Behandeling met pancreasenzymen bij CF

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is de optimale behandeling met pancreasenzymen voor exocriene pancreasinsufficiënte patiënten met CF?

De uitgangsvraag omvat de volgende deelvragen:

- Hoeveel pancreasenzymen (pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy (PERT)) moeten pancreasinsufficiënte patiënten met CF gebruiken (met name maximumdosering)?

- Hoe controleert de arts of de gebruikte dosis pancreasenzymen PERT voldoende is?

- Wat is de optimale timing (voor/tijdens/na voeding) van de toediening van PERT?

- Wanneer is er een indicatie voor toevoeging van een protonpomp remmer bij PERT?

Voor deelvragen 1,3 en 4 is de evidence synthese overgenomen uit de Nutrition Guidelines for Cystic Fibrosis: in Australia and New Zealand, 2017 (Saxby, 2017).

Aanbeveling

Algemene PERT aanbevelingen

- Streef naar de laagst mogelijke dosering.

- Verdeel de enzyminname zo goed mogelijk over de maaltijden afhankelijk van de hoeveelheid vet in het geconsumeerde eten en drinken.

- Monitor gewichtsverloop, groei, buikklachten en ontlastingspatroon.

Dosering: Zie formularium

Onderzoek naar vetmalabsorptie (middels 72-uur vetbalans) is geïndiceerd indien klachten van de patiënt aanleiding geven te denken aan vetmalabsorptie en klinisch handelen door de uitslag zal worden aangepast.

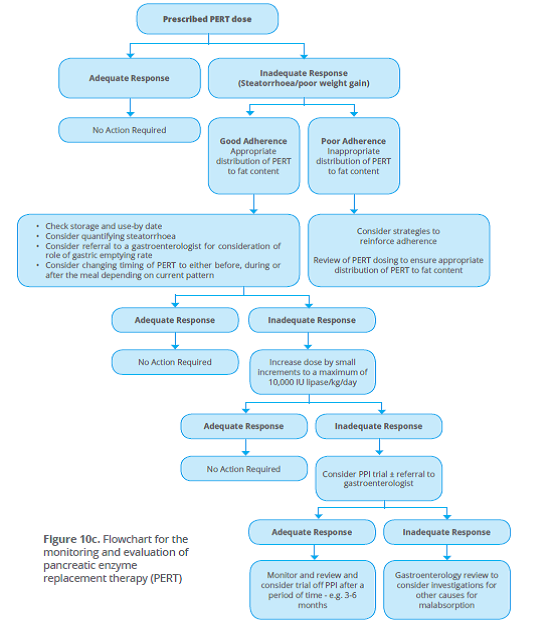

Indien sprake lijkt van onvoldoende effect van PERT, dient allereerst de volgende punten te worden nagegaan:

- Is de patiënt therapietrouw met PERT?

- Is de PERT op de juiste wijze verdeeld over de maaltijd momenten?

- Is de dosis stapsgewijs verhoogd tot een maximum van 10.000 IU lipase/kg/dag?

Overweeg hierna aanpassing in timing (inname voor, tijdens of na de maaltijd) van toediening van PERT en evalueer het effect.

Overweeg het starten van protonpompremmers om de effectiviteit van PERT te verbeteren indien aanpassing in de timing van toediening van PERT onvoldoende effect heeft gehad. Evalueer het effect en staak de protonpompremmer indien dit geen duidelijk effect heeft.

Overwegingen

Kwaliteit van het bewijs en balans tussen voor- en nadelen

Er is geen bewijs dat een bepaalde dosis PERT zorgt voor optimale vetabsorptie. Door de vele en individueel verschillende factoren die werking van PERT beïnvloeden, zoals onder andere maaglediging, zuurgraad in de maag en mogelijk ook het gebruik van CFTR modulatoren, is het onwaarschijnlijk dat er één universele optimale dosering bestaat van PERT. Voor de startdosering van PERT wordt geadviseerd uit te gaan van de startdoseringen geadviseerd in de ESPEN-ESPGHAN-ECFS richtlijn uit 2012 die overeenkomt met de Noord Amerikaanse CF foundation richtlijn uit 2009. Individuele instelling en regelmatige evaluatie van de PERT dosering is noodzakelijk. Doseren van PERT op basis van gram vet in de voeding sluit het dichtst aan bij de fysiologische uitscheiding van pancreasenzymen. Er is echter geen bewijs dat deze doseringswijze in de praktijk superieur is aan een vaste dosering per maaltijd op basis van lichaamsgewicht, deze laatste methode kan eenvoudiger zijn voor sommige patiënten. Derhalve lijkt rationeel te kiezen voor doseren op basis van gram vet in de voeding, maar te kiezen voor een vaste dosering op basis van lichaamsgewicht of een combinatie van beide methoden indien dit voor de patiënt en verzorgers beter haalbaar is.

Er is geen bewijs dat monitoren met testen beter is dan monitoring op groei. De 72-uurs vetbalans is de klinisch meest toegepaste test en wordt beschouwd als meest betrouwbaar. Echter, deze is niet te beschouwen als echte gouden standaard gezien de beperkingen van een 72-uurs fecescollectie. Er is echter momenteel geen betere test beschreven dan de 72-uurs vetbalans voor het monitoren van vetabsorptie. De literatuur suggereert dat mogelijk losse monster feces op één of drie opeenvolgende dagen ook accuraat kan zijn. Studies met adequate power zijn nodig om dit vast te stellen. De 13C-MTG ademtest lijkt bij zuigelingen weinig betrouwbaar. Ook is het een beperking van de studie dat in de vergelijking de testen dichotoom beoordeeld zijn en niet als continue uitkomstmaat hetgeen in de dagelijkse praktijk van monitoren van effect van enzymen wel gebeurt. Verdere kosten (dagopname) en de tijdbelasting zijn ook barrières voor het gebruik van de 13C-MTG ademtest. Er zijn geen gegevens bekend over de accuratesse van deze test bij oudere kinderen.

Het gebruik van de zuur steatocriet als diagnose van ontlastings vetconcentratie en excretie lijkt ook geen alternatief voor de 72 uur verzameling van ontlasting in bij patiënten met CF met milde klachten.

De timing van enzymtoediening op andere momenten dan voor de maaltijd lijkt niet te leiden tot een gemiddeld mindere vetopname. Op individueel niveau kan het potentieel leiden tot betere vetopname. Derhalve is verandering in timing inclusief toediening op meerdere momenten tijdens de maaltijd te overwegen als ondanks compliant gebruik van hoge dosis PERT sprake lijkt te zijn van vetmalabsorptie.

Er is onvoldoende bewijs dat gebruik van protonpompremmers naast PERT leidt tot verbetering in de vetabsorptie. Op basis van de pathofysiologie van de spijsvertering bij CF is er reden om aan te nemen dat maagzuurremming de vetabsorptie positief kan beïnvloeden. Door geen of minder bicarbonaat uitscheiding bij EPI is de voedingsbolus in het duodenum (chymus) zuurder terwijl de werking van verteringsenzymen beter is bij neutrale pH dan een zure pH graad. Ondanks gebrek aan bewijs is derhalve gebruik van maagzuurremming te overwegen indien ondanks compliant gebruik van hoge dosis PERT en aanpassing in de timing van enzymen sprake lijkt te zijn van vetmalabsorptie. Op basis van de beperkte evidence is daarbij de voorkeur voor een proton pompremmer (PPI) boven een H2-antagonist. Evaluatie van het effect, liefst met gebruik van vetbalans, en staken van de protonpompremmers bij ontbreken van gunstig effect is noodzakelijk.

Wat vinden patiënten: patiëntenvoorkeur

Het belang aan het meer of minder gebruiken van PERT en de voorkeur voor doseren per hoeveelheid vet in de voeding of op basis van lichaamsgewicht wordt door patiënten wisselend aangegeven. De 72-uurs fecesverzameling wordt door patiënten en verzorgers in het algemeen als vervelend en belastend ervaren. Een stringente indicatiestelling voor de test en onderzoek naar alternatieve testmethoden zijn om deze reden van belang. Aanpassing in de timing van enzymen en gebruik van protonpompremmers worden in het algemeen als niet erg belastend ervaren.

Wat vinden artsen: professioneel perspectief

Gezien de belasting voor de patiënt en kosten van gebruik van PERT is het wenselijk bij iedere patiënt met CF te streven naar de laagst mogelijk effectieve dosering van PERT. De relatie tussen het gebruik van PERT in dosering boven de 10.000E/kg/dag en optreden van colonopathie is niet duidelijk en derhalve is deze overweging niet leidend voor aanhouden van deze bovengrens in de dosering. Echter bij onvoldoende effect van PERT bij een dosering van 10.000E/kg/dag is het, naast het nagaan van de therapietrouw en juiste wijze verdelen over de maaltijd, wenselijk allereerst alternatieve methoden voor het optimaliseren van de vetabsorptie te proberen zijnde timing van PERT toediening en toevoegen van protonpompremmer. Dit laatste liefst getoetst aan de hand van een vetbalans gezien ontbreken van duidelijke evidence over de effectiviteit van deze toevoeging op populatieniveau. Ook is het wenselijk jaarlijks de noodzaak voor het continueren van protonpompremmer te evalueren, mede aangezien nog niet duidelijk is wat de effecten zijn van chronisch PPI gebruik bij CF. Bij de keuze en dosering van de PPI moet daarnaast rekening gehouden worden met interactie door gelijktijdig gebruik van CFTR modulatoren.

Bij gebrek aan bewijs over beter uitkomst bij monitoring van vetopname middels laboratorium testen ten opzichte van klinisch uitkomstmaten, is er geen indicatie voor vetbalans als standaard jaarlijks onderzoek. Onder behandelaars is er consensus om een 72-uurs vetverzameling toe te passen indien op basis van klinische beoordeling (verminderde groei, ongewenst gewichtsverlies, toegenomen buikklachten en frequente ongewenste defecatie) mogelijk sprake is van niet optimale vetabsorptie, ondanks (verminderde groei, ongewenst gewichtsverlies, toegenomen buikklachten en frequente ongewenste defecatie) en wanneer het niet duidelijk is of er sprake is van niet optimale vetabsorptie, ondanks interventies voor optimaliseren van enzym toediening.

Kosten

Kosten van PERT, protonpompremmer en de genoemde testen in deze module zijn beperkt en spelen geen noemenswaardige rol in de overwegingen

Haalbaarheid

In het algemeen is aanpassing in de dosis van PERT voor patiënten goed haalbaar evenals het aanpassen van de timing van de enzymen of het toevoegen van een protonpompremmer.

Een vetbalans is ook haalbaar in de praktijk, alhoewel bij niet zindelijke kinderen verzamelen moeizaam en minder betrouwbaar kan zijn. Bij zuigelingen wordt ook wel gebruik gemaakt van een laagje plastic in de luier voor fecescollectie.

Samenvattend, de optimale dosis PERT dient individueel te worden vastgesteld en aanpassing in timing van toediening van PERT en toevoegen van PPI kunnen aanvullende strategieën zijn om de vetabsorptie te verbeteren. Evaluatie van effect van deze interventies is noodzakelijk. Er is geen evidence voor benefit van monitoring op basis van testen versus klinische beoordeling van met name groei en gewichtsverloop. Er is onvoldoende bewijs dat minder dan 72-uur fecesverzameling een betrouwbare beoordeling van vetabsorptie geeft. De 13C-MTG ademtest lijkt minder betrouwbaar, maar is alleen getest op zuigelingenleeftijd. Ook zuur steatocriet lijkt niet betrouwbaar in de CF groepen waarin dit is getest.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Circa 80 tot 90% van de patiënten met CF is pancreasinsufficiënt. Dit betekent dat de spijsverteringsenzymen (pancreasenzymen) niet of onvoldoende worden geproduceerd en/of uitgescheiden door de pancreas. Normaal gesproken worden in de alvleesklier pancreasenzymen gevormd, die in de twaalfvingerige darm (duodenum) worden uitgescheiden, waar ze zich mengen met de voedselbrij. Op deze wijze worden macronutriënten (vetten, eiwitten en koolhydraten) tot kleine stukjes afgebroken om zo opgenomen te kunnen worden in het bloed. Deze sappen bestaan uit de enzymen lipase (vertering van vet), amylase (vertering van koolhydraten), protease (vertering van eiwit) en ook bicarbonaat (neutraliseren van maagzuur in duodenum).

