Medicatie

Uitgangsvraag

Welk inductiemiddel heeft de voorkeur om de slagingskans van de intubatieprocedure van de vitaal bedreigde patiënt te verhogen met minimalisering van complicaties?

Aanbeveling

Standaardiseer inductiemedicatie voor vitaal bedreigde patiënten en wijk daar alleen op specifieke indicatie van af.

Gebruik bij voorkeur (es)ketamine als standaard medicament voor intubatie van vitaal bedreigde patiënten vanwege de ruime therapeutische breedte en de relatieve hemodynamische stabiliteit.

Gebruik propofol alleen bij uitgebreide ervaring met het middel en titreer de dosis zorgvuldig gezien de smallere therapeutische breedte en de grote kans op hemodynamische instabiliteit.

Gebruik laagdrempelig een vasopressor indien propofol gebruikt wordt bij de vitaal bedreigde patiënt.

Wees terughoudend met etomidaat bij de intubatie van vitaal bedreigde patiënten, vanwege associaties met verhoogde mortaliteit.

Midazolam is gezien de tragere farmacokinetiek ongeschikt als mono-anestheticum voor inductie van vitaal bedreigde patiënten.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Er is een literatuuronderzoek verricht naar verschillende inductiemiddelen bij vitaal bedreigde patiënten die geïntubeerd worden buiten de operatiekamer. De gunstige en ongunstige effecten van het toevoegen van etomidaat, ketamine en propofol werden vergeleken. Daarbij werden 1) de inductiemiddelen vergeleken als adjunct bij een standaard anesthesieregime en 2) de inductiemiddelen vergeleken met andere inductiemiddelen. Als cruciale uitkomstmaten werden mortaliteit en hartstilstand meegenomen. Als belangrijke uitkomstmaten is gekeken naar hypotensie, hypoxie, aspiratie en first-pass succes.

Voor de vergelijking waarbij etomidaat, ketamine of propofol als adjunct werd toegevoegd aan een anesthesieregime is geen literatuur gevonden. Hier bestaat een kennislacune.

Voor de vergelijking tussen etomidaat en andere inductiemiddelen (6 RCT’s) is er mogelijk een toename in mortaliteit binnen 7 dagen. De bewijskracht is hiervoor laag. Voor de uitkomstmaten mortaliteit binnen 24 uur, hypotensie, hartstilstand en aspiratie konden geen conclusies getrokken worden, vanwege een zeer lage bewijskracht. Voor first-pass succes leek er geen verschil tussen de groepen. Daarom konden de belangrijke uitkomstmaten geen verdere richting geven aan de besluitvorming.

Tijdens de afronding van deze module zijn twee artikelen verschenen die mortaliteit bij gebruik van etomidaat en ketamine onderzocht hebben (Koroki, 2024; Wunsch, 2024). Vanwege de verschijningsdata zijn zij niet meegenomen in de analyse, maar beide artikelen ondersteunen de verdenking dat etomidaat mogelijk leidt tot een verhoogde mortaliteit.

Voor de vergelijking tussen esketamine en andere inductiemiddelen (5 RCT’s) is er mogelijk een afname in mortaliteit binnen 7 dagen. De bewijskracht is hiervoor laag. Voor de uitkomstmaten mortaliteit binnen 24 uur, hypotensie en hartstilstand konden geen conclusies getrokken worden, vanwege een zeer lage bewijskracht. Voor first-pass succes leek er geen verschil tussen de groepen. Daarom konden de belangrijke uitkomstmaten geen verdere richting geven aan de besluitvorming.

Voor de vergelijking tussen propofol en andere inductiemiddelen werd geen literatuur gevonden. Hier ligt een kennislacune. Buiten de literatuurstudie om is de studie van Russotto (2022) van belang. In deze secundaire analyse van een grote observationele studie wordt gevonden dat hemodynamische instabiliteit rondom intubatie de mortaliteit verhoogd bij vitaal bedreigde patiënten en dat propofol onafhankelijk is geassocieerd met het optreden van hemodynamische instabiliteit. Hoewel hier in de gebruikte onderzoeken geen wetenschappelijk bewijs gevonden is, blijkt het preventief opstarten van een vasopressor als onderdeel van de inductie in de praktijkervaring van de werkgroepleden een effectieve strategie te zijn in het mitigeren van hemodynamische schommelingen. De werkgroep adviseert dan ook om dit laagdrempelig te doen. In ieder geval bij gebruik van propofol.

Op basis van de beperkte literatuur is er mogelijk een klein voordeel van esketamine ten opzichte van andere inductiemiddelen bij vitaal bedreigde patiënten die geïntubeerd worden buiten de operatiekamer.

Vitaal bedreigde patiënten zijn niet één type, maar hebben een breed scala aan ziektebeelden die allemaal hun eigen specifieke overwegingen hebben met betrekking tot de keuze en dosering van anesthetica. Dat de literatuurstudie geen overtuigend bewijs van een superieur inductiemiddel vindt is dan ook niet verrassend.

Op basis van wetenschappelijk onderzoek zijn dus geen specifieke aanbeveling te maken, anders dan dat etomidaat waarschijnlijk best vermeden wordt en dat bij propofol de kans op hemodynamische instabiliteit groter is dan bij andere middelen.

Qua subgroepen zijn er diverse overwegingen te maken, maar verschillen zitten vaak in andere factoren, die dan duidelijk belangrijker zijn dan de keuze voor een specifiek anestheticum. Timing en locatie van intubatie dosis van het gebruikte anestheticum, de keuze voor een rapid sequence intubatie of juist een rustiger setting met geleidelijk titreren van het anestheticum.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

Intubatie van een vitaal bedreigde patiënt is een hoog risico verrichting waarbij de patiënt volledig afhankelijk is van de hulpverlener. Het belang van de hulpverlener en de patiënt is identiek, namelijk de patiënt zo veilig door mogelijk deze interventie heen leiden met goed resultaat en zo min mogelijk bijwerkingen. Vrijwel geen enkele patiënt zal voldoende kennis van de materie hebben om mee te kunnen denken in de keus voor medicatie voor inductie. Belangrijker is dat de hulpverlener zelf een afgewogen keus maakt tussen de verschillende soorten medicatie op basis van de bestaande literatuur maar ook op basis van eigen voorkeuren en ervaringen. Hierbij is goed om andere bijwerkingen mee te nemen die voor de hulpverlener minder van belang zijn, zoals het optreden van hallucinaties bij het gebruik van esketamine.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

De regelmatig gebruikte middelen zijn allemaal van patent en zijn kostentechnisch vergelijkbaar. De kosten met betrekking tot het gebruikte anestheticum vallen volstrekt in het niet bij de totale kosten voor een dergelijke vitaal bedreigde patiënt.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

De onderzochte middelen zijn allen beschikbaar in Nederland. In ervaren handen zijn alle mogelijke (combinaties van) anesthetica en neuromusculaire blokkers waarschijnlijk even veilig en even bruikbaar voor alle patiënten. De ervaring die nodig is voor het adequaat anticiperen en interveniëren op complicaties, maar ook voor een adequate inschatting van de benodigde dosis is echter lang niet altijd aanwezig. Voor etomidaat bestaan voorzichtige aanwijzingen dat het de mortaliteit (op 7 dagen) verhoogt. Propofol geeft mogelijk meer hemodynamische instabiliteit waardoor ervaring en titratie nog veel belangrijker worden (Russotto, 2022).

In de setting van een spoedintubatie bij een vitaal bedreigde patiënt moeten in korte tijd veel handelingen uitgevoerd worden en kan de situational awareness met betrekking tot de hemodynamiek in het geding raken. Daarom is, naar de mening van de werkgroep, een voorspelbaar medicatiemengsel belangrijk. Om die reden beveelt de werkgroep aan binnen het ziekenhuis te standaardiseren.

Een middel wat vergevingsgezind is, dat wil zeggen: met minder bijwerkingen en meer therapeutische bandbreedte dan de alternatieven komt het meest in aanmerking voor gebruik als standaard. Volgens de mening van de werkgroep is dat middels esketamine.

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

De literatuur kon beperkt richting geven aan de besluitvorming. Etomidaat lijkt de mortaliteit op 7 dagen te verhogen. Propofol lijkt geassocieerd met meer hemodynamische instabiliteit. Kosten en patiëntvoorkeuren spelen bij de keuze van inductiemiddel een beperkte rol.

In ervaren handen zijn alle mogelijke (combinaties van) anesthetica en neuromusculaire blokkers even veilig en even bruikbaar voor alle patiënten. In de setting van een spoedintubatie bij een vitaal bedreigde patiënt is, naar de mening van de werkgroep, een gestandaardiseerd en goed voorspelbaar medicatiemengsel belangrijk. Om die reden beveelt de werkgroep aan binnen het ziekenhuis te standaardiseren. Qua voorspelbaarheid lijkt Esketamine van de drie middelen het meest geschikt vanwege de beperkte bijwerkingen en goede therapeutische breedte. Overweeg andere medicatie, of toevoeging van andere medicatie, indien verwacht wordt dat patiënt binnen enkele uren weer wakker zal zijn. Esketamine kan dissociatieve symptomen veroorzaken zoals hallucinaties en verwardheid, vooral in de eerste uren na toediening. Dit kan schadelijk zijn voor patiënten die snel ontwaken na de procedure.

