Antivirale behandeling bij kind met koorts

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is de indicatie voor het empirisch starten van antivirale medicatie (i.e. aciclovir) bij kinderen met koorts verdacht van een virale (HSV-geïnduceerde) meningitis (of encefalitis) tijdens het bezoek aan de SEH?

Aanbeveling

Kinderen met koorts en verdacht van een HSV-encefalitis dienen aciclovir intraveneus te krijgen. De diagnose HSV-encefalitis dient te worden overwogen bij:

- Kinderen <1 maand bij wie therapie voor (bacteriële) meningo-encefalitis wordt gestart

- Kinderen ≤ 3 maanden met koorts en prikkelbaarheid/meningeale prikkeling/bomberende fontanel OF verminderd bewustzijn OF focale convulsies/focale neurologische afwijkingen tenzij een evident bacterieel focus.

- Kinderen > 3 maanden met koorts en met een progressieve vermindering van het bewustzijn, bij focale convulsies of andere focale neurologische afwijkingen (tenzij een evident bacterieel focus, of een andere aanwijsbare oorzaak).

Er is geen indicatie voor aciclovir:

- Bij kinderen met eenvoudige convulsies bij koorts.

- Bij kinderen met convulsies zonder koorts (gedocumenteerde koorts of koorts in de anamnese), indien normale immuunstatus en leeftijd > 1 maand.

- Als er een duidelijk andere oorzaak voor de symptomen is (o.a. verstopte VP-drain, bekende epilepsie, een hoofdtrauma, of een intoxicatie).

Overwegingen om aciclovir te staken zijn:

- Als klinische verdenking van HSV-encefalitis laag is bij een voorspoedig klinisch herstel in de eerste dagen na opname, er normaal bewustzijn is, er geen afwijkingen bij neurologische beeldvormende diagnostiek en < 5×106/L leukocyten in de liquor zijn.

- Als klinische verdenking van virale encefalitis laag is EN een negatieve PCR voor HSV in de liquor is die > 72 uur na het beginnen van de neurologische afwijkingen afgenomen is.

- Als een alternatieve diagnose kan worden gesteld.

Een negatieve PCR-uitslag voor HSV in de liquor geeft geen indicatie tot staken van aciclovir bij kinderen met klinische symptomen die persisterend zijn en passend bij een HSV-encefalitis (vooral wanneer er afwijkingen worden gezien op EEG of beeldvormende diagnostiek, of bij afwijkingen in de liquor die kunnen passen bij een HSV-encefalitis).

In het beginstadium van HSV-encefalitis wordt soms geen celverhoging in de liquor gezien en kunnen vals-negatieve PCR-uitslagen voor HSV voorkomen.

Om meer diagnostische zekerheid te krijgen kan de liquorpunctie herhaald worden als de eerste liquorpunctie gedaan is binnen 72 uur na het ontstaan van de symptomen.

Overwegingen

De wetenschappelijke literatuur over het empirisch starten van aciclovir is besproken bij uitgangsvraag 12b (module: Virale diagnostiek bij het kind met koorts met een verdenking op meningitis') en is niet anders dan de literatuur die beschikbaar is voor deze uitgangsvraag. Wanneer diagnostiek naar HSV-infecties wordt ingezet en er dus een klinische verdenking is van een mogelijke HSV-encefalitis, zal ons inziens ook laagdremplig de behandeling met aciclovir moeten worden overwogen.

Het therapeutisch effect van aciclovir bij een (herpes)encephalitis is niet zo snel, zoals bekend van antibiotica bij bacteriële meningitis. Het is dus onjuist om bij een kind verdacht van encefalitis dat in de eerste 48 uur na start aciclovir opknapt, te concluderen dat er sprake is van HSV-encefalitis.

Onderbouwing

Conclusies

Bij deze module zijn geen conclusies geformuleerd.

Samenvatting literatuur

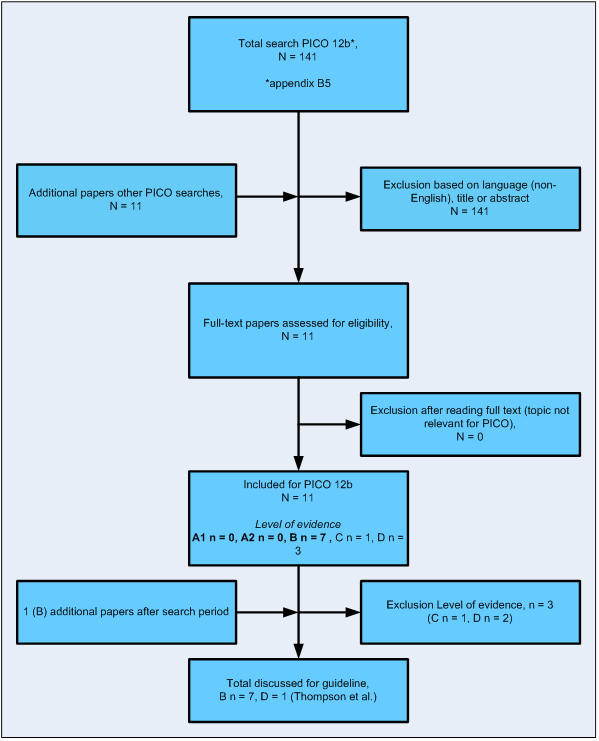

Voor de beschrijving van de evidence van deze uitgangsvraag verwijzen wij naar de Beschrijving evidence uitgangsvraag 12b (module: Virale diagnostiek bij het kind met koorts met een verdenking op meningitis').

Als aanvulling noemen we een recent artikel over encefalitis bij kinderen besproken door Thomson et al. [104]. De auteurs benadrukten dat een richtlijn voor diagnostiek en behandeling van patiënten verdacht van encefalitis wel beschikbaar was voor volwassenen, maar niet voor kinderen. Ze gingen onder meer in op de pathofysiologie, de incidentie en de klinische presentatie van encefalitis bij kinderen. Ze beschreven de ziekteverwekkers van encefalitis bij kinderen en volwassenen in zes grote observationele studies. HSV werd in deze studies als frequente, dan wel meest voorkomende, verwekker van encefalitis genoemd. Daarnaast gaven zij aanbevelingen voor de diagnostiek en de behandeling van kinderen die werden verdacht van een encefalitis. Ten slotte gaven ze adviezen voor diagnostiek en therapie voor kinderen verdacht van encefalitis. Hierbij werden duidelijke adviezen geformuleerd over wanneer aciclovir (wel of niet) moet worden gestart of gestaakt. Deze adviezen zijn met goedkeuring van de werkgroep opgenomen in deze richtlijn.

Zoeken en selecteren

Flowdiagram uitgangsvragen

Zoekstrategie bij uitgangsvragen

Uitgevoerd 21 juni 2012

Medline via OvidSP

(exp Infant/ OR exp child/ OR (infan* OR newborn* OR new born* OR neonat* OR perinat* OR postnat* OR baby OR babies OR child OR schoolchild* OR school child* OR kid OR kids OR toddler* OR teen OR teenage OR boy* OR girl* OR minors OR underag* OR under ag* OR juvenil* OR youth* OR kindergar* OR pubert* OR pubescen* OR schools OR nursery school* OR preschool* OR pre school* OR primary school* OR secondary school* OR elementary school* OR high school* OR highschool* OR school age* OR schoolage*).ab,ti. OR ((adolescent/ OR adolescen*.ab,ti.) NOT exp adult/) ) AND (exp Fever/ OR (fever* OR febril* OR hypertherm* OR pyrexi* OR pyretic* OR hyperpyrex* OR hyperpyretic* OR pyrogen*).ab,ti.) AND ((exp "Arthritis, Infectious"/ OR exp "Bone Diseases, Infectious"/ OR exp "Community-Acquired Infections"/ OR exp Respiratory Tract Infections/ OR exp Sepsis/ OR exp "Skin Diseases, Infectious"/ OR exp Soft Tissue Infections/ OR exp Urinary Tract Infections/ OR exp Meningitis/ OR exp Gastroenteritis/ OR exp encephalitis/ OR exp bacteremia/ OR exp pneumonia/ ) OR (Infect* adj6 (Arthrit* OR bone* OR Communit* OR Respirator* OR skin OR Soft Tissue OR Urinar* OR serious* OR severe*)).ab,ti OR Seps?s.ab,ti. OR Septicaemi*.ab,ti. OR Septicemi*.ab,ti. OR Gastroenteritis.ab,ti. OR encephalitis.ab,ti. OR Bacteremi*.ab,ti. OR Pneumonia*.ab,ti.OR meningitis*.ab,ti. OR exp Morbidity/ OR morbid*.ab,ti. OR exp Mortality/ OR Mortality.xs. OR mortal*.ab,ti.)