Er bestaan kunstmatige pancreasenzymen die voor het nuttigen van voeding genomen moeten worden door patiënten met CF om zo de voedingsstoffen uit de voeding te kunnen opnemen. De dosering van de spijsverteringenzymen gaat meestal op grammen vet in de voeding in combinatie met een maximum aan capsules per kilogram lichaamsgewicht per dag. Indien patiënten het maximum aantal capsules gebruiken maar er nog steeds klachten bestaan van malabsorptie (diarree, opgezette buik, winderigheid, buikpijn, niet goed groeien/aankomen in gewicht) wordt er in de praktijk vaak een protonpompremmer toegevoegd om de pH in het duodenum te verhogen of kan timing van de enzymeninname worden aangepast naar tijdens of direct na de voeding. Deze interventies verbeteren mogelijk de werkzaamheid van de enzymen.

De kennis lacune bestaat uit het feit dat we niet goed weten hoe de individuele dosis enzymen te bepalen voor optimale vetabsorptie, hoe hoog kunnen we gaan (mogelijk ook bijwerkingen bij te hoge dosis PERT), welke test gebruikt kan worden om aan te geven dat de dosis enzymen adequaat is en of vastgesteld is of het toevoegen van een protonpompremmer of aanpassen van de timing van de toediening van enzymen daadwerkelijk kan leiden tot verbetering van vetabsorptie.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

PICO 1 dosing from Nutrition Guidelines for Cystic Fibrosis: in Australia and New Zealand, 2017.

|

Very low GRADE |

There is insufficient evidence to recommend specific doses of PERT required to support optimal fat absorption in people with CF. A wide range of doses have been shown to be effective.

Sources: (Trapnell, 2009; Graff, 2010a; Graff 2010b; Littlewood, 2011; Konstan, 2010; Kashirskaya, 2015; Borowitz, 2006a; Borowitz, 2006b; van de Vijver, 2011; Konstan, 2004; Borowitz, 2012; Wooldridge, 2009; Wooldridge, 2014; Konstan, 2013; Brady, 2006; Baker, 2005; Haupt, 2011; Trapnell, 2011; Munck, 2009, Saxby, 2017) |

PICO 2 monitoring

|

Zeer laag GRADE |

Het is onduidelijk of het nemen van meervoudige ontlastingsmonsters (3 monsters op 3 opeenvolgende dagen) en het meten van het vetpercentage een geschikte alternatieve methode kan zijn voor een 72 uur verzameling van ontlasting met een CFA-berekening.

Bronnen: (Caras, 2011) |

|

Laag GRADE |

De 13C-MTG ademtest stelt geen nauwkeurige diagnose van pancreas insufficiëntie in CF-zuigelingen en er kan niet op worden vertrouwd om deze als alternatief te gebruiken voor de 72-uurs fecale vetbepalingen. Bewijs voor gebruik in andere leeftijdsgroepen ontbreekt.

Bronnen: (Kent, 2018) |

|

Laag GRADE |

Zuur steatocriet stelt geen nauwkeurige diagnose van ontlastings vetconcentratie en ontlastingsvet excretie bij patiënten met CF zonder steatorroe of met milde steatorroe en er kan niet op worden vertrouwd om deze als alternatief te gebruiken voor 72 uur verzameling van ontlasting in deze subgroep.

Bronnen: (Walkowiak, 2018) |

PICO 3 timing from Nutrition Guidelines for Cystic Fibrosis: in Australia and New Zealand, 2017

|

Very low GRADE |

Limited evidence suggests PERT is equally effective when taken before or after a meal in individuals with CF. It also suggests that for some individuals, changing PERT timing in relation to a meal may improve PERT efficacy.

Sources: (van der Haak, 2016) |

PICO 4 PPI from Nutrition Guidelines for Cystic Fibrosis: in Australia and New Zealand, 2017

|

Low GRADE |

There is insufficient evidence to support for or against the use of acid suppression medication to improve PERT efficacy by increasing fat absorption for people with CF.

Bronnen: (Ng, 2014) |

Samenvatting literatuur

Deelvraag 1, 3 en 4 zijn in het Engels beschreven omdat de literatuursamenvatting is overgenomen uit de Nutrition Guidelines for Cystic Fibrosis: in Australia and New Zealand, 2017.

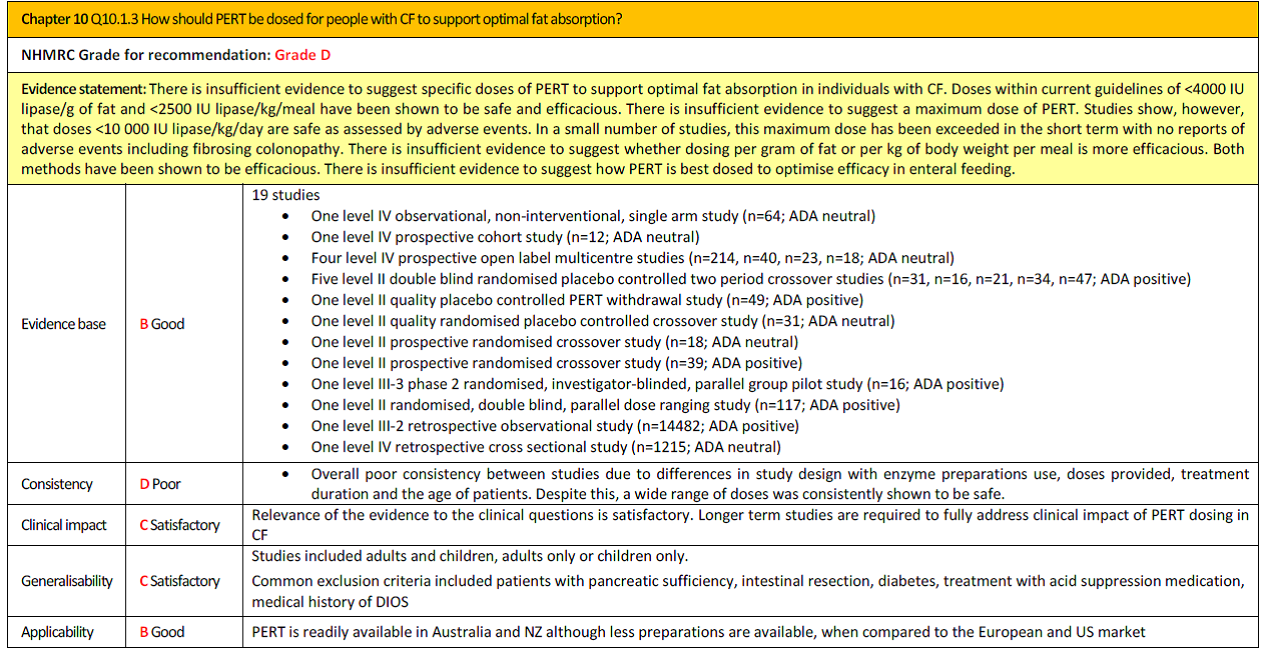

Resultaten (deelvraag 1) as described in Nutrition Guidelines for Cystic Fibrosis: in Australia and New Zealand, 2017.

How should PERT be dosed for people with CF to optimise fat absorption?

Studies looking at optimal PERT dosing in CF differ in enzyme preparation used, dose provided, treatment duration and age of patients. A wide range of doses has been shown to be safe and effective.

Dosing of PERT

Internationally, guidelines give recommendations for both dosing PERT based on units of lipase/kg/meal and units of lipase/g of fat consumed (Turck, 2016; Borowitz, 2009; Stalling, 2008; Borowitz, 2002). Dosing per meal and snack has been used due to ease of adherence with this method compared to dosing per gram of fat intake. In clinical trials, both dosing per gram of fat (Trapnell, 2009; Graff, 2010a) and dosing per meal (Littlewood, 2011; Konstan, 2010; Kashirskaya, 2015; Borowitz, 2006a; Borowitz, 2006b; van de Vijver, 2011; Konstan, 2004; Borowitz, 2012; Wooldridge, 2009; Wooldridge, 2014; Konstan, 2013; Brady, 2006) have been shown to be effective in children and adults.

Guidelines suggest various ranges in which to dose PERT, with a maximum of 2500 IE lipase/kg/meal and 4000 IE lipase/g fat consistently suggested (Turck, 2016; Borowitz, 2009; Stalling, 2008; Borowitz, 2002). Two small prospective dose ranging studies of short duration report no improvements in coefficient of fat absorption (CFA) with doses > 500 IE lipase/kg/meal (Borowitz 2006b; van den Vijver, 2011). Larger retrospective observational studies report conflicting results of no association between PERT dose and growth outcomes (Baker, 2005), and higher BMI percentiles or weight-forage z score and weight-for-length percentiles in those with a higher mean PERT dose per kg per day (Haupt, 2011; Schechter, 2018).

Maximum daily dose

A maximum dose of 10 000 IE lipase/kg/day was recommended 516 following observations that doses above 6000 IE lipase/kg/meal (Freiman, 1996) and a mean of 50 000 IE lipase/kg/day were associated with fibrosing colonopathy (FitzSimmons, 1997). While this maximum is still generally accepted, the median dose in the control group of the US case-control study investigating fibrosing colonopathy was 13.393 IE lipase/kg/day (FitzSimmons, 1997), giving rise to the idea that this maximum may be too conservative.

This may be particularly pertinent to neonates and young infants who in the newborn phase may feed up to 12 times per day and therefore may exceed the recommended dose for a short time (Borowitz, 2013). It can also be challenging to remain below the maximum suggested dose in individuals with particularly high fat diets or who are on oral or enteral nutrition support.

While there is some suggestion that the maximum of 10 000 IE lipase/kg/day may be exceeded without harm in the short term, this should be done with caution and in consultation and regular review with an experienced gastroenterologist and dietitian. Longer term studies are required to determine whether exceeding the suggested upper limit of 10.000 IE lipase/kg/day for an extended time period is safe. Other factors contributing to poor weight gain and malabsorption related to PERT efficacy such as adherence and timing of PERT in relation to a meal should be considered before increasing PERT dose (see figure 10c). Until further evidence is available, it is recommended that health professionals follow the recommendations outlined below when dosing PERT for people with CF.

In conclusion, there is insufficient evidence to suggest specific doses of PERT to support optimal fat absorption in individuals with CF. Doses within current guidelines of < 4000 IE lipase/g of fat and < 2500 IE lipase/kg/meal have been shown to be safe and efficacious. There is insufficient evidence to suggest a maximum dose of PERT. Studies show, however, that doses ≤ 10 000 IE lipase/kg/day are safe as assessed by adverse events. In a small number of studies, this maximum dose has been exceeded in the short term with no reports of adverse events including fibrosing colonopathy. There is insufficient evidence to suggest whether dosing per gram of fat or per kg of body weight per meal is more efficacious. Both methods have been shown to be efficacious. There is insufficient evidence to suggest how PERT is best dosed to optimise efficacy in enteral feeding.

Beschrijving en resultaten studies (deelvraag 2)

Hoe controleert de arts of de gebruikte dosis pancreasenzymen (PERT) voldoende is?

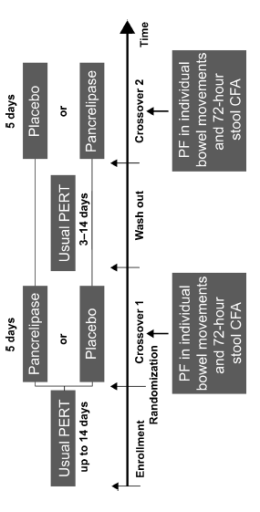

Caras (2011) heeft in een dubbelblinde, gerandomiseerde, placebo-gecontroleerde 2-periode crossover studie onderzocht wat de geschiktheid en klinische bruikbaarheid is van het verzamelen van ontlastingsmonsters voor vetbepaling als een alternatief voor het compleet verzamelen en meten van 72 uur CFA (coefficient of fat absorption) bij patiënten met EPI (exocrine pancreatic insufficiency) veroorzaakt door CF.