De redenen om Esketamine als eerste keuze aan te bevelen liggen deels in de al genoemde literatuur, maar deels ook in de verwachte veiligheidsaspecten van standaardisatie met één middel als eerste keuze.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Acute anesthesie en intubatie van vitaal bedreigde patiënten is een zeer hoog risico procedure. Peri-intubatie reanimatie komt regelmatig voor en de directe mortaliteit van de procedure loopt in studies op tot 4%. De gebruikte anesthetica worden vaak aangewezen als oorzaak van complicaties. Aangezien alle anesthetica in meer of mindere mate hypotensie veroorzaken, is dit niet onlogisch. Over welke medicamenten wel (of juist niet) te gebruiken voor vitaal bedreigde patiënten bestaan veel verschillende meningen en het is onderwerp van uitgebreide discussie.

Binnen deze module beperken wij ons tot de beschikbare anesthetica, aangezien de overgrote meerderheid van vitaal bedreigde patiënten een (relatieve) contra-indicatie heeft voor één van de twee mogelijke neuromusculaire blokkers (succinylcholine) en dus in essentie alleen rocuronium als “standaard” optie overblijft.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

|

No GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding the effect of an anesthetic drug regimen with either propofol, etomidate and/or (S-)Ketamine on mortality, cardiac arrest, hypotension, hypoxia, aspiration and first pass success when compared with an anesthetic drug regimen without the specific drug included in intervention in critically ill patients who are intubated outside the operating room.

Source: - |

Etomidate

Critical outcomes

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of an anesthetic drug regimen with etomidate on mortality at 24 hours when compared to a different induction agent in critically ill patients who are intubated outside the operating room.

Source: Srivilaithon, 2023. |

|

Low GRADE |

An anesthetic drug regimen with etomidate may increase mortality at 7 days when compared to a different induction agent in critically ill patients who are intubated outside the operating room.

Sources: Srivilaithon, 2023; Matchett, 2022. |

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of an anesthetic drug regimen with etomidate on the incidence of cardiac arrest when compared to a different induction agent in critically ill patients who are intubated outside the operating room.

Sources: Jabre, 2009; Matchett, 2022; Smischney 2019; Srivilaithon, 2023. |

Important outcomes

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of an anesthetic drug regimen with etomidate on the incidence of hypotension when compared to a different induction agent in critically ill patients who are intubated outside the operating room.

Sources: Smischney 2019; Srivilaithon, 2023; Tekwani, 2010. |

|

No GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding the effect of an anesthetic drug regimen with etomidate on the incidence of hypoxia when compared with a different induction agent in critically ill patients who are intubated outside the operating room.

Source: - |

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of an anesthetic drug regimen with etomidate on the incidence of aspiration when compared to a different induction agent in critically ill patients who are intubated outside the operating room.

Source: Smischney 2019. |

|

Moderate GRADE |

An anesthetic drug regimen with etomidate likely results in little to no difference in first pass success when compared to adding a different induction agent in critically ill patients who are intubated outside the operating room.

Source: Matchett, 2022; Srivilaithon, 2023. |

Ketamine

Critical outcomes

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of an anesthetic drug regimen with ketamine on mortality at 24 hours when compared to adding a different induction agent in critically ill patients who are intubated outside the operating room.

Source: Srivilaithon, 2023. |

|

Low GRADE |

An anesthetic drug regimen with ketamine may decrease mortality at 7 days when compared to adding a different induction agent in critically ill patients who are intubated outside the operating room.

Sources: Srivilaithon, 2023; Matchett, 2022. |

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of an anesthetic drug regimen with ketamine on the incidence of cardiac arrest when compared to adding a different induction agent in critically ill patients who are intubated outside the operating room.

Sources: Jabre, 2009; Matchett, 2022; Srivilaithon, 2023. |

Important outcomes

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of an anesthetic drug regimen with ketamine on the incidence of hypotension when compared to adding a different induction agent in critically ill patients who are intubated outside the operating room.

Sources: Ali, 2021; Srivilaithon, 2023. |

|

No GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding the effect of an anesthetic drug regimen with ketamine on the incidence of hypoxia when compared with adding a different induction agent in critically ill patients who are intubated outside the operating room.

Source: - |

|

No GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding the effect of an anesthetic drug regimen with ketamine on the incidence of aspiration when compared with adding a different induction agent in critically ill patients who are intubated outside the operating room.

Source: - |

|

Moderate GRADE |

An anesthetic drug regimen with ketamine likely results in little to no difference in first pass success when compared to adding a different induction agent in critically ill patients who are intubated outside the operating room.

Source: Matchett, 2022; Srivilaithon, 2023. |

Propofol

|

No GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding the effect of an anesthetic drug regimen with propofol on mortality, cardiac arrest, hypotension, hypoxia, aspiration and first pass success when compared with adding a different induction agent in critically ill patients who are intubated outside the operating room.

Source: - |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

An overview of the included studies is presented in Table 1.

The prospective, randomized, open-label, single-center trial by Matchett (2022) compared clinical outcomes between critically ill adult patients at the hospital who received etomidate versus ketamine for emergency endotracheal intubation. A total of 801 adult subjects were included, and 400 were assigned to receive 0.2–0.3 mg/kg etomidate and 401 to receive 1-2 mg/kg ketamine. Rocuronium and succinylcholine were used as neuromuscular blocking agents. Primary endpoint was day 7 survival. Secondary endpoints were proportion survived on day 28, duration of mechanical ventilation, intensive care unit (ICU) length-of-stay, usage and duration of vasopressor therapy, serial SOFA scores on day 1 to 4, and an assessment of a new diagnosis of adrenal insufficiency. Exploratory endpoints included immediate technical and hemodynamic outcomes of intubation. Some concerns were raised regarding the risk of bias, as it was an open-label study.

A prospective open-label study by Punt (2014) investigated the mortality rate in patients administered a single dose of etomidate or S-ketamine for tracheal intubation during their stay on ICU. A total of 301 critically ill adults were included, and 161 were assigned to receive 0.2–0.3 mg/kg etomidate and 140 to receive 0.5 mg/kg s-ketamine. To avoid unwanted psychological reactions, midazolam 2.5 mg was added to the S-ketamine. For neuromuscular blocking, rocuronium was used. The primary end point was mortality within 28 days after the administration of the study drugs. Secondary endpoints were ICU length of stay, and the use of norepinephrine during the first 72 hours. The study was judged as low risk of bias.

Smischney (2019) conducted a prospective RCT comparing a ketamine-propofol admixture (KPA) to a reduced dose of etomidate for sedation during emergent intubation in critically ill adults. In total, 160 patients were assigned to receive 0.15 mg/kg etomidate (N=76) or 1 mg/kg KPA (N=84). After the initial induction dose of the study drug, a second dose was available as a rescue. All subjects received a standard 50 mcg intravenous bolus dose of fentanyl. The use of benzodiazepines, additional opioids, and neuromuscular blocking agents were noncontrolled. Primary endpoint was the change in mean arterial pressure (MAP) from baseline. Secondary endpoints included new-onset vasopressor use, narcotic use, intubation difficulty score, new-onset delirium, transfusion needs, ventilator-free days, ICU-free days, and hospital mortality. The study was judged as low risk of bias.

Jabre (2009) conducted a randomized, controlled, single-blind trial to compare early and 28-day morbidity after a single dose of etomidate or ketamine used for emergency endotracheal intubation of critically ill patients. A total of 655 subjects were randomly assigned to receive 0.3 mg/kg of etomidate (N=328) or 2 mg/kg of ketamine (N=327) for intubation. Succinylcholine was given immediately after the sedative as a 1 mg/kg intravenous bolus. Continuous sedation was initiated by use of a standardized protocol with midazolam (0.1 mg/kg/h) combined with fentanyl (2–5 mcg/kg/h) or sufentanil (0.2–0.5 mcg/kg/h). The primary endpoint was the maximum SOFA score during the first 3 days in the ICU. Secondary endpoints were Δ-SOFA score, 28-day all-cause mortality, days free from ICU, and organ support-free days (mechanical ventilation and vasopressor) during the 28-day follow-up. Some concerns were raised regarding the risk of bias, due to a lack of blinding.

A single-center, randomized, single-blind, controlled trial by Srivilaithon (2023) aimed to compare the survival and peri-intubation adverse events after single-dose induction between etomidate and ketamine. A total of 260 septic patients were randomly assigned to receive 0.2–0.3 mg/kg of etomidate (N=130) or 1–2 mg/kg of ketamine (N=130) for intubation. A standardized rapid sequence induction (RSI) protocol was used and administration of neuromuscular blocking agents immediately after induction (succinylcholine 1.5 mg/kg bolus) depended on the clinical state of the patient and any contraindications. The primary outcome was 28-day survival. The secondary outcomes were 24-h survival, 7-day survival, early hemodynamic parameters after intubation, amount of fluid required in the first three hours, and occurrence of adverse events. Some concerns were raised regarding the risk of bias, due to a lack of blinding.

