Telemonitoring bij IBD

Uitgangsvraag

What is the effectiveness or non-inferiority of telemonitoring for children and adolescents with IBD compared to standard care?

Aanbeveling

Aanbeveling-1

Overweeg telemonitoring aan te bieden als aanvulling op reguliere poliklinische controle.

Reduceer het aantal face-to-face consultaties indien de bevindingen bij telemonitoring dit toelaten.

Aanbeveling-2

Bespreek de voor- en nadelen van telemonitoring met de patiënt en/of verzorger(s).

Besluit vervolgens samen met de patiënt en/of verzorger(s) of de patiënt deel gaat nemen aan telemonitoring.

De werkgroep adviseert af te zien van telemonitoring indien:

- De patiënt kortgeleden gediagnosticeerd is (het is wenselijk om eerst een vertrouwensband op te bouwen middels enkele face-to-face consulten).

- Er twijfel bestaat of patiënt en/of ouders verzorgers in staat zijn op een juiste manier deel te nemen aan telemonitoring (bijvoorbeeld bij een taalbarrière/taalachterstand of bij therapieontrouw).

- Lichamelijk onderzoek bij iedere controle noodzakelijk danwel wenselijk is (bijvoorbeeld bij actieve perianale ziekte).

- Comorbiditeit (waarvoor geen telemonitoring strategie bestaat).

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Uit dit systematische literatuuroverzicht komt naar voren dat het ziektebeloop van patienten met IBD mogelijk gelijk is, ongeacht of zij conventionele poliklinische zorg of zorg op afstand kregen. Telemonitoring leidt mogelijk tot een kleine verbetering in de kwaliteit van leven. De telemonitoring strategie zal moeten worden afgestemd op lokale mogelijkheden, de specifieke subgroep van de patiënt (bijvoorbeeld recent gediagnosticeerde patiënten of patiënten met actieve ziekte) en wensen en voorkeuren van patiënten en zorgverleners.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

De meeste patiënten die in onderzoeksverband hebben deelgenomen aan telemonitoring, wensten hiermee door te gaan. Of telemonitoring als nuttige toevoeging aan standaardzorg wordt gezien zal per individu verschillen. Het oordeel hangt af van de mate van de tijdswinst en kostenbesparing, het gevoel van grip op het ziekteproces en de wens tot mondeling overleg met het behandelteam.

Aangezien telemonitoring altijd wordt aangeboden naast standaardzorg (en reguliere face-to-face poliklinische bezoeken dus ook zullen blijven bestaan) zullen patiënt, verzorgers en zorgverlener samen moeten beslissen of deelname aan telemonitoring wenselijk is. Hierbij moeten de voor- en nadelen van telemonitoring met de patiënt en/of verzorger(s) worden besproken.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

Vergeleken met standaardzorg, leidt telemonitoring waarschijnlijk tot een vermindering van zorgkosten. Sinds 1 januari 2023 kan telemonitoring als overig zorgproduct add-on worden geregistreerd en gedeclareerd (18).

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

Het implementeren van een telemonitoring strategie als aanvulling op reguliere poliklinische controles is een multidisciplinaire inspanning. Idealiter worden de met telemonitoring verkregen meetgegevens zichtbaar in het bestaande elektronische patiënten dossier (EPD) om extra handelingen (zoals handmatige invoer van meetgegevens) te voorkomen. Bij veel telemonitoringsystemen zal de smartphone van de patiënt gebruikt worden voor gegevensoverdracht. De afdeling ziekenhuis-ICT heeft een belangrijke taak bij het automatiseren van deze gegevensoverdracht en bij de informatiebeveiliging. Telemonitoring kan leiden tot een herverdeling van zorgtaken. Het aantal face-to-face contacten tussen zorgverlener en stabiele patiënten zal verminderen, waardoor er meer mogelijkheden ontstaan om patiënten met een (dreigende) opvlamming sneller voor een poliklinisch consult uit te nodigen. Of telemonitoring leidt tot een vermindering van de werklast van zorgprofessionals is onbekend.

Rationale van aanbeveling-1: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventie

Telemonitoring leidt mogelijk niet tot een verbetering of verslechtering van het ziektebeloop van kinderen met IBD in vergelijking tot standaardzorg. Mogelijk resulteert telemonitoring in een kleine verbetering van kwaliteit van leven en waarschijnlijk tot een afname van face-to-face contacten. Het aanbieden van telemonitoring kan de zorgkosten waarschijnlijk reduceren ten opzichte van standaardzorg.

Rationale van aanbeveling-2: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventie

Telemonitoring wordt aangeboden naast standaardzorg. Per individuele patiënt moet worden overwogen of telemonitoring wel of niet wenselijk is (door gebruik te maken van shared decision making). In bepaalde situaties is telemonitoring niet haalbaar of niet wenselijk.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

De ziekte van Crohn en colitis ulcerosa zijn chronische inflammatoire darmziekten (IBD) die gekenmerkt worden door perioden van remissie en opvlammingen. Vanwege het risico op opvlammingen worden tieners met IBD over het algemeen regelmatig gecontroleerd op de polikliniek. Vaak is de ziekte op het moment van de controle rustig en wordt het advies gegeven om de behandeling ongewijzigd voort te zetten. Telemonitoring zou een goede aanvulling kunnen zijn op de reguliere poliklinische controles. Bij telemonitoring worden markers van ziekteactiviteit (zoals symptoomscores, kwaliteit van leven en markers voor inflammatie in bloed of ontlasting) op afstand (digitaal) gemeten. Bij afwijkende uitslagen volgt een poliklinische of digitale afspraak om de behandeling tijdig bij te sturen. Hierdoor kunnen tieners hun dagelijkse bezigheden zonder onderbreking voortzetten wanneer de ziekte het toelaat, en naar het ziekenhuis komen wanneer dit nodig is.

In de handreiking Telemonitoring van de Federatie Medische Specialisten, zijn algemene doelstellingen voor telemonitoring geformuleerd, waaronder het beter structureel monitoren van patiënten, het tijdig bijsturen van de behandeling bij (dreigende) verslechtering, het zo stabiel mogelijk houden van de patiënt en het voorkomen of verminderen/verkorten van reguliere (polikliniek) consulten, SEH-bezoeken en opnames (1).

Specifieke aanbevelingen voor telemonitoring bij (tieners met) IBD ontbreken. Het doel van deze systematic review is om te evalueren of telemonitoring non-inferieur is aan standaardzorg bij IBD, met name wat betreft ziekteactiviteit en kwaliteit van leven.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

Disease activity

|

Low GRADE |

Based on evidence from 10 studies (3 pediatric studies), telemonitoring may not worsen disease activity as compared to standard care.

Source: Akobeng (5), Bonnaud (14), Carlsen (6), Cross (8), Cross (9), Del Hoyo (13), De Jong (15, 16), Elkjaer (10), Heida (7), McCombie (11) |

Quality of life

|

Low GRADE |

Based on evidence from 10 studies (3 pediatric studies), including a meta-analysis of 5 studies (1 pediatric study), telemonitoring may result in little to no improvement of quality of life as compared to standard care.

Source: Akobeng (5), Bonnaud (14), Carlsen (6), Cross (8), Cross (9), De Jong (15, 16), Del Hoyo (13), Elkjaer (10), Heida (7), McCombie (11) |

Cost

|

Moderate GRADE |

Based on evidence from 4 studies (2 pediatric studies) telemonitoring likely results in a slight reduction of healthcare costs as compared to standard care alone.

Source: Akobeng (5), De Jong (15, 16), Elkjaer (10), Heida (7) |

Patient-reported experience and engagement measures

|

Moderate to Low GRADE |

Based on evidence from 7 studies (2 pediatric studies), overall, patient satisfaction with telemonitoring is likely to be good, with most patients wishing to continue with telemonitoring. (Moderate GRADE)

Findings regarding medication and telemonitoring adherence were inconsistent across studies, with some studies reporting lower rates of adherence in the telemonitoring group while others found higher or no difference in adherence rates. (Based on 4 studies [2 pediatric studies]; Low GRADE)

Source: Akobeng (5), Bonnaud (14), Carlsen (6), Cross (8), Del Hoyo (13), De Jong (15, 16), Elkjaer (10), Heida (7), Östlund (12) |

Face-to-face outpatient visits

|

Moderate GRADE |

Based on evidence from 8 studies (3 pediatric studies), telemonitoring is likely to reduce the number of face-to-face outpatient visits slightly compared to standard care. None of the studies reported that telemonitoring increased outpatient visits.

Source: Akobeng (5), Bonnaud (14), Carlsen (6), Del Hoyo (13), De Jong (15, 16), Elkjaer (10), McCombie (11), Östlund (12) |

Unplanned ER visits, surgeries or hospitalizations

|

Moderate GRADE |

Based on evidence from 8 studies (2 pediatric studies), telemonitoring may result in little to no reduction in unplanned ER visits, surgeries, or hospitalizations, relative to standard care.

Source: Bonnaud (14), Carlsen (6), Cross (9), De Jong (15, 16), Del Hoyo (13), Elkjaer (10), McCombie (11), Östlund (12) |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

Table 1 contains an overview of characteristics of included studies. All included studies were designed as parallel RCTs, comparing various forms of telemonitoring versus standard care in patients with IBD (e.g. ulcerative colitis [UC] or Crohn’s disease [CD]). The total number of randomized participants ranged between 47 and 909. The proportion of females across the studies ranged between 37% and 64%. Study populations included both children and adults with an age range of 11.2 to 95 years (based on 10 studies reporting age). Three of 11 studies included children only (5-7). One study (8) exclusively included patients with UC, while all the other studies included a combination of UC and CD patients. In two studies (5, 7), all participants were in clinical disease remission at baseline.

