Anticoagulantia bij analyse bloedingsneiging

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is het meest geschikte anticoagulant bij bloedafname voor stollingstesten?

Aanbeveling

Gebruik een citraatconcentratie tussen 0,105-0,109 mol/L. Gebruik één concentratie binnen hetzelfde laboratorium.

Onderbouwing

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

|

Bloedafname Anticoagulantia |

Conclusies (gradatie, aantal studies) |

|

PT |

Aanbevolen wordt om een citraatconcentratie tussen 0,1050,109 mol/L te gebruiken. (3B, n=3) De citraatconcentratie van 0,129 mol/L heeft niet de voorkeur en dient gevalideerd te worden indien toch gebruikt. (3B, n=3) |

|

aPTT |

|

|

D-dimeren |

|

|

Fibrinogeen |

|

|

ROTEM |

|

|

TEG |

|

|

LTA |

Aanbevolen wordt om een citraatconcentratie tussen 0,1050,109 mol/L te gebruiken. (3B, n=4) De citraatconcentratie van 0,129 mol/L wordt afgeraden. (3B, n=4) Het gebruik van gebufferd citraat is niet noodzakelijk. (3B, n=4) |

|

Stollingsfactoren |

Aanbevolen wordt om een citraatconcentratie tussen 0,1050,109 mol/L te gebruiken. (3B, n=3) De citraatconcentratie van 0,129 mol/L heeft niet de voorkeur en dient gevalideerd te worden indien toch gebruikt. (3B, n=3) |

|

Chromogeen FVIII |

|

|

vWF |

Aanbevolen wordt om een citraatconcentratie tussen 0,1050,109 mol/L te gebruiken. (3B, n=3) De citraatconcentratie van 0,129 mol/L heeft niet de voorkeur en dient gevalideerd te worden indien toch gebruikt. (3B, n=3) |

|

Trombinetijd |

|

|

PFA |

Aanbevolen wordt om een citraatconcentratie tussen 0,1050,109 mol/L te gebruiken. (3B, n=4) De citraatconcentratie van 0,129 mol/L wordt afgeraden. (3B, n=4) Het gebruik van gebufferd citraat is niet noodzakelijk. (3B, n=4) |

Samenvatting literatuur

Tri-natriumcitraat is het antistolingsmiddel dat gebruikt wordt in het bloedstollingsonderzoek, in een verhouding van 9 delen volbloed per 1 deel citraat. In de praktijk worden twee concentraties van deze anticoagulantia gebruikt, namelijk 0,105 (3,2%) en 0,129 mol/L (3,8%). Adcock et al. (1997b) beschrijft de effecten van deze twee verschillende citraatconcentraties. Bij gebruik van de 3,8% citraat concentratie is citraat zal meer calcium worden weggevangen wanneer calcium wordt toegevoegd voor recalcificatie, wat resulteert in langere tijden van PT en aPTT dan bij gebruik van 3,2% citraat. Daarnaast waren de PT en aPTT klinisch relevant verlengd bij de hogere concentratie citraat in patiënten die heparine of orale anticoagulantia toegediend hadden gekregen. Vergelijkbare effecten tussen verschillende citraatconcentraties beïnvloeden ook de INR-waardes en ISI van reagentia (Duncan et al., 1994; Lottin et al., 2001). Op basis van deze observaties kan men concluderen dat er gestreefd moet worden naar één citraatconcentratie binnen de laboratoriumdiagnostiek, waarbij een concentratie van 3,2% citraat wordt aanbevolen. Het gebruik van een citraatconcentratie van 0,129 mol/L (3,8%) wordt gedoogd door de CLSI (2008: H21-A5), mits er gebruikt gemaakt wordt van één citraatconcentratie en deze gevalideerd is binnen het laboratorium.

Het gebruik van verschillende citraatconcentraties bij bloedplaatjesfunctie testen is minder onderzocht. Beschreven richtlijnen van BCSH en ISTH-SCC accepteren het gebruik van zowel 0,109 mol/L als 0,129 mol/L tri-natriumcitraat (Harrison et al., 2011; Cattaneo et al., 2013; Hayward et al., 2006). Echter, verschillen door het gebruik van citraatconcentraties van 0,105 en 0,109 mol/L wordt beschreven in een recente studie die laat zien dat bloedplaatjesaggregatie een beter response en meer stabiel is bij een citraat concentratie van 0,109 mol/L dan bij 0,129 mol/L. Daarbij werd ook aangetoond dat de pH niet stabiel is bij gebufferd citraat. Bovendien werd de bloedplaatjesaggregatie niet of nauwelijks beïnvloedt door gebruik van niet-gebufferd citraat (Germanovich et al., 2018).