Tekwani (2010) conducted a prospective RCT of patients with suspected sepsis who were intubated in the emergency department and received either etomidate or midazolam. A total of 122 patients were enrolled; 63 received 0.3 mg/kg etomidate and 59 received 0.1 mg/kg midazolam. The remainder of the patients’ care in the emergency department and ICU was directed according to the treating physician. The primary outcome was hospital length of stay. Secondary outcomes included in-hospital mortality, ICU length of stay, and length of time intubated. The study was judged as low risk of bias.

Ali (2021) aimed to compare a ketamine-based with a fentanyl-based regimen for endotracheal intubation in patients with septic shock undergoing emergency surgery. Patients were randomly allocated to receive 1 mg/kg ketamine (N=23) or fentanyl 2.5 mcg/kg (N=19). Both groups received midazolam (0.05 mg/kg) and succinylcholine (1 mg/kg). The primary outcome was MAP. Secondary outcomes included heart rate, cardiac output, and incidence of postintubation hypotension. The study was judged as low risk of bias.

Table 1. Characteristics of included studies

|

Author, year |

Setting |

N, total |

Population |

Intervention |

Control |

|

Matchett, 2022 |

One medical center with burn, medical, neurological and surgical ICUs, USA |

801 |

Adults requiring emergency intubation |

Etomidate 0.2–0.3 mg/kg |

ketamine 1–2 mg/kg |

|

Punt, 2014 |

ICUs (mixed, surgical, medical), of one large teaching hospital, the Netherlands |

301 |

Critically ill adult patients intubated in the ICU |

Etomidate 0.2–0.3 mg/kg |

S-Ketamine 0.5 mg/kg |

|

Smischney, 2019 |

ICUs (medical, surgical, oncological/transplant) of a tertiary academic medical center, USA |

152 |

Adults admitted to the ICU, requiring emergent intubation |

Etomidate 0.15 mg/kg |

Ketamine 0.5 mg/kg and propofol 0.5 mg/kg |

|

Jabre, 2009 |

12 emergency medical services or emergency departments and 65 ICUs in France |

655 |

Adult patients requiring emergency intubation |

Etomidate 0.3 mg/kg |

Ketamine 2 mg/kg |

|

Srivilaithon, 2023 |

One emergency department of a university hospital, Thailand |

260 |

Adult patients with suspected sepsis requiring emergency intubation |

Etomidate 0.2–0.3 mg/kg |

Ketamine 1–2 mg/kg |

|

Tekwani, 2010 |

One emergency department of a tertiary care hospital, USA |

122 |

Adult patients with suspected sepsis requiring emergency intubation |

Etomidate 0.3 mg/kg |

Midazolam 0.1 mg/kg |

|

Ali, 2021 |

Surgical theatre at an emergency department, Egypt |

42 |

Adult patients with septic shock scheduled for emergency surgery |

Ketamine 1 mg/kg |

Fentanyl 2.5 mcg/kg |

ICU: intensive care unit, USA: United States of America

Results

1. Etomidate, ketamine or propofol vs. no etomidate, ketamine or propofol

No studies were found in which one of the study drugs was administered as an adjunct to a standard anesthesia regimen.

Therefore, no results are described below.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence regarding all outcome measures could not be graded, as no studies were included.

2. Etomidate, ketamine or propofol versus a different induction agent

Etomidate

Six studies compared etomidate to another induction agent. The comparator was either ketamine (Matchett, 2022; Punt, 2014; Jabre, 2009; Srivilaithon, 2023) a ketamine-propofol admixture (Smischney, 2019) or midazolam (Tekwani, 2010).

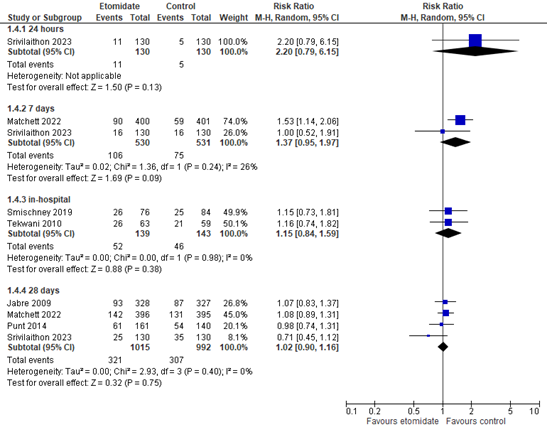

Mortality

All six studies reported mortality rates (Figure 1). The follow-up periods of interest were 24 hours and 7 days.

For 24-hour mortality, the risk ratio (RR) is 2.20 (95% confidence interval (CI) 0.79 to 6.15).

For 7-day mortality, the pooled RR is 1.37 (95% CI 0.95 to 1.97).

The differences are clinically relevant in favor of the control group.

In addition, in-hospital mortality and 28-day mortality were reported.

For in-hospital mortality, the pooled RR is 1.15 (95% CI 0.84 to 1.59).

For 28-day mortality, the pooled RR is 1.07 (95% CI 0.83 to 1.37).

Figure 1. Mortality at 24 hours, 7 days, in-hospital and 28 days, etomidate vs. control

Random effects model; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval; Z: p-value of pooled effect

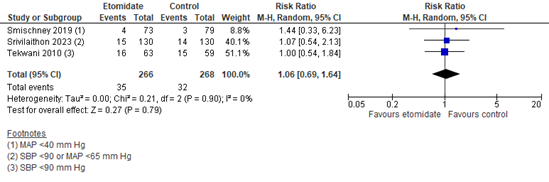

Cardiac arrest

Four studies reported the incidence of cardiac arrest (Figure 2). A total of 22/927 (2.4%) in the etomidate group and 26/931 (2.8%) in the control group experienced cardiac arrest. The pooled RR is 0.86 (95% CI 0.49 to 1.52) in favor of etomidate. This difference is considered clinically relevant.

Figure 2. The incidence of cardiac arrest, etomidate vs. control

Random effects model; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval; Z: p-value of pooled effect

Hypotension

Three studies reported the incidence of post-intubation hypotension (Figure 3). A total of 35/266 (13.2%) in the etomidate group and 32/268 (11.9%) in the control group experienced hypotension. The pooled RR is 1.06 (95% CI 0.69 to 1.64) in favor of the control group. This difference is not considered clinically relevant.

Figure 3. The incidence of hypotension, etomidate vs. control

Random effects model; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval; Z: p-value of pooled effect

Hypoxia

None of the included studies reported the incidence of hypoxia.

Aspiration

Smischney (2019) was the only study reporting aspiration. The incidence of vomiting or aspiration was 3/73 (4%) in the etomidate group and 2/79 (3%) in the control group (RR 1.62; 95% CI 0.28 to 9.44). This difference is considered clinically relevant in favor of the control group. However, the authors state that the events are probably not related to the study drug.

First pass success

Two studies reported first pass success.

Matchett (2022) observed a first pass success rate of 357/396 (91.3%) in the etomidate group and 355/395 (91.3%) in the control group (RR 1.00; 95% CI 0.96 to 1.05). This difference is not clinically relevant.

Srivilaithon (2023) reported the proportion of patients with successful intubation during the first attempt. In the etomidate group 116/130 (89.2%) and in the control group 114/130 (87.7%) had first-pass success (RR 1.02; 95% CI 0.93 to 1.11). This difference is not clinically relevant.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence regarding all outcome measures was based on randomized controlled studies and therefore started at high.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure mortality at 24 hours was downgraded by three levels to VERY LOW because the confidence interval crossed both thresholds for clinical relevance and due to the very limited number of events (imprecision, -3).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure mortality at 7 days was downgraded by two levels to LOW because of conflicting results (inconsistency, -1); and because the confidence interval crossed one threshold for clinical relevance (imprecision, -1).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure cardiac arrest was downgraded by three levels to VERY LOW because of conflicting results (inconsistency, -1); and the confidence interval crossed both thresholds for clinical relevance (imprecision, -2).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure hypotension was downgraded by three levels to VERY LOW because of study limitations (risk of bias due to lack of blinding, -1); and the confidence interval crossed both thresholds for clinical relevance (imprecision, -2).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure aspiration was downgraded by three levels to VERY LOW because of study limitations (risk of bias due to other bias, -1); a wide confidence interval and due to the very limited number of events (imprecision, -2).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure first pass success was downgraded by one level to MODERATE because of study limitations (risk of bias due lack of blinding and other bias, -1).

Ketamine

Five studies compared ketamine to another induction agent. The comparator was either etomidate (Matchett, 2022; Punt, 2014; Jabre, 2009; Srivilaithon, 2023) or fentanyl (Ali, 2021).

