Percutane cementaugmentatie

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is de plaats van percutane cementaugmentatie in de behandeling van patiënten van 50 jaar of ouder met een symptomatische stabiele wervelfractuur?

Aanbeveling

Voer geen percutane cementaugmentatie uit bij patiënten met een stabiele symptomatische acute wervelfractuur (korter dan 6 weken).

Overweeg percutane cementaugmentatie uitsluitend bij patiënten van 50 jaar of ouder met een symptomatische stabiele wervelfractuur indien:

- de patiënt ernstige/onhoudbare lokale pijn blijft ervaren die onvoldoende reageert op pijnmedicatie en maximale conservatieve therapie, en

- de (ernstige) pijn onvoldoende afneemt in de tijd zoals te verwachten bij een normale fractuurgenezing (3 maanden), en

- er sprake is van botoedeem in de betreffende wervel op MRI-overeenkomend met het niveau/de plaats van focale pijnklachten bij lichamelijk onderzoek.

Bespreek daarbij met de patiënt dat de kosten van de interventie voor eigen rekening zullen komen.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Er is literatuuronderzoek verricht naar de effectiviteit en mogelijk nadelige effecten (veiligheid) van percutane cementaugmentatie – dat wil zeggen vertebroplastiek en kyfoplastiek - bij patiënten van 50 jaar of ouder met een symptomatische stabiele wervelfractuur. Voor vertebroplastiek waren er gerandomiseerde vergelijkende studies met een sham behandeling en met conservatieve behandeling beschikbaar, kyfoplastiek is alleen vergeleken met conservatieve behandeling.

De resultaten van de in Nederland uitgevoerde Vertos 5 studie zijn gepubliceerd na het uitvoeren van de literatuursearch en derhalve niet meegenomen in de analyse. Voor de volledigheid nemen we deze in de overwegingen wel mee. De Vertos 5 studie is een gerandomiseerde studie: vertebroplastiek (N=40) versus sham (N=40), die patiënten met een wervelfractuur met botoedeem en 3 maanden of langer pijnklachten heeft geïncludeerd (Carli, 2023).

Vergeleken met placebo (sham) behandeling geeft percutane vertebroplastiek waarschijnlijk geen klinisch relevante verbetering in de cruciale uitkomstmaten pijn en kwaliteit van leven en de belangrijke uitkomstmaat beperkingen in activiteiten van het dagelijks leven (GRADE bewijskracht redelijk). Er lijkt ook geen verschil te zijn tussen behandeling met vertebroplastiek of met placebo ten aanzien van het optreden van nieuwe – aangrenzende en niet aangrenzende - wervelfracturen. Het verschil in opgetreden complicaties was onduidelijk door de zeer lage bewijskracht (klein aantal opgetreden events). Participatie en mortaliteit werden niet gerapporteerd in de geïncludeerde literatuur.

Op basis van waardering van de eerder genoemde studies is de algehele bewijskracht, d.w.z. de laagste bewijskracht voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten, gewaardeerd als redelijk vanwege de beperkte aantallen geïncludeerde patiënten. Concluderend kan gesteld worden dat op basis van de literatuur de voorkeur niet uitgaat naar behandeling van patiënten van 50 jaar of ouder met een symptomatische stabiele wervelfractuur met percutane vertebroplastiek, aangezien er geen zekere meerwaarde ten opzichte van een sham procedure is gevonden.

Vergeleken met standaardzorg (d.w.z. conservatieve behandeling, zoals pijnmedicatie) lijkt percutane vertebroplastiek geen klinisch relevante verbetering te geven in de cruciale uitkomstmaten pijn en kwaliteit van leven (GRADE bewijskracht laag). Wel lijkt vertebroplastiek beperkingen in activiteiten van het dagelijks leven (ADL) te verminderen ten opzichte van standaardzorg (GRADE bewijskracht laag). Daarnaast lijkt er geen verschil te zijn in het optreden van nieuwe wervelfracturen en complicaties tussen vertebroplastiek en standaardbehandeling. Hiermee kan gesteld worden dat vertebroplastiek dus een relatief veilige (invasieve) procedure is. Participatie en mortaliteit werden niet gerapporteerd in de geïncludeerde literatuur.

De algehele bewijskracht (de laagste bewijskracht voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten) komt uit op laag, onder andere vanwege de beperkte aantallen geïncludeerde patiënten en het ontbreken van blindering. Op basis van de literatuur is er alleen op het gebied van ADL een voorzichtige voorkeur voor behandeling met percutane vertebroplastiek ten opzichte van standaardbehandeling bij patiënten van 50 jaar of ouder met een symptomatische stabiele wervelfractuur.

Voor de vergelijking tussen ballon kyfoplastiek en standaardzorg werd maar één studie gevonden. Door beperkingen in de onderzoeksopzet, beperkte patiëntaantallen en risico op publicatiebias is de bewijskracht voor deze vergelijking op alle uitkomstmaten zeer laag. De literatuur kan daardoor geen richting geven aan de besluitvorming.

Kritische punten ten aanzien van de interpretatie van de genoemde studies richten zich op de volgende punten:

1) heterogene en matig beschreven inclusiecriteria;

2) de aard van de sham behandeling: geen ‘echte’ sham, maar een alternatieve pijninterventie (facet- of medial branch blokkade) met lidocaïne en bupivacaine;

3) de relatief korte duur van klachten en tijd tot interventie in verhouding tot het (in het algemeen goedaardige) natuurlijke beloop van de stabiele wervelfractuur bij patiënten >50 jaar.

Inclusiecriteria

Het interpreteren van de literatuur wordt bemoeilijk door de over het algemeen matige beschrijving van de gehanteerde inclusiecriteria (Buchbinder, 2009; Clark, 2016). Met name de aanwezigheid van botoedeem wordt algemeen aangenomen om van cruciaal belang te zijn om onderscheid te maken tussen een geconsolideerde (oude, niet langer pijnlijke) wervelfractuur en niet-geconsolideerde (verse, pijnlijke) wervelfractuur. Focale pijnklachten corresponderend met botoedeem in het wervellichaam is de belangrijkste indicator dat de ervaren pijn ook daadwerkelijk veroorzaakt wordt door een niet-geconsolideerde wervelfractuur (Voormolen, 2006). Patiënten die in aanmerking komen voor een vertebroplastiek dienen botoedeem op MRI in de wervel corresponderend met focale pijn bij lichamelijk onderzoek met een pijnscore (VAS) van 5 of hoger te hebben. Het enige sham gecontroleerde onderzoek dat dit nauwkeurig beschrijft is de Vertos 4 studie van Firanescu (2018). Ook de Vertos 5 studie heeft alleen patiënten met botoedeem op de MRI geïncludeerd (Carli, 2023).

De VERTOS 4 studie is een Nederlandse studie en derhalve representatief voor de Nederlandse populatie en praktijkvoering. Noemenswaardige relevante bevindingen uit deze studie anders dan beschreven in de literatuursamenvatting zijn de volgende:

Na 12 maanden follow-up heeft een significant hoger percentage patiënten in de sham groep (41%; n=30) een VAS score van 5 of hoger vergeleken met patiënten in de vertebroplastiek groep (20%; n=16): (χ2 (1)=8.08, P=0.005).

Ook de analyse van de samengevoegde resultaten van de Vertos 2 (controle behandeling conservatief) en 4 (controle behandeling sham, Firanescu, 2022) laten dit zien; 40.1% van de patiënten in de conservatieve behandeling en sham groep hebben na 12 maanden follow up een VAS ≥ 5. 20.7% van de patiënten in de vertebroplastiek groep hebben na 12 maanden follow up een VAS ≥ 5. Het verschil is significant (χ2(1) = 15.26, p < 0.0001, OR = 2.57, 95% CI = 1.59 - 4.15). Zowel in VERTOS 2 als 4 wordt gekeken naar patienten met recent opgetreden symptomatische wervelfracturen (<6 weken symptomatisch, zogenaamde ‘acute’ wervelfracturen).

Klachtenduur en natuurlijk beloop

Als klinisch relevant verschil in VAS score hebben we een verschil van 20% gedefinieerd. Zeker als patiënten met acute wervelfracturen voor behandeling worden geïncludeerd, weten we uit de normale fractuur genezing dat een groot aantal overbehandeld zal worden, omdat de pijn ook zonder behandeling zal afnemen conform het natuurlijk beloop van fractuurgenezing. (Klazen, 2010). Dan is een verschil van 20% in VAS-score als relevant verschil tussen twee behandelmodaliteiten een strenge eis. Vertebroplastiek is bedoeld voor patiënten die onvoldoende ‘normale fractuurgenezing’ ervaren. Daarmee lijkt de Vertos 5 studie een betere patiëntencategorie te includeren. Zij includeren patiënten met een pijnlijke osteoporotische wervelfractuur (met botoedeem op MRI) en een klachtenduur van ≥ 3 maanden. In deze studie is de pijn afname significant beter in de vertebroplastiek groep dan in de sham groep. Echter, ook hier wordt het verschil van 20% tussen beide groepen niet gehaald (Carli, 2023).

Implementatie

Concluderend kan gesteld worden dat het effect van vertebroplastiek op pijn onzeker blijft. Vertebroplastiek lijkt de kans op hoge pijnscores (VAS>5) na 12 maanden te verminderen in vergelijking met conservatieve therapie en sham procedures ((Firanescu, 2022, Vertos 2 + 4) Tevens beschermt vertebroplastiek de behandelde wervel tegen verdere hoogteafname en daarmee toename van de standsafwijking (Vertos 2), hoewel de klinische relevantie hiervan nog niet vastgesteld is. Desondanks is de toegevoegde waarde van vertebroplastiek te onzeker om deze als standaard zorg aan te bieden.

