Initiële e-FAST

Uitgangsvraag

Moet e-FAST of X-thorax gebruikt worden in de initiële radiodiagnostiek van volwassen patiënten met potentieel meervoudig letsel?

Aanbeveling

Het traumateam dient zich te realiseren dat:

- Een e-FAST slechts ten dele dezelfde parameters meet als de X-thorax, en dat e-FAST dus geen X-thorax kan vervangen.

- De "operator dependence" m.b.t. documentatie en opslag een (potentieel) knelpunt is in het routinematig gebruik van e-FAST voor thoraxonderzoek.

Binnen deze beperkingen van de e-FAST gelden de aanbevelingen:

- Maak een e-FAST voor de detectie van een pneumothorax.

- Overweeg een e-FAST voor de detectie van een hematothorax of longcontusie.

Overwegingen

De werkgroep heeft naast de voor- en nadelen ten aanzien van klinisch handelen en diagnostische accuratesse nog enkele velden van belang geïdentificeerd welke van invloed zijn op de vraag óf en wanneer echo-onderzoek van de thorax een alternatief zijn voor een conventionele X-thorax.

Inherent aan de techniek van het onderzoek hebben X-thorax en echo hun eigen voor en nadelen. Een X-thorax ziet geen diepte, en een e-FAST kan zeer beperkt tot niets zeggen over intrapulmonale en medinastinale aandoeningen. Daarmee zijn de technieken slecht vergelijkbaar Voor de echo geldt daarbij expliciet dat er alleen vanuit vensters naar een orgaan wordt gekeken. Om een indruk te krijgen van de grootte van een afwijking dient op meerdere plaatsen gemeten te worden. Hoewel soms zichtbaar, wordt ook niet gericht naar diafragma- afwijkingen of ribfracturen gekeken met een e-FAST. Een e-FAST kan met al deze beperkingen niet de vervanging zijn van een X-thorax, die weer andere beperkingen heeft; het meet maar ten dele dezelfde parameters.

Wel kan e-FAST een screenend, aanvullend, trendvolgend of surrogaat instrument zijn. Surrogaat bij deelvragen zoals: is er een pneumothorax , vooral als de X-thorax (nog) niet gemaakt zal worden.

De werkgroep ziet een toegenomen beschikbaarheid van echo-apparaten voor vele hulpverleners, ook op de SEH; waaronder persoonlijke handheld echomachines. Steeds meer zorgprofessionals zijn bekwaam in het hanteren van deze echo-apparatuur. Een belangrijke beperking hierbij is echter dat gemaakte echo’s bijna altijd alleen door de maker geïnterpreteerd worden, en dat geen door anderen betrouwbaar (her)beoordeelbaar beeld vastgelegd wordt. Daarbij is het niet aan de werkgroep te oordelen hoe een onderzoeker opgeleid moet zijn alvorens de uitspraak op basis van de echobeelden of X-thorax als valide kan worden beschouwd. De visie van de werkgroep is dat per ziekenhuis er afspraken gemaakt moeten worden de definitie van de e-FAST en over de opleiding van onderzoekers die echografie uitvoeren. De werkgroep stelt voor dat een volledig e-FAST onderzoek zou kunnen bestaan uit de volgende onderdelen:

- Beoordelen intra-abdominaal vrij vocht;

- Beoordeling pericardvocht;

- Beoordelen van de aanwezigheid/afwezigheid van een pneumothorax;

- Beoordelen van de aanwezigheid / afwezigheid pleuravocht

- Beoordelen watercontent van de long ter onderscheid van normale long, of een verhoogde watercontent zoals bij o.m. longcontusie, atelectase, overvulling of infiltraat

Ten aanzien van de sensitiviteit en AUC van zowel de X-thorax als e-FAST dient men zich te realiseren dat deze op basis van studies is, waarbij de incidentie van pneumothorax , hematothorax en longcontusie hoger is dan de geschatte incidentie in de Nederlandse populatie. Dit heeft consequenties voor ondermeer het percentage fout-positieven en fout-negatieven, maar zegt in essentie niets over de diagnostische accuratesse.

Informatie uit de NICE guideline Major Trauma

De NICE guideline Major Trauma (2016) vond, evenals de werkgroep, geen RCT’s, SR’s van RCT’s of quasi-RCT’s waarmee kon worden vastgesteld wat de klinisch meest effectieve en kosteneffectieve initiële ziekenhuisstrategieën zijn om levensbedreigend letsel te beoordelen bij patiënten met ernstig trauma. Wel werden studies gevonden, zowel prospectief als retrospectief, waarin men de diagnostische accuratesse van initiële radiodiagnostische beeldvorming in het ziekenhuis onderzocht (Tabel 2).

Tabel 2. Diagnostische accuratesse van initiële radiodiagnostische beeldvorming in het ziekenhuis ten aanzien van levensbedreigend letsel (NICE guideline Major trauma, 2016).

|

Trauma1 |

Radiodiagnostische beeldvorming| Referentie standaard: |

Diagnostische accuratesse (95% BI) |

Aantal studies, aantal patiënten |

GRADE |

|

Tension pneumothorax |

X-ray Ref: CT |

Sens: 0,24 (0,14-0,35) Spec: 1,00 (0,99-1,00) |

1, 345 |

Zeer laag |

|

|

e-FAST Ref: CT |

Sens: 0,40 (0,28-0.52 Spec: 0,99 (0,97-1,00) |

1, 345 |

Zeer laag |

|

Pneumothorax |

Ultrasound Ref: CT |

Sens: 0,845 (0,678-0,953) Spec: 0,986 (0,974-0,994) |

10, 1921 |

Zeer laag |

|

|

X-ray Ref: CT |

Sens: 0,544 (0,299-0,775) Spec: 0,991 (0,979-0,997) |

10, 19832 |

Zeer laag |

|

Hematothorax |

Ultrasound Ref: CT |

Sens: 0,37 (0,21-0,55) Spec: 0.96 (0,92-0,98) |

1, 119 |

Redelijk |

|

|

Ultrasound Ref: CT |

Sens (median): 0,61 Spec: 1 |

4, 903 |

Zeer laag |

|

Longcontusie |

Ultrasound Ref: CT |

Sens (median): 0,89 Spec (median): 0,89 |

3, 222 |

Laag |

|

|

X-ray Ref: CT |

Sens (median): 0,42 Spec (median): 0,89 |

4, 507 |

Zeer laag |

Ref = referentie standaard

Sens = sensitiviteit

Spec = specificiteit

1 Geen studies gevonden over ‘cardiac tamponade, ‘flail chest’

2 De data van vier studies leenden zich niet om op te nemen in de meta-analyse. Mediane sensitiviteit bedroeg 0,52 en de specificiteit was 1. Bewijskracht: zeer laag.

Balans tussen voor- en nadelen

E-FAST is niet inferieur aan een X-thorax bij pneumothorax diagnostiek. Hoewel de diagnostiek van hematothorax ten opzichte van X-thorax geen significant voordeel biedt, is de diagnostische handeling zeer snel en zo weinig belastend, vooral in combinatie met echografisch pneumothorax diagnostiek, dat het gebruik van echo bij detectie van hematothorax niet ontraden wordt. Opgemerkt dient te worden dat een X-thorax dermate weinig stralenbelasting geeft dat dit geen argument kan zijn om af te zien van de X-thorax.

Kwaliteit van het bewijs

Er is onzekerheid over het (ontbreken van een) verschil in diagnostische accuratesse tussen e-FAST en X-thorax voor het diagnosticeren van pneumothorax en longcontusie (de bewijskracht van de evidence is laag). Er is substantiële onzekerheid over het (ontbreken van een) verschil in diagnostische accuratesse tussen e-FAST en X-thorax voor het diagnosticeren van hematothorax (de bewijskracht van de evidemce is zeer laag).

Wat vinden artsen: professioneel perspectief

Noch X-thorax noch e-FAST zijn de gouden standaard in de detectie van pneumothorax, hematothorax en longcontusie, maar zijn beiden makkelijk bruikbaar. Wel geldt voor beide technieken dat de gebruiker voldoende op de hoogte moet zijn van de indicaties en beperkingen. De huidige standaard van X-thorax heeft beperkingen, maar met inachtneming van de (andere) beperkingen van de e-FAST kan de e-FAST ook een uitspraak doen op gebied van pneumothorax, hematothorax en longcontusie.

Haalbaarheid

De werkgroep verwacht geen problemen ten aanzien van de haalbaarheid. In de module organisatie van zorg wordt hier verder op ingegaan.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Initiële, conventionele radiodiagnostiek bij volwassen patiënten met potentieel meervoudig letsel bestaat conform de ATLS op indicatie uit X-thorax, X-bekken en FAST.

Het echo-onderzoek is van oorsprong bedoeld voor het aantonen van intra-abdominaal vrij vocht (klassieke FAST). In de loop van de tijd kwam daar onderzoek van het pericard, en thoraxonderzoek bij. Dit uitgebreidere echo onderzoek is bekend als e-FAST. Een nadeel van de benaming e-FAST is dat er geen eensluidende definitie is van wat het inhoudt. De meest simpele extensie bestaat uit het beiderzijds op een vaste plaats op de thorax controleren of er geen pneumothorax is. Maar er zijn ook e-FAST programma’s waarbij men op diverse plaatsen evalueert wat aan de binnenzijde van de thoraxwand ligt: normale long, ‘natte’/atelectatische/gecontusioneerde long, vrij lucht, vrij vocht of weefsel. Afhankelijk van de plaats van de probe wordt bepaald of dat een normale bevinding is; door op meerdere plaatsen dit te meten, kan de eventuele grootte van de afwijking worden vastgesteld. De informatie die uit de diverse variaties van de e-FAST uitvoeringen te halen is, is potentieel daardoor enorm verschillend. De werkgroep zal daarom een voorstel doen tot definiëren van e-FAST.

