Fixatie mat bij laparo-endoscopie liesbreuk

Uitgangsvraag

Is het nodig om de mat te fixeren bij een laparo-endoscopische liesbreukoperatie (TEP, TAPP)? Zo ja, welk type fixatie heeft de voorkeur?

Aanbeveling

Bij een TEP of TAPP liesbreukoperatie:

- Fixeer de mat alleen bij patiënten met een grote directie hernia (M3-EHS classificatie) om de recidiefkans te verkleinen. Gebruik tackers om de mat aan het ligament van Cooper en/of de buikwand (achterste rectus, mediaal van de epigastrische vaten) te fixeren.

- Overweeg bij een grote mediale breuk om de breukzak te inverteren en het met tackers vast te zetten aan het ligament van Cooper of aan de achterzijde van de musculus rectus of om de achterwand te reven met een hechting.

Het wordt chirurgen aanbevolen zich te verdiepen in de verschillende soorten tackers en de daarbij horende eigenschappen inclusief kosten, materiaal en indicaties.

Overwegingen

Balans tussen voor- en nadelen

Er werd in de literatuur geen bewijs gevonden dat fixatie van de mat in TEP of TAPP lies-breukherstel de kans op een recidief verkleint. De werkgroep is van mening dat de mat in het geval van een TEP of TAPP liesbreukoperatie bij patiënten met een grote mediale/directe hernia inguinalis wel gefixeerd dient te worden. Deze expert opinion wordt ondersteund in de recent opgestelde wereld richtlijn (HerniaSurge Group, 2018).

In het geval dat de mat wel gefixeerd wordt werd er geen voordeel gevonden van niet-traumatische fixatie versus traumatische fixatie met betrekking tot de kans op het ontstaan van een recidief en (chronische) pijn.

Kwaliteit van het bewijs

De onzekerheid over de effecten (chronische pijn en het ontstaan van een recidief) van wel of geen mat-fixatie in TEP is groot. Voor de uitkomstmaten operatietijd, postoperatieve pijn, chronische pijn en het ontstaan van een recidief is de bewijskracht zeer laag.

De onzekerheid over de effecten (chronische pijn en het ontstaan van een recidief) van wel of geen mat-fixatie in TAPP is zeer groot. Voor de uitkomstmaten operatietijd, postoperatieve pijn, chronische pijn en het ontstaan van een recidief is de bewijskracht zeer laag.

Kosten

Aangezien er geen bewijs is voor het nut van het fixeren van de mat is het logischerwijs kosteneffectief de mat niet te fixeren. In patiënten met een grote mediale/directe hernia is fixatie te verdedigen om de kans op een recidief te verkleinen.

Hoewel hechten van de mat het goedkoopst is in geval van de wens tot fixeren, is dat technisch uitdagend. De werkgroep is daarom van mening dat indien de mat bij een grote mediale/directe hernia wel gefixeerd moet worden tacker fixatie mediaal op de musculus rectus de snelste en gemakkelijkste methode is.

Type tacker

In een aparte search naar verschillen tussen oplosbare en titanium tackers werd geen data gevonden om conclusies te kunnen trekken welk type tacker aan te bevelen is. Het verdient wel aanbeveling dat chirurgen zich verdiepen in de eigenschappen van de verschillende soorten tackers. Zo staat bijvoorbeeld in de bijsluiter van een veel gebruikte oplosbare tacker dat er tenminste 4.2 mm weefsel bedekking dient te zijn boven onderliggend bot om de tacker goed te laten functioneren. Dit kan gevolgen hebben indien de mat -om wat voor reden ook- gefixeerd wordt aan een benige structuur.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Fixatie van de mat in laparo-endoscopische liesbreukoperaties (TEP, TAPP) heeft als doel om de kans op een recidief te verkleinen door het verplaatsen van de mat te voorkomen. Het fixeren van de mat kan gedaan worden op niet-traumatische wijze, door bijvoorbeeld het gebruik van lijm of een zelfklevende mat, of op traumatische wijze door het gebruik van hechtingen of tackers. De wijze van fixatie zou mogelijk invloed kunnen hebben op de belangrijkste postoperatieve parameters zoals recidief en (chronische) pijn.

In deze module werd gekeken of er bewijs is wanneer fixatie van de mat nodig is en zo ja, of er bewijs is welke fixatie methode gebruikt dient te worden.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

1. Is mesh fixation necessary in TEP inguinal/femoral hernia repair in adults?

|

Zeer laag GRADE |

Het is onduidelijk of het wel of niet fixeren van de mat invloed heeft op chronische pijn in het geval van een TEP liesbreukoperatie.

Bronnen: (Buyukasik, 2017; Ayyaz, 2015) |

|

Zeer laag GRADE |

Het is onduidelijk of het wel of niet fixeren van de mat invloed heeft op de kans op een recidief in het geval van een TEP liesbreukoperatie.

Bronnen: (Ayyaz, 2015; Buyukasik, 2017) |

|

Zeer laag GRADE |

Het is onduidelijk of het wel of niet fixeren van de mat invloed heeft op de operatie-tijd in het geval van een TEP liesbreukoperatie.

Bronnen: (Claus, 2016; Buyukasik, 2017) |

|

Zeer laag GRADE |

Het is onduidelijk of het wel of niet fixeren van de mat invloed heeft op de post-operatieve pijn in het geval van een TEP liesbreukoperatie bij mannen.

Bronnen: (Buyukasik, 2017) |

2. Is mesh fixation necessary in TAPP inguinal/femoral hernia repair in adults?

|

Zeer laag GRADE |

Het is onduidelijk of het wel of niet fixeren van de mat invloed heeft op chronische pijn in het geval van een TAPP liesbreukoperatie.

Bronnen: (Smith, 1999) |

|

Zeer laag GRADE |

Het is onduidelijk of het wel of niet fixeren van de mat invloed heeft op de kans op een recidief in het geval van een TAPP liesbreukoperatie.

Bronnen: (Smith, 1999) |

|

Zeer laag GRADE |

Het is onduidelijk of het wel of niet fixeren van de mat invloed heeft op de operatie-tijd in het geval van een TAPP liesbreukoperatie.

Bronnen: (Smith, 1999) |

|

- GRADE |

Er zijn geen data beschikbaar voor de uitkomstmaat post-operatieve pijn. |

3. What are appropriate types of mesh fixation in laparo-endopscopic (i.e. TEP and TAPP) inguinal/femoral hernia repair in adults?

|

Laag GRADE |

Niet-traumatische fixatie van de mat tijdens een laparo-endoscopische liesbreukoperatie lijkt de kans op chronische pijn niet te verminderen in vergelijking met traumatische fixatie van de mat.

Bronnen: (Antoniou, 2016) |

|

Laag GRADE |

Traumatische fixatie van de mat zorgt niet voor een lagere recidiefkans vergeleken met niet-traumatische fixatie in een TEP of TAPP liesbreukoperatie.

Bronnen: (Antoniou, 2016) |

|

Redelijk GRADE |

Niet-traumatische fixatie van de mat zorgt niet voor een langere operatie-tijd vergeleken met traumatische fixatie van de mat in een TEP of TAPP liesbreukoperatie.

Bronnen: (Antoniou, 2016) |

|

Laag GRADE |

Niet-traumatische fixatie van de mat lijkt de postoperatieve pijn niet te verminderen in vergelijking met traumatische mat-fixatie tijdens een TEP of TAPP liesbreukoperatie.

Bronnen: (Antoniou, 2016) |

Samenvatting literatuur

1. Is mesh fixation necessary in TEP inguinal/femoral hernia repair in adults?

A search using the PICO criteria yielded three RCTs relevant for the subject of mesh fixa-tion in endoscopic TEP-repair. All three studies included only patients with inguinal hernia’s. No studies were available on femoral hernias. The study of Buyukasik (2017) compared laparoscopic TEP inguinal repair using mesh with (seven metal spiral Tackers; n=50) and without fixation (n=50). Only male patients were included.

Claus (2016) studied TEP inguinal repair using mesh with and without fixation. In the mesh-fixation group 10 patients were included, the non-fixationgroup consisted of 50 patients. The study was said to be computer-randomized.

The study of Ayyaz (2015) also studied TEP inguinal repair with mesh fixation (n=32) and without mesh fixation (n=31). Follow-up was five years. No information was available on randomization, allocation concealment, loss to follow-up or intention-to-treat analysis.

Results

Chronic pain (critical outcome)

Two studies reported outcomes on chronic pain. The study of Ayyaz (2015) did report a mean chronic pain score (Visual Analogue Scale): 4.7 (±0.638). They did not specify the time-window of the score. Therefore, we could not use these outcomes. Buyukasik (2017) reported chronic pain scores after 1, 6 and 12 months, using the Numering Rating Scale (0 = no pain; 10 = most severe pain). After 1 month, the chronic pain score was 1.5 in the TEP with mesh fixation (±1.2) and 0,3 (±0.8) in the TEP group without fixation (p-value = 0.001). After 6 months, the scores were 0,8 (±1.6) in the fixationgroup and 0.4 (±0.7) in the non-fixationgroup (p-value = 0.109); after 12 months, the scores were 0.5 (±0.8) in the fixationgroup and 0,3 (±0.6) in the non-fixationgroup with a p-value of 0.158.

