Immunosuppression and immunomodulation in JDM

Uitgangsvraag

What is the treatment strategy for patients with juvenile dermatomyositis (JDM)?

Aanbeveling

Verwijs een patiënt bij verdenking JDM direct door naar academisch centrum om beoordeeld en behandeld te worden door een kinderreumatoloog.

Inductiebehandeling bij diagnose

(1) Start met methylprednisolon 3-5 dagen (15-30 mg/kg/dag) in pulses (max. dosis 1000 mg/dag).

(2a) Start daarna met orale prednison (1-2 mg/kg/dag, maximaal 80mg) met toevoeging van vitamine D/calcium.

(2b) Start in de eerste week aanvullend met methotrexaat (15-20 mg/m2/week, maximaal 25mg), bij voorkeur subcutaan, en foliumzuur (eenmaal per week 5mg).

Streef na 6 maanden behandeling een prednisolondosering van ≤0.2 mg/kg/dag na indien de klinische situatie het toelaat.

Streef bij 12-24 maanden behandeling het afbouwen van prednison tot stop.

Staak methotrexaat pas na minimaal een jaar na het stoppen van prednisolon en bij klinisch inactieve ziekte.

Intolerantie

Switch bij intolerantie of ineffectiviteit voor methotrexaat naar ciclosporine A; andere alternatieven zijn Mycofenolaat Mofetil (MMF) of tacrolimus.

Ernstige ziekte

Overweeg bij ernstige ziekte gelijk te starten met immunoglobulinen, cyclofosfamide, of JAK-STAT remmers.

Geef bij ernstige Interstitial Lung Disease (ILD) cyclofosfamide of rituximab.

Refractaire ziekte

Overweeg bij onvoldoende effect van inductiebehandeling:

- Rituximab (in aanvulling op de prednison)

- Immunoglobulinen i.v. (IVIg)

- Anti-TNF-alpha medicatie

- JAK-STAT remmers

- Switch naar ciclosporine

Monitoring

Monitor minimaal bij diagnose, na 3 en na 6 maanden, bij het staken van prednisolon en bij vermoeden van een flare op:

- Klinische symptomen: huidafwijkingen, spierkracht en algehele indruk

- Laboratoriumwaarden: CK en interferon-biomarkers (Galectine-9, CXCL-10 en/of siglec-1). Verhoogde waarden ondersteunen een flare of (toegenomen) ziekteactiviteit.

- Bijwerkingen van prednison en methotrexaat

Voer jaarlijks een longfunctieonderzoek uit voor screening op ILD, evenals 1-2 jaarlijks echo hart en ECG voor cardiale screening.

Overwegingen

Considerations – from evidence to recommendation

Pros and cons of the intervention and the quality of the evidence

An updated Cochrane review (expected, 2024) included 2 RCTs on rituximab, ciclosporin and methotrexate in patients with JDM. The level of evidence from these studies is low to very low; however, a low GRADE is inherent to conditions with low prevalence. Nonetheless, these studies show:

- A better result of methotrexate (MTX) than of ciclosporin A, with regard to functional ability outcomes (CHAQ).

- Equal results of MTX and ciclosporin A with regard to other outcomes, yet both options are better than prednisolone alone.

- More toxicity for ciclosporin A.

We combined these results with experiences from practice, to provide an overview of how stepwise treatment can be administered.

Induction treatment

From the literature analysis, it can be concluded that as induction treatment, MTX in addition to prednisolone should be started in patients with JDM. This is in line with current recommendations from international consensus groups (Belutti Enders, 2017). The working group agrees that treatment in the Netherlands should take place in an academic hospital by a pediatric rheumatologist.

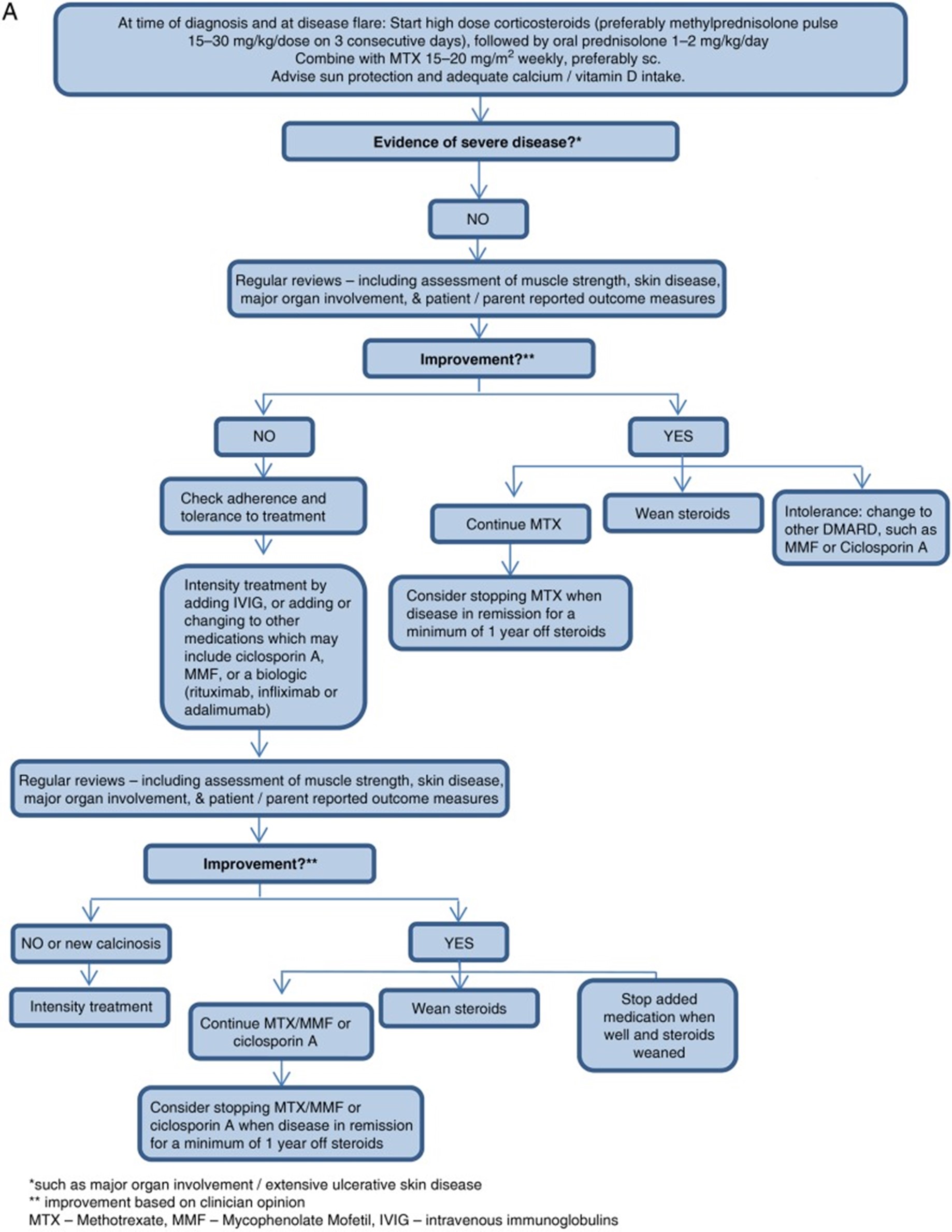

A treatment flow diagram from international guidelines is shown in figure 1 (from Belutti Enders, 2017). It should be noted that a maximum dose of 80 mg of oral prednisone is advised (in line with recommendations for adults). Follow-up should take place at least once a month in the first 6 months (and more frequent on indication) and treatment should lead to improvement within 4 weeks.

