Startcriteria

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is de optimale timing om te beginnen met nierfunctie-vervangende therapie bij kritisch zieke patiënten met acute nierinsufficiëntie op de intensive care?

Aanbeveling

Start direct met nierfunctievervangende therapie bij kritisch zieke patiënten op de IC bij wie sprake is van AKI en hieraan gerelateerde potentieel levensbedreigende verstoringen:

- levensbedreigende diureticaresistente overvulling;

- refractaire, potentieel levensbedreigende hyperkaliëmie;

- ernstige metabole acidose refractair voor conservatieve behandeling;

- uremische complicaties.

Bij het ontbreken van harde criteria voor het starten van RRT moet rekening worden gehouden met andere factoren, zoals de ernst van de overige orgaanschade als gevolg van de acute ziekte en onderliggende comorbiditeit, om de timing van het starten met RRT individueel op de patiënt af te stemmen.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Nierfunctievervangende therapie (renal replacement therapy, RRT) kan op een aantal manieren worden uitgevoerd en tot op heden is niet duidelijk wat de optimale criteria zijn om te beginnen met behandeling. Er is daarom literatuuronderzoek verricht naar de optimale timing om te beginnen met RRT bij kritisch zieke patiënten op de intensive care (IC). Er is één systematische review geïncludeerd die de vergelijking tussen vroege en late start van RRT heeft onderzocht.

Uit de literatuuranalyse werd geconcludeerd dat vroeg beginnen met RRT mogelijk niet resulteert in een verschil in 90-daagse mortaliteit en mortaliteit op de IC (lage bewijskracht), en waarschijnlijk ook niet resulteert in een verschil in 28-daagse mortaliteit en mortaliteit in het ziekenhuis (redelijke bewijskracht), vergeleken met laat starten van RRT. Laat starten met RRT zorgt er waarschijnlijk voor dat het aantal patiënten dat RRT ontvangt, daalt (redelijke bewijskracht). Voor herstel van nierfunctie op 28 en 90 dagen was de bewijskracht te laag en kan geen uitspraak worden gedaan over een richting van effect. De duur van RRT werd niet gerapporteerd. De totale bewijskracht van de cruciale uitkomstmaten komt daarmee uit op zeer laag (de laagste bewijskracht voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten). Er is geen duidelijke richting te zien bij de cruciale uitkomstmaten in de effecten tussen vroege en late start van RRT, behalve voor het wel of niet ontvangen van RRT. Deze uitkomstmaat geeft aan dat laat starten met RRT de voorkeur zou hebben.

De belangrijke uitkomstmaten kunnen in beperkte mate richting geven aan de besluitvorming. Allereerst was de bewijskracht voor de duur van ziekenhuisopname en duur van opname op de IC te laag en kon er geen uitspraak worden gedaan. Voor kwaliteit van leven zijn geen studies gevonden. De uitkomstmaat complicaties kan wel nog verdere richting geven aan de besluitvorming. Er werd gevonden dat laat starten met RRT het risico op hypotensie waarschijnlijk verlaagt, vergeleken met vroeg starten met RRT. De bewijskracht hiervoor was redelijk. Ook werd gevonden dat laat starten met RRT mogelijk het aantal infecties verlaagt (lage bewijskracht). Verlate start met RRT resulteert mogelijk in geen tot een klein verschil in aritmie (lage bewijskracht). De bewijskracht voor bloedingen was te laag om een uitspraak over te kunnen doen.

De studies in Li (2021) hadden een laag risico op vertekening. De redelijke tot zeer lage bewijskracht werd dan ook veelal veroorzaakt door imprecisie rondom de puntschatter door het overschrijden van de klinisch relevante grenzen of door tegenstrijdige resultaten. Daarnaast bestond er veel heterogeniteit tussen de studies voor zowel de patiëntpopulaties als de definiëring van vroege en late RRT startcriteria.

Acute indicatie voor RRT is een exclusiecriterium

Het eenduidige advies van de KDIGO AKI-richtlijn (KDIGO, 2012) is om bij acute nierinsufficiëntie (acute kidney injury, AKI) direct te starten met RRT wanneer hyperkaliëmie, metabole acidose of overvulling niet reagerend op conservatieve maatregelen een gevaar vormen voor de patiënt (KDIGO, 2012).

In de timing studies werden patiënten met deze criteria dan ook geëxcludeerd van randomisatie (Bagshaw 2020; Barbar, 2018; Bouman 2002; Gaudry, 2016; Lumbertgul 2016; Srisawat 2017; Wald 2015; Zarbock 2016). De studies hebben dus onderzocht of in afwezigheid van levensbedreigende RRT startcriteria een vroege behandeling beter is dan een late behandeling.

Heterogeniteit in de ernst van AKI bij inclusie

Patiënten moesten AKI hebben om geïncludeerd te kunnen worden in de timing studies. In geen van de acht geincludeerde studies was de ernst van AKI bij inclusie gelijk, ondanks het toepassen van AKI consensus classificatie definities in 7 studies (zie Tabel 2 in de literatuursamenvatting). Bouman (2002) en Lumlertgul (2016) includeerden patiënten alleen bij oligurie ondanks furosemide. In de late groep werd geen RRT gestart in 16% van de patiënten in Bouman (2002) en in 25% van de patiënten in Lumlertgul (2016), omdat nooit voldaan werd aan de conventionele startcriteria door overlijden of spontaan herstel van nierfunctie.

In de studie van Lumlertgul (2016) ontvingen slechts zes patiënten (13,6%) RRT van de in totaal 44 patiënten die geëxcludeerd werden o.b.v. furosemide respons. Uit de literatuur is gebleken dat het uitblijven van diurese op furosemide een simpele methode is voor het identificeren van de AKI patiënten met een grote kans op AKI progressie en RRT behoefte. De diagnostische waarde van furosemide is groter in de vroege AKI populatie (Chen, 2020). De studies van Srisawat (2016), Wald (2015) en Zarbock (2016) gebruiken naast de AKI consensus definitie ook nog een verhoogde concentratie neutrofiel gelatinase-geassocieerd lipocaline (NGAL). Ook een hoge NGAL-waarde blijkt een voorspeller van meer ernstige AKI (Klein, 2018). Furosemide respons en misschien in de toekomst ook serum NGAL (of andere biomarkers) zijn parameters die meegenomen zouden kunnen worden bij de beslissing voor het starten van RRT.

In de STARRT-AKI trial (Bagshaw, 2020) werden AKI patiënten gerandomiseerd indien er sprake was van ‘equipoise’ bij het behandelend team. Equipoise betekent dat wanneer er verschillende therapeutische opties worden vergeleken in een RCT, er onzekerheid dient te bestaan over welke optie de voorkeur verdient bij het afwegen van de risico’s, en onzekerheid over het therapeutisch nut van elke studiearm (Rodrigues, 2011). De haalbaarheid van een dergelijk studie is eerder aangetoond in een pilotstudie (Wald, 2015). In de STARRT-AKI studie (Bagshaw, 2020) voldeden 11.852 patiënten aan de AKI inclusiecriteria. Echter werden 7.886 (67%) patiënten alsnog geëxcludeerd op basis van een gebrek aan onzekerheid over de timing van RRT bij het behandelend team: 2.196 patiënten moesten volgens de arts direct starten met RRT en bij 5.690 patiënten was er de overtuiging dat RRT uitgesteld kon worden. Data van deze patiënten zijn retrospectief verzameld en gepubliceerd (Bagshaw 2021). Data waren beschikbaar bij 48,9% van de uitgestelde groep en 32,1% van de directe start groep. De uitgestelde groep was minder ziek dan de gerandomiseerde groep en uiteindelijk kreeg 11% RRT. De mortaliteit lag lager dan in de gerandomiseerde populatie (24,7%). De directe groep was zieker dan de gerandomiseerde populatie. 91,1% van de patiënten kreeg RRT en de mortaliteit was 46,9%. Dit was hoger dan de mortaliteit in de studiepatiënten (37,5%). Deze uitkomsten suggereren dat de clinici een goede inschatting konden maken wanneer uitstel van RRT gerechtvaardigd was.

Definitie van vroege en late RRT

Het voldoen aan een AKI ernst stadium is het uitgangspunt om te differentiëren tussen vroeg en laat. Bij een vroege behandeling moest zo snel mogelijk gestart worden, maar in ieder geval binnen 6 tot 12 uur (dit varieert per studie). Bij een late behandeling werd gestart bij het optreden van refractaire hyperkaliëmie, metabole acidose of pulmonale overvulling, maar sowieso na 48 tot 72 uur (ook hier was er weer variatie per studie), tenzij er herstel van nierfunctie optrad. De afgelopen jaren zijn er meerdere studies gepubliceerd die een negatieve associatie laten zien tussen positieve vochtbalans en mortaliteit. In theorie zou het vroeg starten met RRT een ernstig cumulatief positieve vochtbalans kunnen voorkomen bij patiënten met oligurie. Slechts enkele studies vermelden data over de vochtbalans. In de studie van Barbar (2018) was de cumulatieve vochtbalans op dag 2 en dag 7 na randomisatie niet verschillend tussen vroege en late start van RRT. In een post-hoc analyse van de AKIKI 1 studie (Gaudry, 2018) werd ook geen verschil aangetoond tussen vroege en late behandeling in de cumulatieve vochtbalans op dag 2 en 7. Dit gold voor zowel de subgroep analyse in ARDS-patiënten als ook de patiënten met sepsis. Het lijkt er dus op dat in de vroege fase van ernstige ziekte er nog geen ruimte is om vocht te onttrekken, ook niet door het vroeg starten van RRT.

