Trommelvliesbuisjes bij rOMA

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is de effectiviteit van trommelvliesbuisjes bij kinderen met recidiverende otitis media acuta (rOMA)?

Aanbeveling

Overweeg bij recidiverende otitis media acuta (rOMA; 4 in het afgelopen jaar of 3 in het afgelopen half jaar) trommelvliesbuisjes te plaatsen om het aantal recidieven op korte termijn te verlagen.

Weeg samen met de patiënt en ouders/verzorgers de voor- en nadelen van het plaatsen van trommelvliesbuisjes af tegen een afwachtend beleid of behandeling met antibiotica. Gebruik hierbij de ‘keuzehulp trommelvliesbuisjes'

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Op basis van de geïncludeerde studies is er weinig zekerheid over de (on)gunstige effecten van trommelvliesbuisjes vergeleken met een afwachtend beleid of behandeling met antibiotica (behandeling van individuele episodes of profylaxe) bij kinderen met recidiverende otitis media acuta (rOMA).

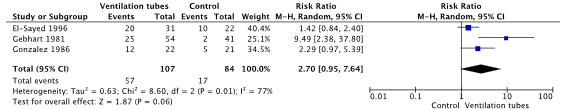

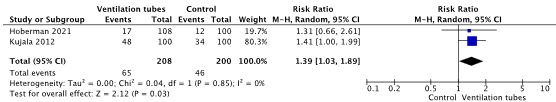

Voor de cruciale uitkomstmaat ‘terugkeer van episoden van OMA’ suggereert het gevonden bewijs dat het plaatsen van trommelvliesbuisjes het aantal recidieven verlaagt. Met name op de korte termijn (6 maanden) lijkt dit effect aanwezig (relatief risico [RR]: 2.70, 95% betrouwbaarheidsinterval [BI]: 0.95 tot 7.64). Op de langere termijn is het mogelijk positieve effect van trommelvliesbuisjes op de terugkeer van OMA episoden minder groot (RR: 1.39, 95% BI 1.03 tot 1.89). Het vertrouwen in het bewijs voor dit gevonden effect is laag. Dit komt mede door beperkingen in de studieopzet (o.a. vanwege gebrek aan blindering en een cross-over tussen behandelgroepen) en het doorkruisen van de 95% betrouwbaarheidsintervallen met de grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming.

Op de belangrijke uitkomstmaat ‘ernst van episoden’ suggereert het gevonden bewijs dat er geen verschil is in effect tussen het plaatsen van trommelvliesbuisjes en een afwachtend beleid. Het aantal recidieven is uiteraard afhankelijk van de verblijfsduur van het buisje in het trommelvlies. Deze verblijfsduur kan variëren per type trommelvliesbuisje. In de meeste studies wordt bovendien niet vermeld welk type buisje werd geplaatst.

Verder leek er in de belangrijke uitkomstmaat ‘kwaliteit van leven van ouders en kinderen’ geen verschil te bestaan tussen de groepen waarin trommelvliesbuisjes werden geplaatst vergeleken met de controlegroepen, noch op de korte termijn (4 maanden) noch op de lange termijn (12 tot 24 maanden). De bewijskracht voor deze uitkomstmaat was laag.

In de praktijk wordt de ziektelast van OMA (oorpijn, slechte nachtrust, verzuim crèche/school/werk) als belangrijk argument voor het plaatsen van trommelvliesbuisjes genoemd. Echter, in Kubba (2004) wordt geconcludeerd: “OM-6 does not adequately reflect disease severity which may limit its usefulness as a discriminative measure”. Dit suggereert dat de huidige literatuur mogelijk een onvoldoende compleet beeld geeft van de werkelijke effecten op de kwaliteit van leven, vanwege het gebrek aan afdoende discriminatieve vragenlijsten.

Naast de resultaten op de vooraf gedefinieerde uitkomstmaten, rapporteerde Hoberman (2021) dat de mediane tijd tot een OMA recidief langer was in de trommelvliesbuisjes groep, dan in de groep kinderen die antibiotica ontving (respectievelijk 4.34 maanden versus 2.33 maanden; HR: 0.68, 95% BI: 0.52 tot 0.90, n = 250). Ook werd er gerapporteerd dat het “totaal aantal dagen met otitis-gerelateerde symptomen anders dan otorroe”, lager was bij de kinderen die trommelvliesbuisjes ontvingen, dan bij de kinderen in de antibioticagroep (respectievelijk, mean 2.00 ± 0.29 dagen, vergeleken met 8.33±0.59 dagen).

In de studies traden weinig complicaties op. Door beperkingen in de studie-opzet en de relatief lage incidentie van complicaties, kon er voor deze belangrijke uitkomstmaat geen harde conclusie getrokken worden wat betreft het optreden van het aantal bijwerkingen/complicaties van het plaatsen van trommelvliesbuisjes vergeleken met een afwachtend beleid. In Hoberman (2021) werd naast de ernstige complicaties ook het falen van het beleid beschreven als complicatie. Dit werd o.a. gedefinieerd als het (alsnog) plaatsen van trommelvliesbuisjes na initiële behandeling van individuele episodes met antibiotica, bijvoorbeeld door het terugkeren van episodes van OMA of op verzoek van de ouders, door persisterende otorroe, otitis media met effusie of een trommelvliesperforatie. Het aantal kinderen met een verandering van het initiële beleid was 56/124 (45%) in de groep kinderen die trommelvliesbuisjes ontving, vergeleken met 74/120 (62%) in de antibioticagroep.

Gevolgen van het plaatsen van trommelvliesbuisjes zijn ten eerste het optreden van een (postoperatief) loopoor. Een loopoor komt bij kinderen met trommelvliesbuisjes geregeld voor (van Dongen, 2013). Een loopoor na plaatsen van buisjes geeft relatief milde klachten en is over het algemeen goed te behandelen met antibiotische oordruppels met een corticosteroïd (van Dongen, 2014). Een loopoor kan zich echter ook ontwikkelen tot een chronisch loopoor, wat weer kan leiden tot frequent gebruik van (lokale) antibiotica. In enkele gevallen is het actief verwijderen van een buisje geïndiceerd, waarvoor opnieuw een ingreep onder narcose nodig is. Bij een deel van de kinderen ontstaat tympanosclerose of blijvende trommelvliesperforaties hetgeen kan leiden tot blijvend, licht gehoorverlies (de Beer, 2004). Wat bovendien niet in de literatuur wordt meegenomen, maar wel een nadeel is van het plaatsen van trommelvliesbuisjes, is dat kinderen in het ziekenhuis een operatie onder narcose moeten ondergaan.

In de geïncludeerde studies ontving een deel van de kinderen in de controlegroepen antibiotica. Het geven van antibiotica kan ook bijwerkingen geven zoals misselijkheid of diarree. Ook kunnen antibiotica leiden tot allergische reacties. Langdurig en herhaald antibiotica gebruik kan resistentie veroorzaken.

