Hoofd- en lichaamspositie

Uitgangsvraag

- Wat is de optimale hoofdpositie bij de intubatieprocedure van de vitaal bedreigde patiënt?

- Wat is de optimale lichaamspositie bij de intubatieprocedure van de vitaal bedreigde patiënt?

Aanbeveling

Positioneer het hoofd bij directe laryngoscopie bij voorkeur in sniffing position of in extensie. Voorkom een flexie positie.

Intubeer vitaal bedreigde patiënten buiten de OK bij voorkeur in semi-zittende positie (25 graden rechtop), met aandacht voor de positie van het hoofd ten opzichte van het bovenlichaam. Overweeg dit met name in patiënten met obesitas en in patiënten met hoog risico op desaturatie tijdens de procedure.

Overweeg een intubatiekussen te gebruiken voor positionering, met name bij patiënten met obesitas en patiënten met hoog risico op desaturatie tijdens de procedure.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Er is literatuuronderzoek gedaan naar de hoofd- en lichaamspositie van vitaal bedreigde patiënten bij intubatie buiten de operatiekamer. De gunstige en ongunstige effecten van werden vergeleken van 1) semi-zittende houding ten opzichte van rugligging, en 2) sniffing position ten opzichte van neutrale houding of extensie van het hoofd. Als cruciale uitkomstmaat werd visualisatie van de stembanden meegenomen. Als belangrijke uitkomstmaten is gekeken naar succes bij eerste intubatiepoging, oxygenatie, hypoxemie, hypotensie en bloeddruk. Er is één gerandomiseerde studie gevonden die een semi-zittende positie (“ramped”, 25 graden) met nek en hoofd in extensie vergeleek met de “sniffing” positie (rugligging met de nek in flexie en het hoofd in extensie). In deze studie werd bij 124 patiënten (50% in sniffing position groep en 45% in de ramped position groep) non-invasief beademd in de periode tussen inductie en laryngoscopie. De initiële intubatiepoging werd in 195 patiënten (75% in groepen) met directe laryngoscopie verricht en in 65 patiënten met videolaryngoscopie. Er werd een klinisch relevant verschil gevonden tussen de posities voor de cruciale uitkomstmaat succes bij eerste intubatiepoging. De bewijskracht van de cruciale uitkomstmaat is laag, door imprecisie en de onvolledige generaliseerbaarheid van de vergelijking ramped/sniffing naar (semi-)zittend/liggend. Hier ligt een kennisvraag. Bij de belangrijke uitkomstmaten leek visualisatie van de stembanden beter bij de sniffing dan bij de ramped houding. Daarentegen leek ernstige hypoxemie (<80%) minder vaak voor te komen bij de ramped dan bij de sniffing positie. Er leek geen verschil te zijn wat betreft oxygenatie, hypoxemie (<90%), hypotensie en bloeddruk.

Voor de vergelijking van de hoofdposities werden één meta-analyse (van 4 RCT’s) en 7 recentere RCT’s geïncludeerd. Er werd geen klinisch relevant verschil gevonden voor de uitkomstmaat visualisatie van de stembanden. De bewijskracht van de cruciale uitkomstmaat is laag. Ook hier ligt een kennislacune. Daarnaast werd voor de belangrijke uitkomstmaten succes bij eerste intubatiepoging, oxygenatie, hypotensie en bloeddruk ook geen klinisch relevant verschil gezien bij de sniffing position ten opzichte van een neutrale positie of hoofdextensie.

Het verhogen van het bovenste deel van een IC-bed om een patiënt in semi-zittende positie te brengen, maakt de toegang tot het hoofd aanzienlijk moeilijker dan in liggende positie. Dit komt door de constructie van het IC-bed, waarvan het onderstel niet kan worden ingekort, en de relatief lange bovenkant, die ervoor zorgt dat patiënten vaak onderuit zakken. Dit bemoeilijkt een correcte positionering van het hoofd. In de studie van Semler (2017) werd bij patiënten in semi-zittende houding het hoofd in extensie gebracht totdat het gezicht parallel aan het plafond lag. Hierdoor werd het hoofd niet in sniffing position of volledige extensie gepositioneerd, wat kan leiden tot een flexiehouding, vooral als de patiënt onderuit zakt. Dit kan de visualisatie van de stembanden bemoeilijken, vooral bij minder ervaren intubatoren, en benadrukt het belang van optimale hoofdpositionering voorafgaand aan intubatie. Hoewel deze specifieke positionering niet werd toegepast in de studie van Semler (2017), is het vaak mogelijk om ook in semi-zittende positie het hoofd in sniffing position of volledige extensie te brengen (Rahiman, 2017). Dit kan worden bereikt door kussens onder de schouders en het hoofd te plaatsen in plaats van alleen het bed in een hoek van 25 graden te zetten. Hiermee wordt het bovenlichaam iets omhoog gebracht en kan het hoofd optimaal worden gepositioneerd. Er zijn speciale positioneringskussens beschikbaar die dit proces vergemakkelijken. Deze kussens maken het mogelijk om patiënten voorafgaand aan intubatie in een halfzittende houding te plaatsen. Met een bijbehorend hoofdkussen kan het hoofd tot 7 cm worden opgetild, waardoor sniffing position haalbaar wordt (Troop, 2016). Hoewel er geen gerandomiseerde studies zijn naar het gebruik van deze kussens, blijft bij gebruik hiervan het hoofd goed bereikbaar en wordt laryngoscopie mogelijk zonder nadelen voor oxygenatie.Door gebruik te maken van kussens in plaats van enkel aanpassingen aan het IC-bed, blijft een goede bereikbaarheid van het hoofd behouden. Indien ook aparte positionering van het hoofd mogelijk blijft, zijn er geen redenen om patiënten niet in semi-zittende positie te intuberen. Hiermee blijven de voordelen van verbeterde oxygenatie behouden terwijl laryngoscopie uitvoerbaar blijft.

Een literatuursearch naar optimale hoofdpositionering laat zien dat zowel sniffing position als volledige extensie overwogen kunnen worden. In de studie van Akihisa (2015) werden geen verschillen gevonden in cruciale eindpunten tussen deze posities. De keuze hangt daarom af van ervaring, waarbij flexie moet worden vermeden. Dit risico is met name aanwezig bij semi-zittende positionering door enkel aanpassingen aan het IC-bed, zoals eerder beschreven.Voor patiënten met morbide obesitas lijkt een positie waarbij de lijn tussen oor en sternum horizontaal is (de ramp position) optimaal (Lee, 2004). Deze houding lijkt anatomisch vergelijkbaar met de sniffing position, omdat vetweefsel op de rug al zorgt voor nekflexie. Het horizontaal uitlijnen van oor en sternum zorgt daarnaast voor extensie van het hoofd (Greenland, 2010).

Aandachtspunten bij positionering:

- Normaal postuur: Bij patiënten met een normaal postuur verbetert zicht op de larynx vaak verder door het hoofd extra op te tillen vanuit sniffing position.

- Morbide obesitas: De ramp position is hier optimaal; deze zorgt ervoor dat de lijn tussen oor en sternum horizontaal blijft.

- Semi-zittende positie: Bij patiënten met normaal postuur moet bij semi-zittende houding worden gezorgd dat het hoofd alsnog in sniffing position wordt gebracht. Let hierbij op goede bereikbaarheid door het bed voldoende laag te brengen.

Deze aandachtspunten benadrukken dat optimale positionering cruciaal is voor succesvolle intubatie en dat flexie moet worden voorkomen, ongeacht de gekozen houding of hulpmiddelen.

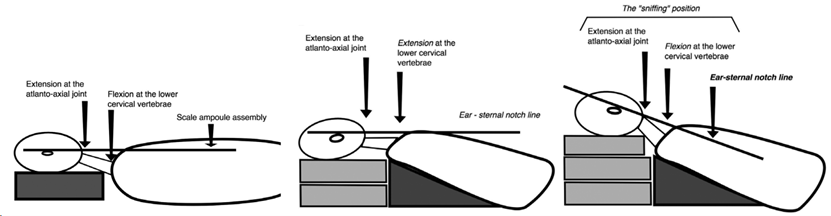

Aandachtspunten bij positionering:

Links: de sniffing position bij patienten met normaal postuur. In het midden de ramp position bij patienten met morbide obesitas. In beide situaties is de lijn tussen oor en sternal notch horizontaal. Bij patiënten met een normaal postuur kan het zicht verder verbeteren bij verder optillen van het hoofd. Bij een semi-zittende positie bij patienten met normaal postuur wordt het hoofd in sniffing position gebracht conform de situatie met horizontale torso. De lijn tussen oor en sternum is in dit geval dalend. Hou hierbij rekening met goede bereikbaarheid van het hoofd door het bed voldoende omlaag te brengen. Figuur overgenomen van Rahiman (2017).

