Anesthesie bij open liesbreukchirurgie

Uitgangsvraag

Welke anesthesietechniek wordt aanbevolen bij open liesbreukchirurgie?

De uitgangsvraag bestaat uit twee delen:

- Lokaal anesthesie of algeheel/spinaal anesthesie?

- Algeheel anesthesie of spinaal anesthesie?

Aanbeveling

Lokaal anesthesie is de eerste keus voor een operatie volgens Lichtenstein bij een primaire reponibele liesbreuk bij mannelijke patiënten met ernstige cardio-pulmonale morbiditeit of op eigen verzoek van de patiënt.

Overwegingen

Liesbreukchirurgie kan zowel met een open, in de regel met een operatie volgens Lichtenstein, als een laparo-endoscopische operatie uitgevoerd worden. Bij een laparo-endoscopische operatie ligt de anesthesietechniek doorgaans vast, namelijk algehele anesthesie. Bij de operatie volgens Lichtenstein zijn echter meerdere anesthesiologische technieken beschikbaar.

Lokaal anesthesie heeft verschillende voordelen heeft ten opzichte van algehele of regionale anesthesie bij een electieve Lichtenstein van een reponibele breuk. Uit analyse van liesbreuk databases lijkt het er wel op dat recidief liesbreuken vaker voorkomen na operaties onder lokaal anesthesie. Ervaring met het toepassen van lokaal anesthesie door de operateur zou wellicht dit nadelige risico kunnen verminderen.

Patiënten met een ernstige systeemziekte (ASA 3 en hoger) die een liesbreukoperatie moeten ondergaan, zouden wellicht kunnen profiteren van het toepassen van lokaal anesthesie in plaats van regionale of algehele anesthesie. Met name het toepassen van een regionale techniek lijkt geassocieerd met een hogere complicatiekans bij patiënten van 65 jaar of ouder (Bay-Nielsen 2008). De auteurs van deze retrospectieve studie geven echter wel aan dat er mogelijk bewust werd gekozen om spinaal anesthesie toe te passen in plaats van algehele anesthesie bij bepaalde hoog-risico patiënten. Urineretentie is een bekende complicatie van spinaal anesthesie. Uit de beschikbare literatuur is het onduidelijk of voor de spinaal anesthesie een kort of langwerkend lokaal anestheticum is gebruikt. Of dat er een opiaat is toegevoegd aan het lokaal anestheticum. Beiden kunnen van invloed zijn op het optreden van urineretentie, waardoor het lastig wordt een goede vergelijking te maken tussen de technieken. De keuze van anesthesietechniek hangt tevens af van de voorkeuren van de patiënt. Voor en nadelen worden besproken tijdens het preoperatief assessment.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Algehele, regionale en lokale anesthesie technieken worden gebruikt bij open liesbreukchirurgie. Regionale anesthesie omvat spinale, epidurale dan wel een paravertebrale techniek. De paravertebrale techniek zal verder niet besproken worden in deze module, onder andere omdat er nauwelijks data over deze techniek voorhanden is.

De ideale anesthesiologische techniek voorziet in zowel goede peroperatieve anesthesie als postoperatieve analgesie, zorgt voor goede operatiecondities, gaat gepaard met zo min mogelijk complicaties en snel ontslag uit het ziekenhuis. Daarnaast is het kosteneffectief. De werkgroep heeft gekozen om in deze module lokaal anesthesie te vergelijken met regionale dan wel algehele anesthesie. Voor een vergelijking van regionale met algehele anesthesie wordt verwezen naar het betreffende module in de internationale richtlijn (HerniaSurge Group, 2018).

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

|

Zeer laag GRADE |

Het gebruik van lokaal anesthesie lijkt pijn te verminderen na een liesbreukoperatie, wanneer vergeleken wordt met regionale anesthesie.

Bronnen: (Pere, 2016; Prakash, 2017) |

|

Zeer laag GRADE |

Het effect van lokaal anesthesie op pijn en urineretentie na een liesbreukoperatie is niet geheel duidelijk wanneer vergeleken wordt met algehele anesthesie

Bronnen: (Pere, 2016; Reece-Smith, 2009) |

|

Zeer laag GRADE |

Het gebruik van lokaal anesthesie lijkt het optreden van urineretentie te verminderen na een liesbreukoperatie, wanneer vergeleken wordt met regionale anesthesie.

Bronnen: (Pere, 2016; Prakash, 2017) |

|

Zeer laag GRADE |

Het is niet geheel duidelijk wat het effect is van lokale anesthesie op recidief, verblijfsduur in het ziekenhuis en patiënttevredenheid na een liesbreukoperatie, wanneer vergeleken wordt met regionale of algehele anesthesie.

Bronnen: (Pere, 2016; Prakash, 2017; Reece-Smith, 2009) |

|

Zeer laag GRADE |

Het is niet geheel duidelijk of het gebruik van lokaal anesthesiebij liesbreukoperaties kosteneffectief is, wanneer vergeleken wordt met algehele anesthesie.

Bronnen: (Nordin, 2007) |

Samenvatting literatuur

A search using the PICO criteria identified two systematic reviews with meta-analysis (Prakash, 2017; Reece-Smith, 2009), one RCT (Pere, 2016) and one RCT-based cost-effectiveness analysis (Nordin, 2017). The SR of Prakash (2017) included 11 studies representing 10 unique cohorts that compared local with spinal anaesthesia in 1377 unilateral inguinal hernia patients, 24 patients were women. The SR of Reece-Smith (2009) included 5 RCTs comparing local with general anaesthesia in 895 patients, 19 patients were women. One of the RCTs (O’Dwyer, 2003) included both unilateral (91.8%) and bilateral (8.2%) inguinal hernia patients. Another RCT included both primary (91.3%) and recurrent (8.7%) inguinal hernia patients. The review of Reece-Smith (2009) had some methodological shortcoming, for example the quality of individual studies was not assessed. The RCT of Pere (2016) randomized a total of 156 male patients into three groups: local, regional or general anaesthesia. This RCT had a high Risk of Bias (see quality of evidence table). Nordin (2007) used data of 616 patients collected during a RCT comparing local, regional and general anaesthesia to compare the costs of local, regional and general anaesthesia.

Results

Pain (crucial outcome)

Local versus regional anaesthesia

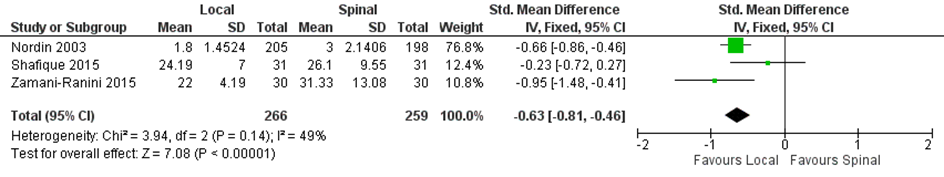

Five studies included in the systematic review of Prakash (2017) that compared local with regional anaesthesia reported on pain. Two studies graphically represented values and three studies (n=525 patients) reported on early post-operative pain (Figure 1). Mean pain score ranged from 1.8 to 24.2 in the local anaesthesia group, the mean pain score ranged from 3 to 31.3 in the regional group. The standardized mean difference was -0.63 (95% CI -0.81 to -0.46) in favour of local anaesthesia. In addition, the RCT of Pere 2016 comparing local with regional anaesthesia in 104 patients reported the median numerical rating scale (NRS) pain score at the first postoperative day and found no differences between groups (median was 4 in both groups). At the seventh postoperative day the median was 1 in both groups, with a range of 0-4 in patients with local anaesthesia and 0 to 7 in patients with regional anaesthesia.

Figure 1. Local versus spinal anaesthesia. Outcome: early post-operative pain

Local versus general anaesthesia

The systematic review of Reece-Smith (2009) compared local with general anaesthesia but did not report on pain. Data extraction of individual studies showed different results. Three studies reported the mean VAS pain at different follow-up moments; two RCTs found a lower early postoperative mean pain in the group with local anaesthesia compared to the general anaesthesia group (time between leaving theatre and discharge from hospital: mean 1.8 (95% CI 1.6 to 2.0) versus 3.3 (95% CI 3.0 to 3.5), n=413; mean pain after 8 hours 2.12 (SD 1) versus 3.58 (SD 1.5), n=50; mean pain after 24 hours 1.2 (SD 1.1) versus 1.8 (SD 1.4), n=50). Another study graphically represented values of 50 patients and found that the local group had lower pain scores at the first hour after surgery. One study reported pain after 30 days, pain did not differ between groups (mean 1.1 (95% CI 0.9 to 1.3) versus 1.1 (95% CI 0.9 to 1.3), n=413). One RCT reported that patients with local anaesthesia had more pain (on movement) after 1 year compared to patients with general anaesthesia (mean VAS (0-100 scale) 8.8 (SD 14.7) versus 6.2 (SD 9.6), n=279). In addition, the RCT of Pere 2016 comparing local with regional anaesthesia in 104 patients reported the median numerical rating scale (NRS) pain score at the first postoperative day and found no differences between groups (median was 4 in both groups). At the seventh postoperative day the median was 1 with a range of 0-4 in both groups.

Quality of the evidence

Evidence originated from RCTs and the level of the quality of the evidence comparing local anaesthesia versus regional or general anaesthesia started therefore at ‘High’. However, the quality of the evidence was downgraded with three levels to ‘Very low’, for serious methodological limitations of the studies (Risk of Bias due to unclear allocation concealment, unclear blinding of outcome assessors and violation of the intent to treat analysis), for inconsistency (different types of surgical techniques, population (unilateral and bilateral, primary and recurrent hernias) and large confidence intervals in studies and indicating either an effect or no effect).

