Diagnostic value of disease symptoms

Uitgangsvraag

What is the diagnostic value of disease symptoms and signs for diagnosing Idiopathic inflammatory myopathy (IIM), juvenile dermatomyositis (JDM) and inclusion body myositis (IBM)?

Wat is de diagnostische waarde van ziekteverschijnselen bij het diagnosticeren van Idiopathic inflammatory myopathy (IIM), juvenile dermatomyositis (JDM) and inclusion body myositis (IBM)?

Aanbeveling

Verwijs laagdrempelig door of overleg met een centrum met expertise bij onvoldoende affiniteit met het vaststellen van spierzwakte, het beoordelen van huidafwijkingen of andere ziektekenmerken.

Verdenking IIM (“myositis”) (inclusief JDM)

Algemeen:

- Heb aandacht voor alle mogelijke ziekteverschijnselen (met name huid-, (hart)spier-, en algemene verschijnselen; tekenen wijzend op een maligniteit; long-, en gewrichtsverschijnselen) die in het kader van een myositis kunnen voorkomen.

Huid:

- Gottronse papels, het teken van Gottron en heliotroop erytheem zijn de meest voorkomende huidafwijkingen bij dermatomyositis.

- Voer een uitgebreid lichamelijk huidonderzoek uit en consulteer een dermatoloog bij niet-kenmerkende huidafwijkingen.

- Verwijs ook patiënten met amyopathische dermatomyositis altijd door naar neuroloog/reumatoloog/expertiseteam voor aanvullend onderzoek (inclusief eventuele maligniteitsscreening)

Spier:

- Denk bij een patiënt met snel progressieve min of meer symmetrische schouder- en bekkengordel spierzwakte aan een myositis.

- Besef dat focale spieratrofie ongebruikelijk is bij myositis.

Verdenking IBM

- Denk bij (geleidelijk progressieve; ≥12 maanden) zwakte van diepe vingerflexoren, zwakte van de knie extensoren en/of asymmetrische zwakte aan inclusion body myositis.

- Besef dat passageklachten bij het slikken het eerste teken kunnen zijn van myositis. Bij IBM kan dit jaren voorafgaan aan andere ziekteverschijnselen

Overwegingen

The literature review for this clinical question is integrated in the considerations because separating these two parts would results in a loss of an integral point of view.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Diagnostic criteria are used to establish a diagnosis of IIM (“myositis”), (including JDM and IBM). In general, these sets of criteria are developed on a basis of consensus and are subject to change over time due to expanding knowledge. Clinical features, laboratory features, and histopathological findings play a key role within these diagnostic criteria. IIM, JDM or IBM can present itself in numerous ways. The sum of symptoms and signs, and the results of ancillary investigations make a diagnosis likely or less likely, but one feature may outweigh the other or may predict a specific clinical subtype.

In the previous guideline, typical skin abnormalities were mentioned as a criterium for dermatomyositis (DM). Lately it has become clear that dermatomyositis-like skin lesions can be present in immune-mediated necrotizing myopathy, although this is rare. In addition, skin lesions can also be present in overlap myositis (OM) as part of the connective tissue disease and in the anti-synthetase syndrome. A revision to clinically recognize the subtype accurately is therefore warranted. Here, we describe symptoms and signs, including patterns of muscle weakness, with a high predictive value for a specific subtype of IIM. The recognition of these symptoms and signs aids the physician to speed up the diagnostic trajectory, to start treatment earlier, and to monitor the clinical course. An attempt will be made to highlight the distinguishing features.

Samenvatting literatuur

Characteristics of skeletal muscles

Common patterns of muscle weakness at presentation:

- Subacute, more or less symmetrical proximal lower and/or upper limb girdle muscle weakness which evolves in weeks to months, is a frequent first sign of IIM, except IBM. The main complaints are difficulty to reach above shoulder height, unstable gait, and difficulty walking stairs without support, or difficulty rising from a chair.

- If weakness is foremost present in the lower extremities compared with the upper extremities, this can point towards immune-mediated necrotizing myopathy (IMNM), as that is the predominant clinical picture in that subtype of idiopathic inflammatory myopathy (IIM) (Allenbach, 2020).

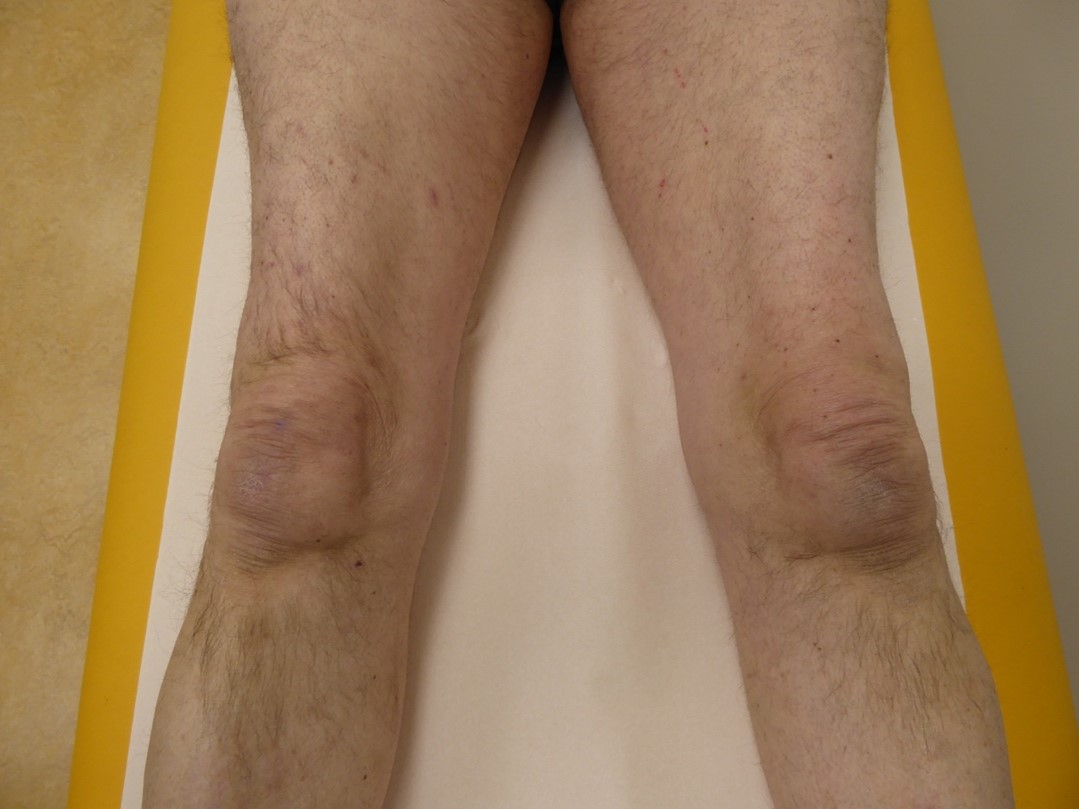

- In IBM, slowly progressive muscle weakness which takes more than 6 months to evolve and to become clinically relevant, especially when there is a debut in the quadriceps (figure 1) or deep finger flexors (figure 2). The main symptoms and signs are problems with rising from a chair, falls, and diminished hand grip strength. Weakness is usually asymmetric, and atrophy of the afflicted muscles can be seen (Rose, 2013).

- Weakness of oropharyngeal muscles can be present in IIM, including JDM and IBM and can result in dysphagia, which may be the first presenting symptom of IIM. A feeling of obstruction or aspiration while swallowing (especially food) are the usual complaints.

Figure 1. Atrophy of the quadriceps muscles in IBM.

Uncommon, but recognizable patterns of muscle weakness at presentation:

- Slowly progressive, more or less symmetrical proximal weakness of arms and legs, which evolves over more than 6 months is a rare presentation for IIM, mimicking a limb-girdle muscular dystrophy, but has been described in IMNM with HMGCR antibodies and SRP antibodies (Allenbach, 2020). Some of these patients may show scapular winging.

- Axial weakness (a dropped head or camptocormia) can be present in IIM, including IBM.

- Distal weakness of the legs leading to a drop foot, mimicking (asymmetric) motor neuropathy, can be the presenting sign in IBM. Atrophy is often apparent.

- Respiratory weakness can be the first presentation of IBM in rare cases (Voermans, 2004).

Figure 2. Asymmetric weakness in IBM of the deep finger flexors, with inability to disguise the fingernails during maximal effort to make a fist.

Figure 2. Asymmetric weakness in IBM of the deep finger flexors, with inability to disguise the fingernails during maximal effort to make a fist.