Additional treatment

If treatment with MTX and prednisone results in insufficient improvement, treatment can be switched to or intensified with intravenous immunoglobulins (IVIg), ciclosporin A, mycophenolate mofetil (MMF), or biological DMARDs (rituximab, infliximab, or adalimumab). Alternatively (not in flowchart), JAK-STAT inhibitors can be considered.

Severe disease

In case of severe disease, the addition of IVIg, cyclophosphamide i.v. or JAK-STAT inhibitors to the MTX + prednisone treatment can be considered earlier in the treatment.

Calcinosis can occur later in the disease course. Primarily, the JDM should be treated and not the calcinosis itself. However, further therapy targeting calcium deposition should be considered. See the module on calcinosis for recommendations on treatment.

Monitoring of response

During treatment, the patient should be periodically monitored for:

- Symptoms: muscle strength (by using CMAS); skin disease (by using (abbreviated) CAT or CDASI score); major organ involvement, and a physician global assessment. In addition, pulmonary function, pulmonary hrCT and cardiac ultrasongraphy should be performed if heart or lungs are affected at diagnosis.

- Laboratory values: creatine kinase (CK) and interferon type I-II biomarkers (Galectin-9, CXCL-10 and Siglec-1)

- Side effects of prednisone and MTX

- A flare can be detected by an increase in disease activity measurements, extra skin/muscle disease activity (such as ILD) or increased CK or increasing IFN-1 biomarkers.

Figure 1. Flowchart for the treatment of mild or moderate disease in patients with JDM (from: Belutti Enders, 2017)

Values and preferences of patients

First and foremost, clear information should be provided to patients and their parents/caregivers. The (trajectory of) diagnosis of JDM can be experienced as a rollercoaster, and ample time should be taken to explain the diagnosis, the advised treatment, the monitoring, and the complications. It should be explored how elaborate information should be provided, adapted to the information need from parents/caregivers. Then a joint decision can be made for the preferred treatment. However, it is important to start intensive treatment quickly, as children are very sick and usually parents/caregivers are worried.

During the course of the disease, different trajectories of treatment response can be observed, which should be counselled clearly:

- Treatment can be stopped when patients have recovered

- Treatment does not cause sufficient improvement (refractory disease)

- Treatment causes sufficient improvement, yet sometimes disease flares occur

In the latter two scenarios, further treatment aims to prevent damage on the long run. If patient/parent-expectations are managed by explaining, more understanding for the need of increasing or adding medication can be effectuated.

Costs

For almost all paediatric conditions, the gain in Quality Adjusted Life Years (QALY) outweigh (possible high) treatment costs. In addition, as JDM has a low prevalence, the impact of treatment costs on societal level are negligible.

Acceptability, feasibility and implementation

Delay in recognition and diagnosing of JDM poses problems, as it also results in a delay in treatment. However, with regard to acceptability and implementation of treatment of JDM, no problems are expected, as recommended treatment options are (already) usual care. No adaptations in organization of care are required to effectuate suggested treatment.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

The estimated annual incidence for children is 2.5 to 4.1 cases per million per year. The peak incidence for juvenile dermatomyositis is at the age of seven years. In the Netherlands an estimated 8-10 new patients per year are diagnosed with JDM (unpublished national data). As there is limited experience nationally with the treatment of JDM, the need for practical guidelines exists.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

Targeted therapies

|

- GRADE |

No GRADE assessment was made for the outcomes:

|

|

Low GRADE |

The evidence suggests a positive effect of rituximab on time to improvement, compared to placebo, in patients with JDM.

Source: Oddis (2013) |

Non-targeted therapies

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of methotrexate or ciclosporin – in comparison to methylprednisolone, on:

in patients with JDM.

Source: Ruperto (2016) |

|

- GRADE |

No GRADE assessment was made for the outcome skin symptoms. |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

One Cochrane reviews [expected, 2024] investigated targeted treatments, the other review [expected, 2024] investigated non-targeted treatments.

In both reviews, a search was performed until February 3rd, 2023 in the following databases: Cochrane Neuromuscular Specialised Register (via CRS‐Web), Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (via the Cochrane Library), Embase (via Ovid SP), US National Institutes of Health Ongoing Trials Register (via ClinicalTrials.gov) and World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform.

Studies were selected based on the following criteria:

- Study design: Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) or quasi-RCTs

- Participants: adults and children with probable or definite DM, (including JDM), IMNM, ASS, OM and PM

- Intervention: treatment with immunosuppressant or immunomodulatory treatments used at any dosage, by any route, in any regimen and for any duration.

No restrictions on type of outcome measures reported or language were applied in the selection process. Risk of bias of included studies was assessed using the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool.

For this analysis, the studies reporting on JDM were used.

Results

Targeted therapies

One trial included pediatric patients. The characteristics of this study can be found in table 1. For the analysis, only the subgroup with JDM was used.

Non-targeted therapies

Two trials including patients with JDM were identified from the Cochrane review, yet one was excluded as it did not report any outcome of interest. The characteristics of the included study can be found in table 1.

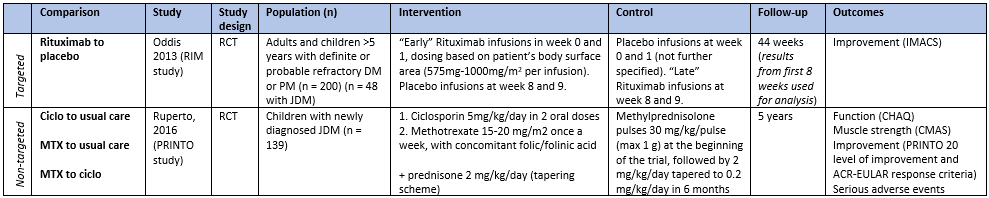

Table 1. Characteristics of included studies reporting on targeted and non-targeted therapies for JDM. (zie ook evidence tabellen)

Abbreviations: CHAQ: Childhood Health Assessment Questionnaire, ciclo: ciclosporin, CMAS: Childhood Myositis Assessment Scale, i.v.: intravenously, IMACS: International Myositis Assessment and Clinical Studies definitions of improvement, (J)DM: (juvenile) dermatomyositis, MTX: methotrexate, PM: polymyositis, RCT: randomized controlled trial

Results

Targeted therapies

One study addressed targeted therapy (i.e. rituximab early and late, see table 1) in patients with JDM (Oddis, 2013; “RIM study”). Primarily, the first 8 weeks of treatment were of interest, in which rituximab was compared to placebo treatment.