Het betrof 16 proefpersonen van 7 tot 11 jaar, geïncludeerd vanuit 10 verschillende centra tussen 13 juni 2008 en 1 december 2008. De mediane leeftijd was 8,0 (range 7 tot 11) jaar, waarvan 12 jongens (71%). De proefpersonen ontvingen PERT van 12.000-lipase-eenheden capsules met vertraagde afgifte.

De proefpersonen waren gerandomiseerd naar één van de twee behandelsequenties gedurende een periode van vijf dagen: PERT vervolgens placebo, of placebo en dan PERT met een uitspoelfase van drie tot 14 dagen tussen hun gebruikelijke PERT. De metingen van vetabsorptie werden verricht in periode met en zonder gebruik van PERT.

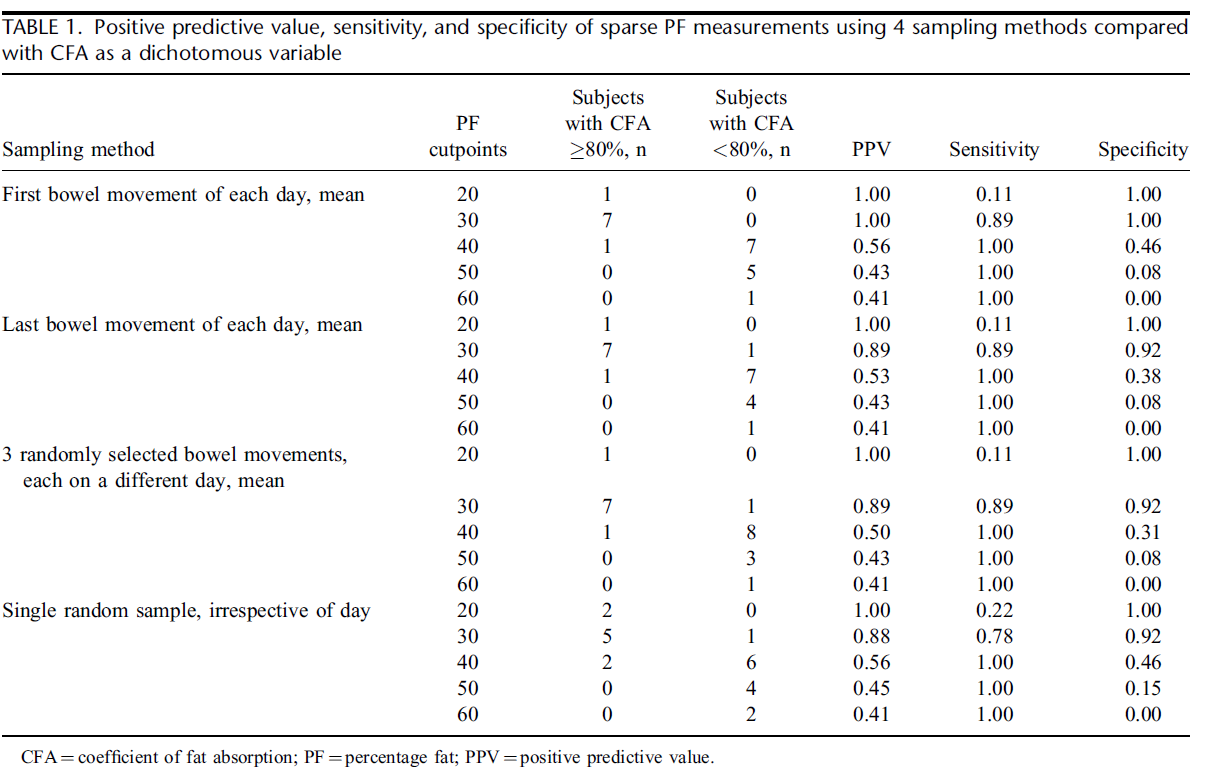

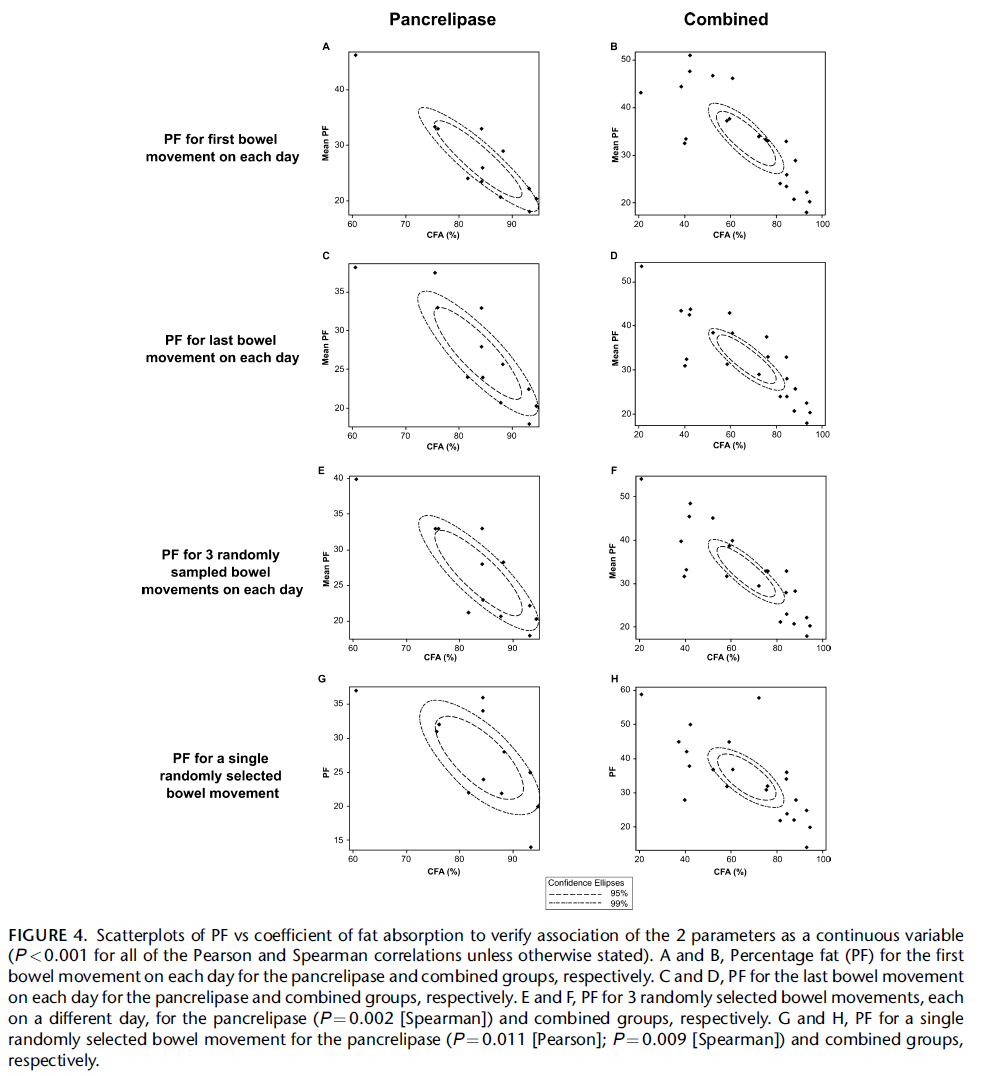

De verkregen ontlastingsmonsters werden geanalyseerd op vet als een percentage van droog gewicht (percentage vet (PF)) met behulp van vier verschillende bemonsteringsmethoden1) de eerste stoelgang op elke dag; 2) de laatste stoelgang op elke dag; 3) willekeurig gekozen stoelgangen, elk op een andere dag; 4) een enkele willekeurige steekproef die is geselecteerd ongeacht dag en werden vervolgens vergeleken met 72-uurs CFA-gegevens die ook werden verzameld.

De totale dagelijkse vetinname werd bepaald aan de hand van de voedingsinname van de proefpersoon, dat werd vastgelegd in een eetdagboek dat bijgehouden werd in de ontlasting verzamelperioden.

Individuele ontlastingsmonsters werden geanalyseerd op vetgehalte. De methoden die werd gebruikt voor de evaluatie van de associatie tussen CFA en PF zag er als volgt uit: De PF-waarden (percentage vet) werden vergeleken met CFA-waarden als continue variabelen met behulp van correlatiecoëfficiënten en checks op lineariteit en als dichotome variabelen met een CFA-cutoff-waarde van 80% omdat een CFA-waarde < 80% over het algemeen wordt beschouwd als een indicatie voor het niet goed absorberen van vet uit de darmen (vet in de ontlasting).

Diagnostische accuratesse vetpercentage methode door middel van meervoudige ontlastingsmonsters ten opzichte van 72-uurs ontlasting verzameling (Caras, 2011)

De PPV’s (positive predictive value), sensitiviteit en specificiteit voor de vergelijking van de PF-waarden (percentage vet) verkregen met behulp van elk van de vier verschillende ontlastingsmonsters methoden in vergelijking met de CFA-waarden als een dichotome variabele worden getoond in tabel in de evidencetabel.

Voor de drie meervoudige steekproefmethoden waren PF-waarden ≤ 30% voorspellend voor CFA-waarden van ≥ 80%, zoals aangetoond door de PPV, sensitiviteits- en specificiteitswaarden van ≥0,89. ROC-curven van gevoeligheid versus 1-specificiteit vertoonde hoge nauwkeurigheid (AUCs ≥ 0,93) voor de meervoudige steekproefmethoden. De PPV en sensitiviteitswaarden van 0,88 en 0,78, waren lager bij de ≤ 30% PF-drempel voor de methode met één steekproef vergeleken met de veelvoudige steekproef methoden; een AUC van 0,91 in de ROC-grafiek gaf iets aan lagere nauwkeurigheid.

De continue data zijn ook geanalyseerd, hierbij werden statistisch significante maar niet excellente associaties gevonden met de Pearson correlatiecoëfficiënt van 0,91 voor de eerste stoelgang op elke dag; 0,86 de laatste stoelgang op elke dag en 0,84 voor drie willekeurig gekozen stoelgangen, elk op een andere dag tussen PF en CFA bij de drie meervoudige steekproefmethoden. De correlaties waren lager (0,70) voor de enkelvoudige steekproefmethode. Dit is zichtbaar gemaakt in scatterplots (figure 4) met betrouwheidselipsen (Caras, 2011). Een langgerektere betrouwbaarheid elips geeft hierbij een beter correlatie aan.

Bron: Caras, 2011

Samenvattend, suggereren de studieresultaten dat drie losse ontlastingsmonsters op drie opeenvolgende dagen en enkelvoudige ontlastingsmonsters mogelijk een alternatief kunnen zijn voor de 72-uurs vetbalans. Gezien het kleine aantal deelnemers is deze studie echter onvoldoende gepowered om hier een betrouwbare uitspraak over te doen. Daarnaast omvat de studie van Caras (2011) geen (externe) validatie van de gevonden resultaten.

De studie van Kent (2018) was gericht op het evalueren van de pancreasfunctie status door gebruik te maken van zowel de 13C Mixed Triglyceride Breath Test (13C-MTG ademtest) met niet-dispersieve infraroodspectroscopie (NDIRS) en de FE1-metingen bij 24 baby’s (variërend in leeftijd van 1 tot 13 maanden (20, < 6 maanden oud)) die borst- (n=12) en flesvoeding (n=12) kregen (10 meisjes en 14 jongens), gediagnosticeerd met CF door neonatale screening. De kwantitatieve 72-uurs fecale vet-excretie-test diende als een gouden standaard voor de vergelijking.

