Videolaryngoscopie

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is de plaats van videolaryngoscopie tijdens de intubatieprocedure van de vitaal bedreigde patiënt buiten de OK?

Aanbeveling

Zorg dat er altijd een videolaryngoscoop beschikbaar is bij intubatie van de vitaal bedreigde patiënt.

Maak, als ervaren intubator, zelf de afweging om videolaryngoscopie of directe laryngoscopie te gebruiken bij intubatie van de vitaal bedreigde patiënt, op geleide van ervaring met elke laryngoscoop, laryngoscoop blad en inschatting van (anatomische) moeilijkheidsgraad van intubatie. Ook voor de ervaren intubator wordt bekwaamheid met videolaryngoscopie aanbevolen.

Onderhoud kennis en kundigheid in directe laryngoscopie.

Hanteer primair videolaryngoscopie bij intubatie van de vitaal bedreigde patiënt voor zorgverleners met beperkte intubatie ervaring.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Er is een literatuuronderzoek verricht naar het effect van videolaryngoscopie ten opzichte van directe laryngoscopie bij de vitaal bedreigde patiënt. In de literatuursamenvatting zijn in totaal vijftien studies meegenomen: veertien RCT’s uit één review en één RCT die later is gepubliceerd. De cruciale uitkomstmaat is first-pass success. Belangrijke uitkomstmaten zijn mortaliteit en systemische complicaties.

De huidige literatuur samenvatting bevat studies gepubliceerd t/m 13 januari 2023. Na deze datum zijn er nog drie relevante systematische reviews met meta-analyses gepubliceerd. Kim (2023) includeert dezelfde studies als Hansel, 2022, aangevuld door enkele pre-hospitale studies (welke voor de huidige richtlijn minder relevant zijn). Araújo (2024) includeert ook dezelfde studies als Hansel (2022), aangevuld door een RCT betreffende DSI in trauma-patiënten en de hieronder benoemde DEVICE-studie (Prekker, 2023). Azam (2024) is een meta-analyse waarin ook observationele studies worden geïncludeerd en lijkt van inferieure kwaliteit.

Gezien de geïncludeerde studies en resultaten van deze meta-analyses grotendeels overeenkomen met onze analyse werd er geen nieuwe literatuursamenvatting verricht. Wel komen de relevante nieuwe gerandomiseerde studies in de onderstaande overwegingen aan bod en wegen zij mee in de aanbevelingen.

Voor de uitkomstmaat first-pass success zien we een mogelijk voordeel voor videolaryngoscopie, waarbij de succesvolle intubatie bij de eerste poging lijkt toe te nemen (GRADE: laag). Er is afgewaardeerd voor risico op bias, omdat studies niet geblindeerd waren en voor imprecisie, omdat het gepoolde effect een grens van klinische besluitvorming doorkruist. De overall bewijskracht van de cruciale uitkomstmaat is daarmee laag. Er wordt wel een klinisch relevant verschil gerapporteerd.

De DEVICE-studie (Prekker, 2023), een grote multicenter RCT in een gerenommeerd blad welke verscheen na de literatuur inclusie voor deze richtlijn, concludeerde dat gebruik van de videolaryngoscoop een hoger percentage succesvolle intubaties bij de eerste poging heeft ten opzichte van de directe laryngoscoop (85,1% vs. 70,8% met een absoluut risico verschil 14.3% (95%CI 9,9 tot 18,7%, p=<0.001). De gerandomiseerde studie van Mo (2023), tevens gepubliceerd na literatuur inclusie voor deze richtlijn, rapporteerde succesvolle intubatie bij de eerste poging in 66,04% met directe laryngoscopie en 86,79% met videolaryngoscopie (p = <0.05). De uitkomsten van deze RCT’s komen overeen met de bevindingen van onze huidige analyse. Het voordeel van de videolaryngoscoop ten aanzien van deze uitkomst lijkt met name voor de minder ervaren intubator aanwezig te zijn. De studies waarbij de artsen die intuberen minder ervaren zijn, laten over het algemeen een groter effect zien in het voordeel van de videolaryngoscoop. In de DEVICE-studie (Prekker, 2023) zijn de meeste intubaties verricht door non-experts, maar het absoluut risico verschil wordt verder vergroot (van 14,3% naar 26,1% (95% CI 15,4 tot 36,8) indien de intubator minder dan 25 intubaties heeft gedaan met de gebruikte laryngoscoop. Aangezien de intubatie van de vitaal bedreigde patiënten ook regelmatig uitgevoerd worden door niet-anesthesiologisch opgeleide artsen, is dit een belangrijke bevinding.

Daarnaast is met een videolaryngoscoop, indien een intubatie in het kader van opleiding uitgevoerd wordt door een AIOS of fellow, de mogelijkheid tot supervisie door een meer ervaren intubator vergemakkelijkt. De supervisor kan direct meekijken met de handelingen en het zicht van de intubator. Dit is waarschijnlijk voordelig in het kader van succesvolle intubatie bij de eerste poging. Een mogelijk nadeel hiervan, is dat de intubatie langer kan duren omdat de supervisor het later overneemt. Tijd tot succesvolle intubatie werd niet als uitkomst meegenomen in de huidige analyse. In de literatuur is het belang van een primaire succesvolle intubatie reeds naar voren gekomen. De kans op complicaties neemt toe met het aantal gefaalde intubatie pogingen. Sakles (2013) rapporteerde een adjusted OR van 7,52 (95%CI 5,86 tot 9,63) voor het ontstaan van één of meer complicaties indien er meer dan één intubatie poging nodig was geweest. Ook retrospectieve data uit de INTUBE-studie (Russotto, 2021) laten zien dat de kans op complicaties hoger is, met een significant absoluut risico verschil bij twee intubatiepogingen van 8,4% (95%CI 3,3 tot 13,5%) en bij drie of meer intubatiepogingen van 14,2% (95%CI 5,2 tot 23,1%). Grote cohortstudies zoals de INTUBE-studie (Russotto, 2023) en de INTUPROS-studie (Garnacho-Montero, 2024) associëren de videolaryngoscoop met een beschermend effect voor een gefaalde intubatie in de IC-populatie.

Het voordeel van de videolaryngoscoop bij de moeilijke luchtweg op anatomische gronden, werd reeds eerder beschreven. In een subgroep analyse van de meta-analyse van Hansel (2022) werd een significant relatief risico gerapporteerd van 0,22-0,37 (afhankelijk van soort videolaryngoscoop) in het voordeel van de videolaryngoscoop ten aanzien van gefaalde intubaties bij patiënten met een geanticipeerde moeilijke luchtweg. Dit zijn grotendeels studies welke zijn uitgevoerd in een populatie die electieve intubatie ondergingen op de operatiekamer en vielen derhalve buiten de patiëntpopulatie van de huidige richtlijn. Het blijkt echter dat de videolaryngoscoop dus niet alleen voordeel kent in de anatomische moeilijke luchtweg, maar ook in de algemene vitaal bedreigde populatie (waarbij de verwacht moeilijke luchtweg vaak is geëxcludeerd uit de populatie).

Er werd in de huidige analyse geen onderscheid gemaakt in het soort videolaryngoscoop dat werd gebruikt. Ook in de recente DEVICE-studie (Prekker, 2023) werd geen onderscheid gemaakt. Er zijn echter wezenlijke verschillen, met name ten aanzien van de noodzakelijke hand-oog coördinatie en de daarbij behorende leercurve. De meest gebruikte onderverdeling kan gemaakt worden in de Macintosh-stijl videolaryngoscopen, de hyperangulaire videolaryngoscopen en de videolaryngoscopen met een kanaal. De meta-analyse van Hansel (2022) maakt hierin wel onderscheid waarbij voor alle soorten videolaryngoscopen een voordeel wordt gezien ten opzichte van de directe laryngoscopie in het kader van first-pass success. Een onderlinge vergelijking wordt niet gemaakt. De uitgebreide Bayesiaanse netwerk meta-analyse van Kim (2023) vergelijkt verschillende soorten videolaryngoscopen waaruit geconstateerd wordt dat een videolaryngoscoop met hyperangulair blad het meeste kans heeft op first-pass success, gevolgd door een videolaryngoscoop met Macintoshblad en daarna een directe laryngoscoop. De videolaryngoscoop met een kanaal worden ingedeeld als minst succesvolle manier van intuberen. Hoewel de recente RCT van Dharanindra (2023) wel een significant verhoogde succesvolle eerste intubatie poging rapporteert bij gebruik van een videolaryngoscoop met een kanaal (95,9% vs. 81,4% bij gebruik van directe laryngoscopie, p < 0.05). Het lijkt dat ervaring met een bepaalde laryngoscoop van groot belang is. Ondanks verbeterd zicht op de stembanden met een videolaryngoscoop, is dit in onervaren handen alsnog geen garantie tot een succesvolle intubatie. De DEVICE-studie (Prekker, 2023) benadrukt dit in een sub-analyse van gefaalde intubaties. Inadequaat zicht op de glottis werd benoemd in 3,7% bij gebruik van videolaryngoscoop versus 17,3% bij gebruik van directe laryngoscoop (absoluut risicoverschil -13,6% (95%CI -16,8 tot -10,3). Echter, onvermogen tot opvoeren van bougie of tube werd benoemd in 7,0% bij gebruik van een videolaryngoscoop vs. 7,2% bij gebruik van een directe laryngoscoop en was dus niet significant verschillend.

Voor de uitkomstmaat mortaliteit werd geen klinisch relevant verschil gevonden (GRADE: laag). Er is afgewaardeerd voor imprecisie, omdat het gepoolde effect beide grenzen van klinische besluitvorming doorkruist. De overall bewijskracht van deze uitkomstmaat is daarmee zeer laag.

