Chirurgische behandeling liesbreuk bij volwassenen

Uitgangsvraag

Welke methode heeft voor de operatieve behandeling van een primaire liesbreuk bij mannen de voorkeur?

- Operatie met een mat of weefselplastiek?

- Operatie volgens Lichtenstein of een andere open flat mesh of gepreformeerde mesh gadgets via een anterieure benadering?

- Operatie volgens Lichtenstein of een open pre-peritoneale benadering?

- Indien laparo-endoscopisch: TEP of TAPP techniek?

- Operatie volgens Lichtenstein of laparo-endoscopische techniek?

- Open posterieure benadering of laparo-endoscopische techniek?

Aanbeveling

Maak de keuze voor een bepaald type liesbreukoperatie op basis van de expertise van de chirurg (leercurves van de technieken verschillen), het type breuk en patiëntgerelateerde factoren (module Risico) en kosten. Er is toenemend aanleiding voor het individualiseren van de techniek keuze (zie module Individualisatie).

Gebruik bij voorkeur voor de operatieve behandeling van een liesbreuk een techniek met mat:

Bespreek met de patient de voor- en nadelen van de verschillende opties.

- Overweeg een laparo-endoscopische operatie volgens TEP of TAPP, omdat er minder postoperatieve en minder chronische pijn bij voorkomt, mits het chirurgisch team goed getraind is. Baseer de keuze voor TAPP of TEP op de ervaring van het chirurgische team.

- Overweeg de operatie volgens Lichtenstein in het bijzonder bij specifieke patiënt- en breuk-karakteristieken:

- Indien er geen laparo-endoscopische expertise aanwezig is (overweeg verwijzing).

- Bij contra-indicaties voor algehele anesthesie.

- Bij contra-indicaties voor laparo-endoscopische operatie.

- Bij wens of noodzaak voor regionale of lokale anesthesie.

- Bij niet reponibele scrotaalbreuken.

- Het gebruik van TIPP, PHS of Plug (and Patch) wordt niet aanbevolen.

- De TREPP is nog onvoldoende onderzocht om een aanbeveling te kunnen geven. Voer deze operatie bij voorkeur uit in onderzoeksverband.

Kies voor een Shouldice:

- wanneer de patiënt voorkeur heeft voor een weefselplastiek. De patient dient zich wel te realiseren dat er een verhoogd risico is op recidief zonder bewezen verminderd risico op (chronische) pijn;

- onder bijzondere omstandigheden, zoals bij infectie.

Draag zorg voor adequate training bij de leercurve voor een laparo-endoscopische operatie. De leercurve is namelijk langer en kent met name aan de start zeldzame, maar ernstige complicaties.

Overwegingen

Algemeen

Wat vinden patiënten: patiëntenvoorkeur en –perspectief?

Uit zowel de inbreng tijdens de invitational conference als de respons op de enquete kwam naar voren dat patiënten het belangrijk vinden om informatie te krijgen over de keuzemogelijkheden (zie ook de module Individualisatie) en gezamenlijk met de arts tot een behandelbesluit te komen. Het is onbekend of patiënten een specifieke voorkeur voor een bepaald type operatie hebben. Er is bij sommige patiënten een zorg betreffende de veiligheid van matten. Indien de patiënt geen mat wenst, dan kan na bespreking van de voor- en nadelen, een Shouldice verricht worden.

1. Welke methode heeft voor de operatieve behandeling van een liesbreuk de voorkeur? Operatie met mat of weefselplastiek?

Balans tussen voor- en nadelen

De internationale richtlijn adviseert in alle electieve gevallen een mat te gebruiken. Enige uitzondering is er bij patiënten die een mat weigeren en onder infectieuze omstandigheden. Er is maatschappelijke onrust betreffende het gebruik van matten en er is twijfel bij chirurgen (met name ‘Hernia specialisten”) of er niet bepaalde patiënten categorieën zijn die beter af zijn zonder mat. Bijvoorbeeld bij jonge mannen met een indirecte breuk. Dit is niet goed onderzocht en het schaarse laag-gradige bewijs dat er wel is wijst op verhoogde recidiefkans als er geen mat gebruikt wordt. Er zijn ook specialistische klinieken (bijvoorbeeld Shouldice Hospital) die hele goede resultaten rapporteren met recidief percentages onder de 2%. Dit betreft helaas alleen retrospectief cohortonderzoek zonder deugdelijk uitgevoerde follow-up. Uit alle evidence (ook uit registeronderzoek met data over meerdere jaren) blijkt dat een mat een lager recidief risico heeft en een vergelijkbaar of lager risico op postoperatieve pijn en chronische pijn. Het niveau van onderzoek is over de hele linie laag en vaak ook heel laag. In studies naar recidief bleek bij analyse van de grootste studie dat in de mat groep een groot deel van de recidieven veroorzaakt werd door 1 chirurg. Indien deze uit de analyse bleef, bleek er een evident significant voordeel van mat versus Shouldice. Bijkomend probleem is dat de Shouldice een technisch moeilijke operatie is en nauwelijks tot niet meer onderwezen of gebruikt wordt in Nederland.

Samenvattend adviseert de Werkgoep een mat te gebruiken bij de operatieve behandeling van liesbreuken. Hier kan van afgeweken worden na overleg met een patiënt en documentatie van de redenen van het afwijken van de richtlijn.

Hoewel er zeer vele RCT’s uitgevoerd zijn blijkt de bewijskracht Laag of Zeer laag (volgens Grade). Dit ligt aan onvoldoende gebruik van de juiste randomisatietechnieken, patiënten selectie, gebrek aan definities van pijn en recidief, te korte follow-up en onzekerheid over het gebruiken van een (gouden) standaard techniek. Er is nog steeds behoefte aan goede RCT’s betreffende jonge mannen met indirecte breuk en de resultaten van gespecialiseerde klinieken.

Kosten

Er moet onderscheid gemaakt worden tussen ziekenhuiskosten en maatschappelijke kosten. Open technieken met mat zijn mogelijk duurder (door de prijs van een matje) dan zonder mat. Laparo-endoscopische operaties zijn door het gebruik van materialen duurder dan open technieken met of zonder mat. hoewel een laparo-endoscopische techniek uitgevoerd kan worden met minimaal gebruik van disposable materialen kan het gebruik van herbruikbare instrumenten de ziekenhuiskosten verlagen. De HerniaSurge Group (2018) concludeerde dat mits de kortere hersteltijd en het eerder terugkeren in het arbeidsproces erbij betrokken wordt waarschijnlijk een laparo-endoscopische techniek het meest kosteneffectief is. Hierbij moet in aanmerking genomen worden dat er een langere leercurve is en er zeldzame ernstige complicaties kunnen voorkomen die bij een open techniek onwaarschijnlijk zijn.

Wat vinden artsen: professioneel perspectief

In Nederland worden 98% van de liesbreukoperaties uitgevoerd met gebruik van een mat. In 2018 werd 53% van de patiënten met een laparo-endoscopische techniek geopereerd. De werkgroep adviseert de internationale richtlijn te volgen. In Nederland worden de meeste patiënten door middel van een Lichtenstein of TEP geopereerd. Een klein aantal ziekenhuizen prefereert een andere techniek zoals TAPP, TREPP, TIPP, Plug en PHS. De laatste twee worden afgeraden door de internationale richtlijn. TREPP is onvoldoende onderzocht om een goed advies te geven.

2. Welke methode heeft voor de operatieve behandeling van een liesbreuk de voorkeur?

Operatie volgens Lichtenstein of andere open vlakke mat en gepreformeerde matten via een anterieure benadering?

Balans tussen voor- en nadelen

De TIPP techniek lijkt in studies met korte follow-up een klein voordeel te geven in hersteltijd en chronische pijn ten opzichte van de Lichtenstein-techniek. Een nadeel van deze techniek is echter dat er door twee vlakken geopereerd wordt (anterieure benadering en plaatsen mat in pre-peritoneale vlak) en de hogere kosten van de mat die hierbij noodzakelijk is. Bij recidief en pijnklachten zijn reoperaties moeilijker. Casuistisch wordt vaak beschreven dat de zogenaamde memory ring verwijderd moet worden ivm pijn en/of verkleving aan darmen. De experts van de internationale richtlijn adviseren de TIPP niet als eerste keus operatie te kiezen (lage evidence).

De PHS heeft als extra nadeel dat er een mat geplaatst worden in beide vlakken en de experts van de internationale richtlijn concluderen dat er een te grote hoeveelheid mesh gebruikt wordt zonder dat er bewijs is dat deze techniek beter is dan een operatie volgens Lichtenstein. Beide bovengenoemde technieken maken gebruik van een veel duurdere mat.

De werkgroepleden, en de HerniaSurge Group, raden het gebruik van plugs af, omdat deze regelmatig verwijderd moet worden in verband met pijn en/of recidief en/of migratie, hoewel dit niet uit de studies met korte follow-up blijkt. Ook bij de plug wordt prothesemateriaal achtergelaten in beide anatomische vlakken en spelen hogere kosten een rol.

De internationale richtlijn adviseert als eerste keus te kiezen uit een Lichtenstein en TEP of TAPP. TREPP moet verder onderzocht en TIPP, PHS en Plugs worden (met lage evidence) afgeraden.

Kwaliteit van het bewijs

De kwaliteit van dit onderzoek is laag. De aanbevelingen zijn door de experts van de interntionale richtlijn door consensus ge-upgrade op basis van anatomische argumenten, klinische expertise en kosten.

Kosten

Wanneer er vergeleken wordt tussen de open technieken dan zijn de kosten van het matje en de operatieduur bepalend. Een Lichtenstein kan met een “simpel” plat matje uitgevoerd worden versus hogere kosten van speciale matjes die nodig zijn bij TREPP, TIPP, PHS en Plug.

Wat vinden artsen: professioneel perspectief

De werkgroep adviseert de internationale richtlijn te volgen. De eerste keus techniek voor een primaire breuk zijn: Lichtenstein, TEP of TAPP. TREPP zou bij voorkeur beter onderzocht moeten worden, bij voorkeur in gerandomiseerde studies vergelijkend met eerder genoemde technieken. Het wordt met lage evidente aangeraden geen TIPP, PHS of Plug techniek uit te voeren.

3. Wat is de voorkeurstechniek: Operatie volgens Lichtenstein of een open preperitoneale benadering?

De update van de literatuur over de periode 2015-2018 heeft geen goede studies met voldoende follow up opgeleverd.

Derhalve blijven de conclusies van de internationale richtlijn overeind.

Op basis van het in de internationale richtlijn gepresenteerde bewijs kan geconcludeerd worden dat de open pre-peritoneale benadering, bij een korte follow up van 1 jaar, even effectief lijkt als de operatie volgens Lichtenstein ten aanzien van recidief en mogelijk minder postoperatieve pijn en een sneller herstel geeft. Echter dit is met name gebaseerd op studies met de TIPP (trans-inguinaal pre peritoneaal) en de volledig posterieure techniek beschreven als Kugel. Overige technieken zijn onvoldoende (lang) onderzocht.

Er is geen studie die preperitoneale technieken met elkaar heeft vergeleken. Hierdoor kan er niet worden gesproken van de optimale open preperitoneale techniek.

Ten aanzien van deze technieken bestaan ook nieuwe zorgen met name ten aanzien van de kosten en de lange termijn veiligheid. Bij de Kugel-techniek werd een ruime hoeveelheid vreemd lichaam geïmplanteerd en waren er problemen met de geheugenring die leiden tot complicaties als pijn en darmperforaties. (de laatste versie heeft een oplosbare geheugenring).

Het wordt vooralsnog aanbevolen om de open preperitoneale technieken in onderzoeksvorm uit te zetten tegen de tot op heden gouden standaard (Lichtenstein-techniek) waarbij met name een lange follow up duur interessante bevindingen zou kunnen leveren. Hierbij dient men zich overigens wel te realiseren dat een trans-inguinale benadering van het preperitoneale vlak zowel het anterieure als posterieure anatomische vlak gebruik waarbij het een theoretisch nadeel is om via 1 van deze benadering een recidief te herstellen.

4. Welke laparo-endoscopische techniek heeft de voorkeur TEP of TAPP? Balans tussen voor- en nadelen

TAPP en TEP zijn beide goede technieken voor de behandeling van liesbreuken. Beide technieken hebben vergelijkbare resultaten wat betreft acute postoperatieve pijn, chronische pijn, recidiefpercentages, postoperatief herstel en kosten. Het risico op serieuze complicaties is zeer laag, met een hogere kans op darmletsel bij TAPP en op vaatletsel bij TEP. Literatuur gepubliceerd na de internationale richtlijn (HerniaSurge Group, 2018) heeft niet geleid tot wijziging van de aanbevelingen. De keuze voor een van de technieken zou gebaseerd moeten zijn op de ervaring van het chirurgische team.