Function

Only baseline data (no follow-up data) on disability (Childhood Disability Index Questionnaire, CHAQ) were available in Oddis (2013, “RIM study”).

Muscle strength

Only baseline data (no follow-up data) on muscle strength (MMT-8) were available in Oddis (2013, “RIM study”).

Improvement

Oddis (2013, “RIM study”) reported the median time to achievement of the IMACS definitions of improvement between the different treatment groups. An 8-week difference was observed between the early and late rituximab group (median time to improvement 11.7 weeks in the early group, compared to 19.6 weeks in the late group). However, the trial was not powered for assessing response in this subset (JDM), and this difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.32). JDM itself (compared adult myositis) was in this study a predictor for a positive response on treatment (additional publication from same study population; Aggarwal, 2014).

Skin symptoms

Only baseline data (no follow-up data) on skin symptoms (Myositis Disease Acitivity Assessment Tool, MDAAT) were available in Oddis (2013, “RIM study”).

Adverse events

Oddis (2013, “RIM study”) reported adverse events only for the entire study population (adults and children, no data specifically for JDM available), and for the entire duration of the study (44 weeks), during which all included patients in the study had received rituximab. No comparison with placebo was made.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measures was downgraded by according to the table below.

|

Outcome measure |

Domains |

Level of evidence |

|

Function |

No GRADE assessment (insufficient data available) |

- |

|

Muscle strength |

No GRADE assessment (insufficient data available) |

- |

|

Improvement |

-2 imprecision (unclear confidence interval, study not powered for assessment of subgroup JDM) |

LOW |

|

Skin symptoms |

No GRADE assessment (insufficient data available) |

- |

|

Serious adverse events |

No GRADE assessment (insufficient data available) |

- |

Non-targeted therapies

The study by Ruperto (2016, “PRINTO”) had a 3-arm design, resulting in the following comparisons:

- Methotrexate versus usual care

- Ciclosporin versus usual care

- Methotrexate versus ciclosporin

Function

Ruperto (2016, “PRINTO”) measured functional ability using the Childhood Health Assessment Questionnaire (CHAQ, score ranging from 0 to 3 in which a higher score is worse). After 6 months, the median outcomes per treatment arm were:

|

Methotrexate group |

(n = 46) |

0.1 (IQR 0 to 0.7) |

|

Ciclosporin group |

(n = 46) |

0.3 (IQR 0 to 0.9) |

|

Prednisolone-only group |

(n = 47) |

0.3 (IQR 0.1 to 1.6) |

Muscle strength

Ruperto (2016, “PRINTO”) measured muscle strength using the Childhood Myositis Assessment Scale (CMAS, in which 14 manoeuvres are scored, score ranging from 0 to 52 in which a higher score is better). After 6 months, the median outcomes per treatment arm were:

|

Methotrexate group |

(n = 46) |

44.5 (IQR 33 to 51) |

|

Ciclosporin group |

(n = 46) |

45.5 (IQR 34 to 51) |

|

Prednisolone-only group |

(n = 47) |

42 (IQR 28 to 48) |

Improvement

Ruperto (2016, “PRINTO”) reported improvement with 2 measures: PRINTO responder status (defined as 20% improvement in at least 3 core set variables with no more than 1 of the remaining variables (muscle strength excluded) worsened by >30%) and the number of participants with minimal, moderate and major improvement according to ACR-EULAR myositis response criteria in JDM. Percentage of patients achieving these outcomes, for the different comparisons, are shown in table 2.

Table 2.

|

Comparison |

Responder status |

ACR-EULAR myositis response criteria |

||

|

RR (95% CI) |

Interpretation |

RR (95% CI) |

Interpretation |

|

|

MTX to usual care |

1.40 (1.01 to 1.96) |

Favouring MTX |

1.34 (0.98 to 1.82) |

Favouring MTX |

|

ciclo to usual care |

1.36 (0.97 to 1.91) |

Favouring ciclo |

1.34 (0.98 to 1.82) |

Favouring ciclo |

|

MTX to ciclo |

1.03 (0.79 to 1.34) |

Favouring MTX |

1.00 (0.78 to 1.27) |

Equal |

Skin symptoms

None of the included studies reported outcomes regarding skin symptoms.

Serious adverse events

In the study by Ruperto (2016, “PRINTO”), 2 patients experienced serious adverse events in the methotrexate group (paronychia and dermohypodermitis, 4.3%), 5 patients in the ciclosporin group (posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome, convulsion, deep vein thrombosis, appendicitis, and sepsis in the context of acute pneumonia, 10.9%) and 1 in the prednisone-only group (subcutaneous abcess, 2.1%).

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measures was downgraded by according to the table below.

|

Outcome measure |

Domains |

Level of evidence |

|

Function |

-1 risk of bias in included study (no blinding), -3 imprecision (broad confidence intervals crossing the borders of clinical relevance, low number of participants) |

VERY LOW |

|

Muscle strength |

-1 risk of bias in included study (no blinding), -3 imprecision (broad confidence intervals crossing the borders of clinical relevance, low number of participants) |

VERY LOW |

|

Improvement |

1 risk of bias in included study (no blinding), -2 imprecision (broad confidence intervals crossing the borders of clinical relevance, low number of participants) |

VERY LOW |

|

Skin symptoms |

No GRADE assessment |

- |

|

Serious adverse events |

1 risk of bias in included study (no blinding), -3 imprecision (broad confidence intervals crossing the borders of clinical relevance, low number of participants) |

VERY LOW |

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question:

What are the effects (benefits and harms) of immunosuppressant and immunomodulatory treatments for JDM?

| P: | Patients with JDM |

| I: |

Immunosuppressant and/or immunomodulatory medication

|

| C: | Placebo or usual care |

| O: |

Function or disability, muscle strength, improvement, skin symptoms, serious adverse events |

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered skin symptoms as a critical outcome measure for decision making; and serious adverse events as an important outcome measure for decision making.

The working group defined the outcome measures with their respective minimal clinically (patient) important difference as follows:

- Function or disability: improvement in a validated function or disability scale; preferred is the (C-)HAQ ((Childhood-)Health Assessment Questionnaire). Clinical relevance is based on the minimal clinical meaningful improvement for the scale used.

- Muscle strength: improvement compared to baseline, preferably measured by the MMT-8 score (Manual Muscle Test-8) or another validated score. Meaningful improvement is ³15% or ³20%.

- Improvement: measured through 6 core set measures from the International Myositis Assessment and Clinical Studies Group (IMACS) definitions of improvement: if three of any six core set measures improve by ≥ 20%, with no more than two worsening by ≥ 25%.