Regarding the intervention, telemonitoring was solely web-based in 5 studies (6-10), mobile app-based in two studies (11, 12), phone-based in one study (5) phone-based or app-based in one study (13), and a combination of mobile app-based and web-based in two studies (14-16). Monitoring intervals were heterogenous, including periodic assessment (e.g. every third month) and assessment depending on symptoms. Control interventions mainly consisted of planned outpatient visits for which the time interval was often unreported or planned according to the specialists’ discretion. For most studies, the follow-up period was 12 or 24 months; one study had a 6-month follow-up period (13).

Regarding outcomes, 10 studies provided some measurement of disease activity (flares, treatment escalation, and disease activity or remission measured with various instruments) and 10 measured QoL with various tools. All studies reporting QoL used IBD-specific measures and two studies also used generic health-related measures. It was not possible to perform meta-analyses for outcomes other than QoL since measurement tools were too heterogeneous across studies. More information on the reported study outcomes is presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Study outcomes

*Meta-analysis was possible for this outcome variable.

† Pediatric studies.

‡ No raw data or results available for QoL meta-analysis.

§ Excluded from meta-analysis. Standard deviations were unreported or only p-values were presented.

¶ Excluded from meta-analysis as only change scores from baseline were reported.

aPCDAI: abbreviated Pediatric Crohn Disease Activity Index; CSQ: consultation satisfaction questionnaire; EMR: Electronic medical record; HBI: Harvey-Bradshaw Index for Crohn’s disease; HMARS: Medication Adherence Report Scale; HRQoL: Health-related quality of life; IBD-IMPACT: IBD quality of life questionnaire; IBDQ: Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire (IBD-specific QoL questionnaire); MCS: Mayo Clinic Score; MMAS: Morisky Medication Adherence Score; NR: Not reported. Outcome has not been incorporated into the study; PCDAI: Pediatric Crohn Disease Activity Index; PUCAI: Pediatric Ulcerative Colitis Activity Index; SSCAI: Simple Clinical Colitis Activity Index; SUS: System usability scale; VAS: Visual Analog Scale

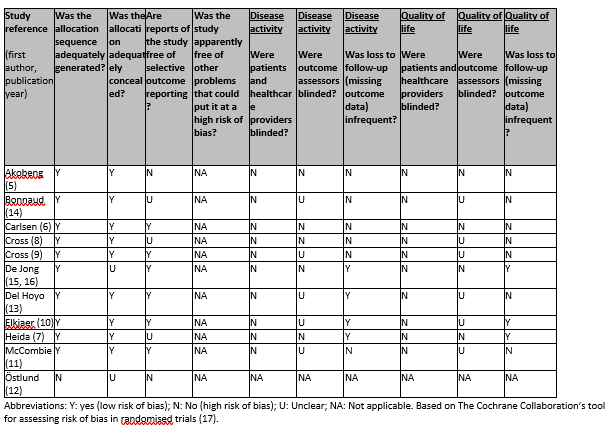

Risk-of-bias assessment

Risk of bias was assessed using the Cochrane risk-of-bias tool for randomized controlled trials (Higgins, 2011). Separate assessments were done for the outcomes disease activity and QoL (Table 3). In general, risk of bias arising from the randomization process was low, except for Östlund (12) that did not have random sequence generation. Six of 11 studies had low risk of bias regarding selective outcome reporting. Overall, blinding of outcome assessors was either absent or unclear. In about half of all studies, missing outcome data was judged to be a major concern. While blinding of patients and providers was lacking in all studies, we did not consider this to be a concern as having knowledge of the assigned intervention is a characteristic of the intervention.

Table 2. Risk of bias judgements for included studies (randomized controlled trials; Cochrane risk of bias tool)

Findings

1. Disease activity

Ten studies (5-11, 13-16) reported data on disease activity (Table 4). Disease activity was assessed by various symptom scores and outcomes varied by data type (numerical, binary, time-to-event, or other). Major endpoints related to disease activity were (cumulative) disease flares (n=4), treatment escalation (n=1), and disease activity or remission measured with various instruments (HBI, PCDAI, Seo-index, SSCAI) (n=6). Pooling of disease activity data was not possible due to the high degree of clinical heterogeneity across studies.

Nine of ten studies, including 3 studies in children, did not show a statistically significant difference in disease activity when comparing telemonitoring to standard care (p>0.05). No consistent direction of effect (either favoring telemonitoring or standard care) was observed in these studies. The remaining study reported statistically significant differences: Elkjaer (10), a study among Irish (n=92) and Danish (n=211) adults, showed that the Irish telemonitoring group had a lower mean number of flares during the 12-month follow-up period than the control group (0.6 [range 0 to 4] vs. 0.2 [range 0 to 1], p=0.02). In the same study, among Danish participants, there was no evidence of a difference between the groups.

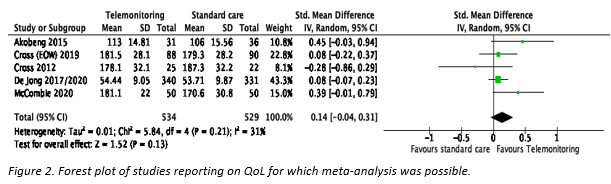

2. Quality of life (QoL)

Four out of ten studies investigating QoL reported statistically significant improvements in QoL in the telemonitoring group compared to standard care (5, 10, 11, 14). Among these four, Akobeng (5) was the only study that reported a significant effect of telemonitoring in children (pediatric IBD-IMPACT score; mean difference [MD] 8.66 [95% CI 1.05 to 16.27], p=0.03). The remaining studies described inconsistent non-significant results both in favor of telemonitoring and standard care (p>0.05), see Table 4.

Five studies (5, 8, 9, 11, 15, 16) reporting IBD-specific QoL were eligible for meta-analysis (Figure 1). Of these five, only Akobeng (5) included children. The pooled standardized mean difference was 0.14 (95% CI -0.04 to 0.31; p=0.13) in favor of telemonitoring. Cross (9) reported two telemonitoring groups: monitoring weekly or every other week. We randomly selected the latter group for the meta-analysis. A sensitivity analysis with the former group showed no difference in results (SMD 0.12 [95% CI -0.07 to 0.31], p=0.20).

3. Cost (any kind)

Four studies (5, 7, 10, 15, 16) reported data on costs (Table 4).

Akobeng (5) was the only study that reported a statistically significant cost reduction in the telemonitoring group. Mean consultation costs in the intervention group and the control group were 35.4 and 51.1 pounds respectively (MD -15.7; 95% CI -11.8 to -19.6; p<0.001).

De Jong (15, 16) conducted a cost-effectiveness analysis. Mean total (in)direct healthcare costs were lower in the intervention group (8934 euros) than in the control group (9481 euros), with a mean difference of -547 euros (95% CI -2108 to 1014).

Elkjaer (10) reported service and medication costs in Danish participants. The intervention group showed lower costs due to outpatient visits than the control group (12,880 versus 34,454 euros). Hospitalization costs were equal in both groups (5202 euros; corresponding to 2 hospitalizations) while the intervention group had higher remote consultation (2247 versus 504 euros) and medication costs (641 versus 578 euros). Overall, excluding medication costs, the financial benefit was 19,831 euros for 105 Danish telemonitoring participants, equivalent to 189 euros/patient/year. No costs were reported for Irish participants.

In Heida (7) a cost-effectiveness analysis showed that the annual cost-savings of telemonitoring, compared to standard care, was 89 euros per person. In participants compliant to the protocol, these savings were 360 euros per person.

4. Patient-reported experience and engagement measures

Nine studies (5-8, 10, 12-16) reported data on patient-reported engagement measures: patient satisfaction/perception of quality of care and adherence.

Seven studies reported results on patient satisfaction/perception of quality of care. There was no difference in patient satisfaction or perception of quality of care between groups in two studies (5, 15, 16), with a mean difference of -0.11 (CI -0.52 to 0.31, p=0.61) reported by De Jong (15, 16). Heida (7) reported that 71% of intervention group participants wished to continue with home telemonitoring care and that 96% considered home telemonitoring as timesaving. In Elkjaer (10), 89% of Danish and 88% of Irish participants were willing to continue using the new telemonitoring system. Bonnaud (14) reported that 83% of participants was satisfied or even very satisfied with the intervention, with 75% of participants feeling more empowered/independent. Östlund (12) reported that 17/24 patients were willing to participate in a phone survey. Of these 17 participants, 15 (88%) had a positive experience with the telemonitoring intervention. In Del Hoyo (13), the patient satisfaction with received care was measured with the Adapted Client Satisfaction Questionnaire. The mean scores were comparable for the telephone, telemonitoring, and control groups (53, 57, and 55 respectively).

Five studies reported data on adherence, of which 4 reported on medication adherence. Two studies (6, 8) did not report any difference between groups regarding medication adherence at the end of the study period (24 and 12 months, respectively). Cross (8) reported 44% adherent participants in the intervention group and 68% in the standard care group (p=0.10) at 12-months, see Table 4. In the study of Elkjaer (10), adherence to 4 weeks of acute treatment with 5-ASA in case of a flare was significantly greater at 12 months in the telemonitoring versus the control group in both Danish and Irish participants (Denmark: 73% versus 42%, p=0.005; Ireland 73% versus 29%, p=0.03). Del Hoyo (13) reported medication adherence in the telephone, telemonitoring and control groups was, respectively, 71%, 86%, and 81% at 24 weeks. One study (7) reported results on adherence to telemonitoring: 57% of participants in the telemonitoring group were compliant to the study protocol (defined as responding to ³80% of automated alerts), whereas in the standard care group 84% was compliant (sending in ≥2 stool samples for calprotectin measurement).

5. Face-to-face outpatient contacts

Eight studies (5, 6, 10-16) reported on face-to-face outpatient contacts. This outcome was reported heterogenously: as count data (N=3), medians (N=3), means (N=3) or as binary data (N=1). Moreover, the type of visit (gastroenterologist, nurse, or a combination) differed between studies. We therefore did not conduct meta-analyses for this outcome.