Kwaliteit van het bewijs

De kwaliteit van het bewijs is hoog en gebaseerd op meerdere meta-analyses en systematic reviews.

Kosten

De kosten van TAPP en TEP zijn vergelijkbaar.

Wat vinden artsen: professioneel perspectief

De belangrijkste factor in de beslissing van de uitvoer van TAPP of TEP is de ervaring van het chirurgische team. Beide technieken zijn geschikt voor de behandeling van liesbreuken.

Haalbaarheid

De TAPP-techniek heeft als voordeel dat de aanwezigheid van een contralaterale liesbreuk vastgesteld kan worden voorafgaand aan de chirurgische exploratie. Bij TEP blijft de chirurg in het extraperitoneale vlak. Factoren zoals twijfel over de aanwezigheid van een contralaterale breuk of voorgeschiedenis van abdominale chirurgie kunnen doorslaggevend zijn voor de keuze voor één van de technieken, mits voldoende expertise aanwezig is bij het chirurgische team.

5. Als recidief, pijn, leercurve, postoperatief herstel en kosten belangrijke uitkomsten zijn, welke techniek heeft dan de voorkeur voor primaire liesbreuken bij mannen: Operatie volgens Lichtenstein of een laparo-endoscopische techniek?

Bij het wegen van de punten postoperatief herstel, postoperatieve pijn en chronische pijn is er steeds meer bewijs dat er winst is voor het gebruik van een laparo-endoscopische techniek. De voorwaarde hiervoor is echter wel dat de chirurg voldoende ervaren is in de techniek. De vele studies gaan echter mank op definitie van pijn, chirurgische ervaring en caseload per chirurg. Hierdoor kan de optimale indicatie voor deze technieken niet bepaald worden. Hierbij dient ook te worden meegewogen dat de leercurve en de (initiële) kosten van deze technieken langer respectievelijk hoger zijn dan bij de operatie volgens Lichtenstein. De leercurve voor de laparo-endoscopische technieken, met name de TEP, is geschat tussen de 50 en 100 procedures waarbij de 1e 30 tot 50 het meest kritisch zijn.

Vanuit het perspectief van het ziekenhuis is een Lichtenstein techniek het meest kosteneffectief. Vanuit een macroeconomisch kosten perspectief inclusief kwaliteit van leven is de laparo-endoscopische techniek gunstiger gezien de lagere incidentie van chronisch pijn en een sneller herstel.

In de 2014 update van de EHS guidelines werd een nieuwe meta-analyse gedaan bij patiënten met een follow up van meer dan 48 maanden. Hier was een niet significant verschil in chronische pijn (p=0.12) en in recidief, mits 1 studie met maar liefst 32% recidief, waarschijnlijk te beschouwen al technisch falen, in de endoscopie groep werd uitgesloten.

Een grotere RCT met een goede externe validiteit en of grote database studies zijn nodig om de laparo-endoscopie en de Lichtenstein techniek in primaire unilatere hernia bij mannen te kunnen vergelijken. Hierbij dient het niveau van de betrokken chirurgen goed gekwantificeerd te worden.

Het wordt aanbevolen om de laparo-endoscopische en Lichtenstein-technieken via een gestructureerd trainingprogramma en gedegen supervisie gedurende de leercurve te onderwijzen.

6. Open posterieure benadering (TIPP/TREPP) of laparo-endoscopische techniek?

Balans tussen voor- en nadelen

Open posterieure technieken worden in enkele ziekenhuizen in Nederland aangeboden en betreffen de TREPP, TIPP, plug en PHS. De laatste twee worden beargumenteerd afgeraden door de internationale richtlijn.

TREPP en TIPP zijn onvoldoende onderzocht om een goed advies te geven. Er zijn op dit moment nog geen resultaten bekend van vergelijkende studies tussen bijvoorbeeld de TREPP-techniek en de laparo-endoscopische technieken. Voor de TIPP geldt dat er in studies met korte follow-up een klein voordeel lijkt te zijn in hersteltijd en chronische pijn ten opzichte van de Lichtenstein-techniek. Een transinguinale benadering van het preperitoneale vlak via zowel het anterieure als posterieure anatomische vlak is een theoretisch nadeel voor herstel van een recidief via één van deze benadering. Ook zijn de kosten voor de benodigde mat hoger dan voor de operatie volgens Lichtenstein. De laparo-endoscopische technieken (TEP, TAPP) zijn beide geschikt voor liesbreukoperatie.

De preperitoneale benadering kan gepaard gaan met blaas- of vaatletsel. Ervaring van de chirurg in het preperitoneale vlak is daarom van belang.

Kwaliteit van het bewijs

De kwaliteit van het bewijs is beperkt, onder andere door het ontbreken van een risk bias assessment in de enige beschikbare metaanalyse.

Kosten

Er is geen informatie over kosteneffectiviteit. Voor het gebruik van laparo-endoscopische technieken is aanvullende laparo-endoscopisch apparatuur nodig en worden kosten gemaakt voor eventuele extra materialen.

Wat vinden artsen: professioneel perspectief

Eerste keus technieken zijn Lichtenstein, TEP en TAPP, mits voldoende ervaring aanwezig is in het chirurgische team. TREPP zou beter onderzocht moeten worden, bij voorkeur in gerandomiseerde studies vergelijkend met eerder genoemde technieken. Het wordt met lage bewijskracht aangeraden om geen TIPP, PHS of Plug repair aan te bieden.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Zoals in de internationale richtlijn goed beschreven is, bestaan er veel technieken om een liesbreuk operatief te behandelen. Deze varieren van “non-mesh” oftewel “weefselplastiek” tot variaties van “open mesh” (open mat technieken) en “laparo-endoscopische mat” (TEP/TAPP) technieken. Teneinde de beste techniek te identificeren zou gekeken moeten worden naar de volgende variabelen: leercurve (complexiteit), veiligheid (complicaties), risico’s op chronische pijn en recidief, postoperatief herstel en kosten. Een specifieke techniek voor alle liesbreuktypes bestaat niet. De internationale richtlijn beveelt aan om te individualiseren op grond van chirurg gerelateerde factoren (expertise, ervaring), patiëntgerelateerde factoren (geslacht, risicofactoren voor complicaties, recidief, pijn, anesthesie opties), liesbreuktype (recidief, scrotaal, reponibel, eerdere operaties) en aanwezige middelen (mogelijkheid tot scopische operaties bijvoorbeeld). De Werkgoep is nagegaan welke technieken geschikt zijn onder de voorspelbare omstandigheden van de primaire liesbreuk. Het is de vraag of er gestandardiseerd kan worden naar één of twee technieken die voldoen voor de verschillende typen liesbreuk. Ook is kritisch gekeken of het soort benadering en het type matje gestandardiseerd kunnen worden. Dit zou potentieel kostenverlagend kunnen werken. Dankzij een enquête onder chirurgen in 2018 is het bekend dat 98% een matje gebruikt, 53% van de patiënten middels een laparo-endoscopische techniek geopereerd wordt en er is een meerderheid die als eerste keus opties een Lichtenstein (60%) of TEP (85%) adviseert. Voorts bleken TREPP, TIPP, Plug en PHS in respectievelijk 6, 2, 2 en 1 ziekenhuis aangeboden te worden. Een Shouldice werd in 1 ziekenhuis aangeboden als een eerste keus optie. Meerdere eerste keus opties konden aangegeven worden. Dit wijst op een grote variatie waarbij ook naar voren komt dat chirurgen binnen een ziekenhuis meerdere technieken adviseren.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

1. Which is the preferred repair method for inguinal hernias: mesh or Shouldice?

Conclusies operatie met mat of weefselplastiek

|

Laag GRADE |

Er lijkt geen verschil in het aantal patiënten met chronische postoperatieve pijn 3 jaar of langer na een liesbreukoperatie met mat vergeleken met een operatie volgens Shouldice.

Bronnen: (Lockhart, 2015 – unpublished results; Wamalwa, 2015; Miserez, 2014) |

|

Laag GRADE |

Een operatie volgens Shouldice lijkt een bijna twee keer zo grote kans op recidief 3 jaar of langer na een liesbreukoperatie te geven vergeleken met een liesbreukoperatie met mat.

Bronnen: (Lockhart, 2015 - unpublished results; Wamalwa, 2015, Miserez, 2014) |

|

Zeer laag GRADE |

Een verschil in postoperatieve pijn (herstelfase <3 maanden) tussen een liesbreukoperatie met mat versus een operatie volgens Shouldice kon niet worden aangetoond, noch verworpen.

Wel lijken er aanwijzingen te zijn dat postoperatieve pijn na een laparo-endoscopische operatie lager is dan na een operatie volgens Shouldice.

Bronnen: (Lockhart, 2015 - unpublished results; Wamalwa, 2015) |

2. Which is the preferred open mesh technique for inguinal hernias: Lichtenstein or other open flat mesh and gadgets via an anterior approach?

Conclusies Operatie volgens Lichtenstein versus andere open flat mesh en gepreformeerde mesh gadgets via een anterieure benadering

Conform de International Guidelines wordt ondanks vergelijkbare resultaten het gebruik van de plug en patch en de PHS niet aanbevolen vanwege de ruime hoeveelheid vreemdlichaam dat geïmplanteerd wordt, het gebruik van zowel het anterieure als het posterieure vlak en de extra kosten voor de mat.

|

Conclusie internationale richtlijn: Recidief kans en postoperatieve pijn zijn wellicht vergelijkbaar tussen plug-and-patch/PHS en een operatie volgens Lichtenstein. Ondanks de vergelijkbare resultaten worden de plug-and-patch/PHS niet aanbevolen vanwege de ruime hoeveelheid vreemdlichaam, de kosten en het gebruik van het anterieure en posterieure vlak in dezelfde procedure.

Bron: (HerniaSurge Group, 2018) |

|

Chronische pijn (>3 maanden): Aanvullend bewijs met lage bewijskracht lijkt geen verschil te tonen in chronische post-operatieve pijn tussen de operatie volgens Lichtenstein, de PHS en de UHS techniek en ook niet tussen de TIPP en Progrip techniek.

Bronnen: (Magnusson, 2016; Čadanová, 2016) |

|

Recidief: Aanvullend bewijs met lage bewijskracht lijkt geen verschil te tonen in recidief kans na 1 jaar tussen Progrip en de TIPP techniek en ook niet tussen de Lichtenstein, PHS en de Rutkow-Robins techniek.

Bronnen: (Čadanová, 2016; Karaca, 2013) |

|

Complicaties: Aanvullend bewijs met lage bewijskracht lijkt meer complicaties te tonen na een Progrip techniek vergeleken met de TIPP techniek 2 weken na operatie. Of er verschil is tussen de operatie volgens Lichtenstein versus andere open anterieure technieken is onzeker.

Bronnen: (Čadanová, 2016; Karaca, 2013) |

3. Which is preferred open mesh technique: Lichtenstein versus open pre-peritoneal?

Conclusies operatie volgens Lichtenstein versus open pre-peritoneale benadering

Bij een open Liesbreukoperatie is er conform de internationale richtlijn geen bewijs om een open preperitoneale benadering aan te bevelen boven een Lichtenstein plastiek. Het gebruik van het anterieure en posterieure anatomische vlak in één technique is op theoretische gronden een reden voor terughoudendheid.

|

Conclusies internationale richtlijn: Er is onzeker bewijs dat open preperitoneale technieken resulteren in een korte termijn winst (na 1 jaar) met betrekking tot direct posteratieve pijn, chronische pijn en postoperatief herstel. Hierbij dient in ogenschouw genomen te worden dat een aantal technieken gelijktijdig het anterieure en posterieure anatomische vlak gebruiken tijdens één procedure hetgeen niet de voorkeur verdient.

Het gebruik van speciale matten ten behoeve van matplaatsing resulteert in verhoogde kosten voor de mat. Tevens is er onzeker bewijs dat er problemen zijn met de geheugenring van sommige matten.

Bron: (HerniaSurge Group, 2018) |

|

Recidief: Aanvullend bewijs met lage bewijskracht (2015 tot 2017) ten aanzien van recidief staat geen nieuwe conclusies toe.

Bronnen: (Azeem, 2015; Andresen, 2017; Mahmoudvand, 2017) |

|

Chronische pijn: Aanvullend bewijs met lage bewijskracht (2015 tot 2017) ten aanzien van chronische pijn staat geen nieuwe conclusies toe.

Bronnen: (Andresen, 2015; Azeem, 2015 Mahmoudvand, 2017) |

|

Postoperatief herstel: Pijn: Aanvullend bewijs met lage bewijskracht (2015 tot 2017) ten aanzien van postoperatieve pijn staat geen nieuwe conclusies toe.

Bronnen: (Andresen, 2015; Mahmoudvand, 2017) |

|

Complicaties: Aanvullend bewijs met lage bewijskracht (2015 tot 2017) en ten aanzien van complicaties staat geen nieuwe conclusies toe.