Wat verder in de overweging om wel of geen buisjes te plaatsen moet worden meegenomen is het seizoen en of het kind op zwemles zit. Wanneer het zomerseizoen nadert kan makkelijker een afwachtend beleid overwogen worden, omdat de kans op OMA in de zomer aanmerkelijk kleiner is. Wanneer een kind op zwemles zit is mogelijk de kans op het ontwikkelen van looporen bij kinderen met trommelvliesbuisjes groter en zal een afwachtend beleid mogelijk de voorkeur hebben. Over dit laatste onderwerp bestaan helaas geen betrouwbare data. Dit is een kennislacune.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

De belangrijkste doelen van de interventie voor de patiënt en hun ouders/verzorgers zijn het verminderen van het aantal en de ernst van de ziekte episodes, daar deze vaker gepaard gaan met (hevige) oorpijn, algehele malaise al dan niet met koorts, het optreden van slapeloze nachten en met het optreden van ziekteverzuim van zowel ouder als kind als gevolg. Opvallend is daarom dat het gevonden bewijs geen effect suggereert van het plaatsen van buisjes op de kwaliteit van leven. In de praktijk lijkt er wel verlichting van klachten op te treden. Deels kan deze discrepantie mogelijk worden verklaard door de gebruikte vragenlijsten zoals hierboven ook wordt aangegeven, maar over het daadwerkelijke effect van trommelvliesbuisjes op kwaliteit van leven bestaat een kennislacune

Een ingreep heeft voor- en nadelen. Het invullen van de keuzehulp trommelvliesbuisjes helpt bij het maken van de beslissing om naar de KNO-arts doorverwezen te worden, omdat hierin duidelijk de voor- en nadelen van het plaatsen van buisjes en de beperkte winst op lange termijn worden beschreven. Ondanks dat ouders en kinderen meestal met de wens tot het plaatsen van trommelvliesbuisjes binnenkomen bij de KNO-arts, blijft het van belang om opnieuw de (beperkte) meerwaarde en de nadelen van trommelvliesbuisjes met ouders en kinderen te bespreken.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

Geen van de geïncludeerde studies rapporteerde gegevens over de belangrijke uitkomstmaat kosteneffectiviteit. Er kon daarom geen conclusie worden getrokken met betrekking tot deze uitkomstmaat. Het is niet met zekerheid te zeggen of de gunstige effecten opwegen tegen de extra kosten voor de patiënt en maatschappij.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

In de praktijk worden trommelvliesbuisjes regelmatig geïndiceerd bij kinderen met rOMA. De werkgroep verwacht dan ook geen problemen wat betreft de aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie en er lijken ook geen belemmerende factoren te zijn. Wel is het belangrijk dat er voldoende toegang is tot de huisarts en/of KNO-arts, zodat de diagnose rOMA met zekerheid gesteld kan worden (en bevestigd middels otoscopie).

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

Recidiverende otitis media acuta is een veel voorkomende aandoening. De kinderen ervaren een grote ziektelast door frequente perioden van oorpijn, algemene malaise, slapeloze nachten en verloren tijd op de crèche of schoolverzuim. Ernstige complicaties zijn zeldzaam. Er zijn aanwijzingen dat het plaatsen van trommelvliesbuisjes het aantal recidieven kan verminderen. Ook is de tijd tot een recidief mogelijk langer na het plaatsen van trommelvliesbuisjes en hebben kinderen mogelijk minder dagen last van otitis-gerelateerde symptomen.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Otitis media acuta (OMA) is één van de meest voorkomende kinderziektes. Veel kinderen krijgen te maken met sporadische OMA episodes, maar er is ook een groep kinderen waarbij sprake is van recidiverende OMA episodes (rOMA), gedefinieerd als drie of meer episodes in zes maanden, of vier of meer in één jaar. Deze subgroep ervaart een grote ziektelast door frequente perioden van oorpijn, algemene ziekte, slapeloze nachten en verloren tijd op de crèche of school (Venekamp et al., 2018). Voor rOMA kunnen trommelvliesbuisjes worden aangeboden. Echter, er is veel discussie rondom het nut van het plaatsen van trommelvliesbuisjes bij kinderen met rOMA. De vraag is of dit opweegt tegen een afwachtend dan wel medicamenteus beleid. Ook bestaat er veel praktijkvariatie: in het ene ziekenhuis wordt veel vaker overgegaan tot het plaatsen van trommelvliesbuisjes dan in het andere. Het is onduidelijk wat de (lange termijn) effecten zijn van het plaatsen van trommelvliesbuisjes bij kinderen met rOMA.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

Recurrence of acute otitis media episodes

|

Low GRADE |

Treatment with ventilation tubes may reduce the number of recurrent acute otitis media episodes at 6 months and at 12 to 24 months, when compared with watchful waiting or (treatment with) antibiotics months in children with recurrent acute otitis media.

Sources: Venekamp (2018), Hoberman (2021) |

Severity of acute otitis media episodes

|

Low GRADE |

Treatment with ventilation tubes may result in little to no difference on severity of acute otitis media episodes, when compared with watchful waiting or (treatment with) antibiotics in children with recurrent acute otitis media.

Sources: Hoberman (2021) |

Complications

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of ventilation tubes on complications, when compared with watchful waiting or (treatment with) antibiotics in children with recurrent acute otitis media.

Sources: Venekamp (2018), Hoberman (2021) |

Quality of life of children and parents

|

Low GRADE |

Treatment with ventilation tubes may result in little to no difference on quality of life at short term (4 months) and at long term (12-24 months)), when compared with watchful waiting or (treatment with) antibiotics in children with recurrent acute otitis media.

Sources: Venekamp (2018), Hoberman (2021) |

Quality-adjusted life year (QALY)

|

No GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding the effect of ventilation tubes on QALY (cost-effectiveness) when compared to watchful waiting or (treatment with) antibiotics in children with recurrent acute otitis media.

Sources: - |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

Venekamp (2018) performed a Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis to assess the benefits and harms of bilateral ventilation tube insertion in children with rAOM, compared to antibiotic prophylaxis, active monitoring, or placebo medication. They searched several databases to December 4, 2017. Inclusion criteria of the review were RCTs, children aged up to 16 years with rAOM (defined as three or more episodes in the previous six months, or four or more in one year), comparing bilateral ventilation tube insertion with either active monitoring, antibiotics prophylaxis or placebo medication). Five RCTs were included in the analysis (Casselbrant, 1992; El-Sayed, 1996; Gebhart, 1981; Gonzalez, 1986; Kujala, 2012) with a total of 805 children with recurring acute middle ear infections. All studies were conducted in secondary and/or tertiary care settings. El-Sayed (1996) compared ventilation tubes to antibiotic prophylaxis, Gebhart (1981) and Kujala (2012) compared ventilation tubes to active monitoring, and Gonzalez (1986) and Casselbrant (1992) compared ventilation tubes to both antibiotic prophylaxis and placebo medication. The age of children included ranged from 0 to 10 years, with 55-63% boys. Follow up ranged from 6 to 24 months. Outcomes included rAOM recurrence, adverse effects and (disease specific) quality of life. Risk of bias was assessed using Cochrane Risk of bias tools. Performance and selection bias were both reported as inducing high risk of bias. Selection bias was low in one study (Kujala, 2012), high in one study (El-Sayed, 1996), and unclear in three studies. In two studies, the loss-to-follow-up rate was high (El-Sayed, 1996; Casselbrant, 1992). Other bias was high in one study (Gonzalez, 1986) and unclear in four studies. Note that in all studies inclusion of children was performed before implementation of the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine.

Hoberman (2021) performed a non-blinded RCT on the effectiveness of ventilation tubes in children with rAOM. The study was conducted at three pediatric hospitals in the USA from December 2015 till March 2020. In total 129 children (67% boys) were randomized to treatment with ventilation tubes and 121 children (60% boys) received medical treatment involving episodic antimicrobial treatment. Age of children ranged from 6 to 35 months. All children received pneumococcal conjugate vaccine. Follow up was every 8 weeks for 2 years. The primary outcome measure was the average number of AOM recurrences. Secondary outcomes included severity of AOM recurrences, frequency distribution of AOM recurrences during the two-year follow-up period, time to first AOM recurrence, type of AOM recurrences, antibiotic consumption, adverse events, antibiotic resistance of nasopharyngeal pathogens, and cost-effectiveness. During the follow-up period 35 children from the medical management group received additional ventilation tubes, another 32 children had deviations from the trial protocol (e.g., children in the medical management group receiving ventilation tubes after parental request or children assigned to ventilation tubes, who not received ventilation tubes.

Results

Recurrence of acute otitis media episodes

No recurrence of acute otitis media episodes at short term follow-up (6 months)

Three trials reported the outcome no recurrence of acute otitis media (AOM) episodes at 6 months follow-up (from Venekamp, 2018: El-Sayed, 1996; Gebhart, 1981; Gonzalez, 1986).