Three studies reported statistically non-significant results when comparing telemonitoring to standard care (5, 12, 14). In Akobeng (5), median consultations per patient was similar in the intervention group (4 [IQR 3 to 4]) compared to the control group (3 [IQR 2 to 4]). The same study reported a non-significant difference in the proportion of attended outpatient consultations between the intervention and the control group (67% versus 71%, p=0.71). In Bonnaud (14), the mean number of gastroenterologist consultations in the intervention group were fewer than the control group (2.2 (SD 2.2) versus 4.1 (SD 2.9), p=0.13), but the difference was not statistically significant. Östlund (12) showed that median healthcare visits (including outpatient visits, ER visits, and endoscopy visits) due to IBD were similar between intervention and control groups (1 [IQR 0 to 2] versus 0 [IQR 0 to 2], p=0.076).

Carlsen (6) reported the number of planned and on-demand outpatient visits. The intervention group had fewer planned (38 versus 146, p<0.001) but slightly more on-demand outpatient visits (47 versus 39, p=0.68). Overall, the intervention group had significantly less outpatient visits compared to the control group (85 versus 185, p<0.0001).

Elkjaer (10) reported less routine hospital visits in the intervention group compared to the control group in both Danish (35 versus 92, p<0.0001) and Irish participants (62 versus 91, p=0.007). In the study of Del Hoyo (13), the total number outpatient visits to the nurse or gastroenterologist were lower in both the telemonitoring (72 visits) and the telephone intervention group (85 visits) than in the control group (131 visits)

Two studies reported significantly fewer gastroenterologist contacts in favor of telemonitoring. De Jong (15, 16) and McCombie (11) reported a mean difference of -0.72 (95% CI -0.87 to 0.57, p<0.0001) and -1.1 (95% CI -1.43 to -0.77, p<0001) contacts, respectively. De Jong (15, 16) also reported results on nurse outpatient visits and overall outpatient visits. Although nurse outpatient visits did not differ significantly between groups (MD -0.07, 96% CI 0.17 to 0.03, p=0.173), overall outpatient visits were fewer in the intervention group (MD -0.79, 95% CI -0.99 to -0.59, p<0.0001).

6. Unplanned ER visits, surgery, and hospitalizations

Eight studies (6, 9-16) reported data on unplanned ER visits, surgery, or hospitalizations. We chose not to perform a meta-analysis due to heterogenous reporting of this outcome. Of all results, only two results from two studies (10, 15, 16) showed a statistically significant difference between comparison groups.

The results of Östlund (12) were described under the previous section ‘face-to-face outpatient contacts’ since outpatient visits, ER visits, and endoscopy visits were all categorized as ‘healthcare visits’.

Four studies reported data on ER visits. Three of them (9, 14-16) did not show evidence of effect when comparing telemonitoring to standard care (p>0.05). No consistent direction of effect (either favoring telemonitoring or standard care) was observed in these studies. The third study reported no differences between the telemonitoring, telephone and standard care groups regarding ER visits (0, 2, and 1 visits, respectively) (13).

Elkjaer (10) reported less acute visits in the telemonitoring group than the control group in Danish participants (21 versus 107 visits, p<0.0001). No difference was noted in Irish participants (9 versus 9 visits). No effect was found in Carlsen (6) regarding acute outpatient visits or hospitalizations (p=0.13).

Three studies reported data on hospitalization in general. Bonnaud (14) and Del Hoyo (13) showed no evidence of effect on hospitalizations when comparing telemonitoring to standard care (p>0.05). In De Jong (15, 16), those in the telemonitoring group experienced less hospitalizations (mean difference -0.05 [95% CI -0.10 to 0.00, p=0.04]). McCombie (11) reported data regarding IBD-related hospitalization and nights spent in the hospital. In both cases there was no evidence of effect in favor of either telemonitoring or standard care (p>0.05).

Data on any surgery was reported in McCombie (11). They did not find evidence of a difference between telemonitoring and standard care (p>0.05). Data on IBD-related surgery were reported in three studies (9, 13, 15, 16). All showed no evidence of effect (p>0.05), with two studies (13, 15, 16) reporting identical number of surgeries between groups.

Level of evidence of the literature

1. Disease activity

The level of evidence regarding this outcome was downgraded by 2 levels for risk of bias (lack of blinding of outcome assessors and missing outcome data) and indirectness (majority of studies were non-pediatric).

2. Quality of life

The level of evidence regarding this outcome was downgraded by 2 levels for risk of bias (lack of blinding of outcome assessors and missing outcome data) and indirectness (majority of studies were non-pediatric).

3. Cost

The level of evidence regarding this outcome was downgraded by 1 level for indirectness (half of studies were non-pediatric). Assessment of risk of bias was not performed for this outcome.

4. Patient-reported experience and engagement measures (patient satisfaction and adherence)

The level of evidence regarding the outcome patient satisfaction was downgraded by 1 level for indirectness. For the outcome adherence, we additionally downgraded by 1 level for inconsistency (studies found lower, higher, or no difference in adherence rates between groups). Assessment of risk of bias was not performed for this outcome.

5. Face-to-face outpatient visits

The level of evidence regarding this outcome was downgraded by 1 level for indirectness (majority of studies were non-pediatric). Assessment of risk of bias was not performed for this outcome.

6. Unplanned ER visits, surgeries or hospitalizations

The level of evidence regarding this outcome was downgraded by 1 level for indirectness (majority of studies were non-pediatric). Assessment of risk of bias was not performed for this outcome.

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question:

| P (patients): | Children and adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease |

| I (intervention): | Telemonitoring of disease activity |

| C (control): | Standard care |

| O (outcome measure): |

|

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered disease activity and quality of life as critical outcome measures for decision making; and costs, ‘patient-reported experience and engagement measures’, face-to-face outpatient contacts, and ‘unplanned ER visits, surgery, and hospitalizations’ as important outcome measures for decision making.

A priori, the working group did not define the outcome measures listed above but used the definitions used in the studies.

The working group defined non-inferiority of telemonitoring compared with standard care alone to be clinically important. The working group did not define thresholds for non-inferiority of telemonitoring (compared with standard care) in advance, as various outcome measurement instruments and tools exist and have been used in studies.

Search and select (Methods)

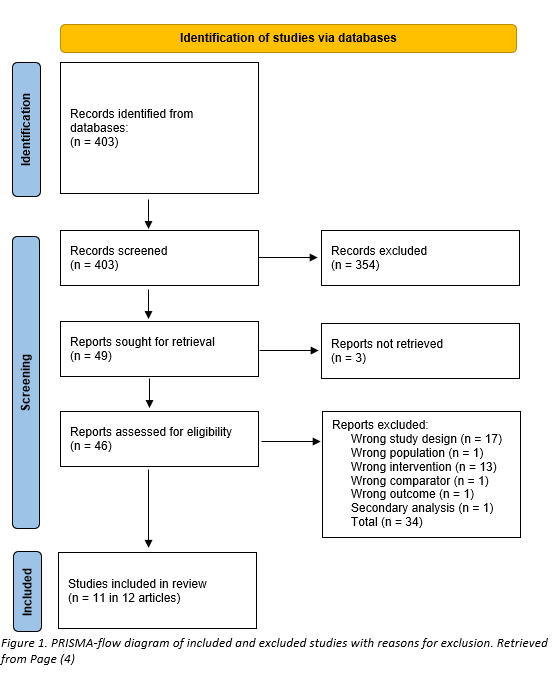

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms until 21-07-2022. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The literature search resulted in 403 hits.

We included randomized controlled trials (RCTs) based on the following criteria: children and adolescents (£ 18 years old) with IBD (though studies on adults were also included as indirect evidence), receiving any kind of telemonitoring (e.g. web-based, mobile-app based, and phone-based). Trials were included if telemonitoring was compared to standard care and if one or more of the following outcomes were reported: disease activity, QoL, costs, face-to-face clinician-patient contacts, and unplanned emergency room attendance or surgery or hospitalizations.

Studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening, and 354 articles were excluded in this stage. After assessment of the full text report, an additional 37 articles were excluded, and 11 unique studies in 12 articles were included, see PRISMA-flow diagram in figure 1.

Meta-analysis could only be performed for the outcome QoL. We used a random effects model of standardized mean differences (SMD) due to heterogeneous measurement instruments. The analysis was performed using Review Manager 5.4 (2). If only medians (with interquartile ranges, minimum and maximum values) were available, we transformed them to means and standard deviations using formulas by Wan (3) for meta-analysis.

Results

11 studies in 12 articles were included. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- 1. Federatie Medisch Specialisten, NVZ, NFU, ZN. Handreiking Telemonitoring, December 2022. 2022.

- 2. The Cochrane Collaboration. Review Manager 5. Copenhagen: The Cochrane Collaboration; 2020.

- 3. Wan X, Wang W, Liu J, Tong T. Estimating the sample mean and standard deviation from the sample size, median, range and/or interquartile range. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2014;14:135. Epub 20141219. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-14-135. PubMed PMID: 25524443; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC4383202.

- 4. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. Epub 20210329. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71. PubMed PMID: 33782057; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC8005924.

- 5. Akobeng AK, O'Leary N, Vail A, Brown N, Widiatmoko D, Fagbemi A, et al. Telephone Consultation as a Substitute for Routine Out-patient Face-to-face Consultation for Children With Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Randomised Controlled Trial and Economic Evaluation. EBioMedicine. 2015;2(9):1251-6. Epub 20150808. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2015.08.011. PubMed PMID: 26501125; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC4588430.

- 6. Carlsen K, Jakobsen C, Houen G, Kallemose T, Paerregaard A, Riis LB, et al. Self-managed eHealth Disease Monitoring in Children and Adolescents with Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23(3):357-65. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000001026. PubMed PMID: 28221247.