- Skin symptoms: change in the Cutaneous Dermatomyositis Disease Area and Severity Index (CDASI) or another validated score for DM.

- Serious adverse events: any untoward medical occurrence that at any dose results in death, is life‐threatening, requires inpatient hospitalization or prolongation of existing hospitalization, results in persistent or significant disability/incapacity or is a congenital anomaly/birth defect.

Search and select (Methods)

No literature search was performed, because of the publication of recent Cochrane reviews with an identical PICO to answer what the effects (benefits and harms) of immunosuppressant and immunomodulatory treatments are for JDM.

Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- Aggarwal R, Bandos A, Reed AM, Ascherman DP, Barohn RJ, Feldman BM, Miller FW, Rider LG, Harris-Love MO, Levesque MC; RIM Study Group; Oddis CV. Predictors of clinical improvement in rituximab-treated refractory adult and juvenile dermatomyositis and adult polymyositis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014 Mar;66(3):740-9. doi: 10.1002/art.38270. PMID: 24574235; PMCID: PMC3987896.

- Bellutti Enders F, Bader-Meunier B, Baildam E, Constantin T, Dolezalova P, Feldman BM, Lahdenne P, Magnusson B, Nistala K, Ozen S, Pilkington C, Ravelli A, Russo R, Uziel Y, van Brussel M, van der Net J, Vastert S, Wedderburn LR, Wulffraat N, McCann LJ, van Royen-Kerkhof A. Consensus-based recommendations for the management of juvenile dermatomyositis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017 Feb;76(2):329-340. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209247. Epub 2016 Aug 11. PMID: 27515057; PMCID: PMC5284351.

- Oddis CV, Reed AM, Aggarwal R, Rider LG, Ascherman DP, Levesque MC, Barohn RJ, Feldman BM, Harris-Love MO, Koontz DC, Fertig N, Kelley SS, Pryber SL, Miller FW, Rockette HE; RIM Study Group. Rituximab in the treatment of refractory adult and juvenile dermatomyositis and adult polymyositis: a randomized, placebo-phase trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2013 Feb;65(2):314-24. doi: 10.1002/art.37754. PMID: 23124935; PMCID: PMC3558563.

- Ruperto N, Pistorio A, Oliveira S, Zulian F, Cuttica R, Ravelli A, Fischbach M, Magnusson B, Sterba G, Avcin T, Brochard K, Corona F, Dressler F, Gerloni V, Apaz MT, Bracaglia C, Cespedes-Cruz A, Cimaz R, Couillault G, Joos R, Quartier P, Russo R, Tardieu M, Wulffraat N, Bica B, Dolezalova P, Ferriani V, Flato B, Bernard-Medina AG, Herlin T, Trachana M, Meini A, Allain-Launay E, Pilkington C, Vargova V, Wouters C, Angioloni S, Martini A; Paediatric Rheumatology International Trials Organisation (PRINTO). Prednisone versus prednisone plus ciclosporin versus prednisone plus methotrexate in new-onset juvenile dermatomyositis: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2016 Feb 13;387(10019):671-678. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01021-1. Epub 2015 Nov 30. PMID: 26645190.

Evidence tabellen

See table 1 in this module, and the individual characteristics of studies in the Cochrane review for study characteristics and risk of bias assessment. The list of excluded studies can be found in the Cochrane review.

Table 1. Characteristics of included studies reporting on targeted and non-targeted therapies for JDM.

Abbreviations: CHAQ: Childhood Health Assessment Questionnaire, ciclo: ciclosporin, CMAS: Childhood Myositis Assessment Scale, i.v.: intravenously, IMACS: International Myositis Assessment and Clinical Studies definitions of improvement, (J)DM: (juvenile) dermatomyositis, MTX: methotrexate, PM: polymyositis, RCT: randomized controlled trial

|

|

Comparison |

Study |

Study design |

Population (n) |

Intervention |

Control |

Follow-up |

Outcomes |

|

Targeted |

Rituximab to placebo |

Oddis 2013 (RIM study) |

RCT |

Adults and children >5 years with definite or probable refractory DM or PM (n = 200) (n = 48 with JDM) |

“Early” Rituximab infusions in week 0 and 1, dosing based on patient’s body surface area (575mg-1000mg/m2 per infusion). Placebo infusions at week 8 and 9. |

Placebo infusions at week 0 and 1 (not further specified). “Late” Rituximab infusions at week 8 and 9. |

44 weeks (results from first 8 weeks used for analysis) |

Improvement (IMACS)

|

|

Non-targeted |

Ciclo to usual care

MTX to usual care

MTX to ciclo |

Ruperto, 2016 (PRINTO study) |

RCT |

Children with newly diagnosed JDM (n = 139) |

1. Ciclosporin 5mg/kg/day in 2 oral doses 2. Methotrexate 15-20 mg/m2 once a week, with concomitant folic/folinic acid

+ prednisone 2 mg/kg/day (tapering scheme) |

Methylprednisolone pulses 30 mg/kg/pulse (max 1 g) at the beginning of the trial, followed by 2 mg/kg/day tapered to 0.2 mg/kg/day in 6 months |

5 years |

Function (CHAQ) Muscle strength (CMAS) Improvement (PRINTO 20 level of improvement and ACR-EULAR response criteria) Serious adverse events |

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Publicatiedatum : 17-09-2024

Beoordeeld op geldigheid : 13-09-2024

Algemene gegevens

Elucidation:

The consultation on this chapter has already taken place in the autumn of 2023. The chapter has now been added for information purposes but does not need to be commented on.

The development of this guideline module was supported by the Knowledge Institute of the Federation of Medical Specialists (www.demedischspecialist.nl/ kennisinstituut) and was financed from the Quality Funds for Medical Specialists (SKMS). The financier has had no influence whatsoever on the content of the guideline module.

Reason for revising the guideline

Idiopathic inflammatory myopathy (IIM, “myositis”) comprises the most commonly acquired myopathies in adults with an estimated incidence of 6-10 per million persons per year and a prevalence of 12 per 100.000 persons (Deenen, 2016). The disease can present at all ages and has a bimodal distribution with peaks in childhood/adolescence and around the 5th decade. The disease is more common in women (F:M = 3:2), with the exception of inclusion body myositis (IBM) (M:F = 2:1). The previous guideline was published in 2005 (NVN, 2005) and since then many developments have taken place that warrant revision.

Doel en doelgroep

Aim of the guideline

The intended effect of the revised guideline is to clarify the diagnostic process of IIM, adding the new topic 'antibodies', and to describe new developments in the field of treatment. This should result in a modular revised guideline in accordance with the current requirements for the development of guidelines for medical specialists.

Scope of the guideline

Which group of patients is described?

