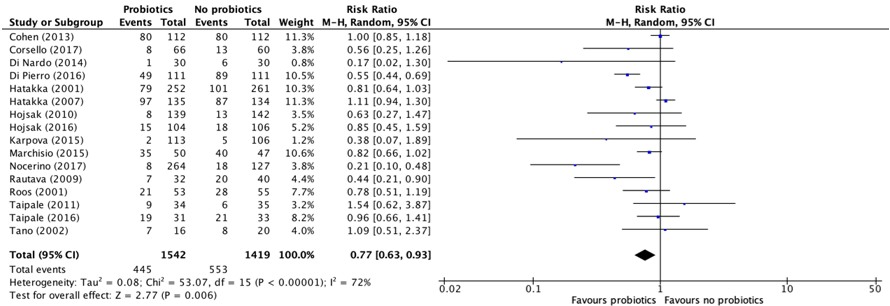

Sixteen studies, retrieved from the systematic review of Scott (2019) reported the proportion of children with an episode of acute otitis media during the treatment (Cohen, 2013; Corsello, 2017; Di Nardo, 2014; Di Pierro, 2016; Hatakka, 2001; Hatakka, 2007; Hojsak, 2010; Hojsak, 2016; Karpova, 2015; Marchisio, 2015; Nocerino, 2017; Rautava, 2009; Roos, 2001; Taipale, 2011; Taipale, 2016; Tano, 2002). The results were pooled in a meta-analysis. The pooled number of children with an episode of acute otitis media in the group who received probiotics was 445/1542 (28.9%), compared to 553/1419 (39.0%) in the group children who did not receive probiotics. This resulted in a pooled relative risk ratio (RR) of 0.77 (95% CI 0.63 to 0.93), in favor of the group who received probiotics (Figure 2). This was considered as a clinically relevant difference.

Figure 2. Forest plot showing the comparison between children receiving probiotics and children who did not receive probiotics for episodes of acute otitis media. Pooled relative risk ratio, random effects model. Z: p-value of overall effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2; statistical heterogeneity.

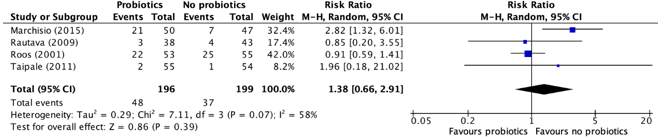

2. (Serious) adverse events

Four studies, retrieved from the systematic review of Scott (2019) reported the number of children with an (serious) adverse event (e.g., gastrointestinal side effects) (Marchisio, 2015; Rautava, 2009; Roos, 2001; Taipale, 2011). The results were pooled in a meta-analysis. The pooled number of children with a (serious) adverse event in the group who received probiotics was 48/196 (24.5%), compared to 37/199 (18.6%) in the group children who did not receive probiotics. This resulted in a pooled relative risk ratio (RR) of 1.38 (95% CI 0.66 to 2.91), in favor of the group who did not receive probiotics (Figure 3). This was considered as a clinically relevant difference.

Figure 3. Forest plot showing the comparison between children receiving probiotics and children who did not receive probiotics for (serious) adverse events. Pooled relative risk ratio, random effects model. Z: p-value of overall effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2; statistical heterogeneity.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence regarding the outcome episodes of acute otitis media was derived from randomized controlled trials and therefore started high. The level of evidence was downgraded by two levels because of the authors' employment with study funder, undeclared conflict of interest, and unstated role of the funder in the study design, analysis, interpretation, and manuscript writing (risk of bias, -1) and the wide confidence interval crossing the lower threshold of clinical relevance (imprecision, -1). The level of evidence was considered as low.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome (serious) adverse events was derived from randomized controlled trials and therefore started high. The level of evidence was downgraded by three levels because of the authors' employment with study funder, undeclared conflict of interest, and unstated role of the funder in the study design, analysis, interpretation, and manuscript writing (risk of bias, -1) and the wide confidence interval crossing both thresholds of clinical relevance (imprecision, -1). The level of evidence was considered as very low.

PICO 3: Antibiotic prophylaxis versus placebo

Summary of literature

Description of studies

Systematic review(s)

The systematic (Cochrane) review of Leach (2006) investigated the effect of long-term antibiotics (six weeks or longer) in preventing acute otitis media. Leach (2006) searched the electronic databases of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (The Cochrane Library 2010, Issue 3) which includes the Acute Respiratory Infections Group’s Specialised Register, MEDLINE (January 1966 to July Week 4, 2010), OLD MEDLINE (1950 to 1965) and EMBASE (1990 to August 2010). Randomized controlled trials that compared long-term antibiotics with placebo or no treatment for preventing acute otitis media were eligible for inclusion. Children with a diagnosis of acute otitis media, acute otitis media with perforation or chronic suppurative otitis media at the time of randomization were excluded. In total, seventeen trials were included (Casselbrant, 1992; Gaskins, 1982; Gonzalez, 1986; Gray, 1981; Leach, 2008; Liston, 1983; Mandel 1996; Maynard, 1972; Perrin, 1974; Persico, 1985; Principi, 1989; Roark, 1997; Schuller, 1983; Schwartz, 1982; Sih, 1993; Teele, 2000; Varsano, 1985). All studies randomized children at increased risk of acute otitis media. In nine studies the antibiotics were given once daily (Casselbrant, 1992; Gray, 1981; Mandel, 1996; Maynard, 1972; Persico, 1985; Principi, 1989; Roark, 1997; Sih, 1993; Teele, 2000). Eight studies used a twice-daily dose (Gaskins, 1982; Gonzalez, 1986; Leach, 2008; Liston, 1983; Perrin, 1974; Roark, 1997, Schuller, 1983; Varsano, 1985). One study included a once-daily treatment arm and a twice-daily treatment arm (Roark, 1997). The reported outcome in Leach (2006) was the proportion of children with (serious) adverse events. Leach (2006) also reported the proportion of children experiencing acute otitis media/chronic suppurative otitis media but did not separately report the proportion of children with only acute otitis media. The outcome did therefore not match the PICO of this guideline and was not included in the analysis of the literature.