- 7. Heida A, Dijkstra A, Muller Kobold A, Rossen JW, Kindermann A, Kokke F, et al. Efficacy of Home Telemonitoring versus Conventional Follow-up: A Randomized Controlled Trial among Teenagers with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2018;12(4):432-41. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjx169. PubMed PMID: 29228230.

- 8. Cross RK, Cheevers N, Rustgi A, Langenberg P, Finkelstein J. Randomized, controlled trial of home telemanagement in patients with ulcerative colitis (UC HAT). Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18(6):1018-25. Epub 20110617. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21795. PubMed PMID: 21688350; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3179574.

- 9. Cross RK, Langenberg P, Regueiro M, Schwartz DA, Tracy JK, Collins JF, et al. A Randomized Controlled Trial of TELEmedicine for Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease (TELE-IBD). Am J Gastroenterol. 2019;114(3):472-82. doi: 10.1038/s41395-018-0272-8. PubMed PMID: 30410041.

- 10. Elkjaer M, Shuhaibar M, Burisch J, Bailey Y, Scherfig H, Laugesen B, et al. E-health empowers patients with ulcerative colitis: a randomised controlled trial of the web-guided 'Constant-care' approach. Gut. 2010;59(12):1652-61. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.220160. PubMed PMID: 21071584.

- 11. McCombie A, Walmsley R, Barclay M, Ho C, Langlotz T, Regenbrecht H, et al. A Noninferiority Randomized Clinical Trial of the Use of the Smartphone-Based Health Applications IBDsmart and IBDoc in the Care of Inflammatory Bowel Disease Patients. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2020;26(7):1098-109. doi: 10.1093/ibd/izz252. PubMed PMID: 31644793.

- 12. Ostlund I, Werner M, Karling P. Self-monitoring with home based fecal calprotectin is associated with increased medical treatment. A randomized controlled trial on patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2021;56(1):38-45. Epub 20201207. doi: 10.1080/00365521.2020.1854342. PubMed PMID: 33284639.

- 13. Del Hoyo J, Nos P, Faubel R, Munoz D, Dominguez D, Bastida G, et al. A Web-Based Telemanagement System for Improving Disease Activity and Quality of Life in Patients With Complex Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial. J Med Internet Res. 2018;20(11):e11602. Epub 20181127. doi: 10.2196/11602. PubMed PMID: 30482739; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC6301812.

- 14. Bonnaud G, Haennig A, Altwegg R, Caron B, Boivineau L, Zallot C, et al. Real-life pilot study on the impact of the telemedicine platform EasyMICI-MaMICI((R)) on quality of life and quality of care in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2021;56(5):530-6. Epub 20210310. doi: 10.1080/00365521.2021.1894602. PubMed PMID: 33691075.

- 15. de Jong MJ, van der Meulen-de Jong AE, Romberg-Camps MJ, Becx MC, Maljaars JP, Cilissen M, et al. Telemedicine for management of inflammatory bowel disease (myIBDcoach): a pragmatic, multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2017;390(10098):959-68. Epub 20170714. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31327-2. PubMed PMID: 28716313.

- 16. de Jong MJ, Boonen A, van der Meulen-de Jong AE, Romberg-Camps MJ, van Bodegraven AA, Mahmmod N, et al. Cost-effectiveness of Telemedicine-directed Specialized vs Standard Care for Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Diseases in a Randomized Trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18(8):1744-52. Epub 20200423. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.04.038. PubMed PMID: 32335133.

- 17. Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gotzsche PC, Juni P, Moher D, Oxman AD, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928. Epub 20111018. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5928. PubMed PMID: 22008217; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3196245.

- 18. NZA. WB/REG-2023-01 Wijzigingsbesluit houdende wijziging van de Regeling medischspecialistische zorg, kenmerk NR/REG-2306a, in verband met enkele technische en redactionele wijzigingen per 1 januari 2023 voor telemonitoring, moleculaire diagnostiek en pathologie. 2023.

- 19. Core-IBD Collaborators, Ma C, Hanzel J, Panaccione R, Sandborn WJ, D'Haens GR, et al. CORE-IBD: A Multidisciplinary International Consensus Initiative to Develop a Core Outcome Set for Randomized Controlled Trials in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Gastroenterology. 2022;163(4):950-64. Epub 20220703. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.06.068. PubMed PMID: 35788348.

- 20. Hanzel J, Bossuyt P, Pittet V, Samaan M, Tripathi M, Czuber-Dochan W, et al. Development of a Core Outcome Set for Real-world Data in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A European Crohn's and Colitis Organisation [ECCO] Position Paper. J Crohns Colitis. 2023;17(3):311-7. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjac136. PubMed PMID: 36190188.

- 21. Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D, Group C. CONSORT 2010 Statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMC Med. 2010;8:18. Epub 20100324. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-8-18. PubMed PMID: 20334633; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC2860339.

- 22. Ankersen DV, Weimers P, Marker D, Bennedsen M, Saboori S, Paridaens K, et al. Individualized home-monitoring of disease activity in adult patients with inflammatory bowel disease can be recommended in clinical practice: A randomized-clinical trial. World J Gastroenterol. 2019;25(40):6158-71. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v25.i40.6158. PubMed PMID: 31686770; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC6824278.

- 23. Ankersen DV, Weimers P, Marker D, Teglgaard Peters-Lehm C, Bennedsen M, Rosager Hansen M, et al. Costs of electronic health vs. standard care management of inflammatory bowel disease across three years of follow-up-a Danish register-based study. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2021;56(5):520-9. Epub 20210228. doi: 10.1080/00365521.2021.1892176. PubMed PMID: 33645378.

- 24. Arrigo S, Alvisi P, Banzato C, Bramuzzo M, Celano R, Civitelli F, et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on the management of paediatric inflammatory bowel disease: An Italian multicentre study on behalf of the SIGENP IBD Group. Dig Liver Dis. 2021;53(3):283-8. Epub 20201226. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2020.12.011. PubMed PMID: 33388247; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC7832380.

- 25. Bensted K, Kim C, Freiman J, Hall M, Zekry A. Gastroenterology hospital outpatients report high rates of satisfaction with a Telehealth model of care. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;37(1):63-8. Epub 20210830. doi: 10.1111/jgh.15663. PubMed PMID: 34402105.

- 26. Bertani L, Barberio B, Trico D, Zanzi F, Maniero D, Ceccarelli L, et al. Hospitalisation for Drug Infusion Did Not Increase Levels of Anxiety and the Risk of Disease Relapse in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease during COVID-19 Outbreak. J Clin Med. 2021;10(15). Epub 20210724. doi: 10.3390/jcm10153270. PubMed PMID: 34362053; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC8348517.

- 27. Bilgrami Z, Abutaleb A, Chudy-Onwugaje K, Langenberg P, Regueiro M, Schwartz DA, et al. Effect of TELEmedicine for Inflammatory Bowel Disease on Patient Activation and Self-Efficacy. Dig Dis Sci. 2020;65(1):96-103. Epub 20190102. doi: 10.1007/s10620-018-5433-5. PubMed PMID: 30604373; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC7883399.

- 28. Carlsen K, Houen G, Jakobsen C, Kallemose T, Paerregaard A, Riis LB, et al. Individualized Infliximab Treatment Guided by Patient-managed eHealth in Children and Adolescents with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23(9):1473-82. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000001170. PubMed PMID: 28617758.

- 29. Carlsen K, Frederiksen NW, Wewer V. Integration of eHealth Into Pediatric Inflammatory Bowel Disease Care is Safe: 3 Years of Follow-up of Daily Care. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2021;72(5):723-7. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000003053. PubMed PMID: 33470751.

- 30. Chee D, Nice R, Hamilton B, Jones E, Hawkins S, Redstone C, et al. Patient-led Remote IntraCapillary pharmacoKinetic Sampling (fingerPRICKS) for Therapeutic Drug Monitoring in patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2022;16(2):190-8. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjab128. PubMed PMID: 34289028.

- 31. Chudy-Onwugaje K, Abutaleb A, Buchwald A, Langenberg P, Regueiro M, Schwartz DA, et al. Age Modifies the Association Between Depressive Symptoms and Adherence to Self-Testing With Telemedicine in Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2018;24(12):2648-54. doi: 10.1093/ibd/izy194. PubMed PMID: 29846623; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC6262196.

- 32. Cross RK, Arora M, Finkelstein J. Acceptance of telemanagement is high in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2006;40(3):200-8. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200603000-00006. PubMed PMID: 16633120.

- 33. Del Hoyo J, Nos P, Bastida G, Faubel R, Munoz D, Garrido-Marin A, et al. Telemonitoring of Crohn's Disease and Ulcerative Colitis (TECCU): Cost-Effectiveness Analysis. J Med Internet Res. 2019;21(9):e15505. Epub 20190913. doi: 10.2196/15505. PubMed PMID: 31538948; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC6754696.

- 34. Dijkstra A, Heida A, van Rheenen PF. Exploring the Challenges of Implementing a Web-Based Telemonitoring Strategy for Teenagers With Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Empirical Case Study. J Med Internet Res. 2019;21(3):e11761. Epub 20190329. doi: 10.2196/11761. PubMed PMID: 30924785; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC6460310.

- 35. El Hajra I, Calvo M, Santos Perez E, Blanco Rey S, Gonzalez Partida I, Matallana V, et al. Consequences and management of COVID-19 on the care activity of an Inflammatory Bowel Disease Unit. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2021;113(2):98-102. doi: 10.17235/reed.2020.7543/2020. PubMed PMID: 33342217.

- 36. Elkjaer M. E-health: Web-guided therapy and disease self-management in ulcerative colitis. Impact on disease outcome, quality of life and compliance. Dan Med J. 2012;59(7):B4478. PubMed PMID: 22759851.

