Drainbeleid na een anatomische longresectie (afkapwaardes)

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is de plaats van de hoeveelheid fluid drainage als verwijdercriterium voor een thoraxdrain na een anatomische longresectie?

Aanbeveling

Verwijder een thoraxdrain vanaf een afkapwaarde van < 450 ml/ 24 uur.

Overweeg een lagere afkapwaarde bij patiënten met een toegenomen risico op een complicatie.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Er is een literatuuronderzoek verricht naar het wel of niet hanteren van een bepaalde afkapwaarde om een thoraxdrain te verwijderen in patiënten die een anatomische longresectie hebben ondergaan in het kader van een curatieve behandeling. Er zijn geen studies gevonden die een vergelijking maken tussen het wel of niet hanteren van een afkapwaarde, maar er kwamen wel een aantal studies naar boven die verschillende afkapwaarden met elkaar vergeleken voor het verwijderen van een thoraxdrain.

Uit deze studies kwam naar voren dat het hanteren van een hogere afkapwaarde voor het verwijderen van de thoraxdrain ervoor zorgt dat de thoraxdrain eerder verwijderd kan worden (Motono, 2019; Xie, 2015, Zhang, 2018). De bewijskracht hiervoor is echter laag. Dit komt doordat de studies die dit hebben onderzocht niet geblindeerd zijn en doordat het betrouwbaarheidsinterval de grens voor klinische relevantie overschrijdt.

Op basis van de belangrijkste uitkomstmaten komt naar voren dat de lengte van ziekenhuisopname korter wordt (redelijke bewijskracht), maar dat het aantal complicaties na het verwijderen van de thoraxdrain mogelijk wel hoger is (erg lage bewijskracht) bij het hanteren van een afkapwaarde van 300 ml/dag of zelfs 450 ml/dag. Ook hier is een van de belangrijkste beperkingen van het onderzoek dat de studies niet geblindeerd zijn en dat het optreden van een complicatie zeldzaam is waardoor je eigenlijk een veel grotere onderzoekspopulatie nodig hebt om dergelijke conclusies te kunnen trekken.

Een van de belangrijkste barrières in herstel na anatomische longresecties is de aanwezigheid van een thoraxdrain. Aangezien langere drainageduur geassocieerd is met pijn, verminderde longfunctie, verminderd mobiliseren van patiënten en geassocieerd is met langere opnameduur, is het van groot belang een zo kort mogelijke drainageduur na te streven (Refai, 2012).

Om een goed onderbouwde beslissing te maken wat betreft het te hanteren afkappunt zijn ook overige argumenten belangrijk om in overweging mee te nemen. In de praktijk wordt meestal een thoraxdrainproductie onder 450 ml per 24 uur als grens genomen om de drain veilig te verwijderen. Belangrijk hierbij is het aspect van het vocht (bloedig, chyleus, helder, etc) wat kan duiden op een mogelijke complicatie of risico op een complicatie. Hierdoor kan het zijn dat de thoraxdrain langer in situ gelaten wordt. Daarnaast kunnen er argumenten zijn om de thoraxdrain te verwijderen bij een lagere productie (bijvoorbeeld verwachte lagere resorptiecapaciteit van de pleura (radiotherapie, adhesies).

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

Om het herstel van de patiënt te bevorderen is het van belang om de thoraxdrain zo snel mogelijk te verwijderen. Zoals eerder genoemd, gaat een langere drainageduur gepaard met pijn, verminderde longfunctie en verminderd mobiliseren van patiënten (Refai, 2012). Dit zorgt er uiteindelijk voor dat een patiënt langer in het ziekenhuis ligt.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

Er zijn geen studies gevonden die de kosten-effectiviteit onderzoeken wat betreft het hanteren van de verschillende afkapwaardes. Echter, een kortere opnameduur resulteert in significante kostenreductie tenzij het aantal complicaties waarvoor heringrepen of heropnames nodig zijn deze kostenreductie teniet zouden doen.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

In de dagelijkse praktijk worden al wisselende waarden in een brede range van 200 ml tot 450 ml per 24uur gehanteerd, hierom verwacht de werkgroep geen problemen wat betreft de aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie van de aanbeveling.

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

Het verwijderen van een thoraxdrain na een anatomische longresectie bij een vochtproductie van 450 ml/ 24 uur en lager is veilig, en zorgt voor een kortere drainage duur dan wanneer een drempel van 200 ml/ 24 uur gekozen wordt. Er lijkt geen significant verschil in aantal complicaties op te treden door het kiezen van 450 ml/ 24 uur in plaats van 200 ml/ 24 uur. De bewijskracht van de beschikbare literatuur is laag tot matig. Daarom is een afweging per individuele patient noodzakelijk, en dient rekening te worden gehouden met het aspect van het drainagevocht (o.a. de aanwezigheid van bloed), trend van productie, en patiënt-gerelateerde factoren.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Er is weinig wetenschappelijke onderbouwing voor optimaal drainbeleid na anatomische longresecties, wat resulteert in grote praktijkvariatie, o.a. in het aantal thoraxdrains, de duur en manier van drainage (zuigen, waterslot, digitaal). Daarnaast is er behoefte aan uniforme criteria waarop besloten kan worden om een drain te verwijderen.

De praktijk is erg wisselend t.a.v. de maximale vochtproductie na een anatomische longoperatie waarop een thoraxdrain veilig verwijderd kan worden. Het is de vraag of het überhaupt nodig is om een afkappunt te hanteren en zo ja, wat dan de juiste waarde hiervoor is.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

Chest tube duration (critical)

|

Low GRADE |

Applying a higher threshold (300 or 450 mL/day) for chest tube removal may decrease the chest tube duration when compared to a lower threshold (200 ml/day) for chest tube removal in patients who underwent an anatomical lung resection as part of a curative treatment. Source: Motono, 2019; Xie, 2015, Zhang, 2018 |

Complications (important)

|

Very Low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of applying a higher threshold (300 or 450 ml/day) for chest tube removal on the number of complications when compared with a lower threshold (200 ml/day) for chest tube removal in patients who underwent an anatomical lung resection as part of a curative treatment. Source: Motono, 2019; Xie, 2015, Zhang, 2018 |

Length of hospital stay (important)

|

Moderate GRADE |

Applying a higher threshold (300 or 450 ml/day) for chest tube removal likely decreases the length of hospital stay when compared to a lower threshold (200 ml/day) for chest tube removal in patients who underwent an anatomical lung resection as part of a curative treatment. Source: Xie, 2015, Zhang, 2018 |

Re-interventions, quality of life

|

No GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding the effect of not applying a threshold (or a higher threshold) for chest tube removal on re-interventions and quality of life when compared to applying a threshold (<250 ml/day) for chest tube removal in patients who underwent an anatomical lung resection as part of a curative treatment. |

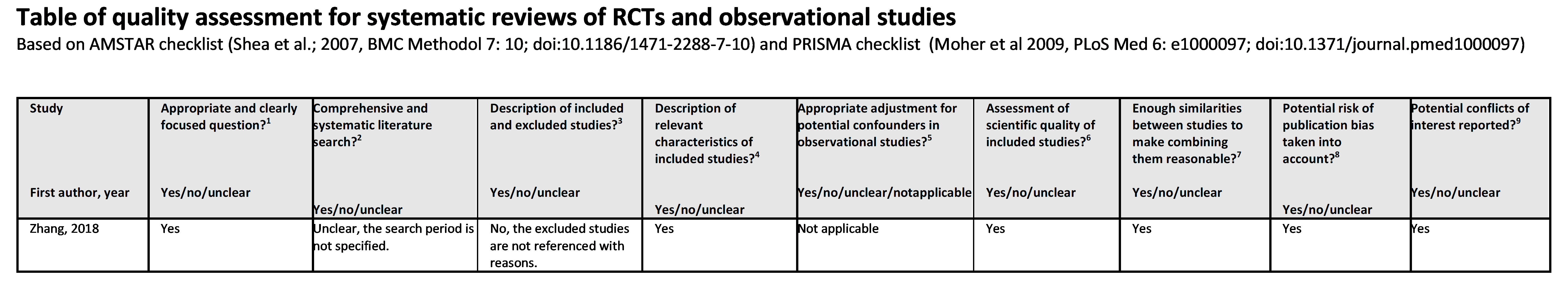

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

Zhang (2018) conducted a meta-analysis of clinical studies comparing the efficacy of a volume threshold of 300 ml/day before removing a chest tube versus 100 ml/day in patients with a lobectomy. They systematically searched multiple databases (Cochrane Library, PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, CNKI, Wanfang, CBMdisc and Google Scholar). The search period is not specified. All published RCTs comparing volume thresholds of 100 and 300 ml/day before removing a chest tube after pulmonary lobectomy or bilobectomy were considered eligible for the meta-analysis. Exclusion criteria are reported in the evidence table. In total, 5 trials were included comprising 301 patients who had their chest tube removed with a threshold of < 100 ml/day, and 314 patients who had their chest tube removed with a threshold of < 300 ml/day. Outcome measures included in this meta-analysis were duration of chest tube drainage, hospital stay, rate recurrent pleural fluid, the need thoracentesis after removing chest tube, and atelectasis. The meta-analysis was performed in RevMan software, using fixed-effects models if there was no statistical significant heterogeneity (P≥0.10, I² < 50%) and the random-effects models if there was significant heterogeneity P<0.10, I² > 50%). The risk of bias for the included studies was assessed by two independent reviewers using the Cochrane ‘Risk of bias’ tool. The duration of follow-up is not reported.