Alle baby’s met CF kregen een 72-uurs ontlasting vetbalansonderzoek, 13C-MTG ademtest en een FE1-metingen (zowel een monoclonal en polyclonale test). Orale inname van het pancreasenzym (PERT; indien al begonnen) werd minstens acht uur vóór het begin van de 13C-MTG-ademhaling test en één dag voor de fecale vet- en FE1-beoordeling gestopt.

FE-1 test is weggelaten uit de resultaten omdat dit niet relevant is voor monitoring.

72-uurs ontlasting vetbalansonderzoek (Kent, 2018)

Ontlastingsmonsters werden verzameld voor alle baby’s met CF gedurende een periode van 72 uur. Tevens werd, voor zuigelingen op flesvoeding, geregistreerd hoeveel en welke voeding de baby had ingenomen. De alvleesklier werd als toereikend gedefinieerd bij fles gevoede zuigelingen jonger dan 6 maanden als 72-uurs fecaal vet uitscheiding < 10% van de vetinname was en bij borst gevoede baby’s jonger dan zes maanden op basis van fecale vetafscheiding < 2 g/dag. Bij baby’s ouder dan zes maanden was dat een 72-uurs fecaal vet uitscheiding ≤ 7% van de orale vetinname.

13C Mixed Triglyceride Breath Test (Kent, 2018)

De database van het IRIS-systeem biedt in zijn software de resulterende gegevens van een groep gezonde individuen de optie om de status van de pancreasfunctie te beoordelen. De bepaling van de status van de alvleesklierfunctie is gebaseerd op de cumulatieve dosis van het % 13C herstelde (cPDR) waarde na vijf uur, met een minimumreferentie van % 13C cPDR-waarde van 13 (gekozen als afkappunt voor PS).

Vergelijking 13C Mixed Triglyceride Breath Test versus 72-uurs ontlasting vetbalansonderzoek (Kent, 2018)

Het gemiddelde gewicht voor de 72-uurs ontlastingsverzameling was 73.8 ±45.6 g. Het gemiddelde vetpercentage was 3.1±2.9 g per dag (range < 0,1 tot 9,4 g/dag).

Van de 24 baby’s met CF, waren er 13 pancreassufficiënt (PS) (ontlasting vetpercentage range < 0,1 tot 1,9 g/dag) en 11 pancreasinsufficiënt (PI) (ontlasting vetpercentage range 2,9 tot 9,4 g/dag).

Voor de MTG was het gemiddelde basale verschil in resultaten bij de 24 baby’s met CF -26.7±3.8%.

De sensitiviteit (optie 1) is 82% voor PI en 38% voor PS. De specificiteitspercentages zijn 38% voor PI en 82% voor PS. De sensitiviteit (optie 2) zijn 100% voor PI en 31% voor PS. De specificiteitsniveaus zijn 31% voor PI en 100% voor PS. Continue data voor vetpercentage van de 72 uurs verbalans versus de ademtestwaarden zijn niet weergegeven in dit artikel.

Samenvattend, de studieresultaten van de 13C-MTG adem test met behulp van NDIRS laten zien dat het geen geschikt alternatief is voor de bepaling van pancreasfenotype in CF-zuigelingen vergeleken met het 72-uurs ontlasting vetbalansonderzoek. Specifiek presteerden beide testen slecht in het herkennen van het PS-fenotype; door de 13C-MTG ademtest werden slechts 7 (optie 1) en 4 (optie 2) van de 13 PS-kinderen op vetbalanstests correct geïdentificeerd met een lage sensitiviteit van 31% tot 38%.

Bewijskracht van de literatuur

De bewijskracht voor de uitkomstmaat diagnostische accuratesse van de vetbalans methode door middel van meervoudige ontlastingsmonsters ten opzichte van 72-uurs ontlasting verzameling (Caras, 2011) is met drie niveaus verlaagd gezien het gebrek aan een gouden standaard (één niveau) imprecisie vanwege het zeer gering aantal proefpersonen (12 kinderen) (één niveau), daarnaast betreft het hier alleen kinderen van 7 tot 11 jaar, het is onduidelijk of deze uitkomsten ook gelden voor baby’s en adolescenten met CF, hierdoor is de bewijskracht met één niveau verder verlaagd (indirectheid) naar in totaal een GRADE van zeer laag. Ook speelt publicatiebias wellicht een rol gezien de studie gesponseerd is door Abbott en de auteurs daar werkten ten tijde van de studie en het schrijven van het artikel.

Bewijskracht

De bewijskracht voor de uitkomstmaat diagnostische accuratesse van de 13C Mixed Triglyceride Breath Test in vergelijking met het 72-uurs ontlasting vetbalansonderzoek is met twee niveaus verlaagd naar een GRADE van laag door het gebrek aan een gouden standaard en imprecisie vanwege het gering aantal proefpersonen (24 baby’s).

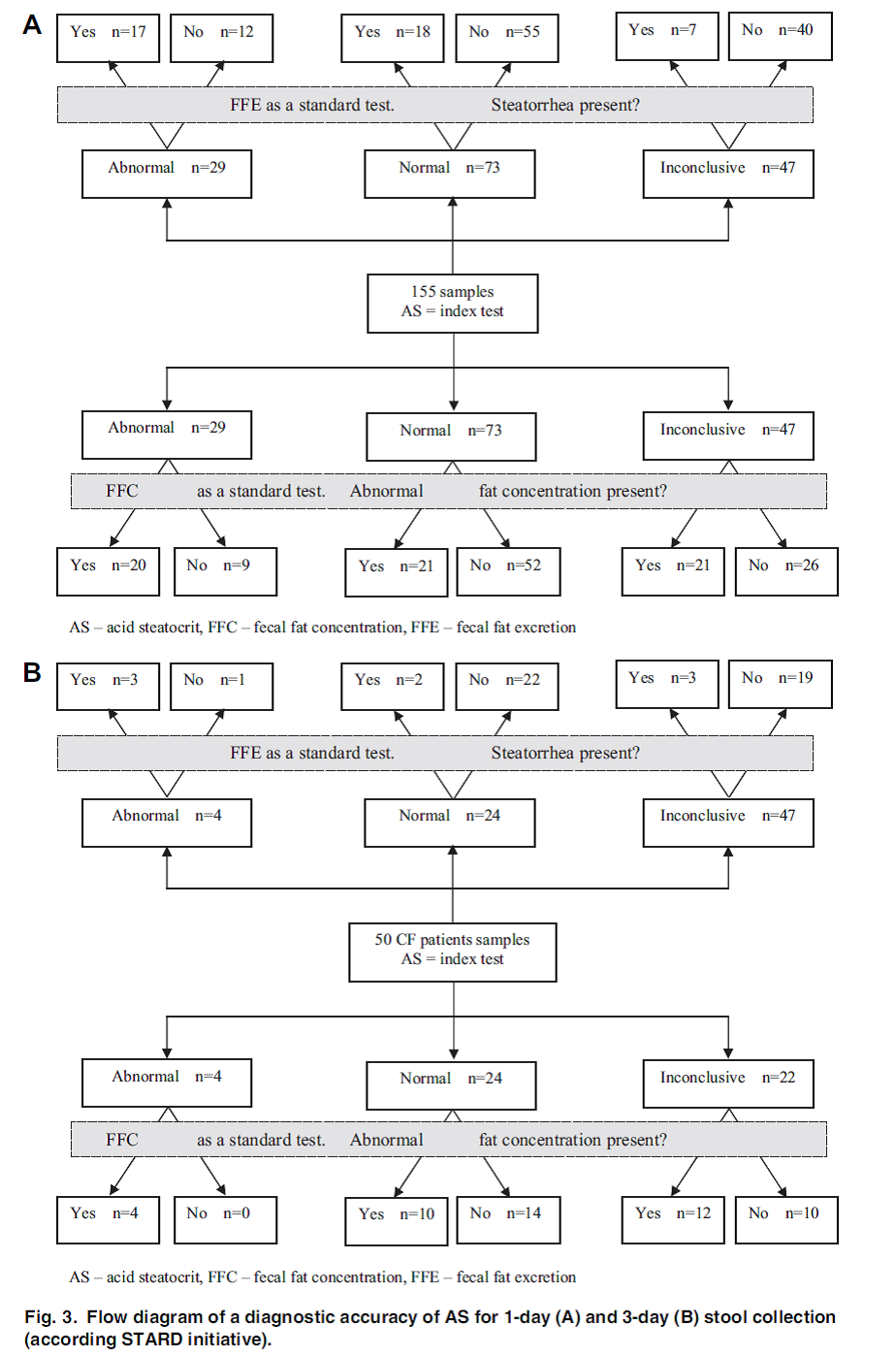

Accuratesse van zuur steatocriet versus ontlasting vetbalansonderzoek

Walkowiak (2010) onderzocht 55 patiënten met CF, in de leeftijd van 7 tot 18 jaar zonder steatorroe of met milde steatoroe (< 10g/dag). Alle patiënten waren pancreasinsufficiënt en ontvingen 2.000 tot 10.000 units lipase/kg lichaamsgewicht per dag. In al deze patiënten werd zuur (acid) steatocriet (AS), ontlasting vet concentratie (FFC) en ontlastingsvet excretie (FFE) gemeten in een 24-uurs ontlasting verzameling (1 tot 3 keer), dit waren in totaal 149 samples. In 50 patiënten was de ontlasting op drie opeenvolgende dagen verzameld en was de AS, FFC en FFC berekend. De gemiddelde waardes werden gebruikt voor de analyse.

AS < 10% werd beschouwd als normaal en > 20% was abnormaal, dit werd gebruikt als afkapwaardes om de sensitiviteit, specificiteit, positief voorspellende waarde (PVW) en negatief voorspellende waarde (NVW) te berekenen. Over het algemeen waren de accuratesse uitkomsten matig (zie tabel 1 en 2).

Tabel 1 Accuratesse van zuur steatocriet voor bepaling van een abnormale ontlastings vet concentratie gebaseerd op 24-uurs en 72-uurs ontlasting verzameling

|

|

Afkapwaarde voor AS |

|||

|

|

24-uurs ontlasting verzameling |

72-uurs ontlasting verzameling |

||

|

|

10% |

20% |

10% |

20% |

|

Sensitiviteit % |

66 |

32 |

62 |

15 |

|

Specificiteit % |

60 |

90 |

58 |

100 |

|

PVW |

54 |

69 |

62 |

100 |

|

NVW |

71 |

65 |

58 |

52 |

AS=Acid steatocriet; PVW=positief voorspellende waarde; NVW=negatief voorspellende waarde

Tabel 2 Accuratesse van zuur steatocriet voor bepaling van de abnormale ontlastings vet excretie gebaseerd op 24-uurs en 72-uurs ontlasting verzameling

|

|

Afkapwaarde voor AS |

|||

|

|

24-uurs ontlasting verzameling |

72-uurs ontlasting verzameling |

||

|

|

10% |

20% |

10% |

20% |

|

Sensitiviteit % |

57 |

41 |

75 |

38 |

|

Specificiteit % |

51 |

89 |

52 |

98 |

|

PVW |

32 |

59 |

23 |

75 |

|

NVW |

74 |

79 |

92 |

89 |

AS=Acid steatocriet; PVW=positief voorspellende waarde; NVW=negatief voorspellende waarde

De correlaties tussen FFE/FFC en AS gebaseerd op de 24-uurs ontlasting verzameling waren zwak, respectievelijk r=0,208, p<0,011 en r=0,362, p<0,00006. De correlaties tussen FFE/FFC en AS gebaseerd op de 24-uurs ontlastingsverzameling waren zwak, respectievelijk r=0,208, p<0,011 en r=0,362, p<0,00006. Dezelfde correlatie voor de 72-uurs ontlasting verzameling was iets sterker, nog steeds relatief zwak, respectievelijk r=0,394, p<0,005 en r=0,454, p<0,001.

Bewijskracht

De bewijskracht voor de uitkomstmaat accuratesse uitkomsten van zuur steatocriet is met twee niveaus verlaagd naar een GRADE van laag door het gebrek aan een gouden standaard en imprecisie vanwege het gering aantal proefpersonen (55 adolescenten).