Bronnen: (Azeem, 2015; Andresen, 2015 en 2017; Mahmoudvand, 2017) |

|

Mortaliteit:

Er is geen nieuw (2015 tot 2017) bewijs ten aazien van de uitkomstmaat ‘mortaliteit’.

Bronnen: - |

4. Which endoscopic technique is preferred in terms of postoperative outcome?

Conclusies TEP versus TAPP

Conform de internationale richtlijn hebben TEP en TAPP vergelijkbare uitkomsten. De keuze voor de techniek kan het beste gebaseerd worden op patiëntfactoren en de vaardigheiden c.q. ervaring van de chirurg.

|

Conclusies internationale richtlijn: Er lijkt geen verschil tussen TAPP en TEP met betrekking tot operatietijden, totaal aantal complicaties, postoperatieve acute en chronisch pijn en recidief percentages.

Hoewel de complicatie zeer zeldzaam is lijkt er een trend naar meer darmletsels bij TAPP.

Hoewel de complicatie zeer zeldzaam is lijkt er een trend naar meer vaatletsels bij TAPP.

Hoewel de complicatie zeldzaam is lijken trocart hernia’s vaker voor te komen bij TAPP. Hoewel het fenomeen zeldzaam is lijkt een conversie bij TEP vaker voor te komen.

Er lijkt geen verschil in kosten tussen TAPP en TEP

Er zijn aanwijzingen dat de leercurve bij TEP langer is dan bij TAPP.

Bron: (HerniaSurge Group, 2018) |

|

Recidief (Follow up > 3 jaar): Er is geen aanvullend bewijs voor de uitkomst recidief (2015 tot 2017).

Bronnen: - |

|

Acute postoperatieve pijn: Het aanvullende bewijs voor de uitkomst acute postoperatieve pijn is van erg lage kwaliteit (2015 en 2017).

Bronnen: (Wei, 2015) |

|

Chronische pijn (>6 maanden) Aanvullend bewijs voor de uitkomst chronische pijn na 6 maanden toonde geen significant verschil tussen TAPP en TEP (2015 tot 2017).

Bronnen: (Bansal, 2017) |

|

Herstel: Aanvullend bewijs voor de uitkomst hersteltijd (tijd tot hervatting van normale activiteiten) is van erg lage kwaliteit (2015 tot 2017).

Bronnen: (Wei, 2015) |

|

Kosten: Aanvullend bewijs betreffende kosteneffectiviteit is van erg lage kwaliteit (2015 tot 2017).

Bronnen: (Wei, 2015) |

5. When considering recurrence, pain, learning curve, postoperative recovery and costs which is preferred technique for inguinal hernias: Best open mesh (Lichtenstein) or a laparo-endoscopic (TEP and TAPP) technique?

Conclusies operatie volgens Lichtenstein versus laparo-endoscopische techniek

Conform de internationale richtlijn wordt bij mannen met een primaire unilaterale liesbreuk aanbevolen om de liesbreuk met een laparo-endoscopische techniek te behandelen in verband met een lagere postoperatieve incidentie van vroege en late postoperatieve pijn. Er zijn echter patient en hernia karakteristieken waarbij de Lichtenstein de 1e keuze is.

|

Conclusies internationale richtlijn: Het lijkt aannemelijk dat een chirurg met voldoende ervaring in de laparo-endoscopische techniek een vergelijkbaar recidief percentage kan halen in vergelijking met de operatie volgens Lichtenstein.

Er lijkt een voordeel aanwezig voor een laparo-endoscopische procedure door een ervaren chirurg in vergelijking met de operatie volgens Lichtenstein ten aanzien van vroege postoperatieve pijn (in rust en bij beweging) en chronische pijn

Er lijkt geen verschil in operatieduur tussen de laparo-endoscopische techniek en de operatie volgens Lichtenstein in handen van een ervaren chirurg. Er lijkt geen verschil tussen percentage reoperaties na laparo-endopische of Lichtenstein operaties in ervaren handen.

Er lijkt een toename in directe operatieve kosten bij het verrichten van laparo-endoscopische operaties. De impact van deze kosten lijkt af te nemen als de macroeconomische kosten worden meegewogen en als de chirurg voldoende ervaring heeft.

Er zijn aanwijzingen dat de leercurve voor laparo-endoscopische operaties (met name TEP) langer is dan die voor de operatie volgens Lichtenstein. Er zijn zeldzame doch ernstige complicaties die vooral optreden aan het begin van de leercurve. Het is dan ook zeer verstandig dat laparo-endoscopische operaties met afdoende supervisie worden onderwezen.

Bron: (HerniaSurge Group, 2018) |

|

Recidief: Er lijkt geen verschil in het aantal patiënten met een recidief tussen Lichtenstein en TEP (data 2015 tot 2017)

Bronnen: (Westin, 2015; Gürbulak 2016) |

|

Vroege en late postoperatieve pijn: Aanvullende data (2015 tot 2017) suggereert meteen laag bewijsniveau een afname van de vroege en late postoperatieve pijn bij laparo-endoscopie in vergelijking met de operatie volgens Lichtenstein.

Bronnen: (Salma, 2015; Westin, 2015; Waris, 2016) |

|

Kosten: Geen aanvullende data (2015 tot 2017) gevonden.

Bronnen: - |

|

Complicaties: Aanvullende data (2015 tot 2017) toonde geen verschil tussen laparo-endoscopische operaties en de operatie volgens Lichtenstein.

Bronnen: (Gürbulak, 2015) |

|

Leercurve: Geen aanvullende data (2015 tot 2017) gevonden.

Bronnen: - |

6. Open posterior or laparoscopic technique?

Conclusies Open posterieure benadering (TIPP, TREPP) of laparo-endoscopische techniek

Conform de internationale richtlijn is er een gebrek aan bewijs door insufficiënte en heterogene data. Een conclusie over deze vraag zal derhalve uitblijven.

|

Conclusie internationale richtlijn: Er is gebrek aan bewijs om een preperitoneale mat te prefereren boven de operatie volgens Lichtenstein. Open pre-peritoneale technieken worden bij voorkeur in onderzoeks verband verricht zodat verdere uitkomsten kunnen worden verzameld. Het is te overwegen om niet tijdens één operatie het anterieure en posterieure anatomische vlak te gebruiken.

Bron: (HerniaSurge Group, 2018) |

|

Recidief: Aanvullend bewijs toonde geen verschil in recidiefkans tussen laparo-endoscopische technieken en open preperitoneale technieken (2015 tot 2017).

Bronnen: (Sajid, 2015) |

|

Potoperatief herstel (complicaties): Aanvullend bewijs toonde dat de kans op postoperatieve complicaties niet toe- of afneemt bij laparo-endoscopische technieken vergeleken met open preperitoneale technieken (2015 tot 2017).

Bronnen: - |

|

Mortaliteit: Er is geen aanvullend bewijs voor de uitkomst mortaliteit (2015 tot 2017) .

Bronnen: - |

Samenvatting literatuur

1. Which is the preferred repair method for inguinal hernias: mesh or Shouldice?

Description of studies

A protocol for a Cochrane systematic review comparing mesh versus non-mesh for inguinal and femoral hernia repair was found (Lockhart, 2015), which will update a previous Cochrane review about the topic (Scott 2001). Authors of the protocol were contacted and they were willing to share their preliminary results. Furthermore, a second relevant Cochrane review that compared Shouldice technique versus other open techniques for inguinal hernia repair was identified (Amato, 2012). In additionan, six randomized, controlled studies (RCTs) were included (Bhatti, 2015; Olasehinde, 2016; Palermo, 2015; Szopinski, 2012; Wamalwa, 2015; Youssef, 2015).

For their update of the Cochrane review of Scott 2001, Lockhart and colleagues searched the following databases up to January 8 2017: Cochrane Colorectal Cancer Group Specialized Register, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, MEDLINE, EMBASE and Web of Science. Trial registers were also searched and references of included studies checked. The review compared mesh with non-mesh (both open and laparoscopic techniques) in adult patients (> 18 years) with inguinal hernia. Twenty-five RCTs were included with a total of 6293 participants. Primary outcome measures in this review were recurrences, complications and mortality. Secondary outcomes were duration of operation, duration of hospital admission, time needed to take up daily life activities and number of operations in which a laparoscopic technique was switched to an open technique.

Sixteen studies comparing Shouldice technique to other open techniques for inguinalhernia repair were included in the Cochrane review by Amato and colleagues (Amato, 2012). Eight of the included studies compared Shouldice to mesh techniques. MEDLINE, EMBASE, and The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) were searched and the review is assessed as up to date until February 2012. Recurrence of hernia was the primary outcome measure and secondary outcomes were postoperative hospital stays, chronic pain, postoperative satisfaction, complication rate, and duration of operation. The main characteristics and results of this systematic review are included in the evidence table (see Appendix 1). Assessment of the quality of the review is presented in Appendix 2.

Of the six additionally identified RCTs, three compared mesh with the Desarda method (Bhatti, 2015; Szopinski, 2012; Youssef, 2015), one compared mesh with the Bassini method (Palermo. 2015), one mesh with the darning technique (Olasehinde, 2016) and one mesh with Shouldice (Wamalwa 2015). In all six RCTs, the mesh operation consisted of a Lichtenstein technique. The size of the study populations varied from 50 to 263. With the exception of the RCT of Bhatti (2015), all RCTs examined the outcomes of pain and recurrences. All RCTs also looked at one or more complications.

The randomization method was clearly described in all RCTs and was considered to be adequate, with the exception of one RCT in which an alternating sequence was used, as a result of which the allocation of the intervention was not concealed (Olasehinde, 2016). For another RCT, in which the randomization sequence with a table was assigned, it was unclear whether this allocation was also concealed (Bhatti, 2015). Blinding of the intervention for patients was unlikely, with the exception of one RCT in which patients were not informed about the chosen surgical technique (Szopinski, 2012). Blinding of caregivers was not possible. The outcome measurement was blinded in one RCT (Szopinski, 2012) for the other RCTs the chance of bias with regard to the outcome measurement was unclear, because it was unclear who, in addition to the results reported by the (unblinded) patients, judged the other outcomes and whether this happened blinded . A study protocol was available for two RCTs and there seemed to be no selective reporting (Szopinski, 2012; Youssef, 2015), for the other RCTs there was no protocol, but the results were reported for all outcomes described in the methods. The probability of bias due to incomplete follow-up or violation of the 'intention-to-treat' principle was not plausible in any of the RCTs. The main study characteristics and results are included in the evidence table (see Appendix 1) and the assessment of the individual study design (Risk of Bias) is included in the risk or bias table (Appendix 2).

Results

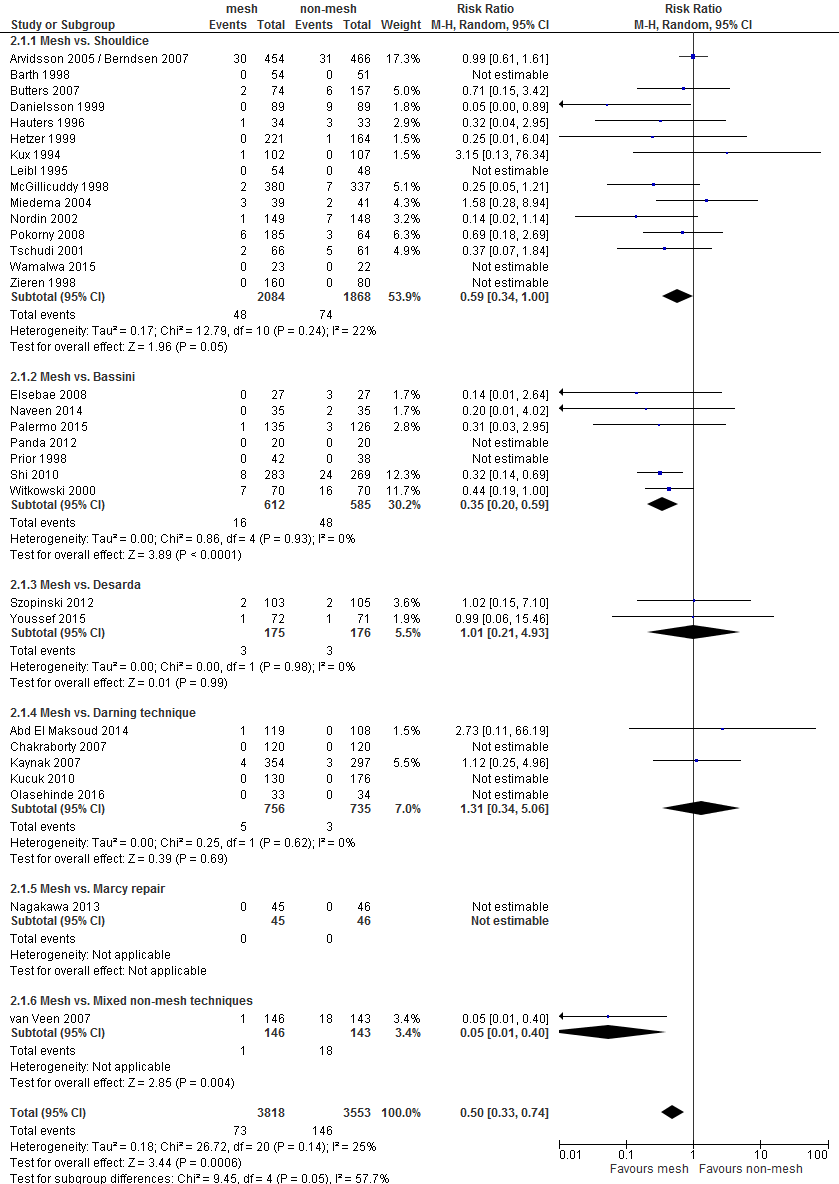

In total, 36 primary studies comparing mesh with no mesh were identified (Overview table in Appendix 1). Looking at the type of non-mesh techniques that were used, the following subgroups can be distinghuised:

