Matten bij liesbreuk volwassenen

Uitgangsvraag

Welke mat is het beste voor liesbreukchirurgie?

De uitgangsvraag omvat de volgende deelvragen:

- Welke mat is het beste voor TEP (en TAPP): “lichtgewicht” of “zwaargewicht”?

- Welke mat is het beste voor Lichtenstein: “lichtgewicht” of “zwaargewicht”?

- Is een zelfklevende mat (Progrip) bij Lichtenstein beter dan een niet- zelfklevende mat?

Aanbeveling

Het wordt chirurgen aanbevolen zich te verdiepen in de verschillende typen matten en de daarbij horende eigenschappen inclusief kosten, gezien de grote variaties hierin. Gebruik bij voorkeur een mat die is onderzocht en beschreven in de literatuur.

Overweeg geen lichtgewicht mat te gebruiken voor een TEP (of TAPP) liesbreukoperatie: er is geen bewezen voordeel ten aanzien van chronische pijn en de kans op een recidief (bij grotere, mediale defecten) is hoger.

Hoewel het verschil in chronische pijn klein is, kan overwogen worden een lichtgewicht mat te gebruiken voor een liesbreukoperatie volgens Lichtenstein. Men moet zich daarbij bewust zijn van een mogelijk beperkt verhoogde kans op een recidief, met name bij patiënten met een groot defect.

Gebruik geen ProGrip zelfklevende mat voor een operatie volgens Lichtenstein aangezien er geen voordeel is ten aanzien van chronische pijn of recidieven vergeleken met een niet zelfklevende mat.

Overwegingen

TEP

Na analyse van de huidige literatuur is er voldoende bewijs dat het gebruik van een “lichtgewicht” mat de kans op een recidief na een TEP verhoogt.

Het is echter opvallend dat de meeste studies beschrijven dat de kans op een recidief met name verhoogd is bij “grote” mediale defecten. Er bestaat geen duidelijke definitie over wat “groot” is. Verschillende studies nemen als afkap punt >3 cm. Het is onduidelijk hoe onderzoekers de grootte van het defect meten. Het berust vaak op een schatting.

De werkgroep heeft een subgroep analyse kunnen verrichten van de studie van Burgmans en Roos. Deze laat zien dat het aantal recidieven significant verhoogd is na het gebruik van een “lichtgewicht” mat bij mediale breuken. Er is geen verschil bij laterale breuken. Van de andere studies van de meta-analyse is het niet mogelijk een subgroep analyse te verrichten. Het aantal recidieven per studie is laag en veel studies zijn te klein, maar er is vaak wel een trend. Om een recidief na TEP te voorkomen, is het gebruik van een “zwaargewicht” mat aan te bevelen.

De vraag blijft dan, of een zwaargewicht mat niet meer kans geeft op chronische pijn. Uit de analyse blijkt dat het gebruik van een “lichtgewicht” mat bij de TEP de kans op chronische pijn mogelijk verlaagt. Het verschil is echter niet significant en de bewijskracht is beperkt. Studies hanteren verschillende definities van pijn (een bepaalde NRS of VAS-score, het verschil tussen geen pijn of wel pijn of het verschil tussen niet klinisch relevante en klinisch relevante pijn). Daarnaast is de follow-up duur niet altijd gelijk. De meest recente RCT met de grootste aantallen en een goede opzet, laat zelf een iets verhoogde kans zien op chronische pijn na het gebruik van een “lichtgewicht” (Ultrapro) mat.

De kosten van een “zwaargewicht” mat zijn lager dan van een “lichtgewicht” mat. Ook is een “zwaargewicht” mat gemakkelijker te hanteren en te positioneren in vergelijking met een “lichtgewicht” mat. Het is belangrijk om dit mee te laten wegen in de keuze voor een mat bij een TEP.

Op basis van de analyse en bovenstaande overwegingen, adviseert de werkgroep in ieder geval een “zwaargewicht” mat te gebruiken bij patiënten met (grotere) mediale defecten. Voor kleinere, laterale defecten zou een “lichtgewicht” mat overwogen kunnen worden.

Het is tot op heden onduidelijk of naast het gebruik van een “zwaargewicht” mat het fixeren van de mat bij grote defecten bijdraagt om de kans op een recidief (en bulging) te verkleinen. Hiervoor verwijzen wij naar module 11: matfixatie. Ook is er discussie over het eventueel verkleinen van de holte van een groot mediaal defect door het reven en sluiten van de uitpuilende fascia transversalis. Deze laatste techniek lijkt de kans op seroom te verkleinen, maar het is niet aangetoond dat de kans op een recidief hiermee ook lager wordt.

Lichtenstein

Na analyse van de huidige literatuur lijkt er een lichte voorkeur voor het gebruik van een “lichtgewicht” mat bij een Lichtenstein plastiek omdat de kans op chronische pijn lager lijkt. De bewijskracht hiervoor is echter beperkt. Daarnaast zijn er zorgen over het aantal recidieven dat na het gebruik van een “lichtgewicht” mat hoger lijkt. Een harde aanbeveling is dus niet te geven.

Bij de keuze tussen een “lichtgewicht” en een “zwaargewicht” mat, zullen meerdere factoren van belang zijn die nauwelijks beschreven zijn in de literatuur. Zo kunnen andere factoren (leeftijd, gewicht, beroep, collageenziekten, type breuk en grootte van het defect) meespelen bij deze keuze. Een lichtgewicht mat is een goede keuze. Als de chirurg de kans op een recidief aanzienlijk groter inschat, is de keuze voor een zwaargewicht mat wellicht beter.

Een recente review van Molegraaf laat zien dat er geen voordeel is voor het plaatsen van een zelf-klevende ProGrip mat ten opzichte van een niet klevende mat. De kans op chronische pijn is niet lager en het aantal recidieven is ook niet minder.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Er bestaat een enorm aanbod van verschillende type matten voor liesbreukchirurgie, variërend in materiaal, gewicht, porie-grootte, vorm en kosten. Het doel van het plaatsen van een mat is het voorkomen van een recidief zonder dat de mat bijwerkingen (chronische pijn of discomfort door een hinderlijk, stijf gevoel) geeft. Daarom moet een mat voldoen aan verschillende eigenschappen zoals elasticiteit met behoud van voldoende kracht (om herhaalde mechanische druk te weerstaan en een recidief te voorkomen) en een goede bio compatibiliteit.

Er bestaan zorgen over het optreden van eventuele bijwerkingen veroorzaakt door de geplaatste mat. Men moet zich evenwel realiseren dat naast de mat er vele andere factoren zijn (type operatie, complicaties, ervaring van de chirurg, patiënt gerelateerde factoren) die kunnen bijdragen aan deze bijwerkingen.

Door de diversiteit van alle typen matten die beschikbaar zijn voor liesbreukchirurgie en door de grote variatie van operatie- en patiënt factoren, is het onmogelijk de ideale mat te beschrijven en aan te bevelen.

Voor een uitgebreid overzicht met verschillende uitgangsvragen aangaande matten, verwijzen wij naar module 10 van de internationale richtlijn (HerniaSurge Group, 2018).

Voor de huidige Nederlandse richtlijn hebben wij de moeilijke discussie over wat de ideale mat zou zijn voor een bepaalde techniek gepoogd te vereenvoudigen door deze toe te schrijven naar de meest voorkomende technieken voor liesbreuk correctie in Nederland: de Lichtenstein plastiek en de TEP en als uitgangsmaat te kijken naar chronische pijn (vanaf 3 maanden) en recidieven (geen termijn). In de analyse hebben wij 3D matten uitgesloten, omdat deze nauwelijks onderzocht zijn voor TEP en niet gebruikt worden voor Lichtenstein. Specifiek voor de operatie volgens Lichtenstein, worden in Nederland ook zelf-fixerende matten gebruikt. Deze zijn vergeleken met matten die met hechtingen in de patiënt gefixeerd zijn.

Omdat de meeste RCT’s onderscheid maken tussen een (grove poriën) “lichtgewicht mat”, (waarbij Ultrapro het meest is onderzocht) en een kleinere poriën “zwaargewicht” mat (polypropyleen), en deze matten ook veel in Nederland worden gebruikt, hebben wij de uitkomsten van deze typen matten opnieuw geanalyseerd. Tot op heden is er geen duidelijke definitie van een “lichtgewicht” en een “zwaargewicht” mat. Voor deze uitgangsvraag is daarom gekozen voor het meest gebruikelijke afkappunt ≤ 50 g/m2 voor “lichtgewicht” en >70 g/m2 voor “zwaargewicht”.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

|

Redelijk GRADE |

Voor patiënten die een TEP (of TAPP) correctie ondergaan lijkt er geen verschil in het risico op chronische pijn met het gebruik van een “lichtgewicht” mat lager dan met een “zwaargewicht” mat. |

|

Hoog GRADE |

Voor patiënten die een TEP (of TAPP) correctie ondergaan is het risico op een recidief hoger na het gebruik van een “lichtgewicht” mat in vergelijking met een “zwaargewicht” mat. Dit risico lijkt met name verhoogd bij patiënten met een (grote) mediale breuk. |

|

Redelijk GRADE |

Voor patiënten die een Lichtenstein correctie ondergaan is het risico op chronische pijn lager na het gebruik van een “lichtgewicht” mat in vergelijking met een “zwaargewicht” mat. |

|

Redelijk GRADE |

Voor patiënten die een Lichtenstein correctie ondergaan lijkt het risico op een recidief hoger na het gebruik van een “lichtgewicht” mat in vergelijking met een “zwaargewicht” mat. |

|

Redelijk GRADE |

De kans op chronische pijn met het gebruik van een zelfklevende ProGrip mat bij patiënten die een Lichtenstein correctie ondergaan is niet lager vergeleken met een niet zelfklevende mat. |

|

Redelijk GRADE |

De kans op een recidief met het gebruik van een zelfklevende ProGrip mat bij patiënten die een Lichtenstein correctie ondergaan is niet lager vergeleken met een niet zelfklevende mat. |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of the studies on endoscopic inguinal hernia repair

Sajid (2013) systematically searched relevant databases till June 2011 and analysed the RCTs on the use of lightweight mesh (LWM) versus heavyweight mesh (HWM) in patients undergoing laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair (LIHR) by both trans-abdominal pre-peritoneal (TAPP) and total extraperitoneal (TEP) approach. Sajid (2013) included the RCTs on patients of any age, any gender, on both elective and emergency LIHR for every indication i.e. groin lump, groin pain, inguinoscrotal lump, unilateral, bilateral, or recurrent hernia. They included eleven RCTs (Agarwal, 2009; Bittner, 2011; Bittner, 2011*; Bringman, 2005; Champault, 2007; Chowbey, 2010; Chui, 2010; Heikkinen, 2006; Langenbach, 2006; Langenbach, 2008; Peeters, 2010) encompassing 2189 patients.