Vertebroplastiek zou in subgroepen wel een mogelijke behandeling kunnen zijn. Er is in de literatuur echter te weinig informatie om een duidelijke subgroep te definiëren. Ongeveer 70% van de patiënten met een pijnlijke acute osteoporotische wervelfractuur ervaart significante pijnafname in de loop van de tijd door normale fractuurgenezing en conservatieve therapie (Klazen, 2010). Bij 30% van de patiënten resulteert een acute osteoporotische wervelfractuur in chronische pijn (>2 jaar). Bij deze groep patiënten, wanneer klachten chronisch dreigen te worden (minimaal 3 maanden pijnklachten (Carli, 2023; Nieuwenhuijse, 2012)) onvoldoende reagerend op conservatieve therapie, zou een interventie overwogen kunnen worden. Voorwaarde is dan wel dat de diagnose niet/onvoldoende geconsolideerde wervelfractuur, gesteld wordt middels de combinatie van focale pijnklachten bij lichamelijk onderzoek corresponderend met een (al dan niet ingezakte) wervel met botoedeem op MRI.

Bij onhoudbare pijnklachten, die onvoldoende reageren op pijnmedicatie zou ook een lokale injectie (lidocaine/bupivacaine/dexamethason/ kenacort) overwogen kunnen worden. Hier is echter geen systematische literatuuranalyse voor uitgevoerd. Medicatie injectie onder röntgendoorlichting wordt op de radiologie vergoed, echter op de pijnpolikliniek is dit afhankelijk van de locatie. Deze kan poliklinisch verricht worden. De effectiviteit van lokale pijnbehandeling is momenteel echter onvoldoende duidelijk.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

Vertebroplastiek is een interventie met weinig complicaties. Het is een minimaal invasieve procedure die onder lokale verdoving (lidocaïne) wordt uitgevoerd. Patiënten krijgen een dagopname en eventuele antistolling kan tijdelijk gestaakt worden. De periprocedurele risico’s en complicaties zijn verwaarloosbaar in Nederland (Vertos 2, 4). Voor veel patiënten is vermindering van pijn zeer belangrijk. Daarom zullen sommige patiënten met persisterende klachten de voorkeur geven aan vertebroplastiek boven conservatieve therapie. Op dit moment is vertebroplastiek in Nederland onverzekerde zorg en zal door de patiënt zelf betaald moeten worden. Bespreek daarom met de patiënt de mogelijkheden van de ingreep, maar ook de risico’s en de kosten.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

Vertebropastiek is kosten-effectief ten opzichte van conservatieve therapie (Pron, 2022). Echter in Nederland is het onverzekerde zorg en zal door de patiënt zelf betaald moeten worden. De kosten bedragen inclusief dagopname rond de 2000 euro (Vertos 2). Pijnmedicatie en fysio-/oefentherapie worden wel (deels) vergoed. De kosten van kyfoplastiek liggen hoger dan vertebroplastiek door het materiaal en veelal ziekenhuisopname, en algehele anaesthesie die bij kyphoplastiek nodig is (Mathis, 2004).

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

Omdat vertebroplastiek in Nederland niet wordt vergoed, kunnen alleen patiënten met voldoende financiële middelen hiervoor kiezen. Deze behandeling is daarom niet voor iedereen toegankelijk. Derhalve wordt de overigens laagcomplexe eenvoudig opschaalbare behandeling momenteel slechts in enkele centra sporadisch of in studieverband verricht.

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

De toegevoegde waarde van vertebroplastiek is te onzeker om deze als standaard zorg aan te bieden. Vertebroplastiek zou in subgroepen wel een adequate behandeling kunnen zijn, echter om welke groepen dit exact gaat is momenteel onvoldoende duidelijk en verdient nader onderzoek om deze te kunnen identificeren. Vertebroplastiek zou overwogen kunnen worden bij patiënten met persisterend onhoudbare pijn langer dan 3 maanden met onvoldoende verlichting door pijnmedicatie. De kans op chroniciteit van de klachten wordt hiermee verminderd. Vertebroplastiek is een interventie met lokale verdoving en weinig complicaties. Nadeel is dat patiënten in Nederland de interventie en dagopname zelf moeten bekostigen. Tevens brengt het eventueel staken van antistolling voor de interventie mogelijk risico’s met zich mee.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Percutane cementaugmentatie wordt sinds 2003 in Nederland verricht in het kader van pijnbestrijding en het behoud van wervelhoogte voornamelijk bij een symptomatische stabiele wervelfractuur (i.e. waarvoor geen operatieve stabilisatie middels osteosynthese is geïndiceerd). Doordat de procedure in Nederland niet meer vergoed wordt door de zorgverzekeraars is deze behandeling alleen voor patiënten die de kosten zelf kunnen/willen betalen beschikbaar. De plaats van percutane cementaugmentatie in de behandeling van symptomatische stabiele wervelfracturen is zodoende nog altijd onduidelijk.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

- Percutaneous vertebroplasty versus sham operation

Critical outcomes

|

Moderate GRADE |

Compared with sham operation, percutaneous vertebroplasty likely results in little to no relevant difference in pain reduction in patients aged ≥50 with a symptomatic stable vertebral fracture.

Source: Li, 2022. |

|

Moderate GRADE |

Compared with sham operation, percutaneous vertebroplasty likely results in little to no relevant difference in disease-specific quality of life as assessed by QUALEFFO from 1 week to 12 months of follow-up, in patients aged ≥50 with a symptomatic stable vertebral fracture.

Sources: Buchbinder, 2018; Firanescu, 2018. |

Important outcomes

|

Moderate GRADE |

Compared with a sham operation, percutaneous vertebroplasty likely results in little to no relevant difference in disability as assessed by Roland-Morris disability questionnaire from 1 week to 6 months of follow-up, in patients aged ≥50 with a symptomatic stable vertebral fracture.

Sources: Buchbinder, 2018; Firanescu, 2018. |

|

Low GRADE |

Compared with sham operation, percutaneous vertebroplasty may result in little to no relevant difference in secondary fractures at 12-month follow-up, in patients aged ≥50 with a symptomatic stable vertebral fracture.

Source: Firanescu, 2018. |

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of percutaneous vertebroplasty on adverse events (other than secondary fractures) when compared with sham operation in patients aged ≥50 with a symptomatic stable vertebral fracture.

Sources: Buchbinder, 2018; Firanescu, 2018. |

|

No GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding the effect of percutaneous vertebroplasty on participation when compared with sham operation in patients aged ≥50 with a symptomatic stable vertebral fracture. |

|

No GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding the effect of percutaneous vertebroplasty on mortality when compared with sham operation in patients aged ≥50 with a symptomatic stable vertebral fracture. |

- Percutaneous vertebroplasty versus usual care

Critical outcomes

|

Low GRADE |

Compared with usual care, percutaneous vertebroplasty may result in little to no relevant difference in pain as assessed by VAS at 1-week to 12-month follow-up, in patients aged ≥50 with a symptomatic stable vertebral fracture.

Sources: Li, 2022; Tantawi, 2022. |

|

Low GRADE |

Compared with usual care, percutaneous vertebroplasty may result in little to no relevant difference in disease-specific quality of life as assessed by QUALEFFO at 1-week to 12-month follow-up, in patients aged ≥50 with a symptomatic stable vertebral fracture.

Source: Buchbinder, 2018. |

Important outcomes

|

Low GRADE |

Compared with usual care, percutaneous vertebroplasty may reduce disability as assessed by Roland-Morris or ODI disability score at 1-week to 6-month follow-up, in patients aged ≥50 with a symptomatic stable vertebral fracture.

Sources: Buchbinder, 2018; Tantawi 2022. |

|

Low GRADE |

Compared with usual care, percutaneous vertebroplasty may result in little to no relevant difference in secondary fractures in patients aged ≥50 with a symptomatic stable vertebral fracture.

Sources: Li, 2022; Tantawi, 2022. |

|

Low GRADE |

Compared with usual care, percutaneous vertebroplasty may result in little to no relevant difference in adverse events in patients aged ≥50 with a symptomatic stable vertebral fracture.

Sources: Li, 2022; Tantawi, 2022. |

|

No GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding the effect of percutaneous vertebroplasty on participation when compared with usual care in patients aged ≥50 with a symptomatic stable vertebral fracture. |

|

No GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding the effect of percutaneous vertebroplasty on mortality when compared with usual care in patients aged ≥50 with a symptomatic stable vertebral fracture. |

- Balloon kyphoplasty versus usual care

Critical outcomes

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of balloon kyphoplasty on pain when compared with usual care in patients aged ≥50 with a symptomatic stable vertebral fracture.

Source: Van Meirhaeghe, 2013 |

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of balloon kyphoplasty on quality of life when compared with usual care in patients aged ≥50 with a symptomatic stable vertebral fracture.

Source: Van Meirhaeghe, 2013 |

Important outcomes

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of balloon kyphoplasty on disability when compared with usual care in patients aged ≥50 with a symptomatic stable vertebral fracture.

Source: Van Meirhaeghe, 2013 |

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of balloon kyphoplasty on secondary fractures when compared with usual care in patients aged ≥50 with a symptomatic stable vertebral fracture.

Source: Van Meirhaeghe, 2013 |

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of balloon kyphoplasty on adverse events (other than secondary fractures) when compared with usual care in patients aged ≥50 with a symptomatic stable vertebral fracture.

