Behandeling ingegroeide teennagel

Uitgangsvraag

Hoe moet een ingegroeide teennagel behandeld worden?

Aanbeveling

Ingegroeide teennagels kunnen worden ingedeeld in 3 stadia:

Stadium I: zwelling van de nagelwal, oedeem, roodheid en pijn bij druk.

Stadium II: conform stadium I met daarnaast inflammatie en infectie van de nagelwal.

Stadium III: een chronische inflammatie die leidt tot vorming van granulatieweefsel.

Overweeg conservatieve behandeling voor stadium I ingegroeide teennagels.

Overweeg operatieve behandeling voor stadium II-III ingegroeide teennagels en bij falende conservatieve behandeling (alle stadia).

- Neem kennis van de anatomie van het nagelcomplex (zie figuren 1 en 2 bij het aanverwante product ‘Stapsgewijze operatieve aanpak’).

- Voer de operatieve behandeling als volgt uit:

- Voer een partiële nagelextractie uit van de ingroeiende nagelrand in combinatie met destructie van het corresponderende deel van de matrix middels één van de volgende mogelijkheden:

-

- Partiële chirurgische matricectomie.

- Chemische destructie met behulp van fenol 85% of kaliumhydroxide (KOH) of trichloorazijnzuur.

-

- Volg bij voorkeur de stapsgewijze operatieve aanpak (zie het aanverwante product: Stapsgewijze operatieve aanpak.)

Overwegingen

De onderstaande overwegingen gelden in principe voor het overgrote deel van de patiëntenpopulatie met een ingegroeide teennagel.

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

De bewijskracht van de literatuur is zeer laag (voor chirurgische behandeling versus niet-chirurgische behandeling) tot laag (voor verschillende typen chirurgische behandeling). Dit betekent dat het werkelijke effect substantieel anders kan zijn ten opzichte van het effect dat uit de studies is gebleken. Methodologische beperkingen van de studies liggen hier aan ten grondslag.

Niet-chirurgische behandeling versus chirurgische behandeling

De werkgroep is van mening dat niet-chirurgische interventie overwogen moet worden wanneer er spraken is van stadium I en de nagel het distale einde van de laterale nagelplooi nagenoeg bereikt heeft. De niet-chirurgische behandelingen zijn eenvoudig uitvoerbaar en minimaal belastend. Soms zijn deze door de patiënt zelf toe te passen.

Chirurgische behandeling

Ondanks dat er op basis van literatuur geen conclusie getrokken kan worden, is er volgens de werkgroep, gezien de dagelijkse praktijk, reden om aan te nemen dat chirurgische behandeling de voorkeur verdient bij ingegroeide teennagel stadium II-III.

Gedegen kennis van de anatomie van het nagelcomplex is, even als een goede operatietechniek, vereist om de kans op een recidief te reduceren. Het laterale deel van de matrix reikt verder naar proximaal dan vaak gedacht waardoor het risico dat vitaal matrix weefsel achterblijft, reëel is.

De werkgroep is van mening dat de stapsgewijze operatieve aanpak (zie het aanverwante product: Stapsgewijze operatieve aanpak) de meest geschikte operatieve behandeling voor een unguis incarnatus weergeeft. De kans op recidief en complicaties is het kleinst, het herstel het snelst, patiënttevredenheid goed en esthetisch resultaat het best. Chemische destructie in plaats van chirurgische excisie/destructie van de matrix kan overwogen worden.

Volledige avulsie van de nagel van de hallux in het kader van de behandeling van een unguis incarnatus wordt ontraden.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en eventueel hun verzorgers)

Patiënten kiezen voor chirurgische behandeling vanwege de kleinere recidiefkans, snelle pijnverlichting en de korte herstelduur. Patiënten voor wie het cosmetisch resultaat van belang is, overwegen wellicht eerder een conservatieve behandeling.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

Alhoewel informatie over kosten ontbreekt, vind de werkgroep het middelenbeslag niet relevant. De behandelopties zijn namelijk relatief goedkoop. De werkgroep acht het niet aannemelijk dat de aanbevelingen impact zullen hebben op ziekenhuis-/afdelingsbudget.

Aanvaardbaarheid voor de overige relevante stakeholders

Niet van toepassing.

Haalbaarheid en implementatie

De werkgroep ziet geen bezwaren ten aanzien van haalbaarheid en implementatie. De operatieve behandeling van een ingroeiende teennagel verdient aandacht, zorgvuldigheid en vaardigheid bij de technische uitvoering. En dient derhalve gedegen onderwezen te worden.

Rationale/ balans tussen de argumenten voor en tegen de interventie

Er is behoefte aan een standaard werkwijze bij de chirurgische behandeling van een ingegroeide teennagel. Het voorstel van de werkgroep is om bij voorkeur te kiezen voor partiële nagelextractie van de ingroeiende nagelrand in combinatie met chirurgische excisie dan wel (chemische) destructie van het corresponderende deel van de matrix. Voor de behandeling is grondige kennis van de anatomie van het nagelcomplex essentieel.

Zie: Stapsgewijze operatieve aanpak (aanverwante producten; figuren 1 en 2).

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Een ingroeiende of ingegroeide teennagel is een veel voorkomende aandoening die regelmatig in de eerste en tweede lijn wordt gezien en behandeld. Hoewel er een mate van algemene overeenstemming lijkt te zijn in de globale behandelindicatie en technieken, ontbreekt de onderbouwing hiervoor. In deze module wordt hier vorm aan gegeven en wordt een voorstel voor een stapsgewijze operatieve aanpak aangereikt.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

Surgical versus non-surgical treatment of ingrown toenails

|

Very low GRADE |

A difference in recurrences after surgical versus non-surgical treatment couldn’t be demonstrated nor refuted.

Sources: (Kruijff, 2008) |

|

- GRADE |

Current literature on surgical versus non-surgical treatment of ingrown toenails did not report on regrowth, pain/discomfort/symptoms, adverse events/complications, patient global assessment/patient satisfaction, (work) participation, or healing time. |

Surgical gutter treatment versus other surgical treatment

|

Very low GRADE |

A difference in recurrences, postoperative infection and patient satisfaction after surgical gutter treatment versus other surgical interventions couldn’t be demonstrated nor refuted.

Sources: (Peyvandi, 2011; Ceren, 2013; AlGhamdi, 2014; Wallace, 1979) |

|

- GRADE |

Current literature on surgical gutter treatment versus other surgical treatment of ingrown toenails did not report on regrowth, pain/discomfort/symptoms, (work) participation, or healing time. |

Surgical procedures alone versus surgical procedures plus destruction of the matrix

|

Low GRADE |

Recurrence may be lower after surgical intervention combined with chemical destruction of the matrix than after surgical intervention without chemical destruction.

Recurrence may not be different between interventions with chemical destruction versus (other) interventions with surgical matrix destruction.

There may be no differences in postoperative pain and patient satisfaction with or without matrix destruction.

Sources: (Vama, 1983; Morkane, 1984; Issa, 1988; Leah,y 1990; Van der Ham, 1990; Sykes, 1988; Anderson, 1990; Gerritsma-Bleeker, 2002; Bos, 2006; Shaath, 2005; Khan, 2014) |

|

- GRADE |

Current literature on surgical procedures alone versus surgical procedures plus destruction of the matrix for ingrown toenails did not report on regrowth, adverse events/complications, (work) participation, or healing time. |

Different types of ablation/destruction of the matrix

|

Low GRADE |

There may be no difference in recurrence, pain and postoperative infection between different types of destruction of the matrix.

Sources: (Álvarez-Jiménez, 2011; Flores, 2006) |

|

- GRADE |

Current literature on different types of destruction of the matrix for ingrown toenails did not report on regrowth, patient global assessment/patient satisfaction, (work) participation, or healing time. |

Surgical interventions with pre-/postoperative treatment versus surgical interventions without pre/postoperative treatment

|

Low GRADE |

There may be no effect of postoperative antibiotic treatment on recurrence, pain and infection of ingrown toenails.

Sources: (Bos, 2006; Reyzelman, 2000) |

|

- GRADE |

Current literature on surgical interventions with or without pre-/postoperative treatment for ingrown toenails did not report on regrowth, patient global assessment/patient satisfaction, (work) participation, or healing time. |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

All studies were comparative studies, with the exception of 1 study in the review, which was a within-patient trial. The study sizes varied from 31 to 424 participants. Most studies compared 2 interventions. Due to the nature of the pathology and interventions, placebo or dummy treatments were not included. The various studies used different primary and secondary outcome measures, and the exact quantifications of the outcomes were not always provided in the publications. For pooling of similar types of interventions, the categories used by Eekhof (2012) were used. Twenty-seven studies reported recurrence as an outcome, 17 studies measured postoperative pain and 13 studies used infection as an outcome measure.