Sajid (2013) concluded that there were significant limitations in the methodological quality of few included RCTs analysed in this review. Methodological limitations included not adequately (reporting of) blinding of the trial participants and outcome assessors, lack of intention-to-treat analysis and potential Risk of Bias in industry-sponsored trials.

Two mistakes in the review by Sajid (2013) were detected. Sajid included the mesh of 55 g/m2 in the study by Bittner (2011)* as a LWM. Moreover, chronic pain in the study of Bringman (2005) was assessed although follow-up was only 2 months. For current analysis both mistakes were adjusted for and the mesh and study were not included in the meta-analyses.

Burgmans(2015 and 2016)/ Roos (2018) conducted a prospective double-blinded RCT in 949 patients. This is the largest sample size in the field up to date. They included adult, male patients with a primary, reducible, unilateral inguinal hernia and no contraindications for TEP repair. All patients underwent TEP repair without the use of any fixation, sealant, adjunct, or glue. Outcomes of chronic pain were assessed up to 2 years and recurrences up to 5 years postoperatively.

Risk of Bias in this study was low.

Prakash (2016) randomised 140 adult patients with uncomplicated inguinal hernia into a HW mesh group or LW mesh group. All the patients underwent LIHR by either TAPP or TEP method. No mesh fixation was used in either group. A total of 131 patients completed a minimum of 3 months follow-up period, 66 in HW mesh group and 65 in LW mesh group. Outcomes were assessed up to 12 months postoperatively.

Risk of Bias in this study was low, the only potential Risk of Bias was due to inadequate blinding of care providers and outcome assessors to treatment allocation.

Kalra (2017) conducted a multi-center RCT comparing TAPP repair with placement of either a LWM or a HWM. Tackers were used for the fixation of the mesh. Patients were 15 to 60 years, with a unilateral, reducible inguinal hernia. Sixty patients were included with a follow-up of 3 months.

Risk of Bias in this study was high due to underreporting. Any form of blinding and loss to follow-up was not reported.

Wong (2017) performed a double-blind RCT in 85 patients with a mean follow-up of 20.3 months (range 12 to 34 months). All patients underwent TEP repair. No device or agent was used to anchor the mesh. Inclusion criteria were age 18 to 81 years and a primary uncomplicated unilateral or bilateral inguinal hernia. The recurrence rate was assessed.

Risk of Bias in this study was low, only the randomization technique was not described.

Results

1. Chronic pain

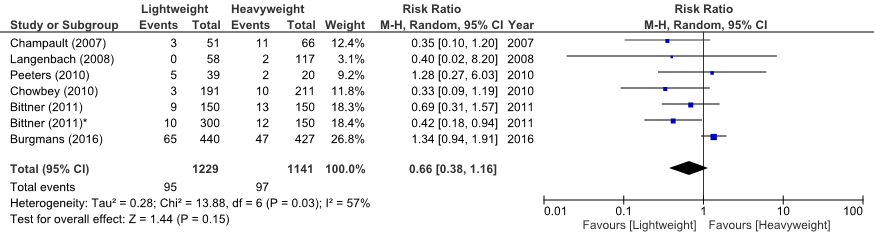

The meta-analysis from Sajid (2013) could be updated with data from Burgmans (2016). Prakash (2016) and Kalra (2017) presented chronic pain outcome as the mean VAS ± SD. We were unable to include these studies in the meta-analysis. The forest plot is shown in figure 1. Overall, the risk of chronic groin pain was estimated to be reduced by 34% when using a LWM compared with a HWM (RR 0.66, 95%CI: 0.38 to 1.16), but the confidence interval was wide and enclosed 1, indicating a not statistically significant and imprecise effect estimate.

There was substantial heterogeneity, possibly due to variation in the duration of follow-up (chi-square = 13.66, df = 6, P = 0.03, I² = 57%) among the RCTs.

Figure 1 Meta-analysis of trials comparing LWM versus HWM in patients undergoing endoscopic surgery for hernia repair (Outcome chronic groin pain)

2. Recurrence

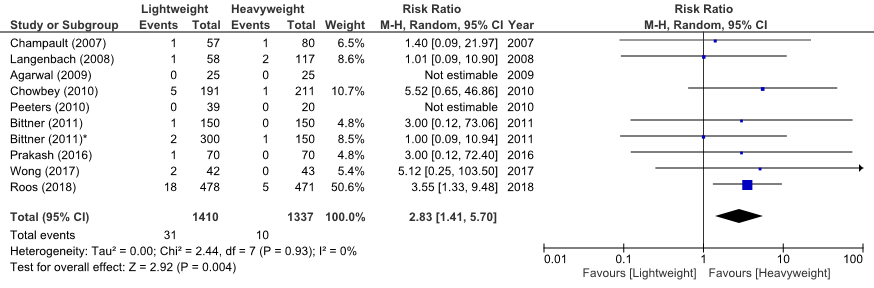

The meta-analysis from Sajid 2013 could be updated with data from Prakash 2016; Wong, 2017 and Roos, 2018. The pooled analysis showed that the risk of recurrences was increased by a factor 2.83 when a LWM was used compared to a HWM (RR 2.83, 95%CI 1.41 to 5.70).

There was no statistical heterogeneity among the RCTs (chi-square = 2.44, df = 7, P = 0.93, I² = 0%).

Figure 2 Meta-analysis of trials comparing LWM versus HWM in patients undergoing endoscopic surgery for hernia repair (Outcome recurrence)

Recurrences after direct or indirect hernia repair:

The study by Burgmans (2016) and Roos (2018) showed significantly more recurrences for LWM after direct hernia repair (LWM n=12, HWM n=1, p=0.003), but no significance for recurrences after indirect hernia repair (LWM n=6, HWM n=4, p=0.545). The study by Wong (2017) does not report on the matter for the 2 recurrences. Prakash 2016 showed 1 recurrence in the LWM-group after an indirect inguinal hernia repair. Bittner (2011)* reported all 3 recurrences (2 LWM, 1 HWM) after direct hernia repair. Bittner 2011 found 1 recurrence after direct hernia repair. Chowbey 2010 found out of five recurrences in the LWM-group, 3 patients had large indirect hernias and 2 patients had large direct hernias. Langenbach (2008) found all 3 recurrences were after direct hernia repair. Champault (2007) does not report on the matter for 2 recurrences.

Quality of the evidence

Evidence originated from RCTs and the level of the quality of the evidence comparing LWM versus HWM started therefore at ‘High’. However, the quality of the evidence regarding chronic pain was downgraded with one level to ‘Moderate’ for imprecision (the confidence interval crosses 1). We did not downgrade further for limitations in the methodological quality of the included RCTs (Risk of Bias).

The quality of the evidence regarding recurrence was not downgraded. The lower boundary of the confidence interval was considered clinically relevant.

Description of the studies on Lichtenstein inguinal hernia repair

Sajid (2012) performed a systematic review with a meta-analysis of the literature on lightweight mesh (LWM) compared with heavyweight mesh (HWM) in open inguinal hernia repair. Relevant databases were searched till May 2011. Any trials that compared LMW with HWM were included. A total of 9 RCT were found and described (Bringman, 2006; Champault, 2007; Koch, 2008; Nikkolo, 2010; O’Dwyer, 2005; Paajanen, 2007; Post, 2004; Smietanski, 2008); Smietanski, 2011; Torcivia, 2011) encompassing 1156 patients with a LWM and 1154 patients with a HWM. In all trials the HWM consisted of polypropylene. In all trials all patients underwent a Lichtenstein technique. All trials scored highly enough to suggest good quality of the included trials.

Sajid (2012( concluded that the duration of operation, postoperative pain, postoperative complications, hernia recurrence rate, risk of testicular atrophy and time to return to work were comparable between LWM and HWM. LWM was associated with a reduced risk of developing chronic groin pain and other groin symptoms.

For the current analysis the short-term results published by Paajanen (2007), Nikkolo (2010) and Smietanski (2008) were replaced with the long-term results published by Paajanen (2012), Nikkolo (2012) and Bury (2012), respectively.

A mistake in the review by Sajid was detected. The review wrongly presented Smietanski (2011) as 5 year follow-up of Smietanski (2008). Smietanski (2011) is an original study, with no previously published short-term results, that investigates a different LWM compared to Smietanski (2008). Bury (2012) is the correct 5 year follow-up of Smietanski (2008). In our analysis we adjusted for this mistake.

Apart from the long-term follow-up studies, in 9 more studies after the latest review and meta-analysis by Sajid another 978 patients with a LWM and 964 patients with a HWM were studied. In all studies the groups were comparable at baseline. In all studies patients were aged over 18 years and most studies included primary unilateral inguinal hernias. Only Pielaciński (2013) and Bona (2018) included bilateral inguinal hernias. Pielaciński (2013) was the only study that included recurrent hernias. In all studies a Lichtenstein technique was performed. Most studies used sutures for fixation of the mesh. In four studies (Paradowski, 2009; Sadowski, 2011, Rutegård, 2017), Bona 92018) mesh fixation was not reported. In the study by Canonico (2012) human fibrin glue was used for fixation of the mesh. Follow-up of the studies ranged from 3 to 60 months. Canonico (2012) and Rutegård (2017) were the only two studies that did not report chronic pain as an outcome. Sadowski (2011) was the only study that did not have recurrence as an outcome.