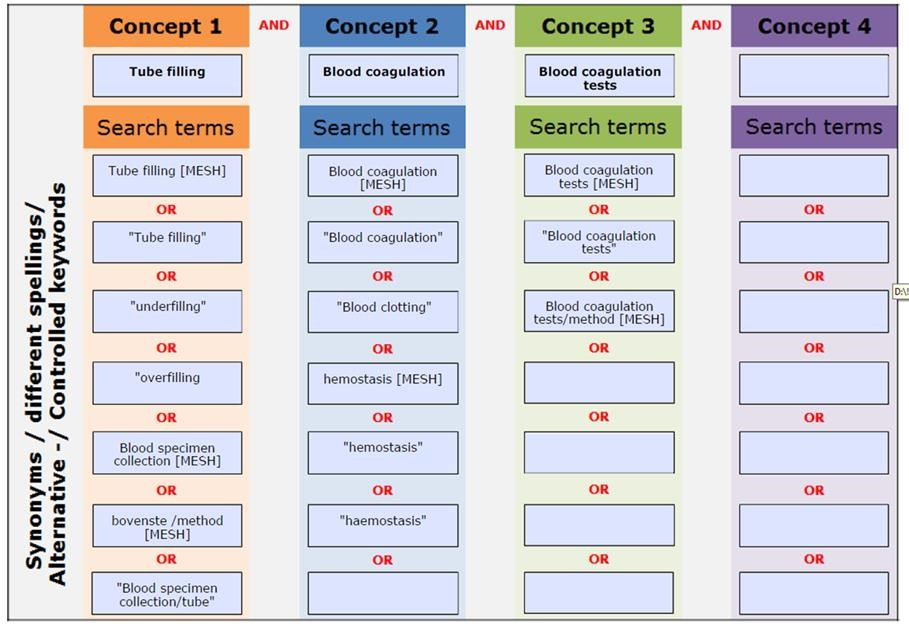

Zoeken en selecteren

De zoekverantwoording is weergegeven onder het tabblad Verantwoording. Zie de zoekverantwoording voor de uitgebreide zoekstrategieën per module.

Referenties

- Adcock DA, Kressin DC, Marlar RA. Are discard tubes necessary in coagulation studies? Lab Med 1997a; 28(8):530-533.

- Adcock DM, Kressin DC, Marlar RA. Effect of 3.2% vs 3.8% sodium citrate concentration on routine coagulation testing. Am J Clin Pathol. 1997b;107(1):105-10.

- Adcock DM, Kressin DC, Marlar RA. Minimum specimen volume requirements for routine coagulation testing: dependence on citrate concentration. Am J Clin Pathol. 1998;109(5):595-9.

- Arambarri M, Oriol A, Sancho JM, Roncales FJ, Galan A, Galimany R. [Interference in blood coagulation tests on lipemic plasma. Correction using n-hexane clearing]. Sangre (Barc). 1998;43(1):13-9.

- Arora S, Kolte S, Dhupia J. Hemolyzed samples sould be processed for coagulation studies: the study of hemolysis effects on coagulation parameters. Ann Med Health Sci Res. 2014;4(2):233-7.

- Austin M, Ferrell C, Reyes M. Do elevated hematocrits prolong the PT/aPTT? Clin Lab Sci. 2013;26(2):89-94.

- Bai B, Christie DJ, Gorman RT, Wu JR. Comparison of optical and mechanical clot detection for routine coagulation testing in a large volume clinical laboratory. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2008;19(6):569-76.

- Bamberg R, Cottle JN, Williams JC. Effect of drawing a discard tube on PT and APTT results in healthy adults. Clin Lab Sci. 2003;16(1):16-9.

- Bamford EJ, Bowen RH, Broad JP, Hawken A, Morgan J, Owen CL, Powell L, Sullivan BC, Tollick H, Wakeman L, Lewis MS, Beddall AC. A capillary whole blood method for measuring the INR. Clin Lab Haematol. 2000;22(5):279-85.

- Boehlen F, Reber G, de Moerloose P. Agreement of a new whole-blood PT/INR test using capillary samples with plasma INR determinations. Thromb Res. 2005;115(1-2):131-4.

- Calam RR, Cooper MH. Recommended "order of draw" for collecting blood specimens into additive-containing tubes. Clin Chem. 1982;28(6):1399.

- Cattaneo M, Cerletti C, Harrison P, Hayward CP, Kenny D, Nugent D, Nurden P, Rao AK, Schmaier AH, Watson SP, Lussana F, Pugliano MT, Michelson AD. Recommendations for the standardization of light transmission aggregometry: a consensus of the working party from the Platelet Physiology Subcommittee of SSC/ISTH. J Thromb Haemost. 2013. Apr 10.

- Chuang J, Sadler MA, Witt DM. Impact of evacuated collection tube fill volume and mixing on routine coagulation testing using 2.5-ml (pediatric) tubes. Chest. 2004;126(4):1262-6.

- CLSI. Collection of diagnostic venous blood specimens. 7th ed. CLSI standard GP41. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2017.

- CLSI. Collection, transport, and processing of blood specimens for testing plasma-based coagulation assays and molecular hemostasis assays; approved guideline – fifth edition. CLSI Document H21-A5. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2008.

- CLSI. Platelet function testing by aggregometry; approved guideline. CLSI Document H58-A. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institue; 2008.

- Cox SR, Dages JH, Jarjoura D, Hazelett S. Blood samples drawn from IV catheters have less hemolysis when 5mL (vs 10-mL) collection tubes are used. J Emerg Nurs. 2004;30(6):529-33.

- Dailey MS, Berger B, Dabu F. Activated partial thromboplastin times from venipuncture versus central venous catheter specimens in adults receiving continuous heparin infusions. Crit Care Nurse. 2014;34(5):27-42.

- Dalton KA, Aucoin J, Meyer B. Obtaining coagulation blood samples from central venous access devices: a review of the literature. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2015;19(4):418-23.

- D'Angelo G, Villa C, Tamborini A, Villa S. Evaluation of the main coagulation tests in the presence of hemolysis in healthy subjects and patients on oral anticoagulant therapy. Int J Lab Hematol. 2015;37(6):819-33.

- D'Angelo G, Villa C. Comparison between siliconized evacuated glass and plastic blood collection tubes for prothrombin time and activated partial thromboplastin time assay in normal patients, patients on oral anticoagulant therapy and patients with unfractioned heparin therapy. Int J Lab Hematol. 2011;33(2):219-25.