In alle studies werd RRT in een deel van de patiënten nooit gestart in de late behandelstrategie, omdat de startcriteria niet werden bereikt als gevolg van voortijdig overlijden of als gevolg van spontaan herstel van de nierfunctie (Tabel 1). Met de late behandelstrategie wordt dus minder vaak RRT gestart zonder nadelige gevolgen op mortaliteit, ligduur en van herstel nierfunctie. Dat laat starten met RRT ervoor zorgt dat minder patiënten uiteindelijk RRT ontvangen, komt ook uit de literatuuranalyse naar voren. Verder viel op dat hoe later de startcriteria in de late behandelgroep gedefinieerd werden, hoe meer patiënten nooit met RRT behandeld werden. Het langste uitstel van behandeling was in de AKIKI 1 studie (Gaudry, 2016). In 157 (51%) patiënten werd in de late groep RRT gestart 57 uur (IQR 25-83) na randomisatie. Persisterende oligurie > 72 uur en serum ureum > 40 mmol/L waren de twee belangrijkste redenen voor RRT. De duur waarmee RRT veilig uitgesteld kan worden in afwezigheid van acute levensbedreigende indicaties blijft echter onduidelijk.

Tabel 1. RRT behandelingen in de late RRT behandelgroepen.

|

Studie |

Geen RRT in de late groep |

Overleden vóór ontvangen van RRT (n) |

Spontaan herstel (n) |

Overig (n) |

|

Bagshaw, 2020 |

559/1462 (38,2%) |

N.R. |

N.R. |

N.R. |

|

Barbar, 2018 |

93/242 (38,4%) |

21 |

70 |

2 |

|

Bouman, 2002 |

6/36 (16,7%) |

2 |

4 |

0 |

|

Gaudry, 2016 |

151/308 (49%) |

N.R. |

N.R. |

N.R. |

|

Lumlertgul, 2016 |

15/60 (25%) |

2 |

13 |

0 |

|

Srisawat, 2018 |

8/20 (60%) |

N.R. |

N.R. |

N.R. |

|

Wald, 2015 |

19/52 (36,5%) |

6 |

13 |

0 |

|

Zarbock, 2016 |

11/119 (9,2%) |

3 |

3 |

5 |

Afkortingen: RRT, renal replacement therapy; N.R., not reported.

De AKIKI 2 trial (Gaudry, 2021) heeft gekeken of een nog meer verlate initiatie van RRT nog veilig was en heeft daarvoor de interventiegroep uit de AKIKI 1 trial (late RRT initiatie) gebruikt als controlegroep. Het nog langer uitstellen van de startcriteria werd bereikt doordat in de meer verlate strategie groep oligurie geen indicatie meer was voor het starten met RRT en de ureum concentratie werd verhoogd van 40 naar 50 mmol/L. De studie is uitgevoerd op 39 IC-units in Frankrijk. Patiënten werden geïncludeerd in de studie als ze opgenomen waren op de ICU met AKI stadium 3 en tevens invasieve mechanische ventilatie, catecholamine of beide ontvingen. De belangrijkste bevinding van deze trial was dat uitstellen van RRT geen voordeel opleverde maar wel geassocieerd was met mogelijke schade. Intention-to-treat analysis toonde geen verschil in het primare eindpunt (RRT-vrije dagen op dag 28 na randomisatie bedroeg 12 [0-25] in de verlate groep versus 10 [0-24] in de meer verlate groep, p=0.93). RRT werd niet gestart in 21% van de patienten in de verlate groep versus 2% in de meer-verlate groep (p<0.0001). Overleving op dag 28 en dag 60 was niet verschillend tussen beide groepen, echter multivariabele analyse toonde dat de mortaliteit op dag 60 hoger was in de meer verlate strategie groep. De conclusie die uit deze studie werd getrokken, is dat in patiënten met AKI stadium 3 met oliguria ≥ 72 uur of ureum concentratie > 40 mmol/L en afwezigheid van levensbedreigende criteria met indicatie voor acute RRT, verder uitstel van start RRT geen additionele voordelen heeft en wel geassocieerd is met potentiële schade.

Heterogeniteit in de AKI populatie

De pathofysiologie van septische AKI en niet-septische AKI verschillen (Bellomo, 2017) en dientengevolge misschien ook het effect van de timing van RRT. De studies waarbij specifiek gekeken is naar septische AKI lieten geen verschil zien tussen vroeg en laat starten van RRT (Barbar, 2018; Gaudry, 2018). Verder heeft de co-morbiditeit (hypertensie, diabetes mellitus, vaatlijden, etc.) een effect op de renale reserve en dus ook op de ernst van AKI en de kans op herstel. Bij RCT’s zullen deze factoren evenredig verdeeld zijn over de behandelgroepen. Op individuele basis zal comorbiditeit en verwachte functionele reserve van nieren (en andere orgaansystemen) meegenomen kunnen worden in de beslissing om te starten met RRT.

Heterogeniteit in RRT behandelingen

Op de Nederlandse IC’s wordt hoofdzakelijk continue RRT (CRRT) toegepast. Slechts twee van de acht timing studies passen alleen CRRT toe. In de overige zes studies werd naast CRRT ook intermitterende hemodialyse (IHD), sustained low-efficiency dialysis (SLED) en prolonged intermittent RRT (PIRRT) toegepast. Er zijn echter binnen de vroege en late behandelgroepen geen statistische verschillen in de toegepaste RRT-technieken.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

De voorkeur van de patiënt voor deze interventies is niet onderzocht en onbekend. Goede voorlichting en communicatie over de behandeldoelen, voor- en nadelen, risico’s en het verwachte resultaat is belangrijk om een goede afweging te maken voor patiënten en naasten. RRT is niet een ‘baat het niet dan schaadt het niet behandeling’, maar is een invasieve behandeling die de patiënt blootstelt aan een hoger risico op bloedingen, onderdoseren van antibiotica, verlies van nutriënten en katheter gerelateerde infectieuze en niet-infectieuze complicaties. Tevens wordt het mobiliseren van de patiënt vaak bemoeilijkt.

Bij een vroege behandelstrategie bestaat de mogelijkheid dat een patiënt onnodig wordt blootgesteld aan de risico’s van RRT. Het is dus aannemelijk dat patiënten bij afwezig voordeel op morbiditeit en mortaliteit niet de voorkeur geven aan vroege behandeling.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

RRT is een kostbare behandeling. Bij de late behandelstrategie blijkt een aanzienlijk deel van de patiënten spontaan te herstellen zonder dat dit resulteert in een langere verblijfsduur of hogere mortaliteit. Hoewel er in de studies geen kosten-batenanalyse gedaan is, lijkt het aannemelijk dat een vroege behandeling leidt tot hogere kosten.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

Late behandeling geeft tijd om het klinisch beloop te evalueren en om indien nodig in een meer electieve setting een dialysekatheter in te brengen. Tevens resulteert late behandeling in minder RRT-behandelingen, waardoor er minder RRT materiaal en personeel noodzakelijk is. Personeelsbesparing zal met name belangrijk zijn in ziekenhuizen waarbij de RRT door de dialyseafdeling wordt uitgevoerd.

In kritisch zieke patiënten met AKI op de intensive care, waarbij geen sprake was van een levensbedreigende diureticaresistente overvulling, ernstige hyperkaliëmie (> 6,0 mmol/L)(Zarbock, 2016, Gaudry, 2016, Investigators S-A, 2020) of ernstige metabole acidose (pH < 7,15)(Zarbock, 2016; Gaudry, 2016; Barbar, 2018; Investigators S-A, 2020), werd in acht gerandomiseerde studies geen voordeel gezien van vroeg starten (binnen 6 tot 12 uur) ten opzichte van laat starten (binnen 48 tot 72 uur) na het voldoen aan AKI stadium 2 tot 3. Bij een deel van de patiënten in de late groep was RRT uiteindelijk niet noodzakelijk (9 tot 60% afhankelijk van de startcriteria in de late groep). Het lijkt dus dat vroege behandeling kan resulteren in “overbehandeling” bij een deel van de patiënten, terwijl RRT invasief, niet zonder risico’s en bovendien een dure behandeling is.

De KDIGO Clinical Practice Guideline for Acute Kidney Injury (2012) beschrijft dat het breed geaccepteerd is om bij uremische complicaties te starten met nierfunctievervangende therapie. De werkgroep sluit zich hierbij aan, maar merkt op dat uremische complicaties in het kader van AKI op de IC zeer zeldzaam zijn.

De criteria om RRT te stoppen zijn onduidelijk. De beschikbare studies die stopcriteria hebben onderzocht zijn zeer beperkt en van matige kwaliteit (Katulka, 2020; Li, 2023). Bovenal ontbreekt prospectieve validatie van de bevindingen. Urine produktie (met name in afwezigheid van diuretica) voorafgaand aan het staken van RRT is de meest onderzochte en robuuste predictor. In de praktijk zal men een inschatting moeten maken of de herstellende nierfuctie voldoende is voor de beoogde behandeldoelen in vochtbalans, elektolythuishouding en zuur-base evenwicht.

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies.

De literatuuranalyse laat zien dat er waarschijnlijk geen verschil in mortaliteit is tussen vroeg of laat starten met RRT. In afwezigheid van levensbedreigende RRT startcriteria, leidt laat starten met RRT waarschijnlijk tot een lager aantal patiënten dat RRT ontvangt. Daarnaast is bij laat starten het risico op hypotensie waarschijnlijk lager en het aantal infecties mogelijk ook.

Furosemide lijkt een simpele methode om de renale functionele reserve in te schatten, maar is onvoldoende belicht bij de indicatiestelling voor RRT.

Er is slechts één studie die rekening heeft gehouden met ‘clinical equipose’, waaruit blijkt dat de behandelend artsen over het algemeen goed kunnen inschatten wanneer RRT veilig uitgesteld kan worden.

Slechts 4 van de 8 studies hebben ureum concentratie meegenomen als startcriterium voor de late start RRT. Een ureumafkappunt van 40 mmol/L resulteerde niet in slechtere uitkomsten. Het toepassen van een ureum van 50 mmol/L was geassocieerd met een slechtere uitkomst in een studie.

Een belangrijk aspect voor timing van RRT welke niet in de studies wordt meegenomen, is het betrekken van de ernst van overige orgaanschade, comorbiditeit en beoogde behandeldoelen. Dit vraagt om een meer individuele benadering van timing van RRT (demand-capacity assesment). In sommige situaties (bijvoorbeeld hoge frailty index of wens van de patiënt) kan er juist afgezien worden afgezien van starten van RRT.

