Voedingsinterventies in de inductiefase

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is de plaats van voedingstherapie (exclusieve enterale voedingstherapie of de nieuwere exclusie diëten) in vergelijking met anti-TNF bij kinderen met de ziekte van Crohn om inductie van remissie te bereiken?

Clinical question

What is the role of nutritional therapy (Exclusive Enteral Nutrition and the newer exclusion diets), compared to anti-TNF treatment in children with Crohn’s Disease to achieve induction of remission?

Aanbeveling

Overweeg voedingstherapie (Exclusive Enteral Nutrition [EEN] of Crohn’s Disease Exclusion Diet [CDED]) als inductie behandeling bij kinderen met mild tot matig actieve ziekte van Crohn (weighted Paediatric CD Activity Index score (wPCDAI) < 40).

Overweeg anti-TNF als primaire inductie therapie bij kinderen met matig tot ernstig actieve ziekte van Crohn (wPCDAI > 40) en bij aanwezigheid van predictors of poor outcome (POPOs).

Indien anti-TNF behandeling onvoldoende effect heeft bij het induceren van remissie, dan is anti-TNF in combinatie met voedingstherapie een optie.

Recommendations

Consider nutritional therapy (Exclusive Enteral Nutrition [EEN] or Crohn's Disease Exclusion Diet [CDED]) as induction treatment in children with mild to moderate Crohn's Disease (wPCDAI < 40).

Consider anti-TNF as primary induction therapy in children with moderate to severe Crohn's disease (wPCDAI > 40 and when POPOs are present).

If anti-TNF treatment is not resulting in induction of remission, consider additional nutritional therapy.

Overwegingen

Advantages and disadvantages of the intervention and quality of the evidence

A literature review was conducted to examine the effectiveness of Exclusive Enteral Nutrition (EEN) and Crohn’s Disease Exclusion Diet (CDED), compared to anti-TNF-alpha therapy for achieving remission in children with luminal Crohn's Disease (CD). In total, one systematic review (including two relevant prospective cohort studies), one retrospective cohort study and one RCT were found that compared EEN to anti-TNF-alpha therapy. However, the study populations in the identified studies were relatively small, and the studies had methodological limitations (including uncertainty about the presence and adjustment for confounding factors, and missing information about selection of non-exposed cohort, adequacy of follow-up, whether the outcome of interest was not present at the start of the study, no blinding and loss to follow-up). Furthermore, the confidence intervals overlap with the thresholds for clinical decision making. As a result, the evidence for the critical outcome measures has been assessed as very low. This implies that future studies might lead to new insights. Based on the literature, strong conclusions cannot be drawn regarding which treatment is most effective and preferable as induction treatment for children with mild to moderate CD.

Induction of remission, preferably accompanied by endoscopic remission (reflecting mucosal healing) is the first treatment aim for both pediatric and adult patients with CD. EEN can effectively induce clinical remission in 80% of pediatric patients with endoscopic remission in a minority of patients (Herrador-López, 2020; Swaminath, 2017; van Rheenen, 2020). While its efficacy equals that of prednisolone, the obvious advantage of EEN is the promotion of growth and lack of side effects. This has resulted in EEN being the first choice treatment for pediatric CD in earlier guidelines (Herrador-López, 2020; Swaminath, 2017; van Rheenen, 2020), although tolerability of a non-solid food regimen can be a problem that will negatively affect adherence and hence, effectiveness. The newer exclusion diets that combine certain allowed solid foods with PEN (CDED) are tolerated better than EEN (Herrador-López, 2020) and have been shown to be equally effective. Anti-TNF-alpha treatments (infliximab or adalimumab) have been shown to be highly effective in inducing clinical and endoscopic remission in both pediatric and adult CD patients. The question that we have addressed in this module is whether there is still a place for EEN (or CDED) as induction treatment in pediatric CD patients. Head to head studies comparing CDED and anti-TNF have not been performed. From the studies described in the literature analysis that directly compare EEN to anti-TNF-alpha treatment, it cannot be concluded that there is a clear difference in clinical efficacy. However, there is a significant difference in endoscopic remission in favor of infliximab, and in adult CD patients, endoscopic remission itself is prognostic for duration of remission as well as prevention of disease complications. (Schnitzler, 2009).

The aim to induce endoscopic remission quickly and effectively in patients is especially important in patients most at risk of disease complications. In practice, the decision to start anti-TNF (or nutritional treatment) will depend on the presence (or absence) of predictors of poor outcome (POPOs). These POPOs are deep colonic ulcerations on endoscopy, persistent severe disease despite adequate induction therapy, extensive (pan-enteric) disease, marked growth retardation (<-2.5 Height Standard Deviation Score, SDS), severe osteoporosis, stricturing and penetrating disease at onset and also perianal disease. According to the ECCO-ESPGHAN guideline, early or first-line anti-TNF should be considered when one or more POPOs is present (van Rheenen, 2020). Interestingly, a recent publication from the German CEDATA real world registry showed that the POPOs, and not presenting symptoms nor initial disease activity scores were suitable candidates for treatment stratification (De Laffolie, 2021).

During the course of treatment, it is important to know that nutritional therapy can be a useful salvage regimen at inducing and maintaining remission for patients failing biological therapy as monotherapy despite dose escalation (Nguyen, 2015; Sigall Boneh, 2017; Jijón Andrade, 2023; Arcucci, 2023).

Compared with corticosteroids, anti-TNF use was associated with reduced mortality in adult patients with CD. Treatment with anti-TNF therapy also yielded greater quality of life for all subgroups of patients with CD despite substantial heterogeneity among CD patients' preferences for medication efficacy and potential harms (Lewis, 2018).

One more aspect to consider, especially in young children, is that nutritional therapy (and not anti-TNF or other immunosuppressive and immunomodulator treatment such as prednisolone or thiopurines) can be started immediately after diagnosis before vaccination status is assessed. It is crucial to ensure the patient is up-to-date with their vaccinations. According to the guidelines completing the recommended vaccination schedule prior to starting immunosuppressive therapy is vital for safeguarding the health of pediatric IBD patients (Manser, 2020; Martinelli, 2020; Kucharzik, 2021).

Patient values and preferences

Balancing control of environmental triggers of disease activity (e.g. diet) with immune suppression (e.g. administration, infectious risk, side-effects profile) is key when deciding on the correct induction therapy. Nutritional therapy poses considerable challenges to patients and families, as it constitutes a radical change in family dynamics affecting mealtime. EEN is more difficult to tolerate than whole-food based dietary interventions such as CDED, primarily due to poor palatability and concerns about not eating solid food. Any diet intervention can lead to adherence difficulties due to the monotony of the diet, costs, social isolation, feeling different from others and integration in school and/or work activities. Implementation of dietary changes requires assessment of the coping strategies of the family (e.g. ability to cook and prepare meals and snacks suitable for the diet at school, work or during holidays) as well as the child, e.g. selective eating, hesitation or rejection to try new foods. The cost of the diet may increase the price of grocery shopping. Therefore, the dietitian’s role is fundamental, and the differences between just providing the diet handout to a more individual approach can change the adherence to diet completely, which will improve the success of dietary therapy (Herrador-López, 2020; Sigall Boneh, 2023). The identification of dietary responsiveness of patients early in the course of their disease might help patients to make the best choice of treatment and could encourage patients in following nutritional therapy (Sigall Boneh, 2021; Sigall Boneh, 2023).

Crohn & Colitis NL evaluated patient preferences (bijlage Resultaten vragenlijst Crohn Colitis), including those concerning nutritional therapy during the induction phase. A total of 86 questionnaires were completed, of which 31 (36%) were filled out by the child with IBD alone, in 14 cases (16%), the child answered the questions together with one of the parents, and 41 times (48%) the questionnaire was completed solely by the parent. The questions about nutritional therapy were only presented to the 44 participants (51%) who had Crohn's disease. The majority of respondents preferred CDED (phases 1 and 2) over EEN, mainly because it does not entail a complete reliance on liquid nutrition, which most respondents find mentally burdensome. Adhering to a diet is perceived as challenging, and most respondents are concerned about whether they can adhere to the diet for the entire recommended time. Shared decision-making with healthcare providers about the choice of diet is essential; taking lifestyle, ease of use, and minimal disruption to daily life into consideration.

Costs

The aspect of treatment costs has been assessed by Jongsma (2022) who found no difference between costs during the first year of treatment in patients receiving first-line infliximab treatment and EEN (or prednisolone).

Acceptability, feasibility and implementation

It is known that pediatric patients with chronic illnesses have poor adherence to oral medication regimens which is related to characteristics of the illness as well as of the child and family. Diseases such as IBD that are characterized by an intermittent and variable course and are treated with complex regimens of multiple medications make consistent medication adherence particularly challenging. As dietary adherence is concerned, the well-established association between IBD and psychological distress in children, adolescents and adults may also be of great influence (LeLeiko, 2013).

