Preventie van navelstrengprolaps - vliezen breken

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is het risico op uitzakken van de navelstreng als gevolg van het breken van de vliezen voor het inleiden van de baring bij à terme zwangere vrouwen met een hoogstaand voorliggend deel?

Aanbeveling

Het breken van de vliezen voor inleiding van de baring in combinatie met maatregelen om indalen van het hoofd te bevorderen lijkt veilig te zijn met betrekking tot uitzakken van de navelstreng, mits er rekening wordt gehouden met andere risicofactoren.

Overwegingen

Considerations – evidence to decision

Advantages and disadvantages of the intervention and quality of the evidence

Regarding amniotomy, there is a variation of practice between countries in the routine use of this method to induce labour. The two principal goals of amniotomy are (1) to induce or augment labour or (2) to facilitate internal fetal monitoring or instrumental vaginal delivery. With rupturing membranes, prostaglandins are released and uterine contractions are enforced, thus improving the chance of giving birth vaginally (Pasko 2019, Penfield 2017).

Three RCTs compared the effect of amniotomy with no amniotomy. Due to trial limitations (e.g. risk of bias and number of included women), the level of evidence was graded ‘very low’ and no firm conclusions could be drawn. In the investigation of rare outcomes, such as cord prolapse, case control studies can sometimes give important insights. However, due to methodological concerns, they start at a ‘low GRADE’ and were further downgraded due to risk of bias to a ‘very low GRADE’, so no certain conclusions could be drawn.

Amniotomy in cases of transverse or unstable lie, mobile presenting part, prior to 37 weeks of gestation and with cord presentation should be avoided to prevent cord prolapse. In the practice of amniotomy, upward pressure on the fetal head should also be avoided (RCOG, 2014). Amniotomy in cases with the aforementioned risk factors should therefore be avoided. Yet, Frigoletto (1995) showed in an RCT, that early amniotomy combined with oxytocin augmentation reduced the median duration of labour. Given the scarce evidence and multiple risk factors, clinicians should take into account all relevant factors before applying amniotomy or a catheter for IOL.

Values and preferences of patients (and their caregivers)

Discuss all options and inform about benefits and harms; make a decision together with the woman.

Costs

Amniotomy and pharmacological methods for IOL like misoprostol are cheap and therefore have a comparable access in different socioeconomic classes and countries.

Acceptability, feasibility and implementation

With regard to routine amniotomy, due to additional risk factors for cord prolapse and older recommendations to defer from routine amniotomy, the practice varies among different countries. An overall recommendation can therefore not be made. In the majority of cases, as in an engaged fetal head with the use of oxytocin augmentation, amniotomy appears to be safe and beneficial for the course of the delivery. The above-mentioned methods of IOL, with the exception of the balloon catheter, are widely available and cheap.

Recommendations

Rational of the recommendation: weighing arguments in favour and against the intervention

Amniotomy in the setting of IOL shortens the induction to birth interval without increasing the caesarean birth rate (De Vivo 2020). A Cochrane Systematic Review (SR) cannot exclude a causative effect of early amniotomy regarding cord prolapse, which is why it is not recommended generally. Yet other variables, e.g. non vertex presentation, preterm birth, polyhydramnion, multifetal pregnancy and multiparity should be considered as stronger risk factors with spontaneous or artificial rupture of membranes. These risk factors should be considered prior to carrying out artificial rupture of membranes. These prerequisites should be taken into account prior to an artificial amniotomy at home deliveries because of the duration of transport to a hospital.

Due to the rarity of cord prolapse, the possibility of confounding and limited number of publications, the level of evidence remains low.

|

Using amniotomy for IOL in combination with methods facilitating head engagement seems safe with regard to umbilical cord prolapse after consideration of other risk factors. |

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Introduction

Cord prolapse is potentially life threatening for an unborn baby. Some common obstetric interventions for inducing labour might increase the risk of umbilical cord prolapse (UCP). However, there is no consensus on the magnitude of this risk. Two of these interventions are addressed here: transcervical insertion of a balloon catheter and artificial rupture of membranes.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of amniotomy versus no amniotomy for IOL on the risk of UCP.

Sources: (Smyth 2013, Ghafarzadeh 2015, Rezaee 2015, Roberts 1997, Uygur 2002.) |

Samenvatting literatuur

Summary of literature

Description of studies

Six studies were included that compared amniotomy with no amniotomy in a comparative design. The primary analysis consists of three RCTs: two included in the Cochrane systematic review by Smyth (2013) and an additional RCT by Ghafarzadeh (2015). The secondary analysis consists of three case control studies.

Randomized controlled trials

The Cochrane review by Smyth (2013) investigated the effectiveness and safety of routine amniotomy. RCTs comparing amniotomy alone versus intention to preserve the membranes were included. The review included pregnant women with singleton pregnancies in spontaneous labour, regardless of parity and gestation status at trial entry. Primary outcomes were length of first stage of labour (minutes), caesarean birth, experience of labour and birth and low Apgar score. Cord prolapse was investigated as one of the secondary outcomes. The databases CENTRAL, MEDLINE, EMBASE (through the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register) were searched until April 30th, 2013. Two trials involving 1615 women were included for the analysis on cord prolapse:

A single centre RCT by Mikki (2007) assessed the effectiveness and safety of amniotomy on labour outcomes. Women with a low-risk full-term pregnancy, singleton pregnancy, cephalic presentation, active labour, intact membranes and a physiological fetal heart rate were included. 690 women were randomized: 340 to an experimental ‘amniotomy’ group and 350 to a control ‘no amniotomy’ group. The study analysed nulliparous and multiparous women separately. Primary outcomes were maternal outcomes: caesarean birth, length of second stage of labour (minutes), prolonged labour, use of pain relief, oxytocin augmentation and dosage used, Apgar score (less than 7 at 5 minutes) and neonatal outcomes: admission to neonatal intensive care or special care nursery. Cord prolapse was determined as part of the maternal complications (Smyth, 2013).

A multicentre study by Fraser (1993), in 10 centres in Canada and one in the USA, assessed the risk of dystocia in women assigned to early amniotomy, compared to women with conservative management of labour. Women with spontaneous labour, nulliparous, at least 38 weeks of gestation, singleton, cephalic presentation and a physiological fetal heart rate were included. Randomisation was stratified for centre and degree of cervical dilatation (less or more than 3 cm). A total of 925 women were randomized: 462 to the experimental group and 463 to the control group. Primary outcomes were maternal outcomes: analgesia, oxytocin use, caesarean birth, instrumental vaginal birth, maternal mortality, length of second stage of labour, prolonged labour and cord prolapse, and fetal/infant outcomes: Apgar score, suboptimal fetal heart rate trace, cephalohaematoma, convulsions, fracture, meconium aspiration, perinatal death, special care baby unit (Smyth, 2013).

A single centre RCT by Ghafarzadeh (2015), from Iran, compared amniotomy with conservative treatment with regard to dystocia risk and caesarean birth. The study included nulliparous women with a singleton and term pregnancy, spontaneous onset of labour, cephalic presentation of the fetus, intact amniotic sac and a physiological fetal heart rate. A total of 300 women were randomized: 150 to the experimental (early amniotomy at cervical dilation <4cm) and 150 to the control (no early amniotomy) group. Primary outcomes were length of labour, dystocia, caesarean birth, placental abruption and UCP.