Door de relatief lage dosis t.o.v. intermitterende hemodialyse zijn ernstige intoxicaties geen indicatie voor continue RRT. In deze situaties dient primair overleg plaats te vinden met de dienstdoend nefroloog. In voorkomende gevallen kan wel alvast gestart worden met plaatsen van de dialysekatheter en/of CRRT met maximaal haalbare dosis in afwachting van starten van IHD. Zie ook module dosering voor een uitgebreidere beschrijving m.b.t. de inzet van RRT bij intoxicaties.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

De optimale timing om te beginnen met nierfunctievervangende therapie (renal replacement therapy, RRT) in kritisch zieke patiënten met acute nierinsufficiëntie (acute kidney injury, AKI) op de intensive care (IC) is omstreden, hetgeen momenteel resulteert in een grote praktijkvariatie. De rationale om vroeg te starten met RRT is het sneller bereiken van homeostase en een potentieel gunstig effect op herstel en overleving. Een late strategie voorkomt echter het onnodig starten van RRT in patiënten die spontaan herstellen.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

Mortality (critical)

|

Moderate GRADE |

Early initiation of renal replacement therapy likely results in little to no difference in ‘28-day mortality’ and ‘hospital mortality’ when compared with delayed initiation of renal replacement therapy in critically ill patients with acute kidney injury admitted to the ICU.

Source: Li, 2021 |

|

Low GRADE |

Early initiation of renal replacement therapy may result in little to no difference in ‘90-day mortality’ and ‘ICU mortality’ when compared with delayed initiation of renal replacement therapy in critically ill patients with acute kidney injury admitted to the ICU.

Source: Li, 2021 |

RRT dependence (critical)

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of early initiation of renal replacement therapy on ‘28-day RRT dependence’ and ‘90-day RRT dependence’ when compared with delayed initiation of renal replacement therapy in critically ill patients with acute kidney injury admitted to the ICU.

Source: Li, 2021 |

Duration of RRT (critical)

|

No GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding the effect of early initiation of renal replacement therapy on duration of RRT when compared with delayed initiation of renal replacement therapy in critically ill patients with acute kidney injury admitted to the ICU. |

Receiving RRT (critical)

|

Moderate GRADE |

Delayed initiation of renal replacement therapy likely reduces the number of patients receiving RRT when compared with early initiation of renal replacement therapy in critically ill patients with acute kidney injury admitted to the ICU.

Source: Li, 2021 |

Hospital length of stay

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of early initiation of renal replacement therapy on ‘hospital length of stay’ when compared with delayed initiation of renal replacement therapy in critically ill patients with acute kidney injury admitted to the ICU.

Source: Li, 2021 |

ICU length of stay

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of early initiation of renal replacement therapy on ‘ICU length of stay’ when compared with delayed initiation of renal replacement therapy in critically ill patients with acute kidney injury admitted to the ICU.

Source: Li, 2021 |

Quality of life

|

No GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding the effect of early initiation of renal replacement therapy on quality of life when compared with delayed initiation of renal replacement therapy in critically ill patients with acute kidney injury admitted to the ICU. |

Complications

|

Moderate GRADE |

Delayed initiation of renal replacement therapy likely reduces hypotension when compared with early initiation of renal replacement therapy in critically ill patients with acute kidney injury admitted to the ICU.

Source: Li, 2021 |

|

Low GRADE |

Delayed initiation of renal replacement therapy may reduce the number of infections when compared with early initiation of renal replacement therapy in critically ill patients with acute kidney injury admitted to the ICU.

Source: Li, 2021 |

|

Low GRADE |

Delayed initiation of renal replacement therapy may result in little to no difference in arrhythmia when compared with early initiation of renal replacement therapy in critically ill patients with acute kidney injury admitted to the ICU.

Source: Li, 2021 |

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of early initiation of renal replacement therapy on bleeding events when compared with delayed initiation of renal replacement therapy in critically ill patients with acute kidney injury admitted to the ICU.

Source: Li, 2021 |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

Li (2021) conducted a systematic review of RCTs and meta-analysis to compare the effects of early RRT initiation versus delayed RRT initiation. Multiple databases were searched (PubMed, EMBASE and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials Library database) from inception through July 20, 2020. Reference lists of the included studies and recent review articles were hand-searched for additional relevant studies. Studies were eligible for inclusion if 1) they included critically ill patients with AKI aged 18 years or older, 2) the intervention group received early RRT, 3) the comparison group received delayed RRT, 4) if the outcomes 28-day, 90-day, or hospital all-cause mortality were available, and 5) if the study design was RCT. Exclusion criteria were no RCTs, children, no focus on critical illness, no clear definition of ‘early’ and ‘delayed’ strategies, and the reason for initiation of RRT was not AKI. No language restriction was applied. Included outcome measures useful for our analysis were 28-day, 90-day, hospital and ICU all-cause mortality, the number of patients who received RRT, RRT dependence at day 28 and 90, length of hospital and ICU stay, RRT-free days up to day 28, and the incidence of adverse events. In total, eleven studies involving 5086 patients were included in this meta-analysis. The criteria for early and delayed RRT initiation differed between the studies. The median time of RRT initiation across studies ranged from 2 to 7.6 hours in the early RRT group and 21 to 57 hours in the delayed RRT group. In contrast to Li (2021), only eight out of eleven studies were included in our analysis (N=4594), as three studies (Jamale, 2013; Combes, 2015; Xia, 2019) included either a patient population that did not meet our PICO, or the inclusion criteria were unclear. Inclusion criteria for the eight included studies are described in Table 1. The Cochrane risk-of-bias tool for randomized trials was used to assess the risk of bias in the included RCTs, only when all items were assessed as low risk of bias, the study was classified as low risk of bias. If not, the study was classified as high risk of bias. Most studies were assessed as low risk of bias.

Table 1. Inclusion criteria for each of the included studies in Li (2021)

|

Study |

Inclusion criteria |

|

Bagshaw, 2020 |

≥ 18 y and AKI KDIGO stage ≥ 2 and clinical equipoise# |

|

Barbar, 2018 |

≥ 18 y, early phase of septic shock (within 48 hours after the start of vasopressor therapy), and AKI stage RIFLE=failure |

|

Bouman, 2002 |

≥ 18 y on ventilator and urine output < 30 ml/h for 6 h; creatinine clearance of < 20 mL/min despite fluid resuscitation, inotropic support, and high-dose diuretics. |

|

Gaudry, 2016 |

≥ 18 y, AKI KDIGO stage 3 |

|

Lumlertgul, 2016 |

≥ 18 y, AKI KDIGO stage ≥ 1 and FST** nonresponsive |

|

Srisawat, 2018 |

≥ 18 y, AKI RIFLE stage ≥ risk and pNGAL > 400 ng/ml |

|

Wald, 2015 |

≥ 18 y and AKI KDIGO stage ≥ 2 and pNGAL > 400 ng/ml and clinical equipoise |

|

Zarbock, 2016 |

≥ 18 y and KDIGO ≥ 2 and pNGAL > 150 ng/mL |

# Clinical equipoise: attending physicians were asked to affirm clinical equipoise by noting the absence of any circumstances that would mandate either immediate initiation of renal-replacement therapy or a deferral of such therapy because of clinical judgment regarding the likelihood of imminent recovery of renal function.

** FST, Furosemide stress test: urine output < 200 ml in 2 h after furosemide 1 mg/kg to naive patients or 1.5 mg/kg to patients with a history of furosemide use within 7 days.

Abbreviations: AKI, acute kidney injury; KDIGO, Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes classification; pNGAL, plasma neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin; RIFLE, risk, injury, failure, loss, and end-stage kidney disease classification system.

The studies included in this analysis compared early and late strategies for the RRT initiation time. In these studies, the early group received RRT as soon as moderate to severe AKI diagnosis was made. In contrast, in the late group, RRT was initiated based on specific indications, including fluid overload, electrolyte imbalance and/or azotemia or persistent AKI > 48-72 h.

Table 2. RIFLE, KDIGO and AKIN classifications (adapted from Tsai, 2017)

|

|

Serum creatinine |

Urine output |

||

|

|

RIFLE |

KDIGO |

AKIN |

|

|

AKI Definition |

SCr increase ≥50% within 7 days |

SCr increase ≥26,5 µmol/l within 48 h Or ≥50% within 7 days |

SCr increase ≥50% of ≥26,5 µmol/l within 48 h |

< 0.5 mL/kg/h for 6 h |

|

RIFLE-risk KDIGO stage 1 AKIN stage 1 |

SCr increase ≥50% or GFR decrease >25% |

SCr increase ≥26,5 µmol/l within 48 h or ≥50% within 7 days |

SCr increase ≥50% or ≥26,5 µmol/l |

< 0.5 mL/kg/h for 6 h |

|

RIFLE-injury KDIGO stage 2 AKIN stage 2 |

SCr increase ≥100% or GFR decrease >50% |

SCr increase ≥100% |

SCr increase ≥100% |

< 0.5 mL/kg/h for 12 h |

|

RIFLE-failure KDIGO stage 3 AKIN stage 3 |

SCr increase ≥200% or GFR decrease >75% or SCr ≥353,6 μmol/L (with an acute rise ≥44,2 μmol/L) |

SCr increase≥200% Or SCr ≥353,6 μmol/L Or need RRT |

SCr increase ≥200% or SCr ≥353,6 μmol/L (with an acute rise ≥44,2 μmol/L) or need RRT |

< 0.3 mL/kg/h for 24 h or anuria for 12 h |

|

RIFLE-loss |

Need RRT for >4 weeks |

|

|

|

|

RIFLE-end stage |

Need RRT for >3 months |

|

|

|

Abbreviations: AKIN, Acute Kidney Injury Network; GFR, glomerular filtration rate; KDIGO, Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcome; RIFLE, risk of renal failure, injury to the kidney, failure of kidney function, loss of kidney function, and end-stage renal failure; RRT, renal replacement therapy; SCr, serum creatinine.