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

Positionering van de patiënt in een liggende positie, oftewel het hele lichaam plat in bed, vooraf aan intubatie kan resulteren in meer benauwdheid dan positionering in een halfzittende positie.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

De hoofd- en lichaamspositie hebben geen directe invloed op de kosten, behoudens eventuele eenmalige aanschaf van een positioneringskussen.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

De mate van bewijs voor de optimale hoofd- en lichaamspositie is beperkt. Daarom geeft de werkgroep een advies, maar behoudt de behandelaar de vrijheid om hiervan af te wijken. Daarbij spelen eerdere ervaringen van behandelaars een rol. Als men vertrouwd is met een procedure die goed bevalt en afwijkt van de hier beschreven adviezen, is dit veelal geen bezwaar.

In een ideale situatie zou het team, arts en verpleegkundigen, het proces eensgezind implementeren. Door a priori variatie te beperken, en er routine ontstaat, zouden incidenten beperkt kunnen worden. Of dit haalbaar is hangt van vele factoren af zoals de grootte van het team en de opbouw hiervan.

Om de patiënt juist te positioneren voor de intubatie is training en scholing vereist. Dit is onderdeel van de opleiding. Echter, voor de voortgang van de leercurve kan het wenselijk zijn dit later te herhalen, bijvoorbeeld onder begeleiding van anesthesiologen en met het eigen intubatieteam.

Vanuit de gesedeerde patiënt zal er geen bezwaar zijn tegen de liggende of half rechtop zittende houding tijdens de veelal kortdurende intubatie handeling.

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

Vanwege de fysiologische voordelen in het kader van tragere afname van oxygenatie en het minder vaak voorkomen van ernstige desaturatie tijdens intubatie is de werkgroep van mening dat de semi-zittende positie de voorkeur heeft boven de liggende positie. Hierbij is het van belang speciaal aandacht te hebben voor het correct positioneren van het hoofd. Het ingeschatte risico op hypoxemie tijdens de procedure zou meegenomen moeten worden in de uiteindelijke keuze van positie.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Luchtwegmanagement bij vitaal bedreigde patiënten is grotendeels gebaseerd op technieken die zijn ontwikkeld voor electieve procedures. Een cruciaal aspect tijdens intubatie is de positionering van de patiënt, omdat dit direct invloed heeft op het succes van laryngoscopie. Dit geldt vooral voor directe laryngoscopie, waarbij het zicht op de luchtweg vaker beperkt is in vergelijking met videolaryngoscopie met hetzelfde blad (Kriege, 2023). In dit document ligt de focus op directe laryngoscopie zonder gebruik van videolaryngoscopie (VL). Intubaties worden doorgaans uitgevoerd in liggende of semi-zittende positie. Onderzoek op de operatiekamer richt zich hierbij op twee belangrijke punten:

- Het first-pass succes en de visualisatie van de stembanden.

- De mogelijkheden tot oxygenatie en het risico op desaturatie tijdens de procedure.

Bij het first-pass succes spelen twee factoren een rol: de positie van het hoofd ten opzichte van het bovenlichaam en die van het bovenlichaam ten opzichte van het horizontale vlak. Een veelgebruikte houding is de sniffing position, waarbij de nek in 35 graden flexie en het hoofd in 15 graden extensie wordt gebracht (Horton, 1989). Dit zorgt ervoor dat het hoofd enkele centimeters naar voren komt, wat een rechtere lijn creëert tussen mondopening en larynx en zo het zicht tijdens laryngoscopie verbetert.

Een alternatieve houding betreft volledige extensie van zowel nek als hoofd (Adnet, 2001). Bij patiënten met morbide obesitas blijkt een semi-zittende houding, waarbij de lijn tussen oor en jugulum (ear-to-sternal notch) horizontaal ligt, effectiever dan de sniffing position (Collins, 2004). Deze zogenaamde ramp position lijkt een vergelijkbare uitlijning te bieden van laryngeale en faryngeale assen als bij patiënten met een normaal postuur (Greenland, 2010). Bovendien biedt deze houding voordelen tijdens pre-oxygenatie en vertraagt het desaturatie tijdens de apneufase. Dit is zowel bij obese als niet-obese patiënten aangetoond (Lane, 2005; Ramkumar, 2011). De semi-zittende positie verhoogt de functionele residuele capaciteit en vermindert pulmonale shunting, wat leidt tot een tragere daling van zuurstofsaturatie tijdens apneu (Ramos, 2022). Dit is vooral relevant bij vitaal bedreigde patiënten, die door atelectase, consolidaties of verhoogd metabolisme een groter risico lopen op desaturatie tijdens intubatie (Ramos, 2022). Buiten de operatiekamer wordt intubatie bij deze patiënten afwisselend uitgevoerd in liggende of zittende positie (Turner, 2017). Deze module biedt een samenvatting van het beschikbare bewijs over optimale hoofd- en lichaamsposities tijdens pre-oxygenatie en intubatieprocedures.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

1. Supine versus inclined position

Critical outcome

|

Low GRADE |

Ramped position (25°) with the head in extension may result a slightly lower first pass success, when compared with supine (sniffing) position in critically ill patients who are intubated outside the operating room.

Source: Semler, 2017. |

Important outcomes

|

Low GRADE |

Ramped position (25°) with the head in extension may impede glottic view as determined by Cormack-Lehane grade, when compared with supine (sniffing) position in critically ill patients who are intubated outside the operating room.

Source: Semler, 2017. |

|

Low GRADE |

Ramped position (25°) may result in little to no difference in lowest oxygen saturation when compared with supine (sniffing) position in critically ill patients who are intubated outside the operating room.

Source: Semler, 2017. |

|

Low GRADE |

Ramped position (25°) may result in little to no difference in hypoxemia (SpO2 < 90%) but may reduce severe hypoxemia (SpO2 < 80%), when compared with supine (sniffing) position in critically ill patients who are intubated outside the operating room.

Source: Semler, 2017. |

|

Low GRADE |

Ramped position (25°) may result in little to no difference in hypotension when compared with supine (sniffing) position in critically ill patients who are intubated outside the operating room.

Source: Semler, 2017 |

|

Low GRADE |

Ramped position (25°) may result in little to no difference in blood pressure when compared with supine (sniffing) position in critically ill patients who are intubated outside the operating room.

Source: Semler, 2017. |

2. Sniffing versus neutral or head extension position

Critical outcome

|

Low GRADE |

Sniffing position may result in little to no difference in Cormack-Lehane grade and glottic view, when compared with head extension position in critically ill patients who are intubated outside the operating room.

Sources: Akihisa, 2015; Gudivada, 2017; Kim, 2016; Mendonca, 2018; Pachisia, 2019; Singh, 2021. |

Important outcomes

|

Low GRADE |

Sniffing position may result in little to no difference in first pass success, when compared with neutral or head extension position in critically ill patients who are intubated outside the operating room.

Sources: Akihisa, 2015; Gudivada, 2017; Mendonca, 2018; Yoo, 2019. |

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of sniffing position on oxygenation when compared with head extension position in critically ill patients who are intubated outside the operating room.

Source: Pachisia, 2019 |

|

No GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding the effect of sniffing position on hypotension when compared with head extension position in critically ill patients who are intubated outside the operating room.

Source: - |

|

No GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding the effect of sniffing position on blood pressure when compared with head extension position in critically ill patients who are intubated outside the operating room.

Source: - |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

1. Supine versus inclined position

Semler (2017) performed a multicenter, randomized trial of ramped position versus sniffing position during endotracheal intubation of critically ill adults. Patients ≥ 18 years of age undergoing endotracheal intubation with the planned use of sedation and neuromuscular blockade were eligible. Patients were excluded if immediate intubation was required with no option for randomization or when treating clinicians felt a specific patient position was required for a safe performance of the procedure. Intubation was performed by a pulmonary and critical care medicine fellow with limited experience in airway management (<100 prior intubations). 260 patients were randomized to the ramped position (head of the bed to 25°) with the head in extended position until the face paralleled the ceiling or the supine position with the head in the sniffing position in a 1:1 ratio in four intensive care units in the USA. The primary outcome was the lowest arterial oxygen saturation measured by pulse oximetry (SpO2) between induction and 2 minutes after successful endotracheal tube placement. Prespecified secondary outcomes included the incidence of hypoxemia (SpO2 < 90%), severe hypoxemia (SpO2 < 80%), desaturation (an absolute decrease in SpO2 > 3%), Cormack-Lehane grade of glottic view, operator-reported difficulty of intubation, number of laryngoscopy attempts, and time from induction to successful intubation. There were some concerns for risk of bias regarding subjective outcomes, due to the lack of blinding of clinicians and study personnel.

2. Sniffing versus neutral/head extension position

Akihisa (2015) performed a meta-analysis to validate the efficacy of the sniffing position in the performance of intubation with direct laryngoscopy. Relevant databases were searched up until August 30, 2014. Six RCTs with 2759 participants were included. All RCTs reported data on glottic visualization, and one or more data associated with intubation performance. Out of the six RCTS, for the current analysis two of these were excluded as they did not meet our inclusion criteria. Collins (2004) compared sniffing position with ramped position and Rao (2008) compared two different ramp position (by adjusting the table versus using blankets).

