Behandeling nasofarynxcarcinoom - inductiechemotherapie

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is de plaats van inductiechemotherapie bij de behandeling van het nasofarynxcarcinoom, subtypen niet-keratiniserend plaveiselcelcarcinoom (EBV positief) en keratiniserend plaveiselcelcarcinoom (meestal EBV negatief)?

Aanbeveling

Voor patiënten < 70 jaar, met een WHO conditie 0 tot 1 met een niet-keratiniserend EBV positief plaveiselcelcarcinoom voor stadium IV en een selectie stadium III wordt inductiechemotherapie gevolgd door concomitante chemoradiotherapie aanbevolen.

Voor stadium T3N0 wordt inductiechemotherapie niet aanbevolen. Voor T3N1 en T4N0 kan inductiechemotherapie worden overwogen.

Voor het keratiniserend EBV negatief plaveiselcelcarcinoom stadium III/IV wordt inductiechemotherapie gevolgd door chemoradiatie niet aanbevolen. Een winst van inductiechemotherapie is niet aangetoond en er is risico op toegenomen toxiciteit.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

De combinatie van inductiechemotherapie met concomitante chemoradiatietherapie lijkt de algehele overleving, ziektevrije overleving en afstandsmetastase vrije overleving van patiënten met stadium III/IV, nasofarynxcarcinoom te verbeteren ten opzichte van concomitante chemoradiatietherapie alleen, maar het leidt mogelijk ook tot meer complicaties en bijwerkingen. De overall bewijskracht van de cruciale uitkomstmaten is laag.

Echter we dienen te beseffen dat het overgrote aantal patiënten komt uit studies uitgevoerd in Aziatische landen waarbij nasofarynxcarcinoom ten dele een andere etiologie heeft en het doorgaans een niet-keratiniserend EBV positief plaveiselcelcarcinoom betreft. Zo worden in het Westen meer tumoren gezien die wel keratiniserend zijn en EBV negatief zijn; dit betreffen plaveiselcelcarcinomen, die waarschijnlijk een correlatie met roken hebben.

Bij analyse van de individuele studies blijkt dat bij alle positieve studies (Cao, 2017; Hong, 2018; Li, 2019; Sun, 2016; Yang, 2019) alleen patiënten met niet-keratiniserend plaveiselcelcarcinoom zijn geselecteerd. Er is dus geen evidence dat inductiechemotherapie bij keratiniserend plaveiselcelcarcinoom leidt tot betere overleving, het type dat in het Westen bij 1 op 3 patiënten wordt gezien. Voor de patiënten met een niet-keratiniserend plaveiselcelcarcinoom werden niet alle stadium III/IV patiënten geselecteerd in de positieve studies. De studie van Hong (2018) betrof alleen stadium IV. Stadium T3N0-N1 werden uitgesloten in de studies van Sun (2016), Cao (2017) en Yang (2019); Stadium T3-T4 N0 in de studie van Li (2019). Op basis van deze analyse luidt de conclusie dat voor stadium IV niet-keratiniserend plaveiselcelcarcinoom er evidence is dat inductiechemotherapie leidt tot betere algehele overleving, ziektevrije overleving en afstandsmetastase vrije overleving. Hiervoor is voor stadium III T3N0 geen evidence. Patiënten met stadium III T3N1 (Cao, 2017; Yang, 2019) en stadium IVa T4N0 (Li, 2019; Sun, 2016) werden in enkele studies uitgesloten. De conclusie voor deze stadia luidt dat inductiechemotherapie mogelijk tot een betere overleving leidt, en voor deze stadia kan worden overwogen om inductiechemotherapie toe te voegen aan concomitante chemoradiatietherapie.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en eventueel hun verzorgers)

Het belangrijkste doel van de interventie voor de patiënt is betere overleving en deze lijkt, met inductiechemotherapie iets beter dan zonder. Dit moet wel worden afgewogen tegen de toegenomen toxiciteit. Derhalve is van belang om te zien welke patiëntencategorie het meeste voordeel heeft bij toevoeging van inductiechemotherapie. Op basis van de boven vermelde analyse betreft dit de groep patiënten met een niet-keratiniserend EBV positief carcinoom, omdat deze patiëntengroep de grootste kans op afstandsmetastasen heeft. Tevens dienen patiënten, gezien de toxiciteit van de behandeling en de nog volgende chemoradiatie, in principe < 70 jaar te zijn en een WHO 0-1 te hebben om in aanmerking te komen voor inductiechemotherapie. Het risico bestaat anders dat patiënten niet aan hun concomitante chemotherapie toekomen, welke waarschijnlijk belangrijker voor de overleving is dan inductiechemotherapie. Voor keratiniserend EBV negatief carcinomen van de nasofarynx is superioriteit van inductiechemotherapie niet aangetoond en heeft ook gezien de verhoogde toxiciteit concomitante chemoradiotherapie zonder inductiechemotherapie de voorkeur.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

Inductiechemotherapie gevolgd door concomitante chemoradiotherapie leidt tot een aanzienlijke verlenging van de behandelduur voor de patiënt, en hogere kosten als gevolg van de toegevoegde inductiechemotherapie. Daarnaast kan verhoogde toxiciteit ook tot een toename in kosten leiden. Dit moet gewogen worden tegen een besparing door minder noodzaak tot eventuele salvage therapie (waarvan mogelijkheden voor de primaire tumor beperkt zijn) en een (beperkt) verlies in levensjaren. Voor de Nederlandse situatie zijn geen studies naar kosteneffectiviteit voor de behandeling van nasofarynxcarcinomen uitgevoerd.

Voor de subgroep met een goede algehele conditie < 70 jaar en een niet-keratiniserend EBV positief carcinoom, stadium III (exclusief T3N0 en mogelijk T3N1) en met name stadium IV zijn de baten mogelijk hoger dan de kosten.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

Inductiechemotherapie gevolgd door concomitante chemoradiotherapie wordt vaker toegepast bij zeer uitgebreide hoofd-halstumoren en wordt in het algemeen redelijk verdragen, maar er is wel een risico dat (bij een klein percentage, te halen uit de gerandomiseerde studies) dat door de toxiciteit van het inductie deel het concomitante deel (samen met de radiotherapie) niet of niet volledig kan worden gegeven. Chemotherapie is een haalbare interventie, maar de patiënt moet wel jonger dan 70 jaar zijn en in een WHO conditie 0 tot 1, een goede nierfunctie en geen aanmerkelijk gehoorverlies hebben.

Als bezwaar geldt een toegenomen belasting voor de patiënt tegenover een relatief kleine winst. In Nederland heeft iedereen voldoende toegang tot een hoofd-halsoncologisch centrum zodat implementatie van inductiechemotherapie goed haalbaar is. Deze zorg wordt alleen geleverd in een hoofd-halsoncologisch centrum, waarvan er 8 in Nederland zijn en 6 een preferred partner hebben. Daar is voldoende expertise aanwezig. Wanneer in plaats van fotonen, op basis van geschatte lagere kans op toxiciteit, protonen een deel van de behandeling vormen, dan kan de reisafstand een belemmering vormen, niet in financiële maar in praktische zin. Het kan betekenen dat de chemotherapie en radiotherapie in twee centra plaatsvinden of dat naast de radiotherapie ook de chemotherapie in het protonencentrum zal worden gegeven. Er is een goede afstemming nodig tussen het hoofd-halsoncologisch centrum en het protoneninstituut.

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

Op basis van een meta-analyse van gerandomiseerde studies uitgevoerd in voornamelijk Aziatische landen naar het voordeel van inductiechemotherapie gevolgd door concomitante chemoradiotherapie voor stadium IV en geselecteerde patiënten met stadium III nasofarynxcarcinomen kan worden geconcludeerd dat hiermee de ziektevrije overleving wordt verbeterd, met name de afstandsmetastase vrije overleving en in mindere mate de algehele overleving, ten koste van een verhoogde acute toxiciteit. Dit geldt echter niet voor patiënten met stadium T3N0. Voor stadium T3N1 en stadium T4N0 geldt dat ze in diverse studies zijn uitgesloten. Voor patiënten met deze stadia kan inductiechemotherapie gevolgd door chemoradiatie worden overwogen.

In de Aziatische landen zijn de nasofarynxcarcinomen voornamelijk niet-keratiniserend EBV positief plaveiselcelcarcinomen. In Nederland is 1/3 van de tumoren een keratiniserend EBV negatief plaveiselcelcarcinoom met een associatie met roken, een hoger risico op locoregionaal recidief en minder kans op afstandsmetastasen.

Voor het keratiniserend EBV negatief plaveiselcelcarcinomen is er geen bewijs om in stadium III/IV inductiechemotherapie gevolgd door concomitante chemoradiotherapie aan te bevelen. De beperkte winst moet afgewogen worden tegen de toegenomen toxiciteit en dit moet met de patiënt besproken worden.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

De toevoeging van chemotherapie als inductie of adjuvant regime aan chemoradiatie therapie is in verschillende studies onderzocht, met wisselende resultaten. De toxiciteit van systemische therapie na chemoradiatie blijft een actueel onderwerp.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

Crucial outcome measures

Overall survival (5 year)

|

Low GRADE |

Induction chemotherapy combined with concurrent chemoradiation therapy may result in a slight increase of overall survival in WHO subtype 2/3, stage III/ IV, excluding T3N0 nasopharyngeal cancer patients at 5-year follow-up, when compared to concurrent chemoradiation therapy alone.

Sources: (Hong, 2018; Li, 2019; Yang, 2019) |

Disease-free survival (5 year)

|

Low GRADE |

Induction chemotherapy combined with concurrent chemoradiation therapy may result in an increase of disease-free survival in WHO subtype 2/3, stage III/ IV, excluding T3N0 nasopharyngeal cancer patients at 5-year follow-up, when compared to concurrent chemoradiation therapy alone.

Sources: (Hong, 2018; Li, 2019; Yang, 2019) |

Important outcome measures

Distant metastasis-free survival (5 year)

|

Low GRADE |

Induction chemotherapy combined with concurrent chemoradiation therapy may result in an increase of distant metastasis-free survival in WHO subtype 2/3, stage III/ IV, excluding T3N0 nasopharyngeal cancer patients at 5-year follow-up, when compared to concurrent chemoradiation therapy alone.

Sources: (Hong, 2018; Li, 2019; Yang, 2019) |

Complications/adverse events

|

Low GRADE |

Induction chemotherapy combined with concurrent chemoradiation therapy may increase grade ≥ 3 adverse events in advanced nasopharyngeal cancer patients when compared to concurrent chemoradiation therapy alone.