Quality of the evidence

Evidence originated from RCTs and the level of the quality of the evidence comparing rates of chronic pain for fixation versus no fixation in TEP repair started therefore at ‘High’. However, the quality of the evidence was downgraded with two levels for substantial methodological limitations of the studies (high Risk of Bias, for example due to unclear randomization process). The level of the quality of the evidence was further downgraded one level for substantial imprecision (low number of patients).

Recurrence (critical outcome)

Ayyaz 2015 reported 1 event of recurrence in the non-fixation group and no events in the mesh fixation group, five years post-surgery. The study of Buyukasik (2017) reported zero recurrence events in both groups.

Quality of the evidence

Evidence originated from RCTs and the level of the quality of the evidence comparing recurrence rates for fixation versus no fixation in TEP repair started therefore at ‘High’. However, the quality of the evidence was downgraded with two levels for substantial methodological limitations of the studies (high Risk of Bias, for example due to unclear randomization process). The level of the quality of the evidence was further downgraded two levels for substantial imprecision (very low number of events).

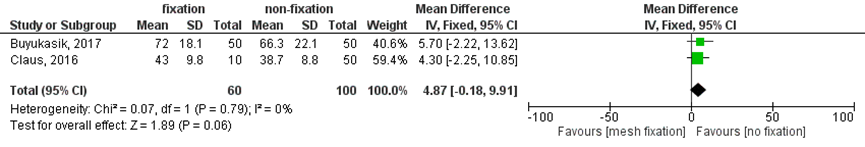

Operative time (other outcome)

Claus (2016) and Buyukasik (2017) reported data on operative time. The technique without fixation was less time-consuming compared to fixation, however, the difference was not statistically significant.

Figure 1 Mesh fixation versus no fixation in TEP inguinal repair. Outcome: operative time

Quality of the evidence

Evidence originated from RCTs and the level of the quality of the evidence comparing the amount of operative time for fixation versus no fixation in TEP repair started therefore at ‘High’. However, the quality of the evidence was downgraded one level for substantial methodological limitations of the studies (high Risk of Bias, for example due to uncertainty about intention to treat analysis and loss to follow up). The level of the quality of the evidence was further downgraded two levels for serious imprecision (low number of patients, very wide confidence intervals that crossed 0,0 indicating ambiguity between recommending and not recommending either the intervention or control)

Post-operative pain (other outcome)

Buyukasik (2017) reported post-operative pain (defined as pain prior to discharge). In the fixation group, the mean pains core (Numeric Rating Scale) was 1.9 (±1.6) and in the non-fixation group, the mean score was 1.3 (±1.2) with a p-value of 0,034

Quality of the evidence

Evidence originated from RCTs and the level of the quality of the evidence comparing rates of post-operative pain for fixation verus no fixation in TEP repair started therefore at ‘High’. However, the quality of the evidence was downgraded one level for substantial methodological limitations of the studies (high Risk of Bias, for example due to incomplete outcome data). The level of the quality of the evidence was further downgraded two levels for serious imprecision (low number of patients).

2. Is mesh fixation necessary in TAPP inguinal/femoral hernia repair in adults?

One RCT Smith (1999) was relevant for comparing mesh fixation versus no fixation in laparoscopic transabdominal preperitoneal (TAPP) repair.

Smith (1999) compared stapled and non-stapled TAPP inguinal hernia repair. They randomized a total of 502 patients undergoing elective inguinal hernia repair. Mean follow-up was 17 months (range 3 to 29 months). No information was available on randomization, allocation concealment or intention-to-treat analysis.

Results

Chronic pain (critical outcome)

Smith (1999) reported that no statistically significant difference was observed between the two groups in chronic pain, but details were not reported.

Recurrence (important outcome)

Smith (1999) reported three events of recurrence in the stapled group and no events in the non-stapled group (p=0.09).

Operative time (other outcome)

Smith (1999) reported a duration of 30 minutes for both procedures.

Quality of the evidence

Evidence originated from one RCT and the level of the quality of the evidence started therefore at ‘High’. However, the quality of the evidence was downgraded with three levels for substantial methodological limitations of this one study (high Risk of Bias, for example due to unclear randomization process). The level of the quality of the evidence was further downgraded two levels for serious imprecision (one study, low number of patients).

3. What are appropriate types of mesh fixation in laparo-endopscopic (i.e. TEP and TAPP) inguinal/femoral hernia repair in adults?

A search using the PICO criteria yielded two systematic reviews (Antoniou, 2016; Shi, 2017) relevant for the subject of mesh fixation in laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair. Antoniou 2016 compared noninvasive and invasive mesh fixation in both TEP and TAPP hernia repair. The SR of Shi (2017) compared only mesh fixation using fibrin glue versus staple in TAPP repair. Therefore, we chose to include the study of Antoniou. One RCT (Boldo, 2008) cited in the SR of Shi (2017), but not in Antoniou (2016), was not added to the collection of Antoniou (2016), because they did not specify number of patients between the intervention and outcome groups.

The cumulative study population comprised 1,454 patients subjected to inguinal hernia repair with non-traumatic fixation (n=577) or mechanical fixation (n=877). In four studies TEP was applied (Lau, 2005; Subwongcharoen, 2013; Melissa, 2014; Moreno-Egea, 2014) and in five TAPP (Lovisetto, 2007; Olmi, 2007; Brügger, 2012; Fortelny, 2012; Tolver, 2013).

Between two and ten staples or Tackers were used for mesh fixation. Absorbable sutures were used in three studies. One study included only patients subjected to bilateral her-nia repair (Moreno-Egea, 2014).

Table 1 Number of studies and patients for each non-penetrating mesh fixation com-pared to mechanical fixation

|

Comparison |

Studies (n); Patients (n) |

|

TEP |

|

|

Fibrin glue |

2; 222 |

|

Biosynthetic glue |

2; 166 |

|

TAPP |

|

|

Fibrin glue |

4; 986 |

|

Biosynthetic glue |

1; 77 |

Results

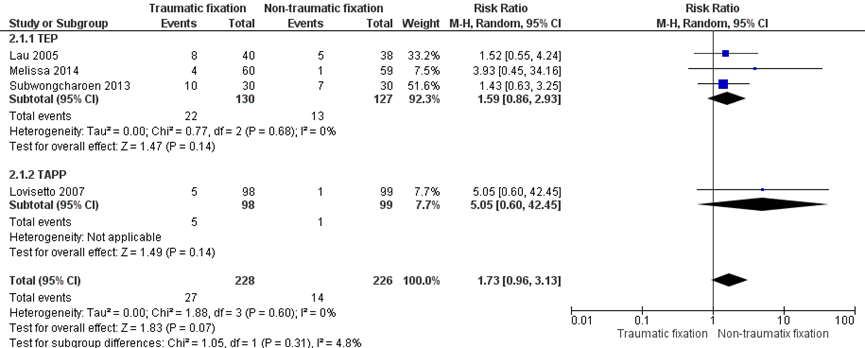

Chronic pain (critical outcome)

A total of 4 RCTs (n=454) (Lau, 2005; Lovisetto, 2007; Subwongcharoen, 2013; Melissa, 2014) reported on chronic pain (Figure 2). Chronic pain was reported in 12% (27/228) of the patients receiving mesh repair with mechanical fixation versus 6% (14/226) of those receiving non-traumatic fixation (RR 1.73 (95% CI 0.96 to 3.13).

Quality of the evidence

Evidence originated from RCTs and the level of the quality of the evidence comparing rates of chronic pain after traumatic and non-traumatic mesh fixation started therefore at ‘High’. However, the quality of the evidence was downgraded one level for some methodological limitations of the studies (Risk of Bias, for example due to possible selection bias). The level of the quality of the evidence was further downgraded two levels for serious imprecision (very few events and sample size <2000). We acknowledge the variety in types of inguinal hernia repair, but we did not downgrade for clinical heterogeneity. Instead, we reported results for the two types of operative techniques for inguinal hernia repair separately.

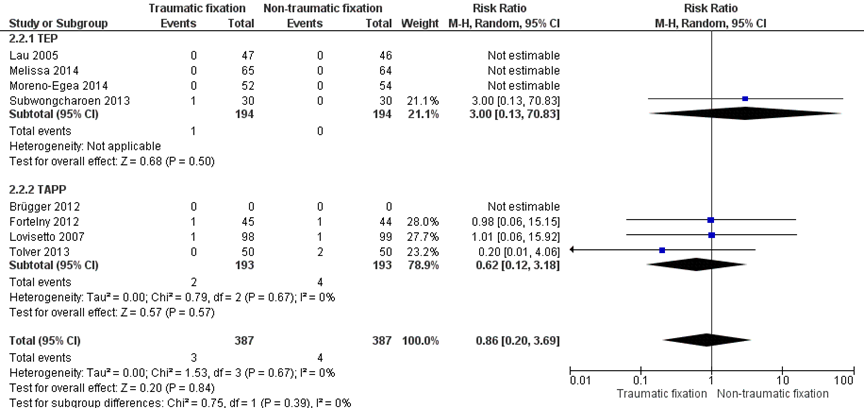

Recurrence (critical outcome)

Eight RCTs (n=774) reported recurrence rates (Figure 3). Both TEP and TAPP were used in four studies. In the group of patients that received traumatic mesh fixation a total of three patients reported a recurrence compared to four patients among those that received nontraumatic fixation (RR 0.86 (95% CI 0.20 to 3.69).