Results

1. Episodes of otitis media

None of the included studies in this guideline reported information regarding episodes of otitis media for treatment with antibiotic prophylaxis compared placebo.

2. (Serious) adverse events

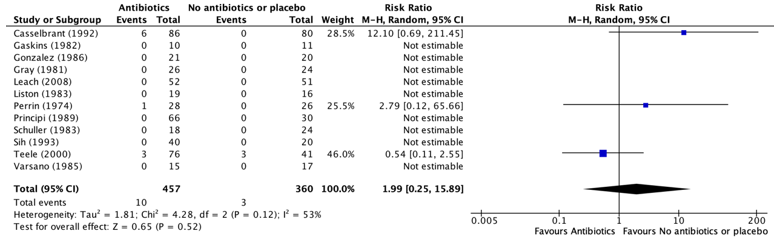

Twelve studies, retrieved from the systematic review of Leach (2006) reported the number of children with an (serious) adverse event during the treatment(any clinical side effect, such as diarrhea and vomiting or allergic reactions that are sufficient to recommend cessation of intervention) (Casselbrant, 1992; Gaskins, 1982; Gonzalez, 1986; Gray, 1981; Leach, 2008; Liston, 1983; Perrin, 1974; Principi, 1989; Schuller, 1983; Sih, 1993; Teele, 2000; Varsano, 1985). The results were pooled in a meta-analysis. The pooled number of children with a (serious) adverse event in the group who received antibiotic prophylaxis was 10/457 (2.2%), compared to 3/360 (0.8%) in the group children who did not receive antibiotic prophylaxis. This resulted in a pooled relative risk ratio (RR) of 1.99 (95% CI 0.25to 15.89), in favor of the group who did not receive antibiotic prophylaxis (Figure 4). This was considered as a clinically relevant difference.

Figure 4. Forest plot showing the comparison between children receiving antibiotic prophylaxis and children who did not receive antibiotic prophylaxis for (serious) adverse events. Pooled relative risk ratio, random effects model. Z: p-value of overall effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2; statistical heterogeneity.

Level of evidence of the literature

Since none of the included studies reported this outcome, it was not possible to GRADE the literature for episodes of acute otitis media for the comparison of antibiotic prophylaxis versus no antibiotic prophylaxis or placebo in children aged between zero and eighteen years of age.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome (serious) adverse events was derived from randomized controlled trials and therefore started high. The level of evidence was downgraded by three levels because of the small number of events and the wide confidence interval crossing both thresholds of clinical relevance (imprecision, -3). The level of evidence was considered as very low.

Zoeken en selecteren

PICO 1: Vaccinations for acute otitis media (AOM) related pathogens (such as pneumococcal conjugate vaccination, influenza vaccination) versus standard of care, placebo, no vaccination, or non-AOM related vaccinations

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question: What are the (un)beneficial effects of preventive interventions (such as pneumococcal conjugate vaccination, influenza vaccination) versus standard of care, placebo, no preventive interventions, or preventive interventions compared with each other on the preventive effect of otitis media in children aged between zero and eighteen years of age?

P: Children aged between 0-18 years of age.

I: Pneumococcal conjugate vaccination or influenza vaccination.

C: Standard of care, placebo, no pneumococcal conjugate vaccination or influenza vaccination, oligosaccharide, or different vaccines compared with each other.

O: Preventive effect on otitis media (episodes of acute otitis media, (serious) adverse events).

PICO 2: Probiotics or breastfeeding versus no probiotics, no breastfeeding, standard of care, or placebo

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question: What are the (un)beneficial effects of preventive interventions (such as probiotics) versus standard of care, placebo, or no preventive interventions on the preventive effect of otitis media in children aged between zero and eighteen years of age?

P: Children aged between 0-18 years of age.

I: Probiotics or breastfeeding.

C: No probiotics or breastfeeding, standard of care, or placebo.

O: Preventive effect on otitis media (incidence numbers, episodes, (serious) adverse events).

PICO 3: Antibiotic prophylaxis versus placebo

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question: What are the (un)beneficial effects of treatment with antibiotic prophylaxis versus placebo on the preventive effect of otitis media in children aged between zero and eighteen years of age?

P: Children aged between 0-18 years of age.

I: Antibiotic prophylaxis.

C: Placebo.

O: Preventive effect on otitis media (incidence numbers, episodes (serious) adverse events).

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered the preventive effect on otitis media as a critical outcome measure for decision making.

The guideline development group defined a difference of one episode of otitis media per person-year and a difference of 25% (RR <0.80 or >1.25) in relative risk for vaccines as a minimal clinically (patient) important difference.

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms until the 30th of November 2021. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 1006 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria: Systematic reviews, randomized controlled trials, and observational studies on various forms of preventive treatment for children with otitis media. Twenty-nine studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening for PICO 1, PICO 2, and PICO 3 combined. After reading the full text, 25 studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and four studies were included.

Results

Two studies were included in the analysis of the literature for PICO 1 and one study was included in the analysis of the literature for PICO 2. The search also resulted in one included study for the analysis of PICO 3. Important study characteristics and results of the included studies are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- Black S, Shinefield H, Fireman B, Lewis E, Ray P, Hansen JR, Elvin L, Ensor KM, Hackell J, Siber G, Malinoski F, Madore D, Chang I, Kohberger R, Watson W, Austrian R, Edwards K. Efficacy, safety and immunogenicity of heptavalent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in children. Northern California Kaiser Permanente Vaccine Study Center Group. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2000 Mar;19(3):187-95. doi: 10.1097/00006454-200003000-00003. PMID: 10749457.