Sources: (Cao, 2017; Sun, 2016; Tan, 2015; Zhang, 2019) |

Quality of life

|

Very low GRADE |

We are unsure about the effect of induction chemotherapy combined with concurrent chemoradiation therapy on quality of life in advanced nasopharyngeal cancer patients when compared to chemoradiation therapy alone.

Sources: (Tan, 2015) |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

We included the SR of Wang (2020) in the analyses. They searched the scientific literature up to September 2019. Inclusion criteria of this systematic review were: prospective studies in previously untreated patients with nasopharynx carcinoma (NPC); studies were registered clinical trials and registration numbers were provided; study design was randomized controlled clinical studies; the experimental group was treated with induction chemotherapy (IC) combined with concurrent chemoradiation therapy (CCRT), and the control group was treated with CCRT alone; and studies were published in English language. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy described in the articles was deemed as induction chemotherapy. Exclusion criteria were: IC or CCRT was combined with target therapy, or conference abstracts.

In total, nine papers, describing the results of seven RCTs were included, with 2311 patients, of whom 1160 patients were randomised to IC+CCRT and 1151 patients were randomised to CCRT alone. Type and dosage of IC, chemotherapy (CT) and radiotherapy (RT) are described in the evidence table.

Four studies reported results after three-year follow-up (Fountzilas, 2012; Frikha, 2018; Tan, 2015; Zhang, 2019), two studies reported results on both three- and five-years follow-up, in two separate articles (Cao, 2017 & Yang, 2019; Sun, 2016 & Li, 2019), and one study reported results after five-year follow-up (Hong, 2018). Three studies were done in China (Cao, 2017 & Yang, 2019; Sun, 2016 & Li, 2019; Zhang, 2019), and the rest in Taiwan (Hong, 2018), Singapore (Tan, 2015), France/Tunisia (Frikha, 2018), and Europe (country not specified) (Fountzilas, 2012). Study characteristics and distributions of important patient characteristics (WHO types and clinical stage) is reported per study in Table 1.

Wang (2020) performed a meta-analysis using a fixed-effect model. All enrolled trials were identified as high quality (a score of ≥3), using the Jadad scoring scale. This SR was considered to have high quality, according to the AMSTAR criteria.

Table 1 Overview of study characteristics included in the SR of Wang (2020)

|

Author (year) |

Country |

Patient population |

Scheme |

Pathology |

WHO |

Intervention |

Control |

Clinical stage |

Intervention |

Control |

|

Fountzilas (2011) |

Europe |

Biopsy-proven, previously untreated WHO type I, II or III NPC; stage IIB–IVB (AJCC 2002) |

Cis/VP16/Taxol |

|

I |

7 (10%) |

5 (7%) |

IIB |

14 (19%) |

15 (22%) |

|

II |

15 (21%) |

15 (22%) |

III |

27 (38%) |

27 (39%) |

|||||

|

III |

50 (69%) |

49 (71%) |

IVA |

19 (26%) |

10 (14%) |

|||||

|

IVB |

12 (17%) |

17 (25%) |

||||||||

|

Tan (2015) |

Singapore |

Newly diagnosed with World Health Organization type 2 or 3 NPC, Union for International Cancer Control (1997) stage T3-4NxM0 or TxN2-3M0 |

Taxane versus non-Taxane |

|

II |

6 (7%) |

6 (7%) |

III |

50 (58%) |

53 (62%) |

|

III |

80 (93%) |

80 (93%) |

IVA |

16 (19%) |

11 (13%) |

|||||

|

IVB |

20 (23%) |

22 (26%) |

||||||||

|

Sun/Li (2016/ 2019) |

China |

Patients with previously untreated, non-distant metastatic, newly histologically confirmed non-keratinising stage III–IVB nasopharyngeal carcinoma (except T3–4N0; 7th UICC and AJCC)). Age <59 years. |

TPF |

non-keratinising |

Not reported |

III |

129 (54%) |

133 (56%) |

||

|

IVA |

73 (30%) |

80 (33%) |

||||||||

|

IVB |

39 (16%) |

26 (11%) |

||||||||

|

Cao/Yang (2017/ 2019) |

China |

Previously untreated, biopsy-proven WHO types II-III NPC; Stage III-IVB disease, excluding T3N0-1 (UICC/AJCC 6th edition). Age <60 years |

Cis/5-FU |

|

Not reported |

II |

1 (<1%) |

0 (0%) |

||

|

III |

117 (49%) |

133 (56%) |

||||||||

|

IV |

120 (50%) |

105 (44%) |

||||||||

|

Frikha (2018) |

France/ Tunisia |

Histological WHO type 2 or 3, stage T2b, T3, T4 and/or N1-N3, M0 |

TPF |

WHO II-III |

II |

4 (10%) |

7 (17%) |

Not reported |

||

|

III |

36 (90%) |

34 (83%) |

||||||||

|

Hong (2018) |

Taiwan |

Histologically proved stage IVA or IVB NPC (fifth edition of the AJCC/UICC staging system, 1997). Ages <70 years. |

MEPFL |

|

I |

1 (<1%) |

0 (0%) |

IVA-T4N0–2 |

111 (46%) |

113 (47%) |

|

IIa |

65 (27%) |

71 (30%) |

IVB-N3a |

57 (24%) |

56 (23%) |

|||||

|

IIb |

173 (72%) |

169 (70%) |

IVB-N3b |

71 (30% |

71 (30%) |

|||||

|

Zhang (2019) |

China |

Histologic confirmation of nonkeratinizing nasopharyngeal carcinoma; no previous treatment for cancer; nondistant metastatic, newly diagnosed stage III to IVB (AJCC–UICC 7th edition). Age <65 years. |

Cis/Gem |

non-keratinising |

Not reported |

III |

111 (46%) |

120 (50%) |

||

|

IVA |

104 (43%) |

94 (40%) |

||||||||

|

IVB |

27 (11%) |

24 (10%) |

||||||||

Results

Crucial outcome measures

Overall survival

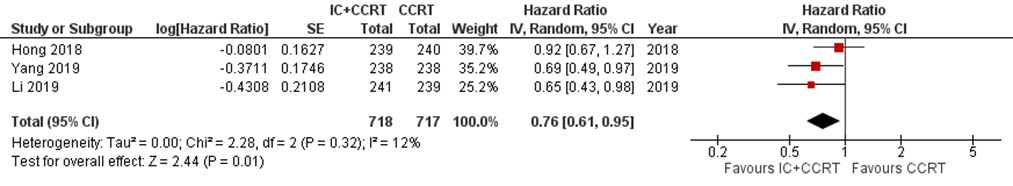

Three studies addressed this outcome at five-year follow-up (Hong, 2018; Li, 2019; Yang, 2019). In total, 1435 patients were analysed, with 718 patients in the IC+CCRT arm and 717 in the CCRT arm. In the IC+CCRT arm 588/718 (82%) patients were alive at 5 years follow-up, and in the CCRT arm 532/717 (74%). The hazard ratio was 0.76 (95% CI 0.61 to 0.95) in favour of IC+CCRT, using a random-effect model (Figure 1). The risk difference was 8% (95% CI: 4 to 12), which is clinically relevant.

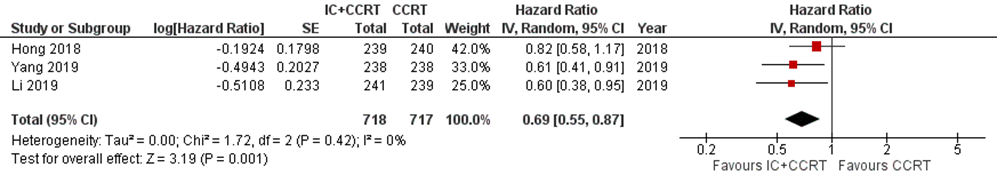

Figure 1 Forest plot for 5-year overall survival of IC+CCRT versus CCRT alone

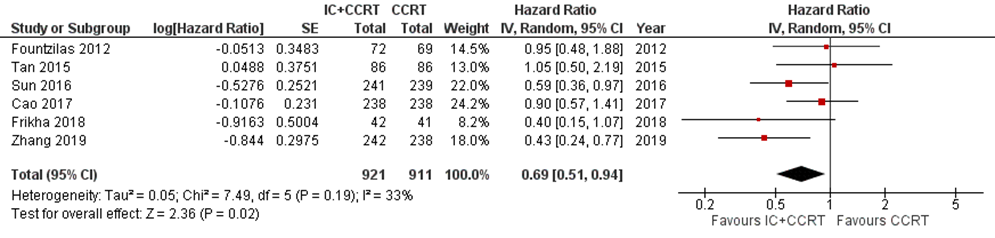

Six studies addressed this outcome at three-year follow-up (Cao, 2017; Fountzilas, 2012; Frikha, 2018; Sun, 2016; Tan, 2015; Zhang, 2019). In total, 1832 patients were analysed, with 921 patients in the IC+CCRT arm and 911 patients in the CCRT arm. The hazard ratio was 0.69 (95% CI 0.51 to 0.94) in favour of IC+CCRT (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Forest plot for 3-year overall survival of IC+CCRT versus CCRT alone

Disease-free survival

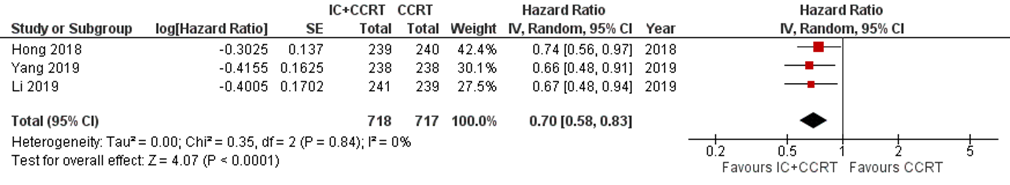

Three studies addressed this outcome at five-year follow-up (Hong, 2018; Li, 2019; Yang, 2019). In total, 1435 patients were analysed, with 718 patients in the IC+CCRT arm and 717 in the CCRT arm. In the IC+CCRT arm 507/718 (71%) patients were disease-free at 5 years follow-up, and in the CCRT arm 429/717 (60%). The hazard ratio was 0.70 (95% CI 0.51 to 0.94) (Figure 3). The risk difference was 11% (95% CI: 6 to 16), which is clinically relevant.

