Internal fixation of open limb fractures

Uitgangsvraag

What type of internal fixation should be used in open fracture of the lower limb?

Subsidiary clinical questions

- What are the favourable and unfavourable effects of nailing or plating in patients with an open distal fracture of the lower limb?

- What are the favourable and unfavourable effects of an unreamed nail in patients with an open fracture of the lower limb?

Aanbeveling

Aim to achieve primary internal fixation with nail or plate if good soft tissue cover is possible and ensure the best possible way to bear weight.

- Apply a spanning external fixator if definitive fixation and immediate soft tissue cover are not carried out at the time of initial debridement

- Replace external fixation with internal fixation as quickly as possible

- Open lower limb fractures of the shaft should preferably be fixed with a reamed intramedullary nail

- Fix open distal/proximal metaphyseal lower limb fractures with a fixed angle plate or with an intramedullary nail.

Overwegingen

On the grounds of the literature it is not possible to say unequivocally if it is best to treat open fractures of the lower limb with an intramedullary nail or with a plate. This is possibly due to the heterogeneity of the patient populations studied. In shaft fractures, the advice of the working party is to use an intramedullary nail, with the aim of making a construction that that can weight bear at an early stage. Fractures of the proximal and distal tibial metaphyses that are stabilised with an intramedullary nail are at a biomechanical disadvantage compared with those stabilised with a plate. In very distal or proximal fractures there is less contact between bone and implant which leads to lower intrinsic stability. A consequence of this is more pressure on the locking screws, which may lead to implant failure or loss of alignment. The potential for malalignment and worsened stability may contribute to the development of malunion, delayed healing and non-union. Recent developments in intramedullary nail technology including more distal locking options and the possibility of siting fixed-angle locking screws, and improved techniques including Poller’s interference screws, have made intramedullary nail fixation more suitable for the treatment of metaphyseal fractures. The potential advantages of plate fixation include open reduction thus enabling better alignment. A potential disadvantage is the higher risk of soft tissue complications such as delayed wound healing, superficial and deep infections and more implant-related irritation. Those RCTs that included mainly closed fractures showed no significant differences in outcomes or complications between these techniques.

The working party recognises that each open fracture of the lower limb has its own distinct characteristics (fracture pattern and soft tissue status), and that the surgical team should base their decisions on which fixation technique to use in each case individually. In doing this, early weight bearing should feature strongly in their decision-making as this accelerates rehabilitation.

In the treatment of an open fracture of the lower limb, there is no difference between reamed and an unreamed nail if the following are taken into account: 1) time to fracture consolidation, 2) number of reoperations, 3) prevention of compartment syndrome. However, the risk of infection increases slightly if an unreamed nail is used. In the event of doubt about prior contamination, the working party advises using a reamed nail. Screw or nail fracture occurs more commonly in thinner, unreamed nails. Taking the above-mentioned factors into consideration, it is unclear if this affects clinical outcomes disadvantageously. Nonetheless, on the basis of this the working party is of the opinion that the reamed nail is preferable.

Open fractures of the lower limb carry the risk of the development of compartment syndrome, certainly as they are often high-energy injuries. An open injury does not exclude the possibility that pressure can build up in compartments in the lower limb. The development of compartment syndrome must be checked for at all times. On suspicion of this, the working party advises carrying out a four-compartment fasciotomy.

In polytrauma, the principles of Damage Control Orthopaedics should be followed. The fracture should be primarily stabilised with an external fixator and definitive fixation carried out at a later stage. As soon as the patient’s condition permits it, the external fixator should be replaced with internal fixation after adequate soft tissue coverage has been achieved.

From the perspective of the patient, there is no evidence that treatment with nail or with plate fixation is preferred. However, this does not discharge treating physicians from their responsibility of discussing the advantages and disadvantages of the various treatment options with the patient. Concerning availability and cost, none of the implants has an advantage over the others.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

In open lower limb fractures with severe soft tissue injury, it is essential to formulate a multidisciplinary treatment plan quickly. At the damage control stage of treatment, a spanning external fixator is generally placed after debridement. In the past, the definitive placement of internal fixation was often delayed until the soft tissues had settled down. One disadvantage of waiting too long is that intramedullary contamination may develop via one of the fixation pins, and with it an increased risk of a deep infection. Early coverage of the soft tissues and early placement of the definitive internal fixation both reduce the risk of contamination considerably. If possible, these procedures should be carried out in the primary setting.

Fixation can be achieved with either an intramedullary nail or a plate. When treating tibial shaft fractures, stable fixation requiring a minimum of soft tissue dissection can be best achieved by using an intramedullary nail. However, choice of treatment for fractures of the proximal or distal metaphyses is less clear-cut. The development of fixed-angle, anatomically pre-formed plates and the advancement of minimal invasive techniques have contributed to effective treatment options. Which technique is currently preferred for open metaphyseal fractures of the lower limb is unclear.

If an intramedullary nail is chosen, then then the decision needs to be made if it should be reamed or unreamed. Historically, unreamed nails have mainly been used to repair tibial fractures. However, the reamed intramedullary nail is clearly favoured in the treatment of closed fractures as this is associated with faster consolidation and fewer complications. For these reasons it has become the preferred treatment of closed fractures of the lower limb. The preferred technique to treat open fractures of the lower limb is much less obvious.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

Plate versus nail

Consolidation

|

Very low GRADE |

Following internal fixation of an open fracture of the lower limb, it is not clear if consolidation is achieved more often and more quickly with a nail or with a plate.

Sources (Im, 2005; Guo, 2010; Vallier, 2011) |

Infections

|

Very low GRADE |

There are limited indications that there is no difference in the occurrence of infections following internal fixation of an open fracture of the lower limb with a nail or with a plate.

Sources (Im, 2005; Guo, 2010; Vallier, 2011) |

Functioning

|

Very low GRADE |

No difference in functioning could be shown following internal fixation of open fracture of the lower limb with a nail or with a plate.

Sources (Im, 2005; Guo, 2010) |

Pain

|

Very low GRADE |

At 12 months no difference in pain could be shown following internal fixation of open fracture of the lower limb with a nail or with a plate.

Source (Guo, 2010) |

Complications

|

Very low GRADE |

There are limited indications that there is no difference in the occurrence of complications following internal fixation of an open fracture of the lower limb with a nail or with a plate.

Sources (Im, 2005; Guo, 2010; Vallier, 2011) |

Reamed versus unreamed nail

Consolidation

|

Low GRADE |

There are indications that consolidation occurs at the same rate in both reamed and unreamed nails in patients with an open fracture of the lower limb.

Sources (Bahandari, 2012; Keating, 1997; Yin, 2008; Finkemeier, 2000) |

Reoperation

|

Very low GRADE |

There are limited indications that the placement of both reamed and unreamed nails in patients with an open fracture of the lower limb result in an equal number of reoperations.

Sources (Bahandari, 2012; Finkemeier, 2000) |

Infections

|

Very low GRADE |

There are limited indications that the number of infections associated with the use of a reamed nail is lower than that associated with an unreamed nail in patients with an open fracture of the lower limb.

Sources (Bahandari, 2012; Keating, 1997; Yin, 2008; Finkemeier, 2000; Tabatbaei, 2012) |

Complications

|

Low GRADE |

There are indications that the placement of a reamed nail results in fewer implant failures than an unreamed nail.

Sources (Bahandari, 2012; Keating, 1997; Tabatbaei, 2012) |

|

Very low GRADE |

There are limited indications that osteofascial compartment syndrome occurs at the same rate in both reamed and unreamed nails in patients with an open fracture of the lower limb.

Sources (Bahandari, 2012; Keating, 1997; Yin, 2008) |

Samenvatting literatuur

1. What are the favourable and unfavourable effects of a nail and a plate in patients with an open distal fracture of the lower limb?