Motono (2019) performed a prospective randomized single-blind clinical study to evaluate the volume threshold for chest tube removal after pulmonary resection. The study included patients who underwent lobectomy and mediastinal lymphadenectomy, without bleeding, chylothorax, air leakage, or thoracic infection at 2 days after surgery. Patients were excluded if they were younger than 19 years of age and older than 85 years of age, underwent lobectomy with chest wall resection, or underwent pneumonectomy. In total, 70 patients met the inclusion criteria and were randomized at postoperative day 2, with 35 patients assigned to the high group (<450 ml/24 h), and 35 patients assigned to the low group (<200 ml/24h). The reported outcome measures were complications and drainage time. The duration of follow-up is not reported.

Xie (2015) performed a prospective randomized single-blind clinical study to evaluate the volume threshold for chest tube removal following video-assisted thoracoscopic surgical (VATS) lobectomy. The study included patients with non-small-cell lung cancer who underwent elective lobectomy or bilobectomy through VATS with two incisions. The exclusion criteria included intrapericardial resections and lobectomies with chest wall resections and those with nephritic syndrome, chronic renal failure, heart failure and cirrhosis. Patients with adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events, prolonged air leakage (i.e., > 7 days) and a densely bloody, purulent and cloudy pleural effusion were also excluded. In total, 150 patients were included in the analysis and randomly divided into three groups: 49 patients whose chest tubes were removed at a drainage volume of <150 ml/day, 50 patients with their chest tubes removed at a drainage volume of < 300 ml/day, and 51 patients with their chest tubes removed at a drainage volume of <450 ml/day. As the research question of this module concerns whether to apply a threshold, we only included the comparison of <150 ml/day versus <450 ml/day. The reported outcome measures were complications, postoperative hospital stay, and drainage time. The duration of follow-up is not reported.

Results

Chest tube duration (critical)

The outcome measure chest tube duration is reported in three studies (Motono, 2019; Xie, 2015; Zhang, 2018). Zhang (2018) reported the chest tube duration in hours, while Monoto (2019) and Xie (2015) reported the chest tube duration in days. Therefore, the results are presented separately.

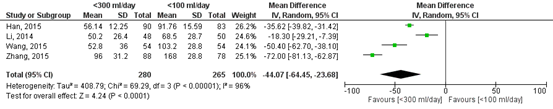

Figure 1 shows the pooled result of the studies included in Zhang (2018) who reported the chest tube duration in hours for patients with a threshold of <300 ml/day (n=280) versus <100 ml/day (n=265). The pooled mean difference was -44.07 hours (95%CI to -64.45 to

-23.68) in favour of the highest threshold (<300 ml/day). This difference is considered clinically relevant.

Figure 1. Forest plot of the chest tube duration (in hours) after surgery.

Z: p-value of the pooled effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval.

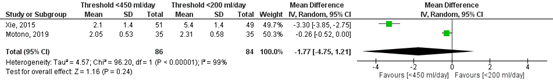

Figure 2 shows the pooled result of the studies who reported the chest tube duration in days (Monoto, 2019; Xie, 2015) with a threshold of <450 ml/day (n=86) versus <200 ml/day (n=84). The pooled mean difference in chest tube duration was -1.77 day (95%CI -4.75 to 1.21) in favour of the highest threshold (<450 ml/day). This difference is considered clinically relevant.

Figure 2. Forest plot of the chest tube duration (in days) after surgery.

Z: p-value of the pooled effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval.

Re-interventions (critical)

None of the included studies reported this outcome measure.

Complications (important)

The outcome measure complications is reported in three studies (Motono, 2019; Xie, 2015; Zhang, 2018). Zhang (2018) reported a pooled analysis of the occurrence of the recurrence of pleural fluid, atelectatis, and thoracentesis. Motono (2019) also reported the occurrence of thoracentesis and was included in the meta-analysis. Xie (2015) also reported the occurrence of re-accumulation of pleural fluid en was included in the meta-analysis.

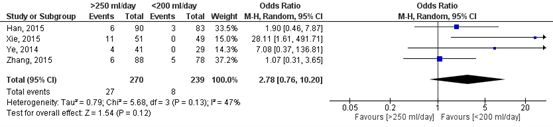

Recurrent pleural fluid

Figure 3 shows the pooled result of the number of patients with recurrent pleural fluid after removing the chest tube. In total, 27 out of the 270 patients (10%) who had their chest tube removed at a higher threshold (>250 ml/day) developed the complication recurrent pleural fluid, compared to 8 out of the 239 patients (3%) who had their chest tube removed at a lower threshold (<200 ml/day). The pooled odds ratio (OR) is 2.78 (95%CI 0.76 to 10.20) in favour of a low threshold (<200 ml/day). This means that patients in which a higher threshold for removing the chest tube is applied have a 2.8 times higher risk on developing the complication recurrent pleural fluid. This difference is considered clinically relevant.

Figure 3. Forest plot of the number of patients with recurrent pleural fluid after removing the chest tube.

Z: p-value of the pooled effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval.

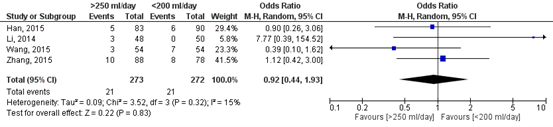

Atelectasis

Figure 4 shows the pooled result of the number of patients with atelectasis after removing the chest tube. In total, 21 out of the 273 patients (8%) who had their chest tube removed at a higher threshold (>250 ml/day) developed the complication atelectasis, compared to 21 out of the 272 patients (8%) who had their chest tube removed at a lower threshold (<200 ml/day). The pooled odds ratio (OR) is 0.92 (95%CI 0.44 to 1.93) in favour of a high threshold (>250 ml/day). This means that patients in which a higher threshold for removing the chest tube is applied have a slightly lower risk on developing the complication atelectasis. This difference is not considered clinically relevant.

Figure 4. Forest plot of the number of patients with atelectasis after removing the chest tube.

Z: p-value of the pooled effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval.

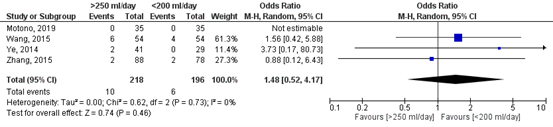

Thoracentesis

Figure 5 shows the pooled result of the number of patients with thoracentesis after removing the chest tube. In total, 10 out of the 218 patients (5%) who had their chest tube removed at a higher threshold (>250 ml/day) developed the complication thoracentesis, compared to 6 out of the 196 patients (3%) who had their chest tube removed at a lower threshold (<200 ml/day). The pooled odds ratio (OR) is 1.48 (95%CI 0.52 to 4.17) in favour of a low threshold (<200 ml/day). This means that patients in which a higher threshold for removing the chest tube is applied have a 1.5 times higher risk on developing the complication thoracentesis. This difference is considered clinically relevant.

Figure 5. Forest plot of the number of patients with thoracentesis after removing the chest tube.

Z: p-value of the pooled effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval.