Therefore, data from the meta-analysis were extracted for the remaining four RCTs and completed with data from seven RCTS published after 2014. Details of study characteristics are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Characteristics of included studies, sniffing versus neutral/head extension

|

Publication |

N |

Comparison |

Setting |

Remarks |

|

Meta-analysis Akihisa (2015) |

||||

|

Adnet, 2001 |

456 |

Sniffing Position vs. simple head extension |

Elective surgery |

Direct laryngoscopy by experienced physician |

|

Bhattarai, 2011 |

400 |

Sniffing Position vs. simple head extension |

Elective surgery under general anesthesia |

Direct laryngoscopy, experience not described. (Predicitive) difficult intubation excluded. |

|

Nur Hafiizhoh, 2014 |

378 |

Sniffing Position vs. Simple Head Extension |

Elective surgery under general anesthesia with endotracheal intubation |

Direct laryngoscopy by experienced physician. (Predicitive) difficult intubation excluded. |

|

Prakash, 2011 |

546 |

Sniffing Position vs. simple head extension |

Elective surgery |

Direct laryngoscopy by experienced physician |

|

Additional RCTs |

||||

|

Pachisia, 2019 |

100 |

Horizontal alignment of external auditory meatus‑sternal notch vs sniffing (7 cm pillow) |

Elective surgery under general anesthesia |

Laryngoscopy‑intubation was performed by two experienced anesthesiologists with at least 6‑year experience in anesthesiology and airway management. |

|

Mendonca, |

200 |

Neutral vs. sniffing position |

Elective surgery and requiring tracheal intubation |

Channelled (KingVision) and a non-channeled (C-MAC D-blade) videolaryngoscope |

|

Yoo, 2019 |

124 |

Neutral vs. head extension |

Patients undergoing general anesthesia |

blind intubation through the AuraGain laryngeal mask |

|

Singh, 2021 |

220 |

Sniffing Position vs. Simple Head Extension |

Elective surgeries under general anesthesia |

Direct laryngoscopy and endotracheal intubation |

|

Gudivada, 2017 |

100 |

Sniffing vs. further head elevation (HE) (neck flexion) |

Adult patients undergoing elective surgery under general anesthesia |

Macintosh number 3 or 4 laryngoscope blade was used depending on the laryngoscopist preference |

|

Kim, 2016 |

18 |

Simple head extension vs. sniffing position vs. elevated sniffing position |

Elective surgery requiring tracheal intubation |

Edentulous patients |

Results

1. Supine versus inclined position

First pass success

Semler (2017) reported first pass success of 99/130 (76.2%) in the ramped group versus 111/130 (85.4%) in the sniffing group, resulting in a relative risk (RR) of 0.89, with a 95% confidence interval (CI) from 0.79 to 1.01. This was considered clinically relevant. In addition, the number of laryngoscopy attempts was reported, as presented in Table 2.

Table 2. Number of laryngoscopy attempts, no. (%)

|

|

Ramped (N=130) |

Sniffing (N=130) |

|

One attempt |

99 (76.2%) |

111 (85.4%) |

|

Two attempts |

21 (16.2%) |

16 (12.3%) |

|

Three attempts |

7 (5.4%) |

2 (1.5%) |

|

Four or more attempts |

3 (2.3%) |

1 (0.8%) |

Cormack-Lehane grade

Semler (2017) reported Cormack-Lehane grade for both groups, as presented in Table 3. Difficult glottic view (Grade III/IV) was present in 33/130 (25.4%) in the ramped position versus 15/130 (11.5%) in the sniffing position, with a clinically relevant difference of RR of 2.20 (95% CI 1.26 to 3.85) in favor of sniffing position.

Table 3. Cormack-Lehane grade for ramped versus sniffing position, no. (%)

|

|

Ramped (N=130) |

Sniffing (N=130) |

|

Grade I |

61 (46.9%) |

63 (48.5%) |

|

Grade II |

36 (27.7%) |

52 (40.0%) |

|

Grade III |

27 (20.8%) |

14 (10.8%) |

|

Grade IV |

6 (4.6%) |

1 (0.8%) |

Lowest oxygen saturation

Semler (2017) reported median (IQR) lowest oxygen saturation and found 93 (84-99) in ramped position versus 92 (79-98) in the sniffing position. The difference is not considered clinically relevant.

Hypoxemia

Semler (2017) reported hypoxemia (SpO2 < 90%) and severe hypoxemia (SpO2 < 80%). Hypoxemia occurred in 50/127 (39.4%) patients in the ramped position versus 53/127 (41.7%) in sniffing position. The RR of 0.94 (95% CI 0.70 to 1.27) is not considered clinically relevant.

Severe hypoxemia was observed in 26/127 (20.5%) patients in ramped position versus 36/127 (28.3%) patients in sniffing position. The RR of 0.72 (95% CI 0.46 to 1.12) in favor of ramped position is considered clinically relevant.

Hypotension

Semler (2017) defined hypotension as a systolic blood pressure < 65 mmHg or new or increased vasopressor administration. Hypotension occurred in 25/130 patients (19.2%) in both groups.

Blood pressure

The median (IQR) lowest systolic blood pressure was 114 (91-133) mmHg in patients in ramped position versus 110 (93-131) in patients in sniffing position. The difference is not considered clinically relevant.

2. Sniffing versus neutral position or head extension position

Cormack-Lehane grade

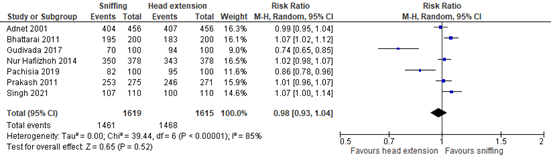

Seven studies reported the Cormack-Lehane grade. All studies compared sniffing position with head extension position. Adequate glottic view (Grade I/II) was present in 1461 (90.2%) in the sniffing position versus 1468 (90.9%) in the neutral/head extension position, with RR 0.98 (95% CI 0.93 to 1.04) (Figure 1). This difference is not considered clinically relevant.

Figure 1. Adequate glottic view (Cormack-Lehane grade I/II)

Random effects model; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval; Z: p-value of pooled effect

Glottic opening score

Mendonca (2018) reported the percentage of glottic opening from 0 to 100 per group. The median was 100% (IQR 100-100) in all four groups.

Kim (2016) reported the glottic opening score (0-100%). The mean scores were 78.9% (±19.7) in the sniffing position, 72.6% (±20.8) in the elevated sniffing position, and 53.8% (25.9) in the head extension group. The mean difference between sniffing and head extension position is 25.10 (95% CI 10.07 to 40.13) and the mean difference between elevated sniffing and head extension position is 18.80 (95% CI 3.45 to 34.15). the difference between sniffing and head extension position is clinically relevant, whereas the difference between elevated sniffing and head extension position is not.

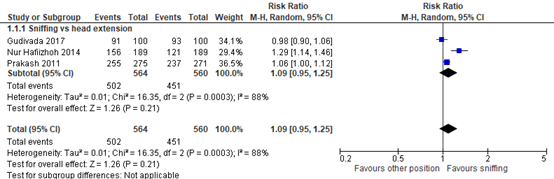

First pass success

Five studies reported the first pass success rate of intubation. Three of these studies compared sniffing with head extension position. This relative risk was 1.09 (95% CI 0.95 to 1.25) (Figure 2). This difference in favor of sniffing position is not considered clinically relevant.

Figure 2: First pass success

Random effects model; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval; Z: p-value of pooled effect

In addition, Mendonca (2018) compared sniffing with neutral position. In the sniffing position, in 94/100 patients first pass success was reported, compared with 95/100 patients in the neutral position (RR 0.99, 95% CI 0.93 to 1.06). This difference in favor of neutral position, was not clinically relevant.

Yoo (2019) compared neutral position with head extension position. In the neutral position, in 29/62 (47%) patients a first pass success was reported, compared with 40/59 (68%) in the head extension position (RR 1.45, 95% CI 1.05 to 1.99). This difference in favor of head extension position was considered clinically relevant.

Oxygenation

Only Pachisia (2019) mentioned that none of the patients (N=100) developed any episode of desaturation during intubation attempts.

Blood pressure and hypotension

None of the included studies reported quantified data on blood pressure and hypotension. Therefore, clinical relevance of the results could not be established. However, Singh (2021) reported no statistically significant difference in sympathetic response in two groups of patients in terms of change in mean arterial pressure and heart rate.

Level of evidence of the literature

1. Supine versus inclined position

For all outcome measures, the level of evidence was based on a randomized controlled trial and therefore started at high. The evidence was downgraded by two levels to LOW due to applicability issues (comparison between sniffing and ramped versus supine and inclined, -1) and because the confidence interval crossed the threshold of clinical decision-making (imprecision, -1).

2. Sniffing versus neutral position or head extension position

For all outcome measures, the level of evidence was based on randomized controlled studies and therefore started at high.

The level of evidence for Cormack-Lehane grade and glottic view were downgraded by two levels to LOW due to limitations in the study design (risk of bias due to lack of blinding, -1) and conflicting results (inconsistency, -1).

The level of evidence for first pass success was downgraded by two levels to LOW due to limitations in the study design (risk of bias due to lack of blinding, -1) and because the confidence interval crossed one threshold of clinical decision-making (imprecision, -1).

The level of evidence for oxygenation was downgraded by three levels to VERY LOW due to absence of events (imprecision, -3).