- 37. Huang VW, Reich KM, Fedorak RN. Distance management of inflammatory bowel disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(3):829-42. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i3.829. PubMed PMID: 24574756; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3921492.

- 38. Jackson BD, Gray K, Knowles SR, De Cruz P. EHealth Technologies in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Systematic Review. J Crohns Colitis. 2016;10(9):1103-21. Epub 20160229. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjw059. PubMed PMID: 26928960.

- 39. Krier M, Kaltenbach T, McQuaid K, Soetikno R. Potential use of telemedicine to provide outpatient care for inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106(12):2063-7. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.329. PubMed PMID: 22138934.

- 40. Lindhagen S, Karling P. A more frequent disease monitorering but no increased disease activity in patients with inflammatory bowel disease during the first year of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. A retrospective study. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2022;57(2):169-74. Epub 20211026. doi: 10.1080/00365521.2021.1993328. PubMed PMID: 34699290.

- 41. Marin-Jimenez I, Nos P, Domenech E, Riestra S, Gisbert JP, Calvet X, et al. Diagnostic Performance of the Simple Clinical Colitis Activity Index Self-Administered Online at Home by Patients With Ulcerative Colitis: CRONICA-UC Study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111(2):261-8. Epub 20160112. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2015.403. PubMed PMID: 26753886.

- 42. Menze L, Wenzl TG, Pappa A. [KARLOTTA (Kids + Adolescents Research Learning On Tablet Teaching Aachen) - randomized controlled pilot study for the implementation of a digital educational app with game of skill for pediatric patients with inflammatory bowel disease]. Z Gastroenterol. 2023;61(2):155-63. Epub 20220607. doi: 10.1055/a-1799-9267. PubMed PMID: 35672003.

- 43. Miloh T, Shub M, Montes R, Ingebo K, Silber G, Pasternak B. Text Messaging Effect on Adherence in Children With Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2017;64(6):939-42. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000001399. PubMed PMID: 27602705.

- 44. Nguyen NH, Martinez I, Atreja A, Sitapati AM, Sandborn WJ, Ohno-Machado L, et al. Digital Health Technologies for Remote Monitoring and Management of Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Systematic Review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2022;117(1):78-97. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000001545. PubMed PMID: 34751673; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC8987011.

- 45. Nielsen AS, Hanna L, Larsen BF, Appel CW, Osborne RH, Kayser L. Readiness, acceptance and use of digital patient reported outcome in an outpatient clinic. Health Informatics J. 2022;28(2):14604582221106000. doi: 10.1177/14604582221106000. PubMed PMID: 35658693.

- 46. Pang L, Liu H, Liu Z, Tan J, Zhou LY, Qiu Y, et al. Role of Telemedicine in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. J Med Internet Res. 2022;24(3):e28978. Epub 20220324. doi: 10.2196/28978. PubMed PMID: 35323120; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC8990345.

- 47. Quinn CC, Chard S, Roth EG, Eckert JK, Russman KM, Cross RK. The Telemedicine for Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease (TELE-IBD) Clinical Trial: Qualitative Assessment of Participants' Perceptions. J Med Internet Res. 2019;21(6):e14165. Epub 20190603. doi: 10.2196/14165. PubMed PMID: 31162128; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC6746080.

- 48. Ramelet AS, Fonjallaz B, Rio L, Zoni S, Ballabeni P, Rapin J, et al. Impact of a nurse led telephone intervention on satisfaction and health outcomes of children with inflammatory rheumatic diseases and their families: a crossover randomized clinical trial. BMC Pediatr. 2017;17(1):168. Epub 20170717. doi: 10.1186/s12887-017-0926-5. PubMed PMID: 28716081; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5513092.

- 49. Schliep M, Chudy-Onwugaje K, Abutaleb A, Langenberg P, Regueiro M, Schwartz DA, et al. TELEmedicine for Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease (TELE-IBD) Does Not Improve Depressive Symptoms or General Quality of Life Compared With Standard Care at Tertiary Referral Centers. Crohns Colitis 360. 2020;2(1):otaa002. Epub 20200131. doi: 10.1093/crocol/otaa002. PubMed PMID: 32201859; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC7067223.

- 50. Shah R, Wright E, Tambakis G, Holmes J, Thompson A, Connell W, et al. Telehealth model of care for outpatient inflammatory bowel disease care in the setting of the COVID-19 pandemic. Intern Med J. 2021;51(7):1038-42. doi: 10.1111/imj.15168. PubMed PMID: 34278693; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC8444910.

- 51. Srinivasan A, van Langenberg DR, Little RD, Sparrow MP, De Cruz P, Ward MG. A virtual clinic increases anti-TNF dose intensification success via a treat-to-target approach compared with standard outpatient care in Crohn's disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2020;51(12):1342-52. Epub 20200507. doi: 10.1111/apt.15742. PubMed PMID: 32379358.

- 52. Yao J, Fekadu G, Jiang X, You JHS. Telemonitoring for patients with inflammatory bowel disease amid the COVID-19 pandemic-A cost-effectiveness analysis. PLoS One. 2022;17(4):e0266464. Epub 20220407. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0266464. PubMed PMID: 35390064; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC8989217.

- 53. Yilmaz H, Duman AE, Hülagü S. Smartphone-based videoconference visits are easy to implement, effective, and feasible in Crohn's Disease Patients: A prospective cohort study. medRxiv. 2021.

- 54. Zand A, Nguyen A, Stokes Z, van Deen W, Lightner A, Platt A, et al. Patient Experiences and Outcomes of a Telehealth Clinical Care Pathway for Postoperative Inflammatory Bowel Disease Patients. Telemed J E Health. 2020;26(7):889-97. Epub 20191031. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2019.0102. PubMed PMID: 31670610.

- 55. Zhang YF, Qiu Y, He JS, Tan JY, Li XZ, Zhu LR, et al. Impact of COVID-19 outbreak on the care of patients with inflammatory bowel disease: A comparison before and after the outbreak in South China. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;36(3):700-9. Epub 20200816. doi: 10.1111/jgh.15205. PubMed PMID: 32738060; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC7436411.

Evidence tabellen

Table 3. Characteristics of included studies

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Telemonitoring type and intervention interval (I) |

Comparison / control and time interval (C) |

Follow-up (months) |

Outcome measures |

|

Akobeng (5) |

Parallel RCT

Participants randomized (n): 86

|

Age classification: Children I: 13.9 [12.1-15.9] |

Telemonitoring type: Phone-based Intervention interval:

|

Regular face-to-face consultation:

Time interval: |

24 |

Disease relapses (³ 1 event(s) PUCAI or aPCDAI score >15)

Impact-QoL

Costs to the UK National Health Service (NHS)

Consultation satisfaction (CSQ)

Consultation attendance |

|

Bonnaud (14) |

Parallel RCT

Participants randomized (n): 54 |

Age classification: Adults

Mean age at enrolment in years (SD): I: 32.7 (10.9) C: 32.7 (12.6)

Female (%): 61

Disease type (%): UC: 41| CD: 59

Active disease (%): 90.5 |

Telemonitoring type: Mobile app-based and Web-based

Intervention interval: Other: every 14 days or at patient's request |

Standard care: Planned outpatient visits' education with guideline-concordant therapy and as-needed phone calls

Time interval: 6 months |

12 |

Disease remission (MCS of ≤1 or HBI of ≤5)

Quality of life (SIBDQ and EQ-5D-3L)

Overall patient telemonitoring satisfaction (VAS-score; percentage; 5-point satisfaction emoji scale)

Gastroenterologist consultations

ER visits or hospitalizations |

|

Carlsen (6) |

Parallel RCT

Participants randomized (n): 53 |

Age classification: Children |

Telemonitoring type: Web-based Intervention interval: Monthly |

Planned outpatient visits

Time interval: Every third month |

24 |

Disease activity (step up in treatment intensity)

HR-QoL

Medical adherence

Outpatient visits (planned/on-demand/total)

Acute (Unplanned emergency room) outpatient visits and hospitalizations

|

|

Cross (8) |

Parallel RCT Participants randomized (n): 47 |

Age classification: Adults

|

Telemonitoring type: Web-based Intervention interval |

Best available care:

Time interval: NR |

12 |

Disease activity (Seo index) Disease-specific QoL (IBDQ)

Medical adherence |

|

Cross (9) |

Parallel RCT

Participants randomized (n): 348 |

Age classification: Adults |

Telemonitoring type: Web-based Intervention interval: |

Best available care:

Time interval: NR |

12 |

Disease activity (HBI; SSCAI)

Disease-specific QoL (IBDQ)

Utilization of healthcare resources: ER visits100/participants/year and IBD-related surgery/100participants/year.

|

|

Del Hoyo (13) |

Parallel RCT

Participants randomized (n): 63 |

Age classification: Adults |

Telemonitoring type: Phone-based or App-based Patients treated with immunosuppressants alone or in combination with biological agents were monitored every 1-2 weeks during the first month, every 2-4 weeks between months 1 to 3, and every 4 weeks from month 3 until the end of follow-up. Patients treated with biological agents alone were monitored every 2-4 weeks during the entire follow-up period. Additionally, all patients visited the IBD clinic at baseline, 12 weeks and 24 weeks." |

Standard care with in-person visits:

Time interval: NR |

6 |

Disease activity (HBI; Walmsley score; Mayo score)

HR-QoL (IBDQ-9)

Patient satisfaction with received care (Adapted Client Satisfaction Questionnaire)

Medical adherence (Morisky-Green Index)

Outpatient visits

Emergency department visits

Hospitalizations

Surgery |

|

De Jong (15, 16) |

Parallel RCT

Participants randomized (n): 909 |

Age classification: Adults |

Telemonitoring type: Web- and Mobile app-based Intervention interval: |

Standard care:

Time interval: |

12 |

Disease outcome (number of flares and IBD-related hospital admissions, emergency visits, surgeries)

Outpatient visits

QoL (SIBDQ)

Patient-reported quality of care (VAS-score based questionnaire)

Medical adherence (Morisky-Green index)

Costs (indirect and direct healthcare costs) |

|

Elkjaer (10) |

Parallel RCT

Participants randomized (n): 333 |

Age classification: Adults

|

Telemonitoring type: Web-based Intervention interval: |

Standard care and historical controls:

Time interval: NR |

12 |

Disease outcome (number and duration of relapse)

QoL (SF-12; SF-36)

Costs (medication and service costs)

Feasibility/willingness to use new system

Compliance (prescription, self-recognition of relapse, following doctor’s advice, self-initiating of acute treatment and adherence to 4 weeks of acute 5-ASA therapy measured with compliance questionnaire (CQ))

Hospital visits (acute and routine) |

|

Heida (7) |

Parallel RCT

Participants randomized (n): 170 |

Age classification: Children |

Telemonitoring type: Web-based Intervention interval: Intermediate-risk stratum participants were subject to a shorter test interval before progressing to a decision. High-risk stratum participants were advised to contact their specialist. When failing to complete the symptom score, two automated reminders were sent in the next two weeks. After denial of three email alerts participants were contacted personally by phone or email. |

Planned outpatient visits and emergency visits.