Results

Due to the wide range of interventions described, the results are presented per intervention category/comparison (only those comparisons that are currently of clinical relevance according to the working group), and subsequently per outcome measure. Patient populations overall were similar, with in some studies certain particular groups like teenagers (Kormaz, 2013) or males in military service (Kim, 2015). Generally, no information was provided about which medical professional performed the intervention.

Surgical versus non-surgical interventions

Recurrence (critical)

Comparisons between surgical and non-surgical interventions should be made with caution, since the classification “non-surgical” was not always consistent between studies/countries. Contrary to the clustering by Eekhof (2012), gutter treatment was considered surgical in three studies (Peyvandi, 2011; Ceren, 2013; AlGhamdi, 2014), because the treatment involved anesthesia, asepsis, tissue resection and/or manipulation of the nail matrix with surgical instrumentation. In the only study comparing non-surgical with surgical treatment, i.e. orthonyxia (orthesis) (8/51 recurrences) versus partial matrix excision (4/58 recurrences), the RR of recurrence was 0.89 (95% CI 0.77 to 1.04) in favour of surgical intervention (Kruijff, 2008). No quantitative data was reported for post-treatment pain, adverse events and other outcomes for the comparison between surgical versus non-surgical interventions.

Surgical gutter treatment versus other surgical treatment

Recurrence (critical)

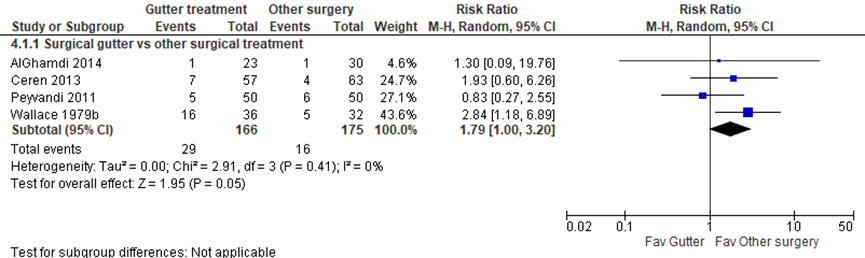

Comparing surgical plastic gutter treatment (i.e. gutter treatment that involved anesthesia, asepsis, tissue resection and/or manipulation of the nail matrix with surgical instrumentation) (n= 166) and other surgical treatments (n=175), the mean relative risk (RR) of recurrence in 4 studies was 1.79 (95% confidence interval (CI) 1.00 to 3.20), favoring other surgical interventions, as presented in figure 1 (Wallace, 1979; Peyvandi, 2011; Ceren, 2013; AlGhamdi, 2014). Notably, there was some variation in the symptom severity of included patients. Peyvandi (2011) included patients aged 12 to 50 with a stage III (“Amplified symptoms, granulation tissue, marked fold hypertrophy”) ingrown toenail of hallux referred to the general surgery ward. In the study of Ceren 2013, the majority of patients had a stage III ingrown toenail (n=33, (57.9%) in the non-surgical group and n=39 (61.9%) in the surgical group). In the study of AlGhamdi (2014) participated patients with stage II and stage III ingrown toenails. Twenty-one of 46 (45.6%) patients previously received some conservative treatment for the ingrown toenail. Twelve of these 21 patients previously underwent partial or complete avulsion. In the study by Wallace (1979) patients aged 11 till 36 had stage II to III ingrown toenails with “pain, swelling, discharge, and obvious granulation tissue present in the nail groove”.

Figure 1 Recurrence after surgical gutter treatment versus other surgical treatment

Z: p-value of pooled effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval

Pain (critical)

The duration (AlGhamdi, 2014) and severity (Ceren, 2011) of postoperative pain were described, and no statistically significant differences between treatments were found. Unfortunately, no values or SDs were provided.

Adverse events: postoperative infection (important)

One study (Peyvandi, 2011) showed that quantified infection was not statistically significant different between surgical plastic gutter treatment (8%) and other surgical treatment (6%) (n=100, RR 1.33, 95% CI 0.31 to 5.65).

Surgical procedures alone versus surgical procedures plus destruction of the matrix

Recurrence (critical)

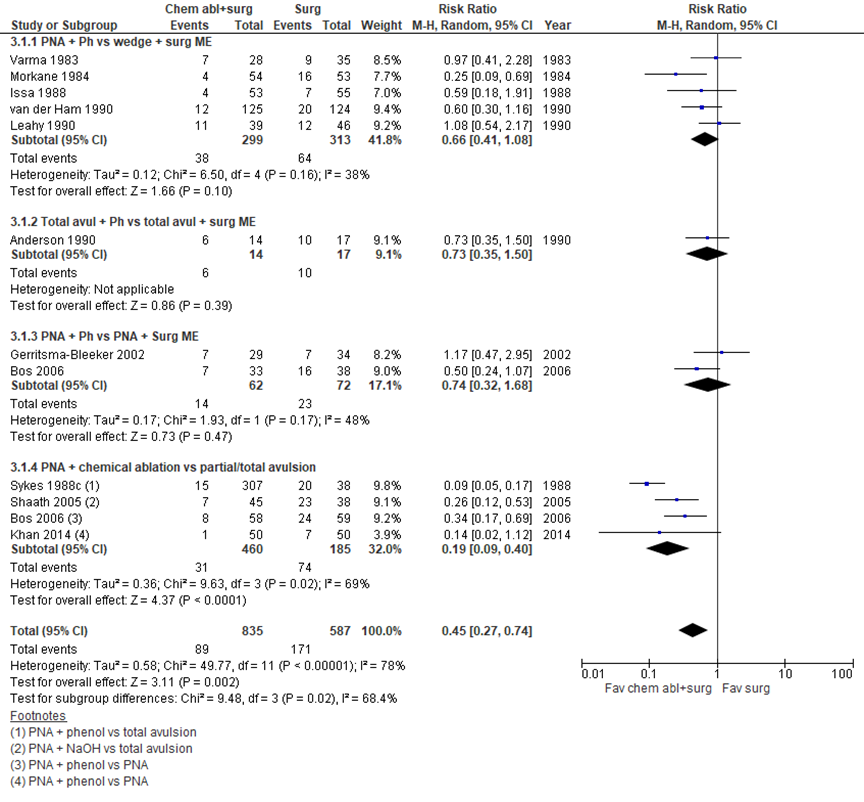

Several studies compared a surgical procedure with and without chemical ablation or other destruction of the matrix (figure 2). Five studies compared partial nail avulsion with phenol application (38/299 (12.7%) recurrences) with wedge treatment and surgical matrix excision (64/313 (20%) recurrences). These studies showed a pooled RR of 0.66 (95% CI 0.41 to 1.08) in favor of the intervention with chemical ablation, but this estimate was not statistically significant (Varma, 1983; Morkane, 1984; Issa, 1998; Van der Ham, 1990; Leahy, 1990). There was no difference in recurrence in a study by Anderson 1990, comparing total avulsion plus phenol (6/14) and total avulsion plus matricectomy (10/17), with a RR of 0.73 (95% CI 0.35 to 1.50). Two studies comparing partial nail avulsion with phenol or matricectomy found no statistically significant differences with a RR of 0.74 and a 95% CI from 0.32 to 1.68 (Gerritsma-Bleeker, 2002; Bos, 2006). In the comparison between partial nail avulsion combined with chemical ablation (6%, 31/460) and partial or total avulsion without ablation (40%, 74/185), the RR of recurrence was 0.19 (95% CI 0.09 to 0.40) in favor of an intervention with ablation (Sykes, 1988; Shaath, 2005; Bos, 2006; Khan, 2014). This difference was clinically relevant. The weighted RR of all these interventions combined is 0.45 in favor of surgical treatment plus chemical ablation, with a confidence interval from 0.27 to 0.74. This difference was also clinically relevant.

Figure 2 Recurrence after surgical procedures with chemical or surgical matrix destruction.

Z: p-value of pooled effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval

Although only two studies (Bos, 2006; Khan, 2004) directly compared the same surgical procedure (partial nail avulsion) with versus without phenol application, by clustering the data (table 1), we found that recurrence after treatments with chemical ablation is lower than after intervention without chemical ablation. No statistically significant differences in recurrence rates between chemical and surgical matrix destruction were found.