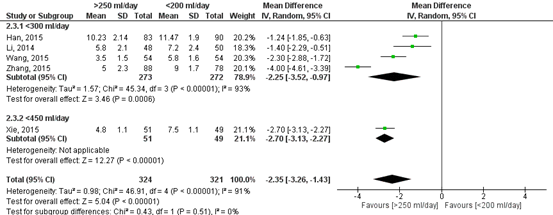

Length of hospital stay (important)

The outcome measure length of hospital stay is reported in two studies (Xie, 2015; Zhang, 2018). A total of 324 patients had their chest tube removed with a threshold >250 ml, versus 321 patients who had their chest tube removed at a threshold of <250 ml. The pooled mean difference in length of hospital stay was 2.35 days (95%CI 1.43 to 3.26) (Figure 6). This means that patients in whom their chest tube was removed at a higher threshold (>250 ml/day) was 2.35 days shorter compared to patients in whom their chest tube was removed at a lower threshold (<200 ml/day). This difference is considered clinically relevant.

Figure 6. Forest plot of the length of hospital stay (in days).

Z: p-value of the pooled effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval.

Quality of life (important)

None of the included studies reported this outcome measure.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure chest tube duration started high due to the inclusion of randomized studies. The level of evidence was downgraded by two levels because of study limitations (risk of bias, -1); and because the confidence interval exceeds the lower limits of clinical relevance (imprecision, -1). The level of evidence is therefore low.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure complications started high due to the inclusion of randomized studies. The level of evidence was downgraded by three level because of study limitations (risk of bias, -1); because of conflicting results (inconsistency, -1); because of a low number of events (imprecision, -1). The level of evidence is therefore very low.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure length of hospital stay started high due to the inclusion of randomized studies. The level of evidence was downgraded by one level because of study limitations (risk of bias, -1). The level of evidence is therefore moderate.

The level of evidence could not be graded for the outcome measures: re-interventions and quality of life as these were not reported in the included studies.

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question:

What are the (un)favorable effects of applying no threshold for removing the chest tube in patients who underwent an anatomical lung resection as part of a curative treatment in comparison with a threshold for removing the chest tube.

P: patients patients (>18 years) who underwent an anatomical lung resection

as part of a curative treatment

I: intervention no threshold for fluid drainage (or threshold limit >250 ml/day)

C: control threshold for fluid drainage (<200 ml/day)

O: outcome measure chest tube duration, re-interventions, complications, length of

hospital stay, quality of life

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered chest tube duration and re-interventions as critical outcome measures for decision making; and complications, length of hospital stay, and quality of life as an important outcome measure for decision making.

A priori, the working group did not define the outcome measures listed above but used the definitions used in the studies.

Per outcome measure:

The working group defined the following differences as minimal clinically (patient) important differences:

- Complications: 10% (RR < 0.90 or > 1.10)

- Number of re-interventions: 10% (RR < 0.90 OR > 1.10)

- Length of hospital stay: 1 day

- Chest tube duration: 1 day

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms until 17-3-2022. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 221 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria: systematic reviews and RCT’s comparing different thresholds for fluid drainage in patients who underwent anatomical lung resection. Six studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After full tekst analysis, 3 studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and 3 studies were included.

Results

Three studies were included in the analysis of the literature. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- Motono N, Iwai S, Funasaki A, Sekimura A, Usuda K, Uramoto H. What is the allowed volume threshold for chest tube removal after lobectomy: A randomized controlled trial. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2019 May 30;43:29-32. doi: 10.1016/j.amsu.2019.05.011. PMID: 31194145; PMCID: PMC6551566.

- Refai M, Brunelli A, Salati M, Xiumè F, Pompili C, Sabbatini A. The impact of chest tube removal on pain and pulmonary function after pulmonary resection. ?EJCTS 41 (2012) 820-823

- Xie HY, Xu K, Tang JX, Bian W, Ma HT, Zhao J, Ni B. A prospective randomized, controlled trial deems a drainage of 300 ml/day safe before removal of the last chest drain after video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery lobectomy. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2015 Aug;21(2):200-5. doi: 10.1093/icvts/ivv115. Epub 2015 May 15. PMID: 25979532.

- Zhang TX, Zhang Y, Liu ZD, Zhou SJ, Xu SF. The volume threshold of 300 versus 100 ml/day for chest tube removal after pulmonary lobectomy: a meta-analysis. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2018 Nov 1;27(5):695-702. doi: 10.1093/icvts/ivy150. PMID: 29741691.

Evidence tabellen

Research question: What are the (un)favorable effects of not applying a threshold for removing the chest tube in patients who underwent an anatomical lungresection as part of a curative treatment in comparison with applying a threshold for removing the chest tube.

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C)

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

Zhang, 2018

PS., study characteristics and results are extracted from the SR (unless stated otherwise) |

SR and meta-analysis of RCTs

Literature search up to unknown.

A: Han, 2015 B: Zhang, 2014 (= Ye, 2014) C: Zhang, 2015 D: Li, 2014 E: Wang, 2015

Study design: RCT

Setting and Country: China

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: This study was supported by Beijing Municipal Administration of Hospitals Ascent Plan [DFL20151501].

No conflicts of interest declared. |

Inclusion criteria SR: All published RCTs comparing volume thresholds of 100 and 300 ml/day before removing a chest tube after pulmonary lobectomy or bilobectomy were considered eligible for the meta-analysis. Trials in which the primary outcome measure was the duration of drainage or the amount of drainage. The secondary outcomes were hospital stay after operation, post-operative complications or the number of patients who need thoracentesis after removing the CT. Language were limited to English and Chinese. Abstract or unpublished data were included only if sufficient information on interventions and outcomes was available and if the final results were confirmed by contact with the first author.

Exclusion criteria SR: Exclusion criteria were as follows: patients who suffer from postoperative prolonged air leakage, densely bloody, purulent or cloudy pleural effusion after surgery, patients who were expected to have increased postoperative haemorrhage such as haemotological diseases and pleural extensive adhesion or patients who suffer from adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events.

5 studies included

Important patient characteristics at baseline:

N (mean age) A: I: 83 (61.22), C: 90 (60.23) B: I: 41 (56), C: 29 (55) C: I: 88 (58.4), C: 78 (58.7) D: I: 48 (unknown), C: 50 (unknown) E: I: 54 (71.44), C: 54 (70.45)

Sex (n/n): A: I: 49, C: 56 B: I: 21, C: 14 C: I: 56, C: 52 D: I/C: unknown E: I: 37, C: 35

Groups comparable at baseline? Both groups were well matched at baseline from the information on all trials. |

Describe intervention:

Removing the chest tube < 300 ml/24 h.

|

Describe control:

Removing the chest tube < 100 ml/24 h.

|

End-point of follow-up: Not reported

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? Not reported.

|

Outcome measure-1 Defined as complications:

Effect measure: OR [95% CI]: A: 1.90 [0.46, 7.78] B: 7.08 [0.37, 136.81] C: 1.07 [0.31, 3.65] D: not reported E: not reported

Pooled effect (fixed effects model): 1.73 [95% CI 0.74, 4.07] favoring 100 ml. Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

Effect measure: OR [95% CI]: A: not reported B: 3.73 [0.17, 80.73] C: 0.88 [0.12, 6.43] D: not reported E: 1.56 [0.42, 5.88]

Pooled effect (fixed effects model): 1.53 [95% CI 0.55, 4.22] favoring 100 ml. Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

Effect measure: OR [95% CI]: A: 0.90 [0.26, 3.06] B: not reported.] C: 1.12 [0.42, 3.00] D: 7.77 [0.39, 154.52] E: 0.39 [0.10, 1.62]

Pooled effect (fixed effects model): 0.97 [95% CI 0.52, 1.81] favoring 100 ml. Heterogeneity (I2): 15%

Outcome measure-3 Defined as re-interventions: not reported

Outcome measure-4: Length of hospital stay Effect measure: mean difference [95% CI]: A: -1.24 [-1.85, -0.63] B: not reported C: -4.00 [-4.61, -3.39] D: -1.40 [-2.29, -0.51] E: -2.30 [-2.88, -1.72]

Pooled effect (random effects model): -2.25 [95%CI -3.52, -0.97] favoring 300 ml. Heterogeneity (I2): 93%

Outcome measure -5: Quality of life: not reported

Outcome measure-6 Defined as chest tube duration after operation

Effect measure: mean difference [95% CI]: A: -35.62 [-39.82, -31.42] B: not reported C: -72.00 [-81.13, -62.87] D: -18.30 [-29.21, -7.39] E: -50.40 [-62.70, -38.10]

Pooled effect (random effects model ): -44.07 [95% CI -64.45 to -23.68] favoring 300 ml Heterogeneity (I2): 96%

|

Facultative:

Conclusion: Our results showed that a higher volume threshold, up to 300 ml/day, is effective in reducing hospitalization times and duration of drainage in patients who undergo a lobectomy.