- Shouldice

- Bassini

- Desarda

- Darning techniques

- Marcy repair

- using multiple non-mesh techniques ('mixed')

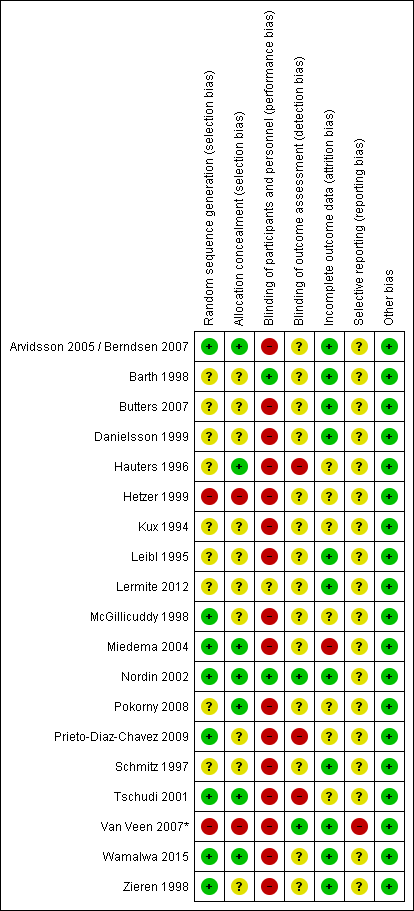

Since Shouldice is the most relevant non-mesh technique for the Dutch situation, in presenting the results and grading of the evidence (GRADE), the focus is on the comparison mesh versus Shouldice. In total, 19 studies addressed this comparison (9 studies comparing Lichtenstein and Shouldice, 3 studies comparing TEP or TAPP with Shouldice, and 7 studies comparing multitple or other mesh techniques such as mesh-plug, with Shouldice) (Overview table in Appendix 1). Risk of Bias of these studies is summarized in Figure 1, in Appendix 2.

Chronic pain (crucial outcome)

Sixteen RCTs that compared postoperative (chronic) pain between mesh and Shouldice techniques are listed in Table 1 (Barth, 1998; Arvidsson, 2005/Berndsen, 2007; Danielsson, 1999; Hauters, 1996; Kux, 1994; Leibl, 2000; Lermite, 2012; McGillicuddy, 1998; Miedema, 2004; Nordin, 2002; Pokorny, 2008; Prieto-Díaz-Chávez, 2009; Schmitz, 1997; Tschudi, 2001; Wamalwa, 2015; Zieren, 1998). The ways and times at which postoperative pain was measured varied greatly between the studies.

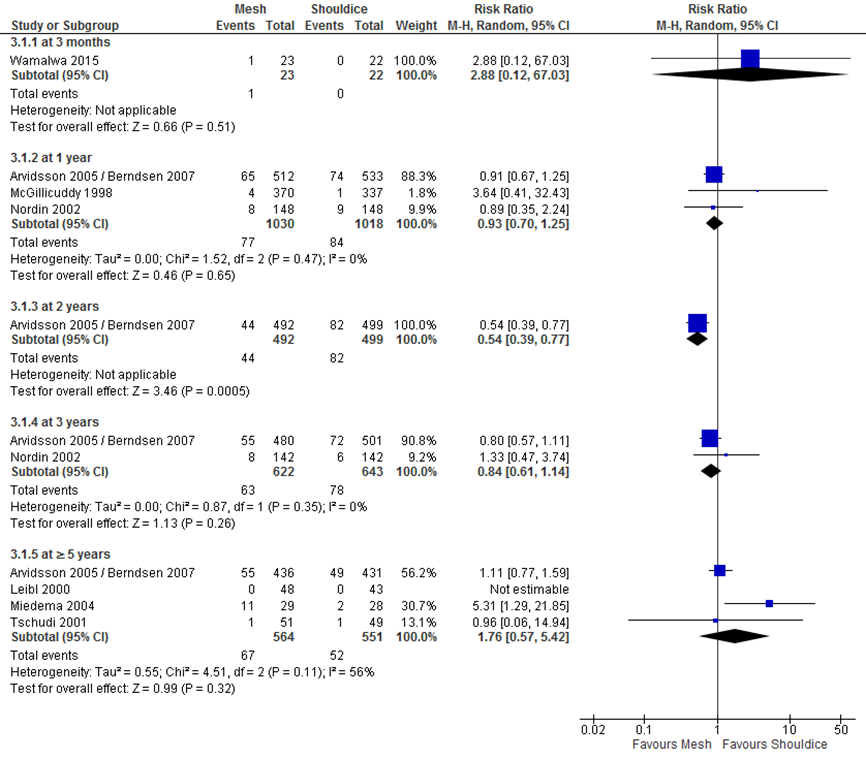

Eight RCTs (n = 2447 participants) reported results for chronic pain (critical outcome; defined as presence of pain measured 3 months or longer after surgery) (Arvidsson, 2005/Berndsen, 2007; Leibl, 2000, McGillicuddy, 1998; Miedema, 2004; Nordin, 2002; Prieto-Díaz-Chávez, 2009; Tschudi, 2001; Wamalwa, 2015). Seven of them are displayed in a forest plot (Figure 1). Due to heterogeneity in measurement methods and follow-up duration, the results were not pooled. With the exception of one study that measured chronic pain 2 years postoperatively (RR 0.54, 95% CI 0.39 to 0.77 in favor of mesh), no differences were found between the study groups treated with mesh and Shouldice for the other time points. The eighth study, with a follow-up of 24 months, reported a significantly lower monthly score on a visual analogue scale (VAS) for mesh, however, it is unclear how such a monthly VAS score should be interpreted (Prieto-Díaz-Chávez, 2009).

Figure 1 Forest plot mesh versus Shouldice for chronic postoperative pain (per follow-up duration) (n=7)

Postoperative pain

The results in 14 RCTs (n = 3106 participants) that examined postoperative pain up to 3 months postoperatively (important outcome) ranged between a benefit for mesh and no difference between mesh and Shouldice.

A benefit for mesh was found in the 7 studies comparing TAPP (Berndsen, 2007; Tschudi, 2001), mesh-plug (Lermite, 2012; Prieto-Diaz-Chavez, 2009), mesh-plug or TAPP (Zieren, 1998), Lichtenstein (Kux, 1994) and a not-specified mesh technique (Hauters, 1996).

No difference between mesh and Shouldice was found in 5 studies comparing Lichtenstein and Shouldice (Barth, 1998; Danielsson, 1999; Miedema, 2004; Nordin, 2002; Wamalwa, 2015), one study comparing another mesh technique with Shouldice (Schmitz, 1997) and one study comparing Lichtenstein, TEP and TAPP with Shouldice (Pokorny, 2008) (Table 1).

Table 1 Overview of reported outcomes regarding postoperative (chronic) pain for mesh versus Shouldice (n=16 RCTs).

|

Study |

Outcome |

Time points |

Measurement tool |

Results |

|

Arvidsson 2005 /Berndsen 2007 |

Postoperative pain |

1 week postoperatively |

Self-report (VAS) |

Median (min-max) VAS (mm) 98 (range 0-405) versus 165 (range 0-450); p <0.001 |

|

|

Chronic post-operative pain or discomfort |

1, 2, 3 and 5 years postoperatively |

Description by patient, classified by two independent observers as mild (occasional pain or discomfort without affecting daily activities), moderate (pain or discomfort that occasionally affects daily activities) or severe (daily pain or discomfort affecting daily activities) . |

1 year 65/512 versus 74/533 - Mild: 48 versus 56 - Moderate: 16 versus 18 - Severe: 1 versus 0

2 years 55/492 versus 82/499 - Mild: 44 versus 67 - Moderate: 11 versus 14 - Severe: 0 versus 1

3 years 55/480 versus 82/501 - Mild: 44 versus 53 - Moderate: 11 versus 19 - Severe: 0 versus 0

5 years 55/436 versus 49/431 - Mild: 24 versus 34 - Moderate: 12 versus 12 - Severe: 1 versus 3 |

|

Barth 1998 |

Postoperative pain at rest |

daily up to 4 weeks postoperatively |

Self-report with respect to 5-point pain score (0 = none, 1 = very mild, 2 = mild, 3 = moderate, 4 = severe, 5 = very severe) |

Average postoperative day (IQR) Mild pain: 1 (0-3) versus 2 (0-3); NS Very mild pain: 3 (2-7) versus 4 (1-7); NS

Postoperative day on which 50% patients without pain: 9 versus 9 |

|

|

Postoperative pain during walking |

daily up to 4 weeks postoperatively |

Self-report with respect to 5-point pain score (0 = none, 1 = very mild, 2 = mild, 3 = moderate, 4 = severe, 5 = very severe) |

Average postoperative day (IQR) Mild pain: 2 (1-5) versus 3 (1-5); NS Very mild pain: 6 versus 6; NS

Postoperative day (IQR) in which 50% of patients without pain: 14 (7-22) versus 12 (8-20) |

|

|

Use of painkillers |

n.a. |

Self-report |

Median number of days 3 versus 4; NS (Within 15 days, everyone stopped taking pain relief) |

|

Danielsson 1999 |

Postoperative pain |

1, 2, and 3 days postoperatively |

VAS (0-100) |

Day 1 postoperative, mean ± SD 48 ± 25 versus 45 ± 25

Day 2 postoperative, mean ± SD 43 ± 23 versus 43 ± 24

Day 3 postoperative, mean ± SD 36 ± 23 versus 35 ± 25 |

|

|

First day without appreciable pain |

Not specified. |

Self-report |

mean ± SD 10 ± 4.9 versus 10 ± 5.2 |

|

Hauters 1996 |

Postoperative pain |

1 day and 3 days postoperatively |

VAS (0-10) |

Day 1 postoperative, mean ± SD 3.4 ± 1.5 versus 5.3 ± 1.9; p <0.001

Day 3 postoperative, mean ± SD 1.3 ± 1.4 versus 2.8 ± 1.8; p <0.005 |

|

Kux 1994 |

Use of painkillers |

1 day postoperatively |

Not reported |

% of people who do not use painkillers on day 1 postoperatively: 29.4 versus ? *

% of people who did not use painkillers at all: 9.8 versus ? *

"The amount of local anesthetic and postoperative pain medication was significantly reduced in the Lichtenstein group"

* Data for Shouldice group not reported.

|

|

Leibl 2000 |

Chronic pain (unspecified) |

Median follow-up duration of 70 months |

Not reported |

0/48 versus 0/43 “Neither of the two therapeutic options led to a chronic pain syndrome” |

|

Lermite 2012 |

Postoperative pain (intensity) |

1 day and 2 days postoperatively |

VAS |

Day 1 postoperative 22.1 versus 27.4; p = 0.003

Day 2 postoperative 13.2 versus 21.4; p <0.0001 |

|

McGillicuddy 1998 |

Chronic pain

|

>1 jaar postoperatively |

Focused physical examination |

4/370 versus 1/337; NS |

|

Miedema 2004 |

Postoperative pain |

30 days postoperative |

Self-report of number of tablets used |

Median number of tablets used 6 versus 7, p=NS |

|

|

Chronic groin pain |

up to 6-9 years follow-up |

Self-report of groin pain, categorized as none, mild, moderate, or severe. |

Number of patients reporting chronic groin pain: 11/29 (38%) versus 2/28 (7%), p<0.05

Severity of groin pain Mild: 3 versus 1 Moderate: 3 versus 0 Severe: 5 versus 1 |

|

Nordin 2002 |

Postoperative pain |

direct postoperative, 8 weeks postoperatively |

VAS (0-10) |

Direct postoperatively, average VAS (?) Lichtenstein (n = 149) versus Shouldice (n = 148) 3.6 versus 3.8