Quality of the evidence

Evidence originated from RCTs and the level of the quality of the evidence comparing recurrence rates after traumatic and nontraumatic mesh fixation started therefore at ‘High’. However, the quality of the evidence was downgraded two levels for serious imprecision (very few events and sample size <2000). We acknowledge the variety in types of inguinal hernia repair that were compared, but we did not downgrade for clinical heterogeneity. Instead, we reported results for the two types of operative techniques for inguinal hernia repair separately.

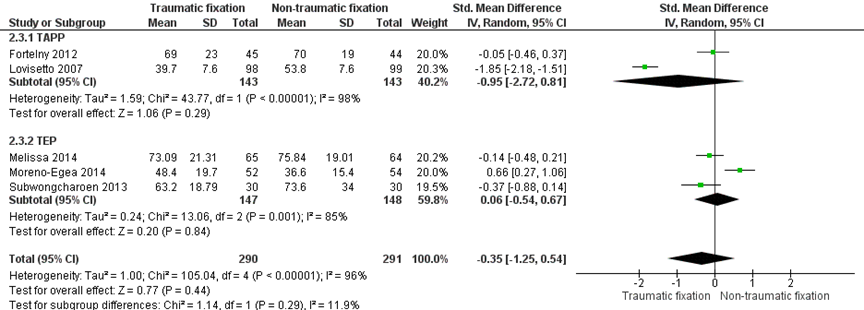

Operative time (other outcome)

Five studies (n=581) reported on operating time as outcome (Figure 4), two studies reported on TAPP and three studies reported on TEP. Mean operating time ranged from 39 to 73 minutes when mechanical fixation was used. When nontraumatic fixation was applied, the mean operating time ranged from 37 to 76 minutes. The mean difference was 3 minutes in favour of traumatic fixation, but this difference was not statistically significant different (CI -14.37 to 7.99). (SMD -0.35, 95% CI -1.25 to -0.54)

Quality of the evidence

Evidence originated from RCTs and the level of the quality of the evidence comparing operating time started therefore at ‘High’. However, the quality of the evidence was downgraded one level for considerable heterogeneity (minimal or no overlap of confidence intervals in studies reporting on the same operative technique and indicating either an effect or no effect, I2 statistic 85% and 98%).

Post-operative pain (other outcome)

Short-term pain assessment was inconsistently reported and the data of several studies were not suitable for use in meta-analysis (due to the reporting of median values and ranges). Five studies reported pain scores 24 to 48 hours after surgery. Four studies (n=342) showed comparable median scores (1 to 2 on a 10-point VAS) in both groups (Lau, 2005; Fortelny, 2012; Subwoncharoen, 2013; Tolver, 2013)). Only one study, OImi (2007), reported a more than two-fold higher pain score in the group receiving mechanical fixation (n=450) compared to the group receiving nontraumatic fixation (n=150) (5.3 points on a 10-point VAS versus 2 points).

Quality of the evidence

Evidence originated from RCTs and the level of the quality of the evidence comparing post-operative pain started therefore at ‘High’. However, the quality of the evidence was downgraded one level for substantial methodological limitations of the studies (high or unclear Risk of Bias, for example due to reporting bias and nondisclosed or present conflicts of interest or industry sponsoring). The quality of the evidence was further downgraded due to considerable heterogeneity (studies reporting on the same operative technique and indicating either an effect or no effect).

Figure 2 Mesh fixation by nonpenetrating mesh fixation (label: Nontraumatic fixation) versus mechanical mesh fixation (label: Traumatic fixation). Outcome: chronic pain

Figure 3 Mesh fixation by nonpenetrating mesh fixation (label: Nontraumatic fixation) versus mechanical mesh fixation (label: Traumatic fixation). Outcome: recurrence

Figure 4 Mesh fixation by nonpenetrating mesh fixation (label: Nontraumatic fixation) versus mechanical mesh fixation (label: Traumatic fixation). Outcome: operating time

Zoeken en selecteren

In order to answer the clinical ‘question’, a systematic literature search was done for the following research questions:

Is mesh fixation necessary in endoscopic TEP inguinal/femoral hernia repair in adults?

PICO 1

P(atients): adults (>18 years) having TEP inguinal/femoral hernia repair;

I(ntervention: fibrin sealant, N-Butyl-2 Cyanoacrylate (NB2C), self-fixing meshes, ab-sorbable Tackers, non absorbable Tackers/ staplers, anchors;

C(ontrol): non fixation;

O(utcome): chronic pain, recurrence, operative time, postoperative pain.

Is mesh fixation necessary in laparoscopic TAPP inguinal/femoral hernia repair in adults?

PICO 2

P(atients): adults (>18 years) having TAPP inguinal/femoral hernia repair;

I(ntervention: fibrin sealant, N-Butyl-2 Cyanoacrylate (NB2C), self-fixing meshes, ab-sorbable Tackers, non absorbable Tackers/ staplers, anchors;

C(ontrol): non fixation;

O(utcome): chronic pain, recurrence, operative time, postoperative pain.

What are appropriate types of mesh fixation in TEP and TAPP inguinal/femoral hernia repair in adults?

PICO 3

P(atients): adults (>18 years) having TEP or TAPP inguinal/femoral hernia repair;

I(ntervention: traumatic fixation, i.e. absorbable Tackers, non absorbable tackers/staplers, anchors;

C(ontrol): non traumatic fixation i.e. Fibrin sealant, N-Butyl-2 Cyanoacrylate (NB2C), self-fixing meshes;

O(utcome): chronic pain, recurrence, operative time, postoperative pain.

Relevant outcome measures

The working group decided that chronic pain and recurrence were crucial outcome measures for decision-making. The working group did not define the mentioned out-come measures beforehand, however, they used the definitions described in the studies.

Searching and selecting (Methods)

The information specialist from the Cochrane Centre in the Netherlands searched Med-line and Embase on April 11th, 2017 and the Cochrane Register on April 12th, 2017 for systematic reviews (SRs) and randomized controlled trials (RCTs) about inguinal hernias, without restrictions on publication date. All duplicates (including duplicates from the former search on the 30th of June, 2015) were removed. The search details can be found in the tab Acknowledgement.

Literature experts excluded studies that were clearly not relevant for answering clinical questions about inguinal hernias. Therefore, 66 SRs and 241 RCTs remained to be judged by the working group.

The working group selected 15 studies (SRs and RCTs) which could be relevant for the research questions about mesh fixation, based on title-abstract.

PICO 1

After reading full text, 12 studies were excluded for the search question about mesh fixation for TEP (see exclusion table in the tab Acknowledgement); finally, three studies (RCTs) were included for analysis (Ayyaz, 2015; Buyukasik, 2017; Claus, 2016).

Three studies were used for the literature analysis. The most important study character-istics and results were extracted from the RCTs. The most important study characteristics and results are shown in the evidence tables. The judgement of the individual study quality (Risk of Bias) is shown in the Risk of Bias tables.

PICO 2

After reading full text, all studies were excluded for the search question about mesh fixation for TAPP (see exclusion table in the tab Acknowledgement); Finally, one study from the former search (30th of June 2015) and described in the world guideline, was selected (Smith, 1999). One RCT was used for the literature analysis. The most important study characteristics and results were extracted from the RCT. The most important study characteristics and results are shown in the evidence tables. The judgement of the individual study quality (Risk of Bias) is shown in the Risk of Bias tables.

PICO 3

After reading full text, 14 studies were excluded for the search question about mesh fixation for TEP and TAPP (see exclusion table in the tab Acknowledgement); finally, one SR was included for analysis (Antoniou, 2016). This SR described 9 RCTs (4 about TEP, 5 about TAPP) and were used for the literature analysis. The most important study characteristics and results were extracted from the SRs or original studies (in case of missing information in the review). The most important study characteristics and results are shown in the evidence tables. The judgement of the individual study quality (Risk of Bias) is shown in the Risk of Bias tables.

Data extraction and analysis

The most important study characteristics and results were extracted from the SRs or original studies (in case of missing information in the review). The most important study characteristics and results are shown in the evidence tables. The judgement of the individual study quality (Risk of Bias) is shown in the Risk of Bias tables.

Relevant pooled and/or standardized effect measures were, if useful, calculated using Review Manager 5.3 (Cochrane Collaboration, Oxford, United Kingdom). If pooling re-sults was not possible, the outcomes and results of the original study were used as reported by the authors.

De working group did not define clinical (patient) relevant differences for the outcome measures. Therefore, we used the following boundaries for clinical relevance, if applicable: for continue outcome measures: RR<0.75 or >1.25 (GRADE recommendation) or Standardized mean difference (SMD=0.2 (little); SMD 0.5 (reasonable); SMD=0.8 (large). These boundaries were compared with the results of our analysis. The interpretation of dichotomous outcome measures is strongly related to context; therefore, no clinical relevant boundaries were set beforehand. For dichotomous outcome measures, the absolute effect was calculated (Number Needed to Treat (NNT) or Number Needed to Harm (NNH)).

