Opiaten Ontgifting symptomatische medicatie

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is er bekend over de effectiviteit van het gebruik van symptomatische medicatie tijdens ontgifting bij opiaatverslaving?

Aanbeveling

Alvorens extra symptomatische medicatie wordt overwogen, moet altijd eerst worden bezien of de dosering opiaatagonist wel voldoende is en of verhoging van deze dosering de noodzaak tot extra symptomatische medicatie niet overbodig maakt.

Voor slaapproblemen tijdens ontgifting kan 5 mg melatonine, 25 mg quetiapine of 15 mg mirtazapine worden gegeven. Als dit onvoldoende effect heeft, kan kortdurend temazepam in een dosering van 10 of 20 mg worden gegeven.

In het geval dat de patiënt ook alcohol gebruikt, dient preventie en behandeling van onthoudingsinsulten en delier met afbouwschema's benzodiazepinen te worden overwogen en te worden ingepast in de behandeling.

Andere aanvullende medicamenteuze interventies voor de behandeling van specifieke onthoudingsverschijnselen moeten selectief worden ingezet omdat niet duidelijk is of dergelijke aanvullende behandelingen wel leiden tot een betere kans op het afmaken van de behandeling en een betere uitkomst op de langere termijn.

Overwegingen

Bij deze module zijn geen overwegingen geformuleerd.

Onderbouwing

Samenvatting literatuur

Voor de aanvullende medicamenteuze behandeling van specifieke ontwenningsverschijnselen kunnen de volgende aanbevelingen worden gedaan (zie ook Richtlijn Detox: De Jong e.a., 2004a).

- Bij hevige diarree kan loperamide worden gebruikt. Hierbij wordt een startdosis gegeven van 4 mg, indien nodig gevolgd door om de 2 uur 2 mg, maximaal 16 mg per dag.

- Bij spier- of botpijn kunnen NSAID's worden gegeven, bijvoorbeeld ibuprofen (600-800 mg, 3-4 keer/dag en maximaal 2.400 mg/dag) of diclofenac (50 mg oraal of intramusculair, maximaal 150 mg per dag). Gezien het effect op het maagslijmvlies wordt geadviseerd een protonpompremmer toe te voegen, bijvoorbeeld 20 mg omeprazol.

- Bij slaapproblemen is het aan te raden waar mogelijk benzodiazepinen te vermijden, vanwege het euforiserende en dus verslavende effect bij mensen met een verslavingsgeschiedenis. Hoewel de literatuur over de effectiviteit niet overtuigend is, kan 3 of 5 mg melatonine worden gegeven (Ferguson e.a., 2010). Ook kan worden gedacht aan sederende antipsychotica of antidepressiva. Voor 100 mg trazodon is een aantal gerandomiseerde onderzoeken beschikbaar, onder meer twee tijdens alcoholontgifting (Ware e.a., 1990; Saletu-Zyhlarz e.a., 2001; Le Bon e.a., 2003; Zavesicka e.a., 2008; Friedmann e.a., 2008). Als er sprake is van comorbiditeit met alcoholafhankelijkheid, is voorzichtigheid geboden, omdat er melding is gemaakt van een negatieve invloed van trazodon op abstinentie daarvan. Ook zijn er enkele positieve onderzoeken over 25 mg quetiapine (Cohrs e.a., 2004; Tassniyom e.a., 2010). Het onderzoek naar mirtazapine is vooral gedaan met doses van 30 mg (Radakishun e.a., 2000; Aslan e.a., 2002; Winokur e.a., 2003), terwijl in de klinische praktijk vooral 15 mg en soms zelfs 7,5 mg mirtazapine wordt voorgeschreven bij slaapproblemen.

- Bij psychotische symptomen tijdens de ontgifting is een psychiatrisch consult aangewezen, evenals bij heftige angst.

Bij dit alles dient men zich te realiseren dat Hillhouse e.a. (2010) laten zien dat het nog maar de vraag is of symptomatische medicatie om ontwenningsverschijnselen te bestrijden effectief is. De groep met aanvullende medicatie bleef korter in behandeling en een subgroep met diarreemedicatie had vaker positieve urines. De ernst van de klachten kan natuurlijk verantwoordelijk zijn voor zowel de behoefte aan extra symptomatische medicatie als voor de uitval en de terugval, maar terugval wordt door extra medicatie in elk geval niet voorkomen.

Referenties

- Amato, L., Davoli, M., Ferri, M., & Ali, R. (2004). Methadone at tapered doses for the management of opioid withdrawal. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2004(4), Article CD003409. The Cochrane Library Database.

- Bernstein, J., Bernstein, E., Tassiopoulos, K., Heeren, T., Levenson, S., & Hingson, R. (2005). Brief motivational intervention at a clinic visit reduces cocaine and heroin use. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 77, 49-59.

- Favrat, B., Zimmermann, G., Zullino, D., Krenz, S., Dorogy, F., Muller, J., e.a. (2006). Opioid antagonist detoxification under anaesthesia versus traditional clonidine detoxification combined with an additional week of psychosocial support: a randomised clinical trial. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 81, 109-116.

- Finney, J.W., Noyes, C.A., Coutts, A.I., & Moos, R.H. (1998). Evaluating substance abuse treatment process models I: Changes on proximal outcome variables during 12-step and cognitive-behavioral treatment. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 59, 371-380.

- Gerra, G., Zaimovic, A., Rustichelli, P., Fontanesi, B., Zambelli, U., Timpano, M., e.a. (2000). Rapid opiate detoxication in outpatient treatment: Relationship with naltrexone compliance. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 18, 185-191.

- Gowing, L. Farrell M, Ali, R., & Whit, J. (2004). Alpha2 adrenergic agonists for the management of opioid withdrawal. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2004(4), Article CD002024. The Cochrane Library Database.

- Gowing, L., Ali, R., & White, J. (2006a). Opioid antagonists under heavy sedation or anaesthesia for opioid withdrawal. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2006(2), Article CD002022. The Cochrane Library Database.

- Gowing, L., Ali, R., & White, J. (2006b). Opioid antagonists with minimal sedation for opioid withdrawal. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2006(1), Article CD002021. The Cochrane Library Database.

- Gowing, L., Ali, R., & White, J.M. (2009). Opioid antagonists with minimal sedation for opioid withdrawal. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2009(4), Article CD002021. The Cochrane Library Database. (Update of Gowing e.a., 2006b.)

- Gowing, L., Ali, R., & White, J.M. (2010). Opioid antagonists under heavy sedation or anaesthesia for opioid withdrawal. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2010(1), Article CD002022. The Cochrane Library Database. (Update of Gowing e.a., 2006a)

- Greenwood, G.L., Woods, W.J., Guydish, J., & Bein E. (2001). Relapse outcomes in a randomized trial of residential and day drug abuse treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 20, 15-23.

- Kleber, H.D., Riordan, C.E., Rounsaville, B., Kosten, T., Charney, D., Gaspari, J., Hogan, I., & O'Connnor. C. (1985). Clonidine in outpatient detoxification from methadone maintenance. Archives of GeneralPsychiatry, 42, 391-394.

- Miller, W.R., Yahne, C.E., & Tonigan, J.S. (2003). Motivational interviewing in drug abuse services: A randomized trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 71, 754-763.

- Minozzi, S., Amato, L., Vecchi, S., Davoli, M., Kirchmayer, U., & Verster, A. Oral naltrexone maintenance treatment for opioid dependence. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2006(1), Article CD001333. The Cochrane Library Database.

- Petry, N.M. (2005). Methadone plus contingency management or performance feedback reduces cocaine and opiate use in people with drug addiction. Evidence-Based Mental Health, 8, 112.

- Petry, N.M., Alessi, S.M., Carroll, K. M., Hanson, T., MacKinnon, S., Rounsaville, B., e.a. (2006). Contingency management treatments: Reinforcing abstinence versus adherence with goal-related activities. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 74, 592-601.

- San, L., Cami, J., Peri, J.M., Mata, R., & Porta, M. (1990). Efficacy of clonidine, guanfacine and methadone in the rapid detoxification of heroin addicts. a controlled clinical trail. Britisch Journal of Addiction, 85, 141-147.

- Senay, E.C., Dorus, W., & Showalter, C.V. (1981). Short-term detoxification with methadone. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 362, 203-216.

- Sorensen, J.L., Hargreaves, W.A., & Weinberg, J.A. (1982). Withdrawal from heroin in three or six weeks. Comparison of methadyl acetate and methadone. Archives of General Psychiatry, 39, 167-171.

- Stitzer, M.L., McCaul, M.E., Bigelow, G.E., & Liebson, I.A. (1984). Chronic opiate use during methadone detoxification: effects of a dose increase treatment. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 14, 37-44.

- Umbricht, A., Hoover, D.R., Tucker, M.J., Leslie, J.M., Chaisson, R.E., & Preston, K.L. (2003). Opioid detoxification with buprenorphine, clonidine, or methadone in hospitalized heroin-dependent patients with HIV infection. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 69, 263-272.