8 weeks postoperatively 1.7 versus 1.7 |

|

|

Persistent pain (not specified) |

8 weeks postoperatively |

VAS |

% of patients with persistent pain 4.0 versus 3.4 |

|

|

Chronic postoperative pain |

1 and 3 years postoperatively |

Questionnaire (1 year postoperative), examination by surgeon who is not aware of the used surgical technique (3 years postoperatively) |

1 year postoperatively % of patients with persistent pain 5.4 versus 6.1

3 years postoperatively % of patients with persistent pain Mild: 4.9 versus 0.7 Moderate: 0.7 versus 2.1 Neuralgia: 0 versus 1.4 |

|

Pokorny 2008 |

Use of painkillers |

2-4 weeks postoperatively |

Not specified |

Number of participants reporting the use of painkillers 11/182 (6%) versus 8/64 (13%); RR 0.48, 95% CI 0.20 to 1.15 |

|

Prieto-Díaz-Chávez 2009 |

(Chronic) postoperative pain |

7 days, 8 weeks, 12 and 24 months postoperatively |

VAS |

VAS (monthly)* 1.75 versus 2.80; p<0.05 * Unclear how to interpret this score |

|

|

Use of painkillers |

Not reported |

Self-report |

No results reported |

|

Schmitz 1997 |

Postoperative pijn while lying down, getting up and walking |

Daily for 6 days postoperatively |

VAS |

"Während am 1. postoperativen Tag im Liegen die Mittelwerte in beiden Gruppen bei 30% des stärksten vorstellbaren Schmerzes lagen, befanden sich die Mittelwerte beim Aufrichten bei 50–60%; beim Gehen lagen sie etwa bei 43%. Die nur geringfügig geringere Schmerzintensität bei den spannungsfrei operierten Patienten ergab keinen signifikanten Unterschied zur Shouldice-Gruppe. Dieser Trend setzt sich bis zum Entlassungstag fort, so daß zu keinem Zeitpunkt ein signifikanter Unterschied entsprechend der Studienhypothese auftrat. Beide Patientengruppen waren nach dem 5. Tag beschwerdefrei." |

|

|

Use of painkillers |

Daily for 6 days postoperatively |

Not reported |

"Beide Gruppen unterschieden sich nicht signifikant voneinander, denn ab dem 2. postoperativen Tag betrug der mittlere Analgeticaverbrauch nur noch 1 Tablette (0,5) täglich. Lediglich am 1. postoperativen Tag lag der mittlere Verbrauch in der Shouldice-Gruppe um 50% über dem der TF-Gruppe. Bei jedoch großer Schwankungsbreite (sx) läßt die relativ kleine Probandenzahl die Aussage nach einer Signifikanzdifferenz allein für den 1. Tag nicht zu, was allerdings auch nicht Gegenstand der Studienfrage war." |

|

Tschudi 2001 |

Postoperative pain |

1 day postoperatively |

VAS (0-100) |

Mean pain score ± SD 24.51 ± 18.37 versus 32.96 ± 21.96, p=0.053 |

|

|

Use of paracetamol and narcotic analgesics (morphine-equivalent dose) |

1 day postoperatively |

Not reported |

Paracetamol in mg, mean ± SD 2549.02 ± 4360.34 versus 4577.55 ± 6441.31, p=0.048

Narcotic analgesics in mg, mean ± SD 6.52 ± 11.21 versus 18.96 ± 23.73, p=0.0005 |

|

Wamalwa 2015 |

Postoperative pain |

24 hours, 2 weeks, 3 months postoperatively |

Asked for the presence of pain. |

24 hours postoperatively 4/23 (17%) versus 3/22 (14%); p-value not reported

2 weeks postoperatively 3/23 (13%) versus 1/22 (5%); p-value not reported

3 months postoperatively 1/23 (4%) versus 0/22 (0%); p-value not reported

“One patient had persistent chronic pain after Lichtenstein repair. This was classified as neuralgia on account of its radiation along the inguinal nerve.” |

|

|

Use of painkillers > 1 week postoperatively |

2 weeks |

Not reported |

Not reported |

|

Zieren 1998 |

Postoperative pain |

3 times a day for a postoperative period of 2 months |

VAS, self-report |

"Mean pain analogue scores and analgesia requirements were comparable between mesh (TAPP and Plug) but both were significantly lower compared with Shouldice (SH)" |

|

|

Chronic postoperative pain (not specified) |

Average follow-up duration of 25 months |

Unclear (VAS?) |

Tapp (n=80) versus Plug (n=80) versus Shouldice (n=80); n (%): 3 (4) versus 2 (3) versus 4 (5); p=NS |

|

|

Use of painkillers |

Unclear (2 months postoperative?) |

Not reported |

Tapp (n=80) versus Plug (n=80) versus Shouldice (n=80); Mean (sd) days 2 (4) versus 3 (7) versus 10 (6); p<0.05 (Shouldice significantly different from Tapp and Plug)

"Mean pain analogue scores and analgesia requirements were comparable between TAPP and PP but both were significantly lower compared with SH" |

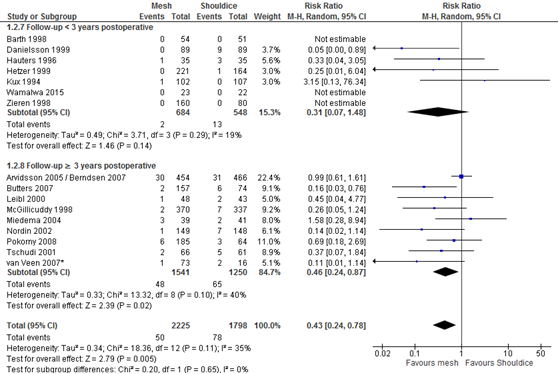

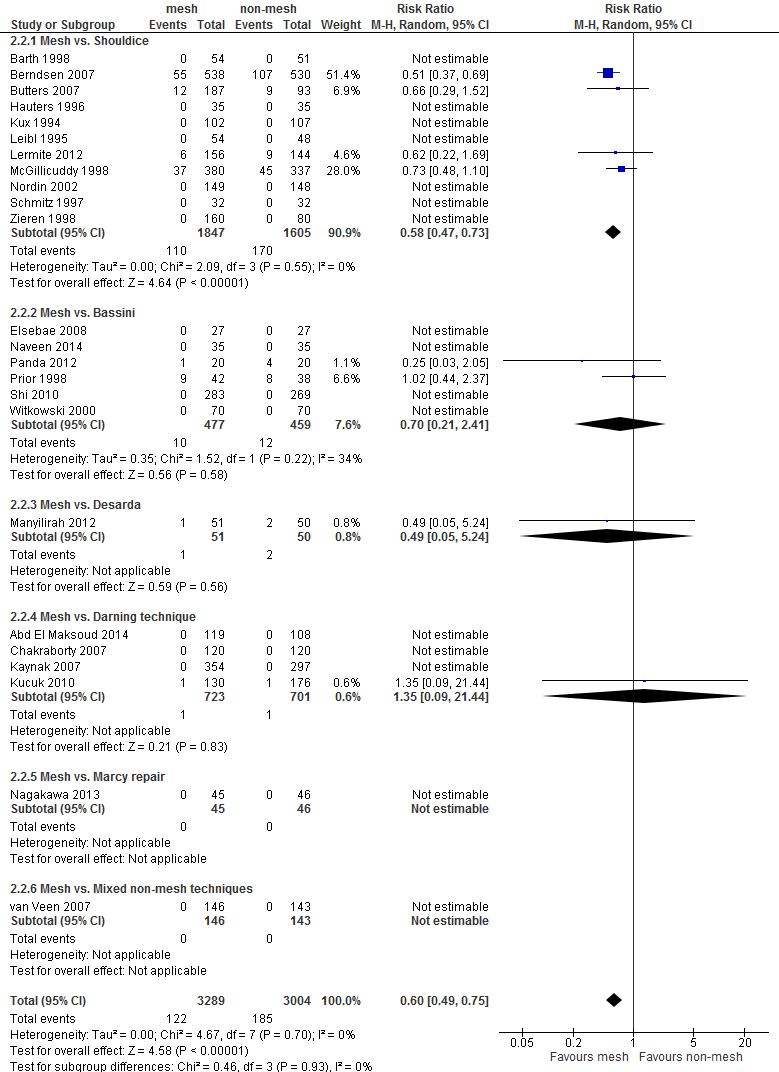

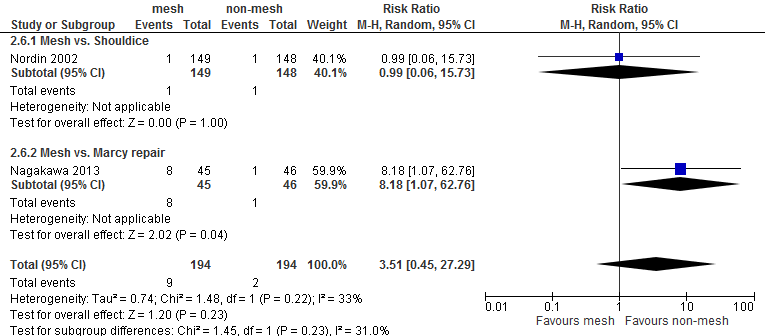

Figure 2 Forest plot mesh versus Shouldice for the outcome 'recurrences' (n = 16)

* In the study of Van Veen patients were randomized to either mesh (Lichtenstein) or non-mesh (surgeon’s choice). Shouldice was among the non-mesh techniques and was chosen by the surgeon in 20% of the patients. As allocation to Shouldice is not completely at random, a sensitivity analysis was performed excluding the study of Van Veen (2007) (resulting overall RR of 0.47, 95% CI 0.26 to 0.85; RR for subgroup ‘≥3 years postoperative’ was 0.52, 95% CI 0.28 to 0.96).

Recurrences (critical outcome) >3jaar

Thirty-one RCTs reported the outcome 'recurrences' for the comparison mesh versus non-mesh (Figure B1 in Appendix 3). In 10 of these there were no recurrences in both study groups. The pooled result of the remaining 21 RCTs shows fewer recurrences after a mesh technique (RR 0.46, 95% CI 0.30 to 0.68).

For the comparison of mesh versus Shouldice 16 RCTs reported the outcome 'recurrences' and these are shown in Figure 2, grouped per follow-up (either shorter or longer than three years postoperatively). There were three RCTs without recurrences in both study groups. The pooled result of the other 13 RCTs, showed a difference in favour of mesh (RR 0.43, 95% CI 0,24 to 0.87). As in the study of Van Veen (2007) allocation to Shouldice was not completely at random, a sensitivity analysis was done excluding this study. The resulting overall pooled RR remained in favour of mesh (RR 0.47, 95% CI 0.26 to 0.85; RR for subgroup ‘≥3 years postoperative’ was 0.52, 95% CI 0.28 to 0.96).

Postoperative complications

An overview of the following postoperative complications is given in Table 2 for the comparison of mesh versus non-mesh and also for the subgroup mesh versus Shouldice: neurovascular or visceral complications, wound infection, hematoma, seroma, postoperative swelling of the wound, wound dehiscence, testicular complications and urinary retention. A graphic representation can be found in Appendix 3.