Case control studies

A multicentre case control study by Rezaee (2015), from four centres in Iran, evaluated the risk factors for UCP, in women who had a caesarean birth. All caesarean births from the hospitals were analysed retrospectively, identifying 103 cases of UCP, which were compared with 318 selected controls. The control group, consisting of women without UCP who had a caesarean birth, was matched to the UCP cases in terms of: “gestational age, maternal age, active phase of labour (with the presence of UCP), fetal birth weight, Apgar score at birth, fetal presentation, parity, rupture of membranes, fetal sex, neonatal complications (e.g., respiratory distress syndrome, prenatal infection, hypothermia, and prenatal mortality), maternal complications (e.g., placental abruption and vaginal bleeding), reduced fetal movement, fetal heart rate drop, and amniotic fluid volume” (Rezaee, 2015). Data were extracted from medical records, available in the hospitals. Retrospectively, the authors analysed if amniotomy had been carried out more frequently in the case group.

A single centre case control study by Roberts (1997), from the University of Mississippi Medical Center in the USA, determined whether intrapartum obstetric interventions are associated with UCP. Through a computer search, including all delivering mothers, the authors identified 37 cases of UCP, and compared them with 74 control patients. The control patients were randomly selected from women in labour with intact membranes, admitted on the same day as the study patient. Data were retrieved from medical records. Retrospectively, the authors analysed if amniotomy had been performed more frequently in the case group.

A single centre case control study by Uygur (2002), from Turkey, assessed risk factors associated with UCP and the perinatal outcome of cases of UCP. Among all births in the hospital from 1997 to 2001, 77 cases of UCP were identified and compared with 235 controls. Three controls per case were randomly selected from the remaining births. Data were retrieved from medical records. Retrospectively, it was assessed if amniotomy had been performed more often in the UCP group, compared to the control group.

Results

None of the studies looked specifically at amniotomy for IOL with a high presenting fetal part.

The point estimates of three RCTs and three case control studies were all in favour of no amniotomy, but not statistically significant.

Randomized controlled trials

Results were analysed for nulliparous and multiparous women separately. Because of the low event rate, risk differences (RD) are reported instead of relative risks (RR).

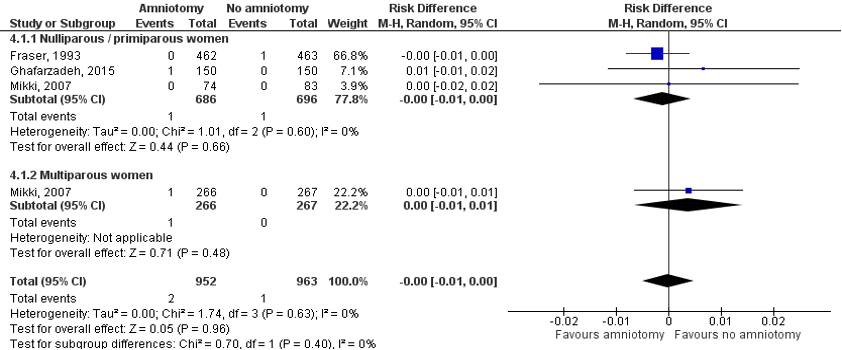

Nulliparous women

Three trials, involving 1382 women, assessed cord prolapse in nulliparous women (Fraser 1993, Ghafarzadeh 2015 and a subset of Mikki 2007). There is no statistically significant difference between the early amniotomy and no early amniotomy group in the incidence of UCP.

Multiparous women

In another subset of the trial by Mikki (2007) UCP was reported as an outcome in 533 multiparous women (Mikki 2007). The study found no statistically significant difference between early amniotomy and no early amniotomy in the incidence of UCP in multiparous women.

Combining the subgroups of nulliparous and multiparous women yields a RD [95% CI] of -0.00 [-0.01 to 0.00].

Figure 1. RCTs comparing amniotomy versus no amniotomy on UCP

Sources: Fraser 1993, Ghafarzadeh 2015 and Mikki 2007. Z: p-value of the pooled effect, df: degrees of freedom, I2: statistical heterogeneity, CI: confidence interval

Case control studies

Results were analysed separately for all births (irrespective whether or not followed by caesarean delivery) and caesarean births only. No subgroup analyses for nulliparous and multiparous women could be done, because none of the studies made this distinction.

All deliveries

Two case control studies, involving 422 women, retrospectively assessed the association between amniotomy and UCP (Roberts, 1997; Uygur, 2002). Amniotomy had not been performed significantly more often in the case group compared to the control group (two studies, 422 women, OR 1.39, 95% CI 0.87 to 2.21).

Caesarean births only

One case control study, involving 843 women who had a caesarean birth, retrospectively assessed the association between amniotomy and UCP (Rezaee, 2015). Amniotomy had not been carried out significantly more often in the case group compared to the control group (one study, 843 women, OR 1.26, 95% CI 0.81 to 1.97).

Meta-analysis of the results of all three case control studies yielded a pooled OR (95% CI) of 1.32 (0.96 to 1.82).

Level of evidence of the literature

1a. Balloon catheter versus no intervention/pharmacological IOL and UCP

No literature was found to answer this question.

1b. Amniotomy versus no amniotomy for IOL and UCP

Randomized controlled trials

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure UCP started high and was downgraded three levels to a ‘very low GRADE’: one level because of study limitations (risk of bias: two RCTs had unclear randomization and allocation concealment methods and additional possible sources of bias); and two levels because of the number of women included and the number of events that occurred (imprecision).

Case control studies

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure UCP started low (because of case control study design) and was downgraded with one level to a ‘very low GRADE’ because of study limitations (risk of bias).

Zoeken en selecteren

Search and select

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question:

P: pregnant women with term pregnancies (≥ 37 weeks), cephalic presentation;

Ia: transcervical insertion of a Foley balloon catheter for induction of labour (IOL)(module balloon catheter);

Ib: artificial rupture of membranes for IOL / Amniotomy;

C: no intervention or pharmacological IOL;

O: umbilical cord prolapse.

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered UCP as a critical outcome measure for decision making by the medical staff in dealing with risk factors for UCP.

A priori, the guideline development group did not define the outcome measures listed above but used the definitions used in the studies.

The guideline development group defined a relative risk ≤ 0.5 or ≥ 2 as a minimal clinically (patient) important difference.

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched using relevant search terms until January 10th, 2020. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 431 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria: studies with a comparative design, involving pregnant women with term (≥ 37 weeks) pregnancies, investigating the cervical insertion of a balloon catheter or artificial rupture of the membranes / amniotomy for the IOL, comparison with no intervention or a conservative treatment and reporting the outcome UCP. Initially, 44 studies were selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, 39 studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and five studies were included. One of these five studies was a systematic review which included two randomized controlled trials (RCTs) reporting the outcome UCP (Smyth, 2013); the original RCTs were included here.

Results

Six studies were included in the analysis of the literature. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables (attached documents). The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables (attached documents).

Referenties

- de Vaan MDT, ten Eikelder MLG, Jozwiak M, Palmer KR, Davies-Tuck M, Bloemenkamp KWM, Mol BJ, Boulvain M. Mechanical methods for induction of labour. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2019, Issue 10. Art. No.: CD001233. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD001233.pub3.