Source: Van Meirhaeghe, 2013 |

|

No GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding the effect of balloon kyphoplasty on participation when compared with usual care in patients aged ≥50 with a symptomatic stable vertebral fracture. |

|

No GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding the effect of balloon kyphoplasty on mortality when compared with usual care in patients aged ≥50 with a symptomatic stable vertebral fracture. |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

The meta-analysis by Li (2022) compared the effectiveness and safety of vertebral augmentation procedures with non-surgical management for treatment of osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures. The primary outcome of this meta-analysis was pain relief evaluated by visual analogue scale (VAS). The review included 20 publications, 9 of which were in line with the PICO for the current analysis. This comprehensive meta-analysis had a low risk of bias. The inclusion criteria for the individual studies are outlined in table 1. Li (2022) did not report the data of individual studies for disability and disease-specific quality of life. Therefore, the review by Buchbinder (2018) was used for these outcome measures for vertebroplasty. For balloon kyphoplasty, the only original RCT reported in this meta-analysis in line with the PICO (Van Meirhaeghe, 2013) was consulted.

The Cochrane review by Buchbinder (2018) included randomised and quasi-randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of adults with painful osteoporotic vertebral fractures, comparing vertebroplasty with placebo (sham), usual care, or another intervention. Major outcomes were mean overall pain, disability, disease-specific and overall health-related quality of life, patient-reported treatment success, new symptomatic vertebral fractures and the number of other serious adverse events. The search was performed in November 2017. The meta-analysis included 19 trials, 9 of which were in line with the PICO for the current analysis.

The RCT by Tantawy (2022), published after the above-mentioned reviews, investigated efficacy of vertebroplasty for osteoporotic vertebral fractures. In this open-label Egyptian single-center study, 35 patients in the intervention group underwent percutaneous vertebroplasty and were compared with 35 patients receiving conservative treatment, consisting of a regular physical therapy program in addition to medical treatment and bracing for three months. Inclusion criteria were painful OVCFs, evidence of osteoporosis (DEXA), bone marrow edema in MRI (acute fracture), pain duration less than one month and vertebral level between thoracic 5 and lumbar 5 (T5-L5). Pain relief (VAS) and improvement of functional disability (ODI) were the primary outcomes. The rate of new vertebral fractures after the procedure was considered the secondary outcome.

In the VERTOS IV trial, Firanescu (2018) investigated whether percutaneous vertebroplasty

results in more pain relief than a sham procedure in patients with acute osteoporotic compression fractures of the vertebral body. The inclusion criteria were: age 50 years or more, 1-3 vertebral compression fractures, T5-L5 focal back pain at the level of fracture for up to six weeks, score of 5 or higher on a VAS, diminished bone density (T score −1 or less) on a dual energy x ray absorptiometry (DEXA) scan, 15% or more loss of vertebral height,

and bone edema on magnetic resonance imaging. The Dutch multicenter RCT included 180 participants requiring treatment for acute osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures and

randomised them to either vertebroplasty (n=91) or a sham procedure (n=89). Main outcome measure was mean reduction in visual analogue scale (VAS) scores at one day,

one week, and one, three, six, and 12 months. Secondary outcome measures were the differences between groups for changes in the quality of life for osteoporosis and Roland-Morris disability questionnaire scores during 12 months’ follow-up.

In the FREE trial, Van Meirhaeghe (2013) compared the efficacy and safety of balloon kyphoplasty (BKP, N=149) and nonsurgical management (NSM, N=151) with NSM alone during 24 months in patients with painful vertebral compression fractures. NSM consisted of analgesics, bed rest, bracing, physiotherapy, rehabilitation programs, and walking aids according to standard practices of participating physicians and hospitals. Patients were eligible for enrolment if they had one to three vertebral fractures from T5 through L5. At least one fracture needed to have edema assessed by MRI and at least one had to show a 15% loss of height or more; single fractures were to meet both these criteria. In addition to the 1- and 2-year quality of life (QOL) outcomes of the fracture reduction evaluation, this multinational multicenter study reported timed up and go, clinical and radiographical outcomes, with a follow-up of 24 months.

Table 2 provides an overview of the study characteristics of the individual trials included in the current analysis.

Five studies reported in the systematic review were not included in the current analysis, because the presence of bone edema was not mentioned as an inclusion criterion, or it was unclear for how many patients an MRI was performed: Chen, 2014; Chen, 2015; Comstock, 2013 (INVEST trial); Kallmes, 2009; Rousing, 2010.

Table 1. Inclusion criteria

|

Study |

Fracture |

Bone edema |

Pain |

|

Blasco, 2012 |

Acute, painful osteoporotic vertebral fracture confirmed by spine radiograph |

Edema present on MRI or positive bone scan if MRI was contraindicated |

Pain at least 4 on a 0-10 VAS |

|

Chen, 2014 |

Osteoporotic thoracolumbar vertebral compression fractures |

Low signal on T1-weighted and high signal on T2-weighted MRI scans |

Persistent back pain |

|

Clark, 2016 VAPOUR |

One or two compression fractures of the vertebrae in the areas T4 to L5 in the previous 6 weeks. |

Fracture confirmed with a sagittal STIR (short tau inversion recovery) and sagittal T1 weighted MRI scan of the spine. |

Pain which is not adequately controlled by oral analgesia or which has required hospitalisation and prevents early mobilisation |

|

Farrokhi, 2011 |

Vertebral compression fracture |

Vacuum phenomenon or bone marrow edema of the vertebral fracture on MRI |

Severe back pain refractory to analgesic medication |

|

Klazen, 2010 VERTOS II |

Vertebral compression fracture on spine radiograph |

Bone edema of vertebral fracture on MRI |

Pain on 0-10 VAS of 5 or more

|

|

Voormolen, 2007 |

Height loss of the vertebral body of a minimum of 15% on plain radiograph of the spine |

Bone edema of the affected vertebra on MRI |

Back pain due to vertebral fracture refractive to medical therapy |

|

Yang, 2016 |

Vertebral compression fracture after acute minor or mild trauma |

Low signal on T1-weighted and high signal on T2-weighted in MRI |

Back pain 5 or more on a 0 to 10 cm VAS |

|

Tantawi, 2022 |

One or two vertebral fractures due to primary or secondary osteoporosis |

Bone marrow edema in MRI (acute fracture) |

Acute back pain |

|

Buchbinder, 2009 |

Presence of one or two recent vertebral fractures |

Bone edema, a fracture line, or both within the vertebral body on MRI or positive bone scan if MRI contraindicated |

Back pain |

|

Firanescu, 2018 VERTOS IV |

Vertebral fracture on X-ray of the spine |

Bone edema on MRI of the fractured vertebral body |

Pain |

|

Van Meirhaeghe, 2013 |

One to three vertebral fractures from T5 through L5 |

At least one fracture needed to have edema assessed by MRI |

Back pain score of 4 points or more on a 0–10 scale. |

MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; VAS: visual analogue scale.

Table 2. study characteristics

|

Study |

N (I/C) |

Mean age (y) (I/C) |

% female (I/C) |

Fracture location |

Duration of back pain (I/C, in weeks) |

|

Percutaneous vertebroplasty versus usual care/conservative therapy |

|||||

|

Blasco, 2012 |

125 (61/64) |

73.3 (71.3/75.3) |

73.0/82.0 |

T4–L5 |

20.0 ± 13.7/20.4 ± 18.6 |

|

Chen, 2014 |

89 (46/43) |

65.5 (64.6/66.5) |

69.6/69.8 |

Not specified |

28.28 ± 12/ 27.24 ± 10.04 |

|

Farrokhi, 2011 |

82 (40/42) |

73.02 (72.0/74.0) |

75.0/71.0 |

T4–L5 |

27 (4–50)/ 30 (6–54) |

|

Klazen, 2010 VERTOS II |

202 (101/101) |

75.3 (75.2/75.4) |

75.3/73.7 |

T5–L5 |

4.2 ± 2.4/ 3.8 ± 2.3 |

|

Voormolen, 2007 |

34 (18/16) |

73.0 (72.0/74.0) |

78.0/88.0 |

T6–L5 |

12.1 (6.7–19.7)/ 10.9 (6.6–20.1) |

|

Yang, 2016 |

107 (56/51) |

76.7 (77.1/76.2) |

64.3/64.7 |

T5–L5 |

1.2 ± 0.66/ 1.2 ± 0.66 |

|

Tantawi, 2022 |

70 (35/35) |

67.2/66.9 |

74.3/68.6 |

T5-L5 |

Not specified (< 1 month) |

|

Percutaneous vertebroplasty versus sham operation |

|||||

|

Buchbinder, 2009 |

78 (38/40) |

76.6 (74.2/78.9) |

82.0/78.0 |

Not specified |

9 (3.8–13.0)/ 9.5 (3.0–17.0) |

|

Firanescu, 2018 VERTOS IV |

176 (90/86) |

75.8 (74.7/76.9) |

74.0/77.0 |

T5-L5 |

5.28 (4.14-7.43)/ 5.14 (3.43-7.29) |

|

Clark, 2016 VAPOUR |

120 (61/59) |

80.5 (80.0/81.0) |

79.0/68.0 |

T4–L5 |

2.8 + 1.6/ 2.4 + 1.4 |

|

Balloon kyphoplasty versus usual care/conservative therapy |

|||||

|

Van Meirhaeghe, 2013 |

300 (149/151) |

72.2/74.1 |

77.2/77.5 |

T5-L5 |

Not specified (≤ 3 months) |

Results

Results are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Pooled differences are (standardized) mean difference or risk ratio (95% confidence interval, CI).

1. Percutaneous vertebroplasty versus sham operation

Pain (critical outcome)

Li (2022) reported postoperative pain assessed by Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) 0-10, in which a higher score indicates more pain.