- Dugan L, Leech L, Speroni KG, Corriher J. Factors affecting hemolysis rates in blood samples drawn from newly placed IV sites in the emergency department. J Emerg Nurs. 2005;31(4):338-45.

- Duncan EM, Casey CR, Duncan BM, Lloyd JV. Effect of concentration of trisodium citrate anticoagulant on calculation of the International Normalised Ratio and the International Sensitivity Index of thromboplastin. Thromb Haemost. 1994;72(1):84-8.

- Ernst DJ, Calam R. NCCLS simplifies the order of draw: a brief history. MLO Med Lab Obs. 2004;36(5):26-7.

- Favaloro EJ, Lippi G, Raijmakers MT, Vader HL, van der Graaf F. Discard tubes are sometimes necessary when drawing samples for hemostasis. Am J Clin Pathol. 2010;134(5):851.

- Fiebig EW, Etzell JE, Ng VL. Clinically relevant differences in prothrombin time and INR values related to blood sample collection in plastic vs glass tubes. Am J Clin Pathol. 2005;124(6):902-9.

- Flanders MM, Crist R, Rodgers GM. A comparison of blood collection in glass versus plastic vacutainers on results of esoteric coagulation assays. Lab Med. 2003;34(10):732-5.

- Frey AM. Drawing blood samples from vascular access devices: evidence-based practice. J Infus Nurs. 2003;26(5):285-93.

- Germanovich K, Femia EA, Cheng CY, Dovlatova N, Cattaneo M. Effects of pH and concentration of sodium citrate anticoagulant on platelet aggregation measured by light transmission aggregometry induced by adenosine diphosphate. Platelets. 2018;29(1):21-6.

- Gosselin RC, Janatpour K, Larkin EC, Lee YP, Owings JT. Comparison of samples obtained from 3.2% sodium citrate glass and two 3.2% sodium citrate plastic blood collection tubes used in coagulation testing. Am J Clin Pathol. 2004;122(6):843-8.

- Gottfried EL, Adachi MM. Prothrombin time and activated partial thromboplastin time can be performed on the first tube. Am J Clin Pathol. 1997;107(6):681-3.

- Grant MS. The effect of blood drawing techniques and equipment on the hemolysis of ED laboratory blood samples. J Emerg Nurs. 2003;29(2):116-21.

- Haas T, Spielmann N, Cushing M. Impact of incorrect filling of citrate blood sampling tubes on thromboelastometry. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 2015;75(8):717-9.

- Hambleton VL, Gomez IA, Andreu FA. Venipuncture versus peripheral catheter: do infusions alter laboratory results? J Emerg Nurs. 2014;40(1):20-6.

- Harrison P, Mackie I, Mumford A, Briggs C, Liesner R, Winter M, Machin S; British Committee for Standards in Haematology. Guidelines for the laboratory investigation of heritable disorders of platelet function. Br J Haematol. 2011;155(1):30-44.

- Hayward CP, Harrison P, Cattaneo M, Ortel TL, Rao AK; Platelet Physiology Subcommittee of the Scientific and Standardization Committee of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis. Platelet function analyzer (PFA)-100 closure time in the evaluation of platelet disorders and platelet function. J Thromb Haemost. 2006;4(2):312-9.

- Hernaningsih Y, Akualing JS. The effects of hemolysis on plasma prothrombin time and activated partial thromboplastin time tests using photo-optical method. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96(38):e7976.

- Hinds PS, Quargnenti A, Gattuso J, Kumar Srivastova D, Tong X, Penn L, West N, Cathey P, Hawkins D, Wilimas J, Starr M, Head D. Comparing the results of coagulation tests on blood drawn by venipuncture and through heparinized tunneled venous access devices in pediatric patients with cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2002;29(3):E26-34.

- Humphries L, Baldwin KM, Clark KL, Tenuta V, Brumley K. A comparison of coagulation study results between heparinized peripherally inserted central catheters and venipunctures. Clin Nurse Spec. 2012 NovDec;26(6):310-6.

- Indevuyst C, Schuermans W, Bailleul E, Meeus P. The order of draw: much ado about nothing? Int J Lab Hematol. 2015;37(1):50-5.

- Kennedy C, Angermuller S, King R, Noviello S, Walker J, Warden J, Vang S. A comparison of hemolysis rates using intravenous catheters versus venipuncture tubes for obtaining blood samples. J Emerg Nurs. 1996;22(6):566-9.

- Koepke JA, Rodgers JL, Ollivier MJ. Pre-instrumental variables in coagulation testing. Am J Clin Pathol. 1975;64(5):591-6.

- Koerner SD, Fuller RE. Comparison of a portable capillary whole blood coagulation monitor and standard laboratory methods for determining international normalized ratio. Mil Med. 1998;163(12):820-5.

- Kratz A, Stanganelli N, Van Cott EM. A comparison of glass and plastic blood collection tubes for routine and specialized coagulation assays: a comprehensive study. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2006;130(1):39-44.

- Krekels JPM, Verhezen PWM, Henskens YMC. Platelet aggregation in healthy participants is not affected by smoking, drinking coffee, consuming a high-fat meal, or performing physical exercise. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 2019 Jan-Dec;25:1076029618782445.

- Krleza JL, Dorotic A, Grzunov A, Maradin M; Croatian Society of Medical Biochemistry and Laboratory Medicine. Capillary blood sampling: national recommendations on behalf of the Croatian Society of Medical Biochemistry and Laboratory Medicine. Biochem Med (Zagreb). 2015;25(3):335-58.

- Laga AC, Cheves TA, Sweeney JD. The effect of specimen hemolysis on coagulation test results. Am J Clin Pathol. 2006;126(5):748-55.