- Adi, Y., Juarez-Garcia, A., Wang, D., Jowett, S., Frew, E., Day, E., e.a. (2007). Oral naltrexone as a treatment for relapse prevention in formerly opioid- dependent drug users: a systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technology Assessment, 11, iii-85.

- Dutra, L., Stathopoulou, G., Basden, S.L., Leyro, T.M., Powers, M.B., & Otto, M.W. (2008). A meta-analytic review of psychosocial interventions for substance use disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry, 165, 179-187.

- Jong, C.A.J. de, Laheij, R.J.F., & Krabbe, P.F.M. (2004c). General anaesthesia does not improve outcome in opioid antagonist detoxification treatment: A randomized controlled trial. Addiction, 100, 206-215.

- Katz, E.C., Chutuape, M.A., Jones, H.E., & Stitzer, M.L. (2002). Voucher reinforcement for heroin and cocaine abstinence in an outpatient drug-free program. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 10, 136-143.

- Krupitsky, E., Nunes, E.V., Ling, W., Illeperuma, A., Gastfriend, D.R., & Silverman, B.L. (2011). Injectable extended-release naltrexone for opioid dependence: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre randomised trial. Lancet, 377, 1506-1513.

- Kunoe, N., Lobmaier, P, Vederhus, J.K., Hjerkinn, B., Hegstad, S., Gossop, M., e.a. (2009). Naltrexone implants after in-patient treatment for opioid dependence: randomised controlled trial. British Journal of Psychiatry, 194, 541-546.

- Lobmaier, P, Kornor, H., Kunoe, N., & Bjorndal, A. (2008). Sustained-release naltrexone for opioid dependence. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2008(2), Article CD006140. The Cochrane Library Database.

- APA. (2006). Practiceguidelines for the treatment of patients with substance use disorders (2nd ed.). Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association.

- Berglund, M., Thelander, S., & Jonsson, E. (2003). Treating alcohol and drug abuse: an evidence based review. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH.

- Fiorentine, R. & Hillhouse, M.P (2000). Drug treatment and 12-step program participation: The additive effects of integrated recovery activities. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 18, 65-74.

- Fudala, PJ., Bridge, T.P., Herbert, S., Williford, W.O., Chiang, C.N., Jones, K., e.a. (2003). Office-based treatment of opiate addiction with a sublingual- tablet formulation of buprenorphine and naloxone. New England Journal of Medicine, 349, 949-958.

- Goldstein, M.F., Deren, S., Kang, S.Y., Des Jarlais, D.C., & Magura, S. (2002) Evaluation of an alternative program for MMTP drop-outs: Impact on treatment re-entry. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 66, 181-187.

- Gossop, M., Griffiths, P., Bradley, B., & Strang, J. (1989). Opiate withdrawal symptoms in response to 10-day and 21-day methadone withdrawal programmes. British Journal of Psychiatry, 154, 360-363.

- Gowing, L., Ali, R., & White, J.M. (2009). Buprenorphine for the management of opioid withdrawal. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2009(3), Article CD002025. The Cochrane Library Database.

- Gowing, L., Ali, R., & White, J.M. (2010). Opioid antagonists under heavy sedation or anaesthesia for opioid withdrawal. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2010(1), Article CD002022. The Cochrane Library Database.

- Hulse, G.K., Morris, N., Arnold-Reed, D., & Tait, R.J. (2009). Improving clinical outcomes in treating heroin dependence: randomized, controlled trial of oral or implant naltrexone. Archives of General Psychiatry, 66, 1108-1115.

- Jong, C.A. de, Roozen, H.G., Rossum, L.G. van, Krabbe, P.F., & Kerkhof, A.J. High abstinence rates in heroin addicts by a new comprehensive treatment approach. American Journal on Addictions, 16, 124-130.

- Jong, C.J. de. (2005). General anaesthesia is patient-friendly in opioid antagonist detoxification treatment. Addiction, 100, 1742-1744.

- Jong, C.J. de. (2006). Detoxification and treating opioid dependence. JAMA, 295, 887.

- Koeter, M.W.J., & Maastricht, A.S. van. (2006) De effectiviteit van verslavingszorg in een justitieel kader. Den Haag: ZonMw.

- McAuliffe, W.E. (1990). A randomized controlled trial of recovery training and self-help for opioid addicts in New England and Hong Kong. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 22, 197-209.

- Moos, R.H., Finney, J.W., Ouimette, P.C., & Suchinsky, R.T. (1999). A comparative evaluation of substance abuse treatment: I. Treatment orientation, amount of care, and 1-year outcomes. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research, 23, 529-536.

- Perry, A., Coulton, S., Glanville, J., Godfrey, C., Lunn, J., McDougall, C., e.a. (2006). Interventions for drug-using offenders in the courts, secure establishments and the community. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2006(3), Article CD005193. The Cochrane Library Database.

- Preston, K.L., Bigelow, G.E., & Liebson, I.A. (1984). Self-administration of clonidine and oxazepam by methadone detoxification patients. NIDA Research Monograph, 49, 192-198.

- Smith, L.A., Gates, S., & Foxcroft, D. (2006). Therapeutic communities for substance related disorder. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2006(1), Article CD005338. The Cochrane Library Database.

- Timko, C., Debenedetti, A., & Billow, R. (2006). Intensive referral to 12-Step self- help groups and 6-month substance use disorder outcomes. Addiction, 101, 678-688.

- Ware, J.C. & Pittard, J.T. (1990). Increased deep sleep after trazodone use: a double-blind placebo-controlled study in healthy young adults. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 51, 18-22.

- Witbrodt, J., Bond, J., Kaskutas, L.A., Weisner, C., Jaeger, G., Pating, D., & Moore, C. (2007). Day hospital and residential addiction treatment: Randomized and nonrandomized managed care clients. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 75, 947-959.

- Aslan, S., Isik, E., & Cosar, B. (2002). The effects of mirtazapine on sleep: A placebo controlled, double-blind study in young healthy volunteers. Sleep, 25, 677-679.

- Buydens-Branch, Branchey, M., & Reel-Brander, C. (2005). Efficacy of buspirone in the treatment of opioid withdrawal. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology, 25, 230-236.

- CBO/Trimbos-instituut. (2009). Multidisciplinaire richtlijn Stoornissen in het gebruik van alcohol: Richtlijn voor de diagnostiek en behandeling van patiënten met een stoornis in het gebruik van alcohol. Utrecht: Trimbos¬instituut.

- Cohrs, S., Rodenbeck, A., Guan, Z., Pohlmann, K., Jordan, W., Meier, A., e.a. (2004). Sleep-promoting properties of quetiapine in healthy subjects. Psychopharmacology, 174, 421-429.

- Comer, S.D., Sullivan, M.A., Yu, E., Rothenberg, J.L., Kleber, H.D., Kampman, K., e.a. (2006). Injectable, sustained-release naltrexone for the treatment of opioid dependence: A randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Archives of General Psychiatry, 63, 210-218.

- Condelli, W.S., Koch, M.A., & Fletcher, B. (2000). Treatment refusal/attrition among adults randomly assigned to programs at a drug treatment campus: The New Jersey Substance Abuse Treatment Campus, Seacaucus, NJ. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 18, 395-407.

- Ferguson, S.A., Rajaratnam, S.M., & Dawson, D. (2010). Melatonin agonists and insomnia. Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics, 10, 305-318.

- Friedmann, P.D., Rose, J.S., Swift, R., Stout, R.L., Millman, R.P., & Stein, M.D. Trazodone for sleep disturbance after alcohol detoxification: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research, 32, 1652-1660.

- Fudala, P.J., Bridge, T.P., Herbert, S., Williford, W.O., Chiang, C.N., Jones, K., e.a. (2003). Office-based treatment of opiate addiction with a sublingual- tablet formulation of buprenorphine and naloxone. New England Journal of Medicine, 349, 949-958.

- Galanter, M., Jaffe, J.H., & Faerber, N. (2001). American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM). Encyclopedia of Drugs, Alcohol, and Addictive Behavior. Encyclopedia.com. Geraadpleegd 8 oct 2013 (http://www.encyclopedia. com/doc/1G2-3403100046.html).

- Geelen, K./Ontwikkelcentrum Kwaliteit en innovatie van zorg. (2003). Zelfhulpgroepen en 12 stappenprogrammas, een literatuurstudie. Amersfoort: Resultaten Scoren.

- Gossop, M., Griffiths, P., Bradley, B., & Strang, J. (1989). Opiate withdrawal symptoms in response to 10-day and 21-day methadone withdrawal programmes. British Journal of Psychiatry, 154, 360-363.

- Gowing, L., Ali, R., & White, J.M. (2009). Buprenorphine for the management of opioid withdrawal. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2009(3), Article CD002025. The Cochrane Library Database.