Figure 3 Forest plot for 5-year disease-free survival of IC+CCRT versusCCRT alone

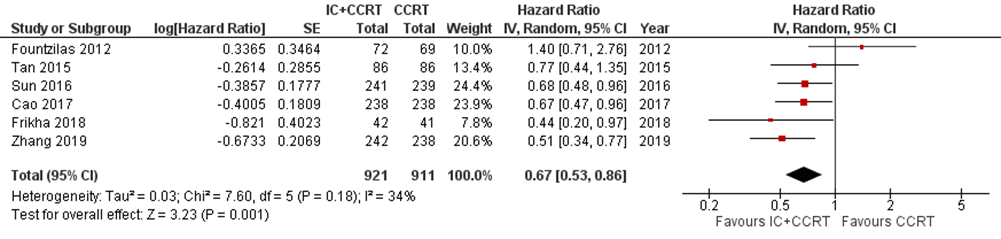

Six studies addressed this outcome at three-year follow-up (Cao, 2017; Fountzilas, 2012; Frikha, 2018; Sun, 2016; Tan, 2015; Zhang, 2019). In total, 1832 patients were analysed, with 921 patients in the IC+CCRT arm and 911 patients in the CCRT arm. The hazard ratio was 0.67 (95% CI 0.53 to 0.86) (Figure 4).

Figure 4 Forest plot for 3-year disease-free survival of IC+CCRT versus CCRT alone

Important outcome measures

Distant metastasis-free survival

Three studies addressed this outcome at five-year follow-up (Hong, 2018; Li, 2019; Yang, 2019). In total, 1435 patients were analysed, with 718 patients in the IC+CCRT arm and 717 in the CCRT arm. The hazard ratio was 0.69 (95% CI 0.55 to 0.87) (Figure 5).

Figure 5 Forest plot for 5-year distant metastasis-free survival of IC+CCRT versus CCRT alone

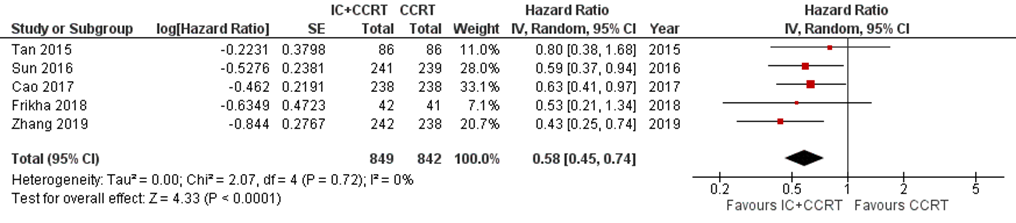

Five studies addressed this outcome at three-year follow-up (Cao, 2017; Frikha, 2018; Sun, 2016; Tan, 2015; Zhang, 2019). In total, 1691 patients were analysed, with 849 patients in the IC+CCRT arm and 842 patients in the CCRT arm. The hazard ratio was 0.58 (95% CI 0.45 to 0.74) (Figure 6).

Figure 6 Forest plot for 3-year distant metastasis-free survival of IC+CCRT versus CCRT alone

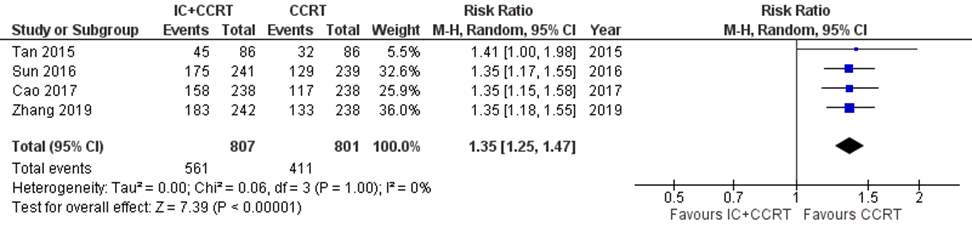

Complications/adverse events

Four studies addressed this outcome (Cao, 2017; Syn, 2016; Tan, 2015; Zhang, 2019). In total, 1608 patients were analysed, with 807 patients in the IC+CCRT arm and 801 in the CCRT arm.

In the IC+CCRT arm 561/807 (70%) reported grade ≥ 3 adverse events, compared to 411/801 (51%) in the CCRT arm (risk ratio (RR): 1.35; 95% CI 1.25 to 1.47), in favour of CCRT (Figure 7).

Figure 7 Forest plot for grade ≥ 3 adverse events of IC+CCRT versus CCRT alone

During overall treatment: In hematological toxicities, there were no significant differences in leukopenia (risk ratio (RR): 1.77, 95% CI: 0.98 to 3.19, p = 0.06) and anemia (RR: 2.97, 95% CI: 0.20 to 44.40, p = 0.43) between IC + CCRT group and CCRT group. However, the IC + CCRT group showed significantly higher risks of neutropenia (RR: 3.93, 95% CI: 1.78 to 8.68, p = 0.0007) and thrombocytopenia (RR: 6.55, 95% CI: 2.58 to 16.63, p < 0.0001) than the CCRT group.

In non-hematological toxicities, patients treated with IC + CCRT showed significantly higher risks of nausea (RR: 1.43, 95% CI: 1.09 to 1.87, p = 0.01), vomiting (RR: 1.40, 95% CI: 1.08 to 1.82, p = 0.01) and hepatotoxicity (RR: 5.37, 95% CI: 1.40 to 20.58, p = 0.01) rather than mucositis (RR: 1.04, 95% CI: 0.87 to 1.24, p = 0.68) and dermatitis (RR: 0.73, 95% CI: 0.37 to 1.44, p = 0.37) in comparison with patients treated with CCRT.

Quality of life (QoL)

One study addressed this outcome (Tan, 2015), with 86 patients in the IC+CCRT arm and 86 in the CCRT arm. They reported that the mean global QOL scores of the EORTC QLQ-30 module were balanced between the 2 arms. The IC+CCRT arm had significantly poorer symptom scores for dyspnea (24.3 versus 15.3; P=0.014) and diarrhea (15.2 versus 9.3; P=0.018) during CCRT compared with the CCRT alone arm. However, these differences were no longer significant during follow-up. There were no statistically significant differences in any of the functional scales between the two arms. For the EORTC H&N35 module, the control arm had significantly poorer scores for pain, swallowing, and use of pain killers during CCRT, and for social contact at the third month of follow-up, compared with the GCP arm.

Certainty of the evidence

Crucial outcome measures

Overall survival (5 year)

The certainty of the evidence regarding overall survival started high, as the evidence originated from an RCT. The level of evidence was downgraded by one level for imprecision (the pooled estimate crossed the line of clinically relevant difference), and indirectness (study population may not be comparable to Dutch population of nasopharynx carcinoma patients). We did not downgrade for risk of bias (lack of blinding), because overall survival was considered as a ‘hard’ outcome measure. Level of evidence was graded as low.

Disease-free survival (5 year)

The certainty of the evidence regarding disease-free survival started high, as the evidence originated from an RCT. The level of evidence was downgraded by one level for imprecision (the pooled estimate crossed the line of clinically relevant difference), and indirectness (study population may not be comparable to Dutch population of nasopharynx carcinoma patients). We did not downgrade for risk of bias (lack of blinding), because disease-free survival was considered as a ‘hard’ outcome measure. Level of evidence was graded as low.

Important outcome measures

Distant metastasis-free survival (5 year)

The certainty of the evidence regarding distant metastasis-free survival started high, as the evidence originated from an RCT. The level of evidence was downgraded by one level for imprecision (the pooled estimate exceeded clinically relevant difference), and indirectness (study population may not be comparable to Dutch population of nasopharynx carcinoma patients). We did not downgrade for risk of bias (lack of blinding), because distant metastasis-free survival was considered as a ‘hard’ outcome measure. Level of evidence was graded as low.

Complications/adverse events

The certainty of the evidence regarding complications/adverse events started high, as the evidence originated from an RCT. The level of evidence was downgraded by one level for risk of bias (participants, care providers and outcome assessors were not blinded) and one level for imprecision (small number of included patients). Level of evidence was graded as low.

Quality of life

The certainty of the evidence regarding quality of life started high, as the evidence originated from an RCT, and was downgraded by three levels because of risk of bias (one level for study limitations: participants, care providers and outcome assessors were not blinded); very serious imprecision (two levels because data originated from only one study with a very small number of included patients); publication bias. Level of evidence was graded as very low.

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question:

What are the effects of induction chemotherapy or induction chemotherapy + concurrent chemoradiation therapy compared with concurrent chemoradiation therapy alone in patients with T3/T4 nasopharynx carcinomas?

P: patients with nasopharynx carcinoma (T-stage 3-4);

I: induction chemotherapy or induction therapy + concurrent chemoradiotherapy;

C: concurrent chemoradiotherapy;

O: overall survival, disease-free survival, distant metastasis-free survival, complications/adverse events, quality of life.

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered overall survival, disease-free survival and toxicity as a critical outcome measure for decision making; and distant metastasis-free survival, complications/adverse events and quality of life as important outcome measures for decision making.

The guideline development group defined the outcome measures as follows:

|

Overall survival |

Time from randomisation to death from any cause, with a minimum follow-up of 5 years |

|

Disease-free survival |

Time during and after cancer treatment that the patient survives without any signs or symptoms of cancer recurrence, with a minimum follow-up of 5 years |

|

Distant metastasis-free survival |

Time to appearance of a distant metastasis, with a minimum follow-up of 5 years |

|

Complications/adverse events/toxicity |

All negative effects related to the treatment (lethal, acute/serious, chronic) |

|

Quality of life (QoL) |

Overall QoL or regarding a specific domain, measured with a validated and reliable instrument, such as the SF-36 or EORTC QLQ-C30. |

Clinically relevant difference

The guideline development group defined a minimal clinically relevant difference at a minimum of a median follow-up period of three years) (in line with “NVMO-commissie ter Beoordeling van Oncologische Middelen (BOM)”) of:

- Overall survival: > 5% difference, or > 3% and HR< 0.7.

- Relapse-free/disease-free survival: HR <0.7.

And, in case of absence of a clinically relevant difference in overall survival or relapse-free survival:

- Quality of life: A minimal clinically important difference of 10 points on the quality of life instrument EORTC QLQ-C30 or a difference of a similar magnitude on other quality of life instruments.

- Complications/adverse events: Statistically significant less complications/adverse events.

Data-analysis

A meta-analysis was performed to pool the results of the included studies. We used a random-effect model.

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms until June 17th, 2020. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 189 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria:

- included patients with nasopharynx carcinoma;

- compared induction chemotherapy or induction therapy + concurrent chemoradiotherapy with concurrent chemoradiotherapy alone;

- reported at least one of the outcomes of interest;

- the study design is a systematic review (SR) (preferably of randomized controlled trials; RCTs), or RCT;

- written in English language.

Based on title and abstract screening, 44 studies were initially selected. After reading the full text and thorough assessment of the studies, 43 studies were excluded (see table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and one study was included.