Results

Mortality

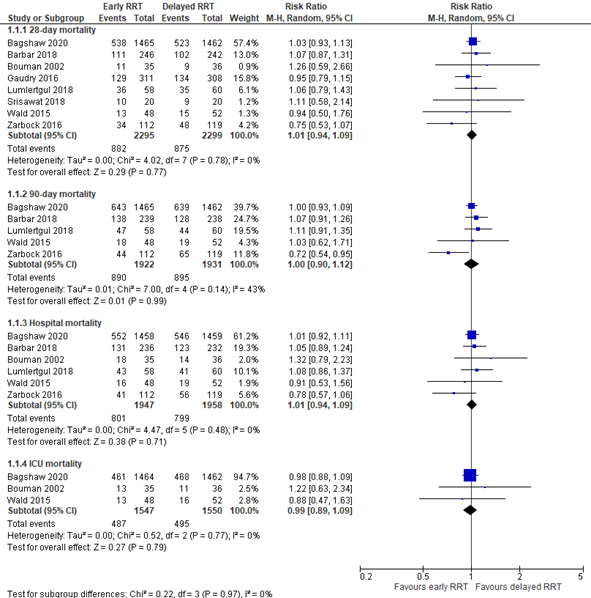

Li (2021) reported 28-day mortality, 90-day mortality, hospital mortality and ICU mortality. The results were pooled (Figure 1). The pooled risk ratio (RR) was 1.01 (95% CI 0.94 to 1.09) for 28-day mortality, 1.00 (95% CI 0.90 to 1.12) for 90-day mortality, 1.01 (95% CI 0.94 to 1.09) for hospital mortality, and 0.99 (95% CI 0.89 to 1.09) for ICU mortality. These differences were not considered to be clinically relevant.

Figure 1: 28-day, 90-day, hospital and ICU mortality; early versus delayed RRT.

Z: p-value of overall effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval; RRT: renal replacement therapy.

Recovery of renal function (RRT dependence)

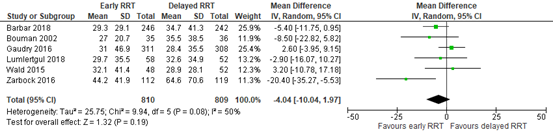

Li (2021) reported 28- and 90-day RRT dependence among survivors. Pooled results are depicted in Figure 2. The pooled RR at day 28 was 0.87 (95% CI 0.54 to 1.42), in favor of early RRT. The pooled RR at day 90 was 1.24 (95% CI 0.70 to 2.21), in favor of delayed RRT. Both differences were considered to be clinically relevant.

Figure 2: 28-day and 90-day RRT dependence; early versus delayed RRT.

Z: p-value of overall effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval; RRT: renal replacement therapy.

Hospital length of stay

Li (2021) reported hospital length of stay. The results are pooled in Figure 3. The pooled mean difference (MD) was -4.04 days (95% CI -10.04 to 1.97), in favor of early RRT. This was considered to be a clinically relevant difference.

Figure 3: hospital length of stay; early versus delayed RRT.

Z: p-value of overall effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval; RRT: renal replacement therapy.

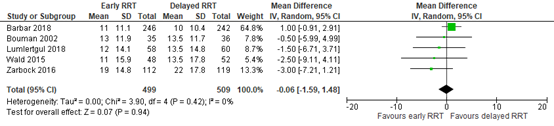

ICU length of stay

Li (2021) reported ICU length of stay. The results are pooled in Figure 4. The pooled mean difference (MD) was -0.06 days (95% CI -1.59 to 1.48), in favor of early RRT. This was not considered to be a clinically relevant difference.

Figure 4: ICU length of stay; early versus delayed RRT.

Z: p-value of overall effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval; RRT: renal replacement therapy.

Duration of RRT

Li (2021) did not report duration of RRT.

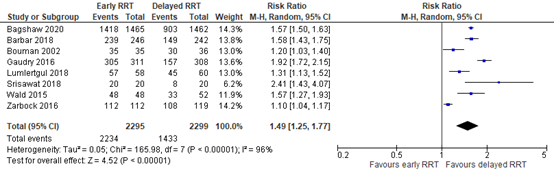

Receiving RRT

Li (2021) reported the number of patients who received RRT. The results were pooled (Figure 5). The pooled RR was 1.49 (95% CI 1.25 to 1.77), in favor of delayed RRT. This was a clinically relevant difference.

Figure 5: the number of patients receiving RRT; early versus delayed RRT.

Z: p-value of overall effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval; RRT: renal replacement therapy.

Quality of life

Quality of life was not reported in Li (2021).

Complications

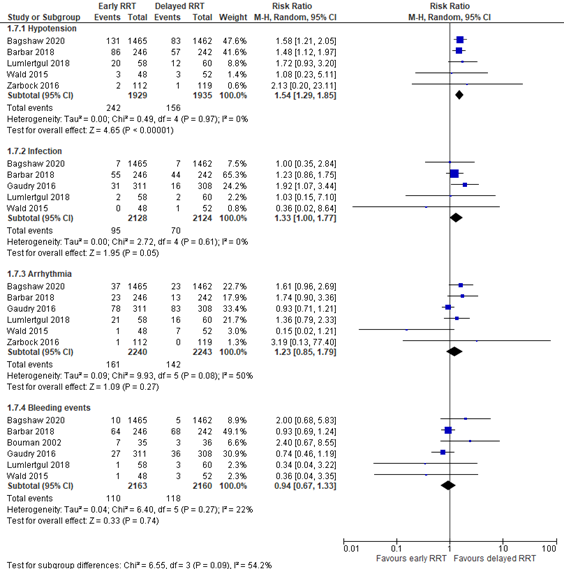

Li (2021) reported hypotension, infection, arrhythmia, and bleeding events. The pooled results are depicted in Figure 6. The pooled RR’s were 1.54 (95% CI 1.29 to 1.85) for hypotension, 1.33 (95% CI 1.00 to 1.77) for infection, 1.23 (95% CI 0.85 to 1.79) for arrhythmia, and 0.94 (95% CI 0.67 to 1.33) for bleeding events. The pooled RR’s for hypotension and infection were considered to be a clinically relevant difference in favor of delayed RRT, whereas the pooled RR’s for arrhythmia and bleeding events were not considered to be a clinically relevant difference.

Figure 6: complications; early versus delayed RRT.

Z: p-value of overall effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval; RRT: renal replacement therapy.

Level of evidence of the literature

Mortality

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measures ‘28-day mortality’ and ‘hospital mortality’ was downgraded from high to moderate, because of heterogeneity between the studies in the patient populations and in the timing of RRT initiation in the two groups (inconsistency, -1).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure ‘90-day mortality’ was downgraded from high to low, because of heterogeneity between the studies in the patient populations and in the timing of RRT initiation in the two groups (inconsistency, -1), and the confidence interval around the point estimate crossing the upper threshold for clinical relevance (imprecision, -1).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure ‘ICU mortality’ was downgraded from high to low, because of heterogeneity between the studies in the patient populations and in the timing of RRT initiation in the two groups (inconsistency, -1), and the confidence interval around the point estimate crossing the lower threshold for clinical relevance (imprecision, -1).

Recovery of renal function (RRT dependence)

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measures ‘28-day RRT dependence’ and ‘90-day RRT dependence’ was downgraded from high to very low, because of heterogeneity between the studies in the patient populations and in the timing of RRT initiation in the two groups (inconsistency, -1), and the confidence interval around the point estimate crossing both thresholds for clinical relevance (imprecision, -2).

Hospital length of stay

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure ‘hospital length of stay’ was downgraded from high to very low, because of heterogeneity between the studies in the patient populations and in the timing of RRT initiation in the two groups (inconsistency, -1), and the wide confidence interval around the point estimate (imprecision, -2).

ICU length of stay

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure ‘ICU length of stay’ was downgraded from high to very low, because of heterogeneity between the studies in the patient populations and in the timing of RRT initiation in the two groups (inconsistency, -1), and the confidence interval around the point estimate crossing both thresholds for clinical relevance (imprecision, -2).

Duration of RRT

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure duration of RRT could not be established, as none of the studies in Li (2021) reported duration of RRT.

Receiving RRT

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure ‘receiving RRT’ was downgraded from high to moderate, because of heterogeneity between the studies in the patient populations and in the timing of RRT initiation in the two groups (inconsistency, -1).

Quality of life

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure quality of life could not be established, as none of the studies in Li (2021) reported quality of life.

Complications

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure ‘hypotension’ was downgraded from high to moderate, because of heterogeneity between the studies in the patient populations and in the timing of RRT initiation in the two groups (inconsistency, -1).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measures ‘infection’ and ‘arrhythmia’ was downgraded from high to low, because of heterogeneity between the studies in the patient populations and in the timing of RRT initiation in the two groups (inconsistency, -1), and the confidence interval around the point estimate crossing the upper threshold for clinical relevance (imprecision, -1).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure ‘bleeding events’ was downgraded from high to very low, because of heterogeneity between the studies in the patient populations and in the timing of RRT initiation in the two groups (inconsistency, -1), and the confidence interval around the point estimate crossing both thresholds for clinical relevance (imprecision, -2).

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question:

What are the benefits and harms of early renal replacement therapy (RRT) initiation versus watchful waiting strategies for RRT initiation in critically ill adult patients with acute kidney injury (AKI)?

P: critically ill adult patients with AKI

I: early RRT initiation

C: late RRT initiation

O: mortality, recovery of renal function, hospital length of stay, ICU length of stay, duration of RRT, receiving RRT, quality of life, complications.

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered mortality, recovery of renal function, duration of RRT and receiving RRT as critical outcome measures for decision making; and hospital length of stay, ICU length of stay, quality of life, and complications (bleedings and infections, complications due to introducing central venous catheter, complications due to postponing RRT) as important outcome measures for decision making.

The working group did not define early/late RRT initiation and the outcome measures a priori, but followed the definitions used in the studies.

The working group defined 10% (RR < 0.9 or > 1.1) as a minimal clinically patient important difference for mortality and recovery of renal function, 2 days for duration of RRT and hospital length of stay, 1 day for ICU length of stay, a difference of 10% for quality of life-questionnaires, and 25% (RR < 0.8 or > 1.25) for receiving RRT and complications.

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms until July 12th 2022. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 476 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria:

- Systematic reviews and RCTs;

- comparing an early start with a late start of renal replacement therapy for ICU-patients.

A total of 29 studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, 28 studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and one study (a systematic review) was included.