Table 1 Summary of the effect of chemical matrix destruction on recurrence

|

Favored intervention |

Control |

Statistical difference |

Clinical relevant difference? |

References |

|

Interventions with chemical matrix destruction versus (other) interventions without chemical matrix destruction |

||||

|

Partial nail avulsion + phenol |

Partial nail avulsion |

Significant |

yes |

Bos, 2006; Khan, 2004 |

|

Partial nail avulsion + sodium hydroxide |

Total avulsion |

Significant |

yes |

Shaath, 2005 |

|

Partial nail avulsion + phenol |

Total avulsion |

Significant |

yes |

Sykes, 1988 |

|

Interventions with chemical matrix destruction versus (other) interventions with surgical matrix destruction |

||||

|

Partial nail avulsion + phenol |

Wedge + surgical matrix excision |

Not significant |

no |

Varma, 1983; Morkane, 1984; Issa, 1988; Leahy, 1990; Van der Ham, 1990 |

|

Total avulsion + phenol |

Total avulsion + surgical matrix excision |

Not significant |

no |

Anderson, 1990 |

|

Partial nail avulsion + phenol |

Partial nail avulsion + surgical matrix excision |

Not significant |

no |

Gerritsma-Bleeker, 2002; Bos, 2006 |

Pain (critical)

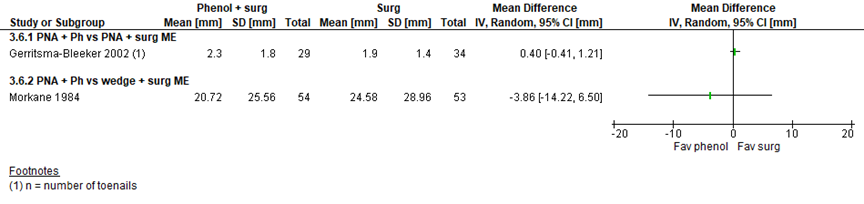

There was no statistically significant difference in postoperative pain (figure 3) as assessed by a VAS in the study by Gerritsma-Bleeker (2002), when partial nail avulsion (PNA) and phenol was compared to PNA and matrix excision (MD 0.40, 95% CI -0.41 to 1.21), or in the study by Morkane (1984) when PNA and phenol was compared with wedge excision and matricectomy (MD -3.86, 95% CI -14.22 to 6.50).

Figure 3 Pain score after surgical procedures with chemical or surgical matrix destruction

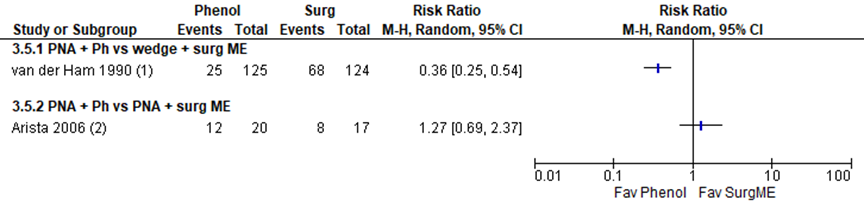

When phenol was added to the surgical intervention, there was significantly less postoperative analgesic used in the phenol group (van der Ham, 1990: RR 0.36, 95% CI 0.25 to 0.54). However, there was no statistically significant difference in postoperative analgesic use in the 2 groups in the study by Arista from 2006 (RR 1.27, 95% CI 0.69 to 2.37), as presented in figure 4.

Figure 4 Analgesic use after surgical procedures with or without matrix destruction

Patient satisfaction

Patient satisfaction (“yes” or “no”) after total avulsion and phenol treatment or total avulsion and matricectomy was not different with a RR of 0.40 and a 95% CI from 0.02 to 9.12 (Anderson 1990).

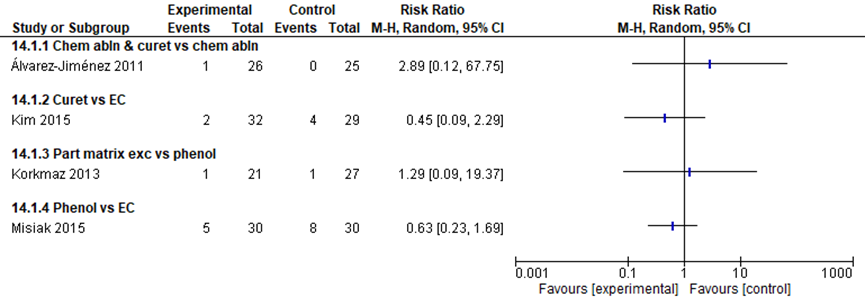

Different types of matrix destruction

Recurrence (critical)

No statistically significant differences in recurrence were observed in 4 studies that directly compared different types of matrix destruction, as depicted in figure 5. The number of recurrences were low (range 0 till 8).

Figure 5 Recurrence after different types of matrix destruction

Curet = curettage; EC = electrocauterisation

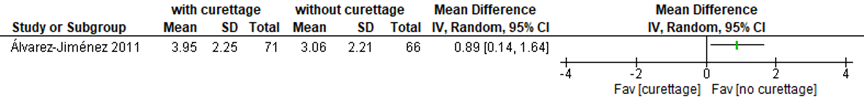

Pain (critical)

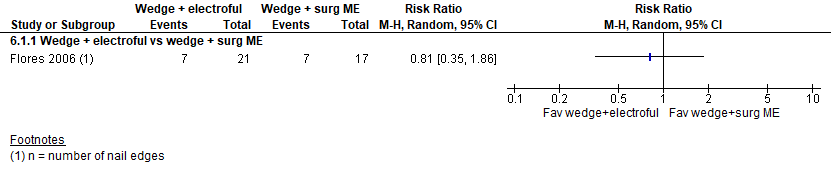

The mean difference in pain score 2 days postoperatively (VAS 0 to 10) was 0.89 (95% CI 0.14 to 1.64) favoring phenol application without curettage (mean VAS 3.06 ± 2.21) over phenol application with curettage (mean VAS 3.95 ± 2.25) (Álvarez-Jiménez, 2011). Although the difference was statistically significant, it was not clinically relevant (difference < 2 points) (Figure 6). The addition of electrofulguration to a surgical intervention did not significantly reduce postoperative pain (“yes” versus “no”; RR 0.81, CI 0.35 to 1.86) in one study (Flores, 2006) (Figure 7).

Figure 6 Postoperative pain score after different types of matrix destruction

Figure 7 Postoperative pain after different types of matrix destruction

Surgical interventions with pre-/postoperative treatment versus surgical interventions without pre/postoperative treatment

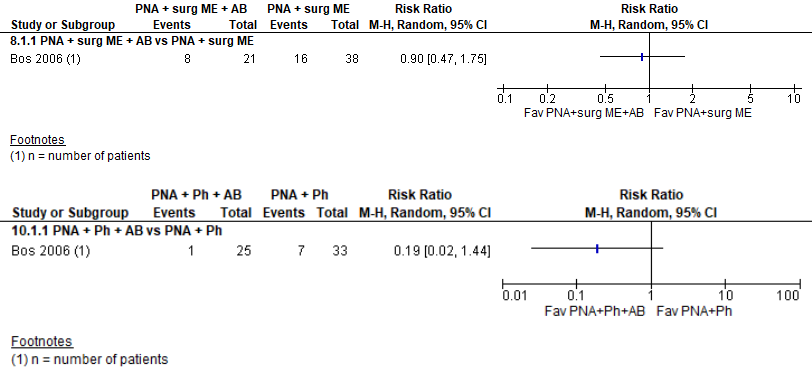

Recurrence (critical)

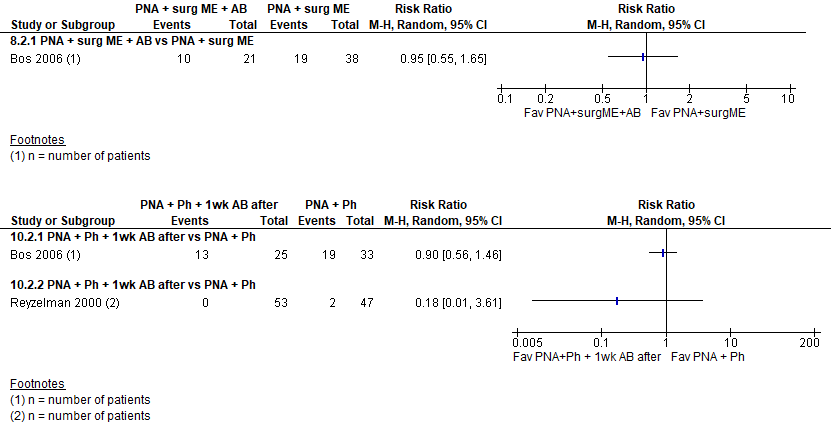

In the study by Bos (2006), antibiotic treatment was combined with various surgical interventions. No statistically significant differences in recurrence rates were found between interventions with or without antibiotic therapy, as presented in figure 8. The RR was not statistically significant lower after:

- PNA and surgical matrix excision (ME) without antibiotic treatment versus antibiotic treatment (38.1% versus 42.1%, RR 0.90, 95% CI 0.47 to 1.75).