Results

One SR was included in the analysis of the literature. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- Cao, S. M., Yang, Q., Guo, L., Mai, H. Q., Mo, H. Y., Cao, K. J.,... & Lin, Z. X. (2017). Neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by concurrent chemoradiotherapy versus concurrent chemoradiotherapy alone in locoregionally advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma: a phase III multicentre randomised controlled trial. European journal of cancer, 75, 14-23.

- Fountzilas, G., Ciuleanu, E., Bobos, M., Kalogera-Fountzila, A., Eleftheraki, A. G., Karayannopoulou, G.,... & Dionysopoulos, D. (2012). Induction chemotherapy followed by concomitant radiotherapy and weekly cisplatin versus the same concomitant chemoradiotherapy in patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma: a randomized phase II study conducted by the Hellenic Cooperative Oncology Group (HeCOG) with biomarker evaluation. Annals of oncology, 23(2), 427-435.

- Frikha, M., Auperin, A., Tao, Y., Elloumi, F., Toumi, N., Blanchard, P.,... & Alfonsi, M. (2018). A randomized trial of induction docetaxel–cisplatin–5FU followed by concomitant cisplatin-RT versus concomitant cisplatin-RT in nasopharyngeal carcinoma (GORTEC 2006-02). Annals of Oncology, 29(3), 731-736.

- Hong, R. L., Hsiao, C. F., Ting, L. L., Ko, J. Y., Wang, C. W., Chang, J. T. C.,... & Liu, T. W. (2018). Final results of a randomized phase III trial of induction chemotherapy followed by concurrent chemoradiotherapy versus concurrent chemoradiotherapy alone in patients with stage IVA and IVB nasopharyngeal carcinoma-Taiwan Cooperative Oncology Group (TCOG) 1303 Study. Annals of Oncology, 29(9), 1972-1979.

- Li, W. F., Chen, N. Y., Zhang, N., Hu, G. Q., Xie, F. Y., Sun, Y.,... & Xu, X. Y. (2019). Concurrent chemoradiotherapy with/without induction chemotherapy in locoregionally advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma: Long‐term results of phase 3 randomized controlled trial. International journal of cancer, 145(1), 295-305.

- Sun, Y., Li, W. F., Chen, N. Y., Zhang, N., Hu, G. Q., Xie, F. Y.,... & Hu, C. S. (2016). Induction chemotherapy plus concurrent chemoradiotherapy versus concurrent chemoradiotherapy alone in locoregionally advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma: a phase 3, multicentre, randomised controlled trial. The lancet oncology, 17(11), 1509-1520.

- Tan, T., Lim, W. T., Fong, K. W., Cheah, S. L., Soong, Y. L., Ang, M. K.,... & Yip, C. (2015). Concurrent chemo-radiation with or without induction gemcitabine, carboplatin, and paclitaxel: a randomized, phase 2/3 trial in locally advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma. International Journal of Radiation Oncology* Biology* Physics, 91(5), 952-960.

- Wang, B. C., Xiao, B. Y., Lin, G. H., Wang, C., & Liu, Q. (2020). The efficacy and safety of induction chemotherapy combined with concurrent chemoradiotherapy versus concurrent chemoradiotherapy alone in nasopharyngeal carcinoma patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC cancer, 20, 1-13.

- Yang, Q., Cao, S. M., Guo, L., Hua, Y. J., Huang, P. Y., Zhang, X. L.,... & Xie, Y. L. (2019). Induction chemotherapy followed by concurrent chemoradiotherapy versus concurrent chemoradiotherapy alone in locoregionally advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma: long-term results of a phase III multicentre randomised controlled trial. European Journal of Cancer, 119, 87-96.

- Zhang, Y., Chen, L., Hu, G. Q., Zhang, N., Zhu, X. D., Yang, K. Y.,... & Cheng, Z. B. (2019). Gemcitabine and cisplatin induction chemotherapy in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. New England Journal of Medicine, 381(12), 1124-1135.

Evidence tabellen

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C) |

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

Wang, 2020

|

SR and meta-analysis of RCTs

Literature search up to 11/09/2019

A: Fountzilas, 2012 B: Tan, 2015 C1: Sun, 2016 C2: Li, 2019 D1: Cao, 2017 D2: Yang, 2019 E: Frikha, 2018 F: Hong, 2018 G: Zhang, 2019

Study design: A: phase II RCT B: phase II/III RCT C: phase III RCT D: phase III RCT E: phase III RCT F: phase III RCT G: phase III RCT

Setting and country: A: Europe B: Singapore C: China D: China E: France/Tunisia F: Taiwan G: China

Inclusion period: A: 2003–2008 B: 2004–2012 C: 2011–2013 D: 2008–2015 E: 2009–2012 F: 2003–2009 G: 2013–2016

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: Non-commercial funding was reported. Authors reported no conflicts of interest. |

Inclusion criteria SR: (1) prospective studies in previously untreated patients with NPC (2) studies were registered clinical trials, and registration numbers were provided (3) randomized controlled clinical studies (4) the experiment group was treated with IC combined with CCRT, and the control group was treated with CCRT alone (5) neoadjuvant chemotherapy described in the articles was deemed as induction chemotherapy (6) studies published in English.

Exclusion criteria SR: (1) IC or CCRT combined with target therapy was excluded (2) conference abstracts

9 articles reporting on 7 studies were included

Important patient characteristics at baseline:

N, total, intervention/control A: 141, 72/69 B: 172, 86/86 C: 480, 241/239 D: 476, 238/238 E: 83, 42/41 F: 479, 239/240 G: 480, 242/238

Mean age (range) A: I: 49 (19–82) C: 51 (15–79) B: I: 49 (42–55) C: 52 (457) C: I: 42 (36–49) C: 44 (39–50) D: I: 44 (19–65) C: 42 (21–66) E: I: 46 C: 48 F: I: 45 (15–69) C: 47 (19–70) G: I: 46 (18–64) C: 45 (20–64)

Sex, n/N (%) A: I: 55/72 (76%) C: 48/69 (70%) B: I: 71/86 (83%) C: 63/86 (73%) C: I: 193/241 (80%) C:174/239 (73%) D: I: 173/238 (73%) C: 190/238 (80%) E: I: 28/42 (67%) C: 32/41 (78%) F: I: 176/239 (74%) C: 179/240 (75%) G: I: 182/242 (75%) C: 164/238 (69%)

Stage A: IIb - IVb B: III - IVb C: III - IVb D: III - IVb E: T2b, T3, T4 and/or N1-N3, M0 F: IVa-IVb G: IVa-IVb

WHO type (I, II, III) n (%) A: I: 7 (10%) / 15 (21%) / 50 (69%) C: 5 (7%) / 15 (22%) / 49 (71%) B: I: 0 (0%) / 6 (7%) / 90 (93%), C: 0 (0%) / 6 (7%) / 90 (93%) C: not reported D: not reported E: I: 0 (0%) / 4 (10%) / 36 (90%), C: 0 (0%), 7 (17%) / 34 (83%) F: I: I: 1 (<1%) / IIa: 65 (27%) / IIb: 173 (72%), C: I: 0 (0%) / IIa: 71 (30%) / IIb: 169 (70%), G: not reported

History of smoking Yes, n (%) A: I: 28 (39%), C: 25 (36%) B: not reported C: not reported

Groups comparable at baseline? Not reported in SR

|

A: Epi 75 mg/m2, Pac 175 mg/m2 and DDP 75 mg/m2 every 21 days for 3 cycles B: Gem 1000 mg/m2, CBP area under the concentration-time-curve 2.5, and Pac 70 mg/m2 (day 1 and 8) every 21 days for 3 cycles C: Doc 60mg/m2, DDP 60 mg/m2 and 5-FU 600 mg/ m2 every 21 days for 3 cycles D: DDP 80mg/m2 and 5-FU 800 mg/m2 (day 1–5) every 21 days for 2 cycles E: Doc 75mg/m2, DDP 75 mg/m2 and 5-FU 750 mg/ m2/day day (1–5) every 21 days for 3 cycles F: Mit 8 mg/m2, Epi 60 mg/m2, and DDP 60 mg/m2 on day 1, 5-FU 450 mg/m2 and Leu 30 mg/m2 on day 8 G: Gem 1 g/m2 (day 1 and 8) and DDP 80 mg/m2 every 21 days for 3 cycles

Epi: epirubicin Pac: paclitaxel DDP: cisplatin Gem: gemcitabine CBP: carboplatin Doc: docetaxel: 5-FU: 5-fluorouracil Mit: mitomycin Leu: leucovorin

|

Radiotherapy: A: 2D-CRT, 3DCRT B: 2D-CRT, IMRT C: IMRT D: 2D-CRT, IMRT E: IMRT, non-IMRT F: 3D-CRT, IMRT G: IMRT

A: DDP 40 mg/m2 every week B: DDP 40 mg/m2 every week C: DDP 100 mg/m2 every 21 days for 3 cycles D: DDP 80 mg/m2 every 21 days for 3 cycles E: DDP 40 mg/m2 every week F: DDP 30 mg/m2 every week G: DDP 100 mg/m2 every 21 days for 3 cycles

2D/2D-CRT: 2/3-dimensional conformal radiotherapy IMRT: intensity modulated radiotherapy DDP: cisplatin |

End-point of follow-up:

A: 3 years B: 3 years C: 3 years / 5 years D: 3 years / 5 years E: 3 years F: 5 years G: 3 years

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? Not reported. |

5-year overall survival Effect measure: Hazard ratio (95% CI):

A: not reported B: not reported C2: 0.65 (0.43 – 0.98) D2: 0.69 (0.49 – 0.97) E: not reported F: 0.92 (0.67 – 1.27) G: not reported

Pooled effect (random effects model): 0.76 (95% CI 0.61 to 0.95) favoring IC+CCRT Heterogeneity (I2): 12%

3-year overall survival Effect measure: Hazard ratio (95% CI):

A: 0.95 (0.48 – 1.88) B: 1.05 (0.50 – 2.19) C1: 0.59 (0.36 – 0.97) D1: 0.90 (0.57 – 1.41) E: 0.40 (0.15 – 1.07) F: not reported G: 0.43 (0.24 – 0.77)

Pooled effect (random effects model): 0.69 (95% CI 0.51 to 0.94) favoring IC+CCRT Heterogeneity (I2): 33%

Failure-free survival (FFS): FFS was defined as the date of randomization to documented disease progression (the date of locoregional/distant failure or death from any cause, whichever occurred first) Effect measure: Hazard ratio (95% CI): A: not reported B: not reported C2: 0.67 (0.48 – 0.94) D2: 0.66 (0.48 – 0.91) E: not reported F: 0.74 (0.56 – 0.97) G: not reported

