Behandeling verdenking bacteriële keratitis (onbekende verwekker)

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is de optimale behandeling bij verdenking op een bacteriële keratitis?

Aanbeveling

Neem een kweek af nadat de patiënt is geïnformeerd over de procedure en de noodzaak van de kweek.

Start bij verdenking op een bacteriële keratitis (ulcus > 2 mm) als er nog geen kweekuitslag bekend is, zo snel mogelijk met fluorochinolonen antibioticum oogdruppels, volgens onderstaand schema:

|

Dag |

Dosering |

|

Start zo snel mogelijk met mono antibiotica met een van de fluorochinolonen |

|

|

Dag 1 |

Ieder uur (ook gedurende de nacht) |

|

Dag 2 |

Ieder uur (ook gedurende de nacht) |

|

Dag 3 |

6 – 12 keer per dag, overweeg zalf voor de nacht |

|

Dag 4 |

6 – 12 keer per dag, overweeg zalf voor de nacht |

Pas de medicatie aan op geleide van de kweek, zo nodig in overleg met de arts-microbioloog en bouw medicatie af op basis van het klinische beeld.

Continueer de antibiotica zolang het epitheel niet gesloten is.

Benadruk het belang van compliance van de frequentie van druppelen bij de patiënt.

Vraag de patiënt naar de aanwezigheid van een partner of andere betrokkene die de compliance van druppelen kan helpen waarborgen.

*zie bijlage: Hoe materiaal af te nemen en het stroomschema start empirische behandeling en het stroomschema empirische behandeling 1 week.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Voor de cruciale uitkomstmaat kans op genezing lijkt er geen verschil tussen het gebruik van fluorochinolonen als monotherapie vergeleken met een combinatie therapie van antibiotica. De bewijskracht hiervoor is redelijk. Van belang is wel dat de aangeraden hoge druppelfrequentie wordt aangehouden. De studies geïncludeerd in de literatuursamenvatting hanteren vergelijkbare druppelschema’s, deze zijn als basis gebruikt voor het druppelschema zoals weergegeven in Tabel 2. . Voor de uitkomstmaat tijd tot genezing lijkt ook geen verschil in duur tussen monotherapie en combinatie therapie, de bewijskracht hiervoor is echter laag. De gevonden studies konden niet gepoold worden omdat resultaten verschillend waren gerapporteerd. De overall bewijskracht voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten komt daardoor op ‘laag’ uit.

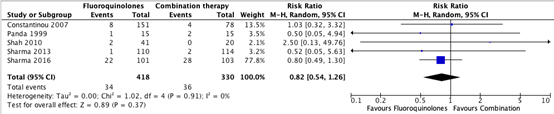

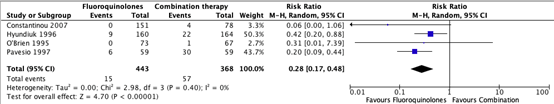

Voor de belangrijke uitkomstmaat ernstige complicaties werd een zeer lage bewijskracht gevonden: er is zodanig veel onzekerheid rondom het gevonden resultaat RR: 0,82 (95% BI: 0,54 – 1,26), dat het effect zowel in het voordeel van fluorochinolonen als in het voordeel van combinatietherapie kan liggen. Voor de belangrijke uitkomstmaat bijwerkingen werd een RR van 0,28 (95% BI: 0,17 – 0,48) gevonden, een statistisch significant en klinisch relevant effect. Bijwerkingen lijken minder vaak op te treden bij het gebruik van fluorochinolonen in vergelijking tot combinatie therapie. Bijwerkingen werden gedefinieerd als effecten die gerelateerd waren aan de medicatie zoals oculair ongemak (bijvoorbeeld pijn, brandend gevoel, stekend gevoel, irritatie, jeuk), chemische conjunctivitis (bijvoorbeeld oculaire, conjunctivale toxiciteit of bulbaire ulceratie) of witte precipitaten. De bewijskracht hiervoor is laag. Voor de belangrijke uitkomstmaat visus lijkt geen verschil tussen de mono-of combinatietherapie, de bewijskracht hiervoor is laag. Een vergelijking van de effecten van beide behandelopties op visus laat zien dat de waardes voor visus in een vergelijkbare range liggen. De daarbij horende brede interkwartiele afstand en grote SD’s suggereren ook een vergelijkbaar resultaat. Door het gebrek aan 95% betrouwbaarheids intervallen, was het niet mogelijk om te beoordelen of de verschillen klinisch relevant of statistisch significant waren. Er lijkt echter geen verschil te zijn tussen gebruik monotherapie met fluorochinolonen of combinatietherapie op de uitkomst visus.

Er werd bij alle uitkomstmaten afgewaardeerd voor risk of bias vanwege een gebrek aan blindering, onduidelijkheid over de allocatie methode en betrokkenheid van de studie sponsor bij de uitvoering van de studie.

Monotherapie met fluorochinolonen lijkt even effectief te zijn als combinatie therapie van aminoglycoside met cefolosporine met oogdruppels bij de initiële behandeling bij onbekende verwekker, indien gebruikt in een hoge frequentie van toediening. De gevonden uitkomsten gelden alleen zolang de verwekker onbekend is. Het kan zijn dat er op basis van het klinisch beeld al voordat de kweekuitslag bekend is toch gekozen wordt voor een combinatie behandeling van verschillende antibiotica. Uit de literatuur search blijkt dit echter niet beter te zijn dan in hoge frequentie druppelen met fluorochinolonen. Bij het bekend worden van de kweek kan het noodzakelijk zijn de ingestelde medicatie aan te passen. Zo hebben levofloxacine en moxifloxacine binnen de groep van fluorochinolonen een betere grampositieve dekking. Het is bekend dat Pseudomonas aeruginosa als veroorzaker bij contactlens- gerelateerde ulcera een grotere rol speelt. Pseudomonas is minder gevoelig voor moxifloxacine vergeleken met ofloxacine. Antibiotica resistentiecijfers zijn zeer geografisch verschillend en dynamisch en dienen dus gemonitord te worden teneinde mogelijk aanpassingen in het antibioticum schema te doen. De onderzochte studies gebruikten allen een hoog doseringsschema (Tabel 2) van tenminste 48 uur, ieder uur een antibioticum druppel bij ulcera > 2 mm. Het kan zijn dat er in een lagere dosering een hogere resistentie is. Bij een infiltraat ≤ 2 mm volstaat mogelijk een lagere druppelfrequentie, de druppelfrequentie kan worden bepaald op basis van het klinisch beeld.

Tabel: druppelschema behandeling verdenking ernstige bacteriële keratitis (>2 mm) met monotherapie

|

Dag |

Dosering |

|

Start zo snel mogelijk met mono antibiotica met een van de fluorochinolonen |

|

|

Dag 1 |

Ieder uur (ook gedurende de nacht) |

|

Dag 2 |

Ieder uur (ook gedurende de nacht) |

|

Dag 3 |

6 – 12 keer per dag, overweeg zalf voor de nacht |

|

Dag 4 |

6 – 12 keer per dag, overweeg zalf voor de nacht |

|

Nadien op geleide van klinisch beeld of kweek, zo nodig in overleg met arts-microbioloog, aanpassen |

|

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

Patiënten zijn gebaat bij een zo snel mogelijke start van de behandeling ten einde het beste eindresultaat te behalen. Bij geen aangetoond voordeel van een combinatie therapie, zal monotherapie de voorkeur hebben. Bijwerkingen zoals pijn en irritatie lijken minder vaak op te treden bij het gebruik van fluorochinolonen druppels in vergelijking tot combinatie therapie. Therapietrouw is naar verwachting hoger bij monotherapie dan bij een combinatietherapie. De frequentie van druppelen is niet anders voor monotherapie vergeleken met combinatie therapie, maar het aantal druppels per dag is wel de helft minder. Bij beide vormen moet worden nagegaan of patiënten dit zelf kunnen, er hulp bij nodig hebben of zelfs voor dienen te worden opgenomen. De aanwezigheid van een partner of betrokkene lijkt compliance te verhogen. Het is goed als de behandelend arts actief naar de mogelijkheid van hulp van derden bij het druppelen te vragen. In geval van onmogelijkheid te voldoen aan het druppelschema en een klinische opname onwenselijk is, kan overwogen worden 6x per dag ofloxacine zalf te gebruiken als alternatief voor het ieder uur druppelen.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

In het algemeen zal monotherapie kosteneffectiever zijn dan een combinatietherapie bij gelijk klinisch resultaat. Versterkte antibiotica druppels worden door de apotheek bereid waardoor de kosten ten opzichte van standaardbereidingen fors hoger zijn.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

In Nederland zijn de volgende van alle hiervoor genoemde antibioticum oogdruppels verkrijgbaar: ofloxacine (fluorochinolone) moxifloxacine (fluorochinolone), gentamicine (aminoglycoside), tobramycine (aminoglycoside), ceftazidim (cefalosporine) en cefazoline (cefalosporine), al dan niet als een geregistreerd product of een doorgeleverde gestandaardiseerde bereiding. Ciprofloxacine en gatifloxacin zijn niet in Nederland beschikbaar. Omdat niet alle antibiotica even gangbaar zijn en apotheekopslag beperkt is, kan het goed zijn om met lokale apotheken afspraken te maken over minimale beschikbaarheid van specifieke medicatie voor bacteriële keratitis teneinde direct te kunnen starten met de voorkeursbehandeling. Voor versterkte antibioticavormen zijn magistrale bereidingen nodig, waardoor medicatie vaak niet direct leverbaar is en later dan gewenst gestart wordt met behandelen. Helaas zijn beschikbaarheidsproblemen van diverse medicatie regelmatig aan de orde. Te overwegen valt om dan alsnog te kiezen voor combinatietherapie (van een aminoglycoside met cefalosporine), als dat wel verstrekt kan worden. Voor patiënten is het van belang om snel, gemakkelijk en zonder extra kosten over de benodigde medicatie te beschikken.

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

Bij een verdenking op bacteriële keratitis waar de verwekker nog niet bekend is kan gekozen worden voor monotherapie met fluorochinolonen of een combinatie-behandeling van aminoglycoside met cefalosporine (fortified) antibiotica. Beide behandelingen hebben een gelijke frequentie van druppelen. Monotherapie is gemakkelijker in gebruik voor de patiënt. Op basis van de uitgebreide literatuuranalyse kon er wat betreft behandelsucces en tijd tot herstel geen duidelijk verschil worden aangetoond voor mono- dan wel combinatie therapie. Wat betreft het bijwerkingenprofiel van de oogdruppels is er een licht voordeel voor monotherapie. Op basis hiervan, het voordeel voor de patiënt voor monotherapie, verwachte kosteneffectiviteit en beschikbaarheid van de medicatie is monotherapie met fluorochinolonen (ofloxacine of moxifloxacine) de eerste keuze. Van de fluorochinolonen in Nederland is alleen de ofloxacine beschikbaar als zalf. Pseudomonas is minder gevoelig voor moxifloxacine vergeleken met ofloxacine. Om voorgaande redenen heeft bij contactlens dragers ofloxacine de voorkeur boven moxifloxacine bij monotherapie met fluorochinolonen.

Combinatietherapie blijft een goed alternatief gezien de beperkt gevonden verschillen. Start bij verdenking op een bacteriële keratitis als er nog geen kweekuitslag bekend is, zo snel mogelijk met fluorochinolonen oogdruppels. Een voorbeeld van een druppelschema is gegeven in Tabel 2. Er is een laag bijwerkingenprofiel van deze medicatie en een hoge beschikbaarheid, zonder dat er een mindere effectiviteit wordt gevonden ten opzichte van combinatie antibiotica behandeling.

Combinatie therapie geeft een vergelijkbaar klinisch resultaat als monotherapie met fluorochinolonen. Mogelijk kan combinatie behandeling gunstiger zijn ter preventie van resistentie ontwikkeling, maar in de onderzochte studies leidde monotherapie niet vaker tot therapie falen. Het is mogelijk dat door de hoge frequentie van druppelen resistentie minder opspeelt. Ook andere klinische bevindingen kunnen leiden tot een keuze voor combinatie therapie ten faveure van monotherapie door het klinisch beeld, zoals het dragen van contactlenzen, eerdere infecties, ernst van de infectie, dreigende perforaties etc. Combinatie antibiotica therapie, mits dit ook direct gestart kan worden, is geen ‘slechter’ alternatief en kan een weloverwogen optie zijn.

Wanneer de druppelfrequentie voor een patiënt thuis niet goed mogelijk is en een klinische opname onwenselijk kan als alternatief ofloxacine oogzalf 6x per dag worden overwogen.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Bij een keratitis, waarvan gedacht wordt dat deze door een bacterie wordt veroorzaakt, is de startbehandeling erg afhankelijk van waar de patiënt zich als eerste presenteert. In de huisartspraktijk wordt bij een rood oog veelal met chlooramfenicol of andere antibiotische oogzalf gestart. Diverse academische centra beginnen bij verdenking op een bacteriële keratitis met een combinatie behandeling van verschillende antibiotische middelen, vaak ook nog in een versterkte vorm. Fortified antibiotica zijn niet commercieel verkrijgbare antibiotische oogdruppels met een hogere concentratie antibiotische stof ten opzichte van het wel commercieel verkrijgbare preparaat. Protocollen in andere ziekenhuizen geven monotherapie met fluorochinolonen als eerste keuze. Voor zowel het middel als de frequentie van gebruik bestaat geen consensus. De kosten van met name versterkte antibiotische druppels zijn ten opzichte van standaardbereidingen fors en versterkte antibiotische druppels zijn vaak lastiger/later te verkrijgen, waardoor de start van de behandeling ongewenst later is. Aan de andere kant zijn er risico’s door een uit de hand gelopen bacteriële keratitis op een slecht eindresultaat wat betreft visus en een noodzakelijk langdurige behandeling. In eerste instantie moet worden aangetoond met welk antibiotisch middel bij verdenking op een bacteriële keratitis met nog onbekende verwekker gestart dient te worden. Afhankelijk van of dit monotherapie, dan wel combinatie therapie of behandeling met versterkte antibiotische druppels is, moeten zorgprocessen zo ingericht worden dat patiënten zo snel mogelijk de best passende behandeling kunnen krijgen, met zo weinig mogelijk delay.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

|

Moderate GRADE |

Treatment success

Treatment with monotherapy with fluoroquinolones probably does not reduce or increase treatment success when compared with treatment with a combination of antibiotics (aminoglycoside and cephalosporin) in patients with suspected bacterial keratitis.

Source: McDonald, 2014 (Constantinou, 2007; Hyundiuk 1996; Kosrirukvongs 2000; O’Brien 1995; Panda, 1999; Pavesio 1997 Shah 2010; Sharma, 2013); Sharma, 2016

|

|

Low GRADE |

Time to cure

Treatment with monotherapy with fluoroquinolones may not reduce or increase time to cure when compared with a combination therapy of antibiotics (aminoglycoside and cephalosporin) in patients with suspected bacterial keratitis.

Source: McDonald 2014 (Constantinou, 2007; Panda 1999; Shah 2010) |

|

Very low GRADE |

Serious complications

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of treatment with monotherapy with fluoroquinolones on serious complications when compared with treatment with a combination of antibiotics (aminoglycoside and cephalosporin) in patients with suspected bacterial keratitis.

Source: McDonald, 2014 (Constantinou, 2007; Panda, 1999; Shah 2010; Sharma, 2013) Sharma 2016) |

|

Low GRADE |

Adverse effects

Treatment with monotherapy with fluoroquinolones may result in a reduction in adverse effects when compared with treatment with a combination of antibiotics (aminoglycoside and cephalosporin) in patients with suspected bacterial keratitis.

Source: McDonald, 2014 (Constantinou, 2007; Hyundiuk, 1996; O’Brien, 1995; Pavesio 1997) |

|

No GRADE |

Visual acuity

Due to differences in measuring and reporting visual acuity, conclusion for the effect of monotherapy with fluoroquinolones on visual acuity when compared with treatment with combination therapy (aminoglycoside and cephalosporin) in patients with suspected bacterial keratitis could not be drawn.

Source: Mc Donald (Shah 2010; Sharma 2013, Panda, 1999) Sharma 2016 |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

Systematic review

McDonald (2014) performed a systematic review and meta-analysis using the Cochrane Methodology on the effectiveness of topical antibiotics in the treatment of bacterial keratitis. The databases Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), PubMed, MEDLINE, EMBASE, Scopus, BioMed Central, Trials Central, Clinical Trials, Controlled Clinical Trials, Web of Science, Latin American and Caribbean Health Sciences Literature (LILIACS) and relevant online medical journal websites were searched for relevant articles, published until the end of March 2013. RCTs comparing two or more topical ocular antibiotics administered for at least 7 days, with intensive topical ocular antibiotic cover (drops administered every 30-60 min) for the first 48 h, followed by at least 2-4 h regime until day 5, were included in the systematic review. Placebo controlled trials were excluded. In total 16 studies were included in the systematic review, of which eight studies described interventions relevant for this guideline (Constantinou, 2007; Hyundiuk, 1996; Kosirukvongs 2000, O’Brien, 1995; Pavesio 1997; Shah, 2010; Sharma, 2013). In these studies, the participants diagnosed with bacterial infection of the cornea (either by cultures or clinical judgement) were randomized to treatment with fluoroquinolones or to a combination of antibiotics. The fluoroquinolones moxifloxacin, ofloxacin, ciprofloxacin and gatifloxacin were compared with a combination therapy consisting of an aminoglycoside (tobramycin 1.3%; gentamicin 1.4%) and a cephalosporin (cefazolin 5%; cefuroxim 5%). Duration of the treatment differed from 7 days until 3 months. In some studies, the endpoint of therapy was when healing or epithelialization occurred. All of the relevant included studies (eight) described the outcome ‘treatment success’. Four studies described the outcome ‘time to cure’ (Constantinou, 2007; Kosrirukvongs, 2000; Panda, 1999; Shah, 2010), six studies described the outcome serious complications (referring to corneal perforation, therapeutic keratoplasty and/or enucleation) (Constantinou, 2007; Kosrirukvongs 2000; Panda, 1999; Pavesio, 1997; Shah, 2010; Sharma, 2013) and four studies described the outcome adverse effects (referring to ocular discomfort, chemical conjunctivitis, toxicity and/or white precipitate) (Constantinou 2007, Hyundiuk, 1996; Kosrirukvongs, 2000; O’Brien, 1995; Pavesio 1997). In three studies (Panda, 1999; Shah, 2010; Sharma, 2013) visual acuity was assessed as outcome. A risk of bias assessment was performed for the studies included in the systematic review, however, publication bias was not taken into account, which might introduce bias. There were no other concerns regarding risk of bias. The individual study characteristics of the included studies are described in the evidence tables.

Randomized controlled trial

Sharma (2016) performed a RCT in which treatment of bacterial corneal ulcers with gatifloxacin was compared to treatment with fortified tobramycin/cefazolin.

In total, 204 patients with proven bacterial corneal ulcers, aged 12 years and older were enrolled in the study. Patients with suspected fungal, viral or Acanthamoeba ulcers, patients with known allergies to one of the treatment conditions and pregnant and lactating women were excluded. Patients randomized to the intervention conditions (n = 103) received monotherapy with gatifloxacin 0.3% and patients randomized to the control condition received combination therapy (cefazolin sodium 5% and tobramycin sulfate 1.3%). Dosage schedule was similar for both treatment arms. The first 72 hours, antibiotics were given every hour, after 72 hours treatments were administered every 2 hours for the next 7 days, then reduced to 4 times a day until the ulcer was healed. Follow-up was at day 4, day 7, day 14, day 21 and the final follow-up was at 3 months. In total, six patients were lost to follow-up in the monotherapy group, and seven patients in the combination therapy group. Outcomes included resolution of keratitis and healing of the ulcer at 3-month follow-up. If worsening of the ulcer occurred, this was also reported, this was classified as serious complication. Visual acuity was also assessed, expressed as mean LogMAR Best Corrected Visual Acuity (BCVA). The investigator dispensing the treatments was blinded, but there was no information on blinding of patients or others involved in the study. This lack of blinding might introduce bias. The characteristics of this study are presented in the evidence table.

Results

All the included studies reported outcomes for the main comparison monotherapy (fluoroquinolones) versus combination therapy. This main comparison could be subdivided into three sub-comparisons, based on the type of antibiotics that were analyzed in the studies. The three subcomparisons were:

- fluoroquinolones vs. gentamicin/cefazolin

- fluoroquinolones vs. tobramycin/cefazolin

- fluoroquinolones vs. gentamicin/cefuroxim

The types of fluoroquinolones that were analyzed in the studies included moxifloxacin, ofloxacin, ciprofloxacin and gatifloxacin.

- The effects of the individual fluoroquinolones were combined and if possible, a pooled effect was calculated for each of the three subcomparisons. Per outcome, the results for these three subcomparisons are presented.

- The effects of the individual fluoroquinolones (moxifloxacin/ofloxacin/ciprofloxacin/gatifloxacin) compared to the combination therapy were also presented for each outcome.

- Finally, the results, the level of evidence and GRADE conclusions were presented for the main comparison: monotherapy (fluoroquinolonen) compared to combination therapy (gentamicin/cefazolin or tobramycin/cefazolin or gentamicin/cefuroxime)

Treatment success

The relevant studies included in the systematic review (McDonald, 2014) and the RCT of Sharma (2016) all reported the outcome treatment success (referring to the number of patients cured) as outcome.

Subcomparison 1: fluoroquinolonen vs. gentamicin/cefazolin

One study compared fluoroquinolones with gentamicin/cefazolin (Kosrirukvongs, 2013). The RCT performed by Kosrirukvongs (2000) compared ciprofloxacin with gentamicin/cefazolin. The number of patients with treatment success in the fluoroquinolones group was 12/17 (70.6%) compared to 15/24 (62.5%) in the patients treated with gentamicin/cefazolin. A RR of 1.13 (95% CI: 0.73 – 1.75) was found. This was not statistically significant, and not considered clinically relevant.

None of the included studies reported the outcome treatments success for moxifloxacin, ofloxacin or gatifloxacin compared to gentamicin/cefazolin.

Subcomparison 2: fluoroquinolones vs. tobramycin/cefazolin

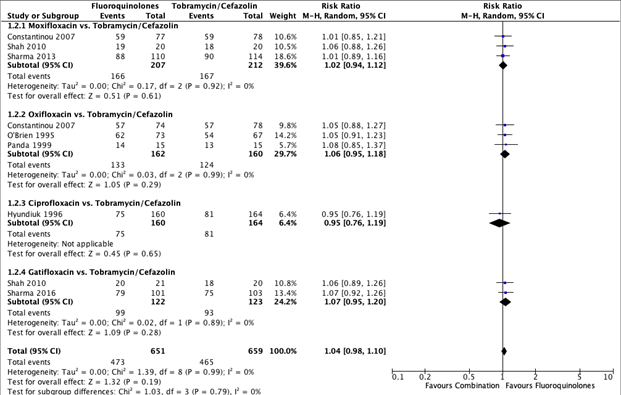

Seven of the included studies reported treatment success for the subcomparison fluoroquinolones versus tobramycin/cefazolin. The pooled number of patients with treatment success in the monotherapy group (fluoroquinolones) was 473/651 (73%), compared to 465/659 (70%) in the tobramycin/cefazolin group. The pooled RR was 1.04 (95% CI: 0.98 – 1.10). This was not statistically significant, and not considered clinically relevant (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Forest plot showing the comparison between monotherapy with fluoroquinolones to combination therapy with tobramycin/cefazolin for the outcome treatment success. Pooled relative risk ratio, random effects model. Z: p-value of overall effect; df: degrees of freedom; SD: standard deviation; I2; statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval.

Specified per fluoroquinolone

Three studies reported treatment success for the comparison moxifloxacin with tobramycin/cefazolin (Constantinou, 2007; Sharma, 2013; Shah, 2010). The pooled number of participants with treatments success in the moxifloxacin group was 166/207 (80.2%) and 167/212 (78.8%) in the tobramycin/cefazolin group. The pooled RR for this sub-comparison was 1.02 (95% CI: 0.94 – 1.12) (Figure 1).

Three studies reported treatment success for the comparison ofloxacin with tobramycin/cefazolin (O’Brien 1995; Constantinou, 2007; Panda 1999). The pooled number of participants with treatments success in the ofloxacin group was 133/162 (82.1%) and 124/160 (77.5%) in the tobramycin/cefazolin group. The pooled RR for this sub-comparison was 1.06 (95% CI: 0.95 – 1.18) (Figure 1).

One study reported treatment success for the comparison ciprofloxacin with tobramycin/cefazolin (Hyundiuk, 1996). The number of participants with treatment success in the ciprofloxacin group was 75/160 (46.9%) and 81/164 (49.4%) in the tobramycin/cefazolin group. A RR of 0.95 (95% CI: 0.76 – 1.19) was found (Figure 1).

Two studies reported treatment success for the comparison gatifloxacin with tobramycin/cefazolin (Shah, 2010; Sharma, 2016). The pooled number of participants with treatment success in the gatifloxacin group was 99/122 (81.1%) and 93/123 (75.6%) for the tobramycin/cefazolin group. The pooled RR for this sub-comparison was 1.07 (95% CI: 0.95 – 1.20) (Figure 1).

Subcomparison 3 : fluoroquinolonen vs. Gentamicin/cefuroxim.

One study compared fluoroquinolones with gentamicin/cefuroxim (Pavesio, 1997). In this RCT ofloxacin was compared with gentamicin/cefuroxime. The number of patients with treatment success in the fluoroquinolones group was 36/59 (61.0%) compared to 38/59 (64.4%) in the patients treated with gentamicin/cefazolin. A RR of 0.95 (95% CI: 0.72 – 1.25) was found, favoring gentamicin/cefuroxime treatment. This was not considered clinically relevant.

Time to cure

Subcomparison 1: fluoroquinolones vs. gentamicin/cefazolin

None of the included studies reported the outcome time to cure for fluoroquinolones (moxifloxacin, ofloxacin, ciprofloxacin, gatifloxacin) compared to gentamicin/cefazolin.

Subcomparison 2: fluoroquinolones vs. tobramycin/cefazolin

The results of the individual studies reporting mean time to cure for fluoroquinolones compared to tobramycin/cefazolin, could not be pooled into a meta-analysis due to variety in reporting. Therefore, only the results specified per fluoroquinolone are presented.

Specified per fluoroquinolone

Two studies reported the mean time to cure for moxifloxacin compared to tobramycin/cefazolin (Constantinou, 2007; Shah 2010). In the systematic review of McDonald (2014) these studies were pooled and a mean difference of -1.24 (95% CI: -7.40 to 4.92) was found, with a random effect model with low hetereogeneity (I2 = 0%). This difference was not clinically significant (<5 days difference), nor clinically relevant. A forest plot for these pooled results was not presented in the systematic review of McDonald (2014) and could not be created due to the variety in outcome measures reported in the individual studies. It was reported that the range of days to cure was 24 – 36 days for the moxifloxacin group and 25 – 28 days for the tobramycin/cefazolin group. Results of the individual studies were also presented. Constantinou (2007) reported a mean time to cure (days) of 36.4 (95% CI: 27.8 – 44.9) for the moxifloxacin group, and 38.2 (95% CI: 29.7 – 46.8) for the tobramycin/cefazolin group. Shah (2010) reported a to cure (median) of 24 (IQR: 4-45) for moxifloxacin compared to 24.5 (IQR: 4-48) for combination therapy.

Two studies reported mean time to cure for ofloxacin compared to tobramycin/cefazolin (Constantinou, 2007; Panda 1999). In the systematic review of McDonald (2014) these studies were pooled and a mean difference of -3.57 (95% CI: -4.23 to 11.37) was found with a random effect model with low hetereogeneity (I2 = 11%). This difference was not clinically significant, nor clinically relevant. A forest plot for these pooled results was not presented in the systematic review of McDonald (2014) and could not be created due to the variety in outcome measures reported in the individual studies. Furthermore, it was reported that the range of days to cure was 24-26 for the ofloxacin group and 15-28 for the tobramycin/cefazolin group. Results of the individual studies were also presented. Constantinou (2007) reported a mean time to cure (days) of 46.2 (95% CI: 37.5 – 54.9) for the oflaxacin group, and 38.2 (95% CI: 29.7 – 46.8) for the tobramycin/cefazolin group. Panda (1999) reported a mean time to cure (days) of 15 ± 3.86 for ofloxacin compared to 15.46 ± 3.86 for the combination therapy.

None of the included studies reported the mean time to cure for the comparison ciprofloxacin to tobramycin/cefazolin.

The RCT of Shah (2010) reported the mean time to cure for gatifloxacin. The time to cure (median) for the patients treated with gatifloxacin was 27.5 days (IQR: 5-45), compared to 24.5 (IQR: 4-48) days for the tobramycin/cefazolin group.

Subcomparison 3: fluoroquinolones vs. Gentamicin/cefuroxim.

None of the included studies reported the outcome time to cure for fluoroquinolones (moxifloxacin, ofloxacin, ciprofloxacin, gatifloxacin) compared to gentamicin/cefuroxim.

Serious complications

Subomparison 1: fluoroquinolonen vs. Gentamicin/cefazolin

None of the included studies reported the outcome adverse effects of the other fluoroquinolones (moxifloxacin, ofloxacin, ciprofloxacin, gatifloxacin) compared to gentamicin/cefazolin.

Subcomparison 2: fluoroquinolonen vs. Tobramycin/cefazolin

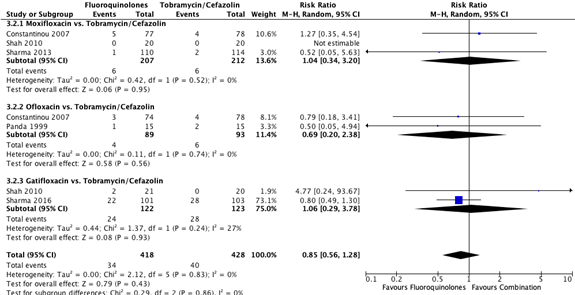

Five studies reported serious complications for the subcomparison fluoroquinolones versus tobramycin/cefazolin (Constantinou, 2007; Panda, 1999; Shah 2010; Sharma, 2013; Sharma, 2016;). The pooled number of patients with serious complications in the monotherapy group (fluoroquinolones) was 34/418 (8.2%), compared to 40/428 (9.3%) in the tobramycin/cefazolin group. The pooled RR for serious complications was 0.85 (95% CI: 0.56 – 1.28), favoring fluoroquinolones. This was not considered clinically relevant (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Forest plot showing the comparison between monotherapy with fluoroquinolones to combination therapy with tobramycin/cefazolin for the outcome serious complications. Pooled relative risk ratio, random effects model. Z: p-value of

overall effect; df: degrees of freedom; SD: standard deviation; I2; statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval.

Specified per fluoroquinolone

Three studies reported serious complications for the comparison moxifloxacin with tobramycin/cefazolin (Constantinou, 2007; Shah, 2010; Sharma, 2013;). The pooled number of participants with serious complications in the moxifloxacin group was 6/207 (2.9%) and 6/212 (2.8%) in the tobramycin/cefazolin group. The pooled RR for this sub-comparison was 1.04 (95% CI: 0.34 – 3.20) (Figure 2).

Two studies reported serious complications for the comparison ofloxacin with tobramycin/cefazolin (Constantinou, 2007; Panda, 1999). The pooled number of patients with serious complications in the ofloxacin group was 4/89 (4.5%), compared to 6/93 (6.5%) in the tobramycin/cefazolin group. The pooled RR was 0.69 (95% CI: 0.20 – 2.38) (Figure 2).

Two studies reported serious complications for the fluoroquinolone gatifloxacin (Shah, 2010; Sharma, 2016). The pooled number of patients with serious complications in the gatifloxacin group was 24/122 (19.7%), compared to 28/123 (22.8%) in the tobramycin/cefazolin group. The pooled RR was 1.06 (95% CI: 0.29 – 3.78) (Figure 2).

Subcomparison 3: fluoroquinolones vs. Gentamicin/cefuroxim.

None of the included studies reported the outcome serious complications of the fluoroquinolones (moxifloxacin, ofloxacin, ciprofloxacin, gatifloxacin) compared to gentamicin/cefuroxim.

Adverse effects

Subcomparison 1: fluoroquinolones vs. gentamicin/cefazolin

None of the included studies reported the outcome adverse effects of fluoroquinolones (moxifloxacin, ofloxacin, ciprofloxacin, gatifloxacin) compared to gentamicin/cefazolin.

Subcomparison 2: fluoroquinolones vs. tobramycin/cefazolin

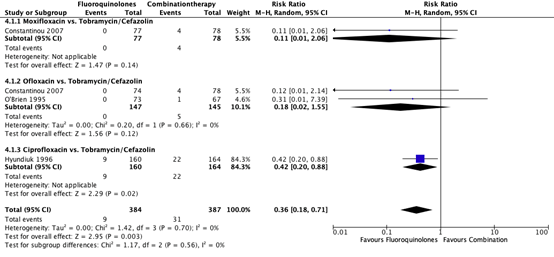

Three studies reported adverse effects for the sub-comparison fluoroquinolones vs. tobramycin/cefazolin (Constantinou, 2007; Hyundiuk, 1996; O’Brien, 1995). The pooled number of patients who experienced adverse effects in the monotherapy group (fluoroquinolones) was 9/384 (2.3%) compared to 31/387 (8.0%) in the tobramycin/cefazolin group. The pooled RR for adverse effects was 0.36 (95% CI: 0.18 – 0.71), favoring fluoroquinolones (Figure 3). This was considered clinically relevant.

Figure 3. Forest plot showing the comparison between monotherapy with fluoroquinolones to combination therapy with tobramycin/cefazolin for the outcome adverse effects. Pooled relative risk ratio, random effects model. Z: p-value of

overall effect; df: degrees of freedom; SD: standard deviation; I2; statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval.

Specified per fluoroquinolone

One study reported adverse effects for the comparison of moxifloxacin with tobramycin/cefazolin (Constantinou 2007). In the patients treated with moxifloxacin 0/77 (0%) patients experienced adverse effects, while in the patients treated with tobramycin/cefazolin 4/78 (5.1%) patients experienced adverse effects. A RR of 0.11 (95% CI 0.01 – 2.06) was found (Figure 3).

Two studies reported adverse effects of ofloxacin (Constantinou, 2007; O’Brien 1995). The pooled number of patients with serious complications in the ofloxacin group was 0/147 (0%) compared to 5/145 (3.4%) in the tobramycin/cefazolin group. The pooled RR was 0.18 (95% CI: 0.02 – 1.55) (Figure 3).

One study reported adverse effects of ciprofloxacin (Hyundiuk 1996). In patients treated with ciprofloxacin 9/160 (5.6%) experienced adverse events, compared to 22/164 (13.4%) in the patients treated with tobramycin/cefazolin. A RR of 0.42 (95% CI: 0.20 – 0.88) was found, favoring ciprofloxacin (Figure 3).

Comparison 3: fluoroquinolones vs. gentamicin/cefazolin

One study compared fluoroquinolones (ofloxacin) with gentamicin/cefazolin (Pavesio, 1997). A toxic reaction was found in 6/59 (10.2%) patients treated with ofloxacin, compared to 30/59 (50.8%) patients treated with gentamicin/cefuroxime. A RR of 0.20 (95% CI: 0.09 – 0.44) was found, favoring ciprofloxacin.

Visual acuity

Comparison 1: fluoroquinolones vs. gentamicin/cefazolin

None of the included studies reported the effects of fluoroquinolones (moxifloxacin, ofloxacin, ciprofloxacin, gatifloxacin) compared to gentamicin/cefazolin on the outcome visual acuity.

Comparison 2: fluoroquinolones vs. tobramycin/cefazolin

Two studies compared the effects of moxifloxacin with tobramycin/cefazolin on visual acuity (Shah, 2010; Sharma, 2013). Shah (2010), assessed Snellen visual acuity with pinhole, presented as median (range) LogMAR. In the moxifloxacin group, baseline LogMAR was 1.63 (IQR: 0.2 – 2.3), and 1.18 (IQR: 0.18 – 2) at follow-up. In the tobramycin/cefazolin group baseline LogMAR was 1.63 (IQR: 0.18 – 2.7) and 0.78 (IQR: 0.18 – 2.7) at follow-up. In the study of Sharma (2013) Best-Corrected Visual Acuity (BCVA) LogMAR visual acuity was assessed, presented as mean LogMAR ± SD. In the moxifloxacin LogMar was 1.55 ± 0.46 at baseline and 1.34 ± 0.53 at 3-month follow-up. In the tobramycin/cefazolin, the LogMAR was 1.59 ± 0.44 at baseline and 1.3 ± 0.51 at 3-month follow-up.

The study of Panda (1999) reported BCVA for the comparison ofloxacin with tobramycin/cefazolin. Visual acuity at baseline was light perception (PL), projection of rays (PR) and count fingers (CF) (PL, PR to CF) for both the ofloxacin group and tobramycin/cefazolin group. At follow-up, visual acuity was CF to 20/60 for the ofloxacin group and CF to 20/80 for the tobramycin/cefazolin group.

Two studies reported the visual acuity for the comparison gatifloxacin with tobramycin/cefazolin (Shah, 2010; Sharma, 2016). Shah (2010), assessed Snellen visual acuity with pinhole, presented as median (range) LogMAR. In the gatifloxacin group, LogMAR was 1.48 (IQR: 0.3 – 2.3) at baseline and 1.18 (IQR: 0.18 – 2.3) at follow-up. In the tobramycin/cefazolin group, LogMAR, was 1.63 (IQR: 0.18 – 2.7) at baseline and 0.78 (IQR: 0-18 – 2.7) at follow-up. In Sharma (2016) Best-Corrected Visual Acuity (BCVA) was assessed and presented as LogMAR± SD. In the gatifloxacin group LogMAR was 1.44 ± 0.41 at baseline, and 1.14 ± 0.55 at 3-month follow-up. In the tobramycin/cefazolin group, LogMAR ± SD was 1.49 ± 0.42 at baseline and 1.25 ± 0.54 at 3-month follow-up.

None of the studies reported the effects of ciprofloxacin on visual acuity.

Comparison 3: fluoroquinolones vs. gentamicin/cefuroxime.

None of the included studies reported the effects of fluoroquinolones (moxifloxacin, ofloxacin, ciprofloxacin or gatifloxacin) compared to gentamicin/cefuroxime on the outcome visual acuity.

Overall effect main comparison: monotherapy compared to combination therapy

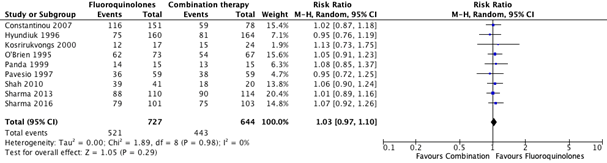

Treatment success

All data on treatment success reported in the nine individual studies describing this outcome were pooled for the main comparision monotherapy with fluoroquinolones (moxifloxacin/ofloxacin/ciprofloxacin/gatifloxacin) versus combination therapy with aminoglycosides and cephalosporin (tobramycin/gentamicin/cefazolin/cefuroxime). The pooled number of patients with treatment success in the monotherapy group was 521/727 (71.7%), compared to 443/644 (68.8%) in the combination therapy group. The pooled relative risk ratio for treatment success was 1.03 (95% CI: 0.97 – 1.10). This was not considered clinically relevant (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Forest plot showing the comparison between monotherapy with fluoroquinolones to combination therapy for the outcome treatment ochran. Pooled relative risk ratio, random effects model. Z: p-value of

overall effect; df: degrees of freedom; SD: standard deviation; I2; statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval.

Time to Cure

Due to variety in reporting, results could not be pooled for the main comparison.

Results for the subcomparisons were as follows:

- Moxifloxacin vs. tobramycin/cefazolin: MD = -1.24 (95% CI – 7.40 to 4.92, I2 = 0%). Based on two studies, total study population: n = 195 (97 in moxifloxacin group vs. 98 in combination therapy group). Range of days to cure moxifloxacin: 24-36. Range of days to cure combination therapy: 25-38 Median time to cure moxifloxacin: 24 (IQR: 4-45). Combination therapy: 24.5 (IQR: 4-48)

- Ofloxacin vs. tobramycin/cefazolin: MD = -4.23 (95% CI – 4.23 to 11.37, I2 = 11%) Based on two studies, total study population: n = 185 (92 in ofloxacin group vs. 93 in combination therapy group). Range of days to cure ofloxacin: 15-46. Range of days to cure combination: 15-38.

- Gatifloxacin vs. tobramycin/cerazolin. Median time to cure gatifloxacin: 27.5 days (IQR: 5-45). Combination therapy: 24.5 (IQR: 4-48)

None of the differences found for the subcomparisions were statistically significant, nor clinically relevant.

Serious complications

All data on serious complications reported in the five individual studies describing this outcome were pooled for the main comparison monotherapy with fluoroquinolones (moxifloxacin/ofloxacin/ciprofloxacin/gatifloxacin) versus combination therapy with aminoglycosides and cephalosporin (tobramycin/gentamicin/cefazolin/cefuroxim)orThe pooled number of patients with serious complications in the monotherapy group was 34/418 (8.3%), compared to 36/330 (10.9%) in the combination therapy group. The pooled relative risk ratio for serious complications was 0.82 (95% CI: 0.54 – 1.26). On average, patients treated with monotherapy with fluoroquinolones experienced less serious complications. This was not considered clinically relevant (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Forest plot showing the comparison between monotherapy with fluoroquinolones to combination therapy for the outcome serious complications. Pooled relative risk ratio, random effects model. Z: p-value of

overall effect; df: degrees of freedom; SD: standard deviation; I2; statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval.

Adverse effects

All data on adverse effects reported in the four individual studies describing this outcome were pooled for the main comparison monotherapy with fluoroquinolones (moxifloxacin/ofloxacin/ciprofloxacin/gatifloxacin) versus combination therapy with aminoglycosides and cephalosporin (tobramycin/gentamicin/cefazolin/cefuroxime)The pooled number of patients with adverse effects in the monotherapy group was 15/443 (3.2%), compared to 57/368 (15.4%) in the combination therapy group. The pooled relative risk for adverse effects was 0.28 (95% CI: 0.17 – 0.48), favoring fluoroquinolones. On average, patients treated with monotherapy with fluoroquinolones experiences less adverse effects. This difference was considered clinically relevant (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Forest plot showing the comparison between monotherapy with fluoroquinolones to combination therapy for the outcome serious complications. Pooled relative risk ratio, random effects model. Z: p-value of

overall effect; df: degrees of freedom; SD: standard deviation; I2; statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval.

Visual acuity

Due to variety in reporting, results could not be pooled for the main comparison. As a consequence, it was not possible to draw a conclusion. Visual acuity at follow-up for the different treatments at follow-up was as follows (Table 1)

Table 1: visual acuity at follow-up for treatment with either monotherapy (fluoroquinolones) or combination therapy

|

|

Monotherapy |

Combination therapy (tobramycin/cefazolin) |

|

Moxifloxacin Median (IQR) |

1.18 (IQR: 0.18 – 2.0) |

0.78 (IQR: 0.18 – 2.7) |

|

Moxifloxacin Mean ± SD |

1.34 ± 0.53 |

1.3 ± 0.51 |

|

Ofloxacin |

CF 20/60 |

CF to 20/80 |

|

Gatifloxacin Median (IQR) |

1.18 (IQR: 0.18 – 2.3) |

0.78 (IQR: 0.18 – 2.7) |

|

Gatifloxacin Mean ± SD |

1.14 ± 0.54 |

1.25 ± 0.54 |

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence regarding the outcome treatment success was derived from randomized controlled trials and therefore started high. The level of evidence was downgraded by 1 level because of study limitations including unclear role/involvement of the industry and uncertainty in randomization, allocation and blinding procedures (-1 risk of bias). The level of evidence was not downgraded because of conflicting results (inconsistency); applicability (bias due to indirectness); number of included patients (imprecision) or publication bias. The final level of evidence for treatment success was graded ‘moderate’.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome time to cure was derived from randomized controlled trials and therefore started high. The level of evidence was downgraded by 2 levels because of study limitations including lack of blinding and uncertainty on randomization and allocation procedures (-1 risk of bias) and the small number of included patients and the 95% confidence intervals crossing the boundaries of clinical decision making (-1 imprecision). The level of evidence was not downgraded because of conflicting results (inconsistency); applicability (bias due to indirectness) or publication bias. The final level of evidence for time to cure was graded ‘low’.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome serious complications was derived from randomized controlled trials and therefore started high. The level of evidence was downgraded by 3 levels because of study limitations including lack of blinding of the study participants and personnel (-1 risk of bias), the 95% confidence intervals crossing the boundaries of clinical decision making and small number of cases (-2 imprecision). The level of evidence was not downgraded because of conflicting results (inconsistency); applicability (bias due to indirectness) or publication bias. The final level of evidence for the outcome serious complications was graded ‘very low’.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome adverse effects was derived from randomized controlled trials and therefore started high. The level of evidence was downgraded by 2 levels because of study limitations including unclear role/involvement of the industry (-1 risk of bias) and small number of cases (-1 imprecision). The level of evidence was not downgraded because of conflicting results (inconsistency); applicability (bias due to indirectness) or publication bias. The final level of evidence for the outcome adverse effects was graded ‘low’.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome visual acuity was not graded because it was not possible to pool the results and draw a(n) (overall) conclusion.

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question:

What is the effectiveness and safety of monotherapy antibiotics (fluoroquinolones) compared to treatment with a combination of antibiotics in patients with suspected bacterial keratitis?

P: Patients with suspected bacterial keratitis

I: Monotherapy with fluoroquinolones (such as moxifloxacin, ofloxacin)

C: A combination of treatments of (fortified or non-fortified) antibiotics

(such as gentamicin, tobramycin, cefazolin)

O: Treatment success, time to cure, serious complications, adverse effects,

visual acuity

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered treatment success and time to cure as critical outcome measures for decision making; and serious complications, adverse effects, visual acuity as important outcome measures for decision making.

The working group defined the outcome measures as follows: treatment success was defined as complete re-epithelialization of the cornea; time to cure was defined as the number of days treatment was instilled before physician’s judgment designated bacterial keratitis as cured; serious complications were defined as complications requiring surgical intervention typically related to ocular bacterial infection rather than trial medication (e.g. corneal perforation, therapeutic keratoplasty or enucleation)adverse effects were defined as any effects related to application of trial medication such as ocular discomfort (e.g., pain, pruritus, burning, stinging, irritation), chemical conjunctivitis (e.g., ocular/conjunctival toxicity or bulbar ulceration) or white precipitate. Visual acuity was defined as visual acuity assessed at follow-up with either LogMAR chart or Snellen chart and presented as LogMAR value. Both visual acuity and best (spectacle) corrected visual acuity (BCVA/BSCVA) were taken into account.

The working group defined a relative risk (RR) for dichotomous outcomes of <0.80 and >1.25 as a minimal clinically (patient) important difference. This applies to the outcomes treatment success, serious complications and adverse effects. For the outcome time to cure, a threshold of 5 days was set as a minimal clinically important difference. For the outcome visual acuity a value of 0.2 LogMAR (referring to 2 lines) was predefined as a minimal clinically important difference.

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms until the 22nd of March 2022. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 110 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria: systematic reviews and randomized controlled trials comparing the treatment of bacterial keratitis with monotherapy antibiotics (fluoroquinolones) with treatment with a combination of antibiotics. Twenty studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, 18 studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and two studies were included.

Results

Two studies (one systematic review and one RCT) were included in the analysis of the literature. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- McDonald EM, Ram FS, Patel DV, McGhee CN. Topical antibiotics for the management of bacterial keratitis: an evidence-based review of high quality randomized controlled trials. Br J Ophthalmol. 2014 Nov;98(11):1470-7.

- Sharma N, Arora T, Jain V, Agarwal T, Jain R, Jain V, Yadav CP, Titiyal J, Satpathy G. Gatifloxacin 0.3% Versus Fortified Tobramycin-Cefazolin in Treating Nonperforated Bacterial Corneal Ulcers: Randomized, Controlled Trial. Cornea. 2016 Jan;35(1):56-61.

Evidence tabellen

Evidence table for systematic review of RCTs and observational studies (intervention studies)

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control I

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

McDonald 2014

Study characteristics and results are extracted from the SR (unless stated otherwise*) |

SR and meta-analysis of RCT’s

Literature search up to March 2013

A: Constantinou (2007) B: Hyundiuk (1996) C: Kosrirukvongs (2000) D: O’Brien (1995) E: Panda (1999) F: Pavesio (1997) G: Shah (2010) H: Sharma (2013)

Study design: RCT

Setting and Country: A: Australia B: Multinational C: Thailand D: USA, multicentre E: India F: UK G: India, single centre H: India, single centre

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: A, B, F: pharmaceutical company (unrestricted grant), no conflicts of interest: D: pharmaceutical company, involvement of company not clear: C, G, H: Non-commercial funding / no conflicts of interest. E: not stated:

|

Inclusion criteria SR: Trials comparing 2 or more topical ocular antibiotics administered for at least 7 days, with intensive topical ocular antibiotic cover (drops administered every 30-60 min) for the first 48 h, followed by at least 2-4 h regime until day 5.

Exclusion criteria SR: Placebo controlled trials

16 studies included of which 8 included relevant treatment options

Important patient characteristics at baseline:

N, mean age A: n = 229, 28,2 yrs B: n = 324, 45.2 yrs C: n = 41, 47.6 yrs D: n = 140, 46 yrs E: n = 30, ? yrs F: n = 122, 48.6 yrs G: n = 61, 39.7 yrs H: n = 224, 12-90 yrs

Sex: A: 59% male B: 47% male C: 65.9% male D: 46% male E: 60% male F: 58% male G: 66% male H: not stated

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes

|

fluorochinolonen (monotherapy)

A1: Moxifloxacin 0.3% drops for 7 days / until epithelialization A2: Ofloxacin 0.3% drops for 7 days / until epithelialization B: Ciprofloxacin 0.3% for 14 days C: Ciprofloxacin 0.3% until healing D: Ofloxacin 0.3% until healing E: Ofloxacin 0.3% for 1 week until 1 week after complete resolution F: Ofloxacin 0.3% until re-epithelialization G1: moxifloxacin 0.5% until re-epithelialization G2: gatifloxacin 0.3% until re-epithelialization H: moxifloxacin 0.5% until ulcer healed

Subcomparison 1 : Fluoroquinolones

Subcomparison 2 : Fluoroquinolones

Subcomparison 3 : Fluoroquinolones |

Aminoglycoside/cephalosporin (combination therapy)

A: Tobramycin 1.33% / cefazolin 5% for 7 days / until epithelialization B: Tobramycin 1.3% / cefazolin 5% for 16 days + if required C: Gentamicin 1.4% / cefazolin 5% until healing D: Tobramycin 1.5% / cefazolin 10% for 28 days or after healing E: Tobramycin 1.5% / cefazolin 10% until 1 week after complete resolution F: Gentamicin 1.4% / Cefuroxime 5% until re-epithelialization G: Tobramycin 1.3% / cefazolin 5% H: Tobramycin 1.3% / cefazolin 5% for 3 months

Subcomparison 1: Gentamycin/cefazolin

Subomparison 2: Tobramycin/cefazolin

Subcomparison 3: Gentamycin/cefuroxime |

End-point of follow-up:

A: epithelialization, final visit at 2-3 months B: 14 days/16 days+, participants stopped drug once re-epithelialized C: until healing, duration not stated D: until healing/28 days or after healing occurred E: 1 week after healing F: until healing G: until ulcer healed H: until ulcer healed / 3 months

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? It is stated that: “all trials accounted for all participants”

|

RR (95% CI) of treatment success *Data extracted from the individual studies A1*: 1.01 (0.85 – 1.21) A2*: 1.05 (0.88 – 1.27) B: 0.95 (0.76 – 1.19) C: 1.13 (0.73 – 1.75) D: 1.05 (0.91 – 1.23) E: 1.08 (0.85 – 1.37) F: 0.95 (0.72 – 1.25) G1*: 1.06 (0.88 – 1.26) G2*: 1.06 (0.89 – 1.26) H: 1.01 (0.89 – 1.16)

Time to cure (days): mean difference ± SD (95% CI) I vs. C A1*: 36.4 (27.8-44.9) vs. 38.2 (29.7 – 46.8) A2*: 46.2 (37.5 – 54.9) vs. 38.2 (29.7 – 46.8) C*: 15.6 vs. 14.6 E*: 15.0 ± 3.86 vs. 15.46 ± 3.86 G1*: 24 (range: 4 – 45) vs. 24.5 (range: 4 – 48) G2*: 27.5 (5-45) vs. 24.5 (range: 4 – 48)

- moxifloxacin vs. Tobramycin/cefazolin: pooled MD -1.24 (95% CI: - 7.40 to 4.92), I2: 0% - ofloxacin vs tobramycin/cefazolin: pooled MD: -3.57 (95% CI: -4.23 to 11.37), I2 = 11%

RR of serious complications I VS. C – RR (95% CI) A1*: 5/77 vs. 4/78 – RR: 1.27 (0.35 – 4.54) A2*: 3/74 vs. 4/78 – RR: 0.79 (0.18 – 3.41) C*: no data E*: 1/15 vs. 2/15 – RR: 0.50 (0.05 – 4.94) F*: ? G1*: 0/20 vs 0/20 – RR: 0 G2*: 2/21 vs 0/20 – RR: 4.77 (0.24 – 93.67) H*: 1/110 vs 2/114 – RR: 0.52 (0.05 – 5.63)

RR of adverse effects I vs. C – RR (95% CI) A1*: 0/77 vs. 4/78 – RR: 0.11 (0.01 – 2.06) A2*: 0/74 vs. 4/78 – RR: 0.12 (0.01 – 2.14) B*: 9/160 vs. 22/164 – RR: 0.42 (0.20 – 0.88) C*: no data D*: 0/73 vs. 1/67 – RR: 0.31 (0.01 – 7.39) F*: 6/59 vs. 30/59 – RR 0.20 (0.09 – 0.44)

Outcome 5: visual acuity E: CF to 20/60 vs. CF to 20/80 G1: 1.18 (IQR: 0.18 – 2) vs. 0.78 (IQR: 0.18 – 2.7) G2: 1.18 (IQR: 0.18 – 2.3) vs. 0.78 (0.18 – 2.7) H: 1.34 ± 0.53 vs. c: 1.3 ± 0.51

|

Facultative:

The author concluded that: “there was no difference in the efficacy of monotherapy with fluoroquinolones in the treatment of bacterial corneal ulcers when compared with combination therapy of fortified antibiotics”

Some of the pooled effects were not retrieved from the systematic review but calculated by hand since some of the studies included for the review were not considered relevant for the research question.

Outcome measures with a * were retrieved from the individual studies.

Risk of Bias RS = random sequence generation AC = allocation concealment BP = blinding participants and personnel BO = blinding outcome assessment IO = incomplete outcome OB = other Bias low = low risk of bias high = high risk of bias unclear risk of bias

A: RS = low; AC = unclear; BP = high; BO = unclear; IO = low; OB = high B: RS = low; AC = low; BP = low; BO = low; IO = low; OB = high C: RS = unclear; AC = unclear; BP = unclear; BO = unclear; IO = low; OB = unclear D: RS = low; AC = low; BP = low; BO = low; IO = low; OB = high E: RS = unclear; AC = low; BP = low; BO = low; IO = low; OB = unclear F: RS = low; AC = unclear; BP = low; BO = unclear; IO = low; OB = high G: RS = low; AC = low; BP = high; BO = high; IO = low; OB = low H: RS = low; AC = low; BP = unclear; BO = low; IO = unclear; OB = low

|

Evidence table for intervention studies studies (randomized controlled trials and non-randomized observational studies [cohort studies, case-control studies, case series])1

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics 2 |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control I 3

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size 4 |

Comments |

|

Sharma 2016 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: Single centre, India

Funding and conflicts of interest: None |

Inclusion criteria: -patients with proven bacterial corneal ulcers -patients > 12 years

Exclusion criteria: -Patients with suspected fungal, viral, or Acanthamoeba ulcers. -Patients with known allergy to fluoroquinolones, aminoglycosides or cephalosporins - Pregnant and lactating women

N total at baseline: Intervention: 101 Control: 103

Important prognostic factors2: For example age ± SD: I: 34.7% aged 30-49 42.6% aged 50-69

C: 33% aged 30-49 44.7% aged 50-69

Sex: not reported

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes

|

Gatifloxacin 0.3%

*dosage schedule: for the first 72 hours treatment was given hourly, after 72 hours treatment was given every 2 hours, for the next 7 days, then reduced to 4 times/day until ulcer was healed

|

Fortified Tobramycin (1.4%) + fortified Cefazolin (5% mg/ml)

*dosage schedule: for the first 72 hours treatment was given hourly, after 72 hours treatment was given every 2 hours, for the next 7 days, then reduced to 4 times/day until ulcer was healed

|

Length of follow-up: Follow-up at: day 4, day 7, day 14, day 21. Endpoint of follow-up: day 90 (3 months)

Loss-to-follow-up: I: n = 6 (6%) Reasons: not described

C: n = 7 (7%) N (%) Reasons: not described

Incomplete outcome data: No incomplete outcome data

|

Resolution of keratitis + healing of the ulcer at 3 months follow-up: I: 79/101 (78.2%) C: 75/103 (72.8%) % healing difference: 5.4% (90% CI -4.5 to 15.3)

Visual acuity at 3-month follow-up (mean ± SD) I: 1.14 ± 0.55 C: 1.25 ± 0.54

|

Instead of a 95% CI, a 90% CI was reported in the article, 95% CI was calculated by hand

|

Table of quality assessment for systematic reviews of RCTs and observational studies

Based on AMSTAR checklist (Shea et al.; 2007, BMC Methodol 7: 10; doi:10.1186/1471-2288-7-10) and PRISMA checklist (Moher et al 2009, PloS Med 6: e1000097; doi:10.1371/journal.pmed1000097)

|

Study

First author, year |

Appropriate and clearly focused question?1

Yes/no/unclear |

Comprehensive and systematic literature search?2

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of included and excluded studies?3

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of relevant characteristics of included studies?4

Yes/no/unclear |

Appropriate adjustment for potential confounders in observational studies?5

Yes/no/unclear /notapplicable

|

Assessment of scientific quality of included studies?6

Yes/no/unclear |

Enough similarities between studies to make combining them reasonable?7

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential risk of publication bias taken into account?8

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential conflicts of interest reported?9

Yes/no/unclear |

|

McDonald (2014) |

Yes;

Reason: PICO and inclusion criteria were predefined. |

Yes;

Reason: search period and search strategy were described. Database Medline + EMBASE were searched |

No;

Reason: general description of reason for exclusion but not without references to individual studies |

Yes;

Reason: table with characteristics of included studies included as a supplement

|

n.a.

Reason: only RCTs were included |

Yes;

Reason: risk of bias was assessed for the individual studies and presented in a risk of bias table |

Yes;

I2 calculated for comparisons, I2 = low |

No;

Reason: no funnel plot or test included; neither publication bias was assessed in Risk of Bias table |

Yes;

Reason: described for the SR and source of funding/conflicts of interest described in Risk of Bias assessment + characteristics table |

Risk of bias table for interventions studies (cohort studies based on risk of bias tool by the CLARITY Group at McMaster University)

|

Study reference

(first author, publication year) |

Was the allocation sequence adequately generated?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was the allocation adequately concealed?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Blinding: Was knowledge of the allocated interventions adequately prevented?

Were patients blinded?

Were healthcare providers blinded?

Were data collectors blinded?

Were outcome assessors blinded?

Were data analysts blinded?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no

|

Was loss to follow-up (missing outcome data) infrequent?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Are reports of the study free of selective outcome reporting?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was the study apparently free of other problems that could put it at a risk of bias?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Overall risk of bias If applicable/necessary, per outcome measure

LOW Some concerns HIGH

|

|

Sharma 2016 |

Definitely yes;

Reason: a computer-generated random number table was used to randomise the patients |

Definitely yes;

Reason: medications were dispensed by an investigator who was unaware of the clinical findings and investigations |

Probably no

Reason: only reported that the investigator dispensing the treatments was blinded, no other information on blinding of patients or healthcare providers

|

Definitely yes;

Reason: follow-up was infrequent and similar across groups |

Definitely yes

Reason: outcomes predefined in the study protocol are reported |

Probably yes;

Reason: no other sources of bias could be identified |

Low

Reason: only potential source of bias can be caused by the lack of blinding |

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Publicatiedatum : 02-09-2024

Beoordeeld op geldigheid : 27-08-2024

Algemene gegevens

De ontwikkeling van deze richtlijnmodules werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten (www.demedischspecialist.nl/kennisinstituut) en werd gefinancierd uit de Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS). De financier heeft geen enkele invloed gehad op de inhoud van de richtlijnmodule.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijnmodule is in nov 2021 een multidisciplinaire werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen (zie hiervoor de Samenstelling van de werkgroep) die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor infectieuze keratitis.

Werkgroep

- Mevr. Dr. C.A. (Cathrien) Eggink, Oogarts, Nederlands Oogheelkundig Gezelschap (NOG), voorzitter werkgroep

- Mevr. dr. M.C. (Marjolijn) Bartels, Oogarts, Nederlands Oogheelkundig Gezelschap (NOG)

- Dhr. drs. J. (Jeroen) van Rooij, Oogarts, Nederlands Oogheelkundig Gezelschap (NOG)

- Mevr. dr. L. (Lies) Remeijer, Oogarts, Nederlands Oogheelkundig Gezelschap (NOG)

- Mevr. dr. N. (Nienke) Visser, Oogarts, Nederlands Oogheelkundig Gezelschap (NOG)

- Dhr. dr. E. (Erik) Schaftenaar, Arts-microbioloog, Nederlandse Vereniging voor Medische Microbiologie (NVMM)

- Mevr. drs. C. (Claudy) Oliveira dos Santos, Arts-microbioloog, tot 11 april 2023, Nederlandse Vereniging voor Medische Microbiologie (NVMM)

- Dhr. prof. dr. P.E. (Paul) Verweij, Arts-microbioloog, vanaf 11 april 2023, Nederlandse Vereniging voor Medische Microbiologie (NVMM)

- Dhr. dr. W. (Wouter) Bult, Ziekenhuisapotheker, Nederlandse Vereniging van Ziekenhuisapothekers (NVZA)

- Dhr. M. (Michel) Versteeg MCM, Patiëntvertegenwoordiger, Hoornvlies patiënten vereniging (HPV)

Klankbord

- Mevr. drs. C.M. (Chantal) van Luijk, Oogarts, Nederlands Oogheelkundig Gezelschap (NOG)

- Mevr. I. (Inger) Larsen, huisarts, Nederlands Huisartsen Genootschap (NHG)

- Mevr. dr. N. (Nienke) Miltenburg-Soeters, optometrist, Optometristen Vereniging Nederland (OVN)

Met ondersteuning van

- Mw. MSc. D.G. (Dian) Ossendrijver, junior adviseur, Kennisinstituut van Medisch Specialisten.

- Mw. dr. A.C.J. (Astrid) Balemans, senior adviseur, Kennisinstituut van Medisch Specialisten.

Belangenverklaringen

De Code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling is gevolgd. Alle werkgroepleden hebben schriftelijk verklaard of zij in de laatste drie jaar directe financiële belangen (betrekking bij een commercieel bedrijf, persoonlijke financiële belangen, onderzoeksfinanciering) of indirecte belangen (persoonlijke relaties, reputatiemanagement) hebben gehad. Gedurende de ontwikkeling of herziening van een module worden wijzigingen in belangen aan de voorzitter doorgegeven. De belangenverklaring wordt opnieuw bevestigd tijdens de commentaarfase.

Een overzicht van de belangen van werkgroepleden en het oordeel over het omgaan met eventuele belangen vindt u in onderstaande tabel. De ondertekende belangenverklaringen zijn op te vragen bij het secretariaat van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

|

Werkgroeplid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

Mevr. Dr. C.A. (Cathrien) Eggink |

Oogarts in Radboudumc

|

Geen

|

Persoonlijke financiële belangen Geen.

Persoonlijke relaties Geen.

Extern gefinancierd onderzoek Geen.

Intellectuele belangen en reputatie Geen.

Overige belangen Geen. |

Geen. |

|

Mevr. dr. M.C. (Marjolijn) Bartels |

Oogarts Deventer Ziekenhuis

|

Refractie chirurg (Iris Eye Clinics) detachering via Deventer Ziekenhuis.

|

Persoonlijke financiële belangen Geen.

Persoonlijke relaties Geen.

Extern gefinancierd onderzoek ZonMW gefinancierd onderzoek: 1. BICAT studie afgerond. 2. Net opgestart EPICAT studie. 3. DSAEK versus DMEK studie afgerond Intellectuele belangen en reputatie Geen.

Overige belangen Geen. |

Geen, onderzoeken gaan niet over keratitis. |

|

Dhr. drs. J. (Jeroen) Rooij |

Oogarts |

Geen. |

Persoonlijke financiële belangen Geen.

Persoonlijke relaties Geen.

Extern gefinancierd onderzoek Gefinancierd, belangenloos en zonder restricties, door Stichtingen Stichting Blindenbelangen Rotterdam Stichting Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek Oozgiekenhuis (SWOO; Rotterdam) Stichting Ophthalmic Researsch Rotterdam Hoornvliesstichting Nederland tbv promotietraject ‘Epidemiology and Improved diagnosis of Acanthamoeba keratitis’.

Intellectuele belangen en reputatie Publicaties mbt Acanthamoeba zouden mogelijk positief beïnvloed worden Overige belangen Geen. |

Geen. |

|

Mevr. dr. L. (Lies) Remeijer |

Oogarts met aandachtsgebied HSV keratitis |

Geen.

|

Persoonlijke financiële belangen Geen.

Persoonlijke relaties Geen.

Extern gefinancierd onderzoek Clinical implications of asymptomatic corneal shedding of herpesviruses start 2019 (restricted grant, financiering door Stichting Ooglijders)

Intellectuele belangen en reputatie Geen.

Overige belangen Geen. |

Geen |

|

Mevr. dr. N. (Nienke) Visser |

Oogarts (MUMC)

|

- Lid cornea werkgroep European Society of Cataract and Refractive Surgeons (onbetaald)

|

Persoonlijke financiële belangen Geen.

Persoonlijke relaties Geen.

Extern gefinancierd onderzoek European Society of Cataract and Refractive Surgeons: EPICAT study: Effectiveness of Periocular drug Injection in CATaract surgery (gefinancierd door ESCRS, het gaat hierbij om een restricted grant, de ESCRS heeft op voorhand akkoord gegeven voor de specifieke opzet, uitvoering, en terugkoppeling van de EPICAT studie)

Intellectuele belangen en reputatie Geen.

Overige belangen Geen. |

Geen, onderzoeken gaan niet over keratitis. |

|

Dhr. dr. E. (Erik) Schaftenaar |

Arts-microbioloog, vrijgevestigd medisch specialist

|

Geen. |

Persoonlijke financiële belangen Geen.

Persoonlijke relaties Geen.

Extern gefinancierd onderzoek Geen.

Intellectuele belangen en reputatie Geen.

Overige belangen Geen. |

Geen.

|

|

Mevr. drs. C. (Claudy) Oliveira dos Santos (tot 11 april 2023) |

Arts-microbioloog

|

Promovendus Radboudumc - Medische mycologie (onbetaald)

|

Persoonlijke financiële belangen Geen.

Persoonlijke relaties Geen.

Extern gefinancierd onderzoek Geen.

Intellectuele belangen en reputatie Geen.

Overige belangen Geen. |

Geen. |

|

Dhr. prof. dr. P.E. (Paul) Verweij |

Arts-microbioloog

|

SWAB - adhoc voorzitter richtlijn commissie CAPA en IAPA

|

Persoonlijke financiële belangen Geen persoonlijke financiële belangen. Eventuele vergoedingen en honoraria komen ten goede van de werkgever.

Persoonlijke relaties Geen.

Extern gefinancierd onderzoek JPIAMR, surveillance van resistentie bij schimmels, Projectleider ja

Intellectuele belangen en reputatie Geen.

Overige belangen Geen. |

Producten van Mundipharma, Gilead Sciences en F2G komen in de RL niet aan bod. Is geen trekker van een van de modules. |

|

Dhr. dr. W. (Wouter) Bult |

Ziekenhuisapotheker

|

Geen. |

Persoonlijke financiële belangen Niet van toepassing.

Persoonlijke relaties Niet van toepassing.

Extern gefinancierd onderzoek Niet van toepassing.

Intellectuele belangen en reputatie Niet van toepassing.

Overige belangen Niet van toepassing. |

Geen. |

|

Dhr. M. (Michel) Versteeg |

Verengingsmanager van de Hoornvlies Patiënten Vereniging. Honorering is op basis van 'kostenneutraal'.

|

|

Persoonlijke financiële belangen Niet van toepassing.

Persoonlijke relaties Niet van toepassing.

Extern gefinancierd onderzoek Niet van toepassing.

Intellectuele belangen en reputatie Niet van toepassing.

Overige belangen Patiëntenperspectief |

Geen. |

|

Mevr. drs. C.M. (Chantal) van Luijk - Klankbord |

Oogarts, corneaspecialist, UMC Utrecht

|

deelname adviesraad eczeem medicatie

|

Persoonlijke financiële belangen 2019: deelname adviesraad eczeemmedicatie waarvoor financiële vergoeding, Sanofi/Regeneron

Persoonlijke relaties Niet van toepassing.

Extern gefinancierd onderzoek 2022: retrospectief wetenschappelijk onderzoek waarvoor sponsoring door Santen Europe.

Intellectuele belangen en reputatie niet van toepassing. enigszins bijzondere expertise omtrent oogheelkundige eczeemzorg, welke niet direct gelinkt is aan infectieuze keratitis

Overige belangen Patiëntenperspectief |

Geen. |

|

Mevr. I. (Inger) Larsen – klankbord |

Huisarts

|

NHG richtlijn rood oog en oogtrauma

|

Persoonlijke financiële belangen Niet van toepassing.

Persoonlijke relaties Niet van toepassing.

Extern gefinancierd onderzoek Niet van toepassing.

Intellectuele belangen en reputatie Niet van toepassing.

Overige belangen Niet van toepassing. |

Geen. |

|

Mevr. dr. N. (Nienke) Miltenburg-Soeters - klankbord |

Optometrist bij Visser Contactlenzen, 0.2 fte

|

Column en redactiewerk voor ContactlensInside.nl, betaald

|

Persoonlijke financiële belangen Niet van toepassing.

Persoonlijke relaties Niet van toepassing.

Extern gefinancierd onderzoek Niet van toepassing.

Intellectuele belangen en reputatie Niet van toepassing.

Overige belangen Niet van toepassing. |

Geen. |

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Er werd aandacht besteed aan het patiëntenperspectief door het uitnodigen van de Patiëntenfederatie Nederland en de Hoornvlies Patienten Vereniging voor de invitational conference en door een patiëntenvertegenwoordiger van de Hoornvlies Patienten Vereniging in de werkgroep. De verkregen input is meegenomen bij het opstellen van de uitgangsvragen, de keuze voor de uitkomstmaten en bij het opstellen van de overwegingen. De conceptmodules zijn tevens voor commentaar voorgelegd aan de Patiëntenfederatie Nederland en de Hoornvlies Patienten Vereniging en de eventueel aangeleverde commentaren zijn bekeken en verwerkt.

Wkkgz & Kwalitatieve raming van mogelijke substantiële financiële gevolgen

Kwalitatieve raming van mogelijke financiële gevolgen in het kader van de Wkkgz

bij de richtlijn is conform de Wet kwaliteit, klachten en geschillen zorg (Wkkgz) een kwalitatieve raming uitgevoerd of de aanbevelingen mogelijk leiden tot substantiële financiële gevolgen. Bij het uitvoeren van deze beoordeling zijn richtlijnmodules op verschillende domeinen getoetst (zie het stroomschema op de Richtlijnendatabase).

Uit de kwalitatieve raming blijkt dat er waarschijnlijk geen substantiële financiële gevolgen zijn, zie onderstaande tabel.

Module |

Uitkomst raming |

Toelichting |

|

Module Behandeling verdenking bacteriële keratitis |

Uitkomst 1: Geen financiële gevolgen |

Uit de toetsing volgt dat de aanbeveling(en) niet breed toepasbaar zijn (<5000 patiënten) en zal daarom naar verwachting geen substantiële financiële gevolgen hebben voor de collectieve uitgaven. |

Werkwijze

AGREE

Deze richtlijnmodule is opgesteld conform de eisen vermeld in het rapport Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 van de adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwaliteit. Dit rapport is gebaseerd op het AGREE II instrument (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II; Brouwers, 2010).

Knelpuntenanalyse en uitgangsvragen

Tijdens de voorbereidende fase inventariseerde de werkgroep de knelpunten in de zorg voor patiënten met een (verdenking op) infectieuze keratitis. Tevens zijn er knelpunten aangedragen door middel van een invitational conference. Een verslag hiervan is opgenomen onder aanverwante producten.

Op basis van de uitkomsten van de invitational conference zijn door de werkgroep concept-uitgangsvragen opgesteld en definitief vastgesteld.

Uitkomstmaten

Na het opstellen van de zoekvraag behorende bij de uitgangsvraag inventariseerde de werkgroep welke uitkomstmaten voor de patiënt relevant zijn, waarbij zowel naar gewenste als ongewenste effecten werd gekeken. Hierbij werd een maximum van acht uitkomstmaten gehanteerd. De werkgroep waardeerde deze uitkomstmaten volgens hun relatieve belang bij de besluitvorming rondom aanbevelingen, als cruciaal (kritiek voor de besluitvorming), belangrijk (maar niet cruciaal) en onbelangrijk. Tevens definieerde de werkgroep tenminste voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten welke verschillen zij klinisch (patiënt) relevant vonden.

Methode literatuursamenvatting

Een uitgebreide beschrijving van de strategie voor zoeken en selecteren van literatuur is te vinden onder ‘Zoeken en selecteren’ onder Onderbouwing. Indien mogelijk werd de data uit verschillende studies gepoold in een random-effects model. Review Manager 5.4 werd gebruikt voor de statistische analyses. De beoordeling van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs wordt hieronder toegelicht.

Beoordelen van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs

De kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs werd bepaald volgens de GRADE-methode. GRADE staat voor ‘Grading Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation’ (zie www.gradeworkinggroup.org. De basisprincipes van de GRADE-methodiek zijn: het benoemen en prioriteren van de klinisch (patiënt) relevante uitkomstmaten, een systematische review per uitkomstmaat, en een beoordeling van de bewijskracht per uitkomstmaat op basis van de acht GRADE-domeinen (domeinen voor downgraden: risk of bias, inconsistentie, indirectheid, imprecisie, en publicatiebias; domeinen voor upgraden: dosis-effect relatie, groot effect, en residuele plausibele confounding).

GRADE onderscheidt vier gradaties voor de kwaliteit van het wetenschappelijk bewijs: hoog, redelijk, laag en zeer laag. Deze gradaties verwijzen naar de mate van zekerheid die er bestaat over de literatuurconclusie, in het bijzonder de mate van zekerheid dat de literatuurconclusie de aanbeveling adequaat ondersteunt (Schünemann, 2013; Hultcrantz, 2017).

|

GRADE |

Definitie |

|

Hoog |

|

|

Redelijk |

|

|

Laag |

|

|

Zeer laag |

|

Bij het beoordelen (graderen) van de kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs in richtlijnen volgens de GRADE-methodiek spelen grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming een belangrijke rol (Hultcrantz, 2017). Dit zijn de grenzen die bij overschrijding aanleiding zouden geven tot een aanpassing van de aanbeveling. Om de grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming te bepalen moeten alle relevante uitkomstmaten en overwegingen worden meegewogen. De grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming zijn daarmee niet één op één vergelijkbaar met het minimaal klinisch relevant verschil (Minimal Clinically Important Difference, MCID). Met name in situaties waarin een interventie geen belangrijke nadelen heeft en de kosten relatief laag zijn, kan de grens voor klinische besluitvorming met betrekking tot de effectiviteit van de interventie bij een lagere waarde (dichter bij het nuleffect) liggen dan de MCID (Hultcrantz, 2017).

Overwegingen (van bewijs naar aanbeveling)

Om te komen tot een aanbeveling zijn naast (de kwaliteit van) het wetenschappelijke bewijs ook andere aspecten belangrijk en worden meegewogen, zoals aanvullende argumenten uit bijvoorbeeld de biomechanica of fysiologie, waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten, kosten (middelenbeslag), aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie. Deze aspecten zijn systematisch vermeld en beoordeeld (gewogen) onder het kopje ‘Overwegingen’ en kunnen (mede) gebaseerd zijn op expert opinion. Hierbij is gebruik gemaakt van een gestructureerd format gebaseerd op het evidence-to-decision framework van de internationale GRADE Working Group (Alonso-Coello, 2016a; Alonso-Coello 2016b). Dit evidence-to-decision framework is een integraal onderdeel van de GRADE methodiek.

Formuleren van aanbevelingen

De aanbevelingen geven antwoord op de uitgangsvraag en zijn gebaseerd op het beschikbare wetenschappelijke bewijs en de belangrijkste overwegingen, en een weging van de gunstige en ongunstige effecten van de relevante interventies. De kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs en het gewicht dat door de werkgroep wordt toegekend aan de overwegingen, bepalen samen de sterkte van de aanbeveling. Conform de GRADE-methodiek sluit een lage bewijskracht van conclusies in de systematische literatuuranalyse een sterke aanbeveling niet a priori uit, en zijn bij een hoge bewijskracht ook zwakke aanbevelingen mogelijk (Agoritsas, 2017; Neumann, 2016). De sterkte van de aanbeveling wordt altijd bepaald door weging van alle relevante argumenten tezamen. De werkgroep heeft bij elke aanbeveling opgenomen hoe zij tot de richting en sterkte van de aanbeveling zijn gekomen.