Time interval: Regular checks regardless of disease activity and interval varied according to the physician’s discretion. |

12 |

Disease flares

Impact-QoL

Costs (all direct and indirect medical and non-medical costs)

Participants’ opinion about home telemonitoring (Likert-scale based questionnaire)

Adherence to study protocol (intervention: ³80% of automated alerts; control: ³2 requested stool samples for calprotectin measurement) |

|

McCombie (11) |

Parallel RCT

Participants randomized (n): 107 |

Age classification: Adults |

Telemonitoring type: Mobile app-based Intervention interval: |

Standard care:

Time interval: NR |

12 |

HR-QoL

Disease activity (HBI; SSCAI)

Healthcare usage (gastro appointments; surgical appointments; IBD-related hospitalizations; IBD-related nights in hospital)

Patient-reported usability/acceptability of apps (system usability scale)

Intervention adherence to IBDsmart and IBDoc |

|

Östlund (12) |

Parallel RCT

Participants randomized (n): 200 |

Age classification: Adults UC: 64 | CD: 33 Intermediate IBD: 3 |

Telemonitoring type: Mobile app-based Intervention interval: |

Standard care:

Time interval: NR |

12 |

Healthcare visits (total number of outpatient visits, ER visits, and endoscopy visits. Due to inseparable results on the variables, same results presented in face-to-face clinical contacts and unplanned ER/surgery column.

Patient reported experience

|

Table 4. Results per outcome category

|

Study name (year) |

Disease activity (flares, relapses, treatment intensity, etc.) |

QoL |

Costs (any kind) |

Patient reported experience/engagement measures |

Face-to-face outpatient contacts |

Unplanned ER/surgery/hospitalizations |

|

Akobeng (5) |

Disease relapses (³ 1 PUCAI or aPCDAI score >15). RR 0.24 (0.03 to 2.05), p=0.20

|

Paediatric IBD-IMPACT score. **MD: 8.66 (1.05 to 16.27), p=0.03

|

Mean costs in pounds per consultation (n): I: 35.4 (44) C: 51.1 (42)

MD -15.7; 95% CI: -11.8 to 19.6, p<0.001 |

CSQ. MD (child): 1.00 (-1.25 to 3.25), p=0.38 MD (parent): 0.00 (-2.43 to 2.43), p=1.00

|

Consultations per patient. Median [IQR]: I: 4 [3 to 4] C: 3 [2 to 4]

Events (total binary): I: 29 (43) C: 30 (42)

Adjusted OR: 1.06 (95% CI 0.784, 1.43) p = 0.71 |

NR |

|

Bonnaud (14) |

Disease remission. Event (total binary): I: 19 (26) C: 12 (19) p>.05

Overall, 69.6% in remission. |

SIBDQ. Mean (SD), n: I: 14.8 (11.8), 12 C: 6.3 (9.7), 19 p=.02

EQ-5D-3L. Mean (SD), n: I: 18.5 (18.7), 12 C: 2.4 (8.3), 19 |

|

Overall patient telemonitoring satisfaction. 83.3% of patients were satisfied or very satisfied with the intervention (mean score 2.75/5). Telemonitoring considered useful: mean VAS score 7/10 [5 to 10] Feeling of more empowerment/independence: 75% of participants Technical difficulty: 6.5/10 [0 to 10]

|

Gastroenterologist consultations. Mean (SD), n: I: 2.2 (2.2), 12 C: 4.1 (2.9), 19 p=.013 |

ER visits or hospitalization. No differences reported. |

|

Carlsen (6) |

Step-up treatment intensity Log rank test: p=.53 |

Paediatric IBD-IMPACT score. No difference between groups. |

NR |

Medical adherence (MARS and VAS). |

Planned outpatient visits. Number; Median [IQR], n: I: 38; 2 [1 to 2], 15 C: 146; 7 [3 to 7], 18 p<0.0001

On-demand outpatient visits. Number; Median [IQR], n: I: 47; 1 [1 to. 3], 15 C: 39; 1 [0to 2], 18 p=0.68

Total outpatient visits. Number; Median [IQR], n: I: 85; 2 [2; 3], 15 C: 185; 8 [4; 9], 18 p<.0001

|

Acute outpatient visits/hospitalizations. Count; median [IQR], n: I: 10; 0 [0 to 0], 15 C: 3; 0 [0 to 1], 18 p=.13

|

|

Cross (8) |

Disease activity (Seo index) |

IBDQ score. MD: -9.2 (-27.62 to 9.22), p=0.33 |

NR |

Medical adherence (MMAS). Events (total binary): I: 11 (25) C: 15 (22) p=.10 |

NR |

NR |

|

Cross (9) |

Disease activity (HBI). MD (EOW vs control): 0.5 (-0.8 to 1.8), p=0.46 MD (Weekly vs control): -0.5 (-1.8 to 0.8), p=0.44

Disease activity (SSCAI). MD (EOW vs. control): 0.3 (-0.57 to 1.17), p=.50 MD (Weekly vs. control): 0.6 (-0.25 to 1.45), p=.17 |

IBDQ score. MD (EOW vs. control): 2.20 (-6.09 to 10.49), p=0.60 MD (Weekly vs. control): -0.10 (-9.22 to 9.02), p=0.98 |

NR |

NR |

NR |

ER visits/100participants/year: I (TELE-IBD EOW): 18.0 I (TELE-IBD Weekly): 15.2 C: 22.4

IBD-related surgery/100participants/year: I (TELE-IBD EOW): 9.0 I (TELE-IBD Weekly): 7.1 C: 11.2

Both results not statistically significant. |

|

Del Hoyo (13) |

Patients in remission (HBI; Walmsley score; Mayo score). RR (Telemonitoring vs. control): 1.13 (0.81 to 1.59), p=.47 |

HRQoL (IBDQ-9) score. Mean, n: I (Telephone): 53, 21 I (Telemonitoring): 52.5, 21 C: 53, 21 |

NR |

Patient satisfaction with received care (Adapted Client Satisfaction Questionnaire). Mean, n: I (Telephone): 53, 21 I (Telemonitoring): 57, 21 C: 55, 21 Overall intervention effect: OR= 8.93, 95% CI= 2.97-26.84, p<.001

Medical adherence (Morisky-Green index): I (Telephone): 71% I (Telemonitoring (86%) C: 81% Overall intervention effect: OR: 0.051, 95% CI: 0.001 to 0.769 |

Outpatient visits, n participants: I (Telephone): 85, 21 I (Telemonitoring): 72, 21 C: 131, 21 |

ER visits (n participants): I (Telephone): 2 (21) I (Telemonitoring): 0 (21) C: 1 (21) Hospitalizations (n participants): I (Telephone): 2 (21) I (Telemonitoring): 2 (21) C: 1 (21) IBD-related surgery (n participants): I (Telephone): 1 (21) I (Telemonitoring): 1 (21) C: 1 (21) |

|

De Jong (15, 16) |

Number of disease flares.

Adjusted for centre, treatment, subtypes of inflammatory bowel disease, age, sex, disease duration, disease activity at baseline, smoking, and educational level.

|

Short-IBDQ score. MD: 0.73 (-0.70 to 2.16), p=0.32 |

(In)direct healthcare costs in euro.