Pooled effect (random effects model): 0.70 (95% CI 0.58 to 0.83) favoring IC+CCRT Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

Effect measure: Hazard ratio (95% CI): A: 1.40 (0.71 – 2.76) B: 0.77 (0.44 – 1.35) C1: 0.68 (0.48 – 0.96) D1: 0.67 (0.47 – 0.96) E: 0.44 (0.20 – 0.97) F: not reported G: 0.51 (0.34 – 0.77)

Pooled effect (random effects model): 0.67 (95% CI 0.53 to 0.86) favoring IC+CCRT Heterogeneity (I2): 34%

5-year distant metastasis-free survival (DMFS) Effect measure: Hazard ratio (95% CI): A: not reported B: not reported C2: 0.60 (0.38 – 0.95) D2: 0.61 (0.41 – 0.91) E: not reported F: 0.82 (0.58 – 1.17) G: not reported

Pooled effect (random effects model): 0.69 (95% CI 0.60 to 0.87) favoring IC+CCRT Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

3-year distant metastasis-free survival (DMFS) Effect measure: Hazard ratio (95% CI): A: not reported B: 0.80 (0.38 – 1.68) C1: 0.59 (0.37 – 0.94) D1: 0.63 (0.41 – 0.97) E: 0.53 (0.21 – 1.34) F: not reported G: 0.43 (0.25 – 0.74)

Pooled effect (random effects model): 0.58 (95% CI 0.45 to 0.74) favoring IC+CCRT Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

Defined as grade ≥ 3 adverse event rate

B: I: 52%, C: 37%, p<0.05 RR: 1.41 (1.00 – 1.98) C: I: 73%, C: 54%, p>0.05 RR: 1.35 (0.17 – 1.55) D: I: 66%, C: 49%, p<0.05 RR: 1.35 (1.15 – 1.58) E: not reported F: not reported G: I: 76%, C: 56%, p>0.05 RR: 1.35 (1.18 – 1.55)

Pooled effect (random effects model): 1.35 (95% CI 1.25 to 1.47) favoring CCRT Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

Quality of life A: not reported B: measured with EORTC QLQ-C30 and EORTC QLQ-H&N35: The mean global QOL scores of the QLQ-30 module were balanced between the 2 arms. The IC+CCRT arm had significantly poorer symptom scores for dyspnea (24.3 versus 15.3; P=0.014) and diarrhea (15.2 versus 9.3; P=0.018) during CCRT compared with the control arm. However, these differences were no longer significant during follow-up. There were no statistical differences in any of the functional scales between the two arms. For the H&N35 module, the control arm had significantly poorer scores for pain, swallowing, and use of pain killers during CCRT, and for social contact at the third month of follow-up, compared with the GCP arm. C1: not reported C2: not reported D1: not reported D2: not reported E: not reported F: not reported |

Remarks - Authors of the SR presented pooled analysis with a fixed effect model, while we used a random effects model. - Authors used the Jadad scoring scale, and all enrolled trials were identified as high quality (a score of ≥3). - Individual study characteristics and results are extracted from the SR (unless stated otherwise)

- IC combined with CCRT significantly improved the survival in locoregional advanced NPC patients. Moreover, toxicities were well tolerated during IC and CCRT. Further clinical trials are warranted to confirm the optimal induction chemotherapeutic regimen in the future.

Sensitivity analyses Not applicable

Heterogeneity Not applicable |

Quality assessment

Table of quality assessment for systematic reviews of RCTs and observational studies

Based on AMSTAR checklist (Shea, 2007; BMC Methodol 7: 10; doi:10.1186/1471-2288-7-10) and PRISMA checklist (Moher, 2009; PLoS Med 6: e1000097; doi:10.1371/journal.pmed1000097)

|

Study

|

Appropriate and clearly focused question?1

|

Comprehensive and systematic literature search?2

|

Description of included and excluded studies?3

|

Description of relevant characteristics of included studies?4

|

Appropriate adjustment for potential confounders in observational studies?5

|

Assessment of scientific quality of included studies?6

|

Enough similarities between studies to make combining them reasonable?7 |

Potential risk of publication bias taken into account?8 |

Potential conflicts of interest reported?9

|

|

Wang, 2020 |

Yes |

Yes

|

Yes |

Yes |

Not applicable |

Yes (Jadad score)

|

Yes |

No |

Yes |

- Research question (PICO) and inclusion criteria should be appropriate and predefined.

- Search period and strategy should be described; at least Medline searched; for pharmacological questions at least Medline + EMBASE searched.

- Potentially relevant studies that are excluded at final selection (after reading the full text) should be referenced with reasons.

- Characteristics of individual studies relevant to research question (PICO), including potential confounders, should be reported.

- Results should be adequately controlled for potential confounders by multivariate analysis (not applicable for RCTs).

- Quality of individual studies should be assessed using a quality scoring tool or checklist (Jadad score, Newcastle-Ottawa scale, risk of bias table et cetera).

- Clinical and statistical heterogeneity should be assessed; clinical: enough similarities in patient characteristics, intervention and definition of outcome measure to allow pooling? For pooled data: assessment of statistical heterogeneity using appropriate statistical tests (for example Chi-square, I2)?

- An assessment of publication bias should include a combination of graphical aids (for example funnel plot, other available tests) and/or statistical tests (for example, Egger regression test, Hedges-Olken). Note: If no test values or funnel plot included, score “no”. Score “yes” if mentions that publication bias could not be assessed because there were fewer than 10 included studies.

- Sources of support (including commercial co-authorship) should be reported in both the systematic review and the included studies. Note: To get a “yes,” source of funding or support must be indicated for the systematic review AND for each of the included studies.

Table of excluded studies

|

Author and year |

Reason for exclusion |

|

Ahn, 2019 |

Narrative review |

|

Al-Rajhi, 2020 |

Does not match PICO (wrong comparison): low-dose fractioned radiotherapy + IC versus IC alone |

|

Blanchard, 2015 |

Does not add extra RCTs to Wang (2020) |

|

Chen, 2018 |

Does not add extra RCTs to Wang (2020) |

|

Chen, 2018 |

No full-text available |

|

Chen, 2015 |

Does not add extra RCTs to Wang (2020) |

|

Fountzilas, 2012 |

Included in Wang (2020) BMC Cancer |

|

Frikha, 2018 |

Included in Wang (2020) BMC Cancer |

|

He, 2019 |

Does not match PICO (wrong comparison) |

|

Hong, 2018 |

Included in Wang (2020) BMC Cancer |

|

Huang, 2015 |

Does not match PICO (wrong comparison) |

|

Huang, 2012 |

Does not match PICO (wrong comparison) |

|

Huang, 2012 |

Non-English publication |

|

Jin, 2019 |

Does not match PICO (wrong comparison): TPF+CCRT versus PF+CCRT |

|

Kong, 2017 |

Wrong study design (not randomised) |

|

Lee, 2015 |

Does not match PICO (wrong comparison) |

|

Li, 2019 |

Does not add extra RCTs to Wang (2020) |

|

Li, 2019 |

Included in Wang (2020) BMC Cancer |

|

Li, 2017 |

Non-English publication |

|

Liang, 2013 |

Does not add extra RCTs to Wang (2020) |

|

Liu, 2018 |

Does not add extra RCTs to Wang (2020) |

|

OuYang, 2019 |

Does not add extra RCTs to Wang (2020) |

|

Petit, 2019 |

Does not add extra RCTs to Wang (2020) |

|

Ribassin-Majed, 2017 |

Does not add extra RCTs to Wang (2020) |

|

Song, 2015 |

Does not add extra RCTs to Wang (2020) |

|

Song, 2015 |

Duplicate met Song (2015) hierboven |

|

Tan, 2018 |

Does not add extra RCTs to Wang (2020) |

|

Tian, 2015 |

Does not match PICO (wrong comparison) |

|

Wang (Peirong), 2020 |

Does not add extra RCTs to Bi-Chen Wang (2020) |

|

Wang, 2019 |

Does not match PICO (wrong comparison): low HDL-C versus high HDL-C |

|

Xu, 2019 |

Wrong study design (not randomised) |

|

Yang, 2019 |

Included in Wang (2020) BMC Cancer |

|

Yang, 2018 |

Does not match PICO (wrong comparison) |

|

You, 2017 |

Does not add extra RCTs to Wang (2020) |

|

Yu, 2016 |

Does not add extra RCTs to Wang (2020) |

|

Zang, 2018 |

Wrong study design (not randomised) |

|

Zeng, 2016 |

Wrong study design (not randomised) |

|

Zhang, 2019 |

Does not match PICO (wrong comparison) |

|

Zhang, 2019 |

Included in Wang (2020) BMC Cancer |

|

Zhang, 2018 |

Does not match PICO (wrong outcomes, prediction model) |

|

Zhang, 2012 |

Does not match PICO (wrong comparison) |

|

Zhao, 2019 |

Wrong study design (not randomised) |

|

Zhou, 2020 |

Does not add extra RCTs to Wang (2020) |

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Publicatiedatum : 24-07-2025

Beoordeeld op geldigheid :

De geldigheid van de richtlijnmodule komt te vervallen indien nieuwe ontwikkelingen aanleiding zijn een herzieningstraject te starten.

NB: Informatie over de autorisatiedatum, autoriserende partij(en), herbevestiging en regiehouder(s) worden ter zijne tijd na autorisatie toegevoegd aan deze alinea.

|

Module[1] |

Regiehouder(s)[2] |

Jaar van autorisatie |

Eerstvolgende beoordeling actualiteit richtlijn[3] |

Frequentie van beoordeling op actualiteit[4] |

Wie houdt er toezicht op actualiteit[5] |

Relevante factoren voor wijzigingen in aanbeveling[6] |

| Behandeling nasofarynxcarcinoom - inductie chemotherapie |

[1] Naam van de module

[2] Regiehouder van de module (deze kan verschillen per module en kan ook verdeeld zijn over meerdere regiehouders)

[3] Maximaal na vijf jaar

[4] (half)Jaarlijks, eens in twee jaar, eens in vijf jaar

[5] regievoerende vereniging, gedeelde regievoerende verenigingen, of (multidisciplinaire) werkgroep die in stand blijft

[6] Lopend onderzoek, wijzigingen in vergoeding/organisatie, beschikbaarheid nieuwe middelen

Algemene gegevens

De ontwikkeling/herziening van deze richtlijnmodule werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten en werd gefinancierd uit de Stichting Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS). De financier heeft geen enkele invloed gehad op de inhoud van de richtlijnmodule.