In de huidige situatie wordt laagdrempelig een X-thorax gemaakt. Maar er zijn omstandigheden denkbaar dat een X-thorax niet de primaire keuze zou zijn als het echo-onderzoek minstens evenwaardig zou zijn: Men denke onder meer aan wachttijd tot de conventionele foto, of de wachttijd bij een groot aantal patiënten, maar ook ten behoeve van follow-up, gebruik pre-hospitaal of op een klinische afdeling in de ziekenhuis. Afhankelijk van de vraagstelling en de urgentie kan het echo-onderzoek kan daarbij aanvullend, of in sommige omstandigheden (tijdelijk) vervangend zijn voor de X-thorax

Het is onduidelijk wat de effectiviteit is van X-thorax vergeleken met e-FAST in de initiële diagnostiek van volwassen patiënten met potentieel meervoudig letsel.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

|

Geen GRADE |

Er kunnen geen conclusies geformuleerd worden met betrekking tot verschillen in gezondheidswinst voor patiënten met potentieel meervoudig of levensbedreigend letsel wanneer e-FAST of X-thorax wordt gebruikt in de initiële radiodiagnostiek. |

|

Laag GRADE |

Er is misschien geen verschil in fout-negatieven en fout-positieven wanneer e-FAST of X-thorax wordt gebruikt bij het vaststellen van pneumothorax.

Bronnen: Abbasi 2013; Abdulrahman 2015; Blaivas 2005; Hyacinthe 2012; Kirkpatrick 2004; Mumtaz 2016; Nagarsheth 2011; Nandipati 2011; Ojaghi Haghighi 2014; Rowan 2002; Soldati 2006; Soldati 2008; Vafaei 2016; Zhang 2006; Ziapour 2015 |

|

Zeer laag GRADE |

Een verschil in fout-positieven of fout-negatieven tussen e-FAST of X-thorax bij het vaststellen van hematothorax kon niet worden aangetoond noch uitgesloten.

Bronnen: Hyacinthe 2012; Ojaghi Haghighi 2014; Vafaei 2016 |

|

Laag GRADE |

E-FAST leidt misschien tot minder fout-negatieven dan X-thorax bij het vaststellen van longcontusie. Er is misschien geen verschil in fout-positieven wanneer e-FAST of X-thorax wordt gebruikt.

Bronnen: Hosseini 2015 |

Samenvatting literatuur

Beschrijving studies

Vrijwel alle studies vergeleken de diagnostische accuratesse van e-FAST en X-thorax om pneumothorax te diagnosticeren. Vier studies (Hyacinthe 2012; LeBlanc 2014; Ojaghi-Haghighi 2014; Vafaei 2016) richtten zich tevens op de diagnostiek van hematothorax. De SR van Hosseini 2015 richtte zich alleen op de diagnostiek van longcontusie. In alle studies vergeleek men e-FAST en X-thorax met CT-thorax als referentietest. Soms werd daarnaast ook het ontsnappen van intra-pleurale lucht tijdens drainage en/of de diagnose ‘pneumothorax’ op basis van X-thorax beschouwd als referentie om pneumothorax vast te stellen.

De methodologische kwaliteit van de studies was laag. Slechts een klein aantal studies maakten gebruik van een adequate inclusiestrategie die paste bij de PICO (Hyacinthe 2012; Soldati 2006; Soldati 2008). De andere studies gebruikten zogenoemde ‘convenience sampling’, waarbij men alleen de patiënten met een indicatie voor CT includeerde en de klinische follow-up van de overige patiënten niet beschreef.

In de studies was de prevalentie van pneumothorax in de populatie patiënten met potentieel meervoudig of levensbedreigend letsel tussen de 9 en 30%, afhankelijk van het type trauma van de geïncludeerde patiënten. De prevalenties van hematothorax en longcontusie waren 15 tot 31% en 43%, respectievelijk. De werkgroep schat dat in Nederland ongeveer 10% van de traumapatiënten een pneumothorax, hematothorax of longcontusie zal hebben. De werkgroep realiseert zich dat dit een expert opinion is, en dat de gemeten incidentie erg afhankelijk zal zijn van onder meer populatiesamenstelling van een centrum en de gehanteerde diagnostische criteria. Een schatting van de prevalentie is echter nodig om, conform de GRADE-methodiek voor diagnostische tests en teststrategieën, een inschatting te kunnen maken van de patiënt-relevante consequenties, in deze module het aantal fout-positieven en fout-negatieven.

Resultaten

Klinisch handelen, gezondheidswinst (kritieke uitkomstmaten)

Geen van de studies rapporteerde uitkomstmaten direct gerelateerd aan het klinisch handelen of gezondheidswinst.

Diagnostische accuratesse (belangrijke uitkomstmaten)

Pneumothorax

Zestien studies vergeleken de diagnostische accuratesse van e-FAST met X-thorax voor het diagnosticeren van pneumothorax.

In het merendeel van de studies werd e-FAST uitgevoerd door een spoedeisende hulp-arts (SEH-arts) (Blaivas 2005; Soldati 2006; Zhang 2006; Soldati 2008; Abbasi 2013, Ku 2013, Vafaei 2016). In de studies van Brook (2009) en Ziapour (2015) werd e-FAST uitgevoerd door radiologen of SEH-artsen in opleiding. In de andere studies werd e-FAST uitgevoerd door trauma-artsen (Abdulrahman, 2015; Kirkpatrick, 2004; Nandipati, 2011) en echografisten (Rowan, 2002). Mumtaz (2016) vermelde niet wie de e-FAST uitvoerde.

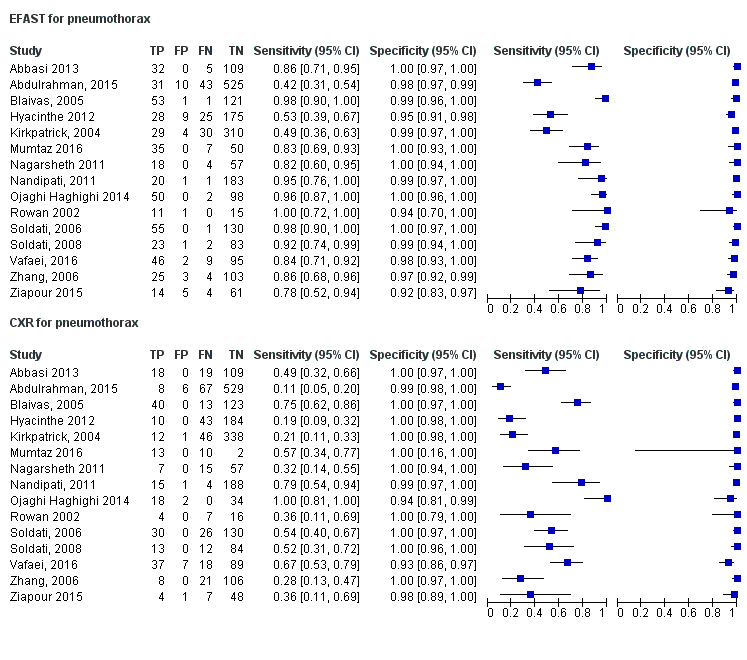

De sensitiviteit van e-FAST om pneumothorax op te sporen varieerde van 42% (Abdulrahman, 2015) tot 100% (Rowan, 2002) (Figuur 1). Drie studies rapporteerden een relatief lage sensitiviteit. Abdulrahman (2015) noemde het gebruik van twee in plaats van drie tekenen van letsel in de e-FAST als mogelijke reden van de lage sensitiviteit. Kirkpatrick (2004) merkte op dat met name de sensitiviteit om een bilaterale pneumothorax op te sporen laag was voor e-FAST. Hyacinthe (2012) noemde o.a. de ruimere inclusiecriteria in hun studie en de relatief lange tijd (één uur) tussen e-FAST en CT als mogelijke oorzaken.

In iedere afzonderlijke studie was de sensitiviteit van röntgenbeelden van de thorax lager dan van e-FAST. De sensitiviteit varieerde van 11% (Abdulrahman, 2015) tot 79% (Nandipati, 2011).

De werkgroep heeft bewust afgezien van het poolen van de data. Heterogeniteit in de studies en grote, niet-overlappende betrouwbaarheidsintervallen stonden het niet toe om een zinvolle en betrouwbaar gemiddelden voor de sensitiviteit te berekenen.

Figuur 1. Diagnostische testeigenschappen van e-FAST en X-thorax voor pneumothorax vergeleken met de referentiestandaard (CT).

De specificiteit van e-FAST voor het diagnosticeren van pneumothorax varieerde van 97% tot 100%. De specificiteit van X-thorax varieerde van 93% tot 100% (Figuur 1). LeBlanc (2014) gaf alleen ROC-curves weer. LeBlanc (2014) vond geen statistisch significante verschillen in diagnostische accuratesse van e-FAST en X-thorax voor het vaststellen van pneumothorax (p = 0,24).

Fout-negatieven pneumothorax

Bij een prevalentie van 10% kan er op basis van de studies geschat worden dat er per 1000 patiënten gemiddeld bij 0 tot 58 patiënten een pneumothorax over het hoofd worden gezien wanneer e-FAST wordt gebruikt. Wanneer X-thorax wordt gebruikt, betreft dit 0 tot 89 patiënten. De betrouwbaarheidsintervallen overlappen en er is mogelijk geen klinisch relevant verschil.

Fout-positieven pneumothorax

Bij een prevalentie van 10% kan er op basis van de studies geschat worden dat er per 1000 patiënten bij 0 tot 72 patiënten onterecht de diagnose pneumothorax worden gesteld wanneer e-FAST wordt gebruikt. Wanneer X-thorax wordt gebruikt geldt dit voor 0 tot 72 patiënten. De betrouwbaarheidsintervallen overlappen en er is mogelijk geen klinisch relevant verschil.