MD: -547.00 (-2108.04 to 1014.04)

|

Patient-reported quality of care (Constructed questionnaire including VAS). MD 0.10 (-0.13 to 0.32), p=0.411

Adjusted for centre, treatment, subtypes of inflammatory bowel disease, age, sex, disease duration, disease activity at baseline, smoking, educational level, and baseline patient-reported values.

|

Mean outpatient visits (SD), n: Gastroenterologist: I: 1.26 (1.18), 465 C: 1.98 (1.19), 444 Nurse: I: 0.29 (0.68), 465 C: 0.36 (0.84), 444 Total: I: 1.55 (1.50), 465 C: 2.34 (1.64), 444

Gastroenterologist: Nurse: MD -0.07 (-0.17 to 0.03) Total: MD -0.79 (-0.99 to -0.59) p<.0001 |

Emergency visits: Mean (SD), n: I: 0.07 (0.35), 465 C: 0.10 (0.54), 444

MD: -0.03 (-0.09 to 0.03), p=0.32

Hospital admissions: Mean (SD), n: I: 0.05 (0.28), 465 C: 0.10 (0.43), 444

MD: -0.05 (-0.10 to 0.00), p=0.04

IBD-related surgery: Mean (SD), n: I: 0.03 (0.16), 465 C: 0.03 (0.16), 444

MD: 0.00 (-0.02 to 0.02), p=1.00

|

|

Elkjaer (10) |

Mean number of relapses (range): I (Denmark): 1.1 (0 to 6); n=105 C (Denmark): 0.8 (0 to 4); n=106 p>0.05

I (Ireland): 0.6 (0 to 4); n=51 C (Ireland): 0.2 (0 to 1); n=41 p=0.02

|

Short-IBDQ and SF-12/SF-36 score. Denmark: Web-group (I) improved statistically significant compared to the control group (C): p=.04

Ireland: General QoL improvement observed in web-group: p=.01

|

Costs (price per visit, hospitalisation and phone consultation in euros)

Outpatient visits I: 12880 C:34454

Hospitalisation: I: 5202 C: 5202

Consultation: I: 2247 C: 504

Medication: I: 641 C: 578

No costs reported for Ireland. |

Feasibility of intervention system: I (Denmark): 88.8% I (Ireland): 88%

Willingness to use new system: C (Denmark): 81% C (Ireland): 68%

Acute treatment adherence in case of relapse: I (Denmark): 73% C (Denmark): 42% p=0.005

I (Ireland): 73% C (Ireland): 29% p=0.03

|

Chronic events (n participants): I (Denmark): 35 (105) C: (Denmark): 92 (106) p<0.0001

I (Ireland): 62 (51) C (Ireland): 91 (41) p=0.007

|

Acute events (n participants): I (Denmark): 21 (105) C (Denmark): 107 (106) p<0.0001

I (Ireland): 9 (51) C (Ireland): 9 (41) p= NA |

|

Heida (7) |

Disease flares |

IBD-specific IMPACT-III score. Mean change score from baseline, n: I: +1.32, 84 C: -0.32, 86 p=.27 |

Annual cost-saving per participant with telemonitoring was 89 euros; 360 euros in those compliant to protocol. |

Telemonitoring opinion (59 (70%) telemonitoring group respondents). 59 respondents (70% of total telemonitoring participants). 96% of respondents agreed that home telemonitoring is time-saving. 56% increased their understanding of the disease. 79% were not disturbed. 71% wished to continue with home telemonitoring care.

Adherence to study protocol, n (%). I: 48 (57) C: 72 (84)

|

NR |

NR |

|

McCombie (11) |

Disease activity (HBI) MD: 0.4 (-0.77 to 1.57), p=0.50

MD: -0.2 (-0.81 to 0.41), p=0.52 |

IBDQ score. MD: 10.50 (0.01 to 20.99), p=0.05

|

NR |

NR |

Mean gastro-appointments (SD), n: I: 0.6 (0.9), 50 C: 1.7 (0.8), 50

MD -1.1 [-1.43 to -0.77], p<0001

Ratio (Combined UC and CD) for IBDsmart/IBDoc (95% CI: 0.36 (0.24 to 0.55) p<.0001 |

Mean (SD), n: Surgical appointments: I: 0.1 (0.4), 50 C: 0.1 (0.4), 50 p=.729 MD: 0.00 (-0.16 to 0.16), p=1.00

IBD-related hospitalization: I: 0.1 (0.3), 50 C: 0.1 (0.4), 50 p=.473 MD: 0.00 (-0.14 to 0.14), p=1.00

IBD-related nights in hospital: I: 0.1 (0.4), 50 C: 0.8 (3.9), 50 p=.629 MD: -0.7 (-1.79 to 0.39), p=0.21 |

|

Östlund (12) |

NR |

NR |

NR |

17/24 compliers accepted to participate in phone survey. 15/17 (88%) patients reported a positive experience of IBD-Home. |

Median healthcare visits due to IBD[IQR], n: I (IBD-Home): 1 [0; 2], 84 I (IBD-Home compliers): 1 [0; 2], 24 I(IBD-Home non-compliers): 0 [0; 2], 60 C: 0 [0;1], 74

IBD-Home versus Control: p=.076 IBD-Home compliers versus non-compliers: p=.524 |

Median healthcare visits due to IBD[IQR], n: I (IBD-Home): 1 [0; 2], 84 I (IBD-Home compliers): 1 [0; 2], 24 I(IBD-Home non-compliers): 0 [0; 2], 60 C: 0 [0;1], 74

IBD-Home versus Control: p=.076 IBD-Home compliers versus non-compliers: p=.524 |

MD: mean difference; QoL: quality of life; SMD: standardized mean difference. All effect estimates are calculated as intervention minus or divided by control. Where applicable, medians (IQR and ranges) were converted to means (SD) using the formulas by Wan (3).

* Variable suitable for meta-analysis

**Median [IQR] scores converted to mean (SD) scores using standardized formulas

***The total number of patients with CD and UC in the study groups were not reported. Therefore, we calculated these numbers based on the total number of IBD patients in the study groups, assuming that the ratio of CD to UC at baseline also applied at 12 months.

Table 5. List of excluded studies after full-text screening and reasons for exclusion

|

Author and year |

Title |

Reason for exclusion |

|

Ankersen (22) |

Individualized home-monitoring of disease activity in adult patients with inflammatory bowel disease can be recommended in clinical practice: A randomized-clinical trial |

Wrong intervention |

|

Ankersen (23) |

Costs of electronic health vs. standard care management of inflammatory bowel disease across three years of follow-up–a Danish register-based study |

Wrong intervention |

|

Arrigo (24) |

Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on the management of paediatric inflammatory bowel disease: An Italian multicentre study on behalf of the SIGENP IBD Group |

Wrong study design |

|

Bensted (25) |

Gastroenterology hospital outpatients report high rates of satisfaction with a Telehealth model of care |

Wrong study design |

|

Bertani (26) |

Hospitalisation for drug infusion did not increase levels of anxiety and the risk of disease relapse in patients with inflammatory bowel disease during covid-19 outbreak |

Wrong intervention |

|

Bilgrami (27) |

Effect of TELEmedicine for Inflammatory Bowel Disease on Patient Activation and Self-Efficacy |

Wrong outcome |

|

Carlsen (28) |

Individualized Infliximab Treatment Guided by Patient-managed eHealth in Children and Adolescents with Inflammatory Bowel Disease |

Wrong study design |

|

Carlsen (29) |

Integration of eHealth Into Pediatric Inflammatory Bowel Disease Care is Safe: 3 Years of Follow-up of Daily Care |

Wrong study design |

|

Chee (30) |

Patient-led Remote IntraCapillary pharmacoKinetic Sampling (fingerPRICKS) for Therapeutic Drug Monitoring in patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease |

Wrong intervention |

|

Chudy-Onwugaje (31) |

Age modifies the association between depressive symptoms and adherence to self-testing with Telemedicine in Patients with inflammatory bowel disease |

Wrong study design |

|

Cross (32) |

Acceptance of telemanagement is high in patients with inflammatory bowel disease |

Wrong study design |

|

Del Hoyo (33) |

Telemonitoring of Crohn's Disease and Ulcerative Colitis (TECCU): Cost-Effectiveness Analysis |

Wrong study design |

|

Dijkstra (34) |

Exploring the Challenges of Implementing a Web-Based Telemonitoring Strategy for Teenagers With Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Empirical Case Study |

Wrong study design |

|

El Hajra (35) |

Consequences and management of COVID-19 on the care activity of an inflammatory Bowel Disease unit |

Wong intervention |

|

Elkjaer (36) |

E-Health: Web-guided therapy and disease self-management in ulcerative colitis: Impact on disease outcome, quality of life and compliance |

Wrong intervention |

|

Huang (37) |

Distance management of inflammatory bowel disease: Systematic review and meta-analysis |

Wrong study design |

|

Jackson (38) |

EHealth technologies in inflammatory bowel disease: A systematic review |

Wrong comparator |

|

Krier (39) |

Potential use of telemedicine to provide outpatient care for inflammatory bowel disease |

Wrong intervention |

|

Lindhagen (40) |

A more frequent disease monitorering but no increased disease activity in patients with inflammatory bowel disease during the first year of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. A retrospective study |

Wrong intervention |

|

Marín-Jiménez (41) |

Diagnostic performance of the simple clinical colitis activity index self-administered online at home by patients with ulcerative colitis: CRONICA-UC study |

Wrong study design |

|

Menze (42) |

KARLOTTA (Kids + Adolescents Research Learning on Tablet Teaching Aachen) randomized controlled pilot study for the implementation of a digital educational app with game of skill for pediatric patients with inflammatory bowel disease |

Wrong intervention |

|

Miloh (43) |

Text messaging effect on adherence in children with inflammatory bowel disease |

Wrong intervention |

|

Nguyen (44) |

Digital Health Technologies for Remote Monitoring and Management of Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Systematic Review |

Wrong study design |

|

Nielsen (45) |

Readiness, acceptance and use of digital patient reported outcome in an outpatient clinic |

Wrong intervention |

|

Pang (46) |

Role of Telemedicine in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials |

Wrong study design |

|

Quinn (47) |

The Telemedicine for Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease (TELE-IBD) Clinical Trial: Qualitative Assessment of Participants' Perceptions |

Wrong study design |

|

Ramelet (48) |

Impact of a nurse led telephone intervention on satisfaction and health outcomes of children with inflammatory rheumatic diseases and their families: A crossover randomized clinical trial |

Wrong population |

|

Schliep (49) |

TELEmedicine for patients with inflammatory bowel disease (tele-IBD) does not improve depressive symptoms or general quality of life compared with standard care at tertiary referral centers |

Secondary analysis (outcome: depression) of Cross (9) |

|

Shah (50) |

Telehealth model of care for outpatient inflammatory bowel disease care in the setting of the COVID-19 pandemic |

Wrong study design |

|

Srinivasan (51) |

A virtual clinic increases anti-TNF dose intensification success via a treat-to-target approach compared with standard outpatient care in Crohn’s disease |

Wrong study design |

|

Yao (52) |

Telemonitoring for patients with inflammatory bowel disease amid the COVID-19 pandemic—A cost-effectiveness analysis |

Wrong intervention |

|

Yilmaz (53) |

Smartphone-based videoconference visits are easy to implement, effective, and feasible in Crohn's Disease Patients: A prospective cohort study |

Wrong intervention |

|

Zand (54) |

Patient Experiences and Outcomes of a Telehealth Clinical Care Pathway for Postoperative Inflammatory Bowel Disease Patients |

Wrong study design |

|

Zhang (55) |

Impact of COVID-19 outbreak on the care of patients with inflammatory bowel disease: A comparison before and after the outbreak in South China |

Wrong study design |

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Laatst beoordeeld : 07-02-2025

Algemene gegevens

De ontwikkeling van de richtlijnmodule werd ondersteund door Cochrane Netherlands in samenwerking met het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten (www.kennisinstituut.nl) en werd gefinancierd door ZE&GG en ZonMw. De financier heeft geen enkele invloed gehad op de inhoud van de richtlijnmodule.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijnmodule is in 2022 een multidisciplinaire werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen (zie hiervoor de Samenstelling van de werkgroep) die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor kinderen met inflammatoire darmziekten.