In El-Sayed (1996) and Gonzalez (1986) a comparison of ventilation tubes with antibiotic prophylaxis was made and in Gebhart (1981) comparison was with children undergoing active monitoring. The results were pooled in a meta-analysis. In the ventilation tubes group the pooled number of children with no recurrence of AOM episodes was 57/107 (53.3%), compared to 17/84 (20.2%) children in the control group. The pooled Relative Risk Ratio (RR) was 2.70 (95% CI 0.95 to 7.64), in favor of children treated with ventilation tubes (Figure 1). This was considered clinically relevant.

Figure 1. Forest plot showing the comparison between ventilation tubes and active monitoring/antibiotic prophylaxis on the outcome no recurrence of acute otitis media episodes at 6 months follow-up. Pooled relative risk ratio, random effects model. Z: p-value of overall effect; df: degrees of freedom; SD: standard deviation; I2; statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval.

No recurrence of acute otitis media episodes at long term follow-up (12-24 months)

Two trials reported the outcome recurrence of AOM episodes at long term follow-up (Hoberman, 2021; Kujala, 2012). In Hoberman (2021) treatment with ventilation tubes was compared to medical management with antibiotics. In Kujala (2012) a comparison was made with active monitoring. In the ventilation tubes group the pooled number of children with no recurrence of AOM episodes was 65/208 (31.3%) compared to 46/200 (23%) children in the control group. The pooled RR was 1.39 (95% CI 1.03 to 1.89), in favor of children treated with ventilation tubes (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Forest plot showing the comparison between ventilation tubes and watchful waiting/antibiotics on the outcome no recurrence of acute otitis media episodes. Pooled relative risk ratio, random effects model. Z: p-value of overall effect; df: degrees of freedom; SD: standard deviation; I2; statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval.

Severity of acute otitis media episodes

Hoberman (2021) reported the outcome severity of acute otitis media episodes.

The patients treated with ventilation tubes (n = 129), experienced in total 366 episodes of AOM, of which 156/366 (46%) were severe episodes, 180/366 (54%) were non-severe episodes of AOM.

The patients treated with antimicrobial treatment (n = 121) experienced in total 333 episodes of AOM, of which 168/333 (50%) were severe episodes, 165/333 (50%) were non-severe episodes of AOM. The risk for severe episodes of rAOM was RR: 1.09 (95% CI 0.97 to 1.21). This was not considered clinically relevant.

Complications

Two trials included in the review by Venekamp (2018) reported significant adverse events, defined as tympanic membrane perforation persisting for three months or longer (Casselbrant, 1992; Gebhart 1981). Gebhart (1981) reported 0/54 persistent tympanic membrane perforations in the children receiving ventilation tubes. Casselbrant (1992) reported 3/76 (4%) children experienced tympanic membrane perforations after ventilation tube insertion. Data on adverse events in the control groups were not presented, as a consequence the RR could not be calculated.

Hoberman (2021) also reported serious adverse events. In the tympanostomy-tube group, there were 3/129 (2%) serious adverse events, compared to 7/121 (6%) in the control group. The RR was 0.40 (95% CI: 0.11 to 1.52), in favor of the children in the tympanostomy group.

Quality of life of children and parents

Quality of life at short-term follow-up (4 months)

One trial included in the review by Venekamp (2018) reported the outcome quality of life at 4 months follow-up (Kujala, 2014). Kujala (2014) assessed quality of life with the Otitis Media-6 questionnaire (OM-6). It was reported that at four months post-randomization there were “no statistically significant differences” on the OM-6 scores between the children receiving ventilation tubes and the children in the control group (total study population n = 85).

Quality of life at long term follow-up (12 – 24 months)

Two trials reported the outcome quality of life at long term follow-up (Hoberman; 2021 and Kujala, 2014 – from Venekamp, 2018). Kujala (2014) assessed quality of life at 12 months follow-up with the OM-6 questionnaire. It was reported that at 12 months post-randomization there were “no statistically significant differences” on the OM-6 scores between the children receiving ventilation tubes and the children in the control group (total study population n = 81). Hoberman (2021) reported quality of life at two years follow-up, assessed with the OM-6 questionnaire and the Caregiver Impact Questionnaire (CIQ) for parents. Mean scores on both scales did not show clinically relevant differences between the two groups (Table 1).

Table 1. Child and parents Quality of Life scores (adapted from Hoberman, 2021)

QoL = Quality of life; SD = standard deviation; 95% CI = 95% Confidence Interval; OM-6 = Otitis Media 6 Questionnaire; CIQ = Caregiver Impact questionnaire.

|

Child and parents QOL assessments |

Grommets group (N = 129) |

Control group (N = 121) |

Estimated Between- Group Difference (95% CI) |

||

|

|

mean |

SD |

mean |

SD |

|

|

Score on OM-6 |

1.5 |

0.03 |

1.55 |

0.03 |

−0.05 (−0.13 to 0.02) |

|

Score on OM-6 overall children |

8.45 |

0.07 |

8.37 |

0.07 |

0.06 (−0.13 to 0.24) |

|

Score on CIQ |

10.82 |

0.53 |

10.93 |

0.55 |

−0.04 (−1.55 to 1.47) |

|

Score on CIQ – overall caregivers |

8.55 |

0.06 |

8.5 |

0.06 |

0.03 (−0.14 to 0.20) |

Quality-adjusted life year (QALY) (cost-effectiveness)

None of the six included RCTs reported on the outcome measure cost-effectiveness. Therefore, this outcome measure could not be assessed.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure recurrence of acute otitis media episodes was retrieved from RCTs and therefore started high. The level of evidence was downgraded by 2 levels because of limitations in study design, including lack of blinding (-1 risk of bias) and the 95% confidence interval crossing the thresholds of clinical decision making (-1 imprecision). The final level of evidence was graded ‘low’.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure severity of acute otitis media episodes was retrieved from RCTs and therefore started high. The level of evidence was downgraded by 2 levels because of limitations in study design, including lack of blinding (-1 risk of bias) and the low number of included patients (-1 imprecision). The final level of evidence was graded ‘low’.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure complications was retrieved from RCTs and therefore started high. The level of evidence was downgraded by 3 levels because of limitations in study design, including lack of blinding (-1 risk of bias) and the 95% confidence intervals crossing the thresholds of clinical decision making (-2 imprecision). The final level of evidence was graded ‘very low’.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure quality of life (short-term and long-term follow-up) was retrieved from RCTs and therefore started high. The level of evidence was downgraded by 2 levels because of limitations in study design, including lack of blinding (-1 risk of bias) and the low number of included patients (-1 imprecision). The final level of evidence was graded ‘low’.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure Quality-adjusted life year (QALY) could not be graded due to the absence of cost-effectivity reports in the included studies.

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question:

What are the favorable or unfavorable effects of ventilation tubes compared to watchful waiting or antibiotics (treatment or prophylaxis) in children with recurrent acute otitis media (rAOM)?

P: children with recurrent acute otitis media (0-18 years)

I: ventilation tubes

C: watchful waiting or antibiotics (treatment or prophylaxis)

O: acute otitis media recurrences, severity of acute otitis media episodes, serious complications, (health-related) quality of life of children and parents, quality-adjusted life year (QALY)/cost-effectiveness

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered the following outcome measures as critical outcome measures for decision making: recurrence of acute otitis media episodes and severity of acute otitis media episodes. Serious complications, (health-related) quality of life of children and their parents, and cost-effectivity were considered important outcome measures for decision making.

A priori, the guideline developing group did not define the outcome measures listed above but used the definitions used in the studies.

For all outcome measures, the default thresholds proposed by the international GRADE working group were used: a 25% difference in relative risk (RR) for dichotomous outcomes, and 0.5 standard deviations (SD) for continuous outcomes.

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms between 1 January 2009 and 27 October 2021. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 108 unique hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria: systematic reviews (SRs) and randomized controlled trials (RCTs) on the effects of tympanostomy/ventilation tubes/ventilation tubes in children with recurrent acute otitis media. Studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, 1 systematic review (Venekamp, 2018; discussing 5 RCTs that matched the PICO (Casselbrant, 1992; El-Sayed, 1996; Gebhart, 1981; Gonzalez, 1986; Kujala, 2012) and 1 RCT were included (Hoberman 2021; see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and 14 studies were excluded.