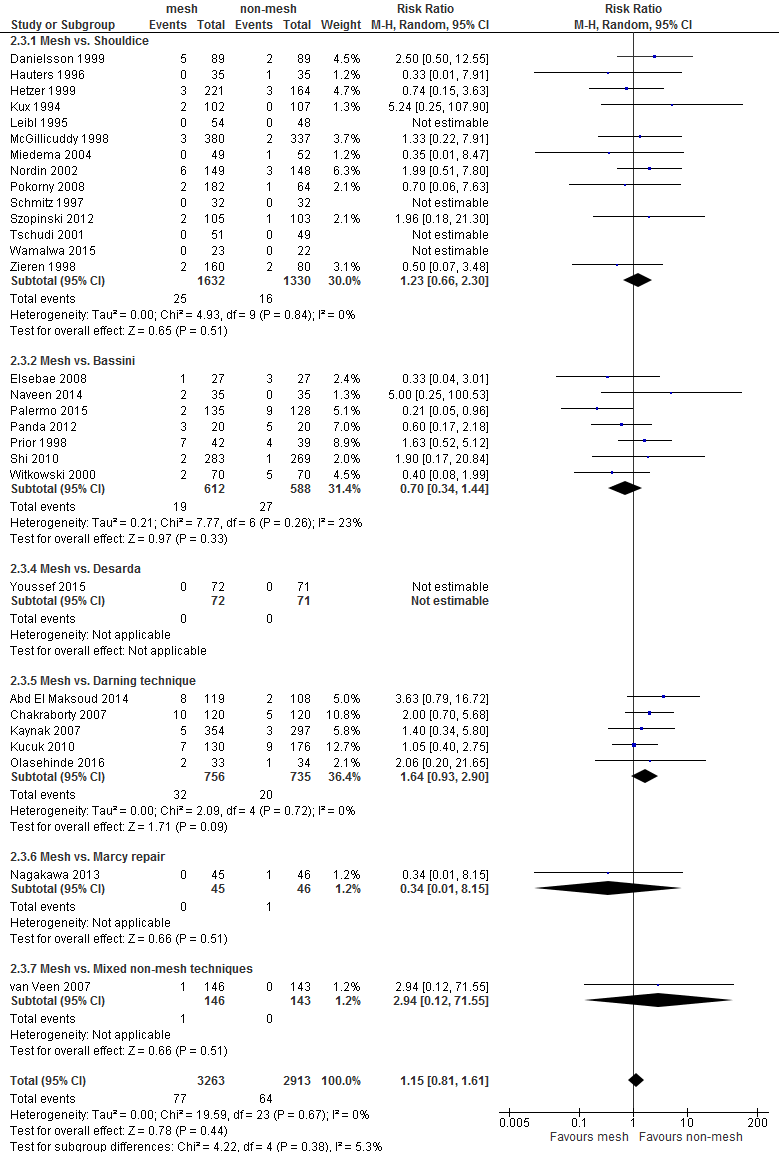

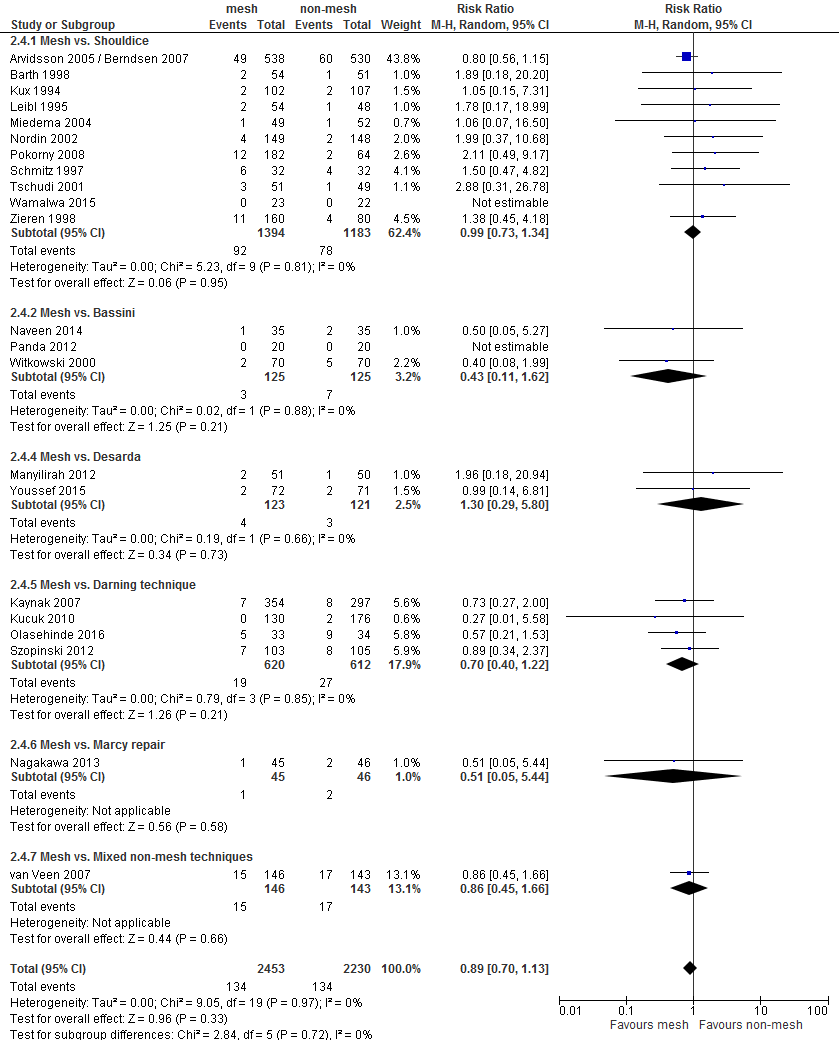

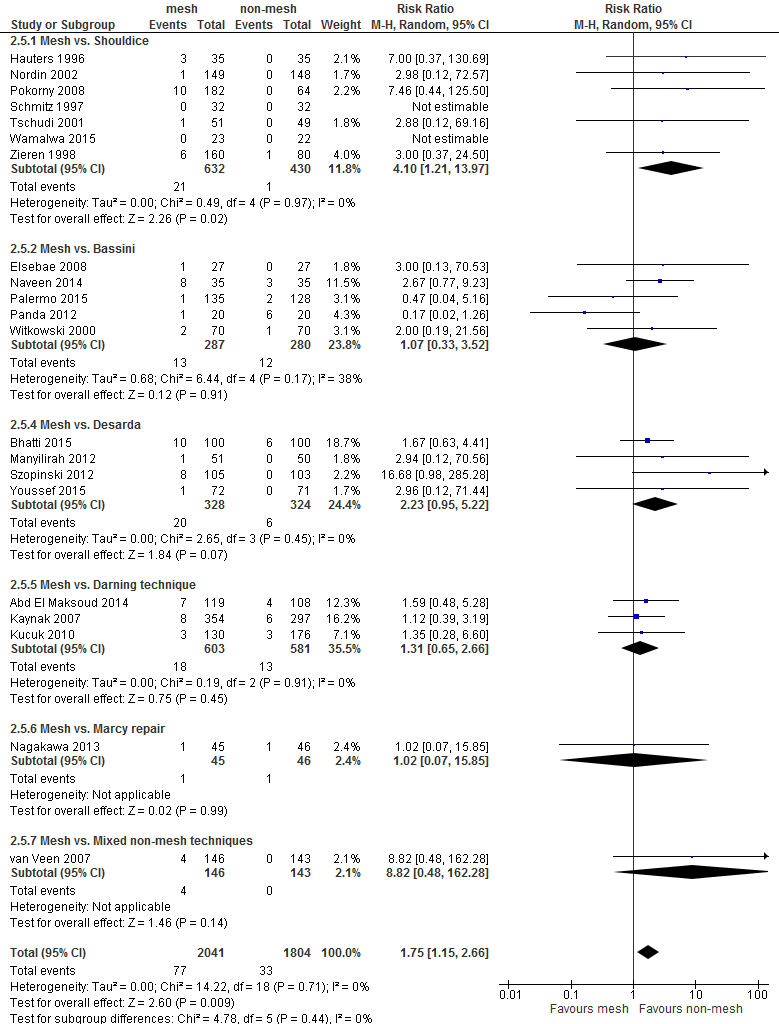

For both comparisons, no differences in post-operative complications were reported between the study groups, with the exception of neurovascular or visceral complications and seroma. Neurovascular or visceral complications occurred less frequently after mesh compared to non-mesh (RR 0.60; 95% CI 0.49 to 0.75) or Shouldice (RR 0.58; 95% CI 0.47 to 0.73). Seroma occurred more frequently after mesh compared to non-mesh (RR 1.75; 95% CI 1.15 to 2.66) or Shouldice (RR 4.10; 95% CI 1.21 to 1.97).

Table 2 Overview of postoperative complications

|

Complication |

mesh versus non-mesh |

mesh versus Shouldice |

||||

|

|

Number of RCTs |

Number of RCTs pooled* |

Pooled RR (95%CI) |

Number of RCTs |

Number of RCTs pooled* |

Pooled RR (95%CI) |

|

Neurovascular or visceral complications |

24 |

8 |

0.60 (0.49-0.75) |

11 |

4 |

0.58 (0.47- 0.73) |

|

Wound infection |

29 |

24 |

1.15 (0.81-1.61) |

16 |

10 |

1.23 (0.66-2.30) |

|

Hematoma |

22 |

20 |

0.89 (0.70-1.13) |

11 |

10 |

0.99 (0.73-1.34) |

|

Seroma |

21 |

19 |

1.75 (1.15-2.66) |

7 |

5 |

4.10 (1.21-13.97) |

|

Swelling of the wound |

2 |

3 |

3.51 (0.45-27.29) |

1 |

1 |

0.99 (0.06-15.73) |

|

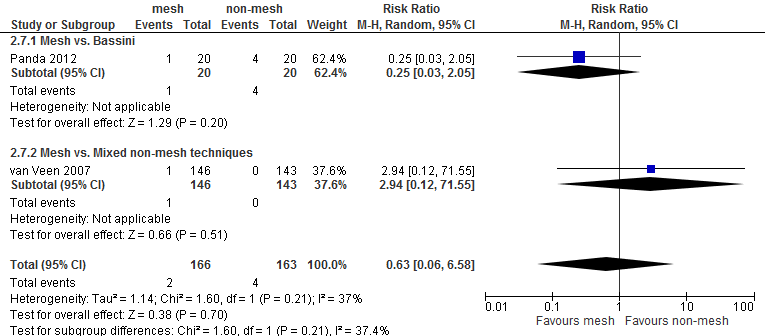

Wound dehiscence |

2 |

2 |

0.63 (0.06-6.58) |

0 |

n.a |

n.a. |

|

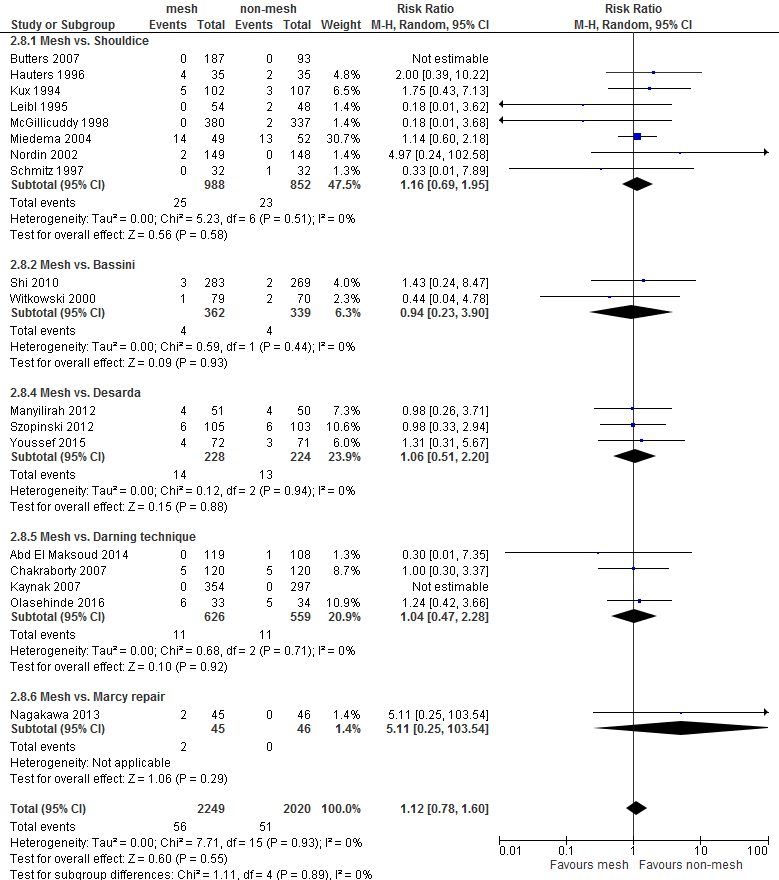

Testicular complications |

18 |

16 |

1.12 (0.78-1.60) |

8 |

7 |

1.16 (0.69-1.95) |

|

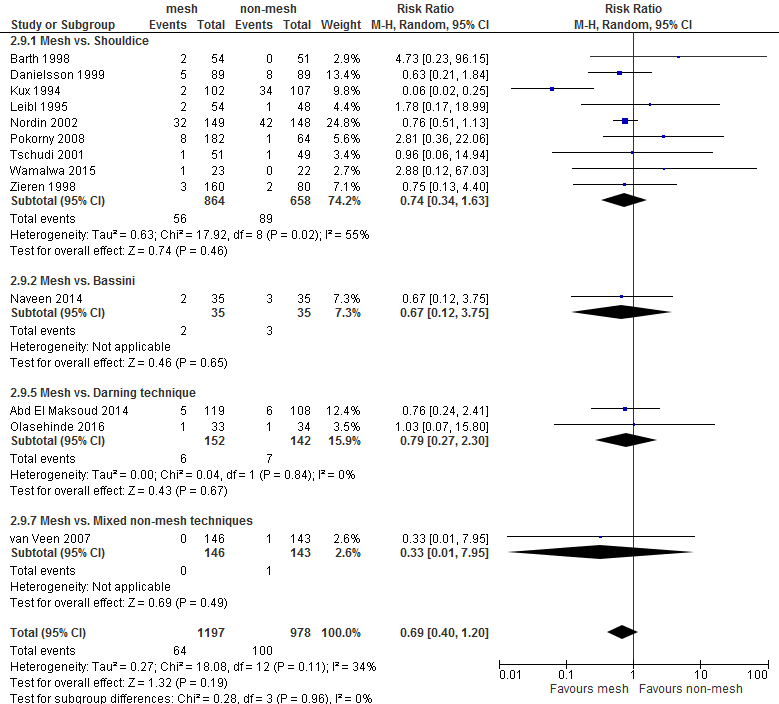

Urinary retention |

12 |

12 |

0.69 (0.40-1.20) |

8 |

8 |

0.74 (0.34-1.63) |

* Results of RCTs with 0 complications in both study groups were not pooled

Evidence of literature

The GRADE profile for the comparison mesh versus Shouldice can be found in Appendix 4. Given limitations in the research design and imprecision, the strength of the evidence for the outcome measure recurrences has been reduced by two levels.