Recurrence (critical outcome)

Local versus regional anaesthesia

The review of Prakash (2017) identified three studies with a total of 562 patients that measured recurrence in the early post-operative period. Only one study reported the incidence of recurrence across both groups, but these rates were not significantly different (no values were reported). The short follow up time frame needs to be considered in the context of these results.

Local versus general anaesthesia

Two RCTs with 329 patients included in the review of Reece-Smith (2009) reported on recurrence. No recurrence was observed in both studies. The follow-up times of the RCTs were 1 year and 6 weeks.

Local versus regional and general anaesthesia

The RCT of Pere (2016) comparing local, regional and general anaesthesia (n=156 patients) with a follow-up of 3 months reported only one patient with recurrence (not reported in which group) in whom about 1.5 months after the primary repair of a large medial hernia a new smaller medial hernia had developed in the same region, and it was successfully repaired laparoscopically.

Quality of the evidence

Evidence originated from RCTs and the level of the quality of the evidence comparing local anaesthesia versus regional or general anaesthesia started therefore at ‘High’. However, the quality of the evidence was downgraded with three levels to ‘Very low’, for serious methodological limitations of the studies (Risk of Bias due to unclear allocation concealment, unclear blinding of outcome assessors and violation of the intent to treat analysis), for inconsistency (different types of surgical techniques, population (unilateral and bilateral, primary and recurrent hernias) and for imprecision (very low number of events).

Urinary retention (important outcome)

Local versus regional anaesthesia

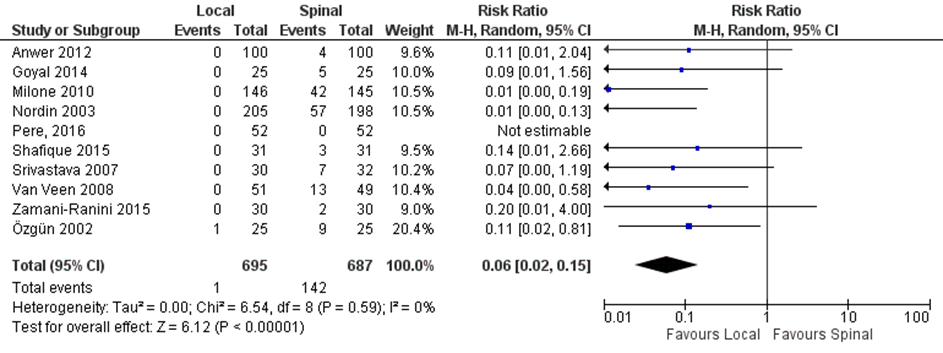

Nine studies included in the systematic review of Prakash (2017) comparing local with regional anaesthesia and the RCT of Pere 2016 reported on urinary retention (Figure 2). Urinary retention was reported in 0.1% (1/695) of the patients in the local anaesthesia group versus 20.7% (142/687) of those with regional anaesthesia (RR 0.06, 95% CI 0.02 to 0.15).

Figure 2. Local versus spinal anaesthesia. Outcome: urinary retention

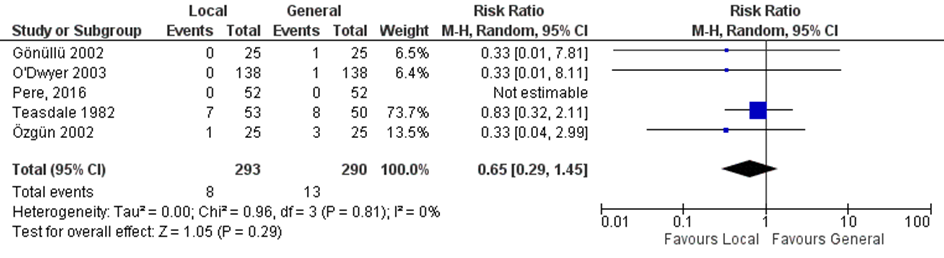

Local versus general anaesthesia

Four studies included in the systematic review of Reece-Smith (2009) comparing local with general anaesthesia and the RCT of Pere (2016) reported on urinary retention (Figure 3). Urinary retention was reported in 2.7% (8/293) of the patients in the local anaesthesia group versus 4.5% (13/290) of those with regional anaesthesia (RR 0.65, 95% CI 0.29 to 1.45).

Figure 3. Local versus general anaesthesia. Outcome: urinary retention

Quality of the evidence

Evidence originated from RCTs and the level of the quality of the evidence comparing local anaesthesia versus regional or general anaesthesia started therefore at ‘High’. However, the quality of the evidence was downgraded with three levels to ‘Very low’, for serious methodological limitations of the studies (Risk of Bias due to unclear allocation concealment, unclear blinding of outcome assessors and violation of the intent to treat analysis), for inconsistency (different types of surgical techniques, population (unilateral and bilateral, primary and recurrent hernias) and for imprecision (very low number of events).

Length of stay (important outcome)

Local versus regional anaesthesia

The outcome measure length of stay was not reported in the systematic review of Prakash (2017). The RCT of Perre (2016) reported the median time from start of anaesthesia until readiness for discharge in minutes. Patients in the local anaesthesia group were discharged after a median of 93 minutes (Inter Quartile Range (IQR) 46) and patients in the regional anaesthesia group were discharged after a median of 190 minutes (IQR 54).

Local versus general anaesthesia

Two studies in the systematic review of Reece-Smith (2009) reported the postoperative stay and both studies found that patients in the local anaesthesia group had a shorter postoperative hospital stay compared with the general anaesthesia group (mean 3.1 (95% CI 2.8-3.4) versus 6.2 (95% CI 5.5-6.8) hours, n=413 and median 22 (range 23) versus 28 (range 17) hours, n=50). Another study reported the mean length of stay in days and found a mean of 3.1 (SD 0.8) days in the local anaesthesia group versus 3.2 (1.2) days in the general anaesthesia group in a total of 279 patients. One study reported discharge at 24 hours, 46 (87%) of the 53 patients in the local anaesthesia group were discharged at 24 hours versus 47 (94%) of the 50 patients in the general anaesthesia group. The RCT of Perre (2016) reported the median time from start of anaesthesia until readiness for discharge in minutes. Patients in the local anaesthesia group were discharged after a median of 93 minutes (Inter Quartile Range (IQR) 46) and patients in the general anaesthesia group were discharged after a median of 142 minutes (IQR 35).

Quality of the evidence

Evidence originated from RCTs and the level of the quality of the evidence comparing local anaesthesia versus regional or general anaesthesia started therefore at ‘High’. However, the quality of the evidence was downgraded with three levels to ‘Very low’, for serious methodological limitations of the studies (Risk of Bias due to unclear allocation concealment, unclear blinding of outcome assessors and violation of the intent to treat analysis), for inconsistency (different types of surgical techniques, population (unilateral and bilateral, primary and recurrent hernias) and studies and indicating either an effect or no effect) and for imprecision (sample size <2000).

Patients satisfaction (important outcome)

Local versus regional anaesthesia

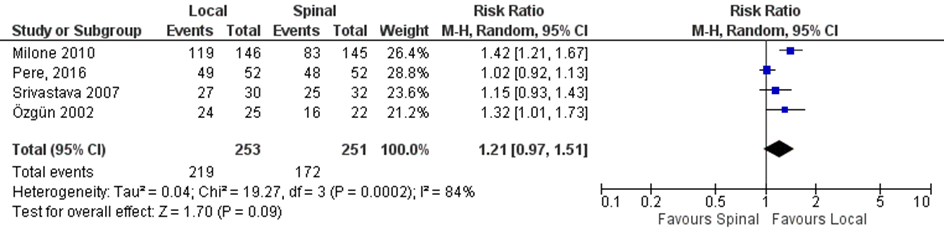

Three studies included in the systematic review of Prakash (2017) comparing local with regional anaesthesia and the RCT of Pere 2016 reported on patients satisfaction (Figure 4). Patients satisfaction was reported in 86.6% (219/253) of the patients in the local anaesthesia group versus 68.5% (172/251) of those with regional anaesthesia (RR 1.21, 95% CI 0.97 to 1.51).

Figure 4. Local versus spinal anaesthesia. Outcome: patient satisfaction

Local versus general anaesthesia

Two studies in the systematic review of Reece-Smith (2009) reported patients satisfaction. One study reported that 96% (24/25) of the patients in the local anaesthesia group versus 71% (17/24) of the patients in the general anaesthesia group were satisfied. Another study reported the mean satisfaction score on a 1 to 10 scale. Patients in the local anaesthesia group had a mean satisfaction score of 8.1 (SD 1.4) compared to patients with a mean satisfaction score of 7.7 (SD 1.5) in the general anaesthesia group. The RCT of Pere (2016) reported that 96% (24/25) of the patients in the local anaesthesia group versus 100% (25/25) of the patients in the general anaesthesia group were satisfied.

Quality of the evidence

Evidence originated from RCTs and the level of the quality of the evidence comparing local anaesthesia versus regional or general anaesthesia started therefore at ‘High’. However, the quality of the evidence was downgraded with three levels to ‘Very low’, for serious methodological limitations of the studies (Risk of Bias due to unclear allocation concealment, unclear blinding of outcome assessors and violation of the intent to treat analysis), for inconsistency (different types of surgical techniques, population (unilateral and bilateral, primary and recurrent hernias) and studies and indicating either an effect or no effect) and for imprecision (sample size <2000).