Included studies have a low risk of bias (adequate sequence generation and incomplete outcome data). Allocation concealment, blinding, free of selective reporting and free of other bias was unclear. |

Evidence table for intervention studies (randomized controlled trials and non-randomized observational studies [cohort studies, case-control studies, case series])1

This table is also suitable for diagnostic studies (screening studies) that compare the effectiveness of two or more tests. This only applies if the test is included as part of a test-and-treat strategy – otherwise the evidence table for studies of diagnostic test accuracy should be used.

Research question:

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics 2 |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C) 3

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size 4 |

Comments |

|

Motono, 2019 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: prospective, single-blind, Japan

Funding and conflicts of interest: |

Inclusion criteria: Patients who had undergone lobectomy and lymph node dissection.

This study included the patients who underwent more than lobectomy and mediastinal lymphadenectomy, without bleeding chylothorax, air leakage, or thoracic infection at 2 days after surgery.

Exclusion criteria: Patients were excluded if they were younger than 19 years of age and older than 85 years of age, underwent lobectomy with chest wall resection, or underwent pneumonectomy.

N total at baseline: Intervention: 35 Control: 35

Important prognostic factors2: For example age ± SD: I: 68.4 (58-78) C: 69.3 (45-84)

Sex: I: 18 M / 17 F C: 15 M / 20 F

Groups comparable at baseline? There were no significant differences between the two groups in terms of the resected lung lobes and areas of lymph node dissection. Furthermore, the wound length, operation time, and amount of bleeding were not significantly different between the two groups. |

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

High group: removal of chest tube when drainage was < 450 ml/24 h

|

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

Low group: removal of chest tube when drainage was < 200 ml/24 h |

Length of follow-up: 30 days after discharge.

Loss-to-follow-up: None.

Incomplete outcome data: None.

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Complications (thoracentesis) Thoracentesis is not reported in both the intervention and control group.

In both the intervention and control group, there is 1 case of atrial fibrillation.

Re-interventions Not reported.

Length of hospital stay not reported.

Quality of life Not reported. Drainage time, days I: 2.05 (SD 0.53) C: 2.31 (SD 0.58)

|

Chest tube management: One chest tube was inserted and positioned into the anterior apical chest after pulmonary resection. The type of chest tube used in this study was a 20-Fr soft polyvinyl chloride tube. The digital drainage system, Thopaz (Medela Healthcare, Zug Switzerland) was used in this study. The chest tubes were subjected to continuous suction (10 cmH2O) until their removal. The tubes were removed when there was no air leakage or densely bloody and chylous pleural effusion.

Randomization Patients were randomized on postoperative day 2.

Procedure Operative procedures were performed by video-assisted thoracic surgery (VATS) in 65 patients (93%) and open thoracotomy in 5 patients (7%). |

|

Xie, 2015 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: prospective, single-blind, China

Funding and conflicts of interest: no conflicts of interest declared.

Nothing reported on funding. |

Inclusion criteria: Patients who underwent elective lobectomy or bilobectomy through VATS with two incisions.

Exclusion criteria: intrapericardial resections and lobectomies with chest wall resections and those with nephritic syndrome, chronic renal failure, heart failure and cirrhosis. Patients with adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events, prolonged air leakage (i.e. >7 days) and a densely bloody, purulent and cloudy pleural effusion were also excluded.

N total at baseline: Intervention: 51 Control: 49

Important prognostic factors2: For example age ± SD: I: 64.5 (7.5) C: 61.9 (8.1)

Sex: I: 34 M C: 36 M

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

removal of chest tube when drainage was <450 ml/24 h

|

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

removal of chest tube when drainage was < 150 ml/24 h |

Length of follow-up: At least one week after surgery.

Loss-to-follow-up: None.

Incomplete outcome data: None.

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Complications Re-accumulation of pleural fluid I: 11 (21.6%) C: 0

Re-interventions Not reported.

Length of hospital stay, days, mean (SD) I: 4.8 (1.1) C: 7.5 (1.1)

Quality of life Not reported.

Drainage time, days – mean, SD I: 2.1 (1.4) C: 5.4 (1.4)

|

Chest tube management: All staple lines and dissection sites were sprayed with a fibrin sealant after an examination for leakage of the bronchus staple line. After the operator confirmed that there were no pneumostasis and haemostasis, one or two 30-French chest tubes were placed at the end of the operation. In addition, one 30-French chest tube was placed at the end of surgery of the upper lung lobes and two at the end of surgical procedures of the lower or (and) middle lung lobes. A positive airway pressure was applied to check the lung expansion until there is no bubbles on water seal and the amount of drainage from each chest tube was recorded every 24 h. Furthermore, a suction of the chest drainage system was considered to be unnecessary after the operation.

Randomization: The randomization was done before surgery with computer-generated lists. |

Notes:

- Prognostic balance between treatment groups is usually guaranteed in randomized studies, but non-randomized (observational) studies require matching of patients between treatment groups (case-control studies) or multivariate adjustment for prognostic factors (confounders) (cohort studies); the evidence table should contain sufficient details on these procedures

- Provide data per treatment group on the most important prognostic factors [(potential) confounders]

- For case-control studies, provide sufficient detail on the procedure used to match cases and controls

- For cohort studies, provide sufficient detail on the (multivariate) analyses used to adjust for (potential) confounders

Risk of bias table for intervention studies (randomized controlled trials; based on Cochrane risk of bias tool and suggestions by the CLARITY Group at McMaster University)

|

Study reference

(first author, publication year) |

Was the allocation sequence adequately generated?

|

Was the allocation adequately concealed?

|

Blinding: Was knowledge of the allocated interventions adequately prevented? |

Was loss to follow-up (missing outcome data) infrequent?

|

Are reports of the study free of selective outcome reporting?

|

Was the study apparently free of other problems that could put it at a risk of bias? |

Overall risk of bias If applicable/necessary, per outcome measure

LOW Some concerns HIGH |

|

Motono, 2019 |

Probably no Reason: Randomization by numbered container method. |

Definitely ye Reason: Patients were blinded, unclear about the enrolling investigators. |

Definitely no Reason: only the patients were blinded. |

Probably yes Reason: no loss to follow-up. |

Definitely yes Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported |

Definitely yes Reason: No other problems noted |

Some concerns (all outcomes) |

|

Xie, 2015 |

Definitely yes Reason: Central randomization with computer generated lists. |

Unclear Reason: not reported. |

Definitely no Reason: only the patients were blinded. |

Definitely yes Reason: no loss to follow-up. |

Definitely yes Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported. |

Definitely yes Reason: No other problems noted |

Some concerns (all outcomes) |

Table of excluded studies

|

Reference |

Reason for exclusion |

|

Younes RN, Gross JL, Aguiar S, Haddad FJ, Deheinzelin D. When to remove a chest tube? A randomized study with subsequent prospective consecutive validation. J Am Coll Surg. 2002 Nov;195(5):658-62. doi: 10.1016/s1072-7515(02)01332-7. PMID: 12437253. |

Does not match PICO: the highest threshold (200 ml/day) is not compatible with ‘no limit’. |

|

Stamenovic D, Dusmet M, Schneider T, Roessner E, Messerschmidt A. A simple size-tailored algorithm for the removal of chest drain following minimally invasive lobectomy: a prospective randomized study. Surg Endosc. 2022 Jul;36(7):5275-5281. doi: 10.1007/s00464-021-08905-0. Epub 2021 Nov 30. PMID: 34846593; PMCID: PMC9160124. |

Does not match PICO: intervention is a size-tailored algorithm for the removal of chest drain removal. |

|

Zhang Y, Li H, Hu B, Li T, Miao JB, You B, Fu YL, Zhang WQ. A prospective randomized single-blind control study of volume threshold for chest tube removal following lobectomy. World J Surg. 2014 Jan;38(1):60-7. doi: 10.1007/s00268-013-2271-7. PMID: 24158313. |

Included in the meta-analysis from Zhang (2018). |

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Publicatiedatum : 21-11-2023

Beoordeeld op geldigheid : 07-11-2023

Algemene gegevens

De ontwikkeling/herziening van deze richtlijnmodule werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten (www.demedischspecialist.nl/kennisinstituut) en werd gefinancierd uit de Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS) en/of andere bron. De financier heeft geen enkele invloed gehad op de inhoud van de richtlijnmodule.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijnmodule is in 2021 een multidisciplinaire werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen (zie hiervoor de Samenstelling van de werkgroep) die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor patiënten die longresectie ondergaan.