For the outcome chronic pain, the strength of the evidence was reduced by three levels given limitations in the research design (Risk of Bias), the variety of measurements of the outcome (indirectness), and imprecision.

The weight of evidence for the outcome postoperative pain was reduced by three levels, due to limitations in the research designs, the variety of measurements of the outcome, and imprecision. For the conflicting results (inconsistency) was not downgraded as the type of mesh technique (i.e. Lichtenstein or lapara-endoscopic) seems to be related to presence of postoperative pain.

2. Which is the preferred open mesh technique for inguinal hernias: Lichtenstein or other open flat mesh and gadgets via an anterior approach?

The search using PICO 2 criteria identified 3 RCTs (Magnusson, 2016; Čadanová, 2016; Karaca, 2013) that were not included in the literature summary of the International Guidelines (HerniaSurge Group, 2018) comparing open mesh techniques for inguinal hernias. The Progrip mesh results will be discussed in module discussing mesh types.

Magnusson (2016) conducted an RCT with three arms in Sweden to compare long-term pain outcomes of the Lichtenstein’s repair (with a with a standard polypropylene mesh (the Prolene Hernia System, PHS), and the UltraPro Hernia System (UHS). The Lichtenstein-group (n=108) had a median age of 60 years (IQR: 49 to 64) and a median BMI of 24.6 (IQR: 23 to 26). A total of 28 participants (26%) had an occupation involving a high physical workload. The PHS-group (n=99) had a median age of 58 (IQR: 48 to 63) and a median BMI of 24.8 (IQR: 23.2 to 26.3). In the PHS group there were 37 persons (37%) with high physical workload in their occupation. Participants in the UHS-group (n=102) had a median age of 59 (IQR: 46 to 66) and a median BMI of 25 (IQR: 23 to 26.5). There were 25 participants (25%) in the PHS-group with high physical workload in their occupation. All participants were male. Pain during rest and activity was measured with a Visual Analogue Scale (VAS, score range: 0 to 10) at 12, 24 and 36 months. At 12 months missing data for VAS-scores among the three groups ranged from 4 to 7%, at 24 months from 12 to 21%, and at 36 months from 4 to 15%. At 36 months there were 27 participants (8%) lost to follow up, however it was unclear to what groups those participants were allocated originally.

Čadanová (2016) compared the ProGrip repair with the transinguinal preperitoneal (TIPP, with a PolySoft mesh) repair on recurrence, complications and number of participants in pain during an RCT in the Netherlands with a follow-up at 2 weeks, 3 months, and 1 year. Participants in the ProGrip-group (n=116, 94.8% males) had a mean age of 57.2 years (range: 54.5 to 59.9) and a mean BMI of 25.1 (range: 24.5 to 25.7). Participants had an ASA status of I (55.2% of the participants), II (38.8% of the participants, or III (6% of the participants). The TIPP-group (n=122, 93.4% male) had a mean age of 59 years (range: 56.5 to 61.4) and a mean BMI of 25.7 (range:25.1 to 26.3). In this group the participants had an ASA status of I (53.3% of the participants), II (41% of the participants), or III (5.7% of the participants). Twenty participants were excluded from analyses because they did not show up for the first follow-up visit, did not receive the assigned treatment, or declined surgery. Follow-up participation rate among the participants declined from 99.6% at 2 weeks to 38.4% at 1 year. Pain was measured with the VAS, the Verbal Descriptor Scale (VDS, a 7-point Likert-scale describing terms to express pain), and the Leeds Assessment of Neuropathic Symptoms and Signs (LARSS).

An RCT conducted by Karaca (2013) compared the Lichtenstein’s repair, the Rutkow-Robbins repair, and the Gilbert double layer repair (Prolene Hernia System, PHS) for complications and recurrence. Randomization and allocation of participants into three groups was performed by throwing heads or tail (presumably with a coin). The Lichtenstein-group (n=50, 86% male) had a mean age of 53.06 years (SD: 13.03) and a mean BMI of 26.45 (SD: 4.94). Participants in de Rutkow-Robbins-group (n=50, 92% male) had a mean age of 51.69 years (SD: 14.66) and a mean BMI of 24.22 (SD: 2.71), while the PHS-group (n=50, 86% male) had a mean age of 48.06 years (SD: 17.27) and a mean BMI of 25.06 (SD: 3.71). Early and late complications were measured, however no timeframe was defined for early and late complications.

Results

Chronic pain (>3 months)

Two RCTs reported pain outcomes after 3 months. Magnussen 2016 found no statistically significant differences between the Lichtenstein’s repair, the PHS repair, and the UHS repair for pain in rest and pain during activity at 12, 24, and 36 months as measured with the VAS (no p-values reported).

At 12, 24, and 26 months the Lichtenstein-group had a median VAS score for pain in rest of 0.2 (IQR: 0 to 0.6), 0.3 (IQR: 0.1 to 0.7), and 0.4 (IQR: 0.2 to 1.7), while for pain during activity the median VAS-score was 0.5 (IQR: 0.2 to 3.1), 0.7 (IQR: 0.4 to 1.5), and 0.6 (IQR: 0.201.7), respectively. For the PHS-group the median VAS score for pain in activity at 12, 24, and 36 months was 0.2 (IQR: 0 to 1.9), 0.3 (IQR: 0.1 to 0.8), and 0.2 (IQR: 0.1 to 2.3), while for pain during activity this was 0.5 (IQR: 0.3 to 3), 0.9 (IQR: 0.4 to 2.1), and 0.4 (IQR: 0.2 to 2.3), respectively. The UHS group had a median VAS score for pain in rest at 12, 24, and 36 months of 1 (IQR: 0.2-2.5), 0.8 (IQR: 0.4 to 1.3), and 1.6 (IQR: 0.7 to 4.6), while they had a median VAS-score of 2.3 (IQR: 0.7 to 2.9), 1.2 (IQR: 0.4 to 2.6), and 1.2 (IQR: 0.4 to 2.6) for pain during activity, respectively. No statistically significant differences between groups were found in the number of participants having pain at 12, 24, and 36 months (no p-value reported). For the Lichtenstein-group at 12, 24, and 36 months there were 15 (15%), 7 (8%), and 6 (6%) participants having pain, while in the PHS-group there were 12 (12%), 12 (14%), and 6 (7%) participants having pain, respectively. For the UHS-group there were 13 participants (13%) in pain at 12 months, 12 participants (15%) having pain at 24 months, and 9 participants (9%) in pain at 36 months.

Čadanová (2016) reported pain at rest, pain in daily activity, and pain in sports or heavy lifting at 3 months and at 1 year for the ProGrip repair compared to the TIPP repair (using a PolySoft mesh). At three months there were statistically significant differences between groups for the number of persons having chronic pain with a VAS-score of 3 or more for pain in rest (ProGrip: 12 participants (13.9%), TIPP: 4 participants (4.3%), p=0.031), for pain in daily activities (ProGrip: 15 participants (16.5%), TIPP: 4 participants (4.3%), p=0.006), and for pain during sports or heavy lifting (ProGrip: 19 participants (20.9%), TIPP: 3 participants (3.2%), p<0.001). At 1 year Čadanová (2016) found no statistically significant differences for the number of participants having chronic pain with a VAS-score of more than 3 for pain in rest (ProGrip: 3 participants (4.3%), TIPP: 5 participants (6.7%), p=0.504), for pain during daily activities (ProGrip: 3 participants (4.3%), TIPP: 6 participants (8%), p=0.332), and for pain during sports or heavy lifting (ProGrip: 3 participants (4.3%), TIPP: 6 participants (8%), p=0.332). No statistically significant differences in proportions between groups were found when pain was categorized as no pain (VAS 0), mild pain (VAS 1 to 3), moderate pain (VAS 4 to 6), and severe pain (VAS ≥7) for pain in rest (p=0.624), daily activity (p=0.494), and during sports or heavy lifting (p=0.570) at 1 year. No statistically significant differences in proportion of participants with neuropathic pain was found between groups at 1 year (p=0.37). In the ProGrip-group there were 11 participants (15.5%) having neuropathic pain measured with the LARSS, while in the TIPP-group there were 9 participants (10.5%) with neuropathic pain. Čadanová (2016) also measured pain with the Verbal Descriptor Scale (VDS) to describe te proportion of participants in both groups having moderate pain or worse. No statistically significant differences were found between groups for moderate pain or worse at 3 months (ProGrip: 8 participants (8.8%), TIPP: 5 participants (5.3%), p=0.356) and at 1 year (ProGrip: 4 participants (4.6%), TIPP: 4 participants (5.4%), p=0.953).

Factors influencing the quality of evidence

Evidence originated from RCTs and the quality of the evidence comparing Lichtenstein versus preperitoneal techniquees is therefore ‘high’. However, the quality of the evidence is reduced due to methodological limitations of the studies (Risk of Bias due to the lack of blinding of care providers (Magnusson, 2016; Čadanová, 2016). Other bias may arise due to a decline in participation rate (38.4%, unclear if loss-to follow-up or missing data) and violation of intention to treat analysis in one RCT (Čadanová, 2016). Furthermore, both RCTs have a relative small sample. The certainty of evidence due to these factors is reflected in the conclusions.

Recurrence

No statistically significant differences were found in recurrences at 2 weeks, 3 months, and 1 year in Čadanová (2016), comparing the ProGrip repair with the TIPP repair (using a PolySoft mesh). Over the period of 1 year there were a cumulative number of 3 recurrences in both the ProGrip and the TIPP-group. At 2 weeks not a single recurrence was reported in in the ProGrip-group, while there was 1 recurrence (0.8%) in the TIPP-group (p=0.331). Both the ProGrip-group and the TIPP-group had 1 new recurrence (1.1% and 1%, respectively) at 3 months (p=0.976). At the 1-year follow-up the ProGrip-group had 2 new recurrences (2.7%) and the TIPP-group had 1 new recurrence (1.3%, p=0.536).

Karaca (2013) did not find any recurrences when comparing the Lichtenstein repair, the PHS repair, and the Rutkow-Robbins repair over the course of 1 year (0 recurrences overall, p-value not reported).

Factors influencing the quality of evidence

Evidence originated from RCTs and the quality of the evidence comparing Lichtenstein versus preperitoneal techniques is therefore ‘high’. However, the quality of the evidence is reduced due to methodological limitations of the studies (Risk of Bias due to the lack of blinding of care providers (Čadanová, 2016; Karaca, 2013), Risk of Bias due to the randomization method and its allocation concealment (Karaca, 2013)). Other bias may arise due to a decline in participation rate (38.4%, unclear if loss-to follow-up or missing data) and violation of intention to treat analysis in one RCT (Čadanová, 2016). Furthermore, both RCTs add a small number of events to the body of evidence. The certainty of evidence due to these factors is reflected in the conclusions.

Complications

Čadanová (2016) presented self-reported complications at 2 weeks, 3 months, and 1 year comparing the ProGrip repair with the TIPP repair (using a PolySoft mesh). Recorded complications were seromas, bleeding, wound infection, hypersensitivity, scrotal pain, testis atrophia, and other (undefined). After 2 weeks a statistically significant difference (p=0.005) was found between groups where 57 participants (50.4%) in the ProGrip-group had at least 1 complication, while the TIPP-group had 39 participants (32.5%) having at least 1 complication. At 3 months there were no significant differences between groups (p=0.140. The ProGrip-group had 19 participants (20.9%) with at leat 1 complication at 3 months and the TIPP-group had 12 participants (12.8%) with at least one complication. No statistically significant differences were found at 1 year (p=0.893), where the ProGrip-group and the TIPP-group had 19 and 12 participants (13.9% and 14.7%) having a complication, respectively.

Karaca (2013) reported early and late complication when comparing the Lichtenstein’s repair, the Rutkow-Robbins repair, and the PHS repair, however the timeframe of early and late complications was not defined. A statistically significant difference (p=0.033) was found between groups for early complications in the Lichtenstein-group (1 participant (2%)), the Rutkow-Robbins-group (5 participants (10%)), and the PHS-group (3 participants (6%)). No post-hoc analyses were conducted to show which groups significantly differed from each other. There were no statistically significant differences (p=0.924) in late complications found between the Lichtenstein-group (5 paricipants (10%)), the Rutkow-Robbins-group (4 participants (8%)), or the PHS-group (5 participants (10.4%)).