Cost-effectiveness (important outcome)

One study (Nordin, 2007) assessed the costs of local, regional and general anaesthesia in non-teaching hospitals in Sweden that did not specialize in hernia surgery. Compared with general and regional anaesthesia, local anaesthesia is less expensive when hospital and total healthcare costs are considered. Compared with total healthcare costs for local anaesthesia, regional and general anaesthesia were €333 (15.7 per cent) and €316 (15.0 per cent), respectively, more expensive. In terms of total relevant costs to society, including loss of production, there was no significant difference in costs between the three groups.

Quality of the evidence

Evidence originated from RCTs and the level of the quality of the evidence comparing local anaesthesia versus regional or general anaesthesia started therefore at ‘High’. However, the quality of the evidence was downgraded with three levels to ‘Very low’, for methodological limitations of the study (it was described as a cost-effectiveness study, but only costs were provided and no cost-effectiveness analysis was performed), indirectness (costs were calculated for Sweden with a different health care system) and for imprecision (only one study with a sample size <2000).

Zoeken en selecteren

The clinical question comparing general or regional anaesthesia was answered based on the International Guidelines (HerniaSurge Group, 2018) and no systematic literature search was done for this question. In order to answer the clinical question Does local anaesthesia influence outcomes after open inguinal hernia repair compared to general or regional anaesthesia? A systematic literature search was done:

Patients: adult male primary unilateral inguinal hernia patients;

Intervention: open repair under local anaesthesia;

Comparison: open repair under general or regional anaesthesia;

Outcome: pain, urinary retention, length of stay, patients satisfaction, cost-effectiveness, recurrence

Relevant outcome measures

The working group decided that pain and recurrence were crucial outcome measures for decision-making and urinary retention, length of stay, patients satisfaction and cost-effectiveness important outcome measures for decision-making. The working group did not define the mentioned outcome measures beforehand, however, they used the definitions described in the studies.

Searching and selecting (Methods)

The information specialist from the Cochrane Centre in the Netherlands searched Medline and Embase on April 11th 2017 and the Cochrane Register on April 12th 2017 for systematic reviews (SRs) and randomized controlled trials (RCTs) about inguinal hernias, without restrictions on publication date. All duplicates (including duplicates from the former search on the 30th of June 2015) were removed. The search details can be found in the tab Acknowledgement.

Literature experts excluded studies that were clearly not relevant for answering clinical questions about inguinal hernias. Therefore, 66 SRs and 241 RCTs remained to be judged by the working group.

The working group selected 49 studies based on title-abstract, that could possibly answer the research question. The world guideline yielded four relevant studies, therefore, 53 studies were read full text. After reading full text, 49 studies were excluded (see exclusion table in the tab Acknowledgement); finally, 4 studies were included for analysis: three studies from the search of the Cochrane Centre and one study from the world guideline (Nordin, 2007; Pere, 2016; Prakash, 2017; Reece-Smith, 2009).

Data extraction and analysis

The most important study characteristics and results were extracted from the SRs or original studies (in case of missing information in the review). The most important study characteristics and results are shown in the evidence tables. The judgement of the individual study quality (Risk of Bias) is shown in the Risk of Bias tables.

Relevant pooled and/or standardised effect measures were, if useful, calculated using Review Manager 5.3 (Cochrane Collaboration, Oxford, United Kingdom). If pooling results was not possible, the outcomes and results of the original study were used as reported by the authors.

De working group did not define clinical (patient) relevant differences for the outcome measures. Therefore, we used the following boundaries for clinical relevance, if applicable: for continue outcome measures: RR<0.75 or >1.25 (GRADE recommendation) or Standardized mean difference (SMD=0.2 (little); SMD 0.5 (reasonable); SMD=0.8 (large). These boundaries were compared with the results of our analysis. The interpretation of dichotomous outcome measures is strongly related to context; therefore, no clinical relevant boundaries were set beforehand. For dichotomous outcome measures, the absolute effect was calculated (Number Needed to Treat (NNT) or Number Needed to Harm (NNH)).

Referenties

- Bay-Nielsen M, Kehlet H. Anaesthesia and post-operative morbidity after elective groin hernia repair: a nation-wide study. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2008;52(2):169-74.

- Nordin P, H. Zetterstro, P. Carlsson and E. Nilsson. (2007) Costeffectiveness analysis of local, regional and genera anaesthesia for inguinal hernia repair using data from a randomized clinical trial. British Journal of Surgery; 94: 500505.

- Pere P, Harju J, Kairaluoma P, et al. (2016) Randomized comparison of the feasibility of three anesthetic techniques for day-case open inguinal hernia repair. J Clin Anesth 34:166-75. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2016.03.062. Epub 2016 May 8.

- Prakash D, Heskin L, Doherty S, et al. (2017) Local anaesthesia versus spinal anaesthesia in inguinal hernia repair: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Surgeon 15(1):47-57. doi: 10.1016/j.surge.2016.01.001. Epub 2016 Feb 16.

- Reece-Smith AM, Maggio AQ, Tang TY, et al. (2009) Local anaesthetic vs. general anaesthetic for inguinal hernia repair: systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Clin Pract. 63(12):1739-42. doi: 10.1111/j.1742Bij-1241.2009.02131.x. Epub 2009 Oct 10.

Evidence tabellen

Evidence table for systematic review of RCTs and observational studies (intervention studies)

Research question: Does local anesthesia influence outcomes after open inguinal hernia repair compared to general or regional anesthesia?

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C) |

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

Prakash 2016

PS., study characteristics and results are extracted from the SR (unless stated otherwise) |

SR and meta-analysis of RCTs

Literature search up to February 2015

A: Anwer 2012 B: Goyal 2014 C: Milone 2010 D: Nordin 2003* E: Nordin 2004 F: Nordin 2007* G: Özgün 2002 H: Shafique 2015 I: Srivastava 2007 J: Van Veen 2008 K: Zamani-Ranini 2015

*2 studies of 1 cohort with different reported outcomes

Study design: RCT

Setting and Country: SR: Department of Surgical Affairs, Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland, Republic of Ireland

A: Pakistan B: India C: Italy D: Sweden E: Sweden F: Sweden G: Turkey H: Pakistan I: India J: The Netherlands K: Iran

Source of funding: Not reported |

Inclusion criteria SR: Population: adults undergoing open inguinal hernia repair for a unilateral hernia (where ≥80% of the study population was >18 years of age); intervention: local anaesthetic used for the repair; comparison: spinal anaesthetic used for the repair; outcomes: the primary outcome was operative time, defined as the time from the first skin incision to the last skin suture. This outcome was the most commonly reported outcome across all the included studies. Secondary outcomes included measures of impairment (pain, wound haematoma, wound infection, urinary retention) and quality of life (patient satisfaction with anaesthesia). Only randomised controlled trials were included.

Exclusion criteria SR: -

11 studies were included representing ten unique cohorts

Important patient characteristics at baseline:

N (I/C) A: 100/ 100 B: 25/ 25 C: 146/ 145 D: 209/ 203 E: 40/ 52 F: 209/ 203 G: 25/ 25 H: 31/ 31 I: 30/ 32 J: 51/ 49 K: 30/ 30

Age, mean (SD) (I/C or overall) A: 38.8 (13.8) B:46.2 (16.6)/ 42.6 (16.7) C: 68/ 71 D: 57 (14)/ 55 (14) E: 58 (15)/ 56 (15.3) F: 57 (14)/ 55 (14) G: 52.4 (14.6)/ 51.4 (15.1) H: 48.9 (15.5)/ 50.9 (11.7) I: 42.4 (9.0)/ 44.1 (10.1) J: 64 (14.8)/ 65 (13) K: 59.5 (9.6)/ 59.2 (12.2)

Sex M:F ratio: A: NR B: 25:0/ 25:0 C: 146:0/ 145:0 D: 204:5/ 200:3 E: 39:1/ 50:2 F: 204:5/ 200:3 G: 25:0/ 25:0 H: 31:0/ 31:0 I: 30:0/ 32:0 J: 48:3/ 47:2 K: 30:0/ 30:0

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

Describe intervention: Local

A: Lichtenstein's alone with local anesthesia B: Lichtenstein's alone with local anesthesia C: Lichtenstein's alone with local anesthesia D: Open mesh repair/ Shouldice repair/ Plug repair/Other open non mesh repair with local anesthesia E: Open mesh repair/ Shouldice repair/ Other open non mesh repair with local anesthesia F: Open mesh repair/ Shouldice repair/ Plug repair/Other open non mesh repair with local anesthesia G: Lichtenstein's alone with local anesthesia H: Lichtenstein's alone with local anesthesia I: Procedure NR, with local anesthesia J: Lichtenstein's alone with local anesthesia K: Lichtenstein's alone with local anesthesia |

Describe control: Spinal

A: Lichtenstein's alone with spinal anesthesia B: Lichtenstein's alone with spinal anesthesia C: Lichtenstein's alone with spinal anesthesia D: Open mesh repair/ Shouldice repair/ Plug repair/Other open non mesh repair with spinal anesthesia E: Open mesh repair/ Shouldice repair/ Other open non mesh repair with spinal anesthesia F: Open mesh repair/ Shouldice repair/ Plug repair/Other open non mesh repair with spinal anesthesia G: Lichtenstein's alone with spinal anesthesia H: Lichtenstein's alone with spinal anesthesia I: Procedure NR, with spinal anesthesia J: Lichtenstein's alone with spinal anesthesia K: Lichtenstein's alone with spinal anesthesia

|

End-point of follow-up:

A: NR B: 1 week C: 12 months D: 30 days E: 1 year F: 30 days G: 6 weeks H: NR I: NR J: 3 months K: NR

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? All studies were reported as low risk with regards to incomplete reporting of outcome data, numbers not reported.

|

Outcome measure-1 Defined as pain (early post-operative pain)

Effect measure: Std. mean difference (95% CI): A: NR B: NR C: NR D: -0.66 (-0.86, -0.46) E: NR F: NR G: graphically represented values H: -0.23 (-0.72, 0.27) I: NR J: graphically represented values K: -0.95 (-1.48, -0.41)

Pooled effect (fixed effects model): -0.63 (95% CI -0.81 to -0.46) favoring local anesthesia Heterogeneity (I2): 49%

Outcome measure-2 Defined as urinary retention

Effect measure: RR (95% CI): A: 0.11 (0.01, 2.04) B: 0.09 (0.01, 1.56) C: 0.01 (0.00, 0.19) D: 0.01 (0.00, 0.13) E: NR F: NR G: 0.11 (0.02, 0.81) H: 0.14 (0.01, 2.66) I: 0.07 (0.00, 1.19) J: 0.04 (0.00, 0.58) K: 0.20 (0.01, 4.00)

Pooled effect (random effects model): 0.06 (95% CI 0.02 to 0.81) favoring local anesthesia Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

Outcome measure-3 Defined as length of stay

Not reported in the SR.