AND (Emperic* OR ((blind OR early) adj3 treat*)).ab,ti. AND (exp Anti-infective Agents/ OR exp Antiviral Agents/ OR (((Anti-Bacterial OR AntiBacterial OR Anti-infective OR Antiinfective OR Anti-viral OR Antiviral) adj3 Agent*) OR antibiotic* OR antibiotherap* OR acyclovir or aciclovir ).ab,ti.)

limit 2 to ed=20060901-20130101

Basis – embase

((infan* OR newborn* OR (new NEXT/1 born*) OR baby OR babies OR neonat* OR perinat* OR postnat* OR child OR 'child s' OR childhood* OR children* OR kid OR kids OR toddler* OR teen* OR boy* OR girl* OR minors* OR underag* OR (under NEXT/2 ag*) OR juvenil* OR youth* OR kindergar* OR puber* OR pubescen* OR prepubescen* OR prepuberty* OR pediatric* OR paediatric* OR school* OR preschool* OR highschool* OR suckling):de,ab,ti OR (adoles*:de,ab,ti NOT adult/exp) OR child/exp OR newborn/exp) AND (Fever/de OR (fever* OR febril* OR hypertherm* OR pyrexi* OR pyretic* OR hyperpyrex* OR hyperpyretic* OR pyrogen*):ab,ti) AND (('infectious arthritis'/exp OR 'Bone Infection'/exp OR 'communicable disease'/exp OR 'Respiratory Tract Infection'/exp OR Sepsis/exp OR 'Skin Infection'/exp OR 'Soft Tissue Infection'/de OR 'Urinary Tract Infection'/de OR Meningitis/exp OR Gastroenteritis/de OR encephalitis/exp OR bacteremia/exp OR pneumonia/exp ) OR (Infect* NEAR/6 (Arthrit* OR bone* OR Communit* OR Respirator* OR skin OR 'Soft Tissue' OR Urinar* OR serious* OR severe*)):ab,ti OR Seps?s:ab,ti OR Septicaemi*:ab,ti OR Septicemi*:ab,ti OR Gastroenteritis:ab,ti OR encephalitis:ab,ti OR Bacteremi*:ab,ti OR Pneumonia*:ab,ti OR meningitis*:ab,ti )

AND (Emperic* OR ((blind OR early) NEAR/3 treat*)):ab,ti AND ('Antiinfective Agent'/exp OR 'Antivirus Agent'/exp OR (((Anti-Bacterial OR AntiBacterial OR Anti-infective OR Antiinfective OR Anti-viral OR Antiviral) NEAR/3 Agent*) OR antibiotic* OR antibiotherap* OR acyclovir or aciclovir ):ab,ti) AND [1-9-2006 ]/sd

Referenties

- Hay, A.D., J. Heron, and A. Ness, The prevalence of symptoms and consultations in pre-school children in the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC): A prospective cohort study. Family Practice, 2005. 22(4): p. 367-374.

- Bouwhuis, C.B., et al., [Few ethnic differences in acute pediatric problems: 10 years of acute care in the Sophia Children's Hospital in Rotterdam]]. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd, 2001. 145(38): p. 1847-51.

- Roukema, J., et al., Randomized Trial of a Clinical Decision Support System: Impact on the Management of Children with Fever without Apparent Source. J Am Med Informatics Assoc, 2008. 15(1): p. 107-13.

- Gill, P.J., et al., Increase in emergency admissions to hospital for children aged under 15 in England, 1999-2010: national database analysis. Arch Dis Child, 2013.

- Elberse, K.E., et al., Changes in the composition of the pneumococcal population and in IPD incidence in The Netherlands after the implementation of the 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine. Vaccine, 2012.

- Conyn-van Spaendonck, M.A., et al., [Significant decline of the number of invasive Haemophilus influenzae infections in the first 4 years after introduction of vaccination against H. influenzae type B in children] Sterke daling van het aantal invasieve infecties door Haemophilus influenzae in de eerste 4 jaar na de introductie van de vaccinatie van kinderen tegen H. influenzae type b. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd, 2000. 144(22): p. 1069-73.

- Baraff, L.J., Management of fever without source in infants and children. Ann Emerg Med, 2000. 36(6): p. 602-14.

- Evidence based clinical guideline: outpatient evaluation and management of fever of uncertain source in children 2 to 36 moths of age; Cincinnati children's hospital medical center. 2003.

- Baraff, L.J., et al., Practice guideline for the management of infants and children 0 to 36 months of age with fever without source. Agency for Health Care Policy and Research [published erratum appears in Ann Emerg Med 1993 Sep;22(9):1490] [see comments]. Ann Emerg Med, 1993. 22: p. 1198-1210.

- Nijman, R.G., et al., Parental fever attitude and management: influence of parental ethnicity and child's age. Pediatr Emerg Care, 2010. 26(5): p. 339-42.

- Kai, J., What worries parents when their preschool children are acutely ill, and why: a qualitative study. Bmj, 1996. 313(7063): p. 983-6.

- van Ierland, Y., et al., Self-Referral and Serious Illness in Children With Fever. Pediatrics, 2012.

- Najaf-Zadeh, A., et al., Epidemiology of malpractice lawsuits in paediatrics. Acta Paediatr, 2008. 97(11): p. 1486-91.

- (2007) Feverish illness in children: a guick reference guide, London, http://guidance.nice.org.uk/CG47/guickrefguide/pdf/english. NICE Clinical Guidelines CG47.

- Berger, M.Y., et al., NHG-Standaard Kinderen met koorts. Huisarts Wet, 2008. 51(6): p. 287-96.

- Oostenbrink, R., M. Thompson, and E.W. Steyerberg, Barriers to translating diagnostic research in febrilechildren to clinical practice: a systematic review. Arch Dis Child, 2011.

- Graneto, J.W. and D.F. Soglin, Maternal screening of childhood fever by palpation. Pediatr Emerg Care, 1996. 12(3): p. 183-4.

- AGREE Next steps consortium. AGREE II. Instrument voor de beoordeling van richtlijnen. Mei 2009.

- NHS., NICE clinical guideline 47: feverish illness in children. Assesment and initial management in children younger than 5 years. 2007: London. N1247.

- Assessment and initial management of feverish illness in children younger than 5 years: summary of NICE guidance. BMJ, 2013. 346: p. f3764.

- Craig, J.V., et al., Temperature measured at the axilla compared with rectum in children and young people: systematic review. BMJ, 2000. 320(7243): p. 1174-8.

- Morley, E.J., et al., Rates of positive blood, urine, and cerebrospinal fluid cultures in children younger than 60 days during the vaccination era. Pediatr Emerg Care, 2012. 28(2): p. 125-30.

- Schuh, S., et al., Comparison of the temporal artery and rectal thermometry in children in the emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care, 2004. 20(11): p. 736-41.

- Van den Bruel, A., et al., Diagnostic value of clinical features at presentation to identify serious infection in children in developed countries: a systematic review. Lancet, 2010. 375(9717): p. 834-45.

- Thompson, M.J., et al., Deriving temperature and age appropriate heart rate centiles for children with acute infections. Arch Dis Child, 2008.

- Nijman, R.G., et al., Derivation and validation of age and temperature specific reference values and centile charts to predict lower respiratory tract infection in children with fever: prospective observational study. BMJ, 2012. 345: p. e4224.

- Elshout, G., et al., Duration of fever and serious bacterial infections in children: a systematic review Review. BMC Fam Pract, 2011. 12: p. 33.