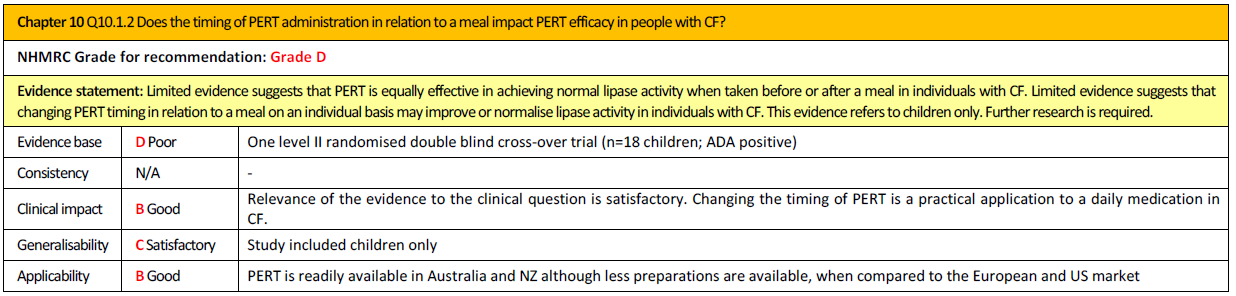

Resultaten (deelvraag 3) as described in Nutrition Guidelines for Cystic Fibrosis: in Australia and New Zealand, 2017.

Does the timing of PERT administration in relation to a meal impact PERT efficacy in people with CF?

One study found that PERT was equally effective in promoting normal lipase activity when taken before or after a meal. This study also showed that for some individuals, changing the timing of PERT from before to after a meal, or vice versa, improved or normalised lipase activity (van der Haak, 2016). A trial of changing PERT timing in relation to a meal can be considered in those with symptoms of fat malabsorption or poor growth once other treatment strategies such as adherence have been considered.

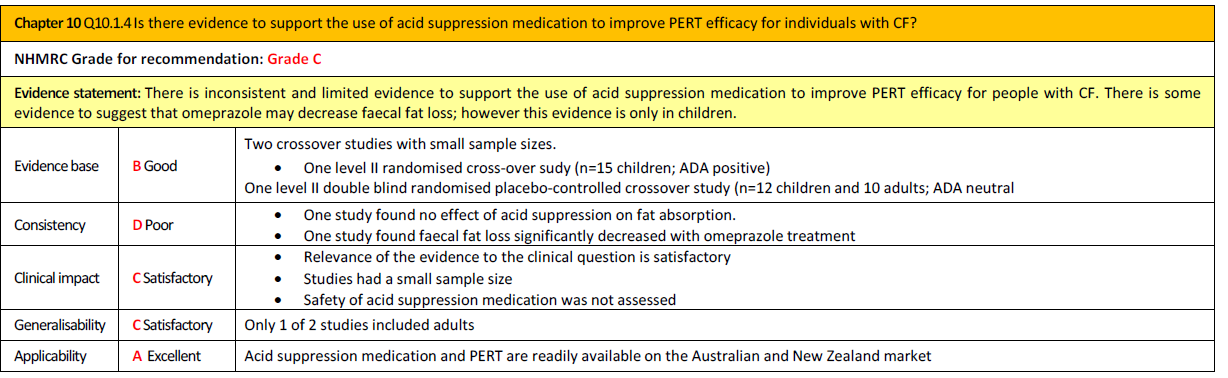

Resultaten (deelvraag 4) as described in Nutrition Guidelines for Cystic Fibrosis: in Australia and New Zealand, 2017.

Is there evidence to support the use of acid suppression medications to improve

PERT efficacy for people with CF?

A Cochrane review investigating drug therapies for reducing gastric acidity concluded that trials have shown limited evidence that agents that reduce gastric acidity improve fat absorption (Ng, 2014).

Zoeken en selecteren

Om de uitgangsvraag te kunnen beantwoorden is er een systematische literatuuranalyse verricht naar de volgende zoekvragen:

Deelvraag 2a. Wat zijn de klinische effecten van instelling van dosis pancreasenzymen (PERT) op basis van symptomen/klinische uitkomsten vergeleken met dosis instelling van PERT op basis van laboratorium methoden in patiënten met CF?

Deelvraag 2b. Wat is de diagnostische accuratesse van de verschillende laboratorium testen om de vetabsorptie te meten ten behoeve van de monitoring van de dosis instelling van PERT.

Voor een aantal deelvragen zijn de zoekactie en evidencetabellen overgenomen van een bestaande richtlijn waarin deze vragen ook onderzocht zijn. Nutrition Guidelines for Cystic Fibrosis: in Australia and New Zealand, (Saxby, 2017). De search is daarbij geüpdatet in april 2018.

Deelvraag 1. Hoe dient PERT te worden gedoseerd voor patiënten met CF om de vetabsorptie te optimaliseren?

Deelvraag 3. Wat is het effect van timing van PERT toediening in relatie tot de maaltijd op de werking van PERT bij patiënten met CF?

Deelvraag 4. Is er bewijs dat het gebruik van zuurremmende medicatie zorgt voor betere werking van PERT bij patiënten met CF?

Relevante uitkomstmaten

De werkgroep achtte verschil in malabsorptie, groei (BMI), kwaliteit van leven en levensverwachting (zoekvraag 2a) en diagnostische accuratesse (zoekvraag 2b) voor de besluitvorming kritieke uitkomstmaten.

De werkgroep definieerde niet a priori de genoemde uitkomstmaten, maar hanteerde de in de studies gebruikte definities.

Zoeken en selecteren (Methode)

In de databases Medline (via OVID) en Embase (via Embase.com) is op 9 april 2018 met relevante zoektermen gezocht naar systematische reviews, RCT’s en observationeel onderzoek. De zoekverantwoording is weergegeven onder het tabblad Verantwoording. De literatuurzoekactie leverde 144 treffers op. Studies werden geselecteerd op grond van de volgende selectiecriteria:

- Studiepopulatie komt overeen met patiëntengroep uit zoekvraag 2a en zoekvraag 2b.

- De test komt overeen met die genoemd in zoekvraag 2a en zoekvraag 2b.

- Betreft primair (origineel) vergelijkend onderzoek of systematische review.

Op basis van titel en abstract werden in eerste instantie 30 studies voorgeselecteerd. Na raadpleging van de volledige tekst, werden vervolgens 28 studies geëxcludeerd (zie exclusietabel onder het tabblad Verantwoording), en twee studies definitief geselecteerd. Deze twee studies beantwoorden echter alleen de vraag over de diagnostische accuratesse van de verschillende laboratorium testen om de vetabsorptie te meten ten behoeve van de monitoring van de dosis instelling van PERT (zoekvraag 2b).

In aan aanvullende search over zuur steatocriet met 133 treffers werden in eerste instantie drie studies voorgeselecteerd. Na raadpleging van de volledige tekst, werden vervolgens twee studies geëxcludeerd (zie exclusietabel onder het tabblad Verantwoording), en één studie definitief geselecteerd voor zoekvraag 2b.

Zoekvraag 2a. Er zijn geen studies geselecteerd om de vraag over de klinische effecten van instelling van dosis pancreasenzymen (PERT) op basis van symptomen/klinische uitkomsten vergeleken met dosis instelling van PERT op basis van laboratorium methoden in patiënten met CF te beantwoorden.

Zoekvraag 2b. Drie accuratesse studies (Caras, 2011; Kent, 2018; Walkowiak, 2010) zijn opgenomen in de literatuuranalyse. De belangrijkste studiekarakteristieken en resultaten zijn opgenomen in de evidencetabellen. De beoordeling van de individuele studieopzet (risk of bias) is opgenomen in de risk of bias tabellen.

Voor de deelvragen 1, 3 en 4 is de search overgenomen uit de Nutrition Guidelines for Cystic Fibrosis: in Australia and New Zealand, 2017:

In de databases Embase, CINAHL, PubMed, AustHealth en Cochrane is gezochtvan januari 2002 tot juni 2016 tot 24 februari 2016 breed gezocht met relevante zoektermen naar studies over pancreasenzym therapie en pancreasinsufficiëntie bij patiënten met CF. De zoekverantwoording is weergegeven onder het tabblad Verantwoording.

Inclusie criteria waren studies specifiek met patiënten met CF en systematische reviews. Exclusie criteria waren studies die niet specifiek ingingen op de onderzoeksvraag, case reports, richtlijnen en consensus documenten en beschrijvende reviews.

De search is daarbij geüpdatet in april 2018.

Deelvraag 1: Er zijn 19 studies (Trapnell, 2009; Graff, 2010a; Graff, 2010b; Littlewood, 2011; Konstan, 2010; Kashirskaya, 2015; Borowitz, 2006a; Borowitz, 2006b; van de Vijver, 2011; Konstan, 2004; Borowitz, 2012; Wooldridge, 2009; Wooldridge, 2014; Konstan, 2013; Brady, 2006; Baker, 2005; Haupt, 2011; Trapnell, 2011; Munck, 2009) geselecteerd over dosering van PERT opgenomen in de literatuuranalyse van de Nutrition Guidelines for Cystic Fibrosis: in Australia and New Zealand, 2017. De update heeft hier één studie aan toegevoegd (Schechter, 2018).

Deelvraag 3: Er is één studie (van der Haak, 2016) geselecteerd over timing van PERT opgenomen in de literatuuranalyse van de Nutrition Guidelines for Cystic Fibrosis: in Australia and New Zealand, 2017. Uit de update zijn er geen nieuwe studies geselecteerd.

Deelvraag 4: Er zijn drie studies (Ng, 2014; Proesmans, 2003; Francisco, 2002) geselecteerd over de meerwaarde van het toevoegen van protonpompinhibitors aan PERT opgenomen in de literatuuranalyse van de Nutrition Guidelines for Cystic Fibrosis: in Australia and New Zealand, 2017.

De belangrijkste studiekarakteristieken en resultaten zijn overgenomen in evidencetabellen van de Nutrition Guidelines for Cystic Fibrosis: in Australia and New Zealand, 2017. Uit de update zijn er geen nieuwe studies geselecteerd.

Referenties

- Baker, SS, Borowitz, D, Duffy, L, Fitzpatrick, L, Gyamfi, J & Baker, RD. Pancreatic enzyme therapy and clinical outcomes in patients with cystic fibrosis. J Pediatr 146, 189-193 (2005).

- Brady, MS, Garson, JL, Krug, SK, Kaul, A, Rickard, KA, Caffrey, HH, et al. An enteric-coated high-buffered pancrelipase reduces steatorrhea in patients with cystic fibrosis: a prospective, randomized study. J Am Diet Assoc 106, 1181-1186 (2006).

- Borowitz, D, Baker, RD & Stallings, V. Consensus report on nutrition for pediatric patients with cystic fibrosis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 35, 246-259 (2002).

- Borowitz, D, Goss, CH, Stevens, C, Hayes, D, Newman, L, O’Rourke, A, et al. Safety and preliminary clinical activity of a novel pancreatic enzyme preparation in pancreatic insufficient cystic fibrosis patients. Pancreas 32, 258-263 (2006a).

- Borowitz, D, Goss, CH, Limauro, S, Konstan, MW, Blake, K, Casey, S, et al. Study of a novel pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy in pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy in pancreatic insufficient subjects with cystic fibrosis. J Pediatr 149, 658-662 (2006b).

- Borowitz, D, Robinson, KA, Rosenfeld, M, Davis, SD, Sabadosa, KA, Spear, SL, et al. Cystic Fibrosis Foundation evidence-based guidelines for management of infants with cystic fibrosis. J Pediatr 155, S73-93 (2009).

- Borowitz, D, Stevens, C, Brettman, LR, Campion, M, Wilschanski, M, Thompson, H, et al. Liprotamase long-term safety and support of nutritional status in pancreatic-insufficient cystic fibrosis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 54, 248-257 (2012).