The level of evidence for blood pressure and hypotension could not be assessed as no quantified data were reported for these outcomes.

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following questions:

1. What are the benefits and harms of (semi)recumbent position compared to supine position in critically ill patients who are intubated outside the operating room?

| P: |

Critically ill patients who are intubated outside the operating room |

| I: |

(semi) recumbent position |

| C: |

Supine position |

| O: | First pass success, Cormack-Lehane grade, glottis view, oxygenation, hypoxemia, blood pressure, hypotension |

2. What are the benefits and harms of the sniffing position compared to neutral position or head extension position in critically ill patients who are intubated outside the operating room?

| P: |

Critically ill patients who are intubated outside the operating room |

| I: | Sniffing position |

| C: |

Neutral position or head extension position |

| O: |

First pass success, Cormack-Lehane grade, glottis view, oxygenation, hypoxemia, blood pressure, hypotension |

Relevant outcome measures

For (semi)recumbent position compared to supine position, the guideline development group considered first pass success as a critical outcome measure for decision making; and Cormack-Lehane grade, glottic view, oxygenation, hypoxemia, blood pressure and hypotension as important outcome measures for decision making.

For sniffing position compared to neutral/head extension position, the guideline development group considered Cormack-Lehane grade and glottic view as a critical outcome measure for decision making; and first pass success, oxygenation, hypoxemia, blood pressure and hypotension as important outcome measures for decision making.

The working group did not define the outcome measures a priori, but followed the definitions used in the studies.

The working group defined 10% as a minimal clinically (patient) important differences for

first-pass success (relative risk <0.91 or >1.10). For other dichotomous outcomes, 25% was considered a clinically relevant difference (relative risk <0.80 of >1.25), i.e. first-pass success, incidence of hypotension or hypoxemia, incidence of difficult intubation based on cormack-lehane grade or glottic opening score.

Search and select (Methods)

On the 12th of June 2023, a systematic search was performed in the databases Embase.com and Ovid/Medline for systematic reviews, RCTs and observational studies on semi recumbent and supine position during intubation and preoxygenation. The search resulted in 630 unique hits. The detailed search strategy is available upon request. Studies were selected based on the following criteria: randomized controlled studies or systematic reviews thereof, comparing either supine with inclined position or sniffing position with neutral position or head extension position, reporting the predefined outcome measurements. The population of interest was critically ill patients. If studies were found that included critically ill patients, studies using other populations (e.g. elective surgery) were excluded. Based on title and abstract screening, twenty studies were selected. After reading the full text, eleven studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and nine publications were included.

Results

For the comparison supine versus inclined position, one RCT in critically ill patients was included in the analysis of the literature.

For the comparison sniffing with neutral/ head extension position one meta-analysis and eleven additional RCTs were included. No studies in critically ill patients were found. The included studies were performed with elective surgery populations. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. Assessment of the risk of bias is presented in the risk of bias table.

Referenties

- Adnet F, Baillard C, Borron SW, et al. Randomized study comparing the 'sniffing position' with simple head extension for laryngoscopic view in elective surgery patients. Anesthesiology 2001; 95: 836-41.

- Akihisa Y, Hoshijima H, Maruyama K, Koyama Y, Andoh T. Effects of sniffing position for tracheal intubation: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Emerg Med. 2015 Nov;33(11):1606-11.

- Bhattarai, B. and Shrestha, S. K. and Kandel, S. Comparison of sniffing position and simple head extension for visualization of glottis during direct laryngoscopy. Kathmandu University Medical Journal. 2011; 9 (33) :58-63.

- Collins JS, Lemmens HJ, Brodsky JB, Brock-Utne JG, Levitan RM. Laryngoscopy and morbid obesity: a comparison of the "sniff" and "ramped" positions. Obes Surg. 2004 Oct;14(9):1171-5. doi: 10.1381/0960892042386869. PMID: 15527629.

- Greenland KB, Edwards MJ, Hutton NJ. External auditory meatus-sternal notch relationship in adults in the sniffing position: a magnetic resonance study. Br J Anaesth. 2010 Feb;104(2):268-9.

- Gudivada, K. and Jonnavithula, N. and Pasupuleti, S. and Apparasu, C. and Ayya, S. and Ramachandran, G. Comparison of ease of intubation in sniffing position and further neck flexion. Journal of Anaesthesiology Clinical Pharmacology. 2017; 33 (3) :342-347

- Horton WA, Fahy L, Charters P. Defining a standard intubating position using 'angle finder'. Br J Anaesth 1989; 62: 6-12.

- Kim, H. and Chang, J. E. and Min, S. W. and Lee, J. M. and Ji, S. and Hwang, J. Y. A comparison of direct laryngoscopic views in different head and neck positions in edentulous patients. American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2016; 34 (9) :1855-1858.

- Kriege M, Noppens RR, Turkstra T, Payne S, Kunitz O, Tzanova I, and Schmidtmann I. A multicentre randomized controlled trial of the McGrathTM videolaryngoscope versus conventional laryngoscopy. Anaesthesia 2023; 78(6):722-729.

- Lane S, Saunders D, Schofield A, Padmanabhan R, Hildreth A, Laws D. A prospective, randomised controlled trial comparing the efficacy of pre-oxygenation in the 20 degrees head-up vs supine position. Anaesthesia. 2005;60(11):1064-7.

- Mendonca, C. and Ungureanu, N. and Nowicka, A. and Kumar, P. A randomised clinical trial comparing the 'sniffing' and neutral position using channelled (KingVision®) and non-channelled (C-MAC®) videolaryngoscopes. Anaesthesia. 2018; 73 (7) :847-855

- Nur Hafiizhoh, A. H. and Choy, C. Y. Comparison of the 'Sniffing the morning air' position and simple head extension for Glottic visualization during direct Laryngoscopy. Middle East Journal of Anesthesiology. 2014; 22 (4) :399-405.

- Pachisia, A. and Sharma, K. and Dali, J. and Arya, M. and Pangasa, N. and Kumar, R. Comparative evaluation of laryngeal view and intubating conditions in two laryngoscopy positions-attained by conventional 7 cm head raise and that attained by horizontal alignment of external auditory meatus - Sternal notch line - Using an inflatable pillow - A prospective randomised cross-over trial. Journal of Anaesthesiology Clinical Pharmacology. 2019; 35 (3) :312-317.

- Prakash S, Rapsang AG, Mahajan S, Bhattacharjee S, Singh R, Gogia AR. Comparative evaluation of the sniffing position with simple head extension for laryngoscopic view and intubation difficulty in adults undergoing elective surgery. Anesthesiol Res Pract. 2011;2011:297913. doi: 10.1155/2011/297913. Epub 2011 Oct 29. PMID: 22110497; PMCID: PMC3205597.

- Prekker ME, Driver BE, Trent SA, Resnick-Ault D, Seitz KP, Russell DW, Gaillard JP, Latimer AJ, Ghamande SA, Gibbs KW, Vonderhaar DJ, Whitson MR, Barnes CR, Walco JP, Douglas IS, Krishnamoorthy V, Dagan A, Bastman JJ, Lloyd BD, Gandotra S, Goranson JK, Mitchell SH, White HD, Palakshappa JA, Espinera A, Page DB, Joffe A, Hansen SJ, Hughes CG, George T, Herbert JT, Shapiro NI, Schauer SG, Long BJ, Imhoff B, Wang L, Rhoads JP, Womack KN, Janz DR, Self WH, Rice TW, Ginde AA, Casey JD, Semler MW; DEVICE Investigators and the Pragmatic Critical Care Research Group. Video versus Direct Laryngoscopy for Tracheal Intubation of Critically Ill Adults. N Engl J Med. 2023 Aug 3;389(5):418-429. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2301601. Epub 2023 Jun 16. PMID: 37326325.

- Rahiman SN, and Keane M. The "Ear-Sternal Notch" line-How should you lie? Anest Analg 2017; 125(6):2162-2164.

- Ramkumar V, Umesh G, Philip FA. Preoxygenation with 20° headup tilt provides longer duration of non-hypoxic apnea than conventional preoxygenation in non-obese healthy adults. J Anesth. 2011;25(2):18994.

- Ramos M, Tau Anzoategui S. Preoxygenation: from hardcore physiology to the operating room. Journal of Anesth 2022; 36:770-781.

- Semler MW, Janz DR, Russell DW, Casey JD, Lentz RJ, Zouk AN, deBoisblanc BP, Santanilla JI, Khan YA, Joffe AM, Stigler WS, Rice TW; Check-UP Investigators(?); Pragmatic Critical Care Research Group. A Multicenter, Randomized Trial of Ramped Position vs Sniffing Position During Endotracheal Intubation of Critically Ill Adults. Chest. 2017 Oct;152(4):712-722. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2017.03.061. Epub 2017 May 6. PMID: 28487139; PMCID: PMC5812765.

- Singh, A. and Kaur, R. and Singh, G. and Gupta, K. K. Evaluation of intubating conditions during direct laryngoscopy using sniffing position and simple head extension - A randomised clinical trial. Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research. 2021; 15 (9) :UC05-UC08

- Troop C. The difficult airway and or obesity and the importance of positioning. Br J Anaesth 2016; 117(5):674

- Turner JS, Ellender TJ, Okonkwo ER, et al. Feasibility of upright patient positioning and intubation success rates at two academic emergency departments. Am J Emerg Med. 2017.