Rationale of the recommendations

Based on the analysis of current studies, it is not clear whether different nutritional therapy or anti-TNF is the most effective induction treatment for children with Crohn's disease. However, the results of the only RCT (Jongsma 2020) do clearly indicate better efficacy of anti-TNF over nutritional therapy in children with moderately severe active Crohn's disease. This landmark study also shows that a large proportion of the patient having received EEN as induction still need to start anti-TNF in the first year of treatment due to disease exacerbation (after stopping nutritional therapy). Given the importance of tolerability and adherence to dietary treatment, it is important to make a well-considered and shared decision with the patient and parents. Although not formally studied, nutritional therapy added to anti-TNF therapy may enhance induction of remission.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

In children with luminal (mild to moderate) Crohn's Disease (CD), Exclusive Enteral Nutrition (EEN) has proven to be as effective as corticosteroids in inducing clinical remission. (Ruemmele, 2019; Borrelli, 2006) Considering the side effects of corticosteroids, and the positive impact of nutritional therapy on growth (Connors, 2017; Cohen-Dolev, 2018), earlier guidelines have established that EEN is preferred for inducing clinical remission. EEN involves a complete polymeric liquid feed given orally or through a nasogastric tube for a period of 6 to 8 weeks. EEN has few side effects but is challenging to maintain because of exclusion of all foods and beverages except water or tea without additives.

Over the past 10 years, several novel dietary strategies have been developed that allow eating alongside the regimen. For example, the Crohn’s Disease Exclusion Diet (CDED) combined with Partial Enteral Nutrition (PEN), includes allowed food to be eaten and other foods to be (temporarily) excluded within this diet, supplemented with a polymeric liquid feed given by nasogastric tube. This diet seems to be better tolerated than EEN and better sustained clinical remission at week 12.

Simultaneously with the development of these exclusion diets, evidence is growing for early or even initial (first-line) treatment of CD in children with biologicals (anti-TNF blockers such as infliximab or adalimumab). To date, it remains unclear which treatment is most effective in achieving remission in children with CD.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

1. Clinical remission

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of exclusion diets (EEN or CDED) on clinical remission when compared with anti-TNF-alpha therapy in children and adolescents with active Crohn’s Disease.

Source: Li, 2019*; Yao, 2022; Jongsma, 2022a,b. *Including: Lee, 2015; Luo, 2017. |

2. Endoscopic remission

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of exclusion diets (EEN or CDED) on endoscopic remission when compared with anti-TNF-alpha therapy in children and adolescents with active Crohn’s Disease.

Source: Li, 2019*; Yao, 2022; Jongsma, 2022a,b. *Including: Luo, 2017. |

3. Biochemical remission

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of exclusion diets (EEN or CDED) on biochemical remission when compared with infliximab in children and adolescents with active Crohn’s Disease.

Source: Li, 2019*; Yao, 2022; Jongsma, 2022a,b. *Including: Lee, 2015. |

4. Tolerability

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of exclusion diets (EEN or CDED) on tolerability when compared with infliximab in children and adolescents with active Crohn’s Disease.

Source: Jongsma, 2022a,b. |

5. Adherence, 6. Time to remission

|

- GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding the effect of exclusion diets (EEN or CDED) on adherence and time to remission compared with anti-TNF-alfa therapy in children and adolescents with active Crohn’s Disease.

Source: - |

Samenvatting literatuur

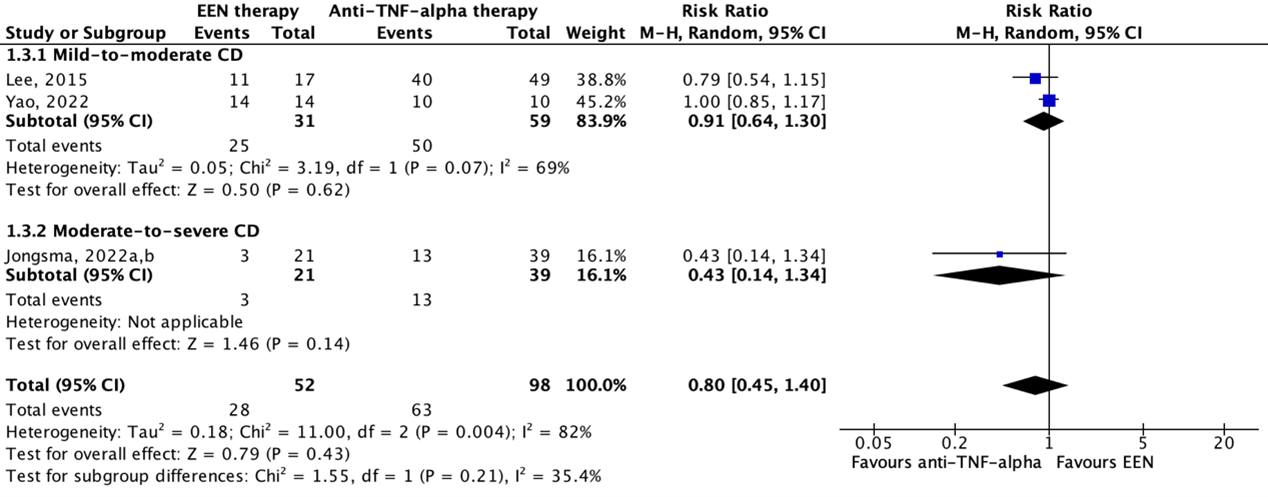

Description of studies

Li (2019) performed a systematic review and meta-analysis to compare the effectiveness and safety of infliximab and conventional therapy for inducing and maintaining endoscopic remission in pediatric patients with Crohn’s Disease (CD). The electronic databases Medline, Embase, and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials were searched with relevant search terms from inception to December 2017. Initially, studies were included if these 1) had a randomized controlled design, 2) examined individuals (<18 years of age) with moderate to severe luminal or fistulizing CD, 3) involved any dose and regimen of infliximab, and 4) compared infliximab treatment with active controls (e.g., corticosteroids, immunomodulators, aminosalicylates, Exclusive Enteral Nutrition (EEN), and other biologicals) or standard of care. No exclusion criteria were reported. The initial search strategy was developed to identify RCTs, but if no RCTs meeting the pre-specified criteria could be found, the protocol allowed the inclusion of prospective non-randomized comparative studies. Eventually, a total of twenty-four studies, including 3 RCTs and 21 prospective cohort studies, were included in the systematic review. Of these, two studies were conform our PICO and therefore described and analyzed in the current literature analysis (Lee, 2015; Luo, 2017). Characteristics of these individual studies are shown in Table 2.

Yao (2022) conducted a retrospective cohort study to investigate whether EEN or infliximab is superior as induction remission therapy for pediatric patients with mild to moderate CD. The study enrolled 58 newly diagnosed pediatric patients (<18 years of age) with CD based on the ESPGHAN Revised Porto Criteria according to clinical manifestations, endoscopic appearance, histology of mucosal biopsies, and radiological findings. Children with a PCDAI ≥40, children who could not tolerate adequate doses of infliximab or children who failed to ingest the total daily amount (100%) of liquid polymeric formula for >3 days were excluded. The included patients were divided into two treatment groups. The infliximab treatment received three intravenous infliximab infusions of 5-10 mg/kg induction therapy at weeks 0, 2, and 6. The EEN group used polymeric feeding as induction therapy for two months. The outcomes clinical remission, endoscopic remission, and biochemical remission were measured after 8 weeks of follow-up. Additional study characteristics are displayed in Table 2.

Jongsma (2022a) conducted an open-label multicenter RCT to compare the efficacy of infliximab treatment with conventional treatment consisting of EEN or prednisolone in moderate-to-severe pediatric patients with CD. Inclusion criteria were 1) 3-17 years of age, 2) new-onset untreated CD (according to revised Porto criteria), 3) baseline wPCDAI >40, and 4) body weight >10 kg at baseline. Patients with an indication for primary surgery, symptomatic stenosis or stricture in the bowel, active perianal fistulas, presence of a serious comorbidity and suspected or definite pregnancy were excluded. A total of 100 pediatric CD patients were included in the study, of which 50 in the infliximab group and 50 in the conventional group. The infliximab treatment group received five intravenous infliximab infusions of 5 mg/kg at weeks 0, 2 and 6, followed by two maintenance infusions every eight weeks. Participants in the conventional treatment group received standard induction treatment with either EEN (56% of participants) for 6-8 weeks or oral prednisolone (42% of participants) for 4 weeks (1 mg/kg daily). In accordance with the treating physician, the choice for EEN or prednisolone was based on patient preference. Both groups additionally received oral azathioprine maintenance treatment once daily 2-3 mg/kg. The outcomes clinical remission, endoscopic remission, and biochemical remission were measured at 10 weeks after start of induction treatment, that is 2-4 weeks after cessation of EEN and 6 weeks after start of prednisolone tapering. Another article published by Jongsma (2022b) about the same study (population) reported results of the conventional treatment group separately for participants that received EEN and prednisolone. These results were used in the analyses. Additional study characteristics are displayed in Table 2.