- PNA and phenol with antibiotics versus without antibiotics (4% versus 21.2%, RR 0.19, 95% CI 0.02 tot 1.44).

It should be noted that recurrence rates in the study by Bos (2006) were considerably higher than in other studies.

Figure 8 Recurrence with or without postoperative treatment

Adverse events: postoperative infection (important)

The four studies that compared postoperative infection after treatment with and without antibiotic therapy found no statistically significant differences between the groups (figure 9).

Figure 9 Postoperative infection with or without postoperative treatment

Level of evidence of the literature

All trials had numerous methodological flaws and were considered at high risk of bias. Most studies did not describe their randomization methods. Moreover, all trials were at high risk of performance bias. Due to the nature of the intervention and control treatment, neither treatment providers nor participants could be blinded, which does not affect the outcome recurrence, but could introduce bias for the other outcomes like pain. Not many studies compared the same interventions or used the same outcome measures. Most studies did not have a published study protocol and the reporting of critical and important outcome measures was limited. In addition, information such as standard deviations (SDs) was not reported in some of the studies.

Surgical versus non-surgical treatment of ingrown toenails

Starting from a high quality level for RCTs, the level of evidence for the outcome measure ‘recurrence’ was downgraded with 1 level for study limitations (risk of bias) and 2 levels for the low number of patients and events (serious imprecision), resulting in a very low level of evidence. We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect.

Different types of surgical procedures

Starting from a high quality level for RCTs, the level of evidence for the outcome measures ‘recurrence’, ‘pain’ and ‘infection’ were downgraded with 1 level for study limitations (risk of bias) and 2 levels for the limited number of included patients and the low number of events (serious imprecision), resulting in a very low level of evidence. We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect.

For all other combinations of outcomes and comparisons, the level of evidence was downgraded by 2 levels because of study limitations (risk of bias) and either conflicting results (inconsistency) or the limited number of included patients (imprecision). The level of evidence for these outcome measures was considered low. Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect.

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question:

What are the effects of treatments for ingrown toenails?

P (patients): patients with ingrown toenails;

I (intervention): surgical or nonsurgical intervention;

C (control): control, i.e. sham or alternative intervention;

O (outcome measure): recurrence, regrowth, pain/discomfort/symptoms, adverse events/complications, patient global assessment/patient satisfaction, (work) participation, healing time.

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered recurrence (regrowth with pain) and (post-operative) pain as critical outcome measures for decision making, while considering adverse events (including infection), patient global assessment and work/hobby participation as important outcome measures for decision making. Finally, healing time was taken into consideration.

The working group defined the outcome measures as follows:

- Recurrence of the ingrown toenail: regrowth with pain, measured after a minimum period of follow-up of six months.

- Regrowth: including nailspikes and spicules as measured after a minimum period of follow-up of six months.

- Pain intensity as measured by visual analogue scale (VAS, with 0 indicating no pain and 100 indicating extremely intense pain), verbal rating scale (VRS) or numerical rating scale (NRS, 0 = no pain; 10 = severe pain).

- Adverse events: all negative effects related to the treatment.

- Patient global assessment: patient satisfaction as reported by the patient.

- (Work) Participation: participation in school, work, informal care.

- The working group did not define the outcome measure ‘healing time’ but used the definition used in the studies.

The working group defined a decrease (difference) of

- 25% recurrences;

- 20 or more points on a VAS (scale from 0 to 100mm) or 2 points on a NRS (scale from 0 to 10) (Olsen, 2018) as a minimal clinically (patient) important difference.

The working group decided to focus on the following comparisons: Non-surgical versus surgical procedures; different types of surgical procedures; surgical procedures alone versus surgical procedures plus destruction of the matrix; different types of matrix destruction (surgical matrix destruction (synonyms: surgical matrix excision, partial matrix excision, matricectomy, curettage or electrocauterisation) versus chemical matrix destruction (synonyms: chemical ablation, phenol application)); surgical interventions with pre- or postoperative treatment versus surgical interventions without pre- or postoperative treatment.

Search and select (Methods)

In an orienting search a published systematic review was found (Eekhof, 2012). This Cochrane review answered the PICO and the working group decided to contact the first author and ask whether an update of this review was available for the working group. This was the case and in February 2019, the working group added the new RCTs to be included in the upcoming update of the Cochrane review.

The Cochrane review included RCTs for the treatment of ingrown toenails (and for the synonyms ’unguis incarnatus’ and ’onychocryptosis’). Randomised trials comparing postoperative treatment were also included. The studies minimum follow-up period was one month.

Results

The Cochrane review by Eekhof published in 2012 included 24 studies with in total 2.826 participants. Eleven studies with a total of 836 participants were added. Important study characteristics and results of these studies are summarized in the evidence table. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias table.

Referenties

- AlGhamdi KM, Khurram H. Nail tube splinting method versus lateral nail avulsion with phenol matricectomy: a prospective randomized comparative clinical trial for ingrown toenail treatment. Dermatological Surgery 2014;40(11):1214-20.

- Álvarez-Jiménez J, Córdoba-Fernández A, Munuera PV. Effect of curettage after segmental phenolization in the treatment of onychocryptosis: a randomized double-blind clinical trial. Dermatological Surgery 2012;38(3):454-61.

- André MS, Caucanas M, André J, Richert B. Treatment of ingrowing toenails with phenol 88% or trichloroacetic acid 100%: A comparative, prospective, randomized, double-blind study. Dermatological Surgery 2018;44(5):645-50.

- Becerro de Bengoa Vallejo R, Losa Iglesias ME, Cervera LA, et al. Efficacy of intraoperative surgical irrigation with polihexanide andnitrofurazone in reducing bacterial load after nail removal surgery. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology 2011;64(2):328-35.

- Ceren E, Gokdemir G, Arikan Y, et al. Comparison of phenol matricectomy and nail-splinting with a flexible tube for the treatment of ingrown toenails. Dermatological Surgery 2013;39(8):1264-9.

- Eekhof JA, Van Wijk B, Knuistingh Neven A, et al. Interventions for ingrowing toenails. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(4):CD001541.

- Khan IA, Shah SF, Waqar SH, et al. Treatment of ingrown toe nail-comparison of phenolization after partial nail avulsion and partial nail avulsion alone. Journal of Ayub Medical College Abbottabad 2014;26(4):522-5.

- Kim M, Song IG, Kim HJ. Partial removal of nail matrix in the treatment of ingrown nails: prospective randomized control study between curettage and electrocauterization. International Journal of Lower Extremity Wounds 2015;14(2):192-5.

- Korkmaz M, Cölgeçen E, Erdo an Y, et al. Teenage patients with ingrown toenails: treatment with partial matrix excision or segmental phenolization. Indian Journal of Dermatology 2013;58(4):327.

- Misiak P, Terlecki A, Rzepkowska-Misiak B, Wcis o S, Brocki M. Comparison of effectiveness of electrocautery and phenol application in partial matricectomy after partial nail extraction in the treatment of ingrown nails. Polski Przeglad Chirurgiczny 2014;86(2):89-93.

- Peyvandi H, Robati RM, Yegane RA, Hajinasrollah E, Toossi P, Peyvandi AA, et al. Comparison of two surgical methods (Winograd and sleeve method) in the treatment of ingrown toenail. Dermatologic Surgery 2011;37(3):331-5.

- Tatlican S, Yamangöktürk B, Eren C, et al. Comparison of phenol applications of different durations for the cauterization of the germinal matrix: an efficacy and safety study. Acta Orthopaedica et Traumatologica Turcica 2009;43(4):298-302.