- Curtis, S., et al., Clinical features suggestive of meningitis in children: a systematic review of prospective data Review. Pediatrics, 2010. 126(5): p. 952-60.

- Brent, A.J., et al., Evaluation of temperature-pulse centile charts in identifying serious bacterial illness: Observational cohort study. Arch Dis Child, 2011. 96(4): p. 368-373.

- Fleming, S., et al., Normal ranges of heart rate and respiratory rate in children from birth to 18 years of age: a systematic review of observational studies. Lancet, 2011. 377(9770): p. 1011-8.

- Thompson, M., et al., Deriving temperature and age appropriate heart rate centiles for children with acute infections. Arch Dis Child, 2009. 94(5): p. 361-5.

- Rudinsky, S.L., et al., Serious bacterial infections in febrile infants in the post-pneumococcal conjugate vaccine era. Acad Emerg Med, 2009. 16(7): p. 585-590.

- Garcia, S., et al., Is 15 days an appropriate cut-off age for considering serious bacterial infection in the management of febrile infants? Pediatr Infect Dis J, 2012. 31(5): p. 455-458.

- Hui C., N.G., Tsertsvadze A., Yazdi F., Tricco A., Tsouros S., Skidmore B., Daniel R., Diagnosis and management of febrile infants (0-3 months). Evidence repot/Technology assessment, 2012. Contract No. HHSA 290-2007-10059-I.

- Huppler, A.R., J.C. Eickhoff, and E.R. Wald, Performance of low-risk criteria in the evaluation of young infants with fever: Review of the literature. Pediatrics, 2010. 125(2): p. 228-33.

- Nijman, R.G., et al., Clinical prediction model to aid emergency doctors managing febrile children at risk of serious bacterial infections: diagnostic study. BMJ, 2013. BMJ 2013;346:f1706 doi: 10.1136/bmj.f1706.

- Nigrovic, L.E., R. Malley, and N. Kuppermann, Meta-analysis of bacterial meningitis score validation studies. Arch Dis Child, 2012. 97(9): p. 799-805.

- Craig, J.C., et al., The accuracy of clinical symptoms and signs for the diagnosis of serious bacterial infection in young febrile children: prospective cohort study of 15 781 febrile illnesses. BMJ, 2010. 340: p. c1594.

- Brent, A.J., et al., Risk score to stratify children with suspected serious bacterial infection: observational cohort study. Arch Dis Child, 2011. 96(4): p. 361-7.

- Thompson, M., et al., How well do vital signs identify children with serious infections in paediatric emergency care? Arch Dis Child, 2009. 94(11): p. 888-893.

- Van Den Bruel, A., et al., Diagnostic value of laboratory tests in identifying serious infections in febrile children: Systematic review. BMJ, 2011. 342(7810).

- Offringa, M., et al., Seizures and fever: can we rule out meningitis on clinical grounds alone? Clin Pediatr (Phila), 1992. 31(9): p. 514-22.

- Nijman, R.G., et al., Can urgency classification of the Manchester triage system predict serious bacterial infections in febrile children? Arch Dis Child, 2011. 96(8): p. 715-722.

- Thompson, M., et al., Systematic review and validation of prediction rules for identifying children with serious infections in emergency departments and urgent-access primary care. Health Technol Assess, 2012. 16(15): p. 1-100.

- Yo, C.H., et al., Comparison of the Test Characteristics of Procalcitonin to C-Reactive Protein and Leukocytosis for the Detection of Serious Bacterial Infections in Children Presenting With Fever Without Source: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Ann Emerg Med, 2012.

- Sanders, S., et al., Systematic review of the diagnostic accuracy of C-reactive protein to detect bacterial infection in nonhospitalized infants and children with fever Review. J Pediatr, 2008. 153(4): p. 570-4.

- Bressan, S., et al., Predicting severe bacterial infections in well-appearing febrile neonates: Laboratory markers accuracy and duration of fever. Pediatr Infect Dis J, 2010. 29(3): p. 227-232.

- Luaces-Cubells, C., et al., Procalcitonin to detect invasive bacterial infection in non-toxic-appearing infants with fever without apparent source in the emergency department. Pediatr Infect Dis J, 2012. 31(6): p. 645-7.

- Manzano, S., et al., Markers for bacterial infection in children with fever without source. Arch Dis Child, 2011. 96(5): p. 440-446.

- Pratt, A. and M.W. Attia, Duration of fever and markers of serious bacterial infection inyoung febrile children. Pediatr Int, 2007. 49(1): p. 31-35.

- Woelker, J.U., et al., Serum procalcitonin concentration in the evaluation of febrile infants 2 to 60 days of age. Pediatr Emerg Care, 2012. 28(5): p. 410-415.

- Mills, G.D., et al., Elevated procalcitonin as a diagnostic marker in meningococcal disease. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis, 2006. 25(8): p. 501-9.

- Dauber, A., et al., Procalcitonin levels in febrile infants after recent immunization. Pediatrics, 2008. 122(5): p. e1119-e1122.

- Maniaci, V., et al., Procalcitonin in young febrile infants for the detection of Serious bacterial infections. Pediatrics, 2008. 122(4): p. 701-710.

- Gomez, B., et al., Diagnostic value of procalcitonin in well-appearing young febrile infants. Pediatrics, 2012. 130(5): p. 815-22.

- Galetto-Lacour, A., et al., Validation of a laboratory risk index score for the identification of severe bacterial infection in children with fever without source. Arch Dis Child, 2010. 95(12): p. 968-973.

- Lacour, A.G., S.A. Zamora, and A. Gervaix, A score identifying serious bacterial infections in children with fever without source. Pediatr Infect Dis J, 2008. 27(7): p. 654-656.

- Cornbleet, P.J., Clinical utility of the band count. Clin Lab Med, 2002. 22(1): p. 101-36.

- Chiesa, C., et al., Procalcitonin as a marker of nosocomial infections in the neonatal intensive care unit. Intensive Care Med, 2000. 26 Suppl 2: p. S175-7.

- Bressan, S., et al., Bacteremia in feverish children presenting to the emergency department: A retrospective study and literature review. Acta Paediatr Int J Paediatr, 2012. 101(3): p. 271-7.

- Greenhow, T.L., Y.Y. Hung, and A.M. Herz, Changing epidemiology of bacteremia in infants aged 1 week to 3 months. Pediatrics, 2012. 129(3): p. e590-e6.

- Krief, W.I., et al., Influenza virus infection and the risk of serious bacterial infections in young febrile infants. Pediatrics, 2009. 124(1): p. 30-9.

- Velasco-Zuniga, R., et al., Predictive factors of low risk for bacteremia in infants with urinary tract infection. Pediatr Infect Dis J, 2012. 31(6): p. 642-5.

- Ralston, S., V. Hill, and A. Waters, Occult serious bacterial infection in infants younger than 60 to 90 days with bronchiolitis: A systematic review. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med, 2011. 165(10): p. 951-6.

- Hsiao, A.L., L. Chen, and M.D. Baker, Incidence and predictors of serious bacterial infections among 57- to 180-day-old infants. Pediatrics, 2006. 117(5): p. 1695-701.

- Hom, J. and K. Medwid, The low rate of bacterial meningitis in children, ages 6 to 18 months, with simple febrile seizures. Acad Emerg Med, 2011. 18(11): p. 1114-20.

- Kimia, A., et al., Yield of lumbar puncture among children who present with their first complex febrile seizure. Pediatrics, 2010. 126(1): p. 62-9.

- Tebruegge, M., et al., The age-related risk of co-existing meningitis in children with urinary tract infection. PLoS ONE, 2011. 6(11): p. e26576.

- Paquette, K., et al., Is a lumbar puncture necessary when evaluating febrile infants (30 to 90 days of age) with an abnormal urinalysis? Pediatr Emerg Care, 2011. 27(11): p. 1057-61.

- Shah, S.S., et al., Sterile Cerebrospinal Fluid Pleocytosis in Young Infants with Urinary Tract Infections. J Pediatr, 2008. 153(2): p. 290-2.