- Dagan R, Sikuler-Cohen M, Zamir O, Janco J, Givon-Lavi N, Fraser D. Effect of a conjugate pneumococcal vaccine on the occurrence of respiratory infections and antibiotic use in day-care center attendees. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2001 Oct;20(10):951-8. doi: 10.1097/00006454-200110000-00008. PMID: 11642629.

- de Sévaux JL, Venekamp RP, Lutje V, Hak E, Schilder AG, Sanders EA, Damoiseaux RA. Pneumococcal conjugate vaccines for preventing acute otitis media in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020 Nov 24;11(11):CD001480. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001480.pub6. PMID: 33231293; PMCID: PMC8096893.

- Eskola J, Kilpi T, Palmu A, Jokinen J, Haapakoski J, Herva E, Takala A, Käyhty H, Karma P, Kohberger R, Siber G, Mäkelä PH; Finnish Otitis Media Study Group. Efficacy of a pneumococcal conjugate vaccine against acute otitis media. N Engl J Med. 2001 Feb 8;344(6):403-9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200102083440602. PMID: 11172176.

- Hoberman A, Greenberg DP, Paradise JL, Rockette HE, Lave JR, Kearney DH, Colborn DK, Kurs-Lasky M, Haralam MA, Byers CJ, Zoffel LM, Fabian IA, Bernard BS, Kerr JD. Effectiveness of inactivated influenza vaccine in preventing acute otitis media in young children: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003 Sep 24;290(12):1608-16. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.12.1608. PMID: 14506120.

- Lum LC, Borja-Tabora CF, Breiman RF, Vesikari T, Sablan BP, Chay OM, Tantracheewathorn T, Schmitt HJ, Lau YL, Bowonkiratikachorn P, Tam JS, Lee BW, Tan KK, Pejcz J, Cha S, Gutierrez-Brito M, Kaltenis P, Vertruyen A, Czajka H, Bojarskas J, Brooks WA, Cheng SM, Rappaport R, Baker S, Gruber WC, Forrest BD. Influenza vaccine concurrently administered with a combination measles, mumps, and rubella vaccine to young children. Vaccine. 2010 Feb 10;28(6):1566-74. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.11.054. Epub 2009 Dec 8. PMID: 20003918.

- Norhayati MN, Ho JJ, Azman MY. Influenza vaccines for preventing acute otitis media in infants and children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015 Mar 24;(3):CD010089. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010089.pub2. Update in: Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 Oct 17;10 :CD010089. PMID: 25803008.

- O'Brien KL, David AB, Chandran A, Moulton LH, Reid R, Weatherholtz R, Santosham M. Randomized, controlled trial efficacy of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine against otitis media among Navajo and White Mountain Apache infants. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2008 Jan;27(1):71-3. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e318159228f. PMID: 18162944.

- Roos, K., Håkansson, E., Holm, S. Effect of recolonisation with interfering streptococci on recurrences of acute and secretory otitis media in children: randomised placebo controlled trial. BMJ 2001;322:1-4.

- Tano, K., Håkansson, E.G., Holm, S.E., Hellström, S. A nasal spray with alpha-haemolytic streptococci as long term prophylaxis against recurrent otitis media. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2002;62:17-23.

- Vesikari T, Fleming DM, Aristegui JF, Vertruyen A, Ashkenazi S, Rappaport R, Skinner J, Saville MK, Gruber WC, Forrest BD; CAIV-T Pediatric Day Care Clinical Trial Network. Safety, efficacy, and effectiveness of cold-adapted influenza vaccine-trivalent against community-acquired, culture-confirmed influenza in young children attending day care. Pediatrics. 2006 Dec;118(6):2298-312. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-0725. PMID: 17142512.

Evidence tabellen

Evidence table for systematic review of RCTs and observational studies (intervention studies)

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C)

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

|

Leach (2006) |

SR and meta-analysis of RCTs

Literature search up to

A: Casselbrant (1992) B: Gaskins (1982) C: Gonzalez (1986) D: Gray (1981) E: Leach (2006) F: Liston (1983) G: Mandel (1996) H: Maynard (1972) I: Perrin (1974) J: Persico (1985) K: Principi (1989) L: Roark (1997) M: Schuller (1983) N: Schwartz (1982) O: Sih (1993) P: Teele (2000) Q: Varsano (1985)

Study design: RCT parallel

Source of funding This study was funded by the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council.

Conflicts of interest: Both review authors were investigators on a randomized controlled trial of antibiotics to prevent otitis media in remote Australian Aboriginal children. This study was funded by the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council.

|

Inclusion criteria SR:

Exclusion criteria SR:

17 studies included

Important patient characteristics at baseline:

N A: N = 264 B: N = 21 C: N = 65 D: N = 48 E: N = 103 F: N = 43 G: N = 111 H: N = 364 I: N = 70 J: N = 111 K: N = 100 L: N = 194 M: N = 80 N: N = 43 O: N = 80 P: N = Q: N =

mean age A: Not reported. B: Not reported. C: Not reported. D: Not reported. E: Not reported. F: Not reported. G: Not reported. H: Not reported. I: Not reported. J: Not reported. K: Not reported. L: Not reported. M: Not reported. N: Not reported. O: Not reported. P: Not reported. Q: Not reported.

Sex (M/F) intervention vs control: A: Not reported. B: Not reported. C: Not reported. D: Not reported. E: Not reported. F: Not reported. G: Not reported. H: Not reported. I: Not reported. J: Not reported. K: Not reported. L: Not reported. M: Not reported. N: Not reported. O: Not reported. P: Not reported. Q: Not reported.

