Tromboprofylaxe

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is de optimale tromboseprofylaxe strategie bij kinderen met inflammatoire darmziekten (IBD)?

Clinical question

What is the optimal strategy for thrombosis prophylaxis in children with inflammatory bowel disease?

Aanbeveling

Overweeg tromboseprofylaxe toe te dienen:

- Bij kinderen/tieners die klinisch opgenomen zijn vanwege actieve colitis (M. Crohn, colitis ulcerosa, of unclassified)

- Bij kinderen/tieners die klinisch opgenomen zijn met actieve IBD (anders dan de colitis als hierboven beschreven; bijv. terminale ileitis) indien 1 of meer risicofactoren aanwezig zijn:

- Gebruik orale anticonceptie

- Gebruik systemische corticosteroïden

- Aanwezigheid van een centrale lijn

- Trombose in de voorgeschiedenis

- Aanwezigheid van hereditaire dan wel verworven trombofilie (factor V Leiden).

Indien gestart, stop de tromboseprofylaxe bij ontslag (dit is een pragmatische aanpak vanwege onvoldoende bewijs uit literatuur).

Recommendations

Consider administering thromboprophylaxis in the following cases:

- In all children/teens hospitalized due to the severity of active colitis (in Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, or unclassified)

- In children/teens hospitalized due to active luminal Crohn's disease (active IBD other than colitis as described above, e.g. inflammation of the terminal ileum) if one or more risk factors are present:

- Use of oral contraception

- Use of systemic corticosteroids

- Presence of a central venous line (catheter)

- History of thrombosis

- Underlying thrombophilia such as factor V Leiden.

If started, discontinue thromboprophylaxis upon discharge (this is a pragmatic approach due to insufficient evidence from the literature).

Overwegingen

Advantages and disadvantages of the intervention and quality of the evidence

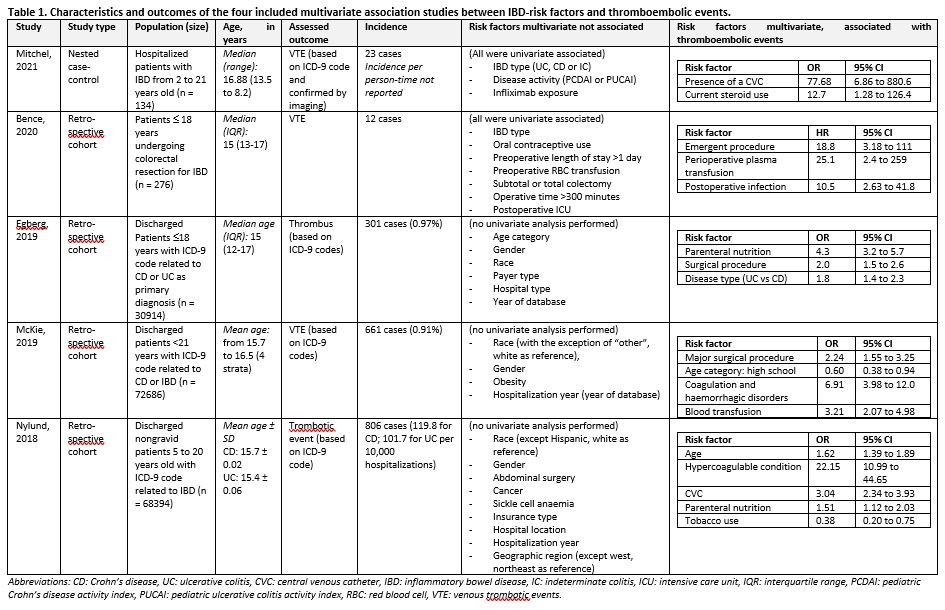

Active IBD, particularly when (the combination of) systemic inflammation, immobilization, and dehydration are present, increases the risk of venous thromboembolic events, potentially resulting in lasting harm. From the systematic literature search, no validated prediction models were available for predicting thromboembolic complications in children with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Some association studies were available, which investigated the association between various potential risk factors and thromboembolic complications. An overview of the association studies can be found in Table 1 Characteristics four included studies. Risk factors reported in multiple studies were: the presence of a central venous catheter, coagulation disorders, parenteral nutrition, undergoing (emergency) surgery, and receiving blood or plasma transfusions. The found association studies have an increased risk of bias due to methodological limitations: moderate risk of attrition bias, moderate risk of bias due to confounding, and some studies overfitted their models (risk of bias from statistical analysis). Confidence in the predictive value of these risk factors is very low due to the absence of prediction models with both internal and external validation. Therefore, no conclusions can be drawn from the findings of these association studies.

In a retrospective cohort study of 2161 adults with a 6-month follow-up after hospital discharge, 66 venous thrombotic complications were reported (McCurdy, 2019). In a point-of-care model (internally validated via bootstrap), the following factors were included: the presence of a central venous catheter (yes/no), length of hospital stay (>1 week or <1 week), admission to the ICU (yes/no), age (>45 or <45 years), and readmission (yes/no). The C-statistic for this model was 0.70 (95% CI 0.58 to 0.77), indicating a reasonably good model. Whether these factors can be extrapolated to the pediatric population is uncertain.

Other pediatric studies without prediction models identified active disease and the need for hospitalization as risk factors for developing thrombotic complications (Aardoom, 2022; De Laffolie, 2022). Both the retrospective adult study and the aforementioned pediatric studies suggest that thromboprophylaxis can be applied to specific IBD-patient groups. In these cases, the risk of bleeding with the use of thromboprophylaxis does not appear significantly elevated: a strong hemoglobin decrease or an increased need for blood transfusion was not observed in a retrospective study of hospitalized children with ulcerative colitis (Story, 2021).

Patient values and preferences

From the patient's perspective, receiving an additional injection is generally undesirable, especially for children who are already ill and may have a fear of needles. Nevertheless, if this additional injection can prevent serious complications, including the risk of permanent damage or, very rarely, mortality, the benefits outweigh the drawbacks. It is essential, however, for healthcare professionals to prioritize a personalized approach, maintain clear communication, and offer effective guidance to address fear of needles.

Crohn & Colitis NL evaluated patient preferences (bijlage Resultaten vragenlijst Crohn Colitis), including those concerning thromboprophylaxis. A total of 86 questionnaires were completed, of which 31 (36%) were filled out by the child with IBD alone, in 14 cases (16%), the child answered the questions together with one of the parents, and 41 times (48%) the questionnaire was completed solely by the parent. 56 respondents (74%) preferred additional injections to prevent thrombosis during hospitalization. If anticoagulants were available in tablets or powder, this would be the preferred form in 38 of 76 respondents (50%). Decisions regarding prophylaxis should be made in consultation with the healthcare provider, with the preferences and wishes of the patient taking priority.

Costs

The cost-effectiveness of low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) injections administered during hospitalizations is justified when compared to the expenses associated with managing thromboembolic events.

Acceptability, feasibility and implementation

Thromboprophylaxis administration is deemed an acceptable intervention, as it does not necessitate significant alterations to hospital procedures or protocols: prophylaxis is already routinely administered in patients with known risk factors for thromboembolic events, such as oral contraception use, systemic corticosteroid use, presence of a central venous line, (first-grade family members with) history of thrombosis, or underlying thrombophilia.

Additionally, acceptability is high as the target patient population is relatively small. In over 90% of cases, thromboprophylaxis can be readily implemented in children with IBD.

As supplementary measures (not intended as replacements), all hospitalized children at risk may benefit from non-pharmacological interventions, including mobilization, maintaining an adequate hydration and nutritional status, disease treatment, administer oral/enteral nutrition when possible, timely identification and adequate treatment of concomitant infections, limit the use of central venous lines, consider the use of stocking for patients with prolonged immobilization and, when feasible, a gradual reduction of corticosteroid use (Klomberg, 2022).

If surgical intervention is considered in active IBD, consultation with the surgeon should take place to determine whether, and during which interval, thromboprophylaxis should be temporarily discontinued.

Rationale of the recommendations

Active IBD, particularly when (the combination of) systemic inflammation, immobilization, and dehydration are present, increases the risk of venous thromboembolic events, potentially resulting in lasting harm or even fatalities.

The risks of venous thromboembolic events outweigh the inconvenience of administering subcutaneous LMWH injections, while LMWH injections do not result in an increased risk of bleeding. Furthermore, the thromboprophylaxis incurs minimal expenses.

For dosing recommendations, Kinderformularium (https://www.kinderformularium.nl/) should be consulted.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Current policies are restrictive regarding administering thromboprophylaxis in children with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and with thrombotic risk factors. Thromboprophylaxis increases the risk of bleeding, and requires subcutaneous injections, which can be experienced as burdensome. Children with IBD are not considered at high risk for thrombosis in current protocols and are therefore being treated conform regular thromboprophylaxis recommendations. However, in clinical practice, it is observed that children with acute severe colitis or clinically severe Crohn’s disease (usually hospitalized) sometimes develop thromboembolic complications. These complications could be prevented, yet it is unclear which patients with IBD would benefit from thromboprophylaxis, when this should be commenced, and how long it should be continued. The question arises whether a different clinical decision score for the use of thromboprophylaxis should be developed for young patients with IBD, or that IBD should be included as a risk factor in this score.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

|

No GRADE |

No validated prediction models were found to determine which children with inflammatory bowel disease would benefit from thromboprophylaxis.