Samenstelling van de werkgroep

Werkgroep

- Drs. E. (Erik) von Meyenfeldt, longchirurg, NVvH (voorzitter)

- Dr. C. (Chris) Dickhoff, longchirurg, NVvH

- Dr. N.J. (Nick) Koning, anesthesioloog, NVA

- Dr. T.J. (Thomas) van Brakel, cardio-thoracaal chirurg, NVT

- Dr. I. (Idris) Bahce, longarts, NVALT

- Drs. L.A. (Lidia) Barberio, directeur, Longkanker Nederland

- Dr. E. (Erik) Hulzebos, fysiotherapeut, KNGF

Meelezers:

- Dr. R. (Richard) van Valen, verpleegkundig specialist cardio-thoracale chirurgie, V&VN

Met ondersteuning van:

- Dr. R. (Romy) Zwarts - van de Putte, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van Medisch Specialisten

- Drs. E.R.L. (Evie) Verweg, junior adviseur, Kennisinstituut van Medisch Specialisten

- Drs. D.W. (Diederik) van Oyen, AOIS, NVvH

Belangenverklaringen

De Code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling is gevolgd. Alle werkgroepleden hebben schriftelijk verklaard of zij in de laatste drie jaar directe financiële belangen (betrekking bij een commercieel bedrijf, persoonlijke financiële belangen, onderzoeksfinanciering) of indirecte belangen (persoonlijke relaties, reputatiemanagement) hebben gehad. Gedurende de ontwikkeling of herziening van een module worden wijzigingen in belangen aan de voorzitter doorgegeven. De belangenverklaring wordt opnieuw bevestigd tijdens de commentaarfase.

Een overzicht van de belangen van werkgroepleden en het oordeel over het omgaan met eventuele belangen vindt u in onderstaande tabel. De ondertekende belangenverklaringen zijn op te vragen bij het secretariaat van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

|

Werkgroeplid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

Von Meyenfeldt |

Longchirurg |

Penningmeester Stichting Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek & Nascholing Heelkunde ASz (onbetaald), buitenpromovendus Vrije Universiteit/AmsterdamUMC (onbetaald) |

Bezig met ERATS Trial en Prehabilitatie-pilot bij longresecties. |

Geen |

|

Bahce |

Longarts |

Commissielid |

Honorering op naam van afdeling voor adviesraden bij diverse farmaceutische bedrijven. |

Geen |

|

Koning |

Anesthesioloog |

Lid Beroepsbelangencommissie NVA, deelname multidisciplinaire werkgroep PACU |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Barberio |

Directeur Longkanker Nederland |

Lid RvT Agora (tot eind 2022), leven tot het einde, bestuur Dutch Lung Cancer Audit (DLCA), vanaf 1 mei 2023 lid van IMAGIO project. |

Longkanker Nederland wordt gefinancierd door KWF en VWS, samenwerking met diverse bedrijven. |

Geen |

|

Dickhoff |

Longchirurg |

Complicatie commissie van de NVVL |

Honorering op naam van afdeling voor adviesraden bij diverse farmaceutische bedrijven. |

Geen |

|

Van Brakel |

Cardiothoracaal chirurg |

Niet van toepassing |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Hulzebos |

Fysiotherapeut |

Secretaris Vereniging voor Hart-, Vaat-, en Longfysiotherapie (VHVL) |

Geen |

Geen |

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Er werd aandacht besteed aan het patiëntenperspectief door de afgevaardigde patiëntenvereniging in de werkgroep. De verkregen input is meegenomen bij het opstellen van de uitgangsvragen, de keuze voor de uitkomstmaten en bij het opstellen van de overwegingen. De conceptrichtlijn is tevens voor commentaar voorgelegd aan de patiëntenvereniging Longkanker Nederland en de Patientenfederatie Nederland en de eventueel aangeleverde commentaren zijn bekeken en verwerkt.

Kwalitatieve raming van mogelijke financiële gevolgen in het kader van de Wkkgz

Bij de richtlijn is conform de Wet kwaliteit, klachten en geschillen zorg (Wkkgz) een kwalitatieve raming uitgevoerd of de aanbevelingen mogelijk leiden tot substantiële financiële gevolgen. Bij het uitvoeren van deze beoordeling zijn richtlijnmodules op verschillende domeinen getoetst (zie het stroomschema op de Richtlijnendatabase).

Uit de kwalitatieve raming blijkt dat er waarschijnlijk geen substantiële financiële gevolgen zijn, zie onderstaande tabel.

Module |

Uitkomst raming |

Toelichting |

|

Module [ERAS] |

Geen substantiële financiële gevolgen |

Uit de toetsing volgt dat de aanbeveling niet breed toepasbaar zijn (<5.000 patiënten) en daarom naar verwachting geen substantiële financiële gevolgen zal hebben voor de collectieve uitgaven. |

|

Module [Mobilisatie] |

Geen substantiële financiële gevolgen |

Uit de toetsing volgt dat de aanbeveling niet breed toepasbaar zijn (<5.000 patiënten) en daarom naar verwachting geen substantiële financiële gevolgen zal hebben voor de collectieve uitgaven. |

|

Module [Drainbeleid verwijdercriteria] |

Geen substantiële financiële gevolgen |

Uit de toetsing volgt dat de aanbeveling niet breed toepasbaar zijn (<5.000 patiënten) en daarom naar verwachting geen substantiële financiële gevolgen zal hebben voor de collectieve uitgaven. |

|

Module [Drainbeleid - Zuigdrainage] |

Geen substantiële financiële gevolgen |

Uit de toetsing volgt dat de aanbeveling niet breed toepasbaar zijn (<5.000 patiënten) en daarom naar verwachting geen substantiële financiële gevolgen zal hebben voor de collectieve uitgaven. |

|

Module organisatie van zorg |

Geen substantiële financiële gevolgen |

Uit de toetsing volgt dat de aanbeveling niet breed toepasbaar zijn (<5.000 patiënten) en daarom naar verwachting geen substantiële financiële gevolgen zal hebben voor de collectieve uitgaven. |

Werkwijze

AGREE

Deze richtlijnmodule is opgesteld conform de eisen vermeld in het rapport Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 van de adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwaliteit. Dit rapport is gebaseerd op het AGREE II instrument (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II; Brouwers, 2010).

Knelpuntenanalyse en uitgangsvragen

Tijdens de voorbereidende fase inventariseerde de werkgroep de knelpunten in de zorg voor patiënten die longresectie ondergaan. Tevens zijn er knelpunten aangedragen door de Nederlandse Vereniging voor Heelkunde, Nederlandse Vereniging voor Anesthesiologie, Longkanker Nederland, Inspectie Gezondheidszorg en Jeugd, Samenwerkende Topklinische opleidings Ziekenhuizen, Koninklijk Nederlands Genootschap voor Fysiotherapie, Nederlandse vereniging van Diëtisten, en Nederlandse Vereniging voor Geriatrie via een schriftelijke knelpuntenanalyse. Een verslag hiervan is opgenomen onder aanverwante producten.

Op basis van de uitkomsten van de knelpuntenanalyse zijn door de werkgroep concept-uitgangsvragen opgesteld en definitief vastgesteld.

Uitkomstmaten

Na het opstellen van de zoekvraag behorende bij de uitgangsvraag inventariseerde de werkgroep welke uitkomstmaten voor de patiënt relevant zijn, waarbij zowel naar gewenste als ongewenste effecten werd gekeken. Hierbij werd een maximum van acht uitkomstmaten gehanteerd. De werkgroep waardeerde deze uitkomstmaten volgens hun relatieve belang bij de besluitvorming rondom aanbevelingen, als cruciaal (kritiek voor de besluitvorming), belangrijk (maar niet cruciaal) en onbelangrijk. Tevens definieerde de werkgroep tenminste voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten welke verschillen zij klinisch (patiënt) relevant vonden.