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes. |

Describe intervention:

A: 2 years amoxicillin (20 mg/kg/d, daily (OD))

B: 6 months TMP/SMX/ 5 to 8/25 to 40 mg/kg/d BD. Mean dose 6.8/34

C: 6 months sulfisoxazole (500 mg for less than 5 years; 1 g for more than 5 years)

D: 12 months sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim (4 mg TMP per 20 mg XI per kg/d). Daily – possibly once daily

E: 6 months amoxicillin (50/mg/kg/d, daily (BD))

F: 3 months Sulfisoxazole 75 mg/kg/d BD

G: 12 months Amoxicillin (20 mg/kg/d OD) H: 12 months Ampicillin (125/5 ml; age 2.5 years 5 ml/d; age more than 2.5 years 10 ml/d)

I: 3 months Sulfisoxazole 500 mg/5 ml. One teaspoon twice daily

J: At least 3 months Potassium phenoxymethyl penicillin V 25 mg/kg/d

K: 6 months Amox: 20 mg/kg/d. Sulfamethoxazole and trimethoprim (SXT): 12 mg/kg/d. OD

L: Up to 90 days or until 2 x AOM (failure). An average of 6.5 weeks (7243 days for 158 children) on study medication (excludes days treated for AOM) Amoxicillin 20 mg/kg/d OD or BD

M: 2 years (second year combined therapies used) Sulfisoxazole 500 mg BD (Group 3)

N: 2 months Sulfisoxazole 25 mg/kg OD O: 3 months TMP-SMX (12 mg/kg/d) AMX (20 mg/kg/d) OD.

P: 6 months Sulfisoxazole (50 mg/kg/d) Amoxicillin (20 mg/kg/d). Frequency not stated. Assumed once daily

Q: 10 weeks Sulfisoxazole (250 mg tablet if less than 2 y; 500 mg if 2 to 5 y BD)

|

Describe control:

A: Placebo B: No treatment controls C: Placebo D: Placebo E: Placebo F: Placebo G: Placebo H: Placebo I: Placebo J: No treatment K: Placebo L: Placebo M: No treatment (1) or antihistamines when nose blocked (2) or Pneumovax (4) or Pneumovax and sulfisoxazole (5) N: Placebo O: Placebo P: Placebo Q: Placebo |

End-point of follow-up:

A: 2 years B: 6 months C: 6 months D: 12 months E: 6 months F: 3 months G: 12 months H: 12 months I: 3 months J: At least 3 months K: 6 months L: Not reported. M: 2 years N: 2 months O: 3 months P: 6 months Q: 10 weeks |

Outcome measure: (serious) adverse events (any clinical side effects during intervention) I: 10/457 (2.2%) C: 3/360 (0.8%) |

|

Norhayati (2017) |

SR and meta-analysis of RCTs

Literature search up to 15 February 2017

A: Belshe (2000) B: Bracco (2009) C: Clements (1995) D: Gruber (1996) E: Hoberman (2003) F: Lum (2010) G: Marchisio (2002) H: Swierkosz (1994) I: Tam (2007) J: Vesikari (2006) K: Kosalaraksa (2015)

Study design: RCT parallel

Source of funding All studies declared funding from vaccine manufacturer.

Conflicts of interest: - Mohd N Norhayati: none known. - Jacqueline J Ho: none known. - Mohd Y Azman: none known.

|

Inclusion criteria SR:

Exclusion criteria SR:

11 studies included

Important patient characteristics at baseline:

N A: N = 1602 B: N = 2821 C: N = 186 D: N = 182 E: N = 786 F: N = 838 G: N = 1120 H: N = 133 I: N = 22 J: N = 2764 K: N = 1616

mean age A: 15 to 71 months at the time of initial vaccination in year 1. B: 6 to 36 months of age C: 6 months to 5 years of age D: 6 to 18 months of age E: 6 to 24 months of age F: 6 months to 17 years at the time of first vaccination. G: 11 to less than 24 months H: 1 to 5 years of age I: 2 to 22 months of age J: 12 to 36 months of age K: 6 to 36 months of age

Sex (M/F) intervention vs control: A: Not reported. B: Not reported. C: Not reported. D: 128/145 vs 75/63 1st cohort 139/113 vs 53/123 2nd cohort E: Not reported. F: Not reported. G: 383/364 vs 175/189 H: 38/29 vs 42/24 I: Not reported. J: 880/773 vs 588/523 K: 495/455 vs 337/328

Groups comparable at baseline? |

Describe intervention:

A: CAIV-T

B: 1 or 2 doses of LAIV

C: 1 or 2 doses of 0.25 mL trivalent subvirion influenza virus vaccine.

D: H1N1

E: Inactivated trivalent subvirion influenza vaccine intramuscularly.

F: 2 intranasal doses of trivalent LAIV

G: 2 doses of intranasal, inactivated, virsomal subunit influenza vaccine on day 1 and 8.

H: 3 doses of 0.5 mL (each) of CAIV intranasally 60 days apart.

I: 2 doses of CAIV-T

J: 0.2 mL (0.1 mL into each nostril) of LAIV intranasally.

K: 2 doses of H5N1 influenza vaccine |

Describe control:

A: Placebo

B1: Placebo B2: Saline placebo

C1: 3rd dose of hepatitis B vaccine 0.25 mL C2: ear examination by parents’ request C3: ear examination

D1: H3N2 D2: Bivalent influenza D3: placebo

E: Placebo intramuscularly

F: Placebo

G: no treatment.

H: Placebo.

I: 2 doses of placebo.

J: Placebo.