Results

One systematic review was included in the analysis of the literature. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- Barbar SD, Clere-Jehl R, Bourredjem A, Hernu R, Montini F, Bruyere R, Lebert C, Bohe J, Badie J, Eraldi JP, et al. Timing of renal-replacement therapy in patients with acute kidney injury and sepsis. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(15):1431-1442.

- Bellomo R, Kellum JA, Ronco C, Wald R, Martensson J, Maiden M, Bagshaw SM, Glassford NJ, Lankadeva Y, Vaara ST, Schneider A. Acute kidney injury in sepsis. Intensive Care Med. 2017 Jun;43(6):816-828. doi: 10.1007/s00134-017-4755-7. Epub 2017 Mar 31. PMID: 28364303.

- Chen JJ, Chang CH, Huang YT, Kuo G. Furosemide stress test as a predictive marker of acute kidney injury progression or renal replacement therapy: a systemic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care. 2020 May 7;24(1):202. Doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-02912-8. PMID: 32381019; PMCID: PMC7206785.

- Gaudry S, Hajage D, Schortgen F, Martin-Lefevre L, Pons B, Boulet E, Boyer A, Chevrel G, Lerolle N, Carpentier D, et al. Initiation strategies for renal-replacement therapy in the intensive care unit. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(2):122-133.

- Gaudry S, Hajage D, Martin-Lefevre L, Lebbah S, Louis G, Moschietto S, Titeca-Beauport D, Combe B, Pons B, de Prost N, Besset S, Combes A, Robine A, Beuzelin M, Badie J, Chevrel G, Bohé J, Coupez E, Chudeau N, Barbar S, Vinsonneau C, Forel JM, Thevenin D, Boulet E, Lakhal K, Aissaoui N, Grange S, Leone M, Lacave G, Nseir S, Poirson F, Mayaux J, Asehnoune K, Geri G, Klouche K, Thiery G, Argaud L, Rozec B, Cadoz C, Andreu P, Reignier J, Ricard JD, Quenot JP, Dreyfuss D. Comparison of two delayed strategies for renal replacement therapy initiation for severe acute kidney injury (AKIKI 2): a multicentre, open-label, randomized, controlled trial. Lancet. 2021 Apr 3;397(10281):1293-1300. Doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00350-0. PMID: 33812488.

- Investigators S-A, Canadian Critical Care Trials Group tA, New Zealand Intensive Care Society Clinical Trials Group tUKCCRGtCNTN, the Irish Critical Care Trials G, Bagshaw SM, Wald R, Adhikari NKJ, Bellomo R, da Costa BR, Dreyfuss D, et al. Timing of initiation of renal-replacement therapy in acute kidney injury. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(3):240-251.

- Katulka RJ, Al Saadon A, Sebastianski M, Featherstone R, Vandermeer B, Silver SA, Gibney RTN, Bagshaw SM, Rewa OG. Determining the optimal time for liberation from renal replacement therapy in critically ill patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis (DOnE RRT). Crit Care. 2020 Feb 13;24(1):50. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-2751-8. PMID: 32054522; PMCID: PMC7020497.

- Klein SJ, Brandtner AK, Lehner GF, Ulmer H, Bagshaw SM, Wiedermann CJ, Joannidis M. Biomarkers for prediction of renal replacement therapy in acute kidney injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Intensive Care Med. 2018 Mar;44(3):323-336. doi: 10.1007/s00134-018-5126-8. Epub 2018 Mar 14. PMID: 29541790; PMCID: PMC5861176.

- Li X, Liu C, Mao Z, Li Q, Zhou F. Timing of renal replacement therapy initiation for acute kidney injury in critically ill patients: a systematic review of randomized clinical trials with meta-analysis and trial sequential analysis. Crit Care. 2021 Jan 6;25(1):15. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-03451-y. PMID: 33407756; PMCID: PMC7789484.

- Li Y, Deng X, Feng J, Xu B, Chen Y, Li Z, Guo X, Guan T. Predictors for short-term successful weaning from continuous renal replacement therapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ren Fail. 2023 Dec;45(1):2176170. doi: 10.1080/0886022X.2023.2176170. PMID: 36762988; PMCID: PMC9930790.

- Rodrigues H, Oerlemans A, van der Berg P. De noodzaak van onzekerheid in klinisch onderzoek. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2011 Dec 5;155:A3846.

- Tsai TY, Chien H, Tsai FC, Pan HC, Yang HY, Lee SY, Hsu HH, Fang JT, Yang CW, Chen YC. Comparison of RIFLE, AKIN, and KDIGO classifications for assessing prognosis of patients on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. J Formos Med Assoc. 2017 Nov;116(11):844-851. doi: 10.1016/j.jfma.2017.08.004. Epub 2017 Sep 2. PMID: 28874330.

- Wald R, Bagshaw SM; STARRT-AKI Investigators. Integration of Equipoise into Eligibility Criteria in the STARRT-AKI Trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2021 Jul 15;204(2):234-237. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202009-3425LE. PMID: 33939598.

- Zarbock A, Kellum JA, Schmidt C, Van Aken H, Wempe C, Pavenstadt H, Boanta A, Gerss J, Meersch M. Effect of early vs delayed initiation of renal replacement therapy on mortality in critically Ill patients with acute kidney injury: the ELAIN randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;315(20):2190-2199

Evidence tabellen

Evidence table for systematic review of RCTs and observational studies (intervention studies)

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C)

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

Li, 2021

PS., study characteristics and results are extracted from the SR (unless stated otherwise)

|

SR and meta-analysis of RCTs

Literature search up to July 2020

Note: three studies that were included in Li (2021) were excluded for our analysis, as the patient population did not match our PICO.

A: Bagshaw, 2020 B: Barbar, 2018 C: Bouman, 2002 D: Gaudry, 2016 E: Lumlertgul, 2018 F: Srisawat, 2018 G: Wald, 2015 H: Zarbock, 2016

Study design: RCT

Setting and Country: A: Canada, multicenter, mixed population B: France, multicenter, septic shock population C: Netherlands, two-center, mixed population D: France, multicenter, mixed population E: Thailand, multicenter, mixed population F: Thailand, two-center, mixed population G: Canada, multicenter, mixed population H: Germany, single-center, mixed population

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: No funding and no competing interests. |

Inclusion criteria SR: - critically ill patients with AKI aged 18 years or older; - the treatment group received early RRT; - the control group received delayed RRT; - outcomes 28-day all-cause mortality, 90-day mortality, or hospital all-cause mortality were available; - and study design RCT.

Exclusion criteria SR: - study type was not RCT; - patients included children; - study not focused on critical illness; - without a clearly defnition of “early” and “delayed” strategies; - and the reason for initiating RRT was not AKI, but others.

8 out of 11 studies in the SR were included in our analysis

Important patient characteristics at baseline:

Total no. of patients (male)/ mean age (SD) A: 2927 (1990)/ 64.6 (14.9) B: 488 (296)/69 (12.2) C: 71 (42)/68.5 (11.6) D: 619 (409)/66.1 (13.9) E: 118 (58)/67.1 (15.8) F: 40 (22)/66.8 (15.9) G: 100 (72)/63.1 (12.8) H: 231 (146)/67 (13.1)

RRT modality A: IHD, CRRT B: IHD, CRRT C: CRRT D: IHD, CRRT E: CRRT, PIRRT, IHD F: CRRT G: IHD, CRRT, SLED H: CRRT, SLED, IHD

Groups comparable at baseline? Groups comparable based on gender and age. |

Intervention: early RRT. Criteria for RRT initiation per study:

A: within 12 h after the onset of KDIGO stage 2 or 3 B: Within 12 h after the onset of failure stage of RIFLE C: Within 12 h if urine output< 30 ml/h for 6 h; creatinine clearance of < 20 mL/min D: KDIGO stage 3 E: AKI (any stage of KDIGO) and no response to furosemide stress test F: AKI (any stage of RIFLE) G: At least two of the following: twofold increase in serum creatinine from baseline; urine output < 6 mL/kg in the preceding 12 h; NGAL ≥ 400 ng/m H: Within 8 h of diagnosis of KDIGO stage 2

|

Control: delayed RRT. Criteria for RRT initiation per study:

A: Serum potassium≥6 mmol/L; pH≤7.2; serum bicarbonate≤12 mmol/L; severe respiratory failure; volume overload; persistent AKI≥72 h B: Serum potassium≥6.5 mmol/; pH≤7.15; severe pulmonary edema refractory to diuretics; no renal function recovery after 48 h C: Plasma urea level of>40 mmol/L; potassium of>6.5 mmol/L or severe pulmonary edema D: Serum potassium>6 mmol/L; severe pulmonary edema refractory to diuretics; pH<7,15; serum urea > 40 mmol/L; oliguria>72 h E: BUN≥100 mg/ dL(35,6 mmol/L); serum potassium>6 mmol/L; serum bicarbonate F: potassium>6.2 mmol/L; pH40 mg/dL G: Serum potassium>6.2 mmol/L; serum bicarbonate < 10 mmol/L, severe pulmonary edema; persistent AKI for>72 h H: Within 12 h of diagnosis of KDIGO stage 3; or serum urea>100 mg/ dL(35,6 mmol/L); serum potassium>6 mmol/L; serum magnesium>4 mmol/L; urine <200 mLper 12 h or anuria; organ edema refractory to diuretics

|

End-point of follow-up: Not reported.