Referenties

- Antoniou S Kohler G Antoniou G et al. (2016) Meta-analysis of randomized trials comparing nonpenetrating vs mechanical mesh fixation in laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair. American Journal of Surgery 211 (1):239-249.e2.

- Ayyaz M Farooka M Malik A et al. mesh fixation vs. non-fixation in total extra peritoneal mesh hernioplasty. JPMA - Journal of the Pakistan Medi-cal Association 2015 vol: 65 (3) pp: 270-272.

- Buyukasik K Ari A Akce B, et al. (2017) Comparison of mesh fixation and non-fixation in laparoscopic totally extraperitoneal inguinal hernia repair. Hernia 21(4):543-548.

- Claus C Rocha G Campos A Bonin E, et al. Prospective, ran-domized and controlled study of mesh displacement after laparoscopic inguinal repair: fixation versus no fixation of mesh. Surgical Endoscopy 2016 vol: 30 (3) pp: 1134-1140.

- HerniaSurge Group. (2018) International guidelines for groin hernia management. Hernia 22(1):1-165. doi: 10.1007/s10029-017-1668-x.

- Smith AI, Royston CM, Sedman PC. (1999) Stapled and nonstapled laparoscopic transabdominal preperitoneal (TAPP) inguinal hernia repair. A prospective randomized trial. Surg Endosc 13:804e6.

Evidence tabellen

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics 2 |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C) 3 |

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size 4 |

Comments |

|

Buyukasik 2017 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting: Single centre

Country: Turkey

Source of funding: ‘’The authors declare no conflict of interest’’ |

Inclusion criteria: -Male patients -No chronic diseases -Diagnosed with non-recurrent inguinal hernia (unilateral and bilateral) between January 2012 to December 2014

Exclusion criteria: -

N total at baseline: Intervention: 50 Control: 50

Important prognostic factors2: For example age ± SD: I: 27,3 ± 7.0 C: 31.1 ± 12.8

Sex: I: 100% M C: 100% M

BMI: I: 28.1 ± 4.7 C: 28.2 ± 4.1

Pre-operative pain: (Numeric Rating Scale) I: 0.9 (±1.6) C: 0.6 (±1.2)

Total number of hernias: I: 70 (30 unilateral 20 bilateral) C: 68 (21 unilateral, 18 bilateral)

Nyhus classification: Intervention: type I + II (indirect hernias): 26 Type 3A (direct): 30 Type 3B (pantaloon): 12 Type 3C (femoral): 2

Control: Type I + II (indirect): 30 Type 3A: 28 Type 3B: 8 Type 3C: 2

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes, they seem to be comparable |

Laparoscopic TEP inguinal hernia repair with mesh fixation, using seven metal spiral Tackers |

Laparoscopic TEP inguinal hernia repair, concluded after spreading of the mesh without any fixation |

Length of follow-up: 12 months

Loss-to-follow-up: Not described

Incomplete outcome data: 14 patients had no complete data for recurrence after 12 months (not specified for intervention / control group, no reasons described) |

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Post-operative pain (Numeric Rating Scale, 0= no pain; 10 = most severe pain) reported as ‘prior to discharge’: I: 1.9 (±1.6) C: 1.3 (±1.2) p-value = 0.034*

Operative time (min) I: 72.0 (± 18.1) C: 66.3 (± 22.1) p-value: 0.136 Mean difference: 5.7 (95%CI: -2.22 to 13.62)

Recurrence: I: 0 C: 0

Chronic pain After 1 month: I: 1.5 (±1.2) C: 0.3 (±0.8) p-value = 0.001*

After 6 months: I: 0.8 (±1.6) C: 0.4 (±0.7) p-value = 0.109

After 12 months: I: 0.5 (±0.8) C: 0.3 (±0.6) p-value = 0.158 |

No measurement of Surgical Site Infection outcome.

Risk of Bias: unclear (no information on loss-to-follow-up, incomplete outcome data, intention-to-treat analysis.

|

|

Claus 2016 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting: Single centre

Country: Brazil

Source of funding: the authors have no conflicts of interest or financial ties to disclose |

Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria: -patients with inguino-scrotal or incarcerated large hernias (L3 or M3 ESGH classification), associated surgical intervention, previous pelvic surgery (prostatectomy and caesarean), coagulopathy or use of antithrombolitic agents, cirrhosis, renal failure -patients not fit to general anesthesia and those who did not agree to participate in the study

N total at baseline: Intervention: 10 Control: 50

Important prognostic factors2: For example age ± SD: I: 49.0 (14.0) C: 51.1 (15.7)

Sex: I: 100% M C: 88% M

Previous hernia repair: I: 1/10 (10%) C: 3/50 (6%)

Groups comparable at baseline? Groups seem comparable at baseline |

Intervention:

mesh fixation (patients underwent laparoscopic inguinal repair, TEP with mesh fixation) |

Control:

No mesh fixation (patients underwent TEP repair with no mesh fixation |

Length of follow-up: ‘at least 3 months’

Loss-to-follow-up: None

Incomplete outcome data: None described |

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Operative time (min) I: 43 (± 9.8) C: 38.7 (± 8.8) p-value: 0.17 Mean difference: 4.3 (95%CI: -2.25 to 10.85) |

No measurement of the following outcome measures: SSI, chronic pain, postoperative pain, recurrence

Risk of Bias: high. No information available on allocation concealment, blinding of participants, loss to follow up, intention-to-treat analysis.

Despite computer randomization, the control consisted of 50 patients and the event group 10 patients |

|

Ayyaz 2015 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting: Single centre

Country: Ireland

Source of funding: Not reported |

Inclusion criteria: -Patients with the diagnosis of reducible incomplete inguinal hernia between the ages of 16-70 Exclusion criteria: Patients with large complete obstructed and strangulated hernias or paediatric hernias N total at baseline: Intervention: 32 Control: 31

Important prognostic factors2: For example age ± SD: I: 44.6 (±16.3) C: 31.3 (±12.5)

Sex: I: 87.5% M C: 90.3 % M

Side of hernia I: 67.7% leftside C: 32.3% leftside

Type of hernia (direct/indirect) I: 18.7% direct C: 19.4% direct

Groups comparable at baseline? Not enough data available to make a good comparison |

Intervention: TEP repair with mexh fixaton (using Tackers) |

Control: TEP repair without mesh fixation |

Length of follow-up: 5 years

Loss-to-follow-up: Not described

Incomplete outcome data: Not described |

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Mean chronic pain score using VAS: I: 4.7 (±0.683) C: 4.1 (±0.860) p<0.001

Recurrence after 5 years: I: 0 C: 1 p>0.05 |

Outcomes were measured at 0,5, 1, 2 and 5 years. However it is not clear how the mean pain score was calculated.

No measurement of the following outcome measures: SSI, postoperative pain, recurrence

Risk of Bias: high. No information available on randomization, allocation concealment blinding of patients, loss to follow up, intention-to-treat analysis. |

Notes:

- Prognostic balance between treatment groups is usually guaranteed in randomized studies, but non-randomized (observational) studies require matching of patients between treatment groups (case-control studies) or multivariate adjustment for prognostic factors (confounders) (cohort studies); the evidence table should contain sufficient details on these procedures.

- Provide data per treatment group on the most important prognostic factors ((potential) confounders).

- For case-control studies, provide sufficient detail on the procedure used to match cases and controls.

- For cohort studies, provide sufficient detail on the (multivariate) analyses used to adjust for (potential) confounders.

|

Study reference

(first author, publication year) |

Describe method of randomisation1 |

Bias due to inadequate concealment of allocation?2

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate blinding of participants to treatment allocation?3

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate blinding of care providers to treatment allocation?3

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate blinding of outcome assessors to treatment allocation?3

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to selective outcome reporting on basis of the results?4

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to loss to follow-up?5

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to violation of intention to treat analysis?6

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

|

Buyukasik 2017 |

‘Closed envelop methods’; |

Unlikely, identical closed envelopes were used |

Not applicable, envelopes were picked during aneshesia of patient |

Likely, however, randomization was done at time of mesh insertion |

Likely |

Unclear |

Unclear |

Unclear |

|

Claus 2016 |

Computer generated however, group sizes were very unequal. |

Unclear |

Unclear |

Unclear |

Unclear |

Unlikely |

Unclear |

Unclear |

|

Ayyaz 2015 |

‘Lottery method’ into even and odd |

Unclear |

Unclear |

Unclear |

Unclear |

Likely, only mean pain scores were reported despite follow-up at five different time points |

Unclear |

Unclear |

- Randomisation: generation of allocation sequences have to be unpredictable, for example computer generated random-numbers or drawing lots or envelopes. Examples of inadequate procedures are generation of allocation sequences by alternation, according to case record number, date of birth or date of admission.

- Allocation concealment: refers to the protection (blinding) of the randomisation process. Concealment of allocation sequences is adequate if patients and enrolling investigators cannot foresee assignment, for example central randomisation (performed at a site remote from trial location) or sequentially numbered, sealed, opaque envelopes. Inadequate procedures are all procedures based on inadequate randomisation procedures or open allocation schedules.