Mortaliteit werd in de literatuur op verschillende manieren gedefinieerd, waarbij peri-procedurele mortaliteit voor de werkgroep het meest van belang is. Er is in bovenstaande analyse gekozen om ziekenhuis mortaliteit te rapporteren. De associatie tussen een intubatie procedure en mortaliteit op langere termijn is echter lastig. Complicaties rondom intubatie (zoals oesofageale intubatie, lastige intubatie procedure met meerdere pogingen en aspiratie) werden in het cohort van de INTUBE-studie (Russotto, 2023) wel in verband gebracht met IC-mortaliteit. Slechts 1 van de geïncludeerde studies (Gao, 2018) rapporteerde peri-procedurele mortaliteit, welke in 0,6% van de patiënten werd benoemd (1,2% vs. 0%, NS). In de DEVICE-studie (Prekker, 2023) wordt ook peri-procedurele mortaliteit gerapporteerd (0,1% in VL en 0,4% in DL, NS) en mortaliteit binnen 1u na randomisatie (2,1% vs. 3,8%, NS).

Ten aanzien van het voordeel van gebruik van de videolaryngoscoop in het voorkomen van systemische complicaties werd met name gekeken naar hypoxie, hypotensie/shock, oesofageale intubatie en cardiaal arrest.

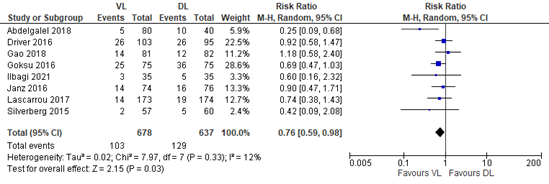

Voor de uitkomstmaat hypoxemie wordt geconcludeerd dat videolaryngoscopie mogelijk de incidentie verlaagt (GRADE: laag). Er is afgewaardeerd voor risico op bias, omdat studies niet geblindeerd waren en voor imprecisie, omdat het gepoolde effect een grens van klinische besluitvorming doorkruist. Er wordt wel een klinisch relevant verschil gerapporteerd.

Voor de uitkomstmaat oesofageale intubatie wordt geconcludeerd dat videolaryngoscopie mogelijk de incidentie verlaagt (GRADE: laag). Er is afgewaardeerd voor risico op bias, omdat studies niet geblindeerd waren en voor imprecisie, omdat er weinig events worden gerapporteerd in de studies. Ook hier wordt een klinisch relevant verschil gevonden.

Ten aanzien van de belangrijke uitkomstmaten hypoxemie en oesofageale intubatie is er dus mogelijk een voordeel voor het hanteren van videolaryngoscopie.

De incidentie van een cardiaal arrest en hypotensie/shock wordt niet gerapporteerd in de meta-analyse van Hansel (2022). Wanneer de geïncludeerde studies uit deze meta-analyse individueel worden bekeken rapporteren enkele studies deze uitkomsten wel. Cardiaal arrest wordt benoemd in Gao (2018), Janz (2016), Lascarrou (2017) en Silverberg (2015), waarbij de incidentie varieert van 0-2.2% en geen significante verschillen worden gezien tussen directe laryngoscopie of videolaryngoscopie. Hypotensie wordt ook door deze studies benoemd. De resultaten hiervan zijn heterogeen qua grootte en richting en zijn allen niet significant.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

Voor zowel de patiënt als degene die de intubatie uitvoert, is de veiligheid van de procedure het belangrijkst. Het initiële doel van een intubatie van een vitaal bedreigde patiënt is namelijk: overleving zonder additionele schade. Daarbij zijn cruciale factoren die meespelen de mate waarin de intubator ervaring heeft met het type laryngoscoop en zich daar vertrouwd mee voelt. Daarom heeft het de voorkeur om de keuze voor het type laryngoscoop aan de intubator over te laten op geleide van diens ervaring. Uitkomsten die voor patiënten mogelijk nog een rol kunnen spelen zijn schade aan tanden of luchtweg. De geïncludeerde studies die deze uitkomst rapporteerden (ernst van schade niet nader gedefinieerd) konden allen geen significant verschil aantonen tussen het gebruik van een videolaryngoscoop of directe laryngoscoop (Abdelgalel, 2018; Dharanindra, 2020; Gao, 2018; Janz, 2016; Lascarrou, 2017; Sanguanwit, 2021; Silverberg, 2015). Van belang hierbij is dat studies een verwacht moeilijke luchtweg vaak excluderen.

In de literatuur betreffende perioperatieve electieve intubaties wordt ook keelpijn vaak benoemd als een uitkomst die als negatief ervaren wordt door de patiënten. Echter, in de intensive care setting lijkt dit van inferieur belang. De patiënten zijn vaker voor langere tijd gesedeerd en bij het ontwaken zitten zowel de tube als een neusmaagsonde al langere tijd in situ, wat significant kan bijdragen aan het ervaren van keelpijn. Deze uitkomst wordt ook niet benoemd in de geïncludeerde literatuur.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

Inmiddels zullen bijna alle IC’s en SEH’s in Nederland één of meerdere videolaryngoscopen beschikbaar hebben. Naar verwachting zullen er dus geen substantiële extra kosten aan verbonden zijn om de videolaryngoscoop standaard te implementeren.

In het algemeen variëren de kosten voor een videolaryngoscoop.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

Door het toenemende gebruik van de videolaryngoscoop zullen de bovengenoemde voordelen ervan, zich over de tijd verder uitvergroten. Met name indien de ervaring met directe laryngoscoop simultaan zal afnemen. Men moet ervoor waken dat de technische kunde voor directe laryngoscopie niet verloren gaat wanneer de videolaryngoscoop meer gebruikt gaat worden. Bij een videolaryngoscoop kunnen technische complicaties ontstaan, waarbij men directe laryngoscopie zal moeten hanteren. Tevens is er luchtwegproblematiek waarbij een videolaryngoscoop soms geen goed beeld kan voorzien (zoals bij een bloeding). Daarom zal deze handeling onderdeel van de opleiding moeten blijven. Gezien het, bij lage exposure aan intubaties, lastig kan zijn om 2 technieken te onderhouden zal hiervoor extra aandacht moeten zijn. Directe laryngoscopie kan op verschillende manieren worden beoefend. Een videolaryngoscoop met een Macinthosh blad kan als directe laryngoscoop worden ingezet, waarbij de intubator het beeldscherm alleen gebruikt indien noodzakelijk. Ook kan de benodigde ervaring bij electieve intubaties op OK worden opgedaan indien hier in samenspraak met de afdeling anesthesiologie ruimte voor is.

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

Videolaryngoscopie is een goede methode om zicht te verkrijgen op de stembanden tijdens de intubatie van de vitaal bedreigde patiënt. Het verhoogt de kans op first-pass success (RR 1,14 (95%CI 1,05-1,24). De kans op met name oesofageale intubatie is verminderd. Uit de literatuur blijkt wel dat vooral de intubator met weinig ervaring baat heeft bij gebruik van de videolaryngoscoop voor een succesvolle intubatie. Een mortaliteitsverschil werd niet aangetoond. Het blijft echter het belangrijkst dat de intubator zich vertrouwd voelt met de device die gebruikt wordt voor laryngoscopie.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Tijdens het plaatsen van een endotracheale tube tracht de zorgverlener optimaal zicht te verkrijgen op de glottis en ingang van de trachea om correcte plaatsing te bewerkstelligen. Dit optimale zicht kan verkregen worden middels directe laryngoscopie (DL) en indirecte laryngoscopie. Het zicht op de trachea wordt geclassificeerd volgens de graden van Cormack&Lehane. Indirecte laryngoscopie kan met verschillende hulpmiddelen uitgevoerd worden waarvan de videolaryngoscoop (VL) de meest gangbare is. De videolaryngoscoop combineert een klassieke (Macintosh) of hyperangulaire laryngoscoop met een camera waarmee de toegang tot de trachea in beeld gebracht wordt. Voor de anatomisch moeilijke luchtweg, waarbij verwacht wordt dat directe laryngoscopie onvoldoende zicht zal verkrijgen, kan daardoor de Cormack&Lehane graad verbeteren. In de praktijk wordt de videolaryngoscoop vaak gebruikt bij een anatomisch moeilijke luchtweg of als ‘rescue device’. Of de videolaryngoscoop gebruikt zou moeten worden als primaire laryngoscoop voor alle intubaties bij vitaal bedreigde patiënten is een punt dat ter discussie staat. Een recente adviserende richtlijn van de ‘Society of Critical Care Medicine’ over de RSI bij vitaal bedreigde patiënten geeft over dit onderwerp geen advies (Acquisto, 2023). Mogelijk zijn er voordelen van de videolaryngoscoop ten opzichte van directe laryngoscopie in zowel de normale luchtweg als de geanticipeerde moeilijke luchtweg, waarbij te denken aan first-pass success rate, snelheid van intubatie en schade aan de luchtweg van de patiënt. Gezien het feit dat buiten de operatiekamers ook zorgverleners intuberen die niet volledig zijn opgeleid binnen de anesthesiologie, kunnen deze voordelen uitvergroot zijn in de vitaal bedreigde populatie.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

Critical outcomes

|

Low GRADE |

Videolaryngoscopy may increase first pass success when compared with direct laryngoscopy in critically ill patients.

Source: Hansel, 2022; Ilbagi, 2021. |

|

Low GRADE |

Videolaryngoscopy may result in little to no difference in mortality when compared with direct laryngoscopy in critically ill patients.

Source: Hansel, 2022. |

Important outcomes

|

Low GRADE |

Videolaryngoscopy may reduce the incidence of hypoxemia when compared with direct laryngoscopy in critically ill patients.

Sources: Hansel, 2022; Ilbagi, 2021. |

|

No GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding the effect of videolaryngoscopy on cardiac arrest and hypotension/shock when compared with direct laryngoscopy in critically ill patients.

Source: - |

|

Low GRADE |

Videolaryngoscopy may reduce the incidence of esophageal intubation when compared with direct laryngoscopy in critically ill patients.