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? Not reported.

|

Mortality, events/total 28-day all-cause mortality A: I: 538/1465; C: 523/1462 B: I: 111/246; C: 102/242 C: I: 11/35; C: 9/36 D: I: 129/311; C: 134/308 E: I: 36/58; C: 35/60 F: I: 10/20; C: 9/20 G: I: 13/48; C: 15/52 H: I: 34/112; C: 48/119 Pooled RR: see results section

90-day all-cause mortality A: I: 643/1465; C: 639/1462 B: I: 138/239; C: 128/238 E: I: 47/58; C: 44/60 G: I: 18/48; C: 19/52 H: I: 44/112; C: 65/119 Pooled RR: see results section

Hospital all-cause mortality A: I: 552/1458; C: 546/1459 B: I: 131/236; C: 123/232 C: I: 18/35; C: 14/36 E: I: 43/58; C: 41/60 G: I: 16/48; C: 19/52 H: I: 41/112; C: 56/119 Pooled RR: see results section

ICU all-cause mortality A: I: 461/1464; C: 468/1462 C: I: 13/35; C: 11/36 G: I: 13/48; C: 16/52 Pooled RR: see results section

Recovery of renal function, events/total 28-day RRT dependence among survivors B: I: 17/134; C: 17/140 C: I: 1/17; C: 0/22 D: I: 22/179; C: 17/178 F: I: 1/10; C: 6/11 H: I: 18/78; C: 26/71 Pooled RR: see results section

90-day RRT dependence among survivors A: I: 85/814; C: 49/815 B: I: 2/101; C: 3/110 G: I: 0/30; C: 2/33 H: I: 9/67; C: 8/53 Pooled RR: see results section

Hospital length of stay, mean (SD) B: I: 29.3 (29.1) n=246; C: 34.7 (41.3) n=242 C: I: 27 (20.7) n=35; C: 35.5 (38.5) n=36 D: I: 31 (46.9) n=311; C: 28.4 (35.5) n=308 E: I: 29.7 (35.5) n=58; C: 32.6 (34.9) n=60 G: I: 32.1 (41.4) n=48; C: 28.9 (28.1) n=52 H: I: 44.2 (41.9) n=112; C: 64.6 (70.6) n=119 Pooled MD: see results section

ICU length of stay, mean (SD) B: I: 11 (11.1) n=246; C: 10 (10.4) n=242 C: I: 13 (11.9) n=35; C: 13.5 (11.7) n=36 E: I: 12 (14.1) n=58; C: 13.5 (14.8) n=60 G: I: 11 (15.9) n=48; C: 13.5 (17.8) n=52 H: I: 19 (14.8) n=112; C: 22 (17.8) n=119 Pooled MD: see results section

Duration of RRT, mean (SD) RRT-free days at 28 days B: I: 13.4 (11.4) n=246; C: 14.8 (11.8) n=242 D: I: 12.6 (12.1) n=311; C: 13.6 (13) n=308 E: I: 6.9 (10.1) n=58; C: 7.8 (12.1) n=60 F: 9.4 (11.3) n=20; C: 10 (13.9) n=20 G: I: 10.9 (11.6) n=48; C: 8.5 (9.8) n=52 Pooled MD: see results section

Receiving RRT, events/total Number of patients who received RRT A: I: 1418/1465; C: 903/1462 B: I: 239/246; C: 149/242 C: I: 35/35; C: 30/36 D: I: 305/311; C: 157/308 E: I: 57/58; C: 45/60 F: I: 20/20; C: 8/20 G: I: 48/48; C: 33/52 H: I: 112/112; C: 108/119 Pooled RR: see results section

Quality of life Not reported.

Complications, events/total Reported as the incidence of adverse events potentially associated with RRT. 1) Hypotension A: I: 131/1465; C: 83/1462 B: I: 86/246; C: 57/242 E: I: 20/58; C: 12/60 G: I: 3/48; C: 3/52 H: I: 2/112; C: 1/119 Pooled RR: see results section

2) Infection A: I: 7/1465; C: 7/1462 B: I: 55/246; C: 44/242 D: I: 31/311; C: 16/308 E: I: 2/58; C: 2/60 G: I: 0/48; C: 1/52 Pooled RR: see results section

3) Arrhythmia A: I: 37/1465; C: 23/1462 B: I: 23/246; C: 13/242 D: I: 78/311; C: 83/308 E: I: 21/58; C: 16/60 G: I: 1/48; C: 7/52 H: I: 1/112; C: 0/119 Pooled RR: see results section

4) Bleeding events A: I: 10/1465; C: 5/1462 B: I: 64/246; C: 68/242 C: I: 7/35; C: 3/36 D: I: 27/311; C: 36/308 E: I: 1/58; C: 3/60 G: I: 1/48; C: 3/52 Pooled RR: see results section

|

Brief description of author’s conclusion: “This meta-analysis suggested that early initiation of RRT was not associated with survival benefit in critically ill patients with AKI. In addition, early initiation of RRT could lead to unnecessary RRT exposure in some patients, resulting in a waste of health resources and a higher incidence of RRT-associated adverse events. Maybe, only critically ill patients with a clear and hard indication, such as severe acidosis, pulmonary edema, and hyperkalemia could benefit from early initiation of RRT.”

|

Table of quality assessment for systematic reviews of RCTs and observational studies

Based on AMSTAR checklist (Shea et al.; 2007, BMC Methodol 7: 10; doi:10.1186/1471-2288-7-10) and PRISMA checklist (Moher et al 2009, PLoS Med 6: e1000097; doi:10.1371/journal.pmed1000097)

|

Study

First author, year |

Appropriate and clearly focused question?1

Yes/no/unclear |

Comprehensive and systematic literature search?2

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of included and excluded studies?3

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of relevant characteristics of included studies?4

Yes/no/unclear |

Appropriate adjustment for potential confounders in observational studies?5

Yes/no/unclear/notapplicable |

Assessment of scientific quality of included studies?6

Yes/no/unclear |

Enough similarities between studies to make combining them reasonable?7

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential risk of publication bias taken into account?8

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential conflicts of interest reported?9

Yes/no/unclear |

|

Li, 2021 |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Not applicable (review of RCTs) |

Yes |

No

Reason: Some heterogeneity in study populations and time of initiation RRT. However, for our analyses we excluded RCTs whose study population did not meet our PICO. |

Yes |

No

Reason: Li (2021) itself was not funded and the authors had no COI. However, the source of funding was not reported for the individual RCTs |

Table of excluded studies

|

Reference |

Reason for exclusion |

|

Chen JY, Chen YY, Pan HC, Hsieh CC, Hsu TW, Huang YT, Huang TM, Shiao CC, Huang CT, Kashani K, Wu VC. Accelerated versus watchful waiting strategy of kidney replacement therapy for acute kidney injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Clin Kidney J. 2022 Jan 14;15(5):974-984. doi: 10.1093/ckj/sfac011. Erratum in: Clin Kidney J. 2022 Mar 25;15(5):1027. PMID: 35498901; PMCID: PMC9050527. |

Matches the PICO but reports mainly Odds Ratio’s without incidence rates |

|

Lan SH, Lai CC, Chang SP, Lu LC, Hung SH, Lin WT. Accelerated-strategy renal replacement therapy for critically ill patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2022 Jul 8;101(27):e29747. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000029747. PMID: 35801785; PMCID: PMC9259140. |

Matches the PICO but reports mainly Odds Ratio’s without incidence rates |

|

Chen JJ, Lee CC, Kuo G, Fan PC, Lin CY, Chang SW, Tian YC, Chen YC, Chang CH. Comparison between watchful waiting strategy and early initiation of renal replacement therapy in the critically ill acute kidney injury population: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intensive Care. 2020 Mar 3;10(1):30. doi: 10.1186/s13613-020-0641-5. PMID: 32128633; PMCID: PMC7054512. |

Matches the PICO, but a more complete review was also found |

|

Gaudry S, Hajage D, Benichou N, Chaïbi K, Barbar S, Zarbock A, Lumlertgul N, Wald R, Bagshaw SM, Srisawat N, Combes A, Geri G, Jamale T, Dechartres A, Quenot JP, Dreyfuss D. Delayed versus early initiation of renal replacement therapy for severe acute kidney injury: a systematic review and individual patient data meta-analysis of randomised clinical trials. Lancet. 2020 May 9;395(10235):1506-1515. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30531-6. Epub 2020 Apr 23. PMID: 32334654. |

Matches the PICO, but a more complete review was also found |

|

Pasin L, Boraso S, Tiberio I. Early initiation of renal replacement therapy in critically ill patients: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. BMC Anesthesiol. 2019 May 1;19(1):62. doi: 10.1186/s12871-019-0733-7. PMID: 31039744; PMCID: PMC6492439. |

Matches the PICO, but a more complete review was also found |

|

Chaudhuri D, Herritt B, Heyland D, Gagnon LP, Thavorn K, Kobewka D, Kyeremanteng K. Early Renal Replacement Therapy Versus Standard Care in the ICU: A Systematic Review, Meta-Analysis, and Cost Analysis. J Intensive Care Med. 2019 Apr;34(4):323-329. doi: 10.1177/0885066617698635. Epub 2017 Mar 21. PMID: 28320238. |

Matches the PICO, but a more complete review was also found |

|

Xiao L, Jia L, Li R, Zhang Y, Ji H, Faramand A. Early versus late initiation of renal replacement therapy for acute kidney injury in critically ill patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2019 Oct 24;14(10):e0223493. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0223493. PMID: 31647828; PMCID: PMC6812871. |

Matches the PICO, but a more complete review was also found |

|

Bhatt GC, Das RR, Satapathy A. Early versus Late Initiation of Renal Replacement Therapy: Have We Reached the Consensus? An Updated Meta-Analysis. Nephron. 2021;145(4):371-385. doi: 10.1159/000515129. Epub 2021 Apr 29. PMID: 33915551. |

Matches the PICO, but includes also quasi-RCT’s |

|

Lin WT, Lai CC, Chang SP, Wang JJ. Effects of early dialysis on the outcomes of critically ill patients with acute kidney injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Sci Rep. 2019 Dec 4;9(1):18283. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-54777-9. PMID: 31797991; PMCID: PMC6892880. |

Matches the PICO, but a more complete review was also found |

|

Xiao C, Xiao J, Cheng Y, Li Q, Li W, He T, Li S, Gao D, Shen F. The Efficacy and Safety of Early Renal Replacement Therapy in Critically Ill Patients With Acute Kidney Injury: A Meta-Analysis With Trial Sequential Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Front Med (Lausanne). 2022 Feb 21;9:820624. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2022.820624. PMID: 35265638; PMCID: PMC8898954. |

Matches the PICO, but search period starts too late |

|

Naorungroj T, Neto AS, Yanase F, Eastwood G, Wald R, Bagshaw SM, Bellomo R. Time to Initiation of Renal Replacement Therapy Among Critically Ill Patients With Acute Kidney Injury: A Current Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Crit Care Med. 2021 Aug 1;49(8):e781-e792. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000005018. PMID: 33861550. |