Outcome measure-4 Defined as patients satisfaction

Effect measure: RR (95% CI): A: NR B: NR C: 1.42 ( 1.21, 1.67) D: NR E: NR F: NR G: 1.32 (1.01, 1.73) H: NR I: 1.15 (0.93, 1.43) J: NR K: NR

Pooled effect (fixed effects model): 1.36 (95% CI 1.20 to 1.53)) favoring Local Heterogeneity (I2): 21%

Outcome measure-5 Defined as patients cost-effectiveness

Not reported in the SR.

Outcome measure-6 Defined as patients recurrence

In this review, we identified three papers (B, F, J) that measured recurrence in the early post-operative period. Only one study reported incidence of recurrence across both groups, but these rates were not significantly different. However, the follow up time frame needs to be considered in the context of these results (no values were reported). |

Facultative:

Author’s conclusion This systematic review evaluated the totality of evidence from ten unique RCTs on the effectiveness of local anaesthesia when compared to spinal anaesthesia in adult patients undergoing open inguinal hernia repair for a primary inguinal hernia. A range of self-report and objective clinical measures were included in the studies. Findings from the pooled analysis demonstrate that there are no significant differences between the groups with regard to operative time, wound haematoma, wound infection and recurrence. However, patients who underwent a local anaesthetic repair presented with significantly less rates of urinary retention, reduced pain scores and lower anaesthetic failures than those who underwent a spinal anaesthetic repair. Patient satisfaction with the anaesthesia was also significantly higher in the local anaesthetic group.

Level of evidence: GRADE in SR not reported |

|

Reece-Smith 2009

PS., study characteristics and results are extracted from the SR (unless stated otherwise) |

SR and meta-analysis of RCTs

Literature search up to May 2008

A: O’Dwyer 2003 B: Teasdale 1982 C: Nordin 2003 D: Özgün 2002 E: Gönüllü 2002

Study design: RCT

Setting and Country: United Kingdom

Source of funding: Not reported. |

Inclusion criteria SR: Randomised controlled trials comparing outcomes from local and general anaesthetic used in inguinal hernia repair. Fifty different outcome measures were recorded in five of the trials identified, but only those assessed in at least three studies were considered for meta-analysis.

Inclusion criteria RCTs: A: All groin hernias (4% femoral hernias) B: Unilateral, reducible hernias C: Elective and emergency groin hernias D: Men of ASA I or II with no contraindication to any anaesthetic E: Men undergoing inguinal hernia repair

Exclusion criteria SR: Review articles and retrospective analyses were excluded.

Exclusion criteria RCTs: A: Recurrent hernias; irreducible inguino-scrotal hernias and emergency operations B: Patients who expressed a preference for either anaesthetic C: Under 18s; recurrent, femoral and bilateral hernias; pregnancy; coagulation abnormalities; patients unfit for general anesthesia D: Scrotal, sliding and recurrent hernias; body mass index over 30; 4 patients who could not tolerate LA during operation E: Chronic respiratory disease; significant comorbidity; morbid obesity; recurrent, incarcerated or bilateral hernias; patients who preferred one anesthetic.

5 studies included

Important patient characteristics at baseline: The five trials were comparable in terms of the patient age and, in those trials that measured it, in terms of body mass index (values not reported).

N A: 279 B: 103 C: 616 of whom 203 received regional anesthesiology and were removed from analysis D: 75 of whom 25 received regional anesthesiology and were removed from analysis E: 50

Sex M:F (n) (I/C)* A: 123:15/ 127:11 B: NR C: 204:5/ 200:3 D: only men included E: only men included

Hernia type (other than primary unilateral inguinal hernia) A: Local group: 9 bilateral, general group: 14 bilateral B: Local group: 4 recurrent hernias, general group: 5 recurrent hernias C-E: -

*Not reported in the SR and extracted from individual studies

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

Describe intervention: Local

A: Tension-free mesh repair. Non-mesh low approach for femoral hernias. Local anesthesia. B: Herniotomy or a standardised herniorrhaphy. Local anesthesia. C: Repair used: 85% Open mesh repair, 8% sholdice repair, 6% mesh plug repair. Local anesthesia. D: Tension-free mesh repair. Local anesthesia. E: Repair used not reported. Local anesthesia. |

Describe control: General

A: Tension-free mesh repair. Non-mesh low approach for femoral hernias. General anesthesia + Bupivicaine in all patients. B: Herniotomy or a standardised herniorrhaphy. General anesthesia. C: Repair used: 85% Open mesh repair, 8% sholdice repair, 6% mesh plug repair. General anesthesia. Infiltration of bupivicaine 83% of cases D: Tension-free mesh repair. General anesthesia. E: Repair used not reported. General anesthesia. |

End-point of follow-up:* A: 1 year B: 7 days C: 30 days D: 6 weeks E: 24 hours

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available?* A: O’Dwyer 2003 Intervention: 72 (51%) at 1 year follow-up Control: 68 (49%) at 1 year follow-up B: NR C: All patients were included in analysis D: Intervention: 0 Control: 1 (4%) E: All patients were included in analysis

*Not reported in the SR and extracted from individual studies |

Outcome measure-1 Defined as pain Not reported in the SR data were extracted from individual studies.

A: mean pain score on movement at 1 year 8.8 (SD 14.7)/ 6.2 (SD 9.6), p=0.0003 B: Number of patients with wound pain after 24h 53/ 49; after 7 days 52/ 47 C: early post-operative VAS pain, mean (95% CI): 1.8 (1.6-2.0)/ 3.3 (3.0-3.5) Mean (95%) VAS pain at 30 days: 1.1 (0.9-1.3)/ 1.1 (0.9-1.3) D: graphically represented values (Postoperatively at the first hour, the local group had lower pain scores) E: VAS pain, mean (SD) at 8h: 2.12 (1)/ 3.58 (1.5), p=0.0001 At 24h: 1.2 (1.1)/ 1.8 (1.4), p=0.848

Outcome measure-2 Defined as urinary retention (only overall effect of the studies was provided in the SR) data were extracted from individual studies.

A: 0 (of the 138)/ 1 (of the 138) B: 7 (of the 53)/8 (of the 50) (difficulty in passing urine) D: 1/ 3 E: 0/ 1

Pooled effect (odds ratio, random effects model): 0.33 (95% CI 0.29 to 2.99) favoring local anesthesia Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

Outcome measure-3 Defined as length of stay Not reported in the SR data were extracted from individual studies.

A: 3.1 (SD 0.8)/ 3.2 (1.2) days B: discharge at 24h: 46/ 47 C: mean (95% CI) stay (h) 3.1 (2.8-3.4)/ 6.2 (5.5-6.8) D: postoperative hospital stay (h), median (range) 22 (23)/ 28 (17)

Outcome measure-4 Defined as patients satisfaction

Not reported in the SR data were extracted from individual studies.

D: (satisfactory/ unsatisfactory): 24/ 1 versus 17/7 E: mean 8.08 (SD 1.41) 7.68 (1.54), p=0.3444

Outcome measure-5 Defined as patients cost-effectiveness

Not reported in the SR.

Outcome measure-6 Defined as patients recurrence Not reported in the SR data were extracted from individual studies.

A: No patient had clinical evidence of a recurrence of hernia after 1 year. D: No recurrence was observed during the short follow-up period of the study. |

Author’s conclusion Meta-analysis of the five trials comparing local and general anaesthesia for inguinal hernia repair fails to confirm the wide-ranging benefits reported by the individual studies. Local anaesthetic reduces nausea and accelerates return to normal activities following open inguinal hernia repair. The benefit of LA is sufficiently small that its use should be dictated by patient and clinician preference.

Level of evidence: GRADE in SR not reported |

Evidence table for intervention studies (randomized controlled trials and non-randomized observational studies (cohort studies, case-control studies, case series))1

Research question: Does local anesthesia influence outcomes after open inguinal hernia repair compared to general or regional anesthesia?

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics 2 |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C) 3 |

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size 4 |

Comments |

|

Pere 2016 |

Type of study: RCT (3 arms)

Setting: University hospital day-surgery center

Country: Finland

Source of funding: Funded by study grants from Finska Läkaresällskapet, Finland |

Inclusion criteria: Male patients, scheduled for open unilateral inguinal herniorrhaphy in the day surgery center for eligibility to participate in the study.