- Mintegi, S., et al., Well appearing young infants with fever without known source in the Emergency Department: Are lumbar punctures always necessary? Eur J Emerg Med, 2010. 17(3): p. 167-9.

- Meehan, W.P. and R.G. Bachur, Predictors of cerebrospinal fluid pleocytosis in febrile infants aged 0 to 90 days. Pediatr Emerg Care, 2008. 24(5): p. 287-93.

- Seltz, L.B., E. Cohen, and M. Weinstein, Risk of bacterial or herpes simplex virus meningitis/encephalitis in children with complex febrile seizures. Pediatr Emerg Care, 2009. 25(8): p. 494-7.

- Shah, S., et al., Detection of occult pneumonia in a pediatric emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care, 2010. 26(9): p. 615-21.

- Murphy, C.G., et al., Clinical Predictors of Occult Pneumonia in the Febrile Child. Acad Emerg Med, 2007. 14(3): p. 243-9.

- Rutman, M.S., R. Bachur, and M.B. Harper, Radiographic pneumonia in young, highly febrile children with leukocytosis before and after universal conjugate pneumococcal vaccination. Pediatr Emerg Care, 2009. 25(1): p. 1-7.

- Mintegi, S., et al., Occult pneumonia in infants with high fever without source: A prospective multicenter study. Pediatr Emerg Care, 2010. 26(7): p. 470-4.

- Bourayou, R., et al., [What is the value of the chest radiography in making the diagnosis of children pneumonia in 2011?] Quel est l'interet de la radiographie du thorax dans le diagnostic d'une pneumonie de l'enfant en 2011 ? Arch Pediatr, 2011. 18(11): p. 1251-4.

- Bramson, R.T., N.T. Griscom, and R.H. Cleveland, Interpretation of chest radiographs in infants with cough and fever. Radiology, 2005. 236(1): p. 22-9.

- Wilkins, T.R. and R.L. Wilkins, Clinical and radiographic evidence of pneumonia. Radiol Technol, 2005. 77(2): p. 106-10.

- Doan, Q., et al., Rapid viral diagnosis for acute febrile respiratory illness in children in the Emergency Department. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2012. 5: p. CD006452.

- Iyer, S.B., et al., Effect of Point-of-care Influenza Testing on Management of Febrile Children. Acad Emerg Med, 2006. 13(12): p. 1259-68.

- Benito-Fernandez, J., et al., Impact of rapid viral testing for influenza A and B viruses on management of febrile infants without signs of focal infection. Pediatr Infect Dis J, 2006. 25(12): p. 1153-7.

- Mintegi, S., et al., Rapid influenza test in young febrile infants for the identification of low-risk patients. Pediatr Infect Dis J, 2009. 28(11): p. 1026-8.

- Dewan, M., et al., Cerebrospinal fluid enterovirus testing in infants 56 days or younger. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med, 2010. 164(9): p. 824-30.

- Gomez, B., et al., Clinical and analytical characteristics and short-term evolution of enteroviral meningitis in young infants presenting with fever without source. Pediatr Emerg Care, 2012. 28(6): p. 518-23.

- Vanagt, W.Y., et al., Paediatric sepsis-like illness and human parechovirus. Arch Dis Child, 2012. 97(5): p. 482-3.

- Verboon-Maciolek, M.A., et al., Severe neonatal parechovirus infection and similarity with enterovirus infection. Pediatr Infect Dis J, 2008. 27(3): p. 241-5.

- King, R.L., et al., Routine cerebrospinal fluid enterovirus polymerase chain reaction testing reduces hospitalization and antibiotic use for infants 90 days of age or younger. Pediatrics, 2007. 120(3): p. 489-96.

- Lin, T.-Y., et al., Neonatal enterovirus infections: emphasis on risk factors of severe and fatal infections. Pediatr Infect Dis J, 2003. 22(10): p. 889-94.

- Rittichier, K.R., et al., Diagnosis and outcomes of enterovirus infections in young infants. Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal, 2005. 24(6): p. 546-550.

- Sharp, J., et al., Characteristics of Young Infants in Whom Human Parechovirus, Enterovirus or Neither Were Detected in Cerebrospinal Fluid during Sepsis Evaluations. Pediatr Infect Dis J, 2012.

- Caviness, A.C., et al., The Prevalence of Neonatal Herpes Simplex Virus Infection Compared with Serious Bacterial Illness in Hospitalized Neonates. J Pediatr, 2008. 153(2): p. 164-9.

- Caviness, A.C., G.J. Demmler, and B.J. Selwyn, Clinical and laboratory features of neonatal herpes simplex virus infection: a case-control study. Pediatr Infect Dis J, 2008. 27(5): p. 425-30.

- Kneen, R., et al., The management of infants and children treated with aciclovir for suspected viral encephalitis. Arch Dis Child, 2010. 95(2): p. 100-6.

- Long, S.S., et al., Herpes simplex virus infection in young infants during 2 decades of empiric acyclovir therapy. Pediatr Infect Dis J, 2011. 30(7): p. 556-61.

- Cohen, D.M., et al., Factors influencing the decision to test young infants for herpes simplex virus infection. Pediatr Infect Dis J, 2007. 26(12): p. 1156-8.

- Davis, K.L., et al., Why are young infants tested for herpes simplex virus? Pediatr Emerg Care, 2008. 24(10): p. 673-8.

- McGuire, J.L., et al., Herpes Simplex Testing in Neonates in the Emergency Department. Pediatr Emerg Care, 2012.

- Byington, C.L., et al., Serious bacterial infections in febrile infants 1 to 90 days old with and without viral infections. Pediatrics, 2004. 113(6): p. 1662-6.

- Rittichier, K.R., et al., Diagnosis and outcomes of enterovirus infections in young infants. Pediatr Infect Dis J, 2005. 24(6): p. 546-50.

- Stellrecht, K.A., et al., The impact of an enteroviral RT-PCR assay on the diagnosis of aseptic meningitis and patient management. J Clin Virol, 2002. 25 Suppl 1: p. S19-26.

- Schwartz, S., et al., A week-by-week analysis of the low-risk criteria for serious bacterial infection in febrile neonates. Arch Dis Child, 2009. 94(4): p. 287-92.

- Thompson, C., et al., Encephalitis in children. Arch Dis Child, 2012. 97(2): p. 150-61.

- Purssell, E., Systematic review of studies comparing combined treatment with paracetamol and ibuprofen, with either drug alone. Arch Dis Child, 2011. 96(12): p. 1175-9.

- Chiappini, E., et al., Management of fever in children: summary of the Italian Pediatric Society guidelines. Clin Ther, 2009. 31(8): p. 1826-43.

- Sullivan, J.E. and H.C. Farrar, Fever and antipyretic use in children. Pediatrics, 2011. 127(3): p. 580-7.

- Grol, R., et al., Attributes of clinical guidelines that influence use of guidelines in general practice: observational study. BMJ, 1998. 317(7162): p. 858-61.

- Nabulsi, M., Is combining or alternating antipyretic therapy more beneficial than monotherapy for febrile children? BMJ (Online), 2010. 340(7737): p. 92-3.

- Southey, E.R., K. Soares-Weiser, and J. Kleijnen, Systematic review and meta-analysis of the clinical safety and tolerability of ibuprofen compared with paracetamol in paediatric pain and fever. Curr Med Res Opin, 2009. 25(9): p. 2207-22.

- Pierce, C.A. and B. Voss, Efficacy and safety of ibuprofen and acetaminophen in children and adults: A meta-analysis and qualitative review. Ann Pharmacother, 2010. 44(3): p. 489-506.

- Goldstein, L.H., et al., Effectiveness of oral vs rectal acetaminophen: A meta-analysis. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med, 2008. 162(11): p. 1042-6.

- Almond, S., D. Mant, and M. Thompson, Diagnostic safety-netting. Br J Gen Pract, 2009. 59(568): p. 872-4; discussion 874.

- Neighbour, R., The inner consultation. 2004, Oxford: Radcliffe Publishing.