Results

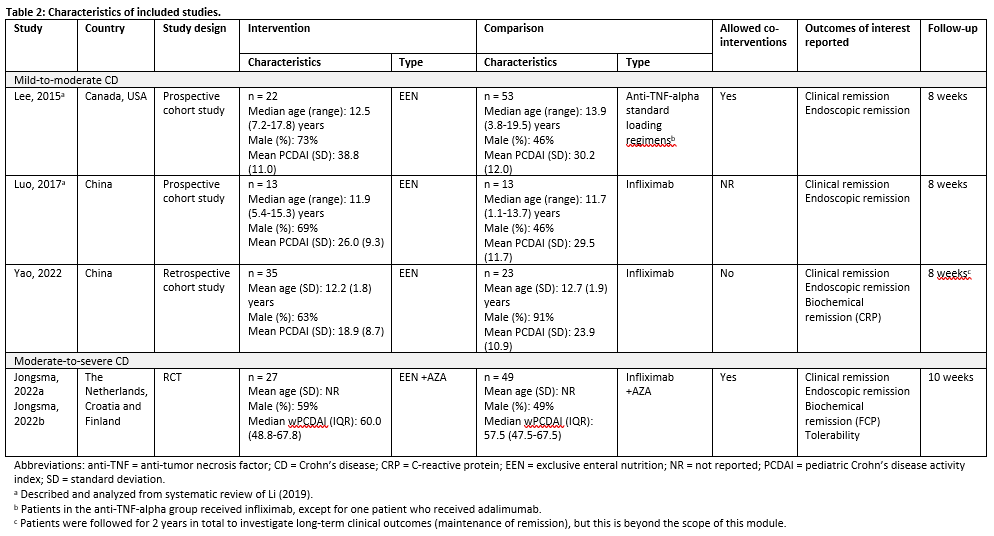

1. Clinical remission

Lee (2015), Luo (2017), Yao (2022) and Jongsma (2022a,b) reported on clinical remission, defined as PCDAI ≤10 after 8 weeks (Lee, 2015; Luo, 2017), PCDAI < 10 after 8 weeks (Yao, 2022) or wPCDAI < 12.5 after 10 weeks (Jongsma, 2022). PCDAI scores can range from 0 to 100 with higher scores representing more active disease.

Figure 1 shows clinical remission in 70.1% (61/87) of patients in the EEN therapy group and in 70.2% (87/124) of patients in the anti-TNF-alpha therapy group. The pooled risk ratio is 0.97 (95%CI 0.74 to 1.26) in favor of anti-TNF-alpha therapy. This difference is considered not clinically relevant.

Figure 1: The effect of EEN therapy compared to anti-TNF-alpha therapy on clinical remission

Z: p-value of the pooled effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistic heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval

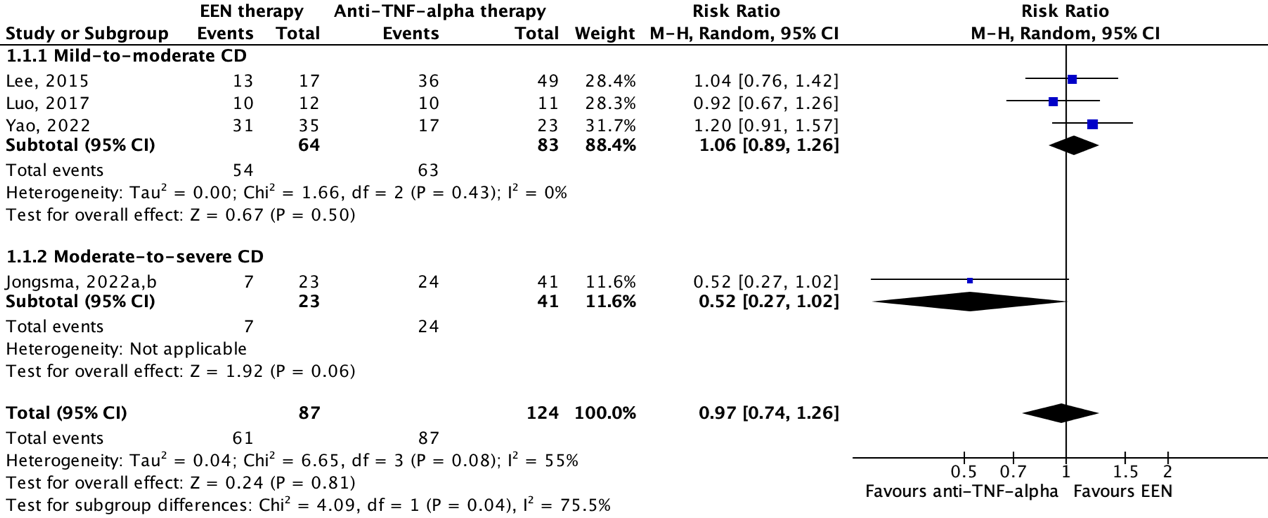

2. Endoscopic remission

Three studies reported on endoscopic remission. Luo (2017) and Yao (2022) reported on endoscopic remission at 8 weeks follow-up defined as a Crohn's Disease Endoscopic Index of Severity (CDEIS) score of ≤3 points. Total CDEIS score ranges from 0 to 44 with higher scores indicating more severe disease. Jongsma (2022a,b) defined endoscopic remission by Simple Endoscopic Score for Crohn’s Disease (SES-CD) score of <3 after 10 weeks (4 weeks after cessation of EEN). The maximum SES-CD score is 56, with higher scores representing more severe disease. Importantly, endoscopy occurred after re-exposure to free diet, as it was scheduled to 4 weeks after the third anti-TNF induction infusion (at week 6). This may have been associated with increase in fecal calprotectin and worse endoscopic outcome in the EEN compared to the anti-TNF group.

Figure 2 shows endoscopic remission in 51.9% (28/54) of patients in the EEN therapy group and in 61.1% (33/54) of patients in the anti-TNF-alpha therapy group. The pooled risk ratio is 0.66 (95%CI 0.24 to 1.82) in favor of anti-TNF-alpha therapy. This difference is considered clinically relevant.

Figure 2: The effect of EEN therapy compared to anti-TNF-alpha therapy on endoscopic remission

Z: p-value of the pooled effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistic heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval

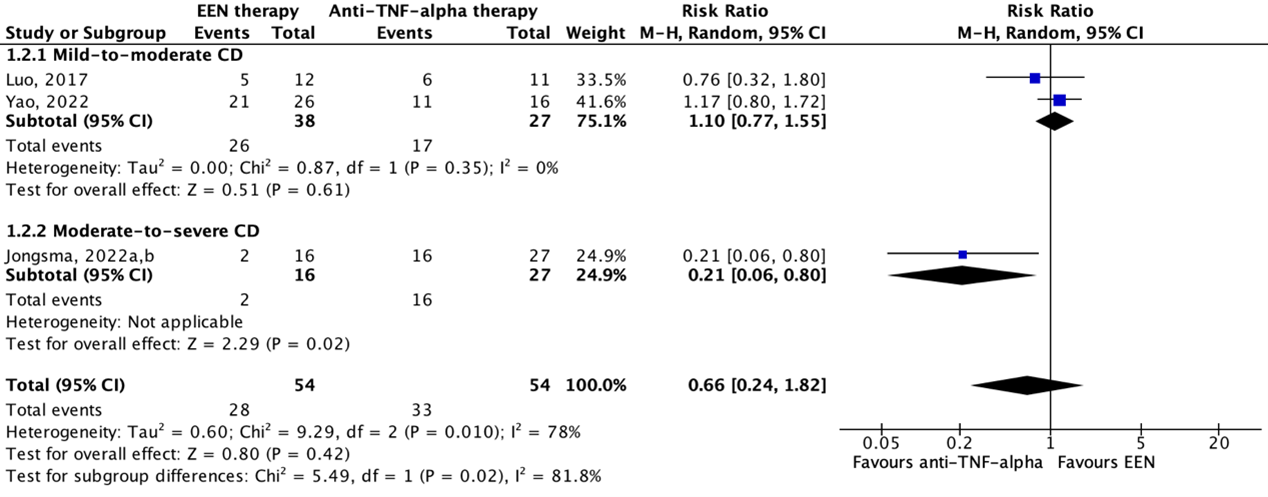

3. Biochemical remission

Lee (2015), Yao (2022) and Jongsma (2022a,b) reported on biochemical remission. Yao (2022) defined biochemical remission as the proportion of participants with normal C-reactive protein (CRP) values after 8 weeks of follow-up. Lee (2015) defined biochemical remission as a fecal calprotectin (FCP) concentration of ≤50 mg/g among participants with baseline FCP >50 mg/g, and FCP ≤250 mg/g among participants with baseline FCP >250 mg/g at week 8. Jongsma (2022a,b) defined endoscopic remission as a FCP concentration of <100 mg/g after 10 weeks of follow-up.

Figure 3 shows biochemical remission in 53.8% (28/52) of patients in the EEN therapy group and in 64.3% (63/98) of patients in the anti-TNF-alpha therapy group. The pooled risk ratio is 0.80 (95%CI 0.45 to 1.40) in favor of anti-TNF-alpha therapy. This difference is considered clinically relevant.

Figure 3: The effect of EEN therapy compared to anti-TNF-alpha therapy on biochemical remission

Z: p-value of the pooled effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistic heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval

4. Tolerability

One study reported about the tolerability of the interventions (Jongsma, 2022a,b). The authors reported that EEN was prematurely ended in 26% (7/27) of EEN-treated patients due to insufficient disease response (n=5) and low compliance (n=2). None of the anti-TNF-alpha-treated patients needed to stop treatment. Risk ratio was 26.79 (95%CI 1.59 to 451.67) in favor of anti-TNF-alpha therapy. This difference is considered clinically relevant.