- Blinding: neither the patient nor the care provider (attending physician) knows which patient is getting the special treatment. Blinding is sometimes impossible, for example when comparing surgical with non-surgical treatments. The outcome assessor records the study results. Blinding of those assessing outcomes prevents that the knowledge of patient assignement influences the proces of outcome assessment (detection or information bias). If a study has hard (objective) outcome measures, like death, blinding of outcome assessment is not necessary. If a study has “soft” (subjective) outcome measures, like the assessment of an X-ray, blinding of outcome assessment is necessary.

- Results of all predefined outcome measures should be reported; if the protocol is available, then outcomes in the protocol and published report can be compared; if not, then outcomes listed in the methods section of an article can be compared with those whose results are reported.

- If the percentage of patients lost to follow-up is large, or differs between treatment groups, or the reasons for loss to follow-up differ between treatment groups, bias is likely. If the number of patients lost to follow-up, or the reasons why, are not reported, the Risk of Bias is unclea

- Participants included in the analysis are exactly those who were randomized into the trial. If the numbers randomized into each intervention group are not clearly reported, the Risk of Bias is unclear; an ITT analysis implies that (a) participants are kept in the intervention groups to which they were randomized, regardless of the intervention they actually received, (b) outcome data are measured on all participants, and (c) all randomized participants are included in the analysis.

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics 2 |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C) 3 |

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size 4 |

Comments |

|

Smith 1999 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting: Single centre

Country: Australia

Source of funding: Not reported |

Inclusion criteria: All patients undergoing elective inguinal hernia repair

Exclusion criteria: Irreducible hernia, previous retropubic prostatectomy, and medical contraindications to general anesthesia.

N total at baseline: 502 Intervention: 250 Control: 252

Important prognostic factors2: Age (median, range): I: 54 (15-86) C: 53 (14-85)

Sex: I: 97% M C: 98% M

Total number of bilateral hernias: I: 24 C: 10

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes, they seem to be comparable |

Laparoscopic transabdominal preperitoneal (TAPP) inguinal hernia repair with mesh fixation using staples |

TAPP inguinal hernia repair, using mesh with no fixation |

Length of follow-up: Median 16 months Up to 29 months 8% <12 months

Loss-to-follow-up: I: N=36 C: N=19 Reasons not described

Incomplete outcome data: not specified for intervention / control group, no reasons described |

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Chronic pain -

Recurrence: I: 3 C: 0, p=0.09

Surgical site infection (SSI) Wound infection: I: 4 C: 4 mesh infection: I: 0 C: 1

Operative time (min, mean) I: 30 C: 30 No mean difference

Post-operative pain - |

Authors conclude that it is not necessary to secure an appropriately placed 10 × 15-cm piece of mesh during a laparoscopic TAPP inguinal hernia repair.

Data for chronic pain not reported, but authors mention “Stapling the mesh made no statistically significant difference to the incidence of recurrence, port-site hernia, or chronic groin pain in this study” |

Notes:

- Prognostic balance between treatment groups is usually guaranteed in randomized studies, but non-randomized (observational) studies require matching of patients between treatment groups (case-control studies) or multivariate adjustment for prognostic factors (confounders) (cohort studies); the evidence table should contain sufficient details on these procedures.

- Provide data per treatment group on the most important prognostic factors ((potential) confounders).

- For case-control studies, provide sufficient detail on the procedure used to match cases and controls.

- For cohort studies, provide sufficient detail on the (multivariate) analyses used to adjust for (potential) confounders.

|

Study reference

(first author, publication year) |

Describe method of randomisation1 |

Bias due to inadequate concealment of allocation?2

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate blinding of participants to treatment allocation?3

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate blinding of care providers to treatment allocation?3

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate blinding of outcome assessors to treatment allocation?3

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to selective outcome reporting on basis of the results?4

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to loss to follow-up?5

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to violation of intention to treat analysis?6

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

|

Smith 1999 |

Not reported |

Unclear |

Unclear |

Unclear |

Unlikely |

Unclear |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

- Randomisation: generation of allocation sequences have to be unpredictable, for example computer generated random-numbers or drawing lots or envelopes. Examples of inadequate procedures are generation of allocation sequences by alternation, according to case record number, date of birth or date of admission.

- Allocation concealment: refers to the protection (blinding) of the randomisation process. Concealment of allocation sequences is adequate if patients and enrolling investigators cannot foresee assignment, for example central randomisation (performed at a site remote from trial location) or sequentially numbered, sealed, opaque envelopes. Inadequate procedures are all procedures based on inadequate randomisation procedures or open allocation schedules.

- Blinding: neither the patient nor the care provider (attending physician) knows which patient is getting the special treatment. Blinding is sometimes impossible, for example when comparing surgical with non-surgical treatments. The outcome assessor records the study results. Blinding of those assessing outcomes prevents that the knowledge of patient assignement influences the proces of outcome assessment (detection or information bias). If a study has hard (objective) outcome measures, like death, blinding of outcome assessment is not necessary. If a study has “soft” (subjective) outcome measures, like the assessment of an X-ray, blinding of outcome assessment is necessary.

- Results of all predefined outcome measures should be reported; if the protocol is available, then outcomes in the protocol and published report can be compared; if not, then outcomes listed in the methods section of an article can be compared with those whose results are reported.

- If the percentage of patients lost to follow-up is large, or differs between treatment groups, or the reasons for loss to follow-up differ between treatment groups, bias is likely. If the number of patients lost to follow-up, or the reasons why, are not reported, the Risk of Bias is unclear.

- Participants included in the analysis are exactly those who were randomized into the trial. If the numbers randomized into each intervention group are not clearly reported, the Risk of Bias is unclear; an ITT analysis implies that (a) participants are kept in the intervention groups to which they were randomized, regardless of the intervention they actually received, (b) outcome data are measured on all participants, and (c) all randomized participants are included in the analysis.

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C) |

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

Antoniou 2016

**data extracted from original study |

SR and meta-analysis of RCTs

Literature search up to 4th of January 2015 (PubMed and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials)

A: Lau 2005; B:Subwongcharoen 2013; C: Melissa; 2014; D: Moreno-Egea 2014 E: Lovisetto 2007; F: Olmi 2007; G: Brügger 2012; H: Fortelny 2012; I: Tolver 2013

Study design: RCT

Setting and Country: A: China B: Italy C: USA D: Spain E: Italy F: Italy G: Switzerland H: Austria I: Denmark

Source of funding** A: non-commercial B: non-commercial C: non-commercial D: non-commercial E: not reported F: not reported G: non-commercial H: industrial co-authorship I: commercial |

Inclusion criteria SR: -RCTs reporting on adult patients (age over 18) with unilateral or bilateral hernia subjected to laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair (TEP or TAPP) with non-penetrating mesh fixation of no fixation (intervention) or mechanical mesh fixation (control)

Exclusion criteria SR: Any method of noninvasive fixation and mechanical fixation in the same patient group was considered a criterion for exclusion

9 studies included in Antoniou 2016, we added the study of Boldo 2008 which was included in the SR of Shi 2017. In total, 10 studies were included.

Important patient characteristics at baseline: Number of patients; characteristics important to the research question and/or for statistical adjustment (confounding in cohort studies); for example, age, sex, bmi, ...

N, mean age Mean age was not reported in the SR A: 93 patients B: 60 patients C: 129 patients D: 106 patients E: 197 patients F: 600 patients G: 77 patients H: 89 patients I: 100 patients

Sex: Not reported

Groups comparable at baseline? Patient characteristics per study were not reported in the SR. |

Describe intervention: (non-traumatic fixation) Fixation method: A: fibrin glue, 2 mL per side B: N-butyl-2-cyanocrylate C: fibrin glue, 2 mL per side D: Cyanoacrylate based, 4 drops E: fibrin glue, 1 mL per side F: fibrin glue, 1 mL per side G: cyanoacrylate based H:fibrin glue, 2 mL per side I: fibrin glue, 2 mL per side |

Describe control: (traumatic fixation Fixation method: A: staples (number not reported) B: Tackers, 7 C: Tackers, <8 D: absorbable Tackers, 2 E: staples, 3 F: staples, Tackers, 7 G: Tackers, number not reported H: staples, number not reported I: Tackers, 8-10 |

End-point of follow-up:

A: 1 year B: 12 months C: 6 months D: 12 months E: 6 months F: 2 days G: 12 months H: 2 days I: 2 days

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? (intervention/control) Not reported |

Outcome measure-1: Chronic pain Defined as number of patients with chronic pain at least 3 months after surgery (reported on a VAS-scale). Subgroup-analysis for TEP (random effects model, risk ratio): study A, B, C: 1.59 (95%CI 0.86 to 2.93) favouring non-traumatic fixation Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

Subgroup-analysis for TAPP (random effects model, risk ratio): study E: 5.05 (95%CI from 0.6 to 42.45) favouring non-traumatic fixation Heterogeneity (I2): not applicable

Overall pooled effect (random effects model), risk ratio: 1.73 (95% CI 0.96 to 3.13) favoring non-traumatic fixation Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

Outcome measure-2: Recurrence Defines as number of patients with hernia recurrence

Subgroup-analysis for TEP (random effects model, risk ratio) for study: A, B, C, D: 3.00 (95%CI 0.13 to 70.83) favouring non-traumatic fixation Heterogeneity (I2): not applicable