Source: N.A. |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

Five observational studies (one nested case-control; four retrospective cohorts) reported on the association between risk factors related to inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and the occurrence of thromboembolic events. The researched populations – though all pediatric - differed strongly (one study only included postoperative patients, one study excluded patients with indeterminate colitis). See table 1 for the characteristics and found associations of the included studies.

Three studies used the same database (Egberg, 2019; McKie, 2019; Nylund, 2018); a cross-sectional national registry from the United States of America called the Kids’ Inpatient Database (KID), which includes data from 2–3 million yearly hospitalizations from 1997–2012. These studies differed with regard to inclusion criteria: Egberg (2019) included children with IBD who had received parenteral nutrition; MckKie (2019) included children with Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis (but excluded children with unclassified colitis), and Nylund (2018) included all hospitalized children, and performed a sub-analysis for children with IBD.

Two studies (Mitchel, 2021; Bence, 2020) reported to have performed univariate analysis to determine which risk factors should be included in the model. Whereas Bence (2020) did not report which risk factors, Mitchel (2021) reported to not have found a univariate association between thromboembolic events and age at IBD diagnosis, BMI, admission in preceding 2 months, platelet count at admission, and birth control use. Those factors that were univariate associated were included in the multivariate model and are presented in table 1.

Level of evidence of the literature

No level of evidence could be determined as no studies were included in this literature analysis that reported models predicting thromboembolic events in pediatric patients with inflammatory bowel disease.

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question:

Which children with IBD would benefit from thromboprophylaxis (to prevent thromboembolic events)?

| P: | Children with IBD |

| I: | Clinical prediction rule (primary choice), or if unavailable: prediction model (with IBD-specific risk factors) for thromboembolic events (secondary choice) |

| C: | Usual clinical practice to determine the use of thromboprophylaxis (primary choice, or if unavailable) other prediction model (secondary choice) |

| O: |

Model performance (Discrimination through area under the curve (AUC) and/or calibration) Timing: use of clinical prediction or model during or after contact with specialist or hospitalization Setting: during hospitalization |

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered area under the curve as a critical outcome measure for decision making.

The working group defined the performance of the included models as follows:

- 0.7≤AUC<0.8: acceptable,

- 0.8≤AUC<0.9: excellent,

- AUC≥0.9: outstanding.

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms from 2000 until February 8th, 2023. The detailed search strategy is available upon request. The systematic literature search resulted in 805 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria:

- Reporting clinical prediction rules, prospective multivariable model or prediction model with thromboembolic events as dependent variable and IBD-specific risk factors as independent variables;

- The described models were at least internally validated (and preferably externally validated);

- The researched population were children with IBD;

- Studies were in English

No studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening, because of the lack of prediction rules and models. Therefore, a pragmatic selection of observational studies focusing on multivariable associations between risk factors and thromboembolic events was performed based on the following criteria:

- The study included at least 30 children with IBD, and

- The study presented baseline characteristics and corrected for the characteristics associated with thromboembolic events (confounders).

Fourteen studies were then selected based on title and abstract screening according to the pragmatic selection criteria. After reading the full text, nine studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the heading Evidence tables).

Results

Five studies were included in the analysis of the literature. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- Aardoom MA, Klomberg RCW, Kemos P, Ruemmele FM; PIBD-VTE Group; van Ommen CHH, de Ridder L, Croft NM; PIBD-SETQuality Consortium. The Incidence and Characteristics of Venous Thromboembolisms in Paediatric-Onset Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Prospective International Cohort Study Based on the PIBD-SETQuality Safety Registry. J Crohns Colitis. 2022 Jun 24;16(5):695-707. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjab171. PMID: 34599822; PMCID: PMC9228884.

- Bence CM, Traynor MD Jr, Polites SF, Ha D, Muenks P, St Peter SD, Landman MP, Densmore JC, Potter DD Jr. The incidence of venous thromboembolism in children following colorectal resection for inflammatory bowel disease: A multi-center study. J Pediatr Surg. 2020 Nov;55(11):2387-2392. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2020.02.020. Epub 2020 Feb 20. PMID: 32145975.

- Egberg MD, Galanko JA, Barnes EL, Kappelman MD. Thrombotic and Infectious Risks of Parenteral Nutrition in Hospitalized Pediatric Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2019 Feb 21;25(3):601-609. doi: 10.1093/ibd/izy298. PMID: 30304444; PMCID: PMC6383858.

- De Laffolie J, Ballauff A, Wirth S, Blueml C, Rommel FR, Claßen M, Laaß M, Lang T, Hauer AC; CEDATA-GPGE Study Group. Occurrence of Thromboembolism in Paediatric Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Data From the CEDATA-GPGE Registry. Front Pediatr. 2022 Jun 3;10:883183. doi: 10.3389/fped.2022.883183. PMID: 35722497; PMCID: PMC9204097.

- Klomberg RCW, Vlug LE, de Koning BAE, de Ridder L. Venous Thromboembolic Complications in Pediatric Gastrointestinal Diseases: Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Intestinal Failure. Front Pediatr. 2022 Apr 28;10:885876. doi: 10.3389/fped.2022.885876. PMID: 35601436; PMCID: PMC9116461.

- McCurdy JD, Israel A, Hasan M, Weng R, Mallick R, Ramsay T, Carrier M. A clinical predictive model for post-hospitalisation venous thromboembolism in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2019 Jun;49(12):1493-1501. doi: 10.1111/apt.15286. Epub 2019 May 8. PMID: 31066471.

- McKie K, McLoughlin RJ, Hirsh MP, Cleary MA, Aidlen JT. Risk Factors for Venous Thromboembolism in Children and Young Adults With Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J Surg Res. 2019 Nov;243:173-179. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2019.04.087. Epub 2019 Jun 7. PMID: 31181463.

- Mitchel EB, Rosenbaum S, Gaeta C, Huang J, Raffini LJ, Baldassano RN, Denburg MR, Albenberg L. Venous Thromboembolism in Pediatric Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Case-Control Study. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2021 May 1;72(5):742-747. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000003078. PMID: 33605670; PMCID: PMC9066981.

- Nylund CM, Goudie A, Garza JM, Crouch G, Denson LA. Venous thrombotic events in hospitalized children and adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2013 May;56(5):485-91. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3182801e43. PMID: 23232326.

- Story E, Bijelic V, Penney C, Benchimol EI, Halton J, Mack DR. Safety of Venous Thromboprophylaxis With Low-molecular-weight Heparin in Children With Ulcerative Colitis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2021 Nov 1;73(5):604-609. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000003231. PMID: 34676833.

Evidence tabellen

Evidence tables

Evidence table for prognostic factor studies

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Prognostic factor(s) |

Follow-up |

Estimates of prognostic effect |

Comments |

|

Mitchel, 2021 |

Type of study: nested case-control Controls matched 5:1 on sex, race, age at and date of hospitalization.

Setting and country: Large referral centre, United States of America

Funding and conflicts of interest: Non-commercial grant, no conflicts of interest |

Inclusion criteria: Patients with IBD hospitalized from January 2008 through December 2018 who were 2 to 21 years old.

Exclusion criteria: Admission for elective surgery or hospitalized for a chief complaint unrelated to IBD diagnosis

N= 134

Age, median (range): Cases 16.88 (13.5 – 18.2) Controls 16.87 (14.9 – 18.1)

Sex: cases 52% M | controls 49%M

Potential confounders or effect modifiers:

|

From clinical chart review:

|

Duration or endpoint of follow-up: December 2018

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? none

Reasons for incomplete outcome data described? n.a. |

23 cases of VTE (1.3%, based on ICD-9 code and confirmed by imaging); incidence not provided.

Through multivariable logistic regression modelling: Univariate testing – not related: Age at IBD diagnosis, BMI, admission in preceding 2 months, platelet count at admission, birthcontrol use

Multivariate testing – not related: IBD type, disease activity, infliximab exposure

Multivariate testing (Adjusted) factor-outcome associations:

OR (95% CI): 77.68 (6.86 to 880.6)

OR (95% CI): 12.7 (1.28 to 126.4) |

Authors’ conclusion: Given the significant clots reported in some of our patients, the safety and efficacy of pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis based on risk stratification needs to be further evaluated. Our study identifies 2 risk factors that should be considered, CVC presence and steroid use.

Remarks: 5 patients requiring invasive intervention for VTE.

8 factors included in model = overfitting. |

|

Bence, 2020 |

Type of study: Retrospective cohort

Setting and country: Tertiary care children’s hospitals (4), United States of America

Funding and conflicts of interest: No funding received. Information on conflict of interest not disclosed. |

Inclusion criteria: Patients £ 18 years who underwent colon or rectal resection for IBD between January 2010 and June 2016.

Exclusion criteria: Procedures limited to the small bowel and perianal procedures.

N=276

Age, median (IQR): 15 (13 – 17)

Sex: 46% M

Potential confounders or effect modifiers: Authors report: “We used a priori knowledge regarding risk factors for VTE to create a model using multivariable time-dependent analysis (Cox regression). Variables with p-value b 0.2 on univariable analysis were included in a Cox regression model to calculate the adjusted hazard ratio”, yet no information was provided on which risk factors were included or tested

|

Unclear how data was collected, presumably from hospital record:

|

Duration or endpoint of follow-up: Median 186 weeks (range 11 days to 455 weeks).