The idiopathic inflammatory myopathies (IIM) (also called myositis) are a heterogeneous group of disorders with striated muscle inflammation that usually lead to loss of strength. Almost all forms of IIM cause subacute, symmetrical proximal muscle weakness. The weakness starts in the hip and thigh regions with difficulties in running, climbing stairs or walking longer distances. Weakness of the shoulder and upper arm muscles often occur. Neck muscle weakness, respiratory problems and dysphagia are less frequent but may be the initial presentation. Muscle pain and subcutaneous edema may be present. The distribution of muscle weakness and disease progression in IBM differs from the other forms of IIM. Systemic or so-called extra-muscular disease activity can occur in various IIM: skin lesions (especially in dermatomyositis), calcinosis, arthritis, Raynaud's phenomenon (in overlap myositis), malignancies, interstitial lung disease (ILD) and/or peri/myocarditis, which can lead to arrhythmias and/or heart failure. These disease manifestations make a multidisciplinary approach essential for this group of patients.

This guideline is limited to four of the most common IIM: dermatomyositis (DM), non-specific/overlap myositis (which also includes anti-synthetase syndrome (ASS), immune-mediated necrotizing myopathy (IMNM), and IBM.

What are the possible interventions/therapies or (diagnostic) tests?

A definitive diagnosis is usually made with histopathological examination of a muscle biopsy. Serum CK activity, EMG, muscle imaging with ultrasound or MRI and myositis antibody assessment can make an important contribution to the diagnosis and together provide detailed information about expected extra-muscular manifestations including malignancies, therapy response and prognosis.

The drug treatment of IIM is mainly based on expert opinion/consensus; for IBM effective drug treatment is currently lacking. The cornerstone of immunosuppressive treatment of IIM (excluding IBM) is still high dosed glucocortiocoids; methotrexate, azathioprine or mycophenolate mofetil (MMF), are usually prescribed as steroid sparing agents without solid evidence to guide decisions (Gordon, 2012).

In the case of rapidly progressive or (expected) refractory disease, or in case of severe ILD, intravenous immunoglobulins (IVIg), rituximab cyclophosphamide, and/or tacrolimus or ciclosporin can be added to the treatment. The hope is that targeted (biological) therapy will greatly improve outcomes in IIM in the future.

Early diagnosis of IIM prevents irreversible muscle fiber damage and permanent physical limitations. Despite treatment, more than 2/3 of IIM patients have a polyphasic or chronic disease course and a comparable proportion of patients have residual limitations such as reduced mobility (van de Vlekkert, 2014).

What are the most important outcome measures relevant to the patient?

Screening for extra-muscular disease activity, especially ILD and malignancies, is relevant because these are important for morbidity and determine mortality in IIM. Pain and fatigue appear to be two of the most important outcome measures in the field of quality of life (QoL) in international research among patients and IIM care providers (Mecoli, 2019; de Groot, 2019). Other important determinants of QoL are degree of physical activity, muscle complaints, lung complaints, joint complaints and skin complaints.

Users of the guideline

This guideline is written for all who provide care for patients with IIM. Users of the guideline include neurologists, rheumatologists, rehabilitation physicians, dermatologists, pulmonologists, paediatricians, pathologists and internists.

Abbreviations and terms

Umbrella term myositis

Within the guideline, myositis and IIM are used as umbrella terms. This includes all autoimmune-mediated forms of myositis.

Myositis is a collective name for a number of diseases. Myositis comes from the Greek word myos (muscle). The ending -itis means inflammation. Myositis is inflammation of skeletal muscles. The muscle inflammation can sometimes be caused by a bacterial or viral infection or a reaction to medication. But usually the cause is unknown (idiopathic); these conditions are therefore also referred to as idiopathic inflammatory myopathies - IIM. There are also dermatological components, without muscle inflammation (yet).

Inflammatory connective tissue diseases: These diseases used to be referred to as 'connective tissue diseases'. They are associated with predominantly lymphocytic inflammation of various organs, including the striated muscles. There is some evidence that they are due to derangements of the immune system. They are also referred to as 'systemic autoimmune diseases'.

Dermatomyositis: this type of IIM is characterized by heliotrope rash and the pathognomonic Gottron’s papules. Muscle weakness can be absent, which is termed amyopathic dermatomyositis when no or insufficient evidence of an inflammatory myopathy is found. Dermatomyositis can be a classic paraneoplastic syndrome; there is an association with cancer.

Juvenile (dermato)myositis: Juvenile dermatomyositis (JDM) (up to 18 years) is distinguished from adult DM because of severe and extensive vasculitis of skin and organs, involvement of joints and oral mucosa, higher incidence of calcinosis, and lack of an association with malignancies. So-called overlap myositis, especially in the context of mixed connective tissue disease, and immune-mediated necrotizing myopathy can also occur in children.

Immune-mediated necrotizing myopathy (IMNM) (earlier necrotizing auto-immune myopathy (NAM): the muscle weakness is usually severe and rapidly progressive. Anti HMGCR IMNM is statin-associated in about 50%. IMNM may be associated with cancer.

‘Inclusion body’-myositis: Inclusion body myositis (IBM) is a slowly progressive striated muscle disease of unknown origin, occurring mainly in the second half of life, with predominantly lymphocytic inflammation in striated muscles and characteristic structural abnormalities in muscle fibers.

Non-specific or overlap myositis (OM): a residual category without the obvious clinical, pathological, or serological features of the other myositis subtypes. Extra-muscular symptoms are common and may be the presenting symptom of a systemic connective tissue disorder such as systemic sclerosis, Sjögren's disease, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), rheumatoid arthritis (RA), or mixed connective tissue disease (MCTD).

Anti-synthetase syndrome (ASS): this syndrome is characterized by a combination of myositis, Raynaud's phenomena, "mechanic's hands", non-erosive polyarthritis and ILD. Not all of these symptoms need to be present.

Polymyositis: Is a controversial entity. It is the rarest form of myositis and is considered a diagnosis by exclusion after all other forms have been ruled out.

Disease activity: The concept of activity is used to indicate the dynamics, the severity of a disease process.

Remission: Disease activity is no longer present.

Relaps: Recurrence or increase of disease activity after a period of low disease activity or remission

Disease damage: Irreversible structural changes in tissue (mostly muscle)

|

Afkorting |

Toelichting |

|

ASS |

Anti-synthetase syndrome |

|

DM |

Dermatomyositis |

|

IBM |

inclusion-body myositis |

|

IIM |

Idiopathic inflammatory myopathies |

|

ILD |

Interstitial lung diseases |

|

IMNM |

Immune-mediated necrotizing myopathy (formerly known as NAM: necrotizing autoimmune myopathy) |

|

Juvenile (dermato)myositis |

|

|

OM |

Non-specific or overlap myositis |

|

PM |

Polymyositis |

|

RA |

Rheumatoid arthritis |

|

SLE |

Systemic lupus erythematosus |

Literatuur

Deenen JC, van Doorn PA, Faber CG, van der Kooi AJ, Kuks JB, Notermans NC, Visser LH, Horlings CG, Verschuuren JJ, Verbeek AL, van Engelen BG. The epidemiology of neuromuscular disorders: Age at onset and gender in the Netherlands. Neuromuscul Disord. 2016 Jul;26(7):447-52. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2016.04.011. Epub 2016 Apr 21. PMID: 27212207.