Subgroup-analysis for TAPP (random effects model, risk ratio) for study: E, G, H, H: 0.62 (95%CI 0.12 to 3.18) favouring traumatic fixaton Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

Pooled effect (random effects model), risk ratio: 0.86 (95%CI 0.2 to 3.69) favouring traumatic fixation Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

Outcome measure-3 Surgical site infection Defines as the number of patients with adverse events related to the method of fixation (infectious complications, allergic or other reactions for tissue adhesives, acute neuralgia for mechanical mesh fixation)

One study reported perioperative events: 4.7% incidence of acute neuralgia following TAPP with mechanical mesh fixation

Outcome measure-4: Operative time Defined as duration of surgery in minutes (not further specified)

Subgroup-analysis for TAPP (random effects model, Std. mean difference) for study E, H: -0.95 (-2.72 to 0.81) favouring traumatic fixation Heterogeneity (I2): 98%

Subgroup-analysis for TEP (random effects model, Std. mean difference) for study B, C, D: 0.06 (95%CI -0.54 to 0.67) favouring non-traumatic fixation Heterogeneity (I2): 85%

Pooled effect (random effects model), standardized mean difference: -0.35 (-1.25 to 0.54) favouring traumatic fixation Heterogeneity (I2): 96%

Outcome measure-5 : post-operative pain Defines as: number of patients having chronic post-operative pain Pooling results was not possible due to scarce reporting of data.

Five studies reported pain scores 24.48 hours after surgery. Four studies (n=342) showed comparable median scores (1-2 on a 10-point VAS-scale) in both groups (study A, B, H, I). One study (F) reported a more than two-fold higher pain score in the group receiving mechanical fixation (n=450) compared to the group receiving non-traumatic fixation (n=150) (5.3 points on a 10-point VAS versus 2 points) |

Facultative:

Brief description of author’s conclusion: ‘’The use of bioglues may be supported as an alternative approsach to mechanical fixation in laparoscopic groin hernia repair without an increase in operative morbidity. Routine application cannot be supported until long-term results are available.’’

Sensitivity analyses: sub-groupanalyses were done to specify outcomes for TEP and TAPP

Heterogeneity: heterogeneity existed in the definition and measurement of end points. |

Table of quality assessment for systematic reviews of RCTs and observational studies

Based on AMSTAR checklist (Shea, 2007; BMC Methodol 7: 10; doi:10.1186/1471-2288-7-10) and PRISMA checklist (Moher, 2009; PLoS Med 6: e1000097; doi:10.1371/journal.pmed1000097)

|

Study

First author, year |

Appropriate and clearly focused question?1

Yes/no/unclear |

Comprehensive and systematic literature search?2

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of included and excluded studies?3

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of relevant characteristics of included studies?4

Yes/no/unclear |

Appropriate adjustment for potential confounders in observational studies?5

Yes/no/unclear/notapplicable |

Assessment of scientific quality of included studies?6

Yes/no/unclear |

Enough similarities between studies to make combining them reasonable?7

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential risk of publication bias taken into account?8

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential conflicts of interest reported?9

Yes/no/unclear |

|

Antoniou 2016 |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Unclear (no patient characteristics reported) |

Not applicable |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

No (not specified for each included study) |

- Research question (PICO) and inclusion criteria should be appropriate and predefined.

- Search period and strategy should be described; at least Medline searched; for pharmacological questions at least Medline + EMBASE searched.

- Potentially relevant studies that are excluded at final selection (after reading the full text) should be referenced with reasons.

- Characteristics of individual studies relevant to research question (PICO), including potential confounders, should be reported.

- Results should be adequately controlled for potential confounders by multivariate analysis (not applicable for RCTs).

- Quality of individual studies should be assessed using a quality scoring tool or checklist (Jadad score, Newcastle-Ottawa scale, Risk of Bias table et cetera).

- Clinical and statistical heterogeneity should be assessed; clinical: enough similarities in patient characteristics, intervention and definition of outcome measure to allow pooling? For pooled data: assessment of statistical heterogeneity using appropriate statistical tests (For example Chi-square, I2)?

- An assessment of publication bias should include a combination of graphical aids (For example funnel plot, other available tests) and/or statistical tests (e.g., Egger regression test, Hedges-Olken). Note: If no test values or funnel plot included, score “no”. Score “yes” if mentions that publication bias could not be assessed because there were fewer than 10 included studies.

- Sources of support (including commercial co-authorship) should be reported in both the systematic review and the included studies. Note: To get a “yes,” source of funding or support must be indicated for the systematic review AND for each of the included studies.

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Publicatiedatum : 05-04-2019

Beoordeeld op geldigheid : 11-12-2020

Voor het beoordelen van de actualiteit van deze richtlijn is de werkgroep in stand gehouden. Uiterlijk in 2022 bepaalt het bestuur van de NVvH of de modules van deze richtlijn nog actueel zijn. Op modulair niveau is een onderhoudsplan beschreven. Bij het opstellen van de richtlijn heeft de werkgroep per module een inschatting gemaakt over de maximale termijn waarop herbeoordeling moet plaatsvinden en eventuele aandachtspunten geformuleerd die van belang zijn bij een toekomstige herziening (update). De geldigheid van de richtlijn komt eerder te vervallen indien nieuwe ontwikkelingen aanleiding zijn een herzieningstraject te starten.

De NVvH is regiehouder van deze richtlijn(modules) en eerstverantwoordelijke op het gebied van de actualiteitsbeoordeling van de richtlijn(modules). De andere aan deze richtlijn deelnemende wetenschappelijke verenigingen of gebruikers van de richtlijn delen de verantwoordelijkheid en informeren de regiehouder over relevante ontwikkelingen binnen hun vakgebied.

Algemene gegevens

De richtlijnontwikkeling werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten en werd gefinancierd uit de Stichting Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS). Patiëntenparticipatie bij deze richtlijn werd medegefinancierd uit de Kwaliteitsgelden Patiënten Consumenten (SKPC) binnen het programma KIDZ.

De financier heeft geen enkele invloed gehad op de inhoud van de richtlijn.

Doel en doelgroep

Doel

Het hoofddoel van de richtlijn is de patiëntresultaten te verbeteren en de meest voorkomende problemen na een liesbreukoperatie te verminderen, met name recidivering en chronische pijn.

Doelgroep

De richtlijn wordt geschreven voor de medisch specialisten die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor patiënten met liesbreuk.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Werkgroep

- Dr. B. (Baukje) van den Heuvel, chirurg, Pantein Zorggroep, Radboudumc, Nijmegen, NVvH (voorzitter)

- Dr. M.P. (Maarten) Simons, chirurg, OLVG, Amsterdam, NVvH

- Dr. Th.J. (Theo) Aufenacker, chirurg, Rijnstate, Arnhem, NVvH

- Dr. J.P.J. (Ine) Burgmans, chirurg, Diakonessenhuis Utrecht, Utrecht, NVvH

- Mw. R. (Rinie) Lammers, beleidsadviseur, Patiëntenfederatie Nederland, Utrecht

- Dr. M.J.A. (Maarten) Loos, chirurg, Maxima Medisch Centrum, Veldhoven, NVvH

- Dr. M. (Marijn) Poelman, chirurg, Sint Franciscus Vlietland Groep, Rotterdam, NVvH

- Dr. G.H. (Gabriëlle) van Ramshorst, chirurg, NKI-Antoni van Leeuwenhoek Ziekenhuis/VU Medisch Centrum, Amsterdam, NVvH

- Drs. J.W.L.C. (Ronald) Schapendonk, anesthesioloog-pijnspecialist, Diakonessenhuis Utrecht, Utrecht, NVA

- Dr. E.J.P. (Ernst) Schoenmaeckers, chirurg, Meander MC, Amersfoort, NVvH

- Dr. N. (Nelleke) Schouten, AIOS heelkunde regio Maastricht, NVvH

- Dr. R.K.J. (Rogier) Simmermacher, chirurg, UMC Utrecht, Utrecht, NVvH

Met medewerking van

- Drs. W. (Wouter) Bakker, arts-onderzoeker heelkunde, Diakonessenhuis Utrecht, Utrecht

Met ondersteuning van

- Dr. J.S. (Julitta) Boschman, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- Dr. W.A. (Annefloor) van Enst, senior adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- Drs. Ing. R. (Rene) Spijker, Informatie Specialist, Cochrane Netherlands

- Dr. C. (Claudia) Orelio, Cochrane Netherlands

- Drs. P. (Pauline) Heus, Cochrane Netherlands

- Prof. dr. R. (Rob) Scholten, Cochrane Netherlands

- Dr. L. (Lotty) Hooft, Cochrane Netherlands

- D.P. (Diana) Gutierrez, projectsecretaresse, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- J. (Jill) Heij, junior projectsecretaresse, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