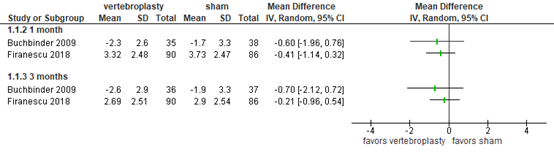

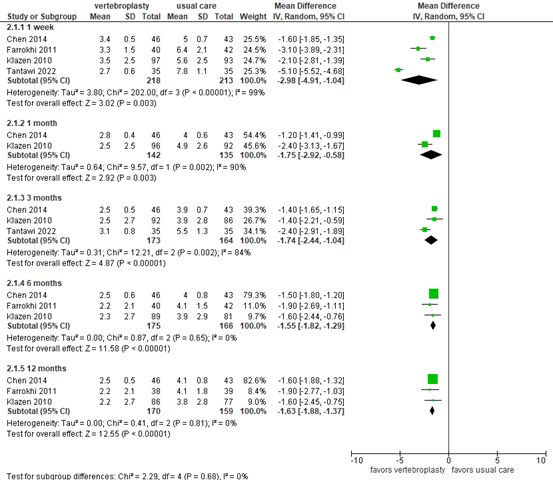

At 2 weeks, the study by Clark (2016) reported 3.9 ± 2.8 in the vertebroplasty group (N=41) versus 4.9 ± 2.8 in the sham group (N=47). The difference of 1.00 (95% CI -2.17 to 0.17) was not considered clinically relevant. Buchbinder (2009) and Firanescu (2018) reported pain improvement and pain score, respectively, at 1 and 3 months. As depicted in figure 1, the vertebroplasty groups (N=125) scored better than the sham groups (N=124), but differences were not considered clinically relevant.

At 12 months, Firanescu (2018) reported 2.72 ± 2.58 in the vertebroplasty group (N=90) versus 3.17 ± 2.68 in the sham group (N=86). The difference of -0.45 (95% CI -1.23 to 0.33) was not considered clinically relevant.

Figure 1. Pain after vertebroplasty versus sham operation

Pain assessed by visual analog score (VAS) 0-10, higher score indicates more pain. Random effects model; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval; Z: p-value of pooled effect.

Disease-specific quality of life (critical outcome)

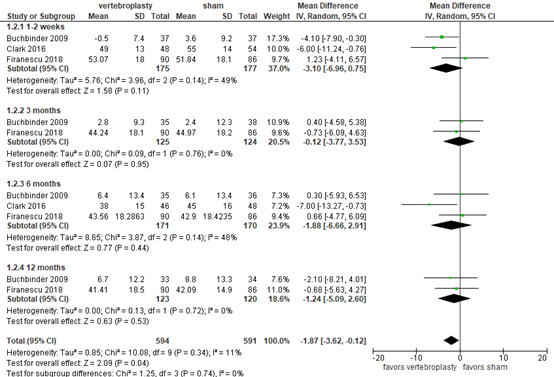

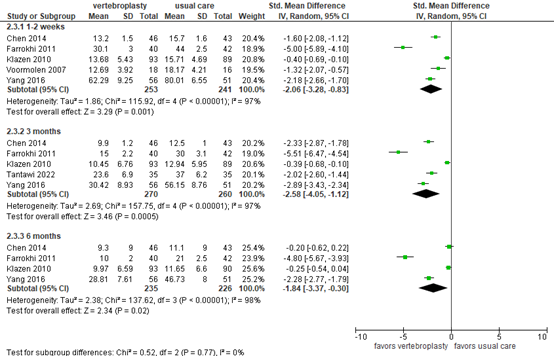

Buchbinder (2018) and Firanescu (2018) reported disease-specific quality of life as assessed by QUALEFFO questionnaire (score 0 to 100), where higher score indicates worse QOL. The results at 1 week and 3, 6 and 12 months are outlined in figure 2. At all time points, differences between the groups were small and not considered clinically relevant.

Figure 2. Disease-specific quality of life after vertebroplasty versus sham operation

Disease-specific quality of life as assessed by QUALEFFO questionnaire (score 0 to 100), higher score indicates worse QOL. Random effects model; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval; Z: p-value of pooled effect.

Activities/limitations of daily living

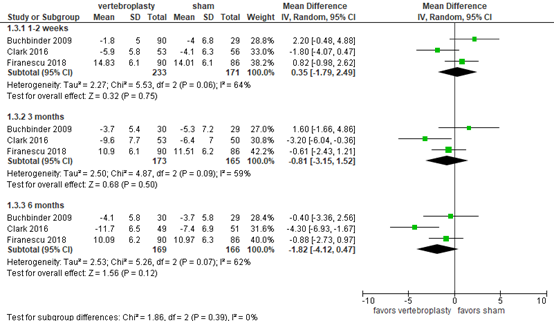

Buchbinder (2018) and Firanescu (2018) reported disability using the Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire (RMDQ), ranging from 0 to 24, with a higher score indicating more disability. At 1-2 weeks, the pooled mean difference was 0.35 (95% CI -1.79 to 2.49; total N=426) in favor of the sham group, as depicted in figure 3. At 3 months, the pooled mean difference was -0.81 (95% CI -3.15 to 1.52; total N=341) in favor of the vertebroplasty group. At 6 months, the pooled mean difference was -1.82 (95% CI -4.12 to 0.47; total N=243) in favor of the vertebropasty group. Overall, the differences were not considered clinically relevant.

Figure 3. Disability after vertebroplasty versus sham operation

Disability as assessed by Roland–Morris Disability Questionnaire (RMDQ, 0 to 24), higher score indicates more disability. Random effects model; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval; Z: p-value of pooled effect.

Secondary fractures

Firanescu (2018) reported new fractures during the 12-month follow-up of the study. 31 new fractures occurred in 15/76 participants in the vertebroplasty group and 28 fractures in 19/76 participants in the sham procedure group. The risk difference of -0.05 (95% CI -0.18 to 0.08) in favor of vertebroplasty was not considered clinically relevant.

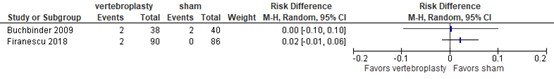

Adverse events

Buchbinder (2009) and Firanescu (2018) reported adverse events and found a risk difference of 0 and 2%, respectively, as outlined in figure 4. The differences were not considered clinically relevant.

Figure 4. Adverse events after vertebroplasty versus sham operation

Adverse events other than secondary fractures. Random effects model; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval; Z: p-value of pooled effect.

Participation (including work)

The outcome participation was not reported in the included publications.

Mortality

The outcome mortality was not reported in the included publications.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence regarding all outcome measures was based on randomized controlled studies and therefore started at high.

For the outcome measures pain, QOL and activities/limitations in daily living, the level of evidence was downgraded by one level to MODERATE because the confidence interval crossed the limit of clinical decision-making (imprecision, -1).

For the outcome measure secondary fractures, the level of evidence was downgraded by 2 levels to LOW because only a single study reported the outcome measure and because of the limited number of included patients (both imprecision, -2).

For the outcome measure adverse events, the level of evidence was downgraded by 3 levels to VERY LOW because of conflicting results (inconsistency, -1) and due to the very limited number of events (imprecision, -2).

For the outcome measures participation and mortality, the level of evidence could not be determined due to a lack of data.

2. Percutaneous vertebroplasty versus usual care

Pain (critical outcome)

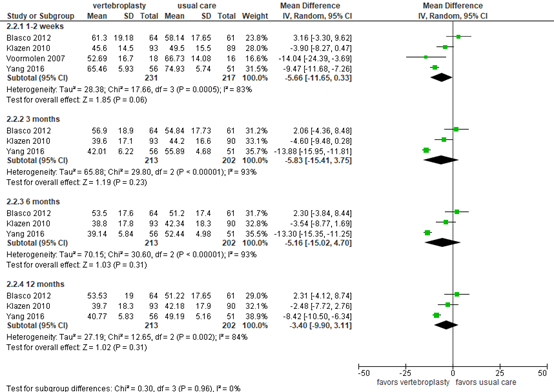

Li (2022) and Tantawi (2022) reported postoperative pain assessed by Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) 0-10, in which a higher score indicates more pain. Pain scores are presented in figure 5.

At 1-week follow-up, the mean difference based on 4 studies was -2.98 (95% CI -4.91 to -1.04) in favor of vertebroplasty (N=218) compared with usual care (N=213) . At 1-month follow-up, Chen (2014) and Klazen (2010) reported mean differences of -1.20 (95% CI -1.41 to -0.99; N=89) and -2.40 (95% CI -3.13 to -1.67; N=188), respectively. At 3-month follow-up, the mean difference from 3 studies was -1.74 (95% CI -2.44 to -1.04) in favor of vertebroplasty (N=173) compared with usual care (N=164). At 6-month follow-up, the mean difference based on 3 studies was -1.55 (95% CI -1.82 to -1.29) in favor of vertebroplasty (N=175) compared with usual care (N=166). At 12-month follow-up, the mean difference from 3 studies was -1.63 (95% CI -1.82 to -1.37) in favor of vertebroplasty (N=170) compared with usual care (N=159). Only the difference in pain relief at 1 week in favour of PVP was considered clinically relevant.

Figure 5. Pain after vertebroplasty versus usual care

Pain assessed by visual analog score (VAS) 0-10. Random effects model; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval; Z: p-value of pooled effect.

Disease-specific quality of life (critical outcome)

Buchbinder (2018) reported disease-specific quality of life as assessed by the QUALEFFO questionnaire (score 0 to 100), where a higher score indicates worse QOL. The scores at 2 weeks to 12 months follow-up are presented in figure 6.