Exclusion criteria: The most common refusal reason (76%) was the patient's own wish for a certain anesthetic technique, while some patients refused to have one of the presented three techniques. Other exclusion criteria were BMI> 40 kg/m2, BMI<15 kg/m2, scrotal hernias, severe renal, cardiac or hepatic insufficiency, coagulation disorder, local anesthetic allergy, lack of co-operation due to cognitive impairment or inadequate ability to communicate because of linguistic problems.

N total at baseline: Intervention (LAI): 52 Control (SPIN): 52 Control (TIVA): 52

Important prognostic factors2: Age, mean (SD): I (LAI): 51 (16) C (SPIN): 51 (15) C (TIVA): 54 (15)

Weight , mean (SD): I (LAI): 78 (8) C (SPIN): 81 (9) C (TIVA): 79 (10)

ASA 1/2/3 (n) I (LAI): 31/ 20/ 1 C (SPIN): 25/ 19/ 5 C (TIVA): 23/ 25/ 3

International Prostatic Symptoms Score, mean (SD): I (LAI): 5.9 (7.2) C (SPIN): 5.9 (5.9) C (TIVA): 7.7 (7.3)

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

Local anesthetic infiltration (LAI) First 15–18 mL of lidocaine 10 mg/mL with epinephrine 5 μg/mL was infiltrated in the skin and the subcutaneous layer of the incisional area. Then 15–18 mL of ropivacaine 7.5 mg/mL was injected into the deeper layers. The rest (left in both 20-mL syringes) of the local anesthetics was infiltrated under the fascia, around the funiculus (spermatic cord) and into the tissues at the base of the hernia sac. Intraoperatively, supplemental lidocaine was infiltrated (maximum 200 mg), as required to anesthetize the deeper layers, and fentanyl (25 or 50 μg IV once or twice) was given as needed if pain was felt by the patient. If adequate analgesia could not be achieved with the supplementation of local infiltration anesthesia, total intravenous anesthesia with propofol and laryngeal mask airway (LMA) was induced.

|

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

Control 1: Spinal anesthesia (SPIN) With the patient in the lateral horizontal position and the side of operation dependent a 27 G needle with pencil-point tip was inserted in the midline through the L3–4 intervertebral space. The drug mixture was hyperbaric bupivacaine 6 mg (Bicain Pond Spinal®, Orion Pharma, Espoo, Finland) and 10 μg of fentanyl. After the injection the operating table was tilted head-down 10° and the lateral position maintained for 5 minutes. Then the patient was placed supine on the table, which was returned to its neutral horizontal position, except when the sensory block had not yet spread to the T10 dermatome level (tested by pin-prick). If analgesia was inadequate during surgery, fentanyl 25 or 50 μg IV was administered. If surgical pain persisted after two doses of fentanyl, anesthesia was supplemented with lidocaine infiltration or total intravenous anesthesia (propofol, remifentanil, LMA and mechanical ventilation). At the end of the operation, the surgeon infiltrated the tissue layers between the fascia and the skin with 20 mL of ropivacaine 7.5 mg/mL.

Control 2: Total intravenous anesthesia (TIVA) Fentanyl 1.5 μg/kg IV was administered followed by propofol 2–2.5 mg/kg, and an LMA was placed, following which the patient was mechanically ventilated. For maintenance propofol and remifentanil were intravenously infused. No anticholinergics or neuromuscular blocking agents were used. Anesthesia depth was maintained at 40–60 on the Entropy™ monitor (GE Healthcare, Helsinki, Finland), and adjusted as needed by changing the infusion rate of propofol. Similarly to the SPIN group, at the end of surgery the wound was infiltrated with 20 mL of ropivacaine 7.5 mg/mL. |

Length of follow-up: 3 months

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention (LAI): 1 (2%) at 3 months interview

Control (SPIN): 0

Control (TIVA): 1 (2%) at 3 months interview

Incomplete outcome data: Intervention (LAI): 1 (2%) Reason: patient was not reached by telephone at 3 months

Control (SPIN): 3 (6%) Reason: patients were excluded because they did not receive allocated intervention after randomization because surgery was cancelled.

Control (TIVA): 2 (4%) Reasons: 1 patient was not reached by telephone at 3 months, 1 patient was excluded because the anaesthetic plan was changed after randomization. |

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Pain First postoperative day NRS pain score, median I (LAI): 4 C (SPIN): 4 C (TIVA): 4

Seventh postoperative day NRS pain score, median (range) I (LAI): 1 (0-4) C (SPIN): 1 (0-7) C (TIVA): 1 (0-4)

Urinary retention Urinary retention was absent in all patients.

Length of stay Defined as time from start of anesthesia until readiness for discharge (min), median (IQR) I (LAI): 93 (46) C (SPIN): 190 (54) C (TIVA): 142 (35) P<0.001

Patients satisfaction I (LAI): 3 patients were dissatisfied with their anesthetic because of pain they had felt intraoperatively C (SPIN): Four patients reported dissatisfaction with their anesthetic, two because of multiple attempts needed to perform the intrathecal puncture and two (one of them very dissatisfied) because of an inadequate block. C (TIVA): 0

Cost-effectiveness Not reported

Recurrence Recurrence was noted in only one patient in whom about 1.5 months after the primary repair of a large medial hernia a new smaller medial hernia had developed in the same region, and it was successfully repaired laparoscopically (not reported in which group). |

Author’s conclusion:

With regard to the day-surgery setting, LAI anesthesia was favorable since the patients could often ambulate immediately after surgery, thus bypassing PACU1, and the discharge criteria were met significantly earlier than in patients having had general or spinal anesthesia. There was no statistically significant difference in the high degree of patient satisfaction with their anesthesia in all three groups. Contrary to the situation in the LAI and SPIN groups with some anesthetic failures, and the frequent need for analgesia supplementation in the LAI group, in the TIVA group the anesthetics were always successful but needed frequently interventional attendance by the anesthesiologist. The lack of postoperative urinary retention in all our patients may be due to the small infused fluid volumes together with the routine bladder scan before and after surgery. Postoperative discomfort or pain in the groin in some patients was not associated with any particular anesthesia technique. |

|

Nordin 2007 |

Type of study: Cost–effectiveness analysis using data from an RCT

Setting: General surgical practice

Country: Sweden

Source of funding: Financial support for the Swedish Hernia Register is provided by the National Board of Health and Welfare, and the Federation of County Councils, Sweden. The study was supported by the Health Research Council of the south-east region of Sweden |

Inclusion criteria: Described in Nordin 2003 (see evidence table for systematic review)

Exclusion criteria: Described in Nordin 2003 (see evidence table for systematic review)

N total for cost-effectiveness analysis: Intervention (local): 199 Control (spinal): 164 Control (epidural): 35

Important prognostic factors2: Described in Nordin 2003 (see evidence table for systematic review)

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

Described in Nordin 2003 (see evidence table for systematic review)

|

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

Described in Nordin 2003 (see evidence table for systematic review) |

Length of follow-up: 1 year

Loss-to-follow-up: Described in Nordin 2003 (see evidence table for systematic review)

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Costs The advantage of local anesthesia was significant for both total hospital and total healthcare costs (P <0.001), but there was no significant difference between regional and general anesthesia. Compared with total healthcare costs for local anesthesia, regional and general anaesthesia were €333 (15.7 per cent) and €316 (15.0 per cent), respectively, more expensive. In terms of total relevant costs to society, including loss of production, there was no significant difference between the three groups (P = 0.112). |

Author’s conclusion:

The use of local anesthesia for inguinal hernia repair was significantly less expensive than regional or general anesthesia. |

Notes:

- Prognostic balance between treatment groups is usually guaranteed in randomized studies, but non-randomized (observational) studies require matching of patients between treatment groups (case-control studies) or multivariate adjustment for prognostic factors (confounders) (cohort studies); the evidence table should contain sufficient details on these procedures.

- Provide data per treatment group on the most important prognostic factors ((potential) confounders).

- For case-control studies, provide sufficient detail on the procedure used to match cases and controls.

- For cohort studies, provide sufficient detail on the (multivariate) analyses used to adjust for (potential) confounders.

Table of quality assessment for systematic reviews of RCTs and observational studies

Based on AMSTAR checklist (Shea, 2007; BMC Methodol 7: 10; doi:10.1186/1471-2288-7-10) and PRISMA checklist (Moher, 2009; PLoS Med 6: e1000097; doi:10.1371/journal.pmed1000097)

|

Study

First author, year |

Appropriate and clearly focused question?1

Yes/no/unclear |

Comprehensive and systematic literature search?2

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of included and excluded studies?3

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of relevant characteristics of included studies?4

Yes/no/unclear |

Appropriate adjustment for potential confounders in observational studies?5

Yes/no/unclear/not applicable |

Assessment of scientific quality of included studies?6

Yes/no/unclear |

Enough similarities between studies to make combining them reasonable?7

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential risk of publication bias taken into account?8

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential conflicts of interest reported?9

Yes/no/unclear |

|

Prakash 2017 |

Yes |

Yes |

No, excluded studies are not described |

Yes |

Not applicable |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

Unclear, not described fort he included studies |

|

Reece-Smith 2009 |

No |

Yes |

No, excluded studies are not described |

Yes |

Not applicable |

No |

No |

No |

No |

- Research question (PICO) and inclusion criteria should be appropriate and predefined.

- Search period and strategy should be described; at least Medline searched; for pharmacological questions at least Medline + EMBASE searched.

- Potentially relevant studies that are excluded at final selection (after reading the full text) should be referenced with reasons.

- Characteristics of individual studies relevant to research question (PICO), including potential confounders, should be reported.