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? 64

Reasons for incomplete outcome data described? All patients from one institution due to missing data for significant variables |

12 cases of VTE (of which 9 porto-mesenteric)

Through Cox regression modelling: Univariate testing – not related: unclear

Multivariate testing – not related: IBD type, oral contraceptive use, preoperative length of stay >1 day, preoperative RBC transfusion, subtotal or total colectomy, operative time >300 minutes, postoperative ICU admission

Multivariate testing (Adjusted) factor-outcome associations:

HR (95% CI): 18.8 (3.18 to 111)

HR (95% CI): 25.1 (2.4 to 259)

HR (95% CI): 10.5 (2.63 to 41.8)

|

Authors’ conclusion: consider chemical prophylaxis in this high-risk population on an individualized basis. Other risk factors for DVT identified here include emergent procedure, perioperative plasma transfusion, and postoperative infectious complications.

Remarks: 11 factors included in model = overfitting.

VTE prophylaxis not included in model. |

|

McKie, 2019 |

Type of study: Retrospective cohort

Setting and country: Cross-sectional national database, United States of America

Funding and conflicts of interest: No funding received. Authors report no conflict of interest |

Inclusion criteria: Discharged patients <21 years with ICD-9 code related to CD or IBD

Exclusion criteria: (1) Cases with concern for indeterminate colitis, (2) trauma involved in the reason for hospitalization, (3) missing data from critical variables, (4) cases with coding errors within the ICD-9 codes

N= 72686

Mean age ± SD: reported per stratum; from 15.7 to 16.5

Sex: 50.7% M

Potential confounders or effect modifiers:

|

Obtained from the Kid’s inpatient database (KID):

|

Duration or endpoint of follow-up: 1 year

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? The exclusion criteria eliminated 16.5% of the 2012 KID, 22.8% in 2009, and 34.3% in 2006. The predominant reasons for exclusion were a missing race (63.9%) and trauma (14.7%).

|

661 cases of VTE (0.91%)

Through multivariable logistic regression modelling: Multivariate testing – not related: Race (with the exception of “other”, white as reference), gender, obesity

Multivariate testing (Adjusted) factor-outcome associations:

OR (95% CI): 2.24 (1.55 to 3.25)

OR (95% CI): 0.60 (0.38 to 0.94)

OR (95% CI): 6.91 (3.98 to 12.0)

OR (95% CI): 3.21 (2.07 to 4.98)

|

Authors’ conclusion: Our data demonstrate the need for consideration of VTE prophylaxis for pediatric patients with IBD or CD in the perioperative setting or those with a hypercoagulable diagnosis.

Remarks: VTE prophylaxis not included in model. Population excluded indeterminate disease. |

|

Nylund, 2013 |

Type of study: Retrospective cohort

Setting and country: Cross-sectional national database, United States of America

Funding and conflicts of interest: No information of funding reported. Authors report no conflicts of interest. |

Inclusion criteria: Non-gravid children and adolescents aged 5 to 20 years, with an ICD-9 code for thrombotic events.

Exclusion criteria: Discharges related to pregnancy

N=68394 with Crohn or UC

Mean age ± SD: CD: 15.7 ± 0.02 UC: 15.4 ± 0.06

Sex: CD 49.3% M | UC 47.5% M

Potential confounders or effect modifiers:

|

ICD-9 codes from Kids’ inpatient database (KID):

|

Duration or endpoint of follow-up: 1 year

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? Not reported

|

806 cases of VTE. Absolute risk of any thrombotic event per 10,000 hospitalizations: CD 119.8 | UC 101.7 (compared to non-IBD population 50.4)

Through multivariable logistic regression modelling (stratum for patients with IBD): Multivariate testing – not related: Gender, abdominal surgery, cancer, sickle cell anemia, race (except Hispanic versus white), insurance type, hospital location, year of database, geographic region (except west versus northeast)

Multivariate testing (Adjusted) factor-outcome associations:

OR (95% CI): 1.62 (1.39 to 1.89)

OR (95% CI): 22.15 (10.99 to 44.65)

OR (95% CI): 3.04 (2.34 to 3.93)

OR (95% CI): 1.51 (1.12 to 2.03)

OR (95% CI): 20.38 (0.20 to 0.75)

|

Authors’ conclusion: in this large US hospital-based database, we found that hospitalized children and adolescents with IBD are at an increased risk for TE. In our multivariable analysis, this risk of TE persists after adjusting for common risk factors for TE. Risk factors among patients with IBD are older age, CVC, PN, and an identified primary hypercoagulable condition. Factors that were protective are tobacco use and Hispanic ethnicity.

Remarks: VTE prophylaxis not included in model. No missing outcome data reported. |

|

Egberg, 2019 |

Type of study: Retrospective cohort

Setting and country: Cross-sectional national database, United States of America

Funding and conflicts of interest: Non-commercial funding (Grant NIH) received. Authors report no conflicts of interest. |

Inclusion criteria: Patients £18 years discharged from hospital with ICD-9 code related to CD or UC as primary diagnosis

Exclusion criteria: Hospitalizations not related to IBD.

N=30914

Median age (IQR): 15 (12-17)

Sex: 50.6% M

Potential confounders or effect modifiers:

|

ICD-9 codes from Kids’ inpatient database (KID):

|

Duration or endpoint of follow-up: discharge

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? Not reported

|

301 cases of VTE (0.97%)

Through multivariable logistic regression modelling: Multivariate testing – not related: Age category, gender, race, payer type, hospital type, year of database (except 2012)

Multivariate testing (Adjusted) factor-outcome associations:

OR (95% CI): 4.3 (3.2 to 5.7)

OR (95% CI): 2.0 (1.5 to 2.6)

OR (95% CI): 1.8 (1.4 to 2.3)

|

Authors’ conclusion: PN use in hospitalized patients is associated with an increase in absolute risk for thrombus. In pediatric IBD hospitalizations involving PN, the presence of an abdominal surgical procedure is independently associated with an increase in the risk for adverse outcomes as well

Remarks: VTE prophylaxis not included in model. No missing outcome data reported. |

Abbreviations: CD: Crohn’s disease, CVC: central venous catheter, IBD: inflammatory bowel disease, IC: indeterminate colitis, OR: odds ratio, RBC: red blood cell, UC: ulcerative colitis

Table of quality assessment – prognostic factor (PF) studies

Based on: QUIPSA (Haydn, 2006; Haydn 2013)

|

Study reference

(first author, year of publication) |

Study participation

Study sample represents the population of interest on key characteristics?

(high/moderate/low risk of selection bias) |

Study Attrition

Loss to follow-up not associated with key characteristics (i.e., the study data adequately represent the sample)?

(high/moderate/low risk of attrition bias) |

Prognostic factor measurement

Was the PF of interest defined and adequately measured?

(high/moderate/low risk of measurement bias related to PF) |

Outcome measurement

Was the outcome of interest defined and adequately measured?

(high/moderate/low risk of measurement bias related to outcome) |

Study confounding

Important potential confounders are appropriately accounted for?

(high/moderate/low risk of bias due to confounding) |

Statistical Analysis and Reporting

Statistical analysis appropriate for the design of the study?

(high/moderate/low risk of bias due to statistical analysis) |

|

Mitchel, 2021 |

Low risk of selection bias

Reason: The study sample represents the population of interest on key characteristics, sufficient to limit potential bias of the observed relationship between PF and outcome |

High risk of attrition bias

Reason: unclear what precise follow-up time or follow-up endpoints were, therefore unclear loss to follow up and whether the response rate of the controls is adequate. |

Low risk of measurement bias related to PF

Reason: Prognostic factors extracted from clinical charts. |

Low risk of measurement bias related to outcome

Reason: diagnosis code for VTE had to be available and it had to be confirmed through imaging. Small VTE might have been missed. |

Moderate-high risk of bias

Reason: Unclear which hypothesized risk factors were assessed. No reporting of anticoagulation use or thromboprophylaxis. |

High risk of bias due to statistical analysis

Reason: the statistical analysis is appropriate for the design of the study, yet 8 factors have been assessed for 23 cases (overfitting). |

|

Bence, 2020 |

Moderate risk of selection bias

Reason: for research question is the pediatric IBD population of interest, not only those who underwent colorectal surgery. |

High risk of attrition bias

Reason: all patients from one center were excluded due to missingness of significant variables (not described which) |

Moderate risk of measurement bias related to PF

Reason: not clear how PF was measured (assumed extraction from medical records) |

Moderate risk of measurement bias related to outcome

Reason: not clear how outcome was measured (assumed extraction from medical records) |

Moderate-high risk of bias

Reason: Unclear which hypothesized risk factors were assessed. |

High risk of bias due to statistical analysis

Reason: the statistical analysis is appropriate for the design of the study, yet >10 factors have been assessed for 12 cases (overfitting). |

|

McKie, 2019 |

Low risk of selection bias

Reason: The study sample represents the population of interest on key characteristics, sufficient to limit potential bias of the observed relationship between PF and outcome |

Moderate risk of attrition bias

Reason: Significant number of cases excluded due to missing data on baseline variables; unclear if missingness could be related to outcome. |