De Groot I, van der Lubbe PAHM, Huisman AM. OMERACT Special Interest Group Myositis: met patiënten op zoek naar patiëntgerapporteerde uitkomstmaten. Nederlands Tijdschrift voor Reumatologie. 2. 2019

Gordon PA, Winer JB, Hoogendijk JE, Choy EH. Immunosuppressant and immunomodulatory treatment for dermatomyositis and polymyositis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012 Aug 15;2012(8):CD003643. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003643.pub4. PMID: 22895935; PMCID: PMC7144740.

Mecoli CA, Park JK, Alexanderson H, Regardt M, Needham M, de Groot I, Sarver C, Lundberg IE, Shea B, de Visser M, Song YW, Bingham CO 3rd, Christopher-Stine L. Perceptions of Patients, Caregivers, and Healthcare Providers of Idiopathic Inflammatory Myopathies: An International OMERACT Study. J Rheumatol. 2019 Jan;46(1):106-111. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.180353. Epub 2018 Sep 15. PMID: 30219767; PMCID: PMC7497902.

Nederlandse Vereniging voor Neurologie. Dermatomyositis, polymyositis en sporadische ‘inclusion body’-myositis. 2005

van de Vlekkert J, Hoogendijk JE, de Visser M. Long-term follow-up of 62 patients with myositis. J Neurol. 2014 May;261(5):992-8. doi: 10.1007/s00415-014-7313-z. PMID: 24658663.

Samenstelling werkgroep

A multidisciplinary working group was set up in 2020 for the development of the guideline module, consisting of representatives of all relevant specialisms and patient organisations (see the Composition of the working group) involved in the care of patients with IIM/myositis.

Working group

- Dr. A.J. van der Kooi, neurologist, Amsterdam UMC, location AMC. Nederlandse Vereniging voor Neurologie (chair)

- Dr. U.A. Badrising, neurologist, LUMC. Nederlandse Vereniging voor Neurologie

- Dr. C.G.J. Saris, neurologist, Radboudumc. Nederlandse Vereniging voor Neurologie

- Dr. S. Lassche, neurologist, Zuyderland MC. Nederlandse Vereniging voor Neurologie

- Dr. J. Raaphorst, neurologist, Amsterdam UMC, locatie AMC. Nederlandse Vereniging voor Neurologie

- Dr. J.E. Hoogendijk, neurologist, UMC Utrecht. Nederlandse Vereniging voor Neurologie

- Drs. T.B.G. Olde Dubbelink, neurologist, Rijnstate, Nederlandse Vereniging voor Neurologie

- Dr. I.L. Meek, rheumatologist, Radboudumc. Nederlandse Vereniging voor Reumatologie

- Dr. R.C. Padmos, rheumatologist, Erasmus MC. Nederlandse Vereniging voor Reumatologie

- Prof. dr. E.M.G.J. de Jong, dermatologist, werkzaam in het Radboudumc. Nederlandse Vereniging voor Dermatologie en Venereologie

- Drs. W.R. Veldkamp, dermatologist, Ziekenhuis Gelderse Vallei. Nederlandse Vereniging voor Dermatologie en Venereologie

- Dr. J.M. van den Berg, pediatrician, Amsterdam UMC, locatie AMC. Nederlandse Vereniging voor Kindergeneeskunde

- Dr. M.H.A. Jansen, pediatrician, UMC Utrecht. Nederlandse Vereniging voor Kindergeneeskunde

- Dr. A.C. van Groenestijn, rehabilitation physician, Amsterdam UMC, locatie AMC. Nederlandse Vereniging van Revalidatieartsen

- Dr. B. Küsters, pathologist, Radboudumc. Nederlandse Vereniging voor Pathologie

- Dr. V.A.S.H. Dalm, internist, Erasmus MC. Nederlandse Internisten Vereniging

- Drs. J.R. Miedema, pulmonologist, Erasmus MC. Nederlandse Vereniging van Artsen voor Longziekten en Tuberculose

- I. de Groot, patient representatieve. Spierziekten Nederland

Advisory board

- Prof. dr. E. Aronica, pathologist, Amsterdam UMC, locatie AMC. External expert.

- Prof. dr. D. Hamann, Laboratory specialist medical immunology, UMC Utrecht. External expert.

- Drs. R.N.P.M. Rinkel, ENT physician, Amsterdam UMC, locatie VUmc. Vereniging voor Keel-Neus-Oorheelkunde en Heelkunde van het Hoofd-Halsgebied

- dr. A.S. Amin, cardiologist, werkzaam in werkzaam in het Amsterdam UMC, locatie AMC. Nederlandse Vereniging voor Cardiologie

- dr. A. van Royen-Kerkhof, pediatrician, UMC Utrecht. External expert.

- dr. L.W.J. Baijens, ENT physician, Maastricht UMC+. External expert.

- Em. Prof. Dr. M. de Visser, neurologist, Amsterdam UMC. External expert.

Methodological support

- Drs. T. Lamberts, senior advisor, Knowledge institute of the Federation of Medical Specialists

- Drs. M. Griekspoor, advisor, Knowledge institute of the Federation of Medical Specialists

- Dr. M. M. J. van Rooijen, advisor, Knowledge institute of the Federation of Medical Specialists

Belangenverklaringen

The ‘Code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling’ has been followed. All working group members have declared in writing whether they have had direct financial interests (attribution with a commercial company, personal financial interests, research funding) or indirect interests (personal relationships, reputation management) in the past three years. During the development or revision of a module, changes in interests are communicated to the chairperson. The declaration of interest is reconfirmed during the comment phase.