Risk of Bias in half of the studies was low (see: Risk of Bias table). Risk of Bias was high in the following studies: Sadowski (2011), Canonico (2012) and Pielaciński (2013) did not report on the randomization technique and concealment of allocation, and bias due to loss to follow-up was likely or unclear. Moreover in the study of Sadowski (2011) and Pielaciński (2013) bias due to blinding was likely or unclear and Canonico (2012) performed selective outcome reporting because the 6 months results were not described. In the study of Nikkolo (2012) blinding was not reported and loss to follow-up was high. Lee (2017) did not report on the randomization technique, concealment of allocation and blinding of outcome assessors. Bona (2018) did not blind the outcome assessors, loss to follow-up was high and bias due to selective outcome reporting was likely because the 12 months results were not described.

Results

1. Chronic pain

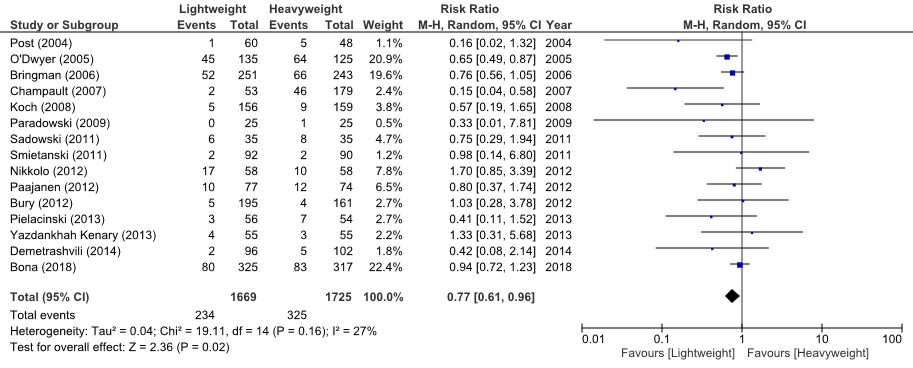

The data from the review by Sajid (2012) could be updated with the long-term follow-up results of Paajanen (2012), Nikkolo (2012) and Bury (2012), and with 6 additional studies (Paradowski, 2009; Sadowski, 2011; Yazdankhah Kenary, 2013; Demetrashvili, 2014; Lee, 2017; Rutegård, 2017; Bona, 2018).

Therefore, 15 trials (n=3394) reported applicable data for meta-analysis on the outcome chronic groin pain. In the LWM-group 234 of 1669 patients reported chronic pain, compared to 325 of 1725 patients in the HWM-group. The risk of having chronic groin pain after a hernioplasty with a LWM was estimated to be 23% lower than with a HWM. The pooled risk ratio estimate was 0.77 (95%CI: 0.61 to 0.96). Inapplicable for meta-analysis, Lee 2017 reported chronic pain as a mean VAS (SD) of 0.7 (1.1) for the LWM and 0.8 (1.4) for the HWM.

There was low statistical heterogeneity among the RCTs (chi-square = 19.11, df = 14, P = 0.16, I² = 27%).

Figure 3 Meta-analysis of trials comparing LWM versus HWM in patients undergoing open surgery for hernia repair (Outcome chronic groin pain)

1. Recurrence

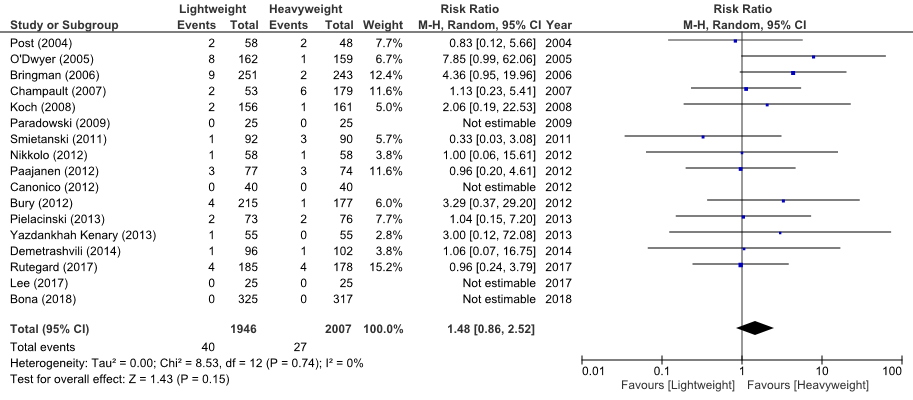

The data from the review by Sajid (2012) could be updated with the long-term follow-up results of Paajanen (2012), Nikkolo (2012) and Bury (2012), and with 8 additional studies (Paradowski, 2009; Canonico, 2012; Pielaciński, 2013; Yazdankhah Kenary, 2013; Demetrashvili, 2014; Lee, 2017; Rutegård, 2017; Bona, 2018).

Seventeen trials (n=3953) reported data on the outcome recurrences. In the combined results 40 patients who received a LWM had a recurrence, while 27 patients with a HWM had a recurrence. The risk for recurrence was therefore increased with the use of LWM with a pooled risk ratio estimate of 1.48 (95%CI: 0.86 to 2.52).

There was no heterogeneity among the RCTs (chi-square = 8.53, df = 12, P = 0.74, I² = 0%).

Figure 4 Meta-analysis of trials comparing LWM versus HWM in patients undergoing open surgery for hernia repair (Outcome recurrence).

Quality of the evidence

Evidence originated from RCTs and the level of the quality of the evidence comparing LWM versus HWM started therefore at ‘High’. However, the quality of the evidence regarding chronic pain was downgraded with one level to ‘Moderate’ for imprecision, as the upper boundary of the confidence is very close to 1 and we therefore cannot rule out that the difference might not be clinically relevant.

The quality of the evidence regarding recurrence was downgraded with one level to ‘Moderate’ for imprecision (the confidence interval crosses 1). We did not downgrade further for limitations in the methodological quality of the included RCTs (Risk of Bias).

Description of the SR on Lichtenstein inguinal hernia repair with ProGrip

The 10 RCTs that were included in the SR of Molegraaf 2018 described 2,541 patients (n = 1,216 self-gripping mesh group, n = 1,245 sutured mesh group). The duration of follow-up ranged from 6 to 72 months.

The quality assessment of the studies by Molegraaf 2018 showed that the quality of 2 trials was poor due the absence of an adequate randomization technique or no information about it, absence of blinding, no power calculations, and no baseline score. The other trials were of moderate or good quality, despite the common absence of blinding and poor reporting of the definition or assessment method of chronic pain. In four studies a baseline pain score was lacking, although preoperative pain is a well-known risk factor for chronic pain. Furthermore, some trials compared different types of meshes in the 2 study groups instead of only changing the method of mesh fixation (polypropylene and polyester, and heavy and low weight).

Results

Chronic pain (critical outcome)

Chronic pain was assessed in all trials and 9 of them reported the incidence of chronic pain according to the definition used in their study protocol. Incidence rates were analysed separately for the different moments of follow-up (3, 6 to 12, 24, 36, and 72 months).

At all follow-up time points, there was no significant difference in the incidence of CPIP between the self-gripping mesh and sutured mesh group (3 months OR = 0.89, 95% CI 0.48 to 1.64 (n=425); 6 to 12 months OR = 1.00; 95% CI 0.75 to 1.34 (n=1517); 24 months OR = 1.00; 95% CI 0.39 to 2.61 (n=372); 36 to 72 months OR = 0.77; 95% CI 0.38 to 1.58 (n=464)).

Recurrence (important outcome)

All trials reported recurrence rates after 12 months of follow-up. Two studies also provided recurrence rates after 24 months, 2 after 36 months and 1 after 72 months. The difference in recurrence rate between the self-gripping mesh group and the sutured mesh group was not significant at 12 months (OR = 1.19, 95% CI 0.61 to 2.31 (n=2435)), 24 months (OR = 1.06, 95% CI, 0.27 to 4.17(n=372)), or 36 months (OR = 0.95, 95% CI, 0.18 to 5.14 (n=450) (Molegraaf 2018).

Quality of the evidence

Evidence comparing open inguinal hernia repair with a self-gripping ProGrip mesh and a conventional Lichtenstein hernioplasty originated from RCTs and the level of the quality of the evidence regarding chronic pain and recurrence after inguinal hernia repair with self-gripping meshes started therefore at ‘High’. However, the quality of the evidence was downgraded one level for substantial methodological limitations of the studies to ‘Moderate’. We did not downgrade for the aforementioned clinical heterogeneity between studies, because the subgroup analyses accounting for mesh weight and including only studies that used a light weighted mesh in both the study and control group also showed no difference in CPIP rates between the self-gripping mesh and sutured mesh (Molegraaf, 2018).

Zoeken en selecteren

In order to answer the clinical ‘question’, a systematic literature search was done for the following research questions:

Which mesh is recommended for endoscopic and open inguinal hernia repair?

PICO 1

P: patients with an inguinal hernia undergoing endoscopic surgery;

I: mesh (Lightweight; ≤50 g/m2);

C: mesh (Heavyweight; >70 g/m2)

O: chronic pain (>3 months), recurrence.

PICO 2

P: patients with an inguinal hernia undergoing Lichtenstein inguinal hernia repair;

I: mesh (Lightweight; ≤50 g/m2);

C: mMesh (Heavyweight; >70 g/m2);

O: chronic pain (>3 months), recurrence.

PICO 3

P: patients with an inguinal hernia undergoing Lichtenstein inguinal hernia repair;

I: self-fixing/self-gripping mesh (ProGrip);

C: mesh with fixation by sutures;

O: chronic pain (>3 months), recurrence.

Relevant outcome measures

The working group decided that chronic pain and recurrences were crucial outcome measures for decision-making. Recurrences after inguinal hernia repair have dropped dramatically with the introduction of tension-free mesh repair and endoscopic preperitoneal approaches. Still, recurrences and chronic pain are the most common long-term complications after inguinal hernia repair. According to the International Association for the Study of Pain, chronic pain is defined as (inguinal) pain lasting a minimum of 3 months. Any level of pain was considered relevant. For the detection of recurrences any time-period was considered relevant for comparison. A distinction between recurrences after direct hernia repairs or indirect hernia repairs was sought for in included endoscopic repair studies.