Sources: Hansel, 2022; Ilbagi, 2021. |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

Hansel (2022) conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to assess whether use of different designs of videolaryngoscopes in adults requiring tracheal intubation reduces the failure rate compared with direct laryngoscopy and assess the benefits and risks of these devices in selected population groups, users and settings. Relevant databases were searched up until February 2021. RCTs in any setting were included. A total of 222 RCTs with 26,149 participants were included. As in the current analysis only studies in the ICU or ED are of interest, studies in other settings were excluded. Hence, 207 studies were excluded. One additional study (Kim, 2016) was excluded as it did not report any of the predefined outcomes. Fourteen RCTs from Hansel (2022) were included.

In addition, an RCT by Ilbagi (2021) was included. They conducted a trial to investigate the

risk of complications and failure of using direct and videolaryngoscopy on patients who underwent endotracheal intubation by emergency medicine residents. Reported outcomes of interest were first pass success, esophageal intubation and reduced oxygen saturation (hypoxemia).

In Table 1, an overview of the included studies is presented.

Table 1. Characteristics of included studies

|

Author, year |

N, total |

Population |

Intervention |

Control |

Intubator experience |

Follow-up |

|

Randomized controlled trials included in Hansel (2022) |

||||||

|

Abdelgalel 2018 |

97 |

Patients in the ED requiring emergency intubation |

GlideScope VL |

Macintosh DL |

>3-year experience in anesthesia and > 30 intubations with VL |

NR |

|

Ahmadi 2015 |

120 |

ICU patients aged ≥ 18 years |

I) GlideScope VL II) Airtraq VL |

Macintosh DL |

2nd or 3rd year emergency medicine residents |

NR |

|

Dey 2020 |

248 |

ICU patients requiring elective tracheal intubation |

C-MAC VL |

Macintosh DL |

>50 VLs. Intubators were categorized into junior (<3 years), senior (3–8 years) and consultant (>8 years) |

NR |

|

Dharanindra 2020 |

140 |

Patients 18–70 years requiring intubation in the ICU for any physiological derangement |

King Vision VL |

Macintosh DL |

NR |

NR |

|

Driver 2016 |

198 |

Adult patients undergoing emergency orotracheal intubation in the ED |

C-MAC VL |

C-MAC Macintosh DL |

3rd year emergency medicine residents with > 4 months regular intubating experience with both devices |

Until hospital discharge |

|

Gao 2018 |

167 |

Adult ICU patients needing tracheal intubation to allow mechanical ventilation |

UEScope VL |

Macintosh DL |

Trained in both DL and VL. Physicians involved had either worked at ICUs for > 5 years or worked at ICUs for > 1 year after receiving > 2 months of anesthesiology training. |

NR |

|

Goksu 2016 |

150 |

Patients (aged ≥ 16 yrs) in the ED due to blunt trauma requiring tracheal intubation |

C-MAC VL |

Macintosh DL |

Different skill mix with unclear prior experience with intubation in general and specifically with VL |

NR |

|

Griesdale 2012a |

40 |

ICU patients > 16 years of age requiring urgent tracheal intubation |

GlideScope VL |

Macintosh DL |

All inexperienced operators (<5 intubations in the preceding 6 months) |

Until hospital discharge |

|

Janz 2016 |

150 |

ICU patients ≥ 18 years old undergoing tracheal intubation |

McGrath MAC (98.6%) or GlideScope (1.4%) VL |

Macintosh or Miller DL |

Pulmonary and critical care medicine fellows with varying experience, but more DL than VL experience |

Until hospital discharge |

|

Lascarrou 2017 |

371 |

ICU patients needing orotracheal intubation to allow mechanical ventilation |

McGrath MAC VL |

Macintosh DL |

Experts (>5 years at ICU or worked at ICUs for > 1 year after receiving > 2 years of anesthesiology training and) and nonexperts (not meeting the criteria) |

28 days |

|

Sanguanwit 2021 |

158 |

age > 18 years requiring intubation in ED, acute respiratory failure |

GlideScope VL |

Macintosh DL |

Varied skill mix, from senior residents (overall > 3 years intubating experience) to medical students (<1 year) |

NR |

|

Silverberg 2015 |

117 |

patients who required urgent or emergent intubation in the ICU |

GlideScope VL |

Macintosh DL |

Critical care fellows, most in their 1st year so likely inexperienced with both devices |

NR |

|

Sulser 2016 |

147 |

Patients aged 18‐99 years undergoing emergency RSI in the ED |

C-MAC VL |

Macintosh DL |

Experienced anesthesia consultants |

NR |

|

Yeatts 2013 |

623 |

Patients who required tracheal intubation in the trauma resuscitation unit |

GlideScope VL |

Macintosh DL |

Residents with a minimum of 1 year of previous intubation experience |

30 days |

|

Additional randomized controlled trial |

||||||

|

Ilbagi 2021 |

70 |

Patients requiring endo-tracheal intubation in ED |

GlideScope VL |

Macintosh DL |

Second year emergency medicine resident with sufficient skill in DL and VL |

NR |

DL: direct laryngoscope; ED: emergency department; ICU: intensive care unit; NR: not reported; RSI: rapid sequence intubation; VL: videolaryngoscope

Results

First pass success

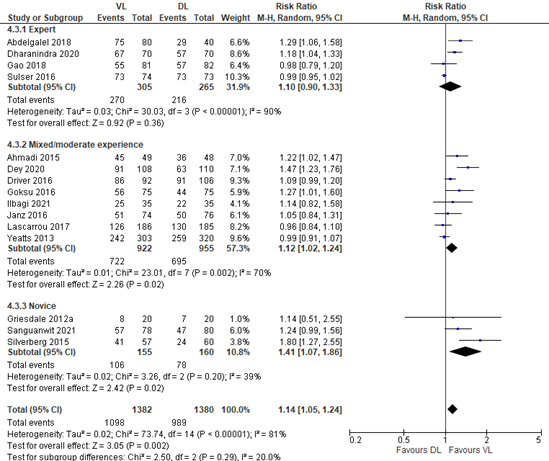

Fifteen studies reported the outcome ‘first pass success’. A pooled risk ratio (RR) of 1.14 (95% confidence interval (CI) 1.05 to 1.24) was found in favor of videolaryngoscopy (Figure 1). This difference was considered clinically relevant.

A subgroup analysis based on intubator experience showed no clinically relevant difference for experts (RR 1.10; 95% CI 0.90 to 1.33), but for a group of intubators with mixed or moderate experience (RR 1.12; 95% CI 1.02 to 1.24) and novice (RR 1.41; 95% CI 1.07 to 1.86), a clinically relevant difference in favor of videolaryngoscopy was found.

Figure 1. First pass success; subgroup analysis for intubator experience

Z: p-value of the pooled effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistic heterogeneity; CI: Confidence Interval; DL: direct laryngoscopy; VL: videolaryngoscopy

Mortality

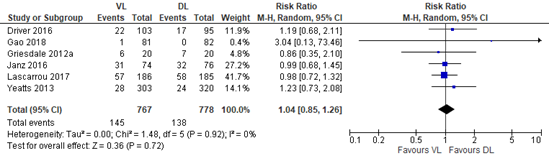

Six studies reported mortality until discharge, including four studies reporting in-hospital mortality (Driver, 2016; Griesdale, 2012a; Janz, 2016; Yeatts, 2013), one reporting ICU-mortality (Lascarrou, 2017) and one reporting death as part of airway management complications (Gao, 2018).

A pooled RR of 1.04 (95% CI 0.85 to 1.26) was found in favor of direct laryngoscopy (Figure 2). This difference was not considered clinically relevant.

Figure 2. Mortality

Z: p-value of the pooled effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistic heterogeneity; CI: Confidence Interval; DL: direct laryngoscopy; VL: videolaryngoscopy

Figure 3. Hypoxemia

Z: p-value of the pooled effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistic heterogeneity; CI: Confidence Interval; DL: direct laryngoscopy; VL: videolaryngoscopy

Cardiac arrest

The outcome measure ‘cardiac arrest’ was not reported in the included studies.

Hypotension/shock

The outcome measure ‘hypotension/shock’ was not reported in the included studies.

Esophageal intubation

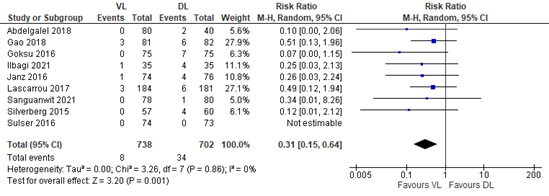

Nine studies reported ‘esophageal intubation’. In the videolaryngoscopy group, esophageal intubation was reported in 8 out of 738 (1.1%) patients and in the direct laryngoscopy group in 34 out of 702 (4.8%) patients.

A pooled RR of 0.31 (95% CI 0.15 to 0.64) was found in favor of videolaryngoscopy (Figure 4). This difference was considered clinically relevant.

Figure 4. Esophageal intubation

Z: p-value of the pooled effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistic heterogeneity; CI: Confidence Interval; DL: direct laryngoscopy; VL: videolaryngoscopy

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence regarding all outcome measures started as high, because the studies were RCTs.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure first pass success was downgraded by two levels because of study limitations (risk of bias due to lack of blinding, -1); pooled confidence interval crossing the threshold of clinical relevance (imprecision, -1). The level of evidence is low.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure mortality was downgraded by two levels because of the pooled confidence interval crossing the thresholds of clinical relevance (imprecision, -2). The level of evidence is low.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure hypoxemia was downgraded by two levels because of study limitations (risk of bias due to lack of blinding, -1); the pooled confidence interval crossing the threshold of clinical relevance (imprecision, -1). The level of evidence is low.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure cardiac arrest could not be graded, as none of the included studies reported this.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure esophageal intubation was downgraded by two levels because of study limitations (risk of bias due to lack of blinding, -1), and a low number of events (imprecision, -1). The level of evidence is low.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure shock could not be graded, as none of the included studies reported this.

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question:

What are the benefits and harms of videolaryngoscopy compared with direct laryngoscopy during intubation of the critically ill patient outside the operating room?

| P: |

Critically ill patient who are intubated outside the operating room |

| I: | Videolaryngoscopy |

| C: | Direct laryngoscopy |

| O: | First pass success, mortality, systemic complications (hypoxemia, cardiac arrest, hypotension/shock, esophageal intubation) |

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered first pass success as a critical outcome measure for decision making; and mortality and systemic complications as important outcome measures for decision making.