K: 2 doses of placebo (0.25 mL of saline).

|

End-point of follow-up:

A: 7 months B: 11 days after treatment in year 1 and 28 days after treatment in year 2. C: 5 months. D: 3 months. E: 6 months. F: 8 months G: Every 4 to 6 weeks for 25 weeks. H: 30 to 60 days postvaccination. I: began on the 11th day after receipt of the first dose of study treatment and continued for 2 years. J: 6 months. K: 1 year.

|

Outcome measure: at least one episode of acute otitis media, n/N (%)

C (Clements, 1995) I: 20/94 (21.3%) C: 34/92 (37.0%)

E (Hoberman, 2003) I: 150/262 (57.3%) C: 83/134 (61.9%)

F (Lum, 2010) I: 45/625 (7.2%) C: 35/312 (11.2%)

J (Vesikari, 2006) I: 274/951 (28.8%) C: 199/664 (30.0%)

Outcome measure: Fever, n/N (%)

G (Marchisio, 2002) I: 26/67 (38.8%) C: 42/66 (63.6%)

J (Vesikar, 2006) I: 148/640 (23.1%) C: 145/450 (32.2%)

Outcome measure: rhinorrhoea, n/N (%)

B (Bracco, 2009) I: 56/1461 (3.8%) C: 30/741 (4.0%)

D (Gruber, 1996) I: 105/138 (76.1%) C: 30/44 (68.2%)

F (Lum, 2010) I: 565/806 (70.1%) C: 206/405 (50.9%)

H (Swierkosz, 1994) I: 9/17 (52.9%) C: 1/5 (20.0%)

I (Tam, 2007) I: 1978/3516 (56.3%) C: 1157/2362 (49.0%)

J (Vesikari, 2006) I: 423/631 (67.0%) C: 268/437 (61.3%)

Outcome measure: pharyngitis, n/N (%)

B (Bracco, 2009) I: 20/1461 (1.4%) C: 12/741 (1.6%)

F (Lum, 2010) I: 98/797 (12.3%) C: 43/406 (10.6%)

J (Vesikari, 2006) I: 72/600 (12.0%) C: 56/424 (13.2%)

|

|

De Sévaux (2020) |

SR and meta-analysis of RCTs

Literature search up to 11 June 2020.

A: Black (2000) B: Dagan (2001) C: Eskola (2001) D: Jansen (2008) E: Kilpi (2003) F: O’Brien (2008) G: Prymula (2006) H: Tregnaghi (2014) I: van Kempen (2006) J: Veenhoven (2003) K: Vesikari (2016)

Study design: RCT parallel

Source of funding Six trials were funded by pharmaceutical companies (Black 2000/Fireman; Eskola 2001/Palmu 2009; Kilpi 2003; Prymula 2006; Tregnaghi 2014/Sáez-Llorens 2017; Vesikari 2016/Karppinen 2019). Three trials reported receiving support from non- commercial (governmental) sources, but study vaccines were supplied by pharmaceutical companies (Jansen 2008; van Kempen 2006; Veenhoven 2003). One trial was supported by both a pharmaceutical company and governmental funding (O'Brien 2008). One trial reported that study vaccines were supplied by a pharmaceutical company (Dagan 2001).

Conflicts of interest: See original publication.

|

Inclusion criteria SR:

Exclusion criteria SR:

11 studies included

Important patient characteristics at baseline:

N A: N = 37868 B: N = 264 C: N = 1662 D: N = 597 E: N = 1666 F: N = 944 G: N = 4968 H: N = 23821 I: N = 74 J: N = 383 K: N = 5095

mean age A: Not reported. B: 12 to 35 months of age C: 2 months D: 18 to 72 months E: 2 months. F: Below 2 years. G: Between 6 weeks and 5 months H: 6 to 16 weeks. I: Between 1 and 7 years J: Between 1 and 7 years K: between 6 weeks and 18 months

Sex: A: Not reported. B: Not reported. C: Not reported. D: not reported. E: Not reported. F: Not reported. G: Not reported. H: Not reported. I: Not reported. J: Not reported. K: Not reported.

Groups comparable at baseline? |

Describe intervention:

A: CRM-197-PCV7.

B: CRM-197-PCV9.

C: CRM-197-PCV.

D: TIV/PCV7.

E: OMPC-PCV7.

F: CRM197-PCV7.

G: PHiD-CV11.

H: PHiD-CV10.

I: CRM197-PCV7 plus PPV23.

J: CRM-PCV7 plus PPV23.

K: PHiD-CV10 3+1. |

Describe control:

A: Meningococcus type C conjugate vaccine.

B: Meningococcus type C conjugate vaccine.

C: Hepatitis B vaccine.

D1: TIV/Placebo. D2: HBV/placebo.

E: Hepatitis B vaccine.

F: Meningococcus type C conjugate vaccine.

G: Hepatitis A vaccine.

H: Hepatitis B vaccine.

I: Hepatitis A vaccine.

J: Hepatitis A or B vaccine.

K1: PHiD-CV10 2+1. K2: Hepatitis A or B vaccine 3+1. K3: Hepatitis A or B vaccine 2+1. |

End-point of follow-up:

A: 6 to 31 months. B: 2 years starting 1 month after complete immunization. C: Up to 24 months of age. D: Started 14 days after the second set of vaccinations and continued for 6 to 18 months, depending on the year of inclusion. E: up to 24 months. F: Maximum of 40 months. G: 24 to 27 months of age. H: Maximum of 4 years. I: 26 months. J: 18 months. K: 18 months.

|

Outcome measure: Frequency of all-cause acute otitis media - Episodes/person-year – intention-to-treat

F (O’Brien, 2008) – Intention-to-treat I: 1.43 episodes/person-year C: 1.36 episodes/person-year

H (Tregnaghi, 2014) – Intention-to-treat I: 0.03 episodes/person-year C: 0.04 episodes/person-year

Outcome measure: Frequency of all-cause acute Otitis Media - Episodes/person-year – Per-protocol

B (Dagan, 2001) – Per-protocol I: 0.66 episodes/person-year C: 0.79 episodes/person-year

C (Eskola, 2001) – Per-protocol I: 1.16 episodes/person-year C: 1.24 episodes/person-year

G (Prymula, 2006) – Per-protocol I: 0.08 episodes/person-year C: 0.13 episodes/person-year