De richtlijn is ontwikkeld in samenwerking met:

- Nederlandse Internisten Vereniging

- Nederlandse Vereniging voor Mondziekten, Kaak- en Aangezichtschirurgie

- Nederlandse Vereniging voor Nucleaire Geneeskunde

- Nederlandse Vereniging voor Pathologie

- Nederlandse Vereniging voor Plastische Chirurgie

- Nederlandse Vereniging voor Radiologie

- Nederlandse Vereniging voor Radiotherapie en Oncologie

- Nederlandse Federatie van Kankerpatiëntenorganisaties | Patiëntenvereniging HOOFD-HALS

- Verpleegkundigen en Verzorgenden Nederland | Oncologie

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijnmodule is in 2019 een multidisciplinaire werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor patiënten met hoofd-halstumoren.

Werkgroep

- Prof. Dr. R. de Bree, KNO-arts/hoofd-halschirurg, UMC Utrecht, Utrecht, NVKNO (voorzitter)

- Dr. M.B. Karakullukcu, KNO-arts/hoofd-halschirurg, NKI, Amsterdam, NVKNO

- Dr. H.P. Verschuur, KNO-arts/hoofd-halschirurg, Haaglanden MC, Den Haag, NVKNO

- Dr. M. Walenkamp, AIOS-KNO, LUMC, Leiden, NVKNO

- Dr. A. Sewnaik, KNO-arts/hoofd-halschirurg, Erasmus MC, Rotterdam, NVKNO

- Drs. L.H.E. Karssemakers, MKA-chirurg-oncoloog/hoofd-hals chirurg, NKI, Amsterdam, NVMKA

- Dr. M.J.H. Witjes, MKA-chirurg-oncoloog, UMC Groningen, Groningen, NVMKA

- Drs. L.A.A. Vaassen, MKA-chirurg-oncoloog, Maastricht UMC+, Maastricht, NVMKA

- Drs. W.L.J. Weijs, MKA-chirurg-oncoloog, Radboud UMC, Nijmegen, NVKMA

- Drs. E.M. Zwijnenburg, Radiotherapeut-oncoloog, Radboud UMC, Nijmegen, NVRO

- Dr. A. Al-Mamgani, Radiotherapeut-oncoloog, NKI, Amsterdam, NVRO

- Prof. Dr. C.H.J. Terhaard, Radiotherapeut-oncoloog, UMC Utrecht, Utrecht, NVRO

- Drs. J.G.M. Van den Hoek, Radiotherapeut-oncoloog, UMC Groningen, Groningen, NVRO

- Dr. E. Van Meerten, Internist-oncoloog, Erasmus MC Kanker Instituut, Rotterdam, NIV

- Dr. M. Slingerland, Internist-oncoloog, LUMC, Leiden, NIV

- Drs. M.A. Huijing, Plastisch Chirurg, UMC Groningen, Groningen, NVPC

- Prof. Dr. S.M. Willems, Klinisch patholoog, UMC Groningen, Groningen, NVVP

- Prof. Dr. E. Bloemena, Klinisch patholoog, Amsterdam UMC, locatie Vumc, Amsterdam, NVVP

- R.A. Burdorf, Voorzitter dagelijks bestuur patiëntenvereniging, Patiëntenvereniging HOOFD-HALS, PvHH

- P.S. Verdouw, Hoofd infocentrum patiëntenvereniging, Patiëntenvereniging HOOFD-HALS, PvHH

- A.A.M. Goossens, Verpleegkundig specialist oncologie, Haaglanden MC, Den Haag, V&VN

- Dr. P. de Graaf, Radioloog, Amsterdam UMC, Amsterdam, NVvR

- Dr. W.V. Vogel, Nucleair geneeskundige/radiotherapeut-oncoloog, NKI, Amsterdam, NVNG

- Drs. G.J.C. Zwezerijnen, Nucleair geneeskundige, Amsterdam UMC, Amsterdam, NVNG

Klankbordgroep

- Dr. C.M. Speksnijder, Fysiotherapeut, UMC Utrecht, Utrecht, KNGF

- Ir. A. Kok, Diëtist, UMC Utrecht, Utrecht, NVD

- Dr. M.M. Hakkesteegt, Logopedist, Erasmus MC, Rotterdam, NVvLF

- Drs. D.J.M. Buurman, Tandarts-MFP, Maastricht UMC+, Maastricht, KNMT

- W. Van der Groot-Roggen, Mondhygiënist, UMC Groningen, Groningen, NVvM

- Drs. D.J.S. Dona, Bedrijfsarts/Klinisch arbeidsgeneeskundige oncologie, Radboud UMC, Nijmegen, NVKA

- Dr. M. Sloots, Ergotherapeut, UMC Utrecht, Utrecht

- J. Poelstra, Medisch maatschappelijk werkster, op persoonlijke titel

Met dank aan

- Maarten Donswijk, Nucleair geneeskundig, AVL

Met ondersteuning van

- Dr. J. Boschman, Senior adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- Dr. C. Gaasterland, Adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- Dr. A. Van der Hout, Adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- Dr. L. Oostendorp, Adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- Drs. M. Oerbekke, Adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- Drs. A. Hoeven, Junior adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

Belangenverklaringen

De Code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling is gevolgd. Alle werkgroepleden hebben schriftelijk verklaard of zij in de laatste drie jaar directe financiële belangen (betrekking bij een commercieel bedrijf, persoonlijke financiële belangen, onderzoeksfinanciering) of indirecte belangen (persoonlijke relaties, reputatiemanagement) hebben gehad. Gedurende de ontwikkeling of herziening van een module worden wijzigingen in belangen aan de voorzitter doorgegeven. De belangenverklaring wordt opnieuw bevestigd tijdens de commentaarfase.

Een overzicht van de belangen van werkgroepleden en het oordeel over het omgaan met eventuele belangen vindt u in onderstaande tabel. De ondertekende belangenverklaringen zijn op te vragen bij het secretariaat van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

|

Werkgroeplid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

Bree, de |

KNO-arts/hoofd-halschirurg, UMC Utrecht |

* Lid Algemeen Bestuur Patiëntenvereniging Hoofd-Hals (onbetaald) * Voorzitter Research Stuurgroep NWHHT * Lid Richtlijnen commissie NWHHT * Lid dagelijks bestuur NWHHT * Lid Clinical Audit Board van de Dutch Head and Neck Audit (DHNA) * Lid wetenschappelijk adviescommissie DORP * Voorzitter Adviescommissie onderzoek hoofd-halskanker (IKNL/PALGA/DHNA/NWHHT) |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Slingerland |

Internist-oncoloog, LUMC |

* 2018-present: Treasurer of the "Dutch Association of Medical Oncology"(NVMO - vacancy fees) * 2018-present: Member of the "Dutch Working Group for Head-Neck Tumors" (NWHHT-Systemic therapy) * 2016-present: Member of the 'Dutch Working Group for Head-Neck Tumors" (NWHHT - study group steering group (coordinating)) * 2016-present: Member of the "Dutch Working Group for Head-Neck Tumors" (NWHHT - Elderly Platform) * 2012-present: Member "Working Group for Head-Neck Tumors" (WHHT) "University Cancer Centre"(UCK) Leiden - Den Haag * 2019: Member CAB DHNA |

Deelname Nationaal expert forum hoofd-halskanker MSD dd 2-5-2018

* Deelname Checkmate studie, sponsor Bristol-Myers Squibb (BMS): An open label, randomized phase 3 clinical trial of nivolumab versus therapy of investigator's choice in recurrent or metastatic platinum-refractory squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (SCCHN) * Deelname Commence studie, sponsor Radboud University, in collaboration with Merck Serono International SA (among several Dutch medical centers): A phase lB-II study of the combination of cetuximab and methotrexate in recurrent of metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. A study of the Dutch Head and Neck Society, MOHN01/COMMENCE study. * Deelname HESPECTA studie: Phase I study: to determine the biological activity of two HPV16E6 specific peptides coupled to Amplivant®, a Toll-like receptor ligand in non-metastatic patients treated for HPV16-positive head and neck cancer. * Deelname PINCH studie (nog niet open): PD-L1 ImagiNg to predict durvalumab treatment response in HNSCC (PINCH) trial; patiënten met biopt bewezen locally recurrent of gemetastaseerd HNSCC * Deelname ISA 101b-HN-01-17 studie (nog niet open): A randomized, Double-blind, Placebo-Controlled, Phase 2 Study of Cemiplimab versus the combination of Cemiplimab with ISA101b in the Treatment of Subjects. |

In de werkgroep participeren 2 internist-oncologen, zodat één van beide de voortrekker is van modules over systemische therapie. Actie: werkgroeplid is uitgesloten van besluitvorming bij modules die betrekking hebben op de onderwerpen van de gemelde onderzoeken: nivolumab, cetuximab + methotrexaat, Amplivant, durvalumab, cemiplimab. |

|

Meerten, van |

Internist-oncoloog, Erasmus MC Kanker Instituut |

Geen |

Op dit moment Principal Investigator voor NL van gerandomiseerde fase III trial naar toegevoegde waarde van pembrolizumab aan chemoradiotherapie bij patiënten met gevorderd hoofdhalskanker. Sponsor: GlaxoSmithKline Research & Development Ltd. Studie is nog lopend, resultaten zullen pas bekend zijn na verschijning van de richtlijn.