Evidence tabellen

Evidence table for systematic review of RCTs and observational studies (intervention studies)

Research question: What is the best treatment for an ingrown toenail?

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C) |

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

New studies, as indicated by the authors, to be added to the Cochrane review by Eekhof, 2012 (currently comprising24 studies with a total of 2826 participants) |

SR and meta-analysis of (RCTs / comparative intervention studies)

Literature search up to January 2019:

A: AlGhamdi, 2014 B: Álvarez-Jiménez, 2011 C: André, 2018 D: Becerro de Bengoa Vallejo, 2010 E: Ceren, 2013 F: Khan, 2014 G: Kim 2015 H: Korkmaz, 2013 I: Misiak, 2015 J: Peyvandi, 2011 K: Tatlican, 2009

Study design: RCT

Setting and Country: Single- (or B: dual-) center studies from Turkey 3x, Spain 2x, Belgium, Saudi Arabia, Pakistan, Korea, Poland, Iran.

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: The authors have indicated no significant interest with commercial supporters, except in F, I, K, where no statement was included. Indicated funding: J was funded by the Skin Research Center, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences. |

Inclusion criteria SR: randomised controlled trials for the treatment of ingrown toenails (and for the synonyms ’unguis incarnatus’ and ’onychocryptosis’). Randomised trials comparing postoperative treatment were also included. The studies must have had a follow-up period of at least one month. We included men and women of any age who required a treatment for ingrown toenail(s). No exclusion criteria were specified.

Important patient characteristics at baseline: 11 additional studies with in total 836 patients, both male and female, from 11 to 64 years of age.

N, mean age A: 53 patients, 27.7 ± 1.3 yrs, 87.8% male. B: 51 patients, 152 hallux nail folds, 34 ± 19 yrs, 35% male. C: 84 patients, 96 hallux nail folds, 36 ± 19 yrs, 49% male. D: 71 patients, 37.09 ± 14.01 yrs, 42% male. E: 107 patients, 120 ingrown toenails, median 18 (11-65) yrs, 55% male. F: 100 patients, mean 18 (14-45) yrs, 69% male. G: 61 patients, mean 20.2 (19-28) yrs, 100% male (military service cohort) H: 39 patients, 16.1 ± 1.9 yrs in group 1, 17.0 ± 1.0 yrs in group 2, 72% male (teenagers). I: 60 patients, 41.42 ± 9.95 (26-64) yrs, 53% male J: 100 patients, 100 hallux nail folds, mean 27.8 (12-47) yrs, sex distribution not described. K: 110 patients, 148 hallux nail folds, 31.9±7.9 yrs group 1, 31.6±10.2 yrs group 2, 32.7±9.6 yrs group 3, 49% male

No significant differences were found between groups at baseline. |

Surgical vs non-surgical (sleeve) procedures: A: Lateral Nail Avulsion With Phenolization E: Partial nail extraction with phenol matricectomy J: Winograd method

Surgical procedures alone versus surgical procedures plus ablation: F: phenolization after partial nail avulsion

Different types of matrix destruction: B: Phenolization with curettage C: Phenol 88% G: Curettage H: Partial matrix excision I: Phenolization K: Phenolization for 2 minutes OR 3 minutes

Other: D: intraoperative antiseptic irrigation with 0.2% nitrofurazone OR 0.1% polihexanide

|

A: Nail Splinting/Sleeve

E: Nail-splinting using a flexible tube J: Sleeve procedure

F: partial nail avulsion without phenolization

B: Phenolization without curettage C: Trichloroacetic Acid 100% G: Electrocauterization H: Segmental phenolization I: Electrocauterization K: Phenolization for 1 minute

D: intraoperative antiseptic irrigation with 0.9% saline solution

|

End-point of follow-up:

A: 6 months

E: 6 months

J: 6 months

F: 6 months

B: 1 month

C: 4 months G: 6 months H: 2.1 ± 0.9 years I: 3 months K: 2 years

D: study set-up describes a follow-up of 9 months, but all reported outcome measures are measured within 1 week from the intervention.

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? (intervention/control) Incomplete outcome data was not described or specified. |

Outcome measure-1 Recurrence (critical) - No significant differences in recurrence between surgical and non-surgical. A: Recurrence avulsion with phenolization 3%, sleeve 4%, not significant. E: 12.2% in the splint group vs 6.3% in the phenol group, not significant. J: Recurrence was similar between groups, with 12% after Winograd and 10% with the sleeve method.

- With/without ablation: F: With phenolization, recurrence was 1%, without 4%, p=0.027.

- Different types of matrix destruction have not resulted in significant differences B: with curettage 1 recurrence, without curettage no recurrence: RR 2.89, CI 0.12-67.75 C: No recurrence in either group. G: After curettage 6.2% recurrence, after electrocauterization 13.8%, p=0.411 – RR 0.45, CI 0.09-2.29 H: 5.9% recurrence after partial matrix excision vs 4.5% after phenolization, p=0.688. RR 1.29, CI 0.09-19.37. I: after phenolization there was 16.7% recurrence vs 26.7% after electrocautery, p=0.35. RR 0.63, CI 0.23-1.69. In diabetic patients (23.3% in both groups) recurrence was higher, with 57.14% in the phenol group vs 71.43% in the EC group, but no statistical analysis was described. K: Phenol application for 1, 2 and 3 minutes resulted in 12.5%, 3.9% and 2.1% recurrence, resp (p=0.092).

D: not reported.

Outcome measure-2 Pain (critical) - No significant differences in pain between nail extraction and sleeve. A: nails avulsion + phenol postoperative pain 29.48 hours vs 21.91 hours after sleeve, no SD reported, not significant. Postoperative shoe-wear discomfort after avulsion 29.56 hours vs 14.89 after sleeve, p<0.001. E: Postoperative pain scores (VAS) were significantly lower than preoperative scores in both groups, with no differences between groups (values not reported). J: not reported.

With/without ablation: F: Patients in phenol group experienced less pain (VAS) as compared to nail avulsion alone group at 3rd day, p=0.018. No differences at day 7.

- Different types of matrix destruction were associated with low pain scores with limited to no differences between interventions. B: With curettage higher VAS score of 3.95 ± 2.25, control 3.06 ± 2.21, p=0.028 C: Linear regression with limited number of observations showed differences between treatments. After TCA, patients report higher initial pain (VAS), but with a faster reduction than phenol. G: not reported. H: None of the patients reported severe pain (VAS). 17.6% of patients experienced moderate pain after partial matrix excision vs 9.0% of phenol-treated patients (p>0.05). I: not reported. K: Phenol application for 1, 2 and 3 minutes resulted in 1.4 ± 1.4, 1.1 ± 1.2 and 1.3 ± 1.3 days of pain, resp. (not significant).

D: not reported

Outcome measure-3 Inflammation/infection (important) - No significant differences in infection reported between nail extraction and sleeve. A: not reported. E: not reported. J: Infection was 6% in the Winograd groups vs 8% in the sleeve group, not significant.

- With/without ablation: F: Infection present in 12% of patients in phenol group, and 4% in nail avulsion (p=0.029)

- Different types of matrix destruction/ablation have an inconsistent effect on infection rates: B: With curettage 2.7%, control 16.5%, Yates chi-squared test p = 0.010 C: 2-week inflammation after TCA 62.1% vs 45.7% phenol, p=0.523; 4-week 45.5% vs 16.7%, p=0.036. No inflammation at 4 months. G: Infection after curettage 15.6% vs 10.3% after electrocauterization, p=0.710. H: no infection was seen in either group. I: not reported. K: not reported.

D: Pretreatment minus posttreatment inocula after Nitrofurazone 2.07 ± 0.84, Polihexanide 2.37 ± 1.19, saline 2.34 ± 0.80. After surgery minus after irrigation solution inocula after Nitrofurazone 1.74 ± 0.91 (96.6%), Polihexanide 2.81 ± 0.95 (99.5%), saline 1.63 ± 1.00 (95.2%).

Outcome measure-4 Healing/healing time - No significant differences in healing time between nail extraction and sleeve. A: The healing period ranged from 1 to 2 weeks, nothing specified for groups. E: tissue damage (scored 0-3) after 2 days improved 93% in the splint group and 6% in the phenol group, p<0.001. Recovery rates at 6 months were 88% with splints and 94% with phenol (p>0.05). No SD given. J: postoperative work day loss was 2.0 weeks for the Winograd group vs 1.1 week in the sleeve group, p<0.001. no SD.