Methode literatuursamenvatting

Een uitgebreide beschrijving van de strategie voor zoeken en selecteren van literatuur is te vinden onder ‘Zoeken en selecteren’ onder Onderbouwing. Indien mogelijk werd de data uit verschillende studies gepoold in een random-effects model. Review Manager 5.4 werd gebruikt voor de statistische analyses. De beoordeling van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs wordt hieronder toegelicht.

Beoordelen van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs

De kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs werd bepaald volgens de GRADE-methode. GRADE staat voor ‘Grading Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation’ (zie http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/). De basisprincipes van de GRADE-methodiek zijn: het benoemen en prioriteren van de klinisch (patiënt) relevante uitkomstmaten, een systematische review per uitkomstmaat, en een beoordeling van de bewijskracht per uitkomstmaat op basis van de acht GRADE-domeinen (domeinen voor downgraden: risk of bias, inconsistentie, indirectheid, imprecisie, en publicatiebias; domeinen voor upgraden: dosis-effect relatie, groot effect, en residuele plausibele confounding).

GRADE onderscheidt vier gradaties voor de kwaliteit van het wetenschappelijk bewijs: hoog, redelijk, laag en zeer laag. Deze gradaties verwijzen naar de mate van zekerheid die er bestaat over de literatuurconclusie, in het bijzonder de mate van zekerheid dat de literatuurconclusie de aanbeveling adequaat ondersteunt (Schünemann, 2013; Hultcrantz, 2017).

|

GRADE |

Definitie |

|

Hoog |

|

|

Redelijk |

|

|

Laag |

|

|

Zeer laag |

|

Bij het beoordelen (graderen) van de kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs in richtlijnen volgens de GRADE-methodiek spelen grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming een belangrijke rol (Hultcrantz, 2017). Dit zijn de grenzen die bij overschrijding aanleiding zouden geven tot een aanpassing van de aanbeveling. Om de grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming te bepalen moeten alle relevante uitkomstmaten en overwegingen worden meegewogen. De grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming zijn daarmee niet één op één vergelijkbaar met het minimaal klinisch relevant verschil (Minimal Clinically Important Difference, MCID). Met name in situaties waarin een interventie geen belangrijke nadelen heeft en de kosten relatief laag zijn, kan de grens voor klinische besluitvorming met betrekking tot de effectiviteit van de interventie bij een lagere waarde (dichter bij het nuleffect) liggen dan de MCID (Hultcrantz, 2017).

Overwegingen (van bewijs naar aanbeveling)

Om te komen tot een aanbeveling zijn naast (de kwaliteit van) het wetenschappelijke bewijs ook andere aspecten belangrijk en worden meegewogen, zoals aanvullende argumenten uit bijvoorbeeld de biomechanica of fysiologie, waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten, kosten (middelenbeslag), aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie. Deze aspecten zijn systematisch vermeld en beoordeeld (gewogen) onder het kopje ‘Overwegingen’ en kunnen (mede) gebaseerd zijn op expert opinion. Hierbij is gebruik gemaakt van een gestructureerd format gebaseerd op het evidence-to-decision framework van de internationale GRADE Working Group (Alonso-Coello, 2016a; Alonso-Coello 2016b). Dit evidence-to-decision framework is een integraal onderdeel van de GRADE methodiek.

Formuleren van aanbevelingen

De aanbevelingen geven antwoord op de uitgangsvraag en zijn gebaseerd op het beschikbare wetenschappelijke bewijs en de belangrijkste overwegingen, en een weging van de gunstige en ongunstige effecten van de relevante interventies. De kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs en het gewicht dat door de werkgroep wordt toegekend aan de overwegingen, bepalen samen de sterkte van de aanbeveling. Conform de GRADE-methodiek sluit een lage bewijskracht van conclusies in de systematische literatuuranalyse een sterke aanbeveling niet a priori uit, en zijn bij een hoge bewijskracht ook zwakke aanbevelingen mogelijk (Agoritsas, 2017; Neumann, 2016). De sterkte van de aanbeveling wordt altijd bepaald door weging van alle relevante argumenten tezamen. De werkgroep heeft bij elke aanbeveling opgenomen hoe zij tot de richting en sterkte van de aanbeveling zijn gekomen.

In de GRADE-methodiek wordt onderscheid gemaakt tussen sterke en zwakke (of conditionele) aanbevelingen. De sterkte van een aanbeveling verwijst naar de mate van zekerheid dat de voordelen van de interventie opwegen tegen de nadelen (of vice versa), gezien over het hele spectrum van patiënten waarvoor de aanbeveling is bedoeld. De sterkte van een aanbeveling heeft duidelijke implicaties voor patiënten, behandelaars en beleidsmakers (zie onderstaande tabel). Een aanbeveling is geen dictaat, zelfs een sterke aanbeveling gebaseerd op bewijs van hoge kwaliteit (GRADE gradering HOOG) zal niet altijd van toepassing zijn, onder alle mogelijke omstandigheden en voor elke individuele patiënt.

|

Implicaties van sterke en zwakke aanbevelingen voor verschillende richtlijngebruikers |

||

|

|

||

|

|

Sterke aanbeveling |

Zwakke (conditionele) aanbeveling |

|

Voor patiënten |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen en slechts een klein aantal niet. |

Een aanzienlijk deel van de patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen, maar veel patiënten ook niet. |

|

Voor behandelaars |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak moeten ontvangen. |

Er zijn meerdere geschikte interventies of aanpakken. De patiënt moet worden ondersteund bij de keuze voor de interventie of aanpak die het beste aansluit bij zijn of haar waarden en voorkeuren. |

|

Voor beleidsmakers |

De aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kan worden gezien als standaardbeleid. |

Beleidsbepaling vereist uitvoerige discussie met betrokkenheid van veel stakeholders. Er is een grotere kans op lokale beleidsverschillen. |

Organisatie van zorg

In de knelpuntenanalyse en bij de ontwikkeling van de richtlijnmodule is expliciet aandacht geweest voor de organisatie van zorg: alle aspecten die randvoorwaardelijk zijn voor het verlenen van zorg (zoals coördinatie, communicatie, (financiële) middelen, mankracht en infrastructuur). Randvoorwaarden die relevant zijn voor het beantwoorden van deze specifieke uitgangsvraag zijn genoemd bij de overwegingen. Meer algemene, overkoepelende, of bijkomende aspecten van de organisatie van zorg worden behandeld in de module Organisatie van zorg.

Commentaar- en autorisatiefase

De conceptrichtlijnmodule werd aan de betrokken (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd ter commentaar. De commentaren werden verzameld en besproken met de werkgroep. Naar aanleiding van de commentaren werd de conceptrichtlijnmodule aangepast en definitief vastgesteld door de werkgroep. De definitieve richtlijnmodule werd aan de deelnemende (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd voor autorisatie en door hen geautoriseerd dan wel geaccordeerd.

Literatuur

Agoritsas T, Merglen A, Heen AF, Kristiansen A, Neumann I, Brito JP, Brignardello-Petersen R, Alexander PE, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Guyatt GH. UpToDate adherence to GRADE criteria for strong recommendations: an analytical survey. BMJ Open. 2017 Nov 16;7(11):e018593. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018593. PubMed PMID: 29150475; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5701989.

Alonso-Coello P, Schünemann HJ, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Rada G, Rosenbaum S, Morelli A, Guyatt GH, Oxman AD; GRADE Working Group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 1: Introduction. BMJ. 2016 Jun 28;353:i2016. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2016. PubMed PMID: 27353417.

Alonso-Coello P, Oxman AD, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Vandvik PO, Meerpohl J, Guyatt GH, Schünemann HJ; GRADE Working Group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 2: Clinical practice guidelines. BMJ. 2016 Jun 30;353:i2089. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2089. PubMed PMID: 27365494.

Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, Burgers JS, Cluzeau F, Feder G, Fervers B, Graham ID, Grimshaw J, Hanna SE, Littlejohns P, Makarski J, Zitzelsberger L; AGREE Next Steps Consortium. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. CMAJ. 2010 Dec 14;182(18):E839-42. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090449. Epub 2010 Jul 5. Review. PubMed PMID: 20603348; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3001530.

Hultcrantz M, Rind D, Akl EA, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Iorio A, Alper BS, Meerpohl JJ, Murad MH, Ansari MT, Katikireddi SV, Östlund P, Tranæus S, Christensen R, Gartlehner G, Brozek J, Izcovich A, Schünemann H, Guyatt G. The GRADE Working Group clarifies the construct of certainty of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017 Jul;87:4-13. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.05.006. Epub 2017 May 18. PubMed PMID: 28529184; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC6542664.

Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 (2012). Adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwalitieit.

Neumann I, Santesso N, Akl EA, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Alonso-Coello P, Agoritsas T, Mustafa RA, Alexander PE, Schünemann H, Guyatt GH. A guide for health professionals to interpret and use recommendations in guidelines developed with the GRADE approach. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016 Apr;72:45-55. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.11.017. Epub 2016 Jan 6. Review. PubMed PMID: 26772609.

Schünemann H, Brożek J, Guyatt G, et al. GRADE handbook for grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. Updated October 2013. The GRADE Working Group, 2013. Available from http://gdt.guidelinedevelopment.org/central_prod/_design/client/handbook/handbook.html.

Zoekverantwoording

Literature search strategy

Algemene informatie

|

Richtlijn: NVvH Longresectie |

|

|

Uitgangsvraag: Wat is het optimale drainbeleid na een anatomische longresectie

|

|

|

Database(s): Ovid/Medline, Embase |

Datum: 17-3-2022 |

|

Periode: |

Talen: nvt |

|

Literatuurspecialist: Ingeborg van Dusseldorp |

|

|

BMI zoekblokken: voor verschillende opdrachten wordt (deels) gebruik gemaakt van de zoekblokken van BMI-Online https://blocks.bmi-online.nl/ Bij gebruikmaking van een volledig zoekblok zal naar de betreffende link op de website worden verwezen. |

|

|

Toelichting: Voor deze vraag is in eerste instantie gezocht naar de combinatie longresectie EN long drainage. Omdat het aantal referenties erg hoog was, is ervoor gekozen om alleen met “tube removal” te zoeken en naastgelegen terminologie. The volume threshold of 300 versus 100 ml/day for chest tube removal after pulmonary lobectomy: A meta-Analysis What is the allowed volume threshold for chest tube removal after lobectomy: A randomized controlled trial Motono N.; Iwai S.; Funasaki A.; Sekimura A.; Usuda K.; Uramoto H. |

|

|

Te gebruiken voor richtlijnen tekst: In de databases Embase en Ovid/Medline is op 17-3-2022 met relevante zoektermen gezocht naar systematische reviews en RCTs . De literatuurzoekactie leverde 221 unieke treffers op. |

|

Zoekopbrengst

|

|

EMBASE |

OVID/MEDLINE |

Ontdubbeld |

|

SRs |

40 |

45 |

63 |

|

RCTs |

118 |

152 |

158 |

|

Observationele studies |

|

|

|

|

Overig |

|

|

221 |

|

Totaal |

|

|

|

Zoekstrategie

Embase

|

No. |

Query |

Results |

|

#20 |

#11 AND #16 |

3 |

|

#19 |

#3 AND #16 sleutelartikelen gevonden in de basisset |

5 |

|

#18 |

#16 NOT #17 |

1 |

|

#17 |

#4 AND #16 |

4 |

|

#16 |

#12 OR #13 OR #14 OR #15 |

5 |

|

#15 |

guidelines AND for AND lung AND recommendations AND of AND the AND enhanced AND recovery AND after AND surgery AND batchelor NOT surgical:ti NOT perspective:ti NOT national:ti |

1 |

|

#14 |

optimizing AND postoperative AND care AND protocols AND in AND thoracic AND surgery AND french NOT pain:ti NOT differences:ti |

1 |

|

#13 |

results AND of AND a AND prospective AND algorithm AND to AND remove AND chest AND tubes AND after AND pulmonary AND resection AND with AND high AND output |

1 |

|

#12 |

early AND chest AND tube AND removal AND after AND 'video assisted' AND thoracic AND surgery AND lobectomy AND with AND serous AND fluid AND production |

2 |

|

#11 |

#4 AND (#7 OR #8) |

948 |

|

#10 |

#4 AND #6 RCT |

118 |

|

#9 |

#4 AND #5 SR |

40 |

|

#8 |

'case control study'/de OR 'comparative study'/exp OR 'control group'/de OR 'controlled study'/de OR 'controlled clinical trial'/de OR 'crossover procedure'/de OR 'double blind procedure'/de OR 'phase 2 clinical trial'/de OR 'phase 3 clinical trial'/de OR 'phase 4 clinical trial'/de OR 'pretest posttest design'/de OR 'pretest posttest control group design'/de OR 'quasi experimental study'/de OR 'single blind procedure'/de OR 'triple blind procedure'/de OR (((control OR controlled) NEAR/6 trial):ti,ab,kw) OR (((control OR controlled) NEAR/6 (study OR studies)):ti,ab,kw) OR (((control OR controlled) NEAR/1 active):ti,ab,kw) OR 'open label*':ti,ab,kw OR (((double OR two OR three OR multi OR trial) NEAR/1 (arm OR arms)):ti,ab,kw) OR ((allocat* NEAR/10 (arm OR arms)):ti,ab,kw) OR placebo*:ti,ab,kw OR 'sham-control*':ti,ab,kw OR (((single OR double OR triple OR assessor) NEAR/1 (blind* OR masked)):ti,ab,kw) OR nonrandom*:ti,ab,kw OR 'non-random*':ti,ab,kw OR 'quasi-experiment*':ti,ab,kw OR crossover:ti,ab,kw OR 'cross over':ti,ab,kw OR 'parallel group*':ti,ab,kw OR 'factorial trial':ti,ab,kw OR ((phase NEAR/5 (study OR trial)):ti,ab,kw) OR ((case* NEAR/6 (matched OR control*)):ti,ab,kw) OR ((match* NEAR/6 (pair OR pairs OR cohort* OR control* OR group* OR healthy OR age OR sex OR gender OR patient* OR subject* OR participant*)):ti,ab,kw) OR ((propensity NEAR/6 (scor* OR match*)):ti,ab,kw) OR versus:ti OR vs:ti OR compar*:ti OR ((compar* NEAR/1 study):ti,ab,kw) OR (('major clinical study'/de OR 'clinical study'/de OR 'cohort analysis'/de OR 'observational study'/de OR 'cross-sectional study'/de OR 'multicenter study'/de OR 'correlational study'/de OR 'follow up'/de OR cohort*:ti,ab,kw OR 'follow up':ti,ab,kw OR followup:ti,ab,kw OR longitudinal*:ti,ab,kw OR prospective*:ti,ab,kw OR retrospective*:ti,ab,kw OR observational*:ti,ab,kw OR 'cross sectional*':ti,ab,kw OR cross?ectional*:ti,ab,kw OR multicent*:ti,ab,kw OR 'multi-cent*':ti,ab,kw OR consecutive*:ti,ab,kw) AND (group:ti,ab,kw OR groups:ti,ab,kw OR subgroup*:ti,ab,kw OR versus:ti,ab,kw OR vs:ti,ab,kw OR compar*:ti,ab,kw OR 'odds ratio*':ab OR 'relative odds':ab OR 'risk ratio*':ab OR 'relative risk*':ab OR 'rate ratio':ab OR aor:ab OR arr:ab OR rrr:ab OR ((('or' OR 'rr') NEAR/6 ci):ab))) |

12970458 |

|

#7 |

'major clinical study'/de OR 'clinical study'/de OR 'case control study'/de OR 'family study'/de OR 'longitudinal study'/de OR 'retrospective study'/de OR 'prospective study'/de OR 'comparative study'/de OR 'cohort analysis'/de OR ((cohort NEAR/1 (study OR studies)):ab,ti) OR (('case control' NEAR/1 (study OR studies)):ab,ti) OR (('follow up' NEAR/1 (study OR studies)):ab,ti) OR (observational NEAR/1 (study OR studies)) OR ((epidemiologic NEAR/1 (study OR studies)):ab,ti) OR (('cross sectional' NEAR/1 (study OR studies)):ab,ti) |

6964877 |

|

#6 |

'randomized controlled trial'/exp OR random*:ti,ab OR (((pragmatic OR practical) NEAR/1 'clinical trial*'):ti,ab) OR ((('non inferiority' OR noninferiority OR superiority OR equivalence) NEAR/3 trial*):ti,ab) OR rct:ti,ab,kw |