- Lancé MD, Henskens YM, Nelemans P, Theunissen MH, Oerle RV, Spronk HM, Marcus MA. Do blood collection methods influence whole-blood platelet function analysis? Platelets. 2013;24(4):275-81.

- Leiria TL, Pellanda LC, Magalhaes E, Lima GG. Comparative study of a portable system for prothrombin monitoring using capillary blood against venous blood measurements in patients using oral anticoagulants: correlation and concordance. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2007;89(1):1-5.

- Lima-Oliveira G, Lippi G, Salvagno GL, Gaino S, Poli G, Gelati M, Picheth G, Guidi GC. Venous stasis and whole blood platelet aggregometry: a question of data reliability and patient safety. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2015;26(6):665-8.

- Lima-Oliveira G, Lippi G, Salvagno GL, Montagnana M, Gelati M, Volanski W, Boritiza KC, Picheth G, Guidi GC. Effects of vigorous mixing of blood vacuum tubes on laboratory test results. Clin Biochem. 2013a;46(3):250-4.

- Lima-Oliveira G, Lippi G, Salvagno GL, Montagnana M, Picheth G, Guidi GC. Sodium citrate vacuum tubes validation: preventing preanalytical variability in routine coagulation testing. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2013b;24(3):252-5.

- Lippi G, Blanckaert N, Bonini P, Green S, Kitchen S, Palicka V, Vassault AJ, Plebani M. Haemolysis: an overview of the leading cause of unsuitable specimens in clinical laboratories. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2008;46(6):764-72.

- Lippi G, Fontana R, Avanzini P, Aloe R, Ippolito L, Sandei F, Favaloro EJ. Influence of mechanical trauma of blood and hemolysis on PFA-100 testing. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2012;23(1):82-6.

- Lippi G, Guidi GC. Effect of specimen collection on routine coagulation assays and D-dimer measurement. Clin Chem. 2004;50(11):2150-2.

- Lippi G, Ippolito L, Favaloro EJ. Technical evaluation of the novel preanalytical module on instrumentation laboratory ACL TOP: advancing automation in hemostasis testing. J Lab Autom. 2013b;18(5):382-90.

- Lippi G, Lima-Oliveira G, Guidi GC. Does fist pumping/clenching during venipuncture activate blood coagulation? Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2016;27(3):357-8.

- Lippi G, Montagnana M, Salvagno GL, Guidi GC. Interference of blood cell lysis on routine coagulation testing. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2006;130(2):181-4.

- Lippi G, Plebani M, Favaloro EJ. Interference in coagulation testing: focus on spurious hemolysis, icterus, and lipemia. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2013a;39(3):258-66.

- Lippi G, Salvagno GL, Brocco G, Guidi GC. Preanalytical variability in laboratory testing: influence of the blood drawing technique. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2005a;43(3):319-25.

- Lippi G, Salvagno GL, Guidi GC. No influence of a butterfly device on routine coagulation assays and D-dimer measurement. J Thromb Haemost. 2005b;3(2):389-91.

- Lippi G, Salvagno GL, Montagnana M, Guidi GC. Influence of primary sample mixing on routine coagulation testing. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2007;18(7):709-11.

- Lippi G, Salvagno GL, Montagnana M, Guidi GC. Short-term venous stasis influences routine coagulation testing. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2005c;16(6):453-8.

- Lottin L, Woodhams BJ, Saureau M, Robert A, Aillaud MF, Arnaud E, Martinoli J. The clinical relevance of the citrate effect on International Normalized Ratio determinations depends on the reagent and instrument combination used. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2001;12(5):399-404.

- Lowe G, Stike R, Pollack M, Bosley J, O'Brien P, Hake A, Landis G, Billings N, Gordon P, Manzella S, Stover T. Nursing blood specimen collection techniques and hemolysis rates in an emergency department: analysis of venipuncture versus intravenous catheter collection techniques. J Emerg Nurs. 2008;34(1):26-32.

- Majid A, Heaney DC, Padmanabhan N, Spooner R. The order of draw of blood specimens into additive containing tubes not affect potassium and calcium measurements. J Clin Pathol. 1996;49(12):1019-20.

- Mani H, Kirchmayr K, Kläffling C, Schindewolf M, Luxembourg B, Linnemann B, Lindhoff-Last E. Influence of blood collection techniques on platelet function. Platelets. 2004;15(5):315-8.

- Marlar RA, Potts RM, Marlar AA. Effect on routine and special coagulation testing values of citrate anticoagulant adjustment in patients with high hematocrit values. Am J Clin Pathol. 2006;126(3):400-5.

- McKay RJ, Jr. Diagnosis and treatment: risks of obtaining samples of venous blood in infants. Pediatrics. 1966;38(5):906-8.

- Nagant C, Rozen L, Demulder A. HIL interferences on three hemostasis analyzers and contribution of a preanalytical module for routine coagulation assays. Clin Lab. 2016;62(10):1979-87.

- NVKC Richtlijn Veneuze bloedafname, Werkgroep Preanalyse (van Dongen-Lases EC, Eppens EF, de Jonge N, Roelofs-Thijssen MAMA), 2013, https://www.nvkc.nl/kwaliteit/richtlijnen/normen-en-richtlijnen.

- Onelov L, Basmaji R, Svensson A, Nilsson M, Antovic JP. Evaluation of small-volume tubes for venous and capillary PT (INR) samples. Int J Lab Hematol. 2015;37(5):699-704.

- Pai SH, Michalaros K. Effect of sample volume on coagulation tests. Lab Med. 1990;21(6):371-3.