Hematothorax

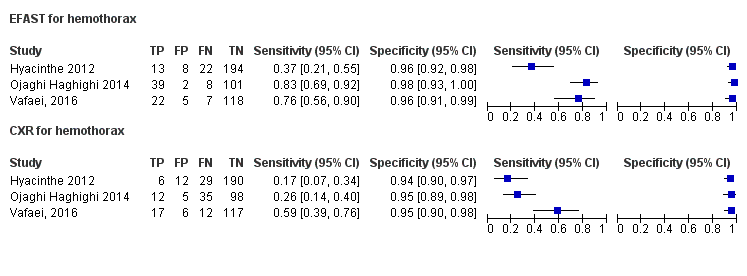

Vier studies vergeleken de diagnostische accuratesse van e-FAST met X-thorax voor het diagnosticeren van hematothorax. De sensitiviteit van e-FAST om hematothorax op te sporen varieerde van 37% (Hyacinthe, 2012) tot 83% (Ojaghi Haghighi 2014) (Figuur 2).

De specificiteit van e-FAST voor het diagnosticeren van hematothorax varieerde van 96% tot 98%. De specificiteit van X-thorax varieerde van 94% tot 95% (Figuur 2).

Figuur 2. Diagnostische testeigenschappen van e-FAST en X-thorax voor hematothorax vergeleken met de referentiestandaard (CT).

Vafaei (2016) en Hyacinthe (2012) vonden geen statistisch significant verschil in de AUC tussen e-FAST en X-thorax (95% BI 0,78 tot 0,94 versus 95% BI 0,68 tot 0,86, respectievelijk, p = 0,08). LeBlanc (2014) vond wel een statistisch significant verschil in diagnostische accuratesse voor het vaststellen van hematothorax (p < 0,05) in het voordeel van e-FAST.

Fout-negatieven hematothorax

Bij een prevalentie van 10% kan er op basis van de studies geschat worden dat er per 1000 patiënten gemiddeld bij 17 tot 63 patiënten een hematothorax over het hoofd worden gezien wanneer e-FAST wordt gebruikt. Wanneer X-thorax wordt gebruikt, betreft dit 41 tot 83 patiënten. De betrouwbaarheidsintervallen overlappen en er is mogelijk geen klinisch relevant verschil.

Fout-positieven hematothorax

Bij een prevalentie van 10% kan er op basis van de studies geschat worden dat er per 1000 patiënten bij 18 tot 36 patiënten onterecht de diagnose hematothorax worden gesteld wanneer e-FAST wordt gebruikt. Wanneer X-thorax wordt gebruikt, geldt dit voor 45 tot 54 patiënten. De betrouwbaarheidsintervallen overlappen niet. Het is aannemelijk dat er sprake is van een verschil in het aantal fout-negatieven, maar het is onduidelijk of dit verschil (9 patiënten of meer) een klinisch relevant verschil is.

Longcontusie

Hosseini (2015) includeerde 12 studies waarin de diagnostische accuratesse van e-FAST en X-thorax voor het vaststellen van longcontusie werd onderzocht. In 8 studies werden e-FAST en X-thorax direct vergeleken en in 4 studies werd alleen de accuratesse van X-thorax onderzocht. De totale studiepopulatie bestond uit 716 patiënten met longcontusie en 965 patiënten zonder longcontusie. Twee van de geïncludeerde studies hadden een retrospectief onderzoeksdesign (Soldati, 2006; Traub, 2007).

De gepoolde sensitiviteit van e-FAST voor het vaststellen van longcontusie was 0,92 (95% BI: 0,81 tot 0,96. I2 = 95,81, p < 0,001). De gepoolde specificiteit was 0,89 (95% BI: 0,85 tot 0,93; I2 = 67,29, p < 0,001).

De gepoolde sensitiviteit van X-thorax voor het vaststellen van longcontusie was 0,44 (95% BI: 0,32 tot 0,58; I2 = 87,52, p < 0,001). De gepoolde specificiteit was 0,98 (95% BI: 0,88 tot 1,0; I2 = 95,22, p < 0,001).

Fout-negatieven longcontusie

Bij een prevalentie van 10% kan er op basis van de studies geschat worden dat er per 1000 patiënten gemiddeld bij 4 tot 19 patiënten een longcontusie over het hoofd worden gezien wanneer e-FAST wordt gebruikt. Wanneer X-thorax wordt gebruikt, betreft dit 42 tot 68 patiënten. De betrouwbaarheidsintervallen overlappen niet. Het is aannemelijk dat er sprake is van een verschil in het aantal fout-negatieven, maar het is onduidelijk of dit verschil (23 patiënten of meer) een klinisch relevant verschil is.

Fout-positieven longcontusie

Bij een prevalentie van 10% kan er op basis van de studies geschat worden dat er per 1000 patiënten bij 63 tot 135 patiënten onterecht de diagnose hematothorax worden gesteld wanneer e-FAST wordt gebruikt. Wanneer X-thorax wordt gebruikt, geldt dit voor 0 tot 108 patiënten. De betrouwbaarheidsintervallen overlappen en er is mogelijk geen klinisch relevant verschil.

Bewijskracht van de literatuur

De bewijskracht voor de uitkomstmaten fout-negatieven en fout-positieven ten aanzien van de diagnostiek van pneumothorax startte ‘hoog’ en is met 2 niveaus verlaagd gezien de methodologische beperkingen (risk of bias) en zeer uiteenlopende resultaten die blijken uit niet-overlappende betrouwbaarheidsintervallen (inconsistentie). Voor bias ten gevolge van indirectheid of publicatiebias is de bewijskracht niet verder verlaagd. De bewijskracht voor de uitkomstmaten fout-negatieven en fout-positieven ten aanzien van de diagnostiek van hematothorax startte ‘hoog’ en is met 3 niveaus verlaagd gezien de methodologische beperkingen (risk of bias) en zeer ernstige imprecisie.

De bewijskracht voor de uitkomstmaten fout-negatieven en fout-positieven ten aanzien van de diagnostiek van longcontusie startte ‘hoog’ en is met 2 niveaus verlaagd gezien de methodologische beperkingen (risk of bias) en zeer uiteenlopende resultaten die blijken uit niet-overlappende betrouwbaarheidsintervallen (inconsistentie). Voor bias ten gevolge van indirectheid of publicatiebias is de bewijskracht niet verder verlaagd.

Zoeken en selecteren

Om de uitgangsvraag te kunnen beantwoorden is er een systematische literatuuranalyse verricht naar de volgende zoekvraag:

Wat zijn de voor- en nadelen van e-FAST ten opzichte van X-thorax ten aanzien van de diagnose en/of klinisch handelen in de initiële radiodiagnostiek van volwassen patiënten met potentieel meervoudig letsel?

PICO:

P (Patiënten): volwassen patiënten (≥18 jaar) met potentieel meervoudig letsel of levensbedreigend letsel;

I (Interventie): initieel radiodiagnostisch onderzoek met e-FAST;

C (Comparison):initieel radiodiagnostisch onderzoek met X-thorax;

R (Reference): CT of klinische follow-up;

O (Outcomes): mortaliteit, morbiditeit, aantal fracturen, aantal klinische interventies, verandering in intensive care opname en verandering in klinisch management, tijdswinst, stralingsbelasting, diagnostische accuratesse.

Relevante uitkomstmaten

De werkgroep achtte uitkomstmaten gerelateerd aan gezondheidswinst en klinisch handelen voor de besluitvorming de kritieke uitkomstmaten, zoals: mortaliteit, morbiditeit, veranderingen in het klinisch handelen, het inzetten van aan diagnostiek gerelateerde procedures/interventies, de incidentie van occulte letsels. Parameters gerelateerd aan de radiodiagnostische accuratesse achtte de werkgroep als belangrijke uitkomstmaten, waaronder: sensitiviteit, specificiteit, fout-positieven, fout-negatieven en area under the curve voor de diagnose van de volgende letsels: pneumothorax, hematothorax, shock (pericardeffusie, volumeload (vullingsgraad) en contractiliteit van het hart), longcontusie, mediastinal widening.

De werkgroep definieerde niet a priori de genoemde uitkomstmaten, maar hanteerde de in de studies gebruikte definities. De werkgroep definieerde geen klinisch (patiënt) relevant verschillen.

Zoeken en selecteren

In de database Medline (via OVID) is op 14 augustus 2017 met relevante zoektermen gezocht naar systematische reviews, vergelijkend onderzoek en observationeel onderzoek. De zoekverantwoording is weergegeven onder het tabblad Verantwoording. De literatuurzoekactie leverde 84 unieke treffers op. Studies werden geselecteerd op grond van de volgende selectiecriteria:

- De studiepopulatie bestaat (hoofdzakelijk) uit volwassen patiënten met potentieel meervoudig letsel of levensbedreigend letsel.

- Het gaat over initiële radiodiagnostiek.

- Betreft richtlijn, systematische review of primair (origineel) onderzoek.

- Er is sprake van een vergelijking tussen e-FAST en/of X-thorax met de referentiestandaard (CT).

- Uitkomstmaten komen overeen met gekozen uitkomstmaten.

Op basis van titel en abstract werden in eerste instantie 19 studies voorgeselecteerd. Na raadpleging van de volledige tekst, werden vervolgens 12 studies geëxcludeerd (zie exclusietabel onder het tabblad Verantwoording), en 7 studies definitief geselecteerd, waarvan één review. Op basis van deze review werden twee studies toegevoegd aan de selectie. Het zoekresultaat van een andere uitgangsvraag van deze richtlijn bevatte nog twee relevante studies en ook die werden toegevoegd aan de selectie. De werkgroep identificeerde ook de systematische review van Hosseini (2015) en voegde deze toe aan de literatuurselectie. De systematische zoekactie leverde geen RCT’s op waarin men een directe vergelijking maakte tussen de behandeling van traumapatiënten na initiële radiologische diagnostiek inclusief e-FAST en de behandeling na initiële diagnostiek zonder e-FAST.

