Algemene ziekteactiviteit

Uitgangsvraag

Wat zijn de behandelopties met csDMARDs/bDMARDs bij patiënten SLE?

- Wat is de effectiviteit van csDMARDs op ziekteactiviteit?

- Wat is de effectiviteit van bDMARDs op ziekteactiviteit?

Aanbeveling

Start met een csDMARD bij een patiënt met aanhoudende of frequente flares van ziekteactiviteit, ondanks behandeling met hydroxychloroquine (en eventueel een kortdurende behandeling met glucocorticoïden).

Maak in overeenstemming met de patiënt de keuze voor een csDMARD, waarbij

- Methotrexaat en azathioprine een vergelijkbaar profiel hebben wat betreft effectiviteit en bijwerkingen.

- Mycofenolaat mofetil eventueel een vervolgkeuze is op basis van een ernstiger bijwerkingenprofiel; mogelijk is het effect van mycophenolaat mofetil krachtiger.

- Tacrolimus, leflunomide en ciclosporine A zijn opties indien bovenstaande csDMARDs niet verdragen worden of ineffectief zijn.

Overweeg een switch te maken van csDMARD of het toevoegen van belimumab of anifrolumab indien het behandeldoel niet bereikt wordt na het voldoende lang, voldoende hoog gedoseerde toevoeging van csDMARD (en hydroxychloroquine).

Indien bovenstaande stappen niet hebben geleid tot het halen van het behandeldoel, overweeg een behandeling middels cyclofosfamide of rituximab bij refractaire ziekteactiviteit.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

In de samenvatting van de literatuur zijn de resultaten per uitkomstmaat beschreven voor csDMARDs, bDMARDs en andere medicatie. Voorafgaande aan het literatuurselectieproces is met de werkgroep afgestemd welke medicamenten veelal gebruikt worden in de Nederlandse praktijk, zie ‘search and select’. Gezien het groot aantal middelen heeft de werkgroep eerst gezocht naar recente systematische reviews. Deze artikelen zijn gebruikt als handvat.

Een korte samenvatting van de resultaten wordt hieronder beschreven. Het is belangrijk om te benoemen dat de evolutie van SLE-studies resulteert in ‘betere’ studies. De recente studies (d.w.z. bDMARDs) zijn beoordeeld middels de GRADE methodiek, wat resulteert in een (hogere) bewijskracht. In de huidige samenvatting van de literatuur zijn verschillende SLE-indices gebruikt als uitkomstmaat voor het meten van effectiviteit. Deze indices bevatten allen aspecten betreffende verschillende manifestaties. De scores van de verschillende manifestaties zijn gecombineerd tot één totaalscore. Om deze reden is het belangrijk in acht te nemen dat een verbetering van de totaalscore niet direct een verbetering van de score in alle categorieën m.b.t. de specifieke manifestaties betekent. Medicamenteuze behandelingen bij deze specifieke manifestaties worden in de volgende sub-modules beschreven; Cutane-, Gewrichts-, Cardiopulmonale - en Hematologische manifestaties.

Noot: niet alle middelen die staan beschreven in de samenvatting van de literatuur zijn geregistreerd voor de behandeling van SLE.

In totaal worden 7 vergelijkingen beschreven waarin verschillende soorten csDMARDs (methotrexaat (MTX), azathioprine (AZA), mycofenolaatmofetil (MMF), cyclofosfamide (CYC), tacrolimus (TAC), leflunomide (LEF) en ciclosporine A (CSA)) worden vergeleken met placebo/controlebehandeling bij patiënten met SLE. Tijdens de studies werd de standaardbehandeling, meestal met hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) (en/of glucocorticoïden (GC’s)), gehandhaafd in beide groepen.

De resultaten voor de uitkomstmaat ‘SLE-scores on disease activity indices’ beschrijven dat behandelingen met csDMARDs (d.w.z., MTX, AZA, MMF, LEF, CSA) effectiever zijn in vergelijking met een controlebehandeling. Dit gaat ook gepaard met een gereduceerde dosering van GC’s. Er worden mogelijk iets vaker bijwerkingen gerapporteerd bij behandelingen met een additionele csDMARD in vergelijking met een controlebehandeling.

Wanneer de csDMARDs met elkaar vergeleken worden zijn er geen evidente verschillen in effectiviteit m.b.t de uitkomstmaat ‘SLE-scores on disease activity indices’. Zo wordt beschreven dat MMF niet inferieur is aan een behandeling met CYC, CSA niet minder effectief is dan AZA en de effectiviteit van een hoge dosering CYC gelijk is aan een traditionele dosering. Ook worden er mogelijk geen verschillen gevonden voor de uitkomstmaten ‘glucocorticoïddosering’ en ‘bijwerkingen’. Gezien de aard van de SR kan er geen uitspraak worden gedaan over de bewijskracht, omdat de resultaten van de samenvatting van de literatuur niet middels GRADE beoordeeld kunnen worden.

Noot: In de review van Pego-Reigosa (2013) wordt mycofenolaatmofetil (mycophenolate mofetil) beschreven. Mycofenolaat mofetil is de prodrug van het werkzame mycofenolzuur, beiden kunnen worden ingezet.

In totaal worden 3 vergelijkingen beschreven waarin verschillende soorten bDMARDs (belimumab (BEL), rituximab (RTX), anifrolumab) worden vergeleken met een placebo/controlebehandeling bij patiënten met SLE. Ook in deze studies werd de standaardbehandeling, meestal met HCQ (en/of GC’s, csDMARDs), gehandhaafd in beide groepen.

Een behandeling met BEL resulteert in een verlaging van de ziekteactiviteit en een gereduceerde dosering GC’s. Er worden geen verschillen gevonden voor de uitkomstmaat bijwerkingen. De bewijskracht voor de verschillende uitkomstmaten varieert van hoog tot laag. Een belangrijke limitatie is dat voor de uitkomstmaat gereduceerde dosering GC’s, alleen is gekeken naar een dosering van >50%. Er zijn ook studies die hebben gekeken naar een reductie van >25%. Twee van de drie studies laten in tegenstelling tot de beschreven studies, geen verschil zien (Furie 2011; Stohl 2017; Zhang 2018.). Ook worden niet alle relevante bijwerkingen gerapporteerd.

Er worden geen verschillen gevonden voor alle uitkomstmaten bij de vergelijking RTX vs. controlebehandeling. De bewijskracht voor de verschillende uitkomstmaten varieert van laag tot zeer laag.

Een behandeling met anifrolumab resulteert in een verlaging van de ziekteactiviteit en een gereduceerde dosering GC’s. Echter worden bijwerkingen vaker gerapporteerd bij een behandeling met anifrolumab in vergelijking met een controlebehandeling. De bewijskracht voor de verschillende uitkomstmaten varieert van redelijk tot zeer laag. Mede door het studie design en de evolutie van SLE-studies is het mogelijk de ‘nieuwere’ studies te graderen middels GRADE en een hogere bewijskracht.

Anifrolumab is een relatief nieuw geneesmiddel voor de behandeling van SLE. Ten tijde van het richtlijnontwikkelingstraject zijn artikelen gepubliceerd (m.n. post-hoc analyses voor verschillende uitkomstmaten). Deze artikelen zijn nu niet meegenomen in de samenvatting van de literatuur. Wanneer de richtlijnmodule een update krijgt, wordt deze literatuur mogelijk toegevoegd. Noot: De review van Lee (2020) beschrijft slechts enkele uitkomstmaten voor effectiviteit gemeten als ziekteactiviteit score (d.w.z. ‘SLE-scores on disease activity indices’). In de huidige samenvatting van de literatuur is deze data aangevuld a.d.h.v. data uit de individuele studies (Furie, 2017; 2019; Morand, 2020). Er is alleen gekeken naar een dosering van 300 mg anifrolumab (i.v.) elke 4 weken. Deze dosering wordt ook gehanteerd in Nederland.

Er kan geen uitspraak worden gedaan over de effectiviteit en veiligheid van het middel intraveneuze immunoglobulinen (IVIg) vs. een controlebehandeling bij patiënten met SLE. Dit wordt veroorzaakt door de bewijskracht van de conclusies van de samenvatting van de literatuur. Deze is zeer laag.

Internationale richtlijnen en overige literatuur:

In de richtlijn van de ‘British Society for Rheumatology’ voor volwassenen met SLE uit 2018 wordt een behandeling met additioneel gebruik van MTX aanbevolen voor controle van de ziekteactiviteit bij patiënten met een mild actieve niet-orgaanbedreigende SLE (Gordon, 2018). Bij een matig actieve SLE wordt aanbevolen een behandeling met additioneel gebruik van MTX, AZA, MMF of CSA te overwegen bij aanwezigheid van artritis, huidaandoeningen, serositis, vasculitis of cytopenie. Voor refractaire gevallen wordt een additionele behandeling met BEL of RTX overwogen (Gordon, 2018). Wanneer er sprake is van ernstig actieve SLE wordt het volgende aanbevolen; additionele behandeling met MMF of CYC bij refractaire ernstige niet-nierziekten, BEL of RTX als basis wanneer patiënten niet/onvoldoende reageren op andere immunosuppressiva vanwege ineffectiviteit of intolerantie, IVIg kan overwogen bij patiënten met o.a. refractaire cytopenie (Gordon, 2018).