Unusual signs:

- Predominating weakness of facial muscles at the beginning of the disease should prompt a different diagnosis and not IIM, JDM or IBM. IBM patients can have prominent symmetrical facial weakness in a later stage of the disease, especially of eye-closure. Usually, the weakness in the face remains mild in IBM.

- External eye muscle weakness or orbital myositis is not a feature in the early stages of the abovementioned forms of inflammatory myopathies, although it has been coined as part of the spectrum of immune-checkpoint inhibitor associated myositis.

No weakness

Dermatomyositis (DM) and JDM can present without clinically noticeable involvement of skeletal muscles, usually referred to as clinically amyopathic dermatomyositis (CADM). More precisely, it is called hypomyopathic when there is no weakness but ancillary investigations point towards muscle involvement, and amyopathic when ancillary investigations do not show muscle involvement either. Up to 20% of DM patients have CADM. In IBM, clinically observable weakness of skeletal muscles is a requirement for the diagnosis.

Characteristics of the skin

Skin changes can be present in DM, JDM, the anti-synthetase syndrome, overlap myositis and IMNM. Skin involvement is not an obvious feature in IBM.

Skin changes in dermatomyositis

According to the literature, skin changes can be either pathognomonic, characteristic, compatible, less common or nonspecific. As there is doubt as to whether these so-called pathognomonic skin changes are really pathognomonic, the workgroup decided to avoid this terminology and to divide the skin lesions into highly suggestive for the disease or those compatible with the diagnosis based on frequency of occurrence. The predominant abnormal feature of the skin is erythema. Other common findings are edema and hyperkeratotic changes. For the elaboration below, several articles have been used (Czirjak, 2014; DeWane, 2019; Didona, 2020; Bogdanov, 2018; Tanimoto, 1995; Mainetti, 2017; Mammen, 2020).

Most common skin abnormalities at presentation, highly suggestive for dermatomyositis:

- Gottron’s papules*$&@#^: Violaceous or purplish slightly elevated lesions and plaques, overlying the metacarpophalangeal, proximal and distal interphalangeal joints of the hands, sometimes with subtle scale. Figure 3. There is an erythematous background over the bony prominences. Depigmentation, atrophy and scaring can be present when lesions resolve.

- Gottron’s sign*&@#^: Erythematous macules or patches in a linear arrangement over extensor surfaces of the hands and the elbows, knees, and ankles. Slight scale may be present.

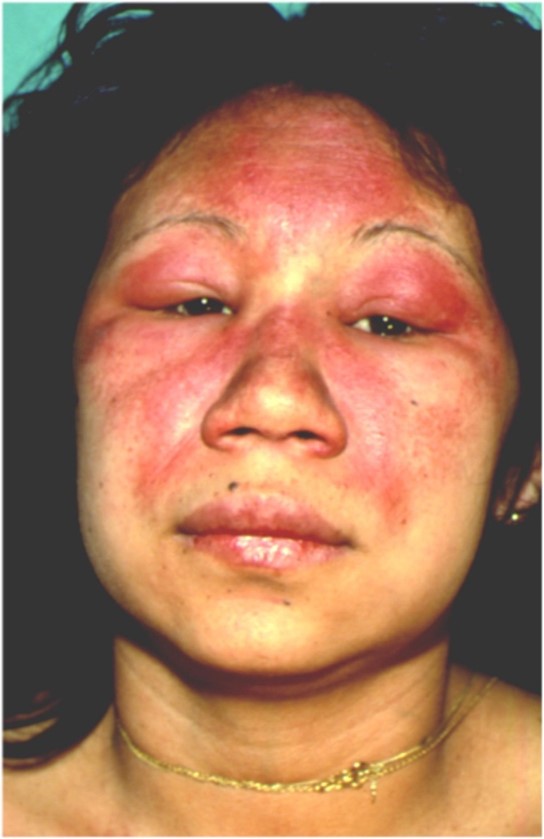

- Heliotrope rash*&$#^: Periorbital edema and erythema, most often of the upper eyelids and symmetrical. Figure 4. The cheeks, nasolabial folds and nose can be involved too.

When two or more of these signs are present, the diagnosis DM can be made (with additional skin biopsy).

Figure 3 Gottron’s papules on interphalangeal and metacarpophalangeal joints

Figure 4: heliotrope erythema of the face, extending to the periorbital region and upper eyelids

Common skin abnormalities compatible with dermatomyositis:

- Periungual changes@: Figure 5. Periungual erythema, edema, telangiectasias, dystrophic cuticles, hemorrhagic nailfold infarcts.

- V-sign$: Erythematous, confluent macules and patches over the lower anterior neck and upper chest. Figure 6. The skin may seem atrophic.

- Shawl sign#: Violaceous or erythematous macules and patches over the back of the shoulders, neck, upper back and possible lateral arms. Poikiloderma (see below for description) may also be present in the same distribution.

- Holster sign: Symmetric poikiloderma of hips and lateral thighs below the trochanter major. Can be reticulated, livedoid, or linear.

- Scalp involvement: Atrophic, erythematous, sometimes pruritic scaly plaques. Alopecia. Mimicking psoriasis or eczema.

Figure 5 Periungual changes

Figure 6 V sign

Less common skin abnormalities compatible with dermatomyositis:

- Vesiculobullous, necrotic or ulcerative lesions*, often associated with cutaneous vasculitis.

- Cutaneous vasculitis%: Petechiae, palpable purpura, livedo reticularis, necrosis, erosions and ulceration.

- Calcinosis cutis%: Superficial bony white papules or nodules, most commonly over bony surfaces or at sites of inflammation, especially elbows, knees and buttocks.

- Poikiloderma (atroficans vasculare)#: Trias of hypo- or hyperpigmentation, telangiectasias, and atrophy, usually found on the upper chest and lateral arms.

- Periorbital swelling and facial swelling: Edema with or without erythema.

Uncommon cutaneous manifestations of dermatomyositis:

- “Mechanic’s hands” *&: Hyperkeratosis, scaling, and fissuring of the lateral parts of the fingers or palms.

- Deck chair sign: Erythematous eruptions sparing transverse skin folds. May be first cutaneous sign preceding classic DM skin findings.

- Panniculitis*: Painful, indurated nodules of buttocks, arms, upper parts of the thighs, and abdomen. Longstanding panniculitis leads to lipodystrophy.

- Flagellate erythema@: Linear erythematous macules and patches on the back.

- Mucinosis: Erythematous papules or plaques, often in a reticular pattern, and scleromyxedema.

- Follicular hyperkeratosis (Wong-type dermatomyositis): Follicular, hyperkeratotic papules on extensor surfaces resembling pityriasis rubra pilaris.

- Erythrodermia: widespread erythema.

- Oral mucosal changes: Variable, but gingival telangiectasias, erosions, ulcers, and leukoplakia-like lesions have been reported, as well as ovoid palatal patches ($)

Common but non-specific abnormalities, compatible with dermatomyositis:

- Raynaud phenomenon: Episodic vasospasm in fingers or toes in response to cold with triphasic color change&

- Palmar hyperkeratosis $

- Psoriasiform plaques $

- Atrophic hypopigmented patches with overlying telangiectasias $

- Painful palmar papules *

- Peripheral oedema ^% D

Note that patients with skin of color will generally show less erythema, or no erythema at all. In a recent case series by Ezeofor (2023) of 14 adults with skin of color, dyschromia was the most prominent cutaneous feature noted (n=8), with patients demonstrating hypopigmentation, hyperpigmentation, and/or poikiloderma. Gottron papules were observed in five patients. Facial erythema was noted in three patients, four had V-neck erythema, and five had a positive shawl sign. Two patients demonstrated a classic heliotrope rash (though subtile), whereas another was found to have periorbital changes described as “hypopigmented patches with telangiectasias, and erythema”.

|

* Often associated with anti-MDA-5 positive dermatomyositis % Rare in adult DM, more common in JDM in association with anti-NXP2 & More common in anti-synthetase syndrome @ More common in Mi2 positive dermatomyositis and antibody negative dermatomyositis $ More common with anti-TIF antibodies # Disproportionately associated with Mi-2 DM in adults ^ Associated with anti-NXP2 associated DM |

Skin changes with other forms of IIM

Skin changes similar to those in DM were reported in a Chinese population with anti-HMGCR IMNM. Out of 21 patients 9 exhibited DM-like skin changes, of which 1 showed a heliotrope rash and 2 showed Gottron’s sign. In the other cases, patients showed erythema and hypo- and hyperpigmentation on their cheeks, limbs, and both sides of the trunk (Hou, 2022). DM-like rashes were also reported in one other Asian populations (Kadoya, 2016)

Skin changes can also be observed in the anti-synthetase syndrome in which mechanic’s hands (Shinoda,2021; Gusdorf, 2019) and Raynaud phenomenon are part of the clinical spectrum (Marguerie, 1990). Describing skin changes of connective tissue disorders/myositis overlap syndromes is beyond the scope of this chapter.