In februari/maart 2018, na de literatuurzoekactie voor deze module, werd de systematische review van Staub (2018) gepubliceerd. Voor deze systematische review werd de wetenschappelijke literatuur tot 2016 doorzocht. In deze review en meta-analyse werd de diagnostische accuratesse van e-FAST voor pneumothorax en hematothorax onderzocht. Deze studie includeerde alleen prospectief diagnostisch accuratesseonderzoek. Wij gingen na welke van de 19 door Staub geïncludeerde studies voldeden aan de inclusiecriteria en de diagnostische accuratesse van e-FAST direct vergeleken met X-thorax. Deze studies werden toegevoegd aan de literatuuranalyse (Abbasi 2013; Hyacinthe 2012; LeBlanc 2014; Mumtaz 2016; Ojaghi Haghighi 2014, Ziapour 2015).

Zeventien originele onderzoeken zijn opgenomen in de literatuuranalyse. De belangrijkste studiekarakteristieken en resultaten zijn opgenomen in de evidencetabellen. De beoordeling van de individuele studieopzet (risk of bias) is opgenomen in de risk-of-biastabellen.

Referenties

- Abbasi S, Farsi D, Hafezimoghadam P, et al. Accuracy of emergency physician-performed ultrasound in detecting traumatic pneumothorax after a 2-h training course. Eur J Emerg Med 2013;20(3):1737

- Abdulrahman Y, Musthafa S, Hakim SY, et al. Utility of extended FAST in blunt chest trauma: is it the time to be used in the ATLS algorithm? World Journal of Surgery. 2015;39(1):172-8.

- Brook OR, Beck-Razi N, Abadi S, et al. Sonographic detection of pneumothorax by radiology residents as part of extended focused assessment with sonography for trauma. J Ultrasound Med. 2009;28(6):749-55.

- Hosseini M, Ghelichkhani P, Baikpour M, et al. Diagnostic Accuracy of Ultrasonography and Radiography in Detection of Pulmonary Contusion; a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Emerg (Tehran). 2015;3(4):127-36.

- Hyacinthe AC, Broux C, Francony G, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of ultrasonography in the acute assessment of common thoracic lesions after trauma. Chest 2012;141(5):117783.

- Kirkpatrick AW, Sirois M, Laupland KB. Hand-held thoracic sonography for detecting post-traumatic pneumothoraces: the extended focused assessment with sonography for trauma (e-FAST). J Trauma. 2004; 57:28895.

- Ku BS, Fields JM, Carr B, et al. Clinician-performed Beside Ultrasound for the Diagnosis of Traumatic Pneumothorax. West J Emerg Med. 2013;14(2):103-8.

- Leblanc D, Bouvet C, Degiovanni F, et al. Early lung ultrasonography predicts the occurrence of acute respiratory distress syndrome in blunt trauma patients. Intensive Care Med 2014;40(10):146874.

- Mumtaz U, Zahur Z, Chaudhry MA, et al. Bedside ultrasonography: a useful tool for traumatic pneumothorax. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak 2016;26 (6):45962.

- Nagarsheth K, Kurek S. Ultrasound detection of pneumothorax compared with chest X-ray and computed tomography scan. Am Surg 2011;77(4):4804.

- Nandipati KC, Allamaneni S, Kakarla R, et al. Extended focused assessment with sonography for trauma (e-FAST) in the diagnosis of pneumothorax: experience at a community based level I trauma center. Injury. 2011;42(5):511-4.

- Ojaghi Haghighi SH, Adimi I, Shams Vahdati S, Sarkhoshi Khiavi R. Ultrasonographic diagnosis of suspected hemopneumothorax in trauma patients. Trauma Mon 2014;19(4):e17498.

- Rowan KR, Kirkpatrick AW, Liu D, et al. Traumatic pneumothorax detection with thoracic US: correlation with chest radiography and CT- initial experience. Radiology. 2002; 225:2104.

- Staub LJ, Biscaro RRM, Kaszubowski E, Maurici R. Chest ultrasonography for the emergency diagnosis of traumatic pneumothorax and haemothorax: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Injury. 2018 Mar;49(3):457-466

- Vafaei A, Hatamabadi HR, Heidary K, et al. Diagnostic Accuracy of Ultrasonography and Radiography in Initial Evaluation of Chest Trauma Patients. Emergency (Tehran, Iran). 2016;4(1):29-33.

- Wilkerson RG, Stone MB. Sensitivity of bedside ultrasound and supine anteroposterior chest radiographs for the identification of pneumothorax after blunt trauma. Academic Emergency Medicine. 2010;17(1):11-7.

- Ziapour B, Haji HS. Anterior convergent chest probing in rapid ultrasound transducer positioning versus formal chest ultrasonography to detect pneumothorax during the primary survey of hospital trauma patients: a diagnostic accuracy study. J Trauma Manag Outcomes 2015;9:9.

Evidence tabellen

Research question: Wordt e-FAST als onderdeel van de initiële radiodiagnostiek versus X-thorax aanbevolen voor het diagnosticeren van letsel bij mensen met levensbedreigend of potentieel meervoudig letsel?

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics

|

Index test (test of interest) |

Reference test

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

Systematic review |

|||||||

|

Wilkerson, 2010

SR of 4 prospective studies: Blaivas et al., 2005 Zhang et al., 2006 Soldati et al., 2006 Soldati et al., 2008

|

Type of study[1]: review of 4 prospective, observational trials of emergency physician (EP)-performed thoracic ultrasonography.

Setting: Emergency Department

Country:

Conflicts of interest: none reported

|

Inclusion criteria: adult emergency department patients in whom pneumothorax was suspected after blunt trauma.

Exclusion criteria: Trials in which the exams were performed by radiologists or surgeons, or trials that investigated patients suffering penetrating trauma or with spontaneous or iatrogenic pneumothoraces

N= 606

Prevalence: pneumothorax: 11.5% to 30.1%

Mean age: 41-52 years

Sex: 57-84% M / 2% F

Other important characteristics: Blunt trauma patients (100%) |

Index test: thoracic ultrasonography for the detection of pneumothorax

Cut-off point(s): none reported

Comparator test[2]: Supine AP chest radiograph during the initial evaluation of the patient

Cut-off point(s): none reported

|

Describe reference test[3]: Computed tomography (CT) of the chest or a rush of air during thoracostomy tube placement (in unstable patients)

Cut-off point(s): none reported

|

Time between the index test and reference test: Not reported in 2 studies. For the other 2 studies: all US examinations were performed within 30 minutes - 1 hour of presentation. CT was performed less than 1 hour after CXR and US exams were completed.

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? Not reported

Reasons for incomplete outcome data described? No |

Outcome measures and effect size (95% CI and p-value if available)4:

e-FAST vs CT Sensitivity: 86.2-98.2% Specificity: 97.2-100%

CXR vs CT Sensitivity: 27.6-75.5% Specificity: 100%

|

Author’s conclusion: US is a more sensitive test than supine AP chest radiography for the detection of pneumothorax during the initial assessment of blunt trauma victims. Our analysis of the four trials showed a higher sensitivity of bedside US performed by EPs for the detection of pneumothorax

|

|

Primaire studies |

|||||||

|

Abbasi, 2013 |

Type of study[4]: single-blinded, prospective cross-sectional study.

e-FAST performed by 4 emergency physicians after a formal course in FAST exam and had performed about 100 FAST exams each.

Setting: two academic EDs with a combined annual ED census of 140 000 visits per year

Country: Iran

Conflicts of interest: none reported

|

Inclusion criteria: adult (>16 years old) ED patients sustaining thoracic trauma (as an isolated injury or a part of multiple trauma).

Exclusion criteria: clinical signs of tension PTX, subcutaneous emphysema, presence of sucking wounds, hemodynamically unstable.

N= 146

Prevalence: pneumothorax: 25.3% (n=37)

Mean age: 37 (±14) years

Sex: 88% M / 12% F

Other important characteristics: Multiple traumas: 120 (82.2%) Penetrating thoracic trauma: 16 (10.9%) Isolated blunt chest trauma: 10 (6.8%) |

Index test: e-FAST to look for pneumothorax

Cut-off point(s): none reported

Comparator test[5]: - CXR

Cut-off point(s): none reported

|

Describe reference test[6]: Spiral chest CT scan

Cut-off point(s): none reported

|

Time between the index test and reference test: After e-FAST, a supine CXR and a spiral chest CT scan were performed

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? Not reported

Reasons for incomplete outcome data described? No |

Outcome measures and effect size (95% CI and p-value if available)4:

Identification of pneumothorax

e-FAST vs CT Sensitivity: 86.4% (70.4–94.9) Specificity: 100% (95.7–100.0) Positive predictive value: 100.0% (86.6-100.0) Negative predictive value: 95.6% (CI 89.5–98.3)

CXR vs CT Sensitivity: 48.6% (32.2–65.3) Specificity: 100% (95.7–100.0) Positive predictive value: 100.0% (78.1–100.0) Negative predictive value: 85.1% (77.5–90.6)

|

Comments: From 37 PTXs diagnosed on the CT scan, 14 patients (37.8%) had small PTXs. US detected nine (64.2%) of 14 small PTXs. No chest drain was inserted in our small-sized PTX group, except one, and no complications because of their PTX were reported during their hospital stay.