5. Adherence, 6. Time to remission

None of the studies reported on the outcome measures adherence and time to remission.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence of the literature was assessed per outcome measure, using the GRADE-methodology. The level of evidence started at low certainty because, besides one RCT, evidence was retrieved from (systematic reviews of) observational studies.

1. Clinical remission

The level of evidence regarding clinical remission started at low and was downgraded by three levels to very low because of uncertainty about presence and adjustment for confounding factors, missing information about selection of non-exposed cohort, adequacy of follow-up, and whether the outcome of interest was not present at the start of the study, no blinding and loss to follow-up (risk of bias: -1), and confidence interval overlap with both thresholds of clinical decision-making (imprecision: -2).

2. Endoscopic remission

The level of evidence regarding endoscopic remission started at low and was downgraded by three levels to very low because of uncertainty about presence and adjustment for confounding factors, missing information about selection of non-exposed cohort, adequacy of follow-up, and whether the outcome of interest was not present at the start of the study, no blinding and loss to follow-up (risk of bias: -1), and confidence interval overlap with both thresholds of clinical decision-making (imprecision: -2).

3. Biochemical remission

The level of evidence regarding biochemical remission started at low and was downgraded by three levels to very low because of uncertainty about presence and adjustment for confounding factors, no blinding and loss to follow-up (risk of bias: -1), and confidence interval overlap with both thresholds of clinical decision-making (imprecision: -2).

4. Tolerability

The level of evidence regarding tolerability started at low and was downgraded by three levels to very low because of no blinding and loss to follow-up (risk of bias: -1), and confidence interval overlap with threshold of clinical decision-making and low number of included patients (imprecision: -2).

5. Adherence, 6. Time to remission

None of the studies reported on the outcome measures adherence and time to remission, and could therefore not be graded.

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question:

What is the effectiveness of exclusion diets (EEN or exclusion diet compared with anti-TNF-alpha therapy in achieving remission for children with Crohn’s Disease (CD)?

| P: | Children and adolescents (<18 years) with active CD |

| I: | Exclusion diets (EEN or Crohn’s Disease Exclusion Diet [CDED]) as induction therapy |

| C: | Anti-TNF-alpha therapy/biologicals (infliximab, adalimumab) as induction therapy |

| O: | Clinical remission, endoscopic remission, biochemical remission, time to remission, tolerability, adherence |

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered endoscopic remission as a critical outcome measure for decision making, and clinical remission, biochemical remission, time to remission, tolerability, and adherence as important outcome measurements for decision making.

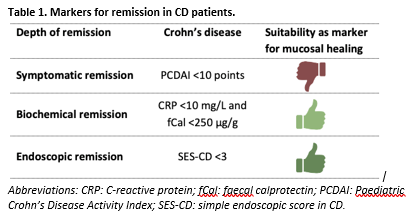

A priori, the working group used Table 1 to define the outcome measurements clinical (or symptomatic) remission, endoscopic remission and biochemical remission. Crohn's Disease Endoscopic Index of Severity (CDEIS) score (≤3 points) was also defined as a marker for endoscopic remission. Biochemical and endoscopic remission are well-validated outcome measures, whereas clinical remission was considered an insufficient proxy for endoscopic remission. The working group did not define the other outcome measures listed above but used the definitions used in the studies.

The working group defined a difference of 20% (0.8 ≥ RR ≥ 1.25) as a minimal clinically important difference.

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms from 2000 to June 7th, 2023. The detailed search strategy is available upon request. The systematic literature search resulted in 179 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria:

- Study design: systematic reviews (searched in at least two databases, detailed search strategy, risk of bias assessment, and results of individual studies available), randomized controlled trials, or other comparative studies (case control or cohort studies);

- Full-text English language publication;

- Studies according to the PICO.

Nine studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, six studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the heading Evidence tables), and three studies were included.

Results

One systematic review, one retrospective cohort study and one RCT were included in the analysis of the literature. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- Arcucci MS, Menendez L, Orsi M, Gallo J, Guzman L, Busoni V, Lifschitz C. Role of adjuvant Crohn's disease exclusion diet plus enteral nutrition in asymptomatic pediatric Crohn's disease having biochemical activity: A randomized, pilot study. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2024 Feb;43(1):199-207. doi: 10.1007/s12664-023-01416-x. Epub 2023 Aug 23. PMID: 37610564.

- Borrelli O, Cordischi L, Cirulli M, Paganelli M, Labalestra V, Uccini S, Russo PM, Cucchiara S. Polymeric diet alone versus corticosteroids in the treatment of active pediatric Crohn's disease: a randomized controlled open-label trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006 Jun;4(6):744-53. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2006.03.010. Epub 2006 May 6. PMID: 16682258.

- Cohen-Dolev N, Sladek M, Hussey S, Turner D, Veres G, Koletzko S, Martin de Carpi J, Staiano A, Shaoul R, Lionetti P, Amil Dias J, Paerregaard A, Nuti F, Pfeffer Gik T, Ziv-Baran T, Ben Avraham Shulman S, Sarbagili Shabat C, Sigall Boneh R, Russell RK, Levine A. Differences in Outcomes Over Time With Exclusive Enteral Nutrition Compared With Steroids in Children With Mild to Moderate Crohn's Disease: Results From the GROWTH CD Study. J Crohns Colitis. 2018 Feb 28;12(3):306-312. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjx150. PMID: 29165666.

- Connors J, Basseri S, Grant A, Giffin N, Mahdi G, Noble A, Rashid M, Otley A, Van Limbergen J. Exclusive Enteral Nutrition Therapy in Paediatric Crohn's Disease Results in Long-term Avoidance of Corticosteroids: Results of a Propensity-score Matched Cohort Analysis. J Crohns Colitis. 2017 Sep 1;11(9):1063-1070. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjx060. PMID: 28575325; PMCID: PMC5881686.

- de Laffolie J, Zimmer KP, Sohrabi K, Hauer AC. Running Behind "POPO"-Impact of Predictors of Poor Outcome for Treatment Stratification in Pediatric Crohn's Disease. Front Med (Lausanne). 2021 Aug 27;8:644003. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2021.644003. PMID: 34513855; PMCID: PMC8430211.

- Herrador-López M, Martín-Masot R, Navas-López VM. EEN Yesterday and Today CDED Today and Tomorrow. Nutrients. 2020 Dec 10;12(12):3793. doi: 10.3390/nu12123793. PMID: 33322060; PMCID: PMC7764146.

- Jijón Andrade MC, Pujol Muncunill G, Lozano Ruf A, Álvarez Carnero L, Vila Miravet V, García Arenas D, Egea Castillo N, Martín de Carpi J. Efficacy of Crohn's disease exclusion diet in treatment -naïve children and children progressed on biological therapy: a retrospective chart review. BMC Gastroenterol. 2023 Jun 29;23(1):225. doi: 10.1186/s12876-023-02857-6. PMID: 37386458; PMCID: PMC10311743.

- Jongsma (a) MME, Aardoom MA, Cozijnsen MA, van Pieterson M, de Meij T, Groeneweg M, Norbruis OF, Wolters VM, van Wering HM, Hojsak I, Kolho KL, Hummel T, Stapelbroek J, van der Feen C, van Rheenen PF, van Wijk MP, Teklenburg-Roord STA, Schreurs MWJ, Rizopoulos D, Doukas M, Escher JC, Samsom JN, de Ridder L. First-line treatment with infliximab versus conventional treatment in children with newly diagnosed moderate-to-severe Crohn's disease: an open-label multicentre randomised controlled trial. Gut. 2022 Jan;71(1):34-42. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-322339. Epub 2020 Dec 31. PMID: 33384335; PMCID: PMC8666701.

- Jongsma (b) MME, Vuijk SA, Cozijnsen MA, van Pieterson M, Norbruis OF, Groeneweg M, Wolters VM, van Wering HM, Hojsak I, Kolho KL, van Wijk MP, Teklenburg-Roord STA, de Meij TGJ, Escher JC, de Ridder L. Evaluation of exclusive enteral nutrition and corticosteroid induction treatment in new-onset moderate-to-severe luminal paediatric Crohn's disease. Eur J Pediatr. 2022 Aug;181(8):3055-3065. doi: 10.1007/s00431-022-04496-7. Epub 2022 Jun 8. PMID: 35672586; PMCID: PMC9352605.

- Kucharzik T, Ellul P, Greuter T, Rahier JF, Verstockt B, Abreu C, Albuquerque A, Allocca M, Esteve M, Farraye FA, Gordon H, Karmiris K, Kopylov U, Kirchgesner J, MacMahon E, Magro F, Maaser C, de Ridder L, Taxonera C, Toruner M, Tremblay L, Scharl M, Viget N, Zabana Y, Vavricka S. ECCO Guidelines on the Prevention, Diagnosis, and Management of Infections in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2021 Jun 22;15(6):879-913. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjab052. Erratum in: J Crohns Colitis. 2023 Jan 27;17(1):149. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjac104. PMID: 33730753.

- Lee D, Baldassano RN, Otley AR, Albenberg L, Griffiths AM, Compher C, Chen EZ, Li H, Gilroy E, Nessel L, Grant A, Chehoud C, Bushman FD, Wu GD, Lewis JD. Comparative Effectiveness of Nutritional and Biological Therapy in North American Children with Active Crohn's Disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015 Aug;21(8):1786-93. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000426. PMID: 25970545.