J (Veenhoven, 2003) – Per-protocol I: 1.1 episodes/person-year C: 0.83 episodes/person-year

I (Van Kempen, 2006) – Per-protocol I: 0.78 episodes/person-year C: 0.67 episodes/person-year

Outcome measure: Frequency of all-cause acute otitis media - Vaccine efficacy (expressed as relative reduction in risk (95% CI) – intention-to-treat

A (Black, 2000) – Intention-to-treat 6% (95% CI 4 to 9)

H (Tregnaghi, 2014) – Intention-to-treat 15% (95% CI -1 to 28)

J (Veenhoven, 2003) – Intention-to-treat -25% (95% CI -57 to 1%)

Outcome measure: Frequency of all-cause acute otitis media - Vaccine efficacy (expressed as relative reduction in risk (95% CI) – Per-protocol

C (Eskola, 2001) – Per-protocol 6% (95% CI 4 to 16)

D (Jansen, 2008) – Per-protocol 57% (95% CI 6 to 80)

E (Kilpi, 2003) – Per-protocol -1% (95% CI -12% to 10%)

G (Prymula, 2006) – Per-protocol 34% (95% CI 21 to 44)

Outcome measure: Frequency of recurrent acute otitis media - Vaccine efficacy (expressed as relative reduction in risk (95% CI) – Intention-to-treat

A (Black, 2000) – Intention-to-treat 9% (95% CI 4 to 14)

C (Eskola, 2001) – Intention-to-treat 9% (95% CI -12 to 27%)

Outcome measure: Frequency of recurrent acute otitis media - Vaccine efficacy (expressed as relative reduction in risk (95% CI) – Per-protocol

A (Black, 2000) 9% (95% CI 3 to 15)

C (Eskola, 2001) 16% (95% CI -6% to 35%)

G (Prymula, 2006) 56% (95% CI -2% to 81%)

|

Evidence table for intervention studies (randomized controlled trials and non-randomized observational studies [cohort studies, case-control studies, case series])1

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics 2 |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C) 3

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size 4 |

Comments |

|

Marchisio (2015) |

Type of study: Prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial.

Setting and country: Pediatric Highly Intensive Care Unit of the University of Milan’s Department of Pathophysiology and Transplantation.

Funding and conflicts of interest: The author(s) declare that they have no competing interest.

This study was supported by a grant obtained from DMG Italia S.r.l.

|

Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

N total at baseline: Intervention: N= 50 Control: N = 50

Important prognostic factors2: Age at baseline I: <2 years: N = 15 2-3 years: N = 25 4-5 years: N = 10 Mean (SD): 2.7 (1.1)

C: <2 years: N = 10 2-3 years: N = 24 4-5 years: N = 13 Mean (SD): 3.1 (1.2)

Sex: Unclear.

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes.

|

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

Children receiving the S. salivarius 24 SMB preparation in each nostril twice per day for 5 consecutive days each month for 3 consecutive months.

|

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

Children placebo in each nostril twice per day for 5 consecutive days each month for 3 consecutive months.

|

Length of follow-up: 6 months.

Loss-to-follow-up: N = 3 in the placebo group because the parents of three subjects in the placebo group refused to continue the study after the first period of treatment.

|

Outcome measure: at least one episode of AOM I: 35/50 (70%) C: 40/47 (85.1%)

Outcome measure: mean (SD) AOM episode I: 1.78 (1.76) episodes C: 1.81 (1.47) episodes

Outcome measure: Local adverse event – at least one I: 21/50 (42.0%) C: 7/47 (14.9%)

Outcome measure: Rhinorrhea I: 1/50 (2.0%) C: 0/47 (0%)

Outcome measure: systematic adverse event I: 0/50 (0%) C: 0/47 (0%)

Outcome measure: severe adverse event I: 0/50 (0%) C: 0/47 (0%)

|

Author’s conclusion: However, the suggestions of this preliminary study have to be confirmed with other evaluations that involve greater numbers of subjects. Specifically, because colonization is essential for reducing the AOM risk, the issue of why some subjects were not colonized despite receiving the same treatment as those with evident colonization requires further study. The elimination of factors that prevent colonization might be useful for significantly increasing the real effectiveness of this treatment. The role in this regard of pathogens that commonly cause AOM and frequently colonize nasopharynx, such as S. pneumoniae and not-typeable H. influenzae, has to be evaluated. Moreover, because S. salivarius 24SMB is extremely sensitive to the drugs that are commonly prescribed to treat AOM and other bacterial diseases [11], the utility of additional doses of S. salivarius 24 SMB following the use of antibiotics for maintaining colonization and assuring long-term protection against AOM should be defined.

|

Risk of bias table for intervention studies (randomized controlled trials; based on Cochrane risk of bias tool and suggestions by the CLARITY Group at McMaster University)

|

Study reference

(first author, publication year) |

Was the allocation sequence adequately generated?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was the allocation adequately concealed?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Blinding: Was knowledge of the allocated interventions adequately prevented?

Were patients blinded?

Were healthcare providers blinded?

Were data collectors blinded?

Were outcome assessors blinded?

Were data analysts blinded?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was loss to follow-up (missing outcome data) infrequent?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Are reports of the study free of selective outcome reporting?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was the study apparently free of other problems that could put it at a risk of bias?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Overall risk of bias If applicable/necessary, per outcome measure

LOW Some concerns HIGH |

|

Black (2000)

|

No information.

Reason: - |

No information.

Reason: - |

Probably no.

Reason: Only outcome assessment was blinded.

|

Probably yes.

Reason: - |

No information.

Reason: - |

No information.

Reason: - |

HIGH

Reason: unclear randomization, allocation concealment, no blinding of patients and personnel, unclear selective outcome reporting.

|

|

Dagan (2001) |

No information.

Reason: - |

Probably yes.