Results

One systematic review (discussing five relevant RCTs) and one RCT were included in the analysis of the literature. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- Beer, de BA, Schilder AGM, Ingels K, Snik AF, Zielhuis GA, Graamans K (2004) Hearing loss in young adults who had ventilation tube insertion in childhood. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Larnygol. 113, 438-444

- van Dongen TM, van der Heijden GJ, Freling HG, Venekamp RP, Schilder AG. Parent-reported otorrhea in children with tympanostomy tubes: incidence and predictors. PLoS One. 2013 Jul 12;8(7):e69062. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0069062. PMID: 23874870; PMCID: PMC3709928.

- Hoberman A, Preciado D, Paradise JL, Chi DH, Haralam M, Block SL, Kearney DH, Bhatnagar S, Muñiz Pujalt GB, Shope TR, Martin JM, Felten DE, Kurs-Lasky M, Liu H, Yahner K, Jeong JH, Cohen NL, Czervionke B, Nagg JP, Dohar JE, Shaikh N. Tympanostomy Tubes or Medical Management for Recurrent Acute Otitis Media. N Engl J Med. 2021 May 13;384(19):1789-1799. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2027278. Erratum in: N Engl J Med. 2022 May 12;386(19):1868. PMID: 33979487; PMCID: PMC8969083.

- Kubba H, Swan IR, Gatehouse S. How appropriate is the OM6 as a discriminative instrument in children with otitis media? Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004 Jun;130(6):705-9. doi: 10.1001/archotol.130.6.705. PMID: 15210550.

- Venekamp RP, Mick P, Schilder AG, Nunez DA. Grommets (ventilation tubes) for recurrent acute otitis media in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018 May 9;5(5):CD012017. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012017.pub2. PMID: 29741289; PMCID: PMC6494623.

Evidence tabellen

Evidence table for systematic review of RCTs and observational studies (intervention studies)

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C) |

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size

|

Comments |

|

Venekamp, 2018

[individual study characteristics deduced from Venekamp, 2018] |

Cochrane SR and meta-analysis of 5 RCTs

Literature search up to December 4th, 2017 A: Casselbrant, 1992 B: El-Sayed, 1996 C: Gebhart, 1981 D: Gonzalez, 1986 E: Kujala, 2012

Study design: A: 3-arm, non-blinded, multicentre, parallel-group RCT B: 2-arm, non-blinded, single-centre parallel-group RCT C: 2-arm, non-blinded, single-centre, parallel-group RCT D: 3-arm, non-blinded, multicentre, parallel-group RCT E: 3-arm, non-blinded, single-centre, parallel-group RCT

Setting and Country: A: USA, Children's Hospital of Pittsburgh Otitis Media Center and 2 private paediatric practices in Pittsburgh (secondary and tertiary care) B: Saudi Arabia, ENT unit of King Abdel Azir University Hospital, Riyadh (tertiary care) C: USA, general ENT practice (secondary care) D: USA, ENT departments of Army Medical Centres (secondary care) E: Finland, ENT department of Oulu University Hospital (tertiary care)

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: A: Funded by a grant from the National Institute of Deafness and Communication Disorders, National In- stitute of Health. Amoxicillin and placebo medication were supplied by Beecham Laboratories, Bristol, TN B: No details provided C: This study was supported in part by a grant from the Medical Research Foundation at Riverside Methodist Hospital and in part by NIH Grant NSO 8854 D: Sulfisoxazole and placebo medication were supplied by Hoffman-LaRoche Inc, NJ E: nothing to declare |

Inclusion criteria: - RCTs irrespective of the randomisation method and blinding procedure. - Children up to age 16 years with rAOM, defined as 3 or more episodes in the previous 6 months, or 4 or more in 1 year

Exclusion criteria: - second phase of cross-over studies and trials where the patient was not the unit of randomisation, i.e., cluster-randomised trials or trials where 'ears' (right versus left) were randomised

5 studies included, 2 in meta-analysis

Important patient characteristics at baseline: N intervention/ control A: 86/90/88 (randomized) B: 31/22 C: 58/50 D: 22/21/20 E: 89/91/96

Mean age (range) A: (7 months – 35 months) B: 20 months (≤3 years) C: 20 months (≤3 years) D: 19 months (6 months – 10 years) E: 16 months (10 months – 2 years)

Sex n (%) boys: A: 155 (59%) B: 29 (55%) C: 60 (63%) D: 38 (60%) E: 110 (55%) |

Describe intervention: SR: Bilateral ventilation tube insertion (of any type).

A: ventilation tubes (Teflon® Armstrong type) B: ventilation tubes (type not described) C: ventilation tubes (Shepard Teflon®) D: ventilation tubes (0.04 mm Paparella design ventilation tube in majority of children) E: ventilation tubes (Donaldson silicon tubes, TympoVent®, Atos) |

Describe control: SR: no (ear) surgery

A: 1) antibiotic prophylaxis; amoxicillin suspension 20 mg/kg/day once daily 2) placebo medication; liquid suspension of similar appearance and taste to antibiotic prophylaxis B: antibiotic prophylaxis; sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim (SMZ-T) 12 mg/kg/day once daily C: active monitoring D: 1) antibiotic prophylaxis; sulfisoxazole suspension 500 mg twice daily if under 5 years or 1 g twice daily if 5 years and older 2) placebo medication; liquid suspension of similar texture and appearance to antibiotic prophylaxis E: 1) active monitoring (also 2) ventilation tubes plus adenoidectomy; not relevant for this review)

|

Endpoint of follow-up: A: 24 months B: 6 months C: 6 months D: 6 months E: 12 months

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? A: Intervention: 20/77 (26%); 6 treatment failure, 14 loss to follow-up Comparison 1: 6/86 (53%); 12 treatment failure, 34 loss to follow-up Comparison 2: 43/80 (51%); 11 treatment failure, 32 loss to follow-up B: 15/68 (22%); 7 non-compliance with medication, 8 loss to follow-up. Insufficient information to calculate the number of excluded children for the ventilation tubes and control groups. C: Intervention: 4/58 (7%); inadequate follow-up in 3 children and parents of 1 child terminated study Control: 9/50 (18%); inadequate follow-up in 7 children and parents or the referring physician of 2 children terminated study D: not reported. E: Intervention: 11/100 (11%) Control: 9/100 (9%) |

Primary outcome measures: Outcome measure 1: Treatment success, defined as the proportion of children who have no AOM recurrences at 3-6 months post-randomisation (intermediate-term follow-up). Outcome measure 2: Significant adverse event: tympanic membrane perforation persisting for 3 months or longer. Secondary outcome measures: Outcome measure 3: Treatment success, defined as the proportion of children who have no AOM recurrences at 6 - 12 months post-randomisation (long-term follow-up). Outcome measure 4: Total number of AOM recurrences at 6 months post-randomisation Outcome measure 5: Total number of AOM recurrences at 12 months post-randomisation Outcome measure 6: Disease-specific health-related quality of life of the child at 4- and 12-months post-randomisation using the OM-6 questionnaire

Comparison 1: Grommets versus active monitoring Outcome 1: Effect measure: RR (95% CI): A: not reported B: not reported C: 9.49 (2.38 to 37.80) D: not reported E: not reported Pooled effect: RR (95% CI): 9.49 (2.38 to 37.80) Heterogeneity (I2): n/a

Outcome 2: n A: not reported B: not reported C: 0 (ventilation tube vs active monitoring) D: not reported E: not reported Pooled effect: RR (95% CI): n/a Heterogeneity (I2): n/a

Outcome 3: Effect measure: RR (95% CI): A: not reported B: not reported C: not reported D: not reported E: 1.41 (1.00 to 1.99) Pooled effect: RR (95% CI): 1.41 (1.00 to 1.99) Heterogeneity (I2): n/a

Outcome 4: mean difference (95% CI): A: not reported B: not reported C: -1.50 (-1.99 to -1.01) D: not reported E: not reported Pooled effect: RR (95% CI): n/a Heterogeneity (I2): n/a