- Results should be adequately controlled for potential confounders by multivariate analysis (not applicable for RCTs).

- Quality of individual studies should be assessed using a quality scoring tool or checklist (Jadad score, Newcastle-Ottawa scale, Risk of Bias table et cetera).

- Clinical and statistical heterogeneity should be assessed; clinical: enough similarities in patient characteristics, intervention and definition of outcome measure to allow pooling? For pooled data: assessment of statistical heterogeneity using appropriate statistical tests (For example Chi-square, I2)?

- An assessment of publication bias should include a combination of graphical aids (For example funnel plot, other available tests) and/or statistical tests (For example Egger regression test, Hedges-Olken). Note: If no test values or funnel plot included, score “no”. Score “yes” if mentions that publication bias could not be assessed because there were fewer than 10 included studies.

- Sources of support (including commercial co-authorship) should be reported in both the systematic review and the included studies. Note: To get a “yes,” source of funding or support must be indicated for the systematic review AND for each of the included studies.

Risk of Bias table for intervention studies (randomized controlled trials)

Research question: Does local anesthesia influence outcomes after open inguinal hernia repair compared to general or regional anesthesia?

|

Study reference

(first author, publication year) |

Describe method of randomisation1 |

Bias due to inadequate concealment of allocation?2

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate blinding of participants to treatment allocation?3

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate blinding of care providers to treatment allocation?3

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate blinding of outcome assessors to treatment allocation?3

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to selective outcome reporting on basis of the results?4

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to loss to follow-up?5

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to violation of intention to treat analysis?6

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

|

Pere 2016 |

Patients were randomized using the sealed envelope method. |

Unclear |

Likely |

Likely |

Likely |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

Likely |

- Randomisation: generation of allocation sequences have to be unpredictable, for example computer generated random-numbers or drawing lots or envelopes. Examples of inadequate procedures are generation of allocation sequences by alternation, according to case record number, date of birth or date of admission.

- Allocation concealment: refers to the protection (blinding) of the randomisation process. Concealment of allocation sequences is adequate if patients and enrolling investigators cannot foresee assignment, for example central randomisation (performed at a site remote from trial location) or sequentially numbered, sealed, opaque envelopes. Inadequate procedures are all procedures based on inadequate randomisation procedures or open allocation schedules.

- Blinding: neither the patient nor the care provider (attending physician) knows which patient is getting the special treatment. Blinding is sometimes impossible, for example when comparing surgical with non-surgical treatments. The outcome assessor records the study results. Blinding of those assessing outcomes prevents that the knowledge of patient assignement influences the proces of outcome assessment (detection or information bias). If a study has hard (objective) outcome measures, like death, blinding of outcome assessment is not necessary. If a study has “soft” (subjective) outcome measures, like the assessment of an X-ray, blinding of outcome assessment is necessary.

- Results of all predefined outcome measures should be reported; if the protocol is available, then outcomes in the protocol and published report can be compared; if not, then outcomes listed in the methods section of an article can be compared with those whose results are reported.

- If the percentage of patients lost to follow-up is large, or differs between treatment groups, or the reasons for loss to follow-up differ between treatment groups, bias is likely. If the number of patients lost to follow-up, or the reasons why, are not reported, the Risk of Bias is unclear.

- Participants included in the analysis are exactly those who were randomized into the trial. If the numbers randomized into each intervention group are not clearly reported, the Risk of Bias is unclear; an ITT analysis implies that (a) participants are kept in the intervention groups to which they were randomized, regardless of the intervention they actually received, (b) outcome data are measured on all participants, and (c) all randomized participants are included in the analysis.

Risk of Bias table for cost-effectiveness study

|

|

CHEC-list |

YES |

NO |

|

1. |

Is the study population clearly described? |

X |

|

|

2. |

Are competing alternatives clearly described? |

X |

|

|

3. |

Is a well-defined research question posed in answerable form? |

|

X |

|

4. |

Is the economic study design appropriate to the stated objective? |

|

X |

|

5. |

Is the chosen time horizon appropriate in order to include relevant costs and consequences? |

X |

|

|

6. |

Is the actual perspective chosen appropriate? |

X |

|

|

7. |

Are all important and relevant costs for each alternative identified? |

|

X |

|

8. |

Are all costs measured appropriately in physical units? |

X |

|

|

9. |

Are costs valued appropriately? |

X |

|

|

10. |

Are all important and relevant outcomes for each alternative identified? |

|

X |

|

11. |

Are all outcomes measured appropriately? |

|

X |

|

12. |

Are outcomes valued appropriately? |

|

X |

|

13. |

Is an incremental analysis of costs and outcomes of alternatives performed? |

|

X |

|

14. |

Are all future costs and outcomes discounted appropriately? |

|

X |

|

15. |

Are all important variables, whose values are uncertain, appropriately subjected to sensitivity analysis? |

|

X |

|

16. |

Do the conclusions follow from the data reported? |

X |

|

|

17. |

Does the study discuss the generalizability of the results to other settings and patient/client groups? |

|

X |

|

18. |

Does the article indicate that there is no potential conflict of interest of study researcher(s) and funder(s)? |

|

X |

|

19. |

Are ethical and distributional issues discussed appropriately? |

|

X |

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Publicatiedatum : 05-04-2019

Beoordeeld op geldigheid : 11-12-2020

Voor het beoordelen van de actualiteit van deze richtlijn is de werkgroep in stand gehouden. Uiterlijk in 2022 bepaalt het bestuur van de NVvH of de modules van deze richtlijn nog actueel zijn. Op modulair niveau is een onderhoudsplan beschreven. Bij het opstellen van de richtlijn heeft de werkgroep per module een inschatting gemaakt over de maximale termijn waarop herbeoordeling moet plaatsvinden en eventuele aandachtspunten geformuleerd die van belang zijn bij een toekomstige herziening (update). De geldigheid van de richtlijn komt eerder te vervallen indien nieuwe ontwikkelingen aanleiding zijn een herzieningstraject te starten.

De NVvH is regiehouder van deze richtlijn(modules) en eerstverantwoordelijke op het gebied van de actualiteitsbeoordeling van de richtlijn(modules). De andere aan deze richtlijn deelnemende wetenschappelijke verenigingen of gebruikers van de richtlijn delen de verantwoordelijkheid en informeren de regiehouder over relevante ontwikkelingen binnen hun vakgebied.

Algemene gegevens

De richtlijnontwikkeling werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten en werd gefinancierd uit de Stichting Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS). Patiëntenparticipatie bij deze richtlijn werd medegefinancierd uit de Kwaliteitsgelden Patiënten Consumenten (SKPC) binnen het programma KIDZ.

De financier heeft geen enkele invloed gehad op de inhoud van de richtlijn.

Doel en doelgroep

Doel

Het hoofddoel van de richtlijn is de patiëntresultaten te verbeteren en de meest voorkomende problemen na een liesbreukoperatie te verminderen, met name recidivering en chronische pijn.

Doelgroep

De richtlijn wordt geschreven voor de medisch specialisten die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor patiënten met liesbreuk.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Werkgroep

- Dr. B. (Baukje) van den Heuvel, chirurg, Pantein Zorggroep, Radboudumc, Nijmegen, NVvH (voorzitter)

- Dr. M.P. (Maarten) Simons, chirurg, OLVG, Amsterdam, NVvH

- Dr. Th.J. (Theo) Aufenacker, chirurg, Rijnstate, Arnhem, NVvH

- Dr. J.P.J. (Ine) Burgmans, chirurg, Diakonessenhuis Utrecht, Utrecht, NVvH

- Mw. R. (Rinie) Lammers, beleidsadviseur, Patiëntenfederatie Nederland, Utrecht

- Dr. M.J.A. (Maarten) Loos, chirurg, Maxima Medisch Centrum, Veldhoven, NVvH

- Dr. M. (Marijn) Poelman, chirurg, Sint Franciscus Vlietland Groep, Rotterdam, NVvH

- Dr. G.H. (Gabriëlle) van Ramshorst, chirurg, NKI-Antoni van Leeuwenhoek Ziekenhuis/VU Medisch Centrum, Amsterdam, NVvH

- Drs. J.W.L.C. (Ronald) Schapendonk, anesthesioloog-pijnspecialist, Diakonessenhuis Utrecht, Utrecht, NVA

- Dr. E.J.P. (Ernst) Schoenmaeckers, chirurg, Meander MC, Amersfoort, NVvH

- Dr. N. (Nelleke) Schouten, AIOS heelkunde regio Maastricht, NVvH

- Dr. R.K.J. (Rogier) Simmermacher, chirurg, UMC Utrecht, Utrecht, NVvH

Met medewerking van

- Drs. W. (Wouter) Bakker, arts-onderzoeker heelkunde, Diakonessenhuis Utrecht, Utrecht

Met ondersteuning van

- Dr. J.S. (Julitta) Boschman, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- Dr. W.A. (Annefloor) van Enst, senior adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- Drs. Ing. R. (Rene) Spijker, Informatie Specialist, Cochrane Netherlands

- Dr. C. (Claudia) Orelio, Cochrane Netherlands

- Drs. P. (Pauline) Heus, Cochrane Netherlands

- Prof. dr. R. (Rob) Scholten, Cochrane Netherlands

- Dr. L. (Lotty) Hooft, Cochrane Netherlands

- D.P. (Diana) Gutierrez, projectsecretaresse, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- J. (Jill) Heij, junior projectsecretaresse, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