Authors’ conclusions: Emergency physician-performed US appears to be an accurate modality for the diagnosis of post-traumatic PTX. Ultrasonographic signs of PTX are simple and easy to learn. By a brief learning course, the emergency physicians easily diagnosed PTX in trauma patients with a reasonable accuracy in comparison with CT scan as the gold standard. |

|

Abdulrahman, 2015 |

Type of study[7]: single-blinded, prospective cross-sectional study.

e-FAST performed by trauma surgeons after obtaining the hands-on training prior to initiation of the study.

Setting: Level 1 trauma center

Country: Qatar

Conflicts of interest: none reported

|

Inclusion criteria: Adult blunt chest trauma patients who undergone resuscitation and require further CT chest evaluation according to the ATLS Guidelines.

Exclusion criteria: chest tube was inserted before CT chest examination or patients with penetrating chest trauma or cases with incomplete or inaccurate data were excluded from the study.

N= 305

Prevalence: pneumothorax: 24.6% (n=75)

Median age: 34 (18-75)

Sex: 98% M / 2% F

Other important characteristics: Motor vehicle crash: 46.6 % Fall from height: 22.6 %

|

Index test: e-FAST to look for pneumothorax

Cut-off point(s): none reported

Comparator test[8]: - Clinical examination - CXR

Cut-off point(s): none reported

|

Describe reference test[9]: Following e-FAST, all patients underwent CXR and chest CT scan

Cut-off point(s): none reported

|

Time between the index test and reference test:

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? Not reported

Reasons for incomplete outcome data described? No |

Outcome measures and effect size (95% CI and p-value if available)4:

e-FAST vs CT Sensitivity: 42.7 % (31.3–54.6) Specificity: 98.1% (96.6–99.1) Predictive value: 76.2% (60.6–87.9) Negative predictive value: 92.4 % (89.9–94.5) Missed cases of PTX: n=43

Chest clinical examination Sensitivity: 41.3 (30–53.3) Specificity: 91.2 (88.5–93.5) Positive predictive value: 39.7% (28.8–51.5) Negative predictive value: 91.7% (89–93) Missed cases of PTX: n=44

CXR vs CT Sensitivity: 10.7% (4.7–19.9) Specificity: 98.9% (97.7–99.6) Positive predictive value: 57.1 % (28.9–82.2) Negative predictive value: 88.7% (CI 86–91) Missed cases of PTX: n=67 |

Author’s conclusion: e-FAST is a reliable and time saving bedside test that had superior diagnostic accuracy over the CXR and clinical examination. |

|

Brook, 2009 |

Type of study: prospective cross-sectional study

Setting:

Country:

Conflicts of interest:

|

Inclusion criteria: Consecutive patients with trauma treated at the trauma room in the emergency department who underwent chest radiography, e-FAST, and chest CT when clinically indicated within 2 hours of admission.

Exclusion criteria: Patients with known pneumothoraces or previous chest tube insertion

N=169 (338 lung fields

Prevalence: 13%

Mean age ± SD: 31 years (6 months-88 years)

Sex: 85% M

Other important characteristics:

|

Describe index test: e-FAST to look for pneumothorax

Cut-off point(s): -

Comparator test: CXR

Cut-off point(s): -

|

Describe reference test: CT

Cut-off point(s): -

|

Time between the index test and reference test: within 2 hours or less

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? N (%)

Reasons for incomplete outcome data described? |

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

43 pneumothoraces were diagnosed

e-FAST vs CT Sensitivity: 46.5% (32.5–61.0) Specificity: 99% (97.1–99.7) Predictive value: 86.9% (67.9–95.5) Negative predictive value: 92.6 % (89.3–95.5) Missed cases of PTX: n=23

CXR vs CT Sensitivity: 16.3% (8.1–29.8) Specificity: 100% (98.7–100) Positive predictive value: 100% (64.6–100) Negative predictive value: 89.1% (85.1–92.2) Missed cases of PTX: n=36 |

|

|

Kirkpatrick, 2004

|

Type of study: prospective cross-sectional study

Ultrasonography performed by trauma surgeon

Setting: trauma referral center Country: Canada

Conflicts of interest: unknown

|

Inclusion criteria: critically injured, not requiring immediate invasive interventions

Exclusion criteria: chest drains placed at referring hospital or in the prehospital setting, or those with gross subcutaneous emphysema that obscured the acoustic window for visualization of the pleural interface

N=225

Prevalence pneumothorax: 22% (65 in 52 patients)

Median age: 37 (IQR 25-52.5)

Sex: 74% M

Other important characteristics: Trauma: 207 blunt, 18 penetrating |

Describe index test: e-FAST to look for pneumothorax

Cut-off point(s): none reported

Comparator test: CXR

Cut-off point(s): none reported

|

Describe reference test: Escape or aspiration of intra-pleural air at the time of drainage documented, or if a PTX was identified on either CXR or CT scan

Cut-off point(s): none reported

|

Time between the index test and reference test: unknown

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? 17

Reasons for incomplete outcome data described? Battery failure or a lost probe |

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Identification of pneumothorax

Ultrasonography vs CT Sensitivity: 48.8% (33.3–64.5) Specificity: 98.7% (96.1–99.7) Predictive value: 87.5% (67.6–97.3) Negative predictive value: 90.9% (86.6–94.2)

CXR vs CT Sensitivity: 20.9% (10.0–36.0) Specificity: 99.6% (97.5–100.0) Predictive value: 90.0% (55.5–99.7) Negative predictive value: 86.7% (81.9–90.6) |

Author’s conclusions: While the specificity was comparable to the e-FAST, CXR was of lower sensitivity.

Other remarks: In only one of the 13 bilateral PTX cases were both PTXs detected using the e-FAST examination. In 5 cases of bilateral PTXs, one PTX was missed, and in 7 cases both PTXs were missed.

|

|

Ku, 2013

|

Type of study: prospective cross-sectional study

Ultrasonography performed by trained emergency medicine attendings and residents; and emergency ultrasound fellows

Setting: trauma center Country: U.S.A.

Conflicts of interest: None declared

|

Inclusion criteria: Truncal trauma (both blunt and penetrating)

Exclusion criteria: < 18 years of age, pregnant, were prisoners, or if a tube thoracostomy was performed prior to the ultrasound exam

N=549

Prevalence pneumothorax: 9%

Median age: 38 (IQR 25-51)

Sex: 75% M

Other important characteristics: Trauma: 462 blunt, 87 penetrating |

Describe index test: e-FAST to look for pneumothorax

Cut-off point(s): none reported

Comparator test: CXR, the CXR interpretation from the trauma attending or fellow rather than the radiologist was recorded.

Cut-off point(s): none reported

|

Describe reference test: Composite standard of CCT, escape of air on chest tube insertion, or supine plain radiography followed by clinical observation.

Cut-off point(s): none reported

|

Time between the index test and reference test: unknown

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? not reported

Reasons for incomplete outcome data described? - |

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Identification of pneumothorax

Ultrasonography vs CT Sensitivity: 57% (42–72) Specificity: 99% (98–100) Predictive value: 90% (73–98) Negative predictive value: 96% (94–98)

CXR vs CT (N=365) Sensitivity: 40% (23–59) Specificity: 100% (99–100) Predictive value: 100% (73–100) Negative predictive value: 95% (92–97) |

Author’s conclusions: The current investigation found that thoracic ultrasonography was as sensitive as supine radiography in the detection of traumatic PTX, but still misses more than 40% of PTXs identified on CCT.

Other remarks: Difference in sensitivities of these studies may be associated with the number and training level of enrolling physician sonologists |

|

Mumtaz, 2016 |

Type of study single-blinded, prospective cross-sectional study.

Setting: academic emergency department.

Country: Pakistan

Conflicts of interest: not reported

|

Inclusion criteria: All traumatic (RTA assaults) patients with clinical suspicion of pneumothorax.

Exclusion criteria: Unstable trauma patients who required emergency surgery, non-trauma patients, and pregnant women

N= 46

Prevalence: pneumothorax: 91.3% (n=42)

Mean age: M: 25 (±9.6); F: 32 (±12)

Sex: 65% M / 35% F

Other important characteristics: All patients were with historical features (en dergelijke, pleuritic pain, dyspnea) or examination findings (en dergelijke, rib fracture) that place them at high risk for pneumothorax. |

Index test: e-FAST to look for pneumothorax

Cut-off point(s): none reported

Comparator test: - CXR

Cut-off point(s): none reported

|

Describe reference test: CT scan

Cut-off point(s): none reported

|

Time between the index test and reference test: subsequently

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? Not reported

Reasons for incomplete outcome data described? No |

Outcome measures and effect size (95% CI and p-value if available)4:

Identification of pneumothorax

e-FAST vs CT Sensitivity: 83.3% Specificity: 100% Positive predictive value: 100.0% Negative predictive value: 36.4% Diagnostic accuracy: 84.8%

CXR vs CT Sensitivity: 54.8% Specificity: 100% Positive predictive value: 100.0% Negative predictive value: 17.4 Diagnostic accuracy: 58.7% |

Comments: In addition, we noted that 8.7% (n=4) of all traumatic patients with clinically suspicion and trauma history do not had pneumothorax that was finally diagnosed later on a CT scan.

Authors’ conclusions: Bedside ultrasound sonography as an e-FAST procedure is an accurate examination for diagnosing pneumothorax in trauma patients in emergency. |

|

Nandipati, 2011 |

Type of study: prospective cross-sectional study

Surgeon performed extended focused assessment with sonography for trauma (e-FAST)

Setting: Level I trauma center

Country: U.S.A.