In toekomst mogelijk participatie aan door industrie gesponsorde studies op gebied van behandeling van hoofdhalskanker |

In de werkgroep participeren 2 internist-oncologen, zodat één van beide de voortrekker is van modules over systemische therapie. Actie: werkgroeplid is uitgesloten van besluitvorming bij modules die betrekking hebben op het onderwerp van het gemelde onderzoeken: de toegevoegde waarde van pembrolizumab bij patiënten met gevorderd hoofdhalskanker. |

|

Huijing |

Plastisch chirurg, UMC Groningen |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Sewnaik |

KNO-arts/hoofd Hals chirurg, Erasmus MC |

Sectorhoofd Hoofd-Hals chirurgie |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Vaassen |

MKA-chirurg-oncoloog, Maastricht UMC+ / CBT Zuid-Limburg |

*Lid Bestuur NVMKA *Waarnemend hoofd MKA-chirurgie MUMC |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Witjes |

MKA-chirurg-oncoloog, UMC Groningen |

Geen |

PI van KWF grant: RUG 2015 -8084: Image guided surgery for margin assessment of head & neck Cancer using cetuximab-IRDye800 cONjugate (ICON)

geen financieel belang |

Geen. Financiering door KWF werd niet als een belang ingeschat. |

|

Bloemena |

Klinisch patholoog, Amsterdam UMC (locatie Vumc) / Radboud UMC / Academisch Centrum voor Tandheelkunde Amsterdam (ACTA) |

* Lid bestuur Nederlandse Vereniging voor Pathologie (NVVP) – vacatiegeld (tot 1-12-20) * Voorzitter Commissie Bij- en Nascholing (NVVP) * Voorzitter (tot 1-12-20) Wetenschappelijke Raad PALGA - onbezoldigd |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Willems |

Klinisch patholoog, UMC Groningen |

Vice-vz PALGA, AB NWHHT, CAB DHNA, mede-vz en oprichter expertisegroep HH pathologie NL, Hoofdhalspathologie UMC Groningen |

PDL1 trainer NL voor MSD Onderzoeksfinanciering van Pfizer, Roche, MSD, BMS, Lilly, Novartis, Bayer, Amge, AstraZeneca |

Geen |

|

Karakullukcu |

KNO-arts/hoofd-hals chirurg, NKI/AVL |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Verschuur |

KNO-arts/Hoofd-hals chirurg, Haaglanden MC |

* Opleider KNO-artsen |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Walenkamp |

AIOS KNO, LUMC |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Al-Mamgani |

Radiotherapeut-oncoloog, NKI/AVL |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Terhaard |

Radiotherapeut-oncoloog, UMC Utrecht |

Niet van toepassing |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Hoek, van den |

Radiotherapeut-oncoloog UMCG |

Niet van toepassing |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Zwijnenburg |

Radiotherapeut, Hoofd-hals Radboud UMC |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Burdorf |

Patiëntvertegenwoordiger |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Verdouw |

Hoofd Infocentrum patiëntenvereniging HOOFD HALS |

Geen |

Werkzaam bij de patiëntenvereniging. De achterban heeft baat bij een herziening van de richtlijn |

Geen |

|

Karssemakers |

Hoofd-hals chirurg NKI/AVL

MKA-chirurg-oncoloog Amsterdam UMC (locatie AMC) / vakgroep kaakchirurgie Amsterdam West |

Niet van toepassing |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Goossens |

Verpleegkundig specialist, Haaglanden Medisch Centrum (HMC) |

* Bestuurslid (penningmeester) PWHHT (onbetaald) * Lid Commissie voorlichting PVHH (onbetaald) |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Zwezerijnen |

Nucleair geneeskundige, Amsterdam UMC (locatie Vumc)

PhD kandidaat, Amsterdam UMC (locatie Vumc) |

Lid als nucleair geneeskundige in HOVON imaging werkgroep (bespreken van richtlijnen en opzetten/uitvoeren van wetenschappelijke studies met betrekking tot beeldvorming in de hematologie); onbetaald |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Vogel |

Nucleair geneeskundige/radiotherapeut-oncoloog, AVL |

Geen |

In de afgelopen jaren incidenteel advies of onderwijs, betaald door Bayer, maar niet gerelateerd aan hoofd-hals

KWF-grant speekselklier toxiteit na behandeling. Geen belang bij de richtlijn |

Geen |

|

Graaf, de |

Radioloog, Amsterdam UMC (locatie Vumc) |

Bestuurslid sectie Hoofd-Hals radiologie (onbetaald) |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Weijs |

MKA-chirurg-oncoloog, Radboudumc |

MKA-chirurg, Weijsheidstand B.V. Werkzaam als algemeen praktiserend MKA-chirurg, betaald (0,1 fte) |

Geen |

Geen |

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Er werd aandacht besteed aan het patiëntenperspectief door het uitnodigen van de patiëntenvereniging HOOFD-HALS (PVHH) voor de Invitational conference en met afgevaardigden van de PVHH in de werkgroep. Het verslag hiervan is besproken in de werkgroep. De verkregen input is meegenomen bij het opstellen van de uitgangsvragen, de keuze voor de uitkomstmaten en bij het opstellen van de overwegingen. De conceptrichtlijn is tevens voor commentaar voorgelegd aan de patiëntenvereniging HOOFD-HALS en de eventueel aangeleverde commentaren zijn bekeken en verwerkt.

Methode ontwikkeling

Evidence based

Werkwijze

AGREE

Deze richtlijnmodule is opgesteld conform de eisen vermeld in het rapport Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 van de adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwaliteit. Dit rapport is gebaseerd op het AGREE II instrument (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II; Brouwers, 2010).

Knelpuntenanalyse en uitgangsvragen

Tijdens de voorbereidende fase inventariseerden de werkgroep de knelpunten in de zorg voor patiënten met hoofd-halstumoren. De werkgroep beoordeelde de aanbeveling(en) uit de eerdere richtlijnmodule (NVKNO, 2014) op noodzaak tot revisie. Tevens zijn er knelpunten aangedragen door de patiëntenvereniging en genodigde partijen tijdens de Invitational conference (zie bijlagen). Op basis van de uitkomsten van de knelpuntenanalyse zijn door de werkgroep concept-uitgangsvragen opgesteld en definitief vastgesteld.

Uitkomstmaten

Na het opstellen van de zoekvraag behorende bij de uitgangsvraag inventariseerde de werkgroep welke uitkomstmaten voor de patiënt relevant zijn, waarbij zowel naar gewenste als ongewenste effecten werd gekeken. Hierbij werd een maximum van acht uitkomstmaten gehanteerd. De werkgroep waardeerde deze uitkomstmaten volgens hun relatieve belang bij de besluitvorming rondom aanbevelingen, als cruciaal (kritiek voor de besluitvorming), belangrijk (maar niet cruciaal) en onbelangrijk. Tevens definieerde de werkgroep tenminste voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten welke verschillen zij klinisch (patiënt) relevant vonden.

Methode literatuursamenvatting

Een uitgebreide beschrijving van de strategie voor zoeken en selecteren van literatuur en de beoordeling van de risk-of-bias van de individuele studies is te vinden onder ‘Zoeken en selecteren’ onder Onderbouwing. De beoordeling van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs wordt hieronder toegelicht.

Beoordelen van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs

De kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs werd bepaald volgens de GRADE-methode. GRADE staat voor ‘Grading Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation’ (zie http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/). De basisprincipes van de GRADE-methodiek zijn: het benoemen en prioriteren van de klinisch (patiënt) relevante uitkomstmaten, een systematische review per uitkomstmaat, en een beoordeling van de bewijskracht per uitkomstmaat op basis van de acht GRADE-domeinen (domeinen voor downgraden: risk of bias, inconsistentie, indirectheid, imprecisie, en publicatiebias; domeinen voor upgraden: dosis-effect relatie, groot effect, en residuele plausibele confounding).

GRADE onderscheidt vier gradaties voor de kwaliteit van het wetenschappelijk bewijs: hoog, redelijk, laag en zeer laag. Deze gradaties verwijzen naar de mate van zekerheid die er bestaat over de literatuurconclusie, in het bijzonder de mate van zekerheid dat de literatuurconclusie de aanbeveling adequaat ondersteunt (Schünemann, 2013; Hultcrantz, 2017).

|

GRADE |

Definitie |

|

Hoog |

|

|

Redelijk |

|

|

Laag |

|

|

Zeer laag |

|

Bij het beoordelen (graderen) van de kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs in richtlijnen volgens de GRADE-methodiek spelen grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming een belangrijke rol (Hultcrantz, 2017). Dit zijn de grenzen die bij overschrijding aanleiding zouden geven tot een aanpassing van de aanbeveling. Om de grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming te bepalen moeten alle relevante uitkomstmaten en overwegingen worden meegewogen. De grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming zijn daarmee niet één op één vergelijkbaar met het minimaal klinisch relevant verschil (Minimal Clinically Important Difference, MCID). Met name in situaties waarin een interventie geen belangrijke nadelen heeft en de kosten relatief laag zijn, kan de grens voor klinische besluitvorming met betrekking tot de effectiviteit van de interventie bij een lagere waarde (dichter bij het nuleffect) liggen dan de MCID (Hultcrantz, 2017).

Overwegingen (van bewijs naar aanbeveling)

Om te komen tot een aanbeveling zijn naast (de kwaliteit van) het wetenschappelijke bewijs ook andere aspecten belangrijk en worden meegewogen, zoals aanvullende argumenten uit bijvoorbeeld de biomechanica of fysiologie, waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten, kosten (middelenbeslag), aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie. Deze aspecten zijn systematisch vermeld en beoordeeld (gewogen) onder het kopje ‘Overwegingen’ en kunnen (mede) gebaseerd zijn op expert opinion. Hierbij is gebruik gemaakt van een gestructureerd format gebaseerd op het evidence-to-decision framework van de internationale GRADE Working Group (Alonso-Coello, 2016a; Alonso-Coello, 2016b). Dit evidence-to-decision framework is een integraal onderdeel van de GRADE-methodiek.

Formuleren van aanbevelingen

De aanbevelingen geven antwoord op de uitgangsvraag en zijn gebaseerd op het beschikbare wetenschappelijke bewijs en de belangrijkste overwegingen, en een weging van de gunstige en ongunstige effecten van de relevante interventies. De kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs en het gewicht dat door de werkgroep wordt toegekend aan de overwegingen, bepalen samen de sterkte van de aanbeveling. Conform de GRADE-methodiek sluit een lage bewijskracht van conclusies in de systematische literatuuranalyse een sterke aanbeveling niet a priori uit, en zijn bij een hoge bewijskracht ook zwakke aanbevelingen mogelijk (Agoritsas, 2017; Neumann, 2016). De sterkte van de aanbeveling wordt altijd bepaald door weging van alle relevante argumenten tezamen. De werkgroep heeft bij elke aanbeveling opgenomen hoe zij tot de richting en sterkte van de aanbeveling zijn gekomen.