- Guydish, J., Werdegar, D., Sorensen, J.L., Clark, W., & Acampora, A. (1998). Drug abuse day treatment: A randomized clinical trial comparing day and residential treatment programs. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 66, 280-289.

- Hillhouse, M., Domier, C.P., Chim, D., & Ling, W. (2010). Provision of ancillary medications during buprenorphine detoxification does not improve treatment outcomes. Journal of Addictive Diseases, 29, 23-29.

- Jong, C.A.J. de, Hoek, A F.M. van, & Jongerhuis, M. (redactie). (2004a). Richtlijn Detox: Verantwoord ontgiften door ambulante of intramurale detoxificatie. Amersfoort: GGZ Nederland. Raadpleegbaar via: http://www.ggznederland. nl/scrivo/asset.php?id=306065.

- Jong CAJ de., Roozen HG., Krabbe PFM., & Kerkhof AJFM. (2004b). EDOCRA. Van ontgifting naar abstinentie. Eindrapportage. St. Oedenrode/Nijmegen/ Amsterdam: Novadic-Kentron/ Universitair Medisch Centrum/Vakgroep Klinische Psychologie.

- Kadden, R.M., Litt, M.D., & Cooney, N.L. (1994). Matching alcoholics to coping skills or interactional therapies. Role of intervening variables. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 708, 218-229.

- Kooyman M. (1992). The therapeutic community for addicts: Intimacy, parent involvement and treatment outcome. Rotterdam: Universiteitsdrukkerij Erasmus.

- Le Bon, O., Murphy, J.R., Staner, L., Hoffmann, G., Kormoss, N., Kentos, M., e.a. (2003). Double-blind, placebo-controlled study of the efficacy of trazodone in alcohol post-withdrawal syndrome: Polysomnographic and clinical evaluations. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology, 23, 377-383.

- Longabaugh, R., & Morgenstern, J. (1999). Cognitive-behavioral coping-skills therapy for alcohol dependence. Current status and future directions. Alcohol Research & Health, 23, 78-85.

- Loth, C., Wits, E., Jong, C. de, & Mheen, D. van de. (2012). RIOB: Richtlijn Opiaatonderhoudsbehandeling Herziene versie. Amersfoort: Resultaten Scoren.

- Mayet, S., Farrell, M., Ferri, M., Amato, L., & Davoli, M. (2005). Psychosocial treatment for opiate abuse and dependence. Cochrane Review Library. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005 Jan 25;(1):CD004330. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2005(1), Article CD004330. The Cochrane Library Database.

- McCaul, M.E., Stitzer, M.L., Bigelow, G.E., & Liebson, I.A. (1984). Contingency management interventions: effects on treatment outcome during methadone detoxification. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis., 17, 35-43.

- McCusker, J., Vickers-Lahti, M., Stoddard, A., Hindin, R., Bigelow, C., Zorn, M., e.a. (1995). The effectiveness of alternative planned durations of residential drug abuse treatment. American Journal of Public Health, 85, 1426-1429.

- McCusker, J., Bigelow, C., Vickers-Lahti, M., Spotts, D., Garfield, F., & Frost R. (1997). Planned duration of residential drug abuse treatment: Efficacy versus effectiveness. Addiction, 92, 1467-1478

- NICE. (2007a). Drugmisuse: Opioid detoxification. London: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence.

- NICE. (2007b). Drug misuse: Psychosocial interventions. London: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence.

- Nielsen, A.L., Scarpitti, F.R., & Inciardi, J.A. (1996). Integrating the therapeutic community and work release for drug-involved offenders The CREST Program. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 13, 349-358.

- Nuttbrock, L.A., Rahav, M., Rivera, J.J., Ng-Mak, D.S., & Link, B.G. (1998). Outcomes of homeless mentally ill chemical abusers in community residences and a therapeutic community. Psychiatric Services, 49, 68-76.

- Polen, M.R., Whitlock, E. P, Wisdom, J.P., Nygren, P, & Bougatsos, C. (2008). Screening in primary care settings for illicit drug use: Staged systematic review for the United States Preventive Services Task Force. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

- Radhakishun, F.S., Bos, J. van den, Heijden, B.C. van der, Roes, K.C., & O'Hanlon, J.F. (2000). Mirtazapine effects on alertness and sleep in patients as recorded by interactive telecommunication during treatment with different dosing regimens. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology, 20, 531-537.

- Rash, C.J., Olmstead, T.A., & Petry, N.M. (2009). Income does not affect response to contingency management treatments among community substance abuse treatment-seekers. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 104, 249-253.

- San, L., Cami, J., Fernandez, T., Olle, J. M., Peri, J.M., & Torrens, M. (1992). Assessment and management of opioid withdrawal symptoms in buprenorphine-dependent subjects. British Journal of Addiction, 87, 55-62.

- Schaap, G.E. (1987). De therapeutische gemeenschap voor alcoholisten: diagnostiek, behandeling en effectiviteit bij afhankelijkheidsproblemen. Assen: Van Gorcum.

- Sorensen, J.L., Andrews, S., Delucchi, K.L., Greenberg, B., Guydish, J., Masson, C.L., & Shopshire, M. (2009). Methadone patients in the therapeutic community: A test of equivalency. Drug & Alcohol Dependence, 100, 1-2, 100-106.

- Saletu-Zyhlarz, G.M., Abu-Bakr, M.H., Anderer, P., Semler, B., Decker, K., Parapatics, S., e.a. (2001). Insomnia related to dysthymia: Polysomnographic and psychometric comparison with normal controls and acute therapeutic trials with trazodone. Neuropsychobiology, 44, 139-149.

- Tassniyom, K., Paholpak, S., Tassniyom, S., & Kiewyoo, J. (2010). Quetiapine for primary insomnia: A double blind, randomized controlled trial. Journal of the MedicalAssociation of Thailand, 93, 729-734.

- Wildt, W. de, Rietdijk, E.A., Brink W. van den, Dijk, A.A., Schippers, G.M., & Walburg, J.A. (2001). Achilles Leefstijl 2: Resultaten Scoren/ Ontwikkelcentrum Kwaliteit en innovatie. Zeist: Cure&Care publishers.

- Winokur, A., DeMartinis, N.A., III, McNally, D.P., Gary, E.M., Cormier, J.L., & Gary, K.A. (2003). Comparative effects of mirtazapine and fluoxetine on sleep physiology measures in patients with major depression and insomnia. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 64, 1224-1229.

- Zavesicka, L., Brunovsky, M., Horacek, J., Matousek, M., Sos, P., Krajca, V., & Höschl, C. (2008). Trazodone improves the results of cognitive behaviour therapy of primary insomnia in non-depressed patients. Neuro Endocrinology Letters, 29, 895-901.

Evidence tabellen

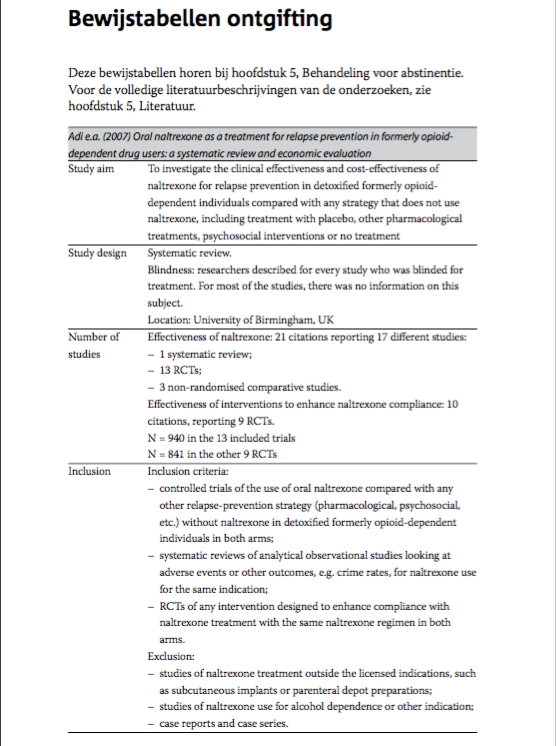

Adi e.a. (2007) Oral naltrexone as a treatment for relapse prevention in formerly opioid-dependent drug users: a systematic review and economic evaluation

|

Study aim |

To investigate the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of naltrexone for relapse prevention in detoxified formerly opioid-dependent individuals compared with any strategy that does not use naltrexone, including treatment with placebo, other pharmacological treatments, psychosocial interventions or no treatment. |

|

Study design |

Systematic review. Blindness: researchers described for every study who was blinded for treatment. For most of the studies, there was no information on this subject. Location: University of Birmingham, UK |

|

Number of studies |

Effectiveness of naltrexone: 21 citations reporting 17 different studies: - 1 systematic review; - 13 RCTs; - 3 non-randomised comparative studies. Effectiveness of interventions to enhance naltrexone compliance: 10 citations, reporting 9 RCTs. N = 940 in the 13 included trials N = 841 in the other 9 RCTs. |

|

Inclusion |

Inclusion criteria: - controlled trials of the use of oral naltrexone compared with any other relapse-prevention strategy (pharmacological, psychosocial, etc.) without naltrexone in detoxified formerly opioid-dependent individuals in both arms; - systematic reviews of analytical observational studies looking at adverse events or other outcomes, e.g. crime rates, for naltrexone use for the same indication; - RCTs of any intervention designed to enhance compliance with naltrexone treatment with the same naltrexone regimen in both arms.