Characteristics of the lungs

Interstitial lung disease (ILD) can present itself rapidly progressive, or following a slowly progressive course, or as an asymptomatic feature. Usual complaints are dyspnea on exertion, (dry) cough, and decreased tolerance to exercise. In DM, muscle disease usually precedes ILD, but this is not always the case. Rapidly progressive ILD is more common in CADM patients, especially in patients with MDA5 antibodies, and is associated with a higher mortality. Additionally, ILD is part of the ASS. In IMNM, ILD is rare and does not normally result in clinical symptoms or signs, and thus has no clinical implications (Allenbach, 2020).

Characteristics of the heart

Myocarditis is a well-known manifestation of IIM with uncertain prevalence. There is limited information on heart involvement in IIM, both due to the rarity of the diseases and because manifest cardiac complications in these patients are uncommon (Cheng, 2022; Fairley, 2021; Opinc, 2021; Zhang, 2012). In most of the literature, cardiac involvement in IIM has been demonstrated by ancillary investigations. Rhythm and conduction abnormalities are the most frequently reported cardiac abnormalities in patients with IIM. Cardiac abnormalities can also present with chest pain, palpitations, congestive heart failure, electrocardiographic or electrophysiologic abnormalities or MRI abnormalities.

Malignancies

Malignancies are found in adult patients with a recent diagnosis of IIM, with a Standardized Incidence Ratio (SIR) varying between 2.0-2.5 (for IIM in general) to 2.0-8.0 (for DM) (Tiniakou & Mammen, 2017). Cancer-associated myositis is defined as a malignancy occurring within 3 years before or after the diagnosis of IIM (Lilleker, 2018; Opinc, 2022; Kaneko, 2020). Associated malignancies can be either solid or hematological. In DM, lung and gastrointestinal tumors have been reported the most, but also ovarian, breast, prostate, kidney and nasopharynx tumors, with differences in prevalence between populations.

Malignancies have been described in 12 patients with JDM only up to date. These were mainly hematological of origin. These patients exhibited splenomegaly, lymphadenopathy or atypical rash (Morris, 2010). Malignancies and IBM or overlap myositis are not associated.

General symptoms and signs

Fever, malaise and weight loss are present in most patients with JDM. They can also be present in adult forms of IIM. Arthralgia, myalgia and fatigue are often mentioned in the presence of IIM, but exact prevalence numbers at case presentation were not found. Myalgia is not an obvious symptom in IBM.

Differential diagnosis

Below a differential diagnosis list for muscular and skin features is given for IIM, JDM or IBM. Please note that these are not comprehensive lists but meant as an aid to facilitate swift diagnosis.

Muscle:

- Subacute, more or less symmetrical proximal muscle weakness

- Metabolic myopathies (hypothyroidism, hypoparathyroidism), sarcoidosis, infectious disorders (e.g. Lyme’s disease, pyomyositis, trichinellosis, toxoplasmosis), toxic (e.g. colchicine myopathy, amiodarone myopathy), sporadic late onset nemaline myopathy, subacute polyradiculopathies, chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy (motor predominant), motor neuron disease, myasthenic syndromes, meningitis carcinomatosa, critical illness myopathy, other types of IIM (for example Graft versus host disease, eosinophilic myositis, immune checkpoint inhibitor associated myositis, CANDLE syndrome (chronic atypical neutrophilic dermatosis with lipodystrophy and elevated temperature).

- Disorders in which proximal muscle weakness may be perceived as recently developed such as limb girdle muscular dystrophies, facioscapulohumeral dystrophy, Pompe disease and others.

- Slowly progressive muscle weakness with predominantly

- Quadriceps involvement: Becker muscular dystrophy, limb girdle muscular dystrophy (anoctamin5, dysferlin), radiculopathies, femoral neuropathy, motor neuron disease, Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome, steroid myopathy

- asymmetric involvement: limb girdle muscular dystrophy (anoctamin5, caveolin, calpain, dysferlin, Duchenne female carriers), VCP/IBM-P-FTD myopathy, facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy, motor neuron disease, multifocal motor neuropathy, plexopathy, radiculopathy, mononeuropathy

- finger flexor involvement: myotonic dystrophy, Becker muscular dystrophy, myofibrillar myopathy, sarcoid myopathy, amyloid myopathy, ACTA1-myopathy, GNE-myopathy, VCP-myopathy, limb girdle muscular dystrophies (dysferlin, LGMD-D3), Pompe’s disease, LAMA2-muscular dystrophy) (Nicolau, 2020).

- weakness of oropharyngeal muscles: oculophayngeal muscular dystrophy, myotonic dystrophy, myasthenia gravis, motor neuron disease, sarcoid myopathy, facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy (Vivekanandam, 2020).

Skin:

Differential diagnosis of cutaneous lesions:

- Gottron’s papules: lichen planus, cutaneous lupus erythematodes, knuckle pads

- Gottron’s sign: psoriasis vulgaris

- Heliotrope erythema can also be mistaken for an (aerogenic) contact dermatitis

- Shawl sign/V-sign: sun burn, phototoxic reaction, photoallergic reaction, more diffuse chronic discoïd lupus erythematodes, foto(recall) dermatitis, radio(recall)dermatitis

- Holster sign: when reticulated or livedoid, it can also match with the diverse diseases that can cause a livoid vasculopathy (e.g., polyarteriitis nodosa, antiphospholipid syndrome)

- Scalp involvement can be misdiagnosed as seborrheic dermatitis, eczema or psoriasis

- Poikiloderma: Civatte poikiloderma (suninduced), radio(recall)dermatitis). Poikiloderma at the thighs and hips can be found in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma or mycosis fungoides.

- Periorbital oedema and facial swelling can be found in for example angioeodema or morbus Morbihan.

- The differential diagnosis of vasculitis is very broad.

- Calcinosis cutis can for example also be found in more sclerodermiformic dermatosis as an (post)inflammatory sign.

- Mechanic’s hands: (rhagadiform) hand eczema, keratoderma (also paraneoplastic), Bazex syndrome

- Flagellate erythema can be present in adult-onset Still’s disease, bleomycin-induced dermatitis, and shiitake dermatitis.

- Deck chair sign can also be found in Sezary’s syndrome (a form of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma)

- Folliculair hyperkeratosis can be found in pityriasis rubra pilaris, lichen spinulosis, follicular lichen planus or keratosis pilaris, however, it could also be a sign of folliculotropic mycosis fungoides

- The differential diagnosis of panniculitis is very broad.

- Erythroderma is very unspecific and can be observed in in a wide varity of dermatosis.

- The oral mucosal changes are very broad and the differential diagnosis falls beyond the scope of this guideline.

In children consider CANDLE and SAVI (STING-Associated Vasculopathy with onset in infancy) syndrome.

Zoeken en selecteren

To answer the clinical question, an exploratory search was conducted into the symptoms and signs of IIM, including JDM and IBM. These signs and symptoms result from the history and findings of physical (including neurological) examinations.

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched exploratory using relevant search terms until July 21st, 2021. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The exploratory literature search resulted in 699 hits. Systematic reviews and guidelines were assessed for usability, resulting in a first selection of 18 articles for full text assessment. After reading the full text, none of the articles were included due to limited description of individual clinical signs or symptoms. A table with reasons for exclusion is presented under the heading Evidence tables.

Results

Based on our review of the literature, the diagnostic value of distinct clinical features or patterns of disease presentation was not found to have been investigated systematically. Instead, a description of the most frequent and characteristic signs and disease patterns is given for IIM, including JDM and IBM, in particular those items that could discriminate between the different subtypes. The presence of these signs or patterns should aid the clinician to suspect one of the subtypes of the above-mentioned disorders. However, the suspicion on one or the other cannot be made without knowledge about the likelihood of the disorder based on age (at onset), incidence or prevalence in the population. The sequence in which signs of a disease present themselves and progress can vary between individuals.

Referenties

- Allenbach Y, Benveniste O, Stenzel W, Boyer O. Immune-mediated necrotizing myopathy: clinical features and pathogenesis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2020 Dec;16(12):689-701. doi: 10.1038/s41584-020-00515-9. Epub 2020 Oct 22. PMID: 33093664.