At 2-week follow-up, the mean difference based on 4 studies was -5.66 (95% CI -11.65 to 0.33) in favor of vertebroplasty (N=231) compared with usual care (N=217). At 3-month follow-up, the mean difference based on 3 studies was -5.83 (95% CI -15.41 to -3.75) in favor of vertebroplasty (N=213) compared with usual care (N=202). At 6-month follow-up, the mean difference based on 3 studies was -5.16 (95% CI -15.02 to 4.70) in favor of vertebroplasty (N=213) compared with usual care (N=202). At 12-month follow-up, the mean difference from 3 studies was -3.40 (95% CI -9.90 to -3.11) in favor of vertebroplasty (N=213) compared with usual care (N=202). The differences were not considered clinically relevant.

Figure 6. Disease-specific quality of life after vertebroplasty versus usual care

Disease-specific quality of life as assessed by QUALEFFO questionnaire. Random effects model; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval; Z: p-value of pooled effect.

Activities/limitations of daily living

For the outcome measure activities/limitations in daily living, Buchbinder (2018) reported disability assessed by RMDQ (0 to 24, higher score indicates more disability) and Oswestry Disability Index (ODI, 0-100, higher score indicates more disability). As presented in figure 7, the standardized mean difference based on 5 studies was -2.06 (95% CI -3.28 to -0.83) in favor of vertebroplasty (N=253) compared with usual care (N=241) at 1 to 2 weeks follow-up. At 3-month follow-up, the mean difference based on 5 studies was -2.58 (95% CI -4.05 to -1.12) in favor of vertebroplasty (N=270) compared with usual care (N=260). At 6-month follow-up, the mean difference based on 4 studies was -1.84 (95% CI -3.37 to -0.30) in favor of vertebroplasty (N=235) compared with usual care (N=226). These differences were considered clinically relevant.

Figure 7. Disability after vertebroplasty versus usual care

Disability as assessed by Roland–Morris Disability Questionnaire (RMDQ, 0-24) or Oswestry Disability Index (ODI, 0-100). Random effects model; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval; Z: p-value of pooled effect.

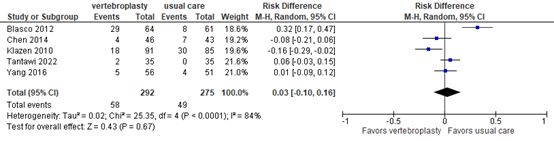

Secondary fractures

Li (2022) and Tantawi (2022) reported secondary fractures. Based on 5 studies with follow-up ranging from 3 to 31 months, 58 secondary fractures occurred in 292 patients after vertebroplasty versus 49 fractures in 275 patients receiving usual care. The risk difference was 0.03 (95% CI -0.10 to 0.16) , as outlined in figure 8. The RR of 1.20 (95% CI 0.45 to 3.19) was not considered clinically relevant. The studies did not specify whether the secondary fracures were adjacent to the primary fractures.

Figure 8. Secondary fractures after vertebroplasty versus usual care

Secondary fractures after 3-31 months follow-up. Random effects model; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval; Z: p-value of pooled effect.

Adverse events

Tantawi (2022) and Li (2022) reported adverse events (other than new fractures). Tantawi reported no events in either groupat 3 motnhs follow-up (both N=35). Yang (2016) reported 9/56 (16%) adverse events in the vertebroplasty group versus 18/51 (35%) in the usual care group at 12 months follow-up. The risk differences of 0 and 19% were not considered clinically relevant.

Participation (including work)

The outcome participation was not reported in the included publications.

Mortality

The outcome mortality was not reported in the included publications.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence regarding all outcome measures was based on randomized controlled studies and therefore started at high.

For the outcome measures pain, disease-specific quality of life and activities/limitations in daily living, the level of evidence was downgraded by 2 levels to LOW because of study limitations (risk of bias due to lack of blinding, -1), and the limited number of included patients (imprecision, -1).

For the outcome measures secondary fractures and adverse events, the level of evidence was downgraded by 2 levels to LOW because of conflicting results (inconsistency, -1) and the limited number of included patients (imprecision, -1).

For the outcome measures participation and mortality, the level of evidence could not be determined due to a lack of data.

3. Balloon kyphoplasty versus usual care

Pain (critical outcome)

Van Meirhaeghe (2013) reported pain with a VAS 0-10. At 1 month, the difference between the groups was most pronounced, with a mean (95% CI) of 3.52 (3.14 to 3.90) in the BKP group (N=149) versus 5.48 (5.08 to 5.87) in the control group (N=151), resulting in a difference of 1.96. At 3, 6, 12 and 24 months, the difference between the groups in favor of treatment was 1.59, 1.62, 0.98 and 0.83, respectively. The differences were not considered clinically relevant.

Quality of life (critical outcome)

Van Meirhaeghe (2013) did not report disease-specific QOL, but reported the physical component score SF-36 PCS (0-100, lower score indicates more disability). In addition, general QOL was assessed by EQ-5D (0–1). For PCS, all scores were in favor of the BKP group. At 1, 3, 6, 12 and 24 months, differences between the groups were 5.9, 4.5, 3.87, 2.1 and 2, respectively. The differences were not considered clinically relevant.

With QOL as assessed by EQ-5D, the most pronounced difference (i.e. 0.17) was reported at 1 month, with a mean (95% CI) of 0.54 (0.49 to 0.60) in the BKP group (N=149) versus 0.37 (0.31 to 0.42) in the control group (N=151). At 3, 6, 12 and 24 months, the differences between the groups in favor of treatment were 0.10, 0.13, 0.10 and 0.08, respectively. The differences were not considered clinically relevant.

Activities/limitations of daily living

Van Meirhaeghe (2013) reported disability with RMDQ (0 to 24). At 1 month, the difference between the groups was most pronounced, with a mean (95% CI) of 10.9 (9.9 to 11.8) in the BKP group (N=149) versus 15.1 (14.1 to 16.0) in the control group (N=151), resulting in a difference of 4.2. At 3, 6, 12 and 24 months, the differences between the groups in favor of treatment were 3.69, 3.05, 2.9 and 1.43, respectively. The differences were not considered clinically relevant.

Secondary fractures

Van Meirhaeghe (2013) reported 11/149 (7%) new fractures in the BKP group, of which 5 were considered possibly related to cement by local investigator. In the control group, 7/151 (5%) new fractures were observed. The risk difference of 0.03 (-0.03 to 0.08) was not considered clinically relevant.

Adverse events

Van Meirhaeghe (2013) reported adverse events within 30 days of surgery/enrollment and found 49/149 (33%) in the BKP group versus 55/151 (36%) in the control group. The risk difference of -0.04 (-0.14 to 0.07) was not considered clinically relevant. For serious adverse events within 30 days of surgery/enrollment, the study reported 24/149 (16%) in the BKP group versus 17/151 (11%) in the control group. The risk difference of 0.05 (-0.03 to 0.13) was not considered clinically relevant.

Participation (including work)

The outcome participation was not reported in the included publications.

Mortality

The outcome mortality was not reported in the included publications.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence regarding all outcome measures was based on a randomized controlled trial and therefore started at high.

For the outcome measures pain, disease-specific quality of life and activities/limitations in daily living, the level of evidence was downgraded to VERY LOW because of study limitations (risk of bias due to lack of blinding, considerable loss to follow-up, -2), the limited number of included patients (imprecision, -1) and publication bias (single study, sponsored, -1).

For the outcome measures secondary fractures and adverse events, the level of evidence was downgraded by 2 levels to VERY LOW because of study limitations (risk of bias due to considerable loss to follow-up, -1), the limited number of included patients (imprecision, -1) and publication bias (single study, sponsored, -1).

For the outcome measures participation and mortality, the level of evidence could not be determined due to a lack of data.

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question: What are the (un)favorable effects of percutaneous vertebroplasty or balloon kyphoplasty in patients aged 50 years or older with a symptomatic stable vertebral fracture, compared to a sham operation or usual care?

PICO 1

P: patients aged 50 years or older with a symptomatic stable vertebral fracture (bone edema in the fractured vertebra on MRI and local pain);

I: percutaneous vertebroplasty;

C: sham operation;

O: pain, quality of life, activities/limitations of daily living, secondary fractures, (other) adverse events, participation (including work), mortality.

PICO 2

P: patients aged 50 years or older with a symptomatic stable vertebral fracture (bone edema in the fractured vertebra on MRI and local pain);

I: percutaneous vertebroplasty;

C: usual care / conservative treatment;

O: pain, quality of life, activities/limitations of daily living, secondary fractures, (other) adverse events, participation (including work), mortality.

PICO 3

P: patients aged 50 years or older with a symptomatic stable vertebral fracture (bone edema in the fractured vertebra on MRI and local pain);

I: balloon kyphoplasty;

C: usual care / conservative treatment;

O: pain, quality of life, activities/limitations of daily living, secondary fractures, (other) adverse events, participation (including work), mortality.

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered pain and quality of life (QOL) as critical outcome measures for decision making; and activities/limitations of daily living, secondary fractures, complications and participation (including work) as important outcome measures for decision making.

The working group defined the outcome measure pain as quantified by a VAS score, NRS score, and/or use of pain medication. Most relevant time points for pain were considered 2 weeks, 3 months and 6 months after treatment. For quality of life, the osteoporosis-specific QUALEFFO was preferred over EQ5D. The working group did not define the other outcome measures a priori, but followed the definitions as used in the studies.

The working group defined for pain and QOL a 20% reduction of the maximum score as a minimal clinically important difference for the patient, 30% of the baseline score for RMDQ (Jordan, 2006), 9.5 points for ODI (Monticone, 2012), 25% for risk ratios and 0.5 for standardized mean differences.

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Embase and Ovid/Medline were searched with relevant search terms from 2017 until 23-6-2022. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 387 unique hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria: (1) randomized controlled trials or a meta-analysis thereof; (2) comparison between percutaneous vertebroplasty and sham operation or conservative treatment; (3) patients with at least one symptomatic stable vertebral fracture (inclusion criteria included presence of bone edema and local back pain). Thirty studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, 26 studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and two meta-analyses and two RCTs were included. In addition, one original RCT reported in a meta-analysis was analyzed to retrieve all relevant outcome measures.