- Yoo, S. and Park, S. K. and Kim, W. H. and Hur, M. and Bahk, J. H. and Lim, Y. J. and Kim, J. T. The effect of neck extension on success rate of blind intubation through Ambu® AuraGain™ laryngeal mask: a randomized clinical trial. Canadian Journal of Anesthesia. 2019; 66 (6) :639-647.

Evidence tabellen

Evidence table for intervention studies (randomized controlled trials and non-randomized observational studies [cohort studies, case-control studies, case series])

Research questions:

1. What are the benefits and harms of (semi)recumbent position compared to supine position in critically ill patients who are intubated outside the operating room?

2. What are the benefits and harms of sniffing position compared to neutral/head extension position in critically ill patients who are intubated outside the operating room?

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C) |

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

Semler, 2017

NCT 02497729 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: Randomized multicenter pragmatic trial, USA

Funding and conflicts of interest: M. W. S. was supported by a National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute T32 award [Grant HL087738 09]. Data collection used the Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) tool developed and maintained with Vanderbilt Institute for Clinical and Translational Research grant support [Grant UL1 TR000445 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences/National Institutes of Health]. Funding institutions had no role in conception, design, or conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, interpretation, or presentation of the data; or preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

The authors have reported to CHEST the following: T. W. R. served on an advisory board for Avisa Pharma, LLC, and as the Director of Medical Affairs for Cumberland Pharmaceuticals, Inc. None declared by the other authors. |

Inclusion criteria: Patients undergoing endotracheal intubation in ICUs of four tertiary care centers in the United States. Patients ≥ 18 years of age undergoing endotracheal intubation by a pulmonary and critical care medicine fellow with the planned use of sedation and neuromuscular blockade were eligible.

Exclusion criteria: (1) intubation was required too emergently to perform randomization or (2) treating clinicians felt a specific patient position was required for the safe performance of the procedure

N total at baseline: Intervention: 130 Control: 130

Important prognostic factors2: Age, median (IQR) I: 56 (47-65) C: 56 (45-64)

Sex: I: 60.8% M C: 60.8% M

BMI, median (IQR) I: 26.7 (23.9-33.3) C: 27.3 (24.0-32.6)

APACHE II score, median (IQR) I: 21 (18-27) C: 22 (18-26)

Groups were comparable at baseline. |

Ramped position:

electronic bed controls were used to elevate the head of the bed to 25, keeping the lower half of the bed parallel to the floor. The patient’s occiput was positioned on the superior edge of the mattress such that the patient’s face was roughly parallel to the ceiling. |

Sniffing position:

the entire bed remained horizontal while folded blankets or towels were placed beneath the patient’s head and neck to flex the neck relative to the torso and to slightly extend the head relative to the neck. In the sniffing position group, elevation of the shoulders or torso was not permitted. |

Length of follow-up: Hospital discharge

Loss-to-follow-up: None

Incomplete outcome data: None

|

First pass success I: 99/130 (76.2%) C: 111/130 (85.4%) P=0.02

Cormack-Lehane grade Grade I I: 61 (46.9%) C: 63 (48.5%)

Grade II I: 36 (27.7%) C: 52 (40.0%)

Grade III I: 27 (20.8%) C: 14 (10.8%)

Grade IV I: 6 (4.6%) C: 1 (0.8%)

Lowest oxygen saturation Median (IQR) I: 93 (84-99) C: 92 (79-98) P=0.27

Hypoxemia SpO2 < 90% I: 50/127 (39.4%) C: 53/127 (41.7%) P=0.70

SpO2 < 80% I: 26/127 (20.5%) C: 36/127 (28.3%) P=0.14

Hypotension Systolic blood pressure < 65 mmHg or new or increased vasopressor I: 25 (19.2) C: 25 (19.2) P=0.99

Lowest systolic blood pressure I: 114 (91-133) C: 110 (93-131) P=0.69 |

Author’s conclusion: Ramped positioning of critically ill adults during endotracheal intubation does not appear to significantly improve oxygenation compared with intubation in the sniffing position. Ramped positioning may worsen glottic view and increase the number of attempts required for intubation. |

|

Pachisia, 2019 |

Type of study: A prospective randomised cross‑over trial

Setting and country: India

Funding and conflicts of interest: No financial support or conflicts of interest |

Inclusion criteria: ASA gradeI‑II patients, 18‑65 years of age, with modified Mallampatti classI‑III, of either sex scheduled for elective surgery under general anaesthesia, requiring endotracheal intubation

Exclusion criteria: Patients who refused consent, had unstable cervical spine or mouth opening <3 cm and those planned for awake intubation, nasal intubation or rapid sequence induction

N total at baseline: Intervention: 50 Control: 50

Important prognostic factors2: Age, mean ±SD I: 33.68±10.51 C: 31.10±9.96

Sex: I: 26% M C: 20% M

Groups were comparable at baseline. |

Sniffing position:

7cm uncompressible pillow was placed below the patient’s head for attaining first laryngoscopy position, followed by horizontal alignment of external auditory meatus ‑ sternal notch (AM‑S) line for attaining second laryngoscopy position followed by intubation. |

Head extension:

horizontal alignment of external auditory meatus ‑ sternal notch (AM‑S) line was done using an inflatable pillow for attaining first laryngoscopy position, followed by using 7 cm uncompressible pillow for second laryngoscopy position followed by intubation. |

Length of follow-up: Until end of intubation

Loss-to-follow-up: None

Incomplete outcome data: None

|

Cormack-Lehane grade Grade I I: 27/100 C: 45/100

Grade II I: 55/100 C: 50/100

Grade III I: 18/100 C: 5/100

Lowest oxygen saturation None of the patients developed any episode of desaturation during intubation attempts

|

Author’s conclusion: External Auditory Meatus-Sternal notch (AM-S) line alignment provides better laryngeal view, better intubating conditions and requires lesser time to intubate as compared to a conventional 7-cm-head raise. The size of pillow used for head raise should be individualised |

|

Mendonca, 2018 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: UK

Funding and conflicts of interest: No external funding or competing interests declared. |

Inclusion criteria: adult patients of ASA physical status 1–3, scheduled to undergo elective surgery and requiring tracheal intubation

Exclusion criteria: Were deemed to require awake tracheal intubation, tracheal intubation via nasal route, rapid sequence induction, had known oropharyngeal pathology, limited cervical spine movement, were less than 18 years of age, were pregnant or had a BMI > 40 kg/m2.

N total at baseline: Intervention 1: 49 Intervention 2: 51 Control 1: 51 Control 2: 49

Important prognostic factors2: Age, mean (SD) I1: 49.6 (17.7) I2: 51.7 (18.3) C1: 51.0 (15.9) C2: 49.8 (15.4)

Sex: I1: 59% M I2: 55%M C1: 45% M C2: 49%M

Groups were comparable at baseline. Yes |

Sniffing position:

I1: KingVision I2: C-MAC

The ‘sniffing’ position was achieved by placing a standard 7-cm high positioning non-compressible pad provided with the Oxford Help Pillow (Alma Medical, Oxford, UK) under the head and adjusting the bed headrest to elevate the occiput to achieve flexion of the neck and extension at the atlanto-occipital joint. The appropriateness of the ‘sniffing’ position achieved was then assessed for each patient by observing the external auditory meatus and the sternal notch brought in the same plane

tracheal intubations were performed by three experienced anaesthetists, who had performed more than 50 prior intubations with each device |

Neutral position:

C1: KingVision C2: C-MAC

The neutral position was achieved by not placing any pillow under the head to avoid any degree of flexion of the lower cervical spine or extension of the atlanto-occipital joint

tracheal intubations were performed by three experienced anaesthetists, who had performed more than 50 prior intubations with each device |

Length of follow-up:

Loss-to-follow-up: None

Incomplete outcome data: None

|

First pass success I1: 46/49 (94%) I2: 48/51 (94%) C1: 48/51 (94%) C2: 47/49 (96%)

Percentage of glottic opening, median (IQR) I1: 100 (100-100) I2: 100 (100-100) C1: 100 (100-100) C2: 100 (100-100) P=0.010

|

Author’s conclusion: In conclusion, we could not demonstrate any difference in the ease of intubation between the ‘sniffing’ and the neutral position in patients undergoing tracheal intubation when using a channelled (King Vision) and a non-channelled (C-MAC D-blade) videolaryngoscope. Like direct laryngoscopy, videolaryngoscopy should be regarded as a dynamic process in which a change in position of the patient’s head and neck should be considered if difficulties during intubation are encountered. |

|

Yoo, 2019 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: South Korea

Funding and conflicts of interest: None declared. |

Inclusion criteria: adult patients (aged > 18 yr) scheduled for procedures under general anesthesia with tracheal intubation

Exclusion criteria: emergency operation, oropharyngeal disease, cervical spine disorder, insufficient npo time, esophageal disease, pregnancy, weak dentation, mouth opening < 2 cm, and other contraindications for insertion of SAD