Searching and selecting (Methods)

A literature search, for open and for endoscopic inguinal hernia repair, was conducted in MEDLINE, EMBASE and the Cochrane Library at June 6th 2018. The search was not limited by publication date or language. The search details can be found in the tab Acknowledgement. Subsequently, a filter for identifying RCTs was used to filter out nonrandomized trials. All duplicates were removed. Literature experts excluded non-relevant studies based on title and abstract and/or full-text screening.

For the comparison of lightweight versus heavyweight meshes after endoscopic inguinal hernia repair the working group selected 19 studies based on title-abstract that could possibly answer the research questions. After reading full text, 2 studies were excluded (see exclusion table in the tab Acknowledgement). Finally, the studies from the latest review and meta-analysis for endoscopic mesh comparison by Sajid 2013 and 6 additional original studies that were not included in Sajid (2013) were included for analysis (Burgmans, 2015; Burgmans, 2016; Prakash, 2016; Kalra, 2017; Wong, 2017 and Roos, 2018).

For the comparison of lightweight versus heavyweight meshes after open inguinal hernia repair the working group selected 25 studies based on title-abstract, that could possibly answer the research questions. After reading full text, 2 studies were excluded (see exclusion table in the tab Acknowledgement). Finally, the studies from the latest review and meta-analysis for open mesh comparison by Sajid (2012) and 12 additional original studies that were not included in Sajid 2012 were included for analysis (Paradowski, 2009; Sadowski, 2011; Bury, 2012; Nikkolo, 2012; Canonico, 2013; Paajanen, 2013; Pielaciński, 2013; Yazdankhah Kenary, 2013; Demetrashvili, 2014; Lee, 2017; Rutegård, 2017; Bona, 2018).

The 2 SRs with meta-analyses (Sajid, 2012 and Sajid, 2013), containing 20 RCTs were included in the literature analysis. These SRs were updated with the recent RCTS.

During the preparation and writing of the guideline text of this module, a relevant systematic review was published that answered PICO 3 (Molegraaf, 2018). Molegraaf (2018) performed a systematic review of the literature to identify RCTs comparing open inguinal hernia repair with a self-gripping ProGrip mesh and a conventional Lichtenstein hernioplasty. The working group decided that this SR and meta-analysis provided the most up-to-date overview of RCTs regarding self-gripping (ProGrip) mesh.

Data extraction and analysis

The most important study characteristics and results were extracted from the SRs or original studies (also, in case of missing information in the review). The most important study characteristics and relevant results are shown in the evidence tables. The judgement of the individual study quality (Risk of Bias) is shown in the Risk of Bias tables.

It was agreed that the blinding of the care providers (operating surgeon) was impossible. The Risk of Bias however was rated as low, since the type of mesh used is an unlikely influence on the success of surgery execution. In the case of not reported intention-to-treat analysis it was considered an unlikely Risk of Bias due to the inability to cross-over. The lack of an adequate randomization technique (or not reported), inadequate blinding (or not reported) and a high or non-proportionally divided loss to follow-up was considered a high Risk of Bias.

The summary of included studies, study characteristics and quality of the SRs by Sajid are presented in the evidence table for SRs and the quality assessment table for SRs.

Relevant pooled and/or standardised effect measures were, if useful, calculated using Review Manager 5.3 (Cochrane Collaboration, Oxford, United Kingdom). If pooling results was not possible, the outcomes and results of the original study were used as reported by the authors.

The working group did not define clinical (patient) relevant differences for the outcome measures. Therefore, we used the following boundaries for clinical relevance, if applicable: for continue outcome measures: RR <0.75 or >1.25 (GRADE recommendation) or Standardized mean difference (SMD=0.2 (little); SMD 0.5 (reasonable); SMD=0.8 (large). These boundaries were compared with the results of our analysis. The interpretation of dichotomous outcome measures is strongly related to context; therefore, no clinical relevant boundaries were set beforehand. For dichotomous outcome measures, the absolute effect was calculated (Number Needed to Treat (NNT) or Number Needed to Harm (NNH)).

Referenties

- Bona S, Rosati R, Opocher E, et al. SUPERMAT Study Group. (2018) Pain and quality of life after inguinal hernia surgery: a multicenter randomized controlled trial comparing lightweight vs heavyweight mesh (Supermesh Study). Updates Surg 70(1):77-83.

- Burgmans JP, Voorbrood CE, Schouten N, et al. (2015) Three-month results of the effect of Ultrapro or Prolene mesh on post-operative pain and well-being following endoscopic totally extraperitoneal hernia repair (TULP trial). Surg Endosc 29(11):3171-3178.

- Burgmans JP, Voorbrood CE, Simmermacher RK, et al. (2016) Long-term Results of a Randomized Double-blinded Prospective Trial of a Lightweight (Ultrapro) Versus a Heavyweight mesh (Prolene) in Laparoscopic Total Extraperitoneal Inguinal Hernia Repair (TULP-trial). Ann Surg 263(5):862-866.

- Bury K, Smietanski M, Polish Hernia Study Group. (2012) Five-year results of a randomized clinical trial comparing a polypropylene mesh with a poliglecaprone and polypropylene composite mesh for inguinal hernioplasty. Hernia 16(5):549-553.

- Canonico S, Benevento R, Perna G, et al. (2013) Sutureless fixation with fibrin glue of lightweight mesh in open inguinal hernia repair: effect on postoperative pain: a double-blind, randomized trial versus standard heavyweight mesh. Surgery 153(1):126-130.

- Demetrashvili Z, Khutsishvili K, Pipia I, et al. (2014) Standard polypropylene mesh vs lightweight mesh for Lichtenstein repair of primary inguinal hernia: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Surg 12(12):1380-1384.

- Kalra T, Soni RK, Sinha A. (2017) Comparing Early Outcomes using Non Absorbable Polypropylene mesh and Partially Absorbable Composite mesh through Laparoscopic Transabdominal Preperitoneal Repair of Inguinal Hernia. J Clin Diagn Res 11(8):PC13-PC16.

- Lee SD, Son T, Lee JB, et al. (2017) Comparison of partially-absorbable lightweight mesh with heavyweight mesh for inguinal hernia repair: multicenter randomized study. Ann Surg Treat Res 93(6):322-330.

- Molegraaf M, Kaufmann R, Lange J. (2018) Comparison of self-gripping mesh and sutured mesh in open inguinal hernia repair: A meta-analysis of long-term results. Surgery 163 351360.

- Nikkolo C, Murruste M, Vaasna T, et al. (2012) Three-year results of randomised clinical trial comparing lightweight mesh with heavyweight mesh for inguinal hernioplasty. Hernia 16(5):555-559.

- Paajanen H, Ronka K, Laurema A. (2013) A single-surgeon randomized trial comparing three meshes in lichtenstein hernia repair: 2- and 5-year outcome of recurrences and chronic pain. Int J Surg 11(1):81-84.

- Paradowski T, Olejarz A, Kontny T, et al. (2009) Polypropylene vs. ePTFE vs. WN mesh for Lichtenstein inguinal hernia repair - A prospective randomized, double blind pilotstudy of one-year follow-up. Wideochir Inne Tech Ma?oinwazyjne 4(1):6-9.

- Pielacinski K, Szczepanik AB, Wroblewski T. (2013) Effect of mesh type, surgeon and selected patients' characteristics on the treatment of inguinal hernia with the Lichtenstein technique. Randomized trial. Wideochir Inne Tech Maloinwazyjne 8(2):99-106.

- Prakash P, Bansal VK, Misra MC, et al. (2016) A prospective randomised controlled trial comparing chronic groin pain and quality of life in lightweight versus heavyweight polypropylene mesh in laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair. J Minim Access Surg 12(2):154-161.

- Roos M, Bakker WJ, Schouten N, et al. (2018) Higher Recurrence Rate After Endoscopic Totally Extraperitoneal (TEP) Inguinal Hernia Repair With Ultrapro Lightweight mesh: 5-Year Results of a Randomized Controlled Trial (TULP-trial). Ann Surg 268(2):241-246.

- Rutegard M, Gumuscu R, Stylianidis G, et al. (2018) Chronic pain, discomfort, quality of life and impact on sex life after open inguinal hernia mesh repair: an expertise-based randomized clinical trial comparing lightweight and heavyweight mesh. Hernia 22(3):411-418.

- Sadowski B, Rodriguez J, Symmonds R, et al. (2011) Comparison of polypropylene versus polyester mesh in the Lichtenstein hernia repair with respect to chronic pain and discomfort. Hernia 15(6):643-654.

- Sajid MS, Leaver C, Baig MK, et al. (2012) Systematic review and meta-analysis of the use of lightweight versus heavyweight mesh in open inguinal hernia repair. Br J Surg. 99(1):29-37. doi: 10.1002/bjs.7718. Epub 2011 Oct 31. Review. PubMed PMID: 22038579.

- Sajid MS, Kalra L, Parampalli U, et al. (2013) A systematic review and meta-analysis evaluating the effectiveness of lightweight mesh against heavyweight mesh in influencing the incidence of chronic groin pain following laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair. Am J Surg 205(6):726-736. PubMed PMID: 23561639.

- Wong JC, Yang GP, Cheung TP, et al. (2018) Prospective randomized controlled trial comparing partially absorbable lightweight mesh and multifilament polyester anatomical mesh in laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair. Asian J Endosc Surg 11(2):146-150.

- Yazdankhah Kenary A, Afshin SN, Ahmadi Amoli H, et al. (2013) Randomized clinical trial comparing lightweight mesh with heavyweight mesh for primary inguinal hernia repair. Hernia 17(4):471-477.

Evidence tabellen

Evidence table for systematic review of RCTs and observational studies (intervention studies)

Research question: Which mesh is recommended for endoscopic and open inguinal hernia repair?