- With/without ablation: F: not reported

- Phenolization accelerates healing (but shorter exposure is better), and curettage seems to have an additional positive effect. B: With curettage healing time was 7.49 ± 1.76 days vs 12.38 ± 3.01 days after phenol only, p = 0.001. C: not reported. G: not reported. H: Return to work after partial matrix excision 12.8 ± 1.0 days, after phenol 3.0 ± 1.2 days p<0.001. I: Healing time >10 days was 66.7% in the phenol group vs 90.0% in the EC group, p=0.02. OR: 4.5, 95% CI: 1.09-18.50. K: Phenol application for 1, 2 and 3 minutes resulted in 13.5 ± 3, 17.5 ± 2.8, and 17.1 ± 2.6. days until healing completed, resp. Application of 2 and 3 minutes were significantly different from 1 minute (p<0.001), but not from each other.

D: not reported.

Outcome measure-5 Postoperative bleeding/drainage/oozing - No significant differences in bleeding/drainage reported between nail extraction and sleeve. A: drainage after surgery 26.43 vs 22.92 hours with sleeve, no SD reported, not significant. E: Not reported. J: not reported.

- With/without ablation: F: not reported.

Additional treatment and longer exposure to phenol increase postoperative bleeding. B: Curettage after phenolization increased postoperative abundant bleeding to 42.9% vs 5.4% in controls, p < .001. C: 2-week postop oozing in TCA 77.8% vs 35.1%, 4-week oozing 39.4% vs 9.4%, p<0.01. No oozing at 4 months. G: not reported. H: not reported. I: not reported. K: Phenol application for 1, 2 and 3 minutes resulted in 12.6 ± 4.0, 16.4 ± 4.0 and 16.1 ± 3.5. days of drainage, resp. Application of 2 and 3 minutes were significantly different from 1 minute (p<0.001), but not from each other.

D: not reported. |

Levels of evidence:

Surgical vs non-surgical: High quality level for RCT, however, significant risk of bias and imprecision.

Surgical procedures alone versus surgical procedures plus ablation: High quality level for RCT, however, significant risk of bias.

Different types of matrix destruction: High quality level for RCT, however, significant risk of bias and inconsistency of the data. |

Risk of bias table for intervention studies (randomized controlled trials)

Research question: What is the best treatment for an ingrown toenail?

|

Study reference

(first author, publication year) |

Describe method of randomisation |

Bias due to inadequate concealment of allocation?

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate blinding of participants to treatment allocation?

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate blinding of care providers to treatment allocation?

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate blinding of outcome assessors to treatment allocation?

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to selective outcome reporting on basis of the results?

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to loss to follow-up?

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to violation of intention to treat analysis?

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

|

AlGhambi, 2014 |

Not reported. |

Unclear, not specified. |

Likely, presence of splint cannot be concealed |

Likely, the techniques are completely different. |

Likely, outcome measures are soft and blinding is not reported. |

Likely, several outcome measures are described but not systematically quantified in the results. |

Unlikely, no loss to follow up (described). |

Not reported, but unlikely due to the nature of the invention. |

|

Álvarez-Jiménez, 2011 |

Treatment of the two groups was randomized intraoperatively by drawing a numbered ball from a bag. |

Unlikely. |

Unlikely, all wounds were dressed equally. |

Unlikely, apart from initial surgery, follow-up standard wound care would not be affected by treatment allocation. |

Unlikely, observers blinded to treatment allocation evaluated clinical efficacy and adverse effects. |

Unlikely, all outcome parameters described in the methods are reported in the results. |

Likely, there was an dissimilar loss between the groups: of the 152 nail folds, 13 (16.5%) of the control group and two (2.7%) of the experimental group were excluded from completion of the study because they presented a clinical pattern of postoperative infection. |

Not reported, but unlikely due to the nature of the invention. |

|

André, 2018 |

Not described. |

Unlikely. |

Unlikely, patients were blinded to the intervention. |

Likely, the surgeon could not ignore the cauterant used because of the characteristic smell of phenol. |

Unlikely, postoperative evaluation was performed both by an observer and by the patient, who were both blinded to the treatment. |

Unlikely, all outcome parameters described in the methods are reported in the results. |

Likely, loss to follow-up is considerable and dissimilar with 10.9% vs 16.0% in the treatment groups. |

Not reported, but unlikely due to the nature of the invention. |

|

Becerro de Bengoa Vallejo, 2010 |

Not specified. |

Unlikely. |

Unlikely. |

Unclear, not specified. |

Samples were blinded before analysis. |

Unlikely, all outcome parameters described in the methods are reported in the results. |

Unlikely. The authors describe 6.6% loss to follow-up, but it is unclear at which phase. However, the reported parameters are all acquired perioperatively. |

Not reported, but unlikely due to the nature of the invention. |

|

Ceren, 2013 |

Not described. |

Unclear. |

Likely, blinding of participants was not possible due to the difference of the interventions. |

Likely, during initial wound care the different interventions were discernible. |

Unclear whether outcome assessors were blinded for later scoring of the soft outcome parameters. |

Likely, one of the two outcome measures was described but quantifications were not presented. |

Unclear, loss to follow-up was not described. |

Not reported, but unlikely due to the nature of the invention. |

|

Khan, 2014 |

Random allocation with the “lottery method”. |

Likely, the study was not blinded. |

Likely, study was not blinded. |

Likely, study was not blinded. |

Likely, study was not blinded. |

Unlikely, all outcome parameters described in the methods are reported in the results section. |

Unclear, loss to follow-up was not described. |

Not reported, but unlikely due to the nature of the invention. |

|

Kim 2015 |

Patients were randomly allocated to 2 treatment groups “in a 1:1 ratio by using permuted block randomization with a size-4 block”. |

Likely, the study was not blinded. |

Likely, the study was not blinded. |

Likely, the study was not blinded. |

Likely, the study was not blinded. |

Unlikely, all outcome parameters described in the methods are reported in the results section. |

Unlikely. Even though loss to follow-up was high, partly due to retirement from military service, this affected both treatment groups similarly. |

Not reported, but unlikely due to the nature of the invention. |

|

Korkmaz, 2013 |

Not described. |

Likely, the study was not blinded. |

Likely, the study was not blinded. |

Likely, the study was not blinded. |

Likely, the study was not blinded. |

Unlikely, all outcome parameters described in the methods are reported in the results section. |

Unclear, loss to follow-up was not described. |

Not reported, but unlikely due to the nature of the invention. |

|

Misiak, 2015 |

Not described. |

Likely, the study was not blinded. |

Likely, the study was not blinded. |

Likely, the study was not blinded. |

Likely, the study was not blinded. |

Unlikely, all outcome parameters described in the methods are reported in the results section. |

Unclear, loss to follow-up was not described. |

Not reported, but unlikely due to the nature of the invention. |

|

Peyvandi, 2011 |

patients were randomly assigned to one of two groups using convenience sampling |

Likely, the study was not blinded. |

Likely, the study was not blinded. |

Likely, the study was not blinded. |

Likely, the study was not blinded. |

Likely, outcome parameters were not identified in the methods section. |

Unclear, loss to follow-up was not described. |

Not reported, but unlikely due to the nature of the invention. |

|

Tatlican, 2009 |

Not described. |

Likely, the study was not blinded. |

Likely, the study was not blinded. |

Likely, the study was not blinded. |

Likely, the study was not blinded. |

Unlikely, all outcome parameters described in the methods are reported in the results section. |

Unclear, loss to follow-up was not described. |

Not reported, but unlikely due to the nature of the invention. |

Table of excluded studies

Not applicable, see Eekhof (2012).

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Publicatiedatum : 27-07-2020

Beoordeeld op geldigheid : 06-05-2020

Voor het beoordelen van de actualiteit van deze richtlijn is de werkgroep niet in stand gehouden. Uiterlijk in 2025 (publicatiedatum plus vijf jaar) bepaalt het bestuur van de Nederlandse Vereniging voor Heelkunde of de modules van deze richtlijn nog actueel zijn. Op modulair niveau is een onderhoudsplan beschreven. Bij het opstellen van de richtlijn heeft de werkgroep per module een inschatting gemaakt over de maximale termijn waarop herbeoordeling moet plaatsvinden en eventuele aandachtspunten geformuleerd die van belang zijn bij een toekomstige herziening (update). De geldigheid van de richtlijn komt eerder te vervallen indien nieuwe ontwikkelingen aanleiding zijn een herzieningstraject te starten.