The studies included are three RCTs (Im, 2005; Guo, 2010 and Vallier, 2011) with a total of 253 patients and concern closed tibial fractures or open fractures Gustilo type I, II and IIIA. In these studies the results were compared with an intramedullary nail with open (Im, 2005 en Vallier, 2011) or closed (Guo, 2010) reduction and internal fixation with plate and screws. In Guo’s study, fixed-angle plates were used, in the Im and Vallier study non-fixed-angle plates were used. Vallier included 40 (38%) open fractures although the type was not mentioned. The studies of Guo and Im excluded Gustilo type II and III open fractures. Im’s study included 13 (20%) type I open fractures, Guo’s study did not specify this. The studies report on the outcome measures time to consolidation, complications including fracture alignment and infections, and functional outcome. Distance walked and speed of walking were not mentioned in any of the three studies.

Consolidation

Two studies (Im, 2005; Guo, 2010) reported time to radiological consolidation. No significant differences were found (Im: 18 weeks (range 12 to 64) for the nail and 20 weeks (range 12 to 72) for the plate, Guo: 17.7 weeks (range 16.7 to 18.6) for the nail and 17.6 weeks (range 16.9 to 18.3) for the plate. In Im’s study, delayed consolidation (nine months) was seen in three (9%) patients in the nail group and in two (7%) in the plate group. Guo’s study reported all fractures were consolidated, no delayed consolidation was reported. Vallier reports delayed consolidation in six patients, two (4%) who were treated with a plate and four (7%) with an intramedullary nail (p-0.25). After further procedures, all fractures consolidated.

Strength of evidence of the literature:

The strength of evidence for consolidation was lowered by three levels due to imprecision (small numbers, no significant differences), and to indirectness (closed and Gustilo I tibial fractures). The strength of evidence for study limitation was not lowered despite the fact that blinding was not reported. It was assumed that blinding did not influence consolidation.

Malalignment/malunion

Vallier reports primary postoperative malalignment in seventeen patients (16%), four of whom were treated with a plate and thirteen (23%) with an intramedullary nail. This difference is significant (p=0.02). Ultimately, treatment resulted in malunion in eleven (13%) of patients who were treated with a plate, and 36 (27%) patients who were treated with a nail (p=0.006). Im describes radiological malalignment in four (12%) patients following nailing compared with none following plating (significance not specified). Guo reports only clinical alignment or malalignment and was not included in this analysis.

Infections

All three studies looked at infection. Im reported more wound infection in the plate group (n=7: six superficial, one deep) than in the nail group (n=1: superficial), p=0.03. Guo found nine superficial infections, six in patients with a plate (14.6%) and three in patients with a nail (6.8%), p<0.05. Vallier reported six (6%) patients who got a deep infection, three had been treated with a nail and three with a plate. In five of the six cases this was on open fracture. No superficial infections were found.

Strength of evidence of the literature

The strength of evidence for complications was lowered by three levels as blinding of patients and treating physicians is not described, due to heterogeneity (varying complications and definitions), imprecision (small numbers, no significant differences) and indirectness (Gustilo I tibial fractures).

Functioning

In Im’s study (2005), functioning was evaluated by making a comparison with the unaffected side (Olerud & Molander Score). There is practically no difference between the groups. In the nail group functionality of the healthy side was 88.5% and in the plate group this was 88.2% (p=0.71). Guo (2010) used the AOFAS function subscore as a functional outcome measure and also found no differences: a score of 44.3 in the nail group and 43.2 in the plate group (p=0.05). Vallier (2011) does not report on functional outcomes.

Strength of evidence of the literature

The strength of evidence for functioning was lowered by three levels as blinding of patients and treating physicians is not reported, due to heterogeneity (varying measures of functioning), to imprecision (small numbers, no significant differences) and indirectness (closed and Gustilo I tibial fractures).

Pain

Neither Im (2005) nor Vallier (2011) report specifically on pain. Guo (2010) reports pain in the form of an AOFAS subscore (12 months) and found a score of 32.5 in the nail group and 31.5 in the plate group (p>0.05).

Strength of evidence of the literature

The strength of evidence for pain was lowered by three levels as blinding of patients and treating physicians is not reported, due to heterogeneity (varying degrees of pain), to imprecision (small numbers, no significant differences) and indirectness (closed and Gustilo I tibial fractures).

2. What are the favourable and unfavourable effects of a reamed and an unreamed nail in patients with an open fracture of the lower limb?

The review containing five RCTs described patients with various open tibial fractures (Gustilo type I, II, IIIA or IIIB). The patient population comprised mainly men with an average age of between 34 and 39 years. In one RCT, the average age of patients was under 27 years. In the studies the treatment effects of reamed nails were compared with those of unreamed nails. The outcomes consolidation, time to consolidation, number of reoperations, infections, implant failures and osteofascial compartment syndrome were reported on. None of the studies described outcomes in the area of function or mobility or return to work.

Results: consolidation

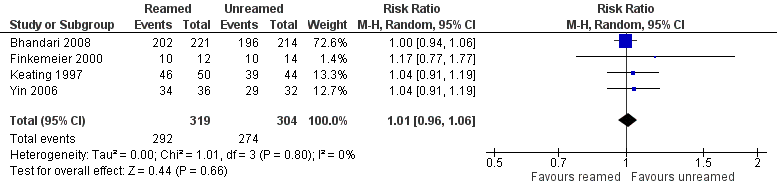

Four studies (N=623) studied the effect on consolidation. A meta-analysis of these results shows that consolidation is practically the same in both reamed and unreamed nails (RR=1.01; 95% CI 0.96 to 1.06; I2=0%) (see Figure 1). One study reported time to consolidation (Tabatabaei, 2012). This was 27.9 weeks (N=61) in the reamed nail group and 30.3 weeks (N=58) in the unreamed nail group. This difference was not significant (p=0.08).

Figure 1 Consolidation

Strength of evidence of the literature

The strength of evidence for consolidation was lowered by two levels due to the fact that in at least three studies the allocation of treatment was not blinded, and in none of the studies was the intervention blinded to the treating physician and patient. Also the number of patients was limited (imprecision).

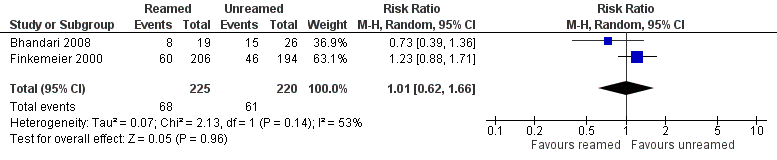

Results: reoperation

Two studies (N=445) reported on the number of reoperations. The pooled result indicates that there is no difference in effect (RR=1.01;95%-CI: 95% CI62 to 1.66; I2=53%) between the two treatment options, but that the confidence interval encompasses a clinically relevant difference in favour of both the intervention and the control group. However, the results of the individual studies are heterogeneous. The results of the study of Bhandari et al. favour the use of an unreamed nail, but Finkemeier’s results favour the use of a reamed nail. The individual studies and the pooled result do not differ significantly (see Figure 2).

Figure 2 Reoperation

Strength of evidence of the literature

The strength of evidence for reoperations was lowered by three levels due to the limitations in the study set-up (no blinding of assignment of treatment and the treatment itself); conflicting results (inconsistency); the fact that the confidence interval encompasses a clinically relevant effect that favours both the intervention and the control groups (imprecision).