Belangenverklaringen

De KNMG-code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling is gevolgd. Alle werkgroepleden hebben schriftelijk verklaard of zij in de laatste drie jaar directe financiële belangen (betrekking bij een commercieel bedrijf, persoonlijke financiële belangen, onderzoeksfinanciering) of indirecte belangen (persoonlijke relaties, reputatiemanagement, kennisvalorisatie) hebben gehad. Een overzicht van de belangen van werkgroepleden en het oordeel over het omgaan met eventuele belangen vindt u in onderstaande tabel. De ondertekende belangenverklaringen zijn op te vragen bij het secretariaat van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

|

Werkgroeplid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

|

Van den Heuvel |

Chirurg |

Onbetaald: - Advies-commissie Kwaliteit EHS (European Hernia Society) - Dutch Hernia Society - International Guidelines Groin Hernia Management (ontwikkeling gesponsord door BARD en Johnson&Johnson - |

geen (03/03/2017) |

niet van toepassing |

|

|

Simons |

Chirurg |

Onbetaald: - Bestuur EHS (European Hernia Society) - Dutch Hernia Society - International Guidelines Groin Hernia Management (ontwikkeling gesponsord door BARD en Johnson&Johnson |

Lid Board van de European Hernia Society (20/7/2017) |

geen |

|

|

Aufenacker |

Chirurg |

Penningmeester DHS (Dutch Hernia Society), onbetaald |

Prevent Studie, (Preventieve matplaatsing bij aanleggen colostoma) ZonMW gesponsord (19/3/2018) |

geen |

|

|

Bakker |

Chirurg io |

- |

- |

niet van toepassing |

|

|

Burgmans |

Chirurg |

Lid bestuur Dutch Hernia Society |

geen (19/3/2018) |

niet van toepassing |

|

|

Lammers |

Beleidsadviseur |

- |

geen (19/6/2017) |

|

|

|

Loos |

Chirurg |

- |

geen (13/6/2017) |

niet van toepassing |

|

|

Poelman |

Chirurg |

Lid bestuur Dutch Hernia Society |

geen (11/7/2017) |

geen |

|

|

van Ramshorst |

Fellow Chirurgie |

|

Sponsor van mijn fellowship, KWF, heeft geen belangen bij deze richtlijn. Publicaties waar ik auteur van ben zouden gebruikt kunnen worden als referentie. (16/4/2018) |

geen |

|

|

Schapendonk |

Anesthesioloog-pijnspecialist |

|

Niet persoonlijk, maar mijn instelling heeft deelgenomen/ neemt deel aan wetenschappelijk onderzoek gesponsord door Medtronic, Spinal Modulaton of St. Jude Medical thans Abbott. Fee ontvangen van St. Jude Medical voor voordracht op scholing pijnverpleegkundigen inzake DRG stimulatie. Daarnaast in 2015 congres bezocht op kosten Spinal Modulation. (3/5/2017) |

geen |

|

|

Schoenmaeckers |

Chirurg |

|

geen (20/6/2017) |

niet van toepassing |

|

|

Schouten |

AIOS Heelkunde |

- |

geen (6/6/2017) |

niet van toepassing |

|

|

Simmermacher |

Chirurg |

- |

geen (21/5/2017 |

niet van toepassing |

|

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Er werd aandacht besteed aan het patiëntenperspectief door inbreng van: 1) patiëntenvereniging Meshed-up tijdens de invitational conference; 2) door de deelname van mevrouw. Lammers (Patiëntenfederatie Nederland) in de werkgroep en 3) door het raadplegen van volwassenen behandeld voor liesbreuk via een door de Patiëntenfederatie uitgezette enquête. De reacties naar aanleiding van deze invitational en enquête (zie aanverwante producten) zijn besproken in de werkgroep en de belangrijkste knelpunten zijn verwerkt in de richtlijn.

Methode ontwikkeling

Evidence based

Implementatie

In de verschillende fasen van de richtlijnontwikkeling is rekening gehouden met de implementatie van de richtlijn (module) en de praktische uitvoerbaarheid van de aanbevelingen. Daarbij is uitdrukkelijk gelet op factoren die de invoering van de richtlijn in de praktijk kunnen bevorderen of belemmeren. Het implementatieplan is te vinden bij de aanverwante producten. De werkgroep heeft geen interne kwaliteitsindicatoren ontwikkeld om het toepassen van de richtlijn in de praktijk te volgen en te versterken (zie Indicatorontwikkeling).

Werkwijze

AGREE

Deze richtlijn is opgesteld conform de eisen vermeld in het rapport Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 van de adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwaliteit. Dit rapport is gebaseerd op het AGREE II instrument (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II; Brouwers, 2010), dat een internationaal breed geaccepteerd instrument is. Voor een stap-voor-stap beschrijving hoe een evidence-based richtlijn tot stand komt wordt verwezen naar het stappenplan Ontwikkeling van Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

Knelpuntenanalyse

Tijdens de voorbereidende fase inventariseerden de voorzitter van de werkgroep en de adviseur de knelpunten en onderwerpen beschreven in de internationale richtlijn (HerniaSurge Group 2018) die in aanmerking kwamen voor de Nederlandse adaptatie en update. De aanwezigen tijdens de invitational conference bevestigden deze knelpunten en onderwerpen. Een verslag hiervan is opgenomen onder aanverwante producten.

Uitgangsvragen en uitkomstmaten

De knelpunten en onderwerpen beschreven in de internationale richtlijn (HerniaSurge Group, 2018) die in aanmerking kwamen voor de Nederlandse adaptatie en update zijn met de werkgroep besproken. Daarna heeft de werkgroep de definitieve uitgangsvragen en modules vastgesteld en vastgesteld welke modules volledig zouden worden geupdate met ondersteuning van het Kennisinstituut en welke modules uit de internationale richtlijn zouden worden geadapteerd door de werkgroep. Voor alle modules, ook de modules die geadapteerd zijn, heeft de werkgroep de recente en relevante literatuur doorgenomen. In de geadapteerde modules zijn nieuwe studies verwerkt bij het formuleren van overwegingen en aanbevelingen. In de volledig geupdate modules zijn nieuwe studies geïntegreerd in de literatuuranalyse, risk of bias assessment en gradering. Hieronder is per module aangegeven of de module volledig is ge-update of geadapteerd:

- Risicofactoren (geadapteerd)

- Diagnostiek (geadapteerd)

- Indicatie behandeling asymptomatische liesbreuken (volledig geupdate)

- Chirurgische behandeling unilaterale liesbreuk (volledig geupdate)

- Mat of Shouldice (volledig geupdate)

- Lichtenstein of een andere open anterieure techniek (geadapteerd)

- Lichtenstein of een open pre-peritoneale techniek (geadapteerd)

- Endoscopische techniek (geadapteerd)

- Lichtenstein of een laparo-endoscopische techniek (geadapteerd)

- Een open posterieure techniek of laparo-endoscopisch (geadapteerd)

- Geïndividualiseerde behandeling (geadapteerd)

- Matten (volledig geupdate)

- Matfixatie (volledig geupdate)

- Open anterieure benadering

- TEP/TAPP

- Liesbreuken bij vrouwen (geadapteerd)

- Femoraalbreuken (geadapteerd)

- Antibioticaprofylaxe (volledig geupdate)

- Anesthesie (volledig geupdate)

- Postoperatieve pijn (geadapteerd)

- Chronische pijn

- Definitie, risicofactoren en preventie (geadapteerd)

- Reductie incidentie CPIP (volledig geupdate)

- Behandeling CPIP (volledig geupdate)

- Behandeling van recidief liesbreuk (geadapteerd)

- Na een anterieure benadering

- Na een posterieure benadering

- Na een anterieure en posterieure benadering

- Acute liesbreukchirurgie (geadapteerd)

- Organisatie van zorg (nieuw)

Vervolgens inventariseerde de werkgroep voor de uitgangsvragen van de modules die waren geselecteerd voor een volledige update welke uitkomstmaten voor de patiënt relevant zijn. Er werd zowel naar gewenste als ongewenste effecten gekeken. De werkgroep waardeerde deze uitkomstmaten volgens hun relatieve belang bij de besluitvorming rondom aanbevelingen, als cruciaal, belangrijk (maar niet cruciaal) en onbelangrijk. Tevens poogde de werkgroep tenminste voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten te definiëren welke verschillen zij klinisch (patiënt) relevant vonden.

Strategie voor zoeken en selecteren van literatuur

De informatiespecialist van Cochrane Nederland doorzocht Medline en Embase (op 11 april 2017) en het Cochrane Register (op 12 april 2017) naar artikelen over de diagnostiek of behandeling van volwassenen met liesbreuk zonder beperkingen op de publicatiedatum. Dit betrof een herhaling van de searches uitgevoerd voor de 2013 European Hernia Society Guidelines on the treatment of inguinal hernia in adult patients en de 2018 International Guidelines for Groin Hernia Management: The HerniaSurge Group (literatuursearch tot 1 januari 2015 en 1 juli 2015 voor level 1 publicaties (RCTs). De literatuurzoekactie leverde voor reviews 583 unieke treffers (waarvan 339 reviews reeds gescreend voor de vorige richtlijnen) op (Medline n=419; Embase n=378; en de Cochrane Library n=12) en voor RCTs 2174 unieke treffers (Medline n=1376; Embase n=1537; en de Cochrane Library n=160).

De werkgroepleden selecteerden per uitgangsvraag in duplo de via de zoekactie gevonden artikelen op basis van vooraf opgestelde selectiecriteria en in eerste instantie de studies met de hoogste bewijskracht. De gehanteerde selectiecriteria zijn te vinden in de module met desbetreffende uitgangsvraag.