Exclusion: - studies of naltrexone treatment outside the licensed indications, such as subcutaneous implants or parenteral depot preparations; - studies of naltrexone use for alcohol dependence or other indication; - case reports and case series. |

|

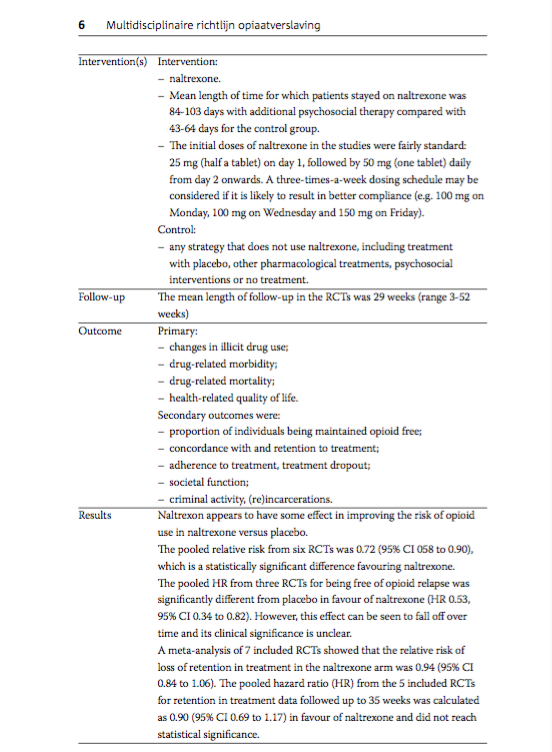

Intervention(s) |

Intervention: - naltrexone. - Mean length of time for which patients stayed on naltrexone was 84-103 days with additional psychosocial therapy compared with 43-64 days for the control group. - The initial doses of naltrexone in the studies were fairly standard: 25 mg (half a tablet) on day 1, followed by 50 mg (one tablet) daily from day 2 onwards. A three-times-a-week dosing schedule may be considered if it is likely to result in better compliance (e.g. 100 mg on Monday, 100 mg on Wednesday and 150 mg on Friday).

Control: - any strategy that does not use naltrexone, including treatment with placebo, other pharmacological treatments, psychosocial interventions or no treatment. |

|

Follow-up |

The mean length of follow-up in the RCTs was 29 weeks (range 3-52 weeks). |

|

Outcome |

Primary: - changes in illicit drug use; - drug-related morbidity; - drug-related mortality; - health-related quality of life.

Secondary outcomes were: - proportion of individuals being maintained opioid free; - concordance with and retention to treatment; - adherence to treatment, treatment dropout; - societal function; - criminal activity, (re)incarcerations. |

|

Results |

Naltrexon appears to have some effect in improving the risk of opioid use in naltrexone versus placebo. The pooled relative risk from six RCTs was 0.72 (95% CI 058 to 0.90), which is a statistically significant difference favouring naltrexone. The pooled HR from three RCTs for being free of opioid relapse was significantly different from placebo in favour of naltrexone (HR 0.53, 95% CI 0.34 to 0.82). However, this effect can be seen to fall off over time and its clinical significance is unclear. A meta-analysis of 7 included RCTs showed that the relative risk of loss of retention in treatment in the naltrexone arm was 0.94 (95% CI 0.84 to 1.06). The pooled hazard ratio (HR) from the 5 included RCTs for retention in treatment data followed up to 35 weeks was calculated as 0.90 (95% CI 0.69 to 1.17) in favour of naltrexone and did not reach statistical significance. |

|

Quality assessment |

Study question:+ Search: + Selection: + Quality assessment: + Data extraction: + Description of original studies: ? Handling heterogeneity: + Statistical pooling: + Finance: This report was commissioned by NHS R&D HTA Programme |

|

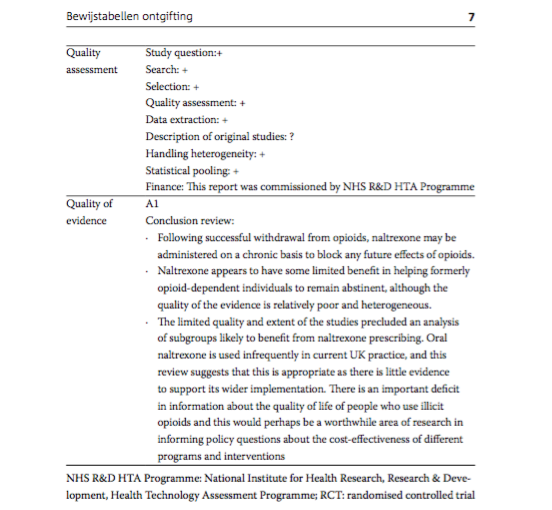

Quality of evidence |

A1

Conclusion review:

|

NHS R&D HTA Programme: National Institute for Health Research, Research & Development, Health Technology Assessment Programme; RCT: randomised controlled trial.

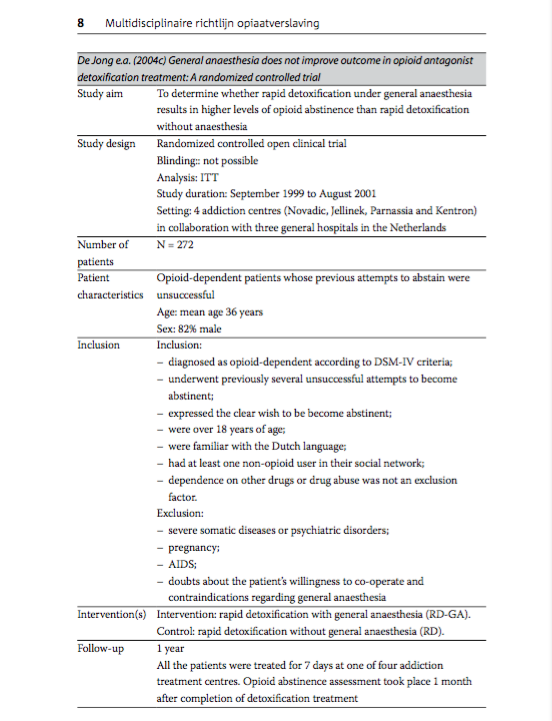

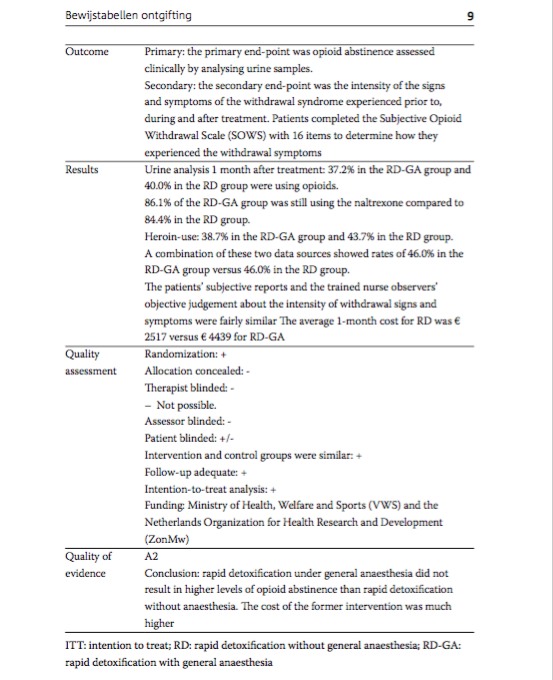

De Jong e.a. (2004c) General anaesthesia does not improve outcome in opioid antagonist detoxification treatment: A randomized controlled trial

|

Study aim |

To determine whether rapid detoxification under general anaesthesia results in higher levels of opioid abstinence than rapid detoxification without anaesthesia. |

|

Study design |

Randomized controlled open clinical trial Blinding: not possible Analysis: ITT Study duration: September 1999 to August 2001 Setting: 4 addiction centres (Novadic, Jellinek, Parnassia and Kentron) in collaboration with three general hospitals in the Netherlands. |

|

Number of patients |

N = 272 |

|

Patient characteristics |

Opioid-dependent patients whose previous attempts to abstain were unsuccessful Age: mean age 36 years Sex: 82% male |

|

Inclusion |

Inclusion: - diagnosed as opioid-dependent according to DSM-IV criteria; - underwent previously several unsuccessful attempts to become abstinent; - expressed the clear wish to be become abstinent; - were over 18 years of age; - were familiar with the Dutch language; - had at least one non-opioid user in their social network; - dependence on other drugs or drug abuse was not an exclusion factor.