- Parenmark A, Landberg E. To mix or not to mix venous blood samples collected in vacuum tubes? Clin Chem Lab Med. 2011;49(12):2061-3.

- Peng Z, Mao J, Li W, Jiang G, Zhou J, Wang S. Comparison of performances of five capillary blood collection tubes. Int J Lab Hematol. 2015;37(1):56-62.

- Preanalytische voorschriften voor de stollingsbepalingen: PT, PT-INR, aPTT, fibrinogeen, FV, FVIII, antitrombine, D-dimeer en lupus anticoagulans: Stichting Kwaliteitsbevordering Stollingsonderzoek; 2016.

- Pretlow L, Gandy T, Leibach EK, Russell B, Kraj B. A quality improvement cycle: hemolyzed specimens in the emergency department. Clin Lab Sci. 2008;21(4):219-24.

- Pretorius L, Janse van Rensburg WJ, Conradie C, Coetzee MJ. Minimum citrate tube fill volume for routine coagulation testing. Int J Lab Hematol. 2014;36(4):493-5.

- Quehenberger P, Kapiotis S, Handler S, Ruzicka K, Speiser W. Evaluation of the automated coagulation analyzer SYSMEX CA 6000. Thromb Res. 1999;96(1):65-71.

- Raijmakers MT, Menting CH, Vader HL, van der Graaf F. Collection of blood specimens by venipuncture for plasma-based coagulation assays: necessity of a discard tube. Am J Clin Pathol. 2010;133(2):331-5.

- Reneke J, Etzell J, Leslie S, Ng VL, Gottfried EL. Prolonged prothrombin time and activated partial thromboplastin time due to underfilled specimen tubes with 109 mmol/L (3.2%) citrate anticoagulant. Am J Clin Pathol. 1998;109(6):754-7.

- Roß RS, Paar D. [Analytically and clinically significant interference effects in coagulation testing: lessons from MDA 180]. J Lab Med. 1998;22(2):90-6.

- Salvagno G, Lima-Oliveira G, Brocco G, Danese E, Guidi GC, Lippi G. The order of draw: myth or science? Clin Chem Lab Med. 2013;51(12):2281-5.

- Shah VS, Ohlsson A. Venepuncture versus heel lance for blood sampling in term neonates. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2011(10):Cd001452.

- Siegel JE, Swami VK, Glenn P, Peterson P. Effect (or lack of it) of severe anemia on PT and APTT results. Am J Clin Pathol. 1998;110(1):106-10.

- Smock KJ, Crist RA, Hansen SJ, Rodgers GM, Lehman CM. Discard tubes are not necessary when drawing samples for specialized coagulation testing. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2010;21(3):279-82.

- Stang LJ, Mitchell LG. Specimen requirements for the haemostasis laboratory. Methods Mol Biol. 2013;992:4971.

- Stauss M, Sherman B, Pugh L, Parone D, Looby-Rodriguez K, Bell A, Reed CR. Hemolysis of coagulation specimens: a comparative study of intravenous draw methods. J Emerg Nurs. 2012;38(1):15-21.

- Sulaiman RA, Cornes MP, Whitehead SJ, Othonos N, Ford C, Gama R. Effect of order of draw of blood samples during phlebotomy on routine biochemistry results. J Clin Pathol. 2011;64(11):1019-20.

- Tang N, Jin X, Sun Z, Jian C. Effects of hemolysis and lipemia interference on kaolin-activated thromboelastography, and comparison with conventional coagulation tests. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 2017;77(2):98-103.

- Tantanate C, Teyateeti M, Tientadakul P. Influence of plasma interferences on screening coagulogram and performance evaluation of the automated coagulation analyzer sysmex® CS-2100i. 2011.

- Toulon P, Aillaud MF, Arnoux D, Boissier E, Borg JY, Gourmel C. Multicenter evaluation of a bilayer polymer blood collection tube for coagulation testing: effect on routine hemostasis test results and on plasma levels of coagulation activation markers. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2006;17(8):625-31.

- van den Besselaar AM, Hoekstra MM, Witteveen E, Didden JH, van der Meer FJ. Influence of blood collection systems on the prothrombin time and international sensitivity index determined with human and rabbit thromboplastin reagents. Am J Clin Pathol. 2007;127(5):724-9.

- van den Besselaar AM, Meeuwisse-Braun J, Schaefer-van Mansfeld H, van Rijn C, Witteveen E. A comparison between capillary and venous blood international normalized ratio determinations in a portable prothrombin time device. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2000;11(6):559-62.

- van den Besselaar AM, Rutten WP, Witteveen E. Effect of magnesium contamination in evacuated blood collection tubes on the prothrombin time test and ISI calibration using recombinant human thromboplastin and different types of coagulometer. Thromb Res. 2005;115(3):239-44.

- van den Besselaar AM, van Vlodrop IJ, Berendes PB, Cobbaert CM. A comparative study of conventional versus new, magnesium-poor Vacutainer(R) Sodium Citrate blood collection tubes for determination of prothrombin time and INR. Thromb Res. 2014;134(1):187-91.

- van den Besselaar AM, van Zanten AP, Brantjes HM, Elisen MG, van der Meer FJ, Poland DC, Sturk A, Leyte A, Castel A. Comparative study of blood collection tubes and thromboplastin reagents for correction of INR discrepancies: a proposal for maximum allowable magnesium contamination in sodium citrate anticoagulant solutions. Am J Clin Pathol. 2012;138(2):248-54.

- ver Elst K, Vermeiren S, Schouwers S, Callebaut V, Thomson W, Weekx S. Validation of the minimal citrate tube fill volume for routine coagulation tests on ACL TOP 500 CTS(R). Int J Lab Hematol. 2013;35(6):614-9.