- Borowitz, D, Gelfond, D, Maguiness, K, Heubi, JE & Ramsey, B. Maximal daily dose of pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy in infants with cystic fibrosis: a reconsideration. J Cyst Fibros 12, 784-785 (2013).

- Caras S, Boyd D, Zipfel L, Sander-Struckmeier S. Evaluation of stool collections to measure efficacy of PERT in subjects with exocrine pancreatic insufficiency. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2011 Dec;53(6):634-40. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3182281c38.

- Francisco, MP, Wagner, MH, Sherman, JM, Theriaque, D, Bowser, E & Novak, DA. Ranitidine and omeprazole as adjuvant therapy to pancrelipase to improve fat absorption in patients with cystic fibrosis. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition 35, 79-83 (2002).

- FitzSimmons, SC, Burkhart, GA, Borowitz, D, Grand, RJ, Hammerstrom, T, Durie, PR, et al. High-dose pancreatic-enzyme supplements and fibrosing colonopathy in children with cystic fibrosis. N Engl J Med 336, 1283-1289 (1997).

- Freiman, JP & FitzSimmons, SC. Colonic strictures in patients with cystic fibrosis: results of a survey of 114 cystic fibrosis care centers in the United States. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 22, 153-156 (1996).

- Graff, GR, Maguiness, K, McNamara, J, Morton, R, Boyd, D, Beckmann, K, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of a new formulation of pancrelipase delayed-release capsules in children aged 7 to 11 years with exocrine pancreatic insufficiency and cystic fibrosis: a ulticentre, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, two-period crossover, superiority study. Clinical Therapeutics 32, 89-103 (2010a).

- Graff, GR, Maguiness, K, McNamara, J, Morton, R, Boyd, D, Beckmann, K, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of a new formulation of pancrelipase delayed-release capsules in children aged 7 to 11 years with exocrine pancreatic insufficiency and cystic fibrosis: a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, two-period crossover, superiority study. Clinical Therapeutics 32, 89-103 (2010b)

- Haupt, M, Wang, D, Kim, S, Schechter, MS & McColley, SA. Analysis of pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy dosing on nutritional outcomes in children with cystic fibrosis. Pediatric Pulmonology 46, 395 (2011).

- Kashirskaya, NY, Kapranov, NI, Sander-Struckmeier, S & Kovalev, V. Safety and efficacy of Creon Micro in children with exocrine pancreatic insufficiency due to cystic fibrosis. Journal of Cystic Fibrosis 14, 275-281 (2015).

- Kent DS, Remer T, Blumenthal C, Hunt S, Simonds S, Egert S, Gaskin KJ. 13C-Mixed Triglyceride Breath Test and Fecal Elastase as an Indirect Pancreatic Function Test in Cystic Fibrosis Infants. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2018 May;66(5):811-815. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000001905.

- Konstan, MW, Stern, RC, Trout, JR, Sherman, JM, Eigen, H, Wagener, JS, et al. Ultrase MT12 and ultrase MT20 in the treatment of exocrine pancreatic insufficiency in cystic fibrosis: Safety and efficacy. Alimentary Pharmacology and Therapeutics 20, 1365-1371 (2004).

- Konstan, MW, Liou, TG, Strausbaugh, SD, Ahrens, R, Kanga, JF, Graff, GR, et al. Efficacy and safety of a new formulation of pancrelipase (Ultrase MT20) in the treatment of malabsorption in exocrine pancreatic insufficiency in cystic fibrosis. Gastroenterology Research and Practice (2010).

- Konstan, MW, Accurso, FJ, Nasr, SZ, Ahrens, RC & Graff, GR. Efficacy and safety of a unique enteric-coated bicarbonate-buffered pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy in children and adults with cystic fibrosis. Clinical Investigation 3, 723-729 (2013).

- Littlewood, JM, Connett, GJ, Sander-Struckmeier, S & Henniges, F. A 2-year post-authorization safety study of high-strength pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy (pancreatin 40,000) in cystic fibrosis. Expert Opinion on Drug Safety 10, 197-203 (2011).

- Munck, A, Duhamel, JF, Lamireau, T, Le Luyer, B, Le Tallec, C, Bellon, G, et al. Pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy for young cystic fibrosis patients. Journal of Cystic Fibrosis 8, 14-18 (2009).

- Ng, SM & Franchini, AJ. Drug therapies for reducing gastric acidity in people with cystic fibrosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 7, CD003424 (2014).

- Proesmans, M & De Boeck, K. Omeprazole, a proton pump inhibitor, improves residual steatorrhoea in cystic fibrosis patients treated with high dose pancreatic enzymes. Eur J Pediatr 162, 760-763 (2003).

- Saxby N., Painter C., Kench A., King S., Crowder T., van der Haak N. and the Australian and New Zealand Cystic Fibrosis Nutrition Guideline Authorship Group (2017). Nutrition Guidelines for Cystic Fibrosis in Australia and New Zealand, ed. Scott C. Bell, Thoracic Society of Australia and New Zealand, Sydney.

- Schechter MS, Michel S, Liu S, Seo BW, Kapoor M, Khurmi R, Haupt M. Relationship of Initial Pancreatic Enzyme Replacement Therapy Dose With Weight Gain in Infants With Cystic Fibrosis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2018 Oct;67(4):520-526. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000002108.

- Stallings, VA, Stark, LJ, Robinson, KA, Feranchak, AP & Quinton, H. Evidence-based practice recommendations for nutrition-related management of children and adults with cystic fibrosis and pancreatic insufficiency: results of a systematic review. J Am Diet Assoc 108, 832-839 (2008).

- Trapnell, BC, Maguiness, K, Graff, GR, Boyd, D, Beckmann, K & Caras, S. Efficacy and safety of Creon 24,000 in subjects with exocrine pancreatic insufficiency due to cystic fibrosis. Journal of Cystic Fibrosis 8, 370-377 (2009).

- Trapnell, BC, Strausbaugh, SD, Woo, MS, Tong, SY, Silber, SA, Mulberg, AE, et al. Efficacy and safety of PANCREAZE for treatment of exocrine pancreatic insufficiency due to cystic fibrosis. Journal of Cystic Fibrosis 10, 350-356 (2011).

- Turck, D, Braegger, CP, Colombo, C, Declercq, D, Morton, A, Pancheva, R, et al. ESPEN-ESPGHAN-ECFS guidelines on nutrition care for infants, children, and adults with cystic fibrosis. Clin Nutr 35, 557-577 (2016).

- Van der Haak, N, Boase, J, Davidson, G, Butler, R, Miller, M, Kaambwa, B, et al. Preliminary report of the (13)C-mixed triglyceride breath test to assess timing of pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy in children with cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros 15, 669-674 (2016).

- Van De Vijver, E, Desager, K, Mulberg, AE, Staelens, S, Verkade, HJ, Bodewes, FA, et al. Treatment of infants and toddlers with cystic fibrosis-related pancreatic insufficiency and fat malabsorption with pancrelipase MT. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition 53, 61-64 (2011).

- Walkowiak J, Lisowska A, Blask-Osipa A, Drzymała-Czyz S, Sobkowiak P, Cichy W, Breborowicz A, Herzig KH, Radzikowski A. Acid steatocrit determination is not helpful in cystic fibrosis patients without or with mild steatorrhea. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2010 Mar;45(3):249-54. doi: 10.1002/ppul.21149.

- Wooldridge, JL, Heubi, JE, Amaro-Galvez, R, Boas, SR, Blake, KV, Nasr, SZ, et al. EUR-1008 pancreatic enzyme replacement is safe and effective in patients with cystic fibrosis and pancreatic insufficiency. Journal of Cystic Fibrosis 8, 405-417 (2009).

- Wooldridge, JL, Schaeffer, D, Jacobs, D & Thieroff-Ekerdt, R. Long-term experience with ZENPEP in infants with exocrine pancreatic insufficiency associated with cystic fibrosis. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition 59, 612-615 (2014).

Evidence tabellen

Evidence table for diagnostic test accuracy studies

Research question: What is the diagnostic accuracy of the different laboratory tests to measure the fat absorption for the purpose of monitoring the dose setting of PERT?

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Index test (test of interest) |

Reference test

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Caras, 2011 |

Type of study[1]: double-blind, randomized, placebocontrolled, 2-period crossover trial

Setting and country: At 10 centers across the United States between June 13, 2008 and December 1, 2008.

Funding and conflicts of interest: funded by Abbott Products Inc, à S.C., D.B., and L.Z. were employees of Abbott, Marietta, GA, at the time of this analysis and writing of the manuscript. S.S.S. is an employee of Abbott, Hannover, Germany. |

Inclusion criteria: - Subjects ages 7 to 11 years who had a confirmed diagnosis of CF and EPI; - Patients must have been receiving treatment with a commercially available PERT product at a stable dose for >3 months. They had to be in clinically stable condition, without evidence of acute respiratory disease, for at least 1 month before enrollment. - only patients with a stable body weight (defined as a decline of no more than 5% within 3 months of enrollment) -Patients had to be able to swallow capsules and to consume a standardized diet designed to provide sufficient fat to require a minimum of 12,000 lipase units of pancreatic enzyme supplementation per meal.

Exclusion criteria: - if they had severe medical conditions that might limit participation in or completion of the study or if they had recently undergone major surgery (excluding appendectomy). - a body mass index percentile for age of <10%; ileus or acute abdomen; malignancy of the digestive tract (excluding pancreatic cancer); HIV; celiac disease; Crohn’s disease; known allergy to pancrelipase (pancreatin) or the inactive ingredients in pancrelipase delayed-release capsules; or exposure to an experimental drug within 30 days of the start of the study.

N= 17 subjects (8 received placebo then pancrelipase, 9 received pancrelipase then placebo)

median age (range): 8,0 (7–11) years

Boys: n= 12 (70,6%)

mean daily lipase dose: 4472 U/g fat consumed.

Other important characteristics: 12 subjects from 8 of the 10 centers provided samples for this analysis (10 in both treatment periods and 2 in only 1 period); the median age was 9.0 years, all subjects were of white race, and 9 (75,0%) were boys.

|

Describe index test: Sparse stool sampling for percentage fat (PF) analysis

Bowel movements were collected individually to facilitate determination of the PF in each sample.

Individual stool samples were analyzed for fat content by removing a 5-g aliquot from the remaining 50% of each homogenized bowel movement. Therefore, PF sampling did not affect the CFA determination. Stool fat was determined by nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) methods PF was calculated based on the dry weight of each bowel movement

Comparator test[2]: PF values for each subject were derived using 4 different sparse-sample methods (3 multiple-sample methods and 1 singlesample method): - mean PF from the first bowel movement on each day; - mean PF from the last bowel movement on each day; - mean PF from 3 randomly selected bowel movements, each on a different day; - PF from a single random sample selected irrespective of day

|

Describe reference test[3]: 72-hour CFA

The CFA (coefficient of fat absorption) is calculated from fat intake and stool fat output data collected during a 72-hour period.

Subjects were administered 2 doses of blue food dye (250mg of FD and C Blue #2 indigo carmine) 72 hours apart to mark the beginning and end of the stool collections, which were performed during both crossover periods. Stool collection began after passage of the first blue-stained bowel movement and ended with passage of the second

Stool fat was determined by nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) methods

Cut-off point: 80%

|

Time between the index test en reference test:

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? N=1 (5,9%)

Reasons for incomplete outcome data described? Not reported |

Outcome measures The comparison of PF with CFA as a dichotomous variable (CFA <80% vs CFA ≥80%) included evaluation of sensitivity, specificity, and positive predictive value (PPV).