- Goldman, R.D., M. Ong, and A. Macpherson, Unscheduled return visits to the pediatric emergency department-one-year experience. Pediatr Emerg Care, 2006. 22(8): p. 545-9.

- Wahl, H., et al., Health information needs of families attending the paediatric emergency department. Arch Dis Child, 2011. 96(4): p. 335-9.

- Doan, Q., et al., Rapid viral diagnosis for acute febrile respiratory illness in children in the Emergency Department. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2009(4): p. CD006452.

- American College of Emergency Physicians Clinical Policies, C. and F. American College of Emergency Physicians Clinical Policies Subcommittee on Pediatric, Clinical policy for children younger than three years presenting to the emergency department with fever. Ann Emerg Med, 2003. 42(4): p. 530-45.

- American College of Radiology. ACR Appropriateness Criteria. Fever without source - Child. . 1999 (last update: 2011).

Evidence tabellen

Aanvullende observationele diagnostische studies (publicatiedatum na verschijnen van systematische reviews): uitgangsvragen

|

|

Reference |

Level |

Study type |

patients, setting |

Prevalentce |

indextest |

referencetest |

Results |

Other remarks |

|

[93] |

Caviness, A.C., et al., The Prevalence of Neonatal Herpes Simplex Virus Infection Compared with Serious Bacterial Illness in Hospitalized Neonates. J Pediatr, 2008. 153(2): p. 164-9 |

B |

Retrospective study |

Setting: hospitalized children admitted from ED, US, 2001 – 2005

Patients: hospitalized children aged ≤28 days who were evaluated at the ED with any chief complaint |

|

|

HSV infection: positive tests result in both the hospital database record, and the diagnostic virology database: HSV DNA detection by PCR, HSV antigen detection by direct fluorescence assay, and viral culture on any tissue or body fluid obtained before or after death.

Non HSV viral infections: positive viral test results other than HSV from any source (cultures, PCR, rapid antigen detection by immunochromatographic or OF assays)

Bacterial meningitis: positive CSF culture; bacteraemia: positive blood culture; UTI positive urine culture.

Pleiocytosis was defined as ≥20×106/L WBCs and more than 1 WBC per 500 ×106/L RBCs

|

5817 children ≤28 days were admitted from the ED, median age 12 days (IQR 8 – 22 days)

8.6% of 5817 had viral infections 995% CI 7.9 – 9.3%), of whom 0.2% had HSV infection and 8.4% had non-HSV infection (viral tests were performed in 28% of the children)

Prevalence HSV infection was highest in 8-14 days old children: 0.6%

HSV infection: n=10 Among hypothermic neonates (n=187): 1.1% vs 0.3% (n=3) among febrile neonates (NS)

Incidence bacterial meningitis was 0.4% Among children with pleiocytosis and polymorphonuclear cell predominance: bacterial meningitis 14.9% vs HSV infection 0.0%.

960 neonates had fever: 17.2% had viral infection (95% CI 14.9 – 19.7%), 14.2% had SBI (95% CI 12.0 – 16.5%) Of neonates with fever 160 had no CSF available: none had HSV, 19 had non-HSV viral infections, 14 had UTI, none had bacteraemia 204/960 had fever and pleiocytosis: 1.0% had HSV infection (95% CI 0.1 – 3.5%, n=2) and 5.4% had bacterial meningitis (2.7 – 9.4%). 124/960 had fever and mononuclear CSF pleiocytosis: 1.6% had HSV infection, 0.8% had bacterial meningitis.

In total study population: Viral infection: 499 pathogens identified, 13% enteroviruses, 2% HSV (n=10, 7 without fever), 47% RSV, 16% rhinoviruses. SBI: n=269, bacterial meningitis 21 (10 without fever), bacteraemia 71, UTI 177 20 children both UTI and bacteraemia; 11 had meningitis and bacteraemia.

Of HSV infections: 3 disseminated disease, 3 CNS disease, 4 SEM disease. 3 children with HSV infections had fever: 1 was well appearing, one was lethargic, one had vesicals on eye lid. 5 presented with rash; 6 presented with vesicular lesions (scalp, eyelid, generalized, genitourinary area) |

|

|

[94] |

Caviness, A.C., G.J. Demmler, and B.J. Selwyn, Clinical and laboratory features of neonatal herpes simplex virus infection: a case-control study. Pediatr Infect Dis J, 2008. 27(5): p. 425-30 |

B |

Historic case control study |

Setting: tertiary hospital, US, 1991 – 2005

Patients; neonates ≤28 days old, admitted to the hospital from the ED, or transferred from another hospital, who underwent evaluation for HSV infection

Controls were 160 neonates 1:4 matched on time of presentation (within 2 weeks of case) with 2 controls before and 2 controls after; controls had to be admitted for non surgical reasons, had to undergo HSV testing, and were not diagnosed with HSV infection

Controls could not be neonates who were not admitted from the ED, were HSV positive at a different laboratory than used for study purposes and not confirmed by the for this study used virologic laboratory database, or had evidence of intrauterine HSV infection, defined as scarred skin lesions, chorioretinitis, retinal dysplasia, hydroencephaly, microencephaly, and/or intracranial calcification.

|

|

|

HSV infection: HSV DNA PCR, HSV antigen detection by direct IF assay, viral culture, performed on any tissue pre- or post-mortem, if infection was confirmed by virologic test result and in patient chart.

Disseminated disease: hepatitis, pneumonitis, disseminated intravascular coagulopathy, and/or positive liver/lung/blood HSV PCR/viral culture CNS infection: hypotonia, seizures, abnormal brain imaging, abnormal EEG, CSF pleiocytosis, CSF proteinosis, findings on autopsy consistent with HSV infection of the brain, and/or positive CSF HSV PCR/viral culture

SEM: HSV by IF assay/PCR/viral culture in lesions of skin, eye, mouth, and no evidence of disseminated HSV disease and/or CNS HSV infection

Leukocytosis: preterm neonates >50×106/L WBCand term neonates>20×106/L WBC in liquor |

40 neonates had HSV infection: HSV type 1 in 27.5% and HSV type 2 in 72.5%

Disseminated disease: 37.5%, CNS disease 37.5%, SEM disease 25%

All children with CNS disease received acyclovir, but not all children with disseminated disease received acyclovir therapy (87%, 2 never, 4 at admission, 9 later during hospitalisation). Disseminated diseased had a 80% mortality, all children with CNS disease and SEM disease could finally be discharged from hospital.

HSV infection was associated with maternal fever: OR 5.8, 95% CI 2.3 – 14.5., Especially in children with disseminated disease (60% vs 7% CNS disease vs 20% SEM disease)

Associated with disseminated disease only: Respiratory distress (73%), hypothermia (27%), jaundice (23%), thrombocytopenia (53%), elevated hepatic enzymes (AST 73%, ALT 47%)

Associated with CNS disease only: Seizure (36%)

Among children with vesicular rash and HSV infection: (95% CI are wide and given in paper) Postnatal HSV contact, sens 21%, spec 97% CSF pleiocytosis: sens 50%, spec 76% Postnatal HSV contact and CSF pleiocytosis: sens 6%, spec 98%

Among children without vesicular rash and HSV infection: Maternal fever: sens 43%, spec 95% Mechanical ventilation for respiratory distress: sens 48%, spec 98% CSF pleiocytosis: sens 64%, spec 83% Maternal fever and respiratory distress: sens 29%, spec 100% Maternal fever and CSF pleiocytosis: sens 9%, spec 100%

Among children without vesicular rash and HSV infection: (model also adjusted for prematurity, delivery type, postgestational neonatal age) Maternal fever OR 28.9 (95% CI 1.3 – 631.1) Severe respiratory distress OR 2.7 (95% CI 1.0 – 641.8) CSF pleicytosis OR 19.9 (95% CI 1.9 – 208.6) 2nd Model HSV contact postnatal: OR 9.0 (95% CI 1.3 – 60.4) CSF pleiocytosis: OR 3.4 (95% CI 1.0 – 11.0) |

|

|

[95] |

Kneen, R., et al., The management of infants and children treated with aciclovir for suspected viral encephalitis. Arch Dis Child, 2010. 95(2): p. 100-6. |

B |

|

Setting: admitted children, pediatric ward, UK, 6 month period in 2005

Patients: previously healthy infants and children, mean age 2 years old (range 2 days to 14 years), who received acyclovir for suspected encephalitis, defined as a child with fever or history of febrile illness and a reduced level of consciousness, irritability, or a change in personality or behaviour or focal neurologic signs.. Children who received acyclovir but had localised skin infection or cutaneous varicella zoster infection were excluded. |

|

|

Proven viral encephalitis: viral cause identified

Clinically diagnosed encephalitis: clinical picture, CSF findings and other investigations consistent with viral encephalitis, but no virus was identified. |

2 out 52 children had proven HSV encephalitis, 2 had clinical encephalitis with no causative agent identified.