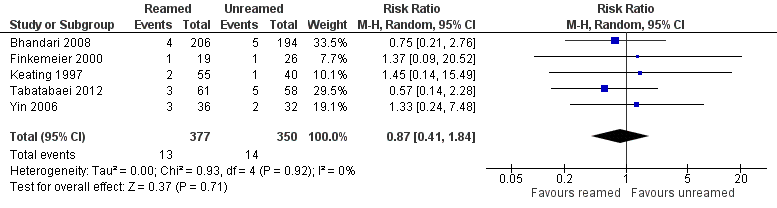

Results: infection

Five studies (N=727) describe the number of infections that occurred following the placement of a reamed or unreamed nail. Meta-analysis shows that there is a non-significant advantage to applying a reamed nail (RR=0.87; 95%CI: 0.41 to 1.84; I2=0%). This result is based on a very small number of infections, i.e. 27. The confidence interval encompasses a clinically relevant difference in favour of both the intervention and the control groups.

Figure 3 Infection

Strength of evidence of the literature

The strength of evidence for the outcome infection was lowered by three levels due to the limitations in the study design (no blinding of assignment of treatment and the treatment itself); and two levels due to the fact that the confidence interval encompasses a clinically relevant effect that favours both the intervention and the control groups (imprecision).

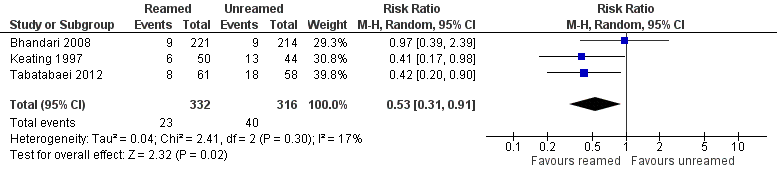

Results: implant failure (complications)

Three studies (N=648) describe implant failures such as fracture of nails or screws. Meta-analysis of these results shows the risk of failure for a reamed nail is 47% less than for an unreamed nail. The difference between these treatment options was statistically significant (RR=0.53; 95%-CI: 0.31 to 0.91; I2=17%).

Figure 4 Implant failure

Strength of evidence of the literature

The strength of evidence for the outcome implant failure was lowered by two levels, taking into account the limitation of the study design and the limited number of patients (imprecision).

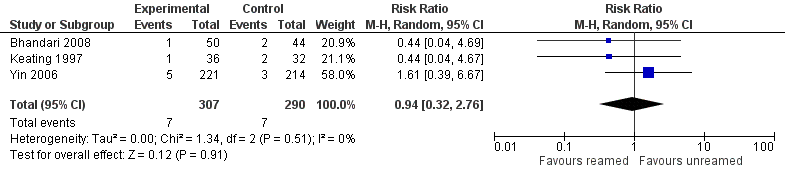

Results: osteofascial compartment syndrome (complications)

Three studies described the incidence of osteofascial compartment syndrome. A meta-analysis of these studies showed no differences between these treatment options (RR=0.94; 95%CI:0.32 to 2.76; I2=0%). The analysis is based on fourteen events.

Figure 5 Osteofascial compartment syndrome

Strength of evidence of the literature

The strength of evidence for the outcome osteofascial compartment syndrome was lowered by three levels due to the limitations in the study design (no blinding of assignment of treatment, and the treatment itself); and two levels due to the fact that the confidence interval encompasses a clinically relevant effect that favours both the intervention and the control groups (imprecision).

Zoeken en selecteren

In order to answer this scientific question a systematic literature analysis was carried out into the following research questions:

What are the favourable and unfavourable effects of a nail or a plate in patients with an open distal fracture of the lower limb?

P: Patient with a grade III distal open fracture of the lower limb

I: Internal fixation with a nail

C: Internal fixation with plate and screws

O: Osteitis, osteomyelitis, number of readmissions, functioning (ADL), pain (VAS), complications, return to work, mobility (distance walked, speed of walking).

What are the favourable and unfavourable effects of reamed and of unreamed nails in patients with an open fracture of the lower limb?

P: Patient with a grade III open fracture of the lower limb

I: Reamed nail

C: Unreamed nail

O: Osteitis, osteomyelitis, number of reoperations, time to consolidation, complications, return to work, mobility (distance walked, speed of walking).

Relevant outcome measures

The working party judged consolidation, osteitis and osteomyelitis to be outcomes critical to the decision-making process, and functioning, pain, and complications to be outcomes important in the decision-making process.

Method of searching and selection

To answer these questions, on 31 October 2014 using the relevant search terms, the databases Medline (OVID) and Embase were searched for systematic reviews, primary research including randomised controlled trials (RCT) and observational trials. The search strategy is shown under the tab Justification.

The literature search resulted in 514 hits. These were 41 possible systematic reviews, 108 possible RCTs and 365 other studies. Systematic reviews were selected on the grounds of the following selection criteria: a systematic and extensive literature search in which a minimum of two biomedical databases were searched, and whereby literature was selected, evaluated and described in an objective and systematic fashion.

Regarding the search question concerning plate or nail, a review was required to describe RCTs in which patients with an open fracture of the lower limb were included (all Gustilo types) and who underwent fixation with plate or a nail. One review was initially selected on the basis of title and abstract. This review describes both RCTs and observational studies up to 2010. In answering this question only a few RCTs were identified. The literature search for this module of the guidelines was used to identify more recently published research. Five additional studies were pre-selected on the basis of title and abstract. After reading the complete text, four studies were excluded as they concerned observational studies (see study selection table).

Regarding the question concerning choice of reamed or unreamed nail, reviews were required to describe RCTs in which patients with an open fracture of the lower limb were included (all Gustilo types), and who underwent fixation with either a reamed or unreamed nail. Three potential systematic reviews were preselected on the basis of title and abstract. After reading the complete text, two systematic reviews were excluded (see study selection table). The systematic review that was included describes the literature up to December 2012 and was accordingly supplemented with primary research obtained from the literature search for this guideline module.

Primary research was selected using the following criteria: published RCTs, carried out in adults with an open fracture of the lower limb (Gustilo type I, II, IIIA or IIIB) who underwent fixation with a reamed or unreamed nail. Studies were excluded if they had included patients with a Gustilo type IIIC open fracture of the lower limb or old fractures. Non-randomised studies or observational studies were also excluded. Initially, eleven possible RCTs were preselected on the basis of title and abstract. After reading the complete text, ten studies were excluded as they did not meet the inclusion criteria studies (see study selection table).

(Results)

Three studies were included in the literature analysis for search question 1. The evidence tables and assessment of individual study quality can be found under the tab Evidence.

One systematic review was included in the literature analysis of search question 2. This review from Shao, 2014 included four RCTs (Keating, 1997; Finkemeier, 2000; Yin, 2000; and Bhandari, 2008). The review was updated by adding one RCT (Tabatbaei, 2012) to the literature analysis. The evidence tables and assessment of individual study quality can be found under the tab Evidence Base.

Referenties

- Bhandari M, Guyatt G, Tornetta P 3rd, et al. Randomized trial of reamed and unreamed intramedullary nailing of tibial shaft fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90(12):2567-78.

- Finkemeier CG, Schmidt AH, Kyle RF, et al. A prospective, randomized study of intramedullary nails inserted with and without reaming for the treatment of open and closed fractures of the tibial shaft. J Orthop Trauma. 2000;14(3):187-93.

- Keating JF, O'Brien PJ, Blachut PA, et al. Locking intramedullary nailing with and without reaming for open fractures of the tibial shaft. A prospective, randomized study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1997;79(3):334-41.

- Shao Y, Zou H, Chen S, et al. Meta-analysis of reamed versus unreamed intramedullary nailing for open tibial fractures. J Orthop Surg Res. 2014 23;9:74.

- Tabatabaei S, Arti H, Mahboobi A. Treatment of open tibial fractures: Comparison between unreamed and reamed nailing A prospective randomized trial. Pak J Med Sci. 2012 28;5:917-920.

- Yin F, Zhang Z, Li X, et al. Clinic treatment of open tibial fractures with interlocking intramedullary nail. In Book Clinic Treatment of Open Tibial Fractures With Interlocking Intramedullary Nail. vol. 22nd ed. Shanghai, China; 2006.