De EULAR-richtlijn voor volwassenen met SLE uit 2019 beveelt aan om immunosuppressieve therapieën (d.w.z. csDMARDs o.a. MTX, AZA, MMF) in te zetten bij patiënten die niet reageren op een behandeling met HCQ of indien het niet mogelijk is de GC-dosering te verlagen. Wanneer er sprake is van orgaanbedreigende SLE kunnen deze therapieën ook worden ingezet als initiële therapie. De csDMARD CYC kan ingezet worden indien er sprake is van ernstig orgaanbedreigende of levensbedreigende SLE, evenals ineffectiviteit bij gebruik van overige csDMARDs. De bDMARD BEL kan als aanvullende behandeling worden overwogen bij onvoldoende effect van een standaardbehandeling. De bDMARD RTX kan worden overwogen bij orgaanbedreigende SLE of intolerantie voor een standaardbehandeling met csDMARDs (Fanouriakis, 2019).

In de bestaande internationale richtlijnen (Gordon, 2018; Fanouriakis, 2019) wordt het medicament ‘anifrolumab’ niet aanbevolen, omdat het middel ten tijde van deze richtlijnen nog niet beschikbaar was. In december 2021 heeft de European Medicines Agency (EMA) geconcludeerd dat anifrolumab, een monoklonale antistof gericht tegen de IFN-1-receptor, van toegevoegde waarde is bij de behandeling van patiënten met SLE en met matig-ernstige (‘moderate’) tot ernstige (‘severe’) SLE ondanks standaardbehandeling (EMA, 2021). Op basis van de resultaten die staan beschreven in de samenvatting van de literatuur, vindt de werkgroep dat anifrolumab van toegevoegde waarde kan zijn voor patiënten met SLE, en in het bijzonder patiënten met cutane -en/of gewrichtsmanifestaties. De werkgroep neemt het advies uit het NVR-standpunt anifrolumab over omtrent de indicatie om anifrolumab te starten: de indicatie te starten met anifrolumab dient te worden besproken in een overleg met specialisten met uitgebreide kennis van het ziektebeeld: bij voorkeur in de vorm van een multidisciplinair overleg (MDO). Een belangrijk aspect om te benoemen is dat er tot op heden geen tot geringe ervaring is met het gebruik van anifrolumab door de medische specialisten in Nederland.

Een review uit 2015 van Mulhearn beschrijft indicaties voor het gebruik van IVIg bij reumatische ziekten. In de review worden specifieke aanbevelingen geschreven voor ‘lupus flare’, lupus nefritis, en lupus bij zwangere vrouwen. Zo wordt er beschreven dat IVIg overwogen kan worden voor gebruik bij refractaire ziekte waar andere behandelingen hebben gefaald (400 mg/kg/5 dagen) en bij acute ernstige opflakkeringen van SLE, in het bijzonder met koorts, pijn en vermoeidheid.

Het beleid van patiënten met SLE rondom zwangerschap is niet opgenomen in de huidige richtlijn. Hiervoor wordt verwezen naar; ‘Medicatiegebruik bij inflammatoire reumatische aandoeningen rondom de Zwangerschap’.

Uit de bestaande literatuur met betrekking tot verlaging van algemene ziekteactiviteitscores bij non-renale SLE is er geen csDMARD met bewezen hogere effectiviteit in vergelijking met een andere csDMARD. Hierbij moet worden opgemerkt dat CYC relatief de meeste ondersteuning vanuit de literatuur heeft betreffende effectiviteit, echter dient dit slechts in specifieke gevallen als eerste keuze ingezet te worden vanwege het bijwerkingenprofiel, een voorbeeld hiervan is ernstige neuropsychiatrische manifestaties, dat buiten de reikwijdte van deze richtlijn valt (https://ard.bmj.com/content/annrheumdis/69/12/2074.full.pdf).

Tevens is er meer literatuur beschikbaar over het effect van csDMARDs en bDMARDs op renale uitkomsten bij renale manifestaties bij SLE. Echter valt dit buiten de scope van de huidige richtlijn. Om deze reden wordt verwezen naar de richtlijnen van de Nefrologie en de EULAR.

Om tot een specifieke voorkeur te komen omtrent de volgorde van inzet van csDMARDs wordt naast de wetenschappelijke literatuur (zeer geringe ondersteuning), gebruik gemaakt van de kennis beschikbaar over de bijwerkingen van de genoemde csDMARDs bij andere reumatische of auto-immuunziektes en de klinische praktijkervaring. De aanbeveling om als eerste keuze csDMARD te kiezen voor methotrexaat wordt ondersteund door zowel de BSR-richtlijn (Gordon, 2018) als de EULAR-richtlijn (Fanouriakis, 2019). De voorkeur voor azathioprine als eerste keuze wordt ondersteund door de EULAR-richtlijn (Fanouriakis, 2019).

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

Patiënten geven aan waarde te hechten aan duidelijke en tijdige communicatie over de behandeling en de gevolgen indien de behandeling niet effectief is, ofwel verwachtingsmanagement. Om deze reden kunnen patiënten het belangrijk vinden dat de behandeldoelen (zoals beschreven in module Monitoring) in kaart worden gebracht. Bijv. welke factoren dragen bij aan het aanpassen/switchen van de medicatie? Het ‘samen beslissen’ staat o.a. bij het opstellen van de doelen centraal.

Aanhoudende ziekteactiviteit zorgt voor verminderde kwaliteit van leven en verminderde arbeidsparticipatie. Om deze reden geven patiënten aan dat medisch specialisten/ reumaverpleegkundigen aandacht moeten hebben voor het feit dat de behandeling (en het slagen/falen en eventueel bijstellen van deze behandeling) en de verwachtingen daarover invloed hebben op de privé- en arbeidssituatie van patiënten. Zo is het voor de patiënt en Arboarts belangrijk snel duidelijkheid te hebben over de ontwikkeling van de aandoening wanneer zij bijvoorbeeld in de ziektewet zitten of bezig zijn met een re-integratietraject.

Tegelijkertijd hechten de patiënten ook waarde aan een adequate behandeling uitgevoerd door een specialist deskundig op het gebied van SLE. Indien die niet gewaarborgd kan worden (bijv. door de complexiteit van de situatie), benadrukken patiënten het belang om deze specifieke groep door te verwijzen naar een centrum met expertise.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

Het gebruik van bDMARDs gaat gepaard met hogere medicatiekosten in vergelijking met het gebruik van csDMARDs. Om deze reden zullen csDMARDs meer kosteneffectief zijn in vergelijking met bDMARDs. Echter is het gebruik van bDMARDs mogelijk kosteneffectief bij een geselecteerde patiëntengroep. Dit kan echter niet worden onderbouwd met wetenschappelijke literatuur.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

Alleen op indicatie worden csDMARDs en/of bDMARDs voorgeschreven. De behandeling van patiënten met SLE dient te worden verzorgd door een specialist met ervaring over het ziektebeeld. Indien ervaring in onvoldoende mate aanwezig is, dient structureel overleg plaats te vinden of kan de patiënt worden doorverwezen naar een centrum met expertise. Voor de behandeling met csDMARDs of bDMARDs is structurele monitoring op het ontstaan van bijwerkingen essentieel. Dit wordt gedaan middels gericht (bloed)onderzoek. Ook dient de patiënt voor start van de behandeling voldoende voorlichting en inspraak te hebben. De patiënt dient te worden geïnformeerd over de (bij)werking, juiste toediening en belang van frequente monitoring. Daarnaast is het geven van adequate instructies vereist bij het geven/voorschrijven van subcutane injecties (bijv. BEL). Bij intraveneuze infusie met BEL, anifrolumab, RTX en CYC zijn adequate voorzieningen en de beschikbaarheid van bekwaam personeel vereist.

Rationale van de aanbeveling

Uit de literatuur is bekend dat zowel aanhoudende ziekteactiviteit als langdurige behandeling met (hoge dosis) GC’s zorgt voor het ontstaan van schade aan organen en een verhoogde mortaliteit bij patiënten met SLE. Daarnaast zorgt aanhoudende ziekteactiviteit voor verminderde kwaliteit van leven en verminderde arbeidsparticipatie. Bij de behandeling van patiënten met SLE wordt gestreefd naar het behalen van remissie of lage ziekteactiviteit (verwijzing module Behandeldoel en -strategie). In het geval van een opvlamming kan de inzet van GC’s noodzakelijk zijn, maar de behandeling is er op gericht het gebruik van GC’s te minimaliseren. Om dit te bewerkstellen en ziekteactiviteit te verminderen, worden csDMARDs ingezet naast een standaardbehandeling met HCQ. Van verschillende csDMARDs is in wetenschappelijk onderzoek aangetoond dat ze een effect hebben op vermindering van ziekteactiviteit (gemeten in verschillende indices zoals SLEDAI en BILAG) en van een aantal is aangetoond dat het gebruik leidt tot reductie van GC’s.

Wetenschappelijk onderzoek naar de effecten en bijwerkingen van csDMARDs bij patiënten met SLE zijn zeer beperkt in absolute en kwalitatieve zin. Onderlinge vergelijkingen (head-to-head studies) zijn insufficiënt. De beschreven literatuur geeft weinig handvatten voor een keuze van een specifieke csDMARD bij de behandeling van patiënten met SLE. Tegelijkertijd is het niet mogelijk om de bewijskracht van de samenvatting van de literatuur m.b.t. de csDMARDs te graderen. Naast de wetenschappelijke literatuur wordt de aanbeveling betreffende de inzet van csDMARDs voor een groot deel gestoeld op ‘klinische praktijkervaring’.

Wat betreft de bDMARDs, zijn er data uit trials bij patiënten met SLE voor BEL, RTX en anifrolumab. De resultaten van de trials met BEL zijn (gematigd) positief. Op basis van deze literatuur en de klinische praktijkervaring heeft BEL een plaats gekregen als ‘add-on’ middel naast een csDMARD. De resultaten vanuit de literatuur betreffende anifrolumab zijn positief. Dit middel wordt naast BEL geplaatst.