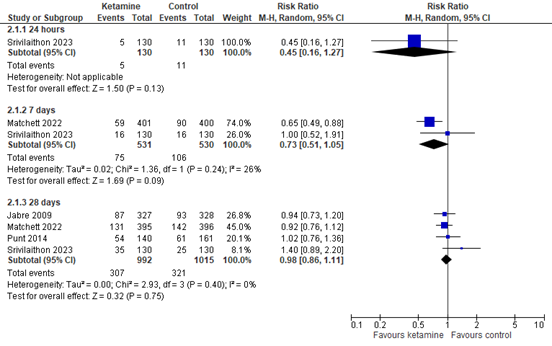

Mortality

Four studies reported mortality rates (Figure 4). Follow-up was at 24 hours, 7 days, and at 28 days. For 24-hour mortality, the risk ratio (RR) is 0.45 (95% CI 0.16 to 1.27). For 7-day mortality, the pooled RR is 0.73 (95% CI 0.51 to 1.05). For 28-day mortality, the pooled RR is 0.98 (95% CI 0.86 to 1.11). The differences are clinically relevant in favor of ketamine for follow-up 24 hours and 7 days. For the 28-day follow-up, the difference is not clinically relevant.

Figure 4. Mortality at 24 hours, 7 days and 28 days, ketamine vs. control

Random effects model; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval; Z: p-value of pooled effect

Cardiac arrest

Three studies reported the incidence of cardiac arrest (Figure 5). A total of 24/852 (2.8%) in the ketamine group and 22/854 (2.6%) in the control group experienced cardiac arrest. The pooled RR is 1.10 (95% CI 0.62 to 1.97) in favor of the control group. This difference is not clinically relevant.

Figure 5. The incidence of cardiac arrest, ketamine vs. control

Random effects model; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval; Z: p-value of pooled effect

Hypotension

Two studies reported the incidence of hypotension.

Ali (2021) reported post-induction hypotension in 11/23 (47.8%) in the ketamine group and 16/19 (84.2%) in the control group (RR 0.57; 95% CI 0.36 to 0.91). This difference is clinically relevant in favor of ketamine.

Srivilaithon (2023) reported hypotension in 14/130 (10.8%) in the ketamine group and 15/130 (11.5%) in the control group (RR 0.93; 95% CI 0.47 to 1.85). This difference is not clinically relevant in favor of ketamine.

Hypoxia

None of the included studies reported the incidence of hypoxia.

Aspiration

None of the included studies reported the incidence of aspiration.

First pass success

Two studies reported first pass success.

Matchett (2022) observed a first pass success rate of 355/395 (91.3%) in the ketamine group and 357/396 (91.3%) in the control group (RR 1.00; 95% CI 0.95 to 1.04). This difference is not clinically relevant.

Srivilaithon (2023) reported the proportion of patients with successful intubation during the first attempt. In the ketamine group 114/130 (87.7%) and in the control group 116/130 (89.2%) had first-pass success (RR 0.98; 95% CI 0.90 to 1.07). This difference is not clinically relevant.

The level of evidence

The level of evidence regarding all outcome measures was based on randomized controlled studies and therefore started at high.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure mortality at 24 hours was downgraded by three levels to VERY LOW because the confidence interval crossed both thresholds for clinical relevance and due to the very limited number of events (imprecision, -3).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure mortality at 7 days was downgraded by two levels to LOW because of conflicting results (inconsistency, -1); and because the confidence interval crossed one threshold for clinical relevance (imprecision, -1).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure cardiac arrest was downgraded by three levels to VERY LOW because of study limitations (risk of bias due to lack of blinding, -1); conflicting results (inconsistency, -1); and the confidence interval crossed both thresholds for clinical relevance (imprecision, -1).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure hypotension was downgraded by three levels to VERY LOW because of wide confidence intervals and due to the very limited number of events (imprecision, -3).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure first pass success was downgraded by one level to MODERATE because of study limitations (risk of bias due lack of blinding, -1).

Propofol

No studies were found investigating the effect of propofol as an induction agent in critically ill patients requiring intubation outside the operating room. Therefore, no results could be described.

The level of evidence

The level of evidence regarding all outcome measures could not be graded, as no studies were included.

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following questions:

1. What are the benefits and harms of adding etomidate/ketamine/propofol to the induction regimen compared with not adding etomidate/ketamine/propofol as (standard) induction method in the critically ill patient requiring emergency intubation outside the operating room?

|

P: |

Critically ill patients requiring emergency intubation outside the operating room |

|

I: |

Anesthetic drug regimen with either propofol, etomidate and/or (S-)Ketamine |

|

C: |

Anesthetic drug regimen without the specific drug included in intervention |

|

O: |

Mortality, cardiac arrest, hypotension, hypoxia, aspiration, first pass success |

2. What are the benefits and harms of adding etomidate/ketamine/propofol to the induction regimen compared with adding a different induction agent than the intervention drug as (standard) induction method in the critically ill patient requiring emergency intubation outside the operating room?

|

P: |

Critically ill patients requiring emergency intubation outside the operating room |

|

I: |

Anesthetic drug regimen with propofol |

|

C: |

Adding a different induction agent than propofol to the induction regimen |

|

O: |

Mortality, cardiac arrest, hypotension, hypoxia, aspiration, first pass success |

|

P: |

Critically ill patients requiring emergency intubation outside the operating room |

|

I: |

Anesthetic drug regimen with etomidate |

|

C: |

Adding a different induction agent than etomidate to the induction regimen |

|

O: |

Mortality, cardiac arrest, hypotension, hypoxia, aspiration, first pass success |

|

P: |

Critically ill patients requiring emergency intubation outside the operating room |

|

I: |

Anesthetic drug regimen with (S-)ketamine |

|

C: |

Adding a different induction agent than (S-)ketamine to the induction regimen |

|

O: |

Mortality, cardiac arrest, hypotension, hypoxia, aspiration, first pass success |

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered mortality and cardiac arrest as critical outcome measures for decision making; and hypotension, hypoxia, aspiration, first pass success as important outcome measures for decision making.

The follow-up periods of interest for the outcome mortality were 24 hours and 7 days.

Cardiac arrest was defined as arrest peri-intubation.

A priori, the working group did not define the other outcome measures listed above but used the definitions used in the studies.

The working group defined the following minimal clinically (patient) important differences:

Mortality: a difference of 5% in relative risk (RR <0.95 or >1.05).

Cardiac arrest: a difference of 5% in relative risk (RR <0.95 or >1.05).

Hypotension: a difference of 25% in relative risk (RR <0.8 or >1.25).

Hypoxia: a difference of 25% in relative risk (RR <0.8 or >1.25).

Aspiration: a difference of 25% in relative risk (RR <0.8 or >1.25).

First pass success: a difference of 10% in relative risk (RR <0.91 or >1.10).

Search and select (Methods)

On the 15th of May 2023, a systematic search was performed for systematic reviews and RCTs about intubating the critically ill patient and the use of propofol/ ketamine/ etomidate in the databases Embase.com and Ovid/Medline. The search resulted in 826 unique hits. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. Studies were selected based on the following criteria: 1) (systematic reviews or meta-analyses of) randomized controlled trials (RCTs); 2) published ≥ 2007; 3) comparing different induction methods including etomidate, ketamine or propofol; 4) in critically ill patients requiring emergency intubation outside the operating room; 5) reporting at least one of the predefined outcomes.

A total of 29 studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, 22 studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and seven studies were included.

Results

Seven studies were included in the analysis of the literature. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- Ali H, Abdelhamid BM, Hasanin AM, Amer AA, Rady A. Ketamine-based Versus Fentanyl-based Regimen for Rapid-sequence Endotracheal Intubation in Patients with Septic Shock: A Randomised Controlled Trial. Rom J Anaesth Intensive Care. 2022 Dec 29;28(2):98-104. doi: 10.2478/rjaic-2021-0017. PMID: 36844112; PMCID: PMC9949025.

- Jabre P, Combes X, Lapostolle F, Dhaouadi M, Ricard-Hibon A, Vivien B, Bertrand L, Beltramini A, Gamand P, Albizzati S, Perdrizet D, Lebail G, Chollet-Xemard C, Maxime V, Brun-Buisson C, Lefrant JY, Bollaert PE, Megarbane B, Ricard JD, Anguel N, Vicaut E, Adnet F; KETASED Collaborative Study Group. Etomidate versus ketamine for rapid sequence intubation in acutely ill patients: a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2009 Jul 25;374(9686):293-300. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60949-1. Epub 2009 Jul 1. PMID: 19573904.

- Koroki T, Kotani Y, Yaguchi T, Shibata T, Fujii M, Fresilli S, Tonai M, Karumai T, Lee TC, Landoni G, Hayashi Y. Ketamine versus etomidate as an induction agent for tracheal intubation in critically ill adults: a Bayesian meta-analysis. Crit Care. 2024 Feb 17;28(1):48. doi: 10.1186/s13054-024-04831-4. PMID: 38368326; PMCID: PMC10874027.

- Matchett G, Gasanova I, Riccio CA, Nasir D, Sunna MC, Bravenec BJ, Azizad O, Farrell B, Minhajuddin A, Stewart JW, Liang LW, Moon TS, Fox PE, Ebeling CG, Smith MN, Trousdale D, Ogunnaike BO; EvK Clinical Trial Collaborators. Etomidate versus ketamine for emergency endotracheal intubation: a randomized clinical trial. Intensive Care Med. 2022 Jan;48(1):78-91. doi: 10.1007/s00134-021-06577-x. Epub 2021 Dec 14. PMID: 34904190.