Reason: Only those two nurses saw that list, and they were not allowed to reveal the child’s allocation to vaccine or placebo to the study team and the parents.

|

Probably no.

Reason: Only outcome assessment was blinded.

|

Probably yes.

Reason: Only 3 lost to follow-ups (2 vs 1). |

No information.

Reason: - |

Probably yes.

Reason: No other bias reported. |

HIGH

Reason: unclear randomization, no blinding of patients and personnel.

|

|

Eskola (2001) |

Definitely yes.

Reason: Patients were randomized. |

No information.

Reason: - |

Definitely yes.

Reason: Double-blind study.

|

…

Reason: All children were followed-up. |

Definitely yes.

Reason: All outcomes were reported. |

Definitely yes.

Reason: No other bias. |

LOW |

|

Hoberman (2003) |

Definitely yes.

Reason: All patients were randomized in a 2:1 ratio. |

No information.

Reason: - |

Definitely yes.

Reason: Double-blind study. |

Probably no.

Reason: More lost to follow-up in intervention group. |

Definitely yes.

Reason: All outcomes were reported. |

Definitely yes.

Reason: No other bias reported. |

SOME CONCERNS

Reason: Lost to follow-up more frequent in intervention group. |

|

Lum (2010) |

Definitely yes.

Reason: Patients were randomized. |

No information.

Reason: -

|

Definitely yes.

Reason: Double-blind study. |

Probably no.

Reason: More lost to follow-up in intervention group.

|

Definitely yes.

Reason: All outcomes were reported. |

Definitely yes.

Reason: No other bias reported. |

SOME CONCERNS

Reason: Lost to follow-up more frequent in intervention group.

|

|

O’Brien (2008) |

Definitely yes.

Reason: Patients were randomized. |

No information.

Reason: -

|

Probably yes.

Reason: Only outcome assessment was not blinded.

|

Probably no.

Reason: More lost to follow-up in intervention group.

|

Definitely yes.

Reason: All outcomes were reported. |

Definitely yes.

Reason: No other bias reported. |

SOME CONCERNS

Reason: no allocation concealment. |

|

Vesikari (2006) |

Definitely yes.

Reason: Patients were randomized. |

Definitely yes.

Reason: Each subject was assigned the next sequential number by the study site investigator and received study product for the treatment assigned to that subject number, according to a preprinted randomization allocation list provided to the study site by Wyeth Vaccines Research. The number sequence was concealed until interventions were assigned.

|

Definitely yes.

Reason: Double-blind study. |

Probably yes.

Reason: Lost to follow-up equal in both groups. |

Definitely yes.

Reason: All outcomes were reported. |

Definitely yes.

Reason: No other bias reported. |

LOW. |

|

Shahbaznejad (2021) |

Definitely yes.

Reason: Patients were randomized. |

Definitely yes.

Neither the participants nor the evaluators were aware of the randomization process or group allocation. |

Definitely no.

After obtaining the written informed consent, amoxicillin suspension was given to the parents of the intervention group. So, this study was not blinded. |

Probably yes.

Reason: Lost to follow-up equal in both groups. |

Definitely yes.

Reason: All outcomes were reported. |

Definitely yes.

Reason: No other bias reported. |

LOW. |

Quality assessm

ent systematic (Cochrane) review of Scott (2019)

See the original publication for the evidence table of the systematic (Cochrane) review of Scott (2019): https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6580359/pdf/CD012941.pdf.

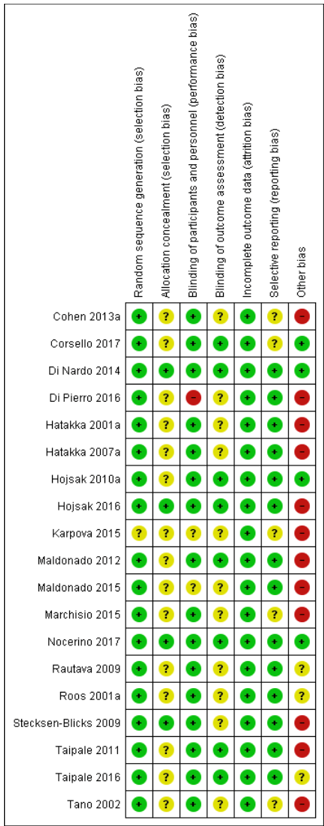

We adapted the risk of bias assessment of the systematic (Cochrane) review of Scott (2019) (see figure below).

Quality assessment systematic (Cochrane) review of Scott (2019)

We adapted the risk of bias assessment of the systematic (Cochrane) review of Leach (2006) (see below).

Risk of bias included studies

The overall quality was high with nine studies providing a description of the random assignment or stating random assignment and providing group similarity details, and nine studies providing adequate information on allocation concealment. Fourteen studies had at least the outcome assessor blinded. Nine studies reported outcomes for all randomized children in each group; 10 studies measured outcomes in over 90% of participants and evaluated withdrawals as treatment failures. Standardized assessments were used in 14 studies. Agreement was highest for blinding (agreement 94%, kappa 0.76) and reporting by allocated group (agreement 88%, kappa 0.75); and lowest for allocation concealment (agreement 69%, kappa 0.35) and outcome assessment (agreement 81%, kappa -0.1). Consensus was readily achieved by re- reviewing original publications. A third author was not required to achieve consensus.

Summary number of studies meeting high quality for each quality measure

- Randomization: nine studies (Casselbrant 1992a; Gonzalez 1986a; Leach 2008; Liston 1983a; Mandel 1996a; Principi 1989a; Roark 1997a; Schwartz 1982a; Teele 2000a).

- Allocation concealment: 10 studies (Casselbrant 1992a; Gonzalez 1986a; Gray 1981; Leach 2008; Liston 1983a; Mandel 1996a; Perrin 1974a; Roark 1997a; Schwartz 1982a; Teele 2000a).