De trials naar RTX laten geen overtuigend positief effect zien op reductie van ziekteactiviteit. Op basis van observationele data en ‘praktijkervaring’ is wel een plaats voor RTX bij refractaire ziekteactiviteit (of ziekteactiviteit ondanks behandeling met csDMARDs).

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Alle patiënten met SLE worden met hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) behandeld, tenzij er een zwaarwegende contra-indicatie is. Bij ziekteactiviteit is er meestal een indicatie voor het starten van een aanvullende behandeling. Vaak worden glucocorticoïden (GC’s) ingezet, in verband met het ongunstige bijwerkingenprofiel van GC’s worden deze bij voorkeur kortdurend ingezet en snel weer afgebouwd. Indien het niet mogelijk is om GC’s voldoende af te bouwen, of er sprake is van ernstige, recidiverende of residuale ziekteactiviteit dan dienen ook andere immunosuppressieve medicamenten gestart te worden. De keuze voor een specifiek medicament wordt bepaald door de mate van de ziekteactiviteit, specifieke orgaanmanifestaties, bijwerkingen en comorbiditeit, eventuele zwangerschapswens en voorkeur van de patiënt. In deze module wordt nagegaan welk bewijs beschikbaar is om de arts en patiënt te steunen bij het maken van een keuze.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

csDMARDs

|

- GRADE |

… Azathioprine, cyclosporin, leflunomide, methotrexate, mycophenolate mofetil, and, tacrolimus may be effective treatment options (regarding disease activity indices and flares) in patients with SLE.

In patients with SLE, cyclosporin is not less effective than azathioprine; mycophenolate mofetil is not less effective than IV cyclophosphamide; high-dose IV cyclophosphamide (50 mg/kg x 4 days) has the same effectiveness than a l IV cyclophosphamide regimen according to the NIH scheme ((750 mg/m2/month for 6 months and then 3 months up to 2 years).

Enteric-coated mycophenolate sodium may be more effective than azathioprine in patients with SLE.

Sources: Pego-Reigosa (2013); Ordi-Ros (2017); Miyawaki (2013); Islam (2012). |

|

- GRADE |

… Mycophenolate mofetil, cyclosporin and, methotrexate may be used to reduce the glucocorticoid dose in patients with (moderate activity and) nonrenal and/or renal refractory SLE.

In patients with active SLE refractory to steroids, cyclosporin and azathioprine have a similar effect on reduction in glucocorticoid in the medium term.

Sources: Pego-Reigosa (2013). |

|

- GRADE |

… Cyclosporin, mycophenolate mofetil and, tacrolimus may cause adverse events in patients with SLE.

No difference in adverse events were observed between cyclosporin and azathioprine, and between high-dose IV cyclophosphamide (50 mg/kg x 4 days) and cyclophosphamide according to the NIH scheme (750 mg/m2/month for 6 months and then 3 months up to 2 years).

Mycophenolate sodium is a safe alternative therapy in SLE patients with extra-renal involvement.

Low-dose methotrexate appears to have an acceptable toxicity profile, compared with CQ in patients with articular and cutaneous manifestations of SLE.

Similar short-term (6 months) adverse events were reported in patients with mild to moderate SLE activity treated with or without leflunomide.

Sources: Pego-Reigosa (2013); Yahya (2013); Islam (2012). |

|

- GRADE |

… No evidence was found regarding the effect of treatment with cyclosporin, mycophenolate mofetil and, cyclophosphamide on quality of life when compared with control treatment in patients with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus.

No evidence was found regarding the effect of treatment with azathioprine, leflunomide, methotrexate and, tacrolimus on quality of life, reduction in glucocorticoid (except methotrexate), adverse events (except tacrolimus) when compared with control treatment in patients with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus.

Sources: Pego-Reigosa (2013). |

bDMARDs

|

High GRADE |

… Treatment with belimumab reduces disease activity (i.e., SLE scores on disease activity indices), glucocorticoid dose when compared with placebo in patients with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus.

Sources: Singh, 2021. |

|

Moderate GRADE |

… Treatment with belimumab probably results in little to no difference in quality of life when compared with placebo in patients with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus.

Sources: Singh, 2021. |

|

Low GRADE |

… Treatment with belimumab may result in little to no difference in adverse events (i.e., SAE, death) when compared with placebo in patients with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus.

Sources: Singh, 2021. |

|

… Treatment with belimumab probably results in little to no difference in adverse events (i.e., serious infection, withdrawals due to AE) when compared with placebo in patients with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus.

Sources: Singh, 2021. |

Rituximab

|

Low GRADE |

… Treatment with rituximab may result in little to no difference in improvement of SLE scores on disease activity indices when compared with placebo in patients with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus.

Sources: Wu, 2020. |

|

- GRADE |

… No evidence was found regarding the effect treatment with rituximab on quality of life, reduction of glucocorticoid when compared with control treatment in patients with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus.

Sources: None. |

|

Low GRADE |

… Treatment with rituximab may result in little to no difference in the occurrence of adverse events (i.e., severe adverse events, deaths, infections, and any infusion related severe adverse events) when compared with placebo in patients with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus.

Sources: Wu, 2020. |

Anifrolumab

|

Moderate GRADE |

… Treatment with anifrolumab probably reduces SLE scores on disease activity indices when compared with placebo in patients with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus.

Sources: Lee, 2020. |

|

Very low GRADE |

… The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of treatment with anifrolumab on quality of life when compared with placebo in patients with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus.

Sources: Lee, 2020. |

|

Moderate GRADE |

… Treatment with anifrolumab probably reduces the glucocorticoid dose when compared with placebo in patients with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus.

Sources: Lee, 2020. |

|

Moderate GRADE |

… Treatment with anifrolumab probably increases the occurrence of adverse events (i.e., any AE) when compared with placebo in patients with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus.

Sources: Lee, 2020. |

|

Low GRADE |

… Treatment with anifrolumab may reduce the occurrence of adverse events (i.e., SAE) when compared with placebo in patients with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus.

Sources: Lee, 2020. |

|

Very low GRADE |

… The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of treatment with anifrolumab on adverse events (i.e., withdrawal due to AE) when compared with placebo in patients with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus.

Sources: Lee, 2020. |

other medication

|

Very low Grade |

… The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of treatment with intravenous Immunoglobulin on SLE scores on disease activity indices, reduction of glucocorticoid when compared with control treatment in patients with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

Sources: Sakthiswary, 2014. |

|

- GRADE |

… No evidence was found regarding the effect treatment with intravenous Immunoglobulin on quality of life, adverse events when compared with control treatment in patients with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus.

Sources: Sakthiswary, 2014. |

Samenvatting literatuur

csDMARDs

The systematic review of Pego-Reigosa (2013) investigated the efficacy and safety of nonbiologic immunosuppressants in treatment of non-renal SLE. A sensitive literature search in Medline, Embase and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials was performed until October 2011. Studies were eligible for inclusion if they included adults with SLE, treatment with a nonbiologic immunosuppressants, a placebo or active comparator group, and outcome measures assessing efficacy and/or safety. Efficacy outcomes were defined as nonrenal manifestations, scores by activity indices, SLE flares, a steroid-sparing effect. Safety outcomes were defined as infections, cardiovascular events, malignancies, etc. The level of evidence and grades of recommendations were based on the Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based medicine, and additionally Jadad-score for RCTs. In total 65 studies were included. Most of them were cohorts, only 11 RCTs were included. In the cohort studies baseline values were used as ‘control’, and post treatment values as ‘intervention’. In the RCT a placebo or control treatment was given in the ‘control’ arm, which was compared with the ‘intervention’ arm. Outcomes were reported per pharmacological therapy (i.e., intervention); methotrexate (MTX), azathioprine (AZA), mycophenolate mofetil (MMF), cyclophosphamide (CYC), tacrolimus (TAC), leflunomide (LEF), and cyclosporin A (CSA). Due to important variability in the selected patients, treatment doses, and outcome measures, no meta-analyses were performed. In addition, 2 RCTs and 3 observational studies were performed in patients with neuropsychiatric SLE. Three observational studies were performed in patients with lupus nephritis.

bDMARDs

The Cochrane review by Singh (2021) investigated the benefits and harms of belimumab (BEL) (alone or in combination) in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). An information specialist searched with a predefined strategy in relevant databases including; detailed strategies for CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL, Web of Science, the World Health Organization (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform, and clinicaltrials.gov. The search for relevant studies was performed until September, 25th 2019. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) or controlled clinical trials (CCTs) of BEL (alone or in combination) compared to placebo or control treatment (immunosuppressive drugs, such as azathioprine, cyclosporine, mycophenolate mofetil or another biologic), in adults with SLE were eligible for inclusion. Studies including patients without a diagnosis of SLE were excluded. The standard methodological procedures expected by Cochrane were used for data collection and analysis. The primary outcome was changes in SLE scores on disease activity indices. This was defined as the Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Index Safety of Estrogen in Lupus National Assessment (SELENA) Modification (SELENA-SLEDAI), modified SELENASLEDAI Flare Index (SFI), British Isles Lupus Assessment Group index (BILAG), other similar validated indices. Secondary outcomes included quality of life, reduction in glucocorticoid dose, serious adverse events (SAE), serious infections, withdrawals due to adverse events, and death. The GRADE method was used to assess the quality of evidence. In total 6 RCTs were included. In these trials BEL was compared to placebo. The study duration ranges from 12 to 76 weeks. These trials were performed in North America (i.e., USA/ Canada, n=2), and several countries over the world (n=4). Regarding risk of bias, this was highest for the domain of attrition bias, followed by selection bias. Detailed information is provided in the risk of bias table (Singh, 2021). The trials predominantly included women from outpatient clinics; the mean age range of the participants was 32 to 42 years. Most often the treatment duration was 52 weeks.