Low risk of measurement bias related to PF

Reason: Prognostic factors extracted from national registry. |

Low risk of measurement bias related to outcome

Reason: identified through VTE diagnosis code. |

Low-moderate risk of bias due to confounding

Reason: researched risk factors defined in methods. No reporting of anticoagulation use or thromboprofylaxis. |

Low risk of bias due to statistical analysis

Reason: multivariable logistic regression appropriate method, no overfitting. |

|

Nylund, 2018 |

Moderate risk of selection bias

Reason: Unclear whether population was first searched for TE and then IBD |

Moderate risk of attrition bias

Reason: amount of missing data/ excluded from analysis not reported. |

Low risk of measurement bias related to PF

Reason: Prognostic factors extracted from national registry. |

Low risk of measurement bias related to outcome

Reason: identified through VTE diagnosis code. |

Low-moderate risk of bias due to confounding

Reason: researched risk factors defined in methods. No reporting of anticoagulation use or thromboprofylaxis. |

Low risk of bias due to statistical analysis

Reason: multivariable logistic regression appropriate method, no overfitting. |

|

Egberg, 2019 |

Low risk of selection bias

Reason: The study sample represents the population of interest on key characteristics, sufficient to limit potential bias of the observed relationship between PF and outcome |

Moderate risk of attrition bias

Reason: amount of missing data/ excluded from analysis not reported. |

Low risk of measurement bias related to PF

Reason: Prognostic factors extracted from national registry. |

Low risk of measurement bias related to outcome

Reason: identified through VTE diagnosis code. |

Moderate risk of bias due to confounding

Reason: researched risk factors defined in methods. No reporting of anticoagulation use or thromboprofylaxis, specific attention for parenteral nutrition. |

Low risk of bias due to statistical analysis

Reason: multivariable logistic regression appropriate method, no overfitting. |

Table of excluded studies

|

Reference |

Reason for exclusion |

|

Aardoom MA, Klomberg RCW, Kemos P, Ruemmele FM; PIBD-VTE Group; van Ommen CHH, de Ridder L, Croft NM; PIBD-SETQuality Consortium. The Incidence and Characteristics of Venous Thromboembolisms in Paediatric-Onset Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Prospective International Cohort Study Based on the PIBD-SETQuality Safety Registry. J Crohns Colitis. 2022 Jun 24;16(5):695-707. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjab171. PMID: 34599822; PMCID: PMC9228884. |

No use of multivariate modelling |

|

De Laffolie J, Ballauff A, Wirth S, Blueml C, Rommel FR, Claßen M, Laaß M, Lang T, Hauer AC; CEDATA-GPGE Study Group. Occurrence of Thromboembolism in Paediatric Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Data From the CEDATA-GPGE Registry. Front Pediatr. 2022 Jun 3;10:883183. doi: 10.3389/fped.2022.883183. PMID: 35722497; PMCID: PMC9204097. |

No use of multivariate modelling |

|

Ding Z, Sherlock M, Chan AKC, Zachos M. Venous thromboembolism in pediatric inflammatory bowel disease: an 11-year population-based nested case-control study in Canada. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2022 Dec 1;33(8):449-456. doi: 10.1097/MBC.0000000000001166. Epub 2022 Nov 7. PMID: 36409922. |

No use of multivariate modelling (was intention, yet too little events) |

|

Horton DB, Xie F, Chen L, Mannion ML, Curtis JR, Strom BL, Beukelman T. Oral Glucocorticoids and Incident Treatment of Diabetes Mellitus, Hypertension, and Venous Thromboembolism in Children. Am J Epidemiol. 2021 Feb 1;190(3):403-412. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwaa197. PMID: 32902632; PMCID: PMC8086240. |

No separate model for IBD-population |

|

Kappelman MD, Horvath-Puho E, Sandler RS, Rubin DT, Ullman TA, Pedersen L, Baron JA, Sørensen HT. Thromboembolic risk among Danish children and adults with inflammatory bowel diseases: a population-based nationwide study. Gut. 2011 Jul;60(7):937-43. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.228585. Epub 2011 Feb 21. PMID: 21339206. |

Wrong population (mixed children and adults), comparison IBD to non-IBD |

|

Kuenzig ME, Bitton A, Carroll MW, Kaplan GG, Otley AR, Singh H, Nguyen GC, Griffiths AM, Stukel TA, Targownik LE, Jones JL, Murthy SK, McCurdy JD, Bernstein CN, Lix LM, Peña-Sánchez JN, Mack DR, Jacobson K, El-Matary W, Dummer TJB, Fung SG, Spruin S, Nugent Z, Tanyingoh D, Cui Y, Filliter C, Coward S, Siddiq S, Benchimol EI. Inflammatory Bowel Disease Increases the Risk of Venous Thromboembolism in Children: A Population-Based Matched Cohort Study. J Crohns Colitis. 2021 Dec 18;15(12):2031-2040. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjab113. PMID: 34175936; PMCID: PMC8684458. |

Wrong study aim (comparison IBD to non-IBD) |

|

Mulder DJ, Khalouei S, Warner N, Gonzaga-Jauregui C, Church PC, Walters TD, Ramani AK, Griffiths AM, Cohn I, Muise AM. Utilization of Whole Exome Sequencing Data to Identify Clinically Relevant Pharmacogenomic Variants in Pediatric Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2020 Dec;11(12):e00263. doi: 10.14309/ctg.0000000000000263. PMID: 33512800; PMCID: PMC7710220. |

Found factor V Leiden as only risk factor, which is not IBD-specific. |

|

Zitomersky NL, Levine AE, Atkinson BJ, Harney KM, Verhave M, Bousvaros A, Lightdale JR, Trenor CC 3rd. Risk factors, morbidity, and treatment of thrombosis in children and young adults with active inflammatory bowel disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2013 Sep;57(3):343-7. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31829ce5cd. PMID: 23752078. |

No use of multivariate modelling |

|

Lazzerini M, Bramuzzo M, Maschio M, Martelossi S, Ventura A. Thromboembolism in pediatric inflammatory bowel disease: systematic review. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011 Oct;17(10):2174-83. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21563. Epub 2010 Dec 3. PMID: 21910180. |

No use of multivariate modelling, includes case reports |

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Publicatiedatum : 10-02-2025

Beoordeeld op geldigheid : 07-02-2025

Algemene gegevens

De ontwikkeling/herziening van deze richtlijnmodules werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten (www.demedischspecialist.nl/kennisinstituut) en werd gefinancierd uit de Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS). Patiëntenparticipatie (in de vorm van een achterbanuitvraag) bij deze richtlijn werd medegefinancierd uit de Kwaliteitsgelden Patiënten Consumenten (SKPC) binnen het programma KIDZ.

De financier heeft geen enkele invloed gehad op de inhoud van de richtlijnmodule.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijnmodule is in 2022 een multidisciplinaire werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen (zie hiervoor de Samenstelling van de werkgroep) die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor kinderen met inflammatoire darmziekten.

Werkgroep

- prof. dr. J.C. (Hankje) Escher, kinderarts-MDL, Erasmus MC, Rotterdam, namens de NVK

- dr. J.E. (Johan) van Limbergen, kinderarts-MDL, Amsterdam UMC, namens de NVK

- dr. L. (Lissy) de Ridder, kinderarts-MDL, Erasmus MC, Rotterdam, namens de NVK

- dr. L.J.J. (Luc) Derijks, ziekenhuisapotheker - klinisch farmacoloog, Máxima MC en Maastricht UMC, namens de NVZA

- drs. M.P. (Menne) Scherpenzeel, patiëntvertegenwoordiger, namens Crohn & Colitis Nederland

- dr. P.F. (Patrick) van Rheenen (voorzitter), kinderarts-MDL, UMC Groningen, namens de NVK

- S. (Suzanne) van Zundert, diëtist kindergeneeskunde, Amsterdam UMC, namens de NVD

- dr. T.G.J. (Tim) de Meij, kinderarts-MDL, Amsterdam UMC, namens de NVK

Klankbordgroep

De klankbordgroepleden hebben gedurende de ontwikkeling van de richtlijn meegelezen met de conceptteksten en deze becommentarieerd.

- drs. C. (Carmen) Willemsen-Vermeer, diëtist, Radboud UMC, Nijmegen, namens de NVD

- dr. D.R. (Dennis) Wong, ziekenhuisapotheker - klinisch farmacoloog, Zuyderland Medisch Centrum, locatie Sittard-Geleen, namens de NVZA

- drs. F.D.M. (Fiona) van Schaik, arts-MDL, UMC Utrecht, namens de NVMDL

- drs. I.A. (Imke) Bertrams-Maartens, kinderarts-MDL, Máxima MC, namens de NVK

- drs. M. (Marieke) Zijlstra, kinderarts-MDL, Maasstad ziekenhuis, Rotterdam, namens de NVK

- drs. M.A.C. (Martha) van Gaalen, verpleegkundig specialist kinder-MDL, Erasmus MC, Rotterdam, namens de V&VN

Met ondersteuning van

- dr. M.M.J. (Machteld) van Rooijen, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- drs. L.C. (Laura) van Wijngaarden, junior adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

Belangenverklaringen

De Code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling is gevolgd. Alle werkgroepleden hebben schriftelijk verklaard of zij in de laatste drie jaar directe financiële belangen (betrekking bij een commercieel bedrijf, persoonlijke financiële belangen, onderzoeksfinanciering) of indirecte belangen (persoonlijke relaties, reputatiemanagement) hebben gehad. Gedurende de ontwikkeling of herziening van een module worden wijzigingen in belangen aan de voorzitter doorgegeven. De belangenverklaring wordt opnieuw bevestigd tijdens de commentaarfase.