Mortality was defined as death during hospital stay.

A priori, the working group did not define the other outcome measures listed above but used the definitions used in the studies.

The working group defined the following as a minimal clinically (patient) important difference:

First pass success: a difference of 10% in relative risk was considered clinically relevant (RR <0.91 or >1.10).

Mortality: a difference of 5% in relative risk was considered clinically relevant (RR <0.95 or >1.05).

Systemic complications: a difference of 25% in relative risk was considered clinically relevant (RR <0.8 or >1.25).

For the outcome measure ‘first pass success’, a subgroup analysis based on intubator experience was performed. The definition of experience of the intubator differs throughout literature. For this subgroup analysis, experienced intubators were defined as those who had equivalent experience in the clinical setting of at least 50 uses with each device, and inexperienced intubators as those with fewer than 50 uses of each device. If number of previous intubations was not stated, a minimum of 5 years’ experience in intensive care (ICU) or the emergency department (ED) was considered ‘expert’, a minimum of 2 years’ experience in ICU/ED was considered ‘moderate experience’ and <2 years’ experience was considered a ‘novice’. At least 1 year of anesthesia training was also considered an experienced intubator. These definitions only apply to this module and were chosen based on rapported data in the included studies.

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms until January 13th, 2023. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 1053 hits. First, the systematic reviews and meta-analyses were screened. These were selected based on the following criteria:

1) systematic reviews or meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials; 2) published ≥ 2002; 3) comparing videolaryngoscopy with direct laryngoscopy; 4) in critically ill patients in the ICU or ED; 5) reporting at least one of the predefined outcomes.

Twenty-nine systematic reviews were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, 28 studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and one Cochrane review was included.

This Cochrane review was included in the current literature analysis. The search of this review was updated in February 2021. Hence for the current analysis, randomized controlled trials (RCTs) published in 2021 or later were screened and selected according to the predefined PICO. Three RCTs were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, two studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and one RCT was included.

Results

One Cochrane review and one additional RCT were included in the analysis of the literature. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- Abdelgalel EF, Mowafy SM. Comparison between Glidescope, Airtraq and Macintosh laryngoscopy for emergency endotracheal intubation in intensive care unit: randomized controlled trial. Egyptian Journal of Anaesthesia. 2018 Oct 1;34(4):123-8.

- Araújo B, Rivera A, Martins S, Abreu R, Cassa P, Silva M, Gallo de Moraes A. Video versus direct laryngoscopy in critically ill patients: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Crit Care. 2024 Jan 2;28(1):1. doi: 10.1186/s13054-023-04727-9. PMID: 38167459; PMCID: PMC10759602.

- Azam S, Khan ZZ, Shahbaz H, Siddiqui A, Masood N, Anum, Arif Y, Memon ZU, Khawar MH, Siddiqui FF, Azam F, Goyal A. Video Versus Direct Laryngoscopy for Intubation: Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cureus. 2024 Jan 5;16(1):e51720. doi: 10.7759/cureus.51720. PMID: 38322075; PMCID: PMC10846758.

- Dharanindra M, Jedge PP, Patil VC, Kulkarni SS, Shah J, Iyer S, Dhanasekaran KS. Endotracheal Intubation with King Vision Video Laryngoscope vs Macintosh Direct Laryngoscope in ICU: A Comparative Evaluation of Performance and Outcomes. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2023 Feb;27(2):101-106. doi: 10.5005/jp-journals-10071-24398. PMID: 36865505; PMCID: PMC9973068.

- Gao YX, Song YB, Gu ZJ, Zhang JS, Chen XF, Sun H, Lu Z. Video versus direct laryngoscopy on successful first-pass endotracheal intubation in ICU patients. World J Emerg Med. 2018;9(2):99-104. doi: 10.5847/wjem.j.1920-8642.2018.02.003. PMID: 29576821; PMCID: PMC5847508.

- Garnacho-Montero J, Gordillo-Escobar E, Trenado J, Gordo F, Fisac L, García-Prieto E, López-Martin C, Abella A, Jiménez JR, García-Garmendia JL; Intubation Prospective (INTUPROS) Study Investigators. A Nationwide, Prospective Study of Tracheal Intubation in Critically Ill Adults in Spain: Management, Associated Complications, and Outcomes. Crit Care Med. 2024 May 1;52(5):786-797. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000006198. Epub 2024 Jan 23. PMID: 38259143.

- Hansel J, Rogers AM, Lewis SR, Cook TM, Smith AF. Videolaryngoscopy versus direct laryngoscopy for adults undergoing tracheal intubation: a Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis update. Br J Anaesth. 2022 Oct;129(4):612-623. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2022.05.027. Epub 2022 Jul 9. PMID: 35820934; PMCID: PMC9575044.

- Ilbagi M, Nasr-Esfahani M. The Efficacy of Using Video Laryngoscopy on Tracheal Intubation by Novice Physicians. Iran J Otorhinolaryngol. 2021 Jan;33(114):37-44. doi: 10.22038/ijorl.2020.43797.2447. PMID: 33654689; PMCID: PMC7897431.

- Janz DR, Semler MW, Lentz RJ, Matthews DT, Assad TR, Norman BC, Keriwala RD, Ferrell BA, Noto MJ, Shaver CM, Richmond BW, Zinggeler Berg J, Rice TW; Facilitating EndotracheaL intubation by Laryngoscopy technique and apneic Oxygenation Within the ICU Investigators and the Pragmatic Critical Care Research Group. Randomized Trial of Video Laryngoscopy for Endotracheal Intubation of Critically Ill Adults. Crit Care Med. 2016 Nov;44(11):1980-1987. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001841. PMID: 27355526; PMCID: PMC5203695.

- Kim JG, Ahn C, Kim W, Lim TH, Jang BH, Cho Y, Shin H, Lee H, Lee J, Choi KS, Na MK, Kwon SM. Comparison of video laryngoscopy with direct laryngoscopy for intubation success in critically ill patients: a systematic review and Bayesian network meta-analysis. Front Med (Lausanne). 2023 Jun 9;10:1193514. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2023.1193514. PMID: 37358992; PMCID: PMC10289197.

- Lascarrou JB, Boisrame-Helms J, Bailly A, Le Thuaut A, Kamel T, Mercier E, Ricard JD, Lemiale V, Colin G, Mira JP, Meziani F, Messika J, Dequin PF, Boulain T, Azoulay E, Champigneulle B, Reignier J; Clinical Research in Intensive Care and Sepsis (CRICS) Group. Video Laryngoscopy vs Direct Laryngoscopy on Successful First-Pass Orotracheal Intubation Among ICU Patients: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2017 Feb 7;317(5):483-493. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.20603. PMID: 28118659.

- Mo C, Zhang L, Song Y, Liu W. Safety and effectiveness of endotracheal intubation in critically ill emergency patients with videolaryngoscopy. Medicine (Baltimore). 2023 Nov 3;102(44):e35692. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000035692. PMID: 37933038; PMCID: PMC10627691.

- Prekker ME, Driver BE, Trent SA, Resnick-Ault D, Seitz KP, Russell DW, Gaillard JP, Latimer AJ, Ghamande SA, Gibbs KW, Vonderhaar DJ, Whitson MR, Barnes CR, Walco JP, Douglas IS, Krishnamoorthy V, Dagan A, Bastman JJ, Lloyd BD, Gandotra S, Goranson JK, Mitchell SH, White HD, Palakshappa JA, Espinera A, Page DB, Joffe A, Hansen SJ, Hughes CG, George T, Herbert JT, Shapiro NI, Schauer SG, Long BJ, Imhoff B, Wang L, Rhoads JP, Womack KN, Janz DR, Self WH, Rice TW, Ginde AA, Casey JD, Semler MW; DEVICE Investigators and the Pragmatic Critical Care Research Group. Video versus Direct Laryngoscopy for Tracheal Intubation of Critically Ill Adults. N Engl J Med. 2023 Aug 3;389(5):418-429. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2301601. Epub 2023 Jun 16. PMID: 37326325; PMCID: PMC11075576.

- Russotto V, Lascarrou JB, Tassistro E, Parotto M, Antolini L, Bauer P, Szu?drzy?ski K, Camporota L, Putensen C, Pelosi P, Sorbello M, Higgs A, Greif R, Grasselli G, Valsecchi MG, Fumagalli R, Foti G, Caironi P, Bellani G, Laffey JG, Myatra SN; INTUBE Study Investigators. Efficacy and adverse events profile of videolaryngoscopy in critically ill patients: subanalysis of the INTUBE study. Br J Anaesth. 2023 Sep;131(3):607-616. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2023.04.022. Epub 2023 May 17. PMID: 37208282.

- Russotto V, Myatra SN, Laffey JG, Tassistro E, Antolini L, Bauer P, Lascarrou JB, Szuldrzynski K, Camporota L, Pelosi P, Sorbello M, Higgs A, Greif R, Putensen C, Agvald-Öhman C, Chalkias A, Bokums K, Brewster D, Rossi E, Fumagalli R, Pesenti A, Foti G, Bellani G; INTUBE Study Investigators. Intubation Practices and Adverse Peri-intubation Events in Critically Ill Patients From 29 Countries. JAMA. 2021 Mar 23;325(12):1164-1172. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.1727. Erratum in: JAMA. 2021 Jun 22;325(24):2507. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.9012. PMID: 33755076; PMCID: PMC7988368.

- Sanguanwit P, Yuksen C, Laowattana N. Direct Versus Video Laryngoscopy in Emergency Intubation: A Randomized Control Trial Study. Bull Emerg Trauma. 2021 Jul;9(3):118-124. doi: 10.30476/BEAT.2021.89922.1240. PMID: 34307701; PMCID: PMC8286653.

- Silverberg MJ, Li N, Acquah SO, Kory PD. Comparison of video laryngoscopy versus direct laryngoscopy during urgent endotracheal intubation: a randomized controlled trial. Crit Care Med. 2015 Mar;43(3):636-41. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000751. PMID: 25479112.