- Punt CD, Dormans TP, Oosterhuis WP, Boer W, Depoorter B, van der Linden CJ, van der Woude MC, Scheeren CI, Zelis GH, Fikkers BG. Etomidate and S-ketamine for the intubation of patients on the intensive care unit: a prospective, open-label study. Sepsis. 2014 Apr 1;58:54.

- Russotto V, Tassistro E, Myatra SN, Parotto M, Antolini L, Bauer P, Lascarrou JB, Szu?drzy?ski K, Camporota L, Putensen C, Pelosi P, Sorbello M, Higgs A, Greif R, Pesenti A, Valsecchi MG, Fumagalli R, Foti G, Bellani G, Laffey JG. Peri-intubation Cardiovascular Collapse in Patients Who Are Critically Ill: Insights from the INTUBE Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2022 Aug 15;206(4):449-458. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202111-2575OC. PMID: 35536310.

- Smischney NJ, Nicholson WT, Brown DR, Gallo De Moraes A, Hoskote SS, Pickering B, Oeckler RA, Iyer VN, Gajic O, Schroeder DR, Bauer PR. Ketamine/propofol admixture vs etomidate for intubation in the critically ill: KEEP PACE Randomized clinical trial. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2019 Oct;87(4):883-891. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000002448. PMID: 31335755.

- Srivilaithon W, Bumrungphanithaworn A, Daorattanachai K, Limjindaporn C, Amnuaypattanapon K, Imsuwan I, Diskumpon N, Dasanadeba I, Siripakarn Y, Ueamsaranworakul T, Pornpanit C, Pornpachara V. Clinical outcomes after a single induction dose of etomidate versus ketamine for emergency department sepsis intubation: a randomized controlled trial. Sci Rep. 2023 Apr 19;13(1):6362. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-33679-x. PMID: 37076524; PMCID: PMC10115773.

- Tekwani KL, Watts HF, Sweis RT, Rzechula KH, Kulstad EB. A comparison of the effects of etomidate and midazolam on hospital length of stay in patients with suspected sepsis: a prospective, randomized study. Ann Emerg Med. 2010 Nov;56(5):481-9. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2010.05.034. Epub 2010 Sep 15. PMID: 20828877.

- Wunsch H, Bosch NA, Law AC, Vail EA, Hua M, Shen BH, Lindenauer PK, Juurlink DN, Walkey AJ, Gershengorn HB. Evaluation of Etomidate Use and Association with Mortality Compared with Ketamine Among Critically Ill Patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2024 Aug 22. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202404-0813OC. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 39173173.

Evidence tabellen

Evidence table for intervention studies (randomized controlled trials and non-randomized observational studies [cohort studies, case-control studies, case series])

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C) |

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

Matchett, 2022 |

Type of study: Single-center RCT

Setting and country: high-volume medical center, USA

Funding and conflicts of interest: Internal funding by Dept. of Anesthesiology & Pain Management. One author receives compensation for serving on the Medical Advisory Board for the industry. |

Inclusion criteria: adult patient 18 years and older in need of emergency endotracheal intubation

Exclusion criteria: children (< 18 years), women known to be pregnant, patients previously enrolled in the trial, patients requiring endotracheal intubation without sedative medication such as those in cardiac arrest, those neurologically obtunded, or those requiring awake intubation, patients with a known allergy to etomidate or ketamine

N total at baseline: Intervention: 400 Control: 401

Important prognostic factors2: age ± SD: I: 55.8 ± 15.2 C: 55.4 ± 16

Sex: I: 61.4% M C: 62% M

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

Etomidate 0.2–0.3 mg/kg IV |

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

ketamine 1–2 mg/kg IV |

Length of follow-up: 7, 28 days

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: N (%): 4 (1%) Reasons: withdrawals (n=4)

Control: N (%): 6 (1.5%) Reasons: withdrawals (n=6)

Incomplete outcome data: The number of attempts to intubate is missing for five patients in the etomidate group and six patients in the ketamine group, all of whom were successfully intubated using non-surgical techniques according to chart documentation |

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Mortality 7 days, n(%) I: 90/400 (22.5) C: 59/401 (14.7) RR 1.53 (1.14 to 2.06)

Mortality 28 days, n(%) I: 142/396 (35.9) C: 131/395 (33.2)

First pass success, n(%) I: 357/396 (91.3) C: 355/395 (91.3)

Post-induction CPR, n(%) I: 13/396 (3.8) C: 18/395 (5.1) |

Author’s conclusion: While the primary outcome of Day 7 survival was greater in patients randomized to ketamine, there was no significant difference in survival by Day 28.

|

|

Punt, 2014 |

Type of study: Cluster-randomized trial

Setting and country: ICU, large teaching hospital, Netherlands

Funding and conflicts of interest: No information |

Inclusion criteria: critically ill adult patients, who were intubated in one of the intensive care units, either shortly after admission or during their period of stay

Exclusion criteria: patients who had received etomidate less than 72 hours before

N total at baseline: Intervention: 161 Control: 140

Important prognostic factors2: age ± SD: I: 66 ± 14 C: 67 ± 13

Sex: I: 59% M C: 63.7% M

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

Etomidate 0.2–0.3 mg/kg |

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

S-Ketamine 0.5 mg/kg and midazolam 2.5 mg. |

Length of follow-up: 28 days

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: not reported, not assumed

Control: not reported, not assumed

Incomplete outcome data: Intervention: not reported, not assumed

Control: not reported, not assumed

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Mortality 28 days, n(%) I: 61/161 (37.9) C: 54/140 (38.6) RR 0.98 (0.74 to 1.31) |

Author’s conclusion: The present study showed that the 28-day mortality after a single dose of etomidate or S-ketamine, administered to patients for tracheal intubation while on the intensive care did not differ. |

|

Smischney, 2019 |

Type of study: Randomized clinical trial

Setting and country: ICU of a tertiary academic medical center, USA

Funding and conflicts of interest: Funding received was institutional. First and second author have a provisional patent filed for the ketamine-propofol admixture. |

Inclusion criteria: Adult patients (≥18 years), admitted to one of three ICUs (medical, surgical, and oncologic/transplant ICU totaling 65 beds) in a tertiary medical center, requiring emergent intubation from July 2014 to October 2017

Exclusion criteria: (1) intubation for cardiac arrest; (2) intracranial pathology with known/ suspected elevation in intracranial pressure; (3) chronic opioid dependence defined by methadone, buprenorphine, buprenorphinenaloxone, or naltrexone use as an outpatient; (4) bipolar and/or schizophrenia disorder; (5) egg allergies; (6) contraindications to fentanyl, midazolam, ketamine, propofol, or etomidate; (7) any weight greater than 140 kg or less than 30 kg; (8) previously enrolled in the study; (9) continuous infusions of propofol, midazolam, lorazepam, fentanyl, or dexmedetomidine in the previous 24 hours; (10) procedural intubation; (11) incarceration; (12) any woman of child-bearing age, between 18 years and 50 years without a pregnancy test.

N total at baseline: Intervention: 76 Control: 84

Important prognostic factors2: age ± SD: I: 60.0 ± 18.3 C: 62.1 ± 17.2

Sex: I: 52% M C: 61% M

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

An induction intravenous dose of 0.15 mg/kg (actual body weight) of etomidate was used.

A second dose of 0.15 mg/kg was available as a rescue.

In both arms, a standard 50 μg intravenous bolus dose of fentanyl was administered to blunt the hemodynamic response. |

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

Ketamine-propofol admixture (KPA):

An initial dose of 1 mg/kg total of KPA (0.5 mg/kg of ketamine and propofol each) was the standard intravenous induction dose.

A second dose of 1 mg/kg KPA (0.5 mg/kg of ketamine and propofol each) was available as a rescue. |

Length of follow-up: Hospital discharge

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: N = 3 (3.9%) Reasons: refused data-analysis (n=3)

Control: N = 5 (6.0%) Reasons: refused data-analysis (n=5)

Incomplete outcome data: Intervention: not reported, not assumed

Control: not reported, not assumed

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Mortality hospital, n(%) I: 26/76 (34.2) C: 25/84 (29.8) RR 1.15 (0.73 to 1.81)

Vomiting/aspiration*: I: 3/73 (4%) C: 2/79 (3%) RR 1.62 (0.28 to 9.44) *study states the events are probably not related to the study drug

Cardiac arrest* I: 0/73 C: 2/79 (3%) RR 0.22 (0.01 to 4.43) *study states that probably 1 event in the control group was related to the study drug

Hypotension (MAP <40 mm Hg)* I: 4/73 (5%) C: 3/79 (4%) RR 1.44 (0.33 to 6.23) *study states that probably 1 event in each group was related to the study drug

|

Author’s conclusion: KPA was not superior to a reduced dose of etomidate in terms of hemodynamic profile and new-onset vasopressor need after emergent intubation in critically ill patients. There were no differences in frequency of delirium or intubation difficulty. KPA appears to be a safe alternative induction agent compared with reduced dose etomidate and should be considered whenever adrenal insufficiency is a concern. |

|

Jabre, 2009 |

Type of study: randomised, controlled, single-blind trial

Setting and country: 12 emergency medical services or emergency departments and 65 ICUs in France