N total at baseline: Intervention: 61 Control: 63

Important prognostic factors2: Age, mean (SD) I: 51 (16) C: 55 (15)

Sex: I: 25% M C:42% M

Groups were comparable at baseline. |

Head extension

The neck was extended using a 5 cm pillow under the shoulder in the extension group, |

Neutral position:

the head and neck were neutrally positioned using a 5 cm pillow under the occiput in the neutral group |

Length of follow-up: 24h

Loss-to-follow-up: I: 2/61 Reason: Did not receive allocated intervention (N=1) Protocol violation (N=1) C: 4/63 Reason: Did not receive allocated intervention (N=1), discharge before 24h (N=3)

Incomplete outcome data: See above

|

First pass success I: 40/59 (68%) C: 29/62 (47%)

|

Author’s conclusion: In conclusion, this study showed that neck extension can facilitate blind intubation through the AuraGainTM. Although blind intubation should not be used as the first-choice technique due to the relatively high failure rate, neck extension can improve the success rate of blind intubation through a SAD, with similar rates of post intubation complications, compared with the conventional neutral head and neck position |

|

Singh, 2021 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: Medical College and Hospital, Faridkot, Punjab,India

Funding and conflicts of interest: None declared |

Inclusion criteria: adult male and female patients of ASA grade I or II, aged 21-50 years, scheduled for elective surgeries under general anaesthesia

Exclusion criteria: anticipated difficult airway {restricted neck movements, bucked teeth, Thyromental Distance (TMD) less than 65 mm, limitation of Temporomandibular Joint (TMJ)}, BMI >30 kg/m2, cervical spine fracture or instability, undergoing head and neck surgery

N total at baseline: Intervention: 110 Control: 110

Important prognostic factors2: Age, mean±SD I: 35.78±8.49 C: 37.64±9.49

Sex: I: 71% M C: 75% M

Groups were comparable at baseline. |

Sniffing position:

patients were placed supine and a cushioned wooden block of 8 cm height was placed under the head. At the time of laryngoscopy, the head was extended on the atlanto-occipital joint maximally. |

Head extension:

patients were placed supine, without wooden block. The head was extended maximally on the atlanto-occipital joint at the time of laryngoscopy. |

Length of follow-up: NR

Loss-to-follow-up: None

Incomplete outcome data: None

|

Cormack-Lehane grade Grade I I: 69/110 C: 51/110

Grade II I: 38/110 C: 49/110

Grade III I: 3/110 C: 10/110

Hypotension No incidence reported, see below

Lowest systolic blood pressure No statistically significant difference was seen in sympathetic response in two groups of patients in terms of change in heart rate and the Mean Arterial Pressure (MAP) at different time intervals |

Author’s conclusion: Placing the head in SP resulted in better glottic visualisation and associated with favorable intubation conditions as compared to SHE position. Hence, this study supported the practice of using SP as the standard position of head and neck for direct laryngoscopy and endotracheal intubation |

|

Gudivada, 2017 |

Type of study: RCT, crossover

Setting and country: India

Funding and conflicts of interest: Nil. |

Inclusion criteria: patients scheduled for elective surgical procedures and requiring general anesthesia with endotracheal intubation were enrolled in this study. All patients belonged to ASA I and II and aged between 18 and 65 years with Mallampati Grade I and II

Exclusion criteria: patients with ASA physical status III and above, structural deformities involving face and airway, reactive airway disease, cervical spine pathology, neck masses, raised intracranial tension, and patients requiring rapid sequence intubation

N total at baseline: Intervention: 50 Control: 50

Important prognostic factors2: Age, mean SD, total 41.8±13.4

Sex: N/A |

Sniffing position:

the patients placed in the standard SP during first laryngoscopy (LS) by placing a cushion under the head such that external auditory meatus and sternal notch are at same horizontal plane (some patients required additional 0.5‑inch gel foams beneath the cushion for this horizontal alignment). Angle of the neck flexion was noted. Laryngoscopic view of the glottis was noted and tracheal intubation was performed and IDS was scored. Then, the endotracheal tube was removed, mask ventilation was performed and after 40 s, second laryngoscopy (LE) was performed with a further HE by placing a 1.5‑inch cushion over first one, and angle of neck flexion was measured |

Head extension:

the patients were placed with an HE of 1.5 inches over the standard SP during the first laryngoscopy (LE) and the laryngeal view was noted, tracheal intubation was done and IDS was scored. Then, the endotracheal tube was removed mask ventilation was performed and after 40 s, second laryngoscopy (LS) was performed with the patients in the SP by removing the 1.5‑inch cushion |

Length of follow-up: After intubation

Loss-to-follow-up: None

Incomplete outcome data: None

|

First pass success I: 91/100 C: 93/100

Cormack-Lehane grade Grade I I: 13/100 C: 35/100

Grade II I: 57/100 C: 59/100

Grade III I: 29/100 C: 6/100

Grade IV I: 1/100 C: 0/100

|

Author’s conclusion: We conclude that HE/further flexion of the neck is better in respect to glottic visualization, number of operators, laryngeal pressure, and lifting force required for intubation over standard SP as assessed by IDS. Hence, HE position was found to be statistically and clinically significant over standard SP |

|

Kim, 2016 |

Type of study: randomized, 3-arm, 3-period open-label, cross-over trial

Setting and country: South Korea

Funding and conflicts of interest: Nil. |

Inclusion criteria: Adult edentulous patients scheduled for elective surgery requiring tracheal intubation

Exclusion criteria: had a known or predicted difficult airway; diseases or anatomical abnormalities in the neck, larynx, or pharynx; or BMI>29 or were at risk for aspiration

N total at baseline: 18 in total

Important prognostic factors2: Age, mean (SD), total 75 (8)

Sex,, total: 44 % M

|

Sniffing position:

1) sniffing position—head extension with an uncompressible pillow of 7 cm; 2) elevated sniffing position—head extension with an uncompressible pillow of 10 cm |

Head extension:

3) simple head extension—head extension without a pillow |

Length of follow-up: After intubation

Loss-to-follow-up: None

Incomplete outcome data: None

|

Glottic opening score (0-100%), mean (SD) I1: 78.9 (19.7) I2: 72.6 (20.8) C: 53.8 (25.9) |

Author’s conclusion: In conclusion, the sniffing and elevated sniffing positions provide better laryngeal views during direct laryngoscopy in edentulous patients. |

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C) |

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

Akihisa, 2015

[individual study characteristics deduced from [1st author, year of publication ]]

PS., study characteristics and results are extracted from the SR (unless stated otherwise) |

SR and meta-analysis of RCTs

Literature search up to April 2014

A: Adnet 2001 B: Bhattarai 2011 C: Nur Hafiizhoh 2014 D: Prakash 2011

Study design: RCT

Setting and Country:

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: [commercial / non-commercial / industrial co-authorship] No external funding and no competing interests declared. |

Inclusion criteria SR: RCTs evaluating sniffing position for glottic visualization and intubation performance during intubation with direct laryngoscopy

Exclusion criteria SR: None reported.

6 studies included, thereof 4 included in our analysis

Important patient characteristics at baseline: Number of patients; characteristics important to the research question and/or for statistical adjustment (confounding in cohort studies); for example, age, sex, bmi, ...

N, mean age A: 456 patients, age N/A B: 400 patients, age N/A C: 378 patients, age N/A D: 546 patients, age N/A

Sex: N/A

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

Describe intervention:

A: Sniffing position B: Sniffing position C: Sniffing position D: Sniffing position |

Describe control:

A: simple head extension B: simple head extension C: simple head extension D: simple head extension |

Endpoint of follow-up:

Not relevant for the current question

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? (intervention/control) Not described

|

Outcome measure-1 Defined as Cormack-Lehane classification

Effect measure: RR [95% CI]: A: 1.13 [1.01; 1.27] B: 1.12 [0.96; 1.30] C: 2.64 [2.23; 3.14] D: 1.16 [1.01; 1.34]

Pooled effect (random effects model): 1.40 [95% CI 0.96 to 2.03] favoring head extension Heterogeneity (I2): 96.3%

Outcome measure-2 success rate of the first intubation C: 1.29 [1.14; 1.46] D: 1.06 [1.00; 1.12]

Pooled effect (random effects model): 1.16 [95% CI 0.94 to 1.44] favoring head extension Heterogeneity (I2): 89.9%

|

Risk of bias (high, some concerns or low): Tool used by authors: in accordance with the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of interventions,

A: Some concerns B: Some concerns C: Some concerns D: Some concerns

Facultative:

Although patients do not benefit from the sniffing position in terms of glottic visualization, success rate of the first intubation, or intubation time, the sniffing position can still be recommended as the initial head position for tracheal intubation because the sniffing position provides easier intubation conditions

|

Risk of bias in the included studies by Akihisa (2015)

|

Source |

Random sequence generation |

Allocation concealment |

Blind participants and personnel |

Incomplete outcome data |

Selective reporting |

Other potential threats to validity |

|

Adnet 2001 |

Y |

Y |

N |

Y |

Y |

Y |

|

Bhattarai 2011 |

Y |

Y |

N |

Y |

Y |

Y |

|

Nur Hafiizhoh 2014 |

Y |

Unclear |

N |

Y |

Y |

Y |

|

Prakash 2011 |

Y |

Unclear |

N |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y, low risk of bias; N, high risk of bias; Unclear, unclear risk of bias

Risk of bias table for intervention studies (randomized controlled trials; based on Cochrane risk of bias tool and suggestions by the CLARITY Group at McMaster University)

Research question: What are the benefits and harms of (semi)recumbent position compared to supine position in critically ill patients who are intubated outside the operating room?

|

Study reference

(first author, publication year) |

Was the allocation sequence adequately generated?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was the allocation adequately concealed?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Blinding: Was knowledge of the allocated interventions adequately prevented?