- Woods K, Douketis JD, Schnurr T, Kinnon K, Powers P, Crowther MA. Patient preferences for capillary vs. venous INR determination in an anticoagulation clinic: a randomized controlled trial. Thromb Res. 2004;114(3):161-5.

- Woolley A, Golmard JL, Kitchen S. Effects of haemolysis, icterus and lipaemia on coagulation tests as performed on Stago STA-Compact-Max analyser. Int J Lab Hematol. 2016;38(4):375-88.

- Yavas S, Ayaz S, Kose SK, Ulus F, Ulus AT. Influence of blood collection systems on coagulation tests. Turk J Haematol. 2012;29(4):367-75.

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Laatst beoordeeld : 05-11-2020

Voor het beoordelen van de actualiteit van deze richtlijn wordt (een deel van) de werkgroep in stand gehouden. Op modulair niveau is een onderhoudsplan beschreven. Bij het afronden van de richtlijn heeft de werkgroep per module een inschatting gemaakt over de maximale termijn waarop herbeoordeling moet plaatsvinden en eventuele aandachtspunten geformuleerd die van belang zijn bij een toekomstige herziening (update). De geldigheid van de richtlijn komt eerder te vervallen indien nieuwe ontwikkelingen aanleiding zijn een herzieningstraject te starten. De NVKC is regiehouder van deze richtlijn(module) en eerstverantwoordelijke op het gebied van de actualiteitsbeoordeling van de richtlijn(module).

Algemene gegevens

De richtlijnontwikkeling werd gefinancierd uit de Stichting Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS).

Doel en doelgroep

Doel

- Het opstellen van laboratorium technische adviezen, voor zover mogelijk Evidence-Based met betrekking tot de pre-analyse van minimaal 10 testen die veel gebruikt worden in Nederland en die noodzakelijk zijn voor de analyse, diagnose en behandeling van patiënten met bloedingsneiging.

- Een bijdrage leveren aan de standaardisatie van hemostase testen en de grotere uitwisselbaarheid van uitslagen en hemostase laboratoriumdiagnostiek tussen ziekenhuislaboratoria.

- Een handreiking geven van de bekende literatuur op het gebied van de pre-analytische fase op het gebied van hemostase (t/m juli 2018).

Doelgroep

Deze richtlijn is een handreiking voor alle laboratoriumspecialisten klinische chemie (NVKC/VHL) die nauw in contact staan met de medisch specialist, waarbij de klinisch chemicus op het gebied van analyse bloedingsneigingen consultaties geeft en (eind)verantwoordelijk is voor de bloedafname, analyse en rapportage van stollingstesten. Indirecte gebruikers van deze voorschriften kunnen artsen en verpleegkundigen zijn, die de diagnose stellen en/of bloed afnemen ten behoeve van stollingsonderzoek. Hierbij kan onderscheid gemaakt worden tussen de huisartsen die basale testen aanvragen en aanvragers van het uitgebreide stollingspakket zoals internisten, internist-hematologen, gynaecologen, anesthesisten, kinderartsen, radiologen, tandartsen, en (kaak)chirurgen.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijn is in 2017 een werkgroep ingesteld. De werkgroep is verantwoordelijk voor de integrale tekst van deze richtlijn.

- Dr.ir. Y.M.C. (Yvonne) Henskens, laboratoriumspecialist klinische chemie, Maastricht UMC+, Maastricht (voorzitter), namens NVKC/VHL

- Dr. Dr. M.L.J (Mike) Jeurissen, onderzoeker, Maastricht UMC+, Maastricht, namens NVKC

- Dr. A.K. (An) Stroobants, laboratoriumspecialist klinische chemie, Amsterdam UMC, locatie AMC, Amsterdam, namens NVKC/VHL

- Dr. M.P.M. (Moniek) de Maat, biochemicus, Erasmus MC, Rotterdam, namens VHL

- C.A.M. (Caroline) Klopper, vakanalist, Amsterdam UMC, locatie AMC, namens NVTH werkgroep Hemostase

- P.W.M. (Paul) Verhezen, vakanalist, Maastricht UMC+, Maastricht, namens NVTH werkgroep Hemostase

- Dr. K.M.T. (Kim) de Bruyn, laboratoriumspecialist klinische chemie, Tergooi, Hilversum, Blaricum, namens NVKC/VHL

- Dr. R.W.L.M. (René) Niessen, laboratoriumspecialist klinische chemie, OLVG, Amsterdam, namens NVKC/SKML

Belangenverklaringen

De KNMG-code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling is gevolgd. Alle werkgroepleden hebben schriftelijk verklaard of zij directe financiële belangen (betrekking bij een commercieel bedrijf, persoonlijke financiële belangen, onderzoeksfinanciering) of indirecte belangen (persoonlijke relaties, reputatiemanagement, kennisvalorisatie) hebben. Een overzicht van de belangen van werkgroepleden is in onderstaande tabel weergegeven; er zijn geen restricties m.b.t. deelname aan de werkgroep.

|

Naam |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

Y. Henskens |

Klinisch chemicus |

Lid LGR Sanquin Voorzitter gebruikersraad Sanquin ZON/Limburg Voorzitter concilium NVKC (opleiding) Lid Kennisplatform Transfusiegeneeskunde ZO Bestuurslid VHL Lid werkgroep Hemostase VHL (allen onbetaald) Richtlijn commissie Antitrombotisch beleid FMS/NIV namens NVKC Richtlijn werkgroep FMS Bloedtransfusie (massaal bloedverlies) (vacatiegeld) |