Conflicts of interest: none reported

|

Inclusion criteria: polytrauma, blunt and penetrating trauma to the chest or thoraco-abdominal area

Exclusion criteria: chest tube placement without sonogram or CXR, patients with penetrating abdominal and extremity injuries

N=204

Prevalence pneumothorax: 21 (10.3%), 4 were considered as occult pneumothorax

Mean age ± SD: 43.0 ± 19.5

Sex: 74.5% M

Other important characteristics: Blunt trauma: n=159 Penetrating trauma: n=45

|

Describe index test: e-FAST to look for pneumothorax

Cut-off point(s): none reported

Comparator test: CXR

Cut-off point(s): none reported

|

Describe reference test: CT

Cut-off point(s): none reported

|

Time between the index test en reference test:

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? N=23 (11%)

Reasons for incomplete outcome data described? “CT scan was performed in 181 patients” |

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Identification of pneumothorax

e-FAST vs CT Sensitivity: 95% Specificity: 99% Predictive value: 95% Negative predictive value: 99% Missed cases of PTX: n=1

Chest clinical examination Sensitivity: 62% Specificity: 98% Predictive value: 76% Negative predictive value: 95% Missed cases of PTX: n=8

CXR vs CT Sensitivity: 79% Specificity: 99% Predictive value: 94% Negative predictive value: 98% Missed cases of PTX: n=4

Occult pneumothorax: 4/21 not recognised either clinical examination or CXR. 3 diagnosed with e-FAST and 1 was missed. |

Author’s conclusions:

Surgeon performed trauma room extended FAST is simple and has higher sensitivity compared to the chest X-ray and clinical examination in detecting pneumothorax. e-FAST has a promising role in the management of polytrauma patients and may be included in the ATLS protocol. |

|

Rowan, 2002 |

Type of study: prospective cross-sectional study

Ultrasonography performed by ‘sonographers’ (either a staff radiologist or a radiology resident who was trained in US pneumothorax detection.

Setting: emergency department

Country: Canada

Conflicts of interest: unknown

|

Inclusion criteria: patients who sustained blunt thoracic trauma, and in the opinion of the attending emergency physician or trauma surgeon, chest imaging was warranted. Included in this study were those who needed to undergo thoracic CT during the course of the study.

Exclusion criteria: treated with tube thoracostomy prior to imaging.

N=27

Prevalence pneumothorax: 11/27 (41%)

Mean age ± SD: unknown 42 years; range: 17–83

Sex: M: 25 / F: 2

Other important characteristics:

|

Describe index test: Ultrasonography to look for pneumothorax

Cut-off point(s): none reported

Comparator test: CXR

Cut-off point(s): none reported

|

Describe reference test: CT

Cut-off point(s): none reported

|

Time between the index test and reference test: unknown

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? not reported

Reasons for incomplete outcome data described? No |

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Identification of pneumothorax

Ultrasonography vs CT Sensitivity: 100% Specificity: 94% Predictive value: 92% Negative predictive value: 100%

CXR vs CT Sensitivity: 36% Specificity: 100% Predictive value: 100% Negative predictive value: 70% |

Author’s conclusions: Ultrasonography was more sensitive than supine chest radiography and as sensitive as CT in the detection of traumatic pneumothoraces |

|

Vafaei, 2016 |

Type of study: prospective cross-sectional study

Chest ultraso-nography carried out by an emergency medicine specialist

Setting: Emergency department

Country: Iran

Conflicts of interest: None reported

|

Inclusion criteria: in need for chest CT scan based on standard indications of advanced trauma life support (ATLS) guidelines

Exclusion criteria: pregnancy, hemodynamic instability, and lack of interest in participating in the study

N= 152

Prevalence: Pulmonary contusion: n= 48 (31.6%) Hematothorax: n= 29 (19.1%) Pneumothorax: n= 55 (36.2%)

Mean age ± SD: 31.4 ± 13.8

Sex: 77.6% M

|

Describe index test: chest ultrasonography to look for pneumothorax, hematothorax, rib fracture, and pulmonary contusion

Cut-off point(s): none reported

Comparator test: radiography

Cut-off point(s): none reported

|

Describe reference test: Thoracic CT

Cut-off point(s): none reported

|

Time between the index test and reference test:

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? Not reported Reasons for incomplete outcome data described? No |

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Please see table A.

Ultrasonography versus radiography Pneumothorax: Area under the curve (AUC): 0.91 (95% CI: 0.86‒0.96) vs 0.80 (95% CI: 0.736‒0.87), p = 0.02

Pulmonary contusion AUC = 0.80 (95% CI: 0.74‒0.88) vs 0.58 (95% CI: 0.5‒0.67), p < 0.001

Hematothorax AUC = 0.86 (95% CI: 0.78‒0.94) vs 0.77 (95% CI: 0.68‒0.86), p = 0.08 |

Author’s conclusions: Ultrasonography is preferable to radiography in the initial evaluation of patients with traumatic injuries to the thoracic cavity. However, the low sensitivity of the ultrasonography technique in comparison to CT scan, its reliance on operator skill, and some other limitations have made it only an initial test, necessitating confirmation using other techniques. |

|

Ziapour, 2015 |

Type of study: prospective cross-sectional study

Single operator; emergency medicine resident performed all the chest ultrasonographies

Setting: emergency department, 65,000 presentations per year.

Country: Iran

Conflicts of interest: not reported

|

Inclusion criteria: Moderate or severe multiple trauma patients who had already been triaged and labeled as level 1, 2 or 3 by the Emergency Severity Index (ESI) Triage Algorithm Version 4.

Exclusion criteria: -

N=45 84 e-FAST exams, 60 CXR results

Prevalence pneumothorax: 18/84 (21%) pneumothorax

Mean age ± SD: not reported

Sex: not reportd

|

Describe index test: e-FAST to look for pneumothorax (PTX)

Cut-off point(s): none reported

Comparator test: CXR Moderate chest injuries were solely imaged using CXR.

Cut-off point(s): none reported

|

Describe reference test: CT Limited to patients with severe multiple trauma who were routinely included in our hospital's whole body scan protocol.

Cut-off point(s): none reported

|

Time between the index test and reference test: consequently

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? N=15

N=30: CT+CXR (60 US exams) N=15: CT (6 uni, 9 bilateral, 24 US exams)

Reasons for incomplete outcome data described? |

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Identification of pneumothorax

e-FAST vs CT Sensitivity: 95% (52-93%) Specificity: 92% (83-97%) Positive predictive value: 74% (49-91) Negative predictive value: 94% (85-98) Missed cases of PTX: n=4/84

CXR vs CT Sensitivity: 36.4% (11-69%) Specificity: 98% (90-100%) Positive predictive value: 80% (28-99%) Negative predictive value: 87% (75-95%) Missed cases of PTX: n=7/84 |

Author’s conclusions: We believe that “Anterior Convergent” chest probing is a practical method for detecting PTX. This approach is a more appropriate screening test than both supine conventional CXR and lung auscultation |

Table A.

|

Outcome measures Vafaei, 2016.

|

||

|

Pneumothorax |

Ultrasonography |

Chest x-ray |

|

Sensitivity |

83.6 (70.7‒91.8) |

67.3 (53.2‒78.95) |

|

Specificity |

97.9 (92.0‒99.6) |

92.7 (85.1‒96.8) |

|

Positive predictive value |

95.8 (84.6‒99.3) |

84.1 (69.3‒92.8) |

|

Negative predictive value |

91.3 (83.8‒95.7) |

83.2 (74.5‒89.5) |

|

Positive likelihood ratio |

45.6 (10.2‒160.7) |

9.2 (4.4‒19.3) |

|

Negative likelihood ratio |

0.17 (0.09‒0.3) |

0.35 (0.24‒0.52) |

|

Hematothorax |

||

|

Sensitivity |

75.9 (56.1‒90.0) |

58.6 (39.1‒75.9) |

|

Specificity |

95.9 (90.3‒98.5) |

95.1 (89.2‒98.0) |

|

Positive predictive value |

81.5 (88.4‒97.5) |

73.9 (51.3‒88.9) |

|

Negative predictive value |

94.4 (88.4‒97.5) |

90.7 (84.0‒94.9) |

|

Positive likelihood ratio |

18.7 (7.7‒45.1) |

12.0 (5.2‒27.8) |

|

Negative likelihood ratio |

0.25 (0.13‒0.48) |

0.1 (0.06‒0.18) |

|

Pulmonary contusion |

||

|

Sensitivity |

68.8 (53.6‒80.9) |

43.8 (29.8‒58.7) |

|

Specificity |

92.3 (84.9‒96.4) |

73.1 (63.3‒81.1) |

|

Positive predictive value |

80.5 (64.6‒90.6) |

42.8 (29.1‒57.7) |

|

Negative predictive value |

86.5 (78.4‒92.0) |

73.7 (64.0‒81.7) |

|

Positive likelihood ratio |

8.9 (4.5‒17.7) |

1.6 (1.0‒2.55) |

|

Negative likelihood ratio |

0.34 (0.2‒0.52) |

0.77(0.6‒0.99) |

Risk-of-bias assessment diagnostic accuracy studies (QUADAS II, 2011)

Research question: e-FAST ten opzichte van X-thorax voor de initiële radiodiagnostiek van volwassen patiënten met potentieel meervoudig of levensbedreigend letsel:

- Wat zijn de voor- en nadelen in termen van klinisch handelen?

- Wat is de diagnostische accuratesse?

|

Study reference |

Patient selection

|

Index test |

Reference standard |

Flow and timing |

Comments with respect to applicability |

|

Wilkerson, 2010

SR of 4 prospective studies: Blaivas et al., 2005 Zhang et al., 2006 Soldati et al., 2006 Soldati et al., 2008

Instrument used by Wilkerson, 2010: Quadas |

See Wilkerson, 2010 for details |

See Wilkerson, 2010 for details |

See Wilkerson, 2010 for details |

See Wilkerson, 2010 for details |

See Wilkerson, 2010 for details |

|

CONCLUSION: Could the selection of patients have introduced bias?