Factors influencing the quality of evidence

Evidence originated from RCTs and the quality of the evidence comparing Lichtenstein versus preperitoneal techniques is therefore ‘high’. However, the quality of the evidence is reduced due to methodological limitations of the studies (Risk of Bias due to the lack of blinding of care providers (Čadanová, 2016, Karaca, 2013), Risk of Bias due to the randomization method and its allocation concealment (Karaca 2013)). Other bias may arise due to a decline in participation rate (38.4%, unclear if loss-to follow-up or missing data) and violation of intention to treat analysis in one RCT (Čadanová, 2016). Furthermore, both RCTs add a small number of events to the body of evidence. The certainty of evidence due to these factors is reflected in the conclusions.

3. Which is preferred open mesh technique: Lichtenstein versus open pre-peritoneal?

The search using PICO 3 criteria identified 4 publications (Andresen, 2015 (short-term results); Andresen, 2017 (long-term results); Mahmoudvand, 2017; Azeem, 2015 2x) that were published after the studies included in the International Guidelines for groin hernia management (HerniaSurge Group, 2018). The publications reported on two RCTs relevant for the subject of preferred open mesh technique: Lichtenstein versus open preperitoneal.

Mahmoudvand (2017) compared Lichtenstein with an open preperitoneal method (flatmesh transinguinal preperitoneal “TIPP” combined with bassini) in a total of 150 patients with a direct inguinal hernia using a follow-up of 6 to 12 months in Iran. The intervention group (n=75, 64% males) received an inguinal hernia repair using the Lichtenstein’s technique after reinforcement of the posterior wall, while the control group (n=75, 54.7% males) received an inguinal hernia repair using a preperitoneal method.

The other RCT in Denmark (Andresen, 2015; Andresen, 2017) compared the Lichtenstein’s technique in the intervention group with the Onstep technique in the control group. A total of 290 patients with a primary inguinal hernia were recruited in this study and were followed for 10 and 30 days (Andresen 2015) and 6 and 12 months (Andresen, 2017). The intervention group (n=144) had a mean age of 53.8 years (SD: 14.6) and had a mean BMI of 24.8 kg/m2 (SD: 2.6). In this group 38 participants (26.4%) were smokers. The control group (n=146) had a mean age of 54.5 years (SD: 15.2) and had a mean BMI of 24.7 kg/m2 (SD:2.9). The control group had 32 participants (21.9%) who were smokers.

Azeem (2015) used an RCT in Pakistan to compare the Lichtenstein’s repair with the modified Kugel repair. Follow-up was at 2 months, 4 months, and 2 years postoperatively. The intervention group (n=87) received the Lichtenstein’s repair (fixation with tackers) and the control group (n=89) received the modified Kugel repair (flat mesh in TEP position with two point fixation as done in TEPP through Kugel open approach. The mean age in the intervention group was 50.01 years (SD: 13.22) and consisted of men and women. The control group had a mean age of 49.4 years (SD: 12.06) and consisted of men and woman. In both study arms one participant was lost-to-follow-up (no reasons presented) and were excluded from analyses. Overall, the methodological quality and reporting of this study was poor.

Andresen (2017) Surgery Reported on the previous onstep group also the data of 259 patients from the above mentioned study (129 Lichtenstein, 130 Onstep) 6 months after surgery regarding pain during sexual activity.

Results

Recurrence (critical outcome)

Recurrence rates were reported in all three RCTs. Mahmoudvand (2017) (n=150 patients) reported five times more recurrences in the Lichtenstein group (n=10) compared to the preperitoneal group (n=2) (RR 5.00 (95% CI 1.13 to 22.05; p=0.016). Andresen (2015 and2017) (n=290 patients) did not find statistically significant differences between the Lichtenstein and the Onstep repairs within 30 days (Lichtenstein: 1 recurrence , Onstep: 3 recurrences, p=0.30) and within 12 months (Lichtenstein: 5 recurrences (4%), Onstep: 6 recurrences (4.8%), p=0.78). Since there were 4 recurrences (1.4%) within 10 days after surgery and 4.4% after one year one might wonder if the surgery was of acceptable/representative quality.

Azzeem (2015) observed a statistically significant difference between the Lichtenstein’s repair and the modified Kugel repair. In the Lichtenstein’s repair group 3 recurrences within 2 years were reported, while none were observed for the modified Kugel repair group (p<0.05).

Factors affecting the quality of the evidence

Evidence originated from RCTs and the quality of the evidence comparing Lichtenstein versus preperitoneal techniques is therefore ‘high’. However, the quality of the evidence is reduced due to methodological limitations of the studies (Risk of Bias due to unclear randomisation, allocation concealment and blinding in two RCTs (Mahmoudvand, 2015; Azeem, 2015) and violation of intention to treat analysis in the other RCT (Andresen, 2015 and 2017). Furthermore, these RCTs showed inconsistent results and add a low number of events to the body of evidence. Also follow up ranged between 10 days and 12 months. Ìn the Mahmoedvand study the surgical techniques are difficult to compare with the standard techniques of the techniques. The certainty of evidence due to these factors is reflected in the conclusions.

Chronic pain (critical outcome)

Andresen (2017) (n=290 patients) did not find differences in chronic pain scores (Visual Analogue Scale (VAS)) between the Lichtenstein and the Onstep techniques at 6 months (Lichtenstein: VAS=0 (IQR: 0 to 2), Onstep: VAS=0 (IQR: 0 to 2), p=0.67) and at 12 months (Lichtenstein: VAS=0 (IQR: 0 to 1), Onstep: VAS=0 (IQR: 0 to 2), p=0.1) after surgery.

Azeem (2015) (n=86 patients) compared Lichtenstein with modified Kugel. Both techniques included tacking of the mesh. Chronic pain was defined as any vas above zero. 3 months after surgery mean VAS was 0,3 for the modified kugel and 0,9 for the Lichtenstein repair (p=0.002).

Factors affecting the quality of the evidence

Evidence originated from two RCT and the quality of the evidence is therefore ‘high’. However, the quality of the evidence is reduced due to violation of the intention to treat analysis (Andresen). For the Azeem study there are methodogical limitations (randomization) and especially technical limitations since the mesh was tacked in place in Lichtenstein repair which does not resemble a standard fixation. Therefore results regarding pain in the Azeem study are not suitable for extrapolation into routine daily practice. Therefore, results originated from only one RCT. The certainty of evidence due to these factors is reflected in the conclusions.

Postoperative recovery: pain (critical outcome)

Pain was reported in all three RCTs. Mahmoudvand (2017) (n=150 patients) reported more patients with pain after surgery in the Lichtenstein group (n=21, 28%) compared to the preperitoneal group (n=9, 12%) (RR 2.33 (95% CI 1.14 to 4.76), p=0.014). However, it is unclear how pain was defined and when it measured in the sample.

The effect of the Lichtenstein’s repair compared to the modified Kugel repair on pain at 4 months was not deducible from Azeem (2015).

Factors affecting the quality of the evidence

Evidence originated from RCTs and the quality of the evidence comparing Lichtenstein versus preperitoneal techniques is therefore ‘high’. However, the quality of the evidence is reduced due to methodological limitations of the studies (Risk of Bias due to unclear randomisation, allocation concealment, blinding and selective reporting and surgical techniques are difficult to compare with the standard techniques of the techniques in one RCT (Andresen, 2015 and 2017). Furthermore, these RCTs showed inconsistent results. The certainty of evidence due to these factors is reflected in the conclusions.

Complications after surgery

Mahmoudvand (2017), Andresen (2015) and Azeem (2015) reported complications after surgery. In the RCT of Mahmoudvand 2017 (n=150 patients) 7 patients in the Lichtenstein group versus 9 patients in the preperitoneal group had a postoperative hematoma (RR 0.78 (95% CI 0.31 to 1.98)) and respectively 8 and 1 patients had a postoperative seroma (RR 8.00 (95% CI 1.03 to 62.40)). Andresen (2015) (n=290 patients) classified complications according to the Clavien-Dindo classification (I, II, IIIa, IIIb) and did not find differences in incidence of complications between the groups. Thirteen patients in the Lichtenstein group reported level I or II classification versus 10 in the Onset group.

Azeem (2015) reported significant differences between observed complications in the Lichtenstein’s repair group and the modified Kugel repair group (p<0.005) at an unclear follow-up period. In the Lichtenstein’s repair group 21 participants (24%) with a complication were observed, while 5 participants (6%) with complications were observed in the modified Kugel repair group.

Andresen (2017) demonstrated pain during sexual activity (6 months postop) in 17 onstep patients (13.1%) compared to 30 lichtenstein patients (23%), p=0.034. In both groups about half of the patients had this pain already before surgery, the others started having pain after surgery. So for inducing new pain the difference is 7/74 (9%) onstep versus Lichtenstein 14/70 (20%), p=0.073 and therefore no relevant conclusions can be drawn.

Factors affecting the quality of the evidence

Evidence originated from RCTs and the quality of the evidence comparing Lichtenstein versus preperitoneal techniques is therefore ‘high’. However, the quality of the evidence is reduced due to methodological limitations of the studies (Risk of Bias due to unclear randomisation, unclear allocation concealment and blinding in two RCT (Mahmoudvand, 2015; Azeem, 2015) and violation of intention to treat analysis in the other RCT (Andresen 2015 and 2017). Furthermore, these RCTs showeded inconsistent results. These RCTs add a low number of events to the body of evidence. The certainty of evidence due to these factors is reflected in the conclusions.

Mortality

The outcome measure mortality was not reported in the RCT’s. The RCT of Mahmoudvand (2017) however had no lost-to-follow-ups or incomplete outcome data suggesting that all the participants survived. The RCT of Andresen (2015 and 2017) mentioned reasons for incomplete outcome data and did not report a deceased participant.

In 2017 a systematic review (Andresen, 2017 AJS) was published describing a total of 67 artikels ranging from retrospective cohort to RCT on open preperitoneal repairs. They concluded that although the techniques seem promising a meta-analysis could not be performed and more RCT with proper length of follow up are needed.

4. Which endoscopic technique is preferred in terms of postoperative outcome?

The HerniaSurge Group (2018) recommended that both TAPP and TEP repair are suitable techniques for the treatment of inguinal hernia. Eight meta-analyses and systematic reviews concluded that there is insufficient evidence to recommend the use of one technique over the other. (Memon, BJS, 2003; McCormack Hernia, 2005; Tolver, Acta Anaesthesiol Scand, 2012; O’Reilly, Ann Surg, 2012; Bracale, Surg Endosc, 2012; Antoniou, Surg, 2013; Wei, Surg Lap Endosc Percutan Techn, 2015; McCormack, Health Technol Assess, 2005)

Both techniques have very low risks of serious complications, with a higher risk of visceral injury in TAPP and of vascular injury in TEPP. These results have been found in randomized controlled trials as well as in ‘real life’ registries such as the German Herniamed registry and the Swiss hernia registry. Minor complications such as seroma, scrotal edema, testicular atrophy, and bladder injury are similar for both techniques.

Early comparative studies between TAPP and TEP were often conducted in the surgeons’ learning curves, were biased and underpowered. Studies failed to report on important technical aspects such as mesh size and type of fixation. The most recently published meta-analysis of ten RCTs failed to show any significant differences in operative times, total complication rates, hospital length of stay, recovery time, pain, recurrence rates or costs between TAPP and TEP. (Weister, Viszeralchirurgie, 2000).

Update of the literature

Wei (2015) performed a systematic review and meta-analyses of RCTs comparing the transabdominal preperitoneal (TAPP) repair for inguinal hernias with the totally extraperitoneal repair (TEP) for unguinal hernias. Pubmed, Embase, the Cochrane library, and Web of Science were searched and yielded 333 hits in March 2014. Inclusion criteria were: participants with unilateral or bilateral inguinal hernia; aged below 71; TAPP and TEP were perfomed; the study reported the outcomes of interest. Exclusion criteria were: the study included patients with previous gastric surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, deep venous thrombosis, or cardiovascular, respiratory, hepatic, or renal disease. Excluded studies were not referenced. After screening 10 RCTs remained for inclusion, originating from Austria, Greece, USA, China, Egypt, or India. The selected RCTs included unilateral, bilateral, recurrent, non-recurrent, direct, and/or indirect inguinal hernias. One study also included femoral hernias. Follow-up in the included studies was heterogenous, ranging from one week to 38 months (with unclear follow-up periods in 2 studies). All studies were reported to contain more than 80% follow-up data. Sample characteristics such as age and gender were not reported.