40 children had lumbar punction: 13 cases provide incomplete data, 19 cases had liquor punction at day of admission; CSF PCR HSV testing was performed in 27 (53%) children, of which 1 was positive.

Initial dose of acyclovir was incorrect in 38 children; median length of acyclovir treatment was 4 days (range 1 to 21 days), with 6 children getting treatment for 10 days or longer

In 14 children there appeared to be no valid indication to start acyclovir treatment according to NICE guidelines: new onset afebrile seizure (n=4), suspected sepsis/meningitis in child < 3 months (n=4), afebrile status epilepticus in child with neurologic comorbidity (n=2), acute cerebellitis, malfunction VP drain, deliberate drug overdose, afebrile seizure after head injury (all n=1)

In 3 children (8%) CSF bacterial culture was positive; in another 4 children bacterial meningitis was diagnosed on positive blood culture (no CSF available) |

|

|

[96] |

Long, S.S., et al., Herpes simplex virus infection in young infants during 2 decades of empiric acyclovir therapy. Pediatr Infect Dis J, 2011. 30(7): p. 556-61. |

B |

Retrospective case study |

Setting: pediatric department,admiited children, US, 1988 – 2009

Patients: children <60 days, that were admitted from the ED, or were sent from the office of primary care provider, or were transferred from another hospital. Children who were transfeered from birth hospital, or after diagnosis of HSV infection was made elsewhere, or onset of HSV disease was at the NICU, were excluded. Cases were identified from virology and serology database (PCR, direct fluorescent antibody test, virall culture), and from discharge DSM diagnoses,. |

|

|

Confirmed HSV infection: compatible clinical course and clinical specimen positive for HSV by OCR assay or culture.

Probable HSV infections: clinical course suggestive of HSV infection (healing vesicular lesions, culture perfomed of lesions after onset acyclovir, or aseptic meningitis without CSF PCR testing) plus some combination of HSV IgG and IgM antibody (positive in CSF or rising during hospitalisation), specific abnormalities on EEG, increased gray matter signal on MRI (t2 or flair or diffusion weighted) in focal/multifocal or nonfocal patterns.

Presenting catergories: Mucocutaneous HSV: presence of vesicles on skin, ulcers in mouth, conjunctivitis/cloudy cornea Neurologic HSV: history of or witnessed seizure in ED, inconsolable irritability, poor tone Non-specific HSV: Fever, hypothermia, poor feeding, decreased activity, apnea in absence of mucocutaneous or neurologic sympotoms or signs.

Final HSV categorisation: Neurologic disease: positive HSV PCR in CSF, or CSF pleiocytosis with HSV infection diagnosed otherwise confirmed or probable.

SEM disease: mucocutaneous lesions at presentation, in absence of criteria for CNS or disseminated disease

Pleiocytosis: ≥2×106/L 0 WBCinfants ≤28 days, or ≥9 ×106/L WBC for children ≥29 days in CSF

|

32 infants had perinatally acquired HSV infection. In 17 children typing was pssible: 15 children (88%) had HSV type 2. Average of 1.5 cases/year.

All 32 received acyclovir at admission.

50% had non specific complaints, 75% had fever. 31% presented with mucocutaneous complaints (n=10), seizures 19% (in all 6 neurologic HSV cases); hypothermia 13% (n=4). 22/29 children appeared nontoxic and not ill appearing (76%)

CNS disease: 75% (n=24), of whom 40% (4/10) of children who presented with mucocutaneous lesions, 83% of children who presented with seizures, and 94% of whom presented with nonspecific complaints (15/16) SEM: 19% (n=6), disseminated: 9% (n=3)

90% of children were aged ≤21 days, and 94% of those with non specific complaints.

Laboratory and CSF findings were not associated with HSV infection.

Of all patients treated empirically with acyclovir 1.3% had HSV infection. |

|

|

[99] |

McGuire, J.L., et al., Herpes Simplex Testing in Neonates in the Emergency Department. Pediatr Emerg Care, 2012. |

B |

Retrospective Nested case control study |

Setting: emergency department, US, 2005 – 2007

Patients: infants aged 0 – 28 days (median age: 14 days, IQR 7 – 22 days)who had lumbar punction performed at the ED. Subjects were identified by the ED billing records and clinical virology records database. |

|

|

CSF pleiocytosis: >22 WBC/mm3 ; traumatic LP when >500×106/L RBC

serious bacterial infections: UTI (culture by suprapubic punction or catheterisation, in association with positive urinalysis), bacteraemia (positive bacterial culture), bacterial meningitis (CSF bacterial culture, or CSF pleiocytosis and positive Gram stain if patients had received antibiotics prior to lumbar punction) |

CSF HSV PCR testing was performed in 266 (47%) of 570 neonates; no children with HSV infection were diagnosed in children who did not undergo lumbar punction.

Prevalence of HSV CNS infection: 0.5% (95% CI 0 – 1.1,n=3) Prevalence of bacterial meningitis: 1.6% (95% CI 0.6 – 2.6%) Prevalence of all SBI 8.4% (95% CI 6.1 – 10.7); UTI 5.1 (95% CI 3.3 – 6.9); bacteraemia 18% (95% CI 0.8 – 3.2%)

3 HSV infections in children were in children aged 6 to 18 days old; one was hypothermic without CSF pleiocytosis, 2 were normothermic with CSF pleiocytosis.

Performance of HSV testing was not associated with known risk factors of HSV infection (ie. CSF mononuclear pleiocytosis, or method of delivery)

HSV PCR testing was associated with: transport from outside hospital: OR 3.91 (95% CI 3.09 – 4.95), concurrent enterovirus testing OR 7.27 (95% CI 5.30 – 9.98), hypothermia OR 1.46 (95% CI 1.17 – 1.83), seizures OR 13.75 (95% CI 5.60 – 33.76), tachypnea OR 3.69 (95% 2.32 – 5.80), hypotension OR 6.89 (95% CI 5.68 – 8.37), and vesicular rash OR 18.70 (95% CI 1.28 – 273.68).

|

|

Verantwoording

Autorisatiedatum en geldigheid

Laatst beoordeeld : 01-12-2013

Laatst geautoriseerd : 01-12-2013

Geplande herbeoordeling : 01-01-2018

De richtlijn dient elke vijf jaar gereviseerd te worden. De geldigheid van de richtlijn komt eerder te vervallen als nieuwe ontwikkelingen aanleiding zijn een herzieningstraject te starten.

Algemene gegevens

Deze richtlijn is tot stand gekomen door financiering van Stichting Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS).

Juridische betekenis van richtlijnen

Richtlijnen zijn geen wettelijke voorschriften, maar ‘systematisch ontwikkelde op evidence’ gebaseerde aanbevelingen bedoeld om hulpverleners en patiënten te ondersteunen in het besluitvormingsproces voor diagnostiek en behandeling. Aangezien deze aanbevelingen hoofdzakelijk gebaseerd zijn op de ‘gemiddelde patiënt’, kunnen zorgverleners op basis van hun professionele autonomie zonodig afwijken van de richtlijn. De aanbevelingen die in de huidige richtlijn staan vermeld, zijn te vertalen naar lokale protocollen die zijn toegespitst op de plaatselijke situatie. Afwijken van richtlijnen is, als de situatie van de patiënt dat vereist, soms zelfs noodzakelijk. Wanneer van een richtlijn wordt afgeweken, dient dit beargumenteerd en gedocumenteerd te worden.