- Bogdanov I, Kazandjieva J, Darlenski R, Tsankov N. Dermatomyositis: Current concepts. Clin Dermatol. 2018 Jul-Aug;36(4):450-458. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2018.04.003. Epub 2018 Apr 12. PMID: 30047429.

- Cheng CY, Baritussio A, Giordani AS, Iliceto S, Marcolongo R, Caforio ALP. Myocarditis in systemic immune-mediated diseases: Prevalence, characteristics and prognosis. A systematic review. Autoimmun Rev. 2022 Apr;21(4):103037. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2022.103037. Epub 2022 Jan 5. PMID: 34995763.

- Czirják L, Kálmán E. Skin manifestation in dermatomyositis. In: Matucci-Cerinic M, Furst D, Fiorentino D, eds. Skin Manifestations in Rheumatic Disease. New York, NY: Springer; 2014. p. 231-238.

- DeWane ME, Waldman R, Lu J. Dermatomyositis: Clinical features and pathogenesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020 Feb;82(2):267-281. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.06.1309. Epub 2019 Jul 4. PMID: 31279808.

- Didona D, Juratli HA, Scarsella L, Eming R, Hertl M. The polymorphous spectrum of dermatomyositis: classic features, newly described skin lesions, and rare variants. Eur J Dermatol. 2020;30(3):229-242. doi:10.1684/ejd.2020.3761

- Ezeofor AJ, O'Connell KA, Cobos GA, Vleugels RA, LaChance AH, Nambudiri VE. Distinctive cutaneous features of dermatomyositis in Black adults: A case series. JAAD Case Rep. 2023 May 22;37:106-109. doi: 10.1016/j.jdcr.2023.05.019. PMID: 37396484; PMCID: PMC10314225.

- Fairley JL, Wicks I, Peters S, Day J. Defining cardiac involvement in idiopathic inflammatory myopathies: a systematic review. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2021 Dec 24;61(1):103-120. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keab573. PMID: 34273157.

- Gusdorf L, Morruzzi C, Goetz J, Lipsker D, Sibilia J, Cribier B. Mechanics hands in patients with antisynthetase syndrome: 25 cases. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2019 Jan;146(1):19-25. doi: 10.1016/j.annder.2018.11.010. Epub 2018 Dec 28. PMID: 30595338.

- Hou Y, Shao K, Yan Y, Dai T, Li W, Zhao Y, Li D, Lu JQ, Norman GL, Yan C. Anti-HMGCR myopathy overlaps with dermatomyositis-like rash: a distinct subtype of idiopathic inflammatory myopathy. J Neurol. 2022 Jan;269(1):280-293. doi: 10.1007/s00415-021-10621-7. Epub 2021 May 21. PMID: 34021410.

- Kadoya M, Hida A, Hashimoto Maeda M, Taira K, Ikenaga C, Uchio N, Kubota A, Kaida K, Miwa Y, Kurasawa K, Shimada H, Sonoo M, Chiba A, Shiio Y, Uesaka Y, Sakurai Y, Izumi T, Inoue M, Kwak S, Tsuji S, Shimizu J. Cancer association as a risk factor for anti-HMGCR antibody-positive myopathy. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2016 Oct 7;3(6):e290. doi: 10.1212/NXI.0000000000000290. PMID: 27761483; PMCID: PMC5056647.

- Kaneko Y, Nunokawa T, Taniguchi Y, Yamaguchi Y, Gono T, Masui K, Kawakami A, Kawaguchi Y, Sato S, Kuwana M; JAMI investigators. Clinical characteristics of cancer-associated myositis complicated by interstitial lung disease: a large-scale multicentre cohort study. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2020 Jan 1;59(1):112-119. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kez238. PMID: 31382295.

- Lilleker JB, Vencovsky J, Wang G, Wedderburn LR, Diederichsen LP, Schmidt J, Oakley P, Benveniste O, Danieli MG, Danko K, Thuy NTP, Vazquez-Del Mercado M, Andersson H, De Paepe B, deBleecker JL, Maurer B, McCann LJ, Pipitone N, McHugh N, Betteridge ZE, New P, Cooper RG, Ollier WE, Lamb JA, Krogh NS, Lundberg IE, Chinoy H; all EuroMyositis contributors. The EuroMyositis registry: an international collaborative tool to facilitate myositis research. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018 Jan;77(1):30-39. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-211868. Epub 2017 Aug 30. PMID: 28855174; PMCID: PMC5754739.

- Mainetti C, Terziroli Beretta-Piccoli B, Selmi C. Cutaneous Manifestations of Dermatomyositis: a Comprehensive Review. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2017 Dec;53(3):337-356. doi: 10.1007/s12016-017-8652-1. PMID: 29090371.

- Mammen AL, Allenbach Y, Stenzel W, Benveniste O; ENMC 239th Workshop Study Group. 239th ENMC International Workshop: Classification of dermatomyositis, Amsterdam, the Netherlands, 14-16 December 2018. Neuromuscul Disord. 2020 Jan;30(1):70-92. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2019.10.005. Epub 2019 Oct 25. PMID: 31791867.

- Marguerie C, Bunn CC, Beynon HL, Bernstein RM, Hughes JM, So AK, Walport MJ. Polymyositis, pulmonary fibrosis and autoantibodies to aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase enzymes. Q J Med. 1990 Oct;77(282):1019-38. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/77.1.1019. PMID: 2267280.

- Morris P, Dare J. Juvenile dermatomyositis as a paraneoplastic phenomenon: an update. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2010 Apr;32(3):189-91. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0b013e3181bf29a2. PMID: 20057323.

- Nicolau S, Liewluck T, Milone M. Myopathies with finger flexor weakness: Not only inclusion-body myositis. Muscle Nerve. 2020 Oct;62(4):445-454. doi: 10.1002/mus.26914. Epub 2020 Jun 1. PMID: 32478919.

- Opinc AH, Makowski MA, ?ukasik ZM, Makowska JS. Cardiovascular complications in patients with idiopathic inflammatory myopathies: does heart matter in idiopathic inflammatory myopathies? Heart Fail Rev. 2021 Jan;26(1):111-125. doi: 10.1007/s10741-019-09909-8. PMID: 31867681.

- Opinc AH, Makowska JS. Update on Malignancy in Myositis-Well-Established Association with Unmet Needs. Biomolecules. 2022 Jan 11;12(1):111. doi: 10.3390/biom12010111. PMID: 35053259; PMCID: PMC8773676.

- Rose MR; ENMC IBM Working Group. 188th ENMC International Workshop: Inclusion Body Myositis, 2-4 December 2011, Naarden, The Netherlands. Neuromuscul Disord. 2013 Dec;23(12):1044-55. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2013.08.007. Epub 2013 Aug 30. PMID: 24268584.

- Shinoda K, Hamaguchi Y, Tobe K. Widespread Mechanic's Hands in Antisynthetase Syndrome With Anti-OJ Antibody. J Rheumatol. 2021 Aug;48(8):1341. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.201043. Epub 2021 Jun 15. PMID: 34329180.

- Tanimoto K, Nakano K, Kano S, Mori S, Ueki H, Nishitani H, Sato T, Kiuchi T, Ohashi Y. Classification criteria for polymyositis and dermatomyositis. J Rheumatol. 1995 Apr;22(4):668-74. Erratum in: J Rheumatol 1995 Sep;22(9):1807. PMID: 7791161.

- Tiniakou E, Mammen AL. Idiopathic Inflammatory Myopathies and Malignancy: a Comprehensive Review. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2017 Feb;52(1):20-33. doi: 10.1007/s12016-015-8511-x. PMID: 26429706.

- Vivekanandam V, Bugiardini E, Merve A, Parton M, Morrow JM, Hanna MG, Machado PM. Differential Diagnoses of Inclusion Body Myositis. Neurol Clin. 2020 Aug;38(3):697-710. doi: 10.1016/j.ncl.2020.03.014. PMID: 32703477.

- Voermans NC, Vaneker M, Hengstman GJ, ter Laak HJ, Zimmerman C, Schelhaas HJ, Zwarts MJ. Primary respiratory failure in inclusion body myositis. Neurology. 2004 Dec 14;63(11):2191-2. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000145834.17020.86. PMID: 15596785.

- Zhang L, Wang GC, Ma L, Zu N. Cardiac involvement in adult polymyositis or dermatomyositis: a systematic review. Clin Cardiol. 2012 Nov;35(11):686-91. doi: 10.1002/clc.22026. Epub 2012 Jul 30. PMID: 22847365; PMCID: PMC6652370.