The review with meta-analysis of Wu (2020) aimed to investigate the efficacy and safety of rituximab (RTX) in patients with SLE. Therefore, the Cochrane Handbook was followed. A literature research was performed using PubMed, Cochrane Library, EMBASE, Clinicaltrials and CNKI and Chinese database of WanFang databases. The search date was unknown. Articles were eligible for inclusion if they compared RTX with placebo (i.e., control group) in SLE patients in RCTs. In cohort studies the baseline group (i.e., when patients did not receive RTX) was used as control group. Further the studies included efficacy and safety results. Efficacy results were defined as BILAG score, SLEDAI score, complement C3/C4 levels, anti-dsDNA antibodies, peripheral CD19+B cells, serum creatinine, 24-h urinary protein and Up/Ucr. Safety results were defined as the incidence of serious adverse events (SAE), deaths, infections, etc. The methodological quality of the included RCTs was assessed with the Jadad score and for observational studies by the Newcastle-Ottaa Scale (NOS). Results were reported as weighted mean differences, standardized mean differences and relative risks. Heterogeneity was assessed using I². In total two RCTs and 12 observational cohort studies were selected (n=742). In the two RCTs, 241 patients received RTX and 160 patients received placebo treatment for 52 weeks. In total 341 patients were included in the observational studies. In these studies, baseline values were used as ‘control’ group, and post-treatment values as ‘intervention’ group. A limitation of the current review is that one of the RCTs, and 3 of the cohort studies included patients with lupus nephritis.

The systematic review of Lee (2020) aimed to investigate the efficacy and safety of anifrolumab in active SLE. A literature research was performed using MEDLINE, EMBASE, and the Cochrane Controlled Trials Registry databases until August 2020. Articles were eligible for inclusion if they compared anifrolumab with placebo in active SLE patients. The primary outcome was BICLA reaction at week 52. This was defined as all of the following: a reduction of all severe (BILAG-2004 A) or moderately severe (BILAG-2004 B) disease activity at baseline to lower levels (BILAG-2004 B, C, or D and C or D, respectively) and no worsening in other organ systems (with worsening defined as ≥1 new BILAG-2004 A item or ≥2 new BILAG-2004 B items); no worsening in disease activity, as determined by the SLEDAI-2K score (no increase from baseline) and by the PGA score (no increase of ≥0.3 points from baseline); no discontinuation of the trial intervention; and no use of restricted medications beyond protocol-allowed thresholds. Secondary outcomes were loss of the glucocorticoid dosage, and safety (i.e., any adverse events (AE), serious adverse events (SAE), number of patients withdrawn owing to adverse events. The methodological quality of the included studies was assessed with the Jadad-score. The meta-analysis was performed in accordance with the guidance provided by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta Analysis (PRISMA) statement. Heterogeneity was assessed using I², and funnel plots for publication bias. In total three RCTs were selected with a duration of 52 weeks. A number of 927 patients were included with a mean age range of 39 to 41 years. All studies were performed in several countries in the world and sponsored by the industry. The Jadad score across the studies ranged from 3 to 4, indicating high quality of the included studies. Detailed information is provided in the publication (Lee, 2020).

other medication

Sakthiswary (2014) performed a systematic review with meta-analysis to determine the therapeutic role of intravenous immunoglobin (IVIg) in patients with SLE. A literature research was performed using MEDLINE, Scopus, EMBASE, and Cochrane controlled trials. The search date was unknown, but all included articles were published between 1989 and 2013. Articles (i.e., RCTs, and cohort studies) were eligible for inclusion if they examined the effects of IVIg in patients with SLE. The diagnosis of SLE was based on validated criteria. Further, placebo treatment or standard treatment was used as comparison. Outcome measures were disease activity scores, defined as Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Index (SLEDAI), Systemic Lupus Activity Measure (SLAM), and Lupus Activity Index-Pregnancy (LAI-P), steroid dose reduction, change in the levels of autoantibodies, change in complement 3 (C3) and 4 (C4) levels, and renal function (proteinuria, creatinine). The quality of evidence was not assessed. Results were reported as standardized mean differences and relative risks. Heterogeneity was assessed using I². In total 13 studies were eligible for inclusion; 1 RCT, 2 non-RCTs, 6 prospective cohort studied, and 3 retrospective cohort studies. Of these, 7 were performed in Europa, 5 in Asia, and 1 in the USA. The study duration ranged between 1 and 24 months. In total 443 patients were included in the 13 studies. The current SR is limited by the fact that only the standardized mean differences in a study were reported, and not the individual outcomes per group. In addition, the RCT and one of the controlled trials were performed in patients with lupus nephritis. The other controlled trial was performed in SLE patients with recurrent spontaneous abortions. One prospective cohort study was performed in SLE patients with thrombocytopenia and one in patients with histologically confirmed cutaneous SLE.

Description of additional RCTs

As described above, additional RCTs were searched if the SR was published before 2020 (i.e., csDMARDs and IVIg).

csDMARDs

Islam (2012) performed a prospective open-label study comparing the efficacy and safety of methotrexate (MTX; 10mg weekly) and chloroquine (CQ; 150mg daily) in adults with SLE over 24 weeks. If adults fulfilling American College of Rheumatology (ACR) criteria of SLE

and suffering from arthralgia, or arthritis and active skin lesions, they were eligible for inclusion. Exclusion criteria were involvement of any other organ systems, pregnancy, lactation, any form of eye problems, history of taking antimalarials within the last 4 months or corticosteroids equivalent to > 20 mg of prednisolone per day, raised serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT), and raised serum creatinine. After giving a written informed consent, patients were randomly assigned to treatment with MTX or CQ. Outcome measures were numbers of swollen and tender joints, duration of morning stiffness, visual analog scale (VAS) for articular pain, physician global assessment index, patient global assessment

index, SLE Disease Activity Index (SLEDAI), disappearance of skin rash and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR). In total 13 patients were allocated to the MTX arm, and 24 to the CQ arm. These patients were mostly female (13 in MTX vs. 23 in CQ) and had a mean age of 24 years. No differences were shown between the treatment arms at baseline. The current study was limited due to the open-label design, the limited sample size, and the relative short follow-up of 24 weeks.

Miyawaki (2012) performed a prospective open-label study to determine the efficacy of methotrexate (MTX) for improving serological abnormalities in adults with SLE. Patients with low serum complement and/or high anti-dsDNA levels during prednisone tapering, and meeting the in- and exclusion criteria, were treated with MTX (7.5 mg weekly, the use of other immunosuppressive agents was prohibited during the study) for 18 months. Outcome measures were C3, C4, anti-dsDNA levels, SLEDAI, MCV of red blood cells, and prednisone dose. In total 30 patients received treatment with MTX, and 18 patients were selected as controls. These patients were all female and had a mean age of 47 years in the MTX arm, and 42 years in the control arm, respectively. Baseline differences between the groups were shown regarding disease activity, which was as suspected higher in the MTX arm. The current study was limited due to the open label design, the limited sample size, and the fact that baseline values were different between the arms.

Yahya (2013) performed a prospective open-label study to assess the efficacy of mycophenolate sodium in extra-renal SLE. SLE patients without renal involvement, and meeting the in- and exclusion criteria, were randomized either to receive mycophenolate sodium (i.e., 360 mg twice daily initially, and later escalated to 720 mg twice daily at week 4 if there were no contraindications) or other immunosuppressive agents for 16 weeks. Outcome measures were SLE Disease Activity Index (SLEDAI) score, other organ-specific parameters immunological parameters, including anti-double stranded DNA and C3, and prednisone dose.

In total 8 patients received treatment with MMF, and 6 patients treatment with other immunosuppressive agents. In the control group, 2 patients were lost to follow-up. Regarding the baseline characteristics, only differences were shown in gender as 4 males were included in the MMF group and none in the control group. The current study was limited due to the open-label design, limited sample size and no standardized treatment in the control group.

Ordi-Ros (2017) performed an open-label randomized trial to compare the efficacy and safety of enteric-coated mycophenolate sodium (EC-MPS) versus azathioprine (AZA) in patients with active systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) disease. SLE patients meeting the in- and exclusion criteria, were randomized and received either EC-MPS (target dose: 1440 mg/day) or AZA (target dose: 2 mg/kg/day) in addition to prednisone and/or antimalarials for 24 months. Outcome measures were proportion of patients achieving clinical remission, assessed by SLE Disease Activity Index 2000 (SLEDAI-2K) and British Isles Lupus Assessment Group (BILAG), at 3 and 24 months. Secondary endpoints included time to clinical remission, BILAG A and B flare rates, corticosteroid reduction and adverse events (AEs). In total 120 patients received treatment with EC-MPS, and 120 patients treatment with AZA. In both arms 2 patients were lost to follow-up and removed from the analysis. Although, a total of 154 patients (64.2%) completed the study: 87 (72.5%) in the EC-MPS arm and 67 (55.8%) in the AZA arm. Regarding the baseline characteristics, no differences were shown between the treatment arms. The current study was limited due to the open-label design.

other medication

No additional RCTs were available, which could be added to the current comparison.

Results

csDMARDs

The results of the systematic review (Pego-Reigos, 2013) are reported at first. Thereafter, additional results from the RCTs (Islam, 2012; Miyawkai, 2012; Yahya, 2013; Ordi-Ros, 2017) are reported per csDMARD.

nonbiologic immunosuppressants

The study of Pego-Reigosa (2013) studies several nonbiologic immunosuppressants namely, cyclophosphamide (CYC), azathioprine (AZA), methotrexate (MTX), leflunomide (LEF), mycophenolate mofetil (MMF), cyclosporin A (CSA), and Tacrolimus (TAC). Outcomes per nonbiologic are described below. The described information is adapted from the study of Pego-Reigosa (2013).