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C)

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

Open inguinal hernia repair |

|||||||

|

Sajid 2012

|

SR and meta-analysis of RCTs

Literature search up to May 2011

A: Bringman (2006) B: Champault (2007) C: Koch (2008) D: Nikkolo (2010) E: O’Dwyer (2005) F: Paajanen (2007) G: Post (2004) H: Smietanski (2008) I: Smietanski (2011) J: Torcivia (2011)

Study design: All RCTs

Setting and Country: A: Sweden and Finland B: France C: Sweden D: Estonia E: UK and Germany F: Finland G: Germany H: Poland I: Poland J: France

Source of funding: Not reported for the included trials or review

|

Inclusion criteria SR:

10 studies included

Important patient characteristics at baseline:

N, age (y) A: 494 patients LWM: 55 HWM: 55 B: 232 patients, 54 C: 317 patients LWM: 56 HWM: 57 D: 135 patients LWM: 59 HWM: 57 E: 321 patients LWM: 55 HWM: 57 F: 233 patients LWM: 56 HWM: 59 G: 108 patients LWM: 60 HWM: 62 H: 392 patients LWM: 56 HWM: 56 I: 182 patients LWM: 55 HWM: 58 J: 47 patients LWM: 54 HWM: 54

Sex: A: All male B: Mixed C: All male D: Mixed E: Mixed F: Mixed G: Mixed H: Mixed I: Mixed J: Mixed

|

Open inguinal hernia repair + Lightweight mesh (LWM)

LWM was defined as surgical mesh with a tensile strength of 16 N/cm, elasticity of 20–35 per cent at a tensile strength of 16 N/cm, pore size more than 1 mm, and containing woven lightweight polymers of biomaterial usually weighing less than 50 g/m2. |

Open inguinal hernia repair + Heavyweight mesh (HWM)

In all trials a polypropylene mesh was used. |

End-point of follow-up:

A: 37 months B: 24 months C: 12 months D: 6 months E: 12 months F: 24 months G: 6 months H: 12 months I: 60 months J: 30 days

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? Not reported

|

Outcome measure-1 Defined as chronic pain, measured as groin pain

Effect measure: RR, [95% CI]: A: 0.76 (0.56-1.05) B: 0.15 (0.04-0.58) C: 0.57 (0.19-1.65) D: 0.57 (0.27-1.22) E: 0.65 (0.49-0.87) F: 3.02 (0.37-24.64) G: 0.16 (0.02-1.32) H: Not reported, due to mistake (see: comments) I: 0.98 (0.14-6.80) J: 0.38 (0.18-0.82)

Pooled effect (fixed effects model): RR 0.61 [95% CI 0.50 to 0.74] favoring LWM. Heterogeneity (I2): 31%

Outcome measure-2 Defined as recurrence

Effect measure: RR, [95% CI]: A: 4.36 (0.95-19.96) B: 1.13 (0.23-5.41) C: 2.06 (0.19-22.53) D: Not estimable E: 7.85 (0.99-62.06) F: 0.75 (0.13-4.42) G: 0.83 (0.12-5.66) H: Not reported, due to mistake (see: comments) I: 0.33 (0.03-3.08)

Pooled effect (fixed effects model): RR 1.82 [95% CI 0.97 to 3.42] favoring HWM. Heterogeneity (I2): 19%

|

Mistake in review detected: Smietanski (2011) is not 5 year follow-up of Smietanski (2008) as wrongly interpreted by Sajid. Smietanski (2011) is original, not previously published, data with a different LWM. Bury (2012) is 5 year follow-up of Smietanski (2008).

Study J was not included in current meta-analyses: J: Only 1 months follow-up

|

|

Endoscopic inguinal hernia repair |

|||||||

|

Sajid 2013

|

SR and meta-analysis of RCTs

Literature search up to June 2011

A: Agarwal (2009) B: Bittner (2011) C: Bittner (2011)* D: Bringman (2005) E: Champault (2007) F: Chowbey (2010) G: Chui (2010) H: Heikkinen (2006) I: Langenbach (2006) J: Langenbach (2008) K: Peeters (2010)

Study design: All RCTs

Setting and Country: A: India B: Germany C: Germany D: Sweden and Finland E: France F: India G: China H: Sweden I: Germany J: Germany K: Belgium

Source of funding: Not reported for the included trials or review

|

Inclusion criteria SR: RCTs comparing the effectiveness of LWM versus HWM (both short-term and long-term outcomes) in patients undergoing LIHR with TEP or TAPP approach. Irrespective of language, country of origin, hospital of origin, blinding, sample size, or publication status.

11 studies included

Important patient characteristics at baseline:

N, age (y) A: 50 patients, 62 B: 300 patients LWM: 53 HWM 52 C: 600 patients LWM: 59 HWM 57 D: 139 patients LWM: 55 HWM 55 E: 137 patients, 54 F: 402 patients LWM: 53 HWM: 52 G: 100 patients, 61 H: 137 patients LWM: 60 HWM: 59 I: 90 patients LWM: 64 HWM: 65 J: 175 patients LWM: 62 HWM: 63 K: 59 patients LWM: 43 HWM: 34

Sex: A: Mixed B: Mixed C: Mixed D: All male E: All male F: Mixed G: Mixed H: All male I: All male J: All male K: All male |

Describe intervention:

A: TEP + 12 X 15-cm polypropylene mesh Weight: lightweight B: TAPP + 10 X 15-cm titanium coated polypropylene Weight: 16 g/m2 C: TAPP + 10 X 15-cm - Titanium coated polypropylene Weight: 35 g/m2 - Polypropylene Weight: 55 g/m2 - Polypropylene-poliglecaprone Weight: 28 g/m2 D: TEP + 12 X 15-cm Vypro II Weight: lightweight E: TEP + 7.5 X 15-cm Polypropylene-beta-glucan Weight: 50 g/m2 F: TEP + 12 X 15-cm Polypropylene-poliglecaprone Weight: 28 g/m2 G: TEP + Polypropylene-polyvinylidene fluoride Weight: 60 g/m2 H: TEP + 12 X 15-cm Polypropylene -Polyglactin mesh (VYPRO II) I: TAPP + 12 X 15-cm Polypropylene -Polyglactin mesh (VYPRO II) Weight: 55 g/m2 J: TAPP + 10 X 15-cm Polypropylene -Polyglactin mesh Weight: 35 g/m2 K: TEP + 13 X 15-cm Polypropylene -Polyglactin mesh Weight: 30 g/m2 TiMesh Weight: 35 g/m2

|

Describe control:

A: TEP + 12 X 15-cm polypropylene (HW) mesh Weight: Heavyweight B: TAPP + 10 X 15-cm polypropylene (HW) mesh Weight: 90 g/m2 C: TAPP + 10 X 15-cm polypropylene (HW) mesh Weight: 90 g/m2 D: TEP + 12 X 15-cm polypropylene mesh Weight: heavyweight E: TEP + 7.5 X 15-cm polypropylene mesh Weight: 105 g/m2 F: TEP + 2 X 15-cm polypropylene mesh Weight: 105 g/m2 G: TEP + polypropylene mesh Weight: heavyweight (>50 g/m2) H: TEP + 12 x 15-cm polypropylene mesh I: TAPP + 12 x 15-cm polypropylene double-filament mesh Weight: 108 g/m2 polypropylene multifilament mesh Weight: 116 g/m2 J: TAPP + 10 X 15-cm polypropylene double-filament mesh Weight: 108 g/m2 polypropylene multifilament mesh Weight: 116 g/m2 K: TEP + 13 X 15-cm polypropylene mesh Weight: 95 g/m2

|

End-point of follow-up: A: 16 months B: 12 months C: 12 months D: 2 months E: 24 months F: 12 months G: 12 months H: 2 months I: 3 months J: 60 months K: 12 months

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? Not stated

|

Outcome measure-1 Defined as chronic pain, measured as groin pain

Effect measure: RR [95% CI]: B: 0.69 (0.31-1.57) C: 0.39 (0.18-0.82) D: 0.34 (0.01-8.16) E: 0.35 (0.10-1.20) F: 0.33 (0.09-1.19) J: 0.40 (0.02-8.20) K: 1.28 (0.27-6.03)

Pooled effect (fixed effects model): 0.48 [95% CI 0.31 to 0.75] favoring LWM Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

Outcome measure-2 Defined as recurrence.

Effect measure: RR, RD, mean difference [95% CI]: A: Not estimable B: 3.00 (0.12-73.06) D: Not estimable E: 1.40 (0.09-21.97) F: 5.52 (0.65-46.86) J: 1.01 (0.09-10.90) K: Not estimable

Pooled effect (fixed effects model): 2.01 [95% CI 0.71 to 5.67] favoring HWM Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

|

Mistake in review detected: C: Sajid included the mesh of 55 g/m2 as a LWM. For current analysis this was adjusted for and the mesh was not included in meta-analyses.

Studies G, H and I not included in meta-analyses of Sajid: G: No LWM H: Only 2 months follow-up I: No LWM

In current analysis in addition study D was excluded from meta-analysis because follow-up was only 2 months.

|

Evidence table for intervention studies (randomized controlled trials and non-randomized observational studies (cohort studies, case-control studies, case series))1

Research question: Which mesh is recommended for endoscopic inguinal hernia repair?

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics 2 |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C) 3

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size 4

|

Comments |

|

Burgmans 2015 |

Type of study: Double-blind RCT

Setting: Single-center

Country: Netherlands

Source of funding: Research grant Johnson & Johnson |

Inclusion criteria: >18 years. Primary unilateral inguinal hernia. No contra-indications TEP-repair.

Exclusion criteria: Collagen or connective tissue disorders. Unlikely cooperation.