De Nederlandse Vereniging voor Heelkunde is regiehouder van deze richtlijn en eerstverantwoordelijke op het gebied van de actualiteitsbeoordeling van de richtlijn. De andere aan deze richtlijn deelnemende wetenschappelijke verenigingen of gebruikers van de richtlijn delen de verantwoordelijkheid en informeren de regiehouder over relevante ontwikkelingen binnen hun vakgebied.

|

Module |

Regiehouder(s) |

Jaar van autorisatie |

Eerstvolgende beoordeling actualiteit richtlijn |

Frequentie van beoordeling op actualiteit |

Wie houdt er toezicht op actualiteit |

Relevante factoren voor wijzigingen in aanbeveling |

|

Behandeling ingegroeide teennagel |

NVVH |

2020 |

2025 |

Eens per 5 jaar |

NVVH |

- |

Algemene gegevens

De richtlijnontwikkeling werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten en werd gefinancierd uit de Stichting Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS). Patiëntenparticipatie bij deze richtlijn werd medegefinancierd uit de Stichting Kwaliteitsgelden Patiënten Consumenten (SKPC) binnen het programma KIDZ. De financier heeft geen enkele invloed gehad op de inhoud van de richtlijn.

Doel en doelgroep

Doel

Het doel van de voorliggende richtlijn is de zorgverlener te adviseren in het maken van een behandelkeuze bij een ingegroeide teennagel.

Doelgroep

De richtlijn is ontwikkeld voor alle zorgverleners in de eerste en tweede lijn die bij de behandeling van patiënten met ingegroeide teennagel betrokken zijn, zoals: huisartsen, chirurgen, dermatologen.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijn is in 2018 een multidisciplinaire werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen.

De werkgroepleden zijn door hun beroepsverenigingen gemandateerd voor deelname.

De werkgroep is verantwoordelijk voor de integrale tekst van deze richtlijn.

Werkgroep

- Dr. G.M. (Gabie) de Jong, chirurg, werkzaam bij Ziekenhuis Gelderse Vallei te Ede, NVvH

- Drs. L. (Leon) Plusjé, dermatoloog, werkzaam bij het Rode Kruis ziekenhuis en Brandwondencentrum te Beverwijk en het Erasmus Medisch Centrum te Rotterdam, NVDV

- Drs. S. (Suzanne) van Putten, waarnemend huisarts/ docent huisartsopleiding, werkzaam bij het UMCU te Zeist, NHG

Met medewerking van

- Prof. dr. E. (Erik) Heineman, chirurg, werkzaam bij het UMCG te Groningen, NVvH (voorzitter richtlijnenproject Algemene Chirurgie)

- Drs. M. (Michiel) van Zeeland, chirurg, werkzaam bij het Ziekenhuis Amstelland, NVvH (vice-voorzitter)

- Drs. K. (Karel) Kolkman, traumachirurg, werkzaam bij Rijnstate te Arnhem, NVvH

- Dr. S. (Steve) de Castro, chirurg, werkzaam bij het OLVG - locatie Oost te Amsterdam, NVvH

- Dr. J. (Jasper) Atema, AIOS chirurgie, werkzaam bij het Amsterdam UMC - locatie AMC te Amsterdam, NVvH

Met ondersteuning van

- Dr. J.S. (Julitta) Boschman, senior adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- E.A. (Ester) Rake, MSc, junioradviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- D.P. (Diana) Gutierrez, projectsecretaresse, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

Belangenverklaringen

De KNMG-code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling is gevolgd. Alle werkgroepleden hebben schriftelijk verklaard of zij in de laatste drie jaar directe financiële belangen (betrekking bij een commercieel bedrijf, persoonlijke financiële belangen, onderzoeksfinanciering) of indirecte belangen (persoonlijke relaties, reputatiemanagement, kennisvalorisatie) hebben gehad. Een overzicht van de belangen van werkgroepleden en het oordeel over het omgaan met eventuele belangen vindt u in onderstaande tabel. De ondertekende belangenverklaringen zijn op te vragen bij het secretariaat van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

|

Werkgroeplid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

Atema |

Arts in opleiding tot specialist (chirurgie) |

Geen |

Geen 4-12-2018 |

Geen |

|

Boschman |

Adviseur |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

|

De Castro |

Chirurg |

Geen |

Geen 18-5-2019 |

Geen |

|

De Jong |

Chirurg |

Lid T1 CRC werkgroep Nederland, onbetaald reviewer NVvH, onbetaald |

Gevraagd als spreker op seminar: 'ingroeiende/ingegroeide nagel', maart 2019. (https://www.asws.nl/congressen/seminar-2018) 4-12-2018 |

Geen |

|

Heineman |

Hoogleraar chirurgie N.P. |

Adviesfunctie Clinical Gouvernance, betaald |

Geen 6-5-2019 |

Geen |

|

Kolkman |

Traumachirurg |

Geen |

Geen 14-12-2018 |

Geen |

|

Van Putten |

Huisartsdocent / Waarnemend Huisarts |

Geen |

Geen 18-12-2018 |

Geen |

|

Van Zeeland |

Algemeen en vaatchirurg |

Geen |

Geen 12-12-2018 |

Geen |

|

Plusjé |

Dermatoloog. Tevens directeur Centrum voor Lipoedeem bv |

Dermatoloog vrijgevestigd en in loondienst (EMC) Directeur/eigenaar Centrum voor Lipoedeem |

Geen 6-11-2018 |

|

|

Rake |

Adviseur |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Er werd aandacht besteed aan het patiëntenperspectief door het uitnodigen van de Patiëntenfederatie Nederland bij de knelpunteninventarisatie (invitational conference). Een verslag hiervan (zie aanverwante producten) is besproken in de werkgroep en de belangrijkste knelpunten zijn verwerkt in de richtlijn. De conceptrichtlijn is tevens voor commentaar voorgelegd aan de Patiëntenfederatie Nederland en Diabetesvereniging Nederland.

Methode ontwikkeling

Evidence based

Implementatie

In de verschillende fasen van de richtlijnontwikkeling is rekening gehouden met de implementatie van de richtlijn en de praktische uitvoerbaarheid van de aanbevelingen. Daarbij is uitdrukkelijk gelet op factoren die de invoering van de richtlijn in de praktijk kunnen bevorderen of belemmeren. Het implementatieplan is te vinden bij de aanverwante producten.

Werkwijze

AGREE

Deze richtlijn is opgesteld conform de eisen vermeld in het rapport Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 van de adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwaliteit. Dit rapport is gebaseerd op het AGREE II instrument (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II; Brouwers, 2010), dat een internationaal breed geaccepteerd instrument is. Voor een stap-voor-stap beschrijving hoe een evidence-based richtlijn tot stand komt wordt verwezen naar het stappenplan Ontwikkeling van Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

Knelpuntenanalyse

Tijdens de voorbereidende fase inventariseerden de voorzitter van de werkgroep en de adviseur de knelpunten ten aanzien van algemeen chirurgische onderwerpen, waaronder ingroeide teennagel. Tevens zijn er knelpunten aangedragen tijdens een invitational conference. Een verslag hiervan is opgenomen onder aanverwante producten.

Uitgangsvragen en uitkomstmaten

Op basis van de uitkomsten van de knelpuntenanalyse zijn door de voorzitter en de adviseur concept-uitgangsvragen opgesteld. Deze zijn met de werkgroep besproken waarna de werkgroep de definitieve uitgangsvragen heeft vastgesteld. Vervolgens inventariseerde de werkgroep per uitgangsvraag welke uitkomstmaten voor de patiënt relevant zijn, waarbij zowel naar gewenste als ongewenste effecten werd gekeken. De werkgroep waardeerde deze uitkomstmaten volgens hun relatieve belang bij de besluitvorming rondom aanbevelingen, als cruciaal (kritiek voor de besluitvorming), belangrijk (maar niet cruciaal) en onbelangrijk. Tevens definieerde de werkgroep tenminste voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten welke verschillen zij klinisch (patiënt) relevant vonden.