Evidence tabellen

Evidence table for intervention studies

Research question: What is the difference in effectiveness between a nail and a plate in patients with an open distal fracture of the lower limb?

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics 2 |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C) 3 |

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size 4 |

Comments |

|

Im, 2005 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting: University Hospital

Country: Korea

Source of funding: not reported |

Inclusion criteria: distal metaphyseal fracture of tibia

Exclusion criteria: open fractures of Gustilo-Anderson type II or III; fractures with displaced intra-articular fragments; impossibility to engage the four cortices of the distal fragment with two interlocking screws.

N total at baseline: 78 patients. 2 died of causes unrelated to injury 12 lost to follow-up

Intervention: 34 Control: 30

Important prognostic factors2: For example age (range): I:42 (19-65) C: 40 (17-60) (p=0.55)

Sex: I: 65% M (22/34) C: 80% M (24/30) (p=0.18)

Smokers I: 35% (12/34) C: 50% (15/30)

The two groups were comparable in the fracture types, according to AO system (p = 0.91), number of open fractures (p = 0.55), and degree of the soft-tissue injury, according to the Tscherne classification (p = 0.45).

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

Closed intramedullary nailing (Group I: IM)

|

Open reduction and fixation with anatomic plates and screws (Group II: ORIF). The date of the operation was delayed up to 14 days after the fracture if the leg swelling and bruise made earlier surgery impossible.

|

Length of follow-up: 2 years Every two weeks for first three months, then every month.

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: N = 5 (13%)? Reasons not reported

Control: N = 9 (23%)? Reasons not reported

Incomplete outcome data: Not reported

|

Osteïtis/Osteomyelitis Not reported.

Consolidation: Time before radiologic union I: 18 weeks (12–64) C: 20 weeks (12–72) (p = 0.89).

Failure of bony union after 9 months: I: n=3 C: n=2

Complications: Wound complication I: n=1 (superficial infection) C n=7 (6 superficial and 1 deep infection) (p = 0.03).

Mean angulation on either antero posterior or lateral roentgenogram I: 2.8 degrees (0–10) C: 0.9 degrees (0–3) (p = 0.01).

Angulation of more than 5 degrees varus or valgus or more than 10 degrees anterior or posterior: I: n=4 C: n=0.

Functioning: Functional score (Olerud): I: 88.5% of normal side C: 88.2% of normal side (p = 0.71).

Pain: Not reported.

Return to work: Not reported.

|

Patients had mainly closed fractures, in group I were eight Gustilo I fractures, in group II five.

“Our results have shown that locked intramedullary nails have an advantage in restoration of motion and reduce wound problems, and anatomic plate and screws can restore alignment better than intramedullary nails. It can be concluded from this study that advantages and disadvantages of either device should be considered in treating patients with distal metaphyseal fractures of tibia.”

Stand afwijking Wound infection time to non union |

|

Guo, 2010 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting: University hospital

Country: China

Source of funding: non commercial funding. |

Inclusion criteria: Distal metaphyseal fracture of tibia, between July 2005 and January 2008. Presence of a distal fragment of at least 3 cm in length with no articular incongruity, which corresponded to an OTA type 43-A fracture.

Exclusion criteria: pathological fractures, non-osteoporotic osteopathies such as endocrine disorders, rheumatologic disorders, diabetes mellitus, renal disease, immunodeficiency states, mental impairment or difficulty in communication. Those with open fractures according to Gustilo and Anderson type II or type III or fractures with a displaced intra-articular fragment were also excluded. If an associated fibular fracture was fixed, the patient was excluded from the study (I 10, C 9).

N total at baseline: Intervention: n=57 Control:n=54

Important prognostic factors2: Age mean (range): I:44.2 (27-70) C:44.4 (23-69)

Sex: I: 59% M C: 59% M

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

Closed intramedullary nailing

|

Percutaneous locking compression plating (LCP) with minimally invasive plate osteosynthesis (MIPO)

|

Length of follow-up: 12 months Every 6 weeks to bony union, 3, 6 and 12 months

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: N (%) Reasons (describe)

Control: N (%) Reasons (describe)

Incomplete outcome data: Intervention: N = 13 (%)

Control: N = 13 (%) 26 patients had not reached one year follow-up by the time of the study.

Analyzed: I: n= 44 C: n= 41

|

Osteitis/Osteomyelitis Not reported.

Consolidation: Time to union I: 17.66 weeks (16.7-18.6) C: 17.59 weeks (16.9-18.3)

Complication: Wound problems (delayed healing and superficial infection) I: n=3 (6.8%) C: n= 6 (14.6%)

Alignment (AOFAS) I: 9.3 C: 9.3 P<0.05??

Implant removal I: 23 C: 24

Functioning: Mobility at 12 months Not reported

Function (AOFAS) I: 44.3 C: 43.2 P<0.05??

Pain (AOFAS?) I: 32.5 C: 31.5 P<0.05??

AOFAS total score I: 86.1 (83.7-88.6) C: 83.9 (81.7-86.1) P<0.05??

Return to work: Not reported

|

|

|

Vallier, 2011 |

Type of study: RCT, matched on age, injury severity score, fracture pattern and presence of open fracture.

Setting: Hospital

Country: USA

Source of funding: A grant was provided by the Orthopaedic Research and Education Foundation |

Inclusion criteria: Patients with displace distal tibia shaft fractures.

Exclusion criteria: associated proximal tibia fractures, tibia plafond fractures, or knee injuries; open fractures requiring soft tissue coverage; fractures associated with vascular injury requiring repair; and pathological fractures.

N total at baseline: Intervention: 48 Control: 56

Important prognostic factors2: Age ± SD: I: 38.5 C: 38.1

Sex: I: 80% M C: 76% M

Mean ISS: I: 14.7 C: 12.6

Open fractures I: 48% C: 47%

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes, there were no apparent differences. |

Plating by fellowship-trained traumatologists

|

Intramedullary nailing by fellowship trained traumatologists |

Length of follow-up: 12 months

Loss-to-follow-up: N=7 (one moved to India, two died during follow up four without a reason: Three had been treated with nails and one had been treated with a tibial plate.)

Incomplete outcome data: Intervention: N (%) Reasons (describe)

Control: N (%) Reasons (describe)

Nineteen patients who met the inclusion criteria were not randomized. Three of them refused participation, two did not sign a consent form, and 14 were not included because of surgeon nonparticipation. The nonrandomized group did not differ from the randomized group in age, gender, Injury Severity Score, mechanism of injury, fracture pattern, or presence of open fracture. Ten were treated with nails, and nine were treated with plates. |

Osteitis/Osteomyelitis I: 3 C: 1

Consolidation: Not reported

Complication: Malalignment: I: 4 C: 13 p-value=0.02

Malunion: I: 3 C: 5

Malunion secondary to immediate weightbearing against medical advice: I: 5 C: 1

Functioning: Not reported

Pain: Not reported

Return to work: Not reported

|

ISS: injury severity score

|

Risk of bias table for intervention studies (randomized controlled trials)

|

Study reference

(first author, publication year) |

Describe method of randomisation1 |

Bias due to inadequate concealment of allocation?2

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate blinding of participants to treatment allocation?3

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate blinding of care providers to treatment allocation?3

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate blinding of outcome assessors to treatment allocation?3

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to selective outcome reporting on basis of the results?4

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to loss to follow-up?5

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to violation of intention to treat analysis?6

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

|

Im, 2005 |

Drawing envelopes |

Unlikely |

Unclear (not reported) |

Likely (blinding of care provider not reported) |

Likely (final examination was performed by independent physician, biostatistician was blinded) |

Unclear (no predefined outcome measures) |

Unclear (reasons not reported) |

Unclear |

|

Guo, 2010 |

Sequential study number |

Unclear |

Likely |

Likely (different operations) |

Likely (outcome assessor not blinded) |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