- De Vivo V, Carbone L, Saccone G, et al. Early amniotomy after cervical ripening for induction of labor: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;222(4):320-329.

- Fraser WD, Marcoux S, Moutquin JM, Christen A. Effect of early amniotomy on the risk of dystocia in nulliparous women. The Canadian Early Amniotomy Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1993;328(16):1145-1149

- Frigoletto FD Jr, Lieberman E, Lang JM, Cohen A, Barss V, Ringer S, Datta S. A clinical trial of active management of labor. N Engl J Med. 1995;333(12):745.

- Ghafarzadeh M, Moeininasab S, Namdari M. Effect of early amniotomy on dystocia risk and cesarean delivery in nulliparous women: a randomized clinical trial. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2015;292:321-5.

- Liu X, Wang Y, Zhang F, et al. Double- versus single-balloon catheters for labour induction and cervical ripening: a meta-analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2019;19(1):358.

- Mikki N, Wick L, Abu-Asab N, Abu-Rmeileh NM. A trial of amniotomy in a Palestinian hospital. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2007;27(4):368-373.

- Mundle S, Bracken H, Khedikar V, et al. Foley catheterisation versus oral misoprostol for induction of labour in hypertensive women in India (INFORM): a multicentre, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2017;390(10095):669-680.

- Pasko DN, Miller KM, Jauk VC, Subramaniam A. Pregnancy Outcomes after Early Amniotomy among Class III Obese Gravidas Undergoing Induction of Labor. Am J Perinatol. 2019 Apr;36(5):449-454.

- Penfield CA, Wing DA. Labor Induction Techniques: Which Is the Best? Obstet. Gynecol. Clin. North Am. 2017 Dec;44(4):567-582.

- RCOG Green Top Guideline No. 50. Umbilical Cord Prolapse. 2014. https://www.rcog.org.uk/globalassets/documents/guidelines/gtg-50-umbilicalcordprolapse-2014.pdf

- Rezaee Z, Shariat M, Valadan M, Ebrahim B, Sedighi B, Kiumarsi M, Bandegi P. Evaluation of Complications and Risk Factors for Umbilical Cord Prolapse, Followed by Cesarean Section. Iranian Journal of Neonatology. 2015; 6(1):13-17.

- Roberts WE, Martin RW, Roach HH, Perry KG Jr, Martin JN Jr, Morrison JC. Are obstetric interventions such as cervical ripening, induction of labor, amnioinfusion, or amniotomy associated with umbilical cord prolapse?. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;176(6):1181-1185.

- Smyth RM, Alldred SK, Markham C. Amniotomy for shortening spontaneous labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(1):CD006167. Published 2013 Jan 31.

- Uygur D, Kiş S, Tuncer R, Ozcan FS, Erkaya S. Risk factors and infant outcomes associated with umbilical cord prolapse. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2002;78(2):127-130.

- Xing Y, Li N, Ji Q, Hong L, Wang X, Xing B. Double-balloon catheter compared with single-balloon catheter for induction of labor with a scarred uterus. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2019;243:139-143.

Evidence tabellen

Evidence table. Research question: What are the procedure related risks for cord prolapse in term pregnant women of artificial rupture of the membranes with high presenting part?

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics 2 |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C) 3

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size 4 |

Comments |

|

Ghafarzadeh, 2015 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: single center in Asali Hospital, Khoramabad, Iran

Funding and conflicts of interest: No conflicts of interest. Funding not reported. |

Inclusion criteria: nulliparous women with singleton and term pregnancy (37–42 weeks gestational age), blood pressure \140/90 mmHg, spontaneous onset of labour, cephalic presentation of foetus, intact amniotic sac, and normal foetal heart rate.

Exclusion criteria: multifetal pregnancy, non-cephalic presentation of foetus, preeclampsia, intrauterine growth retardation, diabetes or other medical conditions, and cervical dilation of 5 cm or more |

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test): Early amniotomy: early amniotomy was done at dilatation of ≤4 cm.

|

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test): No early amniotomy: amniotomy was not performed unless there was obstetric indication (e.g., cervical dilation arrest for at least 2 h, failure of labour progression, or foetal distress).

|

Length of follow-up: Observation until 24 h after a natural delivery and 48 h after a caesarean section. Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: 0 Control: 0

Incomplete outcome data: Intervention:0 Control: 0

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Intervention: 1 /150 (0.67%) Control: 0 /150 *RR [95% CI] = 3.0 [0.12; 73.06]; P = 0.50

RR calculated using ReviewManager 5.3 |

Authors conclusion: “Early amniotomy was associated with shorter length of labor and lower rate of cesarean delivery, cord prolapsed and dystocia. Since, there is controversy about these findings in the literature, we recommend meta-analysis of studies to pool data for a more explicit conclusion.”

|

|

Mikki, 2007 (found through Cochrane review by Smyth, 2013) |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: Palestanian hospital in Jeruzalem

Funding and conflicts of interest: not reported |

Inclusion criteria: nulliparous and multiparous women, low risk full term pregnancy, singleton pregnancy, cephalic presentation, active labour, intact membranes and normal foetal heart rate.

Exclusion criteria: IUGR, induction of labour, suspected large for dates baby ( >4.5 kg), preeclampsia, insulin dependent diabetes mellitus, more than 1 previous caesarean section, antepartum haemorrhage, advanced labour.

Important prognostic factors2: Maternal age ± SD [nulliparous women]: I: 21.7±3.7 C: 21.4±4.2

Maternal age ± SD [multiparous women]: I: 27.3±5.3 C: 26.9±5.1

Gestational age ± SD [nulliparous women]: I: 39.4±1.1 C: 39.5±1.0

Gestational age ± SD [multiparous women]: I: 39.1±1.1 C: 39.3±1.1

Baseline characteristics were similar between groups. |

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test): Early amniotomy: routine amniotomy shortly after randomisation. |

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test): No early amniotomy: no amniotomy unless 2-h arrest of cervical dilation, dystocia, or foetal monitor insertion. |

Length of follow-up: Follow-up was carried out for the period of hospital stay, 24 h for normal birth and three days for caesarean operations.

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: 0 Control: 0

Incomplete outcome data: Intervention:0 Control: 0

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Umbilical cord prolapsed [nulliparous women], N (%):

Intervention: 0/74 Control: 0/83 RR [95% CI] = not estimable

Umbilical cord prolapsed [multiparous women], N (%):

Intervention: 1/266 Control: 0/267 *RR [95% CI] = 3.0 [0.12; 73.6]; p = 0.50

RR calculated using ReviewManager 5.3 |

Authors conclusion: - |

|

Fraser, 1993 (found through Cochrane review by Smyth, 2013) |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: 11 University-affiliated hospitals (10 in Canada and 1 in USA)

Funding and conflicts of interest: not reported |

Inclusion criteria: nulliparous women admitted to the hospital in labour, ≥38 weeks’ gestation and in spontaneous labour, single foetus, cephalic presentation and normal foetal heart rate based on auscultation or electric monitoring.

Exclusion criteria: intrauterine growth retardation, severe preeclampsia, insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus, or cervical dilation >6cm.