- Blinding: 14 studies (Casselbrant 1992a; Gonzalez 1986a; Gray 1981; Leach 2008; Liston 1983a; Mandel 1996a; Maynard 1972a; Perrin 1974a; Persico 1985a; Principi 1989a; Roark 1997a; Schwartz 1982a;Teele 2000a; Varsano 1985a).

- Reporting by allocated group: eight studies (Casselbrant 1992a; Gaskins 1982a; Leach 2008; Mandel 1996a; Maynard 1972a; Principi 1989a; Roark 1997a; Teele 2000a).

- Follow up: 10 studies (Casselbrant 1992a; Gaskins 1982a; Gray 1981; Leach 2008; Mandel 1996a; Maynard 1972a; Perrin 1974a; Persico 1985a; Principi 1989a; Teele 2000a).

- Outcome assessment: 14 studies (Casselbrant 1992a; Gaskins 1982a; Gonzalez 1986a; Leach 2008; Liston 1983a; Mandel 1996a; Persico 1985a; Principi 1989a; Roark 1997a; Schuller 1983a; Schwartz 1982a; Sih 1993a; Teele 2000a; Varsano 1985a).

We categorized four studies as high quality for all six components of quality that we assessed (Casselbrant 1992a; Leach 2008; Mandel 1996a; Teele 2000a). We categorized eight studies as high quality for randomization and allocation concealment (Casselbrant 1992a; Gonzalez 1986a; Leach 2008; Liston 1983a; Mandel 1996a; Perrin 1974a; Roark 1997a; Teele 2000a). We categorized 12 studies as high quality for blinding of outcome assessment (Casselbrant 1992a; Gonzalez 1986a; Leach 2008; Liston 1983a; Mandel 1996a; Maynard 1972a; Perrin 1974a; Persico 1985a; Principi 1989a; Roark 1997a; Teele 2000a; Varsano 1985a). We decided that the studies were sufficiently clinically homogeneous for meta-analysis.

Allocation

Overall, allocation generation and concealment were recorded and was appropriate in 9/17 studies (53%) - see additional Table 1. Any associated bias may exaggerate the pooled estimate of beneficial effect of the intervention.

Blinding

Overall blinding was reported and appropriate in 14/17 studies (82%). This was achieved through the use of placebo medications. Any associated bias is unlikely to have much impact on the pooled estimate of beneficial effect of the intervention.

Incomplete outcome data

Overall, outcome data were reported and complete for more than 90% of participants in 10/17 studies (59%). Any associated bias may alter the pooled estimate of effect of the intervention. The direction of any associated bias is not clear.

Selective reporting

Most of the trials were conducted prior to requirement for trial registration. However, most studies reported the same primary outcome (making selective reporting unlikely). Selective reporting of secondary outcomes is possible.

Other potential sources of bias

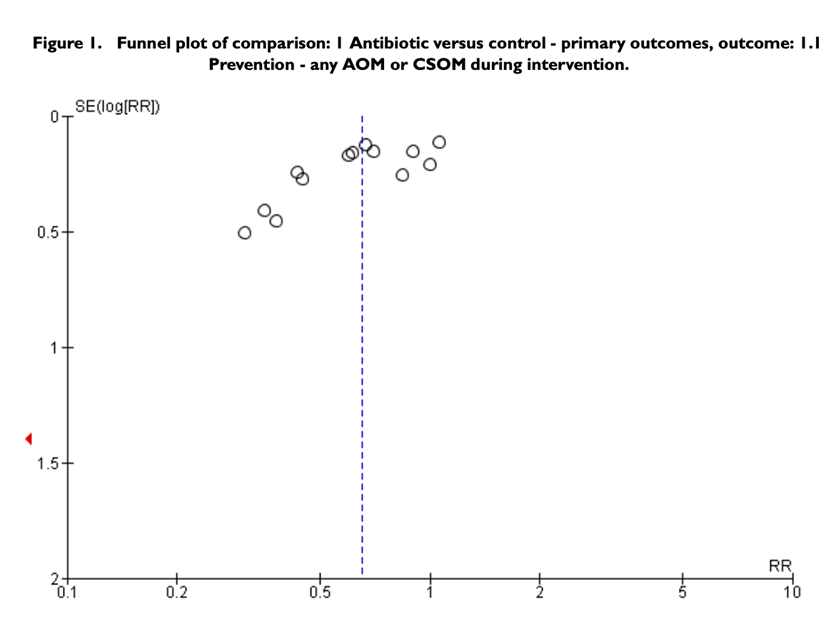

There were no other important sources of bias related to the con- duct of the included studies identified. Publication or small study bias is possible (see Figure 1).

Table of excluded studies

|

Author and year |

Reason for exclusion |

|

Chen (2020) |

Wrong study design. |

|

Chonmaitrie (2003) |

Does not match the updated PICO of this guideline. |

|

Ellul (2015) |

Wrong study design. |

|

El-Makhzangy (2012) |

Wrong comparison of interventions. |

|

Fortanier (2019) |

Duplicate of de Sévaux (2020). |

|

Fortanier (2014) |

Study is already updated (Fortanier, 2019). |

|

Hampton (2021) |

Wrong study design. |

|

Heideman (2016) |

Descriptive review. |

|

Hoberman (2016) |

Wrong comparison of interventions. |

|

Holm (2020) |

SR includes the same studies as the Cochrane review of Venekamp (2015). The methodological quality of Venekamp (2015) is higher than Holm (2020). Holm (2020) was therefore excluded. |

|

Jansen (2009) |

Duplicate of Fortanier (2019). De Sevaux (2020) was an update of Jansen (2009). |

|

Marchisio (2009) |

Wrong outcomes reported. |

|

Marchisio (2015) |

Wrong comparison of interventions. |

|

Niittynen (2012) |

Included studies in this SR are already included in an included more recent systematic review. |

|

Pavia (2009) |