Unlikely? |

|

Vallier, 2011 |

Not randomised, retrospective outcome analysis |

Likely |

Likely |

Likely |

Surgeon assessing malalignment radiographically was blinded. |

Likely (secondary outcomes differ a little in the text) |

Unclear (reasons not reported) |

n.a. |

Evidence table for systematic review of RCTs and observational studies (intervention studies)

Research question: Open vs. Closed hemorrhoidectomy

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C) |

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

Shao, 2014

|

SR of RCTs

Literature search up to December 2012 and updated*

A: Keating, 1997 B: Finkemeier, 2000 C: Yin Feng, 2008 D: Bahandari E: Tabatbaei, 2012 (add during update)

Study design: RCT

Country: A: Canada B: USA C: China D: Canada, USA, the Netherlands E:Iran

Source of funding: Not stated; authors declare no competing interest

|

Inclusion criteria 1) published research literature; 2) adult patients with OTF of Gustilo types I, II, IIIA, and IIIB, except for Gustilo type IIIC and old fracture; 3) RCTs, 4) intervention studies on reamed intramedullary nail fixation to patients with open tifal fracture in the treatment group and on unreamed intramedullary nailing in patients as a contrast.

Exclusion: 1) non-randomized controlled trials, 2) observational studies, 3) case reports or review, 4) the literature research of a sufficient number of patients in treatment and control groups.

5 studies included

Important patient characteristics at baseline:

N, mean age A: 91 patients, 37 yrs B: 45 patients, 33.8 yrs C: unclear: D: 406 patients, 39.5 ± 16.0 E: 119 patients, 26.4 / 26.9 yrs

Fracture classification: A: type-I: 9 type-II: 18 type-IIIA: 16 type-IIIB: 7

B: type-I: 6 type-II: 17 type-IIIA: 19 type-IIIB: 3

C: Unclear

D: type-I: 108 type-II: 161 type-IIIA: 107 type-IIIB: 30

E:Not reported

Groups comparable at baseline? The small sampled RCTs had no significant differences though there groups were not fully comparable in fracture classification. |

Reamed intramedullary nailing

|

Unreamed nailing

|

End-point of follow-up (average):

A: 22 months B: 19 months C: 18 months D: 12 months E:8 months

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? E: A few patients were lost to follow up but the authors called them and collected some of the information. Not reported for

|

Fracture healing

4 studies n=623 participants

Pooled effect (random effects model): 1.01 [0.96, 1.06] favoring both sides Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

Re-operation

2 studies n=445 participants

Pooled effect (random effects model): 1.01 [0.62, 1.66] favouring both sides Heterogeneity (I2): 53%

Failure of implant

2 studies n=529 participants

Pooled effect (random effects model): 0.62 [0.27, 1.46] favouring reamed nailing Heterogeneity (I2): 45%

Infection rate

5 studies n=727 participants Pooled effect (random effects model): 0.87 [0.41, 1.84] favoring reamed nailing Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

Compartment syndrome

3 studies n=597 participants

Pooled effect (random effects model): 0.94 [0.31, 2.85] favoring reamed nailing Heterogeneity (I2): 0% |

*plus the RCT by Tabatbaei, 2012, identified in the updating process. |

Table of quality assessment for systematic reviews of RCTs and observational studies

|

Study

First author, year |

Appropriate and clearly focused question?1

Yes/no/unclear |

Comprehensive and systematic literature search?2

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of included and excluded studies?3

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of relevant characteristics of included studies?4

Yes/no/unclear |

Appropriate adjustment for potential confounders in observational studies?5

Yes/no/unclear/ not applicable |

Assessment of scientific quality of included studies?6

Yes/no/unclear |

Enough similarities between studies to make combining them reasonable?7

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential risk of publication bias taken into account?8

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential conflicts of interest reported?9

Yes/no/unclear |

|

Shao, 2014 |

Yes |

Yes, in multiple databases |

Yes, both were clearly described |

Some characteristics were reported |

Not applicable |

Yes, conform Jaded |

Yes, low heterogeneity |

Unclear (no trial registration) |

Not reported |

Based on AMSTAR checklist (Shea et al.; 2007, BMC Methodol 7: 10; doi:10.1186/1471-2288-7-10) and PRISMA checklist (Moher et al 2009, PLoS Med 6: e1000097;

Risk of bias table for intervention studies (randomized controlled trials)

Research question:

|

Study reference

(first author, publication year) |

Describe method of randomisation1 |

Bias due to inadequate concealment of allocation?2

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate blinding of participants to treatment allocation?3

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate blinding of care providers to treatment allocation?3

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate blinding of outcome assessors to treatment allocation?3

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to selective outcome reporting on basis of the results?4

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to loss to follow-up?5

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to violation of intention to treat analysis?6

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

|

Tabatbaei, 2012 |

Randomisation table |

Unclear, blinding of the randomisation table was not described |

Likely, allocation of treatment was not blinded |

Likely, allocation of treatment was not blinded |

Likely, allocation of treatment was not blinded |

Unlikely, all specified outcomes were reported |

Unclear, not reported |

Unlikely |

Table Excluded after reading complete article

Nail versus plate

|

Author and year |

Reason for exclusion |

|

Yavuz,U 2014 |

Observational (retrospective; N=54) distal tibia shaft fractures and underwent surgical treatment were evaluated retrospectively between 2005 and 2011 |

|

Kayali,C 2009 |

Observational (retrospective; N=45) |

|

Beardi,J. 2008 |

Observational (medical charts; N=26) |

|

Janssen,K.W. 2008 |

Observational (matched-control; N=24) In review |

|

Lindvall,E. 2009 |

Observational (retrospective; N=62) |

|

Vallier,H.A 2011 |

double |

|

Joveniaux, 2010 |

Observational (retrospective; N=101) Plate: N=36 Nailing: N=8 In review |

Table Excluded after reading complete article

Reamed versus unreamed nail

|

Author and year |

Reason for exclusion |

|

Hutchinson,A. 2012 |

External fixation versus intramedullary nailing |

|

Fang,X 2012 |

unreamed nail vs external fixation |

|

Briel,M 2011 |

Observational (medical charts; N=26) |

|

Park,H.J 2007 |

Observational (matched-control; N=24) Under review |

|

Lee,Y.S. 2008 |

Observational (retrospective; N=62) |

|

Finkemeier,C.G. 2000 |

double |

|

Xue,D, 2010 |

Observational (retrospective; N=101) Plate: N=36 Nailing: N=8 In review |

|

Schemitsch,E.H 1998 |

Animal study |

|

Bhandari,M. 2008 |

In review |

|

Schemitsch,E.H. 2012 |

Considerations; prognosis |

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Publicatiedatum : 07-06-2017

Beoordeeld op geldigheid : 01-01-2017

The executive board of the NVvH will assess these guidelines no later than 2020 to determine if they are still valid. If necessary, a new working party will be set up to review the guidelines. If there are new developments, the validity of the guidelines will expire earlier and a review will take place. The working party does not deem it necessary to separately specify validity at a modular level.

As owners of these guidelines, the primary responsibility to keep them up-to-date rests with the NVvH. Other participating professional bodies or users of the guidelines share the responsibility and are required to inform the NVvH about relevant developments in their fields.

Algemene gegevens

The development of these guidelines was financed by the Quality Foundation of the Dutch Medical Specialists (SKMS).

Doel en doelgroep

What is the aim (desired effect) of the guidelines?

The recognition and acknowledgement of the complexity of a fracture of the lower limb with significant soft tissue injury is of the greatest of importance in developing an appropriate multidisciplinary treatment strategy. The specialisations involved must be very aware of their own abilities and limitations, and on the basis of these must work in partnership right from when the patient is first presented. Standardisation of therapeutic options by means of a treatment algorithm is necessary. The development of multidisciplinary, evidence-based guidelines contributes to this.