N total at baseline: Intervention: 464 Control: 464

Important prognostic factors2: Maternal age ± SD (cervical dilation <3cm): I: 26 ± 5 C: 27 ± 5

Gestational age: Not reported

Baseline characteristics were similar between groups. |

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test): Early amniotomy: artificial rupture of the membranes as soon as possible after randomization. |

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test): No early amniotomy: avoidance of amniotomy unless there was a medical indication, such as the need for internal monitoring of the foetal heart rate, an arrest of cervical dilation for at least two hours, or dystocia. |

Length of follow-up: until hospital discharge

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: 2 (one breech presentation not diagnosed at the time of randomization, one who had spontaneous rupture of the membranes before randomization. Control: 1 (breech presentation not diagnosed at the time of randomization)

Incomplete outcome data: Intervention: 0 Control: 0 |

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Umbilical cord prolapsed [nulliparous women], N (%):

Intervention: 0/462 Control: 1/463 RR [95% CI] = 0.33 [0.01; 8.18]; p = 0.50

|

Authors conclusion: “Cord prolapse occurred on one occasion in a woman in the conservative-management group, after spontaneous rupture of the membranes.”

|

|

Rezaee, 2015 |

Type of study: case control study

Setting and country: Valiasr, MirzaKuchak-Khan, Arash, and Shariati hospitals in Tehran, Iran

Funding and conflicts of interest: not reported

|

Inclusion criteria: all deliveries by caesarean section

Cases with cord prolapse (primiparous and multiparous), defined as: “as the descent of umbilical cord to the lower segment of the uterus.”

Controls without umbilical cord prolapse, matching with the cases for: “gestational age, maternal age, active phase of labor (with the presence of UCP), fetal birth weight, Apgar score at birth, fetal presentation, parity, rupture of membranes, fetal gender, neonatal complications (e.g., respiratory distress syndrome, prenatal infection, hypothermia, and prenatal mortality), maternal complications (e.g., placental abruption and vaginal bleeding), reduced fetal movement, fetal heart rate drop, and amniotic fluid volume.”

Exclusion criteria: not reported

N total at baseline: Cases: 103 Control: 318

Important prognostic factors2: Maternal age: Cases: 18-35, N=88 (85.4%) <35, N=15 (14.6%) Controls: 18-35, N=284 (89.4%) <35, N=34 (10.7%)

Gestational age : Cases: *Term: 78(75.7%) Preterm: 23(22.3%) Post term: 2(1.9%)

Controls: *Term: 250(78.6%) Preterm: 68(21.4%) Post term:0(0%)

NB. Groups were matched for age, gestational age and other factors. *Not all included women in this trial had a term gestational age, but 75.7% in the case groep and 78.6% in de controlegroep. |

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test): Amniotomy |

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test): No amniotomy |

Length of follow-up: data retrieved from medical charts / not applicable

Loss-to-follow-up: data retrieved from medical charts / not applicable

Incomplete outcome data: not reported

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Amniotomy, N (%): Cases: 51 /103(49.5%) Controls: 139 / 318(43.7%) P=0.30 |

Authors conclusion: “No significant association was found between UCP and amniotomy.” |

|

Roberts, 1997 |

Type of study: retrospective case cohort

Setting and country: University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson, Mississippi, USA

Funding and conflicts of interest: not reported |

Inclusion criteria: all obstetric patients.

Cases with the diagnosis of nonoccult umbilical cord prolapse.

Controls with intact membranes, admitted in labour on the same day as the study patient.

Exclusion criteria: women with umbilical cord prolapse occurring before the time of hospital admission as a result of spontaneous rupture of the foetal membranes.

N total at baseline: Cases: 37 Control: 74

Important prognostic factors2: Maternal age ± sd: Cases: 24.8 ± 6.6 Controls: 23.4 ± 5.7

Gestational age ± sd: Cases: 34.8 ± 7.2 Controls: 37.1 ± 4.9

NB. Groups were matched to control patients who laboured on the same day (with intact membranes) as the study patient.

|

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test): Amniotomy |

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test): No amniotomy |

Length of follow-up: data retrieved from medical charts / not applicable

Loss-to-follow-up: data retrieved from medical charts / not applicable

Incomplete outcome data: not reported

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Amniotomy, N (%): Cases: 25/37 (68%) Controls: 39/73 (53%) P=0.20

|

Authors conclusion: “There was no statistically significant difference between the groups in regard to the incidence of cervical ripening, labor induction, amnioinfusion, or amniotomy.” |

|

Uygur, 2002 |

Type of study: retrospective case series

Setting and country: Zubeyde Hanim Maternity Hospital, Telsizler, Ankara, Turkey

Funding and conflicts of interest: not reported |

Inclusion criteria: all deliveries

Cases diagnosed with cord prolapse (primiparous and multiparous): “The diagnosis of umbilical cord prolapse was accepted if the umbilical cord was palpated below the presenting fetal part after rupture of membranes.” Three controls per case were randomly selected from the remaining births.

Exclusion criteria: not described

N total at baseline: Cases: 77 Controls: 235

Important prognostic factors2: Maternal age ± sd: Cases: 28 ± 5

Gestational age ± sd: Cases: 34.0 ± 6.0

|

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test): Amniotomy |

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test): No amniotomy |

Length of follow-up: data retrieved from database/ not applicable

Loss-to-follow-up: data retrieved from database/ not applicable

Incomplete outcome data: not reported

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Amniotomy, N (%): Cases: 23/77 (29.8%) Controls: 61 / 235 (26.4%) P>0.05 |

Authors conclusion: “Artificial rupture of membranes seemed not to increase the risk of umbilical cord prolapse.” |

Risk of bias table 1 (randomized controlled trials)

Research question: What are the procedure related risks for cord prolapse in term pregnant women of artificial rupture of the membranes with high presenting part?

|

Study reference

(first author, publication year) |

Describe method of randomisation1 |

Bias due to inadequate concealment of allocation?2

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate blinding of participants to treatment allocation?3

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate blinding of care providers to treatment allocation?3

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate blinding of outcome assessors to treatment allocation?3

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to selective outcome reporting on basis of the results?4

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to loss to follow-up?5

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to violation of intention to treat analysis?6

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

|

*Mikki, 2007: as assessed by Smyth, 2013 |

Unclear risk: Randomisation: randomised controlled trial stratified by parity |

Unclear risk: Allocation concealment: “simple randomisation with sealed envelopes |

High risk: Blinding: woman and caregiver not blinded, no information given regarding blinding of the outcome assessor |

High risk: Blinding: woman and caregiver not blinded, no information given regarding blinding of the outcome assessor |

High risk: Blinding: woman and caregiver not blinded, no information given regarding blinding of the outcome assessor |

High risk: Data on perinatal death not reported in the paper, however, data provided by the author through correspondence outcomes not pre-specified in the methodology. |

Low risk: Follow-up: 100%.

|

High risk: Trial ended due to budget constraints. |

|

*Fraser, 1993: as assessed by Smyth, 2013 |

Low risk: Randomisation: centralised and group assignment stratified according to medical centre and degree of cervical dilatation less than 3 cm vs at least 3 cm |