RISK: LOW |

CONCLUSION: Could the conduct or interpretation of the index test have introduced bias?

RISK: LOW

|

CONCLUSION: Could the reference standard, its conduct, or its interpretation have introduced bias?

RISK: LOW |

CONCLUSION Could the patient flow have introduced bias?

RISK: LOW |

|

|

|

Abbasi, 2013 |

Was a consecutive or random sample of patients enrolled? No

Was a case-control design avoided? Yes

Did the study avoid inappropriate exclusions? Yes

|

Were the index test results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the reference standard? Yes

If a threshold was used, was it pre-specified? Yes

|

Is the reference standard likely to correctly classify the target condition? Yes

Were the reference standard results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the index test? Yes

|

Was there an appropriate interval between index test(s) and reference standard? Unclear

Did all patients receive a reference standard? Yes

Did patients receive the same reference standard? Yes

Were all patients included in the analysis? Yes |

Are there concerns that the included patients do not match the review question? No

Are there concerns that the index test, its conduct, or interpretation differ from the review question? No

Are there concerns that the target condition as defined by the reference standard does not match the review question? No

|

|

|

CONCLUSION: Could the selection of patients have introduced bias?

RISK: HIGH |

CONCLUSION: Could the conduct or interpretation of the index test have introduced bias?

RISK: LOW |

CONCLUSION: Could the reference standard, its conduct, or its interpretation have introduced bias?

RISK: LOW |

CONCLUSION Could the patient flow have introduced bias?

RISK: UNCLEAR |

|

|

Abdulrahman, 2015 |

Was a consecutive or random sample of patients enrolled? Unclear

Was a case-control design avoided? Yes

Did the study avoid inappropriate exclusions? Yes

|

Were the index test results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the reference standard? Yes

If a threshold was used, was it pre-specified? Yes

|

Is the reference standard likely to correctly classify the target condition? Yes

Were the reference standard results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the index test? Yes

|

Was there an appropriate interval between index test(s) and reference standard? Yes

Did all patients receive a reference standard? Yes

Did patients receive the same reference standard? Yes

Were all patients included in the analysis? Yes |

Are there concerns that the included patients do not match the review question? No

Are there concerns that the index test, its conduct, or interpretation differ from the review question? No

Are there concerns that the target condition as defined by the reference standard does not match the review question? No

|

|

|

CONCLUSION: Could the selection of patients have introduced bias?

RISK: HIGH |

CONCLUSION: Could the conduct or interpretation of the index test have introduced bias?

RISK: LOW |

CONCLUSION: Could the reference standard, its conduct, or its interpretation have introduced bias?

RISK: LOW |

CONCLUSION Could the patient flow have introduced bias?

RISK: LOW |

|

|

Brook, 2009 |

Was a consecutive or random sample of patients enrolled? No

Was a case-control design avoided? Yes

Did the study avoid inappropriate exclusions? Yes

|

Were the index test results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the reference standard? Yes

If a threshold was used, was it pre-specified? Yes

|

Is the reference standard likely to correctly classify the target condition? Yes

Were the reference standard results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the index test? Yes

|

Was there an appropriate interval between index test(s) and reference standard? Unclear

Did all patients receive a reference standard? Yes

Did patients receive the same reference standard? Yes

Were all patients included in the analysis? Yes

|

Are there concerns that the included patients do not match the review question? No

Are there concerns that the index test, its conduct, or interpretation differ from the review question? No

Are there concerns that the target condition as defined by the reference standard does not match the review question? No |

|

|

CONCLUSION: Could the selection of patients have introduced bias?

RISK: HIGH |

CONCLUSION: Could the conduct or interpretation of the index test have introduced bias?

RISK: LOW |

CONCLUSION: Could the reference standard, its conduct, or its interpretation have introduced bias?

RISK: LOW |

CONCLUSION Could the patient flow have introduced bias?

RISK: UNCLEAR |

|

|

Kirkpatrick, 2004

|

Was a consecutive or random sample of patients enrolled? Unclear

Was a case-control design avoided? Yes

Did the study avoid inappropriate exclusions? Yes

|

Were the index test results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the reference standard? Yes

If a threshold was used, was it pre-specified? Yes

|

Is the reference standard likely to correctly classify the target condition? Yes

Were the reference standard results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the index test? Unclear

|

Was there an appropriate interval between index test(s) and reference standard? Unclear

Did all patients receive a reference standard? Yes

Did patients receive the same reference standard? No

Were all patients included in the analysis? Yes |

Are there concerns that the included patients do not match the review question? No

Are there concerns that the index test, its conduct, or interpretation differ from the review question? No

Are there concerns that the target condition as defined by the reference standard does not match the review question? No

|

|

|

CONCLUSION: Could the selection of patients have introduced bias?

RISK: HIGH |

CONCLUSION: Could the conduct or interpretation of the index test have introduced bias?

RISK: LOW |

CONCLUSION: Could the reference standard, its conduct, or its interpretation have introduced bias?

RISK: UNCLEAR |

CONCLUSION Could the patient flow have introduced bias?

RISK: HIGH |

|

|

Ku, 2013

|

Was a consecutive or random sample of patients enrolled? No

Was a case-control design avoided? Yes

Did the study avoid inappropriate exclusions? Yes

|

Were the index test results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the reference standard? Yes

If a threshold was used, was it pre-specified? Yes |

Is the reference standard likely to correctly classify the target condition? Yes

Were the reference standard results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the index test? Yes

|

Was there an appropriate interval between index test(s) and reference standard? Unclear

Did all patients receive a reference standard? No (not all patients received CT)

Did patients receive the same reference standard? No

Were all patients included in the analysis? Yes |

Are there concerns that the included patients do not match the review question? No

Are there concerns that the index test, its conduct, or interpretation differ from the review question? No

Are there concerns that the target condition as defined by the reference standard does not match the review question? No

|

|

|

CONCLUSION: Could the selection of patients have introduced bias?

RISK: HIGH |

CONCLUSION: Could the conduct or interpretation of the index test have introduced bias?

RISK: LOW |

CONCLUSION: Could the reference standard, its conduct, or its interpretation have introduced bias?

RISK: LOW |

CONCLUSION Could the patient flow have introduced bias?

RISK: UNCLEAR |

|

|

Mumtaz, 2016 |

Was a consecutive or random sample of patients enrolled? Unclear

Was a case-control design avoided? Yes

Did the study avoid inappropriate exclusions? Yes

|

Were the index test results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the reference standard? Yes

If a threshold was used, was it pre-specified? Yes

|

Is the reference standard likely to correctly classify the target condition? Yes

Were the reference standard results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the index test? Yes

|

Was there an appropriate interval between index test(s) and reference standard? Unclear

Did all patients receive a reference standard? Yes

Did patients receive the same reference standard? Yes

Were all patients included in the analysis? Yes |

Are there concerns that the included patients do not match the review question? Yes

Are there concerns that the index test, its conduct, or interpretation differ from the review question? No

Are there concerns that the target condition as defined by the reference standard does not match the review question? No

|

|

|

CONCLUSION: Could the selection of patients have introduced bias?

RISK: HIGH |

CONCLUSION: Could the conduct or interpretation of the index test have introduced bias?

RISK: LOW |

CONCLUSION: Could the reference standard, its conduct, or its interpretation have introduced bias?

RISK: LOW |

CONCLUSION Could the patient flow have introduced bias?

RISK: UNCLEAR |

|

|

Nandipati, 2011 |

Was a consecutive or random sample of patients enrolled? Unclear

Was a case-control design avoided? Yes

Did the study avoid inappropriate exclusions? Yes

|

Were the index test results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the reference standard? Unclear

If a threshold was used, was it pre-specified? Yes

|

Is the reference standard likely to correctly classify the target condition? Yes

Were the reference standard results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the index test? Unclear

|

Was there an appropriate interval between index test(s) and reference standard? Unclear

Did all patients receive a reference standard? Yes

Did patients receive the same reference standard? Yes

Were all patients included in the analysis? Yes |

Are there concerns that the included patients do not match the review question? No

Are there concerns that the index test, its conduct, or interpretation differ from the review question? No

Are there concerns that the target condition as defined by the reference standard does not match the review question? No

|

|

|

CONCLUSION: Could the selection of patients have introduced bias?

RISK: LOW |

CONCLUSION: Could the conduct or interpretation of the index test have introduced bias?

RISK: UNCLEAR |

CONCLUSION: Could the reference standard, its conduct, or its interpretation have introduced bias?

RISK: UNCLEAR |

CONCLUSION Could the patient flow have introduced bias?

RISK: LOW |

|

|

Vafaei, 2016 |

Was a consecutive or random sample of patients enrolled? Yes

Was a case-control design avoided? Yes

Did the study avoid inappropriate exclusions? Yes

|

Were the index test results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the reference standard? Unclear

If a threshold was used, was it pre-specified? Unclear

|

Is the reference standard likely to correctly classify the target condition? Yes

Were the reference standard results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the index test? Unclear

|

Was there an appropriate interval between index test(s) and reference standard? Unclear (In the present study there was about 1‒2-hour time interval between ultrasonography and CT scan examinations. During this time, the lesions might have extended to reach a size that could make diagnose them easier.

Did all patients receive a reference standard? Yes

Did patients receive the same reference standard? Yes

Were all patients included in the analysis? Yes |

Are there concerns that the included patients do not match the review question? No

Are there concerns that the index test, its conduct, or interpretation differ from the review question? No

Are there concerns that the target condition as defined by the reference standard does not match the review question? No

|

|

|

CONCLUSION: Could the selection of patients have introduced bias?

RISK: LOW |

CONCLUSION: Could the conduct or interpretation of the index test have introduced bias?