Doel en doelgroep

Aanleiding

Koorts komt frequent voor bij kinderen. Elk gezond kind maakt gemiddeld acht infecties met koorts door in de eerste achttien levensmaanden [1]. Voor 20-40% van deze kinderen wordt een arts geconsulteerd in verband met koorts, met de hoogste prevalentie in de leeftijd van 6 tot 18 maanden.

Jaarlijks worden ongeveer 300.000 kinderen gezien op de SEH van Nederlandse ziekenhuizen. Ongeveer de helft van de kinderen die de kindergeneeskundige SEH bezoekt, komt vanwege koorts [2]. Het merendeel van deze kinderen heeft een virale infectie die geen verdere behandeling behoeft. Een ernstige (bacteriële) infectie is aanwezig bij 10-15% van de kinderen met koorts en kan bij te late onderkenning een gecompliceerd of eventueel fataal beloop kennen [3]. Het grote dilemma is het vroegtijdig onderscheiden van kinderen met een ernstige infectie (meningitis, sepsis, urineweginfectie, pneumonie) van de overgrote meerderheid van kinderen met een zelflimiterende aandoening. Als onderdeel van de diagnostische aanpak vindt bij ongeveer de helft van kinderen met koorts die zich op de SEH presenteren, aanvullende diagnostiek (bloedonderzoek, thoraxfoto, urineonderzoek) plaats, bij een derde een observationele opname, die bij een groot deel (achteraf) onnodig blijkt [3]. Vooral de (kortdurende) observationele opname neemt toe [4]. Sinds de introductie van vaccinatiestrategieën (Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib)-vaccinatie in 1993, pneumokokkenvaccinatie in 2006) is het spectrum van diagnoses veranderd [5, 6], en de kans op zeer ernstige diagnoses sterk verlaagd [7]. Bij het verschuiven van het spectrum van bacteriële verwekkers door vaccinatie is er ook een verandering in de indicatie voor diagnostiek en behandeling. Eerdere richtlijnen beoogden vooral het identificeren van het kind met koorts zonder focus [8, 9], met een risico op occulte bacteriëmie, welke diagnose vooral relevant is bij pneumokokkeninfecties. Verder zijn bepaalde typische klinische kenmerken (zoals de hoogte van de koorts bij Hib-infectie) tegenwoordig minder relevant [21].

Een complicerende factor bij de beoordeling van het kind met koorts is dat het veelal jonge kinderen betreft. Het klinische beeld bij jonge kinderen met koorts kan dramatisch verslechteren in korte tijd. Daarentegen kan een kind met een virale infectie aanvankelijk ziek lijken, maar snel herstellen. Daar ernstige ziekten met koorts bij kinderen minder frequent voorkomen bestaat enerzijds het gevaar van overdiagnostiek en -behandeling en anderzijds van het (te) laat onderkennen van het ernstig zieke kind. Per jaar overlijden 23 kinderen in Nederland aan een infectieziekte die (bij tijdige onderkenning) goed te behandelen zou zijn geweest (RIVM, 2011).

De zorg bij ouders over een ernstige oorzaak bij een kind met koorts is groot [10]. In een studie naar de reactie van ouders wanneer hun kind acuut ziek werd, bleek dat ouders hoofdzakelijk bezorgd zijn over koorts, hoesten en de kans op meningitis [11]. Een groot deel van de ouders bezoekt de SEH zonder verwijzing via de huisarts. Bij kinderen met een ernstige infectie hebben ouders vaak hun bezorgdheid terecht geuit [12]. Bij te late onderkenning van ernstige infecties blijkt vaak eerder wel adequaat hulp te zijn gezocht door ouders [13], maar is instructie voor herbeoordeling bij verslechtering onvolledig gebleken. De rol van de ouders en de aard van instructie ten aanzien van follow-up is in de huidige richtlijnen onvoldoende belicht [14, 15].

Doelstelling

Evidence-based onderbouwing van de beoordeling en de eerste behandeling van het kind met koorts in de tweedelijnszorg teneinde enerzijds ernstige infecties vroegtijdig te

herkennen en anderzijds overdiagnostiek te beperken.

Toelichting

In deze richtlijn verstaan we onder ‘ernstige infecties’ die infecties die interventie behoeven, zoals ernstige bacteriële infecties (meningitis, sepsis, pneumonie, urineweginfectie, septische arthritis, osteomyelitis) en encefalitis (HSV). Bij de samenvatting van de aanbevelingen dient te worden opgemerkt dat de brede differentiaal diagnose bij het kind met koorts raakvlakken vertoont met specifieke ziektebeelden, welke in deze algemene richtlijn voor het kind met koorts niet volledig zijn uitgediept.

Doelgroep

Deze richtlijn is bedoeld voor alle zorgverleners in de tweede lijn, betrokken bij de opvang van het kind van 0 - 16 jaar met koorts, verdacht van een infectie. Daarnaast is de richtlijn bedoeld voor ouders van kinderen met koorts. De richtlijn geldt niet voor de neonatale sepsis en de gehospitaliseerde neonaat. De richtlijn sluit aan bij de NHG-standaard [15]. Koorts is een symptoom van infectie. Het is van belang ernstige infecties vroegtijdig te herkennen, zodat adequaat gehandeld kan worden. Van belang is echter ook dat er geen overdiagnostiek plaatsvindt bij kinderen zonder ernstige infectie.

Vanuit dit perspectief is het doel van deze richtlijn:

Evidence-based onderbouwing van de beoordeling, diagnostisch beleid en eerste handelingen bij het kind met koorts in de tweedelijnszorg, teneinde ernstige infecties vroegtijdig te herkennen en overdiagnostiek te beperken.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Projectteam

Mw. dr. R. Oostenbrink (projectleider), kinderarts Erasmus MC-Sophia, Rotterdam

Dhr. drs. R. G. Nijman (arts), Erasmus MC-Sophia, Rotterdam

Mw. drs. M.K. Tuut (epidemioloog, projectadviseur)

Mw. dr. L.M.A.J. Venmans (epidemioloog)

Werkgroepleden

Dhr. dr. G.J. Driessen, SPII, kinderarts-infectioloog/immunoloog, Erasmus MC-Sophia, Rotterdam

Dhr. dr. R.H. Dijkstra, NHG

Mw. A. Horikx, KNMP (meelezer)

Mw. Dr. W.M. Klein, NVvR, radioloog UMCN St Radboud Nijmegen (meelezer)

Dhr. dr. R. Kornelisse, sectie Neonatologie NVK, neonatoloog, Erasmus MC-Sophia, Rotterdam

Mw. dr. T. Krediet, sectie Neonatologie NVK (meelezer)

Mw. drs. N. Oteman, NHG

Mw. H. Rippen, Stichting Kind en Ziekenhuis

Mw. dr. Y.B. de Rijke, NVKC, klinisch chemicus Erasmus MC-Sophia, Rotterdam

Mw. M. Steijn, V&VN, verpleegkundig specialist neonatologie IJsselland ziekenhuis, Capelle a/d IJssel (meelezer)

Drs. L.P. Tan, NVZA, Ziekenhuisapotheker Groene Hart Ziekenhuis, Gouda(meelezer)

Mw. dr. M. Verboon, sectie Neonatologie NVK, neonatoloog UMC Utrecht

Mw. dr. E. de Vries, SPII, kinderarts-infectioloog/immunoloog, Jeroen Bosch Ziekenhuis, ’s-Hertogenbosch

Mw. drs. A. van Wermeskerken, SAP, kinderarts Flevoziekenhuis, Almere

Mw. dr. M. van Westreenen, NVMM, microbioloog Erasmus MC, Rotterdam

Mw. drs. M.P.W. Zaanen-Bink, NVSHA, SEH-arts KNMG, St.Antonius Ziekenhuis, Nieuwegein

De werkgroep is multidisciplinair samengesteld: beoefenaars uit verschillende disciplines betrokken bij de diagnostiek en behandeling van het kind met koorts en verdacht van infectie in de tweede en derde lijn zijn verzocht te participeren. Als aanvulling hierop werden werkgroepleden gevraagd vanuit de wetenschappelijke vereniging van huisartsgeneeskunde en vanuit de patiëntengroep. Leden van de werkgroep werden namens de betreffende (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen verzocht zitting te nemen in de werkgroep op grond van hun persoonlijke expertise en/of affiniteit met het onderwerp. Het projectteam was verantwoordelijk voor het formuleren van de uitgangsvragen, verrichten van de literatuurzoekstrategie, het uitwerken van de uitgangsvragen en het formuleren van de richtlijntekst. De werkgroepleden beoordeelden en adviseerden in deze stappen.