Methotrexate

In total, 7 articles evaluated the efficacy and/or safety of MTX in the treatment of nonrenal manifestations of SLE; 2 were double-blind, placebo-controlled RCTs (Carneiro; 1999; Fortin, 2008), 1 was a crossover open study (Arfi, 1995), and 5 were cohort studies (Pego-Reigosa, 2013) that included 230 patients overall.

The RCT of Carneiro (n=41) compared MTX (20mg/week) treatment with placebo in SLE patients. Mean SLEDAI and VAS scores were significantly lower in MTX patients compared with placebo. In addition, it was possible to decrease the prednisone dose for 13 MTX patients during the study but for only one patient in the placebo group.

The RCT of Fortin (n=86) compared MTX (7.5 mg/week and ↑to 20mg/week) treatment with placebo in SLE patients. Mean SLAM-R and reduction of glucocorticoid dose improved significantly more in the MTX group, compared with placebo. No differences in AEs were reported.

The crossover open study (Arfi, 1995) assessed the efficacy of oral MTX (7.5 mg/week) in SLE patients without major organ involvement and active disease despite >10 mg/day of prednisone. The patients received treatment for 2 periods: 1) 3 months (followed by a 3-month control period without treatment), and then 2) 6 months (followed by a 6-month control period without treatment). In the 13 patients who finished the study, there was a significant reduction of lupus flares during the MTX treatment periods compared with the control phases (P=0.02) without significant differences in the requirements of prednisone.

In summary, the evidence for using MTX in nonrenal SLE treatment is based on high-quality studies, 2 double-blind, placebo-controlled RCTs. However, a small number of patients

were included in these studies (only 61 patients were treated with MTX).

Islam (2012) reported that clinical and laboratory parameters improved significantly over 24 weeks in patients treated with MTX (n=13). Although no statistically significant differences were shown at 24 weeks between patients treated with MTX compared with patients treated with CQ (n=24) for SLEDAI, PGA, VAS pain (i.e., mean (sd) scores for MXT vs. CQ; 2.8 (2.4) vs. 2.5 (2.4); 1.5 (1.1) vs. 1.8 (1.1); 4.2 (2.1) vs.1.8 (1.1)), respectively. The most common side effect ‘anorexia and nausea’ were somewhat more common in patients treated with MTX (54%) compared with CQ (17%).

Miyawaki (2013) reported that SLEDAI significantly reduced in patients treated with MTX (n=30) compared with the control group (n=18) at 18 months. Although, no differences were shown at 18 months as patients in the control group had no active disease at baseline (mean (SD) MTX vs. control at 18 months; 4.9 (0.9) vs. 5.0 (0.9)). However, a statistically significant difference was shown for the outcome ‘prednisone dose’ at 18 months, which was lower in the MTX group (mean 5.8 mg/day) compared with the control group (mean 6.7mg/day). Regarding biomarkers, C3 and/or C4 levels were normalized or elevated at 18 months in 96.7 % of the MTX patients and 33.3 % of the control patients, and anti-dsDNA antibody levels were normalized or lowered in 24 of the 26 MTX patients (92.3 %) and in 50.0 % of the control patients.

1. SLE scores on disease activity indices

Due to important variability in the selected patients, treatment doses, and outcome measures, no meta-analyses were performed. Therefore, the review of Pego-Reigosa (2013) reported only conclusions. The following conclusion was reported for disease activity:

- In patients with moderate activity and nonrenal SLE manifestations despite prednisone, NSAIDs, and antimalarials, treatment with MTX (20 mg/day) reduces in the medium term (12 months) the activity of the disease, particularly in patients without damage, with an additional medium-term steroid-sparing effect.

2. Quality of life

No conclusions were reported for the outcome measure ‘quality of life’.

3. Reduction in glucocorticoid use

The following conclusion was reported for reduction in glucocorticoid use:

- An additional medium-term steroid-sparing effect was shown in treatment with MTX (20 mg/day), compared with control treatment in patients with moderate activity and nonrenal SLE manifestations.

4. Adverse events

No conclusions were reported for the outcome measure ‘adverse events’.

Azathioprine

Only 2 articles assessed the efficacy and/or safety of AZA in the treatment of nonrenal SLE; 1 was an unblinded RCT (n=24; Hahn, 1975) and 1 was a cohort study (Oelzner, 1996) that included 85 patients overall. The RCT, which compared treatment with AZA 3-4 mg/kg + prednisone vs. only prednisone, reported no differences regarding clinical improvement, mean dose prednisone, and AEs. The retrospective cohort study analyzed the influence of AZA (≥2 mg/kg/day) and prednisolone (7–12 mg/day) on the frequency of SLE flares and evaluated the predictors of these flares in 61 patients (38 without renal disease) over

a mean follow-up period of 7.5 years (Oelzner, 1996). In comparison with a preceding period without AZA, this combined regimen resulted in a significant reduction in flares and an

increase in flare-free patient-years.

In summary, there is little evidence for using AZA in the treatment of nonrenal SLE because there is insufficient data.

1. SLE scores on disease activity indices

Due to important variability in the selected patients, treatment doses, and outcome measures, no meta-analyses were performed. Therefore, the review of Pego-Reigosa (2013) reported only conclusions. The conclusion for disease activity is reported as follows:

- The association of AZA with prednisolone treatment might reduce the flare rate.

2. Quality of life

No conclusions were reported for the outcome measure ‘quality of life’.

3. Reduction in glucocorticoid

No conclusions were reported for the outcome measure ‘reduction in glucocorticoid’.

4. Adverse events

No conclusions were reported for the outcome measure ‘adverse events’.

Mycophenolate mofetil / enteric-coated mycophenolate sodium

In total, 8 articles evaluated the efficacy and/or safety of MMF in the treatment of nonrenal manifestations of SLE; 1 was an RCT (Ginzler, 2010) and 7 were cohort studies (Pego-Reigoso, 2013) that included 769 patients overall. The RCT by Ginzler (2010) compared patients treated with MMF to treatment with CYC. No differences were shown for efficacy outcomes.

The RCT by Ginzler (2010) explored also as secondary end points the nonrenal findings of the Aspreva Lupus Management Study (ALMS) (8), a prospective, open-label, parallelgroup

RCT that assessed the effect of MMF compared with CYC as induction treatment for lupus nephritis. Some of the cohort studies specifically addressed safety issues.

In summary, the evidence for using MMF in nonrenal SLE treatment is based on studies with a large number of patients and RCT information is available. However, most patients were included in low-quality studies, and the RCT assessed the nonrenal response in patients with lupus nephritis who received induction treatment including high-dose corticosteroids.

Yahya (2013) reported that mycophenolate sodium reduced SLEDAI scores after 16 weeks in 7/8 patients (median score 8), and in 4/4 (median score 5) patients treated with another immunosuppressant. There was a positive trend of steroid dose reduction in both treatment groups (median dose at 16 weeks 3mg/day vs. 2mg/day). Regarding biomarkers, no differences were shown between patients treated with mycophenolate sodium, compared with patients treated with other immunosuppressants.

Ordi-Ros (2017) reported that at least 8 consecutive weeks of clinical remission (i.e., clinical SLEDAI-2K=0, where serology was permitted (maximum SLEDAI=4)) at 24 months was shown in 84/120 (70%) patients treated with enteric-coated mycophenolate sodium, compared with 57/120 (48%) patients treated with AZA. Mean SLEDAI-2K and BILAG-2001 at 24 months was lower in patients treated with enteric-coated mycophenolate sodium (i.e., 2.1 and 1), compared with patients treated with AZA (i.e., 3.3 and 1). BILAG A/B flares over 24 months were observed in 60/120 (50%) of the patients treated with enteric-coated mycophenolate sodium, and 86/120 (72%) of the patients treated with AZA. Mean glucocorticoid dose at 24 months was lower in patients treated with enteric-coated mycophenolate sodium (i.e., 4), compared with patients treated with AZA (i.e., 7). No differences were shown regarding adverse events (i.e., 71/120 vs. 69/120, respectively).

1. SLE scores on disease activity indices

Due to important variability in the selected patients, treatment doses, and outcome measures, no meta-analyses were performed. Therefore, the review of Pego-Reigosa (2013) reported only conclusions. The following conclusions were reported for disease activity:

- MMF may prevent short-term (6 months) SLE flares when added to the treatment of patients with increasing anti-dsDNA titer.

2. Quality of life

No conclusions were reported for the outcome measure ‘quality of life’.

3. Reduction in glucocorticoid

The conclusion for reduction in glucocorticoid was reported as follows:

- MMF can be used to improve nonrenal activity in patients with nonrenal and/or renal refractory SLE and to reduce the need for corticosteroids.

4. Adverse events

The conclusion for adverse events was reported as follows:

- In patients with renal and/or nonrenal SLE, MMF may cause non–dose-dependent adverse events (particularly in the gastrointestinal system) and drug survival is acceptable with a low withdrawal rate due to adverse events in the medium term (12 months).

Cyclophosphamide

In total, twenty-nine studies evaluated the efficacy and/or safety of CYC in the treatment of nonrenal manifestations of SLE; 4 were unblinded RCTs (Stojanovich, 2003; Gonzalez-Lopez, 2004; Barile-Fabris, 2005; Petri, 2010), 1 was an open prospective study (Boumpas, 1993), and 24 were cohort studies (Pego-Reigosa, 2013) that included 3,742 patients overall. Different nonrenal manifestations were treated, although neuropsychiatric SLE (NPSLE) was studied in a more rigorous way (Stojanovich, 2003; Barile-Fabris, 2005; Petri, 2010). The CYC regimens and duration of CYC treatment and the comedications allowed in those studies varied. The outcome variables used varied, with the most frequent being clinical response to treatment measured by different activity and response indices, serologic response, rate of disease flares, decrease in the dose of prednisone, and adverse events. Some of the studies specifically addressed safety issues such as ovarian failure, neoplasias, or association with damage.