Outcome 5: Effect measure: incidence rate difference (95%CI) A: not reported B: not reported C: not reported D: not reported E: -0.55 (-0.17 to -0.93) Pooled effect: RR (95% CI): n/a Heterogeneity (I2): n/a

Outcome 6: Effect measure: incidence rate difference (95%CI) A: not reported B: not reported C: not reported D: not reported E: no statistically significant differences Pooled effect: RR (95% CI): n/a Heterogeneity (I2): n/a

Comparison 2: Grommets versus antibiotic prophylaxis Outcome 1: Effect measure: RR (95% CI): A: not reported B: 1.42 (0.84 to 2.40) C: not reported D: 2.29 (0.97 to 5.39) E: not reported Pooled effect: RR (95% CI): 1.68 (1.07 to 2.65) Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

Outcome 2: n (%) (same for comparison 3) A: 3 (4%) B: not reported C: not reported D: not reported E: not reported Pooled effect: RR (95% CI): n/a Heterogeneity (I2): n/a

Outcome 3: not reported

Outcome 4: mean difference (95% CI): A: not reported B: not reported C: not reported D: -0.52 (-1.37 to 0.33) E: not reported Pooled effect: RR (95% CI): n/a Heterogeneity (I2): n/a

Outcome 5: not reported

Outcome 6: not reported

Comparison 3: Grommets versus placebo medication Outcome 1: Effect measure: RR (95% CI): A: not reported B: not reported C: not reported D: 3.64 (1.20 to 11.04) E: not reported Pooled effect: RR (95% CI): 3.64 (1.20 to 11.04) Heterogeneity (I2): n/a

Outcome 2: n (%) (same for comparison 2) A: 3 (4%) B: not reported C: not reported D: not reported E: not reported Pooled effect: RR (95% CI): n/a Heterogeneity (I2): n/a

Outcome 3: not reported

Outcome 4: mean difference (95% CI): A: not reported B: not reported C: not reported D: -1.14 (-2.06 to -0.22) E: not reported Pooled effect: RR (95% CI): n/a Heterogeneity (I2): n/a

Outcome 5: not reported

Outcome 6: not reported |

From text: “Low to very low-quality evidence suggests that children receiving ventilation tubes are less likely to have AOM recurrences compared to those managed by active monitoring and placebo medication, but the magnitude of the effect is modest with around one fewer episode at 6 months and a less noticeable effect by 12 months. The low to very low quality of the evidence means that these numbers need to be interpreted with caution since the true effects may be substantially different. It is uncertain whether or not ventilation tubes are more effective than antibiotic prophylaxis.”

Note: no children had received a pneumococcal conjugate vaccine.

Level of evidence: GRADE Comparison 1: Grommets versus active monitoring Outcome 1: low * Outcome 2: low * Outcome 3: low * Outcome 4: low * Outcome 5: low * Outcome 6: low * * We downgraded the evidence from high to low quality due to study limitations and imprecise effect estimates (only one study with a small sample size).

Comparison 2: Grommets versus antibiotic prophylaxis Outcome 1: very low * Outcome 2: not reported Outcome 3: not reported Outcome 4: very low ** Outcome 5: not reported Outcome 6: not reported * We downgraded the evidence from high to very low quality due to study limitations (when we excluded the trial with high risk of bias from the analysis, no statistically significant difference was observed between groups) and imprecise effect estimates (only two studies with small sample sizes). ** We downgraded the evidence from high to very low quality due to study limitations and imprecise effect estimates (only one study with a very small sample size).

Comparison 3: Grommets versus placebo medication Outcome 1: very low * Outcome 2: low ** Outcome 3: not reported Outcome 4: very low * Outcome 5: not reported Outcome 6: not reported * We downgraded the evidence from high to very low quality due to study limitations and imprecise effect estimates (only one study with a very small sample size). ** We downgraded the evidence from high to low quality due to study limitations and imprecise effect estimates (only one study with a small sample size).

Sensitivity analysis: “There were insufficient data to determine whether presence of middle ear effusion at randomisation, type of ventilation tube or age modified the effectiveness of ventilation tubes.”

Heterogeneity: "First, we assessed the level of clinical diversity between trials by reviewing them for potential differences in the types of participants recruited, interventions used, and outcomes measured. We did not pool studies where clinical heterogeneity made it unreasonable to do so. Second, we assessed statistical heterogeneity for each outcome by visually inspecting the forest plots and by using the Chi2 test, with a significance level set at P value < 0.10, and the I2 statistic, with I2 values over 50% suggesting substantial heterogeneity.”

Note: all the children had received a pneumococcal conjugate vaccine.

|

|

Hoberman, 2021 |

Type of study: parallel, open label, randomised trial

Setting and country: USA, UPMC Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh and affiliated practices; Children’s National Medical Center in Washington, D.C.; and Kentucky Pediatric and Adult Research in Bardstown, Kentucky; December 2015 - March 2020

Funding and conflicts of interest: Funded by the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders and others; ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT02567825. |

Inclusion criteria: - Children 6 to 35 months of age with RAOM

Exclusion criteria: none mentioned

N total at baseline: Intervention: 129 Control: 121

Important prognostic factors2: Age: 6-11 months old: I: 46 (36%) C: 45 (37%) 12-23 months old: I: 70 (54%) C: 67 (55%) 24-35 months old: I: 13 (10%) C: 9 (7%)

Sex: n (%) boys I: 87 (67%) C: 73 (60%)

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

Describe intervention ventilation tubes (Teflon® Armstrong-type) insertion |

Describe control active monitoring |

Length of follow-up: 2 years, 8-week intervals

Incomplete outcome data: 229 (92%) completed 1 year of follow-up and 208 (83%) completed 2 years of follow-up; the median duration was 1.96 years in each treatment group

Intervention: N (%): 26 (22.4%) Reasons (describe): 13 Were withdrawn or completed less than full yr (4 in y1, 9 in y2) 8 Were withdrawn or completed less than full yr (all y1) 5 Declined TTP and completed trial

Control: N (%): 13 (19.4%) Reasons (describe): 13 Were withdrawn or completed less than full yr (6 in y1, 7 in y2)

|

Outcome measures and effect size: aRR (95%CI; p-value) 1. Two-year occurrence of episodes of AOM: 0.97 (0.84 to 1.12; p=0.66) 2. treatment failure: 0.73 (0.58 to 0.92) 3. QoL OM6 survey (0-7): −0.05 (−0.13 to 0.02) OM6 survey childrens overall (0-10): 0.06 (−0.13 to 0.24) CIS (0-100): −0.04 (−1.55 to 1.47) CIS caregivers overall (0-10): 0.03 (−0.14 to 0.20)

4. Adverse events Non serious events: Diarrhea: 0.67 (0.44 to 1.03) Diaper dermatitis: 0.79 (0.51 to 1.22) Tube otorrhea: 2.57 (1.91 to 3.48) Serious events: 0.40 (0.11 to 1.52) |

From text: “Among children 6 to 35 months of age with recurrent acute otitis media, the rate of episodes of acute otitis media during a 2-year period was not significantly lower with tympanostomy-tube placement than with medical management.”

|

Risk of bias tables

Table of quality assessment for systematic reviews of RCTs and observational studies

|

Study

First author, year |

Appropriate and clearly focused question?1

Yes/no/unclear |

Comprehensive and systematic literature search?2

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of included and excluded studies?3

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of relevant characteristics of included studies?4

Yes/no/unclear |

Appropriate adjustment for potential confounders in observational studies?5

Yes/no/unclear/not applicable |

Assessment of scientific quality of included studies?6

Yes/no/unclear |

Enough similarities between studies to make combining them reasonable?7

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential risk of publication bias taken into account?8

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential conflicts of interest reported?9

Yes/no/unclear |

|

Venekamp, 2018 |

yes |

yes |

yes |

yes |

Not applicable |

yes |

yes |

yes |

yes |

- Research question (PICO) and inclusion criteria should be appropriate and predefined

- Search period and strategy should be described; at least Medline searched; for pharmacological questions at least Medline + EMBASE searched

- Potentially relevant studies that are excluded at final selection (after reading the full text) should be referenced with reasons

- Characteristics of individual studies relevant to research question (PICO), including potential confounders, should be reported

- Results should be adequately controlled for potential confounders by multivariate analysis (not applicable for RCTs)

- Quality of individual studies should be assessed using a quality scoring tool or checklist (Jadad score, Newcastle-Ottawa scale, risk of bias table etc.)