Belangenverklaringen

De KNMG-code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling is gevolgd. Alle werkgroepleden hebben schriftelijk verklaard of zij in de laatste drie jaar directe financiële belangen (betrekking bij een commercieel bedrijf, persoonlijke financiële belangen, onderzoeksfinanciering) of indirecte belangen (persoonlijke relaties, reputatiemanagement, kennisvalorisatie) hebben gehad. Een overzicht van de belangen van werkgroepleden en het oordeel over het omgaan met eventuele belangen vindt u in onderstaande tabel. De ondertekende belangenverklaringen zijn op te vragen bij het secretariaat van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

|

Werkgroeplid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

|

Van den Heuvel |

Chirurg |

Onbetaald: - Advies-commissie Kwaliteit EHS (European Hernia Society) - Dutch Hernia Society - International Guidelines Groin Hernia Management (ontwikkeling gesponsord door BARD en Johnson&Johnson - |

geen (03/03/2017) |

niet van toepassing |

|

|

Simons |

Chirurg |

Onbetaald: - Bestuur EHS (European Hernia Society) - Dutch Hernia Society - International Guidelines Groin Hernia Management (ontwikkeling gesponsord door BARD en Johnson&Johnson |

Lid Board van de European Hernia Society (20/7/2017) |

geen |

|

|

Aufenacker |

Chirurg |

Penningmeester DHS (Dutch Hernia Society), onbetaald |

Prevent Studie, (Preventieve matplaatsing bij aanleggen colostoma) ZonMW gesponsord (19/3/2018) |

geen |

|

|

Bakker |

Chirurg io |

- |

- |

niet van toepassing |

|

|

Burgmans |

Chirurg |

Lid bestuur Dutch Hernia Society |

geen (19/3/2018) |

niet van toepassing |

|

|

Lammers |

Beleidsadviseur |

- |

geen (19/6/2017) |

|

|

|

Loos |

Chirurg |

- |

geen (13/6/2017) |

niet van toepassing |

|

|

Poelman |

Chirurg |

Lid bestuur Dutch Hernia Society |

geen (11/7/2017) |

geen |

|

|

van Ramshorst |

Fellow Chirurgie |

|

Sponsor van mijn fellowship, KWF, heeft geen belangen bij deze richtlijn. Publicaties waar ik auteur van ben zouden gebruikt kunnen worden als referentie. (16/4/2018) |

geen |

|

|

Schapendonk |

Anesthesioloog-pijnspecialist |

|

Niet persoonlijk, maar mijn instelling heeft deelgenomen/ neemt deel aan wetenschappelijk onderzoek gesponsord door Medtronic, Spinal Modulaton of St. Jude Medical thans Abbott. Fee ontvangen van St. Jude Medical voor voordracht op scholing pijnverpleegkundigen inzake DRG stimulatie. Daarnaast in 2015 congres bezocht op kosten Spinal Modulation. (3/5/2017) |

geen |

|

|

Schoenmaeckers |

Chirurg |

|

geen (20/6/2017) |

niet van toepassing |

|

|

Schouten |

AIOS Heelkunde |

- |

geen (6/6/2017) |

niet van toepassing |

|

|

Simmermacher |

Chirurg |

- |

geen (21/5/2017 |

niet van toepassing |

|

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Er werd aandacht besteed aan het patiëntenperspectief door inbreng van: 1) patiëntenvereniging Meshed-up tijdens de invitational conference; 2) door de deelname van mevrouw. Lammers (Patiëntenfederatie Nederland) in de werkgroep en 3) door het raadplegen van volwassenen behandeld voor liesbreuk via een door de Patiëntenfederatie uitgezette enquête. De reacties naar aanleiding van deze invitational en enquête (zie aanverwante producten) zijn besproken in de werkgroep en de belangrijkste knelpunten zijn verwerkt in de richtlijn.

Methode ontwikkeling

Evidence based

Implementatie

In de verschillende fasen van de richtlijnontwikkeling is rekening gehouden met de implementatie van de richtlijn (module) en de praktische uitvoerbaarheid van de aanbevelingen. Daarbij is uitdrukkelijk gelet op factoren die de invoering van de richtlijn in de praktijk kunnen bevorderen of belemmeren. Het implementatieplan is te vinden bij de aanverwante producten. De werkgroep heeft geen interne kwaliteitsindicatoren ontwikkeld om het toepassen van de richtlijn in de praktijk te volgen en te versterken (zie Indicatorontwikkeling).

Werkwijze

AGREE

Deze richtlijn is opgesteld conform de eisen vermeld in het rapport Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 van de adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwaliteit. Dit rapport is gebaseerd op het AGREE II instrument (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II; Brouwers, 2010), dat een internationaal breed geaccepteerd instrument is. Voor een stap-voor-stap beschrijving hoe een evidence-based richtlijn tot stand komt wordt verwezen naar het stappenplan Ontwikkeling van Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

Knelpuntenanalyse

Tijdens de voorbereidende fase inventariseerden de voorzitter van de werkgroep en de adviseur de knelpunten en onderwerpen beschreven in de internationale richtlijn (HerniaSurge Group 2018) die in aanmerking kwamen voor de Nederlandse adaptatie en update. De aanwezigen tijdens de invitational conference bevestigden deze knelpunten en onderwerpen. Een verslag hiervan is opgenomen onder aanverwante producten.

Uitgangsvragen en uitkomstmaten

De knelpunten en onderwerpen beschreven in de internationale richtlijn (HerniaSurge Group, 2018) die in aanmerking kwamen voor de Nederlandse adaptatie en update zijn met de werkgroep besproken. Daarna heeft de werkgroep de definitieve uitgangsvragen en modules vastgesteld en vastgesteld welke modules volledig zouden worden geupdate met ondersteuning van het Kennisinstituut en welke modules uit de internationale richtlijn zouden worden geadapteerd door de werkgroep. Voor alle modules, ook de modules die geadapteerd zijn, heeft de werkgroep de recente en relevante literatuur doorgenomen. In de geadapteerde modules zijn nieuwe studies verwerkt bij het formuleren van overwegingen en aanbevelingen. In de volledig geupdate modules zijn nieuwe studies geïntegreerd in de literatuuranalyse, risk of bias assessment en gradering. Hieronder is per module aangegeven of de module volledig is ge-update of geadapteerd:

- Risicofactoren (geadapteerd)

- Diagnostiek (geadapteerd)

- Indicatie behandeling asymptomatische liesbreuken (volledig geupdate)

- Chirurgische behandeling unilaterale liesbreuk (volledig geupdate)

- Mat of Shouldice (volledig geupdate)

- Lichtenstein of een andere open anterieure techniek (geadapteerd)

- Lichtenstein of een open pre-peritoneale techniek (geadapteerd)

- Endoscopische techniek (geadapteerd)

- Lichtenstein of een laparo-endoscopische techniek (geadapteerd)

- Een open posterieure techniek of laparo-endoscopisch (geadapteerd)

- Geïndividualiseerde behandeling (geadapteerd)

- Matten (volledig geupdate)

- Matfixatie (volledig geupdate)

- Open anterieure benadering

- TEP/TAPP

- Liesbreuken bij vrouwen (geadapteerd)

- Femoraalbreuken (geadapteerd)

- Antibioticaprofylaxe (volledig geupdate)

- Anesthesie (volledig geupdate)

- Postoperatieve pijn (geadapteerd)

- Chronische pijn

- Definitie, risicofactoren en preventie (geadapteerd)

- Reductie incidentie CPIP (volledig geupdate)

- Behandeling CPIP (volledig geupdate)

- Behandeling van recidief liesbreuk (geadapteerd)

- Na een anterieure benadering

- Na een posterieure benadering

- Na een anterieure en posterieure benadering

- Acute liesbreukchirurgie (geadapteerd)

- Organisatie van zorg (nieuw)

Vervolgens inventariseerde de werkgroep voor de uitgangsvragen van de modules die waren geselecteerd voor een volledige update welke uitkomstmaten voor de patiënt relevant zijn. Er werd zowel naar gewenste als ongewenste effecten gekeken. De werkgroep waardeerde deze uitkomstmaten volgens hun relatieve belang bij de besluitvorming rondom aanbevelingen, als cruciaal, belangrijk (maar niet cruciaal) en onbelangrijk. Tevens poogde de werkgroep tenminste voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten te definiëren welke verschillen zij klinisch (patiënt) relevant vonden.

Strategie voor zoeken en selecteren van literatuur

De informatiespecialist van Cochrane Nederland doorzocht Medline en Embase (op 11 april 2017) en het Cochrane Register (op 12 april 2017) naar artikelen over de diagnostiek of behandeling van volwassenen met liesbreuk zonder beperkingen op de publicatiedatum. Dit betrof een herhaling van de searches uitgevoerd voor de 2013 European Hernia Society Guidelines on the treatment of inguinal hernia in adult patients en de 2018 International Guidelines for Groin Hernia Management: The HerniaSurge Group (literatuursearch tot 1 januari 2015 en 1 juli 2015 voor level 1 publicaties (RCTs). De literatuurzoekactie leverde voor reviews 583 unieke treffers (waarvan 339 reviews reeds gescreend voor de vorige richtlijnen) op (Medline n=419; Embase n=378; en de Cochrane Library n=12) en voor RCTs 2174 unieke treffers (Medline n=1376; Embase n=1537; en de Cochrane Library n=160).

De werkgroepleden selecteerden per uitgangsvraag in duplo de via de zoekactie gevonden artikelen op basis van vooraf opgestelde selectiecriteria en in eerste instantie de studies met de hoogste bewijskracht. De gehanteerde selectiecriteria zijn te vinden in de module met desbetreffende uitgangsvraag.