Evidence tabellen

Evidence table for systematic review of RCTs and observational studies (intervention studies)

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C) |

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

Hansel, 2022

PS., study characteristics and results are extracted from the SR (unless stated otherwise) |

SR and meta-analysis of RCTs

Literature search up to Feb 2021

A: Abdelgalel 2018 B: Ahmadi 2015 C: Dey 2020 D: Dharanindra 2020 E: Driver 2016 F: Gao 2018 G: Goksu 2016 H: Griesdale 2012a I: Janz 2016 J: Kim 2016 K: Lascarrou 2017 L: Sanguanwit 2021 M: Silverberg 2015 N: Sulser 2016 O: Yeatts 2013

Study design: A/B/C/D/E/F/G/H/I/J/K/LM/N/O: RCT, parallel

Setting and Country: A: Egypt, ICU – single center B: Iran, ED - single center C/D: India, ICU – single center E/O: USA, ED – single center F: China, ICU – single center G: Turkey, ED – single center H: Canada, ICU – single center I/M: USA, ICU – single center J: Korea, ED K: France, ICU - multicenter L: Thailand, ED N: Switzerland, ED – single center

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: A/B/C/E/F/L/M: none D: not reported G/J/N: academic support, no conflicts H: non-industry support I/K: financial support from institutes and industry N: departmental and university funding |

Inclusion criteria SR: RCTs of both parallel and cross-over design comparing the use of any model of videolaryngoscopy with a Macintosh DL in adults aged ≥16 yr undergoing tracheal intubation in any setting (details in appendix SR)

Exclusion criteria SR: awake tracheal intubation, optical stylets, flexible fibreoptic intubating devices, tracheal tubes with an integrated camera and the Bullard videolaryngoscope; studies comparing McCoy or Miller blade; non-human participants.

Out of 222 studies from the SR, 15 were included in the current analysis

Important patient characteristics at baseline:

N, mean age A: 120 patients, 42 yrs B: 97 patients, 50 yrs C: 248 patients, 48 yrs D: 140 patients, age NR E: 198 patients, 52 yrs F: 167 patients, 69 yrs G: 150 patients, 39 yrs H: 40 patients, 68 yrs I: 150 patients, 59 yrs J: 140 patients, 61 yrs K: 371 patients, 63 yrs L: 158 patients, 73 yrs M: 117 patients, 65 yrs N: 147 patients, 53 yrs O: 623 patients, 42 yrs

Sex: A: 65% Male B: 59% Male C: 58% Male D/G: NR E: 60% Male F: 69% Male H: 75% Male I: 64% Male J: 63% Male K: 66% Male L: 56% Male M: 47% Male N: 91% Male O: 71% Male

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

Describe intervention:

A: I) GlideScope II) Airtraq B/H/J/L/M/O: GlideScope C/E/G/N: C-MAC D: King Vision F: UEScope I: McGrath MAC (98.6%) or GlideScope (1.4%) K: McGrath MAC |

Describe control:

A/B/C/D/F/G/H/J/K/L/M/N/O: Macintosh E: C-MAC Macintosh direct laryngoscope I: Macintosh (97.4%) or Miller (2.6%) blade |

End-point of follow-up:

A/B/C/D/E/F/G/H/I/J/K/L/M/N/O: Not reported

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? (intervention/control) A/B/E/G/H/I/L/M: 0 C: 16/124 lost in intervention group; 14/124 in control group D: unclear E: 3/84 lost in intervention group, 1/83 in control group F: 3/84 lost in the intervention group; 1/83 lost in the control group J: 61/132 lost in the intervention group; 69/138 lost in control group K: Data for 5 participants (2 in DL arm, 3 in VL arm) were missing for first-pass success N: 1/75 lost in the intervention group; 2/75 in the control group O: 24.2% reported data for successful first attempt and TTI outcomes were missing

|

Outcome measure-1 first attempt successful intubation (assessed at time of intubation)

Effect measure: RR, [95% CI]: A: 1.29 [1.06, 1.58] B: 1.22 [1.02, 1.47] C: 1.47 [1.23, 1.76] D: 1.18 [1.04, 1.33] E: 1.09 [0.99, 1.20] F: 0.98 [0.79, 1.20] G: 1.27 [1.01, 1.60] H: 1.14 [0.51, 2.55] I: 1.05 [0.84, 1.31] K: 0.96 [0.84, 1.10] L: 1.24 [0.99, 1.56] M: 1.80 [1.27, 2.55] N: 0.99 [0.95, 1.02] O: 0.99 [0.91, 1.07]

Pooled effect (random effects model): 1.14 [1.05, 1.25] favoring videolaryngoscopy Heterogeneity (I2): 82%

Outcome measure-2 time to successful intubation, defined as total time required for tracheal intubation at time of intubation

Effect measure: MD, [95% CI]: A: 2.65 [-2.28, 7.58] B: -4.44 [-8.64, -0.24] E: 3.00 [-15.45, 21.45] G: -9.00 [-21.85, 3.85] N: 1.00 [-2.25, 4.25] O: 14.50 [6.61, 22.39]

Pooled effect (random effects model): 1.45 [-3.71, 6.62] favoring videolaryngoscopy Heterogeneity (I2): 75%

Outcome measure-3 Mortality (within 30 days of intubation) E: 1.19 [0.68, 2.11] F: 3.04 [0.13, 73.46] H: 0.86 [0.35, 2.10] I: 0.99 [0.68, 1.45] K: 0.98 [0.75, 1.29] O: 1.23 [0.73, 2.08]

Pooled effect (random effects model): 1.03 [0.86, 1.24] favoring direct laryngoscopy Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

Complications Hypoxemia, defined as oxygen saturation <94% between start of induction and recovery from anaesthesia Effect measure: RR, [95% CI]: A: 0.25 [0.09, 0.68] E: 0.92 [0.58, 1.47] F: 1.18 [0.58, 2.40] G: 0.69 [0.47, 1.03] K: 0.74 [0.38, 1.43] M: 0.42 [0.09, 2.08]

Pooled effect (random effects model): 0.73 [0.53, 1.02] favoring videolaryngoscopy Heterogeneity (I2): 34%

Esophageal intubation, (assessed at time of intubation) Effect measure: RR, [95% CI]: A: 0.10 [0.00, 2.06] F: 0.51 [0.13, 1.96] G: 0.07 [0.00, 1.15] I: 0.26 [0.03, 2.24] K: 0.49 [0.12, 1.94] L: 0.34 [0.01, 8.26] M: 0.12 [0.01, 2.12] N: Not estimable

Pooled effect (random effects model): 0.32 [0.15, 0.68] favoring videolaryngoscopy Heterogeneity (I2): 0% |

Risk of bias (high, some concerns or low): A: Some concerns B: High C: Some concerns D: Some concerns E: Some concerns F: Some concerns G: Some concerns H: Some concerns I: Some concerns J: Unclear K: Some concerns L: Some concerns M: High N: Some concerns O: High

Facultative:

“In this systematic review and meta-analysis of trials of adults undergoing tracheal intubation, VL was associated with fewer failed attempts and complications such as hypoxaemia, whereas glottic views were improved.”

Level of evidence: GRADE (per comparison and outcome measure) including reasons for down/upgrading First attempt successful intubation: low (risk of bias, -1; inconsistency, -1) Time to successful intubation: very low (risk of bias, -1; inconsistency, -2) Mortality: no GRADE Hypoxemia: moderate (risk of bias, -1) Oesophageal intubation: low (risk of bias, -1; imprecision due to wide CIs, -1)

Sensitivity analyses (excluding small studies; excluding studies with short follow-up; excluding low quality studies; relevant subgroup-analyses); mention only analyses which are of potential importance to the research question

Hypoxaemia (RR 0.74, 95% CI 0.57 to 0.94; P = 0.0152), and oesophageal intubation (RR 0.79, 05% CI 0.44 to 1.43; P = 0.4348). This did not alter our interpretation of the primary findings.

|

Table of quality assessment for systematic reviews of RCTs and observational studies

Based on AMSTAR checklist (Shea et al.; 2007, BMC Methodol 7: 10; doi:10.1186/1471-2288-7-10) and PRISMA checklist (Moher et al 2009, PLoS Med 6: e1000097; doi:10.1371/journal.pmed1000097)

|

Study

First author, year |

Appropriate and clearly focused question?1

Yes/no/unclear |

Comprehensive and systematic literature search?2

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of included and excluded studies?3

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of relevant characteristics of included studies?4

Yes/no/unclear |

Appropriate adjustment for potential confounders in observational studies?5

Yes/no/unclear/not applicable |

Assessment of scientific quality of included studies?6

Yes/no/unclear |

Enough similarities between studies to make combining them reasonable?7

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential risk of publication bias taken into account?8

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential conflicts of interest reported?9

Yes/no/unclear |

|

Hansel, 2022 |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

NA |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Risk of bias table, adjusted from Hansel (2022)

|

|

Random sequence generation |

Allocation concealment |

Blinding of participants and personnel |

Blinding of outcome assessment |

Incomplete outcome data |

Selective reporting |

Experience of intubator |

|

Abdelgalel 2018 |

low |

low |

high |

high |

low |

unclear |

low |

|

Ahmadi 2015 |

high |

high |

high |

high |

high |

unclear |

unclear |

|

Dey 2020 |

unclear |

low |

high |

high |

unclear |

unclear |

low |

|

Dharanindra 2020 |

unclear |

low |

high |

high |

unclear |

unclear |

unclear |

|

Driver 2016 |

low |

low |

high |

high |

unclear |

unclear |

unclear |

|

Gao 2018 |

unclear |

unclear |

high |

high |

low |

unclear |

unclear |

|

Goksu 2016 |

unclear |

low |

high |

high |

low |

unclear |

high |

|

Griesdale 2012a |

low |

low |

high |

high |

low |

unclear |

low |

|

Janz 2016 |

low |

low |

high |

high |

low |

low |

high |

|

Lascarrou 2017 |

low |

low |

high |

high |

low |

low |

high |

|

Sanguanwit 2021 |

low |

low |

high |

high |

low |

unclear |

unclear |

Evidence table for intervention studies (randomized controlled trials and non-randomized observational studies [cohort studies, case-control studies, case series])

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

|

Ilbagi, 2021 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: Alzahra University Hospital, Isfahan, Iran – Department of Emergency Medicine

Funding and conflicts of interest: NR |

Inclusion criteria: 1) suitability for undergoing endotracheal intubation, 2) age range of 18-65 years, 3) lack of anatomical problems in the neck and trachea, 4) no drug addiction, and 5) willingness to participate in the study.