Een overzicht van de belangen van werkgroepleden en het oordeel over het omgaan met eventuele belangen vindt u in onderstaande tabel. De ondertekende belangenverklaringen zijn op te vragen bij het secretariaat van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

|

Werkgroeplid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

J.C. (Hankje) Escher |

Kinderarts-MDL, Erasmus MC Sophia |

E-dokter bij Cyberpoli van Stichting Artsen voor Kinderen (onbetaald) Scientific Advisory Committee Develop Registry - Jansen (betaling via ziekenhuis, ter ondersteuning van research) Scientific Advisory Committee van Cape Registry - Abbvie (betaling via ziekenhuis, ter ondersteuning van research) Programma commissie Jeugdartsen congres - Nutricia (betaling via ziekenhuis, ter ondersteuning van research) |

Abbvie, project Trasnitie coordinator Erasmus MC, projectleider MSD, project Biomarkers voor anti-TNF respons bij kinder-IBD, projectleider Stichting Theia, project HAPPY-IBD screen, angst en depressie bij kinder-IBD |

Restricties t.a.v. besluitvorming rondom Biomarkers voor anti-TNF respons. |

|

J.E. (Johan) van Limbergen |

Kinderarts-MDL, Amsterdam UMC |

Nestle Health Science: seminarie 4x/jaar |

Janssen, Nestle Health Science, Novalac Klinisch, translationeel en fundamenteel onderzoek naar voedingstherapie bij kinderen en volwassenen: genetica, microbioom, metaboloom, biomarkers. |

Restricties t.a.v. besluitvorming rondom voedingsinterventies. |

|

L. (Lissy) de Ridder |

Kinderarts-MDL, Erasmus MC |

Bestuurslid NVK (onbezoldigd) Scientific secretary ESPGHAN (onbezoldigd) Voorzitter P-ECCO (onbezoldigd) |

PIBD congres met symposium over integratie wetenschappelijk onderzoek binnen de kinder IBD patiëntenzorg (Janssen); webinars over biosimilarts (speaker's fee Pfizer).

Projectleider (PI) van investigator-initiated TISKids trial (ZonMW, Pfizer levert medicatie en restricted grant voor follow-up studie; heeft geen inbreng op protocol, data-analyse). Verdere medewerking (local investigator) aan klinische trials (Takeda, Abbvie, Ei Lilly). |

Restricties t.a.v. besluitvorming rondom TNF-alpha medicatie/ TDM |

|

L. (Luc) Derijks |

Ziekenhuisapotheker - klinisch farmacoloog, Máxima MC en Maastricht UMC |

Onderwijs (webinar, e-learning, college): webinar in opdracht van Takeda (betaald), e-learning in opdracht van Ferring (betaald), hoorcolleges UU (onbetaald). |

Geen. |

Geen. |

|

M.P. (Menne) Scherpenzeel |

Directeur, Crohn & Colitis Nederland |

Partner adviesbureau Blauwe Noordzee Diverse onbezoldigde bestuursfuncties |

Wij worden betrokken bij extern gefinancierd onderzoek van derden voor het patiëntenperspectief. Het werk van Crohn & Colitis NL wordt mede mogelijk gemaakt door pharma. |

Input patiëntenorganisatie voor alle te ontwikkelen modules middels uitvraag via achterban. |

|

P.F. (Patrick) van Rheenen |

Kinderarts-MDL, UMC Groningen |

Kinderarts lid van Medisch-Ethische Toetsingscomissie van UMCG (vacatiegelden) |

PI van een investigator-initiated onderzoeksproject mede gefinacierd door Europese Crohn en Colitis Organisatie (ECCO). Materiaal voor calprotectine sneltests zijn gedoneerd door BÜHLMANN Laboratories (beide geen invloed op opzet, uitvoering, analyse en rapportage van onderzoek). |

Geen. |

|

S. (Suzanne) van Zundert |

Diëtist kindergeneeskunde, Amsterdam UMC |

Bestuursfunctie Nederlandse KinderDiëtisten (NKD, onder de NVD) |

PECDED, Nestle Health Science: Patiëntervaring van ouders/kinderen bij voedingstherapie CDED. Participatie in wetenschappelijke onderzoeken die binnen de kinder-MDL afdeling van het Amsterdam UMC worden gedaan. |

Geen. |

|

T.G.J. (Tim) de Meij |

Kinderarts-MDL, Amsterdam UMC |

Lid advisory board Nutricia (vergoeding voor onderzoek) |

Principal investigator (PI) van industry-initiated study fase 3 naar tofacitinib (Pfizer). co-PI van investigator-initiated RCT naar probiotica bij antibiotica-geassocieerde diarree gedeeltelijk gesponsord door Winclove (restricted grant, toegekend bij minimum aantal inclusies). Unrestricted grant van Nutricia voor microbioomanalyse op fecessample van kinderen bij wie moeder antibiotica heeft gehad tijdens sectio caesaria. |

Restricties t.a.v. besluitvorming rondom voedingsinterventies. |

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Er werd aandacht besteed aan het patiëntenperspectief door een afgevaardigde van de patiëntenvereniging Crohn&Colitis NL in de werkgroep en een enquête onder alle leden van Crohn&Colitis NL. De verkregen input is meegenomen bij het opstellen van de uitgangsvragen, de keuze voor de uitkomstmaten en bij het opstellen van de overwegingen (zie kop ‘Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten’). De conceptrichtlijn is tevens ter commentaar voorgelegd aan Crohn&Colitis NL en Patiëntenfederatie Nederland, en de eventueel aangeleverde commentaren zijn bekeken en verwerkt.

Werkwijze

AGREE

Deze richtlijnmodule is opgesteld conform de eisen vermeld in het rapport Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 van de adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwaliteit. Dit rapport is gebaseerd op het AGREE II instrument (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II; Brouwers, 2010).

Knelpuntenanalyse en uitgangsvragen

Binnen het SKMS project “Inventarisatie en optimalisatie modulair onderhoud richtlijn kindergeneeskunde” is breed geïnventariseerd welke kindergeneeskundige modules toe waren aan herziening, en er is een onderhoudsplan opgeleverd. De vijf modules van deze richtlijn, herzien in 2022-2024, kwamen uit dit project naar voren. De modules zijn kritisch beoordeeld en de uitgangsvraag en zoekvraag werden aangepast of aangescherpt.

Uitkomstmaten

Na het opstellen van de zoekvraag behorende bij de uitgangsvraag inventariseerde de werkgroep welke uitkomstmaten voor de patiënt relevant zijn, waarbij zowel naar gewenste als ongewenste effecten werd gekeken. Hierbij werd een maximum van acht uitkomstmaten gehanteerd. De werkgroep waardeerde deze uitkomstmaten volgens hun relatieve belang bij de besluitvorming rondom aanbevelingen, als cruciaal (kritiek voor de besluitvorming), belangrijk (maar niet cruciaal) en onbelangrijk. Tevens definieerde de werkgroep tenminste voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten welke verschillen zij klinisch (patiënt) relevant vonden.

Methode literatuursamenvatting

Een uitgebreide beschrijving van de strategie voor zoeken en selecteren van literatuur is te vinden onder ‘Zoeken en selecteren’ onder Onderbouwing. Indien mogelijk werd de data uit verschillende studies gepoold in een random-effects model. Review Manager 5.4 werd gebruikt voor de statistische analyses. De beoordeling van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs wordt hieronder toegelicht.

Beoordelen van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs

De kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs werd bepaald volgens de GRADE-methode. GRADE staat voor ‘Grading Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation’ (zie http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/). De basisprincipes van de GRADE-methodiek zijn: het benoemen en prioriteren van de klinisch (patiënt) relevante uitkomstmaten, een systematische review per uitkomstmaat, en een beoordeling van de bewijskracht per uitkomstmaat op basis van de acht GRADE-domeinen (domeinen voor downgraden: risk of bias, inconsistentie, indirectheid, imprecisie, en publicatiebias; domeinen voor upgraden: dosis-effect relatie, groot effect, en residuele plausibele confounding).

GRADE onderscheidt vier gradaties voor de kwaliteit van het wetenschappelijk bewijs: hoog, redelijk, laag en zeer laag. Deze gradaties verwijzen naar de mate van zekerheid die er bestaat over de literatuurconclusie, in het bijzonder de mate van zekerheid dat de literatuurconclusie de aanbeveling adequaat ondersteunt (Schünemann, 2013; Hultcrantz, 2017).

|

GRADE |

Definitie |

|

Hoog |

|

|

Redelijk |

|

|

Laag |

|

|

Zeer laag |

|

Bij het beoordelen (graderen) van de kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs in richtlijnen volgens de GRADE-methodiek spelen grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming een belangrijke rol (Hultcrantz, 2017). Dit zijn de grenzen die bij overschrijding aanleiding zouden geven tot een aanpassing van de aanbeveling. Om de grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming te bepalen moeten alle relevante uitkomstmaten en overwegingen worden meegewogen. De grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming zijn daarmee niet één op één vergelijkbaar met het minimaal klinisch relevant verschil (Minimal Clinically Important Difference, MCID). Met name in situaties waarin een interventie geen belangrijke nadelen heeft en de kosten relatief laag zijn, kan de grens voor klinische besluitvorming met betrekking tot de effectiviteit van de interventie bij een lagere waarde (dichter bij het nuleffect) liggen dan de MCID (Hultcrantz, 2017).

Overwegingen (van bewijs naar aanbeveling)

Om te komen tot een aanbeveling zijn naast (de kwaliteit van) het wetenschappelijke bewijs ook andere aspecten belangrijk en worden meegewogen, zoals aanvullende argumenten uit bijvoorbeeld de biomechanica of fysiologie, waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten, kosten (middelenbeslag), aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie. Deze aspecten zijn systematisch vermeld en beoordeeld (gewogen) onder het kopje ‘Overwegingen’ en kunnen (mede) gebaseerd zijn op expert opinion. Hierbij is gebruik gemaakt van een gestructureerd format gebaseerd op het evidence-to-decision framework van de internationale GRADE Working Group (Alonso-Coello, 2016a; Alonso-Coello 2016b). Dit evidence-to-decision framework is een integraal onderdeel van de GRADE methodiek.

Formuleren van aanbevelingen

De aanbevelingen geven antwoord op de uitgangsvraag en zijn gebaseerd op het beschikbare wetenschappelijke bewijs en de belangrijkste overwegingen, en een weging van de gunstige en ongunstige effecten van de relevante interventies. De kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs en het gewicht dat door de werkgroep wordt toegekend aan de overwegingen, bepalen samen de sterkte van de aanbeveling. Conform de GRADE-methodiek sluit een lage bewijskracht van conclusies in de systematische literatuuranalyse een sterke aanbeveling niet a priori uit, en zijn bij een hoge bewijskracht ook zwakke aanbevelingen mogelijk (Agoritsas, 2017; Neumann, 2016). De sterkte van de aanbeveling wordt altijd bepaald door weging van alle relevante argumenten tezamen. De werkgroep heeft bij elke aanbeveling opgenomen hoe zij tot de richting en sterkte van de aanbeveling zijn gekomen.

In de GRADE-methodiek wordt onderscheid gemaakt tussen sterke en zwakke (of conditionele) aanbevelingen. De sterkte van een aanbeveling verwijst naar de mate van zekerheid dat de voordelen van de interventie opwegen tegen de nadelen (of vice versa), gezien over het hele spectrum van patiënten waarvoor de aanbeveling is bedoeld. De sterkte van een aanbeveling heeft duidelijke implicaties voor patiënten, behandelaars en beleidsmakers (zie onderstaande tabel). Een aanbeveling is geen dictaat, zelfs een sterke aanbeveling gebaseerd op bewijs van hoge kwaliteit (GRADE gradering HOOG) zal niet altijd van toepassing zijn, onder alle mogelijke omstandigheden en voor elke individuele patiënt.

|

Implicaties van sterke en zwakke aanbevelingen voor verschillende richtlijngebruikers |

||

|

|

||

|

|

Sterke aanbeveling |

Zwakke (conditionele) aanbeveling |

|

Voor patiënten |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen en slechts een klein aantal niet. |

Een aanzienlijk deel van de patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen, maar veel patiënten ook niet. |

|

Voor behandelaars |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak moeten ontvangen. |

Er zijn meerdere geschikte interventies of aanpakken. De patiënt moet worden ondersteund bij de keuze voor de interventie of aanpak die het beste aansluit bij zijn of haar waarden en voorkeuren. |

|

Voor beleidsmakers |

De aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kan worden gezien als standaardbeleid. |

Beleidsbepaling vereist uitvoerige discussie met betrokkenheid van veel stakeholders. Er is een grotere kans op lokale beleidsverschillen. |

Organisatie van zorg

In de knelpuntenanalyse en bij de ontwikkeling van de richtlijnmodule is expliciet aandacht geweest voor de organisatie van zorg: alle aspecten die randvoorwaardelijk zijn voor het verlenen van zorg (zoals coördinatie, communicatie, (financiële) middelen, mankracht en infrastructuur). Randvoorwaarden die relevant zijn voor het beantwoorden van deze specifieke uitgangsvraag zijn genoemd bij de overwegingen. Meer algemene, overkoepelende, of bijkomende aspecten van de organisatie van zorg worden behandeld in de module Organisatie van zorg.

Commentaar- en autorisatiefase

De conceptrichtlijnmodule werd aan de betrokken (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd ter commentaar. De commentaren werden verzameld en besproken met de werkgroep. Naar aanleiding van de commentaren werd de conceptrichtlijnmodule aangepast en definitief vastgesteld door de werkgroep. De definitieve richtlijnmodule werd aan de deelnemende (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd voor autorisatie en door hen geautoriseerd dan wel geaccordeerd.

Literatuur

Agoritsas T, Merglen A, Heen AF, Kristiansen A, Neumann I, Brito JP, Brignardello-Petersen R, Alexander PE, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Guyatt GH. UpToDate adherence to GRADE criteria for strong recommendations: an analytical survey. BMJ Open. 2017 Nov 16;7(11):e018593. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018593. PubMed PMID: 29150475; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5701989.

Alonso-Coello P, Schünemann HJ, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Rada G, Rosenbaum S, Morelli A, Guyatt GH, Oxman AD; GRADE Working Group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 1: Introduction. BMJ. 2016 Jun 28;353:i2016. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2016. PubMed PMID: 27353417.

Alonso-Coello P, Oxman AD, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Vandvik PO, Meerpohl J, Guyatt GH, Schünemann HJ; GRADE Working Group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 2: Clinical practice guidelines. BMJ. 2016 Jun 30;353:i2089. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2089. PubMed PMID: 27365494.

Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, Burgers JS, Cluzeau F, Feder G, Fervers B, Graham ID, Grimshaw J, Hanna SE, Littlejohns P, Makarski J, Zitzelsberger L; AGREE Next Steps Consortium. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. CMAJ. 2010 Dec 14;182(18):E839-42. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090449. Epub 2010 Jul 5. Review. PubMed PMID: 20603348; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3001530.

Hultcrantz M, Rind D, Akl EA, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Iorio A, Alper BS, Meerpohl JJ, Murad MH, Ansari MT, Katikireddi SV, Östlund P, Tranæus S, Christensen R, Gartlehner G, Brozek J, Izcovich A, Schünemann H, Guyatt G. The GRADE Working Group clarifies the construct of certainty of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017 Jul;87:4-13. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.05.006. Epub 2017 May 18. PubMed PMID: 28529184; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC6542664.

Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 (2012). Adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwalitieit.

http://richtlijnendatabase.nl/over_deze_site/over_richtlijnontwikkeling.html

Neumann I, Santesso N, Akl EA, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Alonso-Coello P, Agoritsas T, Mustafa RA, Alexander PE, Schünemann H, Guyatt GH. A guide for health professionals to interpret and use recommendations in guidelines developed with the GRADE approach. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016 Apr;72:45-55. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.11.017. Epub 2016 Jan 6. Review. PubMed PMID: 26772609.

Schünemann H, Brożek J, Guyatt G, et al. GRADE handbook for grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. Updated October 2013. The GRADE Working Group, 2013. Available from http://gdt.guidelinedevelopment.org/central_prod/_design/client/handbook/handbook.html.

Zoekverantwoording

Algemene informatie

|

Cluster/richtlijn: NVK Inflammatoire darmziekten bij kinderen |

|

|

Uitgangsvraag/modules: UV5 Welke tromboprofylactische strategie moet worden toegepast/ Wat is de optimale tromboseprofylactische strategie bij kinderen met IBD? |

|

|

Database(s): Embase.com, Ovid/Medline |

Datum: 8 februari 2023 |

|

Periode: vanaf 2000 |

Talen: geen restrictie |

|

Literatuurspecialist: Alies van der Wal |

|

|

BMI-zoekblokken: voor verschillende opdrachten wordt (deels) gebruik gemaakt van de zoekblokken van BMI-Online https://blocks.bmi-online.nl/ Bij gebruikmaking van een volledig zoekblok zal naar de betreffende link op de website worden verwezen. |

|

|

Toelichting: Voor deze vraag is gezocht op de elementen:

→ De sleutelartikelen worden gevonden met deze search, m.u.v. PMID 35608932. Deze valt niet binnen de gewenste studiedesigns (is expert opinion) → Sensitief RCT filter gebruikt → RCT-bewijs van volwassenen met IBD kan evt. gebruikt worden, daarom ook studies m.b.t. volwassenen meegenomen |

|

|

Te gebruiken voor richtlijnen tekst: Nederlands In de databases Embase.com en Ovid/Medline is op 3 februari 2023 systematisch gezocht naar systematische reviews, RCTs en observationele studies over tromboseprofylaxe/ trombose bij IBD. De literatuurzoekactie leverde 805 unieke treffers op.

Engels On the 3rd of February 2023, a systematic search was performed for systematic reviews, RCTs and observational studies about thromboprophylaxis/ thrombosis and inflammatory bowel disease in the databases Embase.com and Ovid/Medline. The search resulted in 805 unique hits. |

|

Zoekopbrengst

|

|

EMBASE |

OVID/MEDLINE |

Ontdubbeld |

|

SR kind |

26 |

18 |

28 |

|

SR overig |

93 |

80 |

99 |

|

RCT kind |

21 |

8 |

25 |

|

RCT overig |

116 |

92 |

131 |

|

Observationele studies kind |

102 |

67 |

117 |

|

Observationele studies overig |

350 |

355 |

405 |

|

Totaal |

708 |

620 |

805* |

*in Rayyan

Zoekstrategie

Embase.com

|

No. |

Query |

Results |

|

#19 |

#12 NOT #18 = observationeel overig |

350 |

|

#18 |

#12 AND #13 = observationeel kind |

102 |

|

#17 |

#11 NOT #16 = RCT overig |

116 |

|

#16 |

#11 AND #13 = RCT kind |

21 |

|

#15 |

#10 NOT #14 = SR overig |

93 |

|

#14 |

#10 AND #13 = SR kind |

26 |

|

#13 |

'adolescent'/exp OR 'baby'/exp OR 'boy'/exp OR 'child'/exp OR 'minors'/exp/mj OR 'pediatric patient'/exp OR 'pediatrics'/exp OR 'schoolchild'/exp OR infan*:ti,ab OR newborn*:ti,ab OR 'new born*':ti,ab OR perinat*:ti,ab OR neonat*:ti,ab OR baby*:ti,ab OR babies:ti,ab OR toddler*:ti,ab OR minors*:ti,ab OR boy:ti,ab OR boys:ti,ab OR boyfriend:ti,ab OR boyhood:ti,ab OR girl*:ti,ab OR kid:ti,ab OR kids:ti,ab OR child*:ti,ab OR children*:ti,ab OR schoolchild*:ti,ab OR adolescen*:ti,ab OR juvenil*:ti,ab OR youth*:ti,ab OR teen*:ti,ab OR pubescen*:ti,ab OR pediatric*:ti,ab OR paediatric*:ti,ab OR peadiatric*:ti,ab OR school:ti,ab OR school*:ti,ab OR prematur*:ti,ab OR preterm*:ti,ab |

5614183 |

|

#12 |

#5 AND (#8 OR #9) NOT (#10 OR #11) |

452 |

|

#11 |

#5 AND #7 NOT #10 |

137 |

|

#10 |

#5 AND #6 |

119 |

|

#9 |

'case control study'/de OR 'comparative study'/exp OR 'control group'/de OR 'controlled study'/de OR 'controlled clinical trial'/de OR 'crossover procedure'/de OR 'double blind procedure'/de OR 'phase 2 clinical trial'/de OR 'phase 3 clinical trial'/de OR 'phase 4 clinical trial'/de OR 'pretest posttest design'/de OR 'pretest posttest control group design'/de OR 'quasi experimental study'/de OR 'single blind procedure'/de OR 'triple blind procedure'/de OR (((control OR controlled) NEAR/6 trial):ti,ab,kw) OR (((control OR controlled) NEAR/6 (study OR studies)):ti,ab,kw) OR (((control OR controlled) NEAR/1 active):ti,ab,kw) OR 'open label*':ti,ab,kw OR (((double OR two OR three OR multi OR trial) NEAR/1 (arm OR arms)):ti,ab,kw) OR ((allocat* NEAR/10 (arm OR arms)):ti,ab,kw) OR placebo*:ti,ab,kw OR 'sham-control*':ti,ab,kw OR (((single OR double OR triple OR assessor) NEAR/1 (blind* OR masked)):ti,ab,kw) OR nonrandom*:ti,ab,kw OR 'non-random*':ti,ab,kw OR 'quasi-experiment*':ti,ab,kw OR crossover:ti,ab,kw OR 'cross over':ti,ab,kw OR 'parallel group*':ti,ab,kw OR 'factorial trial':ti,ab,kw OR ((phase NEAR/5 (study OR trial)):ti,ab,kw) OR ((case* NEAR/6 (matched OR control*)):ti,ab,kw) OR ((match* NEAR/6 (pair OR pairs OR cohort* OR control* OR group* OR healthy OR age OR sex OR gender OR patient* OR subject* OR participant*)):ti,ab,kw) OR ((propensity NEAR/6 (scor* OR match*)):ti,ab,kw) OR versus:ti OR vs:ti OR compar*:ti OR ((compar* NEAR/1 study):ti,ab,kw) OR (('major clinical study'/de OR 'clinical study'/de OR 'cohort analysis'/de OR 'observational study'/de OR 'cross-sectional study'/de OR 'multicenter study'/de OR 'correlational study'/de OR 'follow up'/de OR cohort*:ti,ab,kw OR 'follow up':ti,ab,kw OR followup:ti,ab,kw OR longitudinal*:ti,ab,kw OR prospective*:ti,ab,kw OR retrospective*:ti,ab,kw OR observational*:ti,ab,kw OR 'cross sectional*':ti,ab,kw OR cross?ectional*:ti,ab,kw OR multicent*:ti,ab,kw OR 'multi-cent*':ti,ab,kw OR consecutive*:ti,ab,kw) AND (group:ti,ab,kw OR groups:ti,ab,kw OR subgroup*:ti,ab,kw OR versus:ti,ab,kw OR vs:ti,ab,kw OR compar*:ti,ab,kw OR 'odds ratio*':ab OR 'relative odds':ab OR 'risk ratio*':ab OR 'relative risk*':ab OR 'rate ratio':ab OR aor:ab OR arr:ab OR rrr:ab OR ((('or' OR 'rr') NEAR/6 ci):ab))) |

13830409 |

|

#8 |

'major clinical study'/de OR 'clinical study'/de OR 'case control study'/de OR 'family study'/de OR 'longitudinal study'/de OR 'retrospective study'/de OR 'prospective study'/de OR 'comparative study'/de OR 'cohort analysis'/de OR ((cohort NEAR/1 (study OR studies)):ab,ti) OR (('case control' NEAR/1 (study OR studies)):ab,ti) OR (('follow up' NEAR/1 (study OR studies)):ab,ti) OR (observational NEAR/1 (study OR studies)) OR ((epidemiologic NEAR/1 (study OR studies)):ab,ti) OR (('cross sectional' NEAR/1 (study OR studies)):ab,ti) |

7485021 |

|

#7 |

'clinical trial'/exp OR 'randomization'/exp OR 'single blind procedure'/exp OR 'double blind procedure'/exp OR 'crossover procedure'/exp OR 'placebo'/exp OR 'prospective study'/exp OR rct:ab,ti OR random*:ab,ti OR 'single blind':ab,ti OR 'randomised controlled trial':ab,ti OR 'randomized controlled trial'/exp OR placebo*:ab,ti |

3722204 |

|

#6 |

'meta analysis'/exp OR 'meta analysis (topic)'/exp OR metaanaly*:ti,ab OR 'meta analy*':ti,ab OR metanaly*:ti,ab OR 'systematic review'/de OR 'cochrane database of systematic reviews'/jt OR prisma:ti,ab OR prospero:ti,ab OR (((systemati* OR scoping OR umbrella OR 'structured literature') NEAR/3 (review* OR overview*)):ti,ab) OR ((systemic* NEAR/1 review*):ti,ab) OR (((systemati* OR literature OR database* OR 'data base*') NEAR/10 search*):ti,ab) OR (((structured OR comprehensive* OR systemic*) NEAR/3 search*):ti,ab) OR (((literature NEAR/3 review*):ti,ab) AND (search*:ti,ab OR database*:ti,ab OR 'data base*':ti,ab)) OR (('data extraction':ti,ab OR 'data source*':ti,ab) AND 'study selection':ti,ab) OR ('search strategy':ti,ab AND 'selection criteria':ti,ab) OR ('data source*':ti,ab AND 'data synthesis':ti,ab) OR medline:ab OR pubmed:ab OR embase:ab OR cochrane:ab OR (((critical OR rapid) NEAR/2 (review* OR overview* OR synthes*)):ti) OR ((((critical* OR rapid*) NEAR/3 (review* OR overview* OR synthes*)):ab) AND (search*:ab OR database*:ab OR 'data base*':ab)) OR metasynthes*:ti,ab OR 'meta synthes*':ti,ab |

899239 |

|

#5 |

#4 AND [2000-2023]/py |

1312 |

|

#4 |

#3 NOT ('conference abstract'/it OR 'editorial'/it OR 'letter'/it OR 'note'/it) NOT (('animal'/exp OR 'animal experiment'/exp OR 'animal model'/exp OR 'nonhuman'/exp) NOT 'human'/exp) |

1615 |

|

#3 |

#1 AND #2 |

3338 |

|

#2 |

'thrombosis prevention'/exp OR 'embolism prevention'/exp OR thromboprophyla*:ti,ab,kw OR ((thromb* NEAR/3 (prophyla* OR prevent*)):ti,ab,kw) OR 'venous thromboembolism'/exp/mj OR 'arterial thromboembolism'/exp/mj OR 'deep vein thrombosis'/exp/mj OR 'lung embolism'/exp/mj OR 'thromboembolism'/mj OR 'blood clotting factor 5 leiden'/de OR (((venous OR vein OR vascular OR arterial OR lung OR pulmonary OR sinus) NEAR/3 (embol* OR microembol* OR thromboembol* OR thrombos* OR thrombotic)):ti,ab,kw) OR vte:ti,ab,kw OR dvt:ti,ab,kw OR cvst:ti,ab,kw OR thromboembol*:ti,ab,kw OR 'thrombo embol*':ti,ab,kw OR ((deep NEAR/3 (thromb* OR 'blood clot*' OR embol*)):ti,ab,kw) OR 'factor v leiden':ti,ab,kw OR 'factor 5 leiden':ti,ab,kw OR ((thromb* NEAR/3 (complication* OR risk)):ti,ab,kw) |

347202 |

|

#1 |

'inflammatory bowel disease'/exp/mj OR 'pancolitis'/exp/mj OR 'enterocolitis'/exp/mj OR ((inflammatory NEAR/3 bowel NEAR/3 dis*):ti,ab,kw) OR ibd:ti,ab,kw OR pibd:ti,ab,kw OR crohn*:ti,ab,kw OR 'cleron dis*':ti,ab,kw OR 'colitis ulcer*':ti,ab,kw OR 'ulcerative col*':ti,ab,kw OR 'idiopathic proctocol*':ti,ab,kw OR 'colitis gravis':ti,ab,kw OR 'regional enteritis':ti,ab,kw OR 'ulcerative proctocol*':ti,ab,kw OR 'ulcerative procto col*':ti,ab,kw OR 'ulcerative proctitis*':ti,ab,kw OR 'mucosal colitis':ti,ab,kw OR 'ulcerous colit*':ti,ab,kw OR ((granulomatous NEAR/3 (ileit* OR enteriti*)):ti,ab,kw) OR ileocolit*:ti,ab,kw OR pancolit*:ti,ab,kw OR enterocolit*:ti,ab,kw |

236893 |

Ovid/Medline

|

# |

Searches |

Results |

|

19 |

12 not 18 = observationeel overig |

355 |

|

18 |

12 and 13 = observationeel kind |

67 |

|

17 |

11 not 16 = RCT overig |

92 |

|

16 |

11 and 13 = RCT kind |

8 |

|

15 |

10 not 14 = SR overig |

80 |

|

14 |

10 and 13 = SR kind |

18 |

|

13 |

(child* or schoolchild* or infan* or adolescen* or pediatri* or paediatr* or neonat* or boy or boys or boyhood or girl or girls or girlhood or youth or youths or baby or babies or toddler* or childhood or teen or teens or teenager* or newborn* or postneonat* or postnat* or puberty or preschool* or suckling* or picu or nicu or juvenile?).tw. |

2860616 |

|

12 |

(5 and (8 or 9)) not (10 or 11) |

422 |

|

11 |

(5 and 7) not 10 |

100 |

|

10 |

5 and 6 |

98 |

|

9 |

Case-control Studies/ or clinical trial, phase ii/ or clinical trial, phase iii/ or clinical trial, phase iv/ or comparative study/ or control groups/ or controlled before-after studies/ or controlled clinical trial/ or double-blind method/ or historically controlled study/ or matched-pair analysis/ or single-blind method/ or (((control or controlled) adj6 (study or studies or trial)) or (compar* adj (study or studies)) or ((control or controlled) adj1 active) or "open label*" or ((double or two or three or multi or trial) adj (arm or arms)) or (allocat* adj10 (arm or arms)) or placebo* or "sham-control*" or ((single or double or triple or assessor) adj1 (blind* or masked)) or nonrandom* or "non-random*" or "quasi-experiment*" or "parallel group*" or "factorial trial" or "pretest posttest" or (phase adj5 (study or trial)) or (case* adj6 (matched or control*)) or (match* adj6 (pair or pairs or cohort* or control* or group* or healthy or age or sex or gender or patient* or subject* or participant*)) or (propensity adj6 (scor* or match*))).ti,ab,kf. or (confounding adj6 adjust*).ti,ab. or (versus or vs or compar*).ti. or ((exp cohort studies/ or epidemiologic studies/ or multicenter study/ or observational study/ or seroepidemiologic studies/ or (cohort* or 'follow up' or followup or longitudinal* or prospective* or retrospective* or observational* or multicent* or 'multi-cent*' or consecutive*).ti,ab,kf.) and ((group or groups or subgroup* or versus or vs or compar*).ti,ab,kf. or ('odds ratio*' or 'relative odds' or 'risk ratio*' or 'relative risk*' or aor or arr or rrr).ab. or (("OR" or "RR") adj6 CI).ab.)) |

5367508 |

|

8 |

Epidemiologic studies/ or case control studies/ or exp cohort studies/ or Controlled Before-After Studies/ or Case control.tw. or cohort.tw. or Cohort analy$.tw. or (Follow up adj (study or studies)).tw. or (observational adj (study or studies)).tw. or Longitudinal.tw. or Retrospective*.tw. or prospective*.tw. or consecutive*.tw. or Cross sectional.tw. or Cross-sectional studies/ or historically controlled study/ or interrupted time series analysis/ |

4376053 |

|

7 |

exp clinical trial/ or randomized controlled trial/ or exp clinical trials as topic/ or randomized controlled trials as topic/ or Random Allocation/ or Double-Blind Method/ or Single-Blind Method/ or (clinical trial, phase i or clinical trial, phase ii or clinical trial, phase iii or clinical trial, phase iv or controlled clinical trial or randomized controlled trial or multicenter study or clinical trial).pt. or random*.ti,ab. or (clinic* adj trial*).tw. or ((singl* or doubl* or treb* or tripl*) adj (blind$3 or mask$3)).tw. or Placebos/ or placebo*.tw. |

2558742 |

|

6 |

meta-analysis/ or meta-analysis as topic/ or (metaanaly* or meta-analy* or metanaly*).ti,ab,kf. or systematic review/ or cochrane.jw. or (prisma or prospero).ti,ab,kf. or ((systemati* or scoping or umbrella or "structured literature") adj3 (review* or overview*)).ti,ab,kf. or (systemic* adj1 review*).ti,ab,kf. or ((systemati* or literature or database* or data-base*) adj10 search*).ti,ab,kf. or ((structured or comprehensive* or systemic*) adj3 search*).ti,ab,kf. or ((literature adj3 review*) and (search* or database* or data-base*)).ti,ab,kf. or (("data extraction" or "data source*") and "study selection").ti,ab,kf. or ("search strategy" and "selection criteria").ti,ab,kf. or ("data source*" and "data synthesis").ti,ab,kf. or (medline or pubmed or embase or cochrane).ab. or ((critical or rapid) adj2 (review* or overview* or synthes*)).ti. or (((critical* or rapid*) adj3 (review* or overview* or synthes*)) and (search* or database* or data-base*)).ab. or (metasynthes* or meta-synthes*).ti,ab,kf. |

652128 |

|

5 |

limit 4 to yr="2000 -Current" |

1350 |

|

4 |

3 not (comment/ or editorial/ or letter/) not ((exp animals/ or exp models, animal/) not humans/) |

1704 |

|

3 |

1 and 2 |

1875 |

|

2 |

Venous Thromboembolism/ or exp Venous Thrombosis/ or exp Pulmonary Embolism/ or exp Thromboembolism/ or ((venous or vein or vascular or arterial or lung or pulmonary or sinus) adj3 (embol* or microembol* or thromboembol* or thrombos* or thrombotic*)).ti,ab,kf. or vte.ti,ab,kf. or dvt.ti,ab,kf. or cvst.ti,ab,kf. or thromboembol*.ti,ab,kf. or 'thrombo embol*'.ti,ab,kf. or (deep adj3 (thromb* or 'blood clot*' or embol*)).ti,ab,kf. or 'factor V Leiden'.ti,ab,kf. or 'factor 5 Leiden'.ti,ab,kf. or (thromb* adj3 (complication* or risk)).ti,ab,kf. or thromboprophyla*.ti,ab,kf. or (thromb* adj3 (prophyla* or prevent*)).ti,ab,kf. |

265066 |

|

1 |

exp Inflammatory Bowel Diseases/ or exp Enterocolitis/ or (inflammatory adj3 bowel adj3 dis*).ti,ab,kf. or ibd.ti,ab,kf. or pibd.ti,ab,kf. or crohn*.ti,ab,kf. or 'cleron disease*'.ti,ab,kf. or 'idiopathic proctocol*'.ti,ab,kf. or 'colitis gravis'.ti,ab,kf. or 'colitis ulcer*'.ti,ab,kf. or 'ulcerative col*'.ti,ab,kf. or 'regional enteritis'.ti,ab,kf. or 'ulcerative proctocol*'.ti,ab,kf. or 'ulcerative procto col*'.ti,ab,kf. or 'ulcerative proctitis*'.ti,ab,kf. or 'mucosal colitis'.ti,ab,kf. or 'ulcerous colit*'.ti,ab,kf. or (granulomatous adj3 (ileit* or enteriti*)).ti,ab,kf. or ileocolit*.ti,ab,kf. or pancolit*.ti,ab,kf. or enterocolit*.ti,ab,kf. |

162599 |