N total at baseline: Intervention: 478 Control: 471

Important prognostic factors2: Median age (range): I: 55 (19-88) C:55 (18-94)

Sex: I: 100% M C: 100% M

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes. |

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

TEP repair + LWM Polypropylene (Ultrapro, 28 g/m2)

Fixation: None.

|

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

TEP repair + HWM Polypropylene (Prolene, 80 g/m2)

Fixation: None.

|

Length of follow-up: 3 months

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: N=15 (3,2%) Reasons (describe): 1 wrongly randomized 8 no respons 4 complications 1 died 1 time consuming

Control: N=17 (3,6%) Reasons (describe): 3 wrongly randomized 5 no respons 2 complications 2 died 1 time consuming 3 not satisfied 1 leukemia |

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Any pain (NRS1-10): I: n=86 (18.6%) C: n=89 (19.6%) p-value: 0.65

Foreign body feeling: I: n=93 (20.0%) C: n=80 (17.6%) p-value: 0.56

Recurrences: I: n=2 (0.4%) C: n=2 (0.4%) p-value: 1.000

|

|

|

Burgmans 2016 |

Type of study: Double-blind RCT

Setting: Single-center. Country: Netherlands

Source of funding: Research grant Johnson & Johnson |

Inclusion criteria: >18 years. Primary unilateral inguinal hernia. No contra-indications TEP-repair.

Exclusion criteria: Collagen or connective tissue disorders. Unlikely cooperation.

N total at baseline: Intervention: 478 Control: 471

Important prognostic factors2: Median age (range): I: 55 (19-88) C:55 (18-94)

Sex: I: 100% M C: 100% M

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes. |

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

TEP repair + LWM Polypropylene (Ultrapro, 28 g/m2)

Fixation: None.

|

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

TEP repair + HWM Polypropylene (Prolene, 80 g/m2)

Fixation: None.

|

Length of follow-up: 24 months

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: N=38 (7,9%) Reasons (describe): Not reported.

Control: N=44 (9,3%) Reasons (describe): Not reported.

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Any pain 1 year (NRS1-10): I: n=52 (11.5%) C: n=48 (10.9%)

Any pain 2 year (NRS1-10): I: n=65 (14.8%) C: n=47 (11.0%)

Foreign body feeling 1 year: I: n= 60 (13.8%) C: n=54 (12.2%) p-value: 0.49

Foreign body feeling 2 years: Percentages unchanged.

Recurrences 2 years: I: n=13 (2.7%) C: n=4 (0.8%) p-value: 0.03

|

2 year follow-up of previous study by Burgmans et al (2015). |

|

Prakash 2016 |

Type of study: Single-blind RCT

Setting: Single-center

Country: India

Source of funding: No funding. |

Inclusion criteria: Age 18-60. ASA I/II. Unilateral or bilateral primary inguinal hernia.

Exclusion criteria: Previous inguinoscrotal surgery. Significant co-morbidities. Obstructed/strangulated inguinal hernia.

N total at baseline: Intervention: 70 Control: 70

Important prognostic factors2: Mean age ± SD: I: 47.1 ± 15.4 C: 43.2 ± 17.3 p-value: 0.24

TEP/TAPP (%): I: 34 (51.5) / 30 (45.5) C: 35 (53.8) / 29 (44.6) p-value: 0.75

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes. |

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

Laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair (TEP/TAPP) + LWM Polypropylene (Prolene soft, 30-45 g/m2) Fixation: None.

|

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

Laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair (TEP/TAPP) + HWM Polypropylene (3D max large, 80-85 g/m2)

Fixation: None.

|

Length of follow-up (mean ± SD): I: 9.8 ± 3.8 months C: 10.1 ± 3.8 months

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: N=5 (7,1%) Control: N=4 (5.7%) Reasons: Not reported.

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Chronic relevant pain (VAS 4-10): I: n=2 (3%) C: n=2 (3%)

Any pain 1 year: 2.3% overall.

Mean ± SD pain 1 year (1-10): I: 0.07 ± 0.2 C: 0.03 ± 0.2 p-value: 0.54

Foreign body feeling 1 year: I: n= 10 (15.4%) C: n=14 (21.2%) p-value: 0.49

Recurrences 1 year: I: n=1 (1.5%) C: n=0 (0.0%) |

|

|

Kalra 2017 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting: Multi-center

Country: India

Source of funding: No funding.

|

Inclusion criteria: Age 15-60 years. Unilateral, reducible inguinal hernia.

Exclusion criteria: Emergency setting. Strangulated, recurrent hernia. Contraindications to endoscopic surgery.

N total at baseline: Intervention: 30 Control: 30

Important prognostic factors2: Mean age ± SD: I: 39.6 ± 11.3 C: 44.2 ± 10.5

Sex: 95% male.

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

TAPP + LWM Polypropylene (Ultrapro, 28 g/m2)

Fixation: Tacks. |

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

TAPP + HWM Polypropylene (3D BARD Max Mesh, 80-100 g/m2)

Fixation: Tacks. |

Length of follow-up: 3 months

Loss-to-follow-up: Not reported.

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Pain (mean VAS score ± SD): I: 2.73 ± 0.944 C: 3.53 ± 0.973 p-value: 0.003

Foreign body sensation 3 months: I: n=5 (16.7%) C: n=11 (36.6%) |

|

|

Wong 2017

|

Type of study: Double-blind RCT

Setting: Single-center

Country: China

Source of funding: No financial ties. |

Inclusion criteria: Age 18-81. Primary uncomplicated unilateral or bilateral inguinal hernia.

Exclusion criteria: Inguino-scrotal hernia. Sliding hernia. Lower abdominal scar. Using anti-coagulant. Bleeding diathesis. Chronic liver disease with ascites or portal hypertension.

N total at baseline: Intervention: 42 Control: 43

Important prognostic factors2: age median (range): I: 62 (27-81) C: 58 (35-78)

Sex: I: 92.3% M C: 100% M

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes. |

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

TEP + LWM Polypropylene-poliglecaprone (Ultrapro, 28 g/m2)

Fixation: None.

|

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

TEP + HWM Polyester multifilament (Parietex, 116 g/m2)

Fixation: None.

|

Length of follow-up: Mean 20.3 months

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: N=4 (9.3%) Control: N=4 (9.5%) Reasons (describe): Not reported.

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Recurrences: I: n=2 (5.1%) C: n=0 (0.0%) p-value: 0.157

Foreign body sensation while resting 1 year: I: n=2 (5.1%) C: n=0 (0%) p-value: 0.16 |

|

|

Roos 2018 |

Type of study: Double-blind RCT

Setting: Single-center

Country: Netherlands

Source of funding: Research grant Johnson & Johnson |

Inclusion criteria: >18 years. Primary unilateral inguinal hernia. No contra-indications TEP-repair.

Exclusion criteria: Collagen or connective tissue disorders. Unlikely cooperation.

N total at baseline: Intervention: 478 Control: 471

Important prognostic factors2: Median age (IQR): I: 55 (45-64) C: 56 (44-64)

Sex: I: 100% M C: 100% M

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes. |

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

TEP repair + LWM Polypropylene (Ultrapro, 28 g/m2)

Fixation: None.

|

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

TEP repair + HWM Polypropylene (Prolene, 80 g/m2)

Fixation: None.

|

Length of follow-up: 60 months

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: N=76 (15.9%) Reasons (describe): 1 Wrongly randomized 13 Death 4 Complications 3 Disease unrelated to hernia repair 6 Withdrawal consent 49 Unresponsiveness.

Control: N=83 (17.6%) Reasons (describe): 3 Wrongly randomized 13 Death 2 Complications 2 Disease unrelated to hernia repair 11 Withdrawal consent 52 Unresponsiveness.

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Recurrences after 5 years: I: n=18 (3.8%) C: n=5 (1.1%) p-value: 0.01

|

5 year follow-up of previous studies by Burgmans et al (2015/2016). |

Notes:

- Prognostic balance between treatment groups is usually guaranteed in randomized studies, but non-randomized (observational) studies require matching of patients between treatment groups (case-control studies) or multivariate adjustment for prognostic factors (confounders) (cohort studies); the evidence table should contain sufficient details on these procedures.

- Provide data per treatment group on the most important prognostic factors ((potential) confounders).

- For case-control studies, provide sufficient detail on the procedure used to match cases and controls.

- For cohort studies, provide sufficient detail on the (multivariate) analyses used to adjust for (potential) confounders.

Evidence table for intervention studies (randomized controlled trials and non-randomized observational studies (cohort studies, case-control studies, case series))1

Research question: Which mesh is recommended for open inguinal hernia repair?

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics 2 |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C) 3

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size 4 |

Comments |

|||||

|

Paradowski 2009 |

Type of study: Double-blind RCT

Setting: Single-center

Country: Poland

Source of funding: Not reported. |

Inclusion criteria: >18 years. Primary inguinal hernia.

Exclusion criteria: Femoral hernia. Emergency operation. Skin infection groin.

N total at baseline: Intervention: 25 Control: 25

Important prognostic factors2: Age, mean ± SD: I: 59. C: 53.9

Sex: I: 100% M C: 84% M

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes, although minimally reported. |

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

Lichtenstein + LWM polyporpylene (Surgimesh WN, 43 g/m2)

Fixation: Not reported. |

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

Lichtenstein + HWM Polypropylene (Surgipro, 80 g/m2)

Fixation: Not reported. |

Length of follow-up: 12 months

Loss-to-follow-up: Overall: 3 months: 100% 12 months: 96% Reasons (describe) Not reported.

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

VAS score 3 months (mean ± SD): I: 0.46 ± 1.22 C: 0.56 ± 1.13 p-value: 0.673

Any pain 3 months(VAS 1-10) I: n=1 (4%) C: n=4 (16%)

Any pain 12 months(VAS 1-10) I: n=0 (0%) C: n=1 (4%)

Recurrences 12 months: I: 0 C: 0

|

|

|||||

|

Sadowski 2011 |

Type of study: Single-blind RCT

Setting: Single-center

Country: USA

Source of funding: Not reported. |

Inclusion criteria: >18 years. Primary inguinal hernia.

Exclusion criteria: Pregnancy. Previous inguinal surgery. Cognitive disorder.

N total at baseline: Intervention: 39 Control: 39

Important prognostic factors2: Age, mean ± SD: I: 54 ± 17. C: 56 ± 16.4

Sex: I: 97% M C: 97% M

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes. |

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

Lichtenstein + LWM Polyester (±40 g/m2)

Fixation: Not reported. |

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

Lichtenstein + HWM Polypropylene (80-100 g/m2)

Fixation: Not reported. |

Length of follow-up: 3 months

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: N=4 (10.3%) Control: N=4 (10.3%) Reasons (describe) Not reported.