RISK: UNCLEAR |

CONCLUSION: Could the reference standard, its conduct, or its interpretation have introduced bias?

RISK: LOW |

CONCLUSION Could the patient flow have introduced bias?

RISK: UNCLEAR |

|

|

Ziapour, 2015 |

Was a consecutive or random sample of patients enrolled? Unclear

Was a case-control design avoided? Yes

Did the study avoid inappropriate exclusions? Yes

|

Were the index test results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the reference standard? Yes

If a threshold was used, was it pre-specified? Yes

|

Is the reference standard likely to correctly classify the target condition? Yes

Were the reference standard results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the index test? Yes

|

Was there an appropriate interval between index test(s) and reference standard? Unclear

Did all patients receive a reference standard? No

Did patients receive the same reference standard? Yes

Were all patients included in the analysis? No |

Are there concerns that the included patients do not match the review question? Yes

Are there concerns that the index test, its conduct, or interpretation differ from the review question? No

Are there concerns that the target condition as defined by the reference standard does not match the review question? No

|

|

|

CONCLUSION: Could the selection of patients have introduced bias?

RISK: HIGH |

CONCLUSION: Could the conduct or interpretation of the index test have introduced bias?

RISK: LOW |

CONCLUSION: Could the reference standard, its conduct, or its interpretation have introduced bias?

RISK: LOW |

CONCLUSION Could the patient flow have introduced bias?

RISK: HIGH |

|

Exclusietabel

Tabel Exclusie na het lezen van het volledige artikel

|

Auteur en jaartal |

Redenen van exclusie |

|

Rambhia, 2017 |

Narrative review |

|

Matsumoto, 2016 |

I en C voldoen niet: "oblique chest radiography" lijkt geen standaard procedure en er worden geen resultaten gerapporteerd voor de vergelijking met CT. |

|

Hamada, 2016 |

Evaluatie van triage-strategie in opvang |

|

Soult, 2015 |

Retrospectief onderzoeksdesign |

|

Kaya, 2015 |

Artikel in Turks | Data slechts gedeeltelijk beschikbaar via Staub, 2018 |

|

Wongwaisayawan, 2015 |

Narrative review |

|

Prosch, 2014 |

Narrative review |

|

Uz, 2013 |

Artikel in Turks |

|

Ball, 2009 |

Narrative review |

|

Schmidt, 2000 |

Artikel in Duits |

|

Hansen, 1997 |

Artikel in Duits |

|

Lichtenstein, 2005 (uit Wilkerson, 2010) |

Retrospectief onderzoeksdesign |

[1] In geval van een case-control design moeten de patiëntkarakteristieken per groep (cases en controls) worden uitgewerkt. NB; case control studies zullen de accuratesse overschatten (Lijmer et al., 1999)

[2] Comparator test is vergelijkbaar met de C uit de PICO van een interventievraag. Er kunnen ook meerdere tests worden vergeleken. Voeg die toe als comparator test 2 etc. Let op: de comparator test kan nooit de referentiestandaard zijn.

[3] De referentiestandaard is de test waarmee definitief wordt aangetoond of iemand al dan niet ziek is. Idealiter is de referentiestandaard de Gouden standaard (100% sensitief en 100% specifiek). Let op! dit is niet de “comparison test/index 2”.

4 Beschrijf de statistische parameters voor de vergelijking van de indextest(en) met de referentietest, en voor de vergelijking tussen de indextesten onderling (als er twee of meer indextesten worden vergeleken).

[4] In geval van een case-control design moeten de patiëntkarakteristieken per groep (cases en controls) worden uitgewerkt. NB; case control studies zullen de accuratesse overschatten (Lijmer et al., 1999)

[5] Comparator test is vergelijkbaar met de C uit de PICO van een interventievraag. Er kunnen ook meerdere tests worden vergeleken. Voeg die toe als comparator test 2 etc. Let op: de comparator test kan nooit de referentiestandaard zijn.

[6] De referentiestandaard is de test waarmee definitief wordt aangetoond of iemand al dan niet ziek is. Idealiter is de referentiestandaard de Gouden standaard (100% sensitief en 100% specifiek). Let op! dit is niet de “comparison test/index 2”.

4 Beschrijf de statistische parameters voor de vergelijking van de indextest(en) met de referentietest, en voor de vergelijking tussen de indextesten onderling (als er twee of meer indextesten worden vergeleken).

[7] In geval van een case-control design moeten de patiëntkarakteristieken per groep (cases en controls) worden uitgewerkt. NB; case control studies zullen de accuratesse overschatten (Lijmer et al., 1999)

[8] Comparator test is vergelijkbaar met de C uit de PICO van een interventievraag. Er kunnen ook meerdere tests worden vergeleken. Voeg die toe als comparator test 2 etc. Let op: de comparator test kan nooit de referentiestandaard zijn.

[9] De referentiestandaard is de test waarmee definitief wordt aangetoond of iemand al dan niet ziek is. Idealiter is de referentiestandaard de Gouden standaard (100% sensitief en 100% specifiek). Let op! dit is niet de “comparison test/index 2”.

4 Beschrijf de statistische parameters voor de vergelijking van de indextest(en) met de referentietest, en voor de vergelijking tussen de indextesten onderling (als er twee of meer indextesten worden vergeleken).

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Publicatiedatum : 28-10-2019

Beoordeeld op geldigheid : 10-07-2019

|

Module |

Regiehouder(s) |

Jaar van autorisatie |

Eerstvolgende beoordeling actualiteit richtlijn |

Frequentie van beoordeling op actualiteit |

Wie houdt er toezicht op actualiteit |

Relevante factoren voor wijzigingen in aanbeveling |

|

e-FAST |

NVvR |

2019 |

2024 |

eens per 5 jaar |

NVvR |

- |

Voor het beoordelen van de actualiteit van deze richtlijn wordt de werkgroep niet in stand gehouden. Uiterlijk in 2024 (publicatiedatum plus vijf jaar) bepaalt het bestuur van de Nederlandse Vereniging voor Radiologie (NVvR) of de modules van deze richtlijn nog actueel zijn en of er eventueel nieuwe modules toegevoegd moeten worden. Op modulair niveau is een onderhoudsplan beschreven. Bij het opstellen van de richtlijn heeft de werkgroep per module een inschatting gemaakt over de maximale termijn waarop herbeoordeling moet plaatsvinden en eventuele aandachtspunten geformuleerd die van belang zijn bij een toekomstige herziening (update). De geldigheid van de richtlijn komt eerder te vervallen indien nieuwe ontwikkelingen aanleiding geven een herzieningstraject te starten.

De NVvR is regiehouder van deze richtlijn en eerstverantwoordelijke op het gebied van de actualiteitsbeoordeling van de richtlijn. De andere aan deze richtlijn deelnemende wetenschappelijke verenigingen of gebruikers van de richtlijn delen de verantwoordelijkheid en informeren de regiehouder over relevante ontwikkelingen binnen hun vakgebied.

Algemene gegevens

De richtlijnontwikkeling werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten en werd gefinancierd uit de Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS). De financier heeft geen enkele invloed gehad op de inhoud van de richtlijn.

Doel en doelgroep

Doel

Deze richtlijn beoogt het beleid ten aanzien van initiële radiologische diagnostiek bij de opvang van traumapatiënten te optimaliseren en te uniformeren. Het is van essentieel belang dat er duidelijkheid ontstaat over de indicatie voor en wijze van beeldvorming bij de opvang van traumapatiënten.

Doelgroep

De richtlijn beperkt zich tot de initiële radiologische diagnostiek bij volwassen patiënten met potentieel meervoudig letsel. Met initieel wordt bedoeld de diagnostiek die verricht wordt na triage en tijdens de opvang van patiënten op de spoedeisende hulp.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijn is in 2017 een multidisciplinaire werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor patiënten met potentieel meervoudig letsel te maken hebben (zie hiervoor de samenstelling van de werkgroep).

De werkgroepleden zijn door hun beroepsverenigingen gemandateerd voor deelname. De werkgroep is verantwoordelijk voor de integrale tekst van deze richtlijn.

Werkgroep:

- drs. M.J. (Maeke) Scheerder, radioloog, Amsterdam UMC Locatie AMC, Amsterdam, NVvR (voorzitter)

- drs. L.F.M. (Ludo) Beenen, radioloog, Amsterdam UMC Locatie AMC, Amsterdam, NVvR (vice-voorzitter)

- dr. E.F.W. (Ewout) Courrech Staal, radioloog, Maasstad Ziekenhuis, Rotterdam, NVvR

- dr. J. (Jaap) Deunk, traumachirurg, Amsterdam UMC Locatie VUmc, NVvH

- drs. P.J.A.C. (Perjan) Dirven, anesthesioloog, Erasmus MC, Rotterdam, NVA

- drs. H.H. (Erik) Dol, SEH-arts KNMG, Jeroen Bosch Ziekenhuis, ’s-Hertogenbosch, NVSHA

- dr. I. (Iain) Haitsma, neurochirurg, Erasmus MC Rotterdam / Albert Schweitzer ziekenhuis, NVvN

- dr. C. (Christiaan) van der Leij, interventieradioloog, Maastricht UMC+, Maastricht, NVvR/NVIR

- prof. dr. J. (Joukje) van der Naalt, neuroloog, UMCG, Groningen, NVN

- drs. ing. D.P.H. (Dirk) van Oostveen, orthopedisch chirurg, Jeroen Bosch Ziekenhuis, ’s-Hertogenbosch, NOV

Met ondersteuning van:

- dr. J.S. (Julitta) Boschman, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- dr. W.J. (Wouter) Harmsen, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- dr. N.H.J. (Natasja) van Veen, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- D.P. Gutierrez, projectsecretaresse, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

Belangenverklaringen