- Clinical and statistical heterogeneity should be assessed; clinical: enough similarities in patient characteristics, intervention, and definition of outcome measure to allow pooling? For pooled data: assessment of statistical heterogeneity using appropriate statistical tests (e.g., Chi-square, I2)?

- An assessment of publication bias should include a combination of graphical aids (e.g., funnel plot, other available tests) and/or statistical tests (e.g., Egger regression test, Hedges-Olken). Note: If no test values or funnel plot included score “no”. Score “yes” if mentions that publication bias could not be assessed because there were fewer than 10 included studies.

- Sources of support (including commercial co-authorship) should be reported in both the systematic review and the included studies. Note: To get a “yes,” source of funding or support must be indicated for the systematic review AND for each of the included studies.

Risk of bias table for intervention studies (randomized controlled trials; based on Cochrane risk of bias tool and suggestions by the CLARITY Group at McMaster University)

|

Study reference

(first author, publication year) |

Was the allocation sequence adequately generated?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was the allocation adequately concealed?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Blinding: Was knowledge of the allocated interventions adequately prevented?

Were patients blinded?

Were healthcare providers blinded?

Were data collectors blinded?

Were outcome assessors blinded?

Were data analysts blinded?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was loss to follow-up (missing outcome data) infrequent?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Are reports of the study free of selective outcome reporting?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was the study apparently free of other problems that could put it at a risk of bias?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Overall risk of bias If applicable/necessary, per outcome measure

LOW Some concerns HIGH |

|

Hoberman, 2021 |

Definitely yes;

Reason: randomization in blocks of 4, at each trial site, and within each stratum. |

Probably yes;

Reason: Assignments were conducted at a University of Pittsburgh data centre and were revealed after enrolment, owing to the impossibility of blinding. |

Definitely no;

Reason: Due to the nature of the intervention (surgery), blinding is impossible. |

Definitely yes;

Reason: proportion of missing data are in similar range |

Definitely yes;

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported |

No information |

LOW

Reason: only potential bias is in non-blinding. But due to the nature of the intervention, blinding is impossible. |

Randomization: generation of allocation sequences have to be unpredictable, for example computer generated random-numbers or drawing lots or envelopes. Examples of inadequate procedures are generation of allocation sequences by alternation, according to case record number, date of birth or date of admission.

Allocation concealment: refers to the protection (blinding) of the randomization process. Concealment of allocation sequences is adequate if patients and enrolling investigators cannot foresee assignment, for example central randomization (performed at a site remote from trial location). Inadequate procedures are all procedures based on inadequate randomization procedures or open allocation schedules.

Blinding: neither the patient nor the care provider (attending physician) knows which patient is getting the special treatment. Blinding is sometimes impossible, for example when comparing surgical with non-surgical treatments, but this should not affect the risk of bias judgement. Blinding of those assessing and collecting outcomes prevents that the knowledge of patient assignment influences the process of outcome assessment or data collection (detection or information bias). If a study has hard (objective) outcome measures, like death, blinding of outcome assessment is usually not necessary. If a study has “soft” (subjective) outcome measures, like the assessment of an X-ray, blinding of outcome assessment is necessary. Finally, data analysts should be blinded to patient assignment to prevents that knowledge of patient assignment influences data analysis.

Lost to follow-up: If the percentage of patients lost to follow-up or the percentage of missing outcome data is large, or differs between treatment groups, or the reasons for loss to follow-up or missing outcome data differ between treatment groups, bias is likely unless the proportion of missing outcomes compared with observed event risk is not enough to have an important impact on the intervention effect estimate or appropriate imputation methods have been used.

Selective outcome reporting: Results of all predefined outcome measures should be reported; if the protocol is available (in publication or trial registry), then outcomes in the protocol and published report can be compared; if not, outcomes listed in the methods section of an article can be compared with those whose results are reported.

Other biases: Problems may include: a potential source of bias related to the specific study design used (e.g. lead-time bias or survivor bias); trial stopped early due to some data-dependent process (including formal stopping rules); relevant baseline imbalance between intervention groups; claims of fraudulent behavior; deviations from intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis; (the role of the) funding body Note: The principles of an ITT analysis imply that (a) participants are kept in the intervention groups to which they were randomized, regardless of the intervention they actually received, (b) outcome data are measured on all participants, and (c) all randomized participants are included in the analysis.

Overall judgement of risk of bias per study and per outcome measure, including predicted direction of bias (e.g., favors experimental, or favors comparator). Note: the decision to downgrade the certainty of the evidence for a particular outcome measure is taken based on the body of evidence, i.e., considering potential bias and its impact on the certainty of the evidence in all included studies reporting on the outcome.

Table of excluded studies

|

Author and year |

Reason for exclusion |

|

Cheong, 2012 |

more recent systematic reviews available |

|

Damoiseaux, 2011 |

more recent systematic reviews available |

|

Demant, 2017 |

wrong publication type: study protocol |

|

Gunasekera, 2009 |

wrong population: also includes non-recurrent AOM |

|

Hellström, 2011 |

wrong population: also includes secretory OM |

|

Kujala, 2012 |

study included in review Venekamp (2018) |

|

Kujala, 2014 |

study included in review Venekamp (2018) |

|

Lau, 2018 |

article is withdrawn |

|

Lous, 2010 |

article in Danish |

|

Lous, 2011 |

more recent systematic reviews available |

|

Schilder, 2017 |

Reviews of better quality available; no meta-analysis performed. |

|

Steele, 2017a |

more recent systematic reviews available |

|

Steele, 2017b |

Also included non-randomized trials; better reviews available |

|

To, 2014 |

Reviews of better quality available |

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Laatst beoordeeld : 29-04-2024

Algemene gegevens

De ontwikkeling/herziening van deze richtlijnmodule werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten (www.demedischspecialist.nl/kennisinstituut) en werd gefinancierd uit de Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS). De financier heeft geen enkele invloed gehad op de inhoud van de richtlijnmodule.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijnmodule is in 2021 een multidisciplinaire werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen (zie hiervoor de Samenstelling van de werkgroep) die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor patiënten met Otitis Media (in de tweede lijn).

Werkgroep

- Dhr. dr. H.J. (Jeroen) Rosingh (voorzitter), KNO-arts, Isala Zwolle; NVKNO

- Mevr. dr. E.H. (Jet) van den Akker, KNO-arts, Meander MC Amersfoort; NVKNO

- Dhr. dr. M.P. (Marc) van der Schroeff, KNO-arts, Erasmus MC Rotterdam; NVKNO

- Mevr. dr. S.A.C. (Sophie) Kraaijenga, KNO-arts, Rijnstate Arnhem; NVKNO

- Mevr. dr. J.E.C. (Esther) Wiersinga-Post, Klinisch Fysicus - audioloog, UMC Groningen; NVKF

- Mevr. H.F. (Francien) Miedema MSc, logopedist/klinisch gezondheidswetenschapper, Jeroen Bosch Ziekenhuis, ’s-Hertogenbosch; NVLF

- Dhr. dr. R.P. (Roderick) Venekamp, huisarts, UMC Utrecht; NHG

- Mevr. H. (Hester) Rippen, patiëntvertegenwoordiger; Stichting Kind en Ziekenhuis

Met ondersteuning van

- Mevr. dr. A. (Anja) van der Hout, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten (vanaf september 2022)

- Mevr. D.G. (Dian) Ossendrijver, MSc, junior adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- Dhr. M. (Mitchel) Griekspoor, MSc, adviseur Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- Mevr. dr. I. (Iris) Duif, adviseur Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten (tot september 2022)

Belangenverklaringen

De Code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling is gevolgd. Alle werkgroepleden hebben schriftelijk verklaard of zij in de laatste drie jaar directe financiële belangen (betrekking bij een commercieel bedrijf, persoonlijke financiële belangen, onderzoeksfinanciering) of indirecte belangen (persoonlijke relaties, reputatiemanagement) hebben gehad. Gedurende de ontwikkeling of herziening van een module worden wijzigingen in belangen aan de voorzitter doorgegeven. De belangenverklaring wordt opnieuw bevestigd tijdens de commentaarfase.

Een overzicht van de belangen van werkgroepleden en het oordeel over het omgaan met eventuele belangen vindt u in onderstaande tabel. De ondertekende belangenverklaringen zijn op te vragen bij het secretariaat van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

|

Werkgroeplid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

Rosingh |

- KNO-arts in lsala, Zwolle (werkend in MSB verband, dus niet in dienst van het ziekenhuis) - Plaatsvervangend opleider - KNO-arts in Ziekenhuis in Suriname, MMC Nickerie (september 2022 en november 2023) |

- Voorzitter Commissie Richtlijnen NVKNO - Opleider KNO en lid van consilium - Voorzitter ad interim commissie Kwaliteit & Veiligheid van (jan. 2023 – sep 2023) |

Geen |

Geen restricties |

|

Van der Schroeff |

KNO-arts, ErasmusMC |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen restricties |

|

Rippen |

- Directeur Stichting Kind en Ziekenhuis - Eigenaar Fiduz management (strategie, advies en projectmanagement) |

- Lid Raad van Toezicht MEEr-groep - Lid Adviesraad Medgezel - Coördinator European Association for Children in Hospital (EACH) - Bestuurslid College Perinatale zorg (CPZ) - AQUA De methodologische Advies- en expertgroep Leidraad voor Kwaliteitsstandaarden (AQUA) - Penningmeester Ervaringskenniscentrum Schouders - Voorzitter Landelijke Borstvoedingsraad - Voorzitter MKS Landelijke coördinatieteam Integrale Kindzorg - Voorzitter Expertiseraad Kenniscentrum kinderpalliatieve zorg - Lid Algemene Ledenvergadering VZVZ - Lid beoordelingscommissie KIDZ |

Geen |

Geen restricties |

|

Kraaijenga |

KNO-arts, Rijnstate ziekenhuis te Arnhem. |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen restricties |

|

Wiersinga-Post |

Klinisch fysicus – audioloog, UMC Groningen |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen restricties |

|

Miedema |

Logopedist, klinisch gezondheidswetenschapper Jeroen Bosch ziekenhuis, ‘s-Hertogenbosch |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen restricties |

|

Van den Akker |

KNO-arts, Meander Medisch Centrum Amersfoort |

-Lid Kerngroep kinder kno van de Nederlandse KNO vereniging, (betaald) - Voorzitter peersupport team meander medische centrum (onbetaald) |

Geen |

Geen restricties |

|

Venekamp |

- Praktiserend huisarts, Huisartsenpraktijk Verwielstraat te Waalwijk - Associate professor, Julius Centrum, UMC Utrecht |

NHG Autorisatiecommissie (vacatiegelden) |

Onze onderzoeksgroep van de afdeling Huisartsgeneeskunde van het Julius Centrum, UMC Utrecht, verricht onderzoek naar alledaagse infectieziekten dat wordt gefinancierd door (semi)overheid, met name ZonMw, en fondsen. |

Geen restricties |

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Er werd aandacht besteed aan het patiëntenperspectief door afvaardiging van Kind en Ziekenhuis in de richtlijnwerkgroep. De verkregen input is meegenomen bij het opstellen van de uitgangsvragen, de keuze voor de uitkomstmaten en bij het opstellen van de overwegingen. De conceptrichtlijn is tevens voor commentaar voorgelegd aan Kind en Ziekenhuis en de eventueel aangeleverde commentaren zijn bekeken en verwerkt.

Kwalitatieve raming van mogelijke financiële gevolgen in het kader van de Wkkgz

Bij de richtlijn is conform de Wet kwaliteit, klachten en geschillen zorg (Wkkgz) een kwalitatieve raming uitgevoerd of de aanbevelingen mogelijk leiden tot substantiële financiële gevolgen. Bij het uitvoeren van deze beoordeling zijn richtlijnmodules op verschillende domeinen getoetst (zie het stroomschema op de Richtlijnendatabase).

Uit de kwalitatieve raming blijkt dat er waarschijnlijk geen substantiële financiële gevolgen zijn, zie onderstaande tabel.

|

Module |

Uitkomst raming |

Toelichting |

|

Trommelvliesbuisjes bij rOMA |

geen financiële gevolgen |

Hoewel uit de toetsing volgt dat de aanbeveling(en) breed toepasbaar zijn (5.000-40.000 patiënten), volgt ook uit de toetsing dat het overgrote deel (±90%) van de zorgaanbieders en zorgverleners al aan de norm voldoet. Er worden daarom geen substantiële financiële gevolgen verwacht. |

Werkwijze

AGREE

Deze richtlijnmodule is opgesteld conform de eisen vermeld in het rapport Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 van de adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwaliteit. Dit rapport is gebaseerd op het AGREE II instrument (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II; Brouwers, 2010).

Need-for-update en uitgangsvragen

Tijdens de voorbereidende fase inventariseerde de werkgroep de geldigheid van de modules binnen de richtlijn Otitis media bij kinderen in de tweede lijn (need-for-update). Naast de betrokken wetenschappelijke verenigingen en patiëntenorganisaties zijn hier ook andere stakeholders voor benaderd in 2020. Ook was er de mogelijkheid om nieuwe onderwerpen voor modules aan te dragen die aansluiten bij de richtlijn.

Op basis van de uitkomsten van deze inventarisatie zijn door de werkgroep geprioriteerd en daarbij zijn de uitgangsvragen opgesteld en definitief vastgesteld tijdens een vergadering.

Uitkomstmaten

Na het opstellen van de zoekvraag behorende bij de uitgangsvraag inventariseerde de werkgroep welke uitkomstmaten voor de patiënt relevant zijn, waarbij zowel naar gewenste als ongewenste effecten werd gekeken. Hierbij werd een maximum van acht uitkomstmaten gehanteerd. De werkgroep waardeerde deze uitkomstmaten volgens hun relatieve belang bij de besluitvorming rondom aanbevelingen, als cruciaal (kritiek voor de besluitvorming), belangrijk (maar niet cruciaal) en onbelangrijk. Tevens definieerde de werkgroep tenminste voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten welke verschillen zij klinisch (patiënt) relevant vonden.

Methode literatuursamenvatting

Een uitgebreide beschrijving van de strategie voor zoeken en selecteren van literatuur is te vinden onder ‘Zoeken en selecteren’ onder Onderbouwing. Indien mogelijk werd de data uit verschillende studies gepoold in een random-effects model. Review Manager 5.4 werd gebruikt voor de statistische analyses. De beoordeling van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs wordt hieronder toegelicht.

Beoordelen van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs

De kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs werd bepaald volgens de GRADE-methode. GRADE staat voor ‘Grading Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation’ (zie http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/). De basisprincipes van de GRADE-methodiek zijn: GRADE-methodiek zijn: het benoemen en prioriteren van de klinisch (patiënt) relevante uitkomstmaten, een systematische review per uitkomstmaat, en een beoordeling van de bewijskracht per uitkomstmaat op basis van de acht GRADE-domeinen (domeinen voor downgraden: risk of bias, inconsistentie, indirectheid, imprecisie, en publicatiebias; domeinen voor upgraden: dosis-effect relatie, groot effect, en residuele plausibele confounding).

GRADE onderscheidt vier gradaties voor de kwaliteit van het wetenschappelijk bewijs: hoog, redelijk, laag en zeer laag. Deze gradaties verwijzen naar de mate van zekerheid die er bestaat over de literatuurconclusie, in het bijzonder de mate van zekerheid dat de literatuurconclusie de aanbeveling adequaat ondersteunt (Schünemann, 2013; Hultcrantz, 2017).

|

GRADE |

Definitie |

|

Hoog |

|

|

Redelijk |

|

|

Laag |

|

|

Zeer laag |

|

Bij het beoordelen (graderen) van de kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs in richtlijnen volgens de GRADE-methodiek spelen grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming een belangrijke rol (Hultcrantz, 2017). Dit zijn de grenzen die bij overschrijding aanleiding zouden geven tot een aanpassing van de aanbeveling. Om de grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming te bepalen moeten alle relevante uitkomstmaten en overwegingen worden meegewogen. De grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming zijn daarmee niet één op één vergelijkbaar met het minimaal klinisch relevant verschil (Minimal Clinically Important Difference, MCID). Met name in situaties waarin een interventie geen belangrijke nadelen heeft en de kosten relatief laag zijn, kan de grens voor klinische besluitvorming met betrekking tot de effectiviteit van de interventie bij een lagere waarde (dichter bij het nul effect) liggen dan de MCID (Hultcrantz, 2017).

Overwegingen (van bewijs naar aanbeveling)

Om te komen tot een aanbeveling zijn naast (de kwaliteit van) het wetenschappelijke bewijs ook andere aspecten belangrijk en worden meegewogen, zoals aanvullende argumenten uit bijvoorbeeld de biomechanica of fysiologie, waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten, kosten (middelenbeslag), aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie. Deze aspecten zijn systematisch vermeld en beoordeeld (gewogen) onder het kopje ‘Overwegingen’ en kunnen (mede) gebaseerd zijn op expert opinion. Hierbij is gebruik gemaakt van een gestructureerd format gebaseerd op het evidence-to-decision framework van de internationale GRADE Working Group (Alonso-Coello, 2016a; Alonso-Coello 2016b). Dit evidence-to-decision framework is een integraal onderdeel van de GRADE methodiek.

Formuleren van aanbevelingen

De aanbevelingen geven antwoord op de uitgangsvraag en zijn gebaseerd op het beschikbare wetenschappelijke bewijs en de belangrijkste overwegingen, en een weging van de gunstige en ongunstige effecten van de relevante interventies. De kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs en het gewicht dat door de werkgroep wordt toegekend aan de overwegingen, bepalen samen de sterkte van de aanbeveling. Conform de GRADE-methodiek sluit een lage bewijskracht van conclusies in de systematische literatuuranalyse een sterke aanbeveling niet a priori uit, en zijn bij een hoge bewijskracht ook zwakke aanbevelingen mogelijk (Agoritsas, 2017; Neumann, 2016). De sterkte van de aanbeveling wordt altijd bepaald door weging van alle relevante argumenten tezamen. De werkgroep heeft bij elke aanbeveling opgenomen hoe zij tot de richting en sterkte van de aanbeveling zijn gekomen.

In de GRADE-methodiek wordt onderscheid gemaakt tussen sterke en zwakke (of conditionele) aanbevelingen. De sterkte van een aanbeveling verwijst naar de mate van zekerheid dat de voordelen van de interventie opwegen tegen de nadelen (of vice versa), gezien over het hele spectrum van patiënten waarvoor de aanbeveling is bedoeld. De sterkte van een aanbeveling heeft duidelijke implicaties voor patiënten, behandelaars en beleidsmakers (zie onderstaande tabel). Een aanbeveling is geen dictaat, zelfs een sterke aanbeveling gebaseerd op bewijs van hoge kwaliteit (GRADE gradering HOOG) zal niet altijd van toepassing zijn, onder alle mogelijke omstandigheden en voor elke individuele patiënt.

|

Implicaties van sterke en zwakke aanbevelingen voor verschillende richtlijngebruikers |

||

|

|

Sterke aanbeveling |

Zwakke (conditionele) aanbeveling |

|

Voor patiënten |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen en slechts een klein aantal niet. |

Een aanzienlijk deel van de patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen, maar veel patiënten ook niet. |

|

Voor behandelaars |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak moeten ontvangen. |

Er zijn meerdere geschikte interventies of aanpakken. De patiënt moet worden ondersteund bij de keuze voor de interventie of aanpak die het beste aansluit bij zijn of haar waarden en voorkeuren. |

|

Voor beleidsmakers |

De aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kan worden gezien als standaardbeleid. |

Beleidsbepaling vereist uitvoerige discussie met betrokkenheid van veel stakeholders. Er is een grotere kans op lokale beleidsverschillen. |

Organisatie van zorg

In de knelpuntenanalyse en bij de ontwikkeling van de richtlijnmodule is expliciet aandacht geweest voor de organisatie van zorg: alle aspecten die randvoorwaardelijk zijn voor het verlenen van zorg (zoals coördinatie, communicatie, (financiële) middelen, mankracht en infrastructuur). Randvoorwaarden die relevant zijn voor het beantwoorden van deze specifieke uitgangsvraag zijn genoemd bij de overwegingen van de verschillende modules.

Commentaar- en autorisatiefase

De conceptrichtlijnmodule werd aan de betrokken (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd ter commentaar. De commentaren werden verzameld en besproken met de werkgroep. Naar aanleiding van de commentaren werd de conceptrichtlijnmodule aangepast en definitief vastgesteld door de werkgroep. De definitieve richtlijnmodule werd aan de deelnemende (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd voor autorisatie en door hen geautoriseerd dan wel geaccordeerd.

Literatuur

Agoritsas T, Merglen A, Heen AF, Kristiansen A, Neumann I, Brito JP, Brignardello-Petersen R, Alexander PE, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Guyatt GH. UpToDate adherence to GRADE criteria for strong recommendations: an analytical survey. BMJ Open. 2017 Nov 16;7(11):e018593. Doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018593. PubMed PMID: 29150475; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5701989.

Alonso-Coello P, Schünemann HJ, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Rada G, Rosenbaum S, Morelli A, Guyatt GH, Oxman AD; GRADE Working Group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 1: Introduction. BMJ. 2016 Jun 28;353:i2016. Doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2016. PubMed PMID: 27353417.

Alonso-Coello P, Oxman AD, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Vandvik PO, Meerpohl J, Guyatt GH, Schünemann HJ; GRADE Working Group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 2: Clinical practice guidelines. BMJ. 2016 Jun 30;353:i2089. Doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2089. PubMed PMID: 27365494.

Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, Burgers JS, Cluzeau F, Feder G, Fervers B, Graham ID, Grimshaw J, Hanna SE, Littlejohns P, Makarski J, Zitzelsberger L; AGREE Next Steps Consortium. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. CMAJ. 2010 Dec 14;182(18):E839-42. Doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090449. Epub 2010 Jul 5. Review. PubMed PMID: 20603348; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3001530.

Hultcrantz M, Rind D, Akl EA, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Iorio A, Alper BS, Meerpohl JJ, Murad MH, Ansari MT, Katikireddi SV, Östlund P, Tranæus S, Christensen R, Gartlehner G, Brozek J, Izcovich A, Schünemann H, Guyatt G. The GRADE Working Group clarifies the construct of certainty of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017 Jul;87:4-13. Doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.05.006. Epub 2017 May 18. PubMed PMID: 28529184; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC6542664.

Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 (2012). Adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwalitieit. http://richtlijnendatabase.nl/over_deze_site/over_richtlijnontwikkeling.html

Neumann I, Santesso N, Akl EA, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Alonso-Coello P, Agoritsas T, Mustafa RA, Alexander PE, Schünemann H, Guyatt GH. A guide for health professionals to interpret and use recommendations in guidelines developed with the GRADE approach. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016 Apr;72:45-55. Doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.11.017. Epub 2016 Jan 6. Review. PubMed PMID: 26772609.

Schünemann H, Brożek J, Guyatt G, et al. GRADE handbook for grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. Updated October 2013. The GRADE Working Group, 2013. Available from http://gdt.guidelinedevelopment.org/central_prod/_design/client/handbook/handbook.html .

Zoekverantwoording

Zoekacties zijn opvraagbaar. Neem hiervoor contact op met de Richtlijnendatabase.