Kwaliteitsbeoordeling individuele studies

Voor de modules die volledig werden ge-update, zijn de geselecteerde artikelen systematisch beoordeeld, op basis van op voorhand opgestelde methodologische kwaliteitscriteria, om zo het risico op vertekende studieresultaten (Risk of Bias) te kunnen inschatten. Deze beoordelingen kunt u vinden in de Risk of Bias (RoB) tabellen. De gebruikte RoB instrumenten zijn gevalideerde instrumenten die worden aanbevolen door de Cochrane Collaboration: AMSTAR – voor systematische reviews; Cochrane – voor gerandomiseerd gecontroleerd onderzoek; ACROBAT-NRS – voor observationeel onderzoek; QUADAS II – voor diagnostisch onderzoek.

Samenvatten van de literatuur

Voor de modules die volledig werden ge-update, zijn de geselecteerde artikelen toegevoegd aan de set relevante artikelen genoemd in de internationale richtlijn. De relevante onderzoeksgegevens van alle geselecteerde artikelen werden overzichtelijk weergegeven in evidence-tabellen. De belangrijkste bevindingen uit de literatuur werden beschreven in de Engelstalige samenvatting van de literatuur. Bij een voldoende aantal studies en overeenkomstigheid (homogeniteit) tussen de studies werden de gegevens ook kwantitatief samengevat (meta-analyse) met behulp van Review Manager 5.

Beoordelen van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs

A) Voor interventievragen (vragen over therapie of screening)

De kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs werd bepaald volgens de GRADE-methode. GRADE staat voor ‘Grading Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation’ (zie http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/).

GRADE onderscheidt vier gradaties voor de kwaliteit van het wetenschappelijk bewijs: hoog, redelijk, laag en zeer laag. Deze gradaties verwijzen naar de mate van zekerheid die er bestaat over de literatuurconclusie (Schünemann 2013).

|

GRADE |

Definitie |

|

Hoog |

|

|

Redelijk |

|

|

Laag |

|

|

Zeer laag |

|

B) Voor vragen over diagnostische tests, schade of bijwerkingen, etiologie en prognose

De kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs werd eveneens bepaald volgens de GRADE-methode: GRADE-diagnostiek voor diagnostische vragen (Schünemann, 2008), en een generieke GRADE-methode voor vragen over schade of bijwerkingen, etiologie en prognose. In de gehanteerde generieke GRADE-methode werden de basisprincipes van de GRADE-methodiek toegepast: het benoemen en prioriteren van de klinisch (patiënt) relevante uitkomstmaten, een systematische review per uitkomstmaat, en een beoordeling van bewijskracht op basis van de vijf GRADE-criteria (startpunt hoog; downgraden voor Risk of Bias, inconsistentie, indirectheid, imprecisie, en publicatiebias).

Formuleren van de conclusies

Voor elke relevante uitkomstmaat werd het wetenschappelijk bewijs samengevat in een of meerdere Nederlandstalige literatuurconclusies waarbij het niveau van bewijs werd bepaald volgens de GRADE-methodiek. De werkgroepleden maakten de balans op van elke interventie (overall conclusie). Bij het opmaken van de balans werden de gunstige en ongunstige effecten voor de patiënt afgewogen. De overall bewijskracht wordt bepaald door de laagste bewijskracht gevonden bij een van de cruciale uitkomstmaten. Bij complexe besluitvorming waarin naast de conclusies uit de systematische literatuuranalyse vele aanvullende argumenten (overwegingen) een rol spelen, werd afgezien van een overall conclusie. In dat geval werden de gunstige en ongunstige effecten van de interventies samen met alle aanvullende argumenten gewogen onder het kopje Overwegingen.

Overwegingen (van bewijs naar aanbeveling)

Om te komen tot een aanbeveling zijn naast (de kwaliteit van) het wetenschappelijke bewijs ook andere aspecten belangrijk en worden meegewogen, zoals de expertise van de werkgroepleden, de waarden en voorkeuren van de patiënt (patient values and preferences), kosten, beschikbaarheid van voorzieningen en organisatorische zaken. Deze aspecten worden, voor zover geen onderdeel van de literatuursamenvatting, vermeld en beoordeeld (gewogen) onder het kopje Overwegingen.

Formuleren van aanbevelingen

De aanbevelingen geven antwoord op de uitgangsvraag en zijn gebaseerd op het beschikbare wetenschappelijke bewijs en de belangrijkste overwegingen, en een weging van de gunstige en ongunstige effecten van de relevante interventies. De kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs en het gewicht dat door de werkgroep wordt toegekend aan de overwegingen, bepalen samen de sterkte van de aanbeveling. Conform de GRADE-methodiek sluit een lage bewijskracht van conclusies in de systematische literatuuranalyse een sterke aanbeveling niet a priori uit, en zijn bij een hoge bewijskracht ook zwakke aanbevelingen mogelijk. De sterkte van de aanbeveling wordt altijd bepaald door weging van alle relevante argumenten tezamen.

Randvoorwaarden (Organisatie van zorg)

In de knelpuntenanalyse en bij de ontwikkeling van de richtlijn is expliciet rekening gehouden met de organisatie van zorg: alle aspecten die randvoorwaardelijk zijn voor het verlenen van zorg (zoals coördinatie, communicatie, (financiële) middelen, menskracht en infrastructuur). Randvoorwaarden die relevant zijn voor het beantwoorden van een specifieke uitgangsvraag maken onderdeel uit van de overwegingen bij de bewuste uitgangsvraag. Meer algemene, overkoepelende, of bijkomende aspecten van de organisatie van zorg worden behandeld in de module Organisatie van Zorg.

Indicatorontwikkeling

Er werden geen interne kwaliteitsindicatoren ontwikkeld. In de module Organisatie van Zorg is een suggestie opgenomen voor een toekomstige registratie.

Kennislacunes

Tijdens de ontwikkeling van deze richtlijn is systematisch gezocht naar onderzoek waarvan de resultaten bijdragen aan een antwoord op de uitgangsvragen. Bij elke uitgangsvraag is door de werkgroep nagegaan of er (aanvullend) wetenschappelijk onderzoek gewenst is om de uitgangsvraag te kunnen beantwoorden. Een overzicht van de onderwerpen waarvoor (aanvullend) wetenschappelijk van belang wordt geacht, is als aanbeveling in de Kennislacunes beschreven .

Commentaar- en autorisatiefase

De conceptrichtlijn werd aan de betrokken (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd ter commentaar. De commentaren werden verzameld en besproken met de werkgroep. Naar aanleiding van de commentaren werd de conceptrichtlijn aangepast en definitief vastgesteld door de werkgroep. De definitieve richtlijn werd aan de deelnemende (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd voor autorisatie en door hen geautoriseerd dan wel geaccordeerd.

Literatuur

Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, et al. (2010) AGREE Next Steps Consortium. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. CMAJ 182(18):E839-42. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090449. Epub 2010 Jul 5. Review. PubMed PMID: 20603348.

Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 (2012). Adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwalitieit. https://richtlijnendatabase.nl/over_deze_site/richtlijnontwikkeling.html.

Ontwikkeling van Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen: stappenplan. Kennisinstituut van Medisch Specialisten.

Schünemann H, Brożek J, Guyatt G, et al. GRADE handbook for grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. Updated October 2013. The GRADE Working Group 2013. Available from http://gdt.guidelinedevelopment.org/central_prod/_design/client/handbook/handbook.html.

Schünemann HJ, Oxman AD, Brozek J, et al. Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations for diagnostic tests and strategies. BMJ. 2008;336(7653):1106-10. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39500.677199.AE. Erratum in: BMJ. 2008;336(7654). doi: 10.1136/bmj.a139. PubMed PMID: 18483053.

Zoekverantwoording

Exclusion table after reading full text

|

Author and year |

Reason for exclusion |

|

Gupta 2016 |

Comparison of ropivacaine with bupivacaine |

|

Acar 2015 |

Comparison of general versus regional anesthesia |

|

Clancy 2017 |

Efficacy of prophylactic alpha-blockade |

|

Ahiskalioglu 2016 |

Intervention is neuromuscular blocker |

|

Law 2015 |

Comparison of paravertebral block within generaland regional anesthesia |

|

Bakota 2016 |

Study protocol |

|

Ryan 1984 |

No RCT |

|

Oakley 1988 |

Effect of local anaesthetic infusion in day-case |

|

Theodoraki 2016 |

Conference abstract |

|

Winkle 2016 |

Conference abstract |

|

Pereira 2015 |

Study protocol |

|

Zadeh 2015 |

Comparison of general versus regional anesthesia |

|

Saeed 2015 |

Comparison of nerve block wit hand without ropivacaine |

|

Numanogly 2014 |

Population: children |

|

Madjdpour 2015 |

Fulltext not available |

|

Pereira 2015 |

Erratum |

|

Na 2015 |

Effect of rocuronium after anesthesia |

|

Saryazdi 2016 |

Population: children |

|

Toker 2016 |

Population: children |

|

Parthasarathy 2016 |

Effect of the addition of polygeline |

|

Tomak 2016 |

Effect of cooled hyperbaric bupivacaine |

|

Su 2015 |

Effect of different concentrations of ropivacaine |

|

Prakash 2017 |

Duplicate |

|

Mihic 1982 |

Comparison of morphine versus placebo |

|

Raof 2017 |

Addition of dexmedetomidine to TAP block |

|

Muriel 1996 |

Spanish |

|

Park 2014 |

Population: children |

|

Venkatraman 2016 |

Intervention for postoperative pain |

|

Razavi 2015 |