In summary, the evidence for using CYC in the treatment of nonrenal SLE is based on studies of a larger number of patients than those that assessed any other nonbiologic agent and RCT information is available, particularly for NPSLE. However, only a small percentage of patients were included in high-quality studies.

1. SLE scores on disease activity indices

Due to important variability in the selected patients, treatment doses, and outcome measures, no meta-analyses were performed. Therefore, the review of Pego-Reigosa (2013) reported only conclusions. Conclusions for disease activity were reported as follows:

- IV CYC is better than methylprednisolone for the long-term treatment of NPSLE and reduction of relapses.

- High-dose IV CYC (i.e., iv CYC 50mg/kg x 4 days) has the same efficacy in the treatment of nonrenal SLE than a traditional IV CYC regimen (i.e., iv CYC 750 mg/ m2/month x 6 months and then every 3 months, up to 2 years).

2. Quality of life

No conclusions were reported for the outcome measure ‘quality of life’.

3. Reduction in glucocorticoid

No conclusions were reported for the outcome measure ‘reduction in glucocorticoid’ specifically. In the method section it is described that ‘efficacy’ outcomes were defined as nonrenal manifestations, scores by activity indices, SLE flares, a steroid-sparing effect.

4. Adverse events

The following conclusions were reported for adverse events:

- High-dose IV CYC has the same adverse event rate than a traditional IV CYC regimen in the treatment of nonrenal SLE.

- IV CYC use is associated with development of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia.

- In women with SLE, oral or IV CYC is independently associated in the short term with ovarian failure.

- In women with SLE, the risk of ovarian failure increases with the cumulative dose of oral or IV CYC and is higher with longer IV CYC regimens.

- In women with SLE, the risk of ovarian failure is associated with an older age at commencement of both oral and intravenous CYC; age itself is a risk factor for ovarian failure.

Tacrolimus

Two studies assessed the efficacy and/or safety of TAC in the treatment of nonrenal manifestations of SLE; both were cohort studies (Suzuki, 2011; Kusunoki, 2009) that included 31 patients. In the open-label prospective 24- week study by Suzuki (2011), 21 patients with mild active SLE treated with oral TAC (1–6 mg/day) were studied. The mean SLEDAI score decreased significantly at 24 weeks (P<0.01). In 8 cases, treatment was discontinued within 24 weeks because of inefficacy (6 cases) and adverse effects (2 cases). Nonserious side effects were observed in only 5 cases (23.8%). The retrospective cohort study investigated whether oral TAC (1–3 mg/day) was effective for treating SLE patients without active nephritis (n=10; Kusunoki, 2009). The mean SLEDAI score and the mean dose of prednisolone decreased significantly after 1 year (P<0.05 for both). Four of the 10 patients had adverse events and 2 patients discontinued treatment.

In summary, there is very little evidence for using TAC because only 2 small studies have been reported, neither of which were RCTs, and almost one-third of all patients studied discontinued the drug because of a lack of efficacy or adverse effects.

1. SLE scores on disease activity indices

Due to important variability in the selected patients, treatment doses, and outcome measures, no meta-analyses were performed. Therefore, the review of Pego-Reigosa (2013) reported only conclusions. The following conclusion was reported for disease activity:

- In patients with active nonrenal SLE despite conventional treatment, the addition of TAC may be useful to improve disease activity in the medium term.

2. Quality of life

No conclusions were reported for the outcome measure ‘quality of life’.

3. Reduction in glucocorticoid

No conclusions were reported for the outcome measure ‘reduction in glucocorticoid’.

4. Adverse events

The conclusion for adverse events was reported as follows:

- In patients with active nonrenal SLE despite conventional treatment, the addition of TAC may cause frequent adverse events.

Leflunomide

In total, 2 articles assessed the efficacy and/or safety of LEF in the treatment of nonrenal SLE; 1 was a double-blind, placebo-controlled RCT (n=12, Tam, 2004) and 1 was a cohort study (Remer, 2001) that included 30 patients overall. The RCT, which compared treatment with LEF vs control treatment without LEF, reported that the reduction in the Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Index (SLEDAI) from baseline to 24 weeks was significantly greater in the leflunomide group than the placebo group (mean 11 in the leflunomide group vs. 4.5 in the placebo group). Similar changes in proteinuria, C3, anti-dsDNA, and prednisone dose were reported, and no differences for AEs. The cohort study retrospectively assessed the efficacy and safety of LEF (100 mg/day for 3 days, followed by 20 mg/day) in 18 SLE outpatients (Remer, 2001). After 2–3 months of therapy, most patients had subjective improvement and significantly lower Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Index (SLEDAI) scores.

In summary, there is very little evidence for use of LEF in nonrenal SLE because the only reported double-blind placebo-controlled RCT included only 6 patients treated with LEF.

1. SLE scores on disease activity indices

Due to important variability in the selected patients, treatment doses, and outcome measures, no meta-analyses were performed. Therefore, the review of Pego-Reigosa (2013) reported only conclusions. The conclusion for disease activity was reported as follows:

- In patients with mild to moderate active SLE in spite of prednisolone, the addition of LEF is more effective than placebo in improving disease activity.

2. Quality of life

No conclusions were reported for the outcome measure ‘quality of life’.

3. Reduction in glucocorticoid

No conclusions were reported for the outcome measure ‘reduction in glucocorticoid’.

4. Adverse events

The conclusion for adverse events was reported as follows:

- Similar short-term (6 months) side effects were reported in patients with mild to moderate active SLE treated with or without LEF.

Cyclosporin

In total, 8 articles evaluated the efficacy and/or safety of CSA in the treatment of nonrenal

SLE; 2 were unblinded RCTs (Dammacco, 2000; Griffiths, 2010), 1 was a prospective open study (Manger, 1996), and 5 were cohort studies (Pego-Reigosa, 2013) that included 319 patients overall.

In the RCT of Dammacco (2000; n=18) patients were treated with CSA vs. control treatment without CSA. During the trial SLEDAI significantly improved more in the intervention group compared to control. The cumulative dose prednisone was significantly lower in the intervention group compared to control. Further, AEs occurred somewhat less in the intervention group, compared with control (i.e, 60% vs. 62.5%).

In the RCT of Griffiths (2010; n=89) patients were treated with CSA (i.e., initial dose 1-2.5mg/kg/d, maximun 3.5mg/kg/d) vs. AZA (i.e., initial dose0.5-2mg/kg/d, maximum 2.5mg/kg/d). No differences were showed in efficacy and safety outcomes between the treatment arms.

The prospective open study investigated the effect of CSA (2.5–5 mg/ kg/day) in 16 patients with active SLE over an average treatment period of 30.3 months (Manger, 1996). The European Consensus Lupus Activity Measurement score decreased significantly (P=0.005) after 6 months, but not at the end of the observation period. The most frequent side effects were hypertension and deterioration of renal function (3 of 16 patients) and hypertrichosis (5 of 16 patients).

In summary, there is little evidence for using CSA in nonrenal SLE treatment because one of the 2 unblinded, non–placebo controlled RCTs that assessed this drug included only 10 patients treated with CSA, and in the other RCT, almost one-third of all patients discontinued the drug because of adverse events or a lack of efficacy.

1. SLE scores on disease activity indices

Due to important variability in the selected patients, treatment doses, and outcome measures, no meta-analyses were performed. Therefore, the review of Pego-Reigosa (2013) reported only conclusions. The following conclusions were reported for disease activity:

- In patients with renal and/or nonrenal SLE refractory to steroids, the addition of CSA may improve disease activity and induce remission in the short term and long term.

- In patients with active SLE refractory to steroids, CSA is not less effective than AZA in reducing renal and/or nonrenal activity.

2. Quality of life

No conclusions were reported for the outcome measure ‘quality of life’.

3. Reduction in glucocorticoid

Conclusions for reduction in glucocorticoid were reported as follows:

-In patients with renal and/or nonrenal SLE refractory to steroids, the addition of CSA has a steroid-sparing effect in the long term.

- In patients with active SLE refractory to steroids, CSA and AZA have both a similar steroid-sparing effect in the medium term.

4. Adverse events

Conclusions for adverse events were reported as follows:

- In patients with renal and/or nonrenal SLE refractory to steroids, the addition of CSA causes frequent adverse events.

- In patients with active SLE refractory to steroids, no significant difference in adverse events were observed between CSA and AZA.

Level of evidence of the literature

As evidence was adapted from the review of Pego-Reigosa (2013), and no detailed information was provided to calculate effect estimates, it was impossible to assess the level of evidence with de GRADE method. Therefore, the conclusion formulated without GRADE. The same method was applied for the literature from the additional RCTs.

Belimumab (10mg/kg)

The current comparison was studied in the Cochrane review of Singh (2021). Data of this review was adapted in the current summary of the literature.

1. SLE scores on disease activity indices

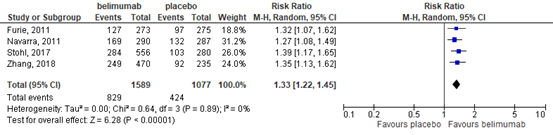

This outcome was reported in four studies at 52 weeks (Furie, 2011; Navarra, 2011; Stohl, 2017; Zhang, 2018). More participants in the belimumab group than in the placebo group showed improvement (at least a 4-point reduction) in SELENA-SLEDAI score. This resulted in a relative risk (RR) of 1.33 (95% confidence interval (CI) 1.22 to 1.45), Figure 1. The absolute difference was 13% (95% CI 8% to 17%) better in the belimumab group with 829 of 1589 (52%) participants versus 424 of 1077 (39%) in the placebo group achieving this reduction.