Exclusion: - severe somatic diseases or psychiatric disorders; - pregnancy; - AIDS; - doubts about the patient's willingness to co-operate and contraindications regarding general anaesthesia |

|

Intervention(s) |

Intervention: rapid detoxification with general anaesthesia (RD-GA). Control: rapid detoxification without general anaesthesia (RD). |

|

Follow-up |

1 year All the patients were treated for 7 days at one of four addiction treatment centres. Opioid abstinence assessment took place 1 month after completion of detoxification treatment. |

|

Outcome |

Primary: the primary end-point was opioid abstinence assessed clinically by analysing urine samples. Secondary: the secondary end-point was the intensity of the signs and symptoms of the withdrawal syndrome experienced prior to, during and after treatment. Patients completed the Subjective Opioid Withdrawal Scale (SOWS) with 16 items to determine how they experienced the withdrawal symptoms. |

|

Results |

Urine analysis 1 month after treatment: 37.2% in the RD-GA group and 40.0% in the RD group were using opioids. 86.1% of the RD-GA group was still using the naltrexone compared to 84.4% in the RD group. Heroin-use: 38.7% in the RD-GA group and 43.7% in the RD group. A combination of these two data sources showed rates of 46.0% in the RD-GA group versus 46.0% in the RD group. The patients' subjective reports and the trained nurse observers' objective judgement about the intensity of withdrawal signs and symptoms were fairly similar The average 1-month cost for RD was € 2517 versus € 4439 for RD-GA. |

|

Quality assessment |

Randomization: + Allocation concealed: - Therapist blinded: - - Not possible. Assessor blinded: - Patient blinded: +/- Intervention and control groups were similar: + Follow-up adequate: + Intention-to-treat analysis: + Funding: Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sports (VWS) and the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development (ZonMw). |

|

Quality of evidence |

A2

Conclusion: rapid detoxification under general anaesthesia did not result in higher levels of opioid abstinence than rapid detoxification without anaesthesia. The cost of the former intervention was much higher. |

ITT: intention to treat; RD: rapid detoxification without general anaesthesia; RD-GA: rapid detoxification with general anaesthesia.

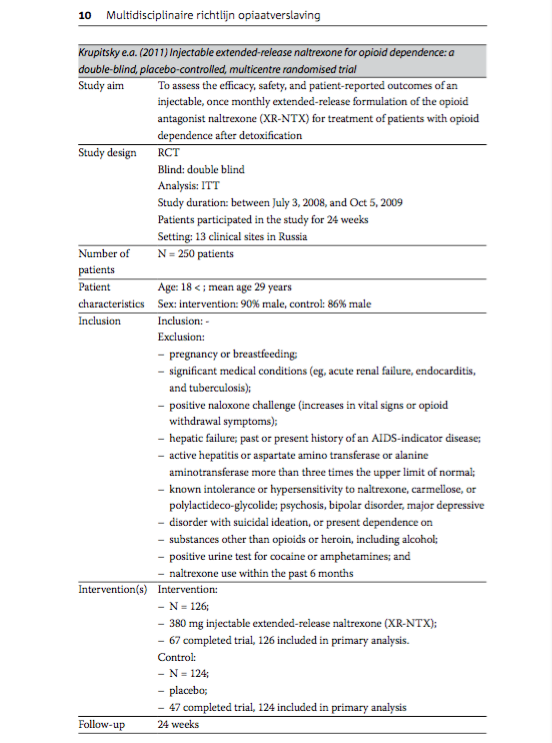

Krupitsky e.a. (2011) Injectable extended-release naltrexone for opioid dependence: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre randomised trial

|

Study aim |

To assess the efficacy, safety, and patient-reported outcomes of an injectable, once monthly extended-release formulation of the opioid antagonist naltrexone (XR-NTX) for treatment of patients with opioid dependence after detoxification. |

|

Study design |

RCT Blind: double blind Analysis: ITT Study duration: between July 3, 2008, and Oct 5, 2009 Patients participated in the study for 24 weeks Setting: 13 clinical sites in Russia. |

|

Number of patients |

N = 250 |

|

Patient characteristics |

Age: 18 < ; mean age 29 years Sex: intervention: 90% male, control: 86% male |

|

Inclusion |

Inclusion: -

Exclusion: - pregnancy or breastfeeding; - significant medical conditions (eg, acute renal failure, endocarditis, and tuberculosis); - positive naloxone challenge (increases in vital signs or opioid withdrawal symptoms); - hepatic failure; past or present history of an AIDS-indicator disease; - active hepatitis or aspartate amino transferase or alanine aminotransferase more than three times the upper limit of normal; - known intolerance or hypersensitivity to naltrexone, carmellose, or polylactideco-glycolide; psychosis, bipolar disorder, major depressive - disorder with suicidal ideation, or present dependence on - substances other than opioids or heroin, including alcohol; - positive urine test for cocaine or amphetamines; and - naltrexone use within the past 6 months |

|

Intervention(s) |

Intervention: - N = 126; - 380 mg injectable extended-release naltrexone (XR-NTX); - 67 completed trial, 126 included in primary analysis. Control: - N = 124; - placebo; - 47 completed trial, 124 included in primary analysis |

|

Follow-up |

24 weeks |

|

Outcome |

Primary: response profile for confirmed abstinence during weeks 5-24, assessed by urine drug tests and self report of non-use Secondary: self-reported opioid free days, opioid craving scores, number of days of retention, and relapse to physiological opioid dependence. |

|

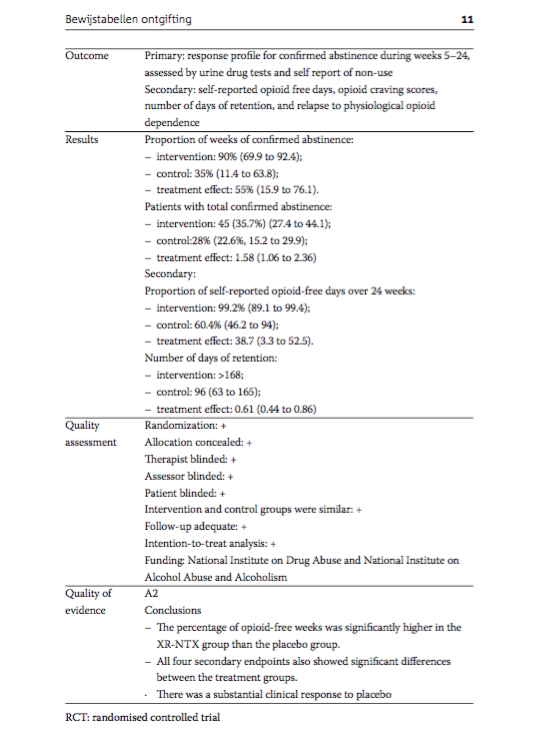

Results |

Proportion of weeks of confirmed abstinence: - intervention: 90% (69.9 to 92.4); - control: 35% (11.4 to 63.8); - treatment effect: 55% (15.9 to 76.1). Patients with total confirmed abstinence: - intervention: 45 (35.7%) (27.4 to 44.1); - control:28% (22.6%, 15.2 to 29.9); - treatment effect: 1.58 (1.06 to 2.36)

Secondary: Proportion of self-reported opioid-free days over 24 weeks: - intervention: 99.2% (89.1 to 99.4); - control: 60.4% (46.2 to 94); - treatment effect: 38.7 (3.3 to 52.5). Number of days of retention: - intervention: >168; - control: 96 (63 to 165); - treatment effect: 0.61 (0.44 to 0.86) |

|

Quality assessment |

Randomization: + Allocation concealed: + Therapist blinded: + Assessor blinded: + Patient blinded: + Intervention and control groups were similar: + Follow-up adequate: + Intention-to-treat analysis: + Funding: National Institute on Drug Abuse and National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism |

|

Quality of evidence |

A2

Conclusions

|

RCT: randomised controlled trial

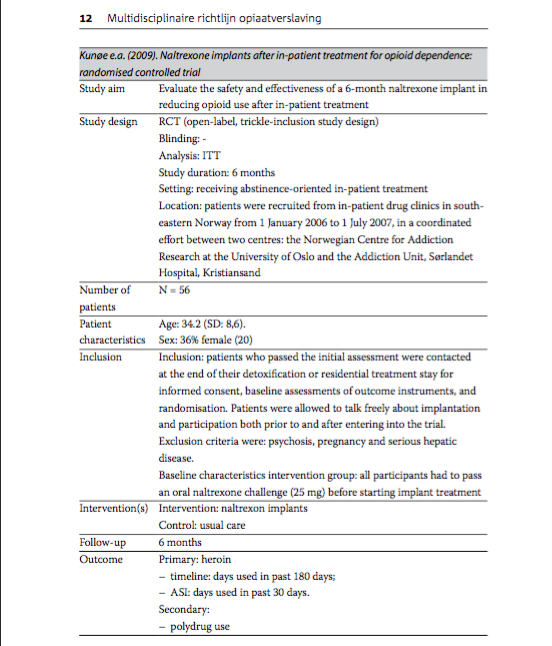

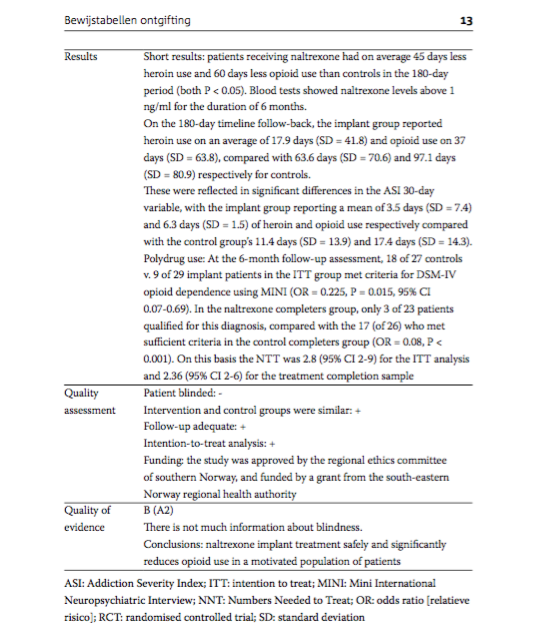

Kunoe e.a. (2009). Naltrexone implants after in-patient treatment for opioid dependence: randomised controlled trial

|

Study aim |

Evaluate the safety and effectiveness of a 6-month naltrexone implant in reducing opioid use after in-patient treatment. |

|

Study design |

RCT (open-label, trickle-inclusion study design) Blinding: - Analysis: ITT Study duration: 6 months Setting: receiving abstinence-oriented in-patient treatment Location: patients were recruited from in-patient drug clinics in south- eastern Norway from 1 January 2006 to 1 July 2007, in a coordinated effort between two centres: the Norwegian Centre for Addiction Research at the University of Oslo and the Addiction Unit, Sorlandet Hospital, Kristiansand |

|

Number of patients |

N = 56 |

|

Patient characteristics |

Age: 34.2 (SD: 8,6). Sex: 36% female (20) |

|

Inclusion |

Inclusion: patients who passed the initial assessment were contacted at the end of their detoxification or residential treatment stay for informed consent, baseline assessments of outcome instruments, and randomisation. Patients were allowed to talk freely about implantation and participation both prior to and after entering into the trial.

Exclusion criteria were: psychosis, pregnancy and serious hepatic disease.

Baseline characteristics intervention group: all participants had to pass an oral naltrexone challenge (25 mg) before starting implant treatment. |

|

Intervention(s) |

Intervention: naltrexon implants Control: usual care |

|

Follow-up |

6 months |

|

Outcome |

Primary: heroin - timeline: days used in past 180 days; - ASI: days used in past 30 days. Secondary: - polydrug use |

|

Results |

Short results: patients receiving naltrexone had on average 45 days less heroin use and 60 days less opioid use than controls in the 180-day period (both P < 0.05). Blood tests showed naltrexone levels above 1 ng/ml for the duration of 6 months. On the 180-day timeline follow-back, the implant group reported heroin use on an average of 17.9 days (SD = 41.8) and opioid use on 37 days (SD = 63.8), compared with 63.6 days (SD = 70.6) and 97.1 days (SD = 80.9) respectively for controls. These were reflected in significant differences in the ASI 30-day variable, with the implant group reporting a mean of 3.5 days (SD = 7.4) and 6.3 days (SD = 1.5) of heroin and opioid use respectively compared with the control group's 11.4 days (SD = 13.9) and 17.4 days (SD = 14.3). Polydrug use: At the 6-month follow-up assessment, 18 of 27 controls v. 9 of 29 implant patients in the ITT group met criteria for DSM-IV opioid dependence using MINI (OR = 0.225, P = 0.015, 95% CI 0.07-0.69). In the naltrexone completers group, only 3 of 23 patients qualified for this diagnosis, compared with the 17 (of 26) who met sufficient criteria in the control completers group (OR = 0.08, P < 0.001). On this basis the NTT was 2.8 (95% CI 2-9) for the ITT analysis and 2.36 (95% CI 2-6) for the treatment completion sample. |

|

Quality assessment |

Patient blinded: - Intervention and control groups were similar: + Follow-up adequate: + Intention-to-treat analysis: + Funding: the study was approved by the regional ethics committee of southern Norway, and funded by a grant from the south-eastern Norway regional health authority. |

|

Quality of evidence |

B (A2) There is not much information about blindness.

Conclusions: naltrexone implant treatment safely and significantly reduces opioid use in a motivated population of patients. |

ASI: Addiction Severity Index; ITT: intention to treat; MINI: Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview; NNT: Numbers Needed to Treat; OR: odds ratio [relatieve risico]; RCT: randomised controlled trial; SD: standard deviation.

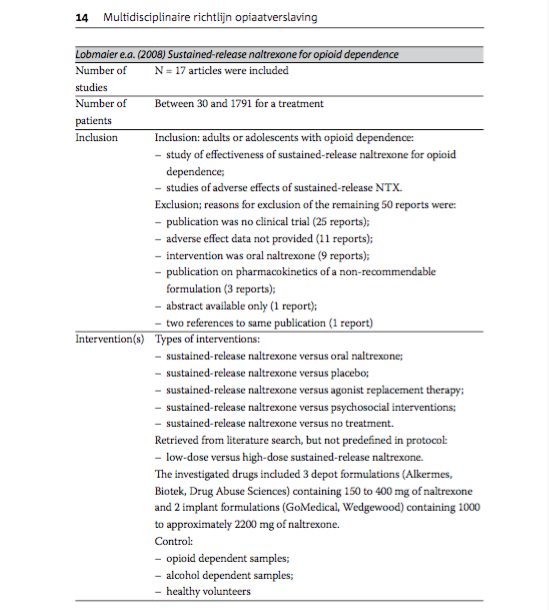

Lobmaier e.a. (2008) Sustained-release naltrexone for opioid dependence

|

Number of studies |

N = 17 articles were included |

|

Number of patients |

Between 30 and 1791 for a treatment |

|

Inclusion |

Inclusion: adults or adolescents with opioid dependence: - study of effectiveness of sustained-release naltrexone for opioid dependence; - studies of adverse effects of sustained-release NTX.

Exclusion; reasons for exclusion of the remaining 50 reports were: - publication was no clinical trial (25 reports); - adverse effect data not provided (11 reports); - intervention was oral naltrexone (9 reports); - publication on pharmacokinetics of a non-recommendable formulation (3 reports); - abstract available only (1 report); - two references to same publication (1 report) |

|

Intervention(s) |

Types of interventions: - sustained-release naltrexone versus oral naltrexone; - sustained-release naltrexone versus placebo; - sustained-release naltrexone versus agonist replacement therapy; - sustained-release naltrexone versus psychosocial interventions; - sustained-release naltrexone versus no treatment. Retrieved from literature search, but not predefined in protocol: - low-dose versus high-dose sustained-release naltrexone. The investigated drugs included 3 depot formulations (Alkermes, Biotek, Drug Abuse Sciences) containing 150 to 400 mg of naltrexone and 2 implant formulations (GoMedical, Wedgewood) containing 1000 to approximately 2200 mg of naltrexone.

Control: - opioid dependent samples; - alcohol dependent samples; - healthy volunteers |

|

Outcome |

Primary, effectiveness outcomes: - opioid use during and after treatment; - treatment adherence. Secondary, safety outcomes: - use of illicit drugs other than opioids during and after treatment; - criminal activity and incarceration; - quality of life; - mental health; - duration of achieved therapeutic naltrexone blood levels |