Evidence tabellen

Exclusietabel

|

Auteur en jaartal |

Redenen van exclusie |

|

Allenbach, 2020. doi: 10.1038/s41584-020-00515-9. |

Did not investigate or describe the diagnostic value of signs or symptoms |

|

Bradley, 2021. doi: 10.1111/pde.14510 |

|

|

Chung, 2021. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2021.62.5.424. |

|

|

DeWane, 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.06.1309. |

|

|

Didona, 2020. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2020.3761. |

|

|

Greenberg, 2019. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41584-019-0186-x |

|

|

Kaneko, 2020. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/kez238 |

|

|

Kostine, 2020. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-217139. |

|

|

Lundberg, 2017. doi:10.1002/art.40320. |

|

|

Muro, 2016. doi:10.1007/s12016-015-8496-5 |

|

|

Nuno-Nuno, 2019. doi: 10.1111/1756-185X.13559 |

|

|

Okiyama, 2021. doi: 10.3390/jcm10081725. |

|

|

Oldroyd, 2020. doi: 10.1002/mus.26859 |

|

|

Opinc, 2019. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10741-019-09909-8 |

|

|

Opinc, 2021. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2020.09.020. |

|

|

Sun, 2021. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2020.11.009. |

|

|

Wong, 2020. doi: 10.1111/ane.13331 |

|

|

Wu, 2020. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12519-019-00313-8 |

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Publicatiedatum : 07-02-2024

Beoordeeld op geldigheid : 07-02-2024

Algemene gegevens

The development of this guideline module was supported by the Knowledge Institute of the Federation of Medical Specialists (www.demedischspecialist.nl/ kennisinstituut) and was financed from the Quality Funds for Medical Specialists (SKMS). The financier has had no influence whatsoever on the content of the guideline module.

Samenstelling werkgroep

A multidisciplinary working group was set up in 2020 for the development of the guideline module, consisting of representatives of all relevant specialisms and patient organisations (see the Composition of the working group) involved in the care of patients with IIM/myositis.

Working group

- Dr. A.J. van der Kooi, neurologist, Amsterdam UMC, location AMC. Nederlandse Vereniging voor Neurologie (chair)

- Dr. U.A. Badrising, neurologist, LUMC. Nederlandse Vereniging voor Neurologie

- Dr. C.G.J. Saris, neurologist, Radboudumc. Nederlandse Vereniging voor Neurologie

- Dr. S. Lassche, neurologist, Zuyderland MC. Nederlandse Vereniging voor Neurologie

- Dr. J. Raaphorst, neurologist, Amsterdam UMC, locatie AMC. Nederlandse Vereniging voor Neurologie

- Dr. J.E. Hoogendijk, neurologist, UMC Utrecht. Nederlandse Vereniging voor Neurologie

- Drs. T.B.G. Olde Dubbelink, neurologist, Rijnstate, Nederlandse Vereniging voor Neurologie

- Dr. I.L. Meek, rheumatologist, Radboudumc. Nederlandse Vereniging voor Reumatologie

- Dr. R.C. Padmos, rheumatologist, Erasmus MC. Nederlandse Vereniging voor Reumatologie

- Prof. dr. E.M.G.J. de Jong, dermatologist, werkzaam in het Radboudumc. Nederlandse Vereniging voor Dermatologie en Venereologie

- Drs. W.R. Veldkamp, dermatologist, Ziekenhuis Gelderse Vallei. Nederlandse Vereniging voor Dermatologie en Venereologie

- Dr. J.M. van den Berg, pediatrician, Amsterdam UMC, locatie AMC. Nederlandse Vereniging voor Kindergeneeskunde

- Dr. M.H.A. Jansen, pediatrician, UMC Utrecht. Nederlandse Vereniging voor Kindergeneeskunde

- Dr. A.C. van Groenestijn, rehabilitation physician, Amsterdam UMC, locatie AMC. Nederlandse Vereniging van Revalidatieartsen

- Dr. B. Küsters, pathologist, Radboudumc. Nederlandse Vereniging voor Pathologie

- Dr. V.A.S.H. Dalm, internist, Erasmus MC. Nederlandse Internisten Vereniging

- Drs. J.R. Miedema, pulmonologist, Erasmus MC. Nederlandse Vereniging van Artsen voor Longziekten en Tuberculose

- I. de Groot, patient representatieve. Spierziekten Nederland

Advisory board

- Prof. dr. E. Aronica, pathologist, Amsterdam UMC, locatie AMC. External expert.

- Prof. dr. D. Hamann, Laboratory specialist medical immunology, UMC Utrecht. External expert.

- Drs. R.N.P.M. Rinkel, ENT physician, Amsterdam UMC, locatie VUmc. Vereniging voor Keel-Neus-Oorheelkunde en Heelkunde van het Hoofd-Halsgebied

- dr. A.S. Amin, cardiologist, werkzaam in werkzaam in het Amsterdam UMC, locatie AMC. Nederlandse Vereniging voor Cardiologie

- dr. A. van Royen-Kerkhof, pediatrician, UMC Utrecht. External expert.

- dr. L.W.J. Baijens, ENT physician, Maastricht UMC+. External expert.

- Em. Prof. Dr. M. de Visser, neurologist, Amsterdam UMC. External expert.

Methodological support

- Drs. T. Lamberts, senior advisor, Knowledge institute of the Federation of Medical Specialists

- Drs. M. Griekspoor, advisor, Knowledge institute of the Federation of Medical Specialists

- Dr. M. M. J. van Rooijen, advisor, Knowledge institute of the Federation of Medical Specialists

Belangenverklaringen

The ‘Code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling’ has been followed. All working group members have declared in writing whether they have had direct financial interests (attribution with a commercial company, personal financial interests, research funding) or indirect interests (personal relationships, reputation management) in the past three years. During the development or revision of a module, changes in interests are communicated to the chairperson. The declaration of interest is reconfirmed during the comment phase.

An overview of the interests of working group members and the opinion on how to deal with any interests can be found in the table below. The signed declarations of interest can be requested from the secretariat of the Knowledge Institute of the Federation of Medical Specialists.

|

Werkgroeplid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

van der Kooi |

Neuroloog, Amsterdam UMC |

|

Immediate studie (investigator initiated, IVIg behandeling bij therapie naive patienten). --> Financiering via Behring. Studie januari 2019 afgerond |

Geen restricties (middel bij advisory board is geen onderdeel van rcihtlijn) |

|

Miedema |

Longarts, Erasmus MC |

Geen. |

|

Geen restricties |

|

Meek |

Afdelingshoofd a.i. afdeling reumatische ziekten, Radboudumc |

Commissaris kwaliteit bestuur Nederlandse Vereniging voor Reumatologie (onkostenvergoeding) |

Medisch adviseur myositis werkgroep spierziekten Nederland |

Geen restricties |

|

Veldkamp |

AIOS dermatologie Radboudumc Nijmegen |

|

Geen. |

Geen restricties |

|

Padmos |

Reumatoloog, Erasmus MC |

Docent Breederode Hogeschool (afdeling reumatologie EMC wordt hiervoor betaald) |

Geen. |

Geen restricties |

|

Dalm |

Internist-klinisch immunoloog Erasmus MC |

Geen. |

Geen. |

Geen restricties |

|

Olde Dubbelink |

Neuroloog in opleiding Canisius-Wilhelmina Ziekenhuis, Nijmegen |

Promotie onderzoek naar diagnostiek en outcome van het carpaletunnelsyndroom (onbetaald) |

Geen. |

Geen restricties |

|

van Groenestijn |

Revalidatiearts AmsterdamUMC, locatie AMC |

Geen. |

Lokale onderzoeker voor de I'M FINE studie (multicentre, leiding door afdeling Revalidatie Amsterdam UMC, samen met UMC Utrecht, Sint Maartenskliniek, Klimmendaal en Merem. Evaluatie van geïndividualiseerd beweegprogramma o.b.v. combinatie van aerobe training en coaching bij mensen met neuromusculaire aandoeningen, NMA). Activiteiten: screening NMA-patiënten die willen participeren aan deze studie. Subsidie van het Prinses Beatrix Spierfonds. |

Geen restricties |

|

Lassche |

Neuroloog, Zuyderland Medisch Centrum, Heerlen en Sittard-Geleen |

Geen. |

Geen. |

Geen restricties |

|

de Jong |

Dermatoloog, afdelingshoofd Dermatologie Radboudumc Nijmegen |

Geen. |

All funding is not personal but goes to the independent research fund of the department of dermatology of Radboud university medical centre Nijmegen, the Netherlands |