Low risk: Allocation concealment: telephone answering service. |

High risk: Blinding: woman and caregiver not blinded, outcome assessor blinded regarding fetal heart tracing assessment |

High risk: Blinding: woman and caregiver not blinded, outcome assessor blinded regarding fetal heart tracing assessment |

High risk: Blinding: woman and caregiver not blinded, outcome assessor blinded regarding fetal heart tracing assessment |

High risk: Additional information on epidural use and narcotic analgesia not pre-specified in methods. There was no difference, however between the intervention and control groups for these outcomes |

Low risk: Follow-up: 100%. |

High risk: Additional analysis of dystocia according to Definition which had not been pre-specified (post-hoc analysis) |

|

Ghafarzadeh, 2015 |

Low risk: Randomisation: block randomization method |

Unclear risk: Allocation concealment not described. |

High risk: Blinding: woman and caregiver not blinded, no information given regarding blinding of the outcome assessor |

High risk: Blinding: woman and caregiver not blinded, no information given regarding blinding of the outcome assessor |

High risk: Blinding: woman and caregiver not blinded, no information given regarding blinding of the outcome assessor |

Low risk: The variables of interest were length of labor (onset of uterine contractions until 1 h after expulsion of placenta), dystocia, cesarean section, umbilical cord prolapse, and placental abruption. |

Low risk: Follow-up: 100%. |

Unclear risk: The two groups were matched for age, weight, gestational age, fetal birth weight, and cervical effacement. This is not described when baseline characteristics are described between groups. |

*For these studies, the risk of bias was assessed by the Cochrane review by Smyth e.a. (2013)

Risk of bias table 2 (case-control studies)

Research question: What are the procedure related risks for cord prolapse in term pregnant women of artificial rupture of the membranes with high presenting part?

|

Study reference

(first author, year of publication) |

Bias due to a non-representative or ill-defined sample of patients?1

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to insufficiently long, or incomplete follow-up, or differences in follow-up between treatment groups?2

(unlikely/likely/unclear)

|

Bias due to ill-defined or inadequately measured outcome ?3

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate adjustment for all important prognostic factors?4

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

|

Rezaee, 2015 |

Likely: Overmatching, unclear how matching for all different variables described was performed. |

Unlikely: Data was retrieved from medical records. No loss to follow up described. |

Unlikely: UCP is a serious complication of labour, which is probably easily retrieved from medical records. |

Unclear: Risk factors /prognostic factors for cord prolapse still largely unclear. |

|

Roberts, 1997 |

Likely: Undermatching, women who admitted labour on the same day as the case patient were selected for the control group. No additional matching was performed. |

Unlikely: Data was retrieved from medical records. No loss to follow up described. |

Unlikely: UCP is a serious complication of labour, which is probably easily retrieved from medical records. |

Likely: Other risk factors for cord prolapse not clearly described or investigated. |

|

Uygur, 2002 |

Likely: Controls were not matched to the cases. |

Unlikely: Data was retrieved from medical records. No loss to follow up described. |

Unlikely: UCP is a serious complication of labour, which is probably easily retrieved from medical records. |

Unclear: Risk factors /prognostic factors for cord prolapse still largely unclear. |

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Publicatiedatum : 30-12-2022

Beoordeeld op geldigheid : 30-12-2022

Validity period

The Board of the Dutch Society of Obstetrics and Gynaecology (NVOG) will assess whether these guidelines are still up-to-date in 2026 at the latest. If necessary, a new working group will be appointed to revise the guideline. The guideline’s validity may lapse earlier if new developments demand revision at an earlier date.

As the holder of this guideline, the NVOG is chiefly responsible for keeping the guideline up to date. Other scientific organizations participating in the guideline or users of the guideline share the responsibility to inform the chiefly responsible party about relevant developments within their fields.

Algemene gegevens

Er is meegelezen vanuit de Nederlandse Vereniging voor Kindergeneeskunde (NVK). De NVK heeft de richtlijn niet geautoriseerd, maar heeft geen bezwaar tegen publicatie.

De Koninklijke Nederlandse Organisatie van Verloskundigen (KNOV) is betrokken geweest bij de ontwikkeling van de richtlijn.

De Patiëntenfederatie Nederland heeft de richtlijn goedgekeurd.

De Vlaamse Vereniging voor Obstetrie en Gynaecologie (VVOG), Royal College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology (RCOG) en Deutsche Gesellschaft für Gynäkologie und Geburtshilfe (DGGG) zijn betrokken geweest bij de ontwikkeling van de richtlijn.

Regiehouder: NVOG

Samenstelling werkgroep

Composition guideline development panel

An international panel for the development of the guidelines was formed in 2019. The panel consisted of representatives from all relevant medical disciplines that are involved in medical care for pregnant women.

All panel members have been officially delegated for participation in the guideline development panel by their (scientific) societies. The panel developed the guidelines in the period from May 2019 until March 2021.

The guideline development panel is responsible for the entire text of this guideline.

All panel members have been officially delegated for participation in the guideline development panel by their scientific societies. The guideline development panel is responsible for the entire text of this guideline.

Guideline development panel

- J.J. Duvekot, obstetrician, Consultant Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Erasmus Medical Centre, Rotterdam, the Netherlands (chair)

- I. Dehaene, obstetrician, Consultant Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Ghent University Hospital Belgium

- S. Galjaard, obstetrician, Consultant Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Erasmus Medical Centre, Rotterdam, the Netherlands

- A. Hamza, obstetrician, Consultant Obstetrics and Gynaecology, University Medical Center of Saarland, Homburg an der Saar, Germany

- S.V. Koenen, obstetrician, Consultant Obstetrics and Gynaecology, ETZ, locatie Elisabeth Ziekenhuis Tilburg, the Netherlands

- M. Kunze, obstetrician, Consultant Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Department of Gynecology& Obstetrics University of Freiburg, Germany

- M.A. Ledingham, obstetrician, Consultant Obstetrics and Gynaecology, the Queen Elizabeth Hospital Glasgow, UK

- B. Magowan, obstetrician, Consultant Obstetrics and Gynaecology, and Co-Chair UK RCOG Guidelines Committee, NHS Borders, Scotland, UK

- G. Page, obstetrician, Consultant Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Jan Yperman Hospital, Ypres, Belgium

- S.J. Stock, Reader and Consultant in Maternal and Fetal Medicine, University of Edinburgh Usher Institute and NHS Lothian, Edinburgh, Scotland, UK

- A.J. Thomson, obstetrician, Consultant Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Royal Alexandra Hospital (NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde), UK

- G. Verhulst, obstetrician, Consultant Obstetrics and Gynaecology, ASZ Aalst/Geraardsbergen/Wetteren, Belgium

- D.C. Zondag, midwife/practice owner verloskundige praktijk De Toekomst-Geldermalsen, the Netherlands

Methodological support

- E. den Breejen, senior advisor, Knowledge Institute of the Dutch Association of Medical Specialists (until June 2019)

- J.H. van der Lee, senior advisor, Knowledge Institute of the Dutch Association of Medical Specialists (since May 2019)

- Y. Labeur, junior advisor, Knowledge Institute of the Dutch Association of Medical Specialists

Belangenverklaringen

The Code for the prevention of improper influence due to conflicts of interest was followed (https://storage.knaw.nl/2022-08/Code-for-the-prevention-of-improper-influence-due-to-conflicts-of-interest.pdf).