Currently, the treatment of an open lower limb fracture is not managed by a scientifically supported and multidisciplinary policy, but more likely by the local traditions of the hospital at which the patient presents. This often causes confusion about the most appropriate method of primary fixation, the timing and the extent of aggressiveness of the debridement and the planning for definitive coverage of the soft tissues.

In the Netherlands, there is currently no standardised treatment for patients with an open fracture of the lower limb. There are British guidelines on this injury (BAPRAS/BOA, 2009), but these are not always applicable to the Dutch situation for a number of reasons, including the differing ways in which care is organised. National, evidence-based guidelines are of considerable importance in supporting health care professionals in their clinical decision-making and in providing transparency to patients and third parties. It covers topics in several areas including the early and late treatment of open fractures of the lower limb, the timing and kind of surgical debridement, bone stabilisation, soft tissue cover and rehabilitation. The ultimate goal is to create a primary multidisciplinary treatment pathway whereby patients with complex open fractures of the lower limb can be treated quickly and to a high standard.

Defining the guidelines

The guidelines are aimed at all patients with an open fracture of the lower limb, and in particular at those patients with a grade III (a, b or c) open injury in accordance with the classification of Gustilo and Anderson. The principles of treatment described in these guidelines are also applicable to open fractures in other parts of the skeleton, such as the ankle.

Envisaged users of the guidelines

These guidelines have been written for all members of those professional groups who are involved in the medical care of adults or children with an open fracture of the lower limb: emergency department physicians, trauma surgeons, orthopaedic surgeons, plastic surgeons, rehabilitation physicians, physiotherapists, nurses and wound consultants.

Samenstelling werkgroep

In 2014, a multidisciplinary working party was set up to develop these guidelines. It comprised representatives from all those relevant specialisations involved in the care of patients with a grade III open fracture of the lower limb (see below).

The members of the working party were mandated for participation by their professional organisation. The working party worked for two years to develop these guidelines.

The working party is responsible for the integral text of these guidelines.

- Dr M.J. Elzinga, trauma surgeon (NVvH), Haga Hospital, The Hague (Chair)

- Dr J.M. Hoogendoorn, trauma surgeon (NVvH), Medical Centre Haaglanden-Bronovo, The Hague, The Netherlands.

- Dr P. van der Zwaal, orthopaedic surgeon (NOV), Medical Centre Haaglanden-Bronovo, The Hague, The Netherlands.

- Dr D.J. Hofstee, orthopaedic surgeon (NOV), Noordwest Hospital Group, The Netherlands

- J.G. Klijnsma, physiotherapist (KNGF), University Medical Centre Utrecht, The Netherlands

- Dr P. Plantinga, emergency department physician (NVSHA), Rijnstate Hospital, Arnhem, The Netherlands.

- Dr H.R. Holtslag, rehabilitation physician (VRA), Academic Medical Centre, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

- Dr E.T. Walbeehm, plastic surgeon (NVPC), Radboud Hospital, Nijmegen, The Netherlands.

- Dr H.A. Rakhorst, plastic surgeon (NVPC), Medisch Spectrum, Twente, The Netherlands.

With the help of:

- Dr W.A. van Enst, senior advisor, Knowledge Institute of Medical Specialists

With thanks to:

- Dr C.W. Ang, medical microbiologist, VU Medical Centre, Amsterdam. The Netherlands.

Belangenverklaringen

The members of the working party have declared in writing if, in the last five years, they have held a financially supported position with commercial businesses, organisations or institutions that may have a connection with the subject of the guidelines. Enquiries have also been made into personal financial interests, interests pertaining to personal relationships, interests pertaining to reputation management, interests pertaining to externally financed research, and interests pertaining to valorisation of knowledge. These Declarations of Interest can be requested from the secretariat of the Knowledge Institute of Medical Specialists. See below for an overview.

|

Name of member of working party |

Interests: Yes/No |

Remarks |

|

M.J. Elzinga |

No |

|

|

Dr J.M. Hoogendoorn |

No |

|

|

Dr P. van der Zwaal |

Yes |

Member of an Orthopaedic & Traumatology partnership financially supported by Biomet in the interests of scientific research |

|

Dr D.J. Hofstee |

No |

|

|

Mr J.G. Klijnsma |

No |

|

|

P. Plantinga |

No |

|

|

Dr H.R. Holtslag |

No |

|

|

Dr E.T. Walbeehm |

No |

|

|

Dr H.A. Rakhorst |

No |

|

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

The perspective of the patient was included by organising a focus group. This report can be found in the appendices. The concept guidelines was presented to the Patient Federation NPCF for their comments.

Methode ontwikkeling

Evidence based

Implementatie

Introduction

This plan has been drawn up with the aim of advancing the implementation of these guidelines. In order to compile this plan, an inventory of factors that could either facilitate or hinder the recommendations was carried out. The guideline working group has made recommendations concerning the timeline for implementation, the preconditions necessary for this and the actions that should be taken by various parties.

Methodology

In order to arrive at this plan, the working party has applied the following to each recommendation in the guidelines:

- the time point by which the recommendations should have been nationally implemented;

- the expected impact of implementation of the recommendation on healthcare costs; preconditions necessary to be able to implement the recommendation; possible barriers to the implementation of the recommendation; possible actions to advance the implementation of the recommendation; the party responsible for the actions to be undertaken.

Readers of this implementation plan should take the differences between ‘strong’ recommedations and ‘weak’ recommendations into account. In the former case, the guideline committee clearly states what should or should not be done. In the latter case, the recommendation is less strong and the working party expresses a preference but leaves more room for alternatives. One reason for this could be that there is insufficient research evidence to support the recommendation. A weak recommendation can be recognised by its formulation and may begin with something like ‘Consider the…’. The working party has considered the implementation of both weak and strong recommendations. A time frame for implementation is only indicated for strong recommendations.

Time frames for implementation

Strong recommendations should be followed as strictly as possible. In most cases, this will mean that the recommedations should be implemented within one year of the publication of the guidelines.

However, some recommedations will not be directly implemented everywhere. This could be due to a lack of facilities, expertise or correct organisational structure. In some cases, account should be taken of the learning curve. In addition, the unavailability of staff or facilities or lack of agreement between professionals may hinder the implementation in the short term.

It is for these reasons that the following recommendations are based on estimates made by the guideline working group, and an implementation period of between one and three years should be allowed for:

|

Recommendation |

Remarks |

|

At the scene, treat patients with an open fracture of the lower limb in accordance with the Netherlands National Protocol of Ambulance Care (LPA) and Prehospital Trauma Life Support (PHTLS) principles.

|

Taking note of the guidelines is sufficient for implementation |

|

Take photographs of the injuries so the temporary dressing does not continually need to be disturbed (important for the privacy of the patient). |

Taking note of the guidelines is sufficient for implementation |

|

Assess the wound, vascular status and nerve injury and classify the injury in accordance with the Gustilo and Andersen classification. |

Taking note of the guidelines is sufficient for implementation |

|

Assess and describe the degree of contamination and the extent of the soft tissue injuries. |

Taking note of the guidelines is sufficient for implementation |

|

Repeat neurovascular status assessment paying special attention to the development of compartment syndrome and acute vascular threat to the leg. |

Taking note of the guidelines is sufficient for implementation |

|

Avoid taking wound cultures in the ED. |

Taking note of the guidelines is sufficient for implementation |

|

Take plain radiographs in two directions (AP and lateral) including the proximal and distal joints. |

Taking note of the guidelines is sufficient for implementation |

|

If peripheral pulsations are intact, then only carry out CT angiography on indication (clinical suspicion or preoperative work-up). |