Geen restricties |

|

Hoogendijk |

Neuroloog Universitair Medisch Centrum Utrecht (0,4) Neuroloog Sionsberg, Dokkum (0,6) |

beide onbetaald |

Geen. |

Geen restricties |

|

Badrising |

Neuroloog Leids Universitair Medisch Centrum |

(U.A.Badrising Neuroloog b.v.: hoofdbestuurder; betreft een vrijwel slapende b.v. als overblijfsel van mijn eerdere praktijk in de maatschap neurologie Dirksland, Het van Weel-Bethesda Ziekenhuis) |

Medisch adviseur myositis werkgroep spierziekten Nederland |

Geen restricties |

|

van den Berg |

Kinderarts-reumatoloog/-immunoloog Emma kinderziekenhuis/ Amsterdam UMC |

Geen. |

Geen. |

Geen restricties |

|

de Groot |

Patiënt vertegenwoordiger/ ervaringsdeskundige: voorzitter diagnosewerkgroep myositis bij Spierziekten Nederland in deze commissie patiënt(vertegenwoordiger) |

|

Geen |

Geen restricties |

|

Küsters |

Patholoog, Radboud UMC |

Geen. |

Geen. |

Geen restricties |

|

Saris |

Neuroloog/ klinisch neurofysioloog, Radboudumc |

Geen. |

Geen. |

Geen restricties |

|

Raaphorst |

Neuroloog, Amsterdam UMC |

Geen. |

|

Restricties m.b.t. opstellen aanbevelingen IvIg behandeling. |

|

Jansen |

Kinderarts-immunoloog-reumatoloog, WKZ UMC Utrecht |

Docent bij Mijs-instituut (betaald) |

Onderzoek biomakers in juveniele dermatomyositis. Geen belang bij uitkomst richtlijn. |

Geen restricties |

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Attention was paid to the patient's perspective by offering the Vereniging Spierziekten Nederland to take part in the working group. Vereniging Spierziekten Nederland has made use of this offer, the Dutch Artritis Society has waived it. In addition, an invitational conference was held to which the Vereniging Spierziekten Nederland, the Dutch Artritis Society nd Patiëntenfederatie Nederland were invited and the patient's perspective was discussed. The report of this meeting was discussed in the working group. The input obtained was included in the formulation of the clinical questions, the choice of outcome measures and the considerations. The draft guideline was also submitted for comment to the Vereniging Spierziekten Nederland, the Dutch Artritis Society and Patiëntenfederatie Nederland, and any comments submitted were reviewed and processed.

Qualitative estimate of possible financial consequences in the context of the Wkkgz

In accordance with the Healthcare Quality, Complaints and Disputes Act (Wet Kwaliteit, klachten en geschillen Zorg, Wkkgz), a qualitative estimate has been made for the guideline as to whether the recommendations may lead to substantial financial consequences. In conducting this assessment, guideline modules were tested in various domains (see the flowchart on the Guideline Database).

The qualitative estimate shows that there are probably no substantial financial consequences, see table below.

|

Module |

Estimate |

Explanation |

|

Module diagnostische waarde ziekteverschijnselen |

No substantial financial consequences |

Outcome 1 No financial consequences. The recommendations are not widely applicable (<5,000 patients) and are therefore not expected to have any substantial financial consequences on collective expenditures. |

|

Module Optimale strategie aanvullende diagnostiek myositis |

No substantial financial consequences |

Outcome 1 No financial consequences. The recommendations are not widely applicable (<5,000 patients) and are therefore not expected to have any substantial financial consequences on collective expenditures. |

|

Module Autoantibody testing in myositis |

No substantial financial consequences |

Outcome 1 No financial consequences. The recommendations are not widely applicable (<5,000 patients) and are therefore not expected to have any substantial financial consequences on collective expenditures. |

|

Module Screening op maligniteiten |

No substantial financial consequences |

Outcome 1 No financial consequences. The recommendations are not widely applicable (<5,000 patients) and are therefore not expected to have any substantial financial consequences on collective expenditures. |

|

Module Screening op comorbiditeiten |

No substantial financial consequences |

Outcome 1 No financial consequences. The recommendations are not widely applicable (<5,000 patients) and are therefore not expected to have any substantial financial consequences on collective expenditures. |

|

Module Immunosuppressie en -modulatie bij IBM |

No substantial financial consequences |

Outcome 1 No financial consequences. The recommendations are not widely applicable (<5,000 patients) and are therefore not expected to have any substantial financial consequences on collective expenditures. |

|

Module Treatment with Physical training |

No substantial financial consequences |

Outcome 1 No financial consequences. The recommendations are not widely applicable (<5,000 patients) and are therefore not expected to have any substantial financial consequences on collective expenditures. |

|

Module Treatment of dysphagia in myositis |

No substantial financial consequences |

Outcome 1 No financial consequences. The recommendations are not widely applicable (<5,000 patients) and are therefore not expected to have any substantial financial consequences on collective expenditures. |

|

Module Treatment of dysphagia in IBM |

No substantial financial consequences |

Outcome 1 No financial consequences. The recommendations are not widely applicable (<5,000 patients) and are therefore not expected to have any substantial financial consequences on collective expenditures. |

|

Module Topical therapy |

No substantial financial consequences |

Outcome 1 No financial consequences. The recommendations are not widely applicable (<5,000 patients) and are therefore not expected to have any substantial financial consequences on collective expenditures. |

|

Module Treatment of calcinosis |

No substantial financial consequences |

Outcome 1 No financial consequences. The recommendations are not widely applicable (<5,000 patients) and are therefore not expected to have any substantial financial consequences on collective expenditures. |

|

Module Organization of care |

No substantial financial consequences |

Outcome 1 No financial consequences. The recommendations are not widely applicable (<5,000 patients) and are therefore not expected to have any substantial financial consequences on collective expenditures. |

Werkwijze

Methods

AGREE

This guideline module has been drawn up in accordance with the requirements stated in the Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 report of the Advisory Committee on Guidelines of the Quality Council. This report is based on the AGREE II instrument (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II; Brouwers, 2010).

Clinical questions

During the preparatory phase, the working group inventoried the bottlenecks in the care of patients with IIM. Bottlenecks were also put forward by the parties involved via an invitational conference. A report of this is included under related products.

Based on the results of the bottleneck analysis, the working group drew up and finalized draft basic questions.

Outcome measures

After formulating the search question associated with the clinical question, the working group inventoried which outcome measures are relevant to the patient, looking at both desired and undesired effects. A maximum of eight outcome measures were used. The working group rated these outcome measures according to their relative importance in decision-making regarding recommendations, as critical (critical to decision-making), important (but not critical), and unimportant. The working group also defined at least for the crucial outcome measures which differences they considered clinically (patient) relevant.

Methods used in the literature analyses

A detailed description of the literature search and selection strategy and the assessment of the risk-of-bias of the individual studies can be found under 'Search and selection' under Substantiation. The assessment of the strength of the scientific evidence is explained below.

Assessment of the level of scientific evidence

The strength of the scientific evidence was determined according to the GRADE method. GRADE stands for Grading Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (see http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/). The basic principles of the GRADE methodology are: naming and prioritizing the clinically (patient) relevant outcome measures, a systematic review per outcome measure, and an assessment of the strength of evidence per outcome measure based on the eight GRADE domains (downgrading domains: risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision, and publication bias; domains for upgrading: dose-effect relationship, large effect, and residual plausible confounding).

GRADE distinguishes four grades for the quality of scientific evidence: high, fair, low and very low. These degrees refer to the degree of certainty that exists about the literature conclusion, in particular the degree of certainty that the literature conclusion adequately supports the recommendation (Schünemann, 2013; Hultcrantz, 2017).

|

Definitie |

|

|

High |

|

|

Moderate |

|

|

Low |

|

|

Very low |

|

When assessing (grading) the strength of the scientific evidence in guidelines according to the GRADE methodology, limits for clinical decision-making play an important role (Hultcrantz, 2017). These are the limits that, if exceeded, would lead to an adjustment of the recommendation. To set limits for clinical decision-making, all relevant outcome measures and considerations should be considered. The boundaries for clinical decision-making are therefore not directly comparable with the minimal clinically important difference (MCID). Particularly in situations where an intervention has no significant drawbacks and the costs are relatively low, the threshold for clinical decision-making regarding the effectiveness of the intervention may lie at a lower value (closer to zero effect) than the MCID (Hultcrantz, 2017).