In de GRADE-methodiek wordt onderscheid gemaakt tussen sterke en zwakke (of conditionele) aanbevelingen. De sterkte van een aanbeveling verwijst naar de mate van zekerheid dat de voordelen van de interventie opwegen tegen de nadelen (of vice versa), gezien over het hele spectrum van patiënten waarvoor de aanbeveling is bedoeld. De sterkte van een aanbeveling heeft duidelijke implicaties voor patiënten, behandelaars en beleidsmakers (zie onderstaande tabel). Een aanbeveling is geen dictaat, zelfs een sterke aanbeveling gebaseerd op bewijs van hoge kwaliteit (GRADE-gradering HOOG) zal niet altijd van toepassing zijn, onder alle mogelijke omstandigheden en voor elke individuele patiënt.

|

Implicaties van sterke en zwakke aanbevelingen voor verschillende richtlijngebruikers |

||

|

|

Sterke aanbeveling |

Zwakke (conditionele) aanbeveling |

|

Voor patiënten |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen en slechts een klein aantal niet. |

Een aanzienlijk deel van de patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen, maar veel patiënten ook niet. |

|

Voor behandelaars |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak moeten ontvangen. |

Er zijn meerdere geschikte interventies of aanpakken. De patiënt moet worden ondersteund bij de keuze voor de interventie of aanpak die het beste aansluit bij zijn of haar waarden en voorkeuren. |

|

Voor beleidsmakers |

De aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kan worden gezien als standaardbeleid. |

Beleidsbepaling vereist uitvoerige discussie met betrokkenheid van veel stakeholders. Er is een grotere kans op lokale beleidsverschillen. |

Organisatie van zorg

In de knelpuntenanalyse en bij de ontwikkeling van de richtlijnmodule is expliciet aandacht geweest voor de organisatie van zorg: alle aspecten die randvoorwaardelijk zijn voor het verlenen van zorg (zoals coördinatie, communicatie, (financiële) middelen, mankracht en infrastructuur). Randvoorwaarden die relevant zijn voor het beantwoorden van deze specifieke uitgangsvraag zijn genoemd bij de overwegingen. Meer algemene, overkoepelende, of bijkomende aspecten van de organisatie van zorg worden behandeld in de module Organisatie van zorg.

Commentaar- en autorisatiefase

De conceptrichtlijnmodule werd aan de betrokken (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd ter commentaar. De commentaren werden verzameld en besproken met de werkgroep. Naar aanleiding van de commentaren werd de conceptrichtlijnmodule aangepast en definitief vastgesteld door de werkgroep. De definitieve richtlijnmodule werd aan de deelnemende (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd voor autorisatie en door hen geautoriseerd dan wel geaccordeerd.

Literatuur

Agoritsas T, Merglen A, Heen AF, Kristiansen A, Neumann I, Brito JP, Brignardello-Petersen R, Alexander PE, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Guyatt GH. UpToDate adherence to GRADE criteria for strong recommendations: an analytical survey. BMJ Open. 2017 Nov 16;7(11):e018593. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018593. PubMed PMID: 29150475; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5701989.

Alonso-Coello P, Schünemann HJ, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Rada G, Rosenbaum S, Morelli A, Guyatt GH, Oxman AD; GRADE Working Group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 1: Introduction. BMJ. 2016 Jun 28;353:i2016. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2016. PubMed PMID: 27353417.

Alonso-Coello P, Oxman AD, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Vandvik PO, Meerpohl J, Guyatt GH, Schünemann HJ; GRADE Working Group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 2: Clinical practice guidelines. BMJ. 2016 Jun 30;353:i2089. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2089. PubMed PMID: 27365494.

Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, Burgers JS, Cluzeau F, Feder G, Fervers B, Graham ID, Grimshaw J, Hanna SE, Littlejohns P, Makarski J, Zitzelsberger L; AGREE Next Steps Consortium. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. CMAJ. 2010 Dec 14;182(18):E839-42. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090449. Epub 2010 Jul 5. Review. PubMed PMID: 20603348; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3001530.

Hultcrantz M, Rind D, Akl EA, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Iorio A, Alper BS, Meerpohl JJ, Murad MH, Ansari MT, Katikireddi SV, Östlund P, Tranæus S, Christensen R, Gartlehner G, Brozek J, Izcovich A, Schünemann H, Guyatt G. The GRADE Working Group clarifies the construct of certainty of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017 Jul;87:4-13. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.05.006. Epub 2017 May 18. PubMed PMID: 28529184; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC6542664.

Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 (2012). Adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwalitieit. https://richtlijnendatabase.nl/over_deze_site/richtlijnontwikkeling.html.

Neumann I, Santesso N, Akl EA, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Alonso-Coello P, Agoritsas T, Mustafa RA, Alexander PE, Schünemann H, Guyatt GH. A guide for health professionals to interpret and use recommendations in guidelines developed with the GRADE approach. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016 Apr;72:45-55. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.11.017. Epub 2016 Jan 6. Review. PubMed PMID: 26772609.

Schünemann H, Brożek J, Guyatt G, et al. GRADE handbook for grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. Updated October 2013. The GRADE Working Group, 2013. Available from http://gdt.guidelinedevelopment.org/central_prod/_design/client/handbook/handbook.html.

Schünemann HJ, Oxman AD, Brozek J, Glasziou P, Jaeschke R, Vist GE, Williams JW Jr, Kunz R, Craig J, Montori VM, Bossuyt P, Guyatt GH; GRADE Working Group. Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations for diagnostic tests and strategies. BMJ. 2008 May 17;336(7653):1106-10. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39500.677199.AE. Erratum in: BMJ. 2008 May 24;336(7654). doi: 10.1136/bmj.a139.

Schünemann, A Holger J (corrected to Schünemann, Holger J). PubMed PMID: 18483053; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC2386626.

Wessels M, Hielkema L, van der Weijden T. How to identify existing literature on patients' knowledge, views, and values: the development of a validated search filter. J Med Libr Assoc. 2016 Oct;104(4):320-324. PubMed PMID: 27822157; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5079497.

Zoekverantwoording

Algemene informatie

|

Richtlijn:Hoofd- halstumoren |

|

|

Uitgangsvraag: UV17.2 inductie chemotherapie |

|

|

Database(s): OVID/Medline, Embase |

Datum: 17-6-2020 |

|

Periode: 2010-2020, 2019-2020 |

Talen: niet van toepassing |

|

Literatuurspecialist: Ingeborg van Dusseldorp |

|

Zoekopbrengst

|

|

EMBASE |

OVID/MEDLINE |

Ontdubbeld |

|

SRs |

34 |

23 |

37 |

|

RCTs |

135 |

88 |

152 |

|

Totaal |

|

|

189 |

OVID/Medline

1 exp Nasopharyngeal Neoplasms/ or ((epipharyn* or nasopharyn* or nasofaryn* or rhinopharyn* or rhinofaryn*) adj4 (cancer* or neoplasm* or tumor* or tumour* or malignan* or carcinom*)).ti,ab,kf. (21563)

2 exp Induction Chemotherapy/ or induction chemotherap*.ti,ab,kf. (9689)

3 1 and 2 (398)

4 limit 3 to yr="2010 -Current" (297)

5 (meta-analysis/ or meta-analysis as topic/ or (meta adj analy$).tw. or (systematic*or literature adj2 review$1).tw. or (systematic adj overview$1).tw. or exp "Review Literature as Topic"/ or cochrane.ab. or cochrane.jw. or embase.ab. or medline.ab. or (psychlit or psyclit).ab. or (cinahl or cinhal).ab. or cancerlit.ab. or ((selection criteria or data extraction).ab. and "review"/)) not (Comment/ or Editorial/ or Letter/ or (animals/ not humans/)) (292565)

6 (exp clinical trial/ or randomized controlled trial/ or exp clinical trials as topic/ or randomized controlled trials as topic/ or Random Allocation/ or Double-Blind Method/ or Single-Blind Method/ or (clinical trial, phase i or clinical trial, phase ii or clinical trial, phase iii or clinical trial, phase iv or controlled clinical trial or randomized controlled trial or multicenter study or clinical trial).pt. or random*.ti,ab. or (clinic* adj trial*).tw. or ((singl* or doubl* or treb* or tripl*) adj (blind$3 or mask$3)).tw. or Placebos/ or placebo*.tw.) not (animals/ not humans/) (1994323)

7 4 and 5 (23) SR

8 4 and 6 (109)

9 8 not 7 (88) RCT

Embase

|

No. |

Query |

Results |

|

#16 |

#10 NOT #9 NOT #8 |

211 |

|

#15 |

#9 NOT #8 RCT |

135 |

|

#14 |

#7 AND #12 Artikel Chen wel gevonden zonder studiedesign filters |

1 |

|

#13 |

#11 AND #12 Artikel Chen niet gevonden met studiedesign filters |

0 |

|

#12 |

nasopharyngeal AND carcinoma AND chen AND 2019 AND lancet |

4 |

|

#11 |

#8 OR #9 OR #10 |

380 |

|

#10 |

#3 AND #7 |

325 |

|

#9 |

#2 AND #7 |

159 |

|

#8 |

#1 AND #7 SR |

34 |

|

#7 |

#6 AND (2010-2020)/py NOT ('conference abstract'/it OR 'editorial'/it OR 'letter'/it OR 'note'/it) NOT (('animal experiment'/exp OR 'animal model'/exp OR 'nonhuman'/exp) NOT 'human'/exp) |

481 |

|

#6 |

#4 AND #5 |

828 |

|

#5 |

'induction chemotherapy'/exp OR 'induction chemotherap*':ti,ab,kw |

19850 |

|

#4 |

'nasopharynx carcinoma'/exp OR 'nasopharynx tumor'/exp OR (((epipharyn* OR nasopharyn* OR nasofaryn* OR rhinopharyn* OR rhinofaryn*) NEAR/4 (cancer* OR neoplasm* OR tumor* OR tumour* OR malignan* OR carcinom*)):ti,ab,kw) |

30696 |

|

#3 |

'major clinical study'/de OR 'clinical study'/de OR 'case control study'/de OR 'family study'/de OR 'longitudinal study'/de OR 'retrospective study'/de OR 'prospective study'/de OR 'comparative study'/de OR 'cohort analysis'/de OR ((cohort NEAR/1 (study OR studies)):ab,ti) OR (('case control' NEAR/1 (study OR studies)):ab,ti) OR (('follow up' NEAR/1 (study OR studies)):ab,ti) OR (observational NEAR/1 (study OR studies)) OR ((epidemiologic NEAR/1 (study OR studies)):ab,ti) OR (('cross sectional' NEAR/1 (study OR studies)):ab,ti) |

5976979 |

|

#2 |

('clinical trial'/exp OR 'randomization'/exp OR 'single blind procedure'/exp OR 'double blind procedure'/exp OR 'crossover procedure'/exp OR 'placebo'/exp OR 'prospective study'/exp OR rct:ab,ti OR random*:ab,ti OR 'single blind':ab,ti OR 'randomised controlled trial':ab,ti OR 'randomized controlled trial'/exp OR placebo*:ab,ti) NOT 'conference abstract':it |

2400633 |

|

#1 |

('meta analysis'/de OR 'meta analysis (topic)'/exp OR cochrane:ab OR embase:ab OR psycinfo:ab OR cinahl:ab OR medline:ab OR ((systematic NEAR/1 (review OR overview)):ab,ti) OR ((meta NEAR/1 analy*):ab,ti) OR metaanalys*:ab,ti OR 'data extraction':ab OR cochrane:jt OR 'systematic review'/de) NOT (('animal experiment'/exp OR 'animal model'/exp OR 'nonhuman'/exp) NOT 'human'/exp) |

523227 |