Inleiding van de baring bij hypertensieve aandoening

Uitgangsvraag

Verbetert inleiding van de baring de maternale en perinatale uitkomsten bij zwangere vrouwen met een hypertensieve aandoening vanaf AD32+0?

Aanbeveling

Bespreek met de zwangere vrouw de maternale en perinatale risico’s bij inleiding en bij een afwachtend beleid.

Leid niet in vóór 37 weken zwangerschap bij vrouwen met zwangerschapshypertensie.

Maak samen met de patiënt een afweging ten aanzien van het beleid, inleiding of monitoring, bij milde zwangerschaphypertensie na 37 weken.

Indien gekozen wordt voor monitoring, her-evalueer en spreek het beleid regelmatig door met de zwangere vrouw.

Leid niet routinematig in vóór 37 weken zwangerschap bij vrouwen met milde pre-eclampsie.

Adviseer inleiding van de baring vanaf 37 weken zwangerschap bij vrouwen met milde pre-eclampsie.

Indien gekozen wordt voor monitoring, her-evalueer en spreek het beleid regelmatig door met de zwangere vrouw.

Adviseer inleiding van de baring bij vrouwen met ernstige pre-eclampsie.

Indien toch gekozen wordt voor monitoring, her-evalueer en spreek het beleid regelmatig door met de zwangere vrouw.

Tekenen van ernstige pre-eclampsie zijn: oncontroleerbare hypertensie, lage zuurstofsaturatie (< 90%), progressieve lever- of nierfunctiestoornis, hemolyse/trombocytopenie, progressie van neurologische klachten, abruptio placentae, of andere foetale indicatie.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Op basis van de literatuuranalyse werden een aantal mogelijke voor- en nadelen van inleiden vergeleken met een afwachtend beleid gevonden bij vrouwen met een hypertensieve aandoening vanaf een zwangerschapsduur vanaf 34 weken. Belangrijke opmerking is dat alle geïncludeerde studies louter vrouwen met een zwangerschapsduur vanaf 34 weken beschreven. In de literatuur zijn geen studies beschikbaar tussen 32 en 24 weken.

In de literatuur werd een afname van het risico op HELLP/eclampsie ((pooled RR 0,47 (95% CI 0,27 tot 0,82)) gezien na inleiden vergeleken met een afwachtend beleid (GRADE ‘moderate’). Wanneer alleen naar eclampsie werd gekeken (dus zonder HELLP) werd geen verschil gezien, mogelijk door de kleine aantallen (GRADE ‘very low’). Ten aanzien van andere relevante neonatale uitkomsten rapporteerde Bernardes (2019) een verhoogd risico op respiratory distress syndrome (RDS) bij direct inleiden vanaf 34 weken (GRADE ‘moderate’). Overall relatief risico op RDS was RR 1,94 (95%CI 1,05 tot 3,59). Gestratificeerd voor het aantal weken zwangerschap was dit RR 1,8 (95%BI 0,8 tot 3,9) (34 weken), RR 5,5 (95%BCI 1,00 tot 29,6) (35 weken), RR 3,4 (95%BI 0,4 tot 30,3) (36 weken) en RR 2,0 (95%BI 0,1 tot 28,4) (≥ 37 weken). Na inleiding lijken er minder kinderen met een laag geboortegewicht (gedefinieerd als geboortegewicht < 10e geboortepercentiel) te zijn (GRADE ‘low’), maar lijkt het aantal NICU opnamen hoger te zijn vergeleken met een afwachtend beleid (GRADE ‘low’). Het aantal kinderen dat exclusieve borstvoeding krijgt 24 uur voor ontslag uit het ziekenhuis is mogelijk lager na inleiding (GRADE ‘low’). Met redelijke zekerheid (GRADE ‘moderate’) werd geconcludeerd dat er geen verschil tussen inleiden en afwachtend beleid lijkt te zijn voor de uitkomstmaten pre-eclampsie en keizersneden. Voor alle andere uitkomstmaten is het onzeker wat het effect van inleiden vergeleken met een afwachtend beleid, deze uitkomstmaten waren beoordeeld met een GRADE ‘very low’.

De overall bewijskracht is gelijk aan de laagst gevonden bewijskracht voor de cruciale uitkomstmaat(en). In dit geval is dat is een GRADE ‘moderate’ voor eclampsie/HELLP. De uitkomstmaat is met één niveau afgewaardeerd wegens mogelijke risico op bias, het is onmogelijk in deze studies om de deelnemers te blinderen voor de interventie. Een kennislacune betreft het gebrek aan studies waarin de volgende uitkomstmaten werden gerapporteerd in de vergelijking tussen inleiden of afwachten bij vrouwen met hypertensieve aandoeningen tijdens de zwangerschap: patiënttevredenheid, PTSS, hechting (moeder-kind) en succesvolle borstvoeding op 6 weken.

Bernardes (2019) rapporteerde daarnaast ook een gecombineerd neonatale uitkomstmaat. Deze uitkomstmaat bestond uit het totaal aantal neonaten met RDS, bronchopulmonaire dysplasie, seizures, intracerebrale bloeding, intraventriculaire bloeding graad III of IV, cerebraal infarct, periventriculaire leukomalacie, hypoxisch ischemische encefalopathie, necrotiserende enterocolitis graad II of hoger en sepsis (op basis van kweek). Voor de gecombineerde uitkomstmaat werd een verhoogd risico van inleiding gevonden (RR 2,3 (95%BI 1,38 tot 3,82)) (Bernardes, 2019). Deze uitkomstmaat werd niet gestratificeerd voor het aantal weken zwangerschap gepresenteerd.

Inleiding reduceert het gecombineerde eindpunt HELLP/pre-eclampsie bij vrouwen met hypertensieve aandoeningen in de zwangerschap. Ten aanzien van het moment van inleidingsindicatie zal het maternale risico op verslechtering moeten worden ingeschat op basis van het fenotype van de hypertensieve aandoening en de neonatale risico’s op RDS.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en eventueel hun verzorgers)

De voorkeur van de zwangere voor de interventie of een afwachtend beleid verschilt per persoon. Zwangere vrouwen (en hun partners) willen graag goed geïnformeerd worden over de voor- en nadelen voor henzelf en hun baby van inleiden versus afwachten. Hierbij dienen ook de (mogelijke) consequenties van inleiden te worden besproken die vrouwen als negatief kunnen ervaren (met name minder ‘agency’/ gevoel van regie/controle). Zwangere vrouwen (en hun partners) willen samen met hun gynaecoloog komen tot een afgewogen keuze die het beste bij hen past (‘samen beslissen’). Onderzoek laat zien dat na afloop van de inleiding dan wel afwachtend beleid de kwaliteit van leven door beide groepen gelijkwaardig is. Een keizersnede wordt als grootste negatieve ervaring beschreven (Bijlenga, 2011a; Bijlenga, 2011b). Onderzoeken in de algemene populatie laten zien dat inleiding een belangrijke rol speelt in ontevredenheid met betrekking tot de baring (Adler, 2020; Falk, 2019).

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

Kosten-effectiviteitsanalyses over de Nederlandse gezondheidszorg zijn beschikbaar van de HYPITAT-I, HYPITAT-II en DIGITAT trials (Van Baaren, 2017; Vijgen, 2010; Vijgen, 2013). De HYPITAT-I trial concludeerde dat inleiding van de baring goedkoper is dan een afwachtend beleid bij vrouwen met zwangerschapshypertensie of milde pre-eclampsie (36+0 tot 41+0 weken) (gemiddeld verschil -€831 (95%BI -€1561 tot -€144). Dit verschil werd voornamelijk verklaard door een ander gebruik van resources in de antepartum periode (Vijgen, 2010).

De HYPITAT-II trial concludeerde dat inleiding van de baring duurder is dan een afwachtend beleid bij vrouwen met milde hypertensieve aandoeningen (34+0 tot 37+0 weken) (gemiddeld verschil €682 (95%BI -€618 tot €2126). Dit verschil werd voornamelijk verklaard door een hoger aantal opnames van de neonaat (Van Baaren, 2017). De studie van Chappell (2019) concludeerde daarentegen dat inleiding van de baring bij vrouwen met pre-eclampsie (34 tot 37 weken) goedkoper zou zijn vergeleken met een afwachtend beleid (-£1478 (95% CI -2354 tot -605). De data van Chappell (2019) gaan over de gezondheidszorg in Engeland en Wales. Verklaring voor het verschil tussen HYPITAT-II trial en Chappell (2019) is dat in de Britse studie er hogere kosten zijn geassocieerd met de langere opname van de moeder in Chappell (2019).

De DIGITAT trial concludeerde dat de kosten van inleiding of een afwachtend beleid vergelijkbaar waren bij vrouwen met verdenking op groeivertraging (vanaf 36+0 weken) (gemiddeld verschil €111 (95%BI: €-1296 tot 1641). Echter, vóór 38 weken waren de kosten lager bij afwachtend beleid en ná 38 weken zwangerschap waren de kosten lager na inleiding (Vijgen, 2013).

De resultaten uit deze kosten-effectiviteitsanalyses suggereren dat preterme inleiding relatief duurder is en aterme inleiding relatief goedkoper dan een afwachtend beleid.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

Er worden geen barrières verwacht ten aanzien van de aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie van de aanbeveling.

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

De resultaten van de literatuuranalyse laten een significante en klinische relevante reductie in het aantal vrouwen met eclampsie/HELLP zien na inleiding van de baring.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Er zijn onder andere in Nederland verschillende studies gedaan waarin is gekeken naar het effect van inleiden vergeleken met afwachtend beleid bij zwangere vrouwen met een hypertensieve aandoening, maar deze studies zijn nog niet opgenomen in een landelijke richtlijn. Daardoor bestaat er waarschijnlijk praktijkvariatie en mogelijk substandard care.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

Maternal outcome measures

|

Moderate GRADE |

Immediate delivery does not reduce the risk of pre-eclampsia compared to expectant management in women suffering from hypertensive disorders of pregnancy after 34 weeks of pregnancy.

Sources: (Bernardes, 2019) |

|

Very low GRADE |

It is uncertain what the effect of immediate delivery compared to expectant management is for the risk of eclampsia in women suffering from hypertensive disorders of pregnancy after 34 weeks of pregnancy.

Sources: (Bernardes, 2019; Chappell, 2019) |

|

Moderate GRADE |

Immediate delivery probably reduces the risk of HELLP syndrome and/or eclampsia compared to expectant management in women suffering from hypertensive disorders of pregnancy after 34 weeks of pregnancy.

Sources: (Bernardes, 2019; Chappell, 2019) |

|

Very low GRADE |

It is uncertain what the effect of immediate delivery compared to expectant management is for the risk of pulmonary oedema in women suffering from hypertensive disorders of pregnancy after 34 weeks of pregnancy.

Sources: (Bernardes, 2019; Chappell, 2019) |

|

Very low GRADE |

It is uncertain what the effect of immediate delivery compared to expectant management is for the risk of hepatic haemorrhage, hepatic rupture or liver failure in women suffering from hypertensive disorders of pregnancy after 34 weeks of pregnancy.

Sources: (Bernardes, 2019; Chappell, 2019) |

|

Very low GRADE |

It is uncertain what the effect of immediate delivery compared to expectant management is for the risk of renal insufficiency or renal failure in women suffering from hypertensive disorders of pregnancy after 34 weeks of pregnancy.

Sources: (Bernardes, 2019; Chappell, 2019) |

|

Very low GRADE |

It is uncertain what the effect of immediate delivery compared to expectant management is for the risk of cerebral haemorrhage in women suffering from hypertensive disorders of pregnancy after 34 weeks of pregnancy.

Sources: (Bernardes, 2019) |

|

Very low GRADE |

It is uncertain what the effect of immediate delivery compared to expectant management is for the risk of placental abruption in women suffering from hypertensive disorders of pregnancy after 34 weeks of pregnancy.

Sources: (Bernardes, 2019; Chappell, 2019) |

|

Moderate GRADE |

Immediate delivery does not increase the risk of a caesarean section compared to expectant management in women suffering from hypertensive disorders of pregnancy after 34 weeks of pregnancy.

Sources: (Bernardes, 2019; Chappell, 2019) |

|

Very low GRADE |

It is uncertain what the effect of immediate delivery compared to expectant management is for the risk of postpartum haemorrhage in women suffering from hypertensive disorders of pregnancy after 34 weeks of pregnancy.

Sources: (Bernardes, 2019) |

|

- GRADE |

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measures patient satisfaction, PTSD and bonding (mother-child) could not be assessed because of lack of data. None of the included studies reported the outcomes when comparing immediate delivery with expectant management in women suffering from hypertensive disorders of pregnancy after 32 weeks of pregnancy. |

|

- GRADE |

None of the included studies reported the effect of immediate delivery compared to expectant management on maternal outcomes in women suffering from hypertensive disorders of pregnancy after 32 weeks of pregnancy. Every included study reported on women suffering from hypertensive disorders of pregnancy after 34 weeks of pregnancy. |

Perinatal outcomes

|

Very low GRADE |

It is uncertain what the effect of immediate delivery compared to expectant management is for the risk of perinatal death in women suffering from hypertensive disorders of pregnancy after 34 weeks of pregnancy.

Sources: (Bernardes, 2019; Chappell, 2019) |

|

Very low GRADE |

It is uncertain what the effect of immediate delivery compared to expectant management is for the risk of intra-uterine death (stillbirth) or neonatal death in women suffering from hypertensive disorders of pregnancy after 34 weeks of pregnancy.

Sources: (Chappell, 2019) |

|

Moderate GRADE |

Immediate delivery likely increases the risk of infant respiratory distress syndrome compared to expectant management in women suffering from hypertensive disorders of pregnancy after 34 weeks of pregnancy.

Sources: (Bernardes, 2019) |

|

Low GRADE |

Immediate delivery might increase the risk of a NICU admission compared to expectant management in women suffering from hypertensive disorders of pregnancy after 34 weeks of pregnancy.

Sources: (Bernardes, 2019; Chappell, 2019) |

|

Low GRADE |

Immediate delivery might reduce the risk of low birth weight for gestational age (defined as birth weight < 10th percentile) compared to expectant management in women suffering from hypertensive disorders of pregnancy after 34 weeks of pregnancy.

Sources: (Bernardes, 2019, Chappell, 2019) |

|

Moderate GRADE |

Immediate delivery likely increases the risk of preterm birth < 37 weeks compared to expectant management in women suffering from hypertensive disorders of pregnancy after 34 weeks of pregnancy.

Sources: (Chappell, 2019) |

|

Low GRADE |

Immediate delivery might lead to less infants receiving exclusive breastfeeding at 24 hours prior to discharge from hospital compared to expectant management in women suffering from hypertensive disorders of pregnancy after 34 weeks of pregnancy.

Sources: (Chappell, 2019) |

|

- GRADE |

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measures successful breastfeeding at 6 weeks could not be assessed because of lack of data. None of the included studies reported the outcome when comparing immediate delivery with expectant management in women suffering from hypertensive disorders of pregnancy after 32 weeks of pregnancy. |

|

- GRADE |

None of the included studies reported the effect of immediate delivery compared to expectant management on perinatal outcomes in women suffering from hypertensive disorders of pregnancy after 32 weeks of pregnancy. Every included study reported on women suffering from hypertensive disorders of pregnancy after 34 weeks of pregnancy. |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

Bernardes (2019) performed an individual participant data meta-analysis to compare immediate delivery with expectant management for prevention of adverse maternal and neonatal outcomes in women with hypertensive disease in pregnancy. CENTRAL, PubMed, MEDLINE and Clinical Trials.gov were searched till 31 December 2017 for RCT’s comparing immediate delivery to expectant management in women presenting with gestational hypertension or pre-eclampsia without severe features from 34 weeks of pregnancy onwards. The primary neonatal outcome was respiratory distress syndrome (RDS) and the primary maternal outcome was a composite of HELLP syndrome (abbreviation for pregnancy complication, characterized by Hemolysis, Elevated Liver enzymes, and a Low Platelet count) and eclampsia. Secondary outcomes were among others pulmonary oedema, renal failure, placental abruption/antenatal haemorrhage, severe postpartum haemorrhage (> 1000 mL), intracerebral haemorrhage and cerebral infarction. Only pooled results were shown for the secondary outcomes. Five RCT’s with a total of 1778 participants were included (Boers, 2010; Broekhuijsen, 2015; Koopmans, 2009; Owens, 2014; van Bulck, 2003). To avoid selection bias, Bernardes (2019) did not use data from the GRIT study (van Bulck, 2003) to calculate preterm delivery rates and median time to delivery because of foetal compromise. Table 1 presents a brief overview of the study characteristics of the included RCTs in Bernardes (2019).

Chappell (2019) performed a parallel-group, non-masked, multicentre, randomised controlled trial to compare initiation of delivery (within 48 hours of randomization) with expectant management (delivery at 37 weeks of pregnancy, or sooner as clinical needs dictated). Pregnant women between 34 to 37 weeks of pregnancy with a diagnosis of pre-eclampsia or superimposed pre-eclampsia with a singleton or dichorionic diamniotic twin pregnancy were included. Women were excluded if the decision to deliver within the next 48 hours had already been made (immediate delivery was indicated according to national guidelines in women with persistent severe features of pre-eclampsia). In total 899 women were eligible for randomization, 448 women (471 infants (5% twins)) were allocated to initiation of delivery and 451 women (475 infants (5% twins)) were allocated to the expectant management group. Groups were comparable at baseline, except that women in the planned delivery group gave birth at 252 days of pregnancy versus 257 days of pregnancy in expectant management, and women in the expectant group were more likely to achieve a spontaneous vaginal delivery (n=2 (<1%) versus n=19 (4%)). Chappell (2019) conducted an intention-to-treat analysis and per protocol analysis (excluding women lost to follow-up (n=1 versus n=2), women who received planned delivery > 48 hours after randomization (n=120 (27%)) in the intervention group, or women who received non-indicated delivery < 37 weeks of pregnancy in the expectant group (n=2 (0.4%)). Results from intention-to-treat analysis and per protocol analysis were similar. Chappell (2019) examined composite score of maternal morbidity and a composite score of perinatal morbidity as co-primary outcome measures.

Table 1 Overview of study characteristics of included RCTs in Bernardes (2019)

|

Study |

Trial participants |

Non-eligible participants (reason: n) |

Eligible participants (n) |

|

GRIT Van Bulck (2003) |

547 pregnant women with foetal compromise between 24+0 and 36+0weeks, umbilical artery Doppler waveform recorded and clinical uncertainty whether immediate delivery was indicated |

Randomized before 34 weeks: 493 |

54 |

|

HYPITAT-I Koopmans (2009) |

756 women with singleton pregnancy between 36+0 and 41+0 weeks and who had gestational hypertension or pre-eclampsia without severe features |

None |

756 |

|

HYPITAT-II Broekhuijsen (2015) |

703 women with non-severe hypertensive disorders of pregnancy between 34+0 and 36+6 weeks of gestation |

None |

703 |

|

DIGITAT Boers (2010) |

650 women with singleton pregnancy between 36+0 and 41+0 weeks with suspected intrauterine growth restriction |

Randomized without hypertensive disorder: 540 |

155 |

|

Deliver or Deliberate Owens (2014) |

169 women who met ACOG 2002 criteria for pre-eclampsia without severe features and gestational dating 34+0 to 36+6 weeks |

Randomized before 34 weeks: 4; HIV: 2; diabetes: 7; major congenital malformations 1. |

703 |

Results

It should be noted at forehand that none of the included studies reported the effect of immediate delivery compared to expectant management on perinatal outcomes in women suffering from hypertensive disorders of pregnancy after 32 weeks of pregnancy. Every included study reported on women suffering from hypertensive disorders of pregnancy after 34 weeks of pregnancy. Meta-analysis with crude data were performed where possible. Subgroup analyses exploring differences between studies including patients with or without suspected foetal growth restriction were performed where possible.

Maternal outcomes

1. Pre-eclampsia

All women in the study by Chappell (2019) had pre-eclampsia at inclusion. Five trials included in the review by Bernardes (2019) reported the number of pregnant women with pre-eclampsia, which was defined as hypertension (blood pressure (BP) levels ≥ 140 mmHg systolic or ≥ 90 mmHg diastolic) and proteinuria (300 mg or more total protein in a 24-h urine sample, recurrent positive protein dipstick test or protein/creatinine ratio of 30 mg/mmol or more) (Boers, 2010; Broekhuijsen, 2015; Koopmans, 2009; Owens, 2014; van Bulck, 2003). Bernardes (2019) only reported the pooled results.

There was no difference in the number of women with pre-eclampsia between the immediate delivery group (392/861) and the expectant management group (378/863) (RR 1.04 (95%CI 0.94 to 1.15)).

2. Eclampsia and/or HELLP syndrome

Two studies examined the outcome measure eclampsia and/or HELLP syndrome (Bernardes, 2019; Chappell, 2019). Five trials included in the review by Bernardes (2019) reported the outcome measure eclampsia (Boers, 2010; Broekhuijsen, 2015; Koopmans, 2009; Owens, 2014; Van Bulck, 2003), which was not defined in text. In addition, Bernardes (2019) reported a composite outcome of HELLP syndrome and/or eclampsia (Boers, 2010; Broekhuijsen, 2015; Koopmans, 2009; Owens, 2014; Van Bulk, 2003). Chappell (2019) also reported HELLP syndrome, but it is unclear if these data overlapped with women with eclampsia.

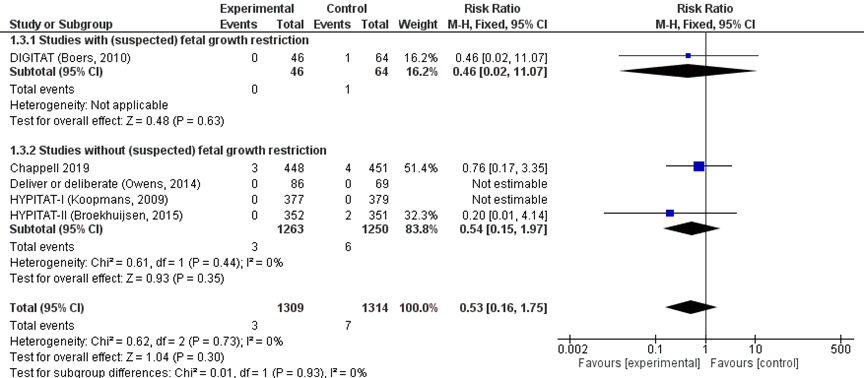

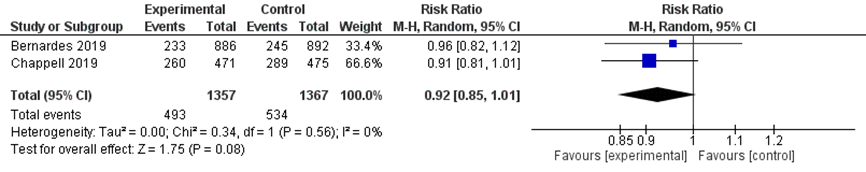

There was no difference in the risk of eclampsia between immediate delivery (3/1309) compared to expectant management (7/1314) (pooled RR 0.53 (95%CI 0.16 to 1.75); Figure 1). Subgroup analysis stratified for study populations with or without suspected foetal growth restriction showed similar effects.

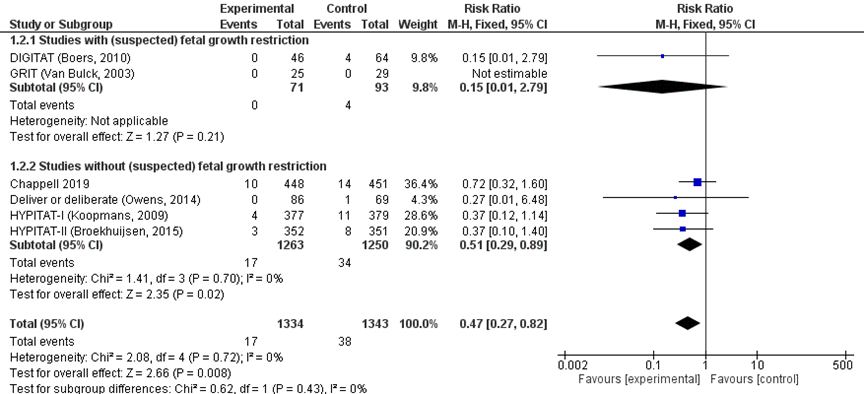

When a composite outcome of HELLP syndrome and/or eclampsia was studied, immediate delivery reduced the risk of HELLP syndrome or eclampsia with 53% (pooled RR 0.47 (95% CI 0.27 to 0.82); Figure 2). The calculated number needed to treat (NNT) is 63. When this analysis was repeated without the number of HELLP cases reported by Chappell (2019), to prevent possible duplication of patients with both HELLP and eclampsia diagnosis, the overall effect was the same (pooled RR 0.39 (95%CI 0.19 to 0.78)). Subgroup analysis stratified for study populations with or without suspected foetal growth restriction showed similar effects.

Bernardes (2019) analysed the composite outcome HELLP syndrome and/or eclampsia stratified for weeks of gestation. Chappell (2019) did not report this subgroup analysis and was therefore not included. There was no difference in the outcome HELLP syndrome and/or eclampsia stratified for weeks of gestation (Table 2). When stratified based on type of hypertensive disorder of pregnancy, Bernardes (2019) reported an increased risk of HELLP syndrome and/or eclampsia in women with pre-eclampsia (RR 0.39 (95%CI 0.15 to 0.98)). For women with gestational hypertension or chronic hypertension it is unclear whether there is an increased risk for HELLP syndrome and/or eclampsia, because the reported 95% confidence intervals contain the value of no (clinically relevant) effect (Table 3).

Figure 1 Eclampsia comparison immediate delivery versus expectant management

Figure 2 HELLP syndrome and/or eclampsia comparison immediate delivery versus expectant management

Table 2 HELLP syndrome and/or eclampsia comparison immediate delivery versus expectant management, subgroup analysis by Bernardes (2019) by weeks of gestations (2019)

|

Subgroup: weeks of gestation |

Relative Risk (95%CI) |

Immediate delivery |

Expectant management |

Weight% |

|

34 to 35 weeks |

0.37 (0.10-1.30) |

2/247 |

8/265 |

33.9% |

|

36 to 37 weeks |

0.44 (0.14-1.30) |

4/371 |

10/338 |

39.8% |

|

38 to 39 weeks |

0.19 (0.02-1.60) |

0/186 |

5/210 |

22.1% |

|

40 to 41 weeks |

0.90 (0.06-14.0) |

1/41 |

1/50 |

4.2% |

Table 3 HELLP syndrome and/or eclampsia comparison immediate delivery versus expectant management, subgroup analysis by Bernardes (2019) by type of hypertensive disorder (2019)

|

Subgroup: hypertensive disorder |

Relative Risk (95%CI) |

Immediate delivery |

Expectant management |

Weight% |

|

Gestational hypertension |

0.29 (0.06 to 1.30) |

1/355 |

7/365 |

29.2% |

|

Chronic hypertension |

0.58 (0.08 to 4.20) |

1/68 |

2/66 |

9.9% |

|

Pre-eclampsia |

0.39 (0.15 to 0.98) |

5/438 |

15/432 |

60.9% |

3. Pulmonary oedema

Two studies reported the outcome measure pulmonary oedema (Bernardes, 2019; Chappell, 2019. The outcome was not defined in text. Three trials included in the review by Bernardes (2019) reported the outcome (Boers, 2010; Broekhuijsen, 2015; Koopmans, 2009), but only the pooled results were reported by the review.

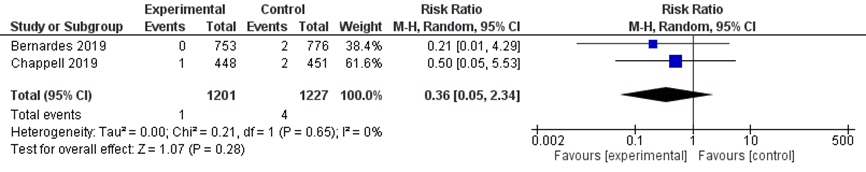

There was no difference in the outcome pulmonary oedema between the immediate delivery group (1/1201) and the expectant management group (4/1227) (RR 0.36 (95% CI 0.05 to 2.34) Figure 3).

Figure 3 Pulmonary oedema comparison immediate delivery versus expectant management

4. Hepatic haemorrhage

No study reported the outcome hepatic haemorrhage specifically. One study reported the outcome hepatic haematoma or rupture (Chappell, 2019). Four trials included in the review by Bernardes (2019) reported the outcome liver failure, which was not defined in text (Boers, 2010; Broekhuijsen, 2015; Koopmans, 2009; Owens, 2014).

No patients in either the immediate delivery group (0/1309) or expectant management group (0/1314) developed liver failure, hepatic haematoma or hepatic rupture, whereby the RR could not be calculated for this outcome.

5. Renal insufficiency

Chappell (2019) reported the outcome renal insufficiency (defined as creatine > 150 µmol/L; no pre-existing renal disease). Four trials included in the review Bernardes (2019) did not report the outcome renal insufficiency, but did report the outcome renal failure, which was not defined in text (Boers, 2010; Broekhuijsen, 2015; Koopmans, 2009; Owens, 2014). Chappell (2019) also reported renal failure, which was defined as creatinine >200 µmol/L; pre-existing renal disease.

No women in either the immediate delivery group (0/448) or expectant management group (0/451) developed renal insufficiency, whereby the RR could not be calculated for this outcome.

No women in either the immediate delivery group (0/1309) or expectant management group (0/1314) developed renal failure, whereby the RR could not be calculated for this outcome.

6. Cerebral haemorrhage

Five trials included in the review by Bernardes (2019) reported the outcome intracerebral haemorrhage, which was not defined in text (Boers, 2010; Broekhuijsen, 2015; Koopmans, 2009; Owens, 2014; van Bulck, 2003).

No women in either the immediate delivery group (0/886) or expectant management group (0/892) developed an intracerebral haemorrhage, whereby the RR could not be calculated for this outcome.

7. Placental abruption

Two studies reported the outcome placental abruption (Bernardes, 2019; Chappell, 2019). Four studies reported the outcome placental abruption. Three trials included in the review by Bernardes (2019) reported the outcome (Boers, 2010; Broekhuijsen, 2015; Koopmans, 2009), but only the pooled results were reported by the review.

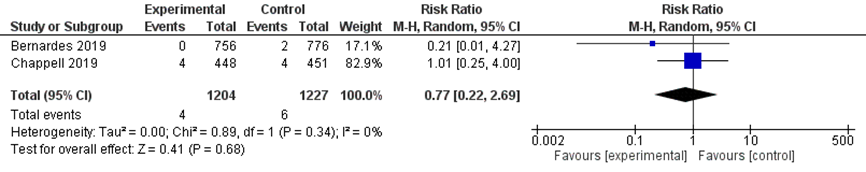

There was no difference in the outcome placental abruption between the immediate delivery group (4/1204) and the expectant management group (6/1227) (RR 0.77; 95% CI 0.22 to 2.69; Figure 4).

Figure 4 Placental abruption comparison immediate delivery versus expectant management

8. Caesarean section

Two studies reported the outcome caesarean section (Bernardes, 2019; Chappell, 2019). Five trials included in the review by Bernardes (2019) reported the outcome (Boers, 2010; Broekhuijsen, 2015; Koopmans, 2009; Owens, 2014, Van Bulck, 2003), but only the pooled results were reported by the review.

Caesarean sections were reported in 493/1357 women undergoing immediate delivery compared to 534/1367 women treated with expectant management (pooled RR 0.92 (95%CI 0.85 to 1.01) figure 5). This was not a clinically relevant difference, as the 95%CI crosses the line of no clinically relevant effect (and the line of no statistically significant effect).

Figure 5 Caesarean section comparison immediate delivery versus expectant management.

9. Postpartum haemorrhage

One study reported the outcome postpartum haemorrhage (Bernardes, 2019). Four trials included by the review of Bernardes (2019) reported the outcome severe postpartum haemorrhage (defined as > 1000 ml blood loss) (Boers, 2010; Broekhuijsen, 2015; Koopmans, 2009; Owens, 2014), but only the pooled results were reported by Bernardes (2019).

Postpartum haemorrhage was reported in 69/861 women undergoing immediate delivery compared to 90/863 women in expectant management (pooled RR 0.77 (95%CI 0.57 to 1.04)). It is uncertain whether this is a clinically relevant difference, as the 95%CI interval includes the limit of no clinically relevant effect (and no statistically significant effect).

10. Patient satisfaction

The outcome measure patient satisfaction was not reported in the included studies.

11. PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder)

The outcome measure PTSD was not reported in the included studies.

12. Bonding (mother-child)

The outcome measure bonding (mother-child) was not reported in the included studies.

Perinatal outcomes

13. Perinatal death (intra-uterine death and neonatal death)

The outcome measure perinatal death was reported by three definitions: perinatal death, intra-uterine death and neonatal death, reported respectively in paragraphs 13.1, 13.2, 13.3. Most studies did not define the outcomes specifically.

13.1. Perinatal death

Five studies in the review by Bernardes (2019) reported the outcome perinatal mortality (Boers, 2010; Broekhuijsen, 2015; Koopmans, 2009; Owens, 2014, Van Bulck, 2003). Chappell (2019) reported the number of stillbirths and neonatal deaths. Both studies did not define the outcomes in text.

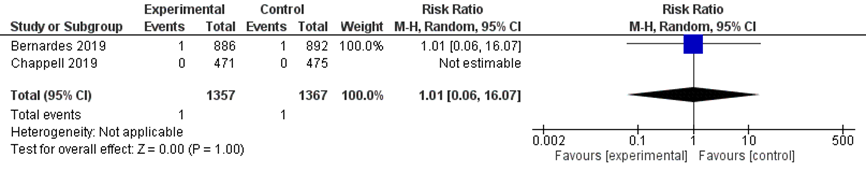

There was no difference in the outcome perinatal death between the immediate delivery group (1/1357) and the expectant management group (1/1367) (pooled RR 1.01 (95% CI 0.06 to 16.07); Figure 6).

Figure 6 Perinatal mortality comparison immediate delivery versus expectant management

13.2. Intra-uterine death

One study reported the outcome intra-uterine death (Chappell, 2019), which was reported as stillbirth, not further defined in text.

There were no stillbirths in either the immediate delivery (0/471 infants) compared to expectant management groups (0/475 infants), hence no RR could be calculated.

13.3. Neonatal death

One study reported the outcome neonatal death (Chappell, 2019), which was not defined in text.

There were no reports of neonatal death in either the immediate delivery group (0/471) or expectant management groups (0/475), whereby the RR could not be calculated for this outcome.

14. Infant respiratory distress syndrome

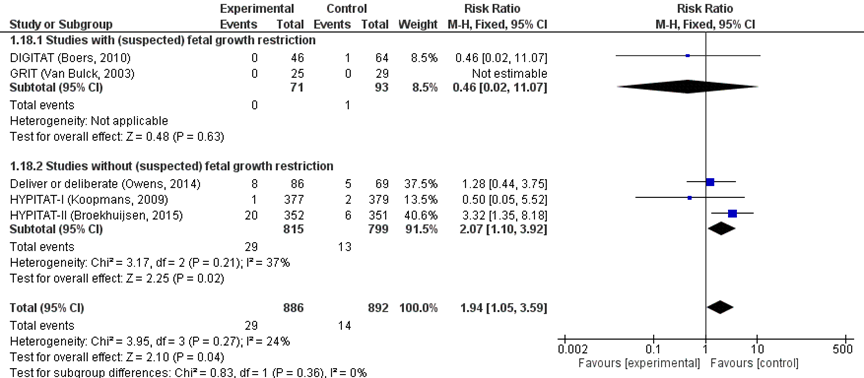

Five studies in the review by Bernardes (2019) reported the outcome infant respiratory distress syndrome (IRDS) (Boers, 2010; Broekhuijsen, 2015; Koopmans, 2009; Owens, 2014, Van Bulck, 2003) (Figure 7). Bernardes (2019) also reported the pooled RR stratified for gestational age (Table 4).

There was an increased risk of IRDS for neonates in the immediate delivery group (29/886) compared to the expectant management group (14/892) (pooled RR 1.94 (95% CI 1.05 to 3.59); Figure 7).

Figure 7 IRDS comparison immediate delivery versus expectant management.

Table 4 IRDS comparison immediate delivery versus expectant management, subgroup analysis by Bernardes (2019) by weeks of gestations (2019)

|

Subgroup: weeks of gestation |

Relative Risk (95%CI) |

Immediate delivery |

Expectant management |

Weight% |

|

34 weeks |

1.8 (0.8 to 3.9) |

16/111 |

9/109 |

58.1% |

|

35 weeks |

5.5 (1.0 to 29.6) |

7/136 |

1/156 |

9.5% |

|

36 weeks |

3.4 (0.4 to 30.3) |

4/259 |

1/232 |

7.0% |

|

≥37 weeks |

2.0 (0.1 to 28.4) |

2/355 |

3/366 |

25.5% |

15 NICU admission

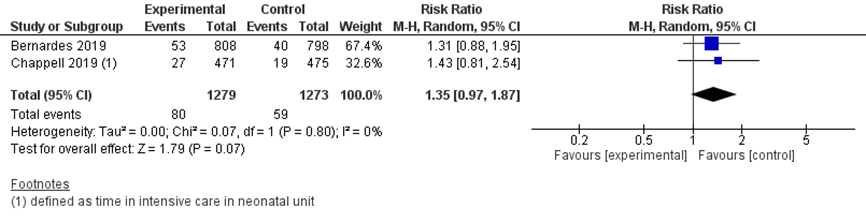

Two studies reported the outcome NICU admissions (Bernardes, 2019; Chappell, 2019). Four studies in the review by Bernardes (2019) reported the outcome (Boers, 2010; Broekhuijsen, 2015; Koopmans, 2009; Owens, 2014), but only the pooled results were reported by Bernardes (2019). Chappell (2019) reported the outcome admission to neonatal unit, which was further specified in categories of care where mother and baby were separated: time in intensive care, time in high dependency care and time in special care. These outcomes were not defined in text by Chappell (2019). For the analysis of the outcome measure NICU admission, the time in intensive care by Chappell (2019) was included in the meta-analysis.

NICU admission was reported in 80/1279 infants in the immediate delivery group compared to 59/1273 infants in the expectant management group (pooled RR 1.35 (95% CI 0.97 to 1.87); Figure 8). It is uncertain whether this is a clinically relevant difference, as the 95%CI interval includes the limit of no clinically relevant effect (and no statistically significant effect).

Figure 8 NICU admission comparison immediate delivery versus expectant management

16. Low birth weight for gestational age

Two studies reported the outcome low birth weight for gestational age (Bernades, 2019; Chappell, 2019). Three trials included in the review by Bernardes (2019) reported the outcome measure as small for gestational age (defined as birth weight < 10th percentile) (Broekhuijsen, 2015; Koopmans, 2009; Owens, 2014), but only the pooled results were reported by Bernardes (2019). Chappell (2019) reported the outcome as birthweight < 10th centile.

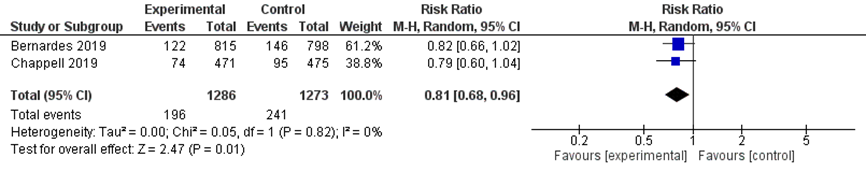

Low birth weight for gestational age (< 10th percentile) was reported in 196/1286 women with immediate delivery (15.2%) compared to 241/1273 women in expectant management (18.9%) (pooled RR 0.81 (95% CI 0.68 to 0.96)) (Figure 9). It is uncertain whether this is a clinically relevant difference, as the 95%CI interval includes the limit of no clinically relevant effect.

Figure 9 Low birth weight for gestational age (<10th percentile) comparison immediate delivery versus expectant management

17. Preterm birth < 37weeks

One study reported the outcome preterm birth < 37 weeks (Chappell, 2019).

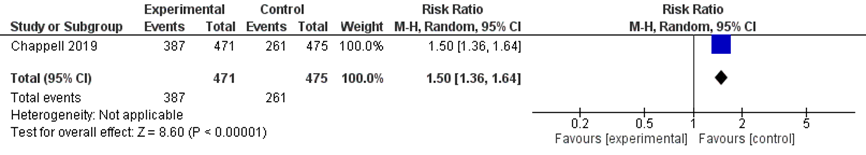

There was an increased risk of preterm birth < 37 weeks of pregnancy in women treated with immediate delivery (387/471) compared to expectant management (261/475) (RR 1.50 (95% 1.36 to 1.64) (figure 10).

Figure 10 Preterm birth < 37 weeks comparison immediate delivery versus expectant management

18. Successful breastfeeding at 6 weeks

The outcome measure successful breastfeeding at 6 weeks was not reported in the included studies. Chappell (2019) reported the outcome method of infant feeding 24 hours prior to discharge, which is reported in Table 5 below.

Exclusive breastfeeding at 24 hours prior to discharge from hospital was reported in 112/471 women in the immediate delivery group compared to 139/475 women in the expectant management group (RR 0.81 (95%CI 0.66 to 1.01)). It is uncertain whether this is a clinically relevant difference, as the 95%CI interval includes the limit of no clinically relevant effect (and no statistically significant effect).

Table 5 Method of feeding 24 hours prior to discharge comparison immediate delivery versus expectant management, extracted from Chappell (2019)

|

Method of feeding 24 h prior to discharge |

Immediate delivery (N/n (% total)) |

Expectant management (N/n (% total)) |

RR (95%CI) |

|

Exclusive breastfeeding |

112/471 (23.8%) |

139/475 (29.3%) |

0.81 (0.66, 1.01) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Mixed feeding |

174/471 (36.9%) |

161/475 (33.9%) |

1.09 (0.92, 1.29) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Exclusive formula feeding |

176/471 (37.4%) |

168/475 (35.4%) |

1.06 (0.89, 1.25) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Missing data |

9/471 (2%) |

7/475 (1.5%) |

1.30 (0.49, 3.45) |

Level of evidence of the literature

RCTs start at a GRADE high.

Maternal outcome measures

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure pre-eclampsia was downgraded by one to a ‘moderate’ level because of risk of bias (impossible to blind participants in Bernardes (2019)).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure eclampsia was downgraded by three levels to ‘very low’ because of imprecision (low number of events, wide 95%CI) and risk of bias (impossible to blind participants in Bernardes (2019) and Chappell (2019)).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure HELLP syndrome and/or eclampsia was downgraded by one level to ‘moderate’ because of risk of bias (impossible to blind participants in Bernardes (2019) and Chappell (2019)).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure pulmonary oedema was downgraded by three levels to ‘very low’ because of imprecision (low number of events, wide 95%CI) and risk of bias (impossible to blind participants in Bernardes (2019) and Chappell (2019)).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure hepatic haemorrhage defined as either liver failure, hepatic heaematoma or hepatic rupture was downgraded by three levels to ‘very low’ because of imprecision (no events) and risk of bias (impossible to blind participants in Bernardes (2019) and Chappell (2019)).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measures renal insufficiency and renal failure were both downgraded by three levels to ‘very low’ because of imprecision (no events) and risk of bias (impossible to blind participants in Bernardes (2019) and Chappell (2019)).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure cerebral haemorrhage was downgraded by three levels to ‘very low’ because of imprecision (no events) and risk of bias (impossible to blind participants in Bernardes (2019)).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure placental abruption was downgraded by three levels to ‘low’ because of imprecision (low number of events, wide 95%CI) and risk of bias (impossible to blind participants in Bernardes (2019) and Chappell (2019)).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure caesarean section was downgraded by one level to ‘moderate’ because of risk of bias (impossible to blind participants in in Bernardes (2019) and Chappell (2019)).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure postpartum haemorrhage was downgraded by three levels to ‘very low’ because of imprecision (95%CI exceeds the limit of no clinically relevant effect) and risk of bias (impossible to blind participants in Bernardes (2019)).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measures patient satisfaction, PTSD and bonding (mother-child) could not be assessed because of lack of data (none of the included studies reported on outcomes).

Perinatal outcome measures

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure perinatal death was downgraded by three levels to ‘very low’ because of imprecision (low number of events, wide 95%CI) and risk of bias (impossible to blind participants in Bernardes (2019) and Chappell (2019)). The level of evidence regarding the outcome measures intra-uterine death (stillbirths) and neonatal death were downgraded by three levels to ‘very low’ because of imprecision (no events) and risk of bias (impossible to blind participants in Chappell (2019)).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure infant respiratory distress syndrome was downgraded by one level to ‘moderate’ because of risk of bias (impossible to blind participants in Bernardes (2019)).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure NICU admission was downgraded by two levels to ‘low’ because of imprecision (95%CI includes the limit of no clinically relevant effect) and risk of bias (impossible to blind participants in Bernardes (2019) and Chappell (2019)).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure low birth weight for gestational age was downgraded by two levels to ‘low’ because of imprecision (95%CI includes the limit of no clinically relevant effect) and risk of bias (impossible to blind participants in Bernardes (2019) and Chappell (2019)).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure preterm birth <37 weeks was downgraded by two level to ‘moderate’ because of risk of bias (impossible to blind participants in Chappell (2019)).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure successful breastfeeding at 6 weeks could not be assessed because of lack of data (none of the included studies reported on outcomes). Proxy outcome measure exclusive breastfeeding at 24 hours prior to discharge from hospital was downgraded by two levels to ‘low’ because of imprecision (95%CI includes the limit of no clinically relevant effect) and risk of bias (impossible to blind participants in Chappell (2019)).

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question:

Is induction of labour improving maternal and perinatal outcomes compared to expectant management in pregnant women with hypertensive disorders in pregnancy > GA 32+0?

P: pregnant women with hypertensive disorders in pregnancy > GA 32+0;

I: induction of labour;

C: expectant management;

O: at least one of the following outcome measures:

Maternal outcomes:

- Pre-eclampsia

- Eclampsia and/or HELLP syndrome

- Pulmonary oedema

- Hepatic haemorrhage

- Renal insufficiency

- Cerebral haemorrhage

- Placental abruption

- Caesarean section

- Postpartum haemorrhage

- Patient satisfaction

- PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder)

- Bonding (mother-child)

Perinatal outcomes:

- Perinatal death (intra-uterine death and neonatal death)

- Infant respiratory distress syndrome (IRDS)

- NICU admission

- Low birth weight for gestational age

- Preterm birth < 37weeks

- Successful breastfeeding at 6 weeks

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered eclampsia as a critical outcome measure for decision making; and pre-eclampsia, pulmonary oedema, hepatic haemorrhage, renal insufficiency, cerebral haemorrhage, placental abruption, caesarean section, postpartum haemorrhage, patient satisfaction, PTSD, bonding (mother-child), perinatal death (intra-uterine death and neonatal death), IRDS, NICU admission, low birth weight for gestational age, preterm birth < 37weeks and successful breastfeeding at 6 weeks as important outcome measures for decision making.

A priori, the working group did not define the outcome measures listed above but used the definitions used in the studies.

For the outcome measures eclampsia, pulmonary oedema, hepatic haemorrhage, renal insufficiency, cerebral haemorrhage, placental abruption and perinatal death (intra-uterine death and neonatal death), any statistically significant difference was considered as a clinically important difference between groups. For the outcome caesarean section, the working group defined a difference of 5% in the relative risk as a minimal clinically important difference. For all other outcome measures, the GRADE default - a difference of 25% in the relative risk for dichotomous outcomes (Schünemann, 2013) and 0.5 standard deviation for continuous outcomes - was taken as a minimal clinically important difference.

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms until October 9th, 2019. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 322 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria:

- the study population had to meet the criteria as defined in the PICO;

- intervention as defined in the PICO;

- original research or systematic review.

Fifty-five studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, 53 studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods) and two studies were included.

Results

One systematic review and one randomized controlled trial (RCT) were included in the analysis of the literature. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- Adler K, Rahkonen L, Kruit H. Maternal childbirth experience in induced and spontaneous labour measured in a visual analog scale and the factors influencing it; a two-year cohort study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020 Jul 21;20(1):415.

- Bernardes TP, Zwertbroek EF, Broekhuijsen K, Koopmans C, Boers K, Owens M, Thornton J, van Pampus MG, Scherjon SA, Wallace K, Langenveld J, van den Berg PP, Franssen MTM, Mol BWJ, Groen H. Delivery or expectant management for prevention of adverse maternal and neonatal outcomes in hypertensive disorders of pregnancy: an individual participant data meta-analysis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2019 Apr;53(4):443-453.

- Bijlenga D, Koopmans CM, Birnie E, Mol BW, van der Post JA, Bloemenkamp KW, Scheepers HC, Willekes C, Kwee A, Heres MH, Van Beek E, Van Meir CA, Van Huizen ME, Van Pampus MG, Bonsel GJ. Health-related quality of life after induction of labor versus expectant monitoring in gestational hypertension or preeclampsia at term. Hypertens Pregnancy. 2011;30(3):260-74.

- Bijlenga D, Boers KE, Birnie E, Mol BW, Vijgen SC, Van der Post JA, De Groot CJ, Rijnders RJ, Pernet PJ, Roumen FJ, Stigter RH, Delemarre FM, Bremer HA, Porath M, Scherjon SA, Bonsel GJ. Maternal health-related quality of life after induction of labor or expectant monitoring in pregnancy complicated by intrauterine growth retardation beyond 36 weeks. Qual Life Res. 2011 Nov;20(9):1427-36.

- Chappell LC, Brocklehurst P, Green ME, Hunter R, Hardy P, Juszczak E, Linsell L, Chiocchia V, Greenland M, Placzek A, Townend J, Marlow N, Sandall J, Shennan A; PHOENIX Study Group. Planned early delivery or expectant management for late preterm pre-eclampsia (PHOENIX): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2019 Sep 28;394(10204):1181-1190.

- Falk M, Nelson M, Blomberg M. The impact of obstetric interventions and complications on women's satisfaction with childbirth a population based cohort study including 16,000 women. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2019 Dec 11;19(1):494.

- Schünemann H, Brożek J, Guyatt G, et al. GRADE handbook for grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. Updated October 2013. The GRADE Working Group, 2013. Available from http://gdt.guidelinedevelopment.org/central_prod/_design/client/handbook/handbook.html.

- van Baaren GJ, Broekhuijsen K, van Pampus MG, Ganzevoort W, Sikkema JM, Woiski MD, Oudijk MA, Bloemenkamp K, Scheepers H, Bremer HA, Rijnders R, van Loon AJ, Perquin D, Sporken J, Papatsonis D, van Huizen ME, Vredevoogd CB, Brons J, Kaplan M, van Kaam AH, Groen H, Porath M, van den Berg PP, Mol B, Franssen M, Langenveld J; HYPITAT-II Study Group. An economic analysis of immediate delivery and expectant monitoring in women with hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, between 34 and 37 weeks of gestation (HYPITAT-II). BJOG. 2017 Feb;124(3):453-461.

- Vijgen SM, Koopmans CM, Opmeer BC, Groen H, Bijlenga D, Aarnoudse JG, Bekedam DJ, van den Berg PP, de Boer K, Burggraaff JM, Bloemenkamp KW, Drogtrop AP, Franx A, de Groot CJ, Huisjes AJ, Kwee A, van Loon AJ, Lub A, Papatsonis DN, van der Post JA, Roumen FJ, Scheepers HC, Stigter RH, Willekes C, Mol BW, Van Pampus MG; HYPITAT study group. An economic analysis of induction of labour and expectant monitoring in women with gestational hypertension or pre-eclampsia at term (HYPITAT trial). BJOG. 2010 Dec;117(13):1577-85.

- Vijgen SM, Boers KE, Opmeer BC, Bijlenga D, Bekedam DJ, Bloemenkamp KW, de Boer K, Bremer HA, le Cessie S, Delemarre FM, Duvekot JJ, Hasaart TH, Kwee A, van Lith JM, van Meir CA, van Pampus MG, van der Post JA, Rijken M, Roumen FJ, van der Salm PC, Spaanderman ME, Willekes C, Wijnen EJ, Mol BW, Scherjon SA. Economic analysis comparing induction of labour and expectant management for intrauterine growth restriction at term (DIGITAT trial). Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2013 Oct;170(2):358-63.

Evidence tabellen

Evidence table for systematic review of RCTs and observational studies (intervention studies)

Research question: Is induction of labour improving maternal and neonatal outcomes compared to expectant management in pregnant women with hypertensive disorders in pregnancy AD32+0?

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C) |

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

Bernardes, 2019

|

SR and meta-analysis of published or registered RCTs

Literature search up to December 2017

A: Koopmans, 2009 (HYPITAT-I) B: Boers, 2010 (DIGITAT) C: Owens, 2014 (Deliver or Deliberate) D: Broekhuijsen, 2015 (HYPITAT-II) E: GRIT study group, 2003 (GRIT)

Study design: RCT

Setting and Country: A: 7 academic and 44 non-academic hospitals, The Netherlands B: 8 academic and 44 non-academic hospitals, The Netherlands C: Single center, USA D: 7 academic and 44 non academic hospitals, The Netherlands E: 69 hospitals in 13 EU countries

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: Not reported.

|

Inclusion criteria SR: published or Registered RCT’s comparing immediate delivery with expectant management in women presenting with gestational hypertension or pre-eclampsia without severe features from 34 weeks of gestation.

Exclusion criteria SR: Participants with signs of severe disease (BP ≥ 160 mmHg systolic or ≥ 110 mmHg diastolic, proteinuria ≥ 5 g/24 h, oliguria, cerebral/visual disturbances, pulmonary edema/cyanosis, epigastric or right upper quadrant pain, impaired liver function and thrombocytopenia), as well as with diabetes mellitus, gestational diabetes requiring insulin treatment, kidney or heart disease, HELLP syndrome or HIV. Pregnancies with suspected or confirmed major structural or chromosomal abnormality.

5 studies included, 4 studies in analysis

Important patient characteristics at baseline: Number of patients; characteristics important to the research question and/or for statistical adjustment (confounding in cohort studies); for example, age, sex, bmi,...

N A: 756 patients B: 110 patients C: 155 patients D: 703 patients E: NA

Age or other characteristics not reported:

Groups comparable at baseline? Not reported |

Describe intervention: A: immediate delivery in women presenting with gestational hypertension or pre-eclampsia without severe features from 36+0 weeks of gestation B: not reported C: immediate delivery in women with pre-eclampsia between 34+0 and 36+6 weeks of gestation D: immediate delivery in women with pre-eclampsia between 34+0 and 36+6 weeks of gestation E: not reported

|

Expectant management

|

End-point of follow-up: not reported

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? 1101/2825 (39%) (54 from GRIT study for which primary outcome was not collected)

|

1. Pre-eclampsia Not reported

2. Eclampsia Defined as HELLP or eclampsia

Effect measure: RR (95% CI): A: 0.37 (0.12 to 1.14) B: 0.15 (0.01 to 2.79) C: 0.27 (0.01 to 6.48) D: 0.37 (0.10 to 1.40)

Pooled effect (fixed effects model): 0.33 (95% CI 0.15 to 0.73) favoring immediate delivery Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

Defined as eclampsia

Effect measure: RR (95% CI): A: not estimable B: 0.46 (0.02 to 11.07) C: not estimable D: 0.20 (0.01 to 4.14)

Pooled effect (fixed effects model): 0.29 (95% CI 0.03 to 2.48) favoring immediate delivery Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

3. Pulmonary edema Defined as pulmonary edema

Effect measure: RR (95% CI): Pooled effect of 3 studies (fixed effects model): 0.20 (95% CI 0.01 to 4.17) favoring immediate delivery Heterogeneity (I2): N/A

4. Hepatic haemorrhage Defined as severe postpartum haemorrhage

Effect measure: RR (95% CI): Pooled effect of 4 studies (fixed effects model): 0.77 (95% CI 0.57 to 1.04) favoring immediate delivery Heterogeneity (I2): 2%

5. Renal insufficiency Defined as liver failure

0 cases in all 4 studies.

6. Cerebral hemorrhage, Defined as intercerebral hemorrhage

0 cases in all 4 studies. |

Brief description of author’s conclusion: In women with hypertension in pregnancy, immediate delivery reduces the risk of maternal complications, whilst the effect on the neonate depends on gestational age. Specifically, women with a-priori higher risk of progression to HELLP, such as those already presenting with pre-eclampsia instead of gestational hypertension, were shown to benefit from earlier delivery.

For secondary outcomes, only pooled results were reported.

Level of evidence: 2. Eclampsia: MODERATE Due to imprecision (wide confidence interval crossing the line of no effect)

3. Pulmonary edema: MODERATE Due to imprecision (wide confidence interval crossing the line of no effect)

4. Hepatic haemorrhage: HIGH

5. Renal insufficiency: N/A

6. Cerebral hemorrhage: N/A

|

Table of quality assessment for systematic reviews of RCTs and observational studies

Based on AMSTAR checklist (Shea, 2007; BMC Methodol 7: 10; doi:10.1186/1471-2288-7-10) and PRISMA checklist (Moher, 2009; PLoS Med 6: e1000097; doi:10.1371/journal.pmed1000097)

|

Study

First author, year |

Appropriate and clearly focused question?1

Yes/no/unclear |

Comprehensive and systematic literature search?2

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of included and excluded studies?3

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of relevant characteristics of included studies?4

Yes/no/unclear |

Appropriate adjustment for potential confounders in observational studies?5

Yes/no/unclear/notapplicable |

Assessment of scientific quality of included studies?6

Yes/no/unclear |

Enough similarities between studies to make combining them reasonable?7

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential risk of publication bias taken into account?8

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential conflicts of interest reported?9

Yes/no/unclear |

|

Bernardes, 2019 |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

No |

NA |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

No |

- Research question (PICO) and inclusion criteria should be appropriate and predefined.

- Search period and strategy should be described; at least Medline searched; for pharmacological questions at least Medline + EMBASE searched.

- Potentially relevant studies that are excluded at final selection (after reading the full text) should be referenced with reasons.

- Characteristics of individual studies relevant to research question (PICO), including potential confounders, should be reported.

- Results should be adequately controlled for potential confounders by multivariate analysis (not applicable for RCTs).

- Quality of individual studies should be assessed using a quality scoring tool or checklist (Jadad score, Newcastle-Ottawa scale, risk of bias table et cetera).

- Clinical and statistical heterogeneity should be assessed; clinical: enough similarities in patient characteristics, intervention and definition of outcome measure to allow pooling? For pooled data: assessment of statistical heterogeneity using appropriate statistical tests (for exampleChi-square, I2)?

- An assessment of publication bias should include a combination of graphical aids (e.g., funnel plot, other available tests) and/or statistical tests (for example Egger regression test, Hedges-Olken). Note: If no test values or funnel plot included, score “no”. Score “yes” if mentions that publication bias could not be assessed because there were fewer than 10 included studies.

- Sources of support (including commercial co-authorship) should be reported in both the systematic review and the included studies. Note: To get a “yes,” source of funding or support must be indicated for the systematic review AND for each of the included studies.

Evidence table for intervention studies (randomized controlled trials and non-randomized observational studies (cohort studies, case-control studies, case series))1

This table is also suitable for diagnostic studies (screening studies) that compare the effectiveness of two or more tests. This only applies if the test is included as part of a test-and-treat strategy - otherwise the evidence table for studies of diagnostic test accuracy should be used.

Research question: Is induction of labour improving maternal and neonatal outcomes compared to expectant management in pregnant women with hypertensive disorders in pregnancy AD32+0?

Notes:

- Prognostic balance between treatment groups is usually guaranteed in randomized studies, but non-randomized (observational) studies require matching of patients between treatment groups (case-control studies) or multivariate adjustment for prognostic factors (confounders) (cohort studies); the evidence table should contain sufficient details on these procedures.

- Provide data per treatment group on the most important prognostic factors ((potential) confounders)

- For case-control studies, provide sufficient detail on the procedure used to match cases and controls.

- For cohort studies, provide sufficient detail on the (multivariate) analyses used to adjust for (potential) confounders.

Risk of bias table for intervention studies (randomized controlled trials)

Research question: Is induction of labour improving maternal and neonatal outcomes compared to expectant management in pregnant women with hypertensive disorders in pregnancy AD32+0?

|

Study reference

(first author, publication year) |

Describe method of randomisation1 |

Bias due to inadequate concealment of allocation?2

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate blinding of participants to treatment allocation?3

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate blinding of care providers to treatment allocation?3

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate blinding of outcome assessors to treatment allocation?3

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to selective outcome reporting on basis of the results?4

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to loss to follow-up?5

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to violation of intention to treat analysis?6

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

|

Chappell 2019 |

Current practice by national guidelines in use during the trial was for immediate delivery of a woman with persistent severe features of pre-eclampsia (including haemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelets syndrome); these women would thus not be eligible for the trial. |

Unlikely |

Unclear, women and clinicians (and data collectors) could not be blinded to the intervention. |

Unclear, women and clinicians (and data collectors) could not be blinded to the intervention. |

Unclear, trial statisticians were not blinded, unclear why this was not possible. |

Unlikely, reported as prescribed in previously published protocol |

Unlikely, in both groups lost to follow-up was low (1/448 in the intervention, 2/451 in the control group).

Intention to treat analysis: I: 448 women (471 infants) C: 451 women (475 infants)

Per protocol analysis: I: 327 women (342 infants) C: 447 women (470 infants)

|

Unlikely, all participants were analyzed as intention to treat. A second, per protocol analysis was conducted that only included patients where protocol was followed.

Difference between ITT and PPA: I: 121 women (129 infants) excluded (1 lost to follow-up; 120 women received planned delivery >48h after randomizations (n=95 women due to logistic delays; n=25 due to patient choice) C: 4 women (5 infants) excluded (2 women lost to follow-up; 2 women received non indicated delivery <37 weeks of pregnancy). |

- Randomisation: generation of allocation sequences have to be unpredictable, for example computer generated random-numbers or drawing lots or envelopes. Examples of inadequate procedures are generation of allocation sequences by alternation, according to case record number, date of birth or date of admission.

- Allocation concealment: refers to the protection (blinding) of the randomisation process. Concealment of allocation sequences is adequate if patients and enrolling investigators cannot foresee assignment, for example central randomisation (performed at a site remote from trial location) or sequentially numbered, sealed, opaque envelopes. Inadequate procedures are all procedures based on inadequate randomisation procedures or open allocation schedules.

- Blinding: neither the patient nor the care provider (attending physician) knows which patient is getting the special treatment. Blinding is sometimes impossible, for example when comparing surgical with non-surgical treatments. The outcome assessor records the study results. Blinding of those assessing outcomes prevents that the knowledge of patient assignement influences the proces of outcome assessment (detection or information bias). If a study has hard (objective) outcome measures, like death, blinding of outcome assessment is not necessary. If a study has “soft” (subjective) outcome measures, like the assessment of an X-ray, blinding of outcome assessment is necessary.

- Results of all predefined outcome measures should be reported; if the protocol is available, then outcomes in the protocol and published report can be compared; if not, then outcomes listed in the methods section of an article can be compared with those whose results are reported.

- If the percentage of patients lost to follow-up is large, or differs between treatment groups, or the reasons for loss to follow-up differ between treatment groups, bias is likely. If the number of patients lost to follow-up, or the reasons why, are not reported, the risk of bias is unclear

- Participants included in the analysis are exactly those who were randomized into the trial. If the numbers randomized into each intervention group are not clearly reported, the risk of bias is unclear; an ITT analysis implies that (a) participants are kept in the intervention groups to which they were randomized, regardless of the intervention they actually received, (b) outcome data are measured on all participants, and (c) all randomized participants are included in the analysis.

Tabel Exclusie na het lezen van het volledige artikel

|

Auteur en jaartal |

Redenen van exclusie |

|

Amorim, 2015 |

geen RCT |

|

Bernardes, 2016 |

voldoet niet aan PICO (secundaire analyse van hypitat trial/ digital trial, subgroep vrouwen onrijpe cervix) |

|

Bernardes, 2019 |

inclusie |

|

Bijlenga, 2011 |

Voldoet niet aan PICO (uitkomstmaten voldoen niet aan PICO). |

|

Bracken, 2014 |

voldoet niet aan PICO (vergelijkt 2 inductie methoden, in plaats van vergeleken met expectant management) |

|

Broekhuijsen, 2015 |

Reeds geïncludeerd in Bernardes (2019) |

|

Broekhuijsen, 2015 |

geen RCT |

|

Broekhuijsen, 2016 |

erratum |

|

Caughey, 2009 |

voldoet niet aan PICO (electieve inductie, algemene populatie zwangeren) |

|

Chappell, 2015 |

narrative review |

|

Chappell, 2019 |

studie protocol PHOENIX trial |

|

Churchill, 2002 |

oudere versie Cochrane review Churchill 2018 |

|

Churchill, 2013 |

oudere versie Cochrane review Churchill 2018 |

|

Churchill, 2018 |

voldoet niet aan PICO (analyses over 24-34 weken, zonder onderscheid tussen weken) |

|

Cluver, 2017 |

Voorkeur voor systematische review en meta-analyse van Bernardes (2019) (analyse van individuele participant data). Cluver (2017) analyseert composiet scores, Bernardes (2019) analyseert uitkomsten los van elkaar. |

|

Cruz, 2012 |

geen RCT |

|

de Sonnaville, 2019 |

secundaire analyse van hyptitat 1 (effect op obstetrisch management) |

|

Dekker, 2014 |

narrative review |

|

Fiolna, 2019 |

voldoet niet aan PICO (geen hypertensieve zwangeren) |

|

Garcia-Simon, 2016 |

voldoet niet aan PICO (economische analyse inleiding (algemeen)) |

|

Gilbert, 2010 |

geen origineel artikel (betreft zogenaamde "info poem" in journal) |

|

Habli, 2007 |

voldoet niet aan PICO (vergelijkt normotensieven versus. hypertensieven) |

|

Hermes, 2013 |

voldoet niet aan PICO (postpartum cardiovasculair risico) |

|

Kawakita, 2018 |

voldoet niet aan PICO (caesarean versus. inductie) |

|

Koopmans, 2007 |

protocol paper hypitat 1 |

|

Koopmans, 2009 |

Reeds geïncludeerd in Bernardes (2019) |

|

Koopmans, 2009 |

Reeds geïncludeerd in Bernardes (2019) |

|

Langenveld, 2011 |

protocol paper hypitat 2 |

|

Magee, 2009 |

geen RCT |

|

Marrs, 2019 |

voldoet niet aan PICO ( betreft reflectie ARRIVE trial) |

|

Martin, 2012 |

congresabstract |

|

Moodley, 1998 |

geen vergelijkend onderzoek (observationele studie) |

|

Nathan, 1994 |

narrative review |

|

Owens, 2014 |

Reeds geïncludeerd in Bernardes (2019) |

|

Shennan, 2010 |

voldoet niet aan PICO (economische analyse Hypitat) |

|

Shepherd, 2017 |

voldoet niet aan PICO (algemene populatie zwangeren; interventies preventie cerebrale parese) |

|

Shibata, 2016 |

geen vergelijkend onderzoek (observationele studie) |

|

Sibai, 1994 |

niet full tekst beschikbaar |

|

Sibai, 2007 |

narrative review |

|

Sibai, 2011 |

narrative review |

|

Snydal, 2014 |

narrative review |

|

Souter, 2019 |

geen RCT |

|

Suzuki, 2014 |

voldoet niet aan PICO (kijkt tot 32 weken en is geen RCT) |

|

Tajik, 2012 |

post-hoc analyse Hypititat over invloed cervical favourability |

|

Tajik, 2012 |

dubbele Tjaik, 2012 |

|

Tajik, 2014 |

voldoet niet aan PICO (kijkt naar predictie IUGR fetuses in DIGITAT trial) |

|

van Baaren, 2017 |

Voldoet niet aan PICO (kijkt naar effect op kosten) |

|

van der Tuuk, 2011 |

secundaire analyse van hyptitat 1 (effect op obstetrisch handelen/gedrag gynaecologen) |

|

van der Tuuk, 2011 |

voldoet niet aan PICO (wordt gekeken naar risico op hoog risico situatie) |

|

Van Der Tuuk, 2015 |

voldoet niet aan PICO (wordt gekeken naar risico op keizersnede bij PE of GH vrouwen) |

|

Vijgen, 2010 |

Voldoet niet aan PICO (kijkt naar effect op kosten) |

|

Wood, 2014 |

voldoet niet aan PICO (algemenere populatie (vrouwen met intact membraan)) |

|

Zwertbroek, 2019 |

voldoet niet aan PICO (kijkt naar lange termijn neonatale uitkomsten >2 jaar) |

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Publicatiedatum : 14-06-2021

Beoordeeld op geldigheid : 22-07-2021

|

Module[1] |

Regiehouder(s)[2] |

Jaar van autorisatie |

Eerstvolgende beoordeling actualiteit richtlijn[3] |

Frequentie van beoordeling op actualiteit[4] |

Wie houdt er toezicht op actualiteit[5] |

Relevante factoren voor wijzigingen in aanbeveling[6] |

|

Inleiding versus afwachtend beleid |

NVOG |

2020 |

2025 |

5 jaar |

NVOG |

Nieuwe evidence |

[1] Naam van de module

[2] Regiehouder van de module (deze kan verschillen per module en kan ook verdeeld zijn over meerdere regiehouders)

[3] Maximaal na vijf jaar

[4] (half)Jaarlijks, eens in twee jaar, eens in vijf jaar

[5] regievoerende vereniging, gedeelde regievoerende verenigingen, of (multidisciplinaire) werkgroep die in stand blijft

[6] Lopend onderzoek, wijzigingen in vergoeding/organisatie, beschikbaarheid nieuwe middelen

Algemene gegevens

De ontwikkeling/herziening van deze richtlijnmodule werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten en werd gefinancierd uit de Stichting Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS). De financier heeft geen enkele invloed gehad op de inhoud van de richtlijnmodule.

Deze richtlijn is ontwikkeld in samenwerking met:

- Patiëntenfederatie Nederland

Doel en doelgroep

Doel

Deze richtlijn beoogt een leidraad te geven voor de dagelijkse praktijk van de zorg van zwangere vrouwen met een hypertensieve aandoening. De richtlijn bespreekt niet de indicaties voor het beëindigen van de zwangerschap op maternale indicatie, maar beperkt zich bij de behandeling tot de medicamenteuze behandeling.

Doelgroep

Deze richtlijn is geschreven voor alle leden van de beroepsgroepen die aan de ontwikkeling van de richtlijn hebben bijgedragen. Deze staan vermeld bij de samenstelling van de werkgroep. Tot de beroepsgroepen die geen zitting hadden in de werkgroep, maar wel beoogd gebruikers zijn van deze richtlijn behoren o.a. klinisch verloskundigen.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijnmodule is in 2019 een werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor vrouwen met hypertensieve aandoeningen in de zwangerschap.

Werkgroep

- Dr. C.J. (Caroline) Bax, gynaecoloog-perinatoloog, werkzaam in het Amsterdam UMC locatie AMC, NVOG, voorzitter stuurgroep.

- Dr. S.V. (Steven) Koenen, gynaecoloog, werkzaam in het ETZ, locatie Elisabeth Ziekenhuis, NVOG, lid stuurgroep.

- Dr. Duvekot, gynaecoloog, werkzaam in het Erasmus MC, NVOG, lid stuurgroep.

- Dr. M.A. (Marjon) de Boer, gynaecoloog-perinatoloog, werkzaam in het Amsterdam UMC, locatie VUmc, NVOG.

- Dr. A.T. (Titia) Lely, gynaecoloog, werkzaam in het UMC Utrecht, NVOG.

- Dr. P.J. (Petra) Hajenius, gynaecoloog-perinatoloog, werkzaam in het Amsterdam UMC locatie AMC, NVOG.

- Dr. J.W.(Wessel) Ganzevoort, gynaecoloog-perinatoloog, werkzaam in het Amsterdam UMC locatie AMC, NVOG.

- Dr. O.W.H. (Olivier) van der Heijden, gynaecoloog-perinatoloog, werkzaam in het Radboud UMC Nijmegen, NVOG.

- MSc F.M. (Fenna) van der Molen, verloskundige, werkzaam in praktijk Veilige Geboorte, KNOV.

- Dr. M.C. (Mignon) van der Horst, klinisch verloskundige, werkzaam in de Gelderse Vallei Ede, KNOV.

- Mw. A.M.M. (Annemijn) Doppenberg, MSc, adviseur, Patiëntenfederatie Nederland.

- Mw. J.C. (Anne) Mooij, MSc, adviseur, Patiëntenfederatie Nederland.

- Mw. K.L.H.E. (Kim) VandenAuweele, beleidsmedewerker HELLP Stichting.

Meelezers

- Leden van de Otterlo - werkgroep (2020)

Met ondersteuning van

- Dr. A. (Anne) Bijlsma-Rutte, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- Dr. L. (Laura) Viester, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- Dr. M.A.C. (Marleen) van Son, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- MSc Y. (Yvonne) Labeur, junior adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

Belangenverklaringen

De Code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling is gevolgd. Alle werkgroepleden hebben schriftelijk verklaard of zij in de laatste drie jaar directe financiële belangen (betrekking bij een commercieel bedrijf, persoonlijke financiële belangen, onderzoeksfinanciering) of indirecte belangen (persoonlijke relaties, reputatiemanagement) hebben gehad. Gedurende de ontwikkeling of herziening van een module worden wijzigingen in belangen aan de voorzitter doorgegeven. De belangenverklaring wordt opnieuw bevestigd tijdens de commentaarfase.

Een overzicht van de belangen van werkgroepleden en het oordeel over het omgaan met eventuele belangen vindt u in onderstaande tabel. De ondertekende belangenverklaringen zijn op te vragen bij het secretariaat van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

|

Werkgroeplid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

Bax (voorzitter stuurgroep) |

Gynaecoloog-perinatoloog Amsterdam UMC, locatie AMC, 0,8 fte |

Gastvrouw Hospice Xenia Leiden (onbetaald) |

|

geen |

|

Duvekot (lid stuurgroep) |

Gynaecoloog, Erasmus MC (full time) |

Directeur 'medisch advies en expertise bureau Duvekot', Ridderkerk, ZZP'er |

|

geen |

|

Koenen (lid stuurgroep) |

gynaecoloog, ETZ , Tilburg |

incidenteel juridische expertise (betaald) |

|

geen |

|

de Boer |

gynaecoloog-perinatoloog AUMC, locatie Vumc |

geen |

|

geen |

|

Hajenius |

Gynaecoloog (1.0 fte), afdeling Obstetrie Amsterdam Universitair Medische Centra (AUMC), locatie Meibergdreef (AMC). |

geen nevenwerkzaamheden |

De module Geboortezorg - Hypertensieve aandoeningen zal in de praktijk worden vertaald naar een lokaal protocol voor de afdeling Obstetrie van het AUMC waar ik werkzaam ben en de lokale protocollen beheer. In die zin zullen naaste collega's (artsen, klinisch verloskundigen en arts assistenten) "baat" hebben bij de uitkomsten van de module. |

geen |

|

Lely |

Gynaecoloog WKZ |

off-road commissie lid ZonMw (onkostenvergoeding, onbetaald) |

|

geen |

|

Van der Heijden |

Gynaecoloog, perinatoloog |

Lid multidisciplinaire richtlijn commissie (NVOG): |

|

geen |

|

Ganzevoort |

Gynaecoloog , Amsterdam UMC |

Redacteur NTOG, onbetaald |

Ik ben PI van enkele ZonMW gefinancierde studies bij foetale groeirestrictie en centrum-contactpersoon voor enkele andere pre-eclampsie studies. Binnen die studies wordt ook door Roche Diagnostics materiaal in-kind ter beschikking gesteld. Er zijn door het bedrijf hieraan geen inhoudelijke voorwaarden gesteld, op geen enkel vlak. |

geen actie, de richtlijnmodules doen geen uitspraak over welke testapparatuur/-methode gehanteerd moet worden voor het bepalen van proteïnurie, alleen dat men dit middels het eiwit-kreatinine ratio doet. |

|

van der Horst |

Klinisch verloskundige, ziekenhuis Gelderse Vallei, Ede |

PKV, KNOV vacatievergoeding |

|

geen |

|

van der Molen |

eerstelijns verloskundige, KNOV |

Ledenraad Eerstelijns Verloskundigen Amsterdam Amstelland (EVAA) - afwisselend voorzitter, notulist en algemeen lid - onbetaald Commissie Kwaliteit en onderzoek EVAA - afwisselend voorzitter, notulist en algemeen lid - onbetaald |

|

geen |

|

van Son |

Beleidsmedewerker KNOV |

Niet van toepassing |

|

geen |

|

Van den Auweele |

Beleidsmedewerker Hellp Stichting |

|

|

geen |

|

Ensink |

Medior adviseur patiëntbelang Patiëntenfederatie |

Niet van toepassing |

|

geen |

|

Mooij |

adviseur Patientenbelang, Patientenfederatie Nederland |

Niet van toepassing |

|

geen |

|

Doppenberg |

adviseur Patientenbelang, Patientenfederatie Nederland |

Niet van toepassing |

|

geen |

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Er werd aandacht besteed aan het patiëntenperspectief door uitnodigen van patiëntvertegenwoordigers van verschillende patiëntverenigingen voor de Invitational conference en afvaardigen van patiëntenverenigingen in de clusterwerkgroep. Het verslag hiervan is besproken in de werkgroep. De verkregen input is meegenomen bij het opstellen van de uitgangsvragen, de keuze voor de uitkomstmaten en bij het opstellen van de overwegingen (zie per module ook ‘Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en eventueel hun verzorgers)’. De conceptrichtlijn wordt tevens ter commentaar voorgelegd aan de betrokken patiëntenverenigingen.

Methode ontwikkeling

Evidence based

Werkwijze

AGREE

Deze richtlijnmodule is opgesteld conform de eisen vermeld in het rapport Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 van de adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwaliteit. Dit rapport is gebaseerd op het AGREE II instrument (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II; Brouwers, 2010).

Knelpuntenanalyse en uitgangsvragen

Tijdens de voorbereidende fase inventariseerden de werkgroep de knelpunten in de zorg voor vrouwen met hypertensieve aandoeningen in de zwangerschap. Tevens zijn er knelpunten aangedragen door patiëntenverenigingen tijdens de Invitational conference. Een verslag hiervan is opgenomen in de bijlagen.

Op basis van de uitkomsten van de knelpuntenanalyse zijn door de werkgroep concept-uitgangsvragen opgesteld en definitief vastgesteld.

Uitkomstmaten