Considerations

In addition to (the quality of) the scientific evidence, other aspects are also important in arriving at a recommendation and are taken into account, such as additional arguments from, for example, biomechanics or physiology, values and preferences of patients, costs (resource requirements), acceptability, feasibility and implementation. These aspects are systematically listed and assessed (weighted) under the heading 'Considerations' and may be (partly) based on expert opinion. A structured format based on the evidence-to-decision framework of the international GRADE Working Group was used (Alonso-Coello, 2016a; Alonso-Coello 2016b). This evidence-to-decision framework is an integral part of the GRADE methodology.

Formulation of conclusions

The recommendations answer the clinical question and are based on the available scientific evidence, the most important considerations, and a weighting of the favorable and unfavorable effects of the relevant interventions. The strength of the scientific evidence and the weight assigned to the considerations by the working group together determine the strength of the recommendation. In accordance with the GRADE method, a low evidential value of conclusions in the systematic literature analysis does not preclude a strong recommendation a priori, and weak recommendations are also possible with a high evidential value (Agoritsas, 2017; Neumann, 2016). The strength of the recommendation is always determined by weighing all relevant arguments together. The working group has included with each recommendation how they arrived at the direction and strength of the recommendation.

The GRADE methodology distinguishes between strong and weak (or conditional) recommendations. The strength of a recommendation refers to the degree of certainty that the benefits of the intervention outweigh the harms (or vice versa) across the spectrum of patients targeted by the recommendation. The strength of a recommendation has clear implications for patients, practitioners and policy makers (see table below). A recommendation is not a dictate, even a strong recommendation based on high quality evidence (GRADE grading HIGH) will not always apply, under all possible circumstances and for each individual patient.

|

Implications of strong and weak recommendations for guideline users |

||

|

|

||

|

|

Strong recommendation |

Weak recommendations |

|

For patients |

Most patients would choose the recommended intervention or approach and only a small number would not. |

A significant proportion of patients would choose the recommended intervention or approach, but many patients would not. |

|

For practitioners |

Most patients should receive the recommended intervention or approach. |

There are several suitable interventions or approaches. The patient should be supported in choosing the intervention or approach that best reflects his or her values and preferences. |

|

For policy makers |

The recommended intervention or approach can be seen as standard policy. |

Policy-making requires extensive discussion involving many stakeholders. There is a greater likelihood of local policy differences. |

Organization of care

In the bottleneck analysis and in the development of the guideline module, explicit attention was paid to the organization of care: all aspects that are preconditions for providing care (such as coordination, communication, (financial) resources, manpower and infrastructure). Preconditions that are relevant for answering this specific initial question are mentioned in the considerations. More general, overarching or additional aspects of the organization of care are dealt with in the module Organization of care.

Commentary and authtorisation phase

The draft guideline module was submitted to the involved (scientific) associations and (patient) organizations for comment. The comments were collected and discussed with the working group. In response to the comments, the draft guideline module was modified and finalized by the working group. The final guideline module was submitted to the participating (scientific) associations and (patient) organizations for authorization and authorized or approved by them.

References

Agoritsas T, Merglen A, Heen AF, Kristiansen A, Neumann I, Brito JP, Brignardello-Petersen R, Alexander PE, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Guyatt GH. UpToDate adherence to GRADE criteria for strong recommendations: an analytical survey. BMJ Open. 2017 Nov 16;7(11):e018593. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018593. PubMed PMID: 29150475; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5701989.

Alonso-Coello P, Schünemann HJ, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Rada G, Rosenbaum S, Morelli A, Guyatt GH, Oxman AD; GRADE Working Group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 1: Introduction. BMJ. 2016 Jun 28;353:i2016. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2016. PubMed PMID: 27353417.

Alonso-Coello P, Oxman AD, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Vandvik PO, Meerpohl J, Guyatt GH, Schünemann HJ; GRADE Working Group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 2: Clinical practice guidelines. BMJ. 2016 Jun 30;353:i2089. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2089. PubMed PMID: 27365494.

Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, Burgers JS, Cluzeau F, Feder G, Fervers B, Graham ID, Grimshaw J, Hanna SE, Littlejohns P, Makarski J, Zitzelsberger L; AGREE Next Steps Consortium. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. CMAJ. 2010 Dec 14;182(18):E839-42. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090449. Epub 2010 Jul 5. Review. PubMed PMID: 20603348; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3001530.

Hultcrantz M, Rind D, Akl EA, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Iorio A, Alper BS, Meerpohl JJ, Murad MH, Ansari MT, Katikireddi SV, Östlund P, Tranæus S, Christensen R, Gartlehner G, Brozek J, Izcovich A, Schünemann H, Guyatt G. The GRADE Working Group clarifies the construct of certainty of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017 Jul;87:4-13. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.05.006. Epub 2017 May 18. PubMed PMID: 28529184; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC6542664.

Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 (2012). Adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwaliteit. http://richtlijnendatabase.nl/over_deze_site/over_richtlijnontwikkeling.html

Neumann I, Santesso N, Akl EA, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Alonso-Coello P, Agoritsas T, Mustafa RA, Alexander PE, Schünemann H, Guyatt GH. A guide for health professionals to interpret and use recommendations in guidelines developed with the GRADE approach. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016 Apr;72:45-55. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.11.017. Epub 2016 Jan 6. Review. PubMed PMID: 26772609.

Schünemann H, Brożek J, Guyatt G, . GRADE handbook for grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. Updated October 2013. The GRADE Working Group, 2013. Available from http://gdt.guidelinedevelopment.org/central_prod/_design/client/handbook/handbook.html.

Zoekverantwoording

Zoekverantwoording

Algemene informatie

|

Richtlijn: NVN Myositis |

|

|

Uitgangsvraag: UV1 oriënterende vraag diagnostische waarde |

|

|

Database(s): Ovid/Medline, Embase |

Datum: 21-7-2021 |

|

Periode: 2015- |

Talen: nvt |

|

Literatuurspecialist: Ingeborg van Dusseldorp |

|

|

BMI zoekblokken: voor verschillende opdrachten wordt (deels) gebruik gemaakt van de zoekblokken van BMI-Online https://blocks.bmi-online.nl/ Bij gebruikmaking van een volledig zoekblok zal naar de betreffende link op de website worden verwezen. |

|

Zoekopbrengst

|

|

EMBASE |

OVID/MEDLINE |

Ontdubbeld |

|

SRs |

192 |

616 |

625 |

|

Guidelines |

33 |

33 |

39 |

|

Clinical features |

45 |

|

35 |

|

Overig |

|

|

|

|

Totaal |

|

|

699 |

Zoekstrategie

Embase

|

No. |

Query |

Results |

|

#19 |

#12 AND #18 |

1 |

|

#18 |

#17 AND (1-1-2015)/sd NOT ('conference abstract'/it OR 'editorial'/it OR 'letter'/it OR 'note'/it) NOT (('animal experiment'/exp OR 'animal model'/exp OR 'nonhuman'/exp) NOT 'human'/exp) Clinical features |

45 |

|

#17 |

#1 AND #15 AND #16 |

98 |

|

#16 |

'meta analysis'/exp OR 'review'/de OR 'meta analysis (topic)'/exp OR metaanaly*:ti,ab OR 'meta analy*':ti,ab OR metanaly*:ti,ab OR 'systematic review'/de OR 'cochrane database of systematic reviews'/jt OR prisma:ti,ab OR prospero:ti,ab OR (((systemati* OR scoping OR umbrella OR 'structured literature') NEAR/3 (review* OR overview*)):ti,ab) OR ((systemic* NEAR/1 review*):ti,ab) OR (((systemati* OR literature OR database* OR 'data base*') NEAR/10 search*):ti,ab) OR (((structured OR comprehensive* OR systemic*) NEAR/3 search*):ti,ab) OR (((literature NEAR/3 review*):ti,ab) AND (search*:ti,ab OR database*:ti,ab OR 'data base*':ti,ab)) OR (('data extraction':ti,ab OR 'data source*':ti,ab) AND 'study selection':ti,ab) OR ('search strategy':ti,ab AND 'selection criteria':ti,ab) OR ('data source*':ti,ab AND 'data synthesis':ti,ab) OR medline:ab OR pubmed:ab OR embase:ab OR cochrane:ab OR (((critical OR rapid) NEAR/2 (review* OR overview* OR synthes*)):ti) OR ((((critical* OR rapid*) NEAR/3 (review* OR overview* OR synthes*)):ab) AND (search*:ab OR database*:ab OR 'data base*':ab)) OR metasynthes*:ti,ab OR 'meta synthes*':ti,ab OR review:ti,ab,kw |