Exclusion criteria: patients with cardiac arrest during laryngoscopy and difficult intubation during attempts to intubate, as well as those in situations when intubation was prohibited (i.e., unstable spinal cord injury)

N total at baseline: Intervention: 35 Control: 35

Important prognostic factors2: age ± SD: I: 45.74±11.289 C: 45.31±11.172

Sex: I: 20 (57.1%) M C: 16 (45.7%) M

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

NR: not reported.

Risk of bias table for intervention studies (randomized controlled trials; based on Cochrane risk of bias tool and suggestions by the CLARITY Group at McMaster University)

|

Study reference

(first author, publication year) |

Was the allocation sequence adequately generated?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was the allocation adequately concealed?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Blinding: Was knowledge of the allocated interventions adequately prevented?

Were patients blinded?

Were healthcare providers blinded?

Were data collectors blinded?

Were outcome assessors blinded?

Were data analysts blinded? Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was loss to follow-up (missing outcome data) infrequent?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Are reports of the study free of selective outcome reporting?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was the study apparently free of other problems that could put it at a risk of bias?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Overall risk of bias If applicable/necessary, per outcome measure

LOW Some concerns HIGH |

|

Ilbagi, 2021 |

Probably yes;

Reason: Randomization based on sequential numbers. Details not described. |

Probably no;

Reason: Not described |

No information;

Reason: Blinding procedure not reported. Potentially open-label. |

Probably yes;

Reason: Loss to follow-up was not reported, but probably non-existent. |

Definitely no;

Reason: Outcome ‘time needed for intubation’ is described in the methods, but not in the results or discussion. |

No information

Reason: Funding or conflicts of interests are not reported. |

HIGH Due to selective outcome reporting and potential other biases |

Table of excluded studies

|

Reference |

Reason for exclusion |

|

Agrò FE, Vennari M. The videolaryngoscopes are now the first choice to see around the corner. Minerva Anestesiol. 2016 Dec;82(12):1247-1249. Epub 2016 Sep 22. PMID: 27654626. |

Wrong publication type |

|

Arulkumaran N, Lowe J, Ions R, Mendoza M, Bennett V, Dunser MW. Videolaryngoscopy versus direct laryngoscopy for emergency orotracheal intubation outside the operating room: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Anaesth. 2018 Apr;120(4):712-724. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2017.12.041. Epub 2018 Feb 26. PMID: 29576112. |

Not the best systematic review conform our PICO |

|

Ba X. A Meta-Analysis on the Effectiveness of Video Laryngoscopy versus Laryngoscopy for Emergency Orotracheal Intubation. J Healthc Eng. 2022 Jan 7;2022:1474298. doi: 10.1155/2022/1474298. PMID: 35035809; PMCID: PMC8759888. |

Not the best systematic review conform our PICO |

|

Bhattacharjee S, Maitra S, Baidya DK. A comparison between video laryngoscopy and direct laryngoscopy for endotracheal intubation in the emergency department: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Clin Anesth. 2018 Jun;47:21-26. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2018.03.006. Epub 2018 Mar 14. PMID: 29549828. |

Not the best systematic review conform our PICO |

|

Cabrini L, Landoni G, Baiardo Redaelli M, Saleh O, Votta CD, Fominskiy E, Putzu A, Snak de Souza CD, Antonelli M, Bellomo R, Pelosi P, Zangrillo A. Tracheal intubation in critically ill patients: a comprehensive systematic review of randomized trials. Crit Care. 2018 Jan 20;22(1):6. doi: 10.1186/s13054-017-1927-3. Erratum in: Crit Care. 2019 Oct 21;23(1):325. PMID: 29351759; PMCID: PMC5775615. |

Not the best systematic review conform our PICO |

|

Chen IW, Li YY, Hung KC, Chang YJ, Chen JY, Lin MC, Wang KF, Lin CM, Huang PW, Sun CK. Comparison of video-stylet and conventional laryngoscope for endotracheal intubation in adults with cervical spine immobilization: A PRISMA-compliant meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2022 Aug 19;101(33):e30032. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000030032. PMID: 35984197; PMCID: PMC9387965. |

wrong population |

|

de Carvalho CC, da Silva DM, Lemos VM, Dos Santos TGB, Agra IC, Pinto GM, Ramos IB, Costa YSC, Santos Neto JM. Videolaryngoscopy vs. direct Macintosh laryngoscopy in tracheal intubation in adults: a ranking systematic review and network meta-analysis. Anaesthesia. 2022 Mar;77(3):326-338. doi: 10.1111/anae.15626. Epub 2021 Dec 1. PMID: 34855986. |

wrong study design |

|

De Jong A, Molinari N, Conseil M, Coisel Y, Pouzeratte Y, Belafia F, Jung B, Chanques G, Jaber S. Video laryngoscopy versus direct laryngoscopy for orotracheal intubation in the intensive care unit: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Intensive Care Med. 2014 May;40(5):629-39. doi: 10.1007/s00134-014-3236-5. Epub 2014 Feb 21. PMID: 24556912. |

Not the best systematic review conform our PICO |

|

Downey AW, Duggan LV, Adam Law J. A systematic review of meta-analyses comparing direct laryngoscopy with videolaryngoscopy. Can J Anaesth. 2021 May;68(5):706-714. doi: 10.1007/s12630-021-01921-7. Epub 2021 Jan 29. PMID: 33512660; PMCID: PMC7845281. |

wrong publication type |

|

Griesdale DE, Liu D, McKinney J, Choi PT. Glidescope® video-laryngoscopy versus direct laryngoscopy for endotracheal intubation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Can J Anaesth. 2012 Jan;59(1):41-52. doi: 10.1007/s12630-011-9620-5. Epub 2011 Nov 1. PMID: 22042705; PMCID: PMC3246588. |

wrong population |

|

Hansel J, Rogers AM, Lewis SR, Cook TM, Smith AF. Videolaryngoscopy versus direct laryngoscopy for adults undergoing tracheal intubation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2022 Apr 4;4(4):CD011136. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011136.pub3. PMID: 35373840; PMCID: PMC8978307. |

Duplicate |

|

Hayes SM, Othman MM, Bobo AM, Elbaser IA. A prospective randomized comparative study of Glidescope versus Macintosh laryngoscope in adult hypertensive patients. Egyptian Journal of Anaesthesia. 2022 Dec 31;38(1):268-75. |

Wrong population |

|

Healy DW, Maties O, Hovord D, Kheterpal S. A systematic review of the role of videolaryngoscopy in successful orotracheal intubation. BMC Anesthesiol. 2012 Dec 14;12:32. doi: 10.1186/1471-2253-12-32. PMID: 23241277; PMCID: PMC3562270. |

Not recently published |

|

Hedge A, Malikarjun DR, Chinnathambi K. Comparison of Haemodynamic Response to Endotracheal Intubation with Videolaryngoscopy and Direct Laryngoscopy in Hypertensive Patients-A Randomised Clinical Trial. Journal of Clinical & Diagnostic Research. 2022 Jul 1;16(7). |

Wrong population |

|

Hinkelbein J, Iovino I, De Robertis E, Kranke P. Outcomes in video laryngoscopy studies from 2007 to 2017: systematic review and analysis of primary and secondary endpoints for a core set of outcomes in video laryngoscopy research. BMC Anesthesiol. 2019 Apr 4;19(1):47. doi: 10.1186/s12871-019-0716-8. PMID: 30947694; PMCID: PMC6449905. |

Wrong population |

|

Hoshijima H, Kuratani N, Hirabayashi Y, Takeuchi R, Shiga T, Masaki E. Pentax Airway Scope® vs Macintosh laryngoscope for tracheal intubation in adult patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Anaesthesia. 2014 Aug;69(8):911-8. doi: 10.1111/anae.12705. Epub 2014 May 13. PMID: 24820205. |

Wrong population |

|

Hoshijima H, Maruyama K, Mihara T, Boku AS, Shiga T, Nagasaka H. Use of the GlideScope does not lower the hemodynamic response to tracheal intubation more than the Macintosh laryngoscope: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020 Nov 25;99(48):e23345. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000023345. PMID: 33235101; PMCID: PMC7710211. |

Wrong population |

|

Hoshijima H, Mihara T, Maruyama K, Denawa Y, Mizuta K, Shiga T, Nagasaka H. C-MAC videolaryngoscope versus Macintosh laryngoscope for tracheal intubation: A systematic review and meta-analysis with trial sequential analysis. J Clin Anesth. 2018 Sep;49:53-62. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2018.06.007. Epub 2018 Jun 9. PMID: 29894918. |

Wrong population |

|

Hoshijima H, Mihara T, Maruyama K, Denawa Y, Takahashi M, Shiga T, Nagasaka H. McGrath videolaryngoscope versus Macintosh laryngoscope for tracheal intubation: A systematic review and meta-analysis with trial sequential analysis. J Clin Anesth. 2018 May;46:25-32. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2017.12.030. Epub 2018 Mar 26. PMID: 29414609. |

Not the best systematic review conform our PICO |

|

Howson A, Goodliff A, Horner D. BET 2: Video laryngoscopy for patients requiring endotracheal intubation in the emergency department. Emerg Med J. 2020 Jun;37(6):381-383. doi: 10.1136/emermed-2020-209962.3. PMID: 32487710. |

wrong publication type |

|

Huang HB, Peng JM, Xu B, Liu GY, Du B. Video Laryngoscopy for Endotracheal Intubation of Critically Ill Adults: A Systemic Review and Meta-Analysis. Chest. 2017 Sep;152(3):510-517. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2017.06.012. Epub 2017 Jun 16. PMID: 28629915. |