An overview of the interests of working group members and the opinion on how to deal with any interests can be found in the table below. The signed declarations of interest can be requested from the secretariat of the Knowledge Institute of the Federation of Medical Specialists.

|

Werkgroeplid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

van der Kooi |

Neuroloog, Amsterdam UMC |

|

Immediate studie (investigator initiated, IVIg behandeling bij therapie naive patienten). --> Financiering via Behring. Studie januari 2019 afgerond |

Geen restricties (middel bij advisory board is geen onderdeel van rcihtlijn) |

|

Miedema |

Longarts, Erasmus MC |

Geen. |

|

Geen restricties |

|

Meek |

Afdelingshoofd a.i. afdeling reumatische ziekten, Radboudumc |

Commissaris kwaliteit bestuur Nederlandse Vereniging voor Reumatologie (onkostenvergoeding) |

Medisch adviseur myositis werkgroep spierziekten Nederland |

Geen restricties |

|

Veldkamp |

AIOS dermatologie Radboudumc Nijmegen |

|

Geen. |

Geen restricties |

|

Padmos |

Reumatoloog, Erasmus MC |

Docent Breederode Hogeschool (afdeling reumatologie EMC wordt hiervoor betaald) |

Geen. |

Geen restricties |

|

Dalm |

Internist-klinisch immunoloog Erasmus MC |

Geen. |

Geen. |

Geen restricties |

|

Olde Dubbelink |

Neuroloog in opleiding Canisius-Wilhelmina Ziekenhuis, Nijmegen |

Promotie onderzoek naar diagnostiek en outcome van het carpaletunnelsyndroom (onbetaald) |

Geen. |

Geen restricties |

|

van Groenestijn |

Revalidatiearts AmsterdamUMC, locatie AMC |

Geen. |

Lokale onderzoeker voor de I'M FINE studie (multicentre, leiding door afdeling Revalidatie Amsterdam UMC, samen met UMC Utrecht, Sint Maartenskliniek, Klimmendaal en Merem. Evaluatie van geïndividualiseerd beweegprogramma o.b.v. combinatie van aerobe training en coaching bij mensen met neuromusculaire aandoeningen, NMA). Activiteiten: screening NMA-patiënten die willen participeren aan deze studie. Subsidie van het Prinses Beatrix Spierfonds. |

Geen restricties |

|

Lassche |

Neuroloog, Zuyderland Medisch Centrum, Heerlen en Sittard-Geleen |

Geen. |

Geen. |

Geen restricties |

|

de Jong |

Dermatoloog, afdelingshoofd Dermatologie Radboudumc Nijmegen |

Geen. |

All funding is not personal but goes to the independent research fund of the department of dermatology of Radboud university medical centre Nijmegen, the Netherlands |

Geen restricties |

|

Hoogendijk |

Neuroloog Universitair Medisch Centrum Utrecht (0,4) Neuroloog Sionsberg, Dokkum (0,6) |

beide onbetaald |

Geen. |

Geen restricties |

|

Badrising |

Neuroloog Leids Universitair Medisch Centrum |

(U.A.Badrising Neuroloog b.v.: hoofdbestuurder; betreft een vrijwel slapende b.v. als overblijfsel van mijn eerdere praktijk in de maatschap neurologie Dirksland, Het van Weel-Bethesda Ziekenhuis) |

Medisch adviseur myositis werkgroep spierziekten Nederland |

Geen restricties |

|

van den Berg |

Kinderarts-reumatoloog/-immunoloog Emma kinderziekenhuis/ Amsterdam UMC |

Geen. |

Geen. |

Geen restricties |

|

de Groot |

Patiënt vertegenwoordiger/ ervaringsdeskundige: voorzitter diagnosewerkgroep myositis bij Spierziekten Nederland in deze commissie patiënt(vertegenwoordiger) |

|

Ik ben als voorzitter van de Nederlandse diagnose werkgroep Myositis (vallend onder Spierziekten Nederland) en lid van onder andere het Myositis Netwerk Nederland (als patiënten vertegenwoordiger) een soort van 'bekend myositis patiënt' in het kleine myositis wereldje. Datzelfde geldt voor een paar internationale projecten. |

Geen restricties |

|

Küsters |

Patholoog, Radboud UMC |

Geen. |

Geen. |

Geen restricties |

|

Saris |

Neuroloog/ klinisch neurofysioloog, Radboudumc |

Geen. |

Geen. |

Geen restricties |

|

Raaphorst |

Neuroloog, Amsterdam UMC |

Geen. |

|

Restricties m.b.t. opstellen aanbevelingen IvIg behandeling. |

|

Jansen |

Kinderarts-immunoloog-reumatoloog, WKZ UMC Utrecht |

Docent bij Mijs-instituut (betaald) |

Onderzoek biomakers in juveniele dermatomyositis. Geen belang bij uitkomst richtlijn. |

Geen restricties |

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Attention was paid to the patient's perspective by offering the Vereniging Spierziekten Nederland to take part in the working group. Vereniging Spierziekten Nederland has made use of this offer, the Dutch Artritis Society has waived it. In addition, an invitational conference was held to which the Vereniging Spierziekten Nederland, the Dutch Artritis Society nd Patiëntenfederatie Nederland were invited and the patient's perspective was discussed. The report of this meeting was discussed in the working group. The input obtained was included in the formulation of the clinical questions, the choice of outcome measures and the considerations. The draft guideline was also submitted for comment to the Vereniging Spierziekten Nederland, the Dutch Artritis Society and Patiëntenfederatie Nederland, and any comments submitted were reviewed and processed.

Qualitative estimate of possible financial consequences in the context of the Wkkgz

In accordance with the Healthcare Quality, Complaints and Disputes Act (Wet Kwaliteit, klachten en geschillen Zorg, Wkkgz), a qualitative estimate has been made for the guideline as to whether the recommendations may lead to substantial financial consequences. In conducting this assessment, guideline modules were tested in various domains (see the flowchart on the Guideline Database).

The qualitative estimate shows that there are probably no substantial financial consequences, see table below.

|

Module |

Estimate |

Explanation |

|

Immunosuppression and immunomodulation in JDM |

No substantial financial consequences |

Outcome 1 No financial consequences. The recommendations are not widely applicable (<5,000 patients) and are therefore not expected to have any substantial financial consequences on collective expenditures. |

Werkwijze

AGREE

This guideline module has been drawn up in accordance with the requirements stated in the Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 report of the Advisory Committee on Guidelines of the Quality Council. This report is based on the AGREE II instrument (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II; Brouwers, 2010).

Clinical questions

During the preparatory phase, the working group inventoried the bottlenecks in the care of patients with IIM. Bottlenecks were also put forward by the parties involved via an invitational conference. A report of this is included under related products.

Based on the results of the bottleneck analysis, the working group drew up and finalized draft basic questions.

Outcome measures

After formulating the search question associated with the clinical question, the working group inventoried which outcome measures are relevant to the patient, looking at both desired and undesired effects. A maximum of eight outcome measures were used. The working group rated these outcome measures according to their relative importance in decision-making regarding recommendations, as critical (critical to decision-making), important (but not critical), and unimportant. The working group also defined at least for the crucial outcome measures which differences they considered clinically (patient) relevant.

Methods used in the literature analyses

A detailed description of the literature search and selection strategy and the assessment of the risk-of-bias of the individual studies can be found under 'Search and selection' under Substantiation. The assessment of the strength of the scientific evidence is explained below.

Assessment of the level of scientific evidence

The strength of the scientific evidence was determined according to the GRADE method. GRADE stands for Grading Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (see http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/). The basic principles of the GRADE methodology are: naming and prioritizing the clinically (patient) relevant outcome measures, a systematic review per outcome measure, and an assessment of the strength of evidence per outcome measure based on the eight GRADE domains (downgrading domains: risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision, and publication bias; domains for upgrading: dose-effect relationship, large effect, and residual plausible confounding).