Figure 1. Forest plot reduction of at least 4 points in SELENA-SLEDAI at 52 weeks; belimumab vs. placebo.

2. Quality of life

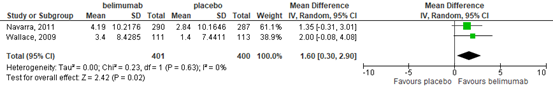

This outcome was defined as change in health-related quality of life on SF-36 at 52 weeks in two trials (Navarra, 2011; Wallace, 2009). These studies showed that there was probably no difference in the health-related quality of life as measured by change in SF-36 PCS in participants in the belimumab group compared with the placebo group (mean difference (MD) 1.60, 95% CI 0.30 to 2.90), Figure 2. The absolute risk difference was 1.60%

(95% CI 0.30% to 2.0%) higher (better) in the belimumab group.

Figure 2. Forest plot change in health-related quality of life at 52 weeks; belimumab vs. placebo.

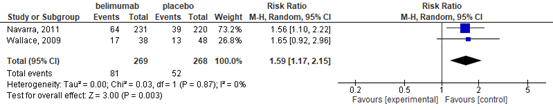

3. Reduction in glucocorticoid

Two of the included trials reported this outcome (Navarro, 2011; Wallace, 2009) defined as reduction of glucocorticoid dose by 50% or more at 52 weeks. The belimumab group showed greater improvement in glucocorticoid dose, with a higher proportion of participants reducing their dose by at least 50%, compared to placebo (RR 1.59, 95% CI 1.17 to 2.15), Figure 3. The absolute risk difference was 11% (95% CI 4% to 18%) better in the belimumab group, with 81 of 269 participants in the belimumab group versus 52 of 268 in the placebo group having at least a 50% reduction in dose.

Figure 3. Forest plot reduction of glucocorticoid dose by 50% or more at 52 weeks; belimumab vs. placebo.

4. Adverse events

Outcome of interest were; serious adverse events, serious infection, withdrawals due to adverse events, and deaths.

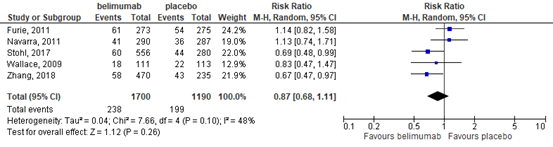

4.1 serious adverse events

This outcome was defined was patients with one or more SAE in five trials (Furie, 2011; Navarra, 2011; Stohl, 2017; Wallace, 2009; Zhang, 2018). These trials showed that there may be little or no difference in the number of serious adverse events in the belimumab group compared with the placebo group (RR 0.87, 95% CI 0.68 to 1.11) Figure 4. The absolute risk difference was 2% (95% CI -6% to 2%) less in the belimumab group with 238 of 1700 (14%) participants in the belimumab group versus 199 of 1190 (17%) in the placebo group experiencing at least one serious adverse event.

Figure 4. Forest plot serious adverse event; belimumab vs. placebo.

4.2 serious infection

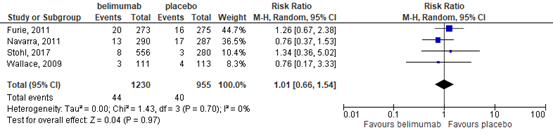

This outcome was studied in four trials (Furie, 2011; Navarra, 2011; Stohl, 2017; Wallace, 2009). These trials showed that there was probably little or no difference in the number of serious infections in the belimumab group compared with the placebo group (RR 1.01, 95% CI 0.66 to 1.54), Figure 5. The absolute risk difference was 0% (95% CI -1% to 1%) with 44 of 1230 (4%) participants in the belimumab group versus 40 of 955 (4%) in the placebo group having at least one serious infection.

Figure 5. Forest plot serious adverse event; belimumab vs. placebo.

4.3 withdrawals due to adverse events

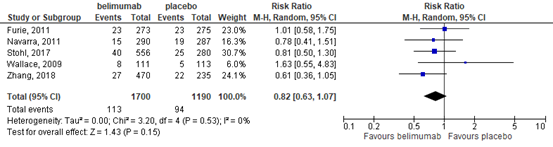

This outcome was studied in five trials (Furie, 2011; Navarra, 2011; Stohl, 2017; Wallace, 2009; Zhang, 2018). These trials showed that there was probably little or no difference in the proportion of participants who withdrew due to adverse events in the belimumab group compared with the placebo group (RR 0.82 (95% CI 0.63 to 1.07), Figure 6. The absolute risk difference was 1% (95% CI -3% to 1%) fewer in the belimumab group with 113 of 1700 (7%) participants in the belimumab group versus 94 of 1190 (8%) in the placebo group withdrawing due to adverse effects.

Figure 6. Forest plot withdrawals due to adverse events; belimumab vs. placebo

4.4 deaths

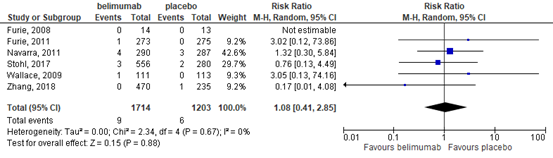

This outcome was studied in six trials (Furie, 2008; 2011; Navarra, 2011; Stohl, 2017; Wallace, 2009; Zhang, 2018). These trials showed that there may be little or no difference in the number of deaths in the belimumab group compared with the placebo group (RR 1.08, 95% CI 0.41 to 2.85), Figure 7. The absolute risk difference was 0% (95% CI -1% to 1%) with nine deaths out of 1714 participants in the belimumab group and six deaths out of 1203

participants in the placebo group.

Figure 7. Forest plot deaths; belimumab vs. placebo.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence (GRADE method) is determined per comparison and outcome measure and is based on results from RCTs and therefore starts at level “high”. Subsequently, the level of evidence was downgraded if there were relevant shortcomings in one of the several GRADE domains: risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision, and publication bias.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure SLE scores on disease activity indices, reduction of glucocorticoid dose was not downgraded.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure quality of life was downgraded by 1 level because of imprecision (the 95% confidence interval includes both no effect and appreciable benefit/harm exceeding a minimal clinically important difference).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure adverse events (i.e., SAE) was downgraded by 2 levels because of imprecision (the 95% confidence interval includes both no effect and appreciable benefit/harm exceeding a minimal clinically important difference), and inconsistency (I2 = 48%).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure adverse events (i.e., serious infection, withdrawals due to AE) was downgraded by 1 level because of imprecision (the 95% confidence interval includes both no effect and appreciable benefit/harm exceeding a minimal clinically important difference).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure adverse events (i.e., death) was downgraded by 2 levels because of imprecision (the 95% confidence interval includes both no effect and appreciable benefit/harm exceeding a minimal clinically important difference, and the total number of events was small (n=15)).

Rituximab

The current comparison was studied in the review of Wu (2020).

1. SLE scores on disease activity indices

This outcome was reported as BILAG score, and clinical response (i.e., combination of complete and partial response) in the two RCTs after a treatment period of 52 weeks. In the observational cohort studies this outcome was reported as BILAG score, and SLEDAI.

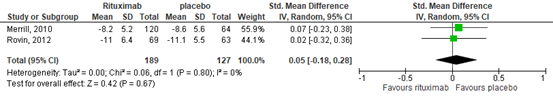

1.1. BILAG score

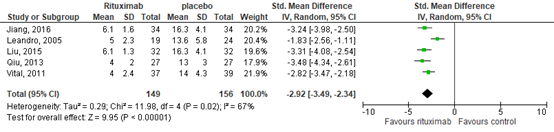

Changes in BILAG score did not differ between the RTX group and the control group in both RCTs over 52 weeks. This resulted in a standardized mean difference of 0.05 (95% confidence interval (CI) -0.18 to 0.28), see Figure 8.

Figure 8. Forest plot change in BILAG score at 52 weeks; rituximab vs. placebo

This outcome was also reported in 5 observational studies. Of them, 2 reported outcomes after 52 weeks of RTX treatment (Liu, 2015; Jiang, 2016), one after 64 weeks (Qiu, 2013), one after 40 weeks (Vital, 2011), and one after 24 weeks (Leonardo, 2005). The BILAG score improved after treatment with RTX. This resulted in a standardized mean difference of -2.92 (95% confidence interval (CI) -3.49 to -2.34), see Figure 9, in favor of RTX.

Figure 9. Forest plot BILAG score after – before (i.e., control); rituximab vs. placebo

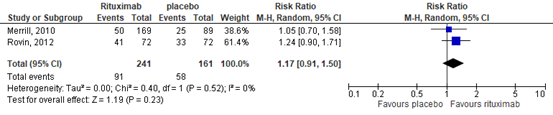

1.2. clinical response

In the RTX group 91/241 (38%) achieved the outcome measure ‘clinical response’, compared with 58/161 (36%) in the placebo group. This resulted in a relative risk (RR) of 1.17 (95%CI 0.91 to 1.50), in favor of the RTX group, see Figure 10. The risk difference was 0.05 (95%CI -0.05 to 0.14).