- LeLeiko NS, Lobato D, Hagin S, McQuaid E, Seifer R, Kopel SJ, Boergers J, Nassau J, Suorsa K, Shapiro J, Bancroft B. Rates and predictors of oral medication adherence in pediatric patients with IBD. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013 Mar-Apr;19(4):832-9. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0b013e3182802b57. PMID: 23446336; PMCID: PMC5704966.

- Lewis JD, Scott FI, Brensinger CM, Roy JA, Osterman MT, Mamtani R, Bewtra M, Chen L, Yun H, Xie F, Curtis JR. Increased Mortality Rates With Prolonged Corticosteroid Therapy When Compared With Antitumor Necrosis Factor-?-Directed Therapy for Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018 Mar;113(3):405-417. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2017.479. Epub 2018 Jan 16. PMID: 29336432; PMCID: PMC5886050.

- Li S, Reynaert C, Su AL, Sawh S. Efficacy and Safety of Infliximab in Pediatric Crohn Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Can J Hosp Pharm. 2019 May-Jun;72(3):227-238. Epub 2018 Jun 30. PMID: 31258168; PMCID: PMC6592657.

- Luo Y, Yu J, Lou J, Fang Y, Chen J. Exclusive Enteral Nutrition versus Infliximab in Inducing Therapy of Pediatric Crohn's Disease. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2017;2017:6595048. doi: 10.1155/2017/6595048. Epub 2017 Aug 8. PMID: 28928769; PMCID: PMC5591912.

- Manser CN, Maillard MH, Rogler G, Schreiner P, Rieder F, Bühler S; on behalf of Swiss IBDnet, an official working group of the Swiss Society of Gastroenterology. Vaccination in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Digestion. 2020;101 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):58-68. doi: 10.1159/000503253. Epub 2020 Jan 22. PMID: 31968344; PMCID: PMC7725278.

- Martinelli M, Giugliano FP, Strisciuglio C, Urbonas V, Serban DE, Banaszkiewicz A, Assa A, Hojsak I, Lerchova T, Navas-López VM, Romano C, Sladek M, Veres G, Aloi M, Kucinskiene R, Miele E. Vaccinations and Immunization Status in Pediatric Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Multicenter Study From the Pediatric IBD Porto Group of the ESPGHAN. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2020 Aug 20;26(9):1407-1414. doi: 10.1093/ibd/izz264. PMID: 31689349.

- Nguyen DL, Palmer LB, Nguyen ET, McClave SA, Martindale RG, Bechtold ML. Specialized enteral nutrition therapy in Crohn's disease patients on maintenance infliximab therapy: a meta-analysis. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2015 Jul;8(4):168-75. doi: 10.1177/1756283X15578607. PMID: 26136834; PMCID: PMC4480570.

- Pigneur B, Lepage P, Mondot S, Schmitz J, Goulet O, Doré J, Ruemmele FM. Mucosal Healing and Bacterial Composition in Response to Enteral Nutrition Vs Steroid-based Induction Therapy-A Randomised Prospective Clinical Trial in Children With Crohn's Disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2019 Jul 25;13(7):846-855. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjy207. PMID: 30541015.

- Schnitzler F, Fidder H, Ferrante M, Noman M, Arijs I, Van Assche G, Hoffman I, Van Steen K, Vermeire S, Rutgeerts P. Mucosal healing predicts long-term outcome of maintenance therapy with infliximab in Crohn's disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009 Sep;15(9):1295-301. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20927. PMID: 19340881.

- Sigall Boneh, R., Westoby, C., Oseran, I., Sarbagili-Shabat, C., Albenberg, L. G., Lionetti, P., Manuel Navas-López, V., Martín-de-Carpi, J., Yanai, H., Maharshak, N., Van Limbergen, J., & Wine, E. (2023). The Crohn's Disease Exclusion Diet: A Comprehensive Review of Evidence, Implementation Strategies, Practical Guidance, and Future Directions. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1093/ibd/izad255.

- Sigall Boneh R, Sarbagili Shabat C, Yanai H, Chermesh I, Ben Avraham S, Boaz M, Levine A. Dietary Therapy With the Crohn's Disease Exclusion Diet is a Successful Strategy for Induction of Remission in Children and Adults Failing Biological Therapy. J Crohns Colitis. 2017 Oct 1;11(10):1205-1212. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjx071. PMID: 28525622.

- Sigall Boneh R, Van Limbergen J, Wine E, Assa A, Shaoul R, Milman P, Cohen S, Kori M, Peleg S, On A, Shamaly H, Abramas L, Levine A. Dietary Therapies Induce Rapid Response and Remission in Pediatric Patients With Active Crohn's Disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021 Apr;19(4):752-759. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.04.006. Epub 2020 Apr 14. PMID: 32302709.

- Swaminath A, Feathers A, Ananthakrishnan AN, Falzon L, Li Ferry S. Systematic review with meta-analysis: enteral nutrition therapy for the induction of remission in paediatric Crohn's disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017 Oct;46(7):645-656. doi: 10.1111/apt.14253. Epub 2017 Aug 16. PMID: 28815649; PMCID: PMC5798240.

- van Rheenen PF, Aloi M, Assa A, Bronsky J, Escher JC, Fagerberg UL, Gasparetto M, Gerasimidis K, Griffiths A, Henderson P, Koletzko S, Kolho KL, Levine A, van Limbergen J, Martin de Carpi FJ, Navas-López VM, Oliva S, de Ridder L, Russell RK, Shouval D, Spinelli A, Turner D, Wilson D, Wine E, Ruemmele FM. The Medical Management of Paediatric Crohn's Disease: an ECCO-ESPGHAN Guideline Update. J Crohns Colitis. 2020 Oct 7:jjaa161. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjaa161. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 33026087.

- Wands DIF, Gianolio L, Wilson DC, Hansen R, Chalmers I, Henderson P, Gerasimidis K, Russell RK. Nationwide Real-World Exclusive Enteral Nutrition Practice Over Time: Persistence of Use as Induction for Pediatric Crohn's Disease and Emerging Combination Strategy With Biologics. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2023 Aug 24:izad167. doi: 10.1093/ibd/izad167. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 37619221.

- Yao LV, Yue L, Yang G, Luo Y, Lou J, Cheng Q, Yu J, Fang Y, Zhao H, Peng K, Chen J. Outcomes of Pediatric Patients with Crohn's Disease Received Infliximab or Exclusive Enteral Nutrition during Induction Remission. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2022 Sep 2;2022:3813915. doi: 10.1155/2022/3813915. PMID: 36089982; PMCID: PMC9462978.

Evidence tabellen

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C) |

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

Li, 2019

PS., study characteristics and results are extracted from the SR (unless stated otherwise) |

SR and meta-analysis of RCTs

Literature search up to December 2017

A: Lee, 2015 B: Luo, 2017

Study design: Prospective cohort studies

Setting and Country: A: USA, Canada B: China

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: Funding was provided by the London Health Sciences Center. The authors reported no competing interests.

|

Inclusion criteria SR: - RCTs, prospective comparative non-randomized studies - Participants <18 years of age - Moderate to severe luminal or fistulizing Crohn disease - Studies comparing infliximab with active controls or standard care

Exclusion criteria SR: Not reported

24 studies included of which two were conform our PICO

Important patient characteristics at baseline: N, median age A: I: 22, 12.5 (7.2-17.8) years C: 53, 13.9 (3.8-19.5) years B: I: 13, 11.9 (5.4-15.3) years C: 13, 11.7 (1.1-13.7) years

Sex (%male): A: I: 73% C: 46% B: I: 69% C: 46%

Groups comparable at baseline? A: Yes B: Median disease duration was shorter in the EN groups and percentage males was also greater in the EN groups |

A: EEN

B: EEN

|

A: Anti-TNF-alpha therapy

B: Infliximab |

Endpoint of follow-up: A: 8 weeks B: 8 weeks

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? (intervention/control) A: I: 5 participants (22.7%) C: 3 participants (5.8%) B: I: 1 participant (7.7%) C: 2 participants (15.4%)

|

Clinical remission Defined as PCDAI ≤10 A: I: 13/17 (76.5%) C: 36/49 (73.5%) B: I: 10/12 (83.3%) C: 10/11 (90.9%)

Endoscopic remission Defined as CDEIS ≤3 or based on FCP concentrations A: I: 2/17 (11.8%) C: 40/49 (81.6%) B: I: 5/12 (41.7%) C: 6/11 (54.5%)

|

Risk of bias: Tool used by authors: Ottawa-Newcastle tool

A: Some concerns B: Some concerns

Author’s conclusion: Infliximab has comparable efficacy compared to other therapies for inducing remission in paediatric Crohn’s disease patients. |

Evidence table individual studies

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C) |

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

Yao, 2022 |

Type of study: Retrospective cohort study

Setting and country: China

Funding and conflicts of interest: This work was partly supported partly by the Zhejiang Provincial National Key Research and Development Program (2019C03037), the Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang Province (LQ22H160006), and Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang Province (LQ19H030010). The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest. |

Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

N total at baseline: Intervention: 35 Control: 23

Important prognostic factors2: Age ± SD: I: 12.2 (1.8) years C: 12.7 (1.9) years

Sex: %M I: 63% C: 91%

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

EEN therapy for 2 months

|

Infliximab intravenous infusions of 5-10 mg/kg for 3 times

|

Length of follow-up: 8 weeks

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: None Control: None

Incomplete outcome data (endoscopic remission): Intervention: 9 (25.7%) Reasons not reported.

Control: 7 (30.4%) Reasons not reported.

|

Clinical remission Defined as PCDAI < 10 I: 31/35 (88.6%) C: 17/23 (73.9%)

Endoscopic remission Defined as CDEIS ≤ 3 points I: 21/26 (80.8%) C: 11/16 (68.8%)

Biochemical remission Based on CRP values I: 100% C: 100% |

Authors’ conclusion: The study demonstrated that for mild to moderate pediatric CD patients, the use of EEN leads to comparable clinical and endoscopic rates of remission compared with infliximab during induction therapy. |

|

Jongsma, 2022 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: The Netherlands, Croatia and Finland

Funding and conflicts of interest: The study was supported by ZonMw (113202001), Crocokids and an investigator-sponsored research award from Pfizer. Potential conflicts of interest are declared. |

Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

N total at baseline: Intervention: 27 Control: 49

Important prognostic factors2: Age ± SD: NR

Sex: %M I: 59% C: 49%

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

EEN + AZA |

Infliximab intravenous infusions of 5 mg/kg for 5 times + AZA |

Length of follow-up: 52 weeks

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: 7 (insufficient disease reaction (n=5), compliance (n=2). Control: 1 (diagnosis UC (n=1))

Incomplete outcome data: Not reported |

Clinical remission Defined as PCDAI < 12.5 I: 7/23 (30.4%) C: 24/41 (58.5%)

Endoscopic remission Defined as SES-CD < 3 I: 2/16 (12.5%) C: 16/27 (59.3%)

Biochemical remission Defined as FCP < 100mg/g I: 3/21 (14.3%) C: 13/39 (33.3%)

Tolerability I: 7/27 (26%) C: 0/49

|

Authors’ conclusion: Children and adolescents with moderate-to-severe CD would benefit from infliximab treatment as an insufficiently effective treatment strategy impacts their growth and development. |

Risk of bias table individual studies

|

Author, year |

Selection of participants

Was selection of exposed and non-exposed cohorts drawn from the same population? |

Exposure

Can we be confident in the assessment of exposure?

|

Outcome of interest

Can we be confident that the outcome of interest was not present at start of study? |

Confounding-assessment

Can we be confident in the assessment of confounding factors?

|

Confounding-analysis

Did the study match exposed and unexposed for all variables that are associated with the outcome of interest or did the statistical analysis adjust for these confounding variables? |

Assessment of outcome

Can we be confident in the assessment of outcome? |

Follow up

Was the follow up of cohorts adequate? In particular, was outcome data complete or imputed?

|

Co-interventions

Were co-interventions similar between groups?

|

Overall Risk of bias

|

|

Definitely yes, probably yes, probably no, definitely no |

Definitely yes, probably yes, probably no, definitely no |

Definitely yes, probably yes, probably no, definitely no |

Definitely yes, probably yes, probably no, definitely no |

Definitely yes, probably yes, probably no, definitely no |

Definitely yes, probably yes, probably no, definitely no |

Definitely yes, probably yes, probably no, definitely no |

Definitely yes, probably yes, probably no, definitely no |

Low, Some concerns, High |

|

|

Yao, 2022 |

Definitely yes

Reason: All participants were enrolled at the Children’s Hospital referral center for children with IBD from January 2015 to June 2021. |

Definitely yes

Reason: Eligible participants used EEN for 2 months or infliximab for 3 times as induction of remission therapy. If not, children were ineligible. |

Definitely yes

Reason: Mean PCDAI scores at baseline were >10 (clinical remission) and mean CDEIS scores at baseline were >3 (endoscopic remission). |

No information |

No information |

Definitely yes

Reason: Data for all participants were derived from their inpatient electronic medical records. |

Definitely yes

Reason: Missing outcome data is balanced in numbers across intervention groups, with similar reasons. |

Definitely yes

Reason: Co-interventions were not allowed. |

Some concerns |

|

Study reference

(first author, publication year) |

Was the allocation sequence adequately generated?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was the allocation adequately concealed?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Blinding: Was knowledge of the allocated interventions adequately prevented?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was loss to follow-up (missing outcome data) infrequent?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Are reports of the study free of selective outcome reporting?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was the study apparently free of other problems that could put it at a risk of bias?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Overall risk of bias If applicable/necessary, per outcome measure

LOW Some concerns HIGH

|

|

Jongsma, 2022 |

Definitely yes

Reason: A validated variable block randomisation model, incorporated in the web-based database was used. |

Definitely yes

Reason: Allocation was concealed for all participants and healthcare providers. |

Definitely no

Reason: Participants, investigators and healthcare providers were not masked to treatment allocation |

Definitely no

Reason: 26% of participants in the intervention group were lost to follow-up/had incomplete outcome data. |

Definitely yes

Reason: Trial is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT02517684). Outcomes are reported as prespecified. |

Definitely yes. |

Some concerns

|

Table of excluded studies

|

Reference |

Reason for exclusion |

|

Jongsma MME, Costes LMM, Tindemans I, Cozijnsen MA, Raatgreep RHC, van Pieterson M, Li Y, Escher JC, de Ridder L, Samsom JN. Serum Immune Profiling in Paediatric Crohn's Disease Demonstrates Stronger Immune Modulation With First-Line Infliximab Than Conventional Therapy and Pre-Treatment Profiles Predict Clinical Response to Both Treatments. J Crohns Colitis. 2023 Aug 21;17(8):1262-1277. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjad049. PMID: 36934327; PMCID: PMC10441564. |

Wrong outcomes (serum immune profiling) |

|

Lee D, Baldassano RN, Otley AR, Albenberg L, Griffiths AM, Compher C, Chen EZ, Li H, Gilroy E, Nessel L, Grant A, Chehoud C, Bushman FD, Wu GD, Lewis JD. Comparative Effectiveness of Nutritional and Biological Therapy in North American Children with Active Crohn's Disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015 Aug;21(8):1786-93. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000426. PMID: 25970545. |

Included in systematic review of Li (2019) |

|

Luo Y, Yu J, Lou J, Fang Y, Chen J. Exclusive Enteral Nutrition versus Infliximab in Inducing Therapy of Pediatric Crohn's Disease. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2017;2017:6595048. doi: 10.1155/2017/6595048. Epub 2017 Aug 8. PMID: 28928769; PMCID: PMC5591912. |

Included in systematic review of Li (2019) |

|

Cozijnsen MA, van Pieterson M, Samsom JN, Escher JC, de Ridder L. Top-down Infliximab Study in Kids with Crohn's disease (TISKids): an international multicentre randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2016 Dec 22;3(1):e000123. doi: 10.1136/bmjgast-2016-000123. PMID: 28090335; PMCID: PMC5223648. |

Wrong publication type (protocol) |

|

Sassine S, Zekhnine S, Qaddouri M, Djani L, Cambron-Asselin C, Savoie-Robichaud M, Lin YF, Grzywacz K, Groleau V, Dirks M, Drouin É, Halac U, Marchand V, Girard C, Courbette O, Patey N, Dal Soglio D, Deslandres C, Jantchou P. Factors associated with time to clinical remission in pediatric luminal Crohn's disease: A retrospective cohort study. JGH Open. 2021 Nov 27;5(12):1373-1381. doi: 10.1002/jgh3.12684. PMID: 34950781; PMCID: PMC8674552. |

Wrong study aim (describe trends of time to clinical remission and identify factors associated with time to clinical remission) |

|

Wan X, Wang J, Li H, Zhou Y, Xu D. A Meta-analysis Showed No Independent Relationship of Infliximab in Comparison to Many Other Types of Treatments in Pediatric Crohn’s Disease. Latin American Journal of Pharmacy. 2022;41(4). |

Full-text not available |

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Laatst beoordeeld : 07-02-2025

Algemene gegevens

De ontwikkeling/herziening van deze richtlijnmodules werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten (www.demedischspecialist.nl/kennisinstituut) en werd gefinancierd uit de Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS). Patiëntenparticipatie (in de vorm van een achterbanuitvraag) bij deze richtlijn werd medegefinancierd uit de Kwaliteitsgelden Patiënten Consumenten (SKPC) binnen het programma KIDZ.

De financier heeft geen enkele invloed gehad op de inhoud van de richtlijnmodule.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijnmodule is in 2022 een multidisciplinaire werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen (zie hiervoor de Samenstelling van de werkgroep) die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor kinderen met inflammatoire darmziekten.

Werkgroep

- prof. dr. J.C. (Hankje) Escher, kinderarts-MDL, Erasmus MC, Rotterdam, namens de NVK

- dr. J.E. (Johan) van Limbergen, kinderarts-MDL, Amsterdam UMC, namens de NVK

- dr. L. (Lissy) de Ridder, kinderarts-MDL, Erasmus MC, Rotterdam, namens de NVK

- dr. L.J.J. (Luc) Derijks, ziekenhuisapotheker - klinisch farmacoloog, Máxima MC en Maastricht UMC, namens de NVZA

- drs. M.P. (Menne) Scherpenzeel, patiëntvertegenwoordiger, namens Crohn & Colitis Nederland

- dr. P.F. (Patrick) van Rheenen (voorzitter), kinderarts-MDL, UMC Groningen, namens de NVK

- S. (Suzanne) van Zundert, diëtist kindergeneeskunde, Amsterdam UMC, namens de NVD

- dr. T.G.J. (Tim) de Meij, kinderarts-MDL, Amsterdam UMC, namens de NVK

Klankbordgroep

De klankbordgroepleden hebben gedurende de ontwikkeling van de richtlijn meegelezen met de conceptteksten en deze becommentarieerd.

- drs. C. (Carmen) Willemsen-Vermeer, diëtist, Radboud UMC, Nijmegen, namens de NVD

- dr. D.R. (Dennis) Wong, ziekenhuisapotheker - klinisch farmacoloog, Zuyderland Medisch Centrum, locatie Sittard-Geleen, namens de NVZA

- drs. F.D.M. (Fiona) van Schaik, arts-MDL, UMC Utrecht, namens de NVMDL

- drs. I.A. (Imke) Bertrams-Maartens, kinderarts-MDL, Máxima MC, namens de NVK

- drs. M. (Marieke) Zijlstra, kinderarts-MDL, Maasstad ziekenhuis, Rotterdam, namens de NVK

- drs. M.A.C. (Martha) van Gaalen, verpleegkundig specialist kinder-MDL, Erasmus MC, Rotterdam, namens de V&VN

Met ondersteuning van

- dr. M.M.J. (Machteld) van Rooijen, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- drs. L.C. (Laura) van Wijngaarden, junior adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

Belangenverklaringen

De Code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling is gevolgd. Alle werkgroepleden hebben schriftelijk verklaard of zij in de laatste drie jaar directe financiële belangen (betrekking bij een commercieel bedrijf, persoonlijke financiële belangen, onderzoeksfinanciering) of indirecte belangen (persoonlijke relaties, reputatiemanagement) hebben gehad. Gedurende de ontwikkeling of herziening van een module worden wijzigingen in belangen aan de voorzitter doorgegeven. De belangenverklaring wordt opnieuw bevestigd tijdens de commentaarfase.

Een overzicht van de belangen van werkgroepleden en het oordeel over het omgaan met eventuele belangen vindt u in onderstaande tabel. De ondertekende belangenverklaringen zijn op te vragen bij het secretariaat van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

|

Werkgroeplid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

J.C. (Hankje) Escher |

Kinderarts-MDL, Erasmus MC Sophia |

E-dokter bij Cyberpoli van Stichting Artsen voor Kinderen (onbetaald) Scientific Advisory Committee Develop Registry - Jansen (betaling via ziekenhuis, ter ondersteuning van research) Scientific Advisory Committee van Cape Registry - Abbvie (betaling via ziekenhuis, ter ondersteuning van research) Programma commissie Jeugdartsen congres - Nutricia (betaling via ziekenhuis, ter ondersteuning van research) |

Abbvie, project Trasnitie coordinator Erasmus MC, projectleider MSD, project Biomarkers voor anti-TNF respons bij kinder-IBD, projectleider Stichting Theia, project HAPPY-IBD screen, angst en depressie bij kinder-IBD |

Restricties t.a.v. besluitvorming rondom Biomarkers voor anti-TNF respons. |

|

J.E. (Johan) van Limbergen |

Kinderarts-MDL, Amsterdam UMC |

Nestle Health Science: seminarie 4x/jaar |

Janssen, Nestle Health Science, Novalac Klinisch, translationeel en fundamenteel onderzoek naar voedingstherapie bij kinderen en volwassenen: genetica, microbioom, metaboloom, biomarkers. |

Restricties t.a.v. besluitvorming rondom voedingsinterventies. |

|

L. (Lissy) de Ridder |

Kinderarts-MDL, Erasmus MC |

Bestuurslid NVK (onbezoldigd) Scientific secretary ESPGHAN (onbezoldigd) Voorzitter P-ECCO (onbezoldigd) |

PIBD congres met symposium over integratie wetenschappelijk onderzoek binnen de kinder IBD patiëntenzorg (Janssen); webinars over biosimilarts (speaker's fee Pfizer).

Projectleider (PI) van investigator-initiated TISKids trial (ZonMW, Pfizer levert medicatie en restricted grant voor follow-up studie; heeft geen inbreng op protocol, data-analyse). Verdere medewerking (local investigator) aan klinische trials (Takeda, Abbvie, Ei Lilly). |

Restricties t.a.v. besluitvorming rondom TNF-alpha medicatie/ TDM |

|

L. (Luc) Derijks |

Ziekenhuisapotheker - klinisch farmacoloog, Máxima MC en Maastricht UMC |

Onderwijs (webinar, e-learning, college): webinar in opdracht van Takeda (betaald), e-learning in opdracht van Ferring (betaald), hoorcolleges UU (onbetaald). |

Geen. |

Geen. |

|

M.P. (Menne) Scherpenzeel |

Directeur, Crohn & Colitis Nederland |

Partner adviesbureau Blauwe Noordzee Diverse onbezoldigde bestuursfuncties |

Wij worden betrokken bij extern gefinancierd onderzoek van derden voor het patiëntenperspectief. Het werk van Crohn & Colitis NL wordt mede mogelijk gemaakt door pharma. |

Input patiëntenorganisatie voor alle te ontwikkelen modules middels uitvraag via achterban. |

|

P.F. (Patrick) van Rheenen |

Kinderarts-MDL, UMC Groningen |

Kinderarts lid van Medisch-Ethische Toetsingscomissie van UMCG (vacatiegelden) |

PI van een investigator-initiated onderzoeksproject mede gefinacierd door Europese Crohn en Colitis Organisatie (ECCO). Materiaal voor calprotectine sneltests zijn gedoneerd door BÜHLMANN Laboratories (beide geen invloed op opzet, uitvoering, analyse en rapportage van onderzoek). |

Geen. |

|

S. (Suzanne) van Zundert |

Diëtist kindergeneeskunde, Amsterdam UMC |

Bestuursfunctie Nederlandse KinderDiëtisten (NKD, onder de NVD) |

PECDED, Nestle Health Science: Patiëntervaring van ouders/kinderen bij voedingstherapie CDED. Participatie in wetenschappelijke onderzoeken die binnen de kinder-MDL afdeling van het Amsterdam UMC worden gedaan. |

Geen. |

|

T.G.J. (Tim) de Meij |

Kinderarts-MDL, Amsterdam UMC |

Lid advisory board Nutricia (vergoeding voor onderzoek) |

Principal investigator (PI) van industry-initiated study fase 3 naar tofacitinib (Pfizer). co-PI van investigator-initiated RCT naar probiotica bij antibiotica-geassocieerde diarree gedeeltelijk gesponsord door Winclove (restricted grant, toegekend bij minimum aantal inclusies). Unrestricted grant van Nutricia voor microbioomanalyse op fecessample van kinderen bij wie moeder antibiotica heeft gehad tijdens sectio caesaria. |

Restricties t.a.v. besluitvorming rondom voedingsinterventies. |

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Er werd aandacht besteed aan het patiëntenperspectief door een afgevaardigde van de patiëntenvereniging Crohn&Colitis NL in de werkgroep en een enquête onder alle leden van Crohn&Colitis NL. De verkregen input is meegenomen bij het opstellen van de uitgangsvragen, de keuze voor de uitkomstmaten en bij het opstellen van de overwegingen (zie kop ‘Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten’). De conceptrichtlijn is tevens ter commentaar voorgelegd aan Crohn&Colitis NL en Patiëntenfederatie Nederland, en de eventueel aangeleverde commentaren zijn bekeken en verwerkt.

Werkwijze

AGREE

Deze richtlijnmodule is opgesteld conform de eisen vermeld in het rapport Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 van de adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwaliteit. Dit rapport is gebaseerd op het AGREE II instrument (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II; Brouwers, 2010).

Knelpuntenanalyse en uitgangsvragen

Binnen het SKMS project “Inventarisatie en optimalisatie modulair onderhoud richtlijn kindergeneeskunde” is breed geïnventariseerd welke kindergeneeskundige modules toe waren aan herziening, en er is een onderhoudsplan opgeleverd. De vijf modules van deze richtlijn, herzien in 2022-2024, kwamen uit dit project naar voren. De modules zijn kritisch beoordeeld en de uitgangsvraag en zoekvraag werden aangepast of aangescherpt.

Uitkomstmaten

Na het opstellen van de zoekvraag behorende bij de uitgangsvraag inventariseerde de werkgroep welke uitkomstmaten voor de patiënt relevant zijn, waarbij zowel naar gewenste als ongewenste effecten werd gekeken. Hierbij werd een maximum van acht uitkomstmaten gehanteerd. De werkgroep waardeerde deze uitkomstmaten volgens hun relatieve belang bij de besluitvorming rondom aanbevelingen, als cruciaal (kritiek voor de besluitvorming), belangrijk (maar niet cruciaal) en onbelangrijk. Tevens definieerde de werkgroep tenminste voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten welke verschillen zij klinisch (patiënt) relevant vonden.

Methode literatuursamenvatting

Een uitgebreide beschrijving van de strategie voor zoeken en selecteren van literatuur is te vinden onder ‘Zoeken en selecteren’ onder Onderbouwing. Indien mogelijk werd de data uit verschillende studies gepoold in een random-effects model. Review Manager 5.4 werd gebruikt voor de statistische analyses. De beoordeling van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs wordt hieronder toegelicht.

Beoordelen van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs

De kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs werd bepaald volgens de GRADE-methode. GRADE staat voor ‘Grading Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation’ (zie http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/). De basisprincipes van de GRADE-methodiek zijn: het benoemen en prioriteren van de klinisch (patiënt) relevante uitkomstmaten, een systematische review per uitkomstmaat, en een beoordeling van de bewijskracht per uitkomstmaat op basis van de acht GRADE-domeinen (domeinen voor downgraden: risk of bias, inconsistentie, indirectheid, imprecisie, en publicatiebias; domeinen voor upgraden: dosis-effect relatie, groot effect, en residuele plausibele confounding).

GRADE onderscheidt vier gradaties voor de kwaliteit van het wetenschappelijk bewijs: hoog, redelijk, laag en zeer laag. Deze gradaties verwijzen naar de mate van zekerheid die er bestaat over de literatuurconclusie, in het bijzonder de mate van zekerheid dat de literatuurconclusie de aanbeveling adequaat ondersteunt (Schünemann, 2013; Hultcrantz, 2017).

|

GRADE |

Definitie |

|

Hoog |

|

|

Redelijk |

|

|

Laag |

|

|

Zeer laag |

|

Bij het beoordelen (graderen) van de kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs in richtlijnen volgens de GRADE-methodiek spelen grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming een belangrijke rol (Hultcrantz, 2017). Dit zijn de grenzen die bij overschrijding aanleiding zouden geven tot een aanpassing van de aanbeveling. Om de grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming te bepalen moeten alle relevante uitkomstmaten en overwegingen worden meegewogen. De grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming zijn daarmee niet één op één vergelijkbaar met het minimaal klinisch relevant verschil (Minimal Clinically Important Difference, MCID). Met name in situaties waarin een interventie geen belangrijke nadelen heeft en de kosten relatief laag zijn, kan de grens voor klinische besluitvorming met betrekking tot de effectiviteit van de interventie bij een lagere waarde (dichter bij het nuleffect) liggen dan de MCID (Hultcrantz, 2017).

Overwegingen (van bewijs naar aanbeveling)

Om te komen tot een aanbeveling zijn naast (de kwaliteit van) het wetenschappelijke bewijs ook andere aspecten belangrijk en worden meegewogen, zoals aanvullende argumenten uit bijvoorbeeld de biomechanica of fysiologie, waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten, kosten (middelenbeslag), aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie. Deze aspecten zijn systematisch vermeld en beoordeeld (gewogen) onder het kopje ‘Overwegingen’ en kunnen (mede) gebaseerd zijn op expert opinion. Hierbij is gebruik gemaakt van een gestructureerd format gebaseerd op het evidence-to-decision framework van de internationale GRADE Working Group (Alonso-Coello, 2016a; Alonso-Coello 2016b). Dit evidence-to-decision framework is een integraal onderdeel van de GRADE methodiek.

Formuleren van aanbevelingen

De aanbevelingen geven antwoord op de uitgangsvraag en zijn gebaseerd op het beschikbare wetenschappelijke bewijs en de belangrijkste overwegingen, en een weging van de gunstige en ongunstige effecten van de relevante interventies. De kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs en het gewicht dat door de werkgroep wordt toegekend aan de overwegingen, bepalen samen de sterkte van de aanbeveling. Conform de GRADE-methodiek sluit een lage bewijskracht van conclusies in de systematische literatuuranalyse een sterke aanbeveling niet a priori uit, en zijn bij een hoge bewijskracht ook zwakke aanbevelingen mogelijk (Agoritsas, 2017; Neumann, 2016). De sterkte van de aanbeveling wordt altijd bepaald door weging van alle relevante argumenten tezamen. De werkgroep heeft bij elke aanbeveling opgenomen hoe zij tot de richting en sterkte van de aanbeveling zijn gekomen.

In de GRADE-methodiek wordt onderscheid gemaakt tussen sterke en zwakke (of conditionele) aanbevelingen. De sterkte van een aanbeveling verwijst naar de mate van zekerheid dat de voordelen van de interventie opwegen tegen de nadelen (of vice versa), gezien over het hele spectrum van patiënten waarvoor de aanbeveling is bedoeld. De sterkte van een aanbeveling heeft duidelijke implicaties voor patiënten, behandelaars en beleidsmakers (zie onderstaande tabel). Een aanbeveling is geen dictaat, zelfs een sterke aanbeveling gebaseerd op bewijs van hoge kwaliteit (GRADE gradering HOOG) zal niet altijd van toepassing zijn, onder alle mogelijke omstandigheden en voor elke individuele patiënt.

|

Implicaties van sterke en zwakke aanbevelingen voor verschillende richtlijngebruikers |

||

|

|

||

|

|

Sterke aanbeveling |

Zwakke (conditionele) aanbeveling |

|

Voor patiënten |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen en slechts een klein aantal niet. |

Een aanzienlijk deel van de patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen, maar veel patiënten ook niet. |

|

Voor behandelaars |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak moeten ontvangen. |

Er zijn meerdere geschikte interventies of aanpakken. De patiënt moet worden ondersteund bij de keuze voor de interventie of aanpak die het beste aansluit bij zijn of haar waarden en voorkeuren. |

|

Voor beleidsmakers |

De aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kan worden gezien als standaardbeleid. |

Beleidsbepaling vereist uitvoerige discussie met betrokkenheid van veel stakeholders. Er is een grotere kans op lokale beleidsverschillen. |

Organisatie van zorg

In de knelpuntenanalyse en bij de ontwikkeling van de richtlijnmodule is expliciet aandacht geweest voor de organisatie van zorg: alle aspecten die randvoorwaardelijk zijn voor het verlenen van zorg (zoals coördinatie, communicatie, (financiële) middelen, mankracht en infrastructuur). Randvoorwaarden die relevant zijn voor het beantwoorden van deze specifieke uitgangsvraag zijn genoemd bij de overwegingen. Meer algemene, overkoepelende, of bijkomende aspecten van de organisatie van zorg worden behandeld in de module Organisatie van zorg.

Commentaar- en autorisatiefase

De conceptrichtlijnmodule werd aan de betrokken (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd ter commentaar. De commentaren werden verzameld en besproken met de werkgroep. Naar aanleiding van de commentaren werd de conceptrichtlijnmodule aangepast en definitief vastgesteld door de werkgroep. De definitieve richtlijnmodule werd aan de deelnemende (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd voor autorisatie en door hen geautoriseerd dan wel geaccordeerd.

Literatuur

Agoritsas T, Merglen A, Heen AF, Kristiansen A, Neumann I, Brito JP, Brignardello-Petersen R, Alexander PE, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Guyatt GH. UpToDate adherence to GRADE criteria for strong recommendations: an analytical survey. BMJ Open. 2017 Nov 16;7(11):e018593. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018593. PubMed PMID: 29150475; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5701989.

Alonso-Coello P, Schünemann HJ, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Rada G, Rosenbaum S, Morelli A, Guyatt GH, Oxman AD; GRADE Working Group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 1: Introduction. BMJ. 2016 Jun 28;353:i2016. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2016. PubMed PMID: 27353417.

Alonso-Coello P, Oxman AD, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Vandvik PO, Meerpohl J, Guyatt GH, Schünemann HJ; GRADE Working Group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 2: Clinical practice guidelines. BMJ. 2016 Jun 30;353:i2089. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2089. PubMed PMID: 27365494.

Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, Burgers JS, Cluzeau F, Feder G, Fervers B, Graham ID, Grimshaw J, Hanna SE, Littlejohns P, Makarski J, Zitzelsberger L; AGREE Next Steps Consortium. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. CMAJ. 2010 Dec 14;182(18):E839-42. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090449. Epub 2010 Jul 5. Review. PubMed PMID: 20603348; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3001530.

Hultcrantz M, Rind D, Akl EA, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Iorio A, Alper BS, Meerpohl JJ, Murad MH, Ansari MT, Katikireddi SV, Östlund P, Tranæus S, Christensen R, Gartlehner G, Brozek J, Izcovich A, Schünemann H, Guyatt G. The GRADE Working Group clarifies the construct of certainty of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017 Jul;87:4-13. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.05.006. Epub 2017 May 18. PubMed PMID: 28529184; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC6542664.

Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 (2012). Adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwalitieit.

http://richtlijnendatabase.nl/over_deze_site/over_richtlijnontwikkeling.html

Neumann I, Santesso N, Akl EA, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Alonso-Coello P, Agoritsas T, Mustafa RA, Alexander PE, Schünemann H, Guyatt GH. A guide for health professionals to interpret and use recommendations in guidelines developed with the GRADE approach. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016 Apr;72:45-55. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.11.017. Epub 2016 Jan 6. Review. PubMed PMID: 26772609.

Schünemann H, Brożek J, Guyatt G, et al. GRADE handbook for grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. Updated October 2013. The GRADE Working Group, 2013. Available from http://gdt.guidelinedevelopment.org/central_prod/_design/client/handbook/handbook.html.

Zoekverantwoording

Zoekacties zijn opvraagbaar. Neem hiervoor contact op met de Richtlijnendatabase.