GRADE distinguishes four grades for the quality of scientific evidence: high, fair, low and very low. These degrees refer to the degree of certainty that exists about the literature conclusion, in particular the degree of certainty that the literature conclusion adequately supports the recommendation (Schünemann, 2013; Hultcrantz, 2017).

|

GRADE |

Definitie |

|

High |

|

|

Moderate |

|

|

Low |

|

|

Very low |

|

When assessing (grading) the strength of the scientific evidence in guidelines according to the GRADE methodology, limits for clinical decision-making play an important role (Hultcrantz, 2017). These are the limits that, if exceeded, would lead to an adjustment of the recommendation. To set limits for clinical decision-making, all relevant outcome measures and considerations should be considered. The boundaries for clinical decision-making are therefore not directly comparable with the minimal clinically important difference (MCID). Particularly in situations where an intervention has no significant drawbacks and the costs are relatively low, the threshold for clinical decision-making regarding the effectiveness of the intervention may lie at a lower value (closer to zero effect) than the MCID (Hultcrantz, 2017).

Considerations

In addition to (the quality of) the scientific evidence, other aspects are also important in arriving at a recommendation and are taken into account, such as additional arguments from, for example, biomechanics or physiology, values and preferences of patients, costs (resource requirements), acceptability, feasibility and implementation. These aspects are systematically listed and assessed (weighted) under the heading 'Considerations' and may be (partly) based on expert opinion. A structured format based on the evidence-to-decision framework of the international GRADE Working Group was used (Alonso-Coello, 2016a; Alonso-Coello 2016b). This evidence-to-decision framework is an integral part of the GRADE methodology.

Formulation of conclusions

The recommendations answer the clinical question and are based on the available scientific evidence, the most important considerations, and a weighting of the favorable and unfavorable effects of the relevant interventions. The strength of the scientific evidence and the weight assigned to the considerations by the working group together determine the strength of the recommendation. In accordance with the GRADE method, a low evidential value of conclusions in the systematic literature analysis does not preclude a strong recommendation a priori, and weak recommendations are also possible with a high evidential value (Agoritsas, 2017; Neumann, 2016). The strength of the recommendation is always determined by weighing all relevant arguments together. The working group has included with each recommendation how they arrived at the direction and strength of the recommendation.

The GRADE methodology distinguishes between strong and weak (or conditional) recommendations. The strength of a recommendation refers to the degree of certainty that the benefits of the intervention outweigh the harms (or vice versa) across the spectrum of patients targeted by the recommendation. The strength of a recommendation has clear implications for patients, practitioners and policy makers (see table below). A recommendation is not a dictate, even a strong recommendation based on high quality evidence (GRADE grading HIGH) will not always apply, under all possible circumstances and for each individual patient.

|

Implications of strong and weak recommendations for guideline users |

||

|

|

||

|

|

Strong recommendation |

Weak recommendations |

|

For patients |

Most patients would choose the recommended intervention or approach and only a small number would not. |

A significant proportion of patients would choose the recommended intervention or approach, but many patients would not. |

|

For practitioners |

Most patients should receive the recommended intervention or approach. |

There are several suitable interventions or approaches. The patient should be supported in choosing the intervention or approach that best reflects his or her values and preferences. |

|

For policy makers |

The recommended intervention or approach can be seen as standard policy. |

Policy-making requires extensive discussion involving many stakeholders. There is a greater likelihood of local policy differences. |

Organization of care

In the bottleneck analysis and in the development of the guideline module, explicit attention was paid to the organization of care: all aspects that are preconditions for providing care (such as coordination, communication, (financial) resources, manpower and infrastructure). Preconditions that are relevant for answering this specific initial question are mentioned in the considerations. More general, overarching or additional aspects of the organization of care are dealt with in the module Organization of care.

Commentary and authtorisation phase

The draft guideline module was submitted to the involved (scientific) associations and (patient) organizations for comment. The comments were collected and discussed with the working group. In response to the comments, the draft guideline module was modified and finalized by the working group. The final guideline module was submitted to the participating (scientific) associations and (patient) organizations for authorization and authorized or approved by them.

References

Agoritsas T, Merglen A, Heen AF, Kristiansen A, Neumann I, Brito JP, Brignardello-Petersen R, Alexander PE, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Guyatt GH. UpToDate adherence to GRADE criteria for strong recommendations: an analytical survey. BMJ Open. 2017 Nov 16;7(11):e018593. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018593. PubMed PMID: 29150475; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5701989.

Alonso-Coello P, Schünemann HJ, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Rada G, Rosenbaum S, Morelli A, Guyatt GH, Oxman AD; GRADE Working Group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 1: Introduction. BMJ. 2016 Jun 28;353:i2016. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2016. PubMed PMID: 27353417.

Alonso-Coello P, Oxman AD, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Vandvik PO, Meerpohl J, Guyatt GH, Schünemann HJ; GRADE Working Group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 2: Clinical practice guidelines. BMJ. 2016 Jun 30;353:i2089. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2089. PubMed PMID: 27365494.

Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, Burgers JS, Cluzeau F, Feder G, Fervers B, Graham ID, Grimshaw J, Hanna SE, Littlejohns P, Makarski J, Zitzelsberger L; AGREE Next Steps Consortium. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. CMAJ. 2010 Dec 14;182(18):E839-42. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090449. Epub 2010 Jul 5. Review. PubMed PMID: 20603348; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3001530.

Hultcrantz M, Rind D, Akl EA, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Iorio A, Alper BS, Meerpohl JJ, Murad MH, Ansari MT, Katikireddi SV, Östlund P, Tranæus S, Christensen R, Gartlehner G, Brozek J, Izcovich A, Schünemann H, Guyatt G. The GRADE Working Group clarifies the construct of certainty of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017 Jul;87:4-13. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.05.006. Epub 2017 May 18. PubMed PMID: 28529184; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC6542664.

Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 (2012). Adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwaliteit. http://richtlijnendatabase.nl/over_deze_site/over_richtlijnontwikkeling.html

Neumann I, Santesso N, Akl EA, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Alonso-Coello P, Agoritsas T, Mustafa RA, Alexander PE, Schünemann H, Guyatt GH. A guide for health professionals to interpret and use recommendations in guidelines developed with the GRADE approach. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016 Apr;72:45-55. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.11.017. Epub 2016 Jan 6. Review. PubMed PMID: 26772609.

Schünemann H, Brożek J, Guyatt G, . GRADE handbook for grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. Updated October 2013. The GRADE Working Group, 2013. Available from http://gdt.guidelinedevelopment.org/central_prod/_design/client/handbook/handbook.html.

Zoekverantwoording

Literature search strategy

See appendices from research protocol for Immunosuppressive and immunomodulatory therapies for idiopathic inflammatory myopathies, available via: https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD014510/appendices/es#CD014510-sec2-0010