Figure 10. Forest plot clinical response at week 52; rituximab vs. placebo

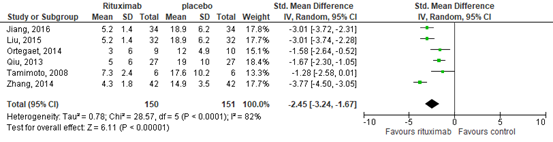

1.3. SLEDAI

This outcome was also reported in 6 observational studies. Of them, 2 reported outcomes after 52 weeks of RTX treatment (Liu, 2015; Jiang, 2016), one after 64 weeks (Qiu, 2013), one after 24 weeks (Zhang, 2014), and two after 48 weeks (Tamimoto, 2008; Ortega, 2010). The SLEDAI score improved after treatment with RTX. This resulted in a standardized mean difference of -2.45 (95% confidence interval (CI) -3.24 to -1.67), see Figure 11, in favor of RTX.

Figure 11. Forest plot SLEDAI score after – before (i.e., control); rituximab vs. placebo

2. Quality of life

This outcome was not reported in the study of Wu (2020).

3. Reduction in glucocorticoid

This outcome was not reported in the study of Wu (2020).

4. Adverse events

Data for the outcome measure ‘adverse events’ was only reported for the RCTs. Outcome of interest were; severe adverse events, deaths, infections, and any infusion related severe adverse events.

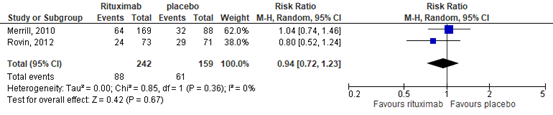

4.1. severe adverse events

In the RTX group 88/242 (36%) achieved the outcome measure ‘severe adverse events’, compared with 61/159 (38%) in the placebo group. This resulted in a relative risk (RR) of 0.94 (95%CI 0.72 to 1.23), in favor of the RTX group, see Figure 12. The risk difference was -0.02 (95%CI -0.12 to 0.08).

Figure 12. Forest plot severe adverse events after 52 weeks; rituximab vs. placebo

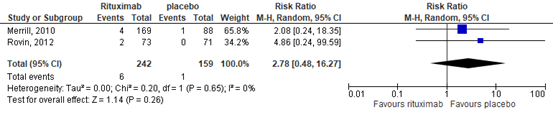

4.2. deaths

In the RTX group 6/242 (2%) died, compared with 1/159 (1%) in the placebo group. This resulted in a RR of 2.74 (95%CI 0.48 to 16.27), in favor of the placebo group, see Figure 13. The risk difference was 0.02 (95%CI -0.02 to 0.04).

Figure 13. Forest plot deaths after 52 weeks; rituximab vs. placebo

4.3. infections

In the RTX group 30/242 (12%) achieved the outcome measure ‘infection’, compared with 29/159 (18%) in the placebo group. This resulted in a RR of 0.73 (95%CI 0.42 to 1.27), in favor of the RTX group, see Figure 14. The risk difference was -0.05 (95%CI -0.13 to 0.02).

Figure 14. Forest plot infections after 52 weeks; rituximab vs. placebo

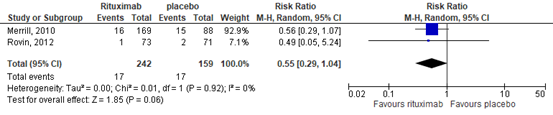

4.4. any infusion related severe adverse events.

In the RTX group 17/242 (3%) achieved the outcome measure ‘any infusion related severe adverse events’, compared with 17/159 (11%) in the placebo group. This resulted in a RR of 0.55 (95%CI 0.29 to 1.04), in favor of the RTX group, see Figure 15. The risk difference was -0.04 (95%CI -0.12 to 0.04).

Figure 15. Forest plot any infusion related severe adverse events after 52 weeks; rituximab vs. placebo

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence (GRADE method) is determined per comparison and outcome measure and is based on results from RCTs or observational studies and therefore starts at level “high” (i.e., RCTs) or “low” (i.e., observational studies). Subsequently, the level of evidence was downgraded if there were relevant shortcomings in one of the several GRADE domains: risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision, and publication bias. For observational studies, it was upgraded if there was a strong association, or a dose-response relation, and/or plausible (residual) confounding.

Based on RCTs:

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure quality of life, reduction of glucocorticoid could not be assessed with GRADE. The outcome measures were not studied in the included studies.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure SLE scores on disease activity indices was downgraded by 2 levels due to imprecision (95%CI of the mean difference includes no significant effect (mean difference=0 or RR=1), no clinically relevant effect (SMD<0.5 or RR 0.75-1.25), and not meeting optimal information size).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure adverse events (i.e., severe adverse events, deaths, infections, and any infusion related severe adverse events) was downgraded by 2 levels because of imprecision (2 levels; the 95% confidence interval includes both no effect and appreciable benefit/harm exceeding a minimal clinically important difference, and not meeting the optimal information size).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure biomarkers was downgraded by 2 levels because of imprecision (2 levels; the 95% confidence interval includes both no effect and appreciable benefit/harm exceeding a minimal clinically important difference, and not meeting the optimal information size).

Based on observational studies:

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure quality of life, reduction of glucocorticoid, adverse events could not be assessed with GRADE. The outcome measures were not studied in the included studies.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure SLE scores on disease activity indices was downgraded by 1 level due to imprecision (not meeting optimal information size).

Anifrolumab

The current comparison was studied in the review of Lee (2020). In this review patients were administrated to placebo or 300 mg anifrolumab via intravenous infusion every 4 weeks.

1. SLE scores on disease activity indices

This outcome was reported as BICLA response in all three studies (Furie, 2017;2019; Morand, 2020). In the individual studies outcomes as BILAG, SLEDAI, and physician’s global assessment were reported as well.

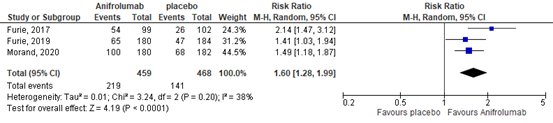

1.1. BICLA

In total 219/459 (48%) patients in the anifrolumab group, compared with 141/468 (30%) in the placebo group achieved BICLA response. This resulted in a relative risk (RR) of 1.60 (95% confidence interval (CI) 1.28 to 1.19), see Figure 25, favoring the anifrolumab group. The risk difference was 0.18 (95%CI 0.95 to 0.28).

Figure 25. Forest plot BICLA response; anifrolumab vs. placebo.

1.2. BILAG

The study of Furie (2017) reported the number of patients who developed new BILAG A flares. This occurred in 12/99 (12%) of the patients in the anifrolumab group, compared with 17/102 (17%) in the control group. This resulted in an RR of 0.73 (95% 0.37 to 1.44).

The study of Furie (2019) reported mean changes from baseline to week 52 in BILAG global score. The mean change (SD) was -13.0 (8.01) in the 143 patients in the anifrolumab group, compared with -10.7 (7.72) in the 147 patients in the control group. This resulted in a standardized mean difference of -0.29 (95%CI -0.52 to -0.06)

1.3. SLEDAI

The study of Furie (2017) reported the number of patients achieving clinical SLEDAI (i.e., ≥4-point reduction in clinical components (no laboratory components) of the SLEDAI). This was achieved in 62/99 (63%) of the patients in the anifrolumab group, compared with 44/102 (43%) in the control group. This resulted in an RR of 1.45 (95% 1.11 to 1.90).

The study of Furie (2019) reported mean changes from baseline to week 52 in SLEDAI-2K. The mean change (SD) was -6.0 (0.34) in the 143 patients in the anifrolumab group, compared with -5.3 (0.33) in the 147 patients in the control group. This resulted in a standardized mean difference of -2.08 (95%CI -2.37 to -1.80)

1.3. Physician’s global assessment

The study of Furie (2017) reported the number of patients achieving an improvement of ≥0.3 points improvement from baseline on physician’s global assessment. This was achieved in 74/99 (75%) of the patients in the anifrolumab group, compared with 55/102 (54%) in the control group. This resulted in an RR of 1.39 (95% 1.12 to 1.71).

The study of Furie (2019) reported mean changes from baseline to week 52 in physician’s global assessment. The mean change (SD) was -1.11 (0.05) in the 143 patients in the anifrolumab group, compared with -0.89 (0.05) in the 147 patients in the control group. This resulted in a standardized mean difference of -4.39 (95%CI -4.82 to -3.96)

2. Quality of life

This outcome was not reported in the study of Lee (2020). But one of the individual studies reported this outcome as ≥3.1-point improvement from baseline in health-related quality of life on SF-36 (PCS; Furie, 2017). This was achieved in 48/99 (49%) in the anifrolumab group, compared with 40/102 (39%) in the placebo group. This resulted in a RR of 1.24 (95% 0.90 to 1.70) in favor of the anifrolumab group.

3. Reduction in glucocorticoid dose

Only an overall outcome was reported for the secondary outcome ‘loss of the glucocorticoid dosage’ (i.e., Reduction of oral corticosteroid dosage to <7.5 mg/day in patients who were receiving >10 mg/day at baseline). This outcome showed a RR of 1.81 (95%CI 1.31 to 2.51), suggesting that the glucocorticoid dosage was more often reduced in the anifrolumab group compared with placebo (Furie, 2017;2019; Morand, 2020).

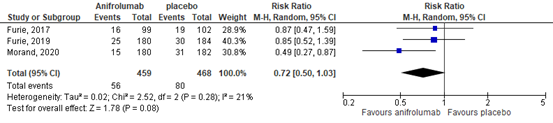

4. Adverse events

Outcome of interest were; adverse events, serious adverse events, and withdrawals due to adverse events.

4.1 adverse events

Only an overall outcome was reported for this secondary outcome based on data of three studies (Furie, 2017;2019; Morand, 2020). The RR was of 1.82 (95%CI 1.26 to 2.61), suggesting that any AEs occurred more often in the anifrolumab group compared with placebo.

4.2 serious adverse events