The working group members have provided written statements about (financially supported) relations with commercial companies, organisations or institutions related to the subject matter of the guideline during the past three years. Furthermore, inquiries have been made regarding personal financial interests, interests due to personal relationships, interests related to reputation management, interest related to externally financed research and interests related to knowledge valorisation. The chair of the guideline development panel is informed about changes in interests during the development process. The declarations of interests are reconfirmed during the commentary phase. The declarations of interests can be requested at the administrative office of the Knowledge Institute of the Dutch Association of Medical Specialists and are summarised below.

|

Last name |

Principal position |

Ancillary position(s) |

Declared interests |

Action |

|

Duvekot (chair) |

Consultant Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Erasmus MC, Rotterdam |

Director Medisch Advies en Expertise Bureau Duvekot, Ridderkerk |

none |

none |

|

Dehaene |

Consultant Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Ghent University Hospital |

none |

none |

none |

|

Galjaard |

Consultant Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Erasmus MC, Rotterdam |

Associated member of Diabetes in Pregnancy Group (DPSG) |

none |

none |

|

Hamza |

Consultant Obstetrics and Gynaecology, University Medical Center of Saarland, Homburg |

part of the advisory board of clinical innovations, which produces Kiwi-Vacuum Extractors® and Ebb Balloon Catheter®;

|

gave ultrasound courses sponsored by ultrasound producing companies: Samsung Germany and Matramed |

Recommendations do not involve either vacuum extractor or Ebb catheter (which is used for postpartum hemorrhage); therefore no actions |

|

Koenen |

Consultant Obstetrics and Gynaecology, ETZ, locatie Elisabeth Ziekenhuis Tilburg |

Chairman 'Koepel Kwaliteit' NVOG |

none |

none |

|

Kunze |

Divison Chief, Maternal-Fetal Medicine and Obstetrics, Departement of Gynecology & Obstetrics, University of Freiburg |

none |

none |

none |

|

Ledingham |

Consultant in Maternal and Fetal Medicine, Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Glasgow |

Co-chair RCOG Guidelines committee, Guideline developer for sign (scottisch intercollegiate guidelines group) |

none |

none |

|

Magowan |

Consultant Obstetrics and Gynaecology, and Co-Chair UK RCOG Guidelines Committee, NHS Borders, Scotland |

Co-chair RCOG Guidelines committee |

none |

none |

|

Page |

Consultant Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Jan Yperman Hospital, Ypres |

none |

none |

none |

|

Stock |

Reader and Consultant in Maternal and Fetal Medicine, University of Edinburgh and NHS Lothian, Edinburgh, Scotland, UK |

Consultant Obstetrician and Subspecialist Maternal and Fetal Medicine, member of the NIHR HTA General committee (grant funding board) and Chair of the RCOG Stillbirth Clinical Studies Group |

Research grants paid to the institution for research into pregnancy problems from National Institute of Healthcare Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA), NIHR Global Research Fund, Wellcome Trust, Medical Research Council, Tommy's Baby Charity, Cheif Scientist Office Scotland. Some of this work focuses on improving risk prediction of preterm labour and researching the benefits and harms of antenatal corticosteroids. Non-financial support from HOLOGIC, non-financial support from PARSAGEN, non-financial support from MEDIX BIOCHEMICA during the conduct of an NIHR HTA study in the form of provision of reduced cost assay kits to participating sites and blinded test assay analysers |

none |

|

Thomson |

Consultant Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Royal Alexandra Hospital (NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde) |

Guideline developer for the RCOG |

none |

none |

|

Verhulst |

Head of Department of Gynaecology and Obstetrics, ASZ Aalst/Geraardsbergen/Wetteren |

none |

none |

none |

|

Zondag |

Midwife/practice owner verloskundige praktijk De Toekomst-Geldermalsen |

Policy adviser at the Dutch association of midwives (KNOV). Teacher at PA clinical midwives - Hogeschool Rotterdam |

none |

none |

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Representation of the patient perspective

Involvement of patient representatives from all four participating countries was challenging. Representatives of patient organisations from three countries (UK, Belgium, the Netherlands) commented on the draft guideline texts and discussed these during an online meeting. They represented the RCOG Women’s Network, the Flemish organisation for people with fertility problems ‘De verdwaalde ooievaar’, the Netherlands Patient Federation, and the Dutch association for people with fertility problems ‘Freya’. The comments were discussed and where relevant incorporated by the guideline development panel.

Methode ontwikkeling

Evidence based

Implementatie

Implementation

Guideline implementation and practical applicability of the recommendations was taken into consideration during various stages of guideline development. Factors that may promote or hinder implementation of the guideline in daily practice were given specific attention.

The guideline is distributed digitally among all relevant professional groups. The guideline can also be downloaded from the following websites: www.nvog.nl, www.vvog.be, www.rcog.org.uk, www.dggg.de,and the Dutch guideline website: www.richtlijnendatabase.nl.

Werkwijze

Method

AGREE

This guideline has been developed conforming to the requirements of the report of Guidelines for Medical Specialists 2.0 by the advisory committee of the Quality Counsel. This report is based on the AGREE II instrument (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II) (www.agreetrust.org)(Brouwers, 2010), a broadly accepted instrument in the international community and on the national quality standards for guidelines: “Guidelines for guidelines” (www.zorginstituutnederland.nl).

Identification of subject matter

During the initial phase of the guideline development the chairman, guideline development panel and the advisor inventoried the relevant subject matter for the guideline. Since this was a pilot project, the content of the questions and the support base in clinical practice was considered of less importance than the process of international collaboration and learning from each other. Key questions were selected in such a way that:

-

-

- they were relevant for obstetric practice in all collaborating countries;

- it was expected that the amount of literature identified for each question would be reasonable, i.e. some literature was expected, but not much;

- the recommendations were expected not to lead to extensive discussion among working group members because no major controversy was expected;

- there were no recent guidelines available for these particular topics in any of the four countries.

-

Clinical questions and outcomes

The guideline development panel then formulated definitive clinical questions and defined relevant outcome measures (both beneficial and harmful effects). The working group rated the outcome measures as critical, important and not important. Furthermore, where applicable, the working group defined relevant clinical differences.

Strategy for search and selection of literature

For the separate clinical questions, specific search terms were formulated and published scientific articles were searched for in (several) electronic databases. Furthermore, studies were scrutinized by cross-referencing for other included studies. The studies with potentially the highest quality of research were searched for first. The panel members selected literature in pairs (independently of each other) based on title and abstract. A second selection was performed based on full text. The databases, search terms and selection criteria are described in the modules containing the clinical questions.

Quality assessment of individual studies

Individual studies were systematically assessed, based on methodological quality criteria that were determined prior to the search, so that risk of bias could be estimated. This is described in the “risk of bias” tables.

Summary of literature

The relevant research findings of all selected articles are shown in evidence tables. The most important findings in literature are described in literature summaries. In case there were enough similarities between studies, the study data were pooled.

Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations

The strength of the conclusions of the scientific publications was determined using the GRADE-method. GRADE stands for Grading Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (see http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/).