1888162 |

|

#5 |

'meta analysis'/exp OR 'meta analysis (topic)'/exp OR metaanaly*:ti,ab OR 'meta analy*':ti,ab OR metanaly*:ti,ab OR 'systematic review'/de OR 'cochrane database of systematic reviews'/jt OR prisma:ti,ab OR prospero:ti,ab OR (((systemati* OR scoping OR umbrella OR 'structured literature') NEAR/3 (review* OR overview*)):ti,ab) OR ((systemic* NEAR/1 review*):ti,ab) OR (((systemati* OR literature OR database* OR 'data base*') NEAR/10 search*):ti,ab) OR (((structured OR comprehensive* OR systemic*) NEAR/3 search*):ti,ab) OR (((literature NEAR/3 review*):ti,ab) AND (search*:ti,ab OR database*:ti,ab OR 'data base*':ti,ab)) OR (('data extraction':ti,ab OR 'data source*':ti,ab) AND 'study selection':ti,ab) OR ('search strategy':ti,ab AND 'selection criteria':ti,ab) OR ('data source*':ti,ab AND 'data synthesis':ti,ab) OR medline:ab OR pubmed:ab OR embase:ab OR cochrane:ab OR (((critical OR rapid) NEAR/2 (review* OR overview* OR synthes*)):ti) OR ((((critical* OR rapid*) NEAR/3 (review* OR overview* OR synthes*)):ab) AND (search*:ab OR database*:ab OR 'data base*':ab)) OR metasynthes*:ti,ab OR 'meta synthes*':ti,ab |

809025 |

|

#4 |

#3 NOT ('conference abstract'/it OR 'editorial'/it OR 'letter'/it OR 'note'/it) NOT (('animal'/exp OR 'animal experiment'/exp OR 'animal model'/exp OR 'nonhuman'/exp) NOT 'human'/exp) |

1268 |

|

#3 |

#1 AND #2 |

1938 |

|

#2 |

'tube removal'/exp OR ((fluid NEAR/2 (turnover OR output OR production)):ti,ab,kw) OR (((high OR low OR median) NEAR/3 (volume OR output)):ti,ab,kw) OR threshold*:ti,ab,kw OR 'cut off':ti,ab,kw OR cutoff:ti,ab,kw OR (((tube* OR drain*) NEAR/3 remov*):ti,ab,kw) |

680870 |

|

#1 |

'lobectomy'/exp AND ('lung'/exp OR 'lung cancer'/exp) OR 'lung lobectomy'/exp OR 'lung resection'/exp OR 'lung resection':ti,ab,kw OR 'lung volume reduction surgery':ti,ab,kw OR 'pneumectomy':ti,ab,kw OR 'pneumonectomy':ti,ab,kw OR 'pneumonic resection':ti,ab,kw OR 'pneumoresection':ti,ab,kw OR 'pulmonary resection':ti,ab,kw OR 'pulmonectomy':ti,ab,kw OR 'resected lung':ti,ab,kw OR 'lung lobe resection':ti,ab,kw OR 'lung lobectomy':ti,ab,kw OR 'pneumolobectomy':ti,ab,kw OR 'pulmonary lobectomy':ti,ab,kw |

60053 |

Ovid/Medline

|

# |

Searches |

Results |

|

11 |

4 and (8 or 9) |

824 |

|

10 |

4 and 6 RCT |

152 |

|

9 |

4 and 5 SR |

45 |

|

8 |

Case-control Studies/ or clinical trial, phase ii/ or clinical trial, phase iii/ or clinical trial, phase iv/ or comparative study/ or control groups/ or controlled before-after studies/ or controlled clinical trial/ or double-blind method/ or historically controlled study/ or matched-pair analysis/ or single-blind method/ or (((control or controlled) adj6 (study or studies or trial)) or (compar* adj (study or studies)) or ((control or controlled) adj1 active) or "open label*" or ((double or two or three or multi or trial) adj (arm or arms)) or (allocat* adj10 (arm or arms)) or placebo* or "sham-control*" or ((single or double or triple or assessor) adj1 (blind* or masked)) or nonrandom* or "non-random*" or "quasi-experiment*" or "parallel group*" or "factorial trial" or "pretest posttest" or (phase adj5 (study or trial)) or (case* adj6 (matched or control*)) or (match* adj6 (pair or pairs or cohort* or control* or group* or healthy or age or sex or gender or patient* or subject* or participant*)) or (propensity adj6 (scor* or match*))).ti,ab,kf. or (confounding adj6 adjust*).ti,ab. or (versus or vs or compar*).ti. or ((exp cohort studies/ or epidemiologic studies/ or multicenter study/ or observational study/ or seroepidemiologic studies/ or (cohort* or 'follow up' or followup or longitudinal* or prospective* or retrospective* or observational* or multicent* or 'multi-cent*' or consecutive*).ti,ab,kf.) and ((group or groups or subgroup* or versus or vs or compar*).ti,ab,kf. or ('odds ratio*' or 'relative odds' or 'risk ratio*' or 'relative risk*' or aor or arr or rrr).ab. or (("OR" or "RR") adj6 CI).ab.)) |

5107766 |

|

7 |

Epidemiologic studies/ or case control studies/ or exp cohort studies/ or Controlled Before-After Studies/ or Case control.tw. or cohort.tw. or Cohort analy$.tw. or (Follow up adj (study or studies)).tw. or (observational adj (study or studies)).tw. or Longitudinal.tw. or Retrospective*.tw. or prospective*.tw. or consecutive*.tw. or Cross sectional.tw. or Cross-sectional studies/ or historically controlled study/ or interrupted time series analysis/ [Onder exp cohort studies vallen ook longitudinale, prospectieve en retrospectieve studies] |

4095298 |

|

6 |

(exp randomized controlled trial/ or randomized controlled trials as topic/ or random*.ti,ab. or rct?.ti,ab. or ((pragmatic or practical) adj "clinical trial*").ti,ab,kf. or ((non-inferiority or noninferiority or superiority or equivalence) adj3 trial*).ti,ab,kf.) not (animals/ not humans/) |

1359441 |

|

5 |

(meta-analysis/ or meta-analysis as topic/ or (metaanaly* or meta-analy* or metanaly*).ti,ab,kf. or systematic review/ or cochrane.jw. or (prisma or prospero).ti,ab,kf. or ((systemati* or scoping or umbrella or "structured literature") adj3 (review* or overview*)).ti,ab,kf. or (systemic* adj1 review*).ti,ab,kf. or ((systemati* or literature or database* or data-base*) adj10 search*).ti,ab,kf. or ((structured or comprehensive* or systemic*) adj3 search*).ti,ab,kf. or ((literature adj3 review*) and (search* or database* or data-base*)).ti,ab,kf. or (("data extraction" or "data source*") and "study selection").ti,ab,kf. or ("search strategy" and "selection criteria").ti,ab,kf. or ("data source*" and "data synthesis").ti,ab,kf. or (medline or pubmed or embase or cochrane).ab. or ((critical or rapid) adj2 (review* or overview* or synthes*)).ti. or (((critical* or rapid*) adj3 (review* or overview* or synthes*)) and (search* or database* or data-base*)).ab. or (metasynthes* or meta-synthes*).ti,ab,kf.) not (comment/ or editorial/ or letter/ or ((exp animals/ or exp models, animal/) not humans/)) |

553153 |

|

4 |

3 not ((exp animals/ or exp models, animal/) not humans/) not (letter/ or comment/ or editorial/) |

1549 |

|

3 |

1 and 2 |

1583 |

|

2 |

Device Removal/ or (fluid adj2 (turnover or output or production)).ti,ab,kf. or ((high or low or median) adj3 (volume or output)).ti,ab,kf. or threshold*.ti,ab,kf. or cut off.ti,ab,kf. or cutoff.ti,ab,kf. or ((tube* or drain*) adj3 remov*).ti,ab,kf. |

487702 |

|

1 |

Pneumonectomy/ or (exp Thoracoscopy/ and Lung/) or exp Lung Neoplasms/su or lung resection.ti,ab,kf. or lung volume reduction surgery.ti,ab,kf. or pneumectomy.ti,ab,kf. or pneumonectomy.ti,ab,kf. or pneumonic resection.ti,ab,kf. or pneumoresection.ti,ab,kf. or pulmonary resection.ti,ab,kf. or pulmonectomy.ti,ab,kf. or resected lung.ti,ab,kf. or lung lobe resection.ti,ab,kf. or lung lobectomy.ti,ab,kf. or pneumolobectomy.ti,ab,kf. or pulmonary lobectomy.ti,ab,kf. or ((lung or pulmonary) adj3 (surger* or segmentectomy)).ti,ab,kf. |

63649 |