Voor alle studies in het kader van MUMC+ onderzoekslijn “laboratory predictors of bleeding” worden IVD gebruikt die geheel of gedeeltelijk worden gesponsord door IVD firma’s |

Geen: het betreft geen IVD in het kader van preanalyse |

|

M. Jeurissen |

Onderzoeker |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

|

A. Stroobants |

Klinisch chemicus |

Bestuurslid VHL Voorzitter werkgroep Hemostase VHL Richtlijn commissie Antitrombotisch beleid FMS/NIV namens NVKC |

Geen |

Geen |

|

M. de Maat |

Biochemicus |

Lid RvT ECAT (vacatievergoeding) Lid Council International Fibrinogen Research (onbetaald) |

Geen |

Geen |

|

C. Klopper |

Vakanalist |

Lid WHD: Werkgroep Hemostase Diagnostiek NVTH (onbetaald) |

Geen |

Geen |

|

P. Verhezen |

Vakanalist |

Lid WHD: Werkgroep Hemostase Diagnostiek NVTH (onbetaald) |

Geen |

Geen |

|

K. de Bruyn |

Klinisch chemicus |

ISO 15189 auditor (betaald) |

Geen |

Geen |

|

R. Niessen |

Klinisch chemicus |

Bestuurslid: SKML sectie Hematologie Sectie SKS-SKML FNT (allen onbetaald) |

Geen |

Geen |

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

De richtlijn richt zich voornamelijk op de bloedstollingstesten die ingezet kunnen worden bij patiënten die verdacht worden van een congenitale (stollingsfactoren, trombopathie) of verworven (anticoagulantia, massaal bloedverlies) bloedingsneiging. In samenspraak met de Nederlandse Vereniging van Hemofilie Patiënten (NVHP) is uitleg opgesteld voor patiënten waarbij bloed wordt afgenomen voor stollingsonderzoek. De uitleg is op B1 niveau geformuleerd, met kernbegrippen waarop een patiënt zelf verder kan zoeken, indien gewenst.

Methode ontwikkeling

Evidence based

Implementatie

Tijdens de richtlijnontwikkeling is rekening gehouden met de implementatie van de richtlijn (module) en de praktische uitvoerbaarheid van de aanbevelingen. Daarbij is gelet op factoren die de invoering van de richtlijn in de praktijk kunnen bevorderen of belemmeren. Het implementatieplan is opgenomen bij de aanverwante producten.

Werkwijze

Knelpuntenanalyse

Tijdens de voorbereidende fase werden de knelpunten geïnventariseerd en een lange lijst van uitgangsvragen opgesteld. Tijdens een bijeenkomst werd door alle werkgroepleden een prioritering ingevuld van de verzamelde uitgangsvragen. De vragen met de hoogste prioriteit werden vervolgens gebruikt voor deze richtlijn.

Uitgangsvragen

De werkgroep heeft de volgende uitgangsvragen geprioriteerd:

- Welke patiënten kenmerken (biologische status) kunnen de uitkomsten van bloedstollingstesten beïnvloeden?

- Welke factoren kunnen invloed hebben op de (kwaliteit van de) bloedafname en hebben daardoor invloed op de uitkomsten van bloedstollingstesten?

- Welke factoren kunnen invloed hebben op het transport van patiëntmateriaal waardoor ze hebben de uitkomst van bloedstollingstesten kunnen beïnvloeden?

- Welke factoren kunnen invloed hebben op de verwerking van patiëntmateriaal tot plasma of plaatjes-rijk plasma waardoor ze de uitkomst van bloedstollingstesten kunnen beïnvloeden?

- Hoe lang kan volbloed en plasma bewaard worden, zonder de uitkomst van bloedstollingstesten te beïnvloeden?

Strategie voor zoeken en selecteren van literatuur

De zoekstrategieën die zijn verricht in het kader van de uitgangsvragen zijn systematisch uitgevoerd. De zoekstrategieën hebben plaats gevonden in het database Pubmed en/of Medline. Enkele zoektermen die veelvoudig zijn gebruikt zijn: blood coagulation, blood coagulation tests, blood clotting, hemostasis, blood collection, blood specimen. Deze zoektermen werden in combinatie gebruikt met specifiekere zoektermen gericht op het onderwerp. Zie de zoekverantwoording voor de uitgebreide zoek strategieën per module.

Samenvatten van de literatuur

De belangrijkste bevindingen uit de wetenschappelijke literatuur zijn beschreven in de samenvatting van de literatuur.

De intentie voor het graderen van literatuur voor deze richtlijn was om gebruik te maken van GRADE. De beschikbare stollingstesten om de primaire en secondaire hemostase te analyseren zijn sterk afhankelijk van pre-analytische variabelen, die de uitslagen van deze testen sterk kunnen beïnvloeden. De literatuur biedt geen consensus in de optimale pre-analytische omstandigheden waarbij bloedstolling testen uitgevoerd kunnen worden. Om kwaliteit en de sterkte van aanbevelingen te kwantificeren werd eerst onderzocht of het GRADE-systeem implementeerbaar is in deze richtlijn. De vraag die wij ons hierbij eerst gesteld hebben is: is GRADE toepasbaar in een pre-analytische setting van de laboratoriumdiagnostiek? Bij GRADE wordt de kwaliteit van de studie per uitkomstmaat bepaald, geformuleerd via het PICO-principe. Vijf factoren bepalen de kwaliteit per uitkomstmaat: publicatiebias, beperking in studieopzet, imprecisie, indirectheid en inconsistentie (Guyatt et al., 2011, Boluyt et al., 2012). Om te kijken of GRADE toepasbaar is hebben we een kleine zoekopdracht uitgevoerd, waarbij gekeken is naar de interferentie van hemolyse op bloedstollingstesten om knelpunten van GRADE te identificeren. Knelpunten werden gevonden in de formulering van de PICO; keuze van populatie (patiënt en gezond), aangezien pre-analytische variaties in elke populatie kan voorkomen en daarbij de keuze van de juiste uitkomstmaat. De zoekopdracht resulteerde in drie studies die de juiste uitkomstmaat gebruikte uit een selectie van ±600 hits. Daarbij toonde de gekozen studies grote verschillen in apparatuur, reagentia, en methode van inductie en definitie van hemolyse. Op basis van de criteria volgens GRADE zou deze uitkomstmaten een zeer lage of geen gradatie krijgen. Onze conclusie was dat de PICO’s binnen GRADE zeer klinisch en patiëntgericht zijn waarbij voornamelijk gekeken wordt naar interventies; daardoor is GRADE niet toepasbaar binnen een preanalytische setting.