Not the best systematic review conform our PICO |

|

Hung KC, Chang YJ, Chen IW, Lin CM, Liao SW, Chin JC, Chen JY, Yew M, Sun CK. Comparison of video-stylet and video-laryngoscope for endotracheal intubation in adults with cervical neck immobilisation: A meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Anaesth Crit Care Pain Med. 2021 Dec;40(6):100965. doi: 10.1016/j.accpm.2021.100965. Epub 2021 Oct 21. PMID: 34687924. |

Wrong population |

|

Jiang J, Kang N, Li B, Wu AS, Xue FS. Comparison of adverse events between video and direct laryngoscopes for tracheal intubations in emergency department and ICU patients-a systematic review and meta-analysis. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2020 Feb 7;28(1):10. doi: 10.1186/s13049-020-0702-7. PMID: 32033568; PMCID: PMC7006069. |

Not the best systematic review conform our PICO |

|

Jiang J, Ma D, Li B, Yue Y, Xue F. Video laryngoscopy does not improve the intubation outcomes in emergency and critical patients - a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Crit Care. 2017 Nov 24;21(1):288. doi: 10.1186/s13054-017-1885-9. PMID: 29178953; PMCID: PMC5702235. |

Not the best systematic review conform our PICO |

|

Lewis SR, Butler AR, Parker J, Cook TM, Schofield-Robinson OJ, Smith AF. Videolaryngoscopy versus direct laryngoscopy for adult patients requiring tracheal intubation: a Cochrane Systematic Review. Br J Anaesth. 2017 Sep 1;119(3):369-383. doi: 10.1093/bja/aex228. PMID: 28969318. |

Has been updated since |

|

Perkins EJ, Begley JL, Brewster FM, Hanegbi ND, Ilancheran AA, Brewster DJ. The use of video laryngoscopy outside the operating room: A systematic review. PLoS One. 2022 Oct 20;17(10):e0276420. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0276420. PMID: 36264980; PMCID: PMC9584394. |

Wrong publication type |

|

Pieters BMA, Maas EHA, Knape JTA, van Zundert AAJ. Videolaryngoscopy vs. direct laryngoscopy use by experienced anaesthetists in patients with known difficult airways: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Anaesthesia. 2017 Dec;72(12):1532-1541. doi: 10.1111/anae.14057. Epub 2017 Sep 22. PMID: 28940354. |

Wrong population |

|

Rombey T, Schieren M, Pieper D. Video Versus Direct Laryngoscopy for Inpatient Emergency Intubation in Adults. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2018 Jun 29;115(26):437-444. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2018.0437. PMID: 30017026; PMCID: PMC6071305. |

Not the best systematic review conform our PICO |

|

Russotto V, Myatra SN, Laffey JG. What's new in airway management of the critically ill. Intensive Care Med. 2019 Nov;45(11):1615-1618. doi: 10.1007/s00134-019-05757-0. Epub 2019 Sep 16. PMID: 31529354. |

Wrong publication type |

|

Singleton BN, Morris FK, Yet B, Buggy DJ, Perkins ZB. Effectiveness of intubation devices in patients with cervical spine immobilisation: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Br J Anaesth. 2021 May;126(5):1055-1066. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2020.12.041. Epub 2021 Feb 17. PMID: 33610262. |

wrong population |

|

van Schuppen H, Wojciechowicz K, Hollmann MW, Preckel B. Tracheal Intubation during Advanced Life Support Using Direct Laryngoscopy versus Glidescope® Videolaryngoscopy by Clinicians with Limited Intubation Experience: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Clin Med. 2022 Oct 26;11(21):6291. doi: 10.3390/jcm11216291. PMID: 36362519; PMCID: PMC9655434. |

Wrong setting |

|

Vargas M, Servillo G, Buonanno P, Iacovazzo C, Marra A, Putensen-Himmer G, Ehrentraut S, Ball L, Patroniti N, Pelosi P, Putensen C. Video vs. direct laryngoscopy for adult surgical and intensive care unit patients requiring tracheal intubation: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2021 Dec;25(24):7734-7749. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_202112_27620. PMID: 34982435. |

Not the best systematic review conform our PICO |

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Publicatiedatum : 24-02-2025

Beoordeeld op geldigheid : 23-02-2025

Algemene gegevens

De ontwikkeling/herziening van deze richtlijnmodule werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten (www.demedischspecialist.nl/kennisinstituut) en werd gefinancierd uit de Stichting Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS).

De financier heeft geen enkele invloed gehad op de inhoud van de richtlijnmodule.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijnmodule is in 2022 een multidisciplinaire werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen (zie hiervoor de Samenstelling van de werkgroep) die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor vitaal bedreigde patiënten die geïntubeerd worden buiten de OK.

Werkgroep

Dr. J.A.M. (Joost) Labout (voorzitter tot september 2023), intensivist, NVIC

Drs. J.H.J.M. (John) Meertens (interim-voorzitter), intensivist, NVIC

Drs. P. (Peter) Dieperink (interim-voorzitter), intensivist, NVIC

Drs. M.E. (Mengalvio) Sleeswijk (interim-voorzitter), intensivist, NVIC

Dr. F.O. (Fabian) Kooij, anesthesioloog/MMT-arts, NVA

Drs. Y.A.M. (Yvette) Kuijpers, anesthesioloog-intensivist, NVA

Drs. C. (Caspar) Müller, anesthesioloog/MMT-arts, NVA

Drs. M.E. (Mark) Seubert, internist-intensivist, NIV

Drs. S.J. (Sjieuwke) Derksen, internist-intensivist, NIV

Dr. R.M. (Rogier) Determann, internist-intensivist, NIV

Drs. H.J. (Harry) Achterberg, anesthesioloog-SEH-arts, NVSHA

Drs. M.A.E.A. (Marianne) Brackel, patiëntvertegenwoordiger, FCIC/IC Connect

Klankbordgroep

Dr. C.L. (Christiaan) Meuwese, cardioloog-intensivist, NVVC

Drs. J.T. (Jeroen) Kraak, KNO-arts, NVKNO

Drs. H.R. (Harry) Naber, anesthesioloog, NVA

Drs. H. (Huub) Grispen, anesthesiemedewerker, NVAM

Met ondersteuning van

dr. M.S. Ruiter, senior adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

drs. I. van Dijk, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

Belangenverklaringen

De Code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling is gevolgd. Alle werkgroepleden hebben schriftelijk verklaard of zij in de laatste drie jaar directe financiële belangen (betrekking bij een commercieel bedrijf, persoonlijke financiële belangen, onderzoeksfinanciering) of indirecte belangen (persoonlijke relaties, reputatiemanagement) hebben gehad. Gedurende de ontwikkeling of herziening van een module worden wijzigingen in belangen aan de voorzitter doorgegeven. De belangenverklaring wordt opnieuw bevestigd tijdens de commentaarfase.

Een overzicht van de belangen van werkgroepleden en het oordeel over het omgaan met eventuele belangen vindt u in onderstaande tabel. De ondertekende belangenverklaringen zijn op te vragen bij het secretariaat van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

|

Werkgroeplid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

Caspar Müller |

Anesthesioloog/MMT-arts ErasmusMC |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen restricties. |

|

Fabian Kooij |

Anesthesioloog/MMT-arts, Amsterdam UMC |

Chair of the Board, European Trauma Course Organisation |

Geen |

Geen restricties. |

|

Harry Achterberg |

SEH-arts, Isala Klinieken, fulltime - 40u/w (~111%) |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen restricties. |

|

John Meertens |

Intensivist-anesthesioloog, Intensive Care Volwassenen, UMC Groningen |

Secretaris Commissie Luchtwegmanagement, Nederlandse Vereniging voor Intensive Care |

Geen |

Geen restricties. |

|

Joost Labout |

Intensivist |

Redacteur A & I |

Geen |

Geen restricties. |

|

Marianne Brackel |

Patiëntvertegenwoordiger Stichting FCIC en patiëntenorganisatie IC Connect |

Geen |

Voormalig voorzitter IC Connect |

Geen restricties. |

|

Mark Seubert |

Internist-intensivist, |

Waarnemend internist en intensivist |

Lid Sectie IC van de NIV |

Geen restricties. |

|

Mengalvio Sleeswijk |

Internist-intensivist, Flevoziekenhuis |

Medisch Manager ambulancedienst regio Flevoland Gooi en Vecht / TMI Voorzitter Commissie Luchtwegmanagement, Nederlandse Vereniging voor Intensive Care |

Geen |

Geen restricties. |

|

Peter Dieperink |

Intensivist-anesthesioloog, Intensive Care Volwassenen, UMC Groningen |

Lid Commissie Luchtwegmanagement, Nederlandse Vereniging voor Intensive Care |

Geen |

Geen restricties. |

|

Rogier Determann |

Intensivist, OLVG, Amsterdam |

Docent Amstelacademie en Expertcollege |

Geen |

Geen restricties. |

|

Sjieuwke Derksen |

Intensivist - MCL |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen restricties. |

|

Yvette Kuijpers |

Anesthesioloog-intensivist, CZE en MUMC + |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen restricties. |

|

Klankbordgroeplid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

Christiaan Meuwese |

Cardioloog intensivist, Erasmus MC, Rotterdam |

Section editor Netherlands Journal of Critical Care (onbetaald) |

Extern gefinancierd onderzoek: - REMAP ECMO (Hartstichting) - PRECISE ECLS (Fonds SGS) |

Geen restricties. |

|

Jeroen Kraak |

KNO-arts & Hoofd-halschirurgie |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen restricties. |

|

Huub Grispen |

Anesthesiemedewerker Zuyderland MC |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen restricties. |

|

Harry Naber |

Anesthesioloog MSB Isala |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen restricties. |

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Er werd aandacht besteed aan het patiëntenperspectief door het uitnodigen van FCIC/IC Connect voor de schriftelijke knelpunteninventarisatie en deelname aan de werkgroep. Het verslag hiervan [zie aanverwante producten] is besproken in de werkgroep. De verkregen input is meegenomen bij het opstellen van de uitgangsvragen, de keuze voor de uitkomstmaten en bij het opstellen van de overwegingen. Ter onderbouwing van de module Aanwezigheid van naaste heeft IC Connect een achterbanraadpleging uitgevoerd. De conceptrichtlijn is tevens voor commentaar voorgelegd aan FCIC/IC Connect en de eventueel aangeleverde commentaren zijn bekeken en verwerkt.