Belangenverklaringen

De werkgroepleden hebben een belangenverklaring ingevuld waarin ze hun banden met de farmaceutische industrie hebben aangegeven. De verklaringen liggen ter inzage bij de NVK.

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Het perspectief van de ouders van patiënten en patiënten is meegenomen door vertegenwoordiging van de directrice van Stichting Kind en Ziekenhuis in de werkgroep.

Methode ontwikkeling

Evidence based

Implementatie

In de verschillende fasen van de ontwikkeling van het concept van de richtlijn is zo veel mogelijk rekening gehouden met de implementatie van de richtlijn en de daadwerkelijke uitvoerbaarheid van de aanbevelingen. De definitieve richtlijn is onder de verenigingen verspreid en via de website van de NVK (www.nvk.nl) elektronisch beschikbaar gesteld. Op wetenschappelijke bijeenkomsten van de betrokken wetenschappelijke verenigingen zijn de aanbevelingen van de richtlijn gepresenteerd. Verder kan de lekensamenvatting uit deze richtlijn dienen als patiëntenvoorlichtingsmateriaal.

Om de implementatie en evaluatie van deze richtlijn te stimuleren, zijn interne indicatoren ontwikkeld aan de hand waarvan de implementatie steekproefsgewijs kan worden gemeten. Indicatoren geven in het algemeen de zorgverleners de mogelijkheid te evalueren of zij de gewenste zorg leveren. Zij kunnen daarmee ook onderwerpen voor verbeteringen van de zorgverlening identificeren. De interne indicatoren die bij de onderhavige richtlijn zijn ontwikkeld, worden behandeld in hoofdstuk 5 van deze richtlijn.

Werkwijze

De ontwikkeling van de richtlijn Koorts bij kinderen is gefinancierd door Stichting Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS). Van januari 2012 tot juli 2013 is aan de ontwikkeling van de richtlijn gewerkt door leden van de (kern)werkgroep.

Allereerst werd een knelpuntenanalyse onder de werkgroepleden uitgevoerd om de huidige werkwijze ten aanzien van de diagnostiek en behandeling van kinderen met koorts in Nederland in kaart te brengen. Tevens werd de leden gevraagd een prioritering aan te brengen in de gemelde knelpunten. De knelpunten werden gecategoriseerd in verschillende groepen: diagnostische waarde van symptomen, diagnostische waarde van laboratoriumparameters, indicatie voor aanvullend onderzoek, indicatie voor virale diagnostiek, indicatie voor empirische behandeling, vragen t.a.v. antipyretica en vragen t.a.v. follow-up. De knelpunten werden vertaald in uitgangsvragen. Vervolgens werd volgens de methode van Evidence-Based Richtlijn Ontwikkeling (EBRO) per vraag een uitgebreid literatuuronderzoek verricht. In eerste instantie werd gezocht naar evidence-based richtlijnen. Hierbij werd gebruik gemaakt van de volgende databases: GIN, SUMSEARCH, Clinical evidence van BMJ, SIGN en de TRIP DATABASE, en www.guidelines.gov (National Guidelines Clearinghouse, USA). De gevonden richtlijnen werden op kwaliteit beoordeeld door de kernwerkgroepleden met behulp van het AGREE II-instrument [18]. Wanneer er een valide richtlijn werd gevonden, werd de evidence uit de richtlijn gebruikt om de vragen te beantwoorden. De met AGREE II vastgestelde domeinscores werden gebruikt als houvast voor de beoordeling van de richtlijn. Wanneer er geen geschikte richtlijn werd gevonden, werd gezocht naar systematische literatuuroverzichten in Medline en Embase. Er werd gebruik gemaakt van zoektermen zoals beschreven in. Aanvullend werden originele studies gezocht vanaf het moment dat de zoekactie in de review eindigde. De geselecteerde literatuur werd beoordeeld op kwaliteit en inhoud met behulp van formulieren van het Cochrane Center (https://netherlands.cochrane.org/beoordelingsformulieren-en-andere-downloads). Aan elk geselecteerd artikel werd een mate van bewijskracht toegekend zoals vermeld in Appendix C. Indeling van onderzoeksresultaten naar mate van bewijskracht. De volledige (evidence-based) uitwerking van de uitgangsvragen met de daarbij geformuleerde conclusies werd geheel voorbereid door het projectteam. De gehele werkgroep formuleerde de definitieve aanbevelingen. Naast de evidence werden hierbij ‘overige overwegingen’ uit de praktijk, die expliciet genoemd werden, meegenomen. De werkgroep kwam in totaal vier keer bijeen: één keer om uitgangsvragen te formuleren, twee keer om de resultaten van een systematische literatuursearch en overige overwegingen te bespreken en één keer om de definitieve aanbevelingen te formuleren. Voor enkele uitgangsvragen, namelijk uitgangsvragen 1, 2, en 16 - 19, was het niet mogelijk om door middel van literatuuronderzoek volgens de EBRO-methode op systematische wijze de antwoorden te zoeken. De formulering van aanbevelingen ter beantwoording van deze vragen is tot standgekomen op basis van consensus binnen de werkgroep.

Indeling van onderzoeksresultaten naar mate van bewijskracht

|

. |

Interventie |

Diagnostisch accuratesse onderzoek |

Schade of bijwerkingen, etiologie, prognose* |

|

A1 |

Systematische review van tenminste twee onafhankelijk van elkaar uitgevoerde onderzoeken van A2-niveau |

||

|

A2 |

Gerandomiseerd dubbelblind vergelijkend klinisch onderzoek van goede kwaliteit van voldoende omvang |

Onderzoek ten opzichte van een referentietest (een ‘gouden standaard’) met tevoren gedefinieerde afkapwaarden en onafhankelijke beoordeling van de resultaten van test en gouden standaard, betreffende een voldoende grote serie van opeenvolgende patiënten die allen de index- en referentietest hebben gehad |

Prospectief cohortonderzoek van voldoende omvang en follow-up, waarbij adequaat gecontroleerd is voor ‘confounding’ en selectieve follow-up voldoende is uitgesloten. |

|

B |

Vergelijkend onderzoek, maar niet met alle kenmerken als genoemd onder A2 (hieronder valt ook patiënt-controleonderzoek, cohortonderzoek) |

Onderzoek ten opzichte van een referentietest, maar niet met alle kenmerken die onder A2 zijn genoemd |

Prospectief cohortonderzoek, maar niet met alle kenmerken als genoemd onder A2 of retrospectief cohortonderzoek of patiëntcontroleonderzoek |

|

C |

Niet-vergelijkend onderzoek |

||

|

D |

Mening van deskundigen |

||

* Deze classificatie is alleen van toepassing in situaties waarin om ethische of andere redenen gecontroleerde trials niet mogelijk zijn. Zijn die wel mogelijk dan geldt de classificatie voor interventies.

Niveau van bewijskracht van de conclusie op basis van het aan de conclusie ten grondslag liggende bewijs

|

|

Conclusie gebaseerd op |

|

1 |

Onderzoek van niveau A1 of tenminste twee onafhankelijk van elkaar uitgevoerde onderzoeken van niveau A2 |

|

2 |

1 onderzoek van niveau A2 of tenminste twee onafhankelijk van elkaar uitgevoerde onderzoeken van niveau B |

|

3 |

1 onderzoek van niveau B of C |

|

4 |

Mening van deskundigen |

Zoekverantwoording

Zoekacties zijn opvraagbaar. Neem hiervoor contact op met de Richtlijnendatabase.