PF values ≤30% were greatly predictive for CFA values ≥80%, as shown by PPV, sensitivity, and specificity values ≥0,89. ROC curves of sensitivity versus 1–specificity showed high accuracy (AUCs ≥0.93) for the multiple-sample methods. PPV= 0,88 sensitivity = 0,78, à were lower at the 30% PF threshold for the single-sample method compared with the multiplesample methods; an AUC of 0,91 in the ROC plot indicated slightly lower accuracy à See table 1 below

the correlation between PF and CFA as a continuous variable based on 3 groups of samples: pancrelipase, placebo, and both combined. à See table 2 below

|

72-hour CFA à hospitalization is required to ensure complete stool collection and a complete record of dietary fat intake

The subjects received 12,000-lipase unit pancrelipase delayed-release capsules. The correct number of capsules to be consumed was calculated to provide a target dose of 4000 lipase units/gram of dietary fat intake according to the upper limit of the recommendation of CF consensus statements (30–32). Each subject received an individualized, prospectively designed diet to maintain normal nutrition, containing at least 40% of energy derived from fat. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Caras, 2011 |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Kent, 2018 |

Type of study: Accuracy study

Setting and country: The Children’s Hospital at Westmead, Sydney, Australia.

Funding and conflicts of interest: This research project was supported by grants from the James Fairfax Institute of Paediatric Nutrition and the Johno Johnston Scholarship (DSK). The authors report no conflicts of interest. |

Inclusion criteria: -identified as having CF by the New South Wales State Program.

Exclusion criteria: -

N= 24 infants (12 breast-fed and 12 formula-fed)

age: ranging in age from 1 to 13 months (20, <6 months of age)

Sex: 10/24 baby girls

Other important characteristics: Mean height: 59,9 cm (± 8.0 [48,0–76,7]) mean weight: 5,8 kg (± 2,0 [3,1–10,3]) |

Describe index test: surrogate IPF testing with 13C-mixed triglyceride breath testing (13C-MTG breath test)

Oral pancreatic enzyme substitution (PERT; if already commenced) was stopped at least 8 hours before the start of the 13C-MTG breath test.

- Infants <6 months of age received 200-mg MTG test substrate mixed in 5 ml expressed breast milk, infant formula or apple gel. - babies (>6 months of age) MTG was mixed in apple-gel or yoghurt. Duplicate breath samples (150 ml) were collected before administration of the test meal and at 30-minute intervals thereafter over the study period of 5 hours. Expired infant’s breath was collected by using an anaesthetic mask, connected via a one-way flap valve to an aluminized plastic bag. Breath samples were analyzed promptly on the same day of the test. 13C enrichment was measured using NDIRS. Breath test results were analyzed and expressed as cumulative percentage dose of 13C recovered (cPDR) over the 5-hour test period (% 13C cPDR).

Cut-off point(s): 13 Option 1 to determine pancreatic function status is based on the %13C cumulative dose recovered (cPDR) value after 5 hours, with a minimum reference %13C cPDR value of 13, therefore, chosen as cut-off point for PS.

Option 2 comparison of the individual results of the 13C cPDR values over the whole 5-hour study period à CF babies are classified to be PS if ≥80% of 13C cumulative dose results are above the minimum values provided by the group of healthy individuals.

Comparator test: fecal elastase-1 testing (FE1 measurements)

Oral pancreatic enzyme substitution (PERT; if already commenced) was stopped at least 1 day before the FE1 assessment.

Monoclonal FE1 levels were determined in all CF infants using a commercially available enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (ScheBo, Biotech, Giessen, Germany).

Polyclonal FE1 levels were determined using a commercially available polyclonal ELISA kit (Bioserv Diagnostics, Rostock, Germany).

Cut-off point(s): Monoclonal FE1 levels FE1 According to manufacturer’s instructions à concentrations <200mg/g stool reflect pancreatic insufficiency

According to Beharry et al (2002) and Loser et al (1996) a cut-off point of 100mg/g stool

Polyclonal FE1 levels According to manufacturer’s instructions, values >200mg elastase/g faeces indicate normal exocrine pancreatic function; values between 100 and 200mg elastase/g faeces indicate moderate exocrine pancreatic insufficiency and values <100mg elastase/g faeces indicate severe exocrine pancreatic insufficiency.

|

Describe reference test: 72-h fecal fat balance test

Oral pancreatic enzyme substitution (PERT; if already commenced) was stopped at least 1 day before the fecal fat assessment.

Stool samples were collected for all CF babies over a 72-hour period. Additionally, for formula-fed infants, a record of the volume and kind of formula ingested over this period were kept. The effectiveness of fat absorption was measured by the coefficient of fat malabsorption (CFA) ([fecal fat (g)/fat intake (g)] [100]).

Cut-off point(s): infants <6 months of age à fecal fat excretion <10% of fat intake in formula-fed infants and based on fecal fat excretion < 2 g/day in breast-fed infants babies >6 months of age à fat excretion ≤7% of oral fat intake.

|

Reasons for incomplete outcome data described? Not reported

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? Not reported

|

Outcome Mean total stool weight (72-hour stool collection): 73,8 ± 45,6 g. Mean fat excretion in faeces: 3,1±2,9 g per day (ranged from <0.1–9.4 g/day).

13/ 24 CF babies were determined PS (fecal fat excretion ranged from <0.1–1.9 g/day) 11/24 infant’s PI (fecal fat excretion ranged from 2.9 to 9.4 g/day).

Mixed Triglyceride Breath Test Mean basal delta results of the 24 CF babies were -26.7±3.8%.

Option 1 17/24 CF babies were determined as PI 7/24 CF babies as PS

Option 2 20/24 babies were determined PI 4/24 CF babies PS.

Comparison of the 13C-Mixed Triglyceride Breath Test Versus the Fecal Fat Balance Test

Option 1 Sensitivity rates PI: 82% PS: 38% specificity rates PI: 38% PS: 82%

Option 2 Sensitivity rates PI: 100% PS: 31% specificity rates PI: 31% PS: 100%

Fecal Elastase-1 Results According to Monoclonal ELISA Assessments manufacturer’s instructions: 18/ 24 CF babies PI 6/24 PS

Beharry et al (2002) and Loser et al. (1996): 17/24 PI 7/ 24 CF PS

Fecal Elastase-1 Results According to Polyclonal ELISA Assessments 16/24 CF babies PI, 3/24 CF babies PS 5/24 CF babies had FE1 concentrations between 100–200mg elastase/g stool, indicating moderate pancreatic insufficiency = PS.

Comparison of the Fecal Fat Balance Test and FE1 Analysis With Monoclonal Kit manufacturer’s cut-off values Sensitivity PI: 100%, PS: 46% Specificity PI: 46% PS: 100%

cut-off value used by Beharry et al (2002) and Loser et al (1996) sensitivity PI: 100% PS: 54% specificity PI: 54% PS: 100%

Comparison of the Fecal Fat Balance Test and FE1 Analysis With Polyclonal Kit Sensitivity PI: 92%, PS: 45% Specificity PI: 45% PS: 92% |

PI à pancreatic-insufficient require oral pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy (PERT)

PS à pancreatic- sufficient |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Walkowiak, 2010 |

Type of study: Accuracy study

Setting and country: Poland

Funding and conflicts of interest: Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education |

Inclusion criteria: -Preselected on the basis of previously performed FFB studies -CF diagnosis -no or mild steathorrea

Exclusion criteria: -

N= 55

age: 7-18 years

Sex: 25 females

Other important characteristics: All were pancreas insufficient All had body weight >3rd percentile All received 2,000-10,000 U of lipase/kg of body weight/day |

AS values lower than 10% were considered to be normal and higher than 20% as abnormal.

|

Reasons for incomplete outcome data described? Not reported

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? For 5 subjects 3 day stool collection was not available

|

Outcome Correlations between FFE/FFC and AS based upon 1-day stool collection FFE: r=0.208, P<0.011; FFC: r=0.362, P<0.000006,

Correlations between FFE/FFC and AS based upon 3-day stool collection FFE: r=0.394, P<0.005 FFC: r=0.454, P<0.001

Accuracy AS for determination of abnormal FFC 1 day stool collection for AS cut off levels:

Accuracy AS for determination of abnormal FFC 3 day stool collection for AS cut off levels:

Accuracy AS for determination of abnormal FFE 1 day stool collection for AS cut off levels:

Accuracy AS for determination of abnormal FFE 3 day stool collection for AS cut off levels:

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Research question PICO 1: Does acid suppression medications improve PERT efficacy for people with CF?

Evidence synthesis from Nutrition Guidelines for Cystic Fibrosis: in Australia and New Zealand, 2017

|

Citation |

Level (NHMRC) and quality (ADA) |

Study design and sample |

Intervention and outcomes |

Results & Conclusions |

Comments |

|

Proesmans, 2003 |

NHMRC Level II

ADA Quality: Positive |

Randomised cross-over design

N=15 (CF subjects; median age 8.7 years)

Inclusion criteria: · Patients with persistent symptomatic steatorrhea despite a daily dose of at least 10,000U lipase/kg per day were candidates for the study

Persistent steatorrhea was defined as >7g faecal fat/day (when fat intake is at least 100g/day) or fat absorption <93%

Exclusion criteria: · Severe lung disease with FEV1 <30% · Pulmonary exacerbation in the previous month or liver cirrhosis with portal hypertension · Median daily lipase intake 13,500U/kg per day |

Intervention: · Patients started at random with ‘no omeprazole’ or ‘omeprazole’ for a 1 month period and then crossed over to the other group · Patients < 20kg were treated with 10mg daily, patients >20kg received 20mg · At the end of each month, a 3 day stool collection and a 3 day weighed food record were obtained allowing calculations of caloric intake, daily intake of fat, protein and carbohydrate

Outcomes: · Daily stool fat loss · Fat absorption |

Results: · Daily intake of calories, fat, carbohydrate and protein was not significantly different between the two treatment periods · Median daily faecal fat loss decreased significantly (p>0.01) during omeprazole treatment, 13g (11.5 – 16.5g/day) to 5.5g (4.9 – 8.1g/day) respectively. · The same improvement was noted when fat reabsorption was calculated, 87% (81 – 89%) versus 94% (90 – 96%) with omeprazole. · In all but one patient fat absorption improved - For this patient treated with 16,000U lipase/kg, fat loss was 10.7g/day (reabsorption 86.3%) without versus 14.3g/day (87.9%) with omeprazole – there was no obvious explanation for his lack of improvement

Conclusions: · Omeprazole can improve fat digestion in CF children with residual steatorrhea despite high – dose lipase treatment |

Author limitations: · Small sample size · Should have included all 24 patients and potentially analysed separately to give a ‘real life’ example of improvements when patients may not be compliant with enzyme supplementation

Appraiser limitations: · No blinding |

|

Francisco, 2002 |

NHMRC Level II

ADA Quality: Neutral |

Double blind randomised placebo-controlled crossover study

N = 22

CF children & adults

Inclusion criteria: · CF & PI Exclusion criteria: · Pregnancy · Cholestasis |

Intervention:

· Measure of baseline PERT · Adjuvant therapy was commenced 3 days prior to admission. - Paeds <40kg had ranitidine 5mg/kg or 10mg/kg daily divided into equal doses 30mins prior to BF & D. - Paeds >40kg & adults received 150mg or 300mg bd 30 mins before BF. · Each group was tested whilst having placebo. · The order of Rx was randomised. · Adults were also tested whilst receiving omeprazole 20mg/d 30 mins before BF. · Fat absorption was calculated & diet controlled.

Outcomes: · Effect of gastric acid suppressant therapy with either ranitidine or omeprazole on CF pts receiving ph sensitive enteric coated microtablet. |

Results:

· The linear model for all subjects showed no overall adjuvant drug effect on fat absorption p=0.32. · In adults only drug treatments showed no difference in fat absorption p=0.15 · Paired t test subgroup analysis of adults showed a 4.97% p= 0.003 in mean fat absorption all other t tests showed no significance comparing low dose ranitidine to placebo. · There was marked inter-subject & intrasubject variability in fat absorption. · No overall sig improvement in fat absorption could be demonstrated

Conclusions: · No overall sig improvement in fat absorption could be demonstrated |

Author limitations:

Adherence with therapy · Timing of PERT · Gastric emptying · Bacterial overgrowth · Bile acid abnormalities · Small bowel disease

Appraiser limitations: · Small sample size |

|

Ng, 2014 |

NHMRC Level I

ADA Quality: Positive |

Systematic Review N= 17 trials (273 participants) Inclusion criteria: · All randomised and quasi randomised trials involving agents that reduce gastric acidity compared to placebo or comparator treatment. · Children and adults with defined CF, diagnosed clinically by sweat or gene testing and including all degrees of severity. · All doses and routes of administration were considered.