Funding and conflicts of interest: Funding by the French Ministry of Health (no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing the report). Nothing else to declare. |

Inclusion criteria: Patients who were 18 years or older and who needed sedation for emergency intubation

Exclusion criteria: cardiac arrest; contraindications to succinylcholine, ketamine, or etomidate; or known pregnancy

N total at baseline: Intervention: 328 Control: 327

Important prognostic factors2: age ± SD: I: 57 ± 18 C: 59 ± 19

Sex: I: 63% M C: 57% M

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

Etomidate 0.3 mg/kg

Both groups: Succinylcholine was given immediately after the sedative as a 1 mg/kg intravenous bolus. After confirmation of intubation and tube placement, continuous sedation was initiated by use of a standardised protocol with midazolam (0·1 mg/kg/h) combined with fentanyl (2–5 μg/kg/h) or sufentanil (0·2–0·5 μg/kg/h). |

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

Ketamine 2 mg/kg |

Length of follow-up: 28 days

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: N = 94 (28.7%) Reasons: withdrew consent (n=1), missing data (n=2) discharged from ICU before 3 days (n=79), died before reaching hospital (n=12)

Control: N 92 (28.1%) Reasons: missing data (n=2) discharged from ICU before 3 days (n=75), died before reaching hospital (n=15)

Incomplete outcome data: Intervention: NR

Control: NR |

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Mortality 28 days, n I: 93/328 C: 87/327 MD 1.07 (0.83 to 1.37)

Cardiac arrest during intubation, n I: 7/328 (3%) C: 4/327 (2%) RR 1.74 (0.52 to 5.90)

|

|

|

Srivilaithon, 2023 |

Type of study: randomized, controlled, single-blind trial

Setting and country: Emergency Medicine Research Group at Tammasat University Hospital (TUH) in Pathum Tani, Thailand

Funding and conflicts of interest: Academic funding, no competing interests |

Inclusion criteria: Patients presenting to the ED with suspected sepsis who were 18 years or older and then needed an induction agent for emergency intubation in the ED

Exclusion criteria: 1) cardiac arrest before intubation, 2) presence of a do-not-resuscitate order, 3) known or suspected adrenal insufficiency, 4) severe hypertension (blood pressure before randomization > 180/110 mmHg), and 5) suspected or evidenced increased intracranial pressure.

N total at baseline: Intervention: 130 Control: 130

Important prognostic factors2:

age ± SD: I: 73.2 (±12.6) C: 70.5 (±14.9)

Sex: I: 59.2% M C: 58.5% M

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

single-dose induction agent consisting of either etomidate (Lipuro, B. Braun Melsungen, Germany) administered as a 0.2–0.3 mg/kg intravenous bolus |

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

ketamine (Ketalar, PAR Pharmaceutical, Ireland) administered as a 1–2 mg/kg intravenous bolus |

Length of follow-up: 28 d

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: N = 0 (0%) Reasons (describe)

Control: N = 0 (0%) Reasons (describe)

Incomplete outcome data: None

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

24h survival I: 119/130 C: 125/130

7d survival I: 114/130 C: 114/130

28d survival I: 105/130 C: 95/130

Cardiac arrest I: 2/130 C: 2/130

Post-intubation hypotension I: 15/130 C: 14/130

Intubation successful in the first attempt I: 116/130 C: 114/130 |

Author’s conclusion:

In patients with clinically suspected sepsis who needed emergency intubation in the ED, there was no difference in early and 28-day survival rates between etomidate and ketamine. However, etomidate was associated with higher risks of early vasopressor use after intubation. |

|

Tekwani, 2010 |

Type of study: prospective, double-blind, randomized study

Setting and country: a large, tertiary care suburban hospital, USA

Funding and conflicts of interest: Financial support by Emergency Medicine Foundation Resident Research Grant. |

Inclusion criteria: Older than 18 years, were intubated in the ED, and had a suspected infectious cause for their illness

Exclusion criteria: younger than 18 years, pregnancy, cardiopulmonary arrest before arrival in the ED, or a do-not resuscitate status

N total at baseline: Intervention: 63 Control:59

Important prognostic factors2: For example age (IQR): I: 70 (60 to 83) C: 73 (60 to 80)

Sex: I: 52% M C: 61% M

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

Etomidate 0.3 mg/kg IV before RSI |

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

Midazolam 0.1 mg/kg before RSI |

Length of follow-up: Hospital stay

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: N = 2 (3.2%) Reasons (describe): transfer to outside institutions.

Control: N = 0 (0%) Reasons (describe)

Incomplete outcome data: Not reported, not assumed

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Hospital mortality I: 26/63 C: 21/59

Low SBP <90 mm Hg I: 16/63 C: 15/59 |

Author’s conclusion: In conclusion, for patients who had suspected sepsis and were intubated in the ED, we found no significant difference in hospital length of stay between patients who received etomidate as an induction agent and those who received midazolam. |

|

Ali, 2021 |

Type of study: randomised double-blinded controlled trial.

Setting and country: surgical theatre at the emergency department of Cairo University Hospital, Egypt

Funding and conflicts of interest: Self-funded, no conflicts of interest |

Inclusion criteria: age between 18 and 65 years; experiencing septic shock; scheduled for emergency surgery to control the source of sepsis

Exclusion criteria: burns, traumatic brain injury or history of any cerebrovascular disorders.

N total at baseline: Intervention: 23 Control: 23

Important prognostic factors2: age (IQR): I: 44 (40-60) C: 56 (46-63)

Sex: I: 11% M C: 8% M

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

Before induction: ketamine 1 mg/kg IV

plus midazolam (0.05 mg/kg) and succinyl choline (1 mg/kg). |

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

Before induction: fentanyl 2.5 mcg/kg IV

plus midazolam (0.05 mg/kg) and succinyl choline (1 mg/kg). |

Length of follow-up: 10 minutes

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: N = 0 (0%) Reasons (describe)

Control: N = 4 (17.4%) Reasons (describe): poor cardiometry (n=2), incomplete data (n=2)

Incomplete outcome data: See above

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Post-induction hypotension, N (MAP ≤ 80% the baseline value during the period from induction of anaesthesia until 10 min) I: 11/23 C: 16/19

|

Author’s conclusion: In conclusion, the ketamine-based regimen provided a better hemodynamic profile compared to the fentanyl-based regimen for rapid-sequence intubation in patients with septic shock undergoing emergency surgery |

Risk of bias table for intervention studies (randomized controlled trials; based on Cochrane risk of bias tool and suggestions by the CLARITY Group at McMaster University)

|

Study reference

(first author, publication year) |

Was the allocation sequence adequately generated?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was the allocation adequately concealed?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Blinding: Was knowledge of the allocated interventions adequately prevented?

Were patients blinded?

Were healthcare providers blinded?

Were data collectors blinded?

Were outcome assessors blinded?

Were data analysts blinded? Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was loss to follow-up (missing outcome data) infrequent?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Are reports of the study free of selective outcome reporting?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was the study apparently free of other problems that could put it at a risk of bias?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Overall risk of bias If applicable/necessary, per outcome measure

LOW Some concerns HIGH |

|

Punt, 2014 |

Definitely no;

Reason: Study is a cluster-randomized trial in which the chosen intensive care unit is the randomized element |

No information

Reason: not described |

Definitely no;

Reason: Study is open-label, no blinding |

Probably yes;

Reason: Loss to follow-up was not assumed. |

Probably yes;

Reason: All relevant outcomes seem to be reported. Study protocol is not accessible. |

Probably yes;

Reason: Funding and conflicts of interest are not reported. |

LOW (mortality) |

|

Matchett, 2022 |

Probably yes;

Reason: Randomization sequence was computer-generated. |

Definitely yes;

Reason: Opaque, sealed envelopes were used. |

Definitely no;

Reason: Study is open-label, no blinding |

Probably yes

Reason: Loss to follow-up was infrequent in intervention and control group. Adequate imputation methods (multiple imputation) were used |

Definitely yes

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported; Study protocol is available. |

Probably yes;

Reason: One author receives compensation for serving on the Medical Advisory Board for the medical industry. This author contributed to the study design, enrolment, and manuscript drafting. |

LOW (mortality) HIGH (first pass success)

Reason: lack of blinding, other bias |

|

Smischney, 2019 |

Definitely yes;

Reason: Computer-generated randomization and stratification by a statistician independent of trial design were carried out in blocks of four patients based on sealed opaque randomization envelopes. The stratification was based on ICU location and hemodynamic compromise |

Definitely yes;

Reason: Opaque, sealed envelopes were used. |

Probably yes;

Reason: Healthcare providers were not blinded. Outcome assessors and statisticians were blinded. Patients were presumed to be not blinded. |

Probably yes;

Reason: Loss to follow-up was infrequent in intervention and control group (≤6%). |

Definitely yes

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported; Study protocol is available. |

Probably no;

Reason: First and second author have a provisional patent filed for the study drug (ketamine-propofol admixture). However, the results suggest this did not skew the data. |

LOW

(all outcomes) |

|

Jabre, 2009 |

Probably yes;