Werkgroep

- Drs. M. Bouhuys, arts-onderzoeker kinder-MDL, UMCG

- Dr. J.E. van Limbergen kinderarts MDL, Amsterdam UMC

- Dr. P.F. van Rheenen, kinderarts MDL, UMCG (voorzitter)

Met ondersteuning van

- Drs. M.P.T. Kusters, junior onderzoeker, Cochrane Netherlands, UMC Utrecht

- Drs. L.F Huis in ’t Veld, junior onderzoeker, Cochrane Netherlands, UMC Utrecht

- Dr. R.W.M Vernooij, universitair docent, Cochrane Netherlands, UMC Utrecht

- Dr. B. Yang, universitair docent, Cochrane Netherlands, UMC Utrecht

Belangenverklaringen

De KNMG-code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling is gevolgd. Alle werkgroepleden hebben schriftelijk verklaard of zij in de laatste drie jaar directe financiële belangen (betrekking bij een commercieel bedrijf, persoonlijke financiële belangen, onderzoeksfinanciering) of indirecte belangen (persoonlijke relaties, reputatiemanagement, kennisvalorisatie) hebben gehad. Een overzicht van de belangen van werkgroepleden en het oordeel over het omgaan met eventuele belangen vindt u in onderstaande tabel. De ondertekende belangenverklaringen zijn op te vragen bij het secretariaat van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

|

Werkgroeplid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

P.F. (Patrick) van Rheenen |

Kinderarts-MDL, UMC Groningen |

Kinderarts lid van Medisch-Ethische Toetsingscomissie van UMCG (vacatiegelden) |

PI van een investigator-initiated onderzoeksproject mede gefinacierd door Europese Crohn en Colitis Organisatie (ECCO). Materiaal voor calprotectine sneltests zijn gedoneerd door BÜHLMANN Laboratories (beide geen invloed op opzet, uitvoering, analyse en rapportage van onderzoek). |

Geen. |

|

J.E. (Johan) van Limbergen |

Kinderarts-MDL, Amsterdam UMC |

Nestle Health Science: seminarie 4x/jaar |

Janssen, Nestle Health Science, Novalac, Abbvie, Eli-Lilly. Klinisch, translationeel en fundamenteel onderzoek naar voedingstherapie bij kinderen en volwassenen: genetica, microbioom, metaboloom, biomarkers. Consulting (adboard) Pfizer. |

Restricties t.a.v. besluitvorming rondom voedingsinterventies. |

|

M. (Marleen) Bouhuys |

arts-onderzoeker kinder-MDL, UMC Groningen |

Geen |

Onderzoeker bij een investigator-initiated onderzoeksproject (De-escalation of anti-TNF-therapy in adolescents and young adults with IBD with tight faecal Calprot) mede gefinacierd door Europese Crohn en Colitis Organisatie (ECCO). Materiaal voor calprotectine sneltests zijn gedoneerd door BÜHLMANN Laboratories (beide geen invloed op opzet, uitvoering, analyse en rapportage van onderzoek). |

Geen. |

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

De conceptmodule is ter commentaar voorgelegd aan Crohn&Colitis NL en de Patiëntenfederatie Nederland, en de eventueel aangeleverde commentaren zijn bekeken en verwerkt.

Kwalitatieve raming van mogelijke financiële gevolgen in het kader van de Wkkgz

Bij de richtlijnmodule is conform de Wet kwaliteit, klachten en geschillen zorg (Wkkgz) een kwalitatieve raming uitgevoerd om te beoordelen of de aanbevelingen mogelijk leiden tot substantiële financiële gevolgen. Bij het uitvoeren van deze beoordeling is de richtlijnmodule op verschillende domeinen getoetst (zie het stroomschema op de Richtlijnendatabase).

|

Module |

Uitkomst raming |

Toelichting |

|

Module Telemonitoring |

geen financiële gevolgen |

Uit de toetsing volgt dat de aanbevelingen niet breed toepasbaar zijn (<5.000 patiënten) en daarom naar verwachting geen substantiële financiële gevolgen zullen hebben voor de collectieve uitgaven. |

Werkwijze

AGREE

Deze richtlijnmodule is opgesteld conform de eisen vermeld in het rapport Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 van de adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwaliteit. Dit rapport is gebaseerd op het AGREE II instrument (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II; Brouwers, 2010).

Knelpuntenanalyse

Er is geen knelpuntenanalyse uitgevoerd voorafgaand aan de herziening van deze module. De afronding van de ZonMw doelmatigheidsstudie over telemonitoring gaf aanleiding tot het herzien van de module.

Uitgangsvraag en uitkomstmaten

Op basis van de uitkomsten van de afgeronde ZonMw doelmatigheidsstudie is door de werkgroepleden en de adviseur een uitgangsvraag opgesteld. Vervolgens inventariseerde de werkgroep welke uitkomstmaten voor de patiënt relevant zijn, waarbij zowel naar gewenste als ongewenste effecten werd gekeken.

Strategie voor zoeken en selecteren van literatuur

Aan de hand van specifieke zoektermen werd gezocht naar gepubliceerde wetenschappelijke studies in (verschillende) elektronische databases. Tevens werd aanvullend gezocht naar studies aan de hand van de literatuurlijsten van de geselecteerde artikelen. In eerste instantie werd gezocht naar studies met de hoogste mate van bewijs. De werkgroepleden selecteerden de via de zoekactie gevonden artikelen op basis van vooraf opgestelde selectiecriteria. De geselecteerde artikelen werden gebruikt om de uitgangsvraag te beantwoorden. De zoekstrategie is opvraagbaar bij de Richtlijnendatabase.

Kwaliteitsbeoordeling individuele studies

Individuele studies werden systematisch beoordeeld, op basis van op voorhand opgestelde methodologische kwaliteitscriteria, om zo het risico op vertekende studieresultaten (risk of bias) te kunnen inschatten. Deze beoordelingen kunt u vinden in de Risk of Bias (RoB) tabellen. Het gebruikte RoB instrument is aanbevolen door de Cochrane Collaboration voor gerandomiseerd gecontroleerd onderzoek

Samenvatten van de literatuur

De relevante onderzoeksgegevens van alle geselecteerde artikelen werden overzichtelijk weergegeven in evidencetabellen. De belangrijkste bevindingen uit de literatuur werden beschreven in de samenvatting van de literatuur. Bij een voldoende aantal studies en overeenkomstigheid (homogeniteit) tussen de studies werden de gegevens ook kwantitatief samengevat (meta-analyse) met behulp van Review Manager 5.

Beoordelen van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs

De kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs werd bepaald volgens de GRADE-methode. GRADE staat voor ‘Grading Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation’ (zie http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/).

GRADE onderscheidt vier gradaties voor de kwaliteit van het wetenschappelijk bewijs: hoog, redelijk, laag en zeer laag. Deze gradaties verwijzen naar de mate van zekerheid die er bestaat over de literatuurconclusie (Schünemann, 2013; Hultcrantz, 2017).

|

GRADE |

Definitie |

|

Hoog |

|

|

Redelijk |

|

|

Laag |

|

|

Zeer laag |

|

Bij het beoordelen (graderen) van de kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs in richtlijnen volgens de GRADE-methodiek spelen grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming een belangrijke rol (Hultcrantz, 2017). Dit zijn de grenzen die bij overschrijding aanleiding zouden geven tot een aanpassing van de aanbeveling. Om de grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming te bepalen moeten alle relevante uitkomstmaten en overwegingen worden meegewogen. De grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming zijn daarmee niet één op één vergelijkbaar met het minimaal klinisch relevant verschil (Minimal Clinically Important Difference, MCID). Met name in situaties waarin een interventie geen belangrijke nadelen heeft en de kosten relatief laag zijn, kan de grens voor klinische besluitvorming met betrekking tot de effectiviteit van de interventie bij een lagere waarde (dichter bij het nuleffect) liggen dan de MCID (Hultcrantz 2017).

Overwegingen (van bewijs naar aanbeveling)

Om te komen tot een aanbeveling zijn naast (de kwaliteit van) het wetenschappelijke bewijs ook andere aspecten belangrijk en worden meegewogen, zoals de expertise van de werkgroepleden, de waarden en voorkeuren van de patiënt, kosten, aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid, implementatie, beschikbaarheid van voorzieningen en organisatorische zaken. Deze aspecten worden, voor zover geen onderdeel van de literatuursamenvatting, vermeld en beoordeeld (gewogen) onder het kopje ‘Overwegingen’.

Formuleren van aanbevelingen