Were patients blinded?

Were healthcare providers blinded?

Were data collectors blinded?

Were outcome assessors blinded?

Were data analysts blinded? Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was loss to follow-up (missing outcome data) infrequent?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Are reports of the study free of selective outcome reporting?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was the study apparently free of other problems that could put it at a risk of bias?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Overall risk of bias If applicable/necessary, per outcome measure

LOW Some concerns HIGH |

|

Semler, 2017 |

Definitely yes;

Reason: Patients were randomized in a 1:1 ratio using computer-generated blocks of 4, 8, and 12, stratified by study site |

Definitely yes;

Reason: Group assignments were placed in sequentially numbered opaque envelopes, which remained sealed until the decision was made that a patient qualified for the study. |

Definitely no;

Reason: Clinicians and study personnel were not blinded to group assignment. |

Definitely yes;

Reason: No loss to follow-up |

Probably yes;

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported, but additional interpretations of predefined outcomes were added |

Probably yes;

Reason: No other problems noted |

Some concerns for subjective outcomes due to a lack of blinding |

|

Mendonca, 2018 |

Definitely yes;

Reason: randomized using computer-generated numbers |

Definitely yes;

Reason: concealed within sealed, opaque, sequentially numbered envelopes |

Definitely no;

Reason: It was not possible to blind the investigators or other healthcare professionals, either to the allocated position or the videolaryngoscope used. |

Definitely yes;

Reason: No loss to follow-up |

Probably yes;

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported |

Probably yes;

Reason: No other problems noted |

Some concerns for subjective outcomes due to a lack of blinding |

|

Yoo, 2019 |

Probably yes;

Reason: We performed blocked randomization with a randomly selected block size of 2 or 4 in a reproducible sequence. The randomization list was kept by the preparing nurse who was not involved in the study |

Definitely yes;

Reason: randomization list was kept by the preparing nurse who was not involved in the study, and group allocation was released only before induction of anesthesia |

Probably no;

Reason: the operator who performed blind intubation was not blinded to group allocation, but patients and outcome assessors were blinded to group allocation and the purpose of this study |

Definitely yes;

Reason: loss to follow-up was infrequent and similar in both groups |

Probably yes;

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported |

Probably yes;

Reason: No other problems noted |

Some concerns for subjective outcomes due to a lack of blinding |

|

Singh, 2021 |

Probably yes;

Reason: using a computer generated randomisation programme. |

Unclear;

Reason: Not reported |

Definitely no;

Reason: not mentioned who is blinded, except for: ‘Major limitation was the unblinded nature of the study as it was impossible to blind the operators to the intubating positions’. |

Definitely yes;

Reason: No loss to follow-up |

Probably yes;

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported |

Probably yes;

Reason: No other problems noted |

Some concerns for subjective outcomes due to a lack of blinding |

|

Gudivada, 2017 |

Probably yes;

Reason: Study participants were randomized into two groups of 50 each by computer‑generated random number |

Unclear;

Reason: Not reported |

Definitely no;

Reason: observers are not blind, further details lack |

Definitely yes;

Reason: No loss to follow-up |

Probably yes;

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported |

Probably yes;

Reason: No other problems noted |

Some concerns for subjective outcomes due to a lack of blinding |

|

Kim, 2016 |

Probably yes;

Reason: Randomization was based on a computer-generated program |

Definitely yes;

Reason: the randomization sequence was kept in opaque and sealed envelopes. An investigator who was not involved in the study determined the order of head positions by opening the envelope in sequence |

Definitely no;

Reason: anaesthesiologist performing the intubation is not blind, further details lack |

Definitely yes;

Reason: No loss to follow-up |

Probably yes;

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported |

Probably yes;

Reason: No other problems noted |

Some concerns for subjective outcomes due to a lack of blinding |

|

Pachisia, 2019 |

Probably yes;

Reason: randomized by computer generated random number table to one of the two groups comprising of 50 patients each. |

Unclear;

Reason: Not reported |

Definitely no;

Reason: anaesthesiologist performing the intubation is not blind, further details lack |

Definitely yes;

Reason: No loss to follow-up |

Probably yes;

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported |

Probably yes;

Reason: No other problems noted |

Some concerns for subjective outcomes due to a lack of blinding |

Table of excluded studies

|

Reference |

Reason for exclusion |

|

Mossie A, Ali SA, Tesema HG. Anesthetic implications of morbid obesity during pregnancy; a literature based review. International Journal of Surgery Open. 2022 Mar 1;40:100444. |

Wrong study design: narrative review |

|

Cabrini L, Landoni G, Baiardo Redaelli M, Saleh O, Votta CD, Fominskiy E, Putzu A, Snak de Souza CD, Antonelli M, Bellomo R, Pelosi P. Tracheal intubation in critically ill patients: a comprehensive systematic review of randomized trials. Critical Care. 2018 Dec;22:1-9. |

Wrong comparison: pre-oxygenation techniques |

|

Rao SL, Kunselman AR, Schuler HG, DesHarnais S. Laryngoscopy and tracheal intubation in the head-elevated position in obese patients: a randomized, controlled, equivalence trial. Anesthesia & Analgesia. 2008 Dec 1;107(6):1912-8. |

Wrong population: elective surgery |

|

Hasanin A, Tarek H, Mostafa M, Arafa A, Safina AG, Elsherbiny MH, Hosny O, Gado AA, Almenesey T, Hamden GA, Mahmoud M. Modified-ramped position: a new position for intubation of obese females: a randomized controlled pilot study. BMC anesthesiology. 2020 Dec;20(1):1-7. |

Wrong comparison: ramped vs modified ramped |

|

Tsan SE, Ng KT, Lau J, Viknaswaran NL, Wang CY. A comparison of ramping position and sniffing position during endotracheal intubation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Revista Brasileira de Anestesiologia. 2021 Feb 3;70:667-77. |

Wrong population: all but one study surgical population |

|

Turner JS, Hunter BR, Haseltine ID, Motzkus CA, DeLuna HM, Cooper DD, Ellender TJ, Sarmiento EJ, Menard LM, Kirschner JM. Effect of inclined positioning on first-pass success during endotracheal intubation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Emergency Medicine Journal. 2023 Apr 1;40(4):293-9. |

Wrong population: all but one study surgical population |

|

Turner JS, Ellender TJ, Okonkwo ER, Stepsis TM, Stevens AC, Sembroski EG, Eddy CS, Perkins AJ, Cooper DD. Feasibility of upright patient positioning and intubation success rates at two academic EDs. The American journal of emergency medicine. 2017 Jul 1;35(7):986-92. |

Wrong study design: observational |

|

Lee S, Jang EA, Hong M, Bae HB, Kim J. Ramped versus sniffing position in the videolaryngoscopy-guided tracheal intubation of morbidly obese patients: a prospective randomized study. Korean Journal of Anesthesiology. 2022 Aug 1;76(1):47-55. |

Wrong population: elective surgery |

|

Nikolla DA, Carlson JN, Jimenez Stuart PM, Asar I, April MD, Kaji AH, Brown III CA. Comparing postinduction hypoxemia between ramped and supine position endotracheal intubations with apneic oxygenation in the emergency department. Academic Emergency Medicine. 2022 Mar;29(3):317-25. |

Wrong study design: registry |

|

Tsan SH, Viknaswaran N, Lau J, Cheong C, Wang C. Effectiveness of preoxygenation during endotracheal intubation in a head-elevated position: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Anaesthesiology intensive therapy. 2022;54(5):413-24. |

Wrong population: all but one study surgical population |

|

Firdous T, Kashif A, Khan SN, Waqar A, Ali S, Tariq S. Compare the Mean Non Hypoxic Apnea Duration of 20° Head up with Conventional Supine Position during Pre-oxygenation in Patients Undergoing Elective Surgery. Pakistan Journal of Medical & Health Sciences. 2022 Aug 23;16(07):397-. |

Wrong population: elective surgery |

|

Park S, Lee HG, Choi JI, Lee S, Jang EA, Bae HB, Rhee J, Yang HC, Jeong S. Comparison of vocal cord view between neutral and sniffing position during orotracheal intubation using fiberoptic bronchoscope: a prospective, randomized cross over study. BMC Anesthesiol. 2019 Jan 5;19(1):3. doi: 10.1186/s12871-018-0671-9. PMID: 30611215; PMCID: PMC6320603. |

Wrong study design (crossover trial, but outcomes are not reported per head position) |

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Publicatiedatum : 24-02-2025

Beoordeeld op geldigheid : 23-02-2025

Algemene gegevens

De ontwikkeling/herziening van deze richtlijnmodule werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten (www.demedischspecialist.nl/kennisinstituut) en werd gefinancierd uit de Stichting Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS).