Reason: computerised random-number generator list provided by a statistician who was not involved in determination of patient eligibility, drug administration, or outcome assessment. |

Probably yes;

Reason: the study drug was sealed in sequentially numbered, identical boxes containing the entire treatment for each patient. |

Probably no;

Reason: emergency physician (who had no influence on the management of the patients) enrolling patients was aware of study group assignment. Nurses and intensivists (caregivers) in the intensive care unit were blinded. Patients were presumed to be not blinded. |

Probably no;

Reason: loss to follow-up was high (≥28%), yet similar in both groups. |

Definitely yes

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported; Study protocol is available. |

Definitely no;

Reason: no other problems noted. |

Some concerns

LOW (mortality) Unclear (all other outcomes)

Reason: lack of blinding |

|

Srivilaithon, 2023 |

Probably yes;

Reason: computer-generated randomization table with a block size of four by a statistician who was not involved in other study procedures |

Definitely yes;

Reason: The drug allocation sequence was kept inaccessible to the research team throughout the study period. Patient assignments were placed into sequentially numbered sealed opaque envelopes |

Probably no;

Reason: the study is single-blind, however it is not mentioned which roles are masked |

Definitely yes;

Reason: no loss to follow-up |

Definitely yes

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported; Study protocol is available. |

Definitely no;

Reason: no other problems noted. |

Some concerns

LOW (mortality) Unclear (all other outcomes)

Reason: lack of blinding |

|

Tekwani, 2010 |

Probably yes;

Reason: computer-generated blocks of 10 randomization |

Probably no;

Reason: not described |

Probably yes;

Reason: study investigators and patients were blinded. |

Probably yes;

Reason: Loss to follow-up was infrequent in intervention and control group (<3.5%) and handled adequately. |

Definitely yes

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported; Study protocol is available. |

Definitely no;

Reason: no other problems noted. |

LOW (all outcomes) |

|

Ali, 2021 |

Probably yes;

Reason: computer-generated sequence of codes which was performed by a statistician |

Probably yes;

Reason: The codes were inserted in opaque envelopes which contained the instructions for preparation of study drugs |

Probably yes;

Reason: study was double-blinded, presumably subjects and investigators. |

Probably yes;

Reason: Loss to follow-up was infrequent in intervention and control group (<17.5%) |

Definitely yes

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported; Study protocol is available. |

Definitely no;

Reason: no other problems noted. |

LOW (all outcomes) |

Table of excluded studies

|

Reference |

Reason for exclusion |

|

Hohl, C. M. and Kelly-Smith, C. H. and Yeung, T. C. and Sweet, D. D. and Doyle-Waters, M. M. and Schulzer, M. (2010) |

Only partly conform current PICO |

|

Albert, S. G. and Ariyan, S. and Rather, A. (2011) |

Only partly conform current PICO |

|

Cohen, L. and Athaide, V. and Wickham, M. E. and Doyle-Waters, M. M. and Rose, N. G. W. and Hohl, C. M. (2015) |

Only partly conform current PICO |

|

Sharda, Saurabh C. and Bhatia, Mandip S. (2022) |

Only partly conform current PICO |

|

Chan, C. M. and Mitchell, A. L. and Shorr, A. F. (2012) |

Only partly conform current PICO |

|

Baekgaard, J. S. and Eskesen, T. G. and Sillesen, M. and Rasmussen, L. S. and Steinmetz, J. (2019) |

Only partly conform current PICO |

|

Bruder, E. A. and Ball, I. M. and Ridi, S. and Pickett, W. and Hohl, C. (2015) |

Only partly conform current PICO |

|

Arteaga Velásquez J, Rodríguez JJ, Higuita-Gutiérrez LF, and Montoya Vergara ME. (2022) |

Only partly conform current PICO |

|

Rabelo, N. N. and Rabelo, N. N. and Machado, F. S. and Joaquim, M. A. S. and Dias Junior, L. A. A. and Pereira, C. U. (2016) |

wrong publication type (narrative review) |

|

De La Grandville, B. and Arroyo, D. and Walder, B. (2012) |

wrong publication type (narrative review) |

|

Trentzsch, H, Münzberg, M, Luxen, J, Urban, B, and Prückner, S. (2014) |

Wrong language |

|

Lysakowski C, Suppan L, Czarnetzki C, Tassonyi E, and Tramèr MR. (2007) |

wrong comparison (true vs modified RSI) |

|

Gu, W. J. and Wang, F. and Tang, L. and Liu, J. C. (2015) |

not the most recent SR |

|

Cabrini, L. and Landoni, G. and Baiardo Radaelli, M. and Saleh, O. and Votta, C. D. and Fominskiy, E. and Putzu, A. and Snak de Souza, C. D. and Antonelli, M. and Bellomo, R. and Pelosi, P. and Zangrillo, A. (2018) |

Not conform PICO |

|

Edwin, S. B. and Walker, P. L. (2010) |

Outdated SR, not conform PICO |

|

Kotani, Y. and Piersanti, G. and Maiucci, G. and Fresilli, S. and Turi, S. and Montanaro, G. and Zangrillo, A. and Lee, T. C. and Landoni, G. (2023) |

original RCTs are included |

|

Hildreth, A. N. and Mejia, V. A. and Maxwell, R. A. and Smith, P. W. and Dart, B. W. and Barker, D. E. (2008) |

wrong population, wrong outcomes |

|

Kim, M. H. and Oh, A. Y. and Han, S. H. and Kim, J. H. and Hwang, J. W. and Jeon, Y. T. (2015) |

wrong population (elective surgery) |

|

Meyancı Köksal G, Erbabacan E, Tunalı Y, Karaören G, Vehid S, and Öz H. (2015) |

wrong outcomes |

|

Kamali, A. and Taghizadeh, M. and Esfandiar, M. and Akhtari, A. S. (2018) |

wrong outcomes |

|

Smischney, N. J. and Beach, M. L. and Loftus, R. W. and Dodds, T. M. and Koff, M. D. (2012) |

wrong population (not emergency) |

|

Jaffrelot, M. and Jendrin, J. and Floch, Y. and Lockey, D. and Jabre, P. and Vergne, M. and Lapostolle, F. and Galinski, M. and Adnet, F. (2007) |

wrong outcomes |

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Laatst beoordeeld : 23-02-2025

Algemene gegevens

De ontwikkeling/herziening van deze richtlijnmodule werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten (www.demedischspecialist.nl/kennisinstituut) en werd gefinancierd uit de Stichting Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS).

De financier heeft geen enkele invloed gehad op de inhoud van de richtlijnmodule.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijnmodule is in 2022 een multidisciplinaire werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen (zie hiervoor de Samenstelling van de werkgroep) die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor vitaal bedreigde patiënten die geïntubeerd worden buiten de OK.

Werkgroep

Dr. J.A.M. (Joost) Labout (voorzitter tot september 2023), intensivist, NVIC

Drs. J.H.J.M. (John) Meertens (interim-voorzitter), intensivist, NVIC

Drs. P. (Peter) Dieperink (interim-voorzitter), intensivist, NVIC

Drs. M.E. (Mengalvio) Sleeswijk (interim-voorzitter), intensivist, NVIC

Dr. F.O. (Fabian) Kooij, anesthesioloog/MMT-arts, NVA

Drs. Y.A.M. (Yvette) Kuijpers, anesthesioloog-intensivist, NVA

Drs. C. (Caspar) Müller, anesthesioloog/MMT-arts, NVA

Drs. M.E. (Mark) Seubert, internist-intensivist, NIV

Drs. S.J. (Sjieuwke) Derksen, internist-intensivist, NIV

Dr. R.M. (Rogier) Determann, internist-intensivist, NIV

Drs. H.J. (Harry) Achterberg, anesthesioloog-SEH-arts, NVSHA

Drs. M.A.E.A. (Marianne) Brackel, patiëntvertegenwoordiger, FCIC/IC Connect

Klankbordgroep

Dr. C.L. (Christiaan) Meuwese, cardioloog-intensivist, NVVC

Drs. J.T. (Jeroen) Kraak, KNO-arts, NVKNO

Drs. H.R. (Harry) Naber, anesthesioloog, NVA

Drs. H. (Huub) Grispen, anesthesiemedewerker, NVAM

Met ondersteuning van

dr. M.S. Ruiter, senior adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

drs. I. van Dijk, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

Belangenverklaringen

De Code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling is gevolgd. Alle werkgroepleden hebben schriftelijk verklaard of zij in de laatste drie jaar directe financiële belangen (betrekking bij een commercieel bedrijf, persoonlijke financiële belangen, onderzoeksfinanciering) of indirecte belangen (persoonlijke relaties, reputatiemanagement) hebben gehad. Gedurende de ontwikkeling of herziening van een module worden wijzigingen in belangen aan de voorzitter doorgegeven. De belangenverklaring wordt opnieuw bevestigd tijdens de commentaarfase.