Strategie voor zoeken en selecteren van literatuur

Er werd eerst oriënterend gezocht naar systematische reviews (in Medline). Vervolgens werd voor de afzonderlijke uitgangsvragen aan de hand van specifieke zoektermen gezocht naar gepubliceerde wetenschappelijke studies in (verschillende) elektronische databases. Tevens werd aanvullend gezocht naar studies aan de hand van de literatuurlijsten van de geselecteerde artikelen. In eerste instantie werd gezocht naar studies met de hoogste mate van bewijs. De werkgroepleden selecteerden de via de zoekactie gevonden artikelen op basis van vooraf opgestelde selectiecriteria. De geselecteerde artikelen werden gebruikt om de uitgangsvraag te beantwoorden. De databases waarin is gezocht, de zoekstrategie en de gehanteerde selectiecriteria zijn te vinden in de module met desbetreffende uitgangsvraag. De zoekstrategie voor de oriënterende zoekactie en patiëntenperspectief zijn opgenomen onder aanverwante producten.

Kwaliteitsbeoordeling individuele studies

Individuele studies werden systematisch beoordeeld, op basis van op voorhand opgestelde methodologische kwaliteitscriteria, om zo het risico op vertekende studieresultaten (risk of bias) te kunnen inschatten. Deze beoordelingen kunt u vinden in de Risk of Bias (RoB) tabellen. De gebruikte RoB instrumenten zijn gevalideerde instrumenten die worden aanbevolen door de Cochrane Collaboration: AMSTAR - voor systematische reviews; Cochrane - voor gerandomiseerd gecontroleerd onderzoek; Newcastle-Ottowa - voor observationeel onderzoek; QUADAS II - voor diagnostisch onderzoek.

Samenvatten van de literatuur

De relevante onderzoeksgegevens van alle geselecteerde artikelen werden overzichtelijk weergegeven in evidencetabellen. De belangrijkste bevindingen uit de literatuur werden beschreven in de samenvatting van de literatuur. Bij een voldoende aantal studies en overeenkomstigheid (homogeniteit) tussen de studies werden de gegevens ook kwantitatief samengevat (meta-analyse) met behulp van Review Manager 5.

Beoordelen van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs

A) Voor interventievragen (vragen over therapie of screening)

De kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs werd bepaald volgens de GRADE-methode. GRADE staat voor ‘Grading Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation’ (zie http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/).

GRADE onderscheidt vier gradaties voor de kwaliteit van het wetenschappelijk bewijs: hoog, redelijk, laag en zeer laag. Deze gradaties verwijzen naar de mate van zekerheid die er bestaat over de literatuurconclusie (Schünemann, 2013).

|

GRADE |

Definitie |

|

Hoog |

|

|

Redelijk* |

|

|

Laag |

|

|

Zeer laag |

|

*in 2017 heeft het Dutch GRADE Network bepaalt dat de voorkeursformulering voor de op een na hoogste gradering ‘redelijk’ is in plaats van ‘matig’

B) Voor vragen over diagnostische tests, schade of bijwerkingen, etiologie en prognose

De kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs werd eveneens bepaald volgens de GRADE-methode: GRADE-diagnostiek voor diagnostische vragen (Schünemann, 2008), en een generieke GRADE-methode voor vragen over schade of bijwerkingen, etiologie en prognose. In de gehanteerde generieke GRADE-methode werden de basisprincipes van de GRADE-methodiek toegepast: het benoemen en prioriteren van de klinisch (patiënt) relevante uitkomstmaten, een systematische review per uitkomstmaat, en een beoordeling van bewijskracht op basis van de vijf GRADE-criteria (startpunt hoog; downgraden voor risk of bias, inconsistentie, indirectheid, imprecisie, en publicatiebias).

Formuleren van de conclusies

Voor elke relevante uitkomstmaat werd het wetenschappelijk bewijs samengevat in een of meerdere literatuurconclusies waarbij het niveau van bewijs werd bepaald volgens de GRADE-methodiek. De werkgroepleden maakten de balans op van elke interventie (overall conclusie). Bij het opmaken van de balans werden de gunstige en ongunstige effecten voor de patiënt afgewogen. De overall bewijskracht wordt bepaald door de laagste bewijskracht gevonden bij een van de cruciale uitkomstmaten. Bij complexe besluitvorming waarin naast de conclusies uit de systematische literatuuranalyse vele aanvullende argumenten (overwegingen) een rol spelen, werd afgezien van een overall conclusie. In dat geval werden de gunstige en ongunstige effecten van de interventies samen met alle aanvullende argumenten gewogen onder het kopje 'Overwegingen'.

Overwegingen (van bewijs naar aanbeveling)

Om te komen tot een aanbeveling zijn naast (de kwaliteit van) het wetenschappelijke bewijs ook andere aspecten belangrijk en worden meegewogen, zoals de expertise van de werkgroepleden, de waarden en voorkeuren van de patiënt (patient values and preferences), kosten, beschikbaarheid van voorzieningen en organisatorische zaken. Deze aspecten worden, voor zover geen onderdeel van de literatuursamenvatting, vermeld en beoordeeld (gewogen) onder het kopje ‘Overwegingen’.

Formuleren van aanbevelingen

De aanbevelingen geven antwoord op de uitgangsvraag en zijn gebaseerd op het beschikbare wetenschappelijke bewijs en de belangrijkste overwegingen, en een weging van de gunstige en ongunstige effecten van de relevante interventies. De kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs en het gewicht dat door de werkgroep wordt toegekend aan de overwegingen, bepalen samen de sterkte van de aanbeveling. Conform de GRADE-methodiek sluit een lage bewijskracht van conclusies in de systematische literatuuranalyse een sterke aanbeveling niet a priori uit, en zijn bij een hoge bewijskracht ook zwakke aanbevelingen mogelijk. De sterkte van de aanbeveling wordt altijd bepaald door weging van alle relevante argumenten tezamen.

Randvoorwaarden (Organisatie van zorg)

In de knelpuntenanalyse en bij de ontwikkeling van de richtlijn is expliciet rekening gehouden met de organisatie van zorg: alle aspecten die randvoorwaardelijk zijn voor het verlenen van zorg (zoals coördinatie, communicatie, (financiële) middelen, menskracht en infrastructuur). Randvoorwaarden die relevant zijn voor het beantwoorden van een specifieke uitgangsvraag maken onderdeel uit van de overwegingen bij de bewuste uitgangsvraag. Meer algemene, overkoepelende, of bijkomende aspecten van de organisatie van zorg worden behandeld in de module Organisatie van zorg.

Kennislacunes

Tijdens de ontwikkeling van deze richtlijn is systematisch gezocht naar onderzoek waarvan de resultaten bijdragen aan een antwoord op de uitgangsvragen. Bij elke uitgangsvraag is door de werkgroep nagegaan of er (aanvullend) wetenschappelijk onderzoek gewenst is om de uitgangsvraag te kunnen beantwoorden. Een overzicht van de onderwerpen waarvoor (aanvullend) wetenschappelijk van belang wordt geacht, is als aanbeveling in de Kennislacunes beschreven (onder aanverwante producten).

Commentaar- en autorisatiefase

De conceptrichtlijn werd aan de betrokken (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd ter commentaar. De commentaren werden verzameld en besproken met de werkgroep. Naar aanleiding van de commentaren werd de conceptrichtlijn aangepast en definitief vastgesteld door de werkgroep. De definitieve richtlijn werd aan de deelnemende (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd voor autorisatie en door hen geautoriseerd dan wel geaccordeerd.

Literatuur

Brouwers, M. C., Kho, M. E., Browman, G. P., Burgers, J. S., Cluzeau, F., Feder, G., ... & Littlejohns, P. (2010). AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 182(18), E839-E842.

Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 (2012). Adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwalitieit. https://richtlijnendatabase.nl/over_deze_site/richtlijnontwikkeling.html

Ontwikkeling van Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen: stappenplan. Kennisinstituut van Medisch Specialisten.

Schünemann H, Brożek J, Guyatt G, et al. GRADE handbook for grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. Updated October 2013. The GRADE Working Group, 2013. Available from http://gdt.guidelinedevelopment.org/central_prod/_design/client/handbook/handbook.html.

Schünemann, H. J., Oxman, A. D., Brozek, J., Glasziou, P., Jaeschke, R., Vist, G. E., ... & Bossuyt, P. (2008). Rating Quality of Evidence and Strength of Recommendations: GRADE: Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations for diagnostic tests and strategies. BMJ: British Medical Journal, 336(7653), 1106.

Wessels, M., Hielkema, L., & van der Weijden, T. (2016). How to identify existing literature on patients' knowledge, views, and values: the development of a validated search filter. Journal of the Medical Library Association: JMLA, 104(4), 320.

Zoekverantwoording

See Eekhof (2012).