GRADE defines four gradations for the quality of scientific evidence: high, moderate, low or very low. These gradations provide information about the amount of certainty about the literature conclusions (http://www.guidelinedevelopment.org/handbook/).

The basic principles of the GRADE method are: formulating and prioritising clinical (patient) relevant outcome measures, a systematic review for each outcome measure, and appraisal of the evidence for each outcome measure based on the eight GRADE domains (domains for downgrading: risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision, and publication bias; domains for upgrading: dose-effect association, large effect, and residual plausible confounding).

GRADE distinguishes four levels for the quality of the scientific evidence: high, moderate, low and very low. These levels refer to the amount of certainty about the conclusion based on the literature, in particular the amount of certainty that the conclusion based on the literature adequately supports the recommendation (Schünemann, 2013; Hultcrantz, 2017).

|

Definition |

|

|

High |

|

|

Moderate |

|

|

Low |

|

|

Very low |

|

For the wording of the conclusions we used the statements suggested by the GRADE working group (Santesso, 2020), as shown below.

Source: Santesso (2020)

The limits of clinical decision making are very important in grading the evidence in guideline development according to the GRADE methodology (Hultcrantz, 2017). Exceedance of these limits would give rise to adaptation of the recommendation. All relevant outcome measures and considerations need to be taken into account to define the limits of clinical decision making. Therefore, the limits of clinical decision making are not one to one comparable to the minimal clinically relevant difference. In particular for interventions of low costs and without important drawbacks the limit of clinical decision making regarding the effectiveness of the intervention may be lower (i.e. closer to no effect) than the Minimal Clinically Important Difference (MCID) (Hultcrantz, 2017).

Considerations (evidence to decision)

Aspects such as expertise of working group members, patient preferences, costs, availability of facilities, and organisation of healthcare aspects are important to consider when formulating a recommendation. For each clinical question, these aspects are discussed in the paragraph Considerations, using a structured format based on the evidence-to-decision framework of the international GRADE Working Group (Alonso-Coello, 2016a; Alonso-Coello, 2016b). The evidence-to-decision framework is an integral part of the GRADE methodology.

Recommendations provide an answer to the primary question, and are based on the best scientific evidence available and the most important considerations. The level of scientific evidence and the importance given to considerations by the working group jointly determine the strength of the recommendation. In accordance with the GRADE method, a low level of evidence for conclusions in the systematic literature review does not rule out a strong recommendation, while a high level of evidence may be accompanied by weak recommendations. The strength of the recommendation is always determined by weighing all relevant arguments.

Knowledge gaps

During the development of this guideline, systematic searches were conducted for research contributing to answering the primary questions. For each primary question, the working group determined whether (additional) scientific research is desirable.

Commentary and authorisation phase

The concept guideline was subjected to commentaries by the scientific societies and patient organisations involved. The draft guideline was also submitted to the following organisations for comment: RCOG Guideline Committee and RCOG Patient Information Committee, German Neonatology and Peaediatric Intensive Care Association (Gesellschaft für Neonatologie und pädiatrische Intensivmedzin e.V.), German Midwives Society (Deutscher Hebammenverband), Flemish Midwives Society (VBOV), Belgian Federal Knowledge Centre for Health Care (KCE), Flemish College of Maternity and Neonatal Medicine (College Moeder Kind), Flemish patient organization for fertility problems (De Verdwaalde Ooievaar), Dutch Pediatric Society (NVK), Dutch College of General Practitioners (NHG), Healthcare Insurers Netherlands (ZN), The Dutch Healthcare Authority (NZA), the Health Care Inspectorate (IGJ), Netherlands Care Institute (ZIN), Dutch Organisation of Midwives (KNOV), Hospital organization (NVZ), Patient organisations Dutch Patient Federation and Freya. The comments were collected and discussed with the working group. The feedback was used to improve the guideline; afterwards the working group made the guideline definitive. The final version of the guideline was offered for authorization to the involved scientific societies and patient organisations and was authorized or approved, respectively.

Legal standing of guidelines

Guidelines are not legal prescriptions but contain evidence-based insights and recommendations that care providers should meet in order to provide high quality care. As these recommendations are primarily based on ‘general evidence for optimal care for the average patient’, care providers may deviate from the guideline based on their professional autonomy when they deem it necessary for individual cases. Deviating from the guideline may even be necessary in some situations. If care providers choose to deviate from the guideline, this should be done in consultation with the patient, where relevant. Deviation from the guideline should always be justified and documented.

Zoekverantwoording

Table of excluded studies

|

First author, year |

Reason for exclusion |

|

Adegbola, 2017 |

Wrong design: no comparison |

|

Behbehani, 2016 |

Wrong intervention: no information on balloon catheter or amniotomy |

|

Boujenah, 2017 |

Wrong intervention: external cephalic version, no information on balloon catheter or amniotomy |

|

Boyle, 2005 |

Wrong design: editorial comment |

|

Critchlow, 1994 |

Wrong intervention: no information on balloon catheter or amniotomy |

|

Davood, 2007 |

Wrong intervention: no information on balloon catheter or amniotomy |

|

Dilbaz, 2006 |

Wrong design: no comparison |

|

El-Jallad, 2004 |

Not available in English |

|

Erdemoglu, 2010 |

Wrong design: no comparison |

|

Gabbay-Benziv, 2014 |

Wrong design: no comparison |

|

Goldman, 1995 |

Wrong comparison: grand multiparas vs. Multiparas and nulliparas |

|

Gonsalves, 2016 |

Wrong design: no comparison |

|

Hasegawa, 2015 |

Wrong design: retrospective survey |

|

Hasegawa, 2016 |

Wrong comparison: poor neonatal outcomes versus no poor neonatal outcomes during cord prolapse |

|

Hasegawa, 2016 |

Wrong design: no comparison |

|

Hehir, 2017 |

Wrong comparison: no information on amniotomy |

|

Hembram, 2017 |

Wrong comparison: perinatal death after cord prolapse |

|

Huang, 2012 |

Wrong intervention: no information on balloon catheter or amniotomy |

|

Huisman, 2019 |

Wrong design: no comparison |

|

Israngura Na Ayudhya, 1988 |

Wrong design: no comparison |

|

Kalu, 2011 |

Wrong intervention: no information about catheter or amniotomy |

|

Kawakita, 2018 |

Wrong design: no comparison |

|

Khan, 2007 |

Wrong design: no comparison |

|

Lawani, 2014 |

Wrong comparison: only information on failed induction and cord prolapse. |

|

Lee, 2012 |

Wrong comparison: early vs. Late membrane rupture, no information on cord prolapse |

|

Nassar, 2006 |

Wrong comparison: external cephalic version and breech presentation. No information on cord prolapse |

|

Nizard, 2005 |

Wrong participants: preterm premature rupture of membranes |

|

Obeidat, 2010 |

Wrong design: no comparison |

|

Prabulos, 1998 |

Wrong population: preterm premature rupture of the membranes |

|

Quist-Nelson, 2017 |

Wrong comparison: external cephalic version and breech presentation (SR) |

|

Sandberg, 2017 |

Wrong comparison: different catheters |

|

Sherer, 1997 |

Wrong design: narrative review. No information on cord prolapse risk factors. |

|

Shoham, 2001 |

Wrong intervention: no information on cord prolapse or balloon catheter. |

|

Silva, 1992 |

Wrong participants: grand grand multiparas (>10 parities). |

|

Usta, 1999 |

Wrong design: no comparison |

|

Xing, 2019 |

Wrong comparison: different catheters |

|

Yamada, 2013 |

Wrong comparison: cerebral palsy umbilical cord prolapse vs. No umbilical cord prolapse cerebral palsy |