Matches the PICO, but a more complete review was also found |

|

Zhang L, Chen D, Tang X, Li P, Zhang Y, Tao Y. Timing of initiation of renal replacement therapy in acute kidney injury: an updated meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Ren Fail. 2020 Nov;42(1):77-88. doi: 10.1080/0886022X.2019.1705337. PMID: 31893969; PMCID: PMC6968507. |

Matches the PICO, but a more complete review was also found |

|

Wald R, Adhikari NK, Smith OM, Weir MA, Pope K, Cohen A, Thorpe K, McIntyre L, Lamontagne F, Soth M, Herridge M, Lapinsky S, Clark E, Garg AX, Hiremath S, Klein D, Mazer CD, Richardson RM, Wilcox ME, Friedrich JO, Burns KE, Bagshaw SM; Canadian Critical Care Trials Group. Comparison of standard and accelerated initiation of renal replacement therapy in acute kidney injury. Kidney Int. 2015 Oct;88(4):897-904. doi: 10.1038/ki.2015.184. Epub 2015 Jul 8. PMID: 26154928. |

Matches the PICO, but also reported in SR’s |

|

Zarbock A, Kellum JA, Schmidt C, Van Aken H, Wempe C, Pavenstädt H, Boanta A, Gerß J, Meersch M. Effect of Early vs Delayed Initiation of Renal Replacement Therapy on Mortality in Critically Ill Patients With Acute Kidney Injury: The ELAIN Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2016 May 24-31;315(20):2190-9. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.5828. PMID: 27209269. |

Matches the PICO, but also reported in SR’s |

|

Bouman CS, Oudemans-Van Straaten HM, Tijssen JG, Zandstra DF, Kesecioglu J. Effects of early high-volume continuous venovenous hemofiltration on survival and recovery of renal function in intensive care patients with acute renal failure: a prospective, randomized trial. Crit Care Med. 2002 Oct;30(10):2205-11. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200210000-00005. PMID: 12394945. |

Matches the PICO, but also reported in SR’s |

|

Gaudry, Stéphane, David Hajage, Fréderique Schortgen, Laurent Martin-Lefevre, Bertrand Pons, Eric Boulet, Alexandre Boyer, e.a. ‘Initiation Strategies for Renal-Replacement Therapy in the Intensive Care Unit’. New England Journal of Medicine 375, nr. 2 (14 juli 2016): 122–33. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1603017. |

Matches the PICO, but also reported in SR’s |

|

STARRT-AKI Investigators; Canadian Critical Care Trials Group; Australian and New Zealand Intensive Care Society Clinical Trials Group; United Kingdom Critical Care Research Group; Canadian Nephrology Trials Network; Irish Critical Care Trials Group, Bagshaw SM, Wald R, Adhikari NKJ, Bellomo R, da Costa BR, Dreyfuss D, Du B, Gallagher MP, Gaudry S, Hoste EA, Lamontagne F, Joannidis M, Landoni G, Liu KD, McAuley DF, McGuinness SP, Neyra JA, Nichol AD, Ostermann M, Palevsky PM, Pettilä V, Quenot JP, Qiu H, Rochwerg B, Schneider AG, Smith OM, Thomé F, Thorpe KE, Vaara S, Weir M, Wang AY, Young P, Zarbock A. Timing of Initiation of Renal-Replacement Therapy in Acute Kidney Injury. N Engl J Med. 2020 Jul 16;383(3):240-251. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2000741. Erratum in: N Engl J Med. 2020 Jul 15;: PMID: 32668114. |

Matches the PICO, but also reported in SR’s |

|

Barbar SD, Clere-Jehl R, Bourredjem A, Hernu R, Montini F, Bruyère R, Lebert C, Bohé J, Badie J, Eraldi JP, Rigaud JP, Levy B, Siami S, Louis G, Bouadma L, Constantin JM, Mercier E, Klouche K, du Cheyron D, Piton G, Annane D, Jaber S, van der Linden T, Blasco G, Mira JP, Schwebel C, Chimot L, Guiot P, Nay MA, Meziani F, Helms J, Roger C, Louart B, Trusson R, Dargent A, Binquet C, Quenot JP; IDEAL-ICU Trial Investigators and the CRICS TRIGGERSEP Network. Timing of Renal-Replacement Therapy in Patients with Acute Kidney Injury and Sepsis. N Engl J Med. 2018 Oct 11;379(15):1431-1442. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1803213. PMID: 30304656. |

Matches the PICO, but also reported in SR’s |

|

Pan HC, Chen YY, Tsai IJ, Shiao CC, Huang TM, Chan CK, Liao HW, Lai TS, Chueh Y, Wu VC, Chen YM. Accelerated versus standard initiation of renal replacement therapy for critically ill patients with acute kidney injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis of RCT studies. Crit Care. 2021 Jan 5;25(1):5. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-03434-z. PMID: 33402204; PMCID: PMC7784335. |

Matches the PICO, but a more complete review was also found |

|

Yang XM, Tu GW, Zheng JL, Shen B, Ma GG, Hao GW, Gao J, Luo Z. A comparison of early versus late initiation of renal replacement therapy for acute kidney injury in critically ill patients: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMC Nephrol. 2017 Aug 7;18(1):264. doi: 10.1186/s12882-017-0667-6. PMID: 28784106; PMCID: PMC5547509. |

Matches the PICO, but a more complete review was also found |

|

Feng YM, Yang Y, Han XL, Zhang F, Wan D, Guo R. The effect of early versus late initiation of renal replacement therapy in patients with acute kidney injury: A meta-analysis with trial sequential analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS One. 2017 Mar 22;12(3):e0174158. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0174158. PMID: 28329026; PMCID: PMC5362192. |

Matches the PICO, but a more complete review was also found |

|

Cui J, Tang D, Chen Z, Liu G. Impact of Early versus Late Initiation of Renal Replacement Therapy in Patients with Cardiac Surgery-Associated Acute Kidney Injury: Meta-Analysis with Trial Sequential Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Biomed Res Int. 2018 Dec 18;2018:6942829. doi: 10.1155/2018/6942829. PMID: 30662912; PMCID: PMC6312615. |

Matches the PICO, but a more complete review was also found |

|

Li Y, Li H, Zhang D. Timing of continuous renal replacement therapy in patients with septic AKI: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019 Aug;98(33):e16800. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000016800. PMID: 31415389; PMCID: PMC6831327. |

Matches the PICO, but a more complete review was also found |

|

Xu Y, Gao J, Zheng X, Zhong B, Na Y, Wei J. Timing of initiation of renal replacement therapy for acute kidney injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized-controlled trials. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2017 Aug;21(4):552-562. doi: 10.1007/s10157-016-1316-2. Epub 2016 Aug 2. PMID: 27485542. |

Matches the PICO, but a more complete review was also found |

|

Andonovic M, Shemilt R, Sim M, Traynor JP, Shaw M, Mark PB, Puxty KA. Timing of renal replacement therapy for patients with acute kidney injury: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Intensive Care Soc. 2021 Feb;22(1):67-77. doi: 10.1177/1751143720901688. Epub 2020 Feb 6. PMID: 33643435; PMCID: PMC7890756. |

Matches the PICO, but a more complete review was also found |

|

Fayad AII, Buamscha DG, Ciapponi A. Timing of renal replacement therapy initiation for acute kidney injury. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018 Dec 18;12(12):CD010612. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010612.pub2. PMID: 30560582; PMCID: PMC6517263. |

Matches the PICO, but a more complete review was also found |

|

Meraz-Muñoz AY, Bagshaw SM, Wald R. Timing of kidney replacement therapy initiation in acute kidney injury. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2021 May 1;30(3):332-338. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0000000000000707. PMID: 33767061. |

Matches the PICO, but a more complete review was also found |

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Laatst beoordeeld : 18-06-2024

Algemene gegevens

De ontwikkeling/herziening van deze richtlijnmodule werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten. (www.demedischspecialist.nl/kennisinstituut) en werd gefinancierd uit de Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS) en/of andere bron.

De financier heeft geen enkele invloed gehad op de inhoud van de richtlijnmodule.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijn is in 2022 een multidisciplinaire werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen (zie hiervoor de Samenstelling van de werkgroep) die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor kritisch zieke patiënten die in aanmerking komen voor continue nierfunctievervangende therapie op de intensive care.

Werkgroep

drs. M. (Meint) Volbeda, internist-intensivist, UMCG Groningen, NVIC (voorzitter)

drs. P.M. (Pauline) Klooster, internist-intensivist, HMC den Haag, NVIC

dr. C.S.C. (Catherine) Bouman, internist-intensivist, Amsterdam UMC locatie AMC, NVIC

drs. C.V. (Carlos) Elzo Kraemer, internist-intensivist, LUMC Leiden, NVIC

dr. C.F.M. (Casper) Franssen, internist-nefroloog, UMCG Groningen, NIV

drs. A.J. (Arend-Jan) Meinders, internist-intensivist, st. Antonius Ziekenhuis, NIV

drs. K. (Koen) de Blok, internist-nefroloog-intensivist, Flevoziekenhuis Almere, NIV

drs. L. (Lea) Duijvenbode – den Dekker, IC-verpleegkundige, Amphia Ziekenhuis, V&VN

Klankbordgroep

Frans van Nynatten, renal practicioner, Amphia Ziekenhuis, V&VN

Dr. H.A. (Harmke) Polinder-Bos, Klinisch Geriater Erasmus MC, NVKG

D.M.C.T. (Daphne) Bolman, FCIC en IC connect

Dr. L. (Lilian) Vloet, Lector Acute Intensieve Zorg, FCIC en IC connect

Met ondersteuning van

drs. F.M. (Femke) Janssen, junior adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

dr. M.S. (Matthijs) Ruiter, senior adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

Belangenverklaringen

De Code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling is gevolgd. Alle werkgroepleden hebben schriftelijk verklaard of zij in de laatste drie jaar directe financiële belangen (betrekking bij een commercieel bedrijf, persoonlijke financiële belangen, onderzoeksfinanciering) of indirecte belangen (persoonlijke relaties, reputatiemanagement) hebben gehad. Gedurende de ontwikkeling of herziening van een module worden wijzigingen in belangen aan de voorzitter doorgegeven. De belangenverklaring wordt opnieuw bevestigd tijdens de commentaarfase.

Een overzicht van de belangen van werkgroepleden en het oordeel over het omgaan met eventuele belangen vindt u in onderstaande tabel. De ondertekende belangenverklaringen zijn op te vragen bij het secretariaat van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

|

Werkgroeplid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

Volbeda, voorzitter |

Internist-intensivist, Intensive Care Volwassenen UMCG. |

Geen |

In 2021 eenmalig betaald deelgenomen aan een digitale meeting van Baxter BV waarin nieuwe ontwikkelingen m.b.t. "blood purification" werden besproken. Extern gefinancierd onderzoek: Does a novel citrate based CRRT protocol lead to improved therapy performance? Financier: Baxter. Rol: project coördinator. |

Restrictie ten aanzien van besluitvorming m.b.t. antistollingsmiddelen. Er is een vice-voorzitter aangesteld voor het bespreken van de betreffende module. |

|

Elzo Kraemer (vice-voorzitter) |

internist-intensivist, LUMC |

Lid NVIC ECLS commissie |

Geen |

Geen restricties |

|

Meinders |

Internist-intensivist St. Antoniusziekenhuis |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen restricties |

|

Franssen |

Internist-nefroloog in UMCG |

Geen |

In 2021 eenmalig betaald deelgenomen aan een digitale meeting van Baxter BV waarin nieuwe ontwikkelingen m.b.t. "blood purification" werden besproken. Extern gefinancierd onderzoek: Does a novel citrate based CRRT protocol lead to improved therapy performance? Financier: Baxter. Rol: principal investigator. |

Restrictie ten aanzien van besluitvorming m.b.t. antistollingsmiddelen |

|

Bouman |

Internist-intensivist Amsterdam UMC |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen restricties |

|

De Blok |

Internist-nefroloog bij Flevoziekenhuis Almere |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen restricties |

|

Duijvenbode - den Dekker |

IC-verpleegkundige |

Docent Erasmus MC academie Assessor en portfolio begeleider EVC Bestuurslid V&VN IC Bestuurslid NKIC & visiteur kwaliteitsvisitaties IC Projectlid Samen Beslissen |

Geen |

Geen restricties |

|

Klooster |

Intensivist HMC IC |

Instructeur ATLS bij stichting ALSG (betaald) docent Care Training Group (onbetaald) auteur hoofdstuk nefrologie voor Intensive Care voor de IC-verpleegkundige (onbetaald) |

Geen |

Geen restricties |

|

Janssen |

Junior adviseur Kennisinstituut |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen restricties |

|

Ruiter |

Senior adviseur Kennisinstituut |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen restricties |

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Er werd aandacht besteed aan het patiëntenperspectief door het uitvragen van knelpunten in de schriftelijke knelpunteninventarisatie bij patiëntenorganisatie Stichting Family and patient Centered Intensive Care en IC Connect (FCIC en IC Connect) en Nierpatiëntenvereniging Nederland. Het verslag hiervan (zie bijlage 2) is besproken in de werkgroep. De verkregen input is meegenomen bij het opstellen van de uitgangsvragen, de keuze voor de uitkomstmaten en bij het opstellen van de overwegingen. Daarnaast was een patiëntvertegenwoordiger van deze organisatie afgevaardigd in de klankbordgroep, en is de conceptrichtlijn voor commentaar voorgelegd aan FCIC en IC Connect en de eventueel aangeleverde commentaren zijn bekeken en verwerkt.

Kwalitatieve raming van mogelijke financiële gevolgen in het kader van de Wkkgz

Bij de richtlijn is conform de Wet kwaliteit, klachten en geschillen zorg (Wkkgz) een kwalitatieve raming uitgevoerd of de aanbevelingen mogelijk leiden tot substantiële financiële gevolgen. Bij het uitvoeren van deze beoordeling zijn de richtlijnmodules op verschillende domeinen getoetst (zie het stroomschema op de Richtlijnendatabase).

Uit de kwalitatieve raming blijkt dat er waarschijnlijk geen substantiële financiële gevolgen zijn, zie onderstaande tabel.

|

Module |

Uitkomst raming |

Toelichting |

|

Module Startcriteria |

geen financiële gevolgen |

Het betreft geen nieuwe manier van zorgverlening of andere organisatie van zorgverlening. Er worden daarom geen substantiële financiële gevolgen verwacht. |

Werkwijze

AGREE

Deze richtlijnmodule is opgesteld conform de eisen vermeld in het rapport Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 van de adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwaliteit. Dit rapport is gebaseerd op het AGREE II instrument (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II; Brouwers, 2010).

Knelpuntenanalyse en uitgangsvragen

Tijdens de voorbereidende fase inventariseerde de werkgroep de knelpunten in de zorg voor kritisch zieke patiënten met een indicatie voor nierfunctievervangende therapie. Tevens zijn schriftelijk knelpunten aangedragen door Nierpatiënten Vereniging Nederland. Een terugkoppeling hiervan is opgenomen onder bijlagen. Op basis van de uitkomsten van de knelpuntenanalyse zijn door de werkgroep concept-uitgangsvragen opgesteld en definitief vastgesteld.

Uitkomstmaten

Na het opstellen van de zoekvraag behorende bij de uitgangsvraag inventariseerde de werkgroep welke uitkomstmaten voor de patiënt relevant zijn, waarbij zowel naar gewenste als ongewenste effecten werd gekeken. Hierbij werd een maximum van acht uitkomstmaten gehanteerd. De werkgroep waardeerde deze uitkomstmaten volgens hun relatieve belang bij de besluitvorming rondom aanbevelingen, als cruciaal (kritiek voor de besluitvorming), belangrijk (maar niet cruciaal) en onbelangrijk. Tevens definieerde de werkgroep tenminste voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten welke verschillen zij klinisch (patiënt) relevant vonden.

Methode literatuursamenvatting

Een uitgebreide beschrijving van de strategie voor zoeken en selecteren van literatuur is te vinden onder ‘Zoeken en selecteren’ onder Onderbouwing. Indien mogelijk werd de data uit verschillende studies gepoold in een random-effects model. Review Manager 5.4 werd gebruikt voor de statistische analyses. De beoordeling van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs wordt hieronder toegelicht.

Beoordelen van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs

De kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs werd bepaald volgens de GRADE-methode. GRADE staat voor ‘Grading Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation’ (zie http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/). De basisprincipes van de GRADE-methodiek zijn: het benoemen en prioriteren van de klinisch (patiënt) relevante uitkomstmaten, een systematische review per uitkomstmaat, en een beoordeling van de bewijskracht per uitkomstmaat op basis van de acht GRADE-domeinen (domeinen voor downgraden: risk of bias, inconsistentie, indirectheid, imprecisie, en publicatiebias; domeinen voor upgraden: dosis-effect relatie, groot effect, en residuele plausibele confounding).

GRADE onderscheidt vier gradaties voor de kwaliteit van het wetenschappelijk bewijs: hoog, redelijk, laag en zeer laag. Deze gradaties verwijzen naar de mate van zekerheid die er bestaat over de literatuurconclusie, in het bijzonder de mate van zekerheid dat de literatuurconclusie de aanbeveling adequaat ondersteunt (Schünemann, 2013; Hultcrantz, 2017).

|

GRADE |

Definitie |

|

Hoog |

|

|

Redelijk |

|

|

Laag |

|

|

Zeer laag |

|

Bij het beoordelen (graderen) van de kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs in richtlijnen volgens de GRADE-methodiek spelen grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming een belangrijke rol (Hultcrantz, 2017). Dit zijn de grenzen die bij overschrijding aanleiding zouden geven tot een aanpassing van de aanbeveling. Om de grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming te bepalen moeten alle relevante uitkomstmaten en overwegingen worden meegewogen. De grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming zijn daarmee niet één op één vergelijkbaar met het minimaal klinisch relevant verschil (Minimal Clinically Important Difference, MCID). Met name in situaties waarin een interventie geen belangrijke nadelen heeft en de kosten relatief laag zijn, kan de grens voor klinische besluitvorming met betrekking tot de effectiviteit van de interventie bij een lagere waarde (dichter bij het nuleffect) liggen dan de MCID (Hultcrantz, 2017).

Overwegingen (van bewijs naar aanbeveling)

Om te komen tot een aanbeveling zijn naast (de kwaliteit van) het wetenschappelijke bewijs ook andere aspecten belangrijk en worden meegewogen, zoals aanvullende argumenten uit bijvoorbeeld de biomechanica of fysiologie, waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten, kosten (middelenbeslag), aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie. Deze aspecten zijn systematisch vermeld en beoordeeld (gewogen) onder het kopje ‘Overwegingen’ en kunnen (mede) gebaseerd zijn op expert opinion. Hierbij is gebruik gemaakt van een gestructureerd format gebaseerd op het evidence-to-decision framework van de internationale GRADE Working Group (Alonso-Coello, 2016a; Alonso-Coello 2016b). Dit evidence-to-decision framework is een integraal onderdeel van de GRADE methodiek.

Formuleren van aanbevelingen

De aanbevelingen geven antwoord op de uitgangsvraag en zijn gebaseerd op het beschikbare wetenschappelijke bewijs en de belangrijkste overwegingen, en een weging van de gunstige en ongunstige effecten van de relevante interventies. De kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs en het gewicht dat door de werkgroep wordt toegekend aan de overwegingen, bepalen samen de sterkte van de aanbeveling. Conform de GRADE-methodiek sluit een lage bewijskracht van conclusies in de systematische literatuuranalyse een sterke aanbeveling niet a priori uit, en zijn bij een hoge bewijskracht ook zwakke aanbevelingen mogelijk (Agoritsas, 2017; Neumann, 2016). De sterkte van de aanbeveling wordt altijd bepaald door weging van alle relevante argumenten tezamen. De werkgroep heeft bij elke aanbeveling opgenomen hoe zij tot de richting en sterkte van de aanbeveling zijn gekomen.