Kwaliteitsbeoordeling individuele studies

Voor de modules die volledig werden ge-update, zijn de geselecteerde artikelen systematisch beoordeeld, op basis van op voorhand opgestelde methodologische kwaliteitscriteria, om zo het risico op vertekende studieresultaten (Risk of Bias) te kunnen inschatten. Deze beoordelingen kunt u vinden in de Risk of Bias (RoB) tabellen. De gebruikte RoB instrumenten zijn gevalideerde instrumenten die worden aanbevolen door de Cochrane Collaboration: AMSTAR – voor systematische reviews; Cochrane – voor gerandomiseerd gecontroleerd onderzoek; ACROBAT-NRS – voor observationeel onderzoek; QUADAS II – voor diagnostisch onderzoek.

Samenvatten van de literatuur

Voor de modules die volledig werden ge-update, zijn de geselecteerde artikelen toegevoegd aan de set relevante artikelen genoemd in de internationale richtlijn. De relevante onderzoeksgegevens van alle geselecteerde artikelen werden overzichtelijk weergegeven in evidence-tabellen. De belangrijkste bevindingen uit de literatuur werden beschreven in de Engelstalige samenvatting van de literatuur. Bij een voldoende aantal studies en overeenkomstigheid (homogeniteit) tussen de studies werden de gegevens ook kwantitatief samengevat (meta-analyse) met behulp van Review Manager 5.

Beoordelen van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs

A) Voor interventievragen (vragen over therapie of screening)

De kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs werd bepaald volgens de GRADE-methode. GRADE staat voor ‘Grading Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation’ (zie http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/).

GRADE onderscheidt vier gradaties voor de kwaliteit van het wetenschappelijk bewijs: hoog, redelijk, laag en zeer laag. Deze gradaties verwijzen naar de mate van zekerheid die er bestaat over de literatuurconclusie (Schünemann 2013).

|

GRADE |

Definitie |

|

Hoog |

|

|

Redelijk |

|

|

Laag |

|

|

Zeer laag |

|

B) Voor vragen over diagnostische tests, schade of bijwerkingen, etiologie en prognose

De kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs werd eveneens bepaald volgens de GRADE-methode: GRADE-diagnostiek voor diagnostische vragen (Schünemann, 2008), en een generieke GRADE-methode voor vragen over schade of bijwerkingen, etiologie en prognose. In de gehanteerde generieke GRADE-methode werden de basisprincipes van de GRADE-methodiek toegepast: het benoemen en prioriteren van de klinisch (patiënt) relevante uitkomstmaten, een systematische review per uitkomstmaat, en een beoordeling van bewijskracht op basis van de vijf GRADE-criteria (startpunt hoog; downgraden voor Risk of Bias, inconsistentie, indirectheid, imprecisie, en publicatiebias).

Formuleren van de conclusies

Voor elke relevante uitkomstmaat werd het wetenschappelijk bewijs samengevat in een of meerdere Nederlandstalige literatuurconclusies waarbij het niveau van bewijs werd bepaald volgens de GRADE-methodiek. De werkgroepleden maakten de balans op van elke interventie (overall conclusie). Bij het opmaken van de balans werden de gunstige en ongunstige effecten voor de patiënt afgewogen. De overall bewijskracht wordt bepaald door de laagste bewijskracht gevonden bij een van de cruciale uitkomstmaten. Bij complexe besluitvorming waarin naast de conclusies uit de systematische literatuuranalyse vele aanvullende argumenten (overwegingen) een rol spelen, werd afgezien van een overall conclusie. In dat geval werden de gunstige en ongunstige effecten van de interventies samen met alle aanvullende argumenten gewogen onder het kopje Overwegingen.

Overwegingen (van bewijs naar aanbeveling)

Om te komen tot een aanbeveling zijn naast (de kwaliteit van) het wetenschappelijke bewijs ook andere aspecten belangrijk en worden meegewogen, zoals de expertise van de werkgroepleden, de waarden en voorkeuren van de patiënt (patient values and preferences), kosten, beschikbaarheid van voorzieningen en organisatorische zaken. Deze aspecten worden, voor zover geen onderdeel van de literatuursamenvatting, vermeld en beoordeeld (gewogen) onder het kopje Overwegingen.

Formuleren van aanbevelingen

De aanbevelingen geven antwoord op de uitgangsvraag en zijn gebaseerd op het beschikbare wetenschappelijke bewijs en de belangrijkste overwegingen, en een weging van de gunstige en ongunstige effecten van de relevante interventies. De kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs en het gewicht dat door de werkgroep wordt toegekend aan de overwegingen, bepalen samen de sterkte van de aanbeveling. Conform de GRADE-methodiek sluit een lage bewijskracht van conclusies in de systematische literatuuranalyse een sterke aanbeveling niet a priori uit, en zijn bij een hoge bewijskracht ook zwakke aanbevelingen mogelijk. De sterkte van de aanbeveling wordt altijd bepaald door weging van alle relevante argumenten tezamen.

Randvoorwaarden (Organisatie van zorg)

In de knelpuntenanalyse en bij de ontwikkeling van de richtlijn is expliciet rekening gehouden met de organisatie van zorg: alle aspecten die randvoorwaardelijk zijn voor het verlenen van zorg (zoals coördinatie, communicatie, (financiële) middelen, menskracht en infrastructuur). Randvoorwaarden die relevant zijn voor het beantwoorden van een specifieke uitgangsvraag maken onderdeel uit van de overwegingen bij de bewuste uitgangsvraag. Meer algemene, overkoepelende, of bijkomende aspecten van de organisatie van zorg worden behandeld in de module Organisatie van Zorg.

Indicatorontwikkeling

Er werden geen interne kwaliteitsindicatoren ontwikkeld. In de module Organisatie van Zorg is een suggestie opgenomen voor een toekomstige registratie.

Kennislacunes

Tijdens de ontwikkeling van deze richtlijn is systematisch gezocht naar onderzoek waarvan de resultaten bijdragen aan een antwoord op de uitgangsvragen. Bij elke uitgangsvraag is door de werkgroep nagegaan of er (aanvullend) wetenschappelijk onderzoek gewenst is om de uitgangsvraag te kunnen beantwoorden. Een overzicht van de onderwerpen waarvoor (aanvullend) wetenschappelijk van belang wordt geacht, is als aanbeveling in de Kennislacunes beschreven .

Commentaar- en autorisatiefase

De conceptrichtlijn werd aan de betrokken (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd ter commentaar. De commentaren werden verzameld en besproken met de werkgroep. Naar aanleiding van de commentaren werd de conceptrichtlijn aangepast en definitief vastgesteld door de werkgroep. De definitieve richtlijn werd aan de deelnemende (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd voor autorisatie en door hen geautoriseerd dan wel geaccordeerd.

Literatuur

Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, et al. (2010) AGREE Next Steps Consortium. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. CMAJ 182(18):E839-42. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090449. Epub 2010 Jul 5. Review. PubMed PMID: 20603348.

Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 (2012). Adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwalitieit. https://richtlijnendatabase.nl/over_deze_site/richtlijnontwikkeling.html.

Ontwikkeling van Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen: stappenplan. Kennisinstituut van Medisch Specialisten.

Schünemann H, Brożek J, Guyatt G, et al. GRADE handbook for grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. Updated October 2013. The GRADE Working Group 2013. Available from http://gdt.guidelinedevelopment.org/central_prod/_design/client/handbook/handbook.html.

Schünemann HJ, Oxman AD, Brozek J, et al. Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations for diagnostic tests and strategies. BMJ. 2008;336(7653):1106-10. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39500.677199.AE. Erratum in: BMJ. 2008;336(7654). doi: 10.1136/bmj.a139. PubMed PMID: 18483053.

Zoekverantwoording

Exclusion table after reading full texts

|

Author, year |

Reason for exclusion |

|

Kockerling 2012 |

Letter to the editor |

|

Antoniou 2016 |

Included in 11.3 (mesh-type for TEP/TAPP, 11.3), excluded for 11.1 and 11.2 |

|

Sun 2017 |

Not relevant for answering these research questions |

|

Shi 2017 |

The RCT of Antionou 2016 was estimated of better quality, since they included only rct’s |

|

Li 2015 |

Antoniou 2016 is more up to date |

|

Naik 2015 |

Abstract |

|

Mills 1998 |

More recent SR was available |

|

Antoniou 2016 |

Conference abstract |

|

Ge 2015 |

Not relevant for answering these research questions |

|

Cingolani 2016 |

Conference abstract |

|

Kim-Fuchs 2011 |

Not relevant for answering these research questions |

|

Fortelny 2011 |

Included in the SR Antioniou 2016 (11.3) |

|

Claus 2016 |

Included in 11.1 (is mesh fixation necessary, TAPP), excluded for 11.2 and 11.3 |

|

Ayyaz 2015 |

Included in 11.1 (is mesh fixation necessary, TAPP), excluded for 11.2 and 11.3 |

|

Buyukasik 2015 |

Included in 11.1 (is mesh fixation necessary, TAPP), excluded for 11.2 and 11.3 |