De financier heeft geen enkele invloed gehad op de inhoud van de richtlijnmodule.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijnmodule is in 2022 een multidisciplinaire werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen (zie hiervoor de Samenstelling van de werkgroep) die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor vitaal bedreigde patiënten die geïntubeerd worden buiten de OK.

Werkgroep

Dr. J.A.M. (Joost) Labout (voorzitter tot september 2023), intensivist, NVIC

Drs. J.H.J.M. (John) Meertens (interim-voorzitter), intensivist, NVIC

Drs. P. (Peter) Dieperink (interim-voorzitter), intensivist, NVIC

Drs. M.E. (Mengalvio) Sleeswijk (interim-voorzitter), intensivist, NVIC

Dr. F.O. (Fabian) Kooij, anesthesioloog/MMT-arts, NVA

Drs. Y.A.M. (Yvette) Kuijpers, anesthesioloog-intensivist, NVA

Drs. C. (Caspar) Müller, anesthesioloog/MMT-arts, NVA

Drs. M.E. (Mark) Seubert, internist-intensivist, NIV

Drs. S.J. (Sjieuwke) Derksen, internist-intensivist, NIV

Dr. R.M. (Rogier) Determann, internist-intensivist, NIV

Drs. H.J. (Harry) Achterberg, anesthesioloog-SEH-arts, NVSHA

Drs. M.A.E.A. (Marianne) Brackel, patiëntvertegenwoordiger, FCIC/IC Connect

Klankbordgroep

Dr. C.L. (Christiaan) Meuwese, cardioloog-intensivist, NVVC

Drs. J.T. (Jeroen) Kraak, KNO-arts, NVKNO

Drs. H.R. (Harry) Naber, anesthesioloog, NVA

Drs. H. (Huub) Grispen, anesthesiemedewerker, NVAM

Met ondersteuning van

dr. M.S. Ruiter, senior adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

drs. I. van Dijk, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

Belangenverklaringen

De Code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling is gevolgd. Alle werkgroepleden hebben schriftelijk verklaard of zij in de laatste drie jaar directe financiële belangen (betrekking bij een commercieel bedrijf, persoonlijke financiële belangen, onderzoeksfinanciering) of indirecte belangen (persoonlijke relaties, reputatiemanagement) hebben gehad. Gedurende de ontwikkeling of herziening van een module worden wijzigingen in belangen aan de voorzitter doorgegeven. De belangenverklaring wordt opnieuw bevestigd tijdens de commentaarfase.

Een overzicht van de belangen van werkgroepleden en het oordeel over het omgaan met eventuele belangen vindt u in onderstaande tabel. De ondertekende belangenverklaringen zijn op te vragen bij het secretariaat van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

|

Werkgroeplid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

Caspar Müller |

Anesthesioloog/MMT-arts ErasmusMC |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen restricties. |

|

Fabian Kooij |

Anesthesioloog/MMT-arts, Amsterdam UMC |

Chair of the Board, European Trauma Course Organisation |

Geen |

Geen restricties. |

|

Harry Achterberg |

SEH-arts, Isala Klinieken, fulltime - 40u/w (~111%) |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen restricties. |

|

John Meertens |

Intensivist-anesthesioloog, Intensive Care Volwassenen, UMC Groningen |

Secretaris Commissie Luchtwegmanagement, Nederlandse Vereniging voor Intensive Care |

Geen |

Geen restricties. |

|

Joost Labout |

Intensivist |

Redacteur A & I |

Geen |

Geen restricties. |

|

Marianne Brackel |

Patiëntvertegenwoordiger Stichting FCIC en patiëntenorganisatie IC Connect |

Geen |

Voormalig voorzitter IC Connect |

Geen restricties. |

|

Mark Seubert |

Internist-intensivist, |

Waarnemend internist en intensivist |

Lid Sectie IC van de NIV |

Geen restricties. |

|

Mengalvio Sleeswijk |

Internist-intensivist, Flevoziekenhuis |

Medisch Manager ambulancedienst regio Flevoland Gooi en Vecht / TMI Voorzitter Commissie Luchtwegmanagement, Nederlandse Vereniging voor Intensive Care |

Geen |

Geen restricties. |

|

Peter Dieperink |

Intensivist-anesthesioloog, Intensive Care Volwassenen, UMC Groningen |

Lid Commissie Luchtwegmanagement, Nederlandse Vereniging voor Intensive Care |

Geen |

Geen restricties. |

|

Rogier Determann |

Intensivist, OLVG, Amsterdam |

Docent Amstelacademie en Expertcollege |

Geen |

Geen restricties. |

|

Sjieuwke Derksen |

Intensivist - MCL |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen restricties. |

|

Yvette Kuijpers |

Anesthesioloog-intensivist, CZE en MUMC + |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen restricties. |

|

Klankbordgroeplid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

Christiaan Meuwese |

Cardioloog intensivist, Erasmus MC, Rotterdam |

Section editor Netherlands Journal of Critical Care (onbetaald) |

Extern gefinancierd onderzoek: - REMAP ECMO (Hartstichting) - PRECISE ECLS (Fonds SGS) |

Geen restricties. |

|

Jeroen Kraak |

KNO-arts & Hoofd-halschirurgie |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen restricties. |

|

Huub Grispen |

Anesthesiemedewerker Zuyderland MC |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen restricties. |

|

Harry Naber |

Anesthesioloog MSB Isala |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen restricties. |

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Er werd aandacht besteed aan het patiëntenperspectief door het uitnodigen van FCIC/IC Connect voor de schriftelijke knelpunteninventarisatie en deelname aan de werkgroep. Het verslag hiervan [zie aanverwante producten] is besproken in de werkgroep. De verkregen input is meegenomen bij het opstellen van de uitgangsvragen, de keuze voor de uitkomstmaten en bij het opstellen van de overwegingen. Ter onderbouwing van de module Aanwezigheid van naaste heeft IC Connect een achterbanraadpleging uitgevoerd. De conceptrichtlijn is tevens voor commentaar voorgelegd aan FCIC/IC Connect en de eventueel aangeleverde commentaren zijn bekeken en verwerkt.

Kwalitatieve raming van mogelijke financiële gevolgen in het kader van de Wkkgz

Bij de richtlijnmodule is conform de Wet kwaliteit, klachten en geschillen zorg (Wkkgz) een kwalitatieve raming uitgevoerd om te beoordelen of de aanbevelingen mogelijk leiden tot substantiële financiële gevolgen. Bij het uitvoeren van deze beoordeling is de richtlijnmodule op verschillende domeinen getoetst (zie het stroomschema op de Richtlijnendatabase).

|

Module |

Uitkomst raming |

Toelichting |

|

Module Hoofd- en lichaamspositie |

Geen substantiële financiële gevolgen |

Hoewel uit de toetsing volgt dat de aanbeveling(en) breed toepasbaar zijn (5.000-40.000 patiënten), volgt ook uit de toetsing dat het geen nieuwe manier van zorgverlening of andere organisatie van zorgverlening betreft. Er worden daarom geen substantiële financiële gevolgen verwacht. |

Werkwijze

AGREE

Deze richtlijnmodule is opgesteld conform de eisen vermeld in het rapport Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 van de adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwaliteit. Dit rapport is gebaseerd op het AGREE II instrument (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II; Brouwers, 2010).

Knelpuntenanalyse en uitgangsvragen

Tijdens de voorbereidende fase inventariseerde de werkgroep de knelpunten in de zorg voor vitaal bedreigde patiënten die geïntubeerd worden buiten de OK. Tevens zijn er knelpunten aangedragen door verschillende stakeholders via een schriftelijke knelpunteninventarisatie. Een verslag hiervan is opgenomen onder aanverwante producten.

Op basis van de uitkomsten van de knelpuntenanalyse zijn door de werkgroep concept-uitgangsvragen opgesteld en definitief vastgesteld.

Uitkomstmaten

Na het opstellen van de zoekvraag behorende bij de uitgangsvraag inventariseerde de werkgroep welke uitkomstmaten voor de patiënt relevant zijn, waarbij zowel naar gewenste als ongewenste effecten werd gekeken. Hierbij werd een maximum van acht uitkomstmaten gehanteerd. De werkgroep waardeerde deze uitkomstmaten volgens hun relatieve belang bij de besluitvorming rondom aanbevelingen, als cruciaal (kritiek voor de besluitvorming), belangrijk (maar niet cruciaal) en onbelangrijk. Tevens definieerde de werkgroep tenminste voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten welke verschillen zij klinisch (patiënt) relevant vonden.

Methode literatuursamenvatting

Een uitgebreide beschrijving van de strategie voor zoeken en selecteren van literatuur is te vinden onder ‘Zoeken en selecteren’ onder Onderbouwing. Indien mogelijk werd de data uit verschillende studies gepoold in een random-effects model. Review Manager 5.4 werd gebruikt voor de statistische analyses. De beoordeling van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs wordt hieronder toegelicht.

Beoordelen van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs