Voedingsinterventies in de onderhoudsfase

Uitgangsvraag

Welke voedingsinterventies kunnen worden ingezet in de onderhoudsfase bij de ziekte van Crohn?

Clinical question

Which nutritional interventions can be used in the maintenance phase for Crohn’s disease?

Aanbeveling

Overweeg voedingstherapie (Partial Enteral Nutrition (PEN), Maintenance Enteral Nutrition (MEN) of het Crohn’s Disease Exclusion Diet (CDED) fase 3), meestal in combinatie met immuunmodulatie, als onderhoudsbehandeling voor kinderen en adolescenten met milde tot matige ziekte van Crohn.

Indien anti-TNF behandeling onvoldoende effect heeft bij het behouden van remissie, dan is anti-TNF in combinatie met voedingstherapie een optie.

Recommendations

Consider nutritional therapy (Partial Enteral Nutrition (PEN), Maintenance Enteral Nutrition (MEN) or Crohn’s Disease Exclusion Diet (CDED) phase 3) in combination with pharmacological treatment as a strategy for maintaining remission in children and adolescents with mild to moderate Crohn’s Disease.

If anti-TNF treatment is not resulting in maintenance of remission, consider additional nutritional therapy.

Overwegingen

Advantages and disadvantages of the intervention and quality of the evidence

A literature review was conducted to examine the effectiveness of maintenance nutritional treatment compared to pharmacological treatment for maintaining remission in children with luminal Crohn’s Disease (CD). In total, one systematic review (including four relevant observational studies) and one retrospective cohort study were found that compared elemental diet, maintenance enteral nutrition (MEN), partial enteral nutrition (PEN) and the specific carbohydrate diet (SCD) with pharmacological treatment (sulfasalazine, prednisone, azathioprine). However, due to methodological limitations (uncertainty about presence and adjustment for confounding factors and assessment of exposure, and missing information about selection of participants), small study populations and broad confidence intervals, the evidence for the critical outcome measures has been assessed as very low. Based on the literature, strong conclusions cannot be drawn whether maintenance nutritional treatment is as effective as or can replace pharmacological treatment in maintaining remission in children and adolescents with CD.

Although strong conclusions cannot be drawn from this literature review, it is known that maintenance dietary therapy is beneficial in terms of weight gain, linear growth and in improving bone health. This particularly applies to children and adolescents with CD due to malabsorption and malnutrition. Because of the adverse effects associated with pharmacological treatment, a more safe and efficient maintenance therapy is desirable (Schulman, 2017). The majority of patients will be requiring pharmacological treatment on the long term, but dietary monotherapy may be considered for highly motivated patients under close supervision by a physician and/or dietitian. Dietary interventions can be used as combination therapy together with pharmacological treatment. Additionally, alternative diets such as the Mediterranean diet and Crohn’s Disease Exclusion Diet (CDED) should also be considered in this setting (Sigall Boneh, 2021).

PEN, as a supplement to a patient’s regular diet in combination with medications, has proven to be beneficial in the maintenance of remission in adult CD, particularly following EEN treatment (Akobeng, 2007; Takagi, 2006; Verma, 2001). Prolonged appliance of PEN has shown to be effective in reducing the risk of relapse and improve the response to biological drugs (Penagini, 2016).

Patient values and preferences

Some patients may encounter difficulties in maintaining dietary interventions due to issues related to palatability and taste fatigue when using additional polymeric formula. Most of the reviewed studies used (nocturnal) nasogastric tube feeding for providing maintenance supplementation. In the Netherlands, we prefer to advise or consider administering PEN or MEN orally to avoid nasogastric tube placement, due to concerns about quality of life.

Offering patients guided dietary therapy in combination with pharmacological treatment for maintaining remission can support them in making long-term changes to their eating habits. A study performed by Martín-Masot (2023) reported an improvement in dietary habits, including a reduced consumption of processed and ultra-processed foods, and greater adherence to the Mediterranean diet, even among participants who did not complete one year (phase 3) of CDED.

Although PEN or MEN may result in adverse effects such as nausea, vomiting, and loose stools, patients also report beneficial effects on disease activity, improved nutritional status, and enhanced linear growth, making it more acceptable to them (Wilschanski, 1996). However, some individuals perceive a lower quality of life due to limited food choices and being on a restrictive diet, which negatively impacts their enjoyment of food and increases their fear of disease relapse (Sigall Boneh, 2021). We also know that nutritional therapy can be a useful salvage regimen at inducing and maintaining remission for patients failing biological therapy as monotherapy despite dose escalation (Nguyen, 2015; Sigall Boneh, 2017; Jijón Andrade, 2023).

Crohn & Colitis NL evaluated patient preferences (bijlage Resultaten vragenlijst Crohn Colitis), including those concerning maintenance nutritional therapy. A total of 86 questionnaires were completed, of which 31 (36%) were filled out by the child with IBD alone, in 14 cases (16%), the child answered the questions together with one of the parents, and 41 times (48%) the questionnaire was completed solely by the parent. The question about maintenance nutritional therapy was answered by 41 participants (48%) who had Crohn's disease. Despite the fact that phase 3 of the CDED requires a long-term adjustment of diet and lifestyle, 28 of 41 respondents (68%) were willing to give it a try.

Costs

The aspects of costs were not considered in the reviewed studies. Enteral formulas administered orally or via nasogastric tube are fully covered when a patient is insured by a Dutch insurance company and has a prescription from a licensed physician or dietitian. This prescription must be extended every few months to a year based on the prescriber’s evaluation. Prescribing PEN or MEN more frequently to pediatric CD patients will increase costs. Furthermore, due to the limitation on the duration of the prescription, physicians or dietitians can easily evaluate patients’ adherence to PEN or MEN during follow-up appointments and collaboratively decide whether to continue or discontinue dietary maintenance therapy.

Another cost aspect is that certain anti-inflammatory foods (fruits, vegetables) can increase the costs on grocery shopping of patients/parents (Herrador-López, 2023).

Acceptability, feasibility and implementation

Patients should be properly guided by a specialized dietitian or other health care professional trained in various dietary therapies that can be considered as a strategy to maintain remission. Compared to the current strategy, where dietary treatment is stopped after a 6-8 weeks course of EEN, continuation of dietary treatment as a maintenance strategy would require more time from dietitians and health care professionals. With the rising incidence of IBD and the increasing health care costs, this may be challenging. The use of patient guiding tools such as apps, cooking videos, FAQ sheets, and websites available in different languages can support patients and families in adhering to maintenance therapy for an extended period of time.

Rationale of the recommendations

Based on the analysis of current studies, it is not clear whether and which of the various nutritional therapies is the most effective maintenance treatment for children and adolescents with Crohn's disease. However, it is known that nutritional therapy in addition to drug therapy is beneficial for weight gain, growth and improvement in bone density. Because of the side effects of medication and the tolerance and compliance of the possible nutritional therapies, it is important to make a well-considered and joint decision with the patient and parents (shared decision making). It is important to know that nutritional therapy in addition to the use of maintenance medication may have an added effect for long-term maintenance of remission. In practice, this will require individualized care by a multidisciplinary team of physicians and specialized dietitians with close follow-up of patients.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Already during induction of remission in patients with luminal Crohn’s disease, a treatment modality should be selected for maintenance of remission. Nutritional interventions can be employed such as partial enteral nutrition (PEN) or maintenance enteral nutrition (MEN). Nutritional treatment could potentially be an alternative to medication such as immunomodulators (thiopurines or methotrexate) or anti-TNF treatment. Nutritional treatment may also be considered as an adjunct to maintenance medication. It is unclear whether PEN or MEN are as effective as the abovementioned medication in maintaining remission, and whether nutritional interventions provide added value such as promotion of normal growth and avoidance of side effects from medical treatment.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

1. Duration of remission

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of maintenance nutritional treatment on duration of remission compared with pharmacological treatment in children and adolescents with CD.

Source: Belli, 1988; Duncan, 2014; Obih, 2015; Wilschanski, 1996; Schulman, 2017. |

2. Clinical disease activity

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of maintenance nutritional treatment on clinical disease activity compared with pharmacological treatment in children and adolescents with CD.

Source: Belli, 1988; Obih, 2015; Schulman, 2017. |

3. Growth

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of maintenance nutritional treatment on growth compared with pharmacological treatment in children and adolescents with CD.

Source: Belli, 1988; Schulman, 2017; Wilschanski, 1996. |

4. Quality of life

|

- GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding the effect of maintenance nutritional treatment on quality of life when compared with pharmacological treatment in children and adolescents with CD

Source: - |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

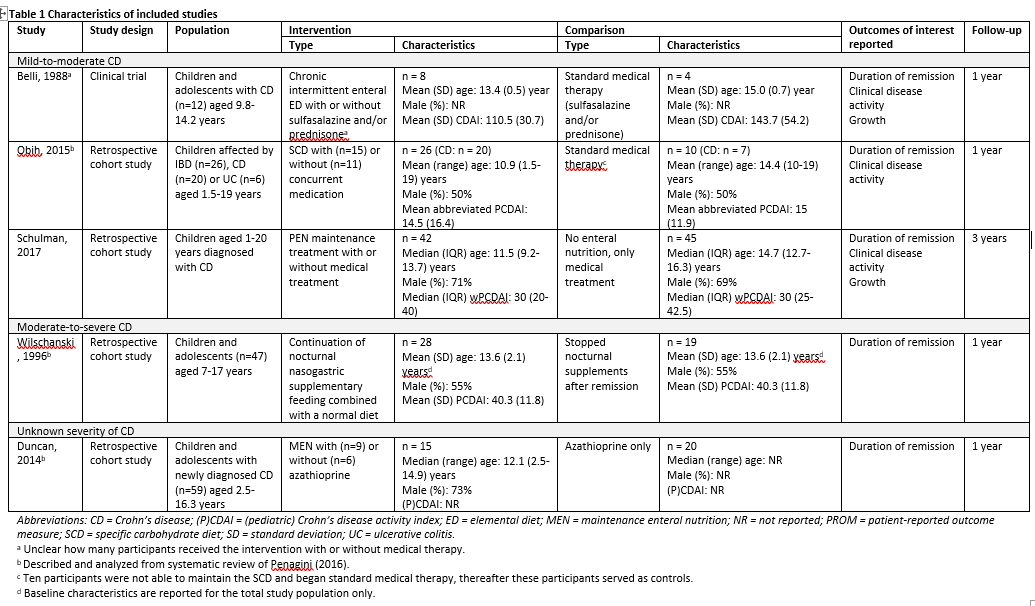

Penagini (2016) performed a systematic review to examine the scientific literature on all aspects of nutrition in pediatric inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), including the most recent advances in nutritional therapy. The electronic databases PubMed, Embase and Medline were searched with relevant search terms from January 1982 up to April 2016. Studies were included if these 1) had a randomized controlled or comparative design, 2) examined pediatric patients with IBD, and 3) involved any nutritional therapy. Studies were excluded if no full-text English paper was available. Eventually, a total of 53 studies were included of which seven focused on nutrition for maintenance of remission. Of these, four studies were conform our PICO and are therefore described and analyzed in the current literature analysis (Belli, 1988; Wilschanski, 1996; Duncan, 2014; Obih, 2015). Obih (2015) included Crohn’s disease (CD) as well as ulcerative colitis (UC) patients, but this literature analysis focuses on results concerning CD patients. Characteristics of the individual studies are shown in Table 1.

Schulman (2017) performed a retrospective cohort study to investigate the efficacy of partial enteral nutrition (PEN) treatment in pediatric CD patients. Children aged 1-20 years with a diagnosis of CD during the period from January 2001 to June 2013 were eligible for inclusion. Exclusion criteria consisted of 1) children who were not treated with EEN followed by PEN, and 2) children for whom lacked data. In total, 42 clinical records from pediatric CD patients were reviewed. Patients entered clinical remission on 4-12 weeks of exclusive enteral nutrition (EEN) and were subsequently maintained on 50% PEN as a supplementary diet. Children with CD who refused enteral nutrition served as the control group. The control group consisted of 45 pediatric CD patients diagnosed between August 2004 and June 2013 derived from the same population. Three types of enteral nutrition were used: 1) Modulen IBD®, 2) Ensure®, and 3) PediaSure. Both treatment groups were allowed to receive concomitant medications (e.g., corticosteroids, thiopurines, anti-TNF agents, methotrexate, and antibiotics). The outcomes duration of remission and growth were reported. Additional study characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Results

1. Duration of remission

Five studies reported on the outcome measure duration of remission. Results could not be pooled due to the variety in study design and reporting of this outcome measure.

Belli (1988) reported on this outcome measure, defined as the incidence of clinical relapses during the one year follow-up period (Crohn’s Disease Activity Index [CDAI] > 150 at least once during follow-up). The authors reported a clinical relapse in 25% (2/8) of patients in the intermittent (one month out of 4 months) elemental diet group during the one year follow-up period. Of the control patients, 75% (3/4) experienced clinical relapse during the one year follow-up period. The risk ratio was 0.33 (95%CI 0.09 to 1.26) in favor of intermittent elemental diet therapy. This difference was considered clinically relevant.

Duncan (2014) reported on duration of remission, defined as remission rates over the first year of follow-up after diagnoses including eight weeks of EEN. Duncan (2014) separately reported results of participants receiving MEN either with or without azathioprine.

- After six months of follow-up, 100% (6/6) of patients receiving MEN without azathioprine were in remission, 89% (8/9) of patients receiving MEN with azathioprine, and 80% (16/20) of patients receiving azathioprine only. Risk ratios were 1.18 (95%CI 0.87 to 1.60) and 1.11 (95%CI 0.81 to 1.53) in favor of MEN treatment (with or without azathioprine). These differences were considered clinically relevant.

- After one year of follow-up, 50% (3/6) of patients receiving MEN without azathioprine, 67% (6/9) of patients receiving MEN with azathioprine, and 65% (13/20) of patients receiving azathioprine only, were still in remission. Risk ratios were 0.77 (95%CI 0.32 to 1.82) in favor of azathioprine treatment which was considered clinically relevant, and 1.03 (95%CI 0.58 to 1.80) which was considered not clinically relevant.

Obih (2015) reported on duration of remission. Remission was defined as Pediatric Crohn’s Disease activity index (PCDAI) ≤ 10. The authors reported that 91% (10/11) of participants receiving the specific carbohydrate diet (SCD) maintained in remission during the follow-up period when beginning the SCD in remission. The other nine participants in the intervention group (ntotal = 20) did not begin the diet in remission. In the standard medical therapy group, 33% (1/3) of participants maintained remission during the study period. The other four participants (ntotal = 7) did not begin the diet in remission. Risk ratio was 2.73 (95%CI 0.54 to 13.66) in favor of SCD diet. This difference was considered clinically relevant.

Wilschanski (1996) reported on duration of remission, defined as the relapse rate (PCDAI > 20 and return of clinical symptoms necessitating additional treatment) over the first year of follow-up after ≥4 weeks of bowel rest and nasogastric tube feeding.

- After six months of follow-up, the authors reported relapse in 17.9% (5/28) of participants in the intervention group receiving partial (nocturnal) feeding and in 78.9% (15/19) of participants in the control group. Risk ratio was 0.23 (95%CI 0.10 to 0.52) in favor of continuation of partial (50-60%) nocturnal nasogastric supplementary feeding. This difference was considered clinically relevant.

- After twelve months of follow-up, they reported relapse in 42.9% (12/28) of participants in the intervention group and in 78.9% (15/19) of participants in the control group. Risk ratio was 0.54 (95%CI 0.33 to 0.88) again clinically relevant in favor of continuation of partial (50-60%) nocturnal nasogastric supplementary feeding.

Schulman (2017) reported on the median length of remission. Weighted PCDAI and physician global assessment were used to assess clinical activity of the disease, with clinical remission as judged by the physician. The authors reported a median (range) length of remission of 6 (0-36) months in the PEN group (n=42) and 6 (0-45) months in the control group (n=45).

2. Clinical disease activity

Three studies reported on this outcome measure.

Belli (1988) reported on mean CDAI values recorded each month during the experimental period of one year. CDAI scores can range from 0 to ~600, in which higher scores represent more severe disease. For the elemental diet group (n=8), mean (SD) CDAI value was 63.0 (13.4). And for the standard medical therapy group (n=4), mean (SD) CDAI value was 128.8 (23.5). Mean difference between the groups was -65.80 (95%CI -90.63 to -40.97) favoring the elemental intermittent diet therapy group. This difference was considered clinically relevant.

Obih (2015) reported on mean (SD) abbreviated PCDAI values after 6 months. PDCAI scores can range from 0 to 100 with higher scores indicating more active disease. The authors reported a mean (SD) PCDAI value of 3.1 (5.1) in participants receiving the SCD (n=20),and for participants receiving standard medical therapy (n=7), a mean (SD) PCDAI value of 9.2 (17.7). Mean difference between the groups was -6.10 (95%CI -19.40 to 7.20) favoring the SCD group. This difference was considered not clinically relevant.

Schulman (2017) reported on median (IQR) wPCDAI after one year of PEN treatment and one year after diagnosis. The score range of the wPCDAI is 0 to 125 with higher scores representing more severe disease. The authors reported a median wPCDAI score of 3.8 (0 to 13.8) in participants receiving PEN (n=42) and 10.0 (0 to 20) in participants receiving no enteral nutrition or the control group (n=45).

3. Growth

Two studies reported on the outcome measure longitudinal growth.

Belli (1988) reported on growth during the experimental period of one year. Participants in the elemental diet group grew on average 7.0 (0.8) cm (n=8), whereas participants in the standard medical therapy group grew on average 1.7 (0.8) cm (n=4) during the one year period. Mean difference between the groups was 5.30 cm (95%CI 4.34 to 6.26) in favor of the elemental diet group. This difference was considered clinically relevant.

Schulman (2017) reported on height after six months of PEN and eight months after diagnosis. The authors reported a mean (SD) height of 1.53 (0.17) meters in the PEN group and 1.60 (0.17) in the control group. Mean difference was -0.07 (95%CI -0.14 to 0.00) meters in favor of the control group. This difference was considered not clinically relevant.

Wilschanski (1996) reported on growth during the treatment year. The authors reported a mean growth of 6.1 (4.2) cm during the treatment year for the enteral supplementation group (n=24) and 4.2 (4.5) cm in the control group (n=7). Mean difference was 1.90 (95%CI -1.83 to 5.63) centimeters in favor of the enteral supplementation group. This difference was considered clinically relevant.

4. Quality of life

None of the studies reported on the outcome measure quality of life.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence of the literature was assessed per outcome measure, using the GRADE-methodology. The levels of evidence started at low certainty because evidence was retrieved from observational studies besides one clinical trial.

1. Duration of remission

The level of evidence regarding duration of remission was downgraded by four levels to very low because of uncertainty about adjustment for confounding factors and assessment of exposure, missing information about the selection of participants, the non-randomized design of the clinical trial, and the formation of the control group in Obih (2015) (risk of bias: -1), the comparison group not receiving pharmacological treatment in Wilschanski (1996) (indirectness: -1), and the low number of included patients and the estimates crossing one or both borders of clinical relevance (imprecision: -2).

2. Clinical disease activity

The level of evidence regarding patient-reported outcome measures was downgraded by three levels to very low because of uncertainty about adjustment for confounding factors and assessment of exposure, missing information about the selection of participants, the non-randomized design of the clinical trial, and the formation of the control group in Obih (2015) (risk of bias: -1), and the low number of included patients and the estimates crossing one or both borders of clinical relevance (imprecision: -2).

3. Growth

The level of evidence regarding growth was downgraded by four levels to very low because of uncertainty about adjustment for confounding factors and assessment of exposure, missing information about the selection of participants, and the non-randomized design of the clinical trial (risk of bias: -1), conflicting results (inconsistency: -1), the comparison group not receiving pharmacological treatment (indirectness: -1), and the low number of included patients and the estimates crossing one or both borders of clinical relevance (imprecision: -1).

4. Quality of life

None of the studies reported on the outcome measure quality of life and could therefore not be graded.

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question:

What is the effectiveness of nutritional therapy compared with pharmacotherapy as maintenance treatment for children with Crohn’s disease (CD)?

| P: | Children and adolescents (<18 years) with CD |

| I: | Maintenance nutritional treatment (as stand-alone or in combination with pharmacotherapy) |

| C: | Pharmacological maintenance treatment (methotrexate, thiopurines (azathioprine, 6-mercaptopurine, thioguanine), anti-TNF biologicals (infliximab, adalimumab)) |

| O: | Duration of remission, clinical disease activity, growth, quality of life |

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered duration of remission as a critical outcome measure for decision making, and clinical disease activity, growth, and quality of life as an important outcome measure for decision making.

A priori, the working group did not define the outcome measures listed above but used the definitions used in the studies.

The working group defined a difference of 10% (0.9 ≥ RR ≥ 1.1) as a minimal clinically (patient) important difference.

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms from 1980 to June 18th, 2023. The detailed search strategy is available upon request. The systematic literature search resulted in 453 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria:

- Study design: systematic reviews (searched in at least two databases, detailed search strategy, risk of bias assessment, and results of individual studies available), randomized controlled trials, or other comparative studies (case control or cohort studies);

- Full-text English language publication;

- Studies according to the PICO.

Nine studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, seven studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and two studies were included.

Results

Two studies were included in the analysis of the literature. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- Akobeng AK, Thomas AG. Enteral nutrition for maintenance of remission in Crohn's disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007 Jul 18;(3):CD005984. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005984.pub2. Update in: Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018 Aug 11;8:CD005984. PMID: 17636816.

- Belli DC, Seidman E, Bouthillier L, Weber AM, Roy CC, Pletincx M, Beaulieu M, Morin CL. Chronic intermittent elemental diet improves growth failure in children with Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 1988 Mar;94(3):603-10. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(88)90230-2. PMID: 3123302.

- Duncan H, Buchanan E, Cardigan T, Garrick V, Curtis L, McGrogan P, Barclay A, Russell RK. A retrospective study showing maintenance treatment options for paediatric CD in the first year following diagnosis after induction of remission with EEN: supplemental enteral nutrition is better than nothing! BMC Gastroenterol. 2014 Mar 20;14:50. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-14-50. PMID: 24645851; PMCID: PMC4234202.

- Herrador-López M, Martín-Masot R, Navas-López VM. Dietary Interventions in Ulcerative Colitis: A Systematic Review of the Evidence with Meta-Analysis. Nutrients. 2023 Sep 28;15(19):4194. doi: 10.3390/nu15194194. PMID: 37836478; PMCID: PMC10574654.

- Jijón Andrade MC, Pujol Muncunill G, Lozano Ruf A, Álvarez Carnero L, Vila Miravet V, García Arenas D, Egea Castillo N, Martín de Carpi J. Efficacy of Crohn's disease exclusion diet in treatment -naïve children and children progressed on biological therapy: a retrospective chart review. BMC Gastroenterol. 2023 Jun 29;23(1):225. doi: 10.1186/s12876-023-02857-6. PMID: 37386458; PMCID: PMC10311743.

- Martín-Masot R, Herrador-López M, Navas-López VM. Dietary Habit Modifications in Paediatric Patients after One Year of Treatment with the Crohn's Disease Exclusion Diet. Nutrients. 2023 Jan 20;15(3):554. doi: 10.3390/nu15030554. PMID: 36771261; PMCID: PMC9921286.

- Nguyen DL, Palmer LB, Nguyen ET, McClave SA, Martindale RG, Bechtold ML. Specialized enteral nutrition therapy in Crohn's disease patients on maintenance infliximab therapy: a meta-analysis. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2015 Jul;8(4):168-75. doi: 10.1177/1756283X15578607. PMID: 26136834; PMCID: PMC4480570.

- Obih C, Wahbeh G, Lee D, Braly K, Giefer M, Shaffer ML, Nielson H, Suskind DL. Specific carbohydrate diet for pediatric inflammatory bowel disease in clinical practice within an academic IBD center. Nutrition. 2016 Apr;32(4):418-25. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2015.08.025. Epub 2015 Nov 30. PMID: 26655069.

- Penagini F, Dilillo D, Borsani B, Cococcioni L, Galli E, Bedogni G, Zuin G, Zuccotti GV. Nutrition in Pediatric Inflammatory Bowel Disease: From Etiology to Treatment. A Systematic Review. Nutrients. 2016 Jun 1;8(6):334. doi: 10.3390/nu8060334. PMID: 27258308; PMCID: PMC4924175.

- Schulman JM, Pritzker L, Shaoul R. Maintenance of Remission with Partial Enteral Nutrition Therapy in Pediatric Crohn's Disease: A Retrospective Study. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;2017:5873158. doi: 10.1155/2017/5873158. Epub 2017 May 8. PMID: 28567370; PMCID: PMC5439067.

- Sigall Boneh R, Sarbagili Shabat C, Yanai H, Chermesh I, Ben Avraham S, Boaz M, Levine A. Dietary Therapy With the Crohn's Disease Exclusion Diet is a Successful Strategy for Induction of Remission in Children and Adults Failing Biological Therapy. J Crohns Colitis. 2017 Oct 1;11(10):1205-1212. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjx071. PMID: 28525622.

- Sigall Boneh R, Van Limbergen J, Wine E, Assa A, Shaoul R, Milman P, Cohen S, Kori M, Peleg S, On A, Shamaly H, Abramas L, Levine A. Dietary Therapies Induce Rapid Response and Remission in Pediatric Patients With Active Crohn's Disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021 Apr;19(4):752-759. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.04.006. Epub 2020 Apr 14. PMID: 32302709.

- Takagi S, Utsunomiya K, Kuriyama S, Yokoyama H, Takahashi S, Iwabuchi M, Takahashi H, Takahashi S, Kinouchi Y, Hiwatashi N, Funayama Y, Sasaki I, Tsuji I, Shimosegawa T. Effectiveness of an 'half elemental diet' as maintenance therapy for Crohn's disease: A randomized-controlled trial. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006 Nov 1;24(9):1333-40. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.03120.x. PMID: 17059514.

- Verma S, Kirkwood B, Brown S, Giaffer MH. Oral nutritional supplementation is effective in the maintenance of remission in Crohn's disease. Dig Liver Dis. 2000 Dec;32(9):769-74. doi: 10.1016/s1590-8658(00)80353-9. PMID: 11215556.

- Wilschanski M, Sherman P, Pencharz P, Davis L, Corey M, Griffiths A. Supplementary enteral nutrition maintains remission in paediatric Crohn's disease. Gut. 1996 Apr;38(4):543-8. doi: 10.1136/gut.38.4.543. PMID: 8707085; PMCID: PMC1383112.

Evidence tabellen

Systematic review

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C) |

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

Penagini, 2016

[individual study characteristics deduced from [Penagini, 2016]] |

SR of (R)CTs, cohort, case-control studies

Literature search up to April 2016

A: Belli, 1988 (CT) B: Duncan, 2014 (retrospective cohort) C: Obih, 2015 (retrospective cohort) D: Wilschanski, 1996 (retrospective cohort)

Setting and Country: Italy

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: Funding source not reported. The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

|

Inclusion criteria SR: - Randomized controlled or comparative study design - Involved pediatric patients with IBD - Involved any nutritional therapy.

Exclusion criteria SR: - No full-text English paper

53 studies included of which 5 were conform our PICO and included in the current literature analysis

Important patient characteristics at baseline: N, mean age A: n=8, aged 9.8-14.2 years B: n=59, aged 2.5-16.3 years C: n=26, aged 1.5-19 years D: n=38, aged 5-16 years E: n=65, aged 7-17 years

Sex: Not reported

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

A: Chronic intermittent enteral ED (plus medical therapy) B: MEN with or without azathioprine C: SCD with or without concurrent medication D: Continuation of nocturnal nasogastric supplementary feeding combined with a normal diet |

A: Conventional medical therapy (sulfasalazine or prednisone, or both) B: Azathioprine only C: Standard medical therapy D: Stopped nocturnal supplements after remission

|

Endpoint of follow-up: A: 1 year B: 1 year C: 1 year D: 1 year

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? A: None B: 11 participants (switched to steroids) C: None D: 9 participants (growth impairment, immunosuppressive drugs)

|

Duration of remission A: I: 2/8 (25%) C: 1/2 (50%) B: I: 9/15 (60%) C: 13/20 (65%) C: I: 10/11 (91%) C: 1/3 (33%) D: I: 5/28 (17.9%) C: 15/19 (78.9%)

PROMs Defined as PCAI or PDCAI A: I: 63.0 (13.4) C: 128.8 (23.5) B: NR C: I: 3.1 (5.1) C: 9.2 (17.7)

Growth A: I: 7.0 (0.8) cm C: 1.7 (0.8) cm B: NR C: NR

Quality of life A: NR B: NR C: NR |

Risk of bias assessment not performed by Penagini (2016), see risk of bias table below

Author’s conclusion Nutrition plays a significant role in pediatric IBD. The scientific society is currently looking for modifying dietary habits to maintain disease remission mainly through exclusion diets. The poor compliance and the risk of nutritional deficits are factors that have to be considered. Despite promising results, available data are not strong enough to recommend these nutritional interventions in clinical practice and new large, controlled studies are needed. |

Individual observational study

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics2 |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C) |

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size4 |

Comments |

|

Schulman, 2017 |

Type of study: Retrospective cohort study

Setting and country: Rambam Medical Center, Haifa, Israel

Funding and conflicts of interest: No funding source reported. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

|

Inclusion criteria: Children aged 1-20 years with a diagnosis of CD during the period from January 2001 to June 2013.

Exclusion criteria: - Children who were not treated with EEN followed by PEN - Children for whom lacked data

N total at baseline: Intervention: 42 Control: 45

Important prognostic factors2: Median age (IQR): I: 11.5 (9.2-13.7) years C: 14.7 (12.7-16.3) years

Sex (%male): I: 71% C: 69%

Groups comparable at baseline? Control group seems older compared to the intervention group at baseline |

PEN maintenance treatment

|

No enteral nutrition

|

Length of follow-up: 3 years

Loss-to-follow-up: Patients on PEN were followed up for a median time of 40 months (25.5-79), while patients in the control group were followed up for a median time of 63 months (52-87).

Incomplete outcome data: Not reported.

|

Duration of remission Median (range) I: 6 (0-36) months C: 6 (0-45) months

PROM wPCDAI I: 3.8 (0-13.8) C: 10.0 (0-20)

Growth Height (m) I: 1.53 (0.17) C: 1.60 (0.17) |

None |

Risk of bias tables

Clinical trials

|

Study reference

(first author, publication year) |

Was the allocation sequence adequately generated?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was the allocation adequately concealed?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Blinding: Was knowledge of the allocated interventions adequately prevented?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was loss to follow-up (missing outcome data) infrequent?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Are reports of the study free of selective outcome reporting?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was the study apparently free of other problems that could put it at a risk of bias?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Overall risk of bias If applicable/necessary, per outcome measure

LOW Some concerns HIGH |

|

Belli, 1988 |

Definitely no

Reason: Non-randomized trial. |

Definitely no

Reason: Non-randomized trial. |

Definitely no

Reason: No blinding performed. |

Definitely yes

Reason: No participants were lost to follow-up. |

Probably no

Reason: No study protocol or registration available. Because of the study quality, there is reason to doubt that the study is free of selective outcome reporting. |

Probably yes

|

HIGH |

Observational studies

|

Study reference |

Selection of participants

Was selection of exposed and non-exposed cohorts drawn from the same population? |

Exposure

Can we be confident in the assessment of exposure? |

Outcome of interest

Can we be confident that the outcome of interest was not present at start of study? |

Confounding-assessment

Can we be confident in the assessment of confounding factors? |

Confounding-analysis

Did the study match exposed and unexposed for all variables that are associated with the outcome of interest or did the statistical analysis adjust for these confounding variables? |

Assessment of outcome

Can we be confident in the assessment of outcome? |

Follow up

Was the follow up of cohorts adequate? In particular, was outcome data complete or imputed? |

Co-interventions

Were co-interventions similar between groups? |

Overall risk of bias |

|

Duncan, 2014 |

Definitely yes

Reason: All patients with active luminal CD who were commenced on EEN aiming to complete 8 weeks of treatment were included in the study. |

Probably yes

Reason: Data was collected retrospectively from departmental notes. |

N/A

Reason: Remission could have been present at start of study because we were interested in the duration of it.

|

No information |

No information |

Probably yes

Reason: Follow- up data was collected at the end of EEN period and then 6 months and 1 year post diagnosis for all EEN patients, not just those who took MEN. Relapses were defined as need for medication. |

Probably no

Reason: Participants were lost to follow-up because they switched to steroid treatment. |

Definitely yes

Reason: No patients required treatment with methotrexate or infliximab during the one year study period. |

Some concerns |

|

Obih, 2015 |

Definitely yes

Reason: Children with CD and UC seen at the Seattle Children’s Hospital from December 2012 to December 2014 who had been on SCD therapy. But the control group consisted of children who were not able maintain the SCD. |

Probably yes

Reason: All data was extracted from electronic medical records. |

N/A

Reason: Remission could have been present at start of study because we were interested in the duration of it.

|

No information |

No information |

Probably yes

Reason: Outcomes of interest were assessed after follow-up period of one year. PCDAI was used to assess remission. |

Definitely yes

Reason: Outcome data was complete for all participants. |

Definitely yes

Reason: Participants in both groups were allowed to use co-interventions. |

HIGH |

|

Wilschanski, 1996 |

Definitely yes

Reason: Children and adolescents that received exclusive elemental or semi-elemental liquid diets to treat active CD between January 1986 and December 1992 were included. |

Probably yes

Reason: Data from the medical records of all patients were used. |

N/A

Reason: Remission could have been present at start of study because we were interested in the duration of it.

|

No information |

No information |

Probably yes

Reason: Outcomes of interest were assessed after follow-up period of one year. PCDAI was used to assess remission. |

Probably no

Reason: Participants were lost to follow-up because of growth impairment, immunosuppressive drugs. |

Probably yes

Reason: Not reported. |

Some concerns |

|

Schulman, 2017 |

Definitely yes

Reason: Clinical records of children aged 1-20 years diagnosed with CD during the period from January 2001 to June 2013 were reviewed. Children with CD who refused EN (during the same period) served as the control group. |

Probably yes

Reason: Data was retrieved from the clinical records. |

N/A

Reason: Remission could have been present at start of study because we were interested in the duration of it.

|

No information |

No information |

Probably yes

Reason: Outcomes were assessed at different timepoints. wPCDAI was used to assess remission. |

Definitely yes

Reason: Outcome data was complete for all participants. |

Definitely yes

Reason: Concomitant medication was allowed in both groups. |

Some concerns |

Table of excluded studies

|

Reference |

Reason for exclusion |

|

Gavin J, Ashton JJ, Heather N, Marino LV, Beattie RM. Nutritional support in paediatric Crohn's disease: outcome at 12 months. Acta Paediatr. 2018 Jan;107(1):156-162. doi: 10.1111/apa.14075. Epub 2017 Oct 13. PMID: 28901585. |

Wrong comparison (MEN versus normal diet) |

|

Jongsma MME, Aardoom MA, Cozijnsen MA, van Pieterson M, de Meij T, Groeneweg M, Norbruis OF, Wolters VM, van Wering HM, Hojsak I, Kolho KL, Hummel T, Stapelbroek J, van der Feen C, van Rheenen PF, van Wijk MP, Teklenburg-Roord STA, Schreurs MWJ, Rizopoulos D, Doukas M, Escher JC, Samsom JN, de Ridder L. First-line treatment with infliximab versus conventional treatment in children with newly diagnosed moderate-to-severe Crohn's disease: an open-label multicentre randomised controlled trial. Gut. 2022 Jan;71(1):34-42. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-322339. Epub 2020 Dec 31. PMID: 33384335; PMCID: PMC8666701. |

Wrong intervention (induction treatment instead of maintenance treatment) |

|

Tsujikawa T, Satoh J, Uda K, Ihara T, Okamoto T, Araki Y, Sasaki M, Fujiyama Y, Bamba T. Clinical importance of n-3 fatty acid-rich diet and nutritional education for the maintenance of remission in Crohn's disease. J Gastroenterol. 2000;35(2):99-104. doi: 10.1007/s005350050021. PMID: 10680664. |

Wrong population (adults, mean age 28 years) |

|

Triantafillidis JK, Stamataki A, Karagianni V, Gikas A, Malgarinos G. Maintenance treatment of Crohn’s disease with a polymeric feed rich in TGF-b. Annals of Gastroenterology. 2010;23(2):113-118. |

Wrong population (adults, 17-70 years of age) |

|

Belli DC, Seidman E, Bouthillier L, Weber AM, Roy CC, Pletincx M, Beaulieu M, Morin CL. Chronic intermittent elemental diet improves growth failure in children with Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 1988 Mar;94(3):603-10. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(88)90230-2. PMID: 3123302. |

Included in Penagini (2016) |

|

Duncan H, Buchanan E, Cardigan T, Garrick V, Curtis L, McGrogan P, Barclay A, Russell RK. A retrospective study showing maintenance treatment options for paediatric CD in the first year following diagnosis after induction of remission with EEN: supplemental enteral nutrition is better than nothing! BMC Gastroenterol. 2014 Mar 20;14:50. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-14-50. PMID: 24645851; PMCID: PMC4234202. |

Included in Penagini (2016) |

|

Wilschanski M, Sherman P, Pencharz P, Davis L, Corey M, Griffiths A. Supplementary enteral nutrition maintains remission in paediatric Crohn's disease. Gut. 1996 Apr;38(4):543-8. doi: 10.1136/gut.38.4.543. PMID: 8707085; PMCID: PMC1383112. |

Included in Penagini (2016) |

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Laatst beoordeeld : 07-02-2025

Algemene gegevens

De ontwikkeling/herziening van deze richtlijnmodules werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten (www.demedischspecialist.nl/kennisinstituut) en werd gefinancierd uit de Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS). Patiëntenparticipatie (in de vorm van een achterbanuitvraag) bij deze richtlijn werd medegefinancierd uit de Kwaliteitsgelden Patiënten Consumenten (SKPC) binnen het programma KIDZ.

De financier heeft geen enkele invloed gehad op de inhoud van de richtlijnmodule.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijnmodule is in 2022 een multidisciplinaire werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen (zie hiervoor de Samenstelling van de werkgroep) die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor kinderen met inflammatoire darmziekten.

Werkgroep

- prof. dr. J.C. (Hankje) Escher, kinderarts-MDL, Erasmus MC, Rotterdam, namens de NVK

- dr. J.E. (Johan) van Limbergen, kinderarts-MDL, Amsterdam UMC, namens de NVK

- dr. L. (Lissy) de Ridder, kinderarts-MDL, Erasmus MC, Rotterdam, namens de NVK

- dr. L.J.J. (Luc) Derijks, ziekenhuisapotheker - klinisch farmacoloog, Máxima MC en Maastricht UMC, namens de NVZA

- drs. M.P. (Menne) Scherpenzeel, patiëntvertegenwoordiger, namens Crohn & Colitis Nederland

- dr. P.F. (Patrick) van Rheenen (voorzitter), kinderarts-MDL, UMC Groningen, namens de NVK

- S. (Suzanne) van Zundert, diëtist kindergeneeskunde, Amsterdam UMC, namens de NVD

- dr. T.G.J. (Tim) de Meij, kinderarts-MDL, Amsterdam UMC, namens de NVK

Klankbordgroep

De klankbordgroepleden hebben gedurende de ontwikkeling van de richtlijn meegelezen met de conceptteksten en deze becommentarieerd.

- drs. C. (Carmen) Willemsen-Vermeer, diëtist, Radboud UMC, Nijmegen, namens de NVD

- dr. D.R. (Dennis) Wong, ziekenhuisapotheker - klinisch farmacoloog, Zuyderland Medisch Centrum, locatie Sittard-Geleen, namens de NVZA

- drs. F.D.M. (Fiona) van Schaik, arts-MDL, UMC Utrecht, namens de NVMDL

- drs. I.A. (Imke) Bertrams-Maartens, kinderarts-MDL, Máxima MC, namens de NVK

- drs. M. (Marieke) Zijlstra, kinderarts-MDL, Maasstad ziekenhuis, Rotterdam, namens de NVK

- drs. M.A.C. (Martha) van Gaalen, verpleegkundig specialist kinder-MDL, Erasmus MC, Rotterdam, namens de V&VN

Met ondersteuning van

- dr. M.M.J. (Machteld) van Rooijen, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- drs. L.C. (Laura) van Wijngaarden, junior adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

Belangenverklaringen

De Code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling is gevolgd. Alle werkgroepleden hebben schriftelijk verklaard of zij in de laatste drie jaar directe financiële belangen (betrekking bij een commercieel bedrijf, persoonlijke financiële belangen, onderzoeksfinanciering) of indirecte belangen (persoonlijke relaties, reputatiemanagement) hebben gehad. Gedurende de ontwikkeling of herziening van een module worden wijzigingen in belangen aan de voorzitter doorgegeven. De belangenverklaring wordt opnieuw bevestigd tijdens de commentaarfase.

Een overzicht van de belangen van werkgroepleden en het oordeel over het omgaan met eventuele belangen vindt u in onderstaande tabel. De ondertekende belangenverklaringen zijn op te vragen bij het secretariaat van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

|

Werkgroeplid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

J.C. (Hankje) Escher |

Kinderarts-MDL, Erasmus MC Sophia |

E-dokter bij Cyberpoli van Stichting Artsen voor Kinderen (onbetaald) Scientific Advisory Committee Develop Registry - Jansen (betaling via ziekenhuis, ter ondersteuning van research) Scientific Advisory Committee van Cape Registry - Abbvie (betaling via ziekenhuis, ter ondersteuning van research) Programma commissie Jeugdartsen congres - Nutricia (betaling via ziekenhuis, ter ondersteuning van research) |

Abbvie, project Trasnitie coordinator Erasmus MC, projectleider MSD, project Biomarkers voor anti-TNF respons bij kinder-IBD, projectleider Stichting Theia, project HAPPY-IBD screen, angst en depressie bij kinder-IBD |

Restricties t.a.v. besluitvorming rondom Biomarkers voor anti-TNF respons. |

|

J.E. (Johan) van Limbergen |

Kinderarts-MDL, Amsterdam UMC |

Nestle Health Science: seminarie 4x/jaar |

Janssen, Nestle Health Science, Novalac Klinisch, translationeel en fundamenteel onderzoek naar voedingstherapie bij kinderen en volwassenen: genetica, microbioom, metaboloom, biomarkers. |

Restricties t.a.v. besluitvorming rondom voedingsinterventies. |

|

L. (Lissy) de Ridder |

Kinderarts-MDL, Erasmus MC |

Bestuurslid NVK (onbezoldigd) Scientific secretary ESPGHAN (onbezoldigd) Voorzitter P-ECCO (onbezoldigd) |

PIBD congres met symposium over integratie wetenschappelijk onderzoek binnen de kinder IBD patiëntenzorg (Janssen); webinars over biosimilarts (speaker's fee Pfizer).

Projectleider (PI) van investigator-initiated TISKids trial (ZonMW, Pfizer levert medicatie en restricted grant voor follow-up studie; heeft geen inbreng op protocol, data-analyse). Verdere medewerking (local investigator) aan klinische trials (Takeda, Abbvie, Ei Lilly). |

Restricties t.a.v. besluitvorming rondom TNF-alpha medicatie/ TDM |

|

L. (Luc) Derijks |

Ziekenhuisapotheker - klinisch farmacoloog, Máxima MC en Maastricht UMC |

Onderwijs (webinar, e-learning, college): webinar in opdracht van Takeda (betaald), e-learning in opdracht van Ferring (betaald), hoorcolleges UU (onbetaald). |

Geen. |

Geen. |

|

M.P. (Menne) Scherpenzeel |

Directeur, Crohn & Colitis Nederland |

Partner adviesbureau Blauwe Noordzee Diverse onbezoldigde bestuursfuncties |

Wij worden betrokken bij extern gefinancierd onderzoek van derden voor het patiëntenperspectief. Het werk van Crohn & Colitis NL wordt mede mogelijk gemaakt door pharma. |

Input patiëntenorganisatie voor alle te ontwikkelen modules middels uitvraag via achterban. |

|

P.F. (Patrick) van Rheenen |

Kinderarts-MDL, UMC Groningen |

Kinderarts lid van Medisch-Ethische Toetsingscomissie van UMCG (vacatiegelden) |

PI van een investigator-initiated onderzoeksproject mede gefinacierd door Europese Crohn en Colitis Organisatie (ECCO). Materiaal voor calprotectine sneltests zijn gedoneerd door BÜHLMANN Laboratories (beide geen invloed op opzet, uitvoering, analyse en rapportage van onderzoek). |

Geen. |

|

S. (Suzanne) van Zundert |

Diëtist kindergeneeskunde, Amsterdam UMC |

Bestuursfunctie Nederlandse KinderDiëtisten (NKD, onder de NVD) |

PECDED, Nestle Health Science: Patiëntervaring van ouders/kinderen bij voedingstherapie CDED. Participatie in wetenschappelijke onderzoeken die binnen de kinder-MDL afdeling van het Amsterdam UMC worden gedaan. |

Geen. |

|

T.G.J. (Tim) de Meij |

Kinderarts-MDL, Amsterdam UMC |

Lid advisory board Nutricia (vergoeding voor onderzoek) |

Principal investigator (PI) van industry-initiated study fase 3 naar tofacitinib (Pfizer). co-PI van investigator-initiated RCT naar probiotica bij antibiotica-geassocieerde diarree gedeeltelijk gesponsord door Winclove (restricted grant, toegekend bij minimum aantal inclusies). Unrestricted grant van Nutricia voor microbioomanalyse op fecessample van kinderen bij wie moeder antibiotica heeft gehad tijdens sectio caesaria. |

Restricties t.a.v. besluitvorming rondom voedingsinterventies. |

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Er werd aandacht besteed aan het patiëntenperspectief door een afgevaardigde van de patiëntenvereniging Crohn&Colitis NL in de werkgroep en een enquête onder alle leden van Crohn&Colitis NL. De verkregen input is meegenomen bij het opstellen van de uitgangsvragen, de keuze voor de uitkomstmaten en bij het opstellen van de overwegingen (zie kop ‘Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten’). De conceptrichtlijn is tevens ter commentaar voorgelegd aan Crohn&Colitis NL en Patiëntenfederatie Nederland, en de eventueel aangeleverde commentaren zijn bekeken en verwerkt.

Werkwijze

AGREE

Deze richtlijnmodule is opgesteld conform de eisen vermeld in het rapport Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 van de adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwaliteit. Dit rapport is gebaseerd op het AGREE II instrument (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II; Brouwers, 2010).

Knelpuntenanalyse en uitgangsvragen

Binnen het SKMS project “Inventarisatie en optimalisatie modulair onderhoud richtlijn kindergeneeskunde” is breed geïnventariseerd welke kindergeneeskundige modules toe waren aan herziening, en er is een onderhoudsplan opgeleverd. De vijf modules van deze richtlijn, herzien in 2022-2024, kwamen uit dit project naar voren. De modules zijn kritisch beoordeeld en de uitgangsvraag en zoekvraag werden aangepast of aangescherpt.

Uitkomstmaten

Na het opstellen van de zoekvraag behorende bij de uitgangsvraag inventariseerde de werkgroep welke uitkomstmaten voor de patiënt relevant zijn, waarbij zowel naar gewenste als ongewenste effecten werd gekeken. Hierbij werd een maximum van acht uitkomstmaten gehanteerd. De werkgroep waardeerde deze uitkomstmaten volgens hun relatieve belang bij de besluitvorming rondom aanbevelingen, als cruciaal (kritiek voor de besluitvorming), belangrijk (maar niet cruciaal) en onbelangrijk. Tevens definieerde de werkgroep tenminste voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten welke verschillen zij klinisch (patiënt) relevant vonden.

Methode literatuursamenvatting

Een uitgebreide beschrijving van de strategie voor zoeken en selecteren van literatuur is te vinden onder ‘Zoeken en selecteren’ onder Onderbouwing. Indien mogelijk werd de data uit verschillende studies gepoold in een random-effects model. Review Manager 5.4 werd gebruikt voor de statistische analyses. De beoordeling van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs wordt hieronder toegelicht.

Beoordelen van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs

De kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs werd bepaald volgens de GRADE-methode. GRADE staat voor ‘Grading Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation’ (zie http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/). De basisprincipes van de GRADE-methodiek zijn: het benoemen en prioriteren van de klinisch (patiënt) relevante uitkomstmaten, een systematische review per uitkomstmaat, en een beoordeling van de bewijskracht per uitkomstmaat op basis van de acht GRADE-domeinen (domeinen voor downgraden: risk of bias, inconsistentie, indirectheid, imprecisie, en publicatiebias; domeinen voor upgraden: dosis-effect relatie, groot effect, en residuele plausibele confounding).

GRADE onderscheidt vier gradaties voor de kwaliteit van het wetenschappelijk bewijs: hoog, redelijk, laag en zeer laag. Deze gradaties verwijzen naar de mate van zekerheid die er bestaat over de literatuurconclusie, in het bijzonder de mate van zekerheid dat de literatuurconclusie de aanbeveling adequaat ondersteunt (Schünemann, 2013; Hultcrantz, 2017).

|

GRADE |

Definitie |

|

Hoog |

|

|

Redelijk |

|

|

Laag |

|

|

Zeer laag |

|

Bij het beoordelen (graderen) van de kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs in richtlijnen volgens de GRADE-methodiek spelen grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming een belangrijke rol (Hultcrantz, 2017). Dit zijn de grenzen die bij overschrijding aanleiding zouden geven tot een aanpassing van de aanbeveling. Om de grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming te bepalen moeten alle relevante uitkomstmaten en overwegingen worden meegewogen. De grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming zijn daarmee niet één op één vergelijkbaar met het minimaal klinisch relevant verschil (Minimal Clinically Important Difference, MCID). Met name in situaties waarin een interventie geen belangrijke nadelen heeft en de kosten relatief laag zijn, kan de grens voor klinische besluitvorming met betrekking tot de effectiviteit van de interventie bij een lagere waarde (dichter bij het nuleffect) liggen dan de MCID (Hultcrantz, 2017).

Overwegingen (van bewijs naar aanbeveling)

Om te komen tot een aanbeveling zijn naast (de kwaliteit van) het wetenschappelijke bewijs ook andere aspecten belangrijk en worden meegewogen, zoals aanvullende argumenten uit bijvoorbeeld de biomechanica of fysiologie, waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten, kosten (middelenbeslag), aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie. Deze aspecten zijn systematisch vermeld en beoordeeld (gewogen) onder het kopje ‘Overwegingen’ en kunnen (mede) gebaseerd zijn op expert opinion. Hierbij is gebruik gemaakt van een gestructureerd format gebaseerd op het evidence-to-decision framework van de internationale GRADE Working Group (Alonso-Coello, 2016a; Alonso-Coello 2016b). Dit evidence-to-decision framework is een integraal onderdeel van de GRADE methodiek.

Formuleren van aanbevelingen

De aanbevelingen geven antwoord op de uitgangsvraag en zijn gebaseerd op het beschikbare wetenschappelijke bewijs en de belangrijkste overwegingen, en een weging van de gunstige en ongunstige effecten van de relevante interventies. De kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs en het gewicht dat door de werkgroep wordt toegekend aan de overwegingen, bepalen samen de sterkte van de aanbeveling. Conform de GRADE-methodiek sluit een lage bewijskracht van conclusies in de systematische literatuuranalyse een sterke aanbeveling niet a priori uit, en zijn bij een hoge bewijskracht ook zwakke aanbevelingen mogelijk (Agoritsas, 2017; Neumann, 2016). De sterkte van de aanbeveling wordt altijd bepaald door weging van alle relevante argumenten tezamen. De werkgroep heeft bij elke aanbeveling opgenomen hoe zij tot de richting en sterkte van de aanbeveling zijn gekomen.

In de GRADE-methodiek wordt onderscheid gemaakt tussen sterke en zwakke (of conditionele) aanbevelingen. De sterkte van een aanbeveling verwijst naar de mate van zekerheid dat de voordelen van de interventie opwegen tegen de nadelen (of vice versa), gezien over het hele spectrum van patiënten waarvoor de aanbeveling is bedoeld. De sterkte van een aanbeveling heeft duidelijke implicaties voor patiënten, behandelaars en beleidsmakers (zie onderstaande tabel). Een aanbeveling is geen dictaat, zelfs een sterke aanbeveling gebaseerd op bewijs van hoge kwaliteit (GRADE gradering HOOG) zal niet altijd van toepassing zijn, onder alle mogelijke omstandigheden en voor elke individuele patiënt.

|

Implicaties van sterke en zwakke aanbevelingen voor verschillende richtlijngebruikers |

||

|

|

||

|

|

Sterke aanbeveling |

Zwakke (conditionele) aanbeveling |

|

Voor patiënten |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen en slechts een klein aantal niet. |

Een aanzienlijk deel van de patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen, maar veel patiënten ook niet. |

|

Voor behandelaars |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak moeten ontvangen. |

Er zijn meerdere geschikte interventies of aanpakken. De patiënt moet worden ondersteund bij de keuze voor de interventie of aanpak die het beste aansluit bij zijn of haar waarden en voorkeuren. |

|

Voor beleidsmakers |

De aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kan worden gezien als standaardbeleid. |

Beleidsbepaling vereist uitvoerige discussie met betrokkenheid van veel stakeholders. Er is een grotere kans op lokale beleidsverschillen. |

Organisatie van zorg

In de knelpuntenanalyse en bij de ontwikkeling van de richtlijnmodule is expliciet aandacht geweest voor de organisatie van zorg: alle aspecten die randvoorwaardelijk zijn voor het verlenen van zorg (zoals coördinatie, communicatie, (financiële) middelen, mankracht en infrastructuur). Randvoorwaarden die relevant zijn voor het beantwoorden van deze specifieke uitgangsvraag zijn genoemd bij de overwegingen. Meer algemene, overkoepelende, of bijkomende aspecten van de organisatie van zorg worden behandeld in de module Organisatie van zorg.

Commentaar- en autorisatiefase

De conceptrichtlijnmodule werd aan de betrokken (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd ter commentaar. De commentaren werden verzameld en besproken met de werkgroep. Naar aanleiding van de commentaren werd de conceptrichtlijnmodule aangepast en definitief vastgesteld door de werkgroep. De definitieve richtlijnmodule werd aan de deelnemende (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd voor autorisatie en door hen geautoriseerd dan wel geaccordeerd.

Literatuur

Agoritsas T, Merglen A, Heen AF, Kristiansen A, Neumann I, Brito JP, Brignardello-Petersen R, Alexander PE, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Guyatt GH. UpToDate adherence to GRADE criteria for strong recommendations: an analytical survey. BMJ Open. 2017 Nov 16;7(11):e018593. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018593. PubMed PMID: 29150475; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5701989.

Alonso-Coello P, Schünemann HJ, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Rada G, Rosenbaum S, Morelli A, Guyatt GH, Oxman AD; GRADE Working Group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 1: Introduction. BMJ. 2016 Jun 28;353:i2016. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2016. PubMed PMID: 27353417.

Alonso-Coello P, Oxman AD, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Vandvik PO, Meerpohl J, Guyatt GH, Schünemann HJ; GRADE Working Group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 2: Clinical practice guidelines. BMJ. 2016 Jun 30;353:i2089. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2089. PubMed PMID: 27365494.

Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, Burgers JS, Cluzeau F, Feder G, Fervers B, Graham ID, Grimshaw J, Hanna SE, Littlejohns P, Makarski J, Zitzelsberger L; AGREE Next Steps Consortium. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. CMAJ. 2010 Dec 14;182(18):E839-42. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090449. Epub 2010 Jul 5. Review. PubMed PMID: 20603348; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3001530.

Hultcrantz M, Rind D, Akl EA, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Iorio A, Alper BS, Meerpohl JJ, Murad MH, Ansari MT, Katikireddi SV, Östlund P, Tranæus S, Christensen R, Gartlehner G, Brozek J, Izcovich A, Schünemann H, Guyatt G. The GRADE Working Group clarifies the construct of certainty of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017 Jul;87:4-13. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.05.006. Epub 2017 May 18. PubMed PMID: 28529184; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC6542664.

Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 (2012). Adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwalitieit.

http://richtlijnendatabase.nl/over_deze_site/over_richtlijnontwikkeling.html

Neumann I, Santesso N, Akl EA, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Alonso-Coello P, Agoritsas T, Mustafa RA, Alexander PE, Schünemann H, Guyatt GH. A guide for health professionals to interpret and use recommendations in guidelines developed with the GRADE approach. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016 Apr;72:45-55. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.11.017. Epub 2016 Jan 6. Review. PubMed PMID: 26772609.

Schünemann H, Brożek J, Guyatt G, et al. GRADE handbook for grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. Updated October 2013. The GRADE Working Group, 2013. Available from http://gdt.guidelinedevelopment.org/central_prod/_design/client/handbook/handbook.html.

Zoekverantwoording

Zoekacties zijn opvraagbaar. Neem hiervoor contact op met de Richtlijnendatabase.