Een overzicht van de belangen van werkgroepleden en het oordeel over het omgaan met eventuele belangen vindt u in onderstaande tabel. De ondertekende belangenverklaringen zijn op te vragen bij het secretariaat van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

|

Werkgroeplid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

Caspar Müller |

Anesthesioloog/MMT-arts ErasmusMC |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen restricties. |

|

Fabian Kooij |

Anesthesioloog/MMT-arts, Amsterdam UMC |

Chair of the Board, European Trauma Course Organisation |

Geen |

Geen restricties. |

|

Harry Achterberg |

SEH-arts, Isala Klinieken, fulltime - 40u/w (~111%) |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen restricties. |

|

John Meertens |

Intensivist-anesthesioloog, Intensive Care Volwassenen, UMC Groningen |

Secretaris Commissie Luchtwegmanagement, Nederlandse Vereniging voor Intensive Care |

Geen |

Geen restricties. |

|

Joost Labout |

Intensivist |

Redacteur A & I |

Geen |

Geen restricties. |

|

Marianne Brackel |

Patiëntvertegenwoordiger Stichting FCIC en patiëntenorganisatie IC Connect |

Geen |

Voormalig voorzitter IC Connect |

Geen restricties. |

|

Mark Seubert |

Internist-intensivist, |

Waarnemend internist en intensivist |

Lid Sectie IC van de NIV |

Geen restricties. |

|

Mengalvio Sleeswijk |

Internist-intensivist, Flevoziekenhuis |

Medisch Manager ambulancedienst regio Flevoland Gooi en Vecht / TMI Voorzitter Commissie Luchtwegmanagement, Nederlandse Vereniging voor Intensive Care |

Geen |

Geen restricties. |

|

Peter Dieperink |

Intensivist-anesthesioloog, Intensive Care Volwassenen, UMC Groningen |

Lid Commissie Luchtwegmanagement, Nederlandse Vereniging voor Intensive Care |

Geen |

Geen restricties. |

|

Rogier Determann |

Intensivist, OLVG, Amsterdam |

Docent Amstelacademie en Expertcollege |

Geen |

Geen restricties. |

|

Sjieuwke Derksen |

Intensivist - MCL |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen restricties. |

|

Yvette Kuijpers |

Anesthesioloog-intensivist, CZE en MUMC + |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen restricties. |

|

Klankbordgroeplid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

Christiaan Meuwese |

Cardioloog intensivist, Erasmus MC, Rotterdam |

Section editor Netherlands Journal of Critical Care (onbetaald) |

Extern gefinancierd onderzoek: - REMAP ECMO (Hartstichting) - PRECISE ECLS (Fonds SGS) |

Geen restricties. |

|

Jeroen Kraak |

KNO-arts & Hoofd-halschirurgie |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen restricties. |

|

Huub Grispen |

Anesthesiemedewerker Zuyderland MC |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen restricties. |

|

Harry Naber |

Anesthesioloog MSB Isala |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen restricties. |

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Er werd aandacht besteed aan het patiëntenperspectief door het uitnodigen van FCIC/IC Connect voor de schriftelijke knelpunteninventarisatie en deelname aan de werkgroep. Het verslag hiervan [zie aanverwante producten] is besproken in de werkgroep. De verkregen input is meegenomen bij het opstellen van de uitgangsvragen, de keuze voor de uitkomstmaten en bij het opstellen van de overwegingen. Ter onderbouwing van de module Aanwezigheid van naaste heeft IC Connect een achterbanraadpleging uitgevoerd. De conceptrichtlijn is tevens voor commentaar voorgelegd aan FCIC/IC Connect en de eventueel aangeleverde commentaren zijn bekeken en verwerkt.

Kwalitatieve raming van mogelijke financiële gevolgen in het kader van de Wkkgz

Bij de richtlijnmodule is conform de Wet kwaliteit, klachten en geschillen zorg (Wkkgz) een kwalitatieve raming uitgevoerd om te beoordelen of de aanbevelingen mogelijk leiden tot substantiële financiële gevolgen. Bij het uitvoeren van deze beoordeling is de richtlijnmodule op verschillende domeinen getoetst (zie het stroomschema op de Richtlijnendatabase).

|

Module |

Uitkomst raming |

Toelichting |

|

Module Medicatie |

Geen substantiële financiële gevolgen |

Hoewel uit de toetsing volgt dat de aanbeveling(en) breed toepasbaar zijn (5.000-40.000 patiënten), volgt ook uit de toetsing dat het geen nieuwe manier van zorgverlening of andere organisatie van zorgverlening betreft. Er worden daarom geen substantiële financiële gevolgen verwacht. |

Werkwijze

AGREE

Deze richtlijnmodule is opgesteld conform de eisen vermeld in het rapport Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 van de adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwaliteit. Dit rapport is gebaseerd op het AGREE II instrument (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II; Brouwers, 2010).

Knelpuntenanalyse en uitgangsvragen

Tijdens de voorbereidende fase inventariseerde de werkgroep de knelpunten in de zorg voor vitaal bedreigde patiënten die geïntubeerd worden buiten de OK. Tevens zijn er knelpunten aangedragen door verschillende stakeholders via een schriftelijke knelpunteninventarisatie. Een verslag hiervan is opgenomen onder aanverwante producten.

Op basis van de uitkomsten van de knelpuntenanalyse zijn door de werkgroep concept-uitgangsvragen opgesteld en definitief vastgesteld.

Uitkomstmaten

Na het opstellen van de zoekvraag behorende bij de uitgangsvraag inventariseerde de werkgroep welke uitkomstmaten voor de patiënt relevant zijn, waarbij zowel naar gewenste als ongewenste effecten werd gekeken. Hierbij werd een maximum van acht uitkomstmaten gehanteerd. De werkgroep waardeerde deze uitkomstmaten volgens hun relatieve belang bij de besluitvorming rondom aanbevelingen, als cruciaal (kritiek voor de besluitvorming), belangrijk (maar niet cruciaal) en onbelangrijk. Tevens definieerde de werkgroep tenminste voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten welke verschillen zij klinisch (patiënt) relevant vonden.

Methode literatuursamenvatting

Een uitgebreide beschrijving van de strategie voor zoeken en selecteren van literatuur is te vinden onder ‘Zoeken en selecteren’ onder Onderbouwing. Indien mogelijk werd de data uit verschillende studies gepoold in een random-effects model. Review Manager 5.4 werd gebruikt voor de statistische analyses. De beoordeling van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs wordt hieronder toegelicht.

Beoordelen van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs

De kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs werd bepaald volgens de GRADE-methode. GRADE staat voor ‘Grading Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation’ (zie http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/). De basisprincipes van de GRADE-methodiek zijn: het benoemen en prioriteren van de klinisch (patiënt) relevante uitkomstmaten, een systematische review per uitkomstmaat, en een beoordeling van de bewijskracht per uitkomstmaat op basis van de acht GRADE-domeinen (domeinen voor downgraden: risk of bias, inconsistentie, indirectheid, imprecisie, en publicatiebias; domeinen voor upgraden: dosis-effect relatie, groot effect, en residuele plausibele confounding).

GRADE onderscheidt vier gradaties voor de kwaliteit van het wetenschappelijk bewijs: hoog, redelijk, laag en zeer laag. Deze gradaties verwijzen naar de mate van zekerheid die er bestaat over de literatuurconclusie, in het bijzonder de mate van zekerheid dat de literatuurconclusie de aanbeveling adequaat ondersteunt (Schünemann, 2013; Hultcrantz, 2017).

|

GRADE |

Definitie |

|

Hoog |

|

|

Redelijk |

|

|

Laag |

|

|

Zeer laag |

|

Bij het beoordelen (graderen) van de kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs in richtlijnen volgens de GRADE-methodiek spelen grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming een belangrijke rol (Hultcrantz, 2017). Dit zijn de grenzen die bij overschrijding aanleiding zouden geven tot een aanpassing van de aanbeveling. Om de grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming te bepalen moeten alle relevante uitkomstmaten en overwegingen worden meegewogen. De grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming zijn daarmee niet één op één vergelijkbaar met het minimaal klinisch relevant verschil (Minimal Clinically Important Difference, MCID). Met name in situaties waarin een interventie geen belangrijke nadelen heeft en de kosten relatief laag zijn, kan de grens voor klinische besluitvorming met betrekking tot de effectiviteit van de interventie bij een lagere waarde (dichter bij het nuleffect) liggen dan de MCID (Hultcrantz, 2017).

Overwegingen (van bewijs naar aanbeveling)

Om te komen tot een aanbeveling zijn naast (de kwaliteit van) het wetenschappelijke bewijs ook andere aspecten belangrijk en worden meegewogen, zoals aanvullende argumenten uit bijvoorbeeld de biomechanica of fysiologie, waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten, kosten (middelenbeslag), aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie. Deze aspecten zijn systematisch vermeld en beoordeeld (gewogen) onder het kopje ‘Overwegingen’ en kunnen (mede) gebaseerd zijn op expert opinion. Hierbij is gebruik gemaakt van een gestructureerd format gebaseerd op het evidence-to-decision framework van de internationale GRADE Working Group (Alonso-Coello, 2016a; Alonso-Coello 2016b). Dit evidence-to-decision framework is een integraal onderdeel van de GRADE methodiek.

Formuleren van aanbevelingen