4200601 |

|

#15 |

'clinical feature'/exp/mj OR 'clinical feature*':ti |

49016 |

|

#14 |

#3 AND #12 |

6 |

|

#13 |

#6 AND #12 |

0 |

|

#12 |

inclusion AND body AND myositis AND clinical AND features AND pathogenesis AND greenberg |

6 |

|

#11 |

#10 AND (1-1-2015)/sd NOT ('conference abstract'/it OR 'editorial'/it OR 'letter'/it OR 'note'/it) NOT (('animal experiment'/exp OR 'animal model'/exp OR 'nonhuman'/exp) NOT 'human'/exp) NOT 'intensive care unit'/exp |

20 |

|

#10 |

#1 AND #2 AND #9 Guidelines |

33 |

|

#9 |

'practice guideline'/exp/mj |

103343 |

|

#8 |

#6 AND #7 |

0 |

|

#7 |

neurological AND toxicities AND following AND the AND use AND of AND different AND immune AND checkpoint AND inhibitor AND regimens AND in AND solid AND tumors |

1 |

|

#6 |

#5 AND (1-1-2015)/sd NOT ('conference abstract'/it OR 'editorial'/it OR 'letter'/it OR 'note'/it) NOT (('animal experiment'/exp OR 'animal model'/exp OR 'nonhuman'/exp) NOT 'human'/exp) SR |

192 |

|

#5 |

#3 AND #4 |

457 |

|

#4 |

'meta analysis'/exp OR 'meta analysis (topic)'/exp OR metaanaly*:ti,ab OR 'meta analy*':ti,ab OR metanaly*:ti,ab OR 'systematic review'/de OR 'cochrane database of systematic reviews'/jt OR prisma:ti,ab OR prospero:ti,ab OR (((systemati* OR scoping OR umbrella OR 'structured literature') NEAR/3 (review* OR overview*)):ti,ab) OR ((systemic* NEAR/1 review*):ti,ab) OR (((systemati* OR literature OR database* OR 'data base*') NEAR/10 search*):ti,ab) OR (((structured OR comprehensive* OR systemic*) NEAR/3 search*):ti,ab) OR (((literature NEAR/3 review*):ti,ab) AND (search*:ti,ab OR database*:ti,ab OR 'data base*':ti,ab)) OR (('data extraction':ti,ab OR 'data source*':ti,ab) AND 'study selection':ti,ab) OR ('search strategy':ti,ab AND 'selection criteria':ti,ab) OR ('data source*':ti,ab AND 'data synthesis':ti,ab) OR medline:ab OR pubmed:ab OR embase:ab OR cochrane:ab OR (((critical OR rapid) NEAR/2 (review* OR overview* OR synthes*)):ti) OR ((((critical* OR rapid*) NEAR/3 (review* OR overview* OR synthes*)):ab) AND (search*:ab OR database*:ab OR 'data base*':ab)) OR metasynthes*:ti,ab OR 'meta synthes*':ti,ab |

746377 |

|

#3 |

#1 AND #2 |

27920 |

|

#2 |

'diagnostic procedure'/exp/mj OR 'sensitivity and specificity'/de OR sensitiv*:ab,ti OR specific*:ab,ti OR predict*:ab,ti OR 'roc curve':ab,ti OR 'receiver operator':ab,ti OR 'receiver operators':ab,ti OR likelihood:ab,ti OR 'diagnostic error'/exp OR 'diagnostic accuracy'/exp OR 'diagnostic test accuracy study'/exp OR 'inter observer':ab,ti OR 'intra observer':ab,ti OR interobserver:ab,ti OR intraobserver:ab,ti OR validity:ab,ti OR kappa:ab,ti OR reliability:ab,ti OR reproducibility:ab,ti OR ((test NEAR/2 're-test'):ab,ti) OR ((test NEAR/2 'retest'):ab,ti) OR 'reproducibility'/exp OR accuracy:ab,ti OR 'differential diagnosis'/exp OR 'validation study'/de OR 'measurement precision'/exp OR 'diagnostic value'/exp OR 'reliability'/exp OR 'predictive value'/exp OR ppv:ti,ab,kw OR npv:ti,ab,kw OR diagnos*:ti,ab |

13691554 |

|

#1 |

'myositis'/exp/mj OR 'immune mediated necrotizing myopathy'/exp OR 'juvenile dermatomyositis'/exp OR 'necrotizing autoimmune myopathy'/exp OR 'necrotizing autoimmune myositis'/exp OR myositi*:ti,ab,kw OR ((('auto-immun*' OR autoimmun* OR immunemediat* OR 'immune mediat*' OR 'idiopathic inflammat*') NEAR/3 myopath*):ti,ab,kw) OR inmn:ti,ab,kw OR 'antisynthetase syndrome':ti,ab,kw OR dermatomyositi*:ti,ab,kw OR polymyositi*:ti,ab,kw |

36318 |

Ovid/Medline

|

# |

Searches |

Results |

|

11 |

3 and 10 Guidelines |

33 |

|

10 |

exp Guideline/ or guideline*.ti,kf. |

113790 |

|

9 |

5 and 7 |

291 |

|

8 |

4 and 7 SR |

616 |

|

7 |

limit 6 to yr="2015 -Current" |

3135 |

|

6 |

3 not ((exp animals/ or exp models, animal/) not humans/) not (letter/ or comment/ or editorial/) |

12926 |

|

5 |

(exp clinical trial/ or randomized controlled trial/ or exp clinical trials as topic/ or randomized controlled trials as topic/ or Random Allocation/ or Double-Blind Method/ or Single-Blind Method/ or (clinical trial, phase i or clinical trial, phase ii or clinical trial, phase iii or clinical trial, phase iv or controlled clinical trial or randomized controlled trial or multicenter study or clinical trial).pt. or random*.ti,ab. or (clinic* adj trial*).tw. or ((singl* or doubl* or treb* or tripl*) adj (blind$3 or mask$3)).tw. or Placebos/ or placebo*.tw.) not (animals/ not humans/) |

2143194 |

|

4 |

((meta-analysis/ or meta-analysis as topic/ or (metaanaly* or meta-analy* or metanaly*).ti,ab,kf. or systematic review/ or cochrane.jw. or (prisma or prospero).ti,ab,kf. or ((systemati* or scoping or umbrella or "structured literature") adj3 (review* or overview*)).ti,ab,kf. or (systemic* adj1 review*).ti,ab,kf. or ((systemati* or literature or database* or data-base*) adj10 search*).ti,ab,kf. or ((structured or comprehensive* or systemic*) adj3 search*).ti,ab,kf. or ((literature adj3 review*) and (search* or database* or data-base*)).ti,ab,kf. or (("data extraction" or "data source*") and "study selection").ti,ab,kf. or ("search strategy" and "selection criteria").ti,ab,kf. or ("data source*" and "data synthesis").ti,ab,kf. or (medline or pubmed or embase or cochrane).ab. or ((critical or rapid) adj2 (review* or overview* or synthes*)).ti. or (((critical* or rapid*) adj3 (review* or overview* or synthes*)) and (search* or database* or data-base*)).ab. or (metasynthes* or meta-synthes*).ti,ab,kf.) not (comment/ or editorial/ or letter/ or ((exp animals/ or exp models, animal/) not humans/))) or review.ti,ab,kf. |

1971497 |

|

3 |

1 and 2 |

14335 |

|

2 |

(exp Sensitivity/ and Specificity/) or (Sensitiv* or Specific*).ti,ab. or (predict* or ROC-curve or receiver-operator*).ti,ab. or (likelihood or LR*).ti,ab. or exp Diagnostic Errors/ or (inter-observer or intra-observer or interobserver or intraobserver or validity or kappa or reliability).ti,ab. or reproducibility.ti,ab. or (test adj2 (re-test or retest)).ti,ab. or "Reproducibility of Results"/ or accuracy.ti,ab. or Diagnosis, Differential/ or Validation Studies.pt. or diagnosis.ti,kf. or exp Diagnosis/ |

13386845 |

|

1 |

exp Myositis/ or Dermatomyositis/ or myositi*.ti,ab,kf. or ((auto-immun* or autoimmun* or immunemediat* or immune mediat* or idiopathic inflammat*) adj3 myopath*).ti,ab,kf. or inmn.ti,ab,kf. or antisynthetase syndrome.ti,ab,kf. or dermatomyositi*.ti,ab,kf. or polymyositi*.ti,ab,kf. |

27553 |