Taking note of the guidelines is sufficient for implementation |

|

If the leg is acutely threatened surgical exploration and shunting be should carried out in order to keep acute ischaemic time to a minimum. The site of the vascular damage can be accurately determined using conventional radiological diagnostics and the level of the area of trauma. |

Taking note of the guidelines is sufficient for implementation |

|

In ED remove those contaminants that are easy to remove, and leave perforating objects (e.g. cables or slivers of metal or glass) in situ. |

Taking note of the guidelines is sufficient for implementation |

|

Wound irrigation should emphatically not take place in the ED. |

Taking note of the guidelines is sufficient for implementation |

|

Cover wounds with sterile gauze soaked in a saline solution. |

Taking note of the guidelines is sufficient for implementation |

|

Align dislocated fractures and apply a splint. |

Taking note of the guidelines is sufficient for implementation |

|

Intravenous antibiotics and a tetanus vaccination should be administered as early as possible in accordance with regional protocol. |

Taking note of the guidelines is sufficient for implementation |

|

Pain relief should be started as quickly as possible and in accordance with local protocol or guidelines on trauma patients in the emergency care pathway. |

Taking note of the guidelines is sufficient for implementation |

|

Debridement should be carried out systematically, working from skin to bone. If necessary, the wound should be lengthened along perforator-sparing fasciotomy lines in order to obtain a good overview of the affected area. Any further operations should be taken into consideration at this time and this should be discussed by the multidisciplinary team. |

Staff training, specifically aimed at the treatment of open fractures of the lower limb |

|

Irrigate under low pressure using plenty of saline solution. |

Staff training, specifically aimed at the treatment of open fractures of the lower limb |

|

Negative pressure therapy is the treatment of preference as a temporary wound cover as it helps to prevent infections and aids patient comfort. |

Staff training, specifically aimed at the treatment of open fractures of the lower limb |

|

If negative pressure therapy is not technically possible, the second choice is saline-soaked gauze dressings which have then been wrung out. |

Staff training, specifically aimed at the treatment of open fractures of the lower limb |

|

The application of a temporary wound cover should not deter the early and definitive covering of soft tissues. |

Dependent on the availability of enough adequately trained staff or on care arrangements with other hospitals. |

|

Aim to achieve primary internal fixation with nail or plate if good soft tissue cover is possible and the leg can be reasonably expected to bear weight.

|

Staff training, specifically aimed at the treatment of open fractures of the lower limb |

|

The working party neither recommends nor discourages primary bone grafting in open fractures. |

- |

|

As little research has been done in the area of primary bone grafting, for the time being this technique should be used in a study setting. |

Registration and permission from ethics committee to collect and study patient data should be organised. |

|

Definitive reconstruction of the soft tissues in open fracture of the lower limb should take place as quickly as possible, within a maximum of one week, if the condition of the patient permits this. |

Dependent on the availability of enough adequately trained staff or on care arrangements with other hospitals. Staff training, specifically aimed at the treatment of open fractures of the lower limb |

|

Keep as much length and tissue as possible and, where feasible, repair soft tissue injury with skin grafts. |

Taking note of the guidelines is sufficient for implementation Supplemented by further training |

|

Involve a rehabilitation physician as quickly as possible following the accident; preferably preoperatively to advise the patient. |

Taking note of the guidelines is sufficient for implementation |

|

If a transtibial amputation is not possible, carry out disarticulation of the knee in preference to transfemoral amputation. |

Taking note of the guidelines is sufficient for implementation |

|

When treating grade III open fractures, an antibiotic such as cefazolin which protects against Staphylococcus aureus should be given. |

Taking note of the guidelines is sufficient for implementation |

|

In grade III open fractures, antibiotics should be given until the soft tissues have been closed, preferably a maximum of 72 hours. |

Taking note of the guidelines is sufficient for implementation |

|

Consult a microbiologist on antibiotic therapy in the event of exceptional contaminants (marine, animal housing or sewerage). In grade III fractures consider adding an extra drug (e.g. an aminoglycoside such as tbramycin, gentamycin or ciprofloxacin), or using a third-generation cephalosporin (a potential disadvantage of these drugs being they are less effective against S aureus). |

Taking note of the guidelines is sufficient for implementation |

|

Consult a microbiologist on antibiotic therapy in the event of exceptional contaminants (marine, animal housing or sewerage). |

Taking note of the guidelines is sufficient for implementation |

|

Start exercise therapy as quickly as possible postoperatively. |

Taking note of the guidelines is sufficient for implementation |

|

Exercise therapy should be primarily aimed at disorders of function as specified in the ICF model (function of leg musculature, ROM of knee and ankle), and secondarily at activities (standing and walking). |

Taking note of the guidelines is sufficient for implementation |

|

In consultation with patient and surgeon set treatment targets for exercise therapy while taking the weight-bearing capacity of bone and soft tissues into consideration. |

Taking note of the guidelines is sufficient for implementation |

|

Over time, adapt these exercise therapy targets to the biological and mechanical possibilities and limitations of the wound, bone and soft tissues, the surgical procedure and potential complications. |

Taking note of the guidelines is sufficient for implementation |

|

Should quantification of physical functioning be called for, six-weekly WOMAC and SF-36 are recommended. |

Taking note of the guidelines is sufficient for implementation |

|

Return to work and quality of life are determined by personal and environmental factors. |

Taking note of the guidelines is sufficient for implementation |

|

If necessary, take measures to prevent talipes equinus. |

Taking note of the guidelines is sufficient for implementation |

|

Nominate a primary treating physician. |

Taking note of the guidelines is sufficient for implementation |

|

Make local or regional arrangements regarding the organisation of care for patients with a grade III open fracture of the lower limb and register this in a protocol. |

Taking note of the guidelines is sufficient for implementation |

|

Arrange to discuss the definitive treatment plan with the patient and family or close friends. Point out the possible treatment options, the risks associated with these options, and the expected results. |

Taking note of the guidelines is sufficient for implementation |

|

The meeting should be led by, or be held in the presence of, the primary treating physician. |

Taking note of the guidelines is sufficient for implementation |

The following recommendations are based on estimates made by the guideline committee, and an implementation period of between three to five years should be allowed for:

|

Recommendation |

Remarks |

|

The initial debridement should be done as quickly as possible, certainly within twelve hours of the initial trauma. It should be carried out by an experienced, trained and well-equipped multidisciplinary team. |

Hospitals should have enough staff available to be able to provide a multidisciplinary team, or they should have arrangements with other institutions who are able to provide care from a multidisciplinary team. |

|

The decision to continue temporary wound dressings for longer than one week is one that should be made by the primary multidisciplinary team. |

Hospitals should have enough staff available to be able to provide a multidisciplinary team, or they should have arrangements with other institutions who are able to provide care from a multidisciplinary team. |

|

Form a multidisciplinary team comprising a minimum of trauma surgeon/orthopaedic surgeon, a plastic surgeon and a rehabilitation physician. |

Hospitals should have enough staff available to be able to provide a multidisciplinary team, or they should have arrangements with other institutions who are able to provide care from a multidisciplinary team. |

|

The multidisciplinary team should see the patient preoperatively (rehabilitation physician if indicated) and together draw up a treatment plan. |

Hospitals should have enough staff available to be able to provide a multidisciplinary team, or they should have arrangements with other institutions who are able to provide care from a multidisciplinary team. |

Impact on healthcare costs

Many of these recommendations will have few or no consequences for the cost of healthcare. However, the deployment of a multidisciplinary team will possibly increase direct costs. Conversely, if the guidelines are adhered to the number of infections and reoperations will be reduced thus reducing costs. The savings are larger than the cost of the multidisciplinary team. Other recommendations do not affect costs, or may even save them.

Actions to be undertaken by each party

Below is a list of actions that in the opinion of the guideline working group should be undertaken to facilitate the implementation of the guidelines.