Kwalitatieve raming van mogelijke financiële gevolgen in het kader van de Wkkgz

Bij de richtlijnmodule is conform de Wet kwaliteit, klachten en geschillen zorg (Wkkgz) een kwalitatieve raming uitgevoerd om te beoordelen of de aanbevelingen mogelijk leiden tot substantiële financiële gevolgen. Bij het uitvoeren van deze beoordeling is de richtlijnmodule op verschillende domeinen getoetst (zie het stroomschema op de Richtlijnendatabase).

|

Module |

Uitkomst raming |

Toelichting |

|

Module Videolaryngoscopie |

Geen substantiële financiële gevolgen |

Hoewel uit de toetsing volgt dat de aanbeveling(en) breed toepasbaar zijn (5.000-40.000 patiënten), volgt ook uit de toetsing dat het geen nieuwe manier van zorgverlening of andere organisatie van zorgverlening betreft. Er worden daarom geen substantiële financiële gevolgen verwacht. |

Werkwijze

AGREE

Deze richtlijnmodule is opgesteld conform de eisen vermeld in het rapport Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 van de adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwaliteit. Dit rapport is gebaseerd op het AGREE II instrument (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II; Brouwers, 2010).

Knelpuntenanalyse en uitgangsvragen

Tijdens de voorbereidende fase inventariseerde de werkgroep de knelpunten in de zorg voor vitaal bedreigde patiënten die geïntubeerd worden buiten de OK. Tevens zijn er knelpunten aangedragen door verschillende stakeholders via een schriftelijke knelpunteninventarisatie. Een verslag hiervan is opgenomen onder aanverwante producten.

Op basis van de uitkomsten van de knelpuntenanalyse zijn door de werkgroep concept-uitgangsvragen opgesteld en definitief vastgesteld.

Uitkomstmaten

Na het opstellen van de zoekvraag behorende bij de uitgangsvraag inventariseerde de werkgroep welke uitkomstmaten voor de patiënt relevant zijn, waarbij zowel naar gewenste als ongewenste effecten werd gekeken. Hierbij werd een maximum van acht uitkomstmaten gehanteerd. De werkgroep waardeerde deze uitkomstmaten volgens hun relatieve belang bij de besluitvorming rondom aanbevelingen, als cruciaal (kritiek voor de besluitvorming), belangrijk (maar niet cruciaal) en onbelangrijk. Tevens definieerde de werkgroep tenminste voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten welke verschillen zij klinisch (patiënt) relevant vonden.

Methode literatuursamenvatting

Een uitgebreide beschrijving van de strategie voor zoeken en selecteren van literatuur is te vinden onder ‘Zoeken en selecteren’ onder Onderbouwing. Indien mogelijk werd de data uit verschillende studies gepoold in een random-effects model. Review Manager 5.4 werd gebruikt voor de statistische analyses. De beoordeling van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs wordt hieronder toegelicht.

Beoordelen van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs

De kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs werd bepaald volgens de GRADE-methode. GRADE staat voor ‘Grading Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation’ (zie http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/). De basisprincipes van de GRADE-methodiek zijn: het benoemen en prioriteren van de klinisch (patiënt) relevante uitkomstmaten, een systematische review per uitkomstmaat, en een beoordeling van de bewijskracht per uitkomstmaat op basis van de acht GRADE-domeinen (domeinen voor downgraden: risk of bias, inconsistentie, indirectheid, imprecisie, en publicatiebias; domeinen voor upgraden: dosis-effect relatie, groot effect, en residuele plausibele confounding).

GRADE onderscheidt vier gradaties voor de kwaliteit van het wetenschappelijk bewijs: hoog, redelijk, laag en zeer laag. Deze gradaties verwijzen naar de mate van zekerheid die er bestaat over de literatuurconclusie, in het bijzonder de mate van zekerheid dat de literatuurconclusie de aanbeveling adequaat ondersteunt (Schünemann, 2013; Hultcrantz, 2017).

|

GRADE |

Definitie |

|

Hoog |

|

|

Redelijk |

|

|

Laag |

|

|

Zeer laag |

|

Bij het beoordelen (graderen) van de kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs in richtlijnen volgens de GRADE-methodiek spelen grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming een belangrijke rol (Hultcrantz, 2017). Dit zijn de grenzen die bij overschrijding aanleiding zouden geven tot een aanpassing van de aanbeveling. Om de grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming te bepalen moeten alle relevante uitkomstmaten en overwegingen worden meegewogen. De grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming zijn daarmee niet één op één vergelijkbaar met het minimaal klinisch relevant verschil (Minimal Clinically Important Difference, MCID). Met name in situaties waarin een interventie geen belangrijke nadelen heeft en de kosten relatief laag zijn, kan de grens voor klinische besluitvorming met betrekking tot de effectiviteit van de interventie bij een lagere waarde (dichter bij het nuleffect) liggen dan de MCID (Hultcrantz, 2017).

Overwegingen (van bewijs naar aanbeveling)

Om te komen tot een aanbeveling zijn naast (de kwaliteit van) het wetenschappelijke bewijs ook andere aspecten belangrijk en worden meegewogen, zoals aanvullende argumenten uit bijvoorbeeld de biomechanica of fysiologie, waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten, kosten (middelenbeslag), aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie. Deze aspecten zijn systematisch vermeld en beoordeeld (gewogen) onder het kopje ‘Overwegingen’ en kunnen (mede) gebaseerd zijn op expert opinion. Hierbij is gebruik gemaakt van een gestructureerd format gebaseerd op het evidence-to-decision framework van de internationale GRADE Working Group (Alonso-Coello, 2016a; Alonso-Coello 2016b). Dit evidence-to-decision framework is een integraal onderdeel van de GRADE methodiek.

Formuleren van aanbevelingen

De aanbevelingen geven antwoord op de uitgangsvraag en zijn gebaseerd op het beschikbare wetenschappelijke bewijs en de belangrijkste overwegingen, en een weging van de gunstige en ongunstige effecten van de relevante interventies. De kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs en het gewicht dat door de werkgroep wordt toegekend aan de overwegingen, bepalen samen de sterkte van de aanbeveling. Conform de GRADE-methodiek sluit een lage bewijskracht van conclusies in de systematische literatuuranalyse een sterke aanbeveling niet a priori uit, en zijn bij een hoge bewijskracht ook zwakke aanbevelingen mogelijk (Agoritsas, 2017; Neumann, 2016). De sterkte van de aanbeveling wordt altijd bepaald door weging van alle relevante argumenten tezamen. De werkgroep heeft bij elke aanbeveling opgenomen hoe zij tot de richting en sterkte van de aanbeveling zijn gekomen.

In de GRADE-methodiek wordt onderscheid gemaakt tussen sterke en zwakke (of conditionele) aanbevelingen. De sterkte van een aanbeveling verwijst naar de mate van zekerheid dat de voordelen van de interventie opwegen tegen de nadelen (of vice versa), gezien over het hele spectrum van patiënten waarvoor de aanbeveling is bedoeld. De sterkte van een aanbeveling heeft duidelijke implicaties voor patiënten, behandelaars en beleidsmakers (zie onderstaande tabel). Een aanbeveling is geen dictaat, zelfs een sterke aanbeveling gebaseerd op bewijs van hoge kwaliteit (GRADE gradering HOOG) zal niet altijd van toepassing zijn, onder alle mogelijke omstandigheden en voor elke individuele patiënt.

|

Implicaties van sterke en zwakke aanbevelingen voor verschillende richtlijngebruikers |

||

|

|

||

|

|

Sterke aanbeveling |

Zwakke (conditionele) aanbeveling |

|

Voor patiënten |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen en slechts een klein aantal niet. |

Een aanzienlijk deel van de patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen, maar veel patiënten ook niet. |

|

Voor behandelaars |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak moeten ontvangen. |

Er zijn meerdere geschikte interventies of aanpakken. De patiënt moet worden ondersteund bij de keuze voor de interventie of aanpak die het beste aansluit bij zijn of haar waarden en voorkeuren. |

|

Voor beleidsmakers |

De aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kan worden gezien als standaardbeleid. |

Beleidsbepaling vereist uitvoerige discussie met betrokkenheid van veel stakeholders. Er is een grotere kans op lokale beleidsverschillen. |

Organisatie van zorg

In de knelpuntenanalyse en bij de ontwikkeling van de richtlijnmodule is expliciet aandacht geweest voor de organisatie van zorg: alle aspecten die randvoorwaardelijk zijn voor het verlenen van zorg (zoals coördinatie, communicatie, (financiële) middelen, mankracht en infrastructuur). Randvoorwaarden die relevant zijn voor het beantwoorden van deze specifieke uitgangsvraag zijn genoemd bij de overwegingen. Meer algemene, overkoepelende, of bijkomende aspecten van de organisatie van zorg worden behandeld in de module Organisatie van zorg.

Commentaar- en autorisatiefase

De conceptrichtlijnmodule werd aan de betrokken (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd ter commentaar. De commentaren werden verzameld en besproken met de werkgroep. Naar aanleiding van de commentaren werd de conceptrichtlijnmodule aangepast en definitief vastgesteld door de werkgroep. De definitieve richtlijnmodule werd aan de deelnemende (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd voor autorisatie en door hen geautoriseerd dan wel geaccordeerd.

Literatuur