Op basis hiervan werd de literatuur gegradeerd m.b.v. het gradatiesysteem dat gebruikt is in de aanverwante richtlijn “Diagnostiek en behandeling van hemofilie en aanverwante hemostasestoornissen 2009”. Het gradatiesysteem dat in deze richtlijn wordt beschreven is gebaseerd op de US Agency for Health Care Policy and Research”. Zie voorbeeld in de onderstaande tabellen.

Tabel 1: Indeling van de literatuur naar mate van bewijskracht

|

Bewijskracht |

Soort bewijs |

|

Graad 1 |

Bewijs verkregen van meta-analyse van gerandomiseerd gecontroleerde onderzoeken (1a) of ten minste één geblindeerd gerandomiseerd gecontroleerd onderzoek (1b) |

|

Graad 2 |

Bewijs verkregen uit ten minste een goed gedefinieerd gecontroleerd onderzoek, zonder randomisatie (2a) of een cohort- of patiëntcontrole-onderzoek van goede kwaliteit (2b) of een systematisch review zonder meta-analyse |

|

Graad 3 |

Bewijs verkregen uit goed gedefinieerde, niet experimentele beschrijvende onderzoeken, zoals vergelijkende onderzoeken, correlatieonderzoeken of patiëntcontroleonderzoeken van slechte kwaliteit |

|

Graad 4 |

Bewijs verkregen van expertpanels of opinies van deskundigen |

Tabel 2: Niveau van aanbeveling

|

Niveau |

Soort bewijs |

|

A |

Een onderzoek van graad 1a of 1b |

|

B |

Ten minste twee onderzoeken van graad 2a, 2b of graad 3 |

|

C |

Berustend op bewijs van graad 4 |

Formuleren van de conclusies

Voor elke relevante uitkomstmaat werd het wetenschappelijk bewijs samengevat in een of meerdere literatuurconclusies waarbij het niveau van bewijs werd bepaald. De werkgroepleden maakten de balans op van elke interventie (conclusie). Bij het opmaken van de balans werden de gunstige en ongunstige effecten voor de patiënt gewogen. De bewijskracht wordt bepaald door de laagste bewijskracht gevonden bij een van de kritieke uitkomstmaten. Bij complexe besluitvorming waarin naast de conclusies uit de systematische literatuuranalyse vele aanvullende argumenten (overwegingen) een rol spelen, werd afgezien van een conclusie. In dat geval werden de gunstige en ongunstige effecten van de interventies samen met alle aanvullende argumenten gewogen onder het kopje ‘Overwegingen’.

Overwegingen (van bewijs naar aanbeveling)

Om te komen tot een aanbeveling zijn naast wetenschappelijke publicaties ook andere aspecten belangrijk om te worden meegewogen, zoals de expertise van de werkgroepleden, kosten, beschikbaarheid van voorzieningen en organisatorische zaken. Deze aspecten worden, voor zover geen onderdeel van de literatuursamenvatting, vermeld en beoordeeld onder het kopje ‘Overwegingen’.

Kennislacunes

Bij elke uitgangsvraag is door de werkgroep nagegaan of er (aanvullend) wetenschappelijk onderzoek gewenst is. Een overzicht van de aanbevelingen voor nader/vervolgonderzoek is opgenomen onder het kopje ‘Kennislacunes’ (bij Aanverwante producten).

Commentaar- en autorisatiefase

De conceptrichtlijn is aan de leden van de NVKC, VHL, SKML subcommissie stolling, NIV en aan Patiëntenfederatie Nederland voorgelegd ter commentaar. De commentaren zijn verzameld en besproken met de werkgroep. Naar aanleiding van de commentaren is de conceptrichtlijn aangepast en definitief vastgesteld door de werkgroep. De autorisatieversie van de richtlijn is ter stemming gebracht tijdens de algemene ledenvergadering van de NVKC, en voorgelegd aan Patiëntenfederatie Nederland ter autorisatie c.q. instemming.

Literatuur

Boluyt N, Rottier BL, Langendam MW. [Guidelines are made more transparent with the GRADE method: considerations for recommendations are explicit in the new method]. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2012; 156: A4379.

Guyatt G, Oxman AD, Akl EA, Kunz R, Vist G, Brozek J, Norris S, Falck-Ytter Y, Glasziou P, DeBeer H, Jaeschke R, Rind D, Meerpohl J, Dahm P, Schünemann HJ. GRADE guidelines: 1. Introduction-GRADE evidence profiles and summary of findings tables. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011; 64: 383-394.

Zoekverantwoording

Zoekacties zijn opvraagbaar. Neem hiervoor contact op met de Richtlijnendatabase.