All academic and professional organisations that are directly involved (NVvH, NVPC, NOV, VRA, KNGF).

- Tell members about the guidelines. Publicise the guidelines by writing about them in journals and disseminating news of them at congresses.

- Provide professional education and training to ensure that the expertise required to follow the guidelines is available.

- Where relevant and possible, develop resources, instruments and/or digital tools to facilitate the implementation of the guidelines.

- Monitor the way in which the recommendations are put into practice by means of audits and quality inspections.

- Include indicators developed for these guidelines in quality registrations and indicator sets.

- Make interprofessional agreements about implementing continuous modular maintenance of the guidelines.

Initiatives to be undertaken by the professional organisation NVvH

- Hospital management boards and other system stakeholders (where applicable), should be kept informed of recommedations that could have an effect on the organisation of care and on costs, and on what may be expected by the party concerned.

- Publicise the guidelines to other interested academic and professional bodies.

Local professional groups / individual medical professionals

- Discuss the recommendations at meetings of professional groups and local working parties.

- Tailor local protocols to fit the recommendations from the guidelines.

- Follow the continuing professional education on these guidelines (yet to be developed).

- Modify local information for patients using the materials that the professional bodies will make available.

- Make agreements with other disciplines involved to ensure the implementation of the recommedations in practice.

- Register pre- and postoperative factors and, as far as is possible, include important considerations for decision-making in existing protocols and the electronic dossier.

The system stakeholders (including health insurers, NZA, hospital managers and their associations, IGZ)

In relation to the financing of care for patients with open fracture of the lower limb, it is expected that hospital management boards will be prepared to make the investments necessary to enable the implementation of these guidelines (see impact on healthcare costs above). In addition, hospital managers are expected to monitor those medical professionals concerned and ascertain how familiar they are with the new guidelines and how they are putting them into practice.

Health insurers are expected to reimburse the costs of the care that is prescribed in these guidelines. When the time frames for implementation have elapsed, health insurers can use the strong recommendations in these guidelines for purposes of purchasing care.

Researchers and subsidy providers

Initiate research into the knowledge gaps, preferably in a European setting.

Knowledge Institute of Medical Specialists

Publicise these guidelines among the staff and contect to development of related guidelines, e.g. on ankle fractures and post-osteosynthesis infection.

Add guidelines to guideline database. Incorporate this implementation plan in a place where all parties will be able to find it.

Werkwijze

AGREE II

These guidelines were developed in accordance with the publication Medical Specialists Guidelines 2.0 report from the advisory committee on Guidelines from the Committee on Quality. This report is based on the AGREE II instrument (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II) (http://www.agreetrust.org/agree-ii/). This is a widely-accepted internationally used instrument and is based on ‘Guideline to guideline for the assessment of quality of guidelines (http://www.zorginstituutnederland.nl/).

Inventory of problem areas

During the preparation stage, the Chair of the Working Party and the Advisor made an inventory of problem areas. The Dutch health insurance companies were invited to contribute their problem areas to the guidelines.

Clinical questions and outcome measures

Based on the outcomes of the problem area analysis, the Chair and the Advisor compiled concept clinical questions. These were discussed with the working party, after which time the working party approved the definitive clinical questions. The working party then decided which outcome measures of each of the clinical questions are relevant to the patient, and both desirable and undesirable effects were examined. The working party then rated these outcome measures and categorised their relative importance as crucial, important or unimportant. In as far as was possible, the working party also defined what they found to be clinically relevant difference in the outcome measures, i.e. if the improvement in outcome was an improvement for the patient.

Strategy for searching and selecting the literature

For purposes of orientation, we looked for existing guidelines from outside the Netherlands (Guidelines International Network, Trip and National guideline clearing house (USA) European and American professional organisations), and systematic reviews (Medline, Embase, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews). Then, using specific search terms from the individual clinical questions, the working party searched for published studies in various electronic databases. Studies from the reference lists of the selected articles were also included in the search. Initially, studies with the highest level of evidence were searched for. The members of working party then went through the articles found in the search and selected articles based on predetermined selection criteria. The selected articles were used to answer the clinical questions. The databases searched, the search action or key words of the search action and the selection criteria used are defined in the search strategy of the clinical question concerned.

Quality evaluation of individual studies

In order to estimate the risk of bias in the study results, individual studies were systematically evaluated on the basis of previously determined methodological quality criteria. These evaluations can be found in the methodological checklists.

Summary of the literature

The relevant data from all studies included are shown in evidence tables. The most important findings from the literature were described in the summary of the literature. In the event of enough agreement between studies, the data were summarised quantitatively in a meta-analysis. This was done with Review Manager software from the Cochrane Collaboration.

Evaluation of the strength of scientific evidence

A) Intervention and diagnostic questions

Evaluation of the strength of scientific evidence was determined in accordance with the GRADE method. GRADE stands for ‘Grading Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation’ (see http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/) (Atkins, 2004).

GRADE distinguishes four grades of quality of evidence, i.e. high, moderate, low and very low. These grades indicate the degree of confidence in the conclusions in the literature (see http://www.guidelinedevelopment.org/handbook/).

|

GRADE |

Definition |

|

High |

|

|

Moderate |

|

|

Low |

|

|

Very low |

|

B) Questions concerning aetiology and prognosis

GRADE cannot be applied in this type of question. The strength of evidence of the conclusion is determined in accordance with the EBRO method (van Everdingen, 2004).

Formulating the conclusions

Evidence concerning questions about the value of diagnostic tests, injury or side effects, aetiology and prognosis, has been summarised in one or more conclusions in which the level of the most relevant evidence is given.

In questions relating to intervention and diagnosis, the conclusion does not refer to one or more articles, but is drawn on the basis of the whole body of evidence. In this the members of the working party did an analysis for each intervention. In making these calculations, the beneficial and unfavourable effects for the patient were weighed off against one other.

Considerations

In order to produce a recommendation, aspects other than research evidence are also important. These include the expertise of the members of the working party, patient preferences, costs, availability of facilities and organisational matters. In as far as they are not part of the literature summary, these aspects are reported under the heading ‘Considerations’.

Development of recommendations

The recommendations answer the clinical question and are based on the best available scientific evidence and the most important considerations. The strength of the scientific evidence and the weight accorded the considerations by the working party together determine the strength of the recommendation. In accordance with the GRADE methodology, a low grade of evidence from a conclusion in the systematic literature analysis does not exclude a strong recommendation, and a high grade of evidence does not exclude a weaker recommendation. The strength of the recommendation is always determined by weighing up all relevant arguments together.

Preconditions (Organisation of care)

In the analysis of problem areas and the development of the guidelines, account was taken explicitly of the organisation of care: all those aspects that are preconditions for the provision of care. These include coordination, communication, materials, financial means, work force and infrastructure. Preconditions that are relevant to the answering of a specific clinical question are part of the considerations related to that specific question.

Development of indicators

At the same time as the concept guidelines were developed, internal quality indicators were also developed in order to be able to follow and to strengthen the application of a guideline in practice. More information about the method of developing indicators can be requested from the secretariat of the Knowledge Institute of Medical Specialists (secretariaat@kennisinstituut.nl).

Knowledge gaps

In the development of these guidelines, we systematically searched for research whose results contributed to answering one of the clinical questions. The working party examined each clinical question and they considered the desirability of further research. An overview of their recommendations for further research can be seen in Knowledge gaps (see related products).

Comment and authorisation stage

To follow (after comment stage)

Implementation

At each stage of the development of the guidelines, account was taken of the implementation of the guidelines and the feasibility of the recommendations in practice. In this, particular attention was paid to factors that may advance or hinder the implementation of the guidelines.

Zoekverantwoording

|

Database(s): |

Search terms |

Total |

|

Medline (OVID) 1946-okt. 2014 |