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

VAS score 3 months (mean ± SD): I: 0.46 ± 1.22 C: 0.56 ± 1.13 p-value: 0.673

Any pain 3 months(VAS 1-10) I: n=6 (17.65%) C: n=8 (23.53%) p-value: 0.5486 |

3 months publication of 2 years of planned follow-up (never published). |

|||||

|

Bury 2012 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting: Multi-center

Country: Poland

Source of funding: Minor grand Ethicon Poland. |

Inclusion criteria: 20-75 years. Primary, unilateral inguinal hernia.

Exclusion criteria: Active treatment for serious comorbidity. Trombocytopenia. Mental illness. Pregnancy.

N total at baseline: Intervention: 215 Control: 177

Important prognostic factors2: Age, median (range): I: 56 (18-80) C: 56 (23-87)

Sex: I: 98.6% M C: 97.7% M

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes. |

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

Lichtenstein + LWM Polypropylene (Ultrapro, 28 g/m2)

Fixation: Three suturing modifications necessary due to mesh specifications. |

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

Lichtenstein + HWM Polypropylene (Prolene, 80 g/m2)

Fixation: Sutures. |

Length of follow-up: 60 months

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: N=20 (9.3%) Reasons (describe) 13 death 4 recurrences

Control: N=16 (9.0%) Reasons (describe) 11 death 1 recurrences

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Recurrences 5 years: I: 1.86% C: 0.57% p-value: 0.493

Pain 5 years: I: n=5 C: n=4

Mean VAS: I: 2.25 (range 2-3) C: 2.4 (range 2-3) Not significant |

5 year follow-up of Smietanski (2008) (see: review Sajid (2012)) |

|||||

|

Nikkolo 2012 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting: Single-center

Country: Estonia

Source of funding: Not reported. |

Inclusion criteria: >18 years. Primary, unilateral inguinal hernia.

Exclusion criteria: Irreducible, strangulated hernia.

N total at baseline: Intervention: 69 Control: 66

Important prognostic factors2: Mean age ± SD: I: 59.2 C: 59.7

Sex: I: 91.0% M C: 93.8% M

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes. |

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

Lichtenstein + LWM Polypropylene (Optilene, 36 g/m2)

Fixation: Sutures. |

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

Lichtenstein + HWM Polypropylene (Premilene, 82 g/m2)

Fixation: Sutures. |

Length of follow-up: 36 months

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: N= 11 (15.9%) Reasons (describe) 5 did not attend follow-up. 5 death 1 recurrence

Control: N= 8 (12.1%) Reasons (describe) 4 did not attend follow-up. 3 death 1 recurrence

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Any pain 6 months: I: 47.8% C: 59.4%

Any pain 3 years: I: n=17 (29.3%) C: n=10 (17.2%) p-value: 0.1323

Median VAS (0-100) 3 years: I: 30.0 C: 30.5

Foreign body feeling: I: 20.7% C: 27.6% p-value: 0.3967

Recurrences 3 years: I: n=1 (1.7%) C: n=1 (1.7%) |

3 years follow-up of Nikkolo et al. (2010) (see: review Sajid (2012)) |

|||||

|

Canonico 2012 |

Type of study: Double-blind RCT

Setting: Single-center

Country: Italy

Source of funding: Not reported. |

Inclusion criteria: >18 years. BMI <35 kg/m2. Uncomplicated primary, unilateral inguinal hernia.

Exclusion criteria: Large hernias (M3 or L3). Concurrent diabetes, immunologic or psychiatric disorders, hypertensitivity to aprotinin. Patients taking anti-inflammatory drugs.

N total at baseline: Intervention: 40 Control: 40

Important prognostic factors2: Mean age ± SD: I: 63 ± 12 C: 66 ± 10 p-value: >0.99

Sex: I: 90% M C: 80 % M p-value: 0.34

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes. |

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

Lichtenstein + LWM Polypropylene (Evolution P3EM, 48 g/m2).

Fixation: Human fibrin glue. |

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

Lichtenstein + HWM Polypropylene (Prolene, 80 g/m2).

Fixation: Human fibrin glue. |

Length of follow-up: 6 months

Loss-to-follow-up: Not reported.

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Recurrences 6 months: I: n=0 C: n=0

|

|

|||||

|

Paajanen 2012 |

Type of study: Double-blind RCT

Setting: Multi-center

Country: Finland

Source of funding: None declared. |

Inclusion criteria: Uni- or bilateral primary or recurrent inguinal hernias.

Exclusion criteria: Recurrent hernias: no mesh repair.

N total at baseline: Intervention: 104 Control: 101

Important prognostic factors2: Mean age ± SD: I: 58 ± 14 C: 61 ± 15

Sex: I: 94.2% M C: 92.1% M

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes. |

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

Lichtenstein + LWM partly absorbable polypropylene-polyglactin (Vypro II, 50 g/m2)

Lichtenstein + LWM polypropylene (Premilene Mesh LP, 55 g/m2)

Fixation: Sutures. |

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

Lichtenstein + HWM polypropylene (Premilene, 82 g/m2)

Fixation: Sutures. |

Length of follow-up: 56 months

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: N=27 (21.2%) Reasons (describe) 11 death 16 not reached

Control: N=27 (26.7%) Reasons (describe) Not given.

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Pain 5 years: I: n=10 (12.9%) C: n=12 (16.2%)

Recurrences 5 years: I: n=3 (3.9%) C: n=3 (4.1%) p-value: 0.8209 |

5 year follow-up of Paajanen et al (2007). (see: review Sajid (2012))

Mesh of 55 g/m2 not applicable for meta-analysis. |

|||||

|

Pielaciński 2013 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting: Not reported.

Country: Poland

Source of funding: Not reported. |

Inclusion criteria: >18 years. Uni- or bilateral, primary or recurrent inguinal hernia.

Exclusion criteria: Other changes in groin or scrotum.

N total at baseline: Intervention: 73 Control: 76

Important prognostic factors2: Median age (range): I:58 (24-87) C:59 (20-89)

Sex: I: 100% M C: 100% M

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes. |

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

Lichtenstein + LWM partially absorbable composite; polypropylene-polyglactin (35 g/m2)

Fixation: Sutures. |

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

Lichtenstein + HWM non-absorbable polypropylene (100 g/m2)

Fixation: Sutures. |

Length of follow-up: 6 months

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: N=17 (23%) Reasons (describe) (does not add up): 5 Intra-operative damage of anatomical structures 9 Post-operative complications or worsening of general condition. 2 recurrence 3 did not show

Control: N=22 (29%) Reasons (describe) (does not add up): 4 Intra-operative damage of anatomical structures 7 Post-operative complications or worsening of general condition. 2 recurrence 7 did not show |

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Recurrences 6 months: I: n=2 (2.94%) C: n=2 (2.81%) OR: 0.97 (0.132-7.093) p-value: 0.977

Pain 6 months (VAS 2-4): I: n=3 (5.4%) C: n=7 (13%)

Foreign body feeling 6 months: I: 17 (30%) C: 23 (43%)

|

Pielaciński (2011) was also encountered in search. After full-text screening this study was interpreted as preliminary data of Pielaciński (2013). |

|||||

|

Yazdankhah Kenary 2013 |

Type of study: Double-blind RCT

Setting: Single-center

Country: Iran

Source of funding: Not reported. |

Inclusion criteria: >18 years. Primary unilateral inguinal hernia.

Exclusion criteria: Inability to walk >500m. Probable loss to follow-up. Irreducible or strangled hernia.

N total at baseline: Intervention: 55 Control: 55

Important prognostic factors2: Mean age ± SD: I: 50.4 ± 16.1 C: 44.0 ± 15.9

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes. |

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

Lichtenstein + LWM Polypropylene (Dynamesh, 36 g/m2)

Fixation: Sutures. |

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

Lichtenstein + HWM Polypropylene (Dynamesh, 72 g/m2)

Fixation: Sutures. |

Length of follow-up: 12 months

Loss-to-follow-up: No loss to follow-up.

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Foreign body feeling 1 year: I: n=0 (0%) C: n=7 (12.7%) p-value: 0.007

Recurrences 1 year: I: n=1 (1.9%) C: n=0 (0%) p-value: 0.3

Pain 6 month: I: n=9 (6.7%) C: n=12 (21.8%) (mean VAS ± SD): I: 2.2 ± 1.2 C: 2.2 ± 0.8 p-value: 0.9

Pain 1 year: I: n=4 (7.4%) C: n=3 (5.5%) (mean VAS ± SD): I: 1.7 ± 0.5 C: 2.2 ± 1.2 p-value: 0.5 |

|

|||||

|

Demetrashvili 2014) |

Type of study: Single-blind RCT

Setting: Single-center

Country: Georgia

Source of funding: None. |

Inclusion criteria: >18 years. Primary unilateral inguinal hernia.

Exclusion criteria: Irreducible or strangulated hernia.

N total at baseline: Intervention: 113 Control: 113

Important prognostic factors2: Mean age ± SD: I: 54.7 ± 14.3 C: 51.3 ± 17.5 p-value: 0.14

Sex: I: 93.8% M C: 90.2% M

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes. |

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

Lichtenstein + LWM Polypropylene (Ultrapro, 28 g/m2)

Fixation: Sutures. |

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

Lichtenstein + HWM Polypropylene (Prolene, 82 g/m2)

Fixation: Sutures. |

Length of follow-up: 36 months

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: N=17 (15%) Reasons (describe) 4 death 12 absence of examination 1 recurrence

Control: N=11 (9.7%) Reasons (describe) 3 death 7 absence of examination 1 recurrence

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Foreign body feeling 3 years: I: n=1 (1.1%) C: n=9 (9.4%) p-value: 0.02

Recurrences 3 years: I: n=1 (1.04%) C: n=1 (0.98%) p-value: 0.99

Pain 3 month: I: n=10 (10.4%) C: n=12 (11.8%) p-value: 0.82 (mean VAS ± SD): I: 2.5 ± 1.4 C: 2.4 ± 1.3 p-value: 0.82

Pain 1 year: I: n=6 (6.3%) C: n=9 (8.8%) p-value: 0.60 (mean VAS ± SD): I: 2.2 ± 1.2 C: 2.4 ± 1.2 p-value: 0.70

Pain 3 years: I: n=2 (2.1%) C: n=5 (4.9%) p-value: 0.45 (mean VAS ± SD): I: 2.0 ± 1.4 C: 2.4 ± 1.1 p-value: 0.71 |

|

|||||

|

Lee 2017 |

Type of study: Single blind RCT

Setting: Multicenter

Country: Korea

Source of funding: None |

Inclusion criteria: Male. Age 20-85 years. Primary unilateral inguinal hernia.