Results

Five studies were included in the analysis of the literature. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- Buchbinder R, Johnston RV, Rischin KJ, Homik J, Jones CA, Golmohammadi K, Kallmes DF. Percutaneous vertebroplasty for osteoporotic vertebral compression fracture. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018 Apr 4;4(4):CD006349. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006349.pub3. Update in: Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018 Nov 06;11:CD006349. PMID: 29618171; PMCID: PMC6494647.

- Carli D, Venmans A, Lodder P, Donga E, van Oudheusden T, Boukrab I, Schoemaker K, Smeets A, Schonenberg C, Hirsch J, de Vries J, Lohle P. Vertebroplasty versus Active Control Intervention for Chronic Osteoporotic Vertebral Compression Fractures: The VERTOS V Randomized Controlled Trial. Radiology. 2023 Jul;308(1):e222535. doi: 10.1148/radiol.222535. PMID: 37462495.

- Jordan K, Dunn KM, Lewis M, Croft P. A minimal clinically important difference was derived for the Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire for low back pain. J Clin Epidemiol. 2006 Jan;59(1):45-52. Doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2005.03.018. Epub 2005 Nov 4. PMID: 16360560.

- Firanescu CE, de Vries J, Lodder P, Venmans A, Schoemaker MC, Smeets AJ, Donga E, Juttmann JR, Klazen CAH, Elgersma OEH, Jansen FH, Tielbeek AV, Boukrab I, Schonenberg K, van Rooij WJJ, Hirsch JA, Lohle PNM. Vertebroplasty versus sham procedure for painful acute osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures (VERTOS IV): 96andomized sham controlled clinical trial. BMJ. 2018 May 9;361:k1551. Doi: 10.1136/bmj.k1551. Erratum in: BMJ. 2018 Jul 4;362:k2937. Smeet AJ [corrected to Smeets AJ]. PMID: 29743284; PMCID: PMC5941218.

- Firanescu CE, Venmans A, de Vries J, Lodder P, Schoemaker MC, Smeets AJ, Donga E, Juttmann JR, Schonenberg K, Klazen CAH, Elgersma OEH, Jansen FH, Fransen H, Hirsch JA, Lohle PNM. Predictive Factors for Sustained Pain after (sub)acute Osteoporotic Vertebral Fractures. Combined Results from the VERTOS II and VERTOS IV Trial. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2022 Jun 9. Doi: 10.1007/s00270-022-03170-7. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 35680675.

- Klazen CA, Verhaar HJ, Lohle PN, Lampmann LE, Juttmann JR, Schoemaker MC, van Everdingen KJ, Muller AF, Mali WP, de Vries J. Clinical course of pain in acute osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2010 Sep;21(9):1405-9. Doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2010.05.018. PMID: 20800779.

- Li WS, Cai YF, Cong L. The Effect of Vertebral Augmentation Procedure on Painful OVCFs: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Global Spine J. 2022 Apr;12(3):515-525. Doi: 10.1177/2192568221999369. Epub 2021 Mar 11. PMID: 33706568; PMCID: PMC9121160.

- Mathis JM, Ortiz AO, Zoarski GH. Vertebroplasty versus kyphoplasty: a comparison and contrast. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2004 May;25(5):840-5. PMID: 15140732; PMCID: PMC7974486.

- Nieuwenhuijse MJ, van Erkel AR, Dijkstra PD. Percutaneous vertebroplasty for subacute and chronic painful osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures can safely be undertaken in the first year after the onset of symptoms. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2012 Jun;94(6):815-20. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.94B6.28368. PMID: 22628598.

- Pron G, Hwang M, Smith R, Cheung A, Murphy K. Cost-effectiveness studies of vertebral augmentation for osteoporotic vertebral fractures: a systematic review. Spine J. 2022 Aug;22(8):1356-1371. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2022.02.013. Epub 2022 Mar 5. PMID: 35257838.

- Tantawy MF. Efficacy and safety of percutaneous vertebroplasty for osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures. Journal of Orthopaedics, Trauma and Rehabilitation. 2022 Jun;29(1):22104917221082310.

- Van Meirhaeghe J, Bastian L, Boonen S, Ranstam J, Tillman JB, Wardlaw D; FREE investigators. A randomized trial of balloon kyphoplasty and nonsurgical management for treating acute vertebral compression fractures: vertebral body kyphosis correction and surgical parameters. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2013 May 20;38(12):971-83. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31828e8e22. PMID: 23446769; PMCID: PMC3678891.

- Voormolen MH, van Rooij WJ, Sluzewski M, van der Graaf Y, Lampmann LE, Lohle PN, Juttmann JR. Pain response in the first trimester after percutaneous vertebroplasty in patients with osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures with or without bone marrow edema. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2006 Aug;27(7):1579-85. PMID: 16908585; PMCID: PMC7977523.

Evidence tabellen

Evidence table for systematic review of RCTs and observational studies (intervention studies)

Research questions:

1. What are the benefits and harms of percutaneous vertebroplasty in patients aged 50 years or older with a symptomatic stable vertebral fracture, compared with sham operation?

2. What are the benefits and harms of percutaneous vertebroplasty in patients aged 50 years or older with a symptomatic stable vertebral fracture, compared with usual care?

3. What are the benefits and harms of balloon kyphoplasty in patients aged 50 years or older with a symptomatic stable vertebral fracture, compared with usual care?

Evidence table for intervention studies (randomized controlled trials and non-randomized observational studies [cohort studies, case-control studies, case series])

Research questions:

1. What are the benefits and harms of percutaneous vertebroplasty in patients aged 50 years or older with a symptomatic stable vertebral fracture, compared with sham operation?

2. What are the benefits and harms of percutaneous vertebroplasty in patients aged 50 years or older with a symptomatic stable vertebral fracture, compared with usual care?

3. What are the benefits and harms of balloon kyphoplasty in patients aged 50 years or older with a symptomatic stable vertebral fracture, compared with usual care?

Table of quality assessment for systematic reviews of RCTs and observational studies

Based on AMSTAR checklist (Shea et al.; 2007, BMC Methodol 7: 10; doi:10.1186/1471-2288-7-10) and PRISMA checklist (Moher et al 2009, PLoS Med 6: e1000097; doi:10.1371/journal.pmed1000097)

|

Study

First author, year |

Appropriate and clearly focused question?1

Yes/no/unclear |

Comprehensive and systematic literature search?2

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of included and excluded studies?3

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of relevant characteristics of included studies?4

Yes/no/unclear |

Appropriate adjustment for potential confounders in observational studies?5

Yes/no/unclear/notapplicable |

Assessment of scientific quality of included studies?6

Yes/no/unclear |

Enough similarities between studies to make combining them reasonable?7

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential risk of publication bias taken into account?8

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential conflicts of interest reported?9

Yes/no/unclear |

|

Li, 2022 |

Yes |

Yes |

No Excluded studies were not.described. |

Yes |

N/A |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Unclear Not specified for included studies |

|

Buchbinder, 2018 |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

N/A |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

- Research question (PICO) and inclusion criteria should be appropriate and predefined

- Search period and strategy should be described; at least Medline searched; for pharmacological questions at least Medline + EMBASE searched

- Potentially relevant studies that are excluded at final selection (after reading the full text) should be referenced with reasons

- Characteristics of individual studies relevant to research question (PICO), including potential confounders, should be reported

- Results should be adequately controlled for potential confounders by multivariate analysis (not applicable for RCTs)

- Quality of individual studies should be assessed using a quality scoring tool or checklist (Jadad score, Newcastle-Ottawa scale, risk of bias table etc.)

- Clinical and statistical heterogeneity should be assessed; clinical: enough similarities in patient characteristics, intervention and definition of outcome measure to allow pooling? For pooled data: assessment of statistical heterogeneity using appropriate statistical tests (e.g. Chi-square, I2)?

- An assessment of publication bias should include a combination of graphical aids (e.g., funnel plot, other available tests) and/or statistical tests (e.g., Egger regression test, Hedges-Olken). Note: If no test values or funnel plot included, score “no”. Score “yes” if mentions that publication bias could not be assessed because there were fewer than 10 included studies.

- Sources of support (including commercial co-authorship) should be reported in both the systematic review and the included studies. Note: To get a “yes,” source of funding or support must be indicated for the systematic review AND for each of the included studies.

Risk of bias table for intervention studies (randomized controlled trials; based on Cochrane risk of bias tool and suggestions by the CLARITY Group at McMaster University)

Research questions:

1. What are the benefits and harms of percutaneous vertebroplasty in patients aged 50 years or older with a symptomatic stable vertebral fracture, compared with sham operation?

2. What are the benefits and harms of percutaneous vertebroplasty in patients aged 50 years or older with a symptomatic stable osteoporotic vertebral fracture, compared with usual care?

3. What are the benefits and harms of balloon kyphoplasty in patients aged 50 years or older with a symptomatic stable vertebral fracture, compared with usual care?

|

Study reference

(first author, publication year) |

Was the allocation sequence adequately generated?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was the allocation adequately concealed?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Blinding: Was knowledge of the allocated interventions adequately prevented?

Were patients blinded?

Were healthcare providers blinded?

Were data collectors blinded?

Were outcome assessors blinded?

Were data analysts blinded? Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was loss to follow-up (missing outcome data) infrequent?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Are reports of the study free of selective outcome reporting?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was the study apparently free of other problems that could put it at a risk of bias?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Overall risk of bias If applicable/necessary, per outcome measure

LOW Some concerns HIGH

|

|

Tantawi, 2022 |

Definitely yes;

Reason: Randomization was done using random number table preferred by the statistician to determine to which group the patient was assigned. |

No information |

Probably no;

Reason: No blinding reported |

Definitely yes;

Reason: There was no loss to follow-up. |

Probably yes;

Reason: the were no indications of selective outcome reporting |

Probably yes;

Reason: No other problems noted |

Some concerns due to lack of blinding |

|

Firanescu, 2018 |

Definitely yes;

Participants were randomised by computer in a block size of six, randomisation ratio 1:1, and a maximum sample size of 84 for each participating centre. |

Definitely yes;

Each participant received two stab incisions at the level of the vertebral body, after which the sealed randomisation envelope was opened. |

Definitely yes;

Participants, internists, and outcome assessors were blinded and remained so during the 12 months’ follow-up. It was not possible to mask the interventional and diagnostic radiologists. |

Definitely yes;

Loss to follow-up was limited and similar between the groups. |

Probably yes;

Reason: the were no indications of selective outcome reporting |

Probably yes;

Reason: No other problems noted |

LOW

for the outcomes of interest |

|

Van Meirhaeghe, 2013 |

Definitely yes;

Computer-generated randomisation was stratified by sex, aetiology, current treatment with corticosteroids, and any bisphosphonate treatment within 12 months before enrolment. A permuted block randomisation (stratifi ed as indicated) was generated before the study start by Advanced Research Associates, (Mountain View, CA, USA), the statistical contract research organisation, by use of SAS PROC PLAN. |

No information |

Definitely no;

The intervention was not blinded. |

Probably no;

Not specified in paper, but in other publications from the FREE trial, loss to follow-up was considerable. |

Probably yes;

Reason: the were no indications of selective outcome reporting |

Probably no;

The study sponsor contributed to the study design, data monitoring, and reporting of results, and paid for statistical analysis, core laboratory services and open access of article |

HIGH |

Randomization: generation of allocation sequences have to be unpredictable, for example computer generated random-numbers or drawing lots or envelopes. Examples of inadequate procedures are generation of allocation sequences by alternation, according to case record number, date of birth or date of admission.

Allocation concealment: refers to the protection (blinding) of the randomization process. Concealment of allocation sequences is adequate if patients and enrolling investigators cannot foresee assignment, for example central randomization (performed at a site remote from trial location). Inadequate procedures are all procedures based on inadequate randomization procedures or open allocation schedules..

Blinding: neither the patient nor the care provider (attending physician) knows which patient is getting the special treatment. Blinding is sometimes impossible, for example when comparing surgical with non-surgical treatments, but this should not affect the risk of bias judgement. Blinding of those assessing and collecting outcomes prevents that the knowledge of patient assignment influences the process of outcome assessment or data collection (detection or information bias). If a study has hard (objective) outcome measures, like death, blinding of outcome assessment is usually not necessary. If a study has “soft” (subjective) outcome measures, like the assessment of an X-ray, blinding of outcome assessment is necessary. Finally, data analysts should be blinded to patient assignment to prevents that knowledge of patient assignment influences data analysis.

Lost to follow-up: If the percentage of patients lost to follow-up or the percentage of missing outcome data is large, or differs between treatment groups, or the reasons for loss to follow-up or missing outcome data differ between treatment groups, bias is likely unless the proportion of missing outcomes compared with observed event risk is not enough to have an important impact on the intervention effect estimate or appropriate imputation methods have been used.

Selective outcome reporting: Results of all predefined outcome measures should be reported; if the protocol is available (in publication or trial registry), then outcomes in the protocol and published report can be compared; if not, outcomes listed in the methods section of an article can be compared with those whose results are reported.

Other biases: Problems may include: a potential source of bias related to the specific study design used (e.g. lead-time bias or survivor bias); trial stopped early due to some data-dependent process (including formal stopping rules); relevant baseline imbalance between intervention groups; claims of fraudulent behavior; deviations from intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis; (the role of the) funding body (see also downgrading due to industry funding https://kennisinstituut.viadesk.com/do/document?id=1607796-646f63756d656e74). Note: The principles of an ITT analysis implies that (a) participants are kept in the intervention groups to which they were randomized, regardless of the intervention they actually received, (b) outcome data are measured on all participants, and (c) all randomized participants are included in the analysis.

Overall judgement of risk of bias per study and per outcome measure, including predicted direction of bias (e.g. favors experimental, or favors comparator). Note: the decision to downgrade the certainty of the evidence for a particular outcome measure is taken based on the body of evidence, i.e. considering potential bias and its impact on the certainty of the evidence in all included studies reporting on the outcome.

Table of excluded studies

|

Reference |

Reason for exclusion |

|

Diamond T, Clark W, Bird P, Gonski P, Barnes E, Gebski V. Early vertebroplasty within 3 weeks of fracture for acute painful vertebral osteoporotic fractures: subgroup analysis of the VAPOUR trial and review of the literature. Eur Spine J. 2020 Jul;29(7):1606-1613. doi: 10.1007/s00586-020-06362-2. Epub 2020 Mar 13. PMID: 32170438. |

Subgroup analysis from RCT |

|

Firanescu CE, de Vries J, Lodder P, Schoemaker MC, Smeets AJ, Donga E, Juttmann JR, Klazen CAH, Elgersma OEH, Jansen FH, van der Horst I, Blonk M, Venmans A, Lohle PNM. Percutaneous Vertebroplasty is no Risk Factor for New Vertebral Fractures and Protects Against Further Height Loss (VERTOS IV). Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2019 Jul;42(7):991-1000. doi: 10.1007/s00270-019-02205-w. Epub 2019 Apr 2. PMID: 30941490. |

No relevant outcomes |

|

Martinez-Ferrer A, Blasco J, Carrasco JL, Macho JM, Román LS, López A, Monegal A, Guañabens N, Peris P. Risk factors for the development of vertebral fractures after percutaneous vertebroplasty. J Bone Miner Res. 2013 Aug;28(8):1821-9. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1899. PMID: 23427068. |

No relevant outcomes |

|

Clark W, Bird P, Gonski P, Diamond TH, Smerdely P, McNeil HP, Schlaphoff G, Bryant C, Barnes E, Gebski V. Safety and efficacy of vertebroplasty for acute painful osteoporotic fractures (VAPOUR): a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2016 Oct 1;388(10052):1408-1416. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31341-1. Epub 2016 Aug 17. Erratum in: Lancet. 2017 Feb 11;389(10069):602. PMID: 27544377. |

Inclusion criteria not in line with PICO |

|

Leali PT, Solla F, Maestretti G, Balsano M, Doria C. Safety and efficacy of vertebroplasty in the treatment of osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures: a prospective multicenter international randomized controlled study. Clin Cases Miner Bone Metab. 2016 Sep-Dec;13(3):234-236. doi: 10.11138/ccmbm/2016.13.3.234. Epub 2017 Feb 10. PMID: 28228788; PMCID: PMC5318178. |

insufficient information about study population and procedures |

|

Klazen CA, Lohle PN, de Vries J, Jansen FH, Tielbeek AV, Blonk MC, Venmans A, van Rooij WJ, Schoemaker MC, Juttmann JR, Lo TH, Verhaar HJ, van der Graaf Y, van Everdingen KJ, Muller AF, Elgersma OE, Halkema DR, Fransen H, Janssens X, Buskens E, Mali WP. Vertebroplasty versus conservative treatment in acute osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures (Vertos II): an open-label randomised trial. Lancet. 2010 Sep 25;376(9746):1085-92. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60954-3. Epub 2010 Aug 9. PMID: 20701962. |

Reported in meta-analysis |

|

Xiao Q, Zhao Y, Qu Z, Zhang Z, Wu K, Lin X. Association Between Bone Cement Augmentation and New Vertebral Fractures in Patients with Osteoporotic Vertebral Compression Fractures: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. World Neurosurg. 2021 Sep;153:98-108.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2021.06.023. Epub 2021 Jun 15. PMID: 34139353. |

more recent/complete meta-analysis used |

|

Zhang L, Zhai P. A Comparison of Percutaneous Vertebroplasty Versus Conservative Treatment in Terms of Treatment Effect for Osteoporotic Vertebral Compression Fractures: A Meta-Analysis. Surg Innov. 2020 Feb;27(1):19-25. doi: 10.1177/1553350619869535. Epub 2019 Aug 18. PMID: 31423902. |

more recent/complete meta-analysis used |

|

Zhao S, Xu CY, Zhu AR, Ye L, Lv LL, Chen L, Huang Q, Niu F. Comparison of the efficacy and safety of 3 treatments for patients with osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures: A network meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017 Jun;96(26):e7328. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000007328. PMID: 28658144; PMCID: PMC5500066. |

Network meta-analysis |

|

Pron G, Hwang M, Smith R, Cheung A, Murphy K. Cost-effectiveness studies of vertebral augmentation for osteoporotic vertebral fractures: a systematic review. Spine J. 2022 Aug;22(8):1356-1371. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2022.02.013. Epub 2022 Mar 5. PMID: 35257838. |

No outcomes as defined in PICO |

|

Zhang H, Xu C, Zhang T, Gao Z, Zhang T. Does Percutaneous Vertebroplasty or Balloon Kyphoplasty for Osteoporotic Vertebral Compression Fractures Increase the Incidence of New Vertebral Fractures? A Meta-Analysis. Pain Physician. 2017 Jan-Feb;20(1):E13-E28. PMID: 28072794. |

more recent/complete meta-analysis used |

|

Fan B, Wei Z, Zhou X, Lin W, Ren Y, Li A, Shi G, Hao Y, Liu S, Zhou H, Feng S. Does vertebral augmentation lead to an increasing incidence of adjacent vertebral failure? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Surg. 2016 Dec;36(Pt A):369-376. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2016.11.082. Epub 2016 Nov 15. PMID: 27871806. |

more recent/complete meta-analysis used |

|

Luo W, Cui C, Pourtaheri S, Garfin S. Efficacy of Vertebral Augmentation for Vertebral Compression Fractures: A Review of Meta-Analyses. Spine Surg Relat Res. 2018 Apr 7;2(3):163-168. doi: 10.22603/ssrr.2017-0089. PMID: 31440664; PMCID: PMC6698519. |

review of meta-analyses, no extractable data |

|

Shi MM, Cai XZ, Lin T, Wang W, Yan SG. Is there really no benefit of vertebroplasty for osteoporotic vertebral fractures? A meta-analysis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012 Oct;470(10):2785-99. doi: 10.1007/s11999-012-2404-6. Epub 2012 Jun 23. PMID: 22729693; PMCID: PMC3442000. |

more recent meta-analysis used |

|

Zhai G, Li A, Liu B, Lv D, Zhang J, Sheng W, Yang G, Gao Y. A meta-analysis of the secondary fractures for osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures after percutaneous vertebroplasty. Medicine (Baltimore). 2021 Apr 23;100(16):e25396. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000025396. PMID: 33879670; PMCID: PMC8078370. |

more recent/complete meta-analysis used |

|

Hinde K, Maingard J, Hirsch JA, Phan K, Asadi H, Chandra RV. Mortality Outcomes of Vertebral Augmentation (Vertebroplasty and/or Balloon Kyphoplasty) for Osteoporotic Vertebral Compression Fractures: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Radiology. 2020 Apr;295(1):96-103. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020191294. Epub 2020 Feb 18. PMID: 32068503. |

more recent/complete meta-analysis used |

|

Zuo XH, Zhu XP, Bao HG, Xu CJ, Chen H, Gao XZ, Zhang QX. Network meta-analysis of percutaneous vertebroplasty, percutaneous kyphoplasty, nerve block, and conservative treatment for nonsurgery options of acute/subacute and chronic osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures (OVCFs) in short-term and long-term effects. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018 Jul;97(29):e11544. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000011544. PMID: 30024546; PMCID: PMC6086478. |

Network meta-analysis |

|

Sun HB, Shan JL, Tang H. Percutaneous vertebral augmentation for osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures will increase the number of subsequent fractures at adjacent vertebral levels: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2021 Aug;25(16):5176-5188. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_202108_26531. PMID: 34486692. |

more recent/complete meta-analysis used |

|

Láinez Ramos-Bossini AJ, López Zúñiga D, Ruiz Santiago F. Percutaneous vertebroplasty versus conservative treatment and placebo in osteoporotic vertebral fractures: meta-analysis and critical review of the literature. Eur Radiol. 2021 Nov;31(11):8542-8553. doi: 10.1007/s00330-021-08018-1. Epub 2021 May 7. PMID: 33963449. |

more recent/complete meta-analysis used |

|

Xie L, Zhao ZG, Zhang SJ, Hu YB. Percutaneous vertebroplasty versus conservative treatment for osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures: An updated meta-analysis of prospective randomized controlled trials. Int J Surg. 2017 Nov;47:25-32. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2017.09.021. Epub 2017 Sep 20. PMID: 28939236. |

more recent/complete meta-analysis used |

|

Lou S, Shi X, Zhang X, Lyu H, Li Z, Wang Y. Percutaneous vertebroplasty versus non-operative treatment for osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Osteoporos Int. 2019 Dec;30(12):2369-2380. doi: 10.1007/s00198-019-05101-8. Epub 2019 Aug 3. PMID: 31375875. |

more recent/complete meta-analysis used |

|

Beall D, Lorio MP, Yun BM, Runa MJ, Ong KL, Warner CB. Review of Vertebral Augmentation: An Updated Meta-analysis of the Effectiveness. Int J Spine Surg. 2018 Aug 15;12(3):295-321. doi: 10.14444/5036. PMID: 30276087; PMCID: PMC6159665. |

more recent/complete meta-analysis used |

|

Halvachizadeh S, Stalder AL, Bellut D, Hoppe S, Rossbach P, Cianfoni A, Schnake KJ, Mica L, Pfeifer R, Sprengel K, Pape HC. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of 3 Treatment Arms for Vertebral Compression Fractures: A Comparison of Improvement in Pain, Adjacent-Level Fractures, and Quality of Life Between Vertebroplasty, Kyphoplasty, and Nonoperative Management. JBJS Rev. 2021 Oct 25;9(10). doi: 10.2106/JBJS.RVW.21.00045. PMID: 34695056. |

more recent/complete meta-analysis used |

|

Pourtaheri S, Luo W, Cui C, Garfin S. Vertebral Augmentation is Superior to Nonoperative Care at Reducing Lower Back Pain for Symptomatic Osteoporotic Compression Fractures: A Meta-Analysis. Clin Spine Surg. 2018 Oct;31(8):339-344. doi: 10.1097/BSD.0000000000000670. PMID: 29901504. |

more recent/complete meta-analysis used |

|

Piazzolla A, Bizzoca D, Solarino G, Moretti L, Moretti B. Vertebral fragility fractures: clinical and radiological results of augmentation and fixation-a systematic review of randomized controlled clinical trials. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2020 Jul;32(7):1219-1232. doi: 10.1007/s40520-019-01289-1. Epub 2019 Aug 30. PMID: 31471888. |

more recent/complete meta-analysis used |

|

Firanescu CE, Venmans A, de Vries J, Lodder P, Schoemaker MC, Smeets AJ, Donga E, Juttmann JR, Schonenberg K, Klazen CAH, Elgersma OEH, Jansen FH, Fransen H, Hirsch JA, Lohle PNM. Predictive Factors for Sustained Pain after (sub)acute Osteoporotic Vertebral Fractures. Combined Results from the VERTOS II and VERTOS IV Trial. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2022 Jun 9. doi: 10.1007/s00270-022-03170-7. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 35680675. |

original publications/more complete meta-analysis used |

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Publicatiedatum : 22-04-2024

Beoordeeld op geldigheid : 18-04-2024

Algemene gegevens

De ontwikkeling van deze richtlijnmodule werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten (www.demedischspecialist.nl/kennisinstituut) en werd gefinancierd uit de Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS). De financier heeft geen enkele invloed gehad op de inhoud van de richtlijnmodule.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijnmodule is in 2022 een multidisciplinaire werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen (zie hiervoor de Samenstelling van de werkgroep) die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor patiënten met symptomatishce stabiele wervelfracturen.

Werkgroep

- prof. dr. P.C. (Paul) Willems, orthopedisch chirurg, Maastricht UMC+, Maastricht, NOV (voorzitter)

- dr. M.J. (Marc) Nieuwenhuijse, orthopedisch chirurg, Amphia Ziekenhuis, Breda, NOV

- dr. H.C.A. (Harm) Graat, orthopedisch chirurg, Noordwest Ziekenhuisgroep, NOV

- dr. E. (Eva) Jacobs, orthopedisch chirurg, Maastricht UMC+, Maastricht, NOV

- dr. A.G. (Annegreet) Vlug, internist-endocrinoloog Jan van Goyen Medisch Centrum en Onze Lieve Vrouwen Gasthuis in Amsterdam, NIV

- dr. C.A.H (Caroline) Klazen, Radioloog, Medisch spectrum Twente, Enschede, NVvR

- prof. dr. W.F. (Willem) Lems, reumatoloog, Amsterdam UMC, Amsterdam, NVR

- dr. H. (Hanna) Willems, Klinisch geriater, Amsterdam UMC, Amsterdam, NVKG

- drs. J. (Joost) Hoekstra, Traumachirurg UMCG, Groningen, NVvH

- drs. E.L.S. (Annelies) Kievit, anesthesioloog-pijnspecialist, Medisch Centrum Leeuwarden, NVA

- drs. C.F.M.G. (Christianne) Bessems, geriatriefysiotherapeut, Bronzwaer Fysiotherapie, Maastricht, KNGF

- H.J.G. (Harry) van den Broek, patiëntvertegenwoordiger Osteoporose Vereniging, Den Haag, Osteoporose Vereniging

Klankbordgroep

- E.E. (Erna) Hiddink, Oefentherapeut Mensendieck, Opella, VvOCM

- H.A.A. (Riekie) van Beers, verpleegkundig specialist, Amphia ziekenhuis, Breda, V&VN

- Dr. I. (Iris) Ketel, wetenschappelijk medewerker NHG, Nederlands Huisartsen Genootschap, Utrecht, NHG

- Dr. M.C. (Marloes) Minnaard, wetenschappelijk medewerker NHG, Nederlands Huisartsen Genootschap, Utrecht, NHG

Met ondersteuning van

Dr. M.S. (Matthijs) Ruiter, senior adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

Belangenverklaringen

De Code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling is gevolgd. Alle werkgroepleden hebben schriftelijk verklaard of zij in de laatste drie jaar directe financiële belangen (betrekking bij een commercieel bedrijf, persoonlijke financiële belangen, onderzoeksfinanciering) of indirecte belangen (persoonlijke relaties, reputatiemanagement) hebben gehad. Gedurende de ontwikkeling of herziening van een module worden wijzigingen in belangen aan de voorzitter doorgegeven. De belangenverklaring wordt opnieuw bevestigd tijdens de commentaarfase.

Een overzicht van de belangen van werkgroepleden en het oordeel over het omgaan met eventuele belangen vindt u in onderstaande tabel. De ondertekende belangenverklaringen zijn op te vragen bij het secretariaat van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

|

Werkgroeplid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

Bessems |