Exclusion criteria: · Not RCT, examining agents which are not used to reduce gastric acidity eg prokinetic agents vs PPI, outcomes irrelevant to the study question. |

Intervention:

· Agents that reduce gastric acidity- PPI or H2 Receptor antagonists. · Other drug therapies such as prostaglandin E2 analogues & sodium bicarbonate. · Compared to placebo mostly

Primary outcome: · Measures of nutritional status as assessed by weight, height and indices of growth. · Symptoms related to increased gastric acidity such as epigastric pain or heartburn · Complications of increased gastric acidity such as gastric or duodenal ulcers.

Secondary outcome: · Faecal fat, faecal nitrogen excretion and other measures of fat malabsorption · Measures of lung function · Measures of quality or life, mortality, any adverse effects reported. |

Results:

Primary outcomes: · Drug therapies that reduce gastric acidity improve gastrointestinal symptoms such as abdominal pain · Seven trials reported significant improvement in measures of fat malabsorption · Two trials report no significant improvement in nutritional status.

Secondary outcomes: · Insufficient evidence to indicate weather there is an improvement in nutritional status, lung function, quality of life or survival.

Conclusions: · Trials have shown limited evidence that agents that reduce gastric acidity are associated with improvements in gastrointestinal symptoms and fat absorption. · Overall not able to draw firm conclusions from the evidence available.

Limitations (author noted) |

Author limitations:

· 14 trials were of a crossover design and did not have the appropriate info to conduct comprehensive meta- analysis. · The number of trials assessing each of the different agents was small. · The included trials were generally not reported adequately enough to allow judgement of risk of bias. · Unable to group outcome data in to 1, 3, 6 and 12 month time points as planned. · Due to lack of trials it was not possible to investigate heterogeneity between trials using chi2 test and I2 statistic. · Unable to identify any reporting biases. No trials described the methods of randomization · Several studies did not adequately blind or discuss blinding risk of bias from incomplete data was unclear in 4 trials.

Appraiser limitations: · 7 trials limited to children and 3 in adults only. · Large variation between the trials in terms of design, duration, treatment and outcome measures. |

Research question PICO 3: How should PERT be dosed for people with CF to support optimal fat absorption?

Evidence synthesis from Nutrition Guidelines for Cystic Fibrosis: in Australia and New Zealand, 2017

|

Citation |

Level (NHMRC) and quality (ADA) |

Study design and sample |

Intervention and outcomes |

Results & Conclusions |

Comments |

|

Littlewood, 2011 |

NHMRC Level IV ADA Quality: NEUTRAL

|

Observational, noninterventional study, single arm study

N=64 CF patients with PI (mean age 20.7)

Inclusion criteria: · PEI patients who had previously taken high doses of pancreatic enzymes (>40000IU lipase/meal). · Also, patients who require at least 40000IU lipase/meal (but were previously taking less than this)

Exclusion: · Hypersensitivity to porcine proteins

|

Intervention: · Change to pancreatin 40,000 capsules from lower dose preparation

Outcomes: · Serious suspected adverse drug reactions including fibrosing colonopathy · Maldigestion symptoms, body weight

|

Results: · No serious suspected adverse drug reactions related to pancreatin 40000 · No cases of fibrosing colonopathy. · Mean number of capsules taken per individual per day was notably reduced from 43.8 lower strength capsules to 24.6 of 40000IU capsules (as expected). · 3 subjects discontinued Pancreatin 40000 due to ‘mild stomach ache/ abdominal pain’ or ‘bowel did not settle.’ · Overall 36% patients had an increase in average daily lipase dose at last visit vs pain reduced- 24.2% at baseline to 10.7% at the end of the study. · Percentage of patients with fatty stools reduced from 30.2% at baseline to 8.9% at the end of the study · Mean body weight increased for patients <18 years of age, but remained stable in >18 years of age.

Conclusions: · No safety concerns arose during this study in which most patients received doses of >10,000 lipase units per kg/day baseline & 55% had a decrease in average daily lipase dose. · Percentage of patients with abdominal for 18 months |

Author limitations: · Due to observational study design with no control or comparison group it is not possible to determine what proportion of improvement in mal-digestion symptoms was due to pancreatin 40000 vs other factors. · Symptom improvement may be due to improved compliance due to increased monitoring during the study period. · Not possible to determine how much weight gain was due to growth in subjects <18years of age, rather than the pancreatin 40000. Conversely a portion of patients had a reduction in body weight, and the reasons for this cannot be determined as this study did not collect info such as pulmonary fx. · Limited sample size

Appraiser limitations: · Non-serious drug reactions were not recorded or reported as part of this study. · Outcome measures of malabsorption and weight are poorly described, subjective measures and prone to bias/ error etc · This study only looked at subjects who required ‘high doses’ of lipase (>40000IU/meal). |

|

Trapnell, 2009 |

NHMRC Level II ADA Quality: POSITIVE

|

Double blind randomised placebo controlled two period crossover trial

N=31 Males & females with CF

Inclusion criteria: · >12 years of age with confirmed CF & EPI · Clinically stable, including stable weight · On commercially available PERT product stable dose for last 3 months.

Exclusion criteria: · Hx of ileus/ DIOS in last 6 months · GI malignancy in last 5 years · Hx of pancreatitis · Fibrosing colonopathy or HIV. · Subjects < 18yrs also excluded if BMI centile less than 10%.

Primary objective of the study was to demonstrate superior efficacy of Creon over placebo in improving fat absorption as measured by the CFA. |

Intervention: · An individualised diet providing at least 100g/day was provided during days 1 to 5 of the crossover period. · Subjects were randomised 1:1 to one of two crossover treatment sequences: Creon then placebo or placebo then Creon. Creon 24000 capsules were administered to achieve a dose of 4000 IU lipase/ g fat. A “washout” period of 3 to 14 days separated the study periods when subjects had usual diet & enzymes. Blinding was maintained by provision of identical capsules and packaging for placebo and Creon.

Outcome: · Efficacy and safety of Creon 24000

|

Results: · Mean CFA was significantly greater with Creon 88.6% than placebo 49.6% p<0.001.

Conclusions: · The data in this study provide strong evidence for the effectiveness of Creon 24000 capsules at a dose of approx. 4000 lipase units/ fat in treatment of EPI in CF.

|

Author limitations: · The relatively high dose of 4000IU lipase/ g fat chosen together with dosing per gram of fat may not be easily compared with dosing practices commonly used in the clinical setting. · Lack of dose response data for PERT · CFA is not routinely etermined in clinical practice · Short term duration of the study does not allow conclusions regarding long term tolerability or symptomatology

Appraiser limitations: · Creon 24000 not a product available in Aust or NZ. · Placebo was not clearly defined, was difficult to tell if it was no enzyme or usual enzyme. · Funding & design of study is an obvious conflict of interest. |

|

Konstan, 2010 |

NHMRC Level II

ADA Quality: Neutral

|

Randomised, placebo controlled study with crossover design

N=31 subjects with CF >7yrs Inclusion criteria: · PI confirmed by faecal Elastase · Clinically stable at study entry · Taking optimal doses of PERT product · Adequate nutrition status per BMI cut-offs specified · Able to swallow, able to eat high fat diet · On birth control · Ok to be on PPI or H2 therapy · Informed consent.

Exclusion criteria: · Known hypersensitivity to Ultrase MT or porcine proteins. · Allergy to stool marker. · Use of narcotics · Regularly taking bowel stimulants · Hx of bowel resection or portal HT. · Acute pulmonary exacerbation, pancreatitis, GI conditions, uncontrolled DM, DIOS or any other conditions known to increase faecal fat loss. |

Intervention: · Dietitian developed, individualised high fat diet (2g fat/kg body wt) taken for entire comparison phase. · Pancrealipase (6-7days)- crossover (up to 10 days)- placebo (6-7 days) OR vice versa. · Pancrealipase dose is at a stabilised, individualised dose as Assessed by the dietitian, administered under supervision with each meal or snack and recorded.

Primary Outcomes: · Stools collected- frequency and characteristics recorded by study personnel. · 72hr faecal fat completed- The CFA%, CAN% calculated using fat and nitrogen content of stool & food. · Adverse events (AE) assessed and recorded using MedDRA codification.

Secondary outcomes: · Medical, physical, biochemical Ax- pre, during and post study.

|

Results: · Patients treated with pancrealipase had significantly higher mean CFA% than those treated with placebo. P<0.00001 · 76% of patients achieved a CFA% of >85% when treated with pancrealipase compared with 19% of placebo treated patients. · Absorption of proteins measured by CAN% showed similar results. P=<0.00001 for the pancrealipase group. · Patients treated with pancrealipase had reduced number of bowel movements per day compared with placebo- 1.7 vs 2.9 normal stool consistency movements respectively (statistical analysis not performed) · 6 patients reported at least 1 treatment related AE on pancrealipase compared to 18 patients while on placebo. Most AEs were GI and consistent with CF. No clinically significant effects of treatment were noted physically, on labs or vital signs.

Conclusions: · This pancrealipase (Ultrase MT with HP- 55 coating, rather than Eudragit) is a safe and effective treatment for malabsorption associated with PEI. |

Author limitations: · Only limitation vaguely stated was short treatment period

Appraiser limitations: · N=31 but only 24 patients provided analysable data. · The study does not describe the reason for drop-outs of poor data collection. · Small sample size · Adverse events only vaguely described as described as ‘GI’ · The study reports measuring compliance to the study drug but does not report any data around how the compliance was with the drug or the diet prescription. · Method of randomisation not described.

|

|

Kashirskaya, 2015 |

NHMRC Level IV |

Prospective open label multicentre study

N=40 children with CF Inclusion criteria: · 1 month to <4 years with EPI · Accessing eight centres in Russia between June and Dec 2012. · Exclusion criteria: Intestinal/bowel resection/solid organ transplant impacting bowel · DIOS, GI malignancy, hx of fibrosing colonopathy

|

Intervention: · Creon micro administered at a dose of 5000 lipase units per 120mL of formula or breastfeed, or 1000 lipase units/Kg body weight/meal, according to the CF Foundation Guidelines. · Creon micro given with liquid with pH <5.5 or by adding it to acidic soft food. Outcomes: · Safety- measured by AE · Efficacy Ax- height and body weight at baseline, month 1 and month 3 and compared with standard population using percentiles/z-scores. Stool frequency and consistency measures were also measures. · Acceptance of treatment and ease of use- using Likert scale for subjects and ease of use as per caregiver.

|

Results: · Adverse events occurred in 40% of subjects- none were serious or led to cessation of treatment · At 3 month mark, mean +/- SD increases from baseline z-scores were height for age 0.13 +/- 0.48, weight for age 0.2 +/- 0.39 and BMI for age 0.29 +/- 0.65. · Treatment was rated easy by 95% of caregivers and acceptance by subjects was good/very good by 90%.

Conclusions: · Creon micro was well tolerated . Growth parameters increased over the 3 month treatment period- owning to good intervention from CF Foundation guidelines.

Limitations (author noted)

|

Author limitations · Difficulties measuring height · Open –label study design · Lack of placebo/control group · Short study duration · Inability to measure clinical symptoms at baseline · Lack of direct measurement of Efficacy

Appraiser limitations: · Unclear if the time of day weight was measured and consistent scales used · Test of caregivers accuracy of dosage/food + PERT diary etc · Lung function was not acknowledged – how severe a disease did this patients have/admissions and this may effect growth · Small numbers |

|

Borowitz, 2006a |

NHMRC Level IV ADA Quality: Neutral

|

Open label multicentre dose ranging study

N=23 subjects from 11 different centres (ages 13-45 years)

Inclusion criteria: · Pancreatic insufficient based on fecal elastase <100ug/g.