|

Yamada, 2013 |

Wrong design: no comparison |

|

Yla-Outinen, 1985 |

Wrong intervention: no information about catheter or amniotomy |

Search justification

|

Research question: Prevention of cord prolapse |

|

|

Search question: a. What are the procedure related risks for cord prolapse in term pregnant women of inserting a balloon catheter for induction of labour? b. What are the procedure related risks for cord prolapse in term pregnant women of artificial rupture of the membranes with high presenting part? |

|

|

Database(s): Medline, Embase |

Date: 10-01-2020 |

|

Period: no restriction |

Language: English |

|

Database |

Search elements |

Total |

|

Medline (OVID)

|

1 ((exp Prolapse/ or prolapse.ti,ab,kf.) and (exp Umbilical Cord/ or cord.ti,ab,kf. or umbilical.ti,ab,kf.)) or ucp.ti,ab,kf. (2891) 2 exp Labor, Induced/ or ((labo*r or delivery or parturition) adj3 (induc* or accelerat* or premature or stimulat*)).ti,ab,kw. or priming.ti,ab,kw. or planned early deliver*.ti,ab,kw. or interventionist*.ti,ab,kw. or iol.ti,ab,kf. or (exp Catheterization/ and (balloon or foley).ti,ab,kf.) or 'balloon catheter'.ti,ab,kf. or foley.ti,ab,kf. or 'double balloon'.ti,ab,kf. or exp Amniotomy/ or prom.ti,ab,kf. or arom.ti,ab,kf. or amniotomy.ti,ab,kf. or ((artificial or spontanous or premature) adj3 'rupture of membrane*').ti,ab,kf. (111679) 3 1 and 2 (100) 4 limit 3 to english language (86) 5 exp Risk Factors/ or exp Risk Assessment/ or risk*.ti,ab,kf. (2491642) 6 1 and 5 (306) 7 limit 6 to english language (279) 8 4 or 7 (316) 9 (meta-analysis/ or meta-analysis as topic/ or (meta adj analy$).tw. or ((systematic* or literature) adj2 review$1).tw. or (systematic adj overview$1).tw. or exp "Review Literature as Topic"/ or cochrane.ab. or cochrane.jw. or embase.ab. or medline.ab. or (psychlit or psyclit).ab. or (cinahl or cinhal).ab. or cancerlit.ab. or ((selection criteria or data extraction).ab. and "review"/)) not (Comment/ or Editorial/ or Letter/ or (animals/ not humans/)) (427388) 10 (exp clinical trial/ or randomized controlled trial/ or exp clinical trials as topic/ or randomized controlled trials as topic/ or Random Allocation/ or Double-Blind Method/ or Single-Blind Method/ or (clinical trial, phase i or clinical trial, phase ii or clinical trial, phase iii or clinical trial, phase iv or controlled clinical trial or randomized controlled trial or multicenter study or clinical trial).pt. or random*.ti,ab. or (clinic* adj trial*).tw. or ((singl* or doubl* or treb* or tripl*) adj (blind$3 or mask$3)).tw. or Placebos/ or placebo*.tw.) not (animals/ not humans/) (1936494) 11 Epidemiologic studies/ or case control studies/ or exp cohort studies/ or Controlled Before-After Studies/ or Case control.tw. or (cohort adj (study or studies)).tw. or Cohort analy$.tw. or (Follow up adj (study or studies)).tw. or (observational adj (study or studies)).tw. or Longitudinal.tw. or Retrospective*.tw. or prospective*.tw. or consecutive*.tw. or Cross sectional.tw. or Cross-sectional studies/ or historically controlled study/ or interrupted time series analysis/ [Onder exp cohort studies vallen ook longitudinale, prospectieve en retrospectieve studies] (3341238) 12 8 and 9 (13) 13 (8 and 10) not 12 (22) 14 (8 and 11) not (12 or 13) (119) 15 12 or 13 or 14 (154)

13 SRs + 22 RCTs + 119 observational studies = 154 in total (48 unique) |

431 |

|

Embase

|

'umbilical cord prolapse'/exp OR 'umbilical cord complication'/exp OR (((cord OR umbilical) NEAR/4 prolapse):ti,ab,kw) OR ucp:ti,ab,kw AND 'labor induction'/exp OR (((labo*r OR delivery OR parturition) NEAR/3 (induction OR induce* OR inducing OR accelerat* OR premature OR stimulat* OR immediate)):ti,ab,kw) OR priming:ti,ab,kw OR 'planned early deliver*':ti,ab,kw OR interventionist*:ti,ab,kw OR iol:ti,ab,kw OR 'balloon catheter'/exp OR 'balloon catheter':ti,ab,kw OR foley:ti,ab,kw OR 'double balloon':ti,ab,kw OR 'amniotomy'/exp OR prom:ti,ab,kw OR arom:ti,ab,kw OR amniotomy:ti,ab,kw OR (((artificial OR spontanous OR premature) NEAR/3 'rupture of membrane*'):ti,ab,kw) OR 'risk assessment'/exp OR 'risk factor'/exp OR risk*:ti,ab,kw AND [english]/lim NOT ('conference abstract'/it OR 'editorial'/it OR 'letter'/it OR 'note'/it) NOT (('animal experiment'/exp OR 'animal model'/exp OR 'nonhuman'/exp) NOT 'human'/exp)

Used filters: Sytematische reviews ('meta analysis'/de OR cochrane:ab OR embase:ab OR psycinfo:ab OR cinahl:ab OR medline:ab OR ((systematic NEAR/1 (review OR overview)):ab,ti) OR ((meta NEAR/1 analy*):ab,ti) OR metaanalys*:ab,ti OR 'data extraction':ab OR cochrane:jt OR 'systematic review'/de) = 25

RCT’s ('clinical trial'/exp OR 'randomization'/exp OR 'single blind procedure'/exp OR 'double blind procedure'/exp OR 'crossover procedure'/exp OR 'placebo'/exp OR 'prospective study'/exp OR rct:ab,ti OR random*:ab,ti OR 'single blind':ab,ti OR 'randomised controlled trial':ab,ti OR 'randomized controlled trial'/exp OR placebo*:ab,ti) = 93

Observational research 'major clinical study'/de OR 'clinical study'/de OR 'case control study'/de OR 'family study'/de OR 'longitudinal study'/de OR 'retrospective study'/de OR 'prospective study'/de OR 'cohort analysis'/de OR ((cohort NEAR/1 (study OR studies)):ab,ti) OR (('case control' NEAR/1 (study OR studies)):ab,ti) OR (('follow up' NEAR/1 (study OR studies)):ab,ti) OR (observational NEAR/1 (study OR studies)) OR ((epidemiologic NEAR/1 (study OR studies)):ab,ti) OR (('cross sectional' NEAR/1 (study OR studies)):ab,ti) = 266

=384 in total (383 unique)

|