Exclusion criteria: Incarcerated or strangulated hernia. Previous urologic or inguinal surgery. Immune disease. Thromboembolic disease or treatment. Hepatic or renal disease. Malignancy.

N total at baseline: Intervention: 25 Control: 25

Important prognostic factors2: Median age (range): I: 64 (24-83) C: 64 (30-76)

Sex: I: 100% M C: 100% M

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes. |

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

Lichtenstein + LWM Partially absorbable lightweight polypropylene-poligecaprone (Proflex, 28-29 g/m2)

Fixation: Sutures. |

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

Lichtenstein + HWM Polypropylene (Marlex, 100 g/m2)

Fixation: Sutures. |

Length of follow-up: 4 months

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: N=1 (4%) Reasons (describe) 1 Adverse event

Control: N=2 (8%) Reasons (describe) 1 withdrawal consent 1 loss to follow-up

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Recurrences 4 months: I: n=0 C: n=0

Foreign body feeling 4 months: I: n=1 (4.2%) C: n=7 (30.4%) p-value: 0.023

Pain (mean VAS ± SD) 4 month: I: 0.7 ± 1.1 C: 0.8 ± 1.4 p-value: 0.746 |

|

|||||

|

Rutegård 2017 |

Type of study: Not-blinded RCT

Setting: Multi-center

Country: Sweden

Source of funding: Västerbotten County Council, VISARE NORR Fund, Northern Country Councils Regional Federation. |

Inclusion criteria: Male. >25 years. Unilateral inguinal hernia.

Exclusion criteria: Bleeding disorders. Use of anti-coagulantia.

N total at baseline: Intervention: 197 Control: 194

Important prognostic factors2: Mean age ± SD: I: 59.1 ± 12.7 C: 58.4 ± 13.0

Sex: I: 100% M C: 100% M

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes. |

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

Lichtenstein + LWM Polypropylene (Ultrapro, 28 g/m2)

Fixation: Not reported. |

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

Lichtenstein + HWM Polypropylene (Bard Flatmesh, 90 g/m2)

Fixation: Not reported. |

Length of follow-up: 12 months

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: N=9 (4.6%) Reasons (describe) 4 Declined follow-up 5 Excluded from analysis

Control: N=19 (9.6%) Reasons (describe) 13 Declined follow-up 2 Operation non-participating hospital. 4 Excluded from analysis

Incomplete outcome data: Intervention: N 36-52 (19.5-28.1%) Reasons (describe) Not reported.

Control: N 34-52 (19.1-29.2%) Reasons (describe) Not reported. |

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Recurrences 1 year: I: 4 (2.2%) C: 4 (2.2%)

Foreign body feeling 1 year: I: 34 (23.6%) C: 21 (14.1%) p-value: 0.051

|

Pain presented on a “worse, no change, better”-scale. Therefore, not applicable for meta-analysis. |

|||||

|

Bona 2018

|

Type of study: Single-blind RCT

Setting: Multi-center

Country: Italy

Source of funding: Not reported. |

Inclusion criteria: >18 years. Primary reducible uni- or bilateral inguinal hernia. No contraindications open inguinal hernia repair.

Exclusion criteria: Emergency surgery.

N total at baseline: Intervention: 411 Control: 397

Important prognostic factors2: Mean age (IQR I-III): I: 59 (47-69) C: 61 (50-70)

Sex: I: 95% M C: 95% M

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes. |

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

Lichtenstein + LWM Polypropylene (Ultrapro, 28 g/m2)

Fixation: Not reported. |

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

Lichtenstein + HWM Polypropylene (80-100 g/m2)

Fixation: Not reported. |

Length of follow-up: 12 months

Loss-to-follow-up 6 months (not further reported): Intervention: N=86 (20.9%) Control: N=80 (20.2%) Reasons (describe) Not reported.

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Pain 6 months: I: n=80 (24.6%) C: n=83 (26.2%) p-value: 0.76 p-value adjusted for baseline characteristics: 0.04

Recurrences 6 months: I: n=0 C: n=0

|

|

|||||

Notes:

- Prognostic balance between treatment groups is usually guaranteed in randomized studies, but non-randomized (observational) studies require matching of patients between treatment groups (case-control studies) or multivariate adjustment for prognostic factors (confounders) (cohort studies); the evidence table should contain sufficient details on these procedures.

- Provide data per treatment group on the most important prognostic factors ((potential) confounders).

- For case-control studies, provide sufficient detail on the procedure used to match cases and controls.

- For cohort studies, provide sufficient detail on the (multivariate) analyses used to adjust for (potential) confounders.

Table of quality assessment for systematic reviews of RCTs and observational studies

Based on AMSTAR checklist (Shea, 2007; BMC Methodol 7: 10; doi:10.1186/1471-2288-7-10) and PRISMA checklist (Moher, 2009; PLoS Med 6: e1000097; doi:10.1371/journal.pmed1000097)

|

Study

First author, year |

Appropriate and clearly focused question?1

Yes/no/unclear |

Comprehensive and systematic literature search?2

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of included and excluded studies?3

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of relevant characteristics of included studies?4

Yes/no/unclear |

Appropriate adjustment for potential confounders in observational studies?5

Yes/no/unclear/notapplicable |

Assessment of scientific quality of included studies?6

Yes/no/unclear |

Enough similarities between studies to make combining them reasonable?7

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential risk of publication bias taken into account?8

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential conflicts of interest reported?9

Yes/no/unclear |

|

Sajid 2012 |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

NA |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

No |

|

Sajid 2013 |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

NA |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

No |

- Research question (PICO) and inclusion criteria should be appropriate and predefined.

- Search period and strategy should be described; at least Medline searched; for pharmacological questions at least Medline + EMBASE searched.

- Potentially relevant studies that are excluded at final selection (after reading the full text) should be referenced with reasons.

- Characteristics of individual studies relevant to research question (PICO), including potential confounders, should be reported.

- Results should be adequately controlled for potential confounders by multivariate analysis (not applicable for RCTs).

- Quality of individual studies should be assessed using a quality scoring tool or checklist (Jadad score, Newcastle-Ottawa scale, risk of bias table et cetera).

- Clinical and statistical heterogeneity should be assessed; clinical: enough similarities in patient characteristics, intervention and definition of outcome measure to allow pooling? For pooled data: assessment of statistical heterogeneity using appropriate statistical tests (For example. Chi-square, I2)?

- An assessment of publication bias should include a combination of graphical aids (For example funnel plot, other available tests) and/or statistical tests (For example Egger regression test, Hedges-Olken). Note: If no test values or funnel plot included, score “no”. Score “yes” if mentions that publication bias could not be assessed because there were fewer than 10 included studies.

- Sources of support (including commercial co-authorship) should be reported in both the systematic review and the included studies. Note: To get a “yes,” source of funding or support must be indicated for the systematic review AND for each of the included studies.

Risk of bias table for intervention studies (randomized controlled trials)

Research question: Which mesh is recommended for endoscopic inguinal hernia repair?

|

Study reference

(first author, publication year) |

Describe method of randomisation1 |

Bias due to inadequate concealment of allocation?2

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate blinding of participants to treatment allocation?3

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate blinding of care providers to treatment allocation?3

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate blinding of outcome assessors to treatment allocation?3

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to selective outcome reporting on basis of the results?4

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to loss to follow-up?5

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to violation of intention to treat analysis?6

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

|

Burgmans 2015 |

Computer generated. |

Unlikely |

Unlikely; patients were blinded for allocation of mesh type. |

Likely; blinding of care providers was not possible. |

Unlikely; researchers were blinded for allocation of mesh type. |

Unlikely |

Unlikely; 3.2%/3.6% in 3 months of follow-up. |

Unlikely; all data were analysed on an intention-to-treat basis. |

|

Burgmans 2016 |

Computer generated. |

Unlikely |

Unlikely; patients were blinded for allocation of mesh type. |

Likely; blinding of care providers was not possible. |

Unlikely; researchers were blinded for allocation of mesh type. |

Unlikely |

Unlikely; 7.9%/9.3% in 2 years of follow-up. |

Unlikely; all data were analysed on an intention-to-treat basis. |

|

Prakash 2016 |

Computer generated. |

Unlikely |

Unlikely; patients were blinded for allocation of mesh type. |

Likely; blinding of care providers was not possible. |

Likely; single-blinded study only for patients. |

Unlikely |

Unlikely; 7.1%/5.7% in 1 year of follow-up.

|

Unlikely; not reported, however unlikely due to inability to cross-over. |

|

Kalra 2017 |

Sealed envelope system. |

Unlikely |

Unclear; not reported. |

Likely; blinding of care providers was not possible. |

Unclear; not reported. |

Unlikely |

Unclear; not reported. |

Unlikely; not reported, however unlikely due to inability to cross-over. |

|

Wong 2017 |

Not reported. |

Unlikely |

Unclear; double-blinded, yet no further report on the method used. |

Likely; blinding of care providers was not possible. |

Unlikely; surgeons assigned to do postoperative assessment were blind to the type of mesh used. |

Unlikely |

Likely; 9.3%/9.5% in 20 months of follow-up. |

Unlikely; not reported, however unlikely due to inability to cross-over. |

|

Roos 2018 |

Computer generated. |

Unlikely |