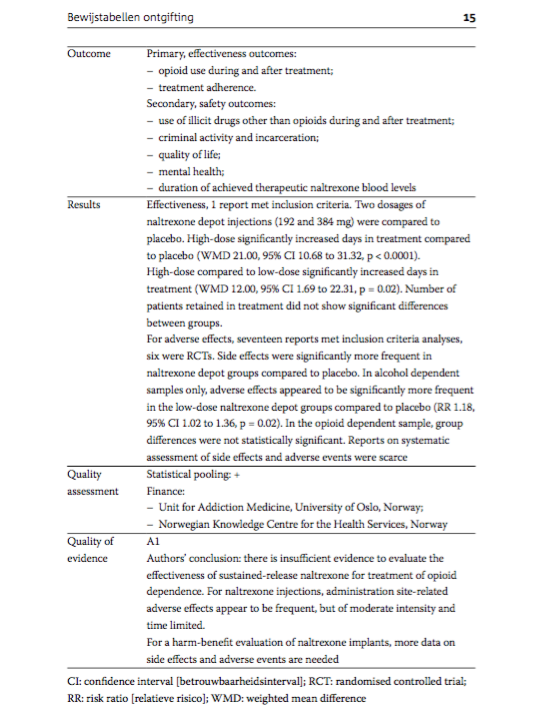

|

Results |

Effectiveness, 1 report met inclusion criteria. Two dosages of naltrexone depot injections (192 and 384 mg) were compared to placebo. High-dose significantly increased days in treatment compared to placebo (WMD 21.00, 95% CI 10.68 to 31.32, p < 0.0001). High-dose compared to low-dose significantly increased days in treatment (WMD 12.00, 95% CI 1.69 to 22.31, p = 0.02). Number of patients retained in treatment did not show significant differences between groups. For adverse effects, seventeen reports met inclusion criteria analyses, six were RCTs. Side effects were significantly more frequent in naltrexone depot groups compared to placebo. In alcohol dependent samples only, adverse effects appeared to be significantly more frequent in the low-dose naltrexone depot groups compared to placebo (RR 1.18, 95% CI 1.02 to 1.36, p = 0.02). In the opioid dependent sample, group differences were not statistically significant. Reports on systematic assessment of side effects and adverse events were scarce. |

|

Quality assessment |

Statistical pooling: + Finance: - Unit for Addiction Medicine, University of Oslo, Norway; - Norwegian Knowledge Centre for the Health Services, Norway |

|

Quality of evidence |

A1

Authors' conclusion: there is insufficient evidence to evaluate the effectiveness of sustained-release naltrexone for treatment of opioid dependence. For naltrexone injections, administration site-related adverse effects appear to be frequent, but of moderate intensity and time limited. For a harm-benefit evaluation of naltrexone implants, more data on side effects and adverse events are needed. |

CI: confidence interval [betrouwbaarheidsinterval]; RCT: randomised controlled trial; RR: risk ratio [relatieve risico]; WMD: weighted mean difference.

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Publicatiedatum : 01-10-2014

Beoordeeld op geldigheid : 01-01-2013

De Nederlandse Vereniging voor Psychiatrie is als houder van deze richtlijn de eerstverantwoordelijke voor de actualiteit van deze richtlijn. Uiterlijk in 2017 bepaalt de NVvP of deze richtlijn nog actueel is. Indien nodig wordt een nieuwe werkgroep geïnstalleerd om de richtlijn te herzien. De geldigheid van de richtlijn komt eerder te vervallen indien nieuwe ontwikkelingen aanleiding zijn om een herzieningstraject te starten.

De andere aan deze richtlijn deelnemende beroepsverenigingen of gebruikers van de richtlijn delen de verantwoordelijkheid voor het bewaken van de actualiteit van de aanbevelingen in de richtlijn; hen wordt verzocht relevante ontwikkelingen kenbaar te maken aan de eerstverantwoordelijke.

Algemene gegevens

Financiering en opdrachtgevers: Centrale Commissie Behandeling Heroïneverslaving (CCBH), Nederlandse Vereniging voor Psychiatrie (NVvP).

Doel en doelgroep

Doelstelling

Deze richtlijn is een document met aanbevelingen ter ondersteuning van de dagelijkse praktijkvoering. In de conclusies wordt aangegeven wat de wetenschappelijke stand van zaken is. De aanbevelingen zijn gericht op het expliciteren van optimaal professioneel handelen in de gezondheidszorg en zijn gebaseerd op de resultaten van wetenschappelijk onderzoek en aansluitende meningsvorming. In deze aanbevelingen zijn naast de wetenschappelijke argumenten ook professionele kennis en ervaringskennis meegenomen, samengevat in de overige overwegingen.

Deze richtlijn beoogt een leidraad te geven voor de dagelijkse praktijk van hulpverleners in de gezondheidszorg die betrokken zijn bij diagnostiek en behandeling van patiënten met opiaatverslaving. Om de implementatie te bevorderen, biedt deze richtlijn aanknopingspunten voor protocollen op plaatselijk, instituuts- of regioniveau en voor transmurale afspraken.

Doelgroep

Deze richtlijn is geschreven voor alle leden van de beroepsgroepen die aan de ontwikkeling van de richtlijn hebben bijgedragen: psychiaters, psychologen, verslavingsgeneeskundigen, verpleegkundigen en verzorgenden in de verslavingszorg (zie ook ‘Samenstelling werkgroep’).

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijn is in december 2009 een multidisciplinaire werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van de Nederlandse Vereniging voor Psychiatrie (NVvP), het Nederlands Instituut van Psychologen (NIP), de Vereniging voor Verslavingsgeneeskunde Nederland (VVGN) en Verpleegkundigen & Verzorgenden Nederland (V&VN), onder voorzitterschap van professor doctor Wim van den Brink, hoogleraar psychiatrie en verslaving aan de Universiteit van Amsterdam.

De werkgroepleden waren door de wetenschappelijke verenigingen gemandateerd voor deelname aan deze werkgroep; de totale samenstelling van de werkgroep is goedgekeurd door alle deelnemende wetenschappelijke verenigingen. De werkgroepleden zijn gezamenlijk verantwoordelijk voor de integrale tekst van deze conceptrichtlijn. De volgende personen hadden zitting in de werkgroep.

- Nederlandse Vereniging voor Psychiatrie (NVvP):

- Wim van den Brink (voorzitter);

- Hein de Haan;

- Pieter-Jan Carpentier.

- Nederlands Instituut van Psychologen (NIP):

- Gerard Schippers (vice-voorzitter);

- Ellen Vedel.

- Vereniging voor Verslavingsgeneeskunde Nederland (WGN):

- Hein Sigling.

- Verpleegkundigen & Verzorgenden Nederland (V&VN):

- Chris Loth.

Voor de ontwikkeling van uitgangsvragen, teksten en aanbevelingen is contact gezocht met de Nederlandse Internisten Vereniging om een vertegenwoordiger te leveren met deskundigheid in het onderwerp methadon en QT-verlenging. Daarop is door deze vereniging Gerard Rongen als werk- groeplid toegevoegd.

Klankbordgroep

Bij het vaststellen van de uitgangsvragen en het vaststellen van de conceptversie van de richtlijn is om input gevraagd van de klankbordgroep. Deze klankbordgroep bestond uit vertegenwoordigers van diverse beroepsverenigingen en belanghebbende partijen. Binnen deze klankbordgroep werd een aparte focusgroep patiëntenparticipatie gevormd. De volgende personen hadden zitting in de klankbordgroep:

- K.A.H. van der Horst, Tactus Verslavingszorg.

- C. Keuch, Cliëntenraad Arkin Jellinek, Amsterdam.

- R. van den Abeele, lsovd.

- R. Ashruf, Vereniging voor Verslavingsgeneeskunde Nederland.

- R. Asma, Cliëntenraad Mondriaan.

- W. Barends, Brijder Verslavingszorg.

- F. Bary, Centrale Cliëntenraad Centrum Maliebaan.

- M. Boonstra, Jellinek.

- J. van Essen, Tactus Verslavingszorg.

- E. Gillet, Cliëntenraad Novadic-Kentron.

- H. Gras, Altrecht.

- M. de Haan, Belangenvereniging Druggebruikers mdhg.

- M. Hazenbroek, lsovd.

- C. de Jong, Vereniging voor Verslavingsgeneeskunde Nederland.

- M. Kat, Regiocliëntenraad Brijder Noord-Holland.

- C. Koster, Cliëntenraad Tactus Verslavingszorg.

- W. Los, Belangenvereniging Druggebruikers mdhg.

- T. Malesevic, ggz Arkin, cluster Verslaving en Psychiatrie.

- M. Merkx, Nederlandse Vereniging van Psychologen.

- G. van Santen, ggd.

- V. dos Santos, Belangenvereniging Druggebruikers mdhg.

- E. Tolkamp, Cliëntenraad Mondriaan.

- P. Vossenberg, Tactus Verslavingszorg.

Externe deskundigen

Voor vier onderwerpen is specifieke input gevraagd aan externe deskundigen. Voor de wijze van dosering van naloxon bij een overdosering opiaten (module ‘Crisisinterventie bij overdosering’) is informatie gevraagd van de heer D. Kagenaar, anesthesist in het Flevoziekenhuis te Almere. Voor module ‘Crisisinterventie bij overdosering’ (Onderzoek somatische gezondheid) is inbreng gevraagd van de heer R. Jamin, tot 1 januari 2012 arts voor verslavingsziekten. Voor de modules over acupunctuur en ibogaïne zijn teksten geleverd door mevrouw C. de Jong, anesthesioloog-verslavingsarts bij Stichting Miroya en onderzoeker via de afdeling Experimentele Anesthesiologie, amc, Amsterdam. Deze teksten zijn na de commentaarfase bewerkt door de werkgroep en door de heer P. Blanken, senior onderzoeker bij Parnassia Addiction Research Centre (parc), Brijder Verslavingszorg.

Belangenverklaringen

Een map met verklaringen van werkgroepleden over mogelijke financiële belangenverstrengeling ligt ter inzage bij de Nederlandse Vereniging voor Psychiatrie. Er zijn geen bijzondere vormen van belangenverstrengeling gemeld.

Methode ontwikkeling

Evidence based

Implementatie

In de verschillende fasen van de richtlijnontwikkeling is geprobeerd rekening te houden met de implementatie van de richtlijn en de daadwerkelijke uitvoerbaarheid van de aanbevelingen. Daarbij is expliciet gelet op factoren die de invoering van de richtlijn in de praktijk kunnen bevorderen of belemmeren.

Deze richtlijn wordt verspreid onder alle relevante beroepsgroepen en instellingen. Daarnaast wordt een samenvatting van de richtlijn gepubliceerd in het Nederlands Tijdschrift voor Geneeskunde en in tijdschriften van de deelnemende wetenschappelijk verenigingen. Ook is de richtlijn te downloaden vanaf de website van het Trimbos-instituut (www.trimbos.nl of www.ggzrichtlijnen.nl) en via de websites van de NVvP en ccbh. Naast de richtlijn zelf wordt ook een versie voor patiënten ontwikkeld, in samenwerking met leden van de focusgroep patiëntenarticipatie, uitgevoerd door Stichting Mainline.

Werkwijze

De multidisciplinaire werkgroep is bij het opstellen van de uitgangsvragen uitgegaan van het proces van diagnostiek, indicatiestelling en behandeling van opiaatverslaving. Daartoe zijn uitgangsvragen opgesteld, waarvoor via de methodiek van evidence-based richtlijnontwikkeling (ebro) antwoorden zijn geformuleerd in de vorm van aanbevelingen. De uitgangsvragen zijn besproken met de klankbordgroep en de focusgroep patiëntenparticipatie.

De werkgroep werkte gedurende 24 maanden (9 vergaderingen) aan de totstandkoming van de conceptrichtlijn. Voor de beantwoording van de uitgangsvragen werd de volgende werkwijze gehanteerd. De Guidelines for the psychosocially assisted pharmacological treatment of opioid dependence (WHO, 2009) werd als basis voor de antwoorden gekozen. Deze richtlijn werd daartoe met behulp van het AGREE-instrument als kwalitatief goed beoordeeld door het Trimbos-instituut.

Daarnaast werden twee richtlijnen gebruikt die door NICE (Engeland) zijn ontwikkeld: Drug misuse: Opioid detoxification (nice, 2007a) en Drug misuse: Psychosocial interventions (nice, 2007b). Omdat NICE-richtlijnen algemeen als gouden standaard voor richtlijnontwikkeling worden beschouwd, zijn deze richtlijnen door de werkgroep als kwalitatief goede richtlijnen geaccepteerd zonder een aanvullende AGREE-beoordeling.

De werkgroep heeft besloten dat van publicaties die worden gebruikt voor beantwoording van uitgangsvragen en die in de genoemde richtlijnen worden besproken, geen nieuwe bewijstabellen (evidencetabellen) zouden worden gemaakt. In de literatuurlijsten zal duidelijk worden aangegeven in welke richtlijn een publicatie is gebruikt en beoordeeld. De geïnteresseerde lezer wordt uitgenodigd om in die richtlijnen informatie over de betreffende publicatie en de beoordeling daarvan te lezen.

Voor het beantwoorden van de uitgangsvragen is ook gezocht naar bronnen die zijn gepubliceerd nadat deze richtlijnen zijn gepubliceerd. En omdat de richtlijnen niet alle uitgangsvragen behandelen, zijn eigen zoekacties uitgevoerd in Pubmed, Psychinfo, Medline en de Cochrane Database en Cinahl. Voor zover dergelijke publicaties zijn opgenomen in de conclusies, zijn van die publicaties zo veel mogelijk bewijstabellen gemaakt, waarin beoordeling van de publicaties en samenvatting van de resultaten is opgenomen.

De leden van de redactie hebben richtlijnteksten geformuleerd (bestaande uit, per uitgangsvraag: inleiding, wetenschappelijke onderbouwing, conclusies op basis van wetenschappelijke onderbouwing, overige overwegingen en aanbevelingen). Deze teksten werden in de werkgroepbijeenkomsten besproken. Op onderdelen leverden de overige werkgroepleden tekstvoorstellen.

Afrondingsfase

De uiteindelijke teksten vormen samen de conceptrichtlijn die in januari 2012 per e-mail in pdf aan alle betrokken beroepsverenigingen, aan de leden van de klankbordgroep, aan de lpggz en via internet aan het veld ter commentaar aangeboden. Dit commentaar is door de werkgroep verwerkt. Alle commentaar is van een reactie voorzien. Deze commentaartabel is voor het publiek in te zien op de website van de NVvP en via www. ggzrichtlijnen.nl. Na verwerking van het commentaar is de richtlijn ter autorisatie aan de betrokken verenigingen en het Landelijk Platform GGz (lpggz) aangeboden.

Wetenschappelijke onderbouwing

De richtlijn is voor zover mogelijk gebaseerd op bewijs uit gepubliceerd wetenschappelijk onderzoek, voor een deel samengevat in de eerdergenoemde richtlijnen van NICE en WHO. Daarnaast werden relevante artikelen gezocht door het verrichten van systematische zoekacties. Er werd gezocht in de Cochrane Database, Medline, Psychinfo, en bij vragen waarvoor dit relevant was ook in Cinahl. Op verzoek zijn de volledige zoekstrategieën beschikbaar. Daarnaast werden artikelen geëxtraheerd uit literatuurlijsten van opgevraagde bronnen.

Er was onvoldoende financiële ruimte om alle genoemde artikelen te wegen via de uitvoering van nieuwe meta-analyses. De werkgroep heeft ervoor gekozen deze publicaties toch op te nemen en te gebruiken in de wetenschappelijke onderbouwing van de conclusies. In een volgende versie van de richtlijn kunnen deze publicaties dan gewogen worden.

In de literatuurlijsten per module wordt duidelijk gemaakt welke publicaties afkomstig zijn uit de genoemde richtlijnen, voor welke publicaties er voor deze richtlijn bewijstabellen zijn gemaakt, en welke publicaties wel gebruikt zijn in deze richtlijn, maar waarvan geen formele bewijstabellen zijn gemaakt.

De keuzes voor de indeling van methodologische kwaliteit van studies en de indeling van niveaus van bewijs van conclusies zijn gebaseerd op de EBRO-methodiek (evidence-based richtlijnontwikkeling). In de volgende tabellen zijn deze indelingen samengevat.

Tabel 1.1 Indeling van methodologische kwaliteit van individuele onderzoeken

|

Classificatie |

Interventie |

Diagnostisch accuratesseonderzoek |

Schade of bijwerkingen, etiologie, prognose |

|

A1 |

Systematische review van ten minste twee onafhankelijk van elkaar uitgevoerde onderzoeken van A2-niveau. |

||

|

A2

|

Gerandomiseerd dubbelblind vergelijkend klinisch onderzoek van goede kwaliteit van voldoende omvang.

|

Onderzoek ten opzichte van een referentietest (een ‘gouden standaard') met tevoren gedefinieerde afkapwaarden en onafhankelijke beoordeling van de resultaten van test en gouden standaard, betreffende een voldoende grote serie van opeenvolgende patiënten die allen de index- en referentietest hebben gehad. |

Prospectief cohortonderzoek van voldoende omvang en follow-up, waarbij adequaat gecontroleerd is voor confounding en selectieve follow-up voldoende is uitgesloten. |

|

B

|

Vergelijkend onderzoek, maar niet met alle kenmerken als genoemd onder A2 (hieronder valt ook patiënt-controleonderzoek, cohortonderzoek). |

Onderzoek ten opzichte van een referentietest, maar niet met alle kenmerken die onder A2 zijn genoemd.

|

Prospectief cohort- onderzoek, maar niet met alle kenmerken als genoemd onder A2, of retrospectief cohortonderzoek, of patiënt- controleonderzoek. |

|

C |

Niet-vergelijkend onderzoek. |

||

|

D |

Mening van deskundigen. |

||

Deze classificatie is alleen van toepassing in situaties waarin om ethische of andere redenen gecontroleerde trials niet mogelijk zijn. Zijn die wel mogelijk dan geldt de classificatie voor interventies.

Tabel 1.2 Niveau van de bewijsvoering in de conclusie

|

Niveau |

Conclusie gebaseerd op |

|

1 |

Onderzoek van niveau A1 of ten minste twee onafhankelijk van elkaar uitgevoerde onderzoeken van niveau A2. |

|

2 |

Eén onderzoek van niveau A2 of ten minste twee onafhankelijk van elkaar uitgevoerde onderzoeken van niveau B. |

|

3 |

Eén onderzoek